* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: The Maple Leaf Vol. II No. 3 March 1853

Date of first publication: 1853

Author: Eleanor H. Lay (1812-1904), Editor

Date first posted: Sep. 16, 2023

Date last updated: Sep. 16, 2023

Faded Page eBook #20230923

This eBook was produced by: John Routh & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

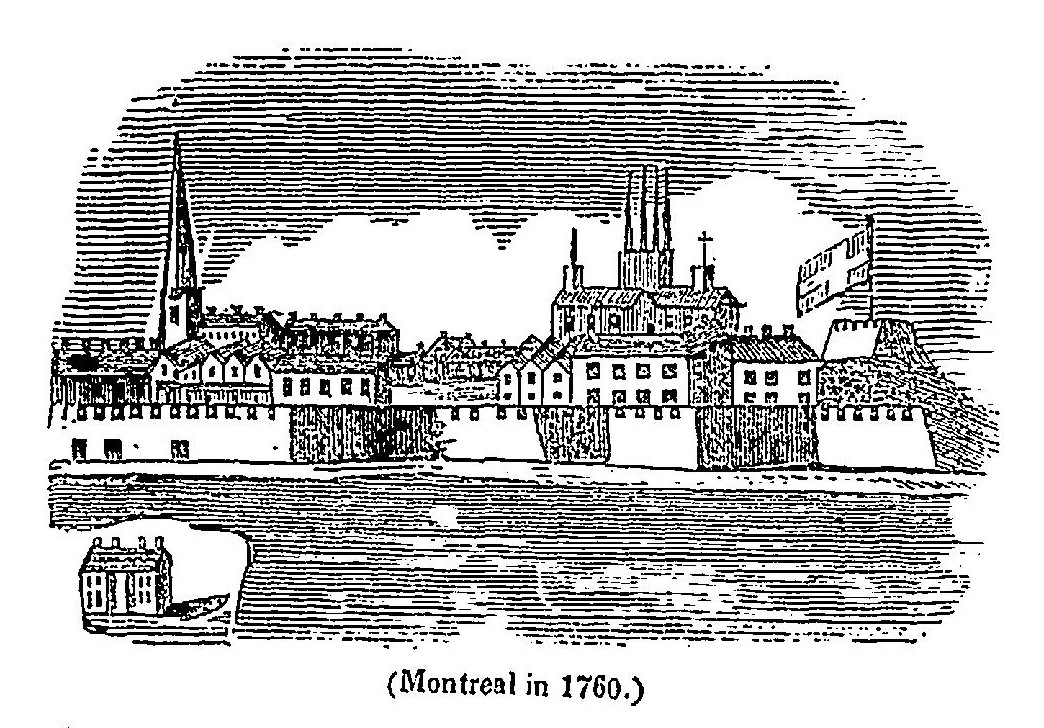

(Montreal in 1760.)

ately, we gave a biographical

sketch of Sir Jeffry Amherst, Knight

of the Bath. A correspondent has

sent us, to complete the work, a copy

of the inscriptions prepared for the

Monument erected to his memory by

his son, Sir J. Amherst, also Knight

of the Bath.

ately, we gave a biographical

sketch of Sir Jeffry Amherst, Knight

of the Bath. A correspondent has

sent us, to complete the work, a copy

of the inscriptions prepared for the

Monument erected to his memory by

his son, Sir J. Amherst, also Knight

of the Bath.

This Monument, which is about 35 or 36 feet high, is situated on a pleasant eminence, opposite Lord Amherst’s dwelling-house, called “Montreal,” near Riverhead, in Kent:—

(FIRST FACE LOOKING ALMOST SOUTH-EAST.)

Dedicated

TO THAT MOST ABLE STATESMAN,

DURING WHOSE ADMINISTRATION

CAPE BRITON AND CANADA WERE CONQUERED;

AND FROM WHOSE INFLUENCE THE BRITISH ARMS

DERIVED A DEGREE OF LUSTRE UNPARALLELED IN PAST AGES.

(SECOND FACE NORTH-EAST.)

TO COMMEMORATE

THE PROVIDENTIAL AND HAPPY MEETING OF THREE BROTHERS,

ON THIS, THEIR PARENTAL GROUND,

ON THE 25TH JANUARY, 1754,

AFTER A SIX YEARS’ GLORIOUS WAR,

IN WHICH THE THREE WERE SUCCESSFULLY ENGAGED,

IN VARIOUS CLIMES, SEASONS, AND SERVICES.

(THIRD SIDE NORTH-WEST.)

LOUISBURG SURRENDERED,

AND SIX FRENCH BATTALIONS PRISONERS OF WAR, THE 26TH OF JULY, 1758.

FORT DU QUESNE TAKEN POSSESSION OF, THE 24TH NOV., 1758.

TICONDEROGA TAKEN POSSESSION OF, THE 26TH JULY, 1759.

CROWN-POINT TAKEN POSSESSION OF, THE 4TH OF AUGUST, 1759.

QUEBEC CAPITULATED, THE 18TH OF SEPT., 1759.

(FOURTH SIDE SOUTH-WEST.)

FORT LEVI SURRENDERED, THE 25TH OF AUGUST, 1760.

ISLE-AUX-NOIX ABANDONED, THE 28TH AUGUST, 1760.

MONTREAL SURRENDERED, AND WITH IT ALL CANADA,

AND TEN FRENCH BATTALIONS LAID DOWN THEIR ARMS,

THE 8TH OF SEPTEMBER, 1760.

ST. JOHNS, NEWFOUNDLAND, RETAKEN, THE 18TH OF SEPT., 1762.

Sweet pearl of the morning, pure daughter of earth,

So brilliant in beauty, so priceless in worth;

Say, why hast thou come from thy radiant sphere,

To gleam as a gem for the herbage to wear?

“I have left my bright courts in the azure built sky,

I have come from the glance of the burning eye,

On the storm-cloud full oft my beauty did glow,

I have shown in the drops of the Covenant bow.

“I have wandered at will ’mid the thunderbolt’s ire,

I have flashed back the light of the meteor’s fire,

I have caught from the glorious sunset a hue,

And symboled the brightness of heaven to view.

“I have mingled at noon ’mid the rivulet’s flow,

And the willow have kissed on the valley below;

On the ocean my chariot has often been borne

And the Roamer’s white pennon my beauty hath worn.

“My eye hath oft flashed to the gems of the night,

I have caught the first rays of the morn’s rosy light;

The sweet star of evening is seen on my crest,

And the beams of night’s queen adorn my clear breast.

“On the field, to the slumbering soldier I’ve come,

And mixed with his tears, as he dreamed of his home;

I have watched with affection the tomb of the fair,

And nourished the evergreens love planted there.

“I’ve tasted the breath of the violet blue,

And lent to the lily its beauteous hue;

On the crown of the rose my palace is set,

In the vine flower I place my pure coronet.

“I’ve come with rich offerings in my tiny hand,

And clothed with rejoicing fill many a land;

The harvest hath owned to my life giving power,

As I stooped to revive in the dark blighting hour.

“I’ve called up the herb from its mansion below,

The garden my summons most potent doth show;

I’ve passed to give sweet to the nectary’s lip,

That the bee from its cup sweet treasures might sip.

“I’ve come to the earth as a gift from the sky,

As formed by the hand of the matchless on high;

And where’er my light footstep rejoicing hath been,

Life, Beauty and Love on my pathway are seen.”

Fair child of the morning, thou beautiful one,

Thou art like to that faith sent down from God’s throne,

Whose love to earth’s valley of sorrow is given,

To nourish and water the spirit for heaven.

In affliction’s dark blight, in adversity’s hour,

It visits the soul with its life giving power;

When the fond heart’s affections are reft in their bloom,

It nurses Hope’s blossoms beyond the dark tomb;

And like thee, when exhaled ’mid the blue of the sky,

It shines most resplendent in glory on high.

“A Persian philosopher being asked by what method he had acquired so much knowledge, answered, ‘By not allowing shame to prevent me from asking questions, when I was ignorant.’ ”

bout five-and-twenty years ago, at the head

of the Long Sault Rapids on the Ottawa, there

resided a family of the name of Drummond.

On that, one of the mightiest water powers in

the new world, Mr. Drummond had erected

saw mills on a gigantic scale, the produce of which, was conveyed

down the rapids to Montreal, by experienced and skilful

raftsmen, or voyageurs. The situation was wild and romantic, in

the extreme. Numerous islands studded the surface of the rapid

river, dividing the stream into many and diversified channels,

through which the waters rushed furiously, in proportion

to their width. Wild duck, and water fowl sported joyously

over its snowy foam. At one part the banks were covered with

luxuriant foliage, at another craggy rocks hung impending over

the waters, entwined with lichens of the brightest colors and

most varied forms.

bout five-and-twenty years ago, at the head

of the Long Sault Rapids on the Ottawa, there

resided a family of the name of Drummond.

On that, one of the mightiest water powers in

the new world, Mr. Drummond had erected

saw mills on a gigantic scale, the produce of which, was conveyed

down the rapids to Montreal, by experienced and skilful

raftsmen, or voyageurs. The situation was wild and romantic, in

the extreme. Numerous islands studded the surface of the rapid

river, dividing the stream into many and diversified channels,

through which the waters rushed furiously, in proportion

to their width. Wild duck, and water fowl sported joyously

over its snowy foam. At one part the banks were covered with

luxuriant foliage, at another craggy rocks hung impending over

the waters, entwined with lichens of the brightest colors and

most varied forms.

The passage of the Long Sault did indeed require, that he who stemmed the perilous rapids should be endowed with strong nerve and powerful arm; but both of these qualities were conspicuous in Mr. Drummond. Of Herculean strength, he not only speedily became remarkably skilful in paddling his birch canoe, but at last fearlessly took his wife and children in the same frail bark. She was a delicate little creature, clinging with all the depth of a true woman’s loving nature to her husband. Their family consisted of four children. The two eldest, a little boy and girl, had been promised by their parents an excursion down the rapids, when the spring ice was entirely dispersed, and they awaited with eager expectation the long looked-for and much anticipated pleasure. It came at last.—The first of June was announced by their papa as that on which they would take the proposed trip. Full of glee and joy the happy children retired to rest the previous night, but their slumber was soon broken by a storm, awful in its grandeur, accompanied with thunder and lightning. It was literally a deluge of rain, and lasted for several hours, with a perfect hurricane of wind. The children feared their excursion must be postponed, but to their glad surprise clear and cloudless broke the morning after the storm, nature looking brighter and fresher from its effects. Mrs. Drummond was early awakened by the voice of the little Ada: “Look, mamma, look; the sun shines for us;—do get up.” The fond mother smiled at the earnestness of the little fairy beside her, and rose in answer to her urgent entreaties.

Their preparations for departure were soon completed. In the first canoe were Mr. and Mrs. Drummond and an experienced voyageur, the children being seated with their mother at the bottom of the canoe on buffalo skins. In the second were two men, and one female servant. The waterfalls and torrents were brought into full activity by the night’s rain, and were dashing madly down the gullies formed by it in the sides of the overhanging rocks. The river boiled furiously along, bearing on its foaming surface large trees, which the wind had broken or uprooted, and it required all the united efforts of the strong men of the party to guide the frail barks in their perilous career. They, however, thought lightly of dangers and obstacles which, to a less experienced hand and eye, would have been deemed insurmountable; yet aware that the slightest want of caution on their part would be fatal. As they neared the St. Anne’s rapids, the mother clasped the little Ada still more closely to her breast; yet did her true heart stay itself courageously on the cool, calm courage of the stronger mind beside her. Not by one word, or exclamation, did she express a shadow of womanly weakness or fear. They flew along, merely using their paddles to steer through the dangers of the way. The canoe, was impelled swiftly forward by the fierce impetuosity of the waters, which presented a foaming barrier a little distance ahead, in the rapids they were approaching. Fragments of water-riven trees had there collected during the hurricane, and dashed about in tumultuous disorder. On they steered in perfect silence; they flew with lightning speed over the first and most intricate channel, and had just cleared it in safety, when the bark struck against a rock, covered by the eddying foam, and in a moment both canoes were engulphed in the furious waters, and carried helplessly down the mighty current. Even in that agonizing moment the presence of mind of Mr. Drummond did not forsake him, though the awful knowledge of the fate of his beloved ones, flashed like lightning across him. Rising to the surface, borne down by the mighty stream, he yet struck out towards shore. Ah! what is that? A faint cry met his ear, and the floating form of the little Ada swept by him. Vainly, with a convulsive grasp, he endeavored to seize the light garments of the child; he saw the fair ringlets, shading the sweet, pale face, hurried past him. Another moment he gained the shore. He sprang up the bank, and gazed around over the scene of desolation. What a sight met that strong, loving heart! He stood alone, where, a moment before, he was surrounded by that heart’s fondest treasures. In vain, with eyes dim with agony, he gazed on the wide expanse of waters rushing on, rushing on; they swept by, as though in mockery of the loving human hearts entombed in them. For one moment, but one, the strong man bent under the pressure of such fearful sorrow, then with a cry of anguish to heaven, sped on by the side of the dark river, in the hope of catching some traces of the lost in the calm expanse of waters a mile or two below. His aching vision wanders over the scene. What is it that arrests his gaze? At some distance he sees—can it be?—one of the canoes turned upside down in the stream. To rush on, spring into the river, and tow it to shore, was speedy work to an arm nerved with desperation; but how does his heart beat with almost overpowering sensations of alternate hope and fear, as he remarks its unusual weight. Yes; there, extended at the bottom of the canoe, lies, though to all appearance lifeless, the form of his beloved wife. On reaching forward to her child, as they neared the rapids, she had placed her hands under the braces of the canoe, and at its upset became fixed under them. To that providential circumstance she owed the preservation of her life. With breathless anxiety Mr. Drummond hung over that pale, mute form. All was still, save the wild beating of his own heart. But see, she moves! Once more those loving eyes are raised to his, and now those beloved lips murmur his name.

Gradually consciousness returned, but with it the fearful truth of her bereavement. “Ada, Ada,” she repeated, wildly stretching forth her arms as if to embrace her. “Hubert, too, where, where are they?”

Mr. Drummond turned for a moment from that look of exquisite anguish, then spoke, in a tone tremulous with emotion, “True wife, he is spared to thee, who once, in joy or in sorrow, thou vowed to follow; prove now the truth of that vow, and come to the heart which, with thee left to it, can bear under all other trials, bitter though they be.”

One moment the bitterness of a mother’s despair overspread her pale features, yet through them, even then, there shone the depth of her devoted affection; the next, she sought and found refuge in the arms opened to receive her. Nobly did that heroic woman bear up, subduing her own untold agony, and calmly reseating herself in the canoe which had proved the tomb of her beloved ones. Again they set forth on their perilous course, to seek aid in searching for the lifeless bodies of their children and servants. Assistance was soon at hand, but it was not till the next day that the body of the little Ada was discovered, quite uninjured, however, by its passage down the stream; and even in death her face wore the same lovely expression which had so characterized it in life. A smile still rested on the sweet lips of the sleeper in that last long sleep; one might have fancied she was aware that her early death had but wafted her to the haven where those who mourned her pain would be. The sorrowing parents returned home with the bodies of their beloved children, and the habitans of the river yet relate, with tender regret, the loss of the little Ada, at the running of the rapids.

C. H., Rice Lake.

January, 1853.

There is something inevitably touching, simple, and beautiful, in the following fact:—some years after Alliston had acquired considerable reputation as a painter, a friend showed him a miniature, and begged he would give a sincere opinion upon the merits, as the young man who drew it had some thoughts of becoming a painter by profession. Alliston, after much pressing and declining to give an opinion, candidly told the gentleman he feared the lad would never do anything as a painter, and advised his following some more congenial pursuit. His friend then convinced him that the work had been done by Alliston himself, for this very gentleman, when Alliston was quite young.

[The following poem, communicated by a friend, is the best we have seen on the death of the Duke of Wellington. It betrays that happy ingenuity in the use of known circumstances, and peculiar style in weaving all into measure, that Longfellow displays, and has been attributed to him]:—

A mist was driving down the British Channel,

The day was just begun;

And through the window-panes, on floor and panel,

Streamed the red Autumn sun.

It glanced on flowing flag, and rippling pennon,

And the white sails of ships;

And, from the frowning rampart, the black cannon

Hailed it with feverish lips.

Sandwich and Romney, Hastings, Hithe, and Dover

Were all alert that day,

To see the French war-steamers speeding over,

When the fog cleared away.

Sullen, and silent, and like couchant lions,

Their cannon, through the night,

Holding their breath, had watched, with grim defiance,

The sea-coast opposite.

And now they roared at drum-beat, from their stations

On every citadel;

Each answering each with morning salutations,

That all was well!

And down the coast, all taking up the burden,

Replied the distant forts,

As if to summon from his sleep the Warden,

And Lord of the Cinque Ports.

Him shall no sunshine from the fields of azure,

No drum-beat from the wall,

No morning gun from the black forts embrazure,

Awaken with their call!

No more surveying, with an eye impartial,

The long line of sea-coast,

Shall the gaunt figure of the old Field-Marshall,

Be seen upon his post!

For in the night, unseen, a single warrior,

In sombre harness mailed,

Dreaded of man—and surnamed the Destroyer,

The rampart wall had scaled.

He passed into the chamber of the sleeper,

The dark and silent room;

And as he entered, darker grew and deeper,

The silence and the gloom.

He did not stop to parley and dissemble,

But smote the Warden hoar;

Ah! what a blow! that made all England tremble,

And groan from shore to shore.

Meanwhile, without, the surly cannon waited,

The sun rose bright o’er head;

Nothing in Nature’s aspect intimated

That a great man was dead!

A young clergyman, in conversation with the Duke of Wellington, was representing what he considered the folly of sending missionaries to India; when he received the following characteristic reproof from the Iron Duke, “Young man, look to your marching orders.”

rs. Bird hastily deposited the various articles

she had collected in a small plain trunk,

and locking it, desired her husband to see it in the

carriage, and then proceeded to

call the woman. Soon, arrayed

in a cloak, bonnet and shawl, that

had belonged to her benefactress,

she appeared at the door with her

child in her arms. Mr. Bird hurried

her into the carriage, and Mrs.

Bird pressed on after her to the

carriage steps. Eliza leaned out of

the carriage, and put out her hand,—a

hand as soft and beautiful as was

given in return. She fixed her large,

dark eyes, full of earnest meaning, on Mrs.

Bird’s face, and seemed going to speak. Her lips moved,—she

tried once or twice, but there was no sound,—and pointing upward,

with a look never to be forgotten, she fell back in the

seat, and covered her face. The door was shut, and the carriage

drove on.

rs. Bird hastily deposited the various articles

she had collected in a small plain trunk,

and locking it, desired her husband to see it in the

carriage, and then proceeded to

call the woman. Soon, arrayed

in a cloak, bonnet and shawl, that

had belonged to her benefactress,

she appeared at the door with her

child in her arms. Mr. Bird hurried

her into the carriage, and Mrs.

Bird pressed on after her to the

carriage steps. Eliza leaned out of

the carriage, and put out her hand,—a

hand as soft and beautiful as was

given in return. She fixed her large,

dark eyes, full of earnest meaning, on Mrs.

Bird’s face, and seemed going to speak. Her lips moved,—she

tried once or twice, but there was no sound,—and pointing upward,

with a look never to be forgotten, she fell back in the

seat, and covered her face. The door was shut, and the carriage

drove on.

What a situation, now, for a patriotic senator, that had been all the week before spurring up the legislature of his native state to pass more stringent resolutions against escaping fugitives, their harborers and abettors!

It was full late in the night when the carriage emerged, and stood at the door of a large farm-house. It took no inconsiderable perseverance to arouse the inmates; but at last the respectable proprietor appeared, and undid the door.

‘Are you the man that will shelter a poor woman and child from slave catchers?’ said the senator, explicitly.

‘I rather think I am,’ said honest John, with some considerable emphasis.

‘I thought so,’ said the senator.

‘If there’s anybody comes,’ said the good man, stretching his tall, muscular form upward, ‘why here I’m ready for him: and I’ve got seven sons, each six foot high, and they’ll be ready for ’em. Give our respects to ’em,’ said John; ‘tell them no matter how soon they call,—make no kinder difference to us,’ said John, running his fingers through the shock of hair that thatched his head, and bursting out into a great laugh. . . .

The senator, in a few words, briefly explained Eliza’s history. . . .

‘Ye’d better jest put up here, now, till daylight,’ said he, heartily, ‘and I’ll call up the old woman, and have a bed got ready for you in no time.’

‘Thank you, my good friend,’ said the senator; ‘I must be along, to take the night stage for Columbus.’

‘Ah! well, then, if you must, I’ll go a piece with you, and show you a cross road that will take you there better than the road you came on. That road’s mighty bad.’

John equipped himself, and, with a lantern in hand, was soon seen guiding the senator’s carriage towards a road that ran down in a hollow, back of his dwelling. When they parted, the senator put into his hand a ten dollar bill.

‘It’s for her,’ he said, briefly.

‘Ay, ay,’ said John, with equal conciseness.

They shook hands, and parted.

A quiet scene now rises before us. A large, roomy, neatly-painted kitchen, its yellow floor glossy and smooth, and without a particle of dust; a neat, well-blacked cooking-stove; rows of shining tin, suggestive of unmentionable good things to the appetite; glossy green wood chairs, old and firm; a small flag-bottomed rocking-chair, and in the chair, gently swaying back and forward, her eyes bent on some fine sewing, sat our old friend Eliza. Yes, there she is, paler and thinner than in her Kentucky home, with a world of quiet sorrow lying under the shadow of her long eyelashes, and marking the outline of her gentle mouth! It was plain to see how old and firm the girlish heart was grown under the discipline of heavy sorrow; and when, anon, her large dark eye was raised to follow the gambols of her little Harry, who was sporting like some tropical butterfly, hither and thither over the floor, she showed a depth of firmness and steady resolve that was never there in her earlier and happier days.

By her side sat a woman with a bright tin pan in her lap, into which she was carefully sorting some dried peaches. She might be fifty-five or sixty; but hers was one of those faces that time seems to touch only to brighten and adorn. The snowy lisse crape cap, made after the strait Quaker pattern,—the plain white muslin handkerchief, lying in placid folds across her bosom,—the drab shawl and dress,—showed at once the community to which she belonged. Her face was round and rosy, with a healthful downy softness, suggestive of a ripe peach. Her hair, partially silvered by age, was parted smoothly back from a high placid forehead, on which time had written no inscription, except peace on earth, good will to men, and beneath shone a large pair of clear, honest, loving brown eyes; you only needed to look straight into them, to feel that you saw to the bottom of a heart as good and true as ever throbbed in woman’s bosom. . . .

‘And so thee still thinks of going to Canada, Eliza?’ she said, as she was quietly looking over her peaches.

‘Yes, ma’am,’ said Eliza, firmly. ‘I must go onward. I dare not stop.’

‘And what’ll thee do, when thee gets there? Thee must think about that, my daughter.’ ‘My daughter’ came naturally from the lips of Rachel Halliday; for hers was just the face and form that made ‘mother’ seem the most natural word in the world.

‘I shall do—anything I can find. I hope I can find something.’

‘Thee knows thee can stay here, as long as thee pleases,’ said Rachel.

‘O thank you,’ said Eliza, ‘but’—she pointed to Harry—‘I can’t sleep nights: I can’t rest. Last night I dreamed I saw that man coming into the yard,’ she said, shuddering. . . .

The door here opened, and a little short, round, pincushiony woman stood at the door, with a cheery, blooming face, like a ripe apple. She was dressed, like Rachel, in sober gray, with the muslin folded neatly across her round, plump little chest.

‘Ruth Stedman,’ said Rachel, coming joyfully forward; ‘how is thee, Ruth?’ she said, heartily taking both her hands. ‘Nicely’ said Ruth, taking off her little drab bonnet. . . .

‘Ruth, this friend is Eliza Harris; and this is the little boy I told thee of.’

‘I am glad to see thee, Eliza,—very,’ said Ruth, shaking hands as if Eliza were an old friend she had long been expecting; ‘and this is thy dear boy,—I brought a cake for him,’ she said, holding out a little heart to the boy, who came up gazing through his curls, and accepted it shyly. . . .

Simeon Halliday, a tall, straight, muscular man, in drab coat and pantaloons, and broad-brimmed hat, now entered.

‘How is thee, Ruth?’ he said, warmly, as he spread his broad open hand for her little fat palm; ‘and how is John?’

‘O! John is well, and all the rest of our folks,’ said Ruth, cheerily.

‘Any news, father?’ said Rachel. . . .

‘Mother!’ said Simeon, standing in the porch, and calling Rachel out.

‘What does thee want, father?’ said Rachel, rubbing her floury hands, as she went into the porch.

‘This child’s husband is in the settlement, and will be here to-night,’ said Simeon.

‘Now, thee doesn’t say that, father?’ said Rachel, all her face radiant with joy.

‘It’s really true. Peter was down yesterday, with the wagon, to the other stand, and there he found an old woman and two men; and one said his name was George Harris; and, from what he told of his history, I am certain who he is. He is a bright, likely fellow, too.’

‘Shall we tell her now?’ said Simeon.

‘Let’s tell Ruth,’ said Rachel. ‘Here, Ruth,—come here.’

Ruth laid down her knitting work, and was in the back porch in a moment.

‘Ruth, what does thee think?’ said Rachel. ‘Father says Eliza’s husband is in the last company, and will be here to-night.’

A burst of joy from the little Quakeress interrupted the speech. She gave such a bound from the floor, as she clapped her little hands, that two stray curls fell from under her Quaker cap, and lay brightly on her white neckerchief.

‘Hush thee, dear!’ said Rachel, gently; ‘hush, Ruth! Tell us, shall we tell her now?’

‘Now! to be sure,—this very minute. Why, now, suppose ’t was my John, how should I feel? Do tell her, right off.’ . .

Rachel came out into the kitchen, where Eliza was sewing, and opening the door of a small bedroom, said, gently, ‘Come in here with me, my daughter: I have news to tell thee.’

Rachel Halliday drew Eliza toward her, and said, ‘The Lord hath had mercy on thee, daughter: thy husband hath escaped from the house of bondage.’

The blood flushed to Eliza’s cheek in a sudden glow, and went back to her heart with as sudden a rush. She sat down, pale and faint.

‘Have courage, child,’ said Rachel, laying her hand on her head. ‘He is among friends, who will bring him here to-night.’

‘To-night!’ Eliza repeated, ‘to-night!’ The words lost all meaning to her; her head was dreamy and confused; all was mist for a moment.

When she awoke, she found herself snugly tucked up on the bed, with a blanket over her, and little Ruth rubbing her hands with camphor. She opened her eyes in a state of dreamy, delicious languor, such as one who has long been bearing a heavy load, and now feels it gone, and would rest. The tension of the nerves, which had never ceased a moment since the first hour of her flight, had given way, and a strange feeling of security and rest came over her; and, as she lay, with her large, dark eyes open, she followed, as in a quiet dream, the motions of those about her. She saw the door open to the other room; saw the supper-table, with its snowy cloth; heard the dreamy murmur of the singing tea-kettle, saw Ruth tripping backward and forward, with plates of cake, and saucers of preserves, and ever and anon stopping to put a cake into Harry’s hand, or pat his head, or twine his long curls round her snowy fingers. She saw Ruth’s husband come in,—saw her fly up to him, and commence whispering very earnestly, ever and anon, with impressive gesture, pointing her little finger toward the room. She saw her, with the baby in her arms, sitting down to tea; she saw them all at table, and little Harry in a high chair, under the shadow of Rachel’s ample wing; there were low murmurs of talk, gentle tinkling of tea-spoons, and musical clatter of cups and saucers, and all mingled in a delightful dream of rest; and Eliza slept, as she had not slept before, since the fearful midnight hour when she had taken her child and fled through the frosty star-light.

She dreamed of a beautiful country,—a land, it seemed to her, of rest,—green shores, pleasant islands, and beautifully glittering water; and there, in a house which kind voices told her was a home, she saw her boy playing a free and happy child. She heard her husband’s footsteps; she felt him coming nearer; his arms were around her, his tears falling on her face, and she awoke! It was no dream. The daylight had long faded; her child lay calmly sleeping by her side; a candle was burning dimly on the stand, and her husband was sobbing by her pillow.

The next morning was a cheerful one at the Quaker house. ‘Mother’ was up betimes, and surrounded by busy girls and boys, whom we had scarce time to introduce to our readers yesterday, and who all moved to Rachel’s gentle ‘Thee had better,’ or more gentle ‘Hadn’t thee better?’ in the work of getting breakfast; for a breakfast in the luxurious valley of Indiana is a thing complicated and multiform. While, John ran to the spring for fresh wafer, and Simeon the second sifted meal for corn-cakes, and Mary ground coffee, Rachel moved gently and quietly about, making biscuits, cutting up chicken, and diffusing a sort of sunny radiance over the whole proceeding generally.

Everything went on so sociably, so quietly, so harmoniously, in the great kitchen,—even the knives and forks had a social clatter as they went on to the table; and the chicken and ham had a cheerful and joyous fizzle in the pan, as if they rather enjoyed being cooked than otherwise;—and when George and Eliza and little Harry came out, they met such a hearty, rejoicing welcome, no wonder it seemed to them like a dream.

At last, they were all seated at breakfast, while Mary stood at the stove, baking griddle-cakes, which, as they gained the true exact golden brown tint of perfection, were transferred quite handily at the table.

Rachel never looked so truly and benignly happy as at the head of her table. There was so much motherliness and full heartedness even in the way she passed a plate of cakes or poured a cup of coffee, that it seemed to put a spirit into the food and drink she offered.

This, indeed, was a home,—home,—a word that George had never yet known a meaning for; and a belief in God, and trust in his providence, began to encircle his heart, as, with a golden cloud of protection and confidence, dark, misanthropic, pining, atheistic doubts, and fierce despair, melted away before the light of a living Gospel, breathed in living faces, preached by a thousand unconscious acts of love and good will, which, like the cup of cold water given in the name of a disciple, shall never lose their reward. . . .

‘I hope, my good sir, that you are not exposed to any difficulty on our account,’ said George.

‘Fear nothing, George, for therefore we are sent into the world. If we would not meet trouble for a good cause, we were not worthy of our name.’

‘And now thou must lie by quietly this day, and to-night, at ten o’clock, Phineas Fletcher will carry thee onward to the next stand,—thee and the rest of thy company. The pursuers are hard after thee; we must not delay.’

‘If that is the case, why wait till evening?’ said George.

‘Thou art safe here by daylight, for every one in the settlement is a Friend, and all watching. It has been found safer to travel by night.’ . . .

The afternoon shadows stretched eastward, and the round red sun stood thoughtfully on the horizon, and his beams shone yellow and calm into the little bedroom where George and his wife were sitting. He was sitting with his child on his knee, and his wife’s hand in his. Both looked thoughtful and serious, and traces of tears were on their cheeks.

‘Yes, Eliza,’ said George, ‘I know all you say is true. You are a good child,—a great deal better than I am; and I will try to do as you say. I’ll try to act worthy of a freeman. I’ll try to feel like a Christian.’

‘And when we get to Canada,’ said Eliza, ‘I can help you. I can do dress-making very well; and I understand fine washing and ironing; and between us we can find something to live on.’

‘Yes, Eliza, so long as we have each other and our boy. O! Eliza, if these people only knew what a blessing it is for a man to feel that his wife and child belong to him! I’ve often wondered to see men that could call their wives and children their own fretting and worrying about anything else. Why, I feel rich and strong, though we have nothing but our bare hands.’

‘But yet we are not quite out of danger,’ said Eliza; ‘we are not yet in Canada.’

‘True,’ said George, ‘but it seems as if I smelt the free air, and it makes me strong.’

At this moment, voices were heard in the outer apartment, in earnest conversation, and very soon a rap was heard on the door. Eliza started and opened it.

Simeon Halliday was there, and with him a Quaker brother, whom he introduced as Phineas Fletcher.

‘Our friend Phineas hath discovered something of importance to the interests of thee and thy party, George,’ said Simeon; ‘it were well for thee to hear it.’ That I have said Phineas.

‘Last night I stopped at a little lone tavern, back on the road. Well, I was tired with hard driving; and, after my supper, I stretched myself down on a pile of bags in the corner, and pulled a buffalo over me, to wait till my bed was ready; and what does I do, but get fast asleep; but when I came to myself a little, I found that there were some men in the room, sitting round a table, drinking and talking. ‘So,’ says one, ‘they are up in the Quaker settlement, no doubt,’ says he. Then I listened with both ears, and I found that they were talking about this very party. This young man, they said, was to be sent back to Kentucky, to his master, who was going to make an example of him, to keep all niggers from running away; and his wife, two of them were going to run down to New Orleans to sell, on their own account, and they calculated to get sixteen or eighteen hundred dollars for her; and the child, they said, was going to a trader, who had bought him; and then there was the boy, Jim, and his mother, they were to send back to their masters in Kentucky. They said that there were two constables, in a town a little piece ahead, who would go in with ’em to get ’em taken up, and the young woman was to be taken before a judge; and one of the fellows, who is small and smooth-spoken, was to swear to her for his property, and get her delivered over to him to take south.’

The group that stood in various attitudes, after this communication, was worthy of a painter. Rachel Halliday, who had taken her hands out of a batch of biscuit, to hear the news, stood with them upraised and floury, and with a face of the deepest concern. Simeon looked profoundly thoughtful; Eliza had thrown her arms around her husband, and was looking up to him. George stood with clenched hands and glowing eyes, and looking as any other man might look, whose wife was to be sold at auction, and son sent to a trader, all under the shelter of a Christian nation’s laws.

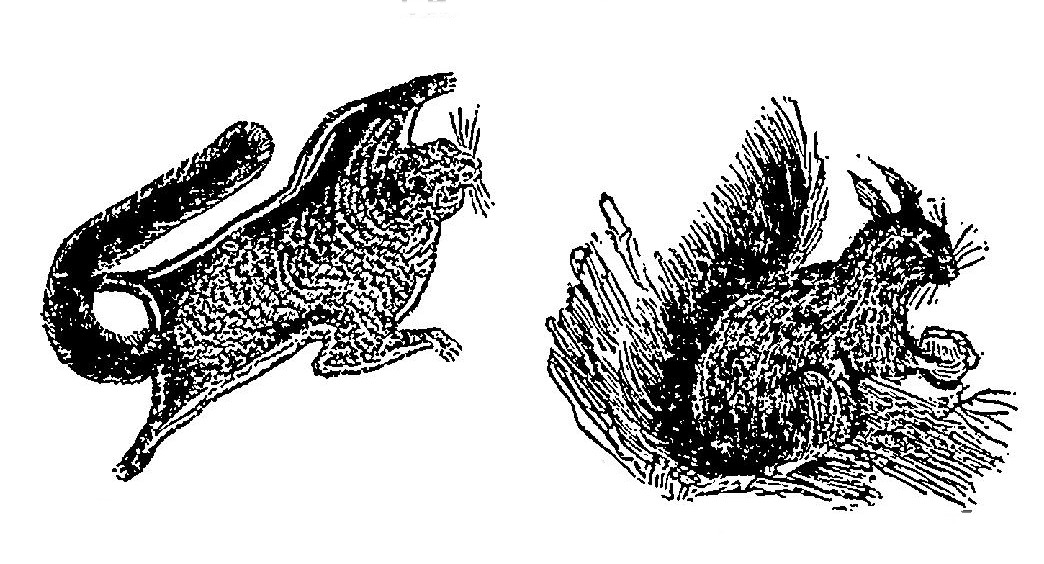

he first settlers

in Maine found,

beside its red faced

owners, other and abundant sources

of annoyance and danger. The majestic

forests which then waved

where now is heard the hum of business,

and where a thousand villages stand, were

the homes of innumerable, wild and savage,

animals. Often at night was the farmer’s family

aroused from sleep by the noise without, which told

that bruin was storming the sheep-pen, or the pig-sty,

or was laying violent hands upon some unlucky calf—and often,

on a cold winter evening did they roll a larger log against the

door, and with beating hearts draw closer around the fire, as the

dismal howl of the wolf echoed through the woods. The wolf

was the most ferocious, blood-thirsty, but cowardly of all, rarely

attacking man, unless driven by severe hunger, and seeking his

victim with the utmost pertinacity. The incident which I am

about to relate occurred in the early history of Biddeford. A

man who then lived on the farm occupied by Mr. H. was one

autumn occupied in felling trees at some distance from his house.

His little son eight years old, was in the habit while his mother

was busy with household cares, of running out into the field and

woods around the house, often going where the father was at

work. One day after the frost had robbed the trees of their foliage,

the father left his work sooner than usual, and started for

home, just on the edge of the forest he saw a curious pile of

leaves—without stopping to think what made it, he cautiously

removed the leaves, when what was his astonishment to find his

own darling boy lying there sound asleep. ’Twas but the work

of a moment to take up the little sleeper, put in his place a small

log, carefully replace the leaves, and conceal himself among the

nearest bushes, then to watch the result. After waiting a short

time he heard a wolf’s distant howl, quickly followed by another

and another, till the woods seemed alive with the fearful sounds.

The howls came nearer, and in a few minutes, a large gaunt,

savage looking wolf leaped into the opening, closely followed by

the whole pack. The leader sprang directly upon the pile of

leaves, and in an instant scattered them in every direction. Soon

as he saw the deception, his look of fierceness and confidence

changed into that of the most abject fear. He shrank back,

cowered to the ground, and passively awaited his fate, for the

rest enraged by the supposed cheat, fell upon him, tore him in

pieces and devoured him on the spot. When they had finished

their comrade, they wheeled around, plunged into the forest and

disappeared; within five minutes from the first appearance not

a wolf was in sight. The excited father pressed his child to his

bosom, and blessed the kind Providence which had led him there

to save his dear boy. The child after playing till he was weary,

had lain down and fallen asleep, and in that situation had the

wolf found him, and covered him with leaves, till he could bring

his comrades to the feast, but himself furnished the repast.

he first settlers

in Maine found,

beside its red faced

owners, other and abundant sources

of annoyance and danger. The majestic

forests which then waved

where now is heard the hum of business,

and where a thousand villages stand, were

the homes of innumerable, wild and savage,

animals. Often at night was the farmer’s family

aroused from sleep by the noise without, which told

that bruin was storming the sheep-pen, or the pig-sty,

or was laying violent hands upon some unlucky calf—and often,

on a cold winter evening did they roll a larger log against the

door, and with beating hearts draw closer around the fire, as the

dismal howl of the wolf echoed through the woods. The wolf

was the most ferocious, blood-thirsty, but cowardly of all, rarely

attacking man, unless driven by severe hunger, and seeking his

victim with the utmost pertinacity. The incident which I am

about to relate occurred in the early history of Biddeford. A

man who then lived on the farm occupied by Mr. H. was one

autumn occupied in felling trees at some distance from his house.

His little son eight years old, was in the habit while his mother

was busy with household cares, of running out into the field and

woods around the house, often going where the father was at

work. One day after the frost had robbed the trees of their foliage,

the father left his work sooner than usual, and started for

home, just on the edge of the forest he saw a curious pile of

leaves—without stopping to think what made it, he cautiously

removed the leaves, when what was his astonishment to find his

own darling boy lying there sound asleep. ’Twas but the work

of a moment to take up the little sleeper, put in his place a small

log, carefully replace the leaves, and conceal himself among the

nearest bushes, then to watch the result. After waiting a short

time he heard a wolf’s distant howl, quickly followed by another

and another, till the woods seemed alive with the fearful sounds.

The howls came nearer, and in a few minutes, a large gaunt,

savage looking wolf leaped into the opening, closely followed by

the whole pack. The leader sprang directly upon the pile of

leaves, and in an instant scattered them in every direction. Soon

as he saw the deception, his look of fierceness and confidence

changed into that of the most abject fear. He shrank back,

cowered to the ground, and passively awaited his fate, for the

rest enraged by the supposed cheat, fell upon him, tore him in

pieces and devoured him on the spot. When they had finished

their comrade, they wheeled around, plunged into the forest and

disappeared; within five minutes from the first appearance not

a wolf was in sight. The excited father pressed his child to his

bosom, and blessed the kind Providence which had led him there

to save his dear boy. The child after playing till he was weary,

had lain down and fallen asleep, and in that situation had the

wolf found him, and covered him with leaves, till he could bring

his comrades to the feast, but himself furnished the repast.

Grotius, Lord Granville, and others.—The memory of Grotius was so retentive that he remembered almost every thing he read. Scaliger could repeat a hundred verses after once reading them. Lord Granville knew the Greek Testament, from the beginning of Matthew to the end of the Revelation.

“Mrs. Frazer, are you very busy just now?” asked Lady Mary, coming up to the table where her nurse was ironing some laces.

“No, my dear, not very busy, only preparing these lace edgings for your frocks. Do you want me to do anything for you?”

“I do not want anything, only to tell you that my Governess has promised to paint my dear squirrel’s picture, as soon as it is tame, and will let me hold it in my lap without flying away. I saw a picture of a flying squirrel to-day, but it was very ugly, not at all like mine; it was long and flat, and its legs looked like sticks, and it was stretched out just like one of those musk-rat skins that you pointed out to me in a fur store. Mamma said it was drawn so, to shew it while it was in the act of flying,—but it is not pretty; it does not shew its beautiful tail, nor its bright eyes, nor soft silky fur. I heard a lady telling Mamma about a nest full of dear, tiny little flying squirrels that her brother once found in a tree in the forest. He tamed them, and they lived very happily together, and would come out and feed from his hand. They slept in the cold weather like dormice; in the day-time they lay very still, and would come out and gambol and frisk about at night;—but some one left the cage open, and they all ran away except one—and that he found in his bed, where it had run for shelter, with its little nose under his pillow. He caught the little fellow, and it lived a long time with him, until the spring, when it grew restless with him; and one day it also got away, and went off to the woods.”

“These little creatures are impatient of confinement, and will gnaw through the wood work of the cage to get free, especially in the spring of the year. Doubtless, my dear, they pine for the liberty which they used to enjoy, before they were made captives by man. It is a sad sight to me to see a caged bird in spring.”

“Nurse, I will not let my little pet be unhappy. As soon as the warm days come again, if my Governess has drawn his picture, I will let him go free. Are there many squirrels in this part of Canada?”

“Not so many as in Upper Canada, Lady Mary. They abound more some years than in others. I have seen, in the birch and oak woods, so many black squirrels at a time, that the woods seemed swarming with them. My brothers have brought in two or three dozen in one day. The Indians used to tell us, that want of food, or very severe weather setting in the north, drives these little animals from their haunts. The Indians, who observe these things more than we do, can generally tell what sort of a winter it will be, from the number of wild creatures that appear in the fall.”

“What do you mean by the fall, nurse?”

“The autumn, my lady. It is so called from the fall of the leaves. I remember the year 1837—that was the year of the Rebellion in Canada, Lady Mary—was remarkable for the great number of squirrels of all kinds, black, grey, red, flying, and the little striped chitmunk or ground squirrel, and also weasels and foxes. They came into the barns and granaries, and into the houses, and destroyed a great quantity of grain, besides gnawing clothes that were laid out to dry. This they did to line their nests with. Next year there were few to be seen.”

“What became of them, nurse?”

“Some, no doubt, fell a prey to their enemies, the cats and foxes, and weasels, which were also very numerous that year; and the rest most likely went back to their own country again.”

“I should like to see a great number of these pretty creatures all travelling together,” said Lady Mary.

“All wild animals, my dear, are more active by night than by day, and probably make their long journeys during that season. They see better in darkness than by daylight. The eyes of many animals and birds, are so formed, that they see best in the dim twilight, as the cats and owls, and others. Our Heavenly Father has fitted all his creatures for the state in which he has placed them.”

“Can squirrels swim like otters and beavers, nurse? If they came to a lake or a river, could they get across it?”

“I think they could, Lady Mary—for, though these creatures are not formed like the otter or beaver, or musk-rat, to get their living in the water, they are able to swim when necessity requires them to do so. I heard a lady say that she was once crossing a lake, between one of the islands and the shore; she was seated in a canoe, with a baby on her lap—she noticed a movement on the surface of the water. At first she thought it might be a water-snake, but the servant lad who was paddling the canoe said it was a red squirrel, and he tried to strike it with the paddle; but the little squirrel leaped out of the water, to the blade of the paddle, and sprang on the head of the baby that lay on the lady’s lap[1]; from thence it jumped to her shoulder, and before she had recovered from her surprise, it was in the water again, and swimming straight for the shore, where it was soon safe in the dark pine woods.”

This feat of the squirrel’s delighted Lady Mary, who expressed her joy at the bravery of the little creature. Besides, being a proof that squirrels could swim, she said that she had heard her governess read out of a book of natural history, that grey squirrels, when they wished to go to a distance in search of food, would all meet together, and collect pieces of bark to serve them for boats, and would set up their broad tails like sails, to catch the wind, and, in this way, cross large sheets of water.

“I do not think this can be true,” observed Mrs. Frazer, “for the squirrel, when swimming, uses his tail as an oar or rudder to help its motion. The tail lies flat on the surface of the water; nor do they need a boat, for God, who made them, has given them the power of swimming when they require it.”

“Nurse, you said something about a ground squirrel, and called it a chitmunk. If you please will you tell me something about it, and why it is called by such a curious name?”

“I believe it is the Indian name for this sort of squirrel, my dear. The chitmunk is not so large as the black, red, or grey squirrels. It is marked along the back with black and white stripes; the rest of its fur is a yellowish tawny colour. It is a very playful, lively, cleanly animal, somewhat resembling the dormouse in its habits. It burrows under ground. Its nest is made with great care, with many galleries, which open at the surface, so that if an enemy attacks it, it can run into one or another for security.”[2]

“How wise of these little chitmunks to think of that?” said Lady Mary.

“Nay, my dear child, it is God’s wisdom, not theirs. These creatures work according to His will, and so they always do what is fittest and best for their own comfort and safety. Men follow after their own wisdom, and so they often err. Man is the only one of all God’s creatures that disobeys him.”

Those words made Lady Mary look grave, till her nurse began to talk to her again about the chitmunk.

“It is very easily tamed, and becomes very fond of its master. It will obey his voice, come at a call or a whistle, sit up and beg, take a nut or an acorn out of its master’s hand, run up a stick, nestle in his bosom, and make itself quite familiar. My uncle had a tame chitmunk that was much attached to him; it lived in his pocket or bosom; it was his companion by day and by night. When he was out in the forest lumbering, or on the lakes fishing, or in the fields at work, it was always with him. At meals, it took its position by the side of his plate, eating any thing that he gave it; but he did not give it meat, as he thought that might injure its health. One day he was in the steamboat, going up to Toronto. This little chitmunk had been shewing off all its tricks to the ladies and gentlemen on board the boat; and several persons offered him money if he would sell it, but my uncle was fond of the little thing, and would not part with it. However, just before he left the boat, he missed his pet. A cunning Yankee pedlar on board had stolen it. My uncle knew that his little friend would not desert his old master; so he went on deck where the passengers were assembled, and whistled the tune that was most familiar to the chitmunk. The little fellow, on hearing it, whisked out of the pedlar’s pocket, and running swiftly along a railing against which he was standing, soon sought refuge in his master’s bosom.”

Lady Mary clapped her hands with joy, and said, “I am so glad, nurse, that the chitmunk ran back to his old friend. I wish it had bitten that Yankee pedlar’s fingers.”

“When angry, they will bite very sharply, set up their tails, and run to and fro, and make a chattering sound with their teeth. The red squirrel is very fearless for its size, and will sometimes turn round and face you, set up its tail, and scold. I have seen them, when busy eating the seeds of the sun-flower, or thistle, of which they are very fond, suffer you to stand and watch them without attempting to run away. When near their granaries, or the tree where their nest is, they are unwilling to leave it, running to and fro, and uttering their angry notes; but if a dog is near, they make for a tree, and, as soon as they are out of his reach, they turn to chatter and scold, as long as the dog remains in sight. When hard pressed, the black and flying squirrels will take prodigious leaps, springing from bough to bough, and from tree to tree. In this manner, they baffle the hunters, and travel for a great distance over the tops of the trees. Once I saw my uncle and brothers chasing a large black squirrel. He kept out of reach of the dogs, and continued so to keep himself out of sight of the men, by passing round and round the tree as he went up, that they could never get a fair shot at him. At last, they got so provoked, that they took their axes and set to work to chop down the tree. It was a big pine tree, and took a long time to cut it down; just as the tree was ready to fall, and was wavering to and fro, the squirrel, who had kept on the topmost bough, sprang nimbly to the next tree, and then to another, and by the time the great pine had reached the ground, the squirrel was far away in his nest, among his little ones, safe from guns, hunters, and dogs.”

“The black squirrel must have wondered, I think, nurse, why so many big men and dogs tried to kill such a little creature as he was. Do the black squirrels sleep in the winter as well as the flying squirrels and chitmunks?”

“No, Lady Mary, I have often seen them of a bright sunny day in winter, chasing each other over logs and brush-heaps, and running gaily up the pine trees. They are easily seen, from the contrast which their jetty black coats make with the sparkling white snow. These creatures feed a good deal on the kernels of the pines and hemlocks; they also eat the buds of some trees. They lay up great stores of nuts, and grain for winter use. The flying squirrels lie heaped upon each other, for the sake of warmth. As many as seven, or eight, may be found in one nest asleep. They sometimes waken, if there comes a succession of warm days, as in the January thaw; for I must tell you, my dear, that in this country we generally have rain and mild weather for a few days in the beginning of January, when the snow nearly disappears from the ground. About the 12th,[3] the weather sets in steadily cold again—then the little animals retire once more to sleep in their winter cradles which they rarely leave till the intense cold weather is over.”

“I suppose, nurse, when they awake, they are glad to eat some of the food they have laid up in their granaries?”

“Yes, my dear, it is for this that they gather it in the milder weather; it also supports them during the spring months, and, possibly, even during the summer, till the grain and fruits are ripe again. I was walking one day in the harvest-field, where my brothers were cradling wheat. As I passed along the fence, I noticed a great many little heaps of wheat lying here and there on the rails, also upon the tops of the stumps in the field. I wondered at first what could have placed them there, but presently noticed a number of red squirrels running very swiftly along the fence, and perceived that they emptied their mouths of a quantity of the new wheat, which they had been diligently employed in collecting from the ears that lay scattered on the ground. These little gleaners did not seem to be at all alarmed at my presence, but went to and fro as busy as bees. On taking some of the grains in my hand, I noticed that the germ or eye of the kernel was bitten clean out.”

“What was that for, nurse, can you tell me?”

“My dear young lady, I did not know at first, till, on shewing it to my father, he told me that the squirrels destroyed the germ of the grain, such as wheat and Indian corn, that they stored up for winter use, that it might not sprout when buried in the ground, or in the hollow tree.”

“This is very strange, nurse,” said the little girl. “But, I suppose,” she added, after a moment’s thought, “it was God who taught the squirrels to do so. But why would biting out the eye prevent the grain from growing?”

“Because the eye or bud contains the life of the plant; from it springs the green blade, and the stem that bears the ear, and the root that strikes down into the earth. The floury part, which swells, and becomes soft and jelly-like, serves to nourish the young plant till the tender fibres of the roots are able to draw moisture from the ground.”

Lady Mary asked if all seeds had an eye or germ?

Her nurse replied, that all had, though some were so minute that they looked no bigger than dust, or a grain of sand; yet each was perfect in its kind, and contained the plant that would, when sown in the earth, bring forth roots and leaves, and buds and flowers, and fruits in due season.

“How glad I should have been to see the little squirrels gleaning the wheat, and laying it in the little heaps on the rail fence. Why did they not carry it at once to their nests?”

“They laid it out in the sun and wind to dry, for if it had been stored away while damp, it would have moulded and been spoiled. The squirrels were busy all that day. When I went again to see them, the grain was gone. I saw several red squirrels running up and down a large pine tree, which had been broken by the wind at the top—and there, no doubt, they had laid up the chief of the grain. These squirrels did not follow each other in a straight line, but ran round and round in a spiral direction, so that they never hindered each other, or came in each other’s way—two were always going up when the other two were coming down. They seem to work in families. The young ones, though old enough to get their own living, usually inhabit the same nest, and help to store up the grain for winter use. They all separate again in the spring. The little chitmunk does not live in the trees, but burrows in the ground, or makes its nest in some large hollow log. It is very pretty to see the little chitmunks on a warm spring day, running about and chasing each other among the moss and leaves. They are not bigger than mice, but look bright and lively. The fur of all the squirrel tribe is used in trimming, but the grey is the best and most valuable. It has been often remarked by the Indians, and others, that the red and black squirrels never live in the same place; for the red, though the smallest, beat away the black ones. The flesh of the black squirrel is very good to eat; the Indians eat the red also.”

Lady Mary was very glad to hear all these things that her nurse had told her, and quite forgot to play with her doll. “Please, Mrs. Frazer,” said the little lady, “tell me now about beavers, and musk-rats, and wood-chucks?”

But Mrs. Frazer was obliged to go out on business. She promised, however, to tell Lady Mary all she knew about these animals another day; but I am afraid that it will be another month before my friend, the Editor of the “Maple Leaf,” will let my young readers know what Mrs. Frazer told the Governor’s daughter.

|

The Authoress was herself the lady who was in the canoe, and her eldest son, the baby, whose cap and frock were wetted by the light shower that was sprinkled on him by the fearless little animal. |

|

The squirrel has many enemies, all the weasel tribe, cats, and even dogs attack them. Cats kill great numbers of these little animals. The farmer shews them as little mercy as he does rats and mice, as they are very destructive, and carry off vast quantities of grain, which they store in hollow trees for use; not contenting themselves with one granary, they have several, in case one should fail, or perhaps become injured by accidental causes. Thus does this simple little folk teach us a lesson of providential care for future events. |

|

This remark applies more particularly to the climate of the Upper Province, where the January thaw generally occurs. |

Lucifer Matches.—According to the Morning Chronicle, in one steam sawing-mill, visited by Mr. Mayhew, the average number of splints made for lucifer matches is 156,000 gross of boxes a year, each box containing 50 splints, altogether 1,123,200,000 matches. For the manufacture of this quantity 400 cubic feet of timber are used in a week, averaging eight trees, or 400 large trees a year for lucifer matches only, in one mill! It is no longer a joke to say a man who deals in matches is a timber merchant.

The readers of the “Maple Leaf,”—a magazine so decidedly Canadian,—may not be particularly desirous or an acquaintance with one, whose corporeal appearance, national predilections, social and political education, form a contrast with their own. Admitting that there may be a shade of difference in some points,—I can confidently assure the readers of this magazine,—a few pages of which may occasionally contain some of my cogitations, that the Constitutional peculiarities common to my most worthy and distinguished ancestors, peculiarities which may have been retained by their descendants, shall in no way render my acquaintance with them less agreeable and profitable. It is pleasant to see, that the feeling of animosity which has been somewhat characteristic of the great nations from which we claim our origin, is giving way to a very different spirit; a spirit which will pervade the nations of the earth, and transform the grand divisions of the Globe, and its subdivisions, into natural and agreeable demarkations of separate homes of the same great family. I have long endeavored to aid in putting down, and banishing into oblivion, every feeling which checks the course of that fellowship which should exist between man and man; and at the same time, have wished to contribute to the happiness and improvement of all those, whose acquaintance and friendship I have the good fortune to enjoy. If then, you are disposed to reciprocate such feelings, and sentiments, you will not complain of the publisher’s arrangement, and the acquaintance thus informally brought about.

When we are able to hold captive to our will such inclinations, as are calculated to mar our happiness, and retard our improvement, we certainly have accomplished much. We have brought our minds and hearts into a state highly favorable for receiving, or imparting instruction. To such the effort required for the acquisition of knowledge is pleasing and exhilarating. There is no easy way to obtain knowledge. “Other things may be seized by might, or purchased with money; but knowledge can be gained only by study.” It may be quite true, that the approach to the temple of learning is by slow graduations, up an acclivity of which the ascent undoubtedly requires a stern and steady effort. If we wish to become eminent in any branch of knowledge, or in any pursuit whatever, we shall find it necessary to toil, and take advantage of all the means within our reach. But this instead of being a repulsive task, can be made the source of the purest and most delightful enjoyment. There is no department of learning so calculated to awaken the dormant energies of the mind, and call into vigorous action the latent virtues and sympathies of the heart, as the study of Natural History. This branch of science is admirably adapted to the flexible mind of the young. While it fixes their attention, it captivates the heart, and cultivates its graces in a natural and agreeable manner.

Nature is loveable, whether exhibited in the foaming cataract, or the solemn grandeur of the wood, or the delicate tints of the flowers with their entrancing fragrance. The music of birds echoing through the shadowy arches of the forest, or sounding out clear and enlivening on the pure morning air; always meets a responsive chord of harmony in the heart of the good man. While the earth was yet young, and no descendant of a spiritual race had walked its green fields, or gazed upon its beauties, a voice of praise went up to the great Creator, and a choir attuned at Nature’s perfect school warbled and caroled notes of thanksgiving.

No country can number more interesting natural features than Canada. If we should take a stand on any of the lofty heights that rise here and there, and variegate its lovely landscapes, we should be charmed with the panoramic view before us. Rivers, whose broad waters dotted with islands, roll onward through a fertile country; lakes lying encircled by mountain and hill; a charming succession of plain, and undulating land, and serpentine stream, and rushing water-fall, with golden, and green, and darker colored tintings among the grain fields, and meadows, all form pictures which the lover of nature must delight to view.

The elegant form, and bright hues of the humming bird, “in whose plumage the ruby, the emerald, and the topaz sparkles,”—the superior brilliancy, and various shading of the butterfly, which, “light, airy, joyous, replete with life; sports in the sunshine, wantons on the flower, and trips from bloom to bloom,”—the outgushing notes of the lark as he joyously rises and soars towards heaven, and pours forth strains that have been compared to hymns of praise,—have all with many other objects of nature delighted thousands. Poets, and Poetesses have “tuned their harps, and lit their fires,” while drawing from natural scenery their most exquisite imagery. From the same source Bible writers have taken their must vivid illustrations. Examples in point, abound in the Book of Job, and other portions of sacred writ. Many master minds of ancient and modern times have been absorbed in examinations of the works of nature. We read that King Solomon bought apes, and peacocks from Ophir, and probably animals, and plants too, were brought to him from other foreign countries. Solomon showed an intimate acquaintance with Natural History, and spoke of trees, from the majestic “cedar of Lebanon, to the hyssop that springeth out of the wall,” and referred to “beasts, and creeping things, and fowls, and fishes.” The Psalmist took up the same theme, when celebrating the glories of the Divine perfections, and discoursing upon the wonders that present themselves “in the heavens above, and the earth beneath,” and exclaimed in transport “O Lord, how manifold are thy works! in wisdom hast thou made them all! the earth is full of thy riches.” Pliny many hundred years later produced a work on Natural History, which, though lacking the fire of inspiration, has been read with delight. Corresponding zeal has been awakened, and kindred emotions expressed in more modern times, as the following extracts which I here transcribe will show:

“How pleasant, nay, how much more pleasant,” says a writer in Blackwood’s Magazine, in reference to the prevailing taste for novel-reading, “to take up by chance from a table, groaning under a load of fashionable novels, some small volume composed by some lover of nature, that has found its way there, like some real rose-bud yielding its fragrance amongst artificial flowers. There are homilies in Nature’s works worth all the wisdom of the schools, if we could but read them rightly, and one of the pleasantest lessons I ever received in a time of trouble, was from hearing the notes of a Lark.”

“From Nature’s largest work to the least insect that frets the leaf, each has organs, and feelings, and habits exactly suited to the place it has to fill. Were it other than it is, it could not fill its place. The flower of the valley would die upon the mountain’s top, and surely would the hardy mountaineer, now flourishing on Alpine height, languish and die, if transplanted to the valley. The maker of the world has made no mistakes,—has done no injustice.”—The Listener.

“See!” exclaimed Linnæus, “the large painted wings of the butterfly, four in number, covered with small imbricated scales, with these it sustains itself in the air the whole day, rivalling the flight of birds, and the brilliancy of the Peacock. Consider this insect through the wonderful progress of its life; how different is the first period of its being from the second, and both from the parent insect; its changes fire an inexpressible enigma to us; we see a green caterpillar furnished with sixteen legs, creeping, hairy, and feeding upon the leaves of a plant; this is changed into a chrysalis, smooth, of a golden lustre, hanging suspended to a fixed point, without feet, and subsisting without food; this insect again undergoes another transformation, acquires wings, and six feet, and becomes a variegated butterfly, living by suction upon the honey of plants. What has nature produced more worthy of imitation.”

“The field daisy,” says one, “insignificant as it apparently is, exhibits on examination a world of wonders. Scores of minute blossoms compose its disk and border, each distinct and useful, each delicately beautiful. The florets of the centre are yellow, or orange, colored, while those of the ray are snow white, tinged underneath with crimson.”

“The beech tree, Fagus sylvatica,” says Mr. White, “is the most lovely of all forest trees, whether we consider its smooth rim or bark, its glossy foliage, or its graceful pendulous boughs. Its autumnal hues are also exceedingly beautiful.”

“The good Isaac Walton, a writer of genuine feeling, and classical simplicity, observes of the Nightingale, she that at midnight, when the very laborers sleep securely, should hear, as I have heard, this clear air, the sweet descants, the natural rising and falling, the doubling and redoubling of her voice, might be lifted above the earth, and say, Lord what music hast thou provided for thy saints in heaven, when thou affordest had men such music upon earth.”

Errata in No. 2, 1853, page 36, line 5, from bottom, read “Song Thrush,” for “Long Thrush.” Page 38, line 5 from bottom read ‘wool,’ for ‘wood.’

N.B. We are compelled, owing to the sickness of our Music compositor, to omit for this month the page of music.

Death having occasion to choose a prime minister, once summoned his illustrious courtiers, and allowed them to present their claims for the office. Fever flushed his cheeks; Palsey shook his limbs; Dropsy inflated his carcass; Gout racked his joints; while Asthma half strangled himself. Plague pleaded his sudden destruction; and Consumption pleaded his certainly. Then came War alluding to his many thousands at a meal. Last came Intemperance, and with a face like fire, shouted, Give way, ye sickly ferocious band of pretenders to the claim of this office. Am I not your parent? Does not your sagacity trace your origin to me? My operations ceasing, whence your power? The grisly monarch here gave a smile of approbation, and placed Intemperance at his right hand, as his favorite and prime minister.

If we were to drop asleep, without warning, in the midst of some active operation, it is easy to see how many daily occurrences, of the most disastrous nature, would ensue. Struck by the unexpected visitant, the seaman, as he ascended the top-mast, or clung on the yard-arm, would relax his grasp, and be plunged into the sea, or dashed to pieces on the deck. The coachman, in the middle of his stage, would drop his reins, and fall senseless from his box. The builder would tumble with his trowel from the wall. The orator in the senate, at the bar, or in the pulpit, would falter, and sink with the unfinished sentence on his lips; and, in one, the fire of his patriotism; in another, the acuteness of his reasoning, or adroitness of his statement; and, in a third, an exhibition of the holy doctrines of the gospel, or of impassioned eloquence in a heart full of zeal, would expire in a sudden drawl, a closing eye, and a countenance in an instant relaxed into an expression of drowsy insensibility.

We know of nothing so swift as light, which moves at the rate of 12,000,000 miles in a minute; and yet light would be at least three years in passing between the sun and Sirius.

Many of the double stars exhibit the curious and beautiful phenomenon of contrasted or complimentary colomes. In such instances, the larger star is usually of a ruddy, or orange hue, while the smaller one appears blue or green. The double star in Cassiopeia, for instance, exhibits the beautiful combination of a large white star, and a small one of a rich ruddy purple. Sir John Herschell, in mentioning these combinations, indulges his fancy in the following somewhat amusing remarks:—“It may be easier suggested in words, than conceived in imagination, what variety of illumination two suns,—a red and a green, or a yellow and a blue one,—must afford a planet circulating about either; and what charming contrasts and ‘grateful recessitudes,’—a red and a green day, for instance, alternating with a white one, and with darkness,—might arise from the presence, or absence, of one or other, or both above the horizon.”

Politeness.—The manners of professional men are too frequently blunt and slovenly. Why are not professional men among the most refined and polite in their manners? It is because their profession is their character. Upon this they rely, and upon this wholly. If the lawyer would have his skill and eloquence remembered, let them be associated with manners refined and inviting. No station, rank, or talents, can ever excuse a man for neglecting the civilities due from man to man. When Clement XIV. ascended the papal chair, the ambassadors of the several States represented at his Court waited on his holiness with their congratulations. As they were introduced, and severally bowed, he also bowed. On this the master of Ceremonies told his holiness, that he should not have returned their salute. “Oh I beg your pardon,” said he, “I have not been pope long enough to forget good manners.”

Music.—Language for the soul’s longings; softener of man’s stormiest passions; sweet disseminator of joy and peace; a voice from the spirit world comforting earth’s sorrowing ones. Sound—It widens, and widens in continuous circles, until at last it seems to blend, and be lost.

We have a painful and melancholy event to state to the readers of the “Maple Leaf.” The former Editor and Publisher, Mr. Robert W. Lay, is now no more. He is gone, we are confident, to a higher, and a better world! He died, suddenly, and unexpectedly, at Toronto, on the 18th inst., from a fit of apoplexy, thus adding another to the many proofs which almost every day presents, that:—

“Death, like an overflowing stream,

Sweeps us away; our life’s a dream;

An empty tale; a morning flower,

Cut down and withered in an hour.

“To-day, we are upon the stream of time; to-morrow, we are floated forth upon the Ocean of eternity. There is no intermediate state of being; no line of separation between this world and the next.”

Mr. Lay was born in the State of Connecticut, U.S., in the year 1814. He was therefore in his 39th year at the time of his death. His native place, Saybrook, is situated in sight of the Atlantic-billows, and is noted in American history, as one of those staunch old towns, closely resembling in genuine honesty, and manly material, the true English characters from which it originated.

Trained in childhood and youth, amid those invigorating, self-relying influences, which the New England sea-coast villages afford, he grew up robust in physical appearance, and early exhibited, not only great perseverance and enterprise, but originality of mind. In the States he practised very successfully, for some years, as a Civil Engineer, but the out-door exposures and anxieties, which the active duties of this profession demanded, seriously injured his health, and he was compelled to abandon it.

In 1845, he came to Canada. Here he saw at a glance, the great dearth of good periodical literature, and the great improvement the country would experience, if more interesting reading could be put in circulation. Although, to the writer’s knowledge, he was, about this time, offered a lucrative situation, he refused it, and preferred the more arduous, the less profitable, but to him, the more useful task of personally endeavoring to circulate, by subscriptions, useful and entertaining works and periodicals throughout the country; but more particularly in our back settlements. With this object, he repeatedly traversed from below Quebec, up to Lake Huron; from the Eastern Townships, to the furthest settlements on the Ottawa.—At the outset of these labors, he was very much impeded by the restrictions which were then placed here upon American republications of English works. We have good reason to know, that his repeated representations to the government of the injuries these restrictions produced on the country, in a great measure led to their repeal. By this change, many a valuable English work is now placed within the reach of our poorer classes, which, formerly, could only have been purchased by the rich.—Mr. Lay was, moreover, noted for his urbanity, his warmth of heart, and his fearless avowal of Christian principles, and it has been remarked of him, by many, that no one ever spent a few moments in his society, without receiving some improving ideas, or hearing some pleasing hints on intellectual and moral subjects.

The “Maple Leaf” will be continued by his widow, for the benefit of herself and children. No pains will be spared to make its pages useful and interesting. In fact, many additional attractions for the magazine are contemplated.

A large amount of arrears are due for the volume of the “Snow Drop,” which was published by Mr. Lay; and also, on the “Maple Leaf” for the current year. We are sure, that no further appeal than is presented by the above circumstances, will be needed, to induce the immediate payment of these sums to Mrs. Lay.

Mis-spelled words and printer errors have been corrected. Where multiple spellings occur, majority use has been employed.

Punctuation has been maintained except where obvious printer errors occur.

When nested quoting was encountered, nested double quotes were changed to single quotes.

A cover was created for this eBook which is placed in the public domain.