* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Canadian Cities of Romance

Date of first publication: 1922

Author: Amelia Beers Warnock Garvin (as Katherine Hale) (1878-1956)

Illustrator: Dorothy Stevens

Date first posted: 17th April, 2024

Date last updated: 17th April, 2024

Faded Page eBook #20240409

This eBook was produced by: Mardi Desjardins, Howard Ross & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

This file was produced from images generously made available by Internet Archives.

Canadian Cities of Romance

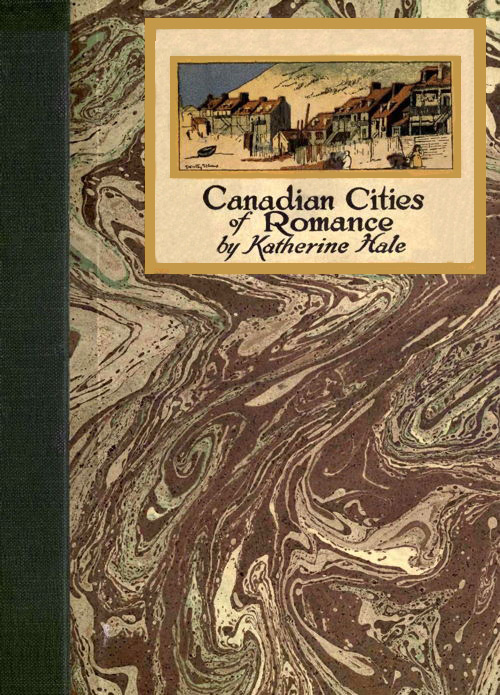

“THE GOTHIC TOWER ON PARLIAMENT HILL.”

CANADIAN CITIES

of ROMANCE

By KATHERINE HALE

(Mrs. JOHN GARVIN)

Author of “Grey Knitting,” “The White Comrade,” etc.

Drawings By

DOROTHY STEVENS

PUBLISHED at TORONTO by

McCLELLAND and STEWART

COPYRIGHT, CANADA, 1922

By McCLELLAND & STEWART, LIMITED, TORONTO

These sketches call attention to a phase of Canadian history largely unregarded, the romantic background of many of our towns and cities. The writer has not described every romantic city of Canada, nor does this claim to be a modern guide book. The portrayals are unique, not only because of the vivid impressions of one who is a poet as well as a prose writer of distinction, but on account of the association established between certain authors and certain places. The volume is therefore a literary sketch book, as well as a book of cities.

The Publisher.

So many of my friends, from one end of Canada to the other, have helped me in the matter of these stories that their names would make a substantial addition to this book. I can only return thanks, and say that each request has been met with the utmost kindness and goodwill.

To the Editor of the Canadian Home Journal, for the use of excerpts from a series of my stories of Canadian cities, I am especially grateful.

Katherine Hale.

| Chapter | page | |

| I. | Quebec—An Immortal | 15 |

| II. | Domes and Dreams of Montreal | 29 |

| III. | Kingston and Her Past | 45 |

| IV. | Halifax—A Holding Place | 57 |

| V. | The Port of St. John | 71 |

| VI. | Fredericton—The Celestial City | 83 |

| VII. | Ottawa—A Towered Town | 95 |

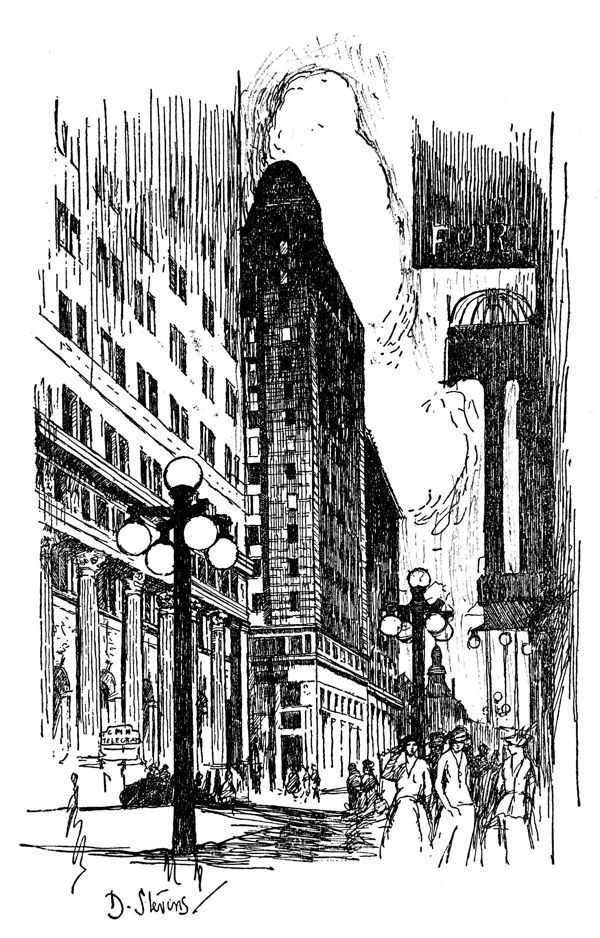

| VIII. | Toronto—A Place of Meeting | 107 |

| IX. | Historic Backgrounds of Brantford | 123 |

| X. | Golden Winnipeg | 133 |

| XI. | Edmonton and Jasper Park | 145 |

| XII. | Calgary and Banff | 161 |

| XIII. | Vancouver—The Western Gateway | 173 |

| XIV. | Victoria—An Island City | 185 |

| “The Gothic Tower of Parliament Hill” | Frontispiece |

| “Quebec . . . takes on a mediaeval aspect” | 19 |

| “She speaks through domes and towers of some far-off dream” | 33 |

| “The Château de Ramesay, for two hundred years a house of importance” | 37 |

| “The Place D’Armes centres the city’s life” | 39 |

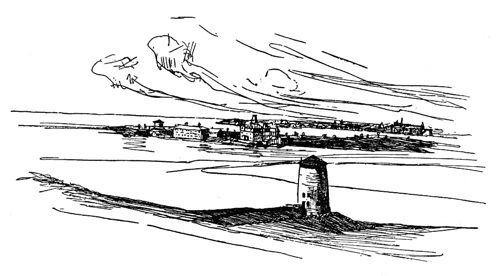

| A distinctive and beautiful feature of Kingston are the Martello Towers | 53 |

| “Looking down from the Citadel” | 61 |

| “There are dreams go down the Harbour with the tall ships of St. John” | 77 |

| “To mark a certain preparedness” | 80 |

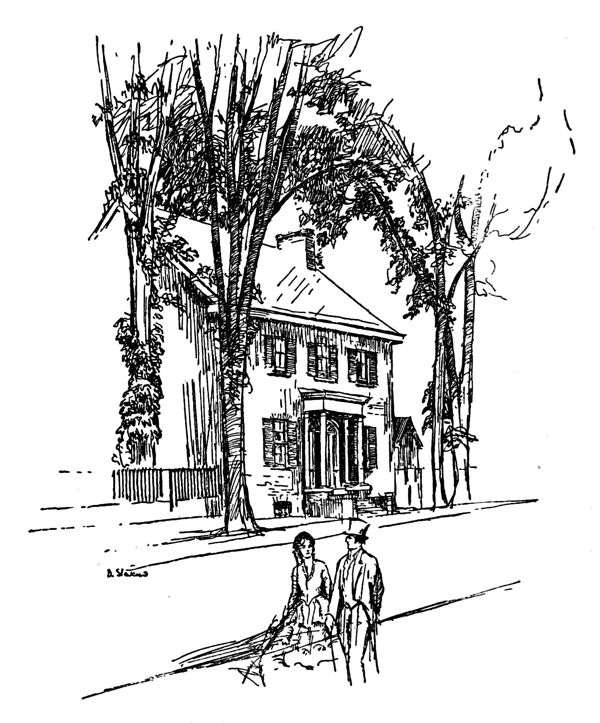

| “That quaint, red brick house, the Rectory” | 88 |

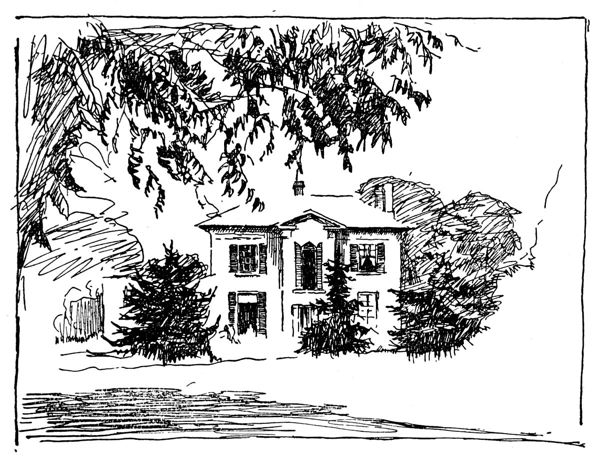

| The old Government House, Fredericton | 91 |

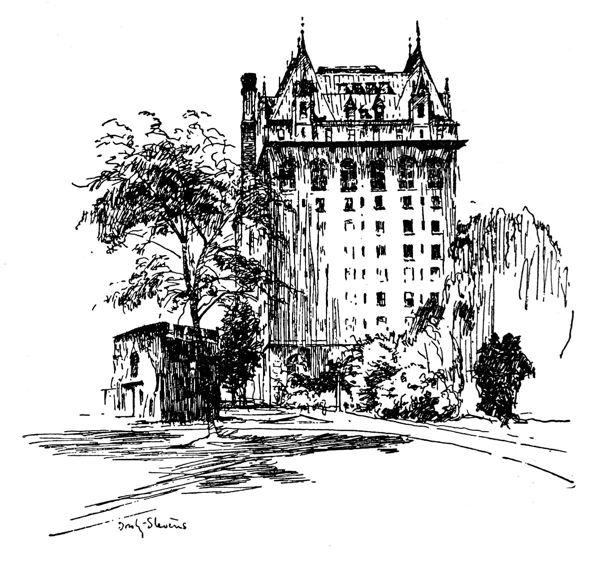

| “Where the splendid Château Laurier on the old canal looks down” | 101 |

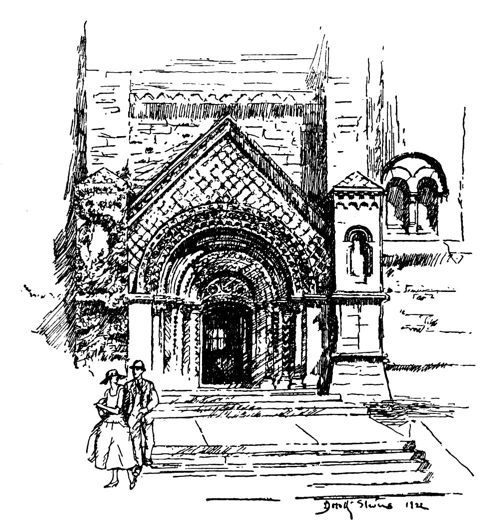

| “The carved stone doorway” | 111 |

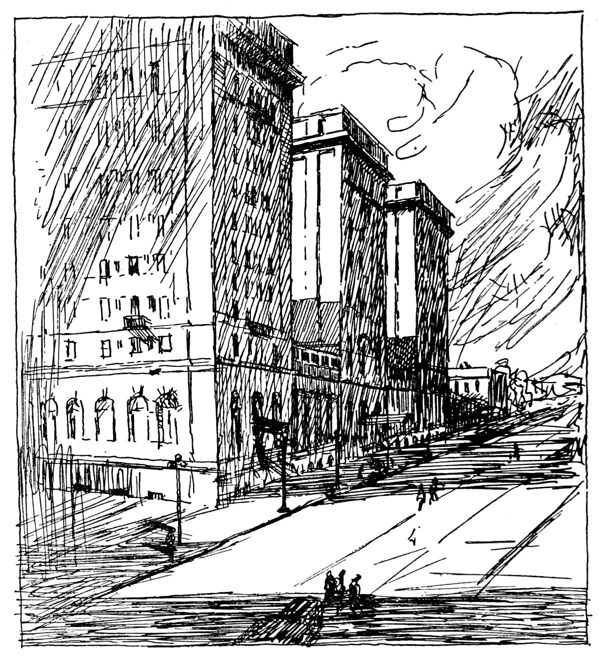

| “The whirlpool of King and Yonge” | 113 |

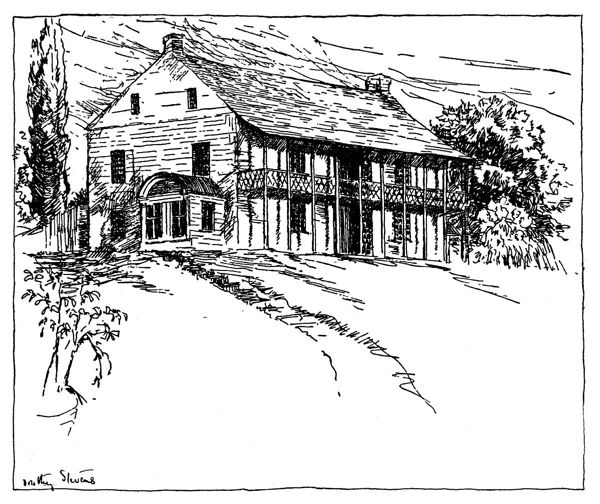

| “Chiefswood” on the ancient reserve of the Six Nations Indians | 127 |

| “Here the first Catholic Mission was established and named St. Boniface” | 138 |

| “From a high window of the Fort Garry Hotel” | 142 |

| “The Great House of the Chief Factor in the 40’s” | 149 |

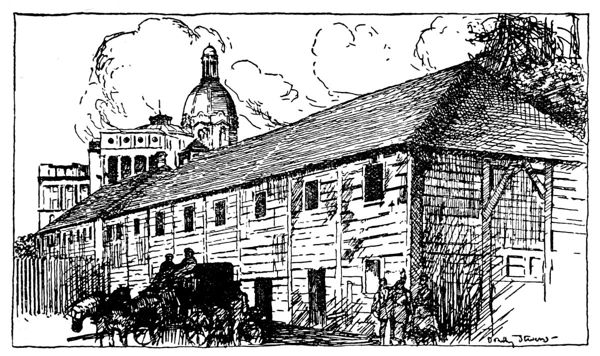

| “The old Hudson Bay Fort huddled up against the Parliament Buildings” | 153 |

| “The busy streets of a modern city” | 166 |

| “A great brown fugue of giant hills” | 170 |

| “This strange young Colossus on the shores of Burrard Inlet” | 178 |

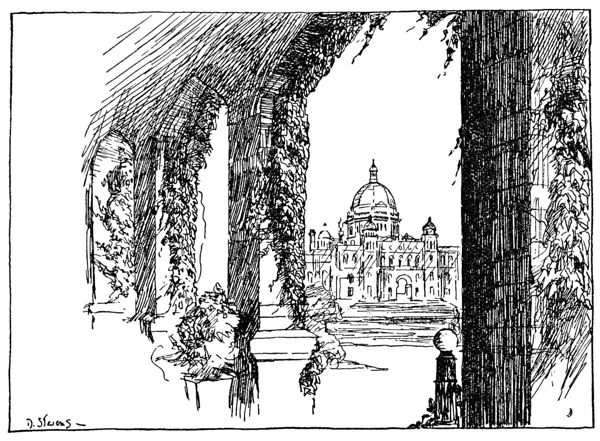

| “Parliament Buildings . . . from the ivy-covered Empress Hotel” | 189 |

The city of Quebec has been loved by generations of Canadians. Like some beautiful old native song there is hidden in her, quaint repetitions and the racial themes that link her, decade by decade, with the past and the present. She has been the priceless subject of many a picture, song and story. Most pictures reflect the tones of spring and summer, when the St. Lawrence runs deep blue and the Laurentians are wrapped in purple. Then in the narrow alleys of the Lower Town and the stony streets that wind up to the Citadel, there are always tourists delighted to be beguiled by the drivers of the old-fashioned calèches.

But Quebec in midwinter is less familiar. A Canadian artist, Horatio Walker, who has depicted this aspect with great beauty, says: “I live in the midst of difficulties, hemmed in by snow on the deserted Island of Orleans, but cannot leave the wonder of Quebec in winter.” Snow in Ontario towns often means a sort of gray gloom. But Quebec under a white cloak is a place set high in air, crystal clear and full of sunshine. The railway route from Montreal runs in places through glittering barbaric jungles of what appear to be enormous silver ferns sometimes changing to avenues of innumerable arches of diamonds, crossing and recrossing in the sparkling air—frozen larches, bent into fantastic curves by the weight of snow.

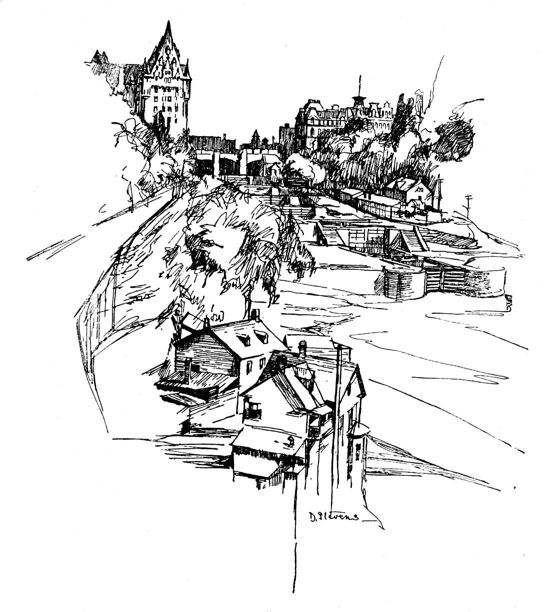

It is enchanting to arrive in a winter twilight when a fading sun is on Point Levis. As we drove to the Château Frontenac, our horses lashed with the native fury of a French-Canadian cocher, the shadows in the city had deepened so that we were not prepared for the beauty of sunset from the Terrace. The rosy light on Levis had dyed itself into deep crimson, and there was an afterglow on the Laurentians and the blossoming of electric stars in buildings far away across the river. It was the sudden finding of new magic in a familiar place, for Quebec at midwinter, cut off from its life of shipping, takes on a mediæval aspect of which the world in general knows nothing.

“QUEBEC . . . TAKES ON A MEDIAEVAL ASPECT.”

From the Château Frontenac, set in a great open space below the Citadel and commanding the St. Lawrence, Levis, and the Laurentians beyond, one glimpses a life altogether Canadian, in the far early sense. The low French sleighs, piled with fur rugs; the driver in his coonskin coat, belted with a gay woollen scarf, standing erect as he drives; nuns in their black robes; friars in dull brown, with careful galoches over what we know are sandalled feet; children, many of them in the gay blanket tobogganing-suits that passed out of existence in other provinces decades since, sailing down and climbing up the slides; all these figures are apt to appear and disappear as you stand by your window and watch the ice blocks pass on the wintry river, silent and inevitable as Fate.

Below, in the city, a strange unknown life is progressing. Here the Ursuline Convent stretches out its long stone walls. Just below is Laval, more like a mediæval palace than a modern university. Suddenly a sun ray strikes the dome of the Basilica; within are the endless whispers of prayers.

If I could paint my Quebec in sound it would be to the ringing of bells, the laughter of French children and the almost inaudible, incessant whisper of prayers.

The romance of Quebec is like charm in an individual, a thing of endowment. From out some hidden spring of being and by long conspiracy of the ages, this place where Canada began possesses beauty that is in itself a heritage.

Three centuries ago the city was founded by Champlain. But nearly a hundred years before that, Jacques Cartier saw and loved Stadacona, (an Indian village ruled by its chief, Donnacona, the “Lord of Canada”) which lay at the meeting of the St. Lawrence and the St. Charles, a stone’s throw from the present city.

The faith of Cartier in his vision of a Canada to be, faith which counted death as nothing, is a memory more keen than the mature affection of Champlain, who succeeded where Cartier had failed to place France in the new world. Yet when Champlain arrived, a century later, there was still need for the courage of a great dream. “When Alexander built Alexandria he could draw with the might of a master upon the resources of three continents. When Constantine built Constantinople he brought to it the treasures of the ancient world—the marbles of Corinth, the serpent of Delphi, and the horses of Lysippus. But from no such origin does the life of Canada proceed. Champlain, in rearing his simple habitation at Quebec, had no other financial support than could be drawn from the fur trade. His hungry handful of followers subsisted largely upon stale pork and smoked eels. Everything that was won from the wilderness cost heroism, self-sacrifice and faith.”

“La Grande Mère of Canadian cities,” her story from her birth in 1608 is alive with incident. French, until the Battle of the Plains of Abraham closed what has been called “the grand but insecure pageant of French Dominions on the shores of the St. Lawrence,” the record is one of hotly contested sieges, blockades and battles. A coveted prize, Quebec for a century and a half was wooed, seized, stolen, tossed about from hand to hand and country to country. Five times, from 1608 to 1775, she was in actual warfare against England and New England, not to speak of perpetual skirmishes with the Indians.

With the British conquest her most picturesque pages closed. An era of progress began:—municipal government, military tribunals, adjustment of laws and languages, newspapers, a Literary and Historical Society with a Royal Charter. And then, hundreds of English ships in the harbour looking for Canadian pine and spruce, because continental ports were closed during the Napoleonic wars. Twenty-five years later the launching, at the Island of Orleans, of the two first large Canadian ships.

To-day one may read the romance of Quebec on a dozen different pages. The streets hold a key to her history, from Little Champlain, which bears the marks of the turbulent centuries, to the Grande Allée of modern residences. The churches and convents are a story in themselves, and the monuments to Champlain, Montcalm, Wolfe, Lavallée, Mercier and a long line of heroes, picture to the mind eras and events.

More fascinating to travellers with a sense of mystery than the rocky precipice up which struggled Wolfe and his companions, the Plains of Abraham themselves, or even the Fortress at Citadel Hill gallantly defended by Montcalm, are the narrow old-world streets of the Lower Town. Little Champlain, for instance, where they used to ‘crimp’ the sailors for loot in the bad old days, is a place where you feel that almost anything might happen as the day draws in to twilight.

“Mon Dieu!”, says the guide, “when they take down these houses so old, what will remain? A graveyard—also very old.”

Encircling the public square in front of the Basilica, run the lines of the clanging trolleys, and the ubiquitous motor car is of course in evidence. Big Business goes on in Quebec, and naturally she will become more and more absorbed by it. At the same time there is no resisting the fact that she is, inherently, a spiritual force. Everywhere you feel the hand of the church.

Once I chanced upon a strange shrine in the chapel of the Church of the Most Blessed Sacrament. Here candles burn forever before an altar at which two nuns in white robes are always at prayer. The shrine is built like a miniature church, separated from the rest of the chapel by a high grille of iron, through the openwork of which are seen four silent forms: two who bow at the altar, and two who kneel in prayer near them. When the moment strikes, the latter move forward to relieve their sisters, another pair entering to take their places. Hence, year in, year out, the light before the altar is unceasing, the shrine is never for a moment deserted, the worship goes on forever. To sit in that church, and in the stillness to watch those motionless figures, is to feel the very hand of eternity in the midst of time.

The Basilica, where hangs the red hat of the Cardinal, is full of ritualistic splendour and wonderful music on a Sunday evening . . . But nearby, in the palm room of the Château, a string orchestra is playing, people are grouped about little tables having coffee and cigarettes. Presently dancing begins. Soon you realize that not even in Paris is there more grace and beauty to be discovered, in like surroundings, than here, among these charming young French-Canadians.

St. Louis is one of the delightful old streets. It was the fashionable thoroughfare of Quebec two hundred years ago. But for a century before that it was a “street,” along which Indians padded silently, along which the good Nuns walked and about which romance has always hovered. It lies on the way from the Ursuline Convent to the Citadel, and is narrow and stony. Each house is apparently set directly on to the pavement. The entrances are mysterious, but certain houses and buildings are known even to the casual tourist. Here is the little low house of the Cooper, Gaubert, where Montgomery’s body was laid out for burial, and the old officers’ quarters, an ancient building which long before garrison days was presented by the Intendent, Bigot, to his beautiful mistress, Angelique de Meloise. A step farther is Kent House, where Queen Victoria’s father lived for a time in residence, and there is another well-known building which served in 1812 as a place of detention for American prisoners taken at Detroit; also the little Ursuline chapel, built now on the site of the famous house of Madame de la Peltrie.

Then—if you know modern Quebec—you may be permitted to ring the door-bell of some old stone house. A French maid will open. “Montez, s’il vous plait!” In a moment one is back in the heart of to-day. Here is a drawing-room in chintz and French wallpaper, with the latest books lying on the centre table. And there is tea and toast and excellent talk . . . Meeting well-known French-Canadians, hearing the music of their speech, feeling in them the sensitive spirit of an inherently poetic race, one cannot believe that the flame of their genius will expire in modern days.

As for the literary traditions of Quebec, they are precious and unique. We are told by French historians that between 1764 and 1830 there existed “a small literary world in Quebec.” Poems were written which circulated in manuscript for want of a printing office, and a public library was opened in 1785. Dramatic Associations also existed in both Montreal and Quebec. They played Molière and some light comedies of the time of Louis XV. His Royal Highness the Duke of Kent, accompanied by Lieutenant-Governors, Clark and Simcoe, attended the performance of “La Comtesse de Escarbagna” and “Le Medecin Malgré Lui” in Quebec, in 1792. “There was a spirit of literature in the air” says Mr. Benjamin Sulte writing of these times, “and this came not only by reading but by the more important practice of conversation and ‘causerie de salon’ which is so thoroughly French.”

From 1832 to 1837 we find young French-Canadian poets writing songs after the manner of Beranger. Garneau was a genuine poet, full of national spirit. And there is a low-raftered room on Buade Street where Octave Crémazie used to spend hours in his brother’s book shop. That was about the year 1884. “Le Drapeau de Carillon” is perhaps his best-known and best-loved poem. Probably the most truly national among the French-Canadian poets of the last century was Louis-Honoré Fréchette. His greatest work, the tragedy of Papineau, was crowned by the French Academy in 1881. Pamphile Le May is another well-known singer. The mystical pathos of the verse belies his spring-like name.

Out on the Ste. Foye Road are two interesting houses; Spencer Grange, the home of Sir James Le Moine, and the adjacent Spencerwood, Government House for the Province of Quebec. Both places are full of mellow, unaffected charm. There is nothing institutional about the simple and dignified hospitality of Spencerwood; and in the library of the picturesque, century-old Grange, whose master is the author of many volumes on the history and legendary lore of the St. Lawrence, the fortunate guest will find a precious collection of Canadiana in old volumes, prints of Quebec, and bric-a-brac.

Quebec people are proud of the work in prose and verse of their fellow-citizen, Canon Frederick George Scott, who is the well-loved “Padre” of thousands of Canadian soldiers.

Perhaps the keen romance of Quebec lies in the fact that in her history extremes have always met:—the natural extremes of a climate that can be bitterly cold and also sun-warm to the core, and extremes of temperament in two races far as the poles apart in their expression of feeling. So the generations find and leave it, town of old dreams and desires, looking out on the river and the hills from under its rocky Citadel over which two flags have flown—Quebec, an immortal city of the new world.

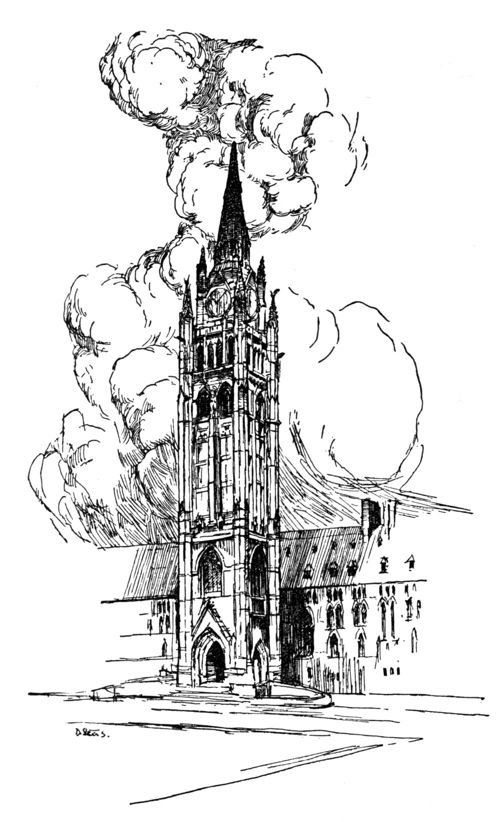

Montreal, a slightly younger sister of Quebec, is more sophisticated and progressive. The largest city in Canada, she is, from a commercial standpoint, undoubtedly the most substantial. And yet, a mystery rests upon her. She speaks through domes and towers of some far-off dream. She suggests a form in space that is circular. Most places are laid out on straight lines. You get the impression of a runner making for a goal—streets, shops, parks, people all straight line. There are few unexpected places. The atmosphere is clear cut. But Montreal is surprising, and vastly attractive. Her spirit is cloudy rather than glowing; and she wears purple best of any colour, though she began in a blaze of light.

To come up the river from the sea, or to go down the river from Toronto and so approach Montreal, is to realize the beauty and the prevalence of her cathedral domes coming like the sound of bells. When the air is misty and a fog is rising from the river, the sound is faint and mysterious. If the sun shines you catch a golden note, and then another and another; and in spite of myriads of roof tops and the unfolding of a great city, laid terrace-like at the foot of Mount Royal, you know that Montreal is a circle.

Remember how she began, in a blaze of light. It was on a May morning, a little less than three hundred years ago, that Maisonneuve and his band of religious enthusiasts landed and on the very spot where, alas for romance, the Customs House now stands, the saintly Dumont planted the grain of mustard seed which it was his belief was “destined to overshadow the land.” Born of the Church, sprung to life out of spiritual zeal—a sword-like French zeal at that—no wonder that Montreal ascends dome-like and wears a purple cloak.

The germ of the city came out of religion, but as she grew, her commanding situation drew commerce towards her. And from first to last Trade has meant fighting.

She was on the outer confines of civilization and at the door of the Iroquois country. Hence the fur trade and with it the necessity for a military garrison. Indians, priests, soldiers; these in their garish or sombre dress held the streets of the town at first. In another hundred years, though the priests and the soldiers were both to be seen, the Indians were beginning to disappear and the fur trader was less crafty. After a while he too disappeared from the life of the modern city.

“SHE SPEAKS THROUGH DOMES AND TOWERS OF SOME FAR-OFF DREAM.”

Apart from religious, political and business relationships, the influence of a dual element is important. It is a well-known fact that there is no Canadian city, and only one other in America, New Orleans, that can compare in picturesqueness with Quebec. No seaport of the continent has more dignity and beauty than Montreal. The attraction is largely composed of solidity, allied to tradition and romance, that makes the French-English combination.

A book might be written on the various approaches to Montreal. Even the route by land from Quebec, over any of several ways across narrow fields facing on the river, is interesting. Here one may pass some of the old manor lands discarded at the termination of French Rule. Visitors from the United States find points of comparison between Quebec and New Orleans, Montreal and Mobile. The lower streets of both Canadian cities recall the Saints, but it was from the north that Bienville brought names to Mobile and New Orleans. The old Manors also, common on the St. Lawrence, were introduced into Louisiana by Louis the XIV. There are now few traces of these seigneurial rights in the South, and in Canada the British Government bought them from the Seigneurs in order to simplify the law system.

Steep streets, wide distances, noble churches, great squares, river-way or mountain summit; yet with all its solidity this is a city of surprises. I hear a church bell ringing, a sandalled monk may pass me, a priest hurries by, book in hand . . . Then, a laugh in the air, and a party of school girls pass, humming an English air. Before the great Banks or Railroad Offices, whose headquarters are stationed here, antiquity is lost in commerce. But just around a corner there is a narrow street whose inhabitants deal, one should fancy, in nothing higher than copper currency.

These glimpses of Montreal make me glad that I do not know it ‘thoroughly.’ I would rather retain flashes that are painted in colours so vivid that they can not easily be effaced.

There was a snowy night when we stopped at the great doors of Notre Dame and slipped in where a thousand candles were burning. Somewhere out of the distance came the vibrant sing-song chant of the French priest. There was the city in the cold blue light of early morning, the streets piled high with snow. The city burning at noon-day under an August glare, the golden angel of the spire of Bonsecours touched by the sun, the drip, drip from the fountain in a Square insisting upon itself intermittently between the onrush of traffic. A city of twilight seen from the mountain with starry lights beginning to twinkle below, a great ship coming lazily in from the sea, the busy docks a faint blur in the distance, and the panorama of streets and squares and towers and steeples all mixed in a haze of coloured light. The city at night with a mid-summer moon floating above a serene street of palatial residences, the silhouettes of great buildings, the blind high walls that guard the Church’s possessions, the shrill laughter of the French town—the old city—this is the meeting of past and present in Montreal’s own way.

When I see candles lit on the altars of Montreal I think of the legend that relates to that May day when she was christened. For we are told that when night fell a Mass was celebrated, and fire-flies, caught and imprisoned in a phial upon the altar, served as lights.

The old houses are full of romance. The Château de Ramesay is a low cottage-like building behind an old-fashioned stone fence. For over two hundred years it has been a house of importance. Now it is gray with age and exceedingly picturesque in spite of the fact that it is a museum. On its left the quaint open market edges close and slightly below it; a crowded, many coloured, odoriferous bouquet. Claude de Ramesay, Governor of Montreal, used the Château for twenty years. After his death it became the property of “La Compagnie des Indes,” and the salons lost the roses and candle light of polite French society and were crowded with Indians from the back country and fur traders. After the Conquest it became the residence of the British Governors. When the American revolutionary army occupied Montreal in 1775, this was Montgomery’s headquarters, and from it issued his manifesto to the Canadian people, urging them to cast off their allegiance to Great Britain. Benjamin Franklin came here at the time, bringing his printing press which was set up in the vaults of the Château.

“THE CHATEAU DE RAMESAY, FOR TWO HUNDRED YEARS A HOUSE OF IMPORTANCE.”

The other day poking underground, as I have so often done, in these stone vaults of castle-like construction I found among ancient trophies a queer phæton-like conveyance with an iron rod sticking up in the centre. It looked at least two hundred years old. I enquired of an ancient guide upstairs. “That,” he said, “is Montreal’s first automobile—a matter of only thirty years ago!”

The neighbourhood of the Château was in 1705 the fashionable part of the town and was occupied by the Baron de Longueuil, the Contrecoeurs, Madame de Portneuf and others of the French aristocracy who naturally chose their houses near the magnificent garden of the Jesuits.

South of Notre Dame Church, indeed, is the region in which romance lingers. Going down St. Sulpice Street to St. Paul Street and then turning east to St. Jean Baptiste, one of the oldest houses in the city may be seen. It is now occupied by a Chemical Company. St. Gabriel Street was laid out in 1680 and one sloping roofed building dates back to 1687. Its heavily vaulted cellars were probably used for storing furs. Jacques Cartier Square also contains its old houses.

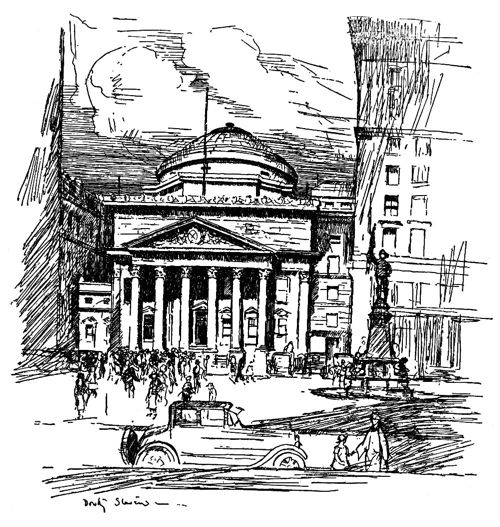

“THE PLACE D’ARMES CENTRES THE CITY’S LIFE.”

The Place D’Armes centres the city’s life. In the Square stands Maisonneuve in bronze, brave in the cuirass and French dress of the 17th Century holding the banner of the fleur-de-lys. The sculptor, Louis Hébert, has suggested phases of early Canadian life in his bas-reliefs and the four figures at the base in bronze, an Indian, a colonist’s wife, a colonist with the legendary dog Pilote, and a soldier. Notre Dame de Montreal faces the Square with its tall stiff façade and towers and here is also the Bank of Montreal, pure classic Corinthian, the white granite Royal Trust Building, and the Post Office with its bas-reliefs in the Portico after designs by Flaxman.

All about Bonsecours, the church and market, you feel the tingling magic of old Canada. The very name was a thank offering for escape from the Iroquois. Maisonneuve felled the first trees for the little church and pulled them out of the forest. That was in 1657. A second larger chapel was built twenty years later and the present church was erected upon its site; the stone foundations go back to 1675. The new church has been too much ‘restored’ and ‘improved.’ But still the miraculous Virgin, whom Sister Marguerite Bourgeoys set up to guard the sailors two centuries ago, looks out towards the water, and there are old paintings and old altars. Old memories too, fading eras slipping by into the centuries with hardly an echo in the sturdy French provincial life of to-day. On the Place Viger, a block from the church, is a statue to Chénier, one of the ‘patriotes’ of 1837 who died fighting furiously in the church of St. Eustache, outside the city, where he had taken refuge. But in the market, where now the habitants flock on Tuesdays and Fridays, there is still a note of the past in the quaint carts, the homespuns and the little chairs that are brought in from the country for sale. Also there are squawking ducks and chickens, and maple sugar, and garlic, and straw hats and native tobac, and rosaries and cheap jewellery. And the barter takes one back to Paris markets, only this is a kindlier commerce.

There is a newer but no less striking romance in the opening up of the mountain district. The upper levels of Westmount, creeping up côte des Neiges; the magnificent driveways; great vistas of plains seen from one mountain, with other mountains dim on the horizon; here a tall column, with an incomparable background of hills, the Cartier Monument on Fletcher’s Field; there a Pleasure Park; to the lower left, if you are looking south, the Molson Stadium, pride of McGill;—every thing on a heroic scale, like masterful young music set to an old Canadian theme.

Because she is a city with a soul it would seem that her literary traditions should be many. As a matter of fact this is hardly the case, though certain outstanding figures are undoubtedly linked with it. Romance rests upon the name of Charles Heavysege, who came to Montreal from Liverpool in 1853. He was a wood-carver by profession and his drama “Saul” shows that he was a poet by birth. George Murray an Oxford man did much literary work in his new home, and so did John Reade who arrived in Canada in 1837 from Belfast and joined the Montreal Gazette, with which journal he was connected until the time of his death in 1919. William D. Lighthall is a Canadian anthologist of note, a poet and also a novelist. Dr. William H. Drummond has for ever left his impress upon the literature of Canada in the habitant verse which has immortalized the French-Canadian farmer, the voyageur and the coureur de bois.

The “Chansons Populaires” of Canada are unique. The songs, which came out of the convents of France in the Middle Ages, were brought to Quebec by its founders. As the years went on the ancient, beautiful songs became Canadianized, in a sort of verbal and musical patois containing much piquant anecdote of the early days. Dr. Drummond in his poems illustrates the life and manners, the humour and the tragedy of the habitant. He does not touch the old songs which are their heritage.

In a different way Mrs. J. W. F. Harrison, “Seranus,” has pictured the life along the St. Lawrence in her exquisite Villanelles, many of them written in or near Montreal. A group of the younger generation of writers at work to-day are also alive to the romance of their city.

During the summer months the entente between Canada and the United States is strong. Montreal is full of Americans, which recalls a tribute from Horace Traubel, late of Philadelphia and long a sojourner in this city which he loved so well. He says: “What we get in New York from our East side we get here in a Latin and sometimes an Oriental way. The distinctly English cities whether on this or the other side of the Border are passionless prose. They need fire. They need colour. They are too respectable to be decent. Montreal is awake, Sundays and weekdays.”

For fully a century Montreal has been alive to the new movement in education, art and science. As far back as 1801 the establishment of non-sectarian free schools was provided for, and shortly after that, the foundation for McGill was laid. It is now one of the great Universities of the world, and such distinguished names as those of Sir William Dawson, William Peterson, LL.D. and Sir Arthur Currie, Commander-in-Chief of the Canadian forces in France during the great war, are associated as its Principals. The Hon. James McGill, a leading merchant and citizen of Montreal, looked forward to a University which should consist of several colleges. Three such are already in existence, the first and original one being that which bears his name.

Montreal is a centre for art and for artists. While the National Gallery at Ottawa contains its treasures, Montreal possesses the most important permanent collection of European pictures in Canada. The new Art Gallery on Sherbrooke Street, beautiful in its classic architecture, was erected through the liberality of a group of Montreal picture lovers.

First the Indians, then the French, then the British; Quebec, Montreal, Kingston; three steps in history, tradition, situation.

As gray as mother of pearl, but an all-encompassing gray that includes violet and blue and a fine sea-green when the sun strikes it, that is Kingston, which, because it is built upon a ridge of limestone, has for long suffered from the dull phrase, “The Limestone City.”

The soft wings of age seem to hover over a town that is more or less of an impression to the traveller; for the main lines of the railways merely skirt it, (leaving to a little stub line the duty of carrying passengers) and it is almost mirage-like as one passes it by water on the way to or from Montreal; a fairy place in a summer dawn, or by moonlight.

Its position on the north shore of Lake Ontario just at its junction with the St. Lawrence was sure to attract a colony from the earliest days. Count Frontenac renamed the Indian “Cataraqui,” or “Clay Fort,” in 1673 after himself. At that time the French fur trade was its reason for being. Two years later Louis XIV made a grant of two thousand acres of surrounding country to his friend, Robert, Cavalier de la Salle, because of the upkeep of the Fort. And then a quarrel arose with La Barre, after the recall of Frontenac, who took possession in his usual unethical fashion, and in 1695 had the Fort rebuilt. It became something of a storm centre. As the French supremacy in Canada drew to a close, and the New England colonies to the south became stronger, the primitive streets of the fortress town echoed the sound of drums until Bradstreet led an army of three thousand men and eleven guns against it, and in August, 1787, it capitulated. Then for a long time there was silence.

Another generation had nearly run its course when it was reclaimed by the United Empire Loyalists, who gave their settlement the name of Kingston.

Among the town’s forefathers were Joseph Brant, the Indian Chief, Neil McLean, Lawrence Herkimer and the Rev. John Stuart, the first Anglican clergyman in Canada, who later founded here a school for boys.

A new town was laid out with a flour mill, a court of Assize, a Whipping-Post and Stocks. In 1792, Kingston became for a short time the capital of Upper Canada with Simcoe as Governor.

Two years later the Duke de la Rochefoucauld-Liancourt, drew the following picture of the little town: “Kingston consists of about 130 houses, none of them distinguished from the rest by a more handsome appearance. The only structure more conspicuous than the others is the barracks, a stone building surrounded by palisades.”

Then came the war of 1812 when the American fleet suddenly appeared off the Upper Gap and shots were interchanged with the shore. But Kingston remained unhurt. Her fortifications were growing. At this time appeared those fascinating block houses, of which only one remains. These block houses constituted a cordon of defense round the town and were connected by a high stockade. They were all of the same pattern; two stories high, the upper stories slightly projecting, and were armed with cannonades.

After the war of 1812 this was the military centre for Upper Canada, and possessed a garrison, a resident Commandant, and a leisure class of military officers and their families. Hence of course social life and ambition. As far back as 1816 we find records of “a large wooden Government House and Theatre built by the Military,” of balls and parties, of “coloured gauzes and laces,” of “Waterloo sarcenets” and “Wellington bombazines.” Horse racing became a favorite amusement with the officers, and at the entertainments which followed, “the loyal dames of Kingston would appear in brilliant dresses with threads of silver forming the motto, ‘God Save the King.’ ” Could patriotism go farther!

The original St. George’s Cathedral, begun in 1794, was described by a visitor in 1820 as “A long low blue building with square windows and a little cupola or steeple for the bell, like the thing on a brewery, placed on the wrong end of the building.” The first building on the present site was begun in 1825, afterwards enlarged, destroyed by fire in 1898, then rebuilt with only the stone pillars on the southern façade belonging to the original building. In the vault of the Church was buried Lord Sydenham, a tablet in the present Cathedral commemorating his memory.

But before this Church, came the Military Barracks, in 1789, known as the Tête du Pont, which stands on the site of the original Fort Frontenac. Here, as within the area of the more modern Military College (a youthful affair opened so late as 1875) the mere dates do not count when one stands upon ancient ground where long-forgotten causes were fought out before the white men came from France or England, old wars that out date memory.

In the modern Cathedral of St. George there hangs from the Cadets’ Gallery, a great flag covered with stars for the fallen in the Great War. Laughing faces of boys arise, vanished in the old cause of freedom that lured their forefathers to this very spot.

Kingston has had some strange karma to work out. Always she has desired military and national power. Always, in spite of great natural resources and gifts, these things have been denied her. But in the year 1841, when she became the temporary seat of Government for the United Provinces of Upper and Lower Canada—an honor soon withdrawn—Queen’s University was incorporated. It struggled at first for a bare existence, because all suitable buildings had been taken over for the Administrative purposes of the Government. Its first classes were conducted in a small frame building on Princess Street.

Now the University is the real centre and glory of Kingston.

A far cry from the old swashbuckler days, the romance of Indian and French intrigue, the knavish fur trade, the wild escapades of smugglers, the delightful arrogance and amours of early British military life, to the deep-thoughted Presbyterianism that has, through seven decades, meant Queen’s. It is as if a quiet pool had been set in the midst of a town that was listening to the call of rushing rapids near by, and the quiet of the pool had gradually stilled the call of the rapids. It is a cool but perhaps a kindly fate.

The system of Martello towers which guard the harbour and city are patterned after those of the 16th Century in Europe and were begun nearly three decades after the block houses. The oldest of them still lacks a few years of the century mark but they look as if they had been there forever, and are a distinctive and beautiful feature of Kingston. Again the note of gray! The lovely Shoal Tower, in the harbour, stands as one writer has said, “its feet in the blue waters of the lake,” like some remembrance from the long ago. So the Murray Tower in Macdonald Park, where, amid large trees and facing the lake is a statue to that great son of Kingston, Sir John A. Macdonald.

The Royal Military College was founded by the Mackenzie Government. Point Frederick, so long associated with the early Naval depot, became the site of the buildings. The Cadets have for years lent a stirring colour to Kingston life.

Interesting old houses abound. One goes about the streets wondering who lived here and there, for many of the stone exteriors have that about them which at once awakens interest and a certain quality of suspense that is the hall-mark of fascination. Many of these places were undoubtedly the abode of gentlefolk of British tradition. The history of most is lost but that of a few we know. “Alvington House,” for instance, was built by the fourth Baron of Le Moyne de Longueuil it was the residence of the Governors-General of Canada for a time. Lord Sydenham lived there in 1841, Sir Charles Bagot and Sir Charles Metcalfe succeeded him. “Rockwood Cottage” was built by the father of Sir Richard Cartwright, and on Rideau Street East stands the house in which Sir John A. Macdonald spent most of his boyhood, while nearly opposite, overlooking the river, is another historic abode, once occupied by Molly Brant, the sister of Joseph Brant, the Mohawk Chief.

A DISTINCTIVE AND BEAUTIFUL FEATURE OF KINGSTON ARE THE MARTELLO TOWERS.

The lover of literary reminiscence will seek out the remains of an ancient cemetery at the end of Clergy Street where was buried an officer of the British Army, a brother of Felicia Hemans, the English poetess. In 1825 she writes in “Graves of a Household”:

“One midst the forests of the West

By a dark stream is laid;

The Indian knows his place of rest,

Far in the cedar’s shade.”

Tom Moore was also a visitor in Kingston.

In the edition of his poems published in 1855 he describes the writing of his famous “Canadian Boat Song” on the St. Lawrence between Kingston and Montreal, a journey which then took five days, “exposed to an intense sun, and at night forced to take shelter from the dews in any miserable hut upon the banks that would receive us.” Moore adds that the magnificent scenery of the St. Lawrence repays all such difficulties.

Miss Agnes Maule Machar, novelist, historian and poet, a daughter of the Rev. John Machar, D.D., second Principal of Queen’s University, in “The Story of old Kingston,” refers to the first Canadian novel published in the English language as “St. Ursula’s Convent, or the Nun of Canada.” It was written by Mrs. George Hart and published in Kingston in 1824.

Charles Sangster was born in 1822 and was the first Canadian to use the material all about him in poetry. He was followed by Charles Mair, a student of Queen’s, whose poems were published in 1868. His Indian drama “Tecumseh,” written in blank verse in lines imbued with the splendour of the early days, will always be a work of importance to Canadians.

To-day upspringing shafts of elevators and spires predominate the gray batteries and the sixteenth century towers. Long iron rails stretch endlessly east and west. Yet they hardly touch a city that was born, and continues to be, a Port, a child of sleepy waterways whom commerce has failed to allure. For the ancient Seigniory of Cataraqui still holds a dream which time has made tranquil but never really disturbed.

“For a hundred and seventy years the Holding Place of the British against the power of enemies and the forces of nature”—so the present Prince of Wales in his first speech on landing in Canada in 1919. As he arrived at the quay the guns of the British, French and Italian warships fired the salute and the echoes reverberated among the hills that surround the town, so that it was hard to tell which was the gun and which the echo. Symbolic, this echo, of a Port that has always been a receiving station—an invitation rather than a command.

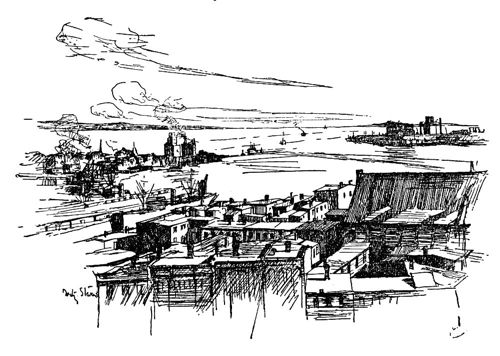

Looking down from the Citadel one sees the ancient town set on a sort of peninsula; a triangle, with its base to the east making a main harbour, the two sides formed by Bedford Basin, twenty miles in circumference, and by the North-West Arm, a three mile strip of water.

The Micmacs saw the harbour first and called it Chebucto—‘Great’—and after the Indians, true to Canadian history, came the French. Champlain named it Baie Saine or ‘Safe Harbour.’

The earliest history and romance of Halifax lies about this Harbour whose magnificence and safety decided her being. “Here gathered the Armadas for the reduction of Louisbourg in 1757-8,” says Professor Archibald MacMechan. “Loudon, Amherst, Boscawen, Rodney, Wolfe, Cook, saw the old Halifax of Short’s Drawings, with its stone-faced batteries lining the waterside and the old flag flying from the top of Citadel Hill, as it does this day. Here came Howe with his defeated regulars after being clawed by the buckskins at Boston. Here floated safe at last the thousands of Loyalists from New York who preferred exile to renouncing their ancient allegiance. In the bitter winter of 1783-4, delicately nurtured women lived in the floating transports while others huddled in the cabooses taken from the ships and pitched like wigwams all along Granville Street. Then during the long wars with the French Republic and with Napoleon the waters of the Harbour never rested from the stirring of keels coming and going. Ships of the line, frigates with intelligence, privateers, prizes, cartels with exchange of prisoners, transports with licence to make war on King George’s enemies. In the war of 1812 there were one hundred and six ships of war in this Harbour. On Sunday, June 6th, 1813, there came a procession of two ships—the little Shannon, proudly leading her prize, the Chesapeake, up to the anchorage by the dockyard. All yards were manned; the bands played; the good folk on the wharves cheered like mad, for at last the stain was cleansed from the flag which Dacres had hauled down on the Guerrier.”

“LOOKING DOWN FROM THE CITADEL.”

Tales of the blockade runners during the American Civil War, notably the episode of the Confederate cruiser, Tallahassee, which three Federal warships watched while she safely escaped by the Eastern passage, are also material for romance.

But these adventures were only a prelude for the mighty drama begun in 1914. Hereafter for five years Halifax perpetually echoed to the tramping feet of thousands upon thousands of Canadian soldiers, who will never forget her welcomes and farewells.

Founded in 1749 by the Hon. Edward Cornwallis as a rival to the French town of Louisburg in Cape Breton, Halifax (named after the second Earl of Halifax) superceded Annapolis as the capital of the province. St. Paul’s Church recalls the early days, in vaults where lie those whose names made the early history of Halifax. Among them are Lieutenant-Governor Lawrence, 1760; Admiral Durell, 1766; Baron Kniphausen, Lieutenant-Governor Wilmot, Baron de Seitz, Michael Francklin, some time Lieutenant-Governor, 1782; Lord Charles Grenville Montagu, son of the Duke of Manchester; Chief Justice Jonathan Belcher and others.

Government House has seen many illustrious inmates but never a gayer period than that of the administration of Sir John Wentworth, 1792-1808, when His Royal Highness, Prince Edward, fourth son of King George III, was stationed in Halifax as “Commander of the Troops on the North American Station.” It was during his stay in Nova Scotia that he was created Duke of Kent.

The records of those rough, warm, full-blooded times come with a heady flavour and an old-world tang to the thin asceticism of to-day.

Halifax from the first contained two predominating elements, Scotch and New England. To this add a dash of English blood and manners. Dr. Arthur W. H. Eaton in his ‘History of Halifax’ gives sidelights on the stir caused in the breasts of estimable and aristocratic New Englanders by the doings of Royalty in the Eighteenth Century. Royalty in the old days was rampant in Halifax. Yet no New Englander among them was more democratic than the son of plain ‘Farmer George’ who used often in Halifax “to put his own hand to the jack-plane and drive the cross-cut saw.”

The Duke of Kent, was not, however, a stern observer of the rules of his mother who, Thackeray says, regarded all deviation from the strict path of conventional morality with disfavour and “hated poor sinners with a rancour such as virtue sometimes has.”

The Duke loved his neighbour as himself, and remained the friend as well as the steady patron of Nova Scotians until his death. His estate was a veritable feudal village, and his lasting public memorial in Halifax is the Citadel, and the Harbour forts which he built and made well-nigh impregnable. But his residence was illuminated by a romance which his godly mother and his virtuous daughter, Queen Victoria, could not but deplore. It had to do with a lady who accompanied him from the West Indies when he came to Halifax, and, “as much as she was permitted by society, shared his social responsibilities and, sincerely attached to his interests and to his person, assiduously ministered to his wants.” In Martinique, the Prince found Madame Alphonsine Therese Bernardine Julie de Montgenet de St. Laurent, Baronne de Fortisson. This noble French woman was his companion during his stay at Halifax, and afterwards until nearly the time of his marriage to the widow who was to become the mother of Queen Victoria.

Soon after the Prince came to Halifax he leased from Sir John Wentworth a small villa set in a beautiful property several miles out of town and quite near the post-road which winds around Bedford Basin. This he beautified and adorned until it became a spacious residence after the Italian style, the gardens containing “charming surprises;” an artificial lake, several Chinese pagodas and Greek and Italian imitation temples. A little Rotunda, containing a single room, richly decorated and hung with paintings, was the special joy of the Prince. It was built for dancing.

Now, all that remains of the gay feudal village called “Prince’s Lodge” is this Rotunda, made over as a dwelling-house, in some prosaic after-time, and now no longer occupied. As early as 1828, Haliburton says: “It is impossible to visit this spot without the most melancholy feelings. The tottering fence, the prostrate gates, the ruined grottoes, the long and winding avenues cut out of the forest, overgrown by rank grass and occasional shrubs, and the silence and desolation that reign around, all recall to mind the untimely fate of its noble and lamented owner, and tell of affecting pleasures and the transitory nature of all earthly things . . . A few years more and all trace of it will have disappeared forever. The forest is fast reclaiming its own, and the lawns and ornamental gardens, annually sown with seeds scattered by the winds from the surrounding woods, are relapsing into a state of nature.”

The social brilliancy of the days of the Wentworths is still a legend in Halifax. We hear of splendid and “most exclusive” entertainments at Government House. “Royal guests and the officers of the army and navy assembled for sumptuous entertainments”, says the Halifax Gazette of 1795. “Cotillions above stairs and during the dancing refreshments of ice, orgeat, capillaire, and a variety of other things . . . supper at twelve . . . Among other table ornaments which were altogether superb, were exact representations of Hartshorne and Tremain’s new flour mill, and of the windmill on the Common. The model of the lighthouse at Shelburne was incomparable, and the tract of the new road from Pictou was delineated in the most ingenious and surprising manner, as was the representation of our fisheries, that great source of wealth in this country.”

The name of Joseph Howe is bound up with the history of his native town. He was born in a cottage on the Arm. His father was a United Empire Loyalist, who became King’s Printer and Post-Master General of Nova Scotia. Young Joseph was early sent to a printer’s office, and later became a journalist, a politician and a Lieutenant-Governor of Nova Scotia. He led his province through the stormy period of the fight for responsible government, without bloodshed. In his “Speeches and Public Letters” much of the history of his day and generation is to be found. In 1835, when he owned and edited The Nova Scotian, the celebrated “Sayings and Doings of Sam Slick” began to appear.

Thomas Chandler Haliburton was a native of Windsor, N.S., and a student of King’s College, but Joseph Howe and Halifax beckoned him. In his delineation of Sam Slick, type of the Yankee pedlar who perambulated Nova Scotia in those days, Haliburton became not only the founder of Canadian but also of American humour. The wit that sparkles through the quaint series of volumes published in London and Halifax in the ’30’s has been copied by a generation of authors less honest than himself.

Marshall Saunders, Macdonald Oxley, Grace D. MacL. Rogers, Dr. J. D. Logan, poet and critic, are all associated with Halifax through birth or habitation.

Robert Norwood, the poet, now of Philadelphia, loves the old city as a part of his youth, and so does Basil King the novelist. They are both King’s College men, and something of the mellowness of that sweet old place remains in their memories. Robert Norwood found great joy as a child in the wharves and shipping up and down the Harbour. “Water Street has always held for me a rare charm” he says. “I would walk up and down it, turning in at every quaint wharf just to hear the men talking and to watch them at their tasks. I loved colour, and the effect of the sun on the wharves with their bales of merchandise lives in lines in my poem ‘Paul to Timothy:’ ‘Tall, Bacchic amphora, and the perfumed bales of Tyrian purple along the quay; the men with arms like anchor cables in their strength.’ The Hill with its Fort and guns was also a place for dreams. The Citadel was a great slope of green that melted at last into the sooty houses below, but beyond the roofs was the sea and the islands, and ships moving up and down the Harbour.”

Speaking of his residence here some years ago when he was rector of St. Luke’s Cathedral, Basil King calls Halifax “one of mankind’s free ports.”

“It is in contact with the great big world to a degree not surpassed by New York, San Francisco, Liverpool or Yokohama. It has a settled life, it is true; but its chief life is that of a magnificent touch-and-go, with a splendid variety of contacts. Going out to dine, your neighbor on one side might be from Gibraltar and on the other side from North Dakota. You could never tell, or speculate beforehand. Varieties of friendship were on the same scale. Somewhat like those formed on board ship, they were quick, warm, impulsive, and short-lived. There was too much of the here-to-day and gone-to-morrow in all life to give much social permanence; but in compensation there was much of rapid exchange . . . It was not so much Halifax that impressed itself on me during the years I spent there; it was first the British Empire; and then it was the world. What I drew from my life there was a world-view through lens of the British Empire. In some ways it is the gift of supreme importance in my life.”

Dr. Archibald MacMechan of Dalhousie College has written much of storied Halifax, and Mr. Henry Piers calls attention to the fact that as early as 1830 there were Art Exhibitions in what was, at that time, a small town.

But there is the record that above all others is written in terms of heroic deeds and great sacrifices that followed the overwhelming disaster caused by the explosion of munitions of war in the harbour in December 1917.

The Wagwaeltic Club on the North-West Arm—mysteriously beautiful is the Arm with its old trees banked down to the water’s edge—the Public Gardens, the drives through the Parks over roads made when the British Regulars were established at the barracks, is a part of modern Halifax, but there are also moats and cannon, subterranean casements, hidden tunnels and secret defences concealing what mystery! Here something crouches, ready to spring forward at a word, though the attitude of dear dilapidated Halifax is beautifully careless. One could hardly expect, and certainly would not desire her to be neat. For she keeps perpetual open house for many and strange guests. When the sea-doors of Quebec and Montreal are locked she is busiest. The Naval Institute is the second largest in America, and to its friendly doors, year in and year out, come all sorts of seamen, many of them sailors in distress, for Halifax is often a ‘port of missing men.’

Steep streets and the ringing of church bells; the distant sea; sunset, and the lovely irregular lines of masts and spars and rigging; the view of a hazy hill topped by a martello tower;—these are some of my pictures of St. John.

An old town long ago linked by trade relations with the West Indies, a port filled with foreign sailors, it contains bales of romance never yet unpacked. I remember crossing Queen Square on a fine spring morning with a lover and historian of his city who spoke not of beauty spots, but of old buildings. “I could show you some shacks, hardly taverns, just shacks, where rum was stored and barrels were opened; and the tales of far lands that came in with the cargoes, the songs, the gestures of the South, were all a part of the old days of St. John.”

When this city plays the pageant of her past she will have nearly every romantic element of the early days to draw from. As she is the oldest incorporated city in British North America such pictures mean history. Four years before Quebec was founded, Champlain cast anchor at the mouth of the river and christened the region in honour of the Saint whose day it was. That was on the 24th of June, 1604. Before that the site was known to the prehistoric peoples. The Micmacs and the Malicites loved it; ‘Glooscap,’ greatest of their demi-gods, had favoured it. Their descendants wondered as they saw a white man plant the golden lilies of France.

The next picture has to do with the Lady of St. John. Her husband, Sieur La Tour, who had taken a desirable site for his French fort, was a friend of Louis XIV. Lady La Tour was a Huguenot and her dream was to found a colony. D’Aunay Charnisay, an enemy, opened a campaign against them. La Tour slipped away to Boston for help. Charnisay entered the Fort. And then occurred the heroic defense by Madame La Tour, who pitted all her slender resources against the enemy, only to meet with tragedy. Her garrison was hanged, and the lady herself died a few weeks following her husband’s return. Her dream lives on in a poem by Whittier and a story by Harriet Chesney. La Tour married his rival’s widow, and for ‘diplomatic reasons’ became a British subject.

The story of St. John is cast in barbaric colours during the hundred years that it was a trading post visited by passing sailors and soldiers of fortune from many lands, and for ever the scene of the jealous little wars of fur traders.

Then French Acadia was given by the Treaty of Utrecht to Great Britain. In 1762 came the first valiant Loyalists—a few families from Massachusetts under the leadership of Captain Francis Peabody. A little later arrived James Simonds, William Hazen and James White, all notable pioneers. The old Hazen house built in 1773 is yet standing, much renovated, at the corner of Simonds and Brook Streets. In 1783 there landed twenty shiploads of United Empire Loyalists. Market Slip where they disembarked may look more picturesque to-day—a ribbon of water lined with shipping, great buildings as a background—but to the Loyalists it was a hope. They built St. John and built it well.

Pictures of this era would show robust gentlemen like the renowned James Simonds, of whom the Venerable Archdeacon Raymond writes in his record of Pioneer Days, who brought the first English bride to the port. She was one of the three lovely daughters of Captain Peabody, who himself served with distinction at the Siege of Quebec a few years before. Early marriages were the rule, and so were large families. Sarah Le Baron of Plymouth, Massachusetts, was only sixteen when she married William Hazen, and James Simonds’ wife was little older. They filled their long lives full of the many interests of fast-growing families and the adventures of a young and thriving community.

There was a motley crew encamped about this Post. The Indians, the original French Acadians, and the workmen who had come with the Loyalists were on the whole wonderfully friendly with one another. Hard times threatened, but did not overcome them. The Loyalists believed that they could conquer the land and even defeat the tides. A pageantry of labour ensued.

For always the land had been harassed by the tides of the Bay of Fundy; murmuring, menacing all devouring tides, full of mystery and fate for the first comers. James Simonds and his companion, White, organized a tremendous enterprise with the result that an aboideau was built, and other dykes were made, and the great marshes of Tantramar were redeemed from the water. Industry was encouraged and paid for. Building operations were begun, and the first warehouses raised in expectation of the industry in shipping. The Loyalists also made themselves stately homes of the colonial type. There were bursts of social gaiety, as when the Duke of York moved his Court for a short time from Halifax to St. John. And there was the ‘old Coffee House’ where the merchants of those days used to gather. To-day the Bank of Montreal stands on a spot that they say was originally bought for a Spanish doubloon and a gallon of old Jamaica. As the city of the Loyalists grew rich through its enormous lumber trade, and famous for fast sailing ships, one can imagine how far reaching became the stories told in the taverns!

“THERE ARE DREAMS GO DOWN THE HARBOUR WITH THE TALE SHIPS OF ST. JOHN.”

In 1784, New Brunswick, which had been a part of Nova Scotia, became a separate Province, and a Royal Charter was granted to the city of St. John. It was a quaint document. To the Mayor was given the office of “garbling of Spices, and the right to appoint the bearer of the great beam,” while the important clauses regarding fishing and fowling rights are set out in language suitable to the Letters Patent of the Hudson Bay Company. Ward Chipman, the maker and recorder of this same Charter, was also Counsel for the Crown. We hear of his successful attempt to abolish the practice of slavery in New Brunswick. Thus did the ‘adherents of despotism,’ as the much abused Loyalists were dubbed, accomplish a reform sixty years before the people of the United States. In the stately old Trinity Church there is an interesting memorial of those days in the Royal Coat of Arms removed by the expatriated Loyalists from the Council Chamber of the Town Hall of Boston.

To-day there is not a great deal in the outward aspect of the place to remind one of a romantic past. St. John is sufficiently picturesque in herself, and beautiful enough in natural surroundings to make one fully content with the present. Still at the foot of Middle Street, in West St. John, may be seen the remains of earth works, marking the site of Fort La Tour erected in 1631. But, alas, the Electric Light Station now stands on the site of the old French Burial Ground where lay Governor Villebon and the heroic Lady La Tour. Indeed the city does not even possess a statue in honour of the latter. Everyone goes to see the old Burial Ground lying near King Square, once on the outskirts of the town and still tree guarded, where many of the founders of St. John are buried. The Court House is an elderly and dignified building that fortunately escaped the fire of 1877 which destroyed two-thirds of the city.

In the two beautiful city Squares, King and Queen, a good deal of the life of the city centres. Many of the prominent houses are nearby, and still on summer evenings that almost archaic entertainment, a band concert, may be enjoyed.

King Square, which in any other town would be called a Park, is that level plot situated at the head of King Street and extending to Sydney. Therein the visitor finds a splendid monument erected to the memory of Sir S. L. Tilley, who was twice Lieutenant-Governor of New Brunswick and at one time Finance Minister of Canada. The statue is the work of Phillippe Hébert of Montreal, the Canadian sculptor. There is also a statue to a brave youth who during a wild storm, lost his life in a fruitless effort to save a boy from drowning. The Court House faces on this Square.

In Queen Square, Champlain, eager even in cold stone, points triumphantly to his harbour, and the old French cannon from Fort La Tour has been set up.

On Carlton Hill a Martello tower was erected to mark a certain preparedness in 1812. It is one of several examples of a romantic type of architecture to be found in Canadian towns and cities. This one was built by the Royal Engineers, then stationed in St. John, who made its walls of stone fully six feet thick.

“TO MARK A CERTAIN PREPAREDNESS.”

Visitors to St. John may some day enquire about a book shop kept in the ’60’s by ‘Messrs. Fillimore and De Mille.’ That is if they are admirers of “The Dodge Club Abroad.” Some day a literary or historic society may go even farther, and actually look up the house in which James De Mille was born in 1833, if by chance it still remains, and note it by a name-plate. For here lived a pioneer of literature in this land who served well his day and generation. It was in 1868 that the Harpers published a serial which is believed by authorities to be a forerunner of Mark Twain’s “Innocents Abroad.” The work reappeared in book form, running through thirty or forty editions. For fifty years the publishers have steadily sold it, and are still selling it. Like the work of Haliburton its life is in its humour. But De Mille wrote a more notable work in “The Strange Manuscript Found in a Copper Cylinder.” As Canada then had no publishing houses he sent what he wrote abroad, and found a wide public. But he lived and worked in his own country. His father was a well to do ship-owner and merchant of St. John, and a Puritan of the Puritans. A student of Acadia College, De Mille afterwards married Anne Pryor, a daughter of the first President of Acadia, and two years later was called to the Classical Chair which he resigned to take that of English literature at Dalhousie, Halifax.

As remembrance the permanent pictures of St. John have to do with her unique setting. She can transport you, in a morning’s drive through Rockwood Park, to Scottish hills and gemlike lakes. An hour later you are on the Atlantic seaboard, facing dancing waves, or else black rocks and tawny sands if the tide is out. The fascination of her rivers is inexhaustible. The ‘Reversing Falls’ is of course one of the wonders of the world, and any guide book will explain the action and reaction of the swirling waters in the winding gorge. But to be interesting it should remain a mystery. I remember two great bridges, shelter houses and rainy weather. I remember that waiting for the tide, staring at red mud where I had imagined glittering waters, seemed more awesome than the spectacle itself, and the rocks, like those of Niagara, more wonderful than the waters.

We sailed out of the harbour for Boston, as so many from the shores of New Brunswick have sailed, bound by the friendship of many a year. I thought of Bliss Carman and his love for his “port of heroes;” “the barren reaches by the tide,” “the long dykes with uneasy foam,” “the marshes full of the sea.” Footsteps of beauty haunt one here, partly because his poetry had haunted one’s childhood. In departing we journeyed with him—

Past the light-house, past the nun-buoy,

Past the crimson rising sun.

There are dreams go down the harbour

With the tall ships of St. John.

And some miles up the river one comes upon the capital of New Brunswick, Fredericton, lying all blue and gold in the sun, encircled by her hills and rivers.

The traveller sees a peaceful yet thriving place, a cathedral city as well as a capital, the military centre of the Province, the seat of the Supreme Judiciary and of the Provincial University. He knows that it is also a centre of lumber trade, and a summer paradise on account of good roads, good fishing, and the joys of motor boating.

The historian harks us back to the days of Villebon, when the site of the present city was an Acadian settlement called St. Anne’s Point. It was an Indian camping place as well, and down the St. John came the canoes of the Malicites, piled with beaver skins. They came to trade with the gentlemen adventurers of France. Villebon, Governor of all Acadia, made the fort just opposite St. Anne’s at the Nashwaak’s mouth his citadel, in place of the abandoned Fort Royal. No one pretended to look for peace in those days. If it was not the Indians it was the New Englanders. Villebon had a certain ‘old Ben Church’ and his fleet of New England vessels to fight. But the Nashwaak guns were too many for them.

Generations later the Loyalists built St. John, and when New Brunswick was made a Province, the first Governor, Thomas Carleton, must have remembered the ancient prowess of St. Anne and her invincible fort, for he made Fredericton its capital. In a little building still standing near the present Queen’s Hotel, known as the King’s Provision Store, the General Assembly met for its third session in July 1788. Two years before the first sermon ever preached in the settlement was delivered here. It was later remarked by the Rev. Samuel Cooke, the Rector, that the inhabitants of Fredericton number four hundred, “of whom one hundred attend church, but many of ye common sort prefer to go fishing.”

I do not know who first named Fredericton the Celestial City, but I think it must have been a poet, for the vision of the poet includes all that the historian knows and all that the traveller sees. That vivid background, Indian haunted and pierced by the conquering note of the French, sharpens his imagination, but he also feels the romance of his city of to-day.

The shimmering waters that surround it, rimmed by green hills, suggest to him certain celestial qualities. They imply a life of leisured intellectual pursuit, an unhurried happy state that seems to mark this community as a thing apart from the usual scramble of modern life.

In a charming account of his early home, written by Charles G. D. Roberts years ago and never before published, the well-known poet and short story writer describes the beautiful setting of Fredericton. “Drawn about her, the broad and gleaming crescent of the St. John, and opposite to her wharves the lovely tributary streams, the Nashwaak and the Nashwaaksis.”

To look over the city from the cupola windows of the University buildings, across Queen’s Park and the spires of the church steeples, piercing the elm tops half a mile away, is to see far. Beyond the house roofs there is the blue sweep of the river and the white villages of St. Mary’s and Gibson, and further still the town of Marysville where the lumber king, Alexander Gibson, rules his domain. The blue river is often dotted with the sails of wood boats. To quote Mr. Roberts again, “Here and there puffs a neighbouring tug, towing an acre or two of dark rafts, or a gang of scows piled high with yellow deals. On all sides is evidence that Fredericton is the centre of the lumber industry . . . The scene is one that fills the eye with gracious colour and harmonious composition. In the Autumn when the trees flame out with amber and scarlet and aerial purple, when the air swims with a faint violet haze, the picture is one that neither the painter’s brush nor the poet’s pen can do more than dimly suggest.”

“THAT QUAINT, RED BRICK HOUSE, THE RECTORY.”

A gentle charm lies everywhere. I remember the overhanging elm trees, which it seems to me should be part of every Cathedral town. The Cathedral itself, though small and plain to the point of austerity, is one of the most perfect examples of Gothic architecture on the continent. Queen Street, with shops on one side and lawns and trees and river glimpses on the other, is equally typical of tranquil Fredericton. Speaking of the public buildings on Queen Street, Mr. Roberts refers to “the severe gray pile of the Barracks where the men drill behind high walls, that the glints of their scarlet may not bedazzle the passing demoiselles.”

The favourite residence portion of the city is within clear call of the Cathedral bells. Here are most of the handsome houses and the well kept grounds. Below the Cathedral, where the street runs close to the water’s edge, where the bank is lined with willows, where rafts tie up at night along the shore, and where the houses all look out across the river, there stands a dwelling which should be dear to American hearts. The author of “Lob-Lie-by-the-Fire” and “The Story of a Short Life” is beloved of her compatriots. This plain brown house, with the bow windows and the river view, is full of memories of Juliena Horatia Ewing who lived here while her husband, a major in an English regiment, was stationed at Fredericton. Another guest not so highly distinguished lived a few hundred yards below Mrs. Ewing’s house, Benedict Arnold, great General and great traitor. At the creek’s mouth near his house, he built small vessels for the river trade.

But the house best known and loved by Canadians in general, naturally within clear call of the Cathedral bells, is the Rectory of the Cathedral, that quaint red brick house now famous as the Roberts’ homestead. Here lived the Rev. George Goodridge Roberts, Canon of Christ Church Cathedral, with his wife Emma Wetmore Bliss, and here Charles G. D., the eldest son, a daughter, Elizabeth, now Mrs. S. A. R. MacDonald, Theodore Goodridge, a younger brother, and their cousin, Bliss Carman, all grew up in the happy atmosphere of the Rectory.

Lloyd Roberts says, “It is any day, any month of the year—for what are seasons among friends?—when word goes round among the Clan that the Rectory is entertaining. That means four hours of undiluted joy, of unrestrained exuberance, a democracy of action that sets aside little differences and tumbles everyone helter skelter into the common basket of enjoyment . . . There is no master of ceremonies. Possibly the youngest and noisiest—probably yourself—shouts for ‘My ship came home from India,’ and the evening is off to a glorious start. How the dust flies from the flowered carpet and the black horsehair sofa! How the knickknacks tremble on whatnot and mantel! How the framed pictures of the animals disembarking from the ark and of Abraham offering up Isaac, sway on their wires until they hang askew! And this is the drawing-room where one came and went sedately on ordinary week days, careful not to disarrange furniture or leave a cushion awry. Grandpa’s explosive gusts, that would have shaken walls less thick, are topped by shrieks and children’s trebles until all is pandemonium and the neighbours, half a block off, shake their heads sympathetically over their knitting.”

THE OLD GOVERNMENT HOUSE, FREDERICTON.

Mrs. C. F. Fraser has written a delightful account of the Rectory in the days of “dear Rector Roberts,” as he was affectionately called by the town. “He was,” Mrs. Fraser tells us, “a scholarly gentleman of old English descent. Of winter evenings the favourite gathering place was about the great centre table in the sitting-room, where the young people were wont to read aloud for each other’s amusement the rhymes or stories which the day had called forth. . . . In summer weather the great old-fashioned garden, haunt of all fragrant and time-honoured flowers, was the favourite spot. There in and about the hammocks with their cousin, Bliss Carman, extending his great length on the turf below, and shaggy Nestor, wisest and most understanding of household dogs, wandering about from one to another for a friendly word or pat, and a score of half tame wild birds fluttering and twittering in the trees above, the young people did indeed see visions and dream dreams. It is of this scented garden that Elizabeth, the sister, too frail to companion her stirring brothers in the active sports in which they delighted, sings so beautifully in many of her poems.”

Associated with the academic life of Fredericton for sixteen years, and a vital force in Bliss Carman’s career, as in that of so many of his students now scattered world-wide, was Sir George Robert Parkin, the well known educator, author, and lecturer on Imperial Federation.

To a sportsman and naturalist the environs of Fredericton, its great forests and the waters, are of more importance than the town itself. The moonlit nights of October are the time for moose-calling; and still in the wild part of the woods, bears, lynx and wild-cats are to be found. The great salmon waters of the Miramichi, and the trout waters of the Tobique, the Squateooks or Green River, the cock and snipe covers and partridge grounds are all fairyland to the hunter as well as to the writer. Out of such a background have come great stories such as “The Heart of the Ancient Wood,” “Kindred of the Wild” and “Earth’s Enigmas” by Charles G. D. Roberts. The Rev. H. A. Cody of Fredericton has written a good lumbering story in the “Fourth Watch,” and the woods of New Brunswick have attracted other than our native writers. Dr. Henry Van Dyke has used them for many an essay and story, and so has Dr. S. Wier Mitchell, the Philadelphian novelist, in “When All the Woods are Green,” a charming idyll of out of door life on the Restigouche.

It may be that only one out of every hundred of the travellers who tarry at the Port of St. John, knows the ancient lovely Capital of the Province, for Fredericton has not yet been discovered by the tourist. Charles G. D. Roberts says that is because “she has sat long aloof, Narcissus-like, admiring her own image in her splendid threshold of water, too loftily indifferent to proclaim her merits to the world.”

Ottawa, the capital of Canada, has been called “The Washington of the North.” No comparison could be wider of the mark. Ottawa is as far removed from Washington as from Rome or Gibraltar. It is true that the thought of a European town may dimly arise in the mind of the observer as he feels the domination of the Gothic Tower on Parliament Hill, and is aware of the lordly mass of buildings set out in splendour on the promontory jutting into the river. But the effect is not continental. The true traveller will tell you that is essentially, almost indescribably, Canadian. Waterfalls, rivers, canals, locks, bordering forests, ridges of glorious rock—these form an essential part of the picture of Ottawa. A wine-like, bracing air gives her the divine essence of youth. Her classic buildings are only the mental side of her.

Like all capitals, Ottawa has to talk a great deal. But since 1914 she has learned some silences. Then too she has for years been loved by a little race, nearly always lost among the talkers, the alien race of poets. Ottawa, indeed, is a mingling of politicians and poets,—Macdonald, Tupper and Laurier, but also Lampman, Campbell and Scott. If there had not been a poet in Macdonald and in Laurier, Canada would have been less a land than she is. Had there not been a moulder and maker in Scott and in Campbell, their poetry would have missed its mark.

I am glad that the statue of Galahad, the shining boy who typifies, in this case, the willingness of Canadian youth to give its life for a friend, was standing on Parliament Hill for years before 1914. I think that many a soldier going out to the greatest war may have saluted it in passing.