* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Beyond the Green Prism

Date of first publication: 1930

Author: A. Hyatt Verrill (1871-1954)

Illustrator: Leopoldo Morey y Pena (as Leo Morey) (1899-1965)

Date first posted: Nov. 16, 2023

Date last updated: Nov. 16, 2023

Faded Page eBook #20231120

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, Pat McCoy & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

This file was produced from images generously made available by Internet Archive/American Libraries.

CONTENTS

When I made public my story relating the true facts regarding the mysterious disappearance of my dear friend, Professor Ramon Amador, and the incredible events that led to it, I had no expectation of ever revisiting that portion of South America where Ramon had vanished before my eyes.

In the first place, my work in the Manabi district had been completed before Ramon attempted his suicidal experiment, and in the second place, the many associations, the thoughts that would be aroused by the familiar surroundings—the holes we had dug, the traces of our camp, the site of Ramon’s field laboratory—would have been more than I could bear; and finally, I would not have dared lift a shovelful of earth, drive a pick into the ground or even walk across the desert for fear of burying the microscopic people and their princess—yes, even Ramon perhaps—beneath avalanches of dislodged sand and dust.

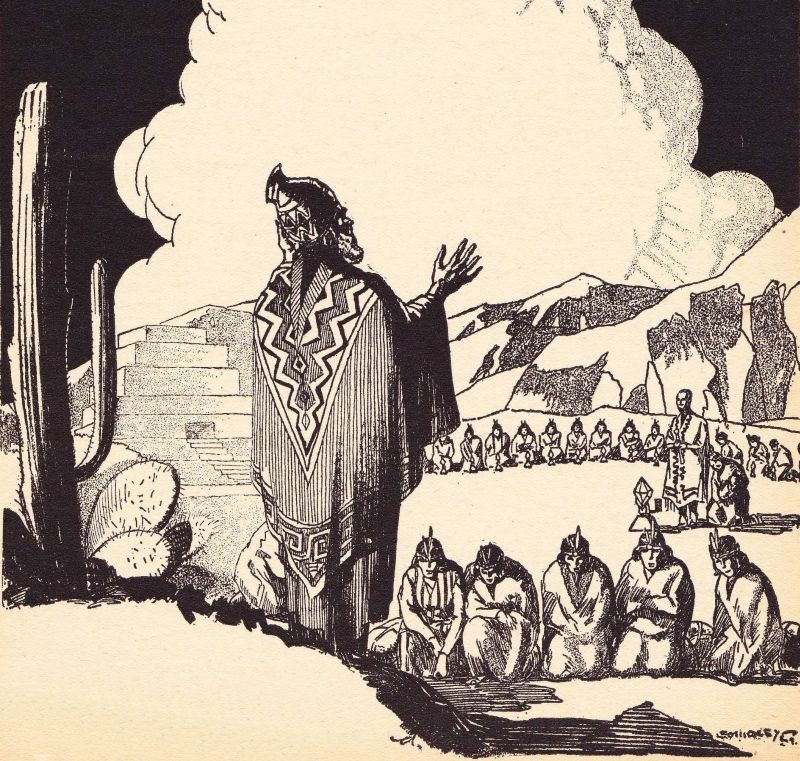

Yet, throughout all the time that had passed since I stood beside Ramon and watched him draw the bow across the strings of his violin, and with a shattering crash the green prism and Ramon vanished together, he had been constantly in my thoughts. Ever I found myself speculating, wondering whether he had succeeded in his seemingly mad determination to reduce himself to microscopic proportions, wondering if he actually had joined his Sumak Nusta, his beloved princess, whose love had called to him across the centuries. How I longed to know the truth, to be sure that he had not vanished completely and forever, to be assured that he was dwelling happily with that supremely lovely princess of the strange lost race we had watched through the green prism for so many days. And what would I not willingly have given to have been able once again to see that minute city with its happy industrious people, to see the inhabitants kneel before their temple of the sun, to see the high priest raise his hands in benediction, and once more see the princess appear before her subjects, perchance now with Ramon walking—erect, proud as the king he was—beside her. But all was idle speculation, all vain supposition. With the shattering of the prism through which we had so often watched the city and its people, all hopes of ever knowing what had occurred had been lost. Never again could I gaze through the marvelous, almost magical, sea-green crystal and see what was transpiring in that city whose mountains were our dust, whose people were invisible to unaided human eyes. No fragment of the strange Manabinite remained, as far as I knew, and even had there been a supply, only Ramon would have been able to construct another prism.

¶ I heard the first crescendo note and then—Ramon, desert, everything seemed swallowed in a dense fog; a gust of wind seemed to lift me, whirl me about.

Yet somehow I could not feel that my beloved friend had failed in his desires. I could not believe that such love as his could have been thwarted by a just and benign Divinity, and my inner consciousness kept assuring me that Ramon had succeeded, that he still lived, and that he was happier with Nusta than he ever could have been among normal fellow beings. Moreover, I had reason and logic on my side. I knew that the donkey and the dog had survived the test, that although they had vanished as mysteriously and as abruptly as had Ramon, yet they had been uninjured by their reduction in size, and so why should Ramon have been affected otherwise? Such thoughts and mental arguments were comforting and reassuring, but they did not still my desire to know the truth, they did not prevent me from speculating continually upon Ramon’s fate, and they did not restore the presence and companionship of the finest, most lovable man I had ever known.

Not until he had disappeared and was forever beyond my reach did I fully realize how much Ramon had grown to mean to me. We had been thrown very close together for months; we had worked side by side, had watched that marvelous miniature city through the same prism, and our hopes, fears, successes and disappointments had been shared equally. Moreover, Ramon had possessed a strange personal magnetism, an indescribable power of intuitively sensing one’s feelings, such as I had never known in any other human being.

And though I am—I flatter myself—a matter-of-fact, hard-headed and wholly unromantic and unsentimental scientist, who—theoretically at least—should be mentally immune to all but proven facts, yet Ramon’s highly romantic and sentimental nature, his readiness to believe in the most extravagant theories, his temperamental moods, his unconquerable optimism and his, to me, incomprehensible mysticism, all found a ready response in my more practical mind, and I loved him the more because he differed so widely from myself. And often, as I sat late at night, smoking contemplatively in the darkness of my study and mentally reviewing those months at Manabi, I recalled incidents that I now realized were proofs of the high courage, the indomitable will-power, the limitless patience and the almost womanly tenderness of my lost friend.

Almost without my realizing it, Ramon and I had grown to be even more than brothers, and often, as I thought of the past and of the present, a lump would come into my throat and my eyes would fill with tears as I realized that never again would I see Ramon alive.

It was, I admit, great comfort and consolation to write the story of our strange experiences and of his disappearance, but after the tale was done, I realized all the more vividly that he had gone forever and my sorrow became all the more poignant. It was like writing “Finis” to the story, and I found myself becoming morose, aloof and avoiding other men. In order to throw off this almost melancholic mood I devoted myself all the more assiduously to my archeological work, striving in my scientific ardor to forget my lost friend.

And then, entirely unexpectedly and as though by a direct act of Providence, a most astonishing event occurred which entirely altered my point of view, my thoughts and my plans.

Among the many wealthy private collectors of the world, Sir Richard Hargreaves, Bart, was perhaps the most widely known for the value—both intrinsically and scientifically—of his archeological treasures. For many years he had been acquiring—both by personal collection and by purchase—the most unique and priceless specimens from all parts of the world. Unlike so many wealthy men—for Sir Richard was many times a millionaire—he was neither a scientist nor a collector in the ordinary sense of the word. To him collecting archeological specimens of the greatest value was not a hobby nor a fad. Rather it was a love of art and of the irreplaceable. He realized how rapidly such objects were disappearing, how many priceless specimens had been lost to science and the world, and he was well aware that, in many if not most cases—museums and public institutions are handicapped by lack of funds and must invest their money in those things that will represent the greatest show or results in the eyes and minds of the directors and patrons.

To spend thousands of dollars for a single unique specimen seems to the lay mind a waste of funds, when the same amount would defray the expenses of an expedition and the acquisition of hundreds, perhaps thousands, of specimens. But Sir Richard, with his millions, could purchase such unique objects, thus preserving them for science, and his collections were always available for study and comparison by any archeologist. He was, in fact, one of the greatest benefactors of science, although no scientist himself, and his mansion near Guildford, Surrey, housed several thousand specimens that had no duplicates in any museum in the world. I had first met Sir Richard in Peru, where he had just purchased a marvelous collection of gold vessels from a Chimu temple-mound. Later I had the opportunity in New York of showing him some of my own finds, and I spent a most delightful fortnight at his magnificent estate, examining and describing his specimens of early American cultural art.

He was a delightful gentleman—the typical British aristocrat—abrupt, sparing of words, incapable of showing excitement, enthusiasm or surprise; but kindly, hospitable, courteous to a degree, and thoroughly unpretentious and wholly democratic. I can see him now as I close my eyes—a big-boned, broad-shouldered, slightly-stooping figure; ruddy faced, sandy-haired; his keen, pale-blue eyes hidden under bushy brows, a close-clipped moustache above his firm lips, and always—even in the tropics—dressed in heavy tweeds. Alert, active, with a swinging stride, no one would have guessed that Sir Richard was well past the three score and ten mark, and no one would have guessed—in fact no one other than himself and his doctor knew—that Sir Richard’s heart was in bad shape and might fail him at any moment.

Hence it came as a great shock when I learned of his sudden death in London, and I wondered what disposal he had made of his collections. As far as I was aware he had no family nor heirs, for his wife had died years before and there had been no children. Probably, I thought, he had willed his specimens to the British Museum and I could picture the elation of Dr. Joyce at such an unexpected acquisition.

But it appeared that Sir Richard had not agreed with my views in this matter. His will—or that portion of it that held any interest for me or has any bearing on this narrative—provided that his collections should be divided between various institutions in England and the United States.

All specimens from British territories went to the British Museum; most of his Oriental specimens went to the University of Pennsylvania Museum; the Mexican and Mayan specimens were left equally to several of our most noteworthy museums, whose studies of the Nahua and Mayan cultures had been most important, while, to my unbounded amazement, his comparatively small but priceless and unique collection of Peruvian and Ecuadorean objects were bequeathed to me in view—so the testament most flatteringly put it—of my deep interest and noteworthy discoveries in the field of Peruvian archeology and the deceased Baronet’s personal esteem and regard.

Naturally I was overwhelmed. Even before I received the collection, I realized what a magnificent and princely gift it was. I had, as I have said, seen the things and had studied them and no one appreciated their character and scientific value more than I did. In fact they were so valuable that I determined that I would at once place them in the museum for safe keeping, loaning them to the institution as long as I lived and leaving them to be preserved intact when I died. Only an ardent scientist can fully appreciate my feelings as I unpacked the cases and gazed at the treasures revealed. Yet, all else were forgotten, all the unwrapped remaining specimens disregarded when, upon removing the tissue paper coverings from one specimen, I found it a rather crudely-carved mass of semi-transparent green crystal.

Instantly I recognized it. It was manabinite—a larger piece than I had ever before seen—and I stared at it with bated breath, as wild thoughts and mad impulses raced through my mind. Here in my hand was the key that might open the closed door of Ramon’s fate. Here might be the “open sesame” to enable me once again to look upon that microscopic village, to set at rest forever the question as to whether Ramon had lived and was happy or whether he had vanished once and for all. And yet—and my heart sank and I felt weak, helpless, bitterly disappointed at the realization that the lump of carved green crystal was useless to me. In its present form it would fail utterly as a lens or a prism, and I possessed none of the deep and profound knowledge of optics, none of the almost uncanny mechanical skill of Ramon. It would be utterly impossible for me to transform the crystal into a lens or a prism, and the knowledge that, although I possessed the raw material, I was incapable of using it, was a blow I could scarcely bear.

For hours I sat, brooding, staring at the translucent mass of green, cursing my lack of optical knowledge, wasting my time in vain regrets at not having learned Ramon’s formula, and racking my brains in an effort to think of some means of making the rough green mass serve to solve the mystery of my beloved friend’s fate.

Then, suddenly, like an inspiration—almost, I thought, as if Ramon had spoken to me—an idea flashed across my mind. I could remember vividly the shape of the prisms Ramon had made. My long years of training, my acquired power to visualize the most minute details of a sculpture, or an inscription enabled me to reconstruct, in my mental vision, every detail of the prisms. Of course I realized, even at that time, that no human eye could measure, much less carry in memory, the exact curvatures and angles of a complex prism or lens. But I was positive of the general form, and trembling with fear lest the image should slip from my mind or that, in trying to revisualize it more clearly, I might become confused and uncertain, I at once made careful drawings of the prisms as I remembered them. With these and my description to guide him, any expert optician could, I felt sure, transform my mass of Manabinite into a prism that, with careful grinding and adjusting, would enable me to again view the city where Nusta—and, I prayed God, Ramon also—ruled their minute subjects. Suddenly I leaped up, shouted, actually danced, as another inspiration came to me. I still had the delicate ingenious device by means of which Ramon had focused the prisms. One had come uninjured through the explosion of the prisms and I had preserved it, together with Ramon’s violin and all else I had salvaged from Manabi.

No doubt, to an expert in optics, the device would be simple and easily understood, and would aid greatly in manufacturing the contemplated prism.

But to whom could I go with my problem? Rapidly I went over in my mind all the specialists, professors and acknowledged experts in optical physics with whom I was acquainted or with whose names I was familiar. They were lamentably few, but one was all I required. Finally I remembered Doctor Mueller, whose monographs and discoveries in his chosen field were world-famed. In view of what I hoped and expected, the fact that he was in Vienna was of no moment. I would gladly have encircled the globe had it been necessary. Within the week I was at sea, speeding as fast as the humming screws of the Bremen could take me across the Atlantic towards Vienna and Dr. Mueller; and locked securely in the Purser’s safe was my priceless lump of manabinite, my drawings and the delicate device that Ramon had so skilfully and painstakingly wrought in his laboratory at Manabi.

Doctor Rudolf Mueller, next to Ramon the world’s greatest authority on optics and physics, greeted me effusively and like an old friend, although I had never before met him. He was a diminutive, dried-up little man of indefinite age, bald as the proverbial billiard ball, with inquisitive eyes behind thick lenses that appeared to be held in place by his bushy overhanging eyebrows, and with such an enormous sandy moustache that I mentally wondered if all the hair which should have been on his head had not been diverted to this hirsute growth that extended fully six inches on either side of the face.

“Hah!” he exclaimed in guttural tones but in excellent English. “So, it is my pleasure to meet with you who have made such works of archeological greatness. Ach! Yes, it was with great interest I have read your so-wonderful story of the Herr Professor Amador.” He shook his head sadly, his moustache waving like hairy banners with the motion.

“Then, Doctor, you will be doubly interested in my purpose in visiting you,” I told him, and as briefly as possible I explained my purpose.

He nodded understandingly. “Yah, yah,” he muttered, “it is a most wonderful matter and most interesting to me. The manabinite—I have so greatly desired to see it, to experiment with it, to test it. And now you come with the crystal that I may make a prism for you that you may seek for your lost friend. No, my friend, I am afraid that you will be disappointed, for sad as it is, I feel that the Herr Professor was utterly destroyed. But we will see, we will see. Permit me the drawings and the instruments to examine.”

He chuckled behind his moustache-screen as he examined my sketches. “From these sketches it would be most hard to work,” he muttered, “but yet do I see in them the idea that is desired to consummate it. And the little instrument is to my eyes a delight, so-most-excellently made is it. Yah, yah, my friend, we will make a prism from the green crystal that will serve your purpose. But—” he threw out his hands in a gesture of finality—“no experiments will I make and no fiddle near my laboratory will I permit. Ach, no! I have no wish yet to vanish nor to be transformed into a microscopic man. And—” he laughed merrily—“if that should occur, then the crystal to you would be lost and everything ended. But—” he again sighed—“it is a so-great pity this wonderful carving to destroy.”

I nodded. “Yes, it is a priceless thing, but what is a specimen—or even archeology—compared to my desire to learn the truth of Ramon’s state? And if, as you fear, he was utterly destroyed, even that knowledge will be better than the uncertainty.”

He agreed. “And maybe yet I can preserve the carvings,” he announced as he examined the crystal. “Perhaps I may slice from the mass a section with the carving intact.”

And so cleverly and skilfully did he work, that no least detail of the sculptured figures was injured or lost.

To relate the details and incidents of the manufacture of the prism would be tedious. It was done secretly, carefully and even though my sketches were of the crudest, yet so incredibly expert was Doctor Mueller that, once having determined the refractive index and other factors of the manabinite, and knowing what was desired and the general form and prismatic principles of Ramon’s invention, and having studied the device for focusing, as it were, the little Austrian cut, ground and polished until he had a perfect replica—as far as I could judge—of the prisms made by Ramon. There was only one real difference. Ramon had built up his prisms from innumerable fragments while this was constructed from a single piece. And when at last the thing was done, and in order to test if it were correctly made we tried its powers of magnification, Doctor Mueller was almost beside himself with excitement and wonder. Yet the moment I gazed into the prism I realized that for some reason it fell far short of those Ramon had made.

Its magnifying powers were, to be sure, astounding—that is to anyone who had never before experienced manabinite’s powers in this field, but as compared with those we had used at Manabi, it seemed scarcely better than an ordinary lens. No traces of atoms, much less of molecules could be seen, and I felt dubious as to the possibility of seeing the microscopic people with the thing. Whether the fault lay in the quality of the crystal—it may have come from some other source, for all I knew—whether it was due to some error in Dr. Mueller’s formula, or whether a built-up prism was superior to one made from a single piece of crystal, neither of us knew. And although by delicate and most painstaking regrinding and slightly altering the angles and facets of the prism some improvement resulted, still it fell far short of my expectations.

“But it is marvelous, most wonderful!” cried the Doctor. “Ach, my friend, if we had a piece of manabinite of so sufficient size, a telescope we could make that the inhabitants upon Mars would reveal. And, my friend, for the love of science, have a care that you do not destroy or lose this so-wonderful crystal.

“Into microscope lenses transformed it would revolutionize the study of biology and germs. Ach, yes, if a source of this manabinite a man could find, he would be a millionaire and the world might turn topsy-turvy.”

I smiled. “I’m afraid that never will happen,” I declared. “As I told you, the crystal is formed only by meteorites striking upon certain mineralized rocks. It is, in a way, a sort of nature-made glass, and I doubt if it has ever occurred in any spot on earth other than at Manabi.”

He shrugged his thin shoulders. “Nature herself is constantly repeating,” he observed. “Maybe tomorrow—next year—some one will find another deposit. But for now, my friend, all that the world of manabinite holds is in your so-competent hands. Much would I be delighted to make further tests and experiments, but it would be too sad were it to explode or vanish when so doing. So I must content myself with what I already have seen and wish with my whole heart that you may see your dear good friend again, alive and happy.”

So, bearing the precious prism that had required months to complete, and with Doctor Mueller’s best wishes and hopes for my success in my ears, I crossed to England and took passage on a Pacific Steam Navigation Company’s ship that would carry me direct to South America. At Panama I outfitted and transferred to a coastwise vessel for Guayaquil and six weeks after leaving Vienna I found myself once more amid familiar scenes. Nothing had changed since my last visit. Guayaquil still steamed and simmered in the sun beside the river. The same dank, pungent odor of bared mud flats and decaying vegetation arose from the mangrove swamps; the same boats swung to their moorings in the stream; the same idle, brown-skinned, cigarette-smoking, open-shirted, rope-sandal-shod customs officials dozed on up-tilted broken-down chairs in the vast bare office of the customs, and I could have sworn that the same pelicans flapped ponderously back and forth and plunged into the muddy water, and that the identical ragged, harness-galled donkeys drew the identical loads of coconuts and plantains through the glaring, roughly-cobbled streets.

The little bongo or sailing vessel that I chartered to carry me to Manabi was so like that in which Ramon and I had traveled that I felt a sharp pang of sadness at not finding him beside me. And though he denied all knowledge of it, and declared he never had seen me before, the fiercely-moustached, swarthy captain might have been the twin brother to him who had navigated our craft when Ramon and I had journeyed northward towards Manabi and the weirdly strange adventures and experiences we were fated to meet.

And when at last I stepped ashore and glanced about, I scarcely could believe that it had not all happened yesterday or a few weeks past. There stretched the distant desert; there were the bare red and dun mountains becoming blue and hazy as they receded to the horizon; there were the spiny cacti, the sparse growths of gray-green shrubs, the mounds of gravel where we had dug. Yes, and there was my old camp—scarcely affected by months of burning sun and drenching rains; and beyond was the framework of Ramon’s laboratory. Somehow, as I gazed about and recognized each familiar scene and detail, I had a strange, indescribable, almost uncanny feeling that Ramon was close at hand.

The moment I stepped ashore all my doubts of his still living fell from me like a discarded garment. I felt absolutely sure he was alive, and I seemed actually to sense his presence near. In fact this was so strong that, as I went about directing my peons and preparing for my camp, I found myself constantly glancing up and half expecting Ramon to appear at any moment. Of course, I reasoned, this was only natural. There where Ramon and I had been so long together, where we had undergone such strange experiences, where he had so mysteriously vanished, and surrounded on every hand by scenes and objects that brought him vividly to my mind, the reflex action of my mind would unquestionably cause such sensations in my brain. Yet despite my matter-of-fact scientific reasoning, I could not help feeling that my sensations were, to some extent at least, a premonition or a promise that Ramon still existed. I turned and gazed towards the spot where I had last seen him standing before the prism, his poncho draped over his shoulders, his violin in hand, ready to take that plunge into the unknown. Only the bare stretch of sand met my gaze. Yet there, invisible to human eyes and among the minute grains of sand, were the microscopic people, the minute city with its temple, the high priest, Nusta the beautiful princess and—perhaps—my lost friend, Ramon. But were they there? My heart skipped a beat and I drew a sharp hard breath as a thousand possibilities raced through my brain. How could I know if some sand storm had not buried them beneath inches of dust and sand? How could I be sure some torrential rain had not washed village and people away? How could I be certain that some creature—or even some man—had not dug or burrowed where the village had stood and had blindly destroyed all? Only by viewing the spot through my precious prism could I assure myself if the people still existed or if they had vanished, and I was not even certain that my prism would be powerful enough to reveal them if they were there. I was beset by terrible fears, by doubts, by the most pessimistic thoughts. I was mad to rush over, set up my prism and put all doubts at rest, and yet I almost dreaded to do so. And I was compelled to control myself, to calm my excited mind, to be patient, for I had arrived late in the day. The sun was rapidly sinking below the Pacific and there was much to be done before darkness fell, over land and sea.

So, fighting back my longings to set up the prism and end my uncertainties at once, I busied my mind with the more practical routine of establishing my camp, for I had planned to remain for some time. In the first place, I realized that it might require days, even weeks perhaps, for me to locate the precise spot where we had discovered the minute city and its people.

We had found it purely by accident and the entire settlement, I knew, occupied an infinitesimal area of the earth—a spot smaller than a pin point. To find such a tiny area amid all that waste of sand would, of course, have been impossible by ordinary means, but if my prism served its purpose as well as I hoped and prayed it might, then it would not be such a hopeless task even if I was not absolutely certain of the exact situation of the village of the lilliputian Manabis. But it would take time, even if, as I hoped and expected, I might still identify the precise spot where we had set up our prisms in the past. And even if I had good luck in locating the village, I intended to remain near for a considerable period. If I saw Ramon among the people, I would have my doubts set at rest but I felt sure that I would be unable to tear myself away for a long time. And if I saw no signs of Ramon, then I would try to forget my bitter sorrow at his loss by making a full and intensive study of the impossible people for the benefit of science.

But as I had no intention of carrying on archeological work, I had not brought any equipment for excavating nor had I engaged a large force of cholos as before. My outfit consisted mainly of supplies and my only companions were two young fellows I had engaged as camp boys and servants. One was a Jamaican whom I had found at Panama and who was to be my cook, the other a Quichua youth who was a sort of general utility man. It might be supposed that a party of three would not require much of a camp and that an hour or so would suffice to see us settled. And it would have been enough under some conditions, but it takes time to unload a cranky bongo (canoe) surrounded by bottomless mud. It is slow work portaging boxes, bundles, bales and packages on heads or shoulders up a perpendicular river bank and across an area of floury sand, and to set up a camp with mosquito netting screening, to arrange goods, chattels and supplies, to unpack, to get the commissary under way and to pay off and bid endless farewells and “May you go with God” wishes to the boatmen. So, by the time all my outfit had been transferred to my old camp site, and the two boys were unpacking food and bedding and the bongo was slipping down stream and Sam’s fire was cracking under his pots and pans and Chico was helping me put up the mosquito bars, the sun had vanished below the horizon, and the gorgeous crimson, gold and purple western sky cast a weird lurid light across the desert and transformed the brown mountains to masses of molten gold.

Rapidly the shadows deepened, the myriad hues faded from the sky, the mountains loomed dark and mysterious against the stars and the desert spread like a black sea on every side. By the light of hurricane lanterns we ate our dinner and—so strange and inconsistent are the workings of one’s brains—my last conscious thoughts as I fell asleep were not of whether or not Ramon still lived, but speculations as to whether or not the microscopic Indians had invented some means of artificially lighting their village after nightfall.

Never have I felt more excited, more keyed up than on the morning after my arrival, when I unpacked my precious prism and its accessories and prepared to learn the truth regarding Ramon’s disappearance. For some reason that I have never been able to explain—even to myself—I had brought along Ramon’s violin. Perhaps it was merely sentiment that had caused me to do so. Possibly I had been actuated by a subconscious, and wholly unrealized feeling that it might please Ramon—or his spirit. But mainly, I think, it was because it was the last thing that he had handled, the only connecting link, so to say, between him and myself, the only tangible object left when he had so suddenly and uncannily vanished with the explosion of the manabinite prism. At any rate, it most certainly was not because I had any thoughts or expectations of making use of it. I had no intention of attempting to reduce myself to microscopic proportions, even if, as I devoutly hoped, I was fortunate enough to find that Ramon had succeeded and had not been harmed by his strange transformation. And even had I desired to do so, it would have been utterly impossible, for although I had had the violin restrung—though I cannot explain why I had done so, for I did not know one note from another as far as producing them on an instrument was concerned. At all events, when on this momentous morning I was unpacking my instruments and prism and came upon the violin, something, some strange inexplicable whim or intuition, urged me to take it with me when I went to make the experiment that would settle my doubts and fears once and for all, or would prove to me that I should never know my dear friend’s real fate.

It was with trepidation, as well as fast-beating pulses and taut nerves, that I approached the spot where, as nearly as I could judge by memory, Ramon and I had set up the prisms before. Somehow I could not rid myself of a most unreasonable fear of treading upon the invisible Indians—even upon Ramon—and utterly annihilating them. Yet I well knew—as we had proved so conclusively before, that a human being might walk directly over the village without causing the least damage. But the whole affair, the village, the people, the amazing condition surrounding them, even Ramon’s disappearance, was one of those incredible things that, even when we know positively that they are so, cannot be believed. But my fears of treading upon the village were dispelled when I reached the spot and glanced about. Fate, Providence or Destiny—as well as Nature and the elements—had favored me. To secure his instruments when we had been preparing for Ramon’s great adventure, he had driven stakes into the sand, and they still remained, infallible marks to enable me to set up my instrument on the precise spot. Though I have ever prided myself upon the steadiness of my nerves and my coolness under all conditions, though I have faced most tense and even perilous situations calmly and with no conscious feelings of excitement or nervousness, and although I do not honestly think that I ever had experienced what is commonly termed a thrill at the prospect of some new sensation or discovery, yet, as I erected the tripod that was to support the prism and realization came to me that within a few minutes I would perhaps be watching the microscopic people and their city, might even look once more upon the face of Ramon, I found myself a-tingle from head to foot, my hands shaking as if I had a severe attack of malaria, and I was aware of a most peculiar and entirely novel sensation in my knees, which seemed suddenly and without reason to have lost their power to support me steadily. In fact, my hands and fingers were so confoundedly shaky, that it was with extreme difficulty that I managed to set up the affair and to adjust the green prism in its supports. But at last all was in readiness, and with beads of perspiration on my forehead, I swung the prism about as nearly as I could judge to the position our former device had occupied, and with a muttered prayer that the prism might not fail me, I looked into its sea-green depths and slowly, carefully adjusted the tiny screws and knurled knobs. For a space I saw nothing but a blurred, greenish haze. Then, so suddenly that I started, the tremendously enlarged sand leaped into view. Even though I had seen the same thing so many times before, even though I might and did expect it, yet for an instant I gasped, almost unable to believe my eyes. As far as all appearances went I was looking through glasses at a vast expanse of tumbled, inexpressibly wild and rugged mountainous country. Immense ridges and hollows were everywhere, their slopes, even their summits, strewn with great jagged, rounded, irregular, even crystalline masses of rock of every hue.

There were huge, shimmering, blood-red crystals like titanic rubies, ice-like octohedrons, that I knew must be diamonds, cyclopean six-sided columns of gleaming transparent material that I identified as quartz, cubes of vivid green, boulders of orange, yellow and amber; great rocks of intense blue, and countless fragments of every shade of brown, gray, ochre with here and there masses of jet black. It was, in fact, a mineralogical wonderland; such an array of rocks, gems, semi-precious stones and metalliferous ores as could exist nowhere on earth save in an accumulation of sand, the detritus of mighty mountains disintegrated, eroded, reduced to their primordial crystals by the elements through endless ages.

I had seen the same astonishing sight many times, as I have said, yet it was as amazing, as fascinating, as though my eyes had never before looked upon it and, for the fraction of a second, my thoughts of the miniature city and—yes, I must confess it—of Ramon were forgotten in my wonder and admiration of this immeasurably magnified yet infinitesimal portion of the dull earth about me. But only for the briefest of moments. The next instant I had moved the prism slowly towards the left, watching as I did so with bated breath, striving to recognize some detail of the enlarged scene before my eyes, expecting at any moment to see the houses or the temple of the city spring into the range of my vision. I drew a sharp breath. Could I be mistaken? No, there was the narrow pass among the boulders—or rather sand grains—down which the miniature, reduced burro had come as Ramon and I had watched him with incredulous, wondering, elated eyes. My breath came in quick short gasps, there was a strange tense feeling about my heart. The village was close at hand—the merest fraction of a fraction of a millimeter from the spot; half a turn of the fine adjusting screw beneath my trembling fingers should bring it into view. A sharp, involuntary gasp escaped my lips. Clearly, as though it stood full-sized before me, I saw a low stone wall, a stone house! By its open door sat a woman spinning or weaving. Beyond were more houses, a street, men and women. I almost shouted with delight. Once more I was gazing at the microscopic Manabi village. Would I see the princess? Would I see Ramon? The crucial, long-dreamed-of moment had arrived. An instant more and——

I felt myself hurled violently aside. I reeled backward, stumbled, strove to recover myself and came down violently with a jar that caused a whole constellation to flash and rotate before my eyes. It had all happened in the fraction of a second, yet, even in that immeasurable period of time, I found myself wondering what had happened, what heavy object had struck me, what it meant. And there is no denying that I was terrified and completely upset—both figuratively and literally—at one and the same time. I was conscious also of a sharp pain and a most disconcerting jar as I fell. In fact the jolt must have been sufficient to have dazed me for a moment—if it did not actually render me unconscious, for I found myself blinking, rubbing my eyes and sitting up.

And what I saw came near causing me to lose my senses altogether. My jaws gaped, I felt paralyzed, as with staring wild eyes I gazed at the apparition bending over me. It could not be. It was impossible. I must be delirious, mad, suffering from delusions. Or had I been killed and was I in the spirit-land? For, as clearly, as plainly as though he were actually beside me, I saw—Ramon!

All these thoughts, these sensations, raced through my brain in the hundredth, perhaps the thousandth of a second. And coincidently with them rushed other wild, impossible thoughts. Had I been, by some unknown means, reduced? Had something gone wrong with the prism and had I, like the burro, the dog, Ramon, been transformed to less than microscopic size? Or was it all an illusion, a figment of my overwrought brain, a chimera born of my excitement, my constant thoughts of Ramon, some injury to my spine or brain caused by my fall?

And as the vision, the ghost, the apparition reached out a hand and touched me, so tense, dazed, utterly bereft of my normal senses was I, that I screamed. Then, instantly, the spell was broken. “Madre de Dios!” the vision exclaimed. “I scared you almost to death. And I must have given you a fearful blow, I——”

The voice was Ramon’s! It was no vision, no hallucination! By some miraculous means he, my long-lost, dearest friend, was there beside me! What if I had been reduced to microscopic size? What if I were lost forever to the world? I had found Ramon! He was alive, unharmed, the same handsome, smiling, kindly-voiced Ramon I had known and loved as only one man may love another.

I leaped to my feet, threw myself upon him, embraced him in the effusive Spanish manner. Never in all my life has such indescribable joy, such great happiness been mine. And even in that moment, when I felt his strong muscular arm about me, a wonder beyond words to describe or express came over me. I had not been reduced. I was not in the village. Not a house was visible. There, lying on the sand within a yard of where I stood, were the tripod, Ramon’s violin, the prism, all normal in size. And there, at the edge of the trees, stood my camp. And Ramon was there, full-sized, normal, in every way just as I had last seen him except that—I stared, puzzled, uncomprehending—he was clad in dazzling, iridescent-hued, shimmering garments unlike anything I had ever—No! Sudden recollection came to me, they were—yes, the counterparts of the garments I had seen upon those microscopic inhabitants of the village. My brain whirled, I seemed to be taking leave of my senses. Ramon’s voice came to me as from a vast distance.

“Por Dios!” he cried, “what a splendid prism! What a magnificent crystal!”

He had caught sight of my prism and, springing towards it, eagerly examined it. “Where did you find this mass of manabinite, amigo mio?” he exclaimed. “It is marvelous, magnifico. And I thought we had searched everywhere and had secured every fragment. No wonder I crashed into you and bowled you over, amigo. But I did not dream you were gazing through this. You see it resulted in my missing my aim, so to speak.”

At last I found my voice. “What on earth are you talking about?” I demanded. “What has that prism to do with knocking me down? Where have you been, what have you been doing all this time? And where did you get that strange thing you’re wearing? Am I dreaming or am I crazy or are you actually here, in flesh and blood, and unchanged? For Heaven’s sake, Ramon, explain yourself.”

He grinned and then roared with laughter until his face was scarlet. “If you could only see your own face, amigo!” he cried, when at last he could control his merriment. “Never, never have I witnessed such a mingling of perplexity, of wonder, of incredulity and of injured pride. But forgive me, my dear friend. Of course it is all most strange and inexplicable. You saw me vanish, you saw me join my princess, my beloved; you saw me become a tiny microbe-like being, and now you see me and hear me talking with you, just as though nothing unusual had occurred. But——”

“Pardon me, Ramon,” I interrupted. “I did not see you join the princess. The prism through which I was watching was shattered by the same note that caused you to disappear. I never knew whether you were reduced or whether you were utterly destroyed and——”

“Caramba, my fiddle!” he exclaimed, ignoring my words and seizing the instrument. “Ah amigo, how thoughtful, how kind, how considerate you were to have brought it! So you were expecting me after all.”

“Confound it!” I ejaculated petulantly. “Can’t you answer my questions? Can’t you explain? Don’t you realize that I have been racked with doubts and fears? That I came here with the one hope—the forlorn hope—of settling once and for all whether or not you lived?”

Ramon smiled, but he was now quite serious. “Forgive me, my dear, dear friend,” he begged. “It is only my joy and delight at being with you again that causes me to be so inconsequential. And of course I did not know that you were ignorant of the result of my experiment. But to reply to your questions. No, amigo, you assuredly are not dreaming, you are very wide awake and, as far as I can judge by your appearance, quite normal mentally. I am here, in flesh and blood, and—at the present moment—quite unaltered. As to what the prism has to do with my knocking you over: everything, my friend. And do you not recognize this garment—you who pride yourself so greatly on your trained eyesight, your ability to note the most minute details, to recall the most insignificant peculiarities of a fractured potsherd after months, years? Do you not remember the garments we both saw upon the microscopic Manabis? And as to what I have been doing, where I have been since that memorable day when I stood before the prism. Ah, amigo mio, I have been experiencing greater happiness, more wonderful love than I had thought could exist in this world. Never has life held such joy, such perfection as has been given me since I joined my Sumak Nusta. But you will understand when you, too, meet her and speak with her, as you will.”

I gasped. What on earth was he talking about. Was he mad? He was trying to make me believe that he had been reduced, that he had joined the princess. And yet I knew that was impossible, for was he not here before me, large as ever, and not a sign of village of Indians visible? Yet, there was his clothing, of that strange, iridescent, opalescent material that, as he reminded me, we had both observed upon the minute Manabis.

Ramon evidently judged correctly the doubts and the questions that were in my mind.

“Of course no one would believe my story,” he said. “But you, my friend, having seen with your own eyes the marvels that the manabinite prisms can perform, should not be skeptical and should be able to comprehend. But I must tell my story. First, amigo mio, let us look through your prism at my people. My beloved one will be worried unless she knows all is well. Already I have been too long without reassuring her. Come, gladden your eyes and set your doubts at rest by again gazing upon the village of my people and upon the loveliest, the most adorable of women—my wife, the queen.”

Still feeling as if in a dream, still beset with fears that Ramon or I were mad, utterly at a loss to understand what it all portended, I saw Ramon adjust the prism, glance through it, and utter a delighted cry.

“Here! Here, amigo!” he cried. “Is she not glorious? Is she not wonderful? And she sees us. She knows you, my dearest, nearest friend, are beside me, that once more we are united. Look, look amigo!”

In a daze, my mind a turmoil, I looked into the green depths of the crystal and as I did so a sharp cry of utter amazement escaped my lips. There, clear, sharp, shining in the morning sunlight, was the temple, the village. And there, lovelier than ever, was the princess, Nusta. And by the wrapt, joyous expression upon her face I knew that, as Ramon said, she was aware of his presence beside me. For a brief instant she looked directly at me—through the prism she appeared life-sized and seemed to be but a few yards distant and gazing into my eyes—and a strange sensation, a feeling of weakness, almost fear, swept over me as I saw those indescribably beautiful eyes so near my own, those half-parted lips seeming about to speak. Then, with a quick movement, she stepped to one side, and to my utter amazement I saw her bend and peer into a green prism that seemed a counterpart of the one before my own eyes. Before I could voice my wonder, before I could collect my thoughts at this incredible sight, she again rose, looked towards me and, touching her fingers to her lips with a lovely graceful gesture, she threw me a kiss.

“My God!” I gasped. “She actually saw me, Ramon! And she has a prism—a manabinite prism! What, what does it all mean?”

Ramon, beaming with happiness, seized me and embraced me enthusiastically.

“Of course she saw you,” he cried delightedly. “She saw you; she saw me. She knows all is well, that we are reunited. But isn’t she the loveliest, the most glorious of women? Ah, mi amigo, is that not proof of the great friendship I have for thee? Is not the fact that I can leave her, if only for a brief moment, proof of how I have longed and waited for the happy hour when once again I could see you, hear your voice, delight in your friendship? And is not the fact that she could permit me to leave, could risk losing me forever, proof of how greatly she values your friendship, of how grateful she is for your aid in bringing us together, of the sublime faith she has in me and my assurances? Santisima madre, amigo, until you have experienced such happiness as has been mine, until you have known such a love as ours, you will not, cannot understand what such a parting, such a risk means. But I felt sure, confident. Every detail of my plan was studied, and Nusta, wonderful being that she is, insisted that I take even that risk in order that you, dearest of our friends, might join us and share something of our happiness.”

With the utmost difficulty I managed to confine my brain to lucid, logical, connected thoughts. If Ramon were crazy, so was I. But the sight of the village and of Nusta had convinced me that neither one of us was mad. There was some explanation, some common sense solution to the whole weirdly incredible affair of Ramon being there beside me and yet talking as if he had been in the microscopic village. And despite the fact that it controverted all common sense, and appeared utterly beyond credence that he should have been reduced and still should be in his normal state and size, yet I realized that it was even more preposterous to assume that he had been living here in the desert alone for all the months that had passed. And I knew, I was positive that he had vanished, had utterly disappeared before my eyes.

But he was speaking, and I concentrated all my senses upon his words, for at last he was serious, and was telling me strange, more incredible, more utterly amazing happenings than any living being ever experienced or that any man ever imagined.

“Though, as you now tell me, you knew nothing of what happened when on that morning I took the plunge and vanished,” he began, “yet I never, of course, realized the fact. And thank God, I did not, for, amigo mio, had I known that you were in ignorance of the results, I should have sorrowed and grieved at thought of the doubts and the uncertainties that might have filled your mind, and my perfect, glorious happiness would have been marred. I cannot in words explain my sensations or just what happened to myself. I remember standing before the prism, of drawing my bow across the strings. Then I seemed lifted, whirled, swept into a greenish, misty vortex. It was not unpleasant—on the contrary it was a rather pleasurable sensation—somewhat like those strange dreams in which one seems to float—a disembodied intellect—in space.

“And then—exactly as though awakening from a dream, unable to know whether the vision had endured for hours or for the fraction of a second, I blinked my eyes to find myself standing before Nusta. With a sharp glad cry she rushed to me, her soft beautiful arms encircled my neck, I held her throbbing glorious body close, and our lips met. I cannot describe to you the wonder, the glory, the heavenly joy of that moment, when, after countless centuries, our two souls were again united in that embrace. And yet my heart was torn with fears that it was only a dream, a vision born of my longings. But Nusta was very real, and presently I forced myself to believe that I had been reduced, that I was among the microscopic people who had gathered, wondering, half-frightened at my appearance, that Nusta my beloved was actually in my arms.

“Yet let me assure you, amigo mio, that even in that time of my new found love and happiness I did not forget you or my promise to you. Though we had no means of knowing if you were watching us, yet I turned and waved my hand, and Nusta at my request threw you the kiss I had promised you. There is no need to relate all the incidents and details now. I was happy—supremely, gloriously happy, and in the temple before the altar, Sikuyan, the priest, made Nusta my wife. Oh, amigo mio, if only I could convey in words some faintest idea of the joy I found with Nusta among her people. Hers is a community of perfect happiness, perfect contentment. There is no poverty, no sickness in that village of the little people. It is almost the land of perpetual youth. The people die only of old age or accident, and—Madre de Dios—the discoveries I have made! The puzzles I have solved! Ah, you must congratulate me, amigo, for among other things I have learned the secret that has puzzled me for years, the secret of how the ancient races cut and carved the enormous stones to build their cyclopean walls. It is a scientific wonderland, a treasure-trove of archeology, amigo mio, for Nusta’s people have preserved all the most ancient traditions, all the knowledge, all the customs of their ancestors for thousands of years. Invisible to human eyes, by their minute size isolated from all the world, they have remained untouched, unaltered, unchanged by outside influences. But come! We are wasting time; you must see for yourself; let us hurry to rejoin my beloved Nusta. I——”

“Look here, Ramon!” I cried, interrupting his words. “This has gone far enough. Do you mean to stand there—full-sized as ever—and calmly try to make me believe you actually have been among those people, have actually met and married Nusta? And what’s all this damned tommy-rot about my going with you to her? Have you got some crazy idea in your head that I’m going to try the mad experiment of being reduced. No, indeed.”

Ramon smiled, but he looked hurt and grieved. “Por Dios!” he exclaimed. “You do not believe me, then? But, pardon me, my dear friend. Of course you would not credit my words; they must sound mad to your ears. Who would believe I spoke the truth? And yet, mi amigo, all I have related is as true as the Gospel. I was reduced, I did marry Nusta, I have dwelt among the microscopic people, and I am going back—yes, within ten minutes. And—” he grinned maliciously—“you, my friend, are going back with me.”

I snorted contemptuously. Still, I thought, if Ramon were mad or if he were merely romancing—and I must confess I was beginning to believe his utterly preposterous tale—it might be well to humor him, to learn just how far he would go.

“Very well,” I assented. “Admitting then that all you have told me is true, how is it, Ramon, that having been reduced as you claim, you are now here, life-size, unchanged.”

He laughed merrily. “By the simplest of means, amigo,” he retorted. “By precisely the same means that reduced me.” Then, more seriously, he continued. “In that microscopic village I found manabinite, quantities of it. To be sure the fragments were—judged by human standards, infinitesimal, particles—mere motes, but in proportion to the size of myself, of the inhabitants, larger than any of the crystals you and I found here. And at once, when I discovered the mineral, a great vista, a wonderful idea came to me. I hoped—I felt sure, that sometime you, my dear friend, would return to this spot, and I grieved to think that you might be here, might actually walk above my head and I would be oblivious of your presence. But with a manabinite prism, and looking through the reverse field, I might be able to so reduce your image as to see you. Santisima Madre, but it was slow, tedious work, fashioning a prism without my tools, my instruments. But the people are marvelously skilful in working the hardest of stone, and by chipping, flaking, grinding and polishing we at last completed the prism. It was a poor, inadequate affair, but it revealed wonders, and elated, I made a second, a third, a dozen, until I had two that I felt would reveal your presence if you came here. Of course, amigo mio, I did not dream that you would have a prism, that you would be able to see me. But it was most fortunate that you did, for never would I have known you had arrived had it not been for your prism. Do you not see? Do you not guess? It was your image, your reflection in your own prism that at last—after days, weeks, months of watching, I saw. By itself, my miserable prism would never have revealed you, but my prism when focused upon the opposite end of yours, did the trick. It was like gazing at the image in the wrong end of field glasses through the other end of a second glass. Ah, Dios mio, how can I describe, how can I put into words the joy, the happiness that thrilled my veins when once again I saw you, my friend, appearing so near to me. And instantly, at once, I put into practice that which I for months had planned should this occasion ever arise, and which I had talked over with my adored Nusta so many times. Having been reduced, I had no fears of attempting the experiment and even Nusta felt confident there was no risk. So, standing behind my prism, I blew the note upon the quena I had prepared, and, as before, came the whirling, dream-like, disembodied sensation. Then a shock, a blow, and I bumped into you, amigo, full-size, unchanged, enlarged by the reverse action of the two prisms in unison. And here I am!”

I sank, speechless, upon the sand. No words suitable to the occasion came to my lips. Of all the absolutely amazing and incredible things I had heard or witnessed, this was the limit. And yet, as my dazed brain began to function, I could see no valid or logical reason why everything Ramon had told me should not be so. If a man, a dog or a burro could be reduced to microscopic size by means of almost magical properties of manabinite, why should a microscopic organism not be enlarged by reversing the process? As I thought of this, a sudden idea flashed into my mind, and I roared with laughter. “Good Lord, Ramon, you took a terrible risk,” I cried. “How did you know that if your experiment worked you would regain your normal size? How did you know that you might not be enlarged to enormous proportions, that the power of the prisms might not transform you to a giant as much larger than ordinary men as they are larger than the little people yonder!”

Ramon smiled. “I knew,” he replied, “because I have learned many secrets of manabinite’s powers of which I knew nothing when I experimented here with you. Objects, reduced by the mineral, cannot be enlarged to more than their original size, and objects enlarged cannot be reduced to smaller dimensions than they possessed before being enlarged. No, amigo, the risk I took was when I reduced myself. I had no positive knowledge that I might not be reduced to such minute proportions that I would be as much smaller than Nusta, as Nusta is smaller than ourselves at this moment. But I felt confident that she and her people had—or rather that their ancestors had—been reduced to the utmost limits which the manabinite could impart. And I had the evidences of the dog and the burro. They, if you remember, were reduced, and yet—though we had no previous idea of how greatly they would dwindle in size—they were in perfect proportion to the size of Nusta and her people. And I had another guide. As we looked at the village through the prism, the people appeared to be normal in size. Hence, I reasoned that as the action of the crystal when acted upon by the vibratory note was merely to make actual the image reflected in it, there would be no alteration in the size of the image when fixed, as I might say. And if Nusta and her people when refracted in the prism appeared normal in size, then, I reasoned, if the image were reversed, if my image were transferred in actual flesh and blood to the same spot upon which the prism were focused, I, when transferred bodily to that spot, would of necessity be exactly the same size as the people there. And I was quite right, amigo. But now, now that I know the powers, the properties, the means of controlling manabinite, and the laws that govern it, there are no risks. And——”

“Hold on,” I broke in. “I saw the princess—your wife, I should say—looking at us through a prism. How did it happen that when you enlarged yourself that other prism was not shattered? That was what occurred here when you were reduced.”

“That my friend, is one of the laws of manabinite. When used as a reducing prism, the stuff flies into dust-gas, I might say. But when used for enlarging an object, no visible alteration takes place in the mineral. But now, come, amigo! I must keep my promise to Nusta. I must return and I must bring you with me.”

I leaped to my feet. “You’re a consummate ass if you think I’m going to try any such experiment,” I declared angrily. “Even if I were willing to risk annihilation by the thing, I have no desire to remain a microscopic being. Why, Ramon, you don’t know how I have worried for fear that at any moment someone, something might come that would bury those people—and yourself—or destroy the village and its inhabitants forever. No, no, my very dear friend. If you really want to please me, if you want me to see and meet your lovely wife, if you wish to help those people, for the love of Heaven, enlarge them all to normal size and be done with it. You have it in your power to do so. Why delay?”

Ramon roared with almost hysterical laughter. “Oh what a timid, nervous old woman Don Alfeo is!” he cried between peals of merriment. “But tell me, amigo, are you, are the great cities, the communities, the inhabitants of this humdrum feverish world you live in, immune to cataclysms, to accidents, to disasters? Are your cities never destroyed by earthquake, by landslides, by hurricanes? Are not thousands killed every year by motor cars, floods, explosions, cave-ins, shipwrecks, volcanic eruptions, falling rocks and ten thousand other causes? Why and how then would we, we little people, be any safer if normal in size? Perhaps—I grant that—if we could be enlarged to—well, say a thousand feet in height or even less, if we could become veritable giants, we might avoid many perils and disasters that decimate ordinary humans. But to be of ordinary size! Ah, amigo, we would be subject to far greater dangers than we are as microscopic beings.

“And why, dear friend, are you so fearful of being reduced? Is life in your present state and form so safe and secure that you have no least fear that some disaster may overtake you? And all your life you have been facing dangers far greater than this; braving new situations, making experiments that held far more uncertainty. I have been reduced, I know it is safe, that there is no danger, but even though you ran a great risk—which you do not—even though there was but one chance in a million that you would survive the test yet, I assure you, amigo, that it would be worth the risk just to see Nusta, to hear her voice, to know her in the flesh. I——”

“You forget,” I reminded him dryly, “that not only is the princess your wife, but that I am an old or at least a middle-aged man, and that Nusta is a glorious youthful woman. And while I do not deny that there may be much of truth in your words regarding her, and though I would be delighted to meet Mrs. Amador—or should I say the Empress Amador? yet you cannot really expect me to have the same ideas as yourself regarding the risk. But, seriously,” I continued, “I do not agree with you in respect to the safety of such a proceeding as you suggest. Possibly, yes, I will go so far as to say positively—there is little or no risk in you or perhaps myself being reduced by the prism. But how do you know that two persons can be safely reduced at the same time? Even if it were possible, is it not within the bounds of possibility that in the process of reduction, two personalities might be combined into one, or that molecules or atomic portions of one might be transferred to the other, or even that the effect might be to totally eliminate both?”

Ramon rolled upon the ground roaring with laughter. “You old scare-head,” he cried, when at last he could control himself. “There is no reason to assume anything of that sort. And now, see here. If some one should tell you that a totally new and unknown civilization had left wonderful remains on the further side of yonder mountains, and that to reach them it was necessary to climb the ridge, face the perils of glaciers, crevasses, landslides, dizzy precipices and the dangers of snow blindness and starvation; or if someone should inform you that to reach an archeological site you would be forced to pass through hostile Indian country with the attendant dangers of disease, insects, snakes, rapids and what not, would you hesitate? Would you weigh the dangers before starting out? Answer me that, amigo. Give me an honest reply to that question.”

I had to grin in spite of myself. Ramon had me there. I shook my head. “I never hesitated and never have considered any dangers that beset the path to scientific discoveries,” I admitted. “But this is——”

“Different, you were about to say,” he interrupted. “But permit me, amigo, to contradict you. Among my—Nusta’s—people, in that village that you have seen only through the prism, you will find scientific treasures, archeological discoveries beyond anything of which you ever have dreamed. And they are at your fingers’ tips, if you will come with me, my friend.”

Ramon had won and he knew it. He was well aware that I could not resist the bait he held out for me, and as a matter of fact, from the very first I had, in my heart, felt sure that I would undertake the experiment. My curiosity to see the place and the people for myself was irresistible. Still, I felt I could not yield so easily. “But suppose I wish to return to this normal world, as I shall,” I asked, “are you sure I can be enlarged?”

“Absolutely,” he assured me. “Was I not enlarged, and I can enlarge you even more readily than myself. No, the only trouble is that unless some one should discover another mass of manabinite, no one in the future can ever be reduced, for as you know, this prism of yours will be shattered when we reduce ourselves. So, my friend, if you leave us and are enlarged, and at any future time should wish to revisit us, you will find it impossible.”

“Hmm,” I muttered. “Well, let us not worry about the future, Ramon. For all I know there may be no future. Your hints of what I may learn in the line of science have decided me. I am willing to take the plunge with you.”

Ramon sprang forward, embraced me, and his eyes sparkled with delight. “I knew you would, amigo mio!” he cried. “Ah, my friend, if you only knew the joy that fills me to know we are not to be parted. And Nusta, too, will be filled with happiness. Come, waste no more precious moments. Everything is in readiness. Stand with me behind the prism and in a moment more we will be looking into Nusta’s glorious eyes, hearing the music of her voice. And—I forgot to tell you, amigo—she speaks Spanish. I have taught her, in expectation of this glorious time, in hopes that some day you would be with us.”

I must admit that, as I stood there with Ramon behind the prism and watched him examine his quena and prepare to produce the note that would cause such miraculous results, I felt nervous, tense, keyed-up and well—I must admit it—somewhat fearful of what was about to occur. I cannot honestly say that I was afraid, for during a long life of adventure and of exploration in the wilder portions of our hemisphere, I had faced too many perils and death in too many forms to know the true meaning of what most persons call fear. Not that I am braver than the average man. I do not lay any claim to that, but merely because familiarity with danger breeds something of contempt for it, and because fear so often brings on disaster that I had trained myself to eliminate fear from my reactions. In fact I sincerely believe that I would have felt less uneasy had I been certain that the note upon Ramon’s quena would result in our complete disintegration, for it was the uncertainty of the matter, the sensation that we or rather I was about to enter the unknown, that affected me. It is this dread of the unknown, I believe, which is the basis of most of human beings’ fears and terrors. It is dread of the unknown that causes men to fear death, that makes children and some adults fear the dark, that has led to the almost universal belief in and fear of ghosts and spirits, and that is the basis of nearly all our superstitions. I might even go further and say that our religious beliefs are the direct results of man’s fear of the unknown. Religion originally was invented in order to calm those fears by explaining the unknown, by picturing it as a delightful place, and by peopling it with personalities, gods or beneficent spirits. And the more highly civilized and intelligent a man is the more, I have found in my experience, he dreads the unknown. Animals do not fear death; neither do primitive savages, for the brute has no conception of the unknown, possesses no imagination, and the savage feels so assured that his conception of after-life is correct that, as far as he is concerned, there is no unknown. And I am sure that the reason that Orientals and some others court death rather than dread it is because they, too, feel convinced that there is nothing unknown before them. The idea of leaving this familiar world, this life with its pleasures and its pains, to be plunged into some state of which we know absolutely nothing and from which no one has ever returned, is, I confess, rather appalling. In fact few persons are capable of imagining anything or any state other than an earthly existence. And I was on the verge of taking a plunge that was not only into the unknown, but that, if I could trust Ramon’s words and assurances, would transform me into a microscopic being; truly a transformation that was so incredible, so utterly beyond reason or the known laws of nature that even my brain could not really conceive of it. To be sure I had one advantage over the man whose life is about to end, and I had one great advantage over Ramon when he had taken the chance in the first place. He had been through the experience and had told me of the sensations, the results. Still, there was the chance, the possibility, that the prism might fail when two persons attempted the experiment, and there was the possibility also, that for some reason or another, the result might be disastrous for us both. How could I be sure this particular prism was precisely like the others? How could I feel certain that the least variation in its composition, its form, its adjustment might not destroy us or reduce us to such infinitesimal proportions that we would be invisible even to Nusta and her people? But I had made up my mind. Ramon’s hints at scientific truths to be discovered would have led me to take far greater risks, and while all these thoughts, misgivings and reasons flashed through my perturbed brain I had no intention of backing out. Then, suddenly, just as Ramon placed the quena to his lips, I remembered something.

“Hold on!” I cried excitedly. “I’d forgotten about my men. It won’t do to vanish without preparing them for my disappearance. What the devil shall I tell them?”

Ramon grinned. “Why tell them anything?” he asked. “After they’ve eaten up all your supplies they’ll find their way back to Guayaquil or Esmeraldas or somewhere, and tell a great story of you being whisked off by devils or getting lost in the desert.”

“Yes, and probably be shot or hanged for murdering me,” I reminded him. “And even if they escaped such a fate I have no desire to have my mysterious death published far and wide, and then later bob up. There’d be some rather incredible explanations to make.”

“You’d really be famous if you vanished, and think what sport it would be to read all the complimentary things the world would say about you. But, honestly and seriously, I see your point. Why not tell the fellows you’re going off alone and not to worry if you don’t return. You might give them a letter stating they were to be held blameless if you never reappeared.”

“Not bad,” I commented, “but suppose they should decide to clear out before I were reenlarged, and I should find no one here, no food, no boat? It would put me in a far from pleasant situation.”

“All the more reasons for you not ever to return to normal size,” he declared. “And I don’t believe you ever will, amigo. But you might set a definite time for your return, and tell them to wait for you until then, and if you fail to reappear, to leave and report your loss. How long will the supplies last them?”

“With reasonable care, about two months,” I replied. “I think your suggestion the only practical one. I’ll tell them I am going off with a friend I have met, in order to visit an ancient city, and that I may be absent two months. I shall surely be ready to have you enlarge me by that time.”

Ramon grinned maliciously but said nothing, and I hurried off to my camp to give instructions to my men. Being unemotional and unimaginative fellows, and quite content to live a lazy life and feast upon my provisions for the next sixty days, they asked no questions, took my announcement as a matter of course, and showed no indications either of wonder or curiosity at sight of Ramon, who was standing near.

This matter having been thus arranged, we returned to the prism and again took up our positions, standing as closely as possible together as Ramon tentatively ran over the scale upon his instrument. Then, with a smile and a nod, he indicated that the moment had come. The next instant the shrill, quavering note rang in my ears. Involuntarily I shut my eyes, clenched my hands, prepared for the strange sensations Ramon had described. But instead of the whirling, dream-like feeling I had expected, I heard an ejaculation from Ramon and opened my eyes. Nothing had happened. We were still there beside the prism, and Ramon was staring, a puzzled, uncomprehending half-frightened expression on his face.

“Nombre de Dios!” he cried. “What is wrong? Santisima Madre! Is it possible? Is it—” he left his sentence half finished, leaped aside and seized his violin, and an expression of delight, of vast relief swept across his features. “Caramba, of course!” he exclaimed. “I should have known. What a fool I was. And for an instant I feared—Valgame Dios how I feared, that something was amiss, that never, never would I be able to return to my beloved one. But it was the quena, amigo mio. Its note—enough to enlarge me—was too weak to work upon this crystal and to reduce us. But now—now, with the note upon my fiddle, in a moment more we will be standing beside my Nusta.”

Oddly enough, as sometimes, in fact so often, happens, all my nervousness and doubts had vanished with the sudden reaction that had followed that tense moment. And as Ramon tucked the violin under his chin and grasped the bow ready to draw it across the strings, I recalled a matter that had puzzled me greatly.

“Just a moment!” I exclaimed. “How was it, Ramon, that when you were reduced your violin remained intact? When I picked it up after you had gone, I found the strings had vanished with you but otherwise it was not affected, and yet the glue that held it together should have vanished also, being animal matter.”

Ramon threw back his head and roared with laughter. “Ah, amigo, for a keen, observant scientist you sometimes are most unobservant. The glue that holds it together, indeed! Why, my dear friend, did you not know, have you not noticed that there is no glue used in this instrument. See—” he held it out for me to examine—“it is not a real violin but a Charanko, a native Peruvian fiddle hollowed complete, body and neck entire, from a single block of wood. And the sounding board, the belly, is attached to the sides, not by glue but by Karamani wax, a cement composed of vegetable gums, the secret of which is known only to the jungle Indians of the upper Amazon. Now, amigo mio, do you understand? And this time, my friend, we will be off. If only I could take my Charanko with me! How Nusta would delight in its music!”

Again he cuddled the instrument beneath his chin; his lips smiled, happiness shone in his fine eyes, his fingers caressed the strings, and with a sudden, swift motion he swept the bow downward. I was watching him intently. I saw the sudden motion of his wrist and elbow, I heard the first crescendo note and then—— Ramon, desert, everything seemed swallowed in a dense fog; a gust of wind seemed to lift me, whirl me about. I seemed floating——a spiritual, weightless, entirely disembodied intellect upon billowy clouds. Yet my mind, my brain was functioning perfectly. I found myself speculating upon what had occurred, upon what was to be the result. I endeavored to correlate, to fix every detail of my sensations in my mind. I recalled the exact motions of Ramon, the precise sound of the note that had preceded my dream-like state, and I wondered, rather vaguely, if my sensations were the same as those of a person who died, and whether I might not really be dead.

I seemed to remain in this peculiar state, drifting like a bit of thistle-down in a faintly luminous haze, for hours. I began to think that I would continue to drift in this state forever, that the experiment had been a failure, that both Ramon and myself had been killed. And then, abruptly, with precisely the same shock of consciousness that one experiences when suddenly awakened from a dream, my mentality seemed to fit itself into a corporeal body, my feet touched firm earth and the mist vanished.

For a moment I could not believe my eyes, could not credit my senses. I was standing in the Manabi village! Everything seemed normal, natural. The houses near me appeared normal-sized houses, the earth seemed ordinary sand; against a blue sky loomed a range of hills, several Indians of ordinary proportions were within range of my vision, and with a sharp, delighted yelp a mongrel dog fawned against my legs. Could it be possible, was it within the bounds of possibility that I had been reduced, that Ramon’s experiment had been such a complete success, that everything appeared perfectly normal and natural, because I, instead of being a full-sized man, was in perfect proportion to my surroundings?

Then, to my confused, whirling brain came the sound of a voice; a voice so musical, so soft, so melodious that the words might have issued from a silver flute. I wheeled at the sound and stood dumb with emotion, speechless with wonder, gazing transfixed at Nusta, who stood almost beside me, clasped in Ramon’s arms. Instantly all doubt vanished from my mind. I had been reduced. I actually was in the miniature village. I was a microscopic being gazing with rapt admiration at the transcendingly beautiful creature whose glorious head rested upon Ramon’s breast, whose wonderful eyes were fixed upon me, whose luscious, adorable lips were half parted in a ravishing smile. Ramon, the villain, was grinning from ear to ear at the expression of bewilderment and amazement upon my face.

“Well, amigo, here we are!” he observed, as he caressed Nusta’s hair. “And,” he continued, “when you have quite recovered from the novelty of your experience I shall be delighted to present you to Her Majesty, Queen Naliche of Urquin, otherwise the Señorita Amador.”

Then, to the superb woman in his arms, he spoke in Spanish: “Did I not say, alma de mi vida, that he would come back with me? Did I not promise thee, corazoncito, that all would be well, and that the staunchest, dearest friend a man ever had would join us here in Urquin?”