* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Wooden Ships and Iron Men

Date of first publication: 1924

Author: Frederick William Wallace (1886-1958)

Date first posted: April 16, 2024

Date last updated: April 16, 2024

Faded Page eBook #20240407

This eBook was produced by: John Routh & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

WOODEN SHIPS AND IRON MEN

Frederick William Wallace

The story of the square-rigged merchant marine of

British North America, the ships, their builders and

owners, and the men who sailed in them.

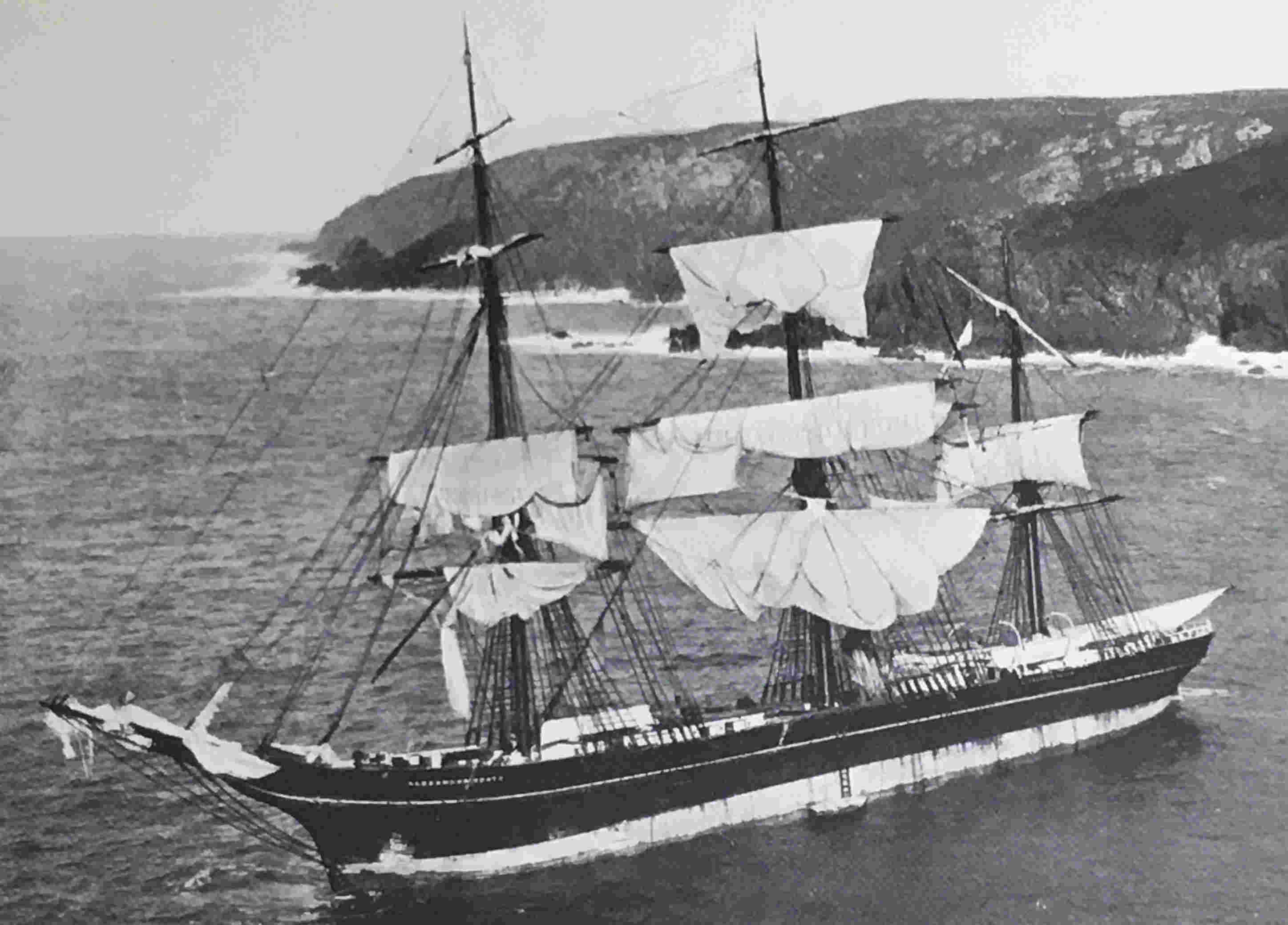

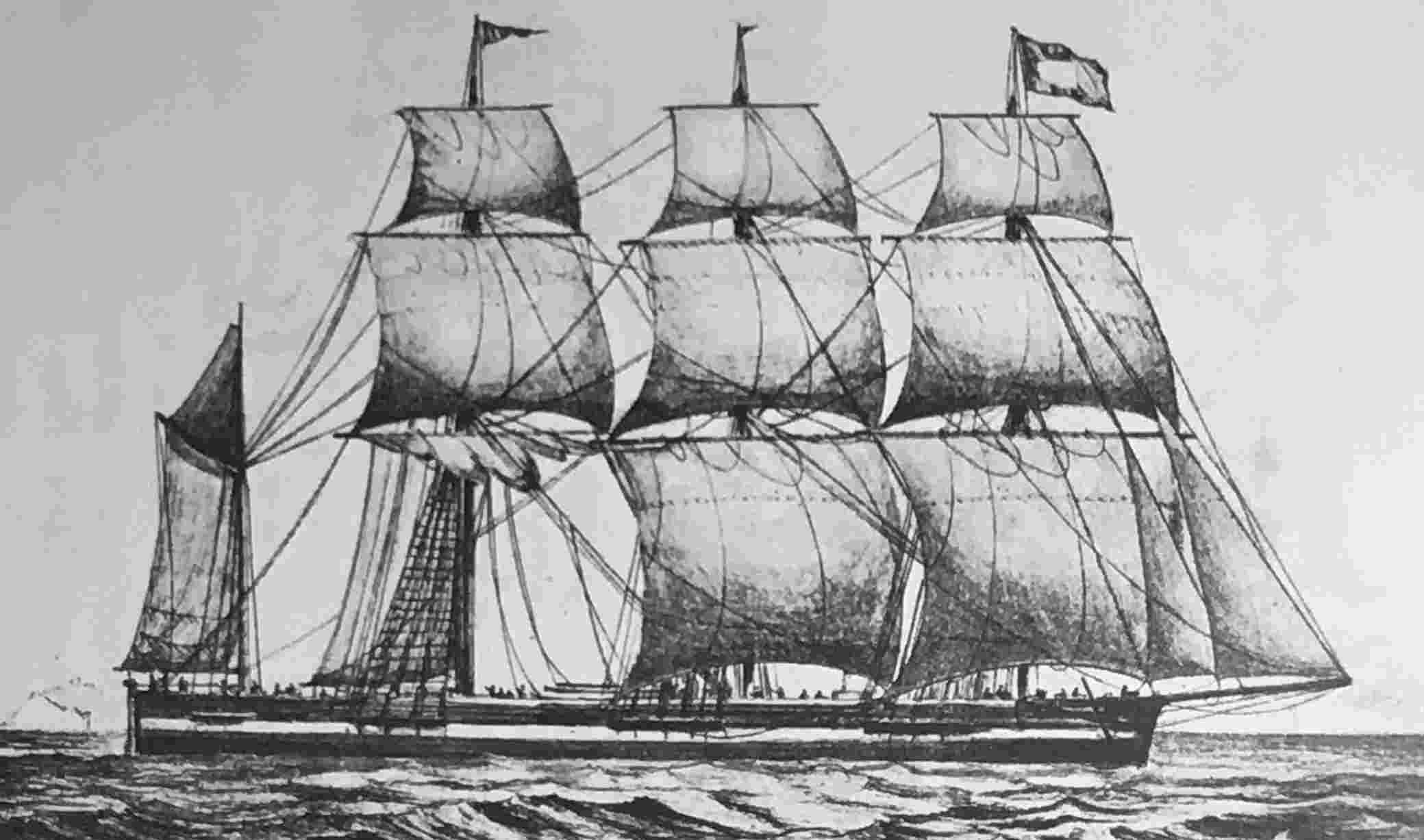

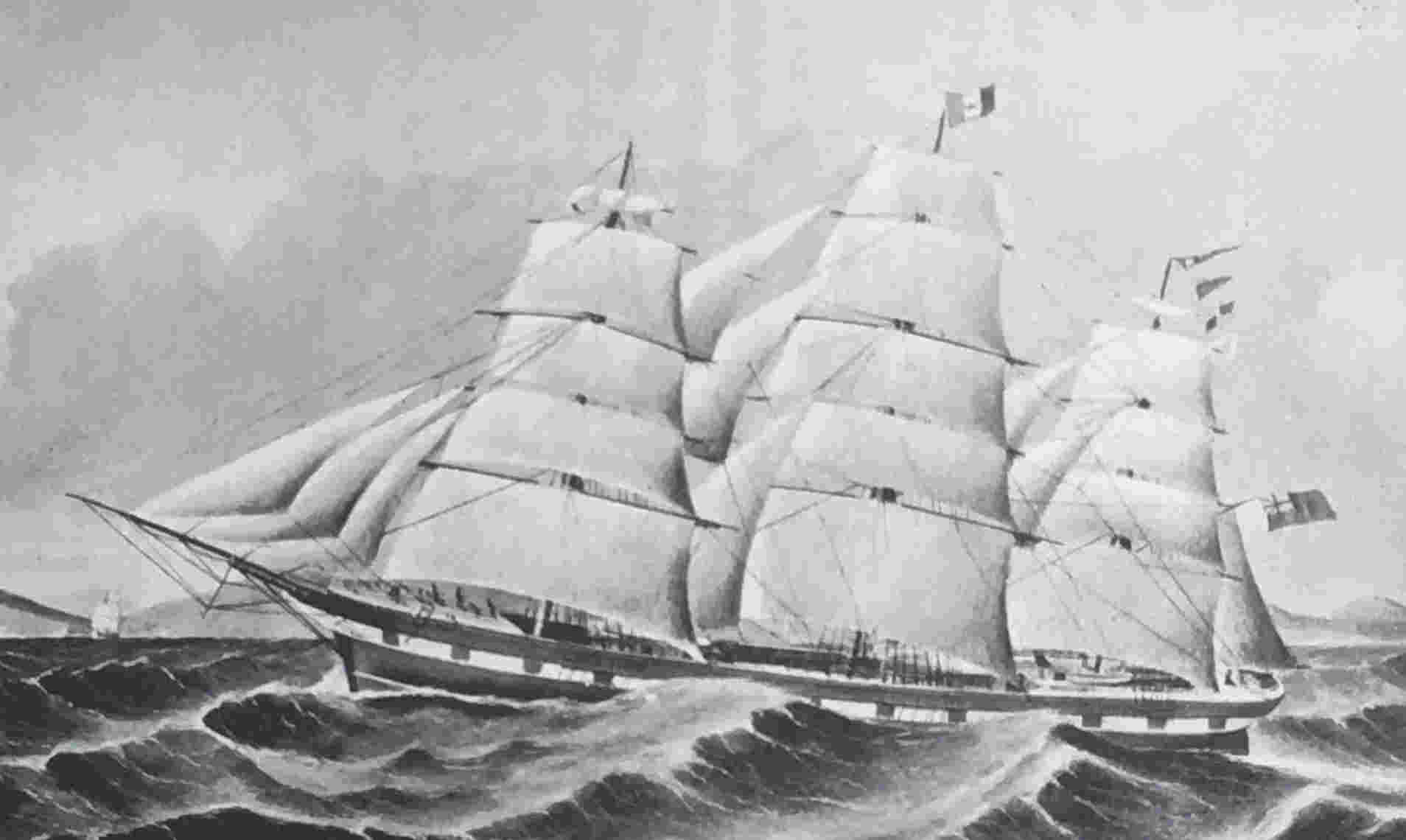

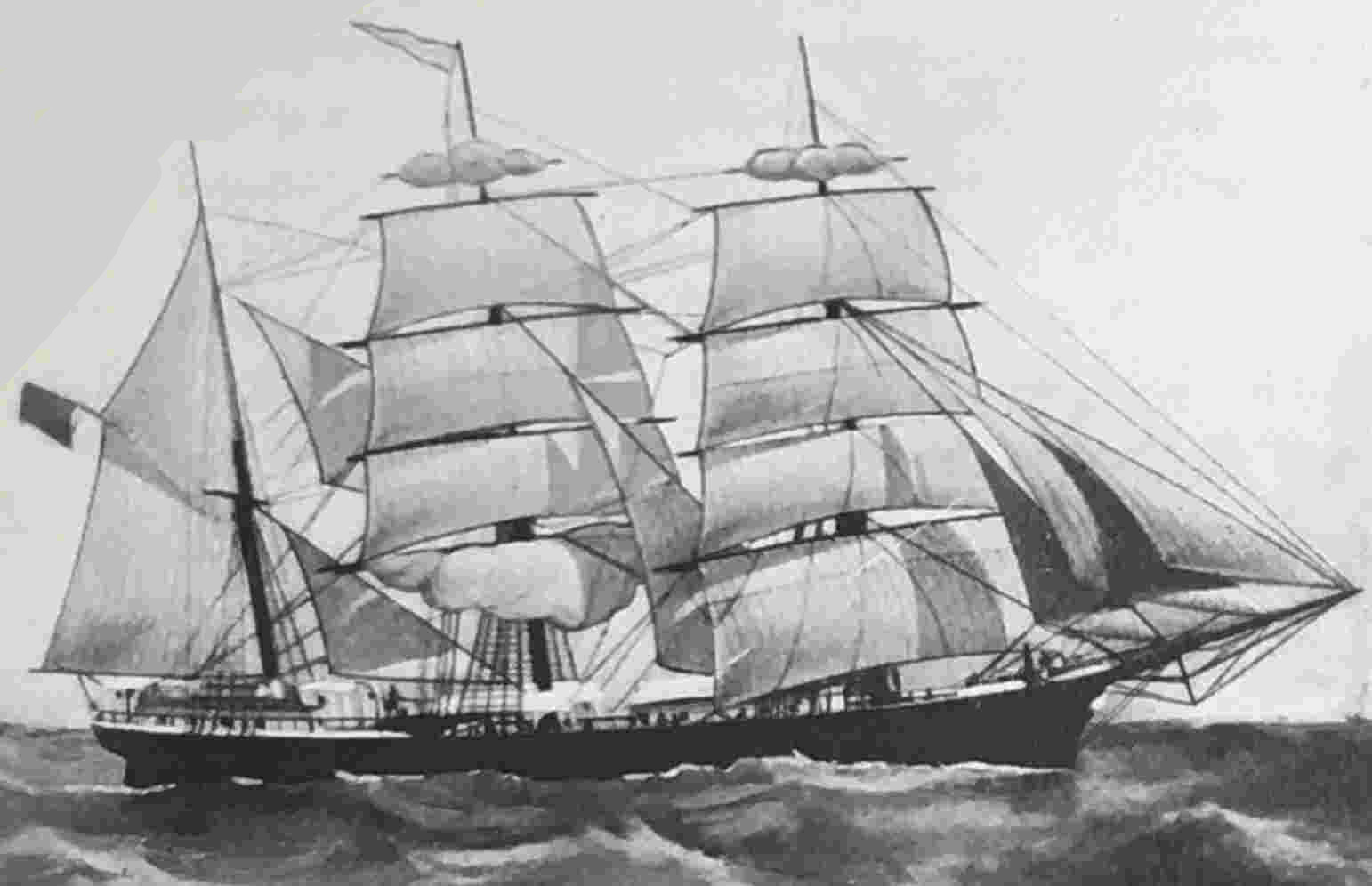

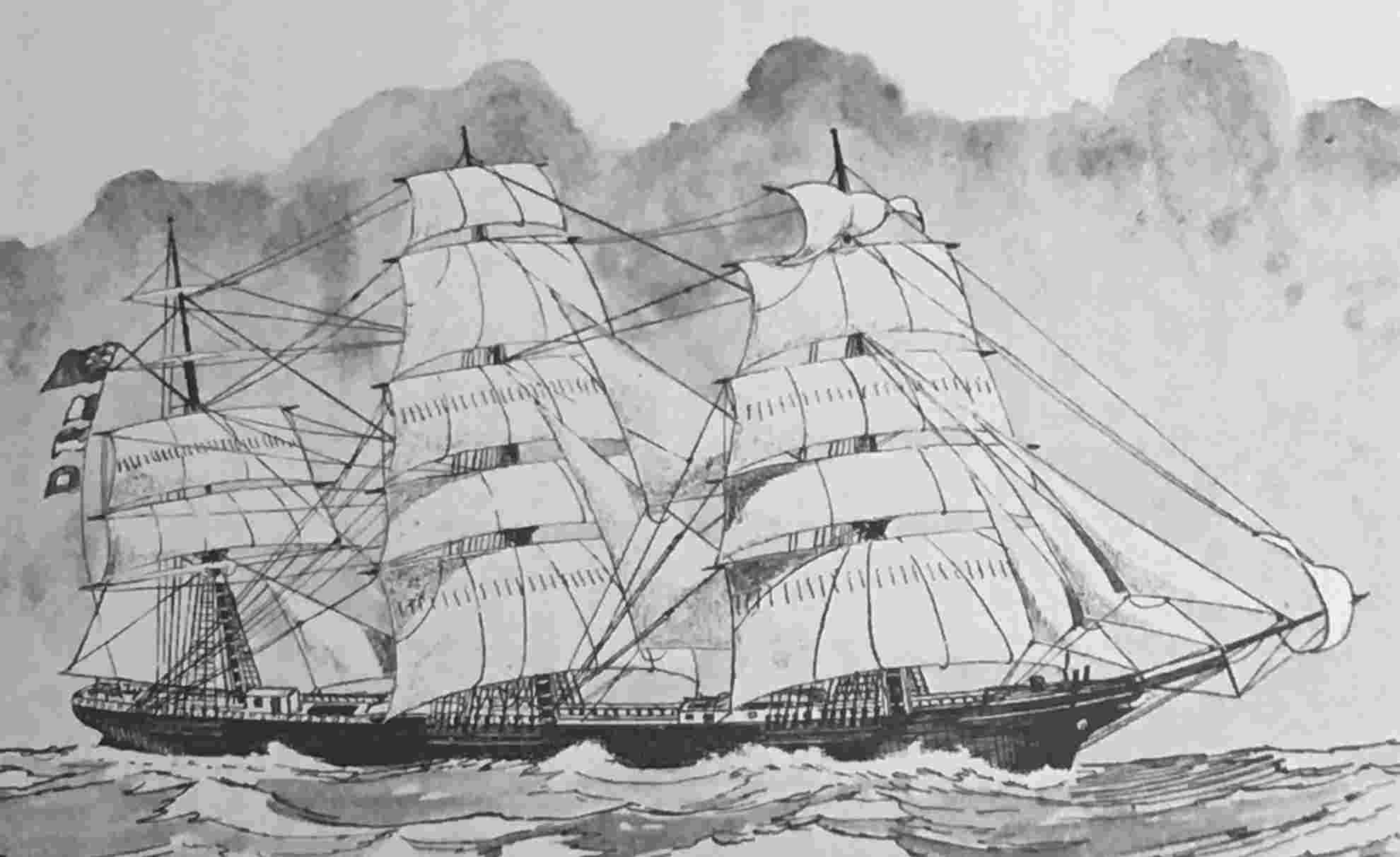

Ship “Alexander Yeats,” 1650 tons.

Built 1876, St. John, N.B. Said to be the finest ship built in St. John. Wrecked near Penzance, Eng.

Copyright © Frederick William Wallace, 1924

First published in the United Kingdom by

Hodder and Stoughton, 1924

Printed in Great Britain by

Biddles Ltd., Guildford, Surrey,

for White Lion Publishers,

138 Park Lane, London W1Y 3DD

TO

JAMES JOHN HARPELL

WITH WHOM THE AUTHOR WAS ASSOCIATED

FOR MANY YEARS

AND TO WHOM HE IS INDEBTED FOR

MUCH ENCOURAGEMENT AND

HELPFUL INTEREST

The compilation of this record was undertaken as a labour of love and to save from oblivion the facts regarding an era of maritime effort and industry which is one of the most inspiring pages in Canadian history, but which, unfortunately, has not yet been adequately appreciated. The gathering of the information presented in the following pages has been carried out under many handicaps. To be really comprehensive, it should have been written forty years ago, when the wooden-hulled windjammers and the intrepid native seamen who commanded them were still in existence, though in the state of dissolution. Two decades have elapsed since the last of the big square-rigged ships was launched, and these twenty years have seen the passing away of the ships, the builders, and the seamen.

I have been collecting information on the subject for many years. But owing to the fact that first-hand sources of information were rapidly vanishing, I have hastened the task of compilation in the hope that the publication of this record might result in an effort being made by public bodies to preserve whatever remains to-day of interest and value in connection with the old-time shipping of the Maritime Provinces of Canada. Great Britain and the United States have individuals and societies who have seen to it that all records pertaining to the shipping history of their respective nations are collected and carefully preserved. In Canada, unfortunately, other interests have overshadowed the necessity for recording past glories, and that in spite of the fact that one of her ablest men, Joseph Howe, once said: “A wise nation preserves its records, gathers up its muniments, decorates the graves of its illustrious dead, repairs the great public structures, and fosters national pride and love of country by perpetual references to the sacrifices and glories of the past.” And Nova Scotia’s great statesman spoke thus to his fellow citizens at a time when the Province was entering the golden years of its maritime greatness, when Nova Scotian ships were sailing every ocean and Nova Scotian seamen were regarded as the most capable of their profession. The men who built, owned, and sailed the splendid British North American ships of the ’sixties, ’seventies and ’eighties have mostly all passed on to meet the Great Pilot. With their passing went much valuable maritime history, and the same has been irretrievably lost.

Without detracting from the work they have done, but rather as an apology for my own shortcomings, I might say that the compilers of shipping histories in Great Britain and the United States have had a much more satisfactory field of research. To these writers, great masses of authentic and carefully recorded information were available. In the Maritime Provinces of Canada, I found a singular scarcity of definite data regarding the days of the wooden ships. Few records were kept, and in many cases such records were destroyed, as so much of value in Canadian history has been destroyed, through storage in wooden buildings afterwards consumed by fire.

In this volume, I have made use of every scrap of information that has come to me. Little has been rejected, as almost every item will be of some value, possibly, to future historians. Some of the facts were obtained from my father and other seamen who sailed as masters, officers, and before the mast in British North American ships, as well as from ship-builders, owners, and persons who lived during the palmy days of sailing ships. The value of these verbally-imparted data cannot be over-estimated, especially in a country where written and printed records are scarce. But where memory is the source of information, error is prone to creep in. It is quite possible that errors have occurred in this record, but I am hopeful that this volume will constitute a basis for future research workers in the field, and they will have an opportunity of correcting my mistakes as well as of throwing still more light upon the material contained herein.

I am indebted to many friends for assistance and information in the writing of this history, and, as space prevents my naming them all, I hereby gratefully acknowledge their co-operation. I must, however, acknowledge the courtesy and assistance of the following persons and institutions: Lloyd’s Registry of Shipping, New York; The American Bureau of Shipping, New York; New York Maritime Register; Major A. G. Doughty, Canadian Archives, Ottawa; Mr. Harry Piers, Provincial Museum, Halifax; Mr. R. E. Armstrong, St. John Board of Trade, St. John; Mr. Fred. G. Layton, Wellington, N.Z.; and the Hon Frank Carrel, Quebec. Much information was gathered from researches among the volumes and manuscripts in the Public, Legislative, and University libraries of Montreal, Ottawa, St. John, Halifax, New York, Boston, Baltimore, and other cities, and I would also acknowledge making free use of the data gathered by Mr. J. Murray Lawson of Yarmouth, N.S., in his books on Yarmouth Shipping, and those pertaining to Canadian-built vessels in Mr. Basil Lubbock’s volume on the Colonial Clippers. And last, but not least, I would record my appreciation of the assistance given me by my wife, Ethel T. Wallace, in selecting and filing hundreds of cards containing particulars of the vessels built in Canada during the period covered by this history. Without her help, the compilation would have been laboriously prolonged.

In conclusion, I might add that there has been no attempt made in this book to embody literary style or to simplify or explain nautical terms and shipping technicalities for the benefit of the uninitiated. When miles are mentioned, it is the nautical mile of 6,080 feet, and not the land, or statute, mile of 5,280 feet.

Frederick William Wallace.

c/o Canadian Club,

New York City.

| CONTENTS | |

| Foreword | |

| CHAPTER I | |

| The Dawn of British North American Shipping | |

| The “Bluenose”—An Unrecorded Era of Maritime Effort—North American Forests Bred Ships—Beginnings of Ship-building in Canada—Early New Brunswick Ship-building—Beginnings of Ship-building in Nova Scotia—Ship-building in Canada from 1800-1840—Ship-building at Quebec, 1800-1840—The Great Ships Columbus and Baron of Renfrew—The Ship United Kingdom—Quebec Builds First Ocean Steamship—Nova Scotia Shipping, 1800-1840—Shipping and Ship-building in New Brunswick, 1800-1840—Models and Plans—Constructing a Wooden Ship—Ship Timber—Fastenings—Sheathing—Ironwork and Fittings—Early Ship-owners—Ships and Ship-building in the ’Forties—Longevity of a Quebec Ship—The Days of ’49—Canadians in the California Gold Rush—Quebec to California on the Panama—Nova Scotians to the Sacramento | |

| CHAPTER II | |

| The Boom Days of the ’Fifties | |

| The ’Fifties—An Era of Famous Ships—The Australian Gold Rush—The Famous Marco Polo—Marco Polo’s First Voyage—The Marco Polo’s Master—Marco Polo’s Second and Later Voyages—Other New Brunswick Ships of 1851—1851, a Big Year in Quebec—Nova Scotia builds Big Ships—Prince Edward Island Ships in 1851—Australian Gold aids Canadian Ship-builders, 1852—Yarmouth Schooner sails for Australia—The Big Boom Year of 1853—The Star of the East—St. John Clippers of 1853—Quebec Clippers of 1853—Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island, 1853—The Clippers of 1854—The Big White Star—The Shalimar and Morning Star—St. John and all New Brunswick Ports Building Ships—Quebeckers of ’54—Nova Scotiamen of ’54—The Clipper Barque Stag—Prince Edward Island Vessels of ’54—The Slump of 1855—The Monster Morning Light—The Wrights—St. John’s Master Ship-builders—New Brunswick Ships of 1855—Quebec and Nova Scotia Ships of 1855—Square-riggers Built on Lakes—Nova Scotia Emigrants to New Zealand—The Year 1856—The Year 1857—Quebec still Leads in 1858—Ship-building at a Low Ebb in 1859—Quebec-built Ship Features in Australian Salvage Case—Nova Scotia Builds Ships and Operates Them | |

| CHAPTER III | |

| The ’Sixties in Quebec and New Brunswick Shipping | |

| The Ship-builders of Quebec—John Munn—Allan Gilmour—G. H. Parke—H. N. Jones—Pierre Valin—J. E. Gingras—P. Brunelle—Heavy Commissions Absorbed Profits—Baldwin and Dinning—G. T. Davie—Other Quebec Builders—James Gibb Ross—Quebec Ship-building in the ’Sixties—Baldwin’s “Empires”—Large Quebeckers of the ’Sixties—Henry Fry of Quebec—Great Timber Trade of Quebec—Quebec Boatmen—Stowing Square Timber—Crimping in Quebec—Two Trips Average Quebec Season—New Brunswick Ships of the ’Sixties—St. John Builders of the ’Sixties and some of their Ships—Thomas Hilyard and his Ships—James Nevins—The Olives—Francis and Joseph Ruddock—John S. Parker—John Fisher—Other Builders of the ’Sixties and their Ships—Large St. John-built Ships of the ’Sixties—Barque Minnehaha—A Well-built Vessel—Ship-owning in New Brunswick—St. John Ship-owners of the ’Sixties—Ship-building Elsewhere in New Brunswick in the ’Sixties | |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| The ’Sixties in Nova Scotia—A Period of Expansion | |

| Nova Scotia Ships, Builders and Owners of the ’Sixties—Yarmouth Fleet of the ’Sixties—Builders of Yarmouth Ships—The Yarmouth Ship Research—The Voyage of Many Rudders—Large Yarmouth Ships of the ’Sixties—The Yarmouth Ship Speculator, a Smart Sailer—Further Voyages of Speculator—Voyages of Yarmouth Ships in the ’Sixties—Quick Voyage of Yarmouth Brig—Yarmouth Marine Insurance Companies—William Law of Yarmouth—“Up the Bay” in the ’Sixties—Bennett Smith of Windsor—Other Windsor Ships of the ’Sixties—The Churchills of Hantsport—The Quebec’s Last Voyage—The Maitland Ships—Lawrence’s Pegasus—Maitland Ships for Halifax Owners—Cornwallis Vessels and Builders—Newport in the ’Sixties—Horton, Parrsboro, and other Head of the Bay Ports—In the Annapolis Basin—Weymouth Ship-building—Around the South-east Shore—Ella Moore, a Quick-Stepper—Pictou County Activities—Captain George McKenzie—Carmichael’s Ships—River John, a Famous Ship-building Centre—James Kitchin, River John—Tatamagouche Ship-building—Pugwash Ships—The City of Halifax—Lake Vessel goes Deep-water | |

| CHAPTER V | |

| The Bluenose Fashion | |

| The B.N.A. Ships, their Equipment, Personnel and Distinctive Characteristics—The Ships, their Rigs and Equipment—The Hull and Accommodations—The Personnel—The Master—The Bluenose Mate—The Second Mate—Boatswain, Carpenter and Sail-maker—The Cook—The Steward—The Crews—Juggling Crews in Rio—Hard Work the Order of the Day | |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| The Nova Scotiamen of the Palmy ’Seventies | |

| The ’Seventies—Great Days for B.N.A. Ships—The Nova Scotiamen of the ’Seventies—The Mutiny on the Ship Lennie—Nova Scotia Ships of 1872—The Speedy Barque J. F. Whitney—The Piskataqua’s Record Trip—Nova Scotiamen of 1873—Loss of the Yarmouth Ship Regina—The Big Year of 1874—Ship Wm. D. Lawrence, Largest Canadian-built Square-rigger—Driving the Wm. D. Lawrence—Maitland and Vicinity in 1874—Yarmouth Ships of 1874—The Loss of the N. W. Blethen—Captain Henry Lewis of Yarmouth—Annapolis Ships—Shelburne and Vicinity—Pictou County Ships of 1874—Nova Scotia Ships of 1875—Yarmouth Craft—A Negro Ship-Master—Racing between the St. Bernard’s and the Bonanza—The Speedy Hectanooga—Up the Bay Ships of 1875—Pictou County Craft of 1875—Nova Scotia Brig’s Good Australian Passage—Noteworthy Nova Scotia Craft of 1876—The Yarmouth Ships—Up the Bay Ships of 1876—Other Nova Scotian Vessels of 1876—The Year 1877 in Nova Scotia—Yarmouth Vessels—The Tollington’s Fast Trip—Windsor and Head of the Bay, 1877—Amherst Barque’s Good Trip—Maitland Barque’s Fast Passage—Sultana’s Fast Maiden Voyage—Elsewhere in Nova Scotia, 1877—Yarmouth Ships of 1878—The Ship Everest and her Record Passage—Other Nova Scotiamen of 1878—Gassed!—A Year of Low Freights, 1879—Yarmouth Ships in 1879, a Year of Disasters—New Yarmouth Tonnage in 1879—The William Law’s Good Passage—Maitland Ships of 1879—The Servia—Hantsport, Windsor and Newport Craft of 1879—The Windsor Clipper Athlon—The Ship Sovereign of Londonderry, N.S.—The Pictou Barque Ameer, a Fast Sailer—The End of the ’Seventies in Nova Scotia | |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| The ’Seventies in New Brunswick Shipping | |

| New Brunswick Shipping in the ’Seventies—The Ships of 1870—St. John Activities—Elsewhere in New Brunswick, 1870—New Brunswick Ships of 1871-1872, a Good Year—St. John Craft—Fast Packets Built in 1872—Other Vessels of 1872—Loss of St. John Barque James W. Elwell—A Woman’s Pluck and Endurance—A Year of Big Ships, 1873—New Brunswick Shipping of 1874—Noteworthy Ships of 1874—The Year 1875 in New Brunswick—David Lynch, a Noted St. John Ship-builder—New Brunswick Ships of 1875—The Year 1876 in New Brunswick—The Alexander Yeats—The Ships of 1877—The Barque Cedar Croft—The Clipper Stormy Petrel—New Brunswick Shipping of 1878—Captain John McLeod, Black River—St. John Barque Cyprus and Captain Raymond Parker—The New Brunswickers of 1879—The Norwood and J. V. Troop, Good Sailers—The Egeria’s Fast Passages—Brig Laura B.’s Quick Trip—The ’Seventies in New Brunswick | |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| The ’Seventies in Quebec, Prince Edward Island and the Lakes | |

| The Quebeckers of the ’Seventies—Quebec Ships of 1871, a Disastrous Year in the Gulf—Quebec Ship-building in 1872—Quebeckers of 1873—The Clydesdale—The Year 1874 in Quebec Shipping—From 1875 to 1879 in Quebec—Captain Joseph Bernier, a Passage-maker—Ship Cosmo, Finest Ever Built in Quebec—Prince Edward Island Shipping of the ’Seventies—The Clipper Gondolier—P.E.I. Vessels of the ’Seventies—Building Square-riggers on the Great Lakes—Ship-building in the ’Eighties | |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| The ’Eighties in Nova Scotia Shipping | |

| Ship-building in the ’Eighties—The Nova Scotiamen of the ’Eighties—The Yarmouth Craft of 1880—Windsor and Head of the Bay Shipping, 1880—The Speedy E. J. Spicer of Parrsboro’—The Murder of the Spicer’s Mate—The Pictou Ships of 1880—Yarmouth Ships of 1881—Windsor and Vicinity in 1881—The Scotland’s Fast Passages—Pictou Ships of 1881—Yarmouth Shipping of 1882—Up the Bay Shipping of 1882—Elsewhere in Nova Scotia, 1882—Yarmouth Ships of 1883—Around Windsor, 1883—Other Nova Scotia Craft of 1883—Yarmouth Shipping, 1884—The County of Yarmouth—Windsor and Vicinity in 1884—River John’s Big Ships—The Warrior—Hot Times on the Warrior—The Beginning of the End, 1885—Yarmouth goes in for Iron—Head of the Bay Shipping in 1885—The Charles S. Whitney—The John M. Blaikie—First Four-mast Barque—The Year 1886 in Nova Scotia—Yellow Jack gets many Bluenose Seamen—Hamburg of Windsor, Largest Canadian-built Barque—Nova Scotia Ships of 1887—Ship George T. Hay of Parrsboro’—Nova Scotia Shipping from 1888 to 1889—The Four-mast Barquentine Canadian | |

| CHAPTER X | |

| The ’Eighties in New Brunswick, Quebec and Prince Edward Island | |

| The ’Eighties in New Brunswick—N.B. Ships of 1881—Ships of 1882—The Honolulu’s Good Passages—New Brunswickers of 1883—St. John Barque Highlands—Barque L. H. De Veber’s Record—Other New Brunswick Vessels of the ’Eighties—New Brunswick Ship-building from 1825 to 1888—The ’Eighties in Quebec Ship-building—Quebec Ships from 1880 to 1887—Quebec owns Old British China Clipper Wylo—Last Full-rigged Ship Built in Quebec—Fast Passages by Quebec Ships—Prince Edward Island Ships of the ’Eighties | |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| The Last of the Bluenose Ships | |

| The Last Stand in Nova Scotia—Square-riggers of the ’Nineties—The Four-mast Barque King’s County—Yarmouth Vessels of 1890—Barque Calburga of Maitland—Other Craft of 1890—Nova Scotiamen of 1891—The Big Ship Canada—The Parrsboro’ Ship Glooscap—Other Craft of 1891 in Nova Scotia—The Last of the Bluenose Ships—The End of Square-riggers in New Brunswick—Quebec Ends her Story—The Passing of a Great Era of Ships and Sailormen | |

| APPENDIX | |

| The Arrival of the Columbus in London—Had a Tempestuous Voyage—Oddly named Vessels—The Ship Beejapore—The Australian Packet Ship Eagle—Henry Eckford and Donald McKay, formerly Canadians—Rev. Norman McLeod and the Barque Margaret—The Bluenose Passion for Paint | |

. . . A breed of seamen; master builders

Skilled with axe and saw—

Creators of tall ships which spun

A web of courses ’round the world.

Out from quiet harbours, from towns

Embosomed by the forests, laved by the tides,

They spread their sails to every breeze—

Steered their splendid ships, north, south, east and west,

And brought great glory to the sea-girt coasts that reared them.

A grey day in high Southern latitudes, with the sunlight veiled by slaty clouds, reveals the sea rolling in huge cresting undulations to the urge of a bitter wind. Snugged down to four topsails, braced sharp up, with canvas distended iron hard and full to the pressure of the breeze and with running gear blown off in great bights to leeward of her swinging masts, a rusty-hulled iron barque with “Liverpool” on her stern is plunging and rolling to the westward with chill water cascading over her decks and sluicing out through scupper-hole and clanking wash-port.

The seas south of fifty are lonely waters. The mate of the Liverpool barque scanned the wide horizon with eyes watering in the nip of the chill wind and his roving glance was arrested by the sight of a pearly gleam of white sail showing against the black murk to windward, where night was receding before the pale dawn. Brightening at the sight of another craft in these desolate wastes of ocean, the officer scans the stranger through binoculars and remarks to his captain: “An American, I think, sir, and coming along fast. He’ll pass us pretty close, I’m thinking——”

The other senses the thought in his mind. “Aye . . . get out the flags. We’ll ask him to report us.”

Within half an hour, with the squalls of wind hounding her along, the stranger came storming up out of the west into plain sight. She was a big ship—a wooden three-master, black-hulled, heavily sparred, and deep-laden—and she was forging through the long green seas with yards almost square and royals and cross-jack furled. The white welter under her bows told of the speed of her onslaught through the water, and the great arcs into which the foot of her bellying sails were curved betrayed the tremendous urge of the wind in their woven fabrics. She rolled steadily, revealing her coppered under-body in a wet gleam of verdigrised green one moment, and, when she listed to port, her white-painted stanchions and rails, scrubbed decks, and a poop largely filled by huge cabin houses.

A man was scrambling up her main-rigging. The watchers saw him gain the royal yard and run along the foot-ropes of the spar. Loosened canvas bellied forth as he cast the confining gaskets off, and while the sailor clambered up to the eyes of the rigging to overhaul the gear the yard was hoisted and the sail sheeted home and set in a manner which savoured of the smartness of a man-o’-war. This exhibition of sail-carrying in a heavy breeze, the well-set and well-trimmed sails and yards, the faultlessly stayed masts, and generally spotless appearance of the big ship evoked two kinds of comment from the Liverpool vessel’s personnel. The master and mate murmured admiration: “A down-east Yankee, sure enough. They put the crews through their paces on those packets.” The men in the Britisher’s fo’c’sle voiced other opinions: “A damned nigger-drivin’ Yankee where they works the soul-case out of the hands and lets you rest when you’re dead.”

A ball of bunting went up to the stranger’s monkey-gaff. A jerk on the flag halliard broke the spun-yarn stop, and, instead of the Stars and Stripes, the red ensign of the British Mercantile Marine flew snapping in the breeze. “She’s an English ship!” piped an apprentice-boy on his first voyage. A sour-visaged Aberdeen carpenter favoured him with a commiserating glance and growled: “English ship? A lot you know about it. She’s a Bluenose.”

Up on the poop, an old shell-back handing code flags was staring pridefully at the big vessel roaring past them. “I know that ship, sir,” he vouchsafed to master and mate. “I sailed in her one time. She’s a Nova Scotiaman—the W. D. Lawrence of Maitland . . . twenty-four hunder’ an’ fifty tons register. A splendid vessel, sir, and the biggest built in Nova Scotia.”

The captain nodded. “Hard packets—these Bluenose ships. Worse than the Yankees, they say.”

The sailor replied somewhat hesitatingly: “Well, sir, they have that name, but for a man what is a sailor an’ knows his book there’s nothin’ better nor a Bluenose to sail aboard of. For bums, hoboes, an’ sojers, sir, they’re a floatin’ hell. They stand for no shenanigans aboard them packets, sir. One bit o’ slack lip or a black look an’ the mates ’ll have ye knocked stiff an’ lookin’ forty ways for Sunday. They works ye hard, but they feeds you good and treats you good if you does yer work.”

Flags snapped from the gaffs of the two ships; messages were exchanged, and when the answering pennant went up on the Nova Scotiaman’s flag halliards, the English captain said: “Alright! He’s got our hoist. Haul it down and put it away.”

A squall of snow blotted out the horizon and the other ship vanished in the whirl of it. When it lifted, she was a black speck in the yellow aura of the sunrise running down her Easting for the Horn and the South Atlantic. “There she goes,” observed the old shell-back who had served in her; “a ramping, stamping, hard-driving Bluenose—wooden ships with iron men commanding them.”

This was in the middle ’seventies, when the Maritime Provinces of Canada built, owned, and operated a mighty fleet of merchant sailing ships. In 1878, Canada ranked fourth among the ship-owning countries of the world with a flotilla of 7196 vessels aggregating 1,333,015 tons. They were wooden ships and driven by sail, but during the half-century between 1840 and 1890—the era of the British North American “windjammers”—they captured a huge share of the world’s carrying trade and built up a reputation for smart ships and native-born seamen that was a legend in nautical history and fo’c’sle story for many years. Like the great ship in the incident which opens this account, a little company of ship-builders and sailors resident on the shores of the Atlantic coasts of Canada created a mercantile marine which burst into ocean commerce, made history and drew the admiration of seamen, and thence vanished utterly into the mists of oblivion.

It was during the nineteenth century that the sailing ship attained its highest development in the hands of the English-speaking nations. Steam, as a means of propulsion, eventually swept the sailing ship into the discard as a prime factor in ocean carriage, but it was the early rivalry of steam which brought the wind-driven ship to the apex of perfection in design and brought out in masters and officers a degree of skill and daring in seamanship which has never been exceeded. The records of the ships and seamen engaged in the trade of the Honourable East India Company; the famous American clipper ships and their record passages to California and in the China trade; the British tea clippers and Australiamen, have all had their historians who have set down the particulars of the ships, their builders, owners, masters, and passages in the most painstaking fashion, and with a degree of accuracy which leaves no doubt as to the authenticity of any recorded statement.

The student of nautical history and the man, excited by the legends of ancient sailormen, who desires to acquaint himself with the days of the American clippers or the various romantic trades in which the sailing ships of Great Britain featured, has a sufficiency of data to enable him to satiate his mental hunger, but of those other famous packets—the Bluenose ships—and the wonderfully capable sailormen who sailed them, to say nothing of builders and owners, practically nothing has been recorded.

At the present time, Canadians know but little about the brave days of wooden ships in which their country cut such a swath in ocean commerce. Even in the very places where the ships were built, the inhabitants have but a vague knowledge of the great shipping era which practically established the city or town in which they reside. Fourth place among the ship-owning nations, building famous vessels and breeding a class of daring and resourceful seamen who are still a legend among seafarers in British and foreign ships, the Maritime Provinces of Canada seem to have forgotten a part of their history of which they should be inordinately proud.

Perhaps circumstances are to blame. Though built in Canada, a vast number of the vessels were sold after construction. Those that were owned and operated by Canadians seldom returned to their home ports, but traded wherever a cargo was to be picked up and transported. The United States had her California clippers plying out of, and into, her own ports east and west; similarly, Great Britain’s ports berthed her Indiamen, her China, and Australian clipper ships loading or discharging. Americans and Britishers saw their ships in their comings and goings. The persons interested in British North American ships viewed them only in their home ports when outward bound after launching, and heard of them afterwards only by letter, cable, or brief notices in obscure newspapers.

The vast timber areas of the British Colonies in North America were directly responsible for the huge fleet of sailing ships constructed there. Timber in various forms and dried fish constituted the principal export trade of the early colonists. With such abundance of wood right at the water’s edge, ship-building came natural to the settlers, who were forced to find their markets in the United States, the West Indies, and Great Britain. Money was scarce, and they could not afford to purchase vessels to transport their products, but conditions of living along the North American coasts developed a type of inhabitant who was handy with axe, adze, and saw; who was something of a sailor, a blacksmith, and general labourer. Wood was to be had for the cutting of it, and labour was cheap, so they built their own ships, loaded them with home products, and sailed them themselves to a market.

They were small craft, these early North American merchantmen, and rudely constructed, but it speaks well for the courage of these pioneers that they took the hazards of venturing forth across long leagues of stormy seas in their shallops, pinks, and schooners. Hostile Indians, the primeval forests, and a rigorous winter climate kept the settlers close to the coast. The sea was their highway of travel; from its depths they gained a substantial part of their livelihood in the fish they caught; it was ever before their eyes, and the roar of the surf rang in their ears; across it lay their markets and communication with the civilised world—these were the circumstances which helped to evolve the natural born ship-builder and seamen who made the Atlantic coast of British North America famous in the days of sail propulsion in wooden ships.

The forests provided the material for the ship and the major part of the cargo also. Woods of the coniferous trees such as spruce and pine were superabundant, and it was of this timber that most of the British North American ships were constructed. Great Britain and the United States built their wooden ships of oak and other hard woods; the Canadian vessels of pine, spruce, and hackmatack were known as “soft-wood” ships.

If it took seamen of the Anglo-Saxon races to sail ships, it took Frenchmen to build them. As ship constructers, the French excelled. During the Napoleonic Wars, the war vessels built by the French were superior in design and construction to those of the British, and the latter were quick to copy French models, especially of the frigate type, which French naval architects developed to a high state of perfection.

The French first colonised the Atlantic coasts of Canada, and history records that the first ships built in New France were two small craft launched at Port Royal (now Annapolis Royal in Nova Scotia) by François Grave in the year 1606. In Quebec, under French domination, a sea-going vessel named the Galiote was built in 1663. In 1666, the Intendant Talon had a vessel of 120 tons built to his orders, and several small craft were constructed up to the year 1672, when a ship of 400 tons burden was built at Anse des Mères.

According to memorials contained in the Documents de Paris, it would appear that ship-building at Quebec was pretty brisk in 1715. The colonists, however, felt that ship construction was retarded owing to the fact that France would not import timber from her North American colonies. In the eyes of the home Government, the fur trade seemed to be the only industry worth encouraging at that time, and they ignored the fact that England was importing mast-wood and ship timber from her New England colonies for the purpose of building war vessels for use against France.

In 1731, however, there was an awakening, and M. de Maurepas, French Minister of Marine, fully realised the importance of encouraging the building of ships in the North American colonies, and he wrote strong despatches to the Governor urging the stimulation of this industry. In his despatches, he stated that ships of war would be built in New France if some good types of merchant vessels were constructed. As an incentive, he offered a premium of 500 francs for every vessel of 200 tons or over built in the colony and sold in France or the Antilles. In 1732, Intendant Hocquart established a large shipyard on the banks of the St. Charles River near Quebec, and, stimulated by the bonus, ten merchant vessels were built during that year.

George Gale, in his Historic Tales of Old Quebec, states: “In 1739, orders were received from the French king to try the experiment of building war vessels. Accordingly, the construction of a corvette of 500 tons was begun, with an engineer named Neree Levasseur acting as contractor or builder for the king. On June 4th, 1742, the first transport for the French Navy, the Canada, was launched here amidst great rejoicing and was sent to Rochefort, France, with a crew of eighty St. Malo men. She was loaded for the voyage with boards, iron, and oil. In the spring of 1744 the Caribou, of 700 tons, carrying 22 guns and a crew of 104 men, left the yard on the St. Charles, and sailed for France in July, followed, in 1745, by the Castor, of 22 guns and 200 men. The Martre, launched in 1747, was the last war vessel to be built on the banks of the St. Charles River, as it was found that the water was not deep enough, even at the highest tides, for the increasing tonnage of war vessels.

“A yard was opened at the Cul de Sac, at the site of the old Champlain market, where the National Transcontinental Railway offices now stand in the Lower Town of Quebec, and the first vessel built there was the St. Laurent, of 60 guns, in 1748. In 1750, the L’Orignal, of 70 guns, followed, but she broke her back on leaving the slip. Timbers from this ship were picked up from the river bottom some years ago. The L’Orignal was followed by the Algonquin in 1753 and the Abenaquis in 1756, the last two being small, lightly-armed corvettes. The frigate Le Quebec was launched in 1757.

“After this, the construction of the bigger war vessels was given up in Quebec—the French naval authorities having found that the Caribou and the St. Laurent did not come up to their expectations, owing to the inferior quality of the wood used in their construction. This was white and red oak, elm, birch, and spruce. The masts were brought from Bay St. Paul, some miles below Quebec, and the Lake Champlain district. The majority of the vessels, especially the war craft, were manned by crews brought out from France, while the foremen carpenters, riggers, block-makers, etc., were also sent out by the French Government in order to instruct the Canadians in the work. The ironwork for the ships was cast at the St. Maurice Forges, located some seven miles from Three Rivers, Quebec, which were opened in 1737. The forges were worked for some years by the French Government, and guns as well as projectiles were cast there.”

After the conquest of Canada by the British in 1759, settlers from the United Kingdom began the construction of ships in Quebec and other places. In 1797, four ships and two brigs were built at Quebec—the largest being the ship Neptune, of 363 tons and 117 feet in length, constructed by Patrick Beatson. In 1799, Beatson built the ship Diamond, of 521 tons, with two decks and 119 feet long. In 1800, he launched the ship Queen, of 429 tons, and the ship Monarch, of 645 tons and 126 feet long. Prior to 1800, John Munn began a notable ship-building career in Quebec, when he launched the brig St. Peter, of 104 tons, in 1798.

Confining ourselves for the nonce to the eighteenth century, we will shift from the St. Lawrence River to New Brunswick. In 1770, James Simonds built a schooner at what is now St. John. Of the building of this pioneer craft, Ven. Archdeacon Raymond states that her keel was laid by Michael Hodge and his assistant, Adonijah Colby, just to the east of Portland Point, and her timbers and planks were cut from the adjoining hill-side. Hodge contracted to build the vessel for twenty-three shillings and fourpence, Massachusetts currency, per ton, and the iron used in her construction was taken out of an old 64-ton sloop. The schooner was named Betsy, and she was launched, rigged, and fitted out, and sailed for Newburyport, Mass., with a cargo on February 3rd, 1770. Jonathan Leavitt sailed in her as master and she was sold in 1771 for £200—her owner expressing himself as being satisfied at the price. Three years later, Jonathan Leavitt and his brother-in-law, Samuel Peabody, built the schooner Menaguashe at the Upper Cove (now the Market Slip, St. John).

William Davidson, a salmon fisherman and a native of Scotland, came to Halifax in 1765 to establish a salmon fishery in Nova Scotia. Later on he went across to New Brunswick and settled on the banks of the Miramichi. In 1773, he built a vessel of 300 tons—the largest thus far constructed in New Brunswick—for the purpose of shipping fish to the Mediterranean. In 1775 he built a vessel of 160 tons which he loaded with his own caught fish, and was en route to Europe when the craft struck on St. John’s Island (now Prince Edward Island) and was lost. This information is contained in a memorial which Davidson addressed to Governor Carleton of New Brunswick.

I find no record of ship-building in New Brunswick under French domination, but there is evidence that they appreciated the value of the timber growing there for ship purposes. In 1700, the 44-gun ship Avenant anchored in St. John harbour and shipped some very fine masts for the French Navy. After the conquest, the British looked to the St. John River valley as a source of supply for masts and spars for the Navy, and a survey was made by a naval timber expert in 1774, who reported that he found “a black spruce fit for yards and topmasts and other timber fit for ship-building.” White pine, 38 inches in diameter and suitable for masts, was plentiful, and there was no lack of smaller timber, capable of being made into lower yards, 110 feet long and 26 inches in diameter. Following his report, the reservation of trees suitable for masts became a Governmental policy and white pine trees were reserved for naval purposes in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia until about 1811.

Coming to Nova Scotia, it is recorded that in 1751 John Gorham built a brig with slave labour at Halifax. In Shelburne, a vessel of 250 tons was built in 1786. In 1763, John Sollows, in Yarmouth, built a shallop of 25 tons which was destined to be the pioneer craft of a splendid fleet of ships built and owned there in later years. But the largest vessel built in Nova Scotia prior to 1800 was the ship Harriet, launched on October 24th, 1798, at Pictou. Of this vessel, Murdoch’s “History” relates that she was built by a Captain Lowden, a native of Scotland, who came to Pictou in 1788. The Harriet was of 600 tons burden and pierced for 24 guns, and was supposed to be the finest ship built up to that time in the Province. Her bottom was composed of oak and black birch timber, and her upper-works, beams, etc., totally of pitch pine. “On account of which mode of construction,” says the record, “she is said to be little inferior in quality to British-built ships, and does peculiar credit, not only to this growing settlement, but to the Province at large.” The Harriet, commanded by Lowden’s son David, and carrying 4 real guns and 20 “quakers,” or wooden imitations, sailed for England to be sold. In those days, it must be remembered, the British were involved in war with France, and the guns on the Harriet were for the purpose of intimidating roving privateers and letters-of-marque.

It is not my intention to set down an intimate record of Canadian ship-building during the forty-year period between 1800 and 1840, as I have found it necessary to confine myself to the most important era beginning with the latter date until the decline of wooden ship-building around 1890. But fully to appreciate the story of Canada’s marine efforts in the days of wooden hulls and square sails, a brief sketch of the builders and the ships constructed in the most important localities must be given adequately to carry the record along.

The shipwrights of Quebec, under the French régime, were the pioneers in the construction of large ships. After the conquest, the French settlers around Quebec City were leavened with Irish, English, and Scotch, many of whom were disbanded British soldiers, and the two nationalities lived and worked together with the utmost harmony. The French-Canadian was an expert worker in wood, and few men of other nationalities could excel him in fashioning timber from the time it was cut down. An axe or an adze in the hands of a French-Canadian could be made to do wonders. With a broad-axe they could square a log of rough timber as true and as smooth as if it had been sawn and planed, and many tales are told of their skill with the adze—one yarn telling of a man who placed his bare foot on a log and, with his adze, shaved a piece of wood from under his sole as thin as a sheet of tissue. It was said that a Quebec ship carpenter could split a playing card edgewise with his adze. Be that as it may, there is no doubt that their skill in fashioning wood was such that they could have built a ship without a piece of metal in her, fastening the timbers and planks together with tree-nails and hard-wood spikes and clever dove-tailing. But such skill, after all, was natural to people raised in a country where timber was superabundant, and from which almost everything had to be made in the pioneer days.

The first prominent ship-builder of the British régime in Quebec appears to be Patrick Beatson, who built the ship Neptune, of 363 tons, in 1797. In 1800, he built the ship Monarch, of 645 tons. This vessel had three masts and two decks and was 126 feet long. John Munn began his famous ship-building career in 1798, when he built the brig St. Peter, of 104 tons. Henry Usborne commenced building in 1804 with the ship Anna Maria, of 348 tons. The famous French-Canadian builder, Hyppolite Dubord, established his yard in 1827, when he launched the brig Bonaparte, of 133 tons. Allan Gilmour began operations in ship construction in 1831 with the ship Wolfe’s Cove, of 587 tons. George H. Parke began his fleet of big ships with the brig William, of 186 tons, in 1835, and in the same year James Jeffery built the ship Calcutta, of 706 tons. Edward Oliver’s first vessel was the barque Premier, of 298 tons, launched in 1838, and Thomas Oliver began building in 1839 with the ship John Bull, of 436 tons. John Nesbit built his first vessel in 1840—the ship Corea, of 734 tons. All these men became prominent in later years and added some splendid examples of ship construction to the Quebec-built fleet.

In 1823, John and Charles Wood, of Port Glasgow, Scotland, naval architects and practical ship-builders, and men of eminent skill in their profession—designers and builders of the Clyde steamboat Comet in 1812—conceived the idea of importing square timber into Great Britain by constructing a solid ship of such timber, sailing her across the Atlantic, and breaking her up on arrival. The main idea behind the scheme was to evade the British Timber Tax on oak and squared pine imported from Canada, and the ships were so designed as to permit of them being constructed as cheaply as possible and in such a manner as to allow of their square timber hulls being taken to pieces without damage to the wood.

Charles Wood came out to Quebec and superintended the construction of the first ship, the Columbus, at Anse du Fort—a spot located at the west end of the Isle of Orleans and about four miles from Quebec City—and on July 28th, 1824, the huge timber drogher was successfully launched. Over five thousand people witnessed the launching from excursion boats and sailing craft, and the band of the 71st Highlanders was in attendance to play the great ship into the water. And she was a great ship for those days, being 301 feet in length, 50·5 feet in beam and 22·5 feet in depth and of 3690 tons. Packed solid with timber and rigged as a four-masted barque, the Columbus, under command of Captain William McKellar, and with Charles Wood aboard, towed down the St. Lawrence in charge of the steamboat Hercules, the only tow-boat on the river then. While towing down to Bic, the Columbus grounded on Bersimis Shoals and some of her timber had to be jettisoned to get her off. The venture proved successful, however, and the ship arrived safely at Blackwall Docks, London. The timber in her holds was discharged, but her owners, against the advice of Wood, demurred against breaking her up just then and sent her across to St. John, New Brunswick, for another timber cargo. On this voyage she foundered, but the crew were saved.[1]

Ere leaving Canada in the Columbus, Wood laid the keel of a still larger ship at Anse du Fort. This was the Baron of Renfrew, 304 feet long, 61 feet beam, and 34 feet deep. She was rigged as a four-masted barque and had five decks with a height of about seven feet between each, and she registered 5294 tons. Other authorities give her tonnage as 5880 tons. The Baron of Renfrew was launched in the summer of 1825, and under the command of Captain Matthew Walker (possibly the originator of the famous knot which bears his name) she sailed for London with her designer and builder aboard and packed with squared timber. She made the English Channel all safe and picked up the pilots and two tow-boats—one of which was the James Watt—but through the stupidity of the pilots she was put aground on the Long Sand Head while in tow. It was evidently blowing hard at the time, as the crew were reported as being “saved through the gallantry of the Dover boatmen.” The Baron of Renfrew ultimately drove ashore near Gravelines on the French coast, and, breaking up, scattered her great timbers on the Channel beaches.

Charles Wood never repeated this experiment, but there is no record that the owners lost money through the scheme. The two ships made the eastbound Atlantic passage successfully, and this fact, no doubt, accounts for the report that insurance on the hulls of both amounting to the immense sum of $5,389,040 was paid on loss.

Both the Columbus and Baron of Renfrew were ships, and not merely rafts. True, they would not have stood many ocean passages had all gone well with them, but they can be accounted as a triumph to the genius of the Scotch designer and the skill of the Quebec shipwrights. It was not until thirty years after, in 1853, that a wooden sailing ship as large as the Quebeckers’ was built in America. This was the clipper ship Great Republic, built by a Nova Scotian of Scotch ancestry, Donald McKay, in his East Boston shipyard. The Great Republic, as originally constructed, was 335 feet in length, 53 feet in beam, and 38 feet deep, with a registered tonnage of 4555 tons. Until she came, Canadians could easily boast of having built the largest wooden sailing ships in the world.

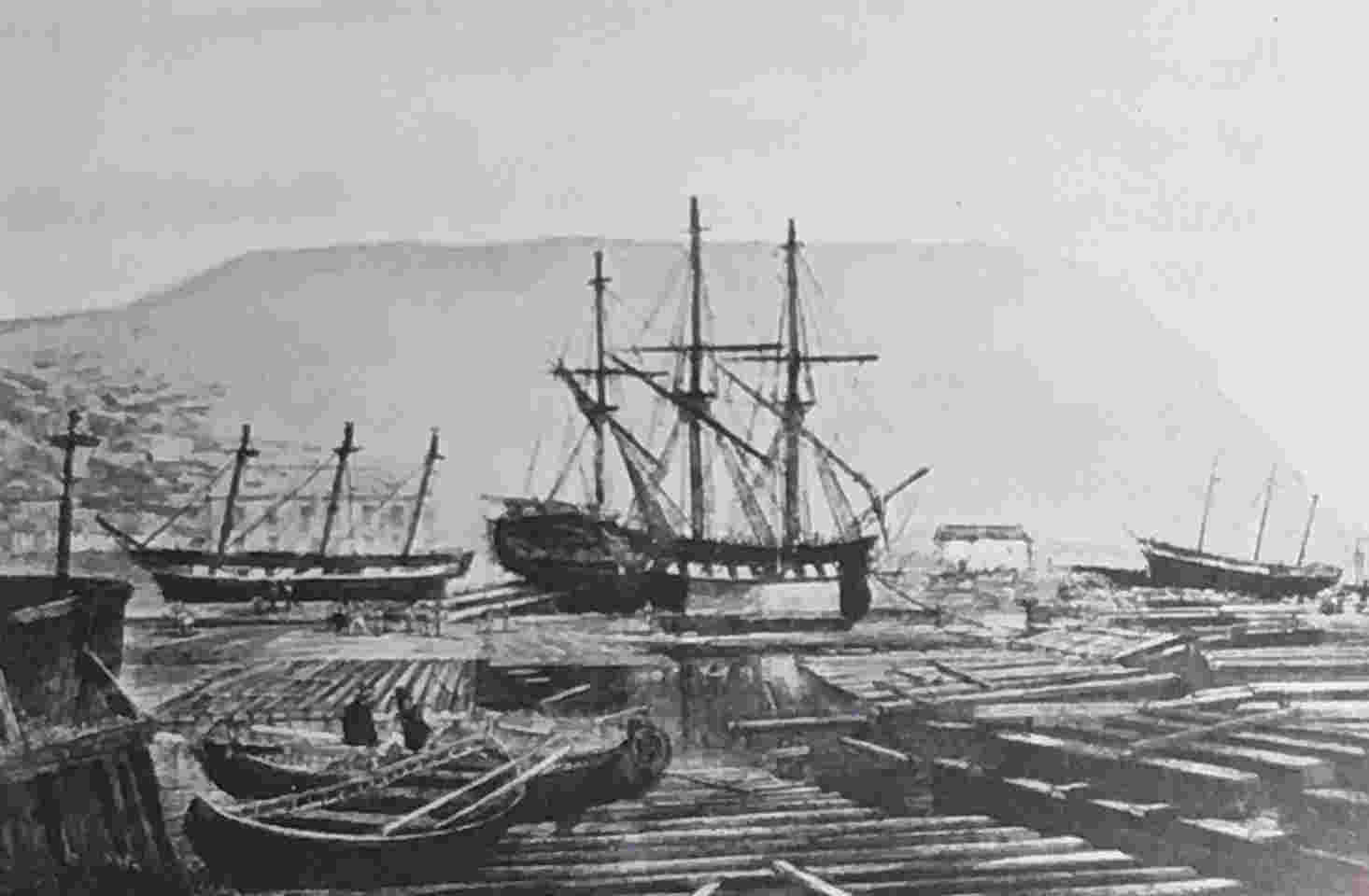

Ship “Columbus,” 3690 tons.

Built 1824, Quebec. Largest vessel of her time.

(From an old litho in the Ross Robertson Collection, Toronto.)

|

See Appendix for further details of this craft. |

In 1839, John Munn built the ship United Kingdom at his Quebec yard. This vessel registered 1267 tons and was 199 feet in length, 31 feet 9 inches beam, and 22 feet 9 inches in depth. This craft was an orthodox ship and was the largest built in Quebec up to that time, and possibly the largest built prior to 1840 in British North America.

Though this record is confined to wooden sailing ships, yet it may not be amiss to mention here the part played by Quebec ship-builders in steam propulsion of ships. A Canadian-built steam packet began running the St. Lawrence River between Quebec and Montreal in 1809—the Accommodation, constructed in Montreal for John Molson. The steamer Lauzon, built on the St. Charles River by John Goudie in 1817, also ran the river between Quebec and Montreal and for ten years did regular ferry duty between Quebec and Levis.

But Quebec claims the honour of having built the first steamship to cross the Atlantic under her own steam. This was the Royal William, built by John Goudie in Black and Campbell’s shipyard at Cape Cove, Quebec, and launched in April, 1831. Goudie, a young Scotch-Canadian who had learned his trade of naval architect and shipwright in Scotland, had seen steamboats built on the Clyde, and he designed the Royal William as a steamer and not as an auxiliary sailing ship such as was the American vessel Savannah.

Most of the ship-builders in Quebec were shareholders in the vessel, and it was intended to place her on the run between Quebec and Halifax. Her dimensions were: 176 feet overall, 146 feet keel, 44 feet over the paddle-boxes in beam, 17 feet 9 inches depth of hold, and 14 feet draught. She was rigged as a three-mast topsail schooner, and had saloon and accommodation for fifty passengers. Her burden was 363 tons. The engines were constructed by Bennett and Henderson, of Montreal, and developed around 200 horse-power.

The Royal William made three successful trips between Quebec and Halifax and then fell upon hard times. For a spell she did tow-boat and excursion work, and made a run to Boston, being the first steamer to enter an American port under the Union Jack. In 1833, her owners decided to send her to England for sale. Under command of Captain John McDougall, she left Quebec on August 5th, 1833, for Pictou, Nova Scotia. She coaled at the latter port and sailed on August 18th for London. Her Pictou clearance papers read: “Royal William, 363 tons, 36 men, John McDougall, master. Bound to London. British. Cargo: 253 chaldrons of coal, a box of stuffed birds and six spars, produce of this Province. One box and one trunk, household furniture and a harp. All British, and seven passengers.”

One can imagine the importance with which the Pictou Customs officer penned this momentous document. He must have felt that he was granting valediction to an astonishing enterprise, and one can sense his feelings almost in the meticulous care with which the “box of stuffed birds and six spars, produce of this Province,” as well as the harp, were noted down. And no doubt he had a patriotic bent when he penned the line—“All British.” He would be a canny Pictou Scotchman, for a certainty, and the record would be made plain enough to confound disputing claimants as to Transatlantic steamship honours.

The Royal William steamed into dirty weather on the Grand Banks and strained her hull. Her starboard engine was disabled, and she leaked badly. But McDougall was out to get her across, and he started his pumps and kept her heading easterly under the port engine for a week. She finally arrived at Cowes, repaired her boiler there, and docked in London after a passage of twenty-five days from Pictou. Her arrival marked the first Transatlantic passage accomplished under steam alone.

In London, she was sold for £10,000 and was chartered by the Portuguese Government, crew and all. In 1834, she was taken over by the Spaniards, and fought against the Carlists. The Spaniards changed her name to Ysabel Segunda, and in May, 1836, she fired the first shot to come from a steam man-of-war. Spain had her until 1840, when she was taken to Bordeaux for repairs. She was in such poor condition then that she was sold for a hulk to the French and her engines were taken out and placed in a second Ysabel Segunda. This, briefly, is the record of the Royal William, which with the Columbus and Baron of Renfrew can be listed in the annals of early marine history as triumphs on the part of the shipwrights of Quebec.

Ship-building in Nova Scotia prior to 1840 was confined to vessels of much smaller tonnage than those built in Quebec, and schooners, brigs, and brigantines comprised the bulk of the fleet. Yarmouth—a great ship-building and ship-owning centre in later years—was building up her local marine, but her largest vessel in 1840 was the barque Sarah, of 537 tons. In Wilmot, N.S., the ship Acadia, of 763 tons, was launched in 1836, and thirty years later she was recorded as being owned in Liverpool, which speaks well for the manner of her building and the quality of her timber. In Pictou and vicinity, ship-building began around 1825 with small vessels built to sell in England. In 1824, Alexander Campbell built the schooner Elizabeth, of 91 tons, at Tatamagouche, Pictou County. In 1827, he built the brig Devon, of 281 tons, and continued building vessels until he attained the sizable ship Mersey, of 734 tons, in 1837. James Campbell, of Tatamagouche, launched the barque Colchester, of 418 tons, in 1833, which vessel was the largest built there until Alexander Campbell exceeded her in 1835 with a barque of 562 tons, also named Colchester.

River John, Pictou County, began a notable ship-building era around 1835, when the barque Charles, 519 tons, was built by Alexander McKenzie. In the same year, the barques Susan, 537 tons, and George, 526 tons, were constructed by other builders there.

It is recorded that two clipper barques were built around Bridgewater, N.S., during the ’thirties. One was the St. Kilda, known as the “clipper of the fleet” between New York and Valparaiso, Chile, and the other, the Scotia, is alleged to have made a passage from New York to Dunedin, New Zealand, in ninety-eight days. The little ship Jean Hastie, 280 tons, built in Yarmouth, N.S., in 1826, and wrecked there in 1844, was known as one of the fastest vessels in the British Mercantile Marine while she was owned in Scotland. It will thus be seen that Nova Scotian ship-builders turned out some smart little vessels in those days of a construction which proved that not all of the craft built there in the ’thirties were “hard-scrabble” packets cheaply and crudely knocked together for sale in England.

Small brigs were built around Lunenburg and Shelburne in the period under review, and in Liverpool, N.S., in 1826, Snow Parker launched the 400-ton ship Mary Parker. All around the Nova Scotia coast were built numerous sloops, schooners, brigantines, and brigs, but prior to 1840 there were but few vessels launched exceeding 500 tons.

With these small vessels, Nova Scotians were cutting into the deep-sea carrying trade. In addition to coasting down the American shores, Nova Scotian schooners and brigs were engaged in trading to the West Indies and the Brazils. Even longer voyaging was undertaken, and we read in Murdoch’s “History” of the arrival in Halifax during the latter end of June, 1826, of the brig Trusty, Finlay, Master, with a valuable cargo from Calcutta and Madras. The Trusty was absent from her home port a whole year.

It is not generally known that the famous John Company ships occasionally called at Halifax, but a shipping note states that on May 29th, 1826, “the Honourable East India Company’s ship Countess of Harcourt, commanded by Thomas Delafons, Esquire, Captain, Royal Navy, arrived at Halifax from Canton. She left Canton 25th January, and St. Helena, 16th May. Her cargo consisted of 6517 chests of tea consigned to Messrs Cunard & Company.” The latter company, composed of Halifax men, afterwards founded the world-famous Cunard Line.

Ship-building in New Brunswick became an important industry prior to 1840, and some fair-sized square-riggers were launched during the ’thirties. Most of the building was done around St. John and the Bay of Fundy ports, and many builders, destined to become famous in after years, became established before 1840. William and James Olive began building ships in 1822, their first vessel being the barque Caledonia, built for English owners. In 1835, these enterprising shipwrights built the ship Belvidere, and rigged her on the stocks. With royal yards crossed and a crowd of spectators aboard, she was sent down the ways, but as soon as she took the water she capsized and spilled her living freight into the harbour. Fortunately, no one was drowned—“the huge cloaks worn in those days spread themselves out on the water and acted as life-preservers.”

The St. John River empties into the harbour of New Brunswick City, and owing to the unusual rise and fall of the tide in the Bay of Fundy it is only possible to enter or leave the river at high water. At low water, the harbour level is below that of the river mouth, and the latter flows tumbling down in a gigantic waterfall. Thus, during one part of the day, the St. John River is cascading down into the salt water and during very high tides the sea is piling over the river. The place where this occurs lies between two steep, rocky cliffs and is known as the Reversible Falls.

John Clark had a shipyard just above the Falls about where the Suspension Bridge now stands on the Carleton side. History relates of his building a ship called the Recorder there, but during the launching, those responsible for handling the gear to check her progress allowed her to take charge and get away from them. The Recorder barged through the Falls and fetched up on Blind Island. All attempts to get her off ended in failure, and she remained until broken up for junk.

Owens and Duncan established their yard at Portland, St. John, in 1832. In George Thompson’s yard, in 1825, the famous Wright brothers, William and Richard, were serving their time and acquiring the art of ship-building. These two men, destined to attain high eminence in ship construction and ship owning in later years, started their yard in Courtenay Bay, St. John, in 1837, their first vessel being a small whaler and their second the steamboat North America, which was placed on the St. John—Boston route.

Towards the end of the ’thirties, ship-building was in full swing all around New Brunswick, and ships of almost 1000 tons were being built, mostly for the timber trade. In St. John the following builders were established: Francis and Samuel Smith, Francis and Joseph Ruddock, John Haws, James Briggs, John W. Smith, and Richard Lovitt and John Parker. James Moran was building at St. Martins, Henry Partelon at Oromocto, George Marr at Quaco, Benjamin Appleby at Hampton, Justus Wetmore at Kingston, James Swim at St. Martins. Duncan Shaw was an early builder at Sackville, and built two vessels which were captured by American privateers during the war of 1812. Shaw was a Perthshire Scotchman, and had served as a midshipman in the British Navy during the American Revolutionary War.

Up on the Gulf shore of New Brunswick, ship-building was being carried on in the Miramichi District, at Chatham, Newcastle, Shediac, Richibucto and other places. Timber ships most of them were, iron-fastened, and built for sale in Great Britain. When the export of deals began in 1822, these cheaply-built “timber droghers” blew in and out of the Bay of Fundy and the Gulf of St. Lawrence in greater numbers yearly, and British North American-built vessels almost dominated the trade between Great Britain and Eastern Canada by the ’fifties.

Not many Canadian wooden square-riggers were built from naval architect’s blue-prints or plans. A few vessels were constructed to designs sent out by British owners, but most of the designing was done by the foreman in charge of the shipyard, who made a miniature model of the intended vessel, embodying in it the features desired by the owners. The model was usually a half-model of the hull fashioned with drawknife and spokeshave, and it was so constructed as to be taken apart in horizontal layers from which the lines of the vessel could be laid off. Some models were made ⅜ inch to the foot, but they varied. The outside of the model represented the outside of the frame of the vessel, not the outside of the planking. The top edge of the model was the rail. A vessel was usually trimmed a few inches lower in the water aft. A fine “run” was desirable in a vessel’s model, but above that the hull should “swell” strongly, otherwise the craft would “bury” deeply aft. A model which turned out a good vessel in actual service would be used over and over again by merely altering the scale when laying off from it.

In examining the dimensions of B.N.A. vessels, I find that they ran to more beam than British ships, the average being 4·9 beams to length.

After the model was prepared and a suitable place selected and levelled up by the water-side, the keel blocks were laid. The first part of the vessel, the keel, was then placed on the keel blocks. This, the backbone of the ship, was made up of huge timbers “scarphed,” or joined together. The foreman then carefully marked on the keel the location of the stem and stern-post and the various frames or ribs. The shipwrights would be engaged building up the stem and stern-post and also the various frames, so that by the time the keel was laid the work of erecting them on the keel could be proceeded with. In a small boat, the frames are in one piece steamed and bent into shape, but in large vessels they had to be built up of several pieces of timber sawed or chopped into the necessary shapes and fastened together with dowels and tree-nails. This work was usually done on a platform.

When a number of frames had been assembled on the framing platform, the work of “raising” them on their destined position on the keel began. This was done by tackles and poles, and when it was accurately placed, the floor frame was bolted to the keel. The stem and stern-post was also raised and fitted securely to the keel by various scarphs, aprons, and other pieces of solid timber designed to hold everything together in the strongest possible manner and bolted through and through.

The “skeleton” of the vessel erected, she was said to be “in frame,” and after all was lined up to the satisfaction of the foreman shipwright, the strengthening timbers were placed in the ship. The first of these was the keelson, laid over the frames and on top of the keel. Then commenced the ceiling, or planking, of the inside of the ship. This protects the frames from the cargo and strengthens the hull, as the ceiling is bolted on to the frame timbers in a fore-and-aft direction. When the vessel was ceiled up to the height of the lower deck, the shelf and clamp timbers were bolted on, these timbers being scarphed together to form a horizontal strake running the whole length of the ship upon which the ends of the deck beams would rest. The deck beams would then be fitted in with heavy knees to brace them. The number of decks would depend upon the size of the vessel; ships of between 500 and 1200 tons would have two decks; larger craft would have three. Sometimes all three were planked or decked, but usually the two upper ones would be planked and the bare beams left unplanked on the third. When the ceiling and beams were bolted and fitted in, the vessel was ready for planking outside.

Planking was usually done from the keel upwards and the planks were fastened to the frames by iron or copper bolts and tree-nails, the latter being a sort of wooden bolt driven through planking, frames, and ceiling, split across the ends, and wedged so that it cannot work out. Care had to be taken that the butts, or ends of the planks, were distributed “out of line,” i.e. to avoid having a tier of planks with their ends joining in a line with the planks above and below, as such would tend to weaken the whole structure. The ends of planks should meet each other on the frames and not between them.

When the vessel was planked, the seams were caulked and made water-tight. Water was pumped into the hull, and wherever a leak was noticed the place would be chalk-marked and made tight. Deck planking would be laid and caulked; hatch coamings fitted and all deck-houses erected. The ship would then be painted, the rudder hung into place, and all necessary blacksmith work, such as channel plates, stay-bolts, etc., fixed to the hull. The vessel was then ready for launching.

Some ships were practically finished on the stocks, and would have all the masts stepped, the rigging in place, and the yards aloft; others would be launched with the lower-masts stepped. The majority were sent into the water as completed hulls and would be sparred and rigged after they were afloat. Prior to sending the vessel into the water, the launching ways under her bottom would be well greased and a cradle constructed under the ship to carry her down the ways into the water. The hull was raised off the keel blocks, and blocks and shores were knocked out until the vessel rested upon the cradle. When the time of high water arrived, the cradle was released and on the greased and sloping ways the hull slipped down into the water after the traditional christening ceremony.

To go into the details of wooden ship-building would demand too much space in this volume and more technical knowledge than is possessed by the writer, but the brief description above may serve to give an idea of the work as practised in the old days. In comparing the old wooden ships with the modern ones of steel, one is struck by the enormous size of the timbers and the thickness of the planking in the wooden craft. In a moderate-sized ship the deck beams would be 14 inches square and the planking would range from 5 inches to 10 inches thick, according to position. In superior ships, the frames would be spaced such a little distance apart that the vessel appeared as a solid mass of timber ere the ceiling and planking were bolted on. With such ponderous timbers and beams and heavy planking, bolted in every direction, and braced by great wooden knees and further re-inforced by long iron knees and straps, it is difficult to comprehend the terrific power of a boarding sea that was able to break such beams and burst asunder the stoutly braced and bolted timbers. Yet this was a common happening.

Great Britain built her wooden ships of oak and teak principally, with some softer woods for decks and interior fittings; American ships were also constructed largely of hard woods. The Canadian ship was invariably classed as a “soft-wood” vessel, as soft wood entered very largely into the construction of nearly all of them.

The principal wood used for ship construction in Canada in the ’forties was tamarac, also known as hackmatack, American larch, cypress, or juniper. Light and durable, some authorities claimed that a tamarac-built ship, being extremely buoyant, was better suited for the carriage of heavy cargoes than a vessel built of oak. Proof of its durability could be found in ships built of this timber being thirty and even forty years old and afloat and still sound and tight. An old authority states, “Few descriptions of wood, if any, are superior to it for ship planks and ship timber, and the clipper ships of New Brunswick, built almost wholly of this larch wood (tamarac), have attained a worldwide celebrity for speed, strength and durability.” In the later years of Canada’s wooden ship-building era, the large tamarac was difficult to secure owing to the prodigal manner in which it had been cut, and it was used principally for knees. When tamarac failed, spruce took its place for ship timbers and planking.

Black birch was much used for the keel, floor timbers, and lower planking of ships, as it lasted well under water. American live and white oak was imported for the stems, stern-posts, keelsons, and beams of superior ships, and pitch pine was also imported for beams. White pine was used for cabins and interior finishing, and for masts; red pine was occasionally used for ceiling and planking, and yellow pine for decks. Black spruce made splendid yards and topmasts, and, in later years, when tamarac gave out as a wood for ship timbers and planking, the spruce grown around the shores of the Bay of Fundy and known as “Bay Shore spruce” became the principal substitute. This particular wood grew very straight, and was tough, strong, and light.

Beech was also used in ship bottoms and has been known to remain sound for forty years. White elm was also used for under-water planking and also for making ship’s blocks. White cedar, such as grows in the Canadian swamps, was also used and passed by Lloyd’s as top timbers and third foot-hooks of ships of the six- and seven-year grade. Maple—a Canadian hard wood—was also used as well as white-heart chestnut.

Red and white oak grows in Eastern Canada, but it never made a successful wood in ship-building. Ships were constructed of Canadian oak at one time, principally at Quebec, but it was affected with dry rot in about five years and this hard wood was seldom used afterwards. Salting and pickling the timbers with brine was a common method employed to prevent rotting. Some vessels were heavily salted.

In the earlier years of Canada’s ship-building era, practically all ships built were iron-fastened. Later on, copper fastenings were used below the water-line and iron above. Then came copper and galvanised iron fastenings. Some ships were copper-fastened throughout, but not many.

A good deal of controversy raged as to the merits and demerits of iron and copper fastenings in ships. The Canadian builders of the earlier days used iron probably because they were too poor to buy copper, and also because the majority of the ships they built were for sale in a cheap market. But many builders of first-class soft-wood ships stuck to iron because they really believed it to make a stronger and better fastening. The advocates of copper declared that iron would rust and corrode under the action of salt water. The champions of iron claimed that a bolt of good black iron could be driven through planks and beams tighter than a copper bolt, and even if it did rust it held the better because of the corrosion. Copper bolts, being of softer metal, could not be driven into the wood like iron, the points of spikes often buckled between plank and timber, and the larger holes bored to take copper spikes and bolts permitted the water to permeate and the bolt to work loose. “I’ve seen these copper-fastened ships on the ways to be repaired and I could pull the bolts, slimy with verdigris, out of her with my hands,” said an old ship-builder. “Iron may rust, but I’ve known what it is to try to drive out an iron bolt rusted into the wood. It holds tighter than the devil himself.” Locust tree-nails were also used to fasten frames, timbers, etc., as well as tree-nails of other hard woods.

Canadian-built ships in the North Atlantic trade were not sheathed as a rule with metal. Some vessels were sheathed with hard wood though, which saved the hull from the wear and tear of ice. Ships destined for voyaging in tropical seas were sheathed with copper or yellow metal, some with zinc, to prevent the accumulation of barnacles and marine growths. If these vessels were iron-fastened throughout, wood sheathing or tarred felt would have to be laid under the copper or yellow metal to prevent corrosive action between the iron and the copper.

Vessels constructed in Canada and bound on Southern voyages were often metalled in Great Britain. As Great Britain was the usual destination of most Canadian ships on their maiden voyages, this could be effected there cheaper than in Canada.

The channel plates, iron straps, and knees, mast, yard, and boom irons, rudder gudgeons, and pintles, and such-like fitted ironwork, were usually made by the ship-builder’s blacksmith or by the persons who did such work in the village or town where the shipyard was located. Many of the larger vessels were diagonally strapped with iron between frames and planking. In a good many places the local smith could shoe horses, make sleigh runners, wheel tyres, and ship’s ironwork with equal facility. In the larger centres of ship-building, ship-smiths were established who made fittings for all the local yards. In the larger towns also would be found block-makers and spar-makers. The sails were often secured from sail-makers in Quebec, St. John, and Halifax, as well as from local men.

Patent and standard fittings, such as windlasses, capstans, pumps, steering gear, binnacles, etc., were imported from the United States or Great Britain, in the early days, but were afterwards made in Canada. Some ships had iron knees placed in them when they arrived in Great Britain.

Some of the ships built in the Maritime Provinces of Canada during the period from 1840 to 1860 were built for Canadian and British owners of superior materials and first-class fittings. Many established ship-builders would not launch anything but a high-grade type of vessel. But there were many wretched specimens of marine architecture constructed in Canada in the early days. These “hard scrabble” packets were turned out as a species of speculative investment. An enterprising merchant would secure a foreman shipwright and draft out the plans for a ship or barque of from 500 to 1000 tons. The promoter would secure a little ready money for initial and necessary expenditures, and stock in the proposed vessel would be given in return. The men who supplied the timber, the blacksmith, the block-maker, sail-maker, and ship-chandler would supply materials on the same basis, and even the labour would be secured in return for shares in the ship. Into a good many such craft went the cheapest and flimsiest materials. Launched, rigged, and loaded with the ubiquitous and ever-ready cargo of timber, the ship would be sent to Great Britain consigned to brokers who made a specialty of selling such vessels. Being new and considerably cheaper than the hard-wood ships of British yards, they sold without much difficulty, and the various shareholders received their money and often made a handsome profit upon their investment. Hundreds of vessels were built and sold in this manner and in many cases not a single dollar in cash was paid out for the construction of the ship.

Such vessels were only fit for carrying timber. Most were not fit to sail in after a year or two afloat, and many were purchased by unscrupulous ship-owners for the purpose of profiting on the insurance. Captain Samuels—the famous master of the Atlantic packet ship Dreadnought—speaks contemptuously of one such craft which he was asked to join in Liverpool. She was the Leander, and he states “. . . . she was a Bluenose, built as they all are in the cheapest and flimsiest manner, of unseasoned timber, iron-fastened, in expectation of being sold to the underwriters.” At the time of which the doughty captain writes there was a ship of that name of 733 tons and built in 1841 by Alex. and Wm. Campbell at Tatamagouche, N.S.

Captain Samuels was a little harsh in condemning all Canadian-built ships as being cheap and flimsy, but at that period there were a large number which fully deserved his criticism, and the output of such “built-for-sale” craft caused underwriters to scan them warily and sailors to regard them with derision. In justice to many of the early builders, it must be said that numerous vessels were turned out to be sold abroad in which workmanship, material, and fittings were of the best, but the flood of “cheap ’uns” during the ’forties, and the fact that practically all Canadian craft were soft-wood ships, placed them in a very low grade for many years.

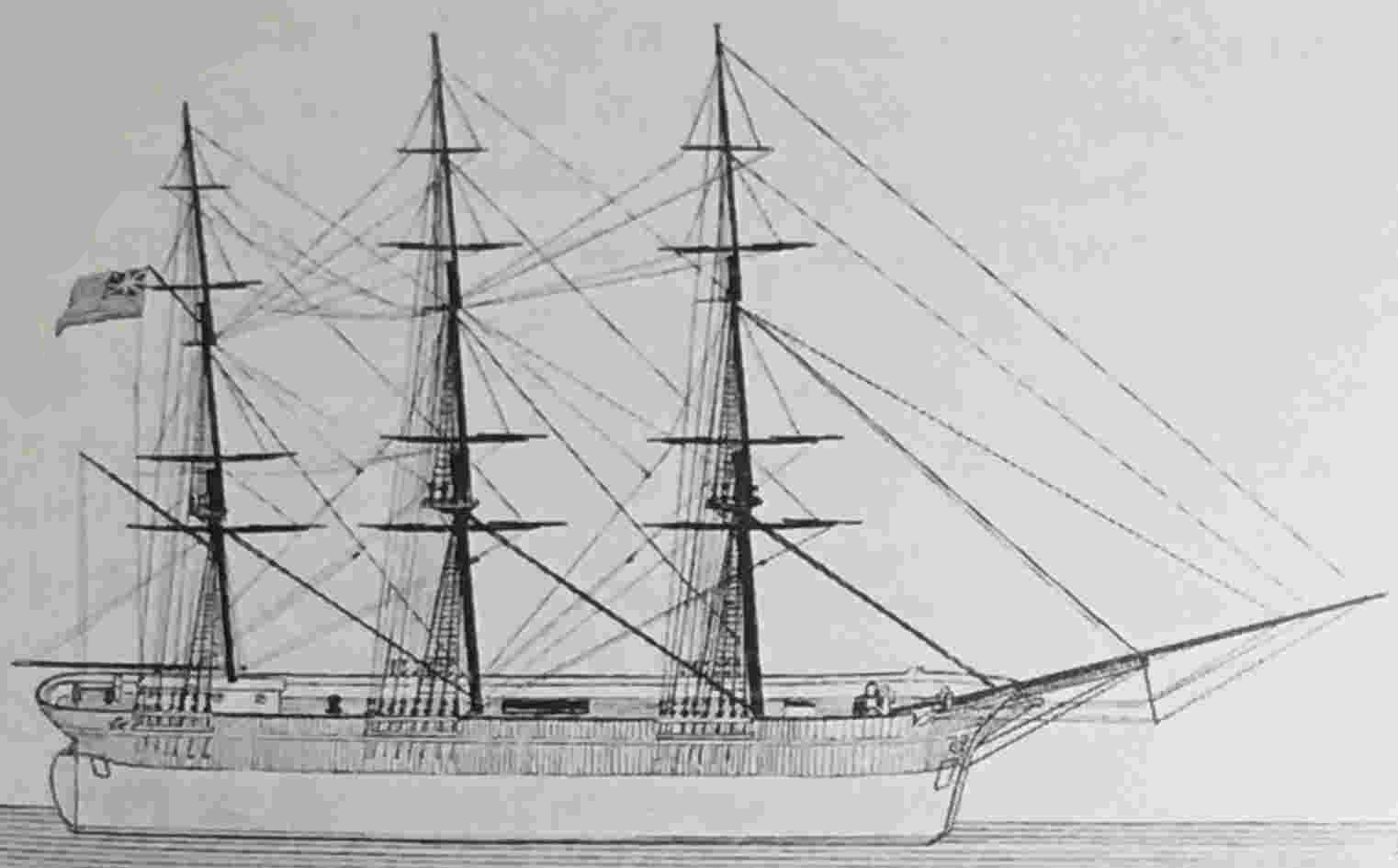

A Wooden Shipyard, showing a Keel on the Blocks.

The largest vessel constructed in 1840 was the ship Queen of the Ocean, 1196 tons, built at St. John, N.B., by Francis and Samuel Smith. In the same year, Justus Wetmore, at Kingston, N.B., launched the ship Speed, 1010 tons. Six other ships ranging from 750 tons to 1000 tons were also built at St. John that year.

In Quebec, 28 ships and barques of between 500 and 1000 tons were built in 1840—the largest being the ship Goliath, 988 tons, launched from John Jeffery’s yard.

In Nova Scotia, Francis Bourneuf, at Clare, built the ship Avon, 1013 tons, and in the same vicinity, at Salmon River, Isaac H. Doane built the ship Jane Augusta, 947 tons. In the same year was built the little barque Sarah, 537 tons, owned by E. W. Moody and others of Yarmouth, N.S. On November 20th, 1849, this little craft, under the command of Captain David Cook of Yarmouth, rescued the crew and 390 passengers of the emigrant ship Caleb Grimshaw, which caught fire off the Azores. Crammed with the survivors, the Sarah carried them into New York, arriving there on January 15th, 1850. The rescue was a marine sensation at the time, and Captain Cook and the crew of the Sarah were accorded a magnificent reception in New York, the master receiving the freedom of the city and $5000 in cash besides a resolution from the U.S. Senate commending his bravery. The officers and other members of the crew were also handsomely rewarded. The Sarah was a genuine Bluenose, being built, owned and commanded by Nova Scotians, and, as she was nine years old at the time of the rescue, it can be safely assumed that she was an example of superior construction. One is constrained to wonder how Captain Cook managed to accommodate and feed over 400 persons on his little ship during fifty-six days of sailing to the westward during winter on the North Atlantic.

In 1841, George Thompson built the ship Princess Royal, 1109 tons, at St. John, N.B.—the largest vessel of that year. On August 6th, 1841, the yard of Owens and Duncan at Portland, St. John, was the scene of a disastrous conflagration. A pot of pitch boiled over and started a fire which spread and caused the destruction of sixty houses. A fine 900-ton ship ready for launching was totally destroyed. This vessel was built in a superior manner and was a mass of hard-wood timber.

No very large ships were constructed in 1842, but in 1843 Allan Gilmour, of Quebec, built the ships Ottawa, 1152 tons, and Rankin, 1120 tons, both for the timber trade, with which he was prominently identified. In Brandy Cove, New Brunswick, Joshua Briggs launched the ship Lord Ashburton, 1009 tons, for Nehemiah Marks, who was both owner and master, and which was probably built for sale in England.

In 1844, I find that a little clipper ship named the Superior, 572 tons, was built in Prince Edward Island for Irish owners. This vessel was a sharp model copper- and iron-fastened, and strapped with iron. Her name, no doubt, indicates the class of vessel she was. The number of vessels of sharp models built in Canada were very few. In the same year, William Porter, of St. Stephen, N.B., built the Schoodiac, 1004 tons, and the largest vessel of the year.

Allan Gilmour, of Quebec, built two large ships in 1845 for his partners in the timber trade—the Argo, 1163 tons, and Agamemnon, 1167 tons. These ships were constructed of oak and hard wood, but iron-fastened. Also in Quebec, John Jeffery built the Malabar, 1175 tons, in 1845, and William Henry, the ship Erin, of 1134 tons. James Smith in his St. John, N.B., yard built the ship Tuskar, 1029 tons, and in the same locality, Owens and Duncan launched the William Penn, 1041 tons, both vessels for sale.