* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

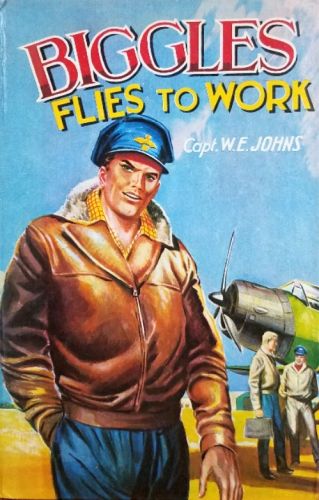

Title: Biggles Flies to Work (Biggles #78)

Date of first publication: 1963

Author: Capt. W. E. (William Earl) Johns (1893-1968)

Date first posted: November 14, 2023

Date last updated: November 14, 2023

Faded Page eBook #20231114

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

This file was produced from images generously made available by Internet Archive/Lending Library.

BIGGLES

FLIES TO WORK

Some unusual cases of Biggles

and his Air Police

BY

CAPT. W. E. JOHNS

MADE AND PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN BY PURNELL AND SONS, LTD.

PAULTON (SOMERSET) AND LONDON

| CONTENTS | ||

| PAGE | ||

| The Case of the Lost Coins | 7 | |

| The Case of the Old Masters | 26 | |

| Mystery on the Moor | 47 | |

| The Two Bright Boys | 69 | |

| Horace Takes a Hand | 85 | |

| Biggles Learns Something | 98 | |

| Dangerous Freight | 111 | |

| A Routine Job | 126 | |

| Dawn Patrol | 142 | |

| The Trick That Failed | 158 | |

| The Case of the Early Boy | 171 | |

Air Commodore Raymond, head of the Air Police Section at Scotland Yard, looked up with a smile as Biggles entered his office and seated himself in his customary chair within easy reach of the desk.

“May I, sir, with respect, share the joke?” inquired Biggles.

“There’s no joke.” The Air Commodore pushed forward the cigarette box. “I was just thinking what a fascinating job this is. One never knows what’s going to turn up next.”

“Fascinating for you—or for me?”

“For both of us; but for you in particular.”

Biggles looked doubtful. “It depends on what you call fascinating.”

“Oh come now, Bigglesworth,” protested the Air Commodore. “You know as well as I do that if yours was a humdrum, routine, cut-and-dried job, you wouldn’t stick it for a month. But let’s not argue about that. I have a little job here that should be right up your street. For a start I’d like to know what you think about it. It’s essentially an air operation.”

Biggles lit a cigarette. “Okay, sir. What is it this time? Or rather, where is it?”

“Albania?”

Biggles frowned. “Iron Curtain stuff, eh. I don’t like that for a start.”

“Only on the fringe. Let me tell you and you can judge for yourself.”

“I’m listening, sir.”

“The principal figure in the case is an extremely wealthy Greek gentleman named Constantine Pelegrinos,” began the Air Commodore, opening a folder that lay on his desk. “He has lived in this country for several years. Before he came here, for reasons which need not concern us, he made his home not in Greece but just over the border, on the Adriatic coast of Albania. Near the small town of Delvaros he bought an estate and built a luxury villa overlooking the sea. I have a photograph of the place here. Actually it stands on a small promontory with low cliffs on three sides dropping almost sheer into the water. Take a look.” The Air Commodore passed the photograph.

“All his life,” he resumed, “Mr. Pelegrinos has been an ardent numismatist, and over a long period of time—he is now eighty years of age—he built up one of the finest collections of ancient coins in the world, mostly gold and silver, of course, because they do not perish like base metals. These are worth a large sum for their intrinsic value alone, but their real value lies in the rarity of the specimens. This wonderful collection he kept at the villa so that he could admire them at any time.”

“How were they kept—as a sort of public exhibition?”

“No. They were contained in a number of specially made leather cases lined with velvet in which had been sunk depressions into which each coin fitted exactly. But to continue. Some years ago, when the communist revolution struck Albania and he realized he would have to leave the country, his first thought, naturally, was for his collection. He knew he would not be allowed to take it with him. In the end he escaped with only the clothes he stood in. Before leaving he tipped all his coins, loose, into an ordinary metal cash box—this was to save space—and buried it in the garden; actually, under the front lawn. The leather cases he disposed of by throwing them from the top of the cliff into the sea. All this, I should say, was done at night.”

Biggles nodded sombrely. “I can guess what’s coming.”

“Don’t anticipate.” The Air Commodore took another document. “Here is a sketch map of the house and garden. It shows the lawn. The figures shown are distances in yards from salient points to the spot where the coins were buried. There should be no difficulty, therefore, in going straight to the place.”

Biggles sighed. “I seem to have heard that before. Why all this fuss, anyway? As the coins are the man’s personal property surely all he has to do is put in a claim for them.”

The Air Commodore shook his head. “I’m afraid, Bigglesworth, you’re still a bit behind the times. The days when certain governments could be relied on to honour their obligations ended with the two World Wars. There is only one certain way to recover the collection and that is to fetch it secretly. Were it hidden somewhere in the interior that would be out of the question; but as it happens to be on the coast, in a lonely part of the country, to fetch the coins shouldn’t be too difficult a task. For obvious reasons the British Government can’t be involved. The mission would have to appear as a private undertaking.”

“I still don’t see why Mr. Pelegrinos should suppose we’re ready to stick our necks out to recover his precious toys for him.”

“He doesn’t. I’ll come to that in a moment. On leaving Albania he returned to Greece, but when political troubles forced him to leave he came to England, where he has lived ever since. He had long given up hope of recovering his collection. One can understand his position. Being what communists call a capitalist he himself dare not go back to Albania. He was afraid to entrust his secret to anyone in case the person ratted on him and kept the coins.”

“So the box is still where he buried it.”

“As far as he knows.”

“It may have been found.”

“He doesn’t think so, for two reasons. In the first place there was nothing left to show where the coins had been buried. Very carefully, alone, in the middle of the night, he lifted a piece of turf, made a small cavity, dropped in the cash box and replaced the turf. Secondly, had the coins been found, they would almost certainly have come on the market. That hasn’t happened. Some of the pieces are unique and Mr. Pelegrinos keeps close watch on sales all over the world.”

“So we are now expected to fetch them.”

“Not exactly. Mr. Pelegrinos, having given the matter a great deal of thought, as one would imagine, has decided it would be a pity if the collection was lost for ever, as might easily happen should he take his secret with him to the grave. That might happen any day. Rather than this should happen he went to the British Museum and made a proposal. He offered to sign a document handing over the collection to the Museum—if they could get it. In that way he would still be able to see his beloved coins any time he wished.”

“Fair enough. Was the offer accepted?”

“It was. The Museum is in no position to make a raid on the villa, although as the coins are now officially their property they would be within their rights if they did. The collection never did belong to Albania.”

“You’re sure it wouldn’t be any use asking the Albanian Government to hand it over.”

“That, Mr. Pelegrinos is convinced, would simply defeat its object; for once it became known that this peculiar treasure was still in Albania the ruling authorities would, if necessary, tear down the villa and dig up the entire estate in their determination to secure it. It all boils down to this. It would be utterly futile to try to get the collection out of Albania, and through all the Customs barriers of Europe, by any ordinary form of transport. The only way the coins could be recovered would be for a plane to land, lift the box and fly straight home with it. It might turn out to be a simple matter, or, as we don’t know what has happened at the villa since it was abandoned, it might not be so easy. One thing is certain. If the raiding party was caught—well, the members would find themselves in a nasty position.”

Biggles smiled wanly. “You needn’t tell me that. I take it there is a flat patch handy where a plane could land?”

“Unfortunately no. That’s the snag. The country around the promontory is wild and rugged. It means a marine aircraft. I can tell you that a path, part natural and part artificial, zig-zags up the face of the cliff. Mr. Pelegrinos had it cut so that he could get down to the water from the villa, either for a bathe or to reach the small boat he kept there. That, I imagine, will have gone by now. If you decide to have a shot at it everything will have to be done under cover of darkness. It wouldn’t do for a foreign aircraft to be seen near the coast in daylight.”

Biggles stubbed his cigarette. “What would be the weight of this money box?”

“I’ve no idea, but it can’t be very heavy or Pelegrinos couldn’t have carried it. Well, there it is. Think about it and let me know how you feel about it. There’s no desperate hurry.”

“You’d like me to have a stab at it?”

“Of course. Who better for such a tricky piece of work? But it’s up to you. It isn’t an order.”

“Anything could have happened at the villa since Pelegrinos was there.”

“That I must admit.”

“Should I have a word with him?”

“If you wish, but I don’t think you will learn anything more than is in this file. It’s all here. The Museum went thoroughly into the matter before it was passed to us.”

Biggles took another cigarette. “It’s worth trying,” he decided. “It’ll mean careful planning, timing, the phase of the moon and so on. Fortunately there’s no tide in the Mediterranean to contend with. I’ll think it over and come back later. I shall need faked papers, of course, in case I run into trouble.”

“Tell me what you want and I’ll see you get it.”

Biggles got up. “Right you are, sir. I’ll get on with it.” Taking the file with him he returned to his own office, and there, Algy, his second in command, being on leave, he told Bertie and Ginger of the proposed assignment.

With the file open on the desk and a map of the Central Mediterranean at hand, the best ways and means of achieving the object were discussed at some length and in detail. On the face of it, from what was known, there appeared to be no great difficulty, the only big doubt arising from what was not known; namely, the present conditions at the villa, whether or not it was still there, and if it was, by whom it was occupied—if in fact it was occupied by anyone. Should there be no one there, so much the better; but as there were no means by which this vital information could be obtained, the risks of not knowing had to be accepted.

The discussion lasted for two days, for a lot of figures were involved and there was much checking to be done; the phase of the moon, the probable weather for the time of the year, and so on. At the finish the aircraft chosen for the operation was the one on their own establishment that had often served for long-distance overseas work. This was the Gadfly, a twin-engined, high-wing, amphibian flying boat which, with an extra tank, had an endurance range of more than two thousand miles—enough to see them to the objective and back without an intermediate landing unless there was a reason for making one. As part of its equipment it carried a collapsible rubber dinghy.

The broad plan was for the aircraft to time its arrival off the coast soon after dark at a high altitude. Cutting the engines for silence it would glide down to make a landing within a mile of the promontory on which the villa stood. In clear weather, with a moon, there should be no difficulty in spotting it. The dinghy would then be inflated and the aircraft towed closer in. Leaving Bertie in charge of the machine the other two would go ashore in the dinghy with the necessary tools for digging, recover the box and return to the aircraft. If all went well the whole thing might be done in a few minutes. Biggles, from experience, did not expect the show to go as smoothly as that; but anything unforeseen would have to be dealt with as it arose.

The tools were simple. A short-handled pick like a soldier’s entrenching tool, a spade with a sharp edge, dulled so as not to reflect the moonlight, and a pointed steel rod for probing the ground in order to locate the box before digging. From these the makers’ names and trade marks would be removed. A knotty problem was whether or not to take weapons. Biggles said he would prefer not to be armed; but against that was a fear that should they be challenged, unable to defend themselves they might be shot without being given a chance to make excuses for being there. It was finally settled that those going ashore should carry pistols, primarily for purposes of intimidation. They would be used only if it became necessary to save their lives. On no account were they to risk being caught with guns on them, for it would be hard to reconcile this with the papers they carried in their pockets, stating the machine was on a long-distance delivery flight.

Three days later, with everything settled to the last detail, the flying boat took off and headed for its destination, carrying, for the overland part of the journey, documents showing it was on official Interpol duty.

* * *

No trouble was expected, nor was any encountered, and at nine o’clock the same evening, with the sun astern, setting behind the “leg” of Italy, the Gadfly was over the Adriatic, cruising at twelve thousand feet with its nose pointing towards the wild, mountainous country for which it was bound.

As far as the weather was concerned it was a typical late summer night in the Central Mediterranean region, sultry, the sky unmarked by a suspicion of a cloud, the sea unruffled by a breath of breeze. With darkness fast dimming the scene lights were beginning to appear on both sides of the water, Italy to the west and Yugoslavia, with Albania farther south, to the east. Far away beyond the “toe” of Italy a lighthouse flashed its beam with mechanical regularity. Apart from these signs of human occupation the aircraft might have had the world to itself.

The sun disappeared, leaving only a dull crimson glow to mark where it had ended its day’s work, and night came quickly into its own. After a few minutes on half throttle the Gadfly’s engines were further retarded, and on a course for the approximate position of the objective the machine lost height quickly. Presently the moon, nearly full, soared up over the horizon like a lopsided silver balloon.

“Now, see if you can spot the promontory,” Biggles told Ginger who was sitting beside him. “According to Pelegrinos it’s not much bigger than a big lump of rock, too small to be shown on anything except a large-scale map; but if, as he says, it’s shaped like a door knob, narrow at the inner end, it shouldn’t be hard to pick up.” He switched off the ignition and cut all lights, which had been on while flying over Italy.

“That cluster of lights should be Delvaros,” remarked Bertie, who was standing in the bulkhead doorway behind them. “If it is, it should give us our bearing. It’s the only place of any size in the district.”

With only the soft sighing of displaced air the aircraft continued to slip off altitude, always drawing nearer to the deeply indented coast. The moon helped to brighten the picture, but it was not yet high enough to penetrate the irregular line of gloom which followed the base of the cliffs.

“I made a slight miscalculation in the timing,” muttered Biggles. “I didn’t allow enough for the height of the mountains in the interior. No matter. We’re in no hurry.”

Two or three minutes passed. “I think I’ve got it,” said Ginger, peering down and ahead. “You’re nearly dead on. Left a little—little more—that’s it. I can see only one bit of land sticking out, so that must be it. There’s a light close behind it. Could be coming from the villa.” He went on sharply: “There’s another light passing behind it now—I’d say the headlights of a car on a road.”

“I’m with you,” returned Biggles. “Confound it. If that light is at the villa it can only mean the place is occupied.”

“Not so good,” murmured Bertie.

“I suppose it was asking too much to expect to find the place empty,” replied Biggles. “All right. This is it. Stand by. I’m going down.”

There was no more talking. The flying boat, dropping now at only a little faster than stalling speed to reduce noise to a minimum, closed with the sea. A final “S” turn, and with the bows pointing to the objective the keel kissed the water which, clinging to it, quickly brought it to a stop, rocking gently, something less than a quarter of a mile from the coast.

“Jolly good, old boy,” breathed Bertie.

“Don’t talk—listen,” ordered Biggles. “We should soon know if we’ve been seen.”

They sat motionless, listening intently, while the ripples they had made crept languidly to the shore, to die against the rocks. The profound hush of a sea at rest settled on the scene. They waited for perhaps ten minutes, eyes on the cliff in front, the only direction from which, as they were alone on the water, danger could come.

“Okay,” said Biggles at last. “Let’s get the dinghy out. Quietly does it. Sounds will carry a long way on a night like this.”

To get the little rubber boat inflated and ready for action took only a few minutes. The tools were put on board. Biggles and Ginger got in, and picking up the paddles began towing the Gadfly closer to the cliff. This, with no wind and no sea running, presented no difficulty, and very soon the flying boat lay like a resting gull within the shadow of the land. Still no sound came from the shore; but the height of the cliff would have prevented any lights above from being seen, should there be any.

Biggles’ last words to Bertie, before he cast off, were: “Start up if you hear us coming back in a hurry.”

It took a little while to find the mooring platform said to be at the foot of the path, and when it was found, protected by a buttress of rock, it raised misgivings. There was a boat already there, a sailing dinghy fitted with an outboard motor.

“Looks as if the path is still used,” whispered Biggles. “Must be someone living in the villa. Hello, what’s this?” A notice had been painted on a flat piece of rock. The language was foreign. “Probably means private, or landing forbidden,” concluded Biggles. “Let’s press on up Jacob’s ladder.” They picked up the tools.

The ascent was steep but otherwise easy, steps having been cut in what originally must have been the most difficult places. Biggles, his face wet with perspiration, was the first to reach the top. He stopped abruptly, staring at something in front of him.

“Anything wrong?” questioned Ginger anxiously, from behind.

“Take a look.”

Ginger looked, and was speechless with dismay. It was not so much that lights were showing at several windows of the villa. It was the lawn, or what had been the lawn. It was no longer the flat area of short grass they had naturally expected to find. Unattended, it had become an overgrown jungle of rank weeds and bushes.

“I suppose we should have been prepared for this,” muttered Biggles, bitterly.

“How are we to measure distances accurately through all this stuff?”

“We shall have to try.”

Then, as they crouched there, another hazard presented itself. Round the end of the villa, within thirty yards of them, strolled a man in uniform, a rifle on his shoulder. At the same time another man, similarly accoutred, appeared from the opposite end. They met at the bottom of the steps that led up to the front door. After a casual conversation lasting about five minutes each man turned about and retraced his steps.

“So there’s a guard on duty,” breathed Biggles. “Guarding what, I wonder? The place must be a naval or military post, or maybe a coastguard station. It’s going to make things awkward. However, let’s get on with the job. We shall have to work quietly, ready to drop flat if those men come back, as I imagine they will at regular intervals.”

With eyes and ears alert they moved forward, taking the easiest course through the shrubs. In this way, without anything happening, they reached a point about ten yards, as near as could be judged, from, and directly in front of, the steps.

“Pelegrinos gave the distance as ten yards and only a foot under the ground, so the box can’t be far away,” whispered Biggles. “You keep watch while I probe.” So saying he went to work.

Time passed. There were several false hopes as the steel rod struck a root or a stone. Twice operations had to be suspended on the appearance of the guards, who behaved as before. As soon as they had gone the work was resumed. At last the rod struck something which Biggles thought felt and sounded like metal. Dropping the probe he started to dig, tearing away roots with his hands. Having removed the top soil he dropped on his knees and groped, throwing out handfuls of dirt.

“This is it,” he panted. “I’ve got the handle.” He started to pull, but stopped, falling flat, when somewhere near at hand words of command were rapped out. They waited. No one appeared. “Must be changing the guard,” said Biggles tersely, returning to his task. Again on his knees, hands reaching down into the hole he had made, he pulled hard, straining, as if the box was heavy. With the top of it just showing above the surface he went over backwards, apparently still holding it. There was a metallic rattle.

“What’s happened?” asked Ginger breathlessly.

“The bottom’s fallen out of the box. Rotten with damp, or salt in the ground.”

“You mean——”

“The coins are at the bottom of the hole.”

“What are we going to do?”

“Get ’em out.”

“We’ve nothing to put ’em in.”

Biggles had already flung off his jacket. He now took off his shirt, tying the sleeves at the wrists to form, as it were, two bags. “Hold this open while I get the boodle,” he ordered.

That was now the position, Ginger holding open the sleeves of the shirt, first one and then the other for balance, while Biggles, lying flat, brought up the coins in his hands and dropped them in. The difficulty was to do this without making a noise. The coins would chink together. The sleeves began to bulge.

“This is going to bust open any minute,” warned Ginger.

“Nearly finished.”

“Leave the rest.”

“I’m not leaving one if I can help it . . . there you are, I think that’s the lot.”

Again they both went flat as a new danger threatened. Somewhere a man was calling and whistling, obviously to a dog. Ginger froze. He had no fear of being seen. What he was afraid of was the dog’s nose.

Presently a guard appeared, the dog at his heels. He met his companion, turned about, and had nearly reached the end of the villa when the dog growled. The man said something to it in a tone of voice that suggested he was not interested and walked on. The dog stood still. When it moved, Ginger, peering through a bush, lost sight of it.

“Let’s get out of this,” he breathed urgently.

“You go first. I’ll guard the rear.”

Abandoning the tools the retreat towards the cliff path began, on all fours, Ginger dragging the shirt. All seemed to be going well and they had nearly reached the top of the narrow descent when the dog appeared. It was in fact a hound of sorts. It raised its head and bayed. Biggles whipped out his gun. To Ginger he snapped: “Go on. Don’t stop for anything. Leave this to me.”

Ginger slung his awkward burden over a shoulder and hurried on, leaving Biggles and the hound facing each other from a distance of a few yards, the animal prancing and making a lot of noise yet for some reason hesitating to attack. Such an uproar could not fail to be heard at the villa, as was proved by several voices calling to each other. The front door was thrown open letting out a stream of light and revealing a figure in a uniform resplendent with gold braid. Biggles was more concerned with a man who came crashing towards him shouting, although what he was talking about, and to whom, Biggles, not understanding the language, had no idea. He was presumably the owner of the dog, for it stopped baying and bounded to meet him.

Biggles snatched the opportunity to back swiftly to the path. As he took the first step down a firearm flashed and a bullet ploughed through the bushes. Biggles fired a shot into the air, his purpose being to let the man know he was armed and so keep him at a distance; which it did, for the man disappeared as he ducked into the bushes.

Biggles bolted down the track at a speed which in ordinary circumstances he would have said was dangerous. What was happening above he could now only guess, but judging from the commotion a general alarm had been raised, as was inevitable. When he was half-way down he heard Bertie start the engines, and by the time he had reached the bottom the machine had come right in, with Ginger holding it by the bows to prevent it from bumping against the rocks.

“Get aboard,” rapped out Biggles as he dashed onto the scene.

Ginger obeyed. Biggles followed and thrust the aircraft clear, none too soon, for loose pieces of rock bouncing down the cliff told their own story. One or two shots were fired, but the shooting was wild and they did no damage.

The end was in the nature of anti-climax. In the scramble into the cabin Ginger tripped over the shirt and fell. One of the sleeves burst, scattering coins all over the floor. Biggles was shouting to Bertie, although by that time the machine was churning round to face the open sea. Within a minute its keel was tearing a gash in the surface of the tranquil water. Another, and it was airborne, turning as it climbed, to present a difficult target. If the aircraft was fired on nothing was known of it.

Biggles, his face streaked with grime and sweat, looked at Ginger and grinned. “How about that for a picnic? Get me a drink. I need one. Then you’d better pick up those tiddlywinks.” He went forward and joined Bertie in the cockpit.

Biggles, at his desk at Air Police Headquarters, replaced the intercom telephone receiver and turned questioning eyes to his assistant pilots who were in the office. “Any of you been in mischief?” he inquired seriously.

There was a chorus of denials.

“That was the Air Commodore speaking,” explained Biggles. “The Chief Commissioner is with him and wants to see me. That’s never happened before. I wondered if he’d come to rap my knuckles. See you presently.” He left the room.

His fears were soon dispelled. “Sit down,” invited the Chief as Biggles entered. “I want to ask you a question,” he went on as Biggles obeyed. “As you must know there has recently been a new angle of crime to give a lot of people headaches. I’m referring to the increasing number of thefts of valuable works of art. There was another case last night when three priceless paintings disappeared from a private exhibition in London. From the way these raids are carried out it’s almost certain they’re the work of one specialized gang, and behind them is a man not only with brains but with a considerable knowledge of pictures. The first question to arise is, where are these paintings going?”

“I can only suppose, sir, there must suddenly be a market for them somewhere, which suggests they’re all going to the same receiver.”

“I agree. But no ordinary receiver would buy an object that could so easily be recognized. Gold can be melted down. Gems can be reset. But there is nothing you can do with a picture except leave it as it is, for only in its original condition has it any value. I can’t imagine anyone in this country showing, much less trying to sell, a well-known painting that had been stolen.”

“They may be going abroad, sir.”

“Exactly. That brings me to the question I came here to ask. You’re the air expert. Would it be difficult to fly these pictures out of the country?”

“Far from being difficult, sir, it would be comparatively easy.”

The Chief’s eyes opened wide. “You astonish me. The airports have been alerted. All large parcels, and a bundle of paintings would make a very large parcel, are being examined.”

“I wasn’t thinking of public air transport, sir. I’m sure that to get these stolen pictures through Customs would be next to impossible. I had in mind a private aircraft, possibly one acquired for this very purpose.”

“Then what are the air police for? Have you done anything about last night’s robbery?”

“No, sir. As the theft took place in London and there was no suggestion of aviation being involved I took it to be a job for ‘C’ Division. We’re doing our best to prevent illegal air operations but the difficulties are enormous. My colleagues on the Continent tell me that smuggling by private aircraft goes on all the time and there’s little they can do to prevent it.”

The Chief frowned. “This is alarming. What are these difficulties?”

“If you’ll bear with me for a moment, sir, I’ll explain. Consider my own position. I have three assistants to help me to cover not just a single frontier but some two thousand miles of coastline. Even if we maintained a non-stop patrol it’s unlikely we’d spot a night-flying aircraft showing no lights. We can’t be at every altitude from the ground up.”

“I appreciate that. Then what do you do?”

“We rely chiefly on radar stations for information. If they pick up an unidentified plane that ignores signals they tip us off. But of course a pilot who knew his job would be able to dodge radar by coming in low, under the beam. Enemy pilots did that in the war. But they could be heard, and there were ground defences to deal with them. Today there’s nothing to prevent a machine creeping in low, and with hardly a sound, having cut its engine at a high altitude. Even if I intercepted such an intruder what could I do about it? I have no authority to shoot down a suspect who might turn out to be an innocent man whose navigation lights and radio equipment were out of order. We don’t carry guns, anyway, so the circumstances couldn’t arise. If a machine carrying valuable pictures was brought down by any means the chances are that the pictures would perish with the aircraft.”

The Chief’s eyes were on Biggles’ face. “Are you telling me there’s nothing to stop a plane coming to this country by night, landing, and then leaving again?”

“That, sir, is exactly what I am saying. I could do it. Of course, such an operation would call for expert preparation and need a lot of money behind it.”

“But if the proceeds of a robbery made it worth while it could be done?”

“Without a doubt. With official connivance it would be simple.”

“What do you mean by that?”

“The only risk such an aircraft would run would be on the ground here, and that need be no more than a matter of minutes. If arrangements were officially made for the flight, from one of the Iron Curtain countries for instance, there would be no trouble in the country of departure. With an accomplice here at a prearranged spot to hand over the parcel the machine could fly straight home.”

“You think this is being done?”

“I’m saying it’s possible, sir. As a private enterprise it would be an expensive business.”

“Then who would spend money on such an operation for a few pictures?”

“Maybe a wealthy collector who would be content to keep them under lock and key and gloat over them in private. Or possibly an Iron Curtain country furnishing a new art gallery.”

“Why this emphasis on an Iron Curtain country?”

“I don’t necessarily mean Russia. What I really meant was a country, any country, where visitors are not welcome. In other words, a country where the pictures could be put on view with little chance of them being recognized as stolen property. I used the term Iron Curtain because with tourists flocking into every city outside it, were the pictures exposed to the public it could only be a question of time before they were spotted. I’m only pointing out the possibilities, sir. If these pictures are going abroad only a very rich man or a government could afford to finance their transportation by air by the method I described a moment ago.”

The Chief drew a deep breath. “Well, what can we do about it?”

“I can only say I’ll think about it, sir. So far it’s all been conjecture. We’ve nothing to work on.”

The Chief nodded. “I appreciate that. However, do the best you can.”

The Air Commodore spoke. “All right, Bigglesworth. That’s all for now. Keep me informed of any action you take. I’m sure the Chief will give us every possible assistance.”

“Yes, sir.” Biggles retired and returned to his own office where he found the others waiting with some anxiety.

“Well, what was it all about?” questioned Ginger.

Seated at his desk Biggles supplied the necessary information.

“So where do we start?” asked Bertie, polishing his eye-glass. “It seems we’re expected to work miracles.”

“I gave up relying on miracles long ago,” returned Biggles, lighting a cigarette. “For a start, pass me the morning papers and we’ll see exactly what we’re looking for. The last three pictures were pinched last night so unless the thieves have moved fast they may still be in the country. I’d wager they won’t be here long. Once they’ve left they’ll be gone for good.”

“Which means,” said Ginger cynically, “we’ve got maybe twenty-four hours to find ’em.”

“Probably less.”

“Ha! What a hope.” Ginger laid the papers on Biggles’ desk.

* * *

There was silence while Biggles read newspaper accounts of the robbery. “This tells us a little,” he said, looking up. “Of a number of pictures in the room only three, the most valuable, were taken. They were a self portrait of Rembrandt, a work called The Boy in Black by El Greco, and the third, Donna Lucia, by Frans Hals, presumably a painting of a lady. These were Old Masters. Modern art wasn’t touched. Apparently it wasn’t considered good enough.”

“And what does that tell us?” asked Algy.

“The thief knew exactly what he was after. That in turn means he was an expert and that he knew the pictures were there. It was the same story in the previous art robberies. That isn’t coincidence. These thefts are the work of one gang. If so, it suggests the pictures are all going to the same destination; in fact, to the same individual, who may be the master mind behind the racket. He finds out where the pictures are and sends experienced cracksmen to get them. Anyhow, that’s how it looks to me. We may ask, how does he know where the pictures are? The obvious answer is that he goes to look at them. I shall assume he’s a foreigner because the pictures would be useless in this country. No man here in his right mind would buy them knowing them to be stolen. He couldn’t sell them. I doubt if the pictures are being sold. They’re going into a collection somewhere—but I wouldn’t try to guess where. Of course, this is really guesswork; but we’ve got to start somewhere. As I said a moment ago it’s no use rushing off without an object.”

“How do we set about establishing an object?” inquired Ginger. “It seems a pretty hopeless business to me.”

“I haven’t had much time to think but I can see two lines of approach, both vague I must admit. But if we don’t do something the Big Chief will conclude we’re a dead loss. If he’s right in believing these pictures are being flown overseas—and there I agree with him—it’s safe to assume that while they’re still in this country, waiting for an aircraft to collect them, they’ll be parked at the nearest available place to their final destination. What I mean is, the pilot of the aircraft won’t want to do more flying over this country than is absolutely necessary. That indicates a landing ground near the east coast.”

“Why the east coast?”

“Because it’s my guess that these pictures are going east. Put it like this. We can rule out north because one can’t imagine them being taken to the North Pole. I eliminate the south coast because pictures are also being stolen from France. I can’t see pictures being taken from here to a country where other pictures are being pinched. No. The pictures being stolen in France are leaving that country in the same way as they are leaving here. As for the west coast, it doesn’t make sense because the cost of an aircraft capable of flying a load non-stop across the Atlantic would be greater than the value of the pictures. Moreover, such a machine would have to operate from an airport. It could hardly take on hundreds of gallons of fuel and oil without questions being asked. So my guess is east, in which case there would be no point in making the machine fly farther into this country than was necessary.”

“There’s a lot of east coast, old boy, if you’re thinking of giving it the once over from topsides,” murmured Bertie.

“We’ll come to that presently,” replied Biggles. “There’s just a chance we may be able to reduce the area to be covered. That brings me to my second line of approach, which is at the London end. I’m still assuming that the man behind these thefts is a foreigner for the simple reason they’d be no earthly use to a local burglar. This man is a picture expert. He knows them by sight and exactly where they are, the room and how they are hung. How does he know? By going to look at them. In short, before the pictures were stolen the thief, or the brain behind the actual burglars, went to the gallery to get the layout. That’s my guess and I shall work on it.” Biggles paused.

“This, Algy, is where you start,” he resumed. “I want you to go to the Bond Street art gallery from where the pictures were lifted last night and have a word with the owner, or manager. Find out how long the missing pictures had been on public view. Ask him if he sent out invitations for the exhibition and note the names of any foreign art dealers or collectors. He may keep a visitors’ book. Some do. Again, check it for foreign names, and, if possible, the addresses. Ask, are any of these people permanently resident in this country? If not, where do they usually stay when they’re here? Query anything else that may occur to you. That’s enough for now. Get on with it. You can take Bertie with you for company. If the pictures haven’t already left the country they won’t be here much longer so we’ve no time to lose.”

When Algy and Bertie had gone Ginger questioned: “What can I do?”

“You can come with me and use your eyes. While there’s daylight left we’ll take the Auster out and have a good look along the east coast for possible landing grounds not on the map. There are plenty in East Anglia. I’m not seriously hoping to see a stray aircraft but we can at least refresh our memories—and one never knows. We shan’t learn anything sitting here. From the air there’s just a chance we may see something that hooks up with what Algy learns in Bond Street. But we’ve done enough guessing. Let’s go.”

Half an hour later the police Auster was in the air, heading east.

Said Ginger, as his eyes roved the Essex marshes with their tidal inlets: “There’s an angle of this picture racket that hasn’t been mentioned. Insurance. Could that be behind it? Could the crooks be waiting for the usual reward to be offered for information leading to their recovery?”

“No.”

“Why not?”

“Because in not one of the previous cases has the reward—one of twenty thousand pounds—been claimed; and that’s real money. That’s the chief reason why I feel sure the thefts are not being made for monetary gain. The pictures are not being sold. Some art enthusiast, a rich collector, is keeping them. He’s the man behind it all. I imagine he lives abroad. If I’m right, once these pictures leave the country they’ll disappear as completely as if they’d been dropped down an abandoned mine shaft.”

The Auster, with the sea in sight, had turned north, following the coast.

After a while Ginger said: “There’s enough flat open country here for a squadron of machines to get down.”

“More than a flat patch is required by our particular bird. There must be a road for a car to bring the pictures to the rendezvous. Even cut out of their frames and rolled they’d make a bulky parcel and weigh quite a bit. The landing ground must be well away from houses, even the odd farm, or someone might spot what was going on. We needn’t consider anything else so that narrows our search.”

The Auster cruised on up the Suffolk coast, always in sight of the sea. As Ginger remarked, between the coastal towns there were plenty of lonely stretches, particularly along and behind the foreshore where the ground was not cultivated, although pools of water and beds of reeds suggested most of this was marsh or swamp. There were occasional inlets, too, running inland from the sea, although it could be supposed that some of these would disappear at low tide. Most of the beaches were shingle, but there were stretches of sand on which, if the wind was right, a light plane could be put down.

Noticing that Ginger was staring down at something on his side Biggles asked: “What are you looking at?”

“I’m not sure. That creek just ahead of us—the one with the biggish house on the rising ground at the inner end. I was wondering what those white things on it could be. They’re not birds. Quite a lot have drifted against the rushes all along the near side.”

Biggles turned the machine to get a view. “Looks like paper, as if some litter-bugs have been having a picnic. Or it may be rubbish from the hamlet you can see a mile or so beyond the house. There may be a mill there which gets rid of its waste by dumping it into the brook that runs into the creek. I can see a small boat moored against a bit of a wharf near the big house. Probably use it for fishing. Wait a minute, though. This reminds me vaguely of something I’ve seen before somewhere. I’ll think of it in a minute. What’s the name of the village?”

Ginger consulted the map. “Frantham.”

“Never heard of it.”

The Auster cruised on as far as The Wash, and after glancing at his watch Biggles remarked: “We’d better be getting back. We haven’t learned much we didn’t know. There are plenty of places where a light plane could get down, certainly if the pilot knew his ground.”

The Auster returned to its base. Biggles and Ginger went back to the office to find Algy and Bertie waiting for them. “Well, how did you get on?” asked Biggles.

“Nothing to get excited about,” answered Algy. “The manager gave us the information you wanted. You were right about the invitations. A lot were sent out, some abroad, for the exhibition which opened last week. Everyone had to sign the visitors’ book. We took note of the foreigners and their addresses.”

“Were any of them resident near the east coast?”

“One, I think.” Algy opened his notebook and ran down the names. “Here we are. Baron Wolfner. He’s a celebrated Hungarian art critic. He always turns up at the big picture sales and exhibitions. He has a place in Suffolk called Frantham Old Hall.”

Biggles frowned. “That’s an odd coincidence—or is it? We had a second look at Frantham not two hours ago.” With a strange expression on his face he stared at Ginger. “The big house by the creek. That might well be the Hall. I told you that white stuff on the water reminded me of something. Now I’ve got it. It was a long time ago in the Lake District. They used the lakes for training seaplane pilots. I needn’t tell you it isn’t easy, in landing a marine aircraft, to judge the surface of dead calm water; so to make it easier for beginners it was the practice to strew sheets of newspaper on it.”

“Well?”

“Those white things we saw were square. It could have been newspaper. There was plenty of it, more than could have got there by accident. I wonder . . . have I been looking up the wrong tree? Naturally, I was thinking only of a landplane; but there’s no reason why the intruder, if there is one, shouldn’t use a marine job. One would have no difficulty in getting down on that creek. It’s a long shot, but I feel like having a closer look at that white stuff to confirm that it is paper, and if so find out how it got there. The place was too far off the beaten track for picnic parties.”

“I didn’t see a road,” put in Ginger.

“If there’s a house there must be a road of sorts leading to it.” Biggles turned back to Algy. “Did you get any other particulars of this Baron what’s-his-name?”

“Wolfner. None to speak of. He’s well known in art circles. Goes abroad for the winter. Comes back for the big summer sales. Runs a Rolls, so obviously he’s not short of cash.”

“Owning a Rolls doesn’t necessarily mean a man is all he should be. This Baron chap may not be the fellow we’re looking for but I’ve got a strong hunch that someone is using that creek, and from the markers put out I can think of no other reason than aviation. A boat wouldn’t need them. The fact that a picture expert lives practically on the bank may be coincidence. That’s something I’m going to settle right away. I wouldn’t exactly call it a clue, but it gives us a line, and we’ve nothing else to work on. The big question is, was that paper thrown on the water for last night—or tonight?”

Bertie spoke. “I’d say tonight. It can’t have been there long or it would have got waterlogged and either sunk or broken up.”

“That makes sense. Bring the car round, Ginger, while I’m having a look at the big scale map; and I shall have to tell the Air Commodore what we’re going to do in case he calls.”

“You won’t fly up?”

“Not likely. Nothing would happen on that creek if an aircraft was already there. It’s in full view of the house. We go by road. We should be there by night-fall. Get cracking.”

* * *

It was nine o’clock when the police car stopped as close to the creek as it could get without using the drive that gave access to the Old Hall, which stood nearly a mile from the village of Frantham. The secondary road the car had taken had followed the hard ground well inside the foreshore, which here was a broad expanse of rough, uncultivated ground that ended at a narrow beach fringing the sea.

It was nearly dark, but the weather was fair, with no wind, and a moon nearly full provided conditions that were near perfect for night flying. There was no traffic on the road. The only light that showed was from a front window of the Hall. The only sound that broke a melancholy silence was the occasional cry of a bird.

“Now listen, everyone,” ordered Biggles. “This is the drill. We march on that light, the idea being to get as near as possible to the landing stage where the boat is moored. If I’ve guessed right, that boat, or the wharf, should come into the picture. When we get there all we can do is park ourselves close by and wait. No talking.”

They set off over what turned out to be marshy ground with frequent puddles. Except for the whirr of wings of a startled bird nothing happened, and in due course the surface of the creek lay as placid as a sheet of ice in front of them. The moon shining on the water made it impossible to see any floating paper, if there was any; but Biggles squelched through mud and water up to the knees to the limit of the reeds, stooped, and returned with a handful of dripping material. “Newspaper,” he breathed. “Let’s see what paper it is. That may give us an idea of where it came from. Make a tent of your jackets to shield the light while I have a look.”

This was done. Biggles, torch in hand, crept under the coats. “Okay,” he said, emerging. “That’s all I wanted to know. It’s a foreign paper; or rather, a magazine. Glossy, high-class stuff, that would more easily remain afloat than newsprint. I can’t read it but there are pictures of antiques. That didn’t come from the village. I’d bet it came from the Hall. Let’s go on.”

Moving slowly, stopping sometimes to listen, they followed the edge of the creek, waded the brook that ran in from the village and reached the side on which the big house stood. It was now fairly close, but no sound came from it. The single light still showed from a window facing the creek. Continuing, they came to a rough staging against which the boat was moored. It was a dinghy. The oars were in the rowlocks as if ready for use. A little farther on a clump of osiers mingled with tall rushes. “This should suit us fine,” decided Biggles softly. “If we sit here we can’t be seen. The question is now, does the boat go out to the plane, if one comes, or does the plane come right in? We can only wait and see.”

They squatted, and a damp, uncomfortable vigil began.

Time dawdled on. Nothing happened. Not a ripple ruffled the surface of the water beside them. The reflection of the moon moved slowly across it. Midges were out in force, and for obvious reasons there could be no smoking to keep them at a distance. Nobody spoke.

It was a little after one o’clock when a sound, the first they had heard, broke the sullen silence. It was the purr of a car and came from the direction of the drive beyond the house. It stopped. A car door was slammed. This was followed by voices as if a visitor was being greeted.

“That’s better,” murmured Biggles.

“Who would come at this time o’ night?” whispered Ginger.

“Somebody bringing the pictures—I hope.”

Another weary hour passed before the next development. It looked as if all the lights of the house had been switched on. Their reflections fell far across the creek, making a landmark, as Biggles observed, that could be seen from fifty miles away.

Nerves became taut as voices approached. Two figures appeared silhouetted against the artificial light, one tall and slim, the other short and stout. The thin man carried on his shoulder a burden that might have been a small roll of linoleum. Both stopped by the wharf, talking casually and confidently but in a language none of the watchers understood.

Cupping his hands round his lips Biggles breathed: “I shan’t wait for the plane. Algy, come with me. Bertie, Ginger, use your initiative according to what happens.” He rose up and strode to the wharf. “We’re police officers,” he announced loudly. “I must ask you to show me the contents of that parcel.”

There were a few seconds of silence as if the men had been stunned by shock. Then things happened swiftly. The man with the parcel dropped it, spun round and ran. Biggles dashed after him. The man turned. A gun cracked, streaming sparks over Biggles’ shoulder. As the man turned to run again Biggles dived at his legs. They fell together, Biggles hanging on to the arm that held the gun. The scuffle did not last long. The man collapsed. Bertie, who apparently had struck him, dragged him clear. Breathing heavily Biggles picked himself up and recovered the gun the man had dropped.

“Put the bracelets on him,” he snapped, and turned to Algy and Ginger who were holding the short man, now protesting volubly in broken English. Biggles cut him off with: “All right. That’s enough. Are you Baron Wolfner?”

“Yes, and I’ll——”

“That’s all I want to know.” Handcuffs clicked. “You’d better keep quiet. Shooting at a police officer in this country is a serious matter.”

The Baron, who it could now be seen was an old man, sank to the ground as if his legs had given way.

“Take care of him Algy, while I have a look at this,” ordered Biggles. With his penknife he started cutting the cords that secured the parcel.

“They’re only pictures,” protested the Baron.

“I want to see if they’re the ones I’m looking for.”

“I imagine so,” answered the Baron in a resigned voice. “You’ll find out, anyhow. Is that all you want to know?”

“No. What time is the plane due here?”

The Baron sighed. “So you know about that, too. It should be here any moment now.”

Biggles looked hard at the two prisoners. “If either of you tries to give a warning to the pilot it will make things worse for you,” he said sternly. “Take them out of the way, Algy.”

Silence fell. Biggles lit a cigarette.

They had not long to wait. From the direction of the sea came the faint whine of air passing over the plane surfaces of a gliding aircraft. A sudden splash, and a line of turbulent water rushed towards the landing stage. A small flying boat, airscrew idling, took shape. A touch of the throttle brought it in close. The airscrew died with a hiss. A man jumped ashore and, having made the machine fast, walked forward.

“Are you alone?” inquired Biggles.

“Yes. Always——” The man broke off as if suddenly suspicious.

“Keep coming,” ordered Biggles. “We’re police officers. We were waiting for you. Don’t try anything stupid.”

The pilot looked over his shoulder to see Ginger standing between him and the aircraft. He shrugged as Ginger advanced and took a gun from his pocket. Again handcuffs clicked.

Biggles turned, as a new voice spoke, to see three figures, two in uniform, coming up. “Want any help?” asked Inspector Gaskin. “I thought I heard a shot.”

Biggles stared. “What are you doing here?”

“The Air Commodore asked me to come along in case you ran into trouble.”

“That was a kind thought, but we’ve managed to get everything buttoned up, thanks.”

“Nothing I can do, then?”

“Yes, you can take these three prisoners off our hands. To get to our car we shall have to walk across the marsh, the way we came. I want to have a look at this aircraft, and immobilize it. Where’s your car?”

“On the drive.”

“Then you might have a look inside the house on the way to it. I don’t know who or what you may find there. I haven’t seen these yet, either.” Stooping, Biggles unrolled the parcel and turned a light on the first of three canvases to reveal a painting of a boy in a black velvet suit. He retied the parcel. “You might take these with you, too,” he requested.

“Ain’t you lucky,” growled Gaskin. “Fastest bit o’ work I ever heard of. You must have second sight—or something.”

Biggles smiled. “That’s right. But experience helped me to know, when I saw something, what I was looking at.”

“How?”

“Somebody left some newspaper scattered about where you’d never have seen it. It was as simple as that.”

“I don’t get it.”

Biggles grinned. “You’d have got your feet wet if you had. I’m going home to get my socks off. See you later.”

From a comparatively low altitude of fifteen hundred feet Police Pilot “Ginger” Hebblethwaite, flying solo in a Service Auster, surveyed methodically in turn the cloudless sky above and around him, the sparkling waters of the English Channel on his left and the undulating panorama of the county of Devonshire on the right. The season was high summer. The time, five a.m.

He was on a regular dawn patrol, not looking for anything in particular but prepared to investigate, within the province of his duties, such matters as might call for explanation. That was his purpose for being in the air. He did not expect to see anything unusual; should he do so, that in itself would be unusual on what was a regular routine task with no particular objective—in the manner of an ordinary constable on his beat. But there was always the possibility, for, as his headquarters at Scotland Yard knew only too well, air transportation was being used more and more by the highly organized modern criminal in an effort to outwit the law.

So far he had seen nothing more exciting than a rubber raft adrift off Sidmouth, presumably having been lost by a careless bather. There was no one on it but he had signalled its position to base for the guidance of the local police.

He was content to be where he was, doing what he was. From horizon to horizon the heavens were clear eggshell blue; the atmosphere through which the Auster pushed its way, practically flying itself, was as soft as milk, and the countryside looked quiet and very beautiful under the rising sun. It was the sort of day when a pilot flying alone permits himself from time to time to hum a snatch of song. Ginger did just that.

Ahead of the Auster, moving slowly towards him, as it seemed, now lay the broad expanse of Dartmoor, the highest parts bristling with those granite teeth called tors, the lower parts dotted with small areas of woodland to form a pleasant contrast to the open moor. A tenuous mist, fast being devoured by the rising sun, still clung to occasional pools and bogs. This was the western extremity of his beat, so leaving the sea behind him he began a wide turn to the north before heading for home. This brought him over the practically uninhabited heart of the moor.

It may have been for this reason that his eyes came to rest on an isolated group of buildings sheltered on the north side by a straggling wood of what looked like ancient oaks. Thinking they made a useful landmark, and wondering who would choose to live in such a remote spot, the tune he was humming died on his lips as his questing eyes picked up and focused on an object, or a part of one, that seemed singularly out of place. Half hidden by the trees stood an aircraft. He made it out to be an Auster like his own. He could not see anyone near it, but the branches of the trees and the shadows they cast prevented him from getting a clear view. For the same reason he was unable to make out the registration letters.

Without altering course he surveyed its immediate surroundings. Close to the trees was a house of fair size, long and low, with a yard and outbuildings. A red-painted tractor, a conspicuous spot of colour, stood on a plot of cultivated ground to suggest the place was a farm. A track wandered across the moor between the house and a distant road.

Ginger consulted the map that lay on his knees and looked again at the ground. The plane was still in the same place although he could see less of it, his own position having moved. A little puzzled, he flew on. What was the machine doing there? On the other hand, there was no reason why it shouldn’t be there. A man living in such an out-of-the-way establishment was the very person to take advantage of private air transport, he pondered.

It was not until the farm was well behind his tail that the thought occurred to him that the pilot might be in trouble, resulting in a forced landing. If so he had probably gone to the house. If it was on the telephone all would be well; he would be able to ’phone for help. If not, he would have to go some distance to find one.

Deciding he had treated the matter too casually Ginger turned, and dropping off five hundred feet of height retraced his course. What he was looking at now was the ground, trying to establish the nature of it as a safe spot on which an aircraft might land. There was not a lot of room, for much of the surface was rough, but he formed the opinion that an experienced pilot should have no difficulty in putting down a light plane. He looked in vain for a marked runway. He could see no wheel tracks. There was no white circle, no windstocking, nothing to suggest the place was a regular landing ground. The only smoke to indicate the direction of the breeze was rising from the farm chimney. This supported the idea of a forced landing.

Ginger resolved to fly low enough to get the registration letters so that on arrival home he would be able to check the ownership of the machine. At least, that was his intention before he observed, with surprise, that the aircraft was no longer there. He couldn’t see it anywhere. Had it taken off? He scanned the air expecting to see it airborne; but he failed to find it. What had become of it? Where could it have gone?

For the first time a little suspicious he pinpointed the spot on his map, shot a couple of oblique photographs with his pistol-grip camera and made the best of his way home.

* * *

He found Biggles alone in the Operations Room when, rather more than an hour later, he walked in with a still-damp photograph in his hand.

“Well?” queried Biggles casually without looking up. “See anything?”

“I saw an aircraft.”

“They’re getting quite common,” returned Biggles with gentle sarcasm.

“Not where I saw this one.”

“And where was that?” Biggles put down his pen.

“On Dartmoor,” answered Ginger, and went on to narrate the circumstances.

Biggles sat back, looking at him. “Seems a bit odd,” he admitted. “Pity you didn’t get the registration when you first spotted it.”

“I’ve told you why I couldn’t, and that may have been the reason why the machine was parked under the trees. The pilot may have dodged under them when he heard me coming.”

“Didn’t it occur to you to land to find out exactly what was going on?”

“Not immediately. There was no landing track and there seemed no point in risking cracking my undercart for no purpose. I’d no real excuse for interfering, anyway. When I got back the machine had gone. Someone must have moved it pretty smartly.”

“Where exactly is this place?”

“About ten miles south of Okehampton. The nearest main road I made out to be the A386 from Okehampton to Tavistock. That would be roughly five miles from the farm. This is the spot.” Ginger laid his photograph on Biggles’ blotter.

“Do you want me to follow it up?” he asked, as Biggles studied the picture.

“I was just wondering what you could do,” answered Biggles, reaching for a cigarette. “Is this place by any chance near the prison?”

“No, that’s miles away to the south. Should I have another look round tomorrow at the same time?”

“If you make a practice of flying low over the farm, and there should be anything improper going on, the people there will take fright and suspend operations.”

“I might land and make direct inquiries at the house. Whatever is going on the people there must know about it.”

“In which case questions would get you nowhere. As things are, the farmer, or whoever lives there, will have no cause to worry merely because you flew over this morning.”

“Then how do we get the answer?”

“It might be better to tackle the job from ground level. Hikers on the moor are not uncommon.” Biggles had picked up his magnifying glass.

“What are you looking at?”

“Those two animals in the yard, near the big barn.”

“I made them out to be pigs—a dark-skinned breed.”

“Could be. They look to me more like dogs. Incidentally, that barn is big enough to house a small aircraft. From what you tell me it must have disappeared pretty quickly this morning as soon as you turned your tail to it.”

“I see what you mean. Like me to go down and have a look?”

“That would settle the matter one way or the other. If there’s nothing wrong the farmer’s wife should ask you in for a cup of tea. If she’s short with you—well, you’d better have a closer look. It’s a nice day for a stroll on the moor. Bertie should be in any moment now. Get him to run you down in his Jag. Park it handy and give your legs some exercise.”

“It’ll be late by the time we get there.”

“So much the better. After dark it’ll be easier to pretend you’ve lost your way. Take care you don’t. On Dartmoor that can be serious. Take a compass—and don’t forget those dogs. They might be vicious.”

“What exactly do you want me to do?”

“Not much for the time being. Ascertain if an aircraft is being kept at the farm and if so get its registration. That’ll tell us who it belongs to and so perhaps give us a line on what it’s doing there. That should be enough to go on with. I can’t recall an application from a private owner to operate from Dartmoor.”

“It might have been a member of a club making a call.”

“Possibly. After all, if a fellow holds a licence there’s nothing to prevent him landing on a friend’s property as long as it doesn’t interfere with other people—provided it hasn’t been overseas, in which case it must land at an authorized Customs aerodrome. At this juncture there’s no need to ask questions at the house unless it’s unavoidable.”

Ginger nodded. “We shan’t be able to see much in the dark.”

“Use your nose. If there’s a plane anywhere near you should be able to smell it.”

“Okay. It shouldn’t take long to get this sorted out,” concluded Ginger.

* * *

Half an hour later he and Sergeant-Pilot Bertie Lissie were on their way to Devon, the immediate objective being Highway A386, which a study of the map had confirmed was the nearest convenient point to the farm, on a main road, which they would be able to reach in the car. They had considered taking lodgings at Okehampton, but as this would mean a much longer walk to the farm, they decided against it unless events should make it necessary.

With a stop for lunch and a fill-up with oil and petrol it was a little after seven o’clock when they passed through Okehampton and presently took the left fork on to A386. The sun was getting low but they reckoned they still had about two hours of daylight left. Not that this was of vital importance as after dark they would have the assistance of a moon three-quarters full; or so they had reason to expect, although the weather had deteriorated somewhat, a slight swing of the wind to the north bringing in a lot of high cloud and putting a chill in the air. But so far there was no sign of rain.

“The way to the farm should be along here on the left,” remarked Ginger. “It can’t be far.”

This soon proved to be correct, and Bertie brought the car to a stop a little beyond the entrance to a track—it could hardly be called a road—which meandered across an undulating vista of moorland, mostly open but broken here and there by a few stunted trees and outcrops of grey rock.

“You’re sure this is the right one, dear boy?” queried Bertie.

“No, I’m not sure, but I think it must be,” answered Ginger. “I saw only one track.”

“Let’s try it,” said Bertie cheerfully, moving on to the verge. “The car should be all right here,” he went on, passing out two haversacks and walking sticks before locking the doors. “How far did you say we shall have to pad the hoof?”

“About five miles. We ought to do it in an hour.”

They set off at a brisk pace, the sooner to get the business finished. No precautions were taken against being seen, as they saw no reason for this and would have found it difficult anyway. As far as they could see they had the moor to themselves. A pair of buzzards wheeled high overhead.

“A car must use this track quite often,” observed Bertie, his eyes on a tangle of tyre marks that furrowed the sandy surface.

“People living at the place I saw could hardly manage without a car, for shopping, and that sort of thing.”

“We could have brought mine across.”

“That wasn’t the idea. What excuse could we have made for going to the farm? We’re hikers who have lost our way—remember? That’s why, for the look of it, we’re carrying haversacks which I trust we shan’t need.”

They trudged on, Ginger from time to time casting an anxious eye on the sky. “This was supposed to be a fine weather job but I wouldn’t bet on it,” he remarked.

Half an hour later came the first spots of rain, presently to develop into what is known locally as a Dartmoor drizzle, which reduced visibility to something less than a hundred yards. However, the track remained plain to see and there was no talk of turning back. They were obviously going to get wet whatever they did. They merely increased their pace. They saw nobody, heard nothing. The terrain became more undulating but with wide flat areas between the rises and falls.

In due course they reached a point where, on level ground, the track ran adjacent to a stand of gnarled, wind-distorted oaks, which Ginger felt sure could only be those under which he had seen the aircraft on his dawn patrol. These were explored but nothing of interest found. Certainly there was no plane there now. By the time they had done this darkness was falling, largely as a result of the weather, and what had promised earlier to be a bright prospect had become such a damp, dismal business that Ginger was beginning to wish he hadn’t noticed the plane.

“We’ll have a look at the farm now we’re here,” he said quietly as they returned to the track. “If we encounter anyone we’ll ask for directions to the nearest main road.”

They went on in silence. A big barn loomed in the murk. Rounding the end of it they found themselves overlooking the yard. On the far side the lighted windows of the house glowed mistily. They stopped as sounds reached their ears: the voices of several men in the house talking loudly and cheerfully.

“Must be having a party,” conjectured Bertie.

“If there’s a plane here it can only be in the barn,” asserted Ginger. “Let’s have a look—if we can get in.”

They proceeded, cautiously now, to the wide double doors. Surprisingly, Ginger thought, they were not locked. He opened one and they stepped inside, his torch cutting a wedge of light that moved slowly round the interior. There was no aircraft. At first glance there was nothing there except some farm implements thrown down at one end.

Ginger sniffed. “I smell doped fabric,” he breathed. “There has been a plane in here and not so long ago. Hello, what’s this?” he went on. On the wall was a low shelf on which lay an assortment of tools, with them a small square of paper. He picked it up. It was a photograph, a rough print of a man standing beside an Auster aircraft. Before he could examine it closely, from outside, fast approaching, came a clamour of ferocious snarls and growls. Instinctively he switched off his torch and put the photo in his pocket as Bertie, just in time, pulled the door shut between them and the dogs which, frustrated, set up a furious barking.

“That’s torn it,” said Bertie lugubriously.

They had not long to wait for the next development. An authoritative voice could be heard approaching, calling off the dogs. Reaching the door it said: “Come on out.”

“What about the dogs?” returned Ginger. The animals were still growling deep in their throats.

“They’re all right.”

Bertie and Ginger stepped out, dazzled by the beam of a torch in their eyes which prevented them from seeing the man behind it.

“What’s the game?” inquired the voice curtly.

“We were looking for shelter,” explained Bertie meekly. “The barn seemed just the job. Hope you don’t mind.”

The light was switched off as the man who held it was joined by three others advancing from the house, apparently curious to know what was going on. Their faces appeared curiously white until it could be observed that they were more or less covered by bandages.

“If we can’t stay here perhaps you’d be kind enough to direct us to the nearest main road,” said Ginger.

“Which way did you come?”

“We were on the moor when the rain started. Coming to a track we followed it.”

There was a pause during which the speaker stepped away a short distance to hold a brief conversation, in a low voice, with his companions. He came back. “Why aren’t you more careful?” he complained. “People like you are a nuisance. Well, you can’t stay here. Follow back the track you came on and it’ll take you to the road.”

“Thanks,” acknowledged Bertie. As an afterthought he added: “It’ll be as black as pitch presently. I wonder if you have an old torch you could sell us, or lend us?”

The man hesitated. “All right. You can have this one. Don’t come back or I won’t be responsible for the dogs.”

“Thanks again,” murmured Bertie, taking the torch. “We’ll be on our way.”

That was all. Nothing more was said. In a minute Bertie and Ginger were on their way back to the car. For some time neither spoke. Then, well clear of the farm, Ginger said: “What do you make of that? It strikes me there’s something queer about it. Why do they need guard dogs? Why were they so anxious to get us off the premises when any decent farmer would have let us stay? And what were those chaps doing with bandages on their faces?”

“One had his hands bandaged, too,” returned Bertie. “What did you pick up off that shelf?”

“A snapshot of a man standing by an Auster. That should tell us something, if not all we want to know. What was the idea of asking for a torch when we had one?”

“Thinking on the same lines as you, old boy, I thought that chap’s fingerprints might be instructive. One way and another we haven’t done so badly.”

They strode on and without difficulty reached the car.

Said Bertie: “Do we sleep somewhere on the way or do we push right on for home?”

“I’m all for sleeping in my own bed,” decided Ginger. “Let’s press on. There shouldn’t be much traffic on the road at this hour so we should be home in time to snatch a few hours’ sleep. We needn’t wake Biggles. We’ll leave the photo and the torch on the table with a note giving him the gen so that it won’t be necessary for him to wake us too early.”

This worked out as planned.

* * *

When Ginger and Bertie got out of bed at ten o’clock the next morning, not surprisingly having overslept, it was to find that Biggles had gone early to the office at Scotland Yard taking the “exhibits” with him. There, an hour later, they joined him.

“Why didn’t you wake us?” protested Ginger.

Biggles smiled. “No hurry. You gave me plenty to go on with. I’ve been busy—but I’ll tell you about that presently. First, what happened on Dartmoor?”

Ginger and Bertie told the story between them. “Have you made anything of it?” asked Ginger at the finish.

“Quite a lot. I was only waiting for your report before going to the Air Commodore for instructions.”

“Then there is something crooked going on!”

“I wouldn’t go as far as to say that, but I now know enough to arouse my curiosity. This is it. Your photo enabled me to check on the aircraft, assuming it was the one you saw. It’s privately owned by a Doctor Alton Bentworth who lives in London, is a member of the Longborne Flying Club and keeps his machine there. From the secretary I’ve learned that Bentworth does a fair amount of flying, mostly very early morning. He did that yesterday, apparently going to Dartmoor. He got back about eleven, so it seems the machine must still have been there, although you didn’t see it, the second time you flew over. It may have been moved into the barn. At some time or other the doctor must have given his friends there this snapshot of himself—a touch of vanity perhaps. He specializes in plastic surgery, which hooks up with what you now tell me about men in bandages.”

“You think he might be running a private clinic or convalescent home for his patients?”

“A natural supposition, but if that is so, although he may not know it he has at least one queer member on his staff. The Fingerprint Department tell me that this torch has been handled by a gentleman named Manton Rushling, once a solicitor, who recently did five years for forgery. He was discharged from prison last year. He is now a free man, but the questions we must ask ourselves are, what is his association with the doctor and what are they both doing at a lonely farm on Dartmoor?”

Bertie answered. “From the gents we saw in bandages I’d say there’s a spot of plastic surgery going on.”

“That’s what it looks like. If that’s correct, who are these men being operated on?”

“How do we find that out?”

“That,” replied Biggles getting up, “is what I am now going to ask the Chief. It may mean a search warrant, and it’s for him to decide if we’re justified in applying for one.” He went out.

He was away for some time, and when he returned it was with Inspector Gaskin of the Criminal Investigation Department. “We’ve moved a step farther,” he told the others. “Gaskin tells me that two years ago Doctor Bentworth was struck off the Medical Register for improper practices; which means that officially he can’t practise his profession. That being so he can’t legally be running a nursing home on Dartmoor—with an ex-criminal solicitor in charge.”

“Then what can he be doing?” asked Ginger.

“That’s what we are going to find out. The quickest way will be to go to Dartmoor, ask some questions and have a look round. Gaskin may recognize someone. He has a search warrant should it be necessary. The ideal thing would be to arrive when the doctor is there. It’s too late for that today so we’ll slip down early tomorrow morning, that apparently being the usual time he makes his visit. We might as well fly down. If one Auster can land so can another. We’ll leave it like that.”

* * *

Shortly after daylight the next morning the police Auster was cruising high in the air within sight of the club airfield at Longborne. As this called for only a slight detour from the direct course for Dartmoor Biggles had decided to look at it on the way. It had proved worth while, for a hangar door could be seen open, and on the tarmac, airscrew spinning, an Auster.

“There he goes,” said Ginger, as the machine left the ground.

“Capital. We’ll go with him,” answered Biggles. “I’ll watch where he lands and follow him in.”

“If he spots you trailing him he may not land,” said Gaskin.

“With the glare of the sun in his eyes if he looks back he won’t see anything.”

Nothing more was said. It was soon clear that the leading Auster was on a direct course for Dartmoor. Biggles kept well behind; with the visibility near perfect there was no risk of him losing his quarry.