* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: A Son of Courage

Date of first publication: 1920

Author: Archie P. McKishnie (1875-1946)

Date first posted: 16th June, 2024

Date last updated: 16th June, 2024

Faded Page eBook #20240609

This eBook was produced by: Marcia Brooks, Al Haines, John Routh & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

“Oh, aren’t they lovely!” cried Erie.

Copyright, 1920

By

The Reilly & Lee Co.

All Rights Reserved

Made in U. S. A.

A Son of Courage

To my sister,

Jean Blewett, who knew and

loved its characters this book

is lovingly dedicated.

The Author.

A Son of Courage

Mrs. Wilson lit the coal-oil lamp and placed it in the center of the kitchen table; then she turned toward the door, her head half bent in a listening attitude.

A brown water-spaniel waddled from the woodshed into the room, four bright-eyed puppies at her heels, and stood half in the glow, half in the shadow, short tail ingratiatingly awag.

“Scoot you!” commanded the woman, and with a wild scurry mother dog and puppies turned and fled to the friendly darkness of their retreat.

Mrs. Wilson stood with frowning gaze fastened on the door. She was a tall, angular woman of some forty years, heavy of features, as she was when occasion demanded it, heavy of hand. Tiny fret-lines marred a face which under less trying conditions of life might have been winsome, but tonight the lips of the generous mouth were tightly compressed and the rise and fall of the bosom beneath the low cut flannel gown hinted of a volcano that would ere long erupt to the confusion of somebody.

As a quick step sounded outside, she lowered herself slowly to a high-backed chair and waited, hands locked closely upon her lap.

The door opened and her husband entered. He cast a quick, apprehensive glance at his wife, and the low whistle died on his lips as he passed over to the long roller towel hanging above the wash-bench and proceeded to dry his hands.

He was a medium sized man, with brown wavy hair and a beard which failed to conceal the glad boyishness of a face that would never quite be old. The eyes he turned upon the woman when she sharply spoke his name were blue and tranquil.

“Yes, Mary?” he responded gently.

“I want’a tell you that I’m tired of bein’ the slave of you an’ your son,” she burst out. “One of these days I’ll be packin’ up and goin’ to my home folks in Nova Scotia.”

Wilson averted his face and proceeded to straighten the towel on the roller. His action seemed to infuriate the woman.

Her lips tightened. Her hands unclenched and gripped the table as she slowly arose.

“You—” she commenced, her voice tense with passion, “you—” she checked herself. Unconsciously one of the groping hands had come in contact with the soft leather cover of a book which lay on the table.

It was the family Bible. She had placed it there after reading her son Anson his evening chapter. Slowly she mastered herself and sank back into her chair.

Wilson came over and laid a work-hardened hand gently on her heaving shoulder.

“Mary,” he said, “what is it? What have I done?”

“Oh,” she cried miserably, “what haven’t you done, Tom Wilson? Didn’t you bring me here to this lonesome spot when I was happy with my son, happy an’ contented?”

“But I told you you’d like find it some lonesome, Mary, you remember?”

“Yes, but did you so much as hint at what awful things I’d have to live through here? Not you! Did you tell me that an old miser ’ud die and his ghost ha’nt this neighborhood? Did you tell me that blindness ’ud strike one of the best and most useful young men low? Did you tell me,” she ran wildly on, “that the sweetest girl in the world ’ud be dyin’ of a heartbreak? Did you tell me anythin’, Tom Wilson, that a woman who was leavin’ her own home folks, to work for you and your son, should a’ been told?”

Wilson sighed. “How was I to know these things would happen, Mary? It’s been hard haulin’, I know, but someday it won’t be so hard. Maybe now, you’d find it easier if you didn’t shoulder everybody else’s trouble, like you do—”

“Shut right up!” she flared, “I’m a Christian woman, Tom Wilson. Do you think I could face God on my knees if I failed in my duty to the sick as calls fer me? Why, I couldn’t sleep if I didn’t do what little I’m able to do fer them in trial; I’d hear weak voices acallin’ me, I’d see pain-wild eyes watchin’ fer me to come an’ help their first-born into the world.”

“But, Mary, there’s a doctor at Bridgetown now and—”

“Doctors!” she cried scornfully. “Little enough they know the needs of a woman at such a time. A doctor may be all right in his place, but his place ain’t here among us woods folk. I tell you now I know my duty an’ I’ll do it because they need me.”

“We all need you, Mary,” spoke her husband quickly. “Didn’t I tell you that when I persuaded you to come? I need you; Billy needs you.”

She looked up at him, tears filming the fire of anger in her eyes.

“No,” she said in low tense tones, “your son don’t need me. I’m nuthin’ to him. Sometimes I think—I think he cares—’cause I’m longin’ fer it, I guess. But somehow he seems to be lookin’ beyond me to someone else.”

Wilson sighed and sank into a chair.

“I guess maybe it’s your fancy playin’ pranks on you, Mary,” he suggested hesitatingly. “Two years of livin’ in this lonesome spot has kinder got on your nerves.”

“Nerves!” she cried indignantly, sitting bolt upright. “Don’t you ’er anybody else dare accuse me of havin’ nerves, Tom Wilson. If I wasn’t the most sensible-minded person alive I’d be throwin’ fits er goin’ off into gallopin’ hysterics every hour, with the things that Willium does to scare the life out of a body.”

“What’s Billy been doin’ now?” asked Wilson anxiously.

She shivered. “Nothin’ out’a the ordinary. What’s that limb allars doin’ to scare the daylights clean outa me an’ the neighbors? If you’d spend a little more of your spare time in the house with your wife an’ less in the barn with your precious stock you wouldn’t need to be askin’ what he’s been adoin’. But I’ll tell you what he did only this evenin’ afore you come home from changin’ words with Cobin Keeler.

“Missus Scraff—you know what a fidgety fly-off-the-handle she is, an’ how she suffers from the asthma—well, she’d come over an’ was stayin’ to supper. I sent that Willium out on the back ridge to gather some wild thimble-berries fer dessert. He comes in just as I had the table all set, that wicked old coon he’s made a pet of at his heels an’ that devil-eyed crow. Croaker, on his shoulder. Afore I could get hold of the broom, he put the covered pail on the table an’ went out ag’in. The coon follered him, but that crow jumped right onto the table an’ grabbed a piece of cake. I made a dash at him an’ he flopped to Missus Scraff’s shoulder. She was chewin’ a piece of slippery-ellum bark fer her asthma, an’ when his claws gripped her shoulder she shrieked an’ like to ’a’ choked to death on it.

“It took me all of half an hour to get her quieted, an’ then I made to show her what nice berries we got from our back ridge. ‘Jest hold your apron, Mrs. Scraff, an’ I’ll give you a glimpse of what we’re goin’ to top our supper off with,’ I says, strivin’ to get the poor soul’s mind off herself.

“She held out her apron, an’ I lefted the lid off the pail and pours what’s in it into her lap.

“An’ what d’ye ’spose was in that pail, Tom Wilson? Four garter snakes and a lizard; that’s what your precious son had gone out and gathered fer our dessert. I spilled the whole caboodle of ’em into her apron afore I noticed, an’ she give one screech an’ fainted dead away. While I was busy bringin’ her around, that Willium sneaked in an’ gathered them squirmin’ reptiles off the floor, I couldn’ do more jest then than look him a promise to settle with him later, ’cause I had my hands full as it was. I found a pail of berries on the table when I got a chance to look about me, an’ I ain’t sayin’ but that boy got them pails mixed, but that don’t excuse him none.”

Wilson, striving to keep his face grave, nodded. “That’s how it’s been, I guess, Mary. He kin no more help pickin’ up every snake and animal he comes across then he kin help breathin’. But he don’t mean any harm, Billy don’t.”

“That’s neither here ner there,” she snapped. “He doesn’t seem to care what harm he does. An’ the hard part of it is,” she burst out, “I can’t take no pleasure in whalin’ him same as I might if I was his real mother; I jest can’t, that’s all. He has a way of lookin’ at me out’a them big, grey eyes of his’n—”

The voice choked up and a tear splashed down on the hand clenched on her lap.

Comfortingly her husband’s hand covered it from sight, as though he sought to achieve by this small token of understanding that which he could not hope to achieve by mere words.

She caught her breath quickly and a flush stole up beneath the sun and wind stain on her cheeks. There was that in the pressure of the hand on hers, strong yet tender, which swept the feeling of loneliness from her heart.

“Mary,” said the man, “I guess neither of us understand Billy and maybe we never will, quite. I’ve often tried to tell you how much your willin’ness to face this life here meant to him and me but I’m no good at that sort’a thing. I just hoped you’d understan’, that’s all.”

“Well, I’m goin’ to do my duty by you both, allars,” Mrs. Wilson spoke in matter-of-fact tones, as she reached for her sewing-basket. “When I feel you need checkin’ up, Tom Wilson, checked you’re goin’ to be, an’ when Willium needs a hidin’ he’s goin’ to get a hidin’. An,” she added, as her husband got up from his chair, saying something about having to turn the horses out to pasture, “you needn’t try to side-track me from my duty neither.”

“All right, Mary,” he agreed, his hand on the door-latch.

“An’ if you’re agoin’ out to the barn do try’nd not carry any more of the barnyard in on your big feet than you kin help. I jest finished moppin’ the floors.”

Wilson stepped out into the spicy summer darkness and went slowly down the path to the barn. As far as eye could reach, through the partially cleared forest, tiny clearing fires glowed up through the darkness, seeming to vie with big low hanging stars. The pungent smoke of burning log and sward mingled pleasantly with the scent of fern and wild blossoms.

Wilson lit his pipe and with arms folded on the top rail of the barnyard fence gazed down across the partially-cleared, fire-dotted sweep to where, a mile distant, a long, densely timbered point of land stood darkly silhouetted against the sheen of a rising moon.

From the bay-waters came the lonely cry of a loon, from the marshes the booming of night-basking bullfrogs. The hoot of the owl sounded faintly from the forest beyond; the yap of a foraging fox drifted through the night’s stillness from the uplands.

A long time Wilson stood pondering. When at length he bestirred himself a full moon swam above a transfigured world. A silvery sheen swept softly the open spaces; through the trees the white bay-waters shimmered; the clearing fires had receded to mere sparks with silvery smoke trails stretching straight up towards a starred infinity.

He sighed and turned to glance back at the cottage resting in the hardwood grove. It looked very homey, very restful to him, beneath its vines of clustering wild grape and honeysuckle. It was home—home it must be always. And Mary loved it just as he loved it; this he knew. She was a fine woman, a great helpmate, a wonderful wife and mother. She was fair minded too. She loved Billy quite as much as she loved her own son, Anson. Billy must be more careful, more thoughtful of her comfort. He would have a heart to heart talk with his son, he told himself as he went on to the barn.

He completed his chores and went thoughtfully back up the flower-edged path to the house. “There’s one good thing about Mary’s crossness,” he reflected, “it don’t last long. She’ll be her old cheerful self ag’in by now.”

But Mrs. Wilson was not her old cheerful self; far from it. Wilson realized this fact as soon as he opened the door. She raised stern eyes to her husband as he entered.

“You see them?” she asked with sinister calmness, pointing to a patched and clay-stained pair of trousers on the floor beside her chair. “Them’s Willium’s. He’s jest gone to bed an’ I ordered him to throw ’em down to be patched.”

Wilson nodded, “Yes, Mary?”

“And do you see this here object that I’m holdin’ up afore your dotin’ father’s eyes?”

He came forward and took the object from her hand.

“It also belongs to your dear, gentle son,” she grated, “leastwise I found it in one of his pants pockets.”

Wilson whistled softly. “You don’t say!” he managed to articulate. “Why, Mary, it’s a pipe!”

“Is it?”

“Yes, a corncob pipe,” he repeated weakly.

“Is it re’lly?” she returned with sarcasm. “I wasn’t sure. I thort maybe it was a fish-line, or a jackknife. Now what do you think of your precious son?” she demanded.

Wilson shook his head. “It’s a new pipe,” he ventured to say, “and,” sniffing the bowl, “it ain’t had nuthin’ more deadly than dried mullen leaves in it so far. Ain’t a great deal of harm in a boy smokin’ mullen leaves, shorely, Mary.”

“Oh, is that so? Haven’t I heered you an’ Cobin Keeler say, time and ag’in, that that’s how you both got the smoke-habit? And look at you old chimbneys now; the pipe’s never out’a your mouths.”

“I’ll talk things over with Billy in the mornin’,” promised Wilson as he took the boot-jack from its peg.

“A pile of good your talkin’ ’ll do,” she cried. “I’m goin’ to talk things over with that boy with a hickory ram-rod, jest as soon as I feel he’s proper asleep; that’s what I’m goin’ to do! Who’s trainin’ that boy, you er me?” she demanded.

“You, of course, Mary.”

“Well then, you best let me be. What I feel he should get, he’s goin’ to get, and get right. You keep out’a this, Tom Wilson, if you want me to keep on; that’s all.”

“It don’t seem right to wake boys up just to give ’em a whalin’, Mary,” he protested. “My Ma used to wake me up sometimes, but never to whale me. I’d rather remember—”

“Shut up! I tell you, I’m goin’ to give him the hickory this night or I’m goin’ to know the reason why. I’ll break that boy of his bad habits er I’ll break my arm tryin’. You let me be!”

“I’m not findin’ fault with your methods of trainin’ boys, Mary,” her husband hastened to say. “You’re doin’ your best by Billy, I know that right well. And Billy is rather a tough stick of first-growth timber to whittle smooth and straight, I know that, too. But the gnarliest hickory makes the best axe-handle, so maybe he’ll make a good man some day, with your help.”

“Humph! well that bein’ so, I’m goin’ to help him see the error of his ways this night if ever I did,” she promised grimly.

Something like a muffled chuckle came from behind the stairway door, but the good woman, intent on her grievance, did not hear it. Wilson heard, however, and let the boot-jack fall to the floor with a clatter. He picked it up and carried it over to its accustomed peg on the wall, whistling softly the tune which he had whistled to Billy in the old romping, astride-neck days:

Oh, you’d better be up, and away, lad.

You better be up and away!

There is danger here in the glade, lad,

It’s a heap of trouble you’ve made, lad—

So you’d better be up and away!

Over beside the table, Mrs. Wilson watched him from, somber eyes.

“That’s right!” she sighed. “Whistle! It shows all you care. That boy could do anythin’ he wanted to do an’ you wouldn’t say a word; no, not a word!”

Wilson did not answer. He was listening for the stairs to creak, telling him that Billy had left his eaves-dropping for the security of the loft.

Billy had heard and understood. When his dad sent him one of those “up and away” signals he never questioned its significance. He didn’t like listening in secret, but surely he reasoned, a boy had a right to know just what was coming to him. And he knew what was coming to him, all right—a caning from the supple hickory ram-rod—maybe!

Up in the roomy loft which he and his step-brother, Anson, shared together, he lit the lamp. Anson was sleeping and Billy wondered just what he would say when he woke up in the morning and found his pants gone. Their mother had demanded that a pair of pants be thrown down to her. Billy needed his own so he had thrown down Anson’s.

But how in the world was he ever going to get out of that window with Anson’s bed right up against it, and Anson sleeping in the bed? Anson would be sure to hear the ladder when Walter Watland and Maurice Keeler raised it against the wall. He must get Anson up and out of that bed!

Billy placed the lamp on a chair and reaching over shook Anson’s long, regular snore into fragments of little gasps. He shook harder and Anson sat up, sandy hair rumpled and pale blue eyes blinking in the light.

“What’s’amatter?” he asked sleepily.

“Hush,” cautioned Billy. “Ma’s downstairs wide awake and she’s awful cross. What you been doin’ to rile her, Anse?”

Anson frowned and scratched his head. “Did you tell her ’bout my lettin’ the pigs get in the garden when I was tendin’ gap this afternoon?” he asked suspiciously.

“No, it ain’t that. I guess maybe she’s worried more’n cross, an’ she’s scared too—scared stiff. Well, who wouldn’t be with that awful thing prowlin’ around ready to claw the insides out’a people in their sleep?”

Anson sat up suddenly.

“What you talkin’ ’bout, Bill? What thing? Who’s it been clawin’? Hurry up, tell me.”

Billy glanced at the window, poorly protected by a cotton mosquito screen, and shivered.

“Nobody knows what it is,” he whispered. “Some say it’s a gorilla and others say it’s a big lynx. Ol’ Harry’s the only one who saw it, an’ he’s so clawed and bit he can’t describe it to nobody.”

“Great Scott! Bill, you mean to say it got ol’ Harry?”

Billy nodded. “Yep, last night. He was asleep when that thing climbed in his winder an’ tried to suck his blood away.”

“Ugh!” Anson shuddered and pulled the bed clothes up about his ears. “How did it get it, Bill? Does anybody know?”

“Well, there was a tree standin’ jest outside his winder same as that tree stands outside this one. It climbed that tree and jumped through the mosquito nettin’ plumb onto ol’ Harry. He was able to tell the doctor that much afore he caved under.”

Anson’s blue eyes were staring at the wide unprotected window. Outside, the moon swam hazily above the forest; shadows like huge, misshapen monsters prowled on the sward; weird sounds floated up and died on the still air.

“Bill,” Anson’s voice was shaking, “I don’t feel like sleepin’ longside this winder. That awful thing might come shinnin’ up that tree an’ gulp me up. I’m goin’ down and ask Ma if I can’t sleep out in the shed with Moll an’ the pups.”

Billy promptly scented a new danger to his plans. “If I was you I wouldn’t do that, Anse,” he advised.

“Well, I’m goin’ to do it.” Anson sat up in bed and peered onto the floor.

“Where the dickens are my pants?” he whispered. “See anythin’ of ’em, Bill?”

“Anse,” Billy’s voice was sympathetic. “I see I have to tell you everythin’. Ma, she’s goin’ to give you the canin’ of your young life, jest as soon as she thinks we’re proper asleep.”

“Canin’? Me? Whatfer?”

“Why, seems she was up here lookin’ fer somethin’ a little while ago. She saw your pants layin’ there an’ she thought maybe they needed patchin’, so she took ’em down with her.”

“Well, what of it?”

“Oh, nuthin’, only she happened to find a pipe in one of the pockets, that’s all.”

“Jerusalem!” Anson’s teeth chattered. “Well, I’m goin’ down anyway, I don’t mind a hidin’, but I’m derned if I’m goin’ to lay here and get clawed up by no gorilla.”

“Anse, listen,” Billy pat a detaining hand on his brother’s shoulder. “You don’t need to do that, an’ you needn’t sleep in this bed neither. I’ll sleep in it, an’ you kin sleep in mine. That gorilla, er whatever it is, can’t hurt me, cause I’ve got that rabbit-foot charm that Tom Dodge give me. I’ll tie it round my neck.”

Anson reflected, shuddering as a long low wail came from the forest.

“That’s the boys,” Billy told himself. “I’ve gotta move fast.”

Aloud he urged: “Come on, Anse. Get out an’ pile into my bed. I ain’t scared to sleep in yours, not a bit. Besides,” he added, “it’ll save you a canin’ from Ma.”

“How will it, I’d like to know?”

“Why this way. Ma’ll come creepin’ up here in the dark, when she thinks we’re asleep an’ she’ll come straight to this—your bed. She’ll turn down the clothes an’ give me a slash or two, thinkin’ it’s you. I’ll let her baste me some—then I’ll speak to her. She’ll be so surprised she’ll ferget all about whalin’ you. She’s that way, you know. Like as not she’ll laugh to think she basted me—an’ she’ll be good-natured. You needn’t worry any about a lickin’, Anse.”

“Well, I’ll take a chance, Bill.”

Anson got out of bed, his white legs gleaming in the yellow lamplight as he tiptoed softly across to Billy’s cot and lay down.

Billy blew out the lamp and went through the motions of undressing. He removed one shoe, let it fall on the floor, waited an interval and let the same shoe fall again. Then he put it back on. By and by he lay down and gave a long, weary sigh. Then he held his breath and listened.

Below his window sounded a whippoorwill’s call. From the opposite side of the room came the long, regular snores of Anson. Billy sat up in bed and started to remove the tacks from the window screen.

Something fell with a thud against the wall outside, and brushed against the boards. A cat mewed directly beneath the window. Gently Billy rolled the bed quilts into an oblong shape resembling a human form, then silently made his way out of the window.

His feet struck the top round of a ladder. A moment more and he was crouching in the shadow of the wall, two shadowy forms squatting beside him.

“All hunky?” a voice whispered in his ear.

“All hunky,” Billy whispered back.

“Then come on.”

But Billy plucked at the speaker’s sleeve. “Wait a minute, Fatty,” he urged. “Anson’s up there asleep, an’ he’s goin’ to have a wakin’ nightmare in about four seconds. I jest heard Ma goin’ up.”

Silence, deep and brooding, fell. Then suddenly from the loft came a long wail, followed by a succession of shorter gasps and gulps, and above the swish of a hickory ram-rod a woman’s voice exclaiming angrily.

“I’ll teach you to smoke on the sly, you young outlaw, you!”

“Now let’s get while the gettin’s good,” whispered Billy; and the three crept off into the shadows.

Down through the night-enshrouded woods the boys made their way noiselessly, Billy leading, Walter Watland, nicknamed Fatty on account of his size, close behind him and Maurice Keeler, Billy’s sworn chum and confidant, bringing up the rear. Occasionally a soft-winged owl fluttered up from its kill, with a muffled “who-who.” Once a heavy object plunged from the trail with a snort, and the boys felt the flesh along their spines creeping. They kept on without so much as a word, crossing a swift creek on a fallen tree, holding to its bank and making a detour into the woods to avoid passing close to a dilapidated log cabin which in the moonlight bore evidence of having fallen into disuse. As they skirted the heavy thicket of pines, which even in the summer night’s stillness sighed low and mournfully, the leader halted suddenly and a low exclamation fell from his lips.

“Look!” he whispered. “Look! There’s a light in the ha’nted house.”

His companions crept forward and peered through the trees. Sure enough from the one unglazed window of the old building came the twinkle of a light, which bobbed about in weird, uncertain fashion.

“Old Scroggie’s ghost huntin’ fer the lost money,” whispered Walter, “Oh, gosh! let’s leg it!”

“Leg nuthin’!” Billy removed his hand from his trousers-pocket and waved something before two pairs of fear-widened eyes.

“ ‘No ghost kin harm where lies this charm,’ ” he recited solemnly. “Now if you fellers feel like beatin’ it, why beat it; but so long as I’m grabbin’ onto this left hind foot of a graveyard rabbit I don’t run away from no ghost—not even old man Scroggie’s.”

“That’s all right fer you, Bill,” returned Walter, “but what’s goin’ t’ happen t’ Maurice an’ me, supposin’ that ghost takes a notion to gallop this way? That’s what I want’a know!”

Billy turned upon him. “Say, Fatty, haven’t I told you that this here charm protects everybody with me?” he asked cuttingly.

“There’s never been a ghost that ever roamed nights been able to get near it. You kin ask Tom Dodge er any of the other Injuns if there has.”

“Oh it might lay an Injun ghost,” said the unreasonable Fatty, “but how about a white man’s? How about old man Scroggie’s, fer instance? You know yourself, Bill, old man Scroggie was a tartar. Nobody ever fooled him while he was alive an’ nobody need try now he’s dead. If he wants to come back here an’ snoop round lookin’ fer the money he buried an’ forgot where, it’s his own funeral. I’m fer not mixin’ up in this thing any—”

“Keep still!” cautioned Billy, “an’ look yonder! See it?”

He pointed through the trees to an open glade in the grove. The full moon, riding high in the sky, threw her light fair upon the fern-sown sod; across the glade a white object was moving—drifting straight toward the watchers. Billy, tightly gripping his rabbit’s foot charm, in one sweaty hand and a rough-barked sapling in the other, felt Walter’s hands clutching his shoulders.

“Oh Jerusalem!” groaned the terrified Fatty, “It’s the ghost! Look, it’s sheddin’ blue grave-mist! Fer the love of Mike let’s git out’a this!”

“Wait,” gulped Billy, but it was plain to be seen he was wavering. His feet were getting uneasy, his toes fairly biting holes through his socks in their eagerness to tear up the sward. But as leader it would never do for him to show the white feather.

The approaching terror had drifted into the shadow again. Suddenly, so near that it fairly seemed to scorch the frowsy top of the sapling to which he was hanging, a weird blue light twisted upward almost in Billy’s eyes. At the same moment a tiny hoot-owl, sleeping off its early evening’s feed in the cedar close beside the boys, woke up and gave a ghostly cry. It was too much for over-strained nerves to stand. Billy felt Fatty’s form quiver and leap even before his agonized howl fell on his ears—a cry which he and Maurice may have echoed, for all he knew.

They were fully a mile away from the place of terror before sheer exhaustion forced them to abate their wild speed and tumble in a heap beneath a big elm tree, along the trail of the forest.

For a time they lay gasping and quivering. Maurice Keeler was the first to speak. “Say, Bill,” he shivered, “is it light enough fer you to see if the hair is scorched off one side o’ my head? That—that ghost’s breath shot blue flame square in my face.”

“It grabbed me in its bony fingers,” whispered Fatty. “Gosh, it tore the sleeve fair out’a my shirt. Look!” And to prove the truth of his statement he lifted a fat arm to which adhered a tattered sleeve.

Billy sat up and surveyed his companions with disgust.

“A nice pair of scare-babies you two are,” he said, scathingly. “A great pair you are to help me find old Scroggie’s will an’ money. Why, say, if you’d only kept your nerve a little, that ghost would’a led us right to the spot, most likely; but ’stead o’ that you take to your heels at first sight of it. Say! I thought you both had more sand.”

Maurice squirmed uncomfortably. “Now look here, Bill,” he protested, “Fatty an’ me wasn’t any scarter than you was, yourself. Who made the first jump, I want’a know; who?”

“Well, who did?” snapped Billy, glowering at his two bosom friends.

“You did,” Maurice affirmed. “An’ you grabbed Fatty by the arm an’ pulled his shirt sleeve out. I saw you. And you can’t say you didn’t run neither, else how did you get here same time as Fatty an’ me?”

“Well, I didn’t run, but I own I follered you,” compromised Billy. “There wasn’t anythin’ else I could do, was there? How did I know what you two scared rabbits ud do? You might’a run plumb into Lake Erie an’ got drownded, you was so scared. Somebody’s had to keep his head,” he said airily.

“Well I kept mine by havin’ a good pair of legs,” groaned Fatty. “I’m not denyin’ that. And by gravy, if they had been good enough fer a thousand miles I’d’ve let ’em go the limit. Scared! Oh yowlin’ wildcats! I’ll see ghosts an’ smell brimstone the rest o’ my life.”

“Boys,” cried Billy in awed tones. “It’s gone!”

“What’s gone?” asked his companions in a breath.

Billy was feeling frantically in his pockets. “My rabbit foot charm,” he groaned. “I fell over a log an’ it must’a slipped out’a my pocket.”

“You had it in your hand when th’ ghost poked its blue tongue in our faces,” affirmed Maurice. “I saw it.”

“You throwed somethin’ at the ghost afore you howled an’ run,” Fatty stated. “Maybe it was the rabbit-foot?”

“ ‘No ghost kin harm where lies this charm,’ ” chuckled Maurice.

Billy turned on him. “If you want’a make fun of a charm, why all right, go ahead,” he said coldly. “Only I know I wouldn’t do it, not if I wanted it to save me from a ghost, anyway.”

Maurice looked frightened. “I wasn’t pokin’ fun at the charm, Bill, cross my heart, I wasn’t,” he said earnestly.

“All right then, see that you don’t. Now, see here, I’ll tell you somethin’. I did throw my rabbit’s foot charm but that was to keep that ghost from follerin’. Maybe you two didn’t hear it snort when it got to that charm an’ tried to pass it, so’s to catch up to us; but I heard it. Oh say, but wouldn’t it be mad though!”

“An’ that’s why you throwed it,” exclaimed the admiring Maurice. “Gosh, nobody else would’a thought of that.”

“Nobody,” echoed Fatty, “nobody but Bill.”

“Well, somebody has to think in a case o’ that kind,” admitted Billy, “an’ think quick. It was up to me to save you, an’ I did the only thing I could think of right then.”

Just here the whistle of bob-white sounded from a little distance along the trail.

“That’s Elgin Scraff and Tom Holt comin’ to look fer us,” cried Maurice.

“Answer ’em,” said Billy.

Maurice puckered up his lips and gave an answering call. It was returned almost immediately. A moment later two more boys came into the moonlight.

“We wondered what kept you fellers, so came lookin’ fer you,” spoke Tom Holt as they came up. “Thought you’d be comin’ by the tamarack swamp trail, an’ we stuck around there fer quite a while, waitin’. Then Elgin said maybe you had come the ha’nted house way, so we struck through the bush an’ tried to pick up your trail. Once we thought we saw the ghost, but it turned out to be old Ringold’s white yearlin’ steer. It had rubbed up ag’inst some will-o-the-wisp fungus an’ it fair showered sparks of blue fire. If we hadn’t heered it bawlin’ we’d have run sure.”

Somewhere behind him Billy heard a giggle, which was immediately suppressed as he turned and looked over his shoulder.

“Yep,” he replied, “we saw that steer, too. We’ve been waitin’ here, hopin’ we’d hear your whistle. I wonder what time it’s gettin’ to be?”

Tom Holt, the proud possessor of a watch, consulted it. “Ten twelve an’ a half,” he answered, holding the dial to the moonlight. “Sandtown’ll be sound asleep. Come on, let’s go down to the lake an’ make a haul.”

“I s’pose we might be goin’,” said Billy. “All right, fellers, come along.”

Arriving at the lake the boys learned after careful reconnoitering that everything was clear for immediate action. Not a light glimmered from the homes of the fishermen, to show that they were awake and vigilant.

The white-fish run was on and when the boys, launching the big flat-bottomed fish boat, carefully cast and drew in the long seine it held more great gleaming fish than they knew how to dispose of.

“Only one thing to do,” reasoned Billy, “take what we want an’ let the rest go.”

And this they did. When they left the beach the moon was low above the Point pines, the draw-seine was back in its place on the big reel and there was nothing to show the lake fishermen that the Scotia Fish Supply Company had been operating on their grounds.

Between the fishermen of Sandtown and the farmers of the community existed no very strong bond of sympathy or friendship. The former were a dissolute, shiftless lot, quite content, with draw-seine and pound-net, to eke out a miserable existence in the easiest manner possible. They were tolerated just as the poor and shiftless of any community are tolerated; their children were allowed to attend the school the same as the children of the taxpayers.

Each spring the farmers attended the fishermen’s annual bee of pile-driving, which meant the placing of the stakes for the pound nets—a dangerous and thankless task. Wet, weary and hungry, they would return to their homes at night with considerable more faith in the reward that comes of helping one’s fellow-men than in the promise of the fishermen to keep them supplied, gratis, with all the fresh fish they needed during the season.

As far back as any of the farmers could remember the fishermen had made that promise and in no case had it been fulfilled. So they came, in time, to treat it as a joke. Nevertheless, they were always on hand to help with the pile-driving. They were an old-fashioned, simple-hearted people, content with following the teachings of their good Book—“Cast thy bread upon the waters, for thou shall find it after many days.”

And find it they did, ultimately, in a mysterious and unexpected way. One late June morning each of the farmers who had for season after season toiled with those fishermen without faintest hope of earthly reward awoke to find a mess of fresh lake fish hanging just outside their respective doors. It was a great and wonderful revelation. The circuit minister, Rev. Mr. Reddick, whose love for and trust in his fellow-men was all-embracing, wept when the intelligence was imparted to him, and took for his text on the Sunday following a passage of scripture dealing with the true reward of unselfish serving. It was a stirring sermon, the rebuke of a father to his children who had erred.

“Oh ye of little faith,” he concluded, “let this be a lesson to you; and those of you, my brothers, whose judgment of humanity has been warped through God-given prosperity, get down on your knees and pray humbly for light, remembering that Christ believed in His fishermen.”

At the conclusion of the service, Deacon Ringold called a few of the leading church members together and to them spoke his mind thus:

“Brothers, you heard what our minister said, an’ he’s right. I, fer one, am ashamed of the thoughts I’ve thought to’rds them fishermen of Sandtown. I’ve acted mean to ’em in lots of ways, I’ll admit. An’ so have you—you can’t deny it!”

The deacon, a florid, full-whiskered man of about sixty, glowered about him. No one present thought of disputing his assertion. The deacon was a power in the community.

“I tell you, brothers,” he continued, waxing eloquent, “the old devil is pretty smooth and he’ll get inside the guard of Christianity every time unless we keep him barred by acts of Christly example. I have been downright contemptuous to them poor sand folks; I have so! Time and ag’in I’ve refused ’em even the apples rottin’ on the ground in my orchard. Now, I tell you what I’m goin’ to do. I’m goin’ to load up my wagon with such fruit an’ vegetables as they never get a smell of, an’ I’m goin’ to drive down there and distribute it among ’em. I ain’t suggestin’ that you men do likewise—that’s between you and your conscience—but,” he added, glaring about him, “I’d like to know if any of you has any suggestions to make.”

A tall, sad-visaged man rose slowly from his seat and took a few steps up the aisle. Like the others he was full bearded; like them his hands bore the calluses of honest toil.

“Fisherman Shipley wanted to buy a cow from me on time,” he said. “I refused him. If you don’t mind, Deacon, I’ll lead her down behind your wagon tomorrow.”

Ringold nodded approval. “All right, Neighbor Watland. Anybody else got anythin’ to say?”

A short, heavy-set man stirred in his seat, and spoke without rising. “I’m only a poor workin’-man, without anythin’ to give but the strength of my arm, but I’m willin’ to go down and help them fishermen build their smoke-houses. I’m a pretty good carpenter, as you men know.”

“That you are, Jim,” agreed the deacon heartily. “We’ll tell ’em that Jim Glover’ll be down to give ’em a hand soon.”

One by one others got up and made their little offers. Cobin Keeler, a giant in stature, combed his flowing beard with his fingers and announced he’d bring along a load of green corn-fodder. Gamp Stevens promised three bags of potatoes. Joe Scraff, a little man with a thin voice, said he had some lumber that the fishermen might as well be using for their smoke-houses. Each of the others present offered to do his part, and then the men separated for their several homes.

“Understand, brothers,” the deacon admonished as they parted, “we must be careful not to let them poor, ignorant people think we’re doin’ this little act of Christianity because they’ve seen fit to fulfill their promise to us regardin’ fish. That would spoil the spirit of our givin’. Let not one man among us so much as mention fish. Brotherly kindness, Christian example. That’s our motto, brothers, and we’ll foller it.”

“You’re right, Deacon,” spoke Cobin Keeler.

“He’s always right,” commented Scraff, who owed the deacon a couple of hundred dollars. “An’,” he added, “while we’re hangin’ strictly to Bible teachin’, might it not be a good idea fer us not to let our left hand know what our right hand’s doin’?”

“Meanin’ outsiders?” questioned Keeler.

“Outsiders and insiders as well; our wives fer instance.” Scraff had a mental vision of a certain woman objecting strenuously to the part he hoped personally to play in the giving.

“Humph,” said the deacon, “Joe Scraff may be right at that. Maybe it would be just as well if we kept our own counsel in this matter, brothers. Tomorrow mornin’, early, let each of us prepare his offerin’ and depart fer the lake. We’ll meet there and make what distribution of our gifts as seems fair to them cheats—I mean them poor misguided fishermen,” he corrected hurriedly.

And so they parted with this understanding. And when their footsteps had died away, a small, dusty boy crawled out from under the penitent bench, slipped like a shadow to a window, opened it and dropped outside.

By mid-afternoon Billy Wilson’s boon companions had learned from him that a good-will offering was to be made the fishermen of Sandtown by the people of Scotia. It was a terrible disgrace—a dangerous state of affairs. The hated Sand-sharkers merited nothing and should receive nothing, if Billy and his friends could help it. Immediate action was necessary if the plan of the farmers was to be frustrated and the outlaw fishermen kept in their proper place. So Billy and his friends held a little caucus in the beach grove behind the schoolhouse. For two hours they talked together in low tones. Then Billy arose and crept stealthily away through the trees. The others silently separated.

Sunset was streaking the pine-tops with spun gold and edging the gorgeous fabric with crimson ribbons; the big lake lay like an opal set in coral. Fishermen Shipley and Sward, seated on the bow of their old fish-boat, were idly watching the scene when Billy Wilson approached, hands in pockets and gravely surveyed them.

Shipley was a small, wizened man with scant beard and hair. He wheezed a “Hello, Sonny” at Billy, while he packed the tobacco home in his short, black pipe with a claw-like finger.

His companion, a tall, thin man, grinned, but said nothing. His red hair was long and straggly; splashes of coal-tar besmeared him from the neckband of his greasy shirt to the bottoms of his much-patched overalls.

“What dye you want, boy?” Shipley’s pipe was alight now and he peered down at Billy through the pungent smoke-wreaths.

“I was sent down here to give you a message, Mr. Shipley,” said Billy.

“Well, what is it, then? Who sent you? Come now, out with it quick, or I’ll take a tarred rope-end to you.”

“It was Deacon Ringold sent me,” Billy answered. “He told me to tell you that he’s got to turn his pigs into the orchard tomorrow an’ that you an’ the other people here might as well come an’ gather up the apples on the ground if you want ’em.”

“What!” Shipley and Sward started so forcibly that their heads came together with a bump. “So the old skinflint is goin’ to give us his down apples, is he?” wheezed Shipley. “Well, he ain’t givin’ much, but we’ll come over tonight and get ’em. It’s a wonder the old hypocrite would let us gather ’em on Sunday night, ain’t it, Benjamin?” he addressed his companion.

“He’s afeerd they’ll make his hogs sick most like,” sneered Sward.

“He says, if you don’t mind, to come about ten or ’leven o’clock,” said Billy.

Shipley threw back his head and chuckled a wheezing laugh. “Loramity! Benjamin,” he choked, “can’t you get his reason fer that? He wants to make sure that all the prayer-meetin’ folks will be gone home. It wouldn’t do fer ’em to see us helpin’ keep the deacon’s pigs from cholery. Ain’t that like the smooth old weasel, though?”

“What’ll I tell Mr. Ringold?” asked Billy as he turned to go.

“You might tell him that he’s an angel if you wanter lie to him,” returned Shipley, “or that he’s a canny old skinflint, if you wanter tell him the truth. I reckon, though, sonny, you best tell him that we’ll be along ’tween ten and ’leven.

“That’s a nice lookin’ youngster,” remarked Sward, as Billy was lost among the pines. “Notice the big eyes of him, Jack?”

“Yes. Oh, I daresay the boy’s all right, Benjamin, but he belongs to them Scotians and they ’re no friends of ourn. I reckon I scared him some when I threatened to give him the rope, eh?”

“Well, he wasn’t givin’ no signs that you did,” Sward returned, “he seemed to me to be tryin’ his best to keep from laughin’ in your face.”

“By thunder! did he now?”

“Fact, Jack. Seems to me them young Scotians don’t scare very easy. However,” sliding off the boat, “that ain’t gettin’ ready for the apple gatherin’. Let’s go and mosey up some sacks and get the others in line.”

Shipley laid a claw-like hand on his friend’s arm and turned his rheumy eyes on Sward’s blinking blue ones. “Benjamin, we’re goin’ after the deacon’s apples, but we ain’t gain’ to take no windfalls.”

“You mean we’ll strip the trees, Jack?” exulted Sward.

“Exactly. And, Benjamin, kin you imagine the old deacon’s face in the mornin’ when he sees what we’ve done?” And the two cronies went off laughing over their prospective raid.

Sunday-night prayer meeting was just over. The worshippers had gone from the church in twos and threes. Deacon Ringold had remained behind to extinguish the church lights and lock up. As he stepped from the porch into the shadows along the path, a small hand gripped his arm.

“Hello!” exclaimed the startled deacon. “Why, bless us, it’s a boy! Who are you, and what do you want?”

Apparently the boy did not hear the first question. “Mr. Ringold,” he whispered, “I waited here to see you. The Sandtown fishermen are comin’ to rob your orchard tonight.”

“What?” The deacon gripped the boy’s arm and shook him. “What’s that you say?” he questioned eagerly.

“I was down to the lake this evenin’,” said the boy, “an’ I heard Shipley and Sward talkin’ together. They was plannin’ a raid on your orchard tonight.”

Mr. Ringold fairly gasped. “Oh, the thankless, misguided wretches!” he exclaimed. “And to think that we were foolish enough to feel that we hadn’t treated ’em with Christian kindness. Did you hear ’em say what time they was comin’, boy?”

“Yes sir. They said ’bout half-past ten.”

“Well, I’ll be on hand to receive ’em,” the deacon promised, “and if I don’t teach them thieves and rogues a lesson it’ll be a joke on me. Now I must run on and catch up with Cobin Keeler and the rest o’ the neighbors. They’ve got to know about this, so, if you’ll jest tell me your name—why, bless me, the boy’s gone!”

The deacon stood perplexedly scratching his head. Then he started forward on a run to tell those who had planned with him a little surprise gift for the fishermen of the perfidy of human nature.

That night the fishermen of Sandtown were caught red-handed, stealing Deacon Ringold’s harvest apples. Like hungry ants scenting sugar they descended upon that orchard, en masse, at exactly ten-thirty o’clock. By ten-forty they had done more damage to the hanging fruit than a wind storm could do in an hour and at ten-forty-five they were pounced upon by the angry deacon and his neighbors and given the lecture of their lives. In vain they pleaded that it was all a mistake, that they had been sent an invitation via a small boy, from the deacon himself.

Ringold simply growled “lying ingrates,” and bade them begone and never again to so much as dare lay a boot-sole on his or his neighbors’ property. And so they went, and with them went all hope of a possible drawing together in Christian brotherhood of the two factions.

“Brothers,” spoke the deacon sadly, as he and his neighbors were about to separate, “I doubt if we have displayed the proper Christian spirit, but even a Christian must protect his property. Oh, why didn’t some small voice whisper to them poor misguided people and warn ’em to be patient and all would be well.”

“It means, o’ course, that we’ll get no more fish,” spoke up the practical Scraff.

“Oh yes you will,” spoke a voice, seemingly above their heads.

“Oh yes you will,” echoed another voice on the left, and on the right still another voice chanted. “You will, you will.”

“Mercies on us!” cried the amazed deacon, clutching the fence for support. “Whose voice was that? You heard it, men. Whose was it?”

The others stood, awed, frightened.

“There was three voices,” whispered Scraff. “They seemed to be scattered among the trees. It’s black magic, that’s what it is—or old Scroggie’s ghost,” he finished with a shudder.

“Joe, I’m ashamed of you,” chided the white-faced deacon. “Come along to my house, all of you, and I’ll have wife make us a strong cup of tea.”

They passed on, and then from the sable-hued cedars bordering the orchard four small figures stole and moved softly away.

Once safely out on the road they paused to look back.

“Boys,” whispered Billy, “she worked fine. Them Sand-sharkers are goin’ to stay where they belong. An’, fellers, seein’ as we’ve promised fish, fish it’s gotta be.” And so was formed the Scotia Fish Supply Company.

Four shadowy forms drifted apart and were lost in deeper shadows. The golden moon rode peacefully in the summer sky.

The morning wood-mists were warm, sweet-scented; the wood-birds’ song of thanksgiving was glad with the essence of God-given life. But the man astride the dejected and weary horse saw none of the beauties of his surroundings, heard none of the harmony, experienced none of the exhilaration of the life all about him, as he rode slowly down the winding trail between the trees. He sat erect in his saddle, eyes fixed straight before him. His face was strong and seamed with tiny lines. The prominence of his features was accentuated by the thinness of the face. Beady black eyes burned beneath the shadows of heavy brows. A shock of iron-grey hair brushed his shoulders. In one hand he held a leather-bound book, a long thumb fixed on the printed page from which his attention had been momentarily diverted by his survey of the woodland scene.

“Desolation!” he murmured, “desolation! the natural home of ignorance.”

At the sound of his voice the old horse stood still. “Thomas,” cried the rider sternly, “did I command you to halt?”

From his leather boot-leg he extracted a long wand of seasoned hickory and brought it down on the bay flank with a cutting swish. The hickory represented the symbol of progress to Mr. George G. Johnston, the new teacher of Scotia school. Certain it was it had the desired effect in this particular instance. The aged horse broke into a jerky gallop which soon carried the rider out into more open country.

Here farms, hemmed in by rude rail-fences, looked up from valley and hillside. Occasionally a house of greater pretensions than its fellows, and built of unplaned lumber, gleamed in the morning sunlight in gay contrast to the dun-colored log ones. But the eternal forest, the primitive offering of earth’s first substance, obtruded even here, and the rider’s face set in a frown as he surveyed the vista before him.

Descending into a valley he saw that the farm homes, which from the height seemed closely set together, were really quite a distance from each other. He reined up before a small frame house and, dismounting, allowed his hungry horse to crop the grass, as he opened the gate and made up the path. A shaggie collie bounded around the corner of the building and down to meet him, bristles erect and all the antagonism of a bush-dog for a stranger in its bearing. It was followed by a big man and a boy.

“Here you, Joe, come back here and behave yourself,” the master thundered and the dog turned and slunk back along the path.

“Mornin’, sir,” greeted Cobin Keeler.

In one hand he carried a huge butcher-knife, in the other a long whetstone. More big knives glittered in the leather belt about his waist. “Jest sharpenin’ my knives ag’in the hog-killin’,” he explained, noting the stranger’s startled look.

The teacher advanced, his fears at rest. “My name is Johnston,” he said, “George G. Johnston. I was directed here, sir. You are Mr. Keeler, are you not, one of the trustees of the school of which I am to have charge?”

Keeler thrust out a huge hand. “That’s me,” he answered. “You’re jest in time fer breakfast. It’s nigh ready. Come ’round back an’ wash up. Maurice, go put the teacher’s horse in the stable an’ give him a feed.”

The teacher followed his host, gingerly rubbing the knuckles which had been left blue by the farmer’s strong grip.

The boy, who had been studying the man before him, turned away to execute his father’s order. If he knew anything about teachers—and he did—he and the other lads of the community were in for a high old time, he told himself. He went down to the gate, the dog trotting at his heels.

“Joe,” he commanded, “go back home,” and the collie lay down on the path, head between his forepaws.

The boy went out through the gate and approached the feeding horse cautiously. His quick eyes appraised its lean sides and noted the long welt made by the hickory on the clearly outlined ribs beneath the bay hide.

“Poor ol’ beggar,” he said gently.

At the sound of his voice the horse lifted his head and gazed at the boy in seeming surprise. A wisp of grass dangled from his mouth; his ears pricked forward. Perhaps something in the boy’s voice recalled a voice he had known far back along his checkered life, when he was a colt and a bare-legged youngster fed him sugar and rode astride his back.

“He ought’a get a taste o’ the gad hisself,” muttered Maurice. “An’ he’s goin’ to be our teacher, oh, Gosh! Well, I kin see where me an’ Billy Wilson gets ourn—maybe.”

He patted the horse’s thin neck. “Come, ol’ feller, I’ll stuff you with good oats fer once,” he promised.

The horse reached forward his long muzzle and lipped one of the boy’s ears. “Say horses don’t understand!” grinned Maurice. “Gee! I guess maybe they do understand, though.”

He gave the horse another pat and led him down the path into the stable. As he unsaddled him Maurice noticed the hickory wand which Mr. Johnston had left inserted between the upper loops of a stirrup.

“Hully gee! ol’ feller, look!” Maurice extracted the wand and held it up before the animal’s gaze. “Oh, don’t put your ears back an’ grin at me. I ain’t goin’ to use it on you,” laughed the lad. “Look! This is what I’m goin’ to do with that ol’ bruiser’s pointer.” From a trouser’s pocket he extracted a jackknife. “Now horsie, jest you watch me close. The next time he makes a cut at you he’s goin’ to get the surprise of his life. There, see? I’ve cut it through. Now I’ll jest rub on some of this here clay to hide the cut. There you be! If I know anythin’ ’bout seasoned hickory that pointer’s goin’ to split into needles right in his hand. I hope they go through his ol’ fist and clinch on t’other side.”

Maurice gave the tired horse a feed of oats, tossed a bundle of timothy into the manger, slapped the bay flank once again and went up the path to his breakfast.

Mrs. Keeler, a swarthy woman, almost as broad as she was tall, and with an habitual cloud of gloom on her features, met him at the door. She was very deaf and spoke in the loud, querulous tone so often used by people suffering from that affliction.

“Have you seen him?” she shouted. “What you think of him, Maurice?”

Maurice drew her outside and closed the door. “Come over behind the wood-pile, Ma, an’ I’ll tell you,” he answered cautiously.

“No, tell me here.”

“Can’t. He might hear me.”

“Then you ain’t took to that new teacher, Maurice?”

“Not what you’d notice, Ma. He ain’t any like Mr. Stanhope. His face—I ain’t likin’ it a bit. Besides, Ma, he flogs his poor horse somethin’ awful.”

“How do you know that?” asked the mother, eying him sharply.

“Cause he left long welts on him. He’s out in the stable. Go see fer yourself.”

“No, I ain’t got time. I got t’ fry some more eggs an’ ham. Go ’long in to your breakfast, an’ see you keep your mouth shut durin’ the meal. An’ look here,” she admonished, “if I ketch you apullin’ the cat’s tail durin’ after-breakfast prayers I’ll wollop you till you can’t stand.”

Maurice meekly followed his mother inside and slipped into his accustomed place at the table.

Mr. Johnston was certainly doing justice to the crisp ham and eggs on the platter before him. Occasionally he lifted his black eyes to flash a look at his host, who was entertaining him with the history of the settlement and its people.

“You’ll find Deacon Ringold a man whose word is as good as his bond,” Cobin was saying. “I’m married to his sister, Hannah, but I ain’t sayin’ this on that account. The deacon is a right good livin’ man, fond of his own opinions an’ all that, an’ close on a bargain, but a good Christian man. He’s better off than anybody else in these parts. But what he got he got honest. I’ll say that, even if he is my own brother-in-law.”

“Yes, yes,” spoke Mr. Johnston, impatiently. “No doubt I shall get to know Mr. Ringold very well. Now, sir, concerning your other neighbors?” Mr. Johnston held a dripping yolk of egg poised, peering from beneath his brows at his host.

“Well, there’s the Proctors, five families of ’em an’ every last one of ’em a brother to the other.”

“Meaning, I presume, that there are five brothers by the name of Proctor living in the community.”

“By Gosh, you’ve hit it right on the head. That’s what eddication does fer a man—makes him sharp as a razor. Yes, they’re brothers an’ so much alike all I’ve got to do is describe one of ’em an’ you have ’em all.”

“Remarkable,” murmured Mr. Johnston. “Remarkable, indeed!”

“Did you say more tea, teacher?” Mrs. Keeler was at his elbow, steaming tea-pot in hand.

“Thank you, I will have another cup,” Mr. Johnston answered, and turned his eyes back to Cobin.

“You have a neighbor named Stanhope, my predecessor, I understand,” he said slowly.

“I’m proud to say we have, sir,” beamed Keeler, “an’ a squarer, finer young man never lived. A mighty good teacher he was too, let me tell you.”

“I have no doubt. I have heard sterling reports of him; if he erred in his task it was because he was too lenient. Tell me, Mr. Keeler, is there not some history attached to him concerning a will, or property left by a man by the name of Scroggie? I’ll admit I have no motive in so questioning save that of curiosity, but one wishes to know all one can learn about the man one is to follow. Is that not so, ma’am?” he asked, turning to the watchful hostess.

“More ham? Certainly.” Mrs. Keeler came forward with a platter, newly fried, and scraped two generous slices onto Mr. Johnston’s plate. “Now, sir, don’t you be affeard to holler out when you want more,” said the hospitable housewife.

“Ma’s deefness makes her misunderstan’ sometimes,” Cobin explained in an undertone to the teacher. “But I was jest about to tell you Mr. Stanhope’s strange history, sir, an’ about ol’ Scroggie’s will. You see the Stanhopes was the very first to drop in here an’ take up land, father an’ son named Frank, who wasn’t much more’n a boy, but with a mighty good eddication.

“Roger Stanhope didn’t live long but while he lived he was a right good sort of man to foller an’ before he died he had the satisfaction of seein’ the place in which he was one of the first to settle grow up into a real neighborhood. Young Frank had growed into a big, strappin’ feller by this time an’ took hold of the work his father had begun, an’ I must say he did marvels in the clearin’ an’ burnin’.

“So things went along fer a few years. Then come a letter from England to Roger Stanhope. Frank read it to me. Seems they wanted Stanhope back home, if he was alive; if not they wanted his son to come. Frank didn’t even answer that letter. He says to me, ‘Mr. Keeler, this spot’s good enough fer me.’ An’ by gosh! he stayed.

“When this settlement growed big enough fer a school, young Frank, who had a school teacher’s di-ploma, offered to teach it. His farm was pretty well cleared by this time, so he got a man named Henry Burke to work it fer him an’ Burke’s wife to keep house. That was five years ago, an’ Frank has taught the Valley School ever since, till now.”

Keeler paused, and sighed deeply. “ ’Course, sir, you’ve heerd what happened an’ how? He was tryin’ to save some horses from a burnin’ stable. A blazin’ beam fell across his face; his eyes they—” Keeler’s voice grew husky.

“I’ve heard,” said Mr. Johnston. “His was a brave and commendable act.”

“But he did a braver thing than that,” cried Cobin. “He giv’ up the girl who was to marry him, ’cause, he said, his days from now on must be useless ones, an’ he wouldn’t bind the woman he loved to his bleakness an’ blackness. Them was his very words, sir.”

To this Mr. Johnston made no audible reply. He simply nodded, waiting with suspended fork, for his narrator to resume.

“Concerning the purported will of the eccentric Mr. Scroggie?” he ventured at length, his host having lapsed into silence.

Keeler roused himself from his abstraction and resumed: “Right next to the Stanhope farm there stood about a thousand acres of the purtiest hardwoods you ever clap’t an eye on, sir. An ol’ hermit of a drunken Scotchman, Scroggie by name, owned that land. He lived in a dirty little cabin an’ was so mean even the mice was scared to eat the food he scrimped himself on. He had money too, lots an’ lots of gold money. I’ve seen it myself. He kept it hid somewhere.

“When the Stanhopes built their home on the farm, which was then mostly woods, old Scroggie behaved somethin’ awful. He threatened to shoot Stanhope. But Stanhope only laughed an’ went on with his cuttin’ an’ stump-pullin’. Scroggie used to swear he’d murder both of ’em, an’ he was always sayin’ that if he died his ghost would come back an’ ha’nt the Stanhopes. Yes, he said that once in my own hearin’.

“One night, two years after Roger Stanhope died, old Scroggie got drunk an’ would have froze to death if Frank hadn’t found him an’ carried him into his own home. Scroggie cursed Frank fer it when he came round but Frank paid no attention to him. After that, Scroggie—who was too sick to be moved—got to takin’ long spells of quiet. He would jest set still an’ watch Frank nights when the two was alone together.

“After a while the old man got strong enough to go home. Soon after that he disappeared an’ stayed away fer nearly three weeks. Then, all at once, he turned up at home ag’in. He came over to Stanhope’s house every now an’ ag’in to visit with him. One night he says to Frank after they had had supper: ‘Frank,’ says he, ‘I’ve been over to Cleveland an’ I’ve made my will. I’ve left you everythin’ I own. You’re the only decent person I’ve known since I lost my ol’ mother. I want that thousand acre woods to stand jest as God made it as long as I’m alive; when I die you kin do what you like with it.’ Then afore Frank could even thank him the old man got up an’ hobbled out.

“Next mornin’,” continued Cobin, “Frank went over to see old Scroggie. He wanted to hear him say what he told him the night afore, ag’in. It was gettin’ along towards spring; the day was warm an’ smelled of maple sap. Scroggie’s cabin door was standin’ ajar, Frank says. The ol’ man was sittin’ in his chair, a Bible upside down on his knees. He was dead!

“Frank told Mr. Reddick, the preacher who came to bury old Scroggie, all that had passed between him an’ the dead man but although they hunted high an’ low fer the will, they never found it. Nor did they find any of the money the ol’ miser must have left behind—not a solitary cent. That was over a year ago, an’ they haven’t found money or will yet. But this goes to show what a real feller Frank Stanhope is. He put a fine grave stone up for ol’ Scroggie an’ had his name engraved on it. Yes he done that, an’ all he ever got from the dead man was his curses.

“Well, soon after they put old Scroggie under the sod, along comes a nephew of the dead man. No doubt in the world he was Scroggie’s nephew. He looked like him, an’ besides he had the papers to prove his claim that he was the dead man’s only livin’ relative. An’ as Scroggie hadn’t left no will, this man was rightful heir to what he had left behin’, ’cordin’ to law. He spent a week er two prowlin’ round, huntin’ fer the dead man’s buried money. At last he got disgusted huntin’ an’ findin’ nuthin’ an’ went away.”

“And he left no address behind?” questioned Mr. Johnston.

“He surely did not,” answered Cobin. “Nobody knows where he went—nor cares. But nobody can do anythin’ with that timber without his sayso. It’s a year or more since ol’ Scroggie died. People do say that his ghost floats about the old cabin, at nights, but of course that can’t be, sir.”

“Superstitious nonsense,” scoffed the teacher. “And so the will was never found?”

“No, er the buried money,” sighed Cobin.

Mr. Johnston pushed his chair back from the table. “Thank you exceedingly, Mr. Keeler. I have enjoyed your breakfast and your conversation very much indeed. Madam,” he said, rising and turning to Mrs. Keeler, “permit me to extend to you my heartfelt gratitude for your share in the splendid hospitality that has been accorded me. I hope to see you again, some day.”

“Certainly,” returned Mrs. Keeler, “Cobin! Maurice! kneel down beside your chairs. The teacher wants to pray.”

Mr. Johnston frowned, then observing his host and hostess fall to their knees, he too got stiffly down beside his chair. He prayed long and fervently and ended by asking God to help him lead these people from the shadow into enlightenment.

It was during that prayer that Maurice, chancing to glance at the window, saw Billy Wilson’s pet crow, Croaker, peering in at him with black eyes. Now, as Croaker often acted as carrier between the boys, his presence meant only one thing—Billy had sent him some message. Cautiously Maurice got down on all fours and crept toward the door.

“Now teacher,” said Keeler, the prayer over, “you jest set still, an’ I’ll send Maurice out after your horse.”

He glanced around in search of the boy. “Why, bless my soul, he’s gone!” he exclaimed. “There’s a youngster you’ll need to watch close, teacher,” he said grimly.

“Well sir, you jest rest easy an’ I’ll get your horse myself.”

“Missus Wilson, where’s Billy?”

Mrs. Wilson turned to the door, wiped her red face on her apron, and finished emptying a pan of hot cookies into the stone crock, before answering, sternly:

“He’s down to the far medder, watchin’ the gap, Maurice. Don’t you go near him.”

“No ma’am, I won’t. Jest wondered where he was, that’s all.”

“I ’low you’re tryin’ to coax him away fishin’ er somethin’.”

“Oh, no ma’am. I gotta get right back home to Ma. She’s not very well, an’ she’ll be needin’ me.”

“Fer land sakes! you don’t say so, Maurice. Is she very bad?” The tones were sympathetic now. Maurice nodded, and glanced longingly at the fresh batch of brown cookies.

“She was carryin’ the big meat-platter on her arm an’ she fell with her arm under her—an’ broke it.”

“Lord love us!” Mrs. Wilson started to undo her apron. “Why didn’t you tell me before, you freckle-faced jackass, you! Lord knows what use you boys are anyways! Think of you, hangin’ ’round here askin’ fer Billy and your poor Ma at home groanin’ in pain an’ needin’ help. Ain’t you ’shamed of yourself?”

“Yes ma’am,” admitted Maurice cheerfully. “I guess I should’a told you first off but Ma she said if you was busy not to say anythin’ ’bout her breakin’ it.”

“Well, we’ll see about that. No neighbor in this here settlement is ever goin’ to say that Mary Wilson ever turned her back on a feller-bein’s distress. I’ll go right over to your place with you now, Maurice. Come along.”

Mrs. Wilson was outside, by this time, and tying on her sun-bonnet. Maurice held back. She grasped his arm and hustled him down the walk.

“Is it broke bad, Maurice?” she asked anxiously.

Maurice, peering about among the trees, answered absently.

“Yes ma’am. I guess she’ll never be able to use it ag’in.”

“Oh pity sake! Let’s hurry.”

Maurice was compelled to quicken his steps in order to keep up to the long strides of the anxious woman. Suddenly he halted. “Missis Wilson,” he said, “you fergot to take that last pan o’ cookies out’a the oven.”

The woman raised her hands in consternation.

“So I did,” she exclaimed. “You stay right here an’ I’ll go back and take it out now.”

“Let me go,” said Maurice quickly. “I know jest how to do it an’ kin get through in less’n half the time it’ll take you.”

“Well, run along then. I best keep right on. Your poor Ma’ll be needin’ me.”

Maurice was off like a shot. As he rounded the house on a lope he ran into Billy, coming from the opposite direction. Billy’s cotton blouse was bulging. In one hand he carried the smoking bake-pan, in the other a fat cookie deeply scalloped on one side.

“Where you goin’ so fast, Maurice?” he accosted, his mouth full.

Maurice glanced fearfully over his shoulder. “Hush, Bill. If your Ma happens to come back here it’ll go bad with me.”

Billy held out the pan to his chum and waited until Maurice had filled his pockets. Then he asked: “Where’s she gone?”

“Over to our place. I told her about Ma fallin’ an’ breakin’ the meat-platter, an’ I guess she misunderstood. She tried to take me along with her. I had an awful time to get ’way from her.”

Billy laughed. “Gee! Ma’s like that. Nobody gets ’way from her very easy. Here, fill your shirt with the rest o’ these cookies, an I’ll take the pan back; then we’ll be goin’.”

“Fish ought’a bite fine today,” said Maurice as he stowed the cookies away in his bosom.

“You bet. The wind’s south. Have you got the worms dug?”

“Yep. They’re in a can in my pocket. Did Croaker come back?” he inquired, as the two made their way down the path.

“Sure he came back. He’s a wise crow, that Croaker, an’, Oh gosh! don’t he hate Ma, though! He gets up in a tree out o’ reach of her broom, an’ jest don’t he call her names in crow talk? Ma says she’ll kill him if ever she gets close enough to him an’ she will, too.”

“Well sir, I nigh died when I seen him settin’ on our winder-sill,” laughed Maurice. “We was havin’ mornin’ prayer; the new teacher was at our place an’ he was prayin’. Croaker strutted up an’ down the sill, peerin’ in an’ openin’ an’ shuttin’ his mouth like he was callin’ that old hawk-faced teacher every name he could think of. I saw he had a paper tied ’round his neck so I crawled on my hands an’ knees past Ma, an’ slipped out. If Ma hadn’t been so deef, she’d have heard me an’ nabbed me sure.”

Billy chuckled. “Then you got my message off of Croaker, Maurice?”

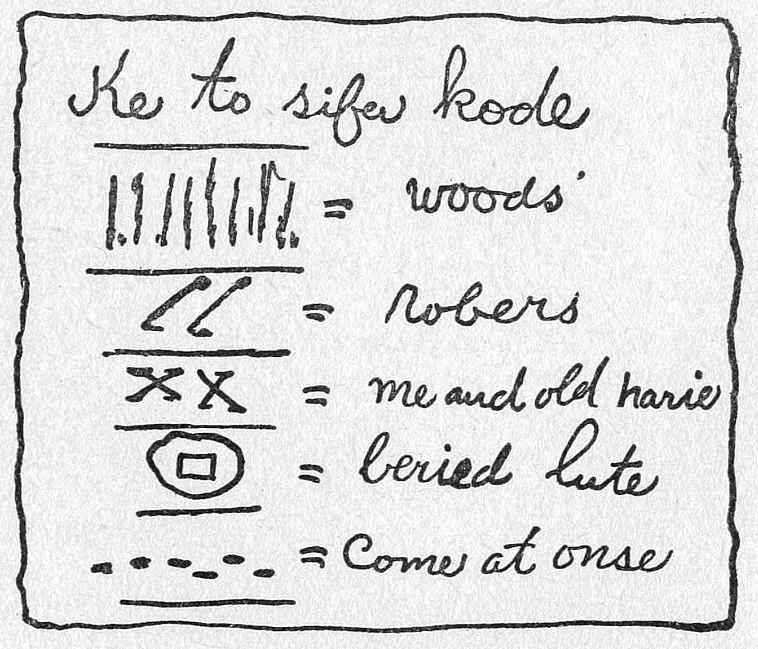

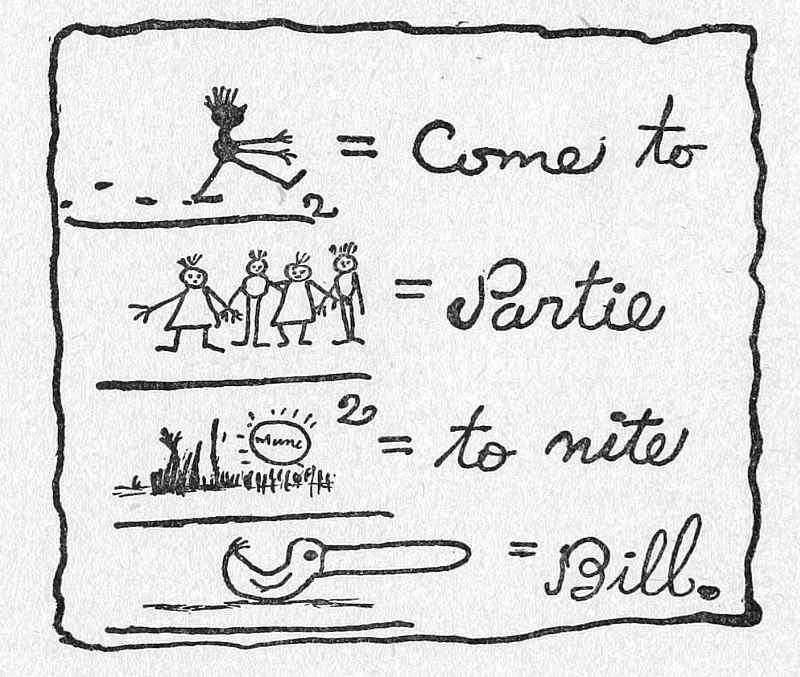

“Yep; but by jinks! I had a awful time guessin’ what you meant by them marks you made on the paper. Darn it all, Bill, why can’t you write what you want ’a say, instead of makin’ marks that nobody kin understan’?”

“There you go, ag’in,” cried Billy. “How many times have I gotta tell you, Maurice, that Trigger Finger Tim never used writin’. He used symbols—that’s what he used. Do you know what a symbol is, you poor blockhead?”

“I should say I do. It’s a brass cap what women use to keep the needle from runnin’ under their finger-nail.”

“Naw, Maurice. A symbol is a mark what means somethin’. Have you got that message I sent you? Well, give it here an’ I’ll show you. Now then, you see them two marks standin’ up ’longside each other?”

“Yep.”

“Well, what do you think they stand fer?”

“I thought maybe you meant ’em fer a couple of trees, Bill.”

“Well I didn’t. Them two marks are symbols, signifyin’ a gap.”

“A gap? Hully Gee!”

“Yep, an’ this here animal settin’ in that gap, what you think it is?”

Maurice shook his head. “It’s maybe a cow?” he guessed hopefully.

“Nope, it’s a dog. Now then, you see these two boys runnin’ away from the gap?”

“Gosh, is that what they be, Bill? Yep, I see ’em.”

“Well, that’s me an’ you. Now then, what you s’pose I meant by them symbols? I meant this. I’ve gotta watch gap. Fetch your dog over an’ we’ll set him to watch it, an’ we’ll skin out an’ go fishin’.”

Maurice whistled. “Well I’ll be jiggered!” he exclaimed. “I wish’t I’d knowed that. Say, tell you what I’ll do. I’ll sneak up through the woods an’ whistle Joe over here now.”

“No, never mind. I bribed Anse to watch that gap fer me.”

“What did you have t’ give him?”

“Nuthin’. Promised I wouldn’t tell him no ghost stories fer a week if he’d help me out.”

They had topped a wooded hill and were descending into a wide green valley, studded with clumps of red willows and sloping towards a winding stretch of pale green rushes through which the white face of the creek flashed as though in a smile of welcome. Red-winged blackbirds clarioned shrilly from rush and cat-tail. A brown bittern rose solemnly and made across the marsh in ungainly flight. A blue crane, frogging in the shallows, paused in its task with long neck stretched, then got slowly to wing, long pipe-stem legs thrust straight out behind. A pair of nesting black ducks arose with soft quacks and drifted up and out, bayward.

Billy, who stood still to watch them, was recalled suddenly to earth by his companion’s voice.

“Bill, our punt’s gone!”

With a bound, Billy was beside him, and peering through the rushes into the tiny bay in which they kept their boat.

“Well, Gee whitticker!” he exclaimed. “Who do you s’pose had the nerve to take it?”

Maurice shook his head. “None of our gang ’ud take it,” he said. “Likely some of them Sand-sharks.”

“That’s so,” Billy broke off a marsh-flag and champed it in his teeth.

Maurice was climbing a tall poplar standing on the bank of the creek. “I say, Billy,” he cried excitedly. “There she is, jest ’round the bend. They’ve beached her in that piece of woods. It’s Joe LaRose an’ Art Shipley that took her, I’ll bet a cookie. They’re always goin’ ’cross there to hunt fer turtle’s eggs.”

“Then come on!” shouted Billy.

“Where to?”

“Down opposite the punt. I’m goin’ t’ strip an’ swim across after her.”

Maurice dropped like a squirrel from the poplar. “An’ leave them boat thieves stranded?” he panted. “Oh gosh! but won’t that serve ’em right!”

“Let’s hustle,” urged Billy. “They may come back any minute.”

They ran quickly up the valley, Billy unfastening his few garments as they ran. By the time Billy had reached the bend he was in readiness for the swim across. Without a thought of the long leeches—“blood-suckers” the boys called them—which lay on the oozy bottom of the creek’s shallows ready to fasten on the first bare foot that came their way, he waded out toward the channel.

“Bill, watch out!” warned Maurice. “There’s a big womper coiled on that lily-root. You’re makin’ right fer it.”

“I see it,” returned Billy. “I guess I ain’t scared of no snakes in these parts.”

“But this beggar is coiled,” cried his friend. “If he strikes you, he’ll rip you wide open with his horny nose. Don’t go, Bill.”

“Bah! he’s uncoilin’, Maurice; he’ll slip off, see if he don’t. There, what did I tell you?” as the long mottled snake slid softly into the water. “You can’t tell me anythin’ ’bout wompers.”

“But what if a snappin’-turtle should get hold of your toe?” shuddered Maurice.

“Shut up!” Billy commanded. “Do you want them Sand-sharks to hear you? You keep still now, I’m goin’ after our punt.”

Billy was out in mid stream now, swimming with swift, noiseless strokes toward the boat. Just as he reached it the willows along shore parted and two boys, both larger than himself, made a leap for the punt. Billy threw himself into the boat and as the taller of the two jumped for it his fist shot out and caught him fairly on the jaw. He toppled back half into the water. Billy seized the paddle and swung it back over his shoulder. The other boy halted in his tracks. Another moment and the punt was floating out in midstream.

LaRose had crawled to shore and sat dripping and sniffing on the bank.

“Now, maybe the next time you boat-thieves find a punt you’ll think twice afore you take it,” shouted Billy.

“How’re we goin’ to get back ’cross the crick?” whined the vanquished LaRose.

“Swim it, same’s I did,” Billy called back.

“But the snakes an’ turtles!” wailed the marooned pair.

“You gotta take a chance. I took one.” Billy urged the punt forward across the creek to where the grinning and highly delighted Maurice waited.

“Jump in here, an’ let’s get fishin’.”

Maurice lost no time. “Where’ll we go, Bill?”

“Up to the mouth. There’s green bass up there an’ lots of small frogs, if we need ’em, fer bait.”

Caleb Spencer, proprietor of the Twin Oaks store, paused at his garden gate to light his corncob pipe. The next three hours would be his busy time. The farmers of Scotia would come driving in for their mail and to make necessary purchases of his wares. His pipe alight to his satisfaction, Caleb crossed the road, then stood still in his tracks to fasten his admiring gaze on the rambling, unpainted building which was his pride and joy. He had built that store himself. With indefatigable pains and patience he had fashioned it to suit his mind. Every evening, just at this after-supper hour, he stood still for a time to admire it, as he was doing now.

Having quaffed his customary draught of delight from the picture before him Caleb resumed his walk to the store, pausing at its door to straighten into place the long bench kept there for the accommodation of visiting customers. As he swung the bench against the wall he bent and peered closely at two sets of newly-carved initials on its smooth surface.

“W. W.” he read, and frowned. “By ding! That’s that Billy Wilson. Now let’s see, ‘A. S.’ I wonder who them initials stand fer?” With a shake of his grizzled mop he entered the store.

A slim girl in a gingham dress stood in front of the counter placing parcels in a basket. She turned a flushed face, lit with brown roguish eyes, on Caleb, as he came in.

“Had your supper, Pa?” she asked.

“Yep.” Caleb bent and scrutinized the basket.

“Whose parcels are them, Ann?” he questioned.

“Mrs. Keeler’s,” his daughter answered. “Billy Wilson left the order.”

“Hump, he did, eh? Well, let’s see the slip.” He took the piece of paper from the counter and read:

One box fruit-crackers.

10 pounds granulated sugar.

Two pounds cheese.

1 pound raisins.

1 pound lemon peel.

4 cans salmon.

50 sticks hoarhound candy.

There were other items but Caleb read no further. He stood back sucking the stem of his pipe thoughtfully. “Whereabouts did that Billy go, Ann?” he asked at length.

“Why, he didn’t go. He’s in the liquor-shop settin’ a trap for that rat, Pa.”

“Oh he is, eh? Well, tell him to come out here; I want to see him.”

Caleb waited until his daughter turned to execute his order, then the frown melted from his face and a wide grin took its place. “The young reprobate,” he muttered. “What’ll that boy be up to next, I wonder? I’ve got t’ teach him a lesson, ding me! if I haven’t. It’s clear enough t’ me that him and that young Keeler are shapin’ fer a little excursion, up bush, and this is the way they take to get their fodder.”

He turned slowly as his daughter and Billy entered from the rear of the shop and let his eyes rest on the boy’s face. “How are you, Billy?” he asked genially.

“I’m well, thanks,” and Billy gazed innocently back into Caleb’s eyes. “I hope your rheumatiz is better, Mr. Spencer.”

“It is,” said Caleb shortly, “and my eyes are gettin’ sharper every day, Billy.”

“That’s good,” said Billy and bent to pick up the basket.