* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: The Jesuit Martyrs of Canada; Together with the Martyrs Slain in the Mohawk Valley

Date of first publication: 1925

Author: E. J. (Edward James) Devine (1860-1927)

Date first posted: 10 March, 2024

Date last updated: June 30, 2024

Faded Page eBook #20240310

This eBook was produced by: Marcia Brooks, Al Haines, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

THE

JESUIT MARTYRS

OF CANADA

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

————

ACROSS WIDEST AMERICA.—Newfoundland to Alaska. With the Impressions of a Two Years’ Sojourn on the Bering Coast. 307 pp. 8vo, cloth, profusely illustrated. Benziger Bros, New York.

A TRAVERS L’AMÉRIQUE.—Terre-Neuve a l’Alaska. Impressions de deux ans de séjour sur la côte de Bering. (Authorized French translation.) 267 pp. in-4to, broché; illustré. F. Paillart, éditeur, Abbeville, France.

THE TRAINING OF SILAS.—A Romance among Books. 332 pp. 8vo, cloth. Benziger Bros, New York.

FIRESIDE MESSAGES.—Fifty-two Essays for Family Reading. 534 pp. 8vo, cloth. The Messenger Press, Montreal.

HISTORIC CAUGHNAWAGA. 1667-1920.—443 pp. 8vo, illustrated. (Awarded the David Prize by the Provincial Government of Quebec). The Messenger Press, Montreal.

OUR TOUR THROUGH EUROPE.—183 pp. 8vo, illustrated. The Messenger Press, Montreal.

—————

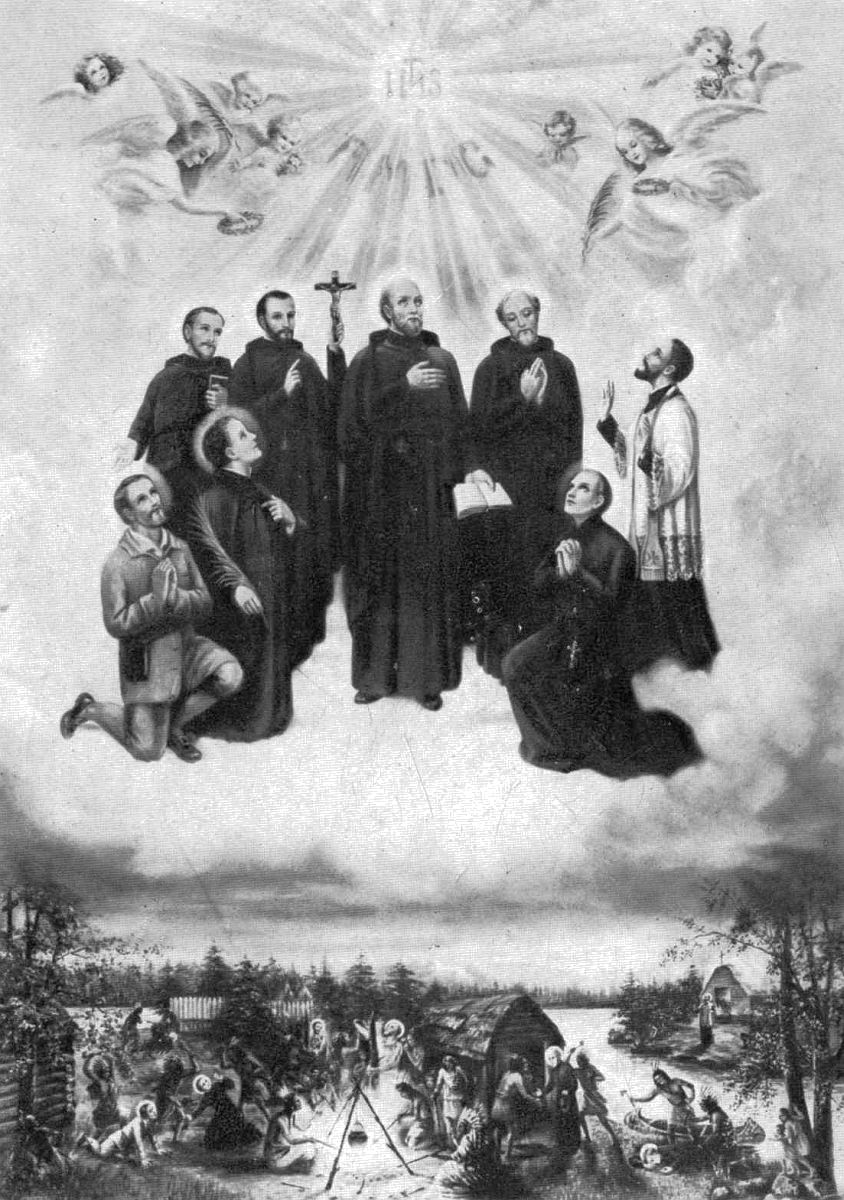

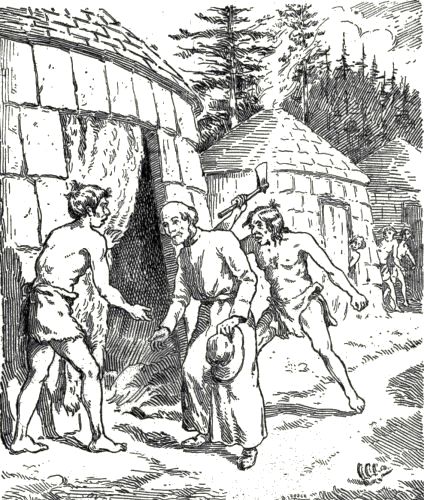

Nealis pinxit

Blessed Jean de Brebeuf and Companions

THE

JESUIT MARTYRS

OF CANADA

TOGETHER WITH THE MARTYRS

SLAIN IN THE MOHAWK VALLEY

BY

E. J. DEVINE, S.J.

Member of the Canadian Authors Association

Member of the Antiquarian and Numismatic Society of Montreal

Lecturer in Canadian History, Loyola College

———

THIRD EDITION

REVISED AND AUGMENTED

———

TORONTO

THE CANADIAN MESSENGER, PUBLISHER

160 Wellesley Crescent

1925

Nihil obstat

Martin P. Reid, P. P., Censor deputatus

Marianopoli, die 8a maii, 1925

Imprimi potest

J. Milway Filion, S.J., Praep. V.-Prov. Canad. Sup.

Toronto, die 31a julii, 1925

Imprimatur

† Neil Mac Neil, Arch. Toron.

Toronto, die 5a octobris, 1925

———

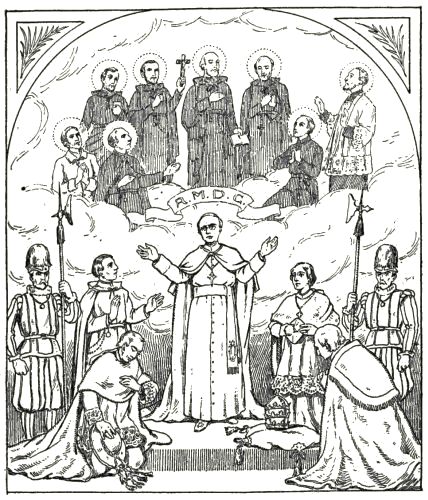

The recent Beatification of the eight martyrs of the Society of Jesus, whose careers are sketched in this volume, reminds us that it is just three hundred years—1625-1925—since the Order to which they belonged began its labours in the solitudes of New France. The dates are suggestive; they seem to indicate that, in honouring the martyred missionaries of New France, the Sovereign Pontiff wished not merely to reward the heroism of those men, but also loyally to recognize a long apostolate of abnegation and suffering, undertaken by the Jesuit Order to extend the boundaries of the kingdom of God in the New World.

Five of the martyrs, Blessed Jean de Brebeuf, Gabriel Lalemant, Antoine Daniel, Charles Garnier and Noël Chabanel, were slain in the land of the Hurons, the section of the Province of Ontario bathed by the waters of Georgian Bay. The other three martyrs, Blessed Isaac Jogues and his companions, René Goupil and Jean de la Lande, fell in the Mohawk valley. This territory, which is a portion of the present State of New York, was, in the seventeenth century and probably for centuries before, known as the home of the Iroquois.

The eight missionaries, whose heroic careers and thrilling martyrdoms merited the triumph recently witnessed in Rome, stand out in bold relief in the army of Christ in America; but it is well to know that they were not the only brave soldiers in the field. Between the year 1625, when the Jesuits first landed at Quebec, and the year 1800, when the last of the Old Guard went to his grave, three hundred and twenty have been accounted for, men who, “having set joy before them, endured the Cross,” and despising the hardships of missionary life, went their way over the American continent, “preaching the Word, reproving, entreating, rebuking in all patience and doctrine,” and rejoicing in the conviction that God would one day be their reward exceeding great. Nearly a score of them, men who very likely will never wear the official crown of martyrdom, were nevertheless heroes who proved the sincerity of their faith by yielding up their lives, often in a tragic manner, in the service of the Master.

Father Philibert Noirot and a lay-Brother, Louis Malot, were lost at sea off Cape Breton, in 1625, while bringing supplies to the newly founded missions in New France. In 1646, the year in which Blessed Isaac Jogues was slain on the Mohawk river, Father Anne de Nouë was frozen to death in crossing the St. Lawrence while on an errand of charity. In 1652, three years after Blessed Jean de Brebeuf and three of his companions perished among the Hurons, Father Jacques Buteux was ambushed and slain by the Iroquois on the River St. Maurice, and in 1655 the lay-Brother, Jean Liégeois, met a similar fate at Sillery. In 1656, Father Léonard Garreau expired from wounds inflicted by the Iroquois on the Lake of Two Mountains, Father Antoine Dalmas was assassinated in 1693, while on an expedition to Hudson’s Bay. Sébastien Râle was cruelly shot down by New England soldiers at Norridgewock, Maine, in 1724, while defending his church and his Abenaquis flock. Father Rodolphe de la Germandière and two other Fathers, whose names are not known, were drowned off Louisburg, N. S., on their way to Canada in 1725. In 1729, Father Paul du Poisson and Jean Souel were slain by the Natchez on the Lower Mississippi. In 1733, Father Vastus Huet was carried off while waiting on the plague-stricken at Quebec. Father Antoine Senat was burned to death at the stake by the Chicasaws, near Vicksburg, Miss., in 1736. In the same year, Father Pierre Aulneau de la Touche, chaplain of the Verendrye expedition, was slaughtered by the Sioux on an island in the Lake of the Woods. In 1759, Father Claude Virot, chaplain of the French army at Niagara, was cut to pieces by the Iroquois.

Those seventeen men, all members of the same Religious Order, all nourished at the breast of the same venerable Mother, the Society of Jesus, shared with Blessed Jean de Brebeuf and his seven companions the hardships of the apostolate in the New World. Like them, they made the supreme sacrifice under one form or another; like them, they are now enjoying the Beatific Vision. The honours of the altar may never be their lot, but those brave old French missionaries, while labouring in America, caught at least a glimpse of the ruddy glow of martyrdom. That is all that was vouchsafed them; the prize in all its fulness was denied them; but undoubtedly they are satisfied. In Heaven there is no room for jealousy. The possession of God for all eternity makes earthly honours—even the honours of Beatification—fade out like stars before the noonday sun. So that far from entertaining thoughts of envy at the great distinction recently conferred upon their more favoured brethren, they are sharing in our present joy and consolation, and are with us in praising the name of the Great and Good God in whose service they, as well as the eight beatified martyrs, suffered and died.

| CONTENTS | ||||

| ——— | ||||

| Chapter | I. | — | Indians and Missionaries | 1 |

| Chapter | II. | — | Blessed Jean de Brebeuf | 29 |

| Chapter | III. | — | Blessed Gabriel Lalemant | 55 |

| Chapter | IV. | — | Blessed Antoine Daniel | 83 |

| Chapter | V. | — | Blessed Charles Garnier | 111 |

| Chapter | VI. | — | Blessed Noël Chabanel | 139 |

| Chapter | VII. | — | Blessed Isaac Jogues | 167 |

| Chapter | VIII. | — | Blessed René Goupil | 195 |

| Chapter | IX. | — | Blessed Jean de la Lande | 221 |

| Chapter | X. | — | The Final Triumph | 237 |

—————

———

The Early Fur Traders of New France—Champlain seeks Missionaries—The Recollects arrive—Aided by the Jesuits—Quebec Captured—Missionaries are Banished—Return of the Jesuits—They go to the Huron Country—The Iroquois—Experiences in the Cantons—Destruction of the Huron Missions—A Colonizing Experiment—Its Failure—Treaty of Peace—The Jesuits among the Iroquois—Caughnawaga and St. Regis—Final Phase of Missionary Activity.

In the beginning of the seventeenth century, when Samuel de Champlain was laying the foundations of the French colony at Quebec, he came in contact with Indian tribes whose ancestors had been living on Canadian soil for centuries; tribes who spoke their own peculiar tongues and followed their own traditions. These were the Montagnais from the Lower St. Lawrence, the Algonquins from the Ottawa valley, the Nipissings from the lake which still bears their name, and the powerful Huron race from the more distant Georgian Bay.

Skilled in hunting and trapping, these natives were welcomed at Quebec every Spring, for they brought with them cargoes of precious furs, the results of the previous season’s hunt. Bales of bear and beaver, fox, marten, and other pelts, were soon spread out on fur counters before the eager eyes of traders from Old France, and days full of excitement followed in the little trading-post at Quebec, when French and Indian bargained amid a din of Gallic eloquence and guttural vociferations. When at last the wild, untutored Indians had bartered their wealth of furs for French blankets, ammunition and trinkets, they disappeared again into their primeval fastnesses just as quickly as they had come. Jumping into their frail canoes when the last pelt had been disposed of, the Montagnais vigorously plied their paddles, and were soon rounding Point Levis on their homeward way to Tadoussac and the Gulf. The tribes from the West usually awaited the incoming tide, and when the current was favourable started in their turn and were soon skimming their way over the St. Lawrence and the Ottawa rivers to Allumette Island and Georgian Bay. The dusky visitors had departed for another year to their distant wigwams, where wives and children were anxiously awaiting both them and the goods they had bought from the French at Quebec. But this annual coming and going of the Indian flotillas, in addition to being a novel sight for the traders from across the sea, was also a satisfying one, to say the least; for with the arrival of each fur-laden canoe they saw rising before them the pleasant prospect of huge profits which the contents would bring them in European markets.

Unhappily, however, these picturesque Indians were poor pagans who had never heard of the true God, and were living their lives in the darkness of infidelity. The degrading superstitions and barbarous customs which had been handed down to them as a legacy by their ancestors would in turn be left to future generations if no effort were made by the French to provide enlightenment. Champlain, a man of lofty ideals, a Christian who knew that the soul is the only thing that matters here below, realized full well that the profits of the fur-trade were paltry when compared with the spiritual welfare of the natives of the country. The sad spectacle of thousands of aborigines lying in the shadow of spiritual death moved to compassion the great heart of the Father of New France, and he resolved to bring a knowledge of the true faith to them as soon as possible.

In 1614, he invited the Recollects of France to come to Canada and conquer a kingdom for God, and by way of response, in the following year, four members of this branch of the Franciscan Order—three priests and a lay-brother—stepped off the good ship Saint-Etienne on its arrival at Quebec, to begin the good work.

The few French colonists in the neighbourhood of Champlain’s “habitation” were the first to feel the effects of the missionaries’ zeal. Leaving these to the care of Father Jamay, before the Summer of 1615 was over Father Dolbeau had gone to Tadoussac to convert the Montagnais, while the third missionary, Father Le Caron, amid incredible hardships, penetrated to the shores of Georgian Bay where the Hurons dwelt. It is of interest to note that a lofty granite cross, erected a few miles west of Penetanguishene, stands on the spot where this Recollect said the first Mass ever celebrated within the limits of the present Province of Ontario.

Their own historian, Sagard, a Recollect who also tasted the bitterness of missionary life in those early years, has left us vivid impressions of the strenuous careers led by his religious brethren in the Huron country; their long wearisome journeys up the Ottawa and the Nipissing valleys, still in primitive wildness; their dreary portages around the falls and rapids that hindered their progress; their camping-out on the way; the exasperating swarms of insects that worried their days and nights; and after they had reached their destination, the filth of the Huron wigwams in which they were obliged to lodge, their ignorance of the Huron language revealing an utter unpreparedness for the task before them; but above all, the degradation of the lives of the Hurons themselves; all these are graphically described by Sagard. The Recollects lived ten years in Huronia where notwithstanding the difficulties they had to surmount, difficulties that would have intimidated less courageous hearts, they succeeded in planting the seeds of Christianity.

After a whole decade spent in this apostolate, these pioneers of the faith began to make plans for the future. The vastness of the field, the magnitude of the task before them, and the paucity of the means at their disposal to accomplish it, all urged them to call for aid from other missionary bodies, and in consequence they sent a delegate to France to invite the Society of Jesus to share their labours in the New World. The invitation was heartily welcomed, for the Jesuits wished to exercise their zeal once more among the tribes of America. Thirteen years previously Fathers Biard and Masse had endeavoured to found a mission on the Acadian coast, and they were on the eve of success when sectarian hatred put an end to their holy enterprise. The Virginian buccaneer, Argall, not content with sending a bullet through the lay-brother, Gilbert du Thet, destroyed the budding mission and drove the Jesuits back to France.

The call of the Recollects brought the Jesuits, Jean de Brebeuf, Ennemond Masse and Charles Lalemant to Quebec in 1625. For a second time Masse had crossed the ocean on his zealous errand and he and Brebeuf were about to set out at once for the missions of Georgian Bay when news of the drowning of a Recollect Father—a crime attributed to three Huron apostates—decided them to postpone their journey for a whole year. Father Nicholas Viel, they learned, while on his way down from the Huron country to Quebec, had been thrown from his canoe with a companion Ahautsic, perishing thus at the hands of the people he had gone to evangelize.

Similar tragedies but far more spectacular, as we shall see, were reserved for the Jesuits at the hands of the Iroquois when those Indians began to terrorize the French colony.

The seizure of Quebec by the English, in 1629, ended for the moment the work of the missionaries in Canada; both Recollects and Jesuits were banished to France, where they remained for three years, uncertain as to their future movements. However, when the colony was restored in 1632, and the way opened again for missionary enterprise, while the Recollects remained in France, the Jesuits hastened to re-cross the Atlantic to the scene of their former labours. Hostile writers have seen in this exclusion of the Recollects from the Canadian missions, in which they had spent ten years of abnegation and hard work, evidence of subtle maneuvring on the part of the Jesuits who apparently wanted the whole field for themselves. But this hardly explains the true inwardness of the affair. In those years, New France, rich only in suffering and heavy crosses, was a land scarcely inviting enough to urge even the Jesuits to use their influence at Court to secure a monopoly of effort there. The real explanation would seem to rest neither in any desire for exclusive occupancy nor in any special aptitude of one body of men over another for missionary work, but rather in the laws and constitutions which governed the missionaries themselves. Vowed to poverty, corporate as well as personal, the Recollects had to depend on the good-will of the fur company for the upkeep of their missions, a burden its Huguenot directors never relished, and would be glad to rid themselves of. The Jesuits, on the contrary, were permitted by the Constitutions of their Order to hold property and receive revenues—a circumstance which would leave them independent of Huguenot patronage[1]. Undoubtedly Cardinal Richelieu and M. de Lauson, president of the trading company, reckoned that this independence would solve the problem of mission support in New France, and were quite willing to give the sons of St Ignatius a monopoly which, it may be remarked in passing, eventually turned out to be a monopoly of self-sacrifice “even unto death,” as the lives of their martyrs in Canada amply prove.

With light hearts the Jesuits returned to the colony the year after the signing of the treaty of St. Germain-en-Laye, to begin a pious enterprise which was to last for nearly two hundred years, and which for persevering effort and heroic devotedness may claim preëminence in the annals of the Catholic Church. Written in letters of life-blood in the history of their Order is the story of the treatment they received at the hands of the Iroquois, a race of Indians who were the sworn enemies of the French and their missionaries on this continent for the greater part of a century.

The Iroquois, known up to the beginning of the eighteenth century as the Five-Nation Indians, occupied the picturesque and fruitful valleys and uplands which extend from the headquarters of the Hudson river to Lake Erie in the present State of New York. Naturally a bellicose race, they have received credit for great skill and cunning in military tactics. They were daring and fearless, and roamed far and wide on their marauding expeditions. They were prompt and spiteful in resenting insults, strong in their hatreds, and inhuman in their treatment of captives who had the misfortune to fall into their hands. Cruelty was perhaps the striking trait of their character. Prisoners taken by them were subjected to fiendish tortures; their scalps and finger-nails were torn off; their flesh cut away piecemeal and eaten before their very eyes; and whenever the unfortunate victims survived those ordeals, they were usually burned at the stake or condemned to a slavery worse than death. Owing to their warlike tendencies, the Iroquois were continually invading the territories of neighbouring Indian tribes “leaving wrack and ruin in their track,” says a modern author, “much like Tartars when they invaded Hindustan, or the Goths, Vandals and Huns, when they overran Europe.”[2]

Historians are not unanimous in deciding why from the earliest years of the colony, the Iroquois became the implacable enemies of the French. An unfortunate encounter[3] with Champlain in 1609, on the shores of the Lake which bears his name, is sometimes ascribed as the initial occasion of all their enmity. It may at least be affirmed that in this first skirmish Champlain taught those Indians the efficacy of firearms, weapons which they easily procured later on from the Dutch settlers on the banks of the Hudson. In a very few years we find their primitive bows and arrows discarded for the more destructive powder and shot.

The proximity of their cantons to the Dutch settlements, then growing along the Hudson and the Mohawk rivers, and the intimate relations which were fostered by the fur-trade, gave the Dutch certain facilities for exercising a strong influence on them[4]. For political purposes, they endeavoured to sustain the bitterness which already existed between the French and the Iroquois, and at the same time found it an easy task to instil into the minds of the ignorant Indians their own religious prejudices.[5] And as the sequel will show, this insidious maneuvring had serious consequences for the French missionaries who went in later years to labour in the cantons.

The Jesuits had been twenty years in Canada before they came in touch with the Iroquois. In the coming chapters we shall see that this first contact was a thrilling one for the Jesuits, thanks to the ill-will intentionally excited against a body of missionaries who aimed at nothing more nor less than the extermination of their sorcery and pagan customs. The poor aborigines had accepted as truth the testimony of their Dutch allies, and they felt justified in their belief that the famines and pestilences and other misfortunes which befell them from time to time were the work of the French missionaries. All this ignorance and prejudice recoiled in years to come on the Jesuits, who paid the full price of their zeal in tortures and death.

But the French and their missionaries were not the only objects of Iroquois resentment. Those Indians extended their hatred to the native tribes who had been converted to Christianity and who remained friendly to the French, while the geographical positions of their strongholds made their warlike incursions against the allies of the French a comparatively simple task. The valley of the St. Lawrence and its tributaries were well within their reach through Lake Champlain and Lake Ontario, over whose waters they could easily move in large war-parties, to carry devastation into the French settlements of Quebec, Montreal and Three Rivers; while from the western fringe of their territory they could advance quickly over Lake Erie into the present Province of Ontario and attack the allied Indian tribes living there. Profiting by these natural advantages and by their desire for vengeance, they had in a few years destroyed the flourishing missions among the Hurons on Georgian Bay, captured hundreds of those unfortunate Indians and killed their missionaries; they had ravaged the Montagnais settlements on the Lower St. Lawrence, the Neutrals along Lake Erie, the Algonquins on the Ottawa river, and the Attikamegs, a peaceful nation living on the Upper St. Maurice. A punitive expedition directed by the French in 1665 reduced the savage marauders to inactivity for a time, but during the rest of the seventeenth century they remained what history tells us they had always been, a cruel, sullen and treacherous race, in whom all humane feelings were dormant.

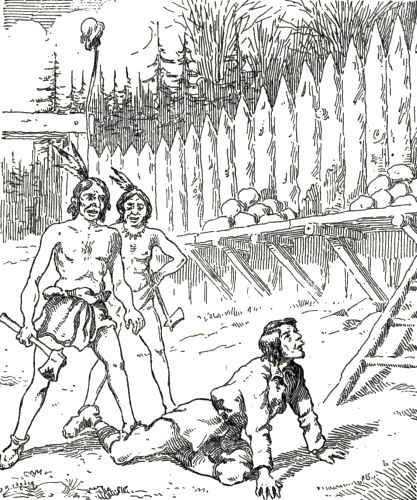

And yet in the strenuous years of that century, long before the strong arm of France had pressed heavily on the barbarous Iroquois, there were Jesuits unlucky enough to fall into their clutches. The first of those heroes of the Cross was Father Isaac Jogues, who with a companion, René Goupil, was seized by them in the year 1642. Goupil was slain six weeks after his capture, while Jogues succeeded in making his escape only after thirteen months of degrading slavery.

Two years later, another Jesuit, François Bressani, was seized and taken to the Mohawk country[6]. Three pathetic letters written by this missionary have come down to us and give details of the tortures inflicted upon him, details which after nearly three centuries still cause a thrill of horror in the reader. The Iroquois began by obliging him to throw away all his writings, fearing that some malicious charm was attached to them. “They were surprised,” he afterwards pathetically remarked, “to witness how sensitive that loss was to me, seeing that I had given no sign of regret for the rest.”[7] After incredible hardship and fatigue, the unhappy captive reached the Mohawk canton, where the tribe received him in a cruel fashion. He was stripped of his clothes and obliged to run the gauntlet between two rows of howling savages who showered blows upon him with clubs and iron rods. With a sharp knife they split his fingers open, one of his hands being nearly cleft in twain. Covered with blood, he was forced to mount a platform in the middle of the village, where he became the object of jeers and insults. This, however, was only the beginning of his sufferings. He was taken from village to village, and in each tortured by fire, his captors’ favourite method being to light their calumets and then push the victim’s fingers into the bowls. Eighteen times fire was applied to his lacerated hands, until they became a mass of festering wounds. These tortures were usually inflicted at night, during which time he was securely tied to stakes and forced to lie uncovered on the bare ground. The poor sufferer relates that when finally he was condemned to be burned at the stake he accepted his fate with resignation, but begged his ruthless captors to despatch him in any way but by fire. “Taken prisoner while on his way to the Hurons,” writes the historian Bancroft, “beaten, mangled, mutilated, driven barefoot over rough paths through briars and thickets, scourged by a whole village, burned, tortured, wounded and scarred, he was eye-witness to the fate of his companions who were boiled and eaten, yet some mysterious awe protected his life.”[8] Bressani himself acknowledged that he received this protection from God and His Blessed Mother[9]. He was given into slavery and remained in that state until, like his predecessor, Father Jogues, he was humanely ransomed by the Dutch[10]. Bressani afterwards returned to Italy and wrote an interesting account of the sufferings of the missionaries of New France, in a volume which was published in Macerata, in 1653.

The experiences of Jogues and Bressani will suffice to show what kind of Indians the Jesuits had to deal with in the work of spreading the Gospel in New France. In blood and tears, those devoted men tried to impress the Divine Master’s message on souls steeped for centuries in the most degrading sorcery and superstition, and those of them who survived the task carried the marks of their heroism in their mutilated members until death.

Between the years 1642 and 1644 the Iroquois grew so daring, and their incursions into the colony were so numerous, that the French population became alarmed. Peaceful farmers were seized by them while working in their fields; Indians were often seen hiding under the very shadow of their dwellings[11], ready to scalp the terror-stricken inmates, war parties were constantly prowling around the Ottawa river and the Lower St. Lawrence, waiting like tigers for their prey. They had blocked the route to the Huron country, a circumstance which menaced not merely the fur trade, but even the very existence of the missions on Georgian Bay. Matters had reached such a pass in 1644 that the colonial governor, Sieur de Montmagny, felt that something should be done, and hoping to put an end to the depredations and the consequent reign of terror which was paralyzing the colony, he suggested a treaty of peace with the Iroquois. Two years later, a conference was held at Three Rivers in which Father Jogues took part. This holy man went with Jean Bourdon to the cantons to discuss terms of peace, but when he returned thither four months later with his companion, Jean de la Lande, to work for souls, both were ruthlessly slain.

The news of this double crime perpetrated by the Iroquois on the Mohawk river reached Quebec in the following year; other similar outrages were soon to be recorded against them on the shores of Georgian Bay, where the Hurons dwelt. The powerful Huron tribe of Indians had been under the spiritual supervision of the Jesuits since 1634. Pestilence had reduced their fighting strength, but they were still quite numerous and lived in dozens of villages dotting the territory now known as Simcoe county, in Ontario. Their two largest villages were Ossossané and Teanaostaye which were supplied with churches and resident missionaries. Other smaller missions were scattered here and there, and the Jesuits were leading lives of isolation and abnegation which only zeal and love for the Cross could explain. When Jerome Lalemant became superior of the Huron missions in 1638, he had a census taken of the entire population, and organized the work of his men so as to produce the best results. Aided by money which Cardinal Richelieu had sent out to him, he built a great central residence on the banks of the Wye, a little river flowing into Georgian Bay. This residence, dedicated to Our Lady Saint Mary, became the headquarters of the missionaries in Huronia, where they could retire to rest after their strenuous labours and gather strength for further conquests among souls. In those years converts were coming in large numbers; rare examples of Christian virtue were being shown by them. Everything promised a brilliant missionary future, when the sudden appearance of the dreaded Iroquois on the horizon checked the good work. Those barbarians, penetrating into the very heart of the Huron country in July, 1648, destroyed Teanaostaye and slew Father Antoine Daniel, the resident missionary. And during the following year four others—Jean de Brebeuf, Gabriel Lalemant, Charles Garnier and Noël Chabanel—were given a similar fate.

After these disasters there still remained in the Huron missions eleven Jesuit Fathers, all of whom saw signs of impending doom. They realized fully that their converts, although numerous, were unable to resist the onslaughts of a well-armed and treacherous tribe like the Iroquois, and in consequence, three months after the martyrdom of Brebeuf and Lalemant, having burned the residence of Ste. Marie in order that it might not fall into the hands of the enemy, they migrated with their goods and chattels to Ahendoë, an island in Georgian Bay, now known as Christian Island. But a year spent there, living in the greatest penury, convinced them that the end had come. Hunger and want had carried away hundreds of their converts, and worst of all, the Iroquois had discovered their whereabouts. It was only then that they came to the grave decision to quit the Huron country forever. Making ready for the long and mournful journey, together with their converts and the personnel of their missions, they were soon on their way to Quebec, arriving there in the Summer of 1650. After various migrations in the immediate neighbourhood, the Hurons finally settled in 1673 at Lorette, a few miles from Quebec, where, it may be of interest to note, their descendants may be seen today.

Three years after the destruction of the missions along Georgian Bay there appeared what seemed to be a turn in the tide of devastation. Three of the Iroquois cantons were at war with the Eries, and feeling that it would be a good policy to have the French on their side, they sent delegates to Quebec to discuss terms of peace[12]. Governor de Lauzon, aware that he had to do with a treacherous horde, and that he had to be prudent in his replies, consulted the Jesuits. These missionaries, who now thought they saw an opening long-looked-for into the Iroquois country, decided to send one of their own men to sound the chieftains and get at the true state of affairs. Father Simon Le Moyne was chosen for this delicate task in the Spring of 1654. The attitude of the Onondagans favourably impressed him, and in the following year he returned, accompanied by two other Jesuits, Claude Dablon and Jean Marie Chaumonot. The Onondagans invited the French to come and live with them—a very flattering invitation; for a settlement in the Iroquois country would be not merely a center of French influence and civilization, but also a barrier against the Dutch and the English who had begun to monopolize the fur-trade. The Jesuits, on their side, had other designs, notably the establishment of a central mission for the Iroquois cantons, and with this end in view they spent the Winter of 1655-56 conferring with the delegates of the Five Nations.

In the Spring Dablon returned to Quebec determined to put his very elaborate scheme into execution. Governor de Lauzon had granted him a block of land, ten leagues square, situated near Lake Onondaga, and an expedition consisting of fifty or sixty persons—soldiers, artizans, and farmers—organized by the Jesuits, with René Menard, François Le Mercier and Jacques Fremin as chaplains, all under the leadership of Dablon, left Quebec in May, 1656. They sailed up the St. Lawrence, the first white expedition to ascend the great river as far as Lake Ontario, and chose Gannatea, in the Onondaga canton, for the new French colony, a site which has never been fully identified. While the missionaries were renewing acquaintance with the Huron converts, many of whom were settled among the Onondagans, the French workmen began to clear the ground. They built a church, the first Catholic temple ever raised within the present limits of New York State; they built houses for themselves and a large residence for the Fathers which could be further enlarged as time went on, and become a replica of Fort Ste. Marie, the “home of peace” near Georgian Bay which they had to abandon three years before.

The plan was an admirable one, and Claude Dablon and his brethren were sanguine of its success. They had hoped to settle down permanently in the cantons and do for the Iroquois what they had done for the Hurons on Georgian Bay; but they soon perceived that they were indulging in vain imaginings. The Iroquois had evil designs and could not be trusted. While the Onondagans were professing a sincere friendship for the French who had come to live among them, their brethren of the other cantons were raiding the valley of the St. Lawrence and were capturing and torturing French prisoners; they were carrying on their depredations even under the very walls of Quebec itself. Dablon and Le Moyne were aware that in case of an uprising the French settlers, not being numerous enough to defend themselves, were at the mercy of the Indian marauders. Having in the interval been privately warned that their Onondagan colony might be attacked at any moment, and fearing a surprise, they decided to abandon the country. Boats were built secretly, and one night under cover of darkness the Jesuits and their little band of colonists disappeared from Gannatea. Paddling down the Oswego river, over Lake Ontario and then on down the St. Lawrence, they reached Quebec at last. And thus with the disappearance of the Blackgowns there also vanished the hope of reproducing in the Iroquois cantons the marvels of conversion witnessed in the Huron country, in former years[13].

After this futile effort all peaceful communication with the Iroquois ceased for ten years. Meanwhile, a radical change was taking place in the administration of the French colony. Louis XIV had cancelled the charter of the fur company and put the local government in the hands of a Sovereign Council. This change had an effect on the Indian policy, but it came none too soon; for continuing their murderous raids, the Iroquois were blocking the waterways and tracking the colonists to their homes, seizing, scalping and carrying them off to their villages, there to undergo torture and death. Conditions had become so desperate that a petition was sent to France to help the colony, otherwise it would perish. In 1665 the Carignan-Sallière regiment, with the aged Marquis de Tracy at its head, arrived in Canada, and at once prepared an expedition against the offending tribes. Accompanied by an army of thirteen hundred men and by four chaplains, two of whom were Jesuits, Charles Albanel and Pierre Raffeix, De Tracy sailed up the Richelieu and over Lake Champlain. He invaded the canton of the Mohawks, burned their villages and destroyed their crops. This staggering blow brought the Five Nations to their senses. They signed a treaty with the French, a treaty which was to last eighteen years and which gave the colony a chance to enjoy peace and prosperity.

The ink had hardly dried on the parchment when three Jesuits, Jacques Bruyas, Jean Pierron and Jacques Fremin, started out to preach the Gospel in the Iroquois cantons. A few months later they were followed by other members of the Order, so that the Venerable Marie de l’Incarnation could write, in 1668, “Since we have begun to enjoy the blessing of peace, the missions are flourishing. It is a wonderful thing to witness the zeal of our Gospel labourers. They have all left for their posts filled with the fervour and the courage which gives us hope for their success[14].” Those tireless missionaries were continually on foot, travelling from village to village, baptizing little children and instructing adults in the Christian truths. A period of intense missionary activity was under way, and men like Jean and Jacques de Lamberville, Etienne de Carheil, Julien Garnier and Pierre Milet, founded permanent missions in the cantons, and were bringing many converts into the fold.

But the activity of the Jesuits among the Indians along the Mohawk river did not meet with the approval of the governors of the Province of New York. Perhaps the most aggressive of these was Thomas Dongan. Although a Catholic, this official showed his resentment at the activity of the French Jesuits, and he determined to restrain their work among the Iroquois. Not that he wished any evil should befall the Fathers or that he rejected the doctrines they preached, but he feared the influence they wielded, and he would have preferred to see them back in Quebec. He had, in fact, arranged for the arrival of Jesuits from England to replace their French brethren in the cantons.

The main grievance of those British governors was the constant flow of the Indian warriors from the Province of New York to the new mission which had been established at Laprairie, near Montreal, in 1667, and the consequent weakening of the fighting strength of the cantons. The Jesuits realized from the beginning of their ministry among the Iroquois that unless they kept their converts away from the corrupting environment of their pagan brethren and from intercourse with the English at Albany, they would make little headway in the work of conversion. At their suggestion, hundreds of neophytes migrated to Laprairie and later to Kahnawaké, where their instruction was completed, and where they could practise their new-found faith in peace. Aided by an ardent convert and apostle, known in American history as Kryn, the Great Mohawk, the stream of converts grew apace until the “praying castle” near Montreal became a flourishing missionary center. Among the illustrious converts who lived at Kahnawaké was the Iroquois maiden, Kateri Tekakwitha, who died there in the odour of holiness in 1680, after having edified the entire colony by her life and virtue, and whose Beatification is being urged at the present time.

The disastrous expedition of Governor de la Barre, in 1686, and the treachery displayed by his successor Denonville, in 1687, in sending forty Iroquois chiefs to be galley-slaves in France, alienated the Five Nations and endangered the lives of the Jesuits labouring among them. Jean de Lamberville, who, according to Denonville himself, was “an excellent man and very clever in dealing with the Indians,” barely escaped the fury of the enraged savages, Pierre Milet was seized and held for seven years in captivity among the Oneidas; the other Fathers escaped to Canada.

Hoping to placate the tribes, Father Jacques Bruyas was sent in the following year to work for peace. Wielding a strong influence throughout the cantons he was on the eve of success. A delegation of Onondagans was already on the way to Montreal to discuss the terms when their interview with Kondiaronk, the wily Huron chief, took place. This historic interview spoiled all Bruyas’ negotiations. The Iroquois, fully persuaded that they were again to be the victims of French double-dealing, started out to wage a more vigorous war than ever on the French colony; the Lachine massacre in August, 1689, and the outrages perpetrated for several years along the St. Lawrence, were the aftermath of the Denonville affair. The Senecas were usually at the bottom of these troubles, and six years later Count Frontenac had to go in person to give them a well-merited chastisement.

While the Iroquois professed their independence of both French and English, the influence of the latter, owing the proximity of the cantons to Albany, told in the long run. The hostility of the British governors, upheld as they were by the stipulations of the Treaty of Utrecht, gradually alienated the Indians from the French and reduced missionary activity to a minimum. The Earl of Bellomont threatened to hang any Jesuit found working in the cantons. Like Dongan, Burnett also complained of this missionary activity, but he was informed by Vaudreuil that the Senecas had sent delegates to Canada who expressed their regret that the missionaries had been removed, and asked that others be sent to take their places. With the exception of a brief visit made by the veteran Julien Garnier to the Onondagans, in 1705, no further attempts seem to have been made to establish footholds in the cantons of what is now the State of New York. The ancient missions there ceased to exist and the Iroquois Catholics and their families began to look on the “praying castle” at Caughnawaga as their permanent home. After 1755 St. Regis shared this privilege with the elder mission which, after various migrations; settled on the present site about the year 1719. In the two villages may still be seen the peaceful descendants of the tribes that made so much Jesuit blood flow in the seventeenth century.

Caughnawaga and St. Regis have histories of their own. Many stirring memories are attached to these two missions, and many well-known names are to be found in the list of Jesuits who continued in the eighteenth century the work their brethren had begun in the seventeenth. Mention may be made of Pierre Cholenec and Claude Chauchetière, friends and advisers of the saintly Kateri Tekakwitha, Pierre de Lauzon, Luc François Nau, Jean Baptiste Tournois, who fell under the frown of La Jonquière, Jacques Quintin de la Bretonnière, chaplain during the Beauharnois expeditions against the Foxes and Chicasaws, Joseph Lafitau, discoverer of the ginseng plant and author of remarkable works on ethnology. Jean Baptiste de Neuville, friend of Bougainville and Montcalm, Antoine Gordan and Pierre Billiard, founders of St. Regis. The last Iroquois missionary, Joseph Huguet, died at Caughnawaga in 1783.

Notwithstanding the heroic efforts put forth and the sacrifices undergone, the Jesuits never succeeded in accomplishing among the Iroquois what they had done among the Hurons along Georgian Bay; but according to Thomas Guthrie Marquis, their priceless contribution to history lay in the example which they gave the world. During the century and a half they laboured among the Iroquois they bore themselves manfully and fought a good fight. Strong in the spirit of faith and zeal, in all that time not one of them is known to have played the coward in the face of danger and disaster.

This chapter has been written to give a brief outline of the efforts made by the Jesuit missionaries for the conversion of the Hurons and the Iroquois. In the succeeding chapters, the reader will be treated to more intimate details concerning the lives and the martyrdoms of eight of the missionaries who shed their blood in the middle of the seventeenth century and on whom the Holy See has recently seen fit to confer the honours of the altar. In the face of tremendous odds occasioned by the uncongenial atmosphere into which these men, mostly men of culture and gentle breeding, suddenly found themselves thrust, when they began their task of spreading the Word amongst the uncouth Iroquois and Huron Indians; despite the never-ending series of discouragements and set-backs which seemed to be their lot, and the ever-present danger of annihilation at the hands of their charges, they strove mightily, carried as they were from sacrifice to sacrifice by an intense love for Christ Crucified; and when at last the supreme trial came upon them, they proved themselves true knights of the standard under which they had elected to march during their earthly careers, even unto death.

[1] De Rochemonteix: Les Jésuites et la Nouvelle France au 17e siècle, I, p. 182.

[2] Buell: Sir William Johnson, New York, 1893, p. 83.

[3] Œuvres de Champlain, Quebec, 1870, Book II, chap. XI, pp. 193-96.

[4] “The settlement of the Dutch is near them; they go thither to carry on their traffic especially in arquebuses; they have at present three hundred of those and use them with great skill and boldness.” Jesuit Relations, Vol. XXIV, p. 271.

[5] Blessed Isaac Jogues wrote during his captivity: “I escaped to a neighbouring hill where in a large tree I had made a great cross... The barbarians did not perceive this till somewhat later. When they found me kneeling as usual before that cross which they hated, and said this it was hated by the Dutch, they began, on this account to trust me worse then before.” Jesuit Relations, Vol. XXXIX, p. 209.

[6] Jesuit Relations, Clev. edit., Vol. XXVI, pp. 33 and seqq.

[7] Letters from France which he was carrying to his brethren in Huronia (Cf. Jesuit Relations, Vol. XXVI, p. 33, et Vol. XXXIX, p. 59).

[8] History of the United States, Book II, p. 793.

[9] Jesuit Relations, Clev. edit., Vol. XXXIX, p. 75.

[10] “The matter was not very difficult,” wrote Bressani, “and they ransomed me cheaply, on account of the small esteem in which they (the Iroquois) held me, because of my want of skill in everything and because they believed that I would never get well of my ailments.”—Jesuit Relations, Vol. XXXIX, p. 77.

[11] “An Iroquois will remain for two or three days without food behind a stump, fifty paces from your house, in order to slay the first who shall fall into his ambush.”—Jesuit Relations, Vol. XXI, p. 119.

[12] Jesuit Relations. Clev. edit., Vol. XLI, p. 81.

[13] Jesuit Relations, Clev. edit., Vol. XLIV, p. 177.

[14] De Rochemonteix: Les Jésuites et la Nouvelle France au 17e siècle, II, p. 402.

BLESSED JEAN DE BREBEUF.

———

His Birth and Early Years—First Experiences in Canada—In the Huron Country—Studies the Language—Lives alone—Sent back to France—Returns to Canada—Again with the Hurons—Success in the Ministry—Persecution—Results of a Vow—The Central Residence—Arrival of the Iroquois—Brebeuf a Prisoner—Endures Tortures—The Supreme Sacrifice—Ragueneau’s Testimony—Relics in Quebec.

The Brebeuf family was of Norman origin, and may be traced back to the middle of the eleventh century. William, Duke of Normandy, had a Brebeuf with him at the battle of Hastings in 1066. Another accompanied St. Louis, two centuries later, in his crusade against the Turks, and bravely led the Norman nobles during the siege of Damietta. In 1251, a Nicholas de Brebeuf is mentioned in the chronicles of the family as one of the chief citizens of Bayeux. According to Du Hamel, the annalist, the Arundels of England and the Brebeufs of Normandy both descended from a common ancestry, but posterity is impressed less by the ties of Norman blood, which may have linked those two ancient families together, than by the sacrifices they both made, even to martyrdom, to preserve their ancient faith. The Iroquois did their grim work in Ontario just as thoroughly as did the headsman of Queen Elizabeth in England.

Jean de Brebeuf was born at Condé-sur-Vire, in the diocese of Bayeux, on March 25th, 1593. No details regarding his early years have come down to us, but the child undoubtedly received the training in piety and learning which was one of the traditions of his race. Besides, it would be hard to believe that religious influences had not moulded the youth of one who was destined in later years to do great deeds for God in the forests of the New World, and who, when the supreme sacrifice was demanded, showed a heroism in torture and suffering almost unparalleled in the history of the Church.

At the age of twenty-four Jean de Brebeuf entered the Jesuit novitiate at Rouen, November 8, 1617. In that home of peace and piety the young man devoted two years to prayer and reflection, and to the cultivation of those little virtues which were to be the foundation stones of his future holiness. Secluded from the distractions of the world, he laboured diligently to acquire self-knowledge, and to exercise himself in the practice of humility, a virtue he pushed so far that he desired to abandon all aspirations to the priesthood, to become a lay-brother in the Order. But his superiors, assured that the humbler the novice the stronger the indications that he would one day give more glory to God in the priesthood, refused Brebeuf’s request and counselled him to accept whatever grade in the Society of Jesus obedience should decide.

At the end of his noviceship the young Jesuit was sent to teach grammar in the college at Rouen. There the religious kept pace with the professor; while Brebeuf taught the rules of grammar to his pupils he did not neglect to implant in their minds and their hearts the principles of Christian virtue. With untiring devotedness he spent two years in this important work; but his zeal in the class-room exacted its price. His labours undermined his health and forced him to retire and seek absolute rest. However, he had been taught to set a high value on the fleeting minutes and could not stay idle. The young man applied himself privately to the study of theology, and acquired sufficient knowledge for the duties of the sacred ministry. He was raised to the priesthood at Pontoise, near Paris, at the beginning of Lent, 1623, and celebrated his first Mass on the transferred feast of the Annunciation, April 4, of the same year. Years of waiting only intensifies one’s consolations when the goal is reached, and the sentiments of the future victim of the Iroquois may be easily gauged on the morning he called down from Heaven, for the first time, the Spotless Victim on the altar and adored Him who lay hidden under the sacramental veil. One grace followed another after his ordination; the health of the young Jesuit priest improved rapidly, and he was named bursar of the college at Rouen.

While the months were thus passing peacefully away in the city of Rouen, an event of vast importance, one which was destined to change the whole course of his life, happened in the little French colony beyond the Atlantic. The Recollects had been labouring there since 1615, and now invited the Jesuits to share their ministry. The invitation was accepted, and in 1625, as we have already seen, three priests, Charles Lalemant, Ennemond Masse and Jean de Brebeuf, were chosen for the arduous missions of New France. Although thirty-two years of age, Brebeuf was the youngest of the three, but he was their equal in virtue. When the order was received to cross the Atlantic, he did not hesitate to sever the ties of blood and family affection, to abandon his homeland and consecrate himself forever to the salvation of the Indians of New World. Nature had well prepared him for this calling; he was now in perfect health and in possession of a herculean frame; he was in the flower of manhood, a splendid type of manliness and strength. These physical qualities, so necessary in a foreign missionary, were crowned with a prudence and a maturity of judgment which made his advice on all matters valuable and eagerly sought after.

Such was Jean de Brebeuf, the missionary, when he reached Quebec in the Summer of 1625. His first impulse on landing was to go at once to the Huron country to begin the study of the language and prepare himself for his ministry; and he was about to start on the long and trying journey up the Ottawa when news of the murder of the Recollect, Nicholas Viel, contrived by treacherous pagan Hurons on the route he would have to pass, made his superior take no risks; Father Charles Lalemant held him in Quebec to await a more favourable moment.

A whole year elapsed before an opportunity for the realization of his ambition presented itself again; meanwhile as a preparation for his future career among the Hurons, the young missionary decided to taste its trials and hardships nearer home. In order to inure himself more thoroughly in the ways of Indian life, he spent the winter of 1625-1626 among the Montagnais, a tribe living along the Lower St. Lawrence. The language of this tribe differed from that of the Hurons, but Brebeuf knew that the time spent in acquiring it would not be lost; it could not fail to be useful some day. That first experience among the Montagnais during the rigours of a Canadian winter would have broken the spirit of a man less hardy than he, but his “iron frame and unconquerably resolute nature” were proof against such bitter trials. In those long winter months his days were spent in following the Indians on the chase, his nights in bark wigwams suffering from cold and hunger, breathing an atmosphere foul with the smoke of the fireplaces. Add to this the continual jibes and insults showered on him by the uncouth Indians for his faults in trying to speak their tongue, and we can form an idea of the life he led during his first months in New France. His success, however, was such that the following spring Charles Lalemant could write in a letter to the General of the Order: “Father de Brebeuf, a pious and prudent man, and of robust constitution, has passed a rude winter season among the savages, and has acquired an extensive knowledge of their tongue.” Brebeuf had begun to show the precious talent which was later to give him such mastery over the Huron language.

The flotilla from the Huron country had reached Quebec early in 1626; the Indians had bartered all their furs and were on the eve of their return homewards. This opportunity could not be lost, and rather than wait another year, Brebeuf made every effort—even urging the intervention of Champlain—to assure his passage in one of the canoes. He had some difficulty, however; the Indians complained of his weight; a frail canoe could not carry him safely hundreds of miles against the swift currents and over the dangerous rapids of the Upper Ottawa. A few gifts solved the objections of the Indian traders, and Brebeuf, accompanied by Father de Nouë and the Recollect, de la Roche Daillon, set out over the famous Ottawa and Nipissing route to the Huron nation. After thirty days of painful effort the three men floated out of French River and coasted down the eastern shore of Georgian Bay. A few wigwams scattered here and there along the shore gave evidences of human occupation, and soon the shouts of his tawny cohorts told Brebeuf that he had reached Otouacha, the landing-place of the Huron village of Toanche[1], and the end of his journey.

The missionary’s first care was to secure a cabin, or “annonchia,” as Sagard called it, built of long poles driven into the ground and then bent forward till their topmost ends met. A covering of bark thrown over this funnel-shaped skeleton provided a cabin into which he could retire. Father de Brebeuf had come to preach the Gospel of Christ to a race of Indians who had never heard of the true God, and he began at once to acquire a knowledge of the Huron tongue, the only means of communication with them. His first weeks were passed in plying them with questions, writing down their answers as they sounded to his ear, thus augmenting daily his stock of words; his evenings beside the camp-fire were spent in classifying them, in forming sentences, and in trying to discover the mechanism of the strange tongue. Nature had given him a retentive memory and a marvellous facility for seizing the laws governing language, gifts he thanked God for more than once, and he made such rapid progress that in a short time he had acquired a tolerable knowledge of the Huron tongue. His two companions were less gifted, and after a sojourn of a year in the Huron country, both Daillon and de Nouë returned to Quebec.

Brebeuf was now alone in the Huron solitude. He began his lonely life by planting a large cross before his cabin, so that its shadow might bless him and his labours. He visited the homes of the Indians, gathered them together, explained to them the rudiments of the Christian faith, and tried to impress on them the existence of God, the duty of serving Him, and other great truths of religion. But the weeks and months were passing and he had not yet been able to make any impression on minds and hearts hardened by centuries of superstition. He struggled on patiently during the Winters of 1627-1628 and 1628-1629, hoping that the hour of grace would soon strike, consoling himself meanwhile with the baptism of a few children in danger of death. More than once, however, during the second year he had the satisfaction of seeing sick and infirm adults yielding to his burning zeal. He had hopes even of forming the nucleus of a congregation among the converts of Toanche and its neighbourhood, when an order came from Charles Lalemant, his superior, summoning him back to civilization.

When the missionary reached Quebec he found the little French colony in the grip of famine. Vessels carrying provisions from the motherland had either foundered at sea, or had been seized by English corsairs in the St. Lawrence. The future looked dark; during the previous year an expedition under Admiral Kerkt had come to capture Quebec; but the haughty reception given him by Champlain had put off the inevitable for the moment. Intent on getting possession of the colony, Kerkt returned again in 1629. Hunger and want obliged Champlain to surrender, and together with the Jesuits, Recollects and a number of French colonists, he was taken back to Europe.

This turn of events wrecked many a bright hope in the heart of Brebeuf. Even the sight of his beloved France, after an absence of four years, could not reconcile him to the loss of the Huron mission. He knew not what the future had in store for the colony on the St. Lawrence, but he did know that the souls of thousands of pagan Hurons were awaiting salvation on Georgian Bay, and he resolved to return thither as soon as the occasion presented itself.

Three years were to elapse before this resolve could be carried out. However, they were years of solid spiritual profit for the future apostle of the Hurons. While at Rouen in 1630, he pronounced his final vows as a Jesuit, thereby binding himself irrevocably to the service of his Divine Master. “A few days before,” he wrote, “I felt a strong desire to suffer something for Jesus Christ; and I said, Lord, make me a man according to Thine own Heart. Let me know Thy holy will. Let nothing separate me from Thy love, neither nakedness, nor the sword, nor death itself. Thou hast made me a member of Thy Society and an apostle in Canada, not it is true by the gift of tongues but by a facility in learning them.” These noble sentiments were still uppermost in his soul when, a year later, he signed with his own blood the following solemn offering of himself:

“Lord Jesus, my Redeemer, Thou hast saved me with Thy Blood and precious Death. In return for this favour, I promise to serve Thee all my life in Thy Society of Jesus, and never to serve anyone but Thee. I sign this promise with my own blood, ready to sacrifice it all as willingly as I do this drop.

Jean de Brebeuf, S.J.”

God did not forget this generous promise, but eighteen years had to elapse before the Iroquois gave Brebeuf the opportunity to redeem it. Meanwhile he was waiting patiently for the moment to return to his Hurons. Negotiations for the transfer of Canada back to France were being pushed forward vigorously, and resulted in the treaty which was signed at Saint-Germain-en-Laye, March 29, 1632. Canada became again a French colony, and the way was open to resume work among the native tribes.

Two Jesuits, Paul Le Jeune and Anne de Nouë, the latter for the second time, were sent at once to Canada, while Brebeuf, notwithstanding his ardent supplications, had to wait another year. He sailed from Dieppe, March 23, 1633, his ship casting anchor before Quebec two months later. He had hardly set foot on Canadian soil when he started for the Huron country, but difficulties again barred his way. The Algonquins of Allumette Island, through whose country the Hurons had to pass on their way up and down, had grown jealous of the trade relations which had sprung up between the latter and the French. They feared the influence of the missionaries, threatening to do them violence if they persevered in their intention to make the journey. And yet Le Jeune wrote: “I never saw more resolute men than Brebeuf and his companions when told that they might lose their lives on the way.” Prudence, however, forbade risking the enmity of the Algonquins, possibly of closing indefinitely the route to the Huron country, and Brebeuf returned to Quebec, as he had done in 1625, to wait another year.

The Summer of 1634 found him at Three Rivers seeking anew an opportunity to embark for Huronia. The objections put forward the previous year by the Indians were again resorted to, but a few presents smoothed negotiations and the zealous missionary found a place in one of the canoes. “Never did I witness a start,” he wrote, “about which there was so much quibbling and opposition, all, I believe, being the tactics of the enemy of man’s salvation. It was by a providential chance that we managed to get away, and by the power of glorious St. Joseph in whose honour God inspired me in my despair to offer twenty Masses.” While on his way westward with Fathers Daniel and Davost, he wrote to Le Jeune, “We are going by short stages, and we are quite well. We paddle all day because our Indians are sick. What ought we not to do for God and for souls redeemed by the Blood of His Son?... Your Reverence will excuse this writing, order, and all; we start so early in the morning, lie down so late and paddle so continually, that we hardly have time for our prayers. Indeed, I have been obliged to finish this letter by the light of the fire.”

The three missionaries travelled in separate canoes, and had been gone a few days when news reached Quebec, news which could not be verified, that Brebeuf was suffering greatly and that Daniel had died of starvation. Le Jeune exclaimed when he heard it: “If Father de Brebeuf dies, the little we know of the Huron tongue will be lost, and then we shall have to begin over again, thus retarding the fruits that we wish to gather on this mission.” Happily the news turned out to be false, and on the Feast of our Lady of the Snows, August 5, 1634, after thirty days’ travel, Brebeuf landed alone on the beach where he had first set foot on Huron territory eight years before. Confiding in the help of the Guardian Angels of the country, he trudged on alone over a trail overgrown and deserted, and finally he was able to contemplate with tenderness and emotion the spot where he had lived and celebrated the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass from 1626 to 1629. But Toanche had disappeared, and after a short stay at Teandeouiata, awaiting the arrival of Daniel and Davost, he and his two companions settled at Ihonatiria[2] on the north shore of the peninsula.

Brebeuf’s sound knowledge of the Huron tongue proved a valuable asset now; he began to visit cabins, instructing adults and baptizing children. He gathered the Indians together, and then clothed in surplice and biretta—“to give majesty to his appearance,” he remarked—he taught them the Sign of the Cross, the Commandments of God, and prayers in their own tongue. On Sundays he assembled them in his cabin to hear Mass and to answer questions in the catechism. Little presents given to the children enkindled in them so great a desire to learn, that the Relations inform us there was not one in Ihonatiria who did not wish to be taught; and as they were all fairly intelligent, they made quite rapid progress. The fruits were being gathered in slowly. “They would be greater,” Father de Brebeuf asserted, “if I could only leave this village and visit others.” Accordingly he made flying visits to the Tobacco nation and to Teanaostaye[3], the largest settlement of the Cord clan. He summed up the results in a letter dated June 16, 1636, claiming eighty baptisms in 1635, whilst he had only fourteen the year before.

The moment had come for greater apostolic activity. Every Summer the Huron flotilla brought up a couple of Jesuits, who as soon as they secured a smattering of the language began to instruct and baptize in many of the hamlets with which the country was dotted. Ossossané, the largest village of the Bear clan, situated on Nottawasaga Bay, had become a residence[4]. The future looked promising enough when a cloud suddenly appeared which threatened to destroy all missionary hopes.

In 1637 a strange pestilence visited the Huron nation and carried hundreds of Indians to the grave. The sorcerers, whose influence among their people was supreme and who feared a loss of prestige, laid the blame for this scourge on the Blackgowns, as the missionaries were named by their Indian charges. Every motive was seized upon to accuse them, and the lives of isolation and hardship which those devoted men underwent were to have an aftermath in persecution. Brebeuf himself was declared to be a dangerous sorcerer, in fact the most dangerous in the country; he was held responsible for the calamities that were weighing heavily on the tribe. Not merely the death of their fellow-Indians, but even the absence of rain, the failure of crops and lack of success on the chase, were laid at his door by the malcontents, who more than once threatened to cleave his head with a tomahawk. Affairs had assumed so serious a turn in the Autumn of 1637, and Brebeuf was so convinced that his hour had come that he wrote to his superior in Quebec a farewell letter, revealing the greatest resignation to whatever fate God might have in store for him.

Wishing to show the superstitious Huron Indians his utter contempt for his own safety and the little value he placed on this miserable life, he invited them to what the Hurons called a “farewell feast,” which those condemned to death were accustomed to provide. Many accepted the invitation and listened in mournful silence while the holy man told them that death had no terrors for him, that it meant eternal life for himself and his brethren; but he warned the Indians of the crime they were about to commit. Meanwhile the days slipped away quietly without any attempt at violence. A complete change had taken place in the hearts of the wretched Hurons, a change which Father de Brebeuf attributed to the intercession of St. Joseph, in whose honour the missionaries had vowed to say Mass for nine consecutive days.

The arrival of Jerome Lalemant, in the Summer of 1638, to replace Brebeuf as superior of the Huron mission, gave the latter greater freedom to go from village to village. Ihonatiria had been abandoned; Ossossané had become the chief residence of the Bear clan; a residence had also been established at Teanaostaye. On these two centers of population depended many minor villages, and with the help of new missionary recruits a crusade was started throughout the length and breadth of Huronia. Numerous striking conversions are recorded in the Relations, showing that sorcery and native superstition were losing their hold on the tribe, and that an era of further expansion would have ensued had not the Iroquois begun their depredations. Those inveterate enemies of the Hurons had become active and irritating. Their presence was a menace both to the missionaries and their neophytes, and it was decided to build a permanent residence and fortify it sufficiently to resist the attacks of those cunning foes of both French and Hurons. The result of this decision was Fort Ste. Marie on the Wye river, built in 1639, a “home of peace” which, while it would protect the missionaries from their enemies, would also be a shelter where they could retire occasionally and recuperate their physical and spiritual strength.[5]

The plans of the Jesuits were being carried out to the letter; the work of catechising the Hurons was going on vigorously, and new converts were asking for instruction, when a fresh scourge swept down on the unfortunate tribe. Smallpox began to ravage Ossossané, Teanaostaye, and the dependent villages. As usual the Blackgowns were held responsible for the new pestilence, and Brebeuf who was looked on as the chief of the French sorcerers had the lion’s share of savage resentment. An accident, the fracture of his shoulder-blade, which happened to him during a visit to the Neutral nation along Lake Erie in 1641, obliged him to go to Quebec for treatment, and he did not return to the Huron country until 1644.

Many changes had taken place there in those three years. The incursions of the Iroquois had become more frequent; small detachments were often encountered; everywhere they were leaving behind them a trail of blood. The terrified Hurons palisaded their villages and took precautions, as best they could, against those onslaughts. As if they had a presentiment of their coming doom and wishing to meet it fully prepared, they flocked around the Fathers in greater numbers than ever to hear the Word of Life. Although in constant peril, Brebeuf and his fellow-missionaries went from village to village, spending themselves in this arduous task. The harvest was growing, hundreds were clamouring for baptism. And yet amid their consolations the Jesuits saw that the clouds were lowering; disaster was following disaster, and all, even the missionaries themselves, were at a loss to say what the future would bring forth. They were soon to learn.

There were now eighteen Jesuits actively engaged among the Hurons, one of these being Gabriel Lalemant, who had arrived only in September, 1648. He had been sent to live with Father de Brebeuf at St. Ignace[6], a small village which had been removed the previous winter to a strongly fortified site about three miles nearer Fort Ste. Marie. It was there, in March, 1649, that the supreme sacrifice, so long sought for, awaited Brebeuf and his companion.

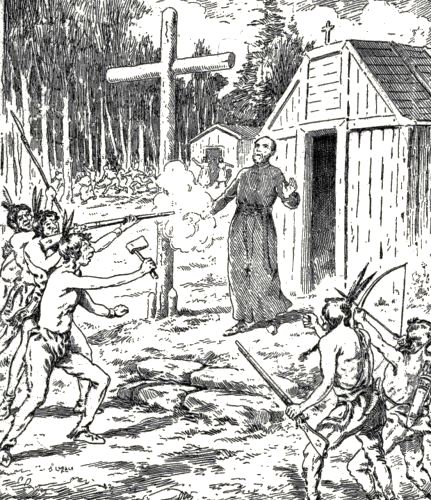

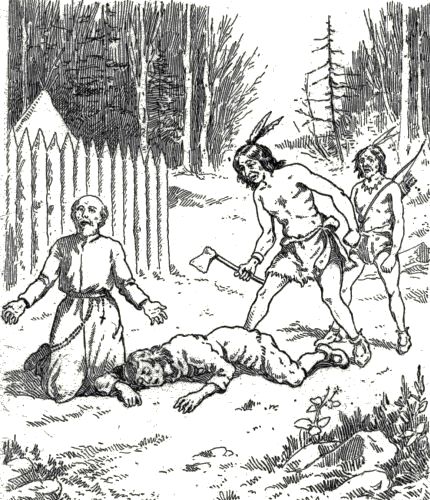

Both missionaries happened to be at the neighbouring village of St. Louis,[7] three miles away, instructing the neophytes, when, at early dawn of March 16, fully a thousand Iroquois stealthily approached St. Ignace.

The merciless invaders flung themselves on the unsuspecting and unprepared Hurons, murdering or making prisoners of them all. Only three escaped and hurried to St. Louis to warn Father de Brebeuf and the people. But at their heels rushed the Iroquois, and another massacre took place at that village. Although the two Jesuits were urged repeatedly to flee and save themselves, they refused to do so. They were seized, bound and brought back to St. Ignace where the inhuman captors had already made preparations for their torture and death.

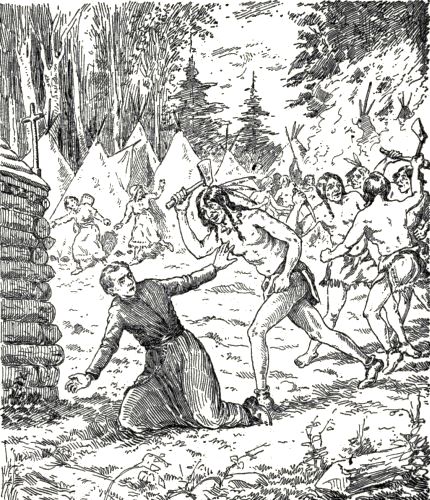

The Relation of 1650 gives us many details of the tragedy, but Christopher Regnaut, a servant who helped to bring the charred bodies back to Fort Ste. Marie, three days after the event, has left us a thrilling account, gathered from the lips of the Huron Christians who had escaped, of the barbarous treatment the two holy missionaries received.[8] “They (the Iroquois) took them both and stripped them entirely naked and fastened each to a post. They tied both their hands together. They tore the nails from their fingers. They beat them with a shower of blows with sticks on their shoulders, loins, legs and faces, no part of their body being exempt from this torment. Although Father de Brebeuf was overwhelmed by the weight of the blows, the holy man did not cease to speak of God and to encourage his fellow-captives to suffer well that they might die well. ‘My children,’ he exclaimed, ‘raise your eyes to Heaven in this affliction; remember that God is watching your sufferings and will soon be your exceeding great reward. Let us die together in the faith, and hope from His goodness the fulfilment of His promises. I pity you more than I do myself. Keep your courage up in the few remaining torments; these will end with your lives; the glory which follows will have no end.’ ”

Whilst he was thus encouraging those good people, a wretched Huron renegade who had remained a captive with the Iroquois, and whom Father de Brebeuf had formerly instructed and baptized, hearing him speak of Paradise and holy baptism, was irritated and said to him, “Echon, (the missionary’s Huron name) thou sayest that baptism and the sufferings of this life lead straight to Paradise; thou shalt go thither soon, for I am about to baptize thee and make thee suffer well, in order that thou mayest go sooner to thy Paradise.” The barbarian having said this, took a kettle full of boiling water which he poured over his head three different times in derision of holy baptism. And each time that he performed this mock ceremony, the barbarian told him with bitter sarcasm, “Go to Heaven, for thou art well baptized.” “After they had made him suffer several other torments,” continued Regnaut, “the first of which was to heat hatchets red-hot and apply them to the loins and under the arm-pits, they made a collar of these red-hot hatchets and put it on the neck of the good Father. Here is the way I have seen the collar made for other prisoners; they heat six hatchets red-hot, take a stout withe, draw the ends together, and then put it around the neck of the sufferer. I have seen no torment which moved me more to compassion than this; for you see a man, bound naked to a post, who having this collar on his neck knows not what posture to take. If he lean forward the hatchets on the shoulder weigh more heavily on him; if he lean back, those on his breast make him suffer the same torment: if he keep erect, without leaning to one side or another, the burning axes, applied equally to both sides, give him a double torture. After that they put on him a belt full of pitch and resin, and set fire to it. This roasted his whole body. During all these torments Father de Brebeuf stood like a rock, insensible to fire and flame, which astonished all the blood-thirsty executioners who tormented him. His zeal was so great that he preached continually to those infidels to try to convert them. His tormentors were enraged against him for constantly speaking to them of God and of their conversion. To prevent him again from speaking of these things, they cut out his tongue and cut off his upper and lower lips. After that they set themselves to stripping the flesh from his legs, thighs and arms, to the very bone, and put it to roast before his eyes, in order to eat it. Whilst they were tormenting him in this manner the wretches derided him, saying, ‘Thou seest well that we treat thee as a friend, since we shall be the cause of thy eternal happiness. Thank us, then, for these good offices which we render thee, for the more thou shalt have suffered the more will thy God reward thee.’ The monsters, seeing that the Father began to grow weak, made him sit down upon the ground, and one of them, taking a knife, cut off the skin from his skull. Another barbarian, seeing that he would soon die, made an opening in the upper part of his chest, tore out his heart, roasted it, and ate it. Others came to drink his blood still warm, which they did with both hands, saying that Father de Brebeuf had been very brave to endure all the pain they had caused him, and that in drinking his blood they would become brave like him.”

After several hours of these inhuman tortures, the holy apostle of the Hurons expired at four in the afternoon, March 16, 1649. He was fifty-six years of age, sixteen of which he had spent in the Canadian missions. His long and painful ministry was at last ended; nothing now remained but the charred and blackened bones and flesh of the missionary. Father Bonin and several Frenchmen who went to St. Ignace to investigate, found there a spectacle of horror: or as Father Paul Ragueneau wrote, “the relics of that love of God which alone triumphs in the death of martyrs.” The bodies of the victims were tenderly carried and given Christian burial in the little cemetery at Fort Ste. Marie.

In 1650, when the Huron mission was abandoned forever, the bones of Father de Brebeuf were raised from the grave and brought to Quebec, where they were held in high veneration. A rich silver reliquary was sent from France, probably by the Brebeuf family, to receive the skull of the venerable victim of the Iroquois. Other portions of his relics were distributed among the Canadian communities; others were sent to France, where they failed to survive the depredations of the French Revolution.

And yet, perhaps the most precious heirloom that has come down to us of this venerable servant of God is the story of his life and labours which has been preserved in the monumental record known as the Jesuit Relations. The heroism of the early Canadian missionaries has always excited the admiration of historians. Not all of them, however, have done complete justice to the lofty motives which could inspire a man like Brebeuf to bury himself in the forests along Georgian Bay and finally sacrifice his life, all he had to sacrifice, for the conversion of the aborigines of New France. Others better qualified to judge have been fairer to his memory, when they give credit to the grace of God for his victories, and make him say with St. Paul, “I can do all in Him who strengthened me.” “His death,” wrote Ragueneau, his superior, “has crowned his life, and perseverance has been the seal of his holiness. He died while preaching and exercising truly apostolic offices, and by a death which the first apostle of the Hurons deserved.”

Jean de Brebeuf was looked on as a martyr from the time of his death, and he would have been proclaimed as such even from that moment had his contemporaries dared to forestall the infallible decision of the Church. “Brebeuf’s gentleness which won all hearts, his courage truly generous in enterprises, his long suffering in awaiting the moments of God, his patience in enduring everything, his zeal in undertaking everything he saw, was for the glory of God.”