* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: The City of the Sacred Well

Date of first publication: 1926

Author: Theodore Arthur Willard (1862-1943)

Date first posted: 26th March, 2024

Date last updated: 26th March, 2024

Faded Page eBook #20240321

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, Pat McCoy & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

This file was produced from images generously made available by Internet Archive/American Libraries.

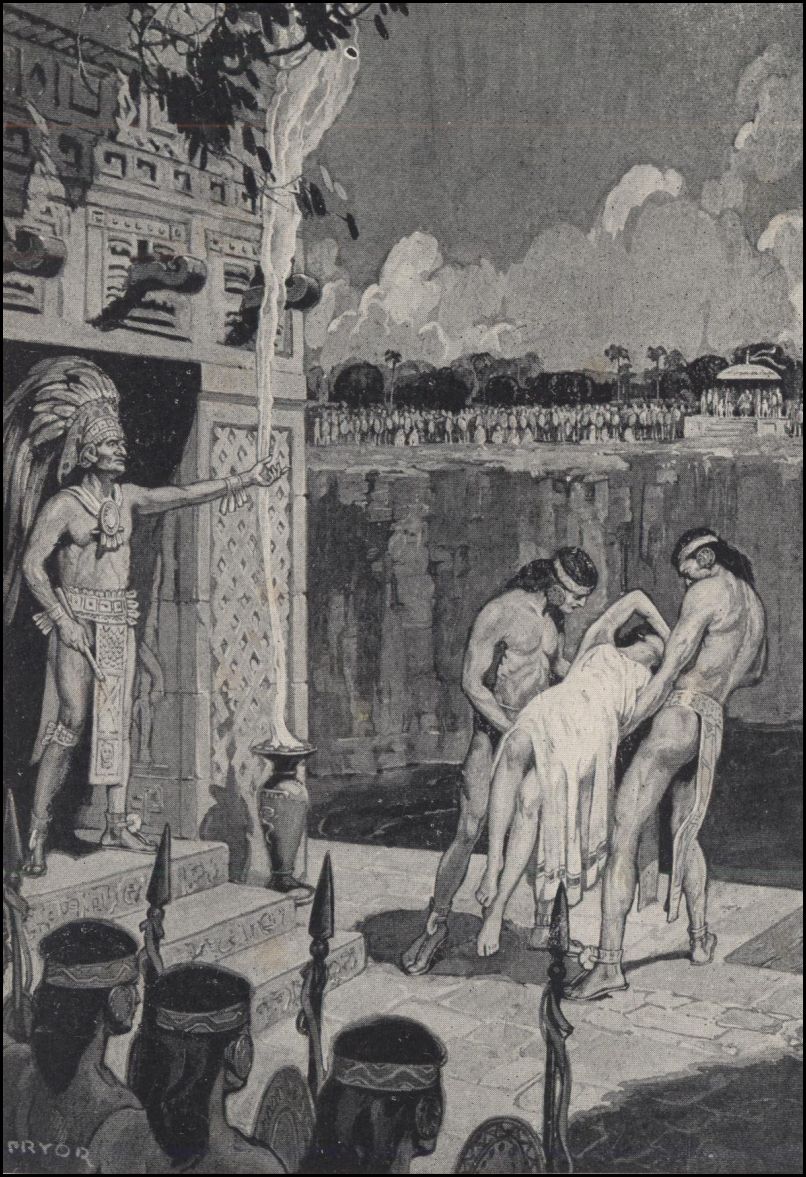

“A last forward swing and the bride of Yum Chac hurtles far out over the well.”

Copyright, 1926, by

The Century Co.

360

Printed in U. S. A.

PREFACE

This book is primarily an attempt to recount the many thrilling experiences of Edward Herbert Thompson in his lifelong quest for archæological treasures in the ancient and abandoned city of Chi-chen Itza, for centuries buried beneath the jungle of Yucatan.

As a boy Mr. Thompson—or Don Eduardo, as he is affectionately known to the natives about the Sacred City—sat in his snug New England home and read of the adventures of Stephens in Yucatan, descriptions of the old Maya civilization, and the legends concerning the Sacred Well at Chi-chen Itza. Then and there he determined that his life-work should be the uncovering of the age-old secrets of the ancient city.

When still a mere youth he was appointed by the President of the United States as the first American Consul to Yucatan, the appointment having been urged by the American Antiquarian Society and the Peabody Museum of Harvard University, both of which were anxious to have a trained investigator on the peninsula.

Enthusiastically Mr. Thompson undertook his double mission. For over twenty-five years he remained at his post as consul. During this long period, sometimes at the head of regularly organized expeditions under the auspices of American archæological institutions, at other times with only his faithful native followers, he discovered ruined cities until then unknown to the world and carried on exhaustive researches among those already discovered.

At last Mr. Thompson resigned the consular office, in order to carry on the various scientific undertakings that required all his time and energy. Chief among these was the search for relics that for hundreds of years had lain buried in the mud at the bottom of the Sacred Well.

Many and many a night, under the gorgeous moonlight of Yucatan or by some cozy fireside in the States, I have listened entranced, as the hours glided by, to the true tales Don Eduardo tells of his experiences or of the customs and the folk-lore of the country. I know intimately this lovable, modest, blue-eyed six-footer, this dreamer and adventurer, gray-haired now but still with the heart of a boy. I know him better, perhaps, than does any other man, and if I do not write down the things he has told me they will never be written, for Don Eduardo will not do it. Therefore I have asked and received his permission to write, from memory and from his notes and my own, this book, which he has read and corrected.

It is a faithful account of the many valuable archæological finds he has made, but, though written as if Don Eduardo himself were speaking, it inevitably lacks the color and fire of his word-of-mouth narrative. It contains, further, such description of the Maya culture and history as may help the reader to understand this ancient civilization. The writer hopes that it may be acceptable to the avid reader of travel and adventure, and there is also the timid hope that it may be of some little educational value to the serious-minded reader, to the end that he may feel that he has not wasted time on a mere “yarn.”

T. A. WILLARD.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The author is indebted, for information and assistance, to many good friends in Yucatan, but chiefly to Señor Juan Martinez H., to the late Teoberto Maler, and to Mr. and Mrs. William James for their timely hospitality.

The books and writings of the old priests, as well as current books on the Maya era, also have been of much aid.

T. A. W.

CONTENTS

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I | Yucatan, the Land of the Mayas | 3 |

| II | The Church of San Isidro and Its Fragrant Legend | 24 |

| III | The First Americans | 32 |

| IV | Don Eduardo’s First View of the City of the Sacred Well | 49 |

| V | The Ancient City | 58 |

| VI | An Idle Day in the Jungle | 88 |

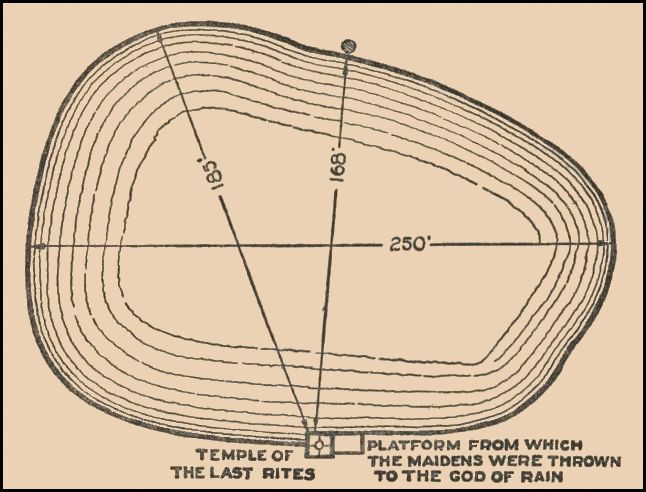

| VII | The Sacred Well | 97 |

| VIII | Sixty Feet Under Water | 118 |

| IX | Two Legends | 150 |

| X | The Conquest | 166 |

| XI | The Finding of the Date-Stone | 179 |

| XII | The Construction of Maya Buildings | 189 |

| XIII | Story-Tellers of Yucatan | 198 |

| XIV | Forgotten Michael Angelos | 211 |

| XV | The Tomb of the High Priest | 236 |

| XVI | The Legend of the Sacrificial Pilgrimage | 261 |

| XVII | Thirty Years of Digging | 278 |

| Appendix | 285 |

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

| A last forward swing and the bride of Yum Chac hurtles far out over the well | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

| The Nunnery, the only three-storied structure in the Sacred City | 64 |

| The second story of the Nunnery | 65 |

| All that remains of the third story of the Nunnery. Several inscribed stones built hit or miss into the wall were doubtless taken from the older city | 65 |

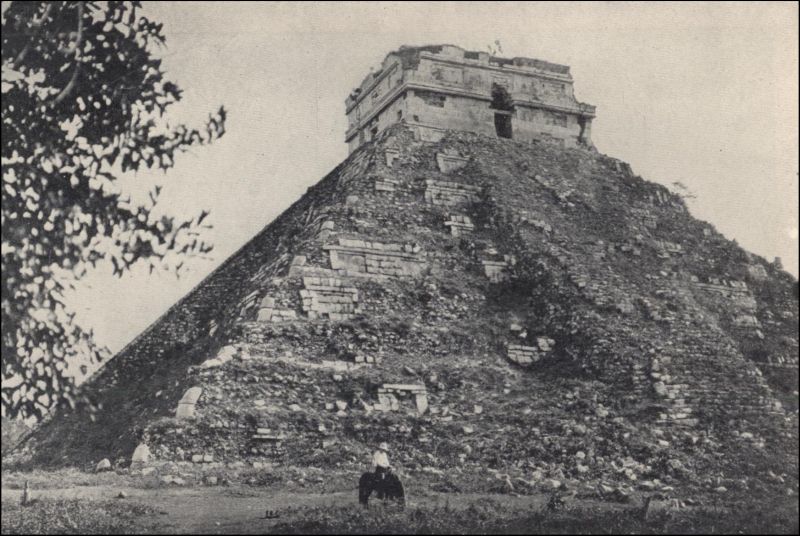

| El Castillo, the Temple of Kukul Can, on its great pyramid, is the center of the Sacred City and the largest edifice | 112 |

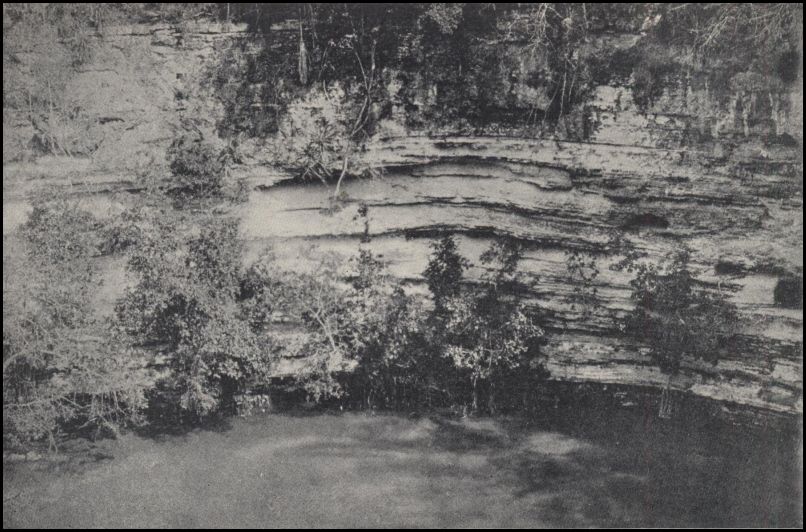

| Looking down into the Sacred Well. Because of the size of the well and the fringe of trees about it, the whole scene cannot be photographed | 113 |

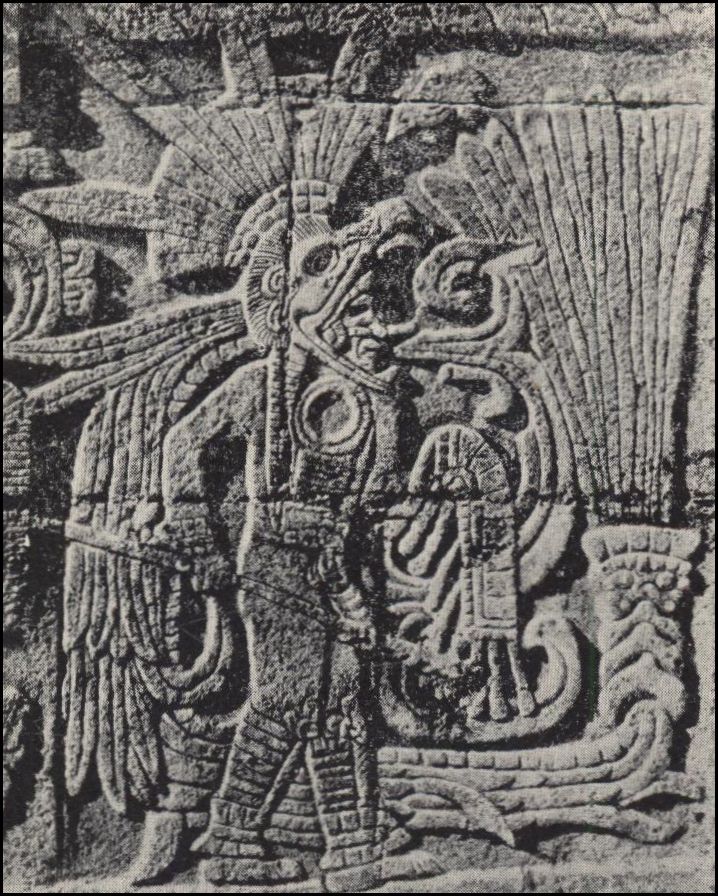

| A sculpture in bas-relief showing a warrior-priest in ceremonial attire, representing the Maya hero-god Kukul Can, the plumed serpent | 240 |

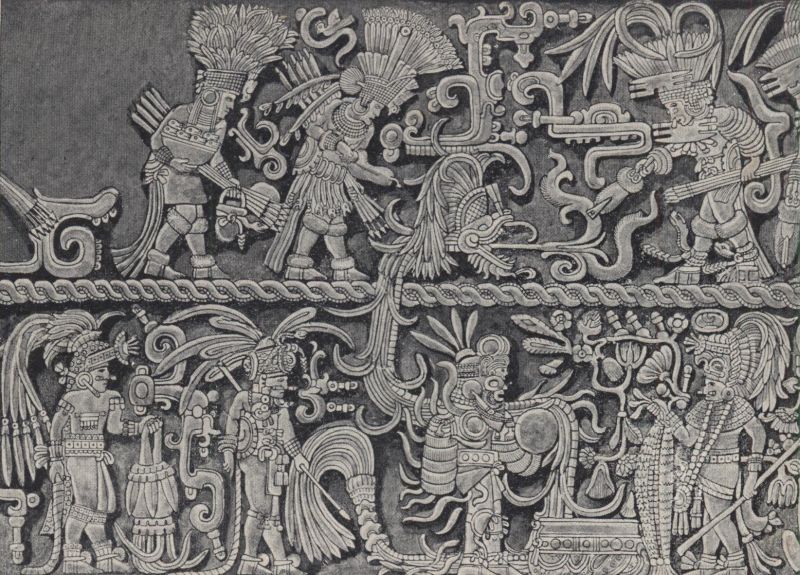

| A religious ceremony depicted in the Temple of Bas-Reliefs. This is but a small section from the interior walls, which contain more than eighty figures | 241 |

THE CITY OF THE SACRED WELL

Imagine yourself the sole owner of a plantation within which lies a city more than twelve square miles in area; a city of palaces and temples and mausoleums; a city of untold treasures, rich in sculptures and paintings. Would you not feel shamefully wealthy? And does it not seem strange that Don Eduardo, the master of such a plantation, takes the fact of his ownership with apparent calmness?

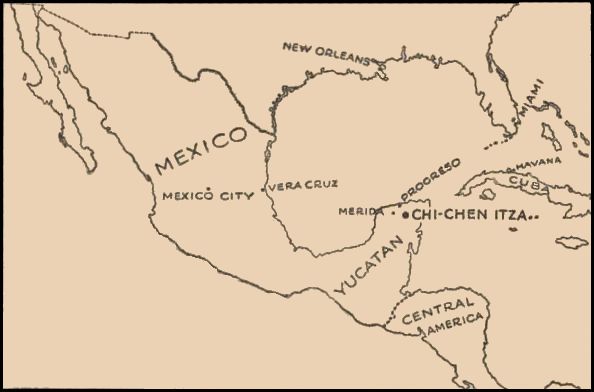

But, before your fancy carries you too far, let me tell you a little more about this remarkable city, which may dampen your ardor for ownership, but which only increases its value in Don Eduardo’s eyes. It is a dead city. Its thousands of inhabitants perished or abandoned it nobody knows how long ago—probably before Columbus first saw the shores of America. And it is in the heart of Yucatan, where Mexico, ending like the upflung tail of a huge fish, juts into the gulf, while Cuba serves as a sentinel a hundred and fifty miles to the eastward.

The Treasure City, the City of the Sacred Well, with the queer-sounding name of the Chi-chen Itza (pronounce it Chee′chen Eet-za′), is for the most part overgrown with tropical jungle. Its treasures are valuable only to the antiquarian.

THE ANCIENT CITY OF CHI-CHEN ITZA IS AT NO GREAT DISTANCE FROM THE UNITED STATES.

Early in our conversations about the City of the Sacred Well, Don Eduardo told me that because at the time of his purchase the plantation was well within the territory dominated by the dreaded Sublevados, the rebellious Maya Indians, no planter dared live in or even visit the region for long, and so he was able to secure the land from its absentee owners cheap, as plantation prices run in Yucatan.

“My life-interest has been American archæology,” he said, “and I came first to Yucatan, thirty years ago, to explore its ruins and relics of an ancient civilization. Even before that I had read of the immense Sacred Well at Chi-chen Itza—a well as wide as a small lake and deep enough to hold a fifteen-story building—and had made up my mind that I would be the man who some day made it yield up its secrets. For a long time I tried to persuade various wealthy Americans to finance the undertaking, but organizing a stock company to raise sunken galleons along the Spanish Main would be a simple task as compared with my difficulties in promoting what seemed a will-o’-the-wisp project. At last, however, I did succeed.”

But I am ahead of my story.

The trip from New York to the City of the Sacred Well requires but a week and may now be accomplished luxuriously, whereas my earlier journeys over the same route were anything but comfortable. Mr. John L. Stephens, who was sent to Yucatan by the United States Government in 1841, describes, in his interesting book “Incidents of Travel in Yucatan,” the difficulties of travel which he met. They might have daunted any spirit less courageous than his. His four volumes, although written nearly eighty years ago, retain their pristine freshness and are still authoritative. I recommend them heartily to the reader.

On any Thursday the traveler destined for the City of the Sacred Well may board at New York a Ward Line steamer bound for Progreso, the only port of Yucatan. The liner stops over at Havana, and a day and a night after leaving that hectic city one awakes in the early dawn to the deep-chanted tones of a sailor who is casting the lead. “Four fathoms,” he cries; then, “Three fathoms,” and finally the engines are hushed and out goes the anchor. Through the port-hole is seen a lighthouse and behind it a faint, foggy vista of low-lying sandy shore.

By the time the unhurried ritual of arising has been performed and one appears on deck all is flooded with brilliant sunshine. The sky above is a cloudless cobalt blue. The day is hot, but the sea-breeze keeps it from being uncomfortably so. One senses, nevertheless, in some subtle way, that he is actually in the tropics. So shallow is the water that ocean-going vessels may not safely approach to within less than five miles of the rather uninspiring port of Progreso, marked by several long piers jutting into the sea and the aforementioned lighthouse. Passengers and goods must be taken off in lighters or in small boats. On approaching the shore one sees rows of pelicans sitting alongside the wharves—the most serious and sad-looking birds imaginable. They remind one of the rows of Glooms frequently portrayed by one of our cartoonists in the daily newspaper comic strip.

There is little reason for tarrying in Progreso, even though it is the third most important seaport in Mexico. It is from here that the henequen of Yucatan is shipped, and the cultivation of this cactus-like plant, from whose fiber rope and twine are made, constitutes the chief enterprise of the province. Two railroads, one narrow-gauge, the other standard, cover the twenty-four miles between Progreso and the lovely city of Mérida, capital of Yucatan. Oddly enough, the fare is higher on the narrower, longer, and poorer road than on the road of standard gauge. The latter is modern in every respect and provided with coaches and locomotives imported from the United States. The daily Peniche Express starts on time and arrives in the same fashion.

The Grand Hotel at Mérida is the customary stopping-place for all foreigners and is a very good and well-operated institution. It faces the beautiful tree-lined Plaza Hidalgo, but is, unfortunately, located close to a number of churches and a cathedral whose cracked bells are rung mightily at various hours and particularly when one wishes to sleep. As a result, persons not yet hardened to this venerable Spanish-American custom are likely to have a broken night’s slumber.

Mérida is a city of 63,000 people and is modern in many respects. It is hot there in the sun but cool in the shade, for there is always a breeze from the perpetually blowing trade-wind. The city is healthful, well paved, electrically lighted, and excellently served with street cars, and it has many handsome buildings and residences. Its population varies all the way from the pure Castilian, through the Mestizos, to the Mayas or full-blooded Indians. Almost every night a band plays in one of the several plazas or parks. North-American airs are favored and I have heard them much more badly played by musicians in our own land than here under the tropical moonlight, in a setting of rarely beautiful and fragrant flowers. During the band concert daintily clean Indian girls, in their voluminous embroidered dresses or huipiles and embroidered sandals, circle about. In another circle stroll their Indian beaux in high-heeled sandals and starched white cotton suits. The ladies of the upper class, dressed in the Spanish or European manner, are driven slowly about the plaza in their automobiles. Formerly carriages—the sort we call, or did call, landeaus—were used, but the automobile has displaced these and in so doing has destroyed half the charm of the scene. Nevertheless it is still charming. The romance of it may be guaranteed to put a thrill into the cold heart of the loan shark from Chicago. It alone is worth the trip to Yucatan and it cannot be described; it has to be experienced at first hand.

During the month of February there is a carnival in Mérida, ending with a fancy-dress ball for the four hundred socially elect. The carnival rivals the Mardi Gras of New Orleans and is enthusiastically celebrated by the whole populace. The floats and decorations are quite as costly and tasteful as any seen in the New Orleans celebration. One year I happened to be in Mérida at the time of the carnival and through the kindly assistance of my good friends Mr. and Mrs. James I received an invitation to the ball. This gorgeous affair would have compared creditably to any similar festivity in New York.

The ball took place at the palatial home of a wealthy Yucateco. This house is built in the usual Yucatan fashion. In front is a large doorway guarded by a heavy wrought-iron grill or gate. On each side of the doorway are the living-quarters, consisting of a dining-room and what we should call a living-room. These rooms form the front of a quadrangular structure surrounding a patio in which are flower beds, fountains, and tiled walks. Around the inner wall of the quadrangle is a promenade wide enough for several people to walk abreast and this is roofed over, the tile roof being supported by pillars and arches of Moorish type. The wings and rear section of the house contain the chambers for the family and guests, the kitchen, and the servants’ quarters. I imagine that this particular residence had cost not much less than a million dollars. The interior is finished in Italian marble and luxuriously furnished in the Parisian manner.

And this is by no means the most palatial residence in the capital. The wealthy people of Yucatan spend much of their time in Europe and their homes show the effect. The houses have beautiful tiled floors and the walls are frequently frescoed or covered with excellent paintings; yet as a rule the rooms are somewhat bare of furniture. One building particularly worthy of mention is the most ancient in Mérida, erected in 1549 by Don Francisco Montejo, the Spanish conqueror of Yucatan. On its façade is a grotesque Indian-Moorish representation of two armored knights trampling on prostrate Indians, while below is a stone tablet bearing the name of Montejo and the date of building.

Recently an American club was started in the city, with a membership of several Americans, three or four Britons, and the remainder Yucatecos who speak English; and some do speak it fluently. The club is predominantly masculine, as the only ladies who attend are those who have lived at some time or other in the States and have acquired our customs. As a rule the women of Yucatan observe the old Spanish custom of seclusion. Girls are not permitted to go out with young men. A girl’s lover may spend the evening standing before the barred window of his inamorata’s home, conversing with her and strumming upon his mandolin or guitar for her edification. If he is finally accredited as a suitor, he is permitted to enter the house and sit in a stiff-backed chair across the room from his sweetheart, but Mamma and Auntie and all the other ladies of the family are there, too, to insure decorous behavior.

The population of Yucatan is chiefly composed of the native Indians or Mayas. They are simple, kindly people and capable of development, for they are highly intelligent. To the best of our knowledge they are the direct descendants of the early Mayas, who in culture and achievements compare favorably to the people of ancient Egypt. Some of the wealthy Yucatecos are descendants of the old Maya nobility and still retain the original names denoting noble birth. But many descendants of Maya kings of old are now sunk in poverty.

Most of the present-day Mayas speak a language which has developed little from its primitive syllabic form. The Japanese, many of whom are found in Yucatan nowadays, learn the Maya tongue easily. In fact, many Japanese and Maya words are identical in sound, but as far as I know they have absolutely no kindred meaning. Some theorists have even advanced the idea that the similarity in form and construction of the Japanese and Maya languages indicates a common prehistoric origin. But there is scant proof of this, inasmuch as all primitive languages are syllabic in form.

The Maya is short in stature but surprisingly sturdy. A native will carry a load of a hundred pounds for fifteen miles without showing signs of undue fatigue. The carrier supports the load on his back and it is held in place with a band or strap passed around the forehead. Occasionally the carriers stop and let down the loads, but never for more than a few moments. An Indian porter will trot upstairs with a trunk which an ordinary mortal to lift upon his back. I remember seeing two Indians carry a piano, supported on poles, for a distance of two blocks, with their customary gliding shuffle when carrying a burden. Had they at any time fallen out of step the piano must surely have been wrecked. This shuffle or trot is half-way between a walk and a run and it eats up distance.

Not uncommonly the Mayas are handsome, with regular, delicate features. Some of the young women are very beautiful, even judged by North-American standards. They are mature at twelve years of age and, like the women of so many races of the tropics, they wither or grow fat at a comparatively early age. The color of the skin is about that of a good summer coat of tan, though possibly a bit more reddish in hue. Dress the average Maya in our mode and put him on any street in our country and he would pass without comment. On closer inspection he might be said to be of foreign ancestry, but certainly he would not be mistaken for a negro.

These people, descendants of a truly great race, are decidedly superior to all other native American peoples. Their mentality is of a fairly high order. At first, in my visits to Yucatan, I had no knowledge of either the Spanish or the Maya tongue and when I had only natives for companions I was compelled to communicate with them by sign language made up on the spur of the moment. Even in the jungle my companions always understood my directions easily and carried them out correctly.

The ordinary, every-day dress of the native men is a pair of white cotton trousers ending half-way between knee and ankle. We should have difficulty in defining them either as long or as short. The upper garment is a short-sleeved undershirt, and the ensemble is topped off with almost any kind of straw hat. Usually they also wear a short blue-and-white-striped apron fastened about the waist. Wide belts are popular—the wider the better. Frequently the men go barefoot, but more often wear sandals, fastened with twine about the ankle, a string passing from the front of the sole and between the first and second toes. When working in the fields the men sometimes discard apron and trousers, wearing only a breech-clout and hat. Sometimes they let their hair grow long so that it falls over their faces and then even the hat is discarded. On Sundays and feast-days the more affluent, at least, blossom out in starched white trousers and jacket and high-heeled wooden sandals.

The women customarily wear a huipile, which garment is neither a Mother-Hubbard nor a nightgown, but belongs, evidently, to the same genus or species. At any rate, it is sufficiently modest. It has a slightly low neck and short sleeves and reaches half-way from the knee to the ground. Beneath this is the pic, a white underskirt tied about the waist with a draw-string. Over all is worn the rebozo, a kind of shawl, and the native woman feels much ashamed if seen without this useless garment. Sandals may or may not be worn. The costume is always essentially the same. Sometimes the huipile is ornately and beautifully embroidered at the neck and on the sleeves. I am told that a girl will spend a year in embroidering a single huipile for her hope-chest. The garment is of ancient origin and I have seen murals in the ruined temples, painted centuries ago, which show women in just such embroidered garments, and at work making tortillas, which are still the main article of food in this land.

Many of the Maya women wear gorgeously embroidered sandals or slippers. The hair is done up in a knot at the nape of the neck and tastefully fastened with a ribbon. Gold chains with various sorts of pendants, such as medallions of the Virgin Mary or crosses, are very popular. Frequently the Maya belle wears several of these chains. And they must be solid gold; plated stuff or alloy may not be worn. It simply isn’t done. In her native costume the Maya girl is very pretty and picturesque, but in European dress she resembles only a shapeless bundle tied in the middle.

The Mayas are all very clean; the daily bath for men, women, and children is universal. A sort of wooden trough serves as a bath-tub as well as the family wash-tub. The bather pours the water over his body and makes a little water go a long way, because water must be carried by hand, usually from a distant well. For a man, even the humblest, to come home at the end of the day and find his bath unprepared is just cause for a rumpus with his wife. Clean bodies and clean clothes are characteristic of the Maya and much of the generally considered more civilized world might well take a lesson from him in this respect.

The women stay at home and attend to their household tasks and take care of their numerous children while the men work in the fields. This custom is universal even among the laboring people, and it is noteworthy because nearly everywhere else in the world both women and men work in the fields. In fact, in many countries the man does the most resting.

The Maya men are exceptionally fond of children and a widow with children stands an excellent chance of finding a stepfather for her brood. It is not uncommon for a man of twenty to marry a widow twice his age, chiefly for the sake of a ready-made family. Incidentally, the unmarried Maya maiden with a child or two, especially if the children are boys, is somewhat more likely to find a husband than her virgin sister. The fact that there may be some question as to the paternity of her offspring is of small consequence in the eyes of her prospective husband. But once married, she may accept no attentions from men other than her spouse. The husband may and does shoot on sight any cavalier found hanging around her. It used to be the custom to suspend a string of shells near the door, and one did not enter a house without giving due warning by shaking the string. A man did not enter at all unless the men of the family were present.

Maya nature is that same human nature found the world over. If abused, these people can be ugly and vengeful. Treated in a reasonably decent manner, they are kindly, generous, hospitable, and scrupulously honest. Personally, I have never been cheated nor overcharged by a native. I suppose that as more and more tourists come to Yucatan the invidious custom of fleecing the traveler will be established here as it has been everywhere else.

As has been said, water is scarce in this land, and frequently the women have to go long distances for even a jugful; yet they are always willing to share their supply with any one. The wayfarer is never turned away from their doors thirsty or hungry, even though he consume the last drop of water or bit of food in the house.

The Indian met anywhere, in the woods or on the trail, invariably removes his hat and voices a polite greeting. There were employed at Chi-chen Itza, during much of Don Eduardo’s work, about one hundred Indians. It was their pleasant habit each evening about sunset to pass in line before the hacienda and bid us good night. The ceremony took place as they were returning from the little near-by church,—for all the natives at that time were good Catholics,—and we saw no more of them until dawn, which was our hour for beginning work.

The modern Maya is devout, but he takes his religion placidly, leaving it to his spiritual adviser to tell him what to do or believe. In nearly every native hut is a shrine before which are dutifully observed the articles of faith—the faith of his conquerors who took away his galaxy of gods and substituted Catholicism.

The Maya home is built much as it was in ancient times. It usually consists of but one large rectangular room. The foundation is of stone held together with plaster called zac-cab, which means “white earth.” The walls are of poles or of stone plastered with zac-cab. The roof is peaked and thatched with straw or with stiff palm-like leaves. The door is of wood and there is sometimes a window, barred but without glass. A wooden cover may be inserted from within to close this opening when desired. No matter how poor the Maya family, there is always a flower garden in the rear of the house. If his domain is very limited, the garden of the Maya may be reduced to what may be grown in a large-sized Standard-Oil can.

Within, the Maya home is very simple. There are no beds as in ancient times; the native has adopted a Spanish innovation, seeking his rest in a hammock suspended from wooden pegs set in the wall. The hammocks are taken down when not in use. A simple stool or two, a bench or a chest, possibly a table, and the ever-present shrine constitute the furniture. Not infrequently there is an American-made sewing-machine. The kitchen is outside, in another smaller building, and the stove consists merely of a crude stone oven or heap of stones. The bath-room and laundry, where there is a wooden trough to hold water, also is outdoors. At meal-times the family sits on stools about a pot or vessel containing the pièce de résistance, and the use of fingers is not frowned upon.

The natives not resident in the towns or cities are for the most part employed on the haciendas, the majority of which are engaged in the raising of henequen. A few years ago there appeared a series of magazine articles, under some such heading as “Barbarous Mexico,” describing in the most approved yellow-journal style the cruelty and tyranny of the Mexican planters. I suppose there really are some isolated cases of cruelty, but in general the treatment of native workers by the plantation-owners leaves little to criticize. The native is free to leave one employer to seek another. His pay is good and he certainly is not overworked. On nearly every hacienda ample provision is made for entertainment and the fiestas and dances so dear to his heart. Many native families have lived and labored on one plantation for several generations—a fair indication that they are not ill-treated. One of the atrocities recited in the magazine articles just mentioned was the tying of an Indian to a post, where he was whipped severely. The whipping-post has existed, but its use was fostered by the Indians themselves and was reserved for the habitual drunkard or him who repeatedly abused his wife and children. Possibly a similar course of treatment might be beneficial to some citizens of the United States.

There was one unfortunate event, however, which reflected no credit on the natives, but for which they were far less to blame than a certain class of whites. Not long ago the creed of bolshevism was spread among these poor credulous people by a Rumanian fanatic, resulting in the murder of several plantation-owners and the burning of several estates. A few Indians at Don Eduardo’s hacienda, who had for some time failed to pay the slight rental required of them, became unruly and the master ordered them to pay up or leave. In reprisal they set fire to his house, Casa Real, and all the out-buildings, destroying many priceless antiquities intended for an American museum of archæology. The house has been rebuilt, but the lost treasures can never be replaced. The Indians also drove off all Don Eduardo’s stock and took everything in the way of valuables that was portable.

Don Eduardo, in relating his experiences as a plantation-owner, once said:

“A certain residue of Indians were never conquered by the Spaniards, nor have they ever been subdued by the Mexican Government; and they pay no taxes. They are called Sublevados and I have been warned ever since I came to Chi-chen Itza that some day the Sublevados would go on the war-path and wipe me and my hacienda clean off the map.

“Eventually I became tired of waiting for them to visit me and enjoy the friendly reception I had prepared for them, which included, among other things, the fortifying of the Great Pyramid. So I decided to make a little reconnaissance. Traveling south into their own country, I lived for some time in their villages, where they still practise the ancient Maya rites and incantations, even though there is a slight veneer of Catholicism among them. Since then I have traveled many times into the Sublevado territory; in fact, have been made a chief of the tribe by solemn bond and ritual. I have found them a peaceful, friendly lot of ignorant Indians, unlikely to do any harm as long as they are left to their own devices and in their present habitat.”

The Maya is happy-go-lucky, improvident, and usually lazy. He dearly loves a good time, a good story, and a good joke, especially if it is of the practical variety in which the other fellow is the butt. He is very fond of fiestas and dances.

The native dances are quite different from ours. The men and women sit close to the walls of the hut or inclosure, sometimes on chairs but more often on stools. On important occasions, the music is furnished by violins, guitars, and perhaps some wind-instruments. But always there is one musician with a long gourd containing stones, which is shaken in time to the music, producing a hollow chuck-a-chuck, chuck-a-chuck sound. Sometimes the only instrument is a flageolet. The music is always in a minor key and is without pause or period or end. A girl—any girl—gets up and proceeds to the center of the floor, where she shuffles about for perhaps a minute. Then from the other end of the room some man, who may be a stranger to the girl, comes forth and shuffles about in front of her. They do not touch each other. They gyrate rather slowly and move in circles, always facing each other. When either becomes weary, he or she retires and another takes up the dance. If the room is sufficiently large there may be as many as three couples dancing continuously in this manner. The dancers do not smile nor appear to be enjoying the occasion; yet they must derive pleasure from it, for throughout the country dances are held frequently.

Knowing the Mayas of to-day, and their customs, it is interesting to follow their history back to the earliest times of which there is authentic record, and from there, through legends and scraps of knowledge, into their most ancient past. For four centuries we may trace them backward through well-known history. For still another century the record is fairly clear. Back of that is only legend, with here and there some startling, incontrovertible fact to prove their antiquity. The flickering light of our knowledge becomes dimmer and dimmer. We know a date in their history about one hundred years before Christ, but on what preceded that no feeblest ray falls to enlighten our ignorance.

To one man, long since departed, we owe a great debt. But for him, our knowledge of the ancient Mayas would be almost nil, and it is only by a lucky chance that what he wrote was not lost to us. This man, Diego de Landa, was Bishop of Yucatan (1573-79), and he came to America on the heels of the Spanish conquerors. His manuscript, —almost our only guide to Maya antiquity and known as “Relacion de las Cosas de Yucatan,”—lay hidden in Madrid for nearly three hundred years ere it was discovered and published.

To show how little the Mayas have changed in four centuries I am going to quote from Landa, using a very free translation but endeavoring to preserve his meaning. I hope the reader will bear in mind that the following is a description of the Mayas of the sixteenth century and is chiefly interesting when compared with the Mayas of to-day:

The Indians of Yucatan are well built, tall and robust. They are generally bow-legged, because mothers customarily carry infants astride their hips. It is considered a mark of beauty to be cross-eyed. The heads and foreheads are flat, having been bound in infancy. Their ears are pierced for ear-rings and are torn by the sacrifices. The men do not have beards and it is said the mothers burns their boys’ faces with hot cloths so that hair does not grow. Some do have beards, but these are very stiff, like the bristles of a pig. The men permit the hair of the head to grow long except on top, where they burn it off. Thus the hair of the crown is short, but the remainder is long and is braided and wound like a wreath around the head, leaving a small tail in the back as tassels or tufts.

Their dress is a strip of cloth about as wide as a hand and wound several times about the waist, with one end hanging in front and the other in the back. The women adorn these ends curiously with feathers. They wear large square blankets, which they fasten to their shoulders, and sandals of hemp or deerskin.

They bathe a great deal and do not try to hide their nudity from the women, except with their hands. The men use mirrors and the women do not. The expression for cuckoldom is that the wife has put the mirror in her husband’s hair above the occiput.

Their houses are roofed with straw or palm-leaves and the roof has a considerable slant. They put a wall lengthwise through the middle of the house and in it some doors. In the back half are the beds and the other section is whitewashed and is the reception room for guests. This room is like a porch, the whole front being open and without a door. The roof over this part of the house extends well down over the walls, to keep out sun and rain. The common people build the houses of the chiefs and house-breaking is considered a grave crime. Beds are made of small rods with a mat and cotton blankets on top. In summer the men especially sleep in the open room or porch, on mats.

All the people unite in cultivating the fields of the chief and supplying food to his household. In hunting, fishing, or bringing salt, a share is always given to the chief. If the chief dies he is succeeded by his eldest son, but his other descendants are respected and helped. The subordinate chiefs help in all things, according to their stations. The priests live from their offices and from the offerings given to them. The chiefs rule the town, settle disputes, and govern all affairs. The principal chiefs travel a great deal and take much company with them. They visit rich people, where they arrange the affairs of the villages, transacting their principal business at night.

The Indians tattoo their bodies, believing that they become more valiant thereby. The process is painful, as the designs are painted on the body and then pricked in with a small poniard. Because of the pain the tattooing is done only a little at a time, and also because the tattooed part becomes inflamed and matterated, causing sickness. Those who are not tattooed are ridiculed. The natives like to be flattered and they like to imitate the Castilian graces and customs and to eat and drink as we do. They are fond of sweet odors and employ bouquets of flowers and sweet-smelling herbs. They are accustomed to paint their faces and bodies red, which does not improve their appearance but which they consider beautifying.

They are very dissolute in getting drunk, from which follow many evils such as murder, arson, rape and incest. . . . They are fond of recreation, especially of dances and of plays containing many jokes and witticisms. They sometimes become servants for a time in a Spanish household just to absorb the conversation and customs and these are later artfully represented in native plays.

Their musical instruments are small kettle-drums played with the hand and another drum made of hollow wood, played with a wooden stick containing on the end a ball made of the milk of a certain tree [rubber]. They have long, slender trumpets fashioned from hollow sticks with gourds fastened at one end. Another instrument is made from a whole turtle-shell, which is played with the palm of the hand and emits a melancholy sound. They have whistles and flutes of reed or bones of the deer and from large snail-shells. These instruments are played for their war-dances. One of these dances is called co-lom-che, meaning reed. A large circle of men is formed. Two go into the center. One has a handful of darts and while dancing in an upright position he casts the darts with all his strength at the second dancer, who dances in a squatting position, from which he deftly catches each dart with a small stick. After the darts are all thrown, these two dancers return to their original places in the circle and two new dancers advance to the center and repeat the dart-throwing. There is another war-dance in which about eight hundred men take part. They carry flags and the tempo is slow. They dance the whole day without stopping and during the whole day not one man gets out of step. In no case do the men dance with the women.

There are many occupations but the people most incline toward trading, taking salt, clothing, and slaves to the lands of Ulna and Tabasco, where they exchange for cocoa and counters of stone which are their money. With these coins they buy slaves, or the chiefs wear them as jewels at feasts. They have other counters and jewelry made of certain shells. These are carried in purses made of network. In the markets are all manner of goods. They loan money without usury and pay their debts with good-will. Some Indians are potters and carpenters who are well paid for the idols of wood and clay which they make. There are surgeons—or, rather, wizards—who cure with herbs and incantations. Above all, there are laborers and those who plant and gather the corn and other produce which they store in granaries to be sold in season. They have no mules or oxen.

The Indians have the good custom of helping one another in all their work. In working the land they do nothing from the middle of January to April except gather manure and burn it. Then come the rains and they plant the fields, using a small pointed stick to poke holes into the ground in each of which they deposit five or six seeds which grow very rapidly in this rainy season. They also congregate in groups of about fifty for hunting or fishing.

When going on a visit, the Indian takes a present to his host and the host gives the guest a present of proportionate value. They are generous and hospitable. They give food and drink to all who come to their houses.

They take much pride in their lineage, especially if they are descendants of some ancient family of Mayapan and they boast of the distinguished men who have been of their family. The whole name of the father is always borne by his sons, but not by his daughters. But the children, both sons and daughters, are called by the compound names of father and mother, in which the name of the father is the given name and that of the mother the surname. Thus the son of Chel and Chan would be Na-Chan-Chel, which means son of Chel by his wife Chan. A stranger coming to a village, especially if he be poor, will be received in all kindness by any family of his name. Men and women of the same name do not marry, for this is considered very wrong.

“One particularly lovely Sunday morning, some time after taking up my abode at Chi-chen Itza,” says Don Eduardo, “I was awakened, as on other occasions, by the softly melodious chiming of the bells in my little church on the hill. As I lay in my hammock, idly listening to the pleasant sound, I could distinguish the different tones of the several bells and it was a pleasant thought to me to know that I had equipped the little church with bells having a superior quality of tone. The sound of them was indeed delightful because while church bells in Yucatan are as plentiful as millionaires in Pittsburgh, they are usually cracked and raucous.

“It was still early when I stood before my manor and turned my gaze eastward toward the little stone church perched cozily on a near-by gently sloping hillside. Both my manor and the little church had for many years been in ruins, unused. Extensive repairs had just been completed on both, to make them habitable. Here and there one of my Indians, or a whole family, dressed in their Sunday best, were already churchward bound, and the chimes continued softly to remind the laggard of his duty. The red rim of the sun was just peeping over the horizon behind the church, while the birds in every tree and thicket were voicing their welcome to this glorious new day. A lazy, blissful breeze laden with the mingled scents of a thousand tropic blossoms ruffled the tree-tops. Before me stretched a vista of wildly beautiful country-side with no sign of the handiwork of man other than the little church. No towering peaks, no gushing streams, no bottomless cañons greeted my eye; merely a terrain that is just saved from being flat. Yet it is all divinely lovely—a study in green and blue with here and there a spot of flaming color. The cloudless sky was of so clear and vivid a blue that I was tempted to stand on tiptoe and take down a handful. Foliage of some sort covered every inch of ground and was of every imaginable shade of green, from the shadowed purple-green where the rising sun had not penetrated, to the pale green of some of the tree-tops, turned golden in the first slanting rays. A gorgeous parrot flashed from tree to tree and disappeared and by his flight brought my eye to rest on a riot of flame-flower high up in a distant tree.

“The sudden silence of the bells warned me that if I too intended to go to church there was no time to lose. My little stone church is not without fame, for in its then-abandoned sacristy that remarkable traveler and historian John L. Stephens made his abode when he visited my City of the Sacred Well. It was here that he wrote his notes on ‘The Ruined City of Chi-chen Itza.’ Though it has been repaired, it looks almost as he left it one cloudy Sunday morning nearly eighty years ago. Its cut-stone walls and bell-tower are the same, but its old roof, bowed with age, has been replaced with a fine new thatch of palm.

“San Isidro is the patron saint of the plantation—for no well-organized plantation is without its patron saint, whose image is venerated by all the natives there employed. The image of San Isidro in this little church on the hill at Chi-chen Itza is of unknown antiquity and is believed to be possessed of miraculous powers which are constantly manifested. Veneration for the image, together with the attraction of the three-belled chimes swinging in their places in the tiny tower, makes the little church a sacred spot not only to the people of my hacienda but likewise to the inhabitants of the near-by village of Pisté and the region for many miles around. Has not the sacred image and the big stone baptismal font been used by the archbishop himself? Was not Mat-Ek healed, who was blinded for many months by the vapor from the ikeban plant, blown into his eyes by the wind while he was gathering his crops? Was he not given back his sight in less than a week after he had prayed for aid and kissed the feet of San Isidro? And did not Mat-Ek, in token of his gratitude, have made an eye of pure silver and give it to the sainted image—an eye which now hangs over the altar for all to see? What more can you ask?

“The church was filled to overflowing in token of a great and special day, for it is only occasionally that the regularly ordained priest comes all the way from Valladolid, and confessions, christenings, and marriage banns await his coming.

“As the congregation slowly drifts into place, the gentle rustling of the unstarched huipiles and pics of the women and the louder rustling of the stiffly starched trousers and jackets of the men sound remarkably like the lapping of summer wavelets upon a sandy beach. The soft laughter of the children outside the building, mingled with the restrained voices of admonishing Indian elders, all combine to create an atmosphere in perfect accord with the surroundings and the low-toned service. Within the chapel many candles of wild beeswax give forth soft lights and heavy odors which, mingling with the fragrant smoke of incense, fall with pleasant, soporific effect upon the congregation.

“The chimes ring their tuneful, familiar message—a message come down the centuries since the Child of Bethlehem was born in a manger; a message brought across the seas to this little stone church, by some unknown, long-departed padre. The solemn peals roll out and up to those gray old temples of another faith, wherein the sacred music of the ancient Mayas, the sound of tunkul, or priestly drum, and dzacatan, once beat in pulsing chorus. These sound symbols of the Sacred Cross are wafted to the altars, still standing, of the Sacred Serpent, whose creed once reigned supreme over this land.

“The beloved priest begins the age-old intoned creed and as the service lengthens through the chants, singing, and sermon, there comes a penetrating, strangely sweet odor. Stronger and stronger it grows, filling the church and floating out into the morning air. The worshipers nod their heads. ‘The xmehen macales have blossomed; God is good to us,’ they murmur. Six graceful, big-leafed plants like large calla-lilies had been placed upon the altar, among other flowering plants. And as I look, the six white buds of these lilies, each slenderly sheathed in green, open slowly to the light, revealing blooms of creamy white. They open in unison, as if at the bidding of an unheard voice. To me it is startling, uncanny. And here is the story about them that met my eager questions at the close of the service:

“Francisco Tata de las Fuentas, caballero of Castile, blue-eyed and yellow-haired, was fair of skin as a Saxon. In his youth he was as hot of blood and of head as a Gascon and traveled the pace with the best and worst of Castile and all the adjoining provinces. His offerings to Venus, to Bacchus, and to the little gods of chance were so fervid and frequent that they soon caused his real castle in Castile to become as those common ones of the air. And his broad lands on the banks of the Guadiana passed to more careful guardians. When nothing remained to him but his horse, Selim, he betook himself with Hernan Cortes to New Spain. Here, under Cortes, he learned discretion bought by hard experience, so that he acquired some wealth. With Francisco de Montejo, trusted friend and lieutenant of Cortes, he came to Yucatan, received a royal grant of land with many natives, and took to himself a wife, the lovely and virtuous daughter of a native chief or batab.

“Time passed and he was gathered to his fathers, leaving an only child, a son named for him. The second Francisco Fuentes inherited the father’s fair skin and bold blue eyes, as well as the gorgeous gold-and-silver trappings of the once fiery Selim, not to mention half a dozen big plantations, houses and lands in Valladolid and Mérida, and scores of minor holdings in several other towns and villages.

“This Francisco Fuentes, or Pancho as his friends called him, had two sons and a daughter. The sons were stalwart, upstanding fellows, recalling in their stature and temper their Spanish ancestry, but showing in their brown skins the admixture of native blood of mother and grandmother.

“Maria, the one beloved daughter, had the plump figure and the sweet temper of her mother, but her proud little head was covered with a wealth of yellow hair and her eyes were of clearest blue, the dauntless eyes of the first Francisco. And now Maria, the idol of her father and worshiped by her brothers, darling of the whole village, was slowly dying; wasting away with a strange fever that could not be abated. By day her body was cool and her brain clear, but with the setting sun came the fever that defied all skill of physicians and nurses. At midnight her frail, fair form was shaken with ague and burned with a fever almost to sear the hands of those who ministered to her as she tossed in delirium. Wasted to a shadow, Maria seemed beckoned by the Grim Reaper.

“The sun again touched the western horizon. The sorrowing family, father and brothers, were at her bedside. Friends and neighbors gathered to watch over the last hours of the helpless little sufferer, for there seemed no hope. A knock sounded at the door, hesitant, timid, as of supplication.

“ ‘It is but one of the beggars who constantly impose on Maria,’ said a sharp-tongued watcher, peering through the window into the dusk.

“Maria, restlessly turning in her hammock in an inner room, heard the knocking and the words of the watcher.

“ ‘I think,’ whispered she, ‘it is old X-Euan, come for some milk I promised her for her orphan grandchild. Fill with milk the clean flask which is on the shelf behind the door and give it to her.’

“Old X-Euan took the flask of milk, but from her lips did not come the whining thanks of the mendicant. Instead, from beneath the tattered folds of her shawl, she brought forth a vase of strange antique make, in which was growing a broad-leafed plant with a single swelling bud at it center. Handing the plant to the watcher, the old Maya woman said:

“ ‘Take this to Maria; place it close by her with the blessing of one to whom she has done as her kind heart, guided by God, has told her to do.’ In her voice was a note of command which brought obedience from those who heard. Old X-Euan departed, but some—those who were nearest and so should have seen clearest—insisted that a faint glow like a halo enveloped her head.

“The hour of twilight had passed. The dreaded time of the quickened pulse and panting delirium had come. Maria lay tossing in her hammock. Close by her the virgin petals of the flower began slowly to unfold. A fragrance, at first almost imperceptible, was wafted through the room. As the blossom opened to full bloom and its perfume permeated the sick-room, the restless turnings, the feverish mutterings grew less and less and at last ceased altogether. A dewy moisture appeared on Maria’s pallid forehead and she sank into deep, refreshing slumber.

“Amid the rejoicing there was a note of awed wonder, for in the very center of the flower the beautiful calyx seemed to have taken the fever heat that was Maria’s, and as her fever abated the heat in the heart of the flower increased, until at midnight it was almost incandescent.

“A week passed. Each night, so the watchers told, the flower took to itself the heat of the fever, while Maria, feverless, slept soundly. And on the morning of the eighth day she was convalescent. But the beautiful blossom was but a withered, brown, shapeless nothing.

“ ‘La flor de la calentura has performed its task,’ exclaimed the joyful natives, but Maria, lovely once more with returning strength, said, ‘Alas! La flor de la calentura, the flower that saved my life, is dead.’

“And thus it was told by Maria to her grandchildren and retold by them to their grandchildren and is now known by every one in the region. Surely it must be true! Why shouldn’t it be? At any rate, it is accepted as literally by my Indians as the less pleasing story of Jonah and the whale.”

It has been said that civilization is but a layer-cake of eras—a building up of strata, with the brute state at the bottom. Layer upon layer, each succeeding generation adds its small bit of culture or knowledge, until a golden age is finally reached. And, sadly enough, from that age of enlightenment, the hope of the world, there has always been a rapid decline, until centuries later, perhaps, again begins the tedious gradual uplift.

And the story of man’s rise and fall, in the passing of the ages, usually is buried in the earth, to be laid bare to our eyes if we have but the patience to find and the ability to understand. Just as a good woodsman can read from a scratch on a tree or a faint footprint on the ground things not obvious to the untrained observer, our men of science have developed remarkable expertness in divining the history of bygone eras from the scanty traces that remain. From a skull, centuries buried in a cave, they reconstruct the Neanderthal man. The fragments of an earthen pot tell them the degree of culture and the period of him who once supped from the vessel.

Wherever there are caves there is the likelihood of uncovering vestiges of aboriginal life, for primitive men everywhere used caverns, either as temporary shelters or as permanent abodes. Beneath the cave floor may be the evidence of many generations of men—the relics buried in layers one upon another as the discarded and broken implements of one generation were trampled underfoot and submerged under the charred embers and rubbish of the succeeding one.

The written record of the Mayas gives but little clue to their origin and no indication at all of their descent from more barbarous ancestors. Did these people, already of a high state of culture, immigrate from some other land? If so, were they the first comers or did they find the country even then inhabited? Or were their ancestors natives of this region for hundreds of centuries before them?

Yucatan is a land of caverns, veritably a honeycomb of caves, and eagerly the paleontologist rolled up his sleeves, shouldered his shovel, and set out to find the answer to these vexing questions. The answer was found and is conclusive but disappointing. Beyond the question of a doubt, the Mayas brought with them their culture, and they were the first inhabitants of this country. Whence they came, or how, or why; from what race they sprang, we know not and probably never shall know. A few conflicting legends of their arrival as recorded in some old Maya writings constitute the sum total of our knowledge on this point.

Many intricately derived meanings of the name Maya have been offered. The most obvious, however, is the direct translation. Ma means “not” and ya means “emotion,” “grief,” “tiresome,” or “difficult.” The combination means, “not arduous,” “not severe.” We know that the Mayas frequently alluded to their country as the Land of the Deer and the Land of the Wild Turkey—U-Lumil-Ceh, U-Lumil-Cutz. “Maya,” therefore, may quite likely have been descriptive of the region as a pleasant, comfortable place of residence. Juan Martinez, who knows the Indian and the language, present and past, as no one else, once said to me: “Work and grief are synonymous to the native mind. Work is grief to the Indian; therefore a land of no grief and no sorrow may well mean a land of no work.” However, any explanation of the derivation of so ancient a name is little more than surmise.

According to one myth, the Mayas came over the sea from the east, under the leadership of a hero deity, Itzamna; hence the name “Itzas” as applied to a part, at least, of the Mayas. In the Maya books Itzamna is represented as an old man with one tooth and a sunken jaw. His glyph or sign is his pictured profile, together with a sign of night, the sign of food, and two or three feathers.

The more credible legend refers to an immigration from the west or north, under a chieftain named Kukul Can. There are reasons for believing that this legend may be founded upon fact. It is mentioned in several of the most ancient of the surviving Maya records and in the testimony of a number of well-versed natives at the time of the Conquest. Farther up the coast, north of Vera Cruz, is another branch of the Maya family called the Huastecs, while in Central America, through Honduras, Guatemala, and even in Costa Rica, are present-day Maya tribes and ruins of ancient Maya civilization. Also, there is a close similarity between the Kukul Can legend and the Aztec annals, indicating a common origin. Everything points to the probability of a remote great migration of their common ancestors from the north.

The Aztec tradition is particularly interesting and describes the arrival by boat of several different tribes at the mouth of the Panuco River, which spot the Aztecs called Panatolan, meaning “where one arrives by sea.” The expedition was headed by the supreme leader, Mexitl, chief of the Mexicans, with whom were other chieftains and their followers. They traveled on down the coast as far as Guatemala, and some turned back and settled at various places along the shore. On this journey an intoxicating drink was originated by one Mayanel, whose name means “clever woman.”[1] There is a possibility that “Maya” is derived from her name. At any rate, one tribal chief, Huastecatl, imbibed too freely and cast aside his garments while intoxicated. His shame was so great when he realized what he had done that he gathered his tribe, the Huastecas, and returned with them to Panatolan and settled there.

[1] The suffix “el” added to any Maya word denotes action. In the glyph sign this often was indicated by adding the wing of a bird to the main hieroglyph; therefore “Mayanel” was an active woman, hence very clever.—Author.

Landa says in his book that some old men of Yucatan related to him the story, handed down for many generations, that the first settlers had come from the east by water. These voyagers were ones “whom God had freed, opening for them twelve roads to the sea.” If there is any truth in this tradition, these progenitors may have been one of the lost tribes of Israel. An interesting side light on this hypothesis is the distinctly Semitic cast of countenance of some of the ancient sculptures and murals found at Chi-chen Itza and in other old Maya cities. The dignity of face and serene poise of these carved or painted likenesses is strikingly Hebraic.[2]

[2] In an article written for “Harper’s Magazine,” by Mr. Edward Huntington, reference is made to the Jewish cast of features of the modern Mayas, and I have often noticed the similarity. One prominent writer on Yucatan considers the possibility of Jewish origin for the Mayas as being the most substantial of the several theories I have mentioned.—Author.

While we are in the field of conjecture, we may as well consider the old Greek myth of the lost continent of Atlantis. From the geological point of view, it is not impossible. The whole of Yucatan is low and was once the bottom of the sea, as is indicated by its surface rock and sand. Furthermore, the stretching out of the Antilles as though to form a bridge with the Azores, and the shallowness of the intervening Atlantic Ocean, lends plausibility to the idea that there may have been a cataclysmic upheaval of the ocean-bed during some past era, and not long ago, geologically speaking—an upheaval which created the land of Yucatan and caused what was land to the eastward to sink beneath the level of the Atlantic. What is more natural to suppose than that in some prehistoric period the lost continent of Atlantis did exist and proved an easy means of passage between Europe and America?

The mist-enshrouded history of the migrations of ancient people, the crossing and recrossing of their pilgrimages and of their blood, is a fascinating study, but one which tells us comparatively little that may be crystallized into fact. And so, in these various speculations as to the origin of the Mayas, no theory contains enough weight of evidence to warrant the assumption that it is the right one. It is, however, pretty clearly established from the ancient Maya writings and legends that there were two main immigrations, the greater one coming from the west or north and the lesser one from the east.

Emerging at last from the purely legendary, we reach the middle ground where the history of the Mayas is still unrecorded but where the word of mouth, as handed down from father to son, is more precise and has some relation to definite dates. Then we suddenly step over the threshold into the historical era.

The first recorded date, which corresponds to 113 b. c., is on a statuette from the ancient city of Tuxtla, and there is some doubt as to whether our reading of this date is correct. The next inscription corresponds to 47 a. d., and here we are on sure ground. A monument in northern Guatemala contains a date prior to 160 a. d., at which point the ancient Maya Codices take up the history of the race and carry it on to the time of the Conquest. And even at this early time, the Mayas had hieroglyphic writings and were skilled in stone-carving and the erection of massive works of architecture. With the written Chronicles, the many hieroglyphed stones,—“precious stones,” I like to call them,—and the history of progress as indicated by the different periods of architecture and sculpture, we are able to verify and correlate most of the subsequent dates.

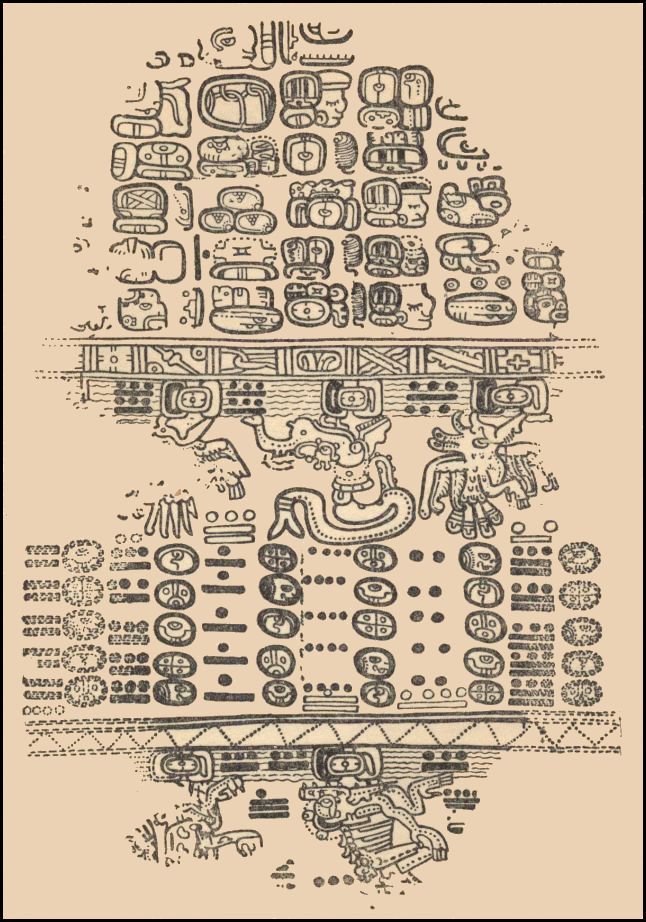

The written Maya records, without which our task of piecing together anything of their history would be almost impossible, are among the most interesting and valuable remains of this bygone civilization. The records are of two kinds. The first, the Codices, are the original texts, written in hieroglyphics. The second, the Chilan Balam, are written in the Maya language but with Spanish characters, and are chiefly transcripts from the more ancient records.

Only three hieroglyphic Codices have survived, and they are known respectively as the Dresden Codex, the Perez Codex, and the Tro-Cortesianus. All are in European museums and many facsimile reproductions have been made of them for use in other museums and libraries. These manuscripts are painstakingly illuminated by hand, in colors, and were done with some sort of brush, possibly of hair or feathers. They are done on paper or, rather, a sort of cardboard which has been given a smooth white surface through the application of a coating of fine lime. The body of the paper is made of the fiber of the maguey plant. The manuscript is folded like a Japanese screen or a railway time-table. According to early accounts, some of these records were also made on tanned or otherwise prepared deerskin and upon bark. None of the hide or bark records has ever been found by present-day explorations. It is known that the Mayas had many records concerning religious history, religious rites and ceremonies, medicine, and astronomy. The Spanish priests caused all of the Maya writings they could find to be gathered together and burned, in the fanatical belief that they were serving the church by so doing.

If only their bigotry had vented itself in some other way, how much these old manuscripts might have told us! Apropos of the burning of the priceless documents Landa says, “We collected all the native books we could find and burned them, much to the sorrow of the people, and caused them pain.”

A PAGE FROM THE PEREZ CODEX, DESCRIBING AN ECLIPSE OF THE SUN. THIS ANCIENT MANUSCRIPT ILLUMINATED IN COLOR IS NOW IN THE LIBRARY OF PARIS

The group of books called the Chilan Balam, which are chiefly ideographic transcripts of the more ancient works, written in the Maya tongue but in Spanish characters, probably were made surreptitiously by some of the educated natives soon after the Conquest. There are sixteen of these books still extant. The meaning of this Maya name, Chilan Balam, is interesting. Chi means “mouth”; lan indicates action. Therefore Chilan is “mouth action,” or “speech.” Balam is synonymous for either “tiger” or “ferocity.” But the tiger was worshiped as a deity and the combination of the words, Chilan Balam, means “Speech of the Gods.” The Maya priests were sometimes called by the name, indicating that they were the mouthpieces of the gods, and doubtless these records took their name from the priestly appellation.

The individual books of the Chilan Balam are known by the names of the villages in which they were found, and in a few cases the name of the village may have been derived from the presence of the book. The most important of these books are Nabula, Chun-may-el (which means “something of the first” or “original”), Kua, Mani, X-kutz-cab, Ixil, Tihosuco, and Tixcocob.

Just when these books were written is not known, but there is evidence that the book of Mani was written prior to 1595 and the book of Nabula tells of an epidemic which occurred in 1663. While teaching the natives to write the Maya language in Spanish characters, Bishop Landa employed a rather original method, which is our only key to reading these writings and which serves as our only clue to the more ancient hieroglyphs. The ancient Maya writings were purely picture writings, but to some extent the hieroglyphs had lost their original picture significance and had come to have a somewhat symbolic meaning.

In arranging the so-called Maya alphabet (which was first used by the priests in writing out the prayers for the Mayas), Landa employed a very ingenious method and one that was practical at the time. He took the Spanish alphabet and beginning with “A” he asked the educated Indian to draw the character for him in which the sound of “A” was predominant. Naturally, after many attempts by the Indian to furnish such a character he finally selected the hieroglyph ac, which is a picture of a turtle’s head and which in Maya means “turtle” or “dwarf” or something having a slow movement. Next he took the letter “B” and eventually chose the character be, which means “road,” “walk,” “run,” and consists of the picture of a footprint. Therefore—not to go into a lengthy description of the system—he had “A” from ac, “B” from be, etc. With this extemporized alphabet the priests were able to write out the Catholic prayers in such a way that the Indian could repeat them in Spanish by using the sound of the first part of his hieroglyph for the sound of each Spanish letter.

It may be seen from the foregoing that Landa’s alphabet cannot be used for translating Maya, for when the hieroglyphs are made to represent the sounds of the Spanish alphabet the result does not indicate the original connection of a Maya word with its glyph. This fact was a great disappointment among archæologists, who at first expected to translate the Maya Codices by the use of the Landa alphabet. Their hopes, however, were short-lived and they even pronounced Landa an impostor. On the contrary, he has unintentionally given us what is almost a Rosetta Stone.

The Codices, I fear, will never yield a connected story, as they are written in a stenographic or shorthand style consisting of disconnected sentences.

Many of the stones, or stelæ, may contain history, and as soon as we know the meanings of, possibly, a thousand glyphs we shall be able to make a decided advance in the art of reading the books. Landa in his book explains not the Maya glyphs but the way the priests used these Maya characters for religious purposes. For example, he says Ma-in-kati means “I do not want,” represented in the ancient Maya by three simple glyphs. Written as the priests had arranged, with a glyph for each sound of a Spanish letter, the result is a combination of five glyphs, which, if given their original Maya pictured meanings, leads to the rather surprising knowledge that “no dead animal was seen at this place,” or, literally, “not see tail [animal] death place.”

Besides the Codices and the Chilan Balam, which together are frequently alluded to as the Maya Chronicles, there are some other documents such as titles to land, records of surveys, etc. There is a unique history of the Conquest, written by a contemporary native chief called Na Kuk Pech, whose name means “house of the feathered wood-tick.” The story was written in the native language, by means of Spanish characters, and has been translated recently by Señor Juan Martinez, whose profound knowledge of the Maya language has eminently fitted him for this task.

The history of Chi-chen Itza is of especial interest because this was the Holy City, the Mecca of all the ancient Maya people. According to the Maya Chronicles, one or several tribes set out from a place called Nonual, in 160 a. d., and apparently spent many years in aimless wandering, arriving finally, in 241 a. d., at a place they named Chac Nouitan. Then follows a gap in our knowledge and the next we learn of these people is that in 445 a. d., while they were residing at a place called Bak-Halal, they heard of Chi-chen Itza. It is clear that Chi-chen Itza was already an inhabited city at that time. Soon after this, these tribes moved to Chi-chen Itza, where they lived until about 600 a. d., when, for some unaccountable reason, they abandoned it utterly and migrated to the land of Chan Kan Putun. And this residence was in turn abandoned two hundred and sixty years later, because of some calamity; one Chronicle speaks of a great fire.

For nearly a hundred years, to quote from the Chronicles, “the Itzas lived in exile and great distress under the trees and under the branches.” Then, some of them reëstablished Chi-chen Itza in 950 a. d., while others founded the city of Uxmal or went to Mayapan. The second residence lasted for some two hundred years. About 1200 a. d., the Itzas, under the ruler Ulumil, invaded the city of Mayapan and at about this same time Chi-chen Itza was attacked and depopulated by foreigners—in all probability the Nahuas (Mexicans), who came down from the north. The last event alluded to in the Chronicles is the coming of the Spaniards under Montejo, who found the Mayas already decadent and their cities long ruined and abandoned.

We have no authentic description of the actual condition of Chi-chen Itza when the Spaniards came, but it is known with certainty that Tiho (place of the five temples), one of the ancient cities, the site of the modern city of Mérida, was in ruins. The temples were dilapidated and overgrown with vegetation and great trees were rooted in the walls. The few inhabitants living around these ruins knew virtually nothing of the founders of the city, nor of those who had lived there when it was in its prime.

At the coming of the Spaniards to Chi-chen Itza, about 1541, the city was inhabited by a few people who were, I think, nothing more than campers—inferior people using as shelters the buildings which they had found there and of whose history they were quite ignorant.

While it has no place in this book, the last known migration of some of the Mayas is interesting and it is certain that a considerable number emigrated between the years 1450 and 1451 southward to Lake Peten,[3] where they built a city on an island and there they survived, together with their ancient culture, until conquered in 1697 by the Spaniards, who destroyed all their temples and books and perforce made either good Christians or “good Indians” of all the inhabitants.

[3] Peten: “Something surrounding an island.”

Landa says, under the heading, “Various Misfortunes Experienced in Yucatan in the Century before the Conquest”:

These people had over twenty years of abundance and health and multiplied greatly. All of the land looked like one town and they built many temples which can be seen to-day in all parts; and crossing the mountains, one can see through the leaves of the trees sides of houses and buildings wonderfully constructed. After all this happiness, one evening in the winter a wind arose about six o’clock and increased until it became a hurricane of the Four Winds.[4] This wind tore out the large trees, made a great slaughter of all kinds of game, tore down all the high houses, which, as they were thatched with straw and had fire inside against the cold, caught fire. Great numbers of people were burned and those that escaped were torn to pieces by falling trees.

This hurricane lasted until noon of the next day. Some who lived in small houses escaped—the young people who were just married, who were accustomed to build small houses in front of those of their parents or parents-in-law, where they lived the first years.

Thus this land then lost its name, which was U-Lumil-Ceh, U-Lumil-Cutz, Land of the Deer, Land of the Wild Turkey, and was without trees. The trees now seen all appear to have been planted at the same time, as they are all of the same height, and, looking at this land from some spot, it seems as though it had been trimmed off with shears.

Those who escaped felt encouraged to rebuild and cultivate the land and they again multiplied greatly, having fifteen years of health and good weather and the last year was the most fruitful of all. At the time of harvest, there came upon the land some contagious fevers which lasted twenty-four hours. After the fever the victim would swell up and burst open, being full of worms, and of this pestilence many people died leaving the fruit ungathered.

After this pestilence there was another sixteen good years in which they renewed their passions and ravagings. In this way one hundred and fifty thousand men died in battle. After this massacre they were more calm and made peace and rested for twenty years. Then came another pestilence. Large pimples formed and they rotted the body and emitted offensive odors in a way that the members fell off by pieces within four or five days.

[4] “The Four Winds” is a Maya expression.

This plague has passed more than fifty years ago, the massacres of the wars twenty years before that; the pestilence of the swelling and worms sixteen years before the wars; and the hurricane another sixteen years before that and twenty-two years after the destruction of Mayapan, which, according to this record, makes one hundred twenty-five years since the destruction. Thus by the wars and other punishments which God sent, it is a wonder there are as many people as are now living, although there are not many.

This quaint account by Landa sheds some light upon the condition of the Mayas during the century preceding the Spanish invasion and indicates that the golden age of the race had occurred not many centuries before.

The legendary history of the coming of the Mayas to Chi-chen Itza is alluded to by Landa in several passages. He states:

It is the opinion among the Indians that with the Itzas who populated Chi-chen Itza, there reigned a great man called Kukul Can, and the principal temple of the city is called Kukul Can. They say he entered from the west, that he was very genteel, and that he had neither wife nor children. After he left Chi-chen Itza he was considered in Mexico one of their gods and called Quetzal Coatl and in Yucatan they also had him for a god.

In another place Landa says:

The ancient Indians say that in Chi-chen Itza reigned three brothers. This was told to them by their ancestors. The three brothers came from the west and they reigned for some years in peace and justice. They honored their god very much and thus built many buildings and beautiful, especially one. These men, they say, lived without wives and in great honesty and virtue, and during this time they were much esteemed and obeyed by all. After a time one of them failed, who had to die, although some of the Indians said he went to Bak-halal. The absence of this one, no matter how he went, was felt so much by those who reigned after him that they began to be licentious and formed habits dishonorable and ungovernable, and the people began to hate them in such a way that they killed them, one after the other, and destroyed and abandoned the city.

Virtually the same stories are contained in a document found at Valladolid and dated 1618, which goes on to state that the newer part of Chi-chen Itza was built about 1200 a. d.

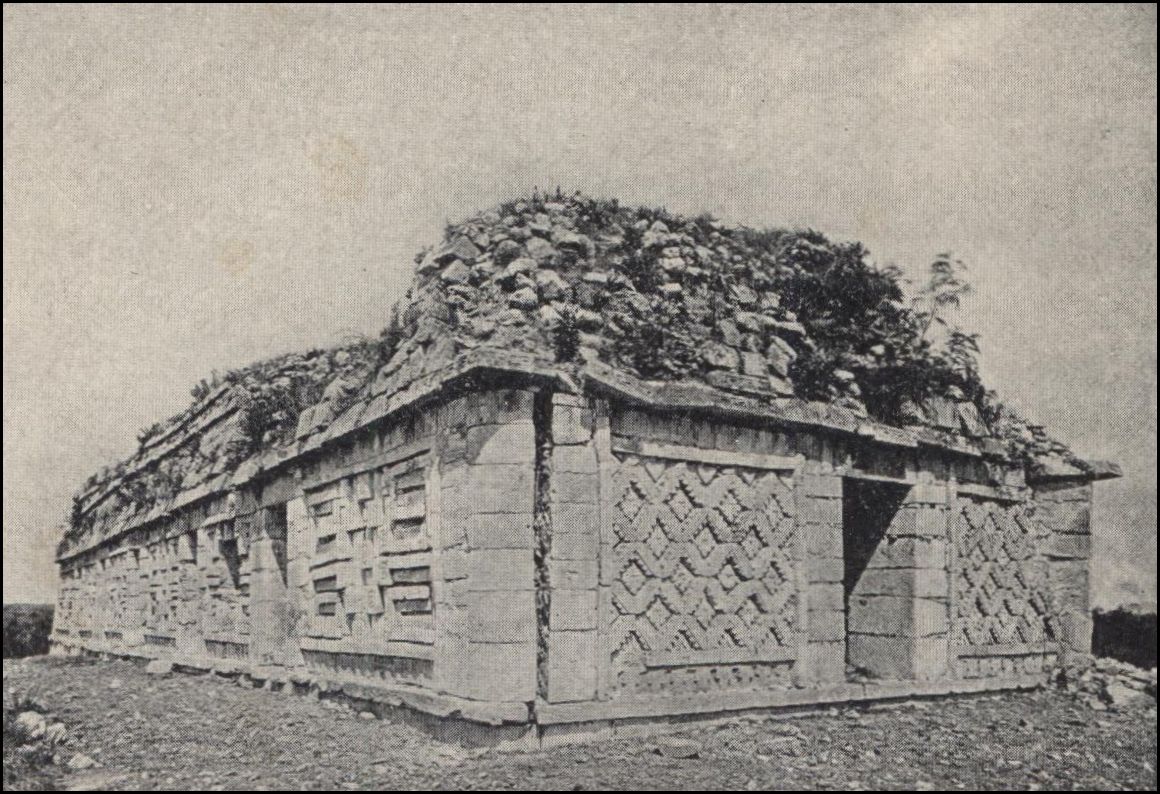

The ancient city consists of two parts, the southern, which is ruined to such as extent that it contains almost no standing edifices, and the newer city built to the north, which contains many buildings—some of them almost perfectly preserved. I believe that much of the older city was built at least a thousand years prior to most of the buildings in the newer city, and there is ample evidence to substantiate the belief that the old city was ruthlessly robbed of its carvings and cut stones for use in the construction of the new.

The Nahuatl influence is seen in the newer buildings. It is thought that Chi-chen Itza reached the height of its civil power, though not its artistic supremacy, after it had been conquered by the Aztec warriors from the north, and the native inhabitants were reduced to slavery and driven by their masters to the speedy building of many temples—an undertaking which they would have gone about in much more leisurely fashion had there been no compulsion.

Don Pedro Aguilar, one of the earliest historians of Yucatan, states that six hundred years before the coming of the Spaniards the Mayas were the vassals of the Aztecs and were forced by them to construct remarkable edifices such as those found at Chi-chen Itza and Uxmal.

Herbert Spinden, in his admirable little book “Ancient Civilizations of Mexico,” has most happily drawn an analogy between the traits of the Mayas and Aztecs and the similar traits of the old Greeks and Romans. The Mayas were like the Greeks, the creative race, while the Aztecs were primarily warriors, as were the Romans.