* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: The Governor and Company of Adventurers of England Trading into Hudson’s Bay

Date of first publication: 1920

Author: William Schooling (1860-1936)

Introduction: Sir Robert Molesworth Kindersley (1871-1954)

Illustrator: Harry Rountree (1878-1950)

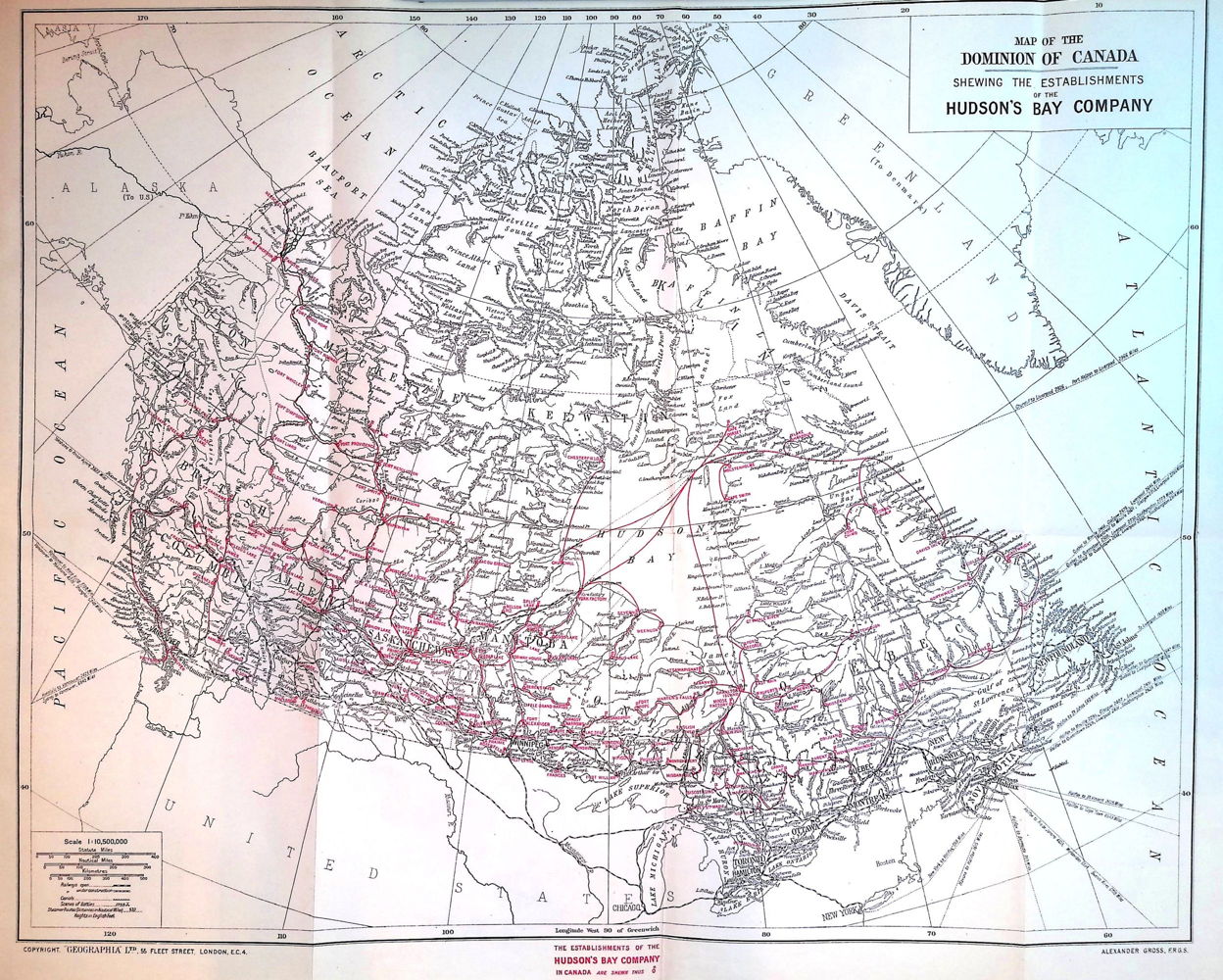

Cartographer: Alexander Gross (1879-1958)

Date first posted: 7th September, 2024

Date last updated: 7th September, 2024

Faded Page eBook #20240902

This eBook was produced by: Mardi Desjardins, Howard Ross & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

This file was produced from images generously made available by (insert appropriately ... Internet Archive/American Libraries).

THE HUDSON’S BAY COMPANY

1670-1920

BY

Sir William Schooling, K.B.E.

PRINCE RUPERT, THE FIRST GOVERNOR OF THE COMPANY.

BEAVER COIN OF THE COMPANY, REPRESENTING ONE BEAVER.

| List of Illustrations | viii. |

| Introduction, by the Governor | xi. |

| Governors of the Company | xiv. |

| Deputy-Governors of the Company | xv. |

| The Committee in 1670 | xvi. |

| The Committee in 1920 | xvi. |

| Chapter I.—The Prelude to the Charter | 1 |

| Chapter II.—The Granting of the Charter | 5 |

| Chapter III.—Exploration and Discovery | 9 |

| Chapter IV.—Life in the Service | 25 |

| Chapter V.—Indians | 35 |

| Chapter VI.—A Chapter of Natural History | 46 |

| Chapter VII.—Landmarks of History | 67 |

| Chapter VIII.—Land and Settlement | 86 |

| Chapter IX.—Forts and Stores | 97 |

| Chapter X.—Fights and Wars | 119 |

| Prince Rupert, the First Governor of the Company | Frontispiece | |

| Beaver Coins | Page | vi. |

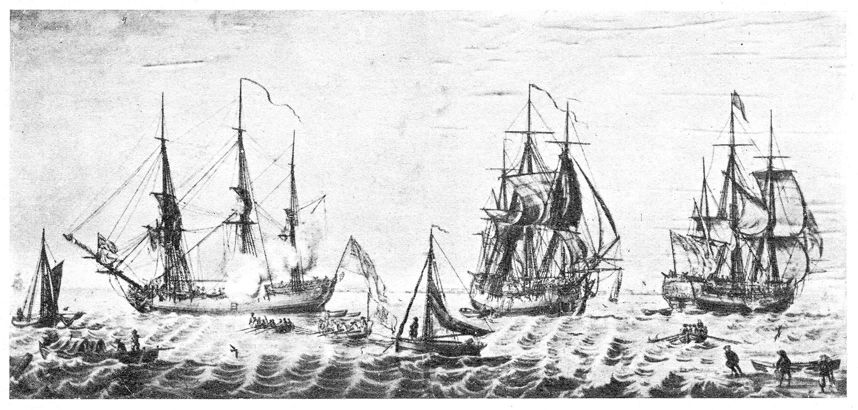

| The Company’s Fleet Leaving Gravesend | Page” | x. |

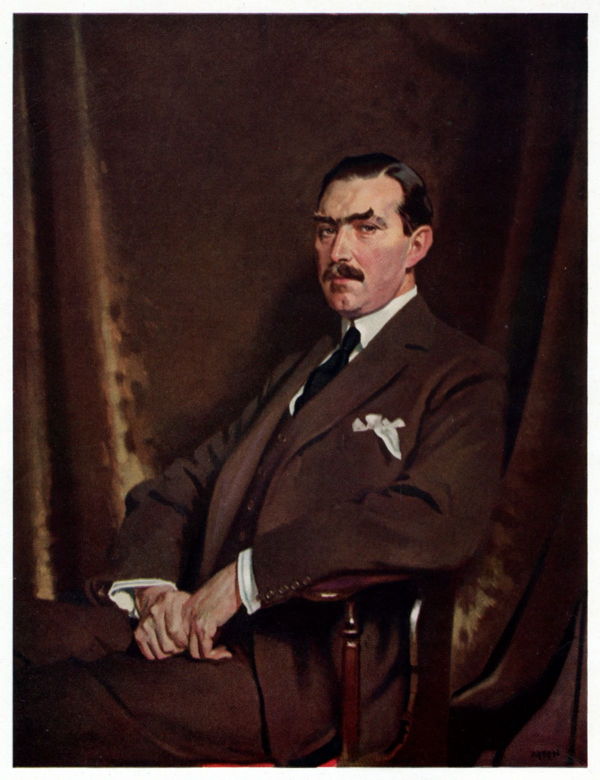

| Sir R. M. Kindersley, G.B.E. (The present Governor of the Company) | Facing Page | xi. |

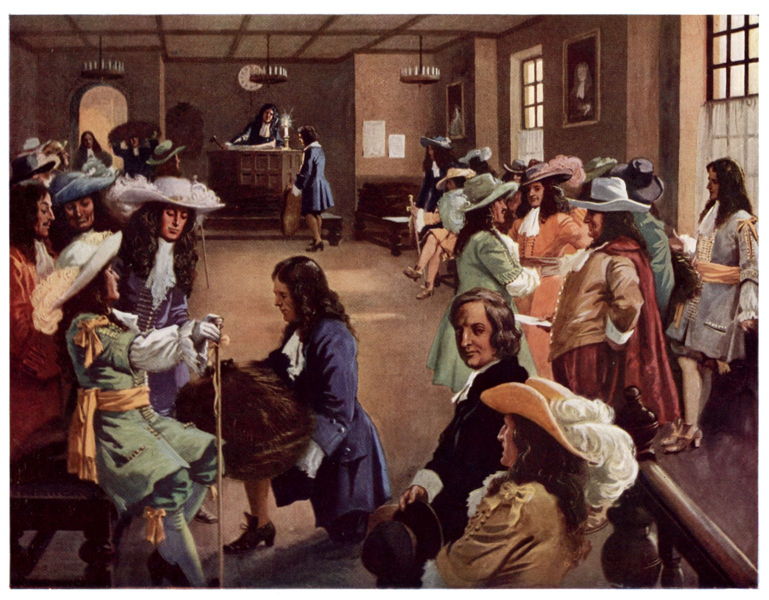

| The Granting of the Royal Charter | Facing” Page” | 5 |

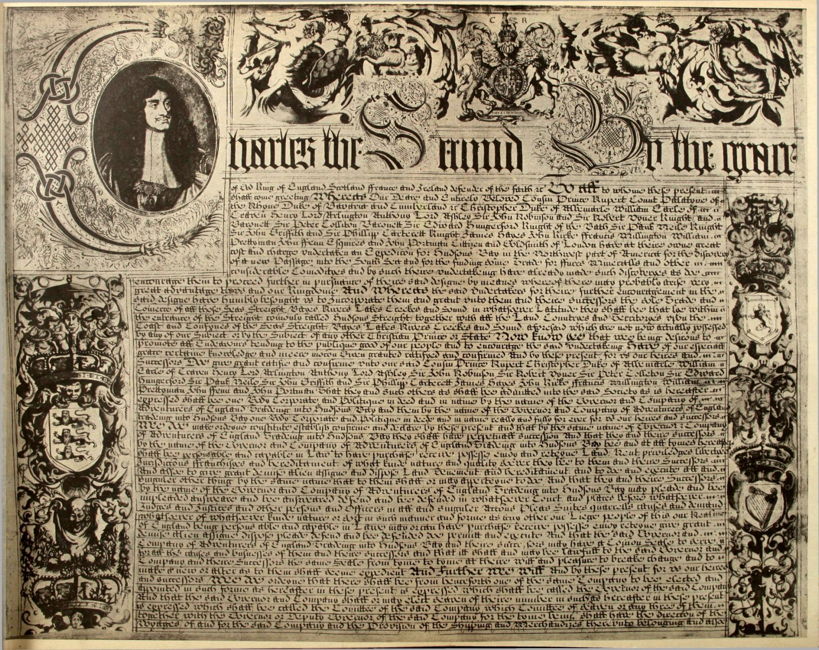

| Facsimile of the First Sheet of the Charter | Facing” Page” | 6 |

| The Great Seal of England | Facing” Page” | 8 |

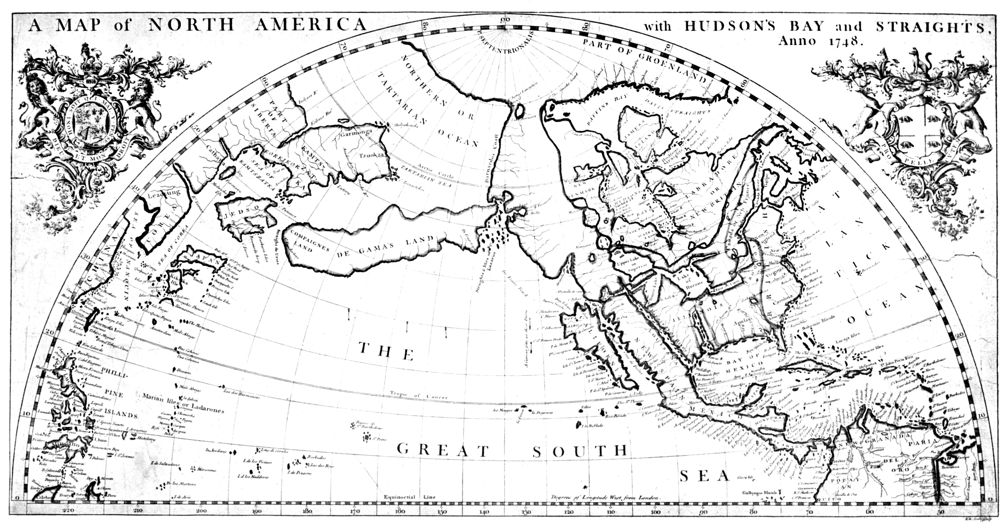

| An Old Map of North America | Facing” Page” | 12 |

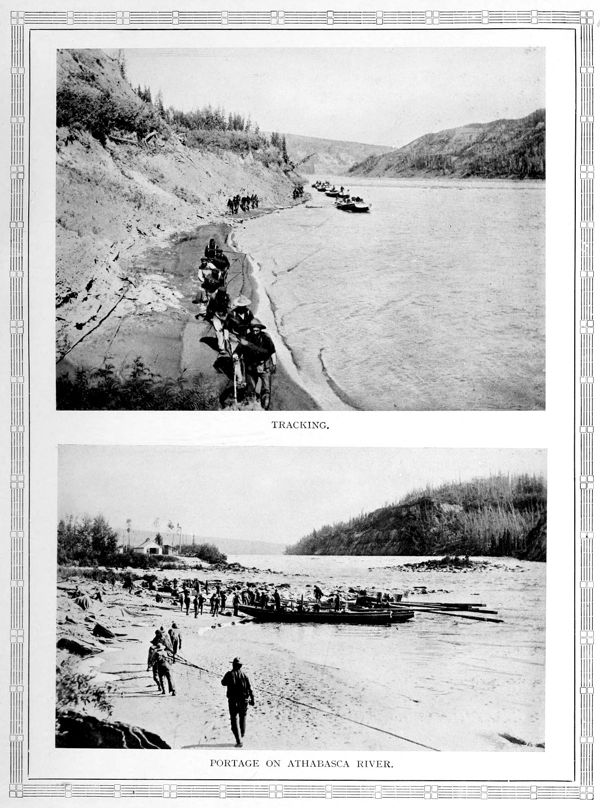

| Tracking | Facing” Page” | 14 |

| Portage on Athabasca River | Facing” Page” | 14 |

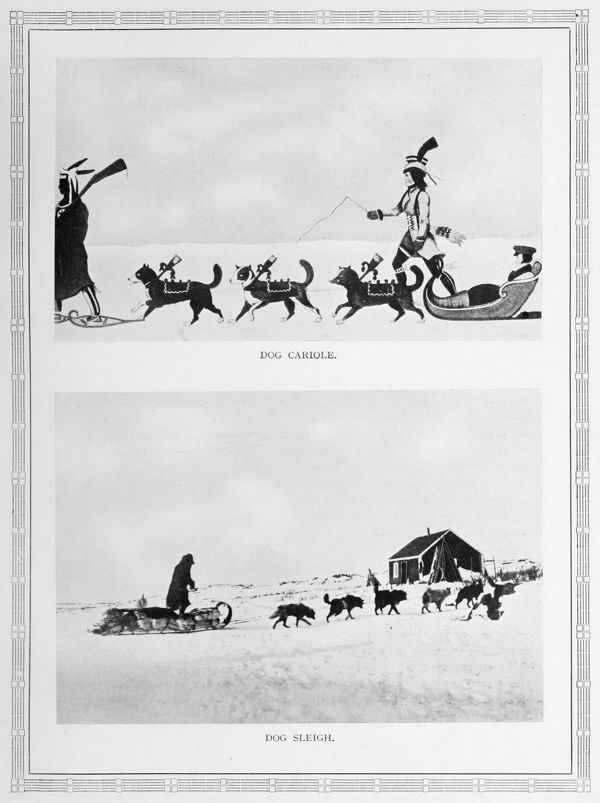

| Dog Cariole | Facing” Page” | 18 |

| Dog Sleigh | Facing” Page” | 18 |

| Lead Coins of the Company | Page | 24 |

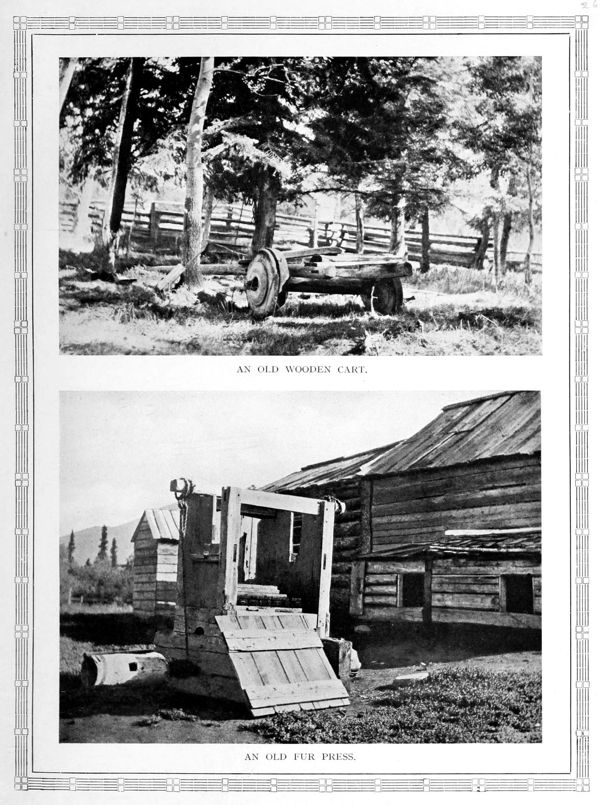

| An Old Wooden Cart | Facing Page | 26 |

| An Old Fur Press | Facing” Page” | 26 |

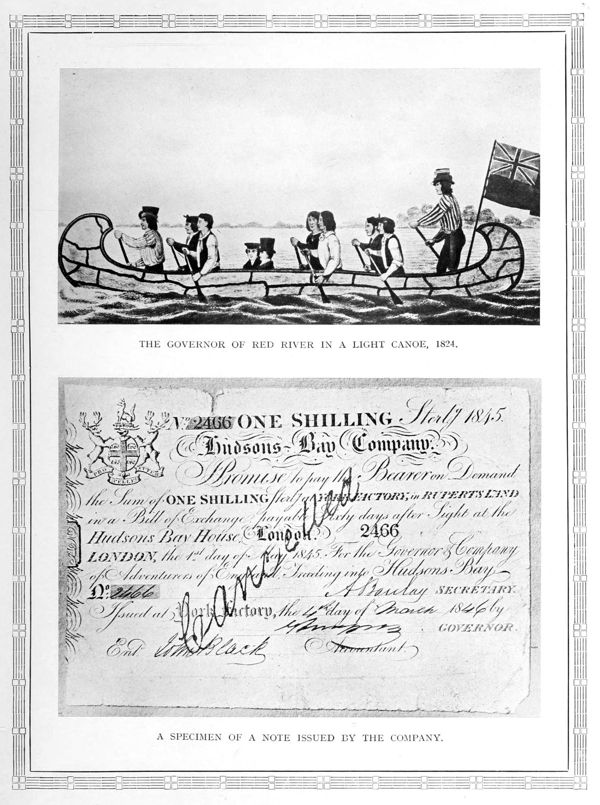

| A Light Canoe | Facing” Page” | 32 |

| A Specimen of a Note issued by the Company | Facing” Page” | 32 |

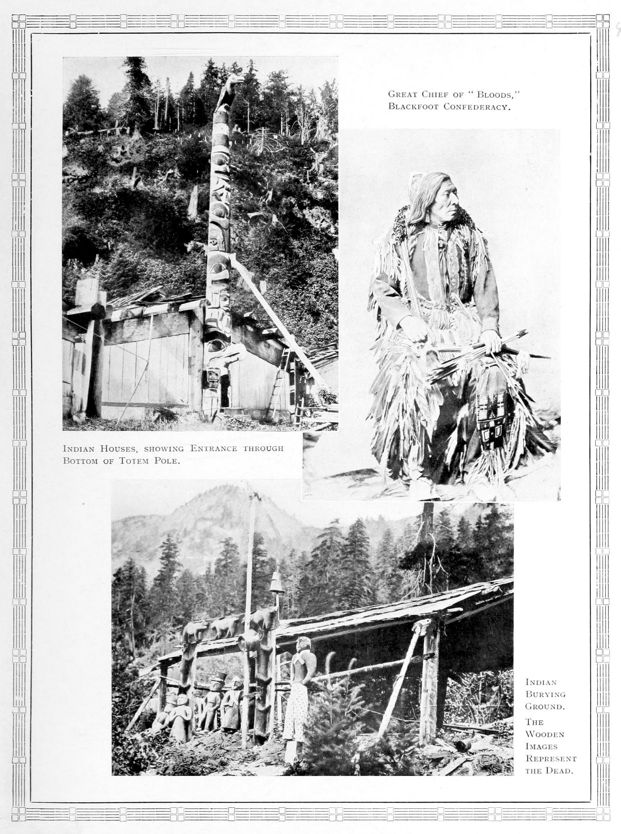

| Great Chief of “Bloods” | Facing” Page” | 40 |

| Indian Houses | Facing” Page” | 40 |

| Indian Burying Ground | Facing” Page” | 40 |

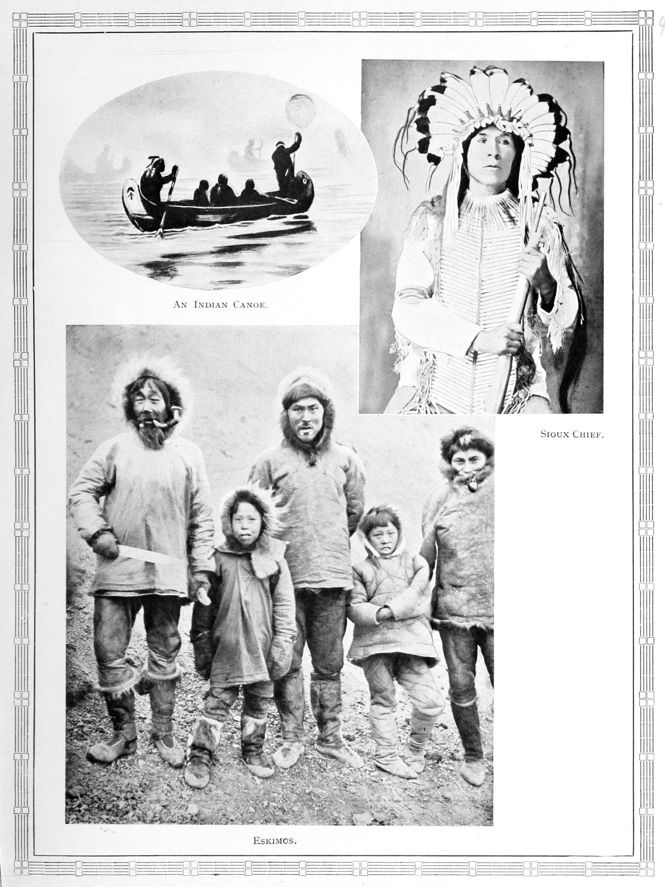

| An Indian Canoe | Facing” Page” | 42 |

| Sioux Chief | Facing” Page” | 42 |

| Eskimos | Facing” Page” | 42 |

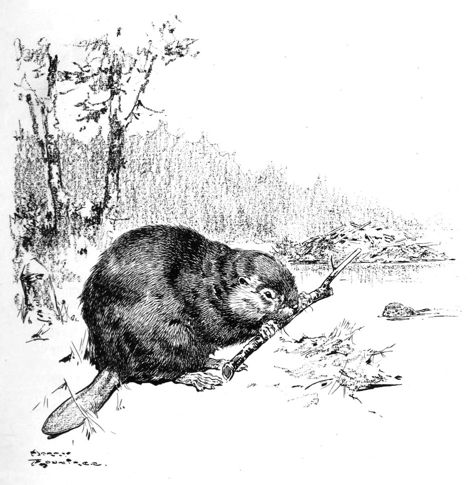

| The Canadian Beaver | Page | 47 |

| The Musquash | Page” | 50 |

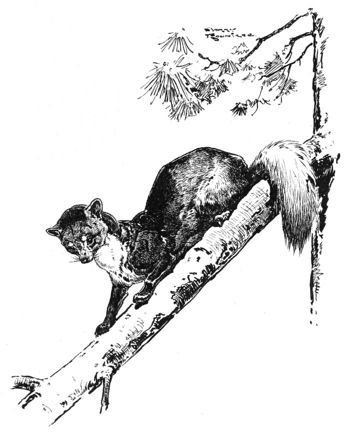

| The Marten | Page” | 51 |

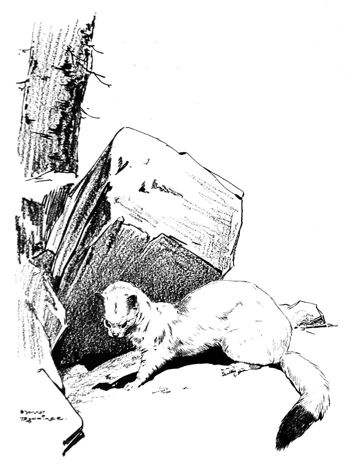

| The Ermine | Page” | 52 |

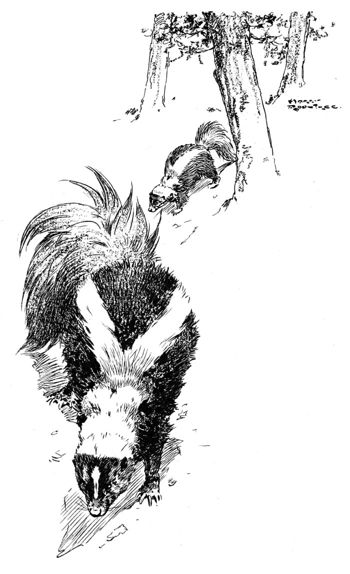

| The Skunk | Page” | 53 |

| The Fisher | Page” | 54 |

| The Mink | Page” | 55 |

| The Wolverine | Page” | 56 |

| The Fox | Page” | 58 |

| The Wolf | Page” | 60 |

| The Otter | Page” | 61 |

| The Lynx | Page” | 62 |

| The Black Bear | Page” | 63 |

| The Raccoon | Page” | 65 |

| The First Sale of Furs | Facing Page | 68 |

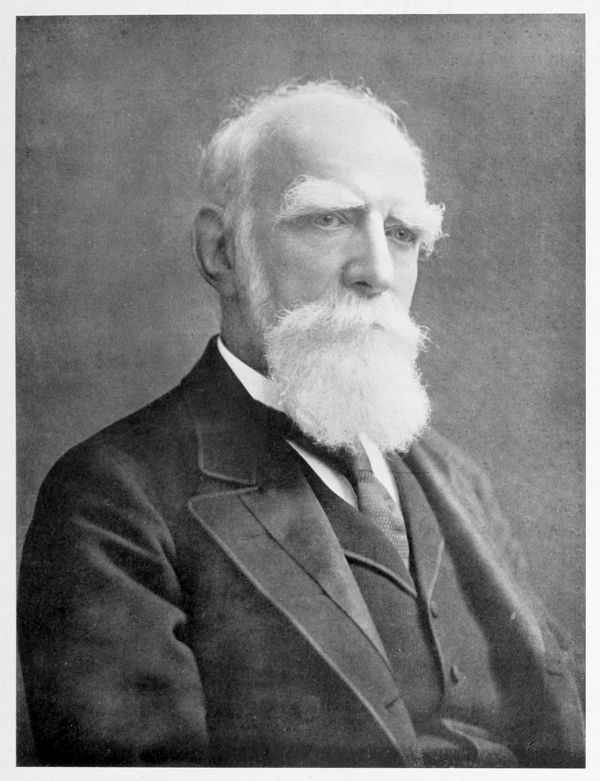

| The Late Lord Strathcona | Facing” Page” | 92 |

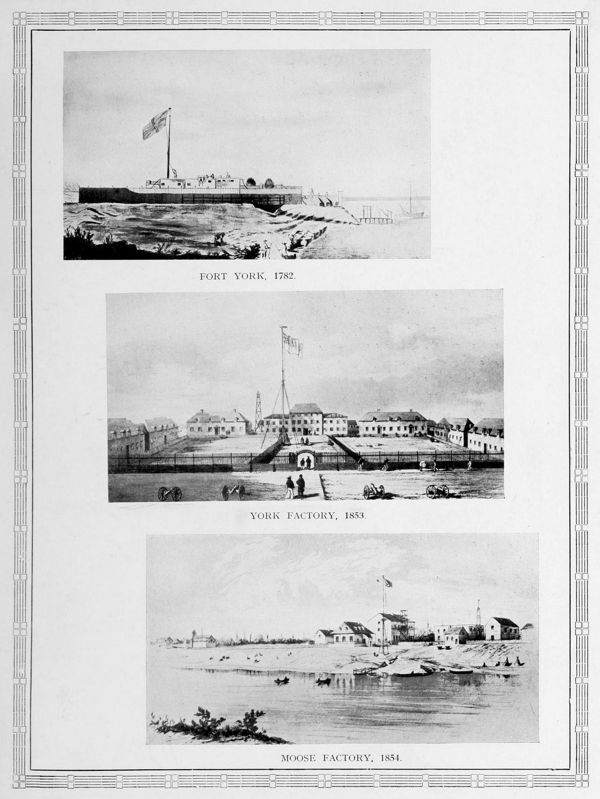

| Fort York, 1782 | Facing” Page” | 98 |

| York Factory, 1853 | Facing” Page” | 98 |

| Moose Factory, 1854 | Facing” Page” | 98 |

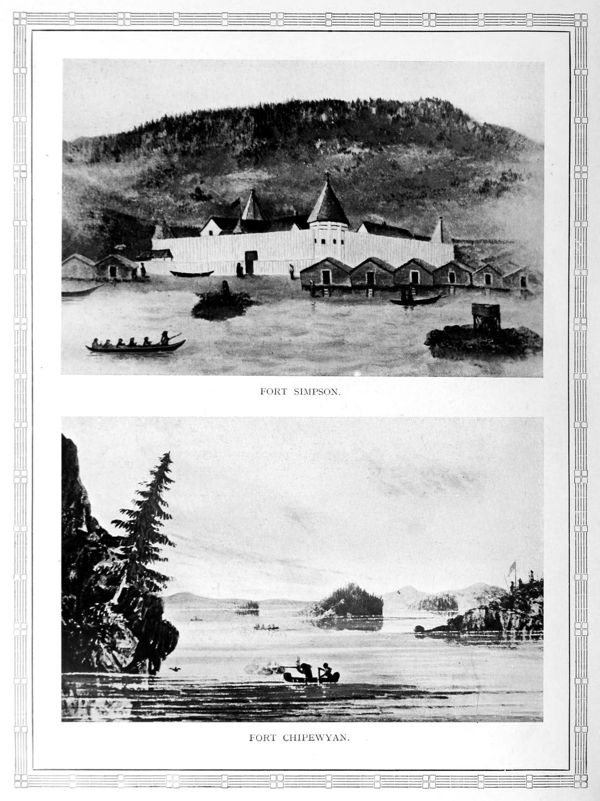

| Fort Simpson | Facing” Page” | 99 |

| Fort Chipewyan | Facing” Page” | 99 |

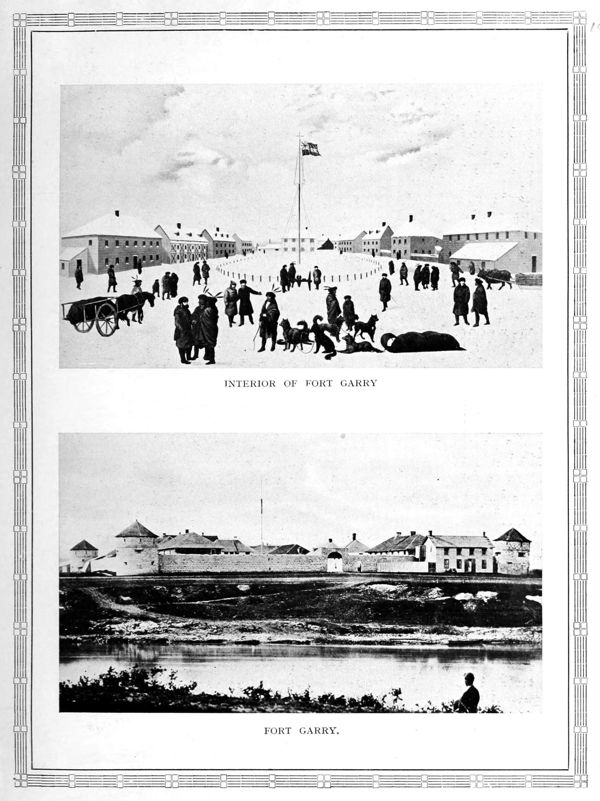

| Fort Garry | Facing” Page” | 102 |

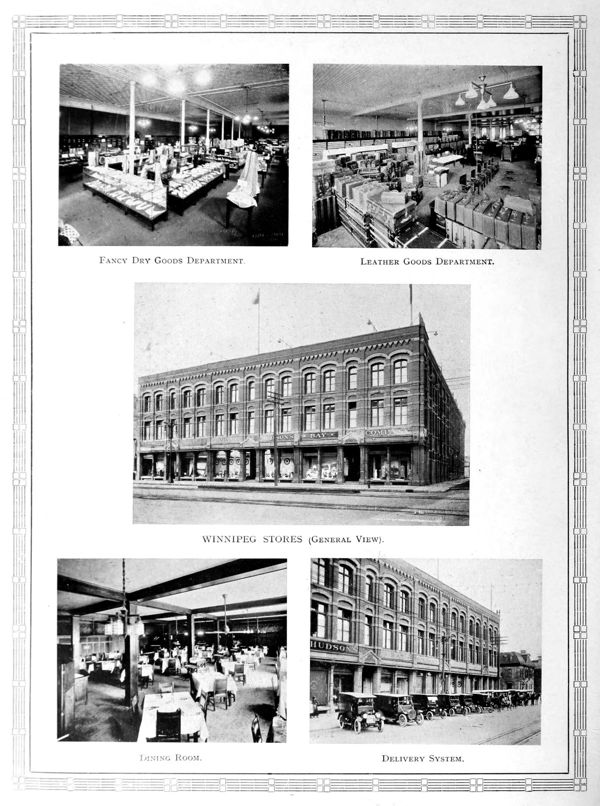

| Winnipeg Store—Exterior and Interior | Facing” Page” | 103 |

| Yorkton Store | Facing” Page” | 104 |

| MacLeod Store | Facing” Page” | 104 |

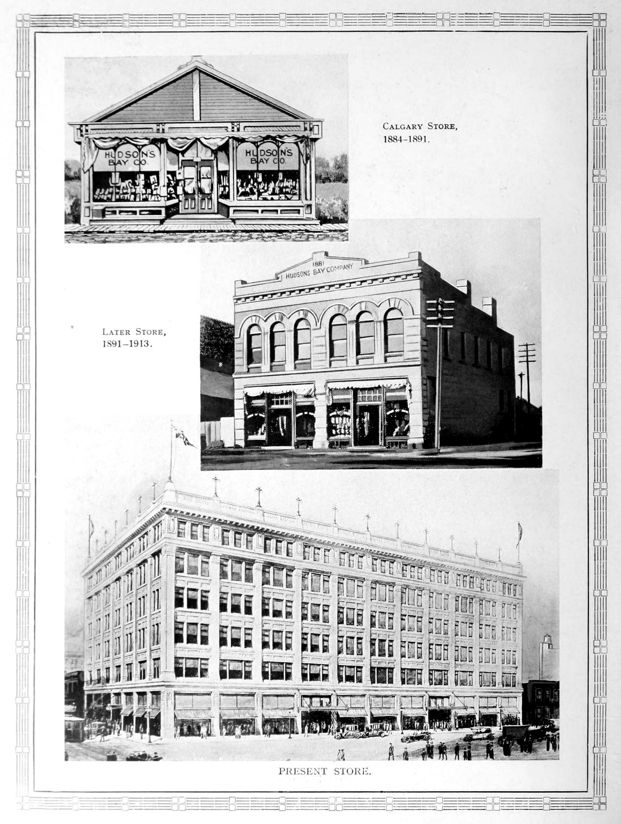

| Calgary—Early, Later and Present Stores | Facing” Page” | 105 |

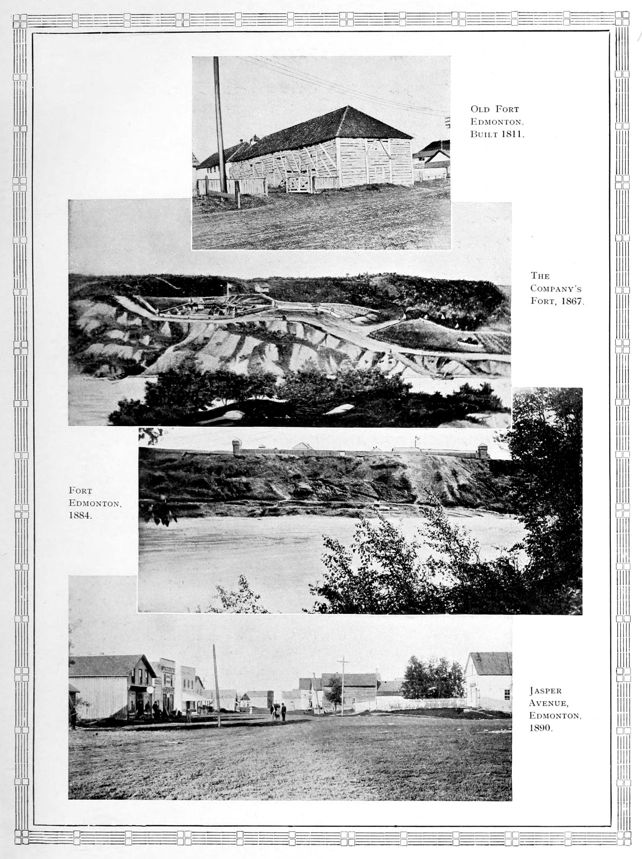

| Edmonton—The Old Forts and Jasper Avenue | Facing” Page” | 108 |

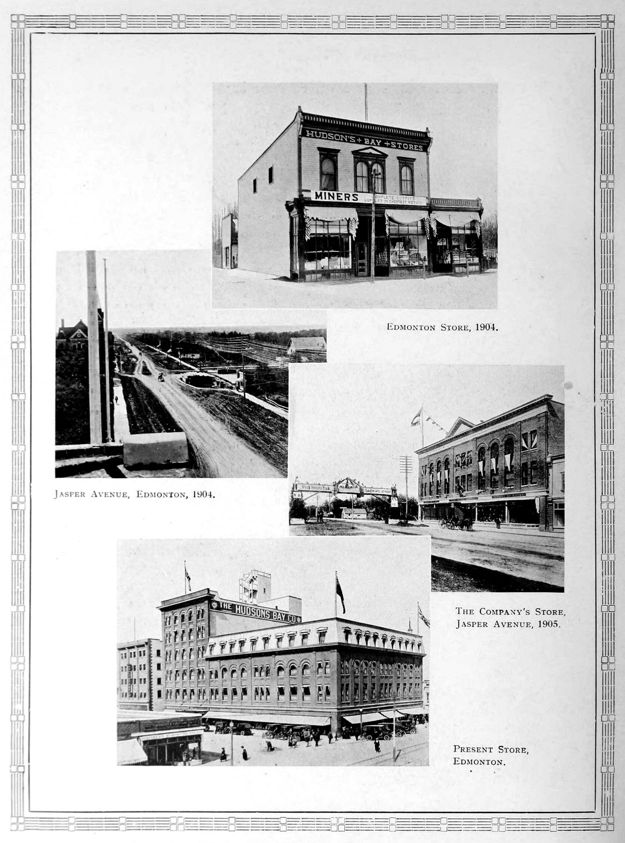

| Edmonton—Later and Present Store, and Jasper Avenue | Facing” Page” | 109 |

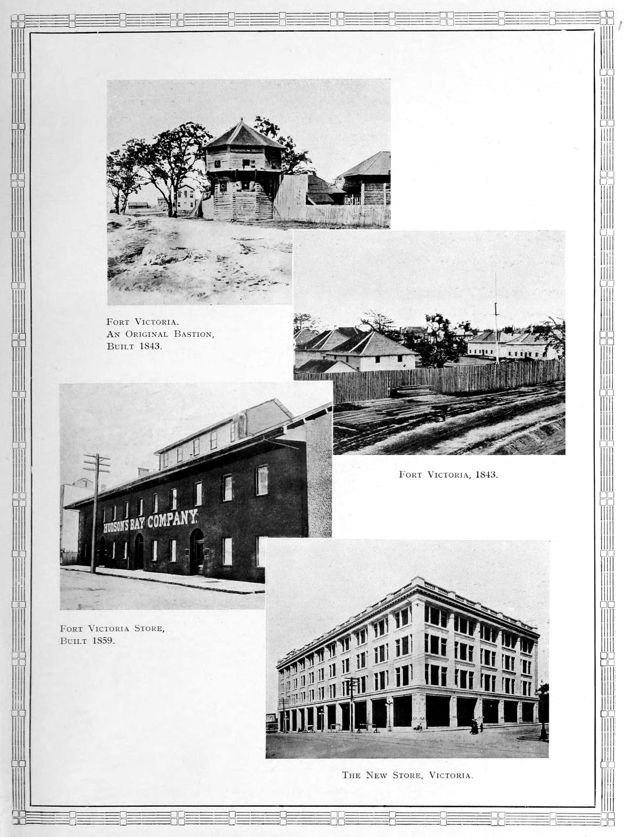

| Victoria—Forts and Stores | Facing” Page” | 112 |

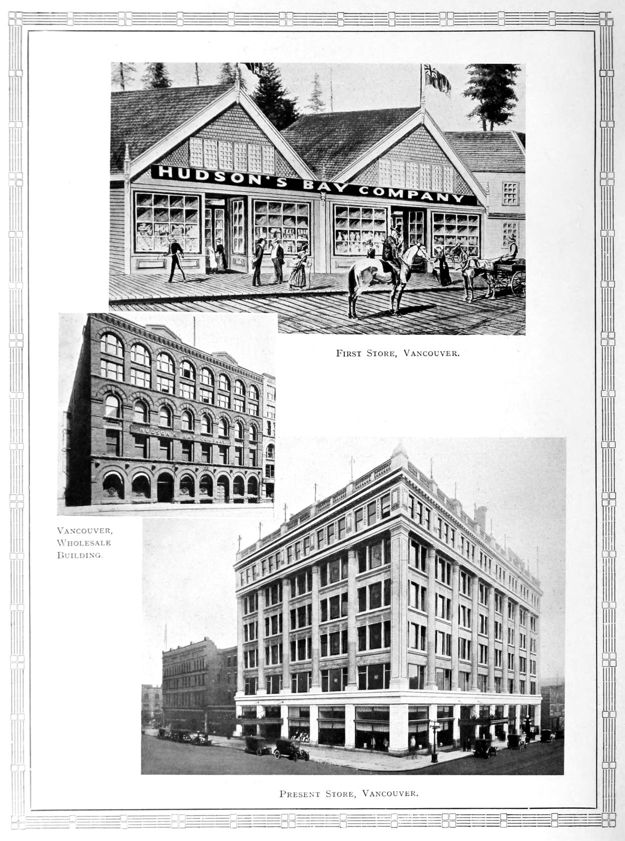

| Vancouver—First Store, Wholesale Building & Present Store | Facing” Page” | 113 |

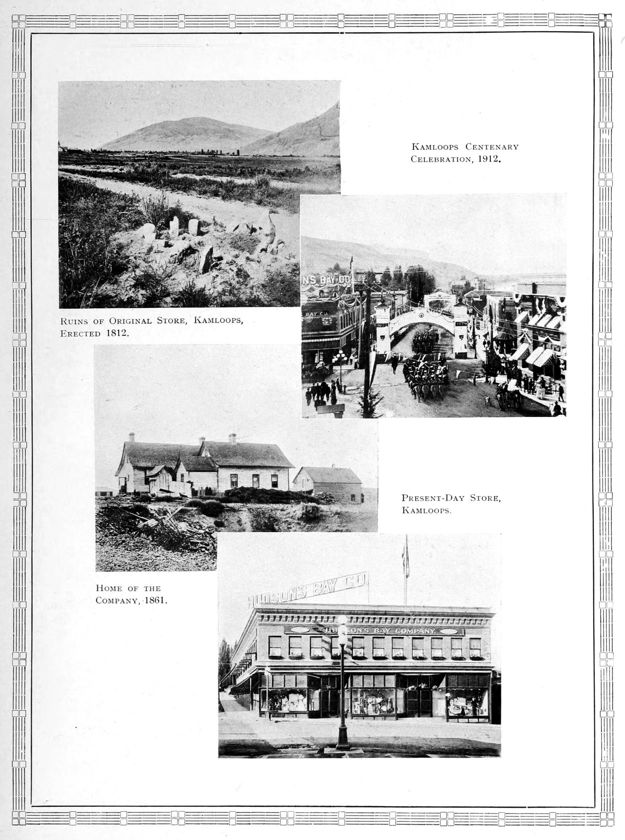

| Kamloops—Various Views | Facing” Page” | 116 |

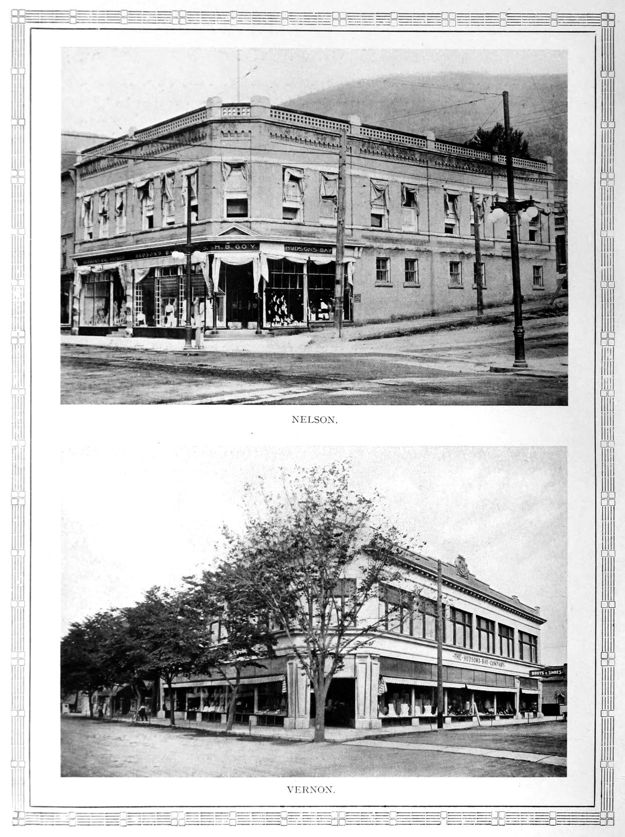

| Nelson Store | Facing” Page” | 117 |

| Vernon Store | Facing” Page” | 117 |

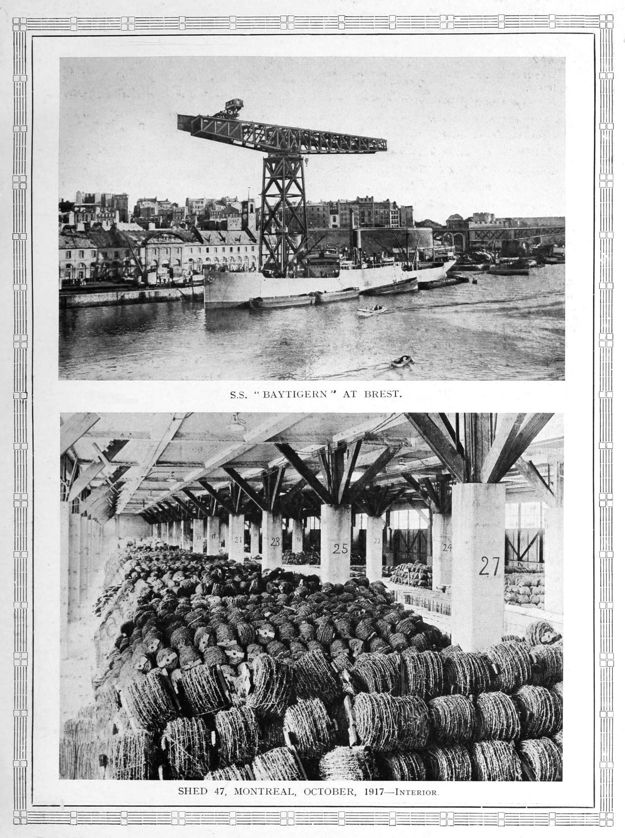

| S.S. “Baytigern” at Brest | Facing” Page” | 120 |

| Shed 47, Montreal | Facing” Page” | 120 |

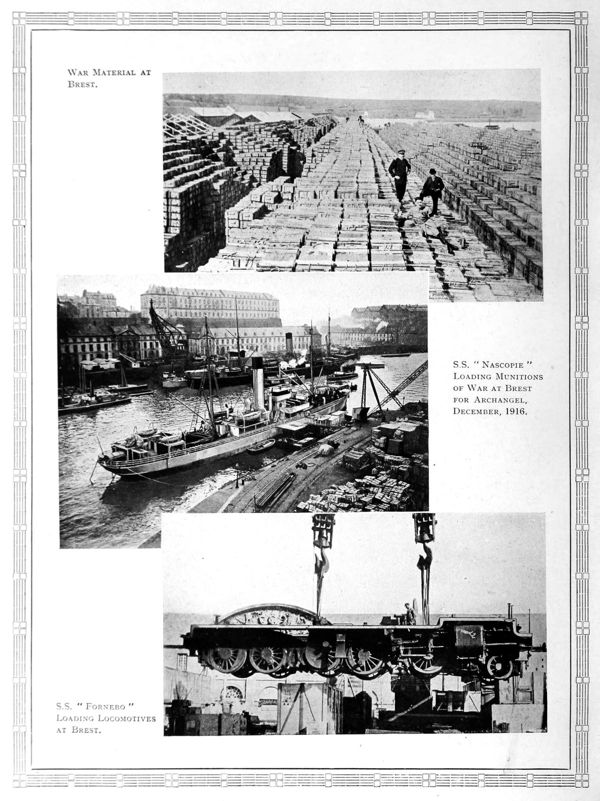

| War Material at Brest | Facing” Page” | 121 |

| S.S. “Nascopie” at Brest | Facing” Page” | 121 |

| S.S. “Fornebo” at Brest | Facing” Page” | 121 |

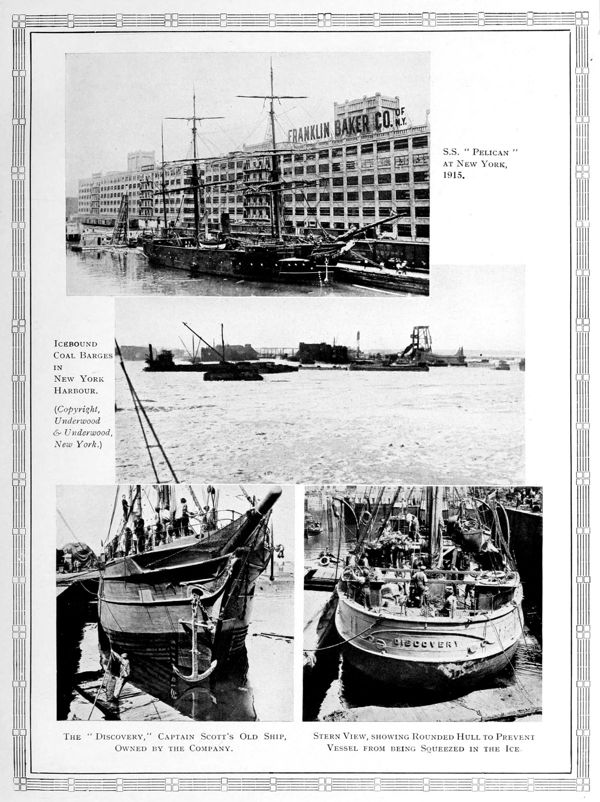

| S.S. “Pelican” at New York | Facing” Page” | 126 |

| Icebound Coal Barges | Facing” Page” | 126 |

| The “Discovery,” Captain Scott’s Old Ship | Facing” Page” | 126 |

THE COMPANY’S FLEET LEAVING GRAVESEND FOR HUDSON BAY, 1767.

SIR ROBERT MOLESWORTH KINDERSLEY, G.B.E.

(The Present Governor of the Company).

By Sir ROBERT MOLESWORTH KINDERSLEY, G.B.E.,

The Governor of the Company.

HE 2nd of May, 1920, is the two hundred and fiftieth

anniversary of the granting of the Charter by King

Charles II. to “The Governor and Company of

Adventurers of England trading into Hudson’s Bay.”

In considering the best means of celebrating this event, the

Committee felt that one feature should be the preparation of some

account of the activities of the Company from May, 1670, to the

present time; but it was recognised that the production of an

adequate history was out of the question, for two reasons: no definite

plans could be made until after the signing of the Armistice, and then

the time for preparing a complete record was far too short. It was

realised also that a long history—and two hundred and fifty years

crowded with episodes in both the New World and the Old would

need a long history—would appeal to but a comparatively few people,

whereas it was desired that the interest should be widespread.

HE 2nd of May, 1920, is the two hundred and fiftieth

anniversary of the granting of the Charter by King

Charles II. to “The Governor and Company of

Adventurers of England trading into Hudson’s Bay.”

In considering the best means of celebrating this event, the

Committee felt that one feature should be the preparation of some

account of the activities of the Company from May, 1670, to the

present time; but it was recognised that the production of an

adequate history was out of the question, for two reasons: no definite

plans could be made until after the signing of the Armistice, and then

the time for preparing a complete record was far too short. It was

realised also that a long history—and two hundred and fifty years

crowded with episodes in both the New World and the Old would

need a long history—would appeal to but a comparatively few people,

whereas it was desired that the interest should be widespread.

For these reasons the following pages are intended to give only a brief outline of the life of the Company in the past and the present.

We start with the Prelude to the Charter, making short references to the discovery of Canada and to the fur trade. In due course, the Governor and the Company were declared to be “the true and absolute Lords and Proprietors” of a vast territory, unexplored and for the most part unknown.

The Charter was granted in London, and the book takes us at once to Hudson Bay, and to the exploration and discovery of the New World. Little by little, trading posts were established from East to West, and from North to South of Canada. They are the background of the life in the Service; and we read of the men who carried on the fur trade which was the precursor of the opening up of great areas for farming and industry.

The Company and its Servants were, of course, brought into close touch with the Indians, of whose characteristics, traditions, and mode of life some account is given. From the earliest days, the confidence and esteem of the Indians were won by treatment that was just, if sometimes, of necessity, stern. No army was maintained, yet, with the exception of rare and trifling outbreaks, there has been unbroken peace with the Indians from first to last. All the products of old-world civilisation may not be suited to races with a very different past, but the Company has carried to the Indians as much as possible of the advantages of the white man’s civilisation with as few as may be of the drawbacks.

The Company owes its origin and growth to the fur trade. It is interesting to think of the processes by which the furs that are worn throughout the world come from the wild animals in the streams and forests of the North, and a chapter is devoted to the fur-bearing animals, which are interesting in themselves and have been essential to the existence of the Company.

After this description of the life and work of the Company in Canada, we are brought back to London, where, in large measure, the chief landmarks in the Company’s history were determined. There were long conflicts with the French, and difficulties to be settled with Russia and the United States. There were attacks upon the Charter and the rights of the Company, which had to be met. There was the rivalry of the North-West Company, terminating in union; and—the crowning event of all—the surrender to the Queen of England of some of the rights under the Charter in order that the territory the Company had ruled might be transferred to the people of Canada.

This was the beginning of a new and momentous era in the Company’s history. By its agreement it acquired a different title from that which the Charter afforded to specified proportions of the “Fertile Belt,” and thus became directly interested in land and settlement, with which it had previously had little concern.

With the rapid growth of Canadian cities there came the need and the opportunity, for providing for the varied wants of the new population. This led to the establishment of numerous Department Stores, which in most cases were the direct descendants of the old trading posts, and in all instances exhibited that adjustment to new conditions which is characteristic of vitality.

In the meanwhile the fur trade continued as of old. For practical purposes it was the sole interest of the Company for two hundred years. It may be said that the surrender of a portion of the chartered rights in 1870 added two new features—land and stores—to the operations of the Company; this three fold activity has made it not less but greater than under the old regime.

The Great War brought responsibilities and opportunities of a new and different kind. For long after the foundation of the Company it was in conflict with the French traders, and, indeed, with France herself; but the days of enmity have long gone by, and it was a singular privilege for the Company to be entrusted by the French Government with great and responsible duties which played some part in winning victory for the Allies.

The Committee of to-day recognise that they are the custodians of a great inheritance, which it is their duty to hand on, enhanced and not impaired, to future generations. The highest prosperity of the Company is, and must continue to be, bound up with the welfare of Canada, and it is no exaggeration to say that the future of the Company depends upon the efficiency of the service it renders to the country it has helped to make.

The Company has good reason to feel that the people of Canada take some pride in an institution, most of the activities of which are carried on in their country, which has its roots in a remote past, and a record which is unique in the history of trading corporations.

The celebration of the two hundred and fiftieth anniversary of the granting of the Chartered Rights will be, I hope, an event of interest, not merely for those connected with the Company, but also for the Canadian people, among whom I hope to be when we are looking back into the past and forward to the future.

R. M. K.

| His Highness Prince Rupert | 1670-1683 |

| H.R.H. James, Duke of York (afterwards King James II.) | 1683-1685 |

| John, Lord Churchill (afterwards Duke of Marlborough) | 1685-1691 |

| Sir Stephen Evance, Kt. | 1691-1696 |

| The Rt. Hon. Sir William Trumbull | 1696-1700 |

| Sir Stephen Evance, Kt. | 1700-1712 |

| Sir Bibye Lake, Bart. | 1712-1743 |

| Benjamin Pitt | 1743-1746 |

| Thomas Knapp | 1746-1750 |

| Sir Atwell Lake, Bart. | 1750-1760 |

| Sir William Baker, Kt. | 1760-1770 |

| Bibye Lake | 1770-1782 |

| Samuel Wegg | 1782-1799 |

| Sir James Winter Lake, Bart. | 1799-1807 |

| William Mainwaring | 1807-1812 |

| Joseph Berens, Junior | 1812-1822 |

| Sir John Henry Pelly, Bart. | 1822-1852 |

| Andrew Colville | 1852-1856 |

| John Shepherd | 1856-1858 |

| Henry Hulse Berens | 1858-1863 |

| Rt. Hon. Sir Edmund Walker Head, Bart., K.C.B. | 1863-1868 |

| Rt. Hon. The Earl of Kimberley | 1868-1869 |

| Rt. Hon. Sir Stafford H. Northcote, Bart., M.P. (Earl of Iddesleigh) | 1869-1874 |

| Rt. Hon. George Joachim Goschen, M.P. | 1874-1880 |

| Eden Colville | 1880-1889 |

| Lord Strathcona and Mount Royal, G.C.M.G. | 1889-1914 |

| Sir Thomas Skinner, Bart. | 1914-1916 |

| Sir Robert Molesworth Kindersley, G.B.E. | 1916 |

| Sir John Robinson, Kt. | 1670-1675 |

| Sir James Hayes, Kt. | 1675-1685 |

| The Hon. Sir Edward Dering, Kt. | 1685-1691 |

| Samuel Clarke | 1691-1701 |

| John Nicholson | 1701-1710 |

| Thomas Lake | 1710-1711 |

| Sir Bibye Lake, Bart. | 1711-1712 |

| Captain John Merry | 1712-1729 |

| Samuel Jones | 1729-1735 |

| Benjamin Pitt | 1735-1743 |

| Thomas Knapp | 1743-1746 |

| Sir Atwell Lake, Bart. | 1746-1750 |

| Sir William Baker, Kt. | 1750-1760 |

| Captain John Merry | 1760-1765 |

| Bibye Lake | 1765-1770 |

| Robert Merry | 1770-1774 |

| Samuel Wegg | 1774-1782 |

| Sir James Winter Lake, Bart. | 1782-1799 |

| Richard Hulse | 1799-1805 |

| Nicholas Caesar Corsellis | 1805-1806 |

| William Mainwaring | 1806-1807 |

| Joseph Berens, Jun. | 1807-1812 |

| John Henry Pelly | 1812-1822 |

| Nicholas Garry | 1822-1835 |

| Benjamin Harrison | 1835-1839 |

| Andrew Colville | 1839-1852 |

| John Shepherd | 1852-1856 |

| Henry Hulse Berens | 1856-1858 |

| Edward Ellice, M.P. | 1858-1863 |

| Sir Curtis Miranda Lampson, Bart. | 1863-1871 |

| Eden Colville | 1871-1880 |

| Sir John Rose, Bart., G.C.M.G. | 1880-1888 |

| Sir Donald A. Smith, G.C.M.G. | 1888-1889 |

| The Earl of Lichfield | 1889-1910 |

| Sir Thomas Skinner, Bart. | 1910-1914 |

| Leonard D. Cunliffe | 1914-1916 |

| Charles Vincent Sale | 1916 |

Prince Rupert, Governor

Sir John Robinson, Deputy Governor

Sir Robert Viner

Sir Peter Colleton

James Hayes

John Kirke

Francis Millington

John Portman

Sir R. M. Kindersley, g.b.e., Governor

Charles V. Sale, Deputy Governor

Leonard D. Cunliffe

V. Hugh Smith

Sir Wm. Mackenzie

Sir A. M. Nanton

Cecil Lubbock

T. Hewitt Skinner

F. S. Oliver

O far as history tells, it was not until about the year

1000 A.D. that anyone, at all in touch with the civilised

world, knew of the existence of the land that has now

become the Dominion of Canada. It was then that

Leif Ericson, a Norseman, led an expedition from

Greenland to the far north shores of the American

Continent. The discovery was barren of result, and it was not till 500

years later that John Cabot reached the shores of Canada in 1497.

O far as history tells, it was not until about the year

1000 A.D. that anyone, at all in touch with the civilised

world, knew of the existence of the land that has now

become the Dominion of Canada. It was then that

Leif Ericson, a Norseman, led an expedition from

Greenland to the far north shores of the American

Continent. The discovery was barren of result, and it was not till 500

years later that John Cabot reached the shores of Canada in 1497.

Cabot was born in Genoa and learned in Mecca, the meeting place of East and West, that the spices, perfumes, silks, and precious stones, which were bartered there in great quantities, were brought by caravan from the north-eastern parts of farther Asia. It occurred to him that a shorter route would be across the Western Ocean. In 1484 he made his way to England, and explained his ideas to the leading merchants of Bristol, who already carried on an extensive trade with Iceland. No great progress had been made with his plans, when the news came that Christopher Columbus had reached the Indies. This stirred Cabot and his friends to action, and Letters Patent were obtained from Henry VII. “to seeke out, discover and finde whatsoever isles, countries, regions or provinces of the heathen and infidels, which before this time have been unknown to Christians.” It was on May 2nd, 1497, that Cabot set sail from Bristol on board the Mathew, manned by eighteen men. It was on May 2nd nearly two centuries later that Charles II. granted a Royal Charter to “The Governor and Company of Adventurers of England trading into Hudson’s Bay.”

After fifty-two days at sea, Cabot reached the northern extremity of Cape Breton Island on June 24th, 1497. The Royal Banner was unfurled and Cabot took possession of the country in the name of King Henry VII. The soil was fertile and the climate temperate, and Cabot was convinced that he had reached the north-eastern coast of Asia.

Soon after this, fishermen from Europe in considerable numbers began to visit the Newfoundland Banks, and in time the coast of the mainland of America. Less than forty years after Cabot’s discovery, Jacques Cartier, a seaman of St. Malo, sent out by the French King, sailed up the St. Lawrence as far as the Lachine Rapids to the spot where Montreal now stands. For the next sixty years, which take us to the close of the sixteenth century, the fisheries and the fur trade were developed, but no colonisation was attempted.

In the early years of the seventeenth century de Champlain, the French explorer, who was employed in the interests of fur trading monopolies, sailed up the St. Lawrence. Five years later—in 1608—he began the settlement of Quebec. He fought with the Algonquins against the Iroquois, established a trading post at Montreal, and penetrated to the eastern ends of Lakes Huron and Ontario. He was one of “The Company of One Hundred Associates,” which was formed under the ægis of Cardinal Richelieu and was granted a monopoly of the trade throughout the whole valley of the St. Lawrence.

It is interesting to note that, whereas the Charter of the Hudson’s Bay Company has continued for two centuries and a half, the Charter of this French company was revoked after a few years, as was that of a subsequent French “Company of the West Indies” which was organised in 1664.

Exploration and missionary activity were the chief interests of de Champlain, and in his eyes trade was only of value as a means to these ends. In both connections the French were active, daring and successful.

Among them were two men, Radisson and Groseilliers, who were destined to play a large part in the formation of the Hudson’s Bay Company, and thereby to influence the future history of what became in time the Dominion of Canada.

In the spring of 1652 Pierre Radisson, a boy of seventeen, set out for a day’s hunting from the stockaded fort of Three Rivers on the north bank of the St. Lawrence. It was a dangerous game, for the Iroquois swarmed in the neighbourhood. His two companions turned back after a time and Radisson kept on alone. The day’s hunting was successful, and he commenced to retrace his steps, only to find the scalped corpses of his companions, and to be himself captured by the Iroquois. He did not yield without a struggle, and his bravery appealed to the Indians. Diplomacy and courage saved his life, and he was given as a son to a woman who had been adopted by the tribe. After a time he escaped, but was almost immediately recaptured, and could have had little expectation of any other fate than death by torture. The Great Council met to decide his case; his adopted father appealed for him; and then his adopted mother glided into the wigwam, singing some battle-song of valour, dancing and gesticulating round and round the lodge in dizzy serpentine circling, that illustrated in pantomime the battles of long ago. The old sachems were disturbed; one after another rose and spoke; in the end, the Chief who had adopted Radisson for his son cut the captive’s bonds and, amid shouts of applause, set the white youth free, to continue for two years his life as a member of the tribe.

Groseilliers was Radisson’s brother-in-law; in him the trader predominated over the explorer, while in Radisson, exploration and adventure were the more pronounced.

In 1658 the two brothers made what was their third expedition to the West, which lasted for two years; on this journey they wintered at Lake Nipigon, which they called Assiniboines. Three years later, without the permission of the Governor, they started on another voyage, in the course of which they explored the northern shore of Lake Superior. On returning to Quebec, Groseilliers was made a prisoner for illicit trading, and the two partners were fined £10,000. They crossed to France in a fruitless search for restitution, and made efforts to obtain support for a voyage to Hudson Bay, of which they had heard from the Indians. Some shipowners promised the use of two vessels for this purpose, but nothing happened. Then the two adventurers met the Royal Commissioners, who were in America on behalf of Charles II., and through the influence of one of these—Sir George Cartwright—they obtained an interview with the King in 1666. Charles promised them a ship, but before it was available, overtures were made to the two Frenchmen by De Witt, the Dutch Ambassador, to go out under the auspices of Holland. These offers were refused, and at last an audience was obtained with Prince Rupert, the King’s cousin.

Prince Rupert was the dominant figure on the Royalist side in the Civil War. In later years he turned Admiral and bore a brilliant part in the Dutch Wars. He is a distinguished figure in the history of Art as one of the earliest mezzotinters, while the curious glass toys, called Prince Rupert’s drops, recall the scientific pursuits which amused the old age of the great cavalry leader of the Civil War. Science had indeed become the fashion of the day. Charles II. was himself a fair chemist; he took a keen interest in the problems of navigation, and, as a consequence, founded the Royal Observatory at Greenwich. In 1662 the Royal Society was established, and, ten years later, Sir Isaac Newton became a member.

It was in this atmosphere of new ideas and wider knowledge that Radisson and Groseilliers gained the support of Prince Rupert, and through him of the King; and it was in such conditions that there came into being the Governor and Company of Adventurers of England trading into Hudson’s Bay, where Henry Hudson, the English navigator and explorer, was deserted by his crew and left to perish in 1611.

The first Stock Book of the Company, which is still in existence, records that in 1667, some three years before the granting of the Charter, substantial sums of money had been provided for the enterprise. The first name on the list is that of the Duke of York, afterwards James II., with “a share presented to him in the stock and adventure by the Governor and Company £300.” Prince Rupert, the Duke of Albemarle, the Earls of Arlington, Craven, and Shaftesbury, with many others, provided various sums.

In June, 1668, Radisson in the Eaglet under Captain Stannard, and Groseilliers on the Nonsuch Ketch—Captain Zachariah Gillam—sailed down the Thames from Gravesend. Prince Rupert and other “Adventurers” inspected the ship and its stores. In the captain’s cabin they drank to the success of the voyage and, as the Prince and his companions rowed ashore, the vessels weighed anchor. The Eaglet crossed the Atlantic but on approaching Hudson Strait, the master thought the enterprise an impossible one and returned to London. The interest centres in the Nonsuch Ketch; she passed through Hudson Bay, to the south of James Bay, which she reached on September 29th. A palisaded fort was built and named after King Charles, while the river which flowed into the bay was called after Prince Rupert. Here the voyagers spent a long and dreary winter, finding the cold excessive and “Nature looking like a carcase frozen to death.” By April, 1669, the ice swept out of the river with a roar, and by June the heat was almost tropical. Groseilliers had been doing an active trade with the Indians, and the Nonsuch sailed for England loaded to the waterline with a cargo of furs.

THE GRANTING OF THE ROYAL CHARTER BY KING CHARLES II. IN 1670.

HE success of Groseilliers’ voyage caused those who had

supported the enterprise to apply to King Charles II.

for a Royal Charter, which, after some delay, was granted

on Friday, May 2nd, 1670.

HE success of Groseilliers’ voyage caused those who had

supported the enterprise to apply to King Charles II.

for a Royal Charter, which, after some delay, was granted

on Friday, May 2nd, 1670.

The Charter sets out that “Whereas Our dear and entirely beloved Cousin, Prince Rupert,” together with other Noblemen, Knights and Esquires, mentioned by name, and “John Portman, Citizen and Goldsmith of London, have, at their own great Cost and Charges, undertaken an Expedition for Hudson’s Bay . . . . for the Discovery of a new Passage into the South Sea, and for the finding some Trade for Furs, Minerals, and other considerable Commodities, and by such their Undertaking, have already made such Discoveries as do encourage them to proceed further in Pursuance of their said Design, by means whereof there may probably arise very great Advantage to Us and Our Kingdom. And Whereas the said Undertakers, for their further Encouragement in the said Design, have humbly besought Us to incorporate them, and grant unto them, and their Successors, the sole Trade and Commerce of all those Seas, Streights, Bays, Rivers, Lakes, Creeks, and Sounds, in whatsoever Latitude they shall be, that lie within the entrance of the Streights commonly called Hudson’s Streights, together with all the Lands, Countries and Territories, upon the Coasts and Confines of the Seas, Streights, Bays, Lakes, Rivers, Creeks and Sounds, aforesaid, which are not now actually possessed by any of our Subjects, or by the Subjects of any other Christian Prince or State. . . . . We give, grant, and confirm, unto the said Governor and Company, and their Successors, the sole Trade and Commerce of all those Seas,” etc., “with the Fishing of all Sorts of Fish, Whales, Sturgeons, and all other Royal Fishes, in the Seas, Bays, Inlets, and Rivers within the Premisses, and the Fish therein taken, together with the Royalty of the Sea upon the Coasts within the Limits aforesaid, and all Mines Royal, as well discovered as not discovered, of Gold, Silver, Gems, and precious Stones, to be found or discovered within the Territories, Limits, and Places aforesaid, and that the said Land be from henceforth reckoned and reputed as one of our Plantations or Colonies in America, called Rupert’s Land. And Further,” We create “the said Governor and Company for the Time being, and their Successors, the true and absolute Lords and Proprietors of the same Territory, Limits, and Places aforesaid.”

Powers are given to the Company to make laws, impose penalties and punishments, and to judge in all causes civil and criminal according to the laws of England. They may employ armed force, appoint commanders, and erect forts. Finally all admirals, and others his Majesty’s officers and subjects, are to aid and assist in the execution of the powers granted by the Charter.

Its general appearance may be gathered from the illustration which is given. It consists of five sheets of parchment, each measuring about 31½ in. by 25 in., consisting in all of some 27 sq. ft. of close writing. On the first of the sheets there are elaborate decorative borders, and attached to the Charter is the Privy Seal, of which we give an illustration.

The Charter is carefully preserved in the principal Board Room in Hudson’s Bay House, London. It is an interesting experience to handle the old document and examine it in detail. Some unknown scribe wrote patiently for days on the skins of unknown animals; here and there he made mistakes, and we can see the erasures and corrections; but for us, after all this long period of time, it is the symbol and the formal instrument of a history full of great consequences. It calls up pictures of early sailing vessels, Atlantic storms, and frozen seas; it carries us to factories and forts; embarks us in frail canoes for long journeys on rivers and lakes, and brings us in contact with the Indian tribes and the fur-bearing animals of the Company’s great territory.

The Charter has been examined and quoted in the Law Courts; its conditions have been subjected to close analysis, but it proved to be well drawn, and it withstood successfully all the attacks that were made upon its legal validity and the rights it gave. Yet the real power which the Charter purported to convey was otherwise derived. At the most, it was the vehicle for the conveyance of an opportunity of limitless value, because it was rightly used, but which would have been of no worth had not those to whom it was granted, and their successors, known how to handle wisely the great affairs entrusted to their charge.

Some two hundred years after it was signed and sealed, many of its more important conditions were abrogated by agreement; but the regulations for the government of the Company remain to a great extent as they were in the reign of King Charles, though modified somewhat to suit changed conditions by subsequent Charters.

FACSIMILE

of the

FIRST SHEET of the CHARTER

The latest Supplemental Charter was considered by the General Court of the Company under the presidency of Lord Strathcona, in 1912, and in due course was granted the Royal Assent of King George V.

To modern ideas, the assumption that a King could dispose of vast and unexplored territories is somewhat curious; but we have to remember that such powers had been commonly exercised for centuries by European monarchs. In Great Britain, the first trading Charters were granted, not to English companies which were then non-existent, but to branches of the famous Hanseatic League, which was a loose but effective federation of North German towns. It was not until 1597 that England was finally relieved from the presence of a foreign chartered company. In that year Queen Elizabeth closed the steel-yard where Teutons had been established for 700 years.

It was in the age of Elizabeth and the early Stuarts that the Chartered Company, in the modern sense of the term, had its rise. The geographical discoveries of those days gave a great impulse to shipping, trade, and the development of the new lands. In France and Holland, no less than in England, the institution of Chartered Companies became a settled method of working. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries more than seventy of such companies came into existence in France, but the Charters were frequently revoked, and the system finally perished in the general sweeping away of privileges that followed the Revolution.

From time to time the validity of Charters, among them that of the Hudson’s Bay Company, was challenged; but invariably the highest legal authorities declared it to be undoubtedly good in law.

The system of limited liability companies had not been invented; the enterprises were too great to be undertaken by private individuals, and the institution of a Chartered Company gave the best, if not the only, opportunity for the establishment of colonies, which was thought to be desirable by England and France, by Holland, Spain, and Portugal.

Many of the Chartered Companies failed through bad administration or organisation; through want of capital, or through the distribution of dividends made prematurely or fictitiously. When under able management, they were able to carry on their enterprise until the development of the countries in which they operated reached a comparatively advanced point, and gave rise to questions of national, or international, policy for the Mother Kingdom by which the Charter was granted. Then some change was needed, such as was the case with the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1869, when a large part of its rights under the Charter were ceded to the Canadian Government on agreed terms.

We shall deal subsequently with this important change. In the meantime it will be well to remember that the Hudson’s Bay and other Chartered Companies, though possessing privileges that could not be disputed by the law of the land, were subject to economic laws from which there was no escape. Their success depended not only on efficient administration, but on successive adaptations to new conditions, and a readiness to forego, as circumstances required, the full exercise of those privileges to which they had a legal right.

It is no less essential to success that duties should be recognised as well as privileges. Against their own apparent financial interests, Chartered Companies have carried on anti-slavery and anti-alcohol campaigns; they have developed countries at an outlay which promised no immediate return; have contributed to the cost of military expeditions; have even prevented national wars; and, at least on some occasions, the shareholders have been compelled to “take out their dividends in philanthropy.”

Whatever status a company may hold in the eye of the law, it could not continue for two hundred and fifty years unless it made constant adjustments to the changing conditions of the times. Sometimes slowly and reluctantly, sometimes with wise forethought, the Hudson’s Bay Company has made these necessary changes, and by its influence, its great resources, and the ability of its Servants, it prepared the way for the development of the great Dominion of Canada, in the further progress of which it is, and will be, a power of the first importance.

OBVERSE AND REVERSE OF THE GREAT SEAL OF ENGLAND ATTACHED TO THE ROYAL CHARTER.

OR long ages before the earth was fit for human habitation,

and during the thousands of years in which ancient

civilisations were rising and falling, the forces of Nature

were determining the distribution of land and water,

the climatic conditions, the fauna and the flora, of that

vast, vaguely defined, territory of which the Charter of

the English King purported to make the Governor and Company of

Adventurers of England trading into Hudson’s Bay “the true and

absolute Lords and Proprietors.”

OR long ages before the earth was fit for human habitation,

and during the thousands of years in which ancient

civilisations were rising and falling, the forces of Nature

were determining the distribution of land and water,

the climatic conditions, the fauna and the flora, of that

vast, vaguely defined, territory of which the Charter of

the English King purported to make the Governor and Company of

Adventurers of England trading into Hudson’s Bay “the true and

absolute Lords and Proprietors.”

Nearly the whole of this Rupert’s Land was then unknown. For the next two centuries, or more, it was to be the scene of adventure and exploration by men who faced difficulties, hardships and death, sometimes for the expansion of trade, sometimes for mere love of discovery and adventure, but always consciously, or unconsciously, making their contribution towards the foundation of a mighty empire.

One reason given for the application for the Charter was “the Discovery of a new Passage into the South Sea.” This enterprise fascinated many generations, and it was long supposed that such a discovery would have practical consequences of great value; but it was other discoveries, which at first were uncontemplated and often embarked upon without any great purpose in view, that were to prove of the most importance.

Without maps, in frail canoes, and with but little in the way of equipment or supplies, men faced the dangers of the unknown. That many such adventures should end in failure and disaster is natural enough, but that, in such circumstances, so many should have succeeded is a matter for continual surprise. To-day a map of Canada, perpetuating the names of explorers, is an epitome of centuries of adventure and heroism, with great consequences already accomplished, and great possibilities that may yet be realised.

In this work of discovery the servants of the Hudson’s Bay Company have throughout played a prominent part; more especially in those explorations which have brought accomplishment rather than possibility; which have led to the growth of great cities and have made large parts of Canada the granary of the world.

It is said that, during the Great War, sixty new kinds of plants were discovered within a short radius of a cavalry camp in Surrey, England. The seeds were brought from many parts of the world in the fodder for the horses, and of course by accident. In corresponding fashion the seeds sown by the enterprise of the servants of the Hudson’s Bay Company have led to the development of an ample and abundant life in ways that were never expected, and which it would have been folly to predict.

Pierre Esprit Radisson has already been mentioned in connection with the founding of the Hudson’s Bay Company, and something has been told of his capture by, and life among, the Indians; but as the first white man to explore the West, the North-West, and the North, his adventures and discoveries deserve fuller notice. He was born in France in about 1636, and we meet him first at Three Rivers, between Quebec and Montreal. After his capture he became the adopted son of an Iroquois Chief and found himself, at the age of seventeen, assigned to a band of young braves who were to raid the borderlands between the Huron country of the upper lakes and the St. Lawrence. He wandered for months round the regions of Niagara and on to the vast forests between Lakes Ontario and Erie. He had hoped for an opportunity for escape but none presented itself; yet his valour on the warpath had established the confidence of the Indians, who took him on a freebooting expedition against the whites of the Dutch Settlements at Fort Orange, Albany. Here his nationality was discovered by a Frenchman, and the Dutch offered to ransom him at any price. Radisson had pledged himself to return to his Indian parents; the Dutch were the enemies of New France, and their offer was declined. Among the Iroquois he was ten times more a hero than he had ever been. In spite of his love for the wilds, the sight of white men and the sound of his own language, as also the repulsive habits and cruelties of the Mohawks, determined him to escape. This was effected with no great difficulty, and he found himself once more at Orange, whence he sailed down the Hudson to New York, which then consisted of some 500 houses; Central Park was a forest, and cows pastured on the Wall Street of to-day. Thence he sailed to Amsterdam, which he reached in the beginning of 1654.

Early in the same year he joined the fishing fleet that left France for the Grand Banks, and once again found himself on the St. Lawrence and at Three Rivers. During his two years’ absence great changes had taken place. A truce had been arranged between the Iroquois and the French, which the Jesuits thought gave them an opportunity for a mission to these Indians, of whom the Mohawks, who had captured Radisson, were one tribe. The Iroquois, however, while generally friendly to the English, were almost invariably hostile to the French. They welcomed the teaching of the priests, whom they led to the Council Lodge and presented with belts of wampum. Then they asked that a French Settlement might be made in the Iroquois country, and fifty colonists established themselves among the Onondagas, another Iroquois tribe. The Jesuits and the Governor of Three Rivers had no suspicion that the motives were to obtain the white men as hostages, miles away from help, so that the Iroquois might safely wage war against the Algonquins without fear of reprisals from Quebec. Against an expedition in which Radisson participated, treachery was planned and carried out. Many men of the Huron tribe, who formed part of the expedition, were massacred by the Iroquois, and the remnants of the party made their way with great difficulty to the little French colony at Onondaga. Here they were besieged throughout the winter by four hundred Mohawks; the river was blocked with ice and there was no means of escape. Radisson’s ingenuity was brought into play; in readiness for the spring, two large flat-bottomed boats were prepared, and then, knowing the customs of the Mohawks, Radisson invited them to a great feast. They ate to repletion, perhaps they were drugged, and the little party escaped in their boats. They had not gone far before the roar of waters told of a cataract ahead; they were four hours carrying baggage and boats over this portage; sleet beat upon their backs; the rocks were slippery with glazed ice, and the men sank to mid-waist in half-thawed snow. Lake Ontario was a rough sea, and the ice was jammed in the St. Lawrence. After a fortnight of difficulties such as these they arrived at Montreal, and three weeks later they moored in safety under the heights of Quebec.

Before Radisson was born, a French explorer had reached Lake Michigan, and a little later the Jesuit martyr Jogues had preached to the Indians of Sault Ste. Marie, but beyond there was an unknown world—the great North-West. From it came the stores of beaver pelts, brought by the Algonquins to Three Rivers; and in it dwelt strange, wild races, whose territory extended North-West and North to unknown, nameless seas. There came news of far distant waters called Lake “Ouinipeg;” of the Crees, who spent their winters on the prairie and their summers on Hudson Bay, and of other tribes who were great warriors—the Sioux—living to the South.

Thirty young Frenchmen, with two Jesuit priests, equipped themselves to return with the Algonquins to these unknown lands. On this expedition sixty canoes left Quebec, but the flotilla was ambushed by the Mohawks. The Jesuit Dreuillettes and one companion alone held on their way; this companion was Groseilliers, who was married to Radisson’s sister, and who, as we have seen, was concerned with the beginnings of the Hudson’s Bay Company. The stories Groseilliers told fired the ambition of Radisson, who, as a captive among the Mohawks, had cherished boyish dreams that it was to be his “destiny to discover many wild nations.” Radisson had been tortured by the Iroquois and besieged among the Onondagas; Groseilliers had been among the Huron missions that were destroyed, and with the Algonquin canoes that were attacked. Both knew the perils that awaited them on the new adventure they determined to undertake.

Shortly after the previous voyage, they joined a party of Algonquins who were returning from Montreal, some of whom had firearms for the first time and thought themselves invincible. A score or more of Frenchmen, gaily ignorant of the dangers that lay ahead, again with two Jesuit priests, made up the party. Their course lay through the country of the hostile Iroquois, but, in spite of this, Radisson and Groseilliers could not persuade their companions to take precautionary measures; the canoes separated, and, as the expedition straggled up to a waterfall where portage was necessary, they were attacked by the Iroquois. Of the white men only Radisson and Groseilliers went on with the Algonquins. They travelled now only at night, and could not hunt, lest Mohawk spies might hear the gunshots. Provisions dwindled, and presently the food consisted of tripe de roche and such few fish as could be caught.

This tripe de roche, a greenish moss boiled into a soup, which stays hunger but gives no nourishment, constantly illustrates the hardships of the early explorers. Sometimes those who followed traced the course of recent pioneers by the places where moss had been cut, and then, it may be came upon a group of skeletons, evidence of privation and hunger.

The two young Frenchmen kept on through Lake Huron into Lake Michigan, and reached the farthest point to which white men had as yet travelled. Here there were signs of Iroquois on the warpath; and before making winter camp, or waiting to be attacked, Radisson led a band of Algonquins to search out the enemy; on the third day Radisson and his Indians caught the Iroquois unprepared and not one escaped.

A MAP OF NORTH AMERICA, SHOWING CANADA OR NEW FRANCE, AND THE TERRITORIES GRANTED THE HUDSON’S BAY COMPANY UNDER THE CHARTER. (1748.)

“Our mind was not to stay here,” writes Radisson, “but to know the remotest people; and, because we had been willing to die in their defence, these Indians consented to conduct us.” Before the spring of 1659 they had been guided across what is now Wisconsin to “a mighty river, great, rushing, profound, and comparable to the St. Lawrence.” This was the Upper Mississippi—literally, Father of Waters—which white men now saw for the first time; they found upon its shores “the people of the fire,” a branch of the Sioux. Radisson had entered the great North-West, and, with all his imagination and his dreams, he could not picture the significance of the discovery.

From the prairie tribes of the Mississippi he heard not only of the Sioux, a warlike nation to the West, but of the Crees, a nomadic tribe to the North, between whom there was a constant state of war. Between them were the Assiniboines, who used earthen pots for cooking and heated their food by throwing hot stones in water. He was told, too, of yet another nation who lived in villages, like the Iroquois, on a great river that divided itself into two branches, one to the West and one to the South; these were the Mandans, the Omahas, or other people of the Missouri. A whole world of discoveries lay ahead. Radisson turned South and struck across the high land between the Mississippi and the Missouri; he appears to have seen something of what are now Wisconsin, South Dakota, and Nebraska, and to have returned through North Dakota and Minnesota to the shore of Lake Superior. By this time it was the fall of 1659, and Radisson determined to venture into the North-West. Groseilliers’ health began to fail from the hardships he had endured, so he remained in camp for the winter, attending to the trade, while Radisson set out with one hundred and fifty Cree hunters for the North-West. In one of the coldest winters known they travelled on snowshoes some 200 miles to what is now Manitoba; they hunted moose on the way, and slept at night round the camp fire. When the ice thawed in the spring, they built some boats and made their way back to Lake Superior.

Groseilliers had all in readiness to depart for Quebec, when news came that more than 1,000 Iroquois were on the warpath. The Indians of various tribes who were with Radisson were terrified, but the Chiefs sent word that 500 young warriors would go to Quebec with the white men. There were many conflicts with the Iroquois, but at last, after two years’ absence, Radisson and Groseilliers arrived at Montreal; they stayed for a short rest at Three Rivers and were then escorted to Quebec. Here they had a great reception, the more cordial because the Iroquois warfare had been so ceaseless that three French ships, lying at anchor, would have returned without a single beaver skin if the explorers had not come.

The adventurous Frenchmen were soon eager to start on another expedition. This time their object was to be the discovery of an overland route to the Bay of the North—Hudson Bay—of which news was brought by the Indians and from the neighbourhood of which came a vast wealth of furs. Permission was sought from the Governor of Three Rivers, who would only give a license on condition that half the profits of the trip should be paid to him. Radisson and Groseilliers refused any such terms and went without permission, knowing that the galleys for life, or even death for a second offence, was the punishment for trading without a license. After many conflicts with the Iroquois, they found themselves by the end of November, 1661, at the western end of Lake Superior, whence they proceeded north-west. The Crees wished to conduct them to the wooded lake region, where Indian families took refuge on the islands from the warlike Sioux, who, invincible on horseback, were not skilful with canoes. The explorers, however, were unable to go with the Crees because they had no means of transporting the goods brought for trade. They sent the Indians on, with instructions to bring back slaves to carry the baggage.

Then a notable thing happened; Radisson and Groseilliers built, somewhere west of Duluth, the first fort and the first fur post between the Missouri and the North Pole. The fur trade discovered and explored the West and made possible the subsequent development. We can look back to this first fort, rushed up in two days by two almost starving men, as the tangible origin of the modern life of the great North-West.

They were 2,000 miles from help and needed sentries; Radisson made his sentries of bells, attached to cords concealed in the grass and branches round the fort. The news of the two white men spread rapidly, and, when the Indians came, Radisson rolled gunpowder in twisted tubes of birchbark and ran a circle of this round the fort. He put a torch to it, and the Indians saw a magic circle of fire, which was to defend the adventurers from all harm. After many hardships and adventures, they found themselves at the Lake of the Woods and discovered the watershed sloping North from the Great Lakes to Hudson Bay.

TRACKING.

PORTAGE ON ATHABASCA RIVER.

They returned to Three Rivers, where, as already recorded, the Governor imprisoned Groseilliers and fined both the explorers. They brought back a cargo worth 300,000 dollars in modern money, and had less than 20,000 dollars left for themselves.

This treatment, for which they could obtain no redress in France, led them in the end to Prince Rupert and the English Court, and, in no indirect way, led to Canada becoming part of the British Empire.

To found the first fort in the West, to cause Canada to be British, were the two achievements of this expedition.

In 1668, Radisson in the Eaglet, and Groseilliers in the Nonsuch, set out to reach Hudson Bay by sea. The French had contemplated the approach to it by land; they forgot the maritime record of England, which once again was to prove decisive in determining supremacy over new lands. The Nonsuch alone reached its destination, passed through Hudson Strait and Bay, and came to anchor at the south of James Bay on September 29th. A palisaded fort was built, where Groseilliers and Gillam, the captain of the Nonsuch, spent the winter, returning to England in the following spring with a rich cargo of furs.

Then came the Charter, and in 1671 Radisson and Groseilliers were again at the Bay. A second post was established at Moose, and Radisson, with Charles Bailey, who had been sent out by the Company as Governor of the territory called Rupert’s Land in accordance with the conditions of the Charter, sailed up the Bay and met the Indians in the neighbourhood of what was to become the great fur capital of the North—York Factory, near Port Nelson.

Some ten years later, Radisson and Groseilliers again sailed into Hudson Bay, but this time under French auspices. They made for Hayes River, just south of Port Nelson. Leaving his brother-in-law to build a fort, Radisson launched a canoe on Hayes River to explore inland. He reached the region of Lake Winnipeg, to which he had come with the Cree hunters by way of Lake Superior, some twenty years before. The course he followed from Hudson Bay to Lake Winnipeg was to be the path of countless traders and pioneers for two centuries. He had passed from the Atlantic to the St. Lawrence; to the Great Lakes and the region of Lake Winnipeg, and thence by Hudson Bay and Hudson Strait to the Atlantic again. He made other voyages to the Bay, once again in the service of the great Company. The place and time of his death are unknown, but probably he died in about 1710 at the age of seventy-four.

To these two Frenchmen, Radisson and Groseilliers, the foundation of the Hudson’s Bay Company was largely due. Two hundred and fifty years later, France, in the hour of her need, obtained the assistance of the Company in the Great War.

For many years after the commencement of the Company, it made no great efforts at exploring its territory. Its main business was the fur trade, and it relied upon the Indians bringing the furs to the forts it had established. The Indians were quite willing to make long and difficult journeys for the sake of obtaining goods which appear to us to be of trifling value. The Company, however, was not having things all its own way, for the French fur traders were vigorous competitors and did their best to prevent the Indians going to the Company’s forts. It was not until 1688 that a really brave and adventurous man appeared among the Company’s servants. This was Henry Kelsey, a lad barely eighteen, who was the forerunner of the British pioneers of the next century. He is described as “delighting much in Indians’ company; being never better pleased than when he is travelling amongst them.” Young as he was, Kelsey volunteered to find a site for a fort on Churchill River, on the west side of the Bay and farther North than Port Nelson. There is no record of this trip, but he repeated it two years later, when he kept a detailed diary. In July, 1691, he despatched a party of Assiniboines, whom he subsequently overtook; he travelled by water seventy-one miles from Dering’s Point and then beached his canoes and continued overland through wooded country for three hundred miles. This brought him to prairie lands for another fifty miles, beyond which he travelled a further eighty, discovering many buffalo and beaver. On one occasion he was attacked by two bears, both of which he shot, to the amazement of the Indians, who named him Miss-top-ashish, or “Little Giant.” He had married a woman after the Indian fashion, whom the Governor, on Kelsey’s return to York Factory, refused to admit. Kelsey threatened to resign, and the Governor gave way. He had penetrated the interior to no slight extent, taking possession of it on behalf of the Company, and had, first among white men, seen the buffaloes of the plains. The example of Kelsey was not yet to be followed by other servants of the Company.

When tracing a river to its source we may appropriately explore some of its tributaries; in like manner, when the discoveries of those who were not servants of the Company have an important bearing upon the development of the Hudson’s Bay Company, we may appropriately consider exploits, which, of great interest in themselves, influenced the development of the Company and further opened up the great North-West. The early explorers of unmapped lands frequently sought a result that proved impossible or unachieved, but which had unintended consequences of much greater importance. The idea of a Western Sea, that was thought to lie like a narrow strait between America and Japan, was a will-of-the-wisp beckoning adventurers to the West. In June, 1731, from a little stockaded fort on the banks of the St. Lawrence, where Montreal stands to-day, there set out a party of fifty grizzled adventurers under the leadership of Sieur Pierre Gaultier de Varennes de la Vérendrye; with him were his three sons of eighteen, seventeen, and sixteen years of age. Merchants of Montreal had advanced goods for trade with the Indians in expectation of huge profits; these were done up in packets of 100 lbs. each, and were stored in the 90 ft. birch canoes, which could be carried on the shoulders of four men. Priests came to bless the departing voyageurs, the chapel bells rang out, and then, at a signal from the chief bowman, the paddles swept the water, and the voyageurs began one of their famous songs. They passed many scenes where previous adventurers had met their death, and they were aware of the perils that awaited them. After more than a month, the canoes left the Ottawa, passed into Lake Huron, and thence with a favourable breeze to the mouth of Lake Michigan. La Vérendrye had been in this country before; had been told vague Indian tales of rivers emptying into the Western Sea, and been given, by an old Indian, maps drawn on birchbark, showing the course.

Eleven weeks after leaving Montreal they reached the fur post at Kaministiquia, near what is now Fort William on Lake Superior; this distance is now covered in two days. The canoemen had received no pay, the winter, with scanty food supplies, would begin in a month, and the voyageurs refused to go on. At last it was agreed that if Vérendrye remained with one half at Lake Superior, the rest of the men would go West with Jemmeraie, his second in command. This expedition erected a fort on Rainy Lake, and drove a thriving trade in furs with the Crees. They returned to Lake Superior in the spring of 1732. Exactly a year from the day he left Montreal, La Vérendrye again started westward, reached Rainy Lake in seven weeks, and was escorted by the Indians to the Lake of the Woods, which he reached in August. Here he built a fort and decided to winter; he was relying upon supplies being brought up by his son and the adventurers were running short when Jean de la Vérendrye arrived. Two cargoes of furs had been sent down and two fur posts established; but the Montreal merchants were dissatisfied and decided to advance provisions only in proportion to earnings. His son pushed forward with a few picked men to Lake Winnipeg, while Vérendrye himself went back and succeeded in convincing the merchants that they must go on with the venture or lose all.

It is easier to feed a few men than many, and the party were distributed in three forts on Rainy Lake, the Lake of the Woods, and Lake Winnipeg. By the spring, one party of the famine-stricken traders were subsisting on parchment, moccasin leather, roots, and their hunting dogs. News came that Jemmeraie had died, and the expedition was in dire straits; it was decided to rush three canoes with twenty voyageurs to Michilimackinac, between Lakes Huron and Michigan, for supplies. This little party was attacked by the Sioux one morning when they had landed for breakfast. A few days later bands of Sautaux came to the camping-ground of the French; the heads of the white men lay on a beaver skin; all of them had been scalped, among them Jean Vérendrye, the leader of the relief expedition.

Difficulties of such kinds continued, but the exploration went on. Vérendrye sent his sons forward to reconnoitre the forts where the Assiniboine River joins the Red and the city of Winnipeg stands to-day. Vérendrye himself went back to Montreal with fourteen great canoes of precious furs, and satisfied the merchants, who agreed to make further advances.

DOG CARIOLE.

DOG SLEIGH.

Vérendrye made his way back to the site of the city of Winnipeg, and in September, 1738, set out for the height of land lying beyond the sources of the Assiniboine. He went up the Souris River to the Mandan country. He was accompanied by a ragged host of six hundred Indians. They were met by a band of Chiefs, whom it was advisable to impress, so the fifty Frenchmen were drawn up in line and the French flag placed four paces to the fore. At a signal, three thundering volleys of musketry were fired; the Mandans fell back prostrated with fear and wonder. In this fashion white men first took possession of the Upper Missouri. The Mandan Chiefs could tell nothing definite of a Western Sea. Six hundred Assiniboine visitors were a tax on the hospitality of the Mandans, who spread a rumour of a Sioux raid; the Assiniboines fled, and a little later Vérendrye and his Frenchmen turned back. Two were left to learn the Missouri dialects, and a French flag, in a leaden box with the Arms of France inscribed, was presented to the Mandan Chief. Vérendrye fell terribly ill, but the party had to go on, half-blinded by snow-glare, buffeted by prairie blizzards, huddling in snowdrifts at night, and uncertain of their course. By February, 1739, they reached the fort on Red River.

This spring no food came up from Montreal, and papers had been served for the seizure of the whole of Vérendrye’s possessions; he set out to contest the lawsuits in Montreal. During Vérendrye’s absence his sons were not idle. The Mandans guided them to the country of the Crows, who took them on to the Horse Indians; these in turn guided the French to their next western neighbours, the Bows, who were preparing to war on the Snakes, a mountain tribe still further West. Pierre de la Vérendrye went with the raiders, and in two weeks was at the foot of the Northern Rockies. No Snakes were to be found, and the Bows, fearing they had decamped to massacre the Bow women and children, fled back to their wives.

At the end of July, 1743, the Frenchmen were once more back on the Assiniboine River. For more than twelve years they had followed a hopeless quest; instead of a Western Sea they had found a sea of prairie, a range of mountains, and two great rivers—the Saskatchewan and the Missouri. The explorer, however, was a ruined man; jealousy and avarice combined against him in his absence; his command was given to another, and although later he was decorated with the Order of the Cross of St. Louis, and given permission to continue his exploration, his work was done. While making preparations for the new expedition, he died suddenly at Montreal.

One of the Hudson’s Bay servants to win fame as an explorer was Samuel Hearne. He was born in London in 1745, and entered the Navy before he was ten years old. At the end of the Seven Years’ War he joined the service of the Hudson’s Bay Company and was stationed at Fort Prince of Wales on the Churchill River. Norton, the Indian Governor of the fort, received instructions from London to despatch his most intrepid explorers for the discovery of unknown rivers, strange lands, rumoured copper-mines, and the North-West Passage that was supposed to lead directly to China. Hearne was one of those who studied the birchbark maps drawn by the Indians, and he undertook to make the adventure. Two attempts failed; on the first of them, when two hundred miles from the fort, Hearne awoke to find his Indian companions marching off with his guns, ammunition, and hatchets. Hearne was left alone with neither ammunition nor food; there was nothing for it but to return. A few weeks later, in February, 1770, he started again with five Indians; they travelled on snowshoes and depended on chance game for food. Presently they were reduced to snow water and pipes of tobacco. The Indians hunted for game while Hearne stayed in his camp, and he thought for a time that he had once again been deserted. Then the Indians came in with the haunches of half-a-dozen deer, and for a time the danger of hunger was over. Hearne’s task was the discovery of new lands, the position of which had to be determined. The second trip was ended by his quadrant being blown over and broken. It was useless to go on to the Arctic Circle without instruments with which to take observations. Once more he made his way back to the Churchill River.

Nearing the fort he ran into a splendid Indian Chief, Matonabbee, who had long been the ambassador of the Hudson’s Bay Company to the Athabascans. At the third attempt Hearne availed himself of the offer, which the Indian had made, to guide the white man to the “Far off Metal”—or Coppermine—river. They left the fort in December, 1770, followed by a party of Indians with dog sleighs, and, on the Chief’s advice, accompanied by women, who were needed to snare rabbits, catch partridges, and attend to the camping. Hearne’s enemy, hunger, still pursued him; Christmas was celebrated by starvation; but presently the Indians found signs that meant relief from famine. Tufts of hair rubbed off on tree trunks, fallen antlers, and tracks on the snow, told that the caribou were on their yearly journey from East to West. In the Barren Lands they had now reached, they were joined by two hundred warriors. Hearne had the suspicion, afterwards confirmed, that these were on their way to obtain furs from the Eskimos. The women were sent to a rendezvous and the others went on under great difficulties, which caused half the Indians to turn back. Hearne, Matonabbee, and the others held on their course. On June 21st the sun did not set; the Arctic Circle had been reached. A month later the explorers reached the mouth of the Coppermine River, on the Arctic Ocean. Here Hearne erected a mark, and took possession of the coast on behalf of the Hudson’s Bay Company. This time Hearne had his quadrant, but either it was badly damaged, or the explorer was unskilled in its use, for the position which he gave proved subsequently to be very inaccurate. On the way down the Coppermine River, Hearne witnessed a massacre of Eskimos by his Indian companions; horror robbed Hearne of his exultation as an explorer; and even from this point of view the result was disappointing. He was in quest of a North-West Passage, and the Coppermine was not the way to it, but Hearne supposed that he had put an end to the disputes concerning it, a conclusion that was doubtless not unwelcome to the Governor and Committee in London, who were being attacked for not seeking the Passage, the discovery of which was one of the objects of the Charter.

Turning South, Hearne reached Lake Athabasca on Christmas Eve; there they found a woman who had escaped from an Indian band which had taken her prisoner; she had not seen a human face for seven months, and had lived by snaring partridges, rabbits and squirrels. Such a picture tells the nature of the territory Hearne had discovered—the Coppermine River, the Arctic Ocean, and the Athabasca country—a region in all as large as half European Russia. After an absence of a little more than eighteen months he was back at Fort Prince of Wales, of which less than a year later, on the death of Norton, Hearne became the Governor.

In 1782 the Fort was attacked by the French with forces against which Hearne could do nothing but surrender; he was taken prisoner, but reached England in 1787 and died there five years later.

Matonabbee was absent when the French came; he returned to find in ruins the fort where he had spent his life, and the English, whom he thought invincible, defeated and prisoners of war. Withdrawing from observation the brave old Chief blew out his brains.

A little north of Lake Athabasca, which figures so prominently in the story of the fur trade, is the Great Slave Lake, the waters of which are emptied into the Arctic Ocean through what is now known as the great Mackenzie River. Studded along the banks of the Mackenzie there have long been, and there still are, numerous forts belonging to the Hudson’s Bay Company. The river was not, however, discovered by the Company’s servants. Alexander Mackenzie was connected with the North-West Company, which was subsequently absorbed by the Hudson’s Bay Company. The partners of the North-West Company seemed to have had no great liking for Mackenzie and sent him to the distant Fort Chipewyan on Lake Athabasca. He saw one great river flowing North and another West, and he determined to follow their courses. The British Government had offered a reward of £20,000 to anyone who should discover a North-West Passage between the Atlantic and the Pacific. Perhaps Mackenzie was more eager to win the honour of discovery than the reward; but, be this how it may, he set out northwards in 1789, and, after many difficulties, reached Great Slave Lake, whence flow two rivers, both of which were then unknown. He chose the one to the West. The perils were too much for the Indian guides, who had to be compelled by force to continue, and who escaped whenever the opportunity offered. Four Canadians, who were with Mackenzie, besought him to return, since they saw impending the necessity for wintering in the Arctic north unless they quickly made their way back. Mackenzie had no intention of leaving his enterprise unfinished, but promised to return if they did not reach the sea within a week. That night the sun did not set, and Mackenzie, like Hearne a little while before, had reached the Arctic Circle. On the night of July 13th the travellers found their baggage floating in rising water; they had reached the tide, and found the sea. This was another part of the Arctic Ocean than that which Hearne had reached by the Coppermine River sixteen years before. Mackenzie’s men indulged in a whale hunt in their frail canoes, and then, having erected the inevitable mark, set out on the return journey to Fort Chipewyan. It had taken six weeks to reach the Arctic, and it took eight to return against the stream. Once again the North-West Passage had not been found. Mackenzie reported his discovery of the great river to the partners of the North-West Company, who received it with utter indifference.

Undeterred, Mackenzie asked, and obtained, permission to explore the river which flows to Lake Athabasca from the West—the Peace River. He went to England to study astronomy and surveying for his next expedition, and was now fired with the same enthusiasm to find the Western Sea, that had sustained Vérendrye through long years of danger and disappointment. It was on May 9th, 1793, that Mackenzie, with Mackay as first assistant, six Canadians and two Indians, started on Peace River. The water flooded with the spring thaw tore down from the mountains. In less than a week, snowcapped peaks crowded the canoe into a narrow cañon where the river was a wild sheet of tossing foam for as far as the eye could see. It seemed impossible to land; but Mackenzie somehow got ashore and with an axe cut footholds on the face of the cliff and signalled to his men to follow. The canoe seemed likely to be smashed to pieces and the tow-line snapped, but by good fortune the canoe was driven ashore and the tow-line regained. The men bluntly declared that it was absurd to go on; but Mackenzie paid no heed to the murmurings. He gave them the best feast he could and went ahead to explore. For as far as he could see there was a continuous succession of cataracts walled in by stupendous precipices; to avoid them they must go nine miles over the mountain. It took one day to travel three miles. Once, when Mackenzie and Mackay had gone ahead with the Indians, the Canadians deserted them, and the leaders were left with no food and little ammunition. After a time the Canadians were found, and though Mackenzie said nothing, he took care not again to allow the crew out of his sight.

The party met some Indians and learned that the Divide had been crossed; but the future course was doubtful. A river that they reached ran South, not West. As a matter of fact, he was on the sources of the Fraser, that winds South through the mountains before turning West into the Pacific. The Indians said it ran for “many moons” through the “shining mountains” before it reached the “mid-day sun.” Mackenzie learnt from the Indians that, by somewhat retracing his steps, he could reach the sea overland in eleven days. He frankly laid the difficulties before his followers, declaring that he was going on alone, and that they need not accompany him unless they voluntarily decided to do so. His courage was contagious and the whole party went on. With much difficulty, they crossed the last range of mountains and then embarked with some Indians for the sea. It was on July 20th, 1793, that Mackenzie came to the Western Sea which, for three hundred years, had defied all approach from overland. The point he reached was near Cape Menzies.

There were ten men on a barbarous coast, with 20 lbs. of pemmican, 15 lbs. of rice, 6 lbs. of flour, and scarcely any ammunition. They had a leaky canoe, and between them and their homes lay half a continent of wilderness and mountains. Mixing up a pot of vermilion, Mackenzie painted his name and the date on the face of a rock. A little more than a month later they were back at the fort.

In the following winter Mackenzie left the West for good. He published the story of his travels, and was knighted by the English King. He died in 1820, on an estate in Scotland where he had lived quietly for some years.

The year previous to Mackenzie’s arrival at the Pacific coast by land, it had been surveyed by George Vancouver, the English navigator. In 1791 he went from Falmouth to Australia and New Zealand, and, after spending some time at the Hawaiian Islands, sighted California in April, 1792. He went far up the coast and circumnavigated Vancouver Island, which is named after him.

In 1805, and twice in 1811, the Pacific was reached overland down the Columbia River, while in 1808 Simon Fraser approached it by the great river that bears his name. Mackenzie, as we have seen, reached the Fraser River, but it was taking him South when his wish was to go West, and he left it for a land march and a journey down the Bella Coola River.

It was not till one hundred and twenty-three years after the granting of the Charter that a white man crossed from the Atlantic to the Pacific. Only five expeditions by men of British stock had reached the Western Sea by land by 1811. The Hudson’s Bay Company had existed for more than one hundred years when the limits of Canada were first vaguely discovered.

With the close of the eighteenth century the boundaries of the Dominion had been found. The story of “Life in the Service of the Company” will tell something of how the details were filled in; will suggest under what difficulties, and at what cost, Canada was made.

LEAD COINS OF THE COMPANY, REPRESENTING THE VALUE OF BEAVER SKINS.

T is no easy matter to give in a few pages any vivid

impression of life in the service of the Company. It

is passed in a territory which extends from Labrador to

British Columbia, and from the Arctic Circle to the

boundary line. It is lived by rivers, lakes and oceans,

under widely different conditions of climate and

temperature. The character of the Indians varies with the locality, as

does plant and animal life. Some of the posts are comparatively accessible;

others are remote; while, if this sketch is not to be too

incomplete, we must take account of the changes, sometimes great and

sometimes little, that have taken place since service in the Company

began in the time of the Stuarts. Perhaps even more significant is

the influence of the life upon the different types of men who have

shared it. For the most part they came to it young, but, even so, their

previous mode of life must have affected their attitude towards it.

They may have been sent from quiet districts in the Orkneys, or have

come from busy towns. In other cases they may have grown up in a

Hudson’s Bay atmosphere through family connections with the service.

They may remain in it for a few years, or for a lifetime, and, in almost

all cases, it is calculated to have a dominating influence upon their

character and their future. To use a modern illustration, we need a

long series of cinematograph films, but must, perforce, take an isolated

picture here and there as typical of the whole. Even were the films

themselves available, they would show us only the externals of the life

and not the more important features and consequences which have

brought the Company into the position it occupies to-day, and have to

so large an extent shaped the past and future of a great part of Canada.

T is no easy matter to give in a few pages any vivid

impression of life in the service of the Company. It

is passed in a territory which extends from Labrador to

British Columbia, and from the Arctic Circle to the

boundary line. It is lived by rivers, lakes and oceans,

under widely different conditions of climate and

temperature. The character of the Indians varies with the locality, as

does plant and animal life. Some of the posts are comparatively accessible;

others are remote; while, if this sketch is not to be too

incomplete, we must take account of the changes, sometimes great and

sometimes little, that have taken place since service in the Company

began in the time of the Stuarts. Perhaps even more significant is

the influence of the life upon the different types of men who have

shared it. For the most part they came to it young, but, even so, their

previous mode of life must have affected their attitude towards it.

They may have been sent from quiet districts in the Orkneys, or have

come from busy towns. In other cases they may have grown up in a

Hudson’s Bay atmosphere through family connections with the service.

They may remain in it for a few years, or for a lifetime, and, in almost

all cases, it is calculated to have a dominating influence upon their

character and their future. To use a modern illustration, we need a

long series of cinematograph films, but must, perforce, take an isolated