* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: My Memoirs

Date of first publication: 1930

Author: Sir Frank Robert Benson (1858-1939)

Date first posted: 12th October, 2024

Date last updated: 12th October, 2024

Faded Page eBook #20241003

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, Howard Ross & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

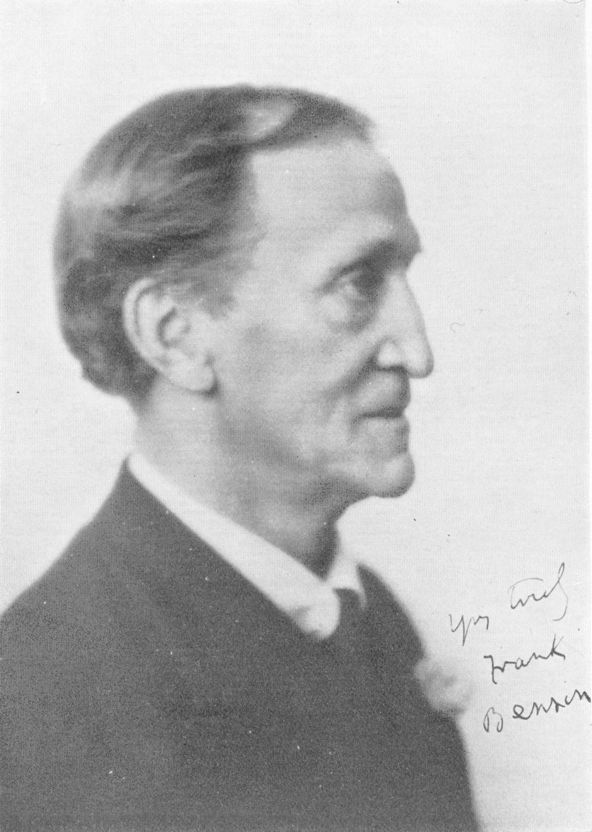

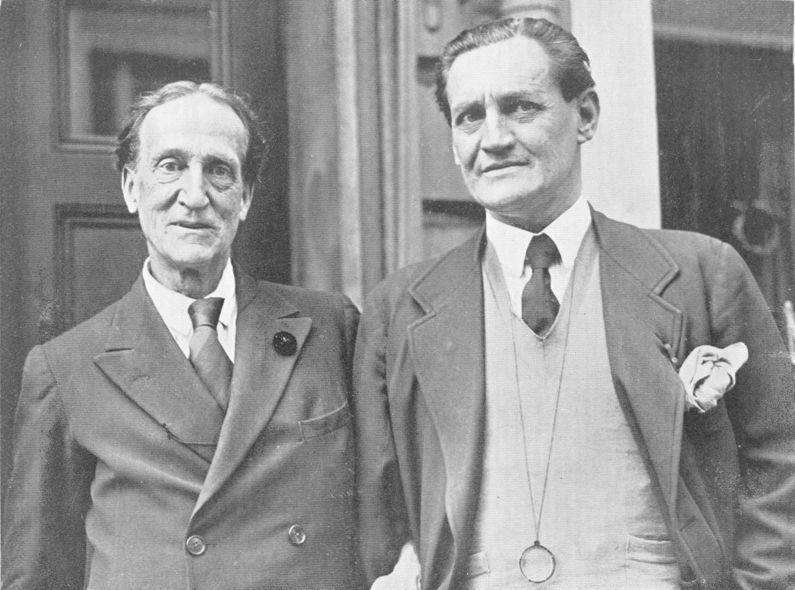

Photo by Guttenberg]

Sir Frank Benson

My Memoirs

by

Sir Frank Benson

D.L., Croix de Guerre

London

Ernest Benn Limited

First Published in

1 9 3 0

and

Printed

in

Great Britain

DEDICATION

Would-be writers like myself generally add to their crime by dedicating their efforts to their innocent friends: in order to complete my villainy I dedicate this screed to my boys and girls, the Bensonians, for many years the loyalest, kindest comrades in work and play that any man could hope to have; to the profession to which I am proud to belong, with specially grateful thoughts of Ellen Terry and George Alexander—who were in a sense my godparents when I started at the Lyceum—of my wife, and of my friend and sometime partner, Otho Stuart; to the audiences from whose sympathy, support, contempt, indifference, anger, patient tolerance or enthusiastic applause I have derived invaluable lessons. Such a list would include too many to enumerate, and I am aware that in these pages I have omitted many outstanding benefactors. The debts I owe are too heavy to set down or attempt adequately to acknowledge. Many of these personalities are so interesting that it would have been a pleasanter task to have attempted to portray them rather than indulge in these egotistical ramblings of a thought-choked pen. I have to acknowledge my indebtedness to the kind courtesy of Mr John Murray, Mr Lewis Melville, Mr Keon Hughes, and my long-suffering publishers, Messrs Ernest Benn, Limited.

I might possibly, may perhaps still, tell a more interesting story of journeys in America and Africa, stories of the Western Front in the Great War, and various changing fortunes by fire and flood, the story of undertakings with my friends Mr Arthur Phillips and Mr Gerald Lawrence, but I have taken the advice of my publishers and contented myself with trying to draw a picture of stage-life and stage-artistry as I have known them for fifty years. It is true that many of the old theatres administered by actor-managers with special companies, specific purpose and ideals, and a permanent clientele, have, to a certain extent, temporarily disappeared. The signs of the times lead one to believe that the older system has already commenced to return, so that when one is asked, “Is all well with the Stage?” one gives an answer full of hope as to the future outlook of drama. One counters the questioner with: “Of what human activity can it ever be said that all is well?” It is sufficient to believe that while our people remain of the same virile fibre that they have hitherto maintained, the theatre will reflect their spirit in a continuous progress towards the Best.

Whatever be the shortcomings of this screed, in time the winds will dry the ink, the sun will dim the writing and the rains of heaven blot out all offence, and so I lay my scroll on a humble altar of green turves pied with daisies in a distant downland near a clear chalk-stream, like to a leaf that, whether brown or green, at one time carried by the wind, at another resting on the bosom of Mother Earth, somehow, however humbly—perhaps only for a second—catches a vibration from the spirit of Universal Life that radiates through land and sea, through sun and moon and stars.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Childhood | 1 |

| II. | Schooldays at Brighton | 42 |

| III. | At Winchester: The Eton-Jacket Period | 52 |

| IV. | At Winchester: The Swallow-Tail Period | 77 |

| V. | Oxford: (1) Work and Play | 90 |

| VI. | Oxford: (2) The Coming of the Call | 115 |

| VII. | Oxford: (3) The Social Side | 132 |

| VIII. | Ideals | 144 |

| IX. | I Commence Actor | 154 |

| X. | With Irving and Ellen Terry at the Lyceum | 182 |

| XI. | I Start in Management | 191 |

| XII. | The Start of the Benson Company, 1883 | 204 |

| XIII. | 1884-1885 | 208 |

| XIV. | 1885 | 234 |

| XV. | Stratford-on-Avon, 1886-1887 | 250 |

| XVI. | 1886-1890 | 272 |

| XVII. | My First London Venture | 285 |

| Chapter the Last | 305 | |

| Appendix A.—The Sautmarket | 319 | |

| Appendix B.—Freedom of Stratford and Knighthood at Drury Lane | 321 | |

| Appendix C.—Concerning our Travelling School | 322 | |

| Sir Frank Benson | Frontispiece | |

| FACING PAGE | ||

| Godfrey Benson, now Lord Charnwood | 20 | |

| Sir Frank Benson | 114 | |

| From a portrait by Hugh Rivière | ||

| Sir Frank Benson | 144 | |

| As “Becket” | ||

| Mr Oscar Asche | 162 | |

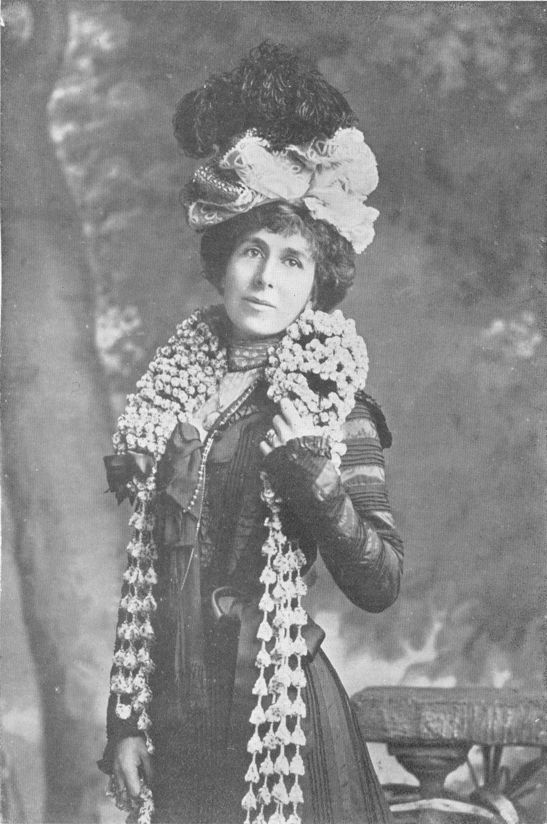

| Lady Benson | 220 | |

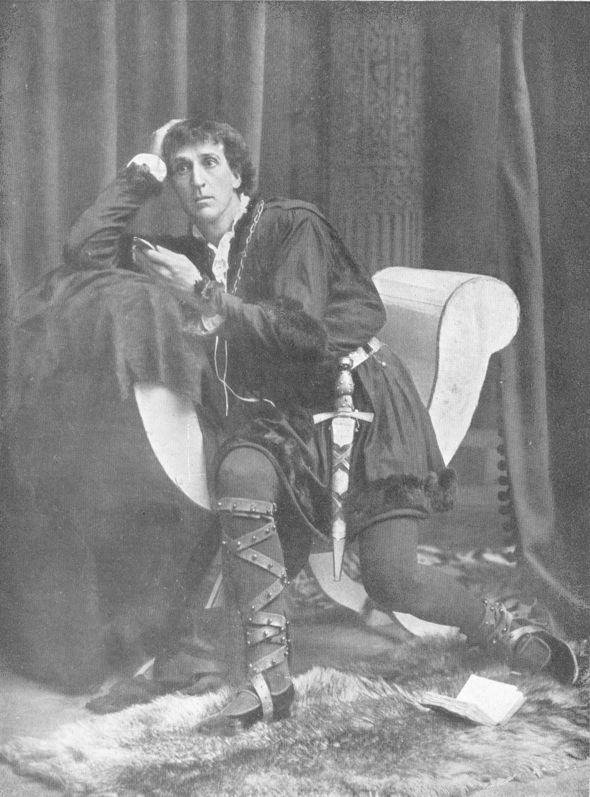

| Sir Frank Benson | 224 | |

| As “Hamlet” | ||

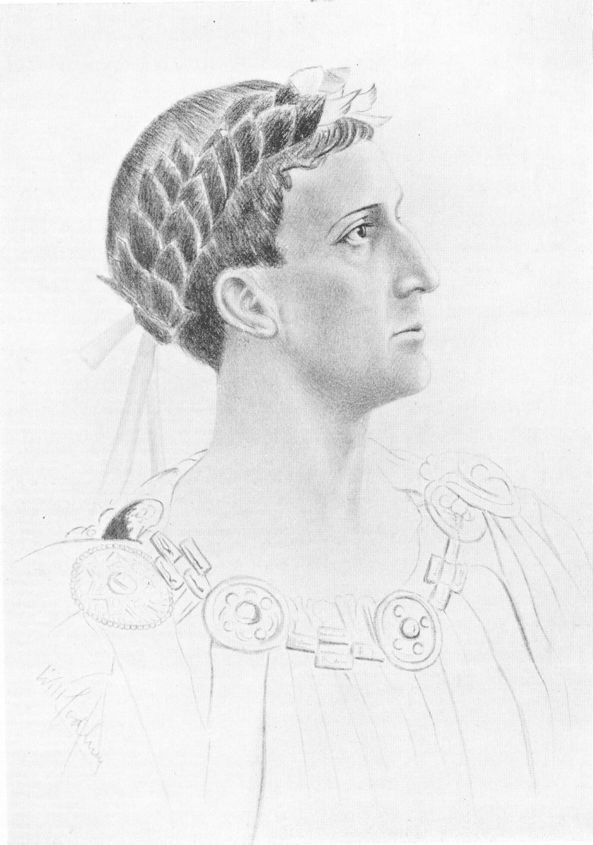

| Mr Otho Stuart | 234 | |

| As “Constantine” in “For the Crown” | ||

| Scottish Historical Pageant | 256 | |

| Mr Alfred Brydone | 272 | |

| Miss Kate Rorke | 284 | |

| As “Helena” | ||

| Sir Frank Benson | 298 | |

| As “Mark Antony” | ||

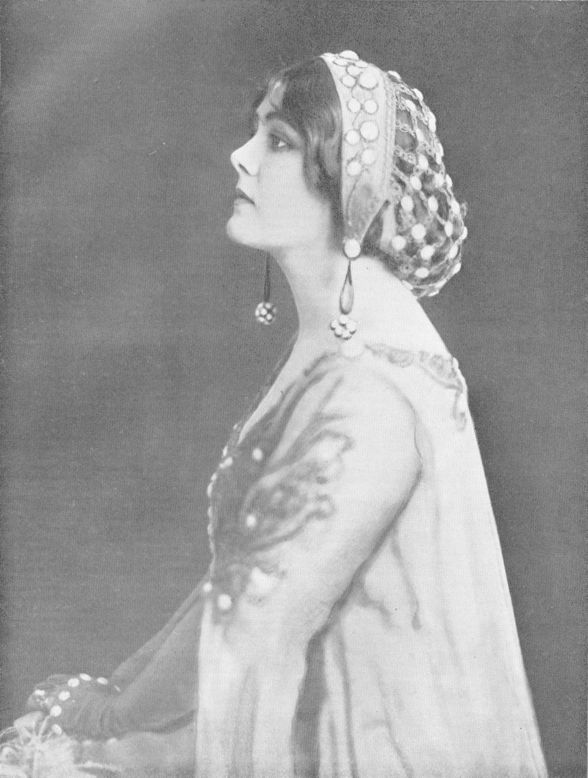

| Miss Lily Brayton | 304 | |

| As “Portia” | ||

| Mr Matheson Lang | 308 | |

| Sir Frank Benson and Mr Henry Ainley | 312 | |

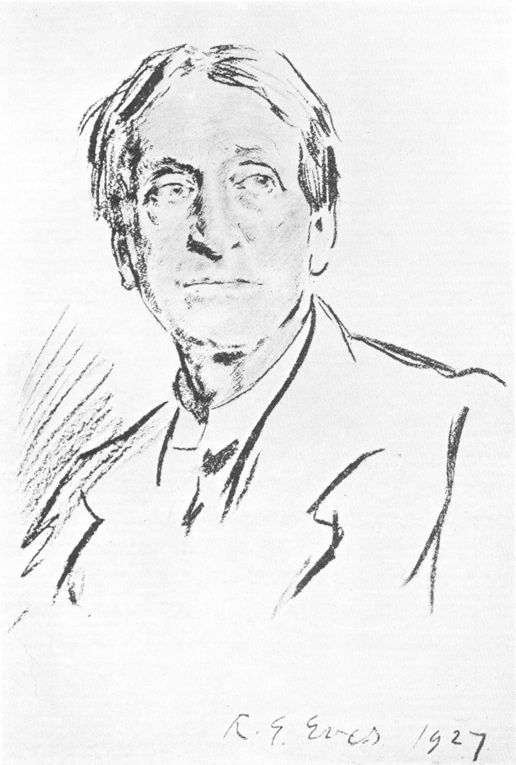

| Sir Frank Benson | 314 | |

| From a drawing by R. G. Eves | ||

My experiences, on the stage and off, cover a considerable and interesting period of English history, stretching as they do from 1880 until to-day.

Those experiences, as hereinafter set down, may possibly help the reader to while away an idle hour.

The Bensons come of an old Viking family in the North of England. They claim distant cousinly connection with such representative strains as Stewart, Bruce, Cromwell, Gordon, Lloyd, Wilson, Rathbone, Forster, Dockray, Braithwaite, etc. The original Scandinavian pirate, apparently about the time of Hereward the Wake, flourished as a Jarl, of some importance and large landed property, in the East Riding of Yorkshire.

The only one of his successors to attain eminence was a poacher of the Norman king’s deer. For piratical invasions of Henry I.’s forest he was promoted by that monarch to an exalted position above his fellows, on a gallows-tree near Whitby, in his own district of Ruywaerp.

His descendants took the hint, and for many generations dwelt in discreet obscurity, occupied for the most part with the cultivation of land round Bramham Moor and the neighbourhood, though now and again we find a Benson blossoming out as a Dean, or a Member of Parliament, or a Diplomat. Much of that holding has now passed into the hands of the Lane-Fox family, one of whom married the daughter and sole heiress of Robert Benson, Lord Bingley. About a.d. 1500 they migrated to the Ulverstone district, and began, in addition to farming, to bestir themselves in trade and commerce, filling also occasionally useful, if not illustrious, positions in the public service, military and civil. In the early part of last century we find them engaged in the cotton industry and railway development of England and America. They were, in conjunction with James Cropper, the first to carry cotton in steamships across the Atlantic to Liverpool. Though our records and traditions for two centuries were interwoven with the family histories of most of the prominent Quakers of England, I am especially proud of my descent from the aforementioned poacher who was hung, of the ancestor who helped one William Wordsworth to build a Roman Catholic Chapel in the Lake District, and of the athletic records of the family in every kind of sport.

I have had many divergent sympathies or inherited memories: I have spread myself in so many directions—“sprawled so much over my work,” as my tutor told me—that I have been something of a conundrum to myself and my friends. At one moment a skald of the Sagas, at the next an Oxford student, an athlete contending with professionals, a rough-rider, or an amateur soldier, I became at length that chameleon personality, an actor-manager. The fact that my race counted its descent from eldest son to eldest son since the time of Stephen argues a prudent, if selfish, resolve to prosper unseen, a certain readiness to accept the conventional standards of the day, a great vitality of constitution, and a firm determination to do nothing that could possibly again attract the attention of the public executioner. In spite, however, of my traditional submissiveness to law, order and respectability, at an early age I had elevated my pirate great-grandfather to the chief position in my shrine of ancestor-worship. To this shrine I brought my offerings of sin, shortcoming and occasional success. Hereto, in the spirit, I recorded my penitence, my prayers for pardon and my oft-broken vows of amendment.

I was wont to say that my kaleidoscopic failures and lapses of faithfulness to the highest ideal were due in part to the fact that the mixtures in my blood of Viking, gleeman, Quaker, artist, wrestler, runner, yeoman, berserker, begging-friar, etc., neutralized and contradicted each other, the result being rather minus than plus. If I had been more of a fool I should have come nearer to being a wise man.

In my memory are dim recollections of my birthplace at Tunbridge Wells—of the Pantiles, and the scent of pinewoods, heather and bracken inhaled at the beautiful country home of my mother’s family, Colebrook Park, in Kent.

The next impression comes from the sea at Hastings, the beach and the story of Battle; a nursemaid from whom I was always endeavouring to escape; a hill that I laboriously climbed for the sole purpose of rolling down again, at great expense to my clothes and my skin—a method of hill-climbing typical of much of our human progress.

Then came a great event for me and the three elder children—William, Margaret, Cecil—the birth of a fifth member of the nursery, Agnes.[1] No one ever entirely gets away from the idea of feminism that the little sister brings with her. Once and for all enters into the mind of the child the partnership in the great mystery of life of man and woman. At first, like other boys, I objected to my nose being put out of joint. I had to learn to give up the centre of the stage, to tread softly when I wanted to jump or run, to modulate my lung power when I wished to shout, or cry, or laugh; and if I did not conform to this necessary discipline the nurse or nursemaid shook me, and my elder brothers and sister cuffed and sat on me. This has been the comradeship of the man-pack and the wolf-pack, the discipline of the school of the woods, long before the days of Froebel and Montessori.

Gradually, in the companionship of the sisters, some of the meaning of Eve, Astarte, Ruth, Athena, Mary and Joan, and the fashioning of the world’s chivalry, stood revealed.

I next recollect being transported by a coach and four horses, for the railway had not then penetrated so far, to an upland valley in the midst of the woods, chalk lanes and turfy downs of Hampshire.

It may be true, as biologists tell us, that modern man in his short span of life lives a million years of the accumulated experience of his ancestors; that in spite of his discoveries and the wonders of modern science, in spite of the great song-words of the god-men and the heroes, he is still little more than the cave-man or the Cro-Magnon in a top-hat. So we are not surprised to find ourselves in the position of Wordsworth’s child of Immortality, full of

“Delight and liberty, the simple creed of childhood,

With new fledged hope still fluttering in his breast.”

Full too

“Of obstinate questionings,

Of sense and outward things. . . .

Those shadowy recollections,

Which, be they what they may,

Are yet the fountain-light of all our day,

Are yet a master-light of all our seeing.”

Thanks to my parents, I had the opportunity, however little use I made of it, of collecting my first early blank misgivings under the happiest conditions. My father had graduated at Cambridge, eaten his dinners at the Temple, and at a comparatively early age married, with the idea of settling down and bringing up his family in the manner of a quiet English gentleman. Though this class seem to be in danger of dying out under the pressure of new conditions, new needs, new growths, the best of their traditions will never die. They are the descendants of the men who always rallied to the call of the commonweal: Armiger the centurion, with horse and lance, and sword and shield; Freemen, Statesmen, leaders and companions of the Brotherhood, the esquires of the Island race, from whose ranks have been recruited so many great captains, in close touch with the life of yeoman, shepherd, herdman and hind—all that our American cousins used to admire most in patriarchal England. Though in 1926 there were only a million workers on the land instead of the three million of a few years back, though, of course, our land tenure may change, the influence of the country gentleman and his ideals will be the main force in the self-supporting re-establishment of “back to the land” and the garden-city. My father and mother were among those numerous landholders who laid more stress on duties than on rights and privileges. They, and those like them, have prepared the way for the reconstruction of a “Merrie England,” with increased opportunities for all in life’s great adventure.

My mother was one of the most beautiful women of her day; my father was accounted very good-looking, and though small, like his brother, was exceedingly strong and active. Years later, in a Liverpool water-polo match, I was reminded by an old attendant of how my Uncle Robert could swim three times the length of the bath under water. Quite unlike myself, my father was something of a dandy in the cut of his coat and the fashion of his hat. When in London, my parents’ well-appointed household, on the moderate but comfortable scale of the average well-to-do Englishman, the showy bay horses and smart carriage, gave that note of completeness and quality so often found in Quaker households.

Under their loving care, in the large rambling country home on the banks of a clear trout-stream flowing through the little market-town of Alresford, I assimilated the rhythms of young life—from the lake formed by the monks centuries ago, full of giant carp and pike; from meadows and lush grass-lands grazed by lowing herds; from sheep-bestudded downs rolling up towards the clear blue sky; from white Roman roads, shining in the sun, marching straight with resistless purpose to their appointed end. For the family the road led to the old British and Roman fort, the West Saxon burgh of Winchester, with its barrows, bridges, churches, red-tiled roofs, grey walls and royal tombs, its Castle and Table Round, the Buttercross, Cathedral and College, the Jacobean barrack-square and the Norman hostel of St Cross. Here in the heart of Wessex, eight miles from its ancient capital, I learned something of the real greatness of the Island story.

At an early age I became acquainted with Arthur, Egbert, Alfred, St Swithin, Dunstan, Canute, Godwin and Harold, with Garth and the monks, with Rufus, Henry and Maude, and William of Wykeham. A goodly company, they often rode with me when from the surrounding hilltops I caught the shimmer of the Solent in the sun, or viewed in blue distance the cliffs of Wight; then would my small Viking soul vibrate sympathetically with the deathless story of Nelson, or bow in silent worship before the ark of our Empire’s covenant, the good ship Victory. I have never got over the impression made on me on first seeing the Victory. I felt this also is one of our great cathedrals.

What a setting for the growth of a human soul! What a privilege! What an opportunity! Only half used, only half appreciated, at the time; but better understood when the spirit of the shires was splendidly made manifest in the test of the Great War. Even clearer shall it stand forth when, after the catharsis by fire and by blood, the victors in that struggle shall begin to write the second volume of our Empire’s annals, and shall commence the redemption of our industry from mechanical materialism and the tyranny of soulless dividend.

Early in my diary comes my first complete conception of home, visualized by a small boy of three and a half alternately dragging or being dragged round the garden on the ancestral model of a toy horse. Real horsehair, mark you! For its switch of a tail real horse hairs—where there were any; for its mane real horse hairs, left in patches on its moth-eaten carcass. Forty years before the little horse had lost an eye in father’s nursery. Its four legs were groggy and its ears were incomplete, but that summer afternoon it carried two small boys into a land of limitless enchantment and adventure. Over the sweet-smelling, close-mown lawn, with the starland of the daisies at their feet, they crawled and ran and tumbled into an eternal acquaintance with flower-beds, greenhouses, copper-beech, cedar, ilex, and old-fashioned walled-in kitchen garden. They had just got as far as the iron railings with the mysterious two-flanged iron gate, which only real grown-ups could open, when they were pounced upon by an athletic young nursemaid, and carried off, protesting and struggling, to be bathed and bedded—I first, by ten minutes, being twelve months younger than Cecil, my inseparable companion in the unforgettable exploration of life’s young mystery. Horse-exercise on the hairless steed and the wonders of the enchanted garden left me hardly time to meditate fretfully upon the injustice of nursery precedence before I fell asleep. In my more wakeful moments, like all youngsters, I brooded, sometimes with tears, over the tyranny of the Medes and Persians.

Why should my cot have four barriers, whereas Cecil’s had only three? Certainly I, for some reason or other, was even in those days prone to fall, but I generally fell on my feet or picked myself up and went on without much damage, whatever the result may have been to my friends and neighbours. Why should I be fenced in in this insulting manner? Let the world wait till I was four, then I’d show them what was what. Surely it was a real grievance that Margaret, who was only two and a half years older, should be allowed to butter her own bread and peel her own egg; that she should have been promoted to a cup and saucer, whereas Cecil and I, especially I, had to spill our little mugs of milk on our pinafores when we failed to make a good shot at our mouths. Why? The tireless, watchful nurse from the Midlands was not a believer in “Why,” and after a huge effigy of that letter had been posted on the wall by my bedside I became less outspoken in my protests.

All childish heartburnings were forgotten when the starlings and the sparrows in the eaves and the ivy woke us to the loveliness of the lilac and the laburnum, the horse-chestnut and the maythorn, red and white and pink and yellow, faint and sweet, strong and intoxicating. Rhythms of colour, and scent of land and sea, drew us with our beloved Rosinante at an early hour to continue our great quest—the search for the Beyond. In after years, in later chapters of the quest, I was told in the sister Isle, “if I would lean my right shoulder against the mountain, grasp the mist with my left hand, keep my head upright in the clouds and tread with untired foot the rock-strewn path upwards, eventually I should arrive somewhere at the back of God-speed among the islands of the Blest.”

Come that moment when it will, for a start that morning we little boys and our steed proceeded to enlarge our experience by gravel path, trim boxwood border and turfed edging down the flower walk to the farmyard. We two knight-errants passed in our triumphal progress by shrubberies and shady trees, peonies, geraniums, snapdragon, wallflower, pinks, larkspur, love-in-a-mist (or devil-in-a-bush), roses, lilies, and all the flowery wealth of May. Around us sang the thrush and the blackbird, the linnet and the lark; the greenfinch piped lazily; pink pink! chirruped the chaffinch; while tomtits, large and small and long-tailed, peered inquisitively at the little pioneers. We had hardly time to look at the blaze of colour, or to listen to the sons of the morning shouting for joy; the Mecca of our bold pilgrimage was the farmyard. Past the yew-trees and the red cedars and the junipers we toddled.

Delight and dismay filled our hearts when the gamecock challenged us from his perch on the big black gate, newly tarred, and alas! the latch high above our heads. With blackened nose and fingers I raised the latch as I stood on the palfrey supported by the stocky shoulders of Cecil. The gate swung open and Paradise was revealed—at least it was when the pyramid had picked itself up, for the opening of the gate had not been achieved without stains of blood, tears and tar, and apprehension of smackings in the nursery hereafter. What matter! The threshold had been won; and, in their morning glory, behold the byre, the pigsties, the cow-houses, the rickyard, the sweet-breathed kine and, wonder of wonders, two small calves! Still more interesting, though not so aromatic, were the pigsties, containing real Hampshires, obstinate, aggressive, self-assertive; the older and larger swine distinctly fierce. Were there not stories in the farmyard chronicle of their own young devoured? of the cowman being bitten? of the small child torn to pieces? It was with some relief, therefore, that we knights found the monstrous Hampshire hog responding with a friendly grunt when his back was scratched with the butt-end of our lance, a goodly hazel wand stolen from the potting-shed. Perhaps, however, ’twere more prudent sport to chase the poultry out of the melon-frames, and to be introduced to the fleas of the fowl-house by the hen-wife—“Why has that hen got the gapes?” “Lawk-a-mussy, just to aggerawate a body, I specks. I ducked her in the cow-trough and gave her two dozen peppercorns last night, and please God she’ll lay now.” She didn’t; she died instead, and thus made half the summer day sad for us little people, who had been introduced to a whole brood of her relations just hatched in an old top-hat placed handy near the hen-wife’s oven. On that wonderful morning too we were allowed to feed the cocks and hens, and bathe our little arms in a sea of golden grain. Perhaps the thing that made us late for lunch in spite of the booming of the one-o’clock bell was the attraction of the duck-pond, and its little furry yellow and black inhabitants. Solemnly Cecil was presented with one duckling and I with another. This proprietorship, we afterwards found to our distress, was merely make-believe. Though beloved quackums were promptly called by sacred or family names, we juvenile owners were not allowed on our own initiative to sell them, or even to carry them off to bed; and though blood-brotherhood had been established, by the sacred ceremony of the chewed-off boot-button, alas! we feudal lords could raise no effectual outcry when in the course of time Elizabeth and Nebuchadnezzar were fattened and killed.

After due punishment for lateness at meals and tar on the clothes, the next days were crowded with stirring incident—haymaking: the swish of the scythe, the music of the whetstone, the rhythm of the swathe, the song of the men and the women with their forks and rakes tossing the new-mown hay to dry in the sun and summer breeze, the small wooden forks for the children, the labour of gathering a sufficient crop to make a nest or a house, or a haystack. Why should my eldest brother, aged nine, be allowed an iron fork? More injustice to the nursery, quickly forgotten in the delight of tea on a haycock.

Even when the hay had vanished from the landscape there was still some consolation in the return of the cows to the Home Park—the cry of the cowherd, “Coup, coup, come along”; the milking of Blossom, Daisy, Lily, Rose, Polly and Beauty; the long narrow path for single file from the far field, the leadership and precedence in the ranks—first Rose, then Polly—varying in favour of the last proud mother in haste to reach her calf. Then the climbing of the big beech, the excitement of a wild duck under the deodar, a wood-pigeon in the tall Scotch pine. Oh, the smell of the walnut leaves! and oh, the new-found friends! the swans on the river, the rushes and the reeds, the coots, waterhens, corncrakes, the trout and the lilies, the duckweed and the millrace, and, mystery of all mysteries, the glimpse of grinding corn! Alas, cruel fate! all efforts to become white like the miller were forestalled by my watchful nurse, who knew it was a habit of mine to get mixed up in the machinery of things.

Then came the reed harvest, long reeds, reeds with a flowery tuft at the end, used for thatching and screens from the sun and wind, but of course really designed by Providence for lances and bows and arrows in mimic warfare. Armed with a light lance eight feet long I watched the herons as they winged their tireless, graceful flight across the meadows to the lake, or stood silent, stately sentinels till the quick, stabbing dart of a razor-like bill accounted for a minnow, a gudgeon, a roach or a frog. The Chinese geese and waterfowl from foreign lands; that fearful joy the turkey gobbler; the wonder of the robin, wren and swallow in their nests; the continual conversation of the sparrows and the starlings; the parliament of the rooks; the occasional swoop of the sparrow-hawk, carried the five little English folk on to the red-letter day called in the chronicles the “Coming of the Ponies.” Henceforth, blacksmiths with bellows, tongs and pincers, hissing red-hot horseshoes, hammers and musical anvils, and saddler, coachman and groom became for the boys the pillars of society.

I had been prepared for giving Taffy a proper reception by frequent contemplation of Punch, Judy and Tommy in the carriage and the stable, and by offerings of sugar to the grey cob that my father rode. Sometimes I was permitted to ride astride her broad back in front of my father. Great, then, was the day when, accompanied by Rover, the fighting terrier, and Leo, the mastiff, I was placed carefully on the padded saddle. Not long did I stay there! Having surreptitiously smitten Taffy with a precious little apple-wand, in spite of leading-rein and gripped knee I soon found myself dislodged from my proud position, safe but disconsolate in the arms of my nurse; whilst Taffy plunged, bucking, kicking and squealing, down the carriage-drive, dragging the groom after him. Taffy had neither mouth nor manners, but he was a first-rate pony whereon to learn to ride—if he didn’t break the neck of his rider.

Then came the days of the governess. Of course it was promotion to be taught with the elder children; but the adventures of the green rabbit and the black cat with pink eyes lost their savour when put before you in French. There was no reason why the learning of A B C should call forth tears and temper, but it usually did.

Reverting to the manners and customs of the Stone Age, Cecil bit my mother’s watch-chain in two, while I gnawed chunks off the table. I soon discovered the truth of the Hellenic axiom that progress generally comes through pain. On the whole, I was neither quicker nor slower than my fellows in the early trials of scholarship. Like other little boys, I fell in love with the governess. I asked her if she would cry or sigh if I prised open my main artery with a pen on the schoolroom table, and was somewhat surprised when this magnanimous offer was answered by a box on the ear.

These details that have been sketched indicate some of the characteristics that count for good and evil in my career. From the first I must have been rather a theatrical child. I was always being turned on to recite for the amusement of a nursery audience. My repertoire included “Friends, Romans, countrymen,” “The quality of mercy,” and a little poem from a red-cotton handkerchief, which ended with: “Says Farmer Gruff, I’ve had enough, I’ll det a tat and till ’em.” This poem appealed to me because it earned me threepenny-bits, and dealt with mice, whose thieving incursions ranked high among life’s entertainments for us children.

Theatrical, too, was my conduct when quarrelling with my sister Margaret on the croquet-lawn. Puffing out my chest and folding my arms I uttered the memorable words: “Strike me, you are a woman!” I thought this was fine and bold and knightly—also prudent, as my sister was bigger and stronger, and would probably knock the stuffing out of me if it came to a serious struggle.

Thus it will be seen that I was of a somewhat complex mentality, rather baffling to my family, except to my elder sister, who all through my life has remained a beloved guide, philosopher and friend. The child’s pastime often becomes the man’s profession. In me there were distinct signs—though not recognized as such—of a certain trend in the direction of the stage. I was a curious mixture of the dramatic and theatrical. At an early age I developed a detached view on life in general; a self-confidence that bordered on conceit; a servile desire to excel and obtain recognition in the centre of the stage and the full glare of the limelight. When we children had whooping-cough I was filled with pride that my whoop was the loudest. When we had measles I took comfort in the thought that I had more measles than the others. There was no moderation in me. But I had not the fine courage that enabled my sister to express her disbelief in fairies even at the price of an empty Christmas stocking. Along the line of least resistance I unquestioningly accepted the Athanasian Creed and the Ten Commandments, and the prospect of hell for the little boy who did not wash his hands or forgot to say his prayers.

An intense desire to do things and achieve something worth while was often rendered nugatory by the desire to be first and a cowardly fear of defeat. Technically, my recitals of poetry and the like were remarkable for their dramatic expression, and though I never took the trouble to learn my schoolroom repetition properly I could without effort or conscious purpose memorize conversations, and reproduce the whole of a performance of the village mummers or the Christy Minstrels.

A curious and rather unpleasant staginess is sometimes observable among Quakers and Methodists. Perhaps it is the repression in theory of the due value of instinct, impulse and emotion that leads them to express their pent-up feelings and vague imaginings in mimicry and drama. When one comes to think of it, all living organisms in their struggle upwards make use of this instinct. The cosmic conscience bids the plant enact the part of a raw beefsteak in order to attract the fertilizing fly. The human efforts at camouflage so much used in the Great War were crude when compared with Nature’s efforts in the same direction. The snake, the tiger, the rabbit and the hare far surpass the scene-painter in their efforts to escape observation. The fluttering plover distracts attention from her nest. The partridge, with maternal love, and the fox, with an appetite for lunch, sham death with the skill that a Conquest or a Corri might envy in their pantomime. Primitive people love to play the priest, the hero, the king, the god or devil that they worship. At its highest, this results in our becoming, like Thomas à Kempis, by imitation, something nobler than ourselves. In practical everyday life it tended to develop a certain egoistic detachment that made me less amiable than my brothers and sisters. The nurse used to say of me that I was the least affectionate of her small charges. At that time I was, of course, unconscious of this drawback. I have often lamented it since. Apparently this is the mark of a second-rate intelligence, that in its desire to understand things cosmic and universal beyond its reach continually breaks its shins over concrete objects at its feet.

So far, at the age of seven, when the conscious and the intellectual processes were beginning to supplement intuition and sense impression, I was undemonstrative, but hungry for affection; somewhat selfish, very obstinate, and with an intense capacity for the mere joy of living; in fact, a very live little wire. The narrowing influences indicated above, which somewhat obscured my instinctive distinction between “I will” and “I want,” were counterbalanced by the common sense and healthy activity of the home and village life around me. Discipline was enforced with a stern hand by an energetic, if somewhat old-fashioned, nurse. “Wills and won’ts must be put in a bag,” “shall and shan’t” ran a small chance of success against shake and slap. If you wanted to be a hero and attract attention, and therefore lost yourself in the shrubbery nearest to the house, it knocked one off the pinnacle one had been sharing with Wellington and Elijah to be collared by the ear, called naughty and, what was worse, silly, and sent supperless to bed. The same fate attended many an heroic escapade: the falling into duck-ponds and brooks, or through the ice—seeing how thin it would bear, and how near the edge I could slide—and the suffocation following concealment in the straw-rick. These efforts savoured rather of the spirit theatrical than the soul greatly adventurous.

This fancy for mock-heroics was a singular trait in my character. When chastised I regarded myself as a martyr at the stake. I was told once in a dispute that I often posed as the hero of the last chapter I had read in history or fiction, whether John the Baptist, Oliver Cromwell or Judas Iscariot—my critic on that occasion informing me that the last-named rôle was the most suitable for me. The desire to be a martyr, to frizzle and scorch for the sake of the limelight rather than the cause, is a common characteristic in the modern fever for publicity. I had yet to learn that the true hero takes no thought for himself; that he simply lives intensely and does his best, and does not care overmuch whether the result is a peerage or the poorhouse. “Do things for keeps and take your medicine smiling.”

Later I learned to differentiate between the bare, hard facts of the gutter and the conventional ideas of the average drawing-room or “Ivy Castle.” A child carefully nurtured, strictly guarded, wrapped in cotton-wool, trained to contemplate the high lights of so-called ideals, finds it difficult to interpret the shadows of reality; sometimes misses his path in the dark; sometimes, like the man in the German legend, loses his own shadow. On the other hand, in the grimness of a slum struggle for existence the striver upward weighs everything, values everything, in relation to the real. At times he too falters, perplexed by “which is which.” Only he who wins through discovers they are one and the same.

In describing my early life I have hardly as yet done justice to the beauty of the country surroundings, the tender loving care of father and mother, the delightful comradeship of brothers and sisters, relations, friends and neighbours, or to the watchful, and often unwelcome, discipline of the family nurse. Nanna was a careful, affectionate guardian, but also a ubiquitous upholder of the conventional respectability which was supposed to be the hall-mark of the “best families and the quality.” She accepted the definition, so deplored by Cecil Rhodes, that a gentleman was one who need not work for his living. “He does nothing: he’s a gentleman born, he is,” was often heard in the sixties.

This standard of high life below-stairs, and the extreme care—not to say coddling—bestowed on me gave me a rather exaggerated idea of my own importance. Fortunately, I was continually having drilled into me by my mother’s old nurse, a shrewd North Country woman and frequent visitor to Langtons, the Chaucerian maxim: “Gentleman is as gentleman does”—an effective counterpoise to the Southerner’s “Gentleman is as gentleman born.” “Come down from that tree, or you’ll break your neck.” “Sit still, or I’ll tie you in your chair, you fidgety phil, you!” “Don’t wet your feet. Come out of that puddle directly s’minute!” “Don’t get yer ’ands dirty.” “Don’t tear your clothes.” “Keep your curls tidy, you figure of fun, you!” “I don’t know what you are doing, but don’t do it, you naughty boy.” “Come off that branch! You’ll kill yourself, as sure as eggs is eggs, or ever you’ve ’ad your tea.” “You’re more bother to me than all my money; drat the boy, he does worrit so!” “There you go again. Mr Abbott, the grocer, is quite ashamed of you. Look at your little sister, look how good she is.” These and similar categorical imperatives from Nanna suggested a pervading atmosphere of naughtiness and original sin, and exaggerated in my mind the dangers of life in general and disobedience in particular.

I was rather an imaginative boy, and the doom of being struck so when I made a face, or being whisked off by a black man coming down the chimney, or being killed before tea-time—I loved my tea, my mother, and my silver mug—might have made me cowardly, had it not been for the example of my more courageous and common-sense brothers, and the arrival, when I was six years old, of the youngest and last of the Bensons.

Poor Godfrey! His advent distracted the attention of the nurses from the other children to the youngest darling. He became the pet and the plaything—and the victim—of the entire household; to be bullied, cherished, educated or played with as occasion required or whim suggested. Being a healthy and exceptionally clever boy, Godfrey stood up against these manifold inconveniences with great success, and has remained a very kind and enduring influence in the life of the brethren. A new interest having thus arisen for the parents and guardians, from this moment I was more free to fill up the measure of my iniquity; to fling stones in the air, careless as to whether they fell on my own nose or other people’s; to put a pat of butter down my eldest brother’s neck, if the elder brother did not bestow on me, as on the others, the halfpenny bun periodically acquired at the rate of seven for threepence; to upset plates and mugs, cut myself with broken bottles, break my knees so often that kneecaps were fastened to my knickerbockers, climb walls forbidden, and trees that broke; in short, realize to the full the joy of existence. Racing round the lawn like dogs let loose, tearing over the meadows like colts turned out to grass, always playing at cattle-drovers, Red Indians, or horses, we learned to run almost before we could walk. Bricks, rocking-boat, rocking-horse, ball play, skipping-ropes, spinning-tops and stables finished up the day’s delights.

We fell in love indiscriminately with widows of forty and belles of fifteen. I kissed the beauty of the dancing-class in the Assembly Rooms, while I learned to polka, in the presence of Mrs Siddons as Lady Macbeth, and Kemble as Hamlet holding the skull. Alas, poor Yorick, only pictures!

This exuberant joy of life counteracted my somewhat egotistical selfish tendencies and theatrical artificiality. Cecil, however, God bless him! never suffered from these weaknesses.

Godfrey Benson, now Lord Charnwood

Prominent among our many friends stood out the admirable cowman, the strong man of the little country town, Angless by name, and true Angle in his staunch courage and active strength. From Angless I learned the poetry of pump and well, from the bottom of which I could see the stars at noonday, and from which gushed laughing, clear, cool water—constant source of much pleasure and more punishment.

We young Bensons had Angless to thank for our never-to-be-forgotten rescue from a savage bull. The moment was critical. The nurse had hoisted her umbrella, and formed herself into a square, with a perambulator as an outwork, in defence of Agnes and the baby. Cecil and I were in an advanced position as skirmishers; I stood wide-eyed and gaping; Cecil, more angry at his own helplessness than afraid of the result, threw stones, uttered threats and brandished his threepenny whip. This demonstration affected the monster not a jot. Fortunately, the bull was fully occupied with the faithful Rover, who was yapping and snapping, now at his heels, now at his nose. Still I gaped and wondered, excited at the heroic prospect of actually being tossed by a bull; dreading the experience, but keenly alive to the undying fame to be gained at the nursery tea-table by the survivors.

The odds seemed at the moment hopelessly against there being any survivors. The great beast, a prize Shorthorn, was seeing red, bellowing and tearing up the ground with hoof and horn. Just as he raised his head and prepared for a final charge, Angless, like Theseus of old, appeared on the scene. The bull paused to take stock of this new champion. Angless walked straight up to him, and with oaken staff and rope smote him on muzzle and horn, dodged the answering savage lunge, and in a moment had him captive, roped and helpless. I observed with amazement how quickly the bull surrendered. To what? It was not a question of individual strength, it was not altogether the cleverness of the cowboy or the bullfighter. That, I realized by comparison with picture-book and story, was not the determining factor in the case. It was my first lesson of what the power of resolute will can accomplish. The bull had just broken through a brick wall with little apparent effort; he weighed considerably over fifteen hundred pounds, the man little more than one hundred and fifty; but the animal gave in and was led submissively off the field, while the man returned to the milking-stool and went on with his job, as if this encounter were all in the day’s work. So it was to him. And so I learned a Wessex lesson: not to make a fuss in the face of an emergency but swiftly, silently, strongly to do the right thing, if possible—or, if not that, the best you can.

Shortly after this we—“the two little boys,” as we were now called in the neighbourhood—passed on to one of the annual landmarks in our life, the Alresford Sheep Fair. The theory of “You’ll be killed before tea-time, certain sure!” condemned us youngsters to view this stirring scene from the sacred precincts of “Ivy Castle.”

“Ivy Castle” was a mound in the corner of the garden, shut in by two brick walls from a chalk lane that wandered off towards the Downs. It overlooked part of the paternal property—a patch of allotments, a sheep-fair ground and a large field devoted to the sports and entertainments of the town—and was impregnable to the assaults of the fiercest bull or the maddest of mad dogs (the nurse had taught us to regard the canine species as a hot-bed for hydrophobia and fleas); with a thick growth of ivy to conceal ourselves from robbers and Red Indians, or our lawful keepers and attendants, with a yew-tree for an outlook turret, and its artillery of red berries in case of war.

This was the Royal Box from which we surveyed thousands of sheep: Hampshire Downs, South Downs, Dorsets and Leicesters, with Africans and a goat or two as star attractions. A few cattle and rough van-horses and ponies added interest and a deeper bass note or shrill trumpet neigh to the never-ending chorus of bleats and baas. Shepherds and peasants in smock-frocks had caps or hats of straw, fur, or battered felt; some, bareheaded and bare-armed, waved crooks, sticks or large cotton umbrellas; gipsies, handsome, dark-skinned Romany Rye, with their picturesque caravans, gaudy-coloured handkerchiefs and roguish eyes; well-to-do farmers in breeches and gaiters or top-boots; gamekeepers clad in velveteens; a surging mêlée of barking dogs of every size and shape—old English sheepdogs, bobtails, collies, terriers, mastiffs, bulldogs, foxhounds, setters, retrievers, spaniels, greyhounds—appeared determined by their incoherent noise to drive their owners and the flocks distracted, into chaos and confusion. Here and there stood ale-tents, cheese-tents and luncheon-tents, where an occasional conjurer and a few hawkers—waifs and strays from the more legitimate wake—cozened the unwary. Butchers and buyers, carters and bailiffs, drovers, tramps and beggars, jostled, bargained, yelled and shouted. Doctors, farmers, lawyers, squires, all the countryside, prodded sheep, handled wool, killed ticks or quenched thirsts. What an excitement! The various sticks, whips, crooks, wands and staves were of sufficiently enthralling interest by themselves. When applied to the savage beast, or the naughty sheep that wouldn’t go the right way—or in extreme cases to a welsher or a pickpocket—they transported the children to the threshold of heaven.

Saints and angels, cherubs, David, sheep, lambs and dogs, what could children want more—unless, perhaps, a touch of their old friend the Devil. This was supplied by the dogs. “Nipper’s got Jock by the throat; he’ll kill ’un.” “Ger hout, yer brute!” They are separated in time to join forces and forget their animosity in a united attack on a Hampshire ram as big as a donkey, who is busily engaged butting a young pig out of the sheepfold into the coffee-stall. How his cousins and his aunts and his uncles squealed, how the rings in their noses glittered, surely they had bells on their toes!—if the children might only go and see for themselves. “Where’s William? Why is he late to man the castle wall? Oh, traitor! Look! No, it cannot be! It is! There’s William in the fair with father!” This is against all family usage. Let us be careful, though—William is the eldest, four years older than I, very quick and clever, the designer of darts, and bows and arrows, ships, steam-engines and weapons of war. We will confine our attack to accidental dropping of earwigs and bits of mortar on his head as he passes, condemn him not to the ordeal of being spat on from the staircase and sent to Coventry in the morning—just punishment though it be, and pronounced against the sister who had been promoted to take her place at dessert at last night’s dinner-party:

“Tell-tale-tit, your tongue shall be split,

And all the dogs in the town shall have a little bit.”

Just sentence, only commuted by a fine of sweetmeats annexed from the banquet.

“Hi, hi, hi!” The talk of Gaffer this and Gammer that, the haggling of Farmer Jones and Farmer Smith, has stopped. “Hi, hi, hi!” A bare-backed pony carries two strong lads over a sheep-hurdle. O glorious achievement! My brothers and I never rested till many moons subsequently we indulged in a similar performance.

The sheep ceased bleating, the cattle and the swine stopped to stare, the jumping pony repeated its performance, and was straightway purchased by the family coachman. The glories of the fair paled after this. Another pony, a real “lepper,” added to the stable! Naught it mattered that the din revived, that the tegs rushed more tumultuously than ever from the pen, paused in the middle of the road, and then leaped over airy nothings, four feet high, followed by their comrades, each repeating the purposeless jump, and then tore madly down the lane towards the beckoning Downs. The bell-wether leading the multitude along the broad road escaped notice at the time, but was remembered by me in after years when I strayed sadly from the fold. It only called forth a shrill blast from Cecil’s penny whistle (I had broken mine) when Leo, the mastiff, averted the renewal of Jock’s and Nipper’s quarrel by chivying both combatants into the goose-pond.

Henceforth the lepper becomes the associate of Dick and Gallop, the stable cats. “Of the children is the Kingdom.” All unwitting, kings of the days that are to be, once more we find them in the Royal Box of the “Ivy Castle,” with the pretty daughter of the parson, to be kissed surreptitiously by me behind the yew-tree when not observed by nurse or the brethren. The spectacle on this occasion is the arrival of Sanger’s Circus—big drums, golden cars, piebald horses, forty cream-coloured ponies, Britannia with a real lion at her feet, clowns, donkeys, mules, and, oh, joy of Eastern Empire! elephants, camels, dromedaries, zebras and black men. It was worth hours of waiting to see the putting up of the tents, the starting of the procession, to see the profound bow bestowed on the children of the Justice of the Peace by the laughing King of Ethiopia, though, in doing homage, he certainly ought not to have winked at the pretty nursemaid. “What next h’indeed, well I never!” Tragic prohibition that we may see only the “ ’oofs of the ’orses,” from outside the circus. On the outside only may my attention be focussed—on the brass band, the pink tights, the great muscles, the loud-mouthed announcement of the cheap prices, the crier and his bell. All the inner meaning of the horsemanship and the double-somersault, the quips of the quick-witted clown, must remain as yet unknown. The Puritan and Quaker objection stands in the way. Circus, theatre and menagerie are labelled naughty: that is enough. It does not matter that we children think it is very nice, and wish to see for ourselves.

This interdict, however, did not extend to penny-readings, charades in the drawing-room or nursery, or to the beloved mummers, waits and handbell-ringers. At Christmas and the New Year, in the hall or the servants’ room, the successors of mystery, miracle and morality players; and Anglo-Celtic gleemen, in high-peaked caps, with a profusion of paper ribbons, and armed with cutlasses, were wont to delight the household. King Garge, or Saint Garge, and his merry men were opposed in Messopotamee by a Turkish knight—presumably some remote reference to Saladin. The heroes, and there were many, including Napoleon, Cardinal Wiseman, Cetewayo and other chieftains from Zululand and New Zealand, walked to and fro, reciting as much of their part as they could remember, improvising the rest. Sometimes they clashed their weapons as they passed each other. Sometimes their debate was for the release and welfare of a hobbledehoy with a reed voice, who was alternately a Princess of Babylon and the King of Spain and Egypt’s darter (daughter). Her history was obscure, but, ultimately, the darter had to be sent across the warter (water). The climax came when Garge, big and bold, had a set-to with Saladin. After a desperate “bloody” fight, overcome by Garge’s might, Saladin knelt down on one knee and died in that position. Straightway, to our bewilderment and our delight, Father Christmas came in as a doctor. After a lament—beginning, “God damn thy wicked soul, what hast thou been and gone and done; lord lovey, thou hast slain mine only son”—there followed a long recitation of popular local quack medicines for the destruction of insect life, remedies for foot-and-mouth disease, and “physic for tissick.” Rejecting all remedies but his own wonderful balsam, he applied his own “Hell-licks-yer” (elixir). The magic balsam instantly had the desired effect. The Princess was married to her own true love; a treaty of peace was solemnly ratified; and the united company sang lustily: “God bless the lady of this house with the gold chain round her neck.” It is but fair to add that sometimes the characters were not doubled and trebled in the confusing manner described. When Tom was not sweeping a path through the snow, or Dick sitting up with a sick cow, some differentiation was attempted between the princesses, the doctor, Father Christmas and the Turkish knight’s father. In later years I came across similar performances in Sussex, Berkshire, Inverness and elsewhere.

The waits and bell-ringers exercised an abiding but more placid influence on the minds of us boys. The hand-bell!—what a friend it became to me throughout my life, that and all the bells!—muffled bells, passing bells, joy bells, the big alarm bell on the top of the house, the dressing bell on the wooden wheel in the western gable, the front-door bell, the luncheon bell, the gong for dinner, the town-crier’s bell, sheep’s bells, cow’s bells, and the bells that jingled so merrily on the proud necks of four bay cart-horses from Stubbs’s farm, mother’s little hand-bell, marriage bells, New Year and Christmas bells; and, later, the warning bell of danger from the aeroplane, the bell of the fire-engine, and the varied calls, exhortations and prohibitions of school and college bells:

“Bells go double, all right. Bells go single, run like blazes.”

Perhaps for me in my early youth the best remembered of all were that brandished by the bellman in blind-man’s-buff and the curfew, with its sleep song to the dying embers of the day.

Does anyone ever get away from the Christmas carols, immortalized by Dickens? Years afterwards, on the battlefield, I heard their message of peace displace the Hymn of Hate.

“What is the good of this long list of influences,” I once asked, “when they have resulted in so little?”

“Be content, my friend; these experiences in your life interest, not because they are specially yours, but because they are common to so many. If, in your case, the bells have jangled you to fates out of tune and harsh, remember that the Lady of Banbury Cross still rides her white horse triumphantly. . . . She shall have music wherever she goes.”

“All right; let them gallop, then: white horse of the Gael, white horse of the Legion, white horse of Hanover, white horse of the nursery, the Godolphin Arabian, Flying Childers, Eclipse, Ormonde; keep ’em going! Let the merry bells sound on in the clumsy chronicle, even if they be the camel bells tinkling across the desert as the camel-driver leads his team through the wilderness to the oasis just the other side beyond. But don’t forget the windows.”

Then I went on to relate how many people of my acquaintance remember things by panes of glass in their different rooms. One old friend I described as doing his work at the windows of the world—panes of history, industry, medicine, science, religion and art. Then I referred to the windows of my home and the outlook they gave me on life—past, present and to come.

To the dining-room just after family prayers, sometimes during their celebration, the sloping green lawn unfolded itself as a parade-ground for the birds, surrounded by shrubberies and trees, beeches brown and green, elm, cedar, walnut, ash, yew, boxwood, juniper, cypress, sycamore and lime. In the foreground were birds of many varieties, while the jays screamed, the magpies laughed and the cuckoo called cuckoo, cuckoo! Sometimes a great green woodpecker or redstart would visit its friends; while at night-time a night-jar or an owl murmured its greeting to the sleeping house, and chased the bats as they fluttered across the rays of the moon. On this little green stage the nymphs of snow and hoar-frost, of dew and mist and rain, first revealed their beauty. Each nymph brought with her a flower that she loved—snowdrop, daffodil and rose. Generally the three cats of the establishment basked in the sun. Sometimes a hare would shyly join in the Amen of family prayers, and bound off with the grace of God and the fellowship that is in us all. Then there were the windows of the hall, with a raised bank and railing hiding the roadway along which periodically marched the regiments, the race-horses or the hunt, leading the eye through a vista of tall elms, beech and walnut, down across the sloping meadows, where cattle, red and black and white, foraged and grew fat, to the enchanted land of the lake, bordered by rushes, to the swan’s nest on the island, happy hunting-ground for wild-duck, dabchick and grebe. Once a pair of storks deigned to visit the pond. Needless to say they were immediately shot by a “celebrated lover of birds.”

“Was this the happiest time in your life?” I have been asked.

“In a way, yes; it was the most complete, the most self-sufficing and satisfying, yet haunted, as all beginnings must be, with the mortal yearning for ‘What comes next?’ ”

In autumn, when the red and green of the tall rushes had turned to golden brown, the starlings in their manœuvring took the place of the white-winged plovers. Ranked in tens of thousands, with a whirl and a rush and a sound of the sea, and a great cry of evensong, they circled round the lake and round the house, and in their mass bent down acres of reeds and willows, broke branches from the trees on the lawn, chattering incessantly. Wheeling for hours in strange evolutions, divided into squadrons, they darkened the setting sun like a cloud, travelling all the time at a terrific pace, literally in millions, in ever-changing ranks and form of flight, without the least disorder, without ever a collision or harm to their uniform of green and gold. Was there one brain controlling, was there one thought-wave common to the flock? In the opinion of the nursery they had captains and sergeants. What is more, the sergeant-major and his family dwelt in the rain-spout by the tiled roof of the servants’ hall. We children ought to have known, because his nest provided us with pale blue eggs for our collection.

He often sat on the nursery window-sill tapping at the pane—a signal that he wanted bread-and-milk; also, year by year, he and his mate solemnly introduced their young recruits for the starling army to the window-ledge, whence they learned to fly and join the winged companies in their autumn drill—training, doubtless, for migration or for war. No hawk, nor even an eagle, could have stood up against the force of those million tiny wings. Anyhow, one thing they did was to help to wing the souls of children for a still wider flight than their own.

Then there was the eastern window in the governess’s room, where the delinquents of the schoolroom were often confined, with hands tied behind their backs. Revenge is sweet, and their bonds were not so tightly fastened but that they could insert a torpid wasp in the slippers of their gaoler. When not revengeful or lachrymose, the prisoners had plenty to do surveying the course of the little river, the Arle, as it wandered down from Bishops-Sutton, ancient hamlet of flint and clay walls, tiles, timber and red brickwork, grinding corn, and watering flocks and herds on its way to the sea. Beyond the old church and the pigeon-loft over the racing-stable could be dimly seen three sets of kennels. First, at Sutton a pack of harriers were wont at sundown to sit in a row on their benches and chant anthems to the rising moon. Farther on, at Ropley, the H.H. foxhounds could be dimly seen and heard. Across the corn-lands and the bleak heights of Medstead an old-fashioned breed of St Huberts, black and tan, “with ears that swept away the morning dew, made musical discord and sweet thunder” in pursuit of hare or stag. Additional interest in this old-time pack was taken by the children in that their owner, rejoicing in the historic name of Neville, was deformed in legs and arms, yet hunted the St Hubert dogs himself. Strapped to the saddle, this quaint, courageous figure somehow linked up with the traditions of William Rufus and the Normans and the neighbouring New Forest.

“Eastward though the sun rise slow,

How slowly;

Westward look! the land is bright.”

So it was with the window on the stairs overlooking the stableyard, thatched barns, black-timbered cottages and back gardens, till the eye rested on the gilt weathercock of the old church tower. Four-square to the winds of heaven erect stood the tower, like an ancient warrior, encircled by a bodyguard of tombstones and nameless graves—the warder of the town, watchman of the living and the dead! Whether at high festival, christening, marriage or funeral, our old friend looked down, always sympathetic and serene. Round this window the swallows marshalled before they winged their journey south. On the broad shelf inside, sleepy little figures, dragged from their beds, watched the meteoric showers in the sky, or on national joy-days blinked at the rockets soaring up from the market-place to greet the falling stars. There, too, we children paused on the stairway leading to the dormitory to gaze at a purple storm-cloud licked by the lightning’s flame, to hear the thunder booming or see the heavy raindrops slake the thirst of the trees and the dust-dried earth, or yawn good-night to the great red sun as he sank to rest behind St Catherine’s Hill. And all night long the church tower smiled and blessed our infant sleep.

“Get your gloves, Master Frankie.” “I don’t know where they are. There’s a button off my boot.” “Drat the child! A pretty figure of fun you’ll look in church this morning! Call yourself a Christian! You’re a regular limb. There, keep yer ’at on yer ’ead for mercy’s sake!” Then followed a vicious snap of elastic under the chin. A hot little hand was forced into an irritating brown-cotton glove, stained and dirty and buttonless, with stiff, broad finger-tips. Oh, those cotton gloves! Perhaps they were the greatest grievance of the nursery days, especially as Cecil had a pair of purple kid. Neat, tidy boy, an aunt had sent them in a letter addressed to his very own self. At that stage of my development the whole fabric of the Christian Church seemed in my small mind to depend mainly on brown-cotton gloves—not white, for they would have become a drab grey in ten minutes on my fingers. Brown-cotton gloves were not among the verities, I knew that: they were among the false shibboleths that added to the obstacles in the straight and narrow path.

It must have been the birds that told me to turn from the formalities of the Creed to the symbolism of the willow blossom that was handed to us on Palm Sunday. Soft, furry little buds, like ducklings; a fragrant branch, tender brown and green, so strong, so supple; and such an admirable whip wherewith to play horses on Monday. I remember vividly, even in old age, the pleasure of Palm Sunday, worshipping like my ancestors the tree-token of the Infinite.

Side by side with this remembrance ranks the little prayer, first lisped, kneeling on a bath-towel, upon the knees of mother, nurse or aunt. The little head leaned on the altar of Madonna’s breast. Thought of all the world, finding its best expression in the art of Spain and Italy, and thenceforth a permanent place in European civilization. The prayer and the palm, to meet me again years after on the battlefields of the Great War.

“God bless the family and, of course, Nanna,” with a long list of my acquaintances with whom I might happen not to be at variance, including Taffy the pony, but not the miller’s bull-terrier, who had cruelly bitten Rover in their last fight. “And make me a good boy, for Christ’s sake, Amen.” Fortified with these two amulets I endured, without undue suffering, the dull respectability of the Sabbath. The day started all right. It was one of the days in the week when we children had eggs for breakfast, always laid, according to the pious fiction of the time, by our particular pet hen—dorking, game fowl, brown granny, Cochin-China, or gold-and-silver-speckled Hamburg. “Nanna, mayn’t I peel my own egg myself? Need I eat it with strips? Cecil and Margaret have not got to.” “Cecil and Margaret know how to behave, and you don’t.” This was quite true. Possibly I never did. Certainly I allowed my appetite to triumph over principle and swallowed my egg in any form in which it was presented to me, with unruffled equanimity. The result in later life may have been an unfortunate predisposition to count my chickens before they were hatched!

After breakfast all joy in the Sabbath disappeared until evening. Church in the morning, church in the afternoon. Church and brown-cotton gloves, and the ignominy of having one’s place found in hymn-book and prayer-book. A service of two hours. Think of having to sit still for two hours! A gleam of good cheer was introduced by old-fashioned roast beef and apple-pie, with fruit for dessert, in the dining-room, and the use of one’s own silver mug and knife and fork. More Church in the afternoon; this time under the charge of the nurse. A mile walk to Old Alresford—the rich living, with huge rectory and picturesque brick church, wherein the son of a prince-bishop ministered. This was the last word in odour of sanctity for the servants’ hall. Here we little boys wrestled with sleep and our gloves in an old-fashioned square pew like a horse-box. In this church we were in deadly fear that the beadle with the long stick might tap us on the head if our dirty boots, by accident, should trample on our little black hats of soft felt with blue ribbon. Small stones, bits of stick or marbles, and other little treasures, could be fingered lovingly or brought out by stealth only when nurse stood erect to repeat the Creed or catch the eye of the rector’s butler. The memories of these efforts at worship hardly affected our theology at that time. One of the few sentences of a sermon that I remember was the announcement by a locum-tenens, or guinea-pig, that “the delights of heaven included the presence among the angels of little dogs in their coats of gold; all glorious within and resplendent without.” This to us little boys was sound, wholesome doctrine. The buildings of jasper, and the streets of onyx and topaz, and the gates of pearl, so often hymned, dazzled, but failed to attract. The promise that we would again meet the beloved Leo, lately laid to rest with much lamentation in the wood walk, or the pugnacious Rover, who could at that moment be heard chasing cats round the church-yard, stamped the Rev. Guinea-pig as infallibly the co-equal of Elisha. Favourite prophet this last! Did he not, like Wombwell and Noah, keep bears in his menagerie? The man who said that he’d be damned if he would go to heaven if the ducks didn’t, would have agreed on this point.

All things come to an end; and that day ended in songs and hymns, including Kathleen Mavourneen and Annie Laurie, with mother and father, round the piano, with intervals of Oft in the Stilly Night and Woodman, spare that Tree, on the music-box. Rat-tat at the door, soap in the eyes, sponge in the mouth, early to bed; to-morrow it will be Monday.

This was Sunday when fine. Sunday when wet meant a box of animals set out on the nursery table, reinforced later by Godfrey with Noah and his family, with ark, animals, trees and cattle-pen complete—generous gift of a truly Christian godmother; Line-upon-Line; Watts’s hymns; a smattering of Pilgrim’s Progress; a chapter or two from A.L.O.E., and The Sunday at Home—The Leisure Hour, which nurse read, was too secular and sensational—the Collect and the Catechism; prolonged meals and continuous eating; till evening came, when we fancied we had arrived nearer the New Jerusalem and a day’s march farther from the bottomless pit.

On the whole, we rejoiced that religious observances were chiefly a matter for Sunday. Angels and giraffes, Adam and Eve, the Flood, a friendly dove, a branch of olive, a devil and serpents, ducks, Mount Ararat, a rainbow and a lion, left varied impressions on our infant minds, doubtless in time assimilated in their proper proportion, with help from their parody form: “Why doth the little busy bee delight to bark and bite?”

In answer to the heartfelt prayer of “O that it were Monday!” the children found themselves again in that little Capitol of their lives, “Ivy Castle,” viewing the match between Married and Single. A faint tradition of the neighbouring Hambledon district, one of the cradles of modern cricket, still obtained round Langtons. Smock-frocks with a top-hat and black trousers were still to be seen among the older cricketers. The dispute as to whether “H’over-h’arm” or “Round-h’arm” were fair; as to whether the legitimate underhand trundler should be allowed to indulge in “daisy cutters,” or “sneaks,” and “grubs,” as they were called; whether you were out if bowled by a full-pitch, were still rife. “H’out, h’out! ’Ow’s that, h’umpire?” shouts the bowler. “H’out!” cries the umpire. “H’out?” says the batsman; “danged if I be, trowler never grounded ’im.” But he had to go, and to discuss his grievances with the sympathetic crowd of benedicts over a mug of ale. How swiftly the sporting lawyer[2] “trowled ’em in round h’arm.” He was the fast bowler of the county and a terror on a bumpy pitch. “Chuck ’er h’up, Butcher’s h’out.” Straightway, Sparry the blacksmith jerked the ball high in the air behind his back. Would it never come down again? Mightn’t it be dangerous for the rooks’ nests? But it did come down, and, what is more, Angless the cowman caught it in his horny palm.

Next day, bows and arrows and darts are laid aside, and William, who was shortly going to school, and was equipped with bats and other implements of war, instructed us in the mysteries of the game. The chief point seemed to be that William should bat, and the small fry should field, bowl and back-stop. Still, it was very grand and grown-up, even if the girls did join in, and certainly brought one within measurable distance of being a schoolboy. I always favoured vocal exercises. I was particularly ambitious to shout “Hooray!” as real grown-up men always do on desert islands, at shipwrecks, and other catastrophes. Therefore when my brother William set out, with book-box, portmanteau, etc., for his first term at school, for the honour of the nursery, for good luck and the speeding of the parting guest, I began to yell “Hooray!” till the nursemaid called me an unfeeling little heathen and proceeded to suffocate me on the coat-rack in the hall.

One day about the time when the mouse that gnawed Margaret’s slippers was discovered in a trap, or as I thought it was when Cecil’s dormouse had just awakened from its winter sleep, Alresford and the neighbourhood awoke to the stupendous fact that Sir Roger Tichborne had returned from Australia to claim his own—an easy task if it depended only on recognition by his mother and the family solicitor, the perjury of his black servant, Bogle, or the welcome at various dinners throughout the county, including Langtons. More difficult, however, when lawyers bearing the names of Hawkins, Ballantyne and Coleridge asked for proof. To the nursery the case was proved at once when the wife of a neighbour stopped her carriage in the market-place, stepped up to a rather common-looking individual of some twenty stone, and exclaimed, in a voice that could be heard all over the town: “How do you do, Sir Roger? Welcome back to your native land.” She then beckoned to us little boys, and asked if we might have the honour of saying how do you do to the Claimant. Off went two little black hats, out went two little hands, one black and one brown, and two little voices piped up the refrain of the countryside, “Welcome back, Sir Roger Tichborne.”

I have always remembered the singularly dull, uninteresting and plebeian appearance of this pretended baronet. Years afterwards I received a request in a distant town, where I was acting, to advance a sovereign for the Claimant’s drinks, on the strength of that meeting in the market-place. Straightway all unkindness was drunk down. So too, as far as I was concerned, was any lingering doubt I may have had as to the rightfulness of the claim.

One morning strange sounds awakened the children all along the valley. The railway had come. With it came felling of woods, delving and digging in fields, building of white-chalk embankments, and complete alteration in the course usually taken by hunted foxes from cover to cover. Timidly gazed we children down the deepest cutting in Hampshire, which bisected the Fair field, and after endless labour of big-muscled navvies did something to widen the outlook of Alresford and us little Bensons.

The Victorian mould in which we little boys were cast was emphasized by such literature as The Penny Magazine, Peter Parley, missionary tales, Cherry Stones, and Sandford and Merton, varied by the fairy stories of Grimm and Andersen, the valour of the little Duke and the Lances of Lynwood, and the Chronicles of Robin Hood. Life-long trails were blazed for us also by Alice in Wonderland, Lear’s Book of Nonsense, Shockheaded Peter, Robinson Crusoe, and The Swiss Family Robinson.

Here endeth the first chapter of “the little boys.” Nursery days are nearly done; school is soon to take its place. Somewhat artificial, formal and conventional, with an over-emphasis on respectability and what ought to be; somewhat sentimental and unreal, for me at any rate, was this early upbringing; but it implanted firmly on the household a reverence for holy, tender things, and the gentle lovingkindness of family life. Into my conventional consciousness, during a visit to the seaside at Hayling Island, came the vision of the first ironclads, the Captain and the Warrior, the Minotaur, the Resolution and the Himalaya, and the Serapis, with funnels scarcely visible amid the forests of towering masts and the network of sails, rigging, spars, yardarms and ropes. With them came, too, stirring stories of the Crimea and the Indian Mutiny, the Six Hundred, Lord Raglan, Havelock, Colin Campbell, Outram, the Lawrences and Nicholson; with a still earlier whisper of Wellington and Waterloo. Fireworks closed the chapter, ringing bells, cheering crowds, bonfires and booming guns welcoming the beautiful daughter of Denmark to the steps of the throne.

Mutterings from Solferino, enthusiasm for Garibaldi and Victor Emmanuel affected the nursery wardrobe and the nursery outlook on mankind. The tragedy of Maximilian in Mexico, the war of North and South, stories of Lincoln, Lee, Stonewall Jackson, Sherman and Grant stand out vividly in my memory. To a less degree, in the background float Cardinal Wiseman, Bismarck, Louis Napoleon, Robert Peel, Grey, Russell, Palmerston, the Chartists and Peterloo.

And still, in my fancy, above this medley of sounds, by the fireside or in the watches of the night, the old starling taps against the nursery window, and the skylark sings triumphant as he soars above the Downs.

|

The Benson family consisted of (1) William (Willy), who married Venice, daughter of Alfred Hunt and sister of Miss Violet Hunt; (2) Margaret, who married Captain Algernon Drummond; (3) Cecil, who married Constance, daughter of G. B. O’Neill; (4) Frank, who married Miss Morshead Samwell; (5) Agnes, who married Heywood Sumner, son of the Bishop of Guildford; and (6) Godfrey (Lord Charnwood), who married Miss Roby Thorpe, a granddaughter of the Right Hon. Anthony John Mundella. |

|

Edward Blackmore, of Beauworth and Alresford. |

At last the great day arrived: I was going to school with my brother Cecil. Under the care of William and our father we two little boys started for Brighton, following somewhat the same road that had been taken by a certain Charles Dickens, once a clerk in old Mr Blackmore’s office, just outside the front gate of Langtons. Great day of emancipation! A hot lunch in the refreshment-room at Portsmouth, choice of the menu—mustard and pepper if you liked; no nurse to say you nay; and you helped yourself to salt and bread, vegetables and pudding, at your own sweet will.

On arrival small beds were allotted. A portmanteau, shared by the two, and the book-box, containing jam and a small library, also between the two, got unpacked. Their contents having been placed on the shelf appointed, the boxes were relegated to the box-room until the joyful day of packing up for the holidays should arrive. Then came tea, where the jam and cake were distributed, the original owner reserving two slices for himself or any special friends. Afterwards two or three boys—new boys like ourselves—sat huddled together in the corner of the schoolroom, undergoing the ordeal by question. “What’s your name?” “How old are you?” “Have you any sisters?” “Are they pretty?” “Where do you live?” “Do you know anything?” “Are you clever?” “Can you play cricket and football?” The presence of my brother William made this ordeal as light as might be for his little brothers. A sudden inrush of late-comers; then supper—a slice of dry bread and a small glass of beer in the long dining-room—and a locking up of treasures, by Cecil in his desk, by me in a brown box which served the same purpose—I was considered too destructive to have a desk. Desks at that period of the schoolboy’s career were the treasured talisman of his existence. Therein you kept your mother’s last letter and your ready cash (having entrusted the capital sum to the headmaster), the revenue accruing from chance tips or your allowance of sixpence a week, stamps, forbidden sweetmeats, photographs of the pretty sister, cousin or sweetheart, if any.

The school list contained some of the most representative names of England: Lowther, Bouverie, Hanbury, Harvey, Hervey, Archdale, Ponsonby, Banks, Peel, Astley, Mitford, Gore-Langton, Hatton, Wrottesley, De Grey, Mellor, Tracey, Stanhope, Mills, Allen, Wingate, Anstruther, Payne, Wingfield, Lee-Warner, Drummond, Newton, Barrett-Lennard, Birkbeck, Gurney—and a curious little figure in yellow stockings, blue coat with brass buttons, knickerbockers, and a broad, white collar—and an enormous stutter—a cheery, good-natured little Dutchman, Bentinck, whom everybody liked and everybody tormented and chaffed, who in after years became the host of the Kaiser, William II., at the end of the Great War.

Many of the above have since become illustrious in the service of their country, notably the big, burly Lowther. A well-grown lad, with an able body and excellent brains, good-natured and bright, he had a pleasant way of enforcing authority—generally with a kindly word, but if need be with a hefty blow of his fist. Years after I met him again, when he was Speaker of the House of Commons, contributing by his humour, quick wit and firm authority, and genius for common sense, more perhaps to our success in the Great War than any other Member of the House.