* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Seigneur D’Haberville (The Canadians of Old)—A Romance of the Fall of New France

Date of first publication: 1929

Author: Phillippe Aubert De Gaspé (1786-1871)

Translator: Georgiana M. Ward Pennée

Date first posted: 25th April, 2024

Date last updated: 25th April, 2024

Faded Page eBook #20240412

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

This file was produced from images generously made available by Internet Archive.

SEIGNEUR D’HABERVILLE

(The Canadians of Old)

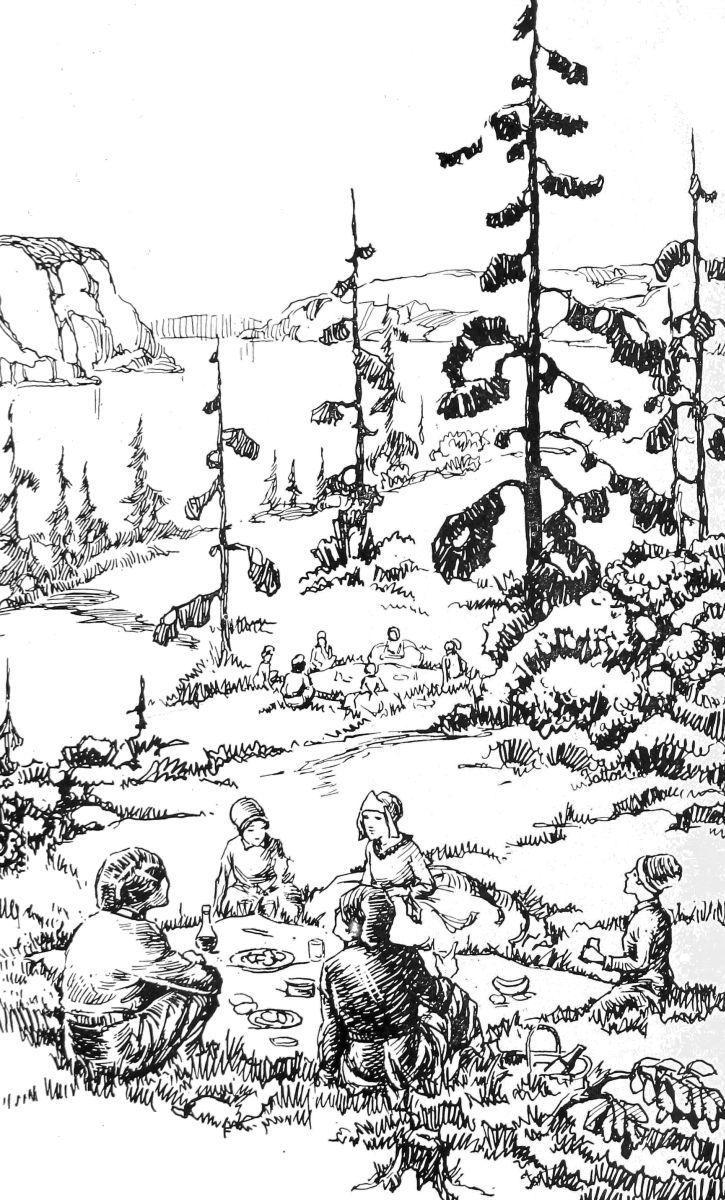

Montmorenci Falls

Seigneur D’Haberville

(The Canadians of Old)

A Romance of the Fall of New France

By

PHILLIPPE AUBERT de GASPÉ

TORONTO

The MUSSON BOOK COMPANY Ltd.

Copyright, 1929

THE MUSSON BOOK COMPANY, LTD.

TORONTO

by The Press of

THE HUNTER-ROSE COMPANY, LIMITED

Philippe Aubert de Gaspé, in his historical romance, which he entitled Les Anciens Canadiens (The Canadians of Old), has as centres the Seigneur d’Haberville and his seigniorial manor house. The book is essentially an intimate account of the d’Habervilles and their friends and retainers. It has therefore been thought best, in publishing a new edition of this invaluable Canadian story, to give as its title “Seigneur d’Haberville.”

In 1864, Mrs. Georgiana M. Pennée published an excellent translation of de Gaspé’s masterpiece. Mrs. Pennée was thoroughly familiar with seigniorial and habitant life and her translation admirably reproduces the spirit of the original. Unfortunately it abounds in printers’ errors, and occasionally a too literal translation has left certain passages obscure to the modern reader. In this edition the errors have been corrected, and some alterations made in the translation. In every case, where the latter has been done, Mrs. Pennée’s translation has been carefully compared with de Gaspé’s original.

| CONTENTS | ||

| ————— | ||

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| Editor’s Note | v | |

| Introduction | ix | |

| I | Leaving College | 1 |

| II | Archibald Cameron of Lochiel—Jules d’Haberville | 7 |

| III | A Night with the Goblins | 20 |

| IV | La Corriveau | 34 |

| V | The Breaking up of the Ice | 43 |

| VI | Supper at a Canadian Seigneur’s | 68 |

| VII | The d’Haberville Manor | 95 |

| VIII | The May-Day Feast | 114 |

| IX | The Feast of St. Jean Baptiste | 125 |

| X | The Good Gentleman | 140 |

| XI | Madame d’Haberville’s Legend | 163 |

| XII | The Conflagration on the South Shore | 178 |

| XIII | A Night with the Indians | 194 |

| XIV | The Plains of Abraham | 216 |

| XV | The Shipwreck of the Auguste | 237 |

| XVI | Lochiel and Blanche | 255 |

| XVII | The Home Circle | 288 |

| XVIII | Conclusion | 306 |

| Appendix | 329 | |

Literature had late development in the Province of Quebec. Before the conquest the inhabitants depended almost entirely on Old France for their reading matter, and after the cession of Canada the French, mainly farmers and laborers, were too busy reconstructing the country, devastated by war, to turn their attention to creative work. A new and powerful impulse was given to the intellectual life of French Canada by the publication of François-Xavier Garneau’s History of Canada in 1845, 1846 and 1848. By this monumental work, a labor of love, young and old were roused to enthusiasm regarding their country’s past, and as they read it “felt the soul of their country throb.”

At this time there was in Quebec a group of intellectuals, men like the Abbé Casgrain, Octave Crémazie, and Antoine Gérin-Lajoie. As a result of their efforts Les Soirées Canadiennes was founded. On this publication was the motto: “Let us make haste to relate the delightful tales of the people before they are forgotten.” Philippe Aubert de Gaspé, a man seventy-four years old, was attracted by these words and set himself to work to produce a story that would preserve the manners, customs, and traditions of the people of New France during the critical period of the fight for Canada and the period of reconstruction after the cession.

De Gaspé was born in the city of Quebec, October 30th, 1786, and was the son of the Hon. Pierre Ignace Aubert de Gaspé, member of the Legislative Council of Lower Canada, and of Catherine Tarieu de Lanaudière. He was a descendant of Charles Aubert de la Chesnaye, a noted fur-trader, who came to Canada in 1655 and who later prepared an important memoir on the commerce of the country and who, in 1693, was granted a patent of nobility by Louis XIV.

At the time de Gaspé began the writing of the story of Seigneur d’Haberville, his family, friends and retainers, he was living in his charming ancestral home, the seigniory of St.-Jean-Port-Joli. This seigniory had originally been granted by Frontenac, on May 25th, 1677, to one Noël l’Anglois, a very excellent carpenter who became such an indolent and unbusinesslike seigneur that his seigniory slipped from his hands and came into the possession of the de Gaspés.

Philippe Aubert de Gaspé was educated, like the two heroes of his romance, at the Quebec Seminary. He studied law under Jonathan Sewell, one of the ablest legal minds of his time, was admitted to the Bar and for a number of years was high sheriff of the district of Quebec. A student and a dreamer, generous to a fault, de Gaspé lacked business sagacity. He was forced to resign his office and for a time was a prisoner for debt. Much of what he writes about Monsieur d’Egmont, “the good gentleman” of his story, is taken from his own experiences, but he had in his character nothing of the misanthropy of d’Egmont. In 1811 he married a daughter of Captain Thomas Allison, of the 6th Regiment, infantry, and of Thérèse Baby. One of his sons, Philippe Aubert de Gaspé, in 1838, published a novel entitled Le Chercheur de trésors, ou l’influence d’un livre. This son died, March 7th, 1841, in Halifax, N.S., where he was employed as a reporter in the Legislative Assembly. In 1893, another son, Alfred Aubert, made a collection of sketches written by his father and brought them out under the title Divers. After his release from prison de Gaspé retired to his manor, St.-Jean-Port-Joli, and amid beautiful surroundings and among his beloved books spent the remaining years of his life. On January 29th, 1871, in Quebec, the most representative of the romantic writers of French Canada passed to his rest.

Amazement is frequently expressed that an untried writer of seventy-four could have produced a literary masterpiece. De Gaspé was not a literary beginner. For years he had been delving into the history and traditions of his native land, and his copious notes to his novel and his volume, Mémoires (1866), show that he was in reality a somewhat prolific writer. Again, he was a close student and an omnivorous reader. He shows scholarly familiarity with the ancient classics and with such writers as Shakespeare, Scott, Goldsmith, Burns, and corresponding writers in Spain, France and Germany. He thus tackled his great story with an experienced hand and a well-stored mind. He did his work in a leisurely manner, his main object being as he says: “To note down some episodes of the good old times” (les bon vieux temps). So well has he done his work that no other Canadian romance so exhaustively and powerfully reproduces the past. The information is first hand. In the story a seigneur details the life of seigneur and censitaire. The book abounds in genial humour, powerful character drawing, and sober judgment on national questions.

There is in the story but one discordant note, one touch of bitterness. De Gaspé apparently accepted the stories passed from lip to lip regarding General Murray, and the reader is apt to infer that Murray was a brutal, overbearing, selfish tyrant. Garneau saw otherwise. He says of Murray: “If General Murray were a stern, he was also an honorable and good-natured man; he loved such Canadians as were docile under his sway, with the affection that a veteran bears to his faithfullest soldiers.” But Garneau adds: “The Governor-General, however, was trammelled in his tendencies by a knot of resident functionaries, some of whose acts made him often ashamed of the administration he was understood to guide. A crowd of adventurers, veteran intriguers, great men’s menials turned adrift, etc., came in the train of the British soldiers.”

It would be well to keep those words of Garneau in mind when reading de Gaspé’s estimate of Murray.

T. G. MARQUIS.

SEIGNEUR D’HABERVILLE

(The Canadians of Old)

Let those who are acquainted with our good city of Quebec transport themselves, either bodily or in the spirit, to the Upper Town market-place, so as to judge of the changes that have taken place in this locality since the year of grace 1757, the date when this story commences.

The cathedral was then the same as now with regard to the edifice, but minus the modern tower, which seems as if seeking some charitable soul, either to raise it higher, or to cut off the head of its giant sister, who is so scornfully gazing on it from the height of her greatness.

The Jesuit College, now metamorphosed into a barrack, appeared much the same as it does at present; but what has become of the church which formerly stood in the spot now occupied by the butcher’s market? Where is the grove of venerable trees, behind the church, which then adorned the court, now bare and desolate, of the house consecrated to the education of Canadian youth? The axe and time, alas! have done their work of destruction. To the merry games, the witty sallies of the young students, to the grave steps of the professors who walked there for relaxation from deep study, to the discourses on the highest philosophy, have succeeded the clang of arms, and the talk of the guard-room, too often free and senseless.

Instead of the present market-place, a small market-house, containing at the most seven or eight stalls, occupied a part of the ground lying between the cathedral and the college. Between this market-house and the college flowed a rivulet, which, descending from Louis street, went down the middle of Fabrique street, and crossed Couillard street and the garden of the Hotel-Dieu on its way to the river St. Charles. It was the end of April; the rivulet had overflowed, and children were amusing themselves by breaking off and throwing in icicles, which, getting smaller and smaller and surmounting many obstructions, finished by disappearing from sight and losing themselves in the immense river St. Lawrence.

The houses which bordered the market-place, unlike our modern edifices, were mostly of one story.

It was noon; the Angelus was sounding from the cathedral belfry, and all the bells in the town were announcing the salutation borne by an angel to the mother of Christ, the beloved protectress of Canada. The habitants, whose carts surrounded the market-house, uncovered their heads and devoutly recited the Angelus.

The students of the Jesuits’ College, generally so noisy during recreation, came silently out of the church where they had been praying. Whence came this unwonted sadness? It was because they were about to lose two beloved companions, two sincere friends. The younger of the two, and the nearer to their own age, was the one who oftener shared their boyish games, and, protecting the weak against the strong, equitably decided their little differences.

The great entrance to the college was opened, and two young men, dressed for travelling, appeared in the midst of their schoolfellows. At their feet lay two leather portmanteaus, about five feet long, and furnished with rings, chains, and padlocks, apparently strong enough to moor a vessel. The younger of the two travellers, slight and of small stature, might be about eighteen. His dark complexion, large black eyes, and restless movements showed his French origin; it was Jules d’Haberville, the son of a seigneur, captain of a naval detachment in the colony.[1]

The second traveller, some two or three years older than the other, was of a larger and stronger build. His fine blue eyes, chestnut hair, fair and slightly florid complexion, a few freckles on his face and hands, and a somewhat prominent chin betrayed a foreign origin. He was Archibald Cameron of Lochiel, commonly called Archy Lochiel, a young Highlander, who had been completing his studies at the Jesuits’ College at Quebec. But how came he, a foreigner, in a French colony? The sequel will show.

The young men were both remarkably good-looking. Their dress was alike—a sort of great-coat with a hood (called a capot), scarlet cloth leggings bound with green, blue knitted garters, a large sash of bright and variegated colors, ornamented with beads, moccasins or shoes of cariboo skin, adorned with porcupine quills; and last, caps of real beaver, brought down over the ears by means of a red silk handkerchief tied round the neck.

The younger one betrayed a feverish agitation, and kept looking down Buade street.

“You are then in a great hurry to leave us, Jules,” said one of his friends, reproachfully.

“Ah, no, Laronde,” answered d’Haberville, “I assure you, no; but since this painful parting must take place, I am in a hurry to have done with it; it unnerves me; besides it is but natural that I should be in haste to see my relations again.”

“That is but right,” replied Laronde, “and besides, you being a Canadian, we may live in hopes of seeing you again soon.”

“It is not so with you, Archy,” said another. “I much fear we part from you forever, if you return to your country. Promise us to come back,” sounded on all sides.

During this conversation, Jules had darted like an arrow towards two men who were walking fast along by the side of the cathedral, each with an oar on his right shoulder. One of them wore the dress of a habitant; capot of black home-made cloth, a grey woollen cap, leggings and garters of the same color, a belt of variegated colors, and large moccasins of untanned leather. The costume of the other one was much the same as that of the young travellers, but not so rich. The former, a tall rough-mannered man, was a Pointe-Lévis boatman; the latter, of middling height and powerful frame, was in the service of Captain d’Haberville, Jules’ father; a soldier in time of war, he had taken up his quarters with the captain during peace. He was of the same age as his captain, and was also his foster-brother. He was the family’s confidential servant, had rocked the cradle of Jules, and often put him to sleep in his arms, singing the lively airs sung by travellers in the upper country.

“How are you, José? and how have you left them all at home?” said Jules, throwing himself into his arms.

“How are you, José? and how have you left them all at home?” said Jules, throwing himself into his arms.

“All well, thank God,” replied José; “they send you many messages, and are in great haste to see you. But how you have grown since I saw you last, eight months ago! My faith! Monsieur Jules, it is a pleasure to see you.”

José, although treated with the most familiar kindness by all the d’Haberville family, never failed in respect to them.

Question followed question; Jules asked about the servants, the neighbors, the old dog which, when in the lower class, he had named Niger, to show his knowledge of Latin. He did not even bear a spite to the greedy cat which, the year before, had munched up alive a young pet nightingale, for which he had a great affection, and which he intended taking with him to college. It is true that in his first transport of rage, he had chased the cat with a thick stick under tables, sheds, and even to the roof of the house, where the wicked animal took refuge as in an impregnable fortress. But now he had forgiven her, her misdeeds, and even asked about her.

“Now then!” said Baron, the boatman, who was not much interested in the scene, “now then!” said he in a rough tone, “when you have done talking of the dogs and cats, perhaps you will be kind enough to start. Tide waits for nobody.”

Notwithstanding Baron’s impatience and crustiness, the farewells of the young men were long and sad. The masters embraced them affectionately.

“Each of you is going to follow the career of arms,” said the superior to them, “and will be perpetually exposed to losing your life on the battlefield; therefore should you doubly love and serve God. If Providence decrees that you should fall, be ready at any moment to present yourself with a pure conscience before His tribunal. Let your war-cry be: ‘For my God, my king, and my country.’ ”

Archy’s last words were: “Farewell, you who have opened your arms and your hearts to an outlawed child; farewell, my noble-hearted friends, whose constant efforts have been to make the poor exile forget that he came of a race alien to your own! Farewell, farewell! perhaps forever.”

Jules was much affected.

“This separation would be a very painful one to me,” said he, “were it not that I have hopes of soon seeing Canada again, with the regiment in which I am going to serve in France.” Then addressing himself to the masters of the college, he said:

“I have abused your kindness, gentlemen, but you all know that my heart has always been more dependable than my head; so excuse the one for the sake of the other, I beg of you. As for you, my dear fellow-students,” he added in a voice that he vainly endeavored to make gay, “I acknowledge that, though I have tormented you terribly with my tricks during my ten years of college life, I have made you ample amends by causing many a hearty laugh.” And taking Archy’s arm, he hurried him away to conceal his emotion.

[1] These detachments served also by land in the colony.

Archibald Cameron of Lochiel, the son of a Highland chieftain and of a French lady, was but four years old when he had the misfortune of losing his mother. Brought up by his father, a true son of Nimrod, who, according to the beautiful Scripture expression, “was a mighty hunter before God,” he, from ten years of age, followed him in his adventurous expeditions in pursuit of the roebuck and other wild animals, climbing the steepest mountains, often swimming across the icy torrents, and sleeping frequently on the damp ground with no other covering than his plaid, no other shelter than the vault of heaven. The child, thus brought up like a Spartan, seemed to delight in this wild and roving life.

Archy was but twelve years old in the year 1745, when his father joined the standard of the young and unfortunate prince, who came like a hero of romance, to throw himself into the arms of his Scotch fellow-countrymen, hoping, with their assistance, to regain the crown which he ought to have renounced forever after the disastrous battle of Culloden. In spite of the rashness of the enterprise, in spite of the numberless difficulties they met with in their unequal struggle against the powerful army of England, none of these brave mountaineers failed him in his hour of need; on the contrary, all responded to his appeal with the enthusiasm of noble, generous, and devoted men, whose hearts were touched by Charles Edward’s confidence in their loyalty, and at the sight of the unfortunate prince as a suppliant.

At the beginning of this sanguinary struggle, courage triumphed over numbers and discipline; and the mountains echoed from afar songs of triumph and victory. Enthusiasm was then at its height; success no longer seemed doubtful. Alas! it was a vain hope; they had to yield, even after the most brilliant feats of arms. Archibald Cameron of Lochiel, the father, shared the fate of so many other brave soldiers who crimsoned the battlefield of Culloden with their blood.

One long groan of rage and despair was heard from the mountains and valleys of old Caledonia. Her children were forced to renounce forever all hopes of obtaining that liberty for which they had desperately and bravely fought for so many centuries. It was the last sob of agony from a heroic nation which is obliged to succumb.

An uncle of Archy’s, who had also followed the standard and the fortunes of the unhappy prince, succeeded, after the disastrous battle of Culloden, in saving his head from the scaffold, and, in spite of a thousand obstacles and dangers, contrived to take refuge in France, taking with him the young orphan.

The old gentleman, proscribed and ruined, was with much difficulty providing for his own and his nephew’s necessities, when a Jesuit, a maternal uncle of the young man’s, relieved him of one part of the heavy burden. Archy, having been received into the Jesuit’s College at Quebec, was just leaving it after completing his studies, when the reader is introduced to him.

Archibald Cameron of Lochiel, precociously matured by the heavy hand of misfortune, did not know, on first entering college, what opinion to form of a roguish, wild boy, an endless lover of practical jokes, who seemed to be the torment of both masters and boys. It is true that this child often got more than he wanted; out of twenty canings or impositions administered to the class by the teacher at least nineteen were pocketed by Jules d’Haberville as his share.

It must also be confessed that the big boys, often quite out of patience, gave him more than his share of cuffs; but one would have thought he rather liked them than otherwise, to judge from his readiness to recommence his tricks. Without being spiteful, he never forgave an injury, always revenging himself in some way or other. His sarcasms, keen darts which just wounded skin-deep, always struck home either to the masters themselves, or to the bigger boys whom he could not reach in any other way.

His maxim was never to allow that he was beaten, and, for the sake of peace and quietness, his foes had at last to beg for peace.

One would certainly think that this child would be universally detested; but, on the contrary, every one was fond of him, and he was the pet of the college. It was because he had such a heart as rarely beats in man’s breast. To say that he was generous even to prodigality, that he was always ready to defend the absent, to sacrifice himself that he might shield others, would hardly give so true an idea of his disposition, as the following anecdote. When he was about twelve years of age, a big boy, losing patience, gave him a good kick, without, however, having any intention of doing him harm. Jules, on principle, never told tales of his schoolfellows to the masters, as he thought it ungentlemanly to do so; he therefore only said to him; “You are too thick-headed, you ferocious animal, for me to pay you out with sarcasms; you would not understand them, but that hide of yours must be drilled through, and, don’t be alarmed, you shall lose nothing by waiting.”

Jules, after having rejected several means of revenge which were tolerably ingenious, fixed upon that of shaving off the boy’s eyebrows whilst he was asleep,—a punishment the more easily inflicted from the fact that Dubuc slept so heavily that even of a morning he had to be roughly shaken to awaken him. Besides it was attacking him at the vulnerable point, as he was a good-looking boy, and took pride in his appearance.

Jules had then decided on this punishment, when he heard Dubuc say to one of his friends who taxed him with being out of spirits:

“I have good reason to be so, for I expect my father to-morrow. In spite of his prohibition, I have run in debt at several stores, and with my tailor, hoping that my mother would come to Quebec and would get me out of trouble unknown to him. My father is stingy, quick-tempered, and violent, and on the impulse of the moment might strike me; I am at a loss to know what to do. I feel almost inclined to run away till the storm is over.”

“But why on earth,” said Jules, who had overheard this, “did you not have recourse to me?”

“Well, I don’t know,” said Dubuc, shaking his head.

“Do you think,” said Jules, “that for the sake of a kick or so, I would let a school-fellow be in trouble and at the mercy of his amiable father? You certainly nearly broke my back, but that is an affair to be settled in the proper time and place. How much do you want?”

“Ah! my dear Jules,” replied Dubuc, “it would be abusing your generosity. It is a good large sum that I am in need of, and I know that just at present you are not in funds, for you emptied your purse to relieve that poor widow whose husband met with an accident and was killed.”

“Did you ever hear such a fellow!” answered Jules, “as if one could not always find money to save one’s friend from a cross, stingy father, who might break his neck for him! How much do you want?”

“Fifty francs!”

“You shall have them this evening,” said the child.

Jules, the only son of a rich family, indulged by everybody, always had his pockets full of money; father, mother, uncles, aunts, and god-parents, even whilst proclaiming aloud the maxim, “that it is very dangerous to let children have too much money at their disposal,” vied with one another in giving it to him unknown to each other. Nevertheless Dubuc had said what was true; at that moment his purse was empty. Besides, fifty francs was a good round sum. The French king only paid his Indian allies fifty francs for each English scalp; the English monarch, richer or more generous, gave a hundred for a French one.

Jules had too much delicacy to apply to his uncles and aunts, the only relations he had in Quebec. His first idea was to borrow fifty francs on his gold watch, which was worth twenty-five pounds. But on reconsidering the matter he thought of an old woman, formerly a servant in his family, to whom his father had given a marriage portion, and to whom he had afterwards advanced a small sum to enable her to establish herself in a business, which had since prospered in her hands. She was well off, and a widow without children.

There were many difficulties in the way; the old lady was stingy and cross, and besides she and Jules had not parted on the best of terms at his last visit to her; indeed, she had chased him into the street with her broomstick. However, the little rogue was only guilty of a peccadillo; he had made her favorite spaniel take a pinch of snuff, and whilst the old lady was flying to the rescue of her dog, he had emptied the rest of the snuff into a dandelion salad which she had been carefully preparing for her supper and called out to her, “See, mammy, here is the seasoning.” No matter; Jules thought it urgent to make peace with the old lady, and so now for the preliminaries. He took her round the neck on entering, notwithstanding the old lady’s efforts to extricate herself from demonstrations that were far too tender, after the affronts he had offered her.

“Come Madeleine,” he exclaimed, “ ‘faluron dondaine,’ as the old song says, I have come to forgive you your offences, as you ought to forgive all who have offended you. Every one says you are stingy and revengeful, but that is nothing to me. You will have to atone for it by broiling in the next world, but I wash my hands of all that.”

Madeleine did not know whether to laugh or be vexed at this beautiful preamble; but as she had a weakness for the child, in spite of his tricks, she took the wisest course and began to laugh.

“Now we are in a good humor again,” pursued Jules, “I want to have a serious conversation with you. I have been playing the fool you see, and have got into debt; I am afraid of being blamed by my father, and still more so of annoying him. I want fifty francs to hush up this business,—can you lend them to me?”

“Yes, indeed, Monsieur d’Haberville,” said the old woman, “if that was all I had in the world, I would give it with my whole heart to save your good father the slightest annoyance, I am under so many obligations to your family.”

“Oh, nonsense!” said Jules, “I will have nothing to say to you if you begin to talk of that; but listen, my good Madeleine, as I may break my neck just at the moment it is least or most to be expected, whilst climbing on the college roof and the various spires in Quebec City, I am going to give you a little word in writing, by way of acknowledgment; however, I hope to discharge my debt to you in a week’s time, at the latest.”

Madeleine became downright angry, refused the acknowledgment, and counted him out the fifty francs. Jules nearly strangled her, whilst embracing her, and jumping out of the window started off towards the college.

At the evening hour of recreation Dubuc was freed from all uneasiness as regarded his amiable father. “But remember,” said d’Haberville, “I still owe you one for that kick.”

“Stop, my dear friend,” said Dubuc, quite overcome, “pay me out at once; break my head or my back with the poker if you will, but put an end to the matter; it would be too painful to me to think you owed me a grudge, after the service you have just rendered me.”

“There you are again,” answered the child; “the idea of my bearing a grudge against any fellow, just because I owe him one of my little rewards! Is that your way? Come, give me your hand and think no more of the matter. At all events you can boast of being the only one who ever scratched me without my drawing blood in return.”

So saying, he sprang on his shoulders like a monkey, pulled his hair a little, just as a relief to his conscience, and ran to rejoin the merry band, who were waiting for him.

Archibald Lochiel, matured by severe trials, and starting with a colder and more reserved disposition than is usual with children of his age, did not quite know on first entering college whether to laugh at or resent the tricks of the little imp, who seemed to have selected him as his butt, and to give him no peace. He did not know that this was Jules’ manner of showing his affection for those he liked best. At last Archy, quite out of patience, said to him one day: “You really are enough to provoke a saint; I am quite in despair about you.”

“The remedy for your woes is in your own hands, however,” said Jules; “just give me a good thrashing and I will leave you alone. It would be easy for you, who are as strong as Hercules.”

In fact Lochiel, accustomed from childhood to the boisterous games of his Highland countrymen, was at fourteen remarkably strong for his age.

“Do you think me cowardly enough to strike a boy younger and smaller than myself?”

“Why! you are like me then,” said Jules, “never even a fillip to a little fellow, but a good wrestle with those of my own age, or even older, and then shake hands and think no more about the matter. You know that fellow Chavigny,” continued Jules, “he is older than I am, but he is so weak and sickly that I have never had the heart to strike him, although he played me one of those tricks that one can hardly forgive, if one is not a second St. Francis de Sales. Only imagine his running up to me once quite out of breath, saying:

“ ‘I have just filched an egg from that greedy fellow Letourneau, who had stolen it in the large dining-room. Quick! hide it, for he is after me.’

“ ‘And where shall I hide it,’ said I to him.

“ ‘In your hat,’ he answered, ‘he’ll never think of looking there for it.’

“I was fool enough to believe him; I ought to have distrusted him, because he entreated me so. Letourneau came running up, and without warning, hit me a blow on the head. The devil of an egg nearly blinded me, and I assure you there was a perfume by no means like that of the rose: it was an addled egg, taken from the nest of a hen who must have left it at least a month. I escaped with the spoiling of my hat, waistcoat and other clothes. Well, my first feeling of anger over, I ended by laughing at it; and if I have a little spite against him, it is because he forestalled me with the trick, which I should have enjoyed playing off on Derome, on account of his powdered head. As for Letourneau, he being far too much of a fool to have invented the trick, I only said to him, ‘Blessed are the poor in spirit,’ and he went away quite proud of the compliment, and well pleased to be quit of me at so little cost.

“Now, my dear Archy,” continued Jules, “let us come to an agreement; I am a merciful potentate, and my terms shall be liberal. I undertake, on my honor as a gentleman, to retrench one-third of the jokes and tricks that you have the bad taste not to appreciate. Come, you ought to be satisfied, if you are not excessively unreasonable! For you see, Archy, I like you; to no one but yourself would I grant such advantageous terms.”

Lochiel could not help laughing, whilst he gave the incorrigible young rascal a shaking.

It was after this conversation that the two boys began their friendship; Archy, at first, with true Scotch cautiousness, but Jules with all the warmth of his French temperament.

A short time afterwards, about a month before the holidays, which then began on the 15th of August, Jules, taking his friend’s arm, said to him: “Come into my room; I have a letter from father which concerns you.”

“Concerns me!” said the other, much surprised.

“What are you astonished at?” replied d’Haberville; “do you think you are not a sufficiently important personage for any one to trouble his head about? All over New France, every one speaks of the handsome Scotchman. It is said that the mothers’ fearing you may quickly set their daughters’ hearts on fire, are intending to present a petition to the superior of the college, in order that you may only go out in the streets when covered with a veil, like the Eastern women.”

“A truce to your nonsense, and let me go on reading.”

“But I am quite in earnest,” said Jules. And dragging away his friend, he read him a passage from his father’s letter, which ran thus:

“What you write to me about your young friend Monsieur Lochiel, interests me exceedingly. It is with the greatest pleasure that I grant your request. Present my compliments to him and beg him to come and pass with us, not only his approaching holidays, but all his others, during his stay at college. If this unceremonious invitation is not sufficient from a man of my age, I will write more formally to him. His father lies low on a nobly-contested field of battle; honor to the grave of a brave soldier. All soldiers are brothers; their children should be so also. Let him come under my roof, and we will receive him with open arms, as one of our own family.”

Archy was so affected by this pressing invitation, that he was some time without answering.

“Well, you proud Scotchman,” continued his friend, “will you do us the honor of accepting? Or, must my father send his majordomo, José Dubé, as ambassador, with a bagpipe across his shoulder,—as I believe is the custom among the chiefs of the mountain clans,—and bearing an epistle in due form?”

“As, happily for me, I am no longer among the mountains of Scotland,” said Archy, laughing, “we may dispense with that formality. I will immediately write Captain d’Haberville, thanking him for his invitation, which is so noble, so handsome, so gratifying to me, an orphan and in a strange land.”

“Then let us talk sensibly,” said Jules, “were it only for the novelty of the thing as regards myself. You think me very frivolous, very foolish, and very hare-brained. I confess I am somewhat of all three; however, that does not prevent my sometimes reflecting more deeply than you give me credit for. For a long time I have been seeking a friend, a real friend, a friend with a noble and generous heart! I have watched you narrowly; you possess all these qualities. Now, Archy Lochiel, will you be that friend?”

“Certainly, my dear Jules, for I have always felt myself attracted to you.”

“Then,” exclaimed Jules, pressing his hand with much emotion, “it is in life and until death with us two, Lochiel!”

Thus, between a child of twelve and another of fourteen, was sealed a friendship which was afterwards exposed to severe trials.

“Here is a letter from my mother,” said Jules, “in which there is a word for you.”

“I hope your friend, Monsieur de Lochiel, will do us the pleasure of accepting your father’s invitation. We are all looking forward to the pleasure of making his acquaintance. His room is ready, next to yours. In the box that José will give you there is a little package addressed to him, which he would pain me much by refusing. Whilst doing it up, I was thinking of the mother he has lost!”

The box contained a similar provision of cakes, sweetmeats, preserves, and other eatables for each boy.

The friendship between the two boys increased daily. The new friends became inseparable, and were commonly called at college, Damon and Pythias, Orestes and Pylades, Nisus and Euryalus; they ended by calling themselves brothers. All the time that Lochiel was at college he passed his holidays in the country, at the d’Habervilles, who seemed to make no difference between the two boys, except that they showed more marked attention to the young Scotchman, who had now become one of the family; it was therefore quite natural that Archy before leaving for England, should accompany Jules in the farewell visit he was to pay his family.

The friendship of the young men was afterwards to be put to cruel tests, when that code of honor, which civilization substituted for the more truthful impulses of nature, forced on them the inexorable duties of men who are fighting under hostile banners. But what avails the dark future! For the ten years that their studies lasted, did they not enjoy that friendship of early manhood, which, like the love of woman, has its passing griefs, its bitter jealousies, its delirious joys, its quarrels and delicious reconciliations?

As soon as the young travellers had arrived at Pointe-Lévis, after crossing the St. Lawrence, opposite the City of Quebec, José hastened to harness a handsome and powerful horse to a sleigh without runners, the only means of transport at that time of year, when there was as much bare ground as snow and ice, and when numerous rivulets had overflowed their banks, thus intercepting the road by which our travellers had to pass. Whenever they met with one of these obstacles, José took the horse out, and all three mounting it, they soon got across. Jules, who held on to José, could not refrain from occasionally making vigorous efforts to unseat him, at the risk of sharing with him the exquisite luxury of a cold bath; however, it was labor in vain, he might as well have tried to throw Cape Tourmente into the St. Lawrence. José, who, though only middle-sized, was as strong as an elephant, laughed to himself and pretended not to notice it. When clear of the impediment, José returned alone for the sleigh, and putting the horse to again, mounted it with the baggage in front of him, for fear of its getting wet, and soon overtook his travelling companions who had not slackened their pace for a moment. Thanks to Jules, conversation did not flag during the journey. Archy was perpetually laughing at the jokes at his own expense.

“Let us make haste,” said d’Haberville, “we have twelve leagues to travel from here to St. Thomas.[2] My uncle de Beaumont sups at seven o’clock, and, if we arrive there too late, we run the risk of making but a poor meal, the best will have been gobbled up, you know the proverb, ‘tarde venientibus ossa.’ ”

“Scotch hospitality is proverbial,” replied Archy, “with us there is the same welcome by night as by day. It is the cook’s business.”

“Credo,” answered Jules; “I believe it as firmly as if I had seen it with my own eyes; otherwise, you see, your man cooks in petticoats would be wanting in skilfulness and good will. Scotch cooking is delightfully primitive! With a few handfuls of oatmeal mixed in the icy water of a brook in wintertime—for in your country there is neither coal nor wood—one can, at small cost, and without needing any great culinary skill, make an excellent ragout, and feast all comers by day and by night. It is true that when some noble personage claims your hospitality—and this frequently happens, as every Scotchman has a load of armorial bearings, enough to break down a camel,—it is true, I say, that then you add to the usual dish a sheep’s head, feet, and nice juicy tail dressed with salt; the rest of the animal is wanting in Scotland.”

Lochiel only looked over his shoulders at Jules, saying:

“ ‘Quis talia fando Myrmidonum, Dolopumve. . .’ ”

“Now, then,” broke in the latter, pretending to be angry, “do you call me a Myrmidon and a Dolopian[3]—I who am a great philosopher! And besides, you great pedant, you insult me in Latin, a language whose quantities you murder so cruelly with your Scotch accent that the shade of Virgil must tremble in its tomb! You call me a Myrmidon, I, the best geometrician of my class!—in proof of which my mathematical tutor predicted I should be a Vauban,[4] or perhaps even—”

“Yes!” interrupted Archy, “on purpose to laugh at you on account of that famous perpendicular line of yours which leaned to the left so much that the rest of the class trembled for the fate of the base it threatened to overwhelm; our tutor, perceiving this, tried to console you by predicting that if ever the tower of Pisa should be rebuilt, the rule and compass would be entrusted to you.”

Jules assumed a mock tragic attitude, and exclaimed:

“ ‘Tu t’en souviens, Cinna! et veux m’assassiner.’ You want to assassinate me here on the highroad by the side of the river St. Lawrence, without being touched by the beauties of nature which surround us on all sides; in sight, to the north, of that beautiful Montmorency fall, which the habitants call ‘la vache’ (the cow), a name, not too poetical, perhaps, but describing well the whiteness of the stream which it continually pours down, like a milch-cow giving forth the milk in which consists the riches of the husbandman. You would assassinate me here before the Isle of Orleans, which, as we advance, is beginning partly to obscure the view of that beautiful fall, which I have described in such glowing colors. Ungrateful man! can nothing soften your heart? not even the sight of poor José, who is highly edified at hearing so much wisdom and eloquence from the lips of such tender youth, as Fénelon would have said, had he written my life and adventures.”

“Do you know,” interrupted Archy, “that you are at least as great a poet as a geometrician?”

“Who doubts it?” said Jules. “No matter, my perpendicular line made you all laugh, and me the first of all. Besides you knew it was a trick of that fellow Chavigny, who had stolen my exercise and substituted one of his own, which I presented to the tutor. You all pretended not to believe me, as you were too glad to see me hoaxed, who am always hoaxing others.”

José, who generally took but little part in the conversation of the young men, and who, besides, had understood nothing at all of the last part of it, muttered to himself: “That must be a funny kind of a country anyhow, where the sheep have only heads, tails, and feet, and no more body than my hand! After all, it is no business of mine, the men, being the masters, can always manage to live well, but the poor horses!”

José, who was a great judge of horse-flesh, had a tender regard for the noble quadruped. Addressing himself to Archy, and touching his hat to him, he said:

“With all respect to you, sir, as all the nobles even eat oats in your country, which I suppose must be for want of something better, what becomes of the poor horses? They must suffer a good deal if they work hard.”

The two young men burst out laughing at this original idea. A little put out by their mirth at his expense, José resumed:

“You must excuse me if I have said anything foolish; one may make a mistake without drinking, like Monsieur Jules, who has just told us that the habitants call the Montmorency Falls ‘la vache,’ because its foam is white like milk; now I believe it is because during certain winds it roars like a cow bellowing; that is what the old people say when they are talking of it.”

“Don’t distress yourself, my good man,” said Jules, “you are probably right. What made us laugh was your inquiring if there were horses in Scotland; it is an animal quite unknown in that country.”

“No horses, sir! How do the poor folks manage to travel?”

“When I say no horses,” said d’Haberville, “you must not take it quite literally. There is certainly an animal which resembles our horses,—an animal a little larger than my big dog Niger, and which lives wild among the mountains like our cariboo, to which, indeed, it also bears a slight resemblance. When a mountaineer wishes to travel, he blows the bagpipe till all the villagers being assembled, he imparts his project to them. The people start off into the woods, or rather among the heather, and after a day or two’s trouble and unheard of efforts, they generally succeed in catching one of these charming animals. Then after another day’s work, or even longer, if the animal is not too headstrong and the mountaineer has sufficient patience, he starts on his journey and sometimes arrives safely at the end of it.”

“Well,” said Lochiel, “it is fine for you to laugh at our Highlanders! You ought to be proud indeed of your princely equipage! Posterity will find it difficult of belief that the high and powerful Seigneur d’Haberville has sent a sleigh used for carting manure to fetch home the presumptive heir of his vast domains! Of course he will send outriders to meet us, that nothing may be wanting to our triumphal entry into the manor of St. Jean-Port-Joli!”[5]

“Well done, Lochiel!” said Jules, “well answered; you have got out of that well! ‘Tit for tat,’ as a saint of your country or somewhere thereabouts said, when he came to blows with his satanic majesty.”

During this colloquy, José was scratching his head with a piteous look. Like Caleb Balderstone in Sir Walter Scott’s “The Bride of Lammermoor,” he was very sensitive about everything affecting the honor of his master’s family. He therefore exclaimed in a doleful voice.

“What a fool I was; it is all my fault! The master has four carriages in the coach-house, and two of them, brand new, are varnished as bright as fiddles; so bright that Sunday last having broken my looking-glass, I shaved myself in the panels of the brightest of them. So when the master said to me the day before yesterday morning, ‘make yourself smart José, for you are going to Quebec to fetch my son and his friend Mr. Lochiel; mind you take care and have a suitable carriage for them;’ I, fool that I was, said to myself, seeing the state of the roads, the only suitable carriage is a sleigh without runners. Ah, indeed I shall catch it finely! I shall be well out of it if I have only my allowance of brandy stopped for a month. At three glasses a day,” added José, shaking his head, “that would make ninety glasses stopped without counting the ‘a-dons’ (occasional extra glasses). But it is all right, I shall have well deserved the punishment.”

The young men were much amused at José’s ingenious lie to shield his master’s honor.

“Now,” said Archy, “that you seem to have emptied your budget of all the nonsense that a French head, destitute of brains, is able to contain, will you please speak rationally, if you possibly can, and tell me the reason why the Island of Orleans is called the Sorcerer’s Island.”

“Why, for the simplest of all reasons,” said Jules; “it is because it is inhabited by a great number of sorcerers.”

“Now there you are again at your nonsense,” said Lochiel.

“Indeed I am in earnest,” answered Jules. “Really the pride of you Scotch is unbearable! You will allow nothing to any other nation! Do you really think you have a monopoly in sorcerers? What pretension! Know, my dear fellow, that we, too, have sorcerers; and two hours ago only, between Pointe-Lévis and Beaumont I could easily have introduced you to a very presentable sorceress. Know, further, that at my honored father’s seigniory, you will see a sorceress of the highest order. My dear fellow, the great difference is that in Scotland you burn them, but here we treat them with all the respect due to their high social position. Now just ask José, if I am telling you lies.”

José was not backward in confirming his statement; the witch of Beaumont and that of St. Jean-Port-Joli, being in his eyes bona fide sorceresses.

“If you would allow me, young gentlemen, I could easily put you right by telling you what happened to my defunct father, who is dead.”

“Oh! do tell us, José; do tell us what happened to your defunct father who is dead,” exclaimed Jules, laying particular stress on the last three words.

“Oh, my good José,” said Lochiel, “I beg of you to do us the pleasure.”

“Well, one day my defunct father, who is dead, had left town a little latish to return home; he had even stopped at Pointe-Lévis a little while to amuse himself—in fact to be pretty jolly with his friends. The good man liked a drop of comfort, and that was why, when he travelled, he always carried a small bottle of brandy in his seal-skin bag. He used to say it was old men’s milk.”

“Lac dulce,” said Lochiel, drily.

“With all due respect, Master Archy,” replied José, a little put out, “it was not soft (douce) water; nor lake water, but good wholesome brandy, that my defunct father carried in his bag.”

“Upon my word, that is excellent!” exclaimed Jules. “You were paid out there for your eternal Latin quotations.”

“Forgive me, José,” said Lochiel, quite seriously; “I had no intention of treating the memory of your defunct father with disrespect.”

“You are excused,” said José, his wrath suddenly appeased. “It happened that, when my father wanted to set out, it was quite dark. His friends did all they could to keep him all night, telling him he would have to pass alone before the iron cage where La Corriveau underwent her punishment for having killed her husband.[6] You have seen her yourselves, gentlemen, when we left Pointe-Lévis at one o’clock; the wicked thing was then quiet enough in her cage, with her skull without eyes; but don’t trust her, she is sly enough, and if she can’t see by day, she knows well enough how to find her way about at night and torment people. Well, my defunct father, who was as brave as his captain’s sword, told them he cared nothing about it and that he owed nothing to La Corriveau, and a heap of other things which I have forgotten. He touched his horse with the whip and away went the swift beast like the wind.

“When he came near the skeleton, he thought he heard a noise like some one groaning; but as a strong southwester was blowing, he thought it must be the wind among the bones of the corpse. Still it bothered him, and he took a good drop to cheer himself up. All things considered, he said to himself, Christians should help one another; perhaps the poor creature wants some prayers. So he took off his cap and devoutly said a dépréfundi (de profundis) in her behalf, thinking, if it did not do her any good, it could not do her any harm, and besides, anyway, he himself would be the better of it.

“Then he went on quite fast, but this did not prevent his hearing behind him ‘tic, tac; tic, tac;’ like a piece of iron striking on stones. He therefore got out, but found everything in its place. He thought it was the tire of his wheel, or some of the iron of his cabriolet which had become unnailed. He whipped his horse to make up for lost time, but he soon again heard the ‘tic, tac; tic, tac,’ on the stones; still, as he was a brave man, he did not pay much attention to it.

“Arrived at the top of St. Michel’s hill, which we passed just now, he felt very sleepy. After all, said my defunct father to himself, a man is not a dog! we will take a nap; both my horse and I will be better for it. So he unharnessed his horse, and tying its forelegs with the reins, said to it: ‘There, pet, there is good grass, and you can hear the brook flow, good night.’

“As my defunct father was going to get into his cabriolet to shelter himself from the dew, he took a notion to find out the hour, so he looked at the Three Kings to the south and the Wain to the north, and concluded it must be midnight. It is the hour when all honest people should be in bed.

“All at once, it appeared to him that the Isle of Orleans was all on fire. He jumped over the ditch and climbing on a fence stared with amazed eyes. At last he saw that the flames were running along the shore, as if all the feux-follets (will-o’-the-wisps) in Canada, the cursed goblins, had come there by appointment to hold their Sabbath. By dint of looking steadily, his sight, which had been confused, became quite clear, and he saw a strange spectacle. There were a number of things shaped like men, but of some extraordinary species, for they had heads as big as a half-bushel measure, dressed up in sugar-loaf caps a yard long; then they had arms, legs, feet, and hands armed with claws, but no body worth speaking of; in fact, their bodies were split up to their ears. They had hardly any flesh, just all bones like skeletons. All these handsome fellows had their upper lip cloven like a hare’s, and there stuck out a rhinosferos (rhinoceros) tooth a good foot long, like what we see, Mr. Archy, in your book of supernatural history. Their nose was hardly worth speaking of; it was neither more nor less than a long, pig-like snout, which they worked round and round at their will, sometimes to the right and sometimes to the left of the big tooth. I suppose it was to whet it. I was nearly forgetting a long tail, twice as long as a cow’s, which hung down their back, and I think they used it to whisk off the mosquitoes.

“The funniest thing was that they had but three eyes between every two phantoms. Those who had only one eye in the middle of their forehead, like the cyroclops (cyclops) which your uncle the chevalier, Monsieur Jules, who is a learned man, read about to us from a big book all Latin, like a priest’s breviary, which he called his Vigil (Virgil); well, those who had but one eye held tight on to two acolytes, who, the cursed things, had all their eyes. From all these eyes there came out flames of fire which lighted the Isle of Orleans like day. These last seemed to have great consideration for their neighbors, who were, as one might say, one-eyed. They saluted them by approaching them and flourishing their arms and legs about like Christians dancing the minuet. The eyes of my defunct father were starting out of his head. It was much worse when they began to skip and dance about, however, without moving from their places, and to sing, in a voice as gruff as that of a choking ox, the following song:—

‘Come, be gay, gossip goblin!

Come, be gay, my neighbor dear.

Come, be gay! gossip pokenose—

Gossip, little idiot, foolish frog.

Of those Christians, of those Christians,

We will make a glorious feast.’

“ ‘Oh, the miserable carnivals’ (cannibals), said my defunct father, ‘only see; an honest fellow cannot be a moment sure of his own property. Not content with stealing my very best song, which I always keep for the last at weddings and junketings, see how they have altered it! It can hardly be recognized. It is on Christians instead of good wine that they want to feast, the wretches!’ And then after that the bogies went on with their infernal song, looking straight at my defunct father and pointing at him with their great rhinosferos teeth.

‘Ah! come hither, gossip François;

Ah! come hither, gossip piggy;

Come, make haste, gossip sausage—

Come, hither, gossip pumpkin pie.

Of the Frenchman, of the Frenchman,

We will make a salting-tub.’

“ ‘All I can tell you, my darlings,’ cried out my defunct father, ‘is, that if you eat no other salt pork than what I shall carry for you, you will not need to skim your soup.’

“However, the bogies seemed in the meantime to be waiting for something, and as they often turned their heads round to look behind, my defunct father looked also. What did he perceive on the hill! A great devil, shaped like the others, but as tall as St. Michel’s steeple, which we passed just now. Instead of a sugar-loaf cap, he wore a cocked hat, surmounted by a spruce-tree by way of a plume of feathers. He had but one eye, the blackguard, but it was worth a dozen; he must have been drum-major to the regiment, for he held in one hand a big pot, twice as large as our sugar caldrons, which hold twenty gallons each; and in the other hand the clapper of a bell, which he had stolen, I believe, the dog of a heretic, from some church before the ceremony of baptising the bell had been performed. He struck one blow on the pot, and all the insecrable (execrable) creatures began to laugh, to jump, and to flutter about, nodding their heads towards my defunct father, as if they were inviting him to come and dance with them.

“ ‘You will have a long time to wait, my sweet creatures,’ thought my defunct father to himself, whilst his teeth chattered in his head as if he had the ague; ‘you will have a long time to wait, my darlings, before you catch me leaving God’s earth for the land of bogies.’ All at once the giant devil struck up an infernal song and dance tune, accompanying himself on the pot, which he kept thumping harder and faster, whilst all the other devils started off like lightning, so that they were not a minute in making a complete tour of the island. My poor defunct father was so bewildered by the uproar that he could only catch three verses of this fine song; here they are:

‘Of Orleans this is our domain,

The country where fine fellows reign.

Tour loure,

Dance around;

Tour loure,

Dance around.

‘All who come we welcome make,—

Witches, lizard, toad, or snake.

Tour loure, etc.

‘Hasten hither all who list.

Infidel or atheist.

Tour loure, etc.’

My defunct father was in a bath of perspiration, and yet he was not at the worst of his adventures.

“But,” added José, “I have a longing to smoke; and with your permission, gentlemen, I will strike a light.”

“All right, José,” said d’Haberville, “but for my part, I have a different longing. By my appetite it must be four o’clock, the time for collation at college. We must eat a morsel.”

[2] Later the village of Montmagny.

[3] Slighting names given by the boys in the upper classes to those not yet in the fourth.

[4] Sébastien le Prestre de Vauban (1633-1707). A distinguished French military engineer, created a marshal of France, 1703.—T.G.M.

[5] On May 25th, 1677, this seigniory was granted to Noël l’Anglois. It was later acquired by the de Gaspé family.—T.G.M.

[6] See Appendix A.

José, having taken the bridle from the horse and given him what he called a mouthful of hay, made haste to open a box which, with his usual busy ingenuity, he had fastened on the sleigh so as to serve, at need, as either a seat or a larder. He drew out a table-cloth, in which were wrapped a couple of chickens, a tongue, some ham, a little flask of brandy, and a good bottle of wine. He was withdrawing to a distance when Jules said to him: “Come and eat with us, my good man.”

“Yes, yes,” said Archy, “come and sit down near me.”

“Oh! gentlemen, I know too well the respect I owe you.”

“Come, no ceremony,” said Jules; “we are bivouacking, all three being soldiers or very nearly so. Will you come, you obstinate one.”

“It is with your permission, gentlemen, and to obey you, my superior officers, that I do so.”

The two young men seated themselves on the box, which also served as table; José seated himself very comfortably on a heap of hay that was still remaining, and all three began to eat and drink with good appetite.

Archy, who was naturally abstemious, had soon finished his collation. Having nothing better to do, he began to philosophize. Lochiel, on the days he felt gay, liked to advance paradoxes for the pleasure of provoking discussion.

“Do you know what interested me most in our friend’s legend?”

“No,” said Jules, attacking another leg of a chicken, “and I shan’t much care for the next quarter of an hour; a hungry stomach has no ears.”

“No matter,” replied Archy, “it was these devils, imps, goblins, whatever you like to call them, who had only one eye. I would like that fashion to increase among human beings, there would be fewer hypocrites, fewer rogues, and consequently fewer dupes. It is certainly consoling to find that virtue is honored even among goblins! Did you notice the high consideration in which the cyclops were held by the other bogies? With what respect they saluted them before approaching them?”

“Oh, yes!” said Jules, “but what does that prove?”

“That proves,” replied Lochiel, “that these cyclops deserve the consideration they meet with, they are the very cream of the goblins. In the first place, they are not hypocrites.”

“Stuff,” said Jules, “I am beginning to fear for your brain.”

“I am not such a fool as you think,” replied Archy. “Here is proof of it. Look at a hypocrite with some one he wants to take in; he has always one eye half shut on himself, whilst his other is wide open noticing the effect which his discourse produces on his interlocutor. If he had but one eye, he would lose this immense advantage, and be obliged to give up playing the hypocrite, which he finds so profitable. There would be one bad man less. Probably my goblin cyclops has many other vices, but he is certainly exempt from that of hypocrisy; hence arises the respect which is felt for him by a class of beings sullied with all the vices that are attributed to them.”

“Your health! Scottish philosopher,” said Jules, swallowing a glass of wine. “Hang me if I understand one word of your arguments.

“Do you know,” continued Jules, “that you are a terrible logician, and bid fair to eclipse some day, even if that day has not already come, such twaddlers as Socrates, Zenon, Montaigne, and other logicians of the same stamp. The only fear is that the logic may carry the logician up to the moon.”

“You may laugh!” said Archy. “Well! let only one pedant, with his pen behind his ear, take the trouble of seriously refuting my theory, and you will see a hundred scribblers rush to the rescue, who will take part for and against, till oceans of ink flow. Oceans of blood have often flowed on account of arguments about as sensible as mine, and that is how many a great man’s reputation has been made!”

“In the meantime,” answered Jules, “your theory may serve as a pendant to the tale that Sancho related to put Don Quixote to sleep. As for me, I very much prefer our friend José’s legend.”

“You shew your good taste!” answered the latter, who had taken a nap.

“Let us hear it,” said Archy.

“ ‘Conticuêre omnes, intentique ora tenebant.’ ”

“ ‘Conticuêre!’ incorrigible pedant!” exclaimed d’Haberville.

“It is not the conte (tale) of a curé (curate),” answered José quickly, “but it is as true as when he speaks to us from the pulpit, for my defunct father never told lies.”

“We believe you, my dear José,” said Lochiel, “but please go on with your charming story.”

“Well, then,” said José, “brave as my defunct father was, he still could not help feeling so decidedly frightened that the perspiration trickled from the end of his nose in a stream as thick as an oat-straw. There he was, the poor dear man, his eyes starting out of his head, and not daring to budge an inch. He fancied, indeed, that he heard behind him the same tic, tac; tic, tac, which he had before heard several times on the road, but he had too much going on before him to be able to trouble himself about what was passing behind him. All at once, just when he least expected it, he felt two great hands as lean as a bear’s paws, laying hold of his shoulders. He turned round, quite scared, and found himself face to face with La Corriveau. She had slipped her hands through the bars of her iron cage and was trying to climb on to his back, but the cage being heavy, at each spring that she took, she fell back to the ground with a clanging sound, but still without letting go of my poor defunct father’s shoulder, who bent under the burden. If he had not held tight to the fence with both his hands, he would have been crushed with the weight. My poor defunct father was so struck with horror, that you might have heard the perspiration drop from his face on to the fence like duckshot!

“ ‘My dear François,’ said La Corriveau, ‘do me the pleasure of conducting me to dance with my friends on the Isle of Orleans.’

“ ‘You limb of the old boy,’ said my defunct father, ‘is it by way of thanking me for my dépréfundi (de profundis) and other good prayers that you want me to take you across to the witches’ sabbath? I was thinking you must be having at least three or four thousand years of purgatory for your pranks. You had only killed two husbands; that was a trifle, so it pained me to think of it, and I, who have a tender heart, said to myself; I must give her a helping hand. And all the thanks I get is, that you want to jump on my shoulders and drag me to hell like a heretic.’

“ ‘My dear François,’ said La Corriveau, ‘do please take me to dance with my dear friends,’ and she knocked her head against my defunct father’s till his skull rattled like a bladder full of flint-stones.

“ ‘That is a fine idea of yours,’ said my defunct father, ‘you limb of Judas Iscariot, that I am going to make a beast of burden of myself to carry you across to dance at the witches’ sabbath with your beloved cronies.’

“ ‘My dear François,’ answered the witch, ‘it is impossible for me to cross the St. Lawrence without the help of a Christian, for the river is blessed.’

“ ‘Get across as you can, you confounded gallows’ bird,’ said my defunct father to her, ‘every one must look after his own affairs. Oh, yes! indeed, a fine idea that I am to carry you across to dance with your crew; but you may just travel as you have been doing already, though how, I can’t make out, and drag after you that fine cage, which must have rooted up all the stones and pebbles on the highway, which will make a fine row some of these days when the overseer comes and sees the wretched state of the roads! Of course it will be the poor habitant who will have to suffer for your pranks, by paying a fine for not having kept the road in proper order.’

“Just then the drum-major left off thumping time on his big pot. All the goblins left off dancing and uttered three cries, or rather three yells, like those given by the Indians when they perform their ‘war dance,’ that terrible dance and song with which they prelude their martial expeditions. The isle trembled to its very foundations. The wolves, the bears, all the wild beasts and the goblins of the northern mountains took up the cry, and the echoes repeated it till it died away in the forests on the shores of the Saguenay.

“My poor defunct father thought that, at the very least, it was the end of the world and the day of judgment. The giant with the spruce-plume struck three loud blows, and the deepest silence succeeded to the infernal din. He raised his arm towards my defunct father, and called out to him in a voice of thunder: ‘Will you make haste, you idle dog, will you make haste, you dog of a Christian, and bring our friend across? We have only fourteen thousand four hundred times more to dance around the island before cock-crow; would you have her lose the best of the fun?’

“ ‘Go to the devil, whence you came, you and yours!’ exclaimed my defunct father, at last losing all patience.

“ ‘Come, my dear François,’ said La Corriveau, ‘be more polite! You are acting foolishly about a mere trifle, and yet you see time presses. Come, my son, just one attempt!’

“ ‘No, no, you hag!’ said my defunct father, ‘I wish you had still that fine necklace which the hangman put about your neck two years ago; you would not then be quite so ready with your tongue.’

“During this dialogue the goblins on the island recommenced their chorus:

‘Dance around.

Tour loure.’

“ ‘My dear François,’ said the witch, ‘if you refuse to take me in flesh and blood, I will strangle you, and fly across to the feast mounted on your soul.’

“So saying, she seized him by the throat, and strangled him.”

“What!” exclaimed the young men, “she strangled your poor defunct father?”

“When I say strangled, it was hardly any better for the poor dear man,” replied José, “for he quite lost his consciousness. When he came to himself, he heard a little bird calling out, que-tu[7]—who are you?”

“ ‘Ah, well,’ said my defunct father, ‘I cannot be in hell, since I hear one of God’s birds.’ So first he opened one eye, and then the other, and saw it was broad daylight; the sun was shining in his face; the little bird perched on a neighboring tree still kept on calling, who are you?

“ ‘My dear child,’ said my defunct father, ‘it is rather hard for me to answer that question, for I really do not know very well myself this morning who I am; yesterday I was a good respectable man who feared God, but I have had so many adventures through the night, that I can hardly be sure it is myself, François Dubé, that is here present in the flesh,’ and then the dear man began to sing:

‘Dance around.

Tour loure.’

He was still half bewitched. However, at last he found that he was lying at full length in a ditch, where, fortunately, there was more mud than water, for otherwise my poor defunct father, who died like a saint, surrounded by all his relations and friends, and furnished with all the sacraments of the Church, without missing one, would have died without confession, like a brute beast in the midst of the woods. When he had dragged himself out of the ditch, in which he was squeezed like a vice, the first thing he saw was his flask on the edge of the ditch, which brought back his courage a little. He stretched out his hand to take a drink of it, but it was empty! The witch had drunk it all!”

“My dear José,” said Lochiel, “I am not particularly cowardly, but if such an adventure had happened to me, I should never have travelled alone again at night.”

“Nor I either,” put in d’Haberville.

“To tell you the truth, gentlemen, since you understand so well, I will tell you in confidence, that my defunct father, who before this adventure would have gone into a graveyard at midnight, was never so courageous afterwards, for he did not dare go alone into the stable to do his work after sunset.”

“He was very right,” said Jules, “but finish your story.”

“It is done already,” answered José. “My defunct father yoked his horse, which appeared to have had no knowledge of anything, the poor beast, and got home as quickly as he could. It was only a fortnight afterwards that he related his adventure to us.”

[7] The author has to acknowledge his ignorance of ornithology. Our excellent ornithologist, M. Le Moine,[A] will perhaps come to our assistance in rightly classifying the little bird whose cry sounds like the two syllables, que-tu (que-es-tu; who are you). This recalls the anecdote of an old man who was non compos mentis and who lived about sixty years ago. Thinking the question addressed to himself when he heard these denizens of the woods, he did not fail to answer, at first very politely, “Père Chamberland, my little children,” but at length losing patience, “Père Chamberland, you little pests.”

[A] Sir James MacPherson Le Moine (1825-1912): A charter member and later President of the Royal Society of Canada; author of numerous books on Quebec and its environment; knighted in 1897.—T.G.M.

The travellers went merrily on their way till, the daylight fading, they proceeded for a time by the light of the stars. Soon, however, the moon rose, throwing her beams far over the calm beauty of the majestic St. Lawrence. At this sight, Jules could not refrain from giving expression to a poetical ebullition, and exclaimed:

“I feel myself inspired, not by the waters of Hippocrene (of which, indeed, I have never drunk, nor have I any wish to drink) but by the juice of Bacchus, which is far more agreeable than all the fountains in the world, even than the limpid wave of Parnassus. All hail to thee, then O beautiful moon! All hail to thee, thou silvery lamp, that now lightest the steps of two mortals who are as free as the denizens of our boundless forests, two mortals but recently escaped from the trammels of college life! How often, O moon, at the sight of thy pale rays, penetrating to my solitary couch, how often, O moon, have I longed to break my chains asunder and join the joyful throngs which were hastening to balls and parties, at the very moment that cruel and barbarous regulations were condemning me to the slumber, which I was doing my utmost to banish! Ah! how many times, O moon, have I not wished to mount on thy disk, and thus even at the risk of breaking my neck, travel over the regions which thou lightest in thy majestic career, even if I had been obliged to pay a visit to another hemisphere. Ah, how many times—”

“Ah, how many times hast thou talked nonsense in thy life,” said Archy, “for folly is contagious. Listen to a true poet, and let your pride be humbled: O moon! thou triple essence that the poets formerly hailed as Diana the huntress, how must thou not delight to leave the gloomy domain of Pluto, as well as the forests, where, preceded by thy barking pack, thou makest row enough to stun all the goblins in Canada; dost thou not delight, O moon! to sail majestically, like a peaceful queen, through the ethereal regions of the sky, in the stillness of a lovely night. Have pity, I pray thee, on thy own work; give back his senses to a poor afflicted mortal, my dearest friend, who—”

“O Phoebe! patroness of madmen!” interrupted Jules, “I address thee no prayer for my friend; thou art innocent of his infirmity; the harm was done—”

“Now then, you gentlemen,” said José, “when you have finished gossiping with the lady moon, whom I did not know one could talk such a lot to, would you be so good as to listen a little to the noise that is going on at the village of St. Thomas.”

All listened attentively; the church-bell was indeed ringing loudly.

“It is the Angelus,” said Jules d’Haberville.

“Of course!” replied José, “the Angelus at half-past eight o’clock in the evening!”

“Then it must be fire,” said Archy.

“Still one cannot see any flames,” replied José; “but anyway, let us make haste: something uncommon must be going on down there.”

By means of urging on the horse full speed, they entered the village of St. Thomas in about half an hour. The deepest silence reigned there; the place appeared deserted, except by several dogs that were shut up in some of the houses, and were barking furiously. Except for the noise of these curs, one might have imagined one’s self transported to the town spoken of in the “Arabian Nights,” where all the inhabitants were turned into marble.

Our travellers were about to enter the church, whose bell was still ringing, when they perceived a light, and distinctly heard noises in the direction of the falls, near the seigniorial manor. To hasten thither was the work of a few minutes only. The pen of a Cooper, or a Chateaubriand, could alone do justice to the sight which they beheld on the banks of the South River.

Captain Marcheterre, an old sea captain of athletic form, still hale and hearty in spite of his age, had been returning home to the village towards dusk, when he heard a sound from the river, like some heavy body falling into the water; and immediately afterwards, the groans, and piteous cries of a man who was calling for help. They came from a foolhardy habitant, Dumais by name, who, thinking the ice which he had passed the evening before (and even then found somewhat bad) was still safe, had again ventured on it with a horse and sleigh, a few hundred yards to the south-east of the village. The ice had given way so suddenly that the horse had disappeared completely under the water. The unfortunate Dumais, who was a man of unusual agility, had just time to spring from the sleigh on to stronger ice; but the tremendous leap which he took to escape from inevitable death was fatal to him. His foot caught in a crack of the ice and he had the misfortune of breaking his leg, which snapped like a glass tube just above the ankle.

Marcheterre, knowing the dangerous state of the ice, which was cracked in many places, called out to him not to stir, even if he had the strength to do so, and that he would soon come back with help. He ran immediately to the sexton, begging him to ring the alarm-bell, whilst he himself summoned his nearest neighbors.

Soon all was hurry and confusion. Men were running to and fro, without any order or definite object; women and children were crying and lamenting; dogs were barking and howling, on every note of the canine gamut; so that the captain, whose experience pointed him out as the fittest person to direct the means of rescue, had much difficulty in making himself heard.

In the meantime, under Marcheterre’s directions, some ran for cables, ropes, planks, and pieces of timber; whilst others robbed the fences and wood piles of cedar and birch-bark to make torches. The scene became more and more animated, and by the light of fifty torches, throwing afar their bright and sparkling refulgence, the crowd spread itself along the shore of the river as far as the spot indicated by the old captain.

Dumais, who had patiently enough awaited the arrival of help, called out to them, as soon as he was able to make himself heard, that they must make haste, as he heard dull sounds which seemed to come from towards the mouth of the river.

“There is not a moment to lose, my friends,” said the old captain, “for everything looks as if the ice would soon break up.”