* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Snow Man--John Hornby in the Barren Lands

Date of first publication: 1931

Author: Malcolm Thomas Waldron (1903-1931)

Date first posted: June 2, 2023

Date last updated: June 2, 2023

Faded Page eBook #20230602

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, Pat McCoy & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

This file was produced from images generously made available by Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries.

SNOW MAN

COPYRIGHT, 1931, BY MARGARET I. WALDRON

The Riverside Press

CAMBRIDGE • MASSACHUSETTS

PRINTED IN THE U.S.A.

TO MY MOTHER

AUTHOR’S NOTE

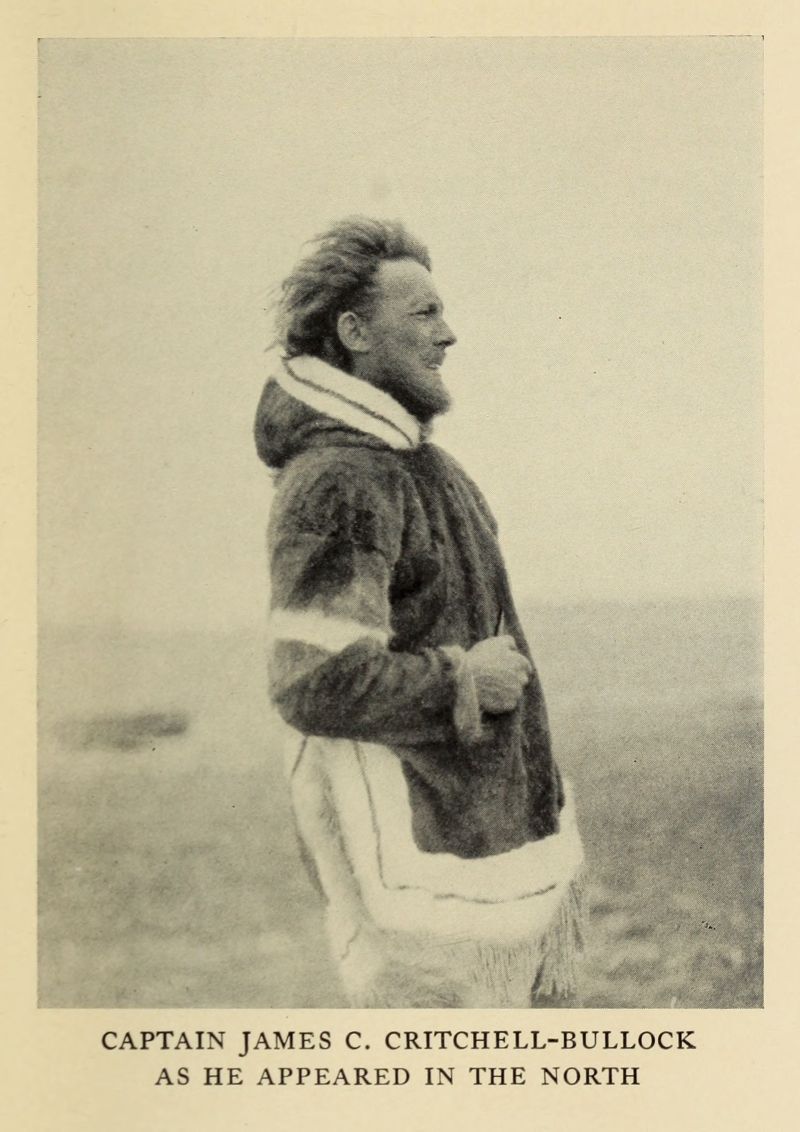

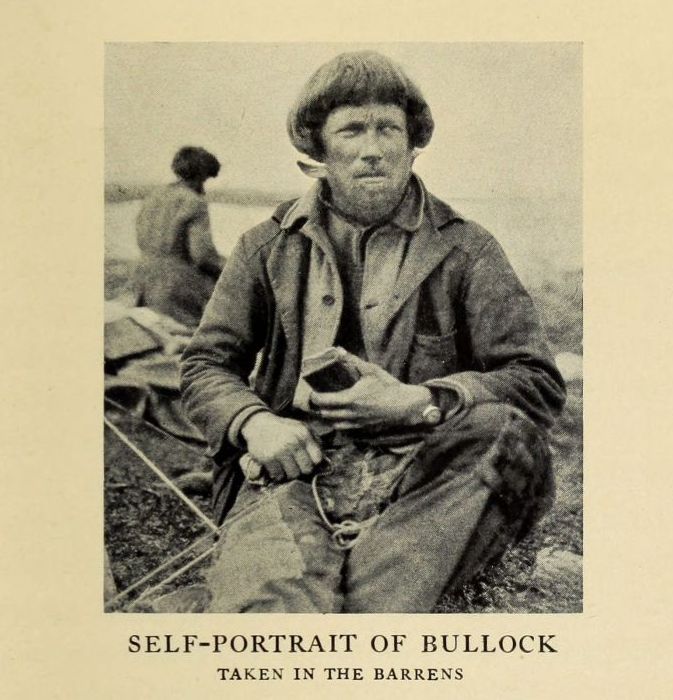

This book has been rewritten rather than written. I found it in its original form in the amazingly extensive diaries and records of Captain James C. Critchell-Bullock, full of the minutiæ of dialogue and deed. The only liberties I have taken have been chronological, and for the purpose of telling a connected story. To Captain Bullock I am indebted as well for the pictures which accompany the text.

MALCOLM WALDRON

ILLUSTRATIONS

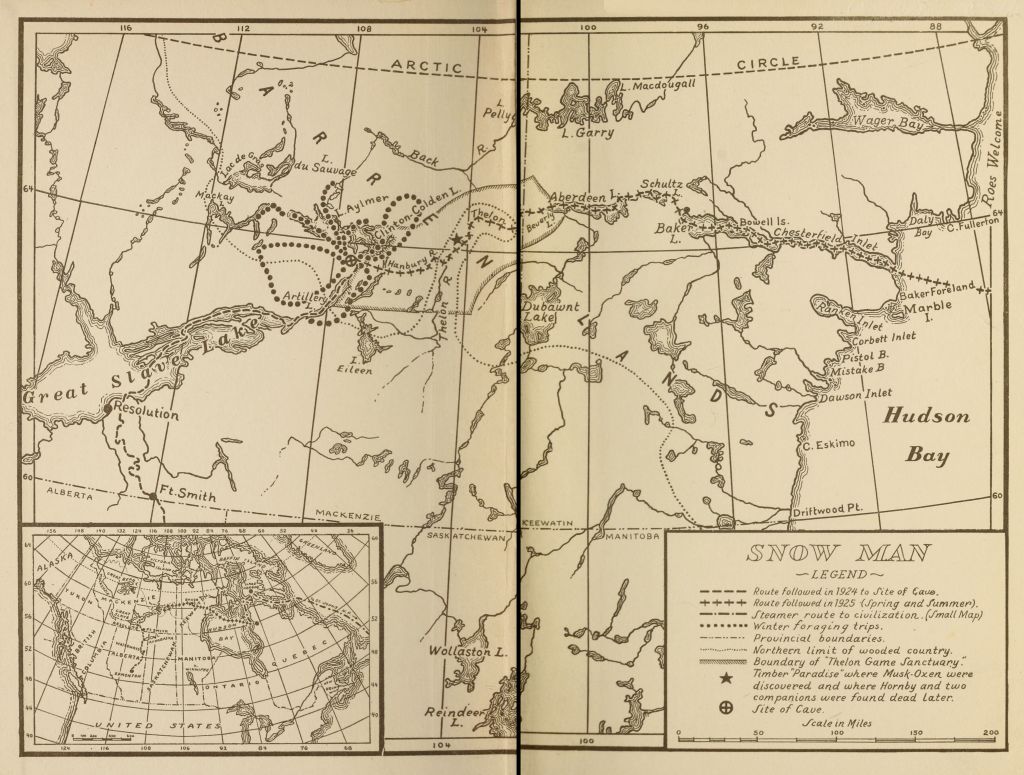

| JOHN HORNBY: A CHARACTER STUDY | Frontispiece |

| CAPTAIN JAMES C. CRITCHELL-BULLOCK AS HE APPEARED IN THE NORTH | 20 |

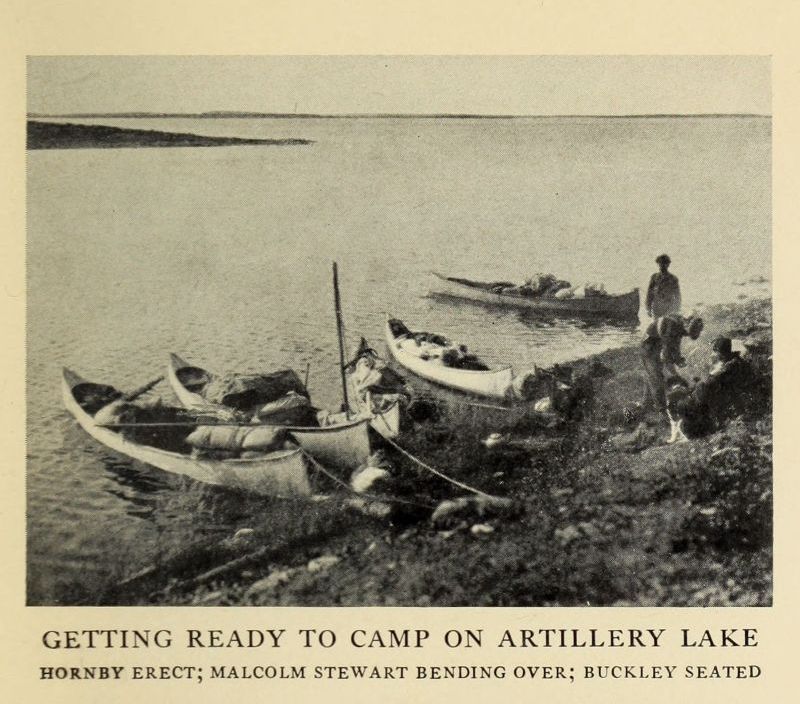

| GETTING READY TO CAMP ON ARTILLERY LAKE: HORNBY, MALCOLM STEWART, AND BUCKLEY | 48 |

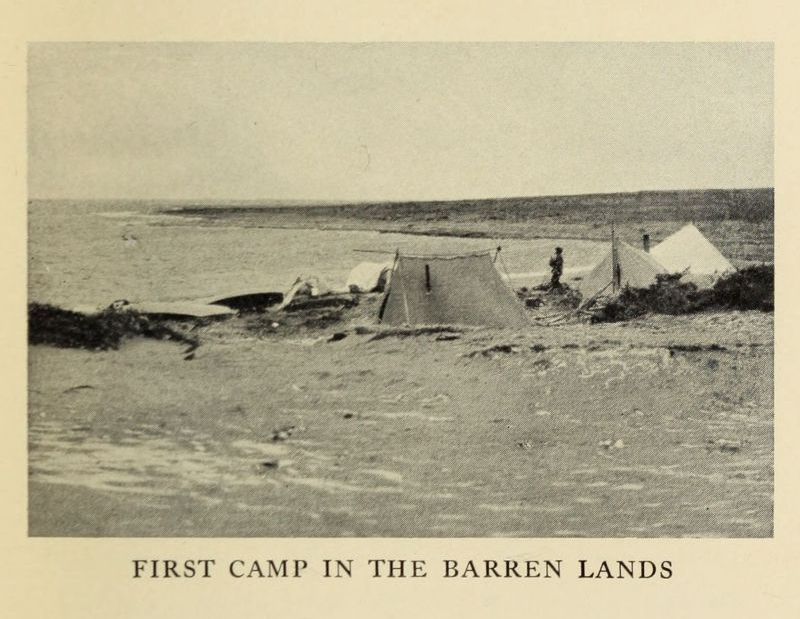

| FIRST CAMP IN THE BARREN LANDS | 48 |

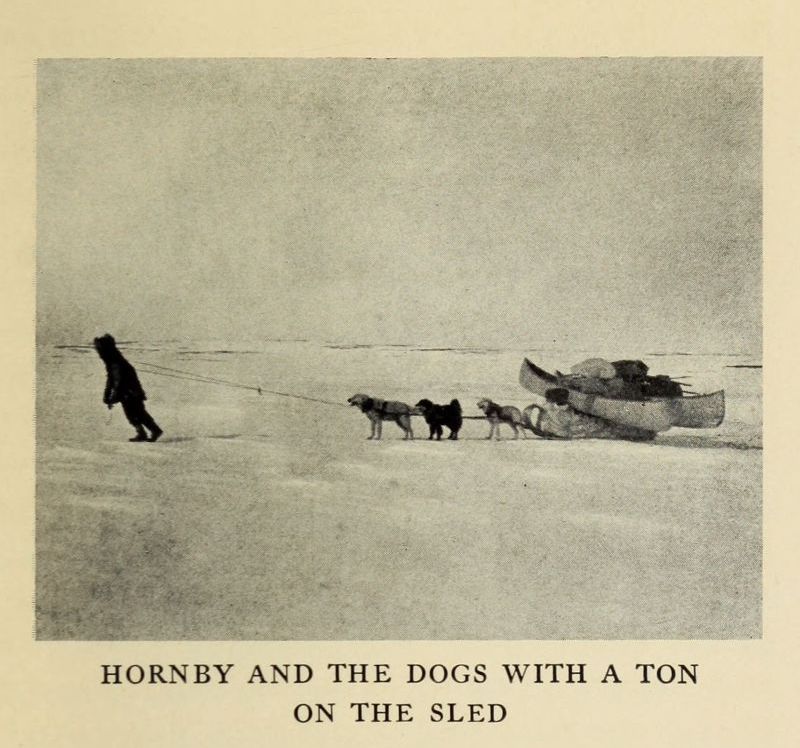

| HORNBY AND THE DOGS WITH A TON ON THE SLED | 70 |

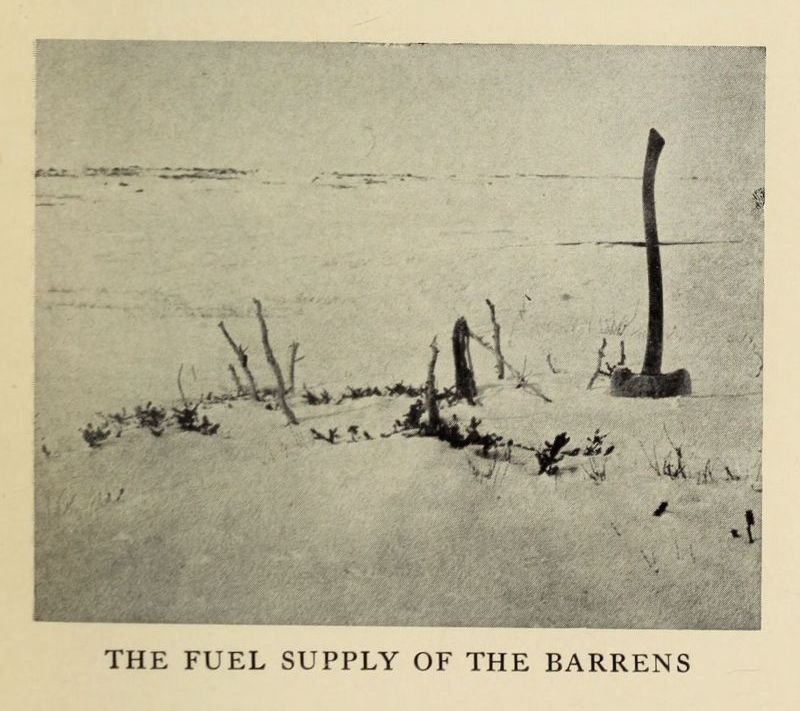

| THE FUEL SUPPLY OF THE BARRENS | 70 |

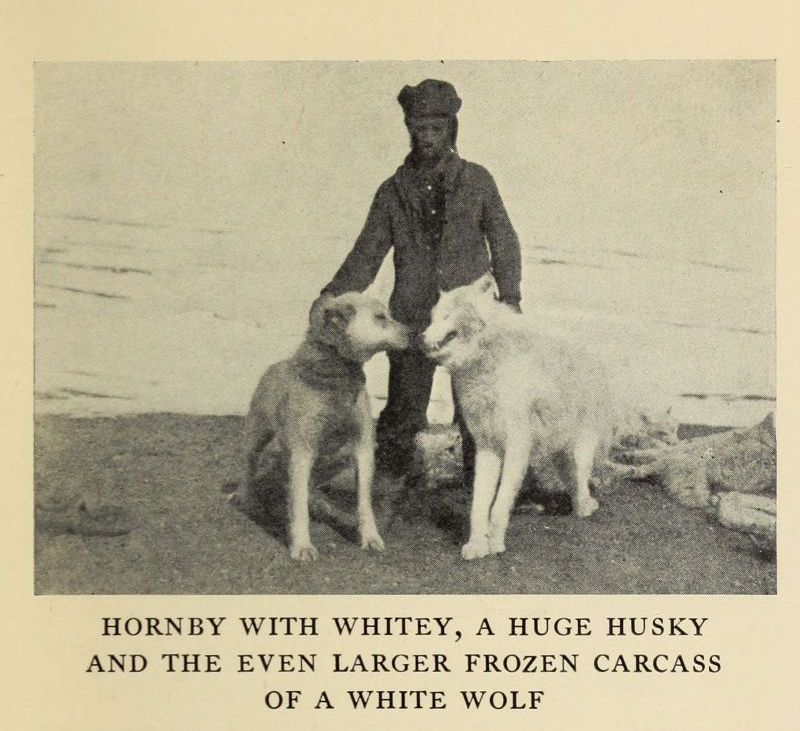

| HORNBY WITH WHITEY, A HUGE HUSKY, AND THE EVEN LARGER FROZEN CARCASS OF A WHITE WOLF | 96 |

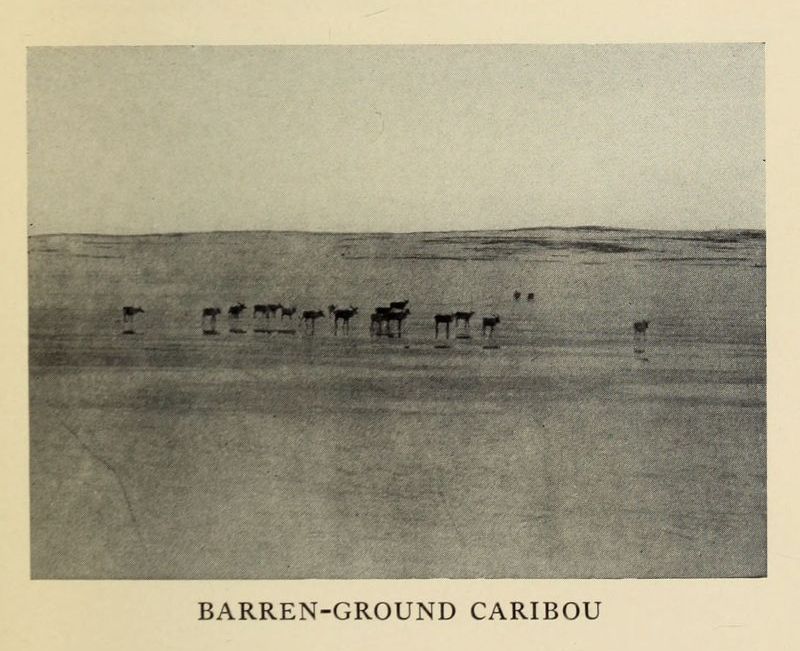

| BARREN-GROUND CARIBOU | 96 |

| SELF-PORTRAIT OF BULLOCK, TAKEN IN THE BARRENS | 124 |

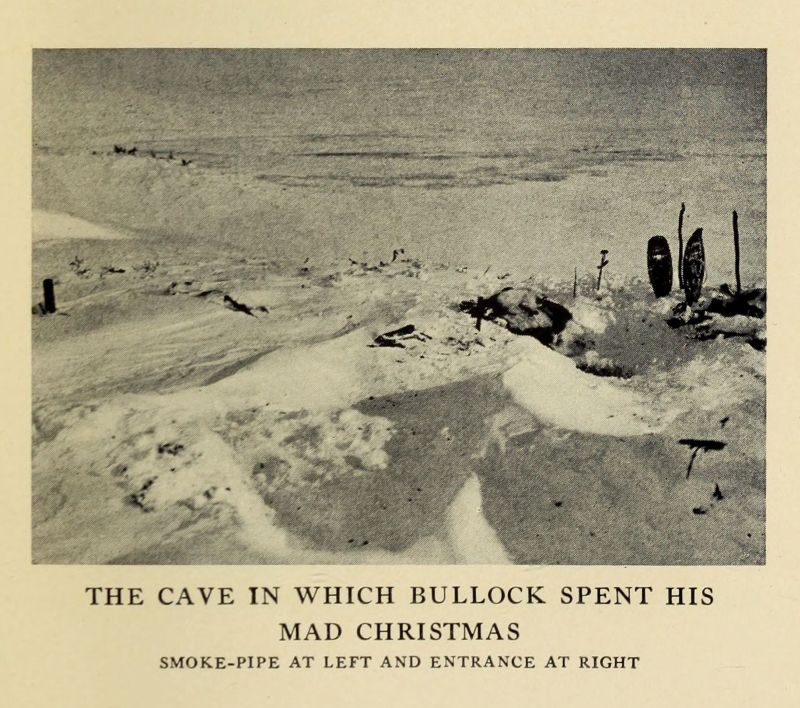

| THE CAVE IN WHICH BULLOCK SPENT HIS MAD CHRISTMAS | 124 |

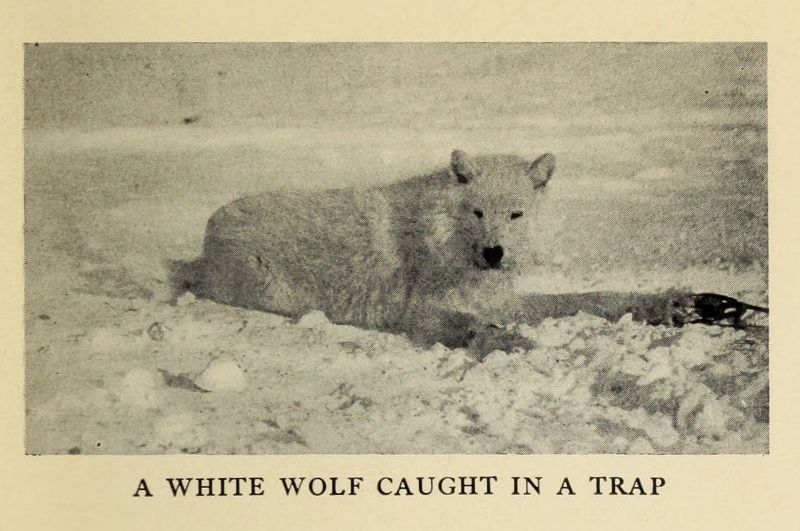

| A WHITE WOLF CAUGHT IN A TRAP | 140 |

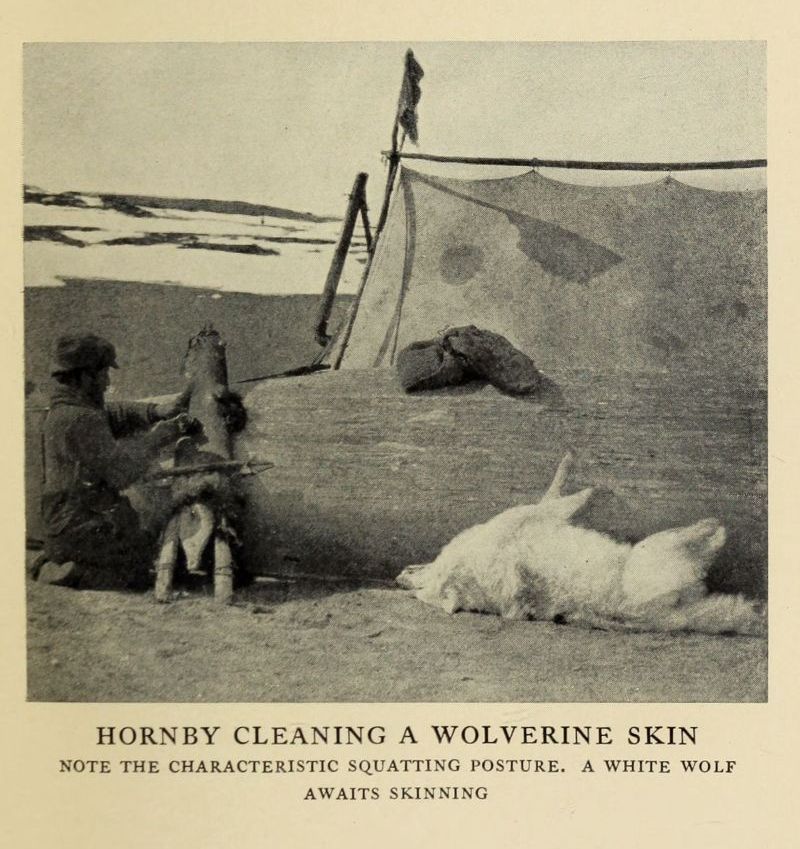

| HORNBY CLEANING A WOLVERINE SKIN | 140 |

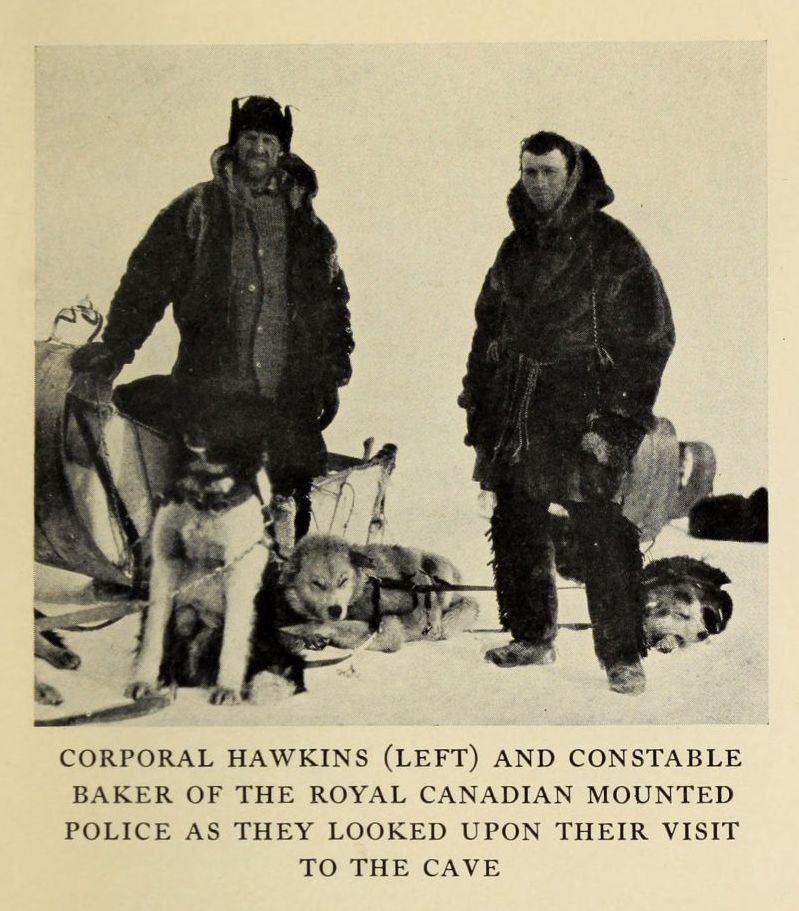

| CORPORAL HAWKINS AND CONSTABLE BAKER OF THE ROYAL CANADIAN MOUNTED POLICE AS THEY LOOKED UPON THEIR VISIT TO THE CAVE | 168 |

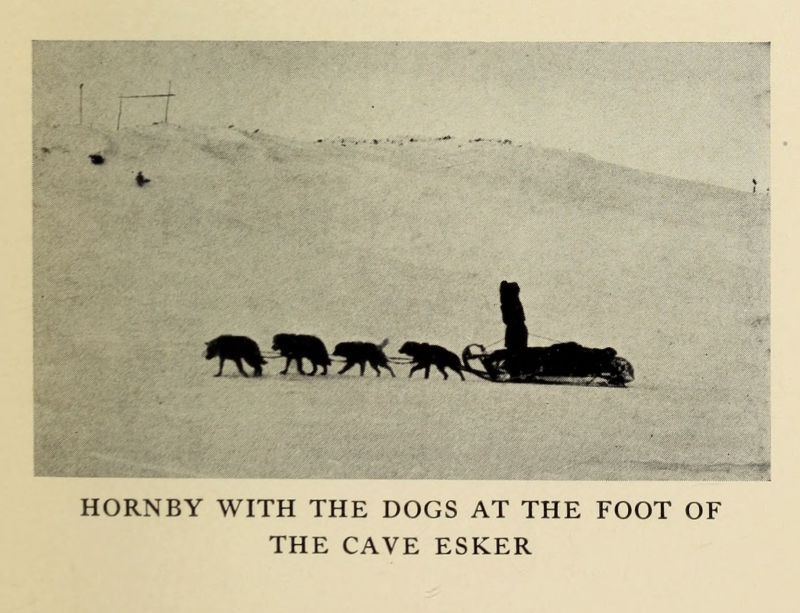

| HORNBY WITH THE DOGS AT THE FOOT OF THE CAVE ESKER | 168 |

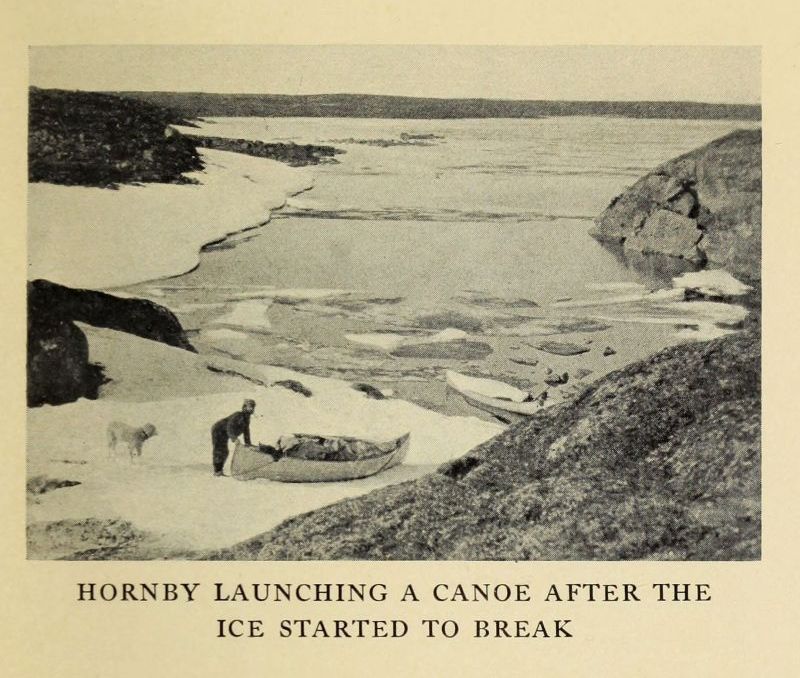

| HORNBY LAUNCHING A CANOE AFTER THE ICE STARTED TO BREAK | 200 |

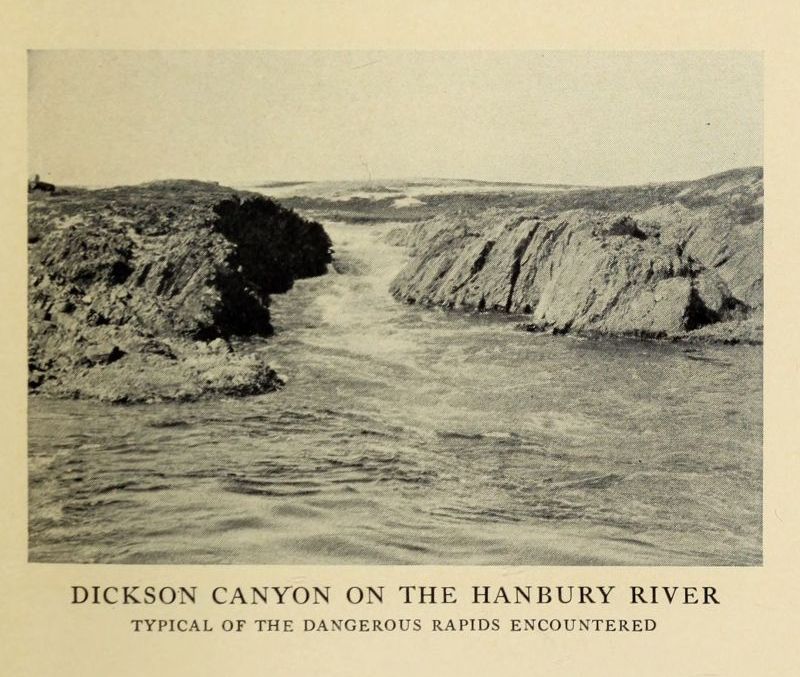

| DICKSON CANYON ON THE HANBURY RIVER, TYPICAL OF THE DANGEROUS RAPIDS ENCOUNTERED | 200 |

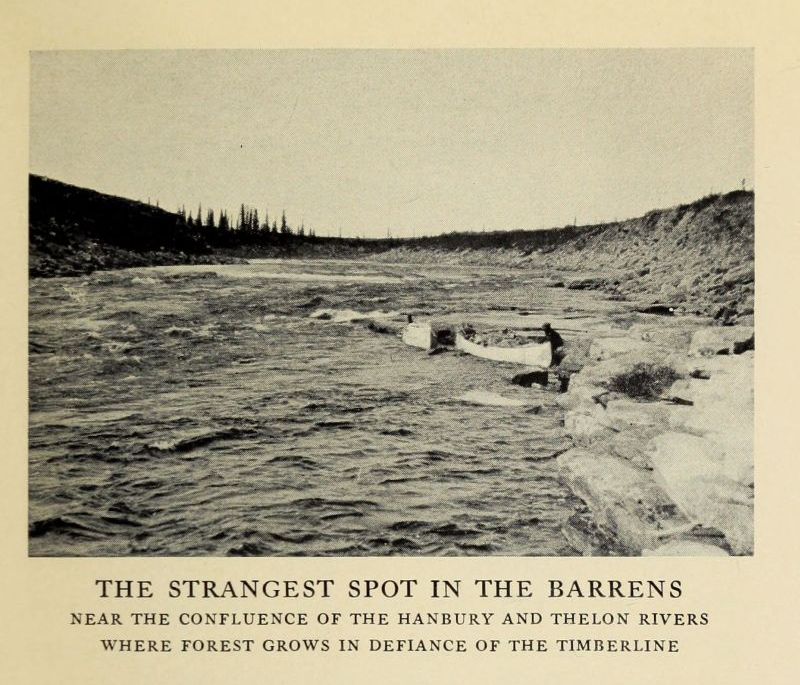

| THE STRANGEST SPOT IN THE BARRENS, NEAR THE CONFLUENCE OF THE HANBURY AND THELON RIVERS, WHERE FOREST GROWS IN DEFIANCE OF THE TIMBERLINE | 216 |

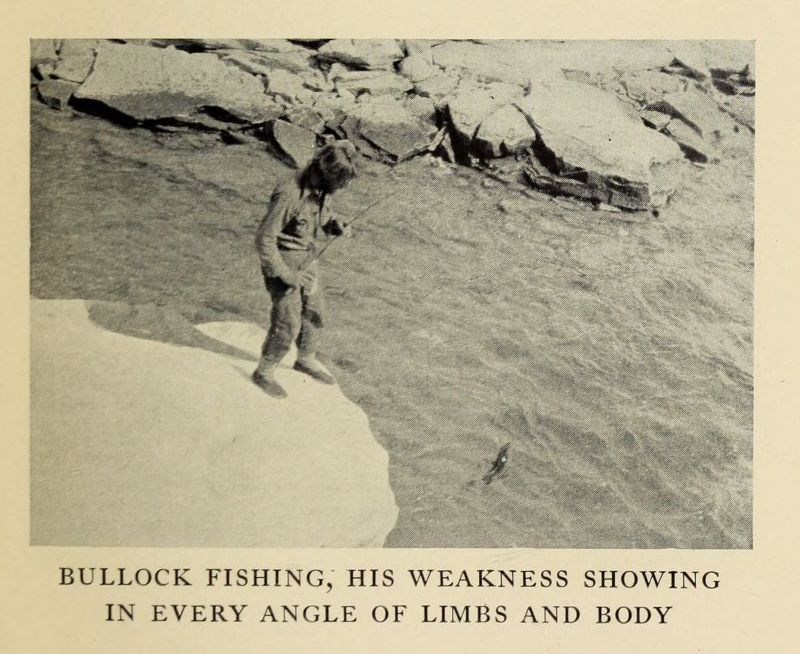

| BULLOCK FISHING, HIS WEAKNESS SHOWING IN EVERY ANGLE OF LIMBS AND BODY | 216 |

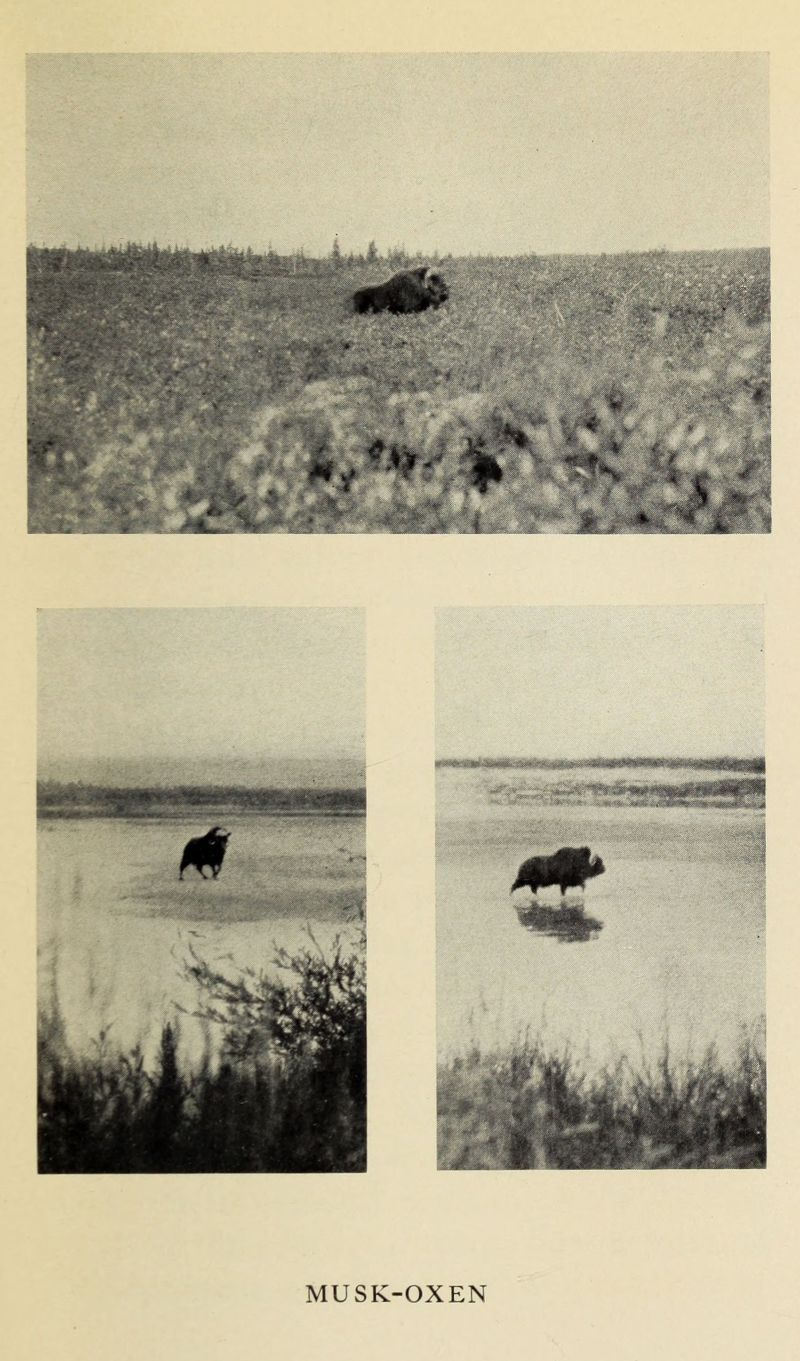

| MUSK-OXEN | 222 |

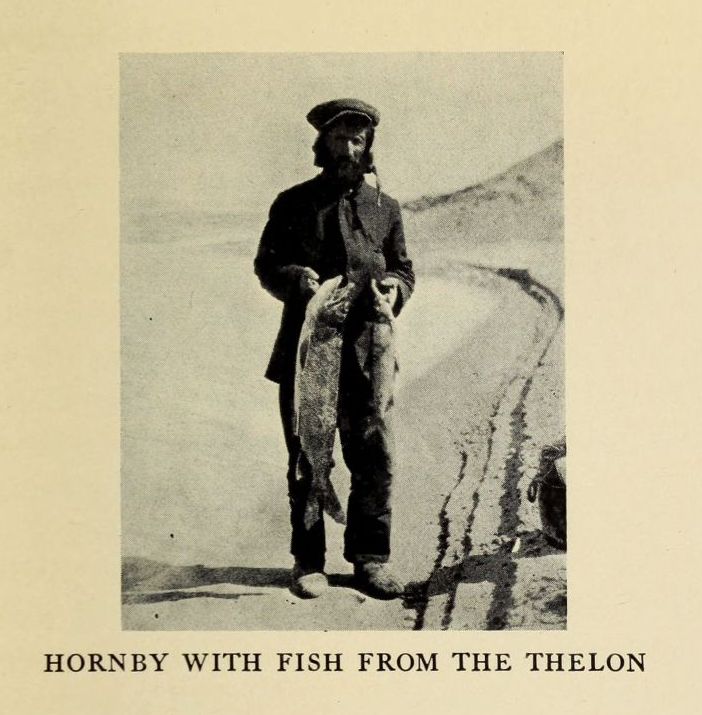

| HORNBY WITH FISH FROM THE THELON | 238 |

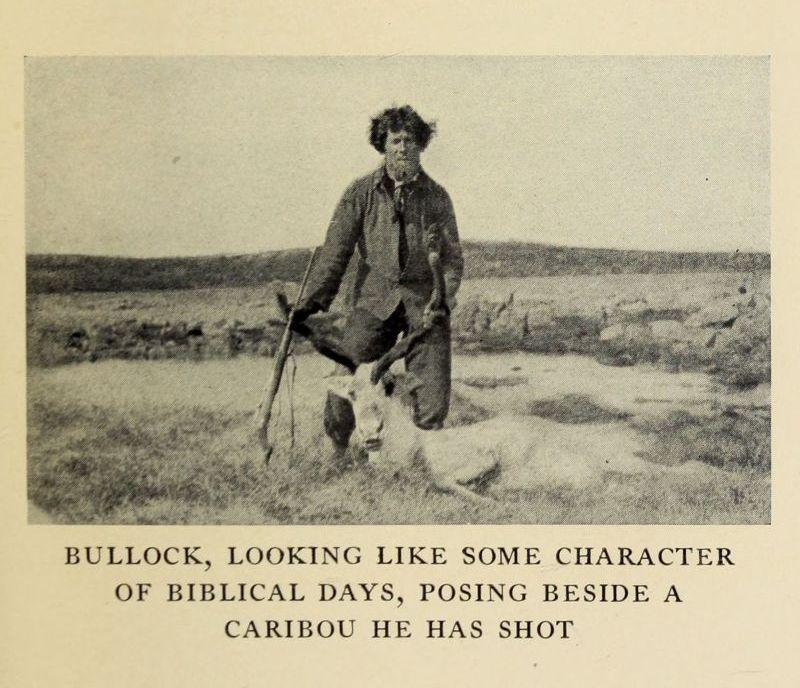

| BULLOCK, LOOKING LIKE SOME CHARACTER OF BIBLICAL DAYS, POSING BESIDE A CARIBOU HE HAS SHOT | 238 |

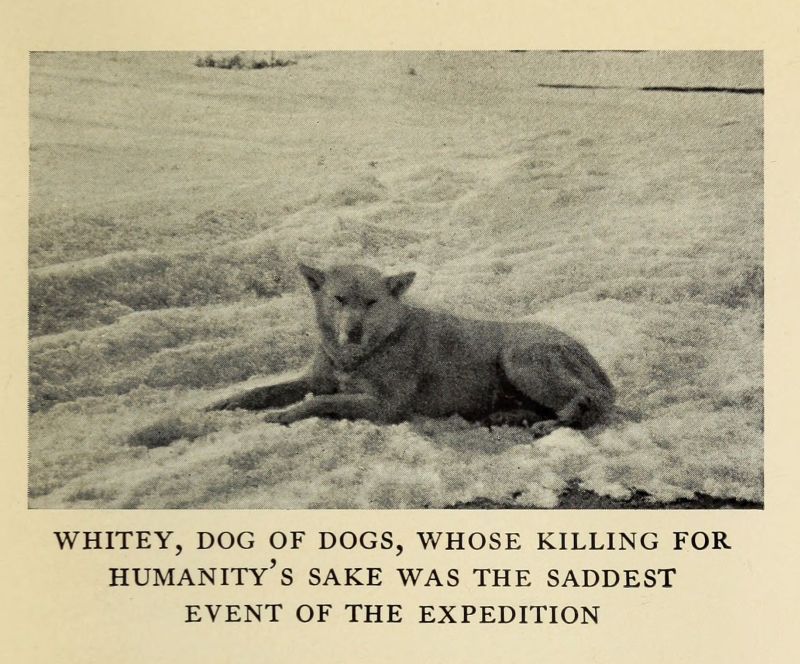

| WHITEY, DOG OF DOGS, WHOSE KILLING FOR HUMANITY’S SAKE WAS THE SADDEST EVENT OF THE EXPEDITION | 258 |

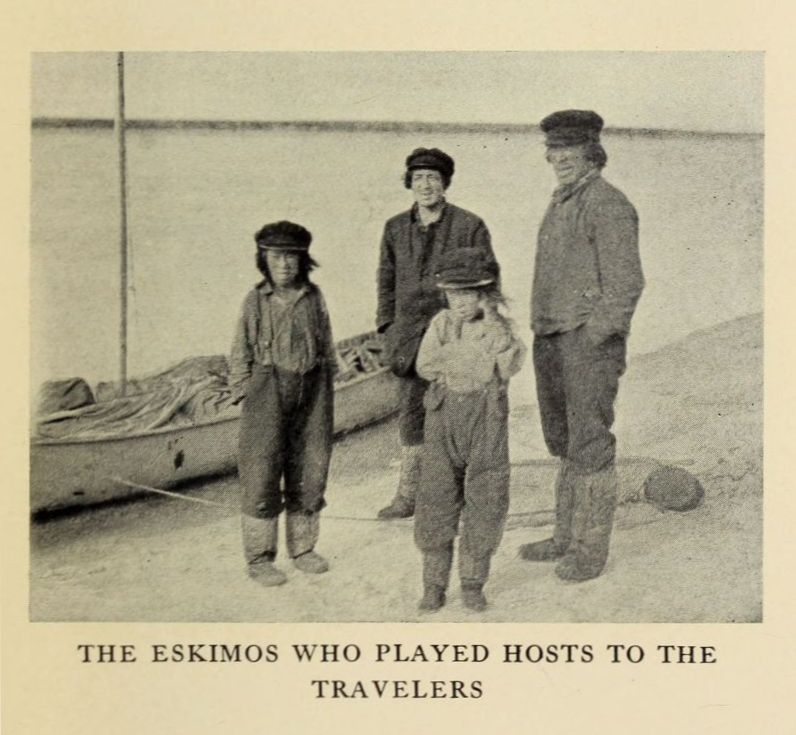

| THE ESKIMOS WHO PLAYED HOSTS TO THE TRAVELERS | 258 |

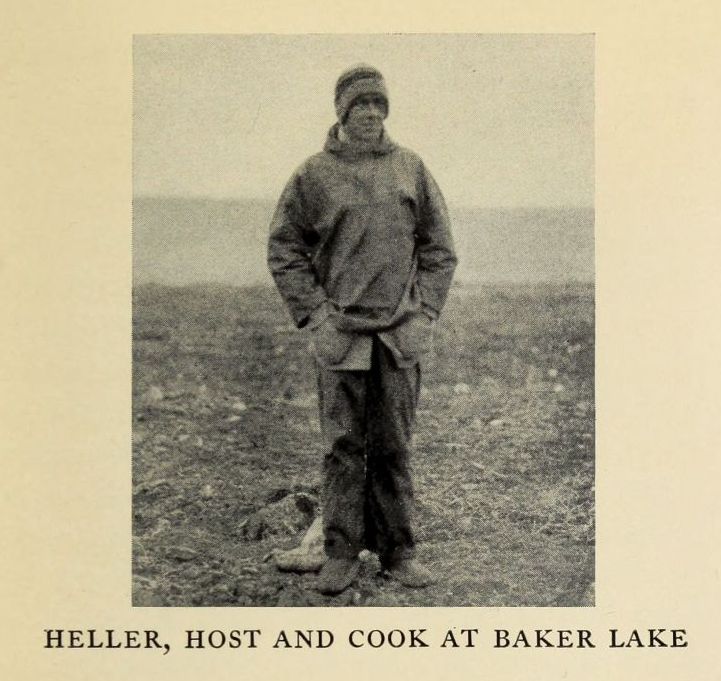

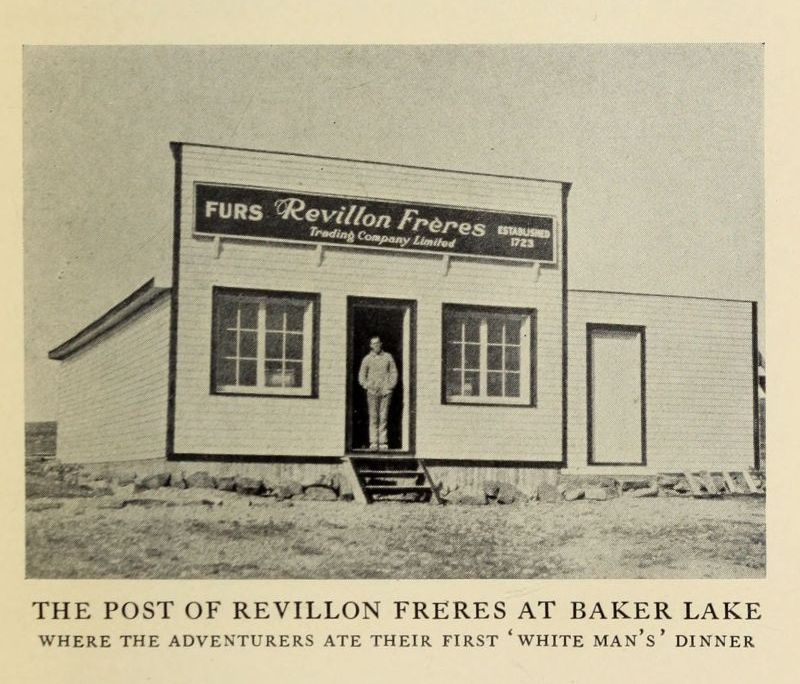

| HELLER, HOST AND COOK AT BAKER LAKE | 272 |

| THE POST OF REVILLON FRÈRES AT BAKER LAKE | 272 |

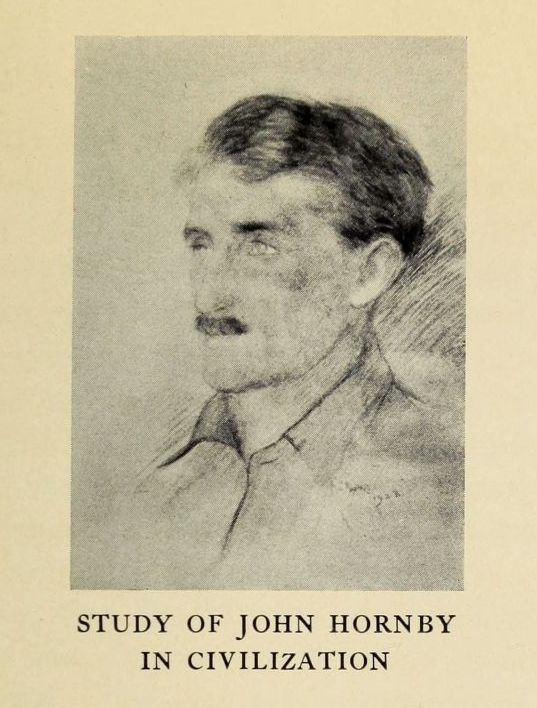

| STUDY OF JOHN HORNBY IN CIVILIZATION | 286 |

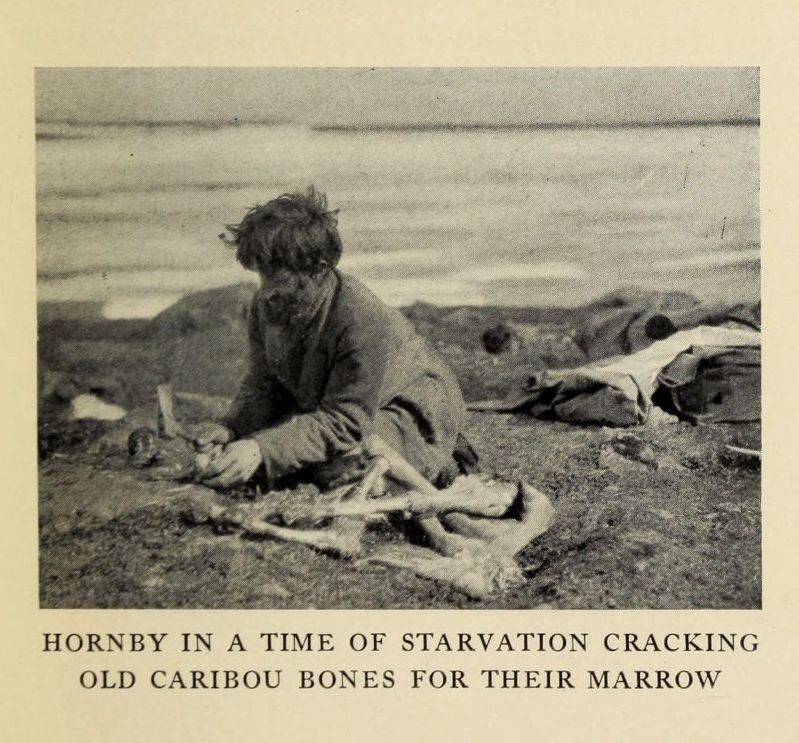

| HORNBY IN A TIME OF STARVATION CRACKING OLD CARIBOU BONES FOR THEIR MARROW | 286 |

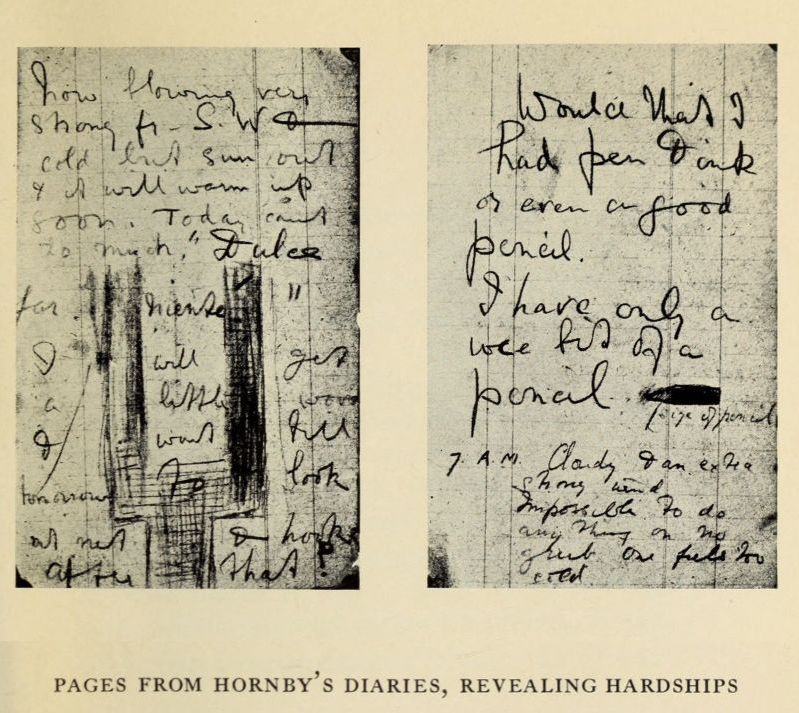

| PAGES FROM HORNBY’S DIARIES, REVEALING HARDSHIPS | 290 |

SNOW MAN

dmonton, Canada’s northernmost city,

is a place of contrasts. It has its gentle

side, its women and its children. But

it is the men who color the picture. In the

winter, tailored overcoat and rough mackinaw

walk side by side, and in the summer, stiff

collar and flannel shirt hobnob in the public

squares. For Edmonton is on the edge of

civilization. It is the jumping-off place for

innumerable expeditions into the forests to

the North, or into the great lone lands which

lie beyond the forests. In and out of the city

flows a tide of adventurers, trappers, prospectors,

and hunters, just back from the wilds,

or just returning to them. They are a hearty,

blandly blasphemous lot, keeping largely to

themselves and silent in the presence of

strangers. The rabble among them scatter to

the multitude of cheap hotels which line certain

of the city’s streets. The more prosperous

frequent, among other places, the King Edward

Hotel, an old establishment on First

Street.

dmonton, Canada’s northernmost city,

is a place of contrasts. It has its gentle

side, its women and its children. But

it is the men who color the picture. In the

winter, tailored overcoat and rough mackinaw

walk side by side, and in the summer, stiff

collar and flannel shirt hobnob in the public

squares. For Edmonton is on the edge of

civilization. It is the jumping-off place for

innumerable expeditions into the forests to

the North, or into the great lone lands which

lie beyond the forests. In and out of the city

flows a tide of adventurers, trappers, prospectors,

and hunters, just back from the wilds,

or just returning to them. They are a hearty,

blandly blasphemous lot, keeping largely to

themselves and silent in the presence of

strangers. The rabble among them scatter to

the multitude of cheap hotels which line certain

of the city’s streets. The more prosperous

frequent, among other places, the King Edward

Hotel, an old establishment on First

Street.

In the lobby of the King Edward, one morning in 1923, sat a man of about twenty-five. Since breakfast he had been surveying the passers-by. He sat with his arms folded and his left foot crossed over his right knee. Casual watchers could have noted his length of limb and the almost moulded set of his shoulders and his blond head. He wore a blond moustache handsomely. His skin was fair. Beneath his slenderness one could sense springy muscles. His face was stern, almost hard, with cold eyes and a sharply cut jaw. It lacked only the quality of softness. Most men have something of woman in their expressions, some trace of sympathy, some shadow of tenderness. He had none of this.

He was not in Edmonton by accident. No one is. He had arrived from England several weeks before. The hotel register bore, in a bold but illegible scrawl, the name, Captain James C. Critchell-Bullock. In the title lay, partly at least, the explanation of his presence. The son of an English family of means and position, he had been commissioned in the Indian Cavalry at eighteen. He had fought in France, and when General Allenby opened his cavalry offensive in the Palestine campaign, Bullock joined his Desert Mounted Corps with the rank of Captain. His six feet and two inches balanced superbly astride a horse. He became known as a magnificent if hard rider. All man-made obstacles he scorned. One thing, however, he could not fight—malaria. His father had been a figure in Africa in other days, but the tropics weakened him. The tendency had been passed on to the son. Blazing days in the Jordan Valley, when the mercury bubbled as high as 130 degrees, flattened even so stubborn a physique as Bullock’s. In August, 1923, he retired from the army as medically unfit. It was a bitter anticlimax. His competence, in the form of a trust income, had been left him by a grandfather whose military complex colored even his dying testament. The income was Bullock’s only so long as he remained a soldier. With a few thousand pounds left out of what otherwise would have been a life trust, Bullock turned to Canada for forgetfulness.

Bullock’s demeanor, in the not too comfortable lobby chair, bespoke patience. That was because he sat almost motionless. A close observer could have seen the restlessness in his eyes. He was not sure why he had come to Edmonton. He had not even a vague idea of what he should do now he was there. Perhaps he would ‘go North.’ It seemed to be a standard remedy for troubles such as his. Philosophical troubles, that is, for in temperate zones his physical ailments vanished. It was possible he would settle in Edmonton. He even played with the idea of joining the Mounted Police, though for the present he preferred self-discipline to that by others.

When one o’clock had passed, he went into the café, sitting alone at a table by the wall. As the meal progressed, he glanced curiously at a man who had taken a seat at the table next to his. The newcomer’s back was toward him. A mass of shaggy, black hair atop a large head moved Bullock to meditate on the features which might go with it. The man’s clothes were untidy and ill-pressed, yet there was something in his bearing which belied the implication of the attire.

When the waitress came to take the stranger’s order, she lingered in conversation. Bullock sensed that she had served him often. Bits of sentences floated back; impersonal, chaffing words. He had supposed the fellow to be one of the horde of adventurers who drift in and out of the King Edward. But his speech was not that of a vagabond; it was the speech of a scholar, chosen and deliberate and softly voiced. At the disappearance of the waitress, Bullock left his chair and went to the other table. With a bluntness almost belligerent because he knew it to be rude, he said:

‘You speak remarkably fine English for this country.’

He was conscious of a pair of very blue eyes glinting amusedly. The mouth beneath them said:

‘I went to Harrow.’

Bullock permitted himself no show of surprise, though Harrow is one of England’s most aristocratic schools. He replied:

‘And I to Sherborne.’

‘Yes, yes?’

The blue eyes glowed.

‘Have the waitress move your things to this table and we’ll talk.’

Thus did John Hornby and Critchell-Bullock meet.

The name of Hornby will not be readily familiar to readers in the United States, but along the whole fringe of Canadian civilization it brings to mind a thousand anecdotes of the snows; tales of a man who loved hardship as other men love comfort, who wandered alone into the most desolate corners of the North for the pure joy of solitude and adventure, who had enlarged a wolf den for his home when the fancy struck him, who bore a reputation as the most reckless nomad in a land which bred hardihood as its stock in trade. In England, as well, one can conjure with the name. John Hornby’s father, the late Albert Neilson Hornby, was, perhaps, the most famous gentleman in the history of English cricket. He poured his wealth and energy into the game to establish it as a national sport. He had captained the Lancashire Cricket Club, to-day led by another son, A. H. Hornby. John, himself a fine athlete in youth, had been destined for a career in the British diplomatic service, but a visit to the Black Forest in Germany in his early twenties brought an infatuation for snow. The crispness of the air, the white mantle which stretched from a slender film in the lowlands to a deep blanket in the hills, robbed England of a diplomat. John Hornby forgot home, tradition, career, and sailed for Canada. For a quarter of a century, save for two years in France as a Captain in charge of Canadian snipers, he had roamed the Arctic and the sub-Arctic.

All of this Bullock did not learn at once. Though an egoist, as are all non-conformists, Hornby did not talk readily about himself. And the young Englishman was not given to questioning. Much of the detail Bullock picked up later around the lobby of the King Edward, where every other man claimed acquaintance with Hornby.

The luncheon began a friendship which was to endure a lifetime. There followed other luncheons, and meetings in Bullock’s room, and long walks. When, after several weeks, Hornby suggested an exploration jaunt into the mountains near the border of Alberta and British Columbia, Bullock agreed delightedly.

The wind which whined down the upper slopes of Mount Coleman caught at the flaps of the tent and strained at the ropes. Outside gaunt and blackened tree-trunks, remains of a recent forest fire, swayed dangerously above the canvas shelter. Night and fatigue had forced Hornby and Bullock to camp in this desolation. Without game, they had made their supper on tea and biscuits. The flames in the tent stove danced. A stubby candle flickered between the two men, reclining on their blankets.

Bullock studied his companion, and remembered the long day just past. They had carried packs of one hundred and twenty pounds each, hour after hour, over steep grades and through ravines. Hornby, though forty-eight years of age, had set a pace that numbed the muscles and strained the wind of the younger man. Yet he weighed but one hundred and forty pounds as against Bullock’s one hundred and ninety, and his five feet, five inches fell below the other’s shoulder.

The fitful light of the candle served to sharpen Hornby’s features. His hair was black, long, and intensely matted. He combed it only under compulsion. His face was swarthy, almost black, from the constant glare of sun and snow. It was a condition of which he was peculiarly proud. His nose was strong and beaked, but with an underlying sensitiveness. Beneath it was a mustache, black and irregular. Elsewhere on the face was the beginning of a beard, which, on long sojourns away from civilization, flowered into a massive growth. The focus of the face, however, was in the eyes. They were of an amazing blue. They seemed to glow with an unearthly light. None who knew him ever forgot his eyes.

Bullock felt a fondness for the little man beside him, and as one will do when he is alone with another, he talked. He told of the war and of the deserts.

‘. . . and on the road to Jerusalem we had in our regiment a wrestler who had only one eye, his left one. His horse, a bloody great animal, had only one eye as well, the left one. Sympathized with each other, I guess. At one spot, where an embankment rose on one side and a precipice dropped off sharply on the other, we met some camels. Wrestler and horse kept their one eye apiece on the camels. Both went over the precipice, since they could not see it, and both broke two ribs. Funny, wasn’t it? . . .’

He talked on, idly, reminiscently. He told of tiger-hunting in India, and of ‘pig-sticking,’ virile sport of cavalrymen. He spoke feelingly of frightful marches under desert suns.

Hornby at last interrupted:

‘You don’t really know what traveling is. All you have told me is tripping, not traveling.’

Bullock bridled.

‘As much as this is, it’s traveling. It’s as hard to stagger through heat as it is to pull up mountains and through snow.’

‘As hard maybe, yes, yes!’

Hornby beamed.

‘As hard, but not as real, Bullock. In the desert you were traveling with a blasted army at your heels. There were Indian servants to wait on you, and big wagons to cart your grub. I know what war is. I was a Captain myself in France. But war isn’t hardship. Nothing is hardship when others help you bear it.’

He paused to watch the younger man’s face. He saw two eyes fixed on him in the half-glow of the candlelight, and a pipe bowl red with fire.

‘The hardship of this country is different, boy. You do everything by yourself, and for yourself. You eat only when you’re man enough to wrest food from the country. Look at us now. We had tea and biscuits to-night. Maybe a forest fire did get here before us and burn out all the game. But we have to eat, anyway. That’s what my life has been, eating when there’s nothing to eat, finding game where there isn’t any. You’re not afraid of starving, are you?’

Bullock grinned. He had heard, in Edmonton, of this scholarly hermit’s delight in adversity.

‘No,’ he said, ‘I’m not at all worried. Frankly, I probably care less than you do whether we eat again or not. Tropical diseases from those damned deserts ended my cavalry career. And my personal affairs are not pressing.’

It was Hornby who grinned now. There was something of the boy in his voice.

‘Bullock, I knew I made no mistake in you. Not many men know how to starve properly, but I think you can be taught. The greatest temptation is to go to sleep. It’s the easiest thing in the world to lie down and die if you have been without food for a long time. Of course to-night’—he waved an expressive hand—‘we can sleep as much as we please. But there may be nights when we shall have to keep awake. Remember that.’

Bullock offered no comment and they lay silent for a moment. The wind shook the canvas and blew down the pipe to make the fire smoke. Beyond the wind’s whistle was silence such as is only heard where no life is. It would have maddened most men. It soothed Hornby and left Bullock unmoved. Through it Hornby’s voice, pitched high for a man so much a man, exploded suddenly:

‘You’re not married?’

‘No.’

‘I should have asked before. It’s most important.’

Bullock wondered at the importance of it. He said:

‘I’m pretty much of a roamer. I’ve known women. I’ve liked most of them. Probably I haven’t liked any of them well enough to settle down.’

He spoke the last sentence slowly, but Hornby did not notice it. He was too intent upon his own thoughts.

‘I tell you, Bullock, I’m glad to hear that. I’ve learned lots of things up here that escape people down in the cities. A woman only marries for a home. There is no such thing as love beyond books and the drivel of young pups. It’s all passion. Yes, yes, passion. I have never spoken a word of love to any woman. I’ve never had anything to do with native women. There isn’t an Indian or an Eskimo in Canada who wouldn’t trust me with his wife. What other white man in the North would they trust likewise?’

Bullock would have liked to dispute him, not because he was in love, but because he was young. But he only said:

‘Let’s have some tea.’

‘Fine.’

Hornby stirred from his blankets and put fresh twigs in the stove. Into an open kettle, already filled with water, he threw a handful of tea. He put the kettle on the center of the stove, where the flames crept highest. He squatted in silence until the black liquid bubbled. Bullock watched him dip two tin cups in the pot. He saw him heap in sugar from a dirty bag. One cup Hornby passed to Bullock and one he kept. The tea was like lye. Hornby sucked from his cup, noisily, and with grimaces, as the hot liquid burned his lips. After some minutes he said:

‘Bullock, did you ever hear of the Barren Lands?’

‘Yes, I’ve heard of them. I don’t think I know much about them.’

‘Would you like to go there?’

It was asked as one might ask, ‘Do you care to step down to the corner with me?’

‘Why?’ said Bullock.

‘Because it’s the only place that isn’t overrun.’

The younger man smiled.

‘Is this place overrun? We haven’t seen a human being in a week.’

‘That isn’t what I mean——’

Hornby had come suddenly alive. He flung the tea grounds behind the stove and squatted, balanced, on his toes.

‘That isn’t what I mean. This country we’re in now has been well explored. There aren’t many here. Probably there’s no one within fifty miles or more. But the Barren Lands, Bullock! They’re virgin. I can name on the fingers the men who have really penetrated beyond the timber. Most of the country is unexplored. Most of it no man has seen. I suppose I know it better than any man alive, and yet I’ve only seen threads of it. Do you follow?’

Bullock had laid aside pipe and cup.

‘Go on,’ he said.

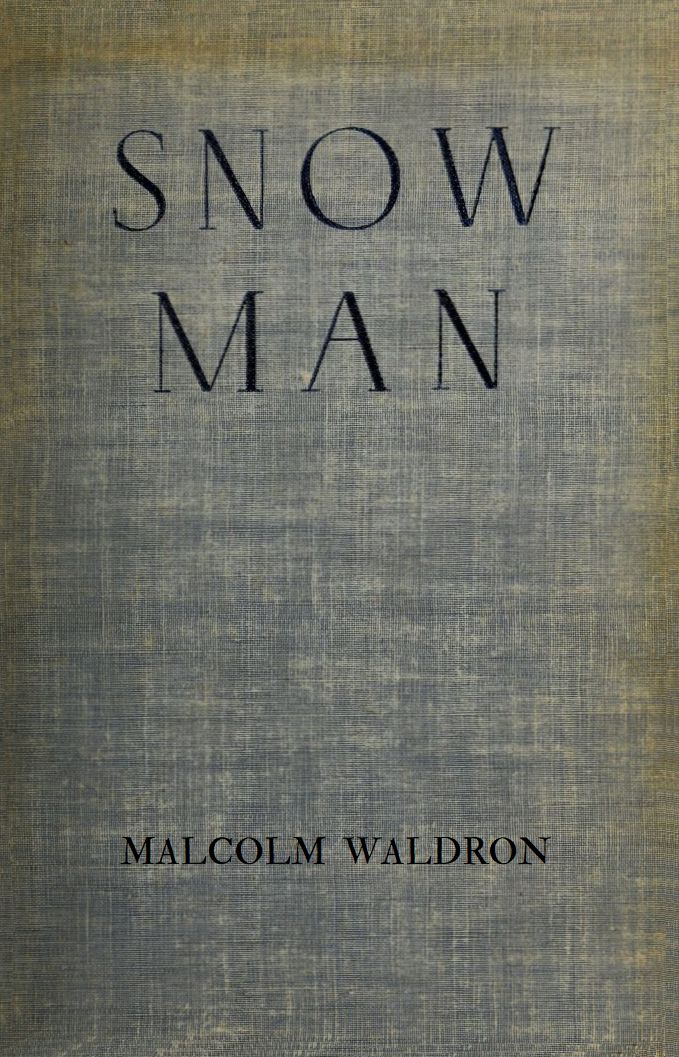

‘You go north, far beyond Edmonton, until you come to Great Slave Lake. You go still farther north into Artillery Lake. There you will be beyond civilization. There will be no cabins, no trading-posts. At a certain spot along the shores of Artillery the timber ends. It doesn’t straggle off. It ends. Beyond stretch plains, almost without a tree or a hill, for as many miles as the eye can see, and for hundreds of miles beyond that. Those plains are the Barren Lands, broken only by rivers and lakes, many of them unknown and unmapped. Those lakes! Sometimes they are like mirrors, blue mirrors. Sometimes they are like rapids when the wind churns them. Mostly, though, they are under ice. The summers are short. For a few weeks there are flowers everywhere. But the winters are long. And they are cold. There is no ocean near to temper the air, as in the Arctic proper. I have known it to fall to eighty below zero. There are no human inhabitants. And the caribou——’

Hornby smiled. It was as if, then, he were looking at a herd of them. His glance was directly at Bullock, but it was focussed far away.

‘There are millions of them there, Bullock. At migration time the whole horizon will be a trembling black mass of them. I have seen tens of thousands at one time gallop by, their hoofs beating like the hoofs of your own precious cavalry horses, and their funny grunts filling the air. There is no sight like it. And the white wolves. Yes, yes. Great fur there. And white foxes, and wolverines. As for fish——’

Bullock listened, enchanted. He struggled to solve the riddle before his eyes. He had heard much in Edmonton of Hornby. He knew the story of his youth and of his self-exile. He had heard murmurs of eccentricity. But here was more than an eccentric. Here was a man. Here was a traveler who asked no quarter, and even spurned it if he got it. Here was, also, a story-teller. Bullock glowed with thoughts from the image Hornby had painted. One shadow fell across his dreams.

‘Why, with the whole Northland to pick from, do you ask me to join you?’

‘Because you are a gentleman.’

Hornby said it quickly and simply.

‘When I consider a trail companion, I look for a gentleman because he’s got backbone. You’ve told me of your family in England. You have had the advantages of care and good feeding as a boy, and that is half the battle. Not only that, but your parents, and their parents before them, had that same care.’

Bullock looked sharply to see if the words might not be in jest. Hornby sensed the thought.

‘I mean every word of it. A gentleman does not know when to stop. Another usually has set ideas about the sufficiency of his labor. It’s the same with grub. A man who has not been accustomed to the best will more likely demand it than a man who has had it all of his life. You can usually tell what sort a man is when the flour sack goes empty. I think we’ll make good partners. Tell me, you have some money?’

‘Several thousand pounds.’

‘Fine. We’ll divide costs and equip a first-class expedition.’

‘But I’m not sure——’

‘Of course you’re sure. Why, I’ve roamed from one end of this continent to the other, and you’re the second man I’ve considered as a partner. The other is dead. Melville. C. D. Melville. He was with me twenty years ago.’

‘What can we do up there?’

Hornby’s eyes burned until Bullock could imagine himself physically raked by the gaze.

‘Do?’

It was spoken in a lowered tone more impressive than any shout.

‘Do? My God, Bullock. There’s no place a man can do more. It’s a forgotten land, I tell you. We can be the first white men ever to winter in the Barrens for one thing. Every one else has gone in the summer, and in winter has retreated to the woods or the shores of Hudson Bay and the Arctic Ocean.’

‘I’ve done a bit of photography,’ Bullock suggested. ‘Could I do anything along that line?’

‘Anything? Everything!’

In his excitement Hornby kept twisting his fingers.

‘You can take wonderful pictures. And there are few good pictures of the Barrens in existence, I know. We might even find the black-faced musk-oxen. Do you know what they are? Like small buffalo, Bullock. And no one’s seen any on this continent for I don’t know how many years. They used to be plentiful, but the Indians killed too many off. Maybe they’re extinct and maybe not. Anyway, we can hunt for them, and I know the most likely places to look. Then there are the skeletons of Franklin’s men. If we found those our names would go around the world.’

‘Skeletons?’

‘Yes, yes. Sir John Franklin, you know. The great English explorer. Eighty years or so ago. He brought over two shiploads of men to explore the Arctic coast-line. Ships and men vanished. There were a few upturned boats on the beach to prove the men landed. A few bones were found near the boats. But most of the men—a hundred and twenty-nine in all—must have plunged inland. They were never heard from. It’s one of Canada’s greatest mysteries. I have my own ideas as to which way the men went.’

Though the little man paused and waited, Bullock kept silent. He was thinking furiously. By nature a vagabond, his blood had been stirred to its ultimate drop by Hornby’s words. Yet there were considerations that had not been put into words, vague ties of the past to bind him. There was his father in England and his brother in India. How much did he owe them in caution? There was the Army, a life which had claimed him as a boy, but which had betrayed him with the soldier’s most despised foe, disease—malaria, dysentery, and other tropical ills.

All of this came to him in a flash of doubt. What of the Barren Lands? To pour his remaining substance into the unknown or to husband it against a change of heart? To cast odds with this colorful wanderer or to succumb to a virtue he secretly scorned—discretion?

Hornby, watching, sensed the struggle. He said softly:

‘Life is hard up there. Harder than anything you’ve ever known before. Maybe you’d better think it over.’

Bullock laughed. There was no mirth in it, only metal.

‘So that’s it. You think I’m soft. You think I’m just another one of those damned remittance men. When do we start?’

‘Next summer. But first I must go to Ottawa and get official recognition for us. Maybe we can even get a stake and carry out a government survey.’

Hornby gave no hint of triumph, but his voice was extraordinarily cheerful.

‘How long shall we be gone?’

‘Maybe two years. Maybe more.’

The pair sat in silence and regarded each other. There seemed little else to say. Bullock could think of no comment but what would sound fatuous. After a few moments he noticed that he felt cold. The fire in the stove had died down, and even the candle stub was little more than a wick in a pool of wax. They had been forgotten, neglected.

‘Shall we turn in?’ he suggested.

Hornby grunted a good-natured acquiescence. The light was gone from his eyes, the spark from his voice. He was once more the veteran putting the tent in order for the night. Flaps were inspected for security. Blankets were carefully arranged, for morning might find the inside of the tent coated with frost, ready to rain down upon the occupants at the least movement within.

When the candle was put out, a darkness and a silence which city dwellers never know fell upon the place. Hornby was asleep almost instantly. But Bullock lay awake for an hour or more. The Barren Lands! He tried to picture them, but his fatigued imagination was not equal to it. He merely got a vision of another desert, with snow instead of sand and cold instead of heat. Try as he would, he could not keep imaginary camels and horses from galloping across the snow.

In the morning, after a breakfast of tea, Bullock sought some scrap with which to light his pipe. By the stove were pieces of a letter Hornby had written and torn up early the previous evening. Bullock played among them with a stick. On one piece he could read:

‘. . . with me a young fellow who’ll have to show me what he’s made of . . .’

Bullock grinned, and Hornby, watching, grinned back.

Both knew why.

ornby and Bullock shared an apartment

on McDougall Street, Edmonton.

On a morning in the early

months of 1924, Hornby was nervous. He had

arisen early, his invariable custom, and now,

with breakfast over, he sat on his heels in an

upholstered chair pretending unconcern. In a

few moments, he knew, Bullock would call a

cab and together they would go to the Canadian

Pacific station. Hornby was ready to entrain

on his pilgrimage to Ottawa. There he

would ask Government recognition and aid for

the Barren Lands expedition.

ornby and Bullock shared an apartment

on McDougall Street, Edmonton.

On a morning in the early

months of 1924, Hornby was nervous. He had

arisen early, his invariable custom, and now,

with breakfast over, he sat on his heels in an

upholstered chair pretending unconcern. In a

few moments, he knew, Bullock would call a

cab and together they would go to the Canadian

Pacific station. Hornby was ready to entrain

on his pilgrimage to Ottawa. There he

would ask Government recognition and aid for

the Barren Lands expedition.

‘They know me at Ottawa,’ he told Bullock, ‘and they’ll be glad to hear I’m going to head a serious expedition. Those Dominion men have always wondered why I jumped about so.’

Bullock was busy repacking a nondescript handbag.

‘Where’s your underwear?’ he asked.

‘There,’ said Hornby, pointing to a roll of garments on the floor.

‘Underwear? Those are pajamas!’

‘Well, they’ll do. You’re too fussy.’

The packing continued. Hornby’s habit of rolling everything had destroyed the crispness of the shirts and collars. Bullock laid the linens out as flat as possible, but in his heart he knew that after the first night on the train shirts, collars, pajamas, and handkerchiefs would be moulded into rolls again. The departing delegate was, after a fashion, precise.

When the clasps were finally snapped on the bag, Bullock stood up and surveyed his companion. He saw the eyes, gleaming as ever; the face still swarthy after a fresh shave which had spared only the mustache; a gray suit newly pressed, but not looking it; a light flannel shirt held at the neck by a tie which must, by its wrinkles, have known other uses; black shoes with heavy toes and black socks sans garters. Hornby was dressed up.

‘I have a comb in my pocket if you want to use it,’ Bullock suggested.

The other grinned.

‘Life’s pretty short to worry about such things.’

‘Let me try, then.’

The younger man tried to comb Hornby’s wiry shock, but somewhat in vain. He managed to produce the semblance of a parting, but the hair was so matted and so heavy that it would not lie down. It came to him that in an association of some months he had never seen Hornby’s hair combed.

‘And now, before I call a cab, where’s your hat?’

‘I haven’t any. You know perfectly well I never wear one.’

‘I know—but going to Ottawa—to meet the highest officials of the Government?’

Hornby rubbed his chin. Then grinned.

‘Perhaps. But have we time to buy one?’

‘No need. I have just the thing.’

The younger man went to a closet and returned with a tropical headpiece, a double affair consisting of two light felt hats telescoping one within the other, with the air space between designed as protection from the brilliant suns. It was more the size and shape of the American ten-gallon hat than of the standard street felt. Bullock took the inner hat and handed it to Hornby.

‘Too small,’ he said, trying to pull it on.

‘Good Lord! It’s a seven and a quarter. Try the outside one, then.’

That was a fair fit. Bullock went to the telephone to summon transportation.

Thus casually did Hornby start on a mission which was to include a bit of tragedy, a bit of comedy, and more than a bit of other things.

To the onlooker, able to see all things and have access to their histories, Hornby’s visit in Ottawa would have seemed pathetic. To the Dominion moguls, all of whom knew him in person and by reputation, it must have been embarrassing. To Hornby himself, as he later confided to Bullock, it was incidental.

Hornby was a vagabond. Ottawa’s official sons were precise and scientific. Hornby loved travel for travel’s sake; he gloried in the trail no matter where it led. The frontiersmen of the Government were students of the compass and the theodolite who endured travel as a necessary prelude to observation. To one play, to the others labor. Play begets zest, labor facts. Ottawa had a passion for facts.

Years before Hornby had run afoul of the material side of the Government. The position of Chief Ranger at the Fort Smith Buffalo Sanctuary had been open. Hornby, not averse to title and authority if they beckoned from the wilderness, applied for the place. Ottawa’s investigation of the application revealed the little man’s uncanny knowledge of the buffalo, and, indeed, of all Northern game. He knew the animals, not as man knew them, but as they knew each other. Friendship with the animals was a fine thing the Dominion men agreed, but there were certain small matters to be taken up as well. Had Mr. Hornby records and diaries to chronicle his years in the Barrens? Two brief and mothy notebooks were all. But surely, out of all his travels, Mr. Hornby had preserved some maps or sketches? There were no maps. Then a few photographs, perhaps? There were no photographs. The Government chieftains shook their heads. A decade in the North and scarcely a line to mark it! A few days later, Hornby was offered a place as common ranger. It was the glove on the cheek, the supreme insult. For months the man became livid if the subject was mentioned.

None of this could Hornby understand. He sometimes suspected that he was a peg with no hole in which to fit. It never occurred to him to reshape the peg. The information, the color, the wisdom of the wilderness which was packed beneath his heavy shock of hair could have brought him riches and fame. His was the mind to mould it into beautiful English, his the humor to flavor it and the touch to dramatize it. The desire was there. He dreamed that his name would go down in the history of the Northland. He had every element save the patience to weave the crazy quilt threads of his life and his philosophy into an intelligent pattern. He was forever talking of the book he would write. It would be called ‘The Land of Feast and Famine.’ A hundred times he had written the title at the head of a virgin sheet of paper. A hundred times the pencil had been dropped for something else. Sometimes it was a caribou going by. Sometimes it was because he couldn’t decide on the opening sentence.

His early and enthusiastic efforts to bring out of the North some worth-while trophies and specimens did not prove encouraging. One time he packed, canoed, sledded, and portaged for a thousand miles a magnificent set of caribou antlers, the finest he had ever seen. With a feeling of parting from a treasure, he presented them to Maxwell Graham, the game commissioner at Ottawa. Years later, they were still on the floor, in a corner of Graham’s office, unmounted.

There was, too, the rather rare set of Eskimo copper implements and primitive arms which he gave to the Alberta Provincial Museum. These items filled two large glass cases, and Hornby never returned to Edmonton without visiting the museum and personally cleaning and rehanging the collection. He was inordinately proud of this gift, but tortured by doubts that the trophies were appreciated. ‘Do you think they really understand the hardship and starvation I went through to get them?’ He would ask this plaintively, so that no answer but ‘Of course’ was possible. But such answers never reassured him.

He wrote Bullock frequently from Ottawa—short, ill-scrawled notes, but couched in the best of English, telling of vague contacts and conferences with officials. They were invariably concluded with a ‘Yrs. V. Sinc.’ Never in the course of their friendship did Bullock receive a letter terminated otherwise. It was as steadfast as the signature itself.

After several weeks word came that Hornby had been appointed ‘Part-Time Research Engineer,’ with a yearly allowance of two hundred dollars and a grub stake. Bullock was bitterly disappointed. He remembered the vivid prophecies his partner had made; how he would ask for and get ‘complete outfits’; how he would arrange to have the expedition commissioned to make an official natural history survey of the Barrens. Disappointment became astonishment when Hornby wrote expressing delight at the turn affairs had taken.

‘We won’t be tied down now,’ his letter said, ‘and we won’t have the bother of submitting a lot of written reports.’

A few days later, Hornby wired that he was sailing for England to see his family and to approach British interests on behalf of the expedition. Bullock, with stolid philosophy, decided that recognition was one of the minor considerations. He busied himself with the purchase of equipment.

His dreams centered largely about black-faced musk-oxen. He had heard, since that night on Mount Coleman, many stories of these creatures. An old Indian told him how the musk-oxen meet their enemies by forming a circle, heads out and rump to rump in the center, and how, as fast as one is killed, the others close in to form a smaller circle, until finally only two may be left.

If there were any black-faced musk-oxen left at all on the North American continent, they were numbered by tens where once they could have been counted by the thousands. Bullock wanted to immortalize them on film, by stills and by motion pictures. He wanted to be the first to bring out of the Barrens a pictorial record of one of its winters, with musk-oxen glowering before the camera and caribou dotting the otherwise unbroken snow. He was a photographer of parts. He had been official cameraman at General Allenby’s triumphal entry into Aleppo.

Dreaming thus, Bullock began his purchases. His eye was not for economy. He bought as though some other purse were to pay. Even life in the Army had given him little idea of the value of money. He had soldiered with sons of the rich who furnished and maintained their own horses and equipment. He had never done a moment’s gainful labor. Hornby, whose usual equipment, even for a journey of months, seldom cost more than two hundred dollars, would have writhed to see Bullock’s ‘list of necessities.’ There were thousands of feet of motion-picture film; a standard motion-picture camera; a portable motion-picture camera; a graflex camera; a folding Kodak; three hundred reels of graflex film; a complete developing outfit; a portable dark-room; a botanical outfit with presses to prepare specimens; an entomological outfit with preserving fluid for small mammals and insects; a series of thermometers; theodolite and three watches for surveying; surgical outfit with anæsthetics, scalpels for simple amputations, sutures, dressings, etc.; a small library on the natural history of the Barren Lands. The photographic equipment alone ran into thousands of dollars. And all these items were only the frills of the equipment. There were also boats to buy, and canoes, and sleds, and dogs, and a hundred other staple articles which were costly and bulky.

While Bullock was contemplating his scientific material, and learning the intricacies of his cameras, there came a curt cable:

Necessary I remain in England. Cancel expedition.

Hornby

Bullock was too stunned to reply immediately. He didn’t ponder long on Hornby’s motive. He assumed it must be sufficient, and turned to the more important matter of his own future. Wisdom seemed to dictate the sale of equipment already bought, and as graceful a withdrawal as possible from the public eye. Some embarrassment would be inevitable. The Edmonton press had not neglected the plans of Hornby and Bullock.

The young man toyed with the idea of business. There was a British wholesaler in Scotch whiskies who had hinted he would like to appoint him agent for the Province of Alberta. The prospect was enticing. Only vanity, a stronger voice than most realize, spoke against it. Bullock was, fundamentally, a fighter. All of his instincts, including the traditional English tenacity, had been heightened by his life as a soldier. He could not see himself a quitter. That word alone probably decided him. No sooner did ‘quitter’ enter his mind than he was on his way to a cable office.

His message was brief. He asked permission to use an old cabin of Hornby’s at the edge of the Barrens. He would go, anyway. Once set upon it, nothing could move him. He was quite unprepared for the almost immediate answer to his request. It read:

Returning by next steamer. Wait for me.

Hornby

The message puzzled Bullock. He did not yet know his partner well enough to sense the subtle thing which had so suddenly turned him about, a strange blending of jealousy and responsibility. Hornby, he later discovered, was madly jealous of the Barrens. So freely had he roamed them and so wholly had they been shunned by most others, he regarded them almost as his Kingdom. He had thought that Bullock, after the first cable, would drop all preparations. Word that his friend meant to persist in the trip aroused him. He knew that Bullock had funds to carry on. He pictured an expedition invading the lands he loved, and without him. In the picture he was conscious of a responsibility. His had been the voice which fired Bullock to enthusiasm for the trip. If anything befell the younger man, the finger of conscience, if not of public opinion, would point at Hornby. With such thoughts to torment him, the errant partner cabled his intention to return. Canada’s call was stronger than England’s ties.

While Hornby was on the high seas, Bullock went ahead, buying canoes, sleds, and supplies. He even engaged an assistant, one Jack Glenn, a former provincial police officer with an imposing physique and a knowledge of it.

Hornby’s home-coming was unemotional. But already Bullock and he were shaping their sentences to each other’s ears. When Bullock took him to a warehouse to view the assembled equipment, Hornby said:

‘By Jeebas, we’re not going to take an army.’

‘A lot of it is my scientific stuff,’ said Bullock.

‘Yes, yes,’ said Hornby, turning to inspect the canoes and sleds.

Bullock thought it a good time to mention Glenn.

‘I’ve engaged a man,’ he said.

Hornby straightened up from his examination of some blankets. Bullock felt in his glance the same assurance of authority he had always sensed in the eyes of his Colonel in India.

‘Who is he?’

‘Jack Glenn. Used to be a member of the provincial police. He’s a strong chap of a fine type. Said he’d love the North.’

Hornby might have been standing at attention.

‘What right has he to say he’d love the North? What color are his eyes?’

‘Color?’ Bullock was more than a bit piqued. ‘What in hell has the color of his eyes got to do with it?’

‘Everything!’ Hornby snapped. ‘I won’t go into the Barrens with any but blue-eyed men. I’ll wager his are brown.’

Bullock ended the conversation by saying nothing. It occurred to him, though, that his own eyes were blue.

The next day Hornby and Glenn met. Glenn, though not a large man, stood almost a head taller. He tried to be bluff and hearty, but Hornby’s stiffness froze him. Bullock watched uncomfortably. Later Hornby said:

‘Did you notice his eyes?’

Bullock nodded. ‘I know they’re brown. But, damn it, man, that’s a funny thing to condemn him for.’

‘He isn’t the kind, Bullock. I know it, I tell you, I know it. The North isn’t for everybody.’

Bullock knew the rub. Only men of Hornby’s choosing must go into the Barrens. After two days of strained atmosphere in the McDougall Street apartment, the younger man suggested a compromise.

‘Let Glenn take his wife with him, and we’ll leave them at the east end of Great Slave Lake. That will be our most southerly back camp. They can guard what things we cache there, and do some trapping for themselves on the side.’

Hornby beamed. His smile came back and his eyes seemed liquid again.

‘Yes, yes. Excellent.’

To himself Bullock permitted a smile, too. The Barrens are some miles beyond the east end of Great Slave Lake.

June 24, 1924, dawned an ordinary day in Edmonton. The sun shone lazily and warmly. Business was not brisk. It never was on a cloudless June day. The usually energetic Canadians seemed content to be lazy. Only at the Dunvegan Yards were there signs of liveliness. There Hornby, hatless and with hair flying, was talking excitedly to Bullock. The latter’s usual mask of calm was gone. His face was red and his pulse up. In a moment or two the expedition would be under way. Off to one side stood Mr. and Mrs. Glenn. In the baggage car of the train near by was most of the equipment.

Hornby was talking:

‘. . . and by taking the next steamer I’ll probably be at Fitzgerald before you are. You are going by canoe and that will take you longer . . .’

Then Bullock:

‘. . . think I have ’most everything. If not, we can buy some stuff at Fort Smith . . .’

‘Yes, yes . . .’

Bullock was on his way. As Edmonton slipped past and the car windows showed small farms and winding rut roads, he was happy. Despite everything the trip was a reality. One night on the train, and on the morrow Waterways, where the canoes would be launched, the supplies stowed aboard, a boat bought or hired to carry the heavier stuff, and the trip down the Athabasca and Slave Rivers begun. Beyond Waterways the river-banks would grow more lonely and wild with each mile. That night on the train Bullock slept well.

In the Athabasca the two canoes were christened. They were named ‘Yvonne’ and ‘Matonabbee,’ the first after the Honorable Yvonne Gage, the second in memory of the Indian Chief. A scow which was found for possible use as a transport was given the fragrant name of ‘Sandbar Queen.’ Bullock had been enchanted by stories of the original Sandbar Queen, a madame of the old school, whose girls had solaced trappers and millionaires without discrimination. She had survived, among other things, the snapping of a shotgun over her head. When Bullock first viewed the scow, with its evidences of use and its ample proportions, he chuckled. After that nothing but Sandbar Queen would do.

The trip down the river to Fort Smith occupied several days and was without incident save on the first night. Part of the canoe load consisted of dogs destined to pull sleds in the Barrens. They were large Huskies, bred for the snows. After camp had been made, Bullock gave some small order to the dogs. One of them failed to respond. He used the lash. At the first howl the other dogs fell upon the unruly one and completed the disciplining in true fashion. Bullock, who had expected at least snarls of disapproval from the rest of the team, was astonished. It was his first introduction to the curious mentality of Northern sled dogs.

From Fort Smith, Bullock went back up the river a few miles to Fort Fitzgerald, the steamer landing, to meet Hornby. The boat arrived without him. Inquiries among the officers were fruitless. Bullock returned to Fort Smith. He wasn’t particularly disturbed at first. Steamers made the run with fair frequency in the summer, and punctuality was never a virtue with Hornby, anyway. But when days ran into weeks, he became worried, then angry. With Glenn and Mrs. Glenn on his hands and with thousands of pounds of supplies and equipment waiting at the waterside, the suspense was maddening. He began to wonder if after all he might not have to venture into the Barrens alone. Faithfully he met every steamer and diligently he questioned every newcomer. He reaped only rumors which disturbed him.

Meanwhile, Hornby, naïvely unaware that Bullock wouldn’t understand his delay, was paddling north on the Peace River in company with four trappers. During the day, when the canoes leapt through the water, the five were not unlike any of the thousands of trappers and prospectors who have at one time or another used the waters of the Peace for a highway. But at night, when tents were erected and the grub eaten, conversation emphasized the contradiction of types.

First, of course, was Hornby himself, the smallest man present, but the most dominant. He said the least and listened the most. But when he spoke there was silence. His diction and soft tones were set off by the colloquialisms of the others.

Two of his companions were the brothers Stewart, Malcolm and Alan, friends of long standing. They were farmers when farming paid, and trappers when it didn’t. Otherwise they were quite dissimilar. Malcolm was about thirty-eight, a large man with reddish-brown hair and a florid complexion. He was inclined to stoutness. Alan was shorter and more slender. He was also older. While Malcolm’s features were almost cherubic, Alan’s were aquiline. Malcolm was a wit, and to believe him, something of a Lothario. There was the time he liked to tell about, for instance, when he escaped with his pants in his hands instead of on his legs. Alan was quiet. He had a softer voice than his brother, seldom indulged in ribaldry, and almost never talked of women. Malcolm chewed tobacco. Alan was an abstainer. Two other qualities the brothers shared; both were powerful, and both had a bit of the gentleman about them. That was why they were old friends of Hornby’s.

Then there was Al Greathouse, an old man, nearing his seventies, or perhaps in them. He was typical, a good man on the trail or with a paddle, but, since the years had come upon him, a dreadful bore. He would lean across the tent and speak in whispers of phenomenally large wolf packs or of ‘caroobee’ of a stature no one else had ever seen. To these tales Hornby would listen patiently, and punctuate them with a ‘Yes, yes,’ spoken as much with his eyes as with his lips. Greathouse would then go solemnly on, delighted that the Master was enthralled. Hornby knew the ways of trappers, particularly of trappers who had grown old. Only in respect to Greathouse’s dog Pat did Hornby permit himself to show annoyance. Pat’s owner fed him ‘white man’s grub,’ an act which was both blasphemy and effeminacy to Hornby.

The fifth member of the group was a youth named Buckley. He was called ‘Buck,’ for no one knew, or at any rate remembered, his first name. First names are of more use in civilization than in the wilds. Buck was a good-looking lad with a charming smile and a strong body. He rather fancied broad wit.

With these men as his entourage Hornby arrived at Fort Smith six weeks late. He greeted Bullock gayly, and without any but meager explanations. Bullock was so glad to see him that explanations would have been superfluous. One thing Bullock wanted to mention, but didn’t; when he was introduced to the quartet, he noticed that Greathouse’s eyes were gray and Buckley’s brown!

Hornby, in an extravagant flush of enthusiasm, bought a huge old hull for transporting supplies and equipment down the Slave River to Great Slave Lake, and two hundred miles across the lake to its northeastern tip. The hull had no motor, but no matter. Several days of frantic search revealed that there was no motor within many miles of Fort Smith big enough to move the ship. So the Empress—it bore so fancy a name—was left to rot. The next purchase was more carefully made, three small flat-bottomed boats, two of them powered. On these the load was distributed, and late in August the entire party got under way. The goal was the site of Fort Reliance, gateway to the Barrens.

What might have been the most pleasant part of the expedition, with August days for paddling and August nights for sleeping, and food for everybody, was marred by spite. Bullock had not been wholly forgiven for bringing Glenn. The result was a divided party, with Bullock, Glenn, and Mrs. Glenn sailing and camping by themselves. The King was gently disciplining his Prince.

It was the last day in August when Reliance was reached. In the midst of the small timber stood a stone chimney, all that remained from the stronghold which once sheltered Sir George Back and lent to the spot the title of Fort. To Hornby the sight of that chimney was like first glimpsing home after a long journey. He had seen it often, sometimes with its stones hot from the sun, sometimes half-buried in the drifting snow. Now, seeing it again, he felt suddenly at peace. To Bullock the shaft meant the beginning of his dream. It meant, too, the end of embarrassment. For there Glenn and his wife were to remain. If Reliance held any special significance for the others, they did not speak of it. To them it was the spot where a cache must be built.

Already ice was forming on the small ponds and the nights were taking on bitterness. The building of the cache was rushed, for the best of the summer weather had gone. A cache is like a small log cabin on stilts. First the uprights were erected, six of them, fresh hewn from the forest. Some twelve feet above the ground a log platform was laid across the uprights. The height was necessary as a protection from raiding animals. On the platform was piled all that was to be stored. Then interlocking log walls were built around the treasure. A roof of sorts topped off the job. To get into the cache after it is finished, one must virtually tear it apart again.

At Hornby’s suggestion that ‘the stuff can be brought up more easily after we are settled,’ Bullock allowed most of his costly scientific apparatus to repose in the cache. He kept out only his cameras.

Just as the cache was finished, several canoes appeared seemingly from nowhere on the waters of the lake. From the first one to touch the beach stepped a little man of the size and build of Hornby. He was Guy Blanchet, Government explorer, back from his summer trip. He greeted Hornby familiarly, and for some time they talked over portages, caribou, white wolves, and kindred subjects. When they parted, Hornby had bought four canoes.

Northeast from Reliance runs the Lockhart River, and at its source is Artillery Lake. The river is short, but broken by a myriad of rapids and falls. Such travelers as go beyond Reliance must take Pike’s Portage, a route of alternating ponds, streams, rocks, hills, and muskeg. It is a man’s route. Over it early in September started Hornby, Bullock, Malcolm, and Alan Stewart, Greathouse, Buckley, and two teams of dogs. They had with them five canoes, four of those bought from Blanchet, and Yvonne. Matonabbee stayed behind. It was not suited for exploration work, Hornby said. Bullock suspected that his jealousy extended even to canoes. Also the party had four tons of equipment. All of it had to travel on the backs of the men over the portages.

‘Packing,’ Hornby had said, ‘is a matter of guts.’ It is also a matter of back and shoulders and legs. It is a process peculiar to the far places. Civilization has no counterpart for it. The bulky chap who helps to juggle pianos in a city would be likely to find his legs turning to custard and his back giving up the first hour on the trail. Muskeg has a devilish habit of sucking down one foot and throwing a man off balance. Ropes and straps grow to feel like newly sharpened band-saws on the longer treks. Even the ability to stagger along with a hundred and a half pounds is only half of it. Getting the pack on your back comes first.

As he had outlined it to Bullock in the mountains:

‘You lie on your side with your back against the pack. The pack may be the size and shape of a five-foot baked potato, or it may be compact. At any rate, it has straps or ropes tied around it. You grasp those ropes and bring them over your shoulder, or over both shoulders if there are two ropes. Then you curl your legs up as far as they’ll go, and, with the aid of your arms, your back, your stomach, and most of the rest of the muscles of your body, roll over on your knees. After that it’s merely a matter of getting to your feet.’

The second day on the portages was torture. A steady drizzle soaked the muskeg to a mud-like consistency and made the rocks slimy. A swarm of black flies completed the misery. The black fly of the North draws blood with its bite. As insects go, it is vicious. Hornby alone seemed immune. But then, he seemed immune to everything, even pain and fatigue.

The second night the party camped beside some Indians. Two or three of the braves came over to powwow with Hornby in the tent he shared with Bullock. Most of the conversation was in grunts and guttural which, although supposed to be English, were beyond Bullock’s understanding. Once Bullock closed his eyes on the scene and was startled to discover that in the undertones Hornby’s voice so blended with the others he could not distinguish it. The Indians spat freely on anything within range, but their white host was in no wise bothered. Before they left for their own camp, Hornby had given them several pairs of moccasins, more than half the food immediately at hand in the tent, and a blanket. Bullock considered that the gifts were needed at home. He said so. Hornby was shocked.

‘We don’t need them as much as they do,’ he said. ‘Those Indians can’t get along as well as we can.’

On one of the short portages the next day a small, sturdy Indian came over to greet Hornby. They stood toe to toe, the Indian and the white man, pumping each other’s hands in welcome. It was young Susie Benjamin, whose father Hornby had befriended with food and clothing during the cruel winter of 1920. The son was one of Hornby’s greatest admirers. He was about twenty-two, and gave the impression of enormous strength, though he stood no taller than his idol. The others, who had stopped to watch the tableau, saw the Indian and the white man talking in whispers. Soon Hornby turned and said:

‘Susie and I are going to show you boys how to pack.’

The supplies and equipment had been moved, but the five canoes still lay at the south end of the portage. Toward these Susie and Hornby went. They juggled the first canoe to their shoulders and started off across the rocky surface at a sprint. They had no pads, but, instead of carrying the canoes inverted, rested the steel keel on their shoulders with only their heavy shirts to soften the weight. The second canoe followed the first, with a youth in front and a middle-aged man behind. At the third canoe there was a bit of agony in Hornby’s expression, but no slackening of pace. All five canoes were run across without a halt. It was a superb feat of endurance. At the end Susie was breathing more heavily than Hornby, but Bullock noticed that the latter’s shirt was stained red where the canoe keels had rested.

‘Hurt you?’ he asked.

Hornby tried to look scornful.

‘No! Nothing can hurt you if you don’t think about it.’

The rest of the day he took care to use his raw shoulder the most. And he took equal care that the younger man should be aware of it.

When Bullock had learned the grind of packing, he felt an itch to assemble his motion-picture camera. He visioned close-ups of strained faces beneath heavy loads, and long-distance shots of men trudging behind each other, through deep muskeg, up wet rocks, fording streams, staggering from water to water with bent backs. Once, when he and Hornby had finished their packing before the rest, he set up his tripod and approached Buck and Malcolm. The pair were coming over the trail, well laden.

‘Do you mind waiting a minute,’ he said, ‘until Alan and Greathouse fetch up so I can get some pictures of you all together?’

The two men stopped for an instant. Malcolm shifted his pack and looked at Buckley. The latter looked back. Then, without speaking, they went on. Bullock felt his face flush as though some one had struck him. They regarded him as an oddity who puttered with cameras and diaries in a land meant for sterner things. Even when he out-packed them and out-paddled them, they held to their opinion. Only Hornby seemed to understand. He posed for several shots when he saw the tripod erected.

To stem his depression, Bullock wandered off alone that night after grub. A blue butterfly effect on one of the little lakes affected him deeply. The sight of it was like food. In its beauty he even forgot his physical troubles, surmounted by a liverish throat which was scalded by every swallow of hot food or drink. He endured the cold for the sake of the solitude after the sun went down. His pipe bowl glowed until late. Before turning into his sleeping-bag, he wrote in his diary: ‘How sweet to be alone!’ He smiled grimly at the thought of the sneers if the others should read it.

There came a night when the packs were set down on the shore of Artillery Lake. Portaging was over for a while. The next morning when camp was broken and the canoes launched, a heavy mist clung to the water. Hornby was more animated than he had been for months. He was nearing home. The start from shore was almost a rite. One by one the men climbed into the canoes and began to paddle. The only sound was the drip-drip of water from the blades. A hundred feet off shore the mist swallowed up the beach they had just left. There was something symbolic about it to Bullock. It was as though the gray-white film which enveloped them betokened the great spaces which were to awe them and surround them farther on.

After several hours the mist, which had been gradually thinning under the mounting sun, vanished altogether. On the western shore, Bullock saw small timber for as far as the eye could see. Hornby was looking at the eastern shore. It was bare of trees, and presented a strange spectacle of emptiness. The timber line cuts Artillery Lake diagonally, from northwest to southeast. Where Hornby’s eyes were focussed, the Barren Lands began.

ne day in October, after the snow had

come and the lake ice was forming near

the shore, Hornby sat on a sand prominence

watching the caribou. He was often to

sit thus during the winter, always in silence,

always alone. He watched as another might

watch the tide of humans in a city street, with

tolerance and amusement, seeking familiar

faces and tableaux. Sometimes a half-mile distant,

sometimes only a few yards away, the

animals drifted in little bands. They were

idling toward the edge of the timber, drawn by

the instincts which each year guide and time

their migrations. In a few days mating would

begin. Already there was a restlessness in the

bulls and a friskiness in the cows. Hornby,

motionless, saw the graceful, thin-flanked

creatures grub beneath the snow for moss. He

could tell of other years when he had walked

into closely packed herds and aroused no more

than passing glances from the deer. The

proudly poised bulls and sleek cows had opened

respectful path for him. Beyond that not one

had moved.

ne day in October, after the snow had

come and the lake ice was forming near

the shore, Hornby sat on a sand prominence

watching the caribou. He was often to

sit thus during the winter, always in silence,

always alone. He watched as another might

watch the tide of humans in a city street, with

tolerance and amusement, seeking familiar

faces and tableaux. Sometimes a half-mile distant,

sometimes only a few yards away, the

animals drifted in little bands. They were

idling toward the edge of the timber, drawn by

the instincts which each year guide and time

their migrations. In a few days mating would

begin. Already there was a restlessness in the

bulls and a friskiness in the cows. Hornby,

motionless, saw the graceful, thin-flanked

creatures grub beneath the snow for moss. He

could tell of other years when he had walked

into closely packed herds and aroused no more

than passing glances from the deer. The

proudly poised bulls and sleek cows had opened

respectful path for him. Beyond that not one

had moved.

To the ears of the man on the sand-bank came now and then the crack of a rifle shot, sharpened and amplified by Northern air. He knew that Bullock, or Malcolm, or Alan, or Greathouse, or Buckley had fired, and that probably some fat bull lay dead or dying in the snow. It was the finger of necessity, not sport, at the trigger. Caribou must be hunted while they are fat. In a few weeks, when true winter became animate and the rutting season was on, the flanks and backs of the deer would grow leaner. Also caribou must be hunted when they are in evidence. For there might be days and weeks when not one would be seen. So on this day, with animals dotting the horizon, rifles spat. To-morrow the flat sweep of the Barrens might be lifeless again.

For the moment Hornby was content to leave hunting to the others. His thoughts were his own. Probably they were vague, as vague as the outlines of the farthest knoll to the west, or the well-nigh invisible shore-line across Artillery Lake to the east. Surely they were the thoughts of a dreamer, for who else would so endure the cold and the monotony? There was even something regal in it all, as when he said to Bullock in their tent late in the afternoon:

‘It’s a wonderful, wonderful country, don’t you think, Bullock? I’ve been watching the caribou grazing. The cows and the calves were skipping like sheep and lambs. A shame to kill them, but man comes first, and men must eat. People don’t understand what brings me to this country—what holds me here—but you do, don’t you?’

Bullock, understanding a little, smiled. He was blood-spattered and dirty from a day of butchering.

‘Yes, I think I do. I can wake up in the morning here and know that I have no troubles beyond keeping alive.’

‘Yes, yes! That’s it!’ Hornby’s eyes were afire again. ‘If I could only stay in the Barrens I should be content. I wish the Government would give me Artillery Lake. They ought to, after all I’ve done. Then I’d build a house on a hill by the shore. From its windows I could see for miles in every direction. When the caribou were in migration, I’d sit and watch. The windows would be open so that I could hear the grunts and hoofbeats. I’d feel as though they were galloping for me, passing in review. Then I’d be really happy . . .’

Such moods Hornby reserved for Bullock. With the others he was always the doer, never the dreamer.

Sometimes in the evenings of early October, the little man and his young companion journeyed to the log cabin which Alan Stewart and Buckley, with help from the others, had erected in an isolated spruce clump a few miles beyond the timber-line. This cabin was the largest of the chain of back camps. It was designed to shelter the whole party in an emergency. Southward, within the timber, was a cabin built by Greathouse. Miles to the north, also in the haven of stray lakeside timber, a semi-dugout was nearing completion. It would house Malcolm Stewart. Somewhere beyond that, in the true Barrens, Hornby and Bullock would eventually settle.

The gatherings at Alan’s cabin were merry. Loneliness and labor proved droll parents. Of them were born masculine quips and arguments never heard in civilized parlors. Laughter was loud, louder than the howl of the wind or the crackle of spruce logs in the stove. Sometimes Malcolm, whose laugh was heartiest and words broadest, would climax a muscular story by asking:

‘That’s the way of it, eh, Jack?’

And Hornby would say:

‘I guess so, Malcolm. But you know more about such things than I do.’

When conversation dragged, Al Greathouse talked. He hinted of secret fox bait which would snare the most wary descendant of Reynard. Or of equally secret hair tonic which had been ‘brewed by an Indian Chief.’ Mention of the tonic was always punctuated by inclinations of his bald head so the rest might see the new fuzz struggling to be visible. Some one asked to see the tonic. The old trapper grinned. It was, it seems, one of those things which were not for infidel eyes. When Hornby suggested that a diet rich in meat was excellent fuzz nutriment, Greathouse was indignant. Almost as indignant as on an earlier night when Pat was missing.

It was while the party was encamped on the shores of Artillery. The dog had not been seen for more than a day and its master was worried. After darkness had fallen, and a group had gathered in one of the tents, there came a howl from some distance outside, Greathouse rushed out, calling, ‘Pat! Pat! Pat!’ Hornby followed, and returned a moment later grinning like a boy.

‘What’s the old fellow doing?’ some one asked.

‘Calling a wolf “Pat,” ’ Hornby chuckled.

One of the events of an evening at Alan’s was the card game. They played Five Hundred, these trappers and frontiersmen, with an enthusiasm never equaled at society Bridge tables. No stakes were needed to pyramid the thrills. The games were conducted with childlike simplicity. To win was good, but to lose was much better than not to play at all. The cards were gummy from handling by fingers which an hour before, perhaps, had been messing with some freshly killed carcass. The men were bearded and untidy. The table was a makeshift. But the game, the everlasting sport of it, was genuine. All were participants at one time or another: Hornby, beaming or frowning with his luck; Bullock impassive; Malcolm calculating; Buckley jocular; Alan serene; Greathouse voluble.

From the shadows near the stove a grotesque figure watched the players, a squat, shaggy shape without head or legs. In the half gloom it had the appearance of an idol hideously carved. Closely examined, it became a matter of caribou hides. Malcolm had contrived it with needle and gut to supplement the light cloth parka he had brought from civilization. Two large hides did service for the body of the garment, and a third one, halved and roughly sewn, was made into sleeves. The tanning and curing had been hasty, so hasty that the skins retained the character of stiff brown paper. When worn, they crackled with each movement of Malcolm’s limbs. Left standing on the floor, as now, the monstrosity kept upright, yet not without a certain state of collapse which lent to it a malignancy. The arms drooped as if weary; the body sagged like the cheeks of a man near death. One night, while Hornby was looking from his cards to return the headless thing’s scrutiny and to see if in the candlelight it didn’t sway as though alive, Malcolm winked broadly at the rest. He was dealing new hands, and before the deal was complete, he became tense.

‘What’s that?’ he whispered. Then a moment later—‘I hear a wolf outside.’

At ‘wolf’ Hornby dropped his cards for a rifle. The larder could do with more fat. When he vanished through the door, Malcolm picked up the cards he had already dealt and turned the whole deck face up on the table. He chose an assortment of aces and face cards, counted out the proper number, and placed them before the little man’s seat. Then he dealt new hands around from the remainder of the deck.

Hornby was back in five minutes.

‘No sign of him,’ he said. ‘I couldn’t even find his tracks in the snow.’

‘Too bad,’ Malcolm sympathized. ‘Maybe I heard wrong.’

Hornby had no poker face. The social graces were his when he chose to exercise them, but not the masks which were worn in conjunction. When he was pleased, or when he wasn’t, he showed it. Just then his eyes shone like cat’s gleams as he waited for play to begin. He got the bid. He took every trick. The others, Malcolm and Buckley in particular, wailed.

‘Damn it, Jack,’ the latter complained, ‘what did you do—stack these cards?’

The winner was concerned.

‘Why, no,’ he said earnestly, ‘Malcolm dealt them, not me. The trouble is you don’t get the psychology of the thing. I’m lucky because I have faith in luck.’

Back in their tent, Hornby brewed tea for himself and Bullock. It was too late to bother with the kettle, and, besides, the new fire wasn’t burning well. Two aluminum cups, each with its portion of leaves and water, were set on the stove. Hornby squatted in bare feet. He had removed his moccasins and socks, as always when he lounged inside. His right hand fingered one of his toes while his left stirred the fire. Sometimes he stared intently at his feet as though expecting to find a toe had come off in his hand.

‘Bare feet are hard and healthy, Bullock.’

‘I fancy so.’

‘If I should hear a wolf or caribou now, I wouldn’t bother with moccasins. That’s the beauty of it here. There are no nails or glass on the ground. And cold won’t hurt your feet if you’re on the run.’

‘What of the rocks?’

‘Oh, I wouldn’t step on the sharp ones.’

Tea in the Barrens was hardly tea at all. The black liquid in the dented cups was hot. That was its virtue. But it didn’t taste like tea. And the cups were greasy from insufficient washing. When water wasn’t handy, Hornby rubbed cups and plates with sand. It did shear off the thicker grease. Bullock remembered Quetta, where one sat on a wide veranda in some officers’ compound and sipped tea of an Indian afternoon. Wild peach trees bloomed in the garden, and the eye commanded a picture of rolling brown plains cut by nullahs. It had been as hot there as it was cold in the Barrens. One wore shorts, a sun helmet, and a khaki shirt with a ‘spine pad’ to keep the blistering rays off your back. In the daytime you couldn’t even sit in a tent with your helmet off. Now he sat on his bunk with parka on. Beneath it was a heavy flannel shirt, and under all thick underwear. Over his legs was stretched a pair of coarse overalls. Moccasins covered his feet. The whole outfit was blood-spattered. Packing fresh meat on your back is not for the fastidious. Was it always the same—too hot yesterday, too cold to-day, too something else to-morrow? Thinking thus, Bullock managed to put into words that which had been in his heart for some days. He tried to be pleasantly casual.

‘I say—when is my scientific stuff going to be moved up from Reliance?’

Hornby set his cup on the stove and grasped his toes with both hands.

‘Sometime soon, Bullock, sometime soon.’

‘But aren’t we wasting time—leaving it down there?’

‘Why, no. No, of course not. We’re getting the Stewarts settled, and Greathouse and Buckley, so they can trap successfully. I’ve been showing them where to set out trap lines, and the best kind of bait to use.’

Something in Bullock’s glance, some tensity in his silence, made Hornby look intently at the younger man. After a moment he said:

‘Look here, I know what you’re thinking. I want to tell you a story. It’s about two trappers who were alone together in a remote part of the woods. They had a disagreement over something and determined to separate, dividing equipment and supplies. They set about putting one sack of flour on one side and a second sack on the other. An axe went to the left, another to the right, and so on through staples, through traps, through fish nets, through ammunition, and even fur. After the division was accomplished, one thing remained—a kettle. The men eyed the thing, each knowing it held the power to stampede them to murder. To leave it was unthinkable. Either might return and steal it. What was to be done? At that moment, when one spoken word might have been fatal, the elder of the men picked up an axe and split the kettle down the center. It was of no further use to either.’

Hornby hesitated, but not long enough to allow the other to comment. Then he said:

‘Let’s turn in.’

Two hours later, Bullock was still awake. An almost continuous rustling disturbed the darkness. It was Hornby, sleeping Indian fashion, twisting and turning in slumber to keep the circulation from sluggishness. Bullock envied him the knack of it.

The moods of Nature are as vagrant as those of her children. What had been snow was now rain, and the two in the tent were miserable. It was four in the afternoon, but already dark. Hornby sat on his haunches trying to heat water and tea leaves in a cup held over a candle. Bullock supposed that Hornby would manage tea on a raft in mid-ocean. Hail hit the canvas like bullets. A few yards away, two heavy canoes, turned bottoms up to shelter a half ton of dunnage, echoed the steady drumming of the ice. Occasionally a growl or half-whine would come from one of the dogs tethered outside. Mostly, though, they were philosophical and made no sound. Or perhaps it wasn’t so much philosophy as it was Whitey. This old leader, who stood as high as a wolf, was a veteran of the trails. His massive shoulders and wolf-like head set him apart from the younger dogs, with whom he enforced discipline by gutturals as commanding as a sergeant major’s ‘Halt!’ Whitey’s hide was weather-proof. Hail was merely an incident, even if cold and driving like this. So, wisely, did Skinny and Porky and Bhaie accept it as such. The names were descriptive. The first was slimly built; the second had been shot full of porcupine quills at Reliance; the third, to whom Bullock took a fancy, became Bhaie because it signified ‘Brother’ in Hindustani. Whitey, of course, was named for his color, which was that of the snows in which he had been bred.

In the tent Hornby juggled the metal cup. The candle flame made it uncomfortably hot.

‘We were lucky to have found this island. We might have been swamped.’

‘I’m as wet as if I had been swamped.’

‘We’ll go on pretty soon. Maybe the storm will let up. Anyway, there’s no sense in spending the night here. We need a fire to help dry us out, and there’s no fuel on this miserable sandbar. I’d like to get into the Casba to-night.’