* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Biggles Fails to Return

Date of first publication: 1943

Author: Capt. W. E. (William Earl) Johns (1893-1968)

Date first posted: Aug. 18, 2023

Date last updated: Dec. 19, 2023

Faded Page eBook #20230837

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

This file was produced from images generously made available by Internet Archive/Lending Library.

Algy did not smile. ‘Stop fooling. Either come in or push off,’ he said curtly.

Bertie threw a glance at Ginger and came in.

‘I wasn’t going to mention this to you, Bertie, but as you’re here you might as well listen to what I have to say,’ resumed Algy.

‘Go ahead,’ said Ginger impatiently. ‘What’s on your mind?’

‘I’m very much afraid that something serious has happened to Biggles.’

There was silence while the clock on the mantlepiece ticked out ten seconds and threw them into the past.

‘Is this—official?’ asked Ginger.

‘No.’

‘Then what put the idea into your head?’

‘This,’ answered Algy, picking up a flimsy, buff-coloured slip of paper that lay on his desk. ‘I’m promoted to Squadron Leader with effect from to-day, and . . . I am now in command of this squadron.’

Captain W. E. Johns was born in Hertfordshire in

1893. He flew with the Royal Flying Corps in the

First World War and made a daring escape from a

German prison camp in 1918. Between the wars he

edited Flying and Popular Flying and became a writer

for the Ministry of Defence. The first Biggles story,

Biggles the Camels are Coming was published in 1932,

and W. E. Johns went on to write a staggering

102 Biggles titles before his death in 1968.

BIGGLES BOOKS

PUBLISHED IN THIS EDITION

First World War:

Biggles Learns to Fly

Biggles Flies East

Biggles the Camels are Coming

Biggles of the Fighter Squadron

Second World War:

Biggles Defies the Swastika

Biggles Delivers the Goods

Biggles Defends the Desert

Biggles Fails to Return

Was this a trap? Bertie wondered.

BIGGLES

FAILS to RETURN

Captain W.E. Johns

RED FOX

BIGGLES FAILS TO RETURN

First published in Great Britain by Hodder and Stoughton 1943

Copyright © W E Johns (Publications) Ltd, 1943

| Contents | ||

| 1 | Where is Biggles? | 7 |

| 2 | The Reasonable Plan | 23 |

| 3 | The Road to Monte Carlo | 34 |

| 4 | The Writing on the Wall | 50 |

| 5 | Bertie Meets a Friend | 66 |

| 6 | Strange Encounters | 80 |

| 7 | Good Samaritans | 86 |

| 8 | Jock’s Bar | 92 |

| 9 | The Girl in the Blue Shawl | 102 |

| 10 | Shattering News | 111 |

| 11 | The Cats of Castillon | 125 |

| 12 | Bertie Picks a Lemon | 136 |

| 13 | Pilgrimage to Peille | 147 |

| 14 | Au Bon Cuisine | 161 |

| 15 | Conference at Castillon | 173 |

| 16 | Biggles Takes Over | 185 |

| 17 | Plan for Escape | 196 |

| 18 | How the Rendezvous Was Kept | 206 |

| 19 | Farewell to France | 215 |

Flight Lieutenant Algy Lacey, D.F.C., looked up as Flying Officer ‘Ginger’ Hebblethwaite entered the squadron office and saluted.

‘Hello, Ginger—sit down,’ invited Algy in a dull voice.

Ginger groped for a chair—groped because his eyes were on Algy’s face. It was pale, and wore such an expression as he had never before seen on it.

‘What’s happened?’ he asked wonderingly.

Before Algy could answer there was an interruption from the door. It was opened, and the effeminate face of Flight Lieutenant Lord ‘Bertie’ Lissie grinned a greeting into the room.

‘What cheer, how goes it, and all that?’ he murmured.

Algy did not smile. ‘Stop fooling. Either come in or push off,’ he said curtly.

Bertie threw a glance at Ginger and came in.

‘I wasn’t going to mention this to you, Bertie, but as you’re here you might as well listen to what I have to say,’ resumed Algy.

‘Go ahead,’ said Ginger impatiently. ‘What’s on your mind?’

‘I’m very much afraid that something serious has happened to Biggles.’

There was silence while the clock on the mantelpiece ticked out ten seconds and threw them into the past.

‘Is this—official?’ asked Ginger.

‘No.’

‘Then what put the idea into your head?’

‘This,’ answered Algy, picking up a flimsy, buff-coloured slip of paper that lay on his desk. ‘I’m promoted to Squadron Leader with effect from to-day, and . . . I am now in command of this squadron.’

‘Which can only mean that Biggles isn’t coming back?’ breathed Ginger.

Which can only mean that Biggles isn’t coming back?

‘That’s how I figure it.’

‘And you had no suspicion, before this order came in, that—’

‘Yes and no,’ broke in Algy. ‘That is to say, I was not consciously alarmed, but as soon as I read that chit I knew that I had been uneasy in my mind for some days. Now, looking back, I can remember several things which make me wonder why I wasn’t suspicious before.’

‘But here, I say, you know, I thought Biggles was on leave?’ put in Bertie, polishing his eyeglass briskly.

‘So did we all,’ returned Algy quietly. ‘That, of course, is what we were intended to think.’

Bertie thrust his hands into his pockets. ‘Biggles isn’t the sort of chap to push off to another unit without letting us know what was in the wind,’ he declared.

‘Let us,’ suggested Algy, ‘consider the facts—as Biggles would say. Here they are, as I remember them, starting from the beginning. Last Thursday week Biggles had a phone call from the Air Ministry. There was nothing strange about that. I was in the office at the time and I thought nothing of it. When Biggles hung up he said to me—I remember his words distinctly—“Take care of things till I get back!” I said “Okay.” Of course, that has happened so many times before that I supposed it was just routine. Biggles didn’t get back that night till after dinner. He seemed sort of preoccupied, and I said to him, “Is everything all right?” He said, “Of course—why not?”’ Algy paused to light a cigarette with fingers that were trembling slightly.

‘The next morning—that is, on the Friday—he surprised me by saying that he was taking the week-end off. I was surprised because, as you know, he rarely goes away. He has nowhere particular to go, and he has more than once told me that he would as soon be on the station as anywhere.’

‘And you think this business starts from that time?’ remarked Ginger.

‘I’m sure of it. Biggles can be a pretty good actor when he likes, and there was nothing in his manner to suggest that anything serious was afoot. He tidied up his desk, and said he hoped to be back on Monday—that is, last Monday as ever was. We need have no doubt that when he said that he meant it. He hoped to be back. In other words, he would have been back last Monday if the thing—whatever it was—had gone off all right. When he went away he looked at me with that funny little smile of his and said, “Take care of things, old boy.” Being rather slow in the uptake, I saw nothing significant about that at the time, but now I can see that it implied he was not sure that he was coming back.’

Ginger nodded. ‘That fits in with how he behaved with me. Normally, he’s a most undemonstrative bloke, but he shook hands with me and gave me a spot of fatherly advice. I wondered a bit at the time, but, like you, I didn’t attach any particular importance to it.’

‘It wasn’t until after he’d gone,’ continued Algy, ‘that I discovered that he’d left the station without leaving an address or telephone number. Knowing what a stickler he is for regulations, it isn’t like him to break them himself by going off without leaving word where he could be found in case of emergency. That was the last we’ve seen of him. I didn’t think anything of it until Wednesday, when I had to ring up Forty Squadron. It was their guest night, and Biggles was to be guest of honour. He had accepted the invitation. Biggles doesn’t accept invitations and then not turn up. When he accepted that one you can bet your life he intended to be there; and the fact that he didn’t turn up, or even ring up, means that he couldn’t make it. It must have been something serious to stop him. I began to wonder what he could be up to. Yesterday I was definitely worried, but when this Group order came in this morning, posting me to the command of the squadron, it hit me like a ton of bricks. To sum up, I suspect the Ministry asked Biggles to do a job, a job from which there was a good chance he wouldn’t come back. He went. Whatever the job was, it came unstuck. He didn’t get back. It takes a bit of swallowing, but there it is. It’s no use blinking at facts, but the shock has rather knocked me off my pins. I thought you’d better know, but don’t say anything to the others—yet.’

Ginger spoke. ‘If the Air Ministry has given you the squadron they must know he isn’t coming back.’

Algy nodded. ‘I’m afraid you’re right.’

Bertie stepped into the conversation. ‘But that doesn’t make sense—if you see what I mean? If the Ministry knows that something has happened to Biggles his name would be in the current casualty list—killed, missing, prisoner, or something.’

‘That depends on what sort of job it was,’ argued Algy. ‘The Ministry might know the truth, but it might suit them to say nothing.’

‘But that isn’t good enough,’ protested Ginger hotly. ‘We can’t let Biggles fade out . . . just like that.’ He snapped his fingers.

‘What can we do about it?’

‘There’s one man who’ll know the facts.’

‘You mean—Air Commodore Raymond, of Intelligence?’

‘Yes.’

‘He won’t tell us anything.’

‘Won’t he, by thunder!’ snorted Ginger. ‘After all the sticky shows we’ve done for him, and the risks we’ve taken for his department, he can’t treat us like this.’

‘Are you going to tell him that?’ asked Algy sarcastically.

‘I certainly am.’

‘But it’s against orders to go direct to the Air Ministry—you know that.’

‘Orders or no orders, I’m going to the Air House,’ declared Ginger. ‘They’re glad enough to see us when they’re stuck with something they can’t untangle; they can’t shut the door when they don’t want to see us. Oh, no, they can’t get away with that. I’m going to see the Air Commodore if I have to tear the place down brick by brick until I get to him. Is he a man or is he a skunk? I say, if he’s a man he’ll see us, and come clean.’

‘You go on like this and we shall all finish under close arrest.’

‘Who cares?’ flaunted Ginger. ‘I want to know the truth. If Biggles has been killed—well, that’s that. What I can’t stand is this uncertainty, this knowing nothing. Dash it, it isn’t fair on us.’

‘I am inclined to agree with you,’ said Algy grimly. ‘Ours has been no ordinary combination, and Raymond knows that as well as anybody. Let’s go and tackle the Air Commodore. He can only throw us out.’

‘Here, I say, what about me?’ inquired Bertie plaintively. ‘Don’t I get a look in?’

‘Come with us, and we’ll make a deputation of it,’ decided Algy.

An hour later an Air Ministry messenger was showing them into an office through a door on which was painted in white letters the words, Air Commodore R. B. Raymond, D.S.O. Air Intelligence. The Air Commodore, who knew Algy and Ginger well, and had met Bertie, shook hands and invited them to be seated.

‘You know, of course, that you had no business to come here on a personal matter without an invitation?’ he chided gently, raising his eyebrows.

‘This is more than a personal matter, sir,’ answered Algy. ‘It’s a matter that concerns the morale of a squadron. You’ve probably guessed what it is?’

The Air Commodore nodded. ‘I know. I was wondering how long you would be putting two and two together. Well, I’m very sorry, gentlemen, but there is little I can tell you.’

‘Do you mean you can’t or you won’t, sir?’ demanded Ginger bluntly.

‘What exactly is it you want to know?’

Algy answered: ‘Our question is, sir, where is Biggles?’

‘I wish I knew,’ returned the Air Commodore slowly, and with obvious sincerity.

‘But you know where he went?’

‘Yes.’

‘Will you tell us that?’

‘What useful purpose would it serve?’

‘We might be able to do something about it.’

‘I’m afraid that’s quite out of the question.’

‘Do you mean—he’s been killed?’

‘He may be. In fact, what evidence we have all points to that. But we have no official notification of it.’

There was a brief and rather embarrassing silence. The Air Commodore gazed through the window at the blue sky, drumming on his desk with his fingers.

‘Knowing what we have been to each other in the past, sir, don’t you think we are entitled to some explanation?’ pressed Algy.

‘The matter is secret.’

‘So were a good many other things you’ve told us about in the past, sir, when you needed Biggles to straighten them out.’

The Air Commodore appeared to reach a decision. He looked round. ‘Very well,’ said he. ‘Your argument is reasonable, and I won’t attempt to deny it. I’ll tell you what I know—in the strictest confidence, of course.’

‘We’ve never let you down yet, sir,’ reminded Algy.

‘All right. Don’t rub it in.’ The Air Commodore smiled faintly, then became serious. ‘Here are the facts. About ten days ago we received information that a very important person whom I need not name, but who I will call Princess X, had escaped from Italy. This lady is an Italian, or, rather, a Sicilian, one of those who hate Mussolini[1] and all his works. Her father, well known before the war for his anti-Fascist views, was killed in what was alleged to be an accident. Actually he was murdered. Princess X knew that, and she plotted against the regime. Mussolini’s police found out, and when Italy entered the war she was arrested. Friends—members of a secret society—inside Italy helped her to escape. She was to make for Marseilles, where we had made arrangements to pick her up. Unfortunately, she was pursued, and in the hope of eluding her pursuers she struck off at a tangent and eventually reached the Principality of Monaco, in the south-east corner of France, where she knew someone, a wealthy Italian business man, a banker, whom she had befriended in the past. She thought he would give her shelter. She reached his villa safely, and got word through to us by one of our agents who was in touch with her, giving us the address, and imploring us to rescue her. By this time the hue and cry was up, and it would have been suicidal for her to attempt to reach Marseilles, or a neutral country—Spain, for instance—alone. We were most anxious to have her here, and we realized that if anything was to be done there was no time to lose. We decided to attempt to rescue her by air. We sent for Bigglesworth, who has had a lot of experience at this sort of thing, and asked his opinion. He offered to do the job.’

‘You mean, go to Monaco, pick up the princess and bring her here?’

‘Yes. But the job was not as easy as it sounds—not that it sounds easy. The difficulty did not lie so much in getting Biggles there, because he could be dropped by parachute; but to pick him up was a different matter. That meant landing an aircraft. There is no landing ground in Monaco itself, which is nearly all rock, and mostly built over as well. For that matter there are very few landing grounds in the Alpes Maritimes—the department of France in which Monaco is situated. It was obviously impossible for Biggles to fly the aircraft himself, because during the period while he would be fetching the princess—perhaps a matter of two or three days—the machine would be discovered. So we called in a man who knows every inch of the country, a man who was born there, a Monégasque[2] who is now serving with the Fighting French[3]. It was decided to drop Biggles by parachute and pick him up twenty-four hours later at a place suggested by this lad, whose name, by the way, is Henri Ducoste. Ducoste suggested a level area of beach just west of Nice, about twenty miles from Monaco, a spot that in pre-war days was used for joy-riding.’

‘Why so far away?’ asked Ginger.

‘Because, apparently, there is nowhere nearer. Monaco is a tiny place. All told, it only covers eight square miles. Almost from the edge of the sea the cliffs rise steeply to a couple of thousand feet, and, except for a few impossible slopes, the whole principality is covered with villas and hotels. The fashionable resort, Monte Carlo, occupies most of it. The actual village of Old Monaco, and the palace, are built on a spur of rock. There is no aerodrome. In fact, there isn’t an airport nearer than Cannes, some thirty miles to the west.’

‘I understand, sir,’ said Ginger.

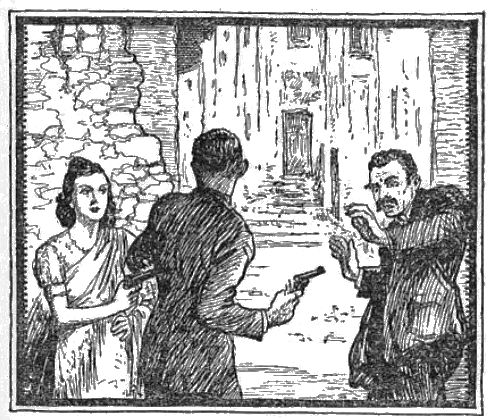

The Air Commodore resumed. ‘Well, Biggles went. Precisely what occurred in Monaco we don’t know; it seems unlikely that we shall ever know, but as far as we have been able to deduce from the meagre scraps of information that our agents have collected, what happened was this. Biggles walked into a trap. The Princess was not at the villa. She had been betrayed by her supposed friend, presumably for the big reward that had been offered, and was in custody, in the civil prison, awaiting an escort to take her back to Italy. It seems that not only did Biggles extricate himself from the trap, but almost succeeded in what must have been the most desperate enterprise of his career. He rescued the Princess from the prison, and actually used an Italian police car to make his getaway. In this car he and the Princess raced to Nice, using that formidable highway that cuts through the tops of the mountains overlooking the sea, known as the Grande Corniche. The car was followed, of course, but Biggles got to the landing ground just ahead of his pursuers. Ducoste was there, waiting. The moon made everything plain to see.’ The Air Commodore paused to light a cigarette.

‘The story now becomes tragic,’ he continued. ‘What I know I had from the lips of Ducoste. Biggles and the princess left the car and ran towards the aircraft, closely followed by the Italians. To enable you to follow the story closely I must tell you that the machine was an old Berline Breguet, a single-engined eight-seater formerly used by the Air France Company on their route between London and the Riviera. As a matter of detail, this particular machine was the one in which Ducoste made his escape from France. The decision to use it was his own. Between the cockpit and the cabin there is a bulkhead door with a small glass window in it so that the pilot can see his passengers. I’m sorry to trouble you with these details, but, for reasons which you will appreciate in a moment, they are important. As I have said, Biggles and the princess, closely pursued, ran towards the machine. Ducoste, who was watching from the cockpit, with his engine ticking over, saw that it was going to be a close thing. Biggles shouted to the princess to get aboard and tried to hold the Italians with his pistol. We can picture the situation—the princess near the machine, with Biggles, a few yards behind, walking backwards, fighting a rearguard action. The princess got aboard, whereupon Biggles yelled to Ducoste to take off without him. Naturally, Ducoste, who does not lack courage, hesitated to do this. What I must make clear is, the princess actually got aboard. Of that there is no doubt. Ducoste felt the machine move slightly, in the same way that one can feel a person getting into a motor-car. He looked back through the little glass window and saw the face of the princess within a few inches of his own. She appeared to be agitated, and made a signal which Ducoste took to mean that he was to take off. I may say that all this is perfectly clear in Ducoste’s mind. He looked out and saw Biggles making a dash for the machine; but before Biggles could reach it he fell, apparently hit by a bullet. Ducoste, from his cockpit, could do nothing to help him. By this time bullets were hitting the machine, and in another moment they must all have been caught. In the circumstances he did the most sensible thing. He took off. Remember, there was no doubt in his mind about the princess being on board. He had actually seen her in the machine. He made for England, and after a bad journey, during which he was several times attacked by enemy fighters, he reached his base aerodrome. Judge his consternation when he found the cabin empty. The princess was not there. The cabin door was open. Poor Ducoste was incoherent with mortification and amazement. The last thing he saw before he took off was Biggles lying motionless on the ground, and two Italians within a dozen yards, running towards him. The last he saw of the princess she was in the machine.’

Algy drew a deep breath. ‘And that’s all you know?’

‘That is all we know.’

‘No word from Monaco?’

‘Nothing.’

There was a brief silence.

‘Ducoste has absolutely no idea of what happened to the princess?’ asked Ginger.

‘None whatever, although the obvious assumption is that she fell from the aircraft some time during the journey from the South of France to England. What else can we think?’

‘No report of her body having been found?’

‘Not a word.’

‘What an incredible business,’ muttered Algy. ‘As far as Biggles is concerned, the Italians must know about him from their Nazi friends. One would have thought that had he been killed the enemy would have grabbed the chance of boasting of it—that’s their usual way of doing things.’

‘One would think so,’ agreed the Air Commodore. ‘But it seems certain that if he wasn’t killed he must have been badly wounded, in which case he would have been captured, which comes to pretty much the same thing. But I don’t overlook the possibility that it may have suited the enemy to say nothing about the end of a man who has given them so much trouble. From every point of view it is a most unsatisfactory business.’

Tell me, sir; how was Biggles dressed for this affair?’ asked Ginger. ‘Was he in uniform?’

‘Well, he was and he wasn’t. I know he has a prejudice against disguises, but this was an occasion when one was necessary. He could hardly walk about Monaco in a British uniform, so he wore over it an old blue boiler suit, which he thought would give him the appearance of a workman of the country.’

‘And you don’t expect to hear anything more, sir?’

‘Frankly, no. There is just one hope—a remote one, I fear. I had a private arrangement with Biggles. Realizing that there was a chance of his picking up useful information which, in the event of failure, he would not be able to get home, he took with him a blue pencil, the idea being that we could profit by what he had learned should he fail, and should we decide to follow up with another agent. He said that should he be in Monaco he would write on the stone wall that backs the Quai de Plaisance, in the Condamine—that is, the lower part of Monaco in which the harbour is situated. If he were in Nice he would write on the wall near Jock’s Bar, below the Promenade des Anglais. His signature would be a blue triangle.’

‘Have you checked up to see if there is such a message?’ queried Algy.

‘No,’ admitted the Air Commodore.

‘Why not?’

‘The place is swarming with police. In any case, there seemed to be no point in it, because whatever Biggles wrote before the rescue would be rendered valueless after what happened on the landing ground. Right up to the finish he must have hoped to get home, and after that time it seems unlikely to say the least that he would have an opportunity for writing.’

‘But, sir,’ put in Ginger, ‘haven’t you thought of trying to rescue Biggles?’

‘I have, but it seemed hopeless.’

‘Why? Nothing is ever hopeless.’

‘But consider the circumstances. Biggles was last seen lying on the ground, dead or unconscious, right in front of his pursuers.’

‘Yet you admit that if they had got him they would probably have issued a statement?’

‘That doesn’t necessarily follow.’

‘Why should they withhold the information?’

‘I could think of several reasons. The princess has friends in Italy, and Mussolini might fear repercussions, if it became known that she had been killed. Again the enemy might think that if they kept silent we should send more agents down to find out what happened, and thus they would catch more birds in the same trap. Neither side willingly tells the other anything, for which reason we have refrained from putting Biggles’ name in the casualty list.’

‘You don’t hold out any hope for him?’

‘How can I?’

‘And the princess?’

‘The chances of her survival seem even more remote. If she was not killed on the landing ground, then she certainly must have lost her life when she fell from the aircraft.’

Algy looked straight at the Air Commodore. ‘I think it’s about time somebody found out just what did happen, sir,’ he said curtly.

‘Absolutely—yes, by Jove—absolutely,’ breathed Bertie.

‘I’m sorry, but I have no one to send.’

‘Then perhaps you would use your influence to get me ten days leave, sir?’ suggested Algy meaningly.

The Air Commodore’s expression did not change. ‘Are you thinking of going to Monaco?’

‘I shan’t sleep at night until I know what happened to Biggles.’

‘That goes for all of us, sir,’ interposed Ginger.

‘But be reasonable, you fellows,’ protested the Air Commodore. ‘I know exactly how you feel, but war isn’t a personal matter . . .’

‘You didn’t take that view when you were trying to rescue the princess,’ returned Algy shortly. ‘Frankly, I don’t care two hoots about her, because I’ve never seen her and I’m never likely to; but Biggles happens to be my best friend. Apart from which, he is one of the most valuable officers in the service. Surely it is worth going to some trouble to try to get him back—or at least, find out what happened to him?’

‘I agree, but the chances of success are so small that they are hardly worth considering.’

‘I am sorry, sir, but I can’t agree with you there,’ replied Algy bluntly. ‘Until I know Biggles is dead I shall assume that he is alive. Get me ten days leave and I’ll find out what happened to him.’

‘Include me in that, sir,’ put in Ginger.

‘And me, sir,’ murmured Bertie.

The Air Commodore looked from one to the other. ‘Just what do you think you are going to do?’

Algy answered. ‘I don’t know, except that we are going to find out what happened to Biggles. If the thing was the other way round, do you suppose he’d be content to sit here knowing that we were stuck in enemy country? Not on your life!’

‘It is my opinion that Biggles is dead,’ asserted the Air Commodore.

‘I had already sensed that, sir, but I don’t believe it,’ retorted Algy. ‘Call it wishful thinking if you like, but I’ll believe it when I’ve seen his body, not before.’

The Air Commodore shrugged his shoulders. ‘All right,’ he said crisply. ‘Have it your own way. Think of a reasonable scheme and I’ll consider it.’

Algy rose and picked up his cap. ‘Thank you, sir. It is now twelve o’clock. We’ll go and have some lunch, and be back here at two.’

The Air Commodore nodded. ‘Very well.’

[1] Benito Mussolini—Fascist dictator of Italy. Joined with Germany in the war against Britain and her allies in 1940.

[2] A native of Monaco.

[3] After France was occupied by the Germans, those members of the French forces who managed to escape set up a new headquarters in Britain led by General de Gaulle. They continued fighting from there and were known as the Fighting French or Free French.

Over lunch, and afterwards, in a secluded corner of the Royal Air Force Club, in Piccadilly, Algy, Bertie and Ginger, discussed the situation that had arisen. Neither Algy nor Ginger had ever been to Monaco, so they were somewhat handicapped; but it turned out that to Bertie the celebrated little Principality was a sort of home from home. For several years he had gone there for the ‘season’ as a competitor in the international motor-car race called the Monte Carlo Rally. He had competed in the motor-boat trials, had played tennis on the famous courts, and golf on the links at Mont Agel. He had stayed at most of the big hotels, and had been a guest at many of the villas owned by leading members of society. As a result, he not only knew the principality intimately, but the country around it.

‘Why didn’t you tell the Air Commodore this?’ asked Algy.

‘Never play your trump cards too soon—no, by Jove,’ murmured Bertie, and then went on to declare that if only they could get to Monaco he knew of places where they could hide.

‘It seems to be taken for granted that we are all going,’ observed Algy.

Bertie and Ginger agreed—definitely.

‘Then the first question we must settle is, how are we going to get there?’

‘There doesn’t seem to be much choice,’ Ginger pointed out. ‘Either we can land on this beach aerodrome near Nice, or we can bale out. But however we go down, someone will have to bring the machine back. We all want to stay there, so I suggest that we ask Raymond to lend us his Monégasque pilot—the bloke who flew Biggles. He must know the lie of the land a lot better than we shall find out from the map.’

‘That’s a good idea,’ agreed Algy. ‘Do we land or do we jump?’

‘If this lad knows the country I’m in favour of landing,’ declared Bertie. ‘It’s pretty rough for jumping—rocks and things all over the place.’

‘All right. Let us say that we land,’ went on Algy. ‘Having landed, do we stay together or do we work separately?’

‘I’m in favour of working separately,’ said Ginger. ‘That gives us three chances against one. If we stay together, and anything goes wrong, we all get captured. If everyone takes his own line we shall avoid that, and at the same time cover more ground. I propose that we work separately, but each knowing roughly what the others are going to do. We might have a rendezvous where we can get in touch and compare notes.’

‘Yes, I think that’s sound reasoning,’ agreed Algy, and Bertie confirmed it. ‘How are we going—I mean, we can’t stroll about Monte Carlo in uniform? I speak French pretty well, so I could put on a suit of civvies and pretend to be a French prisoner of war just repatriated from Germany. That would account for my being out of touch with things. What about you, Bertie?’

‘Well, I speak the jolly old lingo, and I know my way about. That ought to do.’

Algy looked doubtful. ‘People may wonder what an able-bodied chap like you is doing, strolling about with no particular job.’

‘I’ll take my guitar and be an out-of-work musician—how’s that?’ Bertie smiled at the expressions on the faces of the others. ‘Strolling players are common in the South of France,’ he explained. ‘They make a living playing round the pub doors, and that sort of thing. By Jove, yes; I could do the jolly old Blondin act, playing a tune round the likely places, trusting that Biggles would recognize it if he were about. Biggles would know that piece I play with all the twiddly bits. He once told me he’d never forget it.’

Algy smiled. ‘All right. What about you, Ginger?’

Ginger looked glum. ‘My trouble is I can’t speak French—or not enough to amount to anything. I can speak a bit, enough to make myself understood, but I couldn’t pass as a Frenchman. I speak better Spanish. Before the war we spent more time in Spain, and Spanish America, than in France.’

‘But we’re not going to Spain. We’re going to France,’ Algy pointed out sarcastically.

‘Just a minute though, I think I’ve got something,’ put in Bertie. ‘Yes, by jingo, that’s it. Ginger can be a Spaniard.’

‘Doing what?’

‘Selling onions. In the same way those chappies from northern France used to come over to England with their little strings of onions, the lads from Spain surge along the Riviera selling the jolly old vegetable. Or if he likes he can be a bullfighter looking for work—they still have bull-fights in the South of France.’

‘Not for me,’ declared Ginger. ‘I might be offered a job. I’ll sell onions.’

‘Where are you going to get the onions?’ inquired Algy.

‘Plenty on the aerodrome. You forget our lads have turned market gardeners.’

‘Okay, then we’ll call that settled. But we seem to have overlooked the most important thing of all. How are we going to get back?’

‘By Jove, that’s a nasty one,’ muttered Bertie. ‘I’d clean forgotten about the return tickets.’

‘There’s only one way,’ asserted Ginger. ‘Assuming that Ducoste will take us over, he’ll have to pick us up again. We should have to fix a place and time. Naturally, we should all have to keep that date, whatever happened. If we don’t locate Biggles, or find out what happened to him, in that time, the chances are that we never should. If we finish before that time we should just have to lie doggo until the plane came for us. We could flash a light signal to Ducoste to let him know that it was okay to land.’

‘I can’t think of anything better than that,’ admitted Algy. ‘Of course, if we made a mess of things we shouldn’t be there, anyway, in which case Ducoste would push off again. We couldn’t ask him to hang about. Anything else?’

‘That seems to be about as far as we can get,’ opined Ginger. ‘When we get back to the aerodrome, are you going to let the others in on this?’

‘No,’ decided Algy. ‘The whole squadron would want to come. We can’t have that—the show would begin to look like a commando raid, or an invasion. Angus can take over while I’m away. Well, let’s get along and put the proposition to the Air Commodore. We can fix the details later.’

‘What details?’ asked Ginger.

‘We shall need French money, forged identity papers, and so on. Raymond will get those for us if he approves the scheme.’

‘If he does, when are we going to start?’

‘Obviously, just as soon as we are ready,’ answered Algy. ‘The sooner we are on the spot the better. We ought to be away by to-morrow night at latest.’ He got up. ‘Let’s get back to the Ministry. I’m anxious to get this thing settled.’

Half an hour later he was laying the proposition before Commodore Raymond, who listened patiently until he had finished.

‘You fellows are all old enough to know what you’re doing,’ said the Air Commodore quietly, at the conclusion. ‘But for the fact that you have had experience in this sort of deadly work I wouldn’t consider the project. However, your previous successful operations do entitle you to special consideration. I must say, though, that I shall be very much surprised if I see any of you again until the end of the war—if then. By discarding your uniforms you will become spies, in which case, it is hardly necessary for me to tell you, it is no use appealing to me if you are caught[1]. I’m sorry if that sounds discouraging, but we must face the facts. I’ll make arrangements with your Group for you to go on leave, and supply you with such things as you think you will require, as far as it is in my power. I’ll get in touch with Ducoste right away and tell him to telephone you at the squadron. He volunteered for the last show, and I have no doubt he’ll do so again. He can have the Breguet. It will be less likely to attract attention over France than one of our machines, and at the same time save us from using—I nearly said losing—one of ours. If he’s caught he’ll be shot, so don’t let him down. Anything else?’

‘Just one thing, sir,’ requested Ginger. ‘What is the name of the Italian businessman you mentioned, the fellow at whose villa the princess hoped to stay—the skunk who let her down?’

‘The man is a retired Milanese banker named Zabani—Gaspard Zabani. His place is the Villa Valdora, in the Avenue Fleurie. Why did you ask that?’

‘Since, apparently, he is well in with the Italian secret police, he may know how his betrayal of the princess ended. He might be induced to speak.’

A ghost of a smile crossed the Air Commodore’s face. ‘I see. As far as I’m concerned you can do what you like with him. He must be an exceptionally nasty piece of work. But while we are on the subject of the Italian secret police, be careful of a fellow named Gordino. He is in charge of things on the Riviera. He’s a short, dark, stoutish, middle-aged man—usually wears a dark civilian suit. He’s got an upturned black moustache and a scar on his chin. He looks rather like a prosperous little grocer, but don’t be deceived by that. He’s a cunning devil.’

‘What a bounder the blighter must be,’ murmured Bertie in his well-dressed voice.

‘Matter of fact, he is,’ agreed the Air Commodore, smiling. He stood up. ‘And now, gentlemen, if that’s all, I must ask you to be on your way. I’ve a pile of work in front of me. I’ll get Henri Ducoste to ring you later.’

‘Thank you, sir, for giving us so much of your time,’ said Algy. ‘We are grateful to you for being frank and for giving us this chance. Biggles shall know about it—when we find him.’

‘Bring Biggles back alive and I shall be amply repaid,’ returned Air Commodore Raymond. ‘Good luck to you.’

Still discussing the plan the deputation returned to the aerodrome.

At nine o’clock that night an officer in the uniform of the Fighting French Air Force walked into the anteroom. Ginger saw him first, and guessed at once who he was, although they had been expecting a phone call, not a personal appearance. Nudging Bertie, he went to meet the visitor.

‘Henri Ducoste?’ he queried.

Smiling, the French airman nodded assent. He was a slim, dark young man, with straight, rather long black hair, and a shy manner. Ginger had visualized—not that the Air Commodore had given any reason for it—an older man. He judged him to be not more than nineteen.

Having introduced himself and Bertie, Ginger took his arm, saying, ‘Let’s get out of the crowd.’ They went to the station office where Algy was busy clearing up some squadron matters to leave everything shipshape for Angus to take over. Henri was introduced.

‘I have spoken with your Air Commodore,’ he said in fair English. ‘Better than the telephone, I think I come here and talk.’

‘Much better idea,’ agreed Algy. ‘Sit down. Cigarette? Did the Air Commodore tell you just what we had in mind?’

‘Yes, he tells me all you know, I think.’

‘You know we want you to fly us to Monaco?’

‘But yes.’

‘How do you feel about it?’

Henri shrugged his shoulders. ‘How you say? Okay wiz me. I go anywhere. What does it matter?’

‘That’s the spirit,’ returned Algy.

‘Only with one thing I do not agree so much,’ went on Henri, frankly.

‘What’s that?’

‘I understand not quite this making of a landing at Californie, on the beach by Nice.’

‘What’s wrong with that?’

‘Tiens! We have use it one time. The Italian mens are not of the most clever, but they are not always the fools. They stop any more landings at Nice, I think. Perhaps there may be now the trench, the wire, or the big sticks of wood, to make a crash.’ Henri shrugged. ‘I don’t know, but it would be good to make sure.’

‘By Jove, you know, the lad’s right—absolutely right,’ declared Bertie. ‘No bally use busting ourselves right at the word go, or anything like that—if you see what I mean?’

‘I see what you mean all right,’ agreed Algy thoughtfully. ‘It would be taking a pretty hefty risk to use this landing ground without first confirming that there were no obstructions. I always realized that, but I couldn’t think of an alternative. Of course, once we were there we could check up, and if the place was all right we could use it to go home from.’ To Henri he said, ‘Can you think of a better plan?’

‘There are two ways more,’ announced Henri. ‘Either we find another aerodrome or you use the parachute. There is no other aerodrome for many kilometres. Alors! I think it better to use the parachute.’

‘That seems to be a sound argument,’ agreed Algy, ‘but I was given to understand that the country round Monaco was dangerous for parachute landings—rocks and ravines, and so on?’

‘Oui. But there are places where the rocks are not too close. I live all my life at Monaco. I know such a place. It is much nearer to Monaco than Californie, only three, perhaps four, miles. Regardez[2]. Here is my map. I show you.’

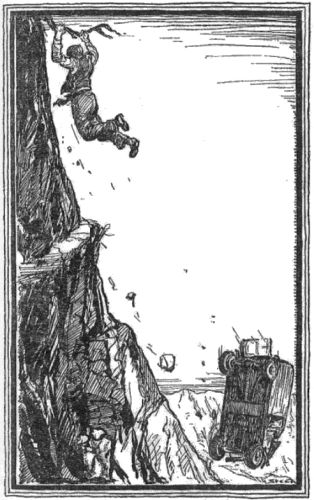

Henri unfolded his map on the desk. ‘Voila!’ he continued. ‘Here we have Monaco. There are three roads. One, she go east to Italy. Two, she go west to Nice, Cannes, and sometime to Marseilles. Three, she go north, very steeply up the mountain, to the village of La Turbie. Behind La Turbie a road the most small she goes to Peille. On the left of the road, we have a wide valley, many kilometres long. Men who make the farm in the valley, they clear away all the big rock. You jump there and you make only four miles down the mountain to Monaco. And there is another thing I tell you. From La Turbie to Monaco you need not the road use. On it perhaps there are the soldiers and the police. See here.’ Henri pointed on the map to a more or less straight line that ran from La Turbie to Monaco. ‘That is the old mountain railway—very steep, very dangerous. One day the train she go down the mountain alone. Zip! Many people they are killed, so the railway she runs no more. But the line is still there, and so when I was a boy we ascend to La Turbie by the iron rails. If you land in my valley you can go straight down the line into Monaco and no one knows—no one see you. How’s that?’

‘Pretty good,’ agreed Algy. ‘But about the parachutes. We have things to carry; they are likely to get broken.’

‘We can heave them over on a special brolly[3],’ suggested Ginger.

‘Yes, of course. But what shall we do with the parachutes, Henri? Is there any place where we can hide them?’

Again Henri stabbed the map with an enthusiastic finger. ‘Here on the Peille road there are no ’ouses. Only one. The stone walls have all fall down. Put your parachutes inside and cover them with stones, and no one sees them. But it is so simple.’

Algy looked at the others. ‘Henri has certainly got the right ideas. We’ll take his advice.’

‘I throw you down in good place,’ promised Henri. ‘I am a Monégasque. I know this country all over.’ His eyes moistened, without shame, as only those of a Latin can. ‘One day I go back and see my mother, and my little sister, Jeanette. My father, he is dead five years now.’

‘And your mother still lives at Monaco?’ asked Algy.

‘But yes.’

‘Where? It might be possible that we could give her a message from you.’

‘La-la? That would be the most marvellous!’ cried Henri. ‘They know I go to the war and for them that is the end. They do not know if I am alive or dead. I dare not try to send the message, because if it is known I fly for De Gaulle perhaps they are put in a concentration camp for hostages.’

‘Where do they live?’

‘At Monaco, on the rock—the old village. Number six, Rue Marinière. It is the first little street opposite the palace. If you see them, say that Pepé’—Henri blushed slightly—‘they call me Pepé,’ he explained. ‘Say that Pepé sends his love and is of the best health, fighting for France.’

‘We ought to be able to manage that,’ asserted Ginger.

‘Let’s have a good look at the map,’ suggested Algy. ‘It would be as well to make ourselves absolutely au fait[4] with the country.’

‘I say, chaps, there’s one thing we seem to have left out of the calculations,’ put in Bertie. ‘What about the jolly old princess?’

‘What about her?’ snorted Ginger. ‘She was the cause of all the trouble. As far as I am concerned she can stay where she is, wherever that may be, or she can splash her own way out of the kettle of fish she put on to boil at Monte Carlo. Let’s forget her.’

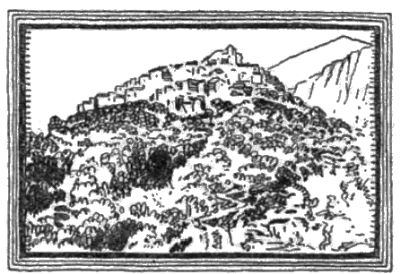

Monaco: The Rock

[1] Soldiers, who were captured by the enemy, were entitled to be humanely treated and held prisoner, but spies on both sides were shot, if captured. If a soldier wore disguise or discarded his uniform he was considered a spy and liable to be shot.

[2] French: look.

[3] Slang: parachute.

[4] French: acquainted.

The following night, a little before twelve, Henri’s Berline Breguet glided quietly at twenty thousand feet, on a southward course, over the grey limestone mass of the departement[1] of France known as the Alpes Maritimes. The air was still, clear and warm, as it is at this pampered spot on three hundred days of the year. Far to the east the silver disc of the moon hung low over Italy, just clearing the peaks of the Ligurian Alps, which, like the edge of a saw, cut a jagged line across the sky. Into the west ran the deeply indented coastline of the French Riviera. To the south, glistening faintly to the moon, lay the age-old Mediterranean Sea, silent, deserted, centre of the bitterest wars of conquest since history began.

Henri nudged Algy, who sat beside him, and pointed ahead. ‘Voila[2]!’ he breathed. ‘Monaco.’

Algy could just make out a town of considerable size, standing, it seemed, knee-deep in the sea between two capes, one large, the other small and blunt, like a clenched fist.

Henri named them. ‘On the left, Cap Martin. On the right, the little one, the rock of Monaco, where I live when I am home. Between, on the hill, Monte Carlo. The big white building, she is the casino. At the bottom of the hill on the right, the harbour, which we call La Condamine. Now we go down.’

Henri circled, losing height, for several minutes, paying close attention to the ground. At last he levelled out and held the machine steady.

‘Now you go,’ he said sharply. ‘We glide straight up the valley. Au revoir[3].’

‘Au revoir, and many thanks,’ answered Algy, and went aft to the cabin in which the others were waiting. ‘This is it,’ he announced crisply, and picked up a bulky bundle from the floor. Opening the door, he tossed it into space. ‘See you on the carpet,’ he said, and followed the bundle into the void.

As soon as the parachute opened he looked down, but it was still a little while before he could make out the details of the ground below. The terrain all looked much the same, the mountains dwarfed by his own altitude. But presently he saw that he was dropping into a long shallow valley, bounded on the eastward side by a slim road cut in the side of a mountain of considerable size, capped by an embattled citadel which he knew, from his study of the map, must be the fort on Mont Agel, overlooking the Principality of Monaco.

A minute later the ground rose sharply to meet him, and he braced himself for the shock of landing. He fell, but was soon on his feet, slipping out of his harness and rolling the parachute into a ball. He sat on it for a little while, listening, then whistled softly. The only other sound was the drone of the departing aircraft. An answering whistle came out of the moonlight; footsteps followed, and a minute or two later Bertie and Ginger appeared together.

Algy rose. ‘Let’s find the equipment,’ he said quietly. ‘Spread out and we shall cover more ground.’

It did not take them long to find the other parachute, which carried for its main load two strangely assorted articles—a guitar, and a sack of onions tied up in strings. Bertie picked up his guitar and Ginger sorted out the onions that were to lend colour to his role of a Spanish pedlar.

‘Now we’ve got to find the broken-down house,’ said Algy. ‘I think I marked it on the road. Bring the stuff along.’

It was a steepish climb to the road, the road which Henri had told them, and confirmed on the map, ran from La Turbie, the mountain village behind Monaco, to Peille. They followed it for about half a mile, and then came upon the ruin they sought. It turned out to be a mere skeleton surrounded by loose stones that had once been the wall of a little garden. From near the gaping doorway sprang the customary twin cypress trees, one of which—so Bertie told them—is planted in the South of France to ensure Peace, and the other Prosperity.

The parachutes were thrown in a heap inside the building, and rocks from the broken walls piled over them until they were hidden from sight—a task that occupied them for the best part of an hour. No traffic of any sort passed along the road. Once a dog barked in the far distance, otherwise they might have been a thousand miles from civilization.

Algy straightened his back. ‘That’s that,’ he remarked. ‘From now we go our own ways, working on our own lines. The first most important thing to remember is that Henri will be at the Californie landing ground this day week, at twelve midnight, waiting for our signal that it is okay for him to land. It means that those who want to go home will have to be there on the dot. In the meantime, our temporary meeting-place, where we can compare notes, is on the Quai de Plaisance, in the Condamine, at the bottom of the steps that lead up to the water company’s offices. Apparently there are steps all over the place in Monte Carlo. They call them escaliers. This particular lot goes by the name of the Escalier du Port. Is that all clear?’

‘Yes,’ answered Ginger.

‘Absolutely,’ confirmed Bertie.

‘Right, then off we go. You can go first, Ginger. Bertie will give you ten minutes and then follow. I’ll go last. Keep straight on down the road for a mile and a narrow cutting on the right will take you down to La Turbie, which sits astride the Grande Corniche Road. Cross the road and you’ll see the old rack-and-pinion railway line that drops down into Monaco. Actually it comes out in Monte Carlo, on a bit of an elevation overlooking the casino gardens. Everyone has got plenty of money, so there should be no difficulty about food.’

Ginger shouldered his onions and set off down the road.

Ginger pulled down over his right ear the rather greasy black beret that he wore, and shouldered his onions. ‘So long,’ he said, and set off down the road.

He knew just where he was, for he had studied the map of Monaco and its environs until he had a clear mental picture of the district in his mind. He had also read a recommended guide-book, which he had found more interesting than he expected. He knew just what he was going to do, for the choice of possibilities was narrow and he had had ample time to formulate a plan of action. Obviously, the first thing was to ascertain if Biggles had left any written messages at either of the places he had named, the Quai de Plaisance at Monte Carlo, and Jock’s Bar below the promenade at Nice. The others would probably do the same, but that didn’t matter. He would go to Monte Carlo first, because that was the nearer. He plodded on, whistling softly, feeling curiously like the part he had decided to play. The road was deserted, as he expected it would be at such an hour. Not a light showed anywhere.

Twenty minutes’ sharp walk and a cutting dipped suddenly to the right, past some cottages. An incline of perhaps a quarter of a mile brought him to a main road, which he had learned from his guide-book was the Grande Corniche, the famous Aurelian Way of the Roman conquerors of Britain. The old Roman posting village of La Turbie lay before him. If confirmation were needed, it was supplied by the towering marble monument erected nearly two thousand years before to the Emperor Augustus. He was amazed at its size. With a strange sensation of living in the past he walked a little way along the road until he came to another time-worn landmark, the Roman milestone number 604—the 604th mile from Rome. And there, almost at his feet, began the overgrown rails of the disused railway, dropping almost sheer into Monte Carlo. Moving his position slightly, he could see the famous international holiday resort snuggling in its little bay, nearly two thousand feet below. On the left of it, Cap Martin thrust a black claw into the sea. On the right, the castle making it unmistakable, was the blunt headland of Monaco itself. Silhouetted against the sky, a short distance from where he stood, rose a single stone column, which he again knew from his book was all that remained of the formidable gallows on which innumerable corsairs, in the distant past, had ended their careers of pillage. Beyond, rolling away, it seemed, to infinity, was the Mediterranean, as devoid of movement as a sheet of black glass. That same sea, he reflected, from the very viewpoint on which he now stood, must have been the last earthly scene on which the condemned pirates had looked.

He was about to start the descent when footsteps approaching from the village sent him creeping into the ink-black shadow of a broad-leafed fig tree. He lay flat and remained motionless. The footsteps came nearer.

A voice said, ‘But I tell you I did hear something.’

Another voice answered, ‘It must have been a dog or a cat.’

The first voice replied, ‘It sounded to me more like someone walking.’

Raising his eyes, Ginger saw two peaked uniform caps outlined against the sky.

‘Anybody there?’ called one of the men, sharply, speaking, of course, in French.

Ginger held his breath.

There was a short interval of silence; then the two men, talking in low tones, strolled away in the direction from which they had come.

As far as Ginger was concerned it was a disconcerting incident, for it warned him that, dead though the country seemed, police or soldiers—he knew not which—were on patrol. Was this just routine, he wondered, or were they on the watch for somebody, and if so, who? This was a question which no amount of surmise could answer, so after waiting for a little while he began a cautious descent of the railway, stopping from time to time to listen, for the unexpected appearance of the two men had tightened his nerves.

He had no intention of going straight down into the town, for the fact of his being abroad at such an hour could hardly fail to arouse the suspicions of the Italian secret police who, the Air Commodore had said, were numerous in Monaco. If that were so, they would certainly take notice of strangers, probably more so by night than by day. So when he was within easy distance of the abandoned railway station he left the track, and finding a comfortable cranny in the herb-covered hillside, he lay down to wait for daylight. In any case there was nothing he could do in the dark. The air was soft and warm, so with the perfume of wild lavender in his nostrils he settled down to sleep.

When he awoke, with a start, the sun was a ball of fire balanced on the horizon beyond Cap Martin, its rays pouring gold across tiny dancing waves. Sounds of life arose from the town, so after a cautious survey of his immediate surroundings, he picked up the onions and continued his descent.

There was no one in the ramshackle station buildings, but on leaving them he nearly collided with a man in a white, red-braided uniform, who was standing at the top of the steps outside, swinging a white batôn[4] from a leathern loop. Ginger knew that he was a policeman of some sort, probably a Monégasque.

‘Hello! Where have you come from?’ asked the man.

Ginger answered in his best French. ‘A fellow must sleep. Why pay for a room when the weather is fine?’

The policeman smiled and looked at the onions. ‘Spanish?’

‘Si.’

‘I could do with an onion to take home,’ suggested the gendarme[5]. ‘I’m just going off duty.’

‘If I had given an onion to every gendarme who has asked for one since I left Barcelona, I should have none to sell,’ answered Ginger, not a little relieved that his companion was such an amiable fellow.

‘Just one?’

‘You find the bread and I’ll supply the onions,’ suggested Ginger smiling.

‘Bread? Oh la la. It isn’t bread any longer. Still, I suppose it’s better than nothing. Let’s see what we can do. Descend, my friend.’

They walked together down the steps to a café where, under a faded awning bearing the name, Café de Lyons, a man in shirt sleeves was wiping down small round tables. A conversation ensued, following which the café proprietor, grinning, went inside and returned with half a loaf of dark-coloured bread and a carafe of thin red wine.

The gendarme unbuttoned his tunic. ‘We can still eat and drink,’ he said. ‘Untie your onions my young friend.’

Ginger set an onion in front of each of them, and the meal began.

‘How are things in Spain?’ asked the gendarme.

‘In Barcelona, where I come from, bad,’ returned Ginger.

‘Not worse than here, I should say,’ observed the proprietor sadly, as he sliced his onion. ‘You know,’ he went on, ‘I have often bought Spanish onions, but I never saw any like these.’

Ginger hadn’t thought of that, but he kept his head. ‘We are trying new sorts,’ he said airily. ‘They say the government is importing seeds from America.’

‘I can’t say I think much of these; they are too strong,’ asserted the gendarme, with tears running down his cheeks. ‘Mon Dieu[6]! They are as bad as English onions. I ate one once, when I went to visit my sister in London.’

Ginger grinned. ‘What do you expect? How can they grow onions in England, where the rain never stops?’

‘No, that’s true, poor devils,’ agreed the proprietor. He glanced around. ‘Talking about the English, they say there was an Englishman here the other day—a spy.’

‘Who says?’ asked Ginger, grimacing as he sipped the rough wine.

‘Everyone knows about it,’ answered the proprietor, and would have gone on, but the gendarme stopped him with a frown.

‘It is better not to talk of these things,’ said he.

The proprietor sighed, which gave Ginger an idea of what he thought of the state of things.

Ginger passed off an awkward situation by offering to sell him some onions.

‘They’re too strong,’ said the proprietor, shaking his head.

‘They go all the farther for that in the pot,’ declared Ginger.

‘That’s the truth, by God,’ said the gendarme, wiping his eyes. ‘I should say this onion I am eating would stop a tank.’

‘Now food is scarce, the idea is to make things go a long way,’ argued Ginger.

‘How much?’ asked the proprietor.

‘Ten francs the kilo.’

‘Too much. I’ll give you five.’

‘Nine.’

‘Six.’

‘I’ll take eight, and not a sou less,’ swore Ginger.

‘Six.’

‘Seven if you take two kilos and throw in a sardine to eat with the bread.’

‘C’est-ca[7].’ The proprietor fetched the scales, and the sardines. Between them they weighed off the two kilogrammes.

‘One for luck,’ said the proprietor, helping himself to two onions and throwing them in the scales.

‘Carramba[8]!’ growled Ginger. ‘And you call us Spaniards thieves.’

Shouting with laughter the cheerful gendarme got up. ‘I have a wife who expects me to come home,’ he said, putting an onion in his pocket. ‘Au revoir.’

Ginger was in no hurry. His introduction to the café proprietor offered possibilities of obtaining information, and he prepared to explore them.

‘What’s all this talk about a spy?’ he asked casually.

The proprietor shrugged his shoulders. ‘What a question! There are more spies in this place than there were sharpers before the war.’

‘You said something about an Englishman?’ prompted Ginger, without looking up.

The Monégasque leaned forward. ‘Nobody knows the truth about that,’ he asserted. ‘But they say there was a woman in the affair, and between them they killed five Italian police.’

‘Phew! Were they caught?’

‘Some say they were, others say they were not. Some say they were both shot. Others say they are still hiding in Monaco, which accounts for the Italian police everywhere. But there, nobody knows what to believe in times like these.’

‘That’s true,’ agreed Ginger.

The proprietor bent still nearer, breathing a pungent mixture of garlic and onions into Ginger’s face. ‘They say Zabani is mixed up in this, and that he has been put on the spot by the Camorra[9] for double-crossing one of them.’

‘Camorra? I thought Mussolini boasted that he had wiped out all the Italian secret societies?’

The proprietor winked. ‘Franco bragged that he had wiped out your Spanish society, the Black Hand,’ he countered. ‘Has he?’

‘For my part,’ said Ginger slowly, ‘I should doubt it.’

The Monégasque eyed him narrowly. ‘You’re not one of them I hope?’

‘Me?’ Ginger laughed. ‘Not likely. I don’t want a knife in my back.’

‘Nor me. Once the Camorra sets its mark on a man he’s as good as dead. If Zabani has betrayed one of them, God help him—not that he deserves any help.’

‘He’s a bad one, eh?’

‘If half what they say of him is true, he is a match for Satan himself.’

‘Is he Italian?’

‘Yes.’

‘If he is an Italian why does he live here?’

‘Like others, to gamble in the casino. He is always in the gaming rooms. He is not Monégasque, you understand. The Monégasques do not go near the tables. I am a Monégasque.’ The man spoke proudly.

The statement reminded Ginger that he had meant to ask Henri just what was a Monégasque. He realized of course that the word described the real natives of Monaco, but from what race they originally sprang he did not know. It seemed to be an opportunity to find out.

‘What is a Monégasque that you are so proud of being one?’ he enquired.

‘Zut! The question!’

‘I am a stranger here,’ reminded Ginger.

‘A Monégasque, my young friend, is—a Monégasque.’

‘Not French?’

‘Name of a name! No.’

‘Italian perhaps?’

‘No, although there are many Italians here, good Italians, who obey the laws of Monaco. Some came to avoid the conscription in Italy—and who shall blame them? There are few true Monégasques—three thousand perhaps. They rule themselves. Most of them live on the Rock.’

‘Where did they come from in the first place?’

‘Ah! That is another question. First of all, long long ago, lived here the Ligurians, wild people with stone clubs. Then came the Phœnicians—they built many of the old villages round about. Later came the Greeks. Then came the Romans who, to mark their conquest, built the great monument at La Turbie—look, you can see it from here. After that came all sorts of people—French, Italians, Lombards, adventurers from the sea, yes, even English, the Crusaders, and such people, as well as Christian prisoners brought by the Saracens. Between them all they leave a type which long ago became called the Monégasque. Do not, my young friend, confuse us with the French, or the Italians, although because we are so near to France and Italy most of us speak the languages of those countries.’

‘I see,’ said Ginger.

‘But I can’t sit here talking,’ went on the proprietor, rising. ‘It is too early in the morning. I have work to do. Call next time you are passing and I may buy some more onions—but next time bring the Spanish. Au revoir.’

‘Au revoir, monsieur.’

Perceiving that there was nothing more to be learned, and well satisfied with the smattering of news he had picked up, Ginger slung his lightened burden over his shoulder and departed. He still did not know what had happened to Biggles, but the bare fact that even in Monaco there was a doubt about his fate, was encouraging. It had evidently leaked out that the princess’s betrayer, Zabani, was concerned with the affair. The café proprietor’s reference to the Camorra, the dreaded Italian secret society, in connection with Zabani, was a new and interesting piece of information.

Thus pondered Ginger as he strode on towards the sea, which could be observed beyond the casino gardens. People were beginning to move about in the streets, ordinary people, as far as he could judge, mostly fellows in simple working clothes, or blue overalls. Their faces were brown, and while a few walked as if with a definite object in view, the majority slouched about, listless, without any set purpose, creating an atmosphere very different from the mental picture he had always held of the famous society playground. Police were conspicuous, although for the most part they seemed to be content to stand at street corners and gossip. They were easily identified by their uniforms. There were the local police, the Monégasques, in the service of the Prince of Monaco. They wore white drill suits with scarlet facings—the colours of the principality—and sun helmets. It was one of these who had invited Ginger to the Café de Lyons. There were a few French gendarmes, in dark blue tunics and khaki slacks; they were usually in pairs. There were also Italians who, officially or unofficially—Ginger was not sure which—were evidently in occupation. There were a few cars outside the big hotels which, like the gardens, and everything else, had a look of neglect. Outside the imposing Hotel de Paris there was a saloon car carrying a swastika pennant on the radiator cap, and another flaunting the Italian flag. He passed without stopping, and going over to the ornamental balustrade on the far side of the road, saw the little port of Monaco below him.

It was the neatest, tidiest port he had ever seen, largely artificial, having been formed by the construction of two moles, one springing from the Monaco village side, and the other from Monte Carlo. Between the ends of the moles, a gap gave access to the open sea. Within the small square harbour itself there were no ships of any size—a few yachts at moorings on one side, and a collection of small craft on the other.

As Ginger looked down, the broad walk on the near side was, he knew, the Quai de Plaisance, his immediate objective. On the opposite side of the harbour, known as the Quai de Commerce, some men were rolling barrels. A short walk took him to the offices of the water company, beside which a steep flight of steps, named the Escalier du Port, led down to the Quai de Plaisance.

Descending to the quay he found himself on a broad concrete pavement, bounded on one side by a high stone wall, and on the other, by deep water. He looked about him. The only people in sight were a few elderly men, and children, fishing with simple bamboo poles. A short distance to the right a man was mopping out a slim motor-boat that floated lightly on its own inverted image. After a cursory glance the people fishing paid no attention to him, so he began to stroll along the wall looking for writing in blue pencil. He did not really expect to find any, but the bare possibility, now that he was actually on the spot, gave him a curious thrill.

He walked along towards the outer mole, his hopes dwindling as he approached the end without seeing anything resembling what he sought. The only writing was the usual French warning notice against the sticking of bills. Returning, he was about to examine the wall beyond the foot of the steps by which he had descended to the quay, when an incident occurred which at first astonished, and then alarmed him.

Along the inner side of the harbour, which ran at right angles to, and connected the Quai de Plaisance with the Quai de Commerce, there was a broad stone pavement similar to the one on which he walked. This pavement was obviously the part given over to local fishermen. It was backed by a number of tiny houses, and boat sheds, from which shipways ran down into the water. There was quite a collection of small craft, both in and out of the water. A number of fishermen, dressed in the usual sun-bleached blue trousers and shirts, were gossiping as they worked on their boats or mended their nets.

From this direction now appeared Bertie, made conspicuous by his guitar. He was strolling along unconcernedly, apparently on his way to examine the wall of the Quai de Plaisance. Watching, Ginger saw him—for no apparent reason—stop suddenly, back a few paces, turn, and walk quickly away. A moment later, the boatman who had been mopping out the motor-boat, sprang up on to the quay and hurried after him. Ginger was not sure, but he thought he heard the boatman call out. Bertie glanced back over his shoulder, and seeing that he was pursued, quickened his pace. The boatman broke into a run.

In a disinterested way Ginger had already noticed this man, first on account of the innumerable patches on his overalls, and secondly, because of his outstanding ugliness. His face might have been that of a heathen idol, carved out of dark wood. To make matters worse his nose was bent, and his eyes, due to a pronounced cast in one of them, appeared to look in different directions. The effect of this was to make it impossible to tell in precisely what direction the man was looking, a state of affairs which Ginger, conscious of the secret nature of his task, found disconcerting.

Still followed by the boatman Bertie disappeared behind a colourful array of sails that were hanging up to dry.

Ginger watched all this with serious misgivings. It was obvious that the boatman was trying to overtake Bertie, and he wondered why. He watched for some time, and the fact that neither of them returned did nothing to allay his anxiety. When twenty minutes had passed, and still Bertie did not return, Ginger gave it up, and continued his interrupted survey of the wall.

[1] French equivalent of an English county

[2] French: There!

[3] French: See you again

[4] French: Short stick carried by the police similar to a truncheon

[5] French: policeman

[6] French: My God!

[7] French: that’s it, OK

[8] Spanish exclamation similar to Blimey! or My God!

[9] A secret criminal society, similar to the mafia

A dozen paces Ginger took and then stopped short, his heart palpitating, Bertie’s strange behaviour forgotten. For there, before his eyes—indeed, within a foot of his face after he had taken a swift step forward—was what he sought, what he prayed might be there, yet dare not truly hope to find. It was writing on the wall, bold blue lettering on the pale grey limestone; and the first thing that caught his excited attention was the final symbol of the message. It was a triangle, quite small, but clear and unmistakable. The actual message consisted of three words only. They were: CHEZ ROSSI. PERNOD.

Ginger’s first reaction as his eyes drank in the cryptic communication was one of disappointment. Doubtless the message contained vital information, but at the moment it told him nothing. Worse still, there was no indication of when it had been written. That Biggles had written the words he had no doubt whatever, and that they were intended to convey important news was equally certain. But—here was the rub—had the message been written before the catastrophe at the Californie landing ground, or afterwards? Upon that factor everything depended. Whatever the words might mean, reflected Ginger, they did not tell him what he was most anxious to know. Was Biggles alive or dead?

He did not stand staring at the message. There was no need for that. The words were engraved on his memory. Nobody appeared to be watching him, so he strolled over and sat down on one of the many benches provided for visitors in less troublous times. It was easy enough to see why the message had been expressed as a meaningless phrase. Obviously, Biggles could not write in plain English. In fact, it seemed that English words had been deliberately avoided. He pondered on the puzzle.

Chez Rossi was almost certainly the name of an establishment, probably a café, bar or restaurant. The word chez, meaning ‘the house of,’ or ‘the home of,’ was a common prefix to public places of that sort. Rossi was probably the name of the owner. Chez Rossi, therefore, was most likely the name of a bar or restaurant in Monaco, run by a man named Rossi. At any rate, the original proprietor would have been thus named. Pernod was a word he did not know, although it sounded like another name. That was something which could perhaps be discovered at the café, bar, or whatever the establishment turned out to be. Clearly, the thing to do was to find out if there was such a place, and if there was, pay it a visit.

Remembering Bertie and his peculiar behaviour he looked along the back of the harbour where he had last seen him, and even walked a short distance in that direction; but there was no sign of him, nor of the boatman with the mahogany face who had followed him. He waited for a little while, and then, loath to waste any more time, made his way up into Monte Carlo, his intention being to call on the friendly proprietor of the Café de Lyons to inquire about the Chez Rossi. He would know if there was such a place.

For the sake of appearance he called at several shops and houses en route[1], and did, in fact, dispose of so much of his stock that he became afraid he might sell out, which did not suit him. So with the two strings that remained he strode on to the Café de Lyons.

It now presented a different appearance. Many of the chairs, which in accordance with French custom had been put out on the pavement, were occupied by people reading newspapers, with a glass or a cup at their elbows. However, this made little difference to Ginger, who had no intention of staying. He managed to catch the eye of the proprietor who, recognizing him, and evidently noticing that his onions had diminished, congratulated him on his sales ability. With that he would have gone on with his work, but Ginger caught him by the arm.

‘One moment, monsieur,’ he appealed. ‘I am told that I might find a customer at Chez Rossi. Could you direct me?’

‘But certainly,’ was the willing response. ‘It is at the back of the town. Take the Boulevard St. Michel, here on the right, and the second turning again on the right. At the corner of the first escalier you will see the Rossi bar-restaurant.’

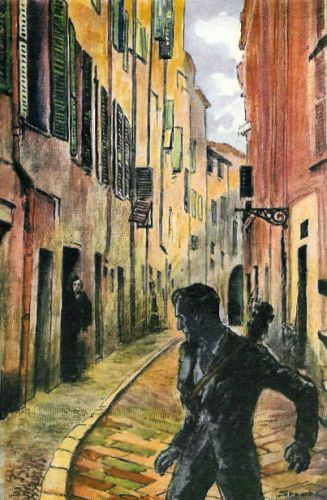

‘Merci, monsieur,’ thanked Ginger, and turned away to the boulevard which, before the war, had clearly been fashionable shops and hotels. But when he took the second turning on the right, the scene and atmosphere changed even more suddenly than a visitor to London finds when turning out of Oxford Street into Soho. This, obviously, was where the people lived, the working classes, the permanent residents, as opposed to the wealthy visitors. The street was narrow. Tall but shabby whitewashed houses rose high on either side. Laundry, strings of bright-hued garments, stretched from window to window. A drowsy hum hung on air that was heavy with sunshine. Caged birds twittered. Through narrow open doorways he saw families eating, lounging or sleeping. Music crept from tiny cafés. Occasionally he passed an unfenced garden overgrown with cacti, geraniums and trailing vines, or shops where objects for which no earthly use could be discovered mixed up with nails, dried fish, bundles of dried herbs, oil and vinegar. Sometimes an escalier, a crazy flight of steps without number, wound into mysterious distances.

Ten minutes walk brought him within sight of his objective, made conspicuous by a faded red awning bearing in white letters the name of the establishment—Chez Rossi. A smaller notice announced the place to be a bar-restaurant. So far so good, thought Ginger. Closer inspection revealed it to be one of the small restaurants, with a bar on one side, common in all French towns. Judging by the name, mused Ginger, the proprietor was, or the original proprietor had been, an Italian. If the latter, the name of the business would not be changed.

Ginger pushed aside the curtain that hung over the entrance and saw at a glance that the place was a typical Mediterranean eating house—small, with numerous tables set uncomfortably close together, but clean. The customary smell, an evasive aroma of garlic, fish and herbs, peculiar to British nostrils, hung in the air.

There were perhaps half a dozen people present, all men, small, dark Italians, southern French or Monégasques. At any rate, they were all typical Mediterraneans. All were eating the same dish which, by the pungent smell, was fish soup, highly flavoured. This was being served by a swarthy, black-browed, heavily-moustached, shirt-sleeved waiter, a middle-aged man with dark, suspicious eyes, and a smooth deportment that enabled him to move among the tables without colliding with them.

Ginger crossed to an unoccupied table, dropped his onions on the floor, and sat down.

The waiter approached. ‘Soup, monsieur?’

‘What is there to eat?’ asked Ginger, thinking that as it was now noon he might as well take the opportunity of having a good meal.

‘Fish soup, monsieur, ten francs, with bread and wine included. We serve only one dish.’

Ginger nodded assent. As the waiter went through to the kitchen to fetch the food he wondered if by any chance he was the proprietor, Rossi, or the Pernod referred to in the writing on the wall. But this possibility was quickly dispelled when one of the other customers called him by name. The name was Mario.

Who, then, was Pernod? wondered Ginger. The curious thing about the word was, every now and then it touched a chord in his memory, as though he had heard it, or seen it, before; but he could not quite remember where; once or twice he nearly had it, but in the end it eluded him and he gave up the mental quest. Instead, having nothing else to do, he started to make a closer scrutiny of his surroundings. It ended abruptly, with a shock. He stared, doubting for once the evidence of his eyes. For there, confronting him across the room, was a single word in bold letters. The word was PERNOD. It was printed on a card, below a picture of a bottle. Evidently an advertisement for a beverage, the card hung on the wall, suspended from a nail.