* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

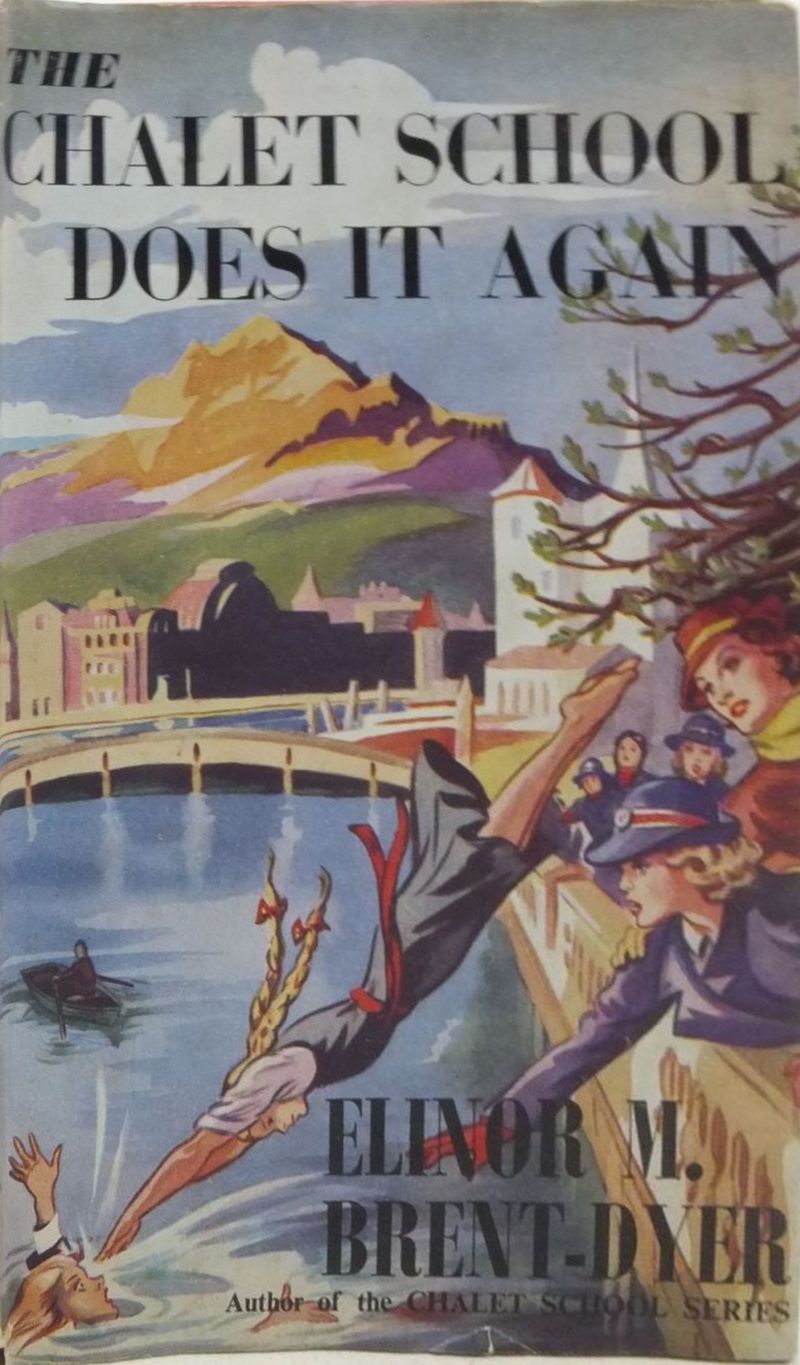

Title: The Chalet School Does It Again

Date of first publication: 1955

Author: Elinor Mary Brent-Dyer (1894-1969)

Illustrator: D. Brook

Date first posted: Dec. 7, 2023

Date last updated: Dec. 7, 2023

Faded Page eBook #20231209

This eBook was produced by: Hugh Stewart, Alex White & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

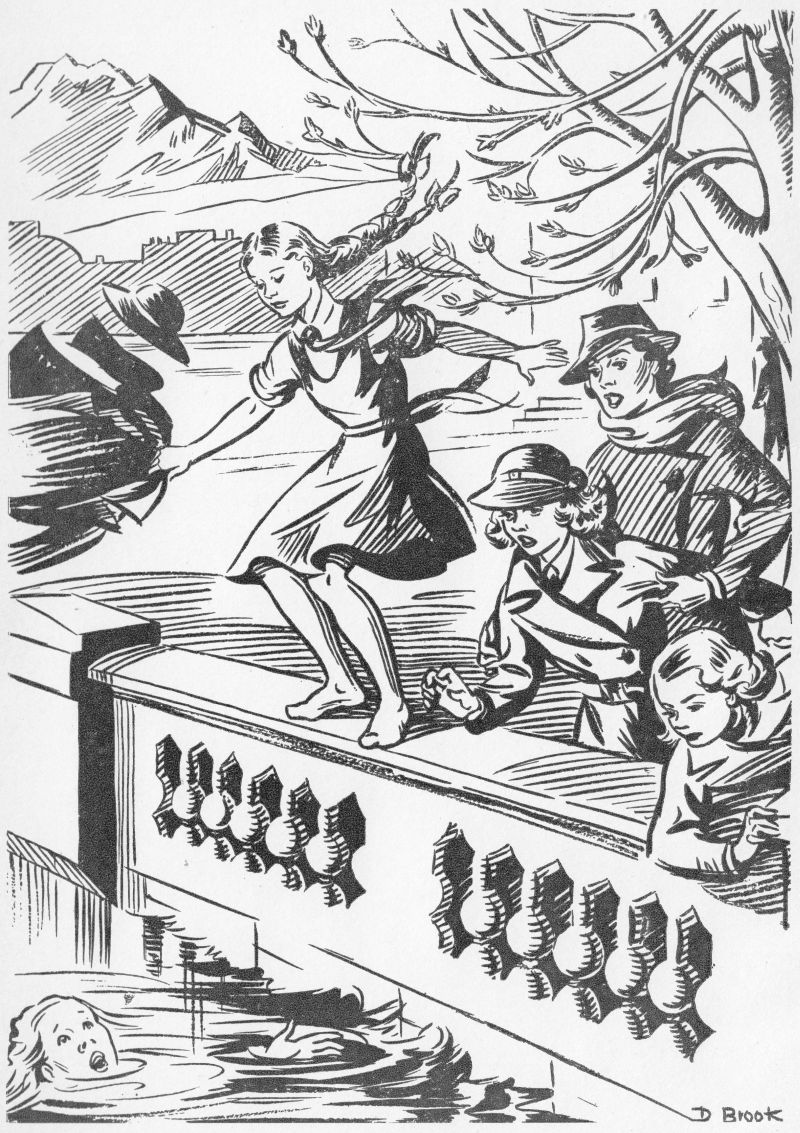

Prunella wrenched off her coat and, before anyone could prevent her, had climbed the railings and dived . . .

THE CHALET SCHOOL DOES IT AGAIN

By

Elinor M. Brent-Dyer

First published by W. & R. Chambers, Ltd. in 1955

| Chap. | Page | |

| I. | A Queer New Girl | 11 |

| II. | Upper IVb | 23 |

| III. | The Fourths are Intrigued | 35 |

| IV. | The Staff on the Subject | 47 |

| V. | Con Creates a Sensation | 59 |

| VI. | Winter Sporting | 71 |

| VII. | “The Willow Pattern” | 85 |

| VIII. | Jo is Called into Council | 99 |

| IX. | Trip to Lucerne | 112 |

| X. | Prunella to the Rescue | 126 |

| XI. | Joey Straightens Things Out | 138 |

| XII. | A “Quiet” Evening | 149 |

| XIII. | Preparations | 160 |

| XIV. | The Sale | 176 |

| XV. | Big Results | 190 |

Len Maynard shot down the stairs, giggling wildly at every step she took. She reached the bottom, turned right and raced along the corridor, through the wooden passage that linked up the chalet which formed one of the school’s Houses—Ste Thérèse de Lisieux, to be accurate—with the main building. This had once been a luxury hotel, but tourism had drifted away from the Görnetz Platz and the proprietor of the hotel had been very glad to dispose of his property to the Chalet School Company.

Once in the main building, Len dropped into a more sedate pace, though she still giggled as she went. She reached a door which she opened just wide enough to allow her to slide in, and closed it behind her. About a dozen girls were in the cheerful room, all chattering eagerly, for this was the first full day of term and everyone had plenty to say about the Christmas holidays now, alas! behind them.

Someone saw Len and gave an exclamation. “Len Maynard! I wondered where you were. Are you three really to be boarders this term?”

Len nodded. “Hello, everyone! Had decent hols? Oh, good!” as half a dozen voices informed her that their holidays had been more than decent. “O.K., Connie. You’ve got it in one. We three are boarders for the rest of our school-life.”

Connie Winter, a mischievous thirteen-year-old, with wicked, blue eyes shining in a face freckled like a plover’s egg, grinned. “Seems rather weird when you live just next door.”

“I know. But Mother says that if the winter here is anything like the winters in Tirol—and she jolly well knows it is because this is the Alps and so is Tirol—then we can’t risk missing days on end because of storms and blizzards. And once we start in as full boarders, we may as well keep on. So there you are!”

“Good!” a thin girl possessed of a sharp, fair prettiness, broke in before any of the others could comment. “Which dormy are you in? Not ours, I know.”

“I’m in Primrose—over at Ste Thérèse’s. Con’s in Wallflower over here and Margot’s planted out in Gentian at St. Hild’s. Jolly mean of Matey, isn’t it? But she always did separate us, if you remember.”

“Primrose? That’s one of the new dormies, isn’t it?” A stocky, young person of twelve joined in. “How many are you and who’s dormy prefect?”

“Seven of us and Betsy Lucy’s our pree. so we’re lucky that way, anyhow,” Len giggled again.

“What’s the joke?” Connie eyed her curiously.

Len swung herself up on the table in the middle of the room and gave vent to a whole series of chuckles. “Oh, my dears! We’ve got the weirdest thing in new girls I’ve ever seen in my life!” She spoke as if she were at least thirty and the rest were suitably impressed.

“A new girl? But how is she weird?” the thin girl demanded.

“You wait till you see her!” Len was swinging her crossed ankles. Her curly, chestnut hair was all on end, thanks to her wild rush, and she kept breaking into little gurgles. “Oh, she’s definitely not your cup of tea, Emerence—at least, I can’t imagine it. If you come to that, I don’t know whose cup of tea she’ll ever be here. Not mine, at any rate!”

“How d’you mean?” Emerence asked, puzzled. “Do go on and tell us something, Len, and don’t sit there giggling like a village idiot!”

“Village idiot yourself!” Len retorted amiably. Then she pulled herself together. “She’s out and out the primmest thing you ever saw.”

“Huh! That’s nothing new to us,” Emerence replied. “What about young Verity-Anne Carey? She’s prim enough for anything!”

“Mother says Verity-Anne isn’t prim exactly. I mean, look at the things she says—and gets away with! Mother says she’s more precise than prim.”

“Oh? Well—yes; perhaps she’s right. But what’s the difference, anyhow?”

“You’ll know when you see our latest,” Len replied darkly. “She’s not in the least like Verity-Anne.”

“But how do you know? You’ve only just seen her, haven’t you?” interjected a boyish-looking individual whose flaming, red hair was cropped short.

Len turned wide, violet-grey eyes on her. “I’ve been showing her how to put her things away. Matey was unpacking her when I went past and she yanked me in and told me to go upstairs with her and show her how drawers and closets had to be kept.”

“What’s her name?” Emerence asked.

“Prunella Davidson. I should think she’s about fourteen, so I don’t suppose we’ll see an awful lot of her. She’s safe to be in one of the Uppers. She’s rather pretty,” she went on consideringly. “She’s got yards and yards of brown hair that she wears in two enormous plaits and she’s a bit bigger than you, Isabel. And the way she talks!” Len stopped to giggle again. “She says ‘Do you not?’ and ‘Have you not?’ and she quotes proverbs—she does, honestly! When I was explaining about the way we have to arrange our drawers, she said, ‘Quite so! A place for everything and everything in its place. I quite understand. Most appropriate!’ I nearly bust in her face!” And Len broke into peals of laughter at the recollection.

The members of Junior common-room received this information with dropped jaws.

“You’re trying to pull our legs,” Connie said accusingly when she had got her breath again.

“I’m not! She honestly does talk that way and that’s exactly what she said.”

“Help!” Connie pretended to swoon into her neighbour’s arms and was jerked to her feet with unfeeling promptness.

“Stand up, you silly ass! I’m not going to hold you up, so don’t think it.” Charlotte Harrison turned back to Len. “What else did she say, Len?”

“Well, she approves of our cubeys. She said,” and Len broke off to gurgle again, “ ‘that one so frequently wants a little privacy’. She did say just ’zackly that!”

“Cripes!” gasped Emerence. “She must be crackers!”

They all agreed with this. Whoever had heard of a girl of fourteen demanding privacy? They gave it up and turned to something else.

“If she’s fourteen, how is it she’s in the same dormy as you?” Charlotte asked.

“We’re a mixed dormy,” Len explained. “There’s Betsy to start with—and she’s sixteen——”

“You said she was dormy pree. She doesn’t count,” Isabel said quickly.

“P’raps not,” Len agreed, unperturbed. “Well, there’s me, and I’m eleven. Then there’s Sue Meadows who’s fourteen, too, and another new girl called Virginia Adams who looks about fourteen. And Nesta Williams who’s twelve. I told you it was a small dormy.”

“No smaller than lots of others,” Emerence told her.

Isabel Drew had been counting on her fingers. “I thought you said seven of you? That’s only six—unless you’re counting Betsy in.”

“I wasn’t. Prees. never do count in,” Len responded. “I’d forgotten. We’re to have Nan Wentworth this term.” Len suddenly looked grave. “Did you know her mother died these hols? Just after Christmas it was. That’s why Matey’s moved Nan in with our lot. She said she thought she’d probably rather not stay in Poppy. There’s twelve of you there, isn’t there, Frankie?”

Frankie—otherwise Francesca Richardson—nodded. “Twelve of us and Dorothy Watson and Nora Penley. Not really, Len? Oh, poor Nan! I’m awfully sorry for her.” She looked anxious for a moment. “I say, we—we shan’t have to—to say anything to her, shall we?”

“Matey said not unless she says anything about it first. She’s just a kid, you know,” went on Len who was a good ten months younger than Nan Wentworth. “She’s to stay on at the school. I heard Daddy telling Mother that it was the best thing for her. Her father’s in the Navy, you know, and he’s hardly ever at home. There’s only her granny and she’s done nothing but cry since Mrs. Wentworth died. She’s awfully old, too. Daddy said Nan would be far better off at school and he meant to tell Commander Wentworth so. Oh, and Mother told me to see that we were all nice to Nan, but not to fuss round her.”

Emerence, who was the eldest of the group, nodded. “I see. It would sort of keep on reminding her. We’re to be just ordinary, but nice ordinary.”

As this was exactly what Mrs. Maynard had meant, Len nodded, “You’ve got it. That’s what Mother meant.” She pricked up her ears. “Someone’s coming!” She turned round to face the door as it opened to admit Matron, beloved and feared of all the girls, together with someone who was unmistakably after Len’s description.

“Girls, this is Prunella Davidson. Look after her, please,” Matron said. Then she fixed Len with an icy glare and that young lady slid off the table in a hurry. “Tables were not meant for sitting on, Len.”

“No, Matron,” Len murmured, flushing red.

“Then don’t let me catch you doing it again, please. Emerence, run along to Senior-Middle Common-room, please, and tell Mary-Lou I’m ready for them now.”

Emerence said very properly, “Yes, Matron,” and departed. Matron followed her out, shutting the door firmly behind her and the dozen or so members of the Junior-Middles were left with the new girl.

Len went up to her. Good manners had been drilled into all the young Maynards from their earliest days, even if the tradition of the school had not been that new girls were to be looked after and helped to feel themselves part of it as quickly as possible.

“We’re all Junior-Middles, Prunella,” she said, “And I expect you’ll be a Senior-Middle. But Matey’s sent for them to unpack so I s’pose she felt you’d rather be with someone than all on your own. Come on, and I’ll tell you who we all are.”

Prunella regarded her gravely. “Thank you. You are most kind,” she said politely. “You told me in the dormitory that you are Helena Maynard, I think?”

“I’ll bet she never did!” Isabel muttered to Charlotte who was next to her and her boon companion. “Len hates her proper name.”

Len herself was replying, “Oh, but no one ever calls me that! I’m always ‘Len’.”

Prunella smiled indulgently at her. “But when one has a proper name it is surely better and wiser to use it and not descend to babyish abbreviations?”

Len looked baffled for a moment. Then she evidently decided to ignore this and proceeded with her introductions. “This is Frankie Richardson who’s in the B division of Lower IV.”

Len had turned to Frankie as she spoke and the eye hidden from Prunella drooped in a wink at that young woman. Prunella “rose” as they had expected.

“Oh, surely not!” she exclaimed, in shocked tones.

“Oh yes; everyone calls her that,” wicked Len replied, her eyes dancing. “And this is Connie Winter—in my form.” She went on, reeling off the names and, where she could, giving shortened forms of them. The rest backed her up. Even Isabel Drew never flinched when solemnly introduced as “Izzie Drew”—a form of her name never used before.

By the time she had finished, Prunella was looking both startled and bewildered—and small blame to her! However, she said, “How do you do?” most properly to the owner of each name. Conversation languished when this was ended. It was revived by the new girl.

“And this is your recreation room?” she said, gazing round approvingly.

“Our Common-room,” Charlotte replied rebukingly. “This is the Junior Common-room. The Upper Fourths are Senior-Middles and have their own and so have the Fifths and Sixths. Of course, the prees. use the prefects’ room.”

“I see. A really excellent arrangement,” Prunella approved.

The younger girls gaped, but before they could say anything, there was a clatter of feet outside and then the rest of the Junior-Middles irrupted into the room, led by a girl who, despite her flood of golden curls, was unmistakably Len’s sister.

“Well, here we are!” she proclaimed in bell-like tones. “We three are full boarders this term! Isn’t it nifty?”

“Len’s just been telling us,” Isabel said. “And it’s no use looking for Emerence. Matey collared her for errands.”

“She would! Oh, well, I’ll see her soon.”

“In the meantime, this is a new girl called Prunella Davidson,” Len said. “This is one of my sisters, Prunella—Margot. And here’s the other. She’s called Con.”

“Constance—or Constantia?” Prunella asked with a little smile.

Con, as dark as Margot was fair, stared at her. “Constance, of course, but no one ever calls me that,” she said firmly. “We’ve got a new girl in Wallflower, called Virginia Adams. She told Matey they called her Virgy at home, though.”

“Don’t blame them,” said one of the newcomers. “Virginia! Help! What a mouthful!”

“Well, it’s better than ‘Ginny’,” said someone else. “We’ve two news in Pansy—both French. One’s Suzanne Élie and the other’s Andrée de Vienne. I say! We look like growing again, don’t we?”

“Mary Woodley’s not coming back,” put in a third.

There was a chorus of exclamations at this. Len finally made herself heard above the rest. “Not coming back? Why ever not? She didn’t say anything about it last term.”

“Don’t suppose she knew—then. Her father’s got a job in Australia—Tasmania, I think. Isn’t Launceston in Tasmania? They’re off next month. My Auntie Joan lives next door to them in Newbury. She and Uncle and the cousins came to spend Christmas with us and when we were having tea, she said, ‘Well, Heather, you’re losing one girl from the Görnetz Platz. The Woodleys are off to Launceston in February. Well, never mind. As soon as Lesley and Anne are old enough they’ll be coming to join you, so they’ll help to make up’.”

“Who’re Lesley and Anne?” Isabel Drew asked.

“My cousins—Auntie Joan’s kids. It’ll be years before they come, though,” Heather added. “Lesley’s only seven and Anne’s four. They’re not bad—for kids, that is.”

“Are they anything like you?” Connie asked sweetly.

Heather giggled. “Just exactly like! One morning, Auntie made us line up and then she said to Mummy, ‘Did you ever see anything to beat it—all exactly alike? Aren’t they monotonous? And the boys—my brother Martin and Auntie’s Peter are just the same, too.”

The door opened to admit Emerence who had escaped from Matron at last and she and Margot fell on each other promptly. As both had the reputation of being thoroughly naughty girls, it was a friendship that no one encouraged, but that didn’t matter to the pair. When they had finished exclaiming, Charlotte gave Emerence the latest news.

“I say, Em, Mary Woodley’s left—gone to Australia.”

“Bad luck for Australia,” grinned Emerence who came from there herself. “I never did like Mary Woodley.” Then she looked round. “Where’s Prunella Davidson? Oh, there you are! I met Mary-Lou Trelawney just outside and she told me to take you to the office. Miss Dene wants to see you. Come on!”

A curly-headed individual gave a shriek. “I’ve got to go and fetch two news called Virginia and Truda. I forgot about it till you spoke, Emmie. Out of the way, Nora!” She burst through the little groups standing about and shot out of the door.

“Just like Elsie Morris!” Emerence said with a grin. “She’d forget her head if it was loose! Come on, Prunella. Can’t keep Deney waiting!”

Prunella followed her into the corridor, across the wide entrance hall and to a door which stood slightly ajar. A very clear, pleasant voice was heard.

“Then that will be all, you two. Truda will be in your form, Elsie, but keep Virginia—what is it, child? Oh, you want to be ‘Virgy’, do you? very well—Virgy, then, with you until someone comes from Upper IVa for her. I know Matron has that crowd for unpacking. You’d rather be with the younger Middles than in the Common-room by yourself, wouldn’t you?”

“Yes, please,” said a fervent voice.

“Run along, then. If the new girl, Prunella Davidson, is outside, Elsie, send her in, will you?”

“Yes, Miss Dene.” There was a pause. Then Elsie’s voice came, “Curtsy, you two. We always curtsy here, you know.”

The door was opened wider in time for Prunella to see Elsie rising from a bobbed curtsy which the other two were imitating. They came out and, as she passed Emerence and her charge, Elsie said, “Miss Dene is ready for Prunella now, Emerence.”

Emerence nodded. She touched Prunella on the arm. “Come along. This is the office.” Then, as she led the way in and bobbed her curtsy, “I’ve brought Prunella Davidson, Miss Dene.”

Miss Dene, a slim, fair person, immaculate from her gleaming, brown hair to the tips of her pretty slippers, gave her a smile. “Thank you, Emerence. Will you wait in the hall? I won’t keep Prunella more than a few minutes.”

Emerence replied, “Yes, Miss Dene,” very properly and went out, shutting the door behind her and Prunella was left alone with the school’s secretary.

Miss Dene, formerly a pupil at the school and for many years a member of its staff, gave the new girl a friendly smile. “So you are Prunella. Come along and sit down.”

Prunella left the door where she had been standing quietly and came up to the big desk. Somehow her grown-up air had vanished and it was an ordinary, rather shy schoolgirl who faced the pretty secretary. Miss Dene indicated a chair nearby and Prunella sat down and regarded the toes of her slippers in silence. The next moment, she had forgotten them, for Miss Dene had taken up a bunch of exam. papers which the new girl recognized as her own. She felt a sudden qualm. Had she done well enough to go into one of the Upper Fourths or was her fate to be with the younger girls?

“These are your papers,” Miss Dene said. She unclipped them and glanced over a printed form, filled in with various handwritings. “I see that your general subjects are well up to standard for your age. Your French is marked Très faible and you seem to have done no German. Your Latin is weak, too. Your art is marked excellent but your needlework is very poor.” She looked at it for a moment while Prunella went hot and cold by turns. Then Miss Dene looked up and smiled again. “Miss Annersley says that, with the extra work everyone has in languages, she thinks you ought to be able to manage to work with Upper IVb. You will have extra coaching in German, French and Latin which should bring you level with the rest by the end of the term. As for your needlework, we can safely leave that to Mdlle. I see that you are to take extra art but not music.” She laid the bundle aside and smiled at the girl again. “Well, that’s settled. Now tell me—I may as well know at once—do they call you ‘Prunella’ at home or do they use a shortened form?”

This was the time for Prunella to inform her as she had done Frankie and Co. that when one had a proper name not to use it was foolish. She did nothing of the sort. She replied meekly, “I’m always ‘Prunella’, Miss Dene.”

“I don’t wonder. It’s a very pretty name—and what’s more, I believe it’s the first time we’ve had it in the school,” Miss Dene told her. “Very well. ‘Prunella’ it shall be. And now, the sooner you meet your own form, the better. Just a moment.” She pressed a button at the side of her desk and a bell shrilled very faintly from the hall. It was evidently a recognized signal, for a minute later, the door opened and Emerence appeared.

“Come in, Emerence. Prunella will be in Upper IVb. Will you take her along to Senior-Middle Common-room and see if you can find anyone to take charge of her? Matron should have finished with some of them by this time. Try to find Clare Kennedy or Maeve Bettany or someone like that. Send whoever it is to the Common-room—or no; go and send them here. Prunella can stay with me till whoever it is turns up. Off you go!”

Emerence went off. When she had gone, the secretary turned again to the new girl. “I thought you’d rather not be alone in a big, strange room, Prunella, and it may take Emerence a few minutes to find someone. I know Matron is busy with that set at the moment.” She paused a moment. Then she went on, “I wonder if you’ve been abroad before?”

“Not exactly,” Prunella replied, meanwhile looking the picture of a demure, well-behaved schoolgirl, with her long plaits dangling over each shoulder to her lap and her hands folded under them. “I was born in Singapore, though. I don’t remember anything about it. We went to Australia when I was two and when we left Australia, we went home to England. I was seven then and I’ve never left England since.”

“Then you’ve done no ski-ing or sledging, of course? Those are joys to come! You’ll enjoy them, I know. You’d be a funny girl if you didn’t. This is likely to have to be our winter-sporting term, for with the deep snow we can’t have any other games.” Miss Dene broke off as there came a tap at the door and called, “Come in!”

A slim girl of fourteen or fifteen entered. Her smooth, black hair was parted in the middle and tied back from an oval face lit by a pair of very dark Irish-grey eyes. With her straight features and sweetly meek air, she looked nun-like in the extreme. But, as Prunella was to find out, Clare Kennedy was not Irish for nothing.

“You sent for me, Miss Dene?” she said in a low, very sweet voice.

“Yes, Clare. I want you to take charge of Prunella Davidson who will be in your form. Prunella, this is Clare Kennedy who is form prefect of Upper IVb. She will look after you until you feel your feet and tell you where to go and what to do. Take her along, Clare, and find someone to tell Nan Herbert to bring Joy Williamson and Chloë Yeates to me.”

“Yes, Miss Dene,” Clare said. She turned to Prunella who had stood up. “Will you come with me, Prunella?”

Prunella prepared to follow her, but Miss Dene checked them for a moment. “I nearly forgot, Clare. Prunella is in Ste Thérèse’s—in Primrose. That’s next door to you, isn’t it? You are still in Jonquil, I suppose?”

“Yes, Miss Dene.” Then the nun suddenly vanished and became an ordinary schoolgirl as Clare asked eagerly, “Oh, Miss Dene, do you mean we’ve grown so much this term that we’ve had to open new dormies?”

Miss Dene laughed and nodded. “We have indeed. I quite expect we shall find that we have to open two or three others next term, too. Now run away. I’ve a great deal to do and very little time in which to do it. Be off!”

Clare curtsied and led the way. Prunella imitated her with a deep, formal curtsy which made Miss Dene open her eyes rather widely though she said nothing. But when she was once more alone and before Nan Herbert of Lower V came with her two charges, she went to a filing cabinet, riffled quickly through the files and finally took from one a letter which she read thoughtfully.

“I—wonder!” she said to herself as she replaced it and shut the drawer. “I really do wonder!”

Once they were outside, Clare turned to the new girl. “Come on!” she said briefly. “Oh, and before I forget, unless we’re sent for to the office or the study, we’re not supposed to show our noses in this part of the house. We use the back corridors and the back stairs.”

Prunella gave her a startled look. “I fear I do not understand,” she said.

“Well, you see,” Clare explained as they crossed the wide entrance hall, “visitors come this way, of course, and it would look rather awful if shoals of girls were skitin’ about in every direction at all hours of the day, as you’ll admit. So, as I just told you, we never use the front part of the stairs and so on. Oh, and another thing. Except for first and last day, we aren’t supposed to talk on the stairs or in the corridors—only in our common-rooms and form-rooms. Sure, ’twould mean too much row altogether! First and last day, though, rules don’t count. However,” she added cheerfully, “ ’tis yourself will be finding out all about it before long. If there’s anything bothering you, come to me, of course, and I’ll explain with all the pleasure in life. Turn round this corner. Now then; here we are!” She opened a door and ushered Prunella into a long room, bright with light, since someone had switched on the lights and drawn the gay, cretonne curtains across the windows.

Clare slipped a hand through Prunella’s arm, steered her into the room and shut the door behind them. Then she walked her captive over to a throng of girls clustered together in a corner between the great porcelain stove and one of the windows and said, “Pipe down, everyone! I’ve brought us our new girl. This is her!”—with a sublime disregard of the rules governing the verb “to be”—“Shove up, Babs, and let the poor creature sit down, can’t you?”

A fair-haired, blue-eyed girl of Prunella’s own age, looked up. “Barbara!” she said, rebuke in every intonation. “I told you last term that I wouldn’t answer anyone who didn’t call me by my proper name and I think you might remember! If you do it again, I’ll start in and call you ‘Clarry’!” she added with a sudden chuckle.

“You do!” Clare retorted threateningly. “Sure, that’s one thing I won’t put up with at all, at all, and so I tell you!”

“Well, you just remember to call me ‘Barbara’!” was the lightning riposte.

“I agree with you,” Prunella remarked with gracious patronage. “If one has a Christian name, surely one should use it and not stoop to babyish abbreviations?”

The jaws of all those near enough to hear dropped. There was a startled silence. Then a mischievous-looking girl said, “Well, I can understand that Barbara doesn’t want to be called ‘Babs’. But let me catch any of you addressing me as ‘Francesca’ and you’ll know all about it!”

“Don’t worry! Life’s a lot too full at school for us to bother with all your syllables,” declared a copper-curled young woman who was balancing miraculously on the extreme end of a bench on which four others were crowded. “You’ve been ‘Francie’ ever since you came and ‘Francie’ you’ll remain to the bitter end!”

“I should hope so!” Francie returned.

Before Prunella could make any remarks, a short, plain girl with a good-humoured face, broke in, “I’m Ruth Barnes, Prunella. And this—this thing that’s squashing me to a jelly is Jocelyn Fawcett. Do get up, Jos! These chairs weren’t made for two. Get a seat of your own, can’t you?”

Jocelyn chuckled. “There wasn’t another in this corner when I came in. But anything to oblige!” She jumped up and went to drag a big wicker armchair up to the circle while Ruth stretched with an exaggerated sigh of relief. “That’s better! You must have bones of iron. They were digging into me at every point!”

“That’s the worst of being a scrag,” observed a pretty girl sitting next to Barbara. “I’m Dora Ripley, Prunella, and the rest of us in this sardine-tin are Dorothy Ruthven next to me, Christine Dawson and Caroline Sanders.”

“And I’m Heather Clayton,” put in another girl who was sitting opposite the “sardine-tin”. “Now you know all of us—Oh, that ginger object on the end of the bench is Maeve Bettany.”

“Anyhow, that isn’t all of us,” Clare remarked as she perched herself on a nearby table. “What have Sue Meadows and Sarah Hewitson and Betty Landon done to be wiped out so completely, the creatures? Where are they, by the way?”

“I have already met Susan Meadows,” Prunella observed. “She is in the same dormitory as I am.”

“But her name isn’t Susan,” Barbara said with a wriggle that nearly dislodged Francie. “She’s plain Sue—christened that way, I mean. She said so last term.”

“Dear me! How very remarkable!” Prunella said primly.

“Oh, I don’t know,” Maeve returned while the rest gaped. “It’s a name all right and quite pretty.”

There was a pause after this. No one could think of anything to say. Prunella looked round for a chair, saw one at the farther side of the room and went to carry it over to the group. By that time, Clare had pulled herself together.

“Have you ever been in Switzerland before, Prunella?”

“No,” Prunella replied gravely as she sat down. “But I was born in Singapore and I have lived in Australia.”

“Have you the basket of the gardener’s son? No, but I have my aunt’s new gloves,” Maeve murmured rapidly to her nearest neighbour who choked audibly.

“Australia? That’s where Emerence Hope in Lower IVa comes from,” Ruth said hurriedly. “Have you ever met her?”

“Not until I came here. She took me to the office to see—Miss Dene, I believe she was called,” Prunella returned. “Australia is quite a large place, you know. In fact, it is a continent. We lived in Brisbane.”

Ruth subsided, crushed, and Jocelyn intervened. “That’s in Queensland, isn’t it? Oh, then you wouldn’t be very likely to meet. Emerence lives in Manly, a suburb of Sydney, when she’s at home.”

Maeve, seizing a moment when Prunella was not looking, patted her hands gently together at this. Jocelyn was keeping her end up, thank goodness!

“Which school were you at before you came here?” Francie asked.

“I was at a preparatory school in the town where I lived with my grandmother until my parents came home from Africa,” Prunella replied.

Everyone was silent. As Clare said to Barbara later on, “You simply can’t think of a thing to say to anyone who talks like the worst kind of French exercise!”

Prunella glanced round the stunned group, a queer glint in her hazel eyes. Not that anyone saw it or would have understood it if they had. The new girl asked a question in her turn. “I presume this is where we are intended to pursue our avocations? A really charming room!”

No one was very sure what “avocations” were, so no one answered. Then Barbara said rather feebly, “Er—er—this is where we spend our free time when we can’t go out. Er—have you any hobbies, Prunella?”

“I am interested in drawing and painting, but I fear I shall have little time to spare for them,” Prunella responded. “I find that my French and German are considered to be far from adequate and I must endeavour to improve them.”

Again the talk fell flat. Dora murmured in an aside to her bosom friend Dorothy Ruthven, “What an awful creature! She talks like her own great-granny!”

“I wonder if she can spell all those long words?” was Dorothy’s reply.

Ruth made an effort. “Oh, but we aren’t allowed to swot in our free time. Anyhow, you needn’t worry. The whole staff jolly well see to it that we don’t get a chance to do anything but improve in modern languages!”

“Indeed?” Prunella spoke with real interest. “Might I inquire what methods they use to accomplish that?”

They nearly fell over themselves in their efforts to enlighten her.

“Two days a week we mayn’t speak a word of anything but French from the moment we wake up until the moment we go to bed,” Barbara told her.

“And the same goes for German on two other days,” Ruth added.

“We speak English on two other days—which is hard lines on the French and German girls in the school—if any!” Maeve contributed her share. “Still, they have the two days of their own languages, so it pans out equal in the end.”

“When you write comps. and essays, you have to do them straight into which ever language it is that day.” This was Dorothy’s share. “All the lessons are taken in that language, you see.”

“Even maths.!” groaned Jocelyn.

“And gym and games!” Clare wound up for them. “You simply can’t help it soaking in when you have to go at it like that. I wouldn’t be worrying, Prunella.”

Prunella had listened to all this in stunned silence. However, by the time Clare finished, she was her own woman again. “Dear me! How truly interesting! At that rate, I can quite imagine that even the dullest pupil must learn something during the term. An excellent idea! On the principle, I presume, that when in Rome one must do as the Romans do! A truly admirable arrangement!”

It was their turn to sit stunned. Whatever sort of a school had this weird new girl come from? But perhaps it was her home that was responsible for the way she talked. They gazed at her, fascinated. Then the door opened and the three missing members of the form came in to be followed by a crowd of other girls led by a masterful-looking young woman of about fifteen with keen, blue eyes and long, light-brown plaits dangling on either side of a pink and white face that was full of character.

Clare stood up with an involuntary sigh of relief. “Oh, Mary-Lou!” she said. She went across the room. “I’m thankful you’ve come!” she muttered. “We’ve the oddest new girl you ever saw!”

Mary-Lou grinned at her. “I’ve just heard Len Maynard on the subject,” she muttered back. Then, aloud, “So you’ve a new girl, too? We have four, but three of them are French. They’re at the office, at the moment.”

“Well, come and meet Prunella,” Clare urged. She tucked her hand through Mary-Lou’s arm and drew her towards the chair where Prunella was sitting, looking round with an air of calm assurance that almost dazed her fellows. “Prunella, this is the Head of the Middle-School—Mary-Lou Trelawney; and here’s Prunella Davidson.”

Prunella stood up and held out her hand. “How do you do?” she said primly.

Mary-Lou, who had been on the point of welcoming the newcomer in her own breezy fashion, waggled the hand limply with a mutter that might have been anything. For once, the wind had been taken completely out of her sails.

“All unpacked?” Barbara asked as the group broke up into little coteries of threes and fours and the girls began to stroll about the room.

Mary-Lou nodded. “The last hanky in its case and my drawers looking immaculate. Matey saw to that all right! How long they’ll stay like that, is another matter. What about you?”

“Oh, I did mine yesterday. The Welsen crowd began two days earlier than us and Vi and I came back with Nancy and Julie and stayed with Auntie Jo for the two days. I got mine done yesterday when you lot were still in the train. I say, I’ve some news for you all!”

“What about?” demanded a charmingly pretty person of Mary-Lou’s age.

“My cousins the Ozannes—Vanna and Nella. They’re leaving at the end of this term.”

“What? But they’re only seventeen, aren’t they?”

“No; eighteen last October. They’re six months older than Julie Lucy and ten months older than Nancy. They were to have had a year at Welsen, but Uncle Paul’s got a job in Singapore and they’re all going out in April, so Vanna and Nella are leaving.”

“What about their brothers?” demanded someone else.

“Oh, they won’t go,” said a girl who had come to stand beside Barbara. “Mike’s not halfway through his training and Bill’s in Germany, doing his National Service.”

“But they’re only in Upper V!” Jocelyn exclaimed.

“Oh, well, you know what they are! Aunt Elizabeth says it’s as far as either of them is likely to get and they may as well stop being schoolgirls and go out and be company for her. She doesn’t really like the idea very much, but it’s a jolly good job for Uncle Paul, so they’re going.”

“What do they say about it?” someone asked. “Have they said anything to you, Vi?”

Vi, who was quite the prettiest girl there, as Prunella noted, laughed. “They don’t know. Vanna says it’ll be fun to see the East, and Nella says she’ll get out of maths., anyhow. But I rather think they’re a bit fed up about it.”

“Well, it’s news all right,” Mary-Lou said. Then she turned to Prunella. “Have you been to the office yet? Oh, but of course you must have as you know which form you’re in. Seen over the place by any chance?”

“Thank you. I have seen my own dormitory, of course, and this room and another like it with younger girls,” Prunella replied gravely. “If I may ask, what else is there to see?”

“Lots!” they informed her. “There’s Hall and your form-room and the Speisesaal——”

“I beg your pardon?”

“Speisesaal—German for dining-room,” Mary-Lou said breezily. “We’re in the German part of Switzerland. Well the name ‘Oberland’ would tell you that. Anyhow, we use lots of German expressions.”

“She’ll see the Speisesaal in a minute now. The gong will sound for Kaffee und Kuchen in a moment,” put in a girl whose English was just touched with a pretty Scots accent. “But we ought to show her Hall and the Honours Boards. Have we time?”

She was answered by a deep, musical throbbing which rang through the corridors and everyone was on her feet at once and forming into lines by the door.

“Half a tick!” Clare exclaimed. “Let’s find where Prunella is sitting.”

She ran across the room to a big board hanging at the far end, scanned it keenly for a moment and then came back. “O.K. She’s between you and Caroline, Francie. Look after her, will you, seeing she’s not at the same table as me.”

She took Prunella by the arm and pushed her gently into line between Francie and Caroline.

“I’ll give an eye to her, Clare,” Francie said kindly. “We always march in in our table places, Prunella, so that there’s no scrambling round the tables. O.K., Mary-Lou. We’re ready now.”

“Lead on, then,” Mary-Lou said amiably. “Oh, and I know rules don’t really count to-day, but we’d better not talk too much as we go. Matey’s somewhere around and she’s pretty well hairless, anyhow, there’s so much to do.”

Warned by this, the girls stopped their chatter and laughter and the long line marched out of the room, down one corridor and half-way along another where a big double door stood open, a babble of talking coming from it. They entered and Prunella saw that they went round to take their places in proper order. Then she looked round the Speisesaal and approval beamed from her face.

It was a long, rather narrow room, with tables running down it in three lines. One stood across the head and one across the foot. The one at the head was empty, but the others were covered with gaily-checked cloths. Plates piled high with crusty bread covered with pale, sweet butter alternated with others holding fancy bread-twists and small cakes. Dishes of a richly-dark jam flanked them and small plates with a cheerful blue and yellow design stood at each place. One big sideboard between the door by which they had entered and another further up were laden with cups and saucers to match and on a table at one end stood a huge coffee-urn from which a slight girl of seventeen or eighteen was rapidly filling cups which she handed to two others who bore them to the tables and set them by the plates. Between two of the three windows at present curtained, stood another table from which a girl with a long, reddish pigtail was pouring hot milk. Three other girls were putting plates piled high with white, dully-glistening oblongs of sugar on each table. It was not in the least like any other dining-room Prunella had ever seen, but it was very gay with its bright lights and coloured cloths and Prunella noted that it was summer-warm, thanks to another of the great porcelain stoves set at one end.

The Senior-Middles were followed by an even longer line of Juniors and when the last girl had taken her place, the coffee distributor left the urn and went to the empty table. Prunella had time to see that she was a handsome girl, with a thick mop of black curls. She wore the school dress for Seniors—a well-cut gentian-blue skirt with cream shirt-blouse and the school tie and blazer. She struck a bell which was the only object on the table and at once the long rows of girls stopped talking, folded their hands and bent their heads.

“Grace!” the Senior said; and then repeated a brief Latin Grace after which she returned to her duties at the urn and the rest pulled out their chairs and sat down.

A pleasant-looking Senior arrived with a tray laden with steaming cups which she set down at the head of the table and the girls began passing them down.

“We always have Kaffee und Kuchen by ourselves,” Francie explained as she offered the new girl a plate of bread-and-butter. “Oh, the prefects are here, of course, but they sit together at the bottom table and they don’t interfere unless we start yelling our heads off. Try some of this jam, Prunella. It’s black cherry and scrummy!”

“Thank you.” Prunella helped herself to the jam and found that Francie had spoken truly. Then she sipped at her cup and nearly dropped it in her surprise. “Why, it’s coffee!” she exclaimed in a completely natural voice.

“Well, of course it is. What did you think Kaffee und Kuchen mean?” Caroline asked cheerfully from her other side. “Coffee and cakes, my dear! Don’t you like it? You can have hot milk if you’d rather. Shall I ask Clem for a cup for you?” She half-turned, nodding towards the red-haired Senior who was looking round to see if everyone was served.

Prunella had recovered from her surprise. “Thank you, Caroline. That is very kind of you, but I like coffee and I do not care for hot milk. But, considering what time it is, I anticipated tea.”

Two or three of the girls who had not been privileged, so far, to meet this extraordinary new girl, stared at her way of talking, as well they might. Caroline grinned before she said placidly, “No tea here. We have this milky coffee for brekker—er—I mean Frühstück and—er—Abendessen.”

Prunella guessed that the last word meant supper, so she asked no questions. In any case, a bespectacled young person was leaning forward and asking eagerly, “I say! Do any of you know when the Welsen panto is coming off?”

“Not the foggiest,” Francie replied. “Not for a week or two anyway. They’ll want to push in a few rehearsals after the hols. Probably the Head’ll say something at Prayers. She said last night that there was lots to tell us only we were so late she would only let us know the really important things—like Mary-Lou being the Head of Middle School. I say! Look out, Pen! You’ll have your cup over if you lean across like that!”

“And will Matey talk!” Pen said sadly as she sat up.

“You bet she will—beginning of term and a clean cloth!” Francie returned with a grin. “Anyhow, you don’t want to start off with a fine, do you?”

“I do not!” Pen was positive on that point.

“Well, then sit up and don’t be an ass! More bread-and-butter, Prunella, or will you have a twist. They’re jolly good.”

“Thank you, I should like to taste a twist. They are new to me.” Prunella helped herself and then asked, “Pray, what do we do after our meal?”

“Well, no prep, of course. We only arrived last night and we’ve been unpacking and settling in most of the day. Oh, we’ve had two walks—one this morning and one this afternoon. To-morrow we’ll have short lessons in every subject so that the staff can give us prep. Then come Saturday and Sunday and we start fair on Monday.”

“We’ll probably dance,” someone from the other side of the table said.

“That’s the most likely thing—after we’ve changed,” Caroline agreed. “It’ll be early bed to-night, anyhow, we were so late last night.”

“What’s that about bed?” demanded tall Clem who was passing them with a cup of milk for someone.

“I just said we’d be sent to bed early because we were so late last night,” Caroline explained. “Oh, Clem, do you know when the Welsen panto’s coming off?”

“Not I! No one’s said anything that I’ve heard of. I don’t suppose it’ll be much before the beginning of next month, though,” Clem said. “Here, Monica, take your milk.”

She handed over the milk and returned to the table near the top door where the prefects had congregated and the Middles were left to their own devices. Prunella bit into her twist and as she ate it decided that it was delicious. As she made a good meal, she reflected that this school certainly gave you no chance to feel out of things. Francie and Caroline named odd girls to her and saw that she was well supplied throughout the meal. Both girls were kept busy chatting to the others, but they turned from time to time to address remarks to her and even tried to draw her into the conversation. Prunella replied primly and precisely, more than once causing one of her new companions to be momentarily bereft of breath at her manner of expressing herself. But she had no neglect to complain of.

When Kaffee und Kuchen ended, everyone seized her crockery, knife and spoon and carried them to an enormous trolley where two prefects piled everything quickly and safely, as she noticed. When it was full, sides of wire netting were pulled up and it was wheeled out of the room, the crockery rattling but secure. It was all done with the utmost speed and ten minutes after the girls had said Grace, the tables were cleared and they were filing out to their common-rooms.

“Dressing-bell will go in a minute or two,” Clare Kennedy told Prunella when they were safely in their own abode. “That won’t worry you, though. You’re changed already.”

“Matron told me to change when I had finished unpacking,” Prunella replied.

“I expect she did. Oh, well, we shan’t be long. There are heaps of mags on the table over there and some of them are English. The others have gorgeous illustrations, too, so you can amuse yourself all right till we come back. Then I expect we’ll go into Hall for dancing and games.”

A bell sounded at that moment and the girls in their tunics raced to line up. Mary-Lou, who seemed to take her duties as head of the Middle-School very seriously, brought them to order almost at once, repeated her warning about making little noise in the corridors and on the stairs before she marched them off and Prunella was left to herself.

She made no attempt to look at the piles of magazines Clare had pointed out to her. Instead, she went to one of the windows and pulled back a curtain. A young moon was rising and the skies were clear and starry. The snow lay white beneath the cold light and all the shadows were clear-cut and black. She stood looking out for a minute or two. Then she swung the curtain back into place and turned round.

“It’s better than I thought,” she said aloud. “So far, anyhow. But I’m jolly well going to show them all and that’s that!”

She went over to the magazine table and chose one and when the rest came down, ready for the evening in their gentian-blue frocks of velveteen with muslin collars and cuffs, the new girl was sitting demurely turning over the pages with a keen eye for the delightful illustrations of a Swiss magazine.

“Hello, Mary-Lou! What does it feel like to be a Head—even if it’s only Head of the Middles?”

Mary-Lou, wrapped up to the tip of her nose for the morning walk which took place every day that was fine enough at this time of year, turned with an infectious gurgle. “Hello, Betsy! I didn’t hear you coming. Oh, it’s all right. Matter of fact, I can’t say I feel at all different. It’s just the look of the thing. I must say it came as a shock first night when the Abbess announced it. I nearly fell through the floor from shock!”

Betsy Lucy leaned against the wall of the corridor. She was a sixteen-year-old, no taller than Mary-Lou who had shot up into a leggy creature after being sturdy not to say stocky for the first thirteen years of her life. Betsy was in the habit of describing herself as the Plain Jane of the family. Actually, there was something very taking about her puckish face, with its sparkling, brown eyes, crooked mouth and very slightly tip-tilted nose. But, as she was wont to point out, when your eldest sister is the image of a handsome father and your younger one is a howling beauty—“Kitten’s too small to say what she’ll turn out,” she generally added—a face like hers was plain enough in all conscience!

“I certainly can’t claim Beauty,” she had said once, “so I must do my best to acquire Brains!”

“Brains aren’t acquired, either. They’re something you’re born with or not,” her chum, Hilary Wilson, had pointed out. “Still, your work’s not at all dusty,” she had added kindly.

During the previous term, Mary-Lou and Betsy had encountered each other at odd intervals and, to quote the latter young lady, they had rather clicked. Both had much the same interests and, if Mary-Lou was a good year the younger in age, she was quite as grown-up in other ways, the fruits of being an only child brought up by her mother and grandmother in a quiet village. Betsy, on the contrary, was third in a family of six, the eldest being her sister Julie who was Head Girl of the school and the youngest their small sister Katharine, who was only six. Betsy was a very normal girl, with the outlook to be expected from a member of a large family. Mary-Lou, on the other hand, still shocked people by her trick of treating grown-ups on a perfect equality. She was never rude and rarely cheeky, but it took a good deal to overawe her.

Now, as Betsy leaned against the wall and settled her shawl more comfortably, she asked, “What’s all this talk that’s going round about a new girl among your lot who talks like her own great-granny?”

Mary-Lou gave a gurgle. “That just about describes it. Name’s Prunella Davidson and if they’d called her Prunes and Prisms they wouldn’t have gone far wrong!”

Betsy’s brown eyes widened. “Really? Worse than our one and only Verity-Anne?”

Mary-Lou frowned as she considered this. “No: she’s not in the least like Verity-Anne,” she said finally.

“Not? Then what are you talking about?”

“It’s rather hard to explain. I mean, Verity-Anne was like that—I mean it’s really part of her. Know what I mean?”

Betsy nodded. “Oh, yes; I see what you’re getting at all right. Prunella isn’t, I suppose?”

“I—wonder. She talks as if she’d walked straight out of Jane Austen—no; further back than that. Fanny Burney might be nearer it——”

“Fanny Burney?” Betsy gasped. “What on earth d’you know about her?”

“Well, I’ve read one book of hers. I was stuck in my bedroom these hols. for nearly a week with a terrific head-cold. Gran said she wasn’t going to have everyone else infected; not if she knew it! So there I was. I read most of the time. There wasn’t anything else to do. When I’d finished all my own books, I went along to Mother’s room and the only think I could see was Evelina so I bagged that. Not bad, though it took some reading.”

“I’ll bet it did!” Betsy spoke in tones of deep conviction. “Really, Mary-Lou, you are the limit!” She stopped short as a sudden thought struck her and her jaw dropped. “Are you telling me that she says things like, ‘La!’ and ‘Lud!’ and—and ‘Stap my vitals!’—for I don’t believe you!”

Mary-Lou went off into peals of laughter at the thought of the stilted Prunella indulging in such expressions. “ ’Course not! Oh, Betsy, what an ass you are! All I meant was that she talks most primly, never uses slang, and flatly refuses to call anyone by a short form of their names. She’s driving Len Maynard completely wild by always addressing her as ‘Helena’, f’rinstance.”

“And does she call you ‘Mary-Louise’?” grinned Betsy.

“Well, as she’s in B, I don’t see too much of her and now you mention it, I don’t remember that she’s ever called me anything but ‘you’,” Mary-Lou said.

“Nameless!” Betsy giggled. “Poor you! But I suppose,” she added teasingly, “that she can hardly call the Head of Middle-School by her full name if she doesn’t use it normally.”

“Actually, I don’t think she’s ever had much reason to speak to me,” Mary-Lou said, ignoring the gibe. “But we have General Lit together and the odd thing is that she isn’t nearly so prim in form as she is out of it. If you ask me,” concluded that shrewd observer, Mary-Lou, “a lot of it is put on—and for a reason. But what the reason is, I can’t tell you.”

Betsy was about to reply to this, when Prunella herself appeared, clad like themselves in big, blue coat with crimson pixie-hood, and shawl and nailed climbing-boots. Like them, she carried an alpenstock, for the deep snow had been frozen hard and was glassy in surface.

“Hello!” Mary-Lou saluted her. “Aren’t the rest ready yet?”

“Almost so. I have no doubt they will be with us shortly,” Prunella said in a prim voice. “Miss o’Ryan detained us beyond the ringing of the bell and thus we are I regret, somewhat behindhand.”

Mary-Lou choked back a giggle as Betsy goggled at this weird specimen speechlessly and asked, “But where’s everyone else? I was having massage for my ankle—I sprained it rather badly last term so I have to go for remedials every day. But what’s happened to the rest of A?”

“I cannot be certain, but I think I heard Clemency Barrass remark to Rosalie Way that the milk had not come at the proper time and the cook was unable, therefore, to heat it punctually,” Prunella replied.

Nothing more was needful, for at that moment, there was a clatter of feet and the rest came swarming out of the Splasheries where they had been changing as fast as they could for the walk. Betsy was claimed by Carola Johnston who had “bagged” her as a partner before Prayers and Vi Lucy came to drag Mary-Lou into line. The Head of Middle-School paused long enough to inquire if Prunella also had a partner and, on hearing that Barbara Chester had asked her, promptly went off with Vi who contrived to look enchantingly pretty, even in their unbecoming if cosy winter outfit.

Left to herself, Prunella turned and saw Barbara coming towards her.

“Come on!” she said in French, which was the language for the day. “Miss o’Ryan and Miss Armitage are waiting for us outside, so hurry up!”

“J’ai attends pour vous,” Prunella replied with an execrable accent.

“Eh bien, maintenant j’y suis,” Barbara returned in the pretty, fluent French which so many of her form envied. She took the new girl’s arm and led her out to the path where the two mistresses, very trig and smart in their ski-ing outfits, were skirmishing round, making sure that every girl had a partner.

The Lower Fourths had congregated at the other side of the house and had already set off along the road to the Sanatorium and the Seniors were in the front drive, waiting for a note the Head had asked them to take to Mrs. Graves, once Hilary Burn and a very popular Old Girl and P.T. mistress, now the wife of Dr. Graves who was on the staff at the Sanatorium. Most of the seniors had cherished a warm affection for their former mistress, so they were delighted with the commission, though it meant very brisk walking, since the Graves’s chalet was two-and-a-half miles away.

The thirty-odd girls who made up the two Upper Fourths set off from the side-door and walked smartly down the path and out at a small entrance on to what was known as “the high road”, though it badly needed re-surfacing and was, to quote Dr. Maynard, Head of the Sanatorium, a very second-class road indeed. Arrived there, they turned left at a word from Miss Armitage and made for the long motor-road that wound through the mountains down to the plain.

It was a glorious day, bitterly cold, of course, at that altitude, but with a bright sun shining down, turning the frozen snow to a glittering whiteness that meant the wearing of coloured glasses as no one wanted snow-blindness.

“The weather really has been gorgeous since we came back,” Barbara said to her partner by way of starting up a conversation. “Let’s hope it keeps on. If we get any blizzards, it means being stuck indoors and that can be an awful bore.”

“So I should imagine,” Prunella responded. “Pray, what do we do in such circumstances?”

“Oh, we do extra lessons to make up for what we miss in weather like this. Then we have gym and dancing and things like that for exercise. But I’d a lot rather be out—though not in a blizzard,” she added. She had had a minor experience of what snow can be like in the Alps during the previous term and she had no wish for another.

“Indeed?” Prunella paused a moment before she added, “I can understand that gymnastics would furnish us with no little exercise; but surely dancing is hardly adequate?”

Barbara gaped at her for a moment before she pulled herself together sufficiently to reply, “Not ordinary ball-room dancing, perhaps. But we do country dancing and you get all the exercise you need in that. You wait till you’ve had a go at ‘Old Mole’ and followed it up with ‘Goddesses’ and ‘Picking up sticks’ with ‘Sellenger’s Round’ to wind up with and you’ll find all you want is to sit down somewhere and get over your aching! I know!” she added darkly.

“Ah, I comprehend now,” Prunella said with an indulgent air. “You mean dances like ‘Sir Roger de Coverley’, I presume?”

Barbara muttered an agreement and the conversation lapsed as it had a habit of doing when Prunella took part in it. Barbara was casting about in her mind for something else to say and Prunella was gazing at the snow-clad mountains, heaving austere shoulders against the pale, blue winter sky with a real delight.

Presently they came to a tall house and, with a sigh of relief, Barbara waved towards it. “That’s Freudesheim where the Maynards live. Dr. Maynard is Head of the big San. at the other end of the Görnetz Platz, you know.”

“Do you mean the father of Helena Maynard?” Prunella inquired.

“And Con and Margot,” Barbara nodded. “Did anyone tell you they are triplets?”

“Yes, Sue Meadows told me so. A most unusual thing, I should imagine. Pray are there any more of the family?”

“I should just think there were!” Barbara exclaimed. “There are the three boys——”

“Pray are they also triplets?” Prunella inquired.

Barbara giggled. “What a ghastly thought! No; they’re singletons, as Auntie Jo says. Then there are the twins—they’re just babies. Perfect ducks, both of them and as wicked as they come, especially Felix. Felicity has only spasms of being bad, but Felix is a demon all the time.”

“They are your cousins, then? I had no idea of that.”

Barbara laughed. “Not real cousins. But we’ve known Auntie Jo and Uncle Jack all our lives and we’ve always called them that and the Maynard crowd call Mother and Daddy Aunt and Uncle, too.”

“Oh, indeed.”

Barbara was too much interested in her subject to notice the crushing reply. She went on, “I wish you could meet Auntie Jo. She’s smash—er—awfully decent.”

Before Prunella could get out the rebuke for using slang that she meditated, Miss o’Ryan called out, “All right, girls! You may break ranks now. Keep together and don’t be getting too far ahead or lagging behind. And don’t yell too much, either.”

They broke ranks promptly and Barbara, by dint of bustling her partner along, contrived to catch up with her cousin Vi Lucy, and two or three more of what were known as The Gang, of which she herself was a proud member. She had made a martyr of herself and taken Prunella for a partner, but she saw no reason why the others should not take their share, too. A walk was very boring if you had a partner who wet-blanketed almost everything you said!

“Auntie Jo hasn’t been over to see us yet,” Vi observed when six of them were walking in a bunch. “I wonder why?”

“Oh, I expect the twins have been cutting teeth or something,” Mary-Lou said airily. “All the same, I wish she’d come. It’s ages since we saw her—not since last term. The hols. were queer with no Plas Gwyn to go scooting over to at intervals.”

“Horrid,” put in a small, very dainty person. “Mother and Gran missed Auntie Jo a lot, too.”

Verity-Anne Carey was not only Mary-Lou’s great friend. Commander Carey had married Mrs. Trelawney in the previous summer and the two girls called themselves “sisters by marriage” in consequence. Verity-Anne was not in the least like Mary-Lou, being tiny, very quiet and retiring, and what Matron called “a mooner”; but those who knew realized that while the elder girl looked after her “sister” and saved her from endless “rows “, it was Verity-Anne who acted as a brake on some of Mary-Lou’s wilder flights.

Prunella now remarked, “I understand that Mrs. Maynard is quite an important person in the school from various remarks I have heard.”

“She jolly well is,” Vi returned. “And then there are her books,” she added vaguely.

“Her books?” Prunella repeated. “Does she own a lending library, then?”

Their shrieks of laughter nearly brought a sharp reprimand on them, but Miss Armitage was restrained by her partner, who murmured, “Sure there’s no one about to mind. Let the creatures enjoy themselves, Cicely!”

Prunella looked rather offended at this reception of her innocent remark. Vi saw it and hastened to put things right. “Sorry, Prunella, but it did sound so mad! Of course Auntie Jo doesn’t run a lending library! She wouldn’t have time. What I meant was her own books—the ones she writes.”

“I see.” Prunella’s brow cleared. “So she is an author? And what books has she written, if I may ask?”

“Oh, piles!” This was Vi. “You must know them, Prunella! There’s Patrol-Leader Nancy, and Tessa in Tirol——”

“And Werner of the Alps—that came last Easter,” Mary-Lou put in.

“And her Christmas one—Buttercups and Daisies, a Guide story,” added Lesley Malcolm, a fifteen-year-old with a clever face. “That did make me homesick for our Guides, but the Head hasn’t said anything so far so I suppose we aren’t restarting them just yet.”

Prunella had had Buttercups and Daisies herself for Christmas. She turned a startled look on Lesley and said as any other girl might, “But—but that was written by Josephine M. Bettany! I’ve read it and I lo—liked it very well,” with a sudden recollection of her present rôle. “Indeed, I have read several of her books. They are really very interesting, though I think it a pity that she puts in so much slang. English especially for schoolgirls, should be pure and undefiled.”

One or two choked at this and Lesley, who had scarcely met Prunella hitherto, stared at her with dropping jaw.

“Oh, gosh!” Barbara muttered to Vi who was next her. “What can one do with such a creature?”

But Mary-Lou had given the new girl a look of deep consideration before she replied, “No modern girl would read them if they weren’t written in—in modern idiom. You couldn’t expect it.”

“And what a grievous pity that is!” Prunella exclaimed. “Do you not think so?”

But Mary-Lou had had enough. “Not in the least,” she said coolly. “People must talk like their neighbours or else other folk will think there’s something wrong with them. Oh, I don’t say slang can’t be rather mad and some of it really is ugly. But on the other hand, a lot of it is frightfully expressive. Besides,” with a sudden memory of a lesson Miss Annersley had given them during the previous term, “language, like everything else, goes on growing. If it doesn’t, it becomes dead. Anyhow, the people in Aunt Joey’s books are just like real people and there’s precious few real people nowadays who go around talking as if they’d just had a session with Elizabeth Bennet or Evelina Belmont!”

“With who?” Vi demanded. Elizabeth Bennet, she recognized. Upper IVa had read Pride and Prejudice as their prose literature the previous term and most of them had enjoyed it. Perhaps one reason for that was that Miss Annersley had arranged some scenes from it for them to act when it was their turn to be hostesses for the Saturday evening. But both Mary-Lou and Vi had really enjoyed the story, although Mary-Lou had been moved to remark that a more ghastly set of snobs she had never met anywhere! But Evelina was new to them.

“Evelina Belmont—heroine of Evelina by Fanny Burney,” Mary-Lou explained. “It’s a priceless book, Vi. Evelina is really the child of Sir John and Lady Belmont. But he left them when he found that she—Lady Belmont, I mean—hadn’t really a fortune though he’d thought she had. Evelina goes to visit some friend in London and goes into Society with a capital S. Everybody falls madly in love with her, even though she has some ghastly relatives. Then she falls in love with Lord Orville, so everyone tries to get her father to recognize that she’s his own child—he’d said she wasn’t!—and he gives them all a shock by saying that his daughter is living with him that minute. Somehow they find out that the nurse had taken her own baby to him and said she was his. They prove it somehow so he recognizes Evelina as his own kid and she marries Lord Orville—and, I suppose, they lived happy ever after!” Mary-Lou finished this masterly resume of Fanny Burney’s great novel with a grin at Vi and fell silent.

“Is it in our library?” Barbara asked, much impressed.

“Sure to be. Ask Madge Herbert if you want to read it. I warn you, though,” Mary-Lou added, “that it’s toughish going, the English is so grand and elegant.”

“The story sounds all right, though,” Barbara argued.

“It is—if you can put up with the way she wrote. She has Jane Austen beaten to a frazzle when it comes to language,” Mary-Lou replied with another infectious grin. “Anyhow, Madge is your best bet if you really want it.”

“That is Margaret Herbert, the school librarian, is it not?” Prunella asked, a certain amount of rebuke in her tone.

The rest looked at each other and chuckled.

“That’s where your toes turn in,” Vi said sweetly, “ ’cos why? Her name isn’t Margaret at all—it’s Magdalen.’

“The more reason, then, to give up such a babyish abbreviation,” Prunella said, her nose in the air.

“Phooey! No one has time for a name like that!” Mary-Lou said flatly. “It’s no go, Prunella. You’ll just have to take it. More than half of us use shortened forms of our names, and we all talk a certain amount of slang—there’s lots that’s forbidden, though,” she added with a grimace.

Prunella said nothing—and said it very haughtily. In fact, she was so supercilious about it, that she failed to notice a heaped-up pile of snow and went headlong over it before anyone could stop her. They shrieked and rushed to her rescue and she was hauled to her feet with real goodwill; but she resented the indignity. Especially when Lesley said, apparently to the wide air, for she addressed no one in particular, “ ‘Pride goeth before a fall’!”

Luckily, Miss o’Ryan chose that moment to call to them and wave agitatedly. Verity-Anne glanced her way and said, “We’ve got to turn back. Miss o’Ryan is waving like mad at us.”

“The sun’s gone in,” Mary-Lou said placidly. “I expect they’re afraid the snow may be coming again. We’ve had none since we came back. Yes; everyone’s turning. Come on, folks! We’ve got rather ahead.”

They turned and ran, warned by the young mistress’s urgency. Mary-Lou had been right when she said they were ahead of everyone. They were now some way behind the others. But they soon caught up with them, Prunella, in particular, sprinting swiftly and easily so that when the rest came up with her, Barbara said rather enviously, “I say—you can—run!” Then she stopped to puff and blow.

For no reason that anyone could see, Prunella went darkly red and stalked along beside her unlucky partner in silence for the rest of the way. Not that any of them had much breath for chattering. The mistresses were afraid of a fresh fall of snow and they bustled the girls along as fast as they could, every now and then casting anxious glances at the sky which was heavily overcast. Mercifully, they were all under cover by the time the first flakes began to eddy softly down.

Once they were safely inside, they were told to hurry and change and then go to their form-rooms for the current lesson. Mary-Lou was kept busy for the rest of the morning and afternoon and found no time to think out the idea which had come to her during the walk. Prunella and her vagaries faded into nothingness beside algebraic progressions, not to mention art and prep. which occupied the afternoon hours. In addition, the snow fulfilled all Miss o’Ryan and Miss Armitage had feared and came down in a wild, swirling dance so that the lights had to be switched on at the beginning of afternoon school.

It was when she was changing for the evening after Kaffee und Kuchen and talking through her curtains to Vi who was at one side of her that she said, “There’s something awfully weird about that girl, Prunella Davidson. I don’t believe for a moment that any girl nowadays talks as she does. If you ask me, it’s put on for some reason and I’m going to find out what’s behind it or my name’s not Mary-Louise Trelawney!”

As by this time both Upper Fourths were becoming hugely intrigued with Prunella and her little ways, everyone was interested and said so. They quite agreed with their leader that there was something odd about the new girl, though they were at a loss to say what it was.

“Just the same if she’s really got some weird secret,” Vi observed as she finished folding her counterpane and laid it on its shelf for the night, “I’m sorry for her. With Mary-Lou on the job, she hasn’t a hope of keeping it a secret very long.”

Mary-Lou finished her second pigtail and tossed it back over her shoulder. Then she asked anxiously, “I say! You don’t mean you think I’m prying or anything like that, do you?”

“Talk sense! Of course I don’t! Anyhow, we simply can’t go on with a Miss Priscilla Prim trying to put us all right on everything. She just won’t fit in—not with us. You can talk about Verity-Anne, but Prunella could give her spades and aces and beat her into fits! You go ahead and find out what’s wrong and then we can put it right—perhaps.”

“If she’ll let us,” Barbara put in from the other side of Mary-Lou.

“Well, anyhow, if she calls me ‘Viola’ once more, I’ll throw the first thing handy at her!” Vi said with sudden heat.

Barbara laughed. “It’s a lovely name, Vi. You needn’t get so mad about it. But I do agree that we ought to do something about it. I’m certain it can’t be right for any girl our age to go on acting and talking like her own great-granny! It—it isn’t natural!”

“It isn’t decent!” Vi retorted as she left her cubicle to join the line forming at the door. “Well, thank goodness she isn’t in our form! We do get a rest from her during lessons! But don’t any of you lot try to catch her disease. It ’ud be too much of a strain for everyone!”

“Don’t you worry,” Barbara assured her, taking her place in the line. “I don’t think we’ve a solitary soul who could!”

Mary-Lou came out of her cubicle and surveyed them. Their dormitory prefect had not yet come up, being occupied with a German coaching, so she had to take charge.

“Are you all ready?” she demanded. “Cubeys all tidy? Good! Silence! Forward—march! And no more talking till we’re in our form-rooms, young Emerence!”

Emerence made a face at her, but left it at that and, as Mary-Lou made an even worse one back at her, honour was satisfied on both sides and Leafy dormitory marched down to evening prep. feeling reasonably pleased with itself.

General work was over for the day and the Chalet School staff were gathered in their own sitting-room, most of them feeling virtuously that duty was over and they were free to enjoy themselves.

It was a very pretty sitting-room. It opened out of the staff-room proper where school jobs were done. Here, they were supposed to rest. The pale green walls were hung with three or four charming reprints of good pictures and one or two water-colours contributed by themselves. The wide window was hidden at present behind its gay cretonne curtains with their design of poppies and cornflowers. Flowering plants stood here and there. There were comfortable chairs, a round table on which stood a handsome silver coffee service, the pride of Mdlle’s heart, and the pretty coffee-cups they had clubbed together to buy. Shelves of gaily-jacketed novels stood against one wall and there was a big, useful closet opposite, where they could keep writing-cases, knitting-bags and other odds and ends. In one corner stood the inevitable porcelain stove which kept the room at summer temperature in the coldest days.

The mistresses, most of them quite young, were scattered about in little groups of threes and fours, drinking coffee and talking hard. Mdlle de Lachennais, the doyenne of the party, sat before the coffee service. Everyone had been served and now she was working on a strip of embroidery intended to adorn a summer dress. Beside her sat Miss o’Ryan, an Old Girl of the school and now history mistress. She was knitting swiftly at an elaborate, lace jumper as she chatted to the language mistress who was also Senior mistress. Not far away, Miss Lawrence, Head of the music staff, was lounging comfortably with the latest thriller. Mathematics and physical training, represented by Miss Wilmot and Miss Burnett, also Old Girls, were having a fierce argument in a corner near the window. At the other side of the room, under a drop-light, sat Miss Derwent, Miss Armitage, Miss Moore and Miss Bertram in the throes of a game of Ten-Rummy at which Miss Armitage was faring very badly, to judge by her frequent groans. Only Frau Mieders and Matron were absent and everyone knew they were having coffee with Miss Annersley and Miss Wilson, Head of the Welson branch, who had come up for the week-end.

Suddenly Miss Armitage, with a louder groan than ever, tossed down her cards. “Someone else can count them! It doesn’t matter, anyway. I’m a long way the worst. I’ve been left in every single hand!” She stood up and shook herself. “I believe there’s a hoodoo on the wretched things! Anyhow, I’m playing no more to-night.” She raised her voice. “Mdlle, is there any more coffee left? There is? Oh, good! I need something to buck me up after that—that fiasco of a game!”

She picked up her cup and brought it to the table. Mdlle filled it, asking sympathetically, “But what, then, is wrong, Cicely, chérie?”

“Me—or the cards. Or perhaps it’s just general bad luck. Anyhow, I’ve been left with a practically full hand every time. What have you two been discussing so earnestly—Thanks, Mdlle—all this time? I looked across once or twice and you looked as if you were settling the affairs of the nation.”

“We’ve been discussing that new child in Upper IVb—Prunella Davidson,” Miss o’Ryan said, finishing her row and holding up her work to examine it critically.

“That’s awfully pretty, Biddy. But it’s not for yourself, is it? If so, you’ve miscalculated the size. It’ll swamp you!”

“It’s for Jo—her Christmas present,” Biddy o’Ryan explained mildly.

“Christmas present? Hasn’t she a birthday before then? Anyhow, you’re somewhat previous, even for that, aren’t you? We’re only just in February.”

“I mean last Christmas,” Biddy said with calm. “I didn’t get time to do it before, though I had the wool and the needles and the design. I gave Jo those on Christmas morning and you could have heard the squawks of her at the summit of the Jungfrau!” She broke off to chuckle softly. “Was she mad! She thought I meant her to knit it herself. However, I told her I’d do it this term, so she calmed down and began to plan for a linen coat and skirt to wear with it. Jo’s a good plain knitter but, as she says herself, anything lacy is beyond her, the creature!”

“It’s really lovely,” Miss Armitage said, examining it more closely. “And that soft green is Jo’s colour beyond a doubt.” She handed the knitting back to its owner. “Oh, Prunella Davidson! What do you two make of that child? I’m worried about her myself.”

“Which child?” In a pause of the argument, Miss Burnett had caught the last words and now got up to come over and join in the talk.

“Prunella Davidson, my dear. What do you think of her?” Miss Armitage made a long leg, hooked her chair towards her with her foot and sat down.

“Very neatly done,” Miss Burnett said approvingly. “What do I think of her? My dear, that’s just what Nancy and I have been discussing.”

By this time, everyone was taking an interest. All of them were baffled by the enigma Prunella presented. In form, she appeared rather shy, very quiet and more or less irreproachable in behaviour. But all of them at one time or another had been privileged to hear her when she was with her contemporaries and they all confessed that though the Chalet School had had its full share of unusual pupils, it had never had one quite like the latest importation.

“The thing that puzzles me,” said Biddy o’Ryan, knitting industriously as she talked, “is how she gets away with it.”

“How do you mean?” Miss Derwent asked.

“Well, here’s a sample. I had to go to speak to Matron early this morning. She was over in Ste Thérèse’s—in Honeysuckle, to be exact—and I had to pass Primrose. The door was open and I was privileged to overhear a specimen of the young lady’s conversation when with her little playmates. It was an eye-opener, I’m telling you!”

“How do you mean?” Miss Lawrence asked.

“Well, Len Maynard had evidently asked for the time, for our young Prunella said, ‘I thought, Helena, that you had your own watch? However, I have no objection to informing you that it is now exactly three minutes past seven.’ Len gave a squawk and shrieked something about being late for her practice and Prunella said, ‘If you make haste, I have no doubt you will be only five minutes late and, you know, “Better late than never” ’.”