* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Joy Meredith

Date of first publication: 1928

Author: Dora Olive Thompson (1893-1934)

Illustrator: E. P. (Edmund Patrick) Kinsella

Date first posted: 9th December, 2024

Date last updated: 9th December, 2024

Faded Page eBook #20241205

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, Pat McCoy & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

MEMORIES

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

LIZZIE ANNE

A DEALER IN SUNSHINE

ADELE IN SEARCH OF A HOME

OF ALL BOOKSELLERS

JOY MEREDITH

by

Dora Olive Thompson

Author of “A Dealer in Sunshine,”

“Adele in Search of a Home,”

“Lizzie Anne,” etc.

☆

Illustrated

by

E. P. KINSELLA

LONDON

THE RELIGIOUS TRACT SOCIETY

MANCHESTER, TORONTO, MADRID, LISBON

AND BUDAPEST

Made In Great Britain

Printed by Richard Clay & Sons, Ltd.

Bungay, Suffolk

CONTENTS

| I. | THE MAGIFFINS AT HOME | 7 |

| II. | OVER THE WIDE-FLOWING WATERS | 16 |

| III. | FIRST IMPRESSIONS | 27 |

| IV. | “AND THAT’S HOW IT ALL BEGAN!” | 37 |

| V. | “AND OF A GOOD COURAGE” | 49 |

| VI. | NO. 43 | 58 |

| VII. | THE OLD HOUSE | 68 |

| VIII. | A PICTURE AND A PUPPY | 81 |

| IX. | THE PRODIGAL’S RETURN | 95 |

| X. | “CHEERIO!” | 106 |

| XI. | “MAKE ROOM FOR JOY!” | 116 |

| XII. | CARVED IN EBONY | 127 |

| XIII. | DOCTOR’S ORDERS | 138 |

| XIV. | SAINT GEORGE AND THE DRAGON | 144 |

| XV. | PERFORMERS—FOUR-FOOTED AND OTHERWISE | 153 |

| XVI. | DAY-DREAMS AND GOLLIWOGS | 166 |

| XVII. | SIR GHOST | 176 |

| XVIII. | “WHEN DUTY WHISPERS” | 184 |

| XIX. | “LENDING OUR LIVES OUT” | 195 |

| XX. | ON DUTY | 206 |

| XXI. | “OUR DEAR LITTLE HERO!” | 212 |

| XXII. | DEALING WITH FUTURES | 221 |

| XXIII. | “OUR LITTLE BLACK JOY!” | 232 |

| XXIV. | NEW BEGINNINGS | 242 |

| XXV. | ACHIEVEMENT | 250 |

JOY MEREDITH

The little Magiffins were all a-quiver with excitement. It was so astonishing as to be almost incredible. They faced their mother across the supper-table and—as Billy Magiffin put it—“listened hard with both ears!”

“But, ma,” it was Alice-Marie, her china-blue eyes wide and eager, “tell her not to come. Tell her we don’t want her!”

“Tell her,” this from Benjamin, “we don’t want any more girls”—he glanced somewhat contemptuously at his sisters—“tell her we’ve enough of them now. If she’d been a boy it’d have been different.”

“I can’t.” Mrs. Magiffin’s high-pitched voice was sharp. “She’s coming, I told you. She’s on the ocean now.”

Billy Magiffin, a round-faced boy of nine or thereabouts, breathed hard and stuck his hands deep into his pockets. “Thrillinger and thrillinger!” he assured himself.

But Mother Magiffin was quite evidently experiencing no pleasurable thrill over the prospect. She glared accusingly across the table at her husband. “I don’t see why the child should be foisted on to us, just because you happen to be her mother’s cousin.”

There was a worried frown between Peter Magiffin’s eyes as he looked across at his wife. He was a tall, big-framed man with the stoop of his thin shoulders and the deep furrow on his forehead indicating that the struggle for daily bread had been hard and weary work. Peter Magiffin was a man of few words, but his wife unhesitatingly supplied the shortage. He spoke slowly now.

“It’s a matter of duty, Jennie,” he said; “we are the little girl’s nearest of kin.”

“Nearest of kin! Nearest! And you only her mother’s cousin! Why didn’t her father provide for her I’d like to know? And his folks, why don’t they do something instead of putting her off on us where she don’t belong?”

Her husband shook his head. “I know very little about any of them. I lost touch with the old land soon after I left, forgot the folks I left behind me—a boy does that unthinkingly. I’ve been sorry ever since. I never knew the man cousin Lucy married, though he wrote me after she died. I think he was a writer, a bit of a poet——”

“A bit of a ne’er-do-well, I guess.”

Peter Magiffin straightened his thin shoulders as if answering some inward challenge. “The little girl is coming to us,” he said; “we must make her welcome.”

“Then you can do the welcoming,” his wife assured him sharply. “I’m not going to pretend to be glad to see her when I’m not.”

“But, ma,” the boy Billy leaned forward, his black eyes anxious, “you won’t tell her you’re sorry she came?”

“Chances are she’ll find out for herself. I can’t act on the outside like I don’t feel inside.” Mrs. Magiffin, who prided herself on outspoken frankness, gave her head a virtuous nod. “It’s all very well for your pa to talk about welcoming her. A man always gets off scot free when there’s extra work to be done. I’m at my wits’ end to know where to sleep her with the house crammed full as it is. The only corner left is that place in the attic. And then to talk about welcoming her as if I had the patience of Job! Job!” Mrs. Magiffin sniffed indignantly; “he may have had boils, but I’ll be bound he never raised a family of five like I’ve done, and then at the end of it all had somebody else’s girl foisted on him!”

“I fancy,” her husband interposed, with a little glint of amusement in the depths of his eyes, “that Job’s family may have numbered considerably more than five. Weren’t there ten of them, seven sons and three daughters?”

Mrs. Magiffin dismissed Job and his family with a wave of her hand and, still bristling with indignation, moved toward the kitchen. “You can welcome your relations to our house,” she flung back over her shoulder; “but I shan’t!”

A few minutes later that indignation was evident as Mrs. Magiffin vigorously washed up. Above the clatter of dishes rose Alice-Marie’s voice, clamorously insistent, “An’ oh, ma, what’s her name? When’ll she come? And’ll she go to school with us? And where’ll she sleep? She can’t have my bed——”

“Nor mine!” this from six-year-old Henrietta.

“But she c’n have my old red dress”—the voice of Alice-Marie was consciously kind and self-satisfied—“ ’cause then I can have a new one.”

But at that moment the baby created a diversion by upsetting a tin of water, and for a few minutes the little unknown traveller on the far-away ocean was forgotten in the imminence of an incipient Niagara close at hand.

Perhaps, after all, there was some excuse to be offered for Mrs. Magiffin’s indignation in this particular case. For it was cramped, that house where the Magiffin family lived at No. 5 Victory Avenue, cramped and inadequate within, smoke-grimed and ugly without.

Victory Avenue was victorious only in name. It was a drab uninteresting street that led from one main thoroughfare to another. The houses, for the most part, were semi-detached, red brick, with a porch at the front door and a window at the side, curving outward in a bow. No. 5 did not deviate from the general rule. No. 5 had its porch, its bow window. But No. 5 possessed something which the others did not—the vigorous, lively young Magiffins. And under the ever-increasing demand No. 5 Victory Avenue was proving sadly inadequate.

The Magiffins rejoiced one and all in high-sounding names bestowed on them by their aggressive, ambitious mother. The two boys, Benjamin—“From the Bible itself!” their never-failing exhibitor was wont to explain; William, or, as his mother put it, “Will-i-am”; and the three little girls, Alice-Marie, Henrietta, and, crowning achievement, Queenie Victoria, the baby.

But the best-laid schemes of mice and mothers “gang aft agley,” and the young Magiffins—as they were known collectively in the neighbourhood—were reduced to simple terms. Henrietta was shortened by urgent brothers and sisters to Hen; Alice-Marie to Al; Benjamin to Ben; William, by all except Mother Magiffin herself, to Billy.

He was a funny-looking little boy, was Billy Magiffin. Black, twinkling, button-like eyes, bright red cheeks, black hair that kinked into tight little curls all over his head; chubby and round as to general outline—that was Billy.

And it was Billy who was really tremendously elated over the prospect of the unknown cousin who was coming to make her home with them. After that evening when his mother had told them of the expected guest he gathered together all the crumbs of information possible to obtain. No one, not even his father, had mentioned her name. “Perhaps,” Billy decided, “perhaps it’ll be Sarah, or”—more hopefully—“Pansy!” There was a girl in school by that name and secretly Billy rather liked it. But his father had proved quite satisfactory about her age after he had done some mental calculating. “I should think between fourteen and fifteen,” he had said. And Billy was more than content. Not a little girl that he would have to “keep an eye on,” as he did with Hen; or yet a littler one still to be wheeled up and down, up and down, after school like Queenie. But a big little girl of fourteen or so, in Billy’s eyes almost grown-up, who would tell him things about that ocean she had crossed, the ocean that in geography lessons had exercised such a curious fascination over Billy.

He even drew a picture on a piece of blotting-paper of a ship with the waves dashing over the side. But that had a natural and disastrous result. Alice-Marie found it, waved it aloft for the others to see. “Look!” she cried, in that teasing little way of hers; “look at Billy’s queer horse with the funny tail!”

And Billy, disdaining to explain that those wavy lines were not the tail of a horse but waves of the ocean, stuck his hands in his pockets and stalked out of the room.

He climbed up one morning to investigate that “place in the attic,” referred to by his mother as the only corner for the expected guest. The attic was “unfinished.” Most of it was used as a store-room for trunks, boxes, discarded clothes, hats, beheaded dolls, broken toys, a mouse-trap, a bird-cage—all of which Mother Magiffin often promised herself she would clear up some day.

But “that place” she had referred to, Billy discovered to be at the back of the store-room, a queer-shaped little place with a ceiling high at one side and sloping to the floor at the other. There was a window under the sloping roof, and a pipe that evidently ran up from the kitchen, for it was warm to his touch.

He descended to the kitchen to question his mother. “Are y’ goin’ to put a bed ’n things in there?” he asked.

Mother Magiffin wrung the dish-mop and shook it vigorously so that Billy was showered with warm water. “Am I goin’ to put a bed in?” she repeated. “Don’t be so silly! Do you suppose I’d let anyone sleep on the floor in my house?”

All Billy’s suppressed delight over their forthcoming guest culminated the night before her arrival. He lay awake in bed, sleepless with excitement. Ben was asleep beside him, but then Ben wasn’t excited, not a bit of it. He had looked surprised when Billy had said, trying to make his voice sound natural, “She’s comin’ to-morrer, I guess.”

And Ben had stared at him and answered, “Well, let ’er, I don’t care!”

Billy, as he stared up into the darkness, was repeating it over and over, almost unbelieving. A girl from across the ocean was coming to live with them! From across the ocean! And she would tell him about it—that wonderful ocean with its waves, its tides, its delightfully mysterious “coral reefs”; its whales and sharks and porpoises; its shells, its stores of hidden treasure.

“Hurray!” he shouted suddenly.

Which roused Ben to immediate protest. “Shut up!” he growled. “What d’you think you’re doin’ anyway!”

Billy subsided. But his round, black, button-like eyes were still a-twinkle with excitement.

Joy Meredith stood on the second-cabin deck of the big steamer and gazed out over the waste of grey waters. It was all grey that afternoon—a dull, lowering, ominous grey, with no welcome glint of sun on the waves. “It looks like I feel,” Joy Meredith thought, and shivered a little as she pulled her coat closer about her.

Perhaps it was but natural that her thoughts should centre themselves about the events of the last few months—events which had made such drastic changes in her own young life.

The death of her father had come unexpectedly, had cut with tragic suddenness into their happy comradeship. Perhaps if there had been more warning John Meredith might have made provision for the future of his little girl, but his thoughts had always turned, with that irrepressible buoyancy that was so characteristic, to the things of the imagination—to the hero of his next story, perhaps, one of those stories that paid the rent and provided the necessities of life. So he had given little thought to the practical side of things and had laid nothing aside for the future which on his death loomed so darkly before his young daughter, Joy.

For a little while the young girl had felt that it was impossible to face that future, impossible to go on, alone. But life, she found, did go on, unfolding itself into an ever-revolving cycle of moments, hours, days.

It was with the idea of getting things settled that Uncle Sidney and Aunt Harriet Hallman had come up from the country. They were, it seemed, intending to take rooms in London for the autumn and winter months, so, instead of further search, installed themselves in the Meredith flat.

“Which I am sure no one would say was anything but generous on our parts,” Aunt Harriet had pointed out to one of the neighbours, “for this place isn’t really what we want at all.”

But the neighbour, knowing that the poor dear gentleman who had died so suddenly, and who was reported to have left next to nothing for his daughter, had, at least, paid his rent in advance, held her own opinion of Aunt Harriet’s generosity.

The Hallmans were distant relations. “Very distant, hardly relations at all,” Aunt Harriet made haste to point out, “and we don’t feel called on to shoulder any responsibility for Joy.” She made that clear, very clear, to all inquirers.

And so for a little while matters had drifted. “What we’re going to do with the girl,” Aunt Harriet was fond of declaring, “goodness only knows.”

Then, quite suddenly, she remembered that a cousin of Joy’s mother, Peter Magiffin by name, had gone out to Canada years before. “So he’s sure to be rolling in wealth by now,” she declared, “and it’s up to him to look after Lucy’s daughter.”

Inquiries had been made and Peter Magiffin finally located. He answered their letter by another of somewhat unpromising tone. “If it’s our duty to take Lucy’s little girl, we must, I suppose. But we have a family of our own to provide for and it is hard to make ends meet as it is.”

“That’s just his way of putting it,” Aunt Harriet declared; “everybody’s rich out there.”

It was Aunt Harriet, of course, who engineered it all. Aunt Harriet loved engineering things. She made minute inquiries and then wrote Peter Magiffin as to the exact steps he must take with Immigration officials on his side of the ocean. She booked Joy’s passage on a boat on which Mrs. Crocket, a friend of hers, was sailing, and then asked Mrs. Crocket to keep an eye on the girl, to which request that good woman somewhat reluctantly consented. Finally, Aunt Harriet wrote Peter Magiffin telling him that Lucy’s daughter would arrive soon after the letter.

And then one evening she broke the news to Joy, putting it quite clearly and concisely.

“It’s settled,” she said; “you’re going to a new home across the ocean, in Canada. You have relations there who want you”—inherent honesty in Aunt Harriet’s nature made her pause—“at least they’re expecting you. And Mrs. Crocket is going to take care of you going over.”

Joy Meredith stood up and stepped back to the wall behind her, a wall which afforded comforting support at the moment, and faced her aunt defiantly.

“Leave England?” she said. “Leave England? I won’t!”

There was something triumphant in the glance which Aunt Harriet threw across at her husband. Hadn’t she told him just the night before that there was a strain of contrariness in the girl? And hadn’t he denied it?

“Not leave England?” she repeated aloud. “You most certainly are going to leave England. It’s settled. That’s what I’m telling you.”

“I won’t go!” the girl said. Then, suddenly, her voice and defiance broke. “Everything I love—is—here.”

Aunt Harriet and Uncle Sidney stared at each other, obviously perplexed.

“You’re not thinking what you’re saying,” Aunt Harriet told her, not unkindly; “except the graves of your father and mother you’ve nothing particular left here so far’s I can see.”

But the girl pressed the palms of her hands tightly over her eyes and answered never a word.

Through the long sleepless night that followed Joy Meredith faced the significance of her own words “Everything I love is here.” How could they understand—how could she expect them to understand—that the memories held by that little flat were all she had left? Memories of her father, of their life together, companionable and happy. Memories he had given her of the mother she could not remember. Memories of his keen interest in her studies, of his eager, vigorous joy in his own work. Memories of their explorations together through the gateway of books into the land of romance. Memories too of those more tangible explorations into their much-loved Museum, or among the storied tombs of Westminster Abbey. And memories of an occasional quiet hour in St. Paul’s when the voices of the choir-boys echoed sweet and high.

In the business-like mind of Aunt Harriet it had, by that time, been definitely and irretrievably settled. She made all necessary arrangements, packed Joy’s meagre little store of personal belongings, and with obvious relief hustled her off to the boat. “You just do what Mrs. Crocket tells you, and you’ll be all right,” she said.

Mrs. Crocket, of uncertain age and ample proportions, eyed the young girl with open hostility.

“I never did like looking after other folks’ children,” she said.

“Oh, don’t worry,” Aunt Harriet told her, suddenly light-hearted under the sense of shifting responsibility; “she’s not exactly anybody’s child now, you know.”

Mrs. Crocket proved quite content that the girl she was looking after should walk up and down the deck while she herself sat with kindred spirits in the cabin, lingering over choice titbits of the ship’s gossip. “It beats me why that girl doesn’t get her death of cold out there,” she remarked sometimes, but made no effort to prevent such a catastrophe.

But to Joy Meredith the cabin was hot and stuffy and the never-ceasing talk of the women unutterably dreary. Outside the air, salt-smelling and vigorous, slapped her cheeks, stinging them to lively response. And occasionally—oh, it was worth while being on deck to catch those moments—occasionally the November sun would shine down from a sky gloriously clear, and would spread a wide golden gleam across the face of the waters.

But there was no glint of gold in the world which presented itself on this particular afternoon, a sombre world it was, which found a dull echo in her heart. She was trying at that moment to find some shred of comfort in the thought of the future which stretched before her with all the terror of the unknown. Perhaps the shores of this strange new country held a welcome; perhaps there would be home-life again, companionship and sympathy, for evidently these relatives had been willing to have her come. “So they must be kind,” Joy thought.

But a little of the sanguine expectation faded as she called to mind Aunt Harriet’s answer when she had questioned her. “There’s quite a family of them, I believe, the best thing in the world for you, Joy, after being an only child and having everything your own way.”

The little gleam of comfort vanished, and it was at that moment that a voice, clear and gay, came suddenly out of the shadows behind her. “My dear little girl, I should think you’d be half frozen standing there so long.”

Joy turned. The owner of that voice was standing on the other side of the division that separated the first from the second cabin deck, and was smiling at the girl’s very evident astonishment. “Did I frighten you? I’ve been walking up and down ever so long while you’ve been standing there. I just couldn’t help speaking.”

“I’m not cold,” Joy told her; “at least, I hadn’t noticed it. It was kind of you to ask.”

The lady was looking reflectively at the young face confronting her, and thinking, though she did not voice the thought, that those brown eyes were made for laughter, not for the unhappiness they held.

“I’ve seen you almost every day since we sailed,” she said aloud; “are you alone?”

Joy shook her head. “I’m supposed to be with Mrs. Crocket, but I’m alone most of the time.” Then suddenly—perhaps the sympathetic interest on the lady’s face broke down the little barrier of reserve—“My father died,” she added, “and I’m on my way to relatives in Canada.”

“Oh!” the lady said, sensing the loneliness and heartbreak behind the words. “So you’re coming out to our Canada? Yes,” she nodded, answering Joy’s unspoken question, “I’m a Canadian. We’ve just been over for a little visit to the old land, my two kiddies and I.”

Joy’s face lighted up. “Are those two kiddies yours? The two little things that look like twins, who wear green coats trimmed with grey fur?”

The lady smiled. “They are mine. And they are twins. And they do wear green coats trimmed with grey fur.”

“One of them offered me a sweet through this railing——”

“That would be Donald, he’s such a generous little soul. Dimples goes on the principle of what I have, I hold.”

“Donald and Dimples!” Joy repeated.

The lady nodded. “Donald after my husband, who died when the twins were three. Dimples’ real name is Lois, like mine, but she’s always been such a dimply little thing that the name just stuck.” She laughed suddenly outright—a laugh that in after years Joy was to learn carried always that clear and buoyant ring. “I seem to be sharing my family history with you, and we don’t even know each other’s names. I am Mrs. Langford, Lois Langford.”

“And I’m Joyce Meredith, but Dad always called me Joy.”

“Joy?” Lois Langford repeated. “Joy? Oh, isn’t it a happy little name!”

And so then and there, as they smiled at each other through the division that separated the first from the second cabin deck, was laid the foundation for that friendship which, unknown to either, was to extend far into the years.

Lois Langford glanced down at the little watch on her wrist. “I must be getting back to the kiddies. Perhaps we’ll see each other to-morrow before we land. But if we don’t, I wish you happiness in the new land, though, of course”—she paused thoughtfully—“it will be lonely at first, but even so, whatever happens, you’ll be of good courage, little girl?”

“Oh,” there was a perceptible catch in Joy’s voice, “Dad used to say that. He loved those words.”

Lois Langford nodded. “One does love them. Oh, look, look, Joy, isn’t it beautiful?” She pointed out over the ocean and softly, almost under her breath, though Joy heard the words quite distinctly, she repeated:

“. . . the God of the Glory draws nigh,

Lo, over the waves of the wide-flowing waters,

Jehovah as King is enthroned on high.”

Down near the horizon the clouds had parted, were touched to vivid beauty as the sun sent across the waters a shining path of gold.

It was the day that the unknown cousin was expected, and Billy Magiffin had skipped out of bed in the morning with an eager bounce. “To-day’s to-day, an’ she’s comin’!” he had told his brother, nothing daunted by Ben’s repeated, “Well, let ’er, I don’t care!” He had gone off to school in the morning telling himself that, “P’raps she’ll be here when I come home.” He had run all the way home at twelve o’clock, had burst into the house with an eager question, “Is she here?” to be doomed to disappointment. He had been determinedly good in school all afternoon to avoid the catastrophe of being kept in, and then—almost at letting-out time—hadn’t he been overcome by an irresistible desire to stick a pin into the fat little calf of Jimmy O’Hagan’s leg twined so invitingly round the desk in front. And of course Jimmy had let out a howl, and of course the teacher had detained Billy for extra lessons after school.

“Jes’ my luck,” Billy told himself, struggling with those lessons; “ ’twasn’t my fault neither. It was that silly ole pin, and Jimmy’s silly ole leg. I’d never have thought of doing it myself!”

And then, although he was late getting home, he was again disappointed. He threw his school-bag on the sofa in the dining-room, letting it slip down behind, for long ago he had discovered that out of sight meant out of his mother’s mind, and Billy was determined that no such blighting influence as lessons should mar his pleasure on such a night as this.

“D’you s’pose she’ll be here soon?” he asked his mother.

“Goodness only knows I hope so! The train’s late. Your poor pa’s wasted most of this afternoon at the station, waiting. A whole afternoon off work just to meet a girl nobody wants——”

“But, ma,”—the words rushed out—“I’m glad she’s comin’!”

“Oh, you are, are you? And a lot of good your bein’ glad does. It’s not payin’ for her board and keep so far’s I can see.”

“She c’n have my rice pudding,” Billy volunteered; “I jes’ hate rice pudding.”

And then hearing a step on the porch he ran out hopefully to open the door. But it was only Alice-Marie, and so he slipped on his coat and went into the street, a street almost picturesque to-night with the lights gleaming through the falling snow. Perhaps, Billy decided, trying to watch both ends of the street at once, perhaps she wouldn’t come after all. Perhaps the ocean had drowned her—the ocean did that to folks sometimes. Or perhaps the train on its way up from Montreal had run off the track—his mother had said it was late—he had heard of trains doing that. Or perhaps she had never started from the other side. Something inside Billy gave a queer little flop. It wasn’t very often that folks got drowned in the ocean, nor very often that a train ran off the track. But a person might easily not start at all.

“Oh, shucks!” Billy said, and trailed disconsolately indoors.

It was when they were at supper that she arrived. “Won’t we wait for her?” Alice-Marie had asked.

“We will not!” her mother assured her.

Just because they were talking all together, after their fashion, no one heard them come in, no one saw her until the door of the dining-room opened and their father’s voice said, “Here’s our English cousin.”

And the English cousin stepped into the light.

A little bit of a thing she seemed by the side of tall Peter Magiffin—a little bit of a girl with a bright colour in her cheeks and a velvety softness in the depths of her dark eyes.

Just for a moment no one said a word, then Mrs. Magiffin, never subdued for long, broke the silence. “So you’ve come at last?” and held out a limp hand.

“Are you Mrs. Magiffin?” the girl asked, in an incredibly soft voice.

“You can call me Aunt Jennie. Would you like to go up and wash before supper? Alice-Marie,” she turned sharply, “supposin’, instead of standing there gaping like you’d never seen a girl before, supposin’ you take her up to her room.”

Silently Alice-Marie led the way upstairs, up the first flight, along the hall, up the steep, dark second flight, across the store-room, her heels tapping the uncarpeted floor. She opened the door of the little room at the back, and switched on the electric bulb that hung by a cord from the ceiling. “There!” she said.

“Shall I—shall I come down when I’m ready?”

“You’d better, supper’s almost over.”

Alice-Marie’s footsteps died away down the stairs, and Joy Meredith, glancing about the bare cheerlessness of the room, gave an involuntary little shiver.

They were still grouped about the table when she went down.

“There’s your seat.” Mrs. Magiffin with a nod of her head indicated the empty chair. “Your name’s Joyce, isn’t it?”

The girl nodded. “They named me Joyce so that I could be called Joy.”

“Joy!” the boy Billy repeated, under his breath, “Joy!”

“Joy?” Mrs. Magiffin was repeating it too and glancing with obvious pride at her much-named young hopefuls. “Whatever did they pick out a name like that for? I’d have done better myself, and me with my handful and your ma with only one.”

It was not an auspicious beginning. There was a little giggle from Henrietta, the beginning of another from Alice-Marie which was strangled by a warning glance from her father.

And then there was silence—a strained and heavy silence. The young Magiffins, who had not been impressed with the necessity of any extra display of politeness, stared at the young stranger with frank, unblinking curiosity.

Mrs. Magiffin herself—smarting under a sense that somebody was taking advantage of her—somebody was, at any rate, thrusting a new and unwanted member into her family—was by no means intent upon extending a welcome. Possibly, too, the fact that the young stranger was pretty aroused unconscious maternal resentment. Not for worlds, of course, would Mother Magiffin have admitted that. “I wouldn’t have my girls thin and delicate-looking like she is for anything, with that flush on her cheeks and all,” she told herself, with a would-be satisfied glance at her own buxom group.

Across the table Alice-Marie was eyeing that same flush with reluctant admiration. “It’s not on her cheeks, it’s in ’em,” she decided after lengthy scrutiny. “She’s older’n me, but not such an awful lot too big for that old red dress. I’ll get rid of it on her.”

Under the undisguised curiosity that hung in the very atmosphere, Joy was overcome with almost paralysing shyness. Would these people never say anything, never do anything to make her feel more at ease? she wondered miserably as her fork dropped from her nervous fingers. Would they just keep on staring, staring? Would that plump little girl directly opposite never take her eyes off her? Or that smaller one farther down? And that funny-looking little boy—but here Joy experienced a sudden sense of relief, for the round, black eyes of the “funny-looking little boy,” encountering hers, dropped shyly to his plate.

Did they always, Joy wondered, eat in this queer silence, broken only by an occasional curt reminder from the sharp-featured woman at the head of the table? Or was it because they were intent only on staring at her?

Overcome at last by something approaching panic she pushed her plate from her and stood up. “Do you mind if I—if I go up?” she asked.

“To your room?” There was disapproval in Mrs. Magiffin’s voice. “What would you be goin’ up there for? You haven’t had your supper yet.”

“Oh, but I can’t eat!” the girl said, and turning, almost ran out of the room.

Just for a moment there was silence, and then Mrs. Magiffin raised those expressive eyebrows of hers significantly at her husband. “You see,” she asked, “you see what it means forcing folks into a house where they don’t belong? Turning up her nose a’ready at the food! Highfalutin ideas she’s got that we’re not good enough for her. Well, she can come down off her high horse, and come down quick!”

“But, ma,” Alice-Marie put in, “she has such lovely brown eyes.” Alice-Marie was seeing at the moment in mental vision her own eyes, round and china-blue.

“And pink cheeks!” Benjamin added, unexpectedly.

“I never did like brown eyes,” their mother snapped, “nor pink cheeks neither. And I never could abide folks who turned up their noses at other folks’ food.”

The boy Billy said never a word, but under the protecting cover of the suddenly animated conversation he quietly slipped a large and sticky sugar-coated bun into his pocket.

Upstairs in the tiny room Joy Meredith was face to face with the sharp terror of heart-breaking loneliness. She had not turned on the light, but finding her way to the bed had flung herself on it, pressing her face into the pillow as if to shut from sight all tangible reminders of this new and unfriendly world.

No one had said they were glad to see her. There had been no word of welcome except the greeting of Peter Magiffin at the station: “So this is Lucy’s little girl, this is Joy?” She had liked that, had liked too his firm handshake, his straight eyes, his clear-cut features. But the kindly tone of his voice had not found echo here—in the little girls who had stared and stared; in the sharp-voiced mother who had repeated her name almost derisively: “Joy? Whatever did they pick out a name like that for?”

As if in answer the words of the lady on the boat suddenly flashed into memory: “Joy? Oh, isn’t it a happy little name!”

“Happy?” Joy repeated. “Happy?” But something, perhaps the mere voicing of that little word, had a curiously stimulating effect on the girl. She dabbed her eyes with a damp ball of a handkerchief and standing up switched on the light.

It was not a cosy nor cheerful little room that was thus suddenly illuminated.

Swinging from the long cord the light cast distorted moving shadows over the bare, white-plastered walls and ceiling. There was a small window, a narrow bed, a chest of drawers with a mirror above. Joy’s eyes fell on her own bag with a sudden sense of relief. It, at least, was familiar and reassuring.

There was a sudden sound in the outside hall, a curious little shuffling sound, and then a timid knock on the door. Joy, summoning her flagging courage, flung it open.

A small boy stood there, the funny little boy she had noticed at supper, the boy they had called Billy. He was holding a bun out toward her. “It’s for you,” he said, his words coming in little gasps as if he was nervous or excited. “I—I saved it for you!”

“For me?” Joy repeated, gazing in amazement at the small boy and the bun.

He nodded. “It’s sort of flat, bein’ in my pocket and gettin’ a little sat on. And I took a tiny, oh, a very tiny bite out of the sugar on top,”—he eyed that large and sticky bun regretfully,—“I jes’ couldn’t help it; but you don’t mind, do you?” All Billy’s heart was in his eyes as he looked pleadingly up at the girl. “You don’t mind jes’ ’cause I took a little wee bite out of the sugar part, do you?”

It was not attractive, that squashed and sticky bun. But something else was attractive—that little overture of friendship in an otherwise friendless world.

Joy smiled ever so little. “How nice of you. I wasn’t hungry downstairs, but perhaps I could eat something now.”

Billy nodded. “I know. It’s jes’ awful bein’ hungry, isn’t it?”

And so he left her, standing there in the doorway of the dimly-lighted attic room, staring down at the bun in her hand.

With a sudden penetrating flash of insight Joy was seeing straight through that sticky bun into the sympathetic heart of a little boy named Billy.

It was still quite dark in the little room when Joy awakened early the next morning. At first her memory of the events of the day before was nebulous and uncertain. Then suddenly she remembered all quite distinctly—the train; the bustle at the station; her uncle; the first glimpse of the others grouped round the table; the trying meal when they had stared and stared; the funny little boy and the large sticky bun.

Opposite the bed the window outlined a vague square of light in the dim room. Joy, obeying a sudden impulse, jumped up and looked out. Directly opposite, only a few feet away, was a red brick wall, blank and windowless. But raising the window and thrusting her head out she gave a start of surprise. The sky was gloriously blue this morning, and silhouetted against that blueness, rising out of a cluster of roofs, was the tall, slender steeple of a church, catching the first glint of rosy light from the early sun.

It seemed as if Nature at least was intent on presenting a kindly aspect to Joy Meredith, for that first snowfall of the season had spread a welcome blanket over much that was grimed and unattractive in Victory Avenue. Making her way shyly downstairs she gave an involuntary expression of delight at sight of the snow. “Oh, isn’t it lovely?” she exclaimed.

“You wouldn’t say it was lovely if you had to sweep it off the front steps like your poor little cousin, Alice-Marie, is doing,” Mrs. Magiffin told her.

There was implied if not direct reproach in her tone, and it was just this attitude, Joy was soon to learn, that characterized Mrs. Magiffin’s outlook on life in general—an attitude of grim, humourless animosity. Most certainly she made no effort to conceal the fact that she resented the presence of the young stranger in their midst. Joy was left in no doubt on that score during the first day and those of the week which followed—days which, long afterwards, she looked back upon as some of the loneliest out of the multitude of lonely days which followed her father’s death.

Mrs. Magiffin’s antagonism seemed to centre for the present on the young girl herself, antagonism ready to flare into open hostility on the slightest excuse. Thrifty to the point of stinginess, Aunt Jennie Magiffin obviously grudged what she considered an extra strain on the family purse.

“You’ll have to give me more money to run the house,” she told her husband, “if you’re goin’ to start an orphan asylum.”

Mrs. Magiffin’s generosity ran only to words. Often during those first days Joy would gaze at her wondering if the supply would ever run out, and came to a silent conclusion. “I expect that’s why Uncle Peter is so quiet, he’s never had the chance to do any talking himself.”

But it was Alice-Marie, reflecting her mother’s attitude, who was the cause of stirring that undercurrent of resentment into active hostility. With her old red dress over her arm Alice-Marie climbed up to Joy’s room one afternoon.

“Look!” She held up the dress, obviously much the worse for wear, for Joy to view. “You c’n have this. It’s far too small for you, of course, but you c’n let down the hem and let out the seams like ma does for Hen, she’s so fat. Red won’t look s’ nice on you as it does on me——” Alice-Marie took a step forward and complacently eyed her indeterminate features in the little mirror. “Ma says she wouldn’t have me with a red complexshun like yours for anything. ’Tisn’t ladylike, ma says. But even if red doesn’t look nice on you, ma says that beggars can’t be choosers. I’m goin’ to get a new dress.” She hesitated, and then evidently answered a doubt in her own mind. “Ma’ll have to let me have it when I haven’t got this any more. Here y’are,” as Joy made no movement to take the dress, Alice-Marie held it out towards her, coaxingly it seemed.

Something which had been smouldering in the heart of Joy Meredith for the past week flared into sudden flame. She took the dress, rolled it into a tight ball and held it aloft. “Get out,” she said, and advanced threateningly, while the surprised Alice-Marie backed towards the door. “Get out of my room and stay out. I’m not a beggar. And I am a lady. I wouldn’t have a face like a half-baked apple-dumpling like yours for anything! And I wouldn’t take your dress, not if you begged me on your bended knees!” Joy’s voice rose hysterically. “Get out, I tell you, and”—with sudden, swift, and accurate aim she flung the tightly rolled dress after the retreating Alice-Marie—“take your old dress with you!”

It hit Alice-Marie with a soft thud right in the middle of her dumpling-like face. She grabbed it, turned and fled, almost falling down the stairs in her break-neck efforts to get down and pour the tale into her mother’s receptive ear.

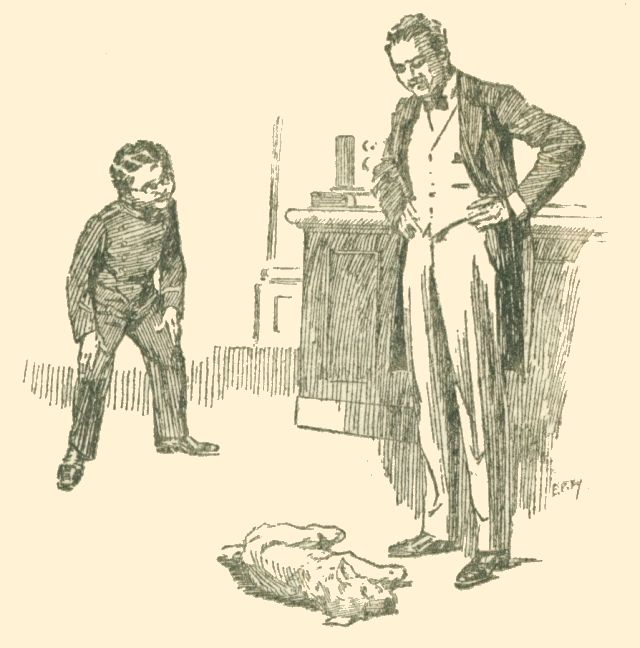

By supper-time the account of it all—somewhat exaggerated and embellished—greeted Peter Magiffin. Mrs. Magiffin drew a deep breath and launched in. “Pushed her out of her room and shoved her downstairs. It’s a wonder every bone in her body wasn’t broke. That’s what your relation did to our daughter. Just because our dear little girl, out of her generous heart, offered her a dress.” At the magnanimous account of her own action a tear of self-pity squeezed itself out of Alice-Marie’s eye and rolled down the side of her nose. “And worse than that, Peter Magiffin, your relation called our daughter names!”

“What kind of names?”

Alice-Marie, directly addressed, hesitated a little. One answered carefully when one’s father spoke in that tone of voice. “S-she s-said something about me looking like an—an apple-dumpling!”

“Tee-hee!” This an audible titter from Benjamin.

“Anything else?”

“I don’t remember ’xactly what, but I’m sure there was lots more.”

Upstairs in her little room Joy had raised the window and the air with welcome freshness fanned her hot cheeks. Some of her indignation had been relieved from fatal repression by her outburst. There was even the beginning of a little twinkle of humour in her eyes. “I told her I was a lady,” she was remembering, “and I didn’t sound like one. No lady would ever call another a half-baked apple-dumpling.”

But the episode marked the beginning of that definite hostility of Alice-Marie.

Perhaps it was just at meal-time that Joy felt most keenly the loneliness and isolation of this new life—meal-time, when the young Magiffins would gather around the table—noisy, clamorous and insistent. Joy’s memory, playing truant, would slip back to the vivid little remembrances of those other meals, gay little meals which she and her father had enjoyed together in the London flat. “Frugal and merry,” he used to declare.

“Listen, ma, listen,” Alice-Marie exclaimed one day, “listen to how she says butter. Buttah, like that.”

“She’d better learn to speak it the way it’s wrote,” Mrs. Magiffin answered, lapsing as she did so frequently under stress into ungrammatic emphasis.

Joy clenched her thin little hands under the table and almost gave way to threatening tears. Almost, but not quite. Perhaps, after all, it was Billy who saved her from that disgrace. For Billy’s black eyes twinkled across the table in such a friendly fashion that one couldn’t give way to tears before such an openly admiring small boy.

Billy, being a normal boy with an inside that constantly demanded more, was eyeing her untasted pudding affectionately. “If you’re not goin’ to eat it——” he suggested tentatively.

By way of answer Joy raised her plate and held it towards him, which Billy decided was jolly nice of her, understanding so quickly without any weary waste of words.

“Oh, but, ma, that isn’t fair,” Alice-Marie declared indignantly; “I’m far, far hungrier than Billy.”

“Me too!” Henrietta’s little voice was shrill with chagrin.

“Billy never remembers ladies first,” Alice-Marie complained; “he’s a little grab-all, that’s what he is.”

But the little “grab-all” effectually silenced that discussion by making short work of the pudding. He grinned cheerfully across at his sisters. “It was swell,” he told them; “oh, um-mm!”

Thus the little bond of friendship strengthened between Joy and Billy. Years afterwards that bond remained a grateful memory of those first trying days. It was when Billy’s shyness wore off a little that she discovered his curiosity about the unknown ocean.

“If only my father were here he’d tell you lots about it,” she said.

“Was he a sailor?”

“No, but he wrote stories about sailors.”

Billy slid up very close to her on the old dining-room sofa. “Tell me some.”

Then did the round eyes of Billy Magiffin grow rounder still under the spell of Bravedick, the sailor. Bravedick who knew no fear, who struck terror into the crew of iron-hearted pirates.

The curiosity of Alice-Marie was aroused. “What’re you talking about?” she demanded.

“Pirates,” Billy told her. “Pirates. You’re only a girl, you wouldn’t understand. Go ’way, Al, you’ll spoil it all.”

Which was precisely what Alice-Marie intended to do. “Pirates!” she scoffed. “Pirates! There’re none of them now. They’re silly old-fashioned things. Ma—oh, ma,” her voice rose shrilly important, “ma! Joy, she’s stuffin’ Billy with pirates.”

It aroused Joy’s immediate protest. “I’m not stuffing Billy. That’s a horrid expression, horrid!”

But Alice-Marie had been sure of maternal support and it did not fail. Mrs. Magiffin was ablaze with indignation. “Don’t you dare—don’t you ever dare contradict Alice-Marie!”

“I will,” Joy told her; “I’ll contradict anyone who says something that isn’t true. I’m not stuffing Billy. I’m telling him stories. So there!” She turned and dashed out of the room, a little whirlwind of indignation.

Mrs. Magiffin’s amazement was not silent for long.

“That’s all the thanks we get,” she flung out her hand dramatically, “that’s all the thanks for taking foreigners into our family, for taking in other people’s children. I told your pa no good ’d come of it. But that girl’s not goin’ to put anything over me. She can learn, and learn quick, that I’m mistress in this house. She’ll contradict me, will she? Well, we’ll see who’ll do the contradicting. And you, Billy, s’posin’ you take your little baby sister for a walk, instead of sittin’ around listenin’ to stories of savages and the like. You ought to be ashamed of yourself, a great big little boy like you!”

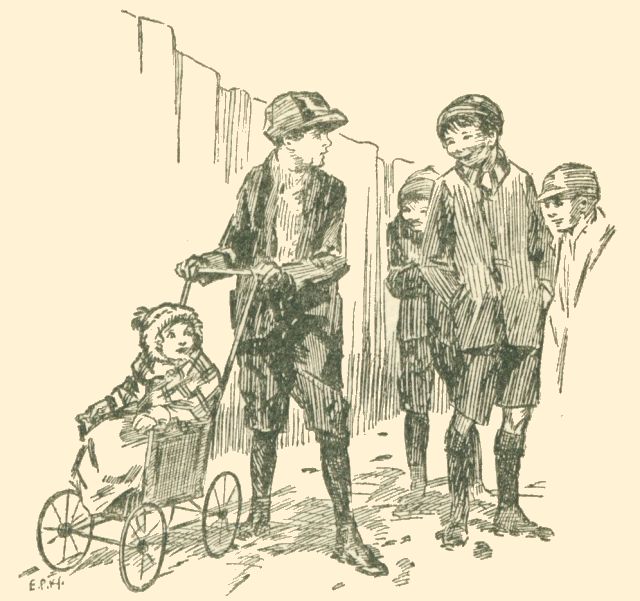

But that was one thing of which he was not ashamed, Billy decided, as he trundled Queenie up and down Victory Avenue. “I could listen to ’em for ever’n ever, always’n always,” he told himself; “I love pirates!”

Billy was recalled from the world of romance and pirates by the call of a school companion. “Hello, nursey; oh, nursey!”

“Shut up!” Billy growled, resisting a temptation to ram Queenie’s go-cart into a brick wall. But with the taunt the pirates faded and the dull work-a-day world was reinstated in their place.

Perhaps there was no portion of Billy’s daily life that he disliked quite so much as that part of the day when it fell to his lot to push Queenie’s go-cart up and down the length of Victory Avenue. Up one side and down the other, up and down, up and down. “Why can’t Alice-Marie do it?” he had asked his mother long ago, “it’s the kind of thing gurls do. Gurls are nursemaids, boys aren’t.”

But Alice-Marie, it seemed, was needed in the house. Benjamin had his paper route, and Henrietta, of course, was too little. In fact Henrietta often trotted along too under the resentful protection of Billy. He had once hit upon the plan of being kept in at school, for that made him gloriously late getting home, but his mother had nipped the scheme in the bud by writing a simple but effectual note to the teacher. “Don’t keep William Magiffin in. I need him at home.”

So there was really no escape. Sometimes he wished that there just wasn’t any Queenie, that she’d take herself off into somebody else’s family. And yet when the big dog belonging to Smith, the grocer, had dashed out so fiercely straight at Queenie, Billy had grabbed him by the collar and held him back. And when Ernie Hobbs, who was a great big boy and something of a bully, was going to snap an elastic-band against her cheek, Billy yelled “Stop!” and with his chubby fists doubled had squared right up to him, looking so fierce that Ernie, to Billy’s intense surprise and relief, pocketed the elastic-band and sauntered off.

Perhaps it was just those gibes of his playmates that made it all so distasteful. “Nursey,” they called him, and “Biddy.” And Billy could never, never think of a more effective retort than just “Shut up!”

It was after he had resisted the temptation to ram the go-cart into the brick wall that he was startled by a voice behind him. “I’ll wheel her for awhile, Billy; wouldn’t you like me to?”

It was Joy, of course; Joy with a queer look about her eyes almost as if—but Billy, as he eagerly relinquished his hold on the handle, dismissed the thought at once. A girl named Joy would never cry, never.

It was really very companionable and friendly walking up and down while Joy pushed the go-cart and stopped every now and then to give the squirming Queenie a surer “tuck in.”

And that’s how it all began. They fell into the way of it quite naturally. Billy would tear home after school, and sometimes Joy and Queenie would meet him at the corner; if not they would certainly be somewhere on Victory Avenue. Billy would hook his school-bag over the handle of the go-cart and they would walk up and down, up and down. But Billy liked it now. Victory Avenue, Queenie and the go-cart, homework, all the drab realities were forgotten, for Bravedick the sailor stalked beside them, Bravedick who knew no fear. “Like me when I grow up,” Billy often told himself, swelling out his chest in anticipation.

“You’ll be something mighty different from a pirate if I have anything to say in the matter,” his mother told him when he carried his hopes and ambitions into the house.

Perhaps, too, the land of romance into which she was admitting Billy had its hold on Joy as well. Perhaps it meant escape from the dull routine of life in Victory Avenue, from the teasing taunts of Alice-Marie, from the nagging tongue of Aunt Jennie Magiffin—escape to the far-flung ocean spaces where valour rode on the wave, and where Bravedick, the sailor, sailed forth on his fearless quests.

It was January now—January that carried with it all the rigour of Canadian winter weather, snowstorms and blizzards and high keen winds. But there were days of brightness too when the air was clear and still in the white light of the winter sunshine.

Joy, pushing the go-cart, would exclaim, “Oh, I love the snow; don’t you, Queenie?”

And Queenie would say “Goo-goo!” waving her fat little arms about, answering as plainly as possible without the aid of words, “Of course I love the snow.”

They were venturing farther afield these days. The sordid dinginess of Victory Avenue, Joy discovered, was not reflected in the streets to which it led. Busy thoroughfares these were with great high buildings, their tops, it seemed, close against the sky; stores with wide plate-glass windows which flamed with colour and beauty through the thin light of the winter afternoons.

Sometimes she even walked as far as the school to meet Billy. Set far back in ample playgrounds the school was a fine, imposing building, red-bricked, many-windowed, pleasingly suggestive of light within. But when the children came out—a noisy, shrieking little mob of humanity—Joy turned and walked away until Billy caught up to her.

“I don’t want to go to school,” she told him one afternoon; “do you think I’ll have to, Billy?”

“Ma said you’d be going to High School.” Then in little-boy fashion he offered comfort. “School’s all right, Joy; ’tisn’t so bad if you know the lessons, and even if you don’t you c’n guess the answers, and sometimes”—Billy grinned, evidently remembering a recent victorious venture—“sometimes you guess right.”

But “ma,” unknown to Billy, or, for that matter, to any of her family, had other plans regarding the education of Joy Meredith.

Perhaps it was the sight of Joy wheeling the go-cart up and down that gave rise to the idea in her mind. “And,” as she herself often declared, “once I get an idea into my head I can’t get it out.”

Assuredly this idea took forcible possession of her thoughts, and the more she turned it over the more feasible and desirable it became. Finally, she broached the matter to her husband.

He shook his head. “There are other things to consider, Jennie, her schooling, for instance——”

“Oh, school!” Mrs. Magiffin dismissed the unwelcome reminder with a wave of her hand. “I’ll manage the school part all right. She’s over fourteen, and I can get her off if she’s necessary as a wage-earner.”

“But she isn’t necessary as a wage-earner.”

“Neither is school necessary. The girl did a lot of studying with her father and knows more now about books and the like than she’ll ever need to know.” To the practical mind of Mrs. Magiffin there was no more to be said.

But her husband was not so easily satisfied. “I am able to give Lucy’s little girl a home and I want to feel that I’m doing it——”

“And haven’t we done it? Aren’t we doing it? Haven’t we shared our last crust with her?”

A rare little sparkle of humour lit Peter Magiffin’s eyes. “There’s generally more in the bread-box, Jennie.”

But Mrs. Magiffin seldom heeded interruption. “Haven’t we treated her like she was one of our own? She’s your relation, Peter, don’t you forget that”—it was not often, in fact, that he was given a chance to forget—“and if you want your wife to scrimp and starve herself to skin and bone while your relation lives on the fat of the land—well, I’ve my opinion of that kind of a man!” And her expression at the moment indicated that her opinion of that kind of a man was far from favourable.

But when Mrs. Magiffin set out with a definite purpose in view she generally carried matters with a high hand, and this case was no exception to the rule. Overcoming obstacles which might have proved stumbling-blocks to one less determined, she greeted her husband triumphantly one evening towards the end of the month.

“It’s all settled. About Joy, I mean. She’s going to help Mrs. Bain.”

“Joy is what?”

Mrs. Magiffin’s nods emphasized her words. “I told you I was going to let Joy go out minding babies. Seein’s she could mind ours she might’s well mind someone else’s. An’ right on top of thinking about it didn’t that little Mrs. Bain, along here on Victory Avenue, meet me one day and start tellin’ me how she’s tried to keep a girl to help with those four children of hers, and how none o’ them would stay, just pick up and go off cool as you please. It struck me all of a heap when she was talking, I’d let her have Joy, let her go right in and live there, I mean.”

That expressive little furrow deepened between Peter Magiffin’s eyes. “What about her school?”

“I told you I’d fix it, Peter, and I did. It’s all settled, I’m tellin’ you.”

“I don’t like the idea at all.”

Something in her husband’s tone made her furtively uneasy. There was just the danger, she realized, that her cherished scheme might even yet fall through. That uneasiness heightened the sharpness of her voice. “Whether you like it or not, Peter Magiffin, it’s settled.”

“Then you must understand, Jennie, that every cent the girl earns will be her own.”

His wife’s china-blue eyes flew open. “Indeed it won’t, after me scrimpin’ and savin’ to give her a home, arranging about placin’ her out and all. Her wages, or part of them, would be only a fair return.”

But Peter Magiffin shook his head. “Then she doesn’t go. If she does go out to work, Jennie, every cent she earns will belong to her absolutely.”

It was seldom that he so asserted himself. And in the light of scant but convincing experience Mrs. Magiffin knew that there would be no chance of changing his decision. It was a crushing disappointment, for she had already been lavish in her anticipation of the spending of Joy’s earnings. There was a hat in a milliner’s window—black with a red rose bearing down the brim at one side—“I can just see it settin’ on my head,” she told herself regretfully, mentally placing the desired hat back in the milliner’s window, and tried to cheer her drooping expectations. “Perhaps he’ll change his mind after a little, see the sense of it after what I’ve done for her and all.”

It was with Joy herself that the project met with unexpected resistance. Mrs. Magiffin’s many-worded explanation left a confused impression on the girl’s mind. “You’re sending me away, somewhere else to live?” she repeated, evidently incredulous.

Mrs. Magiffin made a gesture of impatience. “You’re goin’ to help my friend, Mrs. Bain, just along the street. You’re to help mind the children, run round the house and make yourself useful. She’ll pay you for it.”

Joy stared at her aghast. “You want me to go as a sort of—as a sort of—of servant?”

“You don’t have to put it as plain as all that. You’re to help Mrs. Bain.”

“I won’t go!”

“Oh, you won’t, won’t you? An’ who says so, Miss High’n Mighty?”

“I do. I won’t go.”

For once Mrs. Magiffin effectually economized in words. “You’re goin’!”

“Y’bet y’are when ma says so!” Alice-Marie added, evidently rather relishing the conflict.

It ended in Joy dashing upstairs and throwing herself on the bed, as on that memorable first night, in a paroxysm of grief, face to face once more with that which struck terror into her heart—the horror of the unknown. And as on that memorable first night it was Billy who offered solace.

For after what seemed a long, long time, though in reality it was but a little while, an odd, irregular, compelling little sound attracted her attention. Opening the door she found Billy, woebegone and disconsolate, sitting on the top step of the attic stairs. “You’re goin’!” he said, unconsciously repeating his mother’s words. “You’re goin’. You won’t be here no more to go wheelin’ the go-cart or tell me about Bravedick.”

Joy stared down at him as he sat there. “You’ll have to remember about Bravedick yourself, Billy,” she said slowly; “you must pretend that you are Bravedick and come sailing down to me. I won’t be so far away, your mother says, just a little way down the street.”

But Billy’s imagination had as yet taken few flights of its own. “How could I be Bravedick when I’m Billy Magiffin?” Billy the literal asked. “And how could I sail down to you when I’d be wheelin’ that silly ole go-cart?”

“We can always pretend things.” Joy paused, thinking that at the moment her own feelings were a direct contradiction to her words, and added as an afterthought, “or often, anyway. You can pretend that Queenie’s go-cart is your sailing vessel and that you, Bravedick, are the captain.”

Billy sat a little more erect. “Can I?”

“It’s lots of fun, pretending. Of course if you’re going to pretend to be Bravedick you’ll have to be brave—brave about everything.”

Billy winked very hard as if to wink away all evidences of un-brave tears. “I am brave!” he said.

He went downstairs, and Joy, going into the dark room, switched on the light and faced a rather mournful reflection in the tiny mirror. Playing the comforter to the small boy had at least relieved some of her own rebellious feelings. She nodded emphatically at the reflection which emphatically nodded back. “Whether you like it or not,” she said, “as your Aunt Jennie Magiffin and Billy both told you—you’re going!”

It was during the night which followed that a memory of her father drifted into Joy’s mind—something he had said just two days before he died. “Always hold on to the word Courage,” he had told her, “it’s a splendid word.” His voice, weak by that time, had trailed off, but the phrase came back with startling vividness: “Courage—a splendid word!” Courage, she realized suddenly, had been the key-word of her father’s life—a gallant courage with which he had faced rebuffs and hardships. “Be strong and of a good courage,” he had loved those words, had repeated them often so that Joy had come to know and love them too.

“And it’s courage that I need now,” she was thinking, “courage to take me into another strange house, among strange people. I wonder if Dad knew I’d need courage; I wonder if he ever needed it as much.”

“Be strong and of a good courage.” There was something stimulating in the very repetition of those words as they fixed themselves in her mind with all the fullness and richness of the promise they carried. “Fear not nor be afraid . . . for the Lord thy God, He it is that doth go with thee.”

Joy lay very, very still, staring up into the darkness. “Then I’ll try.” She spoke aloud, and the words cut suddenly into the quietness of the little room. “I’ll try to be strong and of a good courage. I’ll try.”

And it was in the nature of a vow that she said it.

It was at the supper-table the next evening that Mrs. Magiffin looked across at Joy, evidently rather puzzled and resentful.

“You’ve been acting all day like you’re glad you’re goin’,” she said; “seems queer to my way of thinking after what we’ve done for you and all.”

“But I’m going whether I’m glad or not,” Joy answered.

The reply evidently nettled Mrs. Magiffin. “That’s what we get,” she said, the more outspoken because her husband had not come in, “for taking other folks’ children into our family—thanks from nobody!”

“I wouldn’t be you for anything!” Alice-Marie was assuring Joy with that little sneer she never failed to make effective in the liberating absence of her father.

Joy shook her head. “You couldn’t turn into me no matter how hard you tried.”

Which retort infuriated Alice-Marie. “I don’t wa-ant to, I tell you, I wouldn’t be you for anything!”

It was Billy who came near to the truth when he found Joy after supper on the old sofa darning a gaping rent in one of his socks.

“Joy,” he asked, half under his breath, for Alice-Marie was doing her lessons at the table and it would never do for her to hear. “Joy, are you pretending?”

“Pretending about what, Billy?”

“Pretending not to mind goin’ to Mrs. Bain’s? Pretending that you’re sort of glad?”

Joy smiled into those eager black eyes. “Perhaps I am, a little.” She spoke softly, with evident regard for those receptive ears of Alice-Marie. “Pretending helps a lot, Billy. Dad told me that the soldiers in the Great War used to say ‘Cheerio’ to each other, and it had such a cheerful sound that it made them feel ever so much better.”

“Sure!” Billy said, throwing back his shoulders and trying to feel very cheerio and soldier-like indeed. “I say, Joy, is it to-morrer you’re goin’?”

Joy nodded. “To-morrow!” she said.

“To-morrow—tee-hee!” remarked Alice-Marie unexpectedly from the centre table.

At first sight it appeared that Mrs. Bain’s house at No. 43 Victory Avenue conformed to the row of which it formed a part. Semi-detached and of red brick, its porch sheltered the front door and its bow window curved outward just as surely as did those at Nos. 5 or 7 or 9 at the other end of the street. But on second sight it became apparent that No. 43 shared but the lesser part of the roof which covered it, and while No. 45 was slightly larger than the average, No. 43 was but a narrow slip of a house, and a very unprepossessing one at that.

A very different house it was compared with the one in which Mr. and Mrs. Bain had started their married life. That had been an attractively pretty little place on a maple-shaded street far up-town. They had been very much in love with each other, their prospects, and the world in general. And little Mrs. Bain had hung up frilly window curtains and thought how perfectly wonderful it was to have such a good husband and such a dear little house for one’s own.

And then had come the first indication of Mr. Bain’s erring and unsatisfactory ways.

He tendered his resignation at the office. That was his way of putting it. When that proceeding became a frequent occurrence, Mrs. Bain began to realize that it was another way of saying that he had again lost his job. Always the work carried less salary, but always—as he assured his wife—“brilliant prospects.”

“But,” she would answer with the sharpness that became habitual, “we can’t live on prospects.”

Oh, it took shrewd little Mrs. Bain a very short time to realize that she had married a wastrel and a ne’er-do-well. They sold the house as it stood—frilly curtains and all—and rented another. In due time they gave that up and moved still farther down-town, until, just the year before, they had found anchorage in Victory Avenue.

And now, under the struggle that the years had brought, and the vigorous demands of four noisy children, little Mrs. Bain’s nerves were giving way.

She greeted Joy with relief and obvious surprise. “You’re not used to work, are you?” she asked hesitatingly; “I was hoping you’d be a strong girl. You look rather delicate.”

“I’ll help you all I can,” Joy said.

“You may find me a little short-tempered sometimes,” Mrs. Bain remarked rather abruptly; “my nerves are a bit on edge.”

It was this disarming confession which prevented Joy’s protest when Mrs. Bain showed her up to her room. “It’s not exactly a room,” she explained uneasily, “it’s—it’s only part of the landing curtained off, but you’ll find it nice and warm.”

Joy realized that it was warm for the simple reason that there was no window, but by conscious effort she refrained from comment.

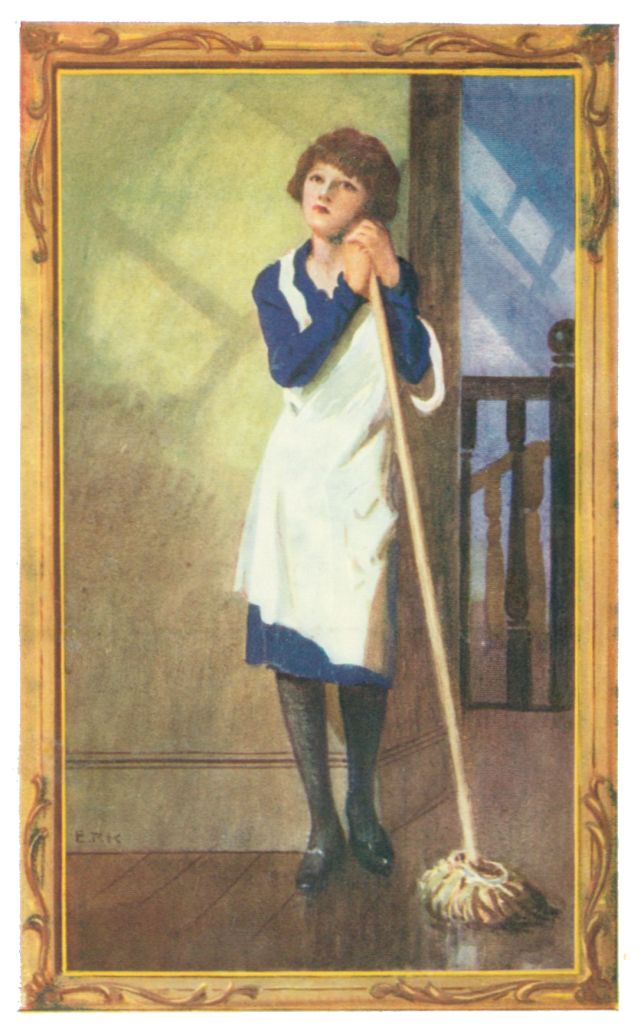

Thus, unpromisingly, began the new life. A life which began afresh with the cold dawn of each new day, to unroll itself into a series of tasks—breakfast, dishes, dusting, dinner; dishes again, sewing, supper, dishes. Sewing again, mending, darning, patching—and always, hindering all progress, the dominating voices of the children, undisciplined and uncontrolled.

Only at night came the all-too-brief respite in the airless little room upstairs where one was free to relax, to sink into a dream-troubled, unrefreshing sleep.

And often those insistent demands obtruded into the night hours as well. Mrs. Bain’s voice, sharply querulous from below: “Joy—Jo-oy, surely you hear baby crying. Why don’t you come down and take him for awhile and give me a chance to rest?”

And there were interruptions other than the baby—Mr. Bain coming in late, slamming the door. Joy came to welcome those nights when he was away on one of his vague, mysterious “business trips.” And there were sounds too from the house next door—queer, disturbing sounds, breaking sharply into the night hours. Oh, those hours were unrestful and unrefreshing at No. 43 Victory Avenue.

Sometimes of an afternoon Joy would notice a small boy with a go-cart hovering around with the Bain children—a round-faced, red-cheeked boy. She would open the window and call out, “Hello, Billy!”

His chubby face lighting up he would answer, “Hello, Joy. Cheerio! I’ve been tryin’ to pretend about Bravedick, but I can’t without you. Come on out, just for a jiff!”

She would hold up a pile of stockings for him to see. “I’ve all these to mend, and anyway I couldn’t tell stories or pretend just now, not if I tried ever and ever so hard.”

Billy, trundling Queenie back along Victory Avenue, would decide that darning socks must be terribly hard work because that was how Joy looked—tired, awfully tired.

To Joy the days seemed to revolve into a never-ceasing cycle—getting up, work, going to bed. Getting up which meant dragging herself out of bed, battling, it seemed, against an unseen force that was holding her down. Work which meant that unceasing scramble to catch up with tasks undone and never accomplished. Going to bed which meant that moment when she was free to lie down—and forget. There was no time for moments of reading, moments which might have carried her mind, self-forgetting, from the present; no time to call to mind those words her father had loved, “Be strong and of a good courage,” words which might have brought comfort and fresh resolve.

One thing alone prevented Joy from voicing the words which came so often to her lips during the days of that month, words which, despite her efforts, almost uttered themselves, “Oh, Mrs. Bain, I’m so tired, so terribly tired, I can’t stay.”

But the one thing that prevented them was just a sound in the night, a sound far more disturbing than the crying of the baby or the bang of the front door. A muffled sound it was, but in spite of that it came quite clearly to her ears. The sound of sobbing. She could hear it plainly if she sat up in bed. “It’s Mrs. Bain,” she would tell herself, horror-stricken, and would grip the bed-clothes tightly with both hands.

It must be terrible, terrible, she decided, sitting there wide-awake and tense in the darkness, to have a husband who stayed out late every night. Why, he might be run over, killed, anything might happen.

Remorseful and filled with pity, Joy would resolve not to tell Mrs. Bain she couldn’t stand the strain of the work, not to tell her that she couldn’t carry on, but to be instead ever so much kinder and more willing. “Because it’s harder for her,” the girl realized, “very much harder for her than it is for me.”

But the next day Mrs. Bain would be red-eyed and sharp of tongue, and Joy, as she struggled to peel the skins off knobby potatoes in the prescribed wafer-like shavings, would wonder miserably why it was always so easy to break resolves.

And then one morning Joy called Mrs. Bain. “I can’t get up,” she said, “I’ve tried and I can’t. I just ache all over.”

Mrs. Bain, alarmed, sent for Aunt Jennie Magiffin, who, alarmed in turn, sent hurriedly for a doctor, at the same time voicing strenuous resentment at the expense incurred.

But that morning, at any rate, Joy did not care if she caused alarm or expense, cared for nothing so long as she was left quiet—quite quiet.

“Nothing organically wrong,” the doctor declared, “it’s a case of nervous exhaustion. The girl must be kept quiet.”

And Joy, catching that word, wondered how he knew so exactly what she wanted—to be kept quiet, quite quiet.

His verdict aroused indignation. “You might have warned me she was such a delicate, high-strung girl,” Mrs. Bain told Mrs. Magiffin when the door shut behind the doctor; “you palmed her off on me as a girl to help with the work. I’m sure I haven’t overworked her.”

But Mrs. Bain’s indignation was nothing to Mrs. Magiffin’s. “I’ll be bound you got your money’s worth out of her. Oh, it’s all very well for you who can shift her off on us now she’s sick. But how about us, I’d like to know, us with a family of our own to provide for without having relations flung at us and having them turn into invalids and I don’t know what!”

But tongue-battles waging about her meant little to Joy just then. She knew that Mrs. Bain gave her medicine three times a day; knew that Mrs. Bain’s hand was unexpectedly gentle and cool on her hot forehead; knew, or thought, that Mrs. Bain whispered once, “Joy, dear, I’m so sorry.”

And then she knew for a certainty that her Uncle Peter had come to take her back to their house, was keenly conscious of his strong arms carrying her, of the freshness of the outside air, of coming to rest on the hard little bed in the queer-shaped room in the attic.

But it was quiet up there, Joy was gratefully conscious of that. Quiet at night save for the roar of traffic, quiet all day too.

Perhaps that very quiet had a part in making her realize that she was better. She began to think again—natural, clear thoughts. Remembered little Mrs. Bain regretfully. Started to feel that she wanted to move, to stretch, to sit up—to stand.

“The normal recovery of a normal girl,” the doctor pronounced one morning two weeks later. So Joy came downstairs into the life of the Magiffins once more—Joy, a little thinner; a little longer—that was Billy’s wondering decision—with dark, purple shadows under her eyes.

And then it was, towards the end of March, when a little colour was returning to her cheeks, a little light to her eyes, that Mrs. Maggie Tibble entered her life.

There was something appealing about the old house, something rather fine and courageous.

The home of Mrs. Maggie Tibble was in John Street, surrounded by factories and warehouses which threw deep, day-long shadows over the streets below. There were freight-yards not far distant where the engines puffed and snorted and sent up volumes of dense, black smoke which hung like a pall over the neighbourhood.

The house was old, reckoned by the standards of time in the hustling new country of which it formed a part. It had been left to Mrs. Tibble by her father and had been in the family for seventy odd years. “And goodness only knows,” Mrs. Tibble was fond of declaring, “how long it was built before that.”

Years before there had been a certain beauty about the house—solid, substantial, set far back in spacious grounds of its own. But the last twenty-five years had left a disfiguring record. The face of the house was soot-encrusted now, dingy and weather-beaten. The grounds had been sold and a factory and a storehouse covered those once spacious and picturesque green lawns. Nevertheless there was something appealing about the old house, something rather fine and courageous as it stood forth, alone in that world about it as if defying the encroachment of commerce.

It was known now quite simply as “Mrs. Tibble’s boarding-house,” and was noted for clean rooms, good beds, and hot, satisfying meals. Someone had once said in Mrs. Tibble’s hearing that she was a good landlady, and had added surprisingly, “And a real good Christian!” Mrs. Tibble had said nothing in reply, but had kept that saying and pondered it in her heart.

Mrs. Tibble’s friendship with Mrs. Magiffin was one of long standing rather than of mutual interest. She had even known Jennie West before she married Peter Magiffin, and had had the privilege of prophesying at the wedding that “he’d find that tongue of hers a bit of a lasher.”

Unknown to anyone but herself, Mrs. Tibble had watched with keen interest the coming of Joy Meredith into the Magiffin family. “If I’m not mistaken, Jennie will make it hard going for anyone as unwelcome as that girl,” she had told herself, with the keen insight into human nature which years and experience had brought.

On her first sight of Joy Meredith, Mrs. Tibble’s mind had done a curious thing. It called up an almost forgotten memory out of the mist of years—a fawn she had once seen on the bank of a forest stream, a fawn standing for a moment quite motionless, poised for flight, its great brown eyes startled, beseeching.

“My land!” Mrs. Tibble had exclaimed, rather startled herself at the vividness of the memory, “whatever made me think of that?”

And so, after Joy Meredith had come back from Mrs. Bain’s, then it was that Mrs. Tibble stepped forward. “Why not let the girl come to me for awhile?” she had asked casually. To appear eager, she knew, would have the opposite to the desired effect on Jennie Magiffin. “I’ll pay her to help a bit, but I won’t overwork her, you needn’t be afraid of that.”

The casual suggestion took root as it was meant to do, Peter Magiffin proving at first—as his wife put it—“stubborn and contrary,” but finally, when Mrs. Tibble herself came round to talk it over, Peter Magiffin gave his consent.

It was Billy who trundled Queenie beside Joy when they walked from Victory Avenue to John Street one April afternoon. He had rebelled against pushing the go-cart, quite determined to carry Joy’s black bag. That was what men were for, to carry bags. And women were meant to push baby carriages. You saw them doing it everywhere and acting as if they liked it. “Babies,” Billy decided from the depths of a hot little heart, “babies are crazy things anyway!”

But his mother had decreed that Joy should carry her own bag and that Billy should push Queenie, “that is, if you’re going at all,” she said.

Of course he was going, go-cart or no go-cart, and when Joy turned at Mrs. Tibble’s door to wave her hand, it was Billy who called, “Cheerio, Joy!”

“Cheerio!” she called back.

It was Mrs. Tibble herself who opened the door to admit Joy, Mrs. Tibble, stout and unwieldy, with tiny, good-natured wrinkles about her tired eyes, and in the blue eyes themselves a kindly light which neither time, nor poverty, nor “the fell clutch of circumstance” could quench.

“Hello!” Mrs. Tibble said, feeling just a little embarrassed and rather puffed with the exertion of coming downstairs—for stairs, either up or down, were wearisome and breath-taking.

Joy smiled in answer, coming to a silent conclusion that there was something jolly nice, something very likeable about this Mrs. Tibble.

And so they smiled at each other across the shadows of that dim old hall, a smile that bridged the chasm of embarrassment, and paved the way to mutual and sympathetic understanding.

The room which Mrs. Tibble allotted to Joy was on the third floor. Long ago the rooms of Mrs. Tibble’s third floor had been eagerly sought after, the reason being that they were cheaper than those on the second, and the excuse offered that they were higher and more airy. But Mrs. Tibble’s following had diminished, there was no denying that fact, and now the second floor amply accommodated the “regulars” and any chance “occasionals” as well.

Joy’s room was large. At first she viewed it with relief after her cramped quarters in Victory Avenue. But she soon discovered that a small room may be cosy, companionable, and its four walls friendly as they close around you and shut you in from an alien world. There was nothing cosy, no friendly feeling about this room. Its ceiling was dingy, remote, and shadowy, the woodwork dingy and drab. The windows rattled noisily in the gusts of spring wind. And in the quiet of night the stretch of uncarpeted floor creaked mysteriously, and from between the walls came the sound of scampering of merry-making mice.

But, despite the depressing influence of the room, sleep claimed Joy for its own as soon as she dropped into bed, sleep that held her unconscious of those creakings and scamperings, of those eerie, mysterious little noises that haunted the old house at night.