* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Letters From Labrador

Date of first publication: 1908

Author: George Francis Durgin (1858-1905)

Date first posted: May 23, 2023

Date last updated: May 23, 2023

Faded Page eBook #20230549

This eBook was produced by: Mardi Desjardins, Pat McCoy & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

LETTERS FROM

LABRADOR

BY

GEORGE FRANCIS DURGIN

————————————————————

Printed for private distribution

in memory of a beloved son,

by his mother

————————————————————

RUMFORD PRINTING COMPANY

Concord, New Hampshire . . . 1908

Copyright

by

Martha E. Durgin

1908.

George Francis Durgin

April 25, 1858

Concord, New Hampshire

May 27, 1905

CONTENTS.

| Page. | |

| Preface | 7 |

| Letter I | 11 |

| Letter II | 25 |

| Letter III | 43 |

| Letter IV | 67 |

| Letter V | 91 |

[Transcriber Note: Preface is not included due to copyright considerations.]

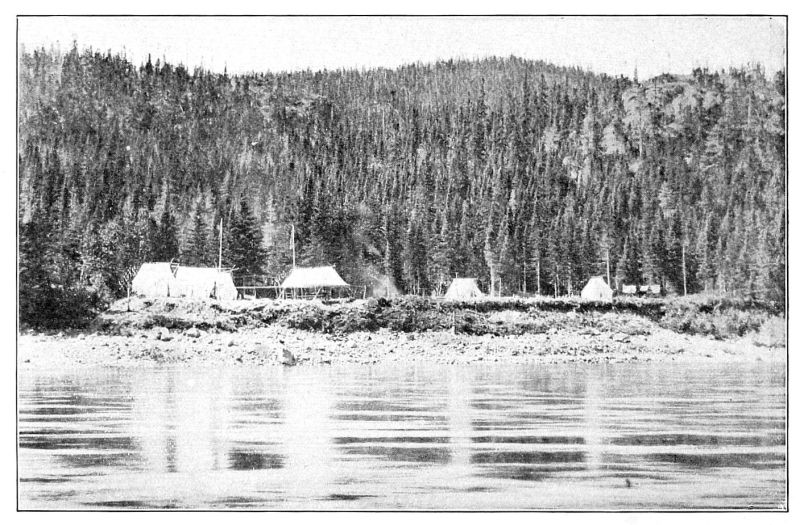

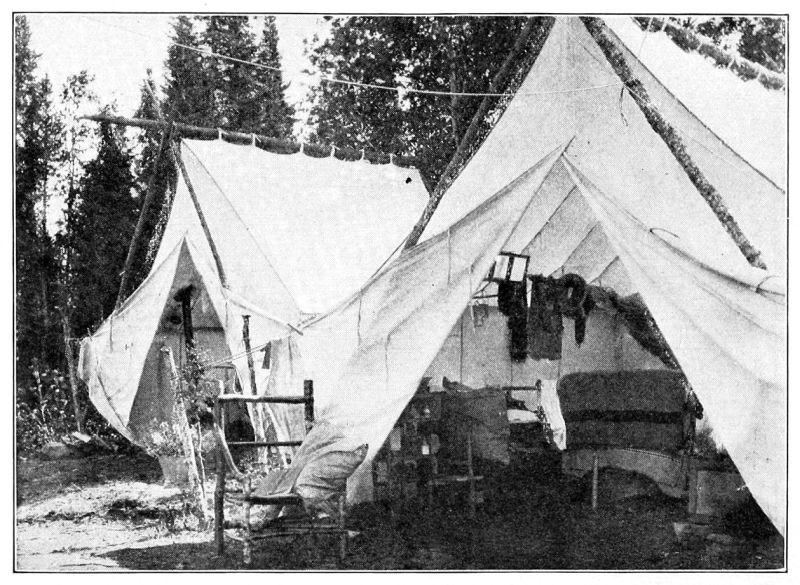

Camp Durgin on Eagle River

Thursday evening, June 18, 1903, the Red Cross steamer Rosalind, plying between New York, Halifax and St. John’s, Newfoundland, passed through the Narrows and docked in fog and rain—a combination of weather not unusual at St. John’s during the month of June. We left Boston by the Plant line, Saturday, June 13, and met the Rosalind at Halifax, sailing thence Tuesday noon, the 16th. This was the beginning of a trip that is an evolution of several previous outings in Newfoundland and one, last summer, to the Labrador.

Four summers ago we took a short excursion to St. John’s, going from Boston to Hawkesbury, thence through the Bras d’Or lakes to North Sidney, where we embarked on the yacht-like steamer Bruce of the Reid-Newfoundland Company and met the trans-island train at Port aux Basques.

For years I had cherished a desire to visit Terra Nova, as Newfoundland, England’s oldest colony, was originally named. I can scarcely tell from what this desire sprang, for my knowledge of the island and prevailing conditions was vague only—a dream of high, rocky shores and rivers that flowed from an unexplored interior. Ways of reaching its fog-bound limits were few and difficult to learn about; but in 1897 the narrow-gauge railroad from Port aux Basques to St. John’s was completed, and its promoters began to tell the world how to avail themselves of its accommodations.

On a bright morning four years ago, as we left our coffee, rolls and marmalade in the cozy salon of the Bruce for a view of the approach to Port aux Basques, an agreeable man came up to us and kindly offered to indicate the points of interest as we steamed towards the cliffs that hold the little harbor. At the dock our luggage was quickly passed by the customs’ officers, and we found seats on the better side reserved in the miniature Pullman car.

Then began a day I shall never forget. Our acquaintance proved to be Mr. H. A. Morine, general passenger agent of the Reid-Newfoundland Company. Nothing of interest was allowed to escape our notice. We passed from rocky, barren shores to bowers of forest verdure, with glimpses here and there through openings, of distant bays, sparkling in the sunlight. From hills on either side flowed flashing streams; some, caught in long log troughs, served to replenish the locomotive boiler. Water seemed everywhere,—foaming rivers, little ponds set among the hills; and the train whirled past great lakes, some fifty or more miles long.

The subject of shooting and fishing was not allowed to flag, and I listened to our mentor’s tales of mighty droves of caribou that traverse the islands in the fall, and descriptions of rivers where pools are alive with the kingly salmon. Not to leave us without proof of the fishing, at one point where the train stopped to take water, a trout rod was produced and we caught trout, dropping our line from the car platform.

That memorable ride crossing the great barrens where we saw caribou from the car windows ended hesitation about a future trip and whetted our appetite for a dip into this sportsman’s paradise I had fostered for years. Therefore plans were made then and there for another year. We were permitted to carry them out, and pitched our first camp July third, 1900, on Robinson’s River, on the southwest coast, flowing into Bay St. George.

Here we fished for salmon three weeks with great success and were the only sportsmen on the river, for the knowledge that the “sport of kings” might here be had, without money and without price, had not reached the outer world to the extent of bringing anglers. At the end of three weeks we broke camp, moving about three hundred miles up the road to a region of river and lake called Terra Nova. Our head guide, John Stroud, who has led the steps of many titled English sportsmen through these wilds, spoke of it as “God’s country,” and so it proved. We camped at the foot of the lake where the water rushed through a narrow “tickle” to make the river. Fifty feet from our tents we could take trout in any quantity we wished.

When the wind was down the lake, as it generally was, it wafted to our nostrils the rarely delicate perfume of the arethusa, an orchid growing here in lavish abundance; the air was heavy with its sweetness, but we were never surfeited. On the marshes stretching far beyond the limits of the human eye, after the height of land above the lake was reached, I found five other beautiful orchids. The delicate pink twin-flower or Linnœa trailed over the moss of the forest in such prodigal profusion that its heavy odor cloyed. All day long the hermit thrushes sang in the dim woods; at intervals the strange insane laugh of the loon echoed across the lake.

Each evening at sunset the wild Canada geese came in flocks to a near by island to fill their crops with gravel. Their approach was heralded by a distant chorus of “honks” that grew as they came nearer, while, to my ears, it seemed a weird elfin band playing behind the hills. At evening the great white gulls winged their even flight in from the distant sea where they fish all day, to feed their nestlings swung on a rock in some dark tarn high on the marshes. The gulls always breed in the interior from twenty-five to sixty or more miles from the ocean, consequently they fly from fifty to one hundred and twenty miles a day to catch the fish and return with it to feed their young.

We took trips up two rivers that flow into Terra Nova Lake and at sunset and early morning watched quietly to see the caribou come to drink. They always came; many were huge beasts (Newfoundland caribou are the largest known) with splendid spreading horns,—in the velvet, however, at that season, so unfit to mount. We were contented with shots from the camera only.

The next year we repeated the plans of the one before. We found the streams about Bay St. George alive with anglers and the charm was gone. It was just as before at our Terra Nova, but we were disappointed about the salmon. One of our men had been on the Labrador coast a great deal and told marvelous tales of the size and abundance of salmon in the Far North, so we returned in 1902, equipped for a Labrador summer.

We left St. John’s June 26 on the Virginia Lake, a powerful steamer, built to battle with the ice. She is owned by the Reids and subsidized by the government to carry mails to the twenty or more thousand fishermen who go North for the cod-fishing each summer; and to bring back reports of the catch to the merchants of St. John’s. We carried tents and canoes, for there are no hotels or stopping places fit for an American on the Labrador, except the Hudson Bay Company’s Posts, where the infrequent tourist is cordially welcomed, but only as an unexpected guest, never being allowed to pay for entertainment. Our objective point was Cartwright, Sandwich Bay, several hundred miles north of Newfoundland.

The Interior of the Camp

Our reception by Mr. Swaffield, master of the Post at Cartwright, and his good wife, was cordial. Their loneliness makes a visitor welcome. Mr. Swaffield has been in the Hudson Bay Company’s service since a boy, at Abitibi in the far northern Canadian wilds and later at Davis’s Inlet in the very far north of Labrador.

The Virginia Lake would not have put in at Cartwright on her northern trip except under orders to land us, which was probably indirectly the means of saving the life of the little son of Mr. Swaffield. A few days earlier the child, while watching the feeding of the savage Eskimo dogs that the Post keeps for the sledges in the winter, fell on the ground, when the pack, true to its instincts, sprang upon the boy, biting and tearing him frightfully. The mother ran to the rescue and beat some of the brutes away and the father quickly followed with his rifle, and shot several that would not quit their prey. The distracted parents had been doing everything in their power, night and day, to relieve and save the child, but the wounds were in bad condition and death seemed the only result.

On our ship was Dr. Simpson and a nurse of the “Royal National Mission for Deep Sea Fishermen,” returning from England to Indian Harbor hospital farther north. The doctor had the child placed in a box lined with furs and soft blankets, and towed to the waiting ship, the poor mother sobbing in the doorway of the Post dwelling. The steam winches clanked the anchor from its bed, the whistle blew, dense smoke poured from the stack and the black steamer rounded the point to the open sea, and disappeared. Then the heart-broken mother, almost alone in this cruel, bitter solitude, showed her stoicism. She turned to us as if nothing had happened and bent all her energies to ministering to our comfort.

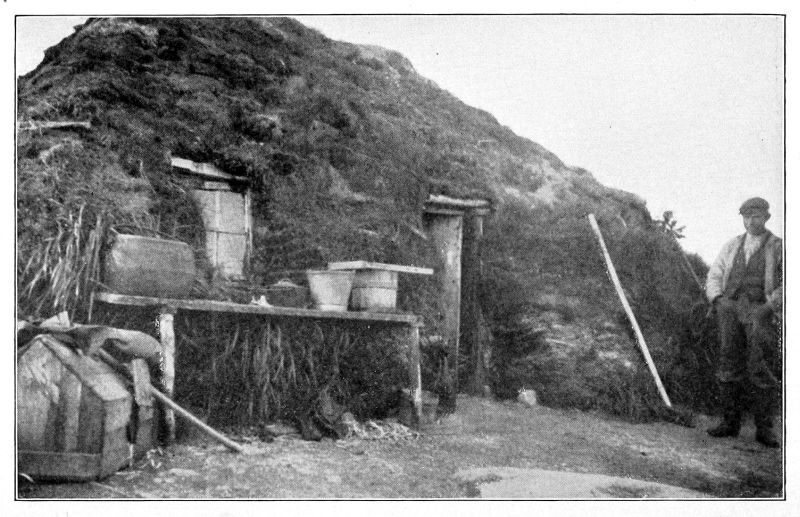

On the second day after our arrival, wind permitting, one of the Company’s schooners and crew were placed at our disposal; and, loaded with our canoes, tents, and provisions we started for the mouth of Eagle River, twenty miles away at the bottom of the bay. The schooner drew too much water to land us as far as we wished to go, so late in the afternoon of July fourth, we went ashore at a small hut owned by the Company and formerly used as a shelter for the men tending the salmon nets. The hut was clean and had a large brick fire-place. We pitched two of our tents back on the hillside and used the hut for a cook-house and dining-room. The men had a tent at no great distance.

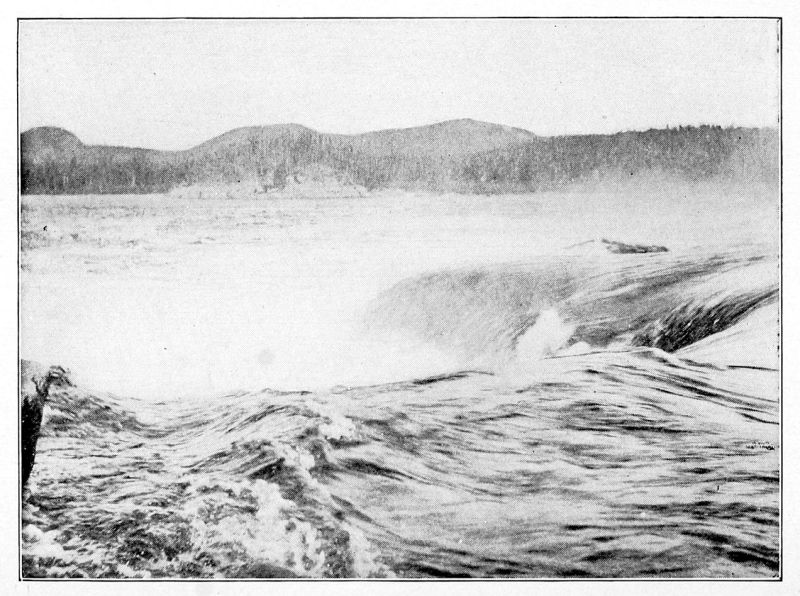

The next morning, in a pouring rain, I went a mile or more up Eagle River and, with the assistance of the Company’s man in charge of the net fishing, selected a camp-site on a bluff above the river, which is, as near as I can judge, about three times the size of our Merrimack at Concord. In two or three days our camp was pitched, balsam beds laid, cook-house built of tarred paper—there being no birch trees in Labrador large enough to furnish bark for that purpose—and the provisions poled through the rapids in the canoes and safely landed. Then the ladies were brought up in security through the foaming, rushing, seething waters, and we were settled for the most delightful five weeks I ever passed.

We fished the pools in front of our camp and trudged over the old salmon trail that wound up a hill and down again to the big pool below the falls, where a canoe was launched and our largest fish taken. The men carried the canoes above the falls and we made trips up the reaches of the river to great ponds, stopping to fish the different pools on the way, and at noon halting to “boil the kettle” and have lunch, returning by daylight, between nine and ten o’clock in the evening, making a long, happy day.

I made a trip of several days up Paradise River, another stream flowing into Sandwich Bay, famous for its natural beauties and the astonishing number of seals that gather there to breed. These are the hair seals, the young of which have a beautifully mottled coat, used now for automobile garments. It is rare sport to hunt these creatures, as they are very shy and in the water offer a mark (the top of the head) no larger than a two-inch circle. We climbed some of the mountains, sailed in the bay and made excursions to some new spot almost daily.

While the attractions of Sandwich Bay seemed little short of inexhaustible, yet we pined to see more of Labrador, to have a wider range, to fish other rivers, and to explore other and more lovely bays. The uncertainty of the arrival of the steamer, and the great labor of breaking camp and packing, added to the inconvenience of our having no craft of our own to take us up the bay to the Post, where the steamer calls, precluded our moving and camping in other bays.

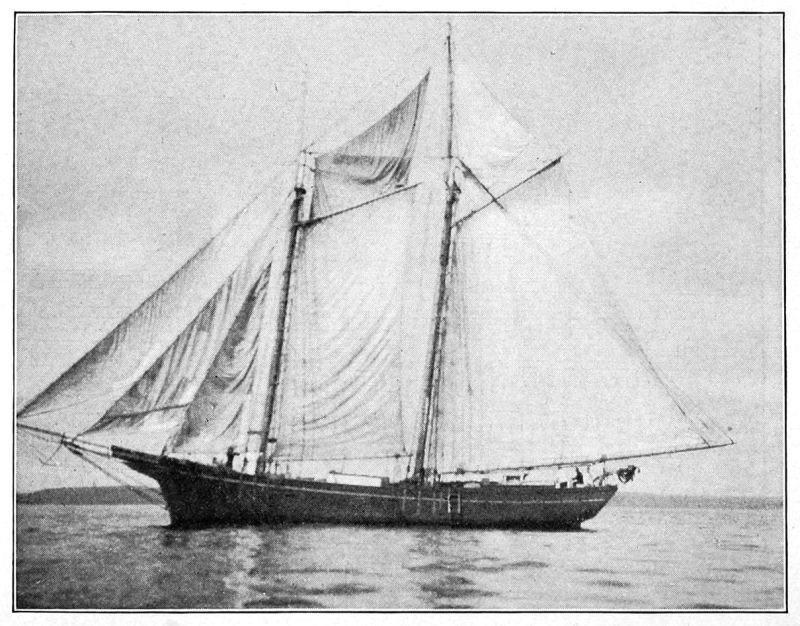

The conviction grew that had we a schooner properly fitted we might cruise at will, pitching camp in any bay we chose, and leaving for fresh pastures as the sport moved, which seemed ideal. We could imagine nothing more perfect except, perhaps, to have an auxiliary yacht and so be independent of contrary winds, but expense prohibited that, so our plans developed this summer of 1903 in our chartering through a St. John’s exporting firm, with the kind assistance of Mr. Morine, the eighty-ton schooner Gladys Mackenzie—Gladys for short.

She is a staunch craft, formerly used as carrier between the ports of Oporto, Spain, and St. John’s, with occasional trips to the West Indies; capable of weathering anything from a September gale off the east coast of Newfoundland to a tropical hurricane. Last year the Gladys was entirely re-topped, which means she was rebuilt from her hull, so she is fresh, clean and sweet.

A floor was laid over the ballast, the entire length of her hold, and partitions put up, making a comfortable and cozy cabin, gained by a flight of railed stairs through a booby hatch amidships. On each side of a passage leading back from the cabin are the staterooms. Over the cabin table is a skylight arranged to open in fair weather, which, with the hatch opening, gives us an abundance of sunlight and fresh air.

A cabin stove supplies our heat. About the walls of the cabin are racks for the guns and fishing-rods, the table glass and crockery, and shelves for the books, for we always bring plenty of reading matter. Across each end of the cabin is a locker that serves, with the help of cushions, rugs and pillows, to make a couch or chairs. An English ensign is draped back of one, and an American flag back of the other; these flags having been used each year to fly from our camps, are consequently associated with much pleasure. At Little Bay a week ago a beautiful pair of Micmac Indian snow-shoes were left us to carry to a member of our party last year, unfortunately not with us now; and these adorn another space. A caribou head holds a vantage point, and a glory of gorgeously colored sweet-grass fans lends a bright patch to one side. I wish you could all see this cabin; it’s not half a bad place in which to sit after darkness has fallen, when the lamp is lighted, and a good novel like Quiller Couch’s latest, “The Adventures of Harry Revel,” lies at hand. If you have not read that story, don’t delay.

The Gladys is owned and sailed by Captain Joseph Osmond of Tizzard’s Harbor, Notre Dame Bay. The mate is the captain’s brother, who has been a trader for years and knows this coast almost with his eyes shut. A Newfoundland trader goes up and down the coast in a schooner, entering all the bays, their arms, coves and harbors, wherever a few fisher-folk live or there are towns. His schooner is laden with flour, pork, molasses, and other provisions, dry goods, tobacco and notions. The people he deals with have no money; the cod-fish and salmon, with such furs as they are able to trap, are their only legal tender. They barter these for the goods the trader carries and, in most cases, this is the only method they have of obtaining the necessities of life. Should the trader fail to guide his craft into their little cove they would starve, for scarcely any possess a boat larger than their fishing punt. In White Bay, Notre Dame Bay, and any of those bays remote from St. John’s, there are many old people living who have never been out of the little cove they were born in.

Besides the captain and mate, there are four seamen, each selected for his knowledge of different parts of the Labrador coast. I have two canoe men, or guides, and a cook and cabin boy. The regular cabin of the schooner is used as a kitchen, the men living forward in the peak. For boats I have a Gerrish canvas canoe, twenty feet long, a canvas boat with canoe ends, seventeen feet long, and a pine dory, twenty feet long, installed with a three horse-power gasoline engine. We have our tents and other paraphernalia and intend to camp in the different bays where there is sport.

Thus equipped we sailed from St. John’s Harbor Saturday afternoon, June 27th, 1903, and turned the schooner’s bow to the North.

The Gladys

After leaving St. John’s Harbor late Saturday afternoon, June 27, the Gladys sped merrily along under a freshening breeze and full spread of canvas. We overtook and passed an old sealing steamer carrying several hundred men to the Labrador fishing stations; the last we saw of her she was headed for Brigus Harbor, as the wind was constantly increasing and the weather getting thick with the coming of night.

We retired with hope for a long run, but woke to find the wind had left us to toss aimlessly about, with the fog coming in and many icebergs in sight. There was not breeze enough to hold the schooner steady, so her motion was anything but conducive to my comfort. All day we rolled to the sounds of creaking booms and flapping canvas. The air was bitter cold; on every berg and piece of pan ice were perched groups of curious birds, called by the natives “hag-dowas,” or fog-birds, and countless numbers flew about the ship uttering their strange cries. The appearance of these birds always indicates the approach of fog, and they are said to disappear suddenly and mysteriously when the fog lifts.

The captain came to suggest we would be more comfortable and in less danger to make a harbor, to which we agreed; and just before nightfall we anchored in Catalina. This town was once prosperous and of much importance, but with the decline of the fisheries it is losing prestige and shows decay, unfortunately a condition obtaining all over the island.

From the old methods of fishing, using a hook and line, the inhabitants have adopted traps. A trap is a square net, generally fourteen fathoms by twelve fathoms and ten fathoms deep. From the corner of one side of the net the mesh runs in towards the center on an angle, thus forming a small door. A leader or mooring line runs through this door and through the trap, one end being attached to a stake on the shore about thirty fathoms away, the other end to a grapnel outside. The distance from the shore is governed by the depth of water; it may be more or less than thirty fathoms. At each of the four corners another mooring line is attached and indicated by buoys; these are securely fixed to grapnels. The cod swim through the converging space made by the angles and enter the trap, from which few escape. The law fixes the size of the mesh at four inches, but the law is sadly violated. The net is laid in leaves, one hundred meshes in a leaf. A good trap costs about $400. It is this method of catching cod in wholesale quantities that is depleting these waters and will inevitably ruin the one industry that supports the inhabitants of this island.

Monday morning found a stiff northeast wind blowing which, being a head wind for us, precluded our leaving the harbor, so we put ashore in the punt and made a tour of the town, which stretches in a semi-circle along the arm that makes the harbor. Many of the houses were evidently of great age and some of very good Colonial architecture. We saw old knockers on the quaintly paneled green-and-yellow front doors that we coveted.

The trees were just bursting their buds June 29th; vegetation was not more advanced than it is with us in late April or early May. All the trees looked wind-swept and forlorn, indicating by their trunks and branches turned in one direction the force of the cruel northeast gales which are the curse of this side of the island.

Fish stages were all about. These are platforms raised on tall poles to a height rendering them safe from the depredation of dogs and covered with evergreen boughs, on which the cod-fish are spread to dry in the sun. When the sun does not appear for many days, and sometimes weeks, as is frequently the case on this east coast, the loss to the fishermen is serious, for while the catch is not ruined, the value is depreciated by a long process of curing.

The capelin were running and everyone was busy. Capelin are small silvery fish resembling the smelt we find in our markets in winter. They are dried on stages in the sun for food and to feed the dogs in winter; but their greater use is for fertilizers to make more productive the pitiful patches of gardens where the women labor like slaves to cultivate a meagre harvest of potatoes, cabbages and turnips. Capelin are practically the only fertilizer the Newfoundlander has, for the people keep few domestic animals, except goats and sheep, which run at will; but dogs are everywhere, vicious looking mongrels whose courage does not bear out their appearance. The capelin begin to run late in June; they come in from the sea in schools that have the appearance of great clouds sweeping just below the surface of the water. The natives draw them in seines and beach their punts loaded to the rail with masses of glittering silver that they pitch on the shore with forks, where the women, in picturesque red petticoats and white sun-bonnets, load them into dog-carts or half-barrels with two carrying poles, and take their weary way to their gardens. A pile of these little fish in the sunlight is a marvel of color. Their sides are iridescent with purple, green and pink, which, with the silver scales, gleam and sparkle like a mass of cleverly set jewels.

We proved a source of much curiosity to the inhabitants. When we entered the harbor we were flying an American flag at the fore peak and a British ensign at the main, with our house flag below the American. Our house flag is large and white with a big crimson D in the middle; the same design of D that appears on articles of luxury in homes all over the world. One old mossback ventured to inquire of the ladies where we were bound, and why the flag at the fore peak. When told the flag was flying because we were citizens of the United States he seemed satisfied, but remarked they saw few flags except those flown by the French and English warships that patrol the coast, and those were not always welcome sights.

In our stroll we saw two boys at a brook filling a barrel set on wheels and drawn by dogs. An astonishing sight was a girl, not over seven or eight years old, with brilliant black eyes and olive complexion, carrying two full pails of water from a yoke across her shoulders, and a hoop depending just below the hips to prevent the pails from swinging. She was slight of figure and the ease with which she bore her burden was surprising. This is the kind of work the women are trained to from their earliest childhood. No task seems too hard, no work too rough. The men go out to their nets and back and their labor seems to end with that, except needed repairs to boats and nets and spreading the latter to dry; but to the women falls the drudgery and toil, the endless round of tasks from dawn through the long day of seventeen or eighteen hours to bed-time. The summer days of the Far North are long. The sun does not set until eight-thirty, the long Northern twilight follows and it is not really dark even here before ten o’clock. Farther north we have been able to read as late as that hour without artificial light.

The Newfoundlanders are a prolific race; large families are the rule, which adds much to the hard lot of the women. They are a sanguine people, not over thrifty, having little care for tomorrow, if there is enough flour, pork and cabbage for today. If they catch enough fish to supply these simple needs they are satisfied, and if the fishing fails it’s: “Oh, well! b’y, there will be more next year, and perhaps the government won’t see us starve.”

In many cases when the famine comes, the traders or the St. John’s merchants who take their fish will furnish supplies on credit, trusting to the Newfoundlanders’ universal honesty to wipe out the score their next good season. But sometimes the bountiful season is long in coming, the sea does not yield plentifully and the score grows. Or there is sickness, or the great gales come and tear and ruin the nets and traps, causing sad loss; but their native cheerfulness and hope never desert them.

Finally, the head of the family is lost on the rocks, or dies of the common disease here, consumption, leaving a heavy debt. In that contingency it is frequently the case that the sons assume the debt, and carry it to their graves, lessening it in good years, only to have it grow in the off seasons, a constant drag, a stone about their necks; yet they never seem discouraged, which is, perhaps, more an indication of an easy, happy-go-lucky disposition, born in them, than the unconscious acceptance of the tenets of a faith promulgated from Concord, of which they probably never heard. It is fair to assume what they obtain from the trader and merchant does not come in a spirit of philanthropy, but enough profit is doubtless made during the years the account runs to warrant a final loss.

The average Newfoundlander is deeply religious and the strictest Sabbatarian with whom I ever came in contact. On that subject they are fanatics, with all the superstition which that implies. Out of respect to these principles I have not insisted on sailing the schooner Sunday, permitting the crew to lay her up in harbor; but on the first occasion of a Sunday morning at Sop’s Arm, in White Bay, when with my rod I departed for the river, a look of absolute horror swept the faces of all. I brought back some fine salmon, enough for all hands, but the crew could not be induced to feast on my ill-gotten fish.

Adverse winds prevailed all day Monday and conditions kept us in harbor until Tuesday noon, when we beat out and found a comfortable breeze. The sun appeared and the breeze strengthened. We went humming through the blue waters at a rate that quickened our pulses and filled us with gladness. Dinner was served on deck in view of the precipitous coast along which we were sailing. Towering mountains of glittering ice met the eye wherever turned, some between us and the shore, others ahead, astern and dimly distant on the sea horizon. These wonderful derelicts from the frozen North are a source of constant wonder and delight. You never see two alike or one that is not strange and interesting in its peculiar way. To the person of imagination icebergs take grand and fantastic shapes. Some reach into domes and pinnacles, Eastern temples of gleaming crystal. Others have the appearance of forts, bastioned and turreted. We saw one that was a perfect huge gondola; another bore striking resemblance to a swan. Under different effects of atmosphere and distance—which an artist would term values—their coloring changes, till from ghostly sheeted forms they merge to palaces of ivory and pearl, sometimes assuming a tinge of faintest blue, at others rosy tints. Where the sea surges against their feet is seen the most wonderful coloring, the purest shades of jade, again a tinge of indigo, or the milky blue of turquoise, and where the sun glints, translucent azure. Some have caverns in their sides, and where the waves have worked beneath the water line to make a cave, the swell dashes in and out with a sound like rapid musketry.

The quiet is almost daily disturbed by a distant roar like that of heavy cannonading, which tells the story of a “foundered” monster and its breaking up. We witnessed the spectacle of one huge mountain of ice “foundering,” and it will never be forgotten. In its pallid splendor it rose and fell as if imbued with life and engaged in a Titanic struggle with the sea. At intervals a great mass would fall with a roar as of thunder and the water would leap high in the air to fall in a churning, seething, boiling foam. It is a trite statement that a berg is nine times larger below the water line than appears above; which if true, can give only a faint conception of what they must be, when they break from their Arctic environment and start on their wasting voyage to the South. Beautiful as they are, yet are they terrible, for they are a constant menace to the mariner. It is impossible to tell by what is seen above water what there may be below. Sometimes the berg reaches wide beyond its visual base, which makes it dangerous for a ship to go near. Take the conditions of numerous bergs, a stiff breeze, fog and the darkness of night, and a harbor is a safer place than the open sea in this locality.

A hail from the watch in the bow called our attention to a school of huge fish just ahead. They seemed to be at play, chasing each other through the water and leaping clear, so their entire bodies could be seen, much as a salmon jumps. These were what our crew called “squid hounds,” but I knew them for the great horse mackerel or, in the vernacular of the wealthy sportsman who frequents Catalina Island off the coast of Southern California, “leaping tuna.” Down there they are taken with a rod and line, the reel a large affair, with a powerful tension or drag. The same methods have been tried here recently, but with no great success, as the fish in the colder waters of the North seems beyond such feeble control. The captain of our schooner, on leaving St. John’s, obtained harpoons and large coils of rope and before my return I hope to capture a tuna, the largest and fiercest fighting game fish that swims.

We had hardly recovered from our excitement over the “squid hounds” when an impertinent whale rose close to our sail; a biscuit might easily have been tossed on his broad back. The captain seized his old musket loaded with shot and fired. The whale went down without delay, leaving flecks of bloody foam on the water, showing he was hit.

As the day waned the wind strengthened until the schooner lay over with her lee sail almost buried and dashed through the splashing flicker of gleaming spray. The sun set behind a mist-bank and a great mass of lurid clouds, leaving the sea a melancholy grey, except where the departing radiance threw a tremulous path of crimson over the changing wave ridges on our starboard side. On our port a full red moon caught the quiver of the waves and paved a glittering path out to sea where the shadows of dusk were deepening. The effect of both orbs shedding their brilliancy at the same hour with strong effect was new and strange to me, for while at home we frequently see the moon rising while yet it is dusk, the sun has so far sunk as to leave only a pale afterglow, too weak to vie with the moon’s radiance.

The next morning we woke to find the Gladys so steady I thought she was anchored. Going on deck I found we were slipping through water as smooth as a mill-pond, between wooded shores under a gentle breeze. This was the beginning of Stag Harbor Run, an inner course of Notre Dame Bay. What the natives call a “run” is a channel of water between the mainland and a chain of islands or between two chains of islands. Almost the entire coast of Labrador can be made through “runs.” A “tickle” is a narrow space of water between land and is smaller and shorter than a “run.”

All day we sailed smoothly through this run and “Middle Tickle,” past hundreds of islands, some green with trees, others sheer piles of rock covered with moss that gave softening tones of grey and brown to their rugged sides. Many icebergs have been blown in from the sea and stranded. We went near one in the launch and photographed it. The water about its base was churned into exquisite hues of blue and green. Later the men went to another in the port and gathered ice. We had brought a freezer from St. John’s and with evaporated cream one of the ladies made delicious ice-cream.

Late in the afternoon we passed small fishing villages clinging to the shores, with high evergreen-clad hills rising back of them and almost invariably an iceberg stranded at their very doors. Early in the evening we rounded an enormous berg, one end of which the waves had carved to the perfect shape of the prow of a giant battleship, and entered Tizzard’s Harbor, where the captain lived. A more picturesque village it would be difficult to imagine. The houses covered the sides of a hill rising from the water and in places were perched on cliffs that swept in a curve and held the harbor.

The buildings were mostly guiltless of paint, but kind Nature had softened all to a restful tone of leaden grey, touched here and there with green, velvety moss. The shore was fringed with the fish-houses and drying stages. We climbed the hill back of the town and interrupted a scene of activity. Women were bearing brimming tubs of capelin to their gardens on the farther slope of the hill. From the crest we looked on a stretch of unusual fertility for Newfoundland. The gardens are laid in long straight beds about three feet wide, between which are deep furrows. The capelin are spread over the beds, and soil from the furrows thrown over the little fish; when decay comes the fertilizing is complete.

Everyone was intent on her work; those not bringing the fish from the harbor were spreading and covering. Two women heavily laden with a tub, set it down to give us greeting and descant on the hard lot of the Newfoundland woman. “You’se don’t have to do this work in you’se country?” inquired one.

In the distance beyond the busy scene the sea was glowing under the setting sun, hermit thrushes and song sparrows were singing their vesper hymns; while faintly from the distance came the bleating of sheep and the tinkle of cow bells.

Our next harbor was Twillingate, perhaps the most important town next to St. John’s on the island. It wears an air of thrift and prosperity and probably has a population of ten or twelve thousand inhabitants. While here the Labrador steamer, Virginia Lake, en route for the Far North, came in. I went aboard and received a cordial greeting from the officers, with whom we spent more than two weeks going and coming last summer. She steamed out with handkerchiefs waving from her bridge to the ladies on our schooner.

After we left Twillingate there came on a hard blow and it was very rough. I felt the pangs of sea-sickness, and lying down went to sleep. My nap was broken by Madame, who called me to come on deck and see the queer place we were in. I found a land-locked harbor with high hills rising sharply from the water’s edge, and everywhere about the hills were white goats grazing and clambering over the rocks.

Weather continuing rough, we remained here two days. I walked into the country about two miles and found a lovely lake set among the hills, in which trout were plentiful. The weather drove us next into Little Triton Harbor. Later we made Little Bay and anchored in sight of the ruins of a deserted copper mine. Newfoundland, as you doubtless know, holds in its rugged grasp many different minerals, but no mining on an extensive scale has been accomplished except at Belle Isle, off St. John’s, where the richest iron deposit ever discovered supplies the enormous plant of the Dominion Iron and Steel Company, at Sidney, Cape Breton. It is said iron of absolute purity is taken from this mine with less expense and labor than from any mine in the world. There is a paying copper mine at Tilt Cove, owned and managed by an English syndicate; and at Sop’s Arm, near the bottom of White Bay, up in a gulch among the hills, we found a gold mine in full operation, with stamps and smelters running briskly. This mine is exciting much interest throughout the island, as it is yielding gold in paying quantities.

The deserted mine at Little Bay is a scene of pathetic desolation, indicative of lack of foresight on the part of its managers. It yielded large returns in the beginning; and in their eagerness to gather its riches, and becoming economical as their wealth increased, they neglected necessary precautions to strengthen the mine and it caved. The owners becoming disheartened, it was left, and today is a heap of slag, ore, dismantled engine, machines and crushers. Tons of iron lie rusting among the rocks from which the smelter chimney rears its giant shape of bare brick. Back from the scene of the works is a pond with sulphur-stained shores and vacant, weather-worn houses about its banks. Beyond towers the strange brown and green hill, bare of vegetation, a cold, stern, menacing pile, stained with its copper treasure. To the northwest ranges of birch-clad hills rise one above the other, draped with wreaths of filmy, curling mist. At my feet were the runs and islands and, way to the north where the run joined the open sea, loomed through the haze of night two weird icebergs, ghostly white. In the west a few bright streaks of waning sunset remained and threw reflections of dim crimson on the black surface of the pond below.

The shadows deepened, silence prevailed and the tenantless houses stood sharply silhouetted against the hills. I thought of the time when this strange place of soundless desolation echoed to the hum of labor, the going and coming of many men, to the blows of hammers, the roar of the stamps, the screams of steam whistles—but this night a dumb ruin in a wilderness.

After leaving Belvoir Bay and starting north, we encountered contrary winds, thick weather, and much ice for two days. We dropped anchor the first night in St. Lunaire Bay and the second evening found us in Griguet, a narrow harbor between long green ridges.

We decided, if the weather continued unfavorable, to beat round Cape Bauld and run into Pistolet Bay, another famous place for fishing frequented only by the British officers; but the morning of the third day brought southwest wind and we ran free, up beyond the Cape, leaving the coast of Newfoundland, and made the open straits of Belle Isle. So good was the breeze that we crossed this famous thoroughfare before night, made Labrador, entering Sizes Harbor Run. As I have explained in a previous letter, a “run,” in the vernacular of the North, is a course or passage of water sheltered from the open sea between the mainland and outlying islands. A large part of the eleven hundred miles of the Labrador coast can be made in peace and comfort through these “runs,” with small concern for the weather outside, no matter how boisterous.

Sizes Harbor Run is a placid reach between great rocky islands undoubtedly naked of vegetation, except for lichens and mosses, that lend delicate tones to the marvelous scheme of color. At intervals wee fishing villages with their picturesque stages and bright colored boats came into view, actually clinging to the sloping sides of the rocks, or nestled snugly in some small estuary. Emerging to the open sea, we sighted Battle Islands across a stretch of heaving, foam-flecked water.

The small white cottages of Battle Harbor, the most important settlement in Labrador, gave a touch of life to this vast impression of grim rock, illimitable reaches of restless deep blue water, and ragged clouds flying across a wild, wind-fretted sky. During our sail through the “run” the wind had been gradually drawing round, so, as we headed for the harbor, we were forced to beating on short tacks, finally getting the breeze dead ahead, blowing right out of the Harbor Tickle.

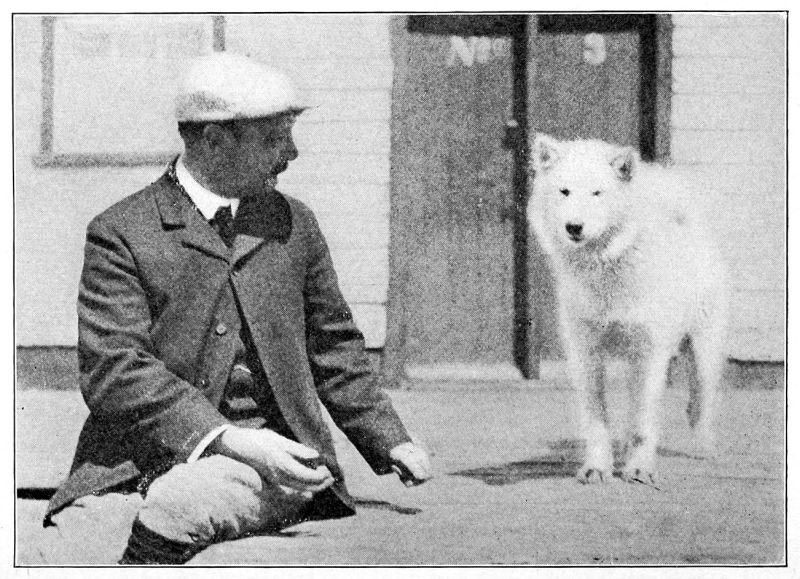

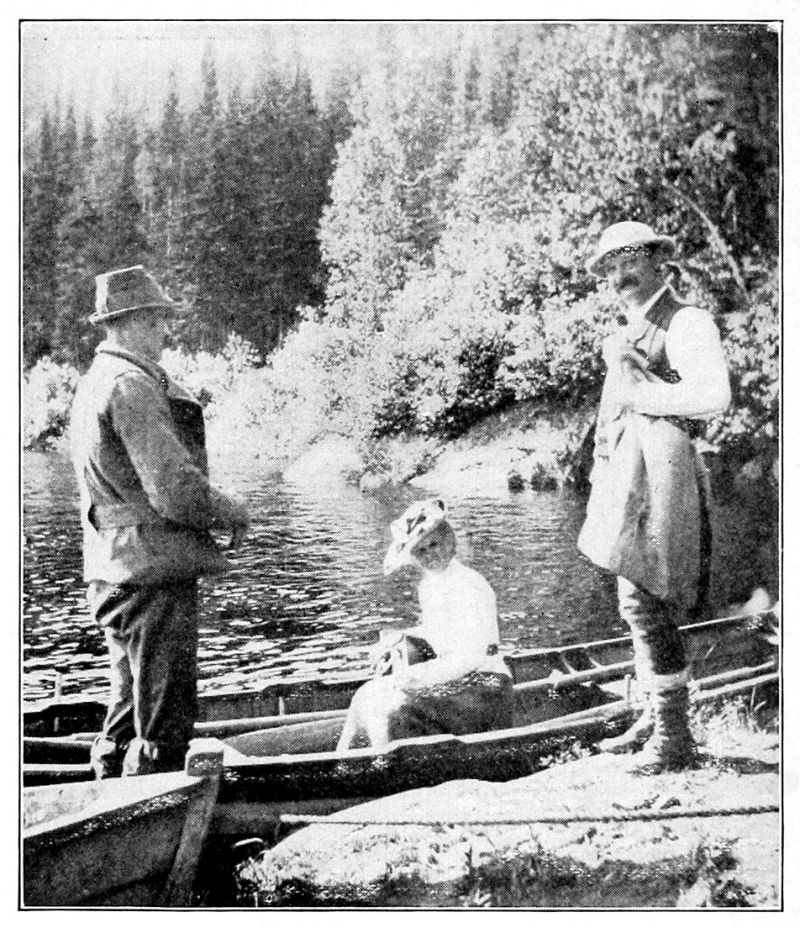

Making Friends

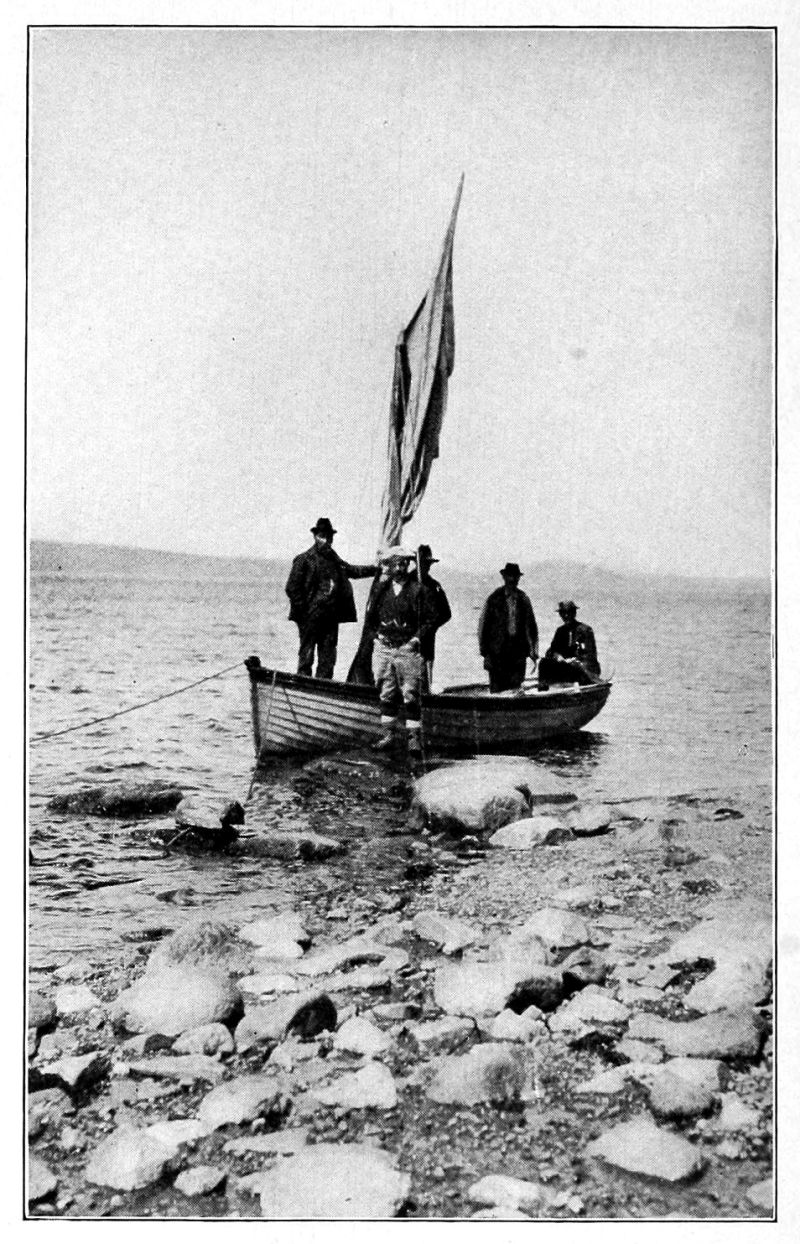

The entrance is narrow, with dangerous rocks and shoals. Our skipper thought it unwise to attempt the passage. We were eager for mail we knew was waiting, so arranged for the schooner to lay to, I to go in with a small boat and two men, get the mail, return and head the schooner back to Sizes Harbor for night anchorage.

The light craft we embarked in was tossed on the angry crested waves like a cork in a whirlpool, but by degrees we worked in and passed the looming sentinels of rock that guard the harbor mouth. At the first wharf was moored the Strathcona, the Mission steam yacht in which Dr. Grenfell makes his errands of mercy along this hungry coast. The doctor put his head out of the deck cabin and called to ask if this was Mr. Durgin. I said “Yes,” and went to the station landing where the doctor arrived before me with Mr. Croutcher, agent for Meyer, Johnston & Company, of St. John’s, owners of the store and fishing station established here. After a cordial greeting they wished to know why the schooner didn’t come in, and learning the reason, Mr. Croutcher dispatched a skipper and crew in a large punt. The skipper took charge of the Gladys, some of our men were put in the punt with the other crew, a line was made fast to the schooner’s bow, and with the long oars we were gradually worked in through the narrows and moored in quiet water.

Battle Harbor is a “tickle” between two long islands of a large group called Battle Islands. It is a legend that a great battle was fought here between the Indians of the Straits and resident Eskimos, from which incident it is said to have obtained its name. The islands are great masses of grey and reddish brown rock rising abruptly in fantastic outlines from the water. They are bare and barren; cruel in the grim force they offer to the clamoring sea that has vainly surged against their bases since the awful convulsion that hurled their weird shapes into outer space.

The two islands that form the harbor rise in long slopes, on one of which hangs the village. The opposite slope is a vacant waste. Close to the water on the inhabited side are the wharves, store houses and other buildings of the fishing station; a short way up the slope are the store, post-office and dwelling connected with the station; and beyond, towards the harbor mouth, are the hospital buildings of the Royal National Mission for Deep Sea Fishermen, two churches and the white cottages of the dwellers.

In the coves and little bights of the general group of islands snuggle isolated cottages and rude “tilts” or huts with their roofs of bright green turf from which wild flowers nod to the ocean’s breath. Perched on stilts close to the water are the fish stages flanked by their long houses with ever gaping doorways ready to receive the cargoes of cod the punts bring in. Above the tumble of rocks gleam here and there spires of ice, and small ice pans blink under the sun’s rays as they are tossed here and there on the restless blue sea.

The morning following our arrival we went ashore, the ladies to the hospital and I to the post-office. Mr. Croutcher introduced me to a gentleman, a member of a New York publishing house, and he presented me to his traveling companion, Mr. Norman Duncan, author of those consummate pieces of literary work portraying Newfoundland life and character that have appeared in the form of short stories in several recent magazines, and are now collected under the title of “The Way of the Sea.”

It was a satisfaction as well as a pleasure to meet Mr. Duncan. My interest in Newfoundland and its people and a knowledge of their condition gained during several summers, enabled me to appreciate his remarkable work more, perhaps, than the casual reader unfamiliar with the subject. I found Mr. Duncan’s personality as delightful as his work. He is the same dreamer I had pictured when I finished his first story. His face is an open page to his sensitive, highly strung nature, and it was easy to understand his ability actually to feel the sad and futile strivings, the disappointments, the pathos of the Newfoundland life.

A slender man slightly over medium height, with regular features, a pallid complexion, dark, expressive eyes, and a mass of wavy dark hair heavily banded with white, he is, in his early thirties, a professor of Rhetoric and English in the Washington and Jefferson College of Pennsylvania.

Wishing to gain some information from Dr. Grenfell with reference to fishing and hunting prospects in the bays farther north, the publisher and I strolled down to the wharf and boarded the Strathcona. We found the doctor in his cabin and, with the aid of his charts, he supplied the desired information. He gave me several flint arrow-heads, relics of the aborigines of Newfoundland. Dr. Kingman, a specialist from Boston and a guest of Dr. Grenfell, was present. He had made the journey to assist Dr. Grenfell in several delicate operations at the Battle Harbor Hospital. Dr. Kingman was accompanied by Colonel Anderson, a veteran of the Civil War and at the present time pastor of Berkeley Temple in Boston.

The dominant figure of the Labrador coast is Wilfred T. Grenfell, superintendent of the Royal National Mission for Deep Sea Fishing. In the performance of his varied duties, he administers the offices of a clergyman of the Church of England, a physician and surgeon, and holds a Board of Trade certificate of competency as master mariner. As soon as ice conditions permit of navigation, the doctor starts in the small Mission steam yacht, the Strathcona, and makes the line of coast to Cape Chidley, the uttermost northern limit of Labrador. He stops in all the harbors where the fishermen have headquarters, enters the bays and penetrates the bights and coves, wherever a human creature lives. He succors the sick and injured, gives religious consolation to the afflicted and sore in heart, feeds the hungry, clothes the naked, buries the dead, performs the marriage ceremony, and christens the new born.

With his powers of magistrate, conferred by the Newfoundland government, he represents the force of the law and brings the guilty to punishment; his duties in this capacity are less than the others, for there is more misery from poverty than crime in Labrador. When he finds patients in some dark hovel too ill to recover without constant care and nursing, they are taken from their foul environment, placed between clean white sheets in swinging cradles on the Strathcona and conveyed to the nearest hospital, either at Battle or Indian Harbor. The sick fishermen are borne from the vile holds of the schooners to the cleanliness and comforts of the hospital, where they have proper food and medical attendance, with the ministrations of the trained nurses in their spotless garb. Better surroundings than most of the poor creatures ever dreamed of; as one said to me: “It is Heaven.”

The reason for the poverty that everywhere prevails in this vast country is, that after the precarious results of the hunter, trapper and fisherman fail to keep body and soul together, there is no other means of livelihood. To afford an opportunity for such as may, to earn their living, Dr. Grenfell has established a few experimental industries in a small way. In one place is a saw-mill, in another a laboratory to refine cod liver oil. To correct the evils of the trading system, small co-operative stores on schooners have been furnished, which provide the necessities without overcharging.

The Mission does not believe in pauperizing the poor by giving help of food and clothes unless they make some return, provided, of course, that they are physically able; so large quantities of birch wood are cut and piled in the various bays, which the Strathcona takes for fuel as she comes up. Oars are made and sold to the fishermen and the Newfoundland government.

The women do beautiful embroideries in silk on caribou skin and make Ranger seal-skin bags worked with beads, also tobacco pouches, bags of loon skins and moccasins, which the Mission sends abroad for sale and offers to the few tourists who venture into these wilds. Withal, poverty holds the upper hand and Dr. Grenfell is put to sore straits to relieve the half he sees. I have been told he has more than once stripped his shoulders of his own warm coat to place it on some shivering, half-frozen creature. I have been witness to his infinite patience, for when his steamer drops anchor all the inhabitants for miles about flock to her deck. Everyone has an ailment or trouble; all are listened to; something is done for each. I wouldn’t be surprised if sometimes a healthy but complaining man gets a bread pill, but he departs satisfied.

The native of Labrador is often weak and childish; many are half-breeds with all the short-comings that implies, and it must take the patience of Job to deal with them. For example, in one bay where we anchored in sight of a Hudson Bay Post, a half-breed man and a widow half-breed with several children were married one evening by an itinerant Methodist preacher. I do not know if the parson got his four dollars prescribed by law up there, but when they passed our schooner in a boat, next morning, on what we may suppose was their wedding trip, they hailed our cook, Joe Flynn, and asked for breakfast. In his richest brogue Joe lectured them on their folly in getting married without knowing whence the next meal; followed that with some rare advice on conjugal duties; and finally said for the sake of the children he would feed them. So the wedding journey began on full stomachs. Dr. Grenfell tells of a couple that stood the minister off for his fee and then borrowed from him the price of a half-barrel of flour to start housekeeping.

Dr. Grenfell has for able assistants Dr. Cluny McPherson at Battle Harbor and Dr. Simpson at Indian Harbor. The latter hospital is closed during the winter, but Battle Harbor remains open and the doctors make long and terrible sledge journeys hundreds of miles into the country, with their teams of wolf dogs. They carry all medicine in the tablet form to avoid freezing.

From the Strathcona,—named by the way for Sir Donald Smith, Lord Strathcona and Mount Royal, Canadian High Commissioner in England, Governor of the Hudson Bay Company, magnate of the Canadian Pacific Railroad, formerly plain Donald Smith in the service of the Hudson Bay Company on this coast, and who presented the yacht to the Mission,—we went to the hospital, where we found the ladies chatting with charming Mrs. McPherson, not long married, living in this silent place the year round, in strong devotion to her stalwart husband and his chosen work.

There is nothing sectarian about this Mission, some of the workers are Episcopalians, some are Methodists and others are Presbyterians. To the best of my judgment, if I am able to judge, and from careful observation, all are real Christians,—some of the very few I feel sure of ever having met.

After a pleasant call in the cosy living-room of the hospital where the whole party except the doctors, who were busy, were gathered, we returned to the schooner for lunch. In the afternoon came an invitation from Dr. Croutcher to be present at a graphophone concert in the evening followed by a reading by Mr. Duncan.

In a pouring rain we were rowed to the landing and, preceded by a man with a lantern, climbed a flight of steps to the long loft of one of the store-houses belonging to the Company. Here, with seats and chairs, lighted by lanterns hanging from the rafters, were gathered many of the Company’s servants. The people from the hospital with the guests soon arrived and took reserved seats with us. The graphophone was a large, fine one of sweet tone, presented to Dr. Grenfell by a friend of the Mission in England. Many of the records were new to me and very pretty. The machine was a wonder to most of the servants as evidenced by their faces. Sousa’s marches followed hymns, and church music gave place to banjo solos.

Following the concert the guests assembled in the large, wainscoted living-room of Mr. and Mrs. Croutcher’s dwelling, and Mr. Duncan with his manuscript on the table before him, his elbow resting on the table and one hand buried in his clustering hair, began to read “A Beat t’Harbor.” At that time the story was unpublished; it appeared subsequently in Harper’s Magazine for September. The reading was a revelation to me, for while I thought my own reading had given me the scope of his powers, I found that I had not grasped the full force and strength of his text. His inflections imitating the Newfoundland manner of speech were perfect; you heard their soft drawl and the peculiar clipping of words. It was easy to see he felt every line he had written. The burden of the story was an inborn fear of the sea, the wind and the fog. Mr. Duncan has this same dread, he never describes the sea in its laughing moods, but always in its somber tones.

Returning in the boat, Madame conceived that she would like to invite our friends over to the schooner the next day for tea or lunch. She thought the “real thing” would be to have some ice-cream, but it was too dark to go out and look for ice. The next day was Sunday and there was no man in our boat who would gather ice Sunday, even at the point of a gun. According to the Newfoundlander such things are wicked.

However, as we neared the schooner a good sized ice pan was hanging about her stern and was soon secured, reminding Madame that “the Lord provideth.” In the morning Colonel Anderson preached, some of our party attending. About four o’clock our guests arrived and filled our cabin. Including the four of us, there were fifteen. We had ice-cream, cake, confectionery, tea and coffee, with cigars and cigarettes for the men. It was a merry party; such a gathering was a rare treat to the Battle Harbor people who see so few new faces.

We had Japanese paper napkins, and Colonel Anderson requested all to place their autographs on his napkin as a souvenir. Then all hands wanted a similar souvenir and we got busy. In the evening Dr. Grenfell preached in the little church on the hill. All of us attended; the publisher manipulated the reluctant keys of the whining parlor organ with great credit. The congregation was composed of the simple fisher folk, and to them Dr. Grenfell preached straight and direct. He told them what their lives should be, in simple but powerful language. He reminded them that they were following the honorable calling of Christ’s disciples, that of fishermen. In his surplice he made a strong impression of a man earnest in his endeavor to help his fellow men.

Returning from church Dr. Grenfell told me he should leave the harbor at daybreak and would tow the Gladys out where we could get the wind if I wished. I thanked him and accepted. The publisher (I don’t use his name because he might not like it) and Mr. Duncan were going north on the Strathcona. The latter had agreed to write a Labrador novel for the publisher, using for a theme the work of this Mission. He was in Labrador to collect material. We were bound for Cartwright to fish Eagle River. The publisher was anxious to fish and had a brand new outfit. I invited him to join us, so as Dr. Grenfell must hasten to Indian Harbor and could steam night and day while on this coast,—we could only sail by day, and if we had the luck of a favorable wind—he agreed to have the publisher back to Cartwright about the time we arrived.

I woke in the morning just enough to realize that we were moving and then sleep claimed me again. Once on deck, we were rolling and pitching in a fog with no wind and the Strathcona gone. The outlook was disheartening, but later a southwest wind blew down and the weather cleared. The sun shone from a pale blue sky flecked with light, fleecy, white clouds and threw dancing light on a tossing sea of the deepest blue. The rocky coast-line and islands were reddish brown at their bases where the water dashed in whitest foam. Above this harmony of blue water, white foam and tawny rock, towered fantastic shapes clothed in browns, blues and purples. Beyond, in the distance, were the faintly blue peaks of mountains, and far away on the sea horizon, seen through openings between the islands, were dim shapes of ice, ghost-like against the filmy blue.

The schooner, carrying all sail, dashed through the leaping water and shook the white smother from her bow. All day the favoring breeze filled our sails and drove us steadily on, to the mysterious North. We passed through Domino Run and Indian Tickle, where many fishing schooners were anchored and several big square-riggers, flying the flags of Norway, England and countries of the Mediterranean. These were here to buy the fish.

The breeze softened with the declining sun, and we anchored in a small harbor shut in between cliffs of rock, holding far up on their ragged sides small fisher huts. Faint rays of yellow light struggled against the gloom through their crevices. Above stretched a canopy of velvet against which pulsed and burned a myriad of golden stars, the glorious dome of a Northern night.

Below, in the black cavern made by the surrounding cliffs, were several fishing schooners. The sea had yielded of his bounty, for on the deck of each boat was a table; to its windward hung a screen of brown canvas tempering the bleak night breeze that came with the dark; and at these tables were men and women working with haste that seemed undue. Great flaring torches shed crimson light over the scene and threw grotesque shadows against the swaying canvas.

The summer breezes favored our journey, wafting the schooner to the north, past a panorama of rocky islands, frowning headlands and mountainous distances, all bathed in a keen, intense, electric blue. The sky was a deep dome of blue, the ocean vivid, flashing blue, and the rocks, hills and trees were drenched in the same riot of color.

There was an element in the air that drove the blood coursing through the veins, creating a spirit of elation, a joy of living in accord with the glories of Nature’s sparkling mood. No care could bide under the stimulus of that blue ether and such a flood of glorious light. With all her paucity of other blessings, Labrador has wonderful air and light to spare, and the day will come when physicians will recognize the value of her summer climate as a curative agent.

The name Labrador conjures romance, Hudson Bay Posts, furs, mighty rivers flowing from an unexplored interior, wandering Indian tribes, Eskimos, terrible sledge journeys into desolation beyond words to depict, great droves of caribou, wolf dogs, long days in summer, long nights and bitter cold in winter. It is a peninsula bounded by the Gulf of St. Lawrence, the North Atlantic Ocean, Hudson Straits, Hudson Bay and towards the southwest by Rupert’s River and two others.

The “Encyclopedia Britannica” says: “Labrador as a permanent abode of civilized man is one of the most uninviting spots on the face of the earth,” which is undoubtedly true; but under the spell of its brief summer as a new resort for those seeking rest and invigorating air, with strange and interesting sights to occupy the mind, it is something more than a vast solitude of rocky hills. The permanent white population numbers five or six thousand, scattered along the coast in the different bays and inlets.

They call themselves “Liveyeres” to distinguish them from the twenty-odd thousand Newfoundlanders that visit the coast each summer for the cod-fishing. North of Hopedale are the Eskimos, and in the interior Indians called by the whites “mountaineers,” which is doubtless a corruption of Montaignais, a branch of the old Algonquin race.

The Indians visit the coast to trade furs with the Hudson Bay Company; they are splendid specimens of humanity, most of the men being of great stature. Some of the whites are descendants of those who fled from England in press-gang days. Some are descendants of sailors wrecked on the coast, and of Newfoundland fishermen. A great number are from those who came out years ago in the service of the Hudson Bay Company, and marrying native women, never returned: the origin of the large proportion of half-breed population.

The “Liveyere,” or native of Labrador, is generally the possessor of two dwellings, a summer hut on an island or outside headland, or in the bay near a river mouth for the salmon and trout netting, and a winter home, far up the bay or inlet, to be near wood and game, and to have the shelter of the forest from the bitter cold and terrible storms.

In the summer the natives fish either for salmon and trout or for the cod outside. In the winter they set their traps for mink, marten, otter, beaver, fox, ermine and bear. What they obtain of fish and furs is sold at the Hudson Bay Company’s Posts or to the agents of St. John’s merchants in charge of the fishing stations in the summer. Money seldom passes; flour, pork and molasses being the principal tender.

It is next to impossible to raise vegetables of any kind so far north, and fresh meat, except game, is unknown. A “Liveyere” will eat anything that comes to his trap or gun, including the disgusting looking porcupine, which is considered a delicacy.

A family with more enterprise than the majority has a small garden, strongly fenced as protection against the dogs, where they plant a few potatoes and turnips. The potatoes rarely ripen, as they are not planted much before July and the frost comes early in September. They eat the turnip tops for greens and sometimes succeed in digging a few half-grown turnip roots. Lettuce and radishes thrive, and at the Mission stations and Hudson Bay Company’s Posts where people live who know their value, an abundance of these luxuries can be found in season.

A few varieties of berries grow on the hills and marshes, which the natives prize highly and gather assiduously. Of these the favorite is the bake-apple, common also in Newfoundland. This berry is cup-shape, similar to a raspberry but larger. While growing on its stalk above a cluster of broad, dark green leaves, it is a rich red; when fully ripe it becomes yellow, like a drop of amber. Covered with water in a bottle tightly closed, the berries will keep indefinitely and are so preserved for the winter. The berry tastes flat and insipid, but the poor “Liveyere” considers it a rare delicacy, and beyond compare when sugar can be had.

Very few natives of Labrador ever saw a horse or cow; within the present year in Sandwich Bay and Hamilton Inlet where lumbering has been started, horses and oxen have appeared, much to the wonder of the people. Live-stock keeping of any kind is out of the question, because of the Eskimo or wolf dogs, which will attack and eat anything. Cows, sheep and goats could only be kept by barricading in a strong shed. The dogs are the curse of the country; anything possible for them to catch and kill they make their prey. Not content with killing, they will destroy anything their teeth will penetrate; boots and shoes are never safe within their reach.

Once the factor of the Post at Rigoulette tried to keep some hens and goats in a strong enclosure. Two dogs succeeded in getting in and four minutes’ time was sufficient to kill eight hens and tear four goats to pieces. Things they cannot eat or destroy they will steal and hide; one man lost his rifle in this way, another two handsome caribou heads. A human being is safe as long as he can stand on his feet; once down, the pack will tear him to pieces.

With all their faults the dogs are considered indispensable. Harnessed to the komatik or Eskimo sledge, they provide the only means of travel in the winter, and can cover distances in remarkably quick time, on but one feeding a day. In the summer months the dogs are rarely fed, but left to forage for themselves. Great quantities of the little fish called capelin are thrown up by the sea and die on the rocks and beaches; these the dogs eat, often wandering long distances from home in their search, remaining for weeks. In winter they are given seal blubber and dried capelin.

On Eagle River

Late one afternoon we entered Cartwright Run and sped on through the islands, familiar points rising on every hand. Soon Curlew Hill, with its observation stand and flag-staff, came into view and, rounding its barren flanks in the glory of a crimson sunset, the schooner slipped through the “tickle” and entered Sandwich Bay. As we came in sight of the Post there was much bustle and excitement. The blood red banner of the Hudson Bay Company fluttered to the peak of the flag-staff, there was a rapid discharge of fire-arms and a howl from the dog packs like all the demons of the lower regions let loose.

A boat shot out from the long wharf and soon we were wringing the hand of our friend Swaffield, master of the Post, and the New York publisher whom Dr. Grenfell had left on his way North instead of bringing him back. We were delighted to find ourselves once more amid the scenes of our happiness the summer before, but couldn’t feel quite happy until we heard again the song of Eagle River on its course through the hills. That song was twenty miles away, down the bay. We told the publisher he should surely catch a salmon to its music, and he did.

The morning following the arrival in Sandwich Bay dawned calm and beautiful. The sun poured a rich flood of golden light from a cloudless vault, striking the pinnacle evergreens against the sky line on the far hill tops to plumes of silvery fire. No breath of wind was abroad to fret the calm water where the hills reflected their strange shapes in the crystal depths. Nature brooded in a warm hush, as loath to stir at the beginning of another day.

A cable length from our mooring slumbered the Post, with its line of low white buildings facing the long plank walk. In the middle of the group stands the master’s dwelling with its greater pretense at architecture, its curtains and the flowers in the windows. Beyond, on either hand, straggle the store-houses, each with its big number in black, conspicuous on the white-washed door; and back on either side are scattered the little houses that go to make the settlement of Cartwright, one of the important points in lonely Labrador.

Back of the village rears big, brown Curlew Hill with its watch-tower and flag-staff; and on its northwest shoulder where everyone wanders at sunset time, to marvel at gorgeous glories such as our latitudes do not afford, and to launch dream ships up through the blue islands to that mysterious North beyond, slumber the dead in peace and silence I would hope to lie in.

A scroll of gray smoke rose into the breathless calm from the servants’ quarters and the sounds of re-awakening life broke the stillness. A boat put off from the wharf and a messenger came to say the master thought a perfect day was promised to visit the islands outside and shoot seals. If I approved, he would hasten arrangements for our early departure so we might anticipate the possible rising of wind later in the day.

After breakfast we paddled ashore equipped with guns and field-glasses. An unpropitious sign was a faint ripple, like a shiver, that crept across the placid bay and whispered of breezes to follow. White-haired Captain Tom, famous bear and seal hunter, was pottering over his boat, getting her ready, but pointed with superior wisdom to the cat’s-paws that were beginning to dimple the surface, and remarked we couldn’t expect to kill seals with a wind blowing. Finally Mr. Swaffield and the publisher joined the council, and as the zephyrs had now strengthened to a good stiff breeze blowing down the bay, we concluded to up anchor and run for the mouth of Eagle River.

So back to the Gladys, up canoes and to the whine and groan and clank of the capstan, we tore the reluctant anchor from its bed, hoisted our head sails and made for the “tickle” that joins that part of the bay forming a basin before Cartwright and the main portion, losing itself in sinuous arms among the mountains. It was cautious work for Captain Tom, who was pilot, to sail, what to him was so large a craft through the intricate course, but we came out safely, cast loose our foresail and mainsail, hoisted the gaff topsail and the main topmast staysail and tore away like mad. Everything was singing and humming with the breeze. Great banks of cloud flew across the sky, trailing blue shadows athwart the sun-lit mountain slopes, like sweeping robes of a hurrying host. Mighty Mealy lifted his ponderous bulk into the distance ahead, a crown of glittering snow adorning his ragged brow, while from the fissures and ravines of his riven flanks welled floods of royal purple to glorify the cold gray rock.

Running free before the wind we were soon in sight of the range of strangely mis-shapen hills out of which flows Eagle River from the south; and to the northwest stretched the line of blue peaks from whose fastnesses pour the waters of White Bear. With Skipper Tom in the bow giving orders and a sailor heaving the lead, we felt our way to anchorage.

The river brings down large deposits of sand, so the channel is constantly changing. Our schooner was larger and drew more water than any previously taken in; consequently it was not strange that we suddenly hit bottom. Fortunately it was only sand, and while the schooner rose and fell on the tide with disconcerting bumps, no damage resulted. The skipper and crew, however, were in a flutter of consternation and excitement. A kedge anchor with a strong cable was taken out in the punt and moored, then with all hands at the windlass the Gladys was warped off with no harm done.

Following that fortunate result we sought a safer spot, the anchor was dropped and we rode at rest on the rising tide. On one hand was the little settlement of Dove Brook, the winter home of many of the inhabitants of Cartwright. Beyond, a spot that a year before was a blade of silver strand piercing the blue water, was now covered with unsightly piles of freshly sawn lumber, and above the tree tops, back from the shore, hung a wreath of smoke showing the location of the mill. When we left the bay in August, the preceding year, it would have been hard to believe we would return to find the forest silence disturbed by the hum of a saw-mill; but it was only a slight illustration of the sure and certain invasion of all the silent places of the earth, where it is possible for greed to lay its hand.

The sun departing in crimson glory behind the western mountains whence flow the waters of White Bear, tipped the ripples of the tide with ruby sparks. The shades of approaching night stole from the forest-clad slopes, while above, the mountain tops were yet bathed in gorgeous lights.

The deck of the Gladys was soon thronged with visitors from the mill and Dove Brook, all hungry for news and anxious to talk. Some of the mill men were Nova Scotians and overjoyed to see people from the outer world. Interesting stories were told of their experiences the winter past, one man, an engineer, giving a thrilling tale of a sledge journey with his dangerously ill wife to the hospital at Battle Harbor.

He started with a team of dogs, his wife snug in a box on the komatik and a native for a guide. The native lost his way and became useless in a panic of fear. The engineer tried every means to spur him to effort, even holding a loaded and cocked revolver to his head, but without avail. Finally when death for all seemed certain, another sledge came through the trees carrying Dr. McPherson on his round of mercy. The wife reached the hospital and her life was saved.

Among our visitors were several who thought themselves in need of surgical and medical aid. One man had a badly lacerated hand from contact with the saw. The wound had been poorly cared for. One of the ladies cleansed and dressed it. Another had a sick wife and a third was the worried parent of a sick baby. We had to do something, so we sent some pellets that could do no harm if the imagination of the patient could assist in their doing no good. One man had a bad cough and another thought he needed a tonic. The writer prescribed for these two with satisfactory results.

Early the following morning the publisher, the writer and George Nichols of Deer Lake, Newfoundland, our canoe-man and guide, embarked and paddled into the mouth of Eagle River, bound for a day’s fishing. I had arranged for the ladies to come later in the ship’s boat with some of the crew and bring the lunch. It was a sparkling morning. The air had the real Labrador snap and was rich with ozone. It did not need the regular dip of the bow paddle to send my blood leaping, but the healthy exercise was in happy accord with the other conditions.

Our light craft slipped by the little clump of houses on Separation Point and drew up to the Hudson Bay Company’s schooner, Alpha, anchored for the night on her cruise around the bay collecting the salmon catch. I must have a word of welcome from Skipper Harry and his crew. Then with our prow pointing to the strange, mis-shapen humps of hills that mark the course of Eagle River we sped up against the strengthening current.

The island of rocks on which perches the Salmon Post gradually rose to our view with its little white house and jumble of half-dismantled buildings where years ago salmon in enormous quantities were canned. Our Pacific Coast canneries long ago drove that industry out, and today the salmon are preserved in huge hogs-heads with salt and shipped to England in barrels holding three hundred pounds, for which the company pays the native twenty dollars per barrel. At the Post on the island the company maintains a crew during the run of the fish and puts its nets at the best points of the river below the large pool.

Just before reaching the island we passed a small, weather-stained hut which was to me of much interest. The summer previous we had visited it to see a strange old man living there, bedridden and in great apparent need. The man’s name was Lethbridge; he was an Englishman, a tinsmith by trade, who came to these wilds a young man more than fifty years ago, to make the tins or cans in which the salmon were preserved. He married an Eskimo woman by whom he had three sons and a daughter, who was caring for him devotedly. His duties as tinsmith occupied him part of the year only, and in the winter he followed trapping. He was successful; but as age crept upon him he became a miser, not of money of which there was little, but of furs. He refused absolutely to sell his furs and stored them in a large chest. When I called, this chest was close to the head of the bed where he lay helpless in body, but with keen intelligence beaming from eyes of unnatural brilliance, long snowy hair falling about his shoulders and a patriarchal beard of white.

In recent years since furs have increased so much in value, the fame of the chest and its contents, guarded so jealously by this grim trapper fighting hard against the creeping shadows of death, has spread, and brought many wandering dealers to try and tempt old Lethbridge to raise the lid and barter his treasure. All approaches, all offers, were repulsed with the hoary head rolling from side to side in negative reply and disdain flashing from the caverned eyes. None knew how many priceless silver fox or splendid sable pelts lay in that chest, and the story told on steamer and schooner, in tilt and lodge lost nothing by repetition.

The master of the Post on whom he was dependent for the issue of such frugal supplies as he was willing to accept, tried vainly to acquire the furs. In late years, for making tin tea-kettles and doing repairs for the Company, it became the miser’s debtor for about a hundred dollars, on which he would consent to draw only enough to keep body and soul together; and no appeal to better his own condition or that of faithful Elizabeth could soften for an instant his hard determination to hold the mystery of the chest with its hoard of pelts.

We carried nourishing food to the lonely hut and some of our men went down from camp and split wood for Elizabeth. Her half-breed brothers never burdened her with attention. When we left it was expected the old man would not live many days. But he had lived another year; and as we passed in the canoe Elizabeth stood at the door shading her eyes with her hand to look at us. When the time comes I will try to describe the scene we witnessed at Cartwright when Elizabeth and her brothers brought all that was mortal of the old man in a boat down through the “tickle” and buried it in the cemetery on the slope of hill looking toward the red sunsets in the west and the blue islands to the north. When we reached the Salmon Post at the foot of the quick water where the river makes its last plunge before it mingles with the tide, we ran the canoe on the smooth shelving rock and stepped out to shake hands with Ned Learning, in charge of the fishing. We took the publisher into the old buildings to see the ruined boilers and other remains of the Post industry; then re-embarked to be ferried to the trail while the guide poled up through the rapids.

The Salmon Pool

The walk of a mile over the narrow winding trail was a joy to be remembered. What we call spring flowers were in their glory, and it was past middle August. The air was heavy with the sweetness of the Linnaea borealis or twin-flower. The growth was mostly spruce and fir, with occasional white birches gleaming like shafts of silver against the somber shade, and now and then, feathery larches. The sunlight filtered through the dim, filmy green, leaving splashes of gold on the forest carpet. A gentle breeze stirred the branches and set the golden splashes dancing and dodging in capers that dazzled the eyes.

We came out at the clearing made the year before where we built the camp, and found George ahead of us. Our nice dining-table of planed pine boards and the frames of our store-houses remained intact. In any other hunting country I have visited, the table would have been stolen by the time we were out of sight.