* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

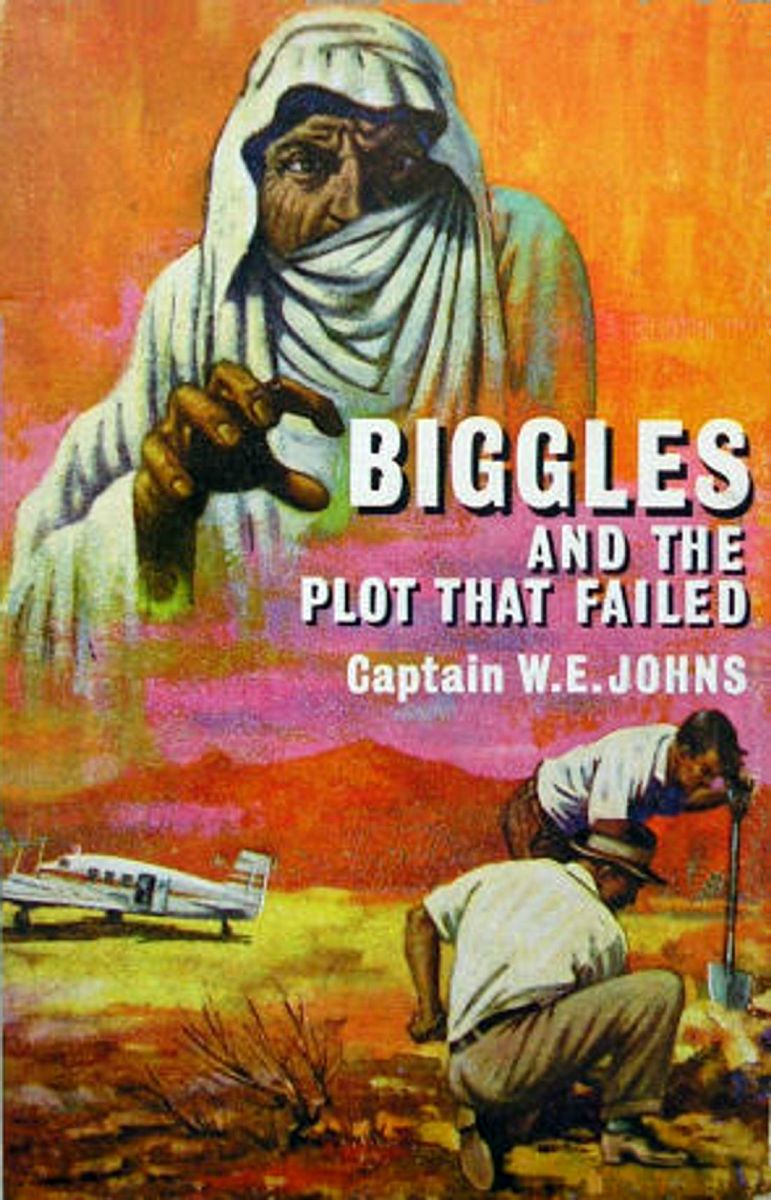

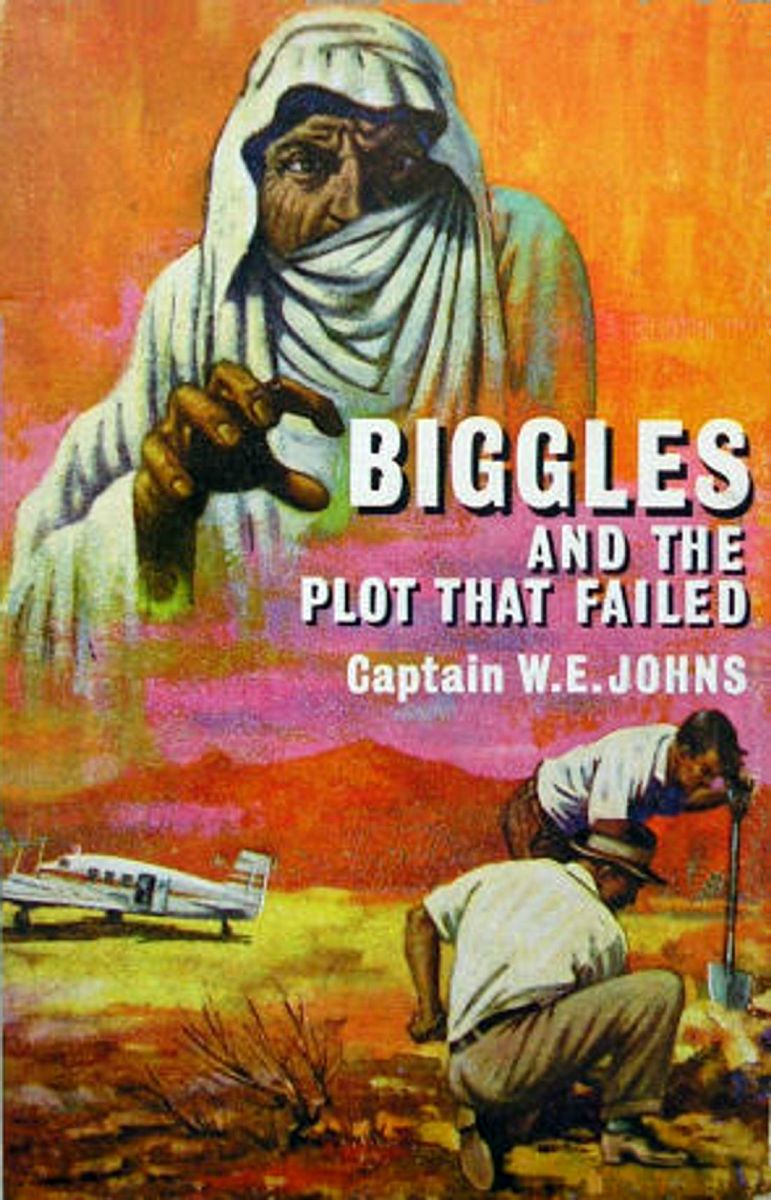

Title: Biggles and the Plot that Failed (Biggles #83)

Date of first publication: 1965

Author: W. E. (William Earl) Johns (1893-1968)

Date first posted: December 25, 2023

Date last updated: December 25, 2023

Faded Page eBook #20231248

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, akaitharam, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

BIGGLES

AND THE PLOT THAT FAILED

‘Where there’s gold there’s trouble,’ says Biggles, and during his trip to the Sahara in search of young Adrian Mander he met plenty of it. The tomb of the desert king held its own terrible secret, and to return to camp to find it sabotaged, petrol cans emptied and a horned viper in residence, was not Biggles’ idea of Oriental hospitality. But by far their biggest enemy was one of the most unmitigated rogues ever to appear in the casebook of the Air Police.

★

BIGGLES

AND THE PLOT

THAT FAILED

CAPTAIN W. E. JOHNS

★

Brockhampton Press

★

First edition 1965

Published by Brockhampton Press Ltd

Market Place, Leicester

Printed in Great Britain by C. Tinling & Co Ltd, Prescot

Text copyright © 1965 Capt. W. E. Johns

★

| CONTENTS | ||

| ★ | ||

| Chapter 1 | THE GREAT SAND SEA | Page 7 |

| 2 | A FATHER SEEKS ADVICE | 19 |

| 3 | AN UNEASY RECONNAISSANCE | 34 |

| 4 | AN UNPLEASANT SURPRISE | 45 |

| 5 | STRANGE DEVELOPMENTS | 56 |

| 6 | ASTONISHING REVELATIONS | 67 |

| 7 | ADRIAN IS OBSTINATE | 78 |

| 8 | THE TOMB | 93 |

| 9 | AN EXPERIMENT THAT WORKED | 104 |

| 10 | ADRIAN GOES ALONE | 115 |

| 11 | WHY ADRIAN DID NOT RETURN | 127 |

| 12 | NO FUN FOR GINGER | 141 |

| 13 | BIGGLES SPEAKS HIS MIND | 153 |

| 14 | SEKUNDER MAKES A MISTAKE | 162 |

| 15 | HOW IT ENDED | 173 |

| ★ | ||

The palms of the abandoned oasis of El Arig, the last outpost of the habitable world, hung motionless under a sky of burnished steel and heat that struck like a hammer.

On the rim of the depression from which the oasis sprang like a miracle Police-pilot ‘Ginger’ Hebblethwaite gazed through double-dark glasses, shaded by a green-lined sun hat, across a world of sand. The great desert, for as far as he could see, lay lifeless. An immense ocean of sand, utterly empty, utterly barren, utterly sterile; the parched skeleton of a land that had died under the merciless flogging of the everlasting sun. There was no shade; no rest for the eyes. No sound. No smell. No life. For nothing can live where no rain ever falls, no water ever flows.

There are deserts in which some forms of life have through the ages adapted themselves to endure eternal heat and drought. Here there was nothing. Only pitiless distances to horizons that reeled drunkenly in the thin, quivering air, the mocking sand, and silence. Absolute silence. The silence that is the silence of death. Everywhere a flat, tortured sameness. Or so it appeared.

Ginger, from past experience, knew better. He knew that this timeless, tideless ocean, was not flat. That the sand rolled in waves, like the waves of a storm-tossed sea suddenly frozen; great dunes, curving like horseshoes, which to the east and south marched in line abreast, if not to eternity as it appeared, then for a thousand miles or more. But with the sun directly overhead they cast no shadows and so could not be seen, either from ground level or from the air.

This was the region that even the Tuareg, those veiled nomads of the Sahara, called the Land of Devils; where, if you heard an echo, it was a devil calling. Ginger also knew that not all the fearful Libyan Desert was like this. He knew that out there beyond his view in the trackless waste a great rock formation broke through the sand, four hundred miles of gaunt black hills and silent canyons; mountains worn down by wind-blown sand to monstrous, misshapen stumps, like rotten teeth.

He also knew that there were vast depressions of cracked hard-baked mud, hundreds of feet below sea level, thought to be the beds of ancient lakes or inland seas. There were still some lakes, mostly salt; some, with vegetation, surprisingly beautiful. Or perhaps it was comparison with the surrounding desolation that made them appear beautiful. But in the great dunes there was nothing. Only sand.

What grim secrets did it hide? Ginger wondered.

He knew, as a matter of historical fact, that beneath this hideous sea lay the mortal remains of at least one army; an army of fifty thousand men, their pack animals, their weapons, their baggage wagons. In the year 525 BC Cambyses, son of Cyrus the Great of Persia, was in Egypt, destroying the Egyptian gods and seeking plunder. From Khargah Oasis in Upper Egypt his army set off across the Great Sand Sea bound for another oasis, Siwa, intending to destroy and sack the fabulously wealthy Temple of Jupiter-Ammon. The distance was four hundred miles. It never arrived. This great host vanished, never to be seen again. What happened? No one knows. But reasonable conjecture is that it was overwhelmed by a storm and buried for all time under the unforgiving sand—the vengeance, the Egyptians claimed, of their outraged gods. The Tuaregs say there are three armies under the sand. Who the others were we do not know; but it could be true, for this land is very, very old, and native legends linger long.

It is now thought that there were civilizations here reckoned to date back to 300,000 years BC. Little is known of these people. Only ruins remain; ruins of dwellings and temples with stones inscribed with an unknown writing; and graveyards of sun-bleached bones that lie as they may have lain for thousands of years.

North Africa was not always as it is today. The Romans called it Libya. It was from here that they obtained the wild beasts for the famous Roman circuses. To them, from the Atlantic to the Nile, was Libya; the southern part, Libya Interior. The modern name, Sahara, was introduced by the Arabs, the word Sahh’ra simply being Arabic for desert. What caused the tremendous change in this mysterious world is a matter for conjecture. There are several theories. One is that the Nile, or perhaps that other great river, the Niger, once flowed through the region, and at some unknown period of time changed its course, so leaving the land to dry up. The sand came on the prevailing wind from the deserts of Asia.

That could have happened. For as if heat alone were not enough to destroy life, here the sun has an ally. Wind. The wind that breeds the sand-storm. It can be born anywhere at any time. There is seldom any warning. A writhing yellow carpet rises from the desert floor. A gust of air as from the open door of a furnace picks it up and drives it forward until it seems the world has turned to sand, searing, blinding, suffocating. The dunes smoke. The sun, bloated and out of shape, disappears. A brown darkness falls. Earth becomes an inferno. Rocks are blasted to dust. Things that are not there appear, dissolve in sand and vanish. Nothing can survive.

After a storm, when the sand falls it can lay another trap. According to the way the grains lie the sand can pack down so hard as not to show a foot-mark. Elsewhere it can be as soft as snow, so that a man can sink up to his knees, and a wheeled vehicle to its axles. An aircraft cannot get off the ground in such conditions. Woe betide the pilot who finds himself bogged down, for under the desert sun the limit of time a man can live without water is twenty-four hours. Then the sun dries him up like an autumn leaf.

Even today the maps of this vast country are deceptive. Boundaries may be shown plainly enough, but they do not present a true picture. Egypt, for example, appears to be a country five hundred miles wide, and so it is as far as land surface is concerned. In actual fact; habitable Egypt is no more than the course of its great river, the Nile, seldom more than fifty miles wide. The rest is sand. Again, the boundary between Egypt and Libya is shown as a straight line running due south for seven hundred miles from the Mediterranean to the Sudan; but it would not be easy to find, for it passes across the Great Sand Sea where there are no marks, only the interminable yellow dunes. This may be the last part of the Earth’s surface to be surveyed.

As we have said, the country could not always have been like this. Of what lost civilizations it hides little is known, but the names of prehistoric kings and queens linger on in the tales of the dying tribes that cling to the oases on the fringe. There are tales of treasure, too; and there may be some truth in these, for there has long been a trickle of gold and precious stones from the region. Where these come from nobody knows, for they are sold surreptitiously, and the Arab finders, taciturn and suspicious of strangers, will not talk. Until recent times it would have been death for a Christian to go near them.

Perhaps the most famous oasis in the Sahara is Siwa, a series of lakes one hundred and twenty-five miles long, with rocky outcrops, inhabited by people who may be the last survivors of the earlier civilizations. Two thousand years ago, and more, it was a magnet that drew to it the greatest men of the known world, kings and conquerors who came to learn their fate at the celebrated Temple of Jupiter-Ammon, founded in 1385 BC. There, an oracle of high priests professed to be able to foretell the future. The ruins can still be seen on the hill of Agourmi. Close by are more ruins, the remains of the huge citadel and palace of the old kings of Ammonia. A quarter of a mile away is the Fountain of the Sun, mentioned by Herodotus in the fifth century BC and other ancient writers.

This was the objective of the ill-fated army of Cambyses. Here, too, among others, came Alexander the Great, to learn from the high priests whether he was human or a god. He had reason to think he was divine, for he lost his way in the desert and ran out of water; and he would surely have perished had not a miracle occurred. It rained—where no rain had fallen for three hundred years. Rocks named after him tell us the course he took. From Marsa Matruh, on the Mediterranean coast (where Cleopatra, the famous Egyptian queen, had her magnificent summer palace) it is about one hundred and ninety miles, ten days’ march, to Siwa.

After this long digression, intended to let the reader know something of the country in which Ginger now found himself, without breaking into the narrative later, let us return to him.

Feeling that his skin was cracking, for in such dry heat perspiration evaporates as it forms, he turned about and walked down into the wadi where, under the palms that formed the oasis, protected by sheets of black polythene stood an aircraft, the Air Police ‘Merlin’. The palms, with some acacia scrub, were there because the floor of the depression, being much lower than the surrounding sands, enabled their roots to get within reach of moisture drawn up by capillary attraction from the reservoir of subterranean water which everywhere has accumulated through the ages deep down in the earth.

This fact was known by men from the earliest times, for which reason they knew where to dig to reach the life-giving water. El Arig was no exception and could boast a shallow pool of blue water. Nearby, a light tent had been pitched, and within its meagre shade Biggles and Bertie sat in earnest conversation.

Seeing Ginger coming Biggles asked: ‘What do you think of it?’

‘I don’t like it,’ answered Ginger shortly, as he joined them. ‘In fact, I hate the sight of it.’

‘I don’t like it, either. I didn’t like it before we started,’ returned Biggles.

‘What are we going to do about it?’

Biggles shrugged. ‘Carry on, I suppose. We shall have to put up some sort of a show. What else can we do? I don’t feel like going home and admitting I was afraid of the sand.’

‘Aren’t you?’ inquired Ginger.

‘Of course I am.’

‘That would be the sensible thing to do, old boy,’ put in Bertie. ‘Frankly, this bally place scares me rigid.’

‘We’ve flown over deserts before,’ reminded Biggles.

‘But not this one, old boy—not this one,’ said Bertie vehemently. ‘Oh no. This is the desert of all deserts. In most, even in the Sahara, a few tough guys, like the Tuareg, who know the drill, manage to scrape along. But not here. They know this is the end and keep well clear of it. So would anyone with a grain of common sense.’

‘Mander must have been out of his mind,’ declared Ginger.

‘A case of a lunatic jumping in where angels fear to tread,’ resumed Biggles. He lit a cigarette and went on: ‘It’s a queer thing, but for some people a desert is an irresistible lure. Once they’ve seen one they can’t keep away from it. If they go they come back. There’s something about it that seems to fascinate them. Perhaps it’s because a desert is one of the few places where there is still peace on earth. I wouldn’t know. You might almost call it a disease. Desert fever. Anyone can catch it.’

‘I shall do my best not to,’ asserted Ginger.

Ignoring the interruption Biggles continued: ‘The British seem particularly susceptible to the disorder—Charles Doughty, Richard Burton, Gertrude Bell, Lawrence of Arabia, to name only one or two. They were prepared to suffer the most appalling discomforts and take the most fearful risks.’

‘And at the end most desert explorers have ended up in the sand,’ put in Bertie. ‘I know a bit about it. Major Laing was strangled by his Arab escort. Davidson, too, was murdered. Richardson died of thirst. Macguire was killed by Tuaregs.’

‘You won’t see any Tuaregs here. Besides, the people you’re talking about travelled on foot.’

‘I hope you’re not trying to kid yourself that flying is any safer,’ argued Ginger. ‘I can think of several machines which, taking a short cut across the desert, were never seen again. General Laparrine was one. He tried air exploring and died in the sand. Dying of thirst isn’t my idea of a comfortable way to end up.’

‘Don’t worry. I’m not taking any short cuts if I can prevent it.’

Bertie broke in. ‘Not all the machines that ended up in the sands were taking short cuts. Nor were they exploring or out to break records. What about that American bomber that went west with a crew of seven?’

‘That was a shocking business,’ admitted Biggles. ‘The result of a blunder.’

‘What was that?’ asked Ginger. ‘I don’t remember it.’

Biggles explained. ‘During the war an American heavy bomber based on North Africa was briefed to crack a target in Italy. It wasn’t seen again until long afterwards when the remains of it, and the crew, were spotted in the sand. That’s how the story got into the news. It was then possible to work out what happened. The bomber did its job, a night operation, and headed for home. Moreover it reached the North African coast. Then, finding visibility poor the pilot asked the base wireless operator for his position.’

‘Which is where the latest navigational aids came unstuck,’ put in Bertie. ‘The pilot must have been right over his own airfield at the time.’

‘Exactly. But he didn’t know that. The tragedy was, neither did the base operator. As far as he was concerned the aircraft was dead on the beam. This is what the pilot was told, so, naturally, he carried straight on, not realizing he had already overshot the airfield and was now heading out over the Great Sand Sea. By the time he spotted the mistake it was too late to do anything about it. He was nearly out of petrol. Remember, he had already been to Italy and back. A crash landing in the dunes now being inevitable he ordered his crew to bale out, which they did. He stuck to his ship and put it down in what turned out to be soft sand. The crew got together and did the only thing left for them. They marched north, hoping to get back to the coast, or somewhere near it. They never got out of the sand. They all died of thirst. The machine went on the “missing” list and for a long time what had happened to it remained a mystery. It was known to have reached the coast. Then what? I believe I’m right in saying it was a native rumour of a machine out in the sand that resulted in a search being made for it. So the lost machine was found.’

‘How do we know what happened?’ asked Ginger.

‘The bodies were spotted, one by one, strung out over a distance as each man had struggled on till he dropped. One of the crew had kept a diary to the end.’

‘I wouldn’t call that the sort of story to tell here,’ muttered Ginger.

‘You asked for it.’

Bertie came in again. ‘Never mind lost machines, what about this emerald mine young Mander was looking for? Do you believe in it?’

‘Who knows what to believe in a place like this? The story could be true. Native rumours, maybe exaggerated, usually have a foundation of fact. Remember, story-telling here, as elsewhere where there is no written word, is a business, a profession. The story-teller carries with him the tools of his trade, in this case a little leather bag filled with pebbles. To us they would all look alike, but not so to the owner. He knows them all. Each one represents a certain story. He takes one out of the bag, haphazard, and tells the story it indicates. The trade—or art if you like—has been handed down from father to son for heaven only knows how long. One of these tales, often told, concerned a fabulous Tuareg queen who once dominated the entire land that is now the Sahara. Her name was Tin-Hinan. According to the tale, when she died she was buried in a great rock tomb with much ceremony—and, of course, with all her treasure of gold and jewels. Few people took this seriously. But one man did, a French explorer with desert experience who knew the Tuareg. Deciding there might be some truth in the story, in 1927 he made a search for the tomb—and found it. There lay what remained of the queen’s body.’

‘But no treasure though, I’d bet,’ put in Ginger.

‘You’d lose your money. The treasure exceeded anything the Count de Prorok—that was the explorer’s name—had imagined; gold and silver ornaments, necklaces and bracelets and strings of precious and semi-precious stones. Apart from their intrinsic value the find caused an archaeological sensation in that it revealed a new page in the history of the world. The treasure is, or was, in the museum in Algiers. As in most places nowadays anything found has to be handed over to the country concerned.’

‘If the Tuareg knew about this why didn’t they rifle the tomb?’ inquired Ginger, practically.

‘They have a saying, the dead are best left alone.’

‘Perhaps Mander is trying to find another tomb like it,’ suggested Bertie.

‘Could be; but if what his father told me is correct, being an ardent archaeologist he’d be less concerned with treasure as a clue that would enable the ancient language to be read. There are certainly plenty of old tombs in North Africa about which nothing is known.’[1]

[1] This is true. The author has seen the huge stone cairn called by the Arabs ‘The tomb of the Christian Maid’. But nobody could tell him who she was or anything about her. Another is said to be the tomb of Cleopatra Selene, daughter of the famous Cleopatra and Marc Antony, who married Juba, who ruled the region once called Mauritania.

‘There is this about it,’ observed Ginger, perhaps trying to strike an optimistic note. ‘The only thing we have to contend with is all this confounded sand.’

‘Don’t you believe it,’ corrected Biggles grimly. ‘At this particular spot, perhaps. But according to Saharan explorers there are some oases, particularly where there are rocks, that fairly swarm with snakes, small but deadly; the cobras, or asps, one of which Cleopatra is said to have used to commit suicide. There is also a horrible little beast, a lizard called the ouragen. It’s only about eighteen inches long, but it has four sets of teeth, each fitted with first-class poison glands. If one of those devils gets his fangs into you, you’ve had it, chum. There’s no known antidote.’

‘Charming, I must say,’ sneered Bertie. ‘Why, I ask you, do we have to come to such a beastly place?’

Which brings us to the point where the reason for the airmen being where they were must be explained.

The assignment had begun three weeks earlier when Air Commodore Raymond, head of the Special Air Police, had called Biggles to his office. With the Air Commodore was a tall, well-built man of perhaps sixty years of age, clean shaven, hair going grey at the temples.

‘This is Brigadier Mander, an old friend of mine,’ introduced the Air Commodore. ‘He’s in trouble and thinks we may be able to help him.’

‘We’ll do our best,’ promised Biggles. ‘What’s the worry?’

‘The Brigadier has lost his son—his only son.’

‘I’m sorry—’

The Air Commodore broke in. ‘No, not that. I’m afraid I put it badly. Naturally, you assumed I meant his son was dead. He may be, but we have no proof of it. What I should have said was, the Brigadier’s son is missing, missing in our sense of the word. That is to say, two months ago he took off in an aircraft and has not returned.’

‘Has nothing been found—on the ground? Wreckage?’

‘Not a thing.’

‘Is it known where he was going?’

‘Yes. He didn’t make a secret of his proposed objective.’

‘Then provided he didn’t get off course it shouldn’t be very difficult to track him.’

The Air Commodore shook his head. ‘I’m afraid it isn’t as easy as that.’

‘Then what was his objective? One of the Poles?’

‘Worse.’

‘Worse! I can’t imagine anything worse.’

‘He set off, with a companion, to look for a tomb which, according to native gossip, is supposed to exist in the southern part of the Libyan Desert.’

Biggles grimaced. ‘You’re right, sir. I agree, that is worse. Much worse.’

The Brigadier spoke for the first time. ‘You talk as if you know what conditions there are like. Have you seen the desert?’

‘Yes, sir. Most RAF pilots who served in Egypt or North Africa must have seen it. Most of them I imagine would take care to keep away from it. That area of the earth has a sinister reputation.’

‘Why sinister?’

Biggles shrugged. ‘A pilot flying over it is trusting his life to a mechanical contrivance and even the best can go wrong. A pilot landing in the sand hasn’t much hope. Even on the fringe prospects are not too good. The natives, the Tuareg and the Senussi, have been pretty well tamed by now, but I wouldn’t care to trust them very far. To put it bluntly, too many aircraft that have flown out over the southern part of the Libyan Desert haven’t been seen since. That also goes, of course, for any other form of transport. It’s a good place to keep away from.’

‘But there have been reports of oases and ruins even in the heart of the desert.’

‘I know, sir. But that has yet to be proved. Most of the people who set off to get proof haven’t come back; or if they have they haven’t lived long. That may be coincidence, but you won’t get the natives to believe it. They say it’s the work of the devils who live in the desert.’

‘Poppycock. Superstition.’

‘No doubt, sir. This talk, apart from native rumours, about oases in the desert, was started by a French civil pilot, in, I believe, 1925. He was blown off his course by a haboob, as sand-storms are called locally. He reported sighting an oasis not marked on the map. He was killed in an accident before he could give more detailed information. Sir Robert Clayton flew out to look for this oasis. He found what from photographs he took appeared to be a fertile wadi. He was making arrangements to go back when he died. It’s very strange, but that has been the story all along the line. Whatever the answer may be, it isn’t surprising the place has got an evil reputation. I have an open mind about it. What on earth induced your son to tackle such a dangerous proposition?’

‘I’d better tell you the story from the beginning,’ answered the Brigadier. ‘It’s rather a long one, but by sticking to the essential facts I’ll make it as brief as possible.’

Biggles sat down, lit a cigarette and prepared to listen.

‘My son, Adrian, is twenty-one,’ began the Brigadier. ‘That is important because he is no longer under my control. He is of age, and a legacy left by his mother, who died some years ago, makes him independent. In plain English he can do as he likes.’

‘Which, from the way you said that, I take it he does,’ put in Biggles dryly.

‘Not always. Don’t mistake me. He is a good boy. He respects my wishes; but when our ideas are in conflict he is in a position to go his own way.’

‘I understand, sir.’

‘Naturally, as we have always been a military family I had assumed he would be a soldier. And so I believe he would have been had not certain events deflected him from that course. It is often said that a man’s life is what he makes of it, and up to a point that is true. But as often as not his actions are dictated by the people he meets; by incidents which, small in themselves, have consequences that could not have been foreseen. So with my son. He was always inclined to be influenced by others. It was meeting an RAF pilot, who had made a forced landing on my property in Surrey, that turned his ideas to aviation. This man stayed a few days at my house and the conversation was of nothing but flying.’

Biggles smiled. ‘There’s nothing unusual about that.’

‘The upshot of it was, Adrian told me he had decided to make the RAF his career, not the army. I raised no objection, but I said I thought he should finish his last year at Oxford, which in fact he did; but that did not prevent him from qualifying as a pilot at a flying school. He spent all his spare time in the air, and as soon as he came of age he bought a plane of his own.’

‘May I ask the type of machine?’

‘I never saw it except in the air over the house, but it was quite small with one engine. I seem to remember him calling it a Cub.’

‘And was this the machine he flew to North Africa?’

‘Yes.’

Biggles frowned.

‘Why? Is there anything wrong with it?’

‘Oh no. It’s reliable enough. But a light plane of any sort isn’t what I’d choose for exploring the Libyan Desert. I’m sorry I interrupted. Go on, sir.’

‘This is where I come to the second part of the story,’ continued the Brigadier. ‘During my service in the Middle East I got to know, and became friendly with, Sir Cedric Goodall, the archaeologist. You may have heard of him. He came home for the hot season from where he was digging up some old ruins in Jordan and accepted my invitation to stay with me for a few days. It was at my house that Adrian met him. Goodall is enthusiastic about his work, so, as you might imagine, the conversation now was about the things he had dug up and what he still hoped to find. Adrian, always impressionable, listened to this, fascinated. The upshot of it was, when Sir Cedric returned to what he called his ‘dig’, Adrian had accepted an invitation to go out and see the site. You see what I meant a moment ago when I said a man’s life can depend on the people he meets. Adrian flew to Jordan in his plane. He thought it was a good opportunity to try a long overseas flight. All went well. He stayed in Jordan for three weeks, long enough for him to become infected with this craze for digging up old pots and pans used by people thousands of years ago. When he flew home he brought with him a new friend he had met there; and so we come to the third man to have a marked influence on my son. By this time, you must understand, this archaeology bug had really got into Adrian’s blood.’

‘So this new friend was, I suppose, an archaeologist?’

‘Yes. Or he claimed to be; and I must admit he could talk as if he knew all the answers. Adrian had met him in Jordan, but in exactly what circumstances I don’t know. His name was Hassan Sekunder—the surname being, so I am told, Arabic for Alexander. I’d put his age at about thirty. He spoke English fluently and claimed to be an Egyptian. I hope I’m not doing the fellow an injustice when I say that in my opinion he could have been anything from a Turk to an Indian.’

‘I gather you didn’t like him,’ said Biggles.

‘There was really nothing you could put a finger on, but I wouldn’t have trusted him a yard out of my sight. He was a bit too suave, too oily, if you know what I mean.’

Biggles nodded. ‘I know the type. Are you sure this wasn’t colour prejudice?’

‘Oh no. Actually, there wasn’t much colour about him. His skin was that pale olive brown one so often sees in the Middle East. I haven’t spent all my life with men without learning to weigh them up.’

‘Did you tell Adrian how you felt about this man?’

‘Yes. But he wouldn’t hear of it. He thought he was wonderful. He could do anything and everything. I seem to be a long time coming to the point of all this, but I haven’t much farther to go. I wanted you to have a clear picture of the situation from the start. I must say that on his favourite subjects, archaeology and the history of the Middle East, he knew what he was talking about. He claimed that he had at one time worked for the Egyptian Archaeological Society. One of his jobs had been to go to an oasis called Siwa to report on some relics that had come to light. While there he had cured an old Arab of some disease, and for this was rewarded with the story which, eventually, was to take Adrian to the Sahara. I could see that coming a mile off, even before Sekunder put forward his proposition.’

‘Which was that Adrian should fly them both somewhere to find something?’

‘Exactly.’

‘What was the proposition?’

‘According to Sekunder the story the Arab told him was this. In the Sahara, somewhere south of a place called Siwa, there was an oasis that had not yet been put on the map. It was at the foot of some mountains that rose from a big depression that had once been a lake. In these mountains were the ruins of an ancient, unknown civilization. If such an oasis exists it was certainly not shown on any map that Adrian was able to procure. But there was more to it than this. This place was the tomb of a once great king of the Tuareg people named Ras Tenazza. Close by was the mine from which he obtained a fabulous collection of emeralds. These, by the way, were buried with him. The tomb was marked by a cairn of stones. It was at the foot of a tall, leaning, pinnacle of rock. It was put there so that when the rock fell it would hide the tomb for ever. At this place, too, there were many other tombs, some with inscriptions carved on the rocks. Adrian swallowed the story, hook, line and sinker, but I didn’t believe a word of it.’

‘Why not?’

‘Would you?’

‘I’d have an open mind about it. Queer things crop up in the Sahara from time to time. Was this place in Egypt or Libya?’

‘Sekunder, not having seen it, and unable to find it on the map, didn’t know. He said Siwa was just on the Egyptian side of the frontier, and the oasis was between two and three hundred miles south, or south-west, of it. I asked Sekunder, if he was so sure the story was true, and if he was convinced the oasis was there, why hadn’t he been there and so got the credit for the discovery? His answer was, such an expedition by camel caravan would be a costly business and he had never been able to afford it. I pointed out that, had he reported what he knew, either the Libyan or Egyptian government would have financed an expedition.’

‘What did he say to that?’

‘He said if he did that he’d get nothing out of it.’

‘He wouldn’t get anything out of it anyway—if he was honest—because by law he would have to hand over anything he found to the government of the country in which the discovery was made. That applies everywhere today.’

‘I didn’t know that. Nor, I am sure, did Adrian.’

‘Sekunder, if he had worked for the Egyptian government, or as a genuine archaeologist, would know it. It sounds to me as if he intended to keep anything of value.’

‘From the way he talked I’m sure of it. He offered a half share to Adrian, although I must say that my son, who was wildly excited about the whole thing, was more concerned with the adventure than making a profit out of the undertaking. Anyhow, to come to the point, Sekunder claimed it would be an easy matter to fly to the place. They would fly first to Marsa Matruh, on the coast, then on to Siwa where there was a landing ground.’

‘That’s true. Our fellows used it in the war.’

‘He also said he would be able to pull the strings to get visas and permits to fly over the desert—which I must admit he did.’

‘So they went.’

‘Yes. I was all against what looked to me like a foolhardy and dangerous business, but I couldn’t forbid it.’

‘How long ago was this?’

‘Two months.’

‘And you have heard nothing since?’

‘Yes. Adrian promised not to be away for more than a month and would keep in touch with me as far as this was possible. He wrote to me from Marsa Matruh saying they had arrived there without trouble. They were pushing on to Siwa the next day, and from there would take a course south, following a line of mapped oases for as far as they extended. Since then I have heard nothing. After a month of silence I began to get worried. When five weeks had passed I went to the Egyptian office in London and asked if they could help me. They were most co-operative and made urgent inquiries; but all they could tell me was, an aircraft had been seen at Siwa. It had stayed there for three days and then flown on without naming its destination. From the Egyptian office I learned something that increased my anxiety. Sekunder had said he had worked for the Egyptian Archaeological Society. It now transpired they had never heard of the man. That confirmed my suspicions that he was a liar, if nothing worse. What could I do? I thought of chartering a plane and flying out to Siwa myself. Then I remembered my friend the Air Commodore and decided to ask for his advice. That’s why I am here.’

The Air Commodore spoke, looking at Biggles. ‘I’ve told him you know something about flying conditions over the Sahara. What do you think of Adrian’s chances?’

Biggles looked dubious. ‘Without knowing exactly where he was making for and what preparations he made that’s a difficult question to answer. The Sahara covers a lot of ground. Even what they call the Great Sands, that is, the big dunes with no known oases, embrace thousands of square miles without a caravan track. From Siwa in the north to the Gilf Kebir Plateau in the south is something like a thousand miles. For five hundred miles east of the Khargah Oasis the map shows nothing except a water-hole on the fringe called El Arig. If Adrian is somewhere in that area where does one start looking? If he’s on the ground, unable to get off, it might be a hundred years before the machine is spotted.’

‘Adrian’s objective must have been within reach of Siwa. That was to be the final stopping place before heading out into the blue,’ stated the Brigadier.

‘Siwa is a biggish place, as oases go,’ explained Biggles. ‘Actually, it’s a long rather narrow string of oases, always getting smaller as they fade out in the desert. It would be the obvious jumping off place in the north.’

The Air Commodore came back. ‘I’ve told the Brigadier that without authority there’s nothing we can do about this. But still, as Adrian is a British subject, there’s just a chance that the government would sanction a rescue party if he was prepared to finance it. This, of course, would mean getting permission from the Egyptian and Libyan governments to fly over their territory. It’s unlikely they would raise any objection as long as they were not involved.’ The Air Commodore looked at Biggles. ‘If I put the proposition to the Higher Authority that we send out a search party would you take charge of it?’

‘Of course.’

‘Very well. We’ll leave it like that for the time being. No doubt if the Brigadier gets any news he’ll let us know.’

Biggles returned to his own office and told the others what was in the wind.

It was a week before he heard any more. Then his Chief sent for him again to tell him that, as the Brigadier had still heard nothing of his son, permission had been given for the Air Police to make a search using their own equipment provided Brigadier Mander was prepared to defray expenses.

That nearly brings us to where we came in. It took another week to make the necessary arrangements and get the permits to fly over the North African territories. Biggles had chosen to use the Merlin[2] brought on the strength of the Air Police for the operation narrated in Biggles’ Special Case.

[2] The Merlin. A twin piston-engined eight-seater originally designed for ‘feeder’ air lines in conjunction with the main air routes. Equipped with every modern device for comfort and efficiency (including a kitchenette and small refrigerator), it has speed combined with a considerable endurance range. It can climb with full load, on one engine if necessary.

The Merlin had landed at Siwa. Learning nothing there that was not already known, the party had gone on to El Arig, the oasis nearest to the region to be searched. Before them now lay the Great Sand Sea.

‘Now we’ve had a rest, tomorrow we’ll start on the real job,’ said Biggles seriously. ‘The only way to tackle it, as far as I can see, is to take the desert section by section, wedge by wedge using this as a base and sticking rigidly to the golden rule of flying over unknown country: which is never to go beyond the point of no return.[3] Two or three days should be time enough to cover the area of desert for which, to the best of our knowledge, young Mander was making. The trouble may be, in the absence of landmarks, to keep a check on what ground we have covered and what we have not. It would be easy to miss out a slice.’

[3] Point of no return. A distance from which an aircraft would not be able to get back to its base. If it did, its only course would be to continue on regardless of what lay ahead.

‘What do you think are the chances of Mander being alive?’ asked Ginger.

‘Pretty small.’

‘Then what are we going to look for?’

‘Frankly—we might as well face it—what I expect to find, if we find anything at all—is an aircraft with two dead men lying under it. It might be intact or it might have crashed. It wouldn’t make much difference. With what water it could carry, only by a miracle could Mander and his friend have survived for two months. Of course, miracles do happen, but not so often that you notice them. There’s one angle about this show, outside the obvious physical dangers, that disturbs me.’

‘What’s that, old boy?’ queried Bertie, seriously.

‘The Brigadier, who from his experience must be a pretty good judge of men, didn’t like this fellow Sekunder. He got the impression he was not to be trusted. He didn’t say so in so many words, but it was clear he thought he had a false card up his sleeve to play when it suited him. In short, Sekunder was not what he pretended to be; and that to some extent was proved when the Egyptian Archaeological Society denied all knowledge of him.’

‘As Sekunder wasn’t a pilot it’s hard to see how he could do anything underhand. I mean to say, he’d have to rely on Mander to fly him home.’

‘We have only Sekunder’s word for it that he knew nothing about flying.’

‘You think he might be able to handle a plane?’

‘It’s unlikely, but possible.’

‘But look here; had he been able to fly he wouldn’t have needed Mander. He could have worked on his own—if you get my meaning.’

‘Maybe it was the plane he wanted. Planes are expensive and he may not have had the money to buy one.’

‘Why did he pick on Mander?’

‘Since you ask me I’d say because he was young, inexperienced, and above all, enthusiastic. He would probably have gone anywhere with anybody if the object interested him.’

‘You think Sekunder told a cock-and-bull story?’

‘No, I’m not saying that. On the contrary, I’m pretty sure Sekunder believed the story he told, or something like it, or he wouldn’t have risked his life flying over such dangerous country as this. If he is playing a game of his own the trouble would blow up if something of value was found. The arrangement was, remember, equal shares. Sekunder might try to grab the lot. But all this is guesswork. Let’s wait until we get some evidence before we condemn the fellow as a trickster. The next day or two should provide the answer—if there is one.’

‘There is this about it, old boy; they haven’t been here or we’d have seen signs—litter lying about, and that sort of thing,’ remarked Bertie.

‘Matter of fact, I was rather hoping to find they’d been here because that would suggest this is the nearest water to wherever they were making for.’

‘Would they know about it?’

‘I’d think so. The oasis is big enough to be shown on the map. I reckon it’s a good half a mile long and half as wide, so they could hardly miss it. From what I’ve seen of it it’s some time since anyone was here. You’ll usually find camel dung round any desert water-hole, but what little there is here looks old stuff.’

‘Isn’t that a bit surprising—if you see what I mean?’

‘I don’t think so. After all, the place isn’t on any regular caravan trail; and there’s nothing beyond it for a long way except sand. Why should anyone come here?’

‘Then you don’t think we need mount a guard tonight?’ put in Ginger.

‘I don’t think that’s necessary. It’s obvious the place is little used. If some Arabs did turn up there’s no reason why they should do us any mischief. If you take my advice you’ll turn in while the sand is warm. It’ll be perishing towards dawn. It’s not so much the heat of the day that knocks you flat as the drop in temperature after midnight. It can fall as much as ninety degrees. Ginger, it wouldn’t be a bad idea if you brewed a dish of tea to replace some of the weight we’ve lost in perspiration. I reckon I’m down ten pounds already. Tomorrow, at sun-up, we’ll start work, leaving everything here as it is. It’s unlikely there will be visitors to interfere with it.’

The stars were still in the sky although losing some of their brilliance when, the next morning, the airmen were on the move, Ginger preparing coffee and the others removing the protective coverings from the aircraft.

‘This is the only time of day white men can work in a climate of this nature,’ Biggles had said. ‘I want to get back here before the sun is high enough to blister our hides. By noon it’ll be hotter than hell in the open desert.’

‘What exactly is the drill?’ asked Ginger, as they crouched round a small fire with coffee and biscuits, for the thin dawn wind that ruffled the palm fronds was bitterly cold.

‘For a first trip I shall fly a straight course out and back, on a compass course that will take in the most easterly area of the desert to be explored. I shall watch ahead. You two will watch each side. Bertie, you take the port side; Ginger the starboard. In that way we shall look over a lot of ground. If there’s anything to be seen we should see it.’

‘And just what are we looking for, old boy?’ questioned Bertie.

‘Anything that isn’t sand. The chances are that’s all we shall see—sand. Obviously, what we’re really looking for is an aircraft, a Piper Cub, down on the carpet, either in one piece or several. Failing that we might spot wheel marks to show where it landed at some time. One thing we can be sure of is: after the time it’s been away it’ll no longer be in the air.’

‘And that’s all?’

‘Not by a long chalk. According to this chap Sekunder, somewhere out in the blue in front of us there should be a range of hills, mountains or merely rock outcrops. I don’t know. If that’s true, and I see no reason to doubt it as no man in his right mind would start off for a nonexistent objective, we should have no great difficulty in finding the hills, anyway. Again, according to Sekunder there should be a conspicuous pinnacle which was to be the final objective. We’ll look for it, because provided the machine behaved properly that’s where we’re most likely to find it. If we locate these alleged hills that’s as far as I shall go. How many trips we shall be able to make will depend, of course, on how far it is to the mountains. All the spare petrol we have is a dozen jerricans. I’d rather not touch that, holding it in reserve for an emergency. We needn’t hump all that extra weight about with us. We’ll leave half of it here, in the tent. No one is likely to touch it. We shall know better how we stand, I hope, after we’ve made our first trip out.’

‘If the mountains are more than two hundred miles from here we shan’t make many trips,’ said Ginger, dryly.

‘You’ve put your finger on our weakest point,’ answered Biggles. ‘Until we know how far it is to the mountains, and established that they are really there, we’re flying blind—so to speak.’

‘And if we spot the machine in the sand are you going to land?’ queried Ginger.

‘At this juncture I’d say not. If the sand was soft we’d simply put ourselves in the same position as the Cub. That would be a daft thing to do. It isn’t as if the crew could still be alive. We’ll leave that until we’ve seen the machine and had a look at the sort of ground it’s standing on. There may be hard patches, but I’m not taking any risks.’

‘I’m with you there—absolutely,’ agreed Bertie.

Biggles got up. ‘All right. Let’s get on with it before the sun starts belting us.’

‘Don’t you think it would be a good thing if one of us stayed here to watch our kit?’ asked Ginger.

‘No.’

‘Why not?’

‘Because if by some wild chance we found the oasis, with Mander and Sekunder on it still alive, I shouldn’t come back here. There’d be no point in it. I’d pick them up and head north for Siwa. Whoever was left here would be stuck for a long time. It’s better the party should stay together.’

‘I see what you mean,’ replied Ginger.

‘Fine. That’s enough talking. Let’s get away.’

In a few minutes, as the glow of the false dawn spread upwards from below the horizon, the Merlin was racing across the hard sand that had packed down in the dry, treeless end of the wadi. It was on this it had landed, having ascertained from inquiries at Siwa that it was safe.

The air was still cold, and without a breath of wind was as stable as air can be; but they were all aware that this ideal state of affairs would not last long. Once the sun got into its stride the atmosphere would be as choppy as a stormy sea. The great dunes, some of them hundreds of feet high, would see to that. There would be no escaping from the ‘bumps’, for over hot desert country they can be felt at a considerable altitude.

However, for the moment flying conditions were near perfect, and having taken the Merlin up to five thousand feet, from which height in the crystal clear atmosphere it was possible to command a view of perhaps fifty miles in every direction, Biggles settled down to his predetermined compass course. Without a landmark of any sort in sight, there was no other way of keeping track of the aircraft’s position.

Ahead, now, lay the Great Sand Sea, a spectacle no man can contemplate, no matter how he may be travelling, without fear in his heart. Gazing across such a landscape he realizes, perhaps for the first time, how puny he is, and how insignificant the ordinary things of life. Ginger, looking through the window on his side, was very conscious of it; but he did not mention it. Such thoughts are better not expressed while in the danger area.

He was not without experience of desert flying, but this awful expanse of the earth’s surface, this world of silence and the ever-present threat of death by thirst, put ‘butterflies’ in his stomach. He knew that already they were all trusting their lives to a mechanical device commonly called the internal combustion engine; and engines, by their very nature, can never be perfect. Therefore, every change, real or imaginary (it can be either) in the note of the two power units caused his nerves to vibrate like banjo strings.

Biggles flew on at a steady cruising speed, his eyes restless, generally scanning the scene ahead, but constantly switching to the instrument panel to check that all was well.

Broad daylight came swiftly, to paint the mighty dome of heaven a blue of unimaginable intensity; not that this would last long; it would gleam like burnished metal as the sun thundered on to its zenith. Although he was wearing the darkest glasses procurable, Ginger knew better than to look directly at it. One glance can cause temporary blindness, and even permanent injury to the eyes.

The Merlin began to rock, sometimes with a short jerky movement, sometimes as if wallowing on a stormy sea.

For half an hour, during which time the oasis that was their base had faded from sight behind, nobody spoke. Then Biggles said quietly: ‘I can see something ahead. From the way it lies along the horizon it could be a range of hills.’

The others peered into the glare.

‘How far away?’ asked Ginger.

‘It isn’t easy to judge distance in this light, but for a rough guess I’d say the best part of fifty miles.’

‘Reckoning we must have covered more than a hundred, whatever it is in front of us can’t be more than a hundred and fifty miles from where we started.’

‘About that. Not too bad.’

Bertie spoke. ‘That isn’t sand we’re looking at; not even tall dunes. The line is too rough, if you see what I mean. It can only be rocks. Pretty hefty rocks, too. Stretches for miles.’

Biggles agreed. ‘We shall soon know. Watch for a fringe of palms against the sky. Palms would mean an oasis, or water not very far down. If it is an oasis it isn’t shown on any of our maps—not that there’s anything remarkable in that. Half the Sahara has yet to be properly surveyed.’

‘The question is,’ went on Ginger thoughtfully, ‘is this the place Mander and his pal were making for?’

‘Could be. We’ve no means of knowing. If it is it begins to look as if they got there. We’ve seen no sign of the machine. Even if they got to their objective it doesn’t follow they’re still alive. That would depend on whether or not they found water. That stuff, so common at home, takes top priority here. In fact, it’s the only thing that matters.’

‘I believe I can see palms,’ said Bertie.

‘Palms would no doubt mean dates. They could keep going on dates for a while, but they’d still need a supply of that stuff which at home we pour down the sink.’

The Merlin bored on through the now turbulent air, Biggles having to work hard with the control column to keep it on even keel. All eyes were on the horizon which had hardened to a jagged line, like a row of broken teeth. There was no longer any doubt. Before them was a range, or, as the line was not continuous, a series of groups, of gaunt black hills.

‘Keep your eyes open for an aircraft on the ground,’ said Biggles, beginning to lose height and taking up a slightly different course. ‘I’m aiming to strike the hills at the eastern end and work along them from there. I doubt if we shall be able to cover the lot today. We’ll see how we go.’

The picture in front was now fairly clear, and it was not a pretty one. Indeed, it was a scene of such utter and complete desolation, a chaos of sand and rock, not easy to describe. It might have been an imaginative artist’s impression of a newly-born unoccupied planet.

The great dunes fell away in diminishing waves to end at a shallow depression so vast that the extremities could not be traced. The sand, or much of it, appeared to have been blown, or washed, away to leave a comparatively smooth floor that could have been the bed of an inland sea or a once great river. From the centre, like the carapace of a giant crocodile, sprang a broad line of hills, of red and black rocks of all sizes and fantastic shapes. They gave an impression that they were the summits of mountains worn down by the erosion of wind and sand. Much of the ground in the broader parts of the depression presented a curious mottled surface, the result, it was presently observed as the aircraft flew lower, of countless small cracks.

Bertie had been right about the palms; but they were miserable specimens, dead or dying, the trunks grey, fronds brown and in tatters. There was no indication of water. The blast of heat flung up by the blistering rocks tossed the aircraft about like a scrap of paper.

‘We shan’t find anyone here,’ declared Ginger. ‘What a horror.’

‘There must have been water here at some time, and not so long ago; the palms are proof of that,’ answered Biggles, turning the machine to follow the depression.

‘Can’t we go a bit lower?’

‘No, thank you. This is low enough for me,’ returned Biggles grimly. ‘My arm’s stiff as it is, trying to keep us right side up.’ His voice rose to a cry of surprise. ‘Look at that!’ He tilted the aircraft so that they could all get a better view of what had caught his eye.

From between some rocks, apparently alarmed by the machine or its shadow, had broken six white, or pale-coloured, horned animals. They raced away in fantastic leaps.

‘Gazelle,’ said Bertie.

‘Oryx,’ said Biggles. ‘That can only mean there’s water at no great distance. Those pretty little beasts can equal the camel when it comes to endurance without water; all the same, they have to eat and drink some time.’

The oryx bounded into a canyon and disappeared.

‘If, as you say, there must be water in these hills, how about landing and looking for it?’ suggested Ginger.

‘Not on your life. It might be fifty miles away.’

‘I can see places where we could get down. That dry mud, or whatever it is, looks firm enough.’

‘We’ll consider that when we have a reason to land—and it’ll have to be a good one,’ answered Biggles grimly. ‘What we’re looking for is a plane, or the remains of one. Another thing we might watch for is a tall pinnacle of rock that looks as if it might topple over. According to Sekunder, at the base there’s a tomb which should be stuffed with gold and precious stones. That, of course, is what brought him here. Gosh! This is hard work.’

‘How much longer are you going to stick it?’ asked Bertie.

‘I’ve had about enough for one day,’ asserted Biggles. ‘Mark that red cliff, on the left, just in front of us. We’ll come back tomorrow and start again there, working along the hills for as far as they go. If Mander got here, as he hasn’t gone home his machine is bound to be here somewhere. We’ve still a lot of ground to cover.’

‘What are those heaps of white things I can see?’ asked Bertie in a puzzled voice.

‘They look to me like bones, probably camel bones. Of course, we don’t know how long they’ve been lying there, but if I’m right it would pretty well prove there must have been water here at one time.’

‘If camels came here, men must have been here, too.’

‘How do you work that out?’

‘Well, old boy, that’s pretty obvious. There are no wild camels, and tame camels would hardly come here by themselves. I mean to say—would they?’

‘They might.’

‘Why should they?’

Biggles smiled faintly. ‘That’s a question only a camel could answer. He does nothing without a reason. If you asked me to guess I’d say camels came here for the only thing that really matters in this part of the world—water.’

‘The camel has always struck me as a pretty dumb brute.’

‘In that case you’re right off the beam. Don’t get wrong ideas about the camel. I know he stinks and may have a foul temper; but who wouldn’t, the life he has to lead? Having said that, he’s just about the most perfect example of adaptation to environment you could find. He’s got a lot more sense than a horse. He can do anything a horse can do and a lot of things a horse can’t do.’

‘Such as?’

‘He can carry a load that would break a horse’s heart. He spends most of his life doing nothing else. Turn him loose and he’ll make straight for the nearest water—which is something you couldn’t do. When he refills his water tank he takes in a couple of gallons without pausing to get his breath. You couldn’t do that, either.’

‘He can’t beat a horse for speed,’ argued Ginger.

‘For a mile or two; but on a day’s journey I’d back the camel to get there first. When the horse has had enough the camel will still be striding along at the same pace without a falter. As I said a moment ago, if what we see down below are the skeletons of camels there must once have been water, no matter whether the beasts were brought here by men or made their own way here. But we’re not looking for camels, not dead ones, anyway. I can’t take any more of this. I’m going home.’

So saying, Biggles turned away from the rock formation and took up a course for the oasis that was their base.

They had covered about half the distance when Bertie let out a cry that might have expressed alarm or astonishment. He pointed to the north. ‘Oh I say! Take a look at that! It isn’t true.’

Far away, looming gigantic, striding across the sky—as it appeared—was a line of six camels. With the almost majestic dignity of their kind they marched in single file. As far as it was possible to judge each one appeared to carry a rider.

‘You’re right,’ said Biggles. ‘It isn’t true; or only partly true. We can’t actually see that caravan. It’s probably beyond the horizon. What we’re looking at is a mirage. They’re common enough in this sort of country.’

‘Who on earth can they be?’

‘I can’t imagine anyone except the Forgotten of God.’

‘The what?’

‘That’s what the Arabs call the Tuareg. Or maybe that’s what they call themselves. I don’t know. I only know that as a tribe there are not a great many left. They’re tough. The French had a lot of trouble with them when they first took over the Sahara.’

‘Unless the picture we see is cockeyed, those camels are making for the hills we’ve just left,’ observed Ginger.

‘Yes,’ returned Biggles thoughtfully. ‘That does surprise me. I wouldn’t have expected to find Tuareg here. What the deuce can be their object, I wonder? I’ll grab a little altitude. We may be able to see the real live animals.’ He gave the engines a trifle more throttle and eased back the control column.

This move defeated its object, for as the Merlin began to climb the picture began to fade, to dissolve, so to speak, in thin air. In a few seconds it had disappeared entirely, leaving only the everlasting sand.

‘Queer business,’ murmured Biggles, dropping back to cruising speed.

‘How about turning north for a bit to find the caravan?’ suggested Ginger.

‘No. It’s no concern of ours. We’d do better to mind our own business.’

The aircraft continued on its way.

The Merlin landed at its temporary base without mishap and taxied on to get as near to the tent as the palms would allow, a matter of fifty yards or so.

‘We’ll have a drink and get the covers on her,’ said Biggles as they got out and started walking. Suddenly he increased his pace, and then stopped, pointing at the ground. ‘Someone has been here,’ he said crisply. ‘These are camel marks.’

‘Well they aren’t here now or we’d see them,’ observed Ginger.

‘I wonder—did they touch our stuff?’ queried Bertie, a note of anxiety in his voice.

‘I wouldn’t think so; anyway, not unless they were desperately short of something,’ replied Biggles.

A few more paces and they stopped, staring. Where the tent had been was a black patch. Ashes. They hurried on. A glance confirmed their worst fears. All their property had been burnt; even the aircraft covers. For a minute no one spoke. Then Biggles said, helplessly: ‘I can’t believe it.’

Investigation revealed that everything had been lost except some foodstuffs that had been buried in the sandy floor to protect them from the heat. These evidently had not been discovered.

‘What about our spare petrol?’ said Ginger.

They strode swiftly to where, in a small depression at the foot of a palm, under a pile of dead palm fronds, six of the reserve cans had been placed.

‘This stuff has been moved,’ stated Biggles, grimly, as they approached.

Ginger was leaning forward to start uncovering the cans, when with a cry of ‘Watch out!’ Biggles thrust him aside.

Ginger looked startled.

Biggles pointed. No words were necessary.

Slowly, so slowly that movement was hardly perceptible, from the base of the heap a snake was emerging. It was small, not more than two feet long. Its head was squat and flat. From just above the cold glittering eyes rose a protuberance like a horn.

Ginger’s face lost some of its colour. ‘Good gracious!’ he gasped.

Biggles picked up a loose frond, stripped the dead leaves, and with the stem, in a single blow, broke the creature’s back. He then beat it to death and tossed the body clear. ‘I don’t any more kill things for fun, but that’s the only thing to do with those little devils,’ he said in a hard voice. ‘Had he got his fangs into you, Ginger, in about ten minutes this party would have been one man short.’

‘A viper?’

‘Horned viper. According to historians this was the asp that ended the life of the famous Cleopatra.’

Said Bertie, gravely: ‘It looks as if we shall have to be careful what we touch and where we put our feet. What was the little beast doing here?’

Biggles shrugged. ‘They’re common all over North Africa. You never know where one is going to pop up. Some oases, particularly where there are old burying grounds, are lousy with them. Near Biskra there’s a hill honeycombed with snake holes. The local Arabs call it The Cursed Site. They say that in the evening the snakes come out in thousands. No one can get near the place. The devil of it is the snakes attack without provocation.’

‘We shall, I trust, have no reason to go near it,’ said Bertie, polishing his monocle thoughtfully.

‘This one must have come here after we dumped the petrol,’ remarked Ginger.

‘Apparently. We made a nice shady spot for it. But never mind snakes. What about our petrol?’ With extreme caution Biggles began removing the fronds one by one. As soon as the top can was exposed he lifted it by the handle. The weight told him all he needed to know. ‘Empty!’ he exclaimed laconically. ‘Good thing we didn’t leave all our reserve fuel.’

‘Now who would do a thing like this?’ asked Bertie, sadly.

‘It must have been that caravan we saw—the mirage,’ declared Ginger. ‘It must have called here.’

‘That’s probably the answer,’ agreed Biggles, lifting out the remaining cans. All were empty.

‘Tell me this, old boy,’ requested Bertie. ‘Why, having scuppered our petrol, did they bother to put the cans back?’

‘They hoped, maybe, we wouldn’t discover the petrol had gone till we needed it.’

‘Or was it,’ put in Ginger, ‘to encourage the snake, which they may have put in, to stay there, hoping it would bite one of us?’

‘That’s a possibility that hadn’t occurred to me,’ admitted Biggles.

‘Oh, come off it,’ objected Bertie. ‘How could they handle the snake?’

‘Some Arabs, like some Indians, can do queer things with snakes,’ reminded Biggles. ‘If there is one anywhere near they can call it up. Don’t ask me how, but it’s a fact. I’ve seen it done. But never mind snake-charmers. This has given me food for thought.’

‘It must have been a party of Tuaregs,’ asserted Ginger.

‘That’s what one would naturally think,’ conceded Biggles. ‘It may be so, yet I rather doubt it.’

‘Why doubt it?’

‘To start with, what possible reason could they have for sabotaging our petrol? It was no use to them. From what I know about desert travel, Arabs in general have a code of unwritten laws about each other’s property. It must be so or they’d slowly exterminate each other. Arabs are Moslems, and to some, I know, it’s a matter of religion. Mahomet, in his wisdom, laid down some rules of behaviour. Even in tribal warfare, for instance, it was forbidden to cut down even the enemy’s fruit trees or date palms. It doesn’t take long to cut down a tree, but you can’t replace it as quickly. But let’s get out of this heat.’

‘Then what do you make of it?’ asked Ginger, when they were in the shade of the palms.

‘If Arabs, Tuareg, Senussi, or what have you, did this, then I’d say they were forced or persuaded by the man in charge of the caravan.’

‘But who could he be? What sort of man?’

‘I have a feeling it was someone who knew we were coming here; knew, or had an idea, of what we were doing. He didn’t want us here, and seeing a chance to make things difficult for us, took advantage of it. That’s all I can think of.’

Bertie chipped in. ‘But look here, old boy. That implies some rascal knew about Mander’s air trip and its purpose.’

‘You can put it like that.’

‘In which case we haven’t much chance of finding Mander alive.’

‘That doesn’t follow. There’s another side to the picture. If Mander was known to be dead, why interfere with us? Mander may be dead, and probably is, but as I see it the man responsible for this didn’t know whether he was dead or alive. And that goes for Sekunder. Someone was wise to what they were after. Of course, the raiders may not have known we were here, or who we were, but they’d see our landing tracks and guess.’

Ginger spoke. ‘I suppose this couldn’t have been the work of that fellow Sekunder? Mander’s father took a poor view of him—said he wouldn’t trust him a yard.’

‘Even so, it’s hard to see why Sekunder should injure us.’

‘Suppose he and Mander found a treasure. He might plan to grab the lot.’

Biggles considered the suggestion. ‘I can’t see how that could happen. Sekunder went with Mander in the aircraft. How could he get here, or back to Siwa, without him?’

Bertie cut in again. ‘Talking about it isn’t going to help us. The kernel of the bally nut, if I may say so, seems to me to be this. What effect has this dirty business had on our arrangements?’

Biggles answered. ‘Very little, beyond the obvious fact that we now know we have unexpected enemies to contend with. We can still make two more trips to the mountains, and that should about cover the lot. If Mander reached them we should see his machine. If he didn’t it would be a waste of time looking for him. I don’t propose to search the entire Sahara. We shall just have to be more careful from now on, that’s all.’

‘Careful?’

‘I’m thinking particularly of fuel and food. As far as food is concerned we should be able to manage on what we have. At a pinch we can help out with dates for the short time we’re likely to be here. Thank goodness the people who came here didn’t interfere with the water. That would have put the lid on us.’

‘They may have left it alone knowing they were coming back this way, and would need it,’ said Ginger.

‘There may be something in that,’ agreed Biggles.

‘I’ll tell you something else,’ went on Ginger. ‘The thought has just occurred to me. If these raiders left here for the mountains, why didn’t we see them, instead of only their shadows?’

‘That’s easy to answer, although we’ve no proof they were heading for the mountains. For the sake of argument let’s assume they were. The range, as we saw, is a long one, running for miles. They may have headed for the far end, in which case they’d be on a different course from us. I mean, we wouldn’t actually fly over them. We may see them tomorrow. I’m not doing any more flying today, in this infernal heat.’

‘Then you intend to carry on?’

‘Of course. As if nothing had happened. Tomorrow we’ll do what we did this morning, taking in a different section of hills. If that’s where the raiders are bound for we shall beat them to it. We reckoned the hills were a good hundred and fifty miles from here. The thieves could only have arrived here after we left, so when we saw the mirage they couldn’t have been far on their way. As camels go, I can’t see them getting to the hills inside four or five days. As far as we know they have no reason to hurry. With no intermediate oasis those camels will be heavily loaded. They’ll have to carry all the water they need with them. Come to think of it, they must be reckoning on finding water in the hills. They couldn’t carry enough to get them there and back here.’

‘A camel can go for days without water.’

‘That may be, but he goes better with a belly full. He doesn’t like going without a drink any more than we do.’

‘Tell me this,’ went on Ginger. ‘As there’s no trail across the big sands, how do they find their way?’

Biggles nodded. ‘You make a point there, one that might answer some of our questions. Desert Arabs know the stars for night travel. The caravan we saw was on the move in daylight. Like us, it could have been on a compass course. To the best of my knowledge Arabs don’t carry compasses. So what? It suggests there’s someone in the party, possibly a white man, who has a compass and knows how to use it. And while we’re on that angle I’ll tell you something else. According to my information, Arabs, even Tuareg, keep clear of the big sands. They’re the home of devils.’

‘What are you getting at?’ asked Bertie.

‘To travel across the open desert to those hills would be a risky undertaking at the best of times. A sand-storm would wipe out a caravan in no time, and the men with those camels must know that as well as we do—probably better. Therefore it seems to me that the people who came here and pinched our stuff, and are presumably now out in the desert on their way to the hills, must have a thundering good reason for risking their lives; because that’s what they’re doing, and they must know it. For what are men prepared to risk their lives?’

‘Money, old boy. Money.’ Bertie supplied the answer.

‘Jolly good. You may have hit the nail right on the head. I would wager that at the end of this trail there’s money, and lots of it.’

Ginger’s eyebrows went up. ‘You don’t mean real money, actual cash?’

‘Of course not. Things worth money.’

‘Treasure?’

Biggles smiled cynically as he lit a cigarette. ‘Perhaps. It depends on what you call treasure. You know how I feel about treasure hunting. There could be some interesting relics in the mountains, but I wouldn’t expect to find a treasure to be compared with, say, the Inca gold of South America. I see two possibilities of a valuable find. They may be linked together. First, there’s this alleged tomb, near a pinnacle of rock, of some ancient king of the region; a chap named Ras Tenazza. In accordance with ancient custom his personal property was buried with him. This was Sekunder’s story and there could be some truth in it. Legend has often been found to have a basis of fact. Obviously Sekunder believed the story, or he wouldn’t have been such a fool as to come here.’

‘All right,’ put in Ginger. ‘Let’s suppose a king named Ras Tenazza was buried in the mountains and his people put his bits and pieces with the body. What do you suppose they would consist of?’

‘We can only judge by what has been found in other old tombs in North Africa. There would, I imagine, be a certain amount of gold and silver, in the shape of jewellery and ornaments, and some precious and semi-precious stones. That may sound fine and romantic, but let’s not forget that we didn’t come here on a treasure hunt. We came here to look for young Mander—at his father’s expense. He’d take a poor view of it if we wasted our time looking for a collection of antiques.’

‘You said yourself there had always been a trickle of emeralds from the interior and no one knew where they came from,’ reminded Ginger.

‘So I’ve been told, and that, I must admit, supports the story of an emerald mine near the tomb of King what’s-his-name, although, of course, the emeralds may have come from other old tombs. Sekunder may have had a second string to his bow. Failing to find the tomb, he may have hoped to find an emerald mine. Obviously he didn’t come here just for the hell of it. He had ideas of getting rich quick.’

‘And if he found an emerald mine he’d get what he wanted, if you see what I mean,’ interposed Bertie.

‘Perhaps. On the other hand he might find he’d been sold a pup.’

‘How do you make that out?’

‘There are emeralds and emeralds. Some are worth practically nothing. To be of any great value a stone must be perfect, and a large perfect emerald is something that doesn’t often happen. As it comes out of the ground an emerald is a green crystal. It can be transparent, or translucent, and it hardens on exposure to the air. Emeralds have been found weighing over a hundred pounds, yet they were worth practically nothing.’

‘Why not? I don’t get it.’

‘Because they were so full of flaws, and so brittle, that they went to pieces at a touch. A large emerald without a flaw, which ruins its natural beauty, is rare. Find one the size of a robin’s egg and you could ask any price you liked for it. It’s the same with rubies. These huge rubies that the Indian princes used to wear are not worth as much as most people imagine. They went in for size; but with all gems it isn’t so much the size that counts as quality. If you try to cut down a big stone to get a perfect piece out of it, it’s liable to fly to dust and you find you’re left with nothing.’

‘How does that happen?’

‘Because the flaws are minute pin-holes of compressed air, ready to explode if they’re touched.’ Biggles frowned. ‘But what’s all this talk about precious stones? We’ve more important things to deal with.’

Ginger grinned. ‘You started it. You thought Sekunder might be looking for an old emerald mine.’

‘Quite right. So I did.’

‘That would go for Mander, too, I suppose.’

‘Maybe. Maybe not. From what his father told me Adrian was more interested in genuine archaeology. Having money of his own, I imagine he’d get a bigger thrill from discovering something that might throw a light on the original inhabitants of what is now the Sahara, before it completely dried up. But that’s enough. I’ve talked myself dry. Ginger, you might slip over to the machine and fetch some soda water from the fridge. Tomorrow we’ll have another bash at the mountains.’

Dawn saw the Merlin again in the air, heading for the hills, this time on a slightly different course, one calculated to strike the objective nearer to the middle; that is to say, beyond the point where the reconnaissance of the previous day had been concluded.

It was thought they might see the caravan that had produced the mirage, and they did. Within a quarter of an hour it could be seen in front of them, six camels in line winding through the great dunes. The caravan did not stop, although the raiders must have heard the plane long before it was over their heads.

‘They must have seen us,’ remarked Ginger, looking down from five thousand feet.

‘Of course,’ replied Biggles. ‘They have no reason to stop; and I could see no reason why we should try to avoid being seen. We’ve no proof that they are concerned with what we are doing. We shall reach the hills, and that must be where they’re making for, long before them. They can’t move any faster.’

The Merlin went on, quickly overtaking the earth-bound travellers. Bertie picked up the binoculars and focused on them.

‘What can you see?’ asked Biggles.

‘Five riders and what seems to be a pack animal, well loaded.’

‘Are they looking up?’

‘I don’t think so.’

‘You can’t see a white face?’

‘No. Their heads seem to be muffled up.’

‘If they’re Tuareg they would be. I can’t imagine anyone else doing what they’re doing. The Tuareg wrap their heads in blue veils, which is why the Arabs sometimes call them the People of the Veil. I’m told they never uncover their faces, even to eat. They merely lift the veil.’

‘But aren’t the Tuareg Arabs?’

‘No. They’re a tribe on their own. Some experts have worked it out that they’re the last descendants of the nation that once occupied all this country. That was before it dried up, of course. They have the reputation of being tough fighters—and fast travellers. Here today and gone tomorrow. I don’t think it happens now, but years ago more than one French outpost of the Foreign Legion was wiped out by them.’

‘Then let’s hope we don’t get in each other’s way,’ said Bertie.

The aircraft bored on under the usual implacable sky of deepest blue. The hills came into view, fringing the horizon like the spine of a prehistoric monster.

Ginger put a question to Biggles. ‘Why do you suppose the caravan went to El Arig before making for the hills, if that’s where they’re going?’

‘Possibly because El Arig was the nearest convenient oasis.’

‘There are other oases to the north. According to the map a string of oases runs out into desert from Siwa. They were no use to us because we were told there were no landing grounds; but that wouldn’t prevent camels travelling that way.’

‘I wouldn’t know the answer to that unless it was because other people use those oases. Maybe the men with the caravan coming this way didn’t want it known where they were going. In the desert people are curious, and news travels fast. I don’t see that it matters, although I must admit it’s a bit queer that a caravan should be on its way to a district, where no one ever goes, at the same time as ourselves. From what I could gather at Siwa no one ever came here, one reason being there was no water, and, secondly, there was nothing to come for. Not even Arabs venture into the big sands for no reason whatsoever. But here we are. Keep a sharp look-out for anyone moving, or anything that looks like wheel tracks or a burnt out plane.’

‘If by some remote chance Mander should still be alive, surely he’d run into the open to show himself when he heard us,’ said Bertie.