* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: [Makers of Canada] Volume 16. Lord Elgin

Date of first publication: 1903

Author: Sir John George Bourinot (1837-1902)

Date first posted: July 28th, 2024

Date last updated: July 28th, 2024

Faded Page eBook #20240712

This eBook was produced by: Mardi Desjardins, Howard Ross & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

This file was produced from images generously made available by Internet Archive.

THE MAKERS OF CANADA

EDITED BY

DUNCAN CAMPBELL SCOTT, F.R.S.C., and

PELHAM EDGAR, Ph.D.

LORD ELGIN

THE MAKERS OF CANADA

LORD ELGIN

BY

SIR JOHN GEORGE BOURINOT

LONDON: T. C. & E. C. JACK

TORONTO MORANG & CO., LIMITED

The late Sir John Bourinot had completed and revised the following pages some months before his lamented death. The book represents more satisfactorily, perhaps, than anything else that he has written the author’s breadth of political vision and his concrete mastery of historical fact. The life of Lord Elgin required to be written by one possessed of more than ordinary insight into the interesting aspects of constitutional law. That it has been singularly well presented must be the conclusion of all who may read this present narrative.

| CHAPTER I | Page |

| EARLY CAREER | 1 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| POLITICAL CONDITION IN CANADA | 17 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| POLITICAL DIFFICULTIES | 41 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| THE INDEMNIFICATION ACT | 61 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| THE END OF THE LAFONTAINE-BALDWIN MINISTRY, 1851 | 85 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| THE HINCKS-MORIN MINISTRY | 107 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| THE HISTORY OF THE CLERGY RESERVES (1791-1854) | 143 |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| SEIGNIORIAL TENURE | 171 |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| CANADA AND THE UNITED STATES | 189 |

| CHAPTER X | |

| FAREWELL TO CANADA | 203 |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| POLITICAL PROGRESS | 227 |

| CHAPTER XII | |

| A COMPARISON OF SYSTEMS | 239 |

| BIBLIOGRAPHICAL NOTE | 269 |

| INDEX | 271 |

The Canadian people have had a varied experience in governors appointed by the imperial state. At the very commencement of British rule they were so fortunate as to find at the head of affairs Sir Guy Carleton—afterwards Lord Dorchester—who saved the country during the American revolution by his military genius, and also proved himself an able civil governor in his relations with the French Canadians, then called “the new subjects,” whom he treated in a fair and generous spirit that did much to make them friendly to British institutions. On the other hand they have had military men like Sir James Craig, hospitable, generous, and kind, but at the same time incapable of understanding colonial conditions and aspirations, ignorant of the principles and working of representative institutions, and too ready to apply arbitrary methods to the administration of civil affairs. Then they have had men who were suddenly drawn from some inconspicuous position in the parent state, like Sir Francis Bond Head, and allowed by an apathetic or ignorant colonial office to prove their want of discretion, tact, and even common sense at a very critical stage of Canadian affairs. Again there have been governors of the highest rank in the peerage of England, like the Duke of Richmond, whose administration was chiefly remarkable for his success in aggravating national animosities in French Canada, and whose name would now be quite forgotten were it not for the unhappy circumstances of his death.[1] Then Canadians have had the good fortune of the presence of Lord Durham at a time when a most serious state of affairs imperatively demanded that ripe political knowledge, that cool judgment, and that capacity to comprehend political grievances which were confessedly the characteristics of this eminent British statesman. Happily for Canada he was followed by a keen politician and an astute economist who, despite his overweening vanity and his tendency to underrate the ability of “those fellows in the colonies”—his own words in a letter to England—was well able to gauge public sentiment accurately and to govern himself accordingly during his short term of office. Since the confederation of the provinces there has been a succession of distinguished governors, some bearing names famous in the history of Great Britain and Ireland, some bringing to the discharge of their duties a large knowledge of public business gained in the government of the parent state and her wide empire, some gifted with a happy faculty of expressing themselves with ease and elegance, and all equally influenced by an earnest desire to fill their important position with dignity, impartiality, and affability.

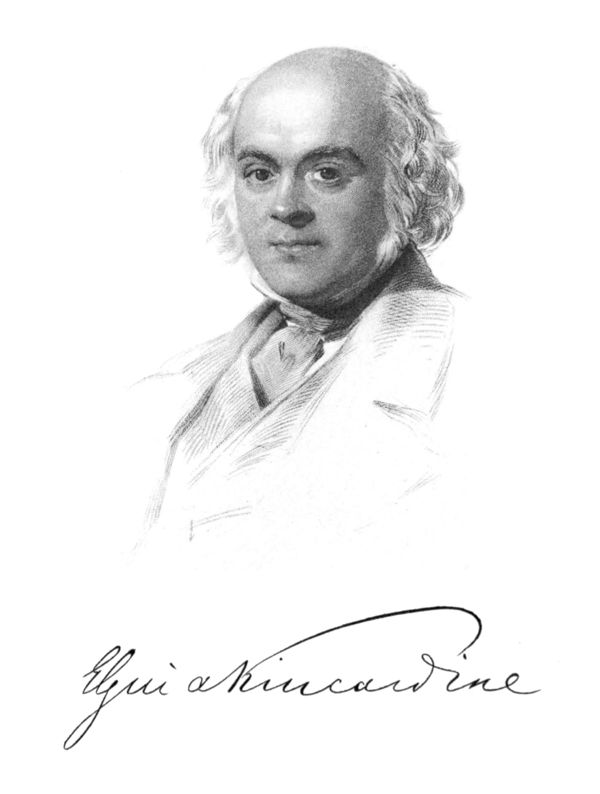

But eminent as have been the services of many of the governors whose memories are still cherished by the people of Canada, no one among them stands on a higher plane than James, eighth earl of Elgin and twelfth earl of Kincardine, whose public career in Canada I propose to recall in the following narrative. He possessed to a remarkable degree those qualities of mind and heart which enabled him to cope most successfully with the racial and political difficulties which met him at the outset of his administration, during a very critical period of Canadian history. Animated by the loftiest motives, imbued with a deep sense of the responsibilities of his office, gifted with a rare power of eloquent expression, possessed of sound judgment and infinite discretion, never yielding to dictates of passion but always determined to be patient and calm at moments of violent public excitement, conscious of the advantages of compromise and conciliation in a country peopled like Canada, entering fully into the aspirations of a young people for self-government, ready to concede to French Canadians their full share in the public councils, anxious to build up a Canadian nation without reference to creed or race—this distinguished nobleman must be always placed by a Canadian historian in the very front rank of the great administrators happily chosen from time to time by the imperial state for the government of her dominions beyond the sea. No governor-general, it is safe to say, has come nearer to that ideal, described by Sir Edward Bulwer Lytton, when secretary of state for the colonies, in a letter to Sir George Bowen, himself distinguished for the ability with which he presided over the affairs of several colonial dependencies. “Remember,” said Lord Lytton, to give that eminent author and statesman his later title, “that the first care of a governor in a free colony is to shun the reproach of being a party man. Give all parties, and all the ministries formed, the fairest play. . . . After all, men are governed as much by the heart as by the head. Evident sympathy in the progress of the colony; traits of kindness, generosity, devoted energy, where required for the public weal; a pure exercise of patronage; an utter absence of vindictiveness or spite; the fairness that belongs to magnanimity: these are the qualities that make governors powerful, while men merely sharp and clever may be weak and detested.”

In the following chapters it will be seen that Lord Elgin fulfilled this ideal, and was able to leave the country in the full confidence that he had won the respect, admiration, and even affection of all classes of the Canadian people. He came to the country when there existed on all sides doubts as to the satisfactory working of the union of 1840, suspicions as to the sincerity of the imperial authorities with respect to the concession of responsible government, a growing antagonism between the two nationalities which then, as always, divided the province. A very serious economic disturbance was crippling the whole trade of the country, and made some persons—happily very few in number—believe for a short time that independence, or annexation to the neighbouring republic, was preferable to continued connection with a country which so grudgingly conceded political rights to the colony, and so ruthlessly overturned the commercial system on which the province had been so long dependent. When he left Canada, Lord Elgin knew beyond a shadow of a doubt that the two nationalities were working harmoniously for the common advantage of the province, that the principles of responsible government were firmly established, and that the commercial and industrial progress of the country was fully on an equality with its political development.

The man who achieved these magnificent results could claim an ancestry to which a Scotsman would point with national pride. He could trace his lineage to the ancient Norman house of which “Robert the Bruce”—a name ever dear to the Scottish nation—was the most distinguished member. He was born in London on July 20th, 1811. His father was a general in the British army, a representative peer in the British parliament from 1790-1840, and an ambassador to several European courts; but he is best known to history by the fact that he seriously crippled his private fortunes by his purchase, while in the East, of that magnificent collection of Athenian art which was afterwards bought at half its value by the British government and placed in the British Museum, where it is still known as the “Elgin Marbles.” From his father, we are told by his biographer,[2] he inherited “the genial and playful spirit which gave such a charm to his social and parental relations, and which helped him to elicit from others the knowledge of which he made so much use in the many diverse situations of his after life.” The deep piety and the varied culture of his mother “made her admirably qualified to be the depository of the ardent thoughts and aspirations of his boyhood.” At Oxford, where he completed his education after leaving Eton, he showed that unselfish spirit and consideration for the feelings of others which were the recognized traits of his character in after life. Conscious of the unsatisfactory state of the family’s fortunes, he laboured strenuously even in college to relieve his father as much as possible of the expenses of his education. While living very much to himself, he never failed to win the confidence and respect even at this youthful age of all those who had an opportunity of knowing his independence of thought and judgment. Among his contemporaries were Mr. Gladstone, afterwards prime minister; the Duke of Newcastle, who became secretary of state for the colonies and was chief adviser of the Prince of Wales—now Edward VII—during his visit to Canada in 1860; and Lord Dalhousie and Lord Canning, both of whom preceded him in the governor-generalship of India. In the college debating club he won at once a very distinguished place. “I well remember,” wrote Mr. Gladstone, many years later, “placing him as to the natural gift of eloquence at the head of all those I knew either at Eton or at the University.” He took a deep interest in the study of philosophy. In him—to quote the opinion of his own brother, Sir Frederick Bruce, “the Reason and Understanding, to use the distinctions of Coleridge, were both largely developed, and both admirably balanced. . . . He set himself to work to form in his own mind a clear idea of each of the constituent parts of the problem with which he had to deal. This he effected partly by reading, but still more by conversation with special men, and by that extraordinary logical power of mind and penetration which not only enabled him to get out of every man all he had in him, but which revealed to these men themselves a knowledge of their own imperfect and crude conceptions, and made them constantly unwilling witnesses or reluctant adherents to views which originally they were prepared to oppose. . . .” The result was that, “in an incredibly short time he attained an accurate and clear conception of the essential facts before him, and was thus enabled to strike out a course which he could consistently pursue amid all difficulties, because it was in harmony with the actual facts and the permanent conditions of the problem he had to solve.” Here we have the secret of his success in grappling with the serious and complicated questions which constantly engaged his attention in the administration of Canadian affairs.

After leaving the university with honour, he passed several years on the family estate, which he endeavoured to relieve as far as possible from the financial embarrassment into which it had fallen ever since his father’s extravagant purchase in Greece. In 1840, by the death of his eldest brother, George, who died unmarried, James became heir to the earldom, and soon afterwards entered parliament as member for the borough of Southampton. He claimed then, as always, to be a Liberal Conservative, because he believed that “the institutions of our country, religious as well as civil, are wisely adapted, when duly and faithfully administered, to promote, not the interest of any class or classes exclusively, but the happiness and welfare of the great body of the people”; and because he felt that, “on the maintenance of these institutions, not only the economical prosperity of England, but, what is yet more important, the virtues that distinguish and adorn the English character, under God, mainly depend.”

During the two years Lord Elgin remained in the House of Commons he gave evidence to satisfy his friends that he possessed to an eminent degree the qualities which promised him a brilliant career in British politics. Happily for the administration of the affairs of Britain’s colonial empire, he was induced by Lord Stanley, then secretary of state for the colonies, to surrender his prospects in parliament and accept the governorship of Jamaica. No doubt he was largely influenced to take this position by the conviction that he would be able to relieve his father’s property from the pressure necessarily entailed upon it while he remained in the expensive field of national politics. On his way to Jamaica he was shipwrecked, and his wife, a daughter of Mr. Charles Cumming Bruce, M.P., of Dunphail, Stirling, suffered a shock which so seriously impaired her health that she died a few months after her arrival in the island when she had given birth to a daughter.[3] His administration of the government of Jamaica was distinguished by a strong desire to act discreetly and justly at a time when the economic conditions of the island were still seriously disturbed by the emancipation of the negroes. Planter and black alike found in him a true friend and sympathizer. He recognized the necessity of improving the methods of agriculture, and did much by the establishment of agricultural societies to spread knowledge among the ignorant blacks, as well as to create a spirit of emulation among the landlords, who were still sullen and apathetic, requiring much persuasion to adapt themselves to the new order of things, and make efforts to stimulate skilled labour among the coloured population whom they still despised. Then, as always in his career, he was animated by the noble impulse to administer public affairs with a sole regard to the public interests, irrespective of class or creed, to elevate men to a higher conception of their public duties. “To reconcile the planter”—I quote from one of his letters to Lord Stanley—“to the heavy burdens which he was called to bear for the improvement of our establishments and the benefit of the mass of the population, it was necessary to persuade him that he had an interest in raising the standard of education and morals among the peasantry; and this belief could be imparted only by inspiring a taste for a more artificial system of husbandry.” “By the silent operation of such salutary convictions,” he added, “prejudices of old standing are removed; the friends of the negro and of the proprietary classes find themselves almost unconsciously acting in concert, and conspiring to complete that great and holy work of which the emancipation of the slave was but the commencement.”

At this time the relations between the island and the home governments were always in a very strained condition on account of the difficulty of making the colonial office fully sensible of the financial embarrassment caused by the upheaval of the labour and social systems, and of the wisest methods of assisting the colony in its straits. As it too often happened in those old times of colonial rule, the home government could with difficulty be brought to understand that the economic principles which might satisfy the state of affairs in Great Britain could not be hastily and arbitrarily applied to a country suffering under peculiar difficulties. The same unintelligent spirit which forced taxation on the thirteen colonies, which complicated difficulties in the Canadas before the rebellion of 1837, seemed for the moment likely to prevail, as soon as the legislature of Jamaica passed a tariff framed naturally with regard to conditions existing when the receipts and expenditures could not be equalized, and the financial situation could not be relieved from its extreme tension in any other way than by the imposition of duties which happened to be in antagonism with the principles then favoured by the imperial government. At this critical juncture Lord Elgin successfully interposed between the colonial office and the island legislature, and obtained permission for the latter to manage this affair in its own way. He recognized the fact, obvious enough to any one conversant with the affairs of the island, that the tariff in question was absolutely necessary to relieve it from financial ruin, and that any strenuous interference with the right of the assembly to control its own taxes and expenses would only tend to create complications in the government and the relations with the parent state. He was convinced, as he wrote to the colonial office, that an indispensable condition of his usefulness as a governor was “a just appreciation of the difficulties with which the legislature of the island had yet to contend, and of the sacrifices and exertions already made under the pressure of no ordinary embarrassments.”

Here we see Lord Elgin, at the very commencement of his career as a colonial governor, fully alive to the economic, social, and political conditions of the country, and anxious to give its people every legitimate opportunity to carry out those measures which they believed, with a full knowledge and experience of their own affairs, were best calculated to promote their own interests. We shall see later that it was in exactly the same spirit that he administered Canadian questions of much more serious import.

Though his government in Jamaica was in every sense a success, he decided not to remain any longer than three years, and so wrote in 1845 to Lord Stanley. Despite his earnest efforts to identify himself with the island’s interests, he had led on the whole a retired and sad life after the death of his wife. He naturally felt a desire to seek the congenial and sympathetic society of friends across the sea, and perhaps return to the active public life for which he was in so many respects well qualified. In offering his resignation to the colonial secretary he was able to say that the period of his administration had been “one of considerable social progress”; that “uninterrupted harmony” had “prevailed between the colonists and the local government”; that “the spirit of enterprise” which had proceeded from Jamaica for two years had “enabled the British West Indian colonies to endure with comparative fortitude, apprehensions and difficulties which otherwise might have depressed them beyond measure.”

It was not, however, until the spring of 1846 that Lord Elgin was able to return on leave of absence to England, where the seals of office were now held by a Liberal administration, in which Lord Grey was colonial secretary. Although his political opinions differed from those of the party in power, he was offered the governor-generalship of Canada when he declined to go back to Jamaica. No doubt at this juncture the British ministry recognized the absolute necessity that existed for removing all political grievances that arose from the tardy concession of responsible government since the death of Lord Sydenham, and for allaying as far as possible the discontent that generally prevailed against the new fiscal policy of the parent state, which had so seriously paralyzed Canadian industries. It was a happy day for Canada when Lord Elgin accepted this gracious offer of his political opponents, who undoubtedly recognized in him the possession of qualities which would enable him successfully, in all probability, to grapple with the perplexing problems which embarrassed public affairs in the province. He felt (to quote his own language at a public dinner given to him just before his departure for Canada) that he undertook no slight responsibilities when he promised “to watch over the interests of those great offshoots of the British race which plant themselves in distant lands, to aid them in their efforts to extend the domain of civilization, and to fulfill the first behest of a benevolent Creator to His intelligent creatures—‘subdue the earth’; to abet the generous endeavour to impart to these rising communities the full advantages of British laws, British institutions, and British freedom; to assist them in maintaining unimpaired—it may be in strengthening and confirming—those bonds of mutual affection which unite the parent and dependent states.”

Before his departure for the scene of his labours in America, he married Lady Mary Louisa Lambton, daughter of the Earl of Durham, whose short career in Canada as governor-general and high commissioner after the rebellion of 1837 had such a remarkable influence on the political conditions of the country. Whilst we cannot attach too much importance to the sage advice embodied in that great state paper on Canadian affairs which was the result of his mission to Canada, we cannot fail at the same time to see that the full vindication of the sound principles laid down in that admirable report is to be found in the complete success of their application by Lord Elgin. The minds of both these statesmen ran in the same direction. They desired to give adequate play to the legitimate aspirations of the Canadian people for that measure of self-government which must stimulate an independence of thought and action among colonial public men, and at the same time strengthen the ties between the parent state and the dependency by creating that harmony and confidence which otherwise could not exist in the relations between them. But while there is little doubt that Lord Elgin would under any circumstances have been animated by a deep desire to establish the principles of responsible government in Canada, this desire must have been more or less stimulated by the tender ties which bound him to the daughter of a statesman whose opinions where so entirely in harmony with his own. In Lord Elgin’s temperament there was always a mingling of sentiment and reason, as may be seen by reference to his finest exhibitions of eloquence. We can well believe that a deep reverence for the memory of a great man, too soon removed from the public life of Great Britain, combined with the natural desire to please his daughter when he wrote these words to her:—“I still adhere to my opinion that the real and effectual vindication of Lord Durham’s memory and proceedings will be the success of a governor-general of Canada who works out his views of government fairly. Depend upon it, if this country is governed for a few years satisfactorily, Lord Durham’s reputation as a statesman will be raised beyond the reach of cavil.” Now, more than half a century after he penned these words and expressed this hope, we all perceive that Lord Elgin was the instrument to carry out this work.

Here it is necessary to close this very brief sketch of Lord Elgin’s early career, that I may give an account of the political and economic conditions of the dependency at the end of January, 1847, when he arrived in the city of Montreal to assume the responsibilities of his office. This review will show the difficulties of the political situation with which he was called upon to cope, and will enable us to obtain an insight into the high qualifications which he brought to the conduct of public affairs in the Canadas.

|

He was bitten by a tame fox and died of hydrophobia at Richmond, in the present county of Carleton, Ontario. |

|

“Letters and Journals of James, eighth Earl of Elgin, etc.” Edited by Theodore Waldron, C.B. For fuller references to works consulted in the writing of this short history, see Bibliographical Notes at the end of this book. |

|

Lady Elma, who married, in 1864, Thomas John Howell-Thurlow-Cumming Bruce, who was attached to the staff of Lord Elgin in his later career in China and India, etc., and became Baron Thurlow on the death of his brother in 1874. See “Debrett’s Peerage.” |

To understand clearly the political state of Canada at the time Lord Elgin was appointed governor-general, it is necessary to go back for a number of years. The unfortunate rebellions which were precipitated by Louis Joseph Papineau and William Lyon Mackenzie during 1837 in the two Canadas were the results of racial and political difficulties which had gradually arisen since the organization of the two provinces of Upper and Lower Canada under the Constitutional Act of 1791. In the French section, the French and English Canadians—the latter always an insignificant minority as respects number—had in the course of time formed distinct parties. As in the courts of law and in the legislature, so it was in social and everyday life, the French Canadian was in direct antagonism to the English Canadian. Many members of the official and governing class, composed almost exclusively of English, were still too ready to consider French Canadians as inferior beings, and not entitled to the same rights and privileges in the government of the country. It was a time of passion and declamation, when men of fervent eloquence, like Papineau, might have aroused the French as one man, and brought about a general rebellion had they not been ultimately thwarted by the efforts of the moderate leaders of public opinion, especially of the priests who, in all national crises in Canada, have happily intervened on the side of reason and moderation, and in the interests of British connection, which they have always felt to be favourable to the continuance and security of their religious institutions. Lord Durham, in his memorable report on the condition of Canada, has summed up very expressively the nature of the conflict in the French province. “I expected,” he said, “to find a contest between a government and a people; I found two nations warring in the bosom of a single state; I found a struggle, not of principles, but of races.”

While racial antagonisms intensified the difficulties in French Canada, there existed in all the provinces political conditions which arose from the imperfect nature of the constitutional system conceded by England in 1791, and which kept the country in a constant ferment. It was a mockery to tell British subjects conversant with British institutions, as Lieutenant-Governor Simcoe told the Upper Canadians in 1792, that their new system of government was “an image and transcript of the British constitution.” While it gave to the people representative institutions, it left out the very principle which was necessary to make them work harmoniously—a government responsible to the legislature, and to the people in the last resort, for the conduct of legislation and the administration of affairs. In consequence of the absence of this vital principle, the machinery of government became clogged, and political strife convulsed the country from one end to the other. An “irrepressible conflict” arose between the government and the governed classes, especially in Lower Canada. The people who in the days of the French régime were without influence and power, had gained under their new system, defective as it was in essential respects, an insight into the operation of representative government, as understood in England. They found they were governed, not by men responsible to the legislature and the people, but by governors and officials who controlled both the executive and legislative councils. If there had always been wise and patient governors at the head of affairs, or if the imperial authorities could always have been made aware of the importance of the grievances laid before them, or had understood their exact character, the differences between the government and the majority of the people’s representatives might have been arranged satisfactorily. But, unhappily, military governors like Sir James Craig only aggravated the dangers of the situation, and gave demagogues new opportunities for exciting the people. The imperial authorities, as a rule, were sincerely desirous of meeting the wishes of the people in a reasonable and fair spirit, but unfortunately for the country, they were too often ill-advised and ill-informed in those days of slow communication, and the fire of public discontent was allowed to smoulder until it burst forth in a dangerous form.

In all the provinces, but especially in Lower Canada, the people saw their representatives practically ignored by the governing body, their money expended without the authority of the legislature, and the country governed by irresponsible officials. A system which gave little or no weight to public opinion as represented in the House of Assembly, was necessarily imperfect and unstable, and the natural result was a deadlock between the legislative council, controlled by the official and governing class, and the house elected by the people. The governors necessarily took the side of the men whom they had themselves appointed, and with whom they were acting. In the maritime provinces in the course of time, the governors made an attempt now and then to conciliate the popular element by bringing in men who had influence in the assembly, but this was a matter entirely within their own discretion. The system of government as a whole was worked in direct contravention of the principle of responsibility to the majority in the popular house. Political agitators had abundant opportunities for exciting popular passion. In Lower Canada, Papineau, an eloquent but impulsive man, having rather the qualities of an agitator than those of a statesman, led the majority of his compatriots. For years he contended for a legislative council elected by the people: and it is curious to note that none of the men who were at the head of the popular party in Lower Canada ever recognized the fact, as did their contemporaries in Upper Canada, that the difficulty would be best solved, not by electing an upper house, but by obtaining an executive which would only hold office while supported by a majority of the representatives in the people’s house. In Upper Canada the radical section of the Liberal party was led by Mr. William Lyon Mackenzie, who fought vigorously against what was generally known as the “Family Compact,” which occupied all the public offices and controlled the government.

In the two provinces these two men at last precipitated a rebellion, in which blood was shed and much property destroyed, but which never reached any very extensive proportions. In the maritime provinces, however, where the public grievances were of less magnitude, the people showed no sympathy whatever with the rebellious elements of the upper provinces.

Amid the gloom that overhung Canada in those times there was one gleam of sunshine for England. Although discontent and dissatisfaction prevailed among the people on account of the manner in which the government was administered, and of the attempts of the minority to engross all power and influence, there was still a sentiment in favour of British connection, and the annexationists were relatively few in number. Even Sir Francis Bond Head—in no respect a man of sagacity—understood this well when he depended on the militia to crush the outbreak in the upper province; and Joseph Howe, the eminent leader of the popular party, uniformly asserted that the people of Nova Scotia were determined to preserve the integrity of the empire at all hazards. As a matter of fact, the majority of leading men, outside of the minority led by Papineau, Nelson and Mackenzie, had a conviction that England was animated by a desire to act considerately with the provinces and that little good would come from precipitating a conflict which could only add to the public misfortunes, and that the true remedy was to be found in constitutional methods of redress for the political grievances which undoubtedly existed throughout British North America.

The most important clauses of the Union Act, which was passed by the imperial parliament in 1840 but did not come into effect until February of the following year, made provision for a legislative assembly in which each section of the united provinces was represented by an equal number of members—forty-two for each and eighty-four for both; for the use of the English language alone in the written or printed proceedings of the legislature; for the placing of the public indebtedness of the two provinces at the union as a first charge on the revenues of the united provinces; for a two-thirds vote of the members of each House before any change could be made in the representation. These enactments, excepting the last which proved eventually to be in their interest, were resented by the French Canadians as clearly intended to place them in a position of inferiority to the English Canadians. Indeed it was with natural indignation they read that portion of Lord Durham’s report which expressed the opinion that it was necessary to unite the two races on terms which would give the domination to the English. “Without effecting the change so rapidly or so roughly,” he wrote, “as to shock the feelings or to trample on the welfare of the existing generation, it must henceforth be the first and steady purpose of the British government to establish an English population, with English laws and language, in this province, and to trust its government to none but a decidedly English legislature.”

French Canadians dwelt with emphasis on the fact that their province had a population of 630,000 souls, or 160,000 more than Upper Canada, and nevertheless received only the same number of representatives. French Canada had been quite free from the financial embarrassment which had brought Upper Canada to the verge of bankruptcy before the union; in fact the former had actually a considerable surplus when its old constitution was revoked on the outbreak of the rebellion. It was, consequently, with some reason, considered an act of injustice to make the people of French Canada pay the debts of a province whose revenue had not for years met its liabilities. Then, to add to these decided grievances, there was a proscription of the French language, which was naturally resented as a flagrant insult to the race which first settled the valley of the St. Lawrence, and as the first blow levelled against the special institutions so dear to French Canadians and guaranteed by the Treaty of Paris and the Quebec Act. Mr. LaFontaine, whose name will frequently occur in the following chapters of this book, declared, when he presented himself at the first election under the Union Act, that “it was an act of injustice and despotism”; but, as we shall soon see, he became a prime minister under the very act he first condemned. Like the majority of his compatriots, he eventually found in its provisions protection for the rights of the people, and became perfectly satisfied with a system of government which enabled them to obtain their proper position in the public councils and restore their language to its legitimate place in the legislature.

But without the complete grant of responsible government it would never have been possible to give to French Canadians their legitimate influence in the administration and legislation of the country, or to reconcile the differences which had grown up between the two nationalities before the union and seemed likely to be perpetuated by the conditions of the Union Act just stated. Lord Durham touched the weakest spot in the old constitutional system of the Canadian provinces when he said that it was not “possible to secure harmony in any other way than by administering the government on those principles which have been found perfectly efficacious in Great Britain.” He would not “impair a single prerogative of the crown”; on the contrary he believed “that the interests of the people of these provinces require the protection of prerogatives which have not hitherto been exercised.” But he recognized the fact as a constitutional statesman that “the crown must, on the other hand, submit to the necessary consequences of representative institutions; and if it has to carry on the government in unison with a representative body, it must consent to carry it on by means of those in whom that representative body has confidence.” He found it impossible “to understand how any English statesman could have ever imagined that representative and irresponsible government could be successfully combined.” To suppose that such a system would work well there “implied a belief that French Canadians have enjoyed representative institutions for half a century without acquiring any of the characteristics of a free people; that Englishmen renounce every political opinion and feeling when they enter a colony, or that the spirit of Anglo-Saxon freedom is utterly changed and weakened among those who are transplanted across the Atlantic.”

No one who studies carefully the history of responsible government from the appearance of Lord Durham’s report and Lord John Russell’s despatches of 1839 until the coming of Lord Elgin to Canada in 1847, can fail to see that there was always a doubt in the minds of the imperial authorities—a doubt more than once actually expressed in the instructions to the governors—whether it was possible to work the new system on the basis of a governor directly responsible to the parent state and at the same time acting under the advice of ministers directly responsible to the colonial parliament. Lord John Russell had been compelled to recognize the fact that it was not possible to govern Canada by the old methods of administration—that it was necessary to adopt a new colonial policy which would give a larger measure of political freedom to the people and ensure greater harmony between the executive government and the popular assemblies. Mr. Poulett Thomson, afterwards Lord Sydenham, was appointed governor-general with the definite objects of completing the union of the Canadas and inaugurating a more liberal system of colonial administration. As he informed the legislature of Upper Canada immediately after his arrival, in his anxiety to obtain its consent to the union, he had received “Her Majesty’s commands to administer the government of these provinces in accordance with the well understood wishes and interests of the people.” When the legislature of the united provinces met for the first time, he communicated two despatches in which the colonial secretary stated emphatically that, “Her Majesty had no desire to maintain any system or policy among her North American subjects which opinion condemns,” and that there was “no surer way of gaining the approbation of the Queen than by maintaining the harmony of the executive with the legislative authorities.” The governor-general was instructed, in order “to maintain the utmost possible harmony,” to call to his councils and to employ in the public service “those persons who, by their position and character, have obtained the general confidence and esteem of the inhabitants of the province.” He wished it to be generally made known by the governor-general that thereafter certain heads of departments would be called upon “to retire from the public service as often as any sufficient motives of public policy might suggest the expediency of that measure.” It appears, however, that there was always a reservation in the minds of the colonial secretary and of governors who preceded Lord Elgin as to the meaning of responsible government and the methods of carrying it out in a colony dependent on the crown. Lord Sydenham himself believed that the council should be one “for the governor to consult and no more”; that the governor could “not be responsible to the government at home and also to the legislature of the province,” for if it were so “then all colonial government becomes impossible.” The governor, in his opinion, “must therefore be the minister [i.e., the colonial secretary], in which case he cannot be under control of men in the colony.” But it was soon made clear to so astute a politician as Lord Sydenham that, whatever were his own views as to the meaning that should be attached to responsible government, he must yield as far as possible to the strong sentiment which prevailed in the country in favour of making the ministry dependent on the legislature for its continuance in office. The resolutions passed by the legislature in support of responsible government were understood to have his approval. They differed very little in words—in essential principle not at all—from those first introduced by Mr. Baldwin. The inference to be drawn from the political situation of that time is that the governor’s friends in the council thought it advisable to gain all possible credit with the public in connection with the all-absorbing question of the day, and accordingly brought in the following resolutions in amendment to those presented by the Liberal chief:—

“1. That the head of the executive government of the province, being within the limits of his government the representative of the sovereign, is responsible to the imperial authority alone, but that nevertheless the management of our local affairs can only be conducted by him with the assistance, counsel, and information of subordinate officers in the province.

“2. That in order to preserve between the different branches of the provincial parliament that harmony which is essential to the peace, welfare, and good government of the province, the chief advisers of the representative of the sovereign, constituting a provincial administration under him, ought to be men possessed of the confidence of the representatives of the people; thus affording a guarantee that the well-understood wishes and interests of the people—which our gracious sovereign has declared shall be the rule of the provincial government—will on all occasions be faithfully represented and advocated.

“3. That the people of this province have, moreover, the right to expect from such provincial administration the exercise of their best endeavours, that the imperial authority, within its constitutional limits, shall be exercised in the manner most consistent with their well-understood wishes and interests.”

It is quite possible that had Lord Sydenham lived to complete his term of office, the serious difficulties that afterwards arose in the practice of responsible government would not have occurred. Gifted with a clear insight into political conditions and a thorough knowledge of the working of representative institutions, he would have understood that if parliamentary government was ever to be introduced into the colony it must be not in a half-hearted way, or with such reservations as he had had in his mind when he first came to the province. Amid the regret of all parties he died from the effects of a fall from his horse a few months after the inauguration of the union, and was succeeded by Sir Charles Bagot, who distinguished himself in a short administration of two years by the conciliatory spirit which he showed to the French Canadians, even at the risk of offending the ultra loyalists who seemed to think, for some years after the union, that they alone were entitled to govern the dependency.

The first ministry after that change was composed of Conservatives and moderate Liberals, but it was soon entirely controlled by the former, and never had the confidence of Mr. Baldwin. That eminent statesman had been a member of this administration at the time of the union, but he resigned on the ground that it ought to be reconstructed if it was to represent the true sentiment of the country at large. When Sir Charles Bagot became governor the Conservatives were very sanguine that they would soon obtain exclusive control of the government, as he was known to be a supporter of the Conservative party in England. It was not long, however, before it was evident that his administration would be conducted, not in the interests of any set of politicians, but on principles of compromise and justice to all political parties, and, above all, with the hope of conciliating the French Canadians and bringing them into harmony with the new conditions. One of his first acts was the appointment of an eminent French Canadian, M. Vallières de Saint-Réal, to the chief-justiceship of Montreal. Other appointments of able French Canadians to prominent public positions evoked the ire of the Tories, then led by the Sherwoods and Sir Allan MacNab, who had taken a conspicuous part in putting down the rebellion of 1837-8. Sir Charles Bagot, however, persevered in his policy of attempting to stifle racial prejudices and to work out the principles of responsible government on broad national lines. He appointed an able Liberal and master of finance, Mr. Francis Hincks, to the position of inspector-general with a seat in the cabinet. The influence of the French Canadians in parliament was now steadily increasing, and even strong Conservatives like Mr. Draper were forced to acknowledge that it was not possible to govern the province on the principle that they were an inferior and subject people, whose representatives could not be safely entrusted with any responsibilities as ministers of the crown. Negotiations for the entrance of prominent French Canadians in opposition to the government went on without result for some time, but they were at last successful, and the first LaFontaine-Baldwin cabinet came into existence in 1842, largely through the instrumentality of Sir Charles Bagot. Mr. Baldwin was a statesman whose greatest desire was the success of responsible government without a single reservation. Mr. LaFontaine was a French Canadian who had wisely recognized the necessity of accepting the union he had at first opposed, and of making responsible government an instrument for the advancement of the interests of his compatriots and of bringing them into unison with all nationalities for the promotion of the common good. The other prominent French Canadian in the ministry was Mr. A. N. Morin, who possessed the confidence and respect of his people, but was wanting in the energy and ability to initiate and press public measures which his leader possessed.

The new administration had not been long in office when the governor-general fell a victim to an attack of dropsy, complicated by heart disease, and was succeeded by Sir Charles Metcalfe, who had held prominent official positions in India, and was governor of Jamaica previous to Lord Elgin’s appointment. No one who has studied his character can doubt the honesty of his motives or his amiable qualities, but his political education in India and Jamaica rendered him in many ways incapable of understanding the political conditions of a country like Canada, where the people were determined to work out the system of parliamentary government on strictly British principles. He could have obtained little assistance from British statesmen had he been desirous of mastering and applying the principles of responsible government to the dependency. Their opinions and instructions were still distinguished by a perplexing vagueness. They would not believe that a governor of a dependency could occupy exactly the same relation with respect to his responsible advisers and to political parties as is occupied with such admirable results by the sovereign of England. It was considered necessary that a governor should make himself as powerful a factor as possible in the administration of public affairs—that he should be practically the prime minister, responsible, not directly to the colonial legislature, but to the imperial government, whose servant he was and to whom he should constantly refer for advice and assistance whenever in his opinion the occasion arose. In other words it was almost impossible to remove from the mind of any British statesman, certainly not from the colonial office of those days, the idea that parliamentary government meant one thing in England and the reverse in the colonies, that Englishmen at home could be entrusted with a responsibility which it was inexpedient to allow to Englishmen or Frenchmen across the sea. The colonial office was still reluctant to give up complete control of the local administration of the province, and wished to retain a veto by means of the governor, who considered official favour more desirable than the approval of any colonial legislature. More or less imbued with such views, Sir Charles Metcalfe was bound to come into conflict with LaFontaine and Baldwin, who had studied deeply the principles and practice of parliamentary government, and knew perfectly well that they could be carried out only by following the precedents established in the parent state.

It was not long before the rupture came between men holding views so diametrically opposed to each other with respect to the conduct of government. The governor-general decided not to distribute the patronage of the crown under the advice of his responsible ministry, as was, of necessity, the constitutional practice in England, but to ignore the latter, as he boldly declared, whenever he deemed it expedient. “I wish,” he wrote to the colonial secretary, “to make the patronage of the government conducive to the conciliation of all parties by bringing into the public service men of the greatest merit and efficiency without any party distinction.” These were noble sentiments, sound in theory, but entirely incompatible with the operation of responsible government. If patronage is to be properly exercised in the interests of the people at large, it must be done by men who are directly responsible to the representatives of the people. If a governor-general is to make appointments without reference to his advisers, he must be more or less subject to party criticism, without having the advantage of defending himself in the legislature, or of having men duly authorized by constitutional usage to do so. The revival of that personal government which had evoked so much political rancour, and brought governors into the arena of party strife before the rebellion, was the natural result of the obstinate and unconstitutional attitude assumed by Lord Metcalfe with respect to appointments to office and other matters of administration.

All the members of the LaFontaine-Baldwin government, with the exception of Mr. Dominick Daly, resigned in consequence of the governor’s action. Mr. Daly had no special party proclivities, and found it to his personal interests to remain his Excellency’s sole adviser. Practically the province was without an administration for many months, and when, at last, the governor-general was forced by public opinion to show a measure of respect for constitutional methods of government, he succeeded after most strenuous efforts in forming a Conservative cabinet, in which Mr. Draper was the only man of conspicuous ability. The French Canadians were represented by Mr. Viger and Mr. Denis B. Papineau, a brother of the famous rebel, neither of whom had any real influence or strength in Lower Canada, where the people recognized LaFontaine as their true leader and ablest public man. In the general election which soon followed the reconstruction of the government, it was sustained by a small majority, won only by the most unblushing bribery, by bitter appeals to national passion, and by the personal influence of the governor-general, as was the election which immediately preceded the rising in Upper Canada. In later years, Lord Grey[4] remarked that this success was “dearly purchased, by the circumstance that the parliamentary opposition was no longer directed against the advisers of the governor but against the governor himself, and the British government, of which he was the organ.” The majority of the government was obtained from Upper Canada, where a large body of people were misled by appeals made to their loyalty and attachment to the crown, and where a large number of Methodists were influenced by the extraordinary action of the Rev. Egerton Ryerson, a son of a United Empire Loyalist, who defended the position of the governor-general, and showed how imperfectly he understood the principles and practice of responsible government. In a life of Sir Charles Metcalfe,[5] which appeared shortly after his death, it is stated that the governor-general “could not disguise from himself that the government was not strong, that it was continually on the brink of defeat, and that it was only enabled to hold its position by resorting to shifts and expedients, or what are called tactics, which in his inmost soul Lord Metcalfe abhorred.”

The action of the British ministry during this crisis in Canadian affairs proved quite conclusively that it was not yet prepared to concede responsible government in its fullest sense. Both Lord Stanley, then secretary of state for the colonies, and Lord John Russell, who had held the same office in a Whig administration, endorsed the action of the governor-general, who was raised to the peerage under the title of Baron Metcalfe of Fernhill, in the county of Berks. Earthly honours were now of little avail to the new peer. He had been a martyr for years to a cancer in the face, and when it assumed a most dangerous form he went back to England and died soon after his return. So strong was the feeling against him among a large body of the people, especially in French Canada, that he was bitterly assailed until the hour when he left, a dying man. Personally he was generous and charitable to a fault, but he should never have been sent to a colony at a crisis when the call was for a man versed in the practice of parliamentary government, and able to sympathize with the aspirations of a people determined to enjoy political freedom in accordance with the principles of the parliamentary institutions of England. With a remarkable ignorance of the political conditions of the province—too often shown by British statesmen in those days—so great a historian and parliamentarian as Lord Macaulay actually wrote on a tablet to Lord Metcalfe’s memory:—“In Canada, not yet recovered from the calamities of civil war, he reconciled contending factions to each other and to the mother country.” The truth is, as written by Sir Francis Hincks[6] fifty years later, “he embittered the party feeling that had been considerably assuaged by Sir Charles Bagot.”

Lord Metcalfe was succeeded by Lord Cathcart, a military man, who was chosen because of the threatening aspect of the relations between England and the United States on the question of the Oregon boundary. During his short term of office he did not directly interfere in politics, but carefully studied the defence of the country and quietly made preparations for a rupture with the neighbouring republic. The result of his judicious action was the disappearance of much of the political bitterness which had existed during Lord Metcalfe’s administration. The country, indeed, had to face issues of vital importance to its material progress. Industry and commerce were seriously affected by the adoption of free trade in England, and the consequent removal of duties which had given a preference in the British markets to Canadian wheat, flour, and other commodities. The effect upon the trade of the province would not have been so serious had England at this time repealed the old navigation laws which closed the St. Lawrence to foreign shipping and prevented the extension of commerce to other markets. Such a course might have immediately compensated Canadians for the loss of those of the motherland. The anxiety that was generally felt by Canadians on the reversal of the British commercial policy under which they had been able to build up a very profitable trade, was shown in the language of a very largely signed address from the assembly to the Queen. “We cannot but fear,” it was stated in this document, “that the abandonment of the protective principle, the very basis of the colonial commercial system, is not only calculated to retard the agricultural improvement of the country and check its hitherto rising prosperity, but seriously to impair our ability to purchase the manufactured goods of Great Britain—a result alike prejudicial to this country and the parent state.” But this appeal to the selfishness of British manufacturers had no influence on British statesmen so far as their fiscal policy was concerned. But while they were not prepared to depart in any measure from the principles of free trade and give the colonies a preference in British markets over foreign countries, they became conscious that the time had come for removing, as far as possible, all causes of public discontent in the provinces, at this critical period of commercial depression. British statesmen had suddenly awakened to the mistakes of Lord Metcalfe’s administration of Canadian affairs, and decided to pursue a policy towards Canada which would restore confidence in the good faith and justice of the imperial government. “The Queen’s representative”—this is a citation from a London paper[7] supporting the Whig government—“should not assume that he degrades the crown by following in a colony with a constitutional government the example of the crown at home. Responsible government has been conceded to Canada, and should be attended in its workings with all the consequences of responsible government in the mother country. What the Queen cannot do in England the governor-general should not be permitted to do in Canada. In making imperial appointments she is bound to consult her cabinet; in making provincial appointments the governor-general should be bound to do the same.”

The Oregon dispute had been settled, like the question of the Maine boundary, without any regard to British interests in America, and it was now deemed expedient to replace Lord Cathcart by a civil governor, who would be able to carry out, in the valley of the St. Lawrence, the new policy of the colonial office, and strengthen the ties between the province and the parent state.

As I have previously stated, Lord John Russell’s ministry made a wise choice in the person of Lord Elgin. In the following pages I shall endeavour to show how fully were realized the high expectations of those British statesmen who sent him across the Atlantic at this critical epoch in the political and industrial conditions of the Canadian dependency.

|

“The Colonial Policy of Lord John Russell’s Administration,” by Earl Grey, London, 1857. See Vol. I, p. 205. |

|

The “Life and Correspondence of Charles, Lord Metcalfe,” by John W. Kaye, London, 1858. |

|

“Reminiscences of his public life,” by Sir Francis Hincks, K.C.M.G., C.B., Montreal, 1884. |

|

See “McMullen’s History of Canada,” Vol. II (2nd Ed.), p. 201. |

Lord Elgin made a most favourable impression on the public opinion of Canada from the first hour he arrived in Montreal, and had opportunities of meeting and addressing the people. His genial manner, his ready speech, his knowledge of the two languages, his obvious desire to understand thoroughly the condition of the country and to pursue British methods of constitutional government, were all calculated to attract the confidence of all nationalities, classes, and creeds. The supporters of responsible government heard with infinite pleasure the enunciation of the principles which would guide him in the discharge of his public duties. “I am sensible,” he said in answer to a Montreal address, “that I shall but maintain the prerogative of the Crown, and most effectually carry out the instructions with which Her Majesty has honoured me, by manifesting a due regard for the wishes and feelings of the people and by seeking the advice and assistance of those who enjoy their confidence.”

At this time the Draper Conservative ministry, formed under such peculiar circumstances by Lord Metcalfe, was still in office, and Lord Elgin, as in duty bound, gave it his support, although it was clear to him and to all other persons at all conversant with public opinion that it did not enjoy the confidence of the country at large, and must soon give place to an administration more worthy of popular favour. He recognized the fact that the crucial weakness in the political situation was “that a Conservative government meant a government of Upper Canadians, which is intolerable to the French, and a Radical government meant a government of French, which is no less hateful to the British.” He believed that the political problem of “how to govern united Canada”—and the changes which took place later showed he was right—would be best solved “if the French would split into a Liberal and Conservative party, and join the Upper Canada parties which bear corresponding names.” Holding these views, he decided at the outset to give the French Canadians full recognition in the reconstruction or formation of ministries during his term of office. And under all circumstances he was resolved to give “to his ministers all constitutional support, frankly and without reserve, and the benefit of the best advice” that he could afford them in their difficulties. In return for this he expected that they would, “in so far as it is possible for them to do so, carry out his views for the maintenance of the connection with Great Britain and the advancement of the interests of the province.” On this tacit understanding, they—the governor-general and the Draper-Viger cabinet—had “acted together harmoniously,” although he had “never concealed from them that he intended to do nothing” which would “prevent him from working cordially with their opponents.” It was indispensable that “the head of the government should show that he has confidence in the loyalty of all the influential parties with which he has to deal, and that he should have no personal antipathies to prevent him from acting with leading men.”

Despite the wishes of Lord Elgin, it was impossible to reconstruct the government with a due regard to French Canadian interests. Mr. Caron and Mr. Morin, both strong men, could not be induced to become ministers. The government continued to show signs of disintegration. Several members resigned and took judgeships in Lower Canada. Even Mr. Draper retired with the understanding that he should also go on the bench at the earliest opportunity in Upper Canada. Another effort was made to keep the ministry together, and Mr. Henry Sherwood became its head; but the most notable acquisition was Mr. John Alexander Macdonald as receiver-general. From that time this able man took a conspicuous place in the councils of the country, and eventually became prime minister of the old province of Canada, as well as of the federal dominion which was formed many years later in British North America, largely through his instrumentality. From his first entrance into politics he showed that versatility of intellect, that readiness to adapt himself to dominant political conditions and make them subservient to the interests of his party, that happy faculty of making and keeping personal friends, which were the most striking traits of his character. His mind enlarged as he had greater experience and opportunities of studying public life, and the man who entered parliament as a Tory became one of the most Liberal Conservatives who ever administered the affairs of a colonial dependency, and, at the same time, a statesman of a comprehensive intellect who recognized the strength of British institutions and the advantage of British connection.

The obvious weakness of the reconstructed ministry was the absence of any strong men from French Canada. Mr. Denis B. Papineau was in no sense a recognized representative of the French Canadians, and did not even possess those powers of eloquence—that ability to give forth “rhetorical flashes”—which were characteristic of his reckless but highly gifted brother. In fact the ministry as then organized was a mere makeshift until the time came for obtaining an expression of opinion from the people at the polls. When parliament met in June, 1847, it was quite clear that the ministry was on the eve of its downfall. It was sustained only by a feeble majority of two votes on the motion for the adoption of the address to the governor-general. The opposition, in which LaFontaine, Baldwin, Aylwin, and Chauveau were the most prominent figures, had clearly the best of the argument in the political controversies with the tottering ministry. Even in the legislative council resolutions, condemning it chiefly on the ground that the French province was inadequately represented in the cabinet, were only negatived by the vote of the president, Mr. McGill, a wealthy merchant of Montreal, who was also a member of the administration.

Despite the weakness of the government, the legislature was called upon to deal with several questions which pressed for immediate action. Among the important measures which were passed was one providing for the amendment of the law relating to forgery, which was no longer punishable by death. Another amended the law with respect to municipalities in Lower Canada, which, however, failed to satisfy the local requirements of the people, though it remained in force for eight years, when it was replaced by one better adapted to the conditions of the French province. The legislature also discussed the serious effects of free trade upon Canadian industry, and passed an address to the Crown praying for the repeal of the laws which prevented the free use of the St. Lawrence by ships of all nations. But the most important subject with which the government was called upon to deal was one which stifled all political rivalry and national prejudices, and demanded the earnest consideration of all parties. Canada, like the rest of the world, had heard of an unhappy land smitten with a hideous plague, of its crops lying in pestilential heaps and of its peasantry dying above them, of fathers, mothers, and children ghastly in their rags or nakedness, of dead unburied, and the living flying in terror, as it were, from a stricken battlefield. This dreadful Irish famine forced to Canada upwards of 100,000 persons, the greater number of whom were totally destitute and must have starved to death had they not received public or private charity. The miseries of these unhappy immigrants were aggravated to an inconceivable degree by the outbreak of disease of a most malignant character, stimulated by the wretched physical condition and by the disgraceful state of the pest ships in which they were brought across the ocean. In those days there was no effective inspection or other means taken to protect from infection the unhappy families who were driven from their old homes by poverty and misery. From Grosse Isle, the quarantine station on the Lower St. Lawrence, to the most distant towns in the western province, many thousands died in awful suffering, and left helpless orphans to evoke the aid and sympathy of pitying Canadians everywhere. Canada was in no sense responsible for this unfortunate state of things. The imperial government had allowed this Irish immigration to go on without making any effort whatever to prevent the evils that followed it from Ireland to the banks of the St. Lawrence and the Great Lakes. It was a heavy burden which Canada should never have been called upon to bear at a time when money was scarce and trade was paralyzed by the action of the imperial parliament itself. Lord Elgin was fully alive to the weighty responsibility which the situation entailed upon the British government, and at the same time did full justice to the exertions of the Canadian people to cope with this sad crisis. The legislature voted a sum of money to relieve the distress among the immigrants, but it was soon found entirely inadequate to meet the emergency.

Lord Elgin did not fail to point out to the colonial secretary “the severe strain” that this sad state of things made, not only upon charity, but upon the very loyalty of the people to a government which had shown such culpable negligence since the outbreak of the famine and the exodus from the plague-stricken island. He expressed the emphatic opinion that “all things considered, a great deal of forbearance and good feeling had been shown by the colonists under this trial.” He gave full expression to the general feeling of the country that “Great Britain must make good to the province the expenses entailed on it by this visitation.” He did full justice to the men and women who showed an extraordinary spirit of self-sacrifice, a positive heroism, during this national crisis. “Nothing,” he wrote, “can exceed the devotion of the nuns and Roman Catholic priests, and the conduct of the clergy and of many of the laity of other denominations has been most exemplary. Many lives have been sacrificed in attendance on the sick, and administering to their temporal and spiritual need. . . . This day the Mayor of Montreal, Mr. Mills, died, a very estimable man, who did much for the immigrants, and to whose firmness and philanthropy we chiefly owe it, that the immigrant sheds here were not tossed into the river by the people of the town during the summer. He has fallen a victim to his zeal on behalf of the poor plague-stricken strangers, having died of ship fever caught at the sheds.” Among other prominent victims were Dr. Power, Roman Catholic Bishop of Toronto, Vicar-General Hudon of the same church, Mr. Roy, curé of Charlesbourg, and Mr. Chaderton, a Protestant clergyman. Thirteen Roman Catholic priests, if not more, died from their devotion to the unhappy people thus suddenly thrown upon their Christian charity. When the season of navigation was nearly closed, a ship arrived with a large number of people from the Irish estates of one of Her Majesty’s ministers, Lord Palmerston. The natural result of this incident was to increase the feeling of indignation already aroused by the apathy of the British government during this national calamity. Happily Lord Elgin’s appeals to the colonial secretary had effect, and the province was reimbursed eventually for the heavy expenses incurred by it in its efforts to fight disease, misery and death. English statesmen, after these painful experiences, recognized the necessity of enforcing strict regulations for the protection of emigrants crossing the ocean, against the greed of ship-owners. The sad story of 1847-8 cannot now be repeated in times when nations have awakened to their responsibilities towards the poor and distressed who are forced to leave their old homes for that new world which offers them well-paid work, political freedom, plenty of food and countless comforts.

In the autumn of 1847, Lord Elgin was able to seek some relief from his many cares and perplexities of government, in a tour of the western province, where, to quote his own words, he met “a most gratifying and encouraging reception.” He was much impressed with the many signs of prosperity which he saw on all sides. “It is indeed a glorious country,” he wrote enthusiastically to Lord Grey, “and after passing, as I have done within the last fortnight, from the citadel of Quebec to the falls of Niagara, rubbing shoulders the while with its free and perfectly independent inhabitants, one begins to doubt whether it be possible to acquire a sufficient knowledge of man or nature, or to obtain an insight into the future of nations, without visiting America.” During this interesting visit to Upper Canada, he seized the opportunity of giving his views on a subject which may be considered one of his hobbies, one to which he devoted much attention while in Jamaica, and this was the formation of agricultural associations for the purpose of stimulating scientific methods of husbandry.

Before the close of the first year of his administration Lord Elgin felt that the time had come for making an effort to obtain a stronger ministry by an appeal to the people. Accordingly he dissolved parliament in December, and the elections, which were hotly contested, resulted in the unequivocal condemnation of the Sherwood cabinet, and the complete success of the Liberal party led by LaFontaine and Baldwin. Among the prominent Liberals returned by the people of Upper Canada were Baldwin, Hincks, Blake, Price, Malcolm Cameron, Richards, Merritt and John Sandfield Macdonald. Among the leaders of the same party in Lower Canada were LaFontaine, Morin, Aylwin, Chauveau and Holmes. Several able Conservatives lost their seats, but Sir Allan MacNab, John A. Macdonald, Mr. Sherwood and John Hillyard Cameron succeeded in obtaining seats in the new parliament, which was, in fact, more notable than any other since the union for the ability of its members. Not the least noteworthy feature of the elections was the return of Mr. Louis J. Papineau, and Mr. Wolfred Nelson, rebels of 1837-8, both of whom had been allowed to return some time previously to the country. Mr. Papineau’s career in parliament was not calculated to strengthen his position in impartial history. He proved beyond a doubt that he was only a demagogue, incapable of learning lessons of wise statesmanship during the years of reflection that were given him in exile. He continued to show his ignorance of the principles and workings of responsible government. Before the rebellion which he so rashly and vehemently forced on his credulous, impulsive countrymen, so apt to be deceived by flashy rhetoric and glittering generalities, he never made a speech or proposed a measure in support of the system of parliamentary government as explained by Baldwin and Howe, and even W. Lyon Mackenzie. His energy and eloquence were directed towards the establishment of an elective legislative council in which his compatriots would have necessarily the great majority, a supremacy that would enable him and his following to control the whole legislation and government, and promote his dominant idea of a Nation Canadienne in the valley of the St. Lawrence. After the union he made it the object of his political life to thwart in every way possible the sagacious, patriotic plans of LaFontaine, Morin, and other broad-minded statesmen of his own nationality, and to destroy that system of responsible government under which French Canada had become a progressive and influential section of the province.

As soon as parliament assembled at the end of February, the government was defeated on the vote for the speakership. Its nominee, Sir Allan MacNab, received only nineteen votes out of fifty-four, and Morin, the Liberal candidate, was then unanimously chosen. When the address in reply to the governor-general’s speech came up for consideration, Baldwin moved an amendment, expressing a want of confidence in the ministry, which was carried by a majority of thirty votes in a house of seventy-four members, exclusive of the speaker, who votes only in case of a tie. Lord Elgin received and answered the address as soon as it was ready for presentation, and then sent for LaFontaine and Baldwin.

He spoke to them, as he tells us himself, “in a candid and friendly tone,” and expressed the opinion that “there was a fair prospect, if they were moderate and firm, of forming an administration deserving and enjoying the confidence of parliament.” He added that “they might count on all proper support and assistance from him.” When they “dwelt on difficulties arising out of pretensions advanced in various quarters,” he advised them “not to attach too much importance to such considerations, but to bring together a council strong in administrative talent, and to take their stand on the wisdom of their measures and policy.” The result was the construction of a powerful government by LaFontaine with the aid of Baldwin. “My present council,” Lord Elgin wrote to the colonial secretary, “unquestionably contains more talent, and has a firmer hold on the confidence of parliament and of the people than the last. There is, I think, moreover, on their part, a desire to prove, by proper deference for the authority of the governor-general (which they all admit has in my case never been abused), that they were libelled when they were accused of impracticability and anti-monarchical tendencies.” These closing words go to show that the governor-general felt it was necessary to disabuse the minds of the colonial secretary and his colleagues of the false impression which the British government and people seemed to entertain, that the Tories and Conservatives were alone to be trusted in the conduct of public affairs. He saw at once that the best way of strengthening the connection with Great Britain was to give to the strongest political party in the country its true constitutional position in the administration of public affairs, and identify it thoroughly with the public interests.

The new government was constituted as follows:

Lower Canada.—Hon. L. H. LaFontaine, attorney-general of Lower Canada; Hon. James Leslie, president of the executive council; Hon. R. E. Caron, president of the legislative council; Hon. E. P. Taché, chief commissioner of public works; Hon. I. C. Aylwin, solicitor-general for Lower Canada; Hon. L. M. Viger, receiver-general.

Upper Canada.—Hon. Robert Baldwin, attorney-general of Upper Canada; Hon. R. B. Sullivan, provincial secretary; Hon. F. Hincks, inspector-general; Hon. J. H. Price, commissioner of crown lands; Hon. Malcolm Cameron, assistant commissioner of public works; Hon. W. H. Blake, solicitor-general.