* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

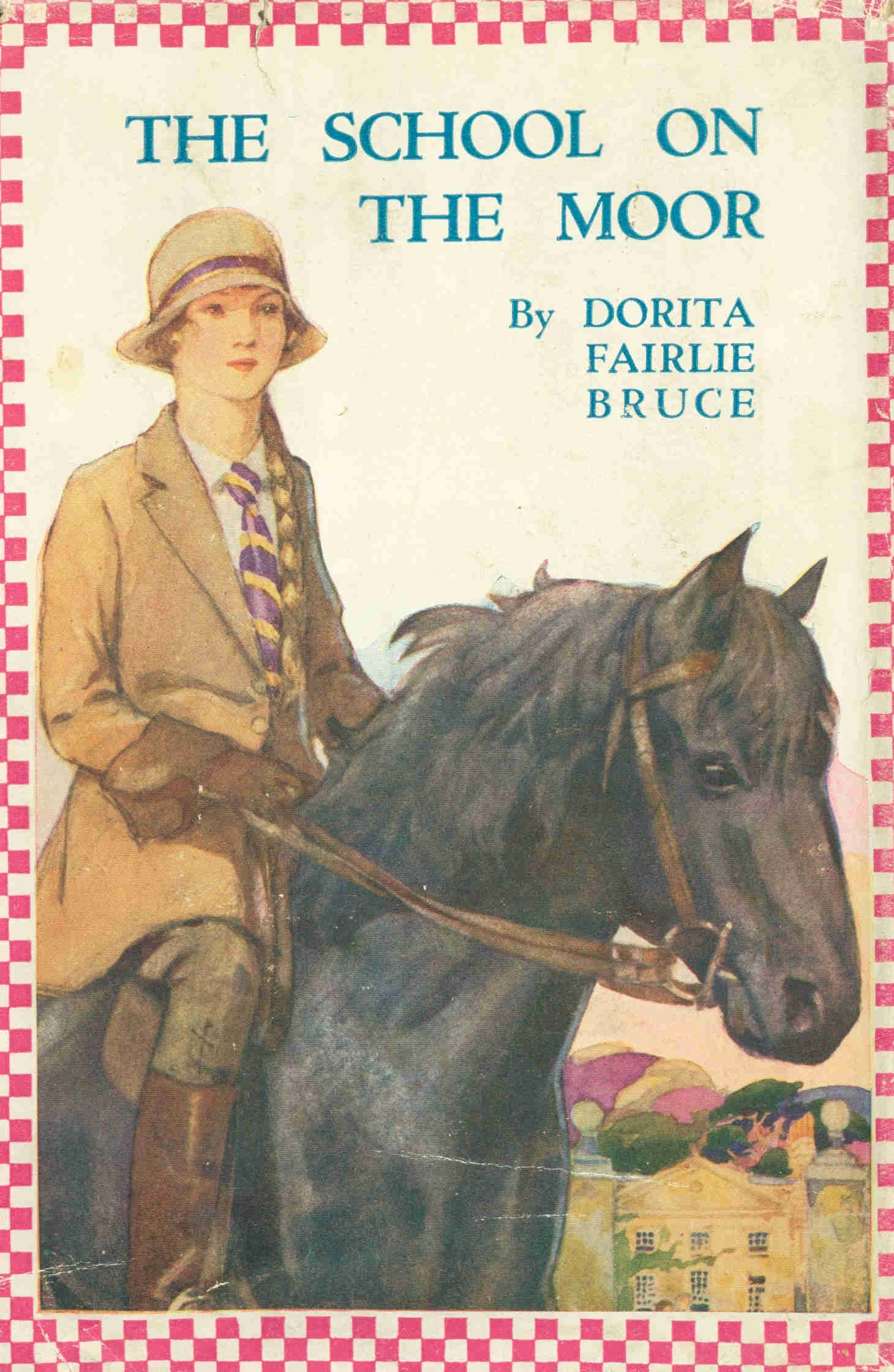

Title: The School on the Moor

Date of first publication: 1931

Author: Dorita Fairlie Bruce (1865-1970)

Date first posted: Oct. 10, 2023

Date last updated: Oct. 10, 2023

Faded Page eBook #20231011

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, John Routh & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

Stories by

DORITA FAIRLIE BRUCE

The Dimsie Books

DIMSIE GOES TO SCHOOL

DIMSIE MOVES UP

DIMSIE MOVES UP AGAIN

DIMSIE AMONG THE PREFECTS

DIMSIE—HEAD GIRL

DIMSIE GROWS UP

DIMSIE GOES BACK

CAPTAIN OF SPRINGDALE

THE SCHOOL ON THE MOOR

THE BEST HOUSE IN THE SCHOOL

THE NEW HOUSE CAPTAIN

THE NEW GIRL AND NANCY

THE GIRLS OF ST. BRIDE’S

NANCY TO THE RESCUE

THAT BOARDING-SCHOOL GIRL

Humphrey Milford

OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS

OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS

AMEN HOUSE, E.C. 4

LONDON EDINBURGH GLASGOW

LEIPZIG NEW YORK TORONTO

MELBOURNE CAPETOWN BOMBAY

CALCUTTA MADRAS SHANGHAI

HUMPHREY MILFORD

PUBLISHER TO THE

UNIVERSITY

REPRINTED 1934 IN GREAT BRITAIN AT THE

UNIVERSITY PRESS, OXFORD, BY JOHN JOHNSON

To my niece

BARBARA JEAN BRUCE

hoping she may like Toby and her

friends as well as she

likes Dimsie

| CONTENTS | |

| I. | THE MEETING IN MRS. PAGE’S SHOP |

| II. | TOBY MAKES HER OWN ARRANGEMENTS |

| III. | TOBY ARRIVES |

| IV. | SHAKING DOWN |

| V. | GILLIAN’S GARDEN |

| VI. | TOBY PLAYS TENNIS |

| VII. | SWEET GALE AND GOLDEN ASPHODEL |

| VIII. | UNPUNCTUALITY AND OTHER SINS |

| IX. | DORINDA THE IMPLACABLE |

| X. | FROM BAD TO WORSE |

| XI. | THE MOLYNEUX PRIZE |

| XII. | ON THE MOOR WITH GILLIAN |

| XIII. | BLUE TOR CLEFT |

| XIV. | DORINDA MAKES AMENDS |

| XV. | FRIENDS WITH DORINDA |

| XVI. | THE INNERMOST SECRET |

| XVII. | MISS MUSGRAVE’S DEPRESSION |

| XVIII. | MIDSUMMER REVELS |

| XIX. | FOOTSTEPS IN BLACKCOMBE LANE |

| XX. | IN HIDING |

| XXI. | WEEK-END HAPPENINGS |

| XXII. | THE RED HERRING THAT FAILED |

| XXIII. | SUNRISE ON THE MOOR |

| XXIV. | THE TREASURE IN BLUE TOR |

| XXV. | THE WRONG JEREMIAH |

| XXVI. | TOBY SCHEMES |

| XXVII. | TOBY VISITS MR. RUSHWORTH |

| XXVIII. | FOUND OUT! |

| XXIX. | PROUD DORINDA |

School on the Moor

‘You know, Daddy, my mind is quite made up.’

Toby Barrett was perched on the wide window-sill of her father’s studio, with her feet firmly planted on the back of a chair below, her elbows on her knees, and her square determined little chin propped in her hands. Over one shoulder fell a long thick plait of golden-brown hair, the remainder of which rippled and waved about a small well-shaped head, breaking into rings and spirals on her temples. For the rest, her face was healthily tanned and not innocent of freckles, and she had a pair of candid hazel eyes which looked out fearlessly on all the world. Toby was one of those fortunate people who had found little to fear in the sixteen years of her life.

‘Do you hear me, Daddy?’ she reiterated sternly. ‘Quite—made—up!’

‘It generally is, my dear,’ rejoined her father placidly, as he took a long step back from his easel, the better to survey his work. ‘And as far as I can remember, I’ve never raised any reasonable objection.’

‘That’s true,’ agreed Toby thoughtfully. ‘But you may, now, because this is going to cost rather a lot—more than most of the things I’ve made up my mind about before.’

Mortimer Barrett glanced up at his daughter with a trace of anxiety. Really, there was no knowing with Toby! and though his popular moorland paintings brought him in a generous income, he was by no means a wealthy man—rather, he might be described by the old Scottish term ‘bien’, a word adapted from the French, and usually expressing material comfort.

‘If it’s to build a Home for Dartmoor Orphans,’ he began firmly, ‘or to provide funds for digging out the Ark of the Covenant from underneath Blue Tor, where you believe Jeremiah carelessly left it lying about——’

‘But it isn’t,’ interrupted Toby. ‘I’ve managed to get all those kids of poor Josh Treggle’s suitably adopted—at least, I hope so. Jan-at-the-Mill hasn’t quite decided about the youngest-but-one yet, though I’ve every reason to hope he will, by the time I’ve finished with him——’

‘I don’t doubt it!’ groaned her father sotto voce.

‘—because I shall tell him’, she proceeded, ignoring the interruption, ‘that a squint brings luck, and Jan and his wife are both frightfully superstitious. As for the Ark of the Covenant—I quite see that I can’t expect you to pay for what you don’t believe in, so I must attend to it myself when I’ve grown up and made some money. That’s the point.’

‘Which point?’ inquired Mortimer Barrett absently, returning to his canvas. ‘I say, Toby! I wish you’d come down out of that window. There isn’t too much light to-day in any case.’

Toby slipped off obediently, and stood beside him, her hands clasped behind her back.

‘The point about which I’ve made up my mind,’ she said. ‘You needn’t bother to see about another governess, because I’m going to school!’

‘Oh!’said Mr. Barrett. ‘You are, are you? And where?’

‘St. Githa’s,’ answered Toby promptly. ‘That big boarding-school on the moor above Priorsford. The head mistress is a Miss Ashley, with yards of letters after her name. I thought I’d go over and see her about it to-morrow afternoon. There’s really no time to be lost if I’m to start this summer term, for it begins in about a fortnight.’

‘How do you know?’ he asked, staring at her in astonishment.

‘I wrote for a prospectus,’ replied Toby tranquilly, ‘when I first thought of going there. The only difficulty is that they don’t take day-girls, but I shall try to persuade her.’

‘And I fully expect you’ll succeed!’ said her father, carefully mixing some more paint on his palette. ‘But has it struck you that it’s a little unusual for a girl to—er—put herself to school? That sort of thing is usually done by parents, and your Miss Ashley may refuse to deal with you.’

‘I thought of that,’ Toby replied readily. ‘It’ll be all right if you’ll give me a letter to her. You can write it this evening, when the light’s gone, so it won’t interfere with your work.’

‘That’s true,’ assented Mr. Barrett absently, as he started in again on his canvas. ‘I couldn’t spare the time, of course, to go over to Priorsford while I’ve got this job on hand, but that doesn’t matter so much since you don’t insist on going as a boarder. I daresay—a letter—might meet the case.’

And Toby, recognizing from his dreamy tone that he had already almost forgotten her existence, went off contentedly on some business of her own.

She was very well satisfied with the result of her attack—not that she had ever had any serious doubts of its issue; for her father rarely denied her anything, and it was a miracle that Toby, growing up in a Dartmoor village, motherless, and with a doting old housekeeper to look after her, had not been thoroughly spoilt. True, there had been governesses from time to time, but none of them would ever stay long at Applecleave, which they regarded as the back of beyond—and perhaps they were not far wrong. It was a very small village, straggling along the side of a hill, and entirely devoid of a railway station, or even an hotel. Its most imposing building was an exceedingly ancient church with a high Norman tower, and next in order came Stepaside, the long, low, whitewashed house in which the Barretts lived.

Toby had been brought there as a toddling, top-heavy person of two and a half, shortly after her mother’s death, and she could remember no other home. To her, Stepaside (perched on a wide grassy shelf where the hill curved round from the village) was all that heart could desire. Its garden, chiefly cultivated by Toby herself, led in a series of smaller shelves to the stony brown beck below, and on the other side rose the moor again, a vast wave of green and gold and purple, and a thousand other nameless colours such as Mortimer Barrett loved to transfer to canvas. He was famous through the length and breadth of England, and even beyond, for his Dartmoor paintings, but he never cared to take advantage of his fame, and seldom strayed for long from Applecleave.

So it came about that Toby had grown up knowing very little of the outside world, except what she could learn from the books in the library, by which she set great store. It is possible that she had educated herself better by these means than through all the efforts of her successive governesses; but of late she had awakened to the fact that there was something missing—something that only a big school and the society of other girls could supply—and, being a practical young woman, she set about getting it for herself.

‘Because’, she argued, with the wisdom born of sixteen years’ experience, ‘there’s no use expecting Daddy to bother. This will be a far more troublesome business than engaging a governess through Aunt Lydia.’

The possibility that Aunt Lydia’s services might be enlisted in the finding of a school had occurred to Toby, and for that reason she had said nothing to her father on the subject till the school had been practically found by herself. She felt—judging from her relation’s taste in governesses—that they were not likely to agree about this even more important choice.

The rain, which had fallen for the better part of a day, was clearing off now, and Toby, catching up a soft felt hat that lay on a chair in the hall, betook herself to the stable.

‘I’ll saddle Blackberry,’ she thought, ‘and go for a gallop up on the moor. He needs exercise, and there’s just time to get to Priorscross and back before supper. I’ll buy some of that cake Daddy likes, which isn’t made in Applecleave. That’s a good idea.’

Toby always looked after her own pony, and the two were great friends; in fact, she depended very much on Blackberry for her longer explorations. They often disappeared together for a whole day, accompanied by Algernon, the Cairn terrier, hunting for the remains of some British camp, or Druid circle, of which the girl had read in the moor records that she found in the library. Anything ancient interested Toby intensely, and she checked the pony’s speed now, as they passed a large monolith that reared itself out of the young heather not far from where she had crossed the beck.

‘I wonder who set it up,’ she thought, ‘and if it was standing there when the Phoenicians came to fetch their tin from the old deserted mines at the head of the Cleave. And I wonder if they took the tin on their mules along the little narrow packman’s paths to Otters’ Bay. I expect they did. It would be the nearest harbourage for their ships.’

Dreaming this way, she rode over a sweep of bare down on which the gorse was coming into flower, and so, by a steep lane between high hedges, into Priorscross. This, compared with Applecleave, was a village of some pretensions, for it boasted of two twisted wriggling streets, and a real post office instead of an ordinary thatched cottage with a red pillar-box in its wall.

Next to the post office was a tiny baker’s shop, and here Toby slid from Blackberry’s back, tying his reins to a post in the fence.

The little shop, with its pleasant smell of new bread, seemed filled to overflowing as she stepped down into it, but in reality there were only two people there besides herself—a tall dark girl of about twenty-six or twenty-seven with a bright clever face, and another, fair and rather colourless, with deep thoughtful eyes.

It was at this second girl that Toby looked again eagerly, as her sight grew accustomed to the indoor twilight, for she recognized her at once. Last year the doctor’s wife had taken her into Exeter for a couple of nights with her own girl—being a motherly creature, anxious to give the lonely child a treat—and part of the treat had been a concert at which they had heard a young ’cellist play. Her music had been a revelation to Toby’s beauty-loving soul, and she had seen her photograph since in various papers and magazines, for Ursula Grey’s name was becoming widely known. Toby had never forgotten the new delight the ’cellist had given her, and it was with a little thrill of excitement that she saw her now, actually standing in Mrs. Page’s shop.

‘Yes, that will do very nicely, thank you,’ Miss Grey’s friend was saying in quick decided tones. ‘I should be able to go in and out, you say, through the orchard gate in the lane? And a ’bus runs through to Priorsford, which I could use in bad weather? Of course, when it’s fine I should prefer to cycle. Very well, then, Mrs. Page—we’ll consider that settled, and I shall take the rooms from the twenty-second. If I find them comfortable I may come back again, you know, after the summer holidays.’

‘Thank you kindly, miss,’ replied Mrs. Page. ‘I’ll have everything put in nice order for you, and many thanks to Miss Ashley for recommending me. We have our summer season here, of course, the same as other places on the moor, but it’s none so easy to get a let, other times in the year, nor such a long one as this.’

The strangers turned to go out, Toby standing aside to let them pass, and she heard the dark girl say, as they went down the street, ‘That’s fixed up then, Ursula, and when you want to come for a rest, there’s always that extra bed; besides, it will be a good thing to be so near——’

The clear pleasant voice dwindled in the distance, and Toby realized with a start that Mrs. Page was waiting to serve her.

‘Nice-spoken ladies, both of them,’ said the baker’s wife garrulously, as she cut off and weighed the cake for which Mr. Barrett had a special affection. ‘The taller one—her that was talking when you came in—is coming to teach the young ladies up to St. Githa’s by Priorsford. That’s why she’s wanting to lodge with me for a bit. Likes living out, she says, and I don’t wonder.’

‘And—and the other?’ asked Toby diffidently, as she searched her purse for the necessary change.

‘Oh! she’s just a friend who’s going round with Miss Musgrave,’ replied Mrs. Page carelessly. ‘Pale-looking she is—needs strong moor air, I’ll be bound. Tenpence-ha’penny—thank you kindly, Miss Toby. Turning out a fine evening, after all, bean’t it?’

Toby mounted her pony again, and rode slowly homewards across the moor smiling now in the rays of the evening sun, and fragrant with all the scents which the rain had brought out. More than ever she was determined to go to St. Githa’s. Fancy being taught anything by a friend of Ursula Grey’s! And it might even be, since she was intimate with this Miss Musgrave, and coming to visit her, that she might come to the school, and Toby might speak to her. Stranger things happened every day. It was strange enough to have been in the same shop with her, and brushed against her waterproof in passing.

Ursula Grey, who was the humblest and most unassuming of mortals, would have laughed heartily if she could have guessed the thoughts of the tall hazel-eyed schoolgirl who had stepped back to let her pass out of Mrs. Page’s shop. But the day was not far distant, though neither she nor Toby guessed it, when their paths were to cross in a manner stranger than they could possibly have foreseen.

Miss Ashley, head mistress of St. Githa’s School, Priorsford, slipped an elastic band over the pile of business papers she had been sorting, and leaned back in her chair.

‘That’s done!’ she exclaimed with satisfaction, and stretched her arms luxuriously above her head. ‘You might give these letters to Nellie, Miss Snaith, when she comes in to clear away the tea; they’ll be in time for the evening post. And ask her to send Joe over to Priorscross on his bicycle with this note for Dr. Jordan. I daresay he’ll be glad to get it tonight.’

Her secretary rose to take the note, and said:

‘May I ask what you’ve decided to do about it, Miss Ashley? It’s sheer curiosity, I own, but I’m interested.’

‘About Penelope Jordan, you mean? Well—it’s departing from my usual rule against day-girls, as you know, but—Dr. and Mrs. Jordan are such old friends that I can’t bring myself to refuse them, especially since they lost their other child. If I don’t take Pen they will have to send her away to school, and I know what a terrible wrench that would be in the circumstances.’

‘So you are going to let her come here as a day-girl?’

Miss Ashley nodded.

‘I am—for the reasons just given. Of course, she’d have a better time as a boarder, but that can’t be helped.’

‘Oh, she won’t do so badly!’ said Miss Snaith. ‘I expect, by the look of her, she’ll be in the Lower Fifth with Gabrielle Marsden, and that lot. I only hope she’ll leaven the lump a little.’

Miss Ashley laughed.

‘Would you call it a lump?’ she asked. ‘It doesn’t seem stolid enough for that description. More lumpishness might make for greater peace all round. And you need hardly pin any hopes to Pen Jordan. From what I’ve seen of her she’s not likely to reform Vb.’

Miss Snaith sighed.

‘I rather wish somebody would!’ she said.

The Head looked amused.

‘Possibly their new form-mistress may manage it,’ she suggested. ‘She struck me as being a purposeful sort of young person. Anyhow, I shouldn’t worry about the Lower Fifth. There’s no harm in them, only perfectly natural high spirits which will tone down as they move up the school. Yes, Nellie? Come in.’

‘Please, mum,’ said the parlourmaid, hesitating in the doorway, ‘there’s a young lady to see you. I put her in the drawing-room.’

‘A young lady? Bring her up here. No, don’t go, Miss Snaith—unless you want to. I expect it’s some one collecting for something.’

‘Surely not,’ protested Miss Snaith. ‘I’ve paid all the local subscriptions that are due. But, of course, there’s always something fresh cropping up—hullo!’

The exclamation, hastily smothered, was forced from her by the apparition in the doorway, so totally different from what they were expecting. Something fresh had certainly cropped up this time.

‘Miss Barrett,’ announced the maid, and departed.

Toby, despite her father’s warning, was supremely unconscious of anything unusual in her errand. She came into the room clad in her fawn riding-coat and breeches, with her old felt hat pulled down on her brow, and held out her hand to Miss Ashley without a trace of embarrassment.

‘How do you do?’ she said. ‘I hope you don’t mind my coming to see you without asking you first if I might. I’m Toby Barrett, who wrote to you for that prospectus.’

Miss Ashley, like her visitor, was not easily taken aback. Probably her training as head mistress of a large school had amply prepared her for anything that might happen. At any rate, she smiled readily, and said:

‘I’m very pleased to see you, and I remember your letter, but I—somehow didn’t think that was the name.’

Toby coloured now.

‘It wasn’t,’ she admitted frankly. ‘I’m really Tabitha, after a great-grandmother, so I shall always have to sign business letters like that, but nobody ever calls me by it. If I come to St. Githa’s, I’d rather be Toby—at least, if you don’t mind?’

‘Oh!’ said Miss Ashley. ‘Are you coming to St. Githa’s?’

Miss Snaith sat back in her chair, and gave herself up to enjoyment of the scene before her. She was a student of character, and this girl in riding-kit, who had come to put herself to school, promised to be something quite out of the common.

‘I hope so,’ said Toby with a wide engaging smile. ‘If you’ll have me, I am. Daddy would have come to see about it himself, but he’s busy with a picture just now, which he must work at whenever the light’s good. I don’t know whether you’ve noticed, but it hasn’t been specially good lately.’

‘I’m afraid I haven’t noticed,’ confessed Miss Ashley, ‘not being an artist, you see. So you are Mortimer Barrett’s daughter?’

Toby nodded.

‘That’s why I have to see about myself a good deal,’ she explained simply. ‘I expect you understand, because you probably know heaps of artists. Anyhow, Daddy wrote this letter, as he couldn’t come, asking you if you’d be kind enough to let me come to school here as a day-girl. Would you mind?’

Miss Ashley pulled forward an inviting chair, as she took the letter.

‘I shall have to think,’ she said. ‘Sit down and talk to Miss Snaith while I see what your father has to say to me. Miss Snaith is my secretary, and she also teaches botany, and a few such oddments.’

‘Do you?’ asked Toby eagerly, as she sat down beside the secretary. ‘I’ve tried to teach myself from books, and the plants I’ve found on the moor. It’s most awfully interesting. Do you believe white heather is really an albino? I found some once which had pink eyes.’

‘They weren’t eyes,’ said Miss Snaith, with a little explosion of laughter. ‘They’ve got a proper botanical name—but I don’t propose to give a lecture, at the present moment. I see you came on horseback. Where do you live?’

‘At Applecleave,’ responded Toby readily. ‘It’s rather a jolly little village—but I expect you know it—up at the top of the Long Cleave, just under Blue Tor.’

While they talked she kept an anxious eye on Miss Ashley, who was reading Mortimer Barrett’s letter with knitted brows. Presently she laid it down on her writing-table, and stared absently out of the window at the mauve line of moor that rose above a nearer stretch of wood. She neither took nor desired day-girls, whom she regarded as fruitful sources of infection for the boarders, and had strong views of her own regarding the mixture of those two types of pupil. Yet, her kind heart, which had already betrayed her that afternoon in the case of Penelope Jordan, was pleading strongly now for Toby. Despite her gallant independence, there was something rather forlorn about the girl which appealed to a warm vein of motherliness in Miss Ashley.

‘What do you do with yourself, all day long, Toby?’ she asked abruptly, as she turned back to her visitor.

‘In the holidays, do you mean? Oh, lots of things!’ Toby answered. ‘I never have time enough for everything. You see, the moor’s so frightfully interesting, and I’m out on it nearly all day with Blackberry and Algernon—they’re my pony and my dog; they’re both waiting for me outside. I don’t sketch, like Daddy, but I poke about the old Druid stones and try to find out what they mean. Do you know that some people say they aren’t Druid at all?’

‘Nobody can tell exactly what they are,’ said Miss Ashley, ‘or who put them there. It’s all guesswork, I fancy.’

Toby leaned forward earnestly, and fixed her wide hazel eyes on the head mistress’s face.

‘Just tell me this,’ she begged, lowering her eager tones to an impressive key: ‘do you believe that Jeremiah may, perhaps, have come here in the Phoenician ships which took him on to Ireland afterwards? You know—when he was escaping from Palestine with the princesses of Israel. Daddy doesn’t believe it, but I do—and what’s more,’ dropping her voice yet further, ‘I shouldn’t be a bit surprised if he buried the Ark of the Covenant under one of our tors.’

If Miss Ashley felt any surprise at the unusual turn the conversation had taken, she did not show it, being a person of great tact and consideration.

‘It’s just possible,’ she said gravely, ‘though I don’t remember having heard it suggested before. If you are coming to St. Githa’s we must have some talks about things. I am glad you are interested in really interesting things.’

‘Then’, said Toby, drawing a long breath, ‘you are really going to have me?’

Miss Ashley smiled.

‘Are you so anxious to come?’ she asked. ‘Well, Toby, I have never before had a day-girl here, but, if I let you come to me, this term, I shall have two—for I have just consented to take Dr. Jordan’s little girl, Penelope. I feel that you and she are both rather exceptional cases—both rather lonely people—so I don’t think—perhaps—I can refuse you.’

Toby left her chair with a little skip of joy.

‘Oh, how heavenly!’ she cried. ‘I was half-afraid you might,’ she added confidentially,’—refuse me, I mean—because I know it isn’t the proper way for a girl to come and see about school for herself, but I can’t exactly help it. And there’s Daddy’s letter, of course.’

‘Yes,’ said Miss Ashley, still smiling, ‘so that makes it quite proper, or very nearly. I shall write an answer for you to take back to him presently, but meantime I want to tell you one or two things. The summer term begins on the twenty-third, and I shall expect you to be here by nine o’clock, in time for prayers; then we’ll find out exactly how much you know, and in which form you’ll be. Till then we shan’t know what books you will require, but I should like you to get the school uniform, and wear it—a plain dark-blue coat-and-skirt, with white blouses and a white straw hat with the school colours, also plain holland frocks for the warm weather. Miss Snaith will give you a list, and you can get the things at Green, Robinson’s in Exeter. The colours are mauve and gold—for the heather and gorse on the moor, you know—and you will require a tie as well as a hat-band. Will you make out the list for her, Miss Snaith, while I take her round the school to give her some idea of what it’s going to be like. I’m afraid you’ll find it all rather new and strange at first.’

‘That will be part of the niceness,’ declared Toby rapturously. ‘I never told any one before, but it’s always been a great ambition of mine to become a schoolgirl. Perhaps you don’t quite understand that? I shan’t be a bit surprised if you don’t, because schoolgirls must seem quite ordinary things to any one who has always been accustomed to them.’

Miss Ashley was well aware that her secretary was looking at her with dancing eyes, but she did not dare to meet them.

‘You’re wrong there, Toby,’ she said decidedly. ‘When I find schoolgirls quite ordinary things I shall give up my job, for I shall be no good at it. To me every one of you is different, though some, I must admit, are more interesting than others. Now come along and have a look at this new world into which you are going to plunge so soon.’

Half an hour later when Toby had ridden off across the moor, with her list and the letter for her father in her pocket, Miss Ashley returned to her study, and dropped limply into a chair.

‘Now at last we can laugh in safety!’ she exclaimed, ‘though I haven’t quite made up my mind yet whether I wouldn’t rather cry. Did you ever know anything so innocent, and so plucky, and so entirely on her own? How her father can leave her to run wild in that careless fashion beats me!’

‘She’s perfectly charming!’ declared Miss Snaith warmly, ‘though you know I don’t always share your enthusiasm for the modern schoolgirl. At times I’m inclined to agree with Toby that they’re apt to be ordinary.’

‘She isn’t, anyhow!’ observed the head mistress. ‘I can’t help foreseeing rocks ahead for her, though. Despite my “enthusiasm”, as you call it, I must admit that schoolgirls are conventional, and Toby Barrett isn’t.’

‘Not exactly!’ assented Miss Snaith drily.

‘Therefore she won’t have an easy time, at first, and may not be altogether popular. I hope she won’t find school less delightful than she supposes.’

‘I hope not! But she’ll have to find her own feet, and I imagine (from the glimpse we’ve had, just now) that she’s quite capable of doing so. Any one with so much character——’

‘That’s just it,’ responded Miss Ashley. ‘I rather fancy she’s got more character than will be altogether convenient at St. Githa’s. What do you suppose Kathleen Wingfield will make of a specimen like that?’

Miss Snaith laughed out.

‘It will be immensely interesting to see. Not that Kathleen is among those who count. Toby will be all right with Gillian Ewing and Dorinda. They’ve got brains enough to appreciate something out of the common.’

‘Nevertheless she’ll be bullied,’ said Miss Ashley, with conviction. ‘And I’m not so sure of Dorinda’s attitude as you appear to be. She’s somewhat unaccountable at times—the artistic temperament, I suppose!’

St. Githa’s had reassembled after the Easter holidays, had unpacked and more or less settled down in the dormitories upstairs, had renewed old friendships and taken stock of the new girls, and was now ready, when Wednesday dawned, to start in upon the term’s work.

‘Which, thank goodness! isn’t quite so strenuous in the summer,’ remarked Dorinda Earle, perching herself on the back of her desk, and swinging her long dark plait over one shoulder. Dorinda was not pretty, but she carried herself with an air which impressed the Lower School when she sailed into their class-rooms to take supervision during ‘prep’. She had a certain attraction of her own, and took some trouble, in her brusque way, to win popularity, and with most of her schoolfellows she succeeded. Her sworn friend and ally, Gillian Ewing, took no trouble whatever, and succeeded even better. As Dorinda herself said, with a good deal of sincerity, ‘Jill’s so pretty, that she doesn’t need to bother’. But Miss Ashley, having studied both girls, came to the conclusion that Gillian’s gay placidity had more to do with it than her good looks. Gillian was a philosopher, while Dorinda worried over most things, big or small. And these two were the acknowledged leaders of the school.

‘I mean to specialize, this term,’ announced Gillian firmly, ‘with an eye to my future career. You know we can when we’re seventeen, and I shall be seventeen in June.’

‘Why not wait till next term, then?’ asked Olive Knighton, idly sharpening a pencil. ‘What are you going to take up, in any case?’

‘That’s just it,’ responded Gillian happily. ‘I can’t afford to waste the summer, because I’m going to be a gardener. Not the daily jobbing kind, but a regular highbrow, thoroughly versed in all the scientific side of it. You know the sort of thing.’

‘How ripping!’ exclaimed Dorinda. ‘That means you will live for ever in the open air. But who’s going to teach you all that at St. Githa’s?’

‘Just what I was wondering,’ remarked Kathleen Wingfield, a good-looking girl who was somewhat spoilt by the hardness of her expression. ‘You ought to go to Swanley, or some place like that.’

‘I may, in time,’ said Gillian, quite unmoved by their doubts, ‘but I’d like to know a little more first, and I’ve laid my plans with the Head. She spent a week-end with us in the holidays, and we thrashed the matter out. I’m to do an extra intensive botany course with Snaithie, and some chemistry, and there’s a new form-mistress coming for Vb, who professes to know something about practical gardening, and she’s going to take me on.’

‘A new form-mistress for Vb!’ exclaimed the other three, their attention at once diverted from Gillian’s future career to a matter of more immediate importance. ‘How do you know? Nobody new has appeared on the staff yet.’

‘I expect she has by now,’ said Gillian tranquilly, ‘but she isn’t living in—not this term, at least. I think Miss Ashley said she had taken rooms at Priorscross. Her name’s Musgrave, and she was at that big school in Kent—the Jane Willard Foundation.’

‘I’ve heard of it,’ said Dorinda. ‘I knew a girl who was there. And she’s coming to take on the Lower Fifth? Poor wretch!’

‘Yes,’ agreed Jill. ‘She’s got all her troubles before her, I should fancy. The present Vb don’t seem able to realize that they’ve grown into the Upper School. Their behaviour reminds one unfavourably of the Third Form.’

‘At its worst,’ added Dorinda. ‘By the way, Jill, you’re likely to come up against them a good deal yourself, this term, aren’t you?’

‘Why me, any more than any other prefect?’ asked Gillian ungrammatically.

Olive laughed.

‘The answer to that’s pretty obvious, isn’t it? Who do you suppose is going to be Head-girl?’

Gillian’s pretty face reddened self-consciously.

‘Dorinda, I should imagine—unless you’re thinking of tackling it yourself, Olive, but I’m inclined to believe you’re too lazy.’

‘Much!’ assented Olive, laughing again. ‘No, I think you’ll find, when it’s formally put to the meeting, as it will be tonight, that the school has chosen you to succeed Grace Pollard. Not a doubt about it, is there, everybody?’

‘Rather not!’ agreed the rest of the Sixth Form, to whom she had raised her voice in appeal, and when the chorus had died down Dorinda added:

‘We’ve elected you without a dissentient voice, and I think you’ll find the rest will follow suit. Also, a deputation of us went to the Head, after supper last night, to get her approval, and she gave it—pressed down and running over.’

Gillian sat silent for a moment, her desk-lid half-open in her hands, and a thoughtful look in her clear steady eyes. Then she said simply:

‘It’s awfully decent of you all to want me, and if Miss Ashley thinks it’s all right, I’m ready to try. But I can’t manage the job single-handed, as Grace Pollard did. I shall need a lot of help from everybody, and especially from the prefects.’

‘You’ll get it, old thing!’ Olive assured her warmly. ‘Grace could have had it too, if she’d chosen to take it, but, as you know, she preferred to act without consulting the rest of us. It will be rather jolly to have a Head-girl who lets us into things.’

‘Yes,’ agreed Kathleen. ‘One likes to know what’s going on, and have a say in the affairs of the school. Otherwise, why be a prefect?’

‘We’re all ready to welcome the new régime,’ said Jane Trevor, the fifth prefect, joining the group round Gillian’s desk. ‘You’ll find, tonight, that you’re every one’s choice, and a jolly popular one at that.’

Dorinda said nothing, but her blue eyes met her chum’s with a look of contented understanding which satisfied Jill. Dorinda was a person of few words where her feelings were concerned, and Gillian herself hardly realized the strength of her friend’s affection, or how proud she was of this unanimous election to their school’s place of honour.

‘Perhaps our friends in the Lower Fifth will now find——’ began Olive; but at that moment the door opened, and a newcomer stood hesitating on the threshold—a newcomer in fawn coat and riding-breeches, though these were surmounted by the school panama, and she wore St. Githa’s mauve-and-gold tie on her soft white shirt.

‘I say!’ she began, a little breathlessly, ‘is this the Sixth Form? Then would one of you please show me where I can change before school begins? I’ve got my skirt here in my case, but of course I couldn’t ride over in it.’

For a moment the Sixth were too much taken aback to respond, and Toby urged again:

‘There isn’t too much time, is there? You see, I had to unsaddle Blackberry, and turn him into the field.’

Gillian was the first to recover herself.

‘Come down to the cloak-room,’ she said. ‘You’ve still got ten minutes before Olive goes to ring the bell. This way, and down these stairs at the end of the passage. You don’t mean to tell us we’re going to have a day-girl?’

‘Yes—do you mind?’ asked Toby, a little wistfully, as she followed her. ‘Miss Ashley thought perhaps you wouldn’t.’

‘Mind? Why on earth should we? You’ll bring a breath of new life into the place, which we shall welcome. Though it’ll be pretty stale for you having to trot off home just when lessons are over, and we’re beginning to enjoy ourselves. What’s your name, by the by? It might be useful to know it. Mine’s Gillian Ewing.’

‘I’m Toby Barrett,’ replied the new girl, reddening self-consciously, and added with haste, ‘I came over for my exam. on Monday, and Miss Ashley said I’d be in the Sixth. That’s why I asked the way to your form-room.’

‘Haven’t you seen Miss Ashley this morning? Then you’ll have to go to her as soon as you’ve changed. Get into your skirt quickly, and I’ll show you the way to her study. Hullo! what’s this? Another day-girl?’

They had reached the small basement room, lined with cupboards, in which the Upper School kept their outdoor garments, and seated on the floor, changing her shoes, was a small vivacious-looking girl of about fifteen, with a turned-up nose, and a bobbed head of thick dark hair. Her coat was off, and she wore school uniform as new and creaseless as Toby’s.

‘Yes—I’m Penelope Jordan. Are there two of us?’ Then, recognizing Toby, as she emerged from behind the Head-girl, ‘Why, it’s Toby Barrett! You never told me you were coming here! But what a blessing you are! I thought I’d be the only day-girl in the place, and it’s bad enough to be new without being peculiar otherwise.’

‘The school,’ observed Gillian, ‘appears to be bristling with surprises to-day. Is no one looking after you?’

‘Dozens!’ replied Penelope promptly. ‘The whole Lower Fifth, I think—but they all disappeared after bringing me here. One said she’d come back before the bell rang, but I’m afraid she’s forgotten. She called herself Gabrielle Marsden.’

‘Then she probably has forgotten,’ said Gillian drily. ‘I never knew Gay Marsden remember anything really useful. She’s made that way. I’d better drop you at the Lower Fifth’s door on my way back. I suppose you’ve seen the Head?’

‘Yes—that’s how I got to know Gabrielle. Miss Ashley sent for her, and told her off to look after me.’

‘Then I’ll tell her off for not doing so!’ rejoined Gillian in a slightly irritated tone. ‘It’s neither kind nor mannerly to let a new girl fend for herself—especially a new day-girl. Ready, both of you? Come on, then!’

She directed Toby to the head mistress’s study, and took Penelope along to the schoolroom where she appeared to belong, returning afterwards to fetch Toby, whom she met emerging from her short interview with Miss Ashley. The new girl’s face lit up with relief at the sight of her.

‘Oh, have you come back for me? How decent of you! It’s rather awkward to find your way about a big place like this alone, when you’re new.’

‘I know,’ said Gillian sympathetically, ‘and you feel a fool if you have to ask people. Come along! the bell’s just gone, but Miss Temple takes us for the first lesson to-day, and she’s usually a trifle late. She’s Va’s form-mistress, and teaches maths.’

They entered the Sixth Form-room at Miss Temple’s heels, barely in time for prayers, which was held in each form separately that morning.

‘It’s not our usual way,’ whispered Jill, ‘but for some reason it always happens on the first day of a new term. Afterwards we all meet together in the hall at a quarter-to-nine, each morning. You’ll have to get here in good time to-morrow.’

There was no other new girl in the Sixth that term, so Toby came in for a good deal of frank scrutiny during the course of the morning, though there was no chance of any conversation until the eleven o’clock break, when Gillian continued her good offices by remarking, with a wave of her hand:

‘Our little stranger’s name is Tony Barrett, and she lives at Applecleave. That’s why she has to ride to school. But she has promised not to shock our eyes by another such apparition as they beheld this morning. She hopes to arrive before us, in future, decently clad and in time for prayers.’

‘I liked her as she was,’ declared Jane Trevor, joining in the general laugh. ‘Is Tony short for Antonia?’

‘No,’ answered the new girl, growing red and embarrassed again, as she always did at any allusion to her unfortunate name. ‘Gillian got it wrong—it’s Toby, not Tony.’

‘But surely that can’t be your real name?’ exclaimed Olive Knighton, in astonishment. ‘It doesn’t sound possible.’

‘It isn’t,’ admitted its owner, then blurted out desperately: ‘It’s no good trying to hide it! You’re bound to find out sooner or later—but it’s not my fault, it’s my grandmother’s for insisting that I should be called after her mother—my real name’s Tabitha, and it’s been the curse of my life!’

A shout of laughter greeted this confession, but there was nothing jeering about it, as Toby’s sensitive ears quickly understood.

‘Poor old soul!’ said Olive, patting her kindly on the back. ‘It’s rough luck, of course, but in time you may live it down. I’ve known heavier curses than that.’

‘I like it,’ declared Jane stoutly, ‘and I don’t see that it’s a scrap worse than mine. You look the world in the face, Toby, and forget all about it! We’ll promise never to cast it up at you here. Why, what in the world has happened to Kathleen Wingfield?’

That damsel, who had dashed off on some errand of her own directly the class was over, burst into the room again, crimson with wrath, but far from speechless.

‘I ran across to see the tennis-courts,’ she cried, ‘just to find out if they were in order for this afternoon, and what do you think I found? A wretched pony prancing all over them, and hoof-marks about a foot deep in all directions! We shan’t be able to start play now for at least a fortnight, and there’s the match with Priorsford Club coming off on the fifteenth!’

‘Goodness!’ exclaimed Jill in consternation. ‘How on earth did it get there? Is it a stray from the moor?’

St. Githa’s prided themselves on the perfection of their tennis-courts and the high standard of their play. To practise for a match on rough spoilt grass was a serious calamity, especially to Dorinda, the games-captain, and Kathleen, who was school champion.

‘I’m afraid,’ said Toby, in a shaking voice, ‘—I expect—I mean, I’m afraid it was Blackberry, my pony. He must have got out of the field I turned him into.’

‘Which field was it?’ demanded Dorinda sharply.

‘The one on the right of the drive as you come in.’

The captain’s groan was echoed by one or two others.

‘The cricket ground! How could you be such a fool? Why didn’t you ask before you turned him in anywhere?’

It seemed a small thing to start a prejudice, and one, indeed, for which Toby was not entirely accountable (since some careless person had left the gate open which led from the cricket ground into the tennis-courts), but from that moment Kathleen Wingfield could see no good in the day-girl. Probably it would have been the same in any case; the two had nothing in common, and Toby’s unconventional ways would certainly have jarred, sooner or later, on the tennis champion. Kathleen was the type of girl who likes every one to conform to pattern, and strongly resents any departures from it. Toby, on the other hand, had not been brought up according to any pattern whatever, and had no idea how to become an ordinary schoolgirl, though she tried her best.

‘You don’t know how badly I want to be just like everybody else,’ she confided to Jane Trevor, one day, a week after the term had commenced. ‘I haven’t had a chance till now, because there was never any one else to be like; but here, at school, with a lot of you, it’s different.’

‘I shouldn’t bother, if I were you,’ said Jane comfortably. ‘We like you as you are. It’s more amusing to have you different from the rest of us. Nobody quite knows what you’re going to do next.’

‘Kathleen doesn’t like it,’ said Toby, a trifle sadly. ‘I’m not at all sure she even likes me—and what’s much worse, I don’t believe Dorinda does either.’

‘Pooh!’ said Jane. ‘What does Dorinda matter? She judges people by their batting or bowling analysis, or the strength of their service at tennis. You’ve had no chance to play games yet, so you’re no good to Dorinda and Kathleen—that’s all.’

‘I’m sure it’s more than that,’ persisted Toby. ‘Still, there’s no use letting it matter, and I don’t really mind much about Kathleen. You can’t expect anything to be absolutely perfect, and school doesn’t fall far short of it. In fact, Dorinda Earle is my only crumpled rose-leaf! I mind about her.’

Jane laughed.

‘Let her crumple, then!’ she exclaimed.

But Toby shook her head.

‘I mean to iron her out, some day,’ she said quaintly, ‘only, at present, I can’t quite see how.’

Jane thoughtfully chewed a blade of grass.

‘People get taken like that about Dorinda,’ she observed. ‘There’s something awfully attractive about her, but it’s no good upsetting yourself when she has moods.’

Certainly Toby had little to complain of otherwise. St. Githa’s had received her in friendly fashion, and she had taken a better place in her form than she had dared to hope. History was her favourite subject, and in this, which the Head herself taught, she showed herself well ahead of the others.

‘It’s only because I read it for fun in the holidays,’ she explained, whereat Kathleen Wingfield snorted scornfully.

‘Ridiculous affectation!’ she muttered. ‘Does any one spend their holidays reading history for fun?’

Toby’s hazel eyes flashed, for a moment, and she answered sturdily: ‘I did, anyhow! Why should it be more affectation than any other way of spending one’s holidays?’

Not having a suitable reply ready, Kathleen hedged, remarking icily:

‘If you’d ever been to school before, Toby Barrett, you’d know that new girls should refrain from being cheeky in their first term.’

Toby opened her lips to make some indignant retort, when Dorinda Earle broke in.

‘Don’t talk like a Third Form kid, Kathleen! You started the argument, so you can’t object to Toby’s carrying it on—though, as a matter of fact, I think you’d both better stop, as it isn’t specially profitable. Will some one let me see the problems Miss Temple set for this evening’s prep.? I don’t think I’ve taken down the last question right. It doesn’t read like sense.’

Kathleen shrugged her shoulders at the rebuke, but said no more, for Dorinda’s opinion carried weight in the school, though her manner of expressing it was sometimes too autocratic. As for Toby, she looked wistfully at her unexpected supporter, and later on, when opportunity arose, she said shyly:

‘Thanks awfully for sticking up for me this morning about the history.’

Dorinda glanced at her indifferently.

‘No need to thank me,’ she answered. ‘I only butted in because Kathleen was unfair, and I dislike unfairness. I’d have done the same for any one.’

And Toby retired, feeling chilled.

During the first week of the term St. Githa’s, as it happened, had very little time to spare for its new girls, especially for the two who spent only part of their time under its roof. There was so much settling-in to be done, so many things to see to, that matters of minor importance were left over for the time being. Jill Ewing’s promotion to the vacant place of Head-girl brought various small changes and rearrangements which fully occupied her for the first few days, otherwise she would probably have continued to befriend Toby, who had attracted her from the beginning.

Toby, however, had no complaint to make. She had her own settling-in to do, and did it more easily when thus left to herself. By the end of the week she knew her way about the house and grounds, had digested most of the written rules, and was able to observe some of the unwritten ones—which was far more difficult. The desire to be ‘like everybody else’, which she had confided to the friendly Jane, led her to watch very carefully against any faux pas. Indeed, Blackberry had made enough of these, during his invasion of the tennis-courts on the opening day of the term, to last for some time; though Toby felt it a trifle hard that the sins of the pony should be visited on the mistress.

One court, providentially, he had spared, and on this the six players who were to be sent against Priorsford Club practised at every available moment. The groundsman, meanwhile, was doing his best to repair the damage done to the others, the cricket-pitch having escaped altogether. It appeared that Blackberry had merely crossed the playing-field, avoiding the pitch, and had devoted himself entirely to the improvement (or otherwise) of the tennis-courts.

On Friday afternoon, when Toby was down in the cloak-room with Penelope Jordan, both preparing to go home, a Junior entered in search of them.

‘Dorinda Earle says, will you please go to the prefects’ room before you leave. She wants to see you about the games,’ she announced blandly, and eyed Toby’s riding-breeches with admiration, adding on impulse, ‘I say! would you let me have a ride on your pony, some day, after school? Just once round the paddock?’

‘All right,’ said Toby good-naturedly, as she restored her house-shoes to their bag. ‘Come and ask me, any morning you like—if you’ll promise to stick on.’

‘Rather!’ cried the child enthusiastically. ‘My name’s Elfrida Rossall. You won’t forget you’ve promised me, will you?’

‘You can remind me, if I do,’ answered Toby, smiling, and the Junior disappeared with a hop-skip-and-jump. The next moment she was back again.

‘There’s my chum,’ she said, ‘Beryl Wingfield. Would you give her a ride too? We always do things together, and it would be mean of me to get on the pony if she didn’t.’

‘You certainly can’t both get on together,’ said Toby, laughing, ‘but I don’t mind if you do it singly. That’s enough though, please! Blackberry can’t carry the whole Lower School.’

Elfrida saw the sense of that, and ran off gleefully in search of Beryl, to tell her of the joys in store for them, while the two day-girls went up to the prefects’ study. Here they found Dorinda alone, seated at the table with some lists spread out before her.

‘Sit down,’ she said, in her usual curt way, plunging straight into the business in hand. ‘I want to see you about the games. Haven’t had time before, with all the usual start-of-term fuss. The point is, can either of you play anything, and if so, what?’

Toby’s eyes twinkled suddenly.

‘I’m awfully good at ping-pong,’ she replied demurely.

Dorinda favoured her with a stare of suspicion and disapproval.

‘I’m not fooling,’ she said severely. ‘I’ve got to find out what you’re capable of. Have you ever played cricket—or tennis?’

‘I can play tennis a bit,’ Toby answered, realizing that a serious matter must be treated seriously, ‘but I’ve never had the chance of cricket, though I’d love to try.’

‘You’ll have to see Miss Musgrave about that, then,’ said Dorinda. ‘She’s games-mistress, and she’ll soon find out if you’re worth while. I’ll test your tennis myself, when I get time. What about you?’ turning to Pen.

‘I’m rotten at tennis,’ replied the Fifth Former cheerfully, ‘but I can bowl a bit. I get practice when the Rectory boys are home for their holidays, and they say I’m not bad.’

‘Overhand or lobs?’ inquired Dorinda.

‘Overhand, of course!’ replied Penelope indignantly. ‘Would boys let you bowl them lobs?’

‘They mightn’t be able to help it, if that was all you were good for,’ responded Dorinda. ‘But I’m glad to hear you can do something. Turn up to-morrow morning, and I’ll try you in one of the practice games. That’s all just now, thanks.’

Penelope turned to go, but Toby lingered for a moment.

‘Do you want me as well to-morrow morning?’ she asked wistfully. Team games had been a part of school life to which she had been looking forward.

But the games-captain answered with cool politeness:

‘No, thanks. I can’t attend to beginners to-morrow. I shall be too busy sorting those who know something about it into teams.’ Then something in Toby’s crestfallen expression moved her to add, ‘Perhaps you had better come over and see Miss Musgrave, though. You’ll be her affair more than mine, you know, until you can play a bit, and she’s sure to be free on a Saturday morning.’

‘Thanks awfully,’ said Toby, brightening up again. ‘I’ll ride across soon after breakfast then.’

And she followed Penelope out.

‘Come round my way,’ urged the younger girl, who was a sociable being. ‘It’s one way to Applecleave, and I can suit my bike’s pace to your pony’s. We haven’t had a chance to compare notes since we joined up last week. How do you like being a day-girl at St. Githa’s?’

‘I love it,’ said Toby simply, as she led the way towards the paddock, where Blackberry now spent the school-hours in blameless seclusion. ‘Can you wait a minute while I put on his saddle and bridle? I always undress him when we get here. It’s more comfortable for him, poor old boy!’

Pen propped herself up between her handlebars and saddle, with an arm on each to steady herself, and watched proceedings with interest.

‘It’s rather a jolly way of coming to school,’ she observed, ‘even if it is more trouble than a bike. But wouldn’t you rather be a boarder? I feel as though we miss a lot by going home every afternoon.’

Toby buckled a strap securely before replying; then she said philosophically:

‘Well, one can’t have everything, you know, and being a day-girl’s a lot better than staying at home with a governess. What’s the Lower Fifth like? I gather, from what I’ve heard, that they’re pretty hot stuff.’

Pen’s merry eyes danced.

‘You’re right. They are—especially Gay Marsden and Nesta Pollard. That’s one reason why I’m sorry not to be a boarder; they have such decent times in the evenings—and at nights! The fact is, they’re rather a young set for that form. They all came up from the Fourth only last term.’

‘What sort of things do they do?’ asked Toby curiously, but Penelope gave her a queer look and laughed.

‘If I told you that,’ she said, ‘I should be giving them away to a Senior. However new you may be, you’re a Sixth Former after all, and no Sixth Former—no matter how humble and unimportant—could hear about some of their goings-on without feeling obliged to interfere.’

‘I’m sure I shouldn’t,’ said Toby. ‘I shouldn’t know how to set about it, for one thing. But you’re giving your form a pretty bad character, aren’t you?’

‘No one could paint them as black as they really are,’ returned Pen, with modest pride. ‘Nesta says that’s what drove their last form-mistress to resign, but I don’t altogether believe that. One of the others said she was offered a better job abroad.’

‘From your own account,’ observed Toby, ‘almost any job would be better than the one she had here. I wonder what Miss Musgrave makes of you.’

Pen grinned, as she free-wheeled down a long slope in the lane, thereby outdistancing Blackberry, who regarded her machine with the utmost contempt. When Toby had overtaken her at the foot, she said:

‘Muskie’s only had a week of us, and, of course, I only see her in school, but I fancy she’ll tame Vb before she resigns! You’ll see something of her to-morrow, if she’s going to take your cricket in hand, and you can let me know what you think of her. We seem to have discussed my form pretty thoroughly—what about yours? Do you like the girls?’

‘Yes,’ said Toby slowly, ‘I think I’m going to like them all before I’m done, but of course a week’s not very long to judge.’

‘A day’s enough for me,’ returned Pen airily. ‘I should think Gillian’s a topping girl, and I like Dorinda Earle, though she’s got a queer abrupt manner. Jane Trevor looks jolly, too.’

‘She is,’ agreed Toby. ‘They all are, but the funny thing is, I believe I like Dorinda the best of the lot.’

‘Why is it a funny thing?’ demanded Pen, jumping off her bicycle as they reached the beginning of the long straggling street which was the greater part of Priorscross.

‘Because,’ said Toby, with an odd little laugh, ‘she can’t stand me at any price! Odd, isn’t it? So long! See you on the playing-field to-morrow, I suppose.’

Dorinda, coming up from an early inspection of the damaged tennis-courts next morning, met Gillian on the terrace-steps and paused to stare at her in amused admiration. Jill’s plain holland frock (the school’s summer uniform) was enveloped in a very practical garden overall, whose capacious pockets held a trowel and a strong pair of scissors, also a small fork and a hank of bass. And its usefulness was not lessened by the fact that it had been fashioned out of a pretty, but gorgeous, cretonne, on which poppies and hollyhocks flared artistically against a background of deep blue.

‘Fairly broken out, haven’t you?’ observed her friend, smiling broadly as she looked her up and down.

‘I made it myself,’ said Gillian proudly. ‘The cretonne was a Liberty remnant. And you’ve only to look at the pockets to see there’s nothing frivolous about me.’

‘The pockets are certainly practical enough for anything,’ Dorinda agreed. ‘Don’t, whatever you do, fall forwards while you’re wearing them, or—between the fork and the scissors—there might be a nasty mess! But are you going to have a lesson now? Because I rather want Miss Musgrave down in the cricket-field at present.’

‘You shall have her in half an hour,’ responded Gillian generously, shouldering her hoe. ‘She promised to start me in, first, in that neglected bit of garden beyond the pines, and after she’s set me my prep., so to speak, she’ll be free to attend to you.’

‘She’s going to coach one or two oddments at the nets,’ exclaimed Dorinda, ‘perfectly hopeless people, who have never handled a cricket bat before and have got everything to learn—Toby Barrett among them.’

Jill paused, her mind distracted for a moment from her own affairs.

‘What? Toby? But she’s in the Sixth—one of ourselves—you can’t mix her up with a pack of new kids from the Lower School. Why not coach her on the quiet for a bit yourself?’

‘Because I haven’t got time,’ replied Dorinda shortly. ‘A lot of our old colours left at Christmas, so I’ve got both teams to pick and rearrange. Besides which Miss Musgrave is keen to start a junior eleven and that will fall on me too.’

‘Then get Kathleen Wingfield——’

Dorinda grinned.

‘That wouldn’t be much kindness to Toby! Kathleen hasn’t got a lot of patience even with people she likes, and Toby Barrett isn’t her sort at all.’

‘No, I suppose not,’ assented Gillian. ‘They’re quite different in every way.’ She stood a moment in thought, then said, ‘Well, I don’t like the idea of her being taught with the kids, and I shouldn’t think Miss Musgrave would either. Send her along to me when she comes, and I’ll see what I can do with her.’

‘You!’ Dorinda’s tone was disapproving.

‘Yes. Why not? Having got my colours, I should know something about the game—enough to send her down a few balls, at any rate, and teach her how to hold her bat.’

‘But what about your gardening?’

‘There’s plenty of time in the day for everything,’ returned Gillian vigorously, as she moved off. ‘Besides, unlike Kathleen, I’ve taken to Toby Barrett. She strikes me as being a bit of a character.’

Dorinda might disapprove, but she was too wise to disobey. Jill, for all her good-natured, easygoing ways, was not head of the school for nothing, and had very decided views of her own on school affairs; her chum knew better than to thwart her. Accordingly, when Toby appeared and hung about the edge of the playing-field, Dorinda called out to her in her abrupt way:

‘Jill Ewing wants you in that waste piece of garden round by the side of the house. You get to it through the pines.’

Toby went, mystified and rather disappointed, for she had ridden over under the impression that she was to learn cricket, and was determined to learn it to such purpose that Dorinda’s unfriendliness could not fail to melt and vanish. She had no wish to waste the perfect morning in talking to even the most charming of Head-girls, for perfect mornings were not too frequent in Devon. When she found Jill, however, ankle-deep in a forest of weeds, a very short explanation served to cheer her up.

‘Miss Musgrave’s just gone off to take the kids at the nets,’ Gillian told her, ‘but I thought it would be rather rotten for you to learn the game with them, so I told Dorinda I’d see to you myself. You’ll have what the prospectuses call “the benefit of individual attention” that way, and get on much faster. At least, I hope so.’

Toby beamed with pleasure.

‘It’s awfully good of you, Gillian,’ she said gratefully. ‘I’m very anxious to get on, and, if you’ll put me up to things, I’ll practise whenever I get a chance.’

Jill stooped to collect a handful of weeds which had fallen to her hoe, and, as she flung them into the basket, she glanced curiously at the day-girl.

‘Why are you so keen to get on?’ she asked. ‘Are you very fond of cricket?’

‘I can’t tell till I’ve tried it,’ Toby reminded her, ‘but I wanted to play that sort of game when I came to school. Most girls can, nowadays, and I hate being different. Besides—I’ve got another reason.’

She did not volunteer what that reason was, and Gillian, too tactful to inquire, went on with her hoeing in silence for a few minutes, while Toby, seated on a fallen pine at the edge of the patch, watched, in her favourite attitude, elbows on knees and her chin resting on her clenched hands. The Head-girl would have been surprised if she could have read her companion’s thoughts at that moment, and known that the hidden motive was an intense desire to ‘count’ with Dorinda Earle. Jane had declared that the games-captain and her lieutenant, Kathleen Wingfield, judged people by their prowess on the playing-field. Toby was supremely indifferent to Kathleen’s opinion, but she longed to stand well with Dorinda.

‘In about half an hour,’ said Gillian, ‘the nets should be free. Miss Musgrave won’t keep those Juniors there longer than that, and the rest are all out on the pitch—except those who are playing tennis. So we’ll go down then and get the place more or less to ourselves. I suppose you don’t mind waiting? It’s still early.’

‘It never really matters at home,’ said Toby, ‘if I’m late for lunch, or any meal except dinner. Daddy likes me to be in time for that. But do you want to stop gardening so soon?’

Jill laughed.

‘It doesn’t feel like “soon” even now,’ she said. ‘Weeding’s warm work. No—don’t you help—thanks awfully, all the same! I want to clear this ground entirely by myself.’

‘And when that’s done?’ asked Toby.

‘Then I’m going to make the wilderness blossom like a rose! The trouble is, I haven’t got a lot of money to spend on plants.’

‘Why not fill up with the rarer wild flowers?’ suggested Toby. ‘There are plenty to be found on the moor if one knows where to look.’

‘I don’t, though,’ said Gillian. ‘Otherwise it’s an idea.’

‘Well, I do,’ said Toby. ‘I could get you heaps. Or tell you where to look for them, if you’d like that better.’

‘Or show me where to look,’ Gillian amended. ‘That would be better still. We could have some glorious rambles on Saturday afternoons, if you’d play guide. Of course, I don’t know the moor, since I don’t live here.’

Toby’s eyes shone.

‘I know it inside out,’ she said simply. ‘We could have ripping times, if you really mean it.’

‘Of course I mean it,’ declared Jill. ‘I can’t imagine a jollier way of furnishing my garden. I expect Miss Musgrave will let me—though I shall have to keep part of the ground for ordinary garden plants, so as to learn their habits. I’d like to put a couple of hydrangeas into that old stone trough in the corner there.’

Toby looked at it.

‘That isn’t a trough,’ she said. ‘It’s a kistvaen. But it would be all right for hydrangeas, all the same.’

‘What on earth’s a kistvaen?’ asked Gillian in surprise.

‘Don’t you know?’ queried Toby, in equal astonishment. ‘They’re a kind of Early British coffin. There are lots of them all over the moor, though I don’t know how this one got in here. Somebody collected it, I expect. Or else, when St. Githa’s was first built on this part of the moor, they found it here, and just left it.’

Gillian examined the kistvaen with increased interest.

‘The Early Britons must have been a stunted race,’ she remarked, ‘if they could squeeze into that. Are you sure, Toby?’

‘Oh yes! They trussed them up somehow. I’ll show you more—and stone circles, too, and menhirs. The neighbourhood’s stiff with them. I’m always hoping to come upon a tomb that’s been overlooked and find something interesting in it.’

‘I wish you luck, then!’ laughed Jill. ‘Come, now, while I put away my tools and pinnie, and then we’ll go down to the nets. I really feel I’ve made a beginning here, and that scheme of yours will be a great help, because it’s something original.’

‘I’m glad,’ said Toby earnestly, as she followed her through the trees to the house. ‘I’d like to do something for you in return for the help with my cricket.’

‘Oh, that’s nothing!’ said Gillian carelessly. ‘If I can make you into a cricketer you won’t be the only one to benefit. You don’t know yet what an obsession it is with Dorinda to find new treasures in the shape of bats or bowlers—I should think it’s worse than your passion for kistvaens! If St. Githa’s loses a match it’s a real tragedy to her, and if I introduced a new star into the firmament of the playing-fields—why Dorinda would probably lick my boots! And she’s not the sort to lick people’s boots easily, you know.’

‘I shouldn’t think she was,’ agreed Toby slowly. ‘I haven’t much hope of starring at games, Gillian, but I’ll try to be a little candle burning in the night!’

‘If that’s all you mean to be,’ said Gillian firmly, ‘I shan’t consider you worth while. I see you had the sense to ride over in your hollands instead of your usual kit. Did you bring your bat?’

Toby came to a standstill and reddened.

‘I—I’m afraid I forgot it,’ she stammered. ‘I’ve got a frightfully bad habit of forgetting the most important things. I’m awfully sorry, Jill!’

Gillian laughed good-naturedly.

‘Never mind. I’ll lend you mine; but I shall have to cure you of forgetting things like bats before I dare turn you over to Dorinda. For heaven’s sake don’t come without your racket on the day she’s going to try your tennis!’

‘I’ll bring it across on Monday and leave it in the pav.,’ declared Toby, ‘so that there may be no danger of such a catastrophe.’

With the borrowed bat in her hands, reinforced by a large amount of determination, she did not acquit herself so badly at the nets; and when Gillian sent her out to bowl, she astonished herself beyond belief by taking her instructress’s wicket in her second over.

‘Of course that was only a fluke,’ she said earnestly, ‘but it’s wonderful how comforting a fluke can be at times. Do you think I’ll ever be any good, Jill?’

‘It’s too soon to tell,’ replied Gillian cautiously, ‘and, of course, you’re starting in extreme old age—but I’ve seen worse beginnings than that. Keep your bat low—your tendency is to lift it far too much—and don’t be reckless. One of the first things to learn in any game is judgement. I suppose, after all, that’s just another name for common sense.’

Toby would have been immensely cheered if she could have overheard a remark made to Gillian that evening by the games-captain.

‘I happened to pass behind the nets this morning when you were coaching Toby Barrett,’ she said. ‘It didn’t look quite such a hopeless task as I feared.’

‘It wasn’t,’ replied Gillian. ‘I don’t say she’s an undiscovered genius—at least, if she is, I haven’t discovered her yet—but she’s far from being an utter fool.’

‘Perhaps not,’ assented Dorinda thoughtfully, ‘though she does rather strike one that way, at times.’

‘Pooh!’ said Jill, ‘that’s only because she’s never been to school before. Give her time, and she’ll shape. Any one can see she’s tremendously keen to be like other people, but she’s had no one to compare herself with till she came here.’

‘She said something like that to me, the other day,’ agreed Jane. ‘Give her a chance, and she’ll be an ornament to St. Githa’s!’

The chief result of the events narrated in the last chapter (as old-fashioned novelists say) was a desultory friendship which sprang up between Toby and Gillian Ewing. It was no more than desultory, because Jill had Dorinda, and, besides, her life as Head-girl was somewhat crowded that term; also Toby, though she liked Jill better than most people at St. Githa’s, felt none of that curious fascination which drew her, half against her will, and wholly against Dorinda’s, towards the games-captain.

Instruction in cricket continued when Gillian could fit it in, and Toby showed herself an apt pupil, eager to learn all she could and as fast as possible. She was secretly very envious of Pen Jordan, who had done so well in her trials that she had been put straight away on the reserve for the second eleven, with every likelihood of playing in a match of some sort before the term ended.

Toby was beginning to fear that her own tennis trial had been completely forgotten, when Dorinda called to her on Friday afternoon as they were leaving the dining-room after dinner.

‘Toby Barrett!’ she said, in her abrupt fashion, ‘I shall want you on the courts at three o’clock. I suppose you’re free to come? No lesson of any sort?’

‘Oh no!’ she answered. ‘I’ve only got my prep this afternoon, and I’m pretty well forward with that, because I want to go on the moor after tea.’

‘Very well, then. Bring your racket, and we’ll see what you can do. I haven’t had time to try you before, but I hope you’re good for something.’

‘I’m used to playing with my father,’ replied Toby. ‘It’s the only kind of exercise he’s keen on, so I get plenty of practice. We’ve got a hard court.’

For the first time Dorinda looked at the day-girl with some interest.

‘Singles on a hard court—and with a man! Humph! you may be useful after all. Come along at three o’clock, at any rate, and we’ll see.’

She went off in the direction of the prefects’ room, and Toby’s heart beat a little faster as she turned into the passage which led to the Sixth Form’s lair. As she passed a couple of girls who had been standing within earshot, she overheard one say:

‘Poor old Dorinda! She’s in a very unpleasant fix, and I don’t see how she can get out of it at such short notice.’

‘Why? What’s wrong?’ asked the other.

‘Oh, haven’t you heard? Lil Peterson of Va, who’s in the school tennis team, has been asked out for the week-end—and she’s gone!’

Toby knew what that meant, and, though her experience of school was only three weeks old, she understood exactly the nature of Lil Peterson’s offence. The tennis-match with Priorsford Club was fixed for to-morrow afternoon, and, unless Dorinda could provide an efficient substitute for Lil, St. Githa’s must either scratch or play with a crippled team. And this was the match, above all others, which Dorinda’s heart was set on winning. As she turned into her form-room, Toby gave a sudden gasp. Was it possible that the games-captain meant to try her in place of the defaulting Lil?

‘What rot!’ she told herself contemptuously, next moment. ‘Why, she hasn’t even seen me play, and there must be lots of girls in the Upper School who could take it on—girls whose style she knows already. Is it likely that she’d give it to an absolute stranger?’

But that was just the trouble. Dorinda, thorough in all she undertook, did know the play of the other Seniors—she made it her business to do so—and there was not one whom she could trust to play at the eleventh hour against Priorsford Club without any previous preparation. In her perplexity she had gone to the new games-mistress, and Miss Musgrave had said:

‘As things are at present, I know much less about it than you. It’s a state of affairs which I am trying to remedy as fast as possible, but meantime my advice is not of much use. I am very sorry, Dorinda. What about the Lower Fifth?’

‘All erratic, except Nesta Pollard, and she’s in the team already.’

‘Is that new day-girl any use? She’s slim and light on her feet and looks as though she’d make a player.’

‘Toby Barrett? I never thought about her. I haven’t tried her yet, but I ought to.’

‘Better try her this afternoon. It’s a forlorn hope, but you’re in a position where you have to clutch at straws. And if you take my advice, Lil Peterson will return to find her name scored off the school team-list.’

‘Rather!’ exclaimed Dorinda bitterly. ‘She knew how much depended on this match and she’s chucked it for her own selfish pleasure! But she shan’t have the chance to do it a second time.’

Toby was waiting at the net when the games-captain arrived, and had carefully screwed it up in readiness for the event. She had expected to find herself pitted against some other Sixth Former, or possibly a girl from Va, while Dorinda took notes from the umpire’s ladder. But, to her surprise, no third person appeared, and Dorinda herself was carrying a racket.

‘Am I to play against you?’ asked Toby, in some astonishment, as the other girl tossed the balls out of their net.

Dorinda nodded.

‘I can’t find anybody more suitable at the moment,’ she said. ‘Do you mind?’

‘Not in the least,’ answered Toby cheerfully, capturing a ball which threatened to roll out of bounds. ‘In fact, I shall feel far less nervous than if you were perched up there watching, as I expected. Do we spin for courts?’

‘Not just now,’ replied Dorinda. ‘If there’s any advantage you’d better have it. So choose your end and take the service. As a matter of fact, there’s not much difference in the courts on a day like this, when there’s no breeze blowing.’

Toby took the end which was likely to suit her best, and picked up her balls. A sense of exhilaration was tingling through her, for she had watched the school tennis during the past week and knew that her own play was slightly above the average. At last the chance had come to show herself of some use to Dorinda, and Lil Peterson’s defection might prove her own opportunity.

The first two balls were faults, as might have been expected under the circumstances; then Toby’s nerves suddenly steadied and the inconvenient mistiness cleared from before her eyes. Dorinda was startled by a smashing serve which was worthy of a boy’s arm, and the ball flew past her before she had quite realized that it was not another fault.

‘Fifteen all!’ sang Toby, as she crossed. ‘Ready?’

Dorinda stopped the next ball, but only to drive it into the net, and the fourth service she hit across the back line. Then, having recovered a little from her first astonishment, she settled down to grapple with the situation, and after the second deuce, managed, by skilful placing, to wrest the first game from her opponent.

‘That’s all right,’ said Toby, as she fired the balls across. ‘Now we know where we are. At least, I think I know what I’m in for, with your service, because I’ve been watching it lately when you practised with Olive—slow and nasty, with an intermittent screw.’

Dorinda laughed, and for the first time since Toby came to school her tone was friendly.

‘The screw’s only intermittent because it doesn’t always come off,’ she said. ‘I prefer a straightforward service like yours, but, unluckily, my muscle isn’t equal to producing such force yet, so I have to make up for it by guile. Ready?’

It cost Toby a game to study the depth of Dorinda’s guile, but she remembered what she had learnt from it and, after winning her first game off her own service, she met her foe’s twisty balls with rather more intelligence—so much so, indeed, that the games-captain had some difficulty in keeping her end up and only won the set by a hard struggle.

‘Thanks awfully!’ she said, as they collected their balls when it was over. ‘Whatever your ignorance of cricket, there’s no doubt you’re going to be a find for St. Githa’s on the tennis-courts, and that’s particularly convenient at the present moment. Heard about Lil Peterson?’

‘A bit,’ said Toby, trying to make her voice sound properly offhand and natural. ‘I heard two people talking about her and saying she’d let the school down over to-morrow’s match.’

Dorinda’s mouth hardened into a straight line.

‘She might have—it’s not her fault if she hasn’t—but after this round with you I feel much happier about things. That is if—I say, are you frightfully keen on going on the moor after tea?’

She flashed a sudden smile on Toby which was full of the peculiar charm she kept for such moments of necessity. Gillian and those who knew Dorinda best were well aware of her fascination, but she seldom troubled to employ it, except in the interests of the school or where she was anxious, for some reason, to win popularity. It occurred to Toby that, for the first time, the games-captain seemed to consider her worth while.

‘I did want to go,’ she admitted honestly, ‘but if you require me for anything I can put it off till another time.’

‘Well, you see, I should like to try you now in a double. Jane and Olive could both play after tea, and Jane would have been Lil’s partner to-morrow. Olive’s mine. If you can fit in decently with Jane—she’s not hard to play with—I’m seriously thinking of putting you into the match.’

Toby had been hoping for something of the sort all along. It had been at the back of her mind all through their set, though she had kept it very far back and tried to forget it. Now that it was actually suggested, she felt that some things were entirely too good to be true.

‘You mean you’d let me—a new girl—play for the school?’ she exclaimed incredulously.

‘My good child!’ said Dorinda impatiently, ‘I’d let the boot-boy play for the school if he was eligible and a decent player! He’s neither, of course, but you are, and all I care about is that St. Githa’s should win. Olive and I combine well, and Kathleen Wingfield and Nesta Pollard are really rather strong. If you suit Jane as a partner there’s no reason why we shouldn’t put up a fairly good show at Priorsford to-morrow afternoon, even if we don’t carry off the honours.’

Toby’s hazel eyes were dancing as they had seldom danced before, but she managed to answer soberly enough: