* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: My Lady of the Snows

Date of first publication: 1908

Author: Margaret A. Brown, (1867-1941)

Date first posted: November 16, 2024

Date last updated: November 16, 2024

Faded Page eBook #20241115

This eBook was produced by: John Routh & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

My Lady of the Snows

Copyright, Canada, 1908, by Margaret A. Brown.

“Love your country, believe in her, honor her, work for her, live for her, die for her; never has any people been endowed with a nobler birthright or blessed with prospects of a fairer future.”

—Lord Dufferin.

“Canada shall be the star towards which all men who love progress and freedom shall go.”

—Sir Wilfrid Laurier.

This work cannot be fully understood unless the reader is aware of the writer’s motives. The book has a twofold meaning—that of a political novel, and that of the portrayal of a great love and a religious drama.

As Disraeli in his novels portrayed the political and social conditions of certain eras of his country, in a simple way this work is intended to portray the conditions existing in Canada at an era when the country was in a state of transition, with the idealistic conception of what the government of a country should be, the conception being based upon a knowledge of the inherent principles of Divine Right and upon Plato’s Republic of Justice.

The scene is laid prior to the last election during Sir John A. Macdonald’s administration. When there are no great questions at issue, politics are seen in their lowest form; the protective tariff had been adopted, and with the advent of machinery the old order of things was passing away; the new order had not yet brought any great issues before the people, and the election, commonly called the “Old Flag” election, was run merely on a sentiment of loyalty to the motherland.

“My Lady of the Snows” is a woman who has been born “great,” and one who has based her life on principles rather than the emotions, or Plato’s theory that the emotions should remain subservient to the will. In her political principles is portrayed the last lingering spirit of “Divine Right” of the “Old Regime in Canada.” The “Man” in the book is the man who is thinking; the man of knowledge, of patriotism, of high ideals, he who has inherited as an heirloom England’s foundational principles of greatness, her sense of duty, her code of honor and her love and fear of God; the man who realizes that the time is fast approaching when, in the evolution of history, in the very nature of things, his country must come forth and take her place in the history of nations.

In the second place: A French critic has recently said that modern books are being left unread because we live in a scientific, commercial, unbelieving world, and writers, having forgotten the poets and classics, are surfeiting the world with materialism, realism and commercial barter, and are leaving the intellectual and spiritual in man unappeased and undeveloped.

Influenced by a realization of some of the emotions, thoughts and truths which entered into the creation of Carlyle’s “Hero-Worship,” Goethe’s “Faust,” Dante’s “Beatrice,” and Tennyson’s “Idylls of the King,” the writer has endeavored to picture a great love and portray a religious drama which would appeal to thinkers and lovers of the poets and classics, and in some measure refute the materialism which is becoming so prevalent within the modern world.

The plot is based upon Tennyson’s “Idylls of the King”—the unholy love of the Knight for his Lady—the poet’s song of Love, free Love—the unhappy circumstances surrounding the Man’s love, creating for a moment within him, despite his inherent and traditional creeds and conventions, a touch of Ibsen, that Free Will and Natural Affinity are foundations for a higher institution than the conventions of the modern world—and his mastery over such a temptation. The “Wife’s” conduct is based upon Mark’s treatment of his wife Isolt, whom he loves but who loves not him.

The “Visions of a New Empire,” which foreshadow Imperialism, were suggested by Tennyson’s description of King Arthur’s Kingdom of Camelot, and were based upon the tradition that this continent, previous to the Mound Builder era and Stone Age, was inhabited by a highly civilized race, and no doubt in the evolution of history will again be inhabited by such.

Julian Hawthorne has said that any novelist truly great will subordinate events to character—that dialogue and mental history will reveal the speakers, and the speakers are the story. During the ten years the writer has been engaged upon this work, Julian Hawthorne’s conception of novel writing has been instinct within her. Events we must have to make a story interesting, but events are very similar to experiences, which are monuments carved by the weapons which have wounded us most; we leave them behind and go on to character built upon knowledge; and to possess true knowledge we must have some knowledge of the origin of things which brings us into the realms of science and religion.

Carlyle tells us in his “Heroes” that “it is well said, in every sense, that a man’s religion is the chief fact with regard to him. A Man’s or a Nation’s! By his religion I do not mean his church creeds and formulæ, but what a man does know in his Mind and Feel in his Heart, and does practically lay to heart, regarding his vital relations to the Unseen Universe and to This Universe. Tell me a man’s religion and a nation’s, and I will tell you what they are and what they will become. Answering to this question is giving us the soul of the history of the man and the nation. And since the spiritual at all times dominates and determines the material, the ‘Man of Letters’ is one of the most important personages of modern times. What his religion is, his nation’s will become.”

The works of the writers of the Periclean Age, an age when the world was truly great, centred round or culminated in two great thoughts—the two forces of Good and Evil, and God tames excessive lifting up of hearts. In “Faust,” as in other writings of modern times, the force of Evil sometimes assumes a definite form and sometimes a mental conflict, while Good is personified in Purified Love, and Fate, Destiny and Free Will play their respective parts. Where Shakespeare moralizes on such great questions as “What is Life?” in language too austere and too pure for common humanity to approach, Tennyson appeals directly to the human heart in such words as:

“For the drift of the Maker is dark, an Isis hid by a veil.

Who knows the ways of the world, how God will bring them about?

Do we move ourselves or are we moved by an Unseen Hand at a game

That pushes us off from the board and others ever succeed?”

“And yet we cannot be kind to each other here for an hour;

Brave it out as we please, we men are a little breed.”

The Religion in this book is outlined in the “Court of Inquiry” and practically applied in the lives of the chief characters in the book. It is based upon the vital principles of Christianity, the basis according to Carlyle being “the ultimate perfection of a principle extant throughout man’s whole history on earth,” and comprises a proper synthesis of faith and works: Goethe’s conception that faith is a question between man and his own heart and that Greatness or Immortality must come through humility; the Socratic theory that knowledge is virtue; ignorance is the only sin; we cannot sin if we know; but love is greater than knowledge and is a gift direct from God—the Vision in the book being the same thought as Tennyson’s “Holy Grail” or Plato’s “Despair of Reason”—that man receives knowledge through a higher faculty than reason, that is, Divine Revelation.

Towards the close of the plot the writer found herself in a dilemma; it was easy to dispose naturally of the minor characters of the book, but the “Woman,” the “Man” and the “Wife” remained—a problem. The poets purified their loves through penance and allowed them to depart in peace, but as the Woman was “My Lady of the Snows,” and as She has not yet won the Immortality of Greatness, and as the writer wanted Her to develop Her in her next work to Imperialism, She could not be disposed of thus. The Man could not be disposed of because he is the man who is striving to make his country what she has been born to be. If the Woman and Man met again, and love were love, the writer was not very sure how much longer their good genius would guard them, and feared for their reputation. If she disposed of the “Wife” as Mark disposed of his wife’s lover, Tristram, the writer’s reputation was endangered from book critics as treating the work conventionally. As patriotism is the key-note to the book, she felt she must sacrifice her own reputation to be consistent and to save her country; but self-love is as instinct within human nature as love, and yet continued to wage war against love, when a train-master gave a wrong order and solved the problem for her.

M. A. B.

| ILLUSTRATIONS. | |

| PLATE I. | |

| 1. | My Lady of the Snows |

| PLATE II. | |

| 2. | Court of Inquiry. “What is happiness?” |

| PLATE III. | |

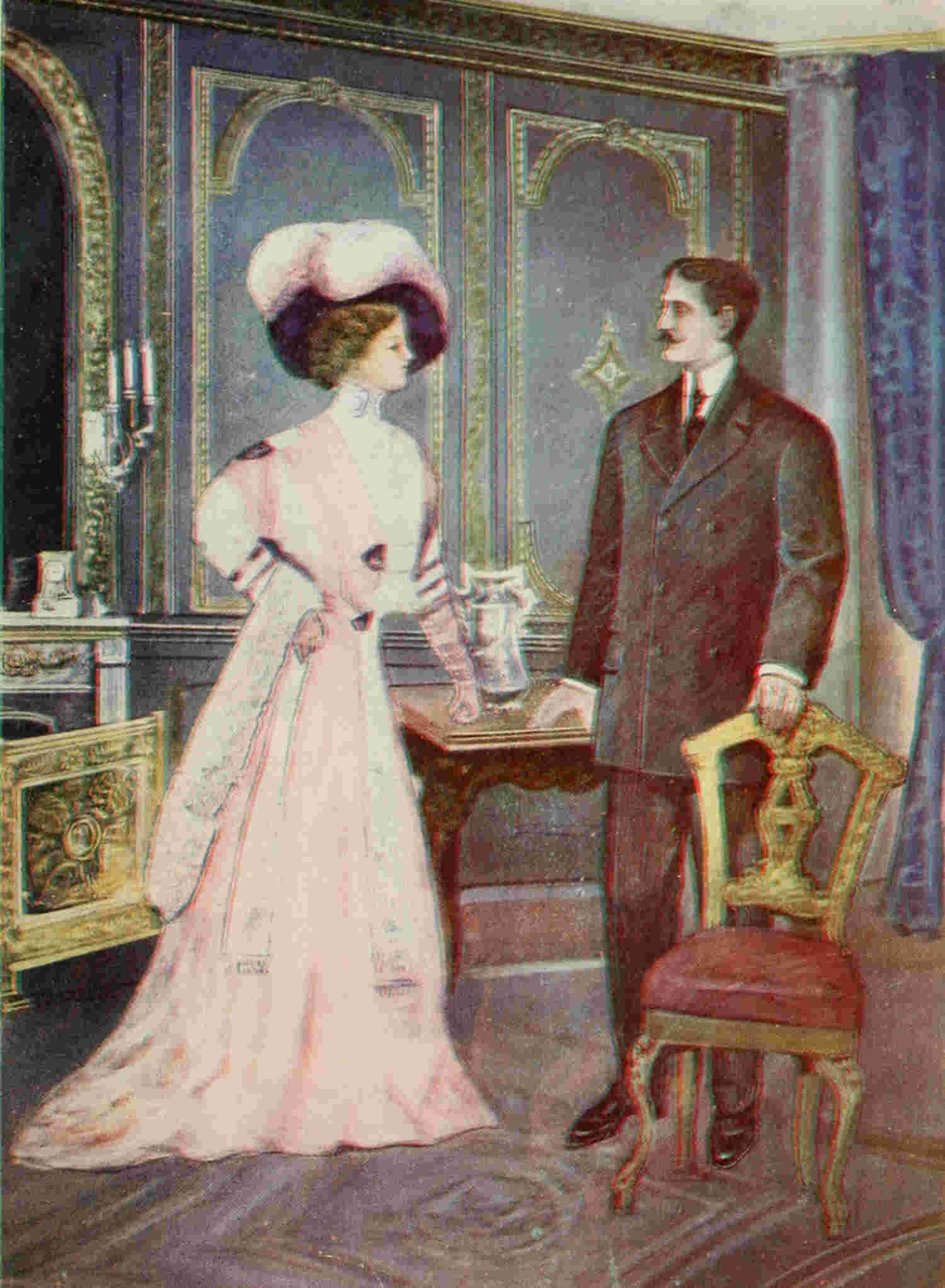

| 3. | “My dear, you have willed it. Don’t you think that in time you will regret it?” |

| PLATE IV. | |

| 4. | A week in the Queen’s City! A day at Versailles with the Sun-King! A morning serenade! |

A Nation spoke to a Nation,

A Queen sent word to a Throne;

“Daughter am I in my mother’s house,

But mistress in my own.”

Government House was one blaze of brilliance.

The newly-appointed Governor-General and his wife had but recently arrived at their new home, and their Excellencies were to entertain for the first time the political and social world under their new regime.

The merry ting-a-ling of winter bells making gay music over a gay white world, the hollow beat of speeding horses’ hoofs and the sleigh’s low bass song were heard far and near in the Rideau suburbs of the Queen’s City. Equipage after equipage swept in through the Lodge gateway, and up the wooded driveway—the occupants of the sleighs, through the break in the foliage, catching glimpses of the broad, gleaming, frost-bound river, the steel-like bastions which lined the opposite shore and the ice-crystalled hills beyond, while the moon swam high through the fleecy clouds of the blue dome of heaven which night had transformed into a diamond-studded canopy, and the cool, crisp northern air made the stars sparkle and scintillate and spread their rays of light like a bed of seeded pearls on the virgin snows beneath—to the main entrance of the low, grey stone Hall with its chequered shadows and lights on the whitened lawns and terraces without.

As sleigh after sleigh approaches the Hall, the massive doors open and close upon the fast-arriving guests, and the group of onlookers in curiosity await for the next to come.

At the grand entrance to Apsley House, one of the most imposing houses of the city, stood a magnificent sleigh drawn by two blacks, which were champing and chafing to get away, waiting for the occupants to convey them to Rideau Hall.

“Is father ready yet? We must not keep him waiting,” said a young girl, the daughter of the owner of the house, as she emerged from an inner room to a suite of rooms adjoining the great central hall.

She was followed by her maid, who carried a long ermine-lined wrap, some flowers and a jewelled fan, and who, after depositing them on a side table, retired from the room.

“Yes, I hear him coming. Are you ready?” answered her companion, Marion Clydene, a young girl almost as beautiful as the mistress of the house, but of an altogether different type.

“Yes,” replied Modena, “I have been waiting some time. You are a connoisseur in dress. Is the draping of this gown graceful? Annette is away; I miss her so much; she had such good taste, but then perhaps one grows too fastidious. What do you say, father?” she asked, as the door opened and an elderly man entered the room.

“What is it, my child?” he asked, with pride beaming in his stern but kind eyes, as he gazed on his only child.

The speaker was Mr. Wellington, the oldest member of the Cabinet, and one of the leading men of the day.

“Will I do?” she asked, not in vanity, but with the same highborn pride reflected in her eyes, as she slowly redressed the room, the many gems in her hair and on her bosom sparkling in the semi-darkness of the subdued lights, the soft folds of her gown, with its drapings of oriental lace, falling in graceful lines about her form, and her train, with its embroideries of white lilies with their golden calyx and fern leaves, sweeping out over the soft velvet of the carpets like a peacock’s gay plumage on the greensward of a lawn.

Her father’s eye lighted as he felt the charm and grace of the room and its inmates. It was her own private room; everything in it was elegantly simple, homelike, artistic and inspiring. It possessed a wealth of colors, but so subdued and harmonious that they softened rather than heightened the general effect. Soft, shady rose-lights, jasmines and lilies of the valley standing on the tables and mantels, the open piano with its old airs on its ebony case, her favorite authors and magazines in the corner, all spoke of the immaculate taste of its owner.

“Look in the glass and see, my child; if you please yourself, no doubt you will do,” answered her father, rather with his eyes than with his lips.

She only glanced in the mirror, but the warm blood mantled her cheeks at what she saw.

“We really do look like peacocks when we get all this war paint on,” she said.

“But come, dear,” continued her father, as he buttoned his great coat about him. “It is cold for the horses. Have you everything you require, Marion? What it is to possess beauty unadorned! You do not need to worry as my daughter does,” he added, smiling kindly at his ward.

“Oh, I would not presume to approach Modena,” replied she, looking at her friend with eyes unglazed with envy. “I feel like a waning moon beside a mid-day sun.”

“The moon was made to be loved,” replied Modena, as her father touched the bell for her woman-servant.

“And the sun to be worshipped; you know the moon is only the inspiration of a sentiment, the sun the source of all things.”

“Then you must have inspired father with a pretty sentiment; he has paid you such a subtle compliment. I have all I want; you have all you require,” said the daughter of the house as she glanced at the graceful simplicity of her companion’s attire.

“One wishes one’s beauty was as indisputable as yours; you have such a faculty of making one feel like a Phyllis, or an Amaryllis, or a Perdita.”

“Have I? I don’t see why I should, for at heart I am one myself. But I wasn’t referring to beauty but to economy, but there! I had forgotten, you never read the sciences! There is such a difference between our needs and our wants. Nature is the basis of your needs; selfishness forms the motives of my frills and feathers and furbelows; you represent moral economy, I modern economy. Isn’t that what Ruskin says, father?”

“Here are your wraps, my dear; we’ll not stop to discuss political and domestic economy while the horses wait in the cold,” replied her father, benignly.

“But why are you so anxious to-night?” he continued, as they descended, together, the broad steps which led down the great central hall.

“It is her Ladyship’s first appearance, and you heard what Jack said at dinner.”

“That her Excellency would expect to meet only tattooed and blanketed red men, with their beaded and ringed, red-petticoated, yellow-turbaned wives and daughters?” smilingly replied Mr. Wellington.

“Yes, and I wish to dispel the delusion and ease her apprehension at once. I hope we will be well represented to-night,” his daughter rejoined, as he handed them into the sleigh.

“And you are usually so indifferent as to what other people say or think. Their frowns and smiles have never been your barometer.”

“Ah, but this is different. This is not a personal matter. It is yours, all of ours, our country’s reputation which is at stake. It is a duty, you know what I mean. All those things are among the necessities of life. They count very much in the game of nations.”

“They certainly do,” admitted Mr. Wellington, rather wearily, for he was beginning to feel sadly the need of rest and repose.

“I have been to her receptions at home in England and you may rest assured, Modena, that your advent will be quite sufficient to dissipate the hallucination at once,” said Marion, as they seated themselves amidst the deep robes of the sleigh.

“Marion is thinking of Marlowe,

“ ‘Oh, thou art fairer than the evening air,

Clad in the beauty of a thousand stars,’ ”

said her father, tenderly.

Her face flushed warm, while her heart swelled with a great tenderness. It was so seldom he said such pretty things.

“Drive to Kenyon Court first, Jackson,” said Mr. Wellington to the coachman.

“Do you think Mrs. Kenyon will go?” asked his daughter.

“I do not know, but I promised Keith that we should call for them.”

“I do not think she will, she has gone out so little since Edna’s death.”

The distance to Kenyon Court was very short, and in a few minutes the sleigh drew up at the Court; but when the footman rang, a young man of splendid build and appearance, clad in a heavy sable-lined coat, appeared alone and took the vacant place in the sleigh beside the mistress of Apsley House.

“I thought perhaps if you would call I could persuade her to accompany us, but it is Edna’s nameday, and I could not prevail upon her to come,” said the young man, with a tinge of sadness in his voice.

“I thought so much of her to-day,” replied Modena, in a low voice and in a tone which the other understood.

“Poor mother! She cannot get over it, but I think she is growing brighter. But where is Jack?” continued he, turning the conversation and addressing Mr. Wellington.

“He had an important editorial to revise; he went down to the office. He and Monteith will take a hack from the office to the Hall,” replied the elder gentleman, as the horses, anxious to return to their own warm stalls, fairly flew over the ground, the balls of snow from their fleeting feet speeding in every direction and the bells floating their joyful music on the frosty air.

“I suppose everybody will be there to-night,” said Keith.

“Yes, it is absolutely necessary that we should go this season,” replied Mr. Wellington. “We have a heavy year’s work before us; the Opposition is thoroughly aroused, and there is a great deal to be done. The politicians of to-day are very much like the knights of the fourteenth century; our responsibility, like their armor, almost smothers one; but then,” he continued in a lighter vein, “if these ladies will only combine business with pleasure, they can help us a great deal in the coming contest.”

“Father has grown so utilitarian of late, he must have been resurrecting Hume and Mill. For his sake one wishes the crisis was past; it augurs grey hairs and wrinkles,” said his daughter.

“Hume and Mill! Their names alone are enough to send cold chills through one’s veins. To regard utility as the ultimate appeal in all ethical questions is enough to cause premature old age!” exclaimed Marion Clydene from the depths of the robes.

“As De Stael thought, you’d prefer thinking that these robes were made to look beautiful and to make you look beautiful and to dream in this cold winter night, rather than to keep you warm,” replied Keith Kenyon as he drew the heavy robes more closely about them, for the night was very cold. “But dream on and think so while you can. Great men and women have done so before and have been happy, why not we?” he continued, smiling at his young friend, who was curled like a dormouse in her corner of the sleigh.

“Your favorite, Merlin, changed the knight’s emblazoned shield of Fame into the Gardener’s Graff. Rich ripe peaches are surely preferable to and more substantial than day-dreams,” said Modena.

“Yon are not fond of day-dreaming,” said the young minister, in a low tone and with an almost personal ring in his voice, addressing her for the first time.

“One hasn’t time, life is too real, everything means something, there is too much to be done; one wishes the moments were minutes, and the days weeks, and the weeks years; one has really so many real duties, that one has no time for day-dreams.”

“That’s what Maria Theresa said, and she lived to see forty-eight; duty without day-dreams is generally conceded to be very dull.”

“Dull!” repeated Modena in exclamation, and in tones which expressed her inability to comprehend the word.

She really didn’t know what it meant.

“One makes one’s own atmosphere, and it’s one’s own fault if the atmosphere round duty is grey and vapid; and duty is generally conceded to be our weapon against the forces of forty-eight.”

“How intensely practical and unromantic you are!” exclaimed Marion in disgust.

“A veritable Aristotle!” said her father, sententiously.

“Oh, Marion knows no more about Aristotle than she knows about tadpoles. She lives on Shelley and Keats,” replied his daughter, knowing well her friend’s dreamy, impracticable, imaginative nature.

“It’s real nice to live with them, one can soar heavenward. Shelley, like Hercules, was translated from a blazing pyre to a place among the immortal gods. I like the company of the gods. Aristotle is like the peaches, he gives one indigestion,” said Marion, indolently.

“We’ll admit that he has given father, if not indigestion, at least grey hairs.”

“But I have one consolation, I am laying the heaviest of the burdens on Keith’s young shoulders.”

“Young shoulders! they have seen thirty winters. I am beginning to feel quite old.”

“You will soon learn, if you take life, as all men should take it, seriously and sincerely, that responsibility and position add many years to your age and many furrows on your brow,” replied the elder man, gravely, and with an accent of weariness and apprehension in his voice, for he was beginning to feel the weight of many long years of strenuous labor, as the horses drew up in line with a score of other belled and robed equipages round Rideau Hall.

“Ah, here you are at last!” exclaimed Jack Mainton, as he and Carlton Monteith came out from the throng and assisted the ladies from the sleigh.

Modena, followed by the other occupants, descended. The admiring group of onlookers, who had been skating on the river, and who, through curiosity and the love of seeing the grand, as is usual in such eases, had been attracted to the entrance to the Hall, drew back and opened up a passage for her, many of them smiling as they recognized who it was, for she was as popular by reputation with the sweep and the boot-black as she was with the gay gathering now in full life behind the closed doors of Government House.

“You are last. We have been waiting. Such weather!” grumbled Jack as they ascended the steps together. “One might as well live in Greenland or at the North Pole as here.”

“This is certainly Greenland, but Greenland with the roses of Mareschal, the beauty of Greece, the costumes of Worth, candelabra and gas pipes addenda. What a brilliant assemblage!” exclaimed Marion to her friend, after they had greeted and been welcomed by their Excellencies, as they stood apart for some moments before the music began.

“Who is that man talking to your father?” continued she, her eyes lighting up with interest and animation as she greeted her many friends.

The mistress of Apsley House looked over to where her father was engaged in earnest conversation with a man of noble countenance, with a brow indicative of great intelligence and with stern expression tempered with benevolent but rather sad smiles.

“Haven’t you met him? Oh, I had forgotten, he has been away for a year in New Zealand taking up practical politics or something; he will come over to us soon.”

“But you haven’t told us who he is!”

“He is Mr. Lester Lester, the nicest man in the room, or the noblest, I should say.”

“My dear cousin, I’m not surprised at your taste, but I am painfully shocked at your heresy. Lester, the leading Whig in the country, and you classing him as the best fellow! That’s surely antagonistic to your principles,” replied her cousin, who stood listlessly beside her chair.

“Whether it be good taste or whether it be heresy, I cannot retract anything I have said, and if you were honest you would confess you are as much of a heretic as I.”

“How is that?” queried Marion.

“He thinks Mr. Lester’s sister Helen is almost as perfect and beautiful as her namesake, Helen of Troy.”

“You never heard me say so,” replied Jack, gloomily, as he glanced across to where Helen Lester was conversing with her Ladyship.

“No, because you talk so much nonsense you have no time for common sense,” replied Modena, smiling at her cousin’s gloomy brow.

“Here comes Monteith: I’ll tell him what you said about Lester.”

The mistress of Apsley House was betrothed to Carlton Monteith, the youngest member of the Senate.

“He will but confirm what I have said,” replied she, but Mr. Monteith had no time to reply before the strains of music from the orchestra were wafted to where they stood, and Keith Kenyon bent over her.

“I believe it is the arrangement we dance the first set together,” he bowed and said.

Keith Kenyon was the youngest man in the Cabinet and the rising man of the day.

As he led his companion to their place in the set of honor, they were the cynosure of all eyes.

“I shall adore our new Governor and her Ladyship from this moment,” said he, smilingly, to his companion.

“Why?” interrogated the dark eyes of his partner.

“For the honor of being your partner; it is almost as enviable as the ribbon our chief wears to-night.”

“I am surely flattered! A compliment from the lips of a Talleyrand!”

“It is not a compliment: a compliment is a base coin tendered to one’s vanity at the expense of one’s intelligence. It would be impossible to offer you one.”

“How nicely you infer another! I have intelligence but no vanity! and yet I am the vainest person in the room. I was admiring myself in the glass before I came, just like a peacock,” she replied lightly, not wishing to admit that she saw that he meant what he said.

“The proudest perhaps, but not the vainest.”

“Your compliments ascend to the height of a subtle art.”

“Because they are based like all art on what is eternally true.”

“Oh! Oh! But you said ‘almost’; Merlin’s shield of Fame still stands between you and—and—day-dreams,” she replied lightly, meeting his eyes fearlessly.

“You wouldn’t have it otherwise,” he replied, as he took her hand as the music began.

When the set was over she was immediately claimed by Carlton Monteith, and then others followed, until an onlooker would have no difficulty in confirming Keith Kenyon’s statement that the most beautiful, and even if the proudest, the most popular person in the room that evening was Modena Wellington. She danced the entire evening; she was too young to tire and too sought after to be allowed a few leisure moments with her friends, but they were all together for a few moments after refreshments, before the music began.

Jack was gazing intently at her Excellency.

“You look very serious, Jack. What are your thoughts? If you gaze much longer at her Ladyship, she will be sending her aide-de-camp to inform her servants to eject you as a wild man of the West, devoid of all manners,” said his cousin, good-humoredly, to him.

“I was wondering what she thinks of us,” replied Jack, gravely, as he withdrew his eyes from the face of their hostess and viewed his cousin.

“She thinks us very nice, indeed. See how pleased and interested she is in what father is telling her.”

At this moment her Excellency was looking with smiling mien and raised brows at some views of the West which had been painted and left behind her by her predecessor, and which Mr. Wellington was now explaining and describing to her.

“Her good breeding makes her appear interested, but one is sure, that inwardly she is laughing at our presumption or lamenting our manners, which must savor of log cabins and the backwoods. How uncouth and undignified we must appear, and how ridiculous our aping Court Etiquette must seem to her; like a parvenu in good society or democracy in a mansion! What better opinion have they of us now than when Voltaire wrote, ‘Well rid of fifteen thousand square miles of snow and ice,’ or when La Pompadour said, ‘The King can now sleep in peace since he has such a bugbear off his mind’?”

Jack’s good-natured smile and cynicism of words irritated his cousin for a moment. She felt her face flush warm. Instinctively she felt that these were the sentiments entertained towards her country by a great many unenlightened foreigners. Had it been a personal matter she would not have cared. Her inborn consciousness of superiority made her wholly indifferent to comment or criticism; but her country! She was intensely patriotic, and it wasn’t just what it might be. It was this fact which made the comments hurt.

She was about to reply, but, knowing her cousin’s nature so well, she forebore, and immediately recovered her composure and good humor.

“How disappointed she will be to-night if she came expecting to meet a class of people similar to our pagan aborigines or our fur-clad Esquimaux!” was the reply she gave to her cousin.

“She sees the feathers and paint.”

“They mean civilization.”

“Not according to Jack’s theory.”

“She will have to admit we have advanced a little from the customs of Champlain and Charlevoix,” said Helen Lester.

“She is wondering which clan you belong to, Modena,” said Jack, laconically.

“She will admit you are the Queen of the clan, anyway,” said Lester, as his deep-grey eyes lingered on her in meditative admiration.

“Will that add to your standing? It will please you, though; you are so conservatively fond of old traditions, age, royalty, and ancient customs and manners,” said Jack, and then he smiled as he continued, “when we return home we shall look into our Almanac De Gotha, the Family Bible, and trace back to see if some of our ancestors were not Kings or Queens of the Forest Tribes. It would give such a prestige to our standing to be descended from some Esquimaux or cannibal about A.D. ——. What do you say, my cousin?”

“I say do not be profane, and I also say if that is the feeling they entertain towards us, they should come in a missionary spirit, as did Paul de Jenne or Madame de la Peltrie, and not with the insignias of Royalty.”

“Missionaries generally derive more benefit than they bestow good.”

“Oh! Oh! What egotism and malevolence! How ungenerous!” exclaimed someone.

“Are we not accusing them of faults and shortcomings of which we ourselves are very guilty?” asked Modena.

“That’s only human nature.”

“It’s a human nature we should not countenance, and seriously speaking, if seriously taken, these are only argumenta ad ignorantiam. They give us a great deal more credit than we deserve. At heart we’re only country mice sighing for our own hayricks and for some one to put a warm covering over us when the skies are stormy and cold. When we come to look at it in a right light, what’s the use of pretending to be anything else or being hurt at their taking us at our real worth?” said Modena.

“How funny you look when you say that, and all the while you look like Maria Theresa, or at least like the crown of strawberry leaves,” said Keith Kenyon, with a low laugh.

It was the second time to-night he had compared her to Maria Theresa.

She appeared to take no notice of it, but she knew that her blood ran warmer in her veins because of it.

“We cannot be honest and deny our primitiveness.”

“Oh, please don’t take life like that. If we have to live on bread and water we want to think we are really eating cake and drinking wine. One would like to see all realism buried at the bottom of the ocean. Do let us have our vanities and our ideals,” pleaded Marion Clydene, and her eyes deepened and darkened with many vague, unfulfilled desires.

“There is no vanity in the question: it is a just pride. We are just what we pretend to be,” asserted the mistress of Apsley House, conscious of the integrity of her motives in life, and unconscious of any egotism or shortcoming. “Ulysses built his own house and raft, swung his scythe and guided his plow in the patriarchal simplicity of the Homeric age. We do the same. The only license put upon Homeric Kings was the time-honored customs of the community. We have violated none to-night,” she continued, as she glanced round at the brilliant assemblage.

“Have we not? From the moment their Excellencies see your dress they will be sighing for the sweet delusions of youth, the time-honored customs of our country,” said Keith Kenyon.

“Why?” asked she, with arched brows.

“Marion’s ideals in their mind would be a tightly fitting tunic of buckskin, fringed and belled at the knees and embroidered with porcupine quills and shells, fringed leggings, beaded moccasins, eagle’s plumage in long black hair, and in that necklace, instead of those pearls, bears’ claws and snakes’ rattles.”

“And that diamond pendant on your neck would be in some dusky maiden’s nose,” said Jack, at which everybody laughed.

“You grow quite provincial in your thoughts and expressions; don’t do so, we really cannot afford to do so,” said Modena.

“You do not give them credit for much intelligence. Their education must have been sadly neglected,” insisted Mrs. Sangster, who was always too much in earnest to see the humorous side of life.

“How much better are we than the aborigines?” asked Mrs. Cecil. “We’re only savages painted white and some with red mountings.”

“But we perfume our paint and use gloves and whitewash.”

“Yes, we do,” said Jack, abruptly; “when the aborigine gave his hand to, or broke bread with another, that person became sacred to him.”

“What would you imply by that dark saying? That we are breaking her Excellency’s bread and then discussing her? It’s not a personal matter, only a political matter, and there’s a moral license in politics to say all the bad things one wishes to say about another. People do not take us seriously when we say them, and there’s no harm in it. I am quite sure she is telling Mr. Wellington what she thinks about us,” said Mrs. Cecil.

“One regrets she does not see the best of us to-night; our climate compels us, like the humming birds and robins, to migrate to a warmer climate for five months in the year,” said Modena.

“There is one thing she will regret not seeing,” continued Mrs. Cecil, with an expression of mingled regret and dismay.

“What is it?”

“That which the modern world lacks, repose, harmony and dignity—our venerable, grim-visaged, long-haired sachems with their wampums and pipes of peace.”

“Oh, no, she will not be disappointed, some of the Senators are here,” said Jack, laconically.

“Jack, that is profane!” exclaimed his cousin, irritably.

“Well, what does she see?” persisted Mrs. Cecil, who, when she had once fastened on a subject liked to worry it well.

“You open up a wide question, and of all present the most competent person to answer the question is my lady here,” said their chief, who was passing the group at the time and who now addressed the mistress of Apsley House. “She is the one who has most faith in our creeds, our country and our contemporaries.”

“Before she could answer it she would have to be like the wise sage of old, ‘Know oneself,’ and that is too much wisdom for one so young. She does not need to know, she only needs to enjoy, and this she does, and so has found the true philosophy of life,” said Mr. Lester, gallantly.

“We have been answering the question all the time with Adam Smith’s eyes, seeing ourselves as others see us,” replied Modena.

“If what Smith says is true, ‘that society is a mirror by which we are enabled to see ourselves and judge ourselves,’ then all her Ladyship can see to-night is a pack of sea-foam beauties, a crowd of cut-away cavaliers and a shoal of sentimentalists,” said Jack, with his good-natured cynical brevity.

“And some satirists, too! One would infer from your looks and tone that we were a people who needed a Persius or a Juvenal, instead of being country mice,” said his friend Lester.

“Were we the people we wouldn’t do so much talking about ourselves. The people never discuss personalities. Her Excellency’s remarks would be rich, ripe, mellow and impersonal.

“What an ungallant truism! If we don’t talk about ourselves, what have we to talk about? The weather, art, war, books? Our weather is too cold to discuss; it would freeze our criticisms. We have no art; we are under age for war; and we have only other peoples’ books. They talked when Hengist and Horsa were with them, and for many years afterwards. One does not need to rant or brag or boast, but one must do a little talking ‘to get there,’ and we’re ‘getting there’; there is more than talk behind our sea-foam beauties and our sweet sentimentalists,” said Mrs. Cecil.

“I think Mr. Mainton was very nice to say ‘sea-foam’; you know he might have said ‘soap bubble’ beauties: sea-foam suggests strength, beauty, purity, simplicity and the joy and light-heartedness which comes from something which in itself is typical of the Infinite; and then, too, he said ‘cavaliers’; that’s very nice; and he has given you credit for having in this age enough emotion to have sentiment; his words are really flattering,” said her Excellency’s niece, the Lady Greta.

“The Lady Greta’s perception is keener than our countrywoman’s,” replied Jack, as he bowed deferentially to her as she passed on, but in an aside he muttered to his friend Lester, “Isn’t Mrs. Cecil right? How much better are we than the aborigines? They at least had the decency to cover their nakedness, if it were only with a blanket, when they appeared at a public gathering, and that’s more than can be said of us.”

“It was only the half-civilized who did that; our middle classes do the same; but this monkey-gallery of ours, which we call the best, imitates the highest among our ancestors; the cannibals, you know, went to their dances and public gatherings quite full-dressed as we understand the term.”

“And they knew what they were eating, too,” continued Jack, again addressing the group, “good tender buffalo or bear meat served up in its own gravy and sirloin soup garnished with leeks, and weren’t bothering their brains over a menu of bon-bons and bouillons, rissols and ragouts, ortolans stuffed with truffles, devilled spaghetti and oyster-cocktails—”

“What a reactionist!” interrupted his cousin. “Our ancestors may have their dishes of human broth, their bear meat and birchbark canoes, but give me the nineteenth century, Government House and—”

“And this is ours,” said Mr. Lester, as the music began.

When the evening was over and they were waiting for the sleigh to be announced, the master of Kenyon Court stood in the shadows of the hall doorway, lighting his cigar and looking at the group within, where the mistress of Apsley House stood talking with Carlton Monteith and Mr. Lester. She was a very beautiful woman, having with her beauty that supreme charm which eclipses beauty, that grace, dignity, courage and harmony which are but the heirlooms of a long line of culture, traditions and the spirit of the “noblesse oblige.” Her hair was dark and waving, her skin very fair, her eyes the rich brown of the stag’s throat and so deep that they shaded into violet, and were proud, meditative, inspiring, and indicative of great reserve of resource and latent power.

She wore a long, rich ermine-lined wrap, and her head was crowned by a small ermine hat, which added stateliness to her form. As they waited for the sleigh, she pushed the mantle back, and the gorgeousness of her dress and the lustre of the satin added beauty and brilliance to her distinction. But it was not so much the grace of her bearing or the beauty of her face and form that appealed to one as the sympathy and love expressed in the depth of her eyes and the sweet smile round her proud mouth.

“Her father did not read her right, when he said that no man would ever have dominion over her life, that there was no passion in her; that would depend very much on how much she loved and how much she was beloved,” thought Keith Kenyon as he watched the scene within. “Her cousin Jack was right, when he said that her nature was one capable of great love. She does not care for the man she is going to marry,” and he smiled at something within himself, but as quickly his face again grew grave. He was a wise man and never overrated his own powers. “She is bound to him by many ties, and she is one who would consider those ties very sacred,” he reflected in after thought, and his brow drew together again in sterner lines, as he watched them take their places in the sleigh and drive away through the now fast falling snow to Apsley House.

The Wellingtons, one of the oldest families in the country, were of United Empire Loyalist descent. Mr. Wellington’s ancestor, Sir Claude Wellington, had come over from England, during the reign of one of the first of the Guelphs, as Governor of one of the New England States, and when the Pilgrim States had severed their relations with the motherland, Sir Claude, being a staunch Loyalist and firm supporter of the Crown’s authority, had refused the pardon offered and rejected the inducements held out to him by the successful Revolutionists, and, leaving all he possessed, had sought a home, or rather a refuge, in a country over which the British flag yet floated. Sir Claude and his family had then disposed of their remaining property in the motherland and had bought large tracts of land from the Home Government, on which they settled, and as time passed and they became reconciled to their life, they entered political life once more, and soon became one of the leading families in the early history of the country; and as one generation succeeded another and they became identified with the birth and development of its interests, that feeling of patriotism and possession began to take deep root, as it can only generate and grow in hearts that have been bred and born in the land of their fathers. One of the wise men of old has said, “As mortars are made by the mortar-makers, so can citizens be manufactured by the law.” But in oath-allegianced citizens there is not the seed or germ of patriotism. They will cling to that which suckled them as Romulus and Remus clung to their mother-wolf. This feeling may spring to life and grow in their children, but not in the alien born. One has to be born in, and intimately identified with the country, before he can become its child. His family ties must become wound in and out and around its trees and meadows, its strifes and battles, its sorrows and its joys, before it becomes endeared to one’s heart. And so it was with the Wellingtons. Its struggles, its hopes, its joys, its attainments, had become theirs, doubly theirs, for the seed from the motherland had never died, but continued to blossom and bear fruit through each generation, and with the blossoms and fruit of loyalty sprang that of intense patriotism for the land of their birth; and the two flourished and grew side by side.

Until ’37 they had been members of the Council, but had strenuously opposed the growing evils of the Family Compact.

The present Mr. Wellington had entered Parliament at an early age. His family had been Conservative in the true sense of the word rather than in its accepted term—that is, they believed in being governed by long-tested principles and in being governed by the best.

During their rule they had been influenced by a strong sense of duty and by a consciousness that they were the fittest to govern, and if let alone could and would govern wisely and well, their motives being altruistic and disinterested; they firmly and fully believed it was their right to govern, and that it was their duty to govern, and that they were responsible to a Higher Power and to a Higher Power alone, a sentiment no doubt, but the governing sentiment of all great men, and a sentiment that has proved the strength and stability of all great nations; but the present Mr. Wellington was wise and possessed sufficient insight to see that submission to Radical demands at the present time was the inevitable necessity, and that expediency, rather than principle, must govern, and that opposition was only prolonging events and retarding movements and changes which were in time certain to occur, because, as he sadly realized, the best had abused their privileges, and the people were almost as a unit demanding reforms in the name of right and liberty.

As far as it lay in his power to do so, he continued to oppose the extreme views of democracy, which had sprung out of the troubles of ’37, but was forced by the spirit of the age to bury his old Conservative convictions, and with his co-patriots attach the Liberal to his name and accept, promote and enforce the principles and progress that the rising generation were demanding as their rights; but as year after year passed by, and as he realized that they were being deprived of their power to do good, and that each year power was slipping more and more from their order, he could not quite subdue a tinge of regret and sadness, which in later years, as the fruits of democracy and the evils so instinct within Responsible Government became more and more apparent, sometimes amounted to resentment and irony.

He had grown up side by side with men who had given their strength, their manhood, their intellect and even their life’s blood to and for the young country, and who had passed away or were now passing away, and as he realized the ingratitude, the misrepresentations, the superficiality, the ephemeral and transient feelings of the present age towards those or towards the memory of those who had fought and died, at times his loyal and tender heart hardened as Scipio’s had done towards the country for which he had given his all. Such feelings as these were not caused by any impatience to consummate his own plans or to bring glory to himself, but only came in those moments which come to every man who has the country’s best interest at heart and who is governed by high standards of action, but who grows disdainful when he contemplates the frailties, the low standards, the ingratitude of human nature and the inherent corruption of modern forms of government. But as such feelings as these passed over his soul, as a wailing chord passes over the strings of a lyre, with great force of will he would rise above them into a broader and higher atmosphere, and like the brave in every line of life he would again throw himself into the fray and do what he could to fulfil the aim and object of life—that of making the world brighter and better.

He had been a strong advocate of Confederation, and had since then been intimately connected with the many movements for the welfare of the country and its people, and was at the present time second minister in the Cabinet and the Chief’s personal friend and adviser.

While travelling in England he had met Marguerite Modena, who was closely related to the famous hero of Waterloo. The following year he had returned to England, and there they had been married. He brought his young bride to his home, and here in the full glow of health and eagerness of life she entered into his ambitions and plans for the civilization and aggrandizement of the infant country.

Her presence soon began to be felt; institutions sprang into life; charities were established; learning began to disseminate; elegance and refinement made their appearance in high circles, and her unconscious influence wherever she passed made life better and brighter for those around her.

But death claimed her at an early age, and when he who loved her so well laid her away beneath the sepulchre of ebony, inlaid in onyx and gold, which ever stood ready in the cloisters of the old Ursuline Chapel on the family estate at Fernwylde, he buried with her all that was brightest in his life. Life was never the same to him again; but he did not succumb to the loss. Their bonds had been too strong for even death to sever. She was ever present with him. Although an invisible and inexorable barrier divided them, it was not strong enough to keep them apart. Although he could not see her, feel her, caress her, or hear her words of love and solace, they were all there ever with him, his guide, his inspiration, his star.

Instinctive hope and philosophy had told him that this world was but an ante-chamber to be used as a preparation to a higher life where things would be better understood. She had but gone “to those blissful climes where all knowledge is gathered in the cycled times,” while he was left to wander on a darkened earth “where all things round him breathed of her.”

She was but waiting for him there; thus perforce had he to strive the more to make his soul mate for hers in that clearer air.

He had resolutely taken up the threads of life where they had been snapped asunder and had gone his way, giving his talents, his energies and his ambitions to his country and to the education of his only daughter.

His daughter resembled his family. The truth of the old adage, “L’enfant de l’amour resemble toujours au pere,” was verified in her. The women of his house had been noble women—women who had invariably built their lives upon great principles and traditions rather than women of sentiment. His daughter possessed the qualities and attributes of the women of his house, but she had also inherited from her mother a lovable heart, an amiability, a tenderness and pliability which had softened and made more womanly her whole character.

He was immensely wealthy, possessing several mines, many houses, and various estates in different parts of the country, but the homes dearest to them were Fernwylde, the old family estate, and Apsley House, the noble and historical home of his fathers.

The first of the Wellingtons had bought Apsley House when it was but a French chateau from a member of one of the oldest families of France.

When Louis, the father of the country, had sent out the Carignans, one of the head officers, an associate of Colbert’s and a pupil of the famous Lebrun, being of an aspiring and sanguine disposition, had been deeply impressed as he sailed up the great river to the Key of the Virgin Country, with the beauty, fertility and extensiveness of the world before him. Who can tell what dreams and what visions filled his mind as he stood on the heights and gazed over an unsurpassed, almost an unequalled panorama, as his predecessor Champlain, filled with the feu sacre, the Amor Patriæ, and visions of a New Empire, had stood in the door of his Chateau St. Louis on what is now called Durham Terrace and had gazed on what appeared to him an earthly paradise! He had but left a Court, one of the most brilliant that ever breathed, and united to its brilliance were both aspiration and intrigue. No doubt, as in Frontenac’s mind, visions of a New France and a miniature Versailles may have entered his; at least he undertook to build himself a mansion in miniature patterned after his home in that smiling Sun-King’s land.

In the midst of his pagan paintings, sculpture and architecture he died, but these were carefully preserved by his family, and years afterwards, when Quebec became the scene of so much turmoil and strife, the family removed to the Queen’s City, taking with them the pagan painted ceilings, the mystic embroidered tapestries, the lancet and oriel windows, emblazoned and deeply embeyed, the valuable carvings and unique collections of art, and bought the picturesque grounds where Apsley House now stands.

The octagonal chateau was built on an eminence and the grounds laid out in lawns, rose-gardens, hothouses, and woody terraces sloping to the little lake, an expansion of a stream which ran down to feed the great river.

Surrounding the grounds were low, ivy-covered stone battlements with massive iron gates, the pillars of which were capped by bronzed lions and on the panels of which were carved the emblems and arms of the Wellingtons.

Broad driveways and walks traversed the grounds and led up to the main entrance, which was a canopy of carved stone supported by massive pillars resting on some of the antique carved pedestals of the Carignans.

Wing after wing had been added by each succeeding generation, until it was now one massive pile of architecture with towers and turrets and soft-tinted windows standing fair and clear against the northern sky, or losing themselves in the hoar frost or rain mists so prevalent in those parts.

On passing through the massive doorway at the front one entered a large octagonal hall which reached to the dome of the house, with a ceiling of the famous paintings. Broad, heavily carved oak stairways in winding curves led to the upper stories; there were several large drawing-rooms and reception rooms with their emblazoned panels and carved mantels, and containing treasures of art from all parts of the world; state dining-rooms with polished floors and Venetian mirrors; long galleries containing, besides the family portraits of generations of Wellingtons, many paintings and pastels from convent and studio, from the classical cities of the Continent, while the library, which had done so much to make the women and men of the house ladies and gentlemen of letters and culture, was considered the best in the city.

The octagonal chateau with its colonnades of porphyry, its mystic painted windows, its mahogany carvings and old tapestries, had been left unmolested, but the present mistress of the place had taken some of the rooms for her own private apartments and had converted the others into a music room and art room combined. It was the most beautiful room in the city, with its St. Cecilias and cherubim, Orpheus with his lyre and Pan piping, peeping out from softly draped windows, while Isis, with her anemone in her hand, and Cupid with his bow, rode on high.

It was here at Apsley House, when not travelling abroad, that Mr. Wellington and his daughter spent many months in the year, but they also spent part of every summer under the maples, the oaks and beeches of their old family home of Fernwylde.

Fernwylde, a few miles from the suburbs of the city, was a remarkably beautiful and fertile estate of many acres, richly wooded, shut in, lonely and stately, away from the hum and stir of man, by a circlet of cascaded waters, heavy Siberian pine forests and the towering summits of its own hills.

In the early history of the country it had been the home of Champlain, who had chosen it for its rugged grandeur, its frowning outlines, the wild primeval aspects of its heights, in such striking contrast to the repose, the serenity and fertility of the scene which lay within its lap.

In the heart of the amphitheatre lay a little lake, lovely and limpid. On the lake shore nestled a monastery, a relic of the days when the church was the “Portals of the Poor” and “Faith was Food,” now the home of a once far-famed dignitary of the church but now a solitary, a seer and a scholar, and some few Jesuit priests who devote their lives to the welfare of the poor. The monastery was long, low, moss and ivy-covered without, but rich with art and literature within, and was almost as hidden beneath the willows and larches of the lake as the oriole’s nest in the trees overhanging the waters.

The monks had given to it their air of peace and repose: its cloisters were cool, calm and consoling; on the evening air its bells would chime forth their Agnus Dei, or an Ave Maria would float peacefully upward, bringing with it rest and sustenance to the villagers after their day’s work was over.

It had been there longer than any of the villagers could remember. It had been there when the present mansion had been but a French chateau; each habitant loved it and felt it was part of his home, and was free to go to it when he would.

Late in the eighteenth century the French chateau had fallen to decay, and now in its place, throned on a hill in the heart of the home, an old Gothic mansion rose, homelike and stately, many-turreted and pinnacled, with its colonnades of grey stone and white marble and its stone staircases leading down the many terraces to the water’s edge.

While the interior had rooms magnificent and stately, on the whole they were more comfortable and homelike. In many of the rooms were the old-fashioned fireplaces with their brass andirons and carved mantelpieces. For many months of the year fires were kept burning on the hearth, for it was its mistress’s delight to run out at all seasons of the year for a few days with intimate house-parties.

When she could leave home she invariably came to Fernwylde, and the happiest moments of her life were spent in and around the old Fernery.

The old Fernery had been built by a former Wellington. It stood at some little distance from the house and was built of massive fire-proof material, and contained large vaults in which the Wellingtons, when leaving their homes, had stored their plate and valuables, but of late years there had been added picturesque porticoes, rustic arbors and alcoves, and several colonnaded rotundas, while at the western side, facing the Idlewylde, was an immense bank of ferns, from which it derived its name.

It was a spot dear to all the country round; one of those spots that tend to make a place a home, a place associated with and consecrated by old tales of love, of family joys and sorrows, loyal traditions and sacred memories.

From childhood its present mistress had dearly loved the old home, and had spared nothing to make the place beautiful and its people happy.

One felt, when approaching its precincts or when entering the portals of any of her doors, that odor and essence of beauty and refinement, that harmonious blending of good taste and magnificence, that silent sympathy and repose which only cultured people can impart to a lavish display of wealth and which alone can inspire ease and true enjoyment within those with whom one is associated.

When his wife died, Mr. Wellington had obtained the services of Mrs. Gwen, an old friend of the family’s, as a companion to his daughter. The other members of the family were Jack Mainton, a nephew of Mr. Wellington’s, and editor of one of the government organs, and Marion Clydene, a daughter of one of Mr. Wellington’s schoolmates, who had died, leaving his only child under the care and guardianship of his life-long friend.

Mrs. Wellington had died while her daughter was yet young, and this had caused Modena to take her place and perform the duties and receive the honors of their homes at a very early age.

Her father’s position entailed much hospitality and much entertainment, and the onerous task had fallen upon her. Her early and constant association with the political world had greatly increased her intelligence and intensified her perceptions, while her responsibility and position had added age and dignity to her youth. She had reflected on and comprehended things much beyond her years, her manners and intelligence being those of a woman of mature years, whereas she was but nineteen.

She dearly loved work, and the work most congenial to her was that in which she was engaged; that of being, as in her youthful enthusiasm she believed herself to be, the Mentor and Mascot, the Lady Devonshire of her own father’s cause.

She believed that great things could be accomplished socially, and was the first to introduce a new era in her country’s politics.

She came from a race who possessed enough greatness within themselves to want no greatness from without. Her one desire, then, was to live well, and to live well one must to a great extent live for others. She loved the world at large, and had within her a great desire to establish conditions which would enable the people on the whole to live temperately and liberally. The cruel contrasts of civilization with which she daily came in contact were to her a constant source of thought and reflection, and engrossed her mind to such an extent that all things else seemed immaterial to her.

But, while her mind was engrossed in her father’s cause of laying the foundation for these conditions and in legislating and in the administration of justice, she was also active in individual cases.

Life to her was a sacred trust; its smallest details serious and important. Like Maria Theresa, she believed that “In our position nothing is a trifle.”

She was known and beloved by the working classes in many parts of the city, and there was not one on their vast estates or in the different works belonging to her father but obeyed her slightest wish. “I have not done anything but what it is my duty to do,” she had once said to one of her father’s employees, who had been helpless the whole winter, and who had depended altogether on her charity for the support of his wife and three little children, and who was blessing her for her kindness.

“Oh! it is not only what you give us, but it is the kindness; you do not appreciate kindness because you have been so accustomed to it that you have become insensible to it; it is different with us. It is almost as nourishing as a meal of meat and Madeira,” he continued, with a deeper feeling than one would expect in so rough a miner.

But, although she was a strong advocate of justice and right to the masses, the democratic tendency of the age was abhorrent to her. “Blood tells,” she was wont to think, “more than any one knows, or thinks.” Generations of culture and intelligence are more capable of ruling for the general welfare of the masses than illiteracy and its companions. Our order is the product of generations of development. It is our privilege, our prerogative and our duty to rule, was her creed.

The next evening after her Excellency’s reception she had gone to a Musical at Monteith House, and she had there said to Mr. Lester, who had but recently returned from studying social conditions in New Zealand, and who was expatiating the merits of the democratic basis of that country. “Equality is impossible, and were it possible it would have the tendency to vulgarity. Variety is the law of life. All republics have their slaves, from Sparta to a bee-hive. It is our prerogative to rule. It is our own fault the people rebel and grumble and do not respect us. If we would only assert and maintain our rights and privileges and make them feel we are leaders in reality and worthy of respect, as did Pitt and Colbert and Marie Antoinette, then it would lie within our power to be good and to do good; but we do not do this; we have lost our courage and our faith in ourselves as leaders, and instead of leading, we follow.”

But Mr. Lester had replied, “The day has gone by for that sort of thing, as Burke says, ‘Never more shall we behold that generous loyalty to rank and set, that proud submission, that dignified obedience, that subordination of the heart which kept alive even in servitude itself, the spirit of an exalted freedom.’ Alas! this is the age of Equality, Right and Reason.”

And Modena had looked at him, not being able to accept or to comprehend all that his truism entailed.

“If the day has gone by we should revive it again; one’s feelings, as well as one’s example, are contagious; and if we haven’t faith and hope and ambition and a strong sense of duty, the people will not have them. It rests with us what our country will become.”

And Mr. Lester had looked at her as she stood before him in all her girlish faith and fervor, and his eyes had deepened and then had saddened as he remembered.

He had had his youthful dreams and his illusions; many times he had been beaten by the rods of the world’s base ingratitude. He had been in earnest, and he had cared and he had suffered. But his eyes again brightened as he remembered. The shadows of his life had begun to lengthen into afternoon, but there were many, many landmarks by the way, and his disillusions had culminated in a wider and greater hope. “Her faith and her fervor were the very essence of life,” he was sure, and he bowed low and deferentially over her hand as he murmured, “Rest assured, my dear, that the unconscious influence of a good woman is greater than all social theories; you are a noble woman.”

And Jack, who was a dozen years her senior, and had seen life in all forms, and who now stood beside her, pulling to pieces a withered rose and rolling the dead petals into a hard mass in the palm of his hand, was inwardly comparing it with his cousin’s hopes and enthusiasms.

The rose had been full of life and beauty when it had left nature’s gardens, but the heated breath of artificial life and contact with the crowded mass had withered its petals and impaired its beauty and fragrance. Unconsciously he recalled Apollo’s words, “Why should I fight for the sake of those miserable mortals who, like the leaves of the tree, last but a short time and then wither and fade away. Let us refrain from fighting and let them carry on the war themselves.”

But this is what Modena had no notion of doing. She did not believe the world to be a world of miserable mortals, but a world as dear as that upon which Phaeton in his Palace of the Sun had gazed with outstretched hands for the reins of the immortal chariot to light the world, and she, as he, was all ambition and sincerity. Experience and the strifes of life had not as yet lifted the rosy veils from reality or washed her eyes with the collyrium of disillusion and shown her things as they really were in their nudity.

“How are you, Mr. Lester? Do you want a walk before dinner? I am going down to see Mrs. Byers; I heard to-day her husband was without work,” said the mistress of Apsley House the next afternoon, as she met Mr. Lester coming home from the House.

She was dressed in a street costume of dark blue trimmed with sable, with hat and ruff to match, and was accompanied by her favorite St. Bernard, Nell Gwynne, and her King Arthur greyhound, Cavall.

It was a wild winter’s day; heavy wracks of clouds were sweeping up from the west; great gusts of snowflakes came up the streets, while the leafless, wind-tormented trees wept, and sighed, and bowed their heads in the dull grey afternoon air.

The cold air blew in her face, tinging it with warm color, while her firm elastic step and litheness of movement told of the great vitality within.

It was fully two miles to where she was going, but she courted the long walk. She loved action. Mr. Lester had frequently accompanied her on such visits, and his face now lit up with pleasure as he raised his hat and turned to go with her.

“There are many unemployed; one fears it will be a very severe winter for some,” he replied, as they resumed their way, Nell Gwynne following, carrying a basket of fruit and flowers for little Lone, who was ill.

“And what are we to do?” she asked. “I spoke to father to-day regarding Mr. Byers, and he said they had too many men now, and were only working part of the time in order to provide employment for all our own men.”

“It is difficult to do anything in a case like this; one cannot offer charity. If poor, they are proud and sensitive, and the pity of the world is to them infinitely worse than its poverty. When one cannot go and say, ‘Mr. Byers, we want more men and will pay fair wages,’ what can one do?” asked Lester.

“When one cannot say that the government should be prepared to say it.”

“Oh! Oh! that’s a very serious assertion; you would advocate its engaging in public works to employ its unemployed. We are yet too young for that.”

“It would be advisable as an emergency,” she replied, as they passed by some large works which had been closed for several months.

“That is very fair in theory, but practice requires the money. Are we not already over-burdened with taxation?” replied Mr. Lester, as they left the thoroughfare and turned towards the lumber districts.

“We could tax the rich to furnish employment for the poor.”

“How would you justify such a course?”

“Labor is the source of all wealth, and if labor fails its product should support it. Nature has her own laws, and this is one of them, or if you will permit me to use another person’s words in lieu of original ones, what we want is, ‘An intelligent principle of law and order in the universe embracing equally man and nature.’ ”

“That’s Plato’s definition of God. Yes, we want it, but we cannot find it. Sometimes it hides itself in funny places on cold days like these.”

“That’s not an expression worthy of you. That is so like our conventional religion which clips and fits the ways of Deity to suit its habits and wishes. If things are wrong, they are the result of our own actions,” replied his companion, gravely.

“Then nature has nothing to do with it?”

“It is not nature that is complaining. Fernwylde wears coarse shoes, woollen stockings and homespun, and they are happy and contented. They are kings and queens on their own estates. It is not the plowboy or the milkmaid, but the mechanic. The modern world has given us the machines. The shop has been the loadstone to the youth and the succursal of the country’s sinews. It has failed for the time being. Its product should now support its source.”

“Who would believe that we should ever hear you advocate Socialism! Last night you were condemning equality.”

“I am not upholding it now.”

“Then your hair-splitting is too fine for my dull eyes and mind.”

“Our wealth is only a trust. We are the guardians of the goose that lays the golden egg. We must not necessarily kill the goose and distribute its bones and flesh equally among our fellow-men. It would do no good if we did. In a few years—very few—conditions would again be the same as they are now. Social grades, distinctions, barriers, all those things are a necessity. The King must guard that which he rules; he is but a hind to whom a space of land is given to plow. Duty is our weapon against envy. It is our duty to guard the goose, but it is also our duty to judiciously distribute the golden eggs equally.”

“You would be a parent to the poor—guardian, rather?”

“I would have intelligence and give justice. Our aim of late has been to encourage the manufacture of machinery. We have tempted the youth from the sod. As we said a moment ago, there is now a temporary depression; we should furnish that youth with employment.”

“You would encourage laziness; no, not laziness, but thriftlessness. It would only dull their invention and ambition and do for them what the machines have done—make them machines instead of artisans. The individual has his duties to perform, and his first duty is to provide for himself, and experience has taught us it is a dangerous thing to intrude on private rights or duties.”

“The State has its functions to perform as well as the individual. Is not the individual’s first duty to the State? Therefore the State’s first duty is to the individual. Its chief object should be to provide conditions in which the people are enabled to aim at the highest and best life possible. It should provide for the happiness and welfare of the many, not the few. At least that is what Aristotle tells us, and all wise men since have upheld his philosophy. It is really the only permanent basis. It is the only basis which will endure. Ethics and politics are inseparable; we want men of intelligence at the helm, with ethics at one end and economics at the other. Our State must have been negligent in some way or we would not now hear those bitter cries. One fears and regrets that in a great many ways it is providing for the few, not the many. We have been raising our voices, but of no avail. It is so often the lost causes which are the noble ones, but since it is so, there is no use wasting one’s time regretting it; all one can now do is to remedy the evil.”

“The evil cannot be remedied; it is easy to philosophize, but all theories and political schemes are impracticable and unworkable, because it is an impossibility to reconcile property, poverty and population. Even your sage, with all his wisdom, in working out a theory advocated and practised infanticide. You surely would not countenance that.”

“There is no need to countenance it. We give bonuses to increase the population.”

“Then the theories which apply in one case will not apply in another.”

“Pardon me! Don’t you think they will? The principles always remain the same; it is only the outside drapings that must be clipped and embellished as the existing circumstances require. It is because men have abused their privileges and forsaken principles that we have this state of affairs. Come here, Nell Gwynne,” she called to her St. Bernard, as she saw her deposit her basket on the frozen snow to defend it against the attacks of a huge mastiff that persisted in sniffing at its contents. “I am afraid we are like Plato’s philosophers,” she continued, smiling, “we have been sky-gazing and failed to see actions and events that are tumbling about at our feet. Poor Lone! Our philosophizing nearly cost him his hot cutlets! He may thank Nell Gwynne for them. She is like Ulysses’ dog, faithful to its trust.”

“Your moral would be to become like Nell Gwynne and cease sky-gazing,” said Mr. Lester, smilingly.

“No, it would be a proper mixture of sky-gazing and common sense.”

“You mean a mean state in life, I am afraid, that can never be,” continued Mr. Lester, gravely and sadly, as they passed some thinly-clad, shivering children, who were returning home to the poorer districts after having delivered the night-men’s evening lunches in the lumber districts. “It seems impossible to establish the system which your sage recommends, that of limiting or providing each man with sufficient property to live temperately and liberally. Doesn’t More tell us, in his ‘Utopia,’ he saw nothing but a conspiracy of rich men procuring their own commodities under the guise and title of Commonwealth? It has ever been thus, and no doubt ever will be thus, until ‘kings have become sages and sages have become kings.’ ”

“But surely, if men will but use the brains and muscles with which nature has endowed them, they will always have the necessaries of life, and the luxuries do not count,” he continued, in an after reflection.

“They do not count if we have a society that looks at things in that light, but our society judges us by our appanages, and when one is in Rome one has to do as the Romans do or she or he is unhappy. The individual is nominally free, but he is also powerless in a world bound hand and foot in the chains of economic necessity and social demands.”

“It would not make me unhappy.”

“No, because you do not care for the world’s opinion. You have the courage to live your own life; but yet, pardon me, if I am too personal, but your happiness is dear to me; you are not always happy. You are sad, at times almost melancholy to pessimism. You have too much of Shelley within you. You rebel against existing circumstances. You are extremely sensitive to what seems to us the cruel contrasts, the rank injustices, and the precariousness of human life. You are continually wondering why this should be. You would find the Heart behind it all—”

“Is there a Heart behind it all?” interrupted Mr. Lester.

His companion looked at him quickly.

“Pardon me. I didn’t mean to say that: forget that I said it. You have found the Heart?”

“Decidedly so. And Mind, too! These contrasts are a necessity, and an evolution from the very nature of things. It has been ever thus, and I suppose ever will be. You remember the story of our own beloved Thor and his going to the land of the Jotuns with his hammer-bolt and his staunch henchman Thialfi, which, by the way, was Manual Labor, and of the great feats given him to perform—the Drinking Horn, from which he drank long and fiercely, but of no avail—the Old Woman with whom he wrestled, only to suffer defeat—and the Cat which he failed to lift—and then Skrymir’s voice, the Earth. ‘You are beaten, yet be not so much ashamed; these are only appearances: The Drinking Horn is the Sea, the Old Woman, Time, and the Cat is the Great World-Serpent, which, tail in mouth, girds and keeps up the whole Created World; had you torn it up, the world must have rushed to ruin.’ Thor’s resentment, and the Giant’s mocking voice, ‘Better come no more to Jotunheim;’ grim humor resting on earnestness and pathos like a rainbow over the tempests of nature. And the world then was young! Ah, how little it has changed! The same World-Serpent and the same Thor cries! What you lack is philosophy. The philosophy of accepting things as they are and going on towards your Ideal. Your happiness depends upon philosophy.”

“I thought happiness depended upon the heart.”

“So it does, but philosophy sets the heart right.”

“You are happy?”

“Yes, happy every moment of my life: happy as the birds in the tree.”

“Even when you have the toothache?” Mr. Lester smiled; his companion smiled too.

“Why will you suggest such a pertinent thing?”

“Be truthful.”

“Oh! no one cares to have the toothache.”

“Why do you have it?”

“One wouldn’t have it if one could help it; nature must answer that charge.”