* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: The Master's Wife

Date of first publication: 1939

Author: Sir Andrew MacPhail (1864-1938)

Date first posted: 22nd October, 2024

Date last updated: 22nd October, 2024

Faded Page eBook #20241009

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, Pat McCoy & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

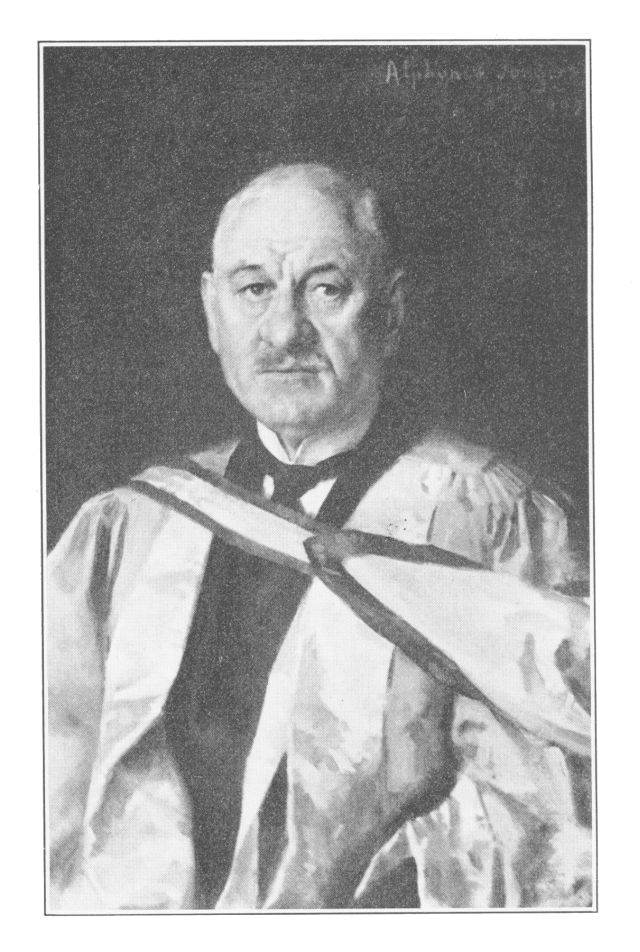

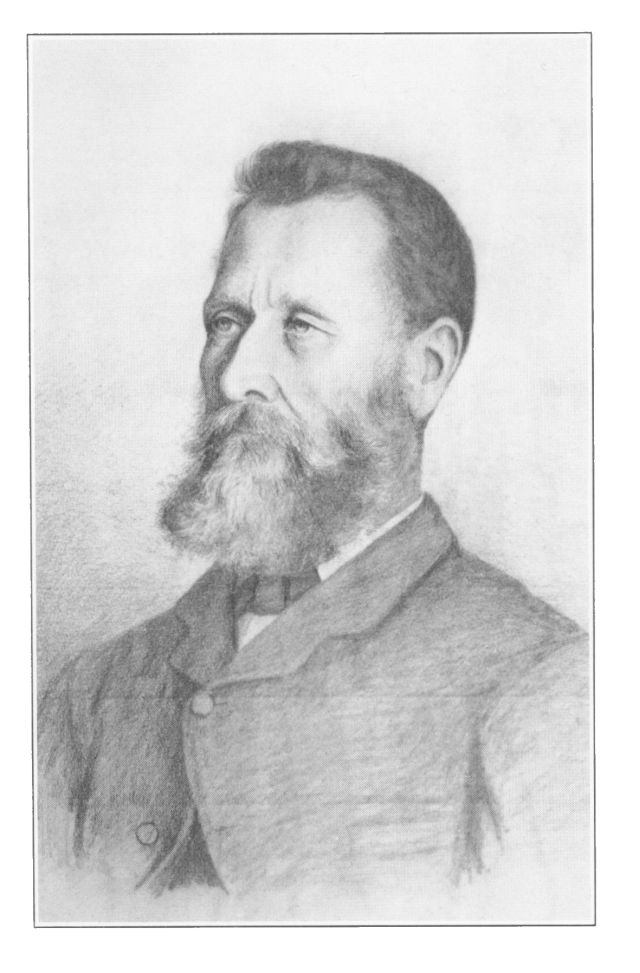

SIR ANDREW MACPHAIL

THE MASTER’S WIFE

By

SIR ANDREW MACPHAIL

(1864-1938)

Jeffrey Macphail and Dorothy Lindsay

MONTREAL

1939

Copyright 1939

The Gnaedinger Printing Company

Montreal

To

Jeffrey and Dorothy

“Good children”

CONTENTS

| Page | ||

| I. | In the Beginning | 1 |

| II. | The Spar-maker | 6 |

| III. | Her People | 16 |

| IV. | The Immigrants | 26 |

| V. | The New World | 37 |

| VI. | The Master Himself | 52 |

| VII. | The World of Sin | 63 |

| VIII. | His Mother | 73 |

| IX. | The Old House | 87 |

| X. | The Economy of the House | 98 |

| XI. | The Written Word | 110 |

| XII. | The Two Races | 121 |

| XIII. | The World of Religion | 126 |

| XIV. | The World of Nature | 153 |

| XV. | The Open Door | 159 |

| XVI. | The Escape | 174 |

| XVII. | Her Humanity | 189 |

| XVIII. | The Two Horses | 201 |

| XIX. | The Musicians | 210 |

| XX. | The Two Princes | 222 |

| XXI. | The Spirit of War | 228 |

| XXII. | False Pride | 239 |

He was master of the school: she was the Master’s Wife. He was my father: she was my mother. Happy the man, says Ronsard, qu’une même maison a vu jeune et vieillard. It is of that house and place, in which I was born, in which I still live, and of those who dwelt therein, that I propose to write, with such skill in the use of words as I first began to learn in it, and have ever since striven to perfect. The remembrance of any life, rich and fresh, should not be lost to the world.

The house and place was Orwell, in Prince Edward Island, correctly known as the garden of the Gulf of St. Lawrence, a world at the time as new as that primeval garden in which other two parents were first blessed, and then faced with the sudden problem of extracting their living from the soil.

The Master and his wife had seen immigrant families who lived in caves of the earth, in shelters built of logs, in houses sawn from the forest by their own hands, and finally in commodious dwellings; but she lived to see one of those houses grow into a place suitable for a table whereon the proper complement of wine glasses might be displayed at one time for the refreshment of important persons. Between these two extremes the whole course of civilization flowed. The history of that old house is the history of man; it is contained within the period of a hundred years. The house may well be called old, for in it five successive generations of one family have found shelter.

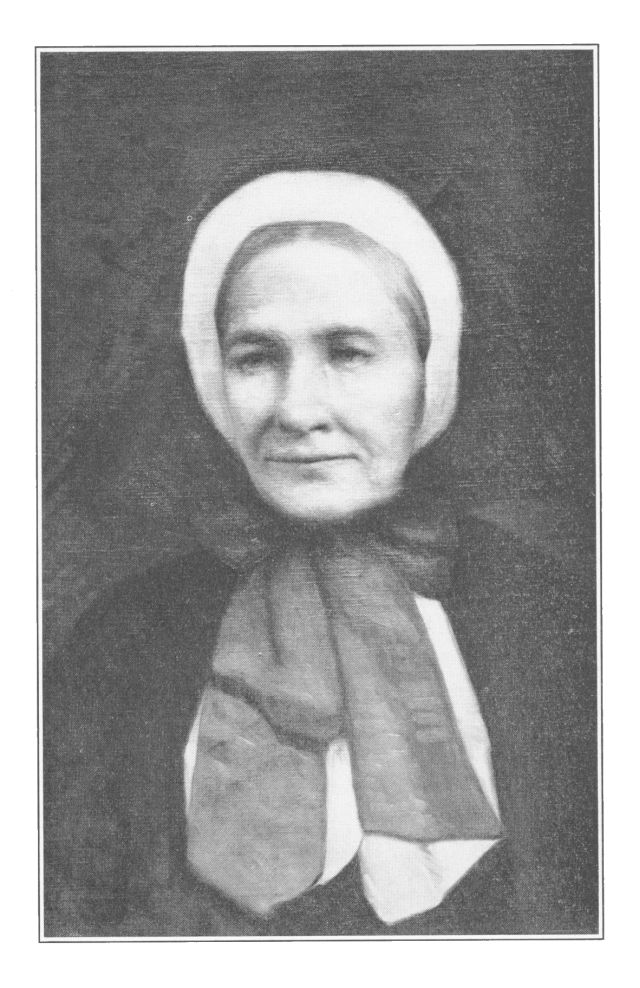

The Master’s wife was commonly described as a “Smith woman,” that is a foreign person whose native place was some miles away. She disliked the designation, as he had the whimsical habit of attributing any peculiarity of conduct in his children to their maternal ancestry. Loud talk, dubious words, inaccessibility or disdain of religious ideas, hardness of heart, pugnacity, a precocious fondness for tobacco or alcohol found that ready explanation. Heredity might be accepted as a fact: it never was allowed to serve as an excuse. Infantile misconduct was merely an aggravation of the sin of Adam, and so liable to the paternal displeasure as well as to the divine wrath. In the mind of the child these two consequences were one and inseparable; he always considered “Adam” to be the generic name of his mother’s people.

And yet even a child was quick enough to discover this rift in the family discipline. We were a family of ten, and ten children in a moderate house must be kept under a strict control if life is to be at all tolerable. The discovery came in a simple way. Her uncle was a sea-captain by a brevet conferred by himself. At the conclusion of every voyage he would come to see us. He rode upon a horse, as the journey was one of five miles through the woods, across the source of streams. He always brought some small presents, a piece of silk, a box of spice, a parcel of strange green tea, a white loaf of sugar, a bottle of French brandy.

His coming was such a tremendous event that the Master found himself quite powerless. Indeed, he could not conceal his own interest and pleasure in the prospect of a breath of intelligence from the larger world. The sea-captain rode solidly, and there were plenty heralds of his approach. As he came up the garden he addressed the Master as William, his wife as Catherine, in a voice as if he were hailing a man in the top. The children were rather embarrassed being witness to the familiarity of his address to persons so august. When he came within, and had distributed his gifts, he called for glasses, and produced his bottle. She understood the ritual, as if she were assisting at a rite which she had long since learned; and we began to suspect a world of experience before our arrival upon the scene.

With his powerful hairy hands the captain sent the tongs crashing through the sugar-loaf, until the whole glistening fabric lay in white lumps upon the table. For the adults he poured hot water in the glass, dropped in a lump of sugar, and filled it up with brandy. He put neither water nor sugar in his own. For the children he put the remainder of the sugar in small glasses until they were full. Then he saturated the sugar with brandy, and handed a glass to each from the eldest to the youngest. The Master sipped his drink with a restraint which was not quite sincere; his wife set her portion in the cupboard against a more leisured moment; the grandmother drank freely, and her eyes shone. The taste of that sugared brandy was delicious in the mouth, and more than one child framed the vow that some day they should have a bottle of their own. They have kept that youthful vow.

When the time came for the sea-captain to leave, he put the remnant of the bottle in his saddle-bag, with a word of apology for his parsimony, “I shall be calling at Nancy’s.”

“And you will tell her we are all well,” the mother charged him.

“Yes, and that they are good children,” he said as he scrambled upon his horse. The Master winced under the concession; the mother smiled at the approval.

“Good children,” he repeated. “And I will tell her too,” he added in his loud chanting voice from the top of his horse, “a man might be amongst them for a week, and not hear as much as ‘God damn your soul.’ ” It was not long before one of the children employed this form of words deliberately and publicly, and when put to the question, quoted his uncle as his authority. The defence was a complete success. He was well aware that his mother would not allow the custom of her family to be impugned beyond a certain point. But he did not repeat the experiment.

It was from this uncle we first learned that there were strange themes in the world, fresh words, and new rhythms, hitherto undiscovered in catechism, Bible, or prayer. He talked of ships and the sea. On his last voyage, during a storm a Russian wished to have a reckoning of his position. The incident was amazing. This man who now sat quietly in that retired house had been in a ship-at-sea in a storm. He had encountered a Russian, or a “Rooshian,” as he called him to our secret amusement; and the Russian was compelled to avail himself of an intelligence superior to his own.

But the sound and savour of his words instructed us even more than the narrative: the Russian was a barque; he ran down the wind; he came up under my stern—an immodest word to use in presence of the Master. He hailed me and asked for his position. He could not hear; I took my speaking trumpet; yet he could not hear against the wind—unshipped my cabin door—wrote with a piece of chalk—slung the door to the starboard mizzen shrouds. He lifted his spy-glass; bowed to the deck; and squared away.

The Master’s wife was the daughter of a spar-maker. To make a spar in the craft of ship-building is like making a sonnet in the craft of letters. He moved from place to place where a ship was being built and ready for her spars. A spar-maker works alone as a poet does. He would set up his benches in a retired grove apart from the yard; he would eat and sleep by himself. His work took him as far as the Miramichi. In that strange place his custom was not known, nor his reticence, as he thought, sufficiently respected. A sailor was incautious. He struck the man with his fist and killed him. The Smiths were a passionate people.

That is the account given to us by his own first cousin, but this cousin was always considered a boaster. We often asked the mother for the truth of the matter, but she evaded a denial. She always disliked the categorical answer. She too wished her family to be thought well of. She did add, however, that her father was a tall straight man with a brown flowing beard; and she had heard that his forearm was as thick as another man’s thigh. The utmost she would admit was that if he had struck the sailor he would have killed him, and “it served him right.”

In later years we often discovered that she had old and secret wishes which we did our best to satisfy. One of the things she “longed for all her life” was to have a suitable stone erected at her father’s grave. At a time when the old family property was “passing to strangers,” she had the design to make that claim, but she concluded it would be just as well to “let the tail go with the hide,” and nothing was done.

I went to the man in Montreal who usually supplied me with grave-stones, ordered a proper monument of granite, and wrote for him the necessary inscription. As he put on his spectacles to read, he said, “I suppose you are in a hurry for this.” When he observed that the date of the death was 1854, he added, “The man has been without a stone for sixty years, and I suppose a week or two either way does not matter.”

In due course the stone arrived, and a day was set apart for its erection. We drove to the cemetery, six miles away—the mother and three of those children, now themselves grown old. Whilst the men were at work, we lit a fire and made tea. We had luncheon in the open. Then she led us about the cemetery, and using each stone as a theme instructed us in biographies that went back a hundred years. She showed us one of fine slate, with the top gently curved, and the apex polished smooth. Sixty years before, she had seen the Minister McLennan sharpen his razor upon that surface preparatory to his Sabbath morning ceremonial. She showed us the first stone ever erected. It bore the name MacMillan. This man was hewing a sill for the original church, and wondered who would be the first to be buried in the fresh graveyard. He himself was.

The monument that aroused her deepest interest was one erected to the memory of a woman who was described upon it as “daughter of the Earl of Selkirk.” She admitted that she knew the woman, “when she was a young girl,” and added, “She used to eat opium, and would walk to the town twenty miles on the ice for the drug, scattering salt before her as she came to a slippery place.” There were no rubbers in those days. Here was an old tragedy. She would say no more. “But it is on the monument,” we pressed. “You cannot believe all you see on a monument,” she said. “You will be putting things on my own that none of yourselves will believe.” But the inscription to the Earl’s daughter is there to this day in the Belfast church-yard, which is now the name misapplied to that lovely region known to the earlier French settlers as Belle-Face.

Her father had taken to wife Margaret Moore. Some said she was part English; others said she was part Methodist. It may have been so. That would account for her own extreme toleration. On several occasions one heard her admit that she had known “many good people among the Methodists.” Indeed there was a further traditional ancestress, Margaret Mayne, “a red haired woman, the most beautiful ever came out of Ireland.” In her hypothetical descendants there is more trace of the redness than of the beauty. The legend may therefore be half true. The Moores lived, and still live, on the rich land that slopes down from Tea Hill to Pownal Bay. There is yet the remains of an old ship-yard at the shore, and it is easy to surmise how the tall straight powerful spar-maker with the flowing brown beard found a wife.

Moores of the third and fourth generation yet live in that old place. It lies on the way from Orwell to the town. We often pass it by, but rarely enter, as the ceremonial of a call would occupy two days at least. At times and in various places one meets the elder occupant, and there is a sudden gush of affection.

The spar-maker died, and left a family of young children, two sons and four daughters. He had no foothold in the land; he followed where ships were built. His children were scattered. Two sons and their mother went to Georgetown to the house of an uncle whose name was John. He was known as “Major,” for no better reason than his rank in a regiment of militia. According to the account given by the Master’s wife, he was a merchant; but we always suspected that the commodity he traded in was rum. Certainly, at Christmas time he would spend the day at his old home, a distance of fifteen miles, and would bring for the event a small keg beautifully made, and bound with hoops of brass.

But she always defined occupations in the light of her own predilections. If she liked the man, a pedlar was a commercial traveller; a money lender was a banker; a politician was a statesman. Otherwise, a man who lent money was a usurer, and the merchant an oppressor of the poor. In like manner, an idiot was merely innocent, backward or dull. Her diagnosis of the various stages of insanity was quite definite. In the case of a person she liked, the woman was at first depressed, then discouraged, then melancholy. When the husband’s mother or sisters talked of putting her to the asylum, the poor creature would lose her mind completely, as a result of such inconsiderate talk. In other cases the condition was due to heredity. There had been one original family in the place with a marked taint of insanity. The malady would break out in the most unexpected persons, but a relationship could always be traced to that family, no matter what name the sufferer might bear. The history was quite clear for five generations, and she had a peculiar gift in tracing it to the original source; possibly in certain cases with an element of satisfaction.

This uncle of hers was otherwise dubious apart from his occupation. He had an illegitimate son. There was no secret about it. The boy’s name, contrary to custom, appears on his father’s monument, although with proper reticence the mother’s name is not given. This young man attained to the status of a school-teacher. He was paralysed on the left side and in the right eye; but he wrote an excellent script. He made some pretension to scholarship, and was in the habit of using the Latin—incorrectly, as one may yet observe, when he was called upon to inscribe a sentiment in an autograph album. Not that she ever held this lapse against her uncle. Indeed, in later years for economic reasons she lamented the decay of illegitimacy. “In my time,” she would say, “there used to be plenty of them; but now the young women in that condition go to the States, and both mother and child are lost as servants in the settlement.”

The fate of children in an alien home is uniformly pathetic. One of these two boys, her brothers, came to see us sixty years after he had left his uncle’s house. He was a tall fair man, not yet frail, and with an unquenchable curiosity. He carried a two-foot rule, and was discovered making careful measurements of the house at Orwell. He announced with as much enthusiasm as if he had just succeeded in measuring the solar universe, that the house was 56 feet across the front and 107 feet “from stem to stern.” This statement like many an other, though true in itself, was quite inadequate, as it gave no account of the height or form of the fabric. To him a house was the work of one’s own unaided hands. This feat in mensuration provided him with a subject of wonder for the rest of his days.

He was a correct man; he wore the ceremonial clothes of black with a white shirt unstarched; he was in some distress as he had lost his “satchel” on the way. His sister had the shirt washed for him surreptitiously, as she thought, whilst he lay in his bed. But she always lived under the illusion that nothing was seen which she did not wish to be seen, nothing heard that she wished to be secret. She herself never believed anything she did not wish to believe. Her account of any event was the best that could be made, and for her it was the truth. That was the source of her courage and her strength. To the Master, this was mere pride, a false or fierce pride; but he never succeeded in breaking that spirit.

The time came when these two boys, her brothers, were to go out of their uncle’s house, and their mother went with them. There was free land “to the westward.” They loaded their belongings upon a cart. The journey was ninety miles. The place was Egmont Bay, and the land had all the disabilities that free land usually has. After sixty years the remembrance of that journey was quite fresh in his mind, and he spent a long summer afternoon in recalling it. But it was the strangeness and humour of the adventure that he remembered best. The worst thing about it was that he had to drive back the cart, and return on foot the distance of ninety miles. The uncle gave them nothing for a beginning in their new world, “not so much as a chalk-line and black-stick.” The truth is that, although he was a “merchant,” he had nothing to give.

To build a house in those days was a simple affair. The tools required for a beginning were a chalk-line and black-stick, a narrow ax, a broad-ax and a whip-saw. A tree was felled, trimmed of branches, and cut to proper length. A strip of the bark was removed. The line was fixed by a brad-awl or nail at one end. It was blackened by passing it over a black-stick, which was a piece of alder-wood charred in the fire. Then the line was drawn taut along the white strip, lifted in the middle, and let go. A black line was left, by which the log could be hewn to a flat surface. With his ax the workman bit into the log to the line at intervals of a foot. With his broad-ax, which has a short handle set off from the blade for greater freedom, he slashed off the sections between the cuts at a single stroke. The log was turned on the flat, and the process repeated until a squared timber was secured.

Sills, posts, plates, rafters, joists, studs, were hewn from trees of corresponding size. The boards were ripped from the largest logs. A pit like a long grave was dug and skids were laid across. The log was rolled on these. One boy would enter the pit; the other would stand upon the timber, and with a two-handled saw they would rip off the boards, the top-sawyer guiding the cut, the bottom-sawyer doing most of the work. For shingles the log was sawn across in short lengths. The block was split with a wide iron wedge; the pieces were thinned at the end with a draw-knife, and the edges made true with a jack-plane. When the lumber was assembled the building of the house was a mere diversion, and the boys learned their trade as the work progressed. To build a framed house was a long labour, and these two young pioneers with their mother were, like their neighbours, content for some years with a house built of unhewn logs; but this is not a book on architecture.

This old man had come to Orwell when he was quite young, although at the time he seemed to be of mature age. One summer morning he and his brother came in a light wagon to the Master’s house. They were dressed in black, their faces severely grave.

“How is mother?” the Master’s wife enquired.

“She is well,” the elder of the two replied, and after a suitable pause added the fatal words:

“I trust.”

The import of his message was apparent to all, for that was the formula in which death was announced. She expressed no emotion. She never did. Forty years afterwards, when it was announced to her by night that the Master was dead, hearing the message, all she said was “Dear, dear,” and arose from her bed, alert for the new duties inseparable from the event. She was never known to shed a tear. I was sixteen years old before I saw a grown woman cry. I thought it a degrading spectacle.

The two young men had come a little in advance. The procession of wagons appeared over the crest of the hill, and soon entered the garden. The coffin was borne on an “express,” a four-wheeled vehicle well sprung but without seats. The distance travelled was eighty miles, and the journey had occupied two days. The horses were driven at a trot, and the innovation was excused on the ground of necessity. Relatives on the route joined, and the funeral procession was now grown to an imposing length. The coffin was opened in the garden, and for the first time we looked death in the face. After a meal the mourners continued on their way six miles further, and “little Mamma” was buried by the side of her husband, the spar-maker, in Belle-Face.

The earliest printed reference to the settlement of these Smiths in Canada is contained in a book by Walter Johnstone entitled, Travels in Prince Edward Island. As a perfect work of history, this book deserves a place with Caesar’s Commentaries and the writings of George Borrow. It contains not one mean word, not one imperfect sentence. A copy was sent to me, probably in jest, by Walter Gow from Toronto, at one time deputy-minister in London. He was a cousin of John McCrae, and supplied me with much material when I was editing In Flanders Fields, a collection of the poems and letters, with a biography, of the dead poet, a labour of love undertaken for his mother. This book of travel is extremely rare; it is also expensive, as the many persons to whom it was lent, in trying to secure a copy for themselves, have bid up the price. Once in a railway train, I observed a man reading the original copy, but I have not seen it since.

Walter Johnstone, who wrote in the year 1821, in deploring the lack of books on the Island, relates that he came into the house of a gentleman from Perthshire, who had a Gaelic Bible. This was the “original Smith settler.” His first name was Alexander; he too is buried at Belle-Face. His native place was in the northern part of Perthshire amongst the Highland foothills. In the year 1798 with his family he left his home on the great American migration. He must have been a considerable person, for he paid thirty guineas for each passage. The place of departure was Portree. The day before sailing he sent all his goods on board, and with his family slept ashore. In the night the ship vanished and left him stranded, without money, without any earthly thing. It was three years before he recovered strength for a fresh adventure, and it was 1802 before he reached the Island.

This pioneer was capable of great and sudden effort, but he was easily discouraged in the labour of clearing the land. With a club in his hand, he killed a bear that had broken into his farmyard; but his wife must pretend to assist him in the more arduous work of piling and burning logs. About this woman there are two legends: that she had been companion to a “titled lady”; that she, herself, was the titled one. In all immigrant societies these legends are common: sometimes they are true.

He took land in the woods at the head of tidewater where a fresh stream fell in. The place was known as Newton. In time he had six sons and three daughters. Their fate would be long to trace in detail. Some married, and settled. One of them was father of the Master’s wife. In the end two sons, William and James, and a daughter, Nancy, remained all unmarried; and they died one by one. It was by these three on the old place that the Master’s wife was adopted as a child when her father died. Their land was good. It yielded an easy living. They were not poor. They had inherited all there was; they had no children to goad them into expense, and land them in debt.

A man who lives on his own land and owes no man anything develops all the dignity inherent in his nature. These three lived a dignified and abundant life, and kept themselves vainly aloof from the later immigration. They were from the “mainland.” The new arrivals were from the Isle of Skye. The Gaelic word for a native of Skye is Sgiathanach. They now call themselves Hebrideans. The term is merely descriptive of one who comes from the “winged isle,” but in time this fine word acquired a suggestion of separateness, and when used with malice, a tinge of reproach. It was never heard in the Master’s house. The use of that term was mortal sin; it signified the sin of pride, and as there was no open sin in the family he was alert for sins of the heart. But the Smiths used the term boldly. When the last survivor was old and fallen on evil times, he brought a nephew into the house with the design of making him the inheritor. But when the young nephew began keeping company with the perfectly proper daughter of a neighbour, whose ancestor had come from Skye, he would not allow it. “Was I going to have a Sgiathanach in my own corner?” he asked absurdly, in justice to himself. These notions had no place in the new world.

In that well ordered house the young Catherine learned all the craft of housewifery, which in those days was something more than asking the cook what she would suggest for dinner. These people had brought with them from Scotland the best practice of farm life. Nearly all that was used in the house was made in the house, and every art and industry must be learned. This involved a knowledge of animals and their products, of fruits, vegetables, and grains. It was not enough to make butter and cheese; the cow and her calf must be learned. Before the sheep was shorn the lamb must be reared. The wool was to be washed at the stream in water warmed in an iron pot over an open fire; dried in the sun; picked free of chaff, burrs, and seeds; carded, spun, and woven into cloth light enough for a woman’s dress, heavy enough for blankets or great-coat for a man. The cloth itself after it left the loom must be scoured, thickened, combed, and dressed under hot irons.

Nor was this all. The white wool and the black wool made white or black cloth; white warp and black woof made various patterns; blended white and black made grey. With cotton warp a lighter fabric for women and children was woven. Warp dyed with indigo could be bought, but all other colours were made in the house. The dyes were found in the woods—oak and hemlock-bark for browns, various species of lichens known as crotals or crottles for other shades. Combined with copperas these materials produced colours from green to inky black.

The utmost the men of that house could do was to kill and dress the animals for food; the details of salting, smoking, and spicing were left to the women. They gained all skill in charcuterie—puddings white and brown, tripe, sweet-breads, hearts, liver, calves-head, known contemptuously to the English as “offal.” During the War the English starved themselves on scanty meat, whilst the aliens amongst them lived luxuriously upon these despised dainties. The killing of the animals in the early winter had all the solemnity of a sacrificial rite, and amongst the Smiths it was performed with full pomp. As a very young child I happened upon the scene in company with the Master. The five tall brothers were standing in a row, contemplating with sorrow their sad but necessary task—two beeves, four pigs, two sheep, and a heifer, hanging in a red but cleanly line above a litter of bright straw to conceal the gruesome and bloody snow.

These animals for years had been loving friends, and now they made a cheerful sacrifice for human need. It sometimes happened that an animal was spared from year to year by reason of the affection it inspired or admiration of its immense size. One such pig grew so heavy it could not stand; it finally “dressed” 642 pounds. After due contemplation and comment, the procession moved into the house, and completed the ceremony with a bottle of Barbados rum. On similar occasions at his own place the Master would complete with family worship, in which those who had assisted took part, as if in expiation for the death of those trusting fellow creatures.

I once asked a German prisoner, as part of my duty, if he had enough food. “Enough, but not plenty,” he said. That was the situation in this house where the Master’s wife was brought up. The food must be wrought for and arranged in advance. One year the flour gave out before the new harvest arrived. The wheat was always reaped with sickles, as it still is in Belgium. She took a sheaf from the field, scorched off the chaff in the fire, beat out the grain, ground it in a hand mill, sifted the flour, and had bread baked when the reapers returned.

The custom was to take the wheat to the mill in the winter, on the ice along the shore and across the rivers. In that year of early need her uncle put a bag of four bushels on the back of a horse, and walked alongside, through the woods by the head of the rivers, to the mill, a distance of twenty-seven miles. He returned the next night with the flour. The Master’s wife often told us that the taste of that bread never left her mouth.

The Smiths limited their desires within the range of the work they desired to do: they never allowed their desires to impose work upon them. They had all those Highland eccentricities so faithfully chronicled by Stuart of Garth; they were equally void of the two chief curses of mankind, luxury and ambition; they were possessed of a proud indolence and held themselves superior to want. They worked with such care that they got little done, and finished nothing. They built themselves a comfortable solid warm house; but they never finished all the rooms inside. The walls were of thick pine planks, halved or rebated, like the hull of a ship. Some of the rooms were properly plastered; some were merely lathed; but the vast “other end” showed the smooth planks; and the upper storey was an open loft filled with treasures—tools, lumber, saddles, chests, and the spoil of ships wrecked upon the coast. In one room under a bed was a gravestone properly inscribed, which they never had the energy or leisure to erect in its final place.

Their land was good and its virgin soil not yet exhausted. Many pine trees remained, and they were easily converted into money. When one of these old men at last found that he had need of a doctor, he cut down one of the pine trees, hauled it to the mill which was now near at hand, had it sawn into boards, and sold them for thirty dollars. He went to the town by the steamer, but it was well understood that resort to a doctor was merely part of the ceremonial of dying. This doctor was an honest man. His son and his son’s son yet practice medicine in that same town. He advised his patient to go home “and save his few coppers.” Another sign of bad omen was a negro on a ship that came in that day from the West Indies. He had never seen a “black man” before. To describe this portent was the chief interest of his few remaining days, and he spoke with great conviction, as if he expected no one to believe him.

It was not unusual in those days for people to stay at home. Many persons never reached as far as the town. Dugald Bell from the South Shore, being a rare visitor, was eighty-seven years old before he saw an organ-grinder and a monkey, although he was a rich man. He gazed upon the creature and reflected, “Old age will come to any man.” The monkey went about, and having gathered the coppers in his cap, thrust them in his mouth. The observer remarked, with fellow feeling for another careful veteran, “The little fellow is very fond of the money, whatever.”

The Master’s wife found something unseemly in her uncle’s consternation over the negro, and protested that “the man was as God made him.” With her intense human sympathy, her passion for all who were oppressed, her devotion to those who were kind, with her inability to believe anything contrary to her desire, she had two explanations of the negro: either he was not a negro, or he could be white if he preferred that colour. After one of her rare journeys by railway, she was asked if the people had been good to her. She selected one for special praise. He would place a pillow, fetch tea, and carry her bag; but she was elaborately vague about his identity. We surmised that this paragon was the coloured porter on the train, and asked her if he was a black man.

“His mother might have been a dark woman” was the utmost of her admission; and yet she always prided herself upon her extreme truthfulness.

To her uncles’ family came the inevitable end. There were no children in the house, and a farm cannot be managed without children. They would not yield to new methods. The open fireplace, the scythe, the sickle, the flail, the gig remained with them long after the appointed time. They would not work. When visitors came, all operations were at an end. In the busiest season they would desert the field and sit by the fire to entertain and be entertained. Even the women who were preparing the meal were not allowed to disturb the entertainment. If they wished access from one side of the stove to the other, they were compelled to pass behind the half circle of chairs. Their sister, Nancy, was now grown bent and aged, but her obscure grumbling was kept under control by fear of their violent reproaches if they were disturbed. When all were dead but one, he sold the place for four thousand dollars. He wasted the money, and in the end sought refuge in the house of a nephew, where he soon died. The nephew himself at the time was a man of seventy, the last of the breed, massive, grave, handsome, kind, but with a deep passionate voice. He recited the tragedy. When he reached the climax, he arose with a deliberate dramatic emphasis, crossed the room to the fireplace, and brought back a chip of wood, which he had selected after just appraisement.

“When the old man came to me,” he said, holding out the chip, “he had not the value of that.”

The Smiths were a peculiar people; they even had a characteristic cough, like the single bark of a fox. It has descended to the fourth generation. They can yet identify one another in the most crowded places. This hereditary gift is not uncommon. I was spending a night with Sir Dawson Williams at St. Omer in a hospital controlled by the Duchess of Sutherland. She was much concerned about his cough, and had a medicine prepared for him. He took the medicine without demur; but he assured her that he was not very hopeful of the result, as he had the cough since the time of his grandfather at least. By the same sign I once identified a third cousin, a Westaway woman, wife of the premier of the province. All of her children are similarly gifted, but in a very minor degree.

The Smiths, as a family, are long since gone. We still make a pilgrimage to the place, now in the hands of strangers; the house yet standing but put to the uses of a modern farm. In that house we found early kindness, humour, and humanity; a pagan refuge from the problems of sin, of its punishment, and even from the complicated process of the salvation from it.

William was the Master’s human name. One seldom heard him so addressed. To her children his wife spoke of him as “your father”; to all else as “the Master.” It was long before we discovered that she used the term in its specific sense, and that this mastery did not extend to the universe, to the family, or to herself. In speaking to him there was no need to use any name. The Highland woman never used her husband’s name; it would be too familiar; she referred to him as “Himself.” The Master’s father also was William, and he was the first of the family to come to Canada. The year was 1832.

This grandfather has vanished from the earth. No one now living has seen him. He died seventy-five years ago. His name is inscribed in Latin upon the books of King’s College, Aberdeen, in the year 1820, where it is also recorded that he was a winner of a prize for Latin prose. It does not even appear that he completed his course to graduation. No picture or letter remains. There is a printed sheet containing rules for correct handwriting, and it bears emendations by his son, as if he contemplated a new edition.

When this grandfather first appeared on the Island, he was accosted by the minister in the Latin tongue. He passed the test, and they conversed in Latin. That was the sign and seal of his learning, his culture, his birth, and breeding. The Master’s wife described him as “a gentleman,” a word of which she was chary; but when she used the term all knew what she meant. He had once visited her uncle’s house, and as he handed his beaver hat to her, he charged her to put it in a safe place.

He died in the year 1852 at the age of fifty-two, and is buried at Brown’s Creek. From that church-yard a bell now rings in his memory, impressed with the words: VIVOS VOCO MORTUOS PLANGO. His neighbours at the time were Irish, and a party of them went in advance to dig the grave. The leader was a man named Roche. When he was asked the meaning of this irruption into a Highland settlement, he said that John Murphy, a rival jester, had hanged himself, and they were going to bury him among the Protestants. The funeral was delayed until they had opened the coffin and looked upon the dead man’s face.

A strange confirmation of this incident came during a recent year. A grandson, who in turn is named William, practiced the profession of engineer in Oregon. One day an old man, tall and straight, entered his office, and said:

“I just came in to see if you looked like your father—and you do.” He told of seeing that funeral halt opposite his father’s house seventy-three years ago when he was a child, and he had wondered ever since what was the cause of the delay.

The young scholar left King’s College on account of the rising difficulties of the Church of Scotland. The trouble was not religious but financial. The scholarship fund on which he existed became involved. He returned to his home in Nairn, and like many Highland scholars found his living in the school. He married Mary Macpherson of the tribe of Cluny. They went to live at Fort William, some sixty miles to the southward, where he continued his occupation for three years. There is a letter written by his mother to him and his young wife, which is worth printing after the lapse of a hundred years. Her family name was Clark; her husband was James. She wrote with an educated hand, which is all the more remarkable, as few Highland women of the time—or English women either—could write at all. Her letter was written from Nairn under date of 21st December, 1829:

“To William Macphail, Schoolmaster,

Cornach, Fort William.

Nairn, December 21st, 1829.

Dear William and Mary:

I received your letter on Thursday, December 15, and was by it happily informed of your good health, and also of Mary’s. Your present circumstances afford us no small pleasure, particularly your house, when contrasted with the mean hovel at Glenbanchor, together with the circumstances mentioned, which I think might well call forth the liveliest expression of gratitude from us to God, the giver of all good; and I hope through the grace given you, that you will never enjoy them but in subordination to His will. You remember that when any situation was proposed to you, it was not at all agreeable unless it was a Highland one, which leads me to remark that it was the appointment of Providence; that it was not any casual or common desire you had to be there, but simply this, that it was the will of God it should be so; moreover, how could you and Mary be joined together but in consequence of this taking place; and now it is my earnest prayer and hope you will be so like Zacharias and Elizabeth, walking in all the commandments of the Lord blameless. I am very sorry that you did not come down at the vacation. You promised to come at Christmas but I forbade you, that it might hurry you to come in harvest; and now I am afraid you cannot come owing to the distance and shortness of the day, although I sincerely wish it. I have many things to say which I cannot state at present, particularly to you, my dear Mary. I never had a brother but I loved as a sister and I expect to love you as a daughter. I’m going to give you an advice. Perhaps you know it already, it is this, the more careful you are at first the happier it will be for you through life. I mean domestic affairs, which you must take upon yourself. If you will not keep, he will not, although not a spender; for he is too liberal and has often left himself bare by giving to others, and I hope he will take this advice from you. Do not think I am a miser although I advise you this way. I have not seen your father these 5 weeks and I am timorous as usual. Alexander intends to go and see you although he was prevented from going at the time of your marriage, and I would send the Rug, but it is still awaiting you.

I am, your affectionate mother,

Isabella Macphail.”

The comment of the Master’s wife upon this letter was that no two persons ever stood in more dire need of advice towards economy, and no two persons ever profited less by it. To them economy was meanness, or a mark of poverty. Late in life, this Mary Macpherson was complaining of the scarcity of sugar in the house.

“Why do you not buy a barrel of it?”

“Because there is not money enough to buy a barrel.”

“Then book it”—that was her remedy. She was not wise in counsel.

“Throw it about their feet,” was her solution of every problem. That is what they appear to have done with the school at Fort William. There was however a legend that a powerful man desired the school for a claimant of his own. His name was MacMillan of Cardross, and to the young mind that name signified the “unjust man” of the scriptures, upon whom retribution is promised. The mother also objected to the term “mean hovel,” contained in the letter; but that was the designation used by the older woman for any house of which she disapproved.

There was now nothing for the pair but emigration to America. They had two children; the elder of the two was the Master. The destination was Montreal. The voyage lasted nine weeks. Ship-fever broke out. The captain ran for Prince Edward Island, where he knew the Earl of Selkirk had established settlements. A storm arose. The passengers were under closed hatches. Panic broke out. The captain was in despair. Mary, the grandmother, began singing the 46th psalm, and all sang with her:

God is our refuge and our strength,

In straits a present aid:

Therefore, although the earth remove,

We will not be afraid:

Though hills amidst the seas be cast;

Though waters roaring make,

And troubled be; yea, though the hills

By swelling seas do shake.

When Highlanders sing psalms their mood is governed by the psalm they sing, and they can find a psalm to fit every mood. The panic was allayed, and the captain assured the woman that she had succeeded where he had failed. He returned to her a part of the passage money. But the storm increased. The ship was dismasted, and finally cast herself away on the north shore of Nova Scotia close to the mouth of the River John. The passengers and crew escaped with their lives only, save for the few bits that came ashore with the wreckage. This was in the year 1832. How would the newspapers rave over such an event to-day; and yet until this moment there has never been a written or printed word about the disaster.

The castaways were kindly cared for by some American fishermen who were drying their nets and “the shining pieces” of silver they gave to the children were never lost in memory. The immigrant brought ashore in his pocket a copy of Horace. It was from that book his grandchildren learned the higher Latin, and it is now in a safe place, still bearing the stain of sea-water. But it was slight equipment for beginning life in a new world, although it was afterwards reinforced, when the tide fell and the wind went down, by a Gaelic Bible and a spinning wheel. These also are yet safe.

In those days shipwreck was a mere incident of travel, an interruption of a journey. His ultimate destination was Napanee, a town beyond Kingston in Ontario, where a cousin of his own was Inspector of Schools. This cousin’s name was MacKerras; his son was afterwards professor of classics in Queen’s University; his portrait yet hangs in Grant Hall. The distance was near a thousand miles, and the stranger made the journey on foot, along the shores of Nova Scotia, through the forests of New Brunswick, up the St. John River to the St. Lawrence, through Quebec, past Montreal, up Ontario to Napanee.

When he arrived, his cousin was not at home, and the women-kind were strangers to the traveller. He did not even announce himself; he left the house of his kinsman to return to his forlorn family. The women upon reflection surmised there was something unusual in the visitor; they followed him through the woods, and properly invited him to return. He remained for a few days. For some inexplicable reason he did not like Ontario. He walked back the thousand miles of the return journey. He reported on arrival that he had enjoyed his walk immensely, but he left no written word to indicate wherein his enjoyment lay.

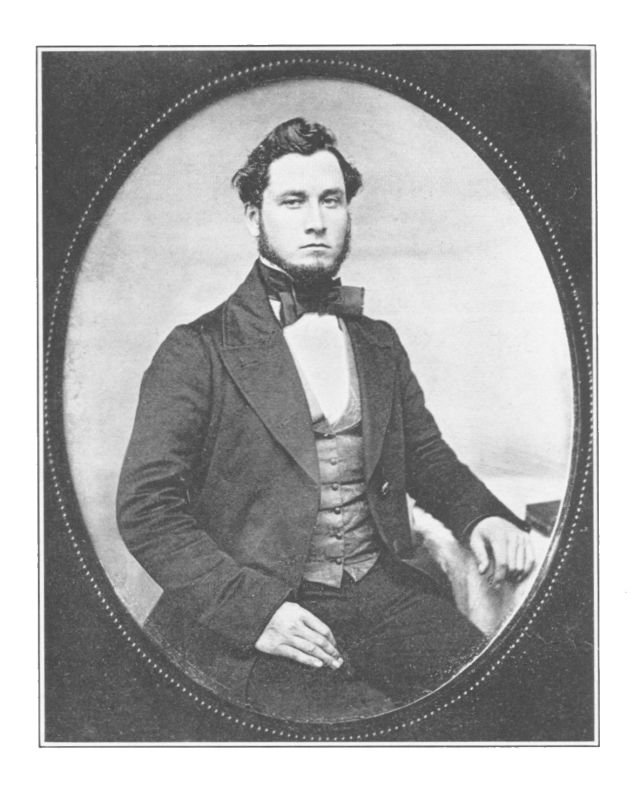

THE MASTER

1860

The record of the next few years is obscure in remembrance; but his third child was born in Nova Scotia, the following one in Cape Breton, and perhaps one other. In those days it was not considered delicate to refer to such events. A child once asked his mother of the exact house in which she was born, but he was promptly given to understand that children had better “attend to their own affairs.”

It was the year 1838 before the family arrived in Prince Edward Island, on the southern shore at Belle Creek, amongst the Comptons, the Humes, the Sanders, the Bars. The site of the first house they occupied, and of the school in which he taught, is yet shown. A teacher was engaged by a few families, and it might well be that after a year they would consider they had extracted from him all the learning that was good for them. By stages he moved inland, and came to a final resting place at Upper Newton, about a mile above the house in which the Smiths lived. There he died in the year 1852, leaving the Master as head of the family, he being at the time twenty-one years of age, and already an elder in the Church of Scotland.

The family was three sons and four daughters. One girl and one boy died about this time. The boy’s name was John. He had repute as a scholar and a wrestler. A collateral descendant was rather a famous wrestler. I went with him to visit the old place, then in possession of an Irishman named Cody, who himself in his youth was a wrestler too, and yet had an eye for form. He scrutinized the stripling boy with an appraising eye, felt his arms, and then very modestly asked him “to strip to the waist.” When the symmetry and strength of arms and torso was revealed to him, he burst out with an invocation to his Saviour to impose upon him the last retribution, if he were wrong in his decision that “this boy could throw his grand-uncle John”—who then had been in his grave for sixty years. Then with delicate fingers he examined the intercostal spaces to satisfy himself, as he surmised, that the ribs were united in a continuous carapace of bone. He knew that strong men were so formed on one side at least; but he had never before seen one who was “solid on both sides.”

The Master was faced with the problem of organizing the household. By some kind of authority he had conferred upon his three sisters and two brothers the rank of “school-teacher.” He himself had inherited the title from his father. There was a sound scholarship in the family. They had learned the rudiments, that is, reading, writing, arithmetic, unconsciously, as a bird learns to fly. They had a correct use of language—and they could discover the grammar of it for themselves. Teaching was only required by those who were intellectually incapable of learning without compulsion, and they were never deliberately taught. The method of learning Latin was unusual, and not a success. As soon as these children had the use of letters, they were set to read aloud from Horace, their father’s theory being that it was as easy to learn and understand Latin words as English words, the letters and sounds being the same.

It might be thought these children were too young for the dignity of school-teacher, yet the Master had formally taught school and drew pay in Cape Breton when he was eight years old; and I myself at the age of twelve drew pay—as a substitute, it is true—for teaching geometry, on the theory that the one-eyed is adequate to lead the blind if the blind are anxious to be led. If not, then there must be a modern school.

There was also the theory that education and the power to teach “ran in families,” and these children were welcomed in the schools where their father had once taught. They went far afield, bearing with them the seed of learning, which by generation is fruitful to this day. One of the girls, Mary by name, to secure an engagement, rode fifty miles in one day on a man’s saddle, the two stirrups being attached to one side for her use. Even through the woods, where there was no eye to see, she would not “ride in any other way.” She would not so much as mention the word “astride.” They all came “home” at the end of the week or at the end of the term according to the distance; but the place was “home” to them, long after they had homes of their own.

The Master was left with his mother in the house at Upper Newton. His school was in lower Newton. Twice a day he passed the place where “Catherine” lived. Indeed for a time she had been a pupil in the school. In due course he married her. The ceremonial seems to have been an affair of some pomp. It was fifty years afterwards when I had a full account of it. I was then visiting pathologist to the Hospital for Insane at Verdun near Montreal. One summer afternoon, the superintendent, Dr. T. J. W. Burgess, informed me that he had admitted a patient from my own country, and she had been enquiring for me. He showed me his new patient sitting on a bench under a tree.

In the Master’s house was a book entitled, The Principles of Aesthetics, which had been presented to him. It was inscribed, “With the hope that it may wile away the ennui of an idle hour.” It was one of the first books I had read. I thought the inscription “elegant,” and was deeply impressed by the word “ennui.” The donor was this same woman; the date 1857, the year before his marriage. She was the daughter of a small dark foreign-looking Englishman who was the country merchant. He had the repute of being a hard man; he “wanted his own”; he had acquired that authority and fear which comes to a man to whom everyone is indebted; it was he who could decide if another man was to have “a handful of hayseed in the spring” for the sowing, or a barrel of flour for his family in the winter. Even the Master’s wife had that traditional fear, and now I thought this demented old woman an ironical spectacle. I sat beside her, and she told me some of the things that are written in this book. I had long been familiar with her history. Her father was hard on her; she became depressed, strange, eccentric, melancholy, according to the usual tolerant account. The thing the demented woman remembered best was this marriage; “There was a procession of carriages, and all had ribands on their whips.”

The little house at Newton was filling up again with a new generation. By the year 1864 there were already three children. In the meantime the Master had obtained a grammar school, and walked morning and evening, a distance of more than two miles. This school was between the two headwaters of the Orwell river. The farm upon which the school stood fell vacant. He bought the farm, and moved in on the Queen’s Birthday, May 24th, 1864.

James Mavor, that famous geographer and economist, during a visit made the discovery that Prince Edward Island was more than an island, more than a continent even; it was a world in miniature. In a morning drive he traversed lowlands, crossed rivers, passed over watersheds, ascended into highlands, where he viewed bays, harbours, and the ocean itself. On a longer excursion he reached the main summit of the Island, and upon the plateau beheld deserts, lakes, and tundras.

If the traveller pushed on to the north side, he could see in time of storm waves that broke on the reefs and leapt over the lighthouse, to lose their force against the sand-dunes which retreat slowly like divisions of an army striving to protect a front. On his return to the south side, he would seem by contrast to have come into a sub-tropical region with its richness and warmth. If he were fortunate, he would see wrecked ships. In one storm, 135 ships were cast away, and the bodies of 600 sailors were washed up on the beach. For many years strangers would be seen searching for their graves.

Passing down the Orwell River into the bay of the same name, into Hillsborough Bay, at low tide this geographer could alight from his canoe by the channel, and there stand upon the Cambrian formation with tree-ferns and coal embedded in the rocks. On either hand would appear a cross section of the geological world extending upwards to the newest red sandstone. If it were an affair of mountains, at times he could look to the north, and there discover against the sky ridges, peaks, and pinnacles that could not be distinguished from cloud masses lit by the evening sun.

This explorer might even stand within an extinct crater, from which I, when young and coming in from the sea, saw fire and smoke and sulphurous vapours erupt as if it were from a lime-kiln, in such volume and symmetry as I have not witnessed from Vesuvius or Etna. This adventurer in that Island also met with tribes speaking a language he had never heard, and saw Indians in their wigwams, making baskets, fish-traps, pottery, bows and arrows, eel-spears, and nets. He declared his opinion that a man who travelled from Antwerp to Bagdad would not see more. Four-and-twenty cement pillars, the foundations, as some say, of a saw mill destroyed by fire, reminded him of ruined temples in the African or Syriac desert. It was in this world of Orwell we had early being, and the whole universe became familiar to us.

There was also evidence of an earlier civilization; burial places with fragments of stone bearing French names; tools of iron, small, soft, and of unusual shape; and in some localities the French language was yet to be heard. A housemaid, daughter of a neighbour, had a visit from her grandfather. He was upwards of eighty years old, and as his farm was by the sea, he wore a semi-nautical cap. He could spare time for the visit, as his day was already broken. He had spent the morning making snug the grave of his own grandmother in the old French burying-ground, where the first settlers laid their dead before they had established a place of their own.

This old French graveyard, unused for a hundred years, was then a forest with trees twenty inches through. More recently, some neighbours who had arranged to visit it with the design of clearing away the undergrowth, and converting it into a solemn park of remembrance, when they reached the spot discovered that the place had been desecrated. Avaricious persons had cut down the trees for their own use; they put fire to the slash. It was all a blackened area; the stones were reduced to the original sand; a few lettered fragments remained; the very mounds were burned level in the fierce fire.

This old man had been a scholar in the Master’s school, and school-mate of the Master’s wife. Having had a drink or two, he continued his round of visits. As I accompanied him to the stile, he said in a mysterious whisper:

“Ask your mother if she ever seen the devil.” There was an old and horrid rumour that the devil had arisen from the sea in the guise of a black man, and from afar off pursued a whole company of school girls, until they sought refuge under the eye of the Master. But the company of girls was so large that no inferential turpitude was attached to any one.

“Tell her it was me,” the old man continued, with desire to free the community from so invidious a charge. According to the long and gleeful account the impersonator made, it seems that he had stripped himself naked in the woods, and plunged into a hole in the marsh. As the tide rose, at the moment of the skailing of the school, he leaped out, black and glistening with mud, and disported himself in the upper air. When I returned to the house, there was no need to put his question, for the Master’s wife remarked.

“He”—this man of eighty—“was a mischievous boy.”

The farm was acquired from the Fletchers. The north and south branches of the Orwell River joined within the area, flowed in a deep wooded ravine, passed through the adjoining property, and met the tide where it was crossed by a bridge. Upon this stream were three mills. Heavy timber grew upon either bank. In course of time, the stream and its borders and the land as far as the salt-water fell to us by inheritance or by sale. The stream now runs upon gravel and rock, through grassy meadows where mill-ponds once were, through gorges where with an unerring instinct the early settlers built their three dams, through woods where trees have grown to immense size, protected by the high banks which prevent their removal. There also, as a neighbour observed, “is all the accommodation a sea-trout could require.”

The farm was not large, a hundred acres, and there was much waste land. The stream and ravine, and a road that followed it, a brook that fell in, clumps of trees, all occupied space; but the remainder was very good, rich and easily worked. The farm also was a world in miniature. There were upon it horses, cattle, sheep, pigs, geese, hens, ducks, wagons, sleighs, and the proper complement of tools and implements. The cart was made by an elder of the church. Fifty-four years afterwards, as appeared from the Master’s books, I sent for this same man to survey the cart, as I suspected it required some repairs. He admitted that the vehicle had not lasted as long as it should, and he feared he “must have put bad stuff in it.” He was willing to make the replacements free of charge, as he wished to maintain his reputation for sound work.

Small as it was, this farm was the scene of all human industry. Wool was shorn, carded, spun, and woven into cloth. Cattle were killed. The hides were tanned by one neighbour, made into shoes by another, or into harness by a third. The geese were caught and lightly plucked, so that the feathers might not fall and be wasted. Bread was made from flour, water, and salt—these three elements alone. It was not polluted with fat nor fermented with yeast. It was made light by persistent kneading under the strong hands of a woman.

And these three mills gave to that young world an air of force and activity. In the springtime, when a dam burst and the water flowed away, a boy could walk upon the foundations of the world as if he were Lucifer himself. The upper and the lower mills ground grain of all kinds—wheat, oats, barley, and buckwheat. The middle mill, which was exactly opposite to the gate, sawed timber with upright saws set in gangs. The circular saw had not yet been imported. In that mill from the earliest times was sawn the timber from which many ships were built in ship-yards that extended down to deep water. A boy would see the ship launched, and in a year or two news would come that she was cast away on the shores of South America “with the loss of all hands.” In earlier days, the founder of the Cunard Line was bottom sawyer to Malcolm Macqueen who gave high praise to his strength and industry. The stumps of the pine trees which these two sawyers cut and sawed are yet to be seen in the woods.

The building of ships demanded many subsidiary industries. Forges clanged the year round. Spars were modelled and canvas was sewn; ropes were made into shrouds, and blocks were shaped. The smell of Stockholm tar spiced the air. This tar in equal parts with port-wine was a sovereign remedy for a cough, and a delectable drink—if the bottle were not shaken, and the wine allowed to come to the top. A cough would last a boy for a whole winter.

Trees were cut and sawn into lumber from which houses were built. Stone was quarried, dressed, and laid up to form cellars. One summer day I found a neighbour in his cellar which was then empty, disclosing its spaciousness and quality; walls thirty feet long, seven feet high, each stone cut to the square and faced with strong even strokes.

“Who quarried the stone?” I asked.

“I quarried it myself.”

“Who cut the stone?”

“I cut it myself.”

“And who laid them up?”

“I laid them up.” He looked upon his work, which was merely an incident in his life; he remembered all his other labours, and said, “No wonder I am in my grave.”

The sea was at the door of these early settlers, and yielded of its abundance in the spring when fresh food was needed most. The salmon crowded the rivers; the herring, the gaspereaux, the caplin appeared on the shores in shoals; the trout ascended the streams; the smelt penetrated into the fields and choked the creeks. The smelts were known as beannachadh, the blessing. They were the earliest to arrive. Whilst the snow yet lay in sheltered places, they would appear in the streams, a moving shimmering mass against the gravelly bottom, and could be scooped out with a net, more than a boy could carry. They were plentiful beyond the need for food and were used to fertilize the ground. A smelt was planted with each potato seed.

From the sea also came marine grass, kelp, dulse, fit for bedding cattle; fine hay from the marsh, which made fodder and might be used to fill a mattress. A man who looked back upon a long life and surveyed the farm he created would confess that “mussel-mud” was the foundation of his fortune. If the nutritive quality of this fertilizer was less than is supposed, the disciplinary value of dredging it from the sea was precious. In the estuaries were beds of decayed shell fish, ten feet thick. When the ice formed, huge “diggers” were set up, operated by horses. A hole was cut in the ice; a long beam armed at the end with a trip-fork was forced by a rude pawl and rack into the face of the bed. The load was lifted by a capstan, and came to the surface, white shells and black mud dripping with sea-water. The treasure was hauled on sleighs far inland and placed in piles upon the snowy fields to be spread in the springtime. For twenty years this shell would dissolve slowly and supply the soil with lime. Assiduity in hauling “mud” was a sign of success, a rite; and it was often put upon land which had no need or could not be improved. One boy, seeing these piles upon an exhausted and abandoned farm, made the judicious observation, “I do not know whether to praise this man for his industry or to reproach him for his folly.”

One winter a farmer fell sick of the slow fever. His neighbours assembled to haul mud for him, twenty of them with twenty sleighs and forty horses. The sick man in return was to provide entertainment in the evening for at least forty persons, men and women. As there would be supper of roast ham, boiled beef, baked puddings, infinite pies and cakes, with accessory cream, butter and bread, besides the conventional bottle of liquor for the fiddler, it is not certain that on balance the financial position of the sick man was materially improved, especially as during the day there had been a halt in the proceedings.

When the fork was first lifted a drowned burden was borne to the surface. It was well known that earlier in the year an Indian had “gone through the ice” and perished. Everyone recognized the unfortunate man by the clothes, the long boots, the heavy mitts, the cap drawn over the face and fastened below the chin. The men stood afar off—to windward—whilst a messenger was dispatched for George Sinclair, Justice of the Peace. When the official person arrived, he demanded that the body be laid out upon the ice. It was an effigy that had been attached to the fork during the night by some mischievous boys and lowered into the sea.

A boy learned something of all trades. By continual discipline he received an education of which the “education” in the schools is trifling, absurd, and grotesque; a travesty of the thing itself. This state of inner discipline arose from a systematic obedience to the laws imposed by nature, against which it was useless to contend by force. But the powers of nature could be subdued and directed to human needs by a continuous effort of the mind and will. The boy learned, and was taught, how and within what limits he could bring into service the hardness of metal, the weight of stone, the lightness of wood, the buoyancy of water, the strength of horses, the fertility of domestic animals, and the hidden riches of the soil. By obedience to those inevitable laws he acquired a morality; by developing the feeling of submission and dependence, as one of the forbidden books affirmed, he acquired the rudiments of religion. Then he could profitably go to school and learn from the recorded experience of those who were wiser and older than himself. The school was at hand, and the discipline of the school was not dissevered from the discipline of the home.

This mill was owned by the Master; it was leased to a man called Malcolm Gillis. He played the bag-pipes, and wore a Scotch bonnet for the ceremonial. He could not play without that emblem. Twice a year he would come to play his pipes in the dairy to drive away the rats, but he wore the Scotch bonnet. It was long before we learned that music is a thing to be enjoyed for itself and not for any ulterior purpose, such as freedom from rats.

It is well for a man that he bear the yoke in his youth: he gains strength to cast it off. Happy is he who learns fortitude from his parents: he is safe through life. In this old mill one child at least had his first serious lesson in fortitude. The logs were piled on the bank in the winter. With the rising water of the spring each lot of logs was rolled into the pond, and floated by spiked poles to the waste-gate. Each log was guided to the runway that reached down from the mill, wet and slippery, into the water. A dog was driven into the butt-end. To the dog was attached a heavy chain which passed around a spindle controlled by a large wheel armed with iron crotches. A second chain connected this wheel with the main driving wheel of the mill, which lay near the water level twenty feet below. When lateral pressure by a lever was put upon this chain it came to its bearing below and above. The spindle took the chain, and the log came with splash and rush to the saw.

But the vertical chain when not in use would fall free from the lower crotches. It could be brought into place by a series of sidelong swings from above, but the simpler method was for a boy to descend by the timbers of the mill, stand upon the watery wheel, and adjust the chain with his hands. This was reckoned a daring feat, and was eagerly sought. One day a boy saw the chance, and darted down. But the man, unaware of his design, started the mill. The boy felt the wheel turn slowly under his feet. He kept his balance by dancing on the wheel, but the torrent of water threw him off. He must have cried out, although he was afraid of blame for causing the mill to be stopped. In falling he was struck on the head by the iron crotch, was carried insensible down the tail-race by the rushing water, and was finally cast ashore. He felt his father’s arms beneath him; they would seem strong and comforting. He carried the child to the house, and said to the mother, “It is a mercy of God.” She said not a word. She put the child to bed, and gave him a cake. The blood had been well washed away, and the wound could be left to take care of itself. In a few hours he awoke with an overwhelming sense of the mercy of God. He had allowed the disaster to proceed to such an extremity that the boy was absolved from blame for having stopped the mill.

Life is not life where there is no tragedy. That little world was a world of death—a wild animal caught in a trap, a partridge slain by a hawk, a cow submerged in the marsh, a dog whose time had come; and always the mild-eyed creatures that must be killed for food. Indeed, a boy himself must learn to take part in that ceremonial, and finally to conduct the sacrifice. Thereafter, he was never the same. It was not uncommon to see a boy in tears before the bound animal.

But there was human tragedy too. A neighbour fell sick of typhoid. In his delirium he escaped to the woods, and there died. His body was borne on a truck past the door. The children saw his face and the helpless feet. Even the dog barked in terror. This terror of the dead was the heaviest trial of sensitive boys in the army. “Why are they so cold and stiff?” one boy asked. A party of sappers was detailed to unload wire. The dump was already occupied by rows of the dead. The living enemy inspired less fear. It was unseemly. The boys were sent away, and the bodies were removed by more experienced hands.

Death is sad; it is not usually malign. Into that world of Orwell, death came once in the most malignant and malevolent form, and created an atmosphere of horror. For years after, a woman would not go out in the dark to take washed clothes from the line. A man who was compelled to visit his own barn by night would awaken a child from sleep for the sake of human company. That same man who entered the office in Oregon and said, “I only came in to see if you look like your father—and you do,” and having given his name, his father’s name, and the designation by which he was commonly known, and having specified the farm on which he lived, and left fifty-seven years ago, made his ultimate talk of that old tragedy. When he was a boy the scene was familiar to him, and he had often to pass the spot, riding on the bare back of a horse. As he came over the rise of ground even by day he “would shut his eyes, put the whip to the horse,” and never open his eyes until he had traversed the valley and reached the hill on the opposite side.

The people were coming out of church. They saw a man running down the slope, bare-footed, and clad only in shirt and trousers; he was crying in Gaelic, Na chunnaic mi, na chunnaic mi. The thing he saw was the murdered body of his sister. The grandmother, always courageous, was one of the first on the spot, and she could ever after secure willing service by a promise to tell what it was she saw. What impressed us most was her description of the heavy hoe with which the deed had been done, and the marks of the struggle on the grass.

An enquiry was held in the schoolhouse and the most rigid criminal test applied. All the inhabitants were compelled to lay a hand on the body; but as the body did not bleed afresh, they were all acquitted of the crime, although a certain woman was under suspicion to the end. The body was buried, and there are one or two persons yet living who will point out the grave.

The account given by the Master’s wife was more elaborate. Many years afterwards, a man told her that on the night of the crime he was returning from the Bridge. He was a blacksmith by trade, and as he approached his own place, he observed that his forge was ablaze with light and roaring with sound. He thought at first that some traveller had lost a shoe from his horse, and was replacing it by his own skill; but as he came nearer he noticed that two persons were at work, the one shaping the shoe with the small hammer, the other “striking” with the maul. But he observed that the sound of the small hammer was as loud as if it were made by the two-handed maul, and the heavier hammer came down with such strokes as he had never heard. He cried out—and all was still and dark. The moment he saw the fatal hoe, he knew who was the intruder into the forge. The marks of the hammers had been made by no human hand. I have seen the weapon, and the forging did seem heavy. But she was careful to add that a man returning by night from the Bridge would be untrustworthy, and this one was cousin to the woman suspected of the crime.

In the summer of 1930, a woman came to see us. She was daughter to the man upon whose land the body was found, and was the second person who had looked upon the spectacle, her age at the time being thirteen years. She conducted us to the spot, and supplied the minutest details of the tragedy that had occurred seventy-three years ago. It is not probable that anything further will ever be known of the cause or circumstances.

Apart from murder, there was no crime in that community except the crime of going in debt. A man who had stolen cattle was publicly whipped in the market place. A negro sailor who stole bread was hanged at Gallows-point. His crime was wanton: it was proved that he had not eaten the crust. Two boys broke the window of a shop, and extracted three balls of twine. Judge Peters sentenced them to death, on the ground that they had broken into an inhabited house, as the merchant and his family slept above the shop. They were not executed although they were known to be “bad boys.” Their sentence was mercifully commuted to twenty-five years imprisonment—and there was no more thieving for a generation. I saw a neighbour carried to gaol with fetters on his feet, as punishment for his failure to pay a debt which had been legally adjudged against him. When imprisonment for debt was abolished, the Master was gravely apprehensive lest worthy men might be denied credit in the hour of their need.

The Master, in respect of figure, height, and weight, was the model for a man. He was neither tall nor short, neither heavy nor light. He bore himself erect as a soldier, alert and quick in every movement. He had abundant brown hair, a short and darker beard that whitened early. His head had good bone with a powerful straight nose and small regular white teeth. When he was upwards of seventy one of his sons remarked to him with professional freedom that he had broken the corner of one tooth. “Yes,” he admitted, “I did that on a chicken bone. I was wishing to consult you about it. I was afraid it might indicate some weakness in my constitution.”

His eyes were clear blue, and his skin of a brilliant whiteness. On his upper arm the letters W. M. were tattoed in purple ink. This gave to him a sense of mystery, and the surmise was that he had fallen into strange company on a desperate voyage he had once made to New York in a schooner. He was a gravely handsome man. His clothes were cut by a good tailor. On the Sabbath he wore broadcloth and a grey beaver hat. The way to church led through a woods, and he would cover the hat with his handkerchief lest a drop of balsam might fall upon it. There is a portrait of him by Alphonse Jongers. It hangs in my dining room at the right of my chair, and many a night I have watched his eye looking down upon me from under a slightly drooping lid in mild reproach.

THE MASTER

1899

This artist was defined by the Master’s wife as “the French gentleman.” She would never place herself at the disadvantage of attempting to pronounce a foreign name unless she were quite sure she had achieved complete mastery. Then she would pronounce it slowly with an air of triumph. The Master was a good chess-player. In the evening he played with the artist, but with a sense of wonder that a “foreigner” could play at all. Having won the game, he would conceal his satisfaction, as he put the board away and “took down the books” for family worship, by saying, “I sometimes think this is a sad mis-spending of the few years that are left to me.” At the time he was quite well, and lived for ten years more. His wife also played chess, but with a sense of grievance when her opponent captured a piece whose precarious situation she had overlooked.

I had learned the rudiments of the game from Stephen Leacock. We would play in the evening, then before dinner, then before tea. When we began before luncheon and continued all day, we both agreed it was time to abandon the game. My skill was therefore not sufficient to contrive an inevitable stale mate, which she looked upon as the legitimate ending of every game. Checkmate to her was a mark of disrespect, a lack of filial gratitude, proof of an eager, crafty, and grasping mind. To yield checkmate to her she suspected was an act of generosity which she craved but would not admit. She would check her daughters willingly on the ground that she was instructing them in the hazard of the play.

On leaving with the artist and Tait McKenzie the sculptor, the Master’s sister, whose name was Janet, met us at the port of departure for a word of greeting. She was easily persuaded to accompany us on the voyage of three hours to the mainland, especially as Captain Cameron with much gallantry asked her to be his official guest. The voyage would not cost her a penny, “nor, indeed, her dinner either.” It was at her school he had begun that education which led to his present high estate.