* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Biggles Sets A Trap

Date of first publication: 1962

Author: Capt. W. E. (William Earl) Johns (1893-1968)

Illustrator: Leslie Stead (1899-1966)

Date first posted: Jan. 8, 2024

Date last updated: Jan. 8, 2024

Faded Page eBook #20240112

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, akaitharam, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

BIGGLES SETS A TRAP

An unusual investigation by

Biggles of the Air Police

Biggles

SETS A TRAP

by

CAPTAIN W. E. JOHNS

HODDER & STOUGHTON

THE CHARACTERS IN THIS BOOK ARE ENTIRELY

IMAGINARY AND BEAR NO RELATION TO ANY

PERSON LIVING OR DEAD

Copyright © 1962 by Captain W. E. Johns

MADE AND PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN FOR

HODDER AND STOUGHTON LIMITED, LONDON

BY C. TINLING AND CO. LIMITED, LIVERPOOL,

LONDON AND PRESCOT

| CONTENTS | ||

| FOREWORD | 7 | |

| I | BIGGLES HAS A VISITOR | 11 |

| II | COINCIDENCE—OR WHAT? | 25 |

| III | STRANGER THAN FICTION | 38 |

| IV | SO IT WAS MURDER | 47 |

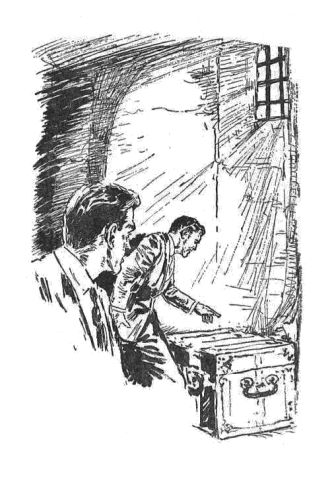

| V | THE OLD OAK CHEST | 61 |

| VI | THE RAVEN CROAKS | 75 |

| VII | A LADY ASKS SOME QUESTIONS | 84 |

| VIII | A GLIMMER OF DAYLIGHT | 93 |

| IX | AT THE SIGN OF THE SPURS | 103 |

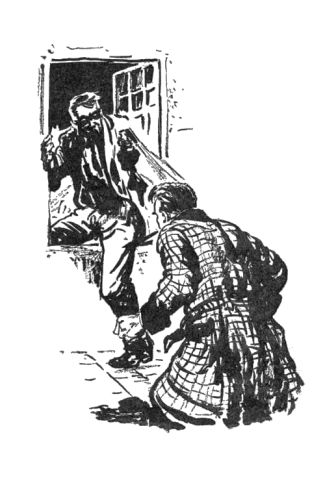

| X | WARNING FOR DIANA | 115 |

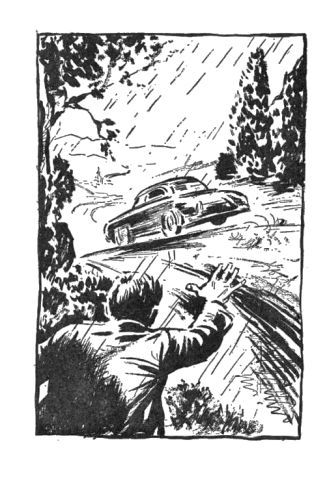

| XI | A NEAR MISS | 127 |

| XII | BIGGLES EXPLAINS | 138 |

| XIII | DEATH CALLS A TRUCE | 150 |

The purpose of the following notes is to inform the reader, or remind him if he has forgotten, of certain events which should give him a better understanding of The Curse of the Landavilles without having to refer to the history book.

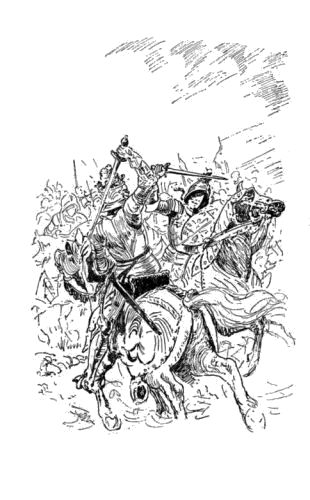

1. Bosworth Field

There is no period of history from which we turn in more horror and disgust than from the Wars of the Roses. Its ferocious battles, fought on personal quarrels and ambitions, its brutal murders and ruthless executions, the shameless treacheries and utter disregard for human life, trampled any pretence of chivalry into the mire of a slaughter-house, all the more ignoble for the selfish ends for which men fought, father against son, brother against brother, in support of the Houses of York or Lancaster.

The casualties, in proportion to the numbers engaged, were appalling, for no quarter was given by either side and battles were fought out to the bitter end. It has been estimated that in the thirty years’ duration of the civil war more than a million men were slain, not including civil massacres and wholesale executions. Among those who died were many thousands of landed gentry, 200 nobles and 12 princes.

This dreadful carnage finally ended with the Battle of Bosworth Field, August 22nd, 1485. On that day fell the brave but ruthless tyrant, Richard III, and with him the Plantagenet line ended. The victor was Henry, Earl of Richmond, the first of the Tudors, afterwards Henry VII.

Richard had sat insecurely on the throne, and it is no matter for wonder that when the Earl of Richmond landed at Milford Haven he was supported by partisans of both York and Lancaster, men actuated by horror at Richard’s most infamous crime—the murder of his two nephews, the Princes in the Tower.

The armies of Richard and Henry met in the pleasant country three miles south of Market Bosworth in Leicestershire. The vanguard of Richard’s army was commanded by the Duke of Norfolk. The king himself, wearing a golden crown, in magnificent armour, on his famous charger “White Surrey”, took the centre. The vanguard of the opposing forces was led by the Earl of Oxford.

Treachery, as so often happened, had already decided the day, for even before battle was joined Richard had been abandoned by the forces under Lord Stanley and the Earl of Northumberland.

The two armies closed, fighting as usual hand to hand. Oxford and Norfolk met and at once engaged. After shivering their lances they drew their swords. Norfolk slashed Oxford’s arm. Oxford hewed off Norfolk’s helmet leaving his head exposed. An instant later it was pierced by an arrow.

In the thick of the fray word was brought to Richard that Henry was a short distance away supported only by a few retainers. With a shout of “Treason” Richard charged, hoping in the fury of his despair to settle the matter there and then. And so the battle might have ended, and the whole course of history been different, had not fresh forces arrived on the scene.

Of all the knights who charged with Richard, only one, Lord Lovell, survived. Richard, as soon as he saw Henry, dug spurs in his horse and fought his way towards him. He unhorsed Sir John Cheyney, and rushing on Sir William Brandon, Henry’s standard bearer, cleft his skull and flung the standard to the ground. He was now within reach of Henry, and might have cut him down had not a young squire intervened. At this vital moment there arrived Sir William Stanley and his men-at-arms. They overpowered Richard, who fell, still fighting furiously, crying, “Treason! Treason! Treason!”

His body, when it was pulled from beneath those who had died with him, was almost unrecognizable from wounds. The crown he had worn, picked up near a hawthorn bush, was placed on the head of the conqueror, who as Henry VII was at once acclaimed king.

The battle is of great historical importance because it marked the end of the feudal system maintained under the Plantagenets and the beginning of a change that was to have tremendous consequences on our social and political life.

2. The Origin of Inn Signs

In the Early and Middle Ages the naming of a tavern was no mere fancy. It had a definite purpose, and through that it is often possible to follow the course of history. The fashion started when knights wore armour and because of the visor the face of the wearer could not be seen. It therefore became necessary, in order that men of the same side did not attack each other, to have some form of recognition. It had to be simple, because few men could read or write. The practice was for a noble to devise a sign—a cognizance, as it was called—which, painted on his shield or surcoat, enabled him at once to be recognized by his supporters. Words were unnecessary and most people soon got to know these symbols.

When travelling a knight would hang his shield outside his lodging to show where he could be found. In course of time these “armorial bearings” were sometimes painted on the inn itself to let it be known that the knight had stayed there, or, in time of civil war, which side was supported by the innkeeper. Sometimes the sign disappeared, but the name of the nobleman remained. Thus we find names like The Duke of York public house, The Norfolk Arms, The Red Lion, etc.

Today, if you see a sign showing a bear holding a pole (The Bear and Ragged Staff) you may assume that the Earl of Warwick (Warwick the King-maker) once rested there, perhaps when he was marching to defeat the Yorkist army at St. Albans. The Star was the cognizance of Oxford, whose leadership decided the Battle of Barnet. The Lion of Norfolk was conspicuous on Bosworth Field, where Richard III lost his life as well as his crown.

The Sun was the cognizance of the ill-fated House of York. The White Swan was the sign of Edward of Lancaster, slain at the Battle of Tewkesbury. Edward IV carried the White Rose of York, but after the Battle of Mortimers Cross he displayed the Rose within a Sun, from a curious spectacle that preceded the battle when three suns were seen (it is said) in the sky, in conjunction.

The White Hart, with a gold chain round its neck, was the badge of Richard II, murdered at Pontefract castle. Richard III wore a Rose supported on one side by a Bull and the other side by a Boar. The Boar became his personal badge. The Antelope was the sign of Henry IV; The Beacon, Henry V; The Feathers, Henry VI.

The Saracens Head is thought to go back to Richard Lionheart and the Crusades. The White Horse, much older, was the standard of the Saxons, but the common pub sign probably came through the House of Hanover. It was the badge of George I when, in 1714, he succeeded to the throne of England.

W.E.J.

“Well old boy, that’s another job done.” Sergeant Bertie Lissie of the Air Police pushed in the drawer of a metal filing cabinet and strolled over to where Biggles was working at his desk. “Anything else? If so I might as well get on with it. This quiet spell can’t last much longer.”

“With Algy and Ginger on leave we’re lucky it’s lasted as long as it has. I’m glad they’ve had fine weather.” Biggles reached for the intercom telephone which had buzzed. “Bigglesworth here. Yes. Who? All right. Bring him up.”

“Who was that?” inquired Bertie.

“Door duty officer. Says there’s a fellow below asking to see me personally. Claims he knows me. As things are quiet I might as well see him.”

A tap on the door and it was opened by a uniformed constable who ushered in the visitor and retired.

The caller stood before them, hat in hand. He was a well-groomed young man of about twenty, slightly built, with sleek black hair and dark eyes set in a pale face. He looked delicate. His expression was serious. Looking at Biggles with a curious, almost apologetic smile, he said in a tone of voice that revealed a certain social position: “Remember me?”

Biggles stood up and held out a hand. “Yes, I remember you. You’re Leofric Landaville, the lad I ran in some time ago for dangerous flying. If I remember rightly you argued you were only flying a bit low, and I said that came to the same thing. I hope you haven’t been up to any more of that nonsense.”

“I couldn’t. That little affair cost me my ticket.”

“Haven’t you applied for it back?”

“No. I’ve finished flying.”

Biggles shrugged. “Pity about that, but you asked for it. Take a seat. What can I do for you? By the way, this is Sergeant Lissie, one of my staff pilots.”

“I’ve come to ask your advice,” said the visitor, after the introduction, sitting down in the chair Bertie had pulled up for him.

“Is this something to do with aviation?” asked Biggles.

“Nothing whatever.”

Biggles raised his eyebrows. “Then why come to me?”

“Because I have a problem and you’re the only man I know who might listen and take me seriously. You were very decent over that crazy flying of mine and it struck me the other day you were just the sort of man of experience to answer a question which, frankly, will not be easy to explain. Some people would call it ridiculous, but to me it’s anything but a joke.”

“Has this anything to do with the police?” asked Biggles, suspiciously.

“It could be, in the long run. That’s another reason why I’ve come to you. It would be pointless for me to tell my story to the village constable however worthy he might be, and you’re the only officer of senior rank I’ve ever met. If nothing comes of this conversation, should you hear that I had died suddenly in what appeared to be an accident would you be good enough to make sure I wasn’t murdered?”

“Are you expecting to be murdered?”

“As a matter of fact I am. I’ve been expecting it for some time.”

“And who is likely to murder you?”

“That’s just it. I haven’t the remotest idea. Do you remember our conversation when you caught me taking risks in the air? You said if I went on like that it was only a question of time before I killed myself; and I said that was probably the best thing that could happen. You asked me what I meant, but I declined to explain. I’m prepared to do so now in the hope that if I die suddenly you’ll catch the murderer and hang him. You see, things have changed since that conversation. A few months ago, Charles, my elder brother was murdered. The title and estate have therefore passed on to me. Believe me, the last thing I wanted was that accursed title, and the curse that goes with it; but I had to have it. I am now Sir Leofric Landaville, the twenty-first baronet of the line, and I shall probably be the last.”

“That would be a pity, Sir Leofric.”

“Never mind the handle. Just call me Landaville, or better still, Leo; it saves time.”

“As you wish.”

“A family, like everything else, must eventually die of old age, but there is a reason why I’d rather mine didn’t die out with me. I’d like to get married.”

“Is there any reason why you shouldn’t?”

“Yes. I carry The Curse of the Landavilles. Tell me this; would you marry a girl knowing that she would soon be a widow; and if she had a son he’d be murdered, too?”

Biggles frowned. “What is all this talk of murder?”

“It’s a long story. I could explain it more easily at home. Moreover, there you might understand it more readily. I wonder if you’d care to run down to my place with me. I could give you a bite of lunch.”

“Where do you live?”

“Ringlesby Hall, near the village of Ringlesby, in Hampshire. It’s in the New Forest, about eighty-five miles from London. If nothing else I’m sure you’d find my story interesting.”

“But look here. If you have a complaint why don’t you report it to the local police?”

“They would no more know what to do than I know—if, in fact, it’s possible for anyone to do anything.”

“Is this situation one that has recently cropped up?”

“As far as I’m concerned, yes. It has arisen since my brother’s death, and is complicated by the question of whether or not I should marry.”

“I’m sorry, Leo, but you can’t expect me to be interested in your matrimonial affairs.”

“I’ve told you the circumstances.”

“Do I understand someone is threatening you?”

“No one is threatening me.”

“Then why worry?”

“Because I know that even if I escape The Curse, as surely as night follows day, if I had a child it would be murdered.”

Biggles looked puzzled. “But by whom?”

“I’ve told you I have no idea. I was hoping you might be able to tell me. You’re a detective, so you should be able to work things out. Of course, you wouldn’t be able to do that sitting here; but if you came home with me I could demonstrate more easily the problem with which I’m faced. I can’t promise you much in the way of hospitality but I’ve no doubt my man could produce something cold and a glass of beer.”

“Do you live alone, then?”

“Except for one old man on his last legs; but at least he’s someone I can trust. He’s grown old in our service. I have a car outside. It’s only a vintage Bentley that belonged to my brother, but I think it will get us there. Will you come?”

Biggles hesitated. “I must say you’ve aroused my curiosity, which I suspect was your intention when you came here. I’ll help you if I can, provided you’ll give me an assurance that you’re not taking me on a wild-goose chase, or anything of that sort,”

The visitor smiled bleakly. “Why should I waste your time? You can take my word for it that this is no laughing matter; or you wouldn’t think so if you were in my shoes. Decline my invitation and one day you may remember this conversation, and have it on your conscience that you did nothing.”

“Have you told anyone else about this?”

“Not a soul. It needed all my nerve to come to you.”

“One last question so that I know what I’m doing. Is this a matter as between man and man, or between you as a member of the public and me as a police officer?”

“It could turn out to be either—or both.”

“Fair enough. In that case I’ll come with you. You won’t mind if I bring my sergeant with me? If he follows in my car there would be no need for you to drive me home. We shall have our own transport.”

“That seems a sound idea.”

“All right. I’ll let my chief know I shall be out for a bit then we’ll press on.”

The two can were soon on their way, Biggles in the old Bentley with its owner and Bertie tracking them in the police car.

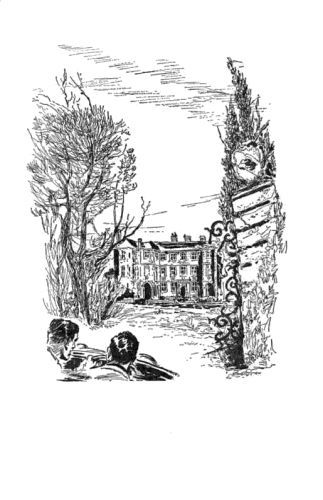

After leaving the outskirts of the sprawling metropolis the route taken by Leo ran through some of the loveliest rural scenery of England, seen at its best perhaps in the weather conditions that prevailed, for it was a perfect early autumn day with the deciduous trees tinged with gold and the green of the bracken already fading to pallid Venetian red and brown. The best came at the end, when the cars cruised between the ancient oaks and beeches that have their roots in history; the New Forest, established for his pleasure by the conquering Norman William 900 years ago, and in the leafy glades of which—as a judgement for his cruelty in evicting the rightful owners of the land, as it was thought—his son and successor, William Rufus, was destined to die from an arrow discharged by an unknown hand.

The cars were still deep in the forest when the Bentley slowed, and leaving the road turned off between a pair of pillars, leaning awry and far gone in dilapidation, that obviously once had supported massive iron entrance gates. The rubber tyres now crunched on a rutted track that might once have been gravel but was now much overgrown with grass and trailing briars. There were even places where the sombre holly that forms so much of the undergrowth of the forest had encroached to flourish unchecked, and so turn what had once been a drive into a narrow lane. At one point it skirted a rush-bounded mere of stagnant water from which coots and waterhens looked up to watch the passage of the cars.

However, after that the track ran straight enough for perhaps a quarter of a mile to end at the front aspect of a long stone mansion house of considerable size, grey with age, and, as could presently be seen, fast falling into ruins to make a melancholy picture which numerous jackdaws on the groups of chimney stacks did nothing to relieve.

“Welcome to Ringlesby Hall,” said the owner, without a hint of apology for its condition.

“So this is where you live,” murmured Biggles, in a curious voice, as his eyes surveyed the scene.

“This is my house, and the land you see around you is the park.”

Biggles’ eyes wandered over a surrounding scene of nature running riot. “And very nice, too,” he congratulated. “But—er—forgive me if I appear impertinent—isn’t it time you did something about it?”

“There’s nothing I can do about it.”

“Why not?”

“I’ve no money.”

“You live in a place this size and you’ve no money!”

“That’s how it is.”

“Don’t you care?”

“Not particularly. It suits me, and it’ll last my time.”

“Would you mind pulling up? I’d like to look at the house.”

The car, now close to the front door, bumped slowly to a stop.

Again Biggles’ eyes surveyed the crumbling sandstone pile, now observing the details of gables, windows and other features which, in spite of their condition, still presented a certain proud dignity.

“Surely it’s a pity to let a grand old place like this fall to pieces,” he remarked. “If you can’t keep it up why not sell it to someone who can.”

“I’m not allowed to sell it.”

“Why not?”

“You’ll understand when you’ve heard the story I’m going to tell you.”

“How long has your family lived here?”

“Since 1486.”

Biggles pursed his lips in a soft whistle and did some quick mental arithmetic. “Four hundred and seventy-six years. That’s quite a time. And how many rooms have you in the house?”

“About forty, I believe. I don’t know exactly. I’ve never seen all of them. In fact, it must be years since some of the doors were opened.”

“What about the servants? Don’t they do them out once in a while?”

“There aren’t any servants. I told you, I have one old man who does all that is necessary. He has one room and the kitchen. I use two rooms. The jackdaws, starlings and sparrows can have the rest.”

“What about the land? That should produce an income.”

“A few pounds a year. I let it to a local farmer for grazing sheep.”

Biggles shook his head. “Two of you in a place that size. Why do you live here at all?”

“I have to for most of the year or I lose it. I’ll tell you more about that presently.”

“Who built the house originally?”

“I don’t know. There’s no record, but there’s a local legend that William Rufus had it built as a hunting lodge. They say he spent his last night here. The next morning, while out hunting, somebody bumped him off with a bow and arrow. The body was brought back here before being buried. That’s what they say. I suppose it could be true. In these rural districts folk-lore can have a long memory. Anyway, there it is.”

“Don’t tell me the ghost of Rufus still hangs around,” joked Biggles.

“If it does I’ve never seen it. If we have a ghost at all it takes care to keep well out of sight. I may have heard it although not in the house.”

“Ghosts are usually pretty quiet.”

“We’ll talk about ghosts presently.”

The car crawled forward up the overgrown drive, bumping over ruts, its wheels scraping through weeds and sun dried grass into what long ago may have been a garden. Nor did the weeds stop there. Thistles, nettles and wild flowers had taken possession of everything even to the walls of the house itself. Some had found a roothold in cracks and crannies of the stonework. A clump of pink valerian, the ancestor of which in the distant past may have escaped from a lady’s herb garden, had managed to elevate itself to a window sill, from where it looked down on a party of fading foxgloves.

The old Bentley came to a stop level with a frowning arched doorway. The keystone had once been fashioned as a shield, tilted slightly forward; but the armorial bearings that had been carved on it were no longer recognizable. From the side of the portal a rusty chain hung down from a heavy bell.

The police car parked alongside the Bentley and Bertie joined the others as they got out.

“I’m sorry, but you won’t find any modern conveniences here; no hot and cold laid on, or anything of that sort,” said the owner, dryly. “If you want a bath you’ll find an old one propped up on bricks in the scullery.”

The heavy oak door, black with age, creaked open, and an old man came out. His age would have been a matter for conjecture, but if his face, as wrinkled as a walnut, was anything to go by, he must have seen not fewer than eighty years pass by. He was in his shirt sleeves, showing a faded red and black striped waistcoat. He wore a green baize apron, much stained, tied round his waist, and on his feet, carpet slippers that had seen better days.

“Oh, Falkner. I’ve brought two guests home with me for lunch,” Leo told him. “I hope you’ll be able to manage a bite for us.”

“I’ll do my best, sir.”

“You might put a jug of cider and some glasses out right away. I’m sure my friends could do with some refreshment.”

“Certainly, sir.” The old man retired.

“My general factotum,” explained Leo. “Heaven help me if anything happened to him, as it must one day. He does the lot, from the kitchen garden to my bedroom. He makes the cider, too, and I think you’ll agree it’s pretty good. You might call him the last of the old brigade of household retainers. When his sort go there won’t be any more. He’s as much a part of the establishment as I am. His family has been here as long as mine, possibly longer, judging by his name.”

“Falkner?” queried Bertie.

“It’s one of the old trade names, and some of them go back to Saxon days. Falkner derives from falconer, a man who trained hawks for hawking. He can still do it. He once trained one for us. It was handy to get a partridge or a pigeon for the larder. Saved cartridges. You can still find plenty of these old trade names in the district although few of the owners are doing the same jobs. Some must go back to Roman times. The Fabers, who were iron workers; Miles were soldiers; Forsters were foresters; Fletchers made arrows; Heywards, the hedge guards; Reeves, the farm workers; the Lorimers, who made brass fittings for harness, and so on. In rural districts of England these names run on, father to son, for centuries, as you can see from the church register. But let’s go in and have a drink. I’d better lead the way or you might get lost.”

Biggles threw Bertie a peculiar smile as they followed their host across the threshold into the hall, empty except for an old coffer, a strip of coconut matting curling up at the edges, a pair of decrepit antlers on the wall and a suit of armour showing several dents. Leo jerked a thumb at this in passing. “That, you may be interested to know, was worn by my namesake at Bosworth Field; the first holder of the title, and, incidentally, the chap who started all the trouble. We used to have quite a lot of armour, and still have some bits and pieces, as you’ll notice; but as complete suits are now worth money to collectors, the good stuff, like everything else of value, has gone to keep the pot boiling. I’ve managed to keep that one suit for sentimental reasons.”

They passed on under a series of Gothic arches into a room so vast and remarkable that Biggles slowed his pace to stare at it. Sunlight filtered in through a range of mullion windows to fall on an enormous oak refectory table, scratched, and in places carved, as if schoolboys had worked on it with knives. Tucked under it, looking dwarfed and ridiculously out of place, were half a dozen cheap kitchen chairs. There was practically no other furniture. A huge fireplace, itself the size of a small room, was piled with logs.

But the outstanding feature was the walls. From end to end they were lined with oil paintings of men in the garments of the period in which they had lived. Some, presumably the earlier ones, wore armour. Conspicuous in most of them was a sword, or a weapon of some sort.

“This is the banqueting hall,” remarked Leo casually. He smiled, “Not that we have any banquets these days.” He pulled out some chairs. “Sit yourselves down, gentlemen.”

“What a room,” breathed Biggles. “I imagine if these walls could talk they’d have some tales to tell.”

“They would indeed. No doubt many a plot has been hatched here, hence the rose.” Leo raised his eyes to the ceiling where, carved on a beam immediately over the table, was a Tudor Rose.

“Ah! I get it,” said Biggles. “We’re sub rosa.[A] Do you mean we’re to take it seriously?”

[A] Sub rosa. In olden days the rose was the symbol of silence, or secrecy. In the days of plots and conspiracies the flower itself might be worn as a sign of faith; but it was also carved, painted or hung, on ceilings where conspirators met. Such meetings were said to be sub rosa—under the rose. When the Roman Catholic religion predominated roses were sometimes placed on the heads of those who came to confess as a guarantee of secrecy.

Leo thought for a moment. “I wish you would. That is, I’d be obliged if you’d treat anything I tell you with the strictest confidence.”

“Certainly,” agreed Biggles, as Falkner came in carrying a tray bearing a jug of cider and glasses. Having put the tray on the table he went out.

“Don’t say this is where you usually take your meals?” queried Biggles, looking slightly amused.

“Always,” returned Leo, calmly. “Why not? We’ve always eaten in this room, although there was a time when it didn’t look like this. There’s nothing like having plenty of elbow room at the table.”

“Well, you’ve certainly got that,” conceded Biggles. “Tell me this. When we were outside you said something about having no modern conveniences. Did you mean that literally?”

“Quite. We’ve no water laid on. It’s drawn by a pump from a well under the kitchen. No gas. No electricity. It’s still lamps and candles after dark so at least we’re not troubled by mechanical breakdowns. We have plenty of wood so we don’t have any coal bills.”

“What about the telephone?”

“I manage without one. The village is only three miles away. I run in once a week, in the old car, to do the shopping. To bring electricity here would need a transformer, and the job, so I’m told, would cost five thousand pounds. As far as I’m concerned it might as well be five million.” While talking Leo had poured out the cider.

“Good health,” said Biggles, raising his glass.

“Thanks. That’s a toast that really means something here.” Leo went on: “Before we get down to serious business, may I ask, are you superstitious?”

“No.”

“Good. Neither am I. Do you believe in coincidence?”

“Up to a point. Why?”

“Because you’ll have to believe in one or the other before I’ve finished talking.”

“Suppose we get on with it?” proposed Biggles.

“I think we’d better, or you’re likely to be late home,” said Leo. “It’s a long story, and one you’re going to find hard to believe, so I warn you.”

“We’re in no hurry,” answered Biggles. “Go ahead. You’ve got me really curious.”

Leo paused, his sombre eyes inscrutable. “Before I start there’s one thing you should know because it may help you to get into the atmosphere of the events I’m going to narrate. You realize that the portraits you see round the walls are those of my ancestors?”

“That is what I had supposed.”

“They cover a period of nearly 500 years, from the original holder of the title to my grandfather, and although their clothes change with the fashion of the day, and the family likeness is not always outstanding, they all had one thing in common. I won’t waste time asking you to guess what it was. In one word we might call it a particular grief. In almost every case, the eldest son of the men you see here died a violent death. A year ago my brother ran true to the tradition. We call it The Curse. The Curse of the Landavilles.”

Silence fell.

“It isn’t easy to know where to begin, but I think perhaps the best plan would be to start at the first chapter and try to keep things in sequence,” resumed Leo. “Don’t hesitate to interrupt if I fail to make myself clear.

“We now go back to the year 1485, when it so happened that an ancestor of mine was lucky enough to find himself on the winning side at the Battle of Bosworth Field, where, you will remember, Henry Tudor, Earl of Richmond, founded the Tudor dynasty by pushing Richard III off the throne; and not before it was time, for Richard seems to have been an exceptionally nasty piece of work. At one moment the result of the battle hung in the balance. Richard made for Henry and actually closed with him. He cut down his standard bearer. The folds of the flag wrapped themselves round the head of Henry’s horse causing it to rear and he was thrown. Richard raised his sword for the blow which, had it fallen, would have changed the course of history. Henry would have died, and our kings and queens from that day to this would have been an entirely different set of people.”

“Fascinating to reflect on, but let’s stick to the facts,” interposed Biggles. “The blow didn’t fall.”

“Quite right, the reason being that a humble squire jumped in, parried the blow and fetched Richard a swipe that knocked him out of the saddle. Then Sir William Stanley arrived at the spot and it was all over bar the shouting. Richard never again stood on his feet. The name of the squire who saved the day, and so avenged the dastardly murder of Richard’s nephews, the two young Princes in the Tower, was Leofric Landaville.”

“I get the drift,” murmured Biggles.

“When things had settled down, and Henry had climbed into the Big Chair at Westminster, in accordance with the custom of the times he handed out rewards to the people who had helped him to get into it. He also took his revenge on the people who had tried to stop him. One of those was a Lord Simon De Warine. My Lord De Warine, to whom this house belonged at the time, seeing the battle lost skipped across to France from where, wisely, no doubt, he never returned; but his son was caught and of course went to the block.

“As far as Henry was concerned the presents for his followers were easy to come by. He simply dispossessed the people who had fought against him and gave their houses and estates to his supporters. He didn’t forget Leofric Landaville. He knighted him and gave him Ringlesby Hall with 100 acres of land and a pension of 400 a year in perpetuity. We’re still here and I still get the pension. In fact, that’s what I live on. I hold the Royal Charter, signed by Henry VII and carrying his Great Seal, and no one, no law of the land, can set it aside, although some people would like to. But what a king gives for services rendered is as secure as anything on this earth can be.”

“Four hundred a year doesn’t sound a lot of money.”

“Not now. But at the time it was awarded it would represent a small fortune. Unfortunately Henry made certain conditions, and I can’t set those aside, either. In that respect the Charter cuts both ways, and while one way works so must the other. Of course, Henry knew what he was doing when he made the award. However grateful kings might be they seldom give away something for nothing.”

“What were these conditions?”

“Actually it was a stipulation to ensure our constant support. He knew what he was doing and he was certainly within his rights. Remember, we’re talking of the days when the Feudal System operated; and that was about the only system that could have worked in the conditions then prevailing. There was a clause in the Charter that while England was at peace the Head of the House of Landaville was compelled to reside here for eleven months of the year, the idea being, of course, so that he would always be on hand with his men-at-arms should his services be needed. Should the rule be broken he would lose everything, money, house and estate.”

“And that still operates today although the need no longer arises?”

“Of course. The Charter must operate in its entirety or not at all. Only in the event of war can I leave the place—to fight for the king or queen, as the case might be.”

“And this rule you say is still effective?”

“Just as much as ever.”

“Now that the original intention no longer applies can’t you get the clause set aside?”

“Not a hope, so the lawyers say. What is written on the Charter must stand to the letter or not at all. As you can see, the house is little more than an empty shell. Through the centuries my ancestors either sold the contents to augment their incomes, which remained stationary while the price of everything went up, or had their possessions seized. In the civil war of the seventeenth century my ancestor fought for the king, as he was bound to. Like many other cavaliers his silverware went into the melting pot for coinage to pay the troops. When the king lost, Cromwell’s roundheads came here, and what they couldn’t carry away they smashed. They stabled their horses in this very room and sharpened their swords on the window sills which, being sandstone, were just the job. You can still see the marks outside, as you can see the cuts in this table where they tested their knives, or wiped them after use. The pension was stopped by Cromwell, but at the Restoration Charles II gave it back to us.”

Biggles smiled. “But he didn’t repair the damage or replace the things you’d lost.”

“Not on your life. The pension was paid by the Treasury. The Stuarts were free enough with public money, but if anything meant putting their hands in their own pockets it was a very different cup of tea.”

Bertie spoke. “Why do you stay here, anyway. Why don’t you clear off and let the whole thing go hang?”

“I’ve sometimes wondered that myself, but I can’t bring myself to do it. It isn’t the pension. It may be that my roots are here, too deep in the ground. Moreover, I feel it would be letting them down if I packed up.” Leo raised a hand towards the grave faces looking at them from the walls. “I feel if they could stick it, so should I. I don’t know quite what it is, but heritage does something to a man. It may not show, but I can feel it in my bones. I wouldn’t like to be the first Landaville to run away from anything.”

Biggles nodded. “I can understand that. Have you ever thought of selling some of these pictures?”

“Never. That would be too much like selling one’s soul, or the dead bodies of one’s parents. Being mostly by unknown artists they wouldn’t fetch much in the market, anyway. While they hang there I can face them without shame. I couldn’t do that if they were in somebody else’s house. In order that you should see them was one of the reasons why I asked you to come here, hoping you’d appreciate that, and realize the tragedy of it when I told you that the elder or eldest son of nearly every one of those men was murdered.”

“Murdered.”

“The alternative is coincidence beyond all imagination.”

“Is it always the eldest son?”

“No. The eldest son goes first, but there have been one or two occasions when the second son has gone, too.”

“So The Curse might fall on you.”

“It might, particularly as that would finish the business, me being the last of the Landavilles. Perhaps one of the most remarkable things about the whole affair is this. There always has been at least one son, and always one with the Christian name of Leofric. There are few cases where a family has run in an unbroken line for centuries. Holders of the title may have had daughters, but always there have been sons to carry on the name. On the distaff side, that is, the female line, should the woman marry her name would of course be changed to that of her husband, in which case there would be no son of hers named Landaville. But that has never happened. There have been daughters born here, but for nearly 500 years there has always been a Leofric Landaville. Why my father named his first son Charles I don’t know. Maybe he thought that by this he would escape The Curse. If that was his idea it failed. For the sake of the tradition, I suppose, he gave his second son, me, the fatal name of Leofric.”

“Very odd. You say you’ve got 100 acres of land. What do you do with it?”

“I let a farmer have it. Actually, being all overgrown there isn’t much feed on it except perhaps for sheep, although he does sometimes put a few head of young bullocks on it. He pays me ten pounds a year in cash and the rest in kind—milk, butter, eggs if I’m short, a fowl once in a while and a turkey at Christmas. Falkner has a few chickens in the vegetable garden, but what the farmer lets me have helps to cut down expenses.”

“You were speaking of your brother. What happened to him?”

“He was shot. The coroner’s jury brought in a verdict of accidental death. Only I knew it was murder. I was prepared for it.”

“How? Why?”

“I had heard the raven croak.”

“What raven?”

“I don’t know. But the croaking of a raven outside has always meant death for the senior male member of the house.”

“Always?”

“Always. That’s the signal that the time has come for a Landaville.”

“Have you ever seen this raven?”

“No. I’ve never seen a raven, any raven, about the place.”

“How very queer.”

“There are a lot of queer things about this establishment.”

“Was the croaking of this raven the only reason you had for thinking your brother had been murdered?”

“No. I had proof of it—anyway, enough to satisfy me.”

“Didn’t you say so?”

“No.”

“Why not?”

“What was the use? The only result would have been a lot of distasteful publicity.”

“Are you expecting me to find the murderer? Is that why you asked me to come here?”

“Certainly not. I’m prepared to let that pass. Nothing can be done about it now. I’m asking for your advice. What would you do if you were in my place. I’m the head of the family. The last survivor. If I marry I may have a son. Would you ask a girl to marry you with that Sword of Damocles hanging over your head—and hers?”

“Before I answer that let’s be practical. How are you going to support a wife—on nothing a year? You couldn’t very well bring her here, and if you lived anywhere else you wouldn’t even have your 400 a year.”

Leo hesitated. “I see I shall have to take you entirely into my confidence in a matter which is more than somewhat delicate. The lady concerned, who I’ve known all my life, understands my financial position. Circumstances compelled me to explain them to her. She happens to be extremely wealthy. She wants me to overcome my natural reluctance to live on her money in order that she can spend it usefully by having this house and estate put in order. Were it not for the fact that I happen to be in love with her my answer would be no, not in any circumstances. But I am in love with her; she knows it, and accuses me of ruining both our lives for the sake of my silly pride, as she puts it.”

“I see you’re on a spot,” said Biggles quietly. “I take it that were it not for The Curse you’d marry her.”

“Yes.”

“I see. How did your father die?”

“He was killed in the war.”

“So as far as he was concerned there was no question of murder.”

“I wouldn’t be too sure of that. All I know for certain is that he went to France with the invasion force and never returned. Anything could have happened to him.”

“What do you mean?”

“I mean that by some uncanny fluke or devilish design every murder through The Curse could be taken to be the result of an accident. One could perhaps cope with plain straightforward murder but not with this.”

“You’re quite sure these murders were not accidents?”

“Certain.”

“Has no one ever been suspected of murder?”

“Not to my knowledge. There’s no record of it.”

“But if what you say is correct it can only mean that a fresh murderer appears with every generation. How do you account for that?”

“I can’t. I’m hoping that’s what you might be able to tell me.”

“Could you be a little more explicit about how these alleged murders happened?” requested Biggles.

“Certainly. Here’s Falkner to lay the table for lunch so it’s a good opportunity. Come over here.” Leo got up and walked to the wall to face the portraits of his ancestors. “These are all Landavilles,” he said, indicating the picture gallery with a wave of his left hand. “I don’t profess to know the history of all of them because there’s little in the way of a written record. Most of what I know, and that’s chiefly about the way they died, has been handed down from father to son by word of mouth. As I happen to be the last Landaville even that will soon be forgotten.”

“You’re not going to tell me that all these men met violent deaths here, in the house or on the estate!” exclaimed Biggles incredulously.

“Oh, no. But quite a few of them did. One would expect that since they all had to reside here. Take my grandfather, for instance. Here he is. There was no question of accident in his case. It was late evening at this time of the year and he was just sitting down to his dinner when there was a gunshot in the park. He jumped to his feet and said to his wife, who was at the table with him: ‘There are those damn poachers at it again. I’ll put a stop to this.’ Those were the last words he was heard to say. Taking a stick from the hall he went out. He didn’t come back. The next morning, when daylight came, he was found in some bushes with his skull bashed in.”

“Was the murderer never found?”

“No. The police had absolutely nothing to work on. Every known poacher in the district was questioned. Every one had an unbreakable alibi.”

Leo walked on a little way and stopped in front of a picture portraying a handsome young man dressed with all the elegance of the late eighteenth century—blue frock coat with brass buttons, lace at the throat and wrists and a tricorn hat under his arm. “Another Leofric Landaville,” he said, without emotion. “I’m rather like him, don’t you think? He was twenty-one when he died in 1793, and the manner of his death was unusual. He was asked by someone he met to deliver a letter to a lady in Paris who was in great trouble. A lot of people were in trouble there at the time because the Revolution was in full swing. He was betrayed. The letter must have been a deliberate trap because the moment he arrived he was arrested as a spy. The letter he carried confirmed it. It was a plan for helping Countess du Barry to escape from prison. As you will remember she went to the guillotine. Leofric lost his head on the same day. No doubt he was innocent, but that was how he died.” Leo nodded towards another picture in passing. “Another Leofric Landaville. He was twenty-five, just married. Notice the date, 1741.”

“What happened to him?”

“He was shot dead one night as he rode home from Ringlesby village. Apparently by a highwayman. Anyhow the man wore a mask. As far as is known there was no reason for it. He wasn’t carrying any money. He wasn’t asked to ‘stand and deliver’. The ruffian simply shot him at point blank range and rode off.”

“How do you know?”

“One of our servants, actually one of Falkner’s forbears, saw it all. He was riding with him. He galloped on to the Hall to report what had happened.”

Leo walked a little farther and stopped again before a youth in his teens. “Another Leofric Landaville. He was drowned in the lake you may have noticed as we came up the drive. He went fishing. He never came back. His body was found in the lake. It could hardly have been an accident.”

“Why not?”

“Because the water is quite shallow, and in any case he was able to swim.”

Leo passed on to the next portrait, a young man dressed in the colourful clothes of the early eighteenth century. “Yet another Leofric Landaville,” he said calmly. “He was killed in a duel.”

“How did that happen?”

“He went to London to order some wine. While there he went one evening into one of the gaming clubs for which London was at that time famous. There was some trouble over a game of cards. He accused a man of cheating. The man—nobody seemed to know who he was—challenged him to a duel. As a matter of honour Leofric had to accept. The weapons chosen were pistols. Leofric fell dead before he had fired his shot, which isn’t surprising since he had never fired a pistol in his life. His opponent was an expert. Afterwards he disappeared. Another unfortunate accident—if you see what I mean. Here’s another.”

This time Leo stopped before a young man wearing the big white ruff and embroidered tunic of the Tudor era. “He was killed in the tilt-yard at Windsor,” he went on. “Henry VIII, who was taking part, saw it happen. It was a lamentable accident, of course—so they said. It turned out that in some unaccountable manner Leofric’s opponent was handed a sharpened spear instead of the blunt one normally used for jousting. You can imagine what happened. Afterwards, when they looked for the man who had done the spearing he couldn’t be found. Nor did anyone know who he was, for the simple reason no one had seen his face. Both parties had their visors down according to the usual practice. We needn’t go any further. It’s more or less the same story all along the line. I see Falkner is serving the soup. Let’s go back to the table.”

“Lunch is served, sir,” said Falkner.

The meal to which they sat down was as simple as they had been led to expect; some excellent soup, cold beef and pickles, cheese and a jug of beer. It was sufficient. In point of fact Biggles was hardly aware of what he was eating, so engrossed was he in the strange story told by his host. The sinister thread of death by violence that ran through the tale chilled him yet at the same time fascinated him. To unravel the mystery, if in fact there was one, did not, strictly speaking, come within the scope of his official duties. There had been no complaint, no report of murder or any other crime; wherefore it seemed that his position was more that of a consultant than a police officer.

He looked at the man in whose house they were. His pale face with its fine aristocratic features showed no sign of fear or even alarm, although if what he had said was true, and he obviously believed it to be true, he was living in the shadow of death by an unknown hand. Indeed, he appeared to accept his position as a matter of course. There was no anger, no resentment. His attitude was similar to the calm dignity with which men of the Middle Ages went to the block, the stake or the scaffold, for the things in which they believed.

How right Leo had been, pondered Biggles, when he had said that in Ringlesby Hall he would be aware of that indefinable thing which is usually described as atmosphere. With those unchanging faces looking down from all sides the feeling that crept over him was as if he had dropped off to sleep in the speed and bustle of the modern workaday world to awake in the slow moving pages of the history book. It was a queer sensation.

For a little while he said nothing. He wanted to think.

It was not until the soft-footed Falkner, himself a character out of the past, had cleared the table, leaving them once more alone, that the conversation was resumed.

Biggles broke the silence. “I’ve been thinking,” he said. “Tell me this, Leo. These forbears of yours who died sudden deaths. Couldn’t they have been warned of their danger?”

“They always were. It has long been a tradition in the family for a father to pass on to his children the story of The Curse; so the eldest son always knew that his expectation of life was short.”

“Did your father tell your elder brother?”

“Of course. He told us both at the same time in the little room he used as a study. He had to tell us while we were still rather young because he was going off to the war.”

“What did you think of it?”

“Naturally, Charles and I sometimes spoke of it. I suppose the knowledge that we were living under a cloud had some slight psychological effect but we got used to it. I imagine one can get used to anything, even the daily expectation of death. Towards the end of his life—he was then twenty-four—I think the only thing that worried Charles was the problem of marriage.” A suspicion of a smile hovered for a moment round Leo’s lips. “When he died he left the problem to me with the rest of the inheritance. Naturally, he was anxious to carry on the line, yet he knew that if he had a son he would eventually become a victim of The Curse. He tried to dodge the issue by avoiding women, for which reason he seldom went off the estate. So he never married. He was lucky in that he never met a woman he wanted to marry. With me, as I have told you, the position is different. I’ve met the girl I want to marry. So, as Shakespeare might say, ‘to marry or not to marry, that is the question’.”

“How exactly did your brother die?” inquired Biggles.

“He was shot. It happened on the estate within 200 yards of where we’re sitting now. He took the twenty-two rifle and went out to knock off something for the pot—hare, rabbit, bird, anything that came along. He often did that. We kept the rifle for that purpose. It helped to keep the larder stocked. I was in the vegetable garden with Falkner, digging some potatoes, when I heard a raven croak. It was the first time I’d heard the sound and I don’t mind admitting I went cold all over. A minute or two later, as I stood there wondering what to do, I heard a shot, and an instant later, another. Even then that struck me as odd—”

“Why?”

“Because the rifle is an old single cartridge type, not a repeater, and the two shots coming so close together I wondered how Charles had been able to reload so quickly, even if the first cartridge didn’t stick in the breech, as it often did, the ejector being worn. I felt something was wrong. In fact, I knew it. Call it instinct, intuition, anything you like, but I felt it. After all, as sometimes happens with brothers Charles and I were pretty close to each other. I dropped what I was doing and ran in the direction from which the sound of the shots had come.”

“Did you see a raven?”

“No.”

“Did you see anyone?”

“No. That is, not until I saw Charles. I found him lying on the edge of a coppice. He was just expiring. He died in my arms. He’d been shot through the heart. As I knelt beside him he said something, and I’m by no means sure he was really conscious then. He had difficulty in getting the words out. He looked up at me with a most extraordinary look in his eyes, as if he’d seen a revelation, and whispered: ‘Beware the three stars, Leo . . . the hollow stars.’ He struggled hard to say something else, as if he was groping for another word, but he couldn’t manage it.” For a moment Leo looked moved, as if his self-control was breaking down. Recovering quickly he went on: “The rifle had been fired. The empty shell was still in the breech. The verdict was inevitable. Accidental death. The jury honestly believed that, and in view of the evidence it was the only verdict they could return, unless it was one of suicide, which would have been even further from the truth.”

“What did you think it was?”

“I knew what it was. Murder.”

“Didn’t you dispute the verdict?”

“No. How could I tell a jury of simple country folk the long rigmarole of The Curse? Would they have believed it? They’d have thought I’d got a bee in my bonnet, or a bug in my brain, and advised me to see a doctor. No. Charles was dead. No argument could bring him back so why make a song and dance about it. I let it pass.”

“Knowing The Curse would fall on you?”

“I didn’t think of that at the time.”

“Why were you so sure this was not an accident?”

“Charles was not shot with his own rifle. He was shot by someone who was in that copse waiting for him; someone, therefore, who knew his habits. It was a case of deliberately premeditated murder. I remembered the speed with which he appeared to have reloaded. The truth was, he hadn’t reloaded. It wouldn’t have been possible in the time. He fired at something, and a split second later was struck by the bullet that killed him. If he had reloaded, assuming for a moment that was possible, the spent cartridge case would have been at his feet, or within a yard of him.”

“Did you look for it?”

“Of course I did. I combed every inch of the ground round the spot where he fell. Remember, there were other factors. First, there was the warning croak of the raven, which practically told me what was about to happen. Then there was the look in his eyes when they looked up into mine. It was a sort of awful understanding, as if a mystery had been revealed. That’s the only way I can describe it. I’m sure he knew the truth about The Curse. He tried so hard to tell me what it was, but it was too late. He was too far gone. Then there were his last words, about the three stars—hollow stars.”

“Do they suggest anything to you?”

“Not a thing, except that he had seen something and was trying to tell me what it was.”

“But if he had seen something surely it must have been his assailant. Why didn’t he name him?”

“Obviously because he couldn’t. If he saw the man who shot him he didn’t, or couldn’t, recognize him. The only way he could identify him to me was by mention of those stars.”

“Which might mean anything.”

“Yes.”

“Could Charles have fallen foul of a poacher?”

“I considered that possibility but dismissed it because I couldn’t see how it could hook up with The Curse, with the raven, or Charles’ last words. I can’t make sense of this raven. I’ve never seen one about here, yet how is it one is always heard when death is about to strike. To suggest that the only time a raven arrives in the vicinity is when a member of my family is about to die is stretching coincidence too far, anyway, for my credulity. Yet the alternative is it must in some way be associated with The Curse. I can’t accept that, either. There was a time when everyone believed in witchcraft, wizardry, black magic, and all that sort of mumbo-jumbo; and there’s no doubt some people practised it. But surely not now. Even if the black arts, as they were called, were practised here in the Middle Ages, their effects, if any, could hardly have survived to this day and age. I think we can forget all that sort of rot.”

“Have you any reason to suppose that black magic ever was practised here?” asked Biggles. “I’m not putting that forward as a theory,” he added quickly, “but merely as a matter of curiosity.”

Leo looked a little uncomfortable. “It’s hardly worth repeating, and I certainly wouldn’t take it seriously, but as a matter of fact there is an old family legend about how The Curse came to be laid on the house.”

“We might as well hear it.”

“Never having paid any attention to it I’m not entirely sure of the details, but here it is for what its worth. The story is that not long after the Landavilles took over Ringlesby Hall, the previous owners having been dispossessed by Henry VII, a man arrived here with a letter for Sir Leofric Landaville. The man was a queer-looking individual—such people always are—in the garb of a monk. Having delivered the letter into the hands of Sir Leofric the monkish postman miraculously disappeared. That again is all in accord with tradition.” Leo smiled cynically.

“What was in the letter?”

“Something to the effect that the House of Landaville had had a curse laid on it by bell, book and candle, so that while they remained in occupation here every heir to the estate would be struck down by the Wrath of God. I don’t know the exact wording. I don’t know what my ancestors thought of it—”

“But it doesn’t worry you?” interposed Biggles.

“Not a bit.”

“It seems to have worked.”

“Rubbish! My dear fellow, this is 1961. I’m not prepared to believe that what has happened here was the result of spells and incantations muttered by the light of a full moon over a witch’s brew of toads’ entrails, vipers’ venom and bats’ blood.”

“What happened to this letter?”

“I have no idea.”

“Could it have been kept?”

“It might have been. I’ve never looked for it. There are a lot of musty old documents in the family chest. I know that because we had to take out the Charter to get it photographed when we were claiming abatement of some of the clauses about being compelled to live here, as I told you. I wouldn’t part with the original. That’s the only time I’ve seen the Charter. I couldn’t read it. It’s part in Latin and part in what I imagine to be Norman French. But there are experts at this sort of thing at the Public Record Office who can decipher such stuff.”

“Tell me, Leo; what happens to this place if you don’t get married? I mean, should you die without children. Have you any relatives?”

“As far as I know, not one. If I die without issue, as the lawyers put it, the estate would revert to the Crown.”

“What would the Crown do with it?”

“I’ve never inquired. I imagine the National Trust might take it over as an Historical Monument. If they didn’t I suppose it would come into the market like any other property.”

“To come back to this letter invoking The Curse on the house. Do you happen to know if it was signed by anyone?”

“No. As I say, if we still have it I’ve never seen it.”

“Did your father, or perhaps grandfather, ever refer to it?”

“Not in my hearing. I’d say they felt the same as I do about it. It’s been a sort of skeleton in the cupboard, best forgotten. Would you, if you owned the house, abandon it on account of some trumped-up nonsense concocted nearly 500 years ago?”

“No. I don’t think I would. But if I were in your place I’d take more interest in its medieval associations if only as a matter of curiosity.”

“You’re not saying that you think an old piece of parchment could have any possible connexion with what happened to my brother, and previous members of my family?” Leo looked surprised.

“Of course not. But I’m trying to keep an open mind about the whole business. If this unpleasant letter is still in existence I’d like to have a look at it. Will you see if you can find it?”

“Why?”

“There’s just a possibility that it might reveal a clue as to what’s been going on.”

“You can look for it yourself if that will give you any satisfaction.”

“Very well. I’ll do that.”

Leo glanced at the window, darkening as the sun sank. “It’s a bit late to start on a job like that today. You’ll need plenty of daylight. Why not come down tomorrow and stay a day or two instead of running to and fro between here and London. We’re not short of rooms. I could get Falkner to fix you up with beds. You could then browse over the contents of the family chest for as long as you liked.”

“I’ll accept that offer. I’d also like to have a look at the place where your brother died.”

“I’ll show you the exact spot.”

“Good. In that case we’ll be getting back to town. You can expect us back tomorrow morning.”

They went out, and the police car was soon on its way back to London.

“Well, and what do you make of that?” asked Bertie, when they had turned out of the overgrown drive on to the main road.

“Not much,” replied Biggles, “All I can say is, it’s the queerest tale I’ve heard for many a long day. I’m not surprised Leo finds himself bogged down in a mixture of superstition and coincidence.”

“You believe these deaths are coincidence?”

“We’ve either got to accept that, or say as many generations of murderers as there have been Landavilles, have been at work here. That’s just as hard, if not harder, to believe. You see what I mean! If these deaths were murders they couldn’t have been committed by the same man. To make myself clear, the man who killed Leofric Landaville in the eighteenth century must have been dead for more than 100 years when Charles Landaville was shot in the park. This is going to take some sorting out.”

“You intend to have a go at it?”

“Definitely. The thing has got me fascinated. If we’re dealing with murder, and Leo is convinced of it, we come up against a brick wall as soon as we ask ourselves the usual first question.”

“The motive.”

“Exactly. Yet if it’s murder there must be one. Where are we going to find it?”

“Where are you going to start looking?”

“That’s what I’m going to think about,” returned Biggles, succinctly. “The answer must be somewhere, and I shan’t sleep o’ nights unless I find it.”

“Could this be the work of a madman?”

“Oh, have a heart, Bertie. Over the last four and a half centuries some twenty Landavilles have come to a sticky end. I’m prepared to admit that in every generation over that period there may have been a lunatic panting to murder someone; but why should it always be a Landaville? Tell me that.”

“Sorry, old boy, I’m afraid I can’t.”

“That’s what I thought,” concluded Biggles.

The following day dawned with the weather still perfect and the police car was early on its return visit to the New Forest. Naturally, the conversation between Biggles and Bertie was confined almost entirely to the extraordinary tale they had been told by the owner of the ancient manor house of Ringlesby.

“I suppose you’ve been thinking a lot about it,” said Bertie.

“Thinking about it! I couldn’t sleep for thinking about it. Such a fantastic story would keep anyone awake.”

“Have you made anything of it?”

“No; that is, not much. But one or two points have occurred to me.”

“Such as?”

“For one thing, these three stars Charles Landaville spoke about a moment before he died. They must mean something. Yesterday I was inclined to take them literally, but thinking it over I’ve decided that might be a mistake. He could have used the term in the figurative sense. The words three stars are sometimes used as an adjective to indicate something of exceptional quality. For instance, travel books talk of three star hotels and restaurants. There are various products which are claimed to be three star. Brandy, for instance. We shall have to keep these stars in mind from every possible angle.”

“Anything else?”

“Yes. I’ve given a lot of thought to this alleged murder of Leo’s brother. It was done with a point two-two rifle. To kill a person with a rifle of such small calibre suggests to me two things. First, for such a weapon to be effective the range would have to be short. Secondly, the man who used it against Charles must have been a first-class marksman. It’s unlikely that a bullet anywhere except in the heart or brain would be fatal. If murder was intended absolute accuracy of aim would have been essential. That means the murderer, if in fact there was one, must have had plenty of confidence in his shooting.”

“Which implies ample practice.”

“Exactly. It was vital that Charles should be killed on the spot. It would have been no use hitting him in the arm or the leg, for instance, because he might have got back to the house; and had he done that he would have talked. He might have sent for the police.”

“Does this mean you’re convinced it was murder?”

“By no means. But if it was it should be possible to find the murderer. On the other hand, if by some incredible chance the whole thing is a matter of coincidence we should be wasting our time looking for a murderer. In that case the thing could go on, and nothing we could do would stop it. We can only deal with facts, not fantasies.”

“If it is murder it might be a good thing to cruise round the district with our eyes and ears open.”

“I intend to do that. There’s always a chance that the man who shot Charles, assuming it wasn’t an accident, could be a local with a grudge against him. Of course, the argument against that is, it might happen once; not over and over again. That would bring us back to coincidence, and that I find hard to entertain. There are one or two questions I shall have to ask Leo. A woman comes into the picture, if only in the background. His girl friend. On a job like this one can’t afford to ignore anything, however irrelevant it may seem. How much does the girl know about all this? If she knows all that Leo has told us what does she think of it? Women have a thing called intuition, a sort of sixth sense, which sometimes hits the nail on the head.”

So the conversation continued, with breaks of silence, until the car turned into the drive and bumped its way over the drive to the front of the Hall.

Leo may have been watching for them, for he appeared at a window and called: “Be with you in a minute.”

Biggles, who had stopped at the front door, while he was waiting looked up at the shield that leaned over it. “Somebody seems to have hacked that about,” he remarked. And when Leo came out, now in an old pair of tweed trousers and open-necked shirt, he said, pointing at the shield: “Did that once carry your family crest?”

“I’ve no idea,” replied Leo.

“Has it always been like that?”

“As far as I can remember. Why?”

“It looks to me as if it had been deliberately defaced.”

“That might well be. Cromwell’s troopers may have done it knowing we’d fought on the other side. They may have been dedicated men but they were terrible vandals. They hated anything that looked like a carving and knocked it down. They knocked the heads off the saints in the parish church. As far as this shield is concerned I don’t think it could have been our armorial bearings or some indication would have remained, even if it hadn’t been kept in repair. Our arms, when we used them, were sable, a bend argent with a rose gules stalked vert.”

Biggles smiled. “Would you mind saying that in plain English? I’ve never taken a course of heraldry.”

“A black shield with a silver band across it carrying a red rose with a green stalk. No doubt the rose had something to do with the red rose of Lancaster, Henry VII tracing his descent from that House.”

“Thanks. Not that I’m much the wiser.”

“Have you made anything of my problem?” inquired Leo.

“It’s a bit early to talk about solutions. This is likely to be a slow business. But there are one or two questions I’d like to ask you. They are chiefly concerned with recent events.”

“Go ahead. I’ll give you all the help I can.”

“Had Charles any enemies? Can you think of anyone who had cause to wish him ill?”

“No one. Charles was a quiet, unassuming chap. He seldom went away. I can’t imagine him even having a quarrel with anyone. Had that happened I’m pretty sure he would have mentioned it to me. He never did.”

“Do you mind if I ask a more personal question?”

“Not at all.”

“This lady you would like to marry. Who is she?”

“Her name’s Diana Mortimore. She may look in later. This is the day she goes into the town and she sometimes drops in on the way to see if I want anything.”

“So she lives near here?”

“On the next estate, about five miles away. Her father is Sir Joshua Mortimore, the banker, but Diana has money in her own right. It was left to her by her mother.”

“Are you actually engaged?”

“No. I’ve told you why.”

“Have you told her what you told us yesterday?”

“You mean—about The Curse?”

“Yes.”

“No, I have not. I wouldn’t want her to think I’m crazy.”

“Good. Then I advise you not to tell her. Does anyone else know about it?”

“Not that I’m aware of.”

“Then keep quiet about it. Don’t mention it to a soul. For one thing, if the story leaked out you’d be pestered with newspaper reporters. That’s understandable. You can imagine the headlines. We don’t want anything like that.”

“I certainly do not.”

“And don’t tell anyone what we’re doing here. If anyone should ask just say we’re a couple of old friends who happened to look in. I’d rather no one knew what we were really doing.”

“I understand.”

“Fine. Then let’s get on. The first thing I want to be certain of is that your brother was murdered, so let’s have a look at the spot where it happened. Have you still got the rifle?”

“Of course.”

“Then you might fetch it and we’ll take it along with us. You might put one or two cartridges in your pocket although I don’t think I shall need them.”

Leo went into the house, soon to reappear with the light rifle in his hand, and with him leading the way the party set off across the rough ground heading for a spinney made up of silver birches, firs and one or two Scots pines.

“Tell me,” said Biggles as they walked. “Was Charles a good shot?”

“Excellent. He seldom missed anything he shot at. Mind you, he disliked wounding anything so he seldom fired unless he was sure of a kill. The spinney in front of us used to swarm with rabbits but I’m afraid the myxomatosis has wiped out most of them. Still, there are a few, apparently those that were immune from the disease.”

Reaching the objective Leo walked a little way along the fringe and stopped. “This is the place,” he said.

“Can you picture the scene exactly as it was when you found Charles lying here?”

“I’m not likely to forget it. I shall see it for as long as I live.”

“Could you demonstrate just how he was lying?”

“Certainly, if you think that is really necessary.”

“It is, or I wouldn’t be asking you to do it. I want to reconstruct everything just as it happened. I know what you believe, and I’m not doubting your sincerity, but unless I can satisfy myself that this was really and truly murder there will always be a doubt in my mind that it could have been an accident. Will you please lie down in the position in which Charles was lying when you arrived?”

Leo arranged his feet, and then, moving like a swimmer in deep water, allowed his body to fall forward.

“Now the rifle.”

“Thanks.” Biggles considered the position, and having looked up and down, went on: “All right. You can get up.”

Leo got to his feet.

Biggles continued. “Now then. Of the two shots you heard fired that day Charles must have fired the first. Obviously he couldn’t have fired after he himself had been struck. The question is, what did he shoot at? You say he was a first-class shot, so let us assume he hit what he fired at, because in that case the remains of the creature, which we’ll presume was a rabbit, should still be where it died. According to you Charles was lying here, head pointing this way.” Biggles pointed. “Because a person struck by a bullet falls forward he must have been facing in this direction when the bullet that hit him was fired. Let’s see if there’s anything left of the creature he killed. It’s a long time since it happened but there may be some remains. Mind where you’re putting your feet.”

So saying, his eyes on the ground, Biggles started walking very slowly along the edge of the coppice. The others did the same, and they had covered perhaps twenty yards in this way when Leo exclaimed: “Here it is! Or this may have been it.” He pointed to the mummified remains of a rabbit, no more than a flat piece of grey fur wrapped round some bones through which the new grass had grown.

“I suppose to find the bullet would be hoping for too much,” said Biggles. “That would depend on where it struck. If it was a soft part of the body like the stomach it would of course go clean through and into the ground; but a bone might stop it.”

“Charles always fired at the head,” contributed Leo. “He believed in a dead hit or a clean miss. It’s no use shooting a rabbit through the stomach. The beast simply gallops away and dies in its burrow.”

Biggles dropped on his knees, and picking up the skull crunched the small bones to splinters. Slowly he allowed them to trickle through his fingers until only a small object remained. He held it up between a forefinger and thumb, a smile of satisfaction on his face. “Here we are,” he said cheerfully. “We’re doing fine. So Charles fired at a rabbit. As he wouldn’t have had time to fire twice—indeed, we know now there would have been no need for him to do so—the empty case in the rifle must have been the one that held this bullet. That, Leo, explains why you couldn’t find a second case near where Charles fell, although you say you looked for it.”

“I did.”

“Did you look anywhere else?”

“No.”

“Then let’s see if we can find it. If it was ejected it shouldn’t be far away. Being copper it wouldn’t rust. It must still be on top of the ground. Let’s go back to the place where you found Charles.”

They did so.

“Now, Leo,” went on Biggles, “I want you to load the rifle, and standing on the spot, as near as you can judge, where Charles must have stood, fire at the place where we found the rabbit. We might as well do the job thoroughly. When you’ve fired stand perfectly still.”

Leo loaded, raised the rifle, took aim, and fired. He remained motionless.

“This was the moment when somebody fired at Charles,” went on Biggles, studying Leo’s posture. “Knowing where Charles was hit the bullet must have come from that direction. It couldn’t have come from any other because of the trees.” Biggles pointed with an outstretched forefinger. “That’s the line. The person was in the wood, and he couldn’t have been far away. Okay, Leo. That’s all. Now let’s see if we can find the other cartridge case. Be careful not to tread it into the ground.”

Fortunately there was little or no herbage, the ground covering being mostly dead pine needles, so the task, supposing the spent case was there, did not look too difficult. Keeping to the line Biggles had indicated they walked three abreast, finally making two or three trips on their hands and knees. At the end their patience was rewarded, and in a rather curious way. Between the roots of a pine that were showing above ground level Bertie found a half of what had once been a cigarette, the paper brown from long exposure and the remains of a cork tip still clung to it. Biggles examined it thoroughly before putting it in an old envelope in his pocket book. While he was doing this Bertie let out a little cry that promised further success and held up the short, slim copper case of a point twenty-two cartridge.

“Great work,” congratulated Biggles. “So now we know. You were right, Leo. It was murder. The murderer must have stood behind this tree while he waited for your brother to come close. He must have been a cold-blooded devil. He had the nerve to smoke a cigarette while he waited, dropping it half smoked when he saw Charles coming. This was what I wanted to know.”

“Then you’re satisfied Charles’ death was not an accident?”

“It’s hard to see how it could have been. There were two bullets, and from the speed at which they were fired, and the distance between this tree and where Charles must have been standing, it would have been impossible for them to have been fired by the same man. So there were two men, each with a twenty-two bore rifle. We might be able to double check that. Have you ejected the cartridge you fired, Leo?”

“Not yet.”

“Then please do so and give the case to me.”

Leo obliged.

Biggles took the empty shell, and holding the two caps towards him compared them. “We don’t need any more proof than this,” he said. “Take a look. The firing pin of that old rifle of yours, Leo, struck the rim of the cap. This last case, the one we picked up here by the tree, was struck dead centre, probably as a result of the rifle being a more modern pattern.”

“What do we do now?” asked Leo.

“Now we know Charles was murdered we shall have to try to find the man who murdered him. The scent, of course, is stone cold, but there is still the motive if we can find it. People don’t commit murder for no reason at all.” Biggles lit a cigarette and drew on it thoughtfully. “If Charles was the inoffensive chap you say he was, why should anyone want to kill him? The murder must have been deliberate. Let us consider the poacher possibility. The man was here, in the spinney. He’d see Charles walking along the outside. He’d see him shoot the rabbit. Up to that time Charles had certainly not seen him or he wouldn’t have gone on after the rabbit. He’d stop and ask the man what he was doing there, with a rifle. Right?”

“Yes, that’s reasonable,” agreed Leo.