* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

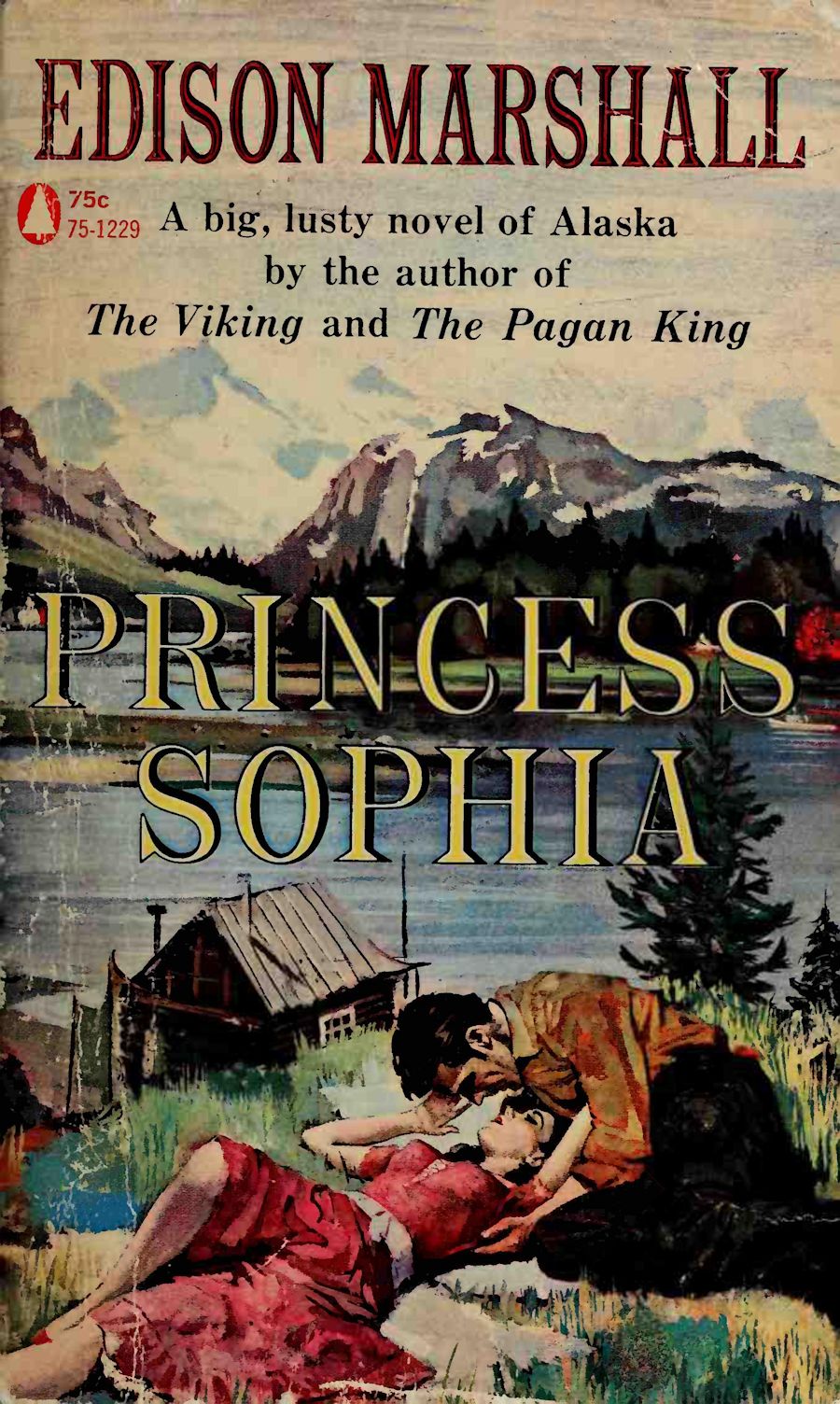

Title: Princess Sophia

Date of first publication: 1958

Author: Edison Marshall (1894-1967)

Date first posted: Sep. 22, 2023

Date last updated: Sep. 22, 2023

Faded Page eBook #20230931

This eBook was produced by: Mardi Desjardins, John Routh & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

This file was produced from images generously made available by Internet Archive/Lending Library.

POPULAR LIBRARY EDITION

Copyright © 1958 by Edison Marshall

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 58-8103

Published by arrangement with Doubleday & Company, Inc.

Doubleday & Company edition published in August, 1958

Published in England by Frederick Muller Ltd. in April, 1959

DEDICATION:

To four true physicians, of the staff

of the Medical College of Georgia, in

order of seniority,

VIRGIL PRESTON SYDENSTRICKER

JOSEPH DEWEY GRAY

WALTER EUGENE MATTHEWS

ROBERT BENJAMIN GREENBLATT

whose art has sustained my unwearied pen.

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

All Rights Reserved

The main characters in this novel are fictitious and are not intended to resemble any real person living or dead.

The story of the S.S. Princess Sophia embraced in this book is true in the main. I have used the real name of her captain, L. P. Locke, and depicted him according to the description given me by one of his fellow ship captains. The scene of his naming of the vessel after Sophia Hill is fictitious. His thoughts and remarks related here are fictitious, although in keeping with my concept of his character. The real names of some of his officers and of the captains of other vessels concerned with the story of the Sophia are given. The behavior of her passengers and crew during the crisis is described according to my concept of the Alaskan.

I am deeply indebted to Captain Lloyd Bayers of Juneau for access to his records of known events at Vanderbilt Reef between 2 a.m., October 24, 1918, and 8 a.m., October 26, 1918. All conjecture beyond what is known is the author’s own.

BOOK ONE

The big house of plantation style where Sophia Hill was born stood in the town of Beaufort, on the South Carolina shore, once the summer resort of the rice aristocracy, whose broad lands fronted the rivers Tulafinney and Combahee. It compared favorably in size and dignity with most southern plantation houses and had somewhat more grandeur, although it fell far short of a few baronial halls near Charleston and Richmond, some millionaire’s mansions in the North, or certain country seats in Europe.

It was of frame, painted white, with long verandas where sitters in the evening could catch the breeze. From the front entrance to the stairs ran a wide hall on which opened four spacious, high-ceilinged rooms, the seaside and the landside parlors, the dining room, and the library. Behind the stairway stood two other rooms, one a pantry and laundry with passage to the separately built kitchen, and a sewing room, which was once the nursery. Four large and airy bedrooms lay overhead, one pair quite fine, the other comfortable; in the rear was an immense bathroom, a linen room, a storeroom, and the narrow stairway leading to the attic. Each of the eight main rooms had a fireplace with a decorative mantel. The main stairs boasted mahogany banisters. The furniture was heavy and rather pompous, fashioned in the last or the next to the last decade before the Civil War, when the rice fields prospered well.

The fact remained that the interior of the big house, throughout its lifetime until now, was never as attractive as its exterior. No doubt the main cause was its setting, a wooded point of land thrust into the bay facing Ladies Island. The high tides of the full moon—“pow’ful tides,” as Sarah Sams described them—rose without sound or foam to the top of its sea wall, and in the mossy gloom of the live oaks the mockingbirds sang almost as sweetly as Keats’s nightingale in her leafy bowers.

In the days when its owners, the Sams family, stood among the foremost of the planter aristocracy, its white paint was spotless and its shutters bright green. Yet even then its effect upon the mind was dimly sad. At close range you could not see its whole: it looked partly overwhelmed, about to be crushed by the moss-hung limbs of the giant trees. Then in those three troubled decades following the Civil War, when the Samses were going to seed, like most of the rest of the rice-planting families, and the paint flaked off in ugly patches and the faded shutters hung awry, it became a study in melancholy. Yet strangely it appeared to possess more real beauty than ever before.

About the year 1888 it began to attract the attention of a few excursionists making their way from northern cities to Charleston, Key West, and newly founded Palm Beach. Already the Old South was becoming legendary, a dream of romance was weaving in the American mind, and when a tourist stopped and gazed at the old mansion he was often compelled to question a venerable Negro, himself born a slave, who cut the lawn and milked the cow and mulched the rose garden. The answer, stripped of its almost incomprehensible Gullah dialect, was of this order:

“Suh, dis hee is de old Sam place. I done took kay of it long befo’ ol’ massa die. But nobody of ’at name live hee now. De las’ was Miss Julia Sam, and she marry de professa ’at come from Bossen. Maybe you hea o’ him? He name Professa Hill, and he ’pointed president of de colud school on Lady Island.

“Yessuh, de rich people up no’th who found Fairbank School for de colud, dey ’point Miss Julia’s husband—befo’ dey marry—de president. Pitty soon she die of de cough, but de professa live hee yet, wif de little girl, she eight yee old now, what Miss Julia bornded.

“Her name Miss Sophy. ’At as good as I can say it. But her las’ name Hill, and so dey ain’t no Sam live hee no more, ’scusin’ Sarah and me, and her pa and me took ’at name when Abe Linkum set us free.”

Sophia’s name came from the Greek word meaning wisdom. Most people, white and colored, mispronounced it Soph-ia, but the correct pronunciation was So-phi-a, the middle syllable rhyming with pie. She lived up to her name, at least in being remarkably quick to learn, and at eight she had picked up and stored away far more knowledge than the house girl, Sarah, could quite realize. For instance, she knew the inward lives of both Sarah and the old gardener, Phineas, better than did her father, whose card read “Stanley Hill, Ph.D.,” but whose real name, in all that really mattered to her yet, was “Dear Papa.” She understood perfectly their Gullah speech. Their words were short and apt, used and reused, although with many picturesque and fanciful connotations. Their occasional attempts to tell secrets in her presence almost always failed; these were so poorly disguised and she was so practiced at listening to Dear Papa, whose learned speech was one long riddle at whose meaning she must grope and guess.

She knew the old house well, from its landside parlor where she sometimes sat, playing grown-up lady, to the recesses of the attic. This she had begun to explore when she could barely toddle up the narrow stairs, and it was still a source of unending fascination. Here were stored, along with much summer heat, such things as broken furniture, chipped china, and cracked glass; a baby carriage, the splendid like of which had not been seen on the Beaufort footpaths these fifty years; bassets covered with leather or pieces of carpet in varied patterns; mahogany sewing boxes with angular tops; albums of pictures of men in uniforms and ladies in satin brocade; a children’s landau that a strong slave or a small pony could draw; dolls that looked good as new except for dust, some of them more beautiful than Sophia’s own best-beloved doll; children’s books with carved wooden covers, and big lithographs and paintings in gilded frames.

Among the dressmakers’ forms, neatly covered in black jersey, stood one at which Sophia would stand and stare with a fast-drumming heart. It was taller and much more slender than the others. It was the most shapely, too, a beautiful young woman’s shape; still, she wished it was not here, that she could go out in the night and dig a hole and bury it in the ground. She knew too well whose body it imitated—this last a Negro term for any likeness. Over the high mantel in the seaside parlor, the best parlor, where Sophia almost never went, hung a portrait of a girl of about fourteen, fresh as in life, whose young body held the promise of this very beauty. And among the big leather trunks, overflowing with mementos of the great days of the Samses, was one as strongly locked as Bluebeard’s room. A long time ago she had asked Sarah what it contained. Sarah had told her, along with the injunction never to meddle with it, never touch it. Well, Sophia had no wish to touch it, let alone open it. She wished she could dig a hole and bury it in the ground.

Sarah never went to the attic with her and sometimes tried to keep her from going, then pretended not to know that she had gone. Sarah was afraid of meeting someone, who walked lightly in silence on the narrow stairs, or seeing that same one, dimly beautiful as a fading sunset, bending over the locked trunk.

The space, the place, the strange deep hollow that she searched most carefully of all was a gilt-framed looking glass, with its ornate base and scroll standing twelve feet tall in the front seaside bedchamber. The face that she found there was not very pretty—yet. In fact, she thought, grown-up people would call it plain. It appeared too broad for its length, the eyes too long and narrow and deep-set, the nose a curved bump like every child’s, the mouth wide and thin, and the chin strong. She knew all that would change—she would make it change. Her skin was not as white as people expected in a girl of such pale gold hair. If it would look better to be whiter, a better match for her fair hair and light-colored eyes, she would make it grow so. Her clothes were not very becoming. Dear Papa did not have much money, so Sarah, who could not sew very well, made her everyday clothes and the second-best child’s dressmaker in town made her Sunday clothes. That did not matter, since Dear Papa liked them, and anyway all that would be different when she grew older. Meanwhile no clothes could be as important as what she saw in the mirror when she wore none at all.

The occasions were not frequent. She was afraid of being caught making this close scrutiny, and it made her flush with guilty excitement, as when Dear Papa bathed her in the big, porcelain-lined, mahogany bathtub. Even so, her main sensation was sharp pleasure. At other times she could not remember, or at least quite believe, that her young body could be so beautiful.

It looked just as it should look, she felt. She would never have to change it, only let it grow in the present pattern. Her legs were already long and rounded, her waist distinct, her shoulders pretty as a picture, her neck long and slim, and—what no boy could boast of—already there was the shadow of a promise, more surmised than seen, of what Sarah called “de fine bus’ of a lady.” When the slow years passed, and the live oaks grew thicker of trunk and wider of branch, the dressmaker’s form that would be made for fitting her long dresses would be just like the beautiful one in the attic. Perhaps it would be even more beautiful, she thought quickly. Then all the stars that twinkled in the warm sky would wake and shine.

When she stood sideways to the mirror, looking over her shoulder, she saw that she stuck out boldly behind and slightly in front. Well, that was all right. Dear Papa had spoken of it once, half in fun, then had told her gravely that it should be so, and she must never be ashamed of any part of the lovely body that nature meant to give all little girls. Then he had said something else, more to himself than to her, which her quick ear caught and her quick mind captured and remembered word for word, although the meaning she did not know.

“There is nothing in the wide world as beautiful to the sight as the human form. To male eyes, the female. To female, the male. Many other visible beauties are its reflections.”

And as for her plain face, she would make it beautiful. She would think and think, and wish and wish, and, perhaps the most powerful magic, dream and dream. All this she must do and, cross her heart and hope to die, she would do, to please Dear Papa.

It was Sophia’s way to wake up at six every morning, make her face shiny bright with soap and water, comb and brush her hair until it shimmered in the mirror, put on a clean dress, then go down to the dining room to wait for Dear Papa. He appeared on the stroke of seven, clean-shaven, hungry, noisy, beautifully dressed, more tall than she had dreamed last night, his bony scholar’s face with its great forehead as gay as his vibrant voice. As soon as he had kissed her he would begin shouting to Sarah to bring breakfast—lots of eggs, country sausage, grits with gravy, and pancakes with maple syrup shipped from his own cold North. He had always time to talk with her awhile—the subject ranging from cockroaches to constellations—before, at ten minutes to eight, he ran to catch the ferry to Ladies Island. From then until about five she moved in a kind of dimness. This brightened a little when she sewed or shelled peas or strung beans with Sarah or when she tagged after old Phineas about the garden, looking at birds’ nests and bugs and little green snakes, but it thickened and became strange and almost frightening when she roamed the big silent rooms alone.

At five in the afternoon she took her seat on the veranda. Her heart would be waiting almost still, like a dog in a doorway, then suddenly it would bound up. Into the walled yard would come Dear Papa, in his bouncing stride. Then began the good time, the time of wishes coming true, when the hard times that had come “a-knockin’ at de do’ ” in the song Dear Papa loved to sing were as far away and unthinkable as the ice and snow of which she sometimes dreamed in a deep, sinking dream in the full black tide of night.

Dear Papa gave her lessons, but these were not work, only a thrilling game, which, by hard listening and strong storing away and quick thinking, she almost always won. Reading and writing came first, these were the most important; unless she mastered these the wonderful gates of the golden cities would not open, and all the roads she could ever travel came to dead ends. There was always geography and history—so she could know where she stood in space and time—and some arithmetic to teach her precision. Best of all, there was always one story—usually of gods and heroes who lived long ago, or great adventurers in the West, or of a battle where tall young men hurled themselves against the guns and died—or always one long poem which Dear Papa read aloud, or a short one she must learn by heart. Dear Papa said that poetry was meat for the imagination, and that she must gorge on it because beautiful witches were hard put to it to do their job of enchanting unless they had been fed on poetry when very young.

Sophia knew what enchant meant. Morgan le Fay had enchanted the great hero, Roland. “But I never want to enchant any man but Dear Papa,” she thought, with a glowing heart.

At eight o’clock school was out, and Dear Papa had emptied a tall glass, misty with coolness, of whisky and water. Between then and half-past eight he had another, while both of them ate the good things Sarah had left in the icebox—fried ma’sh hen, ham smelling of the smokehouse, and sometimes the small sweet oysters that Phineas gathered in his bateau, not a stone’s throw beyond the sea wall, or clams from the beach, or even deviled sea gulls’ eggs, and, in season, sliced duck shot in the abandoned rice fields. And then there came the last act of the day—of the play, she might say, because Dear Papa had already read to her parts of Midsummer Night’s Dream and taken her to see Beauty and the Beast performed in Charleston, and life with him was somehow like a play.

She did not say even to herself that it was the best part of her day. She thought it sometimes, flushing a little, then quickly turned her attention to some other matter. What happened was only a nice warm bath with plenty of soap. When she had undressed and got in the tub Dear Papa would come in, laughing and joking, take off his coat, roll up his sleeves, and make sure she was as clean as a whistle. She did not know why, in that little wait before he came, her heart beat so fast. Sometimes she could hardly follow his gay talk, her attention became so fixed on his strong, silk-smooth hands. Sometimes, though, his words died away and a different look came into his face, and she lay perfectly still in the tub, with her gaze on the ceiling.

The faculty of Fairbanks College usually met on Saturday, when there were no classes, although about once a month he sent word by a colored messenger for Sarah to stay and give Sophia her supper and her bath and sit up in the Big House until he returned, for he would be out late. Every so often he came home, bathed, changed, and went out to dinner to the home of a friend. On such nights Sophia had a good time with Sarah, making clothes for her doll, or hearing stories of Sarah’s childhood on Ladies Island, or talking about hants. But when Sophia went to bed she slept not at all or very lightly with strange, wandering dreams until she heard Dear Papa’s light, quick step on the stairs.

Spring had come again to the Low Country, and the ashes in the big hearth were cold, and the gray moss greened, and the sand fiddlers scuttled wildly in the tide runnels when this lovely order began to change. The first sign of the oncoming crisis was like a pale-colored thunder-head a long way off in the sunny sky, looking hardly bigger than her hand. When she looked again it had become incredibly more tall and broad, and almost before she knew it, it had spread heaven-wide and blotted out the sun and the lightning zigzagged to the ground in furious darts and the thunder crashed and the dark rain roared.

More and more frequently Dear Papa sent word of a late homecoming. He spoke of work piling up at the college: no doubt that was the reason. But instead of getting better, it got worse, until it came about that he stayed away from Sophia two or three evenings every week, and all of Sunday afternoon. Almost nine now, her nipples itching as they swelled, she would not speak of it for all the world, least of all to Dear Papa himself, and Sarah pretended not to notice it. Even when he stayed at home he acted differently, gazing at Sophia with a troubled gaze.

On a sunny Sunday afternoon, when lonesomeness had driven her out of the echoing house onto the lawn, a neighbor boy named Lucas Elliot came running lightly through the gate, bouncing and catching a ball. She was quite sure that she did not like Lucas—in the first place he presumed too much on his being a year and some months her senior, and she found him disturbing in other ways. While indubitably graceful, brunette and tall and handsome like so many of the best boys of the Carolina Low Country, he was self-assured to the point of arrogance, and when he pulled her hair it was not to tease but to hurt. Still, today she found herself welcoming his visit.

“Your pop isn’t home today, so I reckon you won’t mind my dropping by to see you.”

“No, he’s not here. His name is Dr. Hill, not my pop. But you’re welcome as long as you mind your manners.”

“Where is he, by the way?”

“That’s his business, not yours.”

“You always start spittin’ fire as soon as I mention him. But I didn’t have to ask you where he is. I already know.”

“Then you can talk of something else.”

“All Beaufort knows where he is. He’s spending the afternoon with Miss Howard, the young, pretty teacher from Baltimore who took Mr. Thompson’s place when he got sick at Christmas. Her first name is Juliette, somethin’ like your mamma’s first name, Julia. He must think quite a lot of her to be with her two or three nights every week and every Sunday afternoon.”

He had said all this while he bounced his ball, every movement lithe and precise. It was a great stock of ammunition to fire in one burst, but how great he did not know. That he must never know. She did not answer at once; as when Dear Papa put a hard problem to her, she must take her time and think with all her might and main. Lucas liked to hurt her. She did not run after him as did some of the other girls at children’s parties and she knew so many things of which he was ignorant. The fact remained he had somehow guessed a little part of her secret. It took all the strength of her mind and heart not to reveal that he had hurt her more than pulling out one hair at a time till she was bald.

Still this did not mean that he had spoken the truth. That part she could not yet deal with—whether or not he was lying. The immediate emergency was to save her pride.

“I guess you’re too ig’rant to know why he and Miss Howard spend a good deal of time together,” she answered, pretending to look for a four-leaf clover.

“Well, I can guess.”

“Are you sure?”

“Everybody says they’re fixing to get married.” His tone was not now so confident.

“That would be lovely if it turns out so. He says that she’s the smartest young woman anywhere around here. Well, since you don’t know, I’ll tell you. At present they’re writing a book together.”

“A book?”

“One that you wouldn’t be able to read. It’s going to be published in Boston and sent all over the world. It’s to be named Negro Folkways in America, and Their Origin in the Dark Continent.”

She did not know that she had passed the hardest examination ever given to her; anyway it hardly mattered beyond this moment, for nothing in the world that she could say could set at naught what he had said.

Lucas was plainly beaten for the time being. He stopped bouncing his ball and put it under his arm and gave her an uneasy glance.

“I never said they weren’t writing a book. If they wrote it together, that would make it all the more likely they’d get married. And you’ve turned mighty white about something, Sophia.”

“Why should I turn white? You’re seeing things.”

“Anyway, lots of people say that he ought to marry again, if only so you could have a mother. Every girl needs a mother. They say he ought to send you to public school instead of being your whole family and your schoolteacher besides. One lady said it was unhealthy—somethin’ like that—for you and Professor Hill to live all alone in this big house. You might turn out the smartest girl in Beaufort but you still need a woman’s care—a nice stepmother or an old white woman for a housekeeper.”

“I’ll leave it to Dear Papa to say what I need.”

“Well, all right, Sophia, are you invited to Janie Lou Simmons’ birthday party next Thursday at Port Royal?”

“Yes——”

“If you want me to, I’ll have Moses drive by in our carriage and pick you up. He’s going to drive me anyway and it won’t be any trouble.”

“Why, that would be very nice.”

Sophia came quietly into the house. Her head was empty; she made it so. Her heart was empty, too, it seemed, or numbed like her arm when she had lain on it in bed; the only thing she could think of to do now was to look at the clock. A tall clock that one of Dear Papa’s family had shipped to him from Boston stood in a back downstairs room. It was tall and lean and severe-looking, with no decoration and a very plain face, out of keeping with Low Country parlors; still, that was the proper appearance for a clock, she thought. It was on no frivolous business on the earth, it meant exactly what it said; the hour was so-and-so and all the king’s horses and men could not change it one iota; a certain point had been reached in everyone’s life and there was no retreat.

It said five forty-five. She had thought it was later than that. About six hours and a quarter from now she could expect to hear Dear Papa’s step on the stairs; until then she did not know what to do. She wished she could sleep, but, even so, she would dream, gray dreams, weaving slowly and sorrowfully. She wished she could die until then. God was too strict not to let His children die when they liked, stay dead until a wind changed, or a tide went out, or the trouble that they saw had passed away, then come back to life. But once dead, perhaps they would not want to come back, everything was so dark and quiet, and in that case His will would not be done.

When she heard Dear Papa come in she would get up and open the door and ask him to go down with her to the best seaside parlor and light the chandelier. Then with that beautiful young girl looking down at her from the picture, she would ask Dear Papa to speak truth.

Beyond that her thoughts refused to move. Now she walked slowly upstairs, shut the door of her room, took off her pretty Sunday dress, and lay down on her bed. When Sarah would come to tell her that supper was ready—Sarah fixed her nice hot suppers on these days of Dear Papa’s absence—Sophia would tell her that she had taken a headache from looking too long at the sunlit bay.

Not much more than an hour had passed, the sun was barely down and the windows glimmered, when she heard someone running up the stairs. Her door burst open and there stood Sarah, her eyes big.

“Miss Sophy! I couldn’t find you nowhay. Why for you go get in de bed? Now you gotta get up and put on yo’ pitty dress, for dey company come and waitin’ for you in de bes’ room.”

“What company——?”

“De boss done bring a lady and he say for you to come down and make her ’quaintance.”

When Sophia began dizzily to put on her dress Sarah helped her, then poured water in the bowl in which to dampen a cloth and wipe her face, then gave her hair a quick brush.

“You look mighty pitty now,” Sarah told her in her rich voice, “and don’t my Possum be skay, and no matta what yo’ papa tell you, don’t you cry!”

No, she was not scared—she was past all that—and she would never cry in the lady’s hearing. That much was settled.

In a moment more she had entered the seaside parlor, tall as she could walk, a smile on her face. Dear Papa and the visitor had been sitting on the small, high-backed sofa, but both rose, smiling. Dear Papa’s smile looked strained and perhaps his face was not as ruddy as usual, although he was never more handsome or stood so tall and proud. The lady’s smile was sweet. Sophia had not expected her to be so young—not more than twenty-five while Dear Papa was nearly forty. Sophia did expect her to be this beautiful. She had seen her before, as Lucas was talking about her, in a kind of daydream. She looked quite tall, even when standing beside Dear Papa, and was slender and shapely. Her hair was almost raven black and her eyes were a startling blue, yet the bad daydream that Sophia had dreamed had come true. She had a dim but sure resemblance to someone always in this room, who lived here in some strange way, the reality of the image in the lifelike portrait over the fireplace. And that, Sophia thought, with a wave of darkness in her brain, was why Dear Papa loved her.

“Juliette, I wish to present my daughter, Sophia,” Dear Papa was saying in his jubilant voice. “Sweet, this is Miss Juliette Howard, from Baltimore. Now let’s all three sit down, for we have something serious to talk about.”

He smiled at Miss Juliette, and she returned the smile, and then he remembered to give a big smile to Sophia. When they were seated, Sophia’s feet side by side as she had been taught, he spoke on.

“We’ll come straight to it. It is too important to—well—beat about the bush. Sophia, as you probably know, Juliette and I have been seeing a good deal of each other. We have reached the point now that we must make a decision. It concerns you very deeply. The way you feel about it will determine whether she and I shall go on or turn back. We have agreed on that.”

“Perhaps you could state it a little more simply for her,” Juliette suggested, her eyes big and bright.

“I understand perfectly well,” Sophia said.

“Juliette and I are not engaged to be married,” Dear Papa went on. “No matter how much I care for her, I couldn’t ask her to marry me until I got your permission. Some people would think that was a strange thing—and a strange way to put it. I don’t think so and neither does she. The question of your happiness comes first. Both she and I are already happy in our work and lives. We both think we could have a happy, successful marriage, provided you’d be happy too. If not—and although there’s no hurry about your deciding, I feel that you will soon know perfectly well—she and I are not so much in love that we can’t part. If you want our lives to go on as they are, we will part.”

“I don’t think this is quite fair, Stanley,” Juliette broke in, “although I don’t know why. Listen, Sophia, I had a stepmother and it didn’t work out very well. But I remembered my own mother, and you don’t remember yours, and so this might be different—and better. I think I could love you very much, Sophia. Now tell your papa and me whether you think you could love me.”

“I’m sure I could, Miss Juliette,” Sophia answered in a firm voice.

“Do you mean it, darling?” Dear Papa demanded.

“Of course I do. She’s pretty and sweet as my own mamma was, I feel sure. You’ve every right to get married. I’ll be getting married someday—to someone like Lucas Elliot—and I wouldn’t want you to be alone with no one to love you.”

“Stanley——” But Miss Juliette stopped and her lips closed tight.

“What is it, my dear? You’d better say what you’re thinking. This is a critical moment. We’d better not leave any stone unturned.”

“It’s incredible—the way she talks! Stanley, you had no right to let this child be so old for her years. She doesn’t even cry—her eyes are bright as jewels! I feel that there’s something wrong——”

“There’s nothing wrong at all, Miss Juliette. Papa had to have someone to talk to, so he talked to me. I know lots of big words, but that doesn’t change me.”

“Will you kiss me, Sophia?”

“I’d love to kiss you.”

Sophia got up, leaned down a little, and kissed Juliette’s cheek.

“She meant that, Juliette,” Dear Papa said.

“I believe it now. Her lips were so soft.”

“Then we can consider it settled?”

“Yes,” Sophia answered, “and if you please, I’m going up to my room for a little while. This has been a big surprise—and I want to lie down.”

“Certainly you may, my sweet. No one will disturb you, but if you’ll come down and have a little icebox supper with Juliette and me, we’ll be greatly pleased.”

It had not been a big surprise, Sophia thought, as she climbed the stairs. That was a fib, but she had to tell it in order to explain the rest of her sentence, which was true. She wanted to lie down and never get up again. She wanted to go to sleep and never wake. She wanted to be done with Sophia forever, to fix Sophia so she wasn’t any more. She thought of the big knives, long, bright, sharp knives, that would cut open a big beef roast, let alone a soft little girl like her, but these were in the kitchen, out of her reach. She thought of Dear Papa’s guns, a revolver and a shotgun, but either one would make a big noise, and she did not want that; she wanted everything to be very quiet. By the time she had got into her room, a back seaside room almost always cool, breezy in a southeast wind, she saw her way perfectly clearly.

In her deep tall closet lay a wooden box containing many of her summer clothes. With some difficulty, because her hands were shaking and her muscles feeble, she untied the hard knots of the quarter-inch rope with which the box was fastened and pulled it free. Then she tied a noose in it, neat as could be, with a slipknot such as Phineas fixed on his mooring line, and by pulling aside the hangers where hung some of her prettiest dresses she bared three feet of a lead pipe running across the closet from wall to wall. She fumbled and almost fell when, standing on the box, she fastened the end of the rope to the pipe, the noose hanging two feet below and well over four feet above the floor. Her final act of preparation was to push the chest well to one side and stand it on end.

But this last labor spent her strength, and in trying to breathe she sobbed. Running to her bed she fell upon it, shaken with uncontrollable sobbing. She had wanted quietness and still tried to get it by stifling the sound in a pillow. The spell began to pass. Strength was coming back to get up and do what she must do, a last act of love for Dear Papa and of escape and, in some way, of penance for some great sin. It was a hard chore and harsh punishment, although she need not fear the pain. She would jump hard and her pretty little neck would break to check her fall.

And she had started her first movement, slow and weak, to rise from the bed when she heard Dear Papa’s feet drumming fast and loud upon the stairs.

She could not lock her bedroom door because it had no lock. All she could do, in what little time remained, was to slam her closet door. When Dear Papa burst into the room she was standing by her bed, her arms rigid at her sides, her fingers spread and quivering, and her heart fainting.

“Sophia! You’ve been crying.”

“I couldn’t help but cry a little——”

“That’s not all. What else has happened? Why are you so pale? What door was that that slammed?”

“I shut the room door——”

“No, it was your closet door.” He started toward it.

“Please don’t open it! I beg you, Dear Papa. If you love me even a little——”

“A little. God knows I love you more than anyone in the world. I always have. I always will. I knew it as soon as you went out, and I told Juliette. She and I are not going to be married. We’ve broken off for good, and she is as glad as I am. Now tell me what’s in the closet that you don’t want me to see. If you don’t, I’ll have to open it. I’m your father. You’re in my care.”

“Don’t open it. It’s all done with now. I thought—I don’t know what I thought.”

“Were you going to run away?”

“I wanted to go away. But I never will, as long as you stay with me. And I’m so happy!”

“Then I won’t open it. And all will be the same as it was before.”

Her tears ran down her face although she did not make a sound. Dear Papa came up to her and bent down and kissed her in a way that was their secret, his lips lying motionless against hers for a long time. Then he went quietly out of the room.

Within five minutes the box of clothes was again bound with the rope, the knots were retied, and everything else was in place. Anyone could look in the closet and never imagine the evil dream that had almost come true among the pretty dresses hanging on the bar.

All was the same as before in the big house among the live oaks, as Dear Papa had promised. The little change that came a few months after Sophia’s tenth birthday did not count. At least she told herself so, and set her mind not to think about it or hardly notice it. The fact that she dreamed about it, the dream getting stronger or weaker as it wove, like music heard far off, she did not attempt to explain.

It started with Sarah remarking that Possum had been growing like a beanstalk. Possum was her pet name for Sophia, given to her because of her large-pupiled pale-colored eyes that Sarah said could see like a possum—better than a wil’cat—in the dark. Then she went on, for Dear Papa’s notice.

“She done grow out of all her dresses and dey can’t be let out no mo’ cause dey let out all de way.”

A moment or two later Dear Papa took Sophia’s hand and they walked together to the sea wall. They looked at the busy fiddlers and the long green ma’sh and heard a ma’sh hen holler as the tide turned back, and then he took both her hands.

“It’s quite true you’re growing very fast,” he told her gravely. “And I’m afraid it means I have to stop doing something I like to do.”

Sophia looked into his eyes and said, “Well?”

“Giving you your bath. I love to, because your body is so beautiful. But I’m supposed not to look at it any more.”

“Why can’t you look at it as long as you think it’s beautiful? Isn’t that in keeping with what you’ve taught me?”

“I think it is. But different philosophies of life, all with truth in them, are in conflict with one another. Do you understand what I mean?”

“I think so.”

“We must never have secrets from each other. I want you to answer a question—it will help me in this and in future matters. Do you or do you not understand why I must stop giving you your bath?”

Her face flushed, but she continued to gaze at him in profound earnestness.

“I understand why you think you must. Because you take too long.”

“Yes, I take too long. I can’t help it. Now let’s run like hell to where Phineas is cutting hedge. I ‘spec’ he’ll show us a toad-frog.”

They ran, and the incident dropped into the past.

The seasons crept by, the sweet, gently changing seasons of the Carolina Low Country, and they added up to years. Occasionally Dear Papa talked of her going to the public school, or even to a seminary in the cold North, but he’d be damned if he’d send her to one of the finishing schools in Charleston or Baltimore. Actually he did none of these things, but continued to tutor her, and the fact remained that at thirteen she knew more poetry, mythology, and astronomy, and more about the English language, and was better oriented in geography and history than most college freshmen. She had not caught up with herself in mathematics, physics, chemistry, and languages, but there was plenty of time for these. Meanwhile her body was swiftly losing its childish look and her face was changing wonderfully, as though by a fairy’s gift.

Soon after this, trouble set in again, not heavy trouble nor continuous, not knockin’ on de do’, only lightly rapping. One evidence of it was a minister’s calling late in the afternoon and speaking for nearly an hour in an austere voice to Dear Papa. The latter had been able to make only brief sallies in reply, and none at all when, at the doorway, the clergyman shook a solemn finger at him and fired a parting blast.

“You, sir, are an agnostic! See that you don’t raise your beautiful little daughter to be the same!”

When Sophia joined Dear Papa he was sitting in the landside parlor, his feet sprawled and a rueful look upon his face.

“Darling,” he burst out, “I’ve done wrong in not sending you to church. The minister says so—and he had every right to say so, reminding me that he was Julia’s minister before you were born. The vestrymen all say so, and I suppose the whole town. I explained that you knew more about the Bible than nine out of ten of his parishioners. ‘Perhaps so,’ he replied, with great severity, ‘if she has read it like a novel, instead of the Word of God!’ Well, I would have liked to send you to a colored church on Ladies Island if the white people would have stood for it. One to whom God is Ol’ Massa, one without any organ, with only those roof-rocking voices in harmonies beyond harmony, one where they sing ‘How Dey Done My Lawd!’ instead of ‘Beautiful City of Light.’ I told him I had encouraged your religious instincts by having you learn by heart the great Elegy, and by reading about the martyrs and such novels as Ben-Hur and The Christmas Carol. He answered me, ‘Novels, pew! What are they compared to a good, righteous sermon!’ Then I made the mistake of telling him you had read Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Nothing I could say after that assuaged his ire.”

“Well, I’ll go to church if you think best.”

“Do you think best, Sophia?”

“Yes.”

So she did go regularly and listened to the sermons and joined in the singing and the prayers, but the light the preacher promised never shone upon her, and instead a ghost came in and sat beside her and its name was Loneliness.

Then there was the difficulty about children’s parties. She played the guessing games and won most of them, and rather enjoyed kissing games, although, it seemed, in a way different and more secretive than the other girls—a less natural way that made her feel guilty. The boys were attracted to her, she was so patently the prettiest in the bevy, but this might not be the main of her attraction, since they behaved so badly. The other girls united against her and by little undercover acts managed to ostracize her. So it came about that when the invitation to a party was given directly to her she did not tell Dear Papa and did not attend. Before long almost all the party givers ceased to invite her.

She was going on fourteen and had almost got there, and she had already grown into as startling personal beauty as this ancient seagirt breeding ground of beauty could remember, when the Fates, the Three Sisters of Dear Papa’s lore, moved strongly for or against her, which she could not know.

The time was late summer of the year 1894. It happened that a schoolfellow of Dear Papa, later a medical student under Dr. Havelock Ellis at St. Thomas’s Hospital in London, and for the last few years engaged in psychological research in Vienna, touched Charleston on his homeward journey; and, in spite of the pressures of time, took the boat to Beaufort to dine with his old friend. Dear Papa called him Emil and introduced him as Dr. Linden. He was a short man, prematurely bald, with a quiet manner and deep-set eyes. He seemed quite startled by Sophia’s appearance and after he and Dear Papa had had a drink together on the veranda, meanwhile talking in low tones, he seemed particularly attentive to all of her remarks at dinner and noted her smallest actions.

Sophia was allowed to remain at table while the two old schoolmates sipped brandy and coffee. Once, as they were talking away at a great rate, she was given a chance to score.

“Emil, what was the name of the witch who enchanted Ulysses in the sea cave on the island of Ogygia?” Dear Papa had asked. “It slips my mind.”

“Circe,” the doctor replied.

“Hell, no. Circe was the hag that turned his sailors into hogs. Sophia, do you remember?”

“Of course I do. Her name was Calypso, and she kept him captive seven years, until Zeus sent Hermes to rescue him.”

“Touché!” the doctor said, with a faint smile, while Dear Papa’s eyes shone and her heart glowed.

But something quite disturbing happened a few minutes later. Dear Papa became grave and spoke in what Sarah called “he big boss voice,” which he employed when he expected immediate obedience.

“Now run along to bed, my sweet. The doctor and I are going to have a long talk in the library.”

Sophia offered her grave good nights, kissing Dear Papa, shaking hands with the doctor; then she ran along—but not to bed. She walked upstairs, letting her high heels click on the steps, tiptoed down again, and slipped into the landside back room, once a nursery, now a sewing room. It happened that there had been a passage cut through a closet between this room and the library. In it were stored old schoolbooks, biographies of men renowned in their day but now forgotten, outworn histories, sets of sentimental novels no longer readable, and stacks of dusty periodicals. Curtains so rarely opened that they hung in long-fixed folds shut off the closet from the sewing room. To all intents and purposes the opening into the library had been closed by a tall, massive, old-fashioned secretary, but actually it did not stand flush with the wall, and the gaps made an easy passageway for any sound above a whisper.

Perfectly certain that the subject of Dear Papa’s and Dr. Linden’s talk would be herself, and strangely frightened, Sophia slipped between the curtains, blew away the dust from a pile of magazines, and sat down with her ear close to a crack.

She had not long to wait. When the two men entered the library Dr. Linden admired the mellowed leather of the books, then they took chairs, and the sound of matches striking and the pleasant smell of tobacco told her they were lighting pipes or cigars. Then Dear Papa said in an agitated voice.

“Emil, we might as well come to it. What do you think?”

“I don’t think. I know. Sophia is terribly in love with you.”

“She loves me too much, I know, but she’s not in love with me.”

“I meant exactly what I said.”

“Emil, that’s incredible. Whatever it is, it began when she was four—even before that. It hasn’t changed since then——”

“That’s the trouble. It should have died away—taken another form—when she reached four. Stanley, I have the advantage of you because I’ve just come from the most dynamic, the most significant psychological laboratory in Europe. I had a chance to read the manuscript of a forthcoming book, Studien uber Hysterie, by a Jewish neuropathologist you’ve never heard of. I was so impressed by his work that I asked to call, and in the upshot I was invited to have a small part in his studies. Actually his thinking had gone far beyond that book. It had to do with the conflict between the conscious and the unconscious mind. He finds that a great deal of that conflict arises from infantile sexuality, and especially the physical love of a male child for its mother and the female for its father. Mind you, this is perfectly natural and almost universal. Only when it lingers on into later childhood, repressed or denied, perhaps out of shame or guilt or God knows what, it can damage the personality.”

“Do you think Sophia’s personality has been damaged? By God, I don’t. Speak plainly.”

“No, I don’t think it has. But the seeds of tragedy are there; whether they grow or melt away in the good earth remains to be seen. I want her to stop listening to you as though you were a god. I don’t want to see her face reveal emotion when you give her a smile—like Alice in the song.”

“Well, what am I going to do? You’ve diagnosed the ailment—I don’t question it—now what’s the cure?”

“Before I can suggest any I’d like to have a better idea of what caused it. Now it’s your turn to speak plain.”

Dear Papa waited long seconds—while Sophia’s breath stopped and her skin prickled—then he answered quietly, “I will.”

“Love has a terrifying power to beget love,” the doctor said. “You lost your beautiful wife when Sophia was two years old. In time didn’t Sophia take her place in what was once called ‘the wanderings of desire’?”

“I deny that. Or it was so submerged in what you call the unconscious mind that I didn’t know it.”

“You’ll know this much. This is a hard question but I want an answer. This is a medical matter. Did you in dreams—the dreams of sleep I mean—ever . . .” But Dr. Linden’s voice dropped very low and Sophia could not hear.

“It’s a hard answer for me to make, old friend. Remember I am of Puritan upbringing. I broke away, but some of the old stricture remains. No, I never dreamed that. I dreamed I did everything short of that, and when it occurred with anyone else—a woman I could never identify—Sophia was always somewhere about.”

“That means that she was the subject of those dreams, too. The conscious mind was not quite inert and it changed the images conjured up in the unconscious. Stanley, you need tell me nothing more. Now I’m going to prescribe. Sophia must escape from the most—the worst—of your influence. She must find an outlet for her tension in normal ways. I propose that you send her to the local high school for at least one year. She won’t learn anything much and she’ll be lonely as the devil but she’ll shine in her classes and, a little at a time, begin to take some interest in young people’s affairs. You can send her to college at sixteen.”

“Where, for God’s sake? I realize the need is great but the risks are great too.”

“I know the very place. While in Charleston I heard a great deal about the college there, founded before the Revolutionary War. It’s small—all to the good—and has a remarkable faculty and standards. Since a boat makes the round trip daily, she can come home on Friday and go back Sunday afternoon. Thus the rupture wouldn’t be too severe.”

“I don’t know. Still, I’ll follow that course. I have some good friends there——”

Sophia heard no more because she was stealing away, out of the closet, through the sewing room, up the stairs to her bedroom. She had been cold with fright, but now her skin was glowing and in her mind was a rush and tumult of feeling which she could not yet resolve. As the door closed and she gazed upon her familiar surroundings, the truth broke upon her—the lovely, the irrefutable truth.

What did it matter where she went to school, how far off, how long she stayed, how rarely she came home? When she grew lonely and longing she had only to remember that Dear Papa was the same—that he loved her best in the world, always, and in all the ways that she loved him.

The early spring of the year 1898 was stormy, with southeast winds and unusually high tides. Tree moss waved day and night, and shutters rattled, and two fishermen from Ladies Island whom Sarah knew well were drowned off Edisto Island. The Charleston paper, which Sarah could read quite well, told and retold of Uncle Sam’s big boat being blown up in Cuba, and how a big war, maybe as big as the war Abe Linkum fought to set her daddy free, was just about to break. Sarah went often to her church and there she sang with great fervor the troubled song her people learned and remembered from long ago, “Ain’t Goin’ To Study Wa’ No Mo’.”

Since her mind was bent on signs and wonders, she heard more often than before light steps on the attic stairs and across the creaking floor to a corner where stood a locked trunk. So it came about on a Friday night in March, when Sophia was home from college, and the rain beat against the windows and the live oaks groaned in the blast, she was in a mood to grant a request that her darling had made many times before.

“If you knowed how it hurt my head to tell fortunes, you wouldn’t ask me,” Sarah said sorrowfully.

“Just one time, Sarah.”

“It feel like my head goin’ bust open, and de sweat run off me, and my arm and leg get stiff. And when de spell pass I get so sleepy I can’t keep my eyes open. But it a good night to tell it if I ever goin’ to. You and me all alone till de boss come home from facklemeetin’. ’Pears like any fortune I tell tonight will sho’ enough come true.”

Sophia shivered a little, deep inside of her. This year she was going on eighteen, her application to enter Radcliffe College in September had been accepted, yet she felt what seemed a distinct warning against hearing Sarah’s prophecies. But she put it by, took refuge in fatalism, and when Sarah brought to the sewing room a big well-illustrated Bible, her most prized possession left to her by Ol’ Mass’ Sam, she opened it at random as Sarah instructed her.

“Now run yo’ finger down de left-hand page and let it stop when you feel a little jump inside yo’ head.”

Sophia’s finger stopped only a few lines from the top. She had felt nothing inside her head, but there could be no doubt of the sudden, sharp prickling sensation at the back of her neck.

“What do it say, Possum?” Sarah asked, her face drawn and her eyes rounding.

“It’s the eleventh verse of the thirty-third chapter of Numbers. And it reads—it reads—‘And they removed from the Red Sea, and encamped in the wilderness of Sin.’ ”

“Oh Lawd!”

“What does it mean, Sarah?”

“They’s an ol’ plantation nee Watertown what dey call Mount Sinai. I reckon us goin’ move away from de bay—it plenty red someday when de sun goin’ down—and yo’ papa buy ’at old plantation and us live there. It way in de country and mighty wild, wif piney wood and swamp and wil’cats and coons and rattlesnakes.”

“I don’t think it means that. I don’t know what it means. Now I’ll open the Bible at another place.” For she knew the ritual, having seen Sarah tell Phineas’ fortune.

“I tell you what, Possum. Us won’t finish the fortunetellin’ now. Yo’ papa like to come home any minute now, and I got to mend ’em socks he gave me befo’ he come, and after ’at I’ll sew a while on yo’ pitty new dress.” Sarah used a wheedling tone Sophia had heard before.

“We will go on with it. What are you afraid of, Sarah? I’ll open here, and run my finger down the right-hand page——”

It appeared to stop of itself about halfway down the page. The letters seemed to leap out of it, as though they were printed in blacker type. Sarah was staring at her with wild eyes.

“It’s the Book of Ruth, Chapter Four, thirteenth verse,” Sophia said. “And it reads, ‘So Boaz took Ruth, and she was his wife: and when he went in unto her, the Lord gave her conception, and she bare a son.’ ”

“ ‘At’s a good fortune. I hee de story befo’. Ruf came from a long way off, and Boaz, he was a mighty man, wif plenty money. She done lay down beside him when he was asleep, after he been drinking, on a heap o’ co’n in de co’n field, and natuh did de res’. ’At mean you goin’ marry de massa o’ a big plantation makin’ plenty co’n and cotton too.”

“Sarah, did you ever go and lie down beside a man sleeping on a pile of corn?”

“I sho’ ain’t, but one time a boy come and lie down beside me when I was sleepin’ on a bale o’ cotton. And ’at de way it should be, Possum, not like Ruf done.”

“How old were you, Sarah?”

“I reckon I was thu’teen.”

“Good heavens, I’m nearly eighteen. I wonder how much longer I’ll live. Well, we’ll go on with the fortune and see.”

“I don’ tol’ you fo’tune.”

“You’re only half through and you know it. Now it’s your turn to open the Bible and find the verse, first the right-hand page, and then the left nearest the heart.”

“I can’t do it now, Possum.”

“You’ve got to.”

The sweat came out on Sarah’s smooth dark cheeks as she opened the book and her lean black finger ran down the page. As it stopped, she uttered a low moaning sound, as of pain.

“Second Samuel, Chapter Twelve, verse eighteen,” Sophia read. “ ‘And it came to pass on the seventh day, that the child died.’ ”

“ ‘At the wrong place, Possum. You started to open it way back from there, and de pages stuck. ’At ain’t yo’ true fortune. You go back where ’em pages stuck.”

“Very well.” Sophia flipped over with her hand about half the pages in the book. “Now run your finger down and we’ll see. It’s Saint Matthew, Chapter Two, and the verse is number eighteen. Sarah, you didn’t do much better.”

“What is it, Miss Sophy?”

“ ‘In Rama was there a voice heard, lamentation and weeping, and great mourning, Rachel weeping for her children, and would not be comforted, because they are not.’ ”

“You didn’t find the right place you foun’ befo’. ’At spoil de fortunetellin’ for tonight. You run along now, while I mend ’em socks, and you git a book to read.”

“No, I’m opening it again—the last time. You’ve got to find the verse on the left-hand side. Maybe it will tell us something that will change everything.”

“Miss Sophy, dey sompin hee I don’t like. Dis is de wrong night to tell fortune. Listen to ’at wind. I never heard it cry like ’at befo’, like a little los’ child. Ol’ Debbil, he round hee close. It him what make us stop on ’em verses, instead of de right verses ’at tell yo’ fortune true. De rain on de window, it sing instead of rattle, and it’s a song I done hee an old witch sing when I was a li’l girl. De dead are up and out of de graves tonight. Dey come nights like ’is, de ol’ people see ’em and sit close by the fire and not say nothin’. I ain’t gwine open ’at book.”

“The fortune will be told me just the same. Maybe it will be worse because you broke your promise.”

“Yo’ mighty ha’d on me, Miss Sophy. You ain’t ’fraid of nothin’, even de Lawd, and you bent and dete’min as ol’ Mass Sam, who wouldn’t tu’n aside for a ragin’ lion. I’ll run my finga down until I feel ’at little jump inside my head but I won’t look at what it say, and if you look at it, it yo’ business not mine, and I won’t take no blame.”

“That’s all right. Go ahead.”

Sarah’s finger began its tremulous journey, almost paused, moved again. When it stopped, Sophia glanced at the heading, the chapter number on the same page, and started to glance at the verse when her eyes raised to meet Sarah’s wide and popping eyes.

“Sarah, you moved your finger——”

“No, I didn’t, Miss Sophy. ’At de very one whay it stopped——”

“Well, I’m not going to read it. I’d never know whether you cheated or not. Anyway, what’s the use of knowing—it won’t change for better or for worse what’s going to happen.” As she continued to gaze at Sarah, a look that made the colored woman think of conjure women came into the beautiful face. “A long time ago, Sarah, there lived the adopted son of a king, and his name was Oedipus. It was in the country that Mr. Paulos, who runs the Daisy Restaurant, came from. He went to a fortuneteller, who told him that unwittingly he would kill his own father and marry his own mother. He tried to run away, but it wasn’t any use. The evil fortune caught up with him. Well, I’m not going to try to run away. I’m just going to close the book.”

She did so, and she could swear that she had already forgotten what she had read at the top of the page, and the chapter number.

“Now, ’es go and make some nice ham sandwiches,” Sarah proposed. “We got mo’n half of ’at fine country ham us had for Sunday dinner.”

“A little later, Sarah. I think I heard Dear Papa come in and I want to see him.”

Sophia ran out to find her father in the hall, newly shed of his rain-wet hat and coat, standing there apparently aimlessly, his eyes very bright, a dazed expression on his wonderfully chiseled face, and an opened telegram in his hand.

“Darling, something very important has happened,” he told her, in a voice that did not hold quite firm.

She took his free hand and waited.

“Before I tell you what it is, I must tell you something that I hadn’t got around to yet, because the reports I’ve been getting were not quite full. The gist of it is that quite a number of this year’s graduates of Fairbanks College have been taking examinations to enter professional schools and especially teaching. They made quite a remarkable showing, and it has come to the attention of some of the biggest people in the country. In fact I can say we’ve done something toward spiking the brutal, blasphemous lie that only white men, not colored, are made in God’s image. Well, this telegram is from President McKinley. You can read it now.”

His hand trembled as he passed her the page. She held it and read:

I WISH TO OFFER YOU THE DIRECTORSHIP OF GOVERNMENT EDUCATION IN THE DISTRICT OF ALASKA. YOUR TASK WOULD BE TO ESTABLISH OTHER SCHOOLS AS RAPIDLY AS POSSIBLE. YOUR IMMEDIATE HEADQUARTERS WOULD BE SAINT MICHAEL NEAR THE MOUTH OF THE YUKON RIVER, AND A DEPUTY OF YOUR SELECTION WOULD BE STATIONED AT SITKA. YOUR SALARY WOULD BE $5,000 A YEAR WITH ALLOWANCES. ALASKA WOULD BE SERVED AND I WOULD BE PERSONALLY GRATIFIED IF YOU TELEGRAPH IMMEDIATE ACCEPTANCE.

Sophia handed back the telegram and asked quietly, “May I go with you or do you want to go alone?”

“My darling! Of course you can go, although you must be back in Boston in time to enter in January.” Then, in a glowing voice, “Alaska schools may be all right in their way, but I doubt if any of them can quite come up to Radcliffe.”

She remembered there was a gold rush in Alaska just now. Almost anything could happen to one who had caught the notice of the Three Sisters.

In the afternoon of July 6, 1898, the iron steamer Victoria, manned by a crew cold sober after its revels on July Fourth, was about to sail from Seattle to the old Russian town of St. Michael, far and away toward the Arctic Circle on the Alaskan coast. Wonderfully enough, despite the rush of gold seekers buying deck space to sleep on every other Alaska-bound vessel, not all of the Victoria’s cabins had been engaged. The reason was a great joke to those passengers and crewmen who loved the old Vic and her comfortable, leisurely voyages, but not to her owners. For years now she had had the government contract to carry the mails addressed to Dutch Harbor and the Yukon River towns and interior trading posts, by which she must run on schedule on the Outside Route, and not go gallivanting through the Inside Passage to roaring Skagway.

On the passenger list was a name not uncommon in the Northwest—Eric Andersen. Somewhat red of eye and heavy of head when he first came aboard, he was almost immediately cured by the sight of one of his cupmates of two nights before, and of two of his Northland neighbors. The former was heading toward the Nome peninsula on a fool’s quest for gold. The other two, sourdoughs like himself, had trapped last winter fifty and a hundred miles from his diggings, although as soon as they could assemble their belongings, including their pretty squaws, they would be heading upriver to Dawson.

Tall, loose-jointed, blond girls with whom he had danced at the Norwegian social club on the night of the Fourth had considered him somewhat young to be called a sourdough. In the first place the word was almost always used with the prefix “old.” Actually a storekeeper who had spent a rainy winter snug in Ketchikan, in a climate fully as harsh as San Francisco’s, could call himself that. The real sourdoughs let this pass. They knew, too, that a high-smelling method of making bread—using sour dough from the last baking in lieu of yeast—was not the essential hallmark. The new definition, almost always ribald, that drifted through the vast territory every few months was good for laughter but did not pin the matter down. Eric could recognize a fellow sourdough as soon as he opened his mouth. More than that, he had a complex of feelings, which he could not quite put in words, of what made a sourdough, a real one, no better but different than any other species of man in the wide world.

At twenty-three he himself was a real one. He had wandered up from Tacoma to work in a fish crew at the age of eighteen. Previous to that he had made a journey rather common for embryo sourdoughs—from Minnesota west—and his parents had begun the trek in Hammerfest, on the Norwegian coast. Since then he had roamed the District wide and far.

The Norwegians are a tall race. Eric stood an even six feet, but his body was so compact and proportionate that he looked shorter. He did not have the pale or red coloring common among Norwegians: his hair exactly matched the fur of the Far North, back-country martens he sometimes caught in his trap, and was as fine as that, blowing in the wind unless he plastered it down with grease. Not sea-blue like so many Norwegian eyes, Eric’s eyes were a pale, magnetic green between thick dark eyelashes and under heavy dark brows, and his teeth were even, perfect, and a lustrous white. Otherwise—so a girl at the dance had told him—he looked like any other fellow.

This was far from true. The girl had been too young to see much more than young and healthy maleness. Of course no fellow looks like any other in close scrutiny; and the marks of an intense individuality, which is the one thing common to all sourdoughs, had come on him early. He had seen the ice go out of the Yukon three times. He had begun to be large like the river, and small like someone all alone on its banks. His face had begun to give signs of a chisel working, which is at once sad and splendid in a man of twenty-three. Other young people, who by the nature of things cannot pick and choose and must take human kind as it comes, do not like to see it in a contemporary and manage to skip it.

He and Lars Gustavassen and Otto Swanson got together by the rail. It gave them a good feeling, which all enjoyed, hardly knowing it was there. In the back of every sourdough’s mind is the endless awareness of having spent vast periods of time alone and, if he lives on, of the certainty of doing the same hereafter.

Lars and Otto were slightly older than Eric and looked more phlegmatic, although Otto was known to have one of the most terrible tempers north of the Kuskokwim. All were dressed similarly and not very well, the outfits expensive but tacky, since none had the slightest notion of what was becoming to him. All three wore gold nugget stickpins in factory-tied neckties; Eric had a large nugget ring. In each coat lapel was the badge of the Yukon Order of Pioneers, a lodge-like type of fraternity. Their present interest centered on the gangplank by which fellow passengers were boarding.

A good many of these were instantly recognized by all three, in which case they were greeted loudly and jovially. “Hi there, old wolverine,” or, “Howdy, Andy!” or, “There’s old Bill Holbert; I didn’t know he was outside; hey, Bill, where did you get that dude hat?”—these were typical salutations. When a boarder was recognized by only one or two of the three, there followed a brief, muttered biography, stripped to its essentials, to enlighten the ignorant. “That’s Mr. Goldstein. He’s a big fur buyer—one of the best drivers in the Nort’—and I t’ink he’s planning a big trip next winter, to be coming up so early. He already bane west to Kamchatka and east to Demarcation Point.” This last was a span of sixty degrees—about thirty-five hundred miles.

Red Ole Iseksen was “King of Sand Point.” He was said to own a harem of a round-dozen pretty Aleut girls whom now and then he passed around to favored visitors. Sand Point was away to the westward, beyond Kodiak, although not as far west as Unga, which was the headquarters of the robed bishop of the Orthodox Greek Church, with childlike blue eyes, a face which to the knowing would have suggested Count Tolstoy’s, and a venerable beard. He was not the only churchman to come aboard. To the watchers’ astonishment, there were two more, each neatly dressed in black with inverted collars. One, the elder, had no baggage, and obviously had come aboard to say good-bye to his fellow, whom he appeared to treat with the greatest deference. Actually this last was a type of minister none of the three had ever seen. Except for his garb they would have guessed him an English lord, such as now and then passed this way to shoot Kodiak bears or the giant Kenai moose—the democratic kind instead of the haughty. He was tall, slender, lithe, notably handsome, walking as though he owned the ship and yet with such a pleasant manner and easy smile that Eric felt none of the upsurge of resentment that he felt toward dudes.

“I know who he is,” said Lars, in a low, excited tone. “I read about him in an editorial in the Seattle Post. He was the minister of a swell church in New York. It was where the Vanderbilts and the Rockefellers went—the Church of—a long name I can’t remember. But his name is the Reverend Arthur Dudley. He’s only thirty-five, yet he was about to be made Bishop of Long Island. Instead he decided to become a missionary at Allapah Bay!”

“Allapah Bay!” Eric echoed in amazement. “That’s fifty miles on the Godforsaken side of Point Hope and it’s not a bay, only a dent in the coast. We stopped there when I worked on the Alaska Fur Company boat. Allapah means cold, and when an Eskimo says something is cold, by Yesus, it is cold! The Bear comes in once a year for survey. Maybe a trader or two and maybe not. The rest of the time there’s only the Eskimo village and the tundra and the sea.”

Otto uttered his deep laugh. “Well, he won’t stay long. The first time a squaw’s mukluk passes near his nose he’ll long for them incense pots.”

The three sourdoughs were quiet awhile, because each was thinking of his own break with the peopled places, the easy lands. Then Eric thought that Otto should not have mentioned the rank-smelling mukluk because it hit too close to home. That pertained to all three of them in some degree—perhaps to almost every young sourdough who lived away from the towns. But Eric himself lived close to the great river, all year beside it except for occasional journeys, and that caused him to have ideas of relations between man and man, man and woman, even man and God, that he could not discuss with Otto and Lars, or hardly mention to any sourdough lest they think he was putting on airs.

Then his jaw dropped as he gaped. Coming up the gangplank was a tall man, as distinguished-looking as Eric had ever seen, and lightly before him went a tall, slender girl with pale gold hair. She was alien to the West, let alone to Alaska, yet all he could think of in the way of comparison was the northern lights.

Out of a home population of never more than three or four millions the Norwegians had made their mark throughout the Western world, perhaps second only to the mark made by about an equal number of English, Scotch, Irish, and German settlers on the American shore in the spine-tingling last decades of the eighteenth century. It came about partly through the Norwegian’s genius for quick and direct action. Their brains work fast, they are swift to realize what they want, and their bodies are, by and large, marvelously agile. That is one reason they are among the greatest seamen that ever spread a sail.

There was no porter carrying bags to show the newcomers their way. The stewards were setting the tables for dinner and dock laborers were so scarce these days of the gold rush that most hand baggage was lugged aboard by its owners or checked on the dock for later delivery to the staterooms. When the frock-coated gentleman and the summery girl gained the deck Eric was there to meet them, having moved so suddenly that Otto and Lars gaped at him with open mouths.

“Sir, they’re shorthanded today,” he explained, “but I know this ship from taffrail to bowsprit, and if you’ll tell me the numbers of your rooms, I’ll take you there in a yiffy.” Too late he remembered that these nautical terms did not apply to modern steamers but to old windjammers, and he feared, too, that he had not minded his accent as carefully as he liked to do on social occasions.

The fact remained that the two newcomers did not appear in the least astonished and their grave gaze upon him was in no way derogatory.

“We were told we could expect very fine hospitality from the Alaskan people, but we hardly looked for it this soon,” the tall man said. “Our numbers are one and two.”

He led the way down the stairs and along the dim corridors. Cabins one and two were the best on the ship, and the thought struck him that he had thrust his company upon his “betters,” a term used sometimes by English emigrants in Dawson; or at least he had made a fool of himself. True, he had never admitted publicly to having any betters. That was the teaching of his father, Olaf, who had spoken to him solemnly when he was old enough to understand.

“T’is is not Old Country,” Olaf had said. “T’is is U.S.A., where men are created free and equal, by Yiminy! Honor t’em t’at deserve it and shake hand wit’ every man, but if any man turn up his nose at you, you smash it for him goot.”

The fact remained that when Eric had turned the keys in the two doors the gentleman and the young lady seemed in no haste to be rid of him.

“Do you live in Alaska?” the former asked.

“Yes, sir, about five years. I’ve got a little place far up on the Yukon.”

“Are there any Indian schools near where you live?”

“No, but there’s a big Indian village two hours away by dog team. Would you like to have your portholes opened? We’ll be in Inside Passage waters most of the afternoon and you’ll catch a good breeze.”

“Thank you.”

“It’s a nice t’ing you’re on the starboard side instead of the port,” Eric went on as he opened the ports. “That means you’ll have a good view of the Aleutian Range all the way to Dutch Harbor, one of the finest views in the world. The wind’s on the port side usually but there’s plenty for everybody.” Eric smiled a slow smile, thinking of those plentiful winds.

When he turned to go the gentleman made a friendly gesture.

“What is your name, if you’ll please tell us, and where are you bound?” And when Eric had answered, “Well, Eric, we’re to have the whole journey together. I am Dr. Hill, a schoolteacher, and this is my daughter, Sophia.”

They gave him their hands, the professor’s smooth, unacquainted with hard work, yet strong. The girl’s hand differed greatly from any he had ever touched, and he was shocked into a new and deeper degree of perception of her whole person. He felt at once powerfully attracted and estranged. His excitement was increasing in leaps and bounds and he could hardly conceal it. At first he had tried to see her in generalities, a mighty pretty girl whom he might spark a little as the journey progressed, especially in the long stretch from Dutch Harbor to Point Dall, when there was not much to see but gooneys and gray seas. Suddenly he knew that she was not the sparking kind, and that she was not mighty pretty but truly and touchingly beautiful. Strangest of all, he was no longer afraid of her—in the sense that she might disdain him and wound his pride—although he knew better than before that her father was a big gun and she herself a great lady. She might wound him deeper than that, through no fault of her own. This last was as dim an inkling as he sometimes felt before the wild breaking of an Arctic blizzard.

A man may look lightly upon a woman, or with a marksman’s gaze. Although the latter is likely to be embarrassing to both parties, Eric risked it, and the risk paid off. He had a picture that he doubted could ever fade, no matter where he journeyed or how long he lived. If the dressing of her pale hair and her style of clothes said she was eighteen, she still looked sixteen. Her shaping was completely unique, or at least it seemed so because of her posture—her weight, which was little, on the soles of her feet, her heels appearing barely to touch the floor, her legs wonderfully straight, and her body looking as if a powerful man had pressed his hands under her ribs on each side and lifted gently.

But her face was the truest index of the mystery he sensed so strongly. At the moment it expressed surprise and wonder, perhaps a deep-seated and subtle exultation. Her eyes were wide open, the whites framing narrow blue-gray irises that rimmed the immense pupils. He was still puzzling over the structure around the eyes—their clean setting, as of a glacier pool that ever suggests a jewel set in flawless marble, the smooth forehead and the slight bony protuberance of the eyebrows in relation to the cheekbones, the shadows within the sockets and the sheen of taut flesh without, all this of new discovery to him and of thrilling amazement—when another feeling crept into his mind and jarred him out of his spell.

It began with his noticing, vaguely at first, that the impressive man beside her was looking at her too. He seemed to have forgotten Eric’s presence and he was smiling down at her, his gray eyes aglow with pride. And then Eric knew, before he had any cause to know, that these were deep waters, beyond his sounding; and he knew also, more than as a foreboding, and indeed as a stunning fact, that he and Dr. Hill had met in implacable conflict.

“I want to see a great deal of you, Eric, on this voyage,” Sophia’s father told him, with what seemed great cordiality, at the door. “I believe you are just the man to tell me what I will be in for, in the way of doing my job in Alaska.”

Eric bowed his head with a suggestion of Old World courtesy picked up from his emigrant father and went his way. It was his own way because he knew no other. He felt the need of subtlety and finesse; he lacked tact and his direct moves often ended in a bearlike, blundering charge. Nevertheless, he would take Dr. Hill at his word. He had not imagined that dark feeling, but apparently it applied to only one thing, and Dr. Hill would not let it interfere with other things of moment. And good skippers took advantage of every break in the weather and the passing carelessnesses of hostile seas.

His first move would seem especially awkward, Eric thought, except to another squarehead. This did not mean that squareheads lacked imagination—the gift was bounteously given to the whole Norse race—it only meant that they understood one another quite well. They were clannish in the extreme and had been so since the days of the Vikings, and in their wintry homeland, of meager natural wealth, all had been steeped in the doctrine of live and let live. The purser’s name was Stefen Jorgassen. Although three years older than Eric, he had roamed the Tacoma waterfront with him, sharing many a boyhood adventure. Just now he was scurrying all over the ship on various errands, and Eric soon cornered and caught him.

“The last time we were shipmates you admired this ring,” Eric said, slipping off the band of interlinked gold nuggets.

“I sure did. I asked you if you’d sell it. I wanted to give it to my old man, who collects souvenirs of Alaska.”

“If you still want it, I won’t sell it, but I’ll give it to you if you’ll do me a favor.”

“It must be a pretty big favor. I think it would weigh out twenty dollars.”

“That’s only one day’s wash from the Gertrude Placer Mines on Moosejaw Creek,” Eric told him, waving his hands and grinning.

“Well, what do you want me to do?”

“Seat me at table with Dr. Hill and his daughter Sophia.”

“Eric, that’s swell company for a Scandinavian cradle rocker.”

“Man, I’ve got a sluice.”

“Don’t you mean snoose?” the purser asked, with typically heavy squarehead humor. Snoose was their word for snuff, cosily tucked under the upper lip. “Anyway, it’s still pretty swell company. I haven’t seen ’em, but the whole ship’s agog over that girl, and they’ve got cabins one and two. They’ll probably sit at the skipper’s table.”

“Cap’n Borne and my fat’er are old friends. I don’t t’ink he’d mind.”

“I don’t think I can do it but I’ll try. The seating won’t be made till supper; at dinner it’s catch as catch can.”