* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Under Milk Wood

Date of first publication: 1954

Author: Dylan Thomas (1914-1953)

Date first posted: Sep. 1, 2023

Date last updated: Sep. 1, 2023

Faded Page eBook #20230901

This eBook was produced by: John Routh & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

DYLAN THOMAS. Before his tragic death at 39, Dylan Thomas was already recognized as the greatest lyric poet of the younger generation. Wide appreciation of his fiction and other prose writings has been largely posthumous.

Born in 1914 in the Welsh seaport of Swansea, he was early steeped in Welsh lore and poetry, and in the Bible, all of which left their mark on his rich, startling imagery and driving rhythms. As a boy, he said he “was small, thin, indecisively active, quick to get dirty, curly.” His formal education ended with the Swansea Grammar school; and thereafter he was at various times a newspaper reporter, a “hack writer,” an odd-job man, a documentary film scriptwriter.

The rich resonance of his “Welsh-singing” voice led to Dylan Thomas reading other poets’ work as well as his own over the B.B.C. Third Programme. It also brought him to the United States, in 1950, ’52 and ’53, where he gave readings of his own and other poetry in as many as 40 university towns, and made three magnificent long playing records published by Caedmon. “I don’t believe in New York,” he said, “but I love Third Avenue.”

Since Dylan Thomas’s death in 1953 his reputation and popularity have steadily increased. His poetry is studied in hundreds of American colleges, and his prose books such as Adventures in the Skin Trade, Portrait of the Artist as a Young Dog, Quite Early One Morning and A Child’s Christmas in Wales are paperbook bestsellers. Many books have been written about his life and work, while a play about him, in which Alec Guinness portrayed Dylan, was a Broadway hit. New Directions has also published an anthology of the poetry of other poets which Thomas recited at his famous readings entitled Dylan Thomas’s Choice. A motion picture version of Under Milk Wood, which opened the 1971 Venice Film Festival, starred Richard Burton, Elizabeth Taylor, and Peter O’Toole, and was released in the U.S. in October of the following year.

ALSO BY DYLAN THOMAS

Adventures in the Skin Trade

Collected Poems

The Doctor and the Devils

The Notebooks

Portrait of the Artist as a Young Dog

Quite Early One Morning

Rebecca’s Daughters

Selected Letters

A Child’s Christmas in Wales, illustrated by Fritz Eichenberg

A Child’s Christmas in Wales, illustrated by Ellen Raskin

The Poems of Dylan Thomas

Copyright 1954 by New Directions Publishing Corporation. The first

half of this play was published in an earlier form as Llareggub in

Botteghe Oscure IX. All rights reserved. Except for brief passages

quoted in a newspaper, magazine, radio, or television review, no part

of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means,

electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by

any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in

writing from the Publisher. Caution: Professionals and amateurs are

hereby warned that Under Milk Wood, being fully protected under

the copyright laws of the United States, the British Empire including

the Dominion of Canada, and all other countries of the Copyright

Union, and other countries, is subject to royalty. All rights, including

professional, amateur, motion picture, recitation, lecturing, public

reading, radio and television broadcasting, and the rights of

translation into foreign languages, are strictly reserved. Particular

emphasis is laid on the question of readings, permission for which

must be obtained in writing from the author’s agents: Harold Ober

Associates, 40 East 49 Street, New York City. Manufactured in the

United States of America. Published in Canada by George J. McLeod

Ltd., Toronto. New Directions Books are published for

James Laughlin, by New Directions Publishing Corporation,

80 Eighth Avenue, New York 10011.

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 54-9641

ISBN: 0-8112-0209-7

NINETEENTH PRINTING

| CONTENTS |

| Cast of Characters |

| Under Milk Wood |

| Notes on Pronunciation |

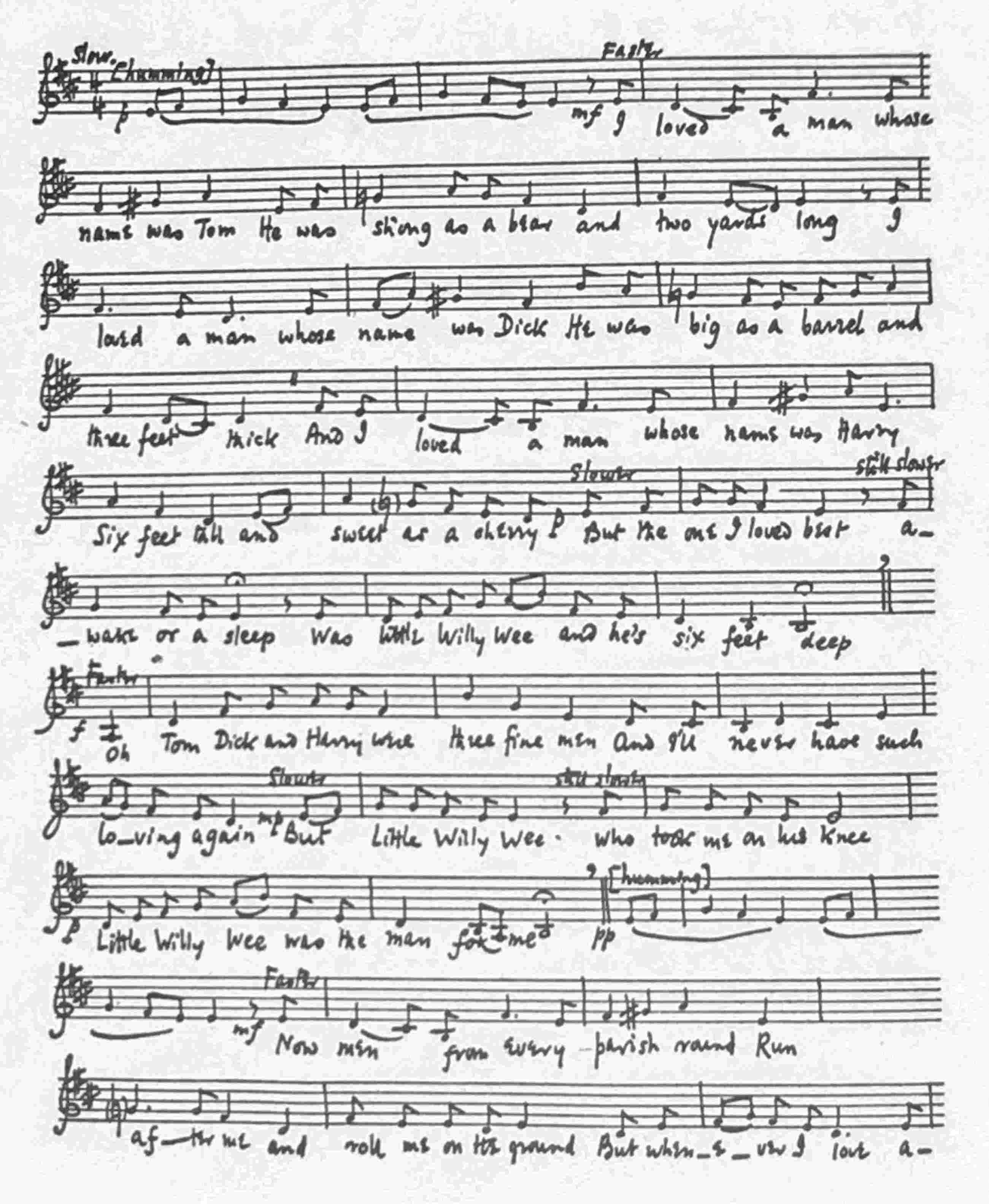

| Music for the Songs |

A trial performance of Under Milk Wood was given on May 14, 1953, under the auspices of the Poetry Center of the Young Men’s and Young Women’s Hebrew Association, New York City. Dylan Thomas directed the production and read the parts of the First Voice, Second Drowned, Fifth Drowned, and the Reverend Eli Jenkins. The other parts were played by Dion Allen, Allen F. Collins, Roy Poole, Sada Thompson, and Nancy Wickwire.

First Voice

Second Voice

Captain Cat

First Drowned

Second Drowned

Rosie Probert

Third Drowned

Fourth Drowned

Fifth Drowned

Mr Mog Edwards

Miss Myfanwy Price

Jack Black

Waldo’s Mother

Little Boy Waldo

Waldo’s Wife

Mr Waldo

First Neighbour

Second Neighbour

Third Neighbour

Fourth Neighbour

Matti’s Mother

First Woman

Second Woman

Third Woman

Fourth Woman

Fifth Woman

Preacher

Mrs Ogmore-Pritchard

Mr Ogmore

Mr Pritchard

Gossamer Beynon

Organ Morgan

Utah Watkins

Mrs Utah Watkins

Ocky Milkman

A Voice

Mrs Willy Nilly

Lily Smalls

Mae Rose Cottage

Butcher Beynon

Reverend Eli Jenkins

Mr Pugh

Mrs Organ Morgan

Mary Ann Sailors

Dai Bread

Polly Garter

Nogood Boyo

Lord Cut-Glass

Voice of a Guide-Book

Mrs Beynon

Mrs Pugh

Mrs Dai Bread One

Mrs Dai Bread Two

Willy Nilly

Mrs Cherry Owen

Cherry Owen

Sinbad Sailors

Old Man

Evans the Death

Fisherman

Child’s Voice

Bessie Bighead

A Drinker

[Silence]

To begin at the beginning:

It is Spring, moonless night in the small town, starless and bible-black, the cobblestreets silent and the hunched, courters’-and-rabbits’ wood limping invisible down to the sloeblack, slow, black, crowblack, fishingboat-bobbing sea. The houses are blind as moles (though moles see fine to-night in the snouting, velvet dingles) or blind as Captain Cat there in the muffled middle by the pump and the town clock, the shops in mourning, the Welfare Hall in widows’ weeds. And all the people of the lulled and dumbfound town are sleeping now.

Hush, the babies are sleeping, the farmers, the fishers, the tradesmen and pensioners, cobbler, schoolteacher, postman and publican, the undertaker and the fancy woman, drunkard, dressmaker, preacher, policeman, the webfoot cocklewomen and the tidy wives. Young girls lie bedded soft or glide in their dreams, with rings and trousseaux, bridesmaided by glow-worms down the aisles of the organplaying wood. The boys are dreaming wicked or of the bucking ranches of the night and the jollyrodgered sea. And the anthracite statues of the horses sleep in the fields, and the cows in the byres, and the dogs in the wet-nosed yards; and the cats nap in the slant corners or lope sly, streaking and needling, on the one cloud of the roofs.

You can hear the dew falling, and the hushed town breathing.

Only your eyes are unclosed to see the black and folded town fast, and slow, asleep. And you alone can hear the invisible starfall, the darkest-before-dawn minutely dewgrazed stir of the black, dab-filled sea where the Arethusa, the Curlew and the Skylark, Zanzibar, Rhiannon, the Rover, the Cormorant, and the Star of Wales tilt and ride.

Listen. It is night moving in the streets, the processional salt slow musical wind in Coronation Street and Cockle Row, it is the grass growing on Llareggub Hill, dewfall, starfall, the sleep of birds in Milk Wood.

Listen. It is night in the chill, squat chapel, hymning in bonnet and brooch and bombazine black, butterfly choker and bootlace bow, coughing like nannygoats, sucking mintoes, fortywinking hallelujah; night in the four-ale, quiet as a domino; in Ocky Milkman’s lofts like a mouse with gloves; in Dai Bread’s bakery flying like black flour. It is to-night in Donkey Street, trotting silent, with seaweed on its hooves, along the cockled cobbles, past curtained fernpot, text and trinket, harmonium, holy dresser, watercolours done by hand, china dog and rosy tin teacaddy. It is night neddying among the snuggeries of babies.

Look. It is night, dumbly, royally winding through the Coronation cherry trees; going through the graveyard of Bethesda with winds gloved and folded, and dew doffed; tumbling by the Sailors Arms.

Time passes. Listen. Time passes.

Come closer now.

Only you can hear the houses sleeping in the streets in the slow deep salt and silent black, bandaged night. Only you can see, in the blinded bedrooms, the combs and petticoats over the chairs, the jugs and basins, the glasses of teeth, Thou Shalt Not on the wall, and the yellowing dickybird-watching pictures of the dead. Only you can hear and see, behind the eyes of the sleepers, the movements and countries and mazes and colours and dismays and rainbows and tunes and wishes and flight and fall and despairs and big seas of their dreams.

From where you are, you can hear their dreams.

Captain Cat, the retired blind seacaptain, asleep in his bunk in the seashelled, ship-in-bottled, shipshape best cabin of Schooner House dreams of

never such seas as any that swamped the decks of his S.S. Kidwelly bellying over the bedclothes and jellyfish-slippery sucking him down salt deep into the Davy dark where the fish come biting out and nibble him down to his wishbone, and the long drowned nuzzle up to him.

Remember me, Captain?

You’re Dancing Williams!

I lost my step in Nantucket.

Do you see me, Captain? the white bone talking? I’m Tom-Fred the donkeyman . . . we shared the same girl once . . . her name was Mrs Probert . . .

Rosie Probert, thirty three Duck Lane. Come on up, boys, I’m dead.

Hold me, Captain, I’m Jonah Jarvis, come to a bad end, very enjoyable.

Alfred Pomeroy Jones, sealawyer, born in Mumbles, sung like a linnet, crowned you with a flagon, tattooed with mermaids, thirst like a dredger, died of blisters.

This skull at your earhole is

Curly Bevan. Tell my auntie it was me that pawned the ormolu clock.

Aye, aye, Curly.

Tell my missus no I never

I never done what she said I never

Yes, they did.

And who brings coconuts and shawls and parrots to my Gwen now?

How’s it above?

Is there rum and lavabread?

Bosoms and robins?

Concertinas?

Ebenezer’s bell?

Fighting and onions?

And sparrows and daisies?

Tiddlers in a jamjar?

Buttermilk and whippets?

Rock-a-bye baby?

Washing on the line?

And old girls in the snug?

Who milks the cows in Maesgwyn?

When she smiles, is there dimples?

What’s the smell of parsley?

Oh, my dead dears!

From where you are, you can hear in Cockle Row in the spring, moonless night, Miss Price, dressmaker and sweetshop-keeper, dream of

her lover, tall as the town clock tower, Samson-syrup-gold-maned, whacking thighed and piping hot, thunderbolt-bass’d and barnacle-breasted, flailing up the cockles with his eyes like blowlamps and scooping low over her lonely loving hotwaterbottled body.

Mr Mog Edwards!

I am a draper mad with love. I love you more than all the flannelette and calico, candlewick, dimity, crash and merino, tussore, cretonne, crépon, muslin, poplin, ticking and twill in the whole Cloth Hall of the world. I have come to take you away to my Emporium on the hill, where the change hums on wires. Throw away your little bedsocks and your Welsh wool knitted jacket, I will warm the sheets like an electric toaster, I will lie by your side like the Sunday roast.

I will knit you a wallet of forget-me-not blue, for the money to be comfy. I will warm your heart by the fire so that you can slip it in under your vest when the shop is closed.

Myfanwy, Myfanwy, before the mice gnaw at your bottom drawer will you say

Yes, Mog, yes, Mog, yes, yes, yes.

And all the bells of the tills of the town shall ring for our wedding.

[Noise of money-tills and chapel bells

Come now, drift up the dark, come up the drifting sea-dark street now in the dark night seesawing like the sea, to the bible-black airless attic over Jack Black the cobbler’s shop where alone and savagely Jack Black sleeps in a nightshirt tied to his ankles with elastic and dreams of

chasing the naughty couples down the grassgreen gooseberried double bed of the wood, flogging the tosspots in the spit-and-sawdust, driving out the bare bold girls from the sixpenny hops of his nightmares.

Evans the Death, the undertaker,

laughs high and aloud in his sleep and curls up his toes as he sees, upon waking fifty years ago, snow lie deep on the goosefield behind the sleeping house; and he runs out into the field where his mother is making welshcakes in the snow, and steals a fistful of snowflakes and currants and climbs back to bed to eat them cold and sweet under the warm, white clothes while his mother dances in the snow kitchen crying out for her lost currants.

And in the little pink-eyed cottage next to the undertaker’s, lie, alone, the seventeen snoring gentle stone of Mister Waldo, rabbitcatcher, barber, herbalist, catdoctor, quack, his fat pink hands, palms up, over the edge of the patchwork quilt, his black boots neat and tidy in the washing-basin, his bowler on a nail above the bed, a milk stout and a slice of cold bread pudding under the pillow; and, dripping in the dark, he dreams of

This little piggy went to market

This little piggy stayed at home

This little piggy had roast beef

This little piggy had none

And this little piggy went

wee wee wee wee wee

all the way home to

Waldo! Wal-do!

Yes, Blodwen love?

Oh, what’ll the neighbours say, what’ll the neighbours . . .

Poor Mrs Waldo

What she puts up with

Never should of married

If she didn’t had to

Same as her mother

There’s a husband for you

Bad as his father

And you know where he ended

Up in the asylum

Crying for his ma

Every Saturday

He hasn’t got a leg

And carrying on

With that Mrs Beattie Morris

Up in the quarry

And seen her baby

It’s got his nose

Oh, it makes my heart bleed

What he’ll do for drink

He sold the pianola

And her sewing machine

Falling in the gutter

Talking to the lamp-post

Using language

Singing in the w.

Poor Mrs Waldo

. . . Oh, Waldo, Waldo!

Hush, love, hush. I’m widower Waldo now.

Waldo, Wal-do!

Yes, our mum?

Oh, what’ll the neighbours say, what’ll the neighbours . . .

Black as a chimbley

Ringing doorbells

Breaking windows

Making mudpies

Stealing currants

Chalking words

Saw him in the bushes

Send him to bed without any supper

Give him sennapods and lock him in the dark

Off to the reformatory

Off to the reformatory

Learn him with a slipper on his b.t.m.

Waldo, Wal-do! What you doing with our Matti?

Give us a kiss, Matti Richards.

Give us a penny then.

I only got a halfpenny.

Lips is a penny.

Will you take this woman Matti Richards

Dulcie Prothero

Effie Bevan

Lil the Gluepot

Mrs Flusher

Blodwen Bowen

To be your awful wedded wife

No, no, no!

Now, in her iceberg-white, holily laundered crinoline nightgown, under virtuous polar sheets, in her spruced and scoured dust-defying bedroom in trig and trim Bay View, a house for paying guests at the top of the town, Mrs Ogmore-Pritchard, widow, twice, of Mr Ogmore, linoleum, retired, and Mr Pritchard, failed bookmaker, who maddened by besoming, swabbing and scrubbing, the voice of the vacuum-cleaner and the fume of polish, ironically swallowed disinfectant, fidgets in her rinsed sleep, wakes in a dream, and nudges in the ribs dead Mr Ogmore, dead Mr Pritchard, ghostly on either side.

Mr Ogmore!

Mr Pritchard!

It is time to inhale your balsam.

Oh, Mrs Ogmore!

Oh, Mrs Pritchard!

Soon it will be time to get up.

Tell me your tasks, in order.

I must put my pyjamas in the drawer marked pyjamas.

I must take my cold bath which is good for me.

I must wear my flannel band to ward off sciatica.

I must dress behind the curtain and put on my apron.

I must blow my nose.

In the garden, if you please.

In a piece of tissue-paper which I afterwards burn.

I must take my salts which are nature’s friend.

I must boil the drinking water because of germs.

I must take my herb tea which is free from tannin.

And have a charcoal biscuit which is good for me.

I may smoke one pipe of asthma mixture.

In the woodshed, if you please.

And dust the parlour and spray the canary.

I must put on rubber gloves and search the peke for fleas.

I must dust the blinds and then I must raise them.

And before you let the sun in, mind it wipes its shoes.

In Butcher Beynon’s, Gossamer Beynon, daughter, schoolteacher, dreaming deep, daintily ferrets under a fluttering hummock of chicken’s feathers in a slaughterhouse that has chintz curtains and a three-pieced suite, and finds, with no surprise, a small rough ready man with a bushy tail winking in a paper carrier.

At last, my love,

sighs Gossamer Beynon. And the bushy tail wags rude and ginger.

Help,

cries Organ Morgan, the organist, in his dream,

there is perturbation and music in Coronation Street! All the spouses are honking like geese and the babies singing opera. P.C. Attila Rees has got his truncheon out and is playing cadenzas by the pump, the cows from Sunday Meadow ring like reindeer, and on the roof of Handel Villa see the Women’s Welfare hoofing, bloomered, in the moon.

At the sea-end of town, Mr and Mrs Floyd, the cocklers, are sleeping as quiet as death, side by wrinkled side, toothless, salt and brown, like two old kippers in a box.

And high above, in Salt Lake Farm, Mr Utah Watkins counts, all night, the wife-faced sheep as they leap the fences on the hill, smiling and knitting and bleating just like Mrs Utah Watkins.

Thirty-four, thirty-five, thirty-six, forty-eight, eighty-nine . . .

Knit one slip one

Knit two together

Pass the slipstitch over . . .

Ocky Milkman, drowned asleep in Cockle Street, is emptying his chums into the Dewi River,

regardless of expense,

and weeping like a funeral.

Cherry Owen, next door, lifts a tankard to his lips but nothing flows out of it. He shakes the tankard. It turns into a fish. He drinks the fish.

P.C. Attila Rees lumps out of bed, dead to the dark and still foghorning, and drags out his helmet from under the bed; but deep in the backyard lock-up of his sleep a mean voice murmurs

You’ll be sorry for this in the morning,

and he heave-ho’s back to bed. His helmet swashes in the dark.

Willy Nilly, postman, asleep up street, walks fourteen miles to deliver the post as he does every day of the night, and rat-a-tats hard and sharp on Mrs Willy Nilly.

Don’t spank me, please, teacher,

whimpers his wife at his side, but every night of her married life she has been late for school.

Sinbad Sailors, over the taproom of the Sailors Arms, hugs his damp pillow whose secret name is Gossamer Beynon.

A mogul catches Lily Smalls in the wash-house.

Ooh, you old mogul!

Mrs Rose Cottage’s eldest, Mae, peals off her pink-and-white skin in a furnace in a tower in a cave in a waterfall in a wood and waits there raw as an onion for Mister Right to leap up the burning tall hollow splashes of leaves like a brilliantined trout.

Call me Dolores

Like they do in the stories.

Alone until she dies, Bessie Bighead, hired help, born in the workhouse, smelling of the cowshed, snores bass and gruff on a couch of straw in a loft in Salt Lake Farm and picks a posy of daisies in Sunday Meadow to put on the grave of Gomer Owen who kissed her once by the pig-sty when she wasn’t looking and never kissed her again although she was looking all the time.

And the Inspectors of Cruelty fly down into Mrs Butcher Beynon’s dream to persecute Mr Beynon for selling

owl meat, dogs’ eyes, manchop.

Mr Beynon, in butcher’s bloodied apron, spring-heels down Coronation Street, a finger, not his own, in his mouth. Straightfaced in his cunning sleep he pulls the legs of his dreams and

hunting on pigback shoots down the wild giblets.

Help!

My foxy darling.

Now behind the eyes and secrets of the dreamers in the streets rocked to sleep by the sea, see the

titbits and topsyturvies, bobs and buttontops, bags and bones, ash and rind and dandruff and nailparings, saliva and snowflakes and moulted feathers of dreams, the wrecks and sprats and shells and fishbones, whale-juice and moonshine and small salt fry dished up by the hidden sea.

The owls are hunting. Look, over Bethesda gravestones one hoots and swoops and catches a mouse by Hannah Rees, Beloved Wife. And in Coronation Street, which you alone can see it is so dark under the chapel in the skies, the Reverend Eli Jenkins, poet, preacher, turns in his deep towards-dawn sleep and dreams of

He intricately rhymes, to the music of crwth and pibgorn, all night long in his druid’s seedy nightie in a beer-tent black with parchs.

Mr Pugh, schoolmaster, fathoms asleep, pretends to be sleeping, spies foxy round the droop of his night-cap and pssst! whistles up

Murder.

Mrs Organ Morgan, groceress, coiled grey like a dormouse, her paws to her ears, conjures

Silence.

She sleeps very dulcet in a cove of wool, and trumpeting Organ Morgan at her side snores no louder than a spider.

Mary Ann Sailors dreams of

the Garden of Eden.

She comes in her smock-frock and clogs

away from the cool scrubbed cobbled kitchen with the Sunday-school pictures on the whitewashed wall and the farmers’ almanac hung above the settle and the sides of bacon on the ceiling hooks, and goes down the cockleshelled paths of that applepie kitchen garden, ducking under the gippo’s clothespegs, catching her apron on the blackcurrant bushes, past bean-rows and onion-bed and tomatoes ripening on the wall towards the old man playing the harmonium in the orchard, and sits down on the grass at his side and shells the green peas that grow up through the lap of her frock that brushes the dew.

In Donkey Street, so furred with sleep, Dai Bread, Polly Garter, Nogood Boyo, and Lord Cut-Glass sigh before the dawn that is about to be and dream of

Harems.

Babies.

Nothing.

Tick tock tick tock tick tock tick tock.

Time passes. Listen. Time passes. An owl flies home past Bethesda, to a chapel in an oak. And the dawn inches up.

[One distant bell-note, faintly reverberating

Stand on this hill. This is Llareggub Hill, old as the hills, high, cool, and green, and from this small circle of stones, made not by druids but by Mrs Beynon’s Billy, you can see all the town below you sleeping in the first of the dawn.

You can hear the love-sick woodpigeons mooning in bed. A dog barks in his sleep, farmyards away. The town ripples like a lake in the waking haze.

Less than five hundred souls inhabit the three quaint streets and the few narrow by-lanes and scattered farmsteads that constitute this small, decaying watering-place which may, indeed, be called a ‘backwater of life’ without disrespect to its natives who possess, to this day, a salty individuality of their own. The main street, Coronation Street, consists, for the most part, of humble, two-storied houses many of which attempt to achieve some measure of gaiety by prinking themselves out in crude colours and by the liberal use of pinkwash, though there are remaining a few eighteenth-century houses of more pretension, if, on the whole, in a sad state of disrepair. Though there is little to attract the hillclimber, the healthseeker, the sportsman, or the weekending motorist, the contemplative may, if sufficiently attracted to spare it some leisurely hours, find, in its cobbled streets and its little fishing harbour, in its several curious customs, and in the conversation of its local ‘characters,’ some of that picturesque sense of the past so frequently lacking in towns and villages which have kept more abreast of the times. The River Dewi is said to abound in trout, but is much poached. The one place of worship, with its neglected graveyard, is of no architectural interest.

[A cock crows

The principality of the sky lightens now, over our green hill, into spring morning larked and crowed and belling.

[Slow bell notes

Who pulls the townhall bellrope but blind Captain Cat? One by one, the sleepers are rung out of sleep this one morning as every morning. And soon you shall see the chimneys’ slow upflying snow as Captain Cat, in sailor’s cap and seaboots, announces to-day with his loud get-out-of-bed bell.

The Reverend Eli Jenkins, in Bethesda House, gropes out of bed into his preacher’s black, combs back his bard’s white hair, forgets to wash, pads barefoot downstairs, opens the front door, stands in the doorway and, looking out at the day and up at the eternal hill, and hearing the sea break and the gab of birds, remembers his own verses and tells them softly to empty Coronation Street that is rising and raising its blinds.

Dear Gwalia! I know there are

Towns lovelier than ours,

And fairer hills and loftier far,

And groves more full of flowers,

And boskier woods more blithe with spring

And bright with birds’ adorning,

And sweeter bards than I to sing

Their praise this beauteous morning.

Or Moel yr Wyddfa’s glory,

Carnedd Llewelyn beauty born,

Plinlimmon old in story,

By mountains where King Arthur dreams,

By Penmaenmawr defiant,

Llareggub Hill a molehill seems,

A pygmy to a giant.

By Sawddwy, Senny, Dovey, Dee,

Edw, Eden, Aled, all,

Taff and Towy broad and free,

Llyfnant with its waterfall,

Claerwen, Cleddau, Dulais, Daw,

Ely, Gwili, Ogwr, Nedd,

Small is our River Dewi, Lord,

A baby on a rushy bed.

By Carreg Cennen, King of time,

Our Heron Head is only

A bit of stone with seaweed spread

Where gulls come to be lonely.

A tiny dingle is Milk Wood

By Golden Grove ’neath Grongar,

But let me choose and oh! I should

Love all my life and longer

To stroll among our trees and stray

In Goosegog Lane, on Donkey Down,

And hear the Dewi sing all day,

And never, never leave the town.

The Reverend Jenkins closes the front door. His morning service is over.

[Slow bell notes

Now, woken at last by the out-of-bed-sleepy-head-Polly-put-the-kettle-on townhall bell, Lily Smalls, Mrs Beynon’s treasure, comes downstairs from a dream of royalty who all night long went larking with her full of sauce in the Milk Wood dark, and puts the kettle on the primus ring in Mrs Beynon’s kitchen, and looks at herself in Mr Beynon’s shaving-glass over the sink, and sees:

Oh there’s a face!

Where you get that hair from?

Got it from a old tom cat

Give it back then, love.

Oh, there’s a perm!

Where you get that nose from, Lily?

Got it from my father, silly.

You’ve got it on upside down!

Oh, there’s a conk!

Look at your complexion!

Oh, no, you look.

Needs a bit of make-up.

Needs a veil.

Oh, there’s glamour!

Where you get that smile, Lil?

Never you mind, girl.

Nobody loves you.

That’s what you think.

Who is it loves you?

Shan’t tell.

Come on, Lily.

Cross your heart, then?

Cross my heart.

And very softly, her lips almost touching her reflection, she breathes the name and clouds the shaving-glass.

Lily!

Yes, mum.

Where’s my tea, girl?

(Softly) Where d’you think? In the cat-box?

(Loudly) Coming up, mum.

Mr Pugh, in the School House opposite, takes up the morning tea to Mrs Pugh, and whispers on the stairs

Here’s your arsenic, dear.

And your weedkiller biscuit.

I’ve throttled your parakeet.

I’ve spat in the vases.

I’ve put cheese in the mouseholes.

Here’s your . . . [Door creaks open

. . . nice tea, dear.

Too much sugar.

You haven’t tasted it yet, dear.

Too much milk, then. Has Mr Jenkins said his poetry?

Yes, dear.

Then it’s time to get up. Give me my glasses.

No, not my reading glasses, I want to look out. I want to see

Lily Smalls the treasure down on her red knees washing the front step.

She’s tucked her dress in her bloomers—oh, the baggage!

P.C. Attila Rees, ox-broad, barge-booted, stamping out of Handcuff House in a heavy beef-red huff, black-browed under his damp helmet . . .

He’s going to arrest Polly Garter, mark my words.

What for, dear?

For having babies.

. . . and lumbering down towards the strand to see that the sea is still there.

Mary Ann Sailors, opening her bedroom window above the taproom and calling out to the heavens

I’m eighty-five years three months and a day!

I will say this for her, she never makes a mistake.

Organ Morgan at his bedroom window playing chords on the sill to the morning fishwife gulls who, heckling over Donkey Street, observe

Me, Dai Bread, hurrying to the bakery, pushing in my shirt-tails, buttoning my waistcoat, ping goes a button, why can’t they sew them, no time for breakfast, nothing for breakfast, there’s wives for you.

Me, Mrs Dai Bread One, capped and shawled and no old corset, nice to be comfy, nice to be nice, clogging on the cobbles to stir up a neighbour. Oh, Mrs Sarah, can you spare a loaf, love? Dai Bread forgot the bread. There’s a lovely morning! How’s your boils this morning? Isn’t that good news now, it’s a change to sit down. Ta, Mrs Sarah.

Me, Mrs Dai Bread Two, gypsied to kill in a silky scarlet petticoat above my knees, dirty pretty knees, see my body through my petticoat brown as a berry, high-heel shoes with one heel missing, tortoiseshell comb in my bright black slinky hair, nothing else at all but a dab of scent, lolling gaudy at the doorway, tell your fortune in the tea-leaves, scowling at the sunshine, lighting up my pipe.

Me, Lord Cut-Glass, in an old frock-coat belonged to Eli Jenkins and a pair of postman’s trousers from Bethesda Jumble, running out of doors to empty slops—mind there, Rover!—and then running in again, tick tock.

Me, Nogood Boyo, up to no good in the wash-house.

Me, Miss Price, in my pretty print housecoat, deft at the clothesline, natty as a jenny-wren, then pit-pat back to my egg in its cosy, my crisp toast-fingers, my home-made plum and butterpat.

Me, Polly Garter, under the washing line, giving the breast in the garden to my bonny new baby. Nothing grows in our garden, only washing. And babies. And where’s their fathers live, my love? Over the hills and far away. You’re looking up at me now. I know what you’re thinking, you poor little milky creature. You’re thinking, you’re no better than you should be, Polly, and that’s good enough for me. Oh, isn’t life a terrible thing, thank God?

[Single long high chord on strings

Now frying-pans spit, kettles and cats purr in the kitchen. The town smells of seaweed and breakfast all the way down from Bay View, where Mrs Ogmore-Pritchard, in smock and turban, big-besomed to engage the dust, picks at her starchless bread and sips lemon-rind tea, to Bottom Cottage, where Mr Waldo, in bowler and bib, gobbles his bubble-and-squeak and kippers and swigs from the saucebottle. Mary Ann Sailors

praises the Lord who made porridge.

Mr Pugh

remembers ground glass as he juggles his omelet.

Mrs Pugh

nags the salt-cellar.

Willy Nilly postman

downs his last bucket of black brackish tea and rumbles out bandy to the clucking back where the hens twitch and grieve for their tea-soaked sops.

Mrs Willy Nilly

full of tea to her double-chinned brim broods and bubbles over her coven of kettles on the hissing hot range always ready to steam open the mail.

The Reverend Eli Jenkins

finds a rhyme and dips his pen in his cocoa.

Lord Cut-Glass in his ticking kitchen

scampers from clock to clock, a bunch of clock-keys in one hand, a fish-head in the other.

Captain Cat in his galley.

blind and fine-fingered savours his sea-fry.

Mr and Mrs Cherry Owen, in their Donkey Street room that is bedroom, parlour, kitchen, and scullery, sit down to last night’s supper of onions boiled in their overcoats and broth of spuds and baconrind and leeks and bones.

See that smudge on the wall by the picture of Auntie Blossom? That’s where you threw the sago.

[Cherry Owen laughs with delight

You only missed me by a inch.

I always miss Auntie Blossom too.

Remember last night? In you reeled, my boy, as drunk as a deacon with a big wet bucket and a fish-frail full of stout and you looked at me and you said, ‘God has come home!’ you said, and then over the bucket you went, sprawling and bawling, and the floor was all flagons and eels.

Was I wounded?

And then you took off your trousers and you said, ‘Does anybody want a fight!’ Oh, you old baboon.

Give me a kiss.

And then you sang ‘Bread of Heaven,’ tenor and bass.

I always sing ‘Bread of Heaven.’

And then you did a little dance on the table.

I did?

Drop dead!

And then what did I do?

Then you cried like a baby and said you were a poor drunk orphan with nowhere to go but the grave.

And what did I do next, my dear?

Then you danced on the table all over again and said you were King Solomon Owen and I was your Mrs Sheba.

And then?

And then I got you into bed and you snored all night like a brewery.

[Mr and Mrs Cherry Owen laugh delightedly together

From Beynon Butchers in Coronation Street, the smell of fried liver sidles out with onions on its breath. And listen! In the dark breakfast-room behind the shop, Mr and Mrs Beynon, waited upon by their treasure, enjoy, between bites, their everymorning hullabaloo, and Mrs Beynon slips the gristly bits under the tasselled tablecloth to her fat cat.

[Cat purrs

She likes the liver, Ben.

She ought to do, Bess. It’s her brother’s.

Oh, d’you hear that, Lily?

Yes, mum.

We’re eating pusscat.

Yes, mum.

Oh, you cat-butcher!

It was doctored, mind.

What’s that got to do with it?

Yesterday we had mole.

Oh, Lily, Lily!

Monday, otter. Tuesday, shrews.

[Mrs Beynon screams

Go on, Mrs Beynon. He’s the biggest liar in town.

Don’t you dare say that about Mr Beynon.

Everybody knows it, mum.

Mr Beynon never tells a lie. Do you, Ben?

No, Bess. And now I am going out after the corgies, with my little cleaver.

Oh, Lily, Lily!

Up the street, in the Sailors Arms, Sinbad Sailors, grandson of Mary Ann Sailors, draws a pint in the sunlit bar. The ship’s clock in the bar says half past eleven. Half past eleven is opening time. The hands of the clock have stayed still at half past eleven for fifty years. It is always opening time in the Sailors Arms.

Here’s to me, Sinbad.

All over the town, babies and old men are cleaned and put into their broken prams and wheeled on to the sunlit cockled cobbles or out into the backyards under the dancing underclothes, and left. A baby cries.

I want my pipe and he wants his bottle.

[School bell rings

Noses are wiped, heads picked, hair combed, paws scrubbed, ears boxed, and the children shrilled off to school.

Fishermen grumble to their nets. Nogood Boyo goes out in the dinghy Zanzibar, ships the oars, drifts slowly in the dab-filled bay, and, lying on his back in the unbaled water, among crabs’ legs and tangled lines, looks up at the spring sky.

I don’t know who’s up there and I don’t care.

He turns his head and looks up at Llareggub Hill, and sees, among green lathered trees, the white houses of the strewn away farms, where farmboys whistle, dogs shout, cows low, but all too far away for him, or you, to hear. And in the town, the shops squeak open. Mr Edwards, in butterfly-collar and straw-hat at the doorway of Manchester House, measures with his eye the dawdlers-by for striped flannel shirts and shrouds and flowery blouses, and bellows to himself in the darkness behind his eye.

I love Miss Price.

Syrup is sold in the post-office. A car drives to market, full of fowls and a farmer. Milk-churns stand at Coronation Corner like short silver policemen. And, sitting at the open window of Schooner House, blind Captain Cat hears all the morning of the town.

[School bell in background. Children’s voices.

The noise of children’s feet on the cobbles

Maggie Richards, Ricky Rhys, Tommy Powell, our Sal, little Gerwain, Billy Swansea with the dog’s voice, one of Mr Waldo’s, nasty Humphrey, Jackie with the sniff . . . Where’s Dicky’s Albie? and the boys from Ty-pant? Perhaps they got the rash again.

[A sudden cry among the children’s voices

Somebody’s hit Maggie Richards. Two to one it’s Billy Swansea. Never trust a boy who barks.

[A burst of yelping crying

Right again! It’s Billy.

And the children’s voices cry away.

[Postman’s rat-a-tat on door, distant

That’s Willy Nilly knocking at Bay View. Rat-a-tat, very soft. The knocker’s got a kid glove on. Who’s sent a letter to Mrs Ogmore-Pritchard?

[Rat-a-tat, distant again

Careful now, she swabs the front glassy. Every step’s like a bar of soap. Mind your size twelveses. That old Bessie would beeswax the lawn to make the birds slip.

Morning, Mrs Ogmore-Pritchard.

Good morning, postman.

Here’s a letter for you with stamped and addressed envelope enclosed, all the way from Builth Wells. A gentleman wants to study birds and can he have accommodation for two weeks and a bath vegetarian.

No.

You wouldn’t know he was in the house, Mrs Ogmore-Pritchard. He’d be out in the mornings at the bang of dawn with his bag of breadcrumbs and his little telescope . . .

And come home at all hours covered with feathers. I don’t want persons in my nice clean rooms breathing all over the chairs . . .

Cross my heart, he won’t breathe.

. . . and putting their feet on my carpets and sneezing on my china and sleeping in my sheets . . .

He only wants a single bed, Mrs Ogmore-Pritchard.

[Door slams

And back she goes to the kitchen to polish the potatoes.

Captain Cat hears Willy Nilly’s feet heavy on the distant cobbles.

One, two, three, four, five . . . That’s Mrs Rose Cottage. What’s to-day? To-day she gets the letter from her sister in Gorslas. How’s the twins’ teeth?

He’s stopping at School House.

Morning, Mrs Pugh. Mrs Ogmore-Pritchard won’t have a gentleman in from Builth Wells because he’ll sleep in her sheets, Mrs Rose Cottage’s sister in Gorslas’s twins have got to have them out . . .

Give me the parcel.

It’s for Mr Pugh, Mrs Pugh.

Never you mind. What’s inside it?

A book called Lives of the Great Poisoners.

That’s Manchester House.

Morning, Mr Edwards. Very small news. Mrs Ogmore-Pritchard won’t have birds in the house, and Mr Pugh’s bought a book now on how to do in Mrs Pugh.

Have you got a letter from her?

Miss Price loves you with all her heart. Smelling of lavender to-day. She’s down to the last of the elderflower wine but the quince jam’s bearing up and she’s knitting roses on the doilies. Last week she sold three jars of boiled sweets, pound of humbugs, half a box of jellybabies and six coloured photos of Llareggub. Yours for ever. Then twenty-one X’s.

Oh, Willy Nilly, she’s a ruby! Here’s my letter. Put it into her hands now.

[Slow feet on cobbles, quicker feet approaching

Mr Waldo hurrying to the Sailors Arms. Pint of stout with a egg in it.

[Footsteps stop

(Softly) There’s a letter for him.

It’s another paternity summons, Mr Waldo.

The quick footsteps hurry on along the cobbles and up three steps to the Sailors Arms.

Quick, Sinbad. Pint of stout. And no egg in.

People are moving now up and down the cobbled street.

All the women are out this morning, in the sun. You can tell it’s Spring. There goes Mrs Cherry, you can tell her by her trotters, off she trots new as a daisy. Who’s that talking by the pump? Mrs Floyd and Boyo, talking flatfish. What can you talk about flatfish? That’s Mrs Dai Bread One, waltzing up the street like a jelly, every time she shakes it’s slap slap slap. Who’s that? Mrs Butcher Beynon with her pet black cat, it follows her everywhere, miaow and all. There goes Mrs Twenty-Three, important, the sun gets up and goes down in her dewlap, when she shuts her eyes, it’s night. High heels now, in the morning too, Mrs Rose Cottage’s eldest Mae, seventeen and never been kissed ho ho, going young and milking under my window to the field with the nannygoats, she reminds me all the way. Can’t hear what the women are gabbing round the pump. Same as ever. Who’s having a baby, who blacked whose eye, seen Polly Garter giving her belly an airing, there should be a law, seen Mrs Beynon’s new mauve jumper, it’s her old grey jumper dyed, who’s dead, who’s dying, there’s a lovely day, oh the cost of soapflakes!

[Organ music, distant

Organ Morgan’s at it early. You can tell it’s Spring.

And he hears the noise of milk-cans.

Ocky Milkman on his round. I will say this, his milk’s as fresh as the dew. Half dew it is. Snuffle on, Ocky, watering the town . . . Somebody’s coming. Now the voices round the pump can see somebody coming. Hush, there’s a hush! You can tell by the noise of the hush, it’s Polly Garter. (Louder) Hullo, Polly, who’s there?

Me, love.

That’s Polly Garter. (Softly) Hullo, Polly, my love, can you hear the dumb goose-hiss of the wives as they huddle and peck or flounce at a waddle away? Who cuddled you when? Which of their gandering hubbies moaned in Milk Wood for your naughty mothering arms and body like a wardrobe, love? Scrub the floors of the Welfare Hall for the Mothers’ Union Social Dance, you’re one mother won’t wriggle her roly poly bum or pat her fat little buttery feet in that wedding-ringed holy to-night through the waltzing breadwinners snatched from the cosy smoke of the Sailors Arms will grizzle and mope.

[A cock crows

Too late, cock, too late

for the town’s half over with its morning. The morning’s busy as bees.

[Organ music fades into silence

There’s the clip clop of horses on the sunhoneyed cobbles of the humming streets, hammering of horseshoes, gobble quack and cackle, tomtit twitter from the bird-ounced boughs, braying on Donkey Down. Bread is baking, pigs are grunting, chop goes the butcher, milk-churns bell, tills ring, sheep cough, dogs shout, saws sing. Oh, the Spring whinny and morning moo from the clog-dancing farms, the gulls’ gab and rabble on the boat-bobbing river and sea and the cockles bubbling in the sand, scamper of sanderlings, curlew cry, crow caw, pigeon coo, clock strike, bull bellow, and the ragged gabble of the beargarden school as the women scratch and babble in Mrs Organ Morgan’s general shop where everything is sold: custard, buckets, henna, rat-traps, shrimp-nets, sugar, stamps, confetti, paraffin, hatchets, whistles.

Mrs Ogmore-Pritchard

la di da

got a man in Builth Wells

and he got a little telescope to look at birds

Willy Nilly said

Remember her first husband? He didn’t need a telescope

he looked at them undressing through the keyhole

and he used to shout Tallyho

but Mr Ogmore was a proper gentleman

even though he hanged his collie.

Seen Mrs Butcher Beynon?

she said Butcher Beynon put dogs in the mincer

go on, he’s pulling her leg

now don’t you dare tell her that, there’s a dear

or she’ll think he’s trying to pull it off and eat it.

There’s a nasty lot live here when you come to think.

Look at that Nogood Boyo now

too lazy to wipe his snout

and going out fishing every day and all he ever brought back was a Mrs Samuels

been in the water a week.

And look at Ocky Milkman’s wife that nobody’s ever seen

he keeps her in the cupboard with the empties

and think of Dai Bread with two wives

one for the daytime one for the night.

Men are brutes on the quiet.

And how’s Organ Morgan, Mrs Morgan?

you look dead beat

it’s organ organ all the time with him

up every night until midnight playing the organ

Oh, I’m a martyr to music.

Outside, the sun springs down on the rough and tumbling town. It runs through the hedges of Goosegog Lane, cuffing the birds to sing. Spring whips green down Cockle Row, and the shells ring out. Llareggub this snip of a morning is wildfruit and warm, the streets, fields, sands and waters springing in the young sun.

Evans the Death presses hard with black gloves on the coffin of his breast in case his heart jumps out.

Where’s your dignity. Lie down.

Spring stirs Gossamer Beynon schoolmistress like a spoon.

Oh, what can I do? I’ll never be refined if I twitch.

Spring this strong morning foams in a flame in Jack Black as he cobbles a high-heeled shoe for Mrs Dai Bread Two the gypsy, but he hammers it sternly out.

There is no leg belonging to the foot that belongs to this shoe.

The sun and the green breeze ship Captain Cat sea-memory again.

No, I’ll take the mulatto, by God, who’s captain here? Parlez-vous jig jig, Madam?

Mary Ann Sailors says very softly to herself as she looks out at Llareggub Hill from the bedroom where she was born

It is Spring in Llareggub in the sun in my old age, and this is the Chosen Land.

[A choir of children’s voices suddenly cries out on one, high, glad, long, sighing note

And in Willy Nilly the Postman’s dark and sizzling damp tea-coated misty pygmy kitchen where the spittingcat kettles throb and hop on the range, Mrs Willy Nilly steams open Mr Mog Edwards’ letter to Miss Myfanwy Price and reads it aloud to Willy Nilly by the squint of the Spring sun through the one sealed window running with tears, while the drugged, bedraggled hens at the back door whimper and snivel for the lickerish bog-black tea.

From Manchester House, Llareggub. Sole Prop: Mr Mog Edwards (late of Twll), Linendraper, Haberdasher, Master Tailor, Costumier. For West End Negligee, Lingerie, Teagowns, Evening Dress, Trousseaux, Layettes. Also Ready to Wear for All Occasions. Economical Outfitting for Agricultural Employment Our Speciality, Wardrobes Bought. Among Our Satisfied Customers Ministers of Religion and J.P.’s. Fittings by Appointment. Advertising Weekly in the Twll Bugle. Beloved Myfanwy Price my Bride in Heaven,

I love you until Death do us part and then we shall be together for ever and ever. A new parcel of ribbons has come from Carmarthen to-day, all the colours in the rainbow. I wish I could tie a ribbon in your hair a white one but it cannot be. I dreamed last night you were all dripping wet and you sat on my lap as the Reverend Jenkins went down the street. I see you got a mermaid in your lap he said and he lifted his hat. He is a proper Christian. Not like Cherry Owen who said you should have thrown her back he said. Business is very poorly. Polly Garter bought two garters with roses but she never got stockings so what is the use I say. Mr Waldo tried to sell me a woman’s nightie outsize he said he found it and we know where. I sold a packet of pins to Tom the Sailors to pick his teeth. If this goes on I shall be in the poorhouse. My heart is in your bosom and yours is in mine. God be with you always Myfanwy Price and keep you lovely for me in His Heavenly Mansion. I must stop now and remain, Your Eternal, Mog Edwards.

And then a little message with a rubber stamp. Shop at Mog’s!!!

And Willy Nilly, rumbling, jockeys out again to the three-seated shack called the House of Commons in the back where the hens weep, and sees, in sudden Springshine,

herring gulls heckling down to the harbour where the fishermen spit and prop the morning up and eye the fishy sea smooth to the sea’s end as it lulls in blue. Green and gold money, tobacco, tinned salmon, hats with feathers, pots of fish-paste, warmth for the winter-to-be, weave and leap in it rich and slippery in the flash and shapes of fishes through the cold sea-streets. But with blue lazy eyes the fishermen gaze at that milkmaid whispering water with no ruck or ripple as though it blew great guns and serpents and typhooned the town.

Too rough for fishing to-day.

And they thank God, and gob at a gull for luck, and moss-slow and silent make their way uphill, from the still still sea, towards the Sailors Arms as the children

[School bell

spank and scamper rough and singing out of school into the draggletail yard. And Captain Cat at his window says soft to himself the words of their song.

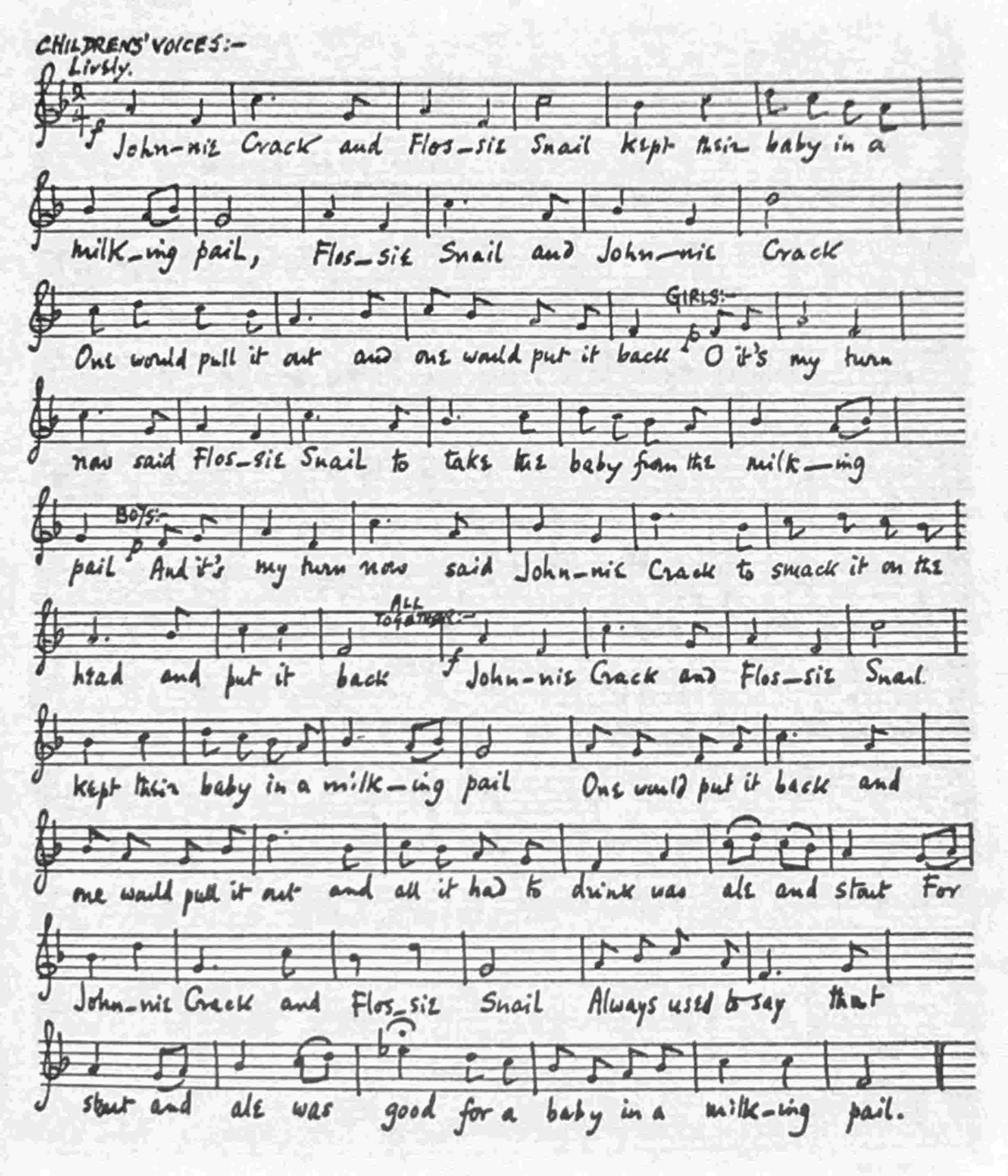

Johnnie Crack and Flossie Snail

Kept their baby in a milking pail

Flossie Snail and Johnnie Crack

One would pull it out and one would put it back

O it’s my turn now said Flossie Snail

To take the baby from the milking pail

And it’s my turn now said Johnnie Crack

To smack it on the head and put it back

Johnnie Crack and Flossie Snail

Kept their baby in a milking pail

One would put it back and one would pull it out

And all it had to drink was ale and stout

For Johnnie Crack and Flossie Snail

Always used to say that stout and ale

Was good for a baby in a milking pail.

[Long pause

The music of the spheres is heard distinctly over Milk Wood. It is ‘The Rustle of Spring.’

A glee-party sings in Bethesda Graveyard, gay but muffled.

Vegetables make love above the tenors

and dogs bark blue in the face.

Mrs Ogmore-Pritchard belches in a teeny hanky and chases the sunlight with a flywhisk, but even she cannot drive out the Spring: from one of the finger-bowls, a primrose grows.

Mrs Dai Bread One and Mrs Dai Bread Two are sitting outside their house in Donkey Lane, one darkly one plumply blooming in the quick, dewy sun. Mrs Dai Bread Two is looking into a crystal ball which she holds in the lap of her dirty yellow petticoat, hard against her hard dark thighs.

Cross my palm with silver. Out of our housekeeping money. Aah!

What d’you see, lovie?

I see a featherbed. With three pillows on it. And a text above the bed. I can’t read what it says, there’s great clouds blowing. Now they have blown away. God is Love, the text says.

That’s our bed.

And now it’s vanished. The sun’s spinning like a top. Who’s this coming out of the sun? It’s a hairy little man with big pink lips. He got a wall eye.

It’s Dai, it’s Dai Bread!

Ssh! The featherbed’s floating back. The little man’s taking his boots off. He’s pulling his shirt over his head. He’s beating his chest with his fists. He’s climbing into bed.

Go on, go on.

There’s two women in bed. He looks at them both, with his head cocked on one side. He’s whistling through his teeth. Now he grips his little arms round one of the women.

Which one, which one?

I can’t see any more. There’s great clouds blowing again.

Ach, the mean old clouds!

[Pause. The children’s singing fades

The morning is all singing. The Reverend Eli Jenkins, busy on his morning calls, stops outside the Welfare Hall to hear Polly Garter as she scrubs the floors for the Mothers’ Union Dance to-night.

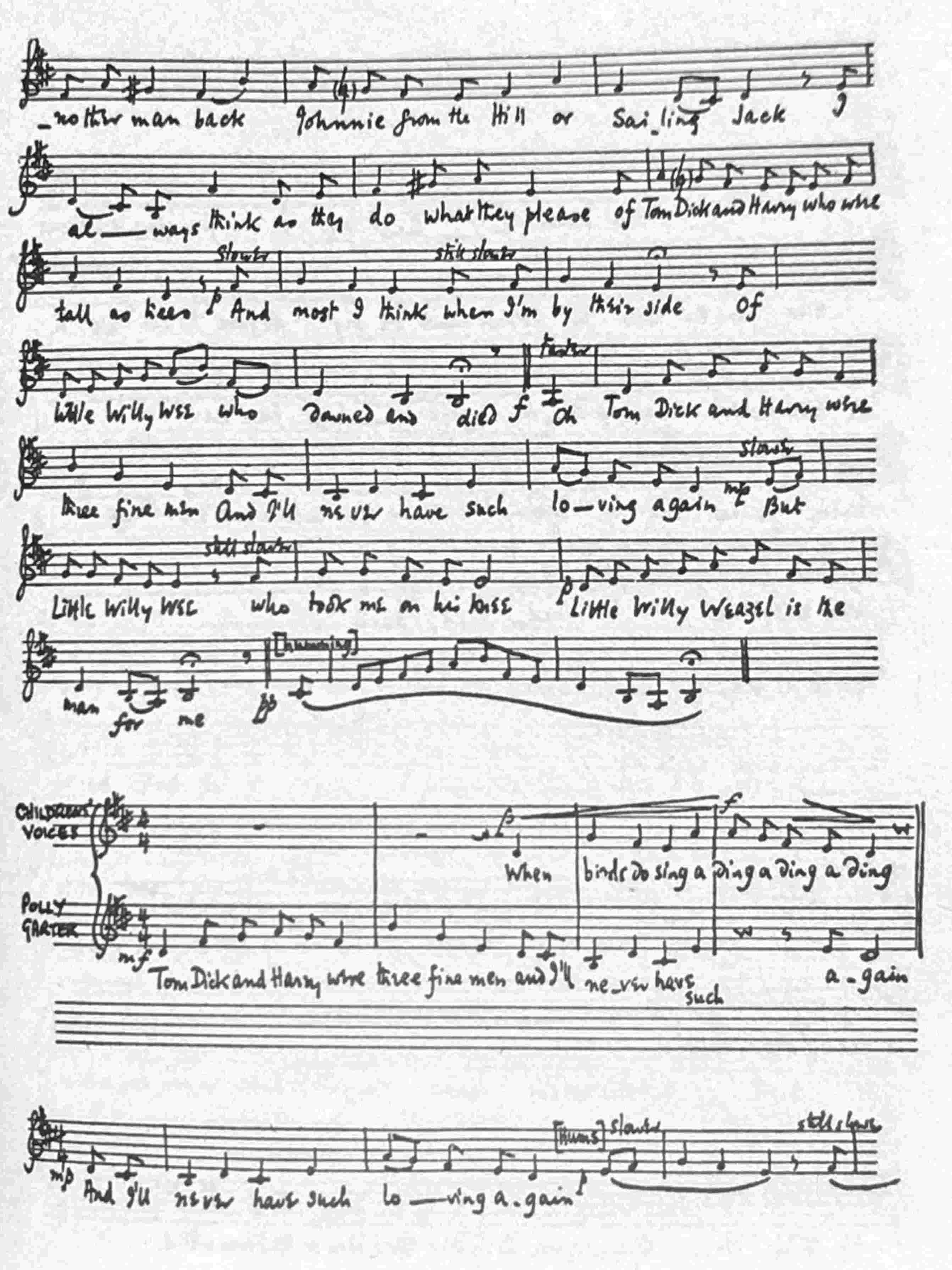

I loved a man whose name was Tom

He was strong as a bear and two yards long

I loved a man whose name was Dick

He was big as a barrel and three feet thick

And I loved a man whose name was Harry

Six feet tall and sweet as a cherry

But the one I loved best awake or asleep

Was little Willy Wee and he’s six feet deep.

O Tom Dick and Harry were three fine men

And I’ll never have such loving again

But little Willy Wee who took me on his knee

Little Willy Wee was the man for me.

Now men from every parish round

Run after me and roll me on the ground

But whenever I love another man back

Johnnie from the Hill or Sailing Jack

I always think as they do what they please

Of Tom Dick and Harry who were tall as trees

And most I think when I’m by their side

Of little Willy Wee who downed and died.

O Tom Dick and Harry were three fine men

And I’ll never have such loving again

But little Willy Wee who took me on his knee

Little Willy Weazel is the man for me.

Praise the Lord! We are a musical nation.

And the Reverend Jenkins hurries on through the town to visit the sick with jelly and poems.

The town’s as full as a lovebird’s egg.

There goes the Reverend,

says Mr Waldo at the smoked herring brown window of the unwashed Sailors Arms,

with his brolly and his odes. Fill ’em up, Sinbad, I’m on the treacle to-day.

The silent fishermen flush down their pints.

Oh, Mr Waldo,

sighs Sinbad Sailors,

I dote on that Gossamer Beynon. She’s a lady all over.

And Mr Waldo, who is thinking of a woman soft as Eve and sharp as sciatica to share his bread-pudding bed, answers

No lady that I know is.

And if only grandma’d die, cross my heart I’d go down on my knees Mr Waldo and I’d say Miss Gossamer I’d say

When birds do sing hey ding a ding a ding

Sweet lovers love the Spring . . .

Polly Garter sings, still on her knees,

Tom Dick and Harry were three fine men

And I’ll never have such

Ding a ding

again.

And the morning school is over, and Captain Cat at his curtained schooner’s porthole open to the Spring sun tides hears the naughty forfeiting children tumble and rhyme on the cobbles.

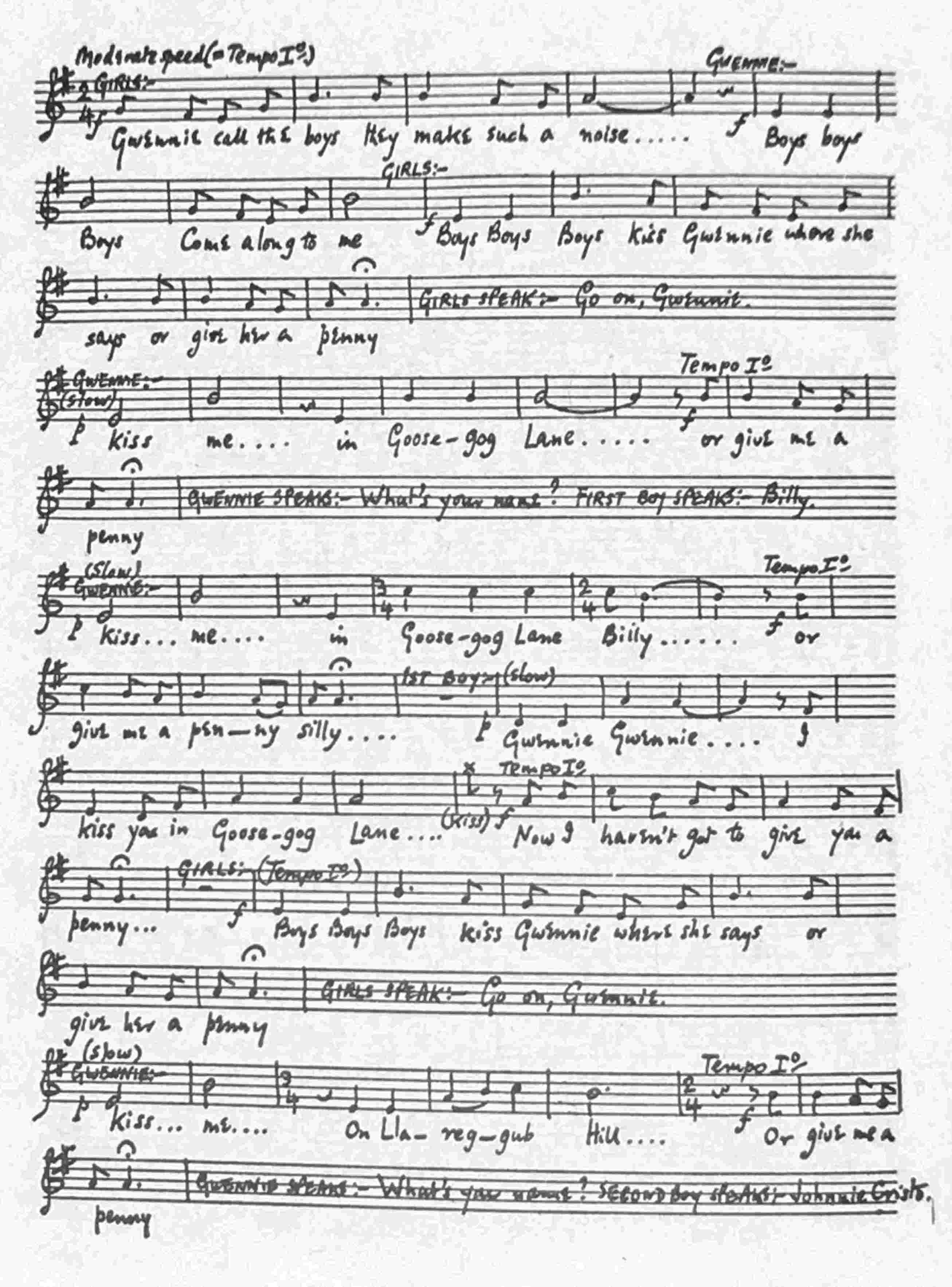

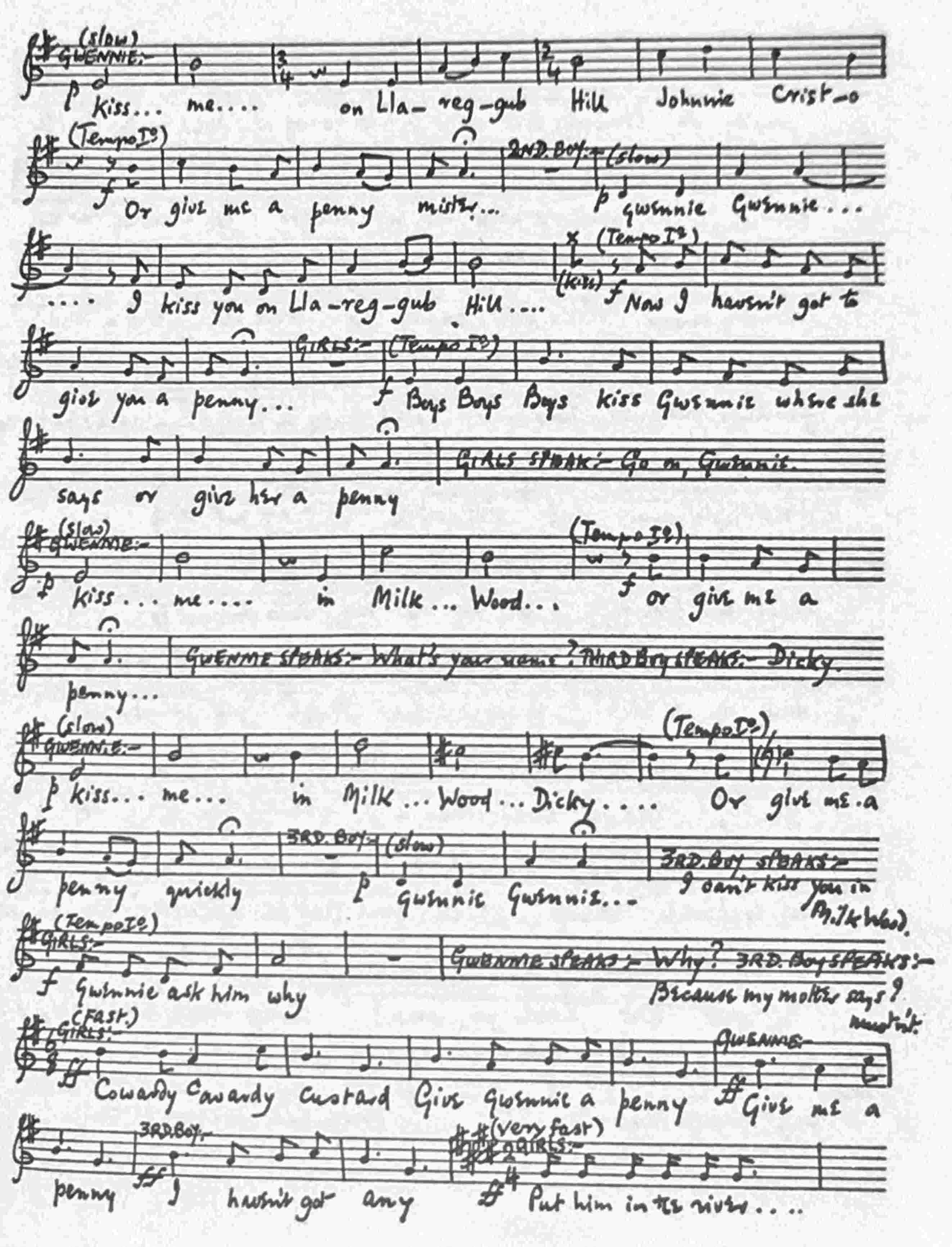

Gwennie call the boys

They make such a noise.

Boys boys boys

Come along to me.

Boys boys boys

Kiss Gwennie where she says

Or give her a penny.

Go on, Gwennie.

Kiss me in Goosegog Lane

Or give me a penny.

What’s your name?

Billy.

Kiss me in Goosegog Lane Billy

Or give me a penny silly.

Gwennie Gwennie

I kiss you in Goosegog Lane.

Now I haven’t got to give you a penny.

Boys boys boys

Kiss Gwennie where she says

Or give her a penny.

Go on, Gwennie.

Kiss me on Llareggub Hill

Or give me a penny.

What’s your name?

Johnnie Cristo.

Kiss me on Llareggub Hill Johnnie Cristo

Or give me a penny mister.

Gwennie Gwennie

I kiss you on Llareggub Hill.

Now I haven’t got to give you a penny.

Boys boys boys

Kiss Gwennie where she says

Or give her a penny.

Go on, Gwennie.

Kiss me in Milk Wood

Or give me a penny.

What’s your name?

Dicky.

Kiss me in Milk Wood Dicky

Or give me a penny quickly.

Gwennie Gwennie

I can’t kiss you in Milk Wood.

Gwennie ask him why.

Why?

Because my mother says I mustn’t.

Cowardy cowardy custard

Give Gwennie a penny.

Give me a penny.

I haven’t got any.

Put him in the river

Up to his liver

Quick quick Dirty Dick

Beat him on the bum

With a rhubarb stick.

Aiee!

Hush!

And the shrill girls giggle and master around him and squeal as they clutch and thrash, and he blubbers away downhill with his patched pants falling, and his tear-splashed blush burns all the way as the triumphant bird-like sisters scream with buttons in their claws and the bully brothers hoot after him his little nickname and his mother’s shame and his father’s wickedness with the loose wild barefoot women of the hovels of the hills. It all means nothing at all, and, howling for his milky mum, for her cawl and buttermilk and cowbreath and welshcakes and the fat birth-smelling bed and moonlit kitchen of her arms, he’ll never forget as he paddles blind home through the weeping end of the world. Then his tormentors tussle and run to the Cockle Street sweet-shop, their pennies sticky as honey, to buy from Miss Myfanwy Price, who is cocky and neat as a puff-bosomed robin and her small round buttocks tight as ticks, gobstoppers big as wens that rainbow as you suck, brandyballs, winegums, hundreds and thousands, liquorice sweet as sick, nougat to tug and ribbon out like another red rubbery tongue, gum to glue in girls’ curls, crimson cough-drops to spit blood, ice-cream comets, dandelion-and-burdock, raspberry and cherryade, pop goes the weasel and the wind.

Gossamer Beynon high-heels out of school. The sun hums down through the cotton flowers of her dress into the bell of her heart and buzzes in the honey there and couches and kisses, lazy-loving and boozed, in her red-berried breast. Eyes run from the trees and windows of the street, steaming ‘Gossamer,’ and strip her to the nipples and the bees. She blazes naked past the Sailors Arms, the only woman on the Dai-Adamed earth. Sinbad Sailors places on her thighs still dewdamp from the first mangrowing cock-crow garden his reverent goat-bearded hands.

I don’t care if he is common,

she whispers to her salad-day deep self,

I want to gobble him up. I don’t care if he does drop his aitches,

she tells the stripped and mother-of-the-world big-beamed and Eve-hipped spring of her self.

so long as he’s all cucumber and hooves.

Sinbad Sailors watches her go by, demure and proud and schoolmarm in her crisp flower dress and sun-defying hat, with never a look or lilt or wriggle, the butcher’s unmelting icemaiden daughter veiled forever from the hungry hug of his eyes.

Oh, Gossamer Beynon, why are you so proud?

he grieves to his Guinness,

Oh, beautiful beautiful Gossamer B, I wish I wish that you were for me. I wish you were not so educated.

She feels his goatbeard tickle her in the middle of the world like a tuft of wiry fire, and she turns in a terror of delight away from his whips and whiskery conflagration, and sits down in the kitchen to a plate heaped high with chips and the kidneys of lambs.

In the blind-drawn dark dining-room of School House, dusty and echoing as a dining-room in a vault, Mr and Mrs Pugh are silent over cold grey cottage pie. Mr Pugh reads, as he forks the shroud meat in, from Lives of the Great Poisoners. He has bound a plain brown-paper cover round the book. Slyly, between slow mouthfuls, he sidespies up at Mrs Pugh, poisons her with his eye, then goes on reading. He underlines certain passages and smiles in secret.

Persons with manners do not read at table,

says Mrs Pugh. She swallows a digestive tablet as big as a horse-pill, washing it down with clouded peasoup water.

[Pause

Some persons were brought up in pigsties.

Pigs don’t read at table, dear.

Bitterly she flicks dust from the broken cruet. It settles on the pie in a thin gnat-rain.

Pigs can’t read, my dear.

I know one who can.

Alone in the hissing laboratory of his wishes, Mr Pugh minces among bad vats and jeroboams, tiptoes through spinneys of murdering herbs, agony dancing in his crucibles, and mixes especially for Mrs Pugh a venomous porridge unknown to toxicologists which will scald and viper through her until her ears fall off like figs, her toes grow big and black as balloons, and steam comes screaming out of her navel.

You know best, dear,

says Mr Pugh, and quick as a flash he ducks her in rat soup.

What’s that book by your trough, Mr Pugh?

It’s a theological work, my dear. Lives of the Great Saints.

Mrs Pugh smiles. An icicle forms in the cold air of the dining vault.

I saw you talking to a saint this morning. Saint Polly Garter. She was martyred again last night. Mrs Organ Morgan saw her with Mr Waldo.

And when they saw me they pretended they were looking for nests,

said Mrs Organ Morgan to her husband, with her mouth full of fish as a pelican’s.

But you don’t go nesting in long combinations, I said to myself, like Mr Waldo was wearing, and your dress nearly over your head like Polly Garter’s. Oh, they didn’t fool me.

One big bird gulp, and the flounder’s gone. She licks her lips and goes stabbing again.

And when you think of all those babies she’s got, then all I can say is she’d better give up bird nesting that’s all I can say, it isn’t the right kind of hobby at all for a woman that can’t say No even to midgets. Remember Bob Spit? He wasn’t any bigger than a baby and he gave her two. But they’re two nice boys, I will say that, Fred Spit and Arthur. Sometimes I like Fred best and sometimes I like Arthur. Who do you like best, Organ?

Oh, Bach without any doubt. Bach every time for me.

Organ Morgan, you haven’t been listening to a word I said. It’s organ organ all the time with you . . .

And she bursts into tears, and, in the middle of her salty howling, nimbly spears a small flatfish and pelicans it whole.

And then Palestrina,

says Organ Morgan.

Lord Cut-Glass, in his kitchen full of time, squats down alone to a dogdish, marked Fido, of peppery fish-scraps and listens to the voices of his sixty-six clocks—(one for each year of his loony age)—and watches, with love, their black-and-white moony loudlipped faces tocking the earth away: slow clocks, quick clocks, pendulumed heart-knocks, china, alarm, grandfather, cuckoo; clocks shaped like Noah’s whirring Ark, clocks that bicker in marble ships, clocks in the wombs of glass women, hourglass chimers, tu-wit-tu-woo clocks, clocks that pluck tunes, Vesuvius clocks all black bells and lava, Niagara clocks that cataract their ticks, old time-weeping clocks with ebony beards, clocks with no hands for ever drumming out time without ever knowing what time it is. His sixty-six singers are all set at different hours. Lord Cut-Glass lives in a house and a life at siege. Any minute or dark day now, the unknown enemy will loot and savage downhill, but they will not catch him napping. Sixty-six different times in his fish-slimy kitchen ping, strike, tick, chime, and tock.

The lust and lilt and lather and emerald breeze and crackle of the bird-praise and body of Spring with its breasts full of riveting May-milk, means, to that lordly fish-head nibbler, nothing but another nearness to the tribes and navies of the Last Black Day who’ll sear and pillage down Armageddon Hill to his double-locked rusty-shuttered tick-tock dust-scrabbled shack at the bottom of the town that has fallen head over bells in love.

And I’ll never have such loving again,

pretty Polly hums and longs.

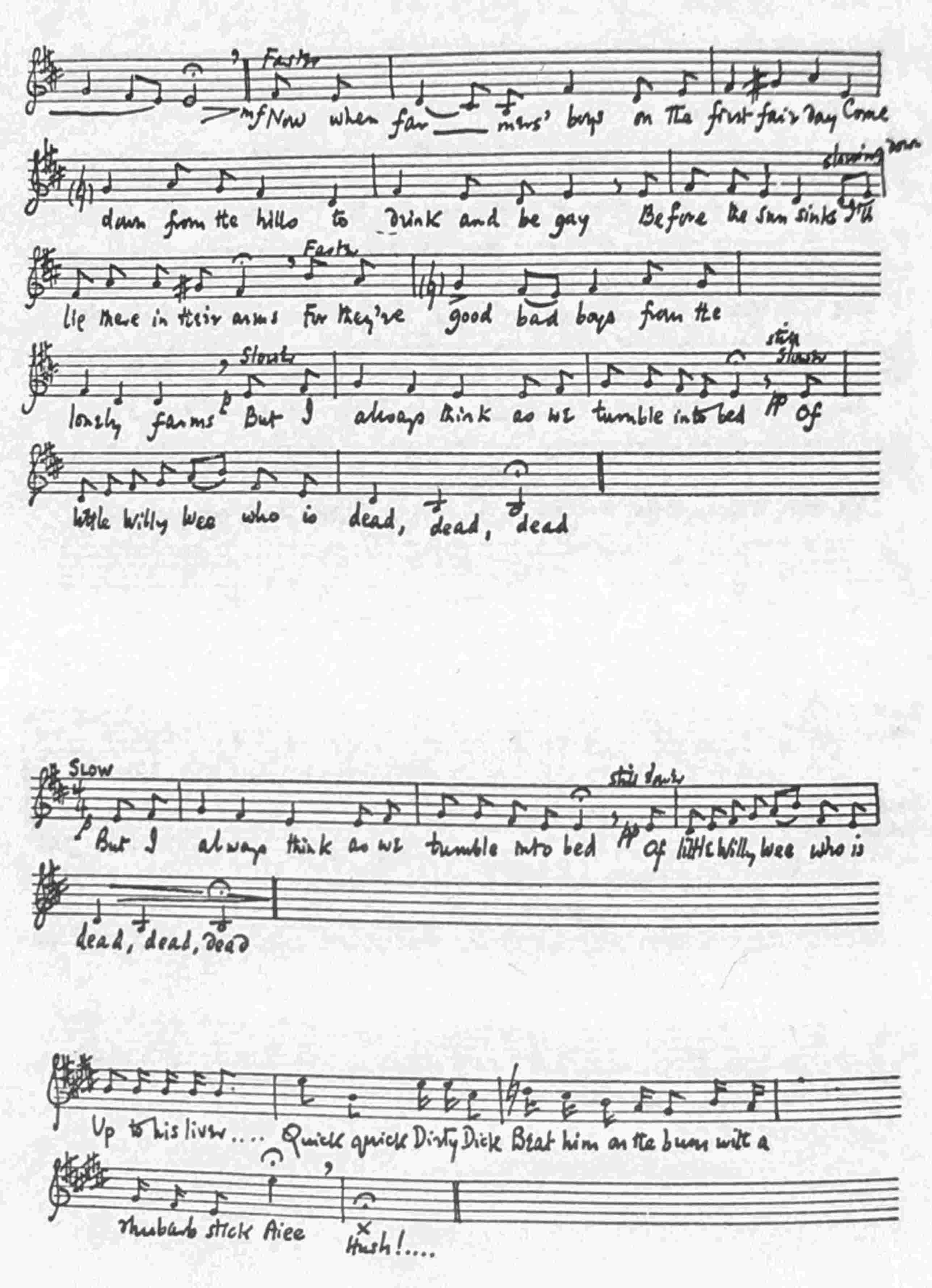

Now when farmers’ boys on the first fair day

Come down from the hills to drink and be gay,

Before the sun sinks I’ll lie there in their arms

For they’re good bad boys from the lonely farms,

But I always think as we tumble into bed

Of little Willy Wee who is dead, dead, dead . . . .

[A silence

The sunny slow lulling afternoon yawns and moons through the dozy town. The sea lolls, laps and idles in, with fishes sleeping in its lap. The meadows still as Sunday, the shut-eye tasselled bulls, the goat-and-daisy dingles, nap happy and lazy. The dumb duck-ponds snooze. Clouds sag and pillow on Llareggub Hill. Pigs grunt in a wet wallow-bath, and smile as they snort and dream. They dream of the acorned swill of the world, the rooting for pig-fruit, the bag-pipe dugs of the mother sow, the squeal and snuffle of yesses of the women pigs in rut. They mud-bask and snout in the pig-loving sun; their tails curl; they rollick and slobber and snore to deep, smug, after-swill sleep. Donkeys angelically drowse on Donkey Down.

Persons with manners,

snaps Mrs cold Pugh

do not nod at table.

Mr Pugh cringes awake. He puts on a soft-soaping smile: it is sad and grey under his nicotine-eggyellow weeping walrus Victorian moustache worn thick and long in memory of Doctor Crippen.

You should wait until you retire to your sty,

says Mrs Pugh, sweet as a razor. His fawning measly quarter-smile freezes. Sly and silent, he foxes into his chemist’s den and there, in a hiss and prussic circle of cauldrons and phials brimful with pox and the Black Death, cooks up a fricassee of deadly nightshade, nicotine, hot frog, cyanide and bat-spit for his needling stalactite hag and bednag of a pokerbacked nutcracker wife.

I beg your pardon, my dear,

he murmurs with a wheedle.

Captain Cat, at his window thrown wide to the sun and the clippered seas he sailed long ago when his eyes were blue and bright, slumbers and voyages; earringed and rolling, I Love You Rosie Probert tattooed on his belly, he brawls with broken bottles in the fug and babel of the dark dock bars, roves with a herd of short and good time cows in every naughty port and twines and souses with the drowned and blowzy-breasted dead. He weeps as he sleeps and sails.

One voice of all he remembers most dearly as his dream buckets down. Lazy early Rosie with the flaxen thatch, whom he shared with Tom-Fred the donkeyman and many another seaman, clearly and near to him speaks from the bedroom of her dust. In that gulf and haven, fleets by the dozen have anchored for the little heaven of the night; but she speaks to Captain napping Cat alone. Mrs Probert . . .

from Duck Lane, Jack. Quack twice and ask for Rosie.

. . . is the one love of his sea-life that was sardined with women.

What seas did you see,

Tom Cat, Tom Cat,

In your sailoring days

Long long ago?

What sea beasts were

In the wavery green

When you were my master?

I’ll tell you the truth.

Seas barking like seals,

Blue seas and green,

Seas covered with eels

And mermen and whales.

What seas did you sail

Old whaler when

On the blubbery waves

Between Frisco and Wales

You were my bosun?

As true as I’m here

Dear you Tom Cat’s tart

You landlubber Rosie

You cosy love

My easy as easy

My true sweetheart,

Seas green as a bean

Seas gliding with swans

In the seal-barking moon.

What seas were rocking

My little deck hand

My favourite husband

In your seaboots and hunger

My duck my whaler

My honey my daddy

My pretty sugar sailor

With my name on your belly

When you were a boy

Long long ago?

I’ll tell you no lies.

The only sea I saw

Was the seesaw sea

With you riding on it.

Lie down, lie easy.

Let me shipwreck in your thighs.

Knock twice, Jack,

At the door of my grave

And ask for Rosie.

Rosie Probert.

Remember her.

She is forgetting.

The earth which filled her mouth

Is vanishing from her.

Remember me.

I have forgotten you.

I am going into the darkness of the darkness for ever.

I have forgotten that I was ever born.

Look,

says a child to her mother as they pass by the window of Schooner House,

Captain Cat is crying.

Captain Cat is crying

Come back, come back,

up the silences and echoes of the passages of the eternal night.

He’s crying all over his nose,

says the child. Mother and child move on down the street.

He’s got a nose like strawberries,

the child says; and then she forgets him too. She sees in the still middle of the bluebagged bay Nogood Boyo fishing from the Zanzibar.

Nogood Boyo gave me three pennies yesterday but I wouldn’t,

the child tells her mother.

Boyo catches a whalebone corset. It is all he has caught all day.

Bloody funny fish!

Mrs Dai Bread Two gypsies up his mind’s slow eye, dressed only in a bangle.

She’s wearing her nightgown. (Pleadingly) Would you like this nice wet corset, Mrs Dai Bread Two?

No, I won’t!

And a bite of my little apple?

he offers with no hope.

She shakes her brass nightgown, and he chases her out of his mind; and when he comes gusting back, there in the bloodshot centre of his eye a geisha girl grins and bows in a kimono of ricepaper.

I want to be good Boyo, but nobody’ll let me,

he sighs as she writhes politely. The land fades, the sea flocks silently away; and through the warm white cloud where he lies, silky, tingling, uneasy Eastern music undoes him in a Japanese minute.

The afternoon buzzes like lazy bees round the flowers round Mae Rose Cottage. Nearly asleep in the field of nannygoats who hum and gently butt the sun, she blows love on a puffball.

He loves me

He loves me not

He loves me

He loves me not

He loves me!—the dirty old fool.

Lazy she lies alone in clover and sweet-grass, seventeen and never been sweet in the grass ho ho.

The Reverend Eli Jenkins inky in his cool front parlour or poem-room tells only the truth in his Lifework—the Population, Main Industry, Shipping, History, Topography, Flora and Fauna of the town he worships in—the White Book of Llareggub. Portraits of famous bards and preachers, all fur and wool from the squint to the kneecaps, hang over him heavy as sheep, next to faint lady watercolours of pale green Milk Wood like a lettuce salad dying. His mother, propped against a pot in a palm, with her wedding-ring waist and bust like a black-clothed dining-table, suffers in her stays.

Oh, angels be careful there with your knives and forks,

he prays. There is no known likeness of his father Esau, who, undogcollared because of his little weakness, was scythed to the bone one harvest by mistake when sleeping with his weakness in the corn. He lost all ambition and died, with one leg.

Poor Dad,

grieves the Reverend Eli,

to die of drink and agriculture.

Farmer Watkins in Salt Lake Farm hates his cattle on the hill as he ho’s them in to milking.

Damn you, you damned dairies!

A cow kisses him.

Bite her to death!

he shouts to his deaf dog who smiles and licks his hands.

Gore him, sit on him, Daisy!

he bawls to the cow who barbed him with her tongue, and she moos gentle words as he raves and dances among his summerbreathed slaves walking delicately to the farm. The coming of the end of the Spring day is already reflected in the lakes of their great eyes. Bessie Bighead greets them by the names she gave them when they were maidens.

Peg, Meg, Buttercup, Moll,

Fan from the Castle,

Theodosia and Daisy.

They bow their heads.

Look up Bessie Bighead in the White Book of Llareggub and you will find the few haggard rags and the one poor glittering thread of her history laid out in pages there with as much love and care as the lock of hair of a first lost love. Conceived in Milk Wood, born in a barn, wrapped in paper, left on a doorstep, big-headed and bass-voiced she grew in the dark until long-dead Gomer Owen kissed her when she wasn’t looking because he was dared. Now in the light she’ll work, sing, milk, say the cows’ sweet names and sleep until the night sucks out her soul and spits it into the sky. In her life-long love light, holily Bessie milks the fond lake-eyed cows as dusk showers slowly down over byre, sea and town.

Utah Watkins curses through the farmyard on a carthorse.

Gallop, you bleeding cripple!

and the huge horse neighs softly as though he had given it a lump of sugar.

Now the town is dusk. Each cobble, donkey, goose and gooseberry street is a thoroughfare of dusk; and dusk and ceremonial dust, and night’s first darkening snow, and the sleep of birds, drift under and through the live dusk of this place of love. Llareggub is the capital of dusk.

Mrs Ogmore-Pritchard, at the first drop of the dusk-shower, seals all her sea-view doors, draws the germ-free blinds, sits, erect as a dry dream on a high-backed hygienic chair and wills herself to cold, quick sleep. At once, at twice, Mr Ogmore and Mr Pritchard, who all dead day long have been gossiping like ghosts in the woodshed, planning the loveless destruction of their glass widow, reluctantly sigh and sidle into her clean house.

You first, Mr Ogmore.

After you, Mr Pritchard.

No, no, Mr Ogmore. You widowed her first.

And in through the keyhole, with tears where their eyes once were, they ooze and grumble.

Husbands,

she says in her sleep. There is acid love in her voice for one of the two shambling phantoms. Mr Ogmore hopes that it is not for him. So does Mr Pritchard.

I love you both.

Oh, Mrs Ogmore.

Oh, Mrs Pritchard.

Soon it will be time to go to bed. Tell me your tasks in order.

We must take our pyjamas from the drawer marked pyjamas.

And then you must take them off.

Down in the dusking town, Mae Rose Cottage, still lying in clover, listens to the nannygoats chew, draws circles of lipstick round her nipples.

I’m fast. I’m a bad lot. God will strike me dead. I’m seventeen. I’ll go to hell,

she tells the goats.

You just wait. I’ll sin till I blow up!

She lies deep, waiting for the worst to happen; the goats champ and sneer.

And at the doorway of Bethesda House, the Reverend Jenkins recites to Llareggub Hill his sunset poem.

Every morning when I wake,

Dear Lord, a little prayer I make,

O please to keep Thy lovely eye

On all poor creatures born to die.

And every evening at sun-down

I ask a blessing on the town,

For whether we last the night or no

I’m sure is always touch-and-go.

We are not wholly bad or good

Who live our lives under Milk Wood,

And Thou, I know, wilt be the first

To see our best side, not our worst.

O let us see another day!

Bless us this night, I pray,

And to the sun we all will bow

And say, good-bye—but just for now!

Jack Black prepares once more to meet his Satan in the Wood. He grinds his night-teeth, closes his eyes, climbs into his religious trousers, their flies sewn up with cobbler’s thread, and pads out, torched and bibled, grimly, joyfully, into the already sinning dusk.

Off to Gomorrah!

And Lily Smalls is up to Nogood Boyo in the wash-house.

And Cherry Owen, sober as Sunday as he is every day of the week, goes off happy as Saturday to get drunk as a deacon as he does every night.

I always say she’s got two husbands,

says Cherry Owen,

one drunk and one sober.

And Mrs Cherry simply says

And aren’t I a lucky woman? Because I love them both.

Evening, Cherry.

Evening, Sinbad.

What’ll you have?

Too much.

The Sailors Arms is always open . . .

Sinbad suffers to himself, heartbroken,

. . . oh, Gossamer, open yours!

Dusk is drowned for ever until to-morrow. It is all at once night now. The windy town is a hill of windows, and from the larrupped waves the lights of the lamps in the windows call back the day and the dead that have run away to sea. All over the calling dark, babies and old men are bribed and lullabied to sleep.

Hushabye, baby, the sandman is coming . . .

Rockabye, grandpa, in the tree top,

When the wind blows the cradle will rock,

When the bough breaks the cradle will fall,

Down will come grandpa, whiskers and all.

Or their daughters cover up the old unwinking men like parrots, and in their little dark in the lit and bustling young kitchen corners, all night long they watch, beady-eyed, the long night through in case death catches them asleep.

Unmarried girls, alone in their privately bridal bedrooms, powder and curl for the Dance of the World.

[Accordion music: dim

They make, in front of their looking-glasses, haughty or come-hithering faces for the young men in the street outside, at the lamplit leaning corners, who wait in the all-at-once wind to wolve and whistle.

[Accordion music louder, then fading under

The drinkers in the Sailors Arms drink to the failure of the dance.

Down with the waltzing and the skipping.

Dancing isn’t natural,

righteously says Cherry Owen who has just downed seventeen pints of flat, warm, thin, Welsh, bitter beer.

A farmer’s lantern glimmers, a spark on Llareggub hillside.

[Accordion music fades into silence

Llareggub Hill, writes the Reverend Jenkins in his poem-room,

Llareggub Hill, that mystic tumulus, the memorial of peoples that dwelt in the region of Llareggub before the Celts left the Land of Summer and where the old wizards made themselves a wife out of flowers.

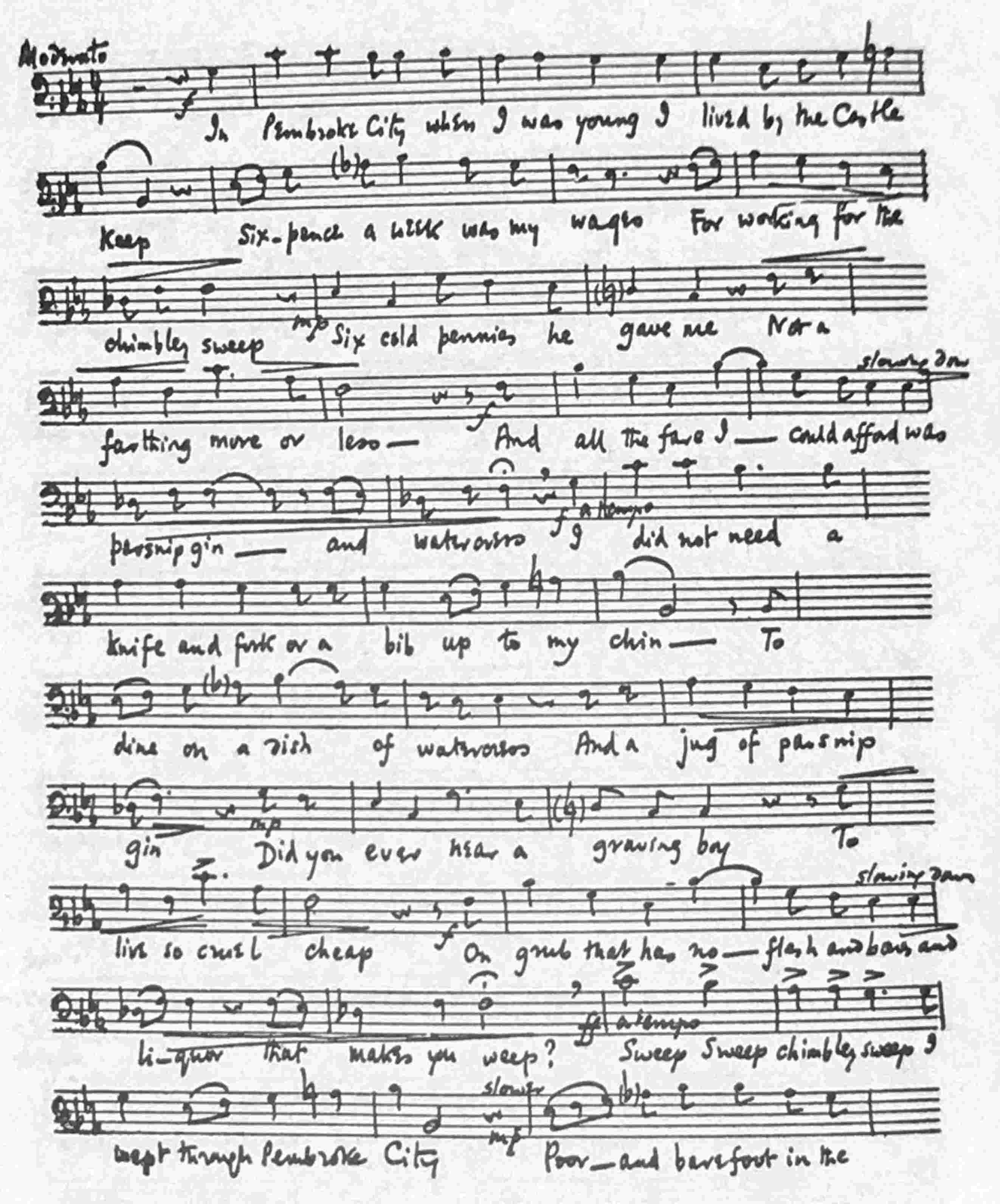

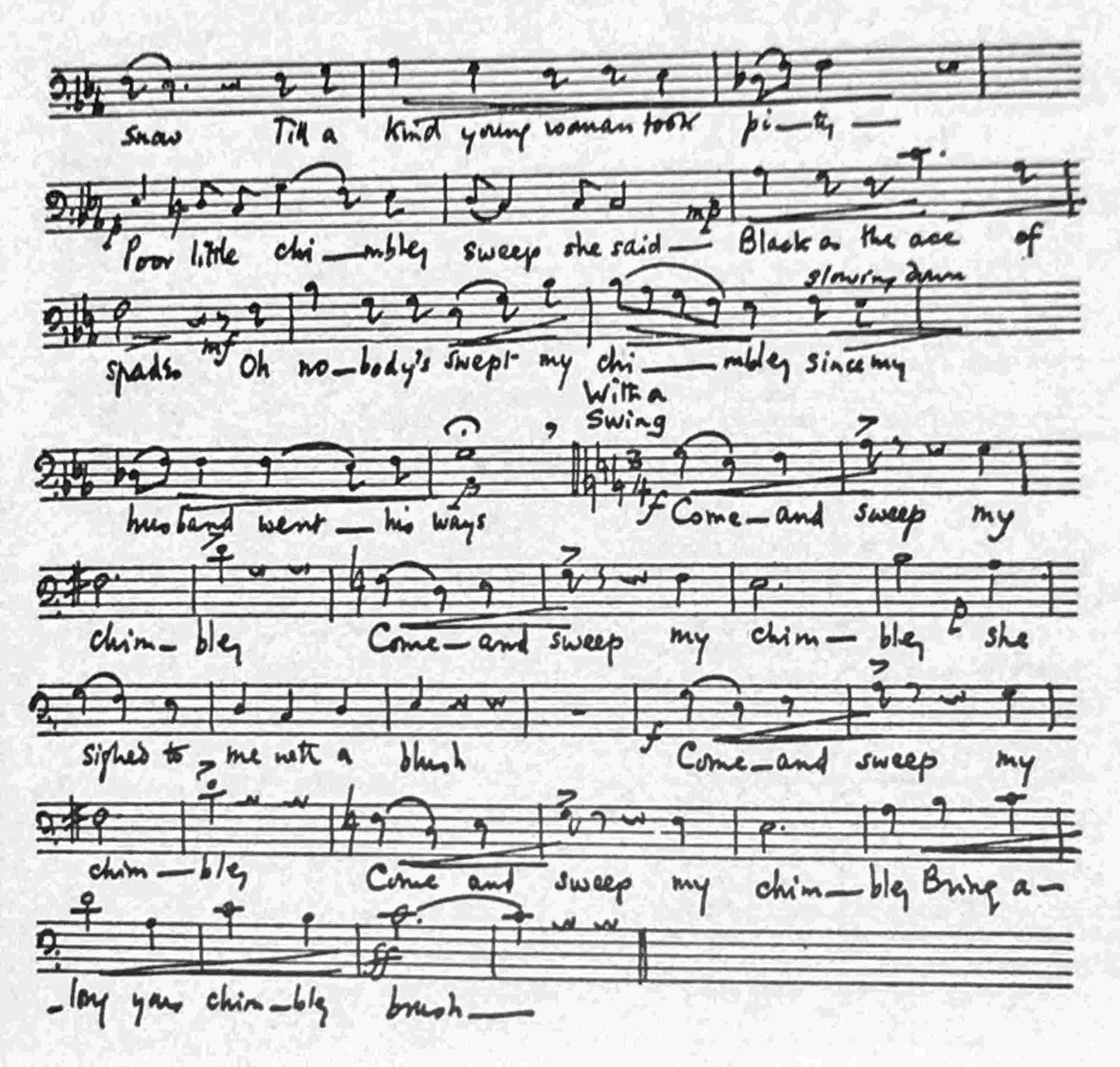

Mr Waldo, in his corner of the Sailors Arms, sings:

In Pembroke City when I was young

I lived by the Castle Keep

Sixpence a week was my wages

For working for the chimbley sweep.

Six cold pennies he gave me

Not a farthing more or less

And all the fare I could afford

Was parsnip gin and watercress.

I did not need a knife and fork

Or a bib up to my chin

To dine on a dish of watercress

And a jug of parsnip gin.

Did you ever hear a growing boy

To live so cruel cheap

On grub that has no flesh and bones

And liquor that makes you weep?

Sweep sweep chimbley sweep,