* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

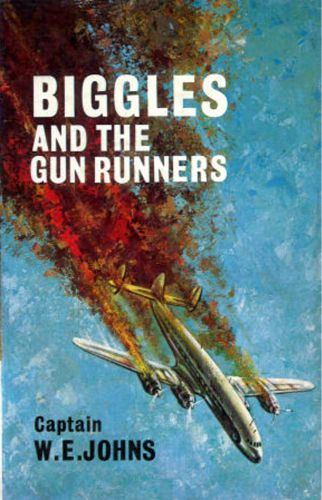

Title: Biggles and the Gun-runners

Date of first publication: 1966

Author: Capt. W. E. (William Earl) Johns (1893-1968)

Date first posted: May 28, 2023

Date last updated: May 28, 2023

Faded Page eBook #20230560

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, akaitharam, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

| Other BIGGLES titles: | |

| BIGGLES GOES TO SCHOOL | |

| BIGGLES, SECRET AGENT | |

| BIGGLES SEES IT THROUGH | |

| SPITFIRE PARADE | |

| BIGGLES SWEEPS THE DESERT | |

| BIGGLES IN BORNEO | |

| BIGGLES FAILS TO RETURN | |

| BIGGLES DELIVERS THE GOODS | |

| BIGGLES’ SECOND CASE | |

| BIGGLES TAKES A HOLIDAY | |

| BIGGLES BREAKS THE SILENCE | |

| ANOTHER JOB FOR BIGGLES | |

| BIGGLES WORKS IT OUT | |

| BIGGLES TAKES THE CASE | |

| BIGGLES FOLLOWS ON | |

| BIGGLES AND THE BLACK RAIDER | |

| BIGGLES IN THE BLUE | |

| BIGGLES IN THE GOBI | |

| BIGGLES CUTS IT FINE | |

| BIGGLES AND THE PIRATE TREASURE | |

| BIGGLES, FOREIGN LEGIONNAIRE | |

| BIGGLES IN AUSTRALIA | |

| BIGGLES TAKES CHARGE | |

| BIGGLES MAKES ENDS MEET | |

| BIGGLES ON THE HOME FRONT | |

| BIGGLES PRESSES ON | |

| BIGGLES ON MYSTERY ISLAND | |

| BIGGLES BURIES A HATCHET | |

| BIGGLES IN MEXICO | |

| BIGGLES’ COMBINED OPERATION | |

| BIGGLES AT WORLD’S END | |

| BIGGLES AND THE LEOPARDS OF ZINN | |

| BIGGLES GOES HOME | |

| BIGGLES AND THE POOR RICH BOY | |

| BIGGLES FORMS A SYNDICATE | |

| BIGGLES AND THE MISSING MILLIONAIRE | |

| BIGGLES GOES ALONE | |

| ORCHIDS FOR BIGGLES | |

| BIGGLES SETS A TRAP | |

| BIGGLES TAKES IT ROUGH | |

| BIGGLES TAKES A HAND | |

| BIGGLES’ SPECIAL CASE | |

| BIGGLES AND THE PLANE THAT DISAPPEARED | |

| BIGGLES AND THE LOST SOVEREIGNS | |

| BIGGLES AND THE BLACK MASK | |

| BIGGLES INVESTIGATES | |

| BIGGLES LOOKS BACK | |

| BIGGLES SCORES A BULL | |

| BIGGLES IN THE TERAI | |

| BIGGLES AND THE BLUE MOON | |

| THE FIRST BIGGLES OMNIBUS | |

| THE BIGGLES AIR DETECTIVE OMNIBUS | |

| THE BIGGLES ADVENTURE OMNIBUS | |

BIGGLES AND

THE GUN-RUNNERS

‘The great thing in life is to keep your sense of humour,’ says Biggles, though getting his Constellation shot down over southern Sudan by a trigger-happy fighter pilot of the Congolese Air Force was no laughing matter. In fact, his privations and those of his co-pilot, Sandy Grant, increased from that very moment in an affair which throughout bristled with spies, lies and deception.

First edition 1966

BIGGLES AND

THE GUN-RUNNERS

CAPT. W. E. JOHNS

Brockhampton Press

First edition 1966

Published by Brockhampton Press Ltd

Salisbury Road, Leicester

Printed in Great Britain by C. Tinling & Co Ltd, Prescot

Text copyright © 1966 Capt. W. E. Johns

| CONTENTS | ||

| Chapter 1 | THREE MEN IN A BOG | page 7 |

| 2 | THE ONLY WAY | 22 |

| 3 | A PROPOSITION | 35 |

| 4 | BIGGLES DOES SOME THINKING | 48 |

| 5 | ALWAYS THE UNEXPECTED | 54 |

| 6 | THE FIRST JOB | 64 |

| 7 | PLAIN SPEAKING | 76 |

| 8 | A QUEER BUSINESS | 88 |

| 9 | PROBLEMS | 94 |

| 10 | ABANDONED | 104 |

| 11 | BRADY COMES BACK | 114 |

| 12 | SERGEANT DUCARD TALKS | 124 |

| 13 | BIGGLES SHOWS HOW | 135 |

| 14 | A SHADOW IN THE TAMARISKS | 145 |

| 15 | DUCARD FORCES A SHOW-DOWN | 157 |

| 16 | ALGY EXPLAINS | 168 |

| 17 | HOW IT ENDED | 177 |

From the second-pilot’s seat of a four-engined Lockheed ‘Constellation’ aircraft, wearing radio telephone equipment, Biggles of the Air Police, from a height of 14,000 ft. gazed down through a quivering heat-haze at the apparently eternal panorama of Central Africa. To be precise, the Southern Sudan in the region of the White Nile.

Beside him, in control of the machine, sat a smallish, sandy-haired man whose puckish but intelligent face was plentifully besprinkled with freckles.

‘Listen, Sandy. They’re still ordering us down,’ said Biggles.

‘Who’s doing the ordering?’

‘I don’t know. They don’t say and I haven’t asked them. You told me to ignore all signals.’

‘Okay. You can tell ’em to go to hell.’

‘I wouldn’t take that line. They might decide to send us there.’

‘How do they reckon they’re going to do that?’

‘I wouldn’t know, but from the way they talk they seem sure they’ve got the edge of us. They say they’ve given us fair warning. If we go on we shall have to be prepared to take the consequences.’

‘What do you take that to mean?’

‘How would I know? But I have a feeling they wouldn’t use that sort of threat unless they were in a position to—’

‘Pah! They’re bluffing.’

‘I wouldn’t gamble on that,’ Biggles said, looking worried.

‘You scared?’ There was a hint of good-humoured sneer in the words.

‘You can call it that,’ returned Biggles, coldly. ‘I’ve been shot at before today, and the older I get the less I like it.’

‘If you don’t like the way I fly you can get out.’

‘Now you’re talking like a fool, Sandy.’

‘Okay, so I’m a fool. What would you do?’

‘Answer their signals. They must know we’re receiving them.’

‘Then what? They’d only repeat the order to go down.’

‘I’d go down to find out what all the fuss was about. We should have done that while we still had an airfield in easy range. We’ve nothing to be afraid of, so why not?’

‘I’m staying here. Let ’em sweat,’ was the curt rejoinder.

‘But for Pete’s sake, Sandy, why take that attitude?’ protested Biggles. ‘We’re not carrying contraband, or any nonsense of that sort. In fact, we’re flying empty except for ourselves.’

‘Listen, pal. If they get us on the ground they may hold us for days, or maybe weeks, asking a lot of questions about where we’re going, what we’re doing, and why we’ve no passengers. To hell with that.’

‘Is there any reason why we shouldn’t tell them?’

‘We’ve no time to waste. I’m in charge of this ship and I’m going on.’

Biggles shrugged. ‘Have it your way. I can only hope you realize we’re asking for trouble. If they should get their hands on us after this we’re likely to get rough treatment.’

‘The Sudd’s in front of us. You keep your eyes skinned for the machine we’re looking for. Our orders were clear enough. Get down beside the ship before anyone finds it, transfer the cargo and bring it home with the pilots.’

‘Why bring it home?’

‘There may be a good reason. Like I say, I obey orders without asking questions.’

‘I’m as conscientious about obeying orders as you are, but I like to know what I’m doing. Whoever gave you orders to land in the Sudd was talking through his hat. He obviously doesn’t know the Sudd. At this time of the year, until the sun dries it out, it’ll be swamp, four hundred miles of water, mud and rushes; and nothing else except elephants. If that machine is down in the Sudd it’s ten to one she’ll be up to her belly either in mud or water.’

‘Quit stalling. We’ll find somewhere to get down. Are they still yapping on the radio?’

‘No. They’ve stopped.’

‘That’s what I thought they’d do when they realized how we felt about it.’

‘I admire your confidence and I hope you’re right; but I wouldn’t care to bet on it,’ returned Biggles. He went on: ‘Okay. So we find the lost machine, and if we’re lucky get down in one piece. Then what?’

‘All we have to do is transfer the cargo.’

‘What does the cargo consist of?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘I imagine it will be heavy.’

‘It usually is.’

‘If we have to carry it far in this heat we shall have to pray for strength.’

‘There’ll be four of us.’

‘Say three.’

‘Why three?’

‘We shall only find one man with the machine. What you appear to have overlooked is that one of them would have to go off to find a post office to send the telegram to say the machine was down in the Sudd. The place isn’t exactly bristling with post offices. Whoever went might have to go as far as Juba or Malakal. That depends on where it came down. Why did it have to come down, anyway?’

‘Search me.’

‘Didn’t the telegram say anything about engine trouble, or structural failure . . .’

‘I didn’t see the telegram. All I was told was, the machine was down in the Sudd and we were to go to fetch the stuff home. I don’t think the boss knew more than that himself. He seemed pretty fed up.’

‘So, for all we know the machine may have crashed?’

‘I suppose so.’

‘And we don’t know at which end of the Sudd it came down. Four hundred miles is a long stretch to search and we may have a job to find it. What was it doing over the Sudd, which most pilots would agree is a good place to keep clear of? Where was it bound for?’

‘Carisville.’

‘Where’s that?’

‘Northern Congo.’

Biggles stared. ‘Then what was it doing over the Sudd?’

‘That’s the way we usually go. Across the Mediterranean, down the Sinai Peninsula and then follow the Nile to the White Nile.’

‘But that would land you miles east of the Congo?’

‘At the southern end of the Sudd we turn sharp west. From there it isn’t too far to the north-east corner of the Congo, and the objective.’

‘It seems a mighty queer business to me,’ stated Biggles. ‘Why make a dog’s-leg of it?’

‘The Count is on good terms with Egypt, so I think the idea is to keep in touch with one of the aerodromes there for emergencies—fuel, and so on.’

Biggles shook his head. ‘I still don’t get it. Had I been told more about the way things were run, before we started, I’d have been in a better position to judge just what we’re doing and what might happen to us.’

‘There’s a lot about it I don’t understand myself,’ admitted Sandy. ‘You’re a new man. No doubt the boss would have told you more in course of time, after he’d seen how you made out.’

‘You’ve no idea who would be likely to order us down?’

‘No, and I don’t care. I’m not taking orders from strangers. I’m captain of this ship and I’m not going home to report I was scared to go through with the job on account of some interfering rascal. Right now I can’t see any place to get down even if I wanted to. You watch the carpet for the Constellation we’re looking for; it’s big enough to see.’

There was a pause in the conversation. Then Biggles said: ‘That’s a nice herd of elephants ahead. The Sudd is about their last stronghold. Even poachers think twice about hunting here. When the last wild African elephant dies it will probably be in this area.’

‘So what? What the hell do elephants matter, anyhow? That looks like smoke farther on. Might be coming from the Constellation, to mark its position for a relief plane.’

‘Could be,’ agreed Biggles. ‘I can also see something else, something which may turn out to be more interesting. Look up, half right.’

Sandy’s eyes moved. ‘A plane. Fighter type. What the devil can he be doing here?’

‘Since you ask, it occurs to me that it might be looking for us. In fact, from the way he has just altered course towards us, I’d say he’s spotted us. As you remarked just now, a Constellation is big enough to see.’

‘He’s only coming over to have a look at us,’ said Sandy, carelessly.

‘Maybe. We shall soon know what he’s after. It doesn’t appear to have struck you that this fellow may have been responsible for putting the other Constellation on the floor.’

Sandy laughed. ‘Oh, come off it. He wouldn’t dare.’

‘We’re not in Europe,’ reminded Biggles, his eyes on the fast approaching aircraft, obviously a military single-seater. ‘He’s coming close. Watch out.’

Biggles’ voice ended on a high note, and both pilots in the big machine flinched instinctively as the fighter flashed across their bows.

‘What the blazes does he think he’s doing?’ shouted Sandy, furiously.

‘At present I’d say he’s only buzzing us, inviting us to comply with orders to land. If we take no notice he may show us his sting. Did you get his nationality marks?’

‘I only noticed something red and black. Maybe one of these new independent African states. Where is the little swine?’

‘He’s turned and is coming in behind us. What are you going to do?’

‘Do? Nothing. Why should I do anything?’

‘Listen, Sandy,’ said Biggles tersely. ‘This fellow must be attached to the ground organization that ordered us down. Now we know what they meant about taking the consequences if we carried on.’

‘I’m not going to be pushed into the ground by that little squirt,’ declared Sandy obstinately.

‘You may change your mind about that,’ returned Biggles evenly. ‘We can’t fight. We’ve nothing to fight with. If you can’t fight it’s time to run away. He’s coming in on the starboard quarter. Hold your hat. He means business.’

Above the roar of the four Cyclone engines now came the snarl of multiple machine-guns. Lines of white tracer bullets flashed across the Constellation’s nose.

‘Missed us,’ snapped Sandy laconically.

‘He didn’t try to hit us. Had he tried he could hardly have missed, I’d say that was the final warning.’

Before Sandy could answer the Constellation quivered like a startled horse as it was struck by whip lashes somewhere astern.

Biggles looked at his companion who, pale faced, was staring at him wide-eyed. ‘Well, now what are you going to do?’ he asked calmly.

‘He hit us, blast him.’

‘Of course. He could hardly miss this flying pantechnicon.’ Biggles went on, now deadly earnest. ‘It’s no use, Sandy. We’re a sitting duck. We can’t hit back. If he gets a tank we’re roast meat.’

‘I suppose I shall have to go down, curse him,’ grated Sandy through his teeth.

‘If he keeps this up we shall be lucky to get down,’ stated Biggles grimly, as another hail of bullets struck the big Lockheed. One must have passed between them into the instrument panel, for a rev counter disappeared in a shower of splintered glass.

Sandy crouched lower in his seat, compressing himself into the smallest possible compass.

‘That won’t help you,’ said Biggles calmly. ‘Have you never been shot at before?’

‘Not in the air.’

‘Nasty feeling, isn’t it?’

Sandy did not answer.

‘Are you saying you’ve had no experience of air combat?’ went on Biggles.

‘Never.’

‘Then you’d better let me take over, because I have; and I know a trick or two.’

‘Okay. She’s all yours.’ Sandy’s face was white.

‘It’s not so bad when you get used to it,’ Biggles said calmly. ‘Don’t worry. Everyone gets butterflies inside first time. Hang on.’

‘D’you think you can make it?’ asked Sandy anxiously.

‘It depends on what experience this fellow has had. If, as I suspect from the way he’s flying, he’s young and green at the game, we may get away with it.’

A swift look at the sky revealed the fighter coming in for another attack. The Constellation’s engines died. Biggles slammed on full right rudder and dragged the control column far over to the left. The effect was a violent skid, jamming both pilots in their seats as the aircraft lay over on its side, port wing pointing at the ground in an almost vertical sideslip, the nose being held up by Biggles’ right foot on the rudder control.

‘What good’s this doing?’ shouted Sandy desperately.

‘Unless he’s an old hand and realizes what I’m doing, it should prevent him from hitting us.’

‘Why should it?’

‘My line of flight is down, but we look as if we’re still going forward. That’ll throw his deflection out. His shots will pass forward of us. See what I mean?’ Biggles added, as more white tracer streamed against the blue sky ahead of the Constellation’s bows.

The fighter flashed past in the wake of his bullets. As it began to pull out of its dive Biggles reversed the position of the Constellation, pointing his starboard wing down and holding it in control with left rudder. Brute force was necessary, as the big machine did not respond as quickly as a small aircraft would have done.

In the pause that followed Biggles snatched a glance at the altimeter and saw the needle, still falling, pass the 9,000-ft. mark.

‘What’s the little swine doing?’ shouted Sandy.

‘Looking for us—I hope. He’d lose sight of us when he overshot. Watch the ground for elephants.’

‘Hell’s bells! Why elephants?’

‘Because they’ll be on dry ground, if there is any. Somehow I’ve got to get this lumbering truck on the carpet.’

By now the fighter must have found them, for they heard its guns. But they saw no bullets. None struck them.

‘He still isn’t wise to it,’ muttered Biggles. ‘We haven’t much farther to go.’

Sandy threw him a sidelong glance. ‘You’ve done this before.’

‘Too true, but not in a kite this size. My arm’s numb, holding her in this position. Try to spot that infernal sting-ray when I pull out. He’ll get a chance when I flatten out.’

‘I can see elephants.’

‘Where?’

‘Straight ahead.’

‘Any trees?’

‘No. Nothing.’

‘Good. Hold on to something. Don’t fall on me.’

Centralizing the controls, Biggles brought the big machine back slowly to even keel. The pressure relaxed.

‘Where is he?’ he asked.

‘Sitting right over us.’

‘Watching to make sure we don’t try to pull a fast one.’

‘What are you going to do?’

‘Land. Or try to.’

‘Why not go on?’

‘Not me. I’ve had enough. We’ve been lucky—so far. I’m not tempting providence.’

‘The boss will say—’

‘Never mind the boss. If he was on board he wouldn’t be able to get out fast enough.’

‘That little swine will get us as you glide in.’

‘He won’t. We’re too low now. If he dives and overshoots us he’ll be into the deck. Hold tight. We’re liable to do some bumping when our wheels touch. Don’t talk. I’m trying to get on the ground in one piece.’

Biggles now concentrated on the task of landing the big machine in conditions far from ideal. There was only one area of clear ground, the place where the elephants, a big herd, were now looking up at them. Judging from their tracks the ground looked reasonably firm.

Biggles opened up his engines and flew low straight at them. This sent them off in a stampede, trunks held high. Only one, an old bull by the size of his tusks, held his ground; but as Biggles made a circuit to get the longest possible run in, he, too, lost his nerve and bolted.

The engines died. Slowly the Constellation lost height. For a little way it skimmed the feathery heads of tall papyrus rushes. These gave way to rough tussocky grass dotted with clumps of scrub, some uprooted by the elephants. The wheels touched; bumped; touched again and bumped again; then, touching again, they remained on the ground. The machine, jolting and swaying a little, rumbled on to a stop.

‘Pretty good,’ panted Sandy, breathing hard.

‘Get out.’

‘What’s the hurry?’

‘The lad upstairs may have a last smack at us.’

They scrambled out in a hurry and looked up. The fighter was gliding in.

‘He’s going to land,’ observed Biggles.

‘Land, eh! He’s got a crust—after shooting at us,’ rasped Sandy. He snatched an automatic from his pocket.

‘What are you going to do with that?’ inquired Biggles.

‘Shoot the little swine.’

‘Put it away,’ Biggles said impatiently.

‘He shot at us, didn’t he?’

‘So what. Use your head, man. What good will shooting him do us? He was doing his job; sent up by someone to stop us. Let him talk and we may learn what all this is about.’

Muttering under his breath, Sandy replaced the pistol in his pocket. They watched their attacker land.

‘What machine is that?’ asked Sandy.

‘Never saw one before.’

‘What are those markings?’

‘I don’t know that, either. They’re new to me. With new states popping up all over the world it’s hard to keep pace.’

The pilot of the aircraft concerned, a dapper figure in uniform, got down and walked briskly towards them. His face was black.

Sandy made a noise as if he was choking. ‘No,’ he cried. ‘A Negro! It isn’t true!’

‘I can’t see that the colour of his skin makes any difference,’ said Biggles, without emotion. ‘It doesn’t affect his guns.’

‘He had the sauce to shoot at us.’

‘It’s the finger on the gun button that counts. Who it belongs to doesn’t matter.’

‘Doesn’t it? I’ll knock his flaming block off.’

‘You’re talking like a twit. You go off at the deep end and you may find your own block knocked off. Let’s hear what he has to say.’

The coloured pilot marched up with the greatest confidence. But there was nothing arrogant in his manner. He was young. Under twenty. He wore a revolver in a holster on his hip, but he did not draw it.

‘You are arrested,’ he announced, in the high-pitched nasal voice common to Africans.

‘Indeed. For what, may I ask?’ inquired Biggles.

‘For supplying arms to the rebels in my country.’

‘And what country is that?’

‘Congo.’

‘Are you Congolese?’

‘I am an officer of the Congolese Air Force.’

‘Then what are you doing here? This isn’t the Congo.’

The officer looked taken aback. ‘Isn’t it?’

‘It is not. This is Sudanese territory.’

‘So I came over the border,’ admitted the pilot, naïvely. ‘Congo is close so it makes no difference.’

‘Doesn’t it, by thunder,’ returned Biggles, crisply. ‘You get the idea you can fly where you like, shooting at anyone you fancy, and you’re heading for trouble. You’d better buy yourself a map.’

‘You ignored signal to land.’

‘What if I did? You can’t order planes to land just to suit you.’

‘We have information that more arms for rebels are expected.’

‘Well, we haven’t got them. You’d better start looking somewhere else.’

‘I will look.’ The Negro took a pace towards the Constellation.

Biggles’ hand fell on his shoulder. ‘No you don’t. You’ll ask my permission before you step into that plane.’

‘May I look?’

‘That’s better. You’re welcome to all the guns you can find.’

‘Why argue with the little rat?’ growled Sandy, as their questioner climbed into the machine. ‘Knock him off and have done with it.’

‘What an impatient fellow you are,’ protested Biggles. ‘He’ll climb off the high horse when he realizes he’s boobed.’

The black pilot returned looking crestfallen. ‘I am sorry,’ he said contritely.

‘So you should be,’ chided Biggles. ‘That would have been small consolation to us had you set us on fire. As it is you’ve damaged our machine. What are you going to do about it?’

‘What can I do? I say I am sorry.’

‘You can go home and tell your commanding officer what you’ve done. He’ll hear more about it.’

‘I will do that. I am very sorry.’

‘So you said before. All right. In future be more careful with those guns.’

‘Is there anything I can do now?’

‘Nothing. We’ll be on our way when we’re ready.’

‘Then I go. If I can help you any time my name is Lieutenant I’Nobo. Good day, gentleman.’ The Negro saluted and marched back to his machine.

As they watched him take off Biggles said, with a curious smile: ‘He’s all right. He’ll do better with more practice. At least he called us gentlemen, a word that’s gone out of fashion where I come from.’ He lit a cigarette. ‘So now we know,’ he added.

‘Know what?’

‘Someone is supplying arms to Congolese rebels. The Congo government is wise to it and they’re putting up planes to stop the racket. We’d better remember that should we come this way again.’

‘This is all the thanks you get for helping them to fill their bellies,’ observed Sandy in a voice of disgust. ‘You let him off light. Had I been alone—’

‘You weren’t, so why talk about it?’

‘I know—I know,’ muttered Sandy. ‘You got the machine down after I’d lost my nerve. Don’t rub it in. I’ll buy you a drink when we get some place where they sell it. What do we do now?’

‘When we’ve got our breath we’d better go on with what we were doing. How far do you reckon we are from that smoke we saw?’

‘Some way. I lost track of it as we came down. I was thinking of something else.’

Biggles smiled. ‘Matter of fact, so was I. No matter. We’ll find it presently.’ He sat on a tussock to finish his cigarette.

This seems to be the time to explain why Biggles was acting as second-pilot in a big commercial air-liner, flying without seats and without passengers over Central Africa. To understand how this unusual circumstance arose it is necessary to start at the beginning, in London.

When, in answer to a call on the intercom telephone, Biggles of the Air Police entered the office of his chief, he found the Air Commodore hanging up his hat and coat.

‘Would I be right, sir, in supposing that something urgent is in the breeze?’ he questioned, quietly.

‘Not in the breeze, Bigglesworth,’ was the answer. ‘Not even a wind. Call it a force nine gale. Sit down. I’ve just come from a high level conference and I shall have to talk to you about it.’

Biggles took his usual chair for such occasions in front of the Air Commodore’s desk. He did not speak.

His chief settled in his own chair and with his eyes on Biggles’ face went on: ‘I’ll come straight to the point. I’ve been given orders to put an end to this gun-running by air racket.’

Biggles smiled faintly. ‘Is that all?’

‘Isn’t it enough?’

‘Too much. What are you going to do?’

‘Stop it.’

Biggles’ smile became cynical. ‘Did the gentleman who gave you that order indicate how it was to be done?’

‘No.’

‘I’ll bet he didn’t. He didn’t because he couldn’t.’

The Air Commodore regarded Biggles reproachfully. ‘This is no time for levity, Bigglesworth. The matter is serious and urgent.’

‘I merely asked a question, sir. I could answer it myself.’

‘Very well. Do so.’

‘No suggestion was made as to how these gun-running planes were to be stopped because, you know as well as I do, there is no way short of shooting them down—and if we did that it might start a blaze too big for us to put out. It’s no use ordering a pilot to land if he doesn’t want to. He can ignore signals on the pretext that his radio had developed a fault. It’s as simple as that.’

The Air Commodore pushed his cigarette box nearer to Biggles. ‘I hope you’re not going to be awkward.’

‘I’m old enough to have learned to face facts, sir. Looking at them sideways gets you nowhere. As far as aviation is concerned I think I can claim to recognize them when I see them.’

‘I have been told that we can go to any lengths to stop this dirty business.’

‘What exactly does that imply?’

‘I take it to mean we can employ any method we like as long as the desired result is achieved.’

‘And that includes the use of guns?’

‘I would say so.’

‘Have you got that in writing?’

‘Well—er—no.’

‘That’s what I thought. So it boils down to this. First I find a plane carrying guns and ammunition to natives who are chucking their weight about. I order it to land. It refuses. So I shoot it down. It may then be found that I have killed a perfectly innocent aviator. I should then be informed in no uncertain terms that I had exceeded my duties. In short, we take the rap. I don’t want a life sentence for murder. That’s what they would call it.’

The Air Commodore looked uncomfortable. ‘You exaggerate the difficulties. Obviously you wouldn’t shoot down a plane unless you knew for certain that it was carrying arms.’

‘And how do I find that out? The racketeers are not likely to advertise what they’re doing and where they’re going.’

‘That’s up to you. Before we go any further how much do you know about this business?’

‘Only what I’ve read in the papers.’

‘Then you may not realize what’s behind it all.’

‘I’ve got a pretty good idea.’

‘Gun-running isn’t what is used to be. Like everything else it has changed. It used to be done by individuals for private gain. It is now a continuation of the Cold War between the Communist states and the West. It has always gone on in spite of all that could be done to stop it. No one wanted to see warring native tribes exterminating each other. Given guns that’s what they were doing. Today, although he may not realize it, the poor ignorant native has become a pawn in power politics; and it’s going on all over the world.’

Biggles nodded. ‘It’s a rotten shame.’

The Air Commodore went on. ‘In the days before aeroplanes what happened was this. A European country would decide to re-equip its army with a more up-to-date type of rifle. This having been done the country concerned found itself with perhaps a hundred thousand obsolete weapons and ammunition to go with them. What could be done with all this stuff? There was no market for it in Europe, so it was sold off in job lots for anything it would fetch—rifles at a few shillings each. This was where unscrupulous traders stepped in. In what we call the undeveloped countries, where men still hunted for their food with bows and arrows, a rifle was worth its weight in gold. It was to these people that the unwanted arms of Europe went. Most civilized countries put an embargo on the sale of rifles and guns to natives in its own particular colonies, but that didn’t prevent a crooked tramp steamer captain from putting a load under his legitimate cargo. The stuff could be unloaded on some lonely stretch of coast where agents could pick it up and sell it for big money. This was how natives all over the world got their rifles—even Red Indians in America. The men who sold the rifles didn’t care what they were used for, and animals weren’t the only things shot. This is past history, and the Navy no longer has to search small craft in the Red Sea for hidden guns. Now this nasty business has come to life again, using modern methods and for a different purpose.’

‘So I gather,’ put in Biggles.

‘The idea now is to cause as much trouble as possible in the ex-colonial countries which the United Nations Organization is trying to help as they get their independence. The weapons being handed out by the communists are no longer the antiquated stuff they used to be, but brand-new mortars, grenades and automatic rifles. At the least they are dangerous. At the worst the consequences could be serious. The pattern of these miserable operations is generally the same. A native with a smattering of education, or more intelligent than the rest, is selected by Soviet agents. He may be taken to Moscow. There he is brain-washed, so that he returns to his country a rabid agitator with his head turned by a lot of fine promises. His job now is to stir up trouble with the ultimate object of making himself the king, or at least the president. Weapons begin to come in for his supporters, so that if he can’t get what he wants by talking he can resort to force of arms. Having made himself master of the situation, at the cost of God knows how many lives, the Soviet agents, under the guise of “advisers”, move in and give orders. Coloured races have always been exploited—let’s admit it—but never more than today.’

‘So the overall picture looks like this,’ Biggles said. ‘On the one hand we and America, through organizations like Oxfam, are trying to help the native with food, clothing, agricultural machinery and education, while the communist countries, by giving them guns to kill each other, are hoping to get control of the country.’

The Air Commodore sighed. ‘That’s the English of it. We strive for peace and a better standard of living. This doesn’t suit Russia and her satellites. They can only win by power, so they keep the coloured countries on the boil with guns and promises of big rewards if they win. Recent events have proved this. The tragedy is, the most backward peoples, poor, simple, misguided fools, believe this. They are naturally delighted to get guns for nothing. They can’t see they stand to gain nothing by killing each other, and will in all probability lose their lives. They are told they are fighting for their freedom. In fact, they’re likely to lose the freedom they already have.’

‘It’s pathetic,’ muttered Biggles. ‘Enough to make any decent man go hot under the collar.’

‘I thought you’d feel like that about it,’ returned the Air Commodore. ‘We had a demonstration of what’s going on when recently a consignment of war material, thought to be bound for the Congo, went adrift. An aircraft, having to make a forced landing at Malta, was found to have on board guns, and parachutes to drop them, worth £90,000.’

‘That was a queer business, and as you may imagine I was more than somewhat interested. It was nothing to do with me and I never heard how it ended,’ Biggles answered. ‘If my memory serves me the machine was a 72-seater Constellation owned by a charter company. It was said the guns were communist stuff and the parachutes were British. There were rumours of another aircraft being involved in the same game, an Argonaut D.C.4. What made the thing look fishy was a change of registration and the adoption of Ghanaian markings. Operators don’t do that sort of thing without a reason. The route to the Congo was thought to be via Egypt, Libya and the Sudan. What shook me was, some of the pilots and air crews were American. Don’t they realize what they’re doing?’

‘The machines were thought to be operating from somewhere in Europe,’ went on the Air Commodore. ‘It doesn’t do to jump to conclusions. There are firms that will sell arms to anyone who can afford to pay for them; which means foreign governments. Ordinary people can’t afford things like tanks or cannon. And in the matter of free-lance pilots, you will remember why an Air Police Force was started. It was thought that some out-of-work pilots might try their hands at criminal enterprises; and that, as we know, has happened. There are still quite a few pilots at a loose end. Some advertise for jobs. “Fly anything, anywhere,” is their slogan. If they engage in crooked business it is the men who employ them who are really to blame.’

Biggles shook his head, slowly. ‘In this matter of guns it’s hard to see what we can do about it. If these planes are taking off from somewhere in Europe half their payload must be taken up by petrol. Knowing what they’re doing they’re not likely to accept orders to land, so how are we going to stop them? If the guns are being run by communist countries, as you seem to think, they wouldn’t be likely to employ their own aircraft and crews. They’d take on pilots of any nationality, fellows who would be attracted by high wages or perhaps just for the hell of it. To me that’s understandable.’

‘It isn’t understandable to me if they realize, as they must, that they’re helping an enemy against their own country,’ declared the Air Commodore sternly.

Biggles shrugged. ‘There have always been men prepared to turn a blind eye to that angle if the money is big enough.’

‘They’re traitors.’

‘All right. So they’re traitors. To whom? Surely that would depend on their nationality. A man can’t be a traitor to a country to which he owes no allegiance. You can reckon that if it came to the point they’d plead ignorance, and deny any such intent as helping an enemy. That could be true. I’d say they have only one interest. Money. Anyway, how are you going to catch ’em? They’d have to be caught red handed to establish a case against them in court, even if what they’re doing is illegal. I see another snag there. Is it illegal?’

The Air Commodore considered the question. ‘What their punishment would be would probably depend on the country in which they were arrested. I don’t think we need quibble about that. Apart from anything else they’re breaking every rule in International Air Traffic Regulations by flying indiscriminately over countries without permission, crossing frontiers without checking in, probably ignoring prohibited areas and the regular civil aviation routes. By doing that they are putting the lives of all air travellers in peril. What is the use of having safety regulations if a few selfish pilots disregard them?’

Biggles answered. ‘Well, be that as it may, you first have to catch these fellows, and as far as I can see that could only happen by accident, as in the case of the machine that had to make an emergency landing at Malta. In my view, the pilots who are flying these machines are not so much to blame as the men who are employing them; and they, I imagine, are nicely tucked away behind the Iron Curtain.’

‘Not necessarily. In view of what happened at Malta there’s reason to believe that, although the finance may be coming from behind the Iron Curtain, the actual operations are being conducted by at least one organization in Western Europe, perhaps with agents in Britain. Some of the equipment found in the machine that landed at Malta was said to be British. If that is correct, how did it happen?’

‘If it comes to that, how was it that the aircraft was an American type?’

‘These are the men we really want to get. If we could lay hands on one of their pilots, and make him see the error of his ways, he might tell us who they are.’

‘It would be optimistic to reckon on that,’ replied Biggles. ‘How do you propose to get hold of one, anyway? I hope you aren’t going to ask me to shoot down British or American pilots, even if I was lucky enough to find one in the air, on the job.’

‘We shall have to think of a way to pick up one of them on the ground.’

‘You say we. Who is we? Why has this unpleasant job been pushed on to us? By us I mean Great Britain. To stop this gun-running racket is in the interest of all the Western powers. Why don’t they do something about it? Why leave us to carry the can?’

‘Although I have no definite information on the subject, I have no doubt they are doing something about it; but they’re not likely to let their methods of dealing with the problem be known because that would be playing straight into the hands of the enemy, who would take steps accordingly.’

Biggles rubbed out his cigarette in the ash-tray. ‘I don’t get it. Russia is openly supplying arms to half a dozen countries that are not exactly friends of ours. As far as I know we do nothing to stop it.’

‘We can’t.’

‘Why not?’

‘That’s a different matter.’

‘In what way?’

‘The countries you have in mind, the Yemen and Indonesia, for instance, have established governments, and as such they are within their rights to buy any weapons they want.’

‘Even if the weapons are in fact a gift, intended to cause trouble for us.’

‘We know that, but how are you going to prove it? The new independent African states, like the Congo, are different. There, weapons are being supplied to overthrow the governments that have been accepted by the Western powers. Remember, these same rebels recently murdered in cold blood a lot of innocent white men and women who were being held as hostages; missionaries, school-teachers and medical people; as well as committing other atrocities. If we accused Russia of supplying weapons to these rebels she could retaliate by pointing out that we were supplying arms to her enemies.’

‘That would not be strictly true. Any arms we have supplied have been purely for defence.’

‘Russia and her satellites would argue on the same lines. Every time a few rebels are killed she howls her head off and lets loose a horde of students to throw bottles through the windows of the British and American Embassies, which the police do not attempt to prevent. But we’re getting away from the point. Forget the political angle. That isn’t for us to sort out. We have been asked to check the illegal flow of war material into countries where we are doing our best to maintain law and order. If these rebels are deprived of guns and ammunition they’ll have to pack up, which in the long run will be for their own good. They haven’t the money to buy them, but while they can get them free they’ll go on shooting their black brothers. Now, how do you suggest we go about it? I’m asking for your advice.’

‘I wish you’d ask me something easier,’ said Biggles.

‘I’ve heard you say there’s always a way of doing anything if it can be found,’ reminded the Air Commodore.

‘This dirty business may be the exception to the rule,’ replied Biggles. ‘I can’t see myself shooting down a machine that could turn out to be unarmed, and possibly flown by a man with whom I’ve had a drink at some time or other. I think, before we do anything else, we should be sure of our facts by finding out what exactly is going on, how the racket is being run and by whom. When I think of the good men I’ve killed in wartime combat it wouldn’t cause me any grief or pain to bump off some of these enemy agents who are inducing these stupid, benighted Negroes, to kill each other.’

‘Very well. Get the information, the facts, to start with. How do you propose to do that?’

‘I can think of only one practical way. I might join the ranks of these “fly anything, anywhere” boys and get myself taken on as a gun-runner. In that way I might get the lowdown on the way the racket is being run.’

The Air Commodore stared. ‘You call that practical! You must be out of your mind.’

‘What’s wrong with the idea?’

‘In the first place you’re too well known. You’d be spotted instantly, and that would be the end of you.’

‘The fact that I’m well known, as you say, might be to my advantage.’

‘How?’

‘Fire me.’

‘Fire you!’

Biggles smiled. ‘Give me the sack. Let it be known that I’ve been a naughty boy so I’m out of a job. If my reputation stands for anything I shouldn’t be out of work for long.’

The Air Commodore sat back in his chair and put his finger-tips together. ‘Do you realize what you’re saying? Smash the reputation it has taken most of your life to build up? Think of the effect such a tragedy would have on your friends.’

‘A fig for reputations. I’m thinking more of the effect being chucked out on my ear would have on my enemies. They’d be tickled to death to see me drawing the National Assistance dole.’

The Air Commodore spoke with a tone of finality. ‘I won’t even consider it. That’s definite. I’m not throwing you to the lions for the sake of cornering a bunch of mercenary rats.’

‘This sort of thing has been done before,’ argued Biggles. ‘Service officers have allowed themselves to be cashiered in order to get into foreign services for espionage work.’

‘Say no more about it,’ requested the Air Commodore curtly.

‘You asked for an idea,’ complained Biggles.

‘I’ve given you my answer. Think of something else.’

‘All right. There’s an alternative. Let it be known that I’ve been retired at my own request, or under the age limit rule.’

‘That wouldn’t be so bad,’ conceded the Air Commodore. ‘But I still don’t like it. It wouldn’t be fair to you.’

‘That doesn’t come into it. It would be so simple. All I’d have to do would be take a two-room flat somewhere and wait for offers of a job to come in.’

‘And if they didn’t come in?’

‘I’d put a small advertisement in certain selected papers saying I was free to take up an appointment. I wouldn’t be able to go near the Yard, but I could keep in touch with you by telephone. Algy, Bertie and Ginger, could carry on here, but for obvious reasons I wouldn’t be able to go near them. I work this on my own. Leave the arrangements to me.’

The Air Commodore pursed his lips. ‘I’ll think about it,’ he decided. ‘And that for the moment is as far as I’m prepared to go.’

‘Do that, sir. You asked for a scheme. I’ve given you one. I can’t see anything against it.’

‘You would, before you were through with it, I’ll warrant,’ retorted the Air Commodore grimly.

‘I’ll get along,’ Biggles said, rising. At the door he turned. ‘It’s the only way.’

‘I’ll call you later,’ promised the Air Commodore. ‘Go and have your lunch.’

Biggles made his way, slowly and deep in thought, to his own office, where he found Algy, Bertie and Ginger, awaiting his return.

‘Well, old boy, what’s the big news?’ inquired Bertie cheerfully.

‘The news, if you can call it big, is that I may soon be leaving you,’ answered Biggles evenly.

‘What are you talking about?’ asked Ginger, suspiciously. ‘Is this some sort of joke?’

‘No.’

‘He’s kidding,’ put in Algy.

‘I’m serious,’ stated Biggles unsmilingly. ‘I’m expecting to be retired in the near future under the age limit rule. If it happens you’ll be on your own. Let’s go to the pub round the corner for a cut from the joint and I’ll tell you about it.’

Biggles, seated at the table in the still strange surroundings of the new, small, first-floor flat he had taken in the Bayswater district (two rooms and a kitchenette) stubbed his cigarette in the ash-tray and turned over the pages of the current number of the magazine Flight. His expression was not one of contentment. It was more one of disappointment, for it had begun to look as though his plan—to which the Air Commodore had reluctantly agreed—was not going to work. Moreover, he was getting bored with doing nothing, and living without the companionship to which he was accustomed.

It was three weeks since, having said au revoir to the Air Commodore, he had walked out of the police office at Scotland Yard for what, officially, was to be the last time, and moved with some clothes and his toilet things into his new quarters. A brief notice of his resignation had appeared in one or two newspapers, and a paragraph or two, mostly about his Air Force career, in the aviation press; but these had not produced the result for which he had hoped, and, indeed, had planned. When at the end of a week he had not received a single offer of employment, or even an inquiry, he had inserted a small advertisement in the personal column of a newspaper which he thought most likely to produce results. In this he had not given his address, merely a box number for replies, in the first place in writing. This, he had decided, would give him time to consider them.

Again the result had been disappointing. When, in three days there had not been a single reply, he repeated the advertisement, giving his name and telephone number. In this, in his impatience, he may have been premature, for on the same day two letters had arrived in the same post, both suggesting an interview. As he did not want two visitors arriving together, which might have been embarrassing, he had seen them at different times.

The first man he dismissed at once. He arrived, slightly tipsy, claiming to be an old R.F.C. pilot. He was hoping to borrow some money.

The second was equally optimistic. A young fellow of about eighteen had thought out a scheme which he claimed was foolproof. The project, boiled down, resolved itself into a plan for smuggling by air. He left the flat crestfallen when he was informed, bluntly, that his brainwave was neither original nor practicable, and if he ever found a pilot stupid enough to co-operate they would both end up in prison.

Biggles was becoming depressed when, the following day, had come a letter from a man signing himself Count Alexander Stavropulos, at present staying at the Grosvenor Hotel, London. It was brief and to the point. The writer stated he was a company director in the air charter business. He was looking for an experienced pilot to fly his aircraft. He was too busy to call, so would Biggles meet him in his suite at the hotel? Biggles called him on the telephone. An appointment was made, and this was the day: time, 12 noon. A glance at his watch told him he still had a little time to spare.

He was not very confident that he had got a bite from the fish, or one of the fish, he was after, but two details encouraged him to think it might be. The first was, the Count was presumably a foreigner, the title ‘Count’ having gone out of use in Britain, although there were still countesses, normally the wives or widows of earls. His English was fluent, although there was a barely perceptible foreign accent, one not easy to place. Few people are able to speak a second language so well that they can pass as a national of another country. Again, the Count was staying at a hotel, which suggested, although it did not prove, that he had no fixed address in Britain. Apart from this, the hotel indicated the Count was well off, for the Grosvenor is not cheap, yet the Count could afford not merely a room but the luxury of a suite.

Still with plenty of time in hand for the appointment, Biggles decided to take some exercise by walking across the park to the hotel. It was with an open mind that he set off, resolved not to prejudge the man he was to meet. He arrived with a few minutes to spare, so he smoked a cigarette in the hall before stating his purpose at the reception desk.

To the man in charge of the keys he said: ‘I have an appointment with Count Stavropulos. I’ve never met him. Do you know him?’

‘Only by sight.’

‘What sort of man is he?’

‘Always very nice to me when he wants his key.’

‘What’s his nationality, do you know?’

‘I’ve always understood he was one of these Greek oil millionaires.’

‘Does he often stay here?’

‘Quite a lot,’ answered the man at the desk, picking up the telephone to call the man under discussion to inform him that a Mr Bigglesworth had arrived to see him. He hung up, beckoned to a page, and in a minute Biggles was in the lift being escorted to the Count’s rooms.

The page knocked on a door. A voice said ‘Come in.’ The page pushed open the door. Biggles entered. The page retired, closing the door behind him, and Biggles advanced into a sitting-room to meet a man who rose from an armchair, putting aside a newspaper.

His greeting gave Biggles a mild shock, for he had not mentioned any rank. ‘Come in, Inspector,’ said the Count. ‘Happy to meet you. My name is Stavropulos.’

‘Why the Inspector?’ queried Biggles.

The Count smiled disarmingly. ‘As far as I know there’s only one Bigglesworth with your reputation.’

‘Well, you might make it mister from now on,’ returned Biggles. ‘I don’t want to be reminded of my sinister past.’

‘Good. Take a seat.’

Biggles sat in a second armchair.

‘Smoke?’ The Count offered his case—a gold one. ‘You may not care for these,’ he went on. ‘I have them specially made for me, but they’re not to everyone’s taste.’

Biggles noticed the colour of the cigarette paper was pale brown, a tint common in Russia and the Near East. ‘I’ll smoke my own if you don’t mind,’ he declined. ‘I have a common taste.’

‘Have a drink?’

‘Not at the moment, thanks. It’s a bit early for me.’

‘That’s what I like to hear from a man who sometimes has other people’s lives in his hands,’ declared the Count. ‘You won’t think me discourteous if I have one?’

‘Of course not. These are your rooms.’

While the Count was pouring his drink at the sideboard Biggles took stock of him. He was still keeping an open mind, for although he knew that first impressions can be important, they are not infallible. There had been nothing questionable in the Count’s behaviour so far. He had at least been hospitable. Curiously, although it sometimes happens, his foreign accent was not as pronounced as it had been on the telephone. The smoke of his cigarette, as it wafted across the room, came from Balkan tobacco. Of course, there was nothing wrong with that. Some smokers prefer it, although it is more usual for a man to smoke the tobacco to which he was first introduced. In England it is usually Virginian.

Biggles judged the Count to be a man a little past middle age; say, between forty-five and fifty. Of average height, he was rather plump, as if he did himself well. His skin, without a wrinkle on it, was that curious colour, almost a pallor, peculiar to the Eastern Mediterranean, Greece in particular. His hair was beginning to recede from the temples. His clothes were immaculate and obviously expensive. He moved easily. In a word, his general appearance might have been described as sleek; sleek in the manner of a well-fed house cat. But there was nothing objectionable about him, in appearance, manner, or the way he spoke. Nevertheless, prejudiced perhaps from unfortunate experience, the man was a type Biggles would not have trusted too far until he knew him better.

The Count, glass in hand, returned to Biggles and sat down facing him. ‘Now suppose we get down to business,’ he said.

‘That is why I am here,’ answered Biggles.

‘You are an aeroplane pilot with a great deal of experience.’ This was a statement rather than a question.

‘I think I can claim to be that.’

‘And you are now out of work?’

‘I’m not flying at the moment.’

‘And you’re open to accept an engagement?’

‘That is why I advertised for a job.’

‘You needn’t answer this question if you don’t want to. Why did you leave your last job?’

‘You know what it was?’

‘Of course. I read the newspapers.’

‘Let us say my time had expired. There comes a time for a man to retire, particularly when his work involves a certain amount of strain.’

‘But you are still fit to fly?’

‘If I wasn’t I wouldn’t be so stupid as to look for another job in aviation.’

‘You could still fly an aeroplane to any part of the world?’

‘Without any difficulty whatever.’

‘And you would be prepared to do that?’

‘Within a certain limit.’

‘What limit?’

‘I wouldn’t fly over Russia or any other country in the communist bloc.’

‘Why not?’

‘I have occasionally come into collision with some of their agents and I’m afraid I may be on their black list.’

‘You are not a communist yourself, then?’

‘No. Are you?’

‘Certainly not. But the question of politics need not arise. I do my best to avoid trouble, so my planes do not fly over Soviet controlled territory.’

‘I’m glad to hear it. That suits me. Where do they fly?’

To wherever my business requires them to go.’

‘You say planes, in the plural. Does that mean you have more than one?’

‘At present I have three; one for my personal use and two for operations.’

‘I take it you run a charter business?’

‘Call it an air transportation service.’

‘Which means you already have pilots and air crews?’

‘Of course. At the moment I am one pilot short.’

‘How did that happen?’

‘I had to discharge him. He drank too much and became careless.’

‘Where are your machines based?’

‘Nowhere in particular. They move about. They remain at wherever they find themselves until the next operation comes along—in the manner of a deep sea tramp steamer looking for a cargo. At present the two freight machines are on the Continent.’ The Count sipped his drink. ‘But you seem to be asking the questions. My intention was to ask you some. Have you ever flown over Africa?’

‘Often.’

‘Then you can find your way about?’

‘I have never had any difficulty.’

‘So you—shall we say—know the ropes? Regulations. How to deal with Customs controls, and so on.’

‘After the years I’ve been flying it’s time I did.’

‘You must understand that you wouldn’t have the special privileges you had on your last job.’

Biggles’ muscles tightened. ‘What do you mean by that, exactly?’

‘Well, I assume in the work you were doing recently you would be provided with extra facilities. To put it bluntly, when you were employed on flying duties for Scotland Yard.’

‘Does what I have been doing make any difference?’

‘Not as far as I’m concerned. It could be an advantage. I had that in mind. If you worked for me you would be expected to keep within the law, not break it. Of course, my business is confidential, in that my clients do not want it to be known to their competitors what they are consigning overseas.’

‘That’s understandable. It applies to most business transactions, surface, as well as air transport.’

The Count’s eyes came to rest on Biggles’ face. With a slight change of tone he asked: ‘Why did you really leave your last job?’

‘I thought the reason had been made public.’

‘What is your own version of it?’

‘I held the job for a long time, but it was getting rather heavy going for a man of my age.’

‘But you still want to go on flying?’

‘Naturally. Once a pilot always a pilot. Moreover, a man must live, and I can’t afford to do nothing. While we are on the subject, let me be frank. Aren’t you afraid to employ a man who has been connected with the police?’

The Count’s eyebrows went up. ‘Why should I be?’

‘It was a thought that struck me. No doubt there are plenty of other pilots ready to fly for hire and reward, as it is called.’

‘Not many with your experience.’

‘What’s so special about flying your machines?’

‘My work calls for knowledge and ability above the average. I need hardly tell you that a modern aircraft is an expensive vehicle, and to lose one, as might happen through carelessness or inefficiency, would mean a severe financial loss. Our pilots must be absolutely reliable. You see, in order to save the expense of landing fees, and so on, we sometimes fly long distances non-stop. As a straight line is the shortest distance between two points it also means a saving on petrol; and aviation spirit isn’t cheap.’

‘Are you saying, when you talk of non-stop flights, that you don’t mind cutting corners, so to speak, should the route—’

‘That is entirely a matter for the pilot to decide,’ broke in the Count. ‘Naturally, I wouldn’t ask a pilot to break the air traffic regulations on my account even though it might save me money. If they care to take risks in order to get to their destination in the shortest possible time, that is their affair. All I ask is, if they are caught at such practices—and there are pilots who do that sort of thing—they must take the consequences and not expect any help from us. We, as the owners of the aircraft, would naturally plead ignorance, and say the pilot was acting contrary to orders.’

A ghost of a smile crossed Biggles’ face. ‘Naturally,’ he repeated dryly. ‘It’s only right that those who break the rules should take the blame.’

‘I’m glad you agree.’ The Count went on. ‘No one would suspect you of doing anything like that, which would be another advantage of having you on our staff. Of course, should it happen, I’m not going to say we would wash our hands over the whole affair. We might have to do that officially, you understand, but we would support our employee as far as possible and compensate him for any financial loss he might sustain—by being fined, for instance.’

‘That’s fair enough,’ Biggles replied. ‘What sort of loads do you usually carry?’

‘We carry anything; general merchandise; but that’s a question I can’t really answer. An inquiry comes through from a customer. He tells us the nature of the consignment, where it is to go, and when, and a price is agreed.’

‘Always taking care that no smuggling is attempted, of course.’

The Count looked shocked. ‘We take care never to touch anything like that, you may be sure. I repeat, we do nothing illegal. Our pilots are warned never to carry privately anything that might be suspect—drugs, and that sort of thing, which may be a temptation.’

‘How many pilots do you employ?’

‘Normally four. They fly dual, with a qualified navigator, if one is available.’

Biggles nodded. ‘Now let us come to the most important point. What salaries do you pay your pilots?’

‘We pay a retaining fee of two thousand pounds a year plus a bonus for actual flying time at the rate of one hundred pounds an hour. Flights are irregular. A pilot doesn’t fly every day, or even every week. We pay all his expenses while he is on the ground, wherever he may be.’

‘That seems generous.’

‘I’m glad you think so. All that remains then, is for you to decide if you would like to join us.’

‘Does that mean you are offering me the job?’

‘Yes.’

‘Don’t you want to see my log-books, or any other proof of my qualifications?’

‘That’s unnecessary. I know as much about you as I need to know. You’re known to everyone in aviation circles, as I discovered when I made some discreet inquiries. With the private lives of our pilots we are not concerned. All we ask is they do what is asked of them, without question, efficiently and consciously. If they fail in these respects we have no further use for them. Have I made myself clear?’

‘Perfectly clear.’

‘Very well. Perhaps you’d like to go now and think it over. If you decide to enter my employment, and happen at the moment to be financially embarrassed, you may draw three month’s pay in advance.’

‘Isn’t that taking a risk?’

‘In what way?’

‘Well, I might draw the money and clear off. You might never see me again.’

The Count’s eyes narrowed. ‘That would be very foolish of you. You would regret it.’

‘What could you do about it?’

‘My organization has long arms. I would see that you never got another job in aviation.’

‘Well, I don’t think that’s likely to arise,’ returned Biggles. ‘There’s nothing for me to think over. This seems to be the sort of job I was hoping to find. I’d like to give it a trial, anyway. I take it I’m at liberty to resign if for any reason I don’t feel inclined to carry on?’

‘Certainly.’

‘Then let’s call it settled. When would you like me to start?’

‘There’s no particular urgency, but as soon as possible. Could you be ready by tomorrow evening?’

‘Yes.’

‘That would suit me because I have to go to the Continent on business. My personal pilot will fly me in my plane. You could come with us. Don’t bring more luggage than is necessary.’

‘Where shall I meet you?’

‘You might as well come here. We’ll go on to the airport in my car.’

‘What airport?’

‘Southend. It’s convenient for the Continent. I leave the ground at six o’clock.’

‘As a matter of professional interest, what’s the type of machine?’

‘A Courier. It has six seats. Twin engines. Do you know it?’

‘I’ve seen one, but I’ve never actually flown one. Being American there aren’t many over here. Where are we going?’

‘That hasn’t been decided yet. I’m waiting for a message now.’ The Count smiled. ‘We shall not be landing the wrong side of the Iron Curtain, if that’s what you’re worried about.’

‘I’m glad to know that,’ Biggles admitted frankly. ‘I have had some unusual jobs to do in my time and I have reasons for keeping clear of that part of the world.’ He got up. ‘Okay, sir. I have no more questions to ask, so if you have none I needn’t occupy any more of your time. See you here, tomorrow evening. What time?’

‘Say, five o’clock.’

‘I’ll be here, ready to travel,’ promised Biggles. With that he departed.

On the pavement outside the hotel Biggles looked for a disengaged taxi, but not seeing one he decided to walk home the way he had come. His head was full of what had passed at the interview and he wanted to turn over in his mind what had been said while the conversation was still fresh. Crossing the park, on the pretext of lighting a cigarette, he looked back to see if he was being followed; but he saw nothing to arouse his suspicions. Noticing an unoccupied bench, the weather being fair, he sat down to try to reach some conclusions.

The first question was, naturally, was he on the right track? Was the Count the man, or one of the top men, of the organization whose activities he had been asked to investigate? It was possible, but by no means certain. Instinct, or intuition, told him the proposition looked—well, odd. For one thing the salary he had been offered was somewhat higher than a legitimate commercial undertaking could afford to pay. That alone made him suspicious. How could a firm show a profit if it paid the pilot alone a bonus of four hundred pounds for a simple flight of four hours; say, two hundred out and two hundred home. If the concern was genuine it would have to enjoy a very profitable line of business.

On the face of it the Count had been frank in answering questions, more so than might have been expected of a man engaged in air operations of a questionable nature; yet, in point of fact, he had disclosed nothing that suggested anything improper.

How much did the Count know about him? He certainly knew something of his career . . . what his previous occupation had been. Yet he was willing, almost anxious, to take him on. If he was doing anything illegal there was something very strange about that. Or was there? When Biggles had hinted at it the Count had put forward reasons that sounded perfectly valid. In the first place he, the Count, was only interested in a pilot of exceptional ability and experience, and apparently in that respect Biggles filled the bill. Again, he wanted someone who knew his way about the world, as against an ex-regular airline pilot whose work may have been confined to one or two particular routes. There was yet another angle not to be overlooked. The Count was aware that Biggles was known at airports everywhere, and in view of his previous occupation would probably be able to command facilities not normally available to a pilot less well known. True, the Count had said he would no longer be able to rely on these facilities; but Biggles would be trusted. His word would be accepted. He had friends in five continents who could be relied on to be helpful in an emergency. Was that the real reason why the Count had been anxious to secure his services? Could be, reasoned Biggles.

Yet in his mind there was a doubt. The money. It was too much. Was it a bribe? To buy what? His silence if anything went wrong? No, the proposition that had been put up to him was—well—peculiar.

To start with there was the man’s name. His title meant nothing. It might, or might not, be genuine. There was nothing much wrong with that, either way. He knew that on the Continent Counts were ten a penny, although few of the men who boasted the title had the right to do so. It was a matter of vanity, such men supposing, presumably, that it lifted them above the common herd. Anyhow, in Britain the title Count was no longer used. So being a Count gave no indication of the man’s nationality beyond the fact that he was not British by birth. But that was evident from his accent, slight though it was.

The name Alexander was no guide. Originally it was Eastern European or possibly Asiatic. Alexander the Great, a Macedonian, to celebrate a victory had laid it down that any male child born in that particular year should be named Alexander. Over the centuries their descendants had spread all over the world taking the name with them—even to Scotland. Stavropulos was of course as Greek as could be. He looked Greek, although that did not mean this was the nationality shown on his passport.

Biggles went on speculating. The Count did not mind him knowing that he smoked Balkan tobacco. That didn’t mean much, although as a man usually smokes the tobacco on which he is brought up, it suggested he was well acquainted with the Near East.

For the most part he could not have been more open. Only in one or two details had he been evasive; his refusal to name their destination when they left Southend, for instance. However, Southend airport seemed a reasonable starting point; there could be nothing phoney about that. He had half expected the Count to name some out-of-the-way landing ground. If he was using a public airport as a base for his aircraft in England he could have nothing to hide. This supported his insistence that what he was doing was legitimate.

This was puzzling. Could he have his own opinion of what was legal and what was not? The importation of weapons and ammunition to undeveloped countries, for example? Even the Air Commodore had been in doubt as to the legality of such an operation. He had taken the view that it would depend on who the weapons were for. An established government would be entitled to buy them, and pay for them. There would be nothing wrong in that. But if they were intended for rebels hoping to overthrow that government, it would be a different matter. Even so, it might be argued that the British, or any other government, had no right to interfere. Looked at like that, it was a moral issue rather than a legal one. It was not much use the United Nations handing out food, money and goods, to improve a native standard of living, and keep the peace, while other people were giving them guns to start a civil war.

Who was supplying the guns? Where were they coming from? Rebels would hardly be in a position to buy them. They were being given away. The obvious answer was Russia, and the reason a political one. By this means Russia was hoping, if the rebels could seize power, to gain control of the country, or countries, concerned. Yet the Count had stated positively that his aircraft never went beyond the Iron Curtain. In that case, if he was a gun-runner, how was he getting the guns? How could he say he never crossed the communist frontiers if it were not true, knowing that sooner or later Biggles was bound to learn facts? It was all very confusing.

The thought crossed Biggles’ mind that the whole thing might be a trick to get him out of the country for motives of revenge. During his career he had made many enemies, not only in the underworld, but among enemy agents. He dismissed the thought, thinking it unlikely that anyone would go to the trouble and expense to kidnap him merely to gratify a grudge. No, that wasn’t the answer, particularly as he had now ostensibly left the police service. He felt reasonably sure that the Count did really want him for flying duties. Could it be that someone in Western Europe or America was playing an underhand game for mercenary or political motives? It was not impossible, but it seemed extremely unlikely. That the Count was in the business for money he did not doubt. He was not the type to put himself out for any other reason.

So pondered Biggles on his park seat. His conjectures had not got him very far. He should, he told himself as he got up and continued on his way home, know what it was all about within the next two or three days. He wondered who his co-pilots would be? It would be odd if one of them turned out to be a man he knew, an old comrade of war-flying days, perhaps. Not that it seemed very likely, although it could happen. That could cut two ways. It might be to his advantage; on the other hand it might prove embarrassing.

Arriving home, the first thing he did was telephone the office at Scotland Yard. Algy answered.

Biggles said: ‘I’ve rung up to let you know I’ve been offered a job in an air charter concern; mostly freight, I gather. I’ve decided to take it, to see where it leads. It’s owned by a man I believe to be Greek. His name is Count Alexander Stavropulos. He has a suite at the Grosvenor Hotel, Victoria. He’s often there. I don’t know quite what to make of him. I can see nothing really wrong so far, although the way the show is run seems a bit unusual. You might check up on him, and if he has a police record let me know. You haven’t much time because tomorrow evening I’m leaving the country with him, in his own personal aircraft, from Southend. I’ll let you know where I am, and what I’m doing, at the first opportunity. That shouldn’t be long. If you don’t hear from me within a week you can assume things are not as they should be . . . No, I don’t know where we are going, but I have the Count’s assurance we shan’t touch the Iron Curtain. That’s about all. Let the Air Commodore know what goes on; and if you dig up any information about my new boss ring me early tomorrow morning. That’s all for now. I expect to be here until tomorrow afternoon. Now I’m going out to get some lunch. So long.’

It was with no small curiosity that Biggles noted the course of the Courier, in which he was a passenger, as soon as it was over the sea.

He had been told they would be going overseas, and within minutes of take-off he observed that this was true. After the machine had made some altitude and settled down to steady flight, he made out the course to be practically due south-east, although this did not mean it would be maintained.

Seated in the comfortable cabin with his new employer, he had no instruments, no compass, to indicate a change of course. In daylight this was not important, but after dark, supposing they had some distance to go, with no landmarks visible, it would be difficult, if not impossible, to work out their probable destination. It was six-thirty when the aircraft had left the ground and already the sun was well on its way down behind them.

Visualizing the map of Europe, he had no difficulty in working out the countries that lay in front of them, as long as the south-easterly course was held. When they made a landfall it would either be the coast of Belgium or Northern France. Then, if they did not land in either of these countries, would come Germany, Austria, Hungary or Yugoslavia, Greece and finally Turkey. He could not imagine going beyond that. Without knowing their final destination it was of course impossible to work out their E.T.A. That is, their estimated time of arrival.

He was still puzzled by the apparently open and above-board way things had gone; so far, anyway. With a minimum of luggage in one light suitcase, he had met the Count in his hotel suite as arranged. Nothing much had been said. The Count’s behaviour had been the same as on the previous occasion. It may have been a little more brisk, although this was to be expected if he had work to do—the alleged business trip, legitimate or otherwise. On this point Biggles was still keeping an open mind. He was still without a scrap of evidence as to the real purpose of this unusual engagement.

‘Are you ready?’ was all the Count had said when he presented himself.

‘I’m ready,’ stated Biggles.

‘Good. Then we might as well get along.’

Below, at the main hotel entrance, a car was waiting; a car with a uniformed chauffeur. From the few words that passed Biggles got the impression that the vehicle was a hired one; either that or the driver was new.

The Count said: ‘You know where we are going?’

‘Yes, sir. Southend Airport.’

‘Correct. Drive carefully.’

‘I always do, sir.’

That was all. Another minute and they were on their way.

The drive to Southend was uneventful. The Count said little and Biggles did not attempt to force conversation. He had plenty to occupy his mind. There were several questions he could have asked, but as these might have hinted at the way his brain was working, he left them unasked. Surely, he thought, as they were going abroad, in the ordinary way the Count would have checked that he had brought his passport—which in fact he had. But the Count hadn’t mentioned a passport. There was something odd about that, unless the Count had taken it for granted.

On the way to the airport the Count said: ‘Would you prefer to draw your salary in cash, or by cheque?’

‘It makes no difference to me,’ answered Biggles.

‘It could.’

‘How?’

‘Well, if you take your money in cash there would be no need to declare it for income tax, particularly if you are domiciled abroad. Some people object to giving half their earnings to the government.’

Biggles hesitated. This was the first suggestion the Count had made that was not strictly on the level. Even so, it was not an uncommon practice.

The Count went on. ‘Or, if you care to give me the name of your bank, I will arrange for your salary to be paid into your account every month.’

‘That might be the best way,’ Biggles decided, as if the matter was of no great importance. ‘I don’t like to carry a lot of money on me.’

‘Very wise,’ said the Count.

After a long pause he continued. ‘I have a feeling you’re still a little anxious about the work you will be asked to do.’

‘Frankly, I am,’ replied Biggles. ‘Not having the least idea of what it will be.’

‘I have already given you my assurance that you will not be asked to do anything illegal.’

‘I haven’t forgotten that,’ returned Biggles, thinking it strange that the Count should make such a remark, because in a genuine concern it would hardly be necessary to say such a thing. Was it that the Count was ‘sailing near the wind’ without doing anything which in court, could be alleged to be criminal?

‘I wouldn’t risk losing my most valuable asset,’ Biggles said flatly.

‘What is that?’

‘My pilot’s licence.’

‘I can understand that. What would you call an illegal transaction?’

‘Smuggling, for instance.’

‘I have already told you we can run our business profitably without anything of that sort,’ returned the Count, stiffly.

‘I wasn’t thinking of you, personally, but I know from experience that air crews, even in the national air operating companies, have been known to try it on. The profits of drug-running, even on a small scale, are high.’

‘Any employee of ours found attempting anything like that would be sacked on the spot,’ declared the Count, severely.

They reached the airport to find the Courier waiting.

There was no trouble. The Count seemed to be well known to the officials and the usual formalities went smoothly. When they went out to the aircraft Biggles caught a glimpse of a face in the control cabin. The man grinned and gave him the ‘thumbs up’ sign. One of the airport staff put the baggage on board and closed the door. Apparently the pilot had already received his instructions, for the Count did not speak to him, nor did he come into the cabin. In a few minutes the Courier was in the air, on its way to wherever it was going.

With the coast behind them, when they had settled down and the Count had lighted one of his ‘special’ cigarettes, he said: ‘We have a long flight in front of us. Is there anything else you would like to know?’