* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

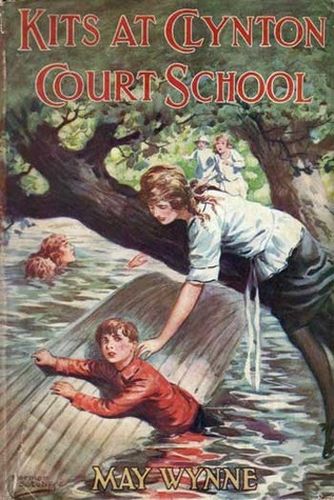

Title: Kits at Clynton Court School

Date of first publication: 1924

Author: Mabel Winifred Knowles (pseudonym May Wynne) (1875-1949)

Illustrator: Norman Sutcliffe

Date first posted: July 3, 2024

Date last updated: July 3, 2024

Faded Page eBook #20240701

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

KITS AT

CLYNTON COURT

SCHOOL

BY

MAY WYNNE

Author of

“The Best of Chums,” “Peggy’s First Term,”

“Angela Goes to School,”

Etc.

LONDON

FREDERICK WARNE AND CO., LTD.,

AND NEW YORK

1924

(All rights reserved)

Printed in Great Britain

Dedicated to

“JOAN”

KITS AT

CLYNTON COURT SCHOOL

“Do come over here, Pearl,” urged Roseleen excitedly, “it’s . . . a girl . . . in the grocer’s cart. It looks as if it might be the new girl who ought to have come last week—only it can’t be! The grocer boy is grinning like anything—and yes! he is handing her down a hockey stick . . . and a bag, and she is actually shaking hands. Really if that’s not the limit! Wherever can Miss Carwell have got her from?”

Pearl Willock crossed to the side of her friend. The two girls were alone in the deserted schoolroom; and their interest for the moment was wholly given to the new arrival.

“One of the new rich class,” drawled Pearl disdainfully, “but I agree with you. It will be horrid getting another girl of that sort in the school. The Welbracks are quite enough. I wish one of the govs. could see her. I have a good mind to tell Miss Pasfold.”

The object of their disdain, a tall, well-built girl of fifteen, with a mop of brown curls had already disappeared into the house. Of course, she must be the new girl—and a horror.

“Let’s go down to the garden room,” suggested Roseleen, “or we shall be asked to look after the freak. All the other girls are in the play ground.”

Too late! Already the schoolroom door was opening, and Miss Carwell, the head-mistress of Clynton Court School, came in with the girl who had just arrived.

Such a happy, merry-eyed girl, with freckled face and a pair of the very bluest of blue eyes; there was an enquiring look about her small, tip-tilted nose, and good-humour round her smiling lips.

“This is Kits Kerwayne, girls,” said Miss Carwell, “your new school-fellow. Kits dear, these are Pearl Willock and Roseleen O’Fyne. I am sure they will take you under their wing and make you feel at home. Pearl, child, take Kits up to Miss Sesson’s room, and she will show her where she is to sleep and help her unpack. By the time you are ready, Kits, it will be dinner time.”

Miss Carwell turned away, she was very busy, and felt quite satisfied that she left the new girl in good hands.

Kits was looking with smiling enquiry from one to the other of those new comrades.

“I’ve never been to school before,” she said frankly, “so I’m awfully at sea. I expect—er—it will be jolly when I’m used to it.”

Pearl shrugged her shoulders, she was a pretty fair girl, extremely lady-like in appearance and slightly affected in manner.

“I can’t say I find school a particularly jolly place myself,” she retorted, with a most unfriendly stare, “but if you’ll come upstairs I’ll show you Miss Sesson’s room.”

Poor Kits! She felt the chill of the remark, and stood suddenly shy and uncomfortable before her critics. Were the girls all going to be like this? Roger and Ned had told her it was a billion to one she would hate school—and they seemed likely to be right—though she had loved the look of this grand old house, with its woods and fields and unschoollike air of ancient romance.

It was at this moment, when the newcomer was really in danger of being frozen stiff, that the door opened and in tumbled a very different-looking young woman, who, leaving the door open, shouted gleefully over her shoulder to some one still mounting the stairs.

“Winner, snail! You’re no good to race. Hullo! are you the new girl?—and did you arrive in the grocer’s cart just now?”

Kits thawed at once. This untidy, jolly maiden with two enormous plaits of red hair, and the roundest of moon faces was—human. She also looked friendly, and Kits responded gratefully.

“Yes, I’m Kits Kerwayne. I couldn’t come back—on the right day because of quarantine, and—I suppose I came by the wrong train to-day—there wasn’t a cab anywhere—and the grocer’s boy was a dear. I couldn’t have walked.”

Trixie roared. She had seen the expressions of superior disdain on the faces of her other school-fellows and knew what they meant.

“You’re a sport,” she applauded, “most new bugs would have sat on their boxes and howled. The grocer’s boy deserves a putty medal. What’s happening? Are you coming to view the domain, or——.”

Roseleen struck in hastily.

“Miss Carwell wants her to go up to Miss Sesson and be shown her room. Will you take her with you, Trixie? Come along, Pearl. We shall have time for a game of tennis.”

Trixie, perched on the edge of one of the long tables, grimaced after the departing pair, then looked at Kits and laughed.

“Fancy falling into the hands of the Prims!” she chuckled. “Poor you! And you shocked them in one act. For the rest of your stay at Clynton Court the Prims will bracket you and the grocer’s cart together. Never mind, don’t take it to heart. The Prims are harmless and concern no one. Come in, Pickles, and be introduced. The grocer’s cart chum is all right.”

Kits laughed outright, but she was no longer forlorn. A pretty imp of a girl, with bobbed hair and the very thinnest of thin arms was peeping in on them.

“Allow me,” quoth Trixie, with mock grandeur, “to introduce Pamela Irene Spandock—otherwise Pickles—the darling of our Crew. Come in and have a good look at Kits, my dear Pickles, she’s worth a survey, though I’ve not yet asked her to be our most faithful and devoted comrade. Are we making your head buzz, Kits? If so, it’s nothing to what it will be during dinner! Come along to Miss Sesson, and ask her to put you in No. 8, we have room for a little one, and I don’t think your constitution would survive being put to bye-byes with the Prims.”

Kits chuckled.

“You’ve done me good,” she said, gratefully, “I . . . well! it’s my first experience of school, and it was awful. Do let me glue myself on to you? And are most of the girls like those first two?”

Pickles skipped in delight.

“A school full of Prims! Why, we should suffocate or require padded rooms,” she gurgled, “but we’re a mixed lot, my angel, and require a lot of weeding out. It’s no use to explain. You’ll have to feel your feet if you’ve never been to school. Has any one taught you the A.B.C.?”

“I’ve always shared a governess with a friend,” replied Kits, nodding, “I went to her house every day. It was quite jolly. Then her mother thought she had better go to Lausanne to be polished off, and, as our Dad didn’t like me to go abroad, I came here. You see, I’ve no sisters, only brothers—four of them, all darlings who don’t count me as a sister—I’m one of themselves. They did pity me, coming to school.”

She pitied herself too at the present moment, though, of course, it would have been ever so much worse without Trixie and Pickles, who took entire possession of her.

Actually, Kits had not known she could be shy till the moment she found herself marshalled to her place in the long dining hall, with thirty pairs of bright, inquisitive eyes regarding her.

Trixie was sympathetic.

“Rude cats,” she said, sotto voce, “don’t you want to put your tongue out at them? I should! Of course, it is because you’ve come back late. New girls don’t generally have so much attention. Lucky for you it is a half holiday. I’ve told Noreen and Jane that we are going for a tramp over the moors. Have you any special and particular liking for a cave—with stalactites and mysterious echoes? It’s the Crew’s happy hunting ground. We are the Crew.”

A thin, high pitched voice came echoing down from the head of the table.

“Beatrix, you disobey! To talk it is not permitted. Taisez-vous. You receive punishment if I speak again.”

Trixie grimaced. After all, she had only been whispering to encourage a shy newcomer, and had hoped Alda Wenton’s broad shoulders were hiding her from Mademoiselle. But it required very broad shoulders, or very dark corners to hide anything from Mademoiselle’s sharp eyes.

Kits decided that she should never like the vinegar-cruet of a woman, with her stiff angles and pointed features. The gentle-faced, grey-haired lady at the other end looked much nicer—not a bit like Kits’ idea of a governess.

The dining hall was a double room, with two long tables running the whole length. To Kits it all seemed a great bustle and bewilderment. She didn’t want her dinner, yet dared not leave it for fear of being spoken to by Mademoiselle. It was real relief when the meal was over and her faithful “protectors” succeeded in drawing her away from the crowd of girls, who were making up for lost time by chatting like a flock of magpies.

“You are sleeping in No. 7 with Joyce Wayde,” said Trixie, as they ran upstairs. “No, she’s not one of the Crew, but quite a good sort, rather quiet and mooney, with eyes for no one but Gwenda. Did you notice Gwen? A big fair girl—with a trick of fluttering her eye-lids. She’s a genius—but not a ripping genius like Crystal Colton—who is one of us—and a perfect scream. She is one of the latecomers, too. She won’t be back till to-morrow, then we shall all sit up and take notice. Here’s No. 7. Oh, you have unpacked of course. Get on a hat and sports coat and wait on the landing. I must collect the others.”

Kits still felt breathless. She wondered whether she ever would get to know this world of girls by name, or how long it would take her to learn the ropes. Trixie was the kindest of teachers, but—well! she did talk rather fast, and Kits had collected only one or two outstanding facts. The girls with whom she was to chum called themselves the “Crew”, and loved fun and mischief, whilst two others at least were known as the Prims, and embodied the perfect sketch that Roger and Ned had made of “Ye youthful school-girl.”

“I’m jolly glad we don’t have to walk two and two,” thought Kits, as she flung open her room door, “but I wonder whether we have to have a governess with us? I thought we always should, and I can picture Mademoiselle in a cave. Oh!”

She came to a halt at sight of the other girl in the room. This would be her bedroom companion Joyce Wayde, and as there was no one else to introduce her she would have to do it herself. Kits grinned and held out her hand.

“I’m Kits Kerwayne,” said she, “and you’re Joyce Wayde I’m sure. Are you coming out on the moors with us?”

Joyce blushed. She was a tall, slender girl, not exactly pretty—she was too pale for that, but she had big grey eyes, and very soft brown hair, which she wore in a plait. Her face suggested a sensitive nature, reserved and shy—by no means the ideal comrade for mad pranks or merry fun, but the sort of friend who would be a friend through thick and thin, if she once gave her love. She shook her head hurriedly at Kits’ question.

“Oh no,” she replied, “I am going into the town with Miss Carwell. Is there anything I can get for you? Oh, I forgot. You have only just come. Can I help you to find anything?”

Kits laughed.

“No thanks,” she replied brightly, “Trixie Dean and some of her friends are taking me for a walk over the moors. I’ve never been in Yorkshire before. The moors look ripping!”

Joyce flushed.

“Of course, I love it,” she replied simply, “Clynton is my home. I live—at least my home is—on the other side of the village about three miles away. The moors are my friends if you can understand?”

Kits nodded.

“Rather! I’ve lived all my life in Kent—near the sea. I hated coming here, but I believe I’ll like it. Now I must bustle, or the others will be waiting.” And, snatching up her cap, Kits ran off whistling. Yes,—actually and openly whistling, to the horror of Mademoiselle—who was just coming upstairs.

Trixie & Co. faded into the back-ground, convulsed with laughter, as the French governess exclaimed in horror at that most deliberate, most unheard-of crime—the whistling on the stairs.

“But you . . . you have ze air of a gamin of ze streets,” Mademoiselle concluded, “it is not so the demoiselles of Clynton Court conduct themselves. It is told me you arrive in the carriage of ze grocaire! And here you stand, ze cap set at ze back of your head—your legs apart, . . . and with your lips you do whistle. It is a disgrace, my dear, you shall not permit to happen again.”

Kits looked quite bewildered, and blushed to her eyes.

“I’m very, very sorry,” she replied, “awfully sorry. I . . . well! I always have whistled, all my life. I never thought of it being wrong.”

Mademoiselle sighed the sigh of hopelessness and despair. This new pupil was, she felt convinced from the first, destined to be a thorn in her side.

Meantime, with the passing of Mademoiselle, merry comrades surrounded Kits once more, whirling her away in consoling fashion which for ever wiped from her vision the picture of demure little maidens walking two and two, neither swinging their arms or turning in their toes!

Clynton Court had never been built for a girls’ school. It was a fine, imposing white house, set in a hollow of the moors, with wooded grounds stretching away almost as far as the banks of the Ribble. There were fields for the playing of hockey and cricket, wooded dells for rambles and picnicking, and . . . an occasional chance for boating when Miss Evelton, the sportsmistress, had time to take a favoured few under her care.

Kits was “all eyes for everything.”

“I love cricket,” she confessed, “nearly all games but croquet are jolly, but the boys and I love birds-nesting and collections of all sorts. Fossils are our favourites. In Kent there are such ripping chalk pits, we go and spend hours in them, and we find all the treasures of the deep. Old arrow heads, fossilized shells and snails, it’s grand fun. I suppose there aren’t any chalk pits round here?”

“Never heard of any,” quoth Trixie, her eyes twinkling, for already she had recognized a kindred spirit, “but there are fossils, and I believe an old coal mine. Crystal will tell you. She collects fossils and antiques, so she’ll welcome you to her heart. Now, Pickles, what are you up to? Is it a bull, or——?”

Pamela had scrambled to the top of a heathery hill, and was viewing the landscape.

“No,” she shouted back regretfully, “no such a thrill, but there’s a car turning in through the gates—and I fancy—I’m almost certain I saw Crys.”

“She said she wasn’t coming till to-morrow,” said Noreen and Jane in a breath, and Kits looked in some amusement at the speakers.

Of all this merry band of new comrades the twins roused her speculations most. They didn’t look as if they were brimming with fun or mischief, though it almost made you smile to look at them at all! They were so exactly like a pair of tall Dutch dolls, with funny little plaits of black hair, rosy cheeks and the roundest brown eyes. Noreen seemed to be the spokeswoman and Jane the echo. How was it they came to be part of the Crew with a Pickles and a Trixie?

Kits rubbed her nose thoughtfully, whilst Pickles, descending from the hill top, tucked her arm through Trixie’s.

“Let’s race for the Cave,” she suggested. “Shew Kits round and get back early. We can go down to the Dell after tea if Crystal has come, and have a meeting to elect Kits in style. Of course, you want to be elected, eh, Kits?”

Kits beamed.

“Does that mean being one of the Crew?” she asked. “Rather! And I shall write to Ned and Roger to-night, and tell them they were absolutely out of it about girls’ schools, though at first—oh, those Prims did give me shocks!”

“Serve you right for mounting ze carriage of ze grocaire,” retorted Trixie. “Now, one, two, three and away! as far as that sort of cairn of rocks to the left, Kits. Off!”

Kits could run—and she meant to let these girls know it. But, alas! running over a heather-clad moor needs practice—and Kits “won her spurs”—not by arriving first at the cairn, but by turning a complete somersault, and picking herself up promptly to continue the race!

Pickles crowed her bravas like a cock, as she stood flapping her long arms from the summit of a rock.

“You’ll do,” said she. “No squashiness about you. Never mind the mud on your skirt, it’s the brown badge of courage. Here’s the Cave. Not a very mysterious affair but O.K. for the Grand Council meetings of the Crew.”

Kits was down on her hands and knees, only too ready to crawl through the rocky opening which led into a circular cave—one of those many hiding places of the moors. Stalactites hung from the roof and thin trickles of water had been petrified against the rocky walls giving an appearance of dampness.

“Here we sit and jawbate,” said Trixie, “or at times, if possible, bring Crystal’s symplelite lamp and make ye olde world toffee which sticks to your ribs, likewise to your teeth. Barring Crystal you now see the Crew complete. We are not law-breakers or secret sinners, we like fun, we love fun, we hate sneakery in all its branches, and we utterly fail to see why girls shouldn’t be as jolly as boys. That’s the idea. We want to be sports, with a sporting code of honour. If we have larks and get caught we own up. We wouldn’t allow any one to be blamed for our pranks. We adore adventure—and we won’t be stiff or starched. There you are, my dear. So if you join up you’ll take us as you find us. Have a stalactite?”

Kits sat back on her heels and laughed for very glee.

“Topping!” she cried, “What luck that I found you all right the first day. We’ll have adventures, we’ll have fun,—and we’ll not let the boys—any boys—all boys—have the crow over us. Oh, I do wish we had the symplelite now, for I’m longing for toffee,—and Miss Carwell told Mums hampers were not allowed.”

“Neither are they,” quoth Pickles, “but they come. Of that anon. I really do feel we ought to return now and welcome Crystal. I’m certain sure it was she,—there’s only one Crystal, eh, girls? and she sent me a p.c. last week to tell me she had made a discovery for eighteen pence. I’m longing to know what it is.”

The vote was carried, and though Kits would have liked to “collect” several of those jolly stalactites she realized that they would not be likely to run away and that she would be returning to the Council chamber many times and oft.

It did not seem nearly such a long walk on the return journey, and the “missing member” was not far to seek. From the top of the slope they saw her—an elf-like figure perched on the right hand pillar which stood sentinel at the gate, an ancestral column having nothing to do with impudent girlhood. Yet, there she sat, a mere wisp of a girl—with a fuzz of light brown hair, and a whimsical expression on her nondescript features, which were only redeemed from plainness by a wonderful pair of green eyes—yes! green absolutely, with curling lashes to shade but not conceal their peculiar colour. Kits stared, fascinated by those eyes and their small, impudent-looking owner, who smiled down at her enquiringly.

“Kits Kerwayne,” sang Trixie, “A new comrade and a sport. Come down, Crys, instanter and tell us all your news from the very beginning. First, what is the discovery?”

Crystal clambered carefully down from her perch.

“A Cookery book,” said she, “A manuscript of the greatest importance. Wait and see! I have brought back a fortune in a nutshell, but I’m not going to tell you all about it yet. We must hold a council, after tea, and I’ll shew you the discovery. What room are you sleeping in, Kits? I’m feeling rather anxious over the answer!”

“No. 7,” said Kits, “with Joyce Wayde. She seems nice.”

Crystal crumpled up and flopped against the gate post.

“Help!” she moaned, “I was hoping . . . hoping . . . hoping I was quartered with Joyce. Friends, your sympathy! There’s no longer any doubt. Miss Sesson has had her revenge and put me with the Prims. With the Prims! Me myself. What will the end be?”

“Collapse of the Prims and solitary confinement for you, my girl,” retorted Trixie positively, “but never mind. You’ll suffer in a good cause. Just think how we shall scream over your experiences.”

“Pig!” raged Crystal, and chased the callous Trixie up the drive. Kits wiped the tears of laughter away from her eyes—and the second post card she sent home that evening was received with smiles by the home folk.

“This is a jolly place. I shall like it awfully. Tons of love. Kits.”

If Mademoiselle had seen that card she would have felt that the new girl ought nevaire . . nevaire to have come to so select an establishment of young ladies as Clynton Court!

Did Mademoiselle know of the existence of the Crew?

Kits liked Joyce. She was quite sure about that. Her room companion was not like the merry comrades of the Crew but she was nice.

What a comfort! Kits could thoroughly sympathize with Crystal Colton doomed to the companionship of the Prims, though she had an idea Miss Crystal would prove herself a match for the petrifying treatment accorded by Pearl and Roseleen.

Joyce was not a bit of a Prim, though Kits could not altogether “place” her. She was rather shy and dreamy, keen on her lessons and possessed of two gifts—a lovely contralto voice, and a genius for friendship. Her greatest friend was Gwenda Handow, the fair girl with the fluttering eye-lids, who Kits had noticed the first evening. Gwenda was older than Joyce and very clever. She was going in for a big scholarship—so was Crystal—and Joyce confided to Kits almost the first day of her coming how she hoped Gwenda would win it.

“You see, she saved my life, four years ago,” added Joyce earnestly, as she sat by the side of her bed nursing her knee. “I should have been burned to death if it had not been for Gwenda, she has a scar right up her arm now. I only wish . . . oh, you don’t know how I wish, I could have the chance of repaying her.”

Kits chuckled.

“You don’t want her to catch fire just for the pleasure of putting her out, do you?” she asked, “but I know what you mean. You want to shew your gratitude.”

“Yes,” said Joyce, “but she is two years older than I am—and . . . and her friends are older than I am. She’s awfully kind, but . . . I always feel she looks on me as a child. Of course, I’m nearly fifteen, but being the eldest of the family makes me young for my age, and I’m no good at games, excepting tennis.”

“What a pity you don’t belong to the Crew,” said Kits, with real regret, “Trixie and the others are jolly. Tell me, Joyce, who is that very dark girl—almost like a gipsy or an Italian—Teresa Tenerlee.”

“Teresa,” replied Joyce. “Oh, she only came last term. Her mother is Italian. I believe she was a great singer. Teresa sings beautifully too. I don’t know much about her. She doesn’t like me a bit . . . and neither does her friend Olna Raykes.”

“I don’t like Olna,” said Kits heartily. “She reminds me of a ferret or a vicious horse. Aren’t I a cat? But do think over what I’ve said about the Crew, Joyce. The girls are so straight, and they like you.”

Joyce blushed.

“I’m too slow,” she sighed, “I’m sorry. I’d love to join—if only because of you. But you’d soon wish I hadn’t. You see, mother always tells me that being the eldest is such a big responsibility. Jennie and May will be looking to me as an example. And . . . though the fun you all have is just the loveliest fun . . . it might lead into rows—and mother is a friend of Miss Carwell’s . . . and would hear at once. I’d rather have the dullest time in the world than worry my mother, for she’s not strong—and such a darling. I do hope,” added poor stammering Joyce shyly, “that you don’t think me a prig. It’s not that a bit. I always was a tom-boy at home—and Jim my brother says I’m as good as a boy, but at school it’s so different. Things you can do at home are really against rules here.”

Kits wrinkled her brows. She did understand Joyce’s meaning, far better than Trixie or Crystal would have done, and her liking for the girl, who would rather have a dull time than give her mother the least uneasiness appealed to her generosity.

“I’d like to shake hands, Joyce,” she replied frankly. “That’s all! And I’m glad we’re pals. Of course, I shall stick to the Crew. Mother wouldn’t mind the jolly fun we have—she’s even a bit of a tom-boy herself, and often goes rabbiting with us in the woods. But . . . I see it is different for you—and I’m awfully glad I’m not the eldest—or an example.”

“But I’m often a bad example,” urged Joyce, in deadly fear of having made herself out to be a pattern. “And perhaps, though I can’t be one of the Crew, you’d let me join your fun—when I can? I know the moors all round, ever so far, and I think I could get leave for us to fish in the stream in Farmer Gale’s meadows, if Miss Evelton came too.”

Kits beamed. She guessed that her friendship would mean a big thing for this girl who had somehow failed to find her niche in school life.

Crystal’s ancient cookery book had been keeping the Crew most unnaturally quiet of late. Even with the aid of a magnifying glass it was quite difficult to make out the old English characters.

Crystal’s patience was admirable.

“It’s no use to be ambitious,” she declared, “we can’t make home-brewed wines or preserves, or a noble venison pasty. But some of these household hints are topping. ‘To make blacking for boots.’ Here’s the milk in the cocoanut! White of egg and lamp-black. Girls! it’s a fortune. Look at the shine those Hessian top-boots must have wanted. We’ll save our money and buy eggs—many eggs. Then the lamp-black and the boot room. What a lark.”

“What shall we do with the yolks of the eggs?” asked Pickles. “Custards, eh? It’s a pity to waste them. Here’s a recipe for mending china. I say, Crystal, that was a well laid out eighteen-pennorth.”

Trixie yawned.

“We’ll get the eggs to-morrow,” said she, “but what shall we do to-day? I don’t feel like cricket, and all the tennis courts are engaged. Come along Crew, and be—er—is it patriotic? I know to-morrow is Primrose Day, and that’s a national in memoriam about something. Is it the Battle of Waterloo? or the Accession of Queen Victoria? Anyhow Horsfold Woods are crammed with primroses, and we’ll decorate the place. Miss Carwell might take the hint and give us a holiday to celebrate the day.”

The idea “caught on”, though Crystal, who liked to stick to her own trail a bit too much, would have preferred a visit to the farm. Baskets were routed out and the bunch of merry girls set off for their afternoon’s fun.

“The Hall has been bought by a Mr. Timothy Plethwaite,” quoth Trixie, tucking her arm through that of Kits. “He is—or was—a rich manufacturer in Leeds, but having made a huge fortune, he has come here, bought the Hall, married a Lady Marigold some one or the other, and is enjoying life. Why not? From all accounts he’s awfully good-natured too. That’s why we’re going to take his primroses.”

“They are lovely woods,” chuckled Kits, as she rolled down a steep bank to where the primroses simply carpeted the mossy ground. A cuckoo sang its gay challenge, brown rabbits scuttled breathlessly away into the undergrowth, and Kits, clapping her hands, sang too, in sheer joy of life.

Would Ned and Roger ever believe her tale of the freedom of girl school life?

“These are primroses with stalks,” declared Pickles, “not weedy little apologies. What are you after, Crystal? We came to pick primroses.”

“Of course, we did,” agreed Crystal, who had already lured Noreen and Jane up into the branches of a grandfather oak. “But primroses have a way of dying unless put in water, so I say let us explore first, and pick afterwards. I want to go as far as the lake; some one told me old Plethwaite was collecting fancy ducks. Honour! Ducks from China, ducks from Australia, blue ducks, green ducks, ducks with red bills, and ducks with yellow bills. I want to see them. I want to see lots of things. Then, when my horizon is widened, I shall come back to primroses. What says the recruit?”

Kits was laughing. Here were comrades after her own pattern. At first she had doubted Crystal’s sportsmanship—now she realized that fairy slimness and a delicate air were deceptive. Crystal was a genius in the best way.

So away tramped as jolly a Crew as ever could be found in any English school. Noreen and Jane, of course, plunged into the tangle of undergrowth and got caught by affectionate briars; Pickles rolled down into an unseen pit, and had to be hauled out. Kits and Crystal were the first to arrive on the banks of the broad sheet of water known as Horsfold Lake. They had hurried on ahead on hearing a loud squeal of terror—evidently the cry of some small boy or girl. And they reached that bank at a crucial moment.

A curly-headed boy—aged about nine—was clinging to an overturned boat, which was drifting towards the middle of the lake, and making gallant efforts to clutch the frock of a small sister, who sank out of sight before the eyes of the newcomers.

Kits did not even wait to throw off her sports coat. Into the water she plunged, swimming with powerful strokes towards the scene of the accident.

Crystal, unable to swim, but no less ready to help, began to climb along the trunk of an ash tree which stretched over the water.

The boy, pale with fear, did not move. He still clutched to the boat, watching Kits rather than Crystal.

The little girl had risen for the second time when Kits reached the spot. Then, the girls on the bank wrung their hands in dread. Noreen turned and hid her face against her twin’s shoulder. Kits and that small child would be drowned, for Kits, weighed down by her clothes, was evidently in difficulties. The child lay a dead weight on one arm, and, though Kits was fighting with every ounce of strength, she could not make any progress. Once, it seemed as if she must sink.

Pickles had left the bank, and was speeding in quest of help.

Crystal, perched monkey-like on the bough, leaned over towards the boy.

“Catch hold, Tommy,” she called, “and I can help you up here. Don’t be afraid.”

The little lad stared upwards in despair.

“Janie,” he whispered. He could not, poor boy, endure the thought of being rescued if his small comrade were still in danger.

Crystal tried to smile.

“Kits has got Janie,” she replied. “You can’t see because of the boat. If you get up here it will help. Make haste!”

He obeyed, stretching up—too stiff and cold to help himself. And Crystal had attempted an impossible task. To drag that helpless laddie on to her own swaying perch was beyond her strength. Did it mean too she must be dragged down into that terrible lake?

To Noreen and Trixie it seemed as if both rescuers must be drowned. Kits was making slow progress, but her face was ghastly, . . . her strength ebbing, whilst Crystal, lying flat along her branch, might be pitched at any moment into the water with the boy.

Then, oh, joy, joy, joy,—steps came hurrying, voices shouted, and two or three men burst through the tangle of bushes on to the bank.

One glance took in the situation, and even as Crystal felt herself slipping round and over into the water, a man came swimming up, . . . managed to right the boat, and, standing up, in what seemed to the watchers, a marvellous way, stretched up his arms for the small boy. Then . . . it was Crystal’s turn, and down she came, feeling as if her arm had been dragged from its socket, whilst a cold mist blurred her vision.

“Hurrah!” panted Trixie from the bank, but her voice wobbled, whilst the twins burst into tears. For already the rescuer of Kits, and the wee girl, had reached the boat with his double burden, and they were safely lifted in.

Others were arriving on the bank by this time, a sobbing nurse ran up and down, calling the names of her charges, another woman was busily arranging the blankets which were to wrap the rescued bairns, whilst a big important-looking gentleman, with a kindly but anxious face, stood waiting with wonderful self-control for the return of the boat.

The boy—a sturdy youngster—was conscious, and began to cry at sight of his father.

“It was all my fault,” he declared. “Oh, daddie, daddie! say Janie isn’t dead? Say she isn’t?”

Janie was not dead, poor mite! but she was unconscious, and the sooner she was taken to the house and tucked up in bed the better. The doctor, fetched from the village, was already in attendance, and Mr. Plethwaite, having seen the children carried safely off, turned before following them to speak to the two girls, who had so bravely saved the lives of his children.

Kits had utterly refused to faint as had been expected of her, but her teeth were chattering with cold, and her eyes had a dazed expression. Crystal looked very white too, and her arm was bleeding where the rough bark of the tree had torn it.

Trixie had to be spokeswoman.

“We are Miss Carwell’s girls,” she told the distressed Mr. Plethwaite, “don’t worry about us. The lodge-keeper’s wife—” and she looked at a motherly woman, who had come up,—“has promised to see after Kits. We’ll get back to Clynton Court as soon as we can. Please go to the children, and don’t bother about us. We do hope the children will be all right.”

“I can never thank you girls enough,” said the poor father, huskily, as he held out his hand. “Another time I shall try . . . to say . . . what I feel. Now . . . won’t you come to the Hall and——?”

But Mrs. Plant, the lodge-keeper’s wife, interfered respectfully.

“The lodge is close, Sir,” said she, “and the kettle boiling. I’ll soon have the young lady in dry clothes, and give them some tea. If you don’t mind my saying, Sir, that’ll be the very best thing to do.”

And Mr. Plethwaite took the hint. Away he hurried after the cortège now on its way to the house, leaving six awed and somewhat limp damsels to be escorted to the snug lodge, where Kits soon regained her colour and spirits under the influence of a roaring fire, dry clothes, and the finest cup of tea.

Mrs. Plant’s hospitality was inexhaustible. She brought out a home-baked cake and cut mighty slices of bread and butter, whilst her visitors, reviving under such ideal surroundings, sat up, took notice and began to grasp the fact that this had been a real adventure. Two at least of their number had been heroines, whilst Mrs. Plant was loud in her praise of Pickles’ presence of mind in running for help.

All was well that ended well, and if Crystal looked rather the worse for wear, and Kits sneezed in a shame-faced way, the heroines would not allow that they were one bit the worse for their adventure.

It was after Plant the gardener, had brought news that Miss Janie had recovered consciousness, and Master Jock was none the worse for his ducking, that the girls started back to school.

“We shall be late for tea and have to report ourselves,” said Trixie, “but—isn’t it a gorgeous feeling, girls?—we can’t get into a row! First time, I’ve ever had to report ‘nothing doing’ in the way of—er—mischief. We ought to be wearing laurel leaves.”

“What a difference having tea makes,” laughed Kits. “If we hadn’t got to return to school I’d love to go primrosing.”

But I fancy there was a wee bit of bravado about that boast, and I am sure neither Kits nor Crystal were sorry to receive Miss Carwell’s strict injunctions to go to bed at once, and not to get up in the morning till after Miss Sesson had seen them!

“Why don’t you get out a drum and fife band at once?” asked Crystal, irritably, “or send our photos to the Daily Mail? Kits and I don’t mind,—only for goodness sake don’t look at us as if we’d suddenly been popped under glass cases. Actually, girls, Mademoiselle herself, came and congratulated Kits. The strain of this glory will break us altogether. We shall do something outrageous. It’s—beastly to be famous!”

And Crystal nursed her cheek as though she had toothache.

Ena Welbrack laughed.

“All the same,” she retorted, “we’re awfully obliged to you girls. Have you heard the latest? Mr. Plethwaite has asked the whole school to spend an afternoon at the Hall. An entertainment and a big tea. So that’s the secret of your popularity, my dears.”

Kits grimaced and fled from the schoolroom. She had thoroughly disliked so much patting on the back by school-fellows, though the worst of the whole ordeal had been when Mr. Plethwaite and his wife had come to thank her and Crystal. There had been tears in Lady Marigold’s eyes, as she kissed the girl who had saved her own wee daughter’s life, and Mr. Plethwaite had spoken so very kindly in thanking them.

As Crystal remarked that would have been “nuff said”. But not a bit of it! and the luckless heroines felt their hearts sinking at the prospect of a fête given in their honour.

Of course, they could not live up to such a reputation, and Crystal was thoroughly sincere in her wish to make it quite plain that the Crew was still the Crew, and incidently, a thorn in the sensitive side of Law and Order.

Kits did not escape far. In the otherwise deserted library she met Teresa Tenerlee, the half Italian girl, who had already made several advances towards friendship.

For some reason—one of those reasons without reason, known so well to school girls—Teresa was not popular with her fellows. Mademoiselle made a favourite of her, so did Miss Pasfold, the junior mistress, but beyond her one girl croney, Olna Raykes, Teresa did not possess a chum in the school.

She greeted Kits gushingly.

“Do have a choc?” she urged, “here’s a beauty. Oh yes, I know we aren’t supposed to keep sweets tucked away in our pockets, but you are not one of the goodies—even though I saw our Pearl smiling tenderly on you. Tell me, do you collect fossils, Kits? I thought you did! Here’s a fossilized frog I was given some time ago. I kept it as a mascot. You’re welcome.”

Kits flushed. She disliked promiscuous gifts being showered on her—especially by a girl she did not care for. But Teresa was so friendly, her manner so wistful, that she felt she could not well refuse. Besides—a fossilized frog was a treasure! Ned would be green with jealousy!

“Are you sure you don’t want it?” she asked, as she bent over the ugly, squat curio. “It is ripping, but I never heard of any one parting with a mascot.”

Teresa laughed airily, as she perched herself on the table. She was a remarkably handsome, dark girl, with fine eyes.

“I’ve got another mascot,” she retorted, “a much nicer one. Do tell me, Kits, how do you like school? You’re in No. 7, aren’t you, with that stodgy Joyce Wayde?”

Kits hesitated. She remembered now what Joyce had said about Teresa, and she studied the latter more carefully. Kits was so honest herself that she did not easily suspect deceit in others.

“Yes,” she replied abruptly, “I am with Joyce in No. 7. But I don’t find her stodgy. We are friends.”

Teresa did not look pleased.

“Tastes differ,” she remarked, “but I doubt if you remain friends for long. Joyce is a queer girl, a very queer girl. Do you think she is straight? I don’t! I wouldn’t trust her. That’s not fair, of course. Use your own eyes. At present you think I’m a sneak, but I am not. Only I like you, so I’m putting you on your guard.”

“Bosh!” retorted Kits indignantly, “Joyce is as straight as can be. I hate that sort of hinting. You can’t tell me anything straight out. No, of course not! And I shouldn’t believe you if you did.”

This was plain speaking, and, as she concluded, Kits laid the fossil on the table.

“I’d rather not take your mascot after all,” she added, and marched out of the library, feeling that Teresa would not be asking for friendship again—and a good thing too!

The party at the Hall was quite an event for the Clynton Court girls.

“It’s the first time the neighbourhood has entertained us in a bunch,” laughed Trixie. “Do you know, Kits, I believe the Prims would agree to bury the hatchet—I mean the grocer’s cart—if you liked to hand out the olive branch. Roseleen is quite impressed by your exemplary conduct.”

Kits chuckled.

“I hate it,” she replied. “I’ll be glad when it is over. Have you heard of Crystal’s great idea? Colossal cheek would be a better name.”

Trixie hugged her knees.

“What is it?” she demanded, “I adore the Professor’s ideas. She’s great. We have slacked horribly since we trod the primrose way.”

“She’s going to ask Mr. Plethwaite to hand us over that old hut in his woods, facing that piece of waste land,” said Kits, rubbing her hands. “If she gets it it is to be the Crew’s property, and we shall really experiment there. Crystal is, of course, the only person in the world who would dare ask for such a thing.”

Trixie shouted in glee.

“Good old Crys! She’ll do it too. Hurrah for landed property! What discoveries lie ahead of us. By the way, we’ve not tried the blacking yet. Now, I must be off to cricket practice. Coming, Kits? Miss Evelton wants you in the eleven, only she can’t say so till Grace Hughes decides whether she is too delicate for such strenuous exercise after measles in the holidays.”

Kits nodded. It was a secret ambition of hers to be in the cricket eleven. She knew she was as good a player as any of the girls, in fact, a better bat than most. Ned was always asking her if she wasn’t being elected for the eleven.

They met the sports mistress near the gate and she beamed on them.

“I was coming in search of you, Kits,” said she, “Grace Hughes has resigned from the eleven. She gets so easily tired since her illness, and her mother did not want her to play. I hope you’ll fill the gap?”

Kits was only too ready, and Hall fêtes and shed experiments were forgotten, as she stood before the wicket making havoc of Miss Evelton’s best balls.

“Luck for us!” applauded the energetic little sports mistress. “You are a bat, my dear, and a bat we needed. Miss Carwell has allowed us to challenge Mr. Martin’s boys at Beech College, so it will be a battle royal at half term this year.”

The girls were delighted. How ripping it would be to beat those very superior youths, who, of course, would consider themselves so vastly superior.

Crystal was frankly disgusted by this new enthusiasm. She was no cricketer. Her “forte” being confined to fields of learning. She and Gwenda Handow were both working hard for the Parraton Scholarship—though Crystal reserved her industry strictly for school hours!

“No excuses,” she told her chums, “you can cricket in reason, but you are members of the Crew, and we have a dozen schemes on hand. Trixie has a new suggestion for the next Council, but it is not ripe yet. She vows it is the exploration of a mystery. Now mysteries are almost as good as inventions, so we must have a special Council meeting after the fête. I wonder what Timothy the Great will give us for tea? Éclairs and ices are very choice. I think of them when I get stage fright.”

The Hall fête was on Saturday, and the day was one of April’s loveliest.

Mr. Plethwaite had asked Miss Carwell to bring her girls early so that there should be plenty of time for the entertainment before tea.

And such a merry entertainment it was, beginning with a clever one-act play, and concluding with a conjuror. Crystal and Kits were greeted by Jock and Janie—the most roguish and curly-wigged darlings, who hugged them vigorously, whilst Jock presented them with gold wrist watches.

“Daddie gave us them to give you,” he explained, “but we put our pennies into the bill too, because we wanted the watches always to say thank you for us.”

How pleased the girls were, and what a nice way of getting over the ordeal they had dreaded. As to the tea, I wonder they were not all ill—in fact, I fancy Alda Wenton did have to retire rather hastily. But—such temptation! Éclairs, cream cakes, sausage rolls, creams, jellies, ices, meringues. It was more like a ball supper than a tea, and the girls did justice to it.

“Of course,” murmured Pickles to Kits, as they walked home across the moors in the gloaming of an April evening, “we all owe you a debt of thanks, but no one will remember that. Why can’t they go and stop runaway horses, or rescue a philanthropic old gentleman from a bull or something equally joyous? Then we’d go to their beanfeast. But no such luck! Hillo, Crys, what are you and Trixie wagging two tails about?”

Crystal, with arm linked in Trixie’s, had joined them.

“Secret as the grave,” retorted Crystal, “whisper it low. Timothy the Great ought to be knighted or canonized, he’s given us the hut—you know, the one opposite the waste land as we call it—which is really a bit of the moors. He is also telling the carpenter to put shelves round, and to fix in a small stove, so we are what one might call ‘made for life’. Of course, I gave my word we’d tell Carwell—in fact, she came up whilst we were talking, and butter would never have melted in the mouth of yours truly, as I asked permission to ‘accept possession’. Neatly put, eh? And we really shall play the game. Picture, mes enfants, that simple hut photoed in future as the birth place of a world-famous blacking or patent pomade—or—”

Mademoiselle’s stern call to loiterers broke through the dream of genius, and taking hands the three girls raced across the rough ground to where their school-fellows awaited them in the road.

It was a very joyous and tired Kits, who reached her bedroom that evening. Joyce was there before her, standing by the chest of drawers; she turned eagerly to greet Kits, who flung one arm lightly round one shoulder.

“Enjoyed yourself, Kid?” she asked, for, though Joyce was actually only six months younger, and the eldest of a large family, she always seemed such a kid to jolly Kits. “Look at my watch, some people have all the luck, don’t they?”

Joyce’s grey eyes sparkled.

“Yes,” she agreed, “and you deserve it, Kits. I never could have jumped into a lake like that. I can’t even swim. But I’ve had good luck to-day—at least mother will be pleased. Mr. Roberts, our singing master, has asked me to sing at a concert in York on the 10th of June. It is ever such an honour. He could not decide at first between me and Teresa, but he brought another man to hear us—and I am chosen. I can’t help being glad because mother will be so pleased.”

Kits patted her back triumphantly.

“Well done!” she applauded. “You’re going to ‘come out’ of that shell of yours after all, Joy, and I’m glad. Was Teresa vexed? I know she would be. I remember you told me she did not like you.”

Joyce sighed.

“No, she doesn’t,” she replied, “and I don’t like her. I never quite know why. I hope it’s not jealousy. I don’t see why rivals should not be friends. Crystal and Gwenda are quite friendly and nice over their scholarship competition, but Gwenda is a much sweeter nature than I am. I . . . I think I must be petty, Kits, such silly things bother me.”

But Kits would not hear of it.

“If you didn’t fuss so it would do you a world of good to join the Crew,” she declared. “We’re quite innocent and harmless. There’s a special meeting to-morrow. Trixie Dean is proposing an adventure. Do come. You,—well! I know you don’t mope, but you would be happier if you got more excited about things. I love enthusiasm. What I should like to see would be you sliding down Farmer Perkins’ hay-rick a few dozen times. Tra-la-lee. I’m going to sleep the clock round and awake as a giant refreshed. Tell me, Joy, if by any chance we planned a pillow fight, would you join the fray?”

But Joyce’s reply was inaudible.

“Hillo, Kits, what’s wrong? Have you picked up sixpence and lost a sovereign? Don’t forget it’s Council day, half holiday, and an exploration rolled into one. Away we go, to ‘deeds of derring do’! And where’s Joyce? I heard she was coming to the Gap to discuss things.”

Kits sighed, smiled, and gave herself an impatient shake.

“Mademoiselle is a cat,” she replied. “She says I’ve been slacking over my French, and actually she went to Miss Carwell about it. I don’t see I’ve slacked at all. I’ve not got a tongue for foreign languages like Teresa.”

“Of course not. You’re All British Goods. Who wants to know that rire means to laugh? Giggling is the same in all languages. I believe in pantomime action. But don’t look glum. We are going to be serious. Trixie gave me a hint about her idea, and it’s prime!”

So Kits banished the memory of rather an unpleasant lecture, and joined the merry “Crew” gathered in the wood close to the playing fields.

Trixie lost no time in beginning. She greeted Joyce quite gushingly.

“You live near here, don’t you?” she said, “so perhaps you can tell us right away. Who is the hermit of the Moor?”

Joyce laughed.

“I couldn’t tell you his name,” she replied, “because ever since I can remember he has always been known round here as Old John. He’s a crank, of course. No one ever goes near his place; it is called the Hermitage—I think that was its name before he was known as the hermit. He has lots and lots of cats and birds—and a servant named Long Dick, who never speaks to any one. But why do you want to know? You can’t explore him—or the Hermitage. It is years and years since any one but Long Dick has been inside the house.”

“What a thrill,” retorted Trixie, “but we are going. Pickles and I adore cats—and cats adore us. It was Kits who in a way put the idea into our heads. We were thinking of how to become heroines,—and, to explore the secret lair of a real live hermit, sounds promising. You’ll come, Joyce?”

Joyce did not know what to say, but—well! it is so very hard to say “no” when girls, who you are longing to have as friends, ask you to do something you feel is not quite right and not actually wrong.

Crystal “capped” all by a suggestion.

“We’ll ask if he has a kitten for sale and offer ten bob,” said she, “that’s quite a good excuse. What fun if he sold one! We’d give it to Mademoiselle as a peace offering. She is such an old cat herself she’d be sure to take to it.”

So, with ten shillings, in readiness in case of being asked their business, the adventure-seekers started off.

“Curiosity killed the cat,” quoth Kits, “but never mind! We shall have fun anyhow.”

The gates of the Hermitage were chained and padlocked. Even though the “barriers” were rusty they held good, and a faint depression cast itself over the spirits of the explorers. It was one thing to walk in at the front gate on the pretext of buying a kitten, and quite another to creep through a hole in the hedge—if one were to be found.

Even Trixie demurred over this.

“He might take us for burglars and have us locked up,” she said. “And anyhow there would be a row. Come along, girls, and we’ll have a scout round the outside of the premises. Something may turn up.”

“It looks mysterious enough for a dozen ghost or burglar stories,” said Noreen. “What are you doing, Pickles?”

Pamela had scrambled up into the boughs of a big chestnut tree, and, balancing herself very carefully, peered over into the tangled, over-grown garden on the other side of a sturdy brick wall.

“Can’t see anything,” she proclaimed, “too many trees. There’s just the outline of a house beyond, but it looks like a ruin. I think the hermit must have gone, and the place is empty, so we might just as well climb over, eh? Hullo!”

“What is it?” chorused her comrade from below. “Can you see anything?”

“Yes,” replied Pickles, “A bird,—a parrot!—a ripper,—grey and pink, it’s a cockatoo I suppose, it’s flying straight for the wall. I believe it has escaped from somewhere. Lie low, chums, and we shall catch it if it comes over. Then in triumph we will invade the Hermitage.”

It was a glorious piece of scouting, though the deep, bracken-filled ditch was not the driest of resting places, and no wonder that cockatoo was interested in the row of outstretched figures lying there so quietly.

Crystal half raised herself.

“Pre-tty poll,” she wheedled. The bird balanced restlessly on the wall, uttering a harsh sqwawk. “Clucko, pretty,” soothed the same voice, and the cockatoo—being perhaps as curious as its would-be-captors—came flitting down amongst the figures in the ditch.

Grab! Trixie had him fast and rose in triumph. That bird must have had acquaintance with sailors, for its language was horrible,—but it could not get free.

Now the road was open indeed. Over the wall scrambled Kits in style, and after her came the Crew, giggling and whispering. This was the finest game of Tom Tiddler’s ground on record! Trixie went second with the Sqwawker as they had at once named the captive. Apart from the mystery of the place, the Hermitage grounds were not inviting.

“The house can’t be inhabited,” urged Crystal, “look at the windows! half are cracked, and the other half have no glass at all. The parrot is just a stray one.”

“I’m going inside,” said Kits firmly, and mounted the grimy steps leading to a door. Grasping the handle, she was about to give a violent push when the inner handle was turned, and the door flung wide. Before the startled girls appeared the very strangest-looking old man they had ever seen. He was tall, and would have been handsome had his grey hair and beard been less shaggy; his eyes were dark, and just at this moment very angry in expression, his black alpaca coat was thread-bare, but in spite of shabbiness there was no mistaking him to be a gentleman.

“How dare you come here,” thundered Old John, preparing to roar out a regular tirade of wrathful denunciation, but Trixie was raising the Sqwawker for inspection.

“He flew over your wall,” said she fearlessly, “And we brought him back. If you don’t want him we’ll keep him.”

Old John fairly spluttered. He was so taken aback he did not know what to say. But he took the cockatoo very tenderly into his embrace, muttering a few words as he smoothed its feathers.

“Good afternoon,” said Trixie. “Next time we see a parrot on the moors we’ll leave it alone.”

And she turned away.

Old John hesitated.

“It was my mistake,” he apologized. “Of course, you did the right thing. I would not have lost him for a bag of money. Now, I suppose you’ll want a reward?”

He fumbled in his pocket, whilst Trixie in a fine blaze of temper, faced him.

“We’re not beggars—or thieves,” said she scornfully. “You can keep your reward—and your sqwawking bird.”

Old John stared. His experience was that young people were all afraid of him. He disliked his fellow creatures, but boys—and girls—were especially hateful.

Yet—as he looked at Trixie of the red locks, her moon face quivering in resentment, he had the grace to feel ashamed.

“I . . . I . . ,” he stammered, “I’m afraid I—”

Crystal slipped forward, smiling sweetly.

“If you are really obliged to us for bringing back Kiwi,” said she, “you might let us just come in and see your cats. We adore cats, and we wanted to see yours.”

The hermit of the moor backed down the passage, he was certainly having an experience!

“Nicholas is in here,” said he, “he is the finest cat in England. I can’t have a herd of school girls running all over the house looking at what doesn’t concern them. Cats and birds are my hobbies—and vastly better ones than most.”

The Crew was on its prettiest behaviour. It did not reply, and if elbows were nudged, and winks exchanged, it was only because the hermit was marching ahead and could not see them.

What a joke it was—actually penetrating the Ogre’s Castle. And what a Castle!

There were no carpets, only thick linoleum, and there was only one big table and one chair in the room into which they were ushered. But if it had been crammed with the grandest of furniture, those girls would not have noticed, for they were all swooping upon the very loveliest cat they had ever seen.

Nicholas was a tortoiseshell Persian of enormous size, with a perfectly ideal coat of long, soft fur. If the Hermit had expected his pet to shew claws to these gurgling girl-worshippers he was mistaken. Trixie had actually gathered him into her arms, and was crooning over the sleek, tiger-like creature as though he were a child, whilst Pickles stroked him into sleepy content.

The Hermit stared amazed, but his resentment against the invaders was melting altogether. Kiwi perched on his shoulder, ruffling perturbed feathers and resigning himself once more to captivity, whilst Nicholas purred lazily, as much as to say “Welcome, strangers!”

“Nicholas does not often approve of strange faces,” said Old John. “You young ladies must be cat-lovers.”

A chorus answered him, whilst Nicholas purred confirmation. The guests were harmless!

Old John the hermit must have had a streak of nice feeling left under the crust of self-love, for he actually smiled, as he invited those girls to come and see his birds.

How eagerly he was followed! And what a surprise awaited the guests.

A large room—a really enormous room, some sixty feet long, had been turned into an aviary, and from cage and perch, from leafy grotto of foliage and twigs, and from the marble edge of large, pool-like basins of water, came the song of feathered choristers.

Kits and Crystal, who were foremost of the group of girls, stood with clasped hands, and eyes wide with admiration.

“How lovely,” they whispered, “how lovely!”

Indeed, it was the prettiest sight; and not the least pathetic was that of Old John, standing with outstretched arms and upturned face, whilst dozens of his little favourites, and the bigger birds too, came circling down to perch on shoulders, arms and head. They loved him as he loved them. It was a charming little idyll in the midst of this hidden home.

The girls were quite sorry when they had to go—and shook hands gratefully with their host.

“It’s so funny to have cats and birds,” said Pickles, to him at parting, “They are such enemies as a rule.”

Old John’s eyes twinkled.

“Even enemies can become friends at times and with careful treatment,” he replied. “There, off you go, and don’t tell any one you’ve been here. Don’t come again, either. After all, I want no one and nothing but my pets. Don’t forget. If you say a word about the Hermitage, I shall consider you are dishonourable and treacherous. Good-bye.”

It didn’t sound very polite, but, as Crystal remarked as they tramped across the moors:

“You couldn’t expect a leopard to change all his spots at once.”

It had been such a successful afternoon, and Kits was “extra glad” Joyce should have been able to enjoy a Crew enterprise unflavoured by law-breaking. So interested were they, too, in discussing Nicholas and his master, that they did not notice the black bank of clouds rolling up over the sky so quickly, and—the storm broke suddenly, as storms have a way of breaking over Yorkshire moors.

A mighty clap of thunder was followed by a few monster drops of rain.

Noreen and Jane, who were leading stopped as if they had been shot.

“Ow!” gasped Jane. “What a jump that gave me.”

“And now for the deluge,” added Pickles, skipping over a tiny stream. “Why didn’t we notice the sky? We’d better run, comrades, and run with a will. There’s going—”

“It’s not going . . ,” retorted Kits, “it’s come!—and I hate lightning.”

A vivid flash had zig-zagged out from the heart of the storm clouds, and was succeeded by another crash. Down came the rain.

“It’s a case of buckets not drops,” said Trixie, turning up her coat collar. “Poor old Crystal! it’s bad luck, for, of course, you’ll have one of your priceless colds.”

Crystal tried to laugh, but she was shivering too. She was very delicate, in contradiction to her high spirits and love of sport, and Trixie’s frown was one of real anxiety as she looked round.

Two miles at least before they reached the school, and it was impossible to walk very fast over the heather. The twins too were huddling close to each other, and trying bravely to hide the fact of nervous fears.

“I hate being out in a thunderstorm,” said Pickles. “Of course, I’m a coward—but I’ll be honest. If we were only near the Cave I should bolt for the burrow.”

“So should we,” chorused the twins, perking up. “It is so much nicer ‘all to be afraid together’ and not have superior comrades poking fun.”

“What about the Hollow?” suggested Crystal. “We shouldn’t get wet, and the undergrowth and all that tangle of thorn trees, and gorse wouldn’t be like sheltering under forest trees.”

“The Hollow it shall be,” replied Trixie. “Take my arm, Crys. That’s right, Kits. We’ll all help each other. There’s a path down to the left.”

The storm was becoming quite alarming. The sky was dark, with lurid linings to the black clouds, and the thunder was so deafening they could hardly hear each other speak.

One by one they clambered down the narrow footpath, sliding rather than walking, and bringing showers of gravel down too. But it was a relief to be sheltered from that deluge of rain, and the thickly growing thorn trees made a splendid refuge.

They had not reached the bottom of the Hollow yet, and, as Kits balanced on a ledge of rock, choosing between two footpaths, she gave a faint exclamation of surprise.

The Hollow was already tenanted; below them were the ragged tents and caravans, which told of a gipsy encampment, in fact, it really seemed like a gipsy colony, though at the present moment there was no sign of the gipsy folk. Yes, though! as the girls stood looking down, a boy—of about sixteen—scurried across from some bushes, uttering a peculiar cry. Instantly half-a-dozen men came out, heedless of the rain, or trusting to the shelter of the trees, as they stared with scowling glances towards unwelcome intruders, who had evidently discovered a secret lair!

“Gipsies,” said Trixie, peeping over Kits’ shoulder. “What horrid looking men. I had an idea present-day gipsies were rather jolly. I don’t think we need climb right down there, eh, Kits?”

“No,” replied Kits, quite positively, “I don’t think we will. They don’t look pleased. One of them is coming to speak to us.”

“And the others are creeping round the other way,” added Noreen. “Sh-shall we climb up again? I don’t like the l-look of them a bit.”

The tall, black-haired man below was shouting up at them, but the roaring of the storm prevented them hearing what was said.

“I think he’s asking what we want,” said Trixie, shaking her head vigorously. “And more gipsies are coming out from the tents. What horrid faces they have. I do believe I’d rather brave the storm, only Crystal——”

“Quite likely the rain is nearly over,” said Crystal, “it couldn’t last at the rate it was coming down. I’d much rather go. There are such crowds of gipsies, and those other men are coming round behind us.”

Pickles did not wait to argue. She was clambering up the path and wishing devoutly it was as easy to go up as it had been to come down.

Some of the younger gipsy boys began to jeer and shout at sight of so hasty a retreat, but the first man called a warning to them not to come again—or to speak about things that did not concern them.

“I don’t understand half what he is saying,” said Kits, who had grown rather pale, “b-but—I believe no one knows they are there. . . . W-we couldn’t see any t-trace of them from the top, could we? and hardly anyone p-passes the Hollow.”

Trixie and Pickles were safe on the moor above. It was still raining far too hard to be pleasant, but perhaps not quite the proverbial cats and dogs. The lightning too was less vivid.

“We can’t be wetter than we are,” shivered Kits. “And it won’t take very long to reach the Court now. Crystal, would you like a sedan chair?”

But Crystal refused with great decision, and managed to keep pace with the longer legs of her companions, though she had no breath and very little life left in her by the time she reached the school.

Miss Trennet and Mademoiselle received them in the hall, and for once Mademoiselle forgot to scold or raise hands of horror, as she helped bundle that dripping, shivering Crew off to Miss Sesson’s room.

Bed, hot bread and milk, and a long lecture on the thoughtlessness of going so far from home in such threatening weather, were the reward and conclusion of a successful adventure, though Crystal’s heavy cold and Pickles’ cough remained for the next week as reminders that they must be more careful in future.

The term was in full swing by the time Crystal finally left the sick list, and many were the sympathizers over her having missed several important classes through that unlucky chill.

But Crystal was not one to complain.

“I’m out to win the Parraton Scholarship,” she laughed. “And I’m not going to be stopped by missing a few classes. Mr. Hinton has been awfully jolly too, and has given me endless notes so that I can link up my French literature and algebra.”

“Does that mean you will be a book-worm till after the exam?” asked Kits, anxiously, “because—there’s the shed, you know, and ye cookery book.”

“Of course,” agreed Crystal gaily. “And we are going to experiment too. I don’t believe in grinding away at the same old tune all the time. All work and no play makes this Jack far too dull a boy. We’ll experiment on the first half hol., and, in the meantime, I’m going to work.”

“Gwenda will have to look out then,” laughed Kits, but she glanced round the room first to be sure Joyce was not present. The Parraton Scholarship was not a subject to be mentioned by the girls in No. 8. Kits knew that Joyce was longing for Gwenda’s success, whilst she herself, naturally hoped Crystal would be winner. Joyce had been “coming out” since the arrival of Kits, who, with friendly enthusiasm, wished to draw the girl into her own set. The Crew was such a jolly, honest little band, and Kits herself could see nothing but fun of the best kind in their frolics, though I think she did understand Joyce’s sensitive fear of failing the darling mother at home.

Kits herself, was liking school better and better. Miss Carwell was one of the best. Severe when necessary, but a real friend to her girls, whilst gentle, clever Miss Trennet was always ready with patience to untangle the skeins of trouble her pupils brought her.

The thorn in Kits’ bed of roses was Mademoiselle, who kept an eagle and disapproving eye on the girl who had arrived at Clynton Court in a grocer’s cart, and had managed to be mixed up in at least half-a-dozen scrapes since!

Crystal was by no means half-hearted in the matter of the Scholarship, and somehow the frolics of the Crew were suspended during the next week or so. There were no more mysterious Hermitages to explore, and the knowledge that that gipsy community was still located in the Hollow prevented the girls from wandering so freely over the moors.

Miss Evelton was delighted to find Kits so regular at her cricket practice, and the girls were growing every day more excited about the cricket match with Beech College fixed for June 20th.

“Ten days after my concert,” said Joyce. “I am glad it is not till then. I am so excited about the concert, only I wish the girls would not talk so much before Teresa. I’m afraid she is disappointed.”

“Nonsense,” retorted Kits. “You sing twice as well as Teresa, who, by the way, is being taken up by the Prims. They asked her out when Mrs. O’Fyne came down last week. Well, they’re welcome. Where are you off to, Joyce?”

For Joyce, basket in hand, was turning down the passage towards the front door, and away from the garden entrance.

Joyce flushed.

“I was only taking some shortbread to a little lad I know,” she replied, “he broke his leg some weeks ago, and Miss Carwell allows me to go and see him. His father works for Farmer Perkins.”

Kits was interested. Joyce was so fond of slipping off alone, and she had often wondered what she did with herself as it would have been too far for her to go home.

“Let me come too,” she coaxed, “I often go with mother on her district, and I rather like it, especially where there are children. Would he like chocolate caramels? I’ve got a box of them. Wait one tick.”

Joyce was quite pleased. She was very fond of Kits, in fact, she had begun to discover for the first time the joy of having a real chum and pal. Gwenda was to her “worshipper” a very superior person to be waited on, served, but never chatted to as an equal.

“Crystal is going to experiment to-morrow,” said Kits, as the two girls tramped along side by side. “We shall have fun. Oldest clothes and linen masks. You’ll come, Joyce? We want you. Of course, you’ll have to end in becoming one of us—and we’ll promise not to include you when we go for a prowl over old Perkins’ hayricks, or invade private woods on a birds-nesting expedition.”

Joyce looked pleased.

“And they don’t think me a prig?” she asked. “I am glad. I am having the nicest term I ever have had at school, and it’s all your doing, Kits. You seem to know, even though you are so different. I’m such a donkey in lots of ways.”

“Especially in taking shortbread to lame kiddies,” retorted Kits, “and helping Miss Trennet with copying when you know she has a headache. We all have eyes in our heads, Joy, and your sisters aren’t the only people to have an example set them. Is this the cottage? There, some one has seen you and has come to the door.”

There was no mistake about the welcome Joyce received from these humble friends of hers. Jimmie’s mother’s smile lighted up her tired face, whilst a shout from the couch was the little cripple’s greeting. Joyce was soon seated beside the boy, shewing him the shortbread, and bringing quite a collection of small books from her pocket. The mother beamed on her visitors.

“The hours Jimmie lies and watches for you, Miss,” she said to Joyce, “you would not believe. And talk of you! Why, there’s no one in the world like his lady with Jim.”

Joyce crimsoned.

“I’ve done so little,” she replied, “but I love coming. And when the leg is better, Jimmie, I am going to get leave to come and help you with your crutches. I had crutches once, and it is quite fun hopping along when you know how to balance.”

“I’ll come too,” smiled Kits, “one on each side. We’ll have some fun, and if you like reading, Jimmie, there are lots of old boys’ books at my home which you would like to read I am sure. I will write and get them for you.”

Jimmie’s eyes sparkled. He loved reading, and he liked these two pretty young ladies coming to see and pet him up. Presently, the younger boy Walter came in, and Kits, who had got over a first shyness, made fresh laughter by shewing some simple conjuring tricks. It was extraordinary how quickly the time flew, and how much they themselves enjoyed the visit. Kits was as sorry as Joyce to leave the cottage, and what a glow it gave her round her heart, as she listened to the poor mother’s thanks. To cheer up Jimmie Wane was almost as nice, and, in some ways, even nicer than a jolly game of tennis or cricket.

Everything was “nice” according to Kits, who was in a wonderfully cheery and self-satisfied mood, as she slid down the bannisters, nearly falling into the arms—not of Mademoiselle—but of Crystal.

“Hillo!” was her gay greeting. “What’s the matter? Toothache, or a singing lesson? You look quite gloomy. Something must have exploded in the wrong place.”

Crystal perked her fuzzy head on one side.

“N-no,” she replied, “but I have had a hectic afternoon looking for some of those notes Mr. Hinton gave me. They’re gone—and I’ve searched everywhere. It’s a nuisance. At present I want to scratch someone, but I don’t know who!”

Kits grimaced. Though Crystal, with a great effort, was trying to make a joke of her loss, it evidently troubled her.

“Let me look?” she urged, good-naturedly, “the boys call me a nailer for finding lost belongings. We’ll begin at the first possible place and go on to the most impossible.”

Crystal gave the speaker’s hand a squeeze.

“You dear,” she replied, “but ‘nuffing doing’. You see, it can’t have got anywhere but where it was,—unless it were taken. And—it can’t have been taken!”

Kits rubbed her forehead.

“It sounds like Peter Piper of the pickling pepper,” she said, “repeat it slowly. Do you mean—the paper must be where it was put, unless it was taken which is impossible? In that case it must still be ‘there’. Where is ‘there’?”

“In my desk. There’s one virtue I do possess, Kits, and that is tidiness. I am tidy—at least in drawers and that sort of thing. Mr. Hinton’s paper was folded and slipped into a rubber band with three other papers. I remember yesterday catching the rubber on the paper pin holding two sheets together. And yet the paper is not there now. It was not there three hours ago. Some one must have taken it. I hate saying it, but it’s true. Only—why?”

“We shall have to find out,” replied Kits, “come back to the schoolroom. Miss Trennet will be there and she will help. Of course, it seems as if it were some one who did not want you to win the Parraton. But that is absurd.”

Crystal chuckled.

“It makes one laugh even to dream of Gwenda,” she said, “and she is the only one directly concerned. No, we must find another solution—and have another hunt.”

But both hunt and brain-racking were useless. The paper had gone. Miss Trennet was most sympathetic.

“Mr. Hinton will be here again next week, dear,” she said, “he will set you another paper.”

“I think I shall write to him,” said Crystal, “for it was just a link-lesson. I can’t get on with my reading unless I do it first. Don’t worry, Miss Trennet. I daresay I mislaid the wretched thing.”

Teresa Tenerlee was seated at her own desk on the other side of the room. She was busy sealing an envelope.

“Do you happen to have asked Joyce Wayde?” she demanded carelessly.

Crystal shot the speaker a quick glance, and her colour rose. She did not pretend to misunderstand.

“Don’t be so beastly mean, Teresa,” she commanded with energy, and walked out of the room, her arm round Kits’ waist.

Kits said nothing, she was too shocked at the bare hint. She frankly disliked Teresa, and had been afraid of taking up the cudgels for Joyce lest a lively quarrel should result. The idea of hinting such a thing!

Crystal made no comment about it, but Kits noticed how she searched out Joyce, and made a special point of persuading her to join the “research” party next afternoon.

Crystal would have spent an hour at least of that spare time in study, but she was handicapped, and at a standstill. But there was no grumbling. Complaints of things being “too bad”, or wild accusations were not in Crystal’s method of life. She was the merriest leader and general supervisor in the afternoon’s proceedings. And oh! what a mess those girls did make of themselves in the pursuit of science!

Pickles, with white of egg and lamp-black, was making an ancient boot polish guaranteed to produce a glorious shine on any boot. It produced a glorious nigger-mask over the pert features of Miss Pickles. Trixie was gingerly stirring a compound guaranteed to mend all broken china, whilst Crystal hovered as high-priestess of the ceremonies over a brew of superlative glue. Kits, perched on a shelf, read aloud from the book of cookery amidst peals of laughter and calls for a repetition of some choice description.

“Something is smelling,” said Noreen, presently, “pooh! how horrid. Crys, it’s the glue, do take it off. Kits, can’t you find a cure for rheumatism? I rather like the medical ones,—or a posset. Find a treacle posset.”

“One sec,” urged Kits, and leaned forward to obtain a better light.

Crack! That shelf had not been designed for a seat, and Kits, thinking only of ye anciente cookery book, clutched, swayed, and fell, knocking Crystal’s arm, as that worthy was in the very act of lifting the saucepan of glue off the stove. Over went the glue amidst squeals, yells, and a general flight. Crystal was dancing with pain as some glue had splashed her hand, though she laughed too, at sight of Noreen trying to plunge aside and escape the fatal flow which encircled her boots.

Glue, glue, everywhere, and oh, the smell too!

It was no sort of luck that Miss Pasfold and Mademoiselle should be passing down the road close by, as Kits flung open the hut door, and staggered laughing out.

The two ladies turned and instantly advanced, Mademoiselle pouring out a stream of rapid enquiries in French.

Kits retreated, Mademoiselle advanced.

“It’s only . . . only our experiments’ hut,” gasped Kits. “Miss Carwell knows all about it. She gave us leave.”

Crystal was on the threshold.

“Do ask Mademoiselle not to come in, Miss Pasfold,” she pleaded, “she won’t like the smell. We’ve spilt some glue.”

Miss Pasfold sniffed. She was a mean-featured woman, who knew perfectly well she was most unpopular with her pupils, and rather gloried in the fact.

“I shall do nothing of the kind, Crystal,” she retorted. “Mademoiselle and I wish to see what you were doing. I am quite sure Miss Carwell has no idea——”

She paused. Crystal, with a naughty twinkle in her eyes, had stepped aside. Mademoiselle passed into the hut, sniffing and jabbering. She insisted on knowing the origin of that so detestable smell—she found the answer beneath her feet!

Now Mademoiselle prided herself not only on her feet but her shoes! She was a plain woman, gawky and angular, but her feet were both small and well-shaped, her patent leather shoes quite irreproachable.