* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: First Stop Honolulu, or Ted Scott over the Pacific

Date of first publication: 1927

Author: Edward Stratemeyer, as Franklin W. Dixon

Illustrator: Walter S. Rogers (1872-1937)

Date first posted: June 3, 2023

Date last updated: June 3, 2023

Faded Page eBook #20230603

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, John Routh & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

This file was produced from images generously made available by Internet Archive/American Libraries.

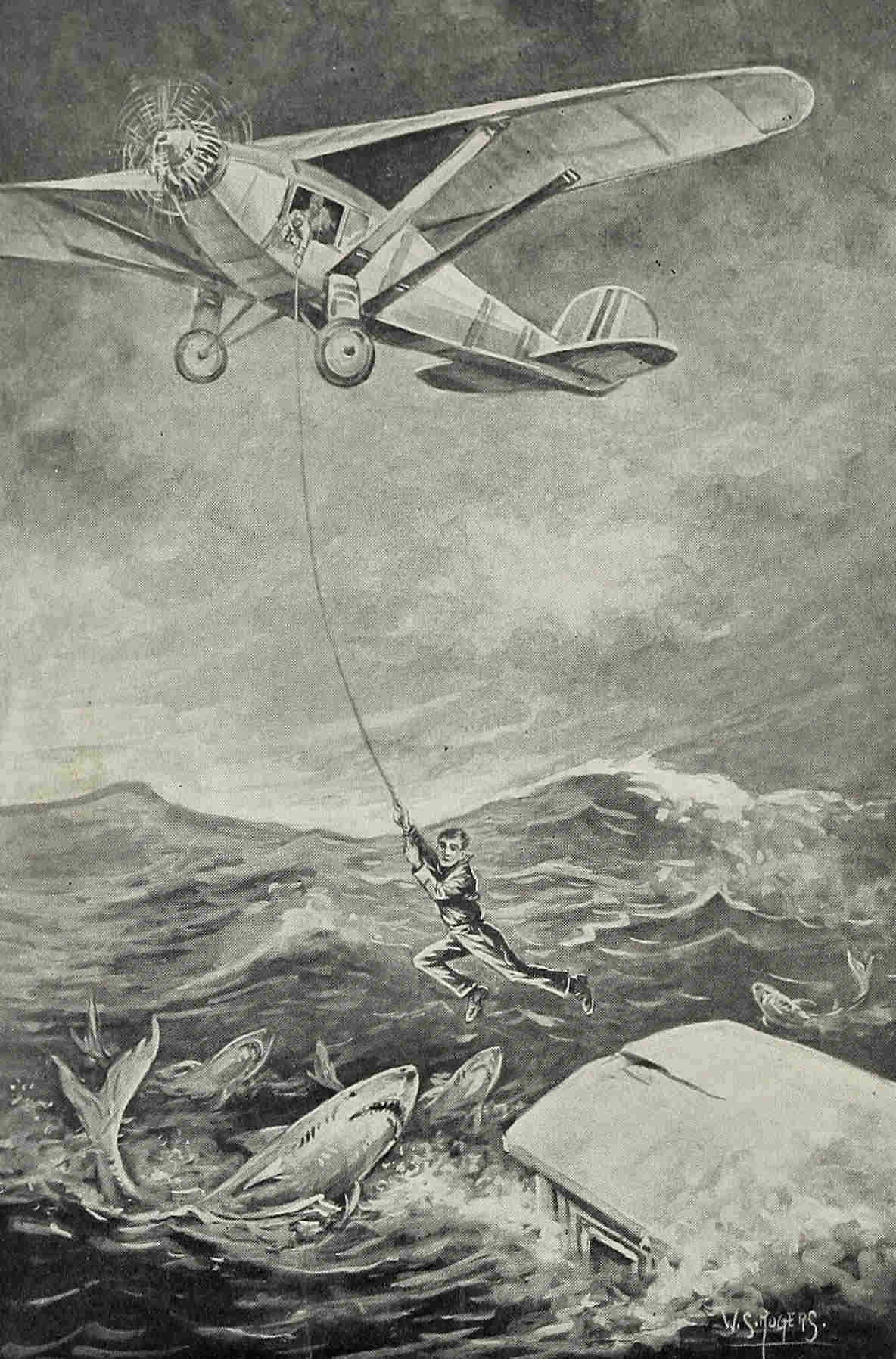

TED SWUNG THE MAN OFF THE WRECKAGE.

TO THE HEROES OF THE AIR

WILBUR WRIGHT—ORVILLE WRIGHT

The first men to fly in a heavier-than-air machine

LOUIS BLERIOT

The first to fly the English Channel

CAPTAIN JOHN ALCOCK

The first to fly from Newfoundland to Ireland

COMMANDER RICHARD E. BYRD

In command flying over the North Pole

COLONEL CHARLES A. LINDBERGH

First to fly alone from New York to Paris

CLARENCE D. CHAMBERLIN

First to fly from New York to Germany

LIEUTENANTS LESTER J. MAITLAND—ALBERT F. HEGENBERGER

First to fly from California to Hawaii

CAPTAIN HERMANN KOEHL—COMMANDANT JAMES C. FITZMAURICE

First to fly Westward across the North Atlantic—Ireland

to Greenely Island

CAPTAIN GEORGE H. WILKINS—CARL B. EIELSON

First to fly over the Polar Sea from Alaska to Spitzbergen

And a host of other gallant airmen of the Past and

Present who, by their daring exploits, have made aviation

the wonderful achievement it is to-day

THIS SERIES OF BOOKS

IS RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED

| CONTENTS | |

| I | Cleaving the Clouds |

| II | Plunging Earthward |

| III | From the Jaws of Death |

| IV | A Close Call |

| V | A Startling Revelation |

| VI | A Thunderbolt |

| VII | Three Against One |

| VIII | On the Trail |

| IX | Was He Guilty? |

| X | Old Enemies |

| XI | A Merited Thrashing |

| XII | A Happy Slogan |

| XIII | Preparations |

| XIV | As One from the Dead |

| XV | On the Wing |

| XVI | The Edge of Peril |

| XVII | A Narrow Escape |

| XVIII | Just in Time |

| XIX | The Burning Ship |

| XX | Racing with Death |

| XXI | The Castaway |

| XXII | Land Ho! |

| XXIII | Winning the Prize |

| XXIV | In Hot Pursuit |

| XXV | Captured |

First Stop Honolulu, or Ted Scott over the Pacific

“Can he do it, do you think?” asked Ed Allenby of Bill Twombley, as the two, clothed in aviators’ costume, stood amid a crowd of people gathered on the flying field, at Denver.

“Can he do it?” repeated Bill, in accents tinged with scorn at the question. “Why, that bird can do anything that he sets out to do! He doesn’t know what it means to fail. He carries my money in anything he starts.”

“Oh, I know Ted!” replied Ed. “You can’t tell me anything about his ability as a flier! But no matter how able a man is, luck enters in sometimes. The pitcher that goes to the well too often gets broken at last.”

“Forty-two thousand feet is an awful lot to beat,” put in Roy Benedict dubiously.

“I don’t care if it’s fifty thousand,” declared Bill loyally. “You just show Ted Scott anything and tell him that’s what he’s got to beat, and he’ll beat it.”

“Of course, there’s always a chance of something going wrong with the plane,” put in Tom Ralston, another aviator who had joined the group.

“Of course,” admitted Bill grudgingly. “But that single-seater he’s going up in has four-hundred horsepower and it’s got an air-cooled engine that’s a dandy. I guess it’ll pull him through, all right.”

It was a beautiful afternoon, and the announcement that Ted Scott, the young fellow who had won the plaudits of the world by his immortal flight across the Atlantic from New York to Paris, was going to try to beat the world’s altitude record had brought out an enormous multitude of people. The field was black with spectators, and automobiles were parked by the hundreds on the rim of the grounds.

It was not merely the magic of Ted’s name that had drawn them there, though that alone always attracted a multitude. Patriotism entered into the affair. For the coveted record for altitude had now been held for a long time by a foreign aviator, and America was anxious to add it to the long list of trophies already won by her sons.

It was chiefly for this reason that Ted had decided to make the attempt. There was no money prize connected with it, and he did not need any addition to the reputation that had already endeared him to his people. But it irked him to feel that there was any feat in the air that a foreigner could accomplish and an American could not.

It appealed, too, to his sporting blood. To hold up a record before him was like shaking a red rag at a bull. He had the impulse to charge it instantly.

Ted’s blood was tingling now as, standing in a little space railed off with ropes to keep the crowd from pressing too close, he made his last preparations for the altitude flight.

“Oh, you Ted!” sang out Bill Twombley as, with the other aviators of his group, he pressed against the ropes.

Ted looked up with the quick, inimitable smile that won all hearts and that had been pictured so many times that all America was familiar with it.

He was tall and lithe, powerfully though slenderly built, with a determined chin, aquiline nose, frank merry eyes and wavy hair.

“Hello, fellows!” he sang back. “Wouldn’t you like to go along?”

“Rather watch it from the ground,” grinned Bill. “I don’t feel good enough to get so close to heaven.”

“How are you feeling, old scout?” asked Roy.

“Fine and dandy,” replied Ted. “Straining at the barrier and r’arin’ to go.”

“Here’s hoping you don’t come down faster than you go up,” put in Ed Allenby.

“I may, at that,” acknowledged Ted laughingly.

“We’re all rooting for you, old boy,” encouraged Tom Ralston.

“Don’t want any ice cream before you start?” asked Bill quizzically, as his eyes took in the heavy clothing Ted was wearing.

“Anything else but,” replied Ted. “I’ll have all the cold I want five minutes from now. With these things I’m wearing, it will be all I can do to squeeze into the cockpit.”

“You’ll need them all,” declared Roy. “You’ll find it ninety degrees below zero up there.”

It looked, however, as though Ted was effectively guarded. He was encased in the heaviest of clothing, with a back pack parachute, several layers of moccasins on his feet and his hands thickly gloved.

“For all the world like a dummy used for tackling by football squads,” was his own comment. “Well, so long, fellows. Here comes the big mogul to give the signal.”

A soldierly looking man, Major Bradley, Ted’s former instructor at the flying school, who happened to be in Denver and had been impressed into service as the master of ceremonies, came up to Ted as he stood by his plane.

“All ready, Ted?” he asked with a smile, as he shook hands.

“To the last notch,” answered Ted, as he stepped into the plane and buckled his strap about him.

“Luck go with you, my boy,” said the major, as he waved his hands to warn the excited crowd back from the ropes that bordered the runway.

A mechanic started the motor roaring and another knocked away the blocks in front of the plane.

The plane started down the runway, gathering speed with every second, and when it had gone five hundred feet Ted lifted it into the air, while the crowd burst into a thunder of acclamations.

The echoes of that roar came to Ted faintly, and a moment later died away altogether as he soared heavenward.

His heart exulted as he found himself in what had grown to be his most familiar element. He felt like an eagle released from its cage. All artificial barriers had dropped away. He was alone in illimitable space, and his spirit expanded in sympathy.

He looked below him. Already the plain beneath had melted into a blur with thousands of tiny dots that he knew to be people. Two minutes later even these dots had passed out of his vision.

In the distance, great mountain peaks seemed to challenge him to go higher, if he could, than they. He accepted the challenge and soon they, too, had faded from view.

Up he went in great sweeping spirals, ever mounting higher and higher until he had reached a height of more than twenty thousand feet.

His engine was working beautifully. It was equipped with a super-charger that, through compression, brought about an approximation of a sea level condition, with the important exception that the process occasioned heating.

He looked at the clock on the board in front of him. He had been in the air about eighteen minutes. His altimeter told him that he was at a height of twenty-three thousand feet.

Nineteen thousand feet still to go if he were to equal the record! Twenty thousand if he were to beat it!

At the height he had reached he could not have breathed the rarefied air without artificial aid. But he had a special oxygen apparatus that gave him a strong flow of the life-giving gas through a tube that he held in his mouth. As long as that flow continued, he might suffer some discomfort, but he would feel no real distress.

Now, with a favorable wind aiding him, he was up to a height of about thirty thousand feet.

Twelve thousand odd yet to go! After that as many more as he could make!

Ted Scott was not content merely to beat the existing record by a scanty margin. He wanted to make his victory overwhelming, to set up a mark that could not be beaten for years, if ever.

It was bitterly cold. Even through his heavy clothing it cut like a knife. Already it was sixty degrees below zero and growing colder with every thousand feet he ascended.

But Ted paid no attention to the cold, for his eyes were glued on the altimeter.

Thirty-two thousand! Thirty-three! Thirty-four! Thirty-five!

The cold now was more insistent. Frost covered the wings of the plane and made it less buoyant. Frost covered his goggles and obscured his sight. Frost was everywhere. His head looked as though it were encased in crystal. And his brain was growing dizzy.

But his heart was hot within him, for now he had covered thirty-eight thousand feet in height. Four thousand odd more to go!

He was mounting more slowly now, owing either to the increasing rarefaction of the air or the decreased buoyancy of the plane or both. He had to jockey his plane as though it were a tiring horse, faltering as it entered the stretch.

Still he mounted. Forty-one thousand! Then five hundred more.

His heart gave a great leap as he reached the forty-second thousand.

But there were still six hundred and fifty-one feet to go to reach the precise figures of the old record.

Ted was conscious now that all was not right with his machine. The engine was not working properly. The plane was laboring in a way that could not be explained solely by the enormous height at which it was flying.

There was a curious vibration of the engine that he did not like. And he was eight miles above the ground!

But he drove away thoughts of danger. The altimeter was the magnet that held his eyes.

It touched at last the forty-three thousand mark!

Ted Scott’s heart thrilled with exultation. He had broken the record! He was higher in the sky than any human being had been since the morning of creation!

It was a thrilling thought, and he reveled in it. He looked up at the sun. No one had ever seen the sun so nearly with unaided vision. He felt a queer sense of kinship with that luminary. He was, as it were, emancipated from the trammels of the flesh.

All the time these emotions were coursing through him he kept the nose of the plane turned upward. He wanted to go up and up and never stop. The sky was the limit. Earth had slipped away from him. It seemed to be something dim and alien.

From this semi-delirium he roused himself with an effort and looked at the altimeter. He was startled. It registered forty-seven thousand feet!

Now, that vibration he had formerly noticed grew into a series of snorts. Something was wrong. With a touch of the joy stick, Ted turned the nose of the plane earthward.

“Nearly nine miles to go,” he murmured to himself.

There was a terrific roar as the engine of the plane exploded!

Two cylinder heads had been blown off by the explosion of the engine and went hurtling through the plane. One of them knocked the oxygen tube from Ted Scott’s mouth.

That tube meant life, and the moment it was torn from his lips Ted began to suffocate, as he could not breathe the rarefied air.

The shock also had thrown him over on his back and he lay there for a moment stunned. The plane was wallowing like a dismasted ship in the trough of the sea.

Choked and desperate, almost unconscious, Ted groped for the oxygen tube. His eyes were dimming, his head reeling, his lungs seemed ready to burst.

For a few seconds nothing rewarded his search, and his senses were rapidly going when his fingers touched the tube. It was above him instead of below him as before, a fact that indicated that the plane had been turned upside down by the explosion.

Ted grasped the tube frantically and inserted it between his lips just in time to keep from passing away. A few draughts of the oxygen restored his strength, and he struggled into position and brought the plane on an even keel.

But it was falling now like a plummet. It had already dropped nearly ten thousand feet while Ted had been struggling for consciousness and breath.

Now five more cylinder heads had joined the first two, tearing through the plane, whizzing by Ted’s head like so many bullets. They crashed through the fuselage and wings, leaving gaping holes in their wake.

As if this were not enough, the engine had caught fire! And Ted was still thirty-five thousand feet above the earth, toward which he was falling like a meteor!

Amid the flames and the hurtling missiles Ted Scott kept his head. The first thing to do was to extinguish the fire. This he did by carrying the plane into a side slip.

But no sooner was one blaze extinguished than another broke out, and four times in the next fifteen thousand feet was Ted compelled to use all his skill to put out the fires.

At twenty thousand feet he had at last mastered the blaze. Then he turned his gaze earthward.

Should he jump? It was the safer way.

But if he did that he would lose the plane, and the instruments on which he relied to establish the fact that he had broken the record would be smashed.

Yet, if he stayed, he seemed doomed to almost certain death, for the crippled plane was like a runaway horse, bent on killing its rider. Its wings were riddled, its balance lost, and Ted could manage it only in part and that with the utmost difficulty.

It was falling now with frightful rapidity. Should he jump or stay?

While Ted Scott is balancing in his quick mind the chances of life and death, it may be well, for the benefit of those who have not read the preceding volumes of this series, to tell who Ted Scott was and what had been his adventures up to the time this story opens.

Where he had been born, who his parents were, whether they were now alive or dead, Ted did not know. His earliest recollections were of being in the home of James and Miranda Wilson, residents of Bromville, a town in the Middle West. They had cared for him kindly and sent him to school, but when he was ten years old they had died within a few months of each other.

The little waif was adopted, however, by Eben and Charity Browning, who had no children of their own. They were goodness itself to him, and he in turn was devoted to them.

Eben Browning had been for many years the proprietor of the Bromville House in the town from which it took its name. He was big-hearted and friendly, and in the early days of the town had a large patronage. Many of his guests were fishermen drawn to the town by the excellent fishing to be found in the Rappock River.

But Eben fell on evil times when the town received a large accession of prosperity from the establishment there of the Devally-Hipson Aero Corporation, makers of airplanes. The mammoth plant brought an army of workmen and others to the town. Several new hotels sprang up to meet the demand, and their spruce and up-to-date appearance and equipment put the Bromville House, now old and shabby, at a disadvantage.

This was bad enough, but a greater blow fell when the great Hotel Excelsior was erected, throwing all others immeasurably in the shade. It was palatial in its appointments and equipment with wide verandas, beautiful grounds, a band pavilion and a superb golf links annexed that offered inducements for tournaments and drew expert players from all parts of the country.

Even this crowning blow might have been borne with more or less philosophy by Eben if he had not had a bitter grievance against the proprietor of the Hotel Excelsior, Brewster Gale.

Eben had owned all the land on which the Hotel Excelsior and golf links were located. Gale had bought it from him at a reasonable price, but, except for the few hundreds paid down to bind the bargain, Eben had never received a dollar of the purchase price. Nevertheless, Gale’s lawyers, as unscrupulous as himself, by a bewildering series of financial juggles—freeze-outs, reorganization, holding companies, and the like—had managed to give to Gale an apparently clear title to the property. Eben Browning had no money to prosecute his fight in the courts, and he and Charity had settled down in dumb misery to the acceptance of their fate.

Ted Scott, as he grew older, had done all he could to help the old folks, painting, repairing and keeping the hotel grounds in shape, and when the Aero Plant was established in the town, he found work there. He was quick and intelligent and was rapidly advanced in position and pay. Most of his wages he handed over to his foster parents every week, and that helped somewhat to keep the wolf from the door.

Ted had become wonderfully proficient in the making of airplanes, the more so because he was intensely interested in flying and hoped at some time to become an aviator. But for this he needed to go to flying school, and as this would cost a good many hundred dollars he could not see his way clear to achieve his ambition.

An opportunity came when Walter Hapworth, a wealthy young man and a golf expert, staying at the Hotel Excelsior, visited the airplane works. Ted was assigned to show him around, and the information the lad possessed impressed the visitor. He learned of Ted’s ambition and in conjunction with a Mr. Paul Monet, whose life Ted had saved, offered to advance enough money to enable Ted to go to a flying school.

Ted accepted the money as a loan, and did his work so well at the school that he became its cleverest and most daring pupil. By exhibitions he earned enough to repay his loan, and then found a position in the Air Mail Service.

Both Mr. Hapworth and Mr. Monet had invested considerable money in the Excelsior golf links, which was under the control of Brewster Gale. They became suspicious of Gale’s honesty because of some queer transactions, and their suspicions were redoubled when Ted told them of the way Gale had swindled Eben.

In the Air Mail Service Ted’s ability and daring speedily put him at the head of the list of pilots. At that time the country was agog with the contest for a twenty-five thousand dollar prize, offered to the airman who should first make a flight across the Atlantic from New York to Paris. Ted was eager to compete, but had not the necessary money for plane and expenses. Mr. Hapworth, however, offered to finance the trip, and Ted secured leave of absence and went to the Pacific Coast to superintend the building of the Hapworth—named after his benefactor.

How Ted, to the amusement at first of the country, ventured into competition with pilots of world-wide fame—how he stirred that same country into flame by his record-breaking flight in two jumps from coast to coast—how in the dim light of a misty morning he mounted into the skies—how he crossed the Atlantic surges amid uncounted perils—how he swooped down like a lone eagle on Paris are told in the first volume of this series, entitled: “Over the Ocean to Paris; Or, Ted Scott’s Daring Long-Distance Flight.”

Numberless offers flowed in on Ted by which he could have made a fortune in the movies, lectures, exhibitions, and various ways. But he did not care to capitalize his fame and devoted himself simply to writing a book of his adventure.

In the meantime, Mr. Hapworth and Mr. Monet had secured enough evidence to bring Brewster Gale to book in the matter of the golf course and to force restitution on that score. But he still refused to do justice to Eben Browning.

The great Mississippi floods had brought disaster to the South, and Ted volunteered in the aviation section of the Red Cross to do what he could for the stricken people. In the course of his work he had many thrilling adventures with snakes, alligators and tottering levees.

Later Ted attached himself to the Air Mail Service in a particularly dangerous section of the Rockies. On one occasion he risked his life in a blizzard to carry a surgeon for an operation on an injured young fellow of Ted’s own age, a youth named Frank Bruin.

How Ted incurred the enmity of another airman who twice made attempts on his life—how he saved a community from a forest fire—how, because of an airplane disaster, he was lost in the wilds—these and many other stirring incidents are related in the preceding volume of this series, entitled: “With the Air Mail over the Rockies; Or, Ted Scott Lost in the Wilderness.”

Now to return to Ted as, with his plane plunging madly earthward, he tried to decide whether he should jump or stay with the plane.

In its downward sweep the plane was soon within fifteen thousand feet of the earth. Ted made his decision. He would stay! He and his plane would perish or triumph together!

But he did not intend to perish. He had been in tight places before and pulled out of them. With every sense alert, with every nerve at its highest tension, yet with his hand as steady as steel, his head as cool as ice, he set himself to the task of mastering his plane in its headlong flight.

It was a tremendous task, for the machine was desperately crippled. The wings were torn and in some places twisted. Its delicate equilibrium was destroyed. The fire had nearly burned through two of the struts and they might break at any moment. The engine was worse than useless.

It was enough to make the stoutest heart quail. But Ted Scott scarcely knew the meaning of quail.

By the time the plane had fallen another five thousand feet, Ted had been able to check somewhat its meteoric speed. It was impossible to keep it on an even keel, but he had regained some measure of control.

A touch here, a touch there, here a side slip to put out a new blaze, there a turn to the right to take advantage of a breath of wind, a hundred different calculations, each one made with lightning quickness! It was a superb exhibition of airmanship on Ted’s part, with his life as the stake if he should make a single mistake.

On the grounds below there was tumult and consternation. The crowd had watched with bated breath as Ted had ascended until he had become a mere dot in the sky and then had vanished from sight.

“Gone!” exclaimed Roy.

“He’ll be back,” declared Bill confidently.

“Yes, but how?” muttered Ed. “Who knows what the cold up there will do to his engine?”

“Don’t worry,” counseled Bill. “He’ll come back safe and sound and he’ll bring the record with him.”

For perhaps forty minutes the spectators stood with faces turned toward the sky. Then from the sharpest-sighted a cry arose.

“There he comes!”

A moment later the excitement was mixed with consternation, for they saw that the plane was diving down with a long stream of white smoke shooting from its tail.

“It’s afire!” yelled Bill in anguish.

“And falling!” groaned Roy.

“Why doesn’t he jump?” cried Ed, beating his hands together desperately.

Many of the spectators covered their faces with their hands, unable to endure the sight of the impending tragedy.

“She’s coming like a rocket stick!” groaned Tom Ralston. “What’s holding Ted? Why doesn’t he jump?”

“Why doesn’t he?” yelled Bill. “I’ll tell you why! Because he doesn’t have to! Look!”

All looked and saw that the headlong descent of the plane had been checked. A moment later the anxious onlookers could detect that it was under some measure of control.

“The old galoot!” fairly screamed Bill Twombley slapping Roy so furiously on the shoulder that he almost knocked him down. “Just watch that boy! See him jockey that plane! Say, is he good? I ask you! Is he good?”

“The best ever!” conceded Tom jubilantly. “He never knows when he’s beaten.”

“There’s only one Ted Scott!” exclaimed Roy Benedict. “No other man alive could handle that plane as he’s handling it.”

Only those expert airmen, of all that breathless crowd, could really understand what Ted Scott was doing. They knew by the wild gyrations of the plane its crippled condition. They knew to what kind of task Ted had set himself. They could picture the lad with his nerves of steel sitting at the controls ten thousand feet in the air and waging his single-handed battle with death.

And they could see that he was winning! He was winning!

Down came the wounded bird, still fluttering wildly, but knowing that it had met its master. Down still further in swooping spirals, broken by sudden halts, but still coming down.

Then at last, as the crowd scattered to give him room, Ted brought the plane to the ground, rushed it along the runway and came to a stop.

His flying comrades were in the van of the crowd that surged about the plane, and Bill Twombley was fairly blubbering as with the others he yanked Ted out of the plane and folded him in his embrace.

“Safe, thanks be!” he cried, and the cry was echoed by a thousand throats.

“You fellows seem glad to see me,” laughed Ted, but his laugh was husky, for he had been under a terrific strain and this welcome threatened to upset him altogether.

“We wouldn’t have given a plugged nickel for your life a few minutes ago!” exclaimed Tom. “How did you do it?”

“Just did it, that’s all,” returned Ted, grinning faintly.

“But what in thunder happened to the plane?” asked Ed.

“What didn’t happen to it, you’d better ask,” said Roy, as he surveyed the wreck.

“Engine exploded,” explained Ted briefly. “Things were lively for a few minutes with the cylinder heads whizzing like bullets through the plane. Then the machine caught fire and I had to put it out four or five times. The oxygen tube was knocked from my mouth. That’s about all.”

“Apart from that, nothing happened?” asked Ed dryly.

There was a general laugh that broke the tension.

“When did the explosion happen?” asked Major Bradley, who had just pressed his way through the crowd and thrown his arm over Ted’s shoulder.

“When I was at the peak of the climb,” returned Ted. “About forty-seven thousand feet.”

“Forty-seven thousand!” exclaimed the major.

“Beat the record with over four thousand to spare!” gasped Tom.

“Something like that,” replied Ted. “There’s the altimeter to tell the story. The barographs in front and rear of the plane will confirm them. That’s the reason I didn’t jump. I wanted to save the instruments.”

“Did I tell you that boy would do it?” crowed Bill exultantly.

His comrades hoisted Ted on their shoulders and bore him through the shouting, turbulent crowd, all anxious to get near enough to pat his shoulders or grasp his hand.

It was with a sigh of relief that the young aviator relaxed when the door of his quarters closed behind him with only his special intimates to keep him company. He was profoundly weary but unreservedly happy. He had been at grips with death and conquered. He had done what he had set out to do. He had added another laurel to the wreath that crowned him as America’s idol. He had brought from abroad the record that had been so long coveted by his country’s airmen.

He stripped off his heavy clothing, took a cold shower and was himself again.

His comrades clustered about him, and there was a babel of questions and exclamations as they made Ted, despite himself, tell all the details of that magnificent battle with death.

“What else is there left to do, Ted?” asked Bill. “You’ve walked off with almost everything.”

“Oh, plenty, I guess,” laughed Ted. “I’ve been so bent on getting this altitude record that I haven’t thought much of anything else.”

“You’ve licked the Atlantic,” put in Roy. “What’s the matter with taking a crack at the Pacific?”

“You mean that flight from California to Hawaii?” asked Ted thoughtfully.

“Just that,” replied Roy. “Why don’t you enter, Ted? I’ll bet you’d cop the prize.”

“Thirty-five thousand dollars!” remarked Bill. “Thirty-five thousand sweet, juicy berries! Makes my mouth water just to think of them.”

“They do sound pretty good, and they could be won in about twenty-four hours of straight flying,” agreed Ted. “But there’ll be a whole lot of fellows trying for it.”

“I see that there are a good many entries,” admitted Roy. “But you know how those things are. Some of the fellows will get cold feet. Other will find that their planes aren’t good enough. Others will meet with accidents while they’re tuning up. By the time the race actually starts there probably won’t be more than two or three pairs left. And I don’t believe any of them would have a chance against you.”

“I don’t believe many of them will have a swifter plane than the Hapworth,” mused Ted, to whom the idea appealed strongly. “But speed isn’t the whole of it. A large part of it will be navigation. Honolulu is a mighty little spot in the Pacific Ocean. It would be the easiest thing in the world to miss it altogether.”

“Not you!” disclaimed Bill. “Didn’t you hit the Irish coast within four miles of your bull’s-eye when you flew across the Atlantic? That was some navigating! And what you did once I’m willing to bet you can do again.”

“Go to it, old boy,” urged Ed. “It’ll be another feather in the cap of the Air Service.”

“I’ll think it over,” promised Ted, “but there’s plenty of time yet to make my entry, and there’s no need for an immediate decision.”

There was a knock at the door and Major Bradley came in. Ted’s friends went out leaving him alone with his former instructor.

“Ted, my boy, I believe that flight of yours was the most thrilling in the history of aviation,” the major said, as he seated himself. “Plunging down with an exploded engine through the air with cylinder heads whizzing about you, with fire breaking out again and again, and yet keeping your head and bringing the crippled machine to a perfect landing! Maybe the newspapers won’t eat it up!”

“Oh, I don’t know,” replied Ted modestly. “I’ll admit it was a bit exciting, but I was too busy to think about it much at the time. But about the record! What do the barographs say? Do they confirm the altimeter?”

“One of them was injured by the fire so that it’s unreliable,” replied the major, “but the one in the front of the plane was all right, and, as far as we could see from a hasty examination, is just the same as the altimeter. We’ll have to send it in to the Bureau of Standards at Washington to have it calibrated before we can tell to a foot the distance. But there’s not the slightest doubt that you’ve beaten the record, and beaten it good and plenty.”

“Bully!” exclaimed Ted. “Now the foreign aviators will have a new mark to shoot at, while we sit back and watch them do it.”

“No doubt they’ll try,” declared the major. “But I doubt if it’ll be equaled in this generation, if ever.”

“No telling what will happen in aviation,” laughed Ted.

“Maybe. But yours was a wonderful exploit. I’m overjoyed that it was at my school you learned to fly.”

“Have you found out yet what caused the explosion?” asked Ted.

“Not yet,” replied the major. “Some of the engineering corps are busy at it now. The machine is a perfect wreck. Of that nine-cylindered engine, seven cylinder heads blew out and the other two are cracked. How you ever got down alive beats me.”

“I’ve been trying to figure out the cause of the trouble myself,” said Ted. “I think the lubricating oil had become affected, even ignited. Then in the swift descent, while I was groping about for the oxygen tube, friction acting on gases made the engine catch fire.”

“As good a guess as any other,” assented the major. “Also, centrifugal force while your plane was whirling about may account for some of the trouble. Anyway, it surely was trouble while it lasted. But now, my boy, it’s up to you to take a good rest. You ought to tumble into bed and sleep the clock around.”

“Can’t,” replied Ted, looking at his watch. “I’ve got to start on my Air Mail route this evening.”

“Forget it,” counseled the major. “Let somebody else take your place to-night. You’ve done enough for one day. Don’t tax yourself too much.”

“I’m feeling as fit as a fiddle, now that I’ve had a shower,” replied Ted. “I’ve never missed a trip yet, and I don’t want to begin now. I’ll have plenty of time of sleep to-morrow.”

“Stubborn as a mule, as of old,” laughed the major. “So I won’t waste my time trying to make you change your mind. But you’ve still got time for forty winks and I’ll leave you. As soon as I get the official report on the barograph from the Bureau of Standards I’ll let you know.”

He left then, and Ted, in the two hours that remained before he must report for duty, got his “forty winks,” from which he woke with his nerves calmed and his strength restored.

It was a royal send-off that he got that evening as, after seeing that the bags of mail were properly stored in the biplane, Ted Scott stepped into the cockpit of his machine and gave the signal for the blocks to be knocked away. The flying field was still buzzing with his marvelous exploit, and a host had hurried out from the city to gaze on the hero of the hour.

“Bad night for flying, Ted,” remarked Major Bradley, as the motor started to roar.

“It is, sure enough,” replied Ted, as he looked at the mist that was settling down. “But I’ve seen worse, and Uncle Sam’s mail has got to go through, no matter what the weather.”

With a wave of the hand he started down the runway, lifted his plane into the air, and was lost to sight.

The beacons from the flying field cast their glare, although with diminished force, through the dense mist, and the lights of Denver also helped him in turning the nose of the plane in the right direction. But he was away from these in a few minutes, and then he found himself in a darkness that could almost be felt.

It was not the darkness, however, but the dense fog that gave him the most concern. On a dry night, even in the absence of moon and stars, he could yet discern objects at some distance ahead of him. At least, they made a deeper blur against the blackness.

But when the fog enshrouded him, as it did to-night, he could not see ten feet in advance of the plane. He had to trust to his altimeter to keep him at a sufficient height to clear buildings, the tops of trees, and, in a mountainous country such as he was now traversing, the summits of lofty cliffs. If his instruments failed him, he would be in the deadliest peril.

As for direction, he had little fear of going astray. He had his trusty inductor compass, the same that had guided him so accurately in his flight over the Atlantic. It had never failed him yet, and he felt confident that with its aid he would be able to go like a homing pigeon straight to his goal.

On he went, with a speed twice as great as an express train. He had attained a height sufficient to clear the loftiest peak that might be in his path.

He had hoped that at that altitude he might find a lessening of the mist, but in this he was mistaken. Everywhere was fog, dank, dripping, enfolding the plane as with a shroud. But there was nothing he could do but to drive on through the night.

As he sat there with his hand on the joy stick and his eyes glued on his instruments, his subconscious mind was busy with many things.

First and foremost was the glorious victory that he had achieved that day. His pulses thrilled as he thought of it. Again he lived that splendid struggle for the mastery of his broken plane, that grim and unyielding combat with death.

He knew that by this time in every big newspaper building of the country, reporters, editors, copy readers and pressmen were putting into print in great headlines the story of how Ted Scott, the idol of the nation, had scored once more and had again made aviation history.

He would not have been human if this had not given him gratification. But far more than the sense of personal victory entered into his elation. It was America of which he thought. The country of which he was so proud had snatched from overseas the record that it coveted, and he rejoiced that he had been the instrument in achieving this triumph for his people.

He was humbly grateful, too, for his marvelous escape from death. Never had he been so near the great beyond. He wondered if dear old Charity Browning had been praying for him. He was sure she had.

The thought of Charity, as always, reminded him of the mystery that enshrouded his birth. Eben and Charity, it is true, had taken for him the place of father and mother. None could have been more devoted to him, and his heart swelled with gratitude toward them.

But, after all, they were not his real parents, his own flesh and blood. Who were they, the man and woman who had given him birth? Where were they now? Were they living or dead?

How could he even be sure that the name he bore was that of his parents? He felt defrauded. In some vague way he seemed to be set apart from his friends and companions. They had or at one time had had parents whom they had known, who had loved and cared for them. They had memories of a home over which presided a father or mother or both. He was denied all these blessed memories. He grew bitter at the thought.

It is true he had made a name for himself. It was a name that stirred his countrymen whenever they heard it. It was a name that had echoed through the world. It was blazoned on the scroll of history. He was one of America’s immortals.

He valued this beyond expression. Yet there were times when he would have given all the fame he had so gloriously won, if, by so doing, he could tear apart the veil of mystery as to his origin.

He was roused from his musings by a roar that came to him through the fog.

Instantly all his senses were on the alert.

He knew at once what that roar meant. It was caused by the motor of an airplane. Some other night rider of the air was abroad!

Now the roar grew nearer. The other plane was coming toward him, whizzing like a bullet through a fog so thick that it was like a solid wall.

Deprived of the advantage to be gained by sight, Ted had now to reply solely on his hearing. The difficulty here was doubled by the fact that the roaring of his own motor mingled with that of the oncoming plane.

In a desperate effort to avoid a collision, Ted shot upward. But the sound that came from the other motor told him that the unknown airman had adopted the same maneuver.

Then Ted dived. So did the other. They were for all the world like two men meeting in the street, when both turn to the left and then to the right at the same time until finally they pass.

But the men in the street could see. Ted and the other pilot were like blind men.

Just then the fog thinned out a little and Ted could see a great black mass hurtling toward him like a catapult!

A swift touch at the controls, and he side-slipped, bringing his plane sharply to the right.

There was a breath-taking instant of suspense, then the other plane zipped by and disappeared in the night.

It was the narrowest of escapes, and Ted felt the perspiration breaking out all over him. Death had grazed him, but not quite gripped him.

Grazed him literally, for the passing had not been effected without damage of some kind. There had been a distinct shock and a sound of cracking, and Ted knew by the erratic way in which the plane was behaving that something was wrong.

How serious the damage was, he had no way of knowing, but he sensed that the trouble was in one of the wings. As he peered from the cockpit he noticed that on the left the wing appeared to be bent and drooping.

It behooved him to make a landing as soon as possible, in order that he might ascertain and remedy the injury.

Now the fog that had been so unfriendly thus far seemed to be relenting, as though it wished to make amends. It was shredding out below him rapidly, and soon thinned to such an extent that he could distinguish the rosy glow that told him he was passing over a town.

It was perilous to try to make a landing under such conditions, but it was still more dangerous to stay aloft with his plane perhaps in such a condition that it might crumple at any moment.

He had no alternative. He must come down!

He sailed around the outskirts of the town in wide spirals until he made out what seemed to be a comparatively level field that formed part of an estate.

With the utmost care he descended and made his landing. To his great relief he found that the ground was as level as a lawn. There were no trees, except at the side, and he brought the plane to a stop within fifty yards of the charming suburban house to which the lawn was attached.

Lights streamed from several windows and Ted could hear the music from a radio inside.

He jumped from the cockpit and made his way to the door. It was necessary for him to apologize for his intrusion on the owner’s grounds. Then, too, he wanted to borrow a lantern and perhaps ask the help of the owner, in case the injuries to the plane proved serious.

He rang the bell. The radio music was turned off, there was a movement inside, and a moment later the door opened and a woman stood framed in the doorway.

She was lovely in form and feature, barely past girlhood, and her beautiful eyes widened as she saw the figure in the aviator’s suit.

Ted removed his helmet and bowed.

“Good evening,” he said. “Please excuse—”

He got no further.

“Ted Scott!” exclaimed the young matron. “Well, of all things! Come in! Oh, I’m so glad to see you! Frank,” she called to a man who was sauntering leisurely toward them, “here’s Ted. Come running!”

There was no need for the urging, for the man rushed forward, dropping his pipe in his eagerness.

He threw his arms around Ted in a bear’s hug and dragged him into the room.

“You old rascal!” he shouted, as he released him and pushed him into an easy chair. “What good wind blew you down this way? You’re as welcome as the flowers in May.”

It was the first time Ted had seen Frank Bruin and the former Bessie Wilburton since their marriage. Ted had been best man at the wedding. It was fitting that he should have been, for it was largely due to his efforts that the marriage had taken place at all. For he had been the messenger of Cupid that had mended their broken romance and brought the young people together again.

“So good of you to come to see us!” exclaimed Bessie happily.

“You bet!” ejaculated Frank. “And you won’t be allowed to get away in a hurry, either.”

Ted grinned.

“I’m pleased beyond words to see you both,” he said; “but I’m afraid you’ll have to guess again. Fact is, I’m a workingman and have to stick to my job. I’m carrying mail to-night, and you know the mail can’t wait. I had a mishap in the air, and had to make a landing to see what the damage was. And good luck brought me right down on your lawn!”

In response to their eager questions he told them of the incident in which he had been one of the participants.

They listened breathlessly and were profoundly grateful at his narrow escape. But they were bitterly disappointed that he had to leave them so soon.

“Let the old mail go,” suggested Bessie. “What if people do have to wait for their letters a little while longer? It won’t hurt them.”

“Uncle Sam doesn’t look at it the same way,” laughed Ted. “But I’ll make a regular visit before long when I can get a few days off.”

“If you don’t, I’ll never forgive you!” declared Bessie, and Frank echoed the threat.

“So you’ve been at your old tricks again, I see,” observed Frank, with a grin.

“What do you mean?” asked Ted.

“Listen to the innocent, Bessie,” Frank appealed to his wife. “What do I mean? Breaking the altitude record. That’s what I mean.”

“Oh, that,” replied Ted.

“Oh, that,” mimicked Frank.

“How did you hear about it so soon?” asked Ted, a little uncomfortably.

“All America has heard about it by this time,” replied Frank. “You forget the radio. Not ten minutes before you came, the announcer was telling us all about it. Forty-seven thousand feet! The engine exploding, the plane on fire, the cylinder heads hurtling through the machine, the tube knocked out of your mouth, the fight to get the mastery of the plane, the perfect landing. Gee, it was a wonderful story, and the announcer spread himself! We were all broken up. Chills were chasing down my spine. I was trembling. Bessie was crying—”

“Stop telling family secrets,” ordered Bessie promptly.

“Well, luck was with me—” began Ted.

“If you say ‘luck’ again, I’ll hand you one,” laughed Frank, doubling his fists. “It was pluck. It was nerve. It was audacity. It was lightning thinking. It was superb airmanship. It was—oh, well, what’s the use?”

“I thought you’d run out of words before long,” grinned Ted, as he rose reluctantly from his seat. “But come along now, old man, and we’ll take a look at the machine. Bring a lantern, will you?”

“While you boys are doing that I’ll get a little lunch ready,” put in Bessie. “But I still have a grudge against that old mail.”

“As long as you don’t have a grudge against this young male it’s all right,” laughed Frank, as he pinched her cheek affectionately.

It was an awful pun, and Bessie punished him by slapping him and telling him to run along. But it was a very gentle slap.

“Gee, Frank, but you’re a lucky dog,” remarked Ted as the young men made their way to where the plane was standing.

“Luck’s no name for it!” declared Frank jubilantly. “She’s the sweetest girl on earth and I’m the happiest man. And you’re responsible for it, Ted. I only hope that when the time comes you’ll have equal luck.”

Ted was relieved to find that the damage to the wing of his plane was not so serious as he had feared. He was an expert mechanic, and while Frank stood by with the lantern and occasionally lent a hand, Ted tinkered away until he had the wing in shape.

“That will do until the end of the trip,” he said at last, as he straightened up after a careful examination of the entire machine. “I’ll have a little more done to it when I reach the flying field.”

“I hope the other fellow wasn’t hurt any more than you were,” remarked Frank, as they made their way back to the house.

“I hope not,” echoed Ted. “I think it was his motor that grazed me, and that’s pretty tough.”

They found the table prettily set and an appetizing lunch prepared. Bessie, flushed and sweet, presided at the coffee urn, and again Ted mentally registered that Frank was a lucky fellow.

It was hard to tear himself away from that cozy dining room and those warm friends and fare away into the night. But duty was imperative, and he had to obey its call.

With repeated urgings to come soon for a long visit, the happy young folks waved and shouted farewell as Ted jumped into his plane and soared away in the darkness.

His last glimpse of them as they stood with arms intertwined remained with Ted as he whizzed along beneath the canopy of heaven, and again the thoughts that had assailed him earlier in the evening returned to plague him.

It was not envy of his friends’ married happiness. He was still heart whole and fancy free. Some day he might meet a girl like Bessie and be as happy as Frank. But at present all his heart and thought were engrossed with his profession.

What he did envy was the normal position the young folks occupied in the world. Their names belonged to them. They knew their parents. All their past was known to them. They had a host of home ties, connections, relatives.

But he, Ted Scott, had none of these. He felt like a branch that had been severed from the trunk. He was rooted somewhere in the past, but did not know just where. If he should marry sometime, he reflected bitterly, he would not even be sure that the name he would offer to a girl was rightfully his own.

But he did not have long to indulge in these musings. For though by now the fog had vanished, the wind had risen, and he had to use all his craftmanship to keep his plane on a level keel.

Moment by moment the gale increased until it had reached the proportions of a miniature cyclone.

He turned the nose of his plane upward, trying to reach a more quiet stratum of air. But everywhere the demons of the wind were howling and the tumult about him became pandemonium.

He stiffened to the task before him. He had been out before many a time in storms and won through. But that had been when his plane had been in perfect condition, and to-night he could not be sure that there had not been some material weakening of the plane from the collision that he had not been able to detect in the necessarily hasty examination he had made.

Now, to the fury of the wind, lightning and thunder were added. Reports like those of a thousand cannon boomed over the mountain gorges. Great jagged sheets of lightning shot across the sky.

With one of the most vivid glares came a shock that shook the plane from end to end!

Following that terrific flash and shock, the plane quivered like a wounded bird.

Then it whirled about and about with such violence that Ted Scott was almost torn from the straps that bound him to his seat.

The glare almost blinded him and his ears were ringing as though the drums had burst.

That the plane had been struck by the lightning he felt certain, and the certainty was increased by the sight of balls of fire running along the motor.

But a moment later he felt sure that it had been but a glancing blow and that the electric current, after delivering a threat, had passed away in search of another victim. For the plane, after the initial quivering had been spent, had gallantly responded to the touch of its master and soon was once more riding the gale, its speed increased by the fact that the wind was coming from the rear.

Yet Ted’s heart was in his throat. He kept casting glances here and there all over the plane, fearing that at any moment he might see some scarlet thread of fire running along the more inflammable portions, and it was only after fully five minutes had elapsed without any such ominous sign appearing that he ventured to relax.

But it was only in a comparative sense that he relaxed, for all his skill and nerve were still needed to manage the plane.

Gradually, however, the storm abated in fury. The rain ceased to fall, the thunder died away in a distant rumble, and the lightning withdrew into its caverns.

With the lessening of the tempest came the dawn, the blessed dawn, that had never been more welcome to Ted Scott.

He was weary almost to the point of exhaustion, for the perils of the night coming as an aftermath to the strain and excitement of the day before had taxed his strength and vitality to the utmost.

He felt an almost irresistible desire to sleep. More than once he felt his eyes closing. But they never entirely closed, for the subconscious urge was on him, and he would arouse himself with a start and again bend over his controls.

It was with infinite relief that at last he reached his terminal airport and delivered the bags of mail. Then he turned the plane over to the mechanics for a thorough overhauling, went to his quarters, and obeyed at last the exhortation of Major Bradley to “sleep the clock around.”

When at last he woke refreshed it was to find that marked excitement had been aroused by the slight collision of the night before.

“Place has been fairly buzzing with phone messages from Denver and other places to know whether you were safe,” one of the mechanics, Alf Holden, told Ted when he appeared on the flying field. “Seems that the other fellow you nearly smashed with landed at Denver and told the story. The folks there figured out that it was your plane that he met, and they were going bugs about it till we told ’em you’d landed here all right.”

“Who was the other fellow?” asked Ted. “Was his plane damaged?”

“Nothin’ but some paint scraped off,” replied Alf. “Seems he was some army guy on his way to the coast. He could feel that he’d hit you, and he was afraid you’d smashed. Gee, they was wild over it till we told ’em different.”

“It sure was a close shave,” observed Ted. “But a miss is as good as a mile. How’s the machine?”

“Fine an’ dandy,” returned Alf. “Us fellows has gone over every inch of it, fixing it up a bit here an’ a bit there and now it’s fit to fly for a man’s life. But shucks, what’s the difference? A feller that came through all you did when you busted that record can’t be hurt, nohow. Say, tell us all about that. The fellers here have been talkin’ of nothin’ else since you done it.”

Again Ted was forced to tell to Alf and the other mechanics and pilots that gathered around him the details of his thrilling exploit.

Denver, too, was still ringing with it when he got back there to be given an enthusiastic welcome by his comrades, which was made all the warmer by the fears they had entertained regarding his safety after the army flyer had made his report of that dramatic episode of the night.

“The old rabbit’s foot is still on the job,” gloated Bill Twombley, as he threw his arm over Ted’s shoulders.

“Can’t kill that fellow with an axe,” beamed Ed Allenby.

“Wish I had his recipe,” grinned Roy Benedict.

“If everybody was like him, the life insurance companies would go out of business,” observed Tom Ralston.

It was a regular reception that Ted held at his quarters, for the reporters and photographers were there in swarms anxious to get stories and pictures of the young hero who again had stirred the heart of the nation, and it was late that night that Ted with a sigh of relief found himself with only Tom Ralston, who had outstayed the others, to keep him company.

Perhaps none of those warm friends of Ted’s were quite as devoted to him as Tom, for Ted had saved his life under circumstances of the deadliest peril.

It had happened when Ted was serving under the Red Cross at the time of a great Mississippi flood and Tom’s plane had caught fire high in the clouds.

Ted, from the ground, had seen the danger, and leaped into his own plane and soared upward. By superb generalship and courage, he had approached the blazing plane and made a daring and thrilling rescue in the clouds.

Tom Ralston had never forgotten that rescue, and from that time on he had fairly worshiped Ted. It was largely the desire to be near the latter that had led Tom to seek employment in the same division of the Air Service to which Ted was attached. At any moment Tom would have laid down his life for his rescuer.

Now their conversation had drifted to the days when they had fought the Mississippi together.

“By the way,” said Ted, as a thought struck him, “do you remember that day in the hospital, Tom, when you were starting to tell me something and the nurse stopped you?”

Tom started and flushed a little.

“Did I?” he asked evasively. “Guess I was chinning a lot of nonsense those days. Delirious part of the time.”

“You weren’t delirious then,” replied Ted. “You started to say something about a man named Scott having saved your father’s life once. You thought it queer that I should have helped you out of a bad fix and that a man of the same name should have done the same thing for your dad.”

“It was rather odd,” agreed Tom uneasily. “But of course there are lots of funny coincidences in life. Guess I’ll be going now,” he added, rising to his feet and yawning. “You must be dead tired, old boy, and I’m keeping you up.”

But the yawn was too elaborate, and Ted’s quick mind sensed something behind it.

“Look here, Tom!” he said. “What are you trying to keep from me? Do you know anything?”

“My teachers never thought so,” replied Tom, with what he thought was an engaging grin.

“Cut out the wise cracks,” commanded Ted. “You know what I mean. Do you know anything about my family?”

“How should I?” countered Tom. “I never met you in my life until I saw you down South.”

Ted shook himself impatiently.

“Can’t you answer a straight question?” he demanded. “What do you know about any one named Scott?”

“It’s a common enough name,” mumbled Tom. “I’ve come across lots of them in my day.”

“Quit your stalling, Tom,” cried Ted, now thoroughly aroused. “This man Scott, who saved your father’s life. How did he do it? Where did he live? Come now, tell me about it.”

“Why, there isn’t much to tell,” said Tom reluctantly. “My father was living at the time in Grantville, a little town down East. He slipped one day as he was getting into a boat and fell into the water. He had hit his head in falling and was being swept toward a dam when this neighbor of his, Scott, plunged in and rescued him just as he was about to go over. Scott had a hard time, but he was a powerful man and finally got my father to shore. I was just a baby at the time, but I’ve often heard my folks talk about it.”

“What was this Scott’s first name?” asked Ted.

“Raymond,” returned Tom. “Raymond Scott.”

“Was he married?” asked Ted.

“He had been, but his wife had died,” Tom replied. “She died when their baby was born. But really, Ted, I’ve got to go now. I have a hard day to-morrow.”

“You’re going to stay right here,” declared Ted decidedly. “You say there was a baby. A boy or a girl?”

“A boy,” replied Tom.

“What was the boy’s name?” queried Ted.

“How do I know?” countered Tom. “I never saw the kid.”

“What was the boy’s name?” pursued Ted relentlessly.

“Any one would think I was a census taker,” complained Tom. “I didn’t keep a record of the name of every kid in Grantville.”

“Look me straight in the eye, Tom, and tell me you don’t know the name of that Scott kid,” commanded Ted.

Tom tried to, but his gaze wavered and fell.

“You’re mighty poor at dishonesty, Tom,” said Ted quietly. “Now out with it.”

“The name was Edward,” said Tom, driven into a corner.

Ted’s heart gave a bound.

“My name!” he exclaimed.

“What of it?” demanded Tom. “I suppose there are thousands of Edward Scotts in the United States.”

“Then you don’t suppose I might have been that kid?” asked Ted, regarding Tom steadily.

“How can I tell?” replied Tom. “I tell you I never saw the kid.”

Ted was silent for a moment.

“Is Raymond Scott still living in Grantville?” he asked.

“No,” replied Tom. “He died nearly twenty years ago.”

Ted’s heart sank. Even if the clue he was pursuing led anywhere, his father and mother were both dead. He was an orphan!

With an effort he mastered his emotion.

“What became of the kid?” he asked at length.

“Some folks adopted him,” replied Tom. “They moved away from Grantville a short time afterward, and I don’t know where they went.”

“Do you know the name of the family that took him?” queried Ted.

Tom was silent.

“Tell me the truth, Tom,” Ted adjured him. “What was the name?”

“Wilson,” muttered Tom.

“James and Miranda Wilson?” asked Ted eagerly.

“Yes,” said Tom.

“Glory hallelujah!” shouted Ted, springing to his feet. “I’ve found out who my folks were. I’ve solved a problem that has tormented me for years. It cuts me to the heart to know that they are dead, but at least I know who I am.”

Tom did not seem to share Ted’s enthusiasm, though he forced himself to murmur a word of congratulation.

“The very first thing I do,” went on Ted, “is to get a leave of absence and go to Grantville.”

“Oh, what’s the use?” protested Tom. “There’s nothing to do or see there. Your folks have been dead for twenty years. It would only make you sad to see their graves.”

“I know it will,” admitted Ted. “But at least it will make me feel that I really belonged to somebody, and I can learn a lot about them from some of the old residents there.”

“All the same, I wouldn’t go,” repeated Tom.

There was something so grave, so ominous in Tom Ralston’s tone that Ted looked at him in surprise and dawning apprehension.

“There’s something behind your words, Tom,” said Ted Scott. “Why shouldn’t I go to Grantville?”

“Oh, just on general principles,” replied Tom evasively. “Let the dead past bury its dead. We’re living in the present. If your parents were living and there was anything you could do for them, it would be a different matter. But they’re dead, and there’s nothing but heartache in thinking about it.”

Ted regarded his companion curiously.

“There’s been something mighty queer about this whole thing, Tom,” he said slowly. “You’ve believed right along, haven’t you, that I was the Ted Scott whose father your family knew in Grantville?”

“Yes,” admitted Tom. “That is, I have for the last year or so. After the flood work was over I went back to the old town and pieced a few things together that made me tolerably certain.”

“And you knew that I’d probably be eager to get all that information you had?” went on Ted.

“I suppose so,” murmured Tom reluctantly.

“Then why haven’t you told me?” asked Ted.

“Oh, it just hasn’t happened to come up,” said Tom uncomfortably.

“That’s no answer,” declared Ted. “But when at last it did come up to-night, why have I had to drag everything from you piecemeal? Why have you tried not to look me in the eyes? Why have you been in a hurry to get away? What have you been keeping from me?”

Tom twisted about miserably but made no answer.

“You might as well tell me, for I am going to Grantville and will find out anyway,” went on Ted.

At this Tom capitulated.

“All right, old pal,” he said, “I’ll have to tell. I wanted to save your feelings, but you’ve driven me into a corner. The fact I was trying to keep from you was that your father died under a cloud.”

“What do you mean?” cried Ted, with a constriction of the throat that made his voice shaky.

“He got into trouble,” went on Tom. “There was a shooting case in connection with a bank and a man was killed. Your father was arrested charged with the murder.”

“Murder!” gasped Ted. His father a murderer!

“That was the charge,” continued Tom, putting his hand on Ted’s shoulder. “Of course there’s a good deal of difference between a charge and actual proof. Lots of people in the town believed he was innocent. But there was evidence that looked bad against him.”

Ted’s brain was reeling. His mouth was hot and dry. His heart was performing curious antics.

He scarcely dared to listen to what was coming next. The hangman’s rope? The electric chair?

As in a daze he heard Tom’s voice. He was saying:

“The case never came to trial. Raymond Scott died of pneumonia in prison.”

It was a terrible revelation and Ted was stricken as though by a thunderbolt. But at least that crowning disgrace had been spared him. His father had not been executed.

“I’m sorry, old man,” said Tom feelingly. “I’d have cut my tongue out rather than have told it to you willingly. But you made me tell you. Heaven knows I tried hard enough to side-step.”

“I know, Tom,” said Ted huskily. “It’s knocked me all in a heap, but I’ll get my bearings presently.”

“Remember this, Ted—” Tom comforted him, “that thousands of innocent men have been arrested for crimes that they never committed. If your father’s case had come to trial, he might have proved his innocence; he had friends who believed in him. You and I might be arrested to-morrow on some false charge. But charging is one thing and proving is another. If you do go to Grantville—though I hope you don’t—but if you do go, you’ll find plenty of people there to tell you that Raymond Scott was simply made a scapegoat for somebody else’s crime. And I, for one, know that no murderer could have a son like the Ted Scott I know.”

He rose and clapped Ted on the shoulder.

“Thanks, old boy,” replied Ted. “But tell me just one more thing before you go. Was anything discovered after my—” he swallowed hard—“after my father died? Was any one else arrested? Was the case followed up?”

“I don’t think so,” replied Tom. “The matter was dropped then and there. There was talk, of course, and once in a while the papers would print some little thing about it, then it gradually died out. Most people there, except the older ones, have forgotten about it. Now, just one word more, Ted. Take a fool’s advice and don’t go to Grantville. You’ve made a wonderful name for yourself. At this minute you’re the most popular young fellow in the United States. You’ve done this on your own, and you deserve everything you’ve won. Nobody dreams that your history is connected with this Grantville affair. Nobody ever will dream of it. Why stir up a lot of scandal. You can’t do your father a bit of good and you may do yourself a lot of harm. The Wilsons are dead. Probably I’m the only man living that knows Raymond Scott was your father. And you know that old Tom will be as dumb as the grave. Dumber, probably,” he added on a light note to conceal his real emotion.

“I know, Tom,” said Ted, grasping his friend’s hand. “I’ll think it all over carefully before I act. Good-night.”

For a long time after Tom left him, Ted Scott sat with his head buried in his hands.

So this was the ending of his dreams!

He had solved the secret of his birth. But what a solution!

His father charged with murder! His father dying in jail!

He, Ted Scott, the son of a man who, if he had lived long enough, might have gone to the electric chair!

Why had he not been content to live in a fool’s paradise? Why had he sought to rend the veil of the past? Why had he fairly dragged from Tom—good old Tom—what the latter had tried so desperately to hide?

He thought of the Wilsons, the kindly couple who had nurtured him during his early years. They of course had known. And in the goodness of their hearts, probably at a great sacrifice, they had torn themselves loose from their old familiar home and come to the Middle West so that the little waif need not grow up in a community where other children might taunt him with being the son of a murderer. His heart warmed toward them.

Did Eben and Charity Browning know? Had the Wilsons, feeling the approach of death, confided to the Brownings under pledge of secrecy the things they felt the latter ought to know?

If so, the kindly old couple had kept the secret well. They had never spoken of his birth of their own accord, and when he had himself alluded to it they had parried his questions with seeming innocence or indifference, so that he had come to the conclusion that they were as ignorant of the matter as himself.

Yet now, as he thought things over, he could not but recall many things that had not struck him particularly at the time, but that now, in view of what he had learned from Tom, were endowed with significance—sudden pauses when he had broken in upon them while they were in earnest converse, little scraps of talk in which the name of Scott had been mentioned, pitying glances cast toward him that he had surprised in casting up his eyes, a host of things, small in themselves, yet which, when put together, gave him the impression that Eben and Charity indeed knew.

He had no resentment at their reticence, for he knew that it was prompted by love for him and the desire not to throw the slightest shadow on his young life.

For a little while, as he pondered these things, all the triumphs that Ted Scott had achieved seemed to him as dust and ashes. His flight over the Atlantic—his marvelous work during the Mississippi floods—his latest breaking of the altitude record—of what avail were they to remove from him the bitterness of knowing that he was the son of a man who had died in jail while awaiting trial for murder?

Then there came a great surge of pity and affection for the father he had never seen or, if he had seen, could not remember. He thought of the anguish and shame that father must have endured, the ignominy heaped upon him. Dying at last in jail, with no one near that loved him to make easier his last moments!

Had he been guilty? Everything in Ted Scott revolted at the thought. He might have shot, but that might have been in self-defense or perhaps in attempting to hinder a crime from being committed. Or, at the worst, it might have been under intolerable provocation for which no jury would have held him to account.

But that his father could have wickedly, cold-bloodedly committed a murder, Ted could not believe. He would not believe it.

He drew some comfort from Tom’s statement that a great many of the people of the town did not believe in his father’s guilt. That pre-supposed at least a certain amount of friendship and esteem in which he was held by the citizens.

Should he go to Grantville? He weighed what Tom had said in trying to dissuade him from such a step. He shrank from the possible scandal that might ensue. He was proud of the reputation he had won, and did not want it to be tarnished. He knew the nine days wonder that would be stirred up if the facts became known, the columns upon columns of newspaper space that would be devoted to it. He writhed under the thought.

Yet he owed it to his dead father to clear his memory if possible, and the conviction grew in him that he would never know a moment’s peace if he failed in that duty.

Yes, he would go to Grantville. But he would not make his identity known. He would pursue his researches as quietly and discreetly as possible. But he would pursue them.

The conclusion he reached helped to calm his turbulent emotions, and at last he rose from his seat and went to bed. Not to sleep, however, for, perhaps for the first time in his healthy young life, sleep failed to come to him. He tossed all night upon his pillow, a prey to a thousand disturbing thoughts, and when he arose, he was feverish and unrefreshed.

He tried to be his usual self that day, but it was evident that he was laboring under great depression.

“I’ve decided, Tom,” he said to his friend the first chance he had to see him alone. “I’m going to Grantville.”

Tom shook his head.

“I’m sorry, Ted,” he said. “But you must be the judge. I know better than to try to move you when you have once made up your mind. I only hope that you will be successful in what you’re going to try to do.”

“What’s eating you, Ted?” asked Ed Allenby inelegantly, as he met him a little while later. “You look as though you had lost your best friend.”

“Yes,” declared Bill, who had come up with Ed, “wouldn’t think to look at you that you’d just beaten the altitude record and that the whole country’s buzzing with it.”

“Had a bad night,” explained Ted lamely. “Hardly got a wink of sleep.”

“Figuring out I suppose how you’re going to win that race over the Pacific to Honolulu,” laughed Ed. “By the way, Ted, have you come to any decision about that? You’ll have to make your entry pretty soon, you know, if you’re going to compete.”

“I may try for it,” replied Ted. “But I’ve got a little private business on hand now that may take me a week. I’m going to try to get a little time off to go to Bromville. There’ll be time enough to enter for the race when I get back.”

Even the information he got from Major Bradley a little later on, that the barograph had been officially calibrated by the Bureau of Standards and had established beyond a doubt that he had made over forty-seven thousand feet, found Ted listless. All honors seemed little to him now until and unless he cleared his father’s name.

Ted had no difficulty in getting a week’s leave of absence from Maxwell Bruin, the head of the Air Service Corporation. The latter had never forgotten how Ted had saved his son’s life, and there was nothing in his gift that Ted could not have for the asking.

Ted had sent a message to Eben and Charity Browning telling them of his coming, but asking them to keep it to themselves. He was in no mood for the ovation that would be sure to be organized for him as Bromville’s most distinguished citizen.

He had planned to reach the town a little after nightfall, but a storm that drove him out of his course delayed him so that it was after midnight when he reached the Bromville flying field.

He knew every inch of it, and had no trouble in making his landing in the dark. Then, after stowing the Hapworth, the monoplane in which he had made his trans-Atlantic flight, in one of the vacant hangars, he started out on foot for the Bromville House.

It was an unsavory part of the town he had to traverse, and just as he was passing a place notoriously known as a liquor dive, the outer door was burst open and a young man staggered out, trying vainly to defend himself against three others who were pummeling him furiously.

A well-directed blow from one of the three struck the young man who was the target of their attack, and only by a desperate effort did he maintain his feet.

But a second blow, still more vigorous, made him measure his length on the sidewalk. And as he struggled to rise the others pounced upon him with fists and feet.

Ted Scott had an antipathy to brawls and ordinarily would have passed on. But three men piling on one who had been knocked from his feet stirred him to anger and disgust.

“Lay off there!” he shouted, intervening between them and the prostrate man and hurling back one of the assailants who was aiming a vicious kick at his victim’s head.

“What are you butting in for?” snarled one of them.

“Give him some of the same kind!” yelled another.

“Knock the head off him!” shouted the third.

They made a concerted rush at Ted, and in a moment he was in a mêlée of flying fists.

There was no help to be looked for from the befuddled fellow in whose behalf Ted had taken up the cudgels, and the young aviator sailed in.

He was never better than when he was fighting against odds, and his furious attack made the three ruffians give ground. Moreover Ted was helped by the fact that all his assailants had been drinking.

Some of their blows reached him, but the majority he ducked and dodged. His own arms were working like flails, and when his blows landed they did mighty execution.

For about two minutes the fight kept up and then the three ruffians began to give ground. Ted kept at them relentlessly and a moment later they broke and fled.

The young aviator waited a minute to get his breath, and then turned to the man, who had wriggled back from the sidewalk and was sitting stupidly with his back against a tree.

He was evidently in no condition to be left alone, and Ted felt disgustedly that he would have to take him home, or at least put him on his way there.

“Where do you live?” asked Ted.

“The Hotel Excelsior,” muttered the man thickly.

Ted was startled. The kind of people who lived at the Excelsior were not apt to be found in a “speakeasy” in a disreputable quarter of the town.

He looked more closely at the intoxicated man. Then he recognized Greg Gale, the dissipated son of the proprietor of the Excelsior!

For a moment he was tempted to turn on his heel and leave him there. For Greg Gale and his equally worthless twin brother, Duckworth, had been Ted’s bitterest enemies. He had reason to believe that they had more than once attempted to cripple or kill him, once when a great stone had whizzed by his head on a dark night and again when the struts on his plane had been maliciously cut. Later on they had tried to run him down with their automobile when he defended a girl against their insults. No, he owed them nothing, except perhaps vengeance.

He hesitated a moment.

But whatever Greg Gale might be, however much the present brawl might have been due to his own faults, Ted could not leave him there at midnight at the mercy of enemies who might return to wreak still further their rage upon him.

He reached down and helped the fellow to his feet, got his hat, which had been knocked off in the struggle, and clapped it on his head.

“You izh good skate,” muttered Greg drunkenly, as Ted took his arm and started him going. “Cleaned out myself, but my father’ll give you some money for takin’ me home.”

“I don’t want your money,” said Ted curtly, as he urged him forward in the direction of the Excelsior.

It was evident that Greg had not the slightest suspicion of the identity of his rescuer.

“You zhum fighter,” muttered Greg admiringly. “Knocked those fellers out like tenpins. Zhum muscle! Good fighter m’self, but kinda sick an’ couldn’ do much.”

Ted made no answer.