* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Canadian Fruit, Flower, and Kitchen Gardener

Date of first publication: 1872

Author: D. W. (Delos White) Beadle 1823-1905

Date first posted: April 24, 2024

Date last updated: April 24, 2024

Faded Page eBook #20240411

This eBook was produced by: Marcia Brooks, Pat McCoy & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

This file was produced from images generously made available by Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries.

advertisment

THE

FRUIT GROWERS ASSOCIATION

OF ONTARIO.

| Rev. R. Burnet, Hamilton, | President. |

| D. W. Beadle, St. Catharines, | Secretary. |

The Annual Report, illustrated with accurately executed engravings, and with one or more finely coloured fruit-plates, contains a large amount of very valuable information, and is sent, post-paid, to every member.

A number of fruit trees are distributed every year to each member for trial. The entire expense of this distribution is borne by the Association, the members being required only to make report to the Association, through the Secretary, of the results of such trial. The Swayzie Pomme Grise Apple tree will be distributed in the Spring of 1875; the Downing Gooseberry in that of 1874; and the Tetofsky Apple in the Spring of 1876. Other selections will be made for distribution from time to time, as the Directors ascertain what varieties it is desirable to test.

Prizes are given for Essays, Canadian Seedling Fruits, &c., of which a full announcement will be found in the Annual Report.

Any person can become a member by sending the annual fee of one dollar to the Secretary. Any member who will take the trouble to send the names and fees of five new members, will receive a double number of trees at the next distribution.

CANADIAN

FRUIT, FLOWER,

AND

KITCHEN GARDENER.

BY

D. W. BEADLE, Esq.,

Secretary of the Fruit Growers’ Association of Ontario, Editor of the

Horticultural Department of the Canada Farmer, &c., &c.

A GUIDE IN ALL MATTERS RELATING TO THE CULTIVATION OF FRUITS,

FLOWERS AND VEGETABLES, AND THEIR VALUE FOR

CULTIVATION IN THIS CLIMATE.

TORONTO:

PUBLISHED BY JAMES CAMPBELL & SON.

1872.

Entered according to the Act of the Parliament of Canada, in the year One Thousand

Eight Hundred and Seventy-two, by James Campbell & Son,

in the Office of the Minister of Agriculture.

GLOBE PRINTING COMPANY, KING ST., EAST, TORONTO.

CONTENTS.

SUBJECTS.

FRUIT GARDEN.

| The Propagation of Fruit Trees— | page | |

| Grafting | 5 | |

| How to Cleft Graft | 6 | |

| How to Whip Graft | 9 | |

| How to make Grafting Wax | 7 | |

| To prepare Waxed Cloth | 11 | |

| To Select Scions | 11 | |

| Budding and when to Bud | 12 | |

| How to Select Buds | 14 | |

| When to Remove the Ligature and Head Back the Stock | 16 | |

| The Pruning of Fruit Trees— | ||

| When to Prune and why | 18 | |

| Where to Prune | 20 | |

| Pruning to Produce Fruit | 21 | |

| Transplanting Trees— | ||

| The best Time to Transplant | 23 | |

| Preparing the Ground | 23 | |

| How to Plant | 25 | |

| The best Trees for Transplanting | 27 | |

| Mulching— | ||

| What is Meant by Mulching | 26 | |

| How to Mulch, and why it is done | 26 | |

| Treatment of Young Orchards— | ||

| To Protect from Mice | 30 | |

| To Keep the Bark Clean and Healthy | 31 | |

| Location of Orchard— | ||

| Soil and Aspect | 31 | |

| Hills and Valleys | 32 | |

| Injurious Insects, and how to get rid of them— | ||

| The Tent Caterpillar | 35 | |

| The Two-striped Borer | 38 | |

| The Buprestis Apple Tree Borer | 40 | |

| The Codling-Worm | 42 | |

| The Plum Curculio | 45 | |

| The Grape Vine Flea Beetle | 49 | |

| The Green Grape Vine Sphinx | 50 | |

| The Gooseberry Saw-fly | 52 | |

| The Production of New Varieties of Fruit— | ||

| How they are produced | 53 | |

| Cross-fertilization | 58 | |

| How to Cross-fertilize | 59 | |

| The Apple— | ||

| Soil best Suited to Apples | 61 | |

| How Propagated | 62 | |

| Gathering and Sorting for Market | 62 | |

| Packing and Marketing the Fruit | 63 | |

| Best Kinds for Market | 64 | |

| Dwarf and Half-standard Trees | 65 | |

| Varieties of Apples, with description of each | 66 | |

| The Apricot— | ||

| Climate and Soil Suitable | 84 | |

| How Propagated | 84 | |

| Varieties, with description | 85 | |

| The Cherry— | ||

| Classes of Varieties and Soil best Suited | 85 | |

| How Propagated and Stocks on which it is Grown | 86 | |

| Varieties, with full description | 87 | |

| The Nectarine— | ||

| Cultivation and Varieties | 92 | |

| The Peach— | ||

| Soil best Adapted and Pruning | 94 | |

| Manuring | 95 | |

| Varieties, with description | 95 | |

| The Pear— | ||

| Best Soil | 97 | |

| Climate and Diseases | 97 | |

| Manures and Propagation | 98 | |

| Standard Trees | 98 | |

| Dwarf Trees and how to Plant them | 99 | |

| How to Prune them | 100 | |

| Thinning Out and Gathering the Fruit | 103 | |

| Growing for Market | 105 | |

| Varieties, with full description | 105 | |

| The Plum— | ||

| Climate and Soil | 118 | |

| Best Fertilizers and Diseases | 118 | |

| How Propagated | 119 | |

| Varieties, with description | 119 | |

| The Quince— | ||

| Where it Can be Grown, and on What Soils | 122 | |

| Best Manures and How Far Apart to Plant | 123 | |

| How Propagated and Varieties | 123 | |

| Hardy Grapes— | ||

| Proper Soils | 124 | |

| Preparing the Ground and Manuring | 125 | |

| Distance Apart and Time and Method of Planting | 125 | |

| Treatment of Young Vines and Pruning and Training | 126 | |

| Trellis and Wire | 127 | |

| Varieties and description | 132 | |

| Mildew, &c. | 138 | |

| Grapes under Glass— | ||

| Shape and Size of Vinery | 140 | |

| How to Build a Vinery | 141 | |

| How to Heat it | 142 | |

| How to Ventilate it | 144 | |

| Best Form of Boiler | 145 | |

| Best Size of Pipe | 148 | |

| Border for the Vines | 148 | |

| Soil for Border, Compost, and Drainage | 149 | |

| Planting the Vines | 150 | |

| Subsequent Treatment of the Vines | 151 | |

| Temperature of Vinery by Day and Night | 152 | |

| Quantity of Fruit that may be left on the Vines | 153 | |

| Ripening the Fruit | 154 | |

| Diseases of Vines—Shanking | 155 | |

| Mildew | 157 | |

| List of Vines most desirable for Vinery | 157 | |

| List for Early Forcing | 158 | |

| Fruiting Exotic Vines in Pots | 158 | |

| The Blackberry— | ||

| Soil | 160 | |

| Cultivation and Propagation | 161 | |

| Varieties, with description | 161 | |

| The Strawberry— | ||

| Sexes | 162 | |

| Soil and Manures | 164 | |

| Best Time for Transplanting and Best Plants | 165 | |

| Preparation of Ground and Planting | 166 | |

| Production of New Varieties | 167 | |

| Varieties, with full description | 168 | |

| The Raspberry— | ||

| How Propagated | 171 | |

| Best Soils and How to Plant | 172 | |

| To Cultivate | 173 | |

| To Prune | 174 | |

| To Protect in Winter | 175 | |

| Varieties, and their description | 175 | |

| The Currant— | ||

| How to Propagate | 180 | |

| How to Cultivate and Prune | 180 | |

| Varieties, with full description | 180 | |

| The Gooseberry— | ||

| The Mildew | 181 | |

| How to Prune and Cultivate | 182 | |

| Varieties | 183 | |

| The Cranberry— | ||

| Preparation of Soil | 183 | |

| Planting and Cultivation | 186 | |

| How to control the Water, so as to flood or drain off at pleasure | 184 | |

| Varieties | 187 | |

| The Huckleberry— | ||

| Natural Soils | 188 | |

KITCHEN GARDEN.

| Asparagus— | ||

| How to Prepare the Soil | 194 | |

| How to Plant and Cultivate | 195 | |

| When and How to Cut and How to Cook | 196 | |

| Varieties | 196 | |

| Beans— | ||

| Dwarf or Bush Varieties | 197 | |

| Running or Pole Varieties and their Cultivation | 199 | |

| Beets— | ||

| How to Prepare the Soil and Cultivate | 201 | |

| Gathering and Preserving in Winter | ||

| Varieties | 203 | |

| Broccoli— | ||

| Culture and Varieties | 204 | |

| Brussels Sprouts— | ||

| Cultivation and Use | 205 | |

| Cabbage— | ||

| Soil and Cultivation | 206 | |

| Varieties | 207 | |

| Carrots— | ||

| How to Prepare the Ground and Cultivate | 210 | |

| Uses and Varieties | 211 | |

| Cauliflower— | ||

| Soil and Manures | 213 | |

| How to Cultivate and to Use | 214 | |

| Best Varieties | 214 | |

| Celery— | ||

| How to Cultivate and Blanch | 216 | |

| To Secure for Winter Use | 218 | |

| Varieties | 219 | |

| Cress or Pepper Grass— | ||

| Soil, Cultivation and Varieties | 220 | |

| Cucumber— | ||

| Soil and Cultivation | 221 | |

| Varieties | 222 | |

| Corn— | ||

| Best Table Varieties | 224 | |

| Endive— | ||

| Cultivation | 224 | |

| Blanching and Preservation during Winter | 225 | |

| Egg Plant— | ||

| Cultivation | 225 | |

| Use and Varieties | 226 | |

| Garlic— | ||

| Cultivation and Use | 226 | |

| Horse-Radish— | ||

| Propagation, Cultivation and Use | 227 | |

| Kohl-rabi— | ||

| Cultivation, Use and Varieties | 228 | |

| Leek— | ||

| Soil and Cultivation | 228 | |

| Use and Sorts | 228 | |

| Lettuce— | ||

| Preparation of Soil and Cultivation | 229 | |

| The Best Varieties | 230 | |

| Melons— | ||

| How to Prepare the Soil | 231 | |

| How to Cultivate, and the Best Varieties | 232 | |

| Onion— | ||

| How to Prepare the Soil and Cultivate | 234 | |

| To Preserve during Winter, and the Best Varieties | 237 | |

| Parsnip— | ||

| Preparation of Soil and Cultivation | 240 | |

| Use and Varieties | 241 | |

| Potato— | ||

| Soil and Manures | 241 | |

| Planting | 242 | |

| Cultivation and Forcing | 243 | |

| Varieties | 244 | |

| Peas— | ||

| Preparation of Soil and Sowing | 245 | |

| Cultivation, Use and Varieties | 246 | |

| Peppers— | ||

| Cultivation | 247 | |

| Use and Varieties | 248 | |

| Radishes— | ||

| Soil and Cultivation | 248 | |

| Spring and Autumn Varieties | 249 | |

| Rhubarb or Pie Plant— | ||

| Preparation of Soil | 250 | |

| Cultivation, Use and Varieties | 251 | |

| Salsify or Oyster Plant— | ||

| Soil | 251 | |

| Cultivation and Use | 252 | |

| Squash— | ||

| Soil and Cultivation | 252 | |

| Summer Varieties | 253 | |

| Autumn and Winter Kinds | 254 | |

| Sea-Kale— | ||

| Preparation of the Ground | 255 | |

| Cultivation | 256 | |

| Blanching, Cutting and Use | 257 | |

| Spinach— | ||

| Soil and Cultivation | 257 | |

| Use and Varieties | 258 | |

| Tomatoes— | ||

| Cultivation | 259 | |

| Soil | 262 | |

| Varieties | 263 | |

| Turnips— | ||

| Soil and Cultivation | 264 | |

| Harvesting | 264 | |

| Varieties | 265 | |

| Hot-Beds— | ||

| Their Construction and Use | 265 | |

| Cold Frames— | ||

| Their Construction and Use | 268 | |

| Tools— | ||

| Steel Rake, Scuffle-Hoe and Digging Fork | 268 | |

FLOWER GARDEN.

| Hardy Flowering Shrubs— | ||

| Berberry | 272 | |

| Carolina Allspice or Calycanthus | 273 | |

| Canadian Judas Tree | 273 | |

| Cornus Florida or Dogwood | 274 | |

| Double Flowering Almonds | 274 | |

| Deutzias, Single and Double-Flowered | 276 | |

| Filbert, Purple-Leaved | 277 | |

| Hawthorns, Scarlet, Rose-colored, etc. | 277 | |

| Honeysuckles, Pink and Red Flowering | 278 | |

| Lilacs, Persian White, etc., etc. | 278 | |

| Prunus Triloba, Double-Flowered | 279 | |

| Purple Fringe or Smoke-bush | 279 | |

| Rose Acacia | 279 | |

| Rose of Sharon or Altheas | 280 | |

| Japan Quince, Double and Single | 280 | |

| Spireas—White and Rose, Single and Double | 281 | |

| Siberian Pea-Tree | 283 | |

| Silver Bell | 283 | |

| Syringa or Mock Orange | 283 | |

| Snowball or Guelder Rose | 283 | |

| Tamarix | 284 | |

| Weigelas, Rose-flowered, Variegated-leaved, etc. | 284 | |

| White Fringe | 285 | |

| Hardy Climbing Shrubs— | ||

| Ampelopsis or Virginia Creeper | 286 | |

| Bignonia or Trumpet-Flower | 286 | |

| Brithwort or Dutchman’s Pipe | 286 | |

| Clematis or Virgin’s Bower, Various Sorts | 286 | |

| Honeysuckles, Various Sorts | 287 | |

| Wistaria or Glycine | 288 | |

| Ivy | 289 | |

| Hardy Herbaceous Flowers— | ||

| Achillea or Milfoil | 290 | |

| Aconite or Monkshood | 290 | |

| Aquilegia or Columbine | 291 | |

| Campanula or Bell-flower | 291 | |

| Carnations | 295 | |

| Convallaria or Lily of the Valley | 293 | |

| Delphinium or Larkspur | 293 | |

| Dianthus, the Pink | 294 | |

| Dictamnus or Fraxinella | 294 | |

| Digitalis or Foxglove | 296 | |

| Dicentra or Bleeding Heart | 297 | |

| Funkia or Day-Lily | 297 | |

| Helleborus Niger or Christmas Rose | 297 | |

| Iris, German, or Fleur-de-lis, &c. | 298 | |

| Lathyrus or Ever-blooming Pea | 299 | |

| Lychnis, Various Sorts | 300 | |

| Pansies | 306 | |

| Peonias, Herbaceous Sorts | 300 | |

| Phloxes, Tall and Short Varieties | 302 | |

| Spirea or Meadow Sweet | 304 | |

| Sweet William, Dianthus Barbatus | 296 | |

| Tricyrtis (very fragrant, new, late-blooming) | 305 | |

| Violets | 305 | |

| Yucca, Filamentosa, or Adam’s Needle | 308 | |

| Bulbous-Rooted Flowers— | ||

| General Observations | 309 | |

| Amaryllis | 315 | |

| Crocus | 318 | |

| Dahlias | 318 | |

| Fritillarias | 320 | |

| Gladiolus | 320 | |

| Hyacinths | 312 | |

| Iris, English, Spanish and Persian | 323 | |

| Lilies of Various Sorts | 324 | |

| Narcissus | 326 | |

| Snow-drops | 327 | |

| Tigridias or Tiger Flower | 327 | |

| Tuberose | 328 | |

| Tulips | 330 | |

| Bedding Plants (Flowering through the Summer)— | ||

| Verbenas, and How to Care for them | 332 | |

| Heliotropes and their Varieties | 334 | |

| Bouvardia, Cultivation and Varieties | 335 | |

| Coleus | 334 | |

| Petunias | 337 | |

| Lantanas | 338 | |

| Lemon Verbenas | 339 | |

| Zonale Geraniums | 340 | |

| Variegated-Leaved Geraniums | 343 | |

| Ivy-Leaved Geraniums | 344 | |

| Annuals— | ||

| Asters | 346 | |

| Balsams | 347 | |

| Calliopsis | 347 | |

| Drummond Phlox | 348 | |

| Marigolds | 348 | |

| Mignonette | 349 | |

| Portulaca | 349 | |

| Rocket Larkspur | 350 | |

| Scabious or Mourning Bride | 350 | |

| Salpiglossis | 350 | |

| Stock, Ten-Weeks’ | 351 | |

| Annuals—Climbing— | ||

| Convolvulus or Morning Glory | 351 | |

| Dolichos or Hyacinth Bean | 352 | |

| Gourds | 352 | |

| Sweet Peas | 352 | |

| Tropeolums | 352 | |

| Annuals—Everlasting Flowers— | ||

| Acroclinium | 353 | |

| Gomphrena, Globe Amaranth | 353 | |

| Helichrysum | 354 | |

| Helipterum | 354 | |

| Rodanthe | 354 | |

| Xeranthemum | 354 | |

| Ornamental Grasses— | ||

| Agrostis Nebulosa | 355 | |

| Briza Maxima | 355 | |

| Erianthus Ravennæ | 355 | |

| Pennisetum | 355 | |

| Stipa Pennata | 355 | |

| Window-Gardening— | ||

| Important Directions | 355 | |

| Plants suitable | 359 | |

| Roses— | ||

| Cultivation in the Garden | 361 | |

| Climbing Roses, Choice Varieties | 370 | |

| Summer Roses, the Best Kinds | 371 | |

| Moss Roses | 373 | |

| Autumnal Roses, Blooming a Second Time | 374 | |

| Monthly Roses, for Window-Gardening | 377 | |

| Climatic Variations— | ||

| General Survey | 379 | |

| Hardy Evergreens— | ||

| American Arbor Vitæ | 383 | |

| American Yew | 384 | |

| Austrian Pine | 384 | |

| Balsam Fir | 384 | |

| Common Juniper | 384 | |

| Eastern Spruce | 384 | |

| Hemlock Spruce | 385 | |

| Lambert’s Pine | 385 | |

| Lawson’s Cypress | 387 | |

| Norway Spruce | 385 | |

| Nordmann’s Fir | 385 | |

| Red Cedar | 385 | |

| Scotch Pine | 386 | |

| Siberian Silver Fir | 386 | |

| Siberian Arbor Vitæ | 386 | |

| Swedish Juniper | 386 | |

| Tartarian Arbor Vitæ | 386 | |

| White Pine | 386 | |

| White Spruce | 387 | |

| White Cedar | 387 | |

| Conclusion— | 389 | |

| Acknowledgments— | 390 | |

ILLUSTRATIONS.

| page | |

| Figures 1 and 2, showing the manner of cleft-grafting; figure 1 being the scion prepared for insertion in the stock, figure 2 the stock with the scions inserted | 6 |

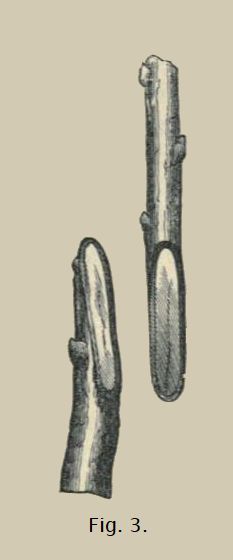

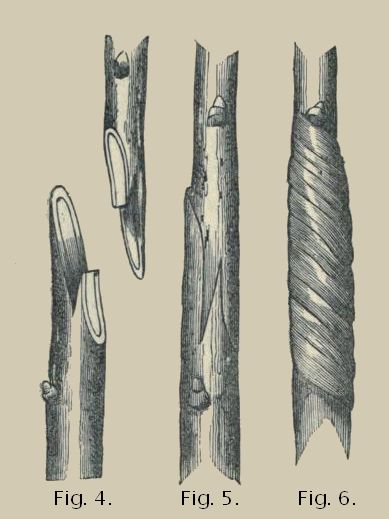

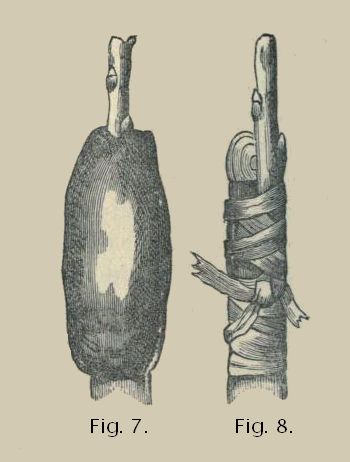

| Figures 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8, showing the method of whip-grafting; figure 3 showing the bevelled surfaces of stock and scion, figure 4 the same tongued, figure 5 the graft and stock put together, figure 6 as tied together with a ligature, figure 7 as covered with grafting wax, and figure 8 as wound with a strip of waxed cotton | 9, 10 |

| Figure 9, a branch or scion prepared for budding | 14 |

| Figure 10, the best form of budding knife | 14 |

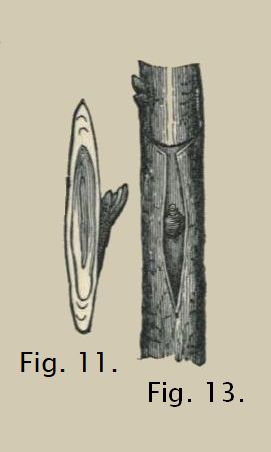

| Figures 11, 12, 13, and 14 show the manner in which the operation of budding is performed; figure 11 is the bud when cut from the scion, figure 12 the stock with the bark loosened and prepared to receive the bud, figure 13 the bud inserted in the stock, and figure 14 the bud and stock bound with its ligature | 14, 15, 16 |

| Figure 15 represents the bud tied to a portion of the stock, in order to keep it upright during the first weeks of its growth. The broken white line across the stock shows where the stock is to be cut off when the bud has grown sufficiently stout to stand erect without support | 17 |

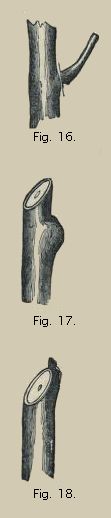

| Figure 16 shows the place at which a branch should be cut when taken from the tree | 20 |

| Figures 17, 18, and 19 show where a small branch should be pruned; figure 17 representing it as cut too far from the bud, figure 18 as cut too close to the bud, and figure 19 when cut at the proper place | 20 |

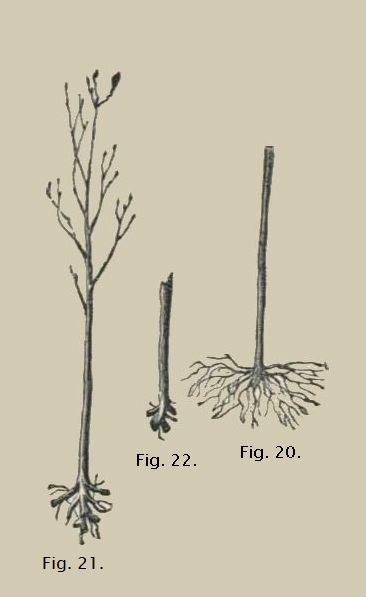

| Figures 20, 21, and 22 represent the proper and improper appearance of the roots of transplanted trees | 27 |

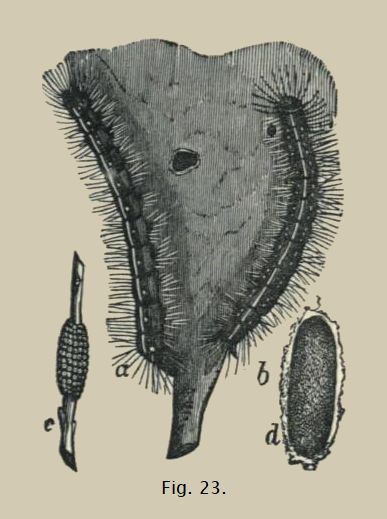

| Figure 23 represents tent caterpillars, with their tent, the eggs from which they are hatched, and the cocoon into which they pass | 35 |

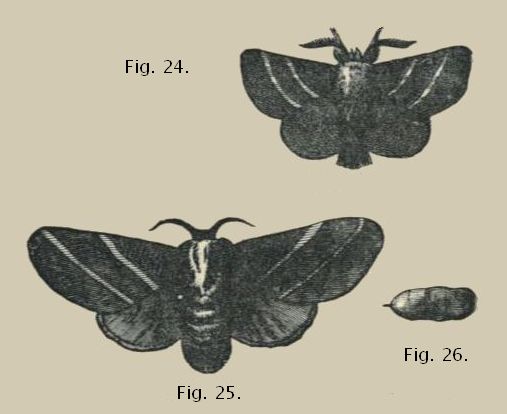

| Figures 24, 25, and 26 are the male and female moths of the tent caterpillar, and the chrysalis from which they are hatched | 37 |

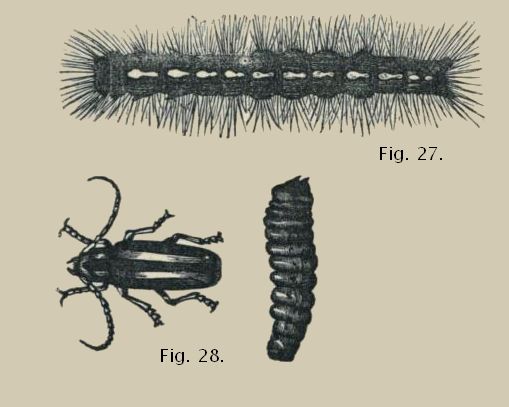

| Figure 27 is a cut of the forest tent caterpillar | 38 |

| Figure 28 represents the two-lined apple tree borer, and the worm from which it is produced | 38 |

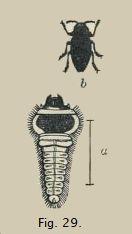

| Figure 29 is the worm and beetle of the buprestis apple tree borer | 41 |

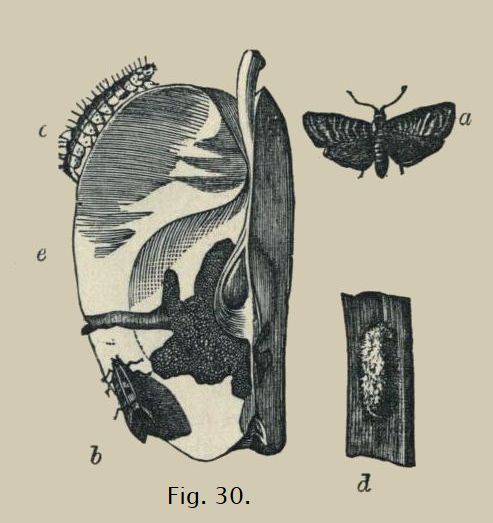

| Figure 30 represents a piece of an apple that has been eaten by the codling worm; the worm is crawling on the outside, and the moth is shown near the apple with the wings expanded, and on the apple with the wings folded. The cocoon is seen attached to a small piece of bark | 42 |

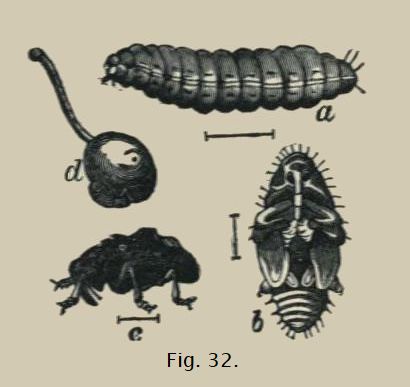

| Figure 32 shows the plum curculio in the beetle, worm and pupa state, magnified; and of the natural size, in the act of depositing its egg upon a cherry | 47 |

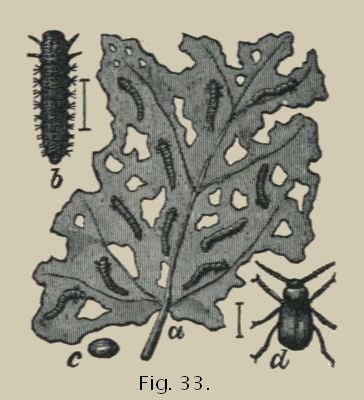

| Figure 33 represents the grape vine flea beetle and the larva, both magnified, and the young larvæ feeding on a leaf of the vine | 49 |

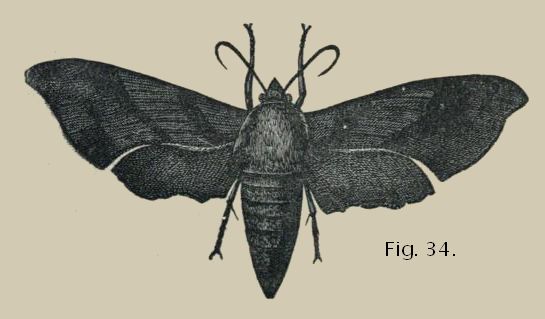

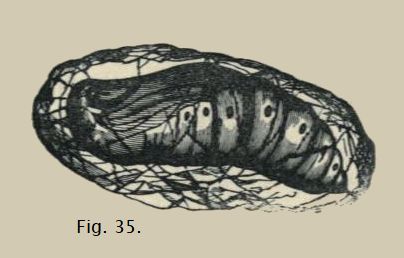

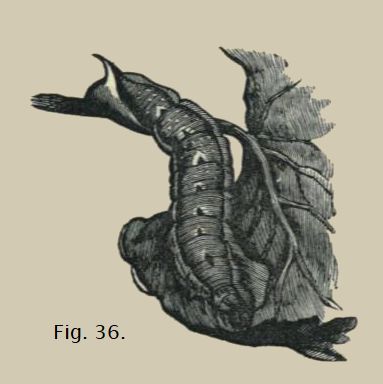

| Figures 34, 35 and 36 represent the green grape vine sphinx in the moth, worm and chrysalis states | 50, 51 |

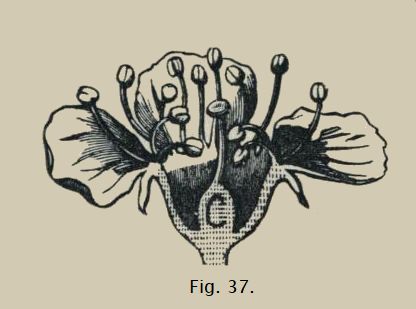

| Figure 37 is a cherry blossom cut open so as to show the ovary, pistil, and stamens | 56 |

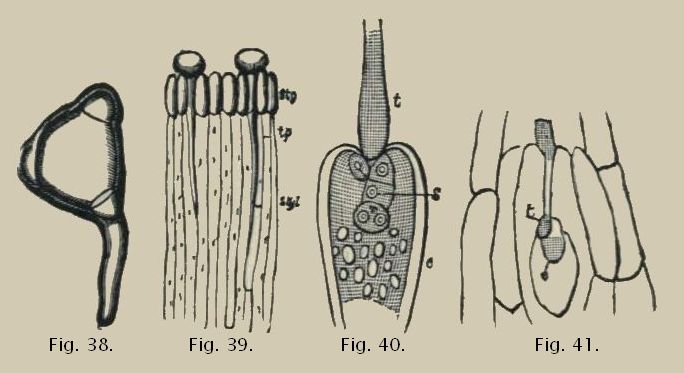

| Figures 38, 39, 40 and 41 show how the pollen enters the pistil, descends to the ovary, enters it and comes in contact with the germ, so imparting to it the power of development | 57 |

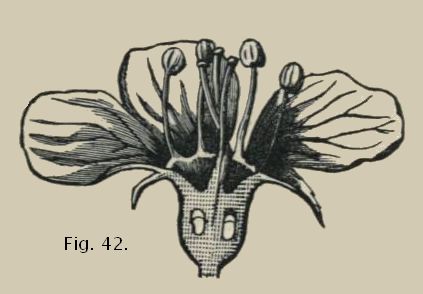

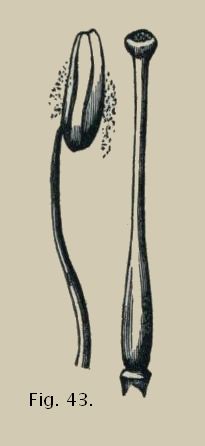

| Figure 42 represents an apple blossom cut open, showing the number of pistils | 57 |

| Figure 43 shows more distinctly the pistil and stamen | 58 |

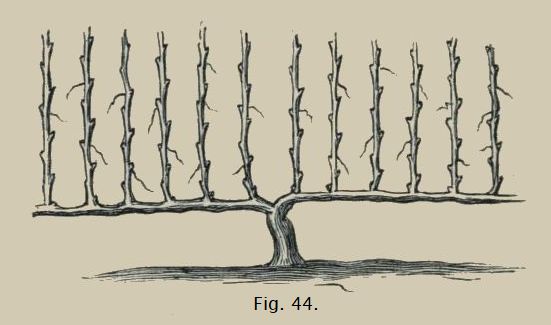

| Figure 44, a grape vine at the end of the third year | 128 |

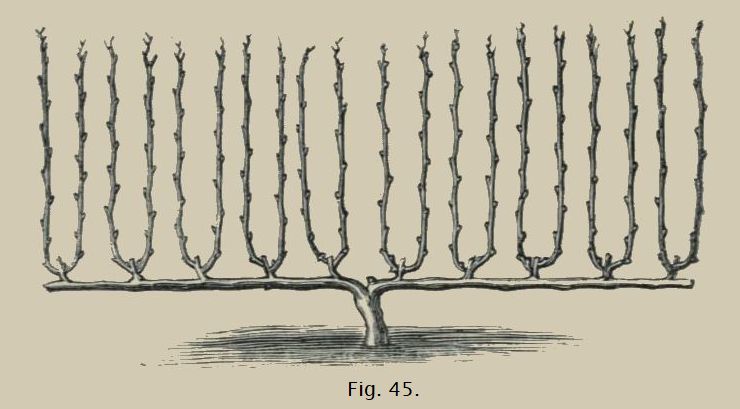

| Figure 45, a grape vine in the autumn of the fourth year | 129 |

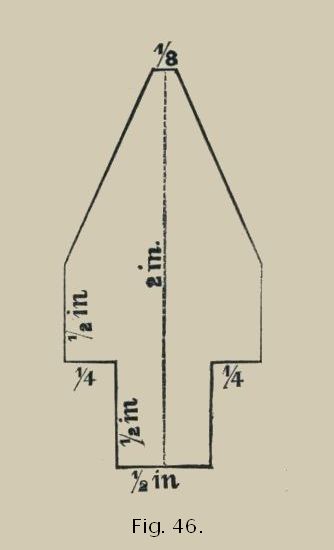

| Figure 46, section of an astragal | 142 |

| Figure 47 represents a dwarf pear tree at one season’s growth from the bud | 100 |

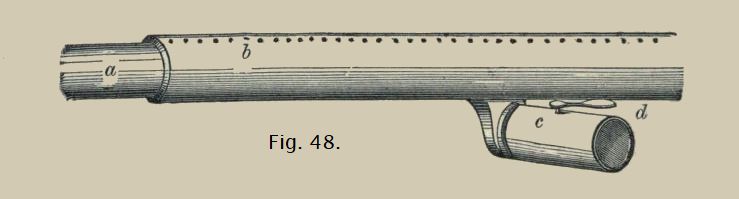

| Figure 48, a dwarf pear tree at two years from the bud | 100 |

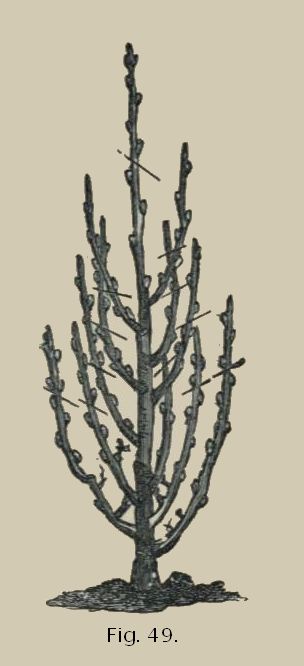

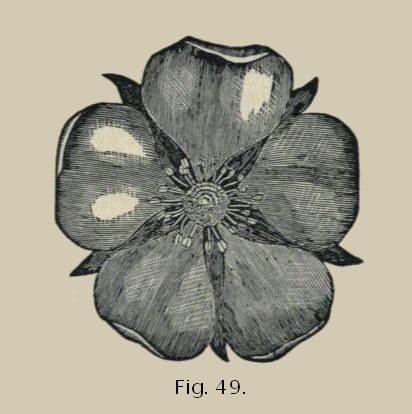

| Figure 49, the same tree at three years from the bud | 101 |

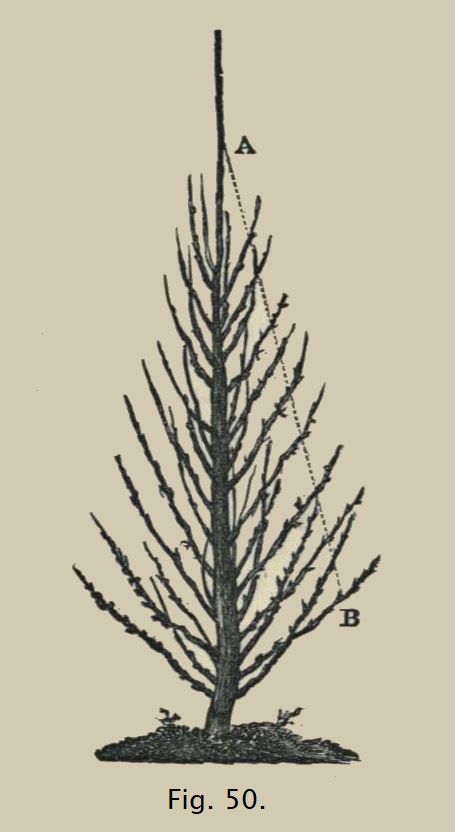

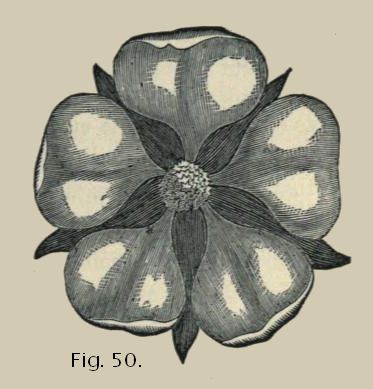

| Figure 50, the same tree at four years from the bud | 101 |

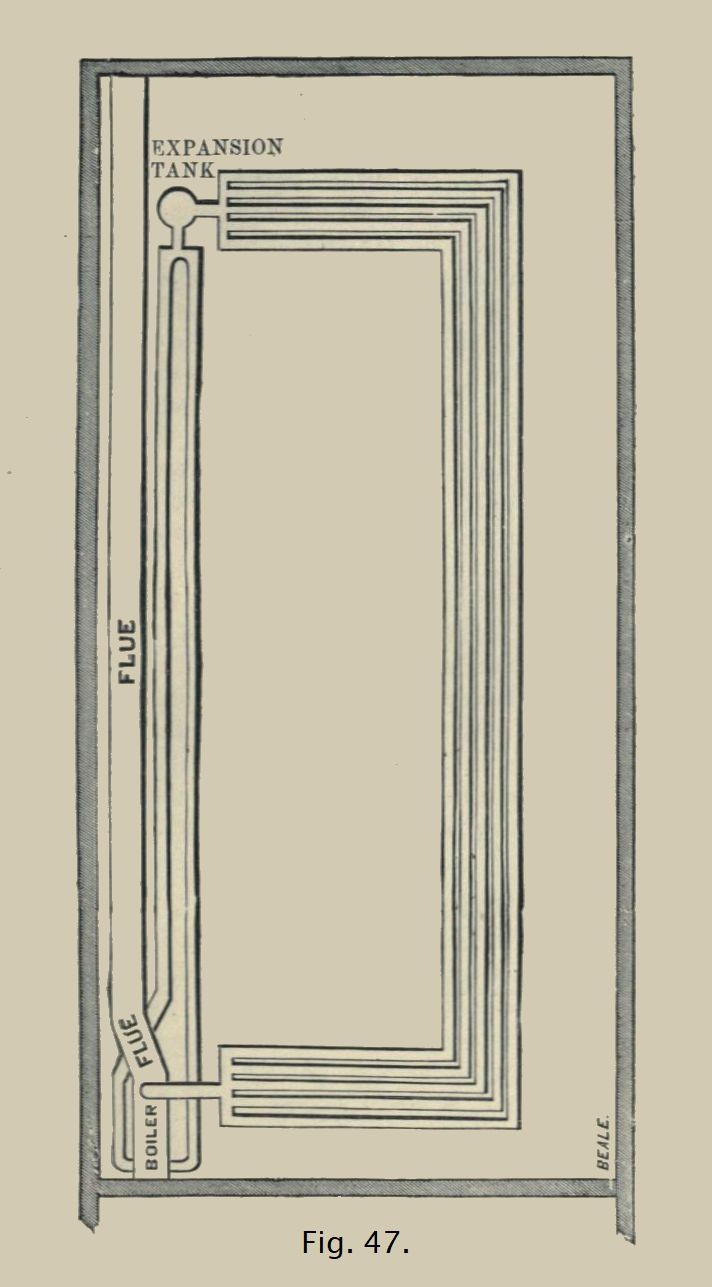

| Figure 47 shows the flow and return pipes, with the boiler and expansion tank in the vinery | 143 |

| Figure 48 represents the method of admitting fresh air into the vinery without creating a cold draught | 144 |

| Figure 49, a perfect strawberry blossom | 163 |

| Figure 50, a pistillate strawberry blossom | 163 |

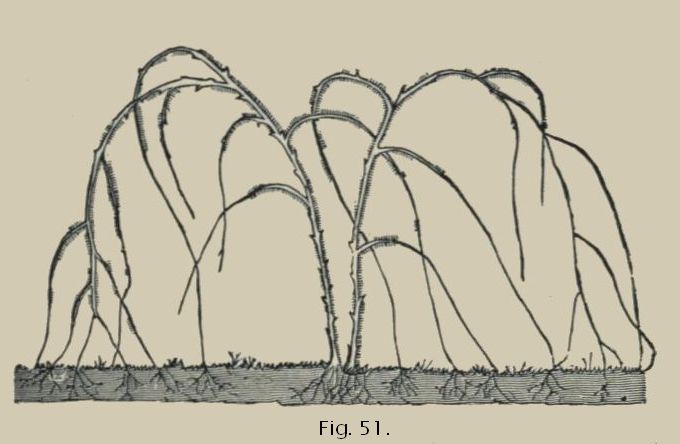

| Figure 51, a blackcap raspberry plant, with the cane tips rooted in the soil | 171 |

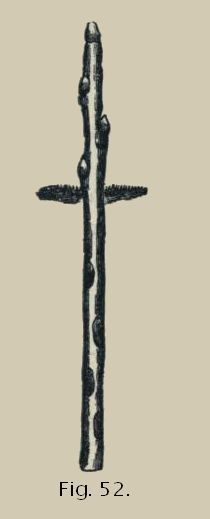

| Figure 52, a cutting prepared and planted | 180 |

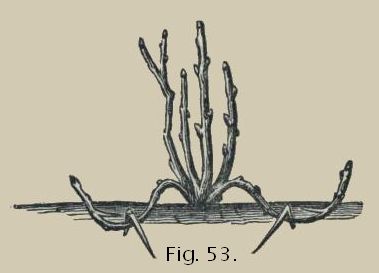

| Figure 53, the mode of layering plants | 182 |

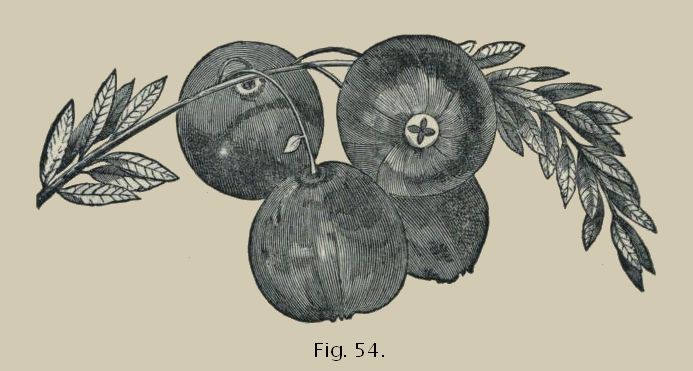

| Figure 54, branch and fruit of the cherry cranberry | 188 |

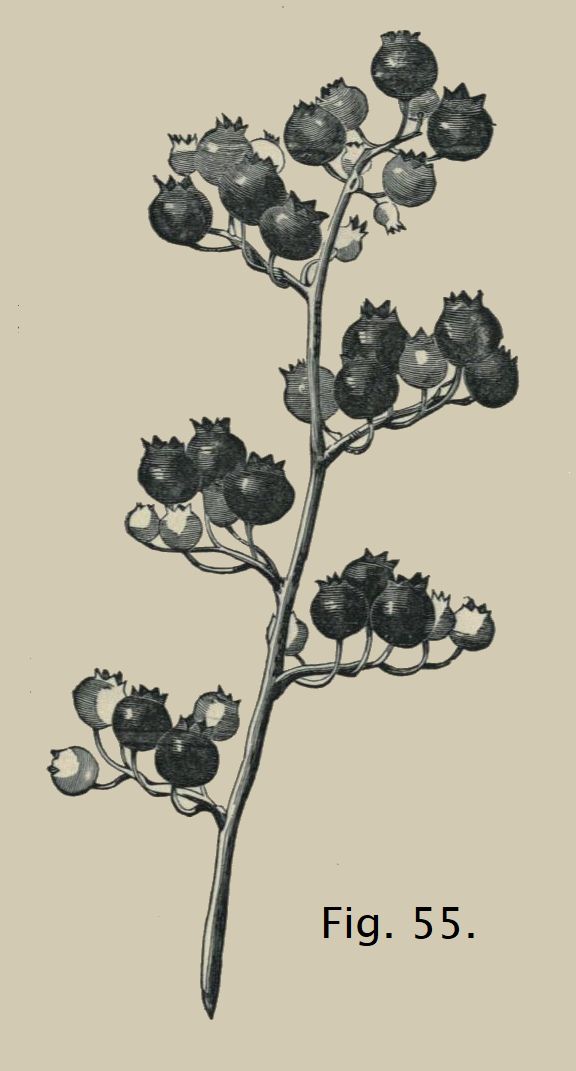

| Figure 55, branch and fruit of the huckleberry | 189 |

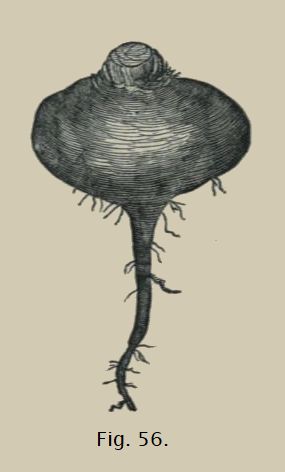

| Figure 56, early bassano beet | 203 |

| Figure 57, Brussels sprouts | 205 |

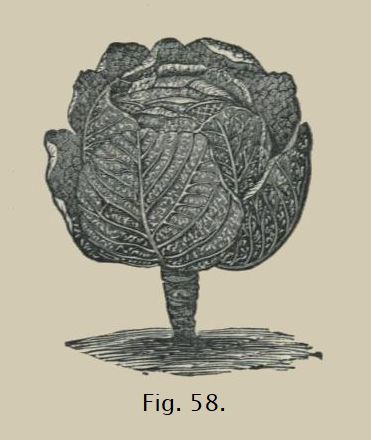

| Figure 58, green globe Savoy cabbage | 209 |

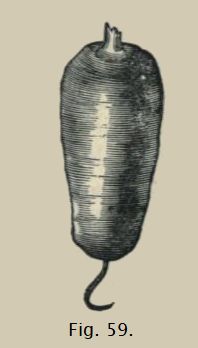

| Figure 59, early horn carrot | 211 |

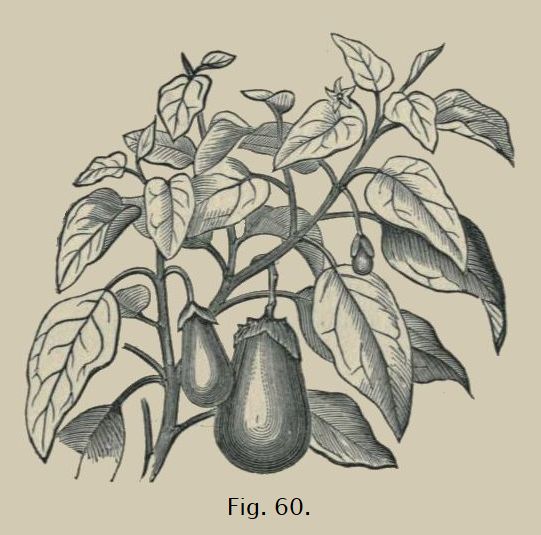

| Figure 60, egg plant and fruit | 225 |

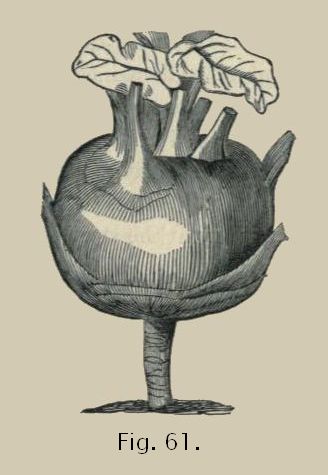

| Figure 61, kohl-rabi | 227 |

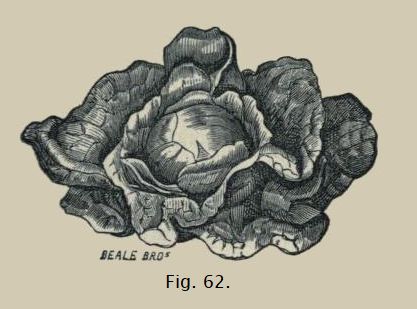

| Figure 62, drumhead lettuce | 230 |

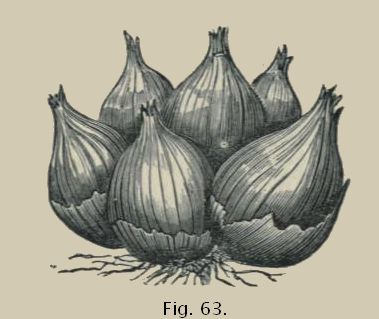

| Figure 63, potato onion | 239 |

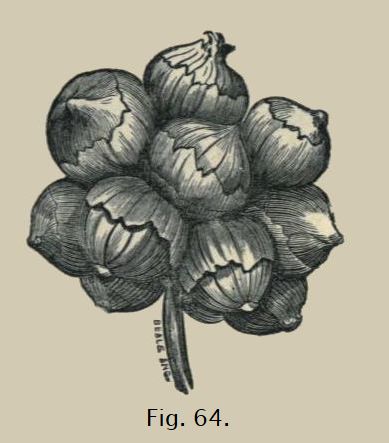

| Figure 64, tree onion | 239 |

| Figure 65, Chinese rose winter radish | 250 |

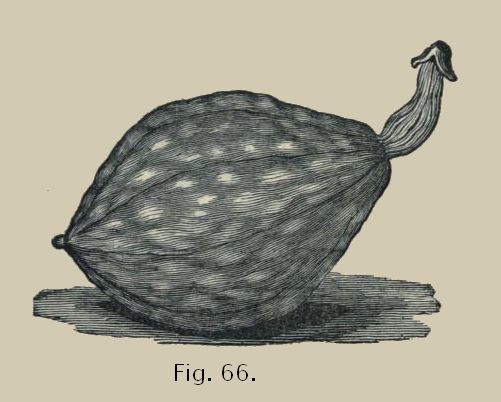

| Figure 66, autumnal marrow squash | 254 |

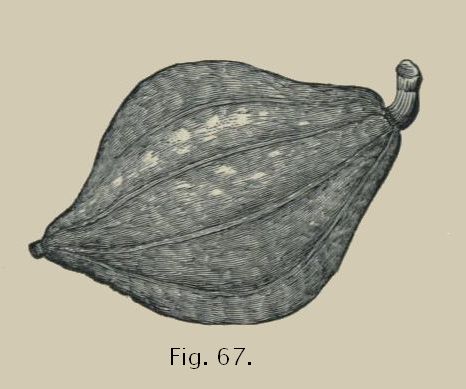

| Figure 67, Hubbard squash | 255 |

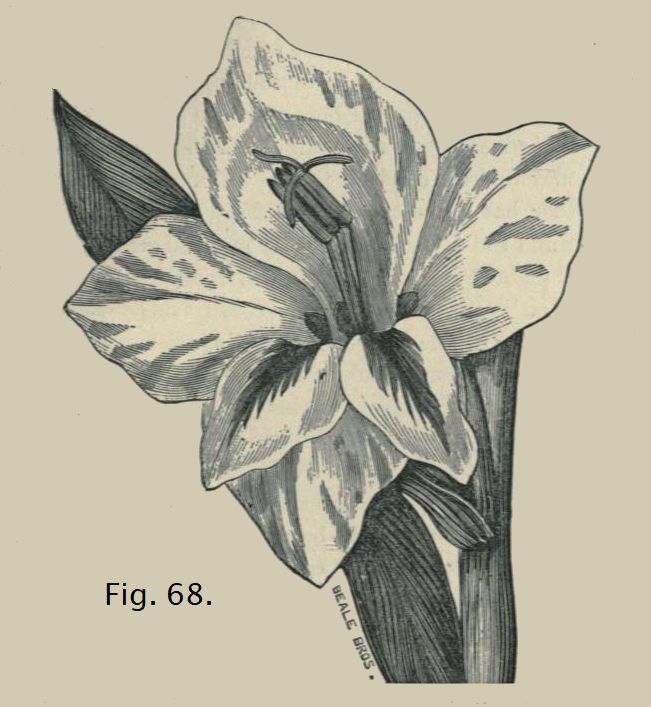

| Figure 68, gladiolus flower | 321 |

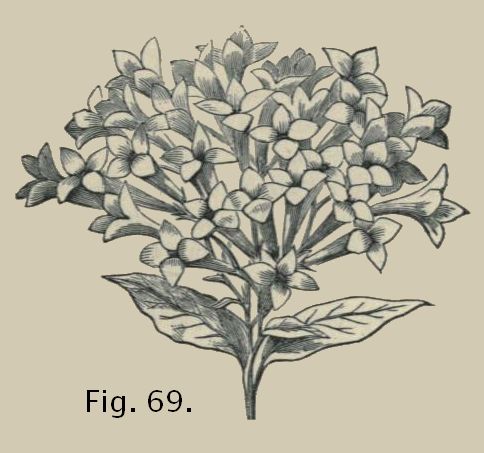

| Figure 69, bouvardia bloom | 335 |

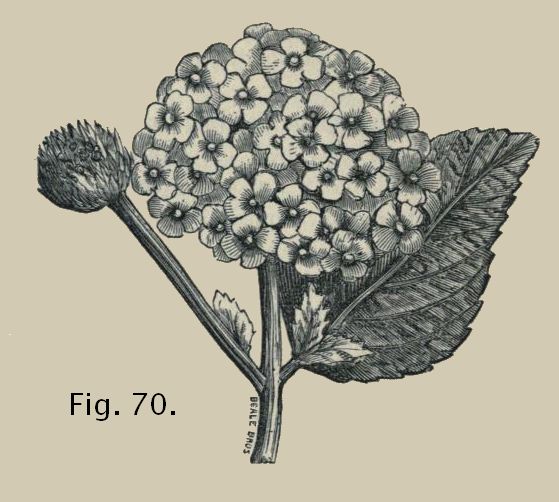

| Figure 70, lantana flower | 338 |

The design of this book is to furnish the Canadian cultivator with a reliable guide in all matters relating to the cultivation of fruit, flowers and vegetables in our climate. It is the result of many years of experience and careful observation, in which the fruits that can be most generally grown in Canada have been the subject of special study. Many hundreds of varieties of the several kinds of fruits have been actually grown by the writer, and their value for cultivation in our climate thoroughly studied and tested. To this has been added the valuable information derived from a wide-spread correspondence with horticulturists in different parts of the Provinces, thus putting the writer in possession of the experience of others, in the several departments of horticulture, throughout the Dominion. Hitherto there has been no work devoted to these subjects which has been written by a Canadian, embodying his own actual experience and observation in these matters, and which Canadians could rely upon as adapted to their own peculiar necessities, and consult in all these interests of the fruit, flower and vegetable garden, with confidence, as embodying the experience of a practical man in these departments, who knows their peculiar position and wants from personal participation in their difficulties. In the hope of meeting these wants, and of helping some of my countrymen in their horticultural labors, these pages have been written, and are now offered to all who love good fruit, pretty flowers, and choice vegetables.

It is now generally understood that the several varieties of our different fruit trees can not be propagated by planting the seeds of any particular sort, but that the only method of increasing the number of trees of any variety of fruit, is by propagating portions of that tree which we wish to multiply. Sometimes a small portion of a young branch, cut off from the tree, can be planted in the ground and made to take root, and grow, and increase in size, until it becomes as large as the parent tree. But this is not generally the case with apple, pear, plum, cherry or peach trees, and in the few instances of the varieties that will thus root from cuttings most freely, they grow slowly, and rarely make a strong, healthy and vigorous tree. To meet this difficulty, recourse is had to the operations known as grafting and budding. By this means one or more wood-producing buds are taken from the tree which we wish to multiply, and are so connected with a living root, that the bud is supplied by this root with the sap which nourishes it, and enables it to expand, and grow, and eventually form, according to the will of the cultivator, either a branch or an entire tree. In grafting, we take a young branch, having usually, three well developed wood buds, and insert this either into the body or branch of another tree; but in budding, we cut out only a single bud, and insert this under the bark of another tree, that we wish to make bear fruit of the sort borne by the tree from whence the bud was taken.

Grafting.—There are several methods of grafting, but for all practical purposes we may confine our attention to the two methods known as cleft-grafting and whip-grafting. Cleft-grafting is practised when the stock into which the grafts are to be inserted is much larger, that is, of much greater diameter than the scion. Whip-grafting, sometimes called splice-grafting, is performed when the graft and stock are nearly of the same size.

From this it will be seen that

Cleft-grafting is to be adopted when a large tree is to be grafted over. This is done by cutting off the branch horizontally with a fine saw, and then carefully paring the stump quite smooth with a sharp knife. The reason for using the knife is, that a smooth cut will heal over more readily than the rough cut of even the finest saw. The stump is then split or cleft about two inches deep with a splitting knife and hammer. Now the lower end of the scion is cut into the form of a wedge with a very sharp, thin-bladed knife, taking care to make one side of the wedge a little thinner than the other, and the wedge-cut an inch or inch and a half in length. Cut off the top of the scion just above a bud, leaving it usually three buds in length. Open the cleft made in the stock by driving a wedge into the split at the heart of the stump; this will prevent bruising the bark, and leave free room for the insertion of the scion. The scion should now be carefully pushed down into the split, with the thicker side of the wedge towards the outside, and having the inner bark of the scion fitting as exactly as possible with the inner bark of the cleft. The circulation of the sap is carried on through the inner bark, and as the bark of the larger tree or stock is usually much thicker than the bark of the scion, if the outer surfaces of the bark are made to fit, it will often be impossible for the ascending sap of the tree to flow into the scion. It is only when the ascending sap of the stock flows into, and sustains the life of the scion, that it will be able to put forth leaves, and elaborate that sap, and send down the woody fibre which shall firmly unite the scion with the stock and establish permanently a vital connection between the graft and the tree. When the stump is large, two scions should be inserted, each being made to fit exactly at the inner bark. This will materially aid in healing over the wound, if both should grow, while it increases the chances of success in making at least one to live. After the scions have been inserted the wedge should be withdrawn, thus allowing the cleft to close tightly upon the scions, and hold them firmly in place. If the outer edge of the wedge-like portion of the scions has been made slightly thicker than the inner, the bark of the stock will be pressed closely and firmly to the bark of the scions. Nothing further remains to be done but to cover the wounds that have been made with something that will exclude the air, and keep it excluded until the union is established and the wounds are healed over. Many substances have been used for this purpose, such as clay, cow-dung mixed with clay, wax, waxed strips of cloth, varnish, &c., but it matters not what is used so long as the end sought is attained. The most convenient material is

Grafting Wax, which is made by melting together two parts of beef tallow, two parts of beeswax and four parts of clear transparent resin, and when quite thoroughly commingled poured into cold water and pulled and worked, as in making shoemakers’ wax or molasses candy. If the weather be cool when the grafting is performed it will be necessary to keep the grafting wax in warm water, so that it may be sufficiently soft to adhere well to the tree. It is of great importance to press the wax closely to all the wounded parts, so that it shall not crack off, covering the cleft and the exposed part of the scion in the cleft a the side, and covering the top of the stump between the two scions, if there be two, pressing it carefully and closely around the graft, and covering with the wax every wounded portion of stock and scion. In doing this, care must be taken not to displace the graft in the least, for if that be moved out of its place, the most careful waxing will not make it grow. If the weather be so warm that the grafting wax becomes too soft to handle conveniently, it will be advantageous to keep it in a dish of cold water. To prevent the wax adhering to the hands, they should be greased with a little lard. The grafter will find it convenient to insert all the grafts he intends to put in the tree upon which he is operating before he commences putting on the wax, and then wax the whole. This will enable him to keep his hands clean and free from grease while he is putting in the scions.

In grafting a large tree, it is advisable not to cut off all the limbs in one season, even if it is intended eventually to graft them all. If they are all cut off and grafted at once, there will not be sufficient foliage formed by the grafts to elaborate the sap that will ascend from the roots, thereby causing an unhealthy condition, which often results in permanent disease and premature decay. The proper way is to graft not more than two-thirds of the branches the first season, and if the scions have made a good growth so as to furnish a good supply of foliage, then the remaining branches may be cut away and grafted the next year. If, however, the scions have made but a feeble growth, it is best to graft but a portion of the remaining branches, leaving a few to the subsequent season.

It is best to graft the top and upper branches first, so that the scions may not be shaded, and because the flow of sap is strongest towards the higher branches, and these, if left on the tree, would rob the scions set in the lower branches. If both the scions grow that were put into one branch of the tree, select the one that promises to be the more vigorous, and partly cut back the other during the month of August, or, if you prefer, at the next spring’s pruning, so as to give the stronger one full room to grow, while you use the other to help heal over the stump, into which they were inserted, until such time as it can be cut away altogether. Do not be too anxious to remove all the sprouts that will start: if they seem to choke the graft, cut such back, but not wholly off; and only remove them entirely when the graft has become a branch.

For a better understanding of this mode of grafting, study the drawings on page 6. Figure 1 shows the graft ready for insertion; and Figure 2, the cleft stock with the scions in place.

The proper time for grafting large trees is in the spring, after the sap has begun to move and the buds to swell. If it be possible, choose a mild, cloudy day, with but little wind, for the wind and sun dry the fresh-cut wood of both stock and scion rapidly, which is to be avoided whenever practicable, and always as much as possible, by covering the wounds with grafting wax the more promptly in drying weather.

The tree to be grafted should be in a healthy and vigorous state; if not in such a condition the scion is less likely to live, and if it lives will make but a feeble growth. Such a tree should be prepared for grafting by thinning out the branches, and top dressing the roots with a liberal supply of manure; then, after it has exhibited signs of returning vigor in improved appearance of foliage and stronger shoots, it can be grafted with much better prospect of success.

Whip-grafting is performed when the scion and stock are nearly of the same size. This method is the one most commonly practised by nurserymen in growing trees for market, and will be used by the farmer or amateur only when grafting the small branches of young trees. To graft in this way, use a very sharp, thin-bladed knife, and with it make a smooth, sloping cut upwards on the stock and downwards on the scion, then form a tongue on each by making a thin upward cleft on the scion and downward on the stock. Now place these sloping cuts together and press the tongue of the scion into the cleft of the stock and the tongue of the stock into the cleft of the scion, taking care that the inner bark of the scion, on one side at least, exactly fits with the inner bark of the stock. If the scion have been well chosen with reference to the size of the stock, the bark can be made to fit on both sides, but though this is to be desired whenever practicable, it is not essential to success, for if the barks correspond on one side, circulation will be established through them between the stock and the scion, and the union between them be cemented. After thus uniting the graft and stock, it is necessary to fasten them, by tying with bass-matting or cotton yarn, or a narrow strip of thin cotton cloth. This is usually done by carefully winding around both stock and scion, where united, a narrow strip of thin cotton cloth, or even thin paper or cotton yarn, which has been covered or saturated with grafting wax. When this is neatly done there is no need of any knot, the wax holding the ligature in its place. In grafting branches of trees in this way, care must be taken to exclude perfectly air and water from the wounded parts. When nurserymen propagate trees in this way, they select strong and vigorous seedlings, which they pack away in the cellar in moist sand before the ground freezes; these they graft with scions of any desired variety at their leisure, during the months of January, February or March, and as soon as grafted pack the grafts in boxes of sand or moist sawdust, and store them in the cellar until ready to plant them in the ground in the spring. When planted out, the place of union between the stock and scion is wholly under ground, and being in this way protected from the sun and air by the surrounding soil, it is not necessary to be so particular to cover the union with grafting wax as in the case of top grafting, where the whole is exposed to all the changes and influences of the atmosphere. It is a common practice with nurserymen to wind cotton yarn into medium-sized balls and boil them in a composition formed by melting together three pounds of resin, a pound and a quarter of lard and a pound and a half of beeswax. The balls are taken out while hot and allowed to drain, and when cool are ready for use. The graft is taken in one hand by the root, with the other the end of the string is laid on the lower end of the lap of the scion, and by twirling the graft in the fingers the thread is wound tightly round both stock and scion at the place of union sufficiently often to hold the parts together firmly, and then the thread is broken off. The wax holds the string in place without any tying, while it also preserves the thread from rotting until the union is perfected, and the expansion of growth causes it gradually to give way.

By consulting the engravings this method of grafting will be readily understood. Figure 3, page 9, shows the sloping cut made upon the stock and scion. Figure 4, page 10, shows the cleft made in them to form the tongue. Figure 5 shows them put together. Figure 6 shows the graft tied with a strip of bass-matting or cotton cloth. Figure 7 shows the same covered with wax to protect the union from the weather, and Figure 8 shows the graft neatly wound with a strip of waxed cotton or paper.

The waxed cloth or paper is prepared by dipping the cloth or paper into the same preparation as that in which the balls of cotton yarn are boiled, when it is quite hot, and then drawing the sheet between a couple of sticks, so as to scrape off the superfluous wax, and when cold, cutting it into strips of the required width. Many use these strips in cleft-grafting, instead of the pure wax. Sometimes when the cloth or paper is too strong, it does not give way under the growth of the tree, and requires to be cut or removed, in order to prevent it from binding and injuring the tree.

Scions should be selected from healthy trees, and should be cut from the thrifty, well ripened shoots of the last season’s growth. In this climate, it is safest to cut them in November, before the severe frosts of winter. Sometimes the cold of the winter is so severe that the young wood is injured. If not cut in November, it is better to wait until early in April, after the shoots have had an opportunity to recover from the severe freezing. They should never be cut from the tree when they are frozen. When cut, they should be packed in a box with damp moss, or sawdust placed in the bottom of the box and over them after they are put in. There should be enough moss or sawdust to prevent the scions from drying out or shrivelling. They should then be stored in the cellar, where they will be kept cool and damp, and free from frost. If there be plenty of moss or sawdust the scions will be preserved quite fresh without any further attention; and if, when taken out for use, they seem to be mouldy, there need be no cause for apprehension, if, on wiping it off, the bark looks bright and fresh. Experience has taught us that this mould does not injure scions. There is danger, however, of keeping scions too wet. The material in which they are packed should be damp only, not filled with water. A scion that has been soaked will not grow. They have been known to fail wholly, after standing for a few weeks with the butt-end in shallow water. The thing to be aimed at, is to keep the grafts as near as possible in the same condition as when first cut. In using the scions, reject the portion at the butt, as far as the buds seem small and imperfectly developed, and likewise the tip, as far as the wood seems soft and spongy.

Budding, or as it is sometimes called, inoculation, is the other method by which any given variety of fruit is perpetuated and multiplied, and in its effects and principles of operation is only another mode of grafting. In both cases, a bud of the variety we desire to propagate is brought into a living union with another root, and made to form the top and branches and fruit-producing portion of the tree. In grafting, we use a branch with several buds and considerable wood; but in budding we use only a single bud, with a very small portion of bark, and less wood.

There are some advantages in budding, as compared with grafting, when the stocks are small, as is the case in nurserymen’s operations; but when the stocks have already become trees, as is usually the case with the farmer and amateur, grafting is the more convenient method, and generally more successful. When small stocks, of one or two seasons’ growth, are used, budding is often more convenient, because the operation can be performed in midsummer, when the hurry of spring work has passed, and in case of failure, can, in many instances, be repeated the same season. Experience has also taught us that in our climate the grafting of stone fruits is attended with considerable uncertainty, and requires to be done with great nicety and skill, while budding is almost uniformly successful.

The season for budding is from July to September, and yet the best time, the time when the operation is most likely to be successful, is variable. The farmer does not cut his grain because a certain day of the month has arrived, but when the grain has reached that state of maturity which he has learned by experience to be the time when he will secure the grain in its best condition. So in budding, the best time is that in which the bud will most speedily and certainly unite with the stock, and experience has taught us that this is while the stock is in a growing state, so that the bark will separate freely from the wood, and yet when the activity of growth is somewhat diminished, which time is indicated by the formation of the terminal bud. At this stage also, the sap under the bark will have thickened and become viscid or sticky, forming what botanists term the cambium. This condition of the stock is the most favorable time for budding, and as a rule it will be found that Plum stocks reach it the earliest in the season, then follow Pear, Quince, Apple, Cherry and Peach stocks, in the order in which they are named. It will be readily understood that the time, when this condition of the stock will be attained, will be very materially influenced by the character of the season, the temperature, moisture, and the like. A cool, moist season, will protract the period of growth and postpone the period when the cambium begins to form, while a hot and dry season will shorten the growth and hasten maturity. A little experience will teach the operator the fitting moment, the general features of which only can be indicated in written directions.

The selection of Scions, from which the buds are to be taken, also requires the exercise of some judgment. Those are best that have formed their terminal bud, but as these are not always to be had, those which have begun to ripen their wood and have well developed buds should be selected, and the very green portion towards the extremity, where the buds are but partially formed, cut away. As soon as the scion has been cut from the tree, the leaves, with about half of the leaf stalk, should be cut off, and the scion wrapped in a cloth of sufficient thickness to protect it from the sun and air. If the cloth be moistened it will be of advantage in keeping the scions cool, but they should never be soaked in a very wet cloth, much less in a vessel of water. Figure 9 represents a scion which has been cut from the tree, with the leaves and a part of the leaf stalk removed, and showing the buds which are to be used in budding.

The Operation of Budding is performed by selecting a smooth place in the stock, and with a sharp, thin-bladed budding knife, (figure 10 shows the best form of budding knife, although any sharp thin-bladed knife may be used) make first a horizontal cut, just deep enough to cut through the bark, and then from the centre of this make a perpendicular cut of the same depth, the two cuts having the form of a T. Figure 12 shows the slits made in the bark. If the stock be small, that is, one or two years of age, the proper place for inserting the bud is as near the ground as can conveniently be done, and, if possible, the south side is to be avoided on account of its greater exposure to the sun. Could we have everything just the most favorable possible, we would select also a cool, cloudy day for the operation. After having made the incisions in the bark as just described, hold the scion or stick of buds in the left hand, and cut out one of the buds, together with a strip of the bark and a very thin slice of the wood, beginning to cut about half an inch above the bud, and bringing the knife out about half an inch below the bud. Figure 11 represents a bud cut from the scion and ready for insertion. If the wood be very ripe and hard, the slice of wood should be exceedingly thin indeed, but if the wood be green and soft, the thickness of the slice of wood may be increased in proportion to its greenness, but never to exceed one-third of the thickness of the stick or scion. Now with the rounded part of the blade of the budding knife gently raise the bark of the stock at the corners, and holding the bud by the leaf stalk, insert the lower end under the bark, and slide it down the perpendicular slit, until the upper end of the bark of the bud coincides with the cross cut or horizontal cut of the T. If a little of the bark of the bud extends above the cross cut, it may be cut off with the budding knife, so as to form a square shoulder, exactly fitting to the bark of the stock above. In practice it is most convenient to hold the bud between the forefinger and thumb of the left hand, and at the same time that the corners of the bark are raised with the right hand, insert the lower end of the bark of the bud under the raised bark. Figure 13 shows the bud in place. After the bud has been inserted it should be tied in its place by winding around the stock a strip of bass-matting that has been previously moistened in water to make it soft or pliable, or woollen or cotton yarn will answer very well, taking care to cover all the wound, leaving only the bud with its foot stalk projecting. It is better to begin to wind at the lower end and proceed upwards, winding the ligature as smoothly and neatly as possible, yet firm and close, so that the bud may be kept in place and the bark smooth and snug to the stock. Figure 14 represents the whole complete with the ligature tied around. Care should be had, in raising the bark of the stock, to avoid disturbing the cambium, the soft, mucilaginous secretion lying next to the wood of the stock.

The After-Treatment of the bud consists in removing the ligature as soon as it begins to bind too tightly around the stock. In from twelve to fourteen days the bud should be examined, and if it appears plump and fresh it has probably begun to unite with the stock, but if it has shrivelled it is dead. If the stock will yet peel, it may be rebudded at once. If the stock has swelled much, so as to tighten the ligature, it may be loosened and re-tied, but, in common practice, where budding is done on an extended scale, the ligature is cut when the growth of the stock is such that the bark swells around the ligature. A little practice will enable the operator to decide when it is necessary to remove the string. Usually it is in about four weeks from the time the bud is put in, but the time will vary according to growth of the stock. Cherry and peach stocks usually swell more rapidly than apple or pear. Sometimes the strings are left on all winter, particularly if the budding has been done late in the season; but in our climate this practice is not to be recommended; the band retains moisture, and in cold weather gathers ice about the bud.

In the following spring the stock should be headed back to within about three inches of the bud as soon as the buds begin to start. This will cause all the buds remaining on the stock to push vigorously, and as soon as the inserted bud begins to grow all the natural buds must be rubbed off, and kept rubbed off from time to time, as often as they start. This is done so that all the sap may be thrown into the inserted bud, and its growth promoted. As soon as it has grown a few inches in length it will probably require tying to the stock, so as to keep it upright. In doing this the string or band should not be wound around the growing shoot, but merely passed round it and tied around the stock, forming a loop within which the growing shoot has room to expand, the string touching it only on one side, the side of the shoot farthest from the stock. Figure 15 represents a growing bud tied to the stock. In the month of July the bud will have acquired sufficient strength to enable it to stand erect without the aid of any support from the stock. The stock should now be cut back down to the bud. The pruning knife used for this should be both strong and sharp, and placing the edge against the stock on the side opposite the bud, with a sloping cut, drawing the knife upwards and towards the bud, the stock should be cut smoothly off in such a way that there shall be not a particle of the stock left above the bud. The white line across the stock, Figure 15, shows the place where the cut should be made, thus taking off all that part of the stock above the white line.

Budding may be performed in the spring, by keeping the scions in a cool place where the buds will not start, and inserting them in the stock after growth has commenced, but it is seldom practised in this country, because success is not as certain, and for want of time at a season when so many things require attention.

Some cultivators have found it advantageous in budding plums, in particular, in which the upper part of the bud frequently dies although the lower part has united with the stock, to use two separate ligatures in tying, covering the part below the bud with one bandage, and the part above with the other. As soon as the bud seems to have taken, the lower bandage is removed, but the other is allowed to remain for two or three weeks longer, which arrests the downward sap and perfects the union of the upper part of the bud with the stock.

When is the best time for pruning fruit trees, is a question often asked, to which the reply of an old gardener was more appropriate than polite, who answered “whenever your knife is sharp.” If fruit trees are properly attended to and pruned every year as much as is requisite, they will need but very little pruning at any time, and it is not of much moment when that little is done. The words of the lamented Downing should be graven upon the memory of every one who takes knife in hand against his fruit trees. He says, “A judicious pruning, to modify the form of our standard trees, is nearly all that is required in ordinary practice. Every fruit tree, grown in the open orchard or garden as a common standard, should be allowed to take its natural form, the whole efforts of the pruner going no further than to take out all weak and crowded branches, those which are filling uselessly the interior of the tree, where their leaves cannot be duly exposed to the light and sun, or those which interfere with the growth of others. All pruning of large branches in healthy trees should be rendered unnecessary, by examining them every season, and taking out superfluous shoots while they are small.”

Yet there is a best time for pruning, and that time depends upon the object for which the pruning is done. The two purposes most commonly intended are all that it will be necessary here to speak of, namely, pruning to regulate the form of standard trees, and pruning to induce fruitfulness.

In pruning to regulate the form of standard trees, if the trees have been properly cared for every year, it will only be necessary to remove small branches, and this may be best done in our climate after the severe frosty weather of our winters is passed, and before the sap is in full flow. This will be in March or early in April, varying with the season and locality. If done at this time, the sap will not have fully ascended into the branch that is taken away, and will be directed into the remaining portions of the tree; if the pruning be done after the sap has ascended, it will be measurably lost to the tree. If the pruning be done before the severe winter frosts are over, experience has taught us that the frost so affects the tree through the wounds, especially if they be large and numerous, as to impair its health and vigor. But if the pruning has been neglected, and there are large branches to be removed, it is best done just after the trees have made their first growth and are taking what has been termed their midsummer rest, which is in July or August in our climate. It has been found that if large branches are taken off at this time the wood remains sound, whereas, if taken off in the spring, particularly if the sap is circulating freely, the wood is apt to decay, and though it may heal over, the part always remains unsound. Yet some caution is needed here, lest too many large branches be removed in one summer, and the vigor of the tree receive too severe a check. Summer pruning tends to lessen the vigor of a tree, and though we advise the removal of large branches at this season because it is better somewhat to check the growth of the tree than to risk the decay of the trunk, yet judgment should be used, lest this be carried too far. When large limbs are removed it is always advisable to use a fine saw, and after smoothing the cut with a sharp knife, to cover the wound with some preparation that will protect it from the weather. Common grafting wax, or a mixture of fresh cow dung and clay, may be used; but the most convenient preparation for this purpose is made by dissolving gum shellac in alcohol until the solution is of the consistence of ordinary paint. This may be applied with a common paint brush and kept in a wide-mouthed bottle, which should be kept well corked. Thus applied to the wounds, it soon hardens and forms a coating that is not affected by changes of weather, yet adheres closely and completely excludes air and moisture, and at the same time does not interfere with the growth of the bark over the wound.

There is also a right place at which to make the cut in removing entire branches; if cut farther from the tree than this point, a portion of the branch remains, which not only gives the tree an unsightly appearance, but which is very sure to throw out sprouts; and if cut closer to the tree, an unnecessarily larger wound is made, which requires more time to heal over. It may be noticed that where a branch unites with the main body there is a shoulder or slight enlargement. This shoulder is shown in Figure 16, and the line indicates the place at which the cut should be made. It is at the point where the branch unites with this shoulder, so that the shoulder, or slight protuberance at the base of the branch, is left on the tree, and the wound made in cutting is no larger than the diameter of the branch. Also in cutting back small branches care should be taken to cut them off just above the bud, not so close as to injure the bud, nor so far from it as to leave a long spur of wood. Figure 17 represents a branch cut back too far from the bud. Figure 18, a branch cut too close to the bud; and Figure 19, one that is cut as it should be. The cut should be made so that the point of the bud will coincide with the edge of the cut. Such a cut will heal over sooner than any other, and the bud at the point will grow vigorously.

The form of standard trees will need only such modification as may be requisite to admit a free circulation of air through the branches, and sufficient light and heat to ensure the fullest development of the fruit. If the top of a tree is permitted to become a thicket of branches, it is quite obvious that some parts will be too crowded, the air can circulate but imperfectly, and the sunlight is wholly excluded. In consequence of this, much of the fruit will be below the normal size of the variety, but partially colored, and very deficient in flavor. This can be remedied by judicious pruning, removing some of the branches from the interior, and keeping the head open to the light and air. On the other hand, pruning can be carried too far, especially by removing so much of the foliage as to leave the nearly horizontal limbs exposed to the full blaze of a nearly vertical sun. The evil effects of this are seen in the death of the bark on the upper side of the large branches thus exposed; the circulation is impeded, and the tree often assumes a stunted and sickly appearance. The pruner, then, must use his own judgment, and adapt his pruning to the special circumstances of his own case. An orchard that is exposed to the sweep of high winds will not suffer from want of circulation of air as one that is sheltered, and, if pruned as would be desirable for the sheltered orchard, might suffer for the want of that protection which the branches afford each other. So then, it is possible only to point out the objects to be sought, and leave to each one the carrying out of the particular amount of pruning, and the details of the work in his own orchard, in the exercise of those reasoning powers which will enable him to so shape his trees that foliage and fruit shall be fully developed in the greatest abundance. And in this exercise of the judgment lies the true secret of excellence.

Pruning to Induce Fruitfulness, is sometimes desirable in the case of trees of very vigorous habit, and that are tardy in coming into bearing. This pruning is applied not only to the branches, but also to the roots. The root-pruning simply consists in cutting off a portion of the roots, thereby lessening the quantity of nourishment derived from the soil. It is done in autumn, by digging a trench about eighteen inches deep around the tree, with a sharp spade, cutting off the roots that reach the trench. The distance that this trench should be from the trunk will vary according to the size of the tree, taking care that it be so far as not to cut off too many and too large roots. The digging of such a trench once will usually so check the wood growth that the tree will form fruit buds, and set its fruit. After having thus thrown the tree into bearing, it is usually necessary to supply the tree with a little well-rotted manure, in order to keep it in sufficient health and vigor to perfect its fruit. The pruning of the branches for this purpose is performed in midsummer, and is not so much a cutting as a pinching off of the tender end of the shoots with thumb and finger. This checks the growth of the shoot, and concentrates the sap in the remaining part of the branch, thus inducing the formation of fruit buds. At least this is the tendency, and the operation usually produces, in a greater or less degree, the desired effect. But it sometimes happens that the tree is growing so vigorously that the buds will break and form shoots. When this is the case, recourse may be had to root-pruning; or by bending down the branches and fastening them in a perfectly horizontal position, or even curving them downwards, such a check will be given to the flow of sap that fruit buds will be formed. When a tree is growing rapidly it can not produce much fruit, and it is only when this wood-producing energy has expended itself by the completion of the growth of the tree, or has been checked artificially, that abundance of fruit will be produced. By this it will be seen that the formation of much wood is antagonistic to the formation of much fruit, and that whatever will lessen the wood growth, without injury to the health of the tree, will increase the production of fruit. A top-dressing of coarse salt, sown broadcast, at the rate of two bushels to the acre, has been found to increase the fruitfulness of some orchards.

Deciduous trees can be best transplanted after the fall of the leaf in autumn, and before the putting forth of leaves in the spring. In mild climates and dry soils the autumn is the best season for transplanting. This gives an opportunity to the wounded roots to heal, and the soil to settle firmly about the tree during the early part of the winter, and the tree is ready at the first approach of warm weather to push out its rootlets into the soil and commence its growth for the season. But in those portions of our Dominion where the ground freezes early, and remains frozen all winter to as great or even greater depth than the roots of the newly planted tree extend, it is impossible that any such healing process should take place in the roots, and if the soil in which it is planted be of a very retentive character, water is apt to collect about the roots in the imperfectly settled earth, and in a greater or less degree prove injurious to the tree. Owing to these causes spring planting has been found to be more generally successful in those parts of Canada, where the ground is not well protected with snow, than fall. Yet there are reasons which sometimes counterbalance all these difficulties, and make it on the whole preferable to transplant the trees in the fall. There may be more leisure in the fall, or it may be more convenient to obtain the trees then, or the distance from the nurseries may be so great, that by the time trees can be procured in the spring the season is too far advanced. From whatever cause the planter may decide to set his trees in the fall, if he will only take care that they do not suffer from water standing about the roots, and that in some way he protects the roots from severe freezing, they will usually pass the winter safely and grow well. This is very easily accomplished by raising a considerable mound of earth around the tree after it is planted, which serves to keep the tree from being rocked about by the wind, sheds off the rain and melting snow, and in some measure keeps out the frost. In the spring, before the dry weather sets in, this mound should be levelled off and the ground mulched as in spring planting.

Preparing the soil for the reception of trees does not receive that attention which its importance demands. If the ground has been well prepared, the growth of the trees will fully compensate for the labor. An excellent method of preparation is to summer-fallow the ground, giving it frequent ploughings and stirrings, so that it may be thoroughly pulverized. If it need manure, it should be put on in a well-rotted condition, as for a crop of grain, and thoroughly mixed and incorporated with the soil. If the whole ground be made thus mellow and rich before the trees are planted, they will live and make a good growth the first season; but if planted in hard soil, very often in a sod, no wonder that many of them die, and that those which live make a starved and sickly growth. Many persons, after preparing the ground in this way, think they cannot afford to lose so much labor just for an orchard, and so, as a matter of economy, they sow wheat or rye or some other grain, and plant their young trees in the grain. This is, beyond question, a false economy; but, if it must be done, let no grain grow within four feet of any tree. The grain will absorb the rains and dews and moisture that the young tree needs, and so rob the tree of its necessary nourishment, for trees can take up nourishment only in a liquid form. The writer was requested by a neighbor to examine his young orchard, which, he said, seemed to be all dying, and he was unable to account for it. The orchard had been planted the year before, in good rich soil, which was well drained, and had been made perfectly mellow, and the trees had not only lived but made a very fine growth. But this year, since the hot weather had set in, the leaves had begun to wilt and wither, and some of them to turn yellow, and the young shoots to shrivel and dry up. On arriving at the orchard, the trees were found standing in a field of most luxuriant rye, reaching, in many places, quite into the branches of the trees. It was at once recommended that the rye should be pulled up around the trees, so that there should be a circle of eight feet in diameter left clear around each tree, and that the rye so pulled up be spread on the ground around the trees as a mulch. This was done, and the trouble was at once arrested; many of the trees revived wholly, some lost only the ends of the young shoots that had become too much wilted to survive, while a few of the trees had already suffered so much that they were past all recovery.

Another thing that must not be overlooked in the preparation of the ground is drainage. Fruit trees cannot grow in water, and care must be taken to draw off all stagnant water not only from the surface soil, but from the subsoil. Much can be done to effect this by ploughing the ground into lands of the same width as the intended space between the rows of trees. By repeated ploughings, turning the furrow always towards the centre of the land, the ground may be thrown up to the required height, and the trees planted along the middle of each land. This method will be found particularly beneficial where the ground is naturally level, or the subsoil cold and sterile. A naturally rolling surface, with a porous subsoil, is to be preferred for fruit trees wherever it can be had.

In Planting, the trees should not be set into the cold and barren subsoil, but if the surface soil be too shallow to receive the roots, it is better to throw the earth up around the tree so as to cover the roots to the proper depth and keep them in the mellow and fertile soil. Trees have been planted where the surface soil is thin, by spreading out the roots on the surface of the ground and covering them with earth, and they lived and grew well, whereas, if they had been planted in holes dug in the ordinary way they would never have been worth anything. It is a common error to plant trees too deep. They should not be set so as to stand any deeper after the ground has become settled than they stood in the nursery. The holes should be dug large enough in diameter to admit of the roots being spread out in their natural position, not coiled up or turned up at the ends, and the soil in the bottom of the hole should be loosened up and made crowning in the centre; upon this the tree should be set, and the roots spread out in a natural way. The rich and thoroughly pulverized surface soil should be carefully filled in, and worked with the fingers among the roots, and pressed down gently with the foot. When all is complete the surface should be left loose and friable, not trodden hard, as is often done, and should be made nearly level with the surrounding soil, if the planting be done in the spring; but if it be done in the fall, make a mound of earth over the roots and around the stem of the tree, as already recommended. In settling the earth about the roots of the tree, do not shake it up and down or swing it about, but let it be held firmly in place while the earth is being placed among and over the roots.

Mulching, by which is meant the spreading of coarse manure, half rotted straw, or any other litter on the ground over the roots of the trees, will be always found of great service in keeping the ground cool and moist, and promoting the growth of newly transplanted trees, particularly if the succeeding summer should be hot and dry. There is a substitute for mulching that is perhaps better than a mulch, but in the hurry of summer work it is so sure to be neglected that the planter had better mulch his trees as soon after planting as possible. If, however, he will keep the ground loose and friable around his trees by frequently stirring the surface, and never allow it to become baked and hard, he may safely dispense with mulching. But because it is recommended to spread coarse manure on the surface of the ground, let it not be therefore inferred that it is ever advisable to place fresh manure in the soil about the roots of the trees. It is very apt to kill newly planted trees, and sure to do more harm than good. If it is thought necessary to enrich the soil, old and perfectly rotted manure may be thoroughly incorporated with it, but the safer way is to place the manure on the surface, and let its fertilizing properties be gradually washed down by the rains. It is very seldom that trees which have been carefully taken up, carefully planted, and well mulched, will require any Watering during the dry summer weather. If it should become necessary, however, to give them water, it should be done thoroughly. A mere moistening of the surface of the ground is worse than none at all. Give enough to penetrate down to where the roots lie and to soak the ground about them thoroughly. And now, if the trees have not been mulched, it should be done immediately, in order to prevent the evaporation of the water that has been given, and the baking and cracking of the earth under the rays of a scorching sun. If no litter can be had with which to mulch, effect the same result by stirring the surface a few hours after the water has been given, and before the sun has baked the earth. If this be not attended to, better not to give any water at all, for the hot sun will only bake the earth the harder for your watering.

The trees most suitable for planting are young, healthy trees of from two to four years’ growth. It is difficult to transplant large trees successfully, on account of the impossibility of preserving the small fibrous roots, which are most numerous towards the extremities of the large roots, in sufficient quantity to support the tree. It is through the small fibrous roots that the tree derives its nourishment from the ground, and, therefore, the more numerous they are the more likely the tree is to thrive, and more of these can be taken up entire in removing a small tree than a large one. Young trees, that have been grown in suitable soil and properly taken up, will be furnished with a good supply of roots. The best soil in which to grow young trees for transplanting is a good, sandy loam. They will make much better and more fibrous roots in such a soil than when grown in stiff clay, and are consequently more likely to live and thrive well when transplanted. Some have entertained the opinion that trees from a sandy soil will not thrive when planted in clay, and that trees from a clay soil will not thrive when removed to sandy soil. This is a great mistake. A tree well supplied with fibrous roots will thrive in any soil, and the nurseryman who consults the best interests of his customers will select a rich, sandy loam in which to grow his young trees, experience having taught us that in such a soil they throw out an abundance of small and fibrous roots. In taking up a tree, it is impossible but that some of the roots will be cut off, but a tree that has been well taken up will have something of the appearance shown in Fig. 20; but trees that resemble Fig. 21 have been badly dug, and those are worse dug that look like Fig. 22.

It may be often of great advantage to procure the trees when they are two years old, plant them out in a nice piece of rich, loamy soil, in rows four feet apart and two feet apart in the row. Trees grown in this way, for a couple of years, make a splendid mass of roots, can be transplanted into orchard form at the owner’s convenience, and are sure to live and do well.

Low, stout-bodied trees are much better than those that are tall and slender. The diameter of the trunk of a tree is of much greater importance than its height. A tree that has a stout body is more surely healthy and well rooted, and will be able to support a top and keep erect, while a tall, slender tree is apt to have slender, tapering roots, and is often too weak-bodied to sustain the top without being tied to a stake. Besides all this, in some parts of the country where the cold is severe, it has been ascertained by actual trial that stout trees, with low heads, are much better able to resist the cold than those which are trained high, with long, exposed trunks. We strongly urge upon planters living in the colder sections of the country to select stout, low-headed trees, and keep them branched low, being assured they will be more healthy and live longer, and yield more and finer fruit than when trained high.

Trees, when received by the planter, should be kept from the drying effect of the sun and wind until he is ready to plant them out. The most convenient and effectual method is to dig a trench, into which the roots are placed and covered with soil. Here the trees can remain safely until it is convenient to plant them. This is called heeling-in. On taking them out for planting the roots should be examined, and any bruised or mutilated parts pared smoothly with a sharp knife, and any injured or broken branches pruned smoothly, or entirely removed. In planting, the roots should be covered with a mat or old bit of rug, or anything, indeed, that will keep them from getting dry. Heeling in may be also practised where it is not desired to plant the trees in the autumn, and it is not practicable or convenient to obtain the trees direct from the nursery in the spring. But in such cases the roots must be well secured from frost, and the tops also should be covered with branches of evergreens. Shortening the side branches and a portion of the top of the tree at the time of transplanting in the spring is advisable, in order to restore the proportions between the root and the top. Judgment must be exercised in this operation, keeping in mind that the object is to lessen the amount of foliage somewhat, because the quantity of roots have been lessened. As a rule, about one-third of the top, including the side branches, may be removed. In cutting away the side branches, it is better merely to cut them back, leaving three or four buds, instead of cutting them off close to the body of the tree. The circulation through the trunk of the tree is kept up by the foliage that will form on these spurs, whereas, if cut off close to the trunk, the exposed wood seasons back into the trunk, and if there be many of them, seriously interferes with the circulation of the sap. For this reason do not cut off the small spurs and leaf-buds which may be on the body of the tree. They materially aid in keeping the body fresh and sound, and the sap in free and healthy circulation. After the tree has become established they may be removed, and then the slight wound will rapidly heal over.

The After-treatment of young orchards consists in keeping the ground mellow and in good heart. Doubtless the very best thing for the trees is to keep the ground thoroughly cultivated, the surface loose and friable, and free from weeds, without attempting to raise any crop; but this is not to be expected of the most of our planters, who hardly feel able to till the soil so thoroughly for so many years without any return. Hoed crops are the best to raise in an orchard, treating each tree as a part of the crop, giving it the same manuring and cultivation as the rest. Cereals, as rye, wheat, barley and oats, are not so suitable, and there can be nothing worse for a young orchard than to seed it down and let it lie in grass to be mown or pastured. If put down in grass, let it never be cut, or if cut, left to decay on the ground where it grew. A top-dressing of lime at the rate of twenty bushels to the acre may be applied with benefit, especially about the time the trees come into bearing, to be renewed every three or four years. Ashes, leached or unleached, crushed or ground bones, gypsum or plaster, chip manure from the old wood pile, horn shavings, wool waste, and occasionally a light coating of well-rotted barn-yard manure, will all be found beneficial to the orchard, applying these in such quantities, and at such intervals, as will keep the orchard in a healthy condition, but not induce an excessive wood growth. After the trees have become so large as to shade most of the ground, it will no longer be profitable to grow crops of any kind in the orchard. It may now be seeded down to grass, which should not be removed from the orchard, but suffered to remain and decay on the ground. This will serve as an excellent protection to the roots, and by its decomposition enrich the soil. A dressing of ashes, bone dust or plaster, should not be neglected; it will be amply returned in the increased beauty, size and quantity of fruit.

To Protect the Trees from Mice, which are often very destructive to young trees by gnawing off the bark at the surface of the ground, and, when they become numerous, injure even bearing trees, the trees may be painted with the following mixture, which is recommended by Downing. Take one spadeful of hot slaked lime, one of clean, fresh cow-dung, half a spadeful of soot, and a handful of flour of sulphur; mix the whole together with sufficient water to bring it to the consistence of thick paint. In the autumn paint the trees with this mixture from the ground to the highest snow line, choosing dry weather in which to apply it. This is a perfectly safe application, and has been proved by repeated trial to be entirely harmless to the tree. In those parts of the country where the snow is seldom deep, it has been found that a mound of earth raised around the tree to the height of a foot or so, enough to be above the ordinary level of the snow, will fully preserve the trees from their ravages, for they always work under the snow, never in open daylight. Coarse paper may be tied around the tree, and smeared with coal tar; and some use strips of roofing-felt fastened around the tree; others, old stove pipe—in short, anything that will keep the mice from gnawing the bark.