* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Mr. Tasker's Gods

Date of first publication: 1925

Author: T. F. (Theodore Francis) Powys (1875-1953)

Date first posted: Dec. 26, 2023

Date last updated: Dec. 26, 2023

Faded Page eBook #20231250

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, John Routh & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

This file was produced from images generously made available by Internet Archive/Lending Library.

Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 72-145246

ISBN 0-403-01161-2

TO

GERTRUDE

| CONTENTS | |

| I: | Mr. Tasker’s Return |

| II: | Father and Son |

| III: | The Feast |

| IV: | Henry Neville |

| V: | Country Matters |

| VI: | Doctor George |

| VII: | The Master’s Voice |

| VIII: | Truth out of Satan’s Mouth |

| IX: | The Tug-of-war |

| X: | Arcadia |

| XI: | Mrs. Fancy |

| XII: | The Drover’s Dog |

| XIII: | Two Letters |

| XIV: | Under the Human Mind |

| XV: | Deserted |

| XVI: | The Good Samaritan |

| XVII: | The Visitation |

| XVIII: | Higher Fees |

| XIX: | The Dying Man |

| XX: | Gentlemen |

| XXI: | ‘Old Lantern’ |

| XXII: | Rose Netley |

| XXIII: | Mrs. Fancy’s Gentleman |

| XXIV: | Sound and Silence |

| XXV: | The Dead and the Living |

| XXVI: | Meerly Heath |

| XXVII: | Mr. Duggs Complains |

| XXVIII: | The Will |

| XXIX: | The Sword of Flame |

| XXX: | A Girl’s Despair |

| XXXI: | The Deliverer |

| XXXII: | The Lost Sound |

| XXXIII: | A Sunshine Holiday |

| XXXIV: | Two Clergymen |

| XXXV: | A Country Word |

| XXXVI: | Too Late |

| XXXVII: | Dancing Stars |

| XXXVIII: | The Reward |

| XXXIX: | Gone to Canada |

Mr. Tasker’s Gods

The servants at the vicarage had gone to bed. Edith had just locked the back door, and Alice had taken the master the hot milk that he drank every evening at ten o’clock. Just after ten the two servants had gone upstairs together.

Indoors there was law, order, harmony and quiet; out of doors there was nothing except the night and one owl.

The servants at the vicarage slept in a little room at the end of the back passage. They slept in one bed, and their tin boxes rested together upon the floor; there was also in the room an old discarded washing-stand. It must be remembered that servants like a room with scant furniture: it means less work and it reminds them of home. The servants at the vicarage did not pull down their blind, there was no need; they never thought that any one could possibly desire to watch them from the back garden. Beyond the back garden there were two large meadows and then the dairy-house.

The delight of being watched from outside, while one moves about a bedroom, is rare in country circles; these kinds of arts and fancies are generally only practised in cities, where the path of desire has taken many strange windings and the imagination is more awake. As a matter of fact, these two girls were much too realistic to believe that any one could possibly stand in the dark and look at them undress. Not one of the young men that they knew would have stood outside their window for an instant, so the vicarage servants had not even the womanly pleasure of pulling down the blind.

They were both very tired; they had been cleaning the house, and they had been washing up the very large number of plates that the family—‘three in number,’ so ran the advertisement—had that day soiled.

Tired girls do not go to bed, it is just the very thing that they won’t do; they will prefer even to darn their stockings, or else they pull out all the little bits of blouse stuff hidden under Sunday frocks, but they never get into bed.

Edith sat upon the end of the bed, partly clothed, and tried in vain to draw a very large hole in the heel of her stocking together. She knew very well about the hole, for a little mite of a girl walking behind her the last Sunday had very plainly and loudly remarked upon it, coming down the church path. Alice, for some reason or other, was looking out of the window.

To the north of the village, in view of the girls’ window, there was a low down, the kind of down that an idle schoolboy with a taste for trying to do things might have attempted to throw a cricket ball over, and receive it, if it were not stopped by the gorse, running down to him again. This down was like a plain homely green wall that kept away the north wind from the village, and in March, when an icy blast blew on a sunny day and beat against it from the north, any old person could sit on the dry grass, the village side, and think of the coming summer.

It was over this hill that a road crept that joined the village to the world; at least this was one way to get there; the other way was round the bottom of the hill—‘down the road,’ as it was called. But the more manly way was for the traveller to go over the hill. Whoever went down the road to get at the world was regarded by the strong-minded as a feeble fellow, or else in possession of a very poor horse that could not face the hill. This was the case of the small farmer of the village, whose old horses never cost him more than eight pounds and who always went down the road to get to the market town.

Alice was peering into the summer night, watching the hill, because at the top there was a light moving. Alice had at first taken this light to be a star; she had heard of the evening star, and she thought it must be that one, until it began to move, and then her reason explained to her that it must be the light of a cart guided by some delayed wanderer in the night.

Just then the owl hooted by the vicarage hedge, near the elm tree, and swept over the house and hooted again on its way to the church tower.

Alice was now sure that something was happening in the darkness, something different from what had happened the evening before, or a good many evenings before,—something exciting. She had begun to hear voices at the dairy-house by the gate that she knew led to the meadow. She could not hear what was being said, but the sound of voices showed very distinctly that something had happened. Alice turned quickly, and her hair, that was already let down, brushed the window. She said excitedly the words of magic, ‘Something’s the matter with Mr. Tasker.’ The voices had come to Alice out of the night in the magical way that voices do come in the dark; she had heard them for more than a minute before she had realized that they were voices. They were curiously natural, and yet she knew that they had no business to be there.

Alice was the youngest of the vicarage servants, and it was Edith who opened the window at the bottom so that they could both lean out into the night and listen. Alice, who had the sharper ears of the two, gave expression to the mysterious sounds that floated in from the fields, the sounds themselves clearly denoting the presence of startled, trembling, human creatures.

Alice whispered to Edith in much the same tone of fear as the sounds, ‘Do you hear them? They be frightened. ’Tis Mrs. Tasker and all of them; they be by the gate waiting—hush—be quiet—let the curtain bide—there’s May’s voice, she did always squeak like a little pig—listen—“Can’t you, Edie”—that’s Elsie, quite plain. Oh, I do wish I could hear what they be saying! There’s the baby crying. What a shame having she out there—listen to Elsie—now they be all talking—they are all there by the gate—and they be so frightened. Something’s the matter with Mr. Tasker. Six o’clock is his time to be home; it must be near twelve. Old Turnbull struck eleven ever so long ago.’

The servants at the vicarage called the hall clock ‘Old Turnbull’ after their master. It was their habit to give nicknames to nearly everything in the house.

‘Mr. Tasker don’t drink, he don’t ever spend anything, he don’t treat Mrs. Green, he don’t spend nothing—something must have happened.’ Alice was beginning to enjoy the fear of it.

Slowly the light moved down the hill, and stopped; the voices by the gate became more high and more terror-stricken as the truth grew nearer, and the girls at the window felt that the dramatic moment had come.

‘He’s opening the mead gate,’ said Edith; ‘whatever can it be?’

They watched the light now moving across the meadow; it moved rather erratically, as though it were glad to be freed from the restraint of a narrow lane. It kept on going out of the path like a lost star, and wandered here and there, the horse or the man having seemingly forgotten the right way to the dairy gate. However, after taking some wide curves, once almost disappearing, the light at last drew near the gate.

The watchers from the window noticed a change in the tone of the voices, which were now calmed down in suppressed excitement, except for the continual wailing of the babe. At last the light arrived at the gate, where the frightened expectant family were waiting, and the servants at the vicarage heard the sound of a man’s voice.

The fact that the voice was as it had always been broke the magic spell: the man’s voice robbed the night of the mystery. Instead of the aching excitement of unknown things, it brought to the girls the cruel fact of nature that man rules, and has ruled, and always will rule: it brought a cold, dreary, real existence of a fact into a night of fiction.

What was the matter with Mr. Tasker that he had returned in such a way that he was mistaken for the evening star?

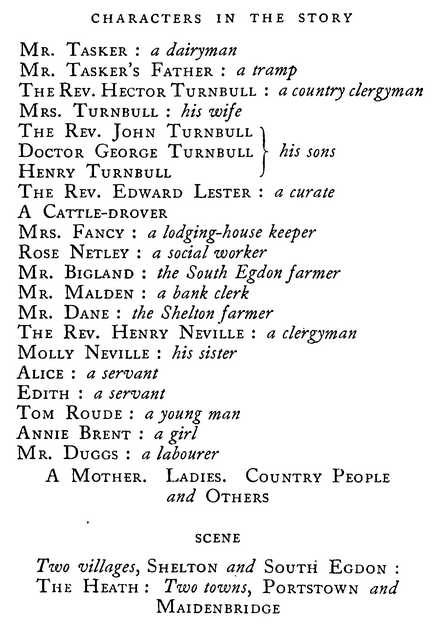

Mr. Tasker was a dairyman of distinction. ‘He did very well in his trade,’ so the village carpenter said, who knew him. Mr. Tasker went to market every Saturday, and it was to market that he had been the Saturday of his star-like return. He was a tall man with a yellow moustache that stuck out about an inch from his upper lip, and the remainder of his face he shaved on Sundays. On Sundays also, about the time of the longest days, Mr. Tasker, his long legs clothed in trousers that had been in the family for about a hundred years, moved over the dairy fields after the evening service so that he might, if possible, catch a naughty little boy or girl breaking down the hedges or smelling the musk thistles.

When Mr. Tasker talked to any train or market companion, he kept his head far away and looked upwards as though he were interested in the formation of clouds, unless it happened that the conversation was about pigs, and then he brought his head down very low and became very attentive and human.

Mr. Tasker worshipped pigs, and a great many of his gods, fat and lean, were always in the fields round his house. He killed his gods himself, and with great unction he would have crucified them if he could have bled them better that way and so have obtained a larger price.

On this particular Saturday Mr. Tasker had started out at his usual time after having given orders to his family to take special care of a certain black sow that he loved the best of all his gods. On the road he passed the usual kind of market women who had missed the carrier. One or two had even the hardihood to ask him to let them ride with him in the wagon; in answer to this the high priest of the pigs only sniffed, and flicked his horse with the whip.

The pigs were duly unloaded into a pen, where they were to be sold. One, the largest, lay down until a pork butcher reminded him of his duty with a knowing prod from an oak stick. Presently, a little bell having tinkled, the auctioneer and his followers, a crowd of eager buyers, and Mr. Tasker with his eyes upon the clouds, approached, and the future of the pigs was assured. In a few weeks they were to be transformed by human magic into smoked sides and gammon. They had been purchased by a mouth filled with a cigar and representing the ‘West County Bacon Supply Co.’

The pigs had sold well, and Mr. Tasker walked very contentedly up the town, where it was his custom to expend sixpence upon bread and cheese. It was just by his favourite inn that the thing obtruded itself that delayed his return. He met his father.

The thing happened like this: As Mr. Tasker went along up North Street, his head well above the market women, and his thoughts with his gods, he saw a disreputable old tramp standing by the door of the very tavern that he himself wished to enter. The old tramp had a face splendid in its colour, almost like the sun. He stood surveying mankind from an utterly detached point of view: he even looked hard at the young ladies, he looked at every one. His look was bold and even powerful. This old tramp regarded Mr. Tasker, when that gentleman so unluckily presented himself before him, with a look of supreme contempt, and then the tramp laughed. His was the laugh of a civilized savage who had kept in his heart all the hate and lust and life of old days. His laugh made a policeman look round from his post by the bank, and even compelled him to walk with the stately policeman-like stride towards the two men, for what legal right had any one to make such a noise of violent merriment in the street?

Mr. Tasker’s mind was filled with a great deal of understanding. His work as a dairyman was a mystery that required a large amount of wise handling and a great deal of patient labour. With his beasts, Mr. Tasker was a perfect father: he waited by them at night when they were ill. Once he nearly killed his little girl—he hit her in the face with his hay-fork—because she had forgotten to carry a pail of water to a sick cow. Mr. Tasker was brave; he could handle a bull better than Jason, and ruled his domain of beasts like a king. At the same time, there were events that Mr. Tasker could not altogether keep in control, and one of them was his father.

On this Saturday Mr. Tasker’s mind had been so full of his pigs that he had not considered the possibility of meeting his father. The last news of his father he had received from the clergyman of the village. The clergyman had stopped him one day by the post office and had said to him:

‘I am sorry to hear, Mr. Tasker, that your father is in prison again. It must be a great distress to you all, and you have my full sympathy in this trouble, and I know how you must feel. I fear he is an old man in sin’—which was quite true. ‘I wonder if you have ever thought of trying to keep him in order yourself? You might allow him, your own father, to live with you. Don’t you think he might help you in feeding the pigs?’

As the clergyman was speaking, Mr. Tasker had withdrawn his gaze farther and farther from the earth as though he were intent upon watching some very minute speck of black dust in the sky. The allusion to his pigs brought him down with a jerk, and, bending towards the clergyman, he said:

‘You cannot mean you think I ought to do that, Mr. Turnbull? My pigs never did any one no harm.—My father feed they pigs!—Why can’t ’e be kept in prison? Don’t I pay rates?’ And slowly Mr. Tasker’s gaze went back to the sky.

The clergyman was a little surprised at the undutiful behaviour of Mr. Tasker, ‘but perhaps,’ he thought, as he walked along the grassy lane that led to the vicarage and tea, ‘perhaps it would be better if they did keep such evil kind of old men in prison.’ Mr. Turnbull was a Conservative.

When the son saw the father by the tavern his first thought was to wish himself somewhere else,—if only he had learnt a little more about his father; if only he had inquired about the time of his being let forth out of the public mansion that had so long been feeding him with bread and beef; if only he had kept his eyes more upon the people in the street and less upon his balance at the bank, he might have had time to turn out of the way. Mr. Tasker’s mind, that was always ready to work out the difficult problems of dairy management, now seemed completely lost. The situation was one that he could not master: he could not even pray to the black sow to help him. He himself had often forced and compelled others, and now it was his turn to be forced and compelled.

His father’s laugh was terrible, and still worse was his handshake. He shook hands like a lion, and would not let go. He dragged Mr. Tasker into the lowest bar of the inn, and putting before him a tankard filled half with spirits and half with beer, bid Mr. Tasker to drink his health. The old tramp sat between his son and the door. He told his son somewhat coarsely that they would stay there till closing time, ‘they had not met for so long,’ he said, ‘and he had plenty of money to pay for more drink,’ and, he added, with another mighty laugh, ‘You bide with me, or, damnation, I go ‘long wi’ you!’

Mr. Tasker did bide. ‘Drink was the best way,’ he thought, ‘to get his father to prison again.’ What if he were to repent and offer to help his son with the pigs? Mr. Tasker himself paid for ‘another of the same.’ How to keep his father out of his gate, was the one thought just then that troubled his mind. It must be done by force, but what kind of force? Mr. Tasker thought hard, and then he remembered that the tramp was afraid of dogs. After that Mr. Tasker even drank his glass with pleasure, looked at the girl and paid for another.

The father and son sat quite near each other until the tavern closed, and they gave the barmaid some entertainment, and she, being a true girl, preferred the father to the son.

The morning after the midnight return of Mr. Tasker was dark for July, owing to great lumbering thunder-clouds that hung like distorted giants’ heads over the church tower. These heads every now and again gave out a muttered growl.

Inside the church tower the owl and her brood were shortly to be awakened by the one solitary bell. They had remained, except for the choir practice, very contentedly for six days, breathing in their loud way, making a noise like the snores of an old watchman. For six days no one had disturbed them, and in their owl minds, that shrewdly think through centuries, they supposed that the happy times of peace in the church tower, that they remembered in the reign of King John, had come again. However, no such rare owl days of church silence had returned, and the old male owl, blinking through a crack in the tower, saw the clergyman’s gardener, a tired, drooping sort of man that they called ‘Funeral’ in the village, slowly ascending the path in order to unlock the church door and enter the vestry, and pull at the solitary bell-rope that had hung for six days on a brass hook near the clergyman’s looking-glass.

This lonely bell had informed the village of the same fact on every seventh day for a great number of years, and now came the little hitch that so often upsets the wise doings of mankind.

The vicarage servants, whose duty it was to serve the vicar with hot water in order that he might serve the gardener, his own son, and one old woman, with bread and wine in the church, were late. Their sacrament of rising and of lighting the fire was delayed by the fact that they were both fast asleep. This condition of theirs was brought to the mind of Mrs. Turnbull by the association of ideas when she heard the feet of the Sunday postman crunching the gravel of the drive. There seemed to her half-awake senses to be something wrong in this event happening when the vicar was in bed by her side, since it happened on other Sundays when the vicar was in church. Thus the startling thought came to her that there must be something the matter with the servants.

The postman’s knock had likewise awakened Edith, Alice being, as she always was when in bed, wholly under the clothes. Edith hardly knew what had happened; so frightful an event as the coming of the postman while they were in bed had never been known before. She endured the torment of a general when the enemy has crept round the camp, overpowered the guard, and begun to cut the throats of the sleeping soldiers.

‘The postman’s come! . . .’

Alice only replied by sleepy grunts to this outcry of terror.

When Edith saw her mistress and took all the blame, Alice was still at the looking-glass doing her hair. Edith had lit the fire before her fellow-servant slowly and crossly came down the back stairs. It was Alice who a few minutes after this served Mr. Turnbull with hot water. But it was not till the evening that the girls found out what had been the matter with Mr. Tasker.

The feeling of something having happened remained with them and gave them a pleasurable excitement all the day. The heavens were also disturbed: the gloomy giants’ heads concluded their growling by perfect torrents of straight rain, and the vicarage servants could not go out for their afternoon. Instead of going out they sat very thoughtfully over the kitchen table, Edith turning over the pages of a ‘Timothy & Co.’ sale catalogue, and Alice writing a letter to her mother.

For his Sunday’s supper Mr. Turnbull ate cold beef and pickles, and also talked very seriously with Mrs. Turnbull and their son, a poor simple fellow who was obliged to stay with his parents because no financier could extract one ounce of real work out of his mind or body.

Mrs. Turnbull and her son waited and listened, looking at the table. Would the conversation follow the lead of the onions, the beef, the sermon, or the Lord? The vicar’s thoughts passed by the Lord, stayed a little with the onions, and last of all fixed upon Mr. Tasker. The vicar always prefaced his remarks by looking first at Mrs. Turnbull and then at his son, as if to give them due warning that he was going to speak and that it would be best for them to keep quiet. He looked at them, coughed, and said:

‘Mr. Tasker spoke to me in the vestry after we had counted the money.’ To the vicar ‘money’ was a word as important as ‘church’ or ‘Lord.’ He pronounced it slowly, and when he came to the ‘y’ he gave a sharp click with his tongue as if he locked his safe. Having with his usual care delivered himself of ‘money,’ he went on with Mr. Tasker.

‘He told me he had met his father.’

‘How very terrible,’ said the foolish son.

Mr. Turnbull had a contempt for this son, and he never took the slightest notice of any remark that his son made. ‘Mr. Tasker’s father is out of prison,’ he went on, which led to an ‘Oh!’ from Mrs. Turnbull.

Alice left the room with an empty plate.

The family at the vicarage lived very quietly: they began the day very quietly and they finished it in the same way. A person with a large inquiring mind upon the subject of gods, watching the life at the vicarage, would no doubt have been puzzled for a long time to find out exactly what god they did serve there. One thing the person would have noticed, that the God, whatever He was, whether fish, man, or ape, was a remarkably easy god to please. He would have seen, had he been a Hindoo or a Tibetan, had he been anything except an orthodox Christian, that no persons in the household ever put themselves out for the sake of their religion. The church service and the family prayers appeared to be a kind of form of instruction for the poor, the church service being a sort of roll-call to enable authority to retain a proper hold upon the people. The clergyman was there to satisfy the people that there was no god to be afraid of; he was put there by authority to prevent any uncertain wanderings in the direction of God. At the vicarage the clergyman showed, by his good example, that his smallest want was preferred before God Almighty.

The vicarage stood, or rather sat—for it was a large low house—in a pleasant valley. Sheep fed on the hills around, and cows lay or stood about in the lowland pastures following their accustomed regulations as ordained by man. The cows had their milk pulled from them, their calves taken away; they were fatted in stalls when old and struck down in pools of blood. However, in the fields round about the vicarage they always ate the grass and looked the picture of content, except for the manlike disturbance and leapings that at times and seasons produced uncertain conduct and doubtful rovings in the bull. In the summer the creatures fed quite contentedly, or else, in very hot weather, they ran about to try to rid themselves of the flies. In the winter they stood with their tails to the big hedges. In the spring they spread themselves over the fields showing their separate backs and colours. In the autumn they got into corners and became a herd instead of mere cows.

The peace and quiet of the village was plain to any observer. No one toiled very hard and there was never any real want. There were quite enough women to take the edge off the male desires and quite enough beer to sharpen at the wrong end the natural stupidity of the countryman. If your special cult led you to write of country matters or draw Egyptian symbols on the farm gate, you could do so any afternoon at your leisure. If you preferred to paint or tar—I think tar is the cheaper—‘Our Lord, He is the Lord’ on any village stile, there would be no one to prevent you. The village demon was permitted to go, within certain limits, in any direction occasion might demand or your bodily needs require. Every little act that you did was quite well known to every one else, and every one shared the personal glory of goodness or vice. Every wise gossip collected and told again the pages of the village novel. All the people lived in a world of fancy, and every item of news was exaggerated and made intensely human, just as fancy chose. News, dull or tame, was made interesting by the addition of a good end, or a bad beginning, or a needful middle. When the clergyman was angry they made him foam at the mouth, and when Mr. Tasker came home they reported him to have been very drunk indeed and gave him a black eye from his father.

The vicar of Shelton, the Rev. Mr. Turnbull, was a sensible man, and he understood a great many very important matters. He was well clad in the righteous armour of a thick and scaly conscience that told him that everything he did was right. Mr. Turnbull was sometimes troubled with his teeth, but on the whole the days passed smoothly with him; the meals coming almost as quickly as the hours, gave him always something to do. Mr. Turnbull liked the world to run easily for him; he did not want jumps or jerks, nor cracks in the floor. Mr. Turnbull thought that he was quite safe in the world: he understood his way about the village and could always find the church or his own mouth when he wanted to. ‘He had a trouble at home,’ so he told the people, and they knew when he said that that he meant his son.

It was not Mr. Turnbull’s fault that his son was always there; the proper thing would have been for his son to have gone away as his other sons had done, one to the Church and one to medicine. The third son had never got beyond the third form of a rather poor preparatory school. And at sixteen, his ignorance being still in such evidence, the head master returned him to his father as quite unsaleable, and suggested farming and America as a cure for a hopelessly muddled education.

Mr. Turnbull, who was a man of action in some things, thought the matter over and shipped Henry off to Canada. The good vicar was a little afraid of the girls in America. In a picture paper that he had secretly smuggled to his study he had once seen a procession of them, asking for votes, in white frocks and carrying flags in their hands. They were tall girls and looked as if they knew what kind of earth they were treading on, and what kind of helpmate they had in man. The vicar had never seen or heard of any of these white-frocked pests—so he believed them to be—carrying flags in Canada. He imagined that there the hard-worked settlers spent their time cutting down endless fir trees, while their gaunt wives, taken for the most part from the Hebrides, suckled tribes of infants outside the doors of wooden huts. Mr. Turnbull thought it over, and then he pronounced the word ‘money’ to Mrs. Turnbull after he had eaten his beef and pickles one wet Sunday evening in November.

Mr. Turnbull thought it over, and shipped his son steerage to Canada.

The steerage of a great ocean liner is not exactly the best place wherein to receive light. But Henry Turnbull was nearer heaven in that lower deck than he had ever been before. One evening, as he was standing in a kind of bypath between two evil smells, a girl from Ireland walked quickly up to him and drew his face to hers and kissed his mouth. Henry never saw the girl again, she had run away with a laugh and was gone. Henry did not understand running after girls; he simply remained where he was and allowed the kiss—kisses do not stop at the lips—to sink into him. It gave him strange new wild feelings and sank at last into that deep lake over which the poets fish for golden minnows.

Those days were the first in his life when he could use his own legs as he liked, and move where he wanted to go. Before that time his legs had not been his own property. At school they were forced to kick footballs, or else to run to the farther end of a cricket ground after a long hit; at home his legs were always used to carry messages, every one used them for that purpose. But now at last he could walk where he liked in the limits of the steerage; and after that manner did Henry Turnbull reach the promised land.

In that new country Henry found himself in a log hut by the side of a steep mountain surrounded by tall fir trees, so large that he could not put his arms round them. In his pocket he had a letter from his father telling him that his duty to God was from that moment to cut down those fir trees. His father might just as well have told him to cut down Mount Cotopaxi.

In the log hut there were twelve bottles of whisky, one empty, a barrel of flour, and his partner. His partner stayed there for twelve days, and at the end of that time there were twelve empty bottles of whisky instead of twelve full ones. His partner was always with the whisky in the log hut. This partner was a second cousin in whom Henry had invested all his capital, the money that his father had lent him. On the twelfth day this amiable partner walked away to the nearest town, a distance of about forty miles, in order, so he said, ‘. . . to buy a new axe.’ He never came back again. He had taken with him to the town what remained of Henry’s money, which, with the help of a merry negress, he soon spent.

Henry was now quite alone with twelve empty whisky bottles, a barrel of musty flour, and the odour of his late partner. He tried to do his best; he picked up sticks and cooked Indian cakes with the flour, and hacked with a very blunt axe at the immense fir trees, beginning with the smallest he could find. In two months the flour was all spent, and the fir still standing, for in one of his attempts to conquer the tree, the first of five or six hundred, Henry had given his foot a nasty blow, and the last month he spent in cooking the cakes he also spent in trying to walk.

A society for the protection of poor aliens helped Henry home again. This society helped Henry to work his passage to Liverpool, having received from him in return everything that his partner had not robbed him of. If a girl’s kiss had made the steerage heaven, the sailors succeeded in giving him on the way home a very true picture of hell.

All this experience of the world’s humour taught Henry to love the vicarage garden and to do exactly what he was told by every one. In the vicarage garden Henry lived the life of an industrious child. He learned to understand turning over the mould in quiet and peace. He had seen quite enough and felt quite enough to prevent his trying to assert himself in any way. The mysterious underground currents that rouse men to the vice of action were quite unable to carry him away. He longed to look at every little thing and quietly to consider its meaning, and he noted all the incidents that happened around him. So far he had seen nothing very horrible, and he was always ready to enjoy a joke.

Henry grew a beard and read curious, old-fashioned little brown books, books written by old forgotten Church Fathers who thought like angels. Henry was surprised to find that these old thinkers were very much like himself. He quite understood their reasons for loving and believing, and he quite understood their deep melancholy that was by no means like the boredom that is sad only because it wants something to play with. He liked the way that these good men spoke of religion—a way individual and restraining, a way beautiful and mysterious, that was more afraid of its own virtue than of the vice of a brother. He delighted in their manner. They spoke of religion rather as an aged housekeeper would have spoken, with great dignity and quiet and peace. Although they often lived in wild times, they seemed to be moving in old palace gardens amongst tall white lilies far from the world and ever contemplating the works of that divine Saviour artist, Jesus Christ.

There were two events, one human and one vegetable, that Henry always remembered of his travels. One was the kiss and the other was the hacked fir tree. Often at night he dreamt of both, of the tree cut through at last and falling upon him, and of the kiss whose influence over his life was not yet gone. There was not much chance of another kiss. The girls of the vicarage—the servants were the only girls there—did not like Master Henry. Alice did not like his beard, nor his quiet manner, and Edith supposed him to be secretly sold to the devil because he spoke in the same gentle manner to every one.

Alice understood quite well what she was meant to do in the world; she felt herself quite plainly budding into a woman, and was well content. This young person possessed a round merry face; bright eyes, rather too green perhaps; brown, rather dark brown, hair; and a dainty, though by no means thin, girl’s body. For a servant she was good enough, for herself she was quite the nicest thing she had known. Alice was conventional, even more so than the vicar himself. She liked a man in his Sunday clothes, and to her mind a coming together must begin in the right way; it did not matter so much how it ended, it must begin with a Sunday walk up the hill, a proper sign to the villagers to watch events.

Alice delighted in Mr. Turnbull’s elder son John, who was a curate, and who came to see them sometimes, dressed in wonderful clothes and mounted upon a snorting motor bicycle. The Rev. John had looked at her once or twice, or perhaps oftener, in the right way, his eyes roving over her frock and stopping for a moment about her mouth and then slowly returning to her feet. The vicarage daily bread had given Alice her rounded form and one or two romantic ideas about John; it had given her the desire for more. She wanted very much to be a lady, and to bully—Mrs. Turnbull never did bully—a servant like herself.

The older girl, Edith, was nearly worked out, she had been at it so long. The vicarage house-cleanings and everlasting plate-wiping had washed all her youth away. She went to the village chapel whenever she could, and there she sang of her last hope—‘salvation.’

One afternoon the vicarage was sleeping peacefully, all the leads of its roof basking in the sunshine. It was quite pleasant to witness the content of this English homestead. The different creepers that climbed about it gave the house the appearance of a friendly arbour, and if a young maiden wearing a white frock and a hat with red poppies had danced down the steps the scene would have been wholly delightful. The stone steps were warm, and the front door was open, and inside was a cool dimness. The vicarage looked at peace with the whole world, and appeared to be under the wing of a very drowsy and sun-loving Godhead.

Alas! the most sleepy content has at times a bad dream, and terrifies the dreamer by showing him an ugly thing.

The Rev. Hector Turnbull stood outside his own door; he was wearing an old straw hat, and held in his hand a note. He looked around him. He was looking for something, he was looking for his son.

And then he called, ‘Henry!’ The tone of his voice was sleek and moist, disclosing the fact, unknown to the doctors, that every man has poison glands under his tongue, and when he speaks most gently he is really making up his mind to use them.

‘Yes, father, here I am,’ came the answer from the garden.

The contrast between the voice of the son and the voice of the father was very striking. The voice of the son expressed a natural melancholy and a candour quite his own, as well as an utter obedience to the will of others.

In a very little while Henry’s somewhat stooping form came up the path from the kitchen garden.

‘I am sorry to trouble you, but please come to me—here. I wish you to take this note—at once—to Mr. Tasker.’ And the father looked at his son with that interesting paternal hatred that the human family so well know, the polite hatred that half closes its eyes over its victim, knowing that the victim is completely in its power.

The reason for these two appearances whose voices met in a garden was that Mr. Turnbull, after his afternoon sleep of an hour, had written a letter to Mr. Tasker about the new church lamp, and when the letter was written, appeared outside the door and uttered the command, and the voice in the kitchen garden replied.

Henry walked away with the note. There was no need for him to hurry. Outside the gate, he noticed a little garden of stones and flowers that two children were building. He watched them for a moment and then passed by and saw something else. At first he did not know what this something else was. ‘What it was’ was being dragged across the meadow towards the dairy.

Henry was quick to notice and ready to love almost everything that he saw. He could note without any disgust a rubbish heap with old tins and broken bottles; he could look with affection at pieces of bones that were always to be found in a corner of the churchyard. The simple and childish manners of men always pleased him, he never drove his eyes away from common sights. He allowed his mind to make the best it could of everything it saw, and so far he had seen nothing very disgusting.

He was now watching a new phenomenon. The thing in question was harnessed to a horse, and it flashed and sparkled in the sun like a splendid jewel. The noise it made was not as pleasing as its colour. There was a sort of slush and gurgle as it moved along at the heels of the horse, sounds that suggested to the mind the breaking out of foul drains.

Henry noted the colour and the noise, and then the appearance coming nearer, showed itself to be the skinned body of a horse.

As he watched the thing, Henry felt as though he held the skinned leg of the horse and was being dragged along too. Anyhow, it went his way, and he followed the track of the carcass towards the dairy-house. Sundry splashes of blood and torn pieces of flesh marked the route. At the yard gate the procession stopped and Henry waited. He wished to know what happened to dead skinned horses that were dragged across fields; he had a sort of foolish idea that they ought to be buried. Anyhow, he had to take his note to the dairy.

There was something wanting in the field as he went through. At first he could not think what he missed, and then he remembered Mr. Tasker’s gods. There was not one of them to be seen. However, a grunting and squealing from the yard showed that they were alive. All at once Mr. Tasker’s long form uprose by the gate, chastising his gods with one hand while he opened the gate with the other. And then the strange thing happened. The carcass of the skinned horse was dragged into the yard and the gods were at it.

Henry Turnbull wished to see what men do and what pigs eat. He walked up to the gate and delivered his note, and watched the feast with the other men.

The pigs, there were over a hundred of them, were at it. They covered the carcass and tore away and devoured pieces of flesh; they covered each other with blood, and fought like human creatures. The stench of the medley rose up in clouds, and was received as incense into the nostrils of Mr. Tasker. At last the horrible and disgusting feast ended, and the pigs were let out, all bloody, into the meadow, and a few forkfuls of rotting dung were thrown upon the bones of the horse.

Henry was beginning to learn a little about the human beings in whose world he dwelt. He had had hints before. But now there was no getting away from what he had witnessed. There had been no actual cruelty in the scene, but he knew quite well where the horror lay. It lay in the fact that the evil spirits of the men, Mr. Tasker’s in particular, had entered into the pigs and had torn and devoured the dead horse, and then again entered, all bloody and reeking, into the men.

It seemed to Henry that he needed a little change after the sight that he had just witnessed, and so he wandered off down the valley through the meads that led to the nearest village, that was only a mile from their own. He thought a cigarette with his friend, who was the priest there, would be the best way to end that afternoon.

This clergyman was not a popular man. He had the distinction of being disliked by the people; he was also avoided by Mr. Turnbull and his other well-to-do neighbours, and was treated with extreme rudeness by the farmers. He lived in a house sombre and silent as the grave. He possessed a housekeeper who did two things: she drank brandy and she told every one about the wickedness of her master.

There were great elm trees round the house, so that in summer only a little corner of the roof could be seen. The place was always in the shade and was always cold. It was one of those old church houses through which doubts and strange torments have crept and have stung men for generations, and where nameless fevers lie in wait for the little children. The place was built with the idea of driving men to despair or to God. Inside the house you felt the whole weight cover you. Outside, the trees, overfed with damp leaf-mould, chilled to the bone. A list of the vicars and their years of office, that was hung in a corner of the church, showed how quickly the evil influence of the house had dealt with them. In the time, or about the time of the Black Death, five different priests had been there in the space of one year, and since then there had been many changes; hardly any incumbent had stayed longer than five years. It was a house intended for a saint or for a devil. Young Henry often went there, though his father very much disapproved of his going, but he went all the same, and Mr. Turnbull never missed him at tea.

The fields were delightful and cool as Henry loitered along them. Summer, full of her divinity, lay stretched before him. No heart could move without beating fast; the life of the sun was lord and king. The sounds that Henry heard were full of summer. The July heat was in a dog’s bark. The colours of the clouds were July colours and the stream trembled over little stones, gaily singing a summer song. A kingfisher darted down from under the bridge, and Henry could hardly believe he had seen it, because it looked so lovely.

Henry’s mind had regained its balance, and he could now drink of the cup that the summer held out to him. He breathed the sweet air and saw that the sun painted the upper part of every green leaf with shining silver. The July dust lay thick like a carpet along the road to the vicarage.

Henry pushed by the heavy gate. It could only open enough to let him pass: the lower hinge was off and the gate was heavy to move like a great log. The postman, who knew how to go about, had made a private gap through the hedge. In the way up to the house there was silence: the tall trees kept out all the wind, and the grass path appeared scarcely trodden.

A grassy way to an English home is a sign of decay and want. In the middle-class drives, clergymen’s or doctors’, a very long time is spent by the gardener every summer in digging out with a knife the seedling grasses that grow between the gravel, and farmers’ daughters are seen, in their shorter drives, performing the same office, kneeling on a mat, not praying to God but grubbing for the wicked trespassers that bring calamity to the household.

Henry’s feelings were not of the ordinary kind; once inside the gate he only felt the very rare human delight of being welcomed, welcomed, do what he might. He knew that if he were to die there of the plague, the hands of his friend would carry him into the house and lay him upon his own bed. He could not possibly have come at an unwelcome hour; no other guest could be there who would prevent the master receiving him with pleasure; there was no business so pressing as his business, that of friendship.

Henry walked up to the house. There was one low window wide open, a window that opened out into and touched the long grass. Henry went up the slightly trodden path towards this window. Mr. Neville, the vicar, was within, reading; his head was bent a little over his book. Had an artist seen him, an artist like William Blake, he would have thought at once of that romantic prophet, Amos the herdsman. The face was more strong than clever; it had indeed none of those hard, ugly lines, those examination lines, that mark the educated of the world. His beard and hair were grey, and his heart, could it have been seen, was greyer still; and no wonder, for he had found out what human unkindness was.

He had, unluckily for himself, broken down the illusions that the healing habit of custom wraps around men, and especially around the clergy. To tear off this vesture, to arrive at nakedness, was to open, perhaps, a way for heavenly voices, but certainly a way for the little taunts and gibes of the world, the flesh and the devil.

In casting off the garments of the world, this priest had not, like his comrades of the cloth, provided himself with a well-fitting black coat made in Oxford. On the other hand, it was easy for him to stay in the Church. He had no desire to make a show of himself or to set himself up in any kind of opposition to his religion, he was too good a catholic to allow any personal trend to undermine the larger movement. He held himself very tenderly and at the same time very closely to the altar, not from any sense of human duty, but because he knew the want of a divine Master.

Henry Neville, for they were two Henrys, these friends, shut the book he was reading and jumped up hastily. A pile of books and papers beside his chair was overturned; he put out his hand to prevent them, and then, seeing that they fell safely, allowed them to lie on the floor, while he, stepping through the window, went out to meet his visitor. They both returned to the study and sat down in cane chairs before the window.

The housekeeper, Mrs. Lefevre, a stout creature, old and unpleasantly human, knocked at the door, and without waiting for an answer, came in and produced a soiled table-cloth, and retired again for cups and plates, leaving the door wide open.

Henry Neville had around him always the hatred of nature and of man. Nature scorned him because he was helpless to dig and to weed and to plant, and because he was always catching cold. He had drawn to himself the malice of man because he had tried and failed to defend the victim against the exploiter. All kinds of difficulties and worries lay about his path like nettles and stung him whenever he moved. Naturally his health was not benefited by this treatment, and he was developing a tendency to cough in the mornings. By reason of all this unkindness Mr. Neville’s appearance was certainly very different from the Rev. Hector Turnbull’s, and Mr. Neville’s smile was not in the least like the smile with which Mr. Tasker greeted his black sow at five o’clock in the morning. There was nothing so different in the world as the smiles of these men.

By the merry means of the hatred of the people Mr. Neville’s mind had been brought to the proper state for the mind of a priest. He had seen himself so long despised and loathed of men, that he had even before our history opens begun to look towards a certain welcome release that would one day come; meanwhile he felt there was no running away at present for him, he must drink the cup that was prepared for him to drink.

The dislike of the people towards him kept him a great deal indoors, and if ever he ventured out into the cornfields he took care to walk apart from the eyes and jeers of the labourers and the coarse jests, always referring to his housekeeper, of the farmers.

Mr. Neville had left town because he had committed an offence. He had been for some years working in the East End of London, but one unlucky evening on his way to church, meeting a girl—he never knew who she was—in a ragged pink frock, he caught her and kissed her. It was the first time he had ever kissed a girl, and it was the last. The people stoned him out of the street and then broke the windows of his mission. His rector and the bishop were filled with amazement at the conduct of this unthinking curate and requested him to remove, because of the anger of the people, to the country. That is how Mr. Neville came to be in the gloomy vicarage of South Egdon.

When he first came down into the country he tried very hard to battle with the place; he tried to cut his own grass, he tried to make his own hay, but he did not succeed any better than Henry Turnbull succeeded with the fir tree. And so he held up his hands and surrendered to the enemy and learned to admire in his prison the beauty of long grass. His polite neighbours saw the long grass, or tried to open the heavy gate, and drove quickly away without calling, poverty in England being regarded as something more vile than the plague.

The bishop of that part of the country, a worthy man whose face resembled a monkey’s, shook his head over Mr. Neville and sighed out with a typical frown, ‘Poor fellow!’ and went on dictating a letter to his lady secretary.

It was part of Mr. Neville’s nature never to retaliate: when the nettle overgrew his garden he let it grow, when his housekeeper robbed him he let her do it, and when this woman told tales in the village about his immorality he never answered them. He knew quite well the kind of men who escape scandal, and he was sure he could never be like them. The people of the village were his warders, the vicarage was his gaol; and to be delivered therefrom, an angel, the dark one, must come to unlock the gate. He attended to his spiritual duties with great care, though he did not visit unless he was invited first, because so many of his parishioners had shut their doors upon him. This pleasant pastime of shutting the door in the clergyman’s face provided the people with many a good story, explaining with what boldness the deed was done, and boasting about it in the same way that the village boys boasted that they had killed a cat with stones.

Mr. Neville was not a great scholar, but he understood the soul of an author and he knew what he liked in a book: and that was the kind of deep note that Bunyan calls the ground of music, the bass note, that modern culture with its peculiar conceit always scoffs at. There was, besides this bass note, a certain flavour of style that he liked, a style that in no way danced in the air but preferred clay as a medium.

The first week he was at South Egdon he brought upon himself the extreme and very weighty dislike of the largest farmer, a man of much substance. Mr. Neville had been down to the village, and heard while at the shop two gun-shots at the farm fired one after the other. On coming out into the road he saw an unfortunate small black dog rolling and struggling along in the gutter, more than half killed, with blood and foam coming out of its mouth, mingled with unutterable howls of pain. The women came out of their doors to watch. ‘The dog,’ they said, ‘had been like that in the ditch for some minutes.’ The reason being, that the farmer, whose income was seventeen hundred pounds a year and who owned two or three farms besides the one he rented, would not expend another twopenny cartridge to destroy it properly. He had used two, and if the dog would not die it was its own affair: anyhow, that is how the farmer left it.

The clergyman had no stick in his hand with which to kill the creature, and the farm-house being near by, he hurried there and knocked loudly at the door. No one came. He waited, and the dog howled and snarled more despairingly down the road; it was furiously biting its own leg. The priest knocked again, and at last Miss Bigland, the farmer’s plump daughter, came to the door and smiled, and while she arranged a pink ribbon, she replied to the clergyman’s hasty request for her father.

‘Oh yes, isn’t it a nice afternoon? You’ve come about that nasty dog. Father has just shot at it. It would go after my chickens. How silly of it not to die!’ and the young lady smilingly explained to the clergyman the trouble the little black dog called ‘Dick’ had given them, the yells of agony continuing only a little way down the road. Just then the father, coming out from the barn, saw the clergyman, and his smiling daughter told him that Mr. Neville had come about ‘that bad dog.’ The farmer, without saying anything, but in his heart cursing the priest for interfering and the dog for not dying, went out with a great stick and beat the dog to death in the road. The girl, composed and plump and smiling, watched this event from her front door. The priest strode away, and meeting the farmer, who carried the dead dog by one leg, walked past him without speaking a word, to his own house.

The farmer, to revenge himself against the clergyman for taking the side of the dog, presented to the village a carefully prepared report that Mr. Neville had a wife and ten children in Whitechapel, and that every night at the vicarage he drank brandy with his housekeeper, out of teacups. The village imagination enlarged and magnified and distorted these tales until they were believed by every one, and a fine time they had of it, these village story-tellers, rounding off their little inventions when any new item of vicarage fiction came their way.

It was easy for the people of the village to hate Mr. Neville, and they hated most of all the vicar’s face. Perhaps because he looked at them gently and forgivingly, as if he forgave them their sins. They did not like his kind of forgiveness; they much preferred a brutal scolding, they asked for the whip. The children very soon learned to call out rude words at him as he went by, their favourite yell being a doggerel rhyme about the Lord’s Prayer, that began:

‘Our Father which art in Heaven,

Went up two steps and came down seven. . . .’

This they shouted out as loud as they could when they saw their priest in the road.

Only that foolish fellow, Henry Turnbull, loved him. And the two friends sat together that July afternoon, and smoked cheap cigarettes, regarding with wakeful interest the great trees and the long grass.

Henry had really been very much shocked that day, and he wanted to see his friend shocked too. Henry had not understood what he had seen. It was to him an isolated incident of terror in the homely life of the village, and he wanted it explained away. Its horror had made a very distinct impression upon his mind; he had never been told before so plainly that all was not right with the world. The girl’s kiss had been wonderful. He always remembered that. And the failure at cutting down the fir tree was only a failure. And his hardships abroad, like a trying campaign, had given him a lasting contentment at home. But now this new thing had appeared, and he wanted his friend to tell him what it meant. He opened the subject by talking about his father’s churchwarden.

‘He is a very hard-working man. He goes to church every Sunday and gives milk to the school tea. He is really a great help to my father. He sits amongst the boys at the back and prevents them spitting at each other, and turns them out sometimes. Father likes him very much, and praises the way he makes his little girls work. Father says there would be no idleness nor want in England if every one were like Mr. Tasker. Only, how can he drag dead skinned horses into his yard to be devoured by pigs?’

Mr. Neville watched the trees as he answered. He said quietly:

‘You must expect men like that to act rather crudely. Mr. Tasker would tell you that he must pay his rent; he would say that, like the Jehovah of old, his pigs cry out for blood and his children for bread. Mr. Tasker wants to get on, to rent a larger dairy, a farm perhaps, or even after a time to buy land, and his pigs are his greatest help. The fault is not Mr. Tasker’s, the fault is in the way the world is made. Mr. Tasker worships his pigs because they are the gods that help him to get on. The symbol of his religion is not a cross but a tusk. Mr. Tasker fulfils his nature. Nothing can prevent your nature fulfilling itself. Every one must act in his own way. No one knows what he may be brought to do. We can enjoy ourselves here and smoke cigarettes, but at any moment we may do something as ugly as he. It is horrible, it always will be horrible, but it is also divine, because the Son of Man suffers here too. Not iron nails alone, but tusks and teeth are red with his blood.’

Henry had listened to his friend with great eagerness. But it was now time for him to go, and his friend of South Egdon conducted him by a new way to the road round the low garden wall, that shut out a field of corn and harboured under its shade a large kind of nettle. When they came opposite the road they found the wily postman’s gap, and there they said farewell rather after the fashion of schoolboys.

Henry Turnbull wandered homeward, but he did not return through the meads. A desire had come to him to see the sun before it finally set. In order to do this it was necessary to climb the hill behind which the sun was hiding. Henry proceeded very much at his ease to climb a grassy lane that led to the top of the rise. He was contented to be alone, and needed quiet. ‘Perhaps it was a good thing,’ he thought, ‘that he had seen the way the dairyman fed his pigs.’ He did not wish to hide from himself anything human or anything that it was well for him to see, his nature was inquisitive enough to wish to know the worst and the best.

Once upon the top of the ridge, he was met by the fresh sweetness of the sea wind. The ridge of down overlooked the village of Shelton, his own village, that spread itself out in a desultory fashion between the downs. Upon the other side, the side of the inner world, the outer world being the way to the sea, the scene was grander and stretched with more varied colour. Towards the north were spread out acres of green woods, the remnants of an ancient forest much loved by King John, who came down there, no doubt, to relieve himself of his spleen against the barons. Farther away still there were, all along the skyline, blue hills over which the sun was loitering, very loath to leave the summer day. Occupying all the middle of the valley was the wild expanse of heathland. The mid region was entirely dominated by the heath, that only allowed a few green fields and fewer ash trees to poach upon its domain. In three or four places the wilderness, with its grey fingers, even crept up and touched the main road to the town.

While Henry stood there watching the last of the sun, a carrier’s van, that had been slowly coming down the main road, stopped beside the white lane that led to the village and was marked by one oak tree. It stopped there because the horse was unable to climb the hill. The small farmer who drove it was forced still to follow the big road in order to return by South Egdon, his customers, however, preferring to walk from this point over the hill to their homes. The van had no cover, and its human burden of country women, and one or two men, was plainly visible from the hill, and there were one or two splashes of red that denoted tiny girl children. Henry could easily see the women stepping out, and once he heard a child’s voice coming very clear out of the vale. Henry was aware that the people who were leaving the cart were bound for the village, and he preferred to stay where he was until they passed by. He knew that they were often met by other relatives, and he wished that evening to have the homeward way to himself. He lay down upon the short grass near a bunch of thyme to wait until the villagers, drawn on by their homes, passed him. He watched the groups slowly appear round the bend of the road that had hid them for a while from his sight. The women carried parcels, paper bags, and each held one or two heavy baskets.

Henry soon recognized the first that moved round the corner as the innkeeper’s wife. She walked with her son, a child who ran in little darts this way and that across the road like a field mouse. After her came the gardener’s wife, a short, stout woman in a heavy black dress that made her look very toadlike in the lane. She was surrounded, almost eaten into, by three or four children,—Henry could not tell how many, as they were always getting behind her, ‘in order,’ so Henry thought, ‘to take sweets out of her basket without being seen by their mother,’ whose efforts to climb the hill were at that moment all she could manage.

Another party, a couple, came slowly along some way behind. These two laggards were strolling along even more slowly than the woman in front of them—and they betrayed themselves. They were a man and a maid, that ancient mystery that was even beyond the wisdom of Solomon to unravel. The man wore black, the symbol of a Sabbath, or of a holiday, in the town. His bowler hat was also proper for those delights, and he flicked, as a gentleman anywhere would flick, at the knapweed by the side of the road. The man—and Solomon wisely puts him first—walked a little way ahead of his companion. She who followed at his heels was very much overloaded with parcels. She was dressed in her holiday white. Often she was so teased by the parcels—they would keep on slipping—that she placed one foot a little way up the bank and tried to rearrange them, letting them rest for a moment upon her knee. The man hardly ever took the trouble to look back at her—he had seen a girl before—but, with one hand in a pocket, he kept on flicking at the hedge. The narrow lane bore the burden of the mystery of these two.

The sun had just departed, leaving behind it a painted cloud to show where it had once been. The road, when it reached the top, ran for a few yards upon the brow of the hill as though to give the traveller a chance to look at the village below him before he descended.

Near this high level of road Henry was resting. When these two last from the van came by, Henry saw that the girl was his mother’s housemaid, Alice. She had seen him too and whispered his name to her companion, who turned his head disdainfully and for just a moment glanced at Henry. Henry knew him to be the son of Mr. Turnbull’s gardener, so wisely named ‘Funeral’ by the village.

‘Funeral’ had been married twice. His first wife he had buried, digging her grave himself. Alice’s companion from the town, an infant then, had been the cause of her death.

Henry’s father had employed ‘Funeral’s’ son for a time in the garden, but after his own son’s return he found him a place as under-clerk in a coal merchant’s office in the town, where he took to himself all the airs of a young man who knows things. Just then this young man’s knowledge took the form of annoyance that he was seen by a clergyman’s son walking with a servant.

Henry waited until the form of Alice, the last of the evening’s travellers, had left his vision, and then he followed the same road, descended into the village and joined his father and mother at supper, it being the habit in this clergyman’s family to devour the remains of a liberal early dinner at nine o’clock in the evening.

The following morning Henry was awakened by a rough wind. For a moment he thought he was lying again in the log hut, until he heard the rude, sharp knock of Miss Alice against his door and a water-can merrily hitting the floor just outside. Henry’s blind had not been pulled down—it never was,—and he watched the angry summer clouds, like mad black sheep, racing each other across the heavens, and he noted the tortured movements of the green leaves of the elm tree that resented being beaten by the wind. Henry was soon downstairs waiting for his father, his mother being already in the dining-room.

That morning Mr. Turnbull came in to read prayers in a friendly mood. He even smiled at his son, who sat looking out into the garden as his habit was. Mrs. Turnbull was finding her place in the Bible. Mr. Turnbull had received that morning a dividend, larger than usual, the reason of its extra value being that in the town where the works were—and in the works was a portion of Mr. Turnbull’s money—there had been much distress amongst the poor, and the factory could hire female labour at a very low price. The babes in the town died in vast numbers of a preventible disease, the most preventible disease of all, simply starvation. The out-of-work men stood about and talked of the ‘to-day’s bride.’ They stood at street corners and said ‘bloody’ a great many times, this particular word denoting a mighty flight of imagination like the sudden bursting of a sewer. The ‘to-day’s bride’ in the picture paper was the niece of a duke. Some of the men thought her very pretty. One of the men, who was especially taken with the innocent look of the young bride—she owned all the poor part of the town—returned to his ‘home,’ the bride’s house too, and found in there a gaunt, haggard woman who was not his wife leaning over a bundle of dirty rags upon which lay his little son, starved, stark, and dead.

Mr. Turnbull’s dividend carefully placed in the study drawer, he sat down to his breakfast with a ‘Thank God for this beautiful morning’ upon his lips. The eggs were good, Mrs. Turnbull very pleased and patient, the idiot son very thoughtful and silent.

Mr. Turnbull began to speak about the poor in his parish. He gave to the poor certain shillings sometimes out of the communion offerings, and twice a year he gave the children a tea. Just as he broke his egg he remembered, or rather his thoughts ran back, and fell down to worship the large dividend. He decided that the extra amount would more than pay the cost of the two teas, and that none of the few extra shillings that did get out of his pocket into the hands of the poor would have the chance to do so this year. Mr. Turnbull was glad. He looked around him, at the room, easy-chair, food, silent wife, silent son; he looked at the garden, at the little black clouds. He was satisfied; all this was very good, and after breakfast he went to the study to lock the dividend inside the safe. Mr. Turnbull then sat down by his table; he was content, he was ready to do what was right—to try to do what was right. He was making a sermon: it was his business to make the people understand sin. He felt serious when he thought of sin, and he also felt hungry.

Mr. Turnbull took an interest in the young women of the village; he always called them ‘young women.’ He spoke to them at the evening service with fatherly prudence, recommending ‘household duties’ in preference to summer evening walks in leafy lanes, and he gave them solemn hints about the fate in store for backsliders. To this subject—about the leafy lanes—he appeared to be bound by a magic spell. He could never let it alone; the sight of a dainty white hat trimmed with a rosebud, in the back pew, was enough. He began, and somehow or other the word—not a very pretty word—‘uncleanness’ came in at the end. It always did come in at the end, and the hat with the flowers often bent forward to hide the face beneath when this peculiarly unpleasant word was uttered.

To Henry it was quite a proper word, and he always applied it to a nasty heap of dirt that had found lodgment in a corner of the vicarage pew and naturally grew larger every Sunday because the church cleaner swept it there. ‘No doubt it was,’ he supposed, ‘against this heap of church dust that his father lifted up his voice in holy anger,’ and Henry wondered if this dust would ever rebel and try to get into his father’s eyes. The sermon was finished, the word ‘uncleanness’ being underlined, and the day passed as quite a usual vicarage day, a day of meals and lazy endurance, a day of slow kitchen labour.

There was, however, a slight activity shown by that stout good-humoured lady, Mrs. Turnbull, who gave sundry directions about the preparing of a bedroom for her eldest son, the Rev. John Turnbull, who was to come the next day.

The Rev. John Turnbull was, as we know, a curate in the West End, and, while enjoying himself in the best possible manner, he had the very serious business of finding a wife with money always before him. He went forth every afternoon, like a hunter, and followed respectable rich families almost to their bankers’ doors. He was polite and genial, the sort of young man who gives cigarettes out of a silver case to tramps. He was very friendly to every one, and enjoyed a good reputation amongst the Church well-wishers because he once or twice a week strode up a side street, in a long black garment that touched his toes, smoking a cigarette and talking to any one he met, and all for the encouragement of the Church. His rector watched him with a kindly eye and a daughter. He was really a very hard-working young man, who could always sign his name quite clearly in red ink. He was indeed a good fellow in his own way and understood his mystery, and lived a very cheerful life in the kindly bosom of the Anglican Church.

His religion was to him a part of the game, a very good game. He could pass the bread and wine, smile condolingly at a drunkard, and sadly, a waywardly sad smile, at a girl of the streets. One hundred poor typists wrote to him every week, or more often, and he referred them to the parish magazine, in which was his photo. He spoke to a member of Parliament about the typists, and the member undertook to look into their long hours. The curate told them all about the member and his kindness in the parish magazine.

The Rev. John began work in his church quite early in the morning, and was really tired when he left off for lunch. At that meal, except on Fridays, he indulged in a half bottle of Burgundy. After lunch he sometimes went to see an old man who was ruptured, so that he might have a little time to compose himself before continuing his hunt after rich girls. At the afternoon tea-table, his quarry having been run to earth, he talked of Socialism and about the way poor people are trodden down by the greedy rich. And if the quarry was touched at his account of the slums, he then went on to tell of the temptations to growing children, in those evil places. And then, if his hearers were not bored, he told them about his friend—he always called him his friend—who lived in a garret. He was the old man with the rupture. The Rev. John explained how his friend lived a beautiful life, spending his sad eternal bedtime in reading the Gospels, and that his friend was writing a book about St. Luke because his own name happened to be Luke.

This happy curate spent his evenings at the Workmen’s Club, and talked a great deal to a radical tailor, who did not go very far with the red flag because he had saved enough money to buy two houses. The young clergyman had a special kind of sickly smile that he brought out for the good tailor. He likewise played billiards with a printer’s devil, holding at the same time a cigarette at the very outside of his lips in true Oxford fashion while he aimed at the balls.

His stroll home at night had been once or twice delayed for a few hours—there is always something a man must do—but generally speaking he arrived at his lodgings at twelve-thirty and read a paper volume of short stories for an hour and then went to bed, very pleased with himself and very pleased with the world, at half-past one.

When at his country home, he patronized his younger brother, the idiot, and gave him cigarettes, a cheaper kind than he gave to tramps, and he talked to him in quite a friendly tone as he did to the gardener. He had now come home to tell his parents that he was engaged to a dear girl, who had Two Thousand Pounds a year. She was the daughter of a manufacturer of glass bottles, and her name was Ruby. He told his mother what a dear girl she was, and how much they loved each other. He spoke of this at dinner while Alice waited at table. Alice was neat and pretty; she meant to be pretty that day, and succeeded. The curate told her that she had grown to be quite a woman. She thought so too. She believed in the curate, and she said to Edith afterwards ‘that she would do anything he asked her to’; she said this in a tone of abandonment. He was just the gentleman for her: his clothes, his way of taking up a book, his cheerful cocksureness, his polite manner, all held within a proper gentlemanly decorum she loved. The Rev. John was attracted to Alice: he liked a pretty servant and Alice liked a nice kind gentleman.

August, the month of holidays, had come to Shelton vicarage. It was the time for delightful family meetings, and the third brother, George the doctor, joined the Turnbull party.

In his profession George worked very hard, and he was not as gay as his brother the priest. He was married because he thought that a doctor ought to be married. Dr. George Turnbull possessed, besides his wife, one little girl of twelve years. This young lady and her mother were left behind to take care of the gentleman who mixed the drugs and saw the patients while the doctor was away. Dr. George had come to Shelton because he wanted a holiday and because August was the proper time to take one.

Dr. George’s life was wisely settled. His practice was large and gave him constant employment. He passed over miles of rude country roads in his grey car, visiting the people who sent for him. He knew a great deal about medicine: he knew what drugs to avoid—the expensive ones—when he filled and corked the bottles. His little girl was pale and sickly owing to the fact that he thought more about leaving her rich than about keeping her well.

Mrs. George Turnbull was made into a proper lady by her marriage. Before that date she had only been a governess. Once married, Dr. George consoled himself with saying that a doctor ought to have a wife, and he made the best of it by turning her into a maid-of-all-work: the real servant, a plump cheerful cook, being very much more the lady.

Dr. George was a man of habit. What he did one year he did the next. Only in his savings did he desire to see a change: he liked that side of events to show a progressive balance, and it was to that balance that the grand trunk line of his thoughts ran.

The first happy day when this family party were all together ended at half-past ten, that being the proper hour in the country for bed. Henry took his candle and walked along the passage to his end room. He was thinking how kind his brothers were to him: they had praised the way he worked in the garden. The two elder brothers found the place quiet. When at home, they were wont to converse and rest upon the garden seat under the great elm, from which they could generally hear the click of Henry’s hoe in the kitchen garden.

The day after the arrival of the doctor the two brothers were sitting watching the flower beds and talking about incomes. Then it occurred to them both at the same time that a walk might be the proper Christian preparation for the next meal, and John thought, in his nice way, that it would be kind to take Henry if he had finished picking the currants for his mother’s jam. Henry had finished and was delighted to come. They even went with him along the road through the village without a word about his old hat and his beard, and John, with brotherly affection, took his arm.

Mr. Tasker, passing them on his way to the farm, touched his hat, a kind of salute that churchwardens do not generally make a practice of using. The three went along the chalk lane that led up the hill, by which Mr. Tasker had descended in the night, and by which young Henry had watched the arrival of the carrier’s cart. Dr. George saluted the lane side with prods of his stick. He was looking for herbs that, he explained to his brothers, were used for medicine.

John, the eldest, was likewise the tallest, and he could gaze over the hedge. Over the hedge there was a pleasant meadow and a girl helping her uncle, the small farmer of the village, load up some late hay upon a wagon. The girl, whose name was Annie Brent, had come from the town to help her uncle with the hay. She was upon the top of the load and her uncle below. The girl was employing her youthful strength to trample down the hay; after taking it in her arms from the top of the fork, she in turn placed it in the middle or the corners of the wagon. Her uncle, whose movements were very slow owing to his having a deformed foot, gave her plenty of time to place the hay and to jump on it, after which she lay down and waited until her uncle could persuade his foot to bring him to the wagon with some more. All this pressing of the warm hay brother John watched from the road. The pearl buttons that held the girl’s cotton frock behind had become undone, partly by reason of her jumping and partly because she was just over sixteen years of age.

The Rev. John Turnbull had a practical mind. He had found a rare girl—‘a dear girl,’ he called her—the proper prize of his hunting, and he decided that the time had come for him to turn another part of his attention to common girls. He did this whenever he had the chance, turning his eyes and his desires and his will-to-power in whatever direction the girl happened to be.