* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

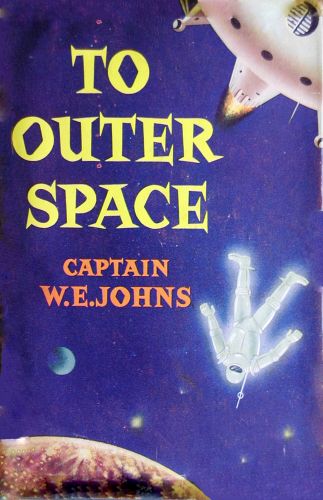

Title: To Outer Space—A Story of Interplanetary Exploration (Space #04)

Date of first publication: 1957

Author: Capt. W. E. (William Earl) Johns (1893-1968)

Illustrator: Leslie Stead (1899-1966)

Date first posted: November 23, 2023

Date last updated: November 23, 2023

Faded Page eBook #20231132

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, akaitharam, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

See here

“Wonderful! Wonderful!” exclaimed the professor, “Vargo, why have you never told me of this?”

TO OUTER SPACE

by

CAPTAIN W. E. JOHNS

Illustrated by Stead

London

HODDER & STOUGHTON

THE CHARACTERS IN THIS BOOK ARE ENTIRELY IMAGINARY AND BEAR NO RELATION TO ANY LIVING PERSON

First Printed 1957

MADE AND PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN FOR HODDER AND STOUGHTON LIMITED, LONDON BY C. TINLING & CO. LTD., LIVERPOOL, LONDON AND PRESCOT

| CONTENTS | ||

| Chapter | Page | |

| I | STRANGE NEW WORLDS | 9 |

| II | REX STARTS AN ARGUMENT | 24 |

| III | VISITORS FROM WHERE? | 34 |

| IV | STONE AGE MARLOK | 44 |

| V | OLD VERSUS NEW | 55 |

| VI | TROUBLE ON ANDO | 62 |

| VII | TIGER GETS TOUGH | 73 |

| VIII | LORNICA | 88 |

| IX | THE RAID | 100 |

| X | WHAT NEXT? | 112 |

| XI | THE CREEPING DEATH | 125 |

| XII | SHADOWS | 135 |

| XIII | SOME ANDOANS ARE LUCKY | 144 |

| XIV | WHERE NOW? | 154 |

| XV | TOUCH AND GO | 165 |

| XVI | REX WORKS IT OUT | 172 |

| CONCLUSION: THE WAY BACK | 182 | |

| LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS | ||

| “Wonderful! Wonderful!” exclaimed the Professor, “Vargo, why have you never told me of this?” | Frontispiece | |

| facing page | ||

| There was a terrifying crash and the ship spun sickeningly | 24 | |

| Such a scene surpassed anything that could have been anticipated | 61 | |

| Even in daylight the heat ray could be seen as clearly as a searchlight beam at night | 92 | |

| The fleet sped like rockets at a velocity almost too great for the eyes to follow | 125 | |

| Up to his waist in a sea of blue . . . he seemed to stagger | 156 |

TO OUTER SPACE

The fourth Space voyage of

Rex Clinton

by

CAPT. W. E. JOHNS

author of

KINGS OF SPACE

RETURN TO MARS

NOW TO THE STARS

“What are you looking so serious about?” Group-Captain ‘Tiger’ Clinton put the question to his son.

“I was wondering,” answered Rex, vaguely, turning his eyes away from a fast-diminishing globe of light below the spaceship, the planet from which they had departed a few hours earlier. As a traveller on Earth, setting out on a voyage, takes a last look at his native land, perhaps a little fearful that he might never see it again, so Rex had regarded the world he called his own.

“What were you wondering?” inquired Tiger, possibly for the sake of making conversation, to pass the time now that the long run to Mars was fairly begun.

Rex smiled wanly. “If the people at home are any happier for knowing that their world, instead of being flat as they once supposed, is round. That the blue moon the crooners moan about is merely a lump of dirt. That a diamond is only a piece of carbon, a pearl a bit of lime, and a rose just a lot of atoms of this, that and the other.”

“If you’re going to talk like that,” put in Doctor ‘Toby’ Paul, “are they any happier living in a house, with everything laid on, instead of a cave, aware that an enemy on the other side of the world could, if he so wished, reduce them to atoms with a hydrogen bomb?”

“The point I was making,” returned Rex, “is this. Assuming that happiness is the thing everyone is looking for, are people any nearer to it than they were, say, five hundred years ago, before chemists started to take everything to pieces to find out what it’s made of? Does it matter what things are made of as long as we have them to enjoy?”

Brushing back his lank hair the Professor gazed at Rex over his spectacles. “I see you’re becoming quite a philosopher. Mortals cannot have everything. The physical discomforts which, knowing no better, they once endured, have been exchanged for mental discomfort, fear of the present and uneasiness for the future. For the mechanical toys they now possess they bartered their peace of mind, and as apparently you suspect, lost on the transaction, getting farther away from true happiness instead of nearer to it. They demanded, and still demand, too much. Unless someone soon puts the brakes on they will end by having nothing.”

“For which they have the scientists to blame,” murmured Rex, softly.

“Not at all. Scientists and engineers merely gave the people what they, like children, were crying for. Not satisfied with a beautiful world they now demand the Moon. Very soon, no doubt, they will have it.”

“Having seen it at close quarters I hope they enjoy it,” said Rex, cynically.

“It wasn’t the people who wanted the Moon,” asserted Tiger. “The scientists started that nonsense.”

“I was not speaking literally,” stated the Professor, with a tinge of asperity. “Considering what you yourself are doing at this moment you should not criticize the people who made it possible. After all, you are here from choice, not compulsion.”

“I wasn’t thinking so much of space travel as these atom-busting thermo-nuclear experiments,” explained Tiger.

“You know my views on that,” rejoined the Professor. “When men were wise instead of being merely clever there was a saying that curiosity killed the cat. It was, no doubt, like all old sayings, based on human experience. The curiosity of a certain type of scientist will in the end destroy him, and everyone else. In his delight at having discovered the atoms of which Earth is composed he now amuses himself by breaking them.”

“Regardless of the people on other planets who have an interest in this matter,” put in Vargo, the Martian, in his thin, precise voice. He had been listening to the conversation. “Such folly is not to be believed. Don’t they realize that should Earth be vaporized, or even moved in its orbit, the whole Solar System, as you call it, would be involved in a catastrophe beyond imagination? They are asking for a repetition of the horror that followed the fragmentation of Kraka. Other worlds are watching these explosions with alarm. These rockets you have been sending up are a menace to everyone. Ships, which you call Saucers, have been sent to watch, and have, I believe, been observed from Earth. Now, you tell me, it is proposed to create artificial satellites, to the peril of all space travellers. You have become the most dangerous planet in the galaxy, and if you continue, your people will have to be destroyed for the safety of others. That is the argument of Rolto, and many now believe him. Why do your scientists do this?”

“To find out what is beyond our atmosphere,” answered the Professor.

“You could tell them.”

“They would not believe me.”

“I, as a man of Mars, could tell them.”

“They would not believe you, either. Don’t forget that Rolto, the only Martian to land on Earth, was put under restraint as a madman for making such a claim.”[1]

[1] See Now to the Stars.

“We could show them a spaceship, and demonstrate it.”

The Professor shook his head. “It is too early for that, for which reason I have said nothing about my voyages. No man could say what effect the shock of knowing there are other peoples in the Universe would have on our civilization. All beliefs, in the past, the present and the future, would crumble, and the result would be chaos. At present, on Earth, the people are afraid only of each other. Fear of attack from space might throw them into a panic, or a state of despair.”

“They are inviting such an attack.”

“It would be no use telling them that.”

“They will have to know one day.”

“It will come with time. At present only a few have the intelligence to grasp the meaning of space travel, and all that it involves.”

“It is not easy,” conceded Vargo. “In early space travel, the most difficult thing is to remove from the mind comparisons with other forms of what you call speed, or velocity. There is no comparison. People must accustom themselves to think of movement faster even than that of light. That is the first step.”

“How did you do that?” asked Rex.

“It comes from a study of the stars. Once they are understood the impossible at once becomes possible.”

“What do you mean, exactly?”

“Let us put it like this. Every star, every planet, including your Earth, is moving through space faster than it is possible to imagine. You may say, truly, I know that Earth is half a million miles away from where it was at this time yesterday. That is hard for the brain to accept. Yet it is only the beginning. It is even harder to imagine anything moving faster than light. Yet that is slow compared with some movements in the Universe. The day came when our scientists said, if a great body of matter like a star can travel faster than light, why not a small, man-made body? So they made what you call a spaceship.”

“That was a big jump forward,” said the Professor.

“But you did that yourself, with your first ship, the Spacemaster. It was, like all first things, a crude device; and a dangerous one, as was demonstrated when it broke up.[2] But it was a step in the right direction.”

[2] See Return to Mars.

The Professor smiled sadly at the memory.

“Space travel is not difficult,” continued Vargo. “Making allowances for the strain of initial acceleration, it is only necessary to place an object within the power of the forces that govern the Universe, by which I mean gravity, cosmic and other rays, to move with them. The longer the journey the swifter can become the movement. There is no known limit to velocity.”

“Having advanced from twenty miles an hour to a thousand, by Earthly terms of measurement, in a mere hundred years, we are beginning to realize that,” said the Professor, soberly.

Vargo continued. “Just as you, at this moment, are unconscious of movement, so, from what you have told me, are the people of Earth unaware of the velocity of the world on which they stand.”

“I would not say that. They are told, but the brain does not comprehend, probably because their lives are not affected.”

“Yet the slightest variation in momentum would hurl them all to destruction.”

“They are not concerned with that, and rightly so, for should such a thing occur they would know nothing about it; so why worry? I doubt if some of them would believe it, anyway.”

“Exactly. Disaster on such a scale is too fantastic for belief. It is hard to prove these things. If they cannot be understood they must be accepted.”

“Generally speaking, our civilization has not yet reached a full understanding of these tremendous—one might also say—terrifying—possibilities,” averred the Professor.

“What is this thing you call civilization?”

The Professor thought for a moment. “It is a state on that part of the Earth most advanced in art and science.”

A shadow of a smile, a somewhat cynical smile, softened Vargo’s taciturn features. “Yet, from what you have told me, these are the areas of the greatest confusion, where men are constantly at war.”

The Professor sighed. “I must confess that is true.”

“And now, to turn confusion into chaos, your scientists behave like little boys with hammers. They must break something. I fear you still have a long way to go to reach real civilization.”

“We have come a long way.”

“Too fast. That is your trouble. Science must proceed with caution or it will take more than it gives, as you yourself have said. How old is your scientific knowledge?”

“Perhaps two or three hundred years.”

“There are planets,” said Vargo, with slow deliberation, “such as Ando, where you wish to go, where scientific thought has been developing for how long no man knows. Thousands of years. Perhaps tens of thousands. The end of yours, as you now proceed, is in sight. Thus claims Rolto, who would destroy you before you destroy others. It is a thought on which you would do well to ponder.”

“Are you telling us that the degree of scientific progress on a planet depends upon its age?”

“No. Neither age nor size bear any relation to the birth of intelligence in the creatures that dwell on it. That includes the species you call man, should it be there; although, to be sure, it often is, perhaps in a very low form. Sometimes the dominant form of life is something quite different. It can be what you would call an insect, or a reptile; but where man appears he invariably, sooner or later, assumes command. At what period he ceases to behave like an animal seems to be a matter of chance.”

“Do you mean it is in the nature of an accident?” queried Rex.

“You might call it that,” answered Vargo. “Put it like this. What you call civilization can only begin when a man is born who employs his hands and brain to do something that has never been done before. Let us say he makes a tool, or a weapon. Why this should happen is in the nature of a mystery. Parents are not responsible, for they can only pass on to their children what they themselves know. However, once such an invention appears other men copy it. One day a man improves on this weapon, or tool, and from that moment begins the slow process which produces men like us, able to invent a vehicle such as the one we are in. Your Earth is æons of ages old, yet, as you have told me, your records go back only for five or six thousand years. For millions of years, therefore, Earthmen must have remained unchanged, each succeeding generation making little or no progress on the previous one. That is not unusual. There are men nearer to animals than any you saw on your last trip. They have got no further than making hunting tools of stone.”

“Earth went through a Stone Age,” said Rex.

“All worlds go through it before they reach the Age of Metals,” declared Vargo. “Thereafter the course their development takes depends on local conditions, what is needed and what is available. Of course, all people out of touch with others, knowing nothing better than what they have, believe themselves to be the most highly civilized—as you do, on Earth. But all this ends when space flight is achieved and new worlds are open for comparison. Then one world learns from others. There may be exceptions to this rule, however.”

“Why should that be?” asked Toby.

“Because, as it seems, some men cannot think for themselves and will not learn from others. Such a world is Marlok, which I could show you, for it is within our galaxy. It is much larger than Earth, and I would say older, yet the man species there live like animals, awaiting that spark of intelligence that will set them on the road to culture. They have physical strength beyond belief and can cast great stones with accuracy, but nothing more. Their bodies grow but not their brains. Nor is it possible to help them, for they attack on sight any ship that lands there. These poor creatures live without clothes, without houses, without cultivation, without anything.”

“Then obviously they have all they need,” declared the Professor. “Progress does not begin until there is a desire for something better. It would be interesting to see a world at the level of the Stone Age.”

“They might claim to be nearer true civilization than your machine makers,” averred Vargo. “Who shall say who is right? The question is to know when to stop. Ando has stopped. Once the Andoans made marvellous things, but when they saw how they caused more trouble than they were worth they put them aside. Now, they say, having reached perfection, they will stop.”

“Until some foreign influence induces a wish for what they do not possess,” said the Professor drily. “Then they will move on again.”

“They are the most contented of all the peoples I know, having much knowledge even before the explosions of Kraka,” said Vargo.

“In the matter of explosions we have one comforting thought,” remarked the Professor. “Should we, on Earth, blow ourselves up, we shall know nothing about it. There will be a flash, and we, and our world, will be as if such things had never been.”

“I don’t find much comfort in that,” muttered Rex.

Silence fell.

The ship sped on through that region of eternal emptiness which men call space, towards the unheeding stars.

The spacecraft was the Tavona, the Minoan ship which had brought them home from Mars, and had now, at their signal as arranged, picked them up from the lonely Highland hill, in a corrie of which, at Glensalich Castle, the Professor had made his home.

Three months had elapsed since their return from the last journey into space, time that had been occupied by the Professor in developing his many photographs, writing up his notes and preparing for the next flight of survey. This, it was agreed, should be the acceptance of the invitation extended to them by the Andoans whom they had found marooned on the planetoid which, by reasons of the pleasant conditions they had found there, they had named Arcadia. It was from Ando, a planet beyond the Solar System, that the Minoans obtained their spaceships. Being of great age it had reached—if reports were correct—a wonderful state of development, a word used in preference to the Earthly term ‘civilization.’

The crew of the Tavona was unchanged. Borron, Senior Navigator of the Minoan Remote Survey Fleet, was in command. With him, to act as interpreter and adviser, was Vargo Lentos, a man of Martian origin who had been found desperately ill on Mars, the sole survivor of a party of Minoan volunteers that had been landed on Mars to find a method of exterminating the hordes of insects with which that planet had become infested following its near-destruction by the exploding planet Kraka, the remains of which now existed only in the form of small bodies called planetoids. The rest of the crew of the Tavona were those who had shared with them the perils of the planetoids.

“How do things go on Mars?” asked Rex, after a little while.

“They go well. You will see changes, and feel changes. There is more oxygen.”

“Where did it come from?” inquired the Professor.

“It must have been picked up in space. There is more than could have come out of the ground, although there it is always forming.”

“On Earth we knew there was much free hydrogen in space but I don’t think anyone anticipated currents of normal atmosphere,” said the Professor.

“You mean atmosphere normal on Earth?” queried Vargo. “In the galaxy as a whole there is no such thing as a normal atmosphere. It varies almost everywhere, in density and composition, yet life can exist in any of them. From what you have told me many of your scientists have a fixed belief that life can only flourish in your particular form of atmosphere. It is a fundamental error you should correct. Atmospheres are always changing, although usually very slowly. Where do you think yours came from in the first place?”

“It is assumed to have always been with us.”

“But that is absurd! It could not have been with you when you were a star, burning like the sun. The burnt-out decaying suns which you call planets both produce and collect their atmospheres. The air of Mars is not quite in the same proportions as yours, and I would not expect it to be. What gases have you?”

“We have four parts of nitrogen to one of oxygen, but there are also small quantities of carbon dioxide, argon, helium, neon, krypton, xenon, and perhaps others.”

“Exactly. Did you believe in this theory that only such an atmosphere, an accidental mixture, could support life?”

“No. I was never a supporter of that theory,” answered the Professor.

“Why not?”

“When I considered the amazing forms of life on Earth, in their infinite variety, flourishing in every conceivable habitude, even under colossal pressure in the eternal darkness of the deepest seas, it seemed to me ridiculous to suppose that life could not exist on other planets however remarkable the conditions might appear to us. The belief that neither Mars nor Venus could support life because they have lower and higher temperatures than ours, on account of their relative distances from the sun, was never acceptable to me. If our highest form of life, man, could live at any of our extremes of temperature, from ninety degrees below zero in Siberia to a hundred and forty degrees in the Sahara, I could see no reason why he should not have survived greater extremes had he been called upon to do so.”

“We were talking particularly of atmospheres,” reminded Vargo.

“Men chose to live in a mixture of nitrogen and oxygen. If other forms of life, fish and marine plants, could live in the mixture of hydrogen and oxygen which we call water, whether pure or containing various salts, I could see no reason why other creatures should not be equally happy in any mixture of gases in which they might find themselves.”

“Given time life can adapt itself to any mixture,” asserted Vargo.

“That may be seen on Earth,” declared the Professor. “Men have made their homes in the rarefied air of the High Andes, having developed large lungs to cope with that particular environment. Had higher ground been available they would, I feel sure, have moved up to it to secure the land, adapting their lungs still further.”

“That is intelligent thinking,” stated Vargo. “Not only does the mixture vary in its proportions on every world, as one would expect, but everywhere it changes constantly as fresh supplies are manufactured by soil and water or are picked up in space. Your atmosphere being deep and dense it would need a large quantity of fresh gas to make a noticeable difference. Where the free gas in space comes from we do not know for certain. It may be discharged by stars, like our Sun. It may be torn from a planet by a passing comet, left in space when the comet expires, to be gathered later by another planet which happens to have an orbit that encounters it. You may be blowing some of yours away, beyond the field of gravity, by these great explosions you are making. Borron will tell you he has often passed through belts of gas in space, even air that could be breathed; but as these are always moving they cannot again be found.”

“I confess I had overlooked that possibility,” admitted the Professor.

“From what you have told me you yourselves must be changing your atmosphere, your millions of engines turning good air into bad,” warned Vargo. “Unless you can find a way to re-convert this bad air into good you may eventually poison yourselves, unless, the process being slow, your lungs adapt themselves to the new mixture.”

“People are beginning to suspect that,” returned the Professor. “Some have already been poisoned by a mixture which they call smog when it is held in a concentrated form by low clouds.”

“Your machines will kill you if you continue with them,” said Vargo, “Answer me this question, for I have often thought of it. How did your machine age begin?”

“I think it can be said to have started when a young man saw the steam of water boiling in a kettle lift the lid. He realized that here was hidden power.”

“The spark of genius of which I spoke a little while ago,” said Vargo. “From that small thing your way of life on Earth was changed, whether for good or bad remains to be seen. Of all the men who must have seen that same thing happen this one alone had the intelligence to read the message. Has it made your lives easier? Are you happier?”

“That question would be difficult to answer,” returned the Professor.

“That message which came from the kettle has not, to my knowledge, been read anywhere else,” averred Vargo.

“You mean, you have never seen steam used for power?”

“Never. It sounds clumsy. With us it was never necessary.”

Tiger stepped in. “It made possible all our other sources of power, such as engines in which wheels are turned by the explosion of gas or oil in cylinders.”

“To me,” said Vargo, “that is more remarkable than the employment of the energy that operates the universe, power that is eternal and indestructible, which you are now approaching in a roundabout way.”

“You jumped straight to that without intermediate machines?”

“As far as I know that is true,” replied Vargo. “If these machines happened with us it must have been so long ago that they have been forgotten. We no longer convert good air into poison.”

The Tavona shot on towards its first objective, Mars.

Rex dozed.

Even at the astronomical velocities at which the Minoan ships moved through space time was needed for even the shortest journeys within that system of planets and planetoids governed by the Sun, called the Solar System, and to Rex one of the problems of space travel was how to occupy himself during the period of transition.

The argument that ship voyages on Earth, such as from the United Kingdom to Australia, still took a month, was not relevant, he felt. On a ship one could move about freely for a change of surroundings, from cabin to lounge and from deck to deck. The crew of the Tavona, he observed, appeared to have found the answer by sinking into a condition near to coma, neither moving nor speaking for hours on end, half asleep or deep in thought; for once the ship was on its course there was nothing for them to do until the time of arrival.

Rex spent a good deal of time reading, but when this palled he sought relief in conversation, and it was natural that this should take the form of questions put to Vargo or Borron concerning their adventures on other worlds. This topic usually brought the others into the conversation.

It was on the second day out—although day and night had ceased to exist as such—that, after being startled by the noise of the Tavona encountering some particles of meteoric dust, he said to Vargo: “To prepare us for what we are going to see don’t you think it would be a good idea to tell us more about Ando?”

“There is so much to tell,” answered Vargo. “How would you start to describe Earth, its population and physical features, to someone who had never been there?”

“There would be a lot to say,” admitted Rex. “Give me a rough idea. What is the atmosphere like?”

“Very good. Special clothes will not be needed. I would say Ando has a better atmosphere than most places.”

“How could it be better? Ours is perfect—anyway for us.”

“So you believe, and it may be true. I can only tell you that the atmosphere of Ando contains a modicum of some rare elemental gas which makes you feel good and energetic, although at first it can be a little strong. That is the effect on our men who go there. But as you know, the atmosphere of Earth is for us somewhat heavy.”

“Is it warm or cold?”

“It is always comfortable.”

“Always? What about the winter?”

“There is no winter. The temperature is always the same.”

“How can that be?”

“The Andoans have achieved complete climatic control. This was largely made possible by having two suns, so no artificial heat is ever needed to warm the body. One sun is larger than the other, but the smaller one is nearer. It is never dark, so no artificial light is needed, either. Rain falls only when they wish, and as the time is known to everyone there is no inconvenience.”

“That sounds fantastic.”

“To you, but not to the Andoans. Again I say you must not compare conditions elsewhere with your own elementary knowledge of the Universe, so recently gained. In outer space there was advanced intelligence long before, within our Solar System, men in our form came into existence. Compared with some we are newcomers. You must be prepared for strange things, things stranger than those you have already seen on the smaller planets.”

“Evidently.”

“At one time, long ago, the people of Ando may have had the troubles your people are having now; but gaining wisdom they controlled their progress, and instead of making life more complicated they strove for simplicity in all things, discarding those that demanded labour and concentrating on those that gave contentment with the least effort. Now everything is under control, whereas on Earth, man, for all his skill, is the only living creature that fills his days with labour, working without stop to make more things that make yet more work.”

“With nothing to do you make Ando sound a dull place.”

“You cannot have both harmony and confusion. It must be one or the other. From what you have told me Earth has rushed on to a state of confusion, each tribe working against the other.”

“I’m afraid it’s true,” admitted Rex, ruefully.

“Then how can you call that culture? Civilized? It is not even intelligent. Unless your people work together they will move ever farther from the happiness all men seek.”

“How big is Ando?” asked Rex.

“Not big. Perhaps half the size of Earth. But there are other, smaller planets, within easy reach, under the same control, so Ando is really a cluster of planets. Spaceships travel from one to the other constantly, and, of course, quickly.”

“A sort of interplanetary bus service,” suggested Rex, smiling at the idea.

“Exactly. There are no other vehicles. None are needed.”

“Are there any seas dividing the land?”

“Not as you have them. All water is organized where it is required.”

“What about the people?”

“They live in small towns where everything is standardized. There is no difference, except that a family is alloted a house according to its size. Everyone has a home, for that has always been the basic unit of a happy community. Some have better brains than others, naturally, but there is a general level of education. They study much astronomy, realizing that at the end everything depends upon the stars keeping in their places. Every child is taught to read the heavens.”

“On Earth most people ignore them.”

“So you have told me. It is a sign of ignorance that they should disregard the things on which their existence depends. But then, every world goes its own path to what it thinks it wants. All start the same way. A world, as you know, is born in heat. It cools. It becomes solid. Life appears. What happens after that depends on the dominant form of life. If there are no men, as with some planetoids you have seen, there is little change. Should men appear, that world becomes what they make of it. Earth goes one way, Ando another, although in the distant past it may have gone through your phase for all I know.”

“How did the Andoans arrive at their present state?”

Vargo thought for a moment. “I think by removing from their natures the original animal instincts.”

“Such as?”

“Greed, for one thing. Do away with money and you have no crime. Without crime you need no laws; just unwritten rules that everyone knows from birth.”

“Does nobody work in this happy land?” inquired Toby, who had been listening.

“Yes, the young men do tasks when their turn comes. Mostly food production. The people are vegetarians. The eating of flesh was abandoned as barbaric long ago. There are no wild animals or birds.”

“How about eggs?”

“The Andoans make their own, in a great variety of flavours. The idea of dependence on birds for them was perceived long ago to be ridiculous. The Andoan eggs have this advantage, too. They will keep indefinitely.”

“Is there any room for a doctor on Ando?” asked Toby, whimsically.

“No. There is no disease. Once the causes, the result of ignorance, were removed, there was nothing to cure. Thus with the soil. If you have no harmful microbes or virus in the soil your crops are disease free. There must, of course, be bacteria to break up dead matter into its original form.”

“I would call that a dangerous situation,” said Toby. “If ever Ando is invaded by a new microbe there will be no method of dealing with it. I imagine that was the reason why the Andoans couldn’t help you to rid Mars of its mosquitoes. It needed a man from that backward world, Earth, to do that,” he concluded slyly.

“You make a point there,” conceded Vargo.

“What do these people do to prevent themselves from dying of boredom?” Tiger wanted to know.

“They grow many flowers, as you will see. Every house and every street is decorated with flowers. They bathe in the public baths, or watch the sky through public telescopes. They have athletic sports, and a theatre where there is singing, dancing and juggling, which are arts practised by everyone. They watch the notice boards for news of births and deaths and the movements of the stars.”

“Does that mean there are no newspapers?”

“There is no need for them if the things people should know are written in public places. On your last voyage you were a long time without newspapers. When you arrived home you found everything going on as usual, so it seems that newspapers are of no real importance.”

“We have more to report than the Andoans,” said Rex. “You couldn’t get it all on a notice board.”

“I have seen one of your newspapers,” continued Vargo. “The news was mostly of wars. On Ando there are no wars. There is nothing to fight about, and nothing to fight with. There must have been fighting long ago, for I have been told there are weapons, swords and spears, in the museum.”

“Do the Andoans have a king, or head man?”

“No. There is a Council of Elders to answer any problem that might arise.”

The Professor put in a question. “How is domestic power produced for the people? Have they coal, or oil?”

Vargo almost smiled. “All power is derived from Solar and Cosmic rays, which are eternal and free for all to use for any purpose, from the fusing of metals to the cooking of a meal. With such energy always available the construction and operation of a spaceship becomes a simple matter, as you can see.”

“This promises to be a particularly remarkable voyage,” averred the Professor, polishing his glasses. “I would very much like to see this Stone Age world, Vargo, which I believe you called Marlok.”

“There would be no difficulty about that, but if you landed I could not accept responsibility for your lives,” stated Vargo. “The inhabitants are little better than beasts, and as I have warned you, they resent intrusion and meet it with force.”

“It is a natural instinct to guard what one has, particularly if one is satisfied with it,” stated the Professor sagely.

“Marlok sounds a bit brighter than Ando,” opined Tiger.

“We may liven things up there,” murmured Rex.

“How do you propose to do that?” inquired the Professor.

“Well, we could introduce some new games, for instance.”

“Such as?”

“Football. I put a ball in my bag.”

The Professor looked at Rex suspiciously. “What else have you smuggled on board?”

“Oh, one or two little things,” answered Rex airily. “Nothing to hurt.”

“What is football?” inquired Vargo curiously.

“You’ll see. You have two sides. The idea is to kick a ball through the other side’s goal.”

“I don’t think the Andoans will like that.”

“Why not. It’s good fun.”

“The Andoans, wearing only soft shoes, would hurt their toes. The only sound you will hear on Ando will be the patter of feet.”

“I’m not talking about a stone ball, or a wooden one. A football will bounce.”

“What is bounce?”

“You’ll see. I’d forgotten you had no rubber.”

Toby looked at Tiger. “Does this place Ando sound like a hand-made paradise to you?”

“It does not. I may be old-fashioned but I can’t imagine a world without animals and birds.”

Toby went on: “I’d say they’ve carried this simple life project a bit too far. With no incentives they’ll go to seed. It’s trouble and competition that keeps people virile. We may blow ourselves up, but we shan’t die a lingering death from boredom, wondering what to do next.”

“The idea of being weaponless sounds delightful in theory,” said Tiger, looking at Vargo. “What happens if Ando is invaded by men from another planet bent on world conquest? Culture wouldn’t help. The Andoans would end up by becoming slaves. You say the Andoans aren’t the only people with spaceships. Think of the mischief we would do if we were looking for a world to conquer.” He pointed to his rifle. “You have seen me use that. Have you ever seen anything like it elsewhere?”

“Never. You talk like Rolto.”

“There are such men on Earth, so we may suppose they are to be found on other worlds.”

“The Andoans are good people,” said Vargo. “No one has ever attacked them. They live to a great age. Three hundred sun-cycles at least. Living as they do their bodies last longer, and the age-length increases.”

“What’s the use of that if you don’t know what to do with all this time on your hands?” argued Toby.

“The idea that a man must always be doing something with himself shows how backward Earth is in its thinking,” stated Vargo. “Why should a man wear out his brain with the problem of how quickly he can wear out his body? Is that intelligence?”

“Perhaps not, if you put it like that,” admitted Toby. “But what is the use of living at all if your life has no purpose?”

“The purpose of life is to accept happiness when you find it, and enjoy it,” declared Vargo. “A man cannot have more than that. On Earth men are pursuing what they imagine is happiness. Always it is just in front. They never catch it. They never will unless, like the Andoans, they stop. Now, striving harder and harder they do more and more work, rushing through life faster and faster. Surely the aim of an intelligent creature should be to do less and less, and so leave himself free to enjoy what he had, enjoy nature as it was intended to be, not as generations of false thinkers have made it. The day may come, if true wisdom opens your eyes, when your men will rise up and destroy the machines that have made them slaves, and thereafter live lives of tranquility.”

“I suggest we reserve judgment until we have seen for ourselves how life works out on Ando,” said the Professor.

Silence fell.

The Tavona sped on towards its still distant objective.

The voyage to Mars, the first world of call, was marked by two incidents, the first startling but understandable, the second astonishing but not, at the time, so alarming.

The first was a collision with a meteorite. It could only have been a small one, certainly not larger than a small pea, Vargo thought, or not even the heavy double skin of orichalcum alloy could have saved the ship.

Rex was well aware that this risk, while remote, was always present in space travel. Vargo said that as there could be no precaution against it the danger had to be accepted. There were always meteors in space and presumably there always would be, some areas being worse than others; but so vast was space that the distances between these missiles were astronomical. The chances of collision, therefore, were so small that they could be almost ignored. It was a factor of space travel about which Rex preferred not to think.

It seems likely that he actually saw this lost projectile as it passed through a belt of gas an unknown distance away. If so, the gas may have saved them by reducing, by friction, the size of the meteorite. At all events, while gazing out of his observation window, slowly revolving as the ship turned alternate sides to the sun to equalize its heat, he saw a flash in the deep blue void. Before he could even begin to wonder what had caused it there was a terrifying crash and the ship spun sickeningly, the result, Vargo afterwards said, of the object striking them a glancing blow.

There was a moment of confusion, of heart-shrinking fear as far as Rex was concerned, while the Tavona was brought under control. By that time the crew were on their feet, seeking a possible puncture. But none was found. The pressure was maintained, and Rex, somewhat pale, breathed again. Why the fear of death in space should seem worse than fear on Earth he did not know, but it was so.

“A meteor,” said Vargo calmly. “I think no damage has been done. We will look for the mark when we land.”

What shook Rex was the knowledge that had the ship been holed the pressure and artificial atmosphere inside the ship would have been lost before space suits could have been donned. One could either accept the risk of sudden death, he perceived, or by travelling in a flimsy garment spend the voyage in discomfort. The only reassuring thing about meteors was Vargo’s assertion that it would need a large one to make a hole too big to repair.

The second incident was more remarkable, and somewhat disconcerting in a different way. Again, possibly because he spent a lot of time looking out of the window at the ever-changing patterns of stars, and the object happened to appear on his side of the ship, Rex was the one to receive the first shock of discovery.

A short distance away, and evidently moving at the same velocity as the Tavona since it looked stationary, appeared a spaceship, but such a vessel as he had never imagined. Where it had come from, and how it had got there without its approach being observed, he did not know. At one moment there was nothing in sight except some distant stars; then, blotting most of them out with its bulk, it was there, a gleaming white object at least ten times as large as the Tavona although not very different in its overall design.

For a few seconds Rex stared at it uncomprehendingly, wondering—stupidly, as he was presently to realize—if the phenomenon was a shadow or a reflection of themselves. Faces at the several portholes told him that it was not. Finding his tongue he cried: “Vargo! Vargo! Come and look at this!”

Something in his voice must have conveyed his apprehension to the others, for there was a rush to his side of the ship.

“Wonderful! Wonderful!” exclaimed the Professor. “Vargo, why have you never told me of this?”

“Never in my life,” answered Vargo, slowly, “have I seen or heard of such a ship as this.”

“Then you have no idea of where it could have come from?”

“I have no idea at all,” said Vargo, staring, shaken for once out of his inscrutable self-control.

“What are they doing?” asked Rex, anxiously.

“Obviously, they’re having a good look at us,” said Tiger.

“They look as if they might be going to attack us.”

“If that is their intention I don’t see what we can do about it,” put in Toby. “If size is anything to go by we should have about as much chance as a yacht taking on a battleship.”

Vargo snapped an order for maximum velocity.

It made not the slightest difference to the relative positions of the two ships. The Tavona might have been fastened to its huge consort.

It stayed with them for what Rex judged to be about five minutes; then it shot ahead faster than the eye could follow to vanish as miraculously as it had appeared.

“That was a sight worth seeing,” declared the Professor enthusiastically. “It is a revelation to me that there are ships of such size. Yet why not? Ships of all sizes sail on our oceans on Earth. Why should not the same development occur in space?”

“There are no such ships as that in our Solar System or I would have known of them,” stated Vargo. “It must have come from outer space. In performance as well as size it is far ahead of anything I have ever seen.”

“What I’d like to know is what it was doing here,” said Tiger.

“Exploring, I’d say. What else could it be doing?” averred Toby. “After all, aren’t we doing the same thing?”

“That ship was a long way, a very long way, from home,” contributed Vargo, looking puzzled.

They continued to discuss this strange visitation for some time, nothing else occurring to interrupt the normal passage of the Tavona. It gave Rex something to think about, and he was not sorry when the orange-yellow globe of Mars began to fill his window.

Very soon he could pick out the now familiar landmarks, and was able to observe the progress that had been made not only in the reopening of the canals but the areas of cultivation on the banks. Presently, as they touched down on the central landing square, he saw two ships already there, one of them Rolto’s, conspicuous by its blue stars. He pointed it out to Vargo.

“For his misbehaviour Rolto is no longer Captain of the Remote Survey Fleet,” said Vargo. “He now only operates between Mino and here, for there is a regular service to bring in men, and food for them.”

When they stepped out, as Vargo had claimed, an improvement in the atmosphere was at once noticeable. Nor did the air, being less thin, feel as cold. After a few minutes of slight breathlessness, and instability produced by a gravity lower than that to which he was accustomed, Rex found himself able to move about freely. Actually, possibly as a result of experience, he found these factors less of a handicap than had been predicted by theorists on Earth. All were agreed on that.

Where all had been lifeless when they had first set foot on the planet[3] was now a scene of activity as men moved about on their various tasks, removing the accumulated dust of centuries from the town, repairing the stonework, excavating the water-courses or tilling the land. Crops, some of them strange, growing on the reclaimed land, at once gave the place a look of healthy occupation. It amazed Rex that so much had been done in so short a time. It astonished him still more that for this promising state of affairs one man, and, moreover, a man from another planet, had been responsible. To have saved a planet from death, he pondered, was an achievement of which few men could boast, or ever would boast.

[3] See Kings of Space.

“Do you think the astronomers on Earth will have noticed any changes yet?” he asked the Professor, who was taking some photographs.

“I don’t think so, Rex,” was the answer. “But if the work goes on at this rate it won’t be long before they do. That big twenty-inch telescope on Mount Palomar will presently produce a photograph that should give the astronomers something to get excited about.” The Professor chuckled. “Tut-tut. They’ll make all sorts of guesses and every one will be wrong.”

“And if you told them the truth they wouldn’t believe you.”

“That, my boy, would be the last thing they’d believe. I don’t really know why. But don’t blame them, for there are moments when I can hardly believe it myself.”

Seeing Rolto standing by his ship Rex walked over to him. “Have you been to Earth lately?” he inquired mischievously.

Coldly and unsmilingly the Minoan space ship Captain answered in his hard voice: “I never again want to see that place of ignorant madmen.”

The smile which Rex had failed to suppress turned to a frown. “What a grumpy fellow you are. You think my people are mad because you don’t know them. Had you come to me instead of slinking in like a spy I would have taken you on a conducted tour. You would have found that very interesting.”

“I preferred to go alone.”

“I know. And you went to the trouble of learning our language for that very purpose. You had covetous eyes on Earth and would have invaded us had you been allowed to have your way.”

“It is only that I seek peace.”

“That’s what all dictators say. That’s their excuse for making war.”

“The day may come when the High Council will regret they did not take my advice.”

“What do you mean?”

“Big trouble is on the way.”

“For whom?”

“For us, on Mino. By going to Earth we might have escaped.”

“Escaped what?”

“You will see,” said Rolto, mysteriously.

“But you can’t go around grabbing other people’s worlds because you’re not satisfied with your own!” protested Rex.

“Other people have done it and may do it again.”

Rex stared. “For goodness sake! You talk as if you were expecting an invasion.”

“I am.”

“You certainly are a man for getting ideas,” scoffed Rex.

Rolto turned his penetrating, luminous eyes, full on Rex’s face.

Knowing the strange power possessed by his people Rex said: “Are you trying to read my mind?”

“I am reading it,” answered Rolto.

Rex shrugged. “Very well. Go ahead. I have no secrets to hide. What have you learned?”

“You saw one of their big ships on your way here.”

“One of whose big ships?”

“I don’t know. But you saw a big ship.”

“We did. It came close to look at us. Vargo could not identify it. Have you seen such a ship?”

“Several have been seen.”

“Always the same ship, no doubt.”

“No. Different ships.”

“What of it?”

“I don’t like it. They are about for no good purpose.”

“Where are they coming from?”

“I don’t know. No one knows. I lost my command because it was said I was a man of war. Now you see why. I tell you, unless we fight these strangers they will take our world, and perhaps yours.”

“You said that Earth was a danger to you.”

“Earth, with its mad experiments, is a danger to itself and everyone else. But now these big ships have appeared we may be in even greater danger, although I think Ando will be the first victim.”

“Victim! What are you talking about? We are thinking of going to Ando. We have been invited.”

“Keep away. There is danger.”

“From what?”

“These great ships. They watch it always. If they land Ando can do nothing.”

“Vargo told us they have no weapons.”

“It is true. If they are attacked they are lost. Are you going straight there?”

“We were going to call at Marlok on the way.”

“That dreadful place? The men are animals.”

“I think I had better tell the Professor what you have told me about these big ships,” said Rex. “Excuse me.”

He turned away and walked to where the others were surveying the work of restoration. “I’ve been talking to Rolto,” he informed them.

“We saw you,” answered Vargo. “Why were you talking to that dangerous man?”

“He gave me some alarming information. It begins to look as if men will settle their national disputes only to be faced with interplanetary wars.”

The Professor pushed up his glasses. “What are you talking about?”

“Rolto says he has seen several of these super-spaceships.”

“Why not. If there is one there must be others.”

“That isn’t all. He says the Andoans are afraid they’re about to be invaded.”

Tiger looked at Vargo. “If there’s any truth in that they’ll be in a mess without weapons.”

“Dear-dear-dear,” muttered the Professor. “Even here there seems to be no escaping these horrid rumours of war. Is interplanetary conquest a natural sequence to world conquest? What a dreadful thought.”

“There have been such rumours before,” averred Vargo.

Said Tiger, “What are we going to do about it?”

“I suggest we push on to Ando and get to the bottom of this tale,” advised Toby.

“I wanted to see this strange place Marlok, of which Vargo has told us,” said the Professor, frowning. “Of course, we shall have to call at Mino to pay respects. We might learn something there about these big ships.”

“Rolto says no one knows where they’re coming from,” put in Rex.

“Look!” cried Tiger, pointing. “Look what’s coming.”

All eyes were turned to the direction indicated by the pointing finger. Descending in a slow spiral was one of the great ships of which they had been speaking.

The workers stopped working. No one moved. All faces were upturned. In the silence that had fallen Rex detected, or thought he detected, a feeling of fear. Knowing that strange faces were looking down at them he himself felt anything but comfortable. Then, suddenly, at a velocity faster than the eye could follow it, the stranger had gone. He drew a deep breath of relief.

“Wonderful,” said the Professor, in an awe-stricken voice. “I would not have missed seeing that for anything.”

“It begins to look as if there was something in what Rolto said,” remarked Tiger, seriously.

“It showed no sign of hostility,” protested the Professor.

“In war,” answered Tiger, “the job of a scout is to look and report what he sees. It is not his business to start a battle.”

“For my part,” returned the Professor, “I hope to see more of these splendid ships.”

“You may,” put in Rolto, who had walked up, “see too much of them.”

“You always were a pessimistic fellow,” the Professor told him. “I can’t believe that men as far advanced in scientific knowledge as the builders of those fine ships, would indulge in such a futile enterprise as war.”

“We shall see,” concluded Rolto, and strode away.

When the Tavona arrived on the planetoid Mino it was to find the usual atmosphere of placid contentment replaced by one of uneasiness, anxiety, and even alarm. The reason for this was not hard to find, for there was only one general topic of conversation. It was the appearance of the unknown spaceships and what the visitation portended, although, as it happened, none was in sight when the Tavona landed.

It seemed to Rex, when he spoke to his girl friend Morino about it, that the root of the fear lay in the fact that whatever the visitors intended there would be no way of preventing it. True, so far there had been no indication of evil intent; but the common belief was that the purpose of the newcomers in the Solar System was not good, or they would have landed and made themselves known. Wherefore the growing feeling of helplessness.

The business had begun, it turned out, when a Minoan ship had returned from Ando with a report that the planet was in a state of something between despondency and terror. Some of the people were in favour of evacuating their homes and seeking a new one elsewhere, although, as Rex argued when he was told, it was hard to see what good purpose could be served by this? If the new arrivals were bent on conquest they would, in their bigger and better ships, follow them, no matter where they went.

Ando, admittedly, had greater cause for alarm than Mino, for at least one ship was usually sitting over them, motionless, watching or waiting . . . for what? Rex had to allow that this constant surveillance would become unnerving. The Andoans, he perceived, were playing mouse to a big cat. He did not say so, but tried to comfort Morino by pointing out that the visitors were doing no harm by watching—as long as they stopped at that.

“But you don’t understand,” answered Morino. “How can people live and be happy in the expectation of death at any instant? If these big ships mean harm, when they strike it will be all over in a moment.”

“How can you say that when you don’t even know if they carry weapons?” argued Rex.

“People who can make great ships like that must be all-powerful,” returned Morino. “The Andoans, who have always been friendly people, have no weapons.”

“I think the Professor will go to Ando, anyway,” asserted Rex.

“But you have no weapons, either.”

“Let’s not talk of weapons until the need for them arises.”

“Then it will be too late.”

“Well, worrying about it won’t help,” contended Rex. “Let us do some wing-flying.”

But Morino did not want to play. She went off to talk to Borron, her father.

Rex walked over to where the others were discussing the situation with members of the Council, Vargo acting as interpreter.

The Professor was talking. “I see no reason why you should distress yourselves with what are as yet only rumours. It may all come to nothing. These ships may depart as mysteriously as they arrived. Nothing can be done. Let these strangers strike the first blow if violence is their purpose.”

Said Tiger, grimly, “In the sort of war I visualize here the first blow will probably be the last.”

“That’s what Morino has just told me,” put in Rex. “People who can build space ships will have long passed the days of bows and arrows.”

“To carry that argument to its logical conclusion, neither would such people be so ill-advised as to employ weapons likely to jeopardize their own existence,” resumed the Professor. “Even if, as has been suggested, these strangers are looking for a new planet to colonize, where would be the sense of destroying it by an atomic explosion, if that’s what you have in mind?”

“In my opinion,” said Toby, “such people will have developed weapons capable of destroying life without injuring the planet. Moreover, if these people intend invasion they won’t stop at Ando. If they do start anything they’ll probably take over the entire Solar System, in which case Earth will go west with the rest. It so happens, I imagine, that Ando and its neighbours are the first places on the line of march, so to speak.”

“Well,” decided the Professor, “as there’s nothing we can do about it, while we’re waiting for our unwelcome visitors to make up their minds what they’re going to do we might as well entertain ourselves by having a look at this Stone Age world Vargo told us about—Marlok.”

“Why not go to Ando?” suggested Tiger.

“With the people upset by this crisis we should not see the planet at its best. We might even be regarded with suspicion. No, I suggest a visit to Marlok. By the time we get back conditions may have returned to normal. What do you think about that proposition, Vargo?”

Vargo, clearly, was not enthusiastic. He was as worried about the threat as anyone. In any case, he reaffirmed, Marlok was a dangerous place.

“If these big ships are looking for a new home it’s a pity they don’t go there,” said Rex.

“They probably will, in due course,” returned the Professor. “Having started, who knows where they’ll stop? It really is a fantastic situation. On Earth when they are attacked the people rush from country to country. In more advanced worlds it seems that people have to fly from one planet to another. Dear-dear, what a muddle it all is.”

After some further debate Vargo agreed to go to Marlok if Borron would take them and provided the Council would permit them to use the Tavona. It was unlikely that they would be allowed to land, he surmised, so they would only be away for a few days.

“From Marlok we might go straight on to Ando and get to the bottom of what may turn out to be only a scare,” suggested the Professor.

“Don’t you think we ought to go home?” said Rex tentatively.

“For what purpose?”

“To warn the people that there might be an invasion from space.”

“Even if they believed us, which is most unlikely, they could do nothing. But things haven’t come to that yet.”

Tiger stepped in again. “Has it occurred to you, Professor, that if these people mean trouble they might attack us in space?”

“The one we saw gave no signs of hostility.”

“Maybe the captain had not received instructions at that time.”

“Tut-tut! We are allowing our imaginations to run away with us,” declared the Professor, impatiently. “Let us give ourselves something else to think about by inspecting these Stone Age persons.”

Borron raised no objection to the proposed trip, nor were the Council unwilling for the Tavona to go, so preparations were made for departure forthwith. It surprised Rex, and disappointed him, that the Minoans could so easily become dispirited. Advancement in culture appeared to have weakened their will to resist. At all events, he could imagine a very different attitude on Earth to the danger, should it arise.

There were more tears from Morino, who implored him not to go; but nothing would have induced him to be left out, and when the Tavona took off he was in his usual place.

Thinking of collision he did not like the idea of there being other ships in the vicinity, but Vargo assured him that in so much space there was less risk of collision with one of the big ships than with a stray meteor.

Once more, as Mino appeared to fall away into the indigo vault that was space, he was conscious of that empty feeling in the stomach caused not so much by velocity as a vague dread of entering the unknown. He never would overcome that, he thought. Even when space travel became an acknowledged fact on Earth, as was bound to happen eventually, it would be a long time before people could embark on such voyages without similar sensations. When that day came, no doubt, someone would think of a device to occupy the travellers during the long hours between ports of call.

He slept, on and off, much of the way to Marlok.

He roused himself, however, when Tiger told him the objective was in sight, and settled down for his first view of a world as Earth might have appeared twenty thousand years ago. At least, that was the limit of his imagination as Marlok grew larger and larger until it filled his observation window.

He knew that Borron had no intention of landing unless he could find an area which he could be sure was not occupied by the primitive inhabitants; but he was a little surprised when, following a terse conversation between the crew in their own language, the ship was brought to a stop so quickly that he thought he was going through the floor. He looked at Vargo expectantly, for this was not Borron’s normal spacemanship, and he could only conclude there had been a reason for it. There was. Vargo informed them that one of the big ships was below them, stationary, apparently keeping Marlok under observation.

“Dear-dear. The confounded things seem to be everywhere,” said the Professor irritably.

The Tavona had been stopped, or nearly stopped, for it was still losing height slowly, at an altitude which Rex judged to be about two thousand feet. With no cloud interference visibility was exceptionally good, and the physical features of the planet stood out clearly; but even so it took Rex a few seconds to pick up the big ship. Actually, he spotted its shadow first, and that gave him a line on it. From his own altitude it appeared to be standing on the ground, but the shadow told him it was not.

As for the surface of the planet itself, it offered nothing remarkable. The general coloration was dull browns and greens. For the most part the terrain seemed to be flat, open plain, split by ravines as if at some time it had been subjected to intense heat; but there were rocky outcrops, of no great height judging from the shadows. Patches of sand and scrub, with an occasional flat-topped tree, reminded him of Central North Africa. There was a drab, greyish area that puzzled him. He could see no water in any form, seas, lakes or rivers, which suggested that the place must be dry. Nor could he see any sign of life other than vegetation. He looked in vain for anything that might have been a human habitation. Nothing moved. In short, Marlok looked as lifeless as a photograph.

“Well, here we are,” said the Professor. “I see nothing to get excited about. What do you suggest we do, Vargo?”

Vargo had a brief conversation with Borron. Then he said: “Borron thinks it would be dangerous to land.”

“Because of the other visitors?”

“For one thing. Also because of the men-creatures.”

“I can’t see any.”

“When they see us they hide in the forest.”

“What forest? I don’t see a forest.”

Vargo indicated the grey-green area that had puzzled Rex. “That is a forest of what I have heard you call moss.”

“Moss! How can there be a forest of moss, which is a dwarf plant?”

“Not here. The moss is the tallest thing that grows.”

“How tall?”

“Twenty times as tall as me.”

“I see,” said the Professor slowly. “That certainly is tall for moss.”

“The people here live in it,” said Vargo. “They make tunnels, in which they run in and out like animals, very fast.”

“If they came out we could take off.”

“Perhaps not fast enough. Borron once had a ship that was damaged by stones.”

“Then let us go low over the forest. Perhaps we shall see them.”

“You will see nothing except moss, for as I have told you, the creatures live in tunnels, deep down.”

“Then they must be afraid of something,” declared the Professor.

“Perhaps they are afraid of us. They may like the way they live and do not wish to be disturbed.”

“Well, as it’s their world they’re entitled to think as they like. Perhaps if we dropped them some presents they would come into the open.”

This suggestion was never followed up, for here Rex stepped into the conversation. “The big ship is going down; I think it’s going to land. Yes, I can see it drawing nearer to its shadow.”

“Capital!” cried the Professor. “We’ll watch what happens. If what Borron says is correct the aborigines should put in an appearance very soon.”

Silence fell as all eyes were turned on the scene below.

Rex knew the ship had landed when he saw sand swirling below it, evidently disturbed by the power units, whatever they might be. It began to settle when, presumably, the power was cut. The atmosphere in the Tavona was now one of expectation, but nothing happened.

The pilot of the big ship had chosen for his landing ground an island, as it were, bounded on one side by the moss forest, and on the other by a deep ravine. Actually, wherever it had landed it would not have been far from a ravine; but it could have avoided the forest, thought Rex, as he watched. It struck him that the spacemen were unaware of the peril which, according to Borron, lurked in the giant moss.

Apparently Vargo was thinking on the same lines, for he remarked: “They cannot know of the barbarians or they would not land so near the forest.”

“They’re probably well able to take care of themselves,” observed Tiger. “I can’t believe that ape men have anything to compete with men who can build a ship like the one below. Brain will beat brawn every time.”

How far he was wrong, at least on this occasion, was soon to be demonstrated.

The doors of the big spaceship must have been opened, for suddenly a squat figure appeared standing beside it. Nothing could be seen of the man himself—if man it was—for the form was completely enveloped in what looked like a suit of armour, or a diver’s equipment that had been sprayed with metallic paint.

“Ah!” breathed the Professor. “This is truly marvellous. May we go a little lower, Vargo, please? We must get a glimpse of this visitor, if it is possible.”

Vargo, as was to be expected, was as interested as anyone, and at his request the Tavona went down to about two hundred feet, keeping a little to one side of the big ship. By the time this move had been made two more figures, clad in exactly the same way, had appeared beside the first. With a stiff gait all moved slowly forward, turning as if to survey the landscape.

The Professor spoke. “These people, whoever they are, must find it necessary to wear spacesuits, although from what you have told us, Vargo, Marlok has an atmosphere much like our own.”

“They may be testing the atmosphere,” was all Vargo could say.

The question was never answered, for at this juncture things began to happen, and they happened so fast, and with such spectacular effect, that there was no time for conversation. Indeed, everyone in the Tavona behaved as though spell-bound, and not without reason.

From out of the moss forest poured a horde of what, from their shape and the fact that they walked erect, must be called men; but such men Rex had never seen before. Tall and broad, they wore no clothes that could be seen, the reason being, apparently, that as they were covered with thin, light-brown hair, they did not need any. The Tavona was still too far away for details to be observed so no scrutiny of their faces was possible. They came out with a rush and swept down as a mob on the spacemen, swinging clubs and hurling large pieces of rock.

It seemed certain from the outset that the spacemen must be caught, for their movements had been slow and clumsy. So were they now, as they backed towards their ship, although in view of what was to follow they may have seen no reason for urgency.

From them, from the level of their hips, leapt long flashes the colour of electric sparks, and in whatever direction these were pointed the ape men fell as if struck by lightning. They were, in fact, mown down. But the rest came on, and such were their numbers that it still looked as if the ship would be overwhelmed.

While the issue hung in the balance a new factor appeared, one which obviously was going to settle the matter. Rex held his breath as a second force of natives sprang from the ravine behind the ship. He had no idea they were there; nor, apparently, had the defenders. With nothing to stop them this fresh mob rushed at the ship hurling stones and clubs which, hitting their mark, must have made a terrible din inside, even if they did no serious damage. Aghast, Rex realized that this might have been their fate had not the big ship been there to give them pause before they landed. It seemed to him now that Borron had underestimated the danger rather than the reverse.

The three spacemen who had left the ship were now close enough to it to be helped inside by their companions, and for a brief moment it looked as if that might be the end of the affair. But no. An ape-man, faster on his feet than the rest, tried to follow them in and before he could be dislodged, those who were attacking from the rear were climbing all over the ship, hammering at it with their clubs in the wildest frenzy of fury imaginable. One or two, sliding down from the top, reached the entrance doors before they could be closed and poured inside. What now took place inside the ship could not of course be seen, but it needed little imagination to picture the frightful confusion.

But the crowning horror was yet to come, and such a scene as the one now presented surpassed anything that could have been anticipated.

The big ship, with the ape men clinging to it like leeches, began to rise, slowly at first but with fast gathering momentum; and as it went up the natives one by one began to slip off, or as their strength gave out, fall off. Some hung on for a little while but in the end they all had to go, to plummet like stones to the ground below.

At this juncture it looked to Rex as if the invaders would succeed in making their escape, which, obviously, was what they were trying to do. But that the struggle was not yet over was revealed when the big ship, instead of increasing its velocity began to slow down, at the same time swaying and spinning in the most sickening manner.

“The ship is out of control,” stated Vargo, looking up at it, for it was now well above the Tavona.

“It must be the creatures that got inside, still fighting,” said Rex in a strangled voice. “How dreadful!”

“Why did the ship stop, anyway,” cried Toby.

“They had to stop it because they couldn’t close the doors,” answered the Professor. “As you can see, the doors are still open. With the doors open it would be fatal for the ship to leave the atmosphere.”

That the fight was still going on inside was proved when a spaceman was flung out, to hurtle down and narrowly miss the Tavona in passing. Rex, dry-lipped, unable to tear his eyes away, watched with morbid fascination the figure of the doomed spaceman turning over and over until it crashed into the moss forest where it disappeared from sight.

That the crew of the ship had not been able to regain control became evident when, after wallowing about for some seconds, it began to fall. Faster and faster it fell until, like a giant bird struck dead in flight, it crashed into the forest to be seen no more.

“This is really shocking!” exclaimed the Professor, running his fingers through his hair in his agitation. “That awful spectacle will haunt me for the rest of my days.”

Borron, who did not seem particularly upset, took the Tavona low over the spot where the big ship had crashed, and for the first time the height of the moss could be appreciated. At the bottom of a deep round hole was the ill-fated ship, having by its weight cut a passage through the foliage to the ground. Over it ape men were crawling like flies on a piece of carrion. Some, seeing the Tavona over them, danced with bestial rage, waving their arms and brandishing their crude weapons.

“That’s one of the big ships gone west,” said Rex, in a voice which he hardly recognized as his own.

“There’s nothing we can do about it,” said the Professor. “To land near the forest would be suicidal. You were right, Vargo, about this being a dangerous place. These Marlokians are nasty people. They attacked without the slightest provocation.”

“As I warned you they would,” returned Vargo, simply.

“It strikes me we’d better do our exploring a little more carefully in future,” said Tiger, seriously. “I’ve seen as much as I want to of Marlok.”

“A machine gun, much less a rifle, would be no use against that crowd,” asserted Toby. “I wonder what those blue flashes were.”

“Certainly a weapon far in advance of anything we have on Earth,” answered Tiger. “From the colour I’d say an electric discharge of some sort. There is this about it. We now have an idea of what’s inside these ships.”

“A very poor idea, I’m afraid,” returned the Professor. “I would have liked very much to see exactly what sort of man was inside those spacesuits. So also would I have liked a close view of one of the uncouth gentlemen who dwell on Marlok. Obviously they are not fellows to meddle with. For sheer ferocity they would be hard to beat. After what we have seen of Man at this stage of his development it is no matter for wonder that on Earth he was able to survive the age of the great prehistoric reptiles, and later, deal successfully with such beasts as the mammoth and the sabre-toothed tiger.”

“These people have a long way to go before they catch up with us,” remarked Toby. “How far, in time, would you think we are in advance of them, Professor?”

“It’s hard to say. For a guess, at least forty thousand years. But as long as they’re happy what does it matter?”

“They didn’t look a very happy lot to me,” put in Tiger.

“You are in no position to judge, my dear Group-Captain,” averred the Professor. “It is natural, but nevertheless quite wrong, to compare other civilizations with ours—from the point of view of happiness, anyway. What may seem horrible to you might be heaven elsewhere. The females of the species below would hardly conform to your idea of beauty, but to the males they may be as glamorous as anything produced by a Hollywood film studio.”

“I think I can see one of them now,” said Rex, who still found it difficult to take his eyes from a scene which, with bodies lying about, looked unpleasantly like a battlefield, as indeed it was. His remark was occasioned by the appearance from the forest of a figure, smaller than the others, which ran from body to body as if seeking a friend or relative among the casualties. Apparently the creature found what it sought, for it stopped, and dropping on its knees, put out its hands as if to caress the fallen warrior. As the hands touched the body there was a bright blue spark, and the kneeling figure collapsed across the one it had touched.

“Did you see that?” cried Rex.

But the others, who were still discussing what they had seen, paid no attention. The Professor was saying: “I can’t help feeling that this is a wonderful opportunity for a close study of true Stone Age Man, one that may never occur again.” He pointed to a crumpled figure that lay at some distance from the rest, one that must have been flung off the ship when it was out of control at a high altitude. “I see no reason why we shouldn’t land over there for a moment, long enough for me to take a photograph which I could study at leisure. Knowing exactly where the danger lies it need not arise, for the body is far enough away from the forest.”

This, on the face of it, was true; but it was clear from the expressions of the others that they did not share the Professor’s confidence. However, when he pressed his point, observing that as the body was on open ground there could be no question of a surprise attack, Vargo, not without reluctance, agreed. So Borron moved the Tavona to a position immediately above the body the Professor had indicated and allowed it cautiously to descend. With everyone keeping a sharp look-out the atmosphere was tested, and when it was ascertained that it was bearable, if not entirely comfortable, being chilly and having a peculiar aroma, the ship touched down and the exit door was opened.

The Professor, with his camera in hand, stepped down. “Behold a type that may have been our ancestor,” he said dramatically.

Rex was content to watch from the door, and it was with sensations that he had never before experienced that he gazed at such a creature as might have existed on Earth in the remote past.

Under a mane of hair the forehead was low and receded sharply from protruding eyebrows. The mouth was large with the lower jaw prominent. The coarse hair that covered the body, thickest on the chest and legs, was sparse enough for the skin to be seen through it. The only garment was a piece of rough hide tied round the middle, and this, with the creature’s weapon, a beautifully worked flint spear-head lashed on a thick stick, proved beyond question that here was a man and not an animal. As the Professor remarked, animals do not clothe themselves, nor do they make weapons, not even crude ones.

Strangely moved by some deep emotion Rex was about to turn away when he saw the Professor, having taken some photographs put out a hand as if to touch the corpse. In a flash he remembered what he had seen, and almost screamed the words: “Don’t touch it!”

The Professor looked round, eyebrows raised. “Why not?”

“It might give off an electrical discharge,” answered Rex, in a voice stiff with anxiety. He described what he had seen.