* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: The New Prefect

Date of first publication: 1921

Author: Dorothea Moore (1880-1933)

Date first posted: Nov. 30, 2023

Date last updated: Nov. 30, 2023

Faded Page eBook #20231142

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, John Routh & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

By the same Author

THE RIGHT KIND OF GIRL

HEAD OF THE LOWER SCHOOL

THE HEAD GIRL’S SISTER

THE NEW GIRL

A PLUCKY SCHOOLGIRL

MY LADY BELLAMY

CECILY’S HIGHWAYMAN

CAPTAIN NANCY

A BRAVE LITTLE ROYALIST

NADIA TO THE RESCUE

TERRY THE GIRL-GUIDE

With a Foreword by Agnes Baden-Powell

THREE FEET OF VALOUR

All these Books are Illustrated

NISBET & CO. LTD.

LONDON, W.1

“WHAT ARE YOU DOING TO THE KID?”

TO

A GREAT MEMORY

| CONTENTS | |

| I. | The Lists |

| II. | Peter goes Marketing |

| III. | And finds Adventure |

| IV. | The Aftermath |

| V. | Enter Vivian |

| VI. | The Bombshell |

| VII. | Rebellion |

| VIII. | The Sing-Song |

| IX. | In the Night |

| X. | What happened next |

| XI. | On Merthyr Moor |

| XII. | The Great Adventure |

| XIII. | And Afterwards |

| XIV. | Peter takes Prep |

| XV. | The Princess who lost her Childhood |

| XVI. | In Lower Sixth |

| XVII. | For Ruthie |

| XVIII. | The Start of the Forty-eight Hours |

| XIX. | Twenty Telegrams |

| XX. | At the Castle |

| XXI. | Tragedy |

| XXII. | Through |

| XXIII. | The Lists Again |

The New Prefect

“I’m not coming back next term; the Pater says it’s a sheer waste of time and money.”

Meriel Roper’s voice sounded rather on the defensive; her companion, big, loose-limbed Cara Stornaway, answered the tone, not the words.

“Well, the School Certificate Exam was rather a bombshell, wasn’t it?”

“There must have been some mistake—the Coll can’t have messed the exam to that extent!”

“I don’t know,” Cara said. “We didn’t make much of a hand at it last year. Any amount of failures.”

“Yes, but a lot were through, if it was a scrape.”

“I admit it wasn’t the débâcle this has been,” Cara acknowledged gloomily. “We’ve about touched bottom this time, I suppose.”

“But it can’t be true, at least not all of it,” Meriel burst out wildly. “I suppose I am down; I did take it too easily. But we can’t all have crashed, Juniors and Seniors.”

“Except Peter Carey.”

“Oh, Petronella; yes, they did put her down as passing, and with distinction in two subjects, too. That shows there must be something wrong with those awful lists, Cara. It’s rankly impossible that Carol Stewart, the Head Girl, should fail and a kid of sixteen pass with distinction. They’ve got it muddled—everyone knows Peter isn’t brainy.”

“I’m not so sure; Sixth at sixteen.”

“Oh, well, Peter sticks at it; but she couldn’t pass with distinction and Carol fail. It must have been the other way about.”

Cara looked thoughtful. “They don’t often make a mistake in the lists,” she said at last, unwillingly.

A rather small figure crossed one end of the garden path down which the two were strolling.

“Isn’t that Peter?” Meriel asked quickly. “Then she’s come down after her interview with the Governors. Let’s ask her what was said, and if they’re sure.”

She shouted. Petronella looked round at the call, and then ran towards them.

She certainly did not look especially elated, was the thought of Meriel and Cara both. Peter looked as she always looked, a rather ordinary girl, with a face that was a thought too square, and eyes too deep-set for beauty. But it was a pleasant enough face for all that, and no one at Windicotes who had seen Peter Carey smile ever thought of her as plain.

“Wanting me?” she inquired, a little breathlessly.

“In a hurry?” Cara asked.

“I’ve got to pack for Aleth and Angela.”

“Can’t they do that themselves, lazy beggars!”

“Well, I’m the youngest,” Peter stated placidly, “and they are getting rather fussed about the boxes being called for before we’re ready, so if you don’t want me for anything very special . . .”

“Half a tick,” Meriel interposed, as Peter turned to go. “You’ve seen the Governors?”

“Yes.” Peter looked grave all at once.

“It isn’t true, is it?”

“What? The mess-up of the exam?”

“There’s some mistake about it, isn’t there?”

Peter added a touch of visible discomfort to her gravity.

“I . . . I don’t think so, Meriel.”

“Is Carol down?”

“ ’Fraid so.”

“And everyone?”

“ ’Fraid so. Look here, Aleth and Angela will be getting frantic . . .”

“They’ve got to wait half a minute longer,” Meriel said doggedly. “Is it true about your passing, and with distinction?”

“It was just luck; I got the things I knew,” Peter stammered. “I say, do you mind if . . .”

“What did they say to you—the Governors, I mean?” Meriel demanded inexorably.

“Oh, they were ever so decent—shook hands and all that. I say, I really must . . .”

“And Miss Meldrum?” Meriel was determined to have it all, and she was more than a year older than Petronella, and ten times as important in the eyes of Windicotes.

“Miss Meldrum? She was ever so decent too. Of course, she was a bit upset about . . .”

“The rest of us? I’m not surprised,” Cara interrupted grimly. “Right you are, Peter; thanks for telling us. Go along and pack for your sisters if you like, but I think the one and only girl who hasn’t let the Coll down might have been exempted from fagging, if you ask me, which you haven’t.”

“Oh, shut up, can’t you!” groaned poor Peter, and departed hastily.

Meriel swallowed something rather bitter, as she looked after the short, sturdy figure of the junior who had succeeded where she herself had failed so lamentably.

“Good old Peter! I’m glad she had luck anyway. But who would have expected anything from her?”

People said that when you found Helver you went back seventy years. Perhaps it was because it lay so much out of the bustling world, folded away as it were into a crease of the great South Downs, that very few people ever did find it, and so it remained to all intents and purposes the Helver of ever so long ago. There, the irregular timbered gabled houses each side of the village street were the real things, no ingenious imitation, and disused “stocks” still stood on the village green, and Phineas Clutterby rang the curfew, night by night, as his father and grandfather had done before him. . . . The last smock-frock must have been seen at Helver, and Phineas always wore an ancient topper on Sundays, and Helver folk talked of the world seven miles away as “foreign parts,” and resented the reeking char-à-bancs which occasionally crushed between the narrow hedges, taking Helver as a curiosity on their way to some haunt of tea-gardens.

It had never really struck Aleth, Angela or Peter that Helver was old-fashioned; it was the only home they knew, and they had all grown up in the little old house, set in a garden of high mellowed walls, and great clumps of rosemary and lavender, and deep-red clove carnations, heavenly to smell. They knew, of course, that you must bicycle or tramp some miles if you wanted anything not supplied by the exceedingly limited ideas of the village shop; they knew that Helver was rather a long way from everything and everybody else; but it was home, a place just to be loved, not criticised. Four generations of seafaring Careys had their roots there, and came joyfully back to the little old house when ashore.

Some earlier owner than the Careys had carved the name “Good Rest” above the old door, but great-grandfather Peter Carey had pronounced it the name of all names for a sailor’s haven. And father had felt the same.

He slept under the North Sea, that jolly, cheery father, who used to come home to the little old house for brief glorious snatches of sunshine during the Great War—“leaves” when the best of everything came out, from the Dresden cups to the girls’ frocks, and no one might go to see him off who could not be trusted to keep the tears from her eyes and a smile to the last. Now Mrs. Carey and the three girls and Robin lived there, upon an income which was a tight fit for all of them, but with the memory of those wonderful leave-times and father’s code to live up to—and they were very happy people on the whole.

Robin was four, twelve whole years younger than Petronella. He came as a present to them all the very day that the Admiralty telegram arrived—the telegram that told of the sinking of Commander Carey’s ship—and, of course, they all thought there was no baby like him.

He was a long way removed, though, from a baby now, in his own eyes at least, upon that sunny August morning which was the beginning of it all. He and Petronella were digging potatoes; that is to say, Peter was digging and he was getting considerably in the way, when Mrs. Carey’s voice came ringing across the garden.

“Peter! Petron-nel-la!”

Petronella straightened herself, and drew the sleeve of her blouse across her forehead, for it was really very hot, and the potatoes were growing scarce and hard to find.

“Let’s hide!” suggested Robin, with a brilliant smile. “Somevone’s calling; let’s hide in a hole like the little worms do.”

“No, it’s Mummy; come on, Babs,” said Peter, and hauled that unwilling young man along with her. Last time she left him to his own devices he climbed into the water-tank to keep cool, and it happened to be Sunday, when all his clothes were clean and starched. Peter was head nurse in the holidays, and the post was no sinecure where Robin was concerned.

She presented herself before her mother, standing on the garden path outside the drawing-room window. “What is it, Mummy?”

Mrs. Carey had an open letter in her hand.

“This ought to have come yesterday,” she explained, half laughing, “but Helver posts are rather irregular. You remember Cousin Alan, my Peter; well, he is bringing Elena, the girl he is just engaged to, you know, over to see us, unless we wire to the contrary, and they’ll be here by lunch-time.”

“By lunch-time? Mercy! and it’s after eleven now,” Peter said. “And what’s for lunch? Six feet three of Cousin Alan—he’ll want a lot, unless love takes away your appetite.”

Mrs. Carey smiled. “Peter, it isn’t a laughing matter, we were just finishing up that scrag-end of mutton in an Irish stew.”

“That—there wasn’t much left but bones yesterday,” Peter pronounced.

“Yes, it would have been a close thing for us, with the enormous appetite of this bonny boy,” Mrs. Carey said, giving Robin a squeeze. “But we could have made out with pudding. What shall we do?”

“Chops,” Peter suggested laconically, “Extrav., but very handy. Shall I bike in to Greenacre, Mummy?”

“My dear, you’ve been working so hard already,” Mrs. Carey said, looking at the earthy hands and the hot face. “I wonder if Angela . . .?”

“Writing,” Peter explained. “I’ll go, Mum! I don’t mind. Only what about Babs? You’ll be making things for tea, I suppose.”

“Yes, and Babs will help mother, won’t he, like a good boy?” Mrs. Carey suggested hopefully, but unsuccessfully, for Robin at once announced his intention of going nowhere but with Peter.

“I’ll take him behind me on the bike, shall I?” Petronella said. “I’ll just finish those potatoes and be off. Come on, Babs; we must hurry.”

Robin obligingly held the basket, and only spilt it once, so the potatoes were finished in a few minutes; and Peter scrubbed her own hands and her small brother’s, pulled a jumper over her shabby blouse, pocketed her mother’s well-worn purse, balanced Robin on a cushion on the carrier, and jumped into the saddle. The three girls owned the bicycle between them, but Peter gave it by far the most use, being the general one to do the marketing.

It was a gorgeous morning, and she pedalled gaily along the pleasant Sussex lanes, where blackberries were flowering, Robin hanging on to the belt of her red jumper, and chattering without stopping. Over the downs soft shadows chased each other; it was a lovely summer morning.

Presently the lanes gave place to roads—cars began to pass, smothering them in dust; then there was a level crossing to be negotiated—always a special joy to Robin—and the gates were shut, so that he had the added pleasure of waiting to see the train go by.

Peter jumped off her bicycle and stood holding it steady, with Robin’s short sturdy legs sticking out each side of the carrier. She looked at her watch. “I suppose that’s the eleven-thirty from Greenacre, but how late it is!”

“Hurry up, twain!” urged Robin, jumping up and down on the carrier.

The train appeared to hear him, and rushed through between the closed gates as he spoke; Robin drew a deep breath. “I do love twains. Will there be anover if we waited, Peter?”

“No; at least I don’t know, there may be, as that one was so late,” Peter said. “But we mustn’t wait, Babsie, or there won’t be any dinner for Cousin Alan and Elena.”

The gates swung back; Peter jumped on her bicycle and bumped over the level crossing, Robin shrieking with joy at every bump. Her mind was upon chops, and what else to get for dinner, if the butcher at Greenacre should be out of that useful stand-by in time of need. There was nothing to tell her that in another ten minutes chops would have ceased to be of any importance at all.

There are two ways into Greenacre from Helver—three, if you count the fields, but then that way meant stiles, and could not be negotiated with a bicycle. When Robin went to Greenacre with Peter, or indeed with any of his three devoted sisters, there was only one, and that the longest—the road that ran along under the railway embankment.

Robin’s passion for trains never allowed his family to take another way, at least unless the one with him happened to be mother, who did now and again make a little stand for discipline. Peter pedalled cheerfully along the hot stretch of dusty road just under the embankment, for all it added nearly a mile to her ride, and time was rather scarce already; and Robin kept his round blue eyes fixed eagerly and hopefully upon the little single line above him. A goods train rewarded him by coming cautiously round the sharp curve where the dreadful railway accident had happened thirty years ago, an accident which Phineas still considered a warning against the new-fangled habit of travelling by train.

“Will there be some more twains, Peter dear?” Robin inquired, breathing heavily under Peter’s arm.

Peter twisted her wrist round to see the time again. “We may see the London express go through, if we’re lucky.”

Robin gurgled joyfully. “Just get off the bicycle, Peter darlin’, and let’s sit on the embankment, you ’n’ me.”

“Babs, we haven’t time, truly,” Peter said.

“You could wide ever so fast, Peter! I’ll be a good boy for ever ’n’ ever if you’ll let us sit on the embankment and see the twain from London. . . .”

Peter jumped off her bicycle and hugged Robin. They all hugged Robin when he coaxed; they couldn’t help it, somehow.

“You couldn’t be a good boy for ever ’n’ ever,” she told him. “It isn’t in you, scaramouch. Well, come along, and just remember you stay outside the fence, and don’t let go of my hand for one single instant.”

She propped the bicycle in the ditch and climbed up the side of the embankment, holding tightly to Robin’s hand. Of course it was a silly thing to do, for Robin had seen the London express many times before, and got too much of his own way at all times, and it wasn’t a day when anybody wanted to ride too fast along three miles of dusty high road and another three of bumpety lanes. But she climbed the embankment very carefully, all the same, and landed herself and Robin behind the slender fence which was supposed to keep trespassers off the line.

It was a splendid post of observation. She lifted Robin up and set him on the fence, keeping an arm firmly round his wriggling little body. They looked to the left along the glittering level of the line towards Ritchling, that tiny station through which London trains ran without stopping, except by signal; and to the right, along to the wicked curve where the accident happened those thirty long years ago. All the trains crawled carefully round the bend in these days, but it was “the accident place” still, and always would be to the people who lived round about Sellingby, Greenacre, Ritchling and Helver.

Peter and Robin had not long to wait; almost at once Peter’s quick ear caught the distant throb from beyond the curve that meant a train from Greenacre.

Robin was staring in the other direction.

“Wrong way, Babs,” she sang out.

“Dere’s a twain my side, too,” shrilled Robin.

Peter’s heart seemed to herself to stand quite still for a second. Then it gave a great thud and began to beat at a truly terrific pace. She scrambled up on to the top rung of the fence; Robin was right, she knew; it was the London train which was bearing down upon them in that absolutely relentless way. Was she wrong about the train from Greenacre? Peter hoped desperately that she was wrong. If she wasn’t—the engine-driver of the London train would never see that the curve wasn’t clear till too late.

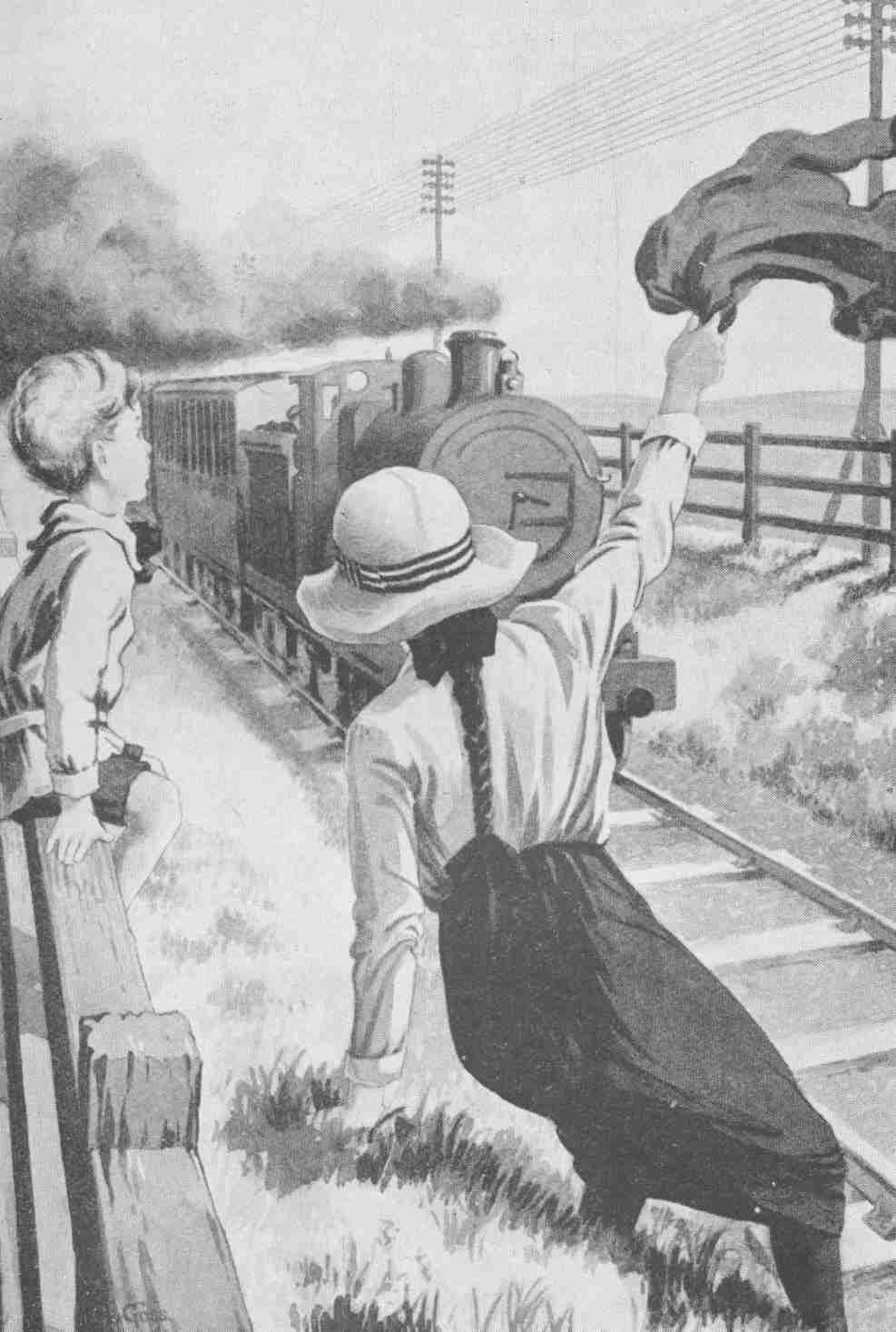

But she wasn’t wrong—she couldn’t see anything because of the sharpness of the curve, but she could hear. . . . The other train had been so late, and there must have been some muddling with the signals. She heard somebody’s voice speaking quite monotonously, rather deadened by the scarlet jumper which she was pulling over her own head.

“Keep still, Babs, don’t move whatever happens. Be a good boy!”

The jumper was off; what a good thing she had worn it—all because her old white silk shirt underneath was quite past mending, and she hadn’t another one clean. She heard the rotten silk go as she tore the jumper off, but raggedness wouldn’t matter now. She scrambled down from the fence, feeling as though the train was almost upon her, shrieking hoarsely and waving the scarlet jumper above her head. It was the first jumper she had made—and she had meant it for the Christmas holidays—hence the flaming hue, and somehow there had seemed so much to do that it hadn’t been finished, and it had only arrived at completion, a little pulled in places and with some dropped stitches inadequately picked up, when she came back for the summer holidays after the great fiasco of the Public Schools Exam. The history of that jumper flashed with absurd vividness before Peter’s mind as she stood in the path of that rushing, roaring monster, waving the badly made garment at which the family had jeered so often, and conscious of the fact that there was a ragged hiatus between her skirt and her old silk shirt.

SHE SCRAMBLED DOWN AND WAVED THE SCARLET JUMPER ABOVE HER HEAD.

The awful earth-shaking roar seemed almost upon her; she wouldn’t look behind her, and she was too sick and blind with fright to look in front; she fixed her eyes on Robin’s tiny figure, sitting holding to the fence with both hands, his eyes absolutely round with amazement, but obedient still. Then there was a grinding screech that seemed to set every tooth in poor Peter’s head on edge, and sudden blessed silence for a second. And Peter, weak about the knees and dry about the mouth, made a futile attempt to tuck her gaping blouse into her skirt, with fingers that were oddly wet and sticky. She was physically incapable of putting on the jumper, which lay, a splotch of brilliant red on the glittering line, not three feet from the front of the engine of the London train. She was too close to the engine to realise that heads were coming out of every window; she only knew that somehow she, and the scarlet jumper between them, had stopped the Express, and presumably the other train as well, for there was no sound. She walked unsteadily towards the embankment, at the top of which Robin still sat obediently on his fence.

“Peter, darling, both the twains is stoppened still and one has tummelled over,” he shrieked at her, and at that Peter found wings for her lagging feet and raced along the line.

The train from Greenacre was half-way round the curve, and at first Peter thought that Robin was drawing on his always decidedly vivid imagination. Then, as she scrambled up on to the embankment, just above the curve, she saw what had happened. Probably the driver of this other train had realised the danger of a collision and put on the brakes too hard in his agitation. The last two coaches had failed to take the curve and had become derailed, Petronella saw. The jerk must have snapped their couplings, and probably they had tried to run up the embankment, for both had turned over on their sides and lay there across the narrow line, half tilted up on the bank, a dreadful danger if there should be any further mistake about the signals.

A chorus of shrill screams from within the overturned coaches, decided Peter upon going to the rescue, even though nobody was in immediate peril. But the screams sounded as though they came from smallish children who were frightened, and Peter always had a soft spot for small children. Of course, people would come to the rescue from the other train, but they hadn’t done it yet.

She climbed up over the wheel of the nearest overturned coach, and looked down through the windows which now formed a sort of skylight.

The compartment into which she looked was packed so tightly with small children as to suggest part of a Sunday-school excursion. Nearly all of them were crying dismally, in spite of the efforts of the only grown-up person there, a rather short lady, with a small thin face and glorious auburn hair from which the hat had fallen. She seemed to be trying to comfort the children, and force up the window from below at the same time.

Peter wrenched at the handle of the door, and nothing happened. Of course, the poor children were frightened; they probably thought there had been a dreadful railway accident, and anyway a railway coach on its side isn’t at all a comfortable resting-place.

She wrenched again at the door and it wouldn’t open—most probably it was locked. She shook the window violently, and it came down with a bang. She leaned across the opening and called down reassuringly.

“You’re as right as rain. Cheer up, kids. Only two coaches tipped over, and people are coming along in two ticks to fetch you out.”

The children stopped crying, partly in surprise, no doubt, and the lady with the auburn hair smiled up at Peter, even though her voice was anxious, as she asked in a low voice:

“The Express? It’s due.”

“Stopped,” Peter said laconically.

After that men came scrambling up to the overturned coaches to rescue their unlucky occupants, and child after child was pulled or hoisted up to the windows and pushed through. There were plenty of volunteers both from the forepart of the wrecked train and from the Express, but Peter didn’t go back to Robin just at once all the same, for when a big cheery-looking man arrived upon the top of her compartment, and directed the lady inside to pass the children up to him because he was too big to get through the window, it appeared that she was lame.

They were all quite little children, probably the infant class of a school. “I’ll get through and pass them up to you,” suggested Peter, and was scrambling through the window and slithering down into the compartment in a moment.

The children greeted her as a deliverer; poor little things, they were really very good, Peter thought, considering how dreadfully they had been frightened. They were most of them hugging sticky bags of buns or sweets, to which they were determined to hang on; but Peter persuaded them to look on the adventure as something of a joke, and she and the auburn-haired lady managed to hoist them up, one by one, to the strong arms reaching down to them through the window. They were all up at last, fourteen of them; and so were their buns and bananas, and most of their rather grubby pocket handkerchiefs. The man above had dropped them neatly over the wheels into the arms of a couple of kind elderly gentlemen below, who caught them and sent them scurrying up the bank, out of harm’s way.

There only remained the lame auburn-haired lady, Petronella herself, and a neat leather dispatch case, labelled G. H. Peter smiled rather shyly at the lady.

“Look here, if I kneel on the edge of the seat, you could get on my shoulders.”

“My dear, I shall be much too heavy for you.”

“You won’t, really,” Peter protested. “You wouldn’t be heavy anyhow, and we learn balance and all that in Gym at Windicotes.”

The auburn-haired lady looked at her with attention. “Are you a Windicotes girl?”

“Rather,” Peter told her casually. “Come on, I’m going to hold the door handle; get your feet on my shoulders. Never mind your bag, you know. I can pass that up after.”

The auburn-haired lady did as she was told. Peter was right; for all her lameness, she was neither heavy nor awkward, and the big man above seized her and pulled her up with comparative ease. Peter watched her through, then picked up the dispatch case. It was not fastened properly; it opened, and a mass of typed manuscript fell out. Peter could not help reading what was written on the outside page: “Lavender Lane. By Georgia Harrington.”

Peter gave a little jump. Then the little auburn-haired lady, who couldn’t stand without a stick, was an author.

Peter had never come across an author, unless she counted Angela, who had published a whole story in Fireside Chatter only last holidays, and a poem of three verses in the local paper.

She put the MS. back with respectful hands, shut the dispatch case, firmly this time, picked up the black, crutch-handled stick, and passed them up to the big cheery man, who appeared to be enjoying quite an animated conversation with Miss Harrington. Perhaps he, too, was interested in authors, Peter thought.

To a girl used to gym it was not difficult to scramble up far enough to meet the cheery man’s outstretched hands, and Peter landed on the top of the coach in a minute, to see a throng of women and children on the bank, and several men with coats off surrounding the overturned coaches, evidently hoping to achieve something even before the arrival of the breakdown gang.

“I wonder what they will do with those poor children,” Miss Harrington said. “Their teachers are taking them to Hastings, I think; two teachers to fifty children—that was why I took charge of a carriageful.”

The man laughed. “I wondered why you had elected to take on a fresh lot of responsibilities. Oh, the kids will be all right—of course the line won’t clear for some time, but we’re quite near Greenacre. I’ll cut along and send out a couple of char-à-bancs.”

Recollections of Cousin Alan and Elena and the needs of dinner began to filter back into Peter’s mind.

“I’ll do that, if you like,” she said quickly. “I’ve got my bike, and I have to go to Greenacre. I have to fetch my little brother and . . .”

“And this, I think.” The big man finished her sentence for her. He picked up something that was hanging forlornly over the edge of the coach, as he had flung it when he scrambled up to Peter’s help. She recognised it as her jumper.

He helped Miss Harrington down to the bank with great care. Peter followed closely on their heels, her jumper on her arm.

Once safely down, the big man turned and looked at Peter.

“Well,” he said. “I’ve heard a good deal about the English schoolgirl since taking on my father’s job as one of the Governors of Windicotes; but I’m slightly flabbergasted when I meet her all the same. I’d like to shake hands, young lady, and to know your name, too, if I may.”

Peter found her voice, though she certainly wished the big man farther.

“I can’t shake hands—I’m all oil and dirt. But my name is Peter—Petronella Carey.”

The auburn-haired lady turned her head, and the corners of the man’s mouth twitched a little. “So you are Petronella Carey!” he observed. “That’s queer, when one comes to think of it.”

Peter would have liked to know why it was queer that she should possess her own name, but she was desperately afraid of more complimentary speeches. Some of the people from the London train were beginning to look at her, and two or three seemed coming towards her. She bundled the tell-tale jumper underneath her arm, and made a dash for Robin, her bicycle, and enviable obscurity.

“Sorry I can’t stop,” she said. “If I don’t rush, there won’t be any lunch at home.”

“Where have you been?”

“Peter! Your new jumper!”

“My dear, give me the chops. Cousin Alan and Elena may be here at any moment—and then go and have a bath. You want it.”

Peter dropped wearily off her bicycle and lifted Robin down.

“It’s steak, Mummy, there weren’t any chops; and he hopes it’s tender, but guarantee things he cannot; and I’m fearfully sorry to be so long, but . . .”

“There were two twains, and Peter stoodened on the line and the twains stopped and one tummelled over,” Robin explained shrilly, determined to get in his say; and then, of course, Peter had to tell her story, while the steak waited to be cooked, and the family hung breathless on her words.

They all fell upon her when she had finished a rather disappointingly brief account of her adventure. Mrs. Carey hugged her, oil, dirt and all; Aleth and Angela thumped her upon the back, and Robin, not to be outdone, embraced her leg ecstatically. They all forgot the steak and the imminence of the expected guests, until a dejected open fly was seen crawling up the lane which Helver called a street, with evident intention of stopping at their gate. Then Aleth flew to the kitchen with the steak, and Peter to the bathroom, while Angela dragged off the unwilling Robin to wash him and the ink-stains off her fingers at the same moment. Mrs. Carey, her eyes very bright and shiny, went to meet the guests.

The steak turned out better than might have been expected, and Peter found that a bath restored her to calm as well as to cleanliness. She came down in time to help lay the table, and relieve Angela from the task of keeping Robin respectable enough to meet the eye of his relations; and luncheon was only about twenty minutes late after all. She went out to tell her mother it was ready, and found the party in the garden getting themselves button-holes of crimson clove carnations—that is to say, Elena was getting one for Alan, and taking a long time about it too.

“Lunch is ready,” announced Peter cheerfully, coming forward to shake hands very properly with her relations.

“This is Peter, Elena,” Cousin Alan said. “She is the third of my cousins—you’ve seen Aleth the future R.A., and Angela the gifted authoress.”

Elena had pretty laughing brown eyes. “And what is Peter?” she asked, holding Peter’s hands in hers.

“Oh, nothing in particular, are you, Peter?” Cousin Alan laughed, and Peter realised, with a little pang, that that was quite a good description of her. Aleth and Angela had their line mapped out; she was just Peter, who would do her lessons, and take the Cambridge Senior next year, as other girls did, and leave school and teach, as lots of other people did, and be nothing in particular all her life.

“And here is the scaramouch,” Alan said, picking Robin up and tickling him till he screamed with laughter, and Elena hugged Robin and said, “Oh, you darling!” And they went in to lunch, and were very cheery, though the potatoes were overdone and the cauliflower boiled to nothingness.

Many lurid experiences had impressed on Mrs. Carey the need of making Robin hold his tongue at meals when any guests were there, so nothing was said about the adventure of the morning; for, of course, Mrs. Carey and the girls would have died sooner than have boasted about the achievements of anybody in the family. So although Elena asked many interested questions about Windicotes, she did not hear anything about the adventure which for the moment made Windicotes a place of no particular importance to the Careys.

“Did you know that my little sister is going this term?” she asked. “You will be good to her, won’t you? She has never been to school before, she has been so delicate.”

“How old is she?” asked Mrs. Carey hospitably. The three girls said nothing. They liked Elena, but it is the drawback of relations, new or old, that they nearly always want to arrange your friends for you. That is a practice which is bearable in the holidays, when you have no dignity to keep up and the serious business of life is in abeyance, but an unmitigated nuisance at school. Aleth and Angela heaved a sigh of relief when they heard that Vivian was sixteen.

“She’ll be Peter’s friend more than ours, I expect,” Angela remarked, and then Peter rose to the occasion and said, “Yes, I hope she will,” with creditable heartiness.

“But I am sorry the school is changing hands just when Vivian is going there,” Elena went on. “Miss Meldrum was so kind and sweet, everybody said.”

“Miss Meldrum going?” it was quite a cry of dismay from the three girls. “Why, she’s been forty years at Windicotes. It won’t be Windicotes without Miss Meldrum.”

“Perhaps I oughtn’t to have told—I only knew it because of Vivian,” Elena apologised. “I remember she did tell me that it wasn’t officially announced yet, for the notices for parents were still at the printers’. You’ll hear all about it in a day or two.”

“Who on earth is coming in her place? Did she say?” demanded Aleth, roused for the moment out of her customary calm.

“Yes, she did say—I noticed the name because it is such an odd one, and, I was sure I had seen it, in magazines, I think. A Miss Georgia Harrington.”

Windicotes was to reassemble in the last week in September.

Long before that date, of course, the expected notice had arrived—a very charming and dignified good-bye to her position as Head from Miss Meldrum, and a warm recommendation of her successor, Miss Georgia Harrington, under whose inspiring care she had no doubt at all that Windicotes would not merely regain its lost glories, but rise to heights hitherto undreamed of.

Mrs. Carey and the three girls had a long talk over the change one evening, when Robin was in bed, and the garden was cool and shadowy and sweet-scented, and the tobacco flowers under the wall gleaming ghost-like through the soft dark.

“I hope Miss Harrington won’t interfere with Windicotes ways,” Aleth remarked.

“She probably will,” Angela said gloomily. Angela hated change.

“She needn’t”—that was Aleth. “Carol could put her in the way of what we do.”

“She could,” agreed Angela, a shade more cheerfully. Peter said nothing, because she felt a shyness in mentioning even to her own people the way in which she knew the name of Miss Georgia Harrington. Also she had an idea at the back of her mind that the Miss Harrington who had taken her danger so calmly was not quite the sort of person who would have all her arrangements made for her, even by Carol Stewart, the Head Girl at Windicotes in right of her seniority in age. It was Mrs. Carey who spoke.

“ ‘The old order changeth, yielding place to new.’ I don’t think it follows that the new order is to model itself entirely on the old, or where would progress be?”

“Miss Meldrum has been good enough for Windicotes, Mummy,” Angela stated, a little defiantly.

“She has been wonderful, and Windicotes girls owe her an enormous debt of gratitude. But you won’t pay it by deciding at the outset that there is only one road to your goal.”

“Yes, Mummy, I know; but this Miss Harrington won’t be popular if she tries to make much in the way of changes at Windicotes,” Angela said obstinately, and Mrs. Carey did not pursue the subject then. There was so much else to talk about, including the important matter of clothes, always a problem where money is scarce. And then Aleth and Angela grew so outrageously; it was really lucky that Peter hadn’t followed their example, for she could still wear their outgrown coats and skirts. The absolutely necessary garments had to be disentangled from the clothes that were wanted but could be done without, and then Aleth and Angela went off to bed. Peter stayed to help Mrs. Carey lock up.

“I wish everything weren’t so desperately dear,” she remarked, putting on the chain to the hall door. “The days of tenpence a sheep would be so handy now.”

Mrs. Carey put her arm round Peter’s shoulders.

“Don’t worry, my Peter, we shall rub along, though, of course, the fit is tight. But I know you girls will manage to bring in some grist to the mill before we have to think of school for Babs—and you are all very good children, and a tremendous comfort to me.”

Peter hugged her mother silently, and went off to bed, but not to sleep as easily and early as usual. She sat up in bed, considering the money-problem very seriously. It was all right for Aleth and Angela; they were almost eighteen, and would soon be leaving school and letting their united talents burst on an admiring world—Aleth as an artist, and Angela as an author of distinction. But, as Cousin Alan had said, she, Petronella, was nothing in particular, and she was only sixteen, and had another two years of being an expense at school, and nothing very brilliant in the way of prospects to follow.

Peter felt rather unusually “down” that night, she remembered; not that she was in the least jealous of her pretty twin sisters, but it was a nuisance to be only sixteen when money was wanted so badly in the Carey family.

She lay awake so long that she was late for breakfast, and so missed the opening of the wonderful letter, which changed everything for her with the magic speed of a conjuring trick.

Mrs. Carey was reading it aloud to Aleth and Angela, and her beautiful dark grey eyes, the eyes which the elder girls had wisely inherited, looked bright and shiny, as they always did when she was specially pleased.

. . . “from what I know of your youngest daughter, Petronella, I believe she is the girl to make good in the post. The Governors of the school therefore empower me to offer her an exhibition giving her two years’ free education at Windicotes, on the condition of her accepting, with the exhibition, the responsibilities of Senior Prefect . . .”

“What, Mummy, me?” shrieked Peter, forgetting grammar, apologies, and everything in the excitement of the moment.

“Yes, you, my Peter,” Mrs. Carey answered, her eyes very bright. “Miss Harrington asks you to be Senior Prefect at Windicotes.”

The Christmas term at Windicotes began on the 23rd of September. About three o’clock that afternoon the greater number of the Windicotes girls foregathered at King’s Cross to go down to Windicotes by the special school train at three-fifteen.

The three Careys were on the look out for Vivian, all with a certain lack of enthusiasm about the business. She was a duty, not a pleasure. However, Aleth and Angela left the job to Peter as soon as they fell in with Carol Stewart, and Peter tramped up and down, looking carefully at every strange girl, exchanging greetings with friends, but not joining any group, though feeling a little victimised.

These were the occasions when Peter wished very heartily that she wasn’t the youngest. She supposed that it would also fall to her lot to show Vivian round the school, and put her in the way of things, and comfort her when she was homesick, and generally devote herself to Elena’s sister until she settled down. And that on the top of the altogether unknown duties of a Senior Prefect.

At the back of her mind Petronella felt distinctly nervous about those duties, but Aleth and Angela did their best to cheer her up.

“They won’t have made a kid of your age anything that matters,” Angela stated comfortably. “I expect all the Upper Sixth are going in for it, and Carol, of course, because of being Senior and Head Girl, and it won’t mean anything really. Just a name, I expect.”

Peter did her best to believe Angela; but remembering Miss Harrington’s determined face, she could not feel it likely that anything arranged by her would be “just a name.” It was all right for Aleth and Angela anyhow; they would never soar beyond Lower Sixth, for this was to be their last term at Windicotes. Peter did not feel that she could take those vague and unexplored responsibilities so easily and lightly.

A girl crossed her line of vision, a girl who was so unusually and extraordinarily pretty that Peter blinked. She had wonderful hair, that made a great rope of a plait, looking as though it had mopped up the late September sunshine; she had beautiful brown eyes, soft and lustrous and appealing, with long lashes; she had a complexion like a pale wild rose, and with it all, features that were as delicately chiselled as Peter’s were blunt, and a figure that was tall and slim and graceful as that of a young nymph. The great brown eyes were wistful and appealing now; she had “new girl” written all over her, but what a new girl!

Peter shook herself awake, and hurried forward. “I say, excuse me, are you Vivian Massingbird?” Her voice sounded unusually blunt, even to herself, just because she wanted so much to be nice and cordial.

The new girl smiled. “Yes, I’m Vivian. I don’t know who you are, I’m afraid.”

“I’m Petronella Carey. Your sister is going to marry my cousin. We were asked to look out for you: those are my sisters, Aleth and Angela—those two tall ones, talking to the Head Girl. Come along and be introduced,” Peter said in a burst, and drew Vivian and her violin-case up to the august group of Seniors.

They were impressed by her beauty; Peter could see that at once. Carol Stewart was always nice to strangers—one could trust the Head Girl to be that—but she was more than gracious now, she was friendly; while Aleth and Angela accepted the quasi-relationship, over which they had groaned a good deal, with easy cheerfulness. They suggested at once that Vivian should travel down in their compartment with the great Carol Stewart; though only on the journey up from Helver that morning they had impressed on Peter that as she was the youngest, it was her bounden duty to take Vivian away, directly the few obvious civilities had been offered, and leave the Seniors of the school to travel together in peace.

Peter was not invited to join her sisters in this very select compartment, but that she didn’t expect. Carol Stewart was two years older than herself, beside being Head Girl, and though Aleth and Angela were very friendly with their younger sister at home, they felt it only right to keep her in her place at school. Peter planted herself serenely in a compartment filled and over-filled with obstreperous Lower Third Babes, and travelled in their rather sticky company.

She didn’t see any more of Vivian until after tea, a very informal meal on the afternoon of arrival at Windicotes, with no staff present. No special places were kept, but the Seniors congregated at the High Table, where the Mistresses usually sat, and discussed the changes in the Windicotes administration with great vigour.

Carol, whose father was a friend of one of the school Governors, had exciting though rather vague ideas about structural alterations; the old Sixth Form room had been done away with, she said, but what was in its place no one knew. Of course, it was unthinkable that the Sixth, Upper and Lower, should not be provided with a special room. Meriel Roper, back at Windicotes in spite of her father’s uncomplimentary opinion of the education, had an idea, based upon nothing particular, that each member of the Sixth was to possess a study. As Windicotes had hitherto known no studies, this idea was hooted as chimerical, but everybody was sure about one thing—there were to be some rather startling changes.

Vivian did not have tea at this High Table, but she was not with Peter either. Aleth had handed her over to Catherine King of the Upper Fifth, and Peter from the next table saw that Vivian seemed getting on with Catherine very well indeed. It did not look as though Vivian would be on Peter’s hands after all. Peter thought she might have been worrying herself just as needlessly over what might be expected from a Senior Prefect. A summons came both for Petronella Carey and Vivian Massingbird directly tea was over. Miss Rowley, the Junior Science Mistress, brought it, and Miss Rowley looked a little out of breath and flustered—even the great Seniors noticed that.

“Miss Harrington wishes to see Petronella Carey and Vivian Massingbird in her room at once,” she proclaimed from the doorway. “Hurry, girls. And Miss Harrington wishes me to say that she will meet the whole school in the Great Hall at half-past seven.”

Peter caught murmurs as she pushed her chair back hastily and made her way to Vivian’s place. “What’s up? The first evening. We always unpack the first evening. What a swizz,” and so forth. Windicotes did not take kindly to innovations, in especial, innovations that touched arbitrarily upon their freedom. Peter did not think that Miss Harrington would find the school in a very easy mood to deal with, unless she had some very attractive alterations to counterbalance. For more years than anybody could remember, the first evening at Windicotes had been one of licence.

Followed by Vivian, she made her way between the long tables, out through the door, across the hall, and down the long corridor to the Head Mistress’s Sanctum. She had been there before in Miss Meldrum’s day, to tea, once or twice—a rather awe-inspiring tea when you wore your best clothes—and rather oftener for private interviews about her work. Also, there had been a terrible occasion not much more than a year back, when the devil had entered into Peter, and she had evolved an original poem about Miss Trail, who in those days hustled the school with aggressive enthusiasm through its botany.

Peter could see again Miss Meldrum’s study, as it had looked then—a study which had suddenly taken to itself the stern look of a Court of Justice, with Miss Meldrum putting on the “black cap.” A sheet of blue-lined exercise paper was spread before her on the table, and she read aloud, with pained solemnity, the lines which Peter had thought gloriously funny when she wrote them.

“Buttercups and daisies, oh the pretty flowers,

Managing to give us several ghastly hours,

Gazing at your sections in despairing hope,

That we may see what isn’t there through a microscope.”

The study looked extraordinarily different on this late September evening. A small wood fire crackled cheerily in the grate—Miss Meldrum never had a fire before the fifteenth of October, whatever the weather.

The furniture was different; in place of the large comfortable sofas and arm-chairs which had crowded up even that big room in Miss Meldrum’s time, there was a sense of space and freedom. The carpet, of which one saw a good deal, was a soft grey; there was a tall oak settle beside the fireplace, and two or three comfortable chairs pulled close as well, but no furniture that one had to thread one’s way between. The firelight gleamed upon old glass and lustre in a cabinet, and upon the burnished copper of an ancient warming-pan hung on the wall; and everywhere around those walls were books, books, books.

Miss Harrington was reading by the firelight, crouched all in a heap upon a black satin “mora”; and an upright angular lady, looking at least a dozen years older, sat upon the settle, knitting vigorously.

“Georgia—the girls!” she said reprovingly, as the door opened.

Miss Harrington did not get up, but she sat more upright, and shut her book.

“That’s right!” she said. “Come and get warm; these evenings are cold. This is Vivian, of course; my dear, what a cold hand! How are you, Petronella?”

It was the clasp of a comrade that she gave Peter. Then she turned to the angular lady on the settle.

“You will have to know the names of all the girls by the end of the week. No excuses accepted by Sunday. So you can begin at once. This is Vivian Massingbird, a new girl; and this is Petronella Carey, our Senior Prefect. Girls, Miss Jane Brooker, who has come to help me with the school, as she has helped me with most things in life so far.”

Miss Jane Brooker laid down her knitting and extended a hand. “Glad to meet you,” she said gruffly. “So you’re the Senior Prefect? You’re rather small.”

“Jane, you are not being tactful!” exclaimed Miss Harrington. “Pull up chairs, girls, or do you like the rug? I always did, before I was lame. Now, can I ask questions?”

“Please do, Miss Harrington,” Peter said very properly, settling down comfortably in front of the blazing fire.

“Would you two girls like to sleep together, or not? I know you are relations, and relations are like our climate, variable. We are just talking now, so you can say exactly what you really feel. Petronella, the Senior Prefect is entitled to a single room if she prefers it. Vivian, you don’t know anyone yet, except your—are they cousins?—but you will have hosts of acquaintances in a day or two, and friends soon after.”

Peter looked at Vivian and Vivian looked back at Peter. It was the first time it had dawned on Peter that her new post carried other advantages than the monetary one. It also seemed to her that it would be rather pleasant to have someone of one’s own age to sleep with, and consult over bothers and so on. Hitherto, since her advancement to the Upper Sixth, she had been Senior in a dormitory full of little ones, who were dears, but a terrible handful to get ready in the morning.

“If Vivian likes, I’d like to share a room with her, thank you very much, Miss Harrington,” she said.

“Thank you so much,” Vivian added, with evident approval, and so it was settled.

Miss Harrington talked more to Vivian after that, asking her what she had read and done. Vivian had never been to school, it appeared; her people lived in the country, and she had been at home with a resident governess.

“Then you are probably well up in a good many subjects, but no good at the Grab game,” Miss Harrington said cheerfully. “School work seems a grab game, after the quiet of home work, you know; but though it’s bewildering at first, it’s such fun trying new ways of getting there. And you are so lucky to have three nice cousins ready to be Guide, Philosopher and Friend.”

“Which is which, Miss Harrington?” Peter asked, with a grin.

“I’ll leave Vivian to find out,” Miss Harrington told her. “Now Petronella—I am afraid it must be Peter when we are being informal—do you mind?—will you take Vivian back to the Gym or wherever you have fires to-night, and introduce her to someone who will show her round and take care of her.”

“Oh, can’t I, Miss Harrington?” asked Peter.

“I’m afraid you can’t,” Miss Harrington said. “I happen to want my Senior Prefect.”

Peter sat staring at Miss Harrington in dead silence. She was trying to take in the altogether astounding things that the new Head had been saying to her.

There was an interval of quite a moment when nobody said anything at all in the big room. Then Miss Brooker broke the silence with a snapped “Well?”

“Give her time,” said Miss Harrington gently.

Peter stammered herself into speech. “But, Miss Harrington, you don’t mean that I’m to be a sort of Head Girl. I c—couldn’t truly. Carol Stewart’s Head Girl, you know; I couldn’t take her place away, really I couldn’t.”

“I’m not asking you to take her place away,” Miss Harrington said quietly. “Carol Stewart will be Head Girl still, as far as that goes. I want something that goes a great deal farther, from my Senior Prefect.”

Peter took another look at the new Head’s face, set in its wonderful auburn hair. Yes, the large well-opened eyes of greenish hazel were quite serious; Miss Harrington did mean what she was saying.

“The girls wouldn’t like it,” she faltered miserably.

Silence from Miss Harrington.

“We never have done that sort of thing,” Peter went on, in a sort of gulp.

Still silence. Rather unnerving that silence.

“I know about the scholarship, and it is most frightfully good of you, and, of course, if I have it I’ll play the game about it; but I didn’t know you were going to ask me to do things I simply can’t,” finished poor Peter.

“Who told you that you can’t?” inquired the Head very calmly.

“Miss Harrington, I’m not brainy.”

“You haven’t chosen yourself.”

“Nor anything in the school. Couldn’t Carol . . .”

“No, she couldn’t,” said Miss Harrington.

There was a little silence. “I don’t want to let you down, you know,” Peter got out at last.

“Of course not. And people needn’t do what they don’t intend,” the Head assured her.

“I think—it’s just as good of you—and, of course, I must write to mother; but I think I would rather not have the scholarship,” Peter said.

Miss Jane Brooker gave a sound that was rather like a snort, rammed her needles deliberately into a black satin knitting-bag, and rose to her feet.

“Told you that you were mistaken, Georgia; told you so all along,” she said.

“I don’t think so, dearest,” Miss Harrington assured her with perfect calm. “But don’t bother to stay if this discussion bores you. Peter and I will meet you and everybody in the Great Hall in half an hour’s time.”

The door shut behind Miss Brooker; it shut very firmly. In a schoolgirl one would almost have called it a slam, only naturally Miss Jane Brooker was above such weaknesses.

Miss Harrington smiled indulgently. “Dear Miss Brooker, I never am properly grown up to her. She was my governess once, you know, Petronella, and when you have failed to make a person see the use of Algebra after many years of effort . . .”

Peter laughed, but she returned to the charge.

“Miss Harrington, it’s awfully wonderful and nice of you to think I could do that sort of thing—but you don’t know me really, you know—I mean, of course, you know all about girls, but you can’t guess about me quite. I just couldn’t—everyone would laugh, and I should make a muddle of it all.”

“Any sort of pioneering wants pluck,” Miss Harrington remarked, so casually that Peter was almost deceived into the idea that she was agreeing with her. “You did show a good deal when you stopped the Express, but it’s a nuisance stretching up all the time, I know.”

“It isn’t that exactly . . .” began Peter. “At least, I suppose it may be just a bit,” she continued lamely.

“I think so too,” agreed Miss Harrington, and then she laid her hand on Peter’s shoulder, as the girl sat there on the black bearskin rug.

“Peter,” she said, “we’ve got a rather stiff run across country before us this term; but no one who can ride may shirk; you don’t want to shirk, do you?”

Peter stared up at Miss Harrington. She had looked like that in the train, when she was expecting a collision and trying to get the children into safety first. Quite suddenly she felt that she would have to say yes to all the dreadful new responsibilities which were being pressed upon her.

“Is it to be the school first?” asked Miss Harrington; and Peter muttered, “I’ll try, anyhow,” which seemed to satisfy the Head.

She took up her stick and limped across to her desk, returning with a paper.

“After consultation with the staff, these are the names of the girls I propose asking to take office as Prefects,” she said. “Twelve of them you see—you are the thirteenth.”

“Unlucky number,” Peter blurted out, feeling the need of saying something.

“Not in this case, I think,” the Head told her. “Among our changes here I have turned a big army hut into a Gymnasium—and a beauty it makes—the old one, which was quite too small for the purpose, has been turned into the Lower School Recreation Room; and that long room at the top of the house where they used to play, to the utter distraction of everyone below, I am told, has been partitioned out into six studies, one for every two Prefects. The seventh study is that little turret room at the angle of the old playroom—and that is for you, Peter.”

“For me—that jolly little place with the cornery windows; how absolutely it!” Peter cried in a tone of such fervour that Miss Harrington laughed.

“Glad you approve. A study is a rather fascinating possession. I have furnished each to some extent, but the owners will supplement to taste, no doubt.”

“Please, when shall we be allowed to be in them?” Peter inquired, with shining eyes.

“Whenever out of actual class-hours your consciences allow you.”

“They’re upstairs.”

“That won’t matter. There will be hardly any rules for Prefects. They are expected to keep the spirit more than the letter.”

“And may we——”

Miss Harrington held up her hand.

“I’LL TRY, ANYHOW.”

“To a large extent you will have the ruling of yourself and others. Keep as your absolute creed ‘The School first,’ and then think for yourself. And now to break our plans to the rest.”

Leaning on Petronella’s arm, Miss Harrington made her slow way to the Great Hall, opening the door exactly on the stroke of the half-hour.

The hall presented a rather disorderly appearance. Girls were strolling about it; some rather languidly placing chairs; Miss Rowley and another very junior mistress were trying, in a rather fussed and flurried way, to get things straight.

Miss Harrington paused at the door and held up her hand.

There was not an instant silence, it is true, but the noise began to die away uncomfortably. When the dropping shots of coughing and feet shifting had followed the voices, Miss Harrington spoke, and her voice sounded like little dropping pellets of ice, not kind and comrady as it had been to Peter in the study.

“I said I should be ready for you at half-past seven, girls.”

Miss Rowley murmured something about not having known how late it was, and it being difficult to collect the girls from their unpacking.

Miss Harrington mounted the platform, still leaning on Peter’s arm, and stood looking down upon the girls, who had by now been got into some sort of order.

“About fifty girls are not here,” she announced after a moment’s pause. “Would you mind, Miss Rowley . . .”

“I am so sorry, but the unpacking is rather a difficulty . . . and Senior girls . . . besides the custom. . . .”

“Would you tell them to come at once, please, Miss Rowley,” the Head requested very quietly. “I should like you to see that every girl is in her place within two minutes.”

Miss Rowley hurried away. Miss Harrington, still leaning upon Peter, surveyed her subjects with much interest. It was an interest with which some of them, very conscious of untidy hair, and clothes rumpled by the unpacking and the ragging in the corridors that generally went with it on the first evening of the term, would gladly have dispensed.

Well within the appointed time there was a stampede on the stairs and across the hall, and the greater number of the missing girls burst into the room. The rest followed three seconds later. Miss Harrington looked round.

“There are two or three little points to which I should like to draw your attention, girls,” she said, her voice reaching without effort to the farthest end of the Great Hall. “I dislike unpunctuality, noise and untidiness. I have met all three at Windicotes to-night. Don’t let it happen again, please. Will the girls who had to be sent for go quietly to their places behind the others?”

The girls went, and very quietly. Whatever they felt, there was not the ghost of a murmur to be heard. There was a pin-drop silence when Miss Harrington began to speak again.

She started by a charming tribute to Miss Meldrum; her untiring work for Windicotes, the vivid interest she felt in its welfare, the obligation on the school to live up to its past reputation. The school clapped as in duty bound, but the enthusiasm would have been more if Miss Harrington had reserved her remarks for what was felt to be the proper time—after prayers next morning, when the business of life had begun.

Then in a brief and business-like manner the new Head outlined the plan of work for the coming term; that was more or less expected and aroused no special excitement, though Meriel Roper looked gloomy and Cara Stornaway frankly sceptical when they heard of lectures on special subjects added to the ordinary school curriculum, and that in spite of the Public Schools Exam to be taken again at Christmas. But aggressive energy was perhaps to be expected from a new Head, and the school in general listened with only moderate disapproval.

Miss Harrington made a slight pause before going on to the burning question of the changes in Windicotes constitution.

“The Governors of the school and I have talked a good deal over the past, present and future of the school,” she said, “and have come to the decision that certain alterations are advisable. Alterations tend to be disagreeable things, both to make and to bear, but you and I have both to consider one thing before any private feelings whatsoever—the good of the School. Government by Prefects always seems to me an essential of any school; for that reason I am placing much of the dealing with school affairs in the hands of Prefects chosen from among yourselves. There will be twelve Prefects at Windicotes, to whom I will talk presently about their duties, responsibilities and privileges. There will be a Senior Prefect, to whom will belong, of course, the casting vote in Prefects’ meetings, and to whom the other twelve will be directly answerable. She is already chosen—Petronella Carey. The twelve Prefects to work with her have still to accept office. I am about to read their names.”

Freda Compton of the Sixth, looking hot and uncomfortable, stood up, in response to an agitated whisper and then a push from her neighbour.

“May I say something, Miss Harrington?”

There was tension in the air; the school felt it. Even Miss Brooker had laid down her knitting, Peter noticed that.

“Have you quite decided to alter ways which have always belonged to Windicotes, Miss Harrington? We are very conservative here—and Carol Stewart is Head Girl.”

Miss Harrington looked full at Freda. “Thank you for mentioning it. I know that Carol has been Head Girl—is still for that matter. Carol and I will talk that matter over later on. But there will be twelve Prefects and one Senior all the same.”

Freda stood up for a second or two longer, as though she wanted to say something else, but she didn’t. She sat down rather suddenly, turning plum colour.

Miss Harrington took up her list as though nothing had happened.

“The names of the girls whom I ask if they are willing to take office for the school are these:

“Cara Stornaway.

“Christine Kington.

“Meriel Roper.

“Sylvia Stockton.

“Jean Adams.

“Nancy Willingdon.

“Doris Carpenter.

“Phyllis Armstrong.

“Margery Cottrill.

“Iris Pemberton.

“Joan Grey.”

A breathless silence, and then a torrent of agitated whispers. Miss Harrington allowed a full minute for those, before she held her hand up.

“To begin from the bottom of the list and go upward—Joan Grey, will you take office as Prefect?”

Joan seemed to find some difficulty in replying, though in general she had plenty to say. She turned very red and stammered a little, was nudged by a neighbour, another Lower Sixth girl, and finally stood up.

“Thank you very much, Miss Harrington, but I think I had rather not accept,” she said.

The school held its breath again as Joan sat down with an embarrassed plop. What would the new Head say?

What she said was “Iris Pemberton?”

“Thank you, Miss Harrington, but I don’t feel fitted for a Prefect.”

“Margery Cottrill?”

Margery was blunter still. “No thank you, Miss Harrington.”

Miss Harrington showed neither annoyance nor surprise. She ran through the list in a perfectly toneless voice, only allowing time for each refusal. Eleven girls declined the honour offered to them; the twelfth, Cara Stornaway, accepted it in a tone that was truculent from sheer embarrassment.

Miss Harrington noted the name down in a little book that she carried with her; the school watched the proceeding with a sense that her bluff was rather good, for she must have known that two Prefects could not rule four houses.

Miss Harrington faced the school again, another paper in her hand.

“I will now read the names of eleven other girls, who are asked if they will take office for the school.”

She began to read at once; it wasn’t bluff, she had another list.

“Patricia Heron.

“Peggy Wren.

“Mary Morton.

“Joan Lindsay.

“Jacynth Caine.

“Helen Wright.

“Catherine King.

“Barbara Slade.

“Barbara Grinstead.

“Martina May.

“Veronica Wynne-Hardinge.”

To say that the school were taken aback would be to express the matter mildly. The move was so entirely unexpected. Veronica Wynne-Hardinge said “Yes” because she could not think of anything else to say, as she afterwards explained, and the rest followed like sheep. The twelve Prefects and one Senior Prefect were duly cheered by a bewildered school, and requested to come to Miss Harrington’s room after supper to be notified of their duties.

Miss Harrington dismissed the school to dress for supper, as calmly as though nothing had happened.

When Peter flew upstairs, after giving the new Head an arm back to her study, she found angry groups standing about in the corridors discussing a situation which it appeared that nobody intended to tolerate for a moment. Unluckily they had borne it for the moment that mattered, the moment when the Prefects were accepting office.

Peter took “Lights Out” according to instruction. When she had done the round she went to her new room, to find Vivian most properly in bed, and Aleth sitting upon hers clad in a blue dressing-gown.

“Hullo?” Peter said inquiringly. There always had been licence on the first night, and Aleth and Angela were in the Sixth, if it was only Lower Sixth. Still, “Lights Out” had been taken; Peter wished very heartily that Aleth was not her elder sister.

“I say, do you mind?” she asked, facing her squarely. “It’s half-past nine.”

“I know. I’m not staying—I’ve only just come to tell you something,” Aleth said. She looked round at Vivian, and Vivian discreetly withdrew under the bedclothes, murmuring something about going to sleep.

“We’ve been talking it over, and someone will have to tackle Miss Harrington. This sort of thing won’t do at Windicotes, making Juniors into Prefects, and so on.”

“The Seniors declined,” Peter interrupted.

“Miss Harrington is new, of course, and she can’t understand about Windicotes,” Aleth went on.

“There is to be a Seniors’ meeting to-morrow, and you must . . .”

Peter stiffened her courage. “Look here, Aleth, I’m sorry, but you must go or be reported. You’re breaking rules.”

Aleth rose in outraged majesty. “My dear kid . . .”

“Sorry, but I did take on the Prefect job,” Peter said stubbornly. “Good-night, Aleth.”

Aleth went out. She looked very tall, and though she returned the good-night, it was from an altitude. Peter foresaw a difficult explanation in the morning. Life presented complications. She began to unhook her evening frock.

“Let me do that, Peter,” Vivian said, sitting up.

Peter sat down on the bed. “Thanks no end.”

“I say, Peter.”

“Um.”

“I’m awfully sorry.”

The sympathy was unexpected. It was also rather nice. “Oh, it’s all in the day’s march,” said Peter. “Come all right in time, I expect.”

She hurried with her undressing and got quickly into bed. “Good-night, Vivian—and thanks.”

Peter stayed awake longer than usual, thinking of the Seniors’ meeting and other rocks ahead. But she also thought that it was rather comforting to have someone in your room who cared how things went with you. She went to sleep at last, feeling comparatively cheerful.

Morning came, bright and sunny, with an exhilarating touch of frost. Peter and Vivian dressed by the open window, Peter busy pointing out historic spots where incidents of note had happened in the Windicotes career. Vivian showed a very proper appreciation of their importance; Peter thought she would be a decided success at school. There seemed a lot to talk about, and the breakfast-bell nearly caught them unready. Only just in time they joined the flying crowd of girls rushing along the corridors and galleries to meet on the great staircase. More girls were in the hall, or streaming up from the dressing-rooms where girls from other houses shed coats and outdoor shoes, and then an army pouring into the enormous refectory.

There was a rule against talking on the stairs, or in the hall; but during the last year of Miss Meldrum’s life, when her health had necessitated her being a good deal away, the rule had become rather slack. Certainly there was a very distinct buzz as the girls crossed the hall in rather disorderly procession and entered the refectory. Peter and Cara Stornaway looked at one another; then Peter nerved herself for a tremendous effort.

“No talking, please.”

The buzz ceased from sheer surprise. Peter, scarlet in the face, stood waiting until the last of the crowd had passed through; then she shut the door and walked to her place. A table marked “Prefects” stood in solitary grandeur in the great bay window. The other Prefects stood near it, looking embarrassed. Peter walked to the head, and glanced at Cara Stornaway. “Let’s sit down.”

The Prefects did not talk much; their position was too new and too conspicuous for ease, and Catherine King, Martina May and Veronica Wynne-Hardinge were only Fifth Form and very conscious of it. But they made a good breakfast; the commissariat was notably improved under the new régime. Just at the end of breakfast, Catherine King remarked nervously:

“I say, Peter, do you know there’s going to be an indignation meeting or something—and it’s Upper School.”

Peter went on eating bread and marmalade.

“So I heard,” she said.

“What shall we do?” asked Patricia Heron.

“See when the time comes,” said Peter.

Miss Brooker was to teach Domestic Science; that had been announced last night, and was a fresh shock to the school. Miss Meldrum had taught nothing personally for years, except Divinity. Windicotes felt that subject belonged to the Head, and that only. Besides, what was Domestic Science?

“Suppose we shall find out,” remarked Peter, to whom the last objection had been addressed, during the interval after breakfast.

“Are you going in for it?”

“Yes, I’ll have to do lots of things in the house, I expect, by and by. We’re not rolling.”

“What’s Miss Brooker like?” asked Phyllida Fayre, a name made for puns, as poor Phyllida knew to her cost.

“You saw her last night, didn’t you?”

“Yes, you silly, but not to talk to.”

“She doesn’t talk very much,” Peter said cautiously.

“Um. How cheery! She’ll expect us to do it all in class, I suppose,” groaned Mary Morton, who had put her name down to take the class last night.

But history was the first lesson that morning. A visiting Professor had taken it last term for all the Forms of the Upper School. He was tremendously learned and rather dull—great on Reform Bills and Constitution and Tonnage and Poundage and so forth. History aroused no enthusiasm at Windicotes; still, a distinction was felt about the Professor’s visits. He hardly ever condescended to a school.

This morning in the big airy Sixth Form room there was no sign of the Professor’s narrow parchmenty face, peering at his class as he edged himself and his voluminous notes in his neat minute handwriting, through the door. Instead, the form had barely seated itself before the tap of a stick outside announced Miss Harrington, and the new Head walked in with a cheery “good morning” to her class. She seemed to feel no doubt that they were pleased to see her. The class stood and responded properly, but a little suspiciously. Another innovation, was the general thought.

Miss Harrington brought no notes or books, she just inquired what the Sixth had been taking in history during the past term. The Sixth were not too definite, suspecting a trap. “The Stuart Period,” was Carol’s description.

“Oh,” said Miss Harrington, and began by a few casual questions. What the Sixth disliked about those questions was their unexpectedness. They had all heard of the Treaty of Dover, though Meriel Roper and Cara Stornaway would have been hard put to it to explain clearly what it was about; but who could be expected to know what else Louis xiv. of France was doing just then, what was the state of Russia, and what were the conditions in Austria which were eventually to lead to the Seven Years’ War?

The catechism didn’t take long—and everyone, including Peter, was glad when it came to an end—and then Miss Harrington began to talk. She didn’t seem to the Sixth to take any particular trouble over it, but facts, and reigns, and people and countries all seemed to come together and to account for one another, instead of remaining in dismal isolation.

When she stopped at last, it was borne in upon the Sixth that there was quite a lot they didn’t know in history!

“Compositions to be handed in on Saturday dealing with the experiences of a girl visiting the English Ambassador’s wife in France, Russia, or Sweden,” Miss Harrington announced cheerfully. “Please take note of the people she would meet. I shall expect most interesting essays”; she smiled her elusive smile. “And, of course, I shall get them.”

Rather against its will, the Sixth smiled back. It had no such flattering hope; but it was difficult not to smile back at Miss Harrington. “But how in the world anyone of us are going to take a subject like that!” groaned Carol Stewart. And Carol liked history, and had always been considered a shining light at it.

Miss Harrington had chosen the break for introducing the Prefects and their studies to each other; Peter wondered a little whether she had realised that the removal of the Prefects gave the opposition in the school a grand opportunity for its indignation meeting. However that might be, it was, of course, impossible to tell her that an indignation meeting was impending. So she followed the new Head upstairs without speaking, only hoping that Carol’s influence would be strong enough to keep down any open expression of defiance.

The studies gave unmixed satisfaction; they really were quite charming. The wooden partitions between them were painted a soft green colour, an admirable background for pictures. There was a little table in each; two or three basket chairs, a small cupboard and bookshelf. As Miss Harrington had said, the rest of the furnishing was to be left to the owner’s individual taste. The Prefects had already arranged themselves in pairs, and took possession with much delight. Patricia paired with Barbara Slade; Jacynth with Catherine King; Peggy Wren and Mary Morton had always been inseparable, and Helen Wright and Joan Lindsay asked permission to share. Barbara Grinstead and Cara Stornaway were obviously intended to pair, and so were Martina May and Veronica Wynne-Hardinge, being so much younger and Lower Fifth only. The Prefects gave Miss Harrington three cheers when she announced that, except for a Prefect on duty for each house, the Prefects could consider themselves free for tea and prep, and could arrange to have tea brought them to their studies if they wished. Windicotes was warmed all over by radiators, but there was still a fireplace at the end of each corridor on which the studies opened, and Miss Harrington said that there would always be a fire there for boiling kettles, and that the cupboards might contain stores of eatables, since Prefects could naturally be trusted not to indulge in midnight suppers and so forth. Then Miss Harrington led the way to the turret-room. “And this is for the Senior Prefect.”

Peter gave a cry of joy as Miss Harrington opened the door. The turret-room was very small, but it seemed to gather into it as much sunshine as the biggest room could hold. There were casement windows, opened wide just now to let in the flooding of that glorious vivid sunshine of late September; there were, as Peter had remembered, many enchanting corners; there was a delicious deep old window-seat, where it would be glorious to sit and do one’s prep.

Miss Harrington had been even more generous with the furniture in this room, just as though she had guessed that the funds at home didn’t run to much not strictly necessary. She had not needed to put in a cupboard, because a long low one was sunk into the least cornery wall. But the bookcase stood on the floor, and was long and white-painted; there was a charming little table of old oak, with queer carved feet; there was a little square of old rose carpet on the floor, and the cushion in the window was the same shade, only rather deeper. Two little white-painted arm-chairs with rose cushions were drawn up suggestively to the fireplace, where a tiny three-cornered grate held a wood fire.

“You Prefects mostly look after your studies yourselves, of course; but coal and wood will be put all ready for you in the little cupboard at the end of the corridor, and I don’t think you will find it difficult.”

“Rather not, Miss Harrington!” That was Cara, a Cara who had quite forgotten to be gloomy.

“You can have the rest of the morning free to arrange your studies,” the Head told the Prefects pleasantly, and they thanked her almost with enthusiasm.