* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Graham's Magazine Vol. XXIII No. 3 September 1843

Date of first publication: 1843

Editor: George Rex Graham (1813-1894)

Date first posted: September 24, 2024

Date last updated: September 24, 2024

Faded Page eBook #20240906

This eBook was produced by: John Routh & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

GRAHAM’S MAGAZINE.

| Vol. XXIII. | PHILADELPHIA: SEPTEMBER 1843. | No. 3. |

| Fiction, Literature and Articles | |

| 1. | The Millionaire |

| 2. | Stealings From a Gentleman’s Journal |

| 3. | Meena Dimity: or Why Mr. Brown Crash Took His Tour |

| 4. | Ugly Lucette |

| 5. | The Jeweler |

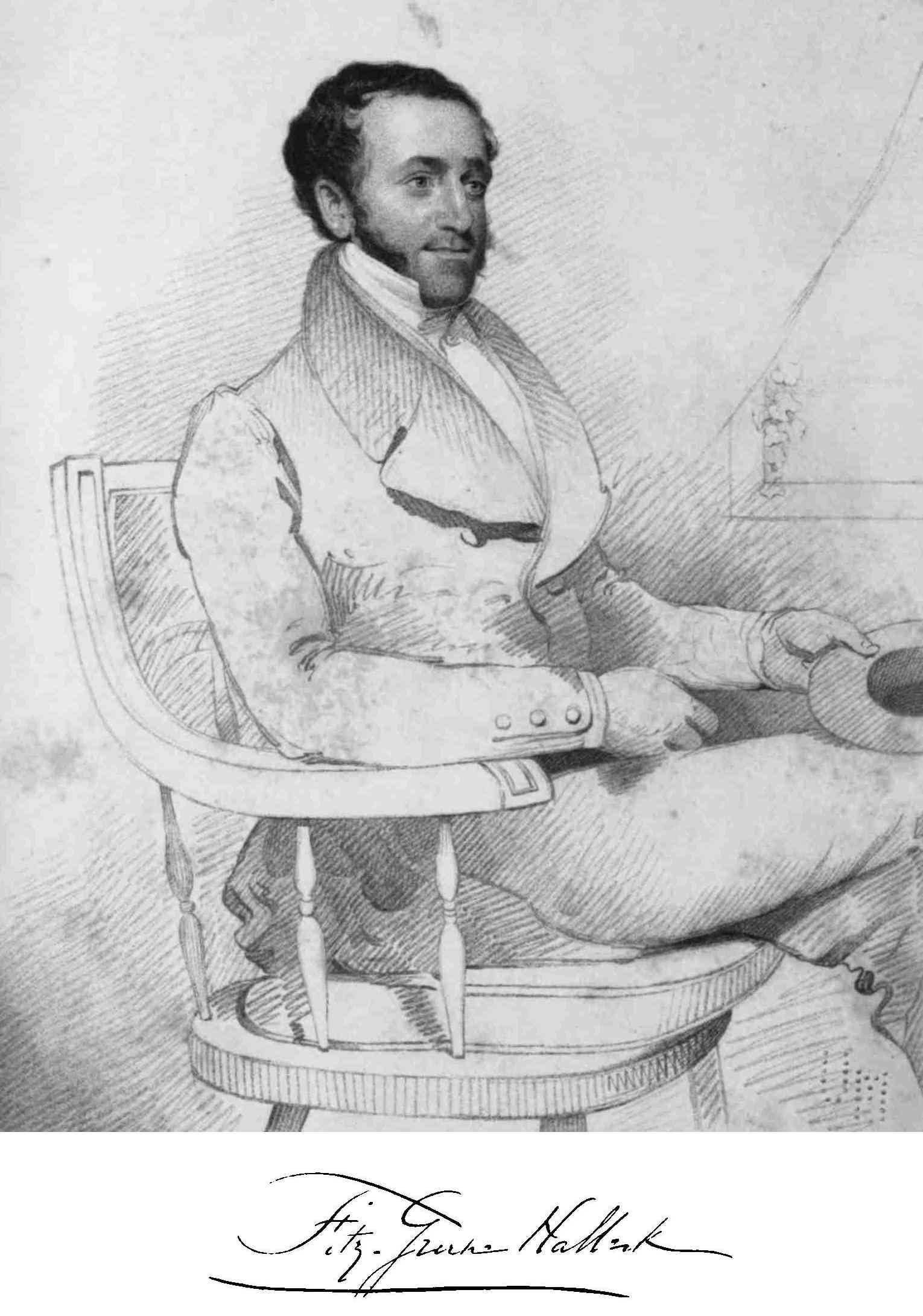

| 6. | Our Contributors—No. VIII: Fitz-Greene Halleck |

| 7. | Review of New Books |

| 8. | Editor’s Table |

| Poetry | |

| 1. | The Patriarch at Haran |

| 2. | The Wreath |

| 3. | The Minstrel’s Curse |

| 4. | Bunker Hill |

| 5. | To —— —— |

| 6. | Ni-Mah-Min |

| 7. | My First Love |

| 8. | The Child and the Watcher |

| 9. | First Truths |

| 10. | Death—The Deliverer |

| 11. | The Wife |

| 12. | My Flowers |

| Illustrations | |

| 1. | Fitz-Greene Halleck |

| 2. | My First Love |

| 3. | My Flowers |

In a certain great city of the new world, which shall be nameless, there once lived, and, in fact, lives still, a citizen, at one time somewhat better known than respected, but who maintained rather a dignified position in society, on the score of the possession of three tin boxes, painted green, one of which was filled with deeds of the kind which may be emphatically called good deeds—the second, with bonds and mortgages—the third, with certificates of the stock of various incorporations, not one of which divided less than ten per cent. per annum. These were his patents of nobility, and gave him equal claims with those highly descended nobles of the old world, possessing a coat of arms with thirty-six quarterings, and a pedigree derived from the most impenetrable obscurity. And why should they not? It would be difficult to give a good reason why bonds, mortgages and stocks, gained by a life of persevering industry, should not confer equal rank and dignity, with lands acquired, for the most part, originally, by rapine and oppression.

Be this as it may; our wealthy citizen, whose name was Caleb Plant, had, by dint of poring over his genealogy in the tin boxes, gradually acquired a considerable degree of self-sufficiency. He would occasionally indulge in various sarcastic innuendos, having reference to upstart pretenders; and as for his good lady, she held her head above the clouds, and trod the world under her feet—by which is meant, that she despised all beneath, and crouched to all above her. If a titled foreigner came in the way of Caleb and his spouse, he might think himself extremely fortunate if he escaped being surfeited by a quick succession, a perfect feu de joie, of horrible attentions. Mrs. Plant having been, at least, fifteen years on the turf of fashion, considered herself one of the aborigines of the beau monde, and her indignation at the intrusion of an interloper was awful. Had it been possible, she would have planted spring-guns and man-traps around the sacred precincts, to deter these insolent poachers. In short, Caleb was a millionaire, which, in all conscience, is equal to the title of count, or marquis, with thirty generations of uninterrupted gentility.

But though Caleb often said so, he never could bring himself to think so, for there was always in a secret corner of his heart a lurking consciousness of inferiority, whenever he came in contact with persons of real merit; for, after all the paltry pretensions of rank and wealth, that is the standard by which men always estimate each other in the end. We may contemplate the distant shadow of a pigmy, as it lengthens over the plain, with admiration for a moment, but the instant we compare it with the substance, the illusion vanishes. In like manner the rank, the splendor, and the power of kings, which overwhelm the imagination with a feeling of awe and reverence, dwindle into objects of contempt and derision, when we find, from the evidence of the senses, that they are in the possession of a fool, or a madman. The way to estimate the real dignity of men, is to bring them into contact with each other, and set them in action. It is then that the great talker often turns out a coward, the rich man incapable of protecting his own wealth, and that the king becomes dependent on the basketmaker. Caleb often learned this lesson; and, though it made him never the wiser, it detracted much from that portion of his happiness which was derived from the ignoble pride of superior wealth. He was perpetually reminded, not by the ill-natured sneers of others, but by his own self-consciousness, that the men he affected to look down upon, were incomparably above him in knowledge, in intellect, and in all the qualities that give one man a natural claim to superiority over another. His great wealth, by investing him with the power to confer benefits and inflict injuries, necessarily gave him a station and influence in society; but, though others might think him great, he always felt himself little; and the latter years of his life had been one incessant struggle to disguise from himself what he often managed to conceal from the world. Hence he was zealous in cultivating the acquaintance of strangers, or rather inviting them to great entertainments, where he sought to dazzle them by outward show, while his inward deficiencies escaped detection in the labyrinth of a crowd, or behind an immense silver tureen.

Caleb Plant had come to the city a poor country boy, and by a series of well directed industry, joined to the most rigid habits of economy, aided by constant prudence, and that occasional good fortune by which it is ever rewarded, about the age of forty-five had amassed a great estate. The prudent mothers of grown up daughters had long had their eyes upon him, but he was too busy, too constantly in action to be hit by the shaft of Cupid, who seldom shoots flying. It is impossible for a man to fall in love while he is running full tilt after Lady Fortune; and friend Caleb never contemplated the desperate throw of the matrimonial die, until one bitter, stormy evening, when the wind whistled, the snows beat against the windows, and the “spirit of the storm,” so often conjured up by modern bards, roared and yelled, and knocked furiously at the doors and windows for admittance. Caleb sat alone at his fireside. He had read the newspaper, and attempted a story in some mammoth sheet, and got along pretty smoothly, until it became necessary to turn over a new leaf, when he lost the track, wandered from one vast region to another, until he became perfectly bewildered, and, at length, so impatient that he cast it into the flames, and thereby incontinently set fire to the chimney. After the hubbub had subsided, he threw himself back in his chair, and began to sum up what he was worth; but not being able to ascertain the point altogether to his satisfaction, he had resort to his tin boxes, and clearly made himself out a millionaire. He pondered on this agreeable circumstance until he fairly got tired—for even the contemplation of wealth is a pleasure that wears thread-bare at last—and could hardly keep his eyes open, though it was only eight o’clock. All at once, however, he started up with great alacrity, and, ringing the bell, ordered a glass of whiskey punch, with which he regaled himself gloriously. But, after all, drinking with oneself, thought Caleb, is a poor business. He had a great mind to call in his factotum Absalom and have a set-to with him, until his dignity came and rescued him from such a groveling alternative. Then he suddenly rose again from his chair, paced the room from right to left, and from one corner to another, with his head declined a little forward, as if in deep thought, and his hands clasped behind him. Thus he continued for some time, when suddenly he seemed to become inspired—he rubbed his hands together, cocked his nose and chin, and exclaimed at intervals, in disjointed sentences, “Yes—yes—I wonder I never thought of it before. I’ll do it, by Jupiter—I’ll look out for a wife, as soon as this infernal storm is over.” Thus a long storm and a glass of whiskey punch brought Caleb Plant to the desperate point of matrimony. How many Benedicts can give better reasons than these?

It cleared up, however, during the night; the snows had all melted away; the morn was bright and cheery; and Caleb remembered he had yet many resources against matrimony. He belonged to three clubs, each meeting once a week; he exchanged dinners, as regularly as clock-work, twice a week with two of his most particular friends; and, on Saturday evenings, he played whist at home, with two old cronies, and dummy. Thus the six days were pretty well disposed of, but the seventh day, and most especially the evening, brought the tug of war; and, for three months from the memorable night of the whiskey punch and the snow storm, he regularly came to a determination to get married every Sunday evening.

But the resolutions of men, and especially of a bachelor of forty-five, are like the sands held in suspension by the current of the stream while in a state of agitation, and which suddenly subside in a state of repose. It was not until about the middle of August following, that the punch and the snow storm received a reinforcement that finally enabled them to carry the day in favor of matrimony. As Caleb was shaving himself one morning, he received two great shocks, in quick succession, which brought him to the feet of Don Cupid in an instant. The first was the discovery of two very considerable circular furrows, ploughed by time, from the tip of his nose to the corners of his mouth; the second, the detection of a slight approximation of some straggling hairs about his ears to gray. He immediately rang the bell furiously, and, the servant entering somewhat in alarm, he exclaimed—

“Absalom!”

“Sir!”

“Get the carriage and horses in order—pack up my clothes, and be ready to-morrow morning to set out for the Springs. And, do you hear, lock up my spectacles—”

“In the portmanteau, sir?”

“No, blockhead, in the cabinet. I shan’t want them.”

The next morning Caleb, having no notes to pay, was off to the Springs, with his splendid equipage, and without his spectacles. Some very sensible, well informed writers have seriously questioned the sagacity of gentlemen seekers, who go to the Springs, or other public resorts, to look for a helpmate; but, for our part, we think the plan of Caleb Plant was very sensible and judicious. There are times that try the souls of women as well as men; and these occur quite as frequently at public places as within the domestic circle. Nay, the excitements are much greater, and the sins more besetting. It is there that human vanity is most successfully assailed; that envy, jealousy, and petty malice find their constant sphere of exercise, as well as their keenest stimulants; and she who can best withstand their instigations is the lady for a bachelor’s money. When he meets with one who speaks low, not from fear that she is saying what she ought not, but from modest diffidence; when he sees her admired without effort; neglected without ill-nature; outshone without envy, and followed without looking behind, let him gather himself together—yea, let him forthwith single her out from the rest of the sinful race of the daughters of Eve; let him cast himself, his equipage and his million at her feet, and if she do not accept him, it will not be the fault of her prudent mamma. But if, on the other hand, he finds a fair and beautiful young damsel, who talks loud in public; laughs like a certain animal called a horse; is impatient of admiration, and splenetic at being overlooked; one who cannot represent a wall flower without turning yellow with envy, or submit to abdicate the throne when claimed by the legitimate heir; one who usurps the prerogative of the Grand Signor, by throwing the handkerchief herself; one, in short, who waltzes with every ferocious stranger, in whiskers, at a moment’s warning. When thou shalt encounter such a damsel, I say unto thee, O! bachelor, flee to the uttermost ends of the earth; bury thyself deep under blankets and comfortables—pile Ossa on Pelion; yea, verily, cut a stick—make tracks, for thou art barking up the wrong tree. Or, if all other means fail, get thyself reported bankrupt, and if that don’t save thee, thou art foredoomed.

His arrival at the Springs created a sensation, and there was a great fluttering among the birds of paradise. It is true, Caleb was no beauty. He was somewhat bandy, his shoulders were as round as those of a fashionable belle; he was suspected of being pigeontoed, and he wanted tournure—he could never catch that indescribable grace with which our fashionable gentlemen carry their hands in their coat pockets. But he was a millionaire. Nor did he pretend to any particular accomplishment; he could neither murder French, dance the waltz, nor drive four in hand. But then he was a millionaire. As to mental cultivation, his pretensions were equally slender. He never read the reviews, consequently he never ventured an opinion on books; all his manuscripts were in his tin boxes, and he valued none except those which began with “Know all men by these presents.” But then he was a millionaire. He had not been two days at the Springs, before he was quite at home with all the ladies of the least pretensions, and hand and glove with all the gentlemen. He was under no necessity to make himself agreeable, for the ladies took all the trouble off his shoulders; and wherever he went he was accompanied by a cortège of men, who listened to his opinions with profound devotion, and reverenced him as an oracle.

There is nothing which so soon upsets the gravity of men of a certain age, as the admiration of the other sex. Men, except they are of entirely different pursuits and professions, seldom admire each other with sincerity; there is apt to be a little spice of envy or jealousy at the bottom. Hence they do not value the respect of each other so much as the homage of the ladies, who, being free from all rivalry with them, are presumed to be perfectly disinterested. Caleb could not withstand these attentions; his head grew dizzy; he actually became frisky, and was one night seduced into the enormous indiscretion of dancing a quadrille with Miss Julia Philbrick, the belle of the Springs, who persuaded him it was the simplest thing in the world. He got through with it awkwardly enough, and would certainly have been laughed at, if he had not been a millionaire. Two other feats are on record in the annals of the Springs. He attempted a waltz, but, the third round, his head began to swim like a top, a whirlwind raged in his ears, the floor rose up before him in great billows, and his partner seemed to be flying in the air. Caleb had just sufficient discretion to dart to a seat, leaving his partner to her fate, who is reported to have whirled round the circle three times before she could stop herself. Such a catastrophe might have been fatal to any other man, but Caleb was a millionaire. His last great feat, was attempting to climb the Lover’s Rock, to which he was imprudently excited by the insinuations of a young gentleman, having pretensions to the good graces of Miss Julia Philbrick, that he was rather old to try the experiment. He had got near the summit, when his evil genius prompted him to look down upon what seemed an abyss of a thousand feet; his knees trembled, his heart throbbed, his head swam, and there is no knowing what might have happened, had not Miss Julia Philbrick reached him the end of a pocket handkerchief, for which she gave forty-eight dollars, by the aid of which he was enabled to reach the top. This was the last performance of the millionaire, who was afterward content to repose under the shade of his laurels.

From that time, he considered Julia as the preserver of his life, and his gratitude corresponded with the benefit. She had saved a million of dollars, and deserved to be rewarded. His attentions became rather particular; he dipped water for her from the Pierian Spring, invited the mother and daughter to ride in his carriage and four, and asked them how they were every morning. Mrs. Philbrick—whose husband was a Mr. Nobody, and therefore not worth mentioning—was gifted with a world of motherly sagacity, and thought it was now time to draw the net a little closer about this precious gold fish. She had, several years before, got some how or other out of health, and was pining away with that singularly incomprehensible malady which baffles the skill of all our physicians, and can only be cured by the salubrious air of Paris. There she had thoroughly got rid of all those vulgar republican notions about mutual affection, exchanges of hearts, parity of age, connubial happiness, and all that sort of nonsense. She had learnt to know that the true end, object and destiny of all young ladies in matrimonial speculations, was obtaining a settlement. As to love without money, it was out of the question; and she held, with the better sort of people, as well as our unsophisticated Indians, that daughters were mere subjects of barter or sale, and that the first duty of an affectionate parent was to get as much for them as possible.

She had attempted to instill this excellent system of philosophy into her daughter, and had succeeded indifferently well. Julia was a clever girl; one of those on whom nature has kindly bestowed a disposition to be amiable and happy. Had she been blessed with a mother such as she deserved, she would have been all the best of mothers could have wished, for she was handsome enough to charm the eye, and might have been good enough to rivet the affections her beauty inspired. But the mother is the daughter’s destiny. Her example is her guide, her precepts her decalogue; and when we see a worthless son, or a willful, wayward, extravagant daughter, one may be almost sure the mother has been neglectful of the plant to which she gave being, but which she never nourished with the dew of affection, or the genial warmth of sleepless maternal care. Happy the child that has a wise and virtuous mother, and wretched should be the mother that has a worthless child, for if she look into her own heart, ten to one she will find that the fault is her own.

It was the unlucky destiny of poor Julia to have such a mother, and to be still more unfortunate in a father whose easy habits of passive indolence were such, that he was content to let every one around him do as they pleased, provided they would only let him alone. He hated trouble so much that he was always in trouble to avoid it; and a straw in his way was equal to an impossibility with other people. It is thus that Providence smooths the path of life into a dead level, where the only real sources of inequality in our portion of enjoyment are evil thoughts and evil deeds, visited, as they always will be, by the scourge of conscience, and haunted by the vindictive fiend remorse.

Poor Julia! no wonder the rich soil of her heart was sown with tares, by the precepts and example of her mother, the indolent neglect of her father. She had the most fashionable education, which, there is too much cause to believe, is not the most effectual barrier against the temptations of this world; and she grew up to place her happiness entirely in the possession of the means of indulging those vapid, heartless pleasures, that give nothing in return for robbing the heart of all its lasting and substantial sources of happiness. The only duty taught her by her mother, was that of implicit obedience; and, in process of time, this salutary obligation became so powerful that it finally superseded all the virtuous impulses of her heart, while it overpowered all the promptings of her reason. Sometimes, indeed, both would rebel; but, at the period of which I am speaking, long habits of submission to the mother’s precepts had almost completely subverted the independence of her mind; while a laborious pursuit of those pleasures which, though they are incapable of satisfying the craving appetite for happiness, render all other aliment distasteful, had hardened her heart to those more gentle and endearing feelings, which gray-beards call dreams, only when they have outlived their enjoyment, and can never hope for their return.

The details of the siege of the citadel of the millionaire, would be too tedious, we will not say disgusting, to those who set a proper value on the purity and dignity of woman. We, therefore, pass over the various manœuvres of the wily mother; the fantastic and original devoirs of Caleb, and the struggles of the victim, Julia, whose heart often rebelled against the sacrifice site was called upon to make to the golden calf, but was as often reduced to obedience by the habit of submission to her mother, aided by those visions of splendid misery presented in perspective from the inexhaustible purse of the millionaire. Before the season was over, Caleb had proposed, was accepted, and Mrs. Philbrick had the satisfaction not only of being the mother-in-law of a millionaire, but of triumphing over her particular friend, Mrs. Mugford, with whom she was very intimate, and who had a daughter her mother would very willingly have substituted in place of poor Julia. But the daughter happened to have a will of her own, and, we will do her the justice to say, was almost the only unmarried lady at the Springs who could resist the millionaire. Her reasons were so conclusive, that we will here record part of a conversation between mother and daughter, for the benefit of all young ladies similarly situated.

“But what objections,” said the mother, “have you to setting your cap at Mr. Plant—don’t you know that he is a millionaire?”

“O, Lord, yes—every body knows that—but I dislike his name—I shouldn’t like to be called Mrs. Plant—it is so common.”

“Well, but, my dear Louisa, he can get his name changed to Plantville, by applying to the Legislature. These millionaires can do any thing, you know. Besides, who knows but his name may be Plantagenet, and that he has changed it to Plant for shortness?”

“But I have other insuperable objections, ma.”

“Well! what are they, my love?”

“Why, he hasn’t got any moustaches—I can’t bear men without moustaches, they look so vulgar. They never can be distingué without moustaches.”

“Well, but, my love, if Mr. Plant cannot be, as you say, astringent—”

“Lord, ma! I said distingué—I meant distinguished, ma.”

“Well, then, why didn’t you say so, my love? But if Mr. Plant can’t be distinguished for mus—moustaches—he can make his with distinguished for her carriage, her house, her furniture, her dress, her jewels, her dinners and her soirées—and what can a reasonable woman want more?”

“My dear ma, it’s useless to talk about Mr. Plant. He can’t waltz—and I never can or will marry a man that can’t waltz; though, for that matter, I should never waltz with him after marriage, for fear of losing my reputation.”

“Very well, my love, you may go further and fare worse. A millionaire is not to be had every day—and—”

“O! Lord, ma, there’s the ball opening, and I am engaged to waltz with the foreign gentleman with such beautiful moustaches—I forget his name, for I have only seen him once this morning. He is just arrived from Europe, and Julia Philbrick, I’m sure, is dying to waltz with him—” and away she ran, leaving the good lady mother at a nonplus.

If Julia was offered, or had offered herself, up a sacrifice to the mammon of unrighteousness, and made herself a martyr, she was determined to enjoy the heaven thus dearly purchased. She resolved at once to become the bell-wether of the flock, the most distinguished of the tribe, the incontestable leader of fashion. This enviable eminence was seldom to be gained, in the great city she inhabited, except by the possession or at least the expenditure of a great deal of money. Either of these answered equally well; and the miser who had amassed his wealth by extortion and abstinence, who never missed a chance of availing himself of the misfortunes of others, or seized an occasion to alleviate distress, was equally an object of profound deference with the dashing spendthrift, who entertained the world at his table, and was equally liberal to his friends as charitable to the poor, at the expense of his creditors.

There are various modes of drilling a bachelor after he has been metamorphosed into a married man, and divers wiseacres have puzzled themselves to account for the facility with which the most silly, superficial women hit upon the shortest, as well as most certain system to train the lordly despot into submission. They do not consider that, with here and there an exception, all that is necessary to the success of the process of taming, is a tolerable insight into the character of the subject of the experiment; and that such are the daily, nay hourly, opportunities afforded in the constant associations or conflicts of domestic life, that little reflection and less sagacity is required to enable either party to comprehend the weak side of the other. A little condescension, a series of doses, dexterously administered to the ruling passion, will, if the good man is not altogether impracticable, by degrees subdue him into quiet acquiescence. There are, however, some men who must be conquered by opposition; open, undisguised rebellion to lawful authority. To humor them, but increases their waywardness, and their obstinacy only becomes more contumacious, by having nothing to encounter.

Such a man was the millionaire. He had begun the world without any of those supposed advantages, which are, in truth, often the greatest disadvantages; he had amassed an immense fortune by his own labors and good management; and, whoever else might doubt, he was perfectly convinced in his own mind that he was a remarkably clever fellow. Doubt the talents of a millionaire—thought Caleb. You may as well deny that a man who has conquered kingdoms is a hero. In addition to this, he had been his own absolute, uncontrolled master up to the age of forty-five, and in that time a man becomes a pretty obstinate twig to bend. Add to this, that he possessed but little sensibility either to menial or personal beauty, and the reader will imagine that Julia had a hard task before her, in reducing her impracticable helpmate to a proper stale of quiescence.

Yet Caleb was in reality the easiest man in the world to manage. He was a bull that might be subdued at once if you only seized him by the horns. In short, he was a passionate fellow; and, what is worse, always blew out his steam before the vessel got fairly under way. He consequently expended all his powder previous to the commencement of the battle, and before the enemy came fairly in sight he was hors de combat, and had nothing left for it but to surrender at discretion. These were the rough materials on which Julia had to operate, and she commenced without loss of time. She began in the last quarter of the honey-moon, when, as every body knows, the planet is pretty well on the wane.

“My dear Mrs. Plant,” said Caleb one morning at breakfast—

“Mrs. Plant!” iterated Julia, turning up her pretty Grecian nose a little superciliously—but a sudden thought coming over her, she checked herself. “My dear,” said she, in tones that might have softened the heart of a tiger—“My dear”—she never could bring herself to call him Caleb—“My dear, I wish you would oblige me in one single thing, and I promise never to ask for the like again.”

“Well, what is it, Julia?”

“Change your name, my dear. You know I’ve changed mine to oblige you, and one good turn deserves another.”

“What!” answered Caleb, dashing down his cup with considerable emphasis—“What! change my name, and be obliged to get all my bonds, deeds, mortgages and certificates of stock altered from Caleb Plant to Caleb Plantville, or I don’t know what?”

“Yes, Plantville—that is a charming name—it sounds like the founder of a city—and now I think of it, you might purchase a site somewhere out in the west, and establish a great emporium to be called after your name, and carry it down to the latest generations. But Plant! O! my dear, dear husband, if you only knew how it puts me in mind of planting cabbages and onions!”

Caleb was a perfect percussion cap—a charge of fulminating powder—in short, he was a millionaire, and things are come to a fine pass when a millionaire can’t fall into a passion ex tempore, just when he pleases.

“I’ll tell you what, my dear Jul—I mean Mrs. Plant—my name is a good name, it will pass for a million on ’Change, and if you don’t like it you may give it me back again, that’s all!” and then, as is always the case with men of his temperament, he gradually inflamed himself by his own words and the sound of his own voice, like a lion lashing himself with his tail—“Yes, madam, Plant is a good name—you’ll not find it in the list of bankrupts, where so many of your fashionable friends cut a figure. But, madam, I’ll tell you where you’ll find it”—and he looked like a hero—“You’ll find it belonging to a man that won’t be made a fool of by his wife, his mother-in-law, his second cousins, nor all of them put together.”

“Well, my dear,” replied Julia, as smooth as oil and perfectly self-possessed, “Well, my dear, whatever you may say of Plant, I hope you don’t mean to defend that awful name Caleb. Why, don’t you know that’s the name the hunters give to the grizzly bears in the great west? Mr. Catlin told me so. Old Caleb! ha! ha! only think of having the same name as the grizzly bear, when you grow old, as you will do in a very few years.”

This speech blew up Caleb into a flame, as well it might, and produced a decisive contest, which ended in his being completely routed. Julia maintained that self-command which is held to be the perfection of good breeding, and said the slyest, cutting things in the most genteel tone and manner possible. Caleb blustered, swore, and actually abused both his wife and mother-in-law, in such a wholesale style, that he thought, on reflection, the only way of making amends was by changing his name as soon as possible. It happened that a friend, a member of the legislature, dropped in while the discussion was going on, to whom Julia immediately applied, stating that her husband, in expectation of inheriting the estate of a distant relative, who had no children, and who had given him several broad hints on the subject, was desirous of changing his name from Caleb Plant to Hyacinth Plantville, and begged the honorable member to interest himself in this behalf. The honorable member immediately proffered his best services—for what member could refuse so small a trifle to a millionaire? The honorable legislature changed his name with as much celerity as legislatures generally pass appropriations for the god of their idolatry, the glorious per diem; the bill was read three times by the clerk, so fast that not a soul could understand it, which was, however, of little consequence, as nobody listened, and passed unanimously—for what honorable body can resist a millionaire? Caleb Plant came out Hyacinth Plantville as clear as a whistle.

“What an impudent jade is that wife of mine,” quoth Caleb, in a short soliloquy, after the honorable member had concluded his visit; “What consummate impudence! but never mind, I paid her beforehand. I gave her a piece of my mind, and there is no use in saying any thing more on the subject. Hyacinth! d—n Hyacinth, it puts me in mind of a flower-pot in a window. But Plantville is not so bad—ville—what’s ville in French? O! now I recollect; a city. I shall certainly follow the suggestion of Julia, and found a great emporium somewhere in Illinois, Iowa, or Wisconsin, to transmit my name to posterity. Upon my word, she is a handsome, sensible hussy after all is said and done.” Self-love will solace itself with such crumbs of comfort sometimes.

This victory was decisive, although it by no means prevented future contests, which all ended in the same way. Caleb—we beg pardon, Hyacinth—scolded sometimes; sometimes swore; and was occasionally a little scurrilous; Julia kept her temper, took it all quietly, let him say what he would, and then did as she pleased afterward. The poets were fools who feigned the lion was subdued by a virgin; a wife is worth a dozen of them in the taming process.

The millionaire having, not long after his subjection was finally achieved, been appointed one of the commissioners to decide on the location of a pump, in a very critical position, was complimented by the title of honorable, and his glory consummated. He bought a site—unsight unseen—at a great price; founded a city on a rock, at the head of the navigation of a river, that contained no water except during heavy rains or the melting of the snows; appointed a long-headed, calculating genius his agent, who laid it out in lots and squares, with most illustrious names; suborned an artist to paint the emporium with all the houses, churches, and public edifices in anticipation, which he got lithographed by an expert builder of cities; and, as a last coup de main, sold several lots at auction, which he bought in himself at a swingeing price.

In the mean time, Mrs. Hyacinth Plantville had become the incontestable leader of that strange, fantastic, indefinable shadow, Fashion, which has never been defined, because it is in reality nothing. Politically we may be free, but there is no people on earth so completely henpecked in every thing relating to modes, manners, dress and opinion as our worthy countrymen, and more especially our charming countrywomen. They are both absolute slaves—one to foreign reviewers, the other to French milliners. Did our limits allow it, we would trace her step by step, and disclose the mysterious process by which she attained this awful pre-eminence. Suffice it to say, that she was a handsome, shrewd, clever woman, and had the advice and assistance of a mother more experienced than herself. But, had she been a simpleton and a dowdy, her husband was a founder of cities and a millionaire. She could afford to waste—at least she wasted—more money than any of her rivals, and the old proverb has a peculiar application to the votaries of fashion, who are supposed to be directly descended from the ancient worshipers of the golden calf.

In process of time, she became the mother of two children, a son and a daughter, and the birth of the former was the crisis of her fate. Had she done what her heart, in the secret core of which nature sometimes made an unavailing struggle, prompted her to do; had she sacrificed those empty delusions which not only never confer happiness themselves, but render their slaves incapable of deriving it elsewhere; had she stopped short in her career of idle, unsubstantial vanity; had she, in one word, assumed and fulfilled the sacred duties of a mother, she might have not only been happy herself, but prevented the happiness of her children from being wrecked forever. But, like the inexperienced mother of our race, she was tempted by the glistening eyes, the golden waving scales, and wicked whisperings of the wily serpent, Vanity, and after a few struggles, the last she ever felt, yielded a final and decisive victory. She who resists and conquers the first fond yearnings of a mother’s heart, need never hope to be overcome by any other impulse of duty or affection; for her fate is ever afterward to starve on empty pleasures, and never to know the purest, most sacred, most delightful and absorbing of all the cares and enjoyments that fall to the lot of woman. She may consider herself forsaken of her God, for she has abandoned the post of honor in which he had placed her, by acting in direct opposition to that heaven-born instinct which impels even the wild beasts of the forest to nurse and protect their offspring in the days of their helplessness.

But Julia had fallen a victim to her mother’s vanity, and she now offered up her children at the shrine of her own. One of the most formidable of her competitors for the bauble sceptre of fashion, just about the period of the birth of her son, had returned from a tour in Europe, during which she had spent a winter in Paris, the paradise of fools. She had brought with her a powerful reinforcement of new manners, fashions and tastes; a French cook, two ignorant nurses to teach the young ladies the true French pronunciation, a poodle, and a whiskered cosmopolite, whether an admirer of herself or her daughters no one could tell. He bore the title of count, was devoted to music and waltzing, and his moustaches were inimitable. The fashionable world began to waver in its allegiance, and the count and the poodle seemed on the point of carrying the day, especially when it was whispered abroad that the latter was of royal lineage, being descended in a direct line from the favorite poodle of the late Duchess of Angoulême, which is said to have been choked by a diamond necklace. A severe contest ensued, in which the tin boxes of the millionaire suffered considerably. Julia sought victory by the splendor of her entertainments, and tried to allure the knights of the moustache by the profusion of wines and delicacies, and the number of pâtes, concocted of a stuffed goose’s liver, she offered for their discussion. Her rival, not being able to dispute this pre-eminence with her, entrenched herself in another stronghold, from which she annoyed the enemy exceedingly. She appealed to the intellectual instead of the corporeal appetite, and to the ears instead of the eyes and palate. She affected a marked simplicity in her establishment and entertainments; she invited a host of famous musicians, all of whom had presided over orchestras, and played before kings; she exhibited the count and the poodle to the greatest advantage; and, in short, various ominous appearances indicated that the count, the poodle, and the fiddlers would carry the day against the millionaire and his tin boxes. A revolution was at hand, and a change of dynasty appeared inevitable. What rendered this state of things still more mortifying and deplorable, Julia, during the most critical period of the contest, was in “the state that ladies wish to be who love their lords,” according to Shakspeare, who, however, is not the best authority in the fashionable world of the present day. This untoward accident greatly embarrassed her exertions and impeded her activity, so that toward the end of the campaign, when she gave birth to a daughter, her rival, or rather the count, the poodle, and the fiddlers, might be said to have almost secured the victory.

Poor Mrs. Hyacinth Plantville suffered dreadfully during the period of her abstraction from the world, to which, however, she hurried back with such imprudent precipitation that she caught a severe cold, of which, like a prudent woman, she availed herself in the most dexterous manner. She saw that for the present her fashionable retainers were irreclaimable, and as the next thing to a victory is a masterly retreat, at once decided that the state of her health required a sea voyage, and a residence in a milder climate. She assured the Honorable Hyacinth that such was the case, and the doctor strenuously advised that no time should be lost, as the spring air was particularly dangerous to the lungs. Hyacinth swore he would not stir a peg; strutted, fretted, scolded and fumed; abused his wife, insulted the doctor, and consigned all Europe, particularly Paris, to eternal perdition. After which, having spoken his mind, and paid Julia off beforehand, as he said, he submitted without further demur, and consented in silence to his approaching martyrdom. No time was to be lost, the spring climate being so dangerous; and things were hurried on at such a rate that Hyacinth had scarcely time to metamorphose some of the contents of his tin boxes into bills of exchange. The truth is, that even millionaires may sometimes want money; and what with the extravagance of Julia, the demands of his long-headed, calculating agent, who always assured him his city was growing so fast that it would soon make a great figure, together with the consequences of that great revulsion which was then fast approaching, and from whose gripe neither rich nor poor have since escaped—however surprising it may seem, our millionaire was often pushed for ready money. One of his tin boxes, or at least the contents, had departed from his custody, and the others were in a fair way of speedily following. Had Hyacinth not relied on his great city in the west to make up his leeway, he would before this time have died of a broken heart.

“Good Lord!” exclaimed Julia, who had been very much puzzled to keep ill enough to require a sea voyage, and a residence in the milder climate of Europe; “Good Lord!” cried she, suddenly recollecting herself and mustering up a violent cough, “what shall we do with the children? I had quite forgot the poor little creatures.”

“Do with them!” quoth Hyacinth—“Why take them with us, to be sure.”

“But, my dear, they are so young, and I am so poorly, that I should never be able to take care of them on board the ship, I’m sure.”

“You can take as much care of them on board ship as you do at home for that matter, and not kill yourself either,” replied Hyacinth bluntly.

This was a home thrust. It was too true to be spoken, and above all to be heard by the mother who felt she had merited the reproach. The first shock brought tears to her eyes, but the fountain was scorched dry in an instant by the first sparks of anger that her husband had ever seen flash from her eyes. She was actually on the very point of pouring vials of wrath on his head, when suddenly recollecting she had a point to carry, she replied with her usual derisive composure.

“Well, suppose you stay and take care of them, while I am seeking that health I fear I shall never more enjoy. It will be an amusement to you, and console you in my absence, my dear.”

“Hum,” quoth the millionaire to the great consternation of Julia, who was never so much afraid of his opposition as when he said nothing, for it was the only sign he ever gave of a determination to do a great deal. The consultation ended in deciding to leave the children at home, with four nurses to take care of them, and two governesses, under the eye of their grandmother, to superintend their morals and education. The arrangement was made in such haste, that there was no time for the necessary inquiries into the morals, habits and qualifications of the two governesses, and the millionaire together with Julia and her suite departed on their tour, leaving, as the latter said, “all their cares behind them.”

We shall not dwell at length on the incidents and adventures, the inconveniences and enjoyments, the anticipations and disappointments which befell the millionaire and his wife, who, if the truth were fairly told, often felt by mortifying experience that they had not left quite all their cares behind them. It is sufficient to the moral of our story, that according to the custom in all similar cases, the wife cut the figure while the husband represented the cipher. Julia’s health mended surprisingly, and had it been the fashion in the old world, where maturity, not to say decay, is preferred to the charm of youthful bloom and freshness, she might have passed for the daughter of the millionaire. She visited Italy, where Hyacinth became something of a connoisseur in painting, by purchasing several original copies, and Julia almost ran mad after music. They visited Switzerland, where our hero mounted a glacier, and was very near being precipitated into an icy chasm so deep that it is doubtful whether he would ever have found the bottom; and Julia became smitten with a violent fit of the picturesque. They visited honest, old-fashioned Germany, the modern court of the muses as well as temple of philosophy; sailed down the Rhine in a steamboat, in the midst of a cloud of tobacco smoke; saw everywhere so much that they could remember nothing; and finally came back to Paris to spend the winter preparatory to their return home. During all this time they received no letters, for Julia had desired her mother and the governesses not to write, since if there was any bad news it would only make her miserable; and if good, before it could be received something ill might have happened.

At Paris Julia laid herself, and especially her husband’s money, out to make a figure in that huge vortex of discontented, aspiring spirits, who, finding no happiness at home, seek for the jewel in other caskets where it is never found. Young, handsome, graceful, accomplished, and with the reputation as well as outward exhibition of great wealth, her vanity might have perhaps been gratified, had she been content to be sought instead of seeking. But the quick-sighted pupils of that great school of life soon discovered her feverish anxiety to excite notice, and be admitted into the circles of the would-be great, and consequently set her down as one of the vulgar herd of Americans, who, while pretending to despise titles, are more abject in their devotion to them than the lowest slave of an eastern despot. Julia courted, and fidgetted, and floundered about in her splendid equipage; gave grand entertainments at the hotel which our millionaire, or rather his better half, had hired for the winter; and, in order to allure the birds of fashion, induced an old dowager of the ancien regime, who had survived all the possessions of the family but their title and their pedigree, to condescend, for an adequate consideration, to receive her guests and do the honors.

But it would not do. All that her own spasmodic exertions, aided by Hyacinth’s money, could accomplish, was to attract a few straggling outcasts of the magic circle, who had preserved the ragged remnant of a title, and were permitted to claim kindred with their illustrious houses, provided they claimed nothing else. Before the winter was fairly over, Julia suddenly discovered the air of Paris did not agree with her; and Hyacinth, who had begun to relish the society of Messieurs the Restaurateurs, was forthwith put under sailing orders for England. In London they were lost in a fog, both literally and metaphorically. They had letters, but not being lions, nobody thought they could derive any éclat or consequence from entertaining them. The American minister was civil, but not being a worshiper of the golden calf, he was nothing more. The banker gave them a dinner to quiet his conscience, and then cut them adrift. Julia found the air of London even worse than that of Paris; and, having accomplished an introduction to the royal levee, turned away from “merry England,” with a solemn declaration that it was the dullest place she ever saw in her life.

On her arrival in the great city, her first inquiries were about the rival queen, who, she found, still possessed the throne, but had many competitors, among which the most formidable was the wife of a man who possessed more property belonging to other people, than any one of his contemporaries. He had founded several cities; was sole proprietor of a bank without capital; and if wealth, as many people believe, consists in the amount of a man’s debts, he certainly was one of the richest men of his day. Julia then called for her children, and attempted to kiss them, telling them she was their mother. But the little girl slapped her in the face, crying out, “You aint my mother—nurse Jenny is my mother;” and the boy, turning up his nose, skipped away to tell his nurse there was a strange woman in the parlor who wanted to make him believe site was his mamma. “What unnatural little monsters!” exclaimed Julia, and she almost hated them.

Her first step was renewing the war against her ancient rival, who, she rejoiced to find, had lost two of her most powerful auxiliaries. The poodle had died under strong suspicion of being poisoned—that being the appropriate fate of all dogs of distinction—and the count had disappeared in a mysterious manner, leaving none behind to lament his fate but his landlord, his tailor, and his shoemaker. Nobody knew what became of him, though there was a vague report that he had begun the world anew, in one of the remote towns of the west, under the auspices of a barber’s pole. The war was commenced with desperate vigor, money on one side and music on the other. Julia renewed and outdid former extravagancies, and talked incessantly of the condescending affability of Queen Victoria, while the tin boxes of the millionaire grew lighter and lighter. But experience soon brought home the mortifying conviction that, however it may be in political revolutions, those who have once abdicated, or been driven from the throne of fashion, can never be restored.

While this fierce contest was going on, the millionaire, finding his resources daily diminishing, and his tin boxes at the point of exhaustion, determined to replenish them by resorting to some of the means by which he had acquired his riches. He plunged by degrees into the vortex of speculation; purchased vast amounts of fancy stocks; became a dealer in city lots, lithographic cities, and broken bank charters. But Fortune, though she may sometimes carry a man on the top of her wheel for a long time, is pretty certain to throw him off in the end, especially if he does not dismount and retire in time. Though she may yield to early youthful addresses, she revolts at the gray-beard and his wrinkled brow, and seldom twice takes the same man for her paramour. Accordingly, she turned her back on the millionaire, and amused herself with enriching a more youthful suitor, with the spoils of her ancient beau. Hyacinth, in short, had commenced at the wrong end, and just at the time the balloon had begun to collapse. Every thing was falling, and as our hero, in pursuance of his old system of doing business, always purchased on the presumption of a rise, he never failed to go in at the big, and come out at the little end of the horn. It is amazing how soon the candle will burn out when you light it at both ends. Julia burnt one end at home, and Hyacinth the other abroad; no wonder it began to flicker in the socket. Julia, for the first time, made a draft on the pocket of the millionaire, which was returned protested.

“I have no money,” said he, with all the coolness of desperation.

“No money! impossible.”

“Such a thing is possible, my dear.”

“But how is it possible to spend a million of money?”

“Much easier than to get it, my dear.”

“I don’t believe a word of it. It’s only one of your stingy fits come over you.”

“The fit will last a long time, I fear.”

“Well, I must have the money, and there’s no use in talking.”

“None in the world, my dear. It’s all talk and no cider.”

“Out upon your filthy, musty old saws. I wish you would say something to the purpose, Mr. Plantville.”

“Well, Mrs. Plantville,” replied the millionaire, drawing himself up with an air almost of sublimity, “for once I will speak to the purpose, and you must hear to the purpose, too. Your extravagance, and my folly, have reduced both of us to beggary. The wealth accumulated by years of honest, persevering industry and economy, has been wasted in almost as few months, in the vain pursuit of what we never could attain. In striving to make up for what was thus wasted in folly and extravagance, I have only plunged into more irretrievable difficulty, and I now tell you, madam, that the utmost I can save from the wreck of my fortune will not exceed twenty thousand dollars.” Hyacinth spoke this with a calm, yet somewhat severe moderation, far different from the peevish irritability with which he was wont to meet the little rubs his wife often threw in his way; so true it is that those whom trifles discompose, often encounter the most severe calamities with unflinching fortitude. The weight of the blow crushed the little thorns and briers, but left the stem of the plant not only unhurt, but reinvigorated, by the absence of these excrescences.

It is needless to dwell on the catastrophe of the millionaire. Hyacinth was a man of at least conventional honesty. In the long course of his business, it had been his interest, if not his principle, to pay his debts punctually, and on this occasion he behaved with the most scrupulous integrity. This being perceived by his creditors, they unanimously agreed to commit to his own hands the settlement of his own affairs; and we will do him the justice to say that he fully justified their confidence. He labored with assiduity, not only from gratitude to his creditors, but because he was striving at the same time for himself, since all he could save from the wreck would be justly his own. In short, he paid all he owed, and saved some twenty thousand dollars, preserving, at the same time, what was of far more worth than the million he had lost, a quiet conscience, and an unsullied name.

It was now, too, that Julia emerged from the total eclipse which bad example and worse precepts had cast over the lustre of her virtues. She was a sensible, clever woman, and of such we need never despair. Nature once more awakened and exerted her prerogative; and, though it may seem strange, it is not in reality so, she began to respect and love her husband. When she saw him laboring incessantly to preserve the remnant of his fortune; how careful he was of the interests of others; with what a decent, manly resignation he, one by one, sacrificed all those splendors which he had devoted his youth and manhood to obtain; and with what delicacy he ever afterward abstained from all allusion to her agency in dissipating his fortune, she could not but acknowledge there was that within him which fully merited a better wile than she had been. She fell much brighter than she rose; and when they retired from their fine establishment to occupy a small house in the outskirts of the city, it was with a fixed determination to make up, as far as it was possible, for the errors of the past, by the exertions of the future.

But she had much to learn, and what is not gained in youth is ever afterward difficult to acquire. The mind, like the muscles, becomes rigid with age, and, as in dancing, the steps we can accomplish without effort in youth, become unattainable in latter years. Julia, however, persevered, and achieved all that could reasonably be expected from one who had passed through such an ordeal. She adapted herself to her new situation; economized as well as she knew how; superintended the operations of the lower region, which we will not outrage the feelings of our fashionable readers by naming; eschewed fancy stores and milliners’ shops, and never afterward talked of the condescending affability of Queen Victoria. Happiness once more began to dawn on her, and might, perhaps, have shone betimes in its meridian splendor, had it not been for one single crime, for which, as she never could atone, she was destined perpetually to suffer.

She had neglected her children; she had committed them to hirelings, to derive their nourishment and imbibe their first impressions. The earliest dawnings of their affections were given to others; their earliest recollections of kindness and care never came home to the bosom of their mother, whose first remembered appearance was that of a stranger; whose first offered kiss was rejected with dislike, and who never could gather, in after times, those fruits, the seeds of which she had not planted in the proper season. The name of mother carries little magic with it, unless connected with the recollection of a mother’s cares, anxieties, sacrifices, and ever watchful tenderness; and she who does not nurse her offspring in their infancy, has no right to expect to be nursed by them in her old age. Julia spoiled them to make them love her, but that only made matters worse, by rendering them more selfish and exacting; and she now every day learned, by painful experience, that the early neglect of our offspring can seldom, if ever, be remedied by after exertions. Whether, when time and reason exert their influence, these unfortunate children may be enabled to correct their errors and reform their conduct, remains to be seen.

They are all still living; and our hero has long since learned, with equal surprise and gratification, that enough is as good as a feast, and the reputation of having once been a millionaire almost equal to being one in reality.

“And Jacob said, Surely the Lord is in this place, and I knew it not.”

The wondering patriarch like a pilgrim trod

The wilds of Haran. As the sun went down,

And pensive twilight dimmed that lonely waste,

Upon his staff he halted wearily.

Nought moved around, except a slender rill

That toward the far-off Chebar wrought its way.

And now and then, some broad-winged bird that made

Its nest in the cleft rock.

Curtained with mist,

And near his footsteps, though he knew it not,

Luz through its groves of almonds richly gleamed,

Half surfeit with their fragrance, while young Spring

Shook at the will of every frolic gale

Their snowy blossoms down. Way-worn and sad,

The traveler rested mid that dreary heath,

And on a stony pillow laid his head.

Back to his swimming sight Beersheba’s trees

Came, waving in the night-wind, and anon,

His father’s blessing, and Rebecca’s voice

Murmuring, and tender as a turtle-dove,

Cheated his ear awhile.

But then, he slept,

And lo! a host of angels, and a path

From heaven to earth, and the Eternal’s voice

Filling his soul with ecstasy and awe.

Yea! God was near him, and he knew it not!

His thoughts, perchance, were of the savage beast

That haunt the wilderness—for he believed

The roaming lion, or the ravening bear

Nearer his bed, than he who rules their rage.

When the young morn came blushing from her cell,

He rose, rejoicing, and pursued his way;

Serene yet serious, and upheld by Him

Who watched beside him, in that desert dream.

Sleeper! beneath a canopy of gold—

Whom the world calleth king—rememberest thou,

Amid thy palace-pride, the King of kings,

Who through thy folded curtains bends his glance,

Reading the heart?

Mourner! whose stifled sob,

Grief’s bitter lullaby, did slowly yield

To slumber, brief and broken as thy joys,

Forget not in thy trance that He is near

Who heareth prayer; and if earth’s helpers fail,

Implore that sympathy which ne’er forsakes

The wounded spirit in its hour of wo.

Fair, cradled creature, whom the angels tend,

He is beside thee, from whose forming hand

So late thou cam’st, our pensioner of love,

A thing of beauty and of mystery.

Commune thy first unfolding thoughts with Him

In secrecy of innocence, which ne’er

Have taken the many colored form of words

To mock the hue of truth, or wake the sigh

Of the recording seraph! Sleep, young babe!

He is beside thee, though thou know’st it not,

He watcheth o’er thee, and the smile that tints

Thy lip in visions, is His whispered love.

Violet! that slumberest on the mossy bank

Till morn, magician sweet, with purple wand

Transmutes the pendent dew-drops on the spray

To sparkling diamonds. Lily of the vale!

That duly, as the spent sun nears the west,

Like a spent child, doth fold thy bells in sleep,

Reclining lightly, on a graceful stem,

Ye know that God is near, and void of care

Wait with sweet faith for his appointed time,

To flourish, or to fade.

Teach our dull hearts

Your perfect worship, and ere that dread day

When, waking from the dust, we meet our Judge,

Instruct us here, by sunshine and by shower,

Like the lone patriarch on his couch of stone,

To see Him, and adore.

“Tuesday Morning, March 28th. Clouds this morning rather threatening, and an impertinent wind, that I fear may spoil our ride. Ladies’ habits should be double shotted, and then a breeze would not be a bugbear. If Laura Annesley is a more splendid creature at one time than another, it is when she is equipped for riding, with her rich locks braided close to her cheek, the single plume floating on her shoulder, and the dark dress showing her faultless outline to perfection. Kate is a pretty girl too, but timid as an unfledged dove; and it is a great fault of hers, that blushing at every thing, so undiscriminatingly. She should never ride with Laura Annesley; her figure looks more petite than ever, by contrast.

“Ernest Hyndford is cultivating a pair of moustaches, in preparation for his European tour. Your handsome men are almost always foppish. Ah! the sun shines out gloriously! Via!

“Wednesday. Our promenade à cheval was charming, with the one single drawback of Hyndford’s puppyism. How can any man be so presuming! He does not need a foreign tour to give him assurance. One would have thought him the accepted lover of both the ladies. He was in riotous spirits, and talked until he inspired even Kate Brooks. Miss Annesley, too, seemed very willing to be entertained, and I was stupid as an owl. A spell seemed to come over me, or Ernest’s chattering had the effect of one. It is always a marvel to me that women of sense can be so easily pleased! However—if Miss Annesley likes Hyndford, I am sure it is no concern of mine. She will only amuse herself by trying the effect of her bewitching looks and tones upon him for awhile, and then cast him off for some new victim. What a stupid world this is! It is wonderful that people desire to live long in it! My head aches horribly, and I must try a walk.

“Thursday. Some of us certainly come into this world foredoomed to be misjudged, even by those nearest to us. I suppose it is vain to struggle against what is written in our foreheads. My friends have always insisted that I am impetuous, headlong, imprudent, while I know that, if I have one fault more obvious than the rest, it is a supine indifference to every thing; a habit of deliberation which is the very opposite of imprudence. My father used to say, ‘Charles always wears his heart upon his sleeve, for daws to peck at—’ Heaven bless him! how completely he was mistaken! Any body but myself would be furious at such treatment as I have received this day, while I am perfectly cool. I will let Miss Annesley know that her power over my feelings is not so great as she may imagine it. To pass me unnoticed in the street—I waiting, like a fool, to catch her eye—and she leaning, so confidentially, on Ernest Hyndford’s arm—very lady-like, truly! What a puppy Ernest has become! I thought that wonderfully seductive moustache was not got up for nothing!

“I have been too often at Mr. Annesley’s, and Miss Laura doubtless supposes me in love. Quite out there, I assure you, most queenly Juno! Never cooler in my life! I should like nothing better than a voyage to the North Pole—to sail to-morrow.

“I will go and see my cousin Kate this evening. She is kind and gentle; handsome enough, yet not so much so as to be insolent from a consciousness of power; Kate would make a sweet little wife—why should I not think of her? Our cousinship is scarcely more than nominal, and she has always liked me. Girls with fair hair and blue eyes are so mild and unpretending—generally, that is—that they must make charming wifes. A great tall woman, with a full dark eye and a majestic step, is enough to make one tremble. Yes! I will go and see Kate to-night.

“Friday. I found Kate at her work-table, sewing as if to-morrow’s bread depended upon the number of stitches accomplished this evening. I wonder that women can spend their time in such an insipid way! Laura Annesley does just so; although she knows that she looks like an angel at the harp. I could not persuade Kate to music, or any thing but the needle. Yet she looked pretty, and quite interesting too, and I thought her manner was even kinder than usual. There was an unusual softness of tone, and I fancied—when I could get a glance at her eye—that she had been crying. She is a sweet girl, certainly, thought I. I drew a chair at her side, and, getting her tiny scissors on the tips of my fingers, began snipping scraps from her spool of thread, for want of something to say.

“ ‘You’re not well to-night, Charles,’ she said, at length, quite tenderly, as I fancied.

“ ‘A head-ache only,’ I replied; ‘but you, coz, do not seem quite as lively as usual.’

“She looked up at me with a half smile, but with suffused eyes. Oh! those dewy eyes, how irresistible they are! I felt at once sure of sympathy, and began forthwith to open my heart—that is to say, as much of it as it is prudent to open—telling Kate what a miserable, false, hollow, heartless world I found this to be, and how very tired I was of it.

“ ‘I cannot agree with you, Charles,’ she said, ‘in thinking there is nothing here worth living for. I believe the means of some degree of happiness are always within our power. We have sorrows and disappointments, it is true, but how far our joys outnumber them!’

“What a commonplace observation! She did not understand my feelings, after all. Still, her tones were all kindness, and I saw a bright tear fall beneath the ringlets that veiled her eyes, even as she uttered this sentiment, intended to be so cheerful. Well! women ought not to have too great depth of feeling. They have not weight of intellect enough for ballast. Laura Annesley to be sure—but she is an exception. And those very intellectual women are apt to be rather overpowering. It is safer to choose a wife who will not expect to dazzle any body. Women accustomed to admiration are always setting traps for it. As these thoughts passed through my mind, I loved her the better (Kate, I mean,) for her simplicity and naturalness.

“ ‘Your experience has been very limited, my dear cousin,’ said I, clipping thread after thread, with the rapidity of fate; ‘the world looks bright to you, because you have seen only its sunny side. Your morn of life has been without a cloud.’

“ ‘And has yours been so very different, Charles?’ said she, with a smile.

“ ‘Different!’ I exclaimed, bitterly enough—‘different! ay, indeed! dark, gloomy, chilling! I meet nothing but treachery and disappointment. For me to trust is to be deceived. I began life with as warm and confiding a heart as ever beat within a human bosom. I was ready to worship the good and the beautiful. Beauty, indeed, I have found, but truth—If I could interest a heart like yours, dearest Kate, kind and true, and full of unselfish feeling—if I had always a ready ear, a faithful adviser, a sympathizing friend, to warn and to encourage me—another self, dear Kate, such as you could be if you would—then, indeed, the world might seem to me, too, to be strewn with roses; then, indeed, I should learn to adopt your sweet and pure philosophy, and to find good every where. Dear Kate! I have never whispered love, but you know I have prized you as a sister. May I dare to hope—’ and here I ventured to take the hand that lay powerless in her lap—‘may I hope some day to be able to excite a dearer interest? May I——’

“ ‘Why Kate! I do really believe you’re asleep!’

“She started up, rubbed her pretty eyes, and looked about her in confusion.

“ ‘Oh, Charles! pray excuse me! Indeed I have heard every word you’ve said until the very last! I heard you say the world had no charms for you; indeed I did! Don’t be so vexed, Charles dear! You know last evening was poor Ernest’s last, and he stayed so late!’

“Ernest! . . . I took my hat and my leave very speedily, pleading my head-ache. A brilliant night’s work, truly! I will sail for New Orleans, and get the Yellow Fever.

“I shall call in the morning and leave a fashionable ‘D.I.O.’ for Miss Annesley. I can be chilling too, as she shall see. False girl!—but they are all alike!

“Saturday, April 1st. Laura says it was all a mistake. She threw me off my guard in a moment, by the frank kindness of her manner, and I told my grievance without intending it. She says she met Ernest by chance, and that he was telling her how happy Kate had made him. He is to return in six months, to be married. And such a look as she gave me when she concluded with, ‘How could you for a moment suspect—but there she is, on the other side of the street.’ ” . . . .

Note, by the Maiden Aunt. A transaction very well suited to the first of April, Master Charlie.

Δρεπων μεν

Κορυφας αρεταν ἀπο πασαν.

Pindar, Olymp. I.

Culling the fairest and the best.

Let others sing the rich, the great,

The victor’s palms, the monarch’s slate;

A purer joy be mine—

To greet the excellent of earth,

To call down blessings on thy worth,

And for the hour, that gave thee birth,

Life’s choicest flowers entwine.

And lo! where smiling from above

(Meet helpmate in the work of love)

O’er opening hill and lawn,

With flowerets of a thousand dyes,

With all that’s sweet of earth and skies,

Soft breathes the vernal dawn.

Come! from her stores we’ll cull the best

Thy bosom to adorn;

Each leaf in livelier verdure drest,

Each blossom balmier than the rest,

Each rose without a thorn;

Fleet tints, that with the rainbow died,

Brief flowers, that withered in their pride,

Shall, blushing into light, awake

And kindlier bloom, for thy dear sake.

And first—though oft, alas! condemned,

Like merit, to the shade—

The Primrose meek,[1] with dews begemmed

Shall sparkle in the braid:

And there, as sisters, side by side,

(Genius with modesty allied,)

The Pink’s bright red,[2] the Violet’s blue,[3]

In blended rays, shall greet our view,

Each lovelier for the other’s hue.

How soft yon Jasmine’s sunlit glow![4]

How chaste yon Lily’s robe of snow,[5]

With Myrtle green inwove![6]

Types, dearest, of thyself and me—

Of thy mild grace and purity,

And my unchanging love,

Of grace and purity, like thine,

And love, undying love, like mine.

In fancifully plumed array,

As ever cloud at set of day,

All azure, vermeil, silver-gray,

And showering thick perfume,

See! how the Lilac’s clustered spray[7]

Has kindled into bloom.

Radiant, as Joy, o’er troubles past,

And whispering, “Spring is come at last!”

Blest Flowers! There breathes not one unfraught

With lessons sweet and new;

The Rose, in Taste’s own garden wrought;[8]

The Pansy, nurse of tender thought;[9]

The Wall-Flower, tried and true;[10]

The purple Heath, so lone and fair,[11]

(O, how unlike the world’s vain glare!)

The Daisy, so contently gay,

Opening her eyelids with the day;[12]

The Gorse-bloom, never sad or sere,

But golden-bright,

As gems of night,

And fresh and fragrant, all the year;[13]

Each leaf, each bud, of classic lore,

Oak,[14] Hyacinth,[15] and Floramore;[16]

The Cowslip, graceful in her wo;[17]

The Hawthorn’s smile,[18] the Poppy’s glow,[19]

This ripe with balm for present sorrow,

And that, with raptures for to-morrow.

The flowers are culled; and each lithe stem

With Woodbine band we braid—

With Woodbine, type of Life’s best gem,

Of Truth, that will not fade:[20]

The Wreath is wove; do Thou, blest Power,

That brood’st o’er leaflet, fruit, and flower,

Embalm it with thy love;

O make it such as angels wear,[21]

Pure, bright, as decked earth’s first-born pair,

Whilst, free in Eden’s grove,

From herb and plant they brushed the dew,

And neither sin nor sorrow knew.

u. May 10th, 1843. u.

|

The Primrose is, in floral language, the emblem of Neglected Worth. |

|

The Red Pink, Genius or Talent. See Flora Historica. |

|

The Violet, of Modesty. |

|

The Jasmine, of Amiability and Grace. |

|

The Lily, of Purity. |

|

The Evergreen Myrtle, of Love. |

|

The Lilac, of Bloom and Joy. |

|

The Rose, of Beauty and Taste—by Nature and the Graces drest. |

|

The Pansy—“That’s for Thoughts,”—(as poor Ophelia says) being a corruption of the French word “pensée,” thought. It has, however, various other names, as “Hearts-ease,” “Forget-me-not,” and “Love-in-idleness,” under which latter name it is noticed by Shakspeare in his celebrated compliment to Queen Elizabeth. See Midsummer Night’s Dream, Act. II. Scene 2. |

|

The Wall-Flower stands as the emblem of Fidelity in Misfortune, because it attaches itself to the desolate, to falling towers and monastic ruins. During the Reign of Terror in France, the misguided populace, not satisfied with destroying royalty, attacked its very monuments, and scattered to the winds the ashes of their sovereigns, which had been deposited under them in the sacred Abbey of St. Denis. Some years after, this spot was visited by the poet Freneuil, who found the sculptured fragments, which had been thus defaced and thrown aside, covered over with fragrant wall-flowers. See Flora Historica and Tombeaux de Saint-Denis. |

|

The Heath is an emblem of Solitude. |

|

The Daisy, or “Day’s Eye,” (as it used to be called, because it went to bed and got up with the sun,) has been an especial favorite with our poets, and is celebrated by Chaucer, Spenser, Shakspeare, Ben Johnson, Milton, Burns, Wordsworth, and Montgomery, in strains that will not die. It is the emblem of contented Innocence. |

|

The Gorse, with its yellow stars, blossoms throughout the year, and is the emblem of Cheerfulness under vicissitudes. |

|

The Oak is the emblem of Courage and Humanity. Most worthy of the oaken wreath The ancients him esteemed, Who, in the battle, had from death Some man of worth redeemed. Drayton. |

|

“The Hyacinth’s for Constancy, wi’ its unchanging blue.” Burns. |

|

Floramore (Flour-Amore) or Three-colored Amaranth has been sometimes made to represent Love and Friendship. Its leaves (says Gerard) “resemble in colours the most faire and beautiful feathers of a parrot, especially those that are mixed with most sundrie colors, as a stripe of red, and a line of yellow, and a ribbe of green, which I cannot with words set foorth, such is the sundrie mixture of colors, that Nature hath bestowed in hir greatest iollitie vpon this flower.” |

|

The Cowslip is the symbol of Pensive Melancholy. The Cowslip wan, that hangs her pensive head. Milton.

The love-sick Cowslip, that her head inclines To hide a bleeding heart. Hurdis. This last line alludes to the red marks, to “the crimson drops in the bottom of the Cowslip,” which Shakspeare speaks of. |

|

The Hawthorn or May-flower— The Hawthorn’s early blooms appear Like youthful Hope upon Life’s year. Drayton. The Hawthorn has been made the emblem of Hope, because the Athenian maidens brought branches of its white flowers to decorate the brows, and formed Flambeaux of its wood to light the chambers of their newly wedded friends; and also, because the Troglodites were in the habit of binding boughs of this shrub around the bodies, and strewing blossoms of it over the graves, of their departed comrades. |

|

The Poppy is the symbol of Forgetfulness or Consolation. The ancients, who regarded sleep as the great physician and restorer of human nature, were accustomed to crown their gods with a wreath of poppies. |

|

The Woodbine, or Honeysuckle, represents True-Love or Stedfastness of Affection. It is described by Chaucer as “Never To love untrue, in word, in thought, ne dede, But aye stedfast.” |

|

As angels wear, etc. Crowns inwove with Amarant and gold, Immortal Amarant, a flower, which once In Paradise, fast by the Tree of Life, Began to bloom; but soon, for man’s offence, To Heaven removed, where first it grew, there grows And flowers aloft, shading the Fount of Life, And where the River of Bliss through midst of Heaven Rolls o’er Elysian flowers her amber stream; With these, that never fade, the spirits elect Bind their resplendent locks. Milton. |

Armado. Comfort me, boy! What great men have been in love?

Moth. Hercules, master.

Armado. Most sweet Hercules! More authority, dear boy! name more; and sweet, my child, let them be of good repute and carriage.

Moth. Samson, master; he was a man of good carriage, great carriage; for he carried the town-gates on his back, like a porter; and he was in love.

Shakspeare.

Fashion is arbitrary, we all know. What it was that originally gave Sassafras street the right to despise Pepperidge street, the oldest inhabitant of the village of Slimford could not positively say. The court-house and jail were in Sassafras street, but the orthodox church and female seminary were in Pepperidge street. Two directors of the Slimford Bank lived in Sassafras street—two in Pepperidge street. The Diaper family lived in Sassafras street—the Dimity family in Pepperidge street; and the fathers of the Diaper girls and the Dimity girls were worth about the same money, and had both made it in the lumber line. There was no difference to speak of in their respective modes of living—none in the education of the girls—none in the family grave-stones, or church pews. Yet, deny it who liked, the Diapers were the aristocracy of Slimford.