* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

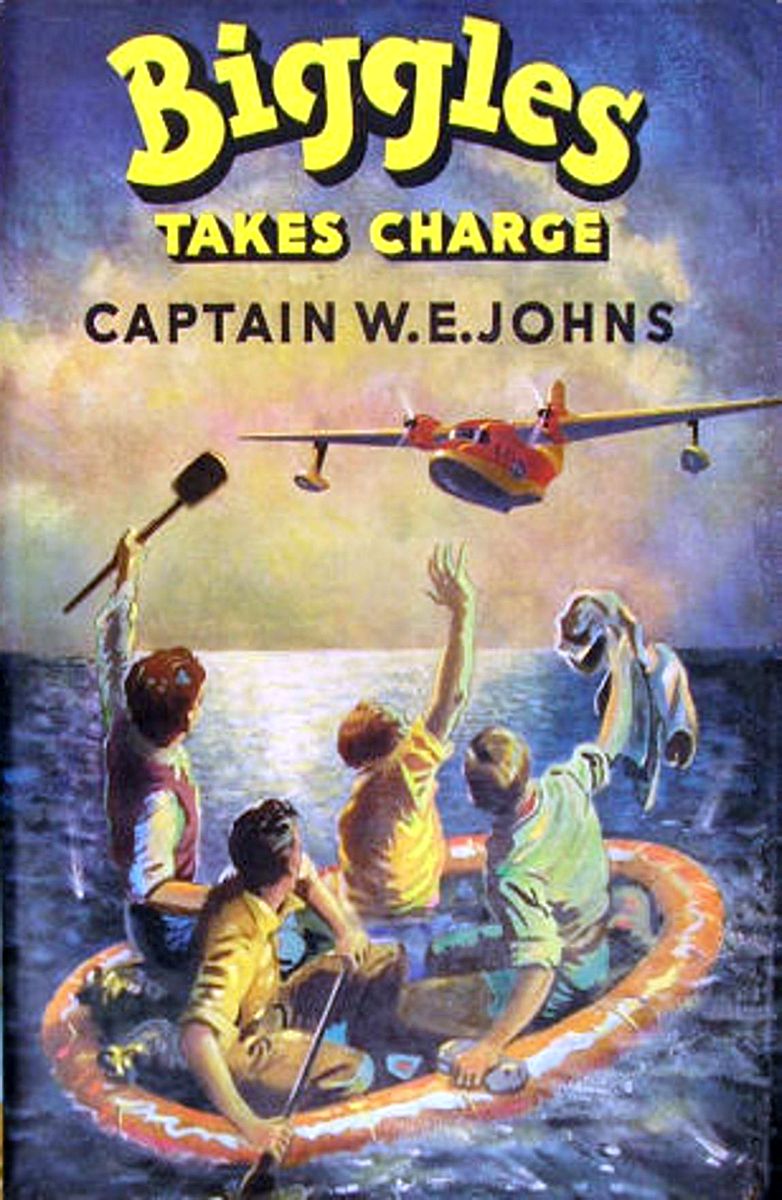

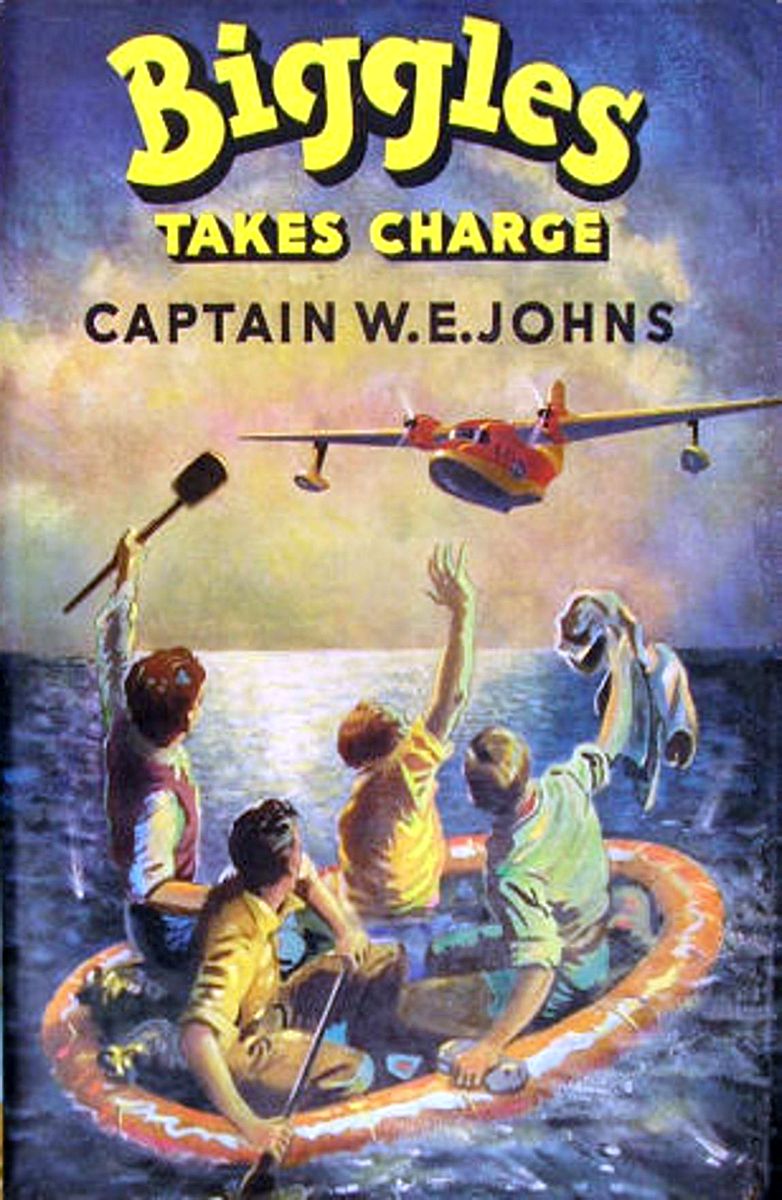

Title: Biggles Takes Charge

Date of first publication: 1956

Author: Capt. W. E. (William Earl) Johns (1893-1968)

Illustrator: Leslie Stead (1899-1966)

Date first posted: Nov. 18, 2023

Date last updated: Nov. 18, 2023

Faded Page eBook #20231124

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, akaitharam, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

BIGGLES

TAKES CHARGE

A ‘Biggles of the Air Police’ Adventure

★

CAPTAIN W. E. JOHNS

Illustrated by Leslie Stead

Brockhampton Press

LEICESTER

First

published 1956

by Brockhampton Press Ltd

Market Place, Leicester

Made and printed in Great Britain

by C. Tinling & Co. Ltd

Liverpool

| CONTENTS | ||

| ★ | ||

| Preface A FEW WORDS ABOUT LA SOLOGNE | page 5 | |

| Chapter | ||

| 1 | CHATEAU GRANDBULON | 10 |

| 2 | A FUGITIVE FROM FEAR | 20 |

| 3 | ALGY MAKES A WAGER | 33 |

| 4 | A MAQUISARD LOADS HIS GUN | 47 |

| 5 | ALGY SPOILS SOME BREAKFASTS | 61 |

| 6 | THE ROAD SOUTH | 70 |

| 7 | MONTE CARLO RALLY | 77 |

| 8 | HARD WORDS AT VILLA CLEMENT | 88 |

| 9 | BACK TO LA SOLOGNE | 98 |

| 10 | THE FOREST SHOWS ITS TEETH | 110 |

| 11 | A VISITOR BY NIGHT | 116 |

| 12 | BIGGLES TURNS THE TRICK | 129 |

| 13 | INTERLUDE FOR DISCUSSION | 139 |

| 14 | GAMBLER’S CHOICE | 151 |

| 15 | MORE WORK IN THE DARK | 158 |

| 16 | AN OLD MAN REMEMBERS | 169 |

| 17 | BETWEEN TWO FIRES | 181 |

France is a country of many parts, each having little resemblance to the others. The terrain is different, the people are different and the conditions of life are different. Most of these districts, which carry a general name but have no visible boundaries, are well known to tourists, notably the ever popular Riviera. Nothing could be more unlike than the Ile de France, with its plains rolling away to the horizon, and the towering Pyrenees.

But unless the voyager has some specific reason for going there, or happens to find himself on the great highway known as Route Nationale 20, it is unlikely that he will hear of La Sologne. Even in that event he will little suspect what lies on either side of the road, for hundreds of square miles of forest, swamp and jungle, are not what he would expect to find in the heart of a country wherein agriculture is a basic industry.

To paint a pen portrait of this strange land of nearly a million and a half acres will not be easy, but we must try, for the reader should know something of it from the outset. Apart from being a land of moods, La Sologne takes care that you do not see all her face at one time. At every turn the scene is different, yet there is no particular view to remember. Indeed, from La Ferté St Aubin in the north (on the map you will find it about twenty-five miles south of Orleans) to Vierzon in the south, a matter of roughly forty miles, the traveller by road may think the countryside monotonous. Actually, it is one of the wildest, and for that reason for some people one of the most fascinating, stretches of country in Western Europe.

For the most part La Sologne is true forest, with stands of oak, chestnut, birch, fir and pine. The ground underfoot may be arid, supporting a tangle of heather, sometimes waist high, or it may be a reedy swamp extending for miles. There are jungles of scrub and undergrowth that are literally impenetrable. Everywhere trailing brambles drag on the feet. Scattered over the whole area are lakes, large and small, more than a thousand of them, dark, solitary, tranquil, fed by furtive-looking streams that glide mysterious courses through the labyrinth. Over all hangs a brooding silence that seems to fall from the sky, and at sunset creates a haunting, often sinister, atmosphere.

This is not to say that so vast a tract of land is uninhabited. On the main road that cuts through it like a knife from north to south there are one or two small towns and villages, and on either side of it you will find an occasional farmer scratching a living in a clearing; for the soil is poor, and in recent years a great many of these homesteads have been abandoned. Apart from the diehards fighting their losing battle with nature, the only man you might meet, except in the shooting season, would be a forester or a gamekeeper. The visitor might walk all day long, as has the writer, without seeing a living soul or hearing sound of one. A man seeking solitude will certainly find it here.

For the bird-watcher it is a paradise, but let him beware of snakes, one species of which is venomous. The lizards are harmless, as are most of the wild creatures that have here found a safe retreat; and that includes the great deer as well as the smaller roe. An exception can be the sanglier, the wild boar, an ugly beast that can weigh up to hundreds of pounds and has tusks that would rip a man to pieces should he fall foul of one in a nasty mood. But even the sanglier, left alone, is not to be feared. By day he retires to the thickest jungle, and there, unless disturbed, he is content to remain until nightfall, when he emerges to foray for food. Upset or wounded, like all his species, he can be a devil incarnate.

In the autumn hunting seasons La Sologne is the Mecca of sportsmen, for game abounds—pheasant, partridge, woodcock, snipe, wild duck, and the like. There are fish, too, in the lakes—enough to satisfy the most ambitious angler. Areas of ground are rented by those who can afford them, and this, in the 19th century (when men had money to spend) produced what at first seems a startling paradox in the form of hunting lodges of a size and splendour seldom found elsewhere—mansions of forty, fifty, or even eighty bedrooms. Some are still occupied; others are empty and have fallen into disrepair, with roses, long untended, fighting a hopeless battle with the weeds.

How did this wild place come into existence? Standing within the forest with the smell of rotting leaves in the nostrils, a buzzard circling overhead and a fox slinking across a glade, one has a feeling that this was how much of Europe must have looked ten thousand years ago. It is said that during the wars of the Middle Ages, and after, when the land was a prey for marauding gangs of disbanded soldiery, the people who dwelt here—those who had not been murdered—fled, leaving the ground to go back to swamp and forest; and since that time the huge sum of money that would be necessary to drain it and restore it to cultivation has not been available. So it remains as the visitor will find it to-day, a land which Nature has won back from men in spite of their machines.

The men who lived in the region during the Dark Ages have left their marks, although these are fast disappearing. One comes upon crumbling, overgrown ruins; fortified, moated sites that once were castles, and even churches. Old foresters whisper darkly of underground passages, too. But the hand of death and decay has fallen heavily on these relics of a forgotten past, and sympathetic nature is fast burying them in a shroud of moss and ivy. Even the rabbits have gone, wiped out by the deadly myxomatosis; and how many there must have been may be judged from the fact that at one time the district exported three million a year. Now the burrows, like so many of the homes, are empty.

La Sologne has had more recent troubles, and if one other thing was needed to complete the atmosphere of tragedy and chill the heart of the visitor it is there. Graves. Graves, sometimes solitary, sometimes in long rows. Little white crosses, everywhere. Usually there is just a name, or names, and below, those significant words that speak for themselves: Mort pour la Patrie: Marts pour la Liberté de leur Pays: or, Morts pour la Résistance. The visitor will come upon this melancholy harvest of war everywhere, in the woods, the fields, or by the roadside. Under each cross lies a Maquisard, one of the boys or girls (many were students) who refused to be conscripted into Hitler’s forces. As one enters La Ferté St Aubin in the north, by the roadside lie forty-five.

La Sologne, by reason of its nature, became a hiding-place, during the occupation of France by Germany, for the Maquis, as they were called, or the Résistance. When they were caught they were shot out of hand. The German method employed to find them was to infiltrate a collaborator into the forest. He would pretend to be a Maquisard, or an escaped prisoner, and having been received by the boys and girls in hiding would later slink away and betray them. To such base treachery can human beings sink. Did I say human? Inhuman would be a better word. So their victims were shot, peasant, priest and pupil, men, women and children whose only crime was patriotism. Many died shouting defiance at their murderers, and to-day, should you pass that way, you may see where they lie. There are British names among them. But times are changing, and perhaps these things are best forgotten.

One need not be too depressed by this, for as an old Maquisard told the author simply, but for this sacrifice how would we know of their courage? Courage of the highest order was needed by these Davids to defy the invading Goliath.

These are not the only thought-provoking things the visitor may find in that strangely beautiful, sometimes gay and sometimes sad, often menacing, always lonely, usually silent area of France that is called La Sologne.

One final note. The events narrated in the following pages occurred some years ago, but for certain good reasons which the reader may guess it was thought desirable at the time to withhold them from publication.

W. E. Johns

At La Sologne,

1955

Flight-lieutenant The Honourable Algernon Lacey, D.F.C., R.A.F. (retired), stopped his car for the second time in five minutes and with a gloved hand wiped away the snow that clogged his windscreen wipers. The frown that furrowed his forehead deepened as he returned to his seat and peered into the whirling flakes which, under a darkening sky, reduced visibility to a few yards. Telling himself that he must have been mad to attempt the trip—for the weather forecast had been ominous—he switched on his headlights, but finding they did nothing to improve matters turned them off again.

As the car crawled on in first gear he found comfort in two redeeming factors. The road, N.20, like most French roads, cut across the countryside on a line as straight as the flight of an arrow; and with the little town of Salbris behind him he knew he must be nearing his destination. What he would find on reaching it was a question open to doubt, but he had no fears on that score. Even if he found the Chateau Grandbulon unoccupied the gamekeeper would be in his cottage nearby. At least, so he had been told. Failing that, he had a key.

The little village that was his next landmark emerged reluctantly from the gloom astride the road, the dilapidated houses looking even more poverty-stricken than is so commonly the case in remote rural France. Not a soul was in sight, although that, considering the weather, was no matter for wonder. Lowering the side window for a clearer view he went on, driving ever more slowly, watching for the second turning on the left which he had been told to take. The blizzard seemed to be getting worse with a rising wind lifting the snow already fallen to dance in swirling eddies with that which still fell. That such weather could occur, in early spring, so far south, astonished him. But he had come too far to turn back now.

The opening which he sought appeared as a narrow break between drooping firs standing shoulder to shoulder. Into it he swung the car to find himself on a track rather than road. But of that he had been warned. Only nine more kilometres, he told himself.

The trees now served a useful purpose, for the track being under snow which was beginning to pile into drifts he found it easier to keep straight by looking up and following the slightly less dark line between the inky silhouettes on either side. Night fell. The track seemed endless, the forest seemed endless and the snow inexhaustible. He saw no one, met no vehicle and encountered no animal. Only he, he told himself bitterly, had been fool enough to be caught out on such a night. One thing was certain. If he managed to reach the house, whether or not there was anyone there he would be benighted in it.

His fear now was that he might overshoot the accommodation drive that gave access to the building that was his objective. The third turning on the right had been his instructions.

So this, he mused, was La Sologne. He had chosen a fine moment to introduce himself. At least the car kept going, which was something to be thankful for. Half a dozen times he had to get out to clear jammed windscreen wipers.

He saw, and passed, the first turning. By the time he had reached the second, which was some distance on, he was becoming worried, for the snow was now some five or six inches deep and he wondered how long it would be before it brought him to a halt. Another anxiety was the narrowness of the tree-lined track, which would prevent him from turning should he go too far; and in such conditions there could be no question of travelling in reverse.

In point of fact he nearly did go too far, and it was only the solid black bulk of a cottage that caused him to step on his brake just in time. Getting out, car-torch in hand, he confirmed that the black object was a cottage, standing a few yards back from the road at the junction of a lane that came in at right angles. Groping about at the corner he found the signpost which he had been told was there. Sweeping it clear of snow, behind a pointing finger he picked out the words Chateau Grandbulon, which told him, to his great satisfaction, that he had arrived. The cottage could only be that of Pierre Sondray, the gamekeeper.

He advanced to the door, for should Pierre prove to be at home there would be no point in going on to the chateau. Not a glimmer of light showed anywhere from door or window which closer inspection revealed had been shuttered. It looked as if no one was at home. However, he beat on the door with his fist. There was no answer. Clearly, the keeper was not within, and turning away, in front of what had been a few square yards of garden he stumbled over the reason.

It was a cross. A rough, home-made wooden cross, painted white. His heart missed a beat. A cross! What was it doing there? He guessed the answer even before he cleared it of snow and turned the light of his torch on the crossbar. ‘Pierre Sondray—Marie Sondray’ he read, his lips unconsciously forming the words. ‘1944. Morts Pour la Patrie.’ Mort Pour la Patrie? A cold hand seemed to settle on his heart as he realized that this fateful epitaph could have only one meaning. Pierre and his wife Marie had died for their country. How? Why here? For a moment Algy’s brain whirled as the significance of the date struck him. They had died together, and together they had been buried near their own front door.

He drew a deep breath. Then his lips came together in a hard line. So the enemy had been here—caught them hiding Maquis, or suspected them of it, which would be enough to seal their doom. Or perhaps they had been helping escaped prisoners, as many did, and so had paid the penalty.

For a moment Algy stood with bowed head, one hand resting on the simple monument which in few words said so much; stood while something seemed to stick in his throat, heedless of the snowflakes that settled on his eyelashes as if to veil the scene. Why he should be so strangely affected he did not know, for he had never known the gamekeeper or his wife. Perhaps the loneliness, or the snow that lay over the humble graves like a white sheet, helped to induce a feeling of personal loss.

Pulling himself together, deep in depressing thoughts he made his way slowly back to the car. Even as he reached it the headlights flickered and went out, presumably the result of a ‘short’ in the ignition caused by accumulated snow. Well, there was nothing he could do about it until daylight, he told himself resignedly.

The car stood foul of the road, so having at some risk moved it nearer to the side he prepared to walk the rest of the way, knowing he had not far to go. He had nothing to carry, not even a handbag, for his intention had been, after having achieved his purpose, to return to Paris forthwith. There was now no possibility of getting back.

The walk to the chateau was nothing much in the way of distance but it was one to make him glad it was not longer. Knee deep in drifted snow he blundered over fallen branches and often had to tear his legs from unseen briars or brambles. Without the torch, he perceived, he would have been hopelessly lost. However, after a twenty minutes’ struggle he collided with a structure that turned out to be a stone terrace, and this told him that he had arrived. Not without difficulty he found the steps leading to the top, and there before him loomed what was obviously the main entrance to the building. He could see little of it, but boarded-up windows told him what he really needed to know. There was no one in residence, not even a caretaker, or the boards would have been removed.

Finding the bell chain he pulled it, more as a matter of courtesy than in the expectation of a response. There was no response. He tried again, and heard the hollow jangle of a bell in the distance. There was no other sound. For a minute he waited, crouching against the doorpost to escape the broad white flakes that still fell in silent procession. When no one came he took from his pocket a large, old-fashioned iron key, inserted it, turned it with an effort, and with another effort pushed open the heavy door on protesting hinges. Removing the key he put it in the lock on the inside and closed the door. He did not trouble to lock it, seeing no reason to do so. There was no one inside to go out, and it seemed highly improbable that there was anyone outside who would wish to come in.

Standing there, just inside the door, having brushed the worst of the snow from his jacket, with the beam of the torch he explored his immediate surroundings. What he saw was what he expected, only rather more so. It was not the sort of place he would have chosen to pass the night; but there had been no choice, and he was in no case to be particular.

He had arrived, he perceived, in the entrance hall. For that he was prepared, but he had not anticipated anything on so grand a scale. It appeared to occupy half the front of the house. So far did it extend on either side of him that his torch only just succeeded in probing the distant shadows.

Facing him was a great fireplace, flanked by leather-covered arm-chairs of appropriate size. From above it the glazed eyes of an antlered head stared down at him unwinkingly in an expression of accusing reproach. As the circle of light thrown by the torch moved slowly along the wall it revealed more heads; deer, large and small; foxes, badgers, and last but not least, a mighty boar, long curving tusks gleaming, its lips parted in an eternal snarl of defiance. Nearby, a stuffed owl regarded it with startled wonder. There were pictures of the chase, too. A war-scarred sanglier led his family through a sunset-tinted glade in the forest; a fox stood astride the bloodstained remains of a pheasant, ears pricked, alert for danger; a mighty stag drank cautiously from a pool dappled with the light of a rising sun. Old guns, duelling pistols, swords and a hunting horn, had been arranged in a pattern between the pictures. The skins and hides of long dead animals rugged the hearth. A broad flight of stone stairs swept up to the next floor.

But the most useful objects in the room Algy only discovered when he walked forward to the fireplace. These were a pair of candlesticks on the overmantel, each holding a few inches of candle. He lost no time in lighting them, and was grateful for the feeble yellow glow they provided. Taking one, he looked around for electric switches, but was neither surprised nor disappointed to find none. No matter. The candles would provide all the light he needed. He blew one out to conserve the meagre illumination.

The next thing, he told himself, was to start a fire. He was not particularly cold, but the room had the damp, musty smell of long disuse, and struck chill. There was a litter of paper in the hearth, and as he stuffed it between the iron bars he observed with mixed feelings of resentment and unreality that some of it was German military orders. So the Boches had been here too, he soliloquized. Well, they had gone, and it would be a pleasure to burn these reminders of their visit.

He found kindling sticks and logs in a small room towards the rear of the house. Well loaded, his footsteps echoing disconcertingly, he returned to the fireplace and dropped his collection on the hearth, startling himself with the crash they made in the eerie silence. However, he soon had a fire going, and with the dry sticks burning briskly, filling the room with flickering shadows, he prepared to make himself comfortable for the night. This called for little effort. He merely threw his cap and gloves on the table and pulled two chairs close together in front of the fire so that he could sit in one and put his feet in the other. He might have gone farther and fared worse, he told himself, as he sank back and lit a cigarette. He hoped the car would start all right in the morning. His only regret was that his journey had been in vain. But still, no harm had been done. When he departed in the morning things would be exactly the same as when he had left Paris: would be the same, in fact, as far as he was concerned, as they had been for nearly ten years. After all, he consoled himself, it had only been a whim, and perhaps a sense of duty prompted by a guilty conscience, that had brought him to the place.

Tossing the stub of his cigarette into the fire he closed his eyes to court sleep.

What is it about an empty house that plays on the nerves to prevent them from fully relaxing? In a small house this sense of wakeful tension may be hardly perceptible, but in a house of size most people are conscious of it. And the larger the house the more acute is this disconcerting feeling likely to be. Algy, to his annoyance, now became aware of it. He could not imagine why, but he found himself listening. For what? Certainly he was afraid of nothing. What was there to be afraid of? The mouse that he could hear gnawing at some woodwork? The creak of shrinking or expanding furniture? Why do such sounds become magnified when one is alone?

‘Stop it, you little beast,’ shouted Algy, hurling a stick at where he judged the mouse to be. The noise stopped. But by the time he had rearranged himself the rodent was hard at work again. With a sigh of resignation he pulled the collar of his coat about his ears to muffle the irritating sound. But in spite of himself he remained alert, and as the sleep he sought became ever more elusive he abandoned the quest and opened his eyes.

A shadow flashing across the candle flame, the draught putting it out, half brought him to his feet, but he sank back again with a sigh when he saw it was only a bat, wheeling in erratic flight, presumably lured falsely from its lair by the unaccustomed light and warmth. Unable to do anything to discourage it, he watched it, and presently with satisfaction in the firelight saw it come to rest on the massive head above the mantelpiece. He did not trouble to relight the candle.

As so often happens in the dead of night when sleep refuses to be won, his mind began to run on thoughts which in the light of day can quickly be dismissed. He remembered Pierre the gamekeeper, under the snow by his own front door, and all unbidden the picture of that last grim scene took shape before his eyes to anger and dismay him. Questions for which he could find no answer perplexed his tired brain. What had the man done to deserve such a dismal fate? At the worst he could only have been guilty of what any man of courage would do. What purpose had been served by the cutting off of his simple life? The Germans had gone. Those whose hands had done the deed had probably forgotten the incident long ago. Perhaps everybody had forgotten the man who had given all he had to give—his life. His friends may have put the cross there lest they too should forget. And now, the futility of it all. The wicked, wanton, useless waste, the heartless cruelty. . . .

Telling himself that these morbid reflections were serving no good purpose, Algy got up, shook himself, and felt for another cigarette. But before the case was in his hand he had spun round, his purpose forgotten, as without warning the door burst open to admit a flurry of snow and a small slim figure which, having nearly fallen, returned swiftly to the door, closed it, and turned the key in the lock. This done the visitor turned, and back to door, breathing heavily, stared at Algy with wide, affrighted eyes.

Algy, his startled brain recovering with the speed necessary for an air pilot who has hopes of survival, stared back; and his nerves relaxed when in the ruby glow of the dying fire he saw that the newcomer was a boy of about fifteen or sixteen years of age.

‘Excusez, monsieur,’ gasped the boy, and would have fled had not Algy called him back.

‘Come in and make yourself at home,’ invited Algy, smiling, and speaking of course in French. ‘What are you doing out at this hour on a night like this?’

The boy advanced slowly, shedding snow from his head and shoulders. ‘I saw a car at the end of the drive,’ he explained. ‘Then I saw the light of your fire through the cracks between the boards. I had to find shelter. I am sorry. . . .’

‘Nothing to be sorry about,’ returned Algy cheerfully. ‘I’m glad to have company. Sit down and warm yourself. Sorry I can offer you no other hospitality, but the truth is I’m an intruder here myself.’

The boy shook the wet beret he wore and sank limply in the proffered chair. ‘May I ask the name of this house, monsieur?’ he requested.

‘This,’ answered Algy, ‘is the Chateau Grandbulon.’

As the boy sat silent, staring into the last dying embers of the fire while he recovered his composure, Algy regarded him critically. He saw a pale, delicate-looking youth, with regular features that are sometimes called refined. His eyes were large and dark, his hair straight and black. A broad forehead with ears set well back suggested intelligence. Something, it may have been rather prominent cheekbones, gave Algy an impression that he was not French—anyway, by ancestry. He looked more as if he had come from farther East. His general expression was one of sadness, but that may have been induced by exhaustion, physical weakness resulting from undernourishment. His clothes were shabby, but made of good quality material.

Having concluded his inspection Algy leaned forward to put some more wood on the fire, a movement that brought a quick request from the boy not to do so.

‘Why not?’ asked Algy, in some surprise.

‘Because the light might be seen from outside.’

‘Is there any reason why the light shouldn’t be seen from outside?’

‘Yes, sir. And for the same reason I must ask you to modulate your voice so that we are not overheard.’

‘On a night like this there is surely little chance of that,’ returned Algy, in a voice that expressed astonishment.

‘You don’t understand.’

‘I certainly do not! Are you afraid of something—of somebody?’ Algy looked at the boy curiously.

‘Yes,’ was the frank answer. ‘Monsieur is, I think, an Englishman,’ added the boy, looking up.

Algy raised his eyebrows. ‘How did you guess that?’

‘Your clothes, your manner, and by your accent.’

‘From which I gather you have been to England.’

‘I was at school there for some time.’

‘In which case let us speak in English. It may be that I can express myself better in my own language.’

‘As monsieur wishes,’ returned the boy quietly, in perfect English.

‘You haven’t yet answered my question about what you were doing out in the forest on a night like this,’ reminded Algy, curiously, and perhaps a little suspiciously.

‘I came to escape from—the storm,’ asserted the boy. ‘I think you must be here for the same reason.’

‘Not exactly,’ replied Algy. ‘I had a purpose in coming here, but finding no one at home I took the liberty of inviting myself to spend the night here.’

‘Was the house not locked up?’

‘It was.’

‘Then how did you get in?’

‘I had a key to the front door.’

The boy frowned. ‘Forgive me if I seem impertinent, worrying you with these questions, but may I ask how you came to have a key? I have a reason for asking. To me it is a matter of great importance.’

‘The key,’ returned Algy slowly, looking hard at his questioner, ‘was given to me by the owner of the chateau.’

The boy looked up sharply. ‘Recently?’

‘No. A long time ago.’

‘Ah! I was afraid you would say that. But you must know him.’

‘Say, rather, I knew him.’

‘Would you care to tell me the name of the gentleman who gave you the key?’

Algy smiled whimsically. ‘You certainly are a lad for asking questions. They suggest to me that you did not arrive here quite by accident, either. Nor did you enter simply to escape from the storm.’

The boy looked embarrassed. ‘I must confess that when I said that I told only half the truth,’ he admitted. ‘I came to La Sologne to find this house and I have been looking for it for three days. I knew the name of the chateau, and that it was somewhere south of Salbris, but no more. It is terrible country to find anything, even a house as large as this. To-night I found it by accident. First I came upon a car.’

‘That must have been mine,’ put in Algy.

‘Stopping to look at it I found the signpost that points the way here. That is the truth. Now will you please tell me the name of the gentleman who gave you the key?’

‘It was given to me by a gentleman named Monsieur Zarrill,’ informed Algy.

‘Did he give it to you here?’

‘No.’

‘Then it would probably be in Paris or Monte Carlo, for he spent most of his time in one or the other.’

‘As a matter of fact it was in Monte Carlo. It is evident that you know this gentleman.’

‘He is my cousin. Or perhaps I should say was.’

‘You seem to be in some doubt about it.’

‘I am. He may have been assassinated.’

Algy stared. He did not overlook the use of the word assassinated rather than murdered. ‘The word assassinated has a political significance,’ he murmured meaningly.

‘That was why I used it,’ admitted the boy, frankly. ‘You see, sir,’ he went on, ‘Zarrill was not my cousin’s only name. He was the Grand Duke Boris Nicolas Zarrill Detziner-Romanov, if that means anything to you.’

‘It does not,’ confessed Algy, who continued to stare. ‘I found him a charming man. Who on earth would want to kill him?’

‘The same men who will kill me if they catch me, and they are not far away,’ answered the boy wearily. ‘That was why I locked the door. Should anyone come I implore you not to open it, for if you do, and they find you with me, they will kill you too.’

‘You may be quite sure, my disconcerting young friend, that I shall not tamely submit to execution,’ asserted Algy grimly.

‘They have pistols.’

‘It so happens that I, too, have a pistol.’

It was the boy’s turn to stare. ‘How remarkable. For what purpose?’

‘I sometimes need one in the course of my business.’

‘It must be a strange business.’

‘Not at all. You see, I happen to be a policeman.’

‘You don’t look like one, or behave like one,’ stated the boy naïvely.

‘I’m gratified to know it,’ returned Algy, smiling. ‘Perhaps it’s because I’m not an ordinary policeman. I don’t direct the traffic—at least, not on the ground.’

‘Where, then?’

‘In the air.’

‘A flying policeman!’

‘Exactly.’

‘That must be fun.’

‘I wouldn’t exactly call it fun,’ murmured Algy dryly. ‘It is sometimes quite uncomfortable. But let us forget that for the moment. As a sensible fellow you will, I am sure, forgive me if I say I find your story a little difficult to swallow.’

‘It is true.’

‘You take it very calmly.’

‘One soon becomes accustomed to the idea of expecting every day to be the last,’ averred the boy with studied nonchalance. ‘Now would you be so kind as to tell me all you know of my cousin? When did you last see him?’

‘I have not seen him since before the war, since 1939 to be precise,’ said Algy, seriously, for although the boy’s story strained his credulity he felt he was telling the truth. ‘It was at Monte Carlo. We found ourselves drawn as partners in the international tennis tournaments at the Country Club. We got on well, and later saw a lot of each other, swimming, playing golf and so on.’

‘Why did he give you the key of Chateau Grandbulon?’

‘We discovered we both liked shooting. He told me he had a hunting lodge at La Sologne. I told him I’d never heard of the place, whereupon he invited me to look at it, and perhaps join him there in October for the pheasant shooting. He said I might even get a chance at a sanglier. However, it didn’t work out like that. The day before we had arranged to travel north together he came to me looking worried and said he was having to leave at once on urgent and important business. But that needn’t prevent me from going to La Sologne alone. As the gamekeeper and his wife might be away on their holidays when I got there he gave me the key of the Chateau, saying I could return it later to an address which he would send me. I never saw him or heard of him again. Nor did I see La Sologne at that time, for the war came suddenly and I had to rush straight home.’

The boy nodded lugubriously. ‘It must have been secret intelligence of the war that called him away.’

‘The war ended and I still had the key,’ continued Algy. ‘No letter came, so I was forced to the conclusion that either he had been killed or had forgotten all about me. The other day, when I had occasion to come to Paris on business, I remembered the key and put it in my pocket. I made inquiries, but it seemed that no one had ever heard of Monsieur Zarrill.’

‘That is understandable. He did not keep any name for long. He changed it as often as it seemed necessary.’

‘I did all I could,’ resumed Algy. ‘I telephoned the Chateau but could get no reply. Then it struck me that as I had nothing in particular to do I would come down and give the key to the gamekeeper, and perhaps see something of La Sologne at the same time. So I hired a car and came, and you have seen the sort of weather I ran into. I found the keeper’s house. There is—er—no one there, so leaving the car I walked on—and here I am. In the morning, weather permitting, I shall return to Paris. And now, as association with you appears to have put me in peril of my life, perhaps you will be good enough to furnish me with some details of your own affairs, so that should these assassins arrive I shall know what the fuss is about.’ Algy’s tone was half bantering, half sceptical.

‘I will do that,’ agreed the boy, with such a depth of feeling that the humour faded from Algy’s eyes. ‘You will understand why I am, and always have been, a fugitive, when I tell you that my cousin Boris is heir to the throne of the ancient kingdom of Moldavia, in Eastern Europe. While he lived, therefore, he would be a danger to the revolutionaries who have seized his palace and usurped his authority.’

‘And where do you come in?’ Algy wanted to know.

‘In the event of my cousin’s death, I, Prince Karl of Moldavia, would be next in line of succession.’

‘I see,’ said Algy, slowly, serious now. ‘Moldavia is part of Russia, isn’t it?’

‘Practically. Actually, my ancestral home is in Rumania, near the frontier, but as the whole territory is under the dominion of the Soviet Union it comes to the same thing. When the trouble burst upon us, Boris, fortunately for him, was abroad, and thus escaped death. His father was murdered, as was mine. My mother, with a faithful manservant named Yakoff, fled across the Black Sea to Turkey, but later went to Paris, where I was born. Our enemies never relaxed their efforts to find us, for what purpose you can guess. Their spies located us in Paris, but before they could strike we flew to friends in England, where we remained until my mother died. After a little while I returned with Yakoff to Paris, hoping to have news of Boris, for we had long been out of touch with each other. I had to know how matters stood. Letters would have been dangerous, even had I known where to send them, and although in France and England I was known simply as Charles Zarrill. I have a French passport and carte d’identité in that name. Yakoff hoped, through friends in secret contact with Moldavia, to find out if cousin Boris was dead or alive.’

‘How did you manage for money over this period?’

‘Mother had some jewels. Yakoff sold them one at a time as it became necessary. There is none left now.’

‘Have you any hope of recovering your throne?’

‘None whatever.’

‘Then why do your enemies continue to pursue you?’

‘There are two reasons. The first is obvious. While we live the Royalist Party in Moldavia will continue to exist. The other reason is less important—at any rate, to me. I am the bearer of a secret which the present rulers of Moldavia would give much to possess. We need not discuss it.’

‘How did it come about that you arrived here to-night, Charles,’ inquired Algy, sympathetically.

‘It came about like this,’ explained Charles. ‘In Paris Yakoff took a room for us in the Hotel Pont-Royal while he proceeded with his intelligence work, and, as I suspect, look for a job, for money was running low. It was a front room. One day, about a month ago, as we stood looking down into the street he turned very white and snatched me away. He then pointed out two men who stood watching. They were, he said, assassins. One, a short, thick-set, middle-aged man with a wide mouth and a tuft of beard on his chin, was a Moldavian named Prutski. He didn’t know the name of the other, a rather tall, grey-faced, military-looking man, but he knew him to be an important secret service agent from behind the Iron Curtain. He told me to remember their faces in case anything happened to him. Why he said that I don’t know, but in view of what happened I’m sure he suspected that he was in danger every time he went out.

‘That night, after dark, we moved to the Hotel St James in the Rue St Honoré. A week later Yakoff was knocked down and killed by a car in the Place de la Concorde. It might have been an accident, but I don’t think so. Poor old Yakoff was murdered. After that I was alone in the hotel. One day last week I stood looking down into the street, wondering what I should do, when I saw those two same dreadful men standing in a doorway on the other side of the road. I confess I fell into a panic.’

‘Couldn’t you have called the police?’

Charles shook his head sadly. ‘Police can do little in cases of this sort. A crime must be committed before they can act, and as on this occasion the crime would be my death, I could see no object in calling on the police for help. Now, as you may, or may not, know, the Hotel St James stands back to back with the Hotel d’Albany, which has its entrance in the Rue de Rivoli. There is a connecting passage. Without stopping to pack, without paying my bill even, through this I ran into the Rue de Rivoli. There I made up my mind that there was only one thing to do, and that was risk all in a last attempt to find Boris. I knew of only two places where he might be, the Chateau Grandbulon in La Sologne or in his apartment in Monte Carlo. La Sologne was the nearer. I had just enough money to buy a second-hand bicycle—for I daren’t go near the railway stations, where there were certain to be watchers. On the bicycle I set out for La Sologne. In Salbris I stopped at a café for a cup of coffee and some sandwiches. As I was coming out a car went past. In it were those two same awful men. They didn’t see me. No need to wonder where they were going. My heart sank when I realized that they knew Boris had a property in La Sologne. But I went on. It was no use turning back. The trouble was, as I have told you, although I knew the name Chateau Grandbulon, I didn’t know exactly where it was, and La Sologne covers a wide area. For three days I have wandered in the forest like a lost dog, not daring to use the roads. To-night, just as I had given up hope, I found the signpost. Now, sir, you know why I am here. Boris is not here. I am lost. If you are wise you will——’

‘Run away and leave you to your fate?’

‘That’s what I was going to say.’

‘Have you forgotten that I am a policeman?’

‘No. But you are an Englishman and this is France.’

‘I have colleagues in France. Tell me this. Since you have been in La Sologne have you seen your pursuers?’

‘Twice. Once in a car on the road. Yesterday I saw them standing under a tree, watching the road, not far from here.’

‘Waiting for you to arrive.’

‘Or Boris. What other reason?’

‘What are you going to do next? You can’t go on like this.’

‘I must. What else can I do?’ Charles made a gesture of helplessness. ‘I have no money, not even for food. Which is all the more infuriating because really I’m very rich.’

‘What do you mean? You can’t be poor and rich.’

‘Just now I told you I possessed a secret. You may as well know what it is, and that will complete my story. When the invaders were on the point of entering Moldavia the most precious of our family jewels were carried away under cover of night and hidden. Of the three people concerned, two, my father and Boris’s father, are dead beyond all doubt. The third member of the party, our head groom, a man named Levescu, is also probably dead by now, even if he survived the revolution.’

‘How many people are there to-day who know where these jewels were hidden?’

‘Not counting Levescu, two; Boris and myself. Yakoff knew; it was he who told me; but he’s dead. Poor old Yakoff. He was faithful to the end.’

Algy nodded. ‘Now I understand why your enemies would like to get hold of you—alive. Do you think Boris may have attempted to recover the jewels?’

Charles considered the question. ‘It is possible, I don’t know. That would be like him. He always was fearless. I know he would like to have the jewels, not so much for himself as to provide money for our friends and supporters at home. But if he tried, he failed.’

‘How would you know that?’

‘Had he succeeded Yakoff would have heard of it through his intelligence channels. Boris too, I’m sure, would have found some way of letting me know. With money one can do anything.’

‘Quite a lot,’ conceded Algy. ‘You believe the jewels are still in the original hiding-place?’

‘I do. Had they been found the news would have leaked out, certainly in Moldavia, in which case, as I say, Yakoff would have heard of it. The jewels would be sold, and I doubt if things of such value could be put on the market without some mention being made in the newspapers.’

‘Don’t you think it would be a good idea if you made a bargain with your enemies—the secret of the jewels in return for your life?’

‘Never! I’d rather die than they should soil them with their dirty hands.’ Charles uttered a low, scornful laugh. ‘It wouldn’t work, anyway. Evidently you don’t know these people. Their word is as fragile as a bubble, and their promises as easily broken. Having secured the jewels they would strive all the harder to kill me, to still my tongue for ever.’

‘Tell me this,’ requested Algy. ‘It is a point I don’t quite understand. You say you came here hoping to find Boris. Why has he made no attempt to find you?’

‘Perhaps he has, assuming that he is still alive. But as neither of us dare use our full names in any sort of advertisement, which would have betrayed us to our enemies, you will see how hard it was for us to get together after losing contact. I hoped, and Yakoff hoped, to find him in Paris. We failed. So I came here.’

‘Did he know you used the name Zarrill?’

‘I think my mother would let him know that when I was a small boy.’

‘Why did you, and he, choose a name that was part of your real name, if it was so dangerous?’

‘Because it happens to be a very common name in my country. With Russian secret agents always on the watch for me there was another difficulty I had to face, and from this there was no escape. In all the male members of my family there was always a strong likeness. Yakoff told me that I grew more and more like cousin Boris.’

‘He told the truth,’ confirmed Algy. ‘I can see the resemblance now. You speak alike, too. When you first came in you reminded me of somebody, but for the moment, strange to say, I couldn’t think who it was.’

‘That likeness may one day cost me my life,’ said Charles, sadly.

Silence fell. The boy, with unseeing eyes, contemplated the last expiring sparks on a smouldering log. Algy drew pensively on a cigarette as if turning over in his mind what he had heard.

In so profound a hush a gentle scraping noise fell harshly on their ears, to bring both heads round sharply to face the door.

The handle was slowly being turned.

Charles turned to Algy, eyes from which all hope had departed.

Algy raised a warning finger to his lips. ‘Go very quietly up the stairs and wait till I call you down,’ he whispered. ‘Make no sound. Keep your head. Have no fear. Leave this to me.’

Charles obeyed, departing with no more noise than a cloud passing across the face of the moon.

The door creaked as if pressure was being applied.

Algy tiptoed softly to it and listened.

From outside came a low murmur of voices.

Algy returned to his chair. He moved slowly, but his brain was racing; and he quickly reached a decision that he would do nothing if the visitors retired, as, finding the door locked, he thought they might. But in case they should force an entrance it would be as well to have a plan of action ready. Had he known at this juncture what he was presently to learn this might have been different from what it was. But he did not know, or even suspect.

There was little time for thought, but it was clear that one of two courses were open to him. The first was to refuse admission and guard the door if necessary by force of arms. That would admit he had something to hide, and, in fact, be in the nature of a declaration of war. The alternative was to allow the people outside to enter and pretend ignorance of their purpose, relying for success on that useful ally, bluff. This was the course he resolved to take.

Meanwhile there was no need to do anything. The initiative could be left to the enemy. What they would do, he thought, would depend on how much they knew. Had they seen Charles enter, or tracked his footprints in the snow to the door, it would be futile to pretend that he was not there, or that he could have entered without him being aware of it. But any footprints would, he hoped, have been erased by the storm.

Of course, reasoned Algy, there was always the chance that the visit might turn out to be a routine call to ascertain if anyone was there, as might be expected if the callers knew that the chateau was the property of Charles’s cousin Boris. If they knew that, and knew also that Charles had headed for La Sologne, they would be safe in assuming that sooner or later they would catch him there. They might have been there before. They would certainly reckon that in such weather the boy would have to find shelter somewhere.

Algy looked at the luminous dial of his wrist-watch. The time was nearly eleven, so there was no question of the men outside being neighbours making a social call. It rather looked as if Charles had been right. His enemies had reason for thinking he was in the building. What Algy did not know was that the snow had stopped, and the sky had cleared for a fine night. Had he known that he might have thought on different lines.

The next thing that happened took him by surprise. He had thought the men at the door would either ring for admission or go away. One of the two. They had, he knew, already ascertained that the door was locked.

That they had another plan was revealed when the key fell out of the lock on to the floor. So that was it! They had pushed out the key so that they could let themselves in with another, presumably a skeleton key.

Algy moved quickly. He lay back in his chair, feet in another, closed his eyes—or almost closed his eyes—and began breathing deeply as if he were asleep. Through half-closed lids he saw the door opening an inch at a time. He did not move. When the door was ajar he saw, silhouetted against a moonlit sky, a dark figure. It glided inside. Another followed. He saw the area of moonlight shrink as the door was closed, heard the key replaced in the lock. The hall was now in darkness but he could hear the two men moving stealthily towards him. Still he did not move, but continued to feign sleep with steady breathing, although his muscles were tensed for instant action.

The beam of a torch suddenly stabbed the darkness. It struck him square in the face. Involuntarily he started. Having moved, revealing that he was awake, he went on moving. Scrambling to his feet, as if violently awakened, he cried: ‘What is it? Who are you? Phew! Mon Dieu, messieurs, but you gave me a fright. If this is your house please pardon my intrusion, but I sought shelter from the storm in which I was in some danger of losing my life.’ He spoke in French.

So saying he struck a match and lit the candle nearest to him. This done, he turned, to receive what was perhaps the most bewildering shock in a career that had known many surprises. Nothing that he could have imagined would have so struck him all of a heap, as the saying is. Of the two men one was Prutski, easily recognizable from Charles’s description of him. The other was the man with whom, in their counter-espionage work, the Air Police had more than once been in collision: Erich von Stalhein, one time Hitler’s crack Intelligence agent, but latterly in the service of the masters of Eastern Germany.

Algy’s lips parted in a gasp of astonishment that was genuine. Such a development, he told himself, was not to be believed. For a brief moment he really wondered if he had fallen asleep and was dreaming. The expression on von Stalhein’s face told him that the ex-Prussian officer was just as shaken.

‘Bless my soul!’ he managed to get out. ‘Von Stalhein! What on earth are you doing here?’ There was no need for Algy to dissemble. Amazement nearly caused his voice to crack.

Von Stalhein stared back at him stonily, his blue eyes as cold and hard as ice. ‘I might ask what are you doing here,’ he returned, in a voice that had not quite recovered its usual imperturbable smoothness.

Algy, steadying himself as he recovered from the initial shock, smiled bleakly. ‘On this occasion, strange to relate, I can tell you the simple truth. An event as remarkable as that should be worth remembering. I came down here this evening from Paris looking for a chap with whom I used to play tennis before the war.’

‘Indeed! What was his name?’

‘It’s unlikely that you’d know him. A fellow named Zarrill.’

‘Is Bigglesworth here?’

‘No. But I told him what I was going to do.’

‘Did you expect to find this man Zarrill here?’

‘I had an open mind about it. Some time ago he invited me to help him shoot his pheasants and gave me a key to the house to enable me to get in should he be out when I arrived. I’ve had it ever since. As I say, being in Paris this afternoon and having nothing in particular to do I thought I’d run down. If Zarrill wasn’t here I might get news of him. In any case I felt it was time to return the key.’

‘A long way to come on the off-chance. Why not telephone to see if he was here?’

‘As a matter of fact I did, but could get no reply.’

‘Then who did you expect to find?’

‘A housekeeper, perhaps. She might have been out when I phoned, shopping or something. Failing finding anyone in the chateau I reckoned on leaving the key with Sondray the gamekeeper. My car stuck in the snow outside his cottage where it still is. I discovered that some of your countrymen had already called on Sondray.’

The German frowned. ‘Let us leave that out of it.’

‘I can well understand your desire to gloss over it,’ replied Algy cuttingly. ‘I walked on here, found no one at home, so having a key I let myself in to wait for an improvement in the weather.’

‘You say there was no one in the house when you got here?’

‘That’s what I said. I haven’t been upstairs. If you’re looking for someone go ahead, but don’t make too much noise because I’m trying to snatch a spot of sleep. You haven’t told me yet what you’re doing here—but let it pass. I couldn’t care less.’

‘Like you, I’m trying to make contact with someone I haven’t seen for some time.’

‘You chose a queer time to call.’

‘So did you.’

Algy smiled. ‘True enough. But I didn’t reckon on a blizzard at this time of the year. I expected to be back in Paris by now. I’ve no kit with me, not even a toothbrush.’

‘I take it that blue Citroën at the end of the drive is yours?’

‘It is—for the moment, anyway. I hired it in Paris. Another reason why I left it where it is was because the lights packed up on me. Don’t worry. I shall be away as soon as it’s light enough to see and you can have the place to yourself—if that’s how you want it.’

Von Stalhein’s lips curled superciliously. ‘You tell a plausible story, Lacey. Do you seriously expect me to believe it?’

Algy shrugged. ‘I don’t care two hoots whether you believe it or not, but it happens to be the truth. I don’t know why I bothered to tell you, knowing that you, judging everyone by yourself, wouldn’t believe it. That’s okay with me.’

‘How long have you been here?’

‘Since about six o’clock. If you have any doubt about that go and feel the radiator of my car. It should be stone cold.’

‘I have already felt it,’ answered von Stalhein suavely. ‘Have you had any other visitors?’

‘Visitors! Have a heart! Who but a lunatic or a thief would be out in the forest on a night like this?’ Algy grinned. ‘Present company excluded, of course. Now I’ve said my piece, how about you answering a few questions? What strange gust of wind brought you here, anyway? Let’s have the truth this time.’

‘I’ve told you. I happened to have some business in the district,’ answered Von Stalhein stiffly. ‘Like you I was caught in the storm. Seeing smoke coming from the chimney, my friend and I sought shelter. However the snow has passed and it is now a fine night.’

‘I didn’t hear you knock on the door,’ answered Algy casually. ‘I must have been asleep. I must also have forgotten to lock the door.’ Actually, he was mentally kicking himself for not thinking of the smoke. But then, he hadn’t realized that it had stopped snowing.

Von Stalhein said something to his companion in a language Algy did not understand, and having received a reply turned back to Algy. ‘My friend thinks you’re not telling the truth.’

Algy looked pained. ‘Oh, come now. What a suspicious fellow you are. Actually, I don’t care what he thinks, but I’ll tell you what I’ll do. Just to see how far your friend is prepared to back his opinion, I’ll bet you five thousand francs that what I’ve said is true, and prove it.’

‘How can you prove it?’

Algy pointed to the telephone on a side table. ‘There’s the phone,’ he said. ‘It’s still in order.’

‘How do you know?’ put in von Stalhein quickly.

‘Well, I assume it is. It was all right this morning, anyway, because as I’ve already told you I put a call through from Paris. No one answered, but I could hear the bell ringing.’

‘I see. Well?’

‘All we have to do is call Bigglesworth in London. With no prompting from me I’ll ask him to tell you exactly what I said when I phoned him this afternoon from the Sûreté. That was when I told him I was coming down here.’

‘You’re bluffing.’

‘Bluffing! What have I to bluff about? If there’s any bluffing it’s on your side—unless you’re scared to speak to Bigglesworth.’ Algy made a gesture of resignation. ‘After all, how can I bluff?’ he protested. ‘To expect Bigglesworth to tell you anything but the absolute truth would presuppose some arrangement with him. That would imply that I knew you were here, which you know as well as I do I did not.’

Actually, Algy was not bluffing. What he was doing was seeking an opportunity to let his chief know where he was, and who was with him, in case things went wrong.

‘I’ll call your bluff,’ decided von Stalhein curtly.

Algy grinned. ‘Capital. Bertie Lissie will laugh himself into stitches when I tell him how I took a fiver off you.’ He laid a five thousand franc note on the table. ‘Cover that, please,’ he requested.

‘Don’t you trust me?’ asked von Stalhein frostily.

‘I should say no, but I’ll say yes, because even though your politics are cock-eyed you’ve still got enough of the gentleman in you to pay a debt of honour. All the same, when I make a bet I like to see the colour of the other man’s money.’

Von Stalhein took out his wallet, selected a five thousand franc note, and placed it deliberately on the one already on the table.

Algy went to the phone and put through the call. ‘There’s no delay,’ he told the others, who were watching closely. After a minute, speaking into the instrument, he went on: ‘That you, Biggles? Fine. Algy here. I’ve just run into von Stalhein. We’ve had a slight argument and he’s as good as called me a liar. He’s standing beside me now. To settle a little wager I want you to tell him where I was when I phoned you earlier in the day, where I said I was going, and for what purpose. That’s all. Here is von Stalhein. Carry on.’

Algy handed over the receiver. ‘Go ahead,’ he requested.

Von Stalhein took the instrument. His face was expressionless. ‘Please proceed,’ he said. ‘I’m listening.’

The only other words he said were, ‘Thank you,’ when, at the end of about half a minute, he hung up. ‘You win,’ he told Algy shortly.

Algy picked up the two notes, folded them, and put them in his case. ‘Well, that seems to be about all,’ he said easily. ‘What are you going to do, trot along or stay here? Either way I’d like to snatch a few minutes shut-eye before making an early start for Paris in the morning.’

Von Stalhein held a brief conversation with his companion, again in the language Algy did not understand. Then he said, briefly, ‘We’re going.’

‘That suits me,’ declared Algy. ‘Excuse me if I don’t see you to the door. You might close it behind you. Thanks.’

The two men strode out without another word or a backward glance.

Algy gave them a minute, then walking quickly to the door he opened it and looked out. The snow had stopped. The wind had fallen. Dead, utter silence reigned over an Arctic scene flooded with blue moonlight. Two figures, one slim and the other stout, trudged through the snow up the track towards the road.

Algy smiled faintly as he watched them out of sight and heard a car starter whirr. Then he closed the door, locked it on the inside leaving the key sideways so that it could not be pushed out again, and returning to his chair called Charles.

Presently, looking anxious, the boy came. ‘Have they gone?’ he asked in a hoarse whisper.

‘They have,’ Algy told him. ‘I don’t think they’ll come back, not to-night, anyway. But I wouldn’t reckon too much on that. You never know with that cunning type of adventurer. Whether they believed my story or not they would pretend to do so to throw me off my guard. And the more they doubted me the more would they try to create an impression that they were satisfied. That’s all part of the technique. Where were you all the time?’

‘On the stairs. I heard everything. You were wonderful. Who’s Bigglesworth?’

‘My chief, in London.’

‘I had a feeling that you had another reason for ringing him on the telephone besides winning five thousand francs.’

‘I had. I wanted him to know where I was, and that von Stalhein was here, too. I didn’t think von Stalhein would fall for such a simple trick. I can only think his brain must have been shaken below its usual standard by the shock of finding me here. By now, realizing what he’s done, he’s probably kicking himself. Whatever else he may or may not suspect he now knows for certain that Biggles—that’s my chief’s nickname—knows where I was, and he was, at eleven o’clock to-night. That’s a trick in our favour.’

‘Is that important?’

‘It could be, if for no other reason than the weather has turned to von Stalhein’s advantage.’

‘In what way?’

‘It has stopped snowing. All round this house is an unbroken sheet of the confounded stuff, which means that no one can enter or leave without making the fact perfectly plain.’

‘I might not have thought of that.’

‘In my line of business you wouldn’t last long if you overlooked factors so obvious,’ announced Algy, cheerfully.

‘You know this man von Stalhein?’

‘Yes, I know him. I have good cause to know him. He used to be a professional German Intelligence expert, but he’s had a bee in his bonnet since the war ended the wrong way for Hitler so he now works from the other side of the Iron Curtain—more to hurt us, I think, than for any money he makes out of it. He’s tough, but not as brutal as some of them. His trouble is, he was born a gentleman; by which I mean he comes from the class which many years ago provided Germany with some of her best officers. That being under his skin there are still times when he behaves like one—in spite of himself. Such a man can have no love for his new employers, but he never lets himself forget that he hates the British. I never let myself forget that, either.’

‘Where do you suppose he’s gone now?’

‘I wish I knew. You say he came to La Sologne three days ago. That means, unless he’s sleeping in his car, which seems unlikely, he must have found accommodation somewhere—either in another hunting lodge or in a hotel. The nearest, I imagine, would be in Salbris. He would have to go somewhere to eat. Which reminds me. How have you managed for food?’

‘I bought bread and sandwiches in Salbris on my way here. I made them last.’

‘You can’t go on like that. We shall have to do something about it. How much money have you?’

‘None.’

Algy grimaced. ‘You are in a bad way. I think you’d better come to England with me.’

‘That is very kind of you, but I can’t do that.’

‘Why not?’

‘I must find out what has happened to Boris. Until I know whether he is alive or dead I shan’t know where I stand.’

‘You won’t be standing at all, much longer, my lad, if you go on wandering about this part of the world. Where are you going to start looking for him?’

‘Yakoff said he wasn’t in Paris. The only other place I can think of is Monte Carlo.’

‘Do you know the address?’

‘I think he had an apartment, but exactly where I don’t know. But Monaco is a small country, so if he is there it should be easy to find him.’

Algy considered the matter. ‘All right, I’ll run you down to Monte Carlo,’ he decided. ‘I’m in no great hurry.’

‘I shall never be able to thank you.’

‘There’s no need to try.’ Algy grinned. ‘Princes in distress don’t come along every day.’

‘When will you start?’

‘I think we’d better start right away, and get clear of La Sologne before daylight. Then, if von Stalhein comes back to have another look at the chateau, as he certainly will, to see who has been in and out, it won’t matter what he sees. I’ll walk up, get the car and bring it here. When I arrive, lock up, bring the key, and step out carefully in my footsteps. We may fool von Stalhein yet. Anyway, we won’t tell him more than is unavoidable. Wait here.’

Algy went to the door and looked out. The moon was still riding high. All around lay the forest, dark, silent, menacing. Not a sound broke the solemn hush. The stillness was the stillness of death. The shroud was snow, unbroken, unmarked except for a double line of tracks up the middle of the overgrown drive. Algy followed them, nerves alert, eyes watchful.

Charles waited, aware of an awful feeling of loneliness now that he was again by himself. He strained his ears to catch the first purr of the car engine. He listened for what seemed a long time, and he listened in vain. When he could no longer bear the suspense he went quietly to the door and looked out. Algy, his footfalls muffled by the snow, was coming up the steps.

‘What has happened?’ asked Charles tersely.

‘The car has a flat tyre,’ announced Algy, briefly.

‘Isn’t there a spare wheel?’

‘There was,’ answered Algy grimly. ‘Someone was thoughtful enough to remove it.’

‘Von Stalhein!’

‘Who else? It was no use sticking a knife in the tyre and leaving the spare wheel.’

‘Can we mend the puncture?’

‘We might if we could get the tyre off. Without the levers, which have disappeared, it’s hardly worth trying,’ averred Algy bitterly. ‘Von Stalhein, you will observe, is very thorough.’

‘But why has he done this?’ Charles opened his eyes wide.

‘Obviously, to keep me here.’

‘But why should he want to keep you here? If he knows you’re a police officer, I would have thought he’d have been glad to get rid of you.’

‘No doubt he’d have been glad to get rid of me,’ assented Algy. ‘What he didn’t want was me to go, taking you with me.’

‘You mean—he knows I’m here! In this house!’

‘He can’t believe I’m here by pure chance. He thinks I came here to look for you, or act in your interests. As we both know, he’s wrong in that; but it doesn’t alter the fact. As I see the position now, he must believe I know where you are, otherwise he wouldn’t have tried to prevent me from leaving—taking you with me, of course. Short of staying out all night, watching, the easiest way of doing that was to immobilize the car.’

‘So what do you suggest we do now?’

‘Get away—somehow. It looks as if we shall have to walk.’

‘I have a bicycle, hidden——’

‘Forget it,’ broke in Algy. ‘A bicycle needs a road, and to use a road near here would be to risk being shot from an ambush. Von Stalhein and Prutski may not be alone. How far are we from the nearest main road?’

‘The Salbris-Vierzon road would be the nearest. It must be about seven miles.’

‘Hm! If we walk we shall leave a trail in the snow that a blind man could follow. Von Stalhein has set us a poser—as was, of course, his intention. When he returns he’ll know I’ve been to the car. He’ll also see that I returned here, and he’ll guess why. It will confirm his belief that you’re here with me. I still feel inclined to beat him and go by car. We have a telephone. I’ll call the operator at Salbris and ask if there is an all-night service garage there. Failing that, what time does the first one open in the morning. If we can’t get a mechanic to repair the damage we’ll hire a car.’

‘You think of everything,’ declared Charles admiringly.

Algy went over to the instrument and lifted the receiver. For half a minute he listened, toying with the call-arm. Then he hung up. ‘Von Stalhein doesn’t forget much, either,’ he asserted bitterly.

‘What do you mean?’

‘The phone’s dead. The wire must have been cut.’ Algy turned to Charles, smiling wanly. ‘Now you see what sort of man we have to deal with, and why Hauptmann Erich von Stalhein was thought so highly of at the Wilhelmstrasse. But don’t worry. We can’t expect to have things all our own way. Let’s hope it’s a little warmer at Monte Carlo than it is here.’

For a little while silence took possession of the chateau while Algy sat, chin in hands, contemplating the situation.

‘Are you thinking of going with me to Monte Carlo?’ asked Charles tentatively.

‘After what has happened you would not expect me to leave you to make your own way there,’ answered Algy. ‘Nor do I see how you could get there without any money,’ he went on. ‘Not being prepared for anything of this sort I haven’t much myself; but no doubt, if we can get clear, I shall be able to get over that difficulty. I’m trying to work out the best way of getting out of this confounded forest without letting your enemies know which way we’ve gone.’

‘That’s very kind of you. But why should you inconvenience yourself with my affairs?’

‘Because, apart from any other reason, your affairs have become my affairs,’ rejoined Algy. ‘If, as it seems, the Iron Curtain supporters have something to gain by liquidating you, it is my duty, being on the other side of the Curtain, to see that doesn’t happen. The position, as I see it, is this. We can’t stay here, if for no other reason than we should slowly starve to death. As, obviously, no one has been here for some time we can assume there is no food in the house. Without a telephone we shall gain nothing by waiting. To-morrow, or the next day, the position will be the same as it is to-day. Wherefore we must go, so the sooner the better. The only question is how.’

‘Will you abandon the car?’

‘It’s no use as it is. We can forget it for the time being. You say you must find Boris. He isn’t in Paris. He isn’t here, so we will go to Monte Carlo to see if he is there. Knowing that his life is in danger we can suppose he has gone into hiding. That would be the sensible thing to do, I want to get away from here, if possible, without engaging in open hostilities with the enemy. I’m not afraid of them, but if somebody were killed it might embarrass the French government and perhaps start an international rumpus. If we can get to the main road all should be well. It means walking. Do you feel able to manage it?’

‘Don’t worry about me.’

‘Good. As we are east of the road we shall travel due west as far as that is possible. Having no compass we shall have to take our course from the stars. When we go we’ll leave by the back door, which is less likely than the front to be watched. I shall carry you on my back until we are under the trees, where there may not be much snow, to leave only one line of tracks.’

‘You’re not going to explore the house?’

‘For what purpose?’

‘There may be some clue to Boris’s whereabouts.’

Algy shook his head. ‘It isn’t worth the risk. To do it now would mean that the light of the torch would be seen from the upper windows should the house be under observation. To wait for daylight would lessen our chances of getting away unseen. If von Stalhein and his precious partner are not here now, I’m pretty sure they’ll be somewhere about as soon as it’s light enough for them to see what they’re doing. Let’s see if there’s any sign of them.’

So saying Algy went to the front door, opened it quietly and looked out. The scene was unchanged except that the moon, its night’s work nearly done, was lower in the sky. A deathly silence reigned.

As they stood there listening, with eyes probing the gloom for any sound or movement, from somewhere far away, rising and falling, came a long drawn-out animal cry so mournful, so sinister in the stilly night, that Algy turned startled questioning eyes to his companion’s face. ‘What on earth was that?’ he asked, in an awe-stricken voice.

‘It sounded like the baying of a hound, probably one of the big St Huberts which I know are used in the forest for wild boar hunting. Belongs to a gamekeeper, no doubt. It may have winded a sanglier on the prowl for food.’

‘It sounded more like the devil himself on the prowl,’ muttered Algy, closing the door, locking it and putting the key in his pocket. ‘Come on; if we’re going let’s go,’ he concluded.

They strode through cold, stone-flagged passages to the rear of the house and so to the back door. The key was in the lock. Algy opened the door to show the black mass of a fir forest standing stark against the sky only twenty paces distant. A little on the near side of it was a pile of logs. There was not a sound. Still nothing moved. He locked the door behind them and put the key in his pocket. ‘I’ve a better idea than carrying you,’ he announced. ‘We’ll make for the woodpile. I’ll walk forwards and you walk backwards. That will leave a track going out and coming back, so should they see it they may think I simply went out for firewood. Not much of a trick but it may work. The longer they think we’re inside the better. Come on.’

In a few minutes they were entering the forest, bending low under branches that drooped under their weight of snow. So close together stood the trees, their branches intermingling, that no ray of moonlight could enter, with the result that the darkness was that of a tomb. For which reason, having with difficulty groped forward a little way, Algy switched on his torch. ‘No use poking our eyes out,’ he remarked, as the beam cut a wedge of light in the darkness.

The going was now fairly easy, for the wide branches of the close-growing trees had caught most of the snow, and except for occasional patches the ground was fairly clear. Thus, they were able to make good time.

‘Did you read fairy tales when you were a kid?’ asked Algy, after a while.

‘Yes. Why?’

‘Now we know what the Babes in the Wood felt like.’

From time to time they stopped to listen for possible indications of pursuit, but the only sound to penetrate the forest’s silent aisles was the occasional melancholy cry of the boar hound.

After a while, dawn, grey bleak and dreary, crept slowly up the glades behind them to confirm that they were still heading westwards. Then came the sun to turn the grey to sullen, misty crimson, and reveal the tracks of other nocturnal travellers in the forest—deer, boar, and an occasional rabbit that had escaped the deadly disease, myxomatosis, that had all but exterminated the species throughout Europe.

With a rising sun came a rise in temperature, and soon the snow was sliding from the overburdened branches, so that from all sides came the swish and slush of snow falling on snow. This turned to a steady drip as the sun set about its work in earnest. They came upon a brook winding a serpentine course towards some distant lake. As they were already soaked to the knees they suffered no discomfort from wading across it.

The firs gave way to pines more sparsely placed. They in turn gave way to oaks. These ended abruptly at an area of open ground. Across this ran a track. Beside the track stood a small house that might have been a farm or a gamekeeper’s establishment. Smoke drifted sluggishly from the chimney. From a wire kennel a battle-scarred boar hound regarded them steadfastly with large, calculating eyes.

Algy, on seeing the house, had come to a halt. ‘I wonder would they give us a cup of coffee,’ he murmured. ‘I could do with one. They might let us dry our shoes and socks.’

‘They could tell us the best way to the main road,’ contributed Charles. ‘In fact, they might give us a lift. I can see an old car there in the shed.’

Algy hesitated, a moment of hesitation which, as they presently observed, was to have consequences more important than they could have imagined.

Round a bend in the track, travelling fast, came a car, a new-looking Simca, painted grey. It stopped at the house. Two men got out. They were von Stalhein and Prutski. They went to the door, knocked, and engaged in conversation a burly, red-faced man who answered it.

Neither Algy nor Charles spoke a word. There was no need. After exchanging startled glances both backed slowly into gloom cast by the oaks. The hound threw up its head and bayed, but this, it must have been supposed, was on account of the men who had arrived by car—as, indeed, it might have been.

The conversation at the door of the house did not last long. At the end of it von Stalhein and Prutski, still talking, walked slowly to the car, the householder, who it could now be seen wore gamekeeper’s uniform, going with them. For a few moments more the three of them lingered by the open door of the car. Then von Stalhein and Prutski got in and drove on down the track. The keeper watched them out of sight and then walked back to the house.

‘I wonder what all that was about,’ muttered Algy. ‘From his manner the keeper didn’t know them. It looked as if von Stalhein was asking the way. I think we might do the same thing. I’m sure we have nothing to fear from a local gamekeeper.’

They were almost to the house when the door opened and the keeper, now with his cap on, came out. On seeing them he halted, turned about, went inside, to emerge a moment later with a gun into which he was putting cartridges. He waited until the visitors were at a distance of about ten paces; then, bringing the gun to his shoulder he cried, ‘Halte-la!’

Algy stopped, staring, taken aback by a greeting as unexpected as it was belligerent. ‘What’s the idea?’ he inquired, speaking of course in French.

‘Move an inch and I’ll shoot the pair of you,’ declared the keeper.

‘Don’t worry, I won’t move,’ said Algy. And he meant it. ‘But you might at least tell us the meaning of this unusual reception,’ he requested.

A buxom, motherly-looking woman appeared in the doorway. ‘They don’t look like criminals,’ she remarked.

‘Criminals!’ cried Algy. ‘What made you think we were criminals?’

‘You don’t speak like a Frenchman.’

‘I’m English. Is there anything wrong with that?’

The man answered. ‘Will you go with me to the police-station?’