* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Young China

Date of first publication: 1927

Author: Lewis Stiles Gannett (1891-1966)

Date first posted: November 6, 2023

Date last updated: November 6, 2023

Faded Page eBook #20231107

This eBook was produced by: Mardi Desjardins, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

This file was produced from images generously made available by Internet Archive/American Libraries).

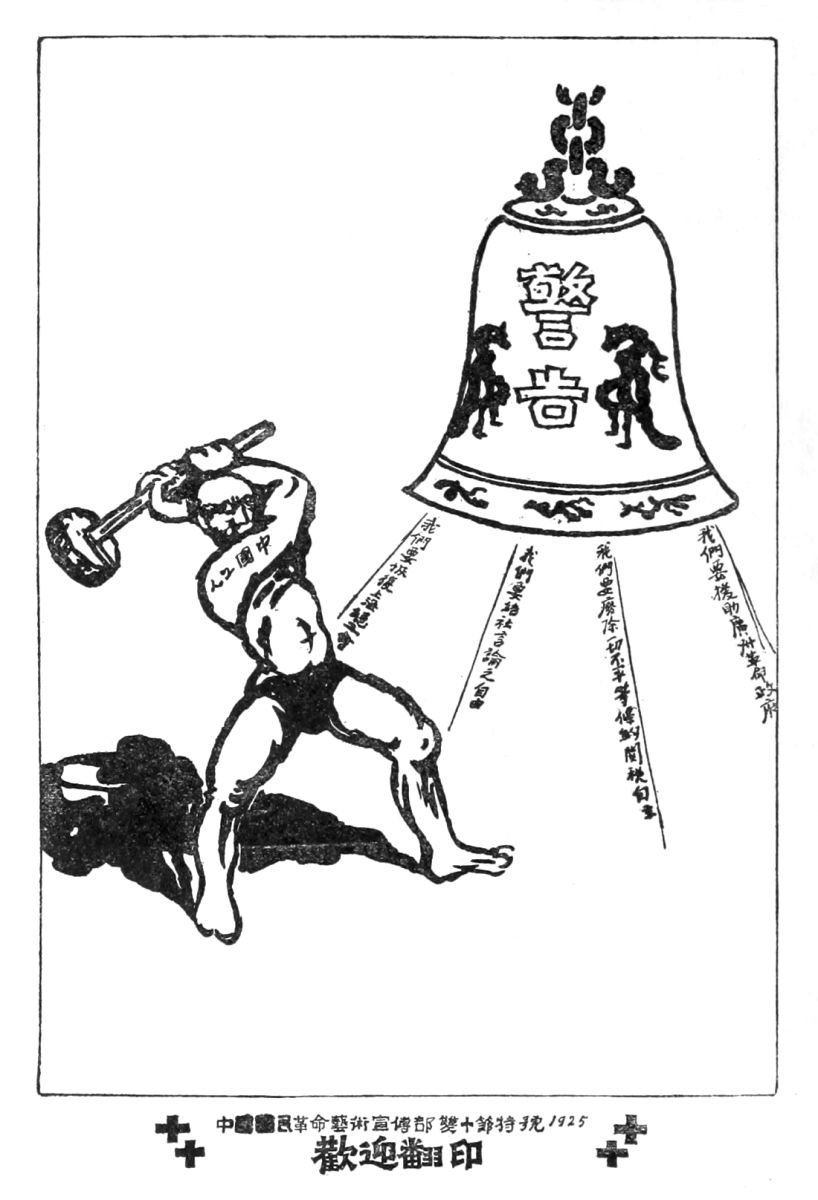

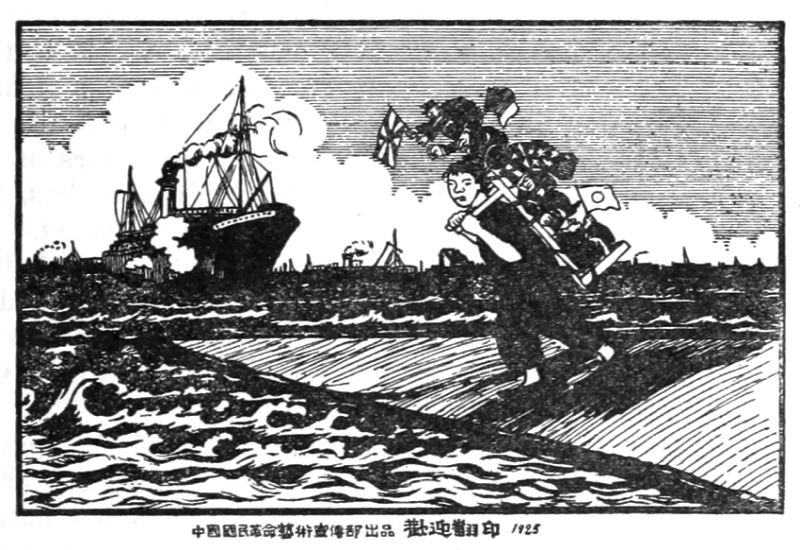

Poster from a Peking Wall.

The characters on the man’s arm spell Workers; those on the bell, Alarm. The strokes from the bell are (1) Restore the Workers’ Federation in Shanghai; (2) We want freedom of speech and assembly; (3) Abolition of unequal treatises: Autonomy of Customs; (4) Support the Canton Government.

That a permanent solution of China’s troubles can come in any immediate future is unlikely. The causes lie too deep. China has moved too far into the twentieth century for any single despot to be able to unite her and rule her with an iron will. The well-meant efforts of various foreigners since the revolution to aid one strong man to dominate the country have only aggravated the immense difficulties of the situation. China is emerging from a patriarchal, stable, medieval civilization into the restless, changing current of the new industrial world. Industrialism has touched her only here and there, but it has destroyed the old equilibrium and upset the old balances, and the present civil war is revolutionizing China, breaking up the ancient stability of the local units, destroying that devotion to the past which was rooted in local customs, local bonds, and local divinities, teaching the Chinese to work together in masses—and creating that national consciousness which China has hitherto lacked.

The nationalism which has found its military and political expression in the Canton movement will take years to work out its destiny. Its immediate goals—to defeat the Northern militarists, to drive out the foreigner from his position of privilege—are simple compared with the larger movement. What kind of new China it will organize, what effect it will have upon the colonial organization of the world, remains to be seen. For the present it needs more patience than the West is wont to give, and more time—time for the new generation to grow into responsibility, time for China to adapt herself to the twentieth century. To expect peace and law and order from a continent which is trying to compress a thousand years of political and economic history into ten is absurd. The following pages are an effort at sympathetic understanding of that enormous process—products of a winter in China as correspondent of The Nation—and are, with the exception of a few paragraphs from an article in Asia and one section from the New York Times Sunday Magazine, a development of articles and editorials which have appeared in The Nation.

| Contents | ||

| Foreword | iii | |

| I. | “Unchanging China” | 1 |

| II. | A Nation of Anarchists | 6 |

| III. | Americanization? | 9 |

| IV. | The Missionaries | 13 |

| V. | China: the World’s Proletariat | 18 |

| VI. | Canton—Nest of Nationalism | 23 |

| VII. | The Canton General | 28 |

| VIII. | Bolshevism? | 32 |

| IX. | America in China | 37 |

| X. | From The Nation’s Editorial Diary | 41 |

Occidentals enter China at Shanghai, the greatest of those hybrid Eurasian cities known as “treaty ports” and, in some eerie way, the most unpleasant city in the world. Here, in what was once a swamp outside the city walls, white men have built the greatest trading city of the East. The old Chinese town is only a suburban slum today; what men call Shanghai is the foreign city, the “International” (British) and French Settlements along the river front. Here, under European flags and protection, the business of China is done.

It is a mighty city that the white men have built upon the banks of the Whangpoo. Broad paved streets; massive stone buildings, as gloomily vast and permanent as any in London’s City; clanging street cars, electric lights in imitation of Broadway; gas, running water, sewers, all the trappings of Western civilization that are so uncomfortably missing in most of China. Automobiles clog the streets; the telephone system works in English; the pretty river-front park is “reserved for the foreign community.” (Shanghai is politer today than when the sign read, “Chinese and dogs not allowed.”) For miles factory chimneys cloud the sky; here, as in the West, men work in droves of thousands. Here, if anywhere, the West seems to have made itself at home in the East.

Yet ten minutes, even in times of calmest peace, in this smoothly functioning city give one a panicky realization that it is neither Europe nor Asia, but something precariously balanced between them. Among the autos dodge swarms of ricksha coolies, clad in every imaginable combination of blue cotton rags, some barefoot, some straw-soled, many naked to the waist—all running, sweating, panting. There is almost no horse traffic. Men—and sometimes women—pull the carts. Watch them—each at his rope, six or eight to a cart, straining up the bridges over Soochow Creek, and you will realize the human meaning of the simple phrase, “Labor is cheap in China.” Nor is it white men who crowd the sidewalks. Oriental figures—a few in ugly Western felt hats, coats and trousers, more in skull-caps and stately long silk robes—make up these sedate throngs. And at every bank, club, hotel, office-building a huge black-bearded turbaned Sikh stands guard, ready to cuff out of the way any saucy yellow man.

In Shanghai, as everywhere in China, one is impressed, and often oppressed, by the sense of the crowd. Here men teem; they swarm; the individual seems as insignificant as a single ant in an ant-hill. No one knows how many human beings live in Shanghai, for the native cities that cluster about the foreign settlements have never been adequately counted; but in the foreign cities alone there are a million and a half Chinese and only 40,000 foreigners, of whom more than half are of races ineligible to citizenship in the United States. The Chinese form 97 per cent of the population of the cities which white men govern; they pay 80 per cent of the taxes; but they have no share in the city administration, their children cannot play in the city park, and if they want to send their sons to school they must pay for it themselves. Most of the foreign clubs (the American Club is no exception) do not admit Chinese even as luncheon guests; the line between white and yellow is drawn as sharply as that between black and white in Georgia; and one ends by understanding the bitter fear psychology of the tiny oligarchy which has built this city, is proud of it, and wants to retain it as a white citadel in a country of 400 million yellow men. One ends, too, by hating Shanghai; no one, foreigner or Chinese, can feel at ease there.

* * * * *

Life is warm and intimate in the narrow old streets of Hangchow. In one shop open broadly to the lane a whole family, from seven to seventy years old, sociably weaves baskets; another family saws wood with ancient Chinese saws, and makes the product into furniture; in a third shop bronze bells are being cast; and across the street one family is making brooms, another idols, a third coffins. They live so close that their lives are interwoven, as is their conversation. No stranger passes but they all note him; no accident but all share in the distress and laughter. The hours are long—indeed, there is no respite except for food and sleep—but there is little strain; work and play are intermingled.

One suddenly becomes aware that this is the Middle Ages. The carved wood railings of the second stories; the richness of color and sound and smell (most of the cooking is done on the street, and the little restaurants send out a rich cargo of Oriental odors); the beautiful shop signs—vertical strips of painted wood inscribed with gilded Chinese characters—this must be very like the medieval back streets of those European cities which still preserve their proudest squares to remind us of what guild life was before the days of factories and efficiency.

Through the narrow streets dodges an endless line of ricksha boys, while the occupants strike little foot-bells to emphasize the musical shouts with which the boys warn of their coming. It seems very ancient, very Oriental. And then one learns that the first ricksha came to Hangchow fifteen years ago, imported from Japan for an American missionary, and that the ricksha itself is a missionary invention only fifty-odd years old. It dawns upon one that China can change, has changed, is changing. There must be thousands of darting ricksha boys in Hangchow today; fifteen years ago the mandarins rode in sedan chairs and the merchants walked. One is no longer surprised to turn the corner from these handworkers’ shops and find, behind high white walls, a great modern silk factory, where thousands of trousered Chinese girls work thirteen hours, and earn, if they are very skilful, almost twenty-five cents a day.

* * * * *

Long before Shanghai Canton, far to the south, was opened to foreign trade. It has been the center of half a dozen wars and near-wars with the “foreign devils,” but by some miracle, which may have its root in the vigor of the Cantonese character, it has maintained its Chinese soul and its Chinese rule. It is proudly tearing down the narrow lanes and opening wide avenues; it razes temples and creates schools; it has its own traffic police and a municipal sprinkling-cart; it even has a ten-story department store, hotel, and moving-picture palace on the Bund (built by a Chinese peanut vendor born in Australia); but it has not succumbed to the West. Stand, if you doubt it, at the South Gate of a morning and watch the long lines of coolies pass out, bearing, trembling from the tips of bamboo poles, great slopping vessels which contain the night’s human refuse without which the Canton delta, the most densely populated region in the world, could never maintain its ancient and intensive agriculture. Or watch the life of the river.

Ocean steamers come up to Canton, but anchor in mid-stream. The sampans, bobbing on the water with their long and short oars, do the rest. Tens of thousands, perhaps hundreds of thousands, of sampans line the shores and dot the river for miles. People are born on them, live their lives on them, die on them. Women with tiny babies on their backs pull at the oars; solemn-faced children a year old sit like silent dolls watching their mothers row. Two- and three-year-olds scamper recklessly from boat to boat; at four or five they help their mothers with the oars. Some sampans carry passengers, others cabbages, pigs, silk, kindling-wood, offal, whatever comes to hand. They go where destiny sends them, and tie up where night finds them—fifteen- or twenty-deep against the river bank. River-folk do not need to go ashore for food; itinerant vendors ply their wares in and out of the narrow fairways, between the masses of sampans, selling cotton cloth, charcoal, bean-cake, rice over the gunwales—the woman working the oars while the man tinkles a bell and sings his wares. They drink the filthy river water and deposit their refuse there—Arabs of the waterway, they know no other home.

For centuries they and their ancestors have lived thus—have watched the first Western ships sail in, seen iron replace wood and steel iron, watched the coming of steam and of oil fuel—and their lives go on unchanged. So it seems. But already a score of motor launches snort up and down the river, doing the work of several hundred Sampans; at Whampoa, nine miles downstream, where the cadets were trained who led the Northern advance of Canton’s Nationalist army, modern docks are being built. Men on strike against British Hongkong dug a road to link Canton and Whampoa; and if ships come alongside and discharge directly what will become of the sampans? The city has an electric-lighting plant, and there are plans for supplying power looms to the home workers who spin silk on Honam Island, between Canton and Whampoa. Already modern-minded Chinese have destroyed the independence of Honam’s silk industry and developed an efficient modern sweatshop system of exploiting home workers.

* * * * *

Men and camels seem like midgets filing along beneath the colossal walls of Peking—walls so vast and powerful that the gates can still be shut to bar out an invading army. The red and gold doorways of the dusty gray lanes of the Tartar City; the bold red walls and the smoldering fire of the glazed tile roofs of the Forbidden City within; the yellows, the blues, the greens, the gleaming contrasts in the painted beams; the vast, perfect proportions of a metropolis laid out as a unit—Peking has something of the grandeur of Rome, the glory of Greece, the charm of Paris, and is the Eternal City of China.

So-called. But in reality Peking is no more eternal than Carthage or Ur. It is already half dead. It was only half a century ago that the “Old Buddha” built the marvelous gardens known as the Summer Palace (to replace still more marvelous gardens sacked by the Vandal British and French, in the Second Opium War), with the infinite richness of old China—the long painted wood gallery, the white marble camel-back bridge, the strange piles of lovely buildings that climb the mountainside. Yet the Summer Palace is already archaeology. It is a museum, a relic of a past that can never be again. If you look for unchanging China, do not seek it in the magnificence of an empire that is gone forever—go to the Chinese village.

* * * * *

In North China the drab villages, built of brown mud bricks, roofed with brown mud, sink colorlessly into the brown mud plain. You do not realize at once how many of them there are. Only a mile or two separates one cluster of houses from the next. But these villages have no shops; they buy and sell at the market-town, and it may be twenty miles from one market-town to the next.

The market-town of Yenchiu is only seven miles from Tung-chow and the railroad, but the seven miles make a breach of centuries. You cross the Grand Canal on an ancient ferry propelled by three wild-looking ruffians with poles, and join the parade of overladen donkeys, rickety horse-carts, and warmly padded Chinese. The road is just a rut across fields of winter wheat, sometimes across nothing but blown sand. It seems to stray and wander aimlessly, finding its true course only in the villages, where the commerce of centuries has worn the roads deep beneath the level of the farmyards. For these villages, rebuilt every few years out of the eternal brown mud, have histories that antedate Charlemagne.

Yenchiu is just one market-town among tens of thousands scattered over the continent that is China. It is big enough to hold two inns, where a Chinese traveler may lodge for about one cent a night; half a dozen herb drug-stores; a wine-shop; two blacksmiths, a draper, four rice merchants, a silversmith, a pewter-shop, a saddler, a salt-dealer, the inevitable vast pawnshop, and a “foreign-goods shop.” Probably it has had most of these since the remote day in the Sung dynasty, a thousand years or so ago, when the town’s first mud wall was built. The “foreign-goods store” has only two foreign commodities—cotton thread, from Japan; wire nails, from America. “We used to make our own thread,” they will tell you; “but the foreign thread was so much cheaper that we stopped; now the price has risen, but we have forgotten how to make our own.” Tobacco and oil, universal in China, of course come from abroad. The cotton goods are of local weave. In the old days, the blacksmith remembers, the coal came down from the Western Hills by camel; now he uses Manchurian coal mined by the Japanese. The iron used to come from Huai-lu on the border of Shansi; now it, too, is Japanese. Apart from that Yenchiu lives as it has lived for centuries—each of the mud-walled villages about it grows its own crops, makes its own products, and takes its goods to the market-town of Yenchiu, there to exchange them for the products of another village. Civil war a hundred miles away hardly touches them.

Coal and iron and cigarettes and kerosene have done little to disturb the minds of these villages. Shingtu, five miles away, boasts two village scholars, one so advanced that he has a daughter studying medicine in far-away America. He is the only man in his village who has ever sent a child away to study; his is the only family that does not bind its daughters’ feet; yet old Yang, scholar and head-man of a village twenty-five miles from Peking, did not know what were the “unequal treaties” that had fired the youth of the treaty ports, caused riots, and put China on the front pages of newspapers in cities ten thousand miles away.

China is an anarchist’s heaven. There is hardly a government worthy of the name; people seem to be happiest where there is least government; and the worst evils of Chinese life obviously spring from the attempts of misguided people to govern her. Where would-be rulers are missing, China does well enough. Go out into the country districts, and you will find the Chinese living much as they have lived for thirty or forty centuries, blissfully unconscious of the necessity for the elaborate paraphernalia of Western law and order.

“It was the appearance of sages,” one of China’s wise old men wrote twenty-odd centuries ago, “which caused the appearance of robbers. . . . The people were innocent until sages came to worry them with ceremonies and music in order to rectify them, and dangled charity and duty to one’s neighbor before them in order to satisfy their hearts—then the people began to stump and limp about in their love of knowledge and to struggle with each other in their desire for gain.”

We of the West can never, I think, understand China, until we recover somewhat from our respect for political institutions and grasp the idea that government is not an end but a means. We are accustomed to thinking in terms of law; the Chinese are not. They have a magnificent contempt for political government, and a fundamental instinct for getting along with one another on a basis of custom and reasonableness which confounds the foreigner appalled by their political chaos. It may be inevitable that we shall force respect for government and written laws upon the Chinese, along with Western efficiency and mechanical ingenuity; but China’s ability to get along in apparent anarchy is really evidence of the profundity of her civilization. Chuang-tzu was right when he said that “ceremonies and laws are the lowest form of government.” China would be in far worse condition today if she had not acquired through the centuries a considerable immunity to the ravages of political misgovemment.

A peasant in West China does not care whether the government in Peking is republican, or monarchist, or soviet-revolutionary, as long as he can harvest and sell his grain in peace, and it would not occur to him that the manner of government could affect the price of grain. He knows that he can deal with his neighbors without a government. Only when men fighting for political control rob his farm-yard, conscript his sons, and ruin his fields is he disturbed. Until the robbers reach his land he watches serenely the coming and going of governments. He feels no need, neither he nor his ancestors has ever felt the need of government. And China is so vast a continent that she can support a dozen local civil wars and still leave most of her population to toil in peace, undisturbed by rackets and roars which often loom larger in the pages of the New York and Paris newspapers than they do in the village life of the bulk of China.

It is possible to paint a ghastly picture of the chaos in China today—and it too will be true. The “Peking Government” is a farce—its writ does not run beyond the walls of the capital, and even within the city the military men defy its orders and collect illegal taxes despite its feeble protests. Chang Tso-lin and his satraps rule Manchuria, Shantung, and Chihli Province, within which the capital lies. Feng Yu-hsiang’s lieutenants hold the Northwest territories as an independent nation. Wu Pei-fu and Sun Chuan-fong, recently great semi-independent rulers, have been reduced to impotence; the Cantonese Nationalist Government gives not even lip-allegiance to Peking, and boldly proclaims itself the true Government of all China; Szechuan in the West is divided between several rival forces; and in far-away Yunnan a local potentate rules almost unconscious of any outer influence except that exerted from the south by France. All the tuchuns and tupans are more or less continuously at war with one another, in variously shifting combinations.

This civil war in China, while relatively courteous—the forces fighting in North China, for instance, frequently declare a temporary armistice during a particularly bitter spell of cold weather—levies a deadly toll on the working population. They pay in taxes, sometimes collected by force for years in advance, in lost work, and in higher prices. Two years of civil war raised the Peking price of millet and kaffir corn (grains much used by the work-people in North China) to an extent which, it is estimated, meant an increased cost of living for a working-class family of $4.50 (gold) a month—an appalling sum in a country where many people earn no more than that. The loss of commerce in North China alone in the sixteen months of civil war ending with December, 1925, amounted to nearly $400,000,000—more than the entire cost of construction of all China’s five thousand-odd miles of railways.

Shantung’s military governor frequently commandeers every freight car in the province for troop movements, leaving not one for commerce—and even in peace times none is available except by payment of an extra “squeeze” of $50 per car. For months the British-American Tobacco Company moved its goods by ox-cart from Tientsin to Peking, over a bad dirt road which parallels a good railway line—because the military had other uses for the freight cars. National universities are months in arrears on faculty salaries.

One could continue this recital of chaos and calamity almost indefinitely. But China is for the most part organized on a medieval village economy which enables her to withstand buffets which would destroy a more developed nation. She suffers most where the foreign-built railways and foreign machinery have upset the old economy and made the country dependent on the cities and their trade. There is no railroad from Canton to Central and North China, and Canton Province—which is itself a nation with more inhabitants than Great Britain or France—can suffer wholesale civil war without affecting other provinces at all. Fighting in North China leaves Shanghai almost undisturbed, and a war in Kiangsu hardly ruffles Peking. Ten miles off the lines of march of contending armies the peasants plow their fields and tend their cabbages in peace.

Even the most modern industrial centers have a local vitality that amazes one accustomed to the intricate interdependence of our Western economic structures. Whenever Canton gets a six months’ respite from local wars she begins to tear down houses in her picturesque narrow lanes and substitute wide modern avenues, to build more horse roads, to prolong the roads into the country, to develop a system of Ford buses; far-away Chengtu in war-ridden Szechuan does likewise; Hangchow, near Shanghai, has transformed itself during a period of civil wars. All over China local communities are building roads, installing electric-light plants, telephone systems, fire companies, even sprinkling carts. While civil war obscures the newspaper horizons the industrial revolution quietly takes its course. Power looms are installed; the small-home unit of production gives way to larger units; sweatshops, small factories, large factories develop like mushrooms. In the same months in which the North China railways, due to civil war, lost $400,000,000 in trade, the number of Chinese-owned cotton mills in all China (mostly about Shanghai and Tsingtao) jumped from fifty-four to sixty-nine, the number of looms from 8,500 to 16,400, and the number of spindles from a million and a half to almost two million.

China is not a modern nation; she is a civilization, a continent bursting out of the Middle Ages. Each of her twenty-one provinces is bigger than most European nations. Canton alone—although the customs receipts are still sent away to pay interest on the foreign loans—has a normal monthly revenue larger than that of many European nations. And a continent can survive civil wars as a nation cannot. The Thirty Years’ War devastated Germany, but France and Italy attended to their own business relatively undisturbed.

Two or three Greek temples, a few structures with traces of Gothic inspiration, and a miscellany of imitation warehouses and factory-buildings stand on the campus of the Chinese government university in Nanking—an architectural hodgepodge worthy of an American State university. Half a mile away are a group of magnificent buildings with heavy black overhanging roofs curling skyward at the corners, carved banisters, and richly painted paneled ceilings, redolent of old China. They are the lovely Asiatic shell of a Christian mission college founded and supported by American Methodists.

That is typical. In fifty years the great port cities of China will have left hardly a trace of the lovely old Chinese architecture—except in the mission-college buildings and in the few joss temples which will doubtless be preserved to gratify the tourist trade. The foreign mission schools, hurriedly Chinafying themselves to meet the nationalist attack, are spending tens of thousands of dollars in adapting the old Chinese style to modern requirements. The sweeping green roofs and gaily painted beams of the Peking Union Medical College, built with Rockefeller money, are a joy to the eye. Nanking University and Ginling College for women near by are good to look upon. But in four months in China I saw only one beautiful recent building which did not owe its existence to foreigners—the Returned Students’ Club in Peking, a remodeled temple; and there the students may be suspected of having learned abroad their respect for old China.

Shanghai is a great British city, of solid British masonry; Tientsin is as foreign; even Canton, which has providentially escaped the curse of great foreign settlements, is enormously proud that Chinese have actually built a ten-story building on its Bund without foreign aid; and Canton’s new buildings are as foreign to China as any suburb of Cleveland, Ohio, or Birmingham, England. Peking, a capital of politics rather than of commerce, resists the current most effectively.

You can buy Standard Oil kerosene in any village in China, and British-American cigarettes. The great corporations behind those products have in a generation taught the Chinese to change their habits in order to make them buy—the Standard Oil, indeed, used to give away lamps in order to create a market for the strange new fuel. If any third foreign product is on sale in the village it may well be Wrigley’s chewing gum. I saw Spearmint gum on sale in the streets of Urga, the capital of Mongolia, 700 miles across the Gobi Desert from the most accessible railroad.

Architecture and chewing gum are outward symptoms of a profound inner change. Western architecture is spreading because it is cheaper. Gum and tobacco cost less than opium. Only American church-people can afford painted paneled ceilings and bright tile roofs with gargoyle corner ornaments. The Chinese—like the Europeans, like the whole world—are abandoning old beauties and old customs for cheaper and more efficient models. They are becoming modernized, standardized, Americanized, like Japan. Mystery, leisure, charm are ebbing; cost accounting is defeating tradition.

The cult of the efficient seems a matter of course to most Westerners and almost all Americans, but to the Chinese it is a revolution. Old “China-hands” will laugh at the suggestion that it has touched Chinese psychology—but old China-hands need a vacation and a perspective. The Chinese has for untold centuries followed tradition and has believed that it was wicked to deviate from it. His young men and young women are beginning to despise custom and tradition; and his middle-aged business men, almost unconsciously, are beginning to ignore it. It was only forty years ago that the first railroad tracks laid in China were torn up by superstitious officials; today they are an indispensable instrument of civil war, as is the once-despised telegraph. The only opposition to them comes from Westernized Chinese who know how easily international politics slips into an engineering contract. Once a contract is let, there is no longer much difficulty about arranging to remove the graves that beset all the short cuts. And a wanderer through the black lanes of an old Chinese city may be surprised to discover that the squeaky Chinese music that wails to the night is produced not by a stringed instrument but by a Victor record.

Foreign railroads, manners, oil, and architecture are prevailing because they are more efficient. American wheat, when it costs a dollar a bushel in Chicago, can be landed in Hankow, ten thousand miles away and six hundred miles up the Yangtze from Shanghai, cheaper than it can be brought from Shensi, only a thousand miles away, where it may sell for twenty-five cents. Railways and steamships make the difference; no wonder they and their products are breaking the crust of old China. Foreign clothes have made less progress because, in cold weather at least, they are less efficient than the old Chinese robes. Foreign hair-dressing—including the bob—is making its way among the women. Curt foreign manners are replacing the leisurely old Chinese courtesy. The streets are being widened, and the intimacy of the old Chinese workshop, opening on a narrow street and aware of all that its neighbors said and did, is disappearing. Foreign machinery is revolutionizing Chinese industry. Foreign ideas—and the railway, taking the young people away from their homes to study and to work—are breaking up the immobile unity of Chinese family life upon which the whole structure of Confucian ethics is based. Boys go away from home to study, and refuse to return to the wives of their parents’ choice. In the port cities one meets sad young men who are homesick for New York, prefer foxtrotting to Mah Jong, and inquire eagerly about the Charleston.

Chinese, with their habit of explaining everything by thousand-year-old parallels, will tell you that there were student revolts in the Han dynasty, before Christ was born. The nationalism of the student movement today, however, passionately denouncing foreigners and all their works, is essentially a part of the cult of Western efficiency. This political nationalism, this conception of national sovereignty as a precious right to be cherished and preserved, has its roots in foreign education and practice—in part in Allied war-time propaganda. The old Chinese patriotism—a patriotism profounder than anything known in the West—was cultural rather than political, inclusive rather than exclusive. It was a loyalty to a civilization rather than to a state, conservative rather than aggressive. It was powerless to halt the intrusion of Western men and methods into the political and economic control of China, and was satisfied because the Westerners were so obviously inferior in the refinements of living. The Chinese students of today belong to our flapper generation; flaunting their posters and banners, parading by thousands against the unequal treaties, and making soap-box speeches about self-determination, they express contempt for the passivity of their elders. Theirs is not the language of old China but of the young West. When it defies us most violently young China is most certainly expressing its determination to be like us.

And this young China has a significance beyond its years. There are no middle-aged men in modern China. There are grand old men, survivals of the old regime; and young men, fresh from Western education. The old men cannot adapt themselves to the swirling changes; the young men are forced to act beyond their capacities. “It is unfortunate for men of talent to be born in China today,” Hu Shih said to me once. “They get too far too easily; they are pushed rapidly to responsibilities beyond their powers—and they are done. Wellington Koo would have been a splendid permanent under secretary of the Foreign Office—he becomes prime minister; Wu Pei-fu an excellent division commander—he has to try to be a generalissimo; two years after I returned from America a newspaper straw ballot declared me one of the twelve greatest living Chinese! When you have made a reputation you have to do one of two things: live up to it or live on it. In the first case, you are ruined physically; in the second, you are ruined morally and intellectually. You try to be a great man; you try to do too many things—and you break.”

Boys out of college perforce assume jobs fit for men of mature years; college students do the work done in the West by men in their thirties; and mere high-school lads do a task of political agitation for which we would consider college men unripe. They do it badly enough, but there is no remedy; the twentieth century will not wait, and the work has to be done. The foreigners, safe in their compounds, complain that the boys are losing their schooling; but the students know that they are making a new China.

An old Chinese maxim said “Be old while you are young.” In the West, Chen Tu-shu told his Peking students, we say “Stay young while you are growing old.” Chen, like many Chinese, exaggerated our virtue, but it was a lesson old China needed. Without the iconoclastic students Sun Yat-sen’s long years of revolutionary activity would have been vain; the students poured their souls and blood into the Second Revolution that seemed to fail in 1913; and it was the students of Peking who, in 1919, overturned a rotten and corrupt government, aroused a sodden nation, and forced a surprised delegation at Paris to refuse to sign the Treaty of Versailles which confirmed Japan—for three short years—in possession of the sacred province of Shantung. It was a group of just returned students who, in the preceding two years, had laid the foundations of a greater revolution by exalting the spoken language of the people, decrying the artificiality of the old written language of the scholars, thus opening the way for a great germination of mass education. It was a student demonstration in Shanghai which, silenced for a minute by police-guns, touched the spark that set the Chinese nation aflame in 1925 with a fire which is still scorching the proud British Empire. It is in the mere children who leave their classes for what seem futile patriotic parades that China’s hope lies.

An Asiatic scholar, asked how the East could preserve its essential Orientalism while suffering industrialization, replied: “I don’t think there is anything peculiarly Oriental and Occidental. There is merely medieval and modern.” The great force which has maintained China’s identity through fifty centuries is her worship of the past, but the mechanical superiority of the present has already proved its power to defy that ancient citadel. And as the other civilizations of antiquity crumbled when their beliefs decayed, so the old China is yielding to the new West. What happens in the port cities of China today will happen throughout China the day after tomorrow. The feverish, abnormal life of those cities has a significance out of all proportion to their share of China’s four hundred million people; the rest of China too will adopt the Western—or modern—method of working hectically while it works, and of playing madly while it plays; it too will forget the Chinese—or medieval—knack of combining work and play so that long hours seem short. The port cities are a hint of China’s tomorrow.

You see a blank high wall breaking the monotony of the swarming close-built Chinese street; you enter a gate, and suddenly find yourself in a miniature Main Street. There are the square-set homely houses, the ample porches, the trees and green lawns, the comfortable space and leisureliness of Any Town in the U. S. A. There are romping white children in relatively clean, neatly darned clothes; the familiar smells of American food float out of the kitchen windows. It is the missionary compound. Large and small, there must be a thousand of them scattered through the cities and villages of China. They are the centers of the greatest foreign propaganda scheme in history; neither George Creel nor the Bolsheviks ever, in numbers, in money spent, or in system and method, approached them.

There are some 8,000 missionaries in China, and of these more than half are Americans. An extraordinary missionary atlas entitled “The Christian Occupation of China,” which in a series of graphic charts portrays the invasion of this alien group, reports that whereas in 1907 37 per cent of the foreign missionaries in China were American and 52 per cent British, by 1922 the proportions had been precisely reversed. This Americanizing tendency is increasing, because America is now spending ten million dollars annually on mission work in China, and no other country can afford a tithe of that sum. Even the Catholic missions are passing from French to American control. Increasingly, the missionary invasion of China is an American campaign, conducted by Americans, with American methods of statistical efficiency, gymnasium camouflage, mass-advertising propaganda, and Rotary Club enthusiasm. Some two and a half million Chinese now call themselves Christians; more than 200,000 children daily attend the 7,000 Christian missionary schools, while 2,000 young men and women are in Christian colleges; and the 330 Christian hospitals with their 18,000 beds form the bulk of the decent hospital facilities of China.

Now, I have never liked missionaries. My Unitarian-Quaker upbringing predisposed me against the militant conquest of souls, and I grew up increasingly skeptical of all those things of which a Christian missionary should feel most sure. It seemed to me that all religions were attempts from various angles to scale a mountain which reaches beyond the capacity of the human mind and that they fill in the unknown and unknowable with more or less satisfactory legends; that the function of the missionaries was to supplant native superstitions with unnatural alien superstitions, paving the way for the denationalization of their victims. Certainly I have never felt that more vividly than when I watched an enthusiastic Minnesotan teaching patient Chinese boys to sing a hymn—which they could not possibly understand—about the “blood of the lamb”; or when I sat through a colorless church service in Chinese in a bare little barn of an American mission church stolidly planted in a colorful Oriental city.

But . . .

What are the missionaries there for? The radicals of China say they are making the way easy for the imperialist-conquerors; the Russians regard them as propagandists for capitalism; the foreign business men say that the missionaries are just stirring up trouble, putting fool ideas into Chinese heads; the old-fashioned circuitriding missionary says they are there to preach the word of Jesus Christ; and the younger generation talk in terms of sanitation, modern schools, improved agriculture, and social work.

In their way all are right. China has missionaries of every description, from the devout Inland Mission workers who used to wear queues and still go about in Chinese costume, living on the rice diet of their congregations, the passionate fundamentalists who preach Christianity exactly as they learned it in tight little American villages, foreign patriots who identify their religion with their nationality, to medical workers who have forgotten creed in healing, teachers who are so absorbed in China that they remember America only when they have to ask for funds, community leaders who belong to the race of Jane Addams and Lillian Wald, and thinkers who have climbed to heights beyond the walls of any single religion. They are all there, and on the whole they are considerably more liberal-minded than the people who support them at home.

These red-hot years have taught the missionaries things about themselves that they had never known, forced movements that had been long in germination to bloom early. New buds appeared upon the branches which the gardeners at home had never suspected were there. Every anti-foreign outbreak seems to work changes in the missionary garden. “Rice Christians” who join the churches for what they can get out of it drop away; and the missionaries learn in blinding flashes what parts of their work have sunk into Chinese hearts and what have not. Some of them suddenly realize how far they have moved since they left home, how much more they care for China than for any form or creed. Others return to tamer tasks.

Historically, of course, the radicals are right. The stain of blood and lawlessness lies on the missions in China. The first American missionaries went to China as the illegal guests of a trading firm; and missionaries helped draft, after the First Opium War, the treaty that established extraterritoriality and gave mission work its treaty basis. Nor did those early apostles heed the treaty terms; long before the Second Opium War forced new concessions from China they made their dangerous way into forbidden cities. As recently as 1897 the death of two missionaries was used as an excuse for the great international grab game in which Germany took Tsingtao, Russia Port Arthur, Great Britain Wei-hai-wei and the Kowloon new territory, and France Kwang-chow-wan. Today American and other foreign gunboats penetrate a thousand miles and more into the interior of China upon the excuse of “protecting missionaries.” However many the missionaries who have come to regret this association of Christianity with the foreign gunboat, it is natural that angry young nationalists should call the Christian organizations and their officers the “hawks and hounds of the imperialists”!

Nor are the Russians so far wrong. Inevitably the missionaries are apostles of the economic system from which they spring. Whether they are conscious of it or not, they are advance agents of the business men from whom they buy. As one of their defenders put it:

The missionary home in the interior is a demonstration of Western life with the comforts and all the means the Westerner has used to give himself comfort. Were the merchant deliberately to make a great advertising campaign for the purpose of putting up a demonstration of Western materials in the interior for sales purposes, he could not put up any better display than the missionary has done gratis.

Naturally the simple coolie identifies the religion of the foreigner with his higher standard of living, and both with the system of production whence it arises. Too often the missionary makes the same mistake.

He is under fire, however, from both sides. The narrow-minded little business communities of China detest the missionary as much as does a Bolshevik; indeed they class missionary and Bolshevik together. For the new nationalism is a product of the schools, and many of the Christian educational leaders have fanned the flames of discontent. Christian students have been shot down along with non-Christians in almost every one of the bloody clashes of native and foreigners that dot the recent calendar. Chinese Christian leaders have sought to prove that they were no whit less patriotic than those who had not been contaminated by foreign religions, and many of the Western Christians in China have openly voiced their sympathy with the patriotic movement. Christian schools have celebrated the national days of mourning and have officially participated in the huge patriotic demonstrations. An increasing group of missionaries has boldly entered the forbidden sphere of politics and insisted that the spirit of Christianity requires abolition of the “unequal treaties.”

In the missionary body itself the debate has been hot and heavy. The missionary press reveals a profound ferment, a passion to justify faith by works. These men and women have seen their own converts and Chinese colleagues watching them with doubt and distrust in their eyes.

I have read scores of resolutions and hundreds of letters from missionaries all over China, and while there is many a voice to say, “Business enterprises would suffer most from abolition and we are dependent upon business men for a very large part of the means with which we carry on our work,” a commoner opinion is that “More is to be gained by letting it be known that we are preaching our gospel with no dependence upon gunboats or laws which give us special favors.”

Dependence upon gunboats and treaties was only one symptom of the alien arrogance of the old missionaries. They believed it their duty to impose Christianity, with all its Western forms, on China. They never stopped to question whether, man for man, we Western Christians were superior to the Chinese. The Christian schools began as Western schools, taught by Westerners, largely as bait for converts. But increasingly they have focused on education as an end in itself rather than upon conversion, and the junior schools have been going under Chinese control; in these last years of ferment the colleges too have had to look for advice and leadership to their Chinese faculties.

The change has brought some unlooked-for results. Two years ago daily chapel attendance was compulsory at virtually every Christian school in China; so were courses in religion. Today nearly half the higher schools have made both voluntary, and another year will see a change in the majority. The Government requires registered schools to eliminate compulsory religious instruction, to have a Chinese president or vice-president, and Chinese majority on the board of control, and to declare that the propagation of religion is not its purpose. The Chinese—faculty and student, Christian and non-Christian—want registration, which opens the road to government jobs for the graduates; and the foreign teachers, sometimes reluctantly, are following their lead. “It would be un-Christian for a school in China not to do willingly what the Government would enforce if it could,” says the president of Yenching University in Peking. And what modern government would permit a corps of aliens, teaching largely in a foreign language, propagating a foreign religion, to dominate its school system? The missionaries begin to see that soon they may not be permitted to give even voluntary courses in religion. “But we can make our education Christian by the spirit in which we conduct it even if we are forbidden to give any direct Christian teaching,” said President Burton. Schools like Lingnan University at Canton are doing that.

Slowly and impressively China gathers into herself the men and women who work there and stamps them with its own ancient civilization. I once argued for hours with an old missionary vainly trying to find some virtue in the Christian teaching for which he could produce no parallel from the Chinese classics. Missionaries who study Chinese thought acquire something of its tolerant eclecticism. The Chinese have never fought religious wars and cannot understand our emphasis on doctrines, our conviction that religions must be mutually exclusive. Our little sects mean nothing to them; if they accept Christianity they but add it to minds already deeply molded by Confucian, Taoist, and Buddhist teaching.

The old type of missionary who refused to show distrust in God by being vaccinated (the smallpox rate among missionaries in China is one hundred times that in the United States, and the typhoid rate is thirty-three times that of the American army) is fading into the hinterland. The new type is an emissary of athletic sports, of hygiene, of schools, of mechanics—needed in China, although incorrigibly alien. Even he may find his role declining; as in Japan, the number of foreign missionaries will fall, and the Christian church in China, if it continues at all, will have to represent a kind of Christianity as much modified by Oriental habits as what we call Christianity has been modified, in two thousand years, by our Western history. The permanent service of the missionaries is likely to be less in the religious field than as a bridge between two civilizations that had lost contact with each other. In the early days the missionaries forced contacts where they were not wanted; but they may somewhat lessen the frictions of tomorrow. Bringing science to the East as a gift of God rather than as an efficient aid to lower production costs, the missionaries may soften the harsh process of adaptation to the industrial West, and ease the break-up of the ancient family system which is an inevitable part of that inevitable process. Romantic lovers of the past will deplore that necessity; but history marches roughshod over romance.

In China the economic and nationalist struggles are inextricably intertwined. For China has the greatest cheap-labor supply on earth. It is good labor, too—and European capital, which at first merely bought native products cheap, has for two or three decades been attempting to install Western factories with Western methods to make Western products with the labor of China. When New England passed anti-child labor laws it exported its low child-size machines to China as well as to our own South, and the little girls of China are today competing with the children of our South Atlantic States. And in China this whole industrial system, whether the immediate employer be a Chinese or a foreigner, is rightly regarded as a Western importation.

The mills have sprouted like mushrooms along the coast and rivers of China. The first cotton mill came to China in 1890; there were 14 in 1906, with 400,000 spindles; 42, with 1,154,000 spindles, in 1916; 83, with 2,666,000 spindles, in 1923; and there is no reason to suppose that the number will not continue to double every six or seven years. China still imports the blue cotton cloth which has become the national uniform of her masses—a fantastic statistician once figured that China’s annual consumption of cotton cloth would pave a roadway sixty feet wide to the moon. And the workers in these mills live in a manner that would shame a self-respecting pig.

All about the industrial outskirts of the great Western city which is the pride of the foreigners in Shanghai one may see the disreputable sheds, built of bamboo, mud, lime, and straw. Six or eight people live in one-room floorless huts, through whose flimsy roofs the rain leaks in a storm; whose walls, falling or riddled with holes, afford no privacy. There is no drainage, no lavatories; garbage-heaps and cess-pools—or rather cess-puddles—surround the hovels. A big rain often floods the whole neighborhood, and the ragged babies wade about coated with mud and filth. In smaller cities, where the concentration is not so great or so sudden, conditions are somewhat decenter. But while a few enlightened Chinese talk of decentralization, the factory owners continue to build their prisons in the overcrowded centers where they can be sure of coal and raw materials—Tienstin Tsingtao, Shanghai, Hangchow, Wusih, Hankow, and the rest.

Wages are desperately low. They can best be understood when translated into goods. A Shanghai cotton-mill worker would have to work two weeks to buy a hat; longer to buy a pair of leather shoes. A pair of sheets would cost a month’s wages, an overcoat three months’ toil; a daily paper one-tenth of the daily income; a ton of coal four months’ earnings. Of course these industrial workers do not use coal, wear hats or shoes or overcoats, or buy newspapers—they live on a lower level. And yet these wages seem high to Chinese of the coolie type; there is no dearth of labor. It flocks in from the country, constantly replenishing the worn-out supply, for the working life of a Chinese mill-hand is generously estimated at from two to eight years.

In the cotton mills and silk filatures (where silk is reeled from cocoons which bob up and down in basins of boiling water) the vast majority of the workers are women and children. Men complain that they are discriminated against in Shanghai, which is true, largely because they are more likely to form labor unions and strike. The Shanghai Child Labor Commission found in 1923-1924 that of 154,000 workers in the mills it studied more than 86,000 were women and more than 22,000 were children under 12. (It is worth while noting that in the Japanese-owned mills of Shanghai only 5.5 per cent of the workers were children under 12, and in the Chinese only 13 per cent; while the British mills had nearly 18 per cent children and the French and Italian 46 per cent. The few American mills had a slightly lower percentage than the Chinese.) In the silk filatures of South China nearly all the workers are women and girls. Often the children are brought in from the country by a contractor, who follows disaster like vultures and pays starving parents about a dollar a month for a contract which amounts to slavery; the girls live for years in his compound, eating his food, or in the factories, eating factory rice, working sometimes fifteen or sixteen hours a day, and often sleeping on the floor beneath their machines.

It is the common excuse of the mill-owner that the mothers do not want to leave their children unguarded at home, and doubtless that is sometimes true. Walking through these dimly lit mill-rooms one sees baskets containing children, sleeping or awake, between the whirring, clacking machines. Sometimes a tot of two or three sits cheerfully playing with cotton waste in the aisles through which the foreman guides the visitor. Girls a little older help their mothers tend the rows of spindles, and the deftness of five-year-old fingers is amazing. But when I asked ages of children smaller than my seven-year-old son, the foreman always replied monotonously “twelve.” Except in the Japanese mills little attempt is made to keep the children out of the mills; there a rigid standard of height is set, and maintained.

Native-owned mills are likely to be dirtier and more dangerous than foreign-owned. The machinery is seldom protected, the ventilation is atrocious, the crowding terrific. But even a foreigner can sense the more human atmosphere. In the Naigaiwata mills (Japanese-owned) of Shanghai, where the great 1925 strike began, wages are fair; hours relatively short (only 10½!), and all sorts of modern welfare-devices have been installed. But the girls stopped talking and kept their eyes rigidly on their machines when the foreman appeared and the foreign visitors passed by. In a far dingier Chinese mill the girls showed no fear of the foreman, and pointed and giggled at the ridiculously garbed aliens who marched through the aisles. One of the demands of the strikers last summer was that foremen should no longer be armed, and the demand was typical of the spirit of the efficient, clean, militaristic Japanese mill.

There are vast profits to be made in these early stages of Chinese industrialization. But I doubt if the white men are to have as large a share in it as they expected. There are fewer British cotton mills in China today than there were three years ago, and there are no American cotton mills. Even the Japanese, who so proudly identify themselves in China with the imperialist West, are feeling the pinch of native competition that is driving the British to the wall. The great Naigaiwata mills have been on a kind of intermittent strike for nearly two years—and it is a safe guess that the strikes are fomented and financed rather by Chinese competitors than by the commonly blamed Russians.

The Chinese employer straddles the class issue. He does not yet identify himself with the employing class of the world. Recently he has openly encouraged the working class to fight for him the national battle against his foreign competitors. The Shanghai strike of 1925 was directed and subsidized by the Chinese Chamber of Commerce; the Canton boycott of Hongkong in 1925-1926 was largely financed by Chinese business men in other parts of China and by the prosperous Chinese community of Singapore in the Straits Settlements. And not unprofitably. In South China the native Nanyang Brothers thus won a monopoly of the vast cigarette business, at the expense of the British-American Tobacco Co., which outstrips them in the North. I shall not soon forget the enthusiasm with which a rich Chinese banker described the Naigaiwata strikes, and continued: “We have waked up. We see now how the foreigners have run China, and we are planning to change things. For instance, the British have a monopoly of Yangtze River shipping. Well, we may not be as efficient mariners as they, but I think we can find ways of making it very hard for them to do business at all.”

If the employer has no clear-cut sense of class interest, the worker too is confused. Class consciousness in the Western sense is only beginning to exist in the treaty ports; but race consciousness takes its place. In foreign households even the domestic servants—the most isolated and individualistic of industrial groups—struck in Shanghai and Canton in 1925; and if the strike was enforced in many instances by terroristic methods it Is still significant that it could be enforced at all among the scattered individuals of the group. I doubt if the domestic servants of Chinese families can be organized for decades to come, but any kind of strike can be enforced against foreigners.

The daily life of the lower classes—poster from a Canton wall

The labor-union movement in China is less than a decade old—inevitably it is younger than the factory movement, although precedents can be found in the history of the guilds. Shanghai organized feeble unions in 1916; not until 1919 were labor unions active in Canton; and the first notably successful industrial strike, that of the Hongkong mechanics, occurred in 1920. The epic peak of the movement is again in Hongkong, in the amazing seamen’s strike of 1922. Twenty-three thousand Chinese seamen struck, and a few days later more than a hundred thousand other workers joined them. Hongkong was paralyzed; the lordly white men had to do their own coolie work. The police forbade meetings, closed the union headquarters, deported leaders. But the strike held. After forty days the seamen won the wage increase they demanded and recognition of their union—and the police had to restore the union signs which they had torn from the union building before the workers would return. That was a year of strikes—in the Pingshiang coal mines and the Hanyang steel mills, among the Peking school-teachers, the weavers of Changsha, the wheelbarrow-coolies of a northern city (they wanted their hours reduced from fourteen to twelve), the ricksha coolies of Soochow, in the Canton silk filatures and matshed factories—all over China. Six months saw thirty-one strikes in Shanghai alone, involving cotton mills, silk mills, the municipal electricity plant and water works, the telephone company, native and foreign tobacco companies, a hospital, the comb-makers, joss-paper workers, cargo coolies, sampan-men, laundrymen, cabinet-makers, and boat-builders. There was a trade boom that year and most of the strikes were quickly won. Enthusiasts saw Chinese labor taking its place with the great organized movements of the West.

But none of these unions had permanent organizations which would withstand a period of depression. When industries are booming in China new workers flock in from the villages; in bad times they return to their cabbage-fields. Except in Shanghai and perhaps in some of the mine-fields there is hardly anywhere a permanent working class. In 1923 Wu Pei-fu smashed the union on the Peking-Hankow Railway and beheaded the leaders, for which act he was heartily praised by the foreign press. A silk workers’ strike in Shanghai was vigorously repressed. The Canton Government encourages the unions; the Northern militarists, more or less allied with foreign as well as native business men, smash the unions with a ruthlessness hardly known even in America.

Unrealized, a strange thing has happened. The unions have become the instruments of the new national consciousness. They were from the first vaguely allied with the radical Kuomintang Party of the South. Sun Yat-sen more and more leaned on them as his most trustworthy supporters. Of course the Russians, wherever they saw an opening, helped swell the rising protest. Naturally, too, the militarists of the old regime and the foreigners opposed them. The great outburst of anti-foreign feeling in 1925, that amazing uprising of a nation, significantly began with a strike in the Japanese mills of Tsingtao and the shots which sparked the flame were fired by British police on strike sympathizers in Shanghai. Chang Tso-lin, who has always been supported by the Japanese, closed the offices of the Shanghai General Labor Union that summer, and a few months later, when the foreign courts of the International Settlement handed over the chairman of the union, Liu Hwa, to agents of Sun Chuan-fong, who was more or less supported by the Anglo-American group in Shanghai, Liu Hwa disappeared and was believed to have been slain at night. The militarists naturally and unconsciously align themselves with foreign capital, and the old compradore type of Chinese merchant works with them. But the young alert business men, precisely those who have had their training under foreign conditions, are likely to join the workers, so intense is their nationalism. If China’s militarists are not strong enough to oust the foreigners by force, there is in the unions a power which can destroy the economic roots of the foreigner’s position.

Canton, February 11, 1926

[This picture of Canton was drawn on the spot in the germinal days of the movement, before the Northern expedition carried its spirit across China.]

In Peking you will see the past of China; in Shanghai, the present; in Canton, the future,” Harry Ward told me before I came to the East. It is true. Canton is, in a real sense, the pulsing heart of China which drives the fresh red blood back into the primitive interior and out into the foreign-ruled treaty ports.

At Swatow, in the north of Canton province, I saw a British sloop floating silent with her powerful guns trained on the flat city. She had ammunition enough behind those guns to blow the little one-storied houses to bits and heap their ancient tiles high in the narrow streets—but she could not make the poverty-stricken people buy British goods, unload British cargoes, or cook or sew or make beds for British subjects. All the science and might and money of the British Empire was helpless before the united national will of those Chinese.

Canton has been pecking at the British Empire for nearly seven months. Gradually the British Empire has become aware that what seemed a mosquito has poison in its bite. Hongkong, the greatest port in the East, is a parasite upon Canton, and when Canton turned against Hongkong, Hongkong paled. In 1924 Hongkong’s harbor averaged 210 vessels a day. When Canton began to strike against Hongkong, and the Hongkong Chinese joined, Hongkong’s shipping dropped to 34 vessels a day. Real-estate values shrank; they have been cut in half. Hundreds of little firms failed. The share values of the great British banks, the strongest financial institutions in the East, like the Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation and the Chartered Bank of India, Australia, and China, dropped more than a hundred points. In six months British shipping at Canton fell from nearly three million tons in 1924 to a third of a million in 1925. To save Hongkong the British Government at London voted a loan of three million pounds sterling. That may not be enough; the strike is still on. Canton is giving the British Empire a hint of what is coming if it attempts to cling to what it has stolen from China.

In the dormitory in Canton where a hundred striking tailors from Hongkong live is a large poster labeled “Crimes of the British in China,” which reads:

1. Opium smuggling; spreading the opium evil.

2. Seizure of Hongkong; encroachment on Tibet.

3. Establishment, by force, of foreign concessions and settlements; creation of mixed court.

4. The British were the first to force China to recognize foreign consular jurisdiction.

5. They forced indemnities upon China and seized the customs control.

6. They fastened upon China a fixed customs tariff detrimental to Chinese industry.

7. They oppress the Hongkong and Shameen workers.

8. They shot down the patriotic students and citizens of Shanghai, Canton, and Hankow.

I cite it as a symptom. Beside it are pasted photographs of the victims of the “Shakee massacre” on June 23, when machine-guns from the foreign settlement on the island of Shameen killed fifty-two Chinese and wounded 117 more.

Shameen itself gives you an eery sense of what a plague-stricken city must be like. You leave the swarming Chinese street with its smells and shouts and its teeming crowds of sweating coolies, stumbling under monumental burdens of squealing pigs, squawking hens, flopping fish; cabbages, oranges, bean-cake, rice; cloth, metal, stone, brick; you wind your way through the barbed-wire and sand-bag defenses, pass the bearded Sikh guards—and suddenly find yourself in a world of incredible and amazing peace. Here are shade-trees; but the grass that was once a smooth lawn has grown high, gone to seed and withered. A row of dead palms in pots slumbers upon the consular fence. Barbed wire and sand-bags are everywhere. Your own footsteps resound alarmingly in the dead silence. Rubbish has not been collected, and fallen leaves cover the bricks of a half-finished building where the Chinese workmen dropped their tools last June. The British Consul sits alone in his office with nothing whatever to do these days except to meditate on June 23. Once a day the British steamer comes up from Hongkong, carrying mail and food for the exiles on Shameen. It is not allowed to berth at the wharf; it anchors in mid-stream, watched by armed picket-boats of the Canton-Hongkong Strike Committee, who see to it that no contraband, human or otherwise, gets ashore. Foreigners may land where they will—the theory seems to be that without employees they are futile and harmless; Chinese may not go to or come from Hongkong without a permit from the strikers; and British goods, except for use on Shameen, are contraband.

“I don’t see why this strike should not continue until next Christmas,” the British Consul said to me.[1] Neither do I, unless a different type of British official supplants him—a new type capable of considering without a shudder the thought of letting Chinese live on Hongkong’s peak and vote for members of Hongkong’s council. The Chinese are learning—particularly in Canton—that by boycott they can hurt the proud foreigners more than the foreigners can hurt them. They still have many scores to settle.

[1] It ended shortly before Christmas, after lasting more than a year and a half.

The particular present trouble in Canton dates back to the “Shakee massacre,” which the British call the “attack on Shameen”; and the Shakee affair had its roots in decades of Chinese history. “They call us revolutionary!” said one Cantonese. “In our forefathers’ day the foreigners threw Chinese overboard because they burned down the foreign factories. Now that they’ve massacred the Chinese we don’t retaliate in blood. Perhaps we ought to.” Shameen itself was built during one of the opium wars, when the British occupied and ruled Canton. Chinese, to the present day, may not sit on the Shameen benches, walk along the Shameen bund, or tie their sampans to the Shameen landing-stages. Until a few years ago Chinese might not enter Shameen through the same gate as white foreigners. These things rankle and are remembered. Coolies do not forget when they are kicked or cuffed. A British officer in Swatow harbor gave an unsympathetic explanation of the boycott there. “The chief Red here,” he said, “the man that stands on the dock and kicks the British cargoes out—he used to be No. 1 man at the Taiku Club. Some bloke must have got tight some night and given him a kick in the rear that he still remembers.” The officer thought it a joke; it may have been painfully true. And if Canton is the future of China, it means something.

Englishmen—and some of the treaty-port Americans—call the Cantonese “Reds.” It is a convenient way to discredit an inconvenient group. But the Cantonese are, in certain significant ways, “Red.” The boycott is maintained primarily by a working-class organization rather than by intellectuals and students. These strikers come from Hongkong and Hongkong and Shanghai are the two centers of working-class consciousness in China today—two cities governed by the British and dominated by British capital. The British complain of Russian propaganda among the Chinese workers, but their own factories and factory methods are doing more to strengthen working-class consciousness in China than all the propaganda agents Russia could export in a hundred years. Not the Russians but the British made this strike. Canton is an interesting study for would-be investors who like gunboats to accompany their dollars.

Russian influence indubitably exists in Canton. Nearly three years ago, discouraged with the Westerners, Sun Yat-sen invited Soviet Russians to help him in the Southern province. Sun had met Adolf Joffe, the Soviet representative, in January, 1923, at Shanghai, where after long conversations they issued to the press a joint statement which is worth recalling: “Dr. Sun Yat-sen holds that the Communistic order or even the Soviet system cannot actually be introduced into China because there do not exist here the conditions for the successful establishment of either Communism or Sovietism. This view is entirely shared by Mr. Joffe, who is further of the opinion that China’s paramount and most pressing problem is to achieve national unification and attain full national independence; and regarding this great task he has assured Dr. Sun Yat-sen that China has the warmest sympathy of the Russian people and can count on the support of Russia.”

In February Dr. Sun returned to become the nominal head of the aforesaid Canton Government, in which in his own lifetime he held little real power. In August Borodin arrived, at Dr. Sun’s invitation, and the Russian-Canton collaboration that so alarms the treaty-port press of China began, on the platform jointly announced by Sun Yat-sen and Joffe. The Soviet Government had already announced its readiness to abolish the unequal treaties in so far as they concerned Russia; the new alliance sought to force the other Powers to do as much. In September Dr. Sun asked the diplomatic corps to instruct the foreign customs official to turn over to his government the customs surplus of Kwangtung Province, as had been done in 1919-1920. The Powers did not reply. In mid-December he threatened to seize the custom-houses; the Powers then announced their refusal, and to support it an international fleet including gunboats flying the British, American, French, Italian, Portuguese, and Japanese flags appeared in the river opposite Canton. Nothing could have strengthened the Russian position more. On December 31 Dr. Sun—who a few years before had been pleading with the Western Powers to invest more capital in China—said in a speech at the Canton Y.M.C.A.: “We no longer look to the West. Our faces are turned toward Russia.” Today there are thirty or forty Russians in the service of the Canton Government. Most of them are aides to Chiang Kai-shek at the Whampoa Military Academy; one is adviser to the Canton navy; one is helping revise the chaotic system of multifarious taxation. “They’ve been a force for honesty and efficiency,” said a responsible American in Canton. “The trouble is, they are Russians. If they were British or Americans we would not object.” I did not find one American or Englishman in Canton who had ever met or tried to meet Borodin or had taken the trouble to attempt to verify any of the wild stories they told about him.

Michael Borodin is a big, strong, black-mustached Russian with a hearty hand-grasp, a deep, serious voice, and a warming smile. He has no authority, officially; he gives no orders; yet many think him the most powerful man in the province. There are no Russian warships to back Borodin; there is not even a large Russian trade interest in Canton. In fact, there have not been twenty thousand tons of Russian shipping in the Pearl River since Borodin arrived a year and a half ago. Borodin has won his influence over the group of men who govern Canton, to whom he cannot speak in their own language, by the proved value of his advice and the power of his personality.

The young men who are governing Canton turn to him for advice; they believe that his counsel has proved disinterested and good. “We have no fear of Russia in South China,” said C. C. Wu, the mayor of Canton, who is regarded as a moderate. “Why should we? She has no trade interests here, and no surplus capital to invest. She has renounced all special privileges, and has no dangerous friends; all the imperialist nations are her enemies. It is to her interest today to have China strong, united, and independent—not a tool which the West can turn against her. That is our interest too. Communism is impossible in China today; it need not even be feared. Ten years hence, when the unequal treaties are abolished, who knows? We may fight Russia then; today, we help each other.”

Sun Yat-sen trusted Russia and trusted Borodin—that is enough for most of the Cantonese, who venerate their dead leader as the Russians venerate Lenin. “Chung Shan’s” picture—they call him “Middle Mountain”—has the place of honor in every hall in Canton; one would not be surprised to see lighted candles and joss-sticks burning before it. Chiang Kai-shek, the general in charge of the Whampoa army, is the only one of the Canton leaders who has ever been to Moscow—and the foreigners, with that curious faith in military men which seems universal among Western exiles in the East, look to him as a possible counterbalance to the Russians. He himself boasts not of his military victories but of his long devotion to Sun Yat-sen. The Chinese will not speak ill of the Russians. Wang Ching-wei, the rosy-cheeked, enthusiastic, boyish chief of the Government, has a respect for Borodin which is the more striking because Borodin has to talk to Wang through an interpreter. T. V. Soong, the young Harvard graduate who is Minister of Finance and manager of the government bank, turns naturally to him, and Borodin calls Soong “a man in a million.” The new president of Kwangtung University is planning to send two hundred and fifty Cantonese boys and girls (another of Canton’s futuristic ideas is that women may amount to something too) to Moscow each year; he thinks a year in Russia will help them more than his own years at Columbia helped him. “Russia’s problems are more like China’s,” he says.

Borodin himself does not think highly of the training given Chinese students in America. “They lose touch with China,” he said. “Go to the Commercial Press in Shanghai—it is the work of returned students. Ask for a book on the agrarian situation in China. They haven’t got it. Ask for a book on labor conditions. None exists. But they have translations of lives of George Washington and Abraham Lincoln and Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson. That’s what the returned students do; they translate America into Chinese.”

The first and most extraordinary thing about Chiang Kai-shek, as a Chinese military leader, is that he would refuse to accept any interpretation of his successes in terms of his own character. He represents a party, and his Kuomintang soldiers, trained in a school of politics as well as in a military academy, are like nothing else in China. When I asked him what he thought of Feng Yu-hsiang, the Christian general whose Northwestern army flirts with the nationalists in the South, he answered: “You cannot tell anything about an army by looking at its general. You must look into it, and see what kind of men makes up the ranks.” I doubt whether such an answer would have occurred to any other of China’s thousand generals.

If you go to see Chang Tso-lin, the war lord of Manchuria and Peking, he will receive you like a king, dressed in fine robes, in a throne room hung with tiger skins; Wu Pei-fu affects the part of the genial classical scholar (always a sympathetic role in China) and lives surrounded by friends and underlings. Sun Chuan-fong used to receive visitors in a magnificent yamen in Nanking with bugles blowing. Six lines of soldiers were drawn up at salute to greet us when, with the American Consul, I called on Sun, and all was pomp and ceremony. When I went to see Chiang Kai-shek in Canton I presented my card at the door of an inconspicuous two-story modern dwelling house; the boy studied it and silently pointed upstairs. At the top of the stairs I met a pleasant-looking young man in an officer’s uniform without distinguishing marks of rank.

“Where Chiang Kai-shek?” I asked in simplified English.

“Yes, Chiang Kai-shek,” the young man replied.

“Where, where Chiang Kai-shek?” I repeated, puzzled.