* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Biggles Goes Home (Biggles #67)

Date of first publication: 1960

Author: Capt. W. E. (William Earl) Johns (1893-1968)

Illustrator: Leslie Stead (1899-1966)

Date first posted: November 25, 2023

Date last updated: May 12, 2024

Faded Page eBook #20231133

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, akaitharam, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

Biggles

GOES HOME

By

CAPTAIN W. E. JOHNS

Illustrated by Stead

HODDER AND STOUGHTON

THE CHARACTERS IN THIS BOOK ARE ENTIRELY IMAGINARY AND BEAR NO RELATION TO ANY LIVING PERSON

Copyright © 1960 by Captain W. E. Johns

Illustrations © 1960 by Hodder and Stoughton

MADE AND PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN FOR HODDER AND STOUGHTON LIMITED, LONDON, BY C. TINLING AND CO. LIMITED, LIVERPOOL LONDON AND PRESCOT

| CONTENTS | ||

| Chapter | Page | |

| I. | PRELUDE TO ADVENTURE | 7 |

| II. | A TOUGH PROPOSITION | 16 |

| III. | THE START | 28 |

| IV. | NOTHING DOING | 35 |

| V. | AN UNEXPECTED CHANCE | 44 |

| VI. | TIGER! | 54 |

| VII. | TROUBLES AT THE LAKE | 66 |

| VIII. | GINGER DROPS IN | 76 |

| IX. | DEATH IN THE NULLAH | 86 |

| X. | HOT WORK | 95 |

| XI. | BIGGLES ARRIVES | 104 |

| XII. | WHAT NEXT? | 114 |

| XIII. | A WAITING GAME | 125 |

| XIV. | HAMID KHAN SHOWS HOW | 134 |

| XV. | A GOOD DAY’S WORK | 143 |

| XVI. | THE FINAL SHOCK | 152 |

The hour was that expectant moment between the false dawn and the true: that fleeting interval of time between the death of the moon and stars and the birth of the sun: those few heart-searching seconds when all nature seems to hold its breath as it waits in twilight for the miracle of another day.

The world lay in a trance, as if on the brink of eternity. The silence was profound. No bird sang. No insect hummed. No reptile croaked. The uneasy sounds of the jungle night had died away; those of the sunlit hours had not begun. Nothing stirred; not a cloud in the sky, not a leaf on a tree nor a ripple on the lonely lake called Timbi Tso. The drooping fronds of the palms, bowing to their reflections in the water, might have been the painted wooden dummies of a stage set.

The dawn marched nearer, the sun, victorious as always, even though it had not yet shown its face, driving out the last reluctant shades of night.

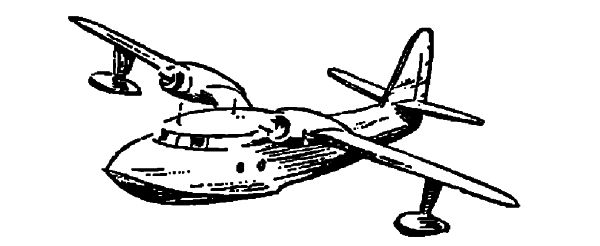

Knee deep in maidenhair fern Police Pilot “Ginger” Hebblethwaite, clad in an open-necked tunic shirt and shorts, stood on the edge of the lake near the Air Police Gadfly amphibious aircraft that floated on its own inverted image, lost in wonder at the beauty of the scene as one by one the seconds passed, to be lost for ever in the sea of Time.

Half veiled in a tenuous mist that contributed an atmosphere of mystery, the picture before him, a harmonious blending of blues and mauves and greys, had more the quality of a dream than factual reality. To add further gratification to the senses the air was heavy with a sweet if rather sickly fragrance.

The light grew stronger. The water gleamed, translucent, with those elusive hues of mother-of-pearl for which no name has yet been found. It might have been a mirror, a sheet of lustre glass, blown by the spirits of the forest which surrounded it, the trees reflecting in it with startling fidelity their every detail. Floating on its surface here and there were the big flat plates of water-lily leaves, the flowers upturned like gold and silver chalices to catch the dew.

Fringing the lake, enclosing it like the walls of a prison designed to keep it for ever in seclusion, was a riot of vegetation not of this world. Some of the trees had trunks and branches of pink and white, so unnatural as to strain credulity. From one that had fallen in the water a spray of orchids sprang like an orange flame. Another had leaves like Indian rugs. The fronds of tree-ferns, six feet long, formed arching curves as if, too long confined, they had burst like rockets to gain their freedom. Over some of them laburnum had hung its golden chains. The pale green lances of bamboos, with their narrow swordlike foliage, stood in close-packed groups as if for mutual protection.

Far, far away, a hundred miles or more, high above the northern confines of the lake, depending as it seemed from heaven itself, ran a ghostly fringe which Ginger knew was some of the nearer Himalayan giants that roof the world; the sacred peaks of Triscul, Kedarath and Badrinath, which, as some hillmen believe, are the homes of the gods that rule the universe.

The sun announced its arrival with lances of white light thrust deep into the heart of a sky of eggshell blue, shivering it into pink. The rim of its disc rose above the horizon and it was day. With it the breathless moment passed and the jungle breathed again. A peacock, a living jewel as the rays of light touched its turquoise and purple breast, rose suddenly. It settled on the branch of a tree and from that safe perch, with its crested head held over sideways, eyed the ground with obvious suspicion. Near by an unseen monkey chattered, scolding.

The cause of the disturbance soon appeared. From behind a thicket of madar scrub, mauve and white with its poisonous blossoms, with lordly bearing and easy gait stepped a tiger, calm and confident, making no more noise in its passage than a fish swimming in deep water. It stopped abruptly in mid-step, one paw raised, as if sensing the presence of the man, and looked directly at him. Ginger met its gaze. He did not move. He made no sound. Neither did the tiger.

For a few seconds the black and yellow monarch of the jungle regarded the man with evident surprise, and then, with casual indifference, walked on, to disappear like a passing shadow into the gloomy depths of the everlasting forest.

Ginger breathed again. Not that he had been particularly afraid, either because the animal had shown no sign of hostility or because it had seemed to fit so perfectly into the picture. Picking up the can of water he had been to the lake to fetch for the early morning tea he went on to a small, square-shaped tent that had been pitched in a little open space a dozen yards from the shore of the lake.

“There’s a tiger outside,” he announced, as he put down the can.

Biggles yawned, stretched, and sat up on the blanket on which he had been sleeping. “What was he doing?” he inquired, without showing any great interest.

“Nothing in particular, as far as I could make out. Just having his morning constitutional from the way he was strolling.”

“Probably looking for his breakfast. He won’t trouble us if we don’t try any tricks on him. Normal tigers like men no more than normal men like tigers.”

“I hope you’re right,” returned Ginger, dubiously. “I, for one, shall do my best to keep out of his way.”

“What’s the weather like?” Biggles lit a cigarette.

“Fine. It’s broad daylight, so get weaving. I’m making the tea.”

From which it may be gathered that to Ginger had fallen the lot of the dawn guard.

He touched Algy and Bertie, who had not moved, with his foot. “Show a leg there,” he ordered. “You’re burning daylight.”

A minute later he nearly dropped the teapot when the quiet that had fallen was shattered by a roar, not far away, so frightful that Algy and Bertie leapt from their blankets like twin Jack-in-the-boxes.

The roar was repeated, blended now with a squeal of fury and a crashing of bushes.

“Oh here! I say, chaps! Dash it all. Who’s doing that? Where’s the rifle! And I’ve dropped my bally eyeglass.” All this was in one breath as Bertie, in his pyjamas, shook his blanket.

Biggles was sitting on his own blanket, his face in his hands, rocking with silent laughter at the panic the uproar had created.

“What’s so funny?” inquired Ginger, indignantly. His face had lost some of its colour.

“You,” replied Biggles, looking up and wiping tears of mirth from his eyes.

The noise outside continued.

“But that’s a tiger,” declared Ginger. “I saw it. I told you.”

“Of course it’s a tiger. What do you think I thought it was—a mouse? Pour me a cup of tea.”

“Aren’t you going to do anything about it?”

“Not me. What do you take me for? He’s not concerned with us.”

“It sounds to me as if he’s mightily concerned with something,” muttered Algy, glancing at the flimsy fabric of the tent as the roaring and snarling went on in a sort of mounting frenzy.

“He’s only concerned with the same thing as I am, and that is some breakfast. How about it?”

“Do you mean all that fuss is because he’s looking for food?”

“No. The fuss is because he’s found it, and by now he’s wishing he hadn’t—the silly fool.”

“What has he found—an elephant?”

“No. A porcupine, and believe you me he’s wishing he’d taken on something easier. Even though it’s his favourite dish I’ve never been able to understand why a tiger knocks his pan out and ruins his temper by fooling with a porcupine.”

“Are you asking me to believe that a thing like a porcupine has a hope against a tiger?” asked Ginger, incredulously.

“Please yourself, but you can take it from me that old Porky can put up a pretty good show. I’d lay my money on him every time. All the same, it’s a pity this had to happen just outside our front door.”

“Why?”

“Because by the time Mr. Stripes throws in the sponge he’ll be in such a foul temper that he’s likely to have a crack at anything he sees moving, and that may be me or you.”

“I don’t get it,” growled Ginger.

“All right. If you’ll quit stalling and pass me a mug of tea I’ll try to explain. As I’ve said, if there’s one thing that makes a tiger smack his lips it’s the thought of some succulent porcupine chops. There are plenty of porcupines about, but unfortunately for him they’re not so easy to get on the plate.”

“I don’t see why.”

“You will if you ever try it yourself. You see, a full grown porky is very well equipped in the matter of armament. He’s as well protected as a tank. On his back and tail—quite a heavy tail, by the way—he sports about fifteen hundred quills, black with white tips, each one having a nasty little barb on it.”

“I know. I’ve used ’em as floats, for fishing.”

“Usually, the first thing that happens when the tiger makes his pounce, he’s pulled up short by a smack in the face with a tail-piece loaded with little spears, some of which stick. That makes him holler—as you may have noticed. It puts him in such a passion that he goes completely round the bend and regardless of consequences fetches old Porky a swipe with a bunch of claws. All he gets for that is a fistful of quills, and from the row he kicks up they must hurt. You would think he’d now have the sense to stand back and do a spot of hard thinking. But no. He goes completely daft and tries using his teeth, which are capable of dealing with most things. But not old Porky. All he gets for that silly show of temper is a mouthful of barbs, so that by this time he’s beginning to look as much like a pincushion as old Porky himself. Sometimes the porcupine gets away with it, sometimes he doesn’t; but whichever way the argument ends one thing is certain; the tiger may get his chops, but he has to pay such a price for ’em that he must wish he’d gone in for fish and chips instead.”

“What does he do about the quills he’s collected?”

“No doubt he manages to get most of ’em out; but not all; there may be some stuck in places he can’t get at. If they turn septic, as they may, he’s in a proper mess, limping about unable to get a bite of anything, every step a groan. Imagine how you’d feel if you had to hunt for your dinner with a row of fish-hooks in the soles of your feet and no hands to get ’em out.”

“All right. I don’t see any need to burst into tears about it,” remarked Algy, coldly. “Whose fault is it, anyway?”

Biggles ignored the interruption. “Hopping mad with pain and hunger, that’s when he becomes really dangerous, ready to have a crack at anything. Some old hunters believe this is one of the reasons why a tiger turns man-eater, which in the ordinary way he isn’t. He prefers to keep clear of men. But when he can’t get anything else, noticing maybe that a native doesn’t have quills, he grabs him, or her, as the case may be. Finding the meat soft and juicy and easy to come by he comes back for more, and if something isn’t done to stop him he may wipe out a whole village. Anyhow, now you know what was going on outside. On this occasion I fancy Porky won the round.”

The noise outside had subsided to deep-throated growls.

“I’d say that’s him trying to get the thorns out of his pads,” went on Biggles. “Had he killed the porky he’d be purring like the cat he is.”

“It won’t be very comfortable here with that devil on the prowl,” said Ginger.

“I shall soon know if he’s about.”

“How?”

“My nose will tell me. Like most carnivora a tiger stinks. Down wind you can smell him quite a way off.”

“How does the tiger get on with the elephant?” Bertie wanted to know. “Old Jumbo should keep him going for a bit.”

“You mean the wild elephants that live in the forest?”

“Yes.”

“For the most part they seem to regard each other with respect. The wild elephant is afraid of only two things; men and fire. Unless he happens to be a rogue he’ll run from either. When he’s moving away from a man he’s like a shadow flitting through the trees, and he makes no more noise than one. Which is something you couldn’t do. How he does it is a mystery. Of course, he makes plenty of noise when he’s feeding, pulling down branches and even small trees. But never mind about tigers and elephants. We’ve a job to do, and we’d better see about getting on with it.”

* * *

Now let us turn the calendar back a month to learn what this job was, and why the Air Police Gadfly amphibian was moored on a remote lake on the north-east frontier of India.

“Tell me, Bigglesworth, where were you born?” Air Commodore Raymond, head of the Special Air Police at Scotland Yard, put the question to his senior operational pilot who, at his request, had just entered his office.

“That’s a bit unexpected,” answered Biggles, pulling up a chair to the near side of his chief’s desk. “India. I thought you knew that.”

“Yes, of course I knew. I should have been more explicit. Where exactly in India?”

Biggles smiled faintly. “I first opened my peepers in the dak bungalow at Chini, in Garhwal, in the northern district of the United Provinces.”

“How did that come about?”

“My father had left the army and entered the Indian Civil Service. He was for a time Assistant Commissioner at Garhwal and with my mother was on a routine visit to Chini when, as I learned later, I arrived somewhat prematurely. However, just having been whitewashed inside and out, the bungalow was nice and clean, and I managed to survive.”

“How long were you there?”

“In the United Provinces? About twelve years. Then, as I was getting recurring bouts of fever I was sent home to give my blood a chance to thicken. I lived with an uncle, who had a place in Norfolk.”

“Do you remember anything of Garhwal?”

“One doesn’t forget the place where one spent the first twelve years of one’s life.”

“Did you like it there?”

“I loved every moment of it. After all, what more could a boy ask for? Elephants to ride on, peacocks in the trees and rivers stiff with fish.”

“You never went back?”

“I didn’t get a chance. I was at school when the first war started, and by the time it was over my people were dead.”

“You remember the country pretty well?”

“If it hasn’t changed, and I don’t suppose it has. When I say I know it I mean as well as any white boy could know it—that is, the tracks from one place to another. I doubt if anyone could get to know the jungle itself. The bharbar, as they call it, the forest jungle that covers the whole of the lower slopes of the eastern Himalayas, is pretty solid, and I reckon it’ll be the last place on earth to be tamed.”

“You did some hunting, I believe.”

“Yes, my father believed in boys making an early start. I used to go out with him and an old shikari who taught me tracking, and so on.”

“Ever get a tiger?”

“No, but one nearly got me.”

“It must have been a dangerous place for a boy.”

“Oh, I don’t know. It’s a matter of familiarity. Here, people are killed on the roads every day but that doesn’t keep us at home. The first thing the Italians, who live on the slopes of Vesuvius, do, every morning, is glance up at the volcano to see if it looks like blowing its top. The first thing I did when I got out of bed was turn my mosquito boots upside down to make sure a krait[1] hadn’t roosted in one of ’em. Thousands of Indians are killed every year by snakes but that doesn’t make people afraid to go out. As a matter of fact a twelve-foot hamadryad lived in our garden.[2] He didn’t worry us so we left him alone because he kept down the rats and ate any other snake that trespassed on his preserves. Here you get used to traffic; there you get used to snakes, tigers, bears and panthers, if you leave the beaten track. If I was scared of anything it was the Bhotiyas—not the tribesmen themselves, but their dogs. The men come down the mountains with sheep and goats which they use as beasts of burden to carry loads of wool and borax. The dogs, enormous hounds like shaggy mastiffs, wearing spiked collars, are trained to protect the herds from bears and panthers, but they’re just as likely to go for you. No. Malaria, the sort called jungle fever, is the real danger. Sooner or later it gets you. It got me.”

[1] A small but very deadly snake.

[2] This is not an uncommon practice in India. The hamadryad or king cobra can grow up to thirteen feet. Its colour is yellow with black crossbands.

“Do you remember the language?”

“Probably. I had friends among the Garhwalis and Kumoan hillmen so I picked up quite a bit of their lingo. I can still speak Hindi and Urdu although it’s some time since I had occasion to use either.” Biggles’ eyes suddenly clouded with suspicion. “Here. Wait a minute. What’s all this about.”

“I was wondering if you’d care to go back.”

“You mean—for a holiday?”

“Well—er—not exactly.”

Biggles nodded. “So that’s it. I should have guessed there was a trick in it. Before we go any further how about explaining this sudden interest in India?”

“I’m coming to that. I was just sounding you out to find out how much you knew about the country. We’ve just learned that a very good friend of ours is somewhere in the jungle of Garhwal, sick, and we’d like to have him brought here.”

“Presumably by me?”

“Of course.”

“Where exactly is he?”

“I don’t know.”

Biggles’ eyes opened wide. “You don’t know?”

“All I know is, he’s hiding in the jungle.”

Biggles looked incredulous. “And I’m supposed to find him?”

“Yes.”

“Oh, have a heart, sir,” protested Biggles. “The jungle you’re talking about covers five thousand square miles. An army could blunder about in it for years without finding a place the size of this building. There’s nowhere to land, anyway. The only spots of open ground are tea gardens and millet fields. I believe there is now an airfield in the province, at Moradabad, but what’s the use of that?”

The Air Commodore raised a hand. “All right. Don’t get in a flap. Things are not quite as bad as they may seem. Sit quietly with a cigarette while I tell you all about it. This is the story. The name of the man with whom we’re concerned is a Mr. Poo Tah Ling. We can call him simply Mr. Poo.”

Biggles raised his eyebrows. “Chinese?”

“Correct.”

“A British agent?”

“No.”

“What’s he doing there?”

“That’s what I’m going to tell you if you’ll let me.”

“Sorry.”

“There was a time, before the Communists took over China, when Mr. Poo was one of the most important merchants in Shanghai—or, for that matter, in China. In that capacity he knew personally many British merchants trading with the Far East. To some he was a close friend. He was one of those Chinese who are a hundred per cent. trustworthy. His word was sacred and he was never known to break it. Talking yesterday to a man who knew him well he told me that although some of the deals he put through involved a great amount of money there was never a contract. Nothing was put in writing, for to Mr. Poo that would have implied distrust. What he said he’d pay, he paid, and that was that.”

Biggles nodded. “I’ve heard of such Chinese. Pity some of our people can’t take a leaf out of Mr. Poo’s book.”

“As you say. Well, the troubles of Mr. Poo began when the country fell to the Communists. He was a rich man, and that of course was enough to put him on the spot as a detestable capitalist. The fact that he had made his money by honest trading in imports and exports made no difference. Knowing what his fate would be he put a few of his most treasured possessions in a sack—he was a collector of rare jade—and dressed as a peasant he set off, on foot, up the Tsangpo river for Thibet. For a man of sixty that was no light undertaking. However, he made it and settled down, as he thought, to spend the rest of his days in quiet retirement on the plateau which is sometimes called the top of the world—Thibet.”

“Why did he go to Thibet? Why not Formosa, where so many refugees went? He’d have been safe there.”

“We know that now, since the Americans have occupied the island; but it was not so obvious then. He was a proud man and apparently decided to go it alone.”

“What was wrong with Hong Kong?”

The Air Commodore shrugged. “I don’t know. He may have thought it would embarrass the British Government if he asked for political asylum. After all, he was, or had been, a rich man, and the Communists would be after him for his wealth. But why he went to Thibet is not important. He probably thought it was the safest place. Well, you know what has happened there. The Chinese Communist armies have marched in and occupied the country, making themselves secure by liquidating half the population. Again the unfortunate Mr. Poo, to save his life, had to flit. He made for the Himalayas and the frontier of India. That’s how he got to Garhwal.”

“A lot of Thibetans got to India. Why didn’t he follow the Dalai Lama’s party?”

“He couldn’t very well do that.”

“Why not?”

“Think! They were Thibetans. He was a Chinese, and the Chinese Communists were the invaders. He might have been taken for a spy. It’s unlikely that he would have been tolerated. His position would have been that of a German retiring with the French before Hitler’s hordes. Realizing this he went his own way. With the help of a Thibetan servant who had remained loyal to him he made his way down the mountain slopes into Garhwal where he collapsed from exhaustion and fever. No doubt he would have died where he fell, deep in the forest and far from anywhere, had not his servant, looking for food, struck the camp of an Englishman, a retired Indian army officer named Captain John Toxan.”

“That was a slice of cake. What was Toxan doing there?”

“Digging. He’d been digging there for six years.”

“For the love of Mike! Digging for what?”

“Rubies. It seems that some years before, while he was still a serving officer, out on a hunting trip during his furlough he had picked up some stones in a dry river bed. They turned out to be rubies. But they were no good. Exposed to the weather they had become friable. He knew that somewhere not far away was the main source from which they had been thrown up, or exposed by erosion, ages earlier. He was digging deeper hoping to find good stones, flawless and valuable. He’d been at it for six years without finding anything but duds. That’s how things were when Mr. Poo arrived. Toxan’s original bearers had all packed up long ago with the exception of a couple of Gurkhas, old soldiers who had served in the British Indian army. They had the guts to see the thing through. Toxan took care of Mr. Poo.”

“Did he know him?”

“No. He’d never even heard of him. But as far as he was concerned here was an old man down on his luck, so he took him under his wing. Mr. Poo, who speaks English like you or me, told him his story.”

“He recovered?”

“Yes.”

“But he still stayed on with Captain Toxan?”

“Yes.”

“Why? Why didn’t he go on down into India like the other Thibetan refugees?”

“For two reasons. In the first place he wasn’t sure he had the strength to travel any distance and he was afraid of getting a recurrence of fever. Secondly, as I said before, he was not a Thibetan. He was a Chinese, and as feeling in India was running high against the Chinese for what they’d done in Thibet, their northern neighbour, he was worried about the sort of reception he’d get. He was certain to be unpopular, so rather than put the Indian Government to any trouble he decided to stay where he was.”

“What’s going to happen if Toxan gets browned off with digging and pulls out?”

“That’s the trouble. He’s thinking of doing that. But he and his two Gurkhas couldn’t carry the old man and they can’t just abandon him there.”

“They might get help from a native village.”

“Toxan says that would be dangerous. He says the natives don’t mind helping the Thibetans but they’d probably kill a Chinese if they got their hands on him.”

“How does Toxan know this? And how, for that matter, do you know all these details?”

“Because we’ve had a long letter from Toxan in which he explains the position. He says the old man has told him he has money in England if only he could get there. Could we do anything about it?”

“How did Toxan get the letter through?”

“He had to send his men to Chini with money for stores, as he was nearly out. They took the letter and posted it. It’s a three weeks’ trip each way from his camp.”

“In asking us for help, Toxan is expecting rather a lot, isn’t he?”

“I don’t think so. Poo would have done as much for us had the position been reversed. He’s that sort of man. And Toxan knows that whatever our enemies may say about us we can’t be accused of abandoning old friends when they’re in a spot. That goes on more often than people imagine, but we don’t make a song and dance about it.”

“So boiled down the position is this: somewhere in the bharbar, the belt of jungle that divides the mountains of the north-east frontier and the plains, there’s a party of five men, one white, one Chinese, two Gurkhas and a Thibetan; and you want to get the Chinaman here.”

“Exactly.”

“And you’re asking me to go to fetch him.”

“That is correct.”

“Now tell me how you expect me to do that?”

“I leave it to you.”

“With all due respect, sir, I suggest you haven’t the foggiest notion of what you’re asking me to do.”

The Air Commodore smiled. “I’ve a rough idea. But the thing is possible, and that being so, you, having the advantage of knowing the country, are the man to do it. If you fail—” the Air Commodore held out his hands “—well, we can at least say we tried.”

“That won’t be much comfort to Mr. Poo, who will probably be dead by the time we get there. I’m thinking more of Toxan, who must be a stout feller to do what he’s doing. All the same, I don’t think he can be very bright in the uptake or he’d have left one of his men at Moradabad, or some place where I could get down, to lead us to his camp. Without a guide we shall never find it.”

“Why is this so difficult? You’ve tackled jungles before. What about South America?”

“That’s a different matter. You can usually get about up the Amazon because the density of the big timber prohibits much in the way of undergrowth. This Indian jungle is real jungle, practically solid. You can cut a way through the bamboo but when you come to rhododendron forest, as it grows there, a mass of intertwined branches as thick as your leg, you’ve had it. With axes a squad of pioneers might do a mile in a month. And look at the size of the bharbar! As I remember it it’s anything from fifty to a hundred miles deep and hundreds of miles long. Native cultivation ends at about six thousand feet; then you’ve nothing but jungle till it begins to thin out at ten thousand. Remember, this isn’t level country. Not only is it on a slope, the foothills of the Himalayas, but it went into convulsions when it was created. It’s ridged and furrowed by gorges, some of them hundreds of feet deep with precipitous sides and water, tributaries of the Ganges, that tear like a mill-race, at the bottom. The only way you can get about is for a guide to take you up one of the tracks cut by our Forestry people when we were there. It’ll surprise me if they’re not all overgrown by now. That doesn’t take long. There are a few native tribes, mostly nomadic, woodsmen who live by hunting, but for all practical purposes you can call the country uninhabited.”

“All right. Having said all that will you go?”

“Of course I’ll go. I’ve simply tried to give you an idea of what we’re up against. There should be no difficulty in getting to Moradabad, but where do we go from there? How do we set about finding Mr. Poo?”

“By aerial survey you may see the smoke of Toxan’s camp fire.”

“And having spent a month on foot getting to the smoke we find a party of Gond hunters cooking their dinner. It’s no use saying I should be able to see Toxan’s tent from the air because the trees are so thick you can’t see what’s underneath. Toxan must realize this. Did he give any indication at all of where he was?”

“Here’s his letter, written in pencil on pieces of mouldy paper. Make what you can of it. He says his camp is at about eight thousand feet a few miles east of, and a little below, a lake called, he believes, Timbi Tso. I’ve checked that with the Indian Survey Department and there is such a lake.”

“That’s a fat lot of use; but I suppose it’s better than nothing. The name of that lake, although I was never anywhere near it, rings a bell. I think it must be the one I sometimes heard referred to as the Blue Lake, or the Blue Water. Why on earth didn’t Toxan make a sketch map showing the exact position of his camp, noting some salient feature, nearer than the lake, as a landmark.”

“Maybe there wasn’t one.”

“Yes, that’s more than likely. From the ground the country all looks very much alike, and no doubt it does from the air. And, of course, Toxan wouldn’t be thinking of an air rescue. Pity we can’t get hold of one of his men to act as guide. That would have simplified matters. They must over a period of years have been down to the low ground many times for stores, so even if there isn’t a track they’d know the way. But it’s no use talking of what Toxan might have done. The bearers who left him have probably forgotten all about him by now.” Biggles got up. “All right, sir. Let me think about this.”

“Don’t think too long or you’ll be too late.”

“Did Toxan date his letter?”

“As you’ll see, he says he didn’t know the date. But as the rains had just stopped he thought it must be November. The letter came air mail, so allowing three weeks for the overland journey to the post office we can reckon it about a month since it was written.”

“Okay, sir. I’ll get on with it.” Biggles walked to the door.

“Is there anything I can get you that might help?” inquired the Air Commodore.

Biggles stopped and thought for a moment. “Yes, there is something you might do.”

“What is it?”

“Get us permits to carry firearms, at all events, our pistols. I’d also like to take a rifle. In the jungle one never knows what one is going to bump into, and no man in his right mind would wander about without some means of self-protection. After all, this is big game country. You could explain that the firearms are strictly for defence should we have to make a forced landing in some out-of-the-way place with the prospect of walking to civilization.”

“Anything else?”

“A camera might be useful. Indian customs might be sticky about an air camera.”

“What reason could I give for that?”

“You can say the camera’s for taking shots for a projected T.V. series.”

“Very well. I’ll have a word with the India Office and if possible get you a Firearm Certificate and a permit for aerial photography.”

“Thank you, sir.” Biggles went out.

As Biggles walked back along the corridor to the operations room he became aware of a curious thrill at the thought of returning to the country where he had been born. The thought struck him, and he wondered why, he had never been back to look at the places of which he had clear and happy memories—marred somewhat, it is true, by the fever that had sapped his strength. He found his assistant pilots waiting for him expectantly.

“Well, what’s the drill?” questioned Ginger, when he walked in.

“Do I remember someone saying he liked his climates hot?” inquired Biggles, flippantly.

“Absolutely, old boy,” answered Bertie, promptly. “That’s me. Every time a coconut.”

“I can’t promise you coconuts,” returned Biggles, lightly. “There’ll be more monkeys in the trees than nuts, where we’re going.”

“And where are we going?”

“India.”

“What part?”

“Garhwal.”

“But I say! Isn’t that where you gave your first bleat?”

“That’s the place.” Biggles sat at his desk.

“What ho! What fun.”

“You may not think it’s so funny when I tell you what we’ve been asked to do.”

“Cough it up, old boy. I can’t wait. Do we go before the chilblain season sets in?”

“Right away.”

“Lovely. Tell us about it.”

With pensive deliberation Biggles lit a cigarette. Having spent his boyhood in Northern India he knew much more about the country than he had had time to tell the Air Commodore. Now, thinking about it, memories of half-forgotten incidents poured in on him.

“Somewhere in the jungle, on the slopes between the plains of India and the frontier of Thibet, there is an elderly Chinese gentleman by the name of Mr. Poo Tah Ling. We’re going there to find him and bring him here,” he announced.

Algy looked incredulous. “Are you serious?”

“Very much so, and with good cause.”

“But why——”

“If you’ll stop asking questions and pay attention for a few minutes I’ll give you the complete gen.” Biggles settled back in his chair and recounted the conversation he had had with the Air Commodore. “That’s the position,” he went on. “On the face of it the job looks simple enough; and so it would be but for one big snag, and that’s the almost complete absence of landing facilities. As far as I know there’s no airfield nearer to the objective than Moradabad, and that’s some distance away. Outside that I can’t visualize a flat patch of ground large enough, or level enough, to put an aircraft on without risk of a crack-up. There could be no question of landing anywhere in the jungle area, although in an emergency one might avoid a bad crack by gliding down to the lower ground and doing a belly-flop on a tea estate or a field of grain.”

“What about this lake Toxan mentions?” suggested Algy.

“That, I imagine, will be our one hope of getting down within marching distance of Mr. Poo. I’m not even sure about that. It might be choked with weeds. I’ve never seen the place, but as I told the Chief, I’ve a vague recollection of having heard tell of it. There’s a piece of water—I don’t know how big it is—which the natives used to call the Blue Lake. I think this must be it. It shouldn’t be hard to locate, provided there’s just one lake and not a dozen. Having got there we’re then faced with the job of finding Toxan’s camp, and having spotted it, of getting to it. That means walking, and I can tell you right away it won’t be easy. In fact, it may turn out to be impossible.”

“If we spotted Toxan’s camp we could drop a note to him saying we were waiting for him at the lake,” offered Ginger.

“The old man may be too feeble to make the journey to the lake. That would probably depend on the distance, which is something we don’t know. The trouble is, assuming we were lucky enough to spot Toxan’s camp from the air he’d have no way of communicating with us. We wouldn’t even know if Mr. Poo was dead or alive. If he was dead it would be pointless to go on with the operation. If Toxan started walking to the lake, and we started walking to his camp, we should certainly miss each other in the jungle and be in a worse mess than ever.”

“Is the going as bad as all that?”

“You’ve no idea until you’ve seen it. I know you’ve seen some rough country but I doubt if you’ve ever struck anything as thick as the Indian jungle. Remember, I know what I’m talking about. I’ve had some of it. But then, when I went out on a hunting trip I was always in the care of a local shikari who knew his way through the tangle of game tracks. Most of these tracks wander about all over the place, often with only a pool or a salt-lick for the objective, so without a guide they wouldn’t be much use to us. I used to go out with a grand old fellow named Josna Kumar, a wonderful tracker. What he didn’t know about the country wasn’t worth knowing. But he must have passed on long ago.”

“Would you call this bharbar bad country?”

“Bad in what way?”

“Any way.”

“Apart from the difficulty of getting about, no. From the spectacular point of view some of it is really magnificent. I’ve seen stands of timber that must have been saplings about the time William the Conqueror was crossing the Channel. Of course, you’ve got to know what you’re doing or you can get in a mess—but that goes for most places. The prospect of going down with fever is always there; that was my trouble; but we’re not likely to be there long enough for that to worry us. Don’t get the wrong idea of the country. It isn’t dangerous in the sense that it’s unexplored, bristling with hostile tribes. Nothing like that. White men have hunted it for years, and most natives, such as there are, are usually delighted to see them. They’re chiefly Gonds. Their original home was in Central India. It was tribal warfare that caused them to retreat to the hills.”

“I had an idea those capital soldiers, the Gurkhas, came from Garhwal,” put in Algy.

“Quite right. Regions of Garhwal and Nepal. They’re grand fellows, but they’re not really jungle folk. We may see Bhotiyas. They look rather like Japs and believe in ghosts. My old shikari always seemed a bit nervous about running into a sort of secret tribe called Rishis, but I never saw any so I can’t say anything about them. None of these jungle people cultivate land for food. They all live by hunting.”

“I was thinking more of dangerous animals,” said Ginger.

“It depends on what you call dangerous. There are plenty of animals—elephant, tiger, panther, bears and what have you, but only in rare circumstances would one be likely to go for a man unless the man started the trouble. On a trip like ours we’re not likely to interfere with any of ’em, we’ve something else to do.”

“What about tiger?”

“Even he does his best to keep out of your way. There are exceptions, naturally. An elephant may turn rogue when he grows old and bad tempered, and so finds himself kicked out of the herd. The odd tiger or leopard may develop a taste for human meat and do a lot of mischief before he’s knocked off. Fortunately they’re uncommon. In my day the natives, not having the proper weapons for the job, couldn’t deal with these pests, so when things became really bad the government would send along a specially trained white hunter to wipe out the scourge. No doubt there are now Indians who handle this sort of business.”

“What about snakes?” asked Bertie. “If there’s one thing that gives me the heeby-jeebies it’s snakes.”

Biggles smiled. “Oh, there’s no shortage of snakes. Most of them are harmless enough but it’s as well not to take chances till you know ’em. The trouble with snakes is, they have a habit of popping up where you least expect them, and are not even thinking of such things. I had several narrow escapes when I was a kid. Once I stooped to pick up a ball, and jumped back just in time. Lying coiled beside it was that frightful little devil, a krait. If he bites you, you’ve had it. Another time I pushed open the bathroom door, and a krait, which must have been lying on the top, fell on my shoulder. Luckily for me he bounced on the floor, and as you can imagine, I bounced into the next room. One forgets about snakes, but when that sort of thing happens you remember ’em. My father was once bitten on the thumb by a Russel Viper and nearly died. He was in agony for days. If anyone’s scared of snakes he’d better stay at home.”

“Don’t you get pythons there?”

“Plenty, but they’re not poisonous. They’re constrictors. As a general rule the little ’uns are the worst. I used to go out looking for pythons. They like water and a cool spot. A great place for ’em was in the narrow irrigation ditches on the tea estates. I once saw one nearly thirty feet long. The natives make all sorts of nice things from their skins. But we shall have plenty of time later to natter about these things. Let’s see about getting organized. We’ll start with the maps. Then we can make a plan of campaign.”

That was how the operation began, and up to the time of arrival at the Blue Lake it proceeded without a hitch. The flight out, via Delhi and Moradabad was ordinary routine, facilitated by documents provided by the Air Commodore and the India Office in London. To the relief of Biggles, for officialdom can on occasion be tiresome and cause delays, nothing was questioned.

The party spent two days in Moradabad while Biggles tried to obtain news of Captain Toxan. There was just a chance, he thought, of making contact, through an agency, with one of Toxan’s bearers who had left his service and was now living in the town. However, this failed. Possibly because he had been away in the wilds for so long no one appeared even to have heard of Captain Toxan. From where the men he sent down from time to time, for stores, obtained them, could not be discovered, so rather than waste any more time, he had, with his tanks topped up, made a reconnaissance to locate the Blue Lake, the first objective. This had proved relatively easy, for there was only one piece of water at the known altitude of Timbi Tso—to give the place its proper name—large enough to be called a lake.

Having examined the surface and finding it clear except for water-lilies in the shallows, seeing no point in using up fuel by returning to Moradabad a landing had been made and an advanced base established. By the time this was done the light was fading and it was therefore too late to start the search for Toxan’s camp that day.

So, watches having been arranged, an automatic though apparently unnecessary precaution, the party spent its first night in the jungle, the plan being to survey, and possibly take photographs which could be examined at leisure, in the morning.

Which brings us to the point where Ginger, fetching water for early tea, saw the tiger.

“Are you going to leave anyone here to keep guard over our stuff?” asked Algy, as the camp was tidied up preparatory to making the first serious reconnaissance.

“I don’t think that’s necessary,” decided Biggles. “This lake can’t be visited by men very often or we’d see marks. There should be game tracks leading to a stretch of water of this size. Most things have to drink. No doubt there are elephant tracks, but the only way we’d find them would be by sweating round the perimeter of the lake, and I’ve no intention of doing that. If a hunting party did come along I don’t think they’d touch our things. The natives I met years ago were mostly honest and trustworthy. In view of what we have to do the more eyes we have in the machine the better. We’ll lace up the flap of the tent to keep monkeys out. I can hear some about. They’re inquisitive little rascals, not to say mischievous. We shan’t be away long.”

“What’s this wonderful aroma I get whiffs of every now and then?” asked Ginger.

“It’s a shrub. I don’t know the botanical name but the local people call it mhowa. It’s common everywhere. If you get too much of it, it can be a bit sickly.”

“The flies are a bit grim now the sun’s up,” observed Bertie.

“You’d be lucky to find a place in the tropics where there are no flies,” Biggles told him, as he secured the tent. “Flies and ants by the million. Before we get airborne I think it might be a good thing if you all had a dekko at this particular type of jungle so that you’ll know what you’re up against if you ever have to walk. Come over here.” Pushing aside the undergrowth he forced a passage, not without difficulty, for a few yards. “Apart from anything else, even if you can make progress it’s almost impossible to keep direction. Naturally, you choose the easiest way, and that means weaving about. If you get lost you’ve had it. The only paths are elephant tracks, and they may lead anywhere except where you want to go. Elephants eat as they wander along, which is why they leave tracks. With all that bulk to keep going they rarely stop eating. My old shikari assured me an elephant eats eighteen hours a day. How true that is I don’t know. I’ve never watched one for that long. As it’s about the only way of getting about, everything else, men as well as animals, use the elephant tracks. Unfortunately the tops of the trees will prevent us from seeing any sort of tracks from the air. I say unfortunately because it might be useful, in an emergency, to know if there are any, and where.”

Biggles stopped when his advance was halted by what looked like the writhing tentacles of a thousand octopuses. “Take a look at that,” he invited. “It’s rhododendron. You can bash a way through palm and bamboo but to get through this stuff you’d need an axe. Even then you wouldn’t get far. This happens to be only a small patch so you could get round it; but you’re quite likely to hit an area of miles of rhododendron. Then what? You can’t get through it. I can tell you that because I’ve tried. Yet to go round may take you so far off your route you’d be lucky to get back to it. A compass is all right in the open, but it isn’t much use in this sort of stuff. You see what I mean.” Biggles indicated what lay before them.

“Are there no roads at all?” inquired Ginger.

“When the British ran India they made a few roads into the bharbar for the use of the Forestry officers, but road making here is a big job so they’re few and far apart. I’ve seen no sign of one anywhere near, so for all our chance of finding one we might as well forget it.”

“Listen! Can I hear an elephant now?”

“No.”

“Then what’s that crackling sound I can hear?”

“A tree. A kind of teak. The natives say when it crackles it’s a sign of hot weather coming.” Biggles smiled. “By the time we leave here you fellows should know quite a bit of jungle-lore.” He pointed to a shrub bearing purple and white blossoms. “Be careful with that,” he warned. “It’s madar, and deadly poison, so don’t try chewing it if you’re thirsty. It’s said that when a native wants to get rid of another he slips a few of those flowers in his drink. But the sun’s well up so we might as well get topsides.”

“What exactly is the scheme, old boy,” asked Bertie, as they retraced their steps.

“Nothing definite, except that we’re going to try to locate Toxan. I can’t say more than that. You can see what we’re up against. I appreciate Toxan’s difficulties but it’s a pity he couldn’t have been a bit more precise about his position. According to our altimeter when we landed the lake is a bit below nine thousand. He says his camp is a few miles to the east of it, and a bit below. What does he mean by a few miles! Ten—twenty—forty? In a country of this size fifty miles could be called close. What does he mean when he says a little below the lake? How far below? He talks of eight thousand feet. I hope he’s right, or we might find ourselves looking for something that doesn’t exist. I suspect the fact of the matter is, he himself isn’t absolutely certain of his position. He may never have seen the lake; just heard native talk about it, and that isn’t to be relied on. Apparently it was the only conspicuous landmark he could think of when he wrote the letter. Without that for a guide, vague though it is, the job would be next to impossible.”

Reaching the cable by which the machine was moored to the bank Biggles began pulling it in.

As a matter of detail the aircraft had been left afloat as a precaution against interference by monkeys. For the same reason the food supply, tinned or packaged, of course, had been left on board, only to be taken ashore as required. Biggles did not expect to find food available on the spot, not even fruit; for contrary to general belief little in the way of food is to be found in a tropical forest, any fruit, berries or nuts that do occur being devoured by birds and monkeys. Any that fall are immediately disposed of by ants and other insects. Nothing much could be expected from a native village even if one happened to be near, the reason being that hillmen, although they may keep an odd cow, a few goats or some scrawny chickens, do not normally practice cultivation beyond, perhaps, a tiny patch of millet.

“The whole bally country seems to be tipped up on a slope, if you see what I mean,” observed Bertie. “Wouldn’t Toxan make his camp on a bit of a plateau—or something of that sort? Any little piece of open ground.”

“I doubt if you’ll see any open ground in the jungle. The slope isn’t regular, either. The ground rises in a series of steps, as it were—pretty big ones, too, some of ’em. Often it’s sheer cliff. The only place where you’d be likely to find ground not smothered in vegetation would be at the bottom of a gorge, where nothing gets a chance to grow because of the seasonal spates. If Toxan’s camp is in a gorge, it’s unlikely we shall be able to spot it from the air.”

“You think his camp might be in a gorge?”

“It’s quite likely. In the first place he’d need to have water handy. Secondly, he says he found his first rubies in a dry river bed, and as here all the rivers flow through gorges or ravines, which they themselves have cut, he must be in some such place. Where else would he be likely to find rubies, or any other precious stones, except in water-washed sand or gravel? He certainly wouldn’t find ’em on the floor of the jungle, which is deep in leaf mould and rotting vegetation, not to mention the ferns and things that nourish on it. The fact that the river was dry when Toxan found the stones doesn’t necessarily mean it’s dry now, just after the monsoon. These aren’t ordinary rivers. They’re sluices, run-offs, for the rains, and the melting snow and ice on the higher ground. The water has to go somewhere, so this entire slope becomes a vast watershed. Through the ages the water, rushing downhill, has cut beds deep into the ground. Hence the gorges, which can be hundreds of feet deep. Sometimes you’ll get two or three of ’em joining up to make one big one. Most of the water eventually finds itself in the Ganges, which drains all these hills. But let’s go and have a look at it. You’ll soon see what I mean.”

By this time they had taken their places in the aircraft. “I shall keep low and fly as slowly as I dare,” went on Biggles. “Everyone watch for smoke, a flag, or piece of rag, or anything that looks as if it might be a signal. The only thing about that is, even if Toxan hears an aircraft he may not suppose it has anything to do with him. Ginger, you keep the camera handy and shoot anything that looks as if it might mean something. Okay, let’s go.”

Biggles took off.

Almost as soon as the machine was airborne the great ocean of primeval forest and jungle could be seen spreading away to hazy horizons. On one side it rose steeply towards the giant Himalayan peaks that fringed the distant northern sky. To the right the green tree tops fell away to be swallowed up in a misty blue haze that hung over the plains of India. The enormity of the task confronting those in the aircraft was at once apparent, although they had of course had a glimpse of it before, when they were looking for the lake.

The machine made its way slowly eastward, sometimes on a gentle zigzag course, up and down, to and fro, and sometimes circling, never at a height of more than a few hundred feet. The only break in the grey-green sea occurred when it was gashed by a deep ravine as if the land had been struck by an axe wielded by one of the gods which the natives believed had their homes in the distant ice-clad mountains. These gorges, which were frequent, mostly ran up and down, that is, across the route taken by the aircraft. More often than not there were foaming rapids at the bottom.

“By the end of the dry season much of that water will have dried up,” remarked Biggles. “It must have been at that time of the year that Toxan picked up his rubies.”

“What would he be doing at the bottom of a ravine, anyway?” asked Ginger.

“He was on a hunting trip. The bottom of a ravine is as good a place as any, because everything has to drink, and even when dry there are usually little pockets of water left in the rocks.”

“Our lake must be the only piece of level ground for miles.”

“We don’t know that that’s level. It might be no more than a whacking great hole. With no way out the water would collect in it, fill it up and become a lake. For all we know it might be hundreds of feet deep in the middle. That’s of no interest to us—provided the water stays there.”

For an hour the Gadfly cruised up and down, covering the ground between seven and nine thousand feet for an estimated distance of forty miles or so from the lake. Not a thing looking remotely like the object of the search was seen. Only to the north, the higher ground, was there any change in the colour of the panorama. In that direction long strands of darker-foliaged spruce and fir imposed a pattern on the otherwise even tint of the lower forest.

“This seems pretty hopeless,” said Bertie, putting his head in the cockpit. “Can’t see a bally thing—not a road, not a village, nothing. The place might be dead.”

“That’s what I thought you’d think when you’d had a good look at it from topsides,” returned Biggles, lugubriously. “I’m going back to the lake. We could go on doing this until we ran out of petrol.”

“What else can we do?”

“Nothing.”

“If Toxan’s still alive he must have heard us, even if he couldn’t see us. Why didn’t he make some sort of signal?”

“I’ve been thinking about that. As I said before, he may not connect an aircraft with a rescue. Another point that occurs to me is this: he may not have had a signal ready. He may be away from camp, without means of lighting a fire, for instance. That’s why I’m going back to the lake. We’ll try again later. If he heard us he will have had time to get some sort of signal ready. I daren’t go on burning petrol at this rate. We can get more at Moradabad, of course, but I don’t want to waste time going to and fro. Besides, people might get curious as to what we’re doing.”

“Even if they knew we were looking for Toxan—what of it?” put in Ginger.

“Certain people might wonder why the British Government should suddenly take such an interest in a casual prospector.”

“You mean—they might think he’s a spy?”

“They might. The Chinese have already claimed that India has spies on the Thibetan frontier. That’s been denied, naturally. We don’t want to cause trouble. We’ll go back to the lake. You’ve seen enough to demonstrate what a futile business it would be to look for Toxan from ground level.”

“No use, old boy. No bally use at all,” agreed Bertie.

Biggles turned west, and still scrutinizing the forest below made his way back to the lake which, from the air, with the sun now high in the heavens, made a wonderful picture.

“You were right about the monkeys!” exclaimed Ginger, as Biggles glided in to land. “They’ve found our camp. The place is crawling with ’em.”

The little animals scattered and fled, however, when Biggles, having touched down, opened the throttle a trifle to take the machine right in to its mooring.

Having gone ashore examination revealed that no harm had been done although the monkeys had obviously done their best to find a way into the tent. But now silence reigned. There was not a monkey in sight.

“They’re shocking little thieves,” remarked Biggles, as he unlaced the flap. “I’d bet they’re watching us now, from cover. Down nearer civilization they became so precocious you daren’t leave a thing about. I remember once travelling with my guv’nor we left the car for a few minutes, carelessly leaving a window open. When we came back monkeys were streaming up the hill taking everything portable they could lay their hands on. Among other things they pinched my camera.”

At this point in Biggles’ story the hush was shattered by an almost human shriek of terror. It ended abruptly.

“That’s one monkey that won’t go home tonight,” said Biggles soberly.

“What happened to it?” asked Ginger.

“I’d say the poor little brute was so interested in us that he didn’t look where he was going and bumped into a panther, or a tiger—probably the one you saw this morning. That’s where meddling with other people’s property has got him. Put on the kettle. We’ll have a cuppa while we talk things over and try to work out some way of making contact with this chap Toxan.”

Over the next three days Biggles made at least one flight per day over the area in which Captain Toxan and the refugee Chinaman, Mr. Poo, were supposed to be encamped; but it was all to no purpose.

These flights were not easy. At the low altitude at which it was necessary to fly the hilly and broken ground made the air extremely bumpy, which was a strain on both the machine and the pilot. The knowledge that a crash would be inevitable in the event of engine failure did nothing to make flying more comfortable.

Biggles, becoming desperate, began to take chances by flying right through some of the deeper gorges; that is to say, below the general level of the forest on either side. Actually, only Ginger knew this because Biggles either went out alone or took only Ginger with him, making the excuse that by saving weight he would save petrol, which, as the gauge showed, was running low. Ginger, consulted privately, had agreed to accept the risks of “shooting the nullah”, as the operation of flying through a ravine was known to the R.A.F. on the North-West Frontier in the days of tribal warfare.

On the afternoon of the fourth day, after Biggles had been out, flying solo, on another fruitless flight, Algy and Bertie, who with Ginger had remained in camp, took the machine to Moradabad to have the tanks topped up. They made no secret of their belief that they were wasting their time, Toxan, having made no signal, being either dead or missing.

The weather was getting hotter every day, and some of the smaller streams that cascaded down from the high mountains already showed signs of shrinking, in that they no longer foamed as they raced towards their parent river, the Ganges. The mosquitoes round the lake were bad, too, rising in hordes when the sun went down. What Biggles was really afraid of was that one or all of them might go down with jungle fever, really a severe form of malaria; for although they made light of the pest, and took reasonable precautions, such as at night wrapping the exposed parts of their bodies in mosquito netting, swollen faces in the morning told their own story. Instinctively during the stifling heat the protective covering was thrown aside. Insect repellant brought a certain amount of relief but it was not entirely effective.

Nothing more could be done about it, and Biggles was near despair when fate took a hand to restore their hopes. It happened like this. Ginger was on his way to the lake for a sponge down when, with something of a shock, he saw two natives standing a little farther along looking at the tent. They appeared to be discussing it. Both carried firearms.

Ginger, promptly changing his mind about a bath, returned quickly to the tent and told Biggles what he had seen.

Biggles lost no time in going out. At first the men could not be seen, apparently having retired; but when Biggles called they reappeared, and at his request advanced towards him. They wore only waist-cloths, and from their dark skins, black curly hair and broad, rather flat noses, he identified them as Gonds. When he spoke to them in their own language they came on with more confidence, and were soon sitting cross-legged on the ground with mugs of tea in their hands. One possessed an old Lee-Enfield rifle which in all probability had once belonged to a British soldier. A bayonet, somewhat rusty, was still attached to the muzzle, and looked as if it was never taken off. The other had a fearsome “gaspipe” gun which looked as if he had made it himself. Both wore Gurkha type kukris[3] and were evidently hunters.

[3] Kukri—a heavy, curved knife, about two feet long and weighing about four pounds. It was standard equipment in the Gurkha regiments of the British army.

This was where Biggles’ knowledge of local languages was such an advantage, for although the Gonds spoke very good English, which is used more or less all over India, when they were at a loss for a word he could help them out. For the rest, English was the language used, so everyone could follow the conversation. Biggles had, of course, explained at once to the others who and what the natives were.

Looking at the two men curiously in view of their obvious reluctance to come straight to the tent Biggles asked them if they were afraid of something.

“Yes, sahib,” answered one, simply. “We were afraid.”

“Afraid of what?”

“Of the soldiers.”

Biggles’ eyebrows went up. “What soldiers?”

After the two men had glanced at each other one answered: “The Chinese soldiers.”

Biggles frowned. “Do you mean Chinese soldiers are down here—in the forest?”

“Yes, sahib.”

“What are they doing here?”

“They came down from the mountains to look for a man.”

“That doesn’t sound so good,” muttered Algy.

Biggles continued his questioning. “Who is this man they are looking for?” Actually, he had a pretty good idea.

The men could not answer this question. They said, with obvious truth, they did not know.

“How many of these soldiers are there?”

Again the men did not know. All they could say was, a party of six had come to their village demanding food. They had said if they were not given food they would burn the village. They had been given a goat and some millet. It was thought these six men were not alone.

Biggles was clearly taking this news seriously. “How long since you saw these soldiers?”

The man thought for a moment and then held up ten fingers.

“Hm. Ten days. Why did you come here?”

“We were out hunting, sahib, and we see plane coming down. We came to see who it is and what happens.”

“How far is it from here to your village?”

“Two days, one night. Down the hill.” The speaker pointed the direction.

“I see. Now tell me this. Have you seen, or heard talk, of a sahib named Captain Toxan?”

The men searched their memories. “No, sahib.”

“Have you heard of a sahib who stays a long time, not far from here?”

“Yes, sahib.” The two Gonds held a brisk conversation in their own language, in which a name was mentioned. The name was Ram Shan. It turned out this was a man of their village who, out on a hunting trip, had seen the camp of a sahib. He had talked of this on his return. If he had learned his name he had not mentioned it The camp was in a nullah. There had been digging—much digging.

“That sounds like Toxan,” said Ginger.

“How long since Ram Shan saw this sahib?” questioned Biggles.

There was some difficulty about getting an answer to this because the Gonds were somewhat hazy, the matter being of no importance to them. Finally the two men agreed it was about two months.

“What are your names?” inquired Biggles.

One of the men was Bira Shah, the other, Mata Dhinn.

“We are looking for Toxan sahib,” explained Biggles. “We must find him. As it seems that Ram Shan could guide me to his camp, will you return to the village and bring him here to me?”

“We will go, sahib, but he will not come.”

“Very well. If I go with you to your village will he lead me to the camp of Captain Toxan?”

“No, sahib.”

Biggles looked puzzled. “Why not?”

“He will not leave the village.”

“But why? Is he ill?”

“No, sahib. He is a man with goats and is afraid to leave them for the tiger. Also he has a wife to protect.”

“Tiger! What tiger? What talk is this between brave men?”

One of the men explained. For some weeks now the village had been harassed by an evil one, a man-eater. It had killed more than twenty men, women and children. Everyone now lived in terror. No one would go out, but even so, the tiger had taken to raiding the village. He had come even in daylight. The bhoomkas could do nothing.

“What’s a bhoomkas?” asked Ginger softly.

“A tiger charmer,” replied Biggles, briefly. “He’s supposed to be able to hold secret conversations with tigers.”

Well, that was it. Ram Shan was a man with a wife and children, and goats. The two visitors were sure he would not leave the village for fear of them falling prey to the evil one.

Biggles drew a deep breath. “What a nuisance,” he said, looking at the others. “Here we get a clue, only to have it fall flat on account of a confounded tiger.”

He turned back to the two Gonds. “You have guns. Can’t you shoot this tiger?”

“No, sahib. We have tried, but bullets do not hurt him. He is under the protection of Shatan.”

“Who says so?”

“The bhoomkas.”

Biggles shrugged, helplessly. “You see,” he said to the others. “When people here get these ideas, that it’s futile to try to kill the tiger, they just pack up and do nothing about it, although they’re not lacking in courage.” Again he turned to the visitors. “If I come with you and kill this devil will Ram Shan guide me to the camp of Toxan sahib?”

They thought he would.

“It looks as if, before we can get on the track of Toxan, I shall have to go and shoot this infernal tiger,” Biggles told the others, grimly. “This chance may never come again, and if Chinese troops are on the prowl—and we can guess who they’re looking for—we’ve no time to lose. We may already be too late. Of course, Chinese soldiers have no right to be here. I’m by no means sure of how they’d treat us if we ran foul of them.”

“Why not report the matter to the Indian government,” suggested Ginger. “They’d soon clear them out.”

“And start a war between India and China? Not likely. The Chinese invaders of Thibet would have excuses ready, I’ve no doubt.”

“Well, what are you going to do?”

“I’m going with these fellows to their village. If nothing else Ram Shan may be able to give me the position of Toxan’s camp. I shall do my best to persuade him to lead me to it. Alternatively, he might come here, and from the machine point out this particular nullah in which Toxan has apparently hidden himself.”

“Without air experience he may not be able to do that,” said Algy, dubiously. “From topsides things will look very different from what they do at ground level.”

“He should be able to recognize a nullah from its size and shape.”

“But you heard what these chaps said. Ram Shan won’t leave home on account of the tiger.”

“In that case it looks as if I shall have to dispose of the tiger.”

“Do you really mean that?”

“Certainly.” Biggles grinned. “When I was a kid the height of my ambition was to shoot a tiger, to establish my reputation as a shikari. This is my chance, and a man-eater, at that. The brute ought to be killed, anyway. If he isn’t he may terrorize the village for years. We could go on for weeks doing what we’ve been doing since we came here without getting anywhere. I’m going to see Ram Shan.”

“Does that mean you’re going by yourself?”

“No. I’d better have somebody with me in case of accident. I’ll take Bertie. He fancies himself as a bit of a shikari so he can lend me a hand if it becomes necessary to do a spot of tiger hunting.”

“Oh here, I say old boy, come off it,” protested Bertie. “I never claimed to be anything of the sort.”

“You’ve done a lot of stalking.”

“Not for tigers.”

“This is your chance.”

“Chance for what?”

“To bag a tiger.”

“More likely get bagged myself.”

“Don’t tell me you’re afraid of tigers?” bantered Biggles.

“Terrified. They have such big teeth to bite you with.”

“Oh, quit fooling,” broke in Ginger. “Of course Bertie will go. What about me and Algy?”

Biggles became serious. “With these Chinese troops about someone will have to keep an eye on our camp kit. They may take a fancy to it. If you like, you and Algy can take turns spotting for Toxan but don’t leave base for too long at a time. And don’t run the machine short of petrol in case I come back in a hurry with Ram Shan and need it.”

“What happens if Ram Shan agrees to take you to Toxan’s camp? That could be a long walk, and you might be away from here for some time. We wouldn’t know where you were or how to get in touch with you.”

Biggles pondered the problem for a minute. “Let’s put it like this,” he decided. “If I’m not back in four days you can reckon I’m on my way to Toxan’s camp with Ram Shan. If I can get to it the rest should be relatively easy. The first thing I’ll do is make a smoke smudge to mark the spot. If Toxan and Mr. Poo are able to travel I shall bring them here, Ram Shan acting as guide. He’ll know the position of the lake. If they’re not fit to do the journey I’ll get Ram Shan, or these two fellows here, to bring us back. It’s time we made contact with Toxan, so let’s do that for a start. I’ll decide on the next step when that’s been done. Of course, if I find Toxan’s camp abandoned there’ll be no point in staying on here. We’d pack up and go home. Okay?”

“Okay,” agreed Algy and Ginger.

Biggles turned back to the two Gonds and explained his plan to them. Without hesitation they announced their willingness to take him to their village. They were about to return home, anyway.

“Right,” said Biggles, briskly. “Let’s get on with it. We shan’t need much in the way of kit. It can all go in one bag. These chaps will carry it. Enough food for two or three days, soap and towel, and, of course, the rifle with a few clips of ammunition.”

In ten minutes all was ready. Biggles’ last orders to Ginger and Algy were: “Don’t leave camp for too long at a stretch. Keep out of trouble with these Chinese, if you can, should they come along this way. If you see smoke rising from a ravine the chances are it’ll be me, because I shall stoke up if I hear the machine. It might be a good thing to take a photo to pin-point the spot so that we should have a record of where the place is. That’s all. See you later.”

Observing that Biggles and Bertie were ready to march the Gonds got up, and picking up their loads led the way, which at first followed the border of the lake. For a little while the going was heavy and therefore slow, the natives often using their kukris to clear a passage; but then, suddenly, and unexpectedly as far as Biggles was concerned, they came upon a muddy path which, emerging from the forest, ended at the water. Biggles recognized it as an elephant track, and made a remark to that effect.

“Yes, sahib,” agreed one of the guides, as they turned into what was a dimly lighted tunnel through the towering timber that entwined their branches overhead.

“Are we likely to meet the elephants?” asked Biggles.

The Gond thought not. He had, he said, come this way to the lake without seeing anything of them.

As for the most part the track took a gentle course downhill the going was now easier. At any rate, it was no longer necessary for the natives to use their kukris, although care had often to be taken to pick a path through broken branches, stripped of their leaves, cast down by the big beasts as they ate their way through the jungle. Scars on the trees on either side showed from where they had been torn; but none was recent.

“This is better, old boy,” remarked Bertie, cheerfully.

“Don’t forget it’ll be uphill coming back,” reminded Biggles.

After that the march continued in silence, through an atmosphere that was oppressive with a sultry heat and the stench of rotting vegetation.

As no incident of interest occurred on the journey that followed it can be passed over quickly.

Secretly, although he found it tiresome, Biggles rather enjoyed it. To him it was like old times, or like re-living a half-forgotten dream. Memories of such trips with his father and their old shikari, both long dead, filled his thoughts. In fact, now that he was back in surroundings once familiar he found that he remembered more than he had anticipated. For this, no doubt, the smells, and the occasional sounds, such as the squabbling of monkeys high overhead or in the distance, were responsible. The strange trees and insects were like old friends there to greet him. So, for the most part the march was made in silence. Nothing in the way of big game was seen, although that is not to say it was not there, as footprints and other signs on the ground often testified.

The track was by no means straight. Far from that it wandered all over the place as it made detours to avoid dells and ravines. Frequently it joined or crossed others, but the guides were never in doubt as to the way.

The first time this happened Biggles said to Bertie: “It isn’t easy, but try to remember the path in case you ever have to go it alone.” Biggles himself was doing this automatically, as his early training had taught him, noting a fallen tree here, an outcrop of rock there, and the like.

The temperature rose as they descended to a lower level, and by the time they were forced by darkness to halt for the night it was reckoned they had dropped something like two thousand feet. It was also realized that their camp by the lake was comparatively cool in comparison.

Preparations for the night were swiftly made by the Gonds who were experienced hunters. They were simple enough. Heaps of fern and twigs were cut for beds, and enough sere wood to keep a small fire going. This was more to discourage the mosquitoes by the smoke than any dangerous beasts that might be near. Sitting on their beds Biggles and Bertie had a frugal supper of sardines and dry biscuits, sharing these with their travelling companions to whom these things were luxuries. Tired, they both slept soundly, the Gonds taking turns to keep guard and replenish the fire.

The first grey of dawn, heralded by the monkeys and the raucous cries of birds in the upper branches of the trees, saw them again on the move. Biggles suspected, and this was later confirmed, that the party was making faster time than if the Gonds had travelled alone; for to them, he knew, time would be of no importance, and they would often stop to investigate prospects of deer and other game.

It was about noon when their approach to the village was announced in no uncertain manner. Biggles knew they were getting near because the guides had increased their pace and no longer bothered themselves with the precautions they had taken earlier.

Suddenly, at no great distance ahead, there was a shout, instantly to be followed by an increasing clamour of yells and the beating of a drum. For a brief moment Biggles thought this was for their benefit; a sort of welcome home; but one glance at the faces of the natives dispelled the idea. They had stopped, and their skins had turned that curious green-brown tint which in coloured races is the equivalent of white men turning pale. It denotes fear, or shock.

“Is that the tiger?” asked Biggles tersely.

“It is he,” was the breathless answer.

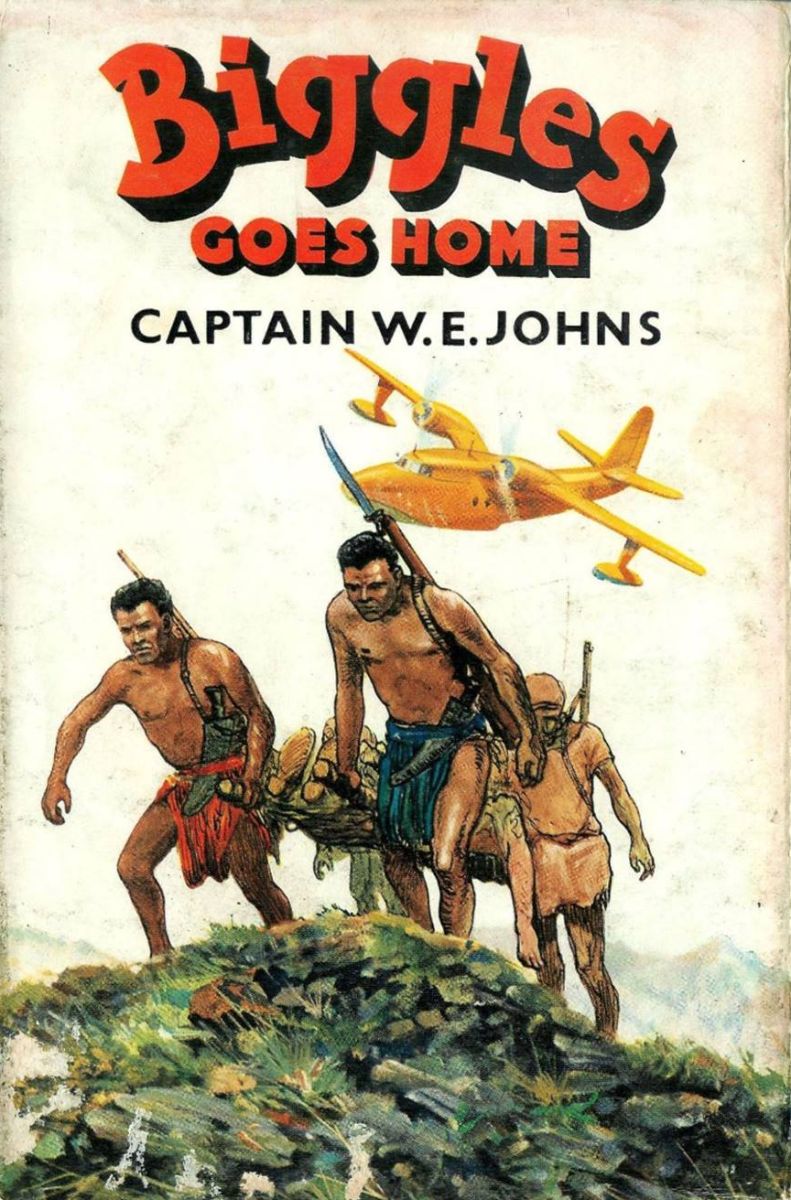

Biggles took his rifle, an Express he had used on previous occasions, which one of the Gonds had been carrying, and jerking a bullet from the magazine into the breech, strode on.

“You’d better keep behind me in case the devil comes this way,” he told Bertie, who had no such weapon.

The shouting had now died away to a sinister silence.

Two hundred yards on, the forest broke down to a small open glade, not very wide but fairly long, carpeted with trodden sun-scorched grass on which had been built a number of shacks—they could hardly be called houses—of rough timber and thatch. At the extremity of these it seemed that the entire population of the village had collected in a group, some forty or fifty persons in all. They made no sound, but stood staring at something farther along the glade where the outlying shrubs of the jungle brought it to an end.

Looking in that direction Biggles saw the dreadful spectacle of a tiger calmly walking away, without the slightest haste, dragging a woman by the shoulder. With her free hand she was beating the tiger’s face, but all to no purpose, for it continued to walk on. No one appeared to be doing anything about it, although to be fair to the natives, without weapons suitable for dealing with such a situation there was nothing much they could do.

Without a word Biggles broke into a run. Pushing his way through the little crowd he continued on, by which time he was within a hundred yards of the man-eater; but he dare not shoot, of course, for fear of hitting the woman. He raced on, closing the gap, with the tiger still walking away, still dragging its victim, and in its confidence not troubling to look behind it. The woman had ceased her futile struggles, but she was still conscious, as her piteous cries revealed.