* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Jesse Ketchum and his Times

Date of first publication: 1929

Author: Ernest Jackson Hathaway (1871-1930)

Date first posted: 31st August, 2024

Date last updated: 31st August, 2024

Faded Page eBook #20240812

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines and Howard Ross & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

This file was produced from images generously made available by Internet Archive.

Jesse Ketchum

AND HIS TIMES

Jesse Ketchum,

1782-1867.

Jesse Ketchum

AND HIS TIMES

Being a Chronicle of the Social Life

and Public Affairs of the Capital of

the Province of Upper Canada during

its First Half Century

BY

E. J. HATHAWAY

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS

McCLELLAND & STEWART,

LIMITED

PUBLISHERS, TORONTO

Copyright, Canada, 1929

by McClelland & Stewart, Limited, Toronto

Printed in Canada

TO THE LITTLE LADY

WHOSE CONSTANT SYMPATHY

AND CORDIAL CO-OPERATION

HAVE MADE POSSIBLE THE

WRITING OF THIS BOOK.

A permanent record of the life of Jesse Ketchum has long been needed. There are few names in the records of the early history of Toronto more enduring or more endearing than that of this gentle yet forceful personality who, during the first half of the last century, gave such conspicuous service to the development of Toronto and its institutions.

Jesse Ketchum has been for many years a sort of legendary figure in the history of Toronto. He came to the City in 1799, five years after it was founded by Governor Simcoe, and lived there until 1845. These were the formative years in the life of the Province of Upper Canada and of the City, the period when sane judgment and unselfish service were most urgently needed, but of which, unfortunately, altogether too little were received.

Though essentially a man of peace he enlisted actively in the fight against arrogance and autocracy in public affairs. He was elected to the Legislative Assembly in 1828 and served as colleague and associate with William Lyon Mackenzie during the most colorful years of the battle with the Family Compact. He was associated with the founding of the first Public School in Toronto and also with the first Sunday school. He was the first Church unionist, anticipating by a full hundred years the great movement which during the present century has swept throughout the country; and during the past three-quarters of a century and more his name has been known to every generation of boys and girls because of the prize books bearing his name which are given from time to time in the Public and Sunday schools in Toronto. In Buffalo, where he lived for the last twenty-two years of his life, his name is held in quite as high esteem because of his benefactions in the interest of education.

This volume, however, aims to be something more than the story of one man’s life. It is an attempt to portray the period during which he lived, to recount the struggle to found a province and establish a system of government; and then, when it is found that the system thus set up is unsound, to tell of that still more important struggle, even to the length of resort to arms, for reconstruction on lines more in harmony with the principles of the British system.

The author is greatly indebted in the writing of this book to Mrs. George Burland Bull, of Orangeville, Ontario, a grand-daughter of Jesse Ketchum, for access to much interesting and valuable information relating to the Ketchum family which she has accumulated with industry and painstaking care. He wishes also to express grateful appreciation to M. O. Hammond, author of Canadian Footprints and Confederation and its Leaders, to E. S. Caswell, historian of the York Pioneers Society, and to A. F. Hunter, Secretary to the Ontario Historical Society, for advice and assistance.

In order to avoid the necessity for attaching an undue number of foot-notes, a bibliography is given of works consulted. These, with the volumes of the Journals of the House of Assembly and the fragmentary fyles of early newspapers of the Province preserved in the Toronto Public Library and Ontario Legislative Library, have furnished much of the material for this study.

| PAGE | ||

| Preface | 7 | |

| Table of Contents | 9 | |

| List of Illustrations | 13 | |

| Chapter I. Youth | ||

| 1. Jesse Ketchum arrives at York | 15 | |

| 2. The Ketchum Family | 18 | |

| 3. Early Youth | 24 | |

| 4. Seneca Ketchum Comes to Canada | 28 | |

| 5. Jesse’s Flight | 36 | |

| Chapter II. At York | ||

| 1. The Beginnings of York | 40 | |

| 2. The Opening of Yonge Street | 46 | |

| 3. At York | 50 | |

| 4. Jesse Ketchum’s Marriage | 55 | |

| Chapter III. The Shadow of the War | ||

| 1. Hunter and Gore | 60 | |

| 2. The Menace of War | 66 | |

| 3. The Expulsion of the Americans | 72 | |

| 4. Jesse Ketchum, Tanner | 76 | |

| 5. The Capture of York | 80 | |

| 6. In the Hands of the Enemy | 89 | |

| Chapter IV. The Struggle for Education | ||

| 1. Early Schools in York | 94 | |

| 2. The Common School Act of 1816 | 100 | |

| 3. Controversy with Dr. Strachan | 109 | |

| Chapter V. After the War | ||

| 1. Gore and Maitland | 123 | |

| 2. York in 1818 | 131 | |

| 3. As School Trustee | 136 | |

| 4. The First Sunday School | 139 | |

| 5. The Building of Knox Church | 144 | |

| Chapter VI. Murmurings of Discontent | ||

| 1. The Family Compact | 149 | |

| 2. Editorial Buccaneers | 158 | |

| 3. Jesse Ketchum Enters Politics | 164 | |

| 4. The Stormy Parliament | 176 | |

| Chapter VII. Rebellion | ||

| 1. Toronto, Née York | 195 | |

| 2. Bond Head | 207 | |

| 3. Approaching a Climax | 220 | |

| 4. Gallows Hill | 231 | |

| Chapter VIII. 1837-1845 | ||

| 1. Out of Parliament | 246 | |

| 2. William Ketchum | 254 | |

| 3. The Union Act | 262 | |

| 4. Dr. Strachan and His University | 274 | |

| 5. Domestic Changes | 282 | |

| 6. Moving to Buffalo | 289 | |

| Chapter IX. Later Years | ||

| 1. Seneca Ketchum | 298 | |

| 2. Buffalo Years | 305 | |

| 3. The Passing of the Patriarch | 311 | |

| Chapter X. The Ketchum Philanthropies | ||

| 1. Churches, Sunday Schools and Temperance | 319 | |

| 2. The Ketchum Trusts, Toronto | 327 | |

| 3. Jesse Ketchum’s Gifts to Buffalo | 335 | |

| Bibliography | 347 | |

| Index | 349 | |

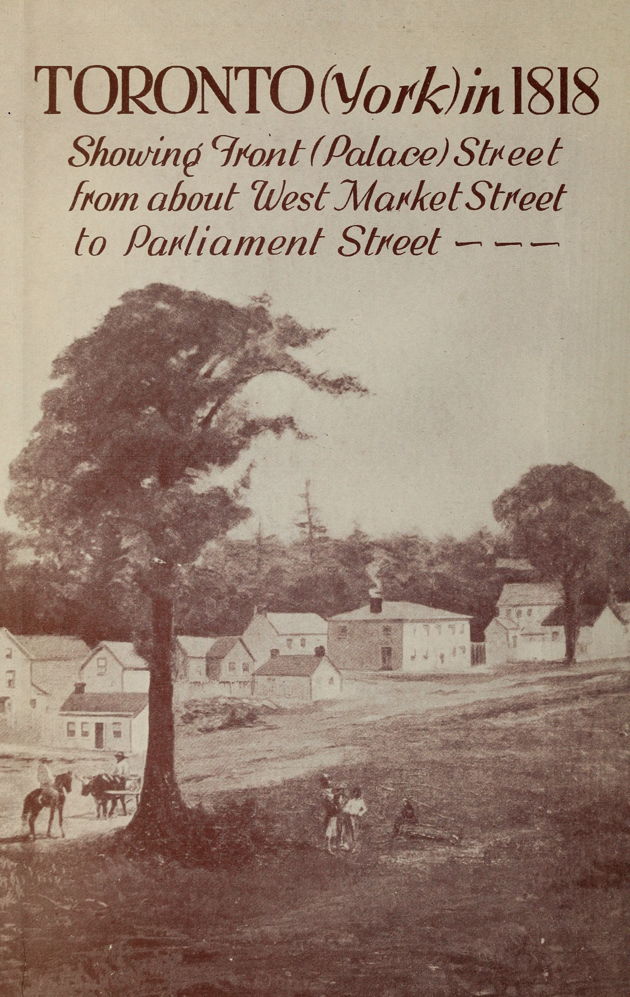

| Toronto (York) in 1818, showing Front (Palace) Street from West Market Street to Parliament Street | Front End Leaf |

| From a painting by Owen Staples, O.S.A., in City Hall, Toronto. | |

| Jesse Ketchum, 1782-1867 | Frontispiece |

| From a painting in the Board Room of Upper Canada Bible Society, Toronto. | |

| PAGE | |

| The First St. James’ Church, York, erected 1803 | 48 |

| From Landmarks of Toronto. | |

| Sir Francis Gore, Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Canada, 1806-1816 | 64 |

| From a portrait in Toronto Public Library. | |

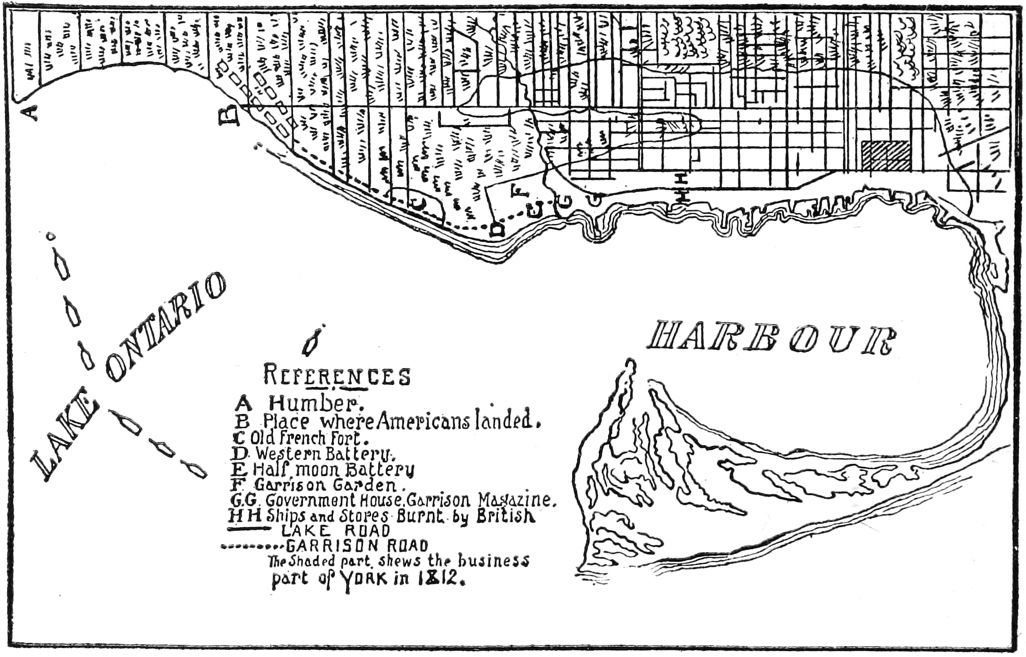

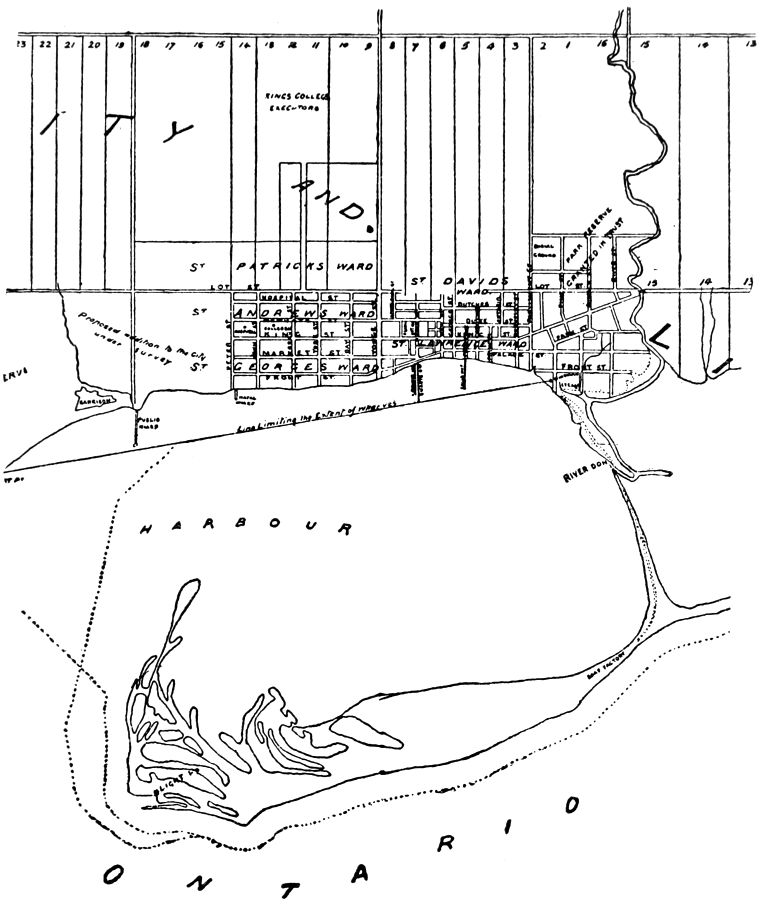

| The Town of York at the time of its capture by United States Troops | 90 |

| From Landmarks of Toronto. | |

| Sir Peregrine Maitland, Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Canada, 1818-1828 | 128 |

| From the John Ross Robertson Historical Collection. | |

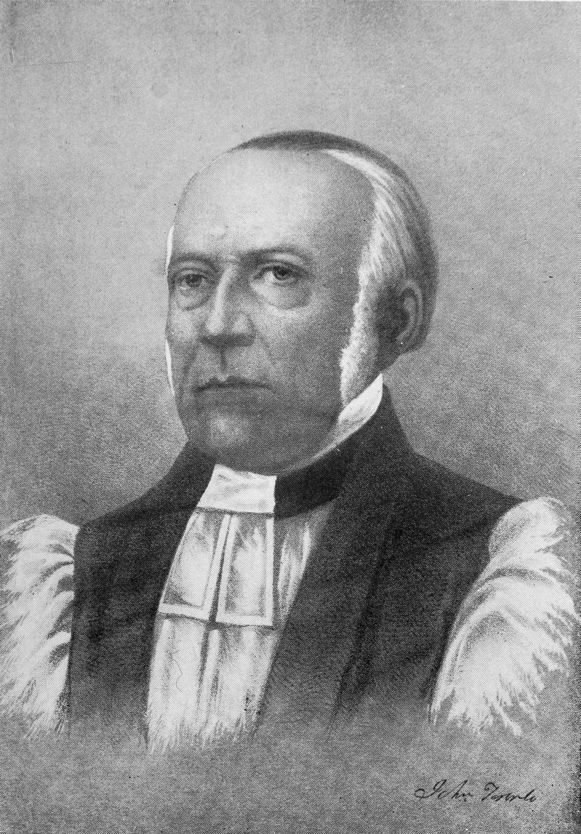

| Reverend Doctor John Strachan, Rector of St. James’ Church, Toronto, afterwards First Bishop of Toronto | 144 |

| From The Canadian Portrait Gallery. | |

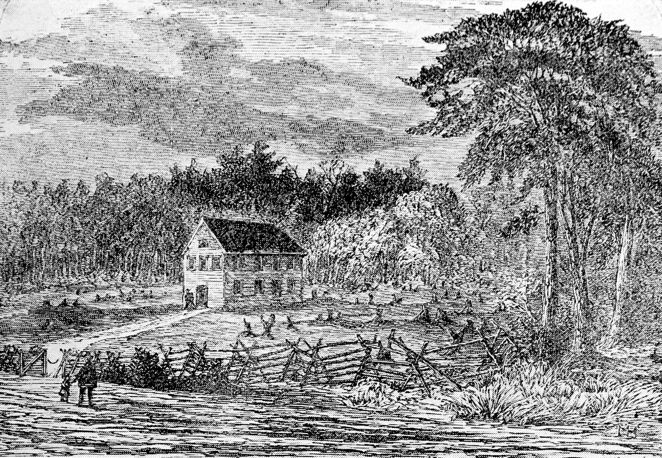

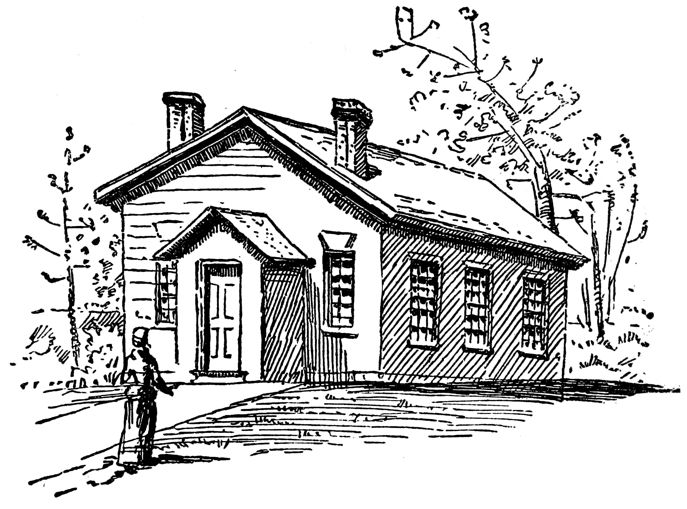

| The First Knox Church, York, erected in 1822 | 146 |

| From Landmarks of Toronto. | |

| William Lyon Mackenzie, Leader of the Reform Movement in Upper Canada | 176 |

| From The Canadian Portrait Gallery. | |

| Sir Francis Bond Head, Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Canada, 1836-1838 | 192 |

| From Life and Times of W. L. Mackenzie. | |

| Plan showing Toronto and its suburbs at the time of its Incorporation in 1834 | 201 |

| From Landmarks of Toronto. | |

| The Home of Jesse Ketchum, N.E. corner of Yonge and Adelaide streets, Toronto | 288 |

| From the John Ross Robertson Historical Collection. | |

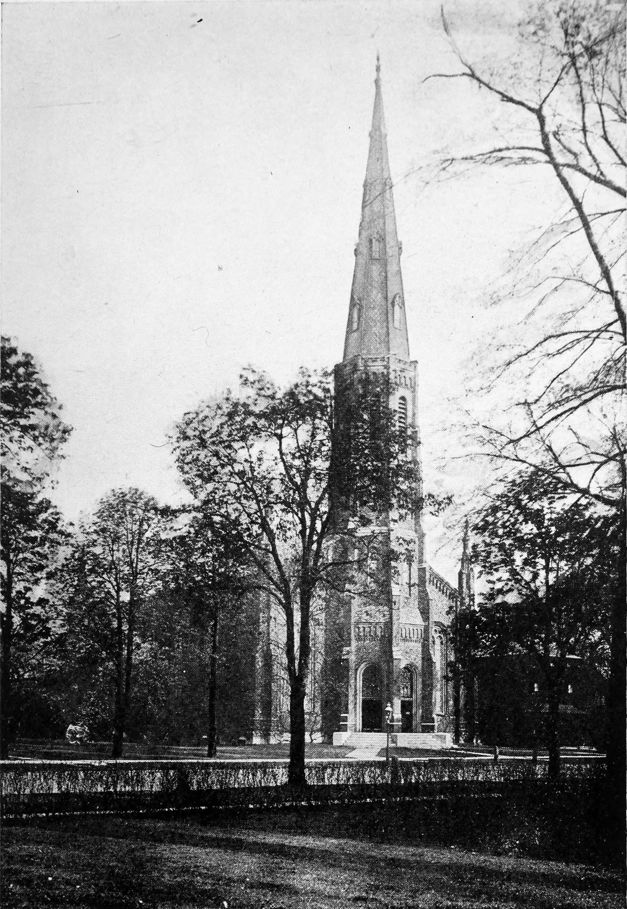

| Westminster Church, Buffalo, erected in 1858 | 304 |

| From a photograph by R. R. McGeorge, Buffalo. | |

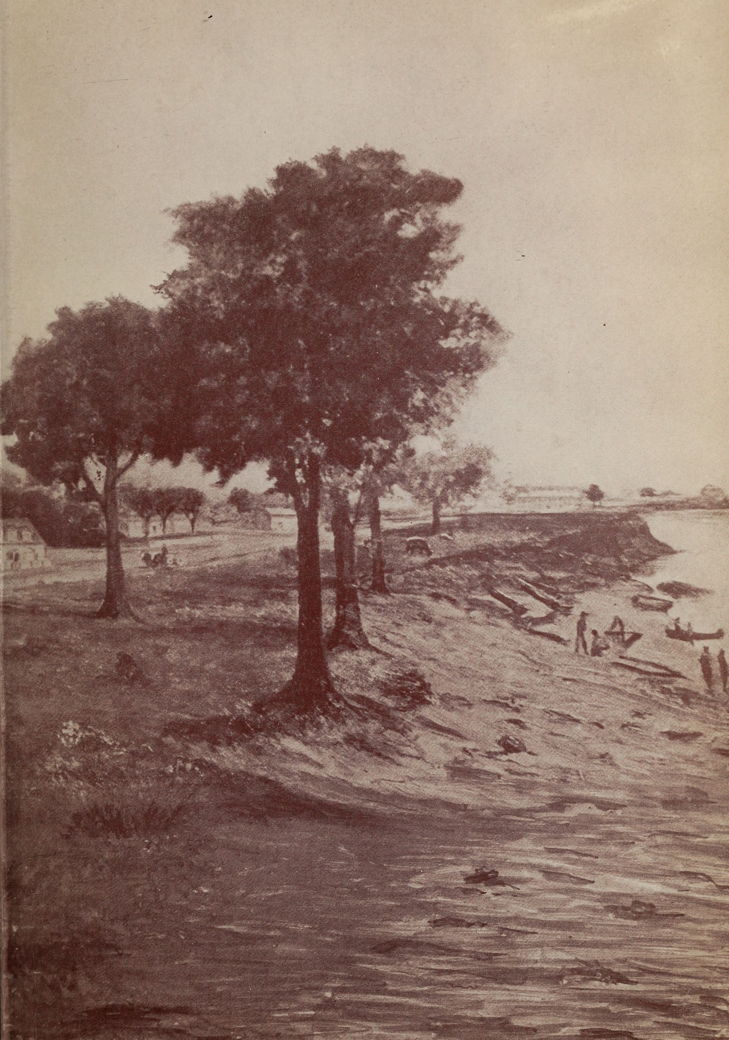

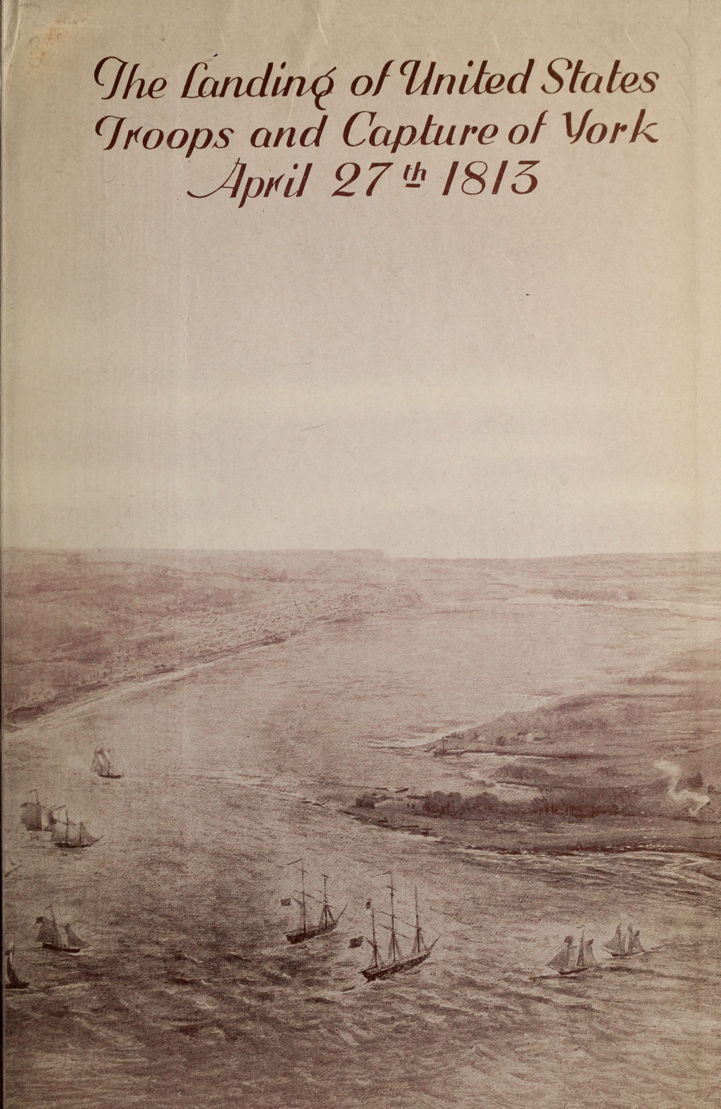

| The Landing of United States Troops and Capture of York, April 27th, 1813 | Back End Leaf |

| From a painting by Owen Staples, O.S.A., in John Ross Robertson Historical Collection. | |

It is an evening in August, 1799. The officers and men of the Queen’s Rangers in the garrison at York, in the new Province of Upper Canada, have been busily engaged for some days in making preparations for the arrival of a distinguished guest. Every tunic has been carefully mended, every button polished, every bunk made scrupulously neat and clean. The flag over the garrison has been flying all day, and the sentries have instructions to report promptly as soon as a sail is visible around the peninsula stretching from the mouth of the Don River across the front of the harbour.

Toward sundown a sail is reported, and keen is the excitement as the men watch the little boat beating its way toward the fort against the heavy north-westerly breeze.

The Speedy is a little sailing vessel of perhaps sixty to seventy tons—“fifty barrels burden” was the official description as to size and capacity of a similar craft of the day—and it is now arriving from Kingston carrying, among others, the newly appointed Governor of Upper Canada, the Honourable Peter Hunter, successor to Governor Simcoe, who had resigned nearly three years before. The Governor is accompanied by his secretary, Major James Green and an orderly.

The seat of Government had been moved from Newark, at the mouth of the Niagara River, by Governor Simcoe, in 1796. He had soon recognized that a position directly under the guns of an enemy fort across the river was no fit place for the Provincial capital; and, after carefully examining every available place he had selected, in 1794, the site of the old French fort at Toronto as the most desirable location. He changed its name from Rouillé to York, in honor of the Duke of York, and arranged for the erection of buildings for the use of the Legislature, houses for the accommodation of the officials, and a fort for the Queen’s Rangers, who formed the garrison.

In selecting York, then without settlement of any kind excepting a few families of Indians, the Governor had an eye to its defensibility in case of attack. In a letter to the Colonial Secretary he described it as the “most important and defensible situation in Upper Canada;” and from the character of the sandbanks which formed the harbour and protected the approach to the town he considered the place capable of being so fortified as to be “impregnable”.

The spot selected for the Government buildings and as a site for the town was at the extreme eastern end of the Bay, and a site for the fort for its protection was found on a knoll of land commanding the entrance to the harbour, washed by the waters of the Lake on the south and bordered by a stream known as the Garrison Creek on the east and north. A stockaded fort was erected at once for the troops, containing barracks, blockhouse, powder magazine and storehouse, with a wharf and canal on the creek for the landing of troops and supplies. Another blockhouse was projected for the sandbanks across the harbour entrance, which he proposed to call “Gibraltar Point”.

Governor Simcoe, who had been transferred to the Island of San Domingo, in the West Indies, in 1796, had lived while at York, during the erection of the Government Buildings and afterwards, in a “canvas house”—a tent, which is said to have once belonged to Captain Cook, the celebrated navigator—which he had set up on the parade grounds within the fort; and as no official home had as yet been built for the new Governor, quarters had been set apart for his accommodation within the fort.

Presently the Speedy in the hands of its skilful sailors is brought around to the entrance at the Garrison Creek and made fast to the wharf. By this time, however, the hour is late, and as His Excellency had already been nearly three weeks in making the trip from Quebec, and an extra night on the boat could not be a matter of great moment, it is decided to defer the official landing and reception until the following morning.

A receiving party from the Queen’s Rangers is on hand early. The men present arms and the Governor and his party are escorted to the quarters in the fort made ready for their accommodation. After a short visit the Governor is taken to town for the purpose of an official call on His Honour President Russell, who has now been Acting Governor for nearly three years. At one o’clock the military officers and Government officials wait upon him to welcome him to York, congratulate him on his appointment to the governorship of the Province, and express their satisfaction at his safe arrival at the capital.

Meanwhile the cargo of supplies from Kingston, Oswego and the east which had been brought by the Speedy is taken off and removed to the storehouses or sent on to its destination in the town; and the crew, their duties of unloading completed, proceed to get the vessel into condition for the return trip by way of Newark.

Presently, however, one of the crew, a stockily built young fellow, apparently not yet out of his ‘teens’ who had taken an active part in the handling of the cargo and cleaning up of the ship, is seen to emerge from the cabin dressed for the road and carrying a small pack over his shoulder. Bidding “good-bye” to his late companions, he crosses the bridge over the Garrison Creek, and following the trail leading eastwardly towards the town, he hurries off and is soon lost to view.

And thus it was that Jesse Ketchum came to Toronto.

When Jesse Ketchum came to York in the summer of 1799 he was but seventeen years of age. His eldest brother, Seneca, ten years his senior, had arrived three years before, and the young lad had now come to join him. Although this family of Ketchums had not taken part in the great movement of population into Canada which had followed on the heels of the Revolution, they were none the less United Empire Loyalists. With a large family of small children it was difficult, if not impossible, for their father, Jesse Ketchum the first, to have taken the risk during the crucial period of the Revolution of venturing into a new and strange country, where it would have been necessary for him actually to hew out a home for his family from the primeval forest.

The Ketchums were among the earliest settlers in New England. The family was of Welsh origin, and the tradition is that three brothers came to America at the same time, early in the seventeenth century. The earliest record of the line is that of Edward Ketchum, who settled at Ipswich, Massachusetts, in 1635. He was a freeman of the Colony, but in 1654 he removed to Southwold, Long Island, and there the family continued to live for many years.

“It is the chief recommendation of long pedigrees,” writes Robert Louis Stevenson, “that we can follow back the career of our component parts and be reminded of our antenatal lives.” The early settlers of Massachusetts were Puritans. They had come to America in the cause of religious liberty. They had no desire for political freedom from the Motherland, for they were proud to continue their allegiance to their King and Country. But with them citizenship in the commonwealth carried with it close communion with one of the churches. Loyalty to God and to their church were of first importance. The churches were organized on the congregational principle, each forming a group and each one independent of the others. Thus these sturdy pioneers laid the foundations of a political system for the Colony at a very early period. But the real leaders of the Colony were not soldiers, nor politicians, but clergymen. Their authority was intellectual and moral, and they held their influence by appeal to the reason and intelligence of the people.

The founding of common schools followed close on the building of churches, and these schools were maintained on terms of equality by all of the citizens. So eager, indeed, were the people for educational advantages, that in the very early years of settlement, and out of their extreme poverty, they established the two Universities of Harvard and Yale.

These New England Puritans were an industrious, intelligent and hard-working folk, and the Ketchums seem to have occupied quite a creditable place in the community life of the time. John Ketchum, of Ipswich, was for a time a member of the Massachusetts Legislature, but in 1648 he also removed to Long Island, settling first at New Town and later at Huntington, where he became overseer, having charge of the issuing of grants of land under the authority of the Government.

Samuel, a younger brother, seems not to have been so fortunate in life. He had established himself on his arrival at Norwalk, Connecticut, where he married Sarah Holbert, of New London, and it was through his family, which consisted of five sons and two daughters, that the Canadian line was established. One of his grandsons joined the United Empire Loyalist movement to New Brunswick in 1783, when so many of the very flower of the intellectual and cultivated people of New England and other parts of the newly-formed Republic, left their homes in order to follow the flag of Britain into Canada.

Jesse Ketchum the first, another grandson, was born at Norwalk on September 22nd, 1740. Although he had had many educational advantages, as education went in those early pioneer days, he does not appear to have made any great success of life. He was, however, a man of some attainments, and is said to have been a writer of moderate reputation, contributing poems and sketches to the local press. He seems also to have had a good deal of personal charm and to have moved in good social circles.

In 1771 he married Mollie Robbins, daughter of Judge Zebulon Robbins, now of Saratoga, New York, the place where, six years later, General Burgoyne and the British forces surrendered to General Gates. The Robbins family had settled near New Canaan, Columbia County, New York, in 1760, and here the Judge was afterwards married. His daughter at this time was but nineteen years of age, while her husband was thirty-one. Immediately on their marriage they took up their home at Spencertown in the same County, a small town lying to the east of the Hudson River, a short distance south of Troy.

Mollie Ketchum was a young woman of education and refinement, a good wife and an affectionate and sympathetic mother. She had come from a good home, where she had been accustomed not only to the comforts but also to many of the luxuries of life. Indeed, so deeply was the memory of her gentle personality impressed upon her little son, Jesse, the second, that although at the time of her death he was but six years of age, he always remembered her with the greatest tenderness and affection. She seems to have been much superior in intellect and ability to her husband, and it was doubtless from her that the lad inherited those qualities of kindliness and sympathy and that deeply religious spirit which characterized him in after life.

Moreover, the father also was a drinker, although that was not looked upon in those days as so discreditable a vice as in these later times; and even if he was not harsh and cruel to her, this was a sore trial to her refined and sensitive nature, and was something that the little Jesse never forgot.

The mother died in 1788, after seventeen years of married life, during which she had borne five sons and six daughters, including two pairs of twins. Though doubtless she had many regrets at the thought of leaving her large family of little children to the care of an improvident father and the mercies of a not very sympathetic world, death probably came to her as a precious relief from the burden and anxieties of living.

Seneca, the eldest of the children, was now sixteen. He probably had had greater advantage than any of the others, and as he had attended the local school and acquired a fair degree of education, he was in a position to look after himself. Soon after the death of his mother he came to Canada, and in 1796 took up land in York County, where, with the exception of the period when he lived near the present town of Orangeville, in Dufferin County, he continued to live until his death in 1850.

Sarah, the eldest daughter, born in January, 1774, was married to Major Ashall Warner, a member of the distinguished Warner family. One of his ancestors was one of the early benefactors of Magdalen and Balliol Colleges, Oxford; and Susan Warner, author of Queechy, Wide, Wide World, and other books, was one of the same family connection. She died in 1837.

Elizabeth, born in 1776, was married at Adolphustown to Alexander Jones, who died shortly afterwards, leaving her with a large family of young children, and for years she made her home at York.

Mary—or Polly, as she was usually called—who was two years younger than Jesse, married Nicholas Hagerman, a well-known lawyer of Adolphustown, and a charter member of the Law Society of Upper Canada. He was the father of Hon. Christopher A. Hagerman. Hannah, another sister, was cared for for many years at the home of her brother Jesse at York.

Zebulon followed Seneca and Jesse to York early in the nineteenth century. In 1806 he purchased a portion of Seneca’s farm on Yonge Street, about four miles north of the town; but he disposed of it later on his removal to Buffalo, New York. He was married to Hester Keel and died at Buffalo in 1854.

Henry Clinton Ketchum had moved to Western New York early in the century, settling at Buffalo, where he built for himself a homestead at the corner of what later were Main and Chippawa streets in that City. His home, however, was burned by Indians during the War of 1812 and he was forced to flee. He settled finally at Holley, New York, not far from Rochester, where he lived for many years. He was married twice, first to Elmira Bushnell, of Buffalo, and afterwards to Elizabeth Powers, a relative of the wife of President Fillmore. Another brother, Oliver Cromwell, had been killed during childhood by marauding Indians, as their home at that time lay close to the Indian trail leading to Lake George.

The youngest sister, Abigail, born just prior to their mother’s death in 1788, remained in the United States, and from her aunt’s home she was married to Samuel Adams, a cousin of the distinguished Massachusetts statesman, John Quincy Adams, one of the Presidents of the United States.

The death of Mollie Ketchum was a serious matter both for her husband and for the members of the family. The pressure of domestic cares and responsibilities had been too heavy for her frail body. The bearing of eleven children, too, had severely taxed her strength and energy. During all the years of her married life she had been the mainstay of the household and its directing head. Without her there was no way of holding it together. Never very competent either in the making of a living or in the handling of affairs, the husband was entirely at sea now that her capable authority was removed.

As soon as the funeral was over a consultation was called to determine what was best to be done. To hold the family intact was manifestly impossible. The children were too numerous and the available means too limited to think of engaging competent help. Seneca was sixteen, he could shift for himself, but obviously he could not assume much responsibility. But the others, down to the baby Abigail, presented a problem in which every member of the family connection was called upon to bear a share.

After carefully canvassing the situation from all angles, it was decided that the children should be distributed among such of the relatives as were willing to accept them. Papers of adoption were not insisted on, but this means of distribution provided at least a temporary solution of what seemed to be a difficult and pressing problem.

The baby Abigail was taken by her uncle and aunt, the parents of Stephen A. Douglas, who was Democratic candidate for the Presidency of the United States against Abraham Lincoln in 1860; while the little six-year old Jesse was taken by a neighbor, William Johnson, and his wife, who had especially asked for him and had agreed to bring him up as their own.

The Johnsons were prosperous farmers who had known the Ketchums for some years. They were hard-working and industrious people, well regarded in the district, and as they had no children of their own this was looked upon as a highly satisfactory arrangement and one that seemed to promise well for the future of the little orphaned boy.

The results, however, were far from those anticipated. Mr. Johnson seems to have been a well-intentioned man, with a certain kindliness of disposition, but his wife was capricious, harsh and tyrannous. Toward the neighbors she was affable and ingratiating, but to the motherless boy she seemed to be entirely lacking in the qualities of maternal affection. Such a thing as an expression of endearment, or even one of encouragement, rarely passed her lips. She was shrewish, full of fault-finding, and cruelty, and Jesse’s life during all of the years which he spent under her roof was full of misery and unhappiness.

As he was naturally of a sunny disposition, Jesse tried hard to gain his foster mother’s good-will and avoid her displeasure; but to her his fun was sheer mischief and his brightness something that must be repressed.

From his parents the lad had inherited a taste for reading and study, but schools in those days were not within easy reach of the children of the poor. In any event, they were not for boys like him who were dependent on others for the very food they ate. He would be better off if he attended to his work on the farm rather than wasting his time over books. His father and mother had had education, and what good had it been to them!

Books, too, were scarce and expensive. They did not often come his way, and such as he was able to get were obtained only at great sacrifice. His foster parents having no patience with his ambitions his days were crowded with duties from early morning until after sunset. In the summer months this allowed little time for reading, and during the winter, when the evenings were long and there were occasional intervals which might have been used for reading, he was denied the use of a light and compelled to gather extra fuel for himself in order to provide light in the fireplace by which to read.

The education which Jesse thus obtained was limited in the extreme. He practically had no opportunity for attending school, no tuition, and no training or direction in his study, and to the hardships which he endured during these years is due the intense interest which throughout his life he always showed in educational matters and his keen desire for the welfare of children during their school years.

Jesse Ketchum in after life rarely spoke of Mr. Johnson, but of his foster mother he had many a story to tell of harshness and ill-temper. These he told, however, not in a spirit of complaint or in order to evoke sympathy because of his unhappy childhood, but rather as illustrative of different kinds of women and distinct types of character.

On one occasion, for example, he recalled that he had by some means acquired a new coat of which he was very proud. Boy-like, however, he wore it one day when out at work in a field. After a time he realized that it would be much easier to work in his shirt sleeves; so he took the coat off and hung it on a bush. When his work was completed he returned to the house, forgetting for the time that he had left his coat behind. Mrs. Johnson later found it, and in order to make it appear that his carelessness alone was responsible, she tore it into ribbons and, taking it back to the house, claimed that he had left it in a place where the hogs had been able to get it.

As Jesse grew older Mrs. Johnson’s petty persecution and tyranny became more acute, and he determined to escape from its bondage at the earliest opportunity. His mistress found him engaged on one occasion in making a pen from a goose-quill which he had picked up in the yard. She immediately flew into a rage and charged him with having plucked it from one of the flock which she had been preparing for the market. He denied this and protested that the quill had been torn from the goose in its struggle to pull itself through a narrow opening in a fence. She refused to accept this explanation, and, although he was seventeen years of age at this time, he was punished for the offence.

This was the last straw. Try as he might it seemed impossible to please this shrewish woman; so, carefully gathering together his few clothes and scanty possessions, the boy slipped out of the house very quietly one midsummer night and set out alone and on foot upon the trail for Canada.

Seneca, the oldest brother, had preceded Jesse to Canada by some years. A year or two after his mother’s death he had, in company with his uncles, Joseph and James Ketchum, joined a company of Loyalists leaving for the promised land across the Canadian border. Conditions for the Loyalists in New England and in the eastern States had become intolerable. During the years of the Revolution these people had done nothing wrong—nothing for which they need be ashamed. As loyal citizens they had fought for the Government under which they had been born, to which they owed allegiance, and which should have given them all the benefits of freedom they desired. True, there had been injustice and oppression on the part of His Majesty’s Government, but constitutional means of redress had by no means been exhausted, and there seemed to be no good reason to believe that the Tea Duty might not, with proper representations, be repealed, nor that the Stamp Tax and the other objectionable measures at issue might not be removed or adjusted satisfactorily.

The great majority of the better class among the citizens of the American Colonies were at first sympathetic to the loyalist view, but the blundering violence of the British Government of the day and the stupidity of its officials and Governors gave encouragement to the movement toward independence which had been originally engineered by a group of English republicans.

It is difficult at this distance of time to indicate at what point in the conflict loyalty to the Crown ceased to be a virtue and became treason to the Commonwealth. But, once the conflict was over, the strife should have been closed with an amnesty similar to that adopted eighty years later on the conclusion of the Civil War. Had this been done it is doubtful whether British North America as it now exists would ever have been made possible.

But instead of an amnesty there ensued a period of vindictive persecution and acrimony against those who had remained faithful to the Crown. Those who had refused to join actively in the cause of the Revolution were branded as traitors and outcasts. Some were banished from the country, others were put to death, while others, still, were persecuted or abused and their homes burned, plundered or confiscated. In consequence of this many thousands of the best citizens of the country were forced to abandon their homes and property to face the hardships and privations of pioneer life in a new land.

In contrast to the vindictiveness of the successful revolutionary party was the sympathetic kindliness and generosity of the British Government to the suffering Loyalists. Liberal grants of free land were set apart in the Canadian provinces, in order to encourage settlement. Farm implements, food, clothing and other necessaries were furnished to those requiring them, and the sum of £3,300,000 was set apart to indemnify them for their lost estates and establish them in their new homes. Thus, while the United States in the first flush of their successful arms, seem to have made every effort to get rid of those who failed to give sympathetic aid to the Revolutionary cause, the Canadian provinces were swelled with a great influx of people, most of them from the educated and more intelligent classes, who could hardly fail to remain enemies of the Republic whence they had come.

During the years immediately following the Revolution—mainly in 1783 and 1784, and to a lesser extent during the succeeding five or six years—upwards of forty to fifty thousand loyal refugees are said to have come into Canada as a result of these persecutions. No such movement of population as this had ever been known in modern times. Into Nova Scotia and Cape Breton, and into the valley of the St. John, in New Brunswick, they swarmed in vast numbers, coming largely by way of the sea from New England ports. Others turned toward the west and made their way by the Hudson River and Lake Champlain to the eastern townships of Quebec, or along the north shore of the St. Lawrence into Ontario, settling in the Bay of Quinté district, at Kingston, and in near-by places. A smaller number entered Ontario by way of Oswego, crossing over to Kingston, or by the Niagara River, from which they planted settlements along the north shore of Lake Erie as far as Detroit.

The party which Seneca Ketchum had joined followed the old Iroquois route by way of the Mohawk River and Oneida Lake to Oswego, making the journey on foot all the way from the Catskills. They travelled, as did most of the Loyalists in those days, in large parties, not only for company but for protection; and from Oswego they completed the trip to Kingston in large flat-bottomed batteaux, skirting the eastern shore of Lake Ontario and crossing the St. Lawrence.

These batteaux were large, unwieldy craft, sufficiently commodious to accommodate four or five families, and having a carrying capacity of about two tons. They were propelled by a double crew, one of which walked along the shore or in the shallow water drawing the boat by a rope attached to the bow, while the other directed its movements from the craft by long steering poles.

The Durham boats, which came later, were considered quite an improvement on the batteaux. These long, shallow craft were operated by means of a long pole to which were attached crossbars of wood something like the rungs of a ladder. The members of the working crew took their places at the bow, two on each side, with the pole extending into the channel; and, grasping the crossbars in succession, the men worked their way toward the stern, thus pushing the boat forward as they walked.

Seneca Ketchum had been intended for the Church. He had looked forward to it as a career from early boyhood, but the circumstances of the war of the Revolution and the trail of horrors which followed it, together with the death of his mother, rendered this impossible of attainment. He had learned, however, of the inauguration of Governor Simcoe, of the possibility that Kingston might become the seat of Government for the Province, and that the community there had under consideration the building of a church. If he could but reach Kingston he might assist the Reverend John Stuart in his ministrations, and perhaps later on take holy orders and enter upon the career on which he had set his heart.

The party with which Seneca had travelled arrived in Kingston in the midsummer of 1792. As the largest and most important settlement in the new Province of Upper Canada, it naturally had high hopes of becoming the seat of Government. As the military and naval headquarters on Lake Ontario it had distinct advantages. Moreover, the fort at Kingston already had a brilliant history extending back more than a century to Frontenac’s day.

The Governor arrived from Quebec on July 8th, 1792, where, surrounded by his Legislative Councillors and in the presence of an audience assembled from the neighboring clearings, he took the oath of office in the barrack-room where divine services were usually held. On the following day the members of the Executive Council were sworn in, together with the officers of the Government who had been appointed by His Excellency. A Proclamation was then issued providing for the division of the Province into nineteen counties; officials were appointed for the holding of an election, and self-government was constituted for the first time in Upper Canada.

A fortnight later the Governor set out on his westward journey, a trip which resulted in the decision to fix his capital at Newark, at the mouth of the Niagara River, although a site on the River La Trenche, where the City of London now stands, was inspected and considered. The hopes of Kingston, therefore, as the seat of government for the Province were shattered.

Kingston at this time contained about fifty small wooden houses, and its population probably did not exceed three hundred, but it had become so important a shipping headquarters and lake port for trade with the United States that a year or two later it was made, officially, a port of entry for American goods entering Canada and granted a Customs House of its own.

But however anxious its citizens might have been to see Kingston the capital of the Province, it apparently had not been seriously considered by the Governor. “The situation of the place,” writes Mrs. Simcoe in her Diary, “is entirely flat and incapable of being rendered defensible; therefore were the situation more central it would still be unfit for the seat of Government.”

The Ketchums with their friends from Columbia County had reached Kingston prior to the arrival of the Governor. The situation of the district was good, and the quality of the soil had much to commend it, and as many of their friends were already there, they decided to remain for the present and make it their home.

But with the decision of the Governor in 1794 to remove the capital from Newark to Toronto—or York as he called it—they also changed their minds. Kingston might have its advantages, but opportunities at the provincial capital were likely to be better. When, therefore, on the completion of the new Legislative buildings in 1796, the Governor moved the offices of the Government to York, Seneca Ketchum and his two elderly uncles, Joseph and James—the former at that time being seventy-eight years of age—arranged for the disposal of their holdings, and again trusting themselves and their worldly possessions to the tender mercies of the batteaux, they moved westward to York.

Joseph Ketchum and James Ketchum were among the first settlers in Scarborough Township, in York County, each receiving land grants from the Crown of large areas in the neighborhood of Port Union. These grants bore the date March 23rd, 1798. Seneca, who at the time of his arrival at York was twenty-six, took up a block of land on the west side of the new road which the Governor had opened up to the north from York to Lake Simcoe, which he called Yonge Street in honor of Sir George Yonge, Secretary for War in His Majesty’s Government. This block, which consisted of 210 acres, was probably rented at first, as the records show that he did not become the registered owner until 1804, when he purchased it for the sum of £25 from Hiram Kendrick to whom it had been granted two years earlier. This property forms a large portion of the present Bedford Park section in North Toronto.

Evidently Seneca had managed to keep in touch with his brothers and sisters in New York State. As the eldest of the family he felt a certain measure of responsibility. Their father, on account of his habits, was not to be depended on, and, as many of the younger children were girls, he must lend them a hand. To keep up a correspondence in those days was quite an undertaking. Not only was it expensive, but the handling of mail was a difficult and hazardous procedure.

Although Governor Simcoe had laid out a military road all the way from Oxford County to the Bay of Quinté, no road actually existed east of York. An occasional sailing vessel carrying supplies for the use of the Government, made the trip from Kingston to York; but as shipping on Lake Ontario was of a primitive type, few persons were willing to commit themselves to any extended voyage without serious apprehension. The Indians, as it is well known, had but two modes of travel—by foot and by canoe. If their course lay along the waterway they used their birch-bark canoes. As horses had not yet come into the Province in any great numbers, the French and English were forced to adopt the same means, and until well on into the nineteenth century canoes were usually employed where light and quick transportation was required.

Jesse, in the home of his foster parents in Columbia County, had been in touch with Seneca’s movements. He knew of his removal to York, of its selection as the new capital of the Province, of the coming of the Government and the meeting of the Legislature. He also knew of Seneca’s farming operations, and it is more than probable that his brother had pointed out, if not to Jesse at least to some of the family, the splendid prospects which seemed to lie before the country.

As the brothers and sisters seem to have been on terms of the closest relationship with one another, although widely separated in their various foster homes, the letters from Canada were passed around from hand to hand. Sometimes, too, a message or a parcel would pass from New York to Canada, carried by some friend or acquaintance who had joined a Loyalist party moving to the north to take advantage of the generous grants of land offered by the Government of Upper Canada. What, therefore, could be more natural than that the young Jesse, stung beyond endurance at the harshness, injustice and ill-temper of his mistress, should have determined to strike out for himself and try to reach his eldest brother away off in Canada? Perhaps, if everything turned out right, other members of the family could join them later.

Jesse was now a sturdy, well set up lad, just past seventeen. He was strong and capable and willing to work at any honest job; but he had no very clear idea of where York might be beyond the fact that it was in Upper Canada. It was in no spirit of bravado and with no vague desire merely to see the world that he left the Johnson home. He was not that kind of a lad. But he refused to stay in a place where there was nothing but hate, envy and malice, when at the other end of the rainbow were joy, happiness and love. So, with but the few clothes that he wore and the small possessions he was able to carry, he started upon his travels into the unknown North.

The little village of Spencertown was on the line of the old Indian trail between New York and Canada. For nearly two centuries the French settlements on the St. Lawrence had been menaced by the Iroquois allies of the English, who occupied the territory extending from the Hudson River to the Niagara. In their raids they followed the Hudson River north and made their way along the narrow line of Lake George and Lake Champlain to the Richelieu. The route to the west was almost equally well travelled, by way of the Mohawk River and Lake Oneida to Lake Ontario, at Oswego.

The young refugee, smarting under a sense of injustice and cruelty, turned his steps towards Canada. In a vague sort of way he knew about the Mohawk trail, but there was no one to consult and none to help. Alone and on foot he followed the trail that led along the Hudson as far as Troy. Crossing the river here by the ferry, he turned his face toward the setting sun along the road which skirted the Mohawk River.

It was a new, a terrifying and a trying experience, and unlike anything the youth had ever known before. His home life had been unhappy, but it at least was a home. Warmth, comfort and human contact were there, even if there was no love. This, too, was his first attempt at sleeping out under the skies. He now also knew something of the dangers of the road and the perils of the darkness; and the sounds of the wild beasts at night at first struck terror into his heart.

And then there was added the fear of being caught. He had done nothing wrong, nothing dishonorable, but that there might be a moral obligation to serve his master until he was of age disturbed his conscience. Yet the memories of more than ten years of unhappiness lent wings to his steps and spurred him on his way.

The way to Oswego was a long and wearisome journey. The countryside was but sparsely settled, and he met few people on the trail. Men did not travel for pleasure in those days; they were too much occupied with the serious things of life. He was lonely, tired and footsore, and at times hard pressed for food, but he pushed bravely on.

The days of tedious travel and the nights of nameless terror soon slipped into weeks, and still Jesse kept on his way. Presently he came within sight of a large sheet of water. At first he thought it must be Lake Ontario, but as the trail along the shore still beckoned, he soon realized that it was Lake Oneida. The way now became easier. He began to meet with occasional travellers on the road and more settlements, and again he had the joy of human intercourse. Oswego could not now be far, and this would mark the completion of the first stage of his journey.

Oswego for nearly a century had been an important trading post. It had been built by the English near the mouth of the Oswego River, in order to try and divert a portion of the rich fur traffic from the French fort at Kingston, on the north shore of Lake Ontario. It was a fine strategic point, for through Oneida Lake it led back to the English settlements on the Atlantic Coast. From the first the post had been successful, and it soon became a thorn in the side of the French, as it robbed them of their monopoly on the lakes and despoiled them of their prestige among the Indians. By the end of the century it had become an important outlet for the English colonies in the East in their trade with the settlements on Lake Ontario and in the West. Much of the traffic was with Kingston, but occasionally a vessel sailed to Newark, and, since the removal there of the capital, some even ventured as far as York.

Fortunately the young traveller found a vessel at Oswego almost ready to sail for Kingston. To wait for one going to York might have detained him for weeks. Even to be in Canada was something. How far it was from Kingston to York he did not know, but he could, if need be, walk there, if only he were on the north shore of the lake. He had no money to pay for his passage, but he was willing to work for it if only they would give him a chance. A few days later he was taken on as a helper, and in a day or two he found himself in Canada.

Kingston on his arrival was in a fever of excitement. General Peter Hunter, the new Governor of Upper Canada, had just arrived from Quebec on his way to York to take over the duties of his office. For three years the Province had been without a Governor, the duties of the office being performed by Honourable Peter Russell, President of the Legislative Council, who acted as Administrator. Governor Simcoe, his predecessor, had ambitious plans for the Province of Upper Canada. He hoped to establish there a strong British settlement, backed with an armed force sufficient to meet any attack from the American Colonies. But Lord Dorchester, the Governor-General, would have none of this. He refused to approve of settlement based on military lines, and Simcoe, backed by the friendship of the British Colonial Secretary, Dundas, forced the issue. In Upper Canadian affairs Governor Simcoe considered himself supreme; but when, under Dorchester’s instruction, the bulk of his regiment known as the Queen’s Rangers, which had been designed to assist in colonization and to help in the building of roads and the erection of public buildings, was withdrawn from the Province, he tendered his resignation and returned to England. His successor, General Peter Hunter, Commander-in-Chief of the British forces in Canada, was not appointed until three years later.

With the prestige of having been a sailor on the vessel from Oswego to Kingston Jesse Ketchum readily secured employment on the Speedy, now outfitting for the journey to York; and three days later, amid much acclaim from the populace, Governor Hunter sailed from Kingston, and the young refugee started on the last lap of his flight to York.

York in 1799 was still in swaddling clothes. It had been the seat of the Provincial Government but three short years, and with the coming of the officials had come its first substantial civil population.

The town as projected by Governor Simcoe was at the eastern end of the harbour with the fort for its protection at its western entrance, nearly three miles distant. The Parliament Buildings occupied a site close to the waterfront, near the mouth of the Don River and at the foot of Parliament Street, now known as Berkeley Street. These buildings, which had been erected by the men of the Queen’s Rangers, consisted of two one-storey log-houses about twenty-five feet by forty feet in size, standing about one hundred feet apart, the space between being subsequently filled in by an additional building. A dozen or more wooden houses were also built at the same time for the officers of the Legislature and those who accompanied the Government.

The town of York as laid out in 1797 under the Governor’s orders consisted of an area of land immediately to the north of the Parliament Buildings covering twelve city blocks, six on the north side and six on the south side of the present King Street and extending from George Street to Parliament Street. In the selection of names for the streets there was no attempt at picturesque titles to catch the attention of prospective buyers of the lots or to gratify the vanity of the founder of the town; they reflected only the personal loyalty of the Governor to his sovereign; and with the exception of Parliament Street and Palace Street, now called Front Street, which led to the Government Buildings from the Fort along the water front, and Ontario Street, which was named after the lake, all were named in compliment to the King and the members of the Royal family.

A few months after the arrival of the Government officials the town limits were extended westward as far as Peter Street and north to Queen Street, then known as Lot Street from the fact that this was the southern boundary of the series of “park” or farm lots into which the district adjoining the capital was divided, and which extended to the north a distance of one and a quarter miles to the second concession, now known as Bloor Street.

When this extension to the town was made allowances were also made for public services, and plots were set apart, though not used for some years, for a public market, and as sites for church, school, gaol and hospital buildings; while two squares were allocated for park purposes, one, known as Russell Square, on King Street, subsequently occupied by Upper Canada College, the other Simcoe Place, on Front Street, upon which the third Parliament Buildings were erected in 1824.

From the first the capital assumed a position of social and intellectual importance in the Province. In its population were a large number of army officers and soldiers and officials of the Government, many of whom drew salaries from Great Britain. Many also were of the United Empire Loyalist refugees who had come to Upper Canada because of the persecution which they had suffered at the hands of the Revolutionists. For the most part these were people of education and refinement, accustomed to many of the comforts of life, who had come in response to the inducements as to settlement offered by the British Government.

The town for some years, however, did not spread much beyond its original limits. In fact it was little more than a bundle of shanties huddled in a group not far from the swampy entrance to the Don River, from which it was but partially screened by a grove of fine forest trees. A path through the bush close to the waterfront led from the Garrison to the Parliament Buildings, and another, known as the Dundas Road, had been opened to the west, leading to the head of the Lake and thence to Newark, the former seat of Government.

When Governor Simcoe left Upper Canada in 1796 to become Governor of the island of San Domingo, in the West Indies, a Provisional Government was established, with the Hon. Peter Russell as President, and he continued to act as Administrator of the Province until the appointment of the Hon. Peter Hunter as Governor in 1799.

Russell Abbey, the home of the President, was at the corner of Palace (now Front) and Princes’ streets and, naturally, was the social centre of the town. Miss Elizabeth Russell, the President’s sister, had charge of the household, and many bright entertainments took place both there and at Castle Frank, the summer home which Governor Simcoe had built for himself on one of the knolls overlooking the beautiful Don ravine, and which President Russell also frequently used during his three years of office. During the summer months the groups which went to Castle Frank for picnics, excursions or dances were usually taken by boats up the winding reaches of the Don river, and in the winter sleighing or carioling parties were organized to make the trip by the ice on the river or by following the route of Parliament Street and through the woods.

The President, a portly, middle-aged gentleman of old world manners and dignified mien, had been Secretary to Sir Henry Clinton, Commander-in-Chief of the British forces in America, from 1778 to 1782, and since 1792 had been associated with Governor Simcoe as a member of the Executive Council of the Province. The official social circle, therefore, consisted largely of members of the Administration and their families, Government officials, and certain officers who, because of distinguished military service to the Crown, had received liberal grants of land in the Province and had settled largely in the neighborhood of York. Among those who formed the President’s court were Hon. Alexander Grant and Hon. James Baby, members of the Executive Council; Chief Justice John Elmsley, Attorney-General John White, John Small, clerk of the Executive Council; D. W. Smith, Surveyor-General; William Jarvis, Secretary and Registrar of the Province; Dr. James Macaulay, Captain Æneas (afterwards Major-General) Shaw, Colonel James Givens, Captain John McGill, formerly an officer in the Queen’s Rangers during the Revolution; Captain John Denison, at one time an officer in the English militia, who for several years occupied Castle Frank; and Colonel William Allan, afterwards the first Collector of Customs in York. These and others formed as it were the social aristocracy of the time, and, whether consciously or not, set in action the movement by which later the right and authority to govern became vested in the hands of those favored by the Governor of the day.

The arrival of General Peter Hunter, the new Governor, was therefore an important event in the life of the capital. The lack of an official head for three years had been felt, not only in the social, but also in the political life of the Province. Hon. Peter Russell had done very well, but he was not the Governor and he could not be expected to carry the prestige of one directly representing His Majesty.

The new Governor soon showed that he had a personality all his own. Having been a military man, he was a strict disciplinarian and accustomed to doing things in his own way. He was a man of few words and impatient of many of the fripperies that went with the vice-regal office. His reply to the elaborate address of welcome extended by the inhabitants of York on his arrival was terse and characteristic: “Gentlemen, nothing that is in my power shall be wanting to contribute to the happiness and welfare of this Colony.” But when, later, the “Mechanics and Husbandmen” of Niagara attempted to present an address on their own account, he refused to accept it on the ground that an address professedly from the “inhabitants” generally had already been presented. This led the Niagara Constellation to recall that, when Governor Simcoe arrived at Kingston on his way to Niagara to assume the government of the Province the “Magistrates and Gentlemen” of that town had presented him with an address, he had replied politely and verbally; but when the “inhabitants of the country and town”—those who were not in the upper circles—presented one on their own account, His Excellency had very politely given his reply in writing, in a document which had been carefully preserved and was still highly treasured.

The Governor, too, was impatient of looseness and indifference in the administrative offices, and he soon acquired such a reputation for severity that, according to Dr. Henry Scadding,[1] officials of the service, “from the Judge on the bench to the humblest employee,” held office literally during pleasure.

It is related, for instance, that a deputation representing a colony of Quakers which had arrived some time before and settled near Yonge street, north of the Oak Ridges, some twenty miles north of the town, had complained that the patents to their lands had been unduly delayed. The Governor, after investigation, finally located the delay in the office of Secretary Jarvis, who pleaded that pressure of work in the office had made it impossible to get them ready.

“Sir!” thundered the Governor, “if they are not forthcoming, every one of them, and placed in the hands of these gentlemen here in my presence at noon on Thursday next (it was now Tuesday), by George! I’ll un-Jarvis you.”

With the coming, too, of Governor Hunter the work of the Legislative Assembly assumed new importance in the life of the Province. The opening and closing of the sessions were attended with much pomp and circumstance; quite unlike those under Governor Simcoe. There was a cavalcade of troops from the garrison in attendance, together with the firing of cannon, the attendance of local personages, the commotion of the crowd of curious sightseers—in miniature much the same kind of ceremonial that attends the opening and closing of parliaments the world over. But the Legislature for the most part was composed of plain, unassuming men, many of them of little education, and they, with the seven Crown-appointed Councillors, set about the laying of the foundations of the laws of the Province.

Governor Simcoe was a man of energy and wide vision. He had seen that the opening of highways was one of the first needs of the Province, and in the winter of 1796 he instructed the Queen’s Rangers to open a road extending from York to Lake Simcoe, a distance of about thirty miles. As this work was accomplished between the fourth of January and the sixteenth of February, it is doubtful if anything was attempted other than merely to blaze a path through the forest, for in the following year, when Balser Munshaw, one of the pioneers of Richmond Hill, made his first trip into the wilderness, so hard was the going that he was forced when reaching a ravine to take his canvas-topped waggon apart and lower the wheels and axles and other equipment by means of strong ropes passed around the trunks of saplings, and then haul them up the ascent on the other side in the same way.

A year or two later the brigades of the North-West Company began to use the same route. Indeed, it is not improbable that in addition to opening the road for the accommodation of the German colony which William Berczy had brought into Markham Township to settle on lands assigned to them, the Governor had had it in his mind to provide a shortcut at this point for traffic to the upper lakes by which the circuitous passage around by Lake Erie might be avoided, and which incidentally would bring prestige to the capital.

“This communication offers many advantages,” writes D. W. Smith, Surveyor-General of the Province, in his Gazetteer of 1799, in referring to this portage. “Merchandize from Montreal to Michilimackinac may be sent this way at ten to fifteen pounds less expense per ton than by the road of the Grand or Ottawa rivers; and the merchandize from New York to be sent up the North and Mohawk rivers for the North-West trade, finding its way into Lake Ontario at Oswego, the advantage will certainly be felt in transporting goods from Oswego to York and from thence across Yonge Street and down the waters of Lake Simcoe into Lake Huron in preference to sending it by Lake Erie.”

The Niagara Constellation of August 3rd, 1799, announces that “it is reported on good authority that the North-West Company has it seriously in contemplation to establish a communication with the Upper Lakes by way of York through Yonge Street to Lake Huron.”

That this passage was so used is, indeed, well authenticated, and the brigades of the Nor’-Westers, in order to avoid any contact with the American frontier, continued for some years to lift their boats over the carrying place of the peninsula across the harbour, where the eastern gap was broken through by the waves about the middle of the last century, and, putting them in the waters of the Bay, take them up the Don River to York Mills, where they were again lifted from the water, placed on wheels, and drawn up Yonge Street through the woods to Holland River. Here they were again placed in the water to make their way by Lake Simcoe and the Severn River to Georgian Bay.

The Upper Canada Gazette of March 9th, 1799, announced that “The North-West Company has given twelve thousand pounds towards making Yonge Street a good road, and the North-West commerce will be communicated through this place (York); an event which must inevitably benefit this country materially, as it will not only tend to augment the population, but will also enhance the present value of landed property.”

So important, indeed, did this traffic become, that Rowland Burr, a Pennsylvania engineer who had come into Upper Canada in 1803, early conceived the idea of connecting Lake Ontario with the Georgian Bay by a canal through Lake Simcoe and the valley of the Humber. This he considered of so vital a necessity that he later published at his own expense a report giving a minute record of an examination he had made of the route which he advocated and recommended.

The First St. James’ Church, York,

Erected 1803.

It is more than probable that the sixty or seventy German families which William Berczy brought into York County before 1800 were the first to bring horses into this district. They had come originally from beyond Philadelphia, cutting their way through the forests, and they were now completing their journey in order to again be under the British flag. The waggons which they brought with them and which carried their belongings were so constructed as to be serviceable under all conditions of travel. The bodies were made of close fitting boards, cleverly caulked at the seams, so that by lifting them from the wheels they served for a transport when crossing streams, carrying not only the families and their goods, but also in turn the wheels themselves.

For some years Yonge Street extended south only as far as Lot Street, but in the popular mind it began only at Yorkville, a mile and a quarter farther north, and the southern portion was spoken of, not as Yonge Street, but as the “road to Yonge Street.” Indeed, this portion was so neglected and impassable for vehicular traffic that a public meeting was called in December, 1800, to consider the best means of opening it up and making it available as an entrance to the town. At the same time a proposal was put forward for the closing of Lot Street as “altogether superfluous,” another street (Hospital Street, now Richmond Street) providing the necessary access to the town a few yards to the south. The suggestion also was made that the proceeds of the sale of the land thus saved might be applied to the improvement of Yonge Street.

Subscriptions were taken for the improvement of the road to Yonge Street by clearing the land, cutting the stumps in the two middle rods close to the ground, and making a causeway eighteen feet wide where a causeway might be required. Further subscriptions were taken up from time to time towards the undertaking, and finally, in June 1802, the subscribers were invited to meet with the committee for the purpose of inspecting the repaired parts “and to take into consideration how far the moneys subscribed by them have been beneficially expended.”

When Jesse Ketchum left the Garrison wharf to find the home of his brother Seneca he began the last short stage of his journey. He was now at York, the home of his dreams, the hope of his ambitions. He made his way eastward towards the Parliament Buildings by the track, called by courtesy Palace Street, which led through the hardwood forests. This road ran close to the high cliffs overlooking the harbour, and as he hurried on he caught glimpses from time to time of the bright blue waters of the Bay as they lay shimmering in the summer sun, while the neighboring marshes and the peninsula beyond were noisy with the song and alive with the movement of myriads of birds and wild fowl. It was an enchanting sight, and his heart beat high at the very thought of being alive amid such wonderful surroundings.

Soon after crossing Garrison Creek, then a stream eighteen feet in width, he passed a little military cemetery where, five years before, Governor Simcoe had buried his baby daughter Katherine, born in Upper Canada a few weeks after the Governor’s arrival. Then came a long stretch of partly cleared and partly burned over land, intersected at Simcoe Street by a stream known as Russell’s Creek (which, later, was traceable in the sunken lawn of the old Government House) until he had come almost to Church Street before he caught sight of any human habitation. This large area formed the new extension of the town, recently authorized but not yet cleared for settlement. No streets had as yet been cut through it to the water’s edge, and even Church Street at this time was considered remote from the business part of the town.

At the Parliament Buildings, then the focal centre of the community, the new arrival took breath to enquire as to the home of his brother Seneca, and he was directed to follow the usual trail up Parliament Street and across the pine lands through the bush in a north-westerly direction to Yonge Street, thence north a distance of about four miles.

Seneca, he found, was well known to the town people. For some time his home out in the country had been a sort of community centre for the neighborhood. There was as yet no church in York, but religious services were held occasionally in the Parliament Buildings; and frequently in the afternoons, at such times, the clergyman or reader would make his way out to the home of Seneca Ketchum, where another service was held for those unable to go to town. Moreover, Seneca had for a year or more been secretary of the Masonic Lodge, and was therefore known personally and favorably to many of the officials and the leading citizens of the town.

It requires but little imagination to picture the arrival towards sundown of young Jesse at the home of his brother. They had not seen one another for seven years, when the younger was but ten years of age and the elder twenty. Jesse at that time had been a weedy little fellow and it was impossible for Seneca to trace in the sturdy, weather-beaten young man who knocked at his kitchen door any resemblance to the brother he had left behind at Spencertown so long before. But he was welcomed none the less gladly, and they sat up until all hours asking and answering the eager questionings as they discussed the health, welfare and prospects of the various members of the family.

Seneca was now comfortably situated, and with the assistance of hired help was farming a considerable portion of his two hundred and ten acre property on the west side of Yonge Street, not far from York Mills, and reaching back to the second concession. The two uncles who had come to Canada in the same party were still with him, although they had already secured land of their own near Port Union. His house, of course, was of logs, as were most of the houses in those far-off, primitive days; and it was roomy enough, too, but there were not many of the necessities and certainly none of the comforts of life.

There was cordial welcome, however, for the wanderer who had come so far and had braved so much. His training in farm work was all that could be desired, and he was immediately made a member of the household and allocated a share in the work, and a share, too, in the financial returns.

The farmers and merchants in York at that time had a distinct advantage over those in most Upper Canadian towns in that so large a proportion of the town population were Government officials and military officers drawing regular salaries and allowances from Great Britain. There was thus plenty of money in circulation. Merchants and citizens, therefore, were able to pay for their purchases when made, and the farmers received cash for their products.

At this time, and until as late as 1817, there was no system of taxation in the Province. The entire expense of carrying on public affairs was borne by His Majesty’s Government, and, with the exception of occasional voluntary subscriptions for specific purposes, all costs of public works and improvements and services of every kind were defrayed by drafts from England.

Although a large section of the land around York and throughout the township had been allotted, the area actually under cultivation at this time was comparatively small. In 1802, according to the Town Clerk’s return as to the inhabitants of the Town of York and of the Townships of York and Etobicoke, the population was but 659, with a cultivated area of only 1109 acres. The live-stock recorded included sixty-eight oxen, one hundred and thirty-three milch cows, forty-eight young horned cattle, and 530 swine, and the townships contained but one grist mill, a couple of saw-mills and two taverns.

When it is recalled that under the provisions of the original Order-in-Council, passed in 1789, providing for grants of land to Loyalist refugees from the thirteen Colonies, daughters as well as sons were each to get two hundred acres, it would appear as though, while many were prepared to take advantage of their opportunities, few were willing to live up to the obligations which these implied. The reason for this is probably not far to seek. A further provision was included requiring that in all records that should be made the names of Loyalists and the members of their families were to be “discriminated from those of future settlers,” and that those who had joined the cause of Great Britain prior to the Treaty of 1783 along with their children were to be distinguished by the letters U.E.L.

In effect, those who were able to qualify as United Empire Loyalists were, by the action of the Government, to be set apart from ordinary citizens. They were to have, as it were, a patent of nobility from the Crown. They need toil not, neither need they spin; but public office should be open to them, the divine rights of Government were to be theirs, and they and their children for years to come were to be entitled to the chief places in the synagogue.

From the first the Ketchums had taken their places in the community life. Seneca, as we have seen, because of his superior education, had been appointed secretary of Rawdon Masonic Lodge, the first one in the district, and holding its warrant from the first Grand Lodge of England. Because of his early studies and his ambitions towards holy orders he took the Church services occasionally, and on the organization of St. James’ Church, in 1803, he became one of its first and most enthusiastic members. He was a man of high-strung, nervous temperament, and not overly strong, either physically or emotionally. Jesse, on the other hand, was strong, rugged and capable in every way, and just the kind of assistant he required. It was not long, therefore, before the younger, though not yet out of his teens, was virtually in charge of the farm work.

A year or two after the arrival of Jesse at York another brother, Zebulon, who was seven or eight years older, decided also to seek his fortune in Upper Canada, and with him came their father, who since the death of his wife had, as it were, been at loose ends. Zebulon had been something of an anchorage for his father, and without him or someone to tie to the latter would have been lost. He also was a capable farmer and had some experience in the handling of affairs.

Their father, now well over sixty years of age, could not be expected at his time of life to make a new start, but he lived with one or other of his sons and enjoyed a certain measure of happiness, if not of entire contentment. He died in 1825 at the age of eighty-five and was buried in the churchyard at York Mills.

In the marriage register of St. James’ Church, York, under date of January 24th, 1804, a few months after the opening of the church, is to be found this entry:

On the Twenty-fourth day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and four, were married, after publication of Banns, Jesse Ketchum, Junior, and Nancy Love, by me, George O’Kill Stuart.

Behind the event covered by this official record is a story of which the following is a free translation.

With the coming of Zebulon and his father Seneca’s house was now in need of a competent housekeeper. He and Jesse were fairly prosperous. They had had good crops, and the returns in cash were satisfactory. Seneca had now secured his deed for the land which he had taken over some years before from its original owner, Hiram Kendrick, and they could well afford the help required for the physical comfort of so large a household of men. They decided to engage a Mrs. Ann Love, a young widow, to take over the domestic duties of the establishment, and a section of the house was set apart for her special use.

The Loves had come of a Loyalist family with connections running back in England to Cromwellian days. They had removed to Pennsylvania many years before and during the Loyalist trek they had come to Canada, settling finally in the neighborhood of Temperanceville, in York County. There were three sons in the family, strong, active men, all in the prime of young manhood and of whom only one, James, was married. On one occasion, in the spring of 1803, when out shooting together, James, by some chance, was shot by a bullet from a rifle fired by one of his brothers which had been aimed at an animal in the woods. The stricken man died soon afterwards, leaving a young widow and a little girl baby.

Unwilling to live with her husband’s family and become a care to others the young widow determined, with an independence quite unusual in those days, to earn her own living and that of her little daughter. It was a sacrifice of social prestige at that time for a young woman to take a situation of any kind. There was not much open to women outside of domestic service. But Mrs. Love was a young woman of unusual qualities and temperament and she was not afraid of censorious comment. Her child needed her personal oversight, and that, she felt, could be given adequately only where she was free from the interference of complaining elders or the observation of critical relatives.

Mrs. Love was also a thorough and accomplished housekeeper, and Seneca and Jesse considered themselves fortunate in securing so competent and careful a person for their domestic establishment.

But the coming of a woman into their home brought with it an element that neither of the men had anticipated. They had known little of the joys and comforts of home life. For years Seneca had shifted for himself, and in the course of his travelling and association with his elderly uncles he had been able to acquire some proficiency in taking care of himself. Jesse also had known nothing of domestic happiness since his mother’s death. They were not prepared, therefore, for the transformation which Mrs. Love was able to make in their somewhat cheerless bachelor home. The presence, too, of the little girl, Lily, was as a ray of sunshine in their lives, and Jesse promptly succumbed to the spell of the child’s winning ways.

The inevitable followed. Jesse fell in love not only with the child but with the mother as well. Ann Love was several years older than he, and although he was now well on into his twenty-second year, and had become the business man of the partnership with his brother, he was quite unused to the society of women and altogether a novice in affairs of the heart.

Having decided in his own mind, however, that his happiness for the future was now in the capable hands of the radiant and charming Mrs. Love, he decided to talk the matter over with Seneca and ask for his advice.

Seneca, however, met the statement of the eager and questioning youth with blank astonishment. The thing was entirely out of the question. It was impossible, preposterous, unthinkable! He wouldn’t consent to it for a moment. Jesse was much too young for the woman and she entirely too old for him. Anyway—she was his housekeeper and he wouldn’t let her go. In fact—er—er—, in fact—er—er—he himself had practically decided to—er—er, himself ask her to marry him. . . .

Here was a trying and difficult situation. Each, quite unknown to the other, had fallen in love with the charming housekeeper. The one, young, impressionable, impulsive, eager; the other, now thirty-one, quiet, thoughtful, self-contained, and temperamentally a little out of normal. What was to be done? How was the difficulty to be settled?