* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

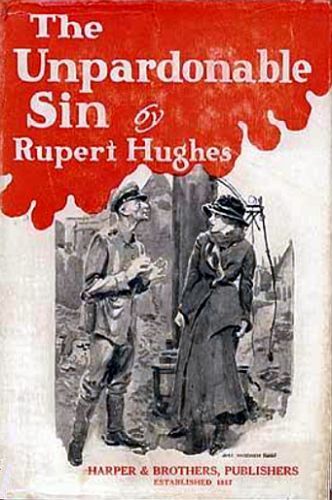

Title: The Unpardonable Sin

Date of first publication: 1918

Author: Rupert Raleigh Hughes (1872-1956)

Illustrator: James Montgomery Flagg (1877-1960)

Date first posted: Jan. 11, 2024

Date last updated: Jan. 11, 2024

Faded Page eBook #20240118

This eBook was produced by: Marcia Brooks, Al Haines, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

Books by

RUPERT HUGHES

THE UNPARDONABLE SIN

LONG EVER AGO

WE CAN’T HAVE EVERYTHING

IN A LITTLE TOWN

THE THIRTEENTH COMMANDMENT

CLIPPED WINGS

WHAT WILL PEOPLE SAY?

THE LAST ROSE OF SUMMER

EMPTY POCKETS

———

HARPER & BROTHERS, NEW YORK

Established 1817

Mrs. Winsor clasped her close, and spoke to her motherly: “My dear, you are with friends. You have been ill, but we love you and you are well again.”

The

Unpardonable Sin

A NOVEL

BY

RUPERT HUGHES

Author of

“We Can’t Have Everything” Etc.

ILLUSTRATED BY

JAMES MONTGOMERY FLAGG

HARPER & BROTHERS PUBLISHERS

NEW YORK AND LONDON

The Unpardonable Sin

——

Copyright, 1918, by Harper & Brothers

Printed in the United States of America

Published June, 1918

1-8

THIS STORY OWES MUCH TO

Captain John Francis Lucey

TO WHOSE GENIUS AND SACRIFICE

COUNTLESS BELGIANS

OWE THEIR LIVES

| ILLUSTRATIONS | ||

| Mrs. Winsor Clasped Her Close, and Spoke to Her Motherly: “My Dear, You Are with Friends. You Have Been Ill, but We Love You and You Are Well Again” | Frontispiece | |

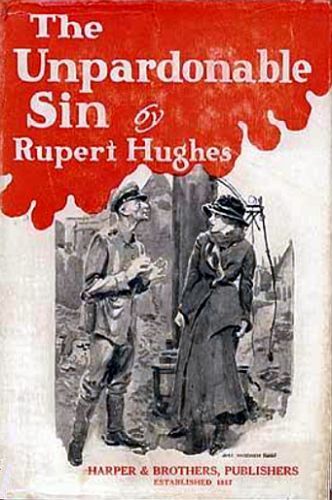

| Mrs. Winsor Felt that if the Great Eyelids Were to Open, They Would Stare in Amazement, and the Long Pale Lips Would Babble a Strange Story | Facing p. 8 | |

| Isolde Could Not Bear to Look but, Turning Aside, Played with All Her Might | Facing p.“ 34 | |

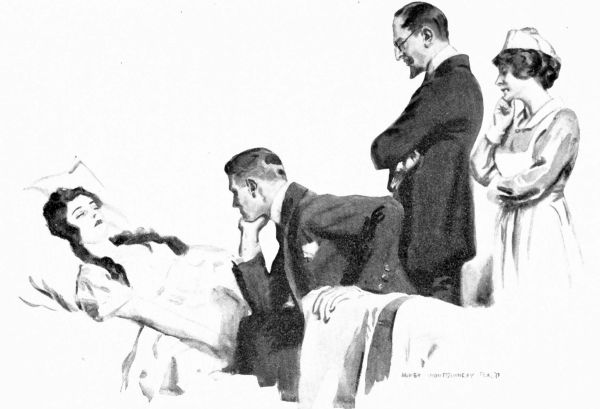

| While the Beautiful Girl Played to the Beautiful Girl, No One Seemed to Hear Isolde or Heed Her, the Sleeping Girl Least of All. It Was She That the Two Men and the Nurse Watched, All Eyes | Facing p.“ 38 | |

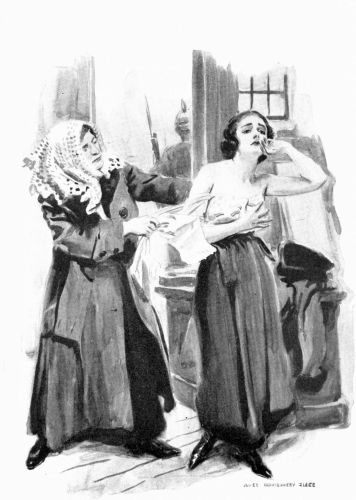

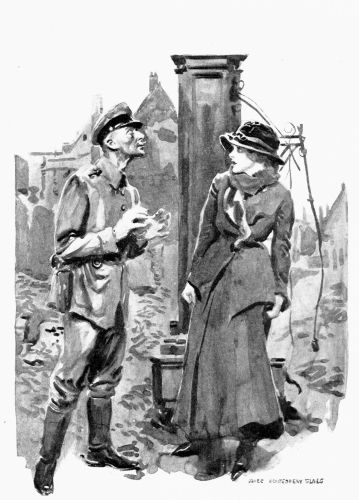

| When Dimny Refused to Proceed with the Door Open, the Matron Threatened to Call the Soldiers to Her Aid | Facing p.“ 174 | |

| “My Name Is Ignatius Duhr—Nazi. I Did Telled You My Name ven You Are in My Arms. Now You Are Remembering, Yes?” “No!” She Groaned. She Cried It Aloud Again, “No!” and Again, “No!” | Facing p.“ 230 | |

| Dimny Ripped Open the Collar of the Wretch’s Tunic, and Groped About His Throat Till She Felt the Pumping Throb of a Great Artery. There She Pressed Her Thumb with All Her Might. And the Blood Jumped No More from the Remnant of His Arm | Facing p.“ 248 | |

| At Any Moment Through That Placid Sea There Might Come a Torpedo. And Then Death Would Be Their Portion. The One Important Thing Was Haste, to Embrace and Make Love Before the Gulf Opened Beneath Their Feet | Facing p.“ 304 | |

THE UNPARDONABLE SIN

The streets of the little mid-Western town were pure gloom save for the occasional arc-lamps, strange incandescent fruit among leafage so thick that they gave off rather a white fog than light. Against their pallor the trunks of the veteran maples loomed black and flat, their shadows pools of tar.

Few people were abroad, and they were so vague in the gloom that they seemed not to be persons walking, but the floating shadows of beings hidden above. Yet their footsteps were audible as they approached and vanished, the rhythm broken by shuffles and stumbles over the hard ripples in the brick pavement.

It was impossible to see who was who, but the old lady on the Winsor porch knew most of her neighbors by their footsteps. There were Trigger-foot Pedlow and wooden-legged Major Rounds. But they were easy. She knew also the stealthy tread of Tawm Kinch, who always seemed to be saving shoe-leather, and the timid patter of old Miss Tiffin’s spinstery feet forever fleeing when no one pursued.

Mrs. Winsor had sat on her front porch or at one of her windows for so many years that people’s feet clicked their autographs for her on the sidewalk. She could tell when there was a stranger among them, if he walked fast. But to-night the few who were abroad went by so slowly that her ears could not read their names. This made her lonelier than usual, for her son was late, and the cook had gone out for the evening.

The poor soul grew afraid to rock her chair: the noise alarmed her; it might attract burglars. She wished her boy would come home; she wondered what kept him. He should have been back long ago, to help her indoors. She was not supposed to be strong enough to walk by herself. If any of those wayfarers had turned suddenly into her gateless, fenceless yard, she could have reached the door with a scream, but she needed some such goad.

She might have called to somebody to help her in. But that would be advertising her solitude. She wished her son would come home. She had had a letter in the late mail, and she wanted to read it to him. It worried her keenly. She felt very old, very much afraid. In the sky there were flickerings of lightning, rubadubs of thunder.

Mrs. Winsor dreaded storms. The next might always be her last. She imagined the lightning stabbing the helpless lands beyond the horizon, and she imagined the people cowering there with no defense against their invaded sky.

She wished her son would come home before the rain broke over the streets. He was, as likely as not, standing out on the high bluff over the river watching the storm come. He liked to go up on high hills or sit on the roof and study the lightning, shouting to it with hilarious defiances that scared his mother like a sacrilege. His professor at the high school had called him a young Ajax, but his name was Oliver. Nearly everybody called him Noll.

His ambitions had a kind of glory about them. He felt things fiercely; he was a ferocious partisan of anything he believed in—his baseball club, his father’s political party, the pattern of skates he wore, his ward school against the schools of all the other wards, his class in his school, his country against all the nations in the world in all times.

His mother wished that he would come home. The storm was advancing; the moon was enveloped—veiled—erased. The lightnings were flashing and fencing well inside the horizon. But yet awhile the air was still and warm, expectant, undecided. The air was in a Mona Lisa mood.

Mrs. Winsor was as helpless a spectator of the clouds driven in herds across the sky as of the phantoms drifting along the sidewalk. It was the lovers’ hour, and occasional couples mooned by dreamily. She smiled as she saw two shadows blurred into one, moving in leisurely colloquy in spite of the omens of wrath. She remembered how she had once gone enarmed along dark lanes and streets. The maples had not been so high then, and electric lamps had not been invented; but the gloaming spirit was as old as Eden and newer than Edison.

From one dual shadow that blurred along she could faintly hear murmurs with a hint of smothered excitement—a man’s diapason, a girl’s boyish treble—but nothing she could understand. She followed the couple with her eyes across the alley till the huge blot of the great tree there absorbed it. The shadow did not emerge into the dim radiance from the lamp at the next corner. She supposed the twain had paused for another embrace.

Then she seemed to feel a little agitation in the air. She seemed to hear a choked outcry ending in a faint gurgle. There was a sense of motion within the tree-shadow, like a quiver in black smoke. She smiled. The girl was probably making herself a little more interesting by the immemorial feint of resistance. Mrs. Winsor had used those tactics herself in her time, though she would never have confessed it even to herself.

But now a single shadow, a man’s, slowly withdrew from the shadow of the tree. The other shadow did not follow. As a patch of ink trickles away from a fallen bottle, the lone shadow flowed swiftly to the next tree-stripe, lost itself a moment there, then moved swiftly to the next, and so on tree by tree to the core of light at the corner, where the shadow seemed to be almost transparent, powdery at least. There it turned to the left against another line of trees and vanished behind the silhouette of the corner house.

All the houses seemed to ponder the riddle. The trees considered it.

Mrs. Winsor wondered what had become of the other shadow, but she stared into the gloom in vain. It was strange for a man to leave a girl there and run away. They might have quarreled, and she might have ordered him never to speak to her again, as girls do. She might have resisted a little too long, and he might have quit her cold. But then he would have marched away, or sulked along. There was something fugitive about this man’s departure. And why didn’t the girl go on home? Was she crying? She made no sound. Perhaps she was petrified with anger and was fighting her mad out, as Mrs. Winsor had done in her time, slowly in black silence.

Mrs. Winsor twisted her chair around and gazed with a kind of violence but with no success. The noise of her chair alarmed her. She began to fear things. The primeval dread of darkness and silence seized her. She wanted sound. Even the lightning made no noise now. She wished her son would come home and shield her from the horror of this quiet thing in the shadow. Perhaps murder had been done.

Then she heard footsteps coming up the right.

She knew their patter. Her son was evidently in a hurry. From his shade came his familiar voice:

“Mother! You’ve been alone. I’m mighty sorry. I couldn’t help it.”

She sobbed with welcome and put out her arms to him.

He was breathing fast. When he kissed her his lips were cold and tremulous. He opened the front door, made a light in the hall, lifted her, and helped her awkwardly inside the house. She loved the light; she was glad to hear the dear old front door slam; it was the portcullis-fall of her castle.

She reveled a little moment in her security before she could bear to send her boy out into the dark to see what was the matter there. Just as she was ready to speak she saw that he had been through an experience of some exciting sort.

She noted a bruise on his face—a barked knuckle. The thought went through her mind like lightning that he would have had time to run around the block and come home if he had been the shadow that fled from the other shadow.

Then he picked her up in his arms, and she marveled at the strength of what was once a babe at her bosom. What she had once carried now carried her.

He toted her up-stairs to her room; he knelt to unbutton her shoes for her, and she marveled at his meekness. She loved him with fear, and she wondered what life was doing to him. He was away so often, in such unknown companies. And she knew how much evil the small town held. The old know the world too well. The deep shadows, the quiet porches, the humble intrigues—she had encountered so much sickening knowledge in her years; such frightful facts emerged now and then from the shadows.

If her boy had been one of the ghosts under the tree, who was the girl? Why had he gone by without speaking to his mother? She told herself that if it had been Noll, he would have called out to her. At least he would never have stopped to quarrel at the very edge of the yard when he knew his mother was on the porch. Or if he had done all those things, they had meant nothing more than a foolish spat. The girl outside had probably hurried home.

The rain came now. And that would send her scurrying. Mrs. Winsor was glad to hear a good wholesome growl from the sky. But her smile went from her, for the thunder was followed by a scream, a kind of white lightning against dark silence.

Then there was a noise of footsteps, like a heavily running rain. They came up on the porch. The door-bell clamored.

Noll stood aghast a moment, then darted down-stairs. Mrs. Winsor heard him unlock the door, heard a man’s voice in agitation:

“Hello, Noll. I want to use your telephone. Where is it? . . . Hello! Hello! Give me the police-station, quick! . . . I don’t know . . . something funny. Hello! Is this Marshal Dakin? Say, Marshal, this is Ward Pennywell. Just now, as I was coming along Fourth Street—with, well, never mind—we stumbled over the body of a girl. She’s dead, I think, or nearly—strangled to death, I guess. I lighted a match to see what it was I fell over. I never saw her before. Better come up. She’s right outside Mrs. Winsor’s house.”

Mrs. Winsor’s heart began to flutter dangerously. A gentler thunder groaned from the deeps of the night. The air was filled with silken whisperings and tappings of soft fingers. The rain was sorry.

The old soul imagined everything now. Her faculties were stampeded with the wildest fantasies. Her boy had killed a girl, and she was the only witness. She would have to testify. One of those cyclones of scandal that tear quiet homesteads to ruins had fallen upon her little house. She cried out: “Noll! Noll!”

He called up the stairs, and ran up as he called:

“Don’t worry, Mother. Something’s happened outside. A girl—hurt—or fainted, I guess. Don’t worry.”

He had so little of crime in his mien that she felt able to think of other humanity. She said:

“You’re going to fetch the poor thing inside out of the rain, aren’t you?”

“Shall I, Mother? You’re not supposed to move people like that till the police come.”

“But it’s terrible to leave anybody out in the—the rain.”

The commonplace dread of wet clothes and lying on the ground in a storm outweighed the unknown significances of unusual tragedy. Noll said, “You’re right; I’ll go get her.”

She checked him to ask, “Who was the girl that screamed—the other girl, the girl with Ward Pennywell?”

“I don’t know, Mother. She ran home alone, I guess. I didn’t see her. He didn’t say who she was.”

He was out and scuttering down the stairs. There was some hesitation below, then a hurry of footsteps on the porch, then a slower movement such as two men would make carrying a body in the dark.

Mrs. Winsor could not endure the suspense. She called her son again and again, but he did not answer. Under the stimulus of anxiety she rose from her chair and stumbled across the room. She lowered herself down the stairway, using the banisters and the wall like crutches.

She found Noll and Ward Pennywell staring at a girl stretched on a sofa. She seemed to be asleep rather than dead. The two young men seemed to be more impressed by her beauty than by her fate.

They turned in an almost guilty surprise as they heard Mrs. Winsor gasp. Noll whirled and turned to support her to a chair. She would not be checked from approaching the strange visitor. First she drew the skirt down below one revealed bruised knee. The skirt would not reach the shoe-tops; it was of a fine stuff. The stockings were of silk, the shoes of an excellent leather. Mrs. Winsor brushed a loop of hair back from the closed eyelids, took off the crumpled hat with difficulty, lifting the head in terror to take the long pins from the wet hair. She saw that the invader was dangerously pretty. There were raindrops on her face like tears, and in her hair like pearls. Mrs. Winsor felt that if the great eyelids were to open, they would stare in amazement, and the long pale lips would babble a strange story.

She put her old, cold hand on the girl’s hand, and it was colder than hers. She could not find a throb in the wrist where the pulse lurks. She studied the palms; they were delicate, without calluses. The fingers were soft and slim, and the nails had been well kept, though they were cut close to the finger-tips. That struck her as odd. The finger-tips themselves were rather blunt.

She marveled at those hands; what instruments of terror they were! Hands can do—those hands might have done—such graceful, such hateful, beautiful, loathsome, terrible, exquisite things.

“We ought to send for a doctor,” she sighed. “My doctor is out of town.”

“The marshal will be here in a minute,” said Ward Pennywell.

Mrs. Winsor sank back into the chair her son brought to her, and gazed at the peculiar visitor from nowhere. She said to Ward Pennywell:

“I heard a girl scream, Ward. It wasn’t this girl.”

“No, it was—it was—the girl I was with.”

“Who was that, Ward?”

“I think I hear the marshal driving up.” He hurried out.

Mrs. Winsor turned to her son and spoke firmly: “What kept you so late, honey?”

“I’ll tell you afterward, Mother.”

“Do you know who this poor creature is?”

“No, Mother.”

“Did you ever see her before?”

“I don’t think so. There’s the marshal. I’ll let him in.”

The marshal arrived, important with his office but very deferential as usual to people he was not in the habit of arresting.

“Evening, Miz Winsor. Kind of rainy to-night. Been looking like rain all day. Kind of looks like all night now. What’s this I hear about finding a girl? That her? Humph! How’d it happen?”

Mrs. Winsor did not tell him that she had seen two shadows enter the shadow of the old maple, and only one shadow come forth and flee. She had an intuition that she ought to keep out of it.

She nodded to Ward Pennywell and let him describe how he was on his way home when he stumbled over something, lighted a match, saw what it was and lost no time in notifying the police. He said this with a sort of boastfulness, as if he were showing what a law-abider he was. He did not mention the fact that he was with a girl who screamed. Neither did Mrs. Winsor. Neither did Noll. Pennywell’s eyes seemed to ask them not to. Mrs. Winsor felt that the mutual forbearance was a fair exchange.

The marshal stood and scowled down at the girl and pulled his long mustaches, as if to milk them of some intelligence. Mrs. Winsor stared from him to the girl and to the young men. The influence of that still white being, the very blossom of youth fallen from the tree, was strangely various.

Mrs. Winsor felt that if the great eyelids were to open, they would stare in amazement, and the long pale lips would babble a strange story.

All four were afraid of her, each with his own fear. Mrs. Winsor noted a kind of resentful anxiety in Pennywell’s eyes, as if he were blaming the girl for getting him into trouble and yet found her enticingly attractive.

Noll regarded her in a kind of ecstasy, his eyes seeming to touch her beauty and her grace with timid attention. Youth was seeing youth wrecked. Mrs. Winsor felt a new fear for her son; a son is a dangerous weapon that a woman forges for another woman’s capture or protection or destruction. And Mrs. Winsor, having been a girl like this one, and after that a wife and a mother and a widow and an elder, understood how much of life this girl had begun and how much she had missed.

The marshal was both citizen and policeman, a sporting-man with a cynical experience, and a man of the law who must not be baffled. He cleared his throat with an effort at importance that only admitted his confusion.

“Kind of nice-lookin’ kid!” he suggested. “Right smart of a dresser. Don’t suppose she’s just kind of fainted, do you?

“Kind of” was with the marshal a kind of deprecating expression, a shading of too downright conviction.

“Put something under her feet,” said Mrs. Winsor, “so that the blood will go back to her head.”

The three men started with surprise at the command, and recoiled a little. Each waited for the other; then Noll went forward and, taking a cushion from the sofa, lifted the feet with reluctance a little, and stuffed the cushion under them. His mother was glad to see how this simple contact terrified him.

The girl’s head was upheld by the opposite arm of the sofa. Mrs. Winsor indicated this with a gesture, and Noll with new qualms laid hold of the girl’s ankles and drew her feet toward him so that her body slid along the sofa. Now her chin, which had pressed down like a bird’s beak preening its breast, went back with the sudden motion of a spasm of agony, and her throat was abruptly revealed, long, slender, and pitiful. And now she seemed to have died indeed. The throat is the home of pathos, and hers was unendurable with tragedy.

Noll gasped and sprang away. The marshal leaned forward with a business-like determination. His coarse fingers went to the satin throat, and he bent close to stare.

“No sign of bein’ choked,” he said. “No wounds anywhere as I can see.”

He lifted a hand and let it fall. The arm flopped, bending at every joint with a hideous lifelessness. Noll gasped aloud. The officer felt for her pulse and could not find it. Noll winced at his roughness with that delicate wrist.

The marshal waited awhile before he spoke again:

“Kind of looks like she ain’t goin’ to come to. She’s gettin’ cold.”

That fatal, icy word sent a shiver through Mrs. Winsor. She knew what it was to have beings that had lived grow cold.

“I guess it’s heart disease or p’ralysis,” the marshal said. “I had a cousin just kind of keeled over once thataway. Maybe she was just goin’ along the street when it kind of took her. Too bad!”

“But how about—” Mrs. Winsor had begun to ask, “But how about the man that was with her and ran away?” But she glanced at her son again, and he was shaken with such agitation that she clenched her lips on the words.

The marshal waited for her to go on. When she did not he said, “What say?”

And she merely asked, “How about sending for a doctor?”

“I guess we better. No need hurrying the coroner.”

This ghastly word smote Noll Winsor like a club.

The marshal went to the hall, leaving the three alone with the girl. They felt unprotected, outnumbered by her terrible powers, with no officer of the law to protect them from her.

The marshal spent an eternity fumbling with the book.

“I’ll go,” said Noll, impatiently.

From where he stood in the hall he could see the girl lying like a form cast up by the sea. He turned from her, looked back. She must have danced well. She was so shapely. He rebuked himself for thinking of the shape of the dead. He felt that people must never dance any more, now that such beauty was ruined. Perhaps she was not quite dead. It seemed impossible that grace like hers should be brought to perfection only to be drowned in nothingness. The doctor might save her, if he came at once. Noll commanded his immediate presence.

Noll’s haste brought a flare of joy in his mother’s heart. He could not be impatient for the doctor’s arrival if he were guilty of the girl’s murder.

She only smiled, reproaching herself for the treachery of her suspicion. She wanted to tell him of it and beg his forgiveness. But the confession was impossible in Ward Pennywell’s presence. And now that the doctor was coming she felt she had no right to tell the marshal of the man who had slunk away. The poor girl might be brought back to life, and be hurt by the publication of her secret. What the marshal got, the newspapers got. So she postponed again.

The marshal was studying the girl. He ran his fingers into her hair and about her head. The sensitive Noll, to whom a woman’s hair was almost sacred, resented his profanation. But the marshal did not notice him. He mumbled:

“Skull’s all right. She ain’t been hit with nothin’—or throttled. If she was stabbed or shot there’d be plenty of signs. It’s kind of mysterious. No sign of poison around her mouth. But she’s kind of still and cold. Who is she, anyway? Any of you ever see her before?”

All three shook their heads. The marshal was shocked.

“I ain’t ever seen her myself. Keep track of ‘most everybody. I meet most of the trains. Nobody like her has stepped off one the last few days. Wonder who her folks are. I guess it’s kind of up to me to search her for what the feller calls a clue.”

He put out his hands, but they kind of retracted themselves before Noll made a leap at him; his only protest was a strangled groan. “Don’t! Don’t touch her!”

The marshal eyed him suspiciously. “What’s it to you, young feller?”

“I can’t bear to see your big old hands on her.”

The marshal laughed sheepishly and said: “Maybe you better do the searchin’, Miz Winsor. It’s a kind of lady’s job.”

“No, thank you,” said Mrs. Winsor. “I guess we’d better all wait till the doctor comes.”

“I’ll be going if you don’t mind,” said Ward Pennywell.

“I do mind,” said the marshal. “Set right where you air!”

There was a long silence. Nobody spoke. All stared and waited for the girl to rise. But she did not budge. Her breast did not lift with a breath; her nostrils were as still as marble. Her attitude was one of such discomfort that a living being would surely have moved. Noll was tempted to go to her assistance, but he lacked the power.

By and by the door-bell whirred and Noll went to admit the doctor.

The silence in the hall was so profound that Mrs. Winsor could hear the rustle of the doctor’s raincoat as he took it off and hung it on the hall-tree. He shook hands with Mrs. Winsor and then turned to the girl. He was amazed. He went in haste to her as if drawn by a rope. He gripped the girl’s wrist, and his two finger-tips listened in vain for the pulse-beat; the other hand went to her forehead. He knelt down and peered into her face as if he would kiss her. He put his cheek close to her lips. He cupped his palm over her heart. He pushed back one eyelid, and he alone knew what color the iris was. He got no reassuring message from the stare that answered him. The pupil was dilated. The eye did not follow his. He lighted a match and moved it before the eye, with no effect. He put his cheek on the girl’s left breast and rested there. He shook his head again. He opened the little hand-bag he had brought in from his car, took out a stethoscope, and, swiftly unfastening the girl’s frock at the neck and throwing it back, set the instrument over the heart. Noll turned away with something of the terror of Noah’s better sons, but Ward Pennywell stared like Ham till Mrs. Winsor glared him away.

“Get me a mirror, will you?” Doctor Mitford mumbled.

Noll ran up the stairs and ran down with his shaving-glass. Kirke held it in front of the girl’s nostrils, then he stared at it, found a dim vapor on its surface and gave a little gasp of joy.

“She’s not gone—yet!” he muttered. And now he was in a mood of snarling rapture. He was the young doctor challenging old Death to a duel. From his knees he spoke to Mrs. Winsor.

“I don’t know what’s wrong, but there’s not much life in her. If I take her to the hospital in this cold rain——”

“Certainly not. The spare room! Noll, run up and make a light.”

Noll hurried, but Mitford was right after him. He rose, gathered the almost soulless bundle of flesh into his arms and carried her up to bed as if she were a Sabine, the girl’s nodding head and swaying arms hanging at Mitford’s shoulder.

Mrs. Winsor hobbled out and labored up the stairs and was glad to find that necessity gave her strength. Necessity is the supreme tonic.

The young doctor called to Noll: “Take off her shoes. No, run fill a hot-water bag—two if you have ’em. Hurry! Mrs. Winsor, you might unfasten these infernal hooks while I take off her shoes and stockings.”

Their struggle for her life rendered the ordinary delicacies contemptible for the moment. The waif had both a valet and a maid.

While Mrs. Winsor was at her task Doctor Mitford was in and out and up and down stairs, equipping himself for the contest. He snatched the hot-water bottles from Noll and sent him to telephone the drug-store for stimulants, the hospital for a pulmotor and a trained nurse, his own boarding-house for his electric battery.

He ran out into the kitchen and used the steaming kettle for a sterilizer. He filled his hypodermic needle. He turned the house upside down, but he gave the comforting impression that he was neglecting nothing.

In one of his charges through the sitting-room he was checked by the marshal:

“Say, Doc, just a moment.”

“Can’t spare a second, Chief.”

“Hold on! I just want to ask you is they any use my hangin’ ’round any longer?”

“Not the slightest; you’re absolutely no use—just in the way.”

“All right. You needn’t wait, neither, Ward. Consider yourself arrested or somethin’. I’ll let you know when I need you. I’m goin’ out to look ’round that tree with my flashlight, and see if she’s lost anything that’ll give a kind of clue or somethin’. Night, Doc.”

A little later the door-bell rang and Noll answered him. It was the marshal.

“Tell the doc I didn’t find nothin’,” he said, and left.

Noll sat on the top step of the stairway, pondering deeply, profoundly shaken by the invasion of this eerie ghost-woman. Meanwhile the young doctor, who had had none too much experience, was trying to make the most of his few weapons.

Mrs. Winsor, acting as a sort of chaperon, hovered about. She spent most of her time examining the girl’s clothes for some clue. There was no dressmaker’s label on her frock, no laundry mark on her linen. The name of the maker of her shoes was blurred.

There was just one bit of treasure trove for Mrs. Winsor. A silk money-belt was fastened about the girl’s waist, and in the pockets of that she found several little clumps of money, new money that had never been spent even once—several thousand dollars in large bills—and two diamond rings. That was all she found.

She showed the wealth to the doctor. He pushed it aside brusquely.

“It doesn’t interest me how much she’s worth. The thing is can I get her back.”

Mrs. Winsor struggled out into the hall and sank down on the step at Noll’s side. She showed him the money and the money-belt. He counted it expertly—four thousand eight hundred and forty-five dollars. It was a larger sum than either of them had ever seen at once before in that house. Noll handled money in bundles at the bank, but this was different. Mrs. Winsor looked over her shoulder and gasped when the doctor opened the door.

“Come here, Noll, and help me,” he commanded.

Noll restored the money-belt to his mother. She pushed it away.

“For Heaven’s sake, keep it. It frightens me to death.”

He showed the money to Mitford.

“Put it up,” said Mitford, “and take hold of her feet and help me carry her over to that couch by the light.”

Noll suffered anguishes of modesty. He seemed to be committing a lynchable offense in embracing this young woman to whom he had never been introduced. She was in one of his mother’s nightgowns now, and she was grotesquely pretty. She was so cold that she appalled him. There was a rigidity about her that chilled him. She was as awkward as a jointed doll.

He had never held a woman so; she was unutterably fearful to him, and yet somehow ineffably dear.

He prayed, for her and to her, not to leave him. He vaguely remembered Walt Whitman’s lines to the wounded soldier:

Hang all your weight on me—

By God, I will not let you die.

He suffered cruelly with the assaults the doctor was making on the citadels of her soul’s retreat. Mitford tried by loud noises, by flashing lights, to startle her to her windows. He set to her nose a bottle of ammonia that almost blinded Noll with its knife-like odor. Noll was nauseated with the loathsome shock of asafetida, but her exquisite nostrils showed no repugnance.

“Don’t!” he growled at last. “You’re hurting her.”

“No, I’m not,” said Mitford. “I’m trying to, but I can’t.”

After every effort Mitford stepped back, baffled yet somehow convinced by failure that success was waiting for the lucky try.

Noll thought of him as of one of the priests of Baal trying to lure his god to answer, while Elijah taunted: “Cry aloud. . . . Either he is talking or pursuing or in a journey.”

Doctor Mitford had not awakened the first hint of life when the trained nurse came and took Noll’s place. He had to leave the room. He felt as if he had deserted his charge. The door was closed on him.

He took up a vigil-place on the stairs. He heard strange noises in the spare room, which Mitford had turned into a laboratory. He wondered what they were doing, the nurse and the doctor. He knew that they were hurting her, or hoping to. There was so much pain on earth, it seemed better to let her sleep on out of the ugly world. And yet it seemed that her life was too precious to be surrendered, at any cost.

He fell asleep at last in the turbulence of his own emotions. He was wakened by Mitford’s shaking his arm. The hall was lighted ambiguously by the gas and by the daylight round the chinks of the curtain. Seeing the desperate look in Mitford’s face, Noll said:

“How is she? Is she——”

“She’s not dead, anyway.”

“Oh, thank God!”

“Don’t be too previous. If it’s the sleeping sickness, she’ll just fade away. I’m all in!”

He stumbled down the stairway, and Noll caught his elbow to keep him from pitching forward headlong.

“What do you think caused her—death-sleep, or whatever it is?”

“I haven’t the faintest idea. I’ve made a thorough examination. I can’t find anything wrong. I wonder who the dickens she is and where the devil she comes from.”

“Good night!”

“Good morning!”

Noll staggered to his own room. As he pulled down the curtain he saw the doctor clambering into his car.

When Noll woke it was nearly ten o’clock. The sound of the door-bell roused him. He sat up in bed with a start and a flush of guilt.

He had heartlessly forgotten the new guest altogether. He was ashamed of himself, especially as it was the doctor whose ring had wakened him. His mother was awake, and had breakfasted. The nurse was a trifle jaded but still alert. Doctor Mitford was coming out of the room by the time Noll was dressed. He asked, anxiously:

“Is she alive?”

“Yes and no.”

“What does that mean?”

“There’s no sign of her waking.”

“Drugged?”

“No.”

“What put her to sleep?”

“I wish I knew.”

“How are you going to wake her?”

“I wish I knew.”

“How long will she sleep?”

“How can I tell? It may be for hours, weeks—it may be forever!”

“I should think she’d starve.”

“She will if I don’t find some way to feed her. If it should be the sleeping sickness, there’s little hope. I’ve been reading that up. It’s pretty nearly unknown among Caucasians except by importation from Africa, and it’s nearly always fatal. A gradual emaciation ends in death without waking.”

Noll’s young soul rejected such a possibility as too cruel to be true—as if anything imaginable were too cruel to be true.

“She’s not going to die. Something tells me that!”

“Something-tells-me is hardly a prognosis,” said Mitford. “But there’s nothing to indicate the sleeping sickness. And there’s nothing to indicate that she is unconscious from a blow. There’s only one other theory left—hysteria.”

“Hysteria? Why, I thought when women had hysteria they made a lot of noise and tore their hair and cried and laughed at the same time.”

“Not always. Sometimes they have fits of sleep. They fall into just such a lethargy as this. They grow cold and white; the heart-beat is almost impossible to trace; they seem to be dead. And sometimes they have been buried in careless haste and have wakened afterward—”

“That’s the cataleptic trance I’ve heard about,” Noll said. “For God’s sake, don’t make any mistakes with her.”

He stared at the girl with a new emotion. His glance was curious, dubious; his eyes quizzed her.

“Hysteria,” he pondered. “That sounds kind of insincere. It’s one way of shamming, isn’t it?”

“That depends on what you mean by shamming,” said Mitford. “Who can tell when the real ends and the sham begins? And when people are shamming, why are they shamming?”

“Because they are insincere, of course.”

“Then why are they insincere? Back of the pretense is a sincere reason somewhere. What is that reason? Maybe when people only pretend, they are just as sincere as when they are perfectly candid.”

“You’re wandering round in circles, Kirke, shaking hands with yourself and telling yourself good-by. About as far as I can follow you is that you seem to claim that people have no self-control. Don’t you believe that people are captains of their souls, as Henley said?”

“No, I don’t!” said the doctor. “Henley wasn’t the captain of his own soul. He was more like the passenger of his soul, and his soul was a passenger in his body, and it was a rickety ship at that. This poor girl, if she’s shamming, must be the victim of herself or something—”

“Or somebody, maybe!” said Noll, then wished he hadn’t.

It seemed grossly unchivalrous to be standing so near to her and discussing her so frankly; for if she were indeed conscious, she must be overhearing their comments. Yet how could she be conscious and keep so still? The self-grip it would require to deny herself all motion, even to the longing for one deep breath, was inconceivable to Noll. His own chest ached at the thought. He had had pleurisy, and he knew the priceless luxury of a great free gulp of air. A spasm of protest went through all his muscles at the thought of so prolonged a voluntary immobility.

He beckoned Mitford to another room. “What sort of thing causes that sort of thing?” he asked, gropingly.

“Some great soul-shock.”

“What sort of shock?”

“Oh, a sudden disillusionment, a terrifying insult or—oh, anything that may shatter a young woman’s innocence or faith in somebody or in herself—some sort of mental lightning-stroke that causes a spiritual lockjaw.”

This opened all the riddles of sphinxdom.

“What on earth could it have been in her case?” Noll groaned. “Who on earth is she, anyway?”

Who she was, and whence, and whither bound, and why—these were problems that had also disturbed Marshal Dakin.

Doctor Mitford canceled all the marshal’s suggested theories of drugs, knock-out drops, knock-out blows, and poison-needles. The marshal, eager to do something and arrest somebody, suggested taking the girl into custody as a vagrant. Doctor Mitford sniffed at that and reminded him that she had money in abundance. That assured her the marshal’s respect.

“Maybe I better put Ward Pennywell in the cooler awhile.”

“For what? No crime has been committed yet.”

“Well, I feel like I kind of ought to be doin’ something. Suppose I send out a general alarm to find out who this girl is. I can put a description of her on the wire to Chicawga, Sent Louis, Sent Paul, Sent Joe, K. C., N’York, Denver—all the big places. How would you describe her? Or wouldn’t it be best to have a photograph taken? I’ll send up somebody.”

“No, you won’t,” Noll broke in. “You let her alone. Suppose you send the alarm all over the country and all the newspapers print the story, and her picture, and she wakes up, and finds that she’s notorious everywhere. She may be just some nice young girl going home from boarding-school, or called back by her sick brother, and she may have lost her way, or lost her head. You’ll ruin her life for her. You’ve no right to expose her to the world that way. Besides, she’s a guest in our house.”

The marshal was human and a father, and like other policemen was addicted to all-day siestas taken standing or slumping in a chair, with bits of excitement few and far between. When Doctor Mitford urged that his patient must not be disturbed, the marshal consented and sauntered back to his chief occupation, waiting for something to happen.

At the jail, however, he went over his lists of missing girls for whom advertisement or confidential inquiry was constantly made. There were portraits of escaped criminals, clever forgers, badgers, shoplifters, bigamists, poisoners, convicts. But none of them resembled ever so faintly the dreamer at the Winsors’.

So the marshal tipped his chair against the whitewashed wall and resumed his characteristic attitude, ambiguous between sodden slumber and intense Oriental umbilical meditation.

Noll remembered with a start that he was supposed to be working down at the bank. He flung off the spell of the witch up-stairs and dashed to the dining-room for a snatch of breakfast.

He gulped his coffee and his eggs and cornbread, popped a kiss on his mother’s cheek and hurried down the street, reading the morning paper as he went, for Chicago and St. Louis morning papers reached the town so early that they had driven the local journals into the afternoon and into the confines of neighborhood news.

This paper, as was the habit of that period of the war, was bristling with the stories of German triumph in arms.

Noll was glad of the German victory, for three reasons: first, because it would make the bank president, Mr. Bebel, more amiable toward Noll’s tardiness, since Bebel was a German; second, because Noll’s own mother was German; and finally, because Noll himself was for her sake pro-German in his sympathies.

He was heart and soul American, and all his father’s people were native to the soil far back into the 1600’s. His paternal ancestors of various branches had landed in Virginia, Maryland, and the Carolinas, had drifted west to Kentucky and Tennessee and then northwesterly into Illinois, Missouri, and Iowa.

But his mother—Meta Wieland was her name—had come over from Germany as a little three-year-old girl with her father and his two brothers, fugitives from monarchical oppressions after the unsuccessful struggle for liberty in 1848.

Meta kept no trace of her German birth in her accent, but her father kept her heart full of love for the Fatherland, and though he hated the Prussian autocracy to his dying day, he adored the more the home from which he had been exiled. His motto was the motto of Kant, “The rights of man are the apple of God’s eye on earth.”

Among all the counterclaims of love and hate Noll’s heart remained that complex thing we call American. When his father died, his mother drifted back to German affiliations. In the mid-Western world where Carthage was there were many Germans, solid, peaceful, likable, lovable people, for the most part. Their broken English had a familiar and comfortable sound.

English born and bred people were almost unknown and the English accent was thought of as an Eastern affectation. An English lord in Carthage opinion was one who said “Fawncy!” and “Baw Jove!” incessantly, misapplied his h’s with opeless hignorance and thought that “Hall Hamericans were Hindians, doncherknow.”

Of the French the Carthage people had only a few—an amiable jeweler and his wife who were really Swiss and a nervous French teacher or two. But it was well accepted in Carthage that with the exception of Lafayette, the French were universally timid, volatile, immoral, universally addicted to the nude in art and the untranslatable in literature. All Frenchmen wore pointed mustaches and pointed goatees, ate frogs, and shrugged their shoulders.

Of the Belgians they knew nothing except what they had heard of the Congo atrocities, which even in the report were no worse than the treatment of the Indians and the negroes, but being foreign and recent were regarded with stupefaction. Russians and Austrians were myth simply. Italians were all road-builders or hand-organists with monkeys. The Balkans were something not understandable at all.

Such was the cosmogony and ethnology of Carthage when the war broke out. The Allies had far less friends than the Germans there, in contrast to the East.

The counterweights against full sympathy with Germany were a sense of contempt for the ridiculous pretensions of the Kaiser, a memory of German hostility to America in Samoa and in Manila and throughout the Spanish War, and a vague acquaintance with the oppressive militarism of the Prussians. The Kaiser’s mustaches were a joke, and the goose-step was a favorite thing to burlesque. The Kaiser was blamed for starting the war and turning hard times into panic.

The mid-West, which abominated Mexican cruelty and spoke of Villa as worse than an Apache, was suddenly bewildered to see Villa outdone by the tender-hearted, music-loving, science-fostering Germans. Men, women, and children who had been brought up to believe that the Americans had done a noble deed when they ambushed the British after Lexington and Concord, who had been proud of the embattled farmers for blazing away from every stone wall and rail fence at the uniformed troops of their king—these people could not understand the policy that burned towns and shot hostages by the score because, forsooth, certain Belgians were accused of firing from windows and fields at the invaders of their soil.

And now England, hastening to the rescue of Belgium, lost her old name of tyrant and became a savior. The French, who had been thought of as weaklings because their petty third Napoleon flung them into an unpopular war and their cheap generals led them into traps and surrendered them wholesale—the French were suddenly redeemed in the far-off mid-Western opinion by their sublime levée en masse.

It was then that the sweet and peaceful name of “German” was cast aside for the indignant sobriquet of “Hun.”

There grew a vast tempest in the simmering teapot of Carthage, and the Germans were hard put to it to uphold their claim on respect and affection. The blacker the crimes of one’s nation, the whiter seems the duty of upholding them against alien criticism.

Noll was troubled enough at first, and he kept quiet during the first turbulent discussions. But when the talk began to run wild that atrocity was natural to the Germans and that all Germans were Huns, his heart suddenly blazed with the fiery truth that his beloved, adored, devoted, ineffably revered mother was a German. And then he grew fanatic in defense.

It was all the Kaiser’s fault that Noll Winsor came home late the night before with bruised knuckles. He had gone to the Y. M. C. A. after supper for a few games of pool. And on his way home he had dropped in at the soda-fountain where the beauty and chivalry of Carthage were wont to convene.

Duncan Guthrie, all dressed up for a party, happened in also to get some courtplaster for a cut he had inflicted on himself in shaving for the dance. He had lingered for a little chatter with a few of the common herd who were, like Noll, omitted from Edna Sperry’s invitation list.

Since the European war affected every conversation, it came up here, and Guthrie tossed the word “Hun” into the discussion. Noll, in fealty to his mother’s fatherland, answered with heat and pressed the debate to a point where fists became arguments.

He sent Duncan Guthrie spinning among the tall stools and the wire chairs about the little tables.

Having proved the thorough gentleness of the Teutonic nature by another bit of Schrecklichkeit and having been ordered from the drug-store by the neutral pharmacist, Noll had gone home to his belated mother and the events of the night before.

He thought of these things this morning as he hastened to the bank, reading of the swift German capture of impregnable Antwerp and the flight of the British by the water and of the Belgians over the back fence on October 10th.

Mr. Bebel, the president, was so rosy with this proof that the war would be brief and glorious that he smiled fatly at Noll and accepted his apology with a jovial “’S macht nichts aus.” That was, indeed, one of the Carthage names for a German—a Moxnixaus.

When Noll went home that afternoon he found guests: old Professor Treulieb, the music-teacher—tall, lean, florid—his roly-poly wife and his daughter, Isolde, a young woman as sweet and graceful as the violin she played.

Old Treulieb had a ferocious temper alternating rapidly with a ferocious tenderness. He had endured for years the piano-side martyrdom of a Teuton from the Leipzig Konservatorioom trying to rap into the knuckles of young American animals the ah-bay-tsays of moozeek.

Noll had been his despair. Noll loved music—but he would not practice it. He had calf-loved the old professor’s daughter Isolde when they were both young, but the girl’s tireless devotion to her fiddle and her scholarship in music had terrified him.

She had wakened a brief fire of jealousy in his breast a year before when one of Noll’s German cousins had visited Carthage. Noll’s mother had a sister who had gone back to Germany as a girl to school; she had married there a man named Duhr and raised a large family. One of her sons, Ignatius, a lieutenant in the Reserve, had visited America on some official business or other which he kept secret. He had taken advantage of this visit to travel all the way to Carthage to see his dear Tante Meta. He had spent many days there in Carthage marveling at the oddities of mid-Western civilization. He had fascinated Isolde Treulieb and many other girls.

Ignatius—or Nazi, as his aunt Meta called him—had thick, babyish lips and soft hands, and cheeks with a daub of dollish red in them. He had kissed the girls’ hands—and their lips, no doubt—when they walked out into the moonlight with him after the dances in which he whirled them giddier than ever with his top-spinning style.

He had sung them the songs of Schubert and Schumann and Franz and Hugo Wolf—the tenderest Lieder ever written—all about Ish leebe dish, and Doo beest vee eine Bloome, Zo holt oont shane oont rine, and the song in which it said, as he explained, “Dytschland is vair de peebles speak Dytsh,” and he had recounted how the girl “kissed the youngk man in Cherman.” Many of the Carthage girls wanted to know how that was done.

Old Treulieb had played Nazi’s accompaniments, and Isolde had sometimes played an obbligato on her violin with heart-searching tones.

Nazi Duhr had left a void in the town, and the word German had since meant homesweetness. His name haunted the feminine memory like an echo that would not die.

But Noll remembered him with resentment as a too-competent rival. In his pique he had neglected Isolde and turned his heart to other girls, fluttering from this one to that. And now Edna Sperry had turned him down, and his heart might have reverted to Isolde if he had not been under the obsession of that girl up-stairs. He resented the presence of callers who would keep him from the study of that pretty puzzle who had come in out of the dark and brought with her clouds of mystery.

This afternoon the Treuliebs were in some agitation. Noll kissed his mother and shook hands all round and asked why they were so solemn on a day of such triumph.

His mother said: “I have been reading a letter from my poor sister. From Germany it is just come. It is very sad.”

Mrs. Winsor pulled her spectacles down from her forehead and translated, slowly, dolefully:

“Dearest sister mine:

“Surely now the world comes to an end. This great war has brought already destruction on our home. What becomes of us God knows only. So soon the mobilization order comes out, the pension of my husband from the old war with France where he takes his wound is stopped. He goes by the savings-bank for money; the bank will not pay. All my three sons are called to their regiments, the Thuringian regiments. My daughters’ husbands are called to theirs.

“My son Nazi you remember from his visit to you. He loved you much. He is gone away. The sons of the neighbors, all have marched away. Such tears, such tears! I have outwept my eyes. And now comes the hunger. The horses are taken. The men are gone. How shall we live? There is little food in the country and in the cities yet less. Where to get to eat man knows not. I have one only comfort: my heart is old and sad, and I shall not live much more.

“But for my children what is to happen? Nothing but wounds for the dear boys, and for the girls hunger. Yes, we are now hungry. If you can send me a little money, please! Remember that your sister is hungry. I do not know if it can reach us through the English blockade, but send money a little. Remember your sister is hungry.

“Ever lovingly,

“Konstanze.”

Meta’s weak voice trailed away into silence. She shook her head, and tears slid down along her cheeks. The only sound was the drip of her tears on the letter that she held in her hands.

Noll felt suddenly the glory of victory tarnished. The word had an evil sound. The plunging splendor of the battle-front hid almost as much woe at home as it created ahead.

Old Professor Treulieb groaned “Hunger!” not with the English but with the German pronunciation. It seemed to have more pain in it, a more animal sound—“Hoong-er!”

Being among Germans, he felt privileged to break into one of his tirades: “And now comes it! At last the war they have wanted and worked for is here. No more moosic, no more art. Shootingk only. To kill men! It is the Kaiser who does this, der oberste Kriegsherr! He begins by burningk Louvain and Malines, where Van Beethoven’s peoples comes out. Beethoven, when he writes his ‘Eroica’ symphony, inscribes it to Napoleon, the soldier of liberty. When Napoleon makes himself emperor, Beethoven tears up the paper. He did the right. The Kaiser will bringk more sorrow by Germany as Napoleon did. More people he will kill. Ach Gott, where ends it now?”

His wife, always hunting comfort, tried to mitigate his frenzy:

“Be glad now that we are in America, where the war cannot come. Here we have music. Isolde learns a new piece only yesterday yet. Play it once, Isolde.”

Meta weakly seconded the invitation. Noll insisted, opened the violin-box, took the violin out, led the dismal professor to the piano-stool, caught Isolde by her long, potent hands and dragged her to her feet.

Thus constrained she played, but with elegiac pathos though the piece was the light serenade by Drdla. High, soaring tones, honeyed double stoppings, ethereal harmonics—all gave gaiety a sorrow in beauty.

As she was fluting forth the harmonics, the trained nurse appeared at the door and spoke with some asperity:

“I beg your pardon, but would you mind not playing? Those high notes seem to disturb my patient. She moves in her sleep, and it makes her shiver!”

Isolde was covered with chagrin and regret. She hastened to put the fiddle away and to explain that she had not known that any one was ill in the house.

Meta made the explanations, such as they were, and the Treuliebs were voluble with wonder. At length they went home; Noll could hardly endure their deliberation at the door.

It had not occurred to Noll at the moment that instead of making Isolde stop playing he should rather have made her keep on, since the doctor had exhausted his ingenuity trying to shake off that leaden stupor. The doctor would call in the morning. The news could wait.

At dinner Noll’s mother talked only of her sister’s wants. She felt remorse at the simple food of her own table. It seemed gluttony to be feasting while her sister starved. No one could have dreamed how long that fast would endure. Everybody counted on a brief and bloody campaign and a long and futile peace-conference. Noll promised that he would send money at once to his aunt Konstanze. Bebel had ways of getting funds to neutral countries and thence over the border.

When at length his mother had been put to bed and for his sake had pretended to go peacefully to sleep, Noll found himself lonely and abandoned.

The nurse asked him if he would listen at the door now and then while she went out for a breath of air.

He moved about his room softly lest he wake his mother or disturb the guest—though his mother was wide awake, and the guest would have resisted the trumpets of Jericho. A theory occurred to Noll that he might trace her origin by taking the numbers of the bank-notes she had, especially as the money was new. He took the money-belt from concealment, counted the bills through again, noted down the numbers and the years. He might find thus the bank that had received them from the Treasury.

He was about to push the money back into the pocket of the belt when he noted that the machine-stitching along one seam had been replaced by a bit of hand-sewing. Inside the lining he felt something crisp—probably more money. He hesitated—then opened the seam and took forth a letter.

He debated about reading it, but not for long; curiosity was backed up by many better arguments. The letter would perhaps tell the whole story and give him the address of the girl’s mother or father or some guardian.

With trepidation he began to read. He noted that it was another letter from a sister to a sister, but from youth to youth. The paper was of foreign make, but the writing and the language were American. There was no date, no name or place, no postmark. This was the letter:

My darling little sister:

You may never get this letter, and perhaps it would be better if you didn’t. I can’t decide what to do. One minute it seems too cruel to write and the next too cruel not to write. So I send it and trust to God to decide.

Oh, my dear little sister, the only bright thing in the world is the thought that you will escape what Mamma and I have had to go through.

If you never know what became of us, you will suffer and wonder and perhaps try to find us. If you do know, you will suffer more terribly for a while, but you will know the worst, and you will give us up as if we were dead—calmly, sweetly, beautifully dead. It’s not being sure that tortures the most; so I write to let you be sure of us.

And now I must tell you. But how can I write it? I can’t—I just can’t.

This is the second day. I couldn’t write you any more for two reasons: First, I couldn’t—that’s all there is about it: and second, they came and interrupted me—the Germans.

We were all so scared here when the war broke out and we learned that Belgium had been invaded. We could see from the convent windows the fugitives stumbling along the roads carrying all sorts of things. Some of them were so pitiful we cried—some of them so awkward we couldn’t help laughing. And now I don’t think I’ll ever laugh or cry again. Pretty soon we began to want to join the flight, but the Sister Superior said that if we weren’t safe in a convent there was no safety anywhere. But we heard such horrible things and saw the horizon red with fires.

Then suddenly Mamma appeared. I couldn’t believe my eyes. To think that she should cross the ocean just to get to me! While all the other Americans were stampeding for home, she was fighting her way to me. Oh, it was good to see her and hold her to my heart. It was sweet and brave of you to let her come, and to stay there all by yourself, but I wish you hadn’t let her come.

She wanted to start back right away, but the horses we arranged for were carried off by a raiding party and we waited for others. Then came the Germans, like an everlasting gray river. We didn’t dare budge. We peeked at them from the windows. They went by and by forever. At noon those that were near halted and had their dinner from big cookstoves on wheels. Then they moved on.

The second day some of them halted for a long stop. There were battles at a distance, and some firing near us. The officers came to the convent looking for spies, they said, and for civilians with arms. They told the Sister Superior how they had shot innocent men because that is their way of discipline by terror: the innocent must suffer for the guilty. For what guilty ones did Mamma suffer, I ask God, and get no answer.

One regiment—I won’t tell you its name—settled down near the convent. There was terrible carousing by some of the men and the officers. They jeered at the Catholics. They treated the priests like dogs and shouted horrible things at the sisters. They began to reel up to the gate demanding food. They insisted on going through to search for spies. When the Sister Superior said there were none, they called her names.

One of the novices tried to run away after dark. We saw her from the window. A few men caught her, and others came up laughing and tried to take her away. They were told, “She is ours. Go get one of your own.” The others howled with joy and came running to the gate. It was dark. There were screams and laughs.

I was so scared. Mamma tried to hide me somewhere. But they found us in a little cell. They fought each other, and then one of them laughed: “The mother is not so bad.” They drew lots. I can’t write. I hope you don’t understand. I wanted to kill myself, but my religion made me afraid to murder myself and die as I am.

They went away, and I saw Mamma and tried to hide, and she tried to hide from me. And we cannot yet look in each other’s eyes, though we cling together now after they have been here. For they have no mercy.

That wicked regiment marched away, and another halted. These officers were different. They beat the men who insulted us. The Sister Superior told what had been done, and one of the officers wept, and promised protection. But he marched away. And others came—more brutal even than the First Thuringians. They were bitter against the Belgians, and when I said that Mamma and I were Americans, they only laughed. They came here as if for their meals.

What the future will bring I don’t know. Mamma and I are to be mothers, and we don’t know who the—so many—I can’t write—I can’t die. Don’t tell Daddy when he comes back, if he ever does. Tell him we were killed in the burning of this town, and you had a letter saying we were dead, and lost it. Of course we won’t speak to the American Ambassador or to any one. So many have been killed and will be killed that we shall not be missed.

Good-by, blessed little sister. We shall never see you again. Think of us as if we were what we wish we were—dead. Mamma tried to tell me to send you her love, but she is choked with weeping. Good-by, my sister, oh, my sweet sister. Don’t try to find us, for we shall not be here long, and we want never to be seen. God be kind to you.

The young man in the quiet little room on the serene little street in the sleepy little town sat and wondered that the world could bear such things. He was dazed and stunned. He sat idle, and mused.

He was beyond horror. He pondered merely that the girl who slept so well in the other room had started from somewhere to go to her mother and sister, and somehow had fallen down in this street, had fallen under her cross.

Who was she, and whence? He knew her whither now. She must be wakened for her holy mission—she must be sped upon her quest. She must save that mother and that sister from those—Huns! He started. He had said the word himself—the word that he had fought another man for saying. But what other word was there?

What could the world do with such a power? What could he do alone against it for this lonely girl? He could not help going into the room to look at her.

Indian summer ruled for its little smiling-while, and warmed the early night of fall with a pleasant dream of October remembering April. The long belated spring wind was as impudently inappropriate as youth astray in a graveyard. It crept through the lifted window and teased the light ringlets of hair about the ice-white brow of the weird girl who had drifted into Noll’s life as curiously as the spring wind that blew through the October trees.

They had told Noll that she only slept, but she gave no proof of life. He thought of the old tradition that hair does not die with the body. He wondered if it were true. He was at the age when he was finding out that traditions are not often true. But the hair of the girl before him was so uncannily merry and the girl so mournfully still.

The frightful letter that he had filched from her money-belt seemed to explain death but nothing more, and young Winsor kept asking that silent figure silent questions: Who are you? Where are you from? What brought you here? What robbed you of your life at my door, of all the doors in the world?

She did not answer. There was no motion visible to his keenest scrutiny except that light and frivolous flaunt of curls at her brow, a mockery of gaiety about a face where frozen anguish gave youth and symmetry a dreadful beauty. She seemed herself engaged in deep revery, locked motionless in complete devotion to one thought.

If he could only waken her! He bent and spoke in deep, low tones, lest his mother hear him in the other room.

“Who are you? Tell me! Tell me who you are. Let me help you!”

But she gave no sign. Once by inadvertence his lips touched the delicate conch of her ear, and they were chilled as if they touched frost, burned and chilled as if they touched frosted iron.

Noll was afraid of the mute witch, afraid for her, afraid with her. He was young too, and without love. He longed to be able to help some one. She seemed to need him. But he could not get word to her that he was there.

He sank into a coma of helpless thought. He read and reread the letter till he had to put it from his sight in his pocket. He put in another pocket the money-belt his mother had found on the girl’s body. He fell so still in his meditation that he grew almost as lifeless as the girl was.

He was so lost to the room, the town, the world, that when the nurse returned and from habit tiptoed into the room and whispered, “I’m back; I was detained,” he was as startled as if he had fallen out of a dream.

He sprang to his feet, knocking his chair backward with a clatter that made his heart race. He was afraid that he might have startled the slumberer. He forgot that his one ambition was to break into her sleep. He looked apologies toward the girl, but there was no stir about her except the little ringlets at her temples.

The nurse, Miss Stowell, whose business it also was to get the patient awake, kept whispering too, and asked, “She hasn’t moved?”

Noll shook his head and would have mentioned the letter he had found but that the nurse, yawning and eager to be asleep, dismissed him with a nursish authority.

“You needn’t wait up any longer.”

She bustled about, dressing the couch, patting up a pillow and murmuring:

“I’ll just make myself comfortable and—and read.”

She had no book, but she said she would read!

Noll, disgusted, went to his room. He thought he ought to speak to Miss Stowell about the letter, but as he turned, he heard the key click in the lock. He sniffed at the dubious compliment she paid herself and him in the precaution.

He sank down on the edge of the bed and unfolded the letter, but was too tired to read it again. It had worn him out with its terrific story. He hated to think that the pretty young girl in the other room had seen it and had understood such things. He wondered what other terrible knowledges were stored up in that whist soul of hers. His brain exhausted its strength with the energy of its wonder.

He blazed with an ambition to go to the rescue of the sister smothered in an avalanche of disaster, though he would have had to cross land and sea and dash backward through time.

The maddening thing about the situation was that the letter contained no mention of places or people except the name of the Thuringian regiment, and that had slipped in through an evident oversight. He had no idea where to go to rescue whom. He simply must get a few names. It annoyed and baffled him not to know what to call the sleeping girl. To think of her as “the girl” or as “she” was becoming unendurable. He would have to make up some title for her. He wondered what the name of the Sleeping Beauty was. He wondered if he might wake this poor little Snow White with a kiss.

Perhaps Doctor Mitford would be able to resuscitate her in the morning at least long enough to ask her who and why and whence. But if not, if she should never open her eyes and her lips, whom could he notify? Where could he send her exquisite clay but to an anonymous grave?

The next morning Noll went to his mother’s room. She had an unbidden guest to worry over, and the knowledge of her sister’s woes in Germany belittled her own distresses. She reminded Noll of his promise to start money on its way to her hungry sister Konstanze. Noll reassured her, but his feelings were bitter against all Germans this morning. He wanted to tell his mother that it was his aunt’s own fault if she starved. Why did she select such a country to be born in? Why had she brought up her sons to be parts of the German machine where every man became a mere soulless cog and rolled on when the engineer pulled a lever and gave the word Vorwärts?

Isolde could not bear to look, but turning aside, played with all her might.

Already an individual experience was turning him against a whole race as readily as he had been turned for it by another individual experience. In other countries old admirations were suddenly turned to contempt; old friends were being regarded as Judases because their nations had ranged themselves on the opposite side. People were hating even the beloved dead, the artists, the poets, the saints of the hostile tribes, and loving their ancient hates because of their alliances.

Noll remembered a legend that the Kaiser, having cut his finger once, had let it flow a moment, saying, “Now I’ve got rid of my English blood.” Noll was tempted to free himself of his German heritage by the same ingenuous device.

But he excused his mother from blame. After all, he told himself, her father had been good enough and wise enough to abandon such a country, and his mother had been good and wise enough to marry an American. He helped her down the stairs to a chair by the window as if he forgave her something.

As he was about to leave the house, Doctor Mitford arrived. Noll found it hard not to speak of the letter, but he held his peace. It was his mother who mentioned the odd fact of the nurse’s complaining that Isolde’s violin had disturbed the sleeper.

“Disturbed her how? When?” Doctor Mitford gasped.

“Yesterday afternoon,” said Mrs. Winsor. “I’m so sorry.”

“And what did you do?”

“Isolde stopped playing, of course,” said Mrs. Winsor.

The doctor roared: “Of course! Damn it—excuse my French. But why didn’t somebody tell me of this?”

“It didn’t seem important. We expected you to call.”

“Important! That nurse is a fool. Where’s Isolde? Get her as soon as you can!”

Isolde could not come till afternoon. Noll found her strangely altered overnight. In her wistful ashen meekness he saw a Hunnish motherhood, the sort of future Hausfrau who would take her place meekly as a stolid breeder and trainer of Hunlets and Hunlettes into a state of idolatry for the Emperor and his God-given anointed powers. She would breed more subjects for an Emperor who said that his crown came not from peoples or parliaments, but from God direct, an Emperor who was sublimely ludicrous enough to treat the great wise manhood of Germany as priests to his glory and consign all German womanhood to the four K’s, the service of Kirche, Kleider, Kinder, and Küche. Isolde’s little Hunlets would grow up and fall into line, march past the Kaiser at the goose-step and salute him with their toes, give him their lives as his due and take from him with gratitude what crumbs of privilege he swept from his banquet-table.

Doctor Mitford explained to Isolde what he had called her for. He did not know what Noll knew, and Noll took an almost malignant delight in his monopoly both of the information and of bewilderment. He was like a scientist who is puzzled about things that other people do not even know that they do not know. Noll was conceited about his higher ignorance.

Isolde took her violin from the case, asked Noll to “give her the A” at the piano, brushed the quaint fifths with her thumb and struck a Venus of Milo attitude plus a pair of excellent arms while she steadied the violin against her thigh and tightened or loosened the pins, brushed the strings again, tightened the pins again and so on till she had the instrument in accord.

Then she took up the bow, drew a sweet phrase or two from the singing strings and said, “I am ready.”

She followed the doctor up the stairs, and Noll followed her. She was excited with a new kind of stage-fright which did not diminish when she entered the room and saw before her her most unusual audience of one. The mad king of Bavaria when he befriended Wagner had been wont to have operas performed for him alone in the empty opera-house where he hid somewhere behind the curtains of a box: Isolde’s mission was to find her solitary auditor still more shy, still more hidden. Noll had once been very fond of Isolde, and it did not help her to see that she was now hardly more than a musical instrument for the sweet awakening of another love.

“What shall I play?” Isolde whispered.

“You don’t have to whisper,” the doctor said with a twang that jarred. “What did you play yesterday?”

“The ‘Serenade’ of Drdla, I think,” said Isolde. “Wasn’t that it, Noll?”

He nodded, and she began, faltered, and paused to say, “It doesn’t sound very well without the piano.”

Mitford motioned her to go on, but it needed all the resolution she had. She could not bear to look, but turning aside, played with all her might.

At another time Noll would have seen how fair she was, and modeled with as clever a scroll-saw as had fashioned the violin she held under chin and cheek.

She played with shut eyes, her body bending and swaying as her left hand tapped the strings with uncanny wisdom and her right arm with the bow for a long eleventh finger kept up its seesaw always in the same plane. It was uncanny that such manipulation of such a machine should educe from a box tones beyond the magic of the nightingale that sings sometimes of nights in Avon near Shakespeare’s tomb.

While the beautiful girl played to the beautiful girl, no one seemed to hear Isolde or heed her, the sleeping girl least of all. It was she that the two men and the nurse watched, all eyes.

When the last note ended with no success visible the doctor cast a reproachful glance nurseward, and Miss Stowell protested:

“I’d have sworn she moved yesterday.”

“How?”

“Her eyelids seemed to—well, throb, and her mouth quivered.”

“It was probably your imagination,” Mitford grumbled. “But try something else, Isolde.”

“What shall I play, Doctor?”

“How should I know? What do I know about fiddle-music?”

“What shall I play, Noll?” Isolde pleaded, and then remembering a tune he had loved once when he thought he loved her, she began the “Liebestod.”

Noll flushed. It seemed hardly the time to be raking up old follies. She had played it for her cousin when he visited America.

“No, play the—the ‘Träumerei.’ ”

She played it, and also that cavatina of Raff’s, a familiar bit of Mendelssohn’s concerto, a part of “The Kreutzer Sonata,” Bach’s “Chaconne,” and various other garments from the well-worn wardrobe of all fiddlers. She played, of course, the “Humoreske” of Dvôřák and also Maude Powell’s arrangement of his poignant lyric “Als die alte Mutter.”

But the soul on whom this serenade was wasted would not come to the balcony. Mitford grew dogged and insisted:

“Try something more cheerful.”

She played Fritz Kreisler’s “Caprice Viennoise,” a reminiscence of the time when Vienna was the home of all cheer, not the fountainhead of blood.

The composer was lying in an Austrian hospital even then after being wounded in battle and trampled by Russian horses whose hoofs threatened the future of that priceless arm. Later he would recover and tour America, devoting himself and his art to the conduct of a fund for foreign musicians interned in Austria, so that music should have some other life in the war besides “The Hymn of Hate” and the clangor of march tunes.

Isolde played the “Caprice” deliciously. It was a rich mingling of tinkling bell-tones and sirupy harmonies; so gay and so tender it was, that it inspired what Dante called “the saddest of sorrows, the remembrance of happier things.”

The doctor grew tired of watching for an effect that was not achieving. He turned away in disappointment. But Noll gripped his arm and whispered, “Look!” He turned again to the girl and saw that among the lashes of one eye there was a spot of wet light. A tear grew and globed and slowly, tarryingly, slipped down her cheek into her hair, where it glistened a moment in jewel brilliance, then vanished.

The eloquence of it was beyond words or music. It quenched with its own pathos the joy it created.

“She weeps! That proves she lives!” said the doctor, not meaning to stoop to an epigram or rise to a sentence.

“Play it again—the same thing!”

Isolde’s violin repeated the “Caprice,” but now it carried new and solemn connotation, as a light song does when soldiers have sung it on their way to the wars.

While the beautiful girl played to the beautiful girl, no one seemed to hear Isolde or heed her, the sleeping girl least of all. It was she that the two men and the nurse watched, all eyes.

On the repetition, however, the music evoked no glint of a tear, no token of any response till the end of it, and then there was barely manifest a slow, a very, very slow, prolonged, mournful taking-in of breath and a deep, complete, deliberate exhalation—that strange business with the air that we call a sigh.

“Play it again! Over and over!” the doctor stormed.

Isolde fought silence with melody under the whip of the doctor’s excitement till her muscles ached and her spirit was fagged out. She played and played, weakening like a groggy boxer. Her skill and her toil had no further influence on that rigid taciturnity. Noll knew why, or thought he did. There were sorrows in that heart which the feigned and artistic woe of music could not reach.

“I can’t—play—any—more.”