* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Gimlet Takes A Job

Date of first publication: 1954

Author: Capt. W. E. (William Earl) Johns (1893-1968)

Illustrator: Leslie Stead (1899-1966)

Date first posted: July 3, 2023

Date last updated: July 3, 2023

Faded Page eBook #20230703

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, akaitharam, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

There, on an old-fashioned horse-hair sofa, sat Mr. Jabez Christian (page 29)

GIMLET

TAKES A JOB

Captain W. E. Johns

Illustrated by

Leslie Stead

Brockhampton Press

First published in 1954

by Brockhampton Press Ltd

Market Place, Leicester

Made and Printed in England

by C. Tinling & Co Ltd

Liverpool, London

and Prescot

The characters in this book are entirely imaginary

and have no relation to any living person

| CONTENTS | ||

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| 1 | The job | 9 |

| 2 | Santelucia | 19 |

| 3 | A visitor tells a tale | 35 |

| 4 | Gimlet asks some questions | 46 |

| 5 | Making a start | 55 |

| 6 | Preliminary sparring | 69 |

| 7 | The first round | 80 |

| 8 | Round two | 91 |

| 9 | A visitor by night | 102 |

| 10 | The Houngan hits back | 114 |

| 11 | Gimlet takes over | 125 |

| 12 | The mill | 137 |

| 13 | The fort | 149 |

| 14 | The answers | 161 |

| 15 | Last words | 173 |

Illustrations

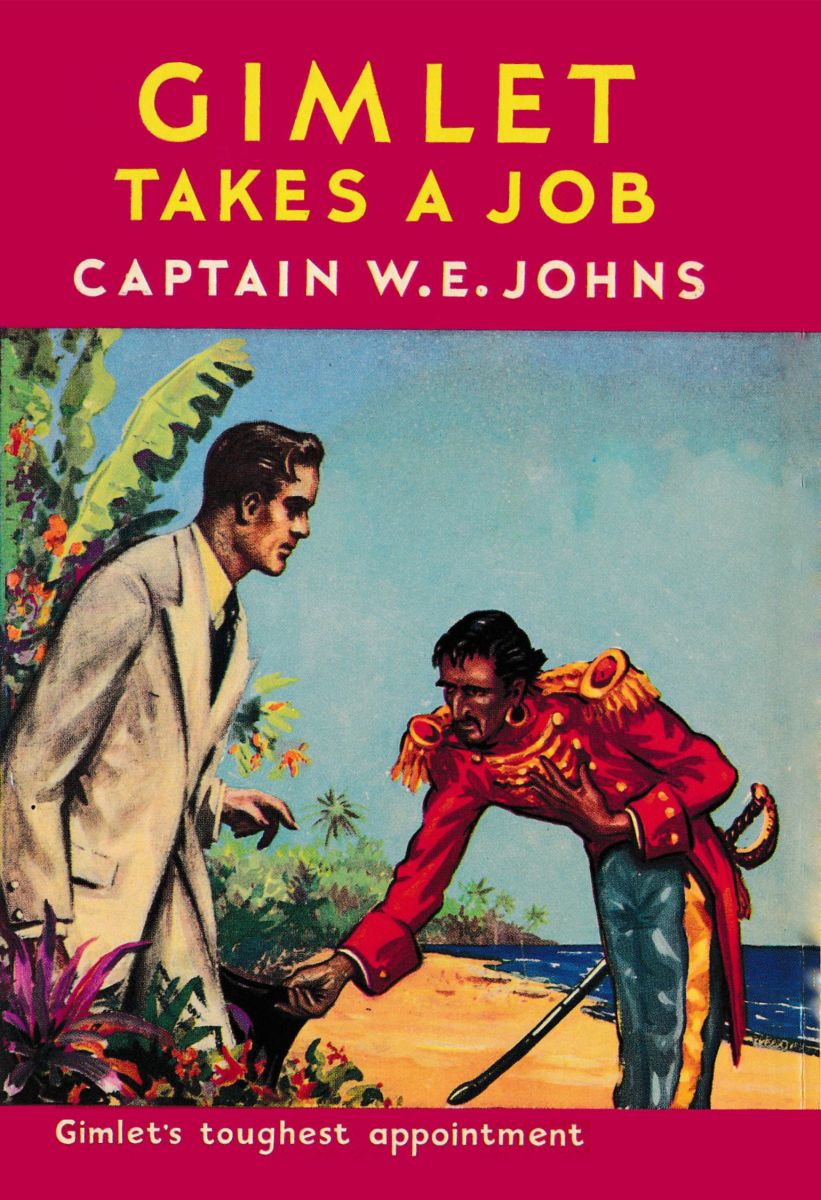

There, on an old-fashioned horse-hair sofa,

sat Mr. Jabez Christian

FACING PAGE 32

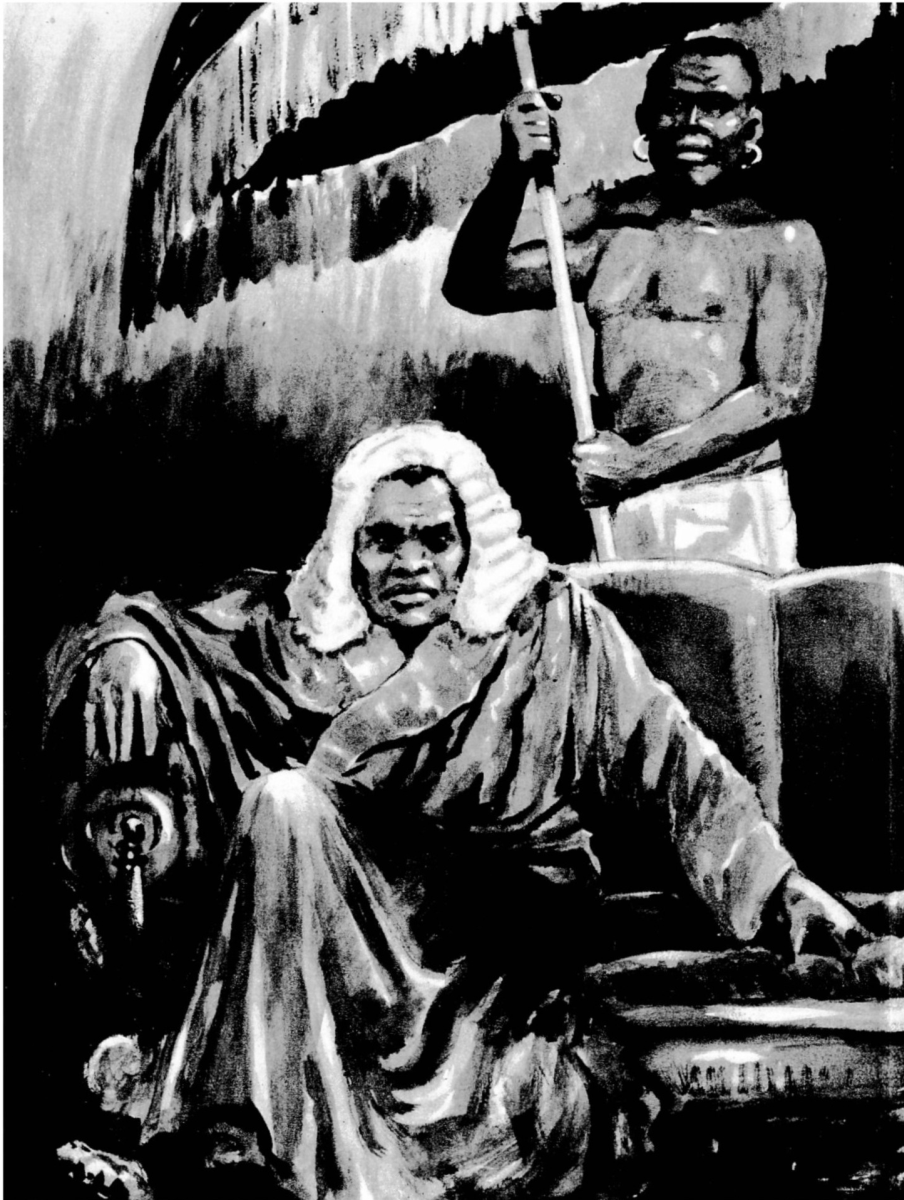

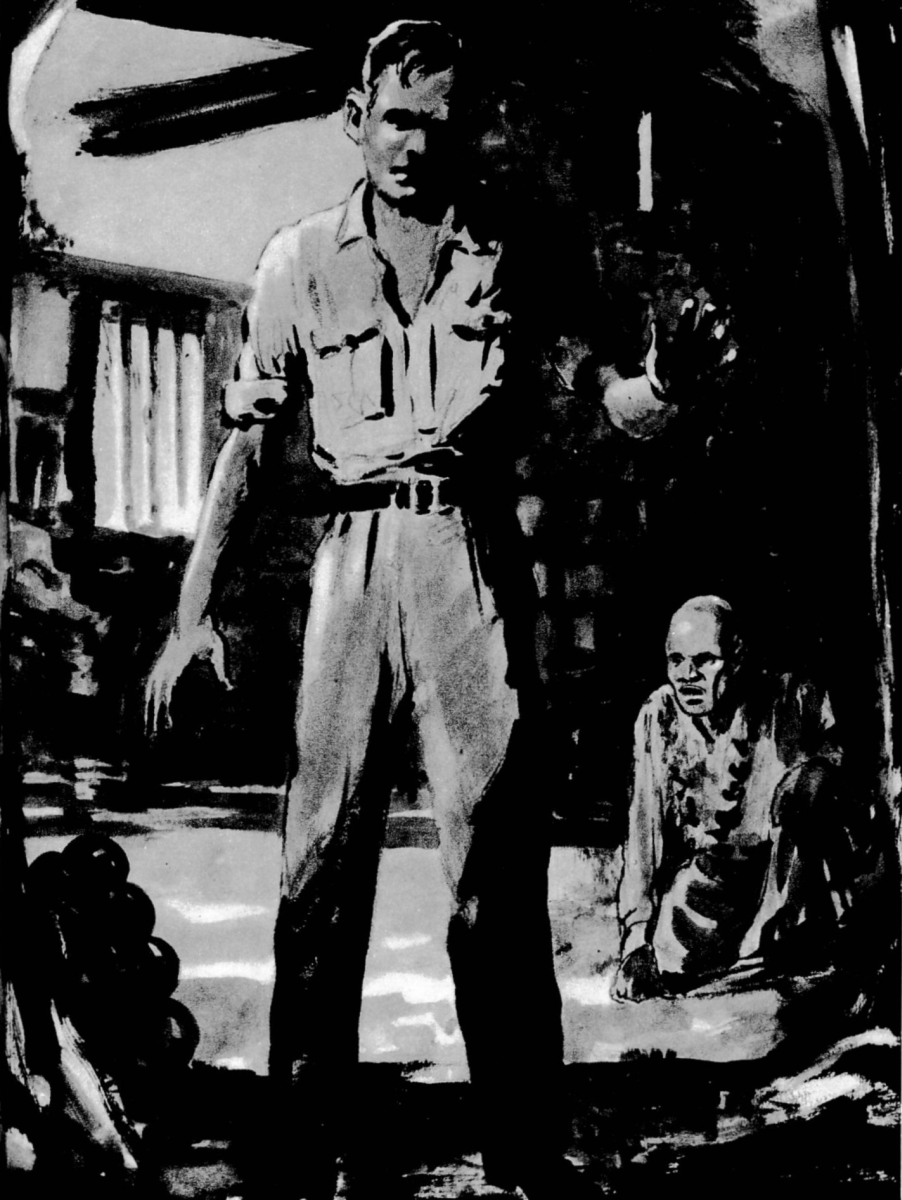

‘Let him go,’ ordered Gimlet

FACING PAGE 96

Sick with loathing, Cub set it free

FACING PAGE 160

Copper was walking with slow deliberate steps

towards the hole in the wall

It was at their annual reunion luncheon that Captain Lorrington King, D.S.O., one time ‘Gimlet’ of the celebrated commando troop known as King’s ‘Kittens’, broke the news of his appointment to the three surviving members of his force with whom he had never lost contact—and had, in fact, undertaken several official missions of a secret nature. They were ex-corporal ‘Copper’ Collson, six foot two of bone and muscle and three times heavyweight champion of the Metropolitan Police—hence his nickname; ‘Trapper’ Troublay, a French Canadian backwoods trapper before the war had brought him to Europe, his face still showing the scars of a hand-to-claw fight with a grizzly; and Nigel Peters, better known in the troop of which he was the junior member, as ‘Cub’.

Naturally, for a while the talk had been of ‘old times’, and exploits of a character so desperate that Cub sometimes wondered if they had really happened. It was when Copper observed heavily that they were now respectable citizens in civvy street, and the good old days were gone for good, that Gimlet dropped his bomb.

‘As a matter of fact,’ he remarked, stirring his coffee pensively, ‘I’ve just taken a job.’

There was a short silence. Everyone stared at him as if the words were not fully comprehended. Then on Copper’s face dawned an expression of frank incredulity. ‘You, skipper? A job? That’s a good ’un. Fancy you clocking in and out. Ha!’

‘It’s unlikely that I shall do any clocking,’ said Gimlet shortly.

‘Don’t say you’re going into Parliament.’

‘No.’

‘Been gambling and lost all your money, mebbe.’

‘I’m quite still independent financially, thank you.’

‘Then what’s the idea? My old Ma used to say nobody’d work if they didn’t ’ave to, and I’ve always reckoned she was about right.’

‘The government has just appointed me Governor of the island of Santelucia.’

‘Never ’eard of it.’

‘Neither had I until the other day. I imagine few people have heard of it. There’s been no reason why they should. Santelucia is one of several hundred islands belonging to us in the West Indies.’

‘What about your ’unting and shootin’?’

‘There’s a chance that there may be both on Santelucia. But the hunting won’t be for foxes and the shooting won’t be at pheasants.’

‘Ah!’ breathed Cooper. ‘Now I get it. Want any ’elp, sir?’

‘Yes, I shall almost certainly need some help,’ answered Gimlet. ‘I intended to ask you fellows if you’d care to come along. Officially I’m entitled to a personal assistant, a valet and a cook. How do you feel, corporal, about taking over the cook-house?’

Copper looked pained. ‘Me? Cooking? At my time o’ life? I can open a tin o’ bully with me teeth and knock up a dixy o’ tea, but that’s about all the cooking I’ve done.’

Gimlet smiled. ‘Don’t worry. These appointments are in name only. What I shall really need is someone I can trust to help me hold down a job from which efforts may be made to remove me.’

‘That sounds better,’ declared Copper, taking his coffee at a gulp. ‘How about giving us the low-down, sir.’

‘I’ll tell you as much as I know myself, which isn’t much, if you’ll refrain from firing questions at me until I’ve finished,’ agreed Gimlet. ‘While I’m talking you’ll wonder why the government doesn’t send an armed force to the island, so I might as well give you the answer to that now. The business must be handled quietly, so the fewer the people who know about it the better. Publicity might result in trouble on some of the other islands. Accusations would certainly be flung at us by the people who are always on the look-out for an excuse to howl about the high-handed methods of British Imperialism. In the old days, the job I’ve been asked to do would have been simplicity itself. The Navy would have landed a party of marines who would have wasted no time putting an end to any nonsense. But, unfortunately you may think, those days are past. The new idea is to appoint a committee to solve these problems.’

‘To do a lot of talking and get nowhere!’ Copper sniffed.

‘Just so. In this case the government has decided to do the job itself, quietly and without any fuss.’

‘Kid glove stuff, eh?’

‘That’s the intention, although whether or not it will work out that way in practice remains to be seen. Now let me tell you what it’s all about. According to the book, Santelucia is a tropic island twenty miles long by about twelve wide. Like many other islands in the region it is actually the crater of an extinct volcano. From the sea it rises sharply on all sides to a central cone-shaped mountain four thousand feet high. The top is hollow and filled with water. At least, it was. Things may have changed, for there’s no record of anyone going to the top for the last hundred years. The lower slopes are virgin forest, and that, in the West Indies, usually means almost impenetrable jungle. The trees thin out on the higher slopes. The top is bare rock—probably lava. The whole island is surrounded by a reef on which many ships have been lost. There’s only one known opening through it, and a dangerous one at that; which explains why the island has been so long neglected. Ships of any size keep clear. Opposite the opening, some distance up the hillside, is Rupertston, the capital, a miserable affair named after that swashbuckling pirate, Prince Rupert, who is said to have used the place. Rupertston is, in fact, the only town—if it can be called a town. A path leads up to it. There isn’t a road on the island. However, there’s a Government House, a courthouse, a jail, and an old fort built by Prince Rupert to guard the anchorage in the days when everybody fought everybody and buccaneers fought the lot. Incidentally, there’s an aspect of the reef, and the town in relation to it, that affects us. It’s the only place where a landing can be made.’

‘So anyone landing has to go ashore in full view of everybody,’ remarked Copper shrewdly. ‘No commando stuff from landing craft.’

‘Exactly. Just how many people there are on the island no one knows, for owing to the complete absence of communications it has been impossible to take a census. The number is reckoned to be about a thousand. The population is almost entirely negro, with a few mulattoes, descendants of slaves who escaped from plantations on the mainland, or perhaps went there when the slaves were liberated. There are no whites—I mean, real whites. At one time, up to fifty years ago, there were some white colonists engaged in the then prosperous sugar trade, but these have faded out since a great hurricane ruined them. The island is, I may say, smack in the middle of the hurricane belt, and over and over again crops and buildings have been blown flat.’

‘What language do the people speak?’ asked Cub.

‘Apparently a queer sort of gibberish that is mostly old-fashioned English. Originally the island belonged to Spain. The Dutch took it from them. France took it from Holland, but they lost it to us during the Napoleonic wars. This sort of chopping and changing in the West Indies went on for hundreds of years. Why there should have been any fuss over Santelucia is hard to see, because the island was never any real use to anybody; but then, in the old days, people fought for the sheer devilment of it.’

‘And loot,’ put in Cub.

Gimlet smiled. ‘Quite right. As you say, and loot. When the sugar business declined a few people took to fruit growing—they say the bananas are enormous—but there was no transport to take the produce to market so there was soon an end to that. The negroes that remained were a poor, impoverished lot, and it was in the hope of brightening their lives that Queen Victoria appointed the first resident commissioner. Some money was spent on buildings and equipment but it all came to nothing. You can’t help people who won’t help themselves. Now let us come to more recent times.

‘During the war, when food productive land of any sort became valuable, the government decided to have another go at Santelucia. It could, at least, they thought, produce much-needed sugar. They did up the government buildings and appointed a man on the spot, a negro who appeared to be more intelligent than most, to the post of Special Commissioner. He was paid a salary and given some money to set things going. It’s always a dangerous thing to put power in the hands of people who aren’t used to it, and so it was in this case. It seems that all the Special Commissioner did was throw his weight about. His name, by the way, is Christian—Jabez Christian. Learning what was going on the government sacked him and sent out a white man, a civil servant named Copland, to put the place in order. Copland, and the two white servants he took with him, died within six months. This was discovered when a naval frigate called with fresh supplies. Not only was Copland dead, but Christian was back in his old job, living in the Government House. He said he had taken over to keep order, and to the skipper of the frigate that didn’t sound unreasonable, although he reported a funny atmosphere about the place. Of course, the Colonial Office was not prepared to accept this state of affairs, so they sent out another man, a retired army colonel named Baker—a D.S.O. holder who had served in Jamaica and knew how to handle blacks. His job was to give Christian twelve months wages in lieu of notice and take over from him. Baker took four men with him. Nothing has been seen or heard of any of them since they landed; but a mulatto, bribed to talk, told the captain of a supply ship a grim story of a white man, out of his mind, wandering about on the island.’

‘What about this swipe Christian?’ asked Copper.

‘He was back in the Government House, still keeping things in order.’

‘Well strike me pink! He’s got a nerve.’

‘If you think so now, you’ll think more so when I tell you the rest,’ resumed Gimlet. ‘It had become obvious to the government that there was something sinister behind this business when an incident occurred that threw the monkey wrench into the gears. Christian, having once been boss of the island, evidently intends to stay boss—if he can. But the other day he went too far, and if anything was needed to expedite his departure from office, this was it. He actually had the brass-faced audacity to levy harbour dues on a Norwegian tanker that ran in for shelter during a storm. And, moreover, he got them.’

Copper looked astonished. ‘You mean, the skipper paid up?’

‘He had to.’

‘Why did he have to?’

‘Because Christian’s special police—apparently he now runs a private police force—had the impudence to arrest four of the sailors who had gone ashore to stretch their legs and collect some fresh fruit and vegetables. Christian held them on a trumped-up charge of attempting to steal fruit. Absolute rot, of course. What could the skipper do? He couldn’t leave his men behind and he couldn’t start a war on a British island. So he paid up and the men were released.’

‘How much did he pay?’ asked Cub.

‘Fifty pounds.’

Copper whistled. ‘Strewth! That was piling it on.’

‘Yes, and a queer point arises there,’ asserted Gimlet. ‘What did Christian want the money for? Money has practically no value on the island for the simple reason there’s nothing worth buying. Anyhow, there’s nothing Christian couldn’t get merely for the asking. But never mind that. Naturally, when the skipper got home he lost no time in making a complaint. The government has refunded the money and promised to see that it doesn’t happen again.’ Gimlet smiled grimly. ‘I’ve been offered the job of Governor to see that it doesn’t. When I go I shall carry authority to kick Christian out and take over. I shall also do what I can to bring prosperity to the place—if that’s possible. I can have anything I need, within reason.’

‘How do we get there?’ asked Cub.

‘By boat in the ordinary way to Port of Spain, in Trinidad. There a sloop will pick us up and take us, with our kit and food stores, to Rupertston. We shall have wireless. The previous people didn’t have it, which was a pity, or we might have known what went wrong. If my report is favourable the government will make a grant of money, tools and equipment, in the hope of putting the place on a self-supporting footing. A regular steamer would be laid on. I have no doubt this rogue Christian will try to make himself awkward. If he does, he’ll find we can be awkward, too.’

‘My oath, he will and all,’ muttered Copper.

‘What about the people?’ asked Cub. ‘Do they support this black boss?’

‘That’s something we don’t know. The two white governors ceased to function before they had time to render a report. It was six months before the vessel that took them there went back. Well, there it is. We’ll get to the bottom of the business. The problem wasn’t one that could be worked out in Whitehall.’

‘Where do we live when we get there?’ inquired Cub.

‘In the Government House, of course.’

‘If Christian is in he’ll probably jib at being turfed out.’

‘He can jib as much as he likes, but out he’ll go.’

‘Too blinkin’ true he will,’ growled Copper. ‘Am I right, Trapper old pal?’

Trapper clicked his tongue, Indian fashion, as was his habit. ‘Every time, chum,’ he agreed softly.

‘Just one last thing, corporal,’ said Gimlet. ‘Treat yourself to a good hair cut before we start. Better bring a pair of scissors with you, too. There are no barbers on Santelucia.’

‘Aye-aye, sir,’ said Copper cheerfully, winking at Cub.

Cub’s first sight of Santelucia, which occurred nearly a month later, produced a sensation of pleasurable anticipation. There was no thought of actual danger in his head, although he realized that there might be some bad feeling at first between them and the self-appointed Commissioner. From the outset he had regarded the project in the light of a holiday, and an unusual one at that, with all expenses paid and a salary into the bargain. It was the same with all of them if the many conversations about the place were any guide. The grasping negro who had made it clear that he was reluctant to abandon his position of authority had not been forgotten; but at worst he was considered in the light of no more than a potential nuisance. After all, reasoned Cub, this was the twentieth century, and the days of petty tyrants were over. Not guessing how soon his judgment was to be proved wrong it was with confidence and content that he leaned on the rail of the sloop that had brought them from Trinidad, watching the island draw nearer.

From the sea, as it lay basking in the blazing white light of the torrid sun, it looked all that a tropic isle can be. In every way it came up to his expectations. Looking over the belt of white foam that marked the encircling reef, it appeared to rise languidly from placid water that could boast every shade of blue from palest turquoise to deepest ultramarine. Beyond the sea, the luxuriant vegetation that enveloped the island like a cloak, was every imaginable variation of green. A network of mangroves was almost black. Patches of sugar cane were of an emerald green so vivid as to appear unreal. Palms were everywhere; coconut palms, cabbage palms, and mighty royal palms that burst their drooping feathery fronds high in the air like green rockets. Only the central peak, to which clung a wisp of cloud left by the trade wind, looked harsh and mysterious. Shadowy ravines scored its flanks.

As the sloop carrying them and their belongings closed the distance it became possible to see the place in more detail. Bright spots of colour marked flaming poinciana trees, golden cassia and crimson hibiscus. In a word, here nature had done its best to create the fairyland of the old story-tellers.

There on the hillside, with its crazy path winding up to it, was the huddle of multi-coloured houses that could only be Rupertston. Above the roofs, a Union Jack, looking somewhat incongruous, fluttered in the breeze. From about the middle rose the squat tower of the church. A little to one side, crowning a bluff just as Cub had imagined it, was Prince Rupert’s fort, its crumbling walls, grey with age, softened by moss, lichen and shrubs, that had got a foothold where storming parties had failed. The advance of the jungle brigade is slow, but it always wins in the end, pondered Cub.

The run through the opening in the reef was a hair-raising affair, an undertaking not to be attempted without a pilot who knew the water. Cub had thought their own pilot, a brown-skinned Hercules, had made rather a business of the approach. Now he understood. For perhaps a minute, on all sides the water boiled and foamed, jagged rocks snarling in the glittering spray; then they were through, with the turmoil behind them and the sloop gliding over calm water, presently to drop anchor near a broad shelf of rock on which half a dozen negroes were standing. There was no wharf, or pier, so a boat was lowered and the new Governor’s party were rowed ashore. The boat at once turned about to fetch the considerable quantity of luggage and stores.

The interval while they were waiting gave them an opportunity to look for the first time at some of the residents. The experience was not encouraging. In fact, it was very much the reverse. Without giving the matter serious thought, in a vague way Cub had imagined there would be a cheerful greeting, possibly an official welcome. There was nothing of the sort. The men did not even move, but stood staring with dull eyes and expressionless faces. They might have been animals.

Cub thought never in his life had he seen such a dirty, miserable, impoverished bunch of human beings. Indeed, he was slightly shocked to discover that men could sink so low anywhere on earth, much less where the Flag flew. Savages he had seen, but they were at least alive. These wretched creatures looked half dead. One was suffering from a skin disease. To say they were dressed in rags would be to pay them a compliment. They were clad in the remnants of rags, and filthy rags at that, which would have been better discarded altogether. He could not imagine any reason why they should be in such a deplorable state. It could not be hunger that ailed them, for there were fish in the sea, and on land an abundance of fruit and vegetables that flourished even without cultivation. He gave it up, glad that arrangements had been made for ratings to carry their stuff up the hill. The wretched creatures standing there looked incapable of physical effort.

He glanced at the others. Gimlet, frowning, seemed puzzled. Trapper’s face expressed a mixture of disgust and pity. Copper’s expression was one of frank bewilderment. He scratched his head. Then, seeing Cub looking at him he observed: ‘Strike old Riley! If this is a sample of what we’ve come to take care of this is going to be no beano. Fair give yer the creeps, don’t they? Where are these hula-hula girls with their ukuleles we always see at the pictures? Don’t tell me they’ve been kiddin’ me all me life. What’s the matter with ’em?’

Gimlet answered. ‘Get rid of any idea that this is a comedy, corporal. These men are scared stiff of something. But we shall have plenty of time presently to talk about that.’

The luggage, which made a formidable pile, for it included radio equipment, a freezing machine, spare clothes and a considerable weight of food, was now ashore, and the sailors were sorting their loads when down the path from the town came three figures so fantastic that Copper let out a guffaw. ‘This looks more like it, chum,’ he told Cub confidentially.

Cub did not answer. He was staring saucer-eyed at a spectacle he had never expected to see outside a stage burlesque.

One of the new arrivals, apparently the leader as he marched in front of his two companions, was a tall mulatto. He was in uniform. From where, or how, he had obtained it, was a matter for speculation. Certainly no white man could have imagined, much less designed, anything so ludicrous. The tunic, cut like an old-fashioned frock coat, was scarlet, laced with broad gold braid and studded with large gilt buttons. Enormous upturned epaulettes shed more gold on the shoulders. The trousers were sky blue with an orange stripe. Lank black hair hung from below a plumed hat. The man wore nothing on his feet, but they had been painted white above the ankles, presumably to represent spats. A sabre hung from his side, and a gold (or brass) ring from one ear.

But in spite of this absurd get-up it was the man’s face that held Cub’s attention. It was long, cadaverous and pock-marked. From it sprang a great hooked nose. Black eyes peered suspiciously from under bushy brows. Round a wide thin mouth, furnished with yellow teeth like fangs, hung a greasy black moustache. Never in all his life had Cub seen a face so stamped with villainy. A man can look repulsive without being a villain; and a man can look a villain without being repulsive. This man was both. From the first moment he saw him Cub was never in any doubt about that. The impression of wickedness destroyed any humour in the outrageous uniform as far as he was concerned. The man, he thought, not unnaturally, was Christian. But in this he was mistaken. The two followers, both full-blooded negroes, also wore garish uniforms, several sizes too small; but they were not to be compared with that of their leader. Over their shoulders they carried rifles.

Happening to look round Cub noticed that the six original spectators had gone—or perhaps it would be more correct to say faded away, for he had not seen them go.

In an expectant silence the mulatto strode up to Gimlet, apparently having the wit to realize that he was in charge of the landing party. ‘What you do? What you come for?’ he demanded, in a peremptory tone of voice.

Gimlet’s piercing blue eyes bored into those of the questioner until, after a flicker, they turned away, stared out of countenance. ‘Who are you?’ he asked curtly.

‘I am General Pedro,’ was the startling reply. ‘Have you permission to land here?’

Gimlet ignored the question. ‘May I ask what army you command?’

‘The army of Santelucia.’

‘Very well,’ returned Gimlet in a brittle voice. ‘The army is now disbanded. Get out of my way and out of that uniform.’ He turned to the sailors who were grinning in delight at this unexpected entertainment. ‘All right. That’s enough,’ he said sternly. ‘Pick up those loads and let’s get along.’

Cub was not grinning. The hate and venom on the General’s face sent a chill down his spine. The idea that this was going to be a holiday received its first set-back.

As the sailors picked up their loads the General stepped into the path as if he intended to bar their way.

Said Gimlet crisply: ‘Listen to me, my fine fellow. If you’re not out of my sight in two minutes, and out of that uniform by the time I reach the town, I’ll have you clapped in gaol, you insolent rascal.’

For a moment the General stared, his jaw sagging as if he couldn’t believe his ears. Then, with a signal to his men, he turned about and set off up the path.

‘That skrimshanker ought to be in gaol, anyway,’ muttered Copper. ‘I’ve seen blokes with mugs like that down the East India Docks. Becha he’s got a razor up his sleeve.’

‘Not so much talking,’ said Gimlet. ‘Let’s move off. I have a feeling we aren’t welcome and it may take us a little while to get things straight.’

The party started up the hill.

‘How about getting our guns out, sir,’ suggested Copper. ‘Those stinkers have got rifles. They might go off.’

‘It’s a bit early to talk of shooting,’ answered Gimlet. ‘We should be able to manage without anything like that. We’ll give it a try.’

‘I’d sleep better o’ nights if that human rainbow was under the daisies,’ whispered Copper to Cub, as they went on.

The path was partly loose stones, and, in the steeper places, steps, worn by the tread of many feet over the years. Sometimes it traversed an open glade, but more often it ran through forest, the nature of which Cub could now judge properly for the first time. The prospect of trying to force a passage through it appalled him. Yet here it was near the track. The track obviously took the easiest route. What, he wondered, must the untouched parts of the forest be like? Bamboos and tree-ferns ran riot with creepers and parasites. There were enormous trees the names of which he did not know, with octopus-like roots sprawling above ground and trunks like columns supported by the rudders of ships. Over and through the tangle coiled and twisted in great loops the inevitable lianas. Underfoot were layers of dead leaves. The sticky humid air reeked of rotting vegetation. He had seen tropical forests before, but even those of the notorious Amazon Basin[1] were no worse than this. The ants were just as numerous, and as busy.

[1] See Gimlet Off The Map.

The climb to the town was a matter of perhaps three hundred feet, but by the time they were there, fit as he was, sweat was pouring down his face. There was no sign of ‘General’ Pedro and his army.

The path ended in what he took to be the town square. Dusty and littered with garbage it lay silent under the blazing sun. There was not a soul in sight. The only things that moved were some scrawny fowls that scratched amongst the rubbish. Two ancient cannon, red with dust, pointed towards the sea. Rust-corroded cannon balls lay near.

One side of the square was open and overlooked the anchorage. Two sides and part of the third were occupied by patchwork ramshackle houses so dilapidated that Cub marvelled that they could look so romantic from a distance. The last part of the square was taken up by a graveyard, so overgrown that had it not been for mouldering wooden crosses, most of them awry, it would not have been recognized as such. Behind stood the little wooden church, pathetic in its drab decay. It looked tired, listless, hopeless, dejected, as if its efforts had been in vain. It was hard to believe that in the days of the island’s prosperity ladies and gentlemen in silk and satin had worshipped there.

There was about the whole place an atmosphere of squalor, of sloth, of degradation. And there was something else, something which Cub found was not easy to define. There was a faint unpleasant smell—but it was not that. Then, suddenly, he got it. It was evil. What could be evil about the place he did not know, but he could sense it; a brooding, furtive wickedness which, with their arrival, had hidden under those shapeless roofs. But it could not conceal its presence. He turned away with a spasm of revulsion. Something horrible, he felt sure, had happened there.

The Union Jack, limp now the breeze was dying with the day, showed them the position of the Government House. Strictly speaking it was a bungalow. A single-storied building of wooden construction, it was, Cub was pleased to note as they walked towards it, in better repair than the rest, although not by any stretch of the imagination could it have been described as attractive. Victorian in design, apart from some ornate features that served no useful purpose, cheapness had clearly been the orders to the builder. There was no time to dwell on this, however, for on a broad verandah that fronted the structure, and to which access was gained by a flight of worm-eaten steps, a military parade had been prepared. It comprised General Pedro and no fewer than eight soldiers, armed with a variety of obsolete weapons—presumably the Santelucian army.

But what a change had come over the General. Gone was his arrogance and surliness. Sweeping off his plumed hat he smiled, and bowed low. ‘Welcome to Santelucia,’ he cried, in a strident voice.

Gimlet, who, of course, was not deceived by this hypocrisy, ignored the salutation. ‘I thought I told you to take that uniform off,’ he said coldly. ‘Because you don’t know me I’ll give you another chance; but mark my words, when you do know me you’ll realize I mean what I say. Is Mr. Christian here?’

The smile had vanished from the General’s face long before Gimlet had finished speaking. Scowling, he waved a hand towards the door.

Gimlet turned to the sailors. ‘All right, you boys. Dump the stuff on the verandah and get back to the ship. The skipper is anxious to get through the reef on the tide.’

The men obeyed the order, saluted and departed. For some time their laughter could be heard as they went down the path.

Followed by the others Gimlet went through the open doorway. It opened into a room of some size furnished in the ponderous style of the Victorian era. A picture of Queen Victoria hung in a cheap frame over the mantelpiece. Cub wasted no time looking at it, for there, on an old-fashioned horse-hair sofa under a red umbrella held by a negro, sat Mr. Jabez Christian. His one garment was a white-spotted heavy silk dressing-gown. On his head was a judicial wig.

As no information had been available concerning the man’s appearance Cub was prepared for almost anything. But not for what he now saw. At his best a negro can be good-looking, and a fine figure of a man. Jabez Christian was the worst type; indeed, worse than the worst Cub had ever seen. Never had a human being of any race filled him with such loathing. Never, he thought, had a man been so inappropriately named.

Christian was, as far as it was possible to judge, between fifty and sixty years of age. His face was heavily jowled. Dull bloodshot eyes and thick pendulous lips suggested dissipation—probably alcoholic. His flesh, what could be seen of it, hung loosely on a frame that might once have been powerful, but was now a wreck. His nose was so flat that it merged into his cheeks, and might have been overlooked but for gaping nostrils. All this made him to Cub a veritable nightmare, a caricature of a man. His pose and expression were of such pompousness that in different circumstances he would have been funny. Such was the man they had come to discharge from his office; and not before time, thought Cub.

‘Mr. Christian?’ questioned Gimlet, crisply.

‘Yaas,’ drawled the self-appointed commissioner.

‘My name is King,’ stated Gimlet. ‘Her Majesty’s Government has appointed me Governor of Santelucia. You will therefore vacate these premises immediately. Later you will furnish me with an explanation of how you dare to come in here without permission. Certain other matters will have to be explained, too. Here is my authority.’ He handed the negro a sheet of paper.

Christian took it like a man in a dream. His eyes never left Gimlet’s face. It seemed to fascinate him. ‘You stay here, huh?’ he said in a hoarse voice.

‘Yes.’

‘Santelucia bad place for white men.’

‘When I need your advice I’ll ask for it. Meanwhile, remove yourself, taking with you any personal property you may have here. I’ll talk to you to-morrow, and to the people here.’

Somewhat to Cub’s surprise Christian rose heavily from his seat. He had been prepared for protest, and, since he had seen the army, perhaps violence.

‘Dis is not a place for white men,’ muttered Christian thickly. ‘You be sorry you came.’

‘Is that a threat?’ asked Gimlet sternly.

‘No, sir. I tell de truth.’

‘It will pay you to do so with me,’ said Gimlet. ‘Your co-operation with me will be more to your advantage than opposition. Tell this man Pedro he won’t be needed any more, and let the people know I’ll speak to them at nine o’clock to-morrow morning. Leave that wig behind. It doesn’t belong to you.’

Christian threw the wig on the floor, revealing a bald pate, and walked past them to the door. On the verandah he could be heard muttering with Pedro.

Gimlet turned to the others. ‘Start to get the stuff unpacked,’ he ordered. ‘Cub, get the radio assembled. Corporal, get the camp kit put up. I hate the idea of sleeping here before the place has been scrubbed down with disinfectant but we’d better have a roof over our heads. To-morrow we’ll take on some staff. Trapper, see what you can do in the food line. Don’t try anything ambitious until we see what sort of state the kitchen quarters are in. Manage with the Primus. Lamps can wait until to-morrow. Candles will give as much light as we shall need to-night.’

‘Queer set-up, sir,’ remarked Copper.

‘Very queer indeed,’ agreed Gimlet. ‘I’m wondering where his lordship got that dressing-gown. He didn’t buy it. For one thing it would cost a lot of money, and for another, that particular garment is made by only one firm in the world, and that’s in Paris. But let’s get on and make the most of daylight.’

They went about their separate tasks.

For some time Christian, Pedro and his men, were there, moving their property, mostly clothes, with Copper keeping a watchful eye on them to make sure they didn’t take anything on the inventory of the house; for the furniture was, of course, government property. Gimlet was making himself acquainted with the building.

There was only one incident. Pedro, carrying out the umbrella, knocked from the sideboard one of those old-fashioned stand-up pictures with the frame covered in red velvet—very much faded. The subject was Queen Victoria and her children. He would have left it on the floor where it had fallen, but Copper touched him on the arm. ‘Ain’t you forgot something, mate?’ he asked quietly.

Pedro glowered.

Copper pointed at the photograph. ‘Pick it up.’

Pedro didn’t move.

‘I said pick it up,’ repeated Copper, in a voice ominously calm, ‘and be careful ’ow you do it, because if you break the glass you’re going to eat it, bit by bit,’ he concluded.

Pedro stooped, picked up the frame, and almost threw it on the sideboard. Had he left matters there all might have been well, but his suppressed fury getting the better of his discretion, he spat at it.

The result must have surprised him, although it surprised neither Cub nor Trapper, who were there. Copper’s fist flew out. Pedro’s plumed headpiece took flight as the fist met his chin with a sound like a chopper falling across a stick. He himself hurtled across the floor until he was halted by the wall. He lay still.

Turning to two of the soldiers who happened to be there Copper barked, ‘Take him outside.’

The soldiers, eyes rolling, obeyed with alacrity.

‘Time somebody took ’im in hand,’ murmured Copper without emotion, as he resumed his work.

Cub noticed that the first valise he unpacked was the one containing their guns and the cartridge magazine. Copper tested the mechanism of each gun carefully, loaded it, and put them together in a convenient drawer.

When darkness fell the only people in the Government House were its lawful tenants. It came with the usual tropical suddenness, and within a few minutes fireflies were waltzing against a coal-black background. Cub closed the door, locked it, and stuck two candles on the table. He lit them and drew the threadbare velvet curtains. Trapper produced plates of sliced bully, biscuits, pickles, butter and a pot of jam.

For a little while they discussed their hostile reception which, said Gimlet, did not particularly surprise him. It was suspected that something was radically wrong on the island: that was why he had been sent. The behaviour of the people they had so far encountered, and the absence of the general population, confirmed the government’s suspicions.

A little later, somewhere in the darkness outside, a drum began to beat. Tumatum-tum-tum, tumatum-tum-tum. . . .

Presently it was answered by another, in the distance.

The drumming continued monotonously, the beats unchanging.

At last Copper said: ‘If that’s their idea of music while you work, I don’t like it.’

‘Those drums are talking,’ said Gimlet.

‘About us?’

‘Probably.’

‘If they’re going to keep that up all night it’ll get on my nerves,’ put in Cub.

‘That, no doubt, is the intention,’ answered Gimlet dryly. ‘I’m afraid we made a bad start, but it couldn’t be prevented. Whatever we had done we should have made enemies of these puffed-up rascals who have been having things their own way for too long. They won’t pack up without a kick, we may be sure of that. To-morrow we’ll hear what the people have to say about it.’

‘If there are any,’ said Cub. ‘The place looked dead to me.’

‘Don’t worry; there are people here,’ asserted Gimlet. ‘Christian, I fancy, has got them where he wants them. We’ll see if he can keep them there.’

Outside, the drums rolled on with the precision of automatic machines. Tumatum-tum-tum, tumatum-tum-tum.

An hour later they were still talking, for the night was sultry and no one felt like sleep. The drums were still making the air vibrate with their unending rhythmic beat, sometimes rising sometimes falling, when on a window pane came an urgent tapping. The sound, brittle and compelling, breaking through the drumbeats, brought them all to their feet.

‘Did you lock the door, Cub?’ asked Gimlet tersely.

‘Yes, sir.’

‘Corporal, go and see who it is. Be careful!’

‘Aye-aye, sir.’

A quick step took Copper to the drawer where he had put the guns. With one in his hand he strode to the door.

With a quick movement Gimlet snuffed the candles.

Copper started to open the door. Instantly it was flung back in his face from outside, and with a shuddering gasp a figure sprawled into the room. Copper was on it in a flash, holding it down. ‘No you don’t, my beauty,’ he growled.

As a match flared in Gimlet’s fingers, Cub jumped to the door and locked it. The candles were lighted and they saw what had entered.

It was a white man who kept muttering over and over again in hysterical repetition: ‘Thank God you’ve come! Thank God you’ve come!’

‘All right, Corporal. Let him go,’ ordered Gimlet. ‘Cub, fetch the brandy from the medicine chest.’ Then, to the man, trenchantly: ‘Stop that noise.’

Although Copper had released him, for a minute the man remained on his knees, panting, gibbering, obviously in an extremity of terror. Gimlet pulled him to his feet and thrust a glass into a hand that so shook that some of the contents were thrown out. ‘Drink it,’ said Gimlet. ‘Trapper, a fresh pot of coffee and make it snappy.’

‘Let him go,’ ordered Gimlet (page 36)

The man who now stood before them, still shaken by great sobs, was young; perhaps in the late twenties. He was emaciated as if in the final phase of a wasting disease. His face was ghastly, his eyes deeply sunken. Long hair was plastered from his head to a tangle of scrubby beard. His legs and bare arms were spotted with jungle sores. His only garments, a shirt and shorts, were torn and stiff with mud. Toes protruded from what had once been a pair of tennis shoes.

Gimlet steered him to a chair into which he flopped like an empty sack. Gradually the sobs subsided, although the man continued to suck his breath in gasps. Trapper had a mug of coffee in his hand. Hot as it was the man gulped it down with grunts of satisfaction. Then he asked for a cigarette.

‘That’s better,’ said Gimlet. ‘But before you start smoking you’d better eat something. It must be some time since you had a square meal.’

It was clear that part of the man’s trouble was starvation; and if proof of this were needed it was provided by the manner in which he wolfed the food Trapper set before him.

‘Take your time,’ said Gimlet. ‘You’ll feel better after that.’ Then, after a little while he went on: ‘That’s enough to go on with. If you stuff an empty stomach you may do yourself a mischief. You can have some more presently. Are you feeling well enough to talk?’

The man drew a deep breath and smiled wanly. ‘I’m all right now, sir. Sorry I—made a—fool of myself.’

‘Had a bad time, eh?’

‘Horrible, sir, horrible.’

Copper gave him a lighted cigarette. The man drew on it hungrily, although he still shook to such an extent that he could hardly hold it.

‘What’s your name?’ asked Gimlet.

‘Gates, sir, Frederick Gates. Birmingham’s my home town.’

‘Where have you just come from?’

‘Out of the forest. Out of the old fort, really.’

‘What were you doing there?’

‘Hiding.’

‘From whom?’

‘These niggers.’

‘Why?’

‘So they couldn’t put a spell on me.’

‘I see,’ said Gimlet slowly. ‘How long have you been here?’

‘I can’t say exactly, sir, but it must be nearly twelve months.’

‘And have you been in hiding all that time?’

‘Oh no. Only the last few months.’

‘How did you get here?’

‘I came with Colonel Baker. I was his batman. There were five of us altogether at the start.’

‘Where are the others?’

‘Dead.’

‘So Colonel Baker is dead?’

‘Yes, sir. Well, he was. Whether he’s still dead I don’t know.’

‘What do you mean by that? If a man’s dead he’s dead—isn’t he?’

‘In most places, but not here. These niggers can bring the dead back to life.’

‘Who told you that?’

‘I’ve seen it done.’

Gimlet smiled tolerantly. ‘They must have some smart conjurers here.’

‘Call it what you like, sir, it ain’t nice.’

‘I can believe that. Now let’s stick to facts. What actually happened to the rest of your party?’

‘They’re all dead except me. Murdered.’

‘Shot?’

‘Oh no, sir. Nothing like that. Nothing so clean. You needn’t be afraid of bodily violence. They don’t work that way. At least, I’ve never seen it. They just put a spell on you and you’ve had it.’

‘How did you escape?’

‘I got the wind up and bolted. Early on I’d spent some time exploring the old fort looking for souvenirs so I got to know my way about it. The niggers won’t go near it because they reckon there’s a duppy there.’

‘What’s that?’

‘A spook. If they didn’t believe it at first they believe it now, for at night I used to sit and howl something horrible. Scared the daylights out of ’em. Not that they weren’t scared before. I kept myself alive on yams and cassava. I saw your ship arrive and I saw you coming up the path. I guessed you’d be here so I’ve come to warn you.’

‘Warn us? Don’t you think we’re capable of taking care of ourselves?’

Gates spoke earnestly. ‘You haven’t a hope, sir. If you stay here you’re dead men—and you’ll never know what killed you. Take my tip and get out. I reckon you’ve seen Christian. Looks like a pantomime turn, but he ain’t, not by a long chalk.’

‘Yes, we’ve seen him.’

‘And Pedro, and his lot?’

‘Yes.’

‘They ain’t the worst. They’re as scared as the rest. The real big noise is a houngan.’

‘What’s a houngan?’

‘A voodoo priest. The whole place is rotten with voodoo. That’s why everyone’s scared stiff. You can’t laugh this voodoo stuff off. It gets you in the end. Look at Colonel Baker. Afraid of nothing on earth. He called it mumbo-jumbo. But it got him. Look at me. I reckoned I was tough. I went through the war, got the D.C.M. and came out smiling. Nobody smiles here. Not likely. I didn’t know what fear was. I do now. So will you if you stay here. You can’t fight something you can’t see. But you can feel it. It’s in the air. It’s everywhere.’ Gates shuddered and gulped more coffee.

‘What exactly are the people afraid of?’ asked Gimlet curiously.

‘Well, for one thing they’re afraid of being turned into zombies.’

‘What’s a zombie?’

‘A zombie is a dead body brought back to life. It has no will of its own. It does what it’s told by the man who owns it. A slave. Works non-stop.’

‘Do you believe that nonsense?’

‘You have to believe it if you stay here, sir. I could show you some zombies. You can tell by their eyes. One of Pedro’s fancy soldiers is a zombie. Pedro shot the man by accident. There he lay, dead as mutton, with a hole in his forehead. I saw it with my own eyes. Now he’s walking about again. You can see the scar. I tell you, these houngans can work miracles.’

Copper stepped in, grinning. ‘Catch bullets in the air, for instance?’

Gates turned serious eyes on him. ‘Don’t kid yourself. It’s nothing to laugh at. This island’s run on Fear, and if you stay here you’ll know what fear is if you never knew before. The place is foul, unclean, with such horrors you couldn’t imagine. It’s one thing to die in battle, but it’s a different matter knowing after you’re dead you may be dug up and turned into a zombie to be a slave for ever.’

‘Blimey, you are in a state,’ observed Copper sympathetically.

‘Wait till you wake up one morning and find the chalk mark on your door.’

‘What does that do to yer?’

‘It means you’ve had it. First thing every morning here people look at their door. They can’t sleep for wondering if the mark of death is there.’

‘Who makes this mark?’ asked Gimlet.

‘Nobody knows. Nobody ever sees it done. That’s what started the trouble here. One morning the mark was on the door. We all laughed, thinking it was a joke. But it wasn’t. Hark at them drums. They do something to you, too. After a time your nerves start beating in time with ’em, and then——’

‘Just a minute,’ broke in Gimlet. ‘You must realize, Gates, that this is a pretty wild yarn you’ve been spinning us. Suppose you start at the beginning and tell us, step by step, what actually happened here from the time of your arrival.’

‘Well, it was like this, sir,’ replied Gates, who was still shaking, although, due no doubt to the presence of white companions, he was getting himself under control. ‘When the Colonel asked me if I’d care to come here with him he told me the people were a happy cheerful lot. Maybe they told you that. Maybe they really think that in London. All I can say is, if ever there was any happiness here it was some time ago. What did we find? A few people skulking about like mangy wolves, afraid of their own shadows. Not a smile anywhere. The Colonel wasn’t worried about it. He said we’d soon put things to rights. After all, there were five of us. There was the Colonel, his secretary—a fellow who used to be in the Royal Corps of Signals—me, the butler and the cook. He was a big jovial fellow named Sims who could make forty different dishes out of a tin o’ bully. We found Christian living here. The Colonel kicks him out, the same as you have, it seems. Says if he has any nonsense he’ll have him deported. Only one person here ever came near us. He wasn’t black. He was an Arab, or something like that. Ran a little mixed shop down the road. One night he came to us and told us some of the things Christian and his pal Pedro were doing here, making people pay him taxes and that sort of thing.’

‘Money?’

‘Yes.’

‘What did he want money for? There’s nothing here to spend it on, is there?’

‘Booze, mostly. Every so often a trading schooner calls here. After it’s gone the place stinks of brandy and gin.’

‘Could the people buy it?’

‘At a price. They had to slave all hours in the sugar plantations to make enough to buy a dram. That’s what this Arab feller told us. The schooner calls every few weeks. It was here last about three weeks ago.’

‘Carry on.’

‘Well, as I was saying, this Arab, who seemed a decent sort of feller, came to see us. After dark it was. He gave us the low-down. Told us all about this voodoo business and how it was paralysing the island with fear. What he really came to see us for, it turned out, he wanted us to push off and take him with us. He said he couldn’t stand it any longer. He told us about the houngans knowing all sorts of deadly vegetable poisons. He said the heart of the thing was a hounfort in the jungle. A hounfort is what they call a voodoo temple. They hold all sorts of beastly rites there, sacrificing white cockerels, and things of that nature. They beat drums, clash cymbals, blow whistles, and so on, to call up spirits. Awful shindy. You can hear it sometimes. Fair makes your blood run cold. The place can’t be far away. All the people go. They have to go. They can’t keep away. If I can remember I’ll tell you more of what this Arab told us.’

‘Why can’t he tell us himself?’

‘He’s dead. When he got home after seeing us the mark was on his door. They must have seen him come here. Eyes are always on you. You can’t see ’em but they’re there, watching every move you make.’

‘And they killed this Arab?’

‘Yes, but you couldn’t prove it. He just sat down and died. And mind you, he had a different religion. He didn’t believe in voodoo. But he died all the same. The Colonel swore he’d been poisoned. They buried him with great ceremony in the cemetery over the way, but whether or not his body is still there I couldn’t say.’

‘More zombie stuff, eh?’ said Copper cheerfully.

Gates didn’t smile. ‘The next night there was digging in the churchyard. We heard it. The Colonel went out to see what was going on. When he came back something seemed to have happened to him. There was a queer look in his eyes. He went to bed. He was never the same again. Seldom spoke. Lost all his energy. Wouldn’t eat. Just wasted away before our very eyes. One day he went out. He didn’t come back. Nobody ever saw him again. I thought I saw him once, in his dressing-gown. But it was Christian wearing it. He was back in Government House by then.’

‘What did the rest of you do?’

‘Nothing. I hate to admit it, but we had the horrors on us. All we wanted to do was get away, but we couldn’t. One by one the others died. Tom Sims was the last to go. I was with him when he died, leaving me alone. After that I don’t know exactly what happened. I think I must have gone mad. When I came to myself I was in one of the dungeons of the old fort, crying like a kid. I’ve been living there like an animal ever since. I think the only thing that saved me from going completely balmy was knowing a government ship was bound to come here sooner or later to see what was going on. I saw you come, but I daren’t leave the fort till it was dark in case they caught me on the way. That’s about all, sir. I’ve told you the honest truth without a word of a lie. Now you take my tip and get out while you’ve got your health, because if you stay here they’ll do you in. If—listen!’

From somewhere in the sullen darkness came an uproar of screams and yells and chanting to a din of drums and clashing cymbals.

Gates started to pant again. ‘That’s ’em at it. What did I tell you? Hark at it.’

Copper, grim-faced, strode to the door and flung it open.

Gates staggered back, a stifled scream on his lips, and a quivering outstretched finger pointing at the door.

The others looked. On the door had been roughly scrawled, in chalk, a cross.

‘It’s the mark,’ moaned Gates. ‘We’re too late. We’ve had it.’

Gimlet flashed round on him. His voice was like cracking ice. ‘That’s enough of that!’ To Copper he said quietly, ‘Shut the door.’

He returned to his chair and sat down.

For a little while there was silence in the room although outside the night was still being made hideous by the barbaric din. Gimlet smoked a cigarette, obviously concentrating his thoughts on the situation that had arisen. The others resumed their seats. Gates’s face was ashen. It was apparent that he was a nervous wreck. Looking at him Cub doubted if he would recover while he remained on the island.

After a few minutes Copper said: ‘Would you like me to go and have a look round outside, sir? See what all this hubbub is about?’

‘Stay where you are,’ answered Gimlet. ‘There’s nothing we can do to-night. We’ll get the lay-out of the place to-morrow, in daylight.’

‘I wouldn’t like ’em to think they’d got us worried, that’s all, sir,’ explained Copper. ‘Strewth! I remember that night——’

‘Forget it,’ requested Gimlet. ‘We’ve never tackled anything like this before and I want to think about it before I rush into action against an enemy on his own ground.’

‘What do you make of it, sir?’ asked Cub.

‘Gates is telling the truth—as he sees it. I don’t see it like that. Neither will you unless you want to get yourselves in the same state that he’s in. Take it from me, this talk of supernatural powers is all poppycock. It’s cleverly organized trickery calculated to reduce these credulous blacks to crawling submission. Fear of the unknown is in their system, and has been for hundreds of years. They brought it with them from Africa—or rather, their forebears did—where it was started by some smart guys who called themselves witch-doctors. No doubt they’ve got some startling tricks up their sleeves; but you can see even better men on the stage in London. There people know it’s trickery and sleight-of-hand, and so on. Here it’s been put over as black magic.’

‘We ought to ’ave brought a conjurer along,’ said Copper.

‘Or a hypnotist,’ suggested Cub.

‘Get this fixed in your heads for a start,’ continued Gimlet. ‘No matter what you may see, no matter how miraculous it seems, it’s trickery. If you ever think otherwise you’re sunk. You’ll be afraid to go to bed at night. Our problem is to make these poor dupes see that. It’s not going to be easy. They’ve had the fear of the devil and all his works knocked into them. We’ve got to knock it out. We shan’t do that with bullets. We’ve got to show them that we don’t care two hoots for these houngans, or whatever it is these fellows call themselves. Our magic is better than theirs. No doubt they’ll be wise enough to anticipate that and do all they can to strengthen their hold on the people. That may account for the tin-can party now in progress.’

‘A troop of commandos would soon mop the whole place up,’ suggested Copper.

Gimlet shook his head. ‘No use. The people would simply hide in the jungle, and you’ve seen what it’s like. We want them to come out into the open.’

‘How about arresting the ringleaders, Christian and Co., and putting them in gaol?’

‘That would make martyrs of them. Besides, that would mean laying on gaolers, which would not only be a dirty job but would tie us to the place.’

‘Well then, how about a little experiment?’

‘Such as?’

‘Putting a forty-five bullet through that stinking half-breed Pedro and then inviting his pals to make him get up and walk. If they’re as smart as they say——’

‘They could do it,’ declared Gates.

‘Oh, shut up,’ snarled Copper. ‘What are you trying to give me? What do you take me for, a canteen-wallah with mummy’s apron strings still round ’im? Old Guy Fawkes went down like any other man when I fetched him a wallop. Spooks my foot. His jaw felt solid enough to me.’

Gates looked horrified. ‘You mean—you hit him?’

‘What d’you think I did—kiss him?’

‘He’ll never forgive you for that.’

‘And what am I supposed to do—lay down and cry me heart out? Forgive me! Ha. That’s a good ’un.’

‘Pipe down,’ ordered Gimlet. ‘Arguing amongst ourselves won’t get us anywhere. Remember, Gates has had a rough passage. He’ll be all right when he’s been with us a little while.’

‘Okay, sir,’ sighed Copper. ‘If we can’t fight what are we going to do?’ He took a crumpled cigarette from his pocket, smoothed it and lit it.

‘I’ll give my orders when I’ve had more time to think about it,’ said Gimlet. ‘I expected a spot of bother but I hadn’t imagined anything quite like this.’

‘We could make a start by stopping that hullaballoo outside,’ suggested Copper hopefully.

‘How?’

‘A hand grenade tossed to ’em to share out would let ’em see we don’t care for their kind o’ music.’

Gimlet looked at Copper suspiciously. ‘Did you bring a bomb with you?’

‘Just a little ’un, sir.’

‘I’ve told you before about carrying bombs in your kit. One day you’ll blow us all up.’

‘Sorry, sir, but it’s got kind of a habit with me. I feel my kit ain’t complete without a squib or two. You know how handy they’ve been to us more than once.’

‘We’re not starting anything like that here,’ said Gimlet shortly. ‘Use your head, man. Think what a beautiful headline that would give the home newspapers. New governor announces arrival by throwing bomb at natives.’

‘I didn’t mean hurt anyone,’ expostulated Copper. ‘I was just hoping to show poor Gates here that he ain’t got nothin’ to be afraid of. I’ve never yet seen a party what a grenade wouldn’t scatter. What say you, Trapper, old pal?’

Trapper clicked his tongue. ‘Every time,’ he muttered softly.

‘You talk too much,’ snapped Gimlet.

‘Take my advice, sir,’ pleaded Gates. ‘Don’t eat anything except out of tins. Remember what I said about poison.’

Gimlet looked at him. ‘What about the water supply?’

‘I think that’s pretty safe, sir. It comes from an artesian well. The pump’s in the kitchen.’

Trapper confirmed this.

‘What sort of poisons do they use here?’ Gimlet asked Gates.

‘According to the Arab they’ve got all sorts, some acting fast and some slow. There’s a vegetable poison called harouma. They get others by boiling down spiders and reptiles. They use graveyard dirt——’

‘Here, hold on,’ protested Copper.

‘What’s the idea of that?’ inquired Gimlet.

‘It isn’t as daft as it sounds,’ said Gates. ‘They used to have a scourge here called yellow fever. The germs are alive in the ground where the victims were buried.’

‘ ’Ow nice,’ sneered Copper.

‘They also use panthers’ whiskers, chopped up fine. The hairs stick in your stomach and start sores.’

‘Trying to give us the nightmare?’ questioned Copper cynically.

‘I’ve heard of leopards whiskers being used in Africa,’ said Gimlet. ‘Thanks, Gates. I’ll be glad of any more information on those lines. In Africa, poison is the witch-doctor’s main equipment, so no doubt the same thing goes on here. Make a note of it everybody. Poison is definitely something we shall have to guard against. Now Gates, I’ll treat those sores of yours. After that, a wash and a shave will make a different man of you. The Corporal will cut your hair, and no doubt we shall be able to fit you out with some better kit than the togs you have on. You’ve nothing to worry about now. We’ve handled stiffer jobs than this. I’d like to ask you one or two more questions. Tell me this. Was this fellow Pedro here when you arrived with Colonel Baker?’

‘Yes, sir. But the Arab told us he didn’t belong to the island.’

‘Do you happen to know where he came from?’

‘The Arab said he thought from one of the bigger islands, a place called Haiti.’

Gimlet nodded. ‘I might have guessed it. Haiti is a hotbed of voodooism. It’s a republic—nothing to do with us. How did your Arab friend learn that Pedro came from Haiti?’

‘He didn’t know for sure. He said he thought so because the ship that calls once in a while, the one I told you about, is manned by Haitians.’

‘What’s the name of this houngan who seems to be behind the trouble?’

‘They call him Papa Shambo.’

‘Have you ever seen him?’

‘No, sir. I don’t think he ever comes out.’

‘Where does he live?’

‘In the forest.’

‘Do you know where, exactly?’

‘No, sir. But his house should be easy enough to find, because with people always going to and fro there’s bound to be a track of sorts.’

‘I see. And where did Christian go when Colonel Baker turfed him out?’

‘To his own house. It’s in the town. I could show it to you.’

‘And Pedro?’

‘He’s got a house not far away, too.’

‘When you bolted to the fort what happened to the stuff you left here? I mean, the personal kit of Colonel Baker and your friends who died?’

‘I left it here.’

‘It isn’t here now.’

‘Then I reckon Christian must have pinched it. I know he’s got the Colonel’s silk dressing-gown because I’ve seen him in it, like I told you.’

‘Were there any weapons here.’

‘No, sir. The only weapon in the party as far as I know was the Colonel’s revolver. He said we wouldn’t want firearms, but when things got difficult he asked me to get his revolver out of his kit, which I did. He had it on him when he went out and I haven’t seen it since.’

‘And this Arab who died. You say he had a shop. What happened to it?’

‘I only saw the shop once afterwards and then it was empty.’

‘Looted?’

‘I expect so, sir.’

Gimlet nodded. ‘All very interesting. Thanks, Gates. I begin to get the hang of things. But that’s enough for to-night. To-morrow I hope to have a word with some of the people; then we shall know even more about it.’

Gates shook his head. ‘You won’t get anything out of the people, sir. They’re too scared to talk. They might as well be dumb.’

‘We shall see.’

‘There’s just one little thing I’d like to do, sir, if you don’t mind,’ said Copper.

‘What’s that?’

‘Take a step or two on the balcony to let ’em see we ain’t scared of their lousy music.’

Gimlet smiled. ‘That’s not a bad idea. It would be a fatal mistake to let them think we were afraid of them. You’d better stay inside, Gates. By the way, these people knew you by sight, I suppose?’

‘Oh yes.’

‘And they think you’re dead?’

‘They couldn’t think anything else.’

‘That’s capital. You’d better stay dead for the time being. We may have a trick there.’

Leaving Gates to start his ablutions in the kitchen they strolled out on to the verandah.

The moon was up, now, flooding the scene with its eerie blue light. The stars glowed like beacons, with the Milky Way a white streamer across the heavens. Beyond the open area of bare earth that fronted the Government House the forest lay black and mysterious. Apart from a few fireflies still waltzing near the trees, nothing moved. The houses, that began a little way to the left, were in darkness. But still the air vibrated to the rhythmic rumbling of the drums.

Tumatum-tum-tum, tumatum-tum-tum.

Copper fetched a rag and rubbed the chalk mark off the door.

The night passed without incident, Gimlet sleeping alone in a side room, and the others, using their camp beds, in the big room. Cub was some time getting to sleep, and he began to realize what Gates had meant by the drums getting on the nerves. They didn’t alarm him. They merely irritated him by their persistence. At what time they stopped he did not know; they were still going when he dropped off to sleep.

He was awakened in the morning by the others moving about. It was seven o’clock and the sun was up, so getting into his white ducks—garments they were all wearing—he had a quick wash and started work on the radio equipment. Copper whistled softly as he stropped the old fashioned cut-throat razor which he still used. Gates, in borrowed kit, looked pale, but was already a different man from what he had been overnight. In the brilliant light of morning the fears that he had brought with him in the hours of darkness had faded away. The aromatic aroma of fresh coffee came from the kitchen.

The front door was wide open. Taking a look outside Cub saw that the square was still deserted. A few children, black and naked, were watching from a distance, but on Cub’s appearance they promptly bolted.

‘Grub up,’ called Trapper.

Gimlet came into the room, immaculate in white.

Over breakfast he announced that he had decided on a policy. Gates, he averred, must have been the white man that rumour had reported to be roaming about the island. ‘I shall do nothing until nine o’clock when I’m due to speak to the people,’ he said. ‘With respect to Gates, I can’t think things are quite as bad here as he imagines. But then he was alone, without a soul to give him moral support. That makes a lot of difference to one’s outlook. We do at least know the cause of the trouble here. I shall take a firm line from the start; anything looking like weakness would be fatal. I shall see Christian and Pedro and make it clear that I’m not prepared to stand for any of their nonsense.’

‘What about this high priest bloke—this houngan, or whatever he is,’ put in Copper, ‘are you going to look for him?’

‘Look for him? Certainly not. I shall send for him.’

‘He won’t come,’ declared Gates.

‘In that case he’ll regret it,’ said Gimlet grimly. ‘I’m not being given the run-around by any insolent voodoo monger. This is a British island and I’m the Governor, so if he wants to stay here he’ll do as he’s told. This isn’t the eighteenth century, and there are no pirates to cock a snoot at authority. We’ll handle this ourselves, for the time being, at any rate. To ask for assistance would look as if we were scared. The Colonial Office would want to know why. What could we say? That we were afraid of spooks, witch-doctors and zombies? They’d laugh at us. Of course, in the event of an open insurrection it would be a different matter. In that case I should have to ask for instructions. Our first job is to find out what happened to Colonel Baker, and the other people who have died or disappeared here. Cub, get the radio functioning, and try to make contact with the station at Trinidad in case we need something we may have forgotten.’

Nothing more was said. Cub got the radio working and had a word with the operator at Trinidad. He said nothing about conditions on the island.

The next hour was spent getting the house in order, Copper putting in some hard work with soap and water. There were some papers in what had been Colonel Baker’s office, but none of recent date. Gimlet said he felt sure that the Colonel would have kept a diary. Gates confirmed this. He said there had been several record books when he had arrived. They could not be found; but their disappearance was no mystery. It was evident that they had been removed, and probably destroyed, by Christian or Pedro, whose names would appear in them, and not to their credit.

The books in the book-case were a strange assortment; a few were fiction by forgotten authors; some were classics, and there were several biographies of eminent Victorians. None was later than the end of the nineteenth century. All were in a hopeless condition, musty-smelling, moth-eaten and generally falling to pieces. No time was wasted on them.

While waiting for nine o’clock Cub and Copper took a short stroll down the main street. It was, in fact, the only street, and hardly worthy of the name. Evil-looking and evil-smelling alleys wound like rat-holes into the jumble of dwellings that comprised the rest of the town, which was really nothing more than a village. From the central block, which had obviously been the original settlement, ramshackle huts straggled away into a mixture of jungle and half-cultivated ground. The crops, mostly weed-choked, were maize, lentils and sugar cane. Apart from a few children, mostly naked, peeping round corners, not a soul was seen.

The shops were few, and shops in name only, the ‘windows’ being open benches on which were exposed a few miserable objects that revealed the poverty of the place. Cheap ornaments, mostly damaged, second-hand rags of clothes, a few bolts of flimsy cotton stuff, home-made wooden goods like bowls and stools, fruit, corn and nuts were the chief wares. To Cub it was all very pathetic. ‘It’s time something was done about this,’ he told Copper moodily.

It was clear that Rupertston had about touched bottom as far as commerce and human occupation were concerned. That something was radically wrong was all too apparent. And, as Cub remarked to Copper, the Government were not to blame, for two successive governors who might have done something had disappeared in mysterious circumstances. They walked back towards the Government House expecting to see the people assembling there, for it was now just on nine.

Not a man or woman was there. Nine o’clock came, and still the square of bare earth lay naked under the blazing sun.

‘Looks as if they ain’t goin’ ter play,’ remarked Copper.

‘Gimlet’s plan is obviously to win the confidence of the people,’ answered Cub. ‘That’s going to be difficult if we can’t find them.’

Gimlet stood on the verandah. His expression was grim. So, when he spoke, was his voice. ‘In the first house on the opposite side a man is peeping at us round that rag of a curtain. I saw him move. Corporal, take Trapper with you and bring him to me.’

‘Aye-aye, sir,’ Copper, with Trapper in step beside him, marched off.

Cub watched them reach the house. Copper knocked. The door remained closed. He opened it and called. There was no response. They went in. A minute later they came out, holding by each arm a passive but reluctant negro. They brought him to the verandah steps where, by the flag-staff, Gimlet stood waiting.

Physically the man was a good specimen, thought Cub; but his eyes were very wide, showing the whites, a sure sign of fear. He was brought to a halt between his escort two paces distant from Gimlet.

‘Man present, sir,’ reported Copper.

Gimlet spoke. ‘Speak English?’

The negro moistened his lips. ‘Yaas, boss.’

‘What’s your name?’

‘J—Joe, sir.’

‘Joe what?’

The man could hardly speak. ‘J-just Joe, boss,’ he stammered.

‘Glad to meet you, Joe. Don’t worry, I’m not going to hurt you. Do you know Mr. Christian?’

‘Yaas, boss.’

‘Did he tell you to be here at nine o’clock this morning?’

‘No, boss.’

‘Do you know what bully beef is?’

‘Yaas, boss.’

‘Do you like it?’

‘Yaas, boss.’

‘Got any?’

‘No, boss.’

‘Like some?’

‘Yaas, boss.’

Gimlet turned to Cub. ‘Fetch him a tin and a couple of packets of biscuits.’

Cub obeyed the order. The man looked as if he couldn’t believe his eyes when the present was put in his hands.

‘If you behave yourself there’s plenty more where that came from,’ Gimlet told him. ‘Do you know where Mr. Christian lives?’

The man hesitated, eyes rolling.

‘Speak up.’

‘Yaas, boss.’

‘Very well. You will now go and tell him that unless he’s here in ten minutes I won’t answer for the consequences.’

The man looked terrified.

‘You’ve nothing to be afraid of,’ said Gimlet. ‘If anyone lays a finger on you he’ll have me to reckon with. I shall need one or two good boys to work for me and you look the right sort. Tell your friends that I’m here to help them. Understand?’

‘Yaas, boss.’

‘Then get along, and come back here afterwards. Are those your children I can see watching us from your house?’

‘Yaas, boss.’

‘Bring them with you when you come. I’ll find something for them.’

‘Yaas, boss.’ The negro turned away.

‘Next thing we’ll be opening a lolly shop,’ muttered Copper.

Gimlet looked at him. ‘Corporal, occasionally you get a flash of inspiration. We’ve got a freezer and some custard powder. Trapper, make ice-cream.’

‘Aye-aye, sir.’

Cub smiled at Copper’s expression. Said Copper, in a low voice: ‘ ’Fore you know where you are, chum, you’ll be running a fish and chip joint.’

Gimlet heard him. Without looking round he said: ‘That’s another good idea. You’re bubbling over with good ideas this morning.’

‘I’d better pipe down,’ murmured Copper sadly.

Five minutes elapsed. Then Christian, still in the dressing-gown, could be seen coming slowly towards them. Reaching them he came to a stop, looking from one to the other. His attitude was apprehensive rather than belligerent, giving Cub an impression that whoever had been the real boss of the island it was not this man. The real power lay either with Pedro, or Papa Shambo the houngan. Christian may have been top dog once, but drink or fear, or both, had sapped his vitality.

Gimlet began without preamble. ‘I asked you to let it be known that I would speak to the people this morning at nine o’clock.’

‘Everybody goes out, mister. I dunno where to find dem,’ answered Christian sullenly.

‘You knew perfectly well where to find them,’ rapped out Gimlet. ‘You were with them—weren’t you?’

‘I don’ understand, mister.’

‘Don’t pretend to be a fool. It won’t fool me. You were all at Papa Shambo’s, making that infernal din.’

Christian was a poor dissembler after all. Expressions of fear and surprise strode across his face. ‘I don’ know nothing ’bout dat,’ he protested.

‘Don’t lie to me,’ said Gimlet sternly. ‘I have someone here who knows all your secrets.’ Raising his voice he called: ‘Gates, come here.’

Gates stepped forward.

Christian’s face turned grey. Cub thought for a moment he was going to faint.

‘Who told you you could have that dressing-gown?’ went on Gimlet. ‘It belonged to Colonel Baker. Take it off.’

Christian’s confusion was not nice to watch. His eyes rolled, but they could not meet those of Gimlet, which never left his face. He took off the garment. Copper relieved him of it. Underneath he wore shorts, also stolen from the Government House, no doubt. But Gimlet let it pass.

‘You will now go and tell the people I want to see them here right away,’ ordered Gimlet curtly.

Christian swallowed. ‘Yaas, suh.’

‘That includes Pedro and his men.’

‘Yaas, suh.’

‘You will then go to Papa Shambo and tell him to report to me here at two o’clock precisely.’

That was too much for Christian. He went to pieces. ‘Don’ ask me to do dat, suh,’ he pleaded. ‘You don’ make me die.’

‘Rubbish,’ snapped Gimlet. ‘I’ve come here to help people and I’m not standing for any nonsense from Shambo or anyone else. I’m giving you a chance to mend your ways. If Shambo isn’t here at two o’clock I shall forbid all meetings except in the church. That’s all for now. Get along.’

Christian turned away like a man sleep-walking.

‘They can’t say I didn’t give them a chance,’ said Gimlet quietly, to the others.

‘Fair enough, sir,’ agreed Copper.

‘Shambo is the trouble. Christian is as scared of him as the rest of them.’

‘Then the quicker he’s winkled out of his shell the better,’ averred Copper. ‘What-ho! Here comes Joe and his kids. Pore little blighters. What a ’ope kids have got here.’

Joe was coming across the square holding—or rather, dragging—a child in each hand. Clearly, the children did not want to come. Other children could be seen peeping round corners. One, a clean-limbed youngster of about fourteen, his ebony body as straight as a lance, with more courage than the rest made a cautious approach. But he stopped at what he evidently considered a safe distance—about ten yards.

Gimlet beckoned him on. ‘Fetch a few bars of chocolate,’ he told Cub, in a quiet aside.

When Cub returned the boy had closed the distance somewhat and was still moving an inch at a time, muscles braced, clearly ready to bolt at the first sign of danger.

Joe came up. Gimlet gave each child a bar of chocolate. He had a job to make them take it. Not a word could he get out of them. He held out a bar to the older boy. ‘What’s your name,’ he asked.

‘Rupert.’

‘What are you afraid of, Rupert?’

‘You.’

‘Why are you afraid of me? No, I shan’t give you the chocolate till you tell me.’

‘White mens eat lil’ boys.’

‘Who told you that?’

‘Shambo, for a dollar,’ put in Copper softly.

‘Ebberyone say dat,’ answered the boy.

Cub gave him the chocolate. Instantly he was flying round the square, making tremendous bounds. Without removing the wrapping he bit a piece off the bar and continued his gymnastics.

Copper watched him admiringly. ‘Blimey! That kid ought to be trained for the high jump,’ he declared.

‘Another good idea,’ said Gimlet. ‘We’ll organize some races later on.’

By this time, seeing that the children had come to no harm, others began to emerge from the places where they had been hiding. Joe still stood there, grinning sheepishly. The faces of his offspring were smeared with chocolate, which the heat had made soft.

‘We’re doing fine,’ said Gimlet. ‘There’s nothing wrong with the kids, anyway.’

Trapper now appeared with a large basin, a spoon, and some paper. To Joe’s children he gave a sickly-looking dollop of the contents of the basin on a piece of paper. The first lick scared them. It was probably the first time in their lives that they had encountered anything cold.

At home, it is unlikely that Trapper’s ice-cream would have passed the test, but here it caused a sensation, and before long he was the centre of a clamouring, shrieking crowd of urchins, mostly naked, although some could boast a girdle of leaves. The bowl was soon empty. Some adults appeared, perhaps to see what all the noise was about.