* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Return to Mars--A Story of Interplanetary Flight (Space #2)

Date of first publication: 1955

Author: Capt. W. E. (William Earl) Johns (1893-1968)

Illustrator: Leslie Stead (1899-1966)

Date first posted: September 10, 2023

Date last updated: September 10, 2023

Faded Page eBook #20230915

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, akaitharam, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

CAPTAIN W. E. JOHNS

————————————————

KINGS OF SPACE

“Captain Johns’ first space adventure book is a winner.”

Daily Mirror.

The ‘Biggles’ Books

| BIGGLES GOES TO SCHOOL | BIGGLES IN BORNEO |

| BIGGLES LEARNS TO FLY | BIGGLES FAILS TO RETURN |

| BIGGLES FLIES EAST | BIGGLES IN THE ORIENT |

| THE RESCUE FLIGHT | BIGGLES DELIVERS THE GOODS |

| BIGGLES HITS THE TRAIL | SERGEANT BIGGLESWORTH, C.I.D. |

| BIGGLES & CO. | BIGGLES’ SECOND CASE |

| BIGGLES IN AFRICA | BIGGLES HUNTS BIG GAME |

| BIGGLES, AIR COMMODORE | BIGGLES TAKES A HOLIDAY |

| BIGGLES FLIES WEST | BIGGLES BREAKS THE SILENCE |

| BIGGLES FLIES SOUTH | BIGGLES GETS HIS MEN |

| BIGGLES GOES TO WAR | ANOTHER JOB FOR BIGGLES |

| BIGGLES IN SPAIN | BIGGLES WORKS IT OUT |

| BIGGLES FLIES NORTH | BIGGLES TAKES THE CASE |

| BIGGLES, SECRET AGENT | BIGGLES FOLLOWS ON |

| BIGGLES IN THE SOUTH SEAS | BIGGLES AND THE BLACK RAIDER |

| BIGGLES IN THE BALTIC | BIGGLES IN THE BLUE |

| BIGGLES DEFIES THE SWASTIKA | BIGGLES IN THE GOBI |

| BIGGLES SEES IT THROUGH | BIGGLES CUTS IT FINE |

| SPITFIRE PARADE | BIGGLES AND THE PIRATE TREASURE |

| BIGGLES IN THE JUNGLE | BIGGLES, FOREIGN LEGIONNAIRE |

| BIGGLES SWEEPS THE DESERT | BIGGLES’ CHINESE PUZZLE |

| BIGGLES, CHARTER PILOT | BIGGLES IN AUSTRALIA |

and

COMRADES IN ARMS

THE FIRST BIGGLES OMNIBUS

RETURN TO MARS

A story of Interplanetary Exploration

by

CAPTAIN W. E. JOHNS

A Sequel to Kings of Space

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BY STEAD

HODDER AND STOUGHTON

THE CHARACTERS IN THIS BOOK ARE ENTIRELY IMAGINARY AND BEAR NO RELATION TO ANY LIVING PERSON

First Printed 1955

MADE AND PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN FOR HODDER AND STOUGHTON LIMITED, LONDON BY C. TINLING & CO. LTD., LIVERPOOL, LONDON AND PRESCOT

| CONTENTS | ||

| Chapter | Page | |

| FOREWORD | 11 | |

| I | OUTWARD BOUND | 17 |

| II | LITTLE DEAD WORLD | 25 |

| III | SHADOWS IN THE NIGHT | 35 |

| IV | ONE THING AFTER ANOTHER | 45 |

| V | THE MAN OF MARS | 53 |

| VI | DISTURBING DISCOVERIES | 62 |

| VII | NIGHTMARE JUNGLE | 71 |

| VIII | VARGO TELLS HIS TALE | 80 |

| IX | A BOLT FROM THE BLUE | 89 |

| X | INTERCEPTED | 99 |

| XI | WORLD OF FIRE | 110 |

| XII | ON TO LENTOS | 118 |

| XIII | VONTOR | 127 |

| XIV | FUN ON WINGS | 137 |

| XV | FOREST OF FEAR | 142 |

| XVI | THE END OF THE SPACEMASTER | 151 |

| LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS | ||

| facing page | ||

| Its name on Earth, was Mars. Its colour, red—and red on Earth was a danger signal | 17 | |

| Leaping across the floor Rex kicked the thing in the face | 32 | |

| He looked dreadfully ill. But as they entered his eyes moved | 65 | |

| . . . . uncoiling like a spring | 80 | |

| “That’s what comes of monkeying with things you don’t understand” | 129 | |

| . . . . like the questing tentacle of an octopus | 144 | |

THE SOLAR SYSTEM

Moving outwards from the Sun. Figures approximate.

| Planets | Diameter | Length of | Length of | No. of | |||

| in Miles | Year | Day | Moons | ||||

| Mercury | 3,100 | 88 | days | 88 | days | ? | |

| Venus | 7,750 | 224 | days | ? | ? | ||

| Earth | 7,900 | 365 | days | 24 | hours | 1 | |

| Mars | 4,200 | 687 | days | 24½ | hours | 2 | |

| Jupiter | 86,700 | 12 | years | 10 | hours | 11 | |

| Saturn | 71,500 | 30 | years | 10 | hours | 10 | |

| Uranus | 32,000 | 84 | years | 11 | hours | 5 | |

| Neptune | 31,000 | 164 | years | 16 | hours | 2 | |

| Pluto | 7,500 | 248 | years | ? | ? | ||

About 2,000 minor planets (planetoids) with orbits mostly between Mars and Jupiter. The largest are Ceres, Pallas, Vesta and Juno, with diameters of between one hundred and five hundred miles. Five hundred have diameters of more than thirty miles.

———————

The increasing lengths of the years is because of the increasing distance from the Sun, resulting in a longer journey which the planet must make round it.

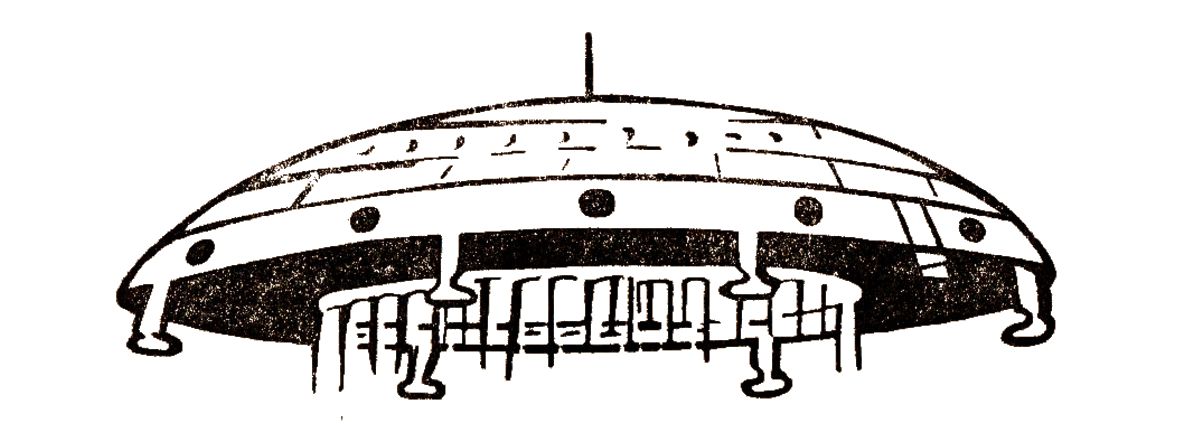

This is the sequel to Kings of Space. In that story Group Captain “Tiger” Clinton and his son Rex, on a deer-stalking holiday in the remote Highlands of Scotland and benighted by bad weather, found refuge in a lonely shooting lodge named Glensalich Castle. There they made the acquaintance of Professor Lucius Brane, a wealthy genius who had for years worked on the project of vertical flight, and had in fact just completed an aircraft of the “Flying Saucer” type which he had named the Spacemaster.

Knowing Tiger by reputation as one of the “back-room boys” at the Royal Aircraft Experimental Establishment, he had, after confiding in him, asked his advice on some constructional details. This had led to discussions on the new science of Astronautics, and the Astronomy to which it is related.

The upshot of this was Tiger and Rex joined the Professor on his preliminary experimental flights. Next, a landing was made on the moon. Then came a trip to Venus, and finally, a journey to Mars, calling at Phobos (one of the two moons of Mars) on the way. On Mars had been found a few surviving members of a dying race of men much like themselves. At the same time, the “red storms” that can be observed from Earth were explained.

It transpired that at a remote period, the Martians, a cultured people, to conserve a diminishing water supply possibly caused by the deforestation of the planet, had cut canals to bring the melting ice from the Poles; but in this vast water system had developed a malignant mosquito, pink in colour, which, multiplying to countless billions, had (supposedly) by the constant inoculation of poison, practically wiped out the “human” population on which it preyed. The “red clouds” that had for long puzzled astronomers on Earth were in fact devastating swarms of insects of the mosquito family. Admittedly, this was largely assumption, but, from the evidence, what had happened seemed fairly obvious. Unfortunately, before confirmation could be obtained, the visitors had themselves been nearly overwhelmed by the deadly clouds and only with difficulty made their escape.

On returning to Earth the Professor had resolved to design and build a bigger and better spaceship, introducing such modifications as experience with Spacemaster I had indicated, with the object of trying to save the few surviving Martians from the fate that threatened them. His great fear was that they would arrive too late. Aside from the humanitarian angle, he asserted, this would be a major tragedy, for with the Martians would die, and so be lost for ever, the history of the planet and its people.

Repetition being wearisome, in order to grasp the known facts of the Solar System and the general principles of Astronautics, as related by the Professor to Tiger and Rex, the reader is advised to read Kings of Space.

After reading it some of the incidents narrated in the present volume may not appear to be outside the bounds of possibility, for interwoven in the story is a good deal of fact. For example, those who would question the invasion of our Solar System by comets from outer space, to the peril of the planets of which Earth is one, should know that such visitations occur hundreds of times in the course of a century. Sometimes these comets stay with us. Sometimes they retire, to return, or perhaps be seen no more. In the long history of mankind we must have been invaded millions of times.

Was there never a collision? We don’t know, although we do know from their orbits that the planetoids Hermes, Apollo and Adonis, must have passed relatively close to Earth many times. It can hardly be coincidence that in the old records of every ancient race there are legends, significantly similar, of visitations causing destruction beyond imagination. Such frightful disasters were of course ascribed to the wrath of the pagan gods, but they appear very much like collisions with the tail of a comet.

How else can we account for the dreadful events described in the Old Testament? Long periods of absolute darkness during which the Earth was bombarded with fire, brimstone and red hot stones: noises beyond description, rains of dust and rocks that slew the people and all the cattle in the fields. The crops and forests were destroyed and the whole land laid waste. Mountains rose up. Seas overran the dry ground. Not even kings could escape. Surely this is precisely what would happen if a comet, or any other body, approached us from space. That these things happened is not to be doubted and may explain why the ancients were terrified of the heavens.

Certainly the Earth has had shakings severe enough to rock it on its axis. How otherwise could we find the remains of tropical life in the Arctic?—coral reefs, fossil palm trees, and the like. Today the great continent of Antarctica, which covers the South Pole, is a frozen waste, without a tree; yet ice breaking off not infrequently carries coal. If there is coal under the ice there must at one time have been forests! Bones, human and animal, have been found hundreds of feet below the present surface of the Earth. How did they get there? Shells and fossil fish found in the sedimentary rock that covers the world’s highest mountains tell us that they were once under the sea. What happened?

Such facts may be disconcerting, but they cannot be ignored on that account.

Phobos, one of the two moons of Mars that comes into our story, sets another problem. These moons were only discovered in 1877, after the telescope made it possible to see them. Yet the ancients must have known of them for they gave them names—the names they still hold. Phobos (meaning Terror) and Deimos (Rout). Homer and Virgil talk of them as the two horses of Mars, dragging his chariot. Why horses? Did they have tails? Comets have tails. Whatever they were they were visible to the naked eye, from which we are forced to the conclusion that Mars, the ancient God of War, was at one time nearer to us than it is today.

Now another word of warning. There is a general and natural tendency to suppose that everything in the Universe works the same way as on Earth; that as things happen here so they happen elsewhere; day and night, the months, years and seasons, all following each other in the procession with which everyone is familiar. This is not the case. There is no fixed order of things, every heavenly body being governed by its own peculiar factors. Because on Earth the sun rises in the East doesn’t mean that it rises in the East everywhere.

Owing to the angle of Earth’s axis in relation to the Sun both our Poles are cold. But the axis of the planet Uranus is so placed that for twenty years one of its Poles is the hottest place on the planet: then the opposite Pole moves round and in turn for twenty years enjoys tropical sunshine. Here our period of a month is governed by the Moon. As we have only one moon our calendar is a simple affair. But how many months has Jupiter, which has eleven moons, some revolving in reverse directions?

These examples will suffice to show the sort of problems that will confront navigators when interplanetary flight becomes as commonplace as air travel is today. To many people Lunar Flight is still fantasy. They should remember that not very long ago talk of any sort of flight was fantasy.

The Planetoids.

The reader should know something about these little worlds that spin about the Solar System. There are quite a lot of them.

The first was discovered in 1801 by an Italian monk named Piazzi. It had a diameter of nearly 500 miles and was named Ceres. A year later a German doctor found another, with a diameter of just over 300 miles which was named Pallas. Two years later another was found, and three years after that, a fourth. These were named Juno and Vesta.

Then the fun started. The eyes of all astronomers were on the skies and fresh discoveries began to pour in. So many were there that names, which had begun as classical female names, began to give out. By 1890 three hundred planetoids had been found. As telescopes became bigger and better still more were added to the list, until today it runs to about two thousand. Names having become exhausted numbers are now used.

A great part of astronomy became the checking of the orbits of these wanderers in space. In some areas they fairly swarm, and have been given group names. Some have come close enough to us to cause alarm; passing between us and Mars, although most of them circle between Mars and Jupiter. That is all we know about them—so far. One day we may know more.

W.E.J.

There was silence in the Spacemaster as it shot through Escape Velocity into space on its estimated eight-day journey to Mars. The five members of the crew, relieved of the strain of the initial acceleration, had relaxed, and were preparing to occupy themselves by such means as had been provided to fill the unchanging hours that lay ahead.

Professor Lucius Brane, the little eccentric scientist-engineer inventor of the spacecraft, sat at the main observation window, hair untidy, spectacles on the end of his nose, notebook on the chart table in front of him, and a bag of caramels, anchored by an elastic band, at his elbow. Judkins, his imperturbable seldom-speaking butler-mechanic, was at the controls—power, gyro and pressure—their relative positions being those of captain and chief engineer of an ocean liner.

Group Captain “Tiger” Clinton, D.S.O., R.A.F. (retired), with his son Rex, were watching the shadow called night sweep across the huge but fast-diminishing globe which once they had called the world, but was now, for purposes of navigation, merely Earth; one of a million units of the Universe within their view. They watched without emotion, for they had seen the spectacle before.

Not so the remaining member of the crew, to whom this was a new and obviously disturbing experience. A doctor had been considered essential to the expedition, and Tiger had found one, a war-time comrade and friend, in Squadron Leader Clarence Paul, M.D., better known in the Service as “Toby”. He was a small, chubby little man of early middle age, with a cheerful expression which, with his figure, had no doubt been responsible for his nickname.

A man of tremendous energy, as small men often are, he had had a great deal of experience in the tropics of disorders caused by insects, malaria, sandfly fever, and the like. A feature of his nature was a sense of humour that could make a joke of trouble. He also possessed, often to the Professor’s bewilderment, a wonderful vocabulary of R.A.F. slang. When Tiger had put the project before him, asking him if he would attend some patients on Mars, he had, not surprisingly, accused him of being “round the bend”. But when Tiger had produced photographs taken on the previous expedition he went to work on preparations to deal with the situation.

Nearly a year had passed since that memorable first journey to Mars, but such had been the activity designing and constructing the new Spacemaster that as far as Rex was concerned the months had flown. Tiger had returned to Farnborough to complete his work there, but had dashed up to Glensalich for as many weekends as he could manage.

Rex, abandoning his apprenticeship, had acted as “runner” between Glensalich and the works where the components of the new ship were being fabricated to the Professor’s specifications. This had left the Professor free to concentrate on research, for here there was much to be done.

Toby now knew all that had happened on the early voyages, for once a month there had been a conference at Glensalich Castle attended by everyone; and it is doubtful if ever before at any meetings there had been discussed matters of such consequence. All were aware of this. What effect the knowledge they already possessed would have on the general public should the facts become known was a matter for surmise. It would certainly—as Toby put it—start a flap. Governments apparently thought so, averred the Professor, from the way they had tried to ridicule the reported sightings of so-called Flying Saucers. The adoption of the harmless-sounding name “Saucer” was part of a plan to offset public fears of the unknown. The official American name, UFO, meaning Unidentified Flying Object, was better.

But then, observed the Professor with a sly smile, the American government could hardly deny the existence of space aircraft when it was itself pressing on with that very project, and planned to have a refuelling base between Earth and Moon within five years.[A] The spacesuits of the operators had already been made and tested. This “cosmodrome” would have to be conspicuously marked, he declared, or there would be a danger of collision with it.

[A] Since this was written Russia has announced a similar project.

The Spacemaster II was larger than its prototype and embodied several modifications, notably in the matter of safety devices. Learning a lesson from their collision with a small meteor, the air supply, an improved mixture of oxygen and helium, was no longer contained in a single compartment but in several small ones, indicated by bulges on the skin of the ship. Damage to one would not affect the others. The chemical air-purifying system was more efficacious, and a double skin would, it was hoped, provide better temperature conditioning. There was more storage space for food, mostly highly concentrated, and the considerable amount of equipment that would be required. An air-lock, in the manner of the escape compartment of a submarine, to make exit possible without losing pressure in the cabin, was a new feature.

The Professor had also been busy in other directions. He had produced an insecticide to deal with the pink mosquitoes. This was not a poison in the accepted sense of the word, for it was out of the question to carry a supply sufficient to spray the entire planet. The Professor’s creation was an organic compound calculated to set up a “hunger” phobia in which the insects, by eating each other, would not only gorge themselves to death but pass on the deadly dose. In other words, the Professor had explained with a chuckle, he proposed to exterminate the pest by giving the little beasts a fatal bilious attack.

A piece of good news to Rex was provided by the analysis of the samples of atmosphere taken on Mars, where there had not been time to test it in actual practice. It revealed that once on the planet spacesuits would not be needed after the explorers had become acclimatized. The air was thin, and the pressure consequently less than that to which they were accustomed at sea level on the surface of the earth. It was, the Professor stated, about the same as would be found on Everest at 26,000 feet, which had been reached without oxygen apparatus. This might be uncomfortable but it would be sufficient to support life. After a little while, provided they were not called to any great exertion, the change would be hardly noticeable.

It should be mentioned that the Professor had “improved” his caramels by the inclusion of a substance sometimes issued during the war to troops engaged in special operations likely to call for superhuman endurance. By putting it in a concentrated form of glucose, to form the caramel, a few of these special sweets would keep a body going for some time with no other food.

There had been one incident that struck Rex as amusing although he had thought it prudent to keep his expression under control. The Professor, without saying that he was speaking from experience, had written a paper for a scientific journal on “probable” moon conditions; the probable conditions, of course, being the actual ones. The editor, refusing to publish it, had returned the manuscript with a curt note which implied that the writer was talking nonsense.

“You see?” said the Professor bitterly. “Tell the truth and you become either a liar or a fool.”

By an unfortunate chance the same post brought a newspaper clipping, an article that dealt with Lunar Flight. Part of it the Professor read aloud: “In case of War, atomic guided missiles could be launched from a Lunar base and aimed by radar at any target on earth.” He flung the paper on the table. “War—war—war,” he said sadly. “That’s all they think about. Mark my words, as soon as interplanetary flight is achieved the first talk will be of a possible war with Mars. One of these days I’ll build a fleet of spaceships and evacuate to another planet the people who in this war-madness see the end of all that is best on Earth. I fear that Earth is heading for such a disaster as defies imagination.”

The day was approaching when Rex was to remember this remark.

At the moment, however, as already stated, through one of the now dimmed windows he was watching night roll its curtain across the face of the world he knew. Around, in a sky deep navy blue, gleamed and twinkled the worlds he did not know.

The Professor broke a lengthy silence. “I’m thinking of making a halt on Phobos, that pathetic little satellite of Mars which we visited on our last trip. From there I hope to get a clearer view of those planetoids which, should we go beyond Mars, may cross our path. Some have orbits uncomfortably close to Mars, and to Earth, for that matter, although it is not generally realized. In 1937 Hermes shot past just beyond our moon. A little nearer and it might have knocked it to pieces, or taken it away from us. It might have been such a near miss that dragged away its atmosphere. But perhaps it’s better not to think about these things, although, to be sure, such accidents are common enough in the Universe, as astronomers know well.” The Professor pushed up his spectacles. “Would anyone like a caramel?”

They all took one.

“How many of these planetoids are there altogether?” asked Rex.

“Nearly two thousand. There may be others, too small to be seen even on the great two hundred inch reflector on Mount Palomar. I’m not worried about the big ones, like Ceres, Pallas, Vesta or Juno. Small ones could be dangerous, like rocks in the sea—the Ocean of Space.”

Rex spoke. “Could the Saucers be coming from these planetoids, now that we know they’re not coming from Mars?”

“It is possible, but surely improbable. I can’t believe people capable of inventing an efficient spacecraft would remain on a tiny world when there must be larger ones within their reach.”

“Could it be that they are now looking at Earth with the object of moving to it?”

“That, Rex, is what some people would very much like to know,” answered the Professor seriously. “It isn’t beyond the bounds of possibility. It would account for the recent activity. One can understand the anxiety these visitations are causing, for it needs only one Saucer to land to throw our civilization into confusion. Well, we may soon know, for I hope to call on some of the larger planetoids. We may learn something of them from a Martian, if we can find one alive, for the orbits of most of them lie between Mars and its giant neighbour, Jupiter; a monster of such size that it would require thirteen hundred Earths to produce an equal mass.”

“As it’s on fire I imagine we shan’t be calling there,” put in Tiger, dryly.

“It would be interesting to know of what its mighty cloud belts, constantly changing form and colour, are composed,” returned the Professor pensively. “It also has more than its share of moons, you know; no fewer than eleven, for which our astronomers have found romantic names—Ganymede, Callisto, Europa, and so on.” The Professor chuckled. “Let us hope they are as romantic by nature.”

Tiger looked at Toby, whose face had recovered something of its usual high colour. “Feeling better, old man?”

Toby smiled wanly. “Yes thanks. I must admit that for a bit I thought I was going for six.”

“So did I, at first,” consoled Tiger. “You’ll soon get used to the sensation of being in the middle of nowhere.”

“Don’t let anything upset you, for you may be running a hospital presently,” put in the Professor.

“I’ll manage, if you can deal with these fantastic swarms of bugs.”

The Professor peered over his spectacles. “Why fantastic?”

“Don’t you think they’re fantastic?”

“No. Haven’t we swarms of microbes on Earth to strike people down with what we call infectious diseases? If you regard the pink mosquitoes as overgrown germs it comes to precisely the same thing. What about the locust hordes that have ravaged areas of Earth since the dawn of history? The wretched people afflicted are able to put up some sort of fight against them because they happen to be by nature vegetarian; but suppose the locusts had developed poison glands and preyed on human blood instead of crops? What then? In spite of all that science can do these swarms persist. In different circumstances they might well have succeeded in depopulating Earth as another species of insect had depopulated Mars.”

“In those parts of the world where the swarms occur, perhaps,” returned Toby.

“Come—come, Doctor,” chided the Professor gently. “Had the locusts’ food supply in the East given out they would have sought new pastures in the West, for such is the cause of migration. Should the temperature of Earth undergo a change that could happen yet. Ha! That would be a pretty problem for the Ministry of Agriculture, wouldn’t it?”

Nobody answered.

“You see,” continued the Professor, “our imaginations are limited to the things we know and understand. Anything beyond that we call fantasy. A man cannot envisage a higher form of life than himself. He cannot make allowances for things which on Earth do not exist. There, perhaps, lies our greatest danger; for it is almost certain that on this trip we shall see things, and do things, which our common sense will tell us cannot be true. So be prepared.”

The Spacemaster sped on through the great loneliness, its portholes dimmed against the fierce solar rays, its cosmic jets silent now that maximum velocity had been achieved. The only sound was the hum of the gyro.

Rex stared through his window at a gleaming disc still far away. Its name, on Earth, was Mars. Its colour, red—and red on Earth was a danger signal.

Was it a warning?

A week later, the ochre-red globe that was the objective, its ice-capped Poles glistening, was cutting a vast curve across the Spacemaster’s field of view. It looked what Rex knew it to be; a place of desolation from which life had almost been liquidated by a single, all-conquering species of insect. The only physical features of any consequence were the weed-choked canals from which the mosquitoes made their daily forays in search of food, giving the planet the appearance of having been caught in a net. A small, dark, round spot, showed where Phobos, one of Mars’ two tiny satellites, was rolling along its never-ending orbit.

For the crew of the Spacemaster the only incident to break the monotony of the long flight was the appearance, in close formation, of three small circular spaceships which had kept them company for a while before darting off at a tangent at a speed that took them out of sight in a few seconds.

“They must wonder who we are as much as we wonder where they came from,” remarked the Professor. “Did you notice how, when they left us, they moved as one machine?”

“Which means that they were in communication with each other,” said Tiger.

“They must have been, and I suspect it is the signals of these space-travellers that our big wireless stations are picking up. Operators on Earth have lately reported getting sounds unlike anything that could emanate from Earth. The sounds are said to be a meaningless jumble which might, however, be an unknown language.”

“If those ships come from outer space, as you seem to think, Professor, they must be away from their bases for a very long time,” said Tiger.

“In our terms of time, yes; but perhaps not in theirs.”

“How do you mean?” questioned Tiger. “Time is time.”

“It is also a matter of proportion,” averred the Professor. “Five years to an earth-dweller would be a big slice out of his normal life-span of three score and ten; but to a man who had a life expectation of five hundred years it would be a mere nibble.”

“Five hundred years!” exclaimed Rex.

“Why not? Look how the life-span on earth has increased in recent years. More people live to be nearly a hundred than ever before. If that trend continues the average seventy years might well become ninety, or more. By the time Earth reaches the present age of Mars men might be living for hundreds of years. There are scientists and doctors who predict that.”

“A staggering thought,” murmured Toby.

“There is likely to be much to stagger us before we return home,” rejoined the Professor, dryly.

Every hour saw the details of the objective planet become more clearly defined. Toby stared, fascinated.

“I shall land on Phobos where I landed before,” decided the Professor. “You’ll need your spacesuits if you get out. It will be an opportunity to test them, and the new high-frequency radio equipment. Be careful how you move or you may hurt yourselves: there’s very little gravity to keep you on the ground. By the way, Doctor, you remember us telling you that we found a dead man on Phobos, perfectly preserved? You might be able to form an opinion as to how long he has been dead. Another interesting question is this. Bearing in mind that there are dwellings on Phobos, which means that there must have been an atmosphere of sorts there at one time, did this man die as a result of the atmosphere disappearing or was the body put there after death? There’s no atmosphere there now.”

“You’re sure there was, at one time?”

“People would hardly build houses in a vacuum. Besides, I noted remains of vegetable life, such as petrified wood.”

“What could have happened to the atmosphere?”

“Mars, or a planetoid passing close, may have dragged it away. Phobos is only a few thousand miles from Mars.”

By this time the Professor was beginning to check the fall preparatory to landing. The cosmic jets roared. The gyro hummed. The dead little moon visibly grew larger.

“Professor!” called Rex suddenly.

“What is it?”

“Somebody’s been there since we were there.”

“Indeed?”

“There’s a much larger mark than the one we made—larger than the one we found there. You can see it distinctly, on the same spot.”

“He’s right, Professor,” confirmed Tiger.

“Well—well! How very interesting,” murmured the Professor. “In view of what we know we needn’t be surprised; although we might wonder why a ship should land there. We may find out.”

The Spacemaster continued on towards a surface that was appalling in its stark monotony and utter desolation. Everywhere it was the same, without any change in colour, without outline, devoid of any sort of vegetation and without one outstanding feature to catch the eye. A naked world. It was, thought Rex, worse than any of the great deserts on Earth, because there one knew there was an end to the wilderness. Here there was no end. This was what Earth would be, stripped of its clothing. He shivered.

The fact that Phobos was tiny, compared with Earth or its satellite Moon, did nothing to soften its harsh sterility. Thus it was, and thus, with never a breath of wind, a cloud, or a drop of rain, it would have to remain. That it was not entirely flat, but ridged and corrugated, was one proof that at a period of its life it must have had an atmosphere of some sort. Petrified vegetable matter suggested water at one time, too. Now these things had gone, leaving nothing but dirt and dust and rock to be flayed by the merciless solar rays, day in and day out for ever and ever; held in the unbreakable grip of gravity, doomed to roll on and on round its allotted orbit for all eternity, unless . . .

There was, Rex knew, an “unless”. A wandering planet, or planetoid, or even a large meteor, thrown off its course by forces beyond human understanding, might come close enough to attract it, and so rescue it—or shatter it entirely.

Rex made out the ridge-surrounded basin in which a huddle of primitive dwellings had determined the place of their previous landing. Soon the jets were setting the dust swirling. The Spacemaster’s legs settled in the sand and the ship came to rest near the marks of other landings, although only one of them was their own.

“Well, here we are,” remarked the Professor nonchalantly. “While I am surveying the sky for possible planetoids I suggest that the Doctor is shown the body of which we told him. Don’t be long away. An hour or so here should suffice for my purpose and enable Judkins to do a bit of tidying up. Then we’ll have a meal and carry on. Test your suits in the air-lock chamber before you step out. And remember, while you will have a little weight it might be only enough to be dangerous. I mention that in case in a moment of forgetfulness you might behave as if you were at home.”

The donning of the spacesuits took some time. Tiger, Toby and Rex then entered the air-lock and while the air in the chamber was released, checked the valves and radio equipment before descending the steps to solid ground.

“Take it easy, Toby,” advised Tiger. “You’ll find the airy-fairy feeling a bit odd at first, but it’s surprising how quickly you get used to it. The thing is to keep your feet on the ground and do nothing in a hurry. With so little gravity we could probably get to the houses in one jump—and maybe knock our brains out when we landed. This way.”

At a slightly bouncing gait, rather as if they were trying to walk in deep water, they made their way to the house in which they had found the body of what there was reason to suppose was a man of Mars. It was still there, looking exactly the same although nearly a year had passed since they had last seen it. But it was not that which caused Tiger to pull up with a cry of astonishment. There were now three bodies, lying side by side.

All were of the same pattern; and, indeed, very much alike. Each was tall, thin, with a skin of creamy brown colour and long flaxen hair. Each was dressed in what was apparently a standard garment of coarse material, something in the style of a Roman toga, but caught in at the waist so that in walking it would look like a short tunic and skirt. Footgear was sandals of the same sort of material, but thicker and more closely woven.

For a minute nobody spoke. Rex could only stare, conscious of a dreamlike sensation of unreality. Indeed, he had had dreams that were much more real.

Tiger broke the silence. “The Professor told us not to be surprised at anything, but this, I must say, takes a bit of believing. Here, at this moment, the expression ‘out of this world’, really means something.”

“I think we can now answer one of the Professor’s questions,” said Toby, in a strange voice. “These men did not die here. They were brought here after death.”

“Are you suggesting that somebody is using Phobos as a cemetery?”

“It looks like it. Why not? People deciding to use it for that purpose would suppose it safe from interference. In my opinion these bodies will remain almost as they are now for a long time—one might say for ever. The only change could be shrinkage due to the evaporation of the water in the system. The man on the bed has been dead much longer than the others. He is, in fact, a mummy, as dry as everything else on Phobos. Here is being done by nature what the ancient Egyptians did by artificial means, in much the same way. Do you know what I think?”

“What?” asked Tiger.

“I’d say these men were members of a crew of a spaceship who died while on a long journey. One could believe that the surviving members of the crew would be reluctant to carry their dead about with them, so they would park them at the first convenient place. At sea, on Earth, a body is put overboard; but one could hardly have bodies floating about in space without them becoming a danger, by risk of collision, for living space travellers. Besides, the idea isn’t a very nice one.”

“That sounds feasible,” agreed Tiger. “This method of burial, if you can call it burial, is as good, if not better, than others one can think of. How long do you think these fellows have been dead?”

“I wouldn’t like to say,” answered Toby, thoughtfully. “The chap on the bed has been dead longer than the others; you can see that from the degree of shrinkage, which looks like emaciation. From certain indications, notably the texture of their skins, I believe these men were very old when they died. Of course, that isn’t conclusive. They might have been born with skins different from ours. I see no signs of disease or injury so I must conclude they died of sheer old age, or from lack of some essential such as food or air.”

Rex walked out into the open, for he found the conversation not merely depressing but conducive to morbid thoughts; and as Toby, his professional interest aroused, went on talking, the idea occurred to him to walk to the top of the ridge surrounding the hollow in which they had landed to see what lay beyond. This, without doubt, was country on which no man of Earth had ever set foot, and the urge to explore was irresistible. The ground underfoot looked firm rock and sand, and as the distance was short he could see no possible danger.

It was at the top that the trouble occurred. He was gazing at the awful vista that stretched away to a curving horizon that cut like a saw into the black dome of heaven when he found himself slipping down the far side of the slope. Slipping is perhaps not quite the right word. On the far side of the ridge, as can happen in any desert, the particles of sand had not packed. Under his weight, slight though it was, they were all rolling down the slope, and he, unable to stop, was going with them. In something like a panic he turned and strove to regain the top; but it was like clutching at water, and the movement only increased the speed of his slide. Rather than lose his balance and roll, as he felt he might, he sat. This did nothing to check his progress and he continued on down in that position. Fortunately there was nothing violent, or even rapid about it; but there was a deliberation that was just as alarming.

He was by this time calling to Tiger; and Tiger’s voice came back, asking him where he was; from which it was clear that neither he nor Toby had seen him go.

The end came with a sheer drop of some twenty feet into a rocky gulley. Seeing that he was bound to fall, but forgetting that he had practically no weight, he gave himself up for lost, for in such a drop he seemed certain to break bones. Nothing of the sort happened. To say that he floated down like a thistle seed would be an exaggeration, but he landed with a lightness that amazed him. He actually bounced a little. And there he stood, heart pounding from shock, and condensation forming on his perspex eye-piece while the sand flowed down around him in slow-motion.

His great fear now was that Tiger and Toby, in their search for him, would make the same mistake as he had and end up in the gulley; or, worse still, another one, from which it might be difficult to get out. Then, in looking for each other, they might become lost. Lost! Lost on a dead moon! The possibility gave him a sinking feeling in the stomach. There was something particularly horrible about it.

Presently a stumble brought him into collision with a jagged-edged rock, and this gave him an even worse fright; for it reminded him that should his spacesuit be damaged he would be dead within a minute. It was bad enough to be lost on this dreadful place of eternal silence, but to die on it, alone, so utterly alone . . . again the thought nearly threw him into a panic.

His father’s voice coming over the radio steadied him. “Where are you?” asked Tiger.

“I’m over the ridge,” answered Rex.

“Are you all right?”

“Yes. Don’t attempt to follow me because the sand is soft and you’ll slide. Stay where you are and I’ll come back to you.”

There appeared to be no great difficulty about this, for there were places where the slope was smooth enough; but, as it turned out, it was smooth because it was sand, and the sand, having so little weight, was soft, like fluff, and as unstable as water. All Rex could do was go on, testing the bank, looking for a place where the ground was firm enough to support him. He thought he had found it when he came upon a rock slope; but the rock was as rotten as thawing snow and broke away in his hands. The way it did this, without a sound, was weird, and frightening. The only sounds that reached his ears were those that came over the radio. He could hear Tiger telling the Professor about the new bodies. The heat was terrific.

A bend presented a view that was not to be believed. Before him was a mighty curving section of Mars, almost the colour of an orange and so vast that it filled a third of a sky that was as black as midnight. Cutting into the lower part of the planet was the chaotic skyline of the little satellite on which he stood. Swaying slightly Rex stared at it, feeling for the first time that the immensity of it all was more than his brain could stand. More than anything he wanted to get away from it, back to the friendly Earth with its green fields and blue sky and the things he understood. He picked up what he took to be a fossilized stick, notched like a malacca cane, to support him.

The end of the gulley produced a nerve-torturing moment, for he realized that if there was no way up here he would have to retrace his steps, and he was fast becoming exhausted; but by traversing a maze of petrified tree trunks lying aslant the slope he managed to top the ridge. His relief when he saw the Spacemaster below him, with the others standing beside it, need not be described.

Feeling rather ashamed of himself for what he now perceived was an act of folly he made his way down, resolved to profit from the experience by refraining from doing any more exploring on his own account. He explained what had happened, making light of his fears now that all was well.

“What’s that in your hand?” asked the Professor.

“I thought it was a piece of wood.”

The Professor took it. “It’s the backbone of a lizard. How truly astonishing. Had anyone told me there had been animal life on this forsaken little ball of rock and sand I would not have believed it. But come along. I have seen as much as I expected to see from here. Through the telescope Jupiter is an incredible spectacle. I have taken some photographs.”

“What do we do next,” inquired Tiger.

“I plan to land on Mars, keeping well away from any canal in the hope of escaping the plague while we take steps to become acclimatized. We should be able to do that by slowly reducing pressure in the cabin, and therefore on ourselves, even while we sleep. We need some rest.”

“I shall be glad to get this suit off,” declared Rex.

“My chief trouble is I can’t get a caramel into my mouth,” said the Professor sadly.

“And I can’t have a draw at my pipe,” put in Tiger.

The doors were closed and the Spacemaster continued on its way.

The approach to Mars for the landing could hardly have been more dramatic. As Tiger remarked, it was as if the insect hordes were turning out at full strength to resist the invaders. In fact, the landing was held up while the red swarms, sweeping over the bare earth like sandstorms in a desert, reduced visibility to zero. This was observed from a thousand feet, where the Professor, remembering how the insects had nearly choked the Spacemaster’s cosmic jets, held the machine until the creatures returned to the moist areas from which they made their daily forays.

Toby stared aghast at the spectacle. “Heavens above!” he exclaimed. “No man ever saw anything more fantastic than that. It shows what can happen if any particular form of life gets the upper hand.”

“Tut-tut, my dear Doctor,” returned the Professor cynically. “You’re not forgetting that on Earth men have got the upper hand, and not satisfied with hunting to death everything else that walks, swims or flies, are now doing their best to wipe out each other.”

There was silence for a moment. Then Toby, wisely perhaps, for he had touched the Professor’s sore spot, changed the subject. “I’m burning to see a live Martian—if it’s possible that any can be left alive after the onslaught we’ve just seen.”

“That won’t be for a day or two,” answered the Professor. “I’m taking no chances of being inoculated with an unknown poison by those little pink brutes. You should know better than most people that without any immunity developed in our systems over a period of time such an injection might well prove fatal.”

“From the width of these canals it’s going to take us all our time to deal with the plague,” said Toby doubtfully.

“I doubt if the actual waterways are as wide as the width of the vegetation might lead one to suppose,” answered the Professor. “As the canals are choked with weeds and overgrown with bulrushes one can’t see the water; but it would be reasonable to suppose it follows the most verdant line that runs down the middle. It’s probably from there that the mosquitoes come. The vegetation is a good deal more lush than when we were here before, presumably because it is now high summer. The ice-caps are smaller, too. But we could have expected that, for such seasonal changes have been noted by astronomers on Earth. Well, as the insects seem to have retired for the night we’ll go on down.”

To Rex, not the least remarkable feature of the phenomenon was the speed with which the mosquitoes vanished at the conclusion of their sortie. In a matter of minutes visibility was crystal clear.

The Professor took the machine low over the town, on the central square of which they had made their original landing. Not a sign of life could be observed.

“It’s hard to believe that the place was ever a Utopia,” remarked Toby, looking down on the simple buildings. And from that time on, for want of another name, the town was known as Utopia.

“There was certainly a civilization there even if, by our standards, it was somewhat austere,” replied the Professor sharply. “But why should we judge others by our standards? Are they so perfect? Here they may have developed the perfect Welfare State.”

For the landing he moved well clear of the canal, and touched down on ground that was as bare as the middle of the Sahara. “If possible, we will make this our base, gentlemen, until we feel our feet,” he announced. “I mean that literally,” he added, with a chuckle. “I suggest we have something to eat and then proceed with the pressure tests.”

“You say, if possible,” queried Tiger. “Is there any doubt about it?”

“By day we shall find the place hot, perhaps too hot; and by night it may be uncomfortably cold. On Earth we have an estimated five hundred mile blanket of air to filter the solar rays; here, I would say, it is not more than fifty or sixty miles. But no matter. If it gets too hot we can move nearer to the Polar ice. Indeed, if necessary we could find the ideal mean temperature and move round the globe with it. The Martian day is practically the same as our own—twenty-four hours thirty-seven minutes of our time. That’s if our experts are right, and I think they are. The big difference is the Martian year, which is nearly double ours. Six hundred and eighty-seven of our days, to be precise. But the figure most likely to affect us until we get used to it is in the matter of what we call weight. What weighed a hundred pounds on Earth will only weigh thirty-eight pounds here—anyway, that is the theory: we shall soon know if it is correct.”

The first reduction in the air content of the cabin—which also, of course, meant a reduction in pressure—was made, and everyone settled down to enjoy a meal in more or less normal conditions; that is to say, free from the uncomfortable feeling of weightlessness. Objects no longer hung in suspension. Night fell, and Rex’s last recollection before he dropped off to sleep was of the Professor studying the heavens through his telescope.

The first streak of dawn found them on the move. For two hours the Spacemaster droned up and down the big canal which, apparently designed to save the population from death by thirst, had only brought disaster in another form. By the end of that time the whole of the green area lay under a thin mist of anti-mosquito mixture, sprayed from a pressure gun similar in design to those used on Earth for aerial crop dusting. How long the stuff would take to operate the Professor admitted frankly that he did not know; or, for that matter, whether it would act at all. For, as he averred, the fact that it had worked on Earth did not necessarily mean that it would act on Mars. Time would show. In the meantime they proceeded with their acclimatization, depressurizing the cabin until it was thought safe to test conditions outside without a spacesuit.

The Professor insisted on making the first test, due precautions being taken against accident. That is to say, Tiger and Toby, in their spacesuits, entered the air-lock chamber with him, ready to snatch him back should he show signs of distress when the outer door was opened.

For some time he leaned against the exit steps breathing deeply, a hand on his heart as if to steady it; then, with a smile, he took a few steps, and presently signalled that all was well. The others soon joined him in the open, some pressure being retained in the cabin, with Judkins at the controls, should anything go wrong. At first Rex had some difficulty in breathing, and his heart thumped uncomfortably; but in a surprisingly short space of time he was able to move about. At least, all except the Professor thought it surprising. He provided as an example of the adaptability of life the case of birds which, normally found at ground level, had been seen by pilots at nearly twenty thousand feet. He pointed out that had there been no atmosphere the mosquitoes would not have been able to fly. By evening they were sitting with the door open.

The sundown flight of the mosquitoes was watched with interest. The Professor thought they were fewer, but Rex, to his disappointment, could see no appreciable difference.

“We must give the stuff time to work,” declared the Professor.

The next evening there was no doubt about it. The cloud was definitely less dense. One curious thing happened. Or it struck Rex as curious. A mosquito crashed against his porthole, and it seemed to him that the creatures were larger than they had supposed. This one looked as large as a wasp. Thinking it might be due to magnification caused by the thick glass—for the window was closed, of course—he said nothing about it.

When darkness fell the Professor declared his intention of making an early morning raid on Utopia, before the mosquitoes were about, in the hope of finding a live Martian. For, as he said, if they were all dead there was not much point in waging war on the mosquitoes. It could be done later, when the planet had been thoroughly explored.

But things were to happen, and Rex was to remember the big mosquito, before anything else was done.

In accordance with acclimatization programme, although the night was as cold as the day had been hot, they were sleeping in the cabin but with the door open. With Rex, the effect of the rarified air was the common one of preventing him from sleeping soundly. From time to time his heart behaved oddly, and he found himself wishing that the Professor had let them have a little oxygen. Phobos was too small to provide much in the way of moonlight, but the sky was ablaze with stars and it was possible to see everything clearly, particularly outside, where the sterile land lay naked under heaven.

He was dozing when on silent wings a shadow flitting across the open doorway brought him to with a start. He watched. Presently the shadow reappeared, and he recognized a moth, a magnificent moth with a wing-span of a foot or more. He lay still. A minute passed and the moth came back. This time, with no more noise than a cloud passing across the face of the moon, it came into the cabin, did an erratic circuit, went out and disappeared. He waited, but it did not return.

More time passed. The thin air became colder as the sand outside gave up its heat, but the others seemed to be sleeping well enough. Their breathing was the only sound in a silence that was profound. A big, glowing orb, that he knew was the planet Earth, moving along its predestined path through space, came level with the open door, to flood the cabin with an eerie light and touch the metalwork with luminous fingers.

Subconsciously at first, but then with a sudden start, Rex became aware of a gentle scraping noise. It was too soft to cause him any concern. He merely wondered what it was, realizing that in the absence of any other sound, any noise, however slight, would have an exaggerated effect. He found it as difficult to locate as the scratching of a mouse in a wainscoting, even though it was constant and became more definite. After some reflection he decided that it was coming from the door, or from that direction. Disinclined to get up, and perhaps disturb the others unnecessarily, he still paid no more attention to it than to raise himself a little higher on his mattress and turn his eyes that way.

A movement on the edge of the entrance step gave him his first twinge of alarm. Two black objects, looking rather like the claws of a lobster, scraped as with slow deliberation they appeared to seek a hold on the smooth metal. It was now plain that something was trying to get in, and the knowledge brought him bolt upright with a jerk, staring all eyes, as the saying is. He was on the point of waking the others when there appeared over the top of the step a face so horrible, so diabolical in its indescribable ugliness, that it brought him to his feet with a gasp on his lips.

Why he did what he did he could never afterwards explain. The action was instinctive rather than the result of thought. Having no weapon handy it may have been prompted by the obvious fact that if he did not do something quickly the horror would be in the cabin with them, for that was obviously its intention. Whether its purpose was innocent or malicious he did not stop to consider. Leaping across the floor he kicked the thing in the face with a force that sent it hurtling across the sand with a noise like the rattle of castanets. Forgetting his negligible weight he nearly fell out after it, and only saved himself by clutching at the cabin wall, with which he collided with some force.

He recovered just in time to see a great black shadow swoop down on the thing he had kicked, and was now throwing itself about in its efforts to get on its feet. When the shadow rose, to disappear without a sound into the night sky, the thing was no longer there. The cry that broke from his lips brought the others to the door with a rush.

“What are you doing?” demanded Tiger irritably. “Why don’t you go to sleep?”

For a moment Rex didn’t answer. He couldn’t. Nearly sick from shock he could only cling to the guard rail, muttering incoherently.

When a light was switched on Toby was the first to realize that something serious must have happened. Glass clinked against glass and he thrust something into Rex’s hand. “Drink that,” he ordered peremptorily.

Rex gulped the liquid, the plastic beaker rattling against his teeth.

“Feeling better?” asked Toby.

“Yes, thanks.”

“Now tell us. What was it. Were you dreaming?”

“No. It wasn’t—a dream.” Rex braced himself and described what had happened.

“What did the thing look like—the one that tried to get in?” asked the Professor.

“It looked like an enormous ant. No, it was more like a beetle, or a scorpion. It was the size of a cat, with enormous claws. I heard it first. Then I saw it. Its mouth was opening and shutting—horrible. I kicked it out. I couldn’t think of anything else to do.”

“What about the creature that pounced on it?”

“It looked like a dragon. It reminded me of something. It had a pointed muzzle, like a fox, with big ears. I’ve got it. It was a bat. An enormous bat. I think it must have been sitting on top of the ship.”

“Are you sure this wasn’t all a nightmare?” inquired Tiger, suspiciously.

Rex held out his bare foot. Blood from the kick was oozing from his big toe. “That looks as if the thing was solid enough, doesn’t it,” he said grimly.

“Why haven’t we seen these things in daylight?” questioned the Professor, showing signs of agitation.

“They could be nocturnal,” Toby pointed out. “Certainly in the case of the bat.”

“This reminds me of something,” put in Rex. He was still pale and trembling a little from shock. “Yesterday a mosquito landed on my window. But it was like none of the others I’ve seen—and I’ve seen plenty. It was huge. It’s body was the size of a wasp. I said nothing about it because I thought somehow the glass must have magnified it. I don’t think so now. It was one of the ordinary mosquitoes grown to an enormous size.”

“I wonder . . .” breathed the Professor.

“Wonder what?” asked Toby, in a queer voice.

“If my anti-mosquito mixture could be having a peculiar effect on life here.”

“That’s a startling thought. I suppose it could happen.”

“I told you anything could happen. The introduction of anything new into a system, even on Earth, can produce astonishing effects. Well, I have introduced something new to Mars, so really we should not be surprised if it results in after-effects beyond our expectations.”

“Giants have been known on Earth,” observed Toby thoughtfully. “What causes that we don’t know. It might be something quite slight. But one can, after all, with chemical manures, greatly increase the size of all forms of vegetable life. Nitrates will double the size of a blade of grass overnight. It looks as if your mixture may be having that effect on animal life on Mars.”

“If so, the damage is done,” said the Professor, in a resigned voice.

“Which means that when we leave the ship we had better go armed,” put in Tiger. “I’m glad I brought my rifle. But I must say I never expected to use it against bugs, bats and beetles.”

“I only hope you don’t have to use it against giant Martians, if the Professor’s dope has had the same effect on them,” murmured Toby. “They seem to have been a tall race anyway.”

“I don’t think there’s any risk of that,” said the Professor confidently. “The super-growth, if in fact I am to blame, could only come as a result of eating the stuff, or some creature that has died from eating it. The Martians, supposing there are any able to move about, would hardly be likely to eat dead mosquitoes; which is, I suspect, what some creatures have done. The sequence would be this. A mosquito finds the stuff, eats ravenously, grows enormous and dies. A beetle comes along, makes a meal of dead mosquitoes, thus absorbing the poison, and the same thing happens to him. A bat eats the beetles—and so it goes on.”

“Yes, but where does it end?” questioned Toby. “If there’s anything here that eats bats we can expect to bump into some monsters.”

The Professor took the remark seriously. “Yes, that’s true. I didn’t think of that. Dear—dear. How easy it is to make a mistake. But as there’s nothing more we can do about it tonight we might as well resume our interrupted rest—this time, I think, with the door shut. It will be interesting to see what shocks tomorrow has in store for us.”

He spoke casually, little guessing what was in store.

Whatever may have been the cause, although no one doubted it was anything but the Professor’s “hunger” mixture, it was soon evident the next morning that things were happening, not only beyond expectation but beyond reasonable credulity.

After a plain breakfast of coffee and biscuits the Professor announced his intention of proceeding forthwith to Utopia to ascertain if there were any Martians left alive; for in view of the effect his insecticide seemed to be having there was little hope left for any that had so far managed to survive. The stuff had, he feared, been too successful. But, as he averred, it was impossible to test Martian conditions on Earth. Wherefore, with the door closed, under its rotors only and keeping low, the Spacemaster moved off towards the town, on the central square of which the Professor said he would land. The same place, in fact, on which the Spacemaster I had landed.

But they did not get as far as that without pause. In order to reach the town it was necessary to cross the canal, and there such a spectacle presented itself that the Professor slowed to a stop while they all stared down, for the moment speechless, their expressions revealing their sensations.

The canal was alive. Literally alive. Seething. The predominant colour was pink. Mosquitoes. Mosquitoes beyond computation. Mosquitoes in layers.

Just what they were doing was not easy to determine, although if they were able to fly they made no attempt to do so. Equally plain was it that these were not the tiny insects they had seen on their first visit. They had grown beyond recognition. These were the size of hornets. It seemed to Rex, as he gazed down on them with eyes round with wonder, that they were engaged in a war of extermination. The Professor, after looking through his glass, declared they had turned cannibal and were devouring each other. This, he reminded, was what he had planned; but he had not anticipated anything on such a scale.

After another look through the glass, which he handed to Tiger, he informed the others that the mosquitoes were not alone. Taking advantage of this unique opportunity, other creatures, which presumably preyed on the mosquitoes, had hurried to the feast. He identified ants; and larger insects which he took to be beetles. Under the influence of the drug they had all assumed enormous proportions. The same with lizards which, no doubt normally quite small, by gorging on the inexhaustible food supply were on their way to becoming crocodiles.

The Professor’s face was pale. “This is what comes of interfering with nature,” he said in an agitated voice. “Fool that I am, I should have foreseen the possibility.”

“I don’t see why you should,” answered Toby. “The stuff didn’t have that effect on Earth.”

“My dear Doctor, we’re not on Earth!” exclaimed the Professor. “The conditions here, the atmosphere, possibly the composition of the water and the very soil itself, may be entirely different. I should have allowed for that eventuality.”

“At least you’ve succeeded in knocking the mosquitoes out,” said Rex. “That’s the main thing. At least, I hope I’m right. They seem to have lost the use of their wings.”

“If they haven’t, and decided to take flight, we should have something to worry about. I’d rather be a bit farther away from that unholy mess.” That was Toby’s view of the situation.

“If their wings haven’t kept pace with the growth of their bodies they wouldn’t be able to get off the ground,” asserted Tiger confidently. “They’d be hopelessly overloaded.”

“Am I going crazy or can I see the grass and the reeds growing,” cried Rex. “Are they feeling the effect, too?”

The Professor dropped the Spacemaster a little lower and stared down through his spyglass. “It isn’t only the grass that’s growing,” he stated, in a startled voice. “There are other forms of plant life breaking through the surface. The seeds must have been dormant in the ground; either that, or insects kept the vegetation down by feeding on it, like rabbits in a cornfield. I can see some disgusting-looking fungi pushing their way up. Dear—dear. What have I done? You see what can happen when a man tries to be too clever and puts his puny wits against nature.”

“I don’t see that you’ve any cause to reproach yourself,” said Tiger. “If you’ve started into life things that we thought were dead, surely that’s all to the good.”

“Provided that by destroying the mosquitoes I haven’t destroyed everything else. It may be some time before we know the ultimate result. I wonder what’s the best thing to do.”

“If you’re asking me,” replied Toby, “I’d suggest we look for a live Martian without further loss of time; because if those beasts in the swamps, mad with hunger, having finished off the mosquitoes decide to invade the town, our chances of finding anyone alive will be pretty remote.”

“I think you’re right,” agreed the Professor. “It occurred to me that by spraying the canals farther away we might cause the pests to move in that direction. It will have to be done sometime. We’ve only treated the minute fraction near the town. But we’d better see what the result is here before we risk doing further mischief. We’ll go on to the town. Forgive me if my head is in a whirl. You must admit that this horrid picture of everything dying and being eaten by something else is disconcerting, to say the least of it.”

“I’d call it disgusting,” murmured Rex, wondering if the water in the canal would ever again be fit to drink.

The Spacemaster moved on, and presently put down its landing legs on the dusty flagstones of the main square. The door was opened, and the Professor, leading the way, made a cautious exit. Rex, Tiger and Toby followed him and then stopped to look about.

To Rex the place looked no different from when they were last there. The buildings on all four sides, plain in design and grey with age, wore the same melancholy, abandoned look. The stone seats were there at intervals, but none was occupied. Dust lay in heaps where it had drifted against the walls. Nothing moved. Not an insect, not a bird. Nothing. Not a speck of colour, not a flower, not even a weed or a blade of grass, caught the eye to relieve the dreary monotony of the scene. Over all hung an awful silence. The silence of death.

“I’m afraid we’ve come too late,” said the Professor sadly. He spoke in a low voice, as at a funeral; but even so the words seemed to be an intrusion. Suddenly, as if making up his mind, he set off at a brisk pace towards the house from which, on their last visit, just before they had been compelled to retreat before the pink blight, they had seen a man emerge.

Tiger was filling his pipe, and Toby was lighting a cigarette, so a few seconds elapsed before they started to follow. But by that time the Professor had stopped, staring down one of the dark, narrow lanes between the houses that gave access to the canal, and so to the water supply. He did not stand still for very long. He started to walk backwards. Then, turning, he ran towards the ship crying: “Back! Back! Go back!”

Actually, the warning was unnecessary, for by this time the cause of the Professor’s behaviour had appeared, moving in short rushes into the open.

It was a spider; or a monstrous creature in the shape of a spider. Before the arrival of the Spacemaster it may have been an ordinary spider. But it had evidently been to the canal, or had encountered and eaten something that had, for it was now a loathsome, hairy-legged beast with a body twice the size of a football. The creature stopped to look around. Then the movement near the Spacemaster caught its eye and it darted forward in a series of zig-zag spurts, making a brittle clicking sound. No one waited for a closer view of it, but dashed into the ship. Toby, the last man in, slammed the door. Which was certainly just as well, for the spider did not stop until it reached the steps. It circled the machine as if looking for a way in. Finding none it took up a position a few yards away, and with light glinting on its multiple eyes stared at portholes. Rex shuddered, for in them, he thought, glowed a frightening expression not only of malevolence but of intelligence.

The Professor, panting, dropped into a chair, and fanning his face with his notebook kept muttering: “This is really frightful.”

“Everything seems to have developed a temper in proportion to its size,” observed Toby calmly.

“Which, I imagine, is in proportion to the amount of my mixture that it has consumed,” answered the Professor. “In destroying the mosquito plague I seem to have set an even more difficult problem.”

Tiger appeared with his rifle, slipping cartridges in the magazine.

“What are you going to do?” cried the Professor, with fresh alarm.

“I’m going to shoot the thing,” returned Tiger. “It may look abnormal, but I’ll wager it behaves normally when a piece of nickel makes a hole through it.”

“Is that really necessary?”

“Obviously we can’t go out while the brute’s there! At least, I’m not going out. Lions and tigers are nice clean beasts, but that horror is something out of a madman’s nightmare.”

“Yes—yes. I suppose it’s the only thing to do,” agreed the Professor. “I had hoped to avoid bloodshed of any sort.”

“I doubt if it has any blood, in which case none will be shed,” put in Toby.

Slowly and quietly Tiger opened the door a few inches—enough to permit him to use the rifle. The spider looked up at him. Its eyes, full of hate, suddenly glowed red. Tiger took aim. The rifle spat. The spider reared up, legs waving, and went over on its back. Tiger gave it another shot. The waving became feeble, then stopped. Under the creature began to form a little yellow pool.

“I see I was wrong about the blood,” said Toby, in a strained voice. “It’s yellow. That’s about the last straw. We have only to meet a rat, or a cat, that’s been eating mosquitoes and I shall vote for a move to a more respectable planet—good old Earth for preference.”

“Yes, indeed, sir,” murmured Judkins.

They looked at each other. All were pale. But Judkins’ remark broke the tension and they all smiled.

Toby opened the door wide. “I’m going to find a Martian, alive or dead,” he announced purposefully. “With monsters like this on the prowl”—he pointed at the spider—“there soon won’t be any. Come on, Tiger. Bring your musket. You like big game shooting so this should be just your cup of tea.”

“I’m coming,” said the Professor. “We shall soon get used to shocks of this sort.”

Rex doubted it—at all events as far as he was concerned. But he followed the others, keeping well clear of the beast still lying where it had fallen.

Judkins stayed in the ship, with orders to keep watch and be ready for a quick take-off should an emergency arise.

Keeping together, with Tiger holding his rifle prepared for instant use, they strode on towards the houses.

The furniture in the first room they entered—there was no door—was as simple as could be imagined. Most of it was of woven basketwork, presumably made from rushes brought from the canal; but a table was of wood and appeared to be of great age; how old, it was impossible to guess. The general keynote of everything was utility, without ornament.

“They must have had timber here at one time,” remarked the Professor, pointing at the table, as they passed on into a small anteroom. It turned out to be a bedroom. A man, identical with the men they had seen on Phobos, lay on the couch. He was dead. It took Toby only a second to confirm it.

“No use wasting time here,” he said briefly. “Our main purpose is to find a survivor—if there is one. If there isn’t—well, we might as well go home . . . unless anyone wants to go bug hunting.”

“Let us go on,” said the Professor. “One live man, just one, could give us the history of the planet. If there isn’t one we shall never know the truth.”

“From what we’ve seen so far I don’t think the Martian civilization could have been very far advanced,” opined Tiger.

“On the other hand they might have been so far ahead of us that they long ago abandoned the trouble-making devices by which we are pleased to judge civilization—so-called. One day in the dim future Earth may return to a more simple code of existence; particularly if it has to pass through a period of major disasters, such as must have happened here even before the mosquitoes took control. As I have said, one survivor may be able to tell about these things.”

They left the house and went on to the next one.

They visited several, most of them empty but some containing corpses, before they found what they sought. In a room like all those they had seen, a man was sitting in a chair. He looked dreadfully ill. But as they entered his eyes moved.

“Ah! This is better,” said Toby softly.

For the first time Rex was able to make a really close study of a living Martian. In physical appearance he was much like themselves, and dressed differently could have walked down a London street without attracting attention. He was tall by Earthly standards, and of a finer, slighter build. His skin, cream rather than white, looked dry, and had a peculiar metallic sheen; the result, Rex supposed, of a thin atmosphere with practically no humidity. His hair, pale gold and silky as a girl’s, reached to his shoulders. A short, curly beard, of the same colour and texture, covered a chin that had obviously never known a razor.

But his most outstanding feature was his eyes, which were large and of a colour not easy to determine. There was a hint of deep red in them. This, and a queer luminous quality, made them seem unnatural and hard to meet. Indeed, Rex found them rather frightening. They were, he felt, looking right into him, as if searching out his thoughts.

In the matter of clothes, those worn by the planetarian were similar in style to those seen on Phobos, comprising an open-necked robe caught in at the waist to form a tunic, with two pockets, and a short skirt, or kilt, leaving the lower half of the legs bare. There was nothing remarkable about this. Rex was reminded vaguely of a picture he had seen of ancient Greeks—or it might have been Romans, or Egyptians. He couldn’t remember.

He could not have named the material. It was rather coarse stuff, closely woven, and had a sheen that gave it a hard, glassy finish. Nevertheless, it hung in soft folds. The colour was an indefinite shade of blue. Sandals, with cross-lacing straps of the same material, protected the feet. It was clear that in the entire get-up simple utility had been the factor foremost in design.

It may as well be said here that later on Rex was to learn that these garments were not only standard on the planet but were practically indestructible, so that one outfit would last a lifetime. They could be repaired or reconditioned by simply dipping them in a certain solution, when they came out like new.

Some small sacks, or bags, of this same material, lay in a corner; for what purpose was not apparent.

On the table within reach of the sick man were several pots and jars of a semi-transparent plastic-like substance. One contained meal, or flour; presumably food of some sort; another held tablets—or, more correctly, lozenges. There was also a carafe of water with a beaker beside it. Where, Rex wondered, had the food come from?

It is not to be supposed that he merely stood and regarded the man as he might have looked at a Zulu or an Eskimo; or even a freak at a circus. Far from it. This was altogether different; an event so tremendous, so deeply moving that it awoke in him sensations not to be described in words. For there were no words to fit the case. He felt it was not true. He wanted to tell himself that this simply wasn’t true. But he knew it was true. And he knew he wasn’t dreaming. Here before him was the answer to the age-old question: were the people of Earth alone in the Universe? They were not. What would be the effect of those three simple words on Earth when the people knew what he knew? The limitless fields of speculation opened up made his brain reel.

Toby, naturally, had moved forward with a clinical thermometer in his hand. Then, as if realizing that temperatures here were not to be judged by Earthly standards, he put it away, with an apologetic smile to the Professor, saying, “What am I doing?”

At that precise moment a strange thing happened, something which, for a while, defied explanation.

Rex, speaking in the flat, trance-like tone of a sleepwalker, found himself saying: “Who are you and where have you come from?” He started violently, looking bewildered.

The Professor looked at him. Tiger looked at him. Toby, turning over his shoulder, also looked.

“Who said that?” asked the Professor, sharply.

“Not me,” denied Rex, in his normal speaking voice.

“But it was you,” asserted the Professor. “I saw your lips move.”

“But why would I say it?” protested Rex, trying to make up his mind whether he had, or had not, spoken.

“That’s what we were wondering,” said Tiger, looking at him suspiciously.

“Who are you and what are you doing here?” said Rex, again in the dreamlike voice.

“What are you talking about?” snapped Tiger.

“I—I didn’t say anything,” stammered Rex, looking really scared.

There was a short, embarrassing silence. Then said Tiger, speaking sharply. “What’s the idea? This is no time to joke!”

Rex didn’t know what to say. He was convinced that he hadn’t spoken yet he knew his lips had moved. “Something’s happening to me!” he exclaimed, helplessly. “I didn’t want to speak. I must be going queer in the head.”

Tiger looked at the Martian, then at Toby. “Did that chap speak?” he asked, pointing at the sick man.