* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Helen Keller in Scotland: A Personal Record Written by Herself

Date of first publication: 1933

Author: Helen Keller (1880-1968)

Editor: James Kerr Love (1858-1942)

Date first posted: June 24, 2024

Date last updated: June 24, 2024

Faded Page eBook #20240610

This eBook was produced by: Mardi Desjardins, Pat McCoy & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

This eBook was produced by images generously made available by Internet Archive/American Libraries.

HELEN KELLER IN

SCOTLAND

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

PEACE AT EVENTIDE

THE WORLD I LIVE IN

THE STORY OF MY LIFE

MIDSTREAM

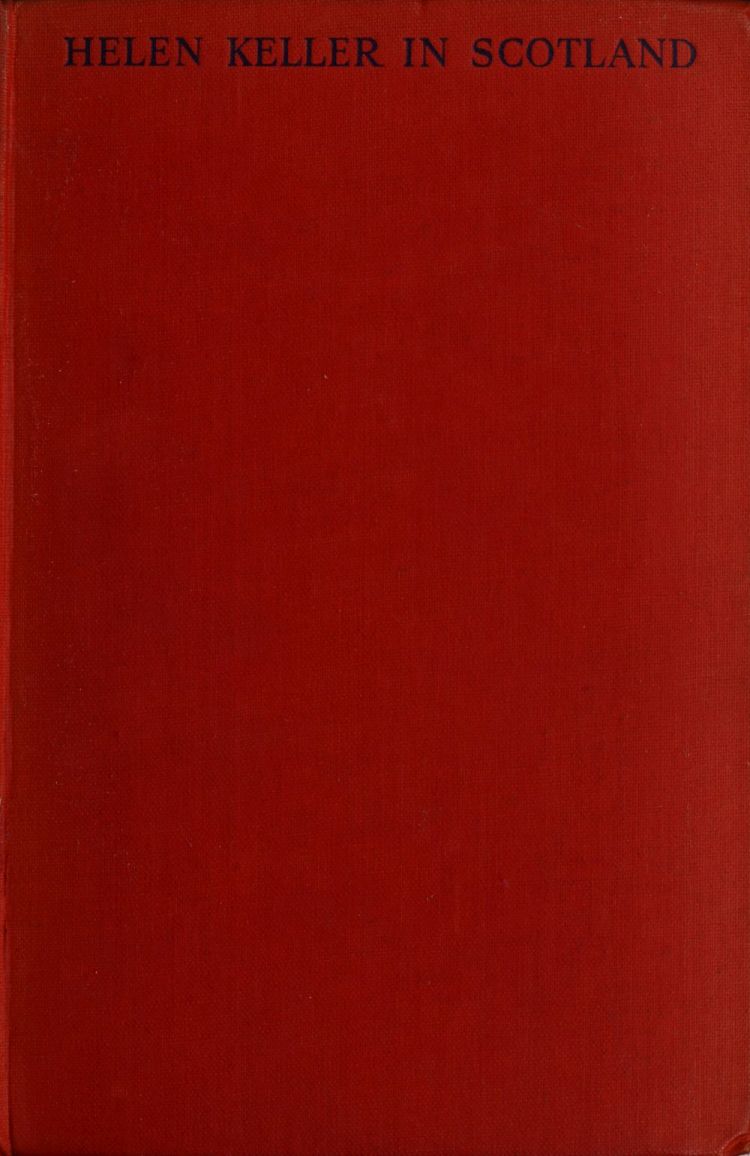

HELEN KELLER IN HER DOCTOR’S ROBES

AT THE PRIEST’S DOOR, BOTHWELL KIRK

First Published in 1933

PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN

PREFACE

This collection of letters and speeches records chiefly experiences surrounding the Honorary Degree conferred upon me by the University of Glasgow last June. The material has been collected and edited by Dr. James Kerr Love, my friend of a quarter of a century. Dr. Love and other friends in Scotland felt that there should be some permanent record of this most significant event in my life. While I am deeply grateful to Dr. Love for the trouble and thought he has put into this volume, he must, if it should be considered presumptuous and the personal element over-emphasized, accept the responsibility.

When the letters were written I had no idea that other eyes than those of the friends to whom they were addressed would read them. The speeches were composed hurriedly as I went from one function to another. The only reason for printing them is the hope that the story they tell of the general outlook upon the education of the handicapped and the lesson they teach of courage and victory over limitation, may prove of some interest and value to people with unimpaired faculties.

If these utterances and happy memories impart a sense of the marvellous kindness that gave my visit to Scotland the glamour of a royal progress, I shall be content. I should like my friends to think of this book as a garland of enkindling experiences woven to coax them for a little while into the bypaths of the deaf and the blind, and, once there, to keep them glad they came; a book easy to take up and lay down, with perhaps a helpful thought or two for the discouraged, and glimpses of a world of dark silence that is beautiful withal.

As I look over these pages, candour prompts the admission that I may have filched phrases from H. V. Morton’s enchanting book, In Search of Scotland. If so, he will not miss them out of his wealth of golden words. I have had such joy in his book that it would be strange if my thoughts did not often keep time to the music of his spirited narrative.

HELEN KELLER

Forest Hills, L.I., N.Y.

October 24, 1932

CONTENTS

| PAGE | |||

| PREFACE | v | ||

| LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS | ix | ||

| INTRODUCTION | 1 | ||

| By James Kerr Love, M.D., LL.D. | |||

| Part | I. | MY PILGRIMAGE | 17 |

| Part | II. | LETTERS | 65 |

| Part | III. | SPEECHES | 179 |

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

| DR. HELEN KELLER | Frontispiece | |

| (Photo: ‘Hamilton Advertiser’) | ||

| FACING PAGE | ||

| HELEN KELLER READING DR. KERR LOVE’S LIPS | 14 | |

| (Photo: George Outram & Co., Ltd.) | ||

| AMONG THE BROOM AT ‘DALVEEN’ | 20 | |

| (Photo: Wide World Photos) | ||

| READING IN SEARCH OF SCOTLAND | 28 | |

| (Photo: Wide World Photos) | ||

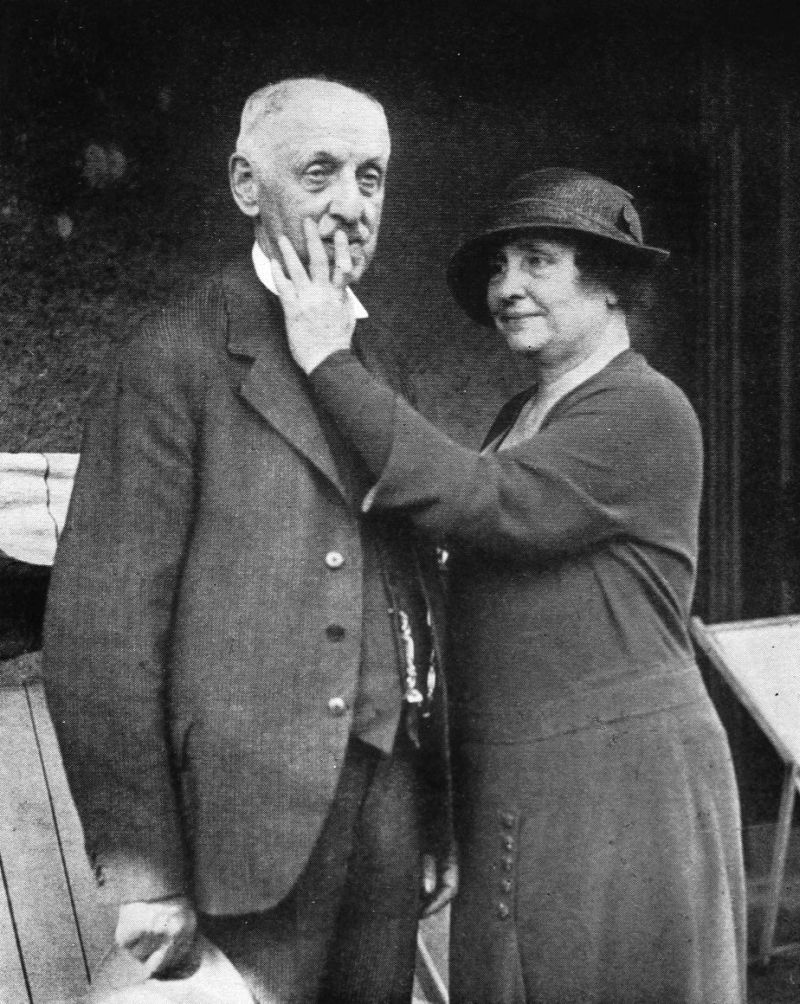

| WITH LORD ABERDEEN AT ‘HOUSE OF CROMAR’ | 56 | |

| FINGER SPELLING | 68 | |

| (Photo: Wide World Photos) | ||

| AT LOOE, CORNWALL | 86 | |

| (Photo: A. R. L. Pout, Exeter) | ||

| AT POLPERRO, CORNWALL | 104 | |

| (Photo: Wide World Photos) | ||

| WITH ‘BEN-SITH’ | 130 | |

| (Photo: Wide World Photos) | ||

| WITH CAPTAIN IAN FRASER, M.P. | 142 | |

| (Photo: Topical Press) | ||

| WITH THE DOGS | 156 | |

| READING THE BIBLE | 192 | |

| (Photo: Underwood & Underwood Studios) | ||

[Transcriber Note: The illustration, FINGER SPELLING, on page 68 was not included in the original text,

so does not appear in the ebook.]

HELEN KELLER IN

SCOTLAND

Helen Keller was born at Tuscumbia, Alabama, in June 1880, a quite normal child. At the age of nineteen months she was struck quite blind and quite deaf by illness, and soon all speech and language disappeared. For five years she led the life of a misunderstood and misunderstanding child. Through the agency of Dr. Graham Bell of telephone fame—himself once a teacher of the deaf, and married to a deaf wife—a teacher was found for Helen in the person of Anne Sullivan, now Mrs. Macy. Never was happier combination of great need and ability to serve. After a struggle in darkness and silence, light re-entered Helen’s mind through the agency of signs and finger-spelling; rebellion gave place to obedience, and the progress of the pupil was rapid. At the age of ten Helen declared that she must speak. This astonishing proposal was one which it had never occurred to those about her to make. But upon its being acceded to her progress was again rapid. It became clear to Miss Sullivan that she had under her care a brilliant and unusual pupil. In due course Helen entered college and, without favour or concession of any kind, graduated in arts. The story of her life is told fully in her books, The Story of My Life and Midstream, while in The World I Live In she has much to say of her moods and pleasures. Enough has been said here to prepare the reader for the perusal of her book on Scotland.

I have known Helen Keller for over a quarter of a century. There was a long-standing promise that she should visit me at West Kilbride when circumstances should allow. The date of the visit was eventually determined in 1932 by the action of the University of Glasgow in conferring upon her the Honorary Degree of Doctor of Laws. The late Professor William James, one of her greatest admirers, described her as ‘a blessing’, and offered to kill anyone who denied this. I, too, think her a blessing, and I looked to her visit to help me to convert the unbelieving and make them missionaries for the deaf. She has fulfilled all my hopes.

Looking back upon my knowledge of Helen Keller, I find that it passed through three stages. There was, first, the pathetic or ‘poor thing’ stage—creditable to the heart, but not of long duration.

This was succeeded by a feeling of admiration, for the pluck, patience, and fortitude which have overcome apparently insuperable difficulties. Most people reach and rest in this stage, and do not know whether to admire more Helen Keller or her beloved teacher, Anne Sullivan, now Mrs. Macy.

Finally came the stage of sheer joy and inspiration in the presence of a great and happy personality.

Professor Macneile Dixon sums up the characteristics of the average Englishman as ‘toleration, humour, humanity’. There you have Helen Keller. But I must add one feature which cannot be claimed for the average Englishman—an absolute assurance of spiritual companionship both in this world and in any world which may follow it. It is this element which gives to Helen Keller the fight which dispels all darkness, the ear which hears music everywhere, and a well-balanced mind over-flowing with ‘gallant and high-hearted happiness’.

Here I can hardly do better than quote what Mr. W. W. McKechnie said of her on June 10, 1932, at the ceremony at which she was presented with her graduation robes.

‘The emancipation of Helen Keller is one of the marvels of educational achievement, brimful of interest and value to Miss Keller herself, and no less full of significance for education in general. While for me, as an individual, it is a rare privilege to preside over your meeting, it is no mere form of words to say that it is a privilege that carries with it a haunting sense of inadequacy. But it would be utterly inconsistent with one of the main lessons of Helen Keller’s life if any of us to-day were to shrink from a task simply because it was difficult.

‘When Miss Keller was a girl of seven she wrote a letter in which she said: “When I go to France I will talk French.” A little French boy will say “Parlez-vous français?” and I will say “Oui, Monsieur, vous avez un joli chapeau. Donnez-moi un baiser.” And in the same letter she used several little Greek phrases: se agapo, I love you; pos echete, how do you do?; chaere, good-bye. That was her Greek at seven. Ten or eleven years later she was simply revelling in Greek and especially in Homer. Of Greek she said: “I think Greek is the loveliest language that I know anything about. If it is true that the violin is the most perfect of musical instruments, then Greek is the violin of human thought.” Surely, then, no one will take it amiss if I allow myself one Greek proverb. It is chalepa ta kala—what is noble is difficult—and it is with that proverb in my mind that I approach my difficult task.

‘Helen Keller has a genius for friendship. Of her friends she says: “They have made the story of my life. In a thousand ways they have turned my limitations into beautiful privileges, and enabled me to walk serene and happy in the shadow cast by my deprivation.” It is sheer joy to see the affection that has existed between her and many of the most distinguished men of her time—Bishop Brooks, Graham Bell, Whittier, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Mark Twain. Of Mark Twain she once said: “His heart is a tender Iliad of human sympathy.” What did Mark Twain say of her? That Napoleon and Helen Keller were the two most interesting persons in the nineteenth century. That is an amazing combination, and coming from Mark Twain it deserves very serious consideration. You will agree with me that the emancipation of Helen Keller from the doom that threatened her almost makes us think that the age of miracles is not dead, any more than the age of chivalry. When we think of her before and after she was restored to her human heritage, we are reminded of La Belle au Bois Dormant and of Ariel. The Sleeping Beauty was imprisoned in the Castle where all was death, till the Prince came and set her free; Ariel was confined in a cloven pine, till Prospero “Made gape the pine and let him out”. Ladies and gentlemen, if Helen Keller is our Ariel and our Belle au Bois Dormant, there is no doubt as to who was cast by destiny for the roles of Le Prince and Prospero. Whittier called Miss Sullivan “the spiritual liberator” of Helen Keller. All honour to Miss Sullivan, Mrs. Macy as she is now, for the genius, untiring perseverance and devotion of her services to her pupil and friend. I have had experience of every kind of teaching, and I am sure that none is so arduous as the teaching of the deaf. When blindness is added to deafness, the task is one for heroes and for heroes alone. I am sure we are all glad to have Mrs. Macy with us this evening.

‘The life of Helen Keller is one of the greatest triumphs of the educator. It is at the same time one of the most inspiring and inspiriting arguments for education that exist in the records of the race. How many imprisoned Ariels has the world lost for want of the culture and encouragement that were needed? It is some consolation to us to know that in our own country the number is small and is every year growing smaller.

‘But we must not exaggerate. There is not an Ariel in every tree, and all the Miss Sullivans in the world could never evoke qualities that are not latent, implanted in their pupils by Nature. There have been many other deaf and blind children. Dickens told us of two of them in his American Notes—Laura Bridgman and Oliver Caswell—and it is most interesting to know that Helen Keller’s mother had her first ray of hope when she read Dickens’s account of what had been done for Laura Bridgman. But few or none of them had the altogether exceptional gifts of the lady we are met to honour.

‘It is embarrassing to speak of Miss Keller in her presence. But I must. And I may be forgiven for recalling the fact that she was sometimes a naughty child—with all the rich promise that naughtiness conveys to the teacher or parent who has the sense and the heart to understand. And as soon as the cruel barriers were beaten down her precocity was manifest. She loved the art of composition. By the age of thirteen she was deeply interested in the history of Greece, Rome, and the United States. Latin Grammar she did not take to at first. Why parse every word? Would it not be at least as useful, she asks, to describe her cat—order, vertebrate; division, quadruped; class, mammalia; genus, felinus; species, cat; individual, Tabby? At that time this amazing child tried, without aid, to master French pronunciation. “It gave me something to do on a rainy day!” And she felt the joy of translating Latin! Arithmetic she found as troublesome as it was uninteresting. I do think our young friend might well have been spared some, if not all, of her mathematical troubles. Her heart was in language. “I cannot see why it is so very important to know that the lines drawn from the extremities of the base of an isosceles triangle to the middle points of the opposite sides are equal. The knowledge doesn’t make life any sweeter or happier. But a new word learned is the key to untold treasure.”

‘Then came College—a most interesting chapter of her life. Listen to her on note-taking in lectures, which critics have been girding against in Scotland for centuries: “If the mind is occupied with the mechanical process of hearing and putting words on paper at pell-mell speed, one cannot pay much attention to the subject or the manner in which it is presented.” At first some disillusionment! “When one enters the portals of learning, one leaves the dearest pleasures—solitude, books, and imagination—outside with the whispering pines.” Her criticism of pedantry is admirable. And listen to her on examinations. You should read the passage in full. Here is a quotation: “But the examinations are the chief bugbears of my life. Although I have faced them many times and cast them down and made them bite the dust, yet they rise again and menace me with pale looks, until, like Bob Acres, I feel my courage oozing out at my finger ends.” “Those dreadful pitfalls called examinations”, she says again, “set by schools and colleges for the confusion of those who seek knowledge.”

‘What surprises me most of all is that in spite of everything she became so soon such a mistress of language, that she wrote so well and that she appreciated literature with such taste and discrimination. The proof of this is everywhere in her writings—what she says about authors in English, French, Latin, Greek, the Bible, about Shakespeare, Burke, Macaulay, La Fontaine, Virgil, Homer.

‘But best of all is the moral outlook. Her courage, her humour, her self-forgetfulness. She feels the bitterness of her fate. “Silence sits immense upon my soul. Then comes hope with a smile and whispers ‘There is joy in self-forgetfulness.’ So I try to make the light in others’ eyes my sun, the music in others’ ears my symphony, the smile on others’ lips my happiness.” We recall her warm friendships, her God-given sense of humour, her deep gratitude to all her teachers, her love of children, her pity for the poor, the weary, and the heavy-laden. We think of her indomitable courage and perseverance: “I slip back many times, I fall, I stand still, I run against the edge of hidden obstacles, I lose my temper and find it again and keep it better, I trudge on, I gain a little, I feel encouraged, I get more eager and climb higher and begin to see the widening horizon. Every struggle is a victory. One more effort and I reach the luminous cloud, the blue depths of the sky, the uplands of my desire.” And last her superb optimism.

‘ “I love”, she wrote, “Mark Twain. Who does not? The gods, too, loved him and put into his heart all manner of wisdom; then, fearing lest he should become a pessimist, they spanned his mind with a rainbow of love and faith. I love all writers whose minds, like Lowell’s, bubble up in the sunshine of optimism—fountains of joy and goodwill, with occasionally a splash of anger here and there, a healing spray of sympathy and pity.” ’

I have by me a unique book—an Anthology to Helen Keller. I like the musical Greek word, which of course means a garland. We are accustomed to anthologies, collections of verses compiled by someone and sold for a certain figure. But this one, called Double Blossoms, is a collection of over seventy poems about or addressed to Helen Keller. I wonder whether in the history of literature such a tribute has ever been paid to a living author? No wonder she was apostrophized by Clarence Stedman, the American poet, in these terms:

‘Not thou! Not thou!

’Tis we are Blind and Deaf and Dumb.’

Helen Keller’s visit to Scotland in 1932 was not the first she had paid to our shores, as a letter which follows will show; her first visit was in 1930 (see p. 85). But then she came for rest—rest for herself and, perhaps more, for her teacher and life-long friend, Mrs. Macy; and that she was justified in thus seeking seclusion was proved by her experience in 1932, when she received incessant calls to make public appearances. In 1931 Helen visited France and made a journey to Yugo-Slavia, where she was the guest of that country and of its King, and did valuable work for the Blind. Most of Helen’s work has been in the interests of the Blind. I was anxious that she should help the Deaf in Britain so that the interests of these equally afflicted ones should no longer remain in the position of relative neglect which they occupied before her visit.

In reading the book which follows, two questions will strike the reader as requiring an answer: What does Helen Keller mean when she talks of ‘seeing’ things? and, How does she work? I have sometimes been tempted to write on ‘The Mind of Helen Keller’, but I have always been deterred by two considerations: the difficulty of the task, and the fact that in her book The World I Live In, which is shortly to be published in an English edition, she has herself done more than perhaps any author could to analyse and expose her mind.

In answering the first question, then, I will quote from The World I Live In. From a newspaper for the blind Helen Keller cites the following sentences:

‘Many poems and stories must be omitted because they deal with sight. Allusions to moonbeams, rainbows, starlight, clouds, and beautiful scenery may not be printed because they serve to emphasize the blind man’s sense of his affliction.’

‘That is to say’, she comments, ‘I may not talk about beautiful mansions and gardens because I am poor. I may not read about Paris and the West Indies because I cannot visit them in their territorial reality. I may not dream of heaven because it is possible I may never go there. Yet a venturesome spirit impels me to use words of sight and sound whose meaning I can guess only from analogy and fancy. Critics delight to tell us what we cannot do. They assume that blindness severs us completely from the things which the seeing and hearing enjoy, and hence assert that we have no moral right to talk about beauty, the skies, mountains, the song of birds, and colours. They declare that the very sensations which we have from the sense of touch are “vicarious”, as though our friends felt the sun for us.’

Later in the same volume she remarks: ‘Many persons having perfect eyes are blind in their perceptions. Many persons having perfect ears are emotionally deaf. Yet these are the very ones who dare to set limits to the vision of those who, lacking a sense or two, have will, soul, passion, imagination.’ I may add that most of the impressions of us five-sensed people, although based on sight and hearing, are really composite and completed by descriptions we have read and forgotten but on which the imagination continues to work. Further, it must not be forgotten that from birth till nearly two years of age Helen had her sight and hearing, and, although she cannot define it, something remains of that bright childhood. To these possessions must be added a very retentive memory, a very vivid imagination, and something of that incalculable thing we call genius.

Consider her description of Skye (see p. 58), which is really a prose-poem. Starting with the meagre foundation of impressions reaching her through her remaining senses, she derives further information from Miss Thomson, who spells into her hand observations on the scenery. But neither Miss Thomson nor any one else could paint the resulting picture. As Helen has indicated in her Preface, the influence of H. V. Morton may be traced in this piece; but the picture—the prose-poem—is her own.

I can give another instance from personal experience. During a motor run from West Kilbride to Gleneagles Hotel in Perthshire, talk ranged over many subjects, and occasional references were made by Miss Thomson to the nature of the country traversed, the words being spoken, for our benefit, as they were spelled into Helen’s hand. The day was wet and misty and the scenery not of the striking type of Skye. Helen alone thought of drawing poetry out of a wet day. The same evening she sent me the following:

‘Gleneagles

June 28, 1932

‘It is not raining rain for me,

It’s raining wild-flowers on the hills!

Let clouds and Scotch mists engulf the sky,

It is not raining rain to me,

It’s raining mounds of golden broom!

‘I salute the happy!

I have no use for him who frets—

A fig for mists and clouds!

It is not raining rain for me,

It’s raining scented briar and larks to-day,

And all of them are saying, “Earth, it is well!”

And all of them are singing, “Life, thou art good!” ’

The second point, How does Helen Keller work? is best illustrated by her preparation of a platform speech. Helen types what she means to say on an ordinary type-writer, and the typescript is then read to her by the fingers and any necessary corrections made. When perfect, the speech is rewritten with her own fingers in Braille, from which version she reads it until she is memory-perfect and ready to deliver it.

HELEN KELLER READING DR. KERR LOVE’S LIPS

AT ‘SUNNYSIDE’, WEST KILBRIDE

The system of finger-spelling familiar to the British public is the two-hand system which is used by the seeing deaf and in addressing the deaf and dumb. But with the blind-deaf like Helen Keller this method is useless. So the one-hand alphabet, spelt from hand to hand, which is probably of Monastic origin, is used by Mrs. Macy and Miss Thomson when direct speech-reading is not possible. Helen Keller’s own speech, and her power to read the speech of others by placing her fingers on the lips of the speaker, are perhaps her most spectacular triumphs. This lip- or rather speech-reading she effects by the contact of her thumb on the larynx and her fingers over the lips or lower part of the face of the speaker; by this means, if the speaker speaks slowly, she succeeds in understanding the words (see Plate facing page 14).

My editorship of this book became necessary when, immediately on her return to America, Helen Keller was plunged into strenuous work for the Blind. The work on Part I was trifling, only a few names of places and persons requiring attention. But the letters in Part II had to be collected from their recipients and any unnecessary repetition eliminated from them. This, in several cases, I found difficult; for the letters were written, for the most part, from one address and during a single month, and accordingly repetition was almost inevitable. If, therefore, in my literary surgery, I have cut out from letters passages which their recipients treasure, I hope I shall be forgiven.

My thanks—and I am sure Helen Keller’s—are due to the recipients of the letters for so kindly furnishing copies. Thanks are due also to Mr. D. MacGillivray, LL.D., for reading the manuscript, and to the Rev. J. Wales Cameron, M.A., for correcting the proofs.

JAMES KERR LOVE

Sunnyside

West Kilbride

Ayrshire

As Fate would have it, the honorary degree conferred upon me by the University of Glasgow in June 1932 cheated us out of the greater part of our holiday. Even in lovely Looe, where we spent most of May, we were under a constant barrage of reporters, photographers, callers, telegrams, and telephone messages. Polly[1] and I rose at six in the morning to get a walk before the fray began. We were literally deluged with invitations of all kinds, and often Polly wrote twenty letters between breakfast and dinner, while I worked on magazine articles and prepared my speeches for the robing and graduation ceremonies.

After our arrival in Scotland the fusillade became more lively, and continued unabated until the end of June. There was some sort of function practically every day. Of course I was glad to visit the schools for the blind and the deaf in Edinburgh and Glasgow about which I had read since I was a child, and to meet friends whose kindness I had so long felt from afar.

Dr. and Mrs. James Kerr Love were the dearest of hosts. They did everything possible to make us comfortable and give us pleasure. The cottage, ‘Dalveen’, at West Kilbride, which they provided for us was adorable with climbing roses and a garden which I shall always remember with joy. There was a tremendous bank of broom at one end of it that filled the garden with golden glory. Teacher[2] said it looked as if the sun had fallen out of the sky, it was so bright. The mingled fragrances of sweetbrier, fir, and honeysuckle are heavenly! The hawthorn, golden privet, laurel, and rhododendron hedges were breath-taking. They are three or four feet wide and higher than my head. One could walk on the tops of them, they are so compact. And the mists and rains keep them fresh and scintillating. One can’t complain of rain which produces such magical effects. It actually seems as if it were raining wild-flowers upon the hills and larks in the fields of Scotland! Teacher and Polly went into ecstasies over the birds—blackbirds and thrushes kept them happily awake half the night. We had a dear little Scotch maid, Peggy, who kept house and cooked for us and chased our new ‘Scottie’ when she ran away, which she did eight times in ten days.

This troublesome darling was given Teacher as a birthday present by Mr. Anderson. A friend of his, a dog-fancier in Scotland, brought Ben-sith (pronounced Benshee—means Fairy in Gaelic) to ‘Dalveen’ the day after we arrived, and the chase began then and there. Ben-sith is a wild little elf in fur, and prefers the hills and braes to a civilized dwelling. She isn’t a year old. I’m afraid she’s going to break many dog-hearts in America. Teacher is devoted to her and spends much time every day making her black coat soft and glossy. She intends to give her in marriage to our wee Darky, if they please each other.

HELEN KELLER AMONG THE BROOM

AT ‘DALVEEN’

Although I had seen Dr. Love only twice in my life, yet I had the sincerest affection for him. I had read his book, The Deaf Child, and had been enlightened by it. We had written to each other occasionally during twenty-five years, and I know that we both had a warm sense of being of one mind about the deaf and their special problems. It was reassuring to me to know that at least one thoughtful physician in Scotland was studying the causes of deafness and seeking ways to prevent it. Dr. Love, almost single-handed, fought the battle of the deaf in conventions of doctors and medical journals. His devotion was the greatest asset their cause could have. Slowly but surely it overcame prejudice and opposition; it convinced and won where appeal to sentiment would scarcely have raised a tremor of interest. This was nothing more nor less than faith in action. Faith and knowledge and courage combined remove mountains. There is no measuring the importance of Dr. Love’s share in breaking ground for progress in the teaching of the deaf. He set the bacillus of enthusiasm at work in schools, clinics, and private consulting offices, and it changed the attitude of medical men toward the deaf and the method of teaching them.

It was with the purpose of spreading this happy contagion that Dr. Love was so anxious that I should come to Scotland. He felt that, if the University of Glasgow set the seal of its approval upon my efforts not to be defeated by my limitations, it would encourage other handicapped people to make something of their capabilities. It was in this spirit that the distinction was conferred upon me. The thought that Dr. Love’s life-work has been given a little shove forward through me is one of the sweetest satisfactions of my life.

Soon after our arrival we called with Dr. Love on a gentleman[3] who has a deaf daughter. He has a wonderful place on a promontory overlooking the Firth of Clyde. I never saw more beauty in a garden! The delphiniums grew to a height of seven and eight feet, also the hollyhocks and lupins. There were roses and lilies—Oh, such lilies! The walls were covered with rare vines and climbing roses. We saw even fig and peach trees growing flat against the sheltering wall. We picked ripe figs and peaches on the 5th of June! The conservatories were full of gorgeous calceolarias, cinerarias, and begonias, making such a blaze of colour as to remind Polly of tropical sunsets. Mingled with the blossoms were ferns of many exquisite varieties, and against the glass hung grapes and pears and peaches. As we sat chatting amid all this loveliness, we watched the ships go by, and looked across the Clyde and saw Goatfell climbing out of the sea like Jack on his bean-stalk.

Our first official appearance was June 10th, when the teachers of the Deaf and the Blind of Scotland presented me with the robes I was to wear at the ‘capping’ ceremony. This was a most generous gesture, and I appreciated it immensely. The robes are gorgeous—crimson and purple, and the ‘trencher’ is black velvet. I was moved to the spring of tears by all the pleasant things that were said about Teacher and me.

Mr. W. W. McKechnie of the Scottish Education Department presided.[4] He made the most brilliant and appreciative speech about Teacher’s work and what she has done for me that I have ever heard.

Dr. Love told the audience in quiet, eloquent words how he had watched my development for twenty-five years, and how by written word and word of mouth he had urged that my teacher’s method should be adopted in the Schools for the Deaf.

The Graduation ceremony took place on June 15th in Bute Hall at the University, which is built on Gilmorehill, dominating the city of Glasgow. The hall is lofty and sombre, and its stained-glass windows give it the appearance of a church. The ceremonies were most impressive, the brilliant robes giving the effect of a religious procession. Degrees, ‘D.D.’, ‘LL.D.’, and ‘D.Sc.’ were conferred upon a number of men who had distinguished themselves in their various professions. Each recipient listened to a eulogy of himself in Latin, and then mounted some steps and knelt on a cushion to receive his diploma from Principal Rait and to be ‘capped’. Very few women have received an honorary degree from Glasgow University, which circumstance gives a special significance to my receiving the degree of LL.D.

The University was founded in 1450, and it has many names upon its roll of honour, among them Adam Smith, James Watt, Lord Lister, and Lord Kelvin.

The assembly gave Teacher a splendid ovation. This pleased me more than the honour paid me.

There was a luncheon where we foregathered with a distinguished company, still in our robes. I made my little speech as best I could; I was terribly embarrassed by a sense of my inadequacy. The other speakers paid Teacher and me handsome compliments, which embarrassed us still more. But the thought that I represented the handicapped stiffened my knees, and I got through safely.

From the luncheon we went straight to Queen Margaret’s, the Radcliffe of Glasgow, and that meant another speech. I spoke on the mission of women to promote peace and enlightenment, as St. Margaret had done centuries before. The women were delightfully cordial, but it seemed as if the day would never come to an end. At last, however, it did come to an end, and, except for the nervous strain, it had all been very easy. It was late that night when we got back to ‘Dalveen’, and I felt as if I should like to sleep for twenty years like Rip Van Winkle. But alas! a few hours’ rest was all that was vouchsafed us. I fully sympathize with Mr. Howells, who said, when he received an honorary degree from Oxford, ‘Such distinction comes rather late in life, and if it does not kill, it cures the desire for more.’

The next day Polly and I went sailing with many hundreds of blind people and their guides down the Clyde to a beautiful estate on Lochgoilhead, a fine picnic-ground, where the blind are taken once every summer for an outing. Again I spoke—and so it was from day to day. Every time I went anywhere the penalty of my appearance was a speech. Teas, dinners, and prize distributions of all sorts continued during our stay in Scotland, and they included a birthday party at Dr. Love’s, where there were more speeches, more compliments, more blushes and thank-yous. There were telegrams and cablegrams and letters from all parts of the world congratulating me and wishing me happiness.

Polly’s brother and his wife and her mother came to see us and had dinner with us. That was about all Polly saw of her family. We had one pleasant week-end with her friends, the Bains, at Stirling. They drove us up into the Highlands as far as Dunkeld and Birnam Wood—places mentioned in Macbeth. One of the great oaks Macbeth knew is said to survive on the banks of the River Tay. Macbeth, I understand, was a real ‘laird’ of Scotland, and not as bad as he is made out to be by Shakespeare.

Another happy memory is of a motor run to Loch Lomond, a loch of a million beauties, renowned in song and story.

On one occasion we were invited by Mr. and Mrs. Sweet, friends of the Loves, to visit the Island of Arran. We crossed the Clyde on a little steamer, and, before landing, had a good view of Goatfell, a rugged mountain that can be seen from a great distance. It is one of the landmarks of Scotland. When our friends met us at the pier, they told us that they were not to have the pleasure of showing us the island after all, as the Duke and Duchess of Montrose wished us to visit them at Brodick Castle. The island, which is about sixty miles in circumference, belongs to the Duchess. Very little grows on it, except heather, but in the spring-time it is a blaze of gorse, broom, and wild-roses. Wild deer, sheep, and cattle browse on it. The castle is ancient, dark brown, and almost buried in a romantic past. The walls are about seven feet thick, and there are holes at various points where guns were formerly mounted to repel invaders. To reach the castle it was necessary to cross a wide open space, which rendered unwelcome visitors conspicuous targets from the battlements.

The Duke and Duchess were charmingly hospitable. We enjoyed our tea and chat with them, and I wished we had more time to see the island with them. The Duke is a handsome man. He wears a kilt, and looks like a Highland chieftain of old in his baronial castle. The Duchess is a fine, active woman. She loves flowers, and has a most beautiful rock-garden which she made herself. Their daughter, Lady Jean, a sweet girl of eleven, picked a bouquet of old-fashioned pinks for me, ‘because they are so sweet’, she said when she presented them. The Duke is hard of hearing, and takes a deep interest in others who are handicapped. In the huge hall of the castle is the rough table at which Robert the Bruce ate venison and wild boar. The worms are doing the eating now. I noticed deep knife-cuts in the wood. In that barbarous age they had no plates, and sometimes the cleaver went clear through the joint to the table.

The Duke of Montrose, by the way, owns Loch Lomond. I believe Buchanan Castle is a marvellous place.

One day Dr. Love drove us to the Burns country in Ayrshire. I was deeply stirred as we passed place after place mentioned by the poet. His birth-place is near Alloway, not far from the ‘Brig o’ Doon’—the ‘clay biggin’ Burns’s father made with his hands. This cottage has three parts: the store-house, where provisions and hay were kept, the barn, where the cow and the horse stood, the ‘but and ben’, consisting of a kitchen and a sort of alcove bedroom. The kitchen has one window and a fireplace. The bed in which Burns was born is built into the wall; and is very narrow. I don’t see how a baby could have been born in such a bed. I sat on the low stool where his mother rocked back and forth as she crooned to him, little dreaming that her wee bairn would be Scotland’s most beloved poet, more famous than any king; and I sat also in the arm-chair where ‘the Priest-like father read the sacred page’. The flagstones of the cottage have been worn flat and smooth by the feet of generations. There is but one door to the cottage. To get out of the kitchen one passes through the cowshed and the store-house.

Beside the humble dwelling stands a modern museum in which all kinds of things associated with the poet are carefully preserved under glass—autographed letters and manuscripts, for example. I put my hand on part of the original manuscript of Tam o’ Shanter, the family Bible, and the spinning-wheel. There were also the pages in brown ink on which Burns described that ‘highland journey, with its birks of Aberfeldy and its milestones of bright eyes’.

I do not think there is another poet in the world who has so sung himself into all the dear common things of everyday life as Burns has. The day spent in the surroundings familiar to him will ever remain in the deep places of my heart.

HELEN KELLER READING AT ‘DALVEEN’

THE BOOK IS THE BRAILLE EDITION OF ‘IN SEARCH OF SCOTLAND’

On our last Sunday in Scotland on this occasion Teacher and I spoke in Bothwell Parish Church, where Polly’s brother is the minister. The church was packed to capacity, and there was an overflow meeting, where we spoke also. The collection was unusually large, and is to be used for the restoration of St. Bride’s. Part of St. Bride’s is very old, going back, I think, to the thirteenth century. The roof is made of stone, which gives it an ancient aspect. The modern structure, which was added during the Reformation, is out of key, and Mr. Thomson is very anxious to bring it into harmony with the older and nobler edifice.

We left West Kilbride on June 30th, for London. ‘It’s hardly in a body’s power’, as Burns would say, to tell how ‘sair’ we felt to leave that bonny, bonny wee countree and a’ the friends we had made there. Tears were in our eyes and a tugging at our heart-strings when we said good-bye to Dr. and Mrs. Love. They had lightened many a hard day with considerate kindness and sweet helpfulness. They made us feel ‘the real guid of life’. ‘There’s wit in their heids and luv in their herts we’ll find nae other where.’

For three days we hid ourselves in the seclusion of the Park Lane Hotel. No one knew we were in Town except Mr. Eagar, Director of the National Institute for the Blind, and Polly’s sister, Margaret. We shopped a little, got ‘dolled up’ by Charles, ‘hairdresser to the Court’, ate strawberries as big as peaches, and prepared ourselves for a plunge into the social whirlpool of London.

We are deeply indebted to Mr. Eagar for his tireless efforts to help us carry out this crowded programme to a fair conclusion. He gave much of his precious time to arranging meetings and interviews. In fact, he put the staff of the National Institute for the Blind at our service, and the force of his fine judgement and tact carried us through. I shall never cease to be grateful to him for his unfailing goodness and serenity while we were in London. He is one of those fine spirits who are ever trying to make straight the path of the handicapped.

The whirl began on July 4th, when I opened a school of massage for the blind under the auspices of the National Institute. There was a luncheon attended by many eminent and interesting men—Sir Beachcroft Towse, a blind veteran of the Boer War, Sir Brace-Porter, Sir William Lister, Surgeon-Oculist to His Majesty’s Household, and others.

At three o’clock I met the British Press. It was one of the most severe ordeals we had yet experienced; for Teacher and I did the talking while they listened and took notes. Afterwards I accompanied the reporters through the massage school, and we had tea with Sir Beachcroft and Lady Towse.

The speed at which we went from one function to another during the next two weeks has made this period a blur in my consciousness. I know that I made three or four or five appearances every day; that I met many distinguished people; that I visited schools and made many speeches and examined the handicrafts of the blind and the deaf; that I lunched with Captain Ian and Mrs. Fraser at St. Dunstan’s, with Lord and Lady Astor, with Lady Paula Jones, and at the Royal Normal College for the Blind, at Leatherhead, Surrey, and at Swiss Cottage, institutions for the sightless; that I had tea with somebody or some group every day; that we dined with the Frasers in the House of Commons, and with Lady Fairhaven and her son, Lord Fairhaven (the daughter and grandson of H. H. Rogers), and that we called on Sir Hilton Young, Minister of Health.

There is always much formality about these official calls in England. Our interview with Sir Hilton Young took place at Whitehall, where Charles I was beheaded—a place where one gets lost and walks miles unless one is properly conducted. One waits in the reception-room of the Minister until the great man is ready. There is an urgency and importance in the manner of the attendants which suggests that a moment’s delay would cause the gravest offence, and be regarded as profoundly disrespectful. However, this feeling vanished when we entered the presence of Sir Hilton Young, who rose from his imposing desk and came forward to meet us, smiling pleasantly. I grasped his outstretched hand, and knew that he was a friend of the unfortunate. We talked about the work for the blind and the deaf; then I told him what I thought should be done for the deaf-blind. He listened attentively, and I believe he will do all in his power to promote their welfare.

The dinner in the House of Commons was most exciting. The lofty halls and corridors stirred me strangely. I was rather confused about the name of the place, as it is sometimes called the Palace of Westminster and at other times the Houses of Parliament. To me neither Westminster Abbey nor the Tower of London is nearly as interesting as the House of Commons; for it incarnates the history of the English race. Here one sees the past continuing into the present. As I sat there, I was conscious of tense faces in the seats of the great hall watching the trial of Charles I and the installation of Oliver Cromwell. From the same seats now, faces not quite so tense are looking upon Mr. Ramsay MacDonald, recently[5] returned from Lausanne. All the Houses of Parliament, except Westminster Hall, date only from the last century, but the ground on which it stands has been the site of a royal palace since the time of Edward the Confessor. The thought came to me that the habitations of historic ghosts may be often rebuilt, but the ghosts do not depart. Like Japanese ancestor-deities, they watch over the destinies of their country. The House of Commons has always been to me a symbol of something great and glorious, and a thrill went down my spine as I walked on the famous terrace where statesmen and leaders so often discuss measures and policies that reach out to the ends of the earth. Here were fashionably dressed men and women smoking, chatting, and laughing, with a glance now and then at the Thames, the bridges, and the great city that stretches along the banks of the river, with Hampstead to the North and Penge to the South.

There were twenty guests at dinner, among them Lady Pearson and her son, Sir Neville. I was particularly glad to make Lady Pearson’s acquaintance, as her husband had been so wonderful to me.

‘What did Sir Arthur Pearson do for you?’ asked Miss Irwin, a charming Canadian newspaper woman who sat opposite me. ‘Oh,’ I replied, ‘whenever I wanted to know anything, I wrote to him; and he had many books embossed especially for me; and his enthusiasm put fighting strength into my elbow when I had a hard job on hand.’

Sir Arthur Pearson has a most able successor at St. Dunstan’s in Captain Fraser. Both he and Mrs. Fraser are a joy to meet. Beside being at the head of St. Dunstan’s, he is an ‘M.P.’, and I shall be surprised if his vigorous, vibrant personality does not make itself felt in Parliament, as it already is felt in the world of the blind.

Ever since I met Lady Astor, I have been wondering why the newspapers give such a wrong impression of her. She is most emphatically not a shrew. She is animated, responsive, eager, and keen. She is very slight and youthful-looking. She has a sweet, friendly way of taking your hand and telling you she has always loved you because you are a southerner. She is as charged with energy as an electric battery. She told me she works fourteen hours every day. She must be heartily sick of people who want to discuss all manner of subjects with her, but there is no impatience or resentment in her bright, courteous, intelligent replies. Perpetually in the public eye, she hates publicity, and avoids interviewers like the plague. ‘No matter what you tell them,’ she said, ‘they will get it all wrong,’ but she smiled good-naturedly as she said it. She agreed reluctantly when I said publicity must be accepted along with the rest of the evils we moderns have fallen heirs to. I had heard Lady Astor described as aggressive and opinionated. She is nothing of the kind. She is a delightful hostess, and draws about her many interesting people. At her luncheon we met Lord and Lady Cushendun; Mr. Foote, Minister of Mines; Miss Ellen Wilkinson, who was known as ‘the Spitfire of the Labour Government’; Miss Brisbane, the daughter of Arthur Brisbane; and Lady Astor’s fascinating daughter, Lady Violet.

On another occasion at Lady Astor’s house we met a representative of Soviet Russia and Bernard Shaw. Lady Astor told us her son had become a Communist, and that they were arranging to send him to Russia in the belief that what he saw there would cure him.

Bernard Shaw was as bristling with egotism as a porcupine with quills. His handshake was quizzical and prickly, not unlike a thistle. Lady Astor tried to interest him in me. ‘You know, Mr. Shaw,’ she said, ‘that Miss Keller is deaf and blind.’

‘Why, of course!’ he replied. ‘All Americans are blind and deaf and dumb.’

I asked him why he had never come to America.

‘Why should I go to America,’ he answered, ‘when all America comes to me?’ He consented to have his picture taken with Lady Astor and me, and the long anticipated meeting with an author whose books I had read with the liveliest pleasure came to an end in as short time as it takes to write it.

After ten days of dashes, rushes, and flurries we three were utterly exhausted. Doing everything at top speed isn’t the way to enjoy a holiday. Polly and I stayed in bed for two days. We were too weary to eat—I actually couldn’t raise a strawberry to my lips! If the lure of Memory Cottage down in Kent hadn’t been so strong, I know not how long we should have slept.

It took two hours on the train to get to Canterbury, which is six miles from Ickham. We had understood that it was much nearer to London. But it was a lovely day, and while the country wasn’t interesting, the smell of the earth was intoxicating, and the life in our veins seemed to respond to its teeming vitality. We found ‘Memory’ a paradise of roses, lilies, carnations, and syringa. The garden is divided by little stone walks bordered by low box hedges. At the beginning and the end of each path the box is cut in the shape of peacocks. It was a delight to have tea in the garden with innumerable birds as our guests. As soon as they saw the tea table being set, they made such a dive we had to scatter crumbs on the box hedges and ground to keep them quiet.

The cottage is picturesque, and oh, so quaint! It has a Saxon foundation and thick, mossy walls. One can touch the ceiling easily, and a tall person must duck or bump, especially on the tiny, steep stairway. The casement windows are very small, and open outward. The only large thing in the cottage is the fireplace, which is huge! Two people could sit in it comfortably and toast their toes. It would all have been pleasant enough if it hadn’t been so dark. The dense foliage obscured the sunlight when there was any, and when it rained, a twilight darkness filled the cottage. Teacher couldn’t read at all, and we three felt imprisoned and smothered in roses! I was reminded of what a townsman said of a house taken by Thomas Hardy: ‘He have but one window, and she do look into Gaol Lane.’ Moreover, every available bit of space was filled with curios and souvenirs from everywhere, so that it looked more like a museum than a dwelling-house.

It was like us—large persons requiring much space to turn in—to take this kind of small-house, almost invisible. The ladies who own the property did everything possible for our comfort. During two weeks we tried to make the best of our mistake. We tried to interest ourselves in our surroundings. We visited Folkestone, looked longingly at the French coast, bathed at Sandwich Beach, and explored Canterbury.

Canterbury is an enchanting old town, even if Wordsworth and his sister were disappointed in it. The Cathedral alone is worth taking a long journey to see. The trouble is that the historical associations which cluster around it are so many and varied and important, it would take years to learn about them. Teacher and I spent a long time in the courtyard surveying the vast structure of the Cathedral, while Polly and Captain van Beek went through the interior. Several tame sparrows and two saucy doves alighted at our feet, and twittered and pirouetted prettily by way of asking crumb alms. Dare I confess that they interested me more than the misty uncertainties that enshroud the building of the venerable Cathedral?

The town is a cluster of irregular, narrow, winding streets. The houses are nearly all built of stone or rubble, softened by time and weather. One catches glimpses of quaint, fantastic gate-ways and gardens. Not a corner, not a gable, but would make an interesting etching. The ancient walls and fortifications fill one with a sense of vanished pomp and terror.

‘Memory’ amused and interested our friends. The only people who weren’t pleased with it were ourselves. We gave a tea to the American Uniform Braille Committee and their wives who were in London, conferring with the National Institute with regard to matters of printing for the blind on both sides of the Atlantic. We were enjoying our tea in the garden when down came an English shower, driving us to shelter precipitately; but it was a merry party ‘for a’ that’. Every one was enthusiastic about the cottage. Mr. Ellis, of the American Printing Press, made sketches of it, and copied the quaint inscriptions and legends on the seats and doorways and over the fireplace. Imagine ten of us crowded into the tiny living-room, tea-cups precariously poised on the arms of chairs and shaky antiques.

We had Mr. Migel to lunch one day. He is one of the most kindly souls I ever met. He is perfectly sweet and patient under the burdens his generosity piles upon him. He was full of friendliness and gay talk at lunch—in short, a most charming person. Captain van Beek also paid us a visit. We are fond of him, and enjoyed his dignified, thoughtful talk on many subjects and his sunny humour. On a rainy Sunday Dr. and Mrs. Love, their daughter and her husband and little girl, Betty, motored out to see us. Again we all huddled together like sheep in that ‘wee housie’ and perilously consumed tea and sandwiches.

If it had been possible to work at ‘Memory’ (I had articles and three months’ correspondence on my conscience!) we should have stuck it out the rest of the summer, especially as we had three important meetings in London later. But the dim religious light worked havoc with Teacher’s nerves, and her sinus gave her a lot of trouble. To make matters worse, both she and Polly fell ill with severe colds which they couldn’t shake off. We were anxious and melancholy, and Teacher must needs add to the natural gloom by sitting up in bed at noon-day and reading De Profundis with the aid of an antique lantern! That made Polly and me realize how imperative it was that we should get out of Kent.

It was arranged that Polly’s sister should take ‘Memory’ for the remainder of the summer.

On the eve of our going to London to attend a meeting of the National Union of Guilds for Citizenship, we received a telephone message from the American Embassy that the Queen especially requested our presence at the Royal Garden Party to be held at Buckingham Palace on July 21st. This was a tremendous compliment, but we didn’t see how we could attend, as we had a public meeting the same afternoon. We were informed by the Embassy that such a request is in the nature of a royal command, taking precedence over other engagements. Very much perturbed, we started for London on the 9.50 a.m. train. We stopped at the American Embassy and learned that tickets had been left for us by the Lord Chamberlain, and that Lady Cynthia Colville, the Queen’s Lady-in-waiting, had called them up three times to ask if they had located us, and if we were coming. We rushed to Margaret’s in Hampstead and dressed for the garden party (we had taken our chiffon frocks in our case). Polly and I had a luncheon engagement with Lady Paula Jones. We hurried the taxi man out of his wits, and he left us at the wrong house! When we greeted the strange lady into whose drawing-room we were ushered as Lady Paula Jones, she smilingly told us there was some mistake. There certainly was. She ordered a taxi for us, and we dashed off to Lady Paula’s, arriving half an hour late! From there we went to the meeting.

Incidentally, I had left the hat I should have worn that afternoon at ‘Memory’. So as soon as the meeting was over, we tumbled into a beautiful Daimler car which Teacher and Margaret had engaged to take us to Buckingham Palace, and asked the driver to take us to Dickins and Jones. He looked bewildered, but obeyed. We bought a hat in five minutes, and then rushed away to the garden party.

Arrived there, we felt like lost sheep in the vast multitude which was assembled in the Palace grounds. It was truly a magnificent spectacle, the ladies resembling flowers in their bright, fluttering gowns, the gentlemen all wearing ‘toppers’, as they call the silk hat in Britain, and morning dress, and gay boutonnières. Mr. Finley, of the American Embassy, guided us to a position opposite the receiving tent. We were informed that their Majesties would be told of our presence, and, as they passed, would pause and speak to us. We could see the King and Queen under a golden and crimson canopy, where they greeted gorgeously apparelled potentates from the East, Parsee ladies in brilliant native costume, and distinguished men from the Dominions overseas. While we waited, a number of the King’s equerries stood near us. One of them asked Teacher if we had had tea. She replied No, but she would give her kingdom for a seat. He said he was sorry he could not provide us with seats, and reminded us that their Majesties had been standing as long as we. Just then Lady Cynthia Colville came up—a lovely woman in dove grey. She asked one of the equerries to introduce her to me. She greeted us pleasantly and said that her Majesty would be pleased that we had come.

While we were speaking, an equerry came and said that the King and Queen would now receive me, Mrs. Macy, and Miss Thomson. So down the sloping lawn, under the eyes of eight thousand wondering people, marched ‘The Three Musketeers’ to the Royal tent and shook hands with Their Majesties. They were both most cordial. The King asked Polly if she could understand everything I said. She replied that she could, and he expressed a wish to see how people communicated with me. Teacher gave a lip-reading and spelling demonstration. Their Majesties were both deeply interested in everything we did. The Queen turned to the King and said, ‘It is wonderful!’ and he replied, ‘And it is all done through vibrations—how extraordinary!’ The Queen asked me if I was enjoying my visit in England. I said it is a green and pleasant land, and told her how I loved the beautiful English gardens. She wanted to know how I could enjoy flowers when I could not see them. I explained that I smell their fragrance and feel their lovely forms.

The Queen was dressed in beige ensemble, with fur collar and cuffs and a turquoise toque. Her left hand rested on a sunshade of the same colour. We liked her very much, she was so direct and friendly, and her quiet stateliness was most queenly.

After a few more questions and answers, Their Majesties shook hands with us again and bade us ‘Good-bye’. Two equerries escorted us through a human lane that had been made especially to allow the King and Queen to pass. Again we braved those eight thousand pairs of eyes. On all sides we could hear a buzz of comment and ‘Who are they?’

Margaret and the car met us at one of the great gates of the Palace, guarded by soldiers in scarlet coats. We drove with all the speed the dense traffic permitted to Mrs. Waggett’s, where we had been invited to tea.

We were two hours late! All the guests were gone. But Mrs. Waggett knew what had happened, and was as sweet as she could be. She and Dr. Waggett are close friends of Lady Fairhaven. We had a cup of tea with her, and sped away to the Grosvenor Hotel, where Mr. Migel and his lovely daughter, Parmenia, had waited for us half the afternoon. There was time only for a hug and a sip of the cup that cheers, and we were off to our own hotel, where Mr. and Mrs. Robert Irwin were wondering if they had made a mistake and come to the wrong place. (We had invited them to dine with us that evening.) We missed the last train to Canterbury, but, to tell the truth, we were rather glad to snuggle down in comfort at the Park Lane Hotel in an airy room and a bed as fresh and sweet as ‘the flowery beds of ease’ in the old hymn.

On July 27th I spoke before the section of the British Medical Association whose pathological provinces are the ear, throat, and nose. Sir St. Clair Thomson presided with great dignity. His beautiful face and noble personality gave a special charm to every word he spoke. Turning to me on the platform he said,

‘Because of you we will be glad and gay,

Remembering you we will be brave and strong,

And hail the advent of each dangerous day

And meet the last adventure with a song.’

I was deeply touched—as who would not be? And exquisitely embarrassed—as who would not be? I spoke on the necessity of a physician’s taking a humanitarian as well as a professional interest in the deaf child. I urged that when the child’s hearing cannot be saved, the aurist should be able to suggest the right school or method of education or the special training which may develop him into an intelligent and useful human being. It was profoundly gratifying to speak to so many intelligent men and women on a subject of vital importance. We were delighted to have Dr. Saybolt, of Forest Hills, and his pretty wife with us—they were on a holiday trip through Europe, and stopped in London for a few days. After the meeting we lunched with Dr. and Mrs. Love at Frascati’s, a well-known Italian restaurant where many foreigners foregather.

That afternoon we drove with the Saybolts to Hampton Court. (I have written about Hampton Court before.) They were amazed at the beauty of the gardens and the vastness of the palace. We had tea on a fascinating little island in the Thames. As is usual in England, the birds joined us, uninvited, but nevertheless welcome. It is enchanting to see everywhere birds perched on park benches, enjoying their ‘tea’ with friendly picnickers. We returned to Park Lane through miles of London’s thoroughfares and parks, crossing and re-crossing the Thames, which kept getting in our way. I was especially fascinated by Richmond Park, where the kings of yore hunted. There are still herds of deer, but they are now so tame that they come right up to the car and feed from your hand.

On Thursday, the 28th, Polly and I lunched with Sir St. Clair Thomson at his house in Wimpole Street, almost opposite the Barrett home, where was enacted that beautiful love drama of Robert Browning and Elizabeth Barrett. Teacher was too ill to go with us. Beside Sir St. Clair Thomson and Dr. Love I met Dr. Jones Phillipson, Dr. Brown Kelly, who was ‘capped’ before me at the Graduation ceremony, Dr. Weill-Hallë from Paris, and an Egyptian surgeon, Ali Mahum Pasha. Sir St. Clair was a most interesting host. There is about him a benignant sweetness that wins all hearts. He turned to me all the hour with luminous attention and talked in the most engaging way about books, where he is as much at home as he is in medicine.

That evening we had one of the surprises of our lives. Just as we were sitting down to dinner, the door opened, and who should walk in out of the dusk of the hall like a ghost but ————! We hadn’t seen him for more than two years. We knew he was in London, and of course he knew how to reach us, but as he didn’t call or write or make any sign of remembering us, we didn’t look him up. His friendship seems to lie dormant for months or years, like mummy-seed, and then flower again. At first he seems to have changed very little, but as he talked we realized that he had lost some of his enthusiasm for life. He is still working on the compass. Polly and I went to bed and left poor Teacher, who was feeling very wretched indeed, to listen as sympathetically as possible to the old story of effort and disappointment. The children are well and happy in their English environment. The compass seems to be a beautiful instrument. It is in high favour with the British Admiralty, but of course there is no sale for nautical instruments at present. Teacher said there was a kind of remote, melancholy grandeur about ———— when he said good-night. I wonder when we shall see him again.

On Friday evening I made my last public appearance in London. We were given a reception by the International Teachers’ Convention. Again Teacher was not able to go; so I represented her at the meeting. She was to have addressed the teachers. What group of men and women, since the world began, has deserved more of our gratitude? What amazing patience and ingenuity is required to open the mind of a child, especially when he lacks one or more of the faculties through which he gathers knowledge! Certainly, teachers have done their best to build bright forts against ignorance and physical disaster in all lands. Our friends, realizing how exhausted we were, permitted us to leave without the usual formality of hand-shaking. Their sweet considerateness turned what we feared would be an ordeal into a pleasant occasion which will long be remembered.

How thankful we were not to have any more engagements or speeches for two months! We were free, we could go where we liked. Where should we go? To Paris? That would be lovely! We had promised Mr. Migel to meet him there, but Teacher wasn’t well enough to enjoy Paris. The doctor said she should go to a higher altitude to break up her cold. The Highlands of Scotland had been calling me for years. Wasn’t this the opportunity I had waited for? The idea of a real holiday in the Highlands appealed to the other members of the Triumvirate as much as to me.

So Saturday morning found us on the ‘Flying Scotsman’, light-hearted and expectant. What a train it is, flying from London to Edinburgh in seven and a half hours without a stop! All the way the English country is beautiful and rural. People who aren’t pleased with its quiet, cultivated loveliness must have blind souls and no power of observation. From Newcastle on there is a fine view of the North Sea and the undulating hills of the Border.

Polly’s brother and Somers Mark met us at the station and welcomed us back to bonnie Scotland.

The Caledonian Hotel, where we stayed, is opposite Castle Rock and in Princes Street. We spent three delightful days there. Edinburgh is one of the most fascinating cities I have ever explored. Teacher could lie in her bed and look up to the sinister Castle Rock and down into the ravine with its famous gardens. Some one has called Princes Street ‘the finest street in the world’.

Most of the time Castle Rock is enveloped in a grey mist that comes in from the ocean, but in the early morning the sun will break through the greyness, revealing the stupendous mass of the rock and a phantom-like city of spires, pinnacles, and towers, which still seems to bristle with swords. This is ancient Edinburgh built on the steep hill. There is a majesty about it that makes one bow one’s head. As we looked up to old Edinburgh a hundred times a day, so old Edinburgh looks down from its commanding height upon new Edinburgh marching along Princes Street. We imagined the ghosts of bygone generations leisurely viewing from their cliff-like abodes passing tram-cars, automobiles, and bustling throngs that tramp up and down the level land. Truly, the ancient city, wrapped in its shroud of mist, is like a dream city built of clouds.

The stretch of pavement between Castle Rock and Holyrood Palace is known as the Royal Mile. From it radiate narrow, straggling lanes called closes, leading up medieval stone steps to the dwellings of the old nobility. Dark, grim dwellings they are! One cannot but shudder a little, sniffing into shadowy corners and up secret stairways where terrible things have happened in the darkness.

One rides or walks down the Royal Mile from Castle Rock past St. Giles and the house of John Knox to the sombre palace; and always in one’s mind is the image of the ill-fated unhappy Mary, Queen of Scots, whose story still touches the world’s heart. One sees her shrinking from the hard eyes and denunciatory tongue of John Knox, and one rides with her on the moors where she sought peace in solitude and the stars.

One glorious afternoon we drove through the great gates of Holyrood out to the Salisbury Crags and the moors. We got out and stood for a long moment listening to the sound of burns, the rustling of bracken, and the twittering of birds. We came back through the Pentland Hills, where Stevenson loved to ramble and sleep under the sky, waking to the little breezes of dawn and the quiet feeding of the cattle in the dewy fields, and watch the sun blinking on cool, silvery streams. For me every hill and lane and dark wood spoke of him and breathed his unfaltering courage.

Speaking of courage brings to my mind the National War Shrine in Edinburgh. It rises above every other building in the city. It faces north, and has an east-and-west transept. Its walls spring from the jagged rock. It is in the style of a sanctuary, and holds the names of the Scots who fell in the World War as the Temple of Jerusalem held the Ark of the Lord. As I stood silent and shaken beside the casket that rests on the altar, guarded by four kneeling angels, I felt that it symbolizes not only the sacrifice and courage of a hundred thousand Scotsmen, but also the sacrifice and courage of the youth of the world who have died in a thousand wars.

On August 3rd we set out for the Highlands, not with harp and pipe, but with glad hearts and a new zest for adventure. About six miles from Edinburgh we went over the Forth Bridge which flings itself across the river to Fife. I felt the train swaying as it rumbled over the vibrating bridge suspended between sky and firth. My friends tried to describe the tremendous structure to me, but without a model of it I couldn’t form a very clear conception of its vast proportions and intricate construction.

The first stop the train made that I can remember was Dunfermline, where Andrew Carnegie was born, and in which stands the Abbey where Robert the Bruce lies buried.

Dunfermline was the capital of Scotland before Edinburgh emerged from the dim twilight of minstrelsy and legend. When her multimillionaire son returned from the Eldorado of the West, the gentle old town must have stopped her spinning-loom and looked about her. It was as if a prince had awakened his old mother from a peaceful dream. I can imagine the bewilderment of the simple folk of Dunfermline when libraries, schools, swimming-pools, public parks, and colleges sprang up in their midst like mushrooms in a field overnight. Even to our ears, jaded by modern miracles, it sounds like a fairy tale!

I have many reasons for being grateful to Mr. Carnegie. Well, I am more grateful to him for giving his native town Pittencrieff Park than for his generosity to me personally. In Mr. H. V. Morton’s In Search of Scotland an old Scot tells the author the reason for the gift.

‘Ye see,’ he said, ‘when the late Mr. Carnegie was a wee lad, he wasna pairmitted to enter the park—it was a private property—and he never forgot it. When the time came, he gave it to Dunfermline, so that no wee child should ever feel locked oot of it as he was. Aye, it was a graund thocht!’ Aye, it was!

Our train did not carry us to Stirling, but I had been there in June, when I had seen the Castle and the Wallace monument, and driven through the Ochils, over the wood-hidden Bridge of Allan and under the shadow of Ben Ledi. If one hadn’t seen Castle Rock in Edinburgh, surely Stirling Castle would hold the first place among one’s pictures of ancient grandeur. It rises abruptly from the lusciously green meadows. My friends did their best to describe to me the marvellous panorama they viewed from it, but I fear I received a fragmentary idea of it which it would take many days and drives and walks to fill in.

After leaving Perth we caught our first glimpses of the Grampians, whose very name conjures up pictures of wild plunging horses. O the wind sweet with bracken and heather as we approached the mountains, which began to surge and tumble about us like a green ocean! No wonder Coleridge called it ‘the dance of the hills’. O the bees making honey in the clover! O the utter solitude of sky and earth ‘in Caledonia stern and wild’! As we climbed up and up, I was both soothed and excited. I thought how once the fiery cross of the clans had leaped from tree to tree and peak to peak, until the air was filled with the sound of charging horses and the clash of claymores. Now all is quiet, but the country is still wild and teeming with romance. I was glad we had Mr. Thomson with us to repeat again and again the names of the peaks in his rich, expressive voice, the names made music in my fingers—Ben Lomond, Ben Venue, Ben Vorlich, Ben Lawers—all giants among the Highlands of Scotland.

We arrived at Inverness in the late afternoon, our spirits as heavy with beauty as bees with honey. We languished over a cup of tea at the station hotel, too sated even to look at Inverness. ‘The River Ness!’ ‘Tarbet Ness!’ ‘Cromarty Firth!’ ‘Moray Firth!’ ‘the Caledonian Canal!’ slipped through my fingers like ordinary water through a sieve. ‘I will visit Inverness another time’, I told Mr. Thomson, and clambered into the little railway carriage that was to take us up to Tain, where we intended to stay at the hotel until we found a nest of our own somewhere in the hills.

Tain is one street and smells of heather and of the sea, and is a place where one’s sleep is deep and sweet. The Thomsons spend their holiday at Tain every summer.

We drove up to Altnamain with Mr. Thomson, where there is a pleasant inn.

The moor begins at the inn door-step. Imagine, if you can, miles and miles of gently rising and falling plain, where the heather stretches like a purple carpet, with naked rocks or little piles of stones on curving knolls over which the indomitable heather rolls like ocean waves.

Even in the bright sunshine I felt like a lovely wild grouse in ten thousand miles of moor. On the moor one’s thoughts go deep, and one is silent. But in the embrace of the heather there is intimacy and nearness to the heart of Mother Earth and her wild children.

We went deeper into the bracken-fronded solitude and we flung ourselves into rough, sweet beds of heather which fluttered in the wind like a curtain that will not rise. Only those who have lain in the heather can know the delicious quietness with which it steeps body and mind.

Out of all this mass of blossoming fire breathes the racy smell of damp bog-land, the energy of fresh, cool dawns, the rapture of wind and rain, throbbing silences, old romances and songs. As my body drank in strength from the arm of the heather about me, all my soul seemed scented with it as the mist of dreams crept over me, and my thoughts wandered off to the land of Immortal Youth.

It was extremely difficult to find the sort of place we wanted at this season of the year, as all the world comes to Scotland during August to shoot grouse and catch trout, and every available dwelling is engaged months in advance. We were almost on the point of returning to England when a friend of Mr. Thomson’s, Dr. McCrae, persuaded his brother to let us have his farm-house at South Arcan, on the little River Orrin, in Muir of Ord, about eighteen miles from Inverness. We transferred ourselves and our belongings to it so quickly one would have thought all God’s beasties were pursuing us.

We love it here. Places, like people, have personality—a vibrant, living quality. When one meets such a personality in a human being or a place, something happens. It is like lifting a shade—the sun pours in and floods you; or like lighting a fire in a cold room. That is what this dear old farm-house does, it radiates cheer, warmth, and gladness.

We are surrounded by great fields of ripening wheat all shimmering gold in the sunlight. The River Orrin runs through the pastures, and the sound of it is like rain on leaves. The drive to the house, which must be about a mile long, is through bracken, gorse, and broom, tall ferns and meadow-sweet. There are clumps of blue harebells that look like patches of the sky fallen on the roadside, also a yellow weed that resembles golden-rod. At every gate-post there are superb oaks, beeches, larches, and silver birches; next the house there are arbor vitae trees, the finest I have ever seen; and just outside the sitting-room window grows a splendid yew-tree.

The pleasantest time in the day is when, our work laid aside, we sip tea under the trees and chat with our genial landlord, Mr. McCrae. He tells us the news from the world beyond the gates, he brings us delicious buttermilk, fresh butter, and eggs just laid, and yesterday he brought us a brace of grouse. We sit out until the evening breeze springs up full of a fresh sweetness from field and moor, and a serene peace fills our hearts and minds.

Sometimes we walk in the sunset glow. Polly can see in the distance the firths of Cromarty and Beauly, and the hills piling to the North-West, range on range, the colour of purple grapes in the darkening atmosphere, she says. They must be like that deep swooning blue which Chinese artists love. We pass farm-steads, the cottages of the farm hands, black Angus cattle grazing contentedly and curlews flying towards the river, their lonely cry disturbing the other birds; dusky lanes, hedges and stone walls mossy with age. Soothed by the silence we go to bed without even a thought of the world of rush and noise in which we so lately moved.

In the morning our walk is quite as interesting. The sun sends long fingers of molten silver through the branches of the trees, whose leaves drip with dew or rain-drops. The corn is a conflagration of gold. A filmy mist hangs over it like a russet veil. The odours rising from the earth are very strong. The birds are active; they flutter out from their leafy dwellings to look at the weather. The robins chirp their good-morrow to the sun, the crows hover over the grain cawing. The monarch of the poultry-yard reminds the hens that the ladies expect fresh eggs for breakfast. I feel like Horace on his sunny farm at the foot of the olive-covered hills of Tivoli. Like him, later on I intend to do a little hoeing and fruit-gathering, that my descriptions of farm life may not be all sentiment.

One glorious sunny morning we motored to Inverness to shop (how shockingly prosaic!) and to see as much of the town as we could. It is, indeed, a unique and romantic town. For while it is quite modern in its life and enterprise, it has managed to preserve an air of great antiquity. The smiling river Ness flows through its heart, and the Firth of Moray curves away to the north of it, reflecting like a mirror the wooded shore and Black Isle and the blue hills. The firths of Cromarty and Beauly lie sweetly cradled in the curving arms of the land. From a window in the highest turret of Urquhart Castle (which is supposed to be the site of Macbeth’s castle) they told me one looks out upon an indescribably magnificent landscape of mountains, forests, lochs, firths, and moors. Below, the broad Ness flows through field and meadow to the sea.

We intend to pay at least one more visit to Inverness before leaving Arcan.[6] There is still the bridge of Inverness for me to walk over; and a stroll to be taken through the park by the river, which is made of a number of wooded islands linked together by rustic bridges, so that you can walk from one to the other, always seeing and hearing the river; and we may go for a sail on the Caledonian Canal.