* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: The Life and Letters of Sir Henry Wotton Volume 1

Date of first publication: 1907

Author: Logan Pearsall Smith (1865-1946)

Date first posted: May 20, 2023

Date last updated: May 20, 2023

Faded Page eBook #20230542

This eBook was produced by: Marcia Brooks, Howard Ross & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

This file was produced from images generously made available by Internet Archive/American Libraries.

Emery Walker Ph Sc

Sir Henry Wotton

‘Aetatis Suae 52 Ao 1620’

From the original painting in the Bodleian Gallery Oxford

THE LIFE AND LETTERS

OF

SIR HENRY WOTTON

BY

LOGAN PEARSALL SMITH

IN TWO VOLUMES

VOL. I

OXFORD

AT THE CLARENDON PRESS

1907

HENRY FROWDE, M.A.

PUBLISHER TO THE UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD

LONDON, EDINBURGH

NEW YORK AND TORONTO

Among the contemporaries of Shakespeare an interesting but little-known figure is that of the poet and ambassador, Sir Henry Wotton. It is still remembered that he was the author of two or three beautiful lyrics which are to be found in every anthology; that he went as ambassador to Venice, and fell into temporary disfavour owing to a witty but indiscreet definition of his office; and that afterwards he became Provost of Eton, where he was visited by the young Milton, and where he fished with Izaak Walton, who quoted his sayings in the Compleat Angler, and wrote an exquisite portrait of his old friend. But behind the tranquil old age described by Walton lay many years of travel and participation in public affairs, much acquaintance with men, and with courts and foreign lands. The period indeed of Wotton’s life covers the whole of what is known as the great age of Elizabethan literature, from the defeat of the Armada to the death of Shakespeare, and extends almost to the outbreak of the Civil Wars. It is hardly necessary, therefore, to apologize for the publication of his letters (which for the most part have remained hitherto unpublished), and a study, longer and more complete than any which has yet been attempted, of his career and character and public services.

Sir Henry Wotton was the most widely cultivated Englishman of his time. A ripe classical scholar, an elegant Latinist, trained in Greek by his studies with Casaubon, he was an admirable linguist in modern languages as well. He corresponded with Bacon about natural philosophy, and was the friend of most of the learned men of that epoch, both at home and on the Continent; the first English collector of Italian pictures, he brought from Italy, where he lived many years, the refined taste in art and architecture, the varied culture of antiquity and the Renaissance, which was then only to be derived from Italian sources. His experiences of life were exceptionally varied, even in that spacious and enterprising age. Leaving England in 1589, he spent some time abroad in study and adventurous travel; he was much about the Court of Queen Elizabeth; he accompanied Essex to Ireland and on his famous voyages; he went in the service of an Italian Duke to the Court of James VI; and when that king succeeded to the English throne, was sent as his ambassador to many princes. Famous in his own day as a ‘wit and fine gentleman’, he deserves to be remembered as a noble example of that much maligned class, the ‘Italianate’ Englishmen—one who, with all his foreign culture, never lost the sincerity and old-fashioned piety of a ‘plain Kentish man’. Although his services as an ambassador were not always of the first importance, and his longer literary works are of a somewhat disappointing character, he yet may be counted as one of the great Elizabethans, with whom high actions were so remarkably combined with high literary expression. For Sir Henry Wotton was endowed with one gift, that of a letter-writer, which none of his more famous contemporaries possessed. Indeed, the very qualities or faults that stood in the way of his complete success, either as a statesman or author; the witty frankness that caused him to be a somewhat indiscreet diplomatist; a certain desultoriness of mind, combined with a great love of leisure and conversation, which hindered the completion of most of his literary tasks, all these made him an admirable correspondent. And letter-writing was not only one of the great pleasures of his life, but, as ambassador, almost his main duty. Among the somewhat formal and colourless epistles of that age his letters are remarkable for their wit, their beauty of phrase, and the impress of his kindly and meditative nature. His shortest note could not have been written by any one else; his long diplomatic dispatches are enlivened by reflections, epigrams, and bits of personal comment and observation. Sometimes eloquent, sometimes intimate, now informed by cynical but not unkindly knowledge of the world, and now by honest religious zeal, he put all his stores of thought and experience into his letters, in a way that was unique at the time and is unusual in any age. Any one who has read those written in the leisure of Venice or Eton will, I think, agree that it is no exaggeration to call Sir Henry Wotton the best letter-writer of his time—the first Englishman whose correspondence deserves to be read for its literary quality, apart from its historical interest. His style, although it may seem at first, to those not familiar with the style of the time, somewhat courtly and elaborate, yet possesses great qualities of beauty and distinction, and much of that quaint richness of thought and phrase which we associate with authors of a later date—George Herbert, Sir Thomas Browne, or Izaak Walton.

Of subsequent writers, Walton owed more than any one else to Sir Henry Wotton, and may be regarded as his disciple and follower. In the Life of Donne and the Compleat Angler he accomplished tasks which Wotton had left unfinished; and he seems to have caught his simple yet courtly grace of style from the example and discourse of the old Provost. The two men, indeed, had much in common; both were lovers of fishing and quiet days; both possessed the same musing piety and serenity of soul; and both were devoted members of the English Church, whose spirit Walton has so beautifully expressed in his Lives, and in whose orders Sir Henry appropriately ended his life, after striving so long as an ambassador for its defence and advancement. Animas fieri sapientiores quiescendo, ‘that minds grow wiser by retirement,’ was the motto in which Wotton summed up the experience of his active years: ‘Learn to be quiet,’ the text his fellow fisherman wrote at the end of his most famous work.

Of Sir Henry Wotton’s correspondence enough was printed in the seventeenth century to give him a high reputation as a letter-writer. In the first edition of the Reliquiae Wottonianae, published in 1651, Izaak Walton added to Wotton’s essays and poems fifty-eight of his letters. Eight more were added to the second edition of 1654, and in 1661 forty-two new letters, almost all addressed to Sir Edmund Bacon, were printed in a little volume, which is now excessively rare. These, with the addition of thirty-one fresh letters and dispatches, were incorporated in the third edition of the Reliquiae in 1672, and finally in 1685 the Reliquiae was republished with thirty-four more letters, all but one addressed to Lord Zouche, and all written in the early period of Wotton’s life. Izaak Walton seems to have put together Sir Henry Wotton’s letters and papers in the Reliquiae Wottonianae pretty much as they came to hand, with small regard to date or order. Little or no improvement was made in the subsequent editions, and the result is extremely confusing. Letters written in the same year are scattered over different portions of the book, many are without date or address, and there are no notes of any kind. No one has yet attempted to re-edit this correspondence, although the Reliquiae Wottonianae has always been prized by lovers of seventeenth-century literature, and the need of a new edition has often been remarked. ‘His despatches,’ Carlyle wrote of Wotton in his Frederick the Great, ‘are they in the Paper Office still? His good old book deserves new editing, and his good old genially pious life a proper elucidation by some faithful man.’[1] When, for lack of a more competent person I had undertaken the task thus indicated by Carlyle, I soon found it to be one of greater magnitude than I had thought at first. For although in 1850 the Roxburghe Club had published a volume containing the sixty-five letters and dispatches of Wotton’s preserved at Eton; and in 1867 thirteen more, preserved at Corpus Christi College, Oxford, had been printed in vol. xl of Archaeologia, much the greater part of his correspondence, and many of his most interesting letters, had never yet been printed, and were to be found widely scattered in various manuscript collections, college libraries, the muniment rooms of country houses, and Italian archives. In the Record office alone there are about five hundred letters and dispatches; others are preserved in the British Museum, the Bodleian, the archives of Venice, Florence, and Lucca. Others, of which the originals have disappeared, have been published in different volumes of memoirs and correspondence. I have found altogether nearly one thousand of Wotton’s letters and dispatches, published and unpublished, and it is possible that there are others which have escaped my search. These documents can be roughly divided into three classes, familiar letters, news-letters, and diplomatic dispatches. The familiar letters are generally short, of an intimate character, and addressed to personal friends. The news-letters are of a type well known to historical students—long accounts of the occurrences of the day, which were sent before the date of newspapers to political correspondents, in exchange for similar budgets of information. The dispatches were addressed to the King or the Secretary of State, and contained the ambassador’s account of his negotiations, and his views on questions of diplomatic policy. But any such classification can only be extremely loose and vague. The familiar epistles and dispatches are often news-letters as well, and the political correspondence frequently contains much of a personal and intimate character.

To print the whole mass of Wotton’s correspondence would require perhaps ten volumes, instead of the two to which I am limited; and many of the dispatches, which are often of great length, giving as they do the history in detail of forgotten and unimportant negotiations, would have little interest save for special students of the foreign policy of James I. The plan of these volumes can be briefly indicated. I have first of all written a life of Sir Henry Wotton, in which I give an account of the events of his career, and his various interests and activities, based on a study of his complete correspondence, and many other contemporary sources of information. I then print in full his familiar letters, and many of his news-letters and dispatches, with extracts from others, choosing those which are most interesting and characteristic, or which give an account of the important negotiations in which he was engaged. While printing as much as possible hitherto unpublished material, I have added in their place the letters from the Reliquiae Wottonianae, which are now for the first time annotated and arranged according to their dates. In the successive editions of the Reliquiae various misprints crept into the text; I have collated each letter with the text of the original publication, which I follow in this edition, except when I state otherwise. The printer, however, of the third edition seems to have had access to the manuscripts of the letters, and in a few cases where the letters are more complete I follow this text. The holographs of some of the printed letters have been preserved, and of these I have collated the text with the originals. As Wotton’s letters are here printed partly from manuscripts written by himself, partly from transcripts of which the originals are lost, partly from letters dictated to secretaries with an orthography of their own, and partly from printed copies in which the original spelling is not preserved, I was met with a dilemma in regard to the spelling and punctuation, for which there was no completely satisfactory solution. To give, as is the modern custom, literal transcripts of the letters printed from manuscripts, with Wotton’s spelling, punctuation (or rather lack of it), and contractions, the varying orthography of his secretaries and transcribers, and the modern spelling of the printed letters, would have resulted in an orthographical chaos which I might have faced had it not been for the long and intricate numerical ciphers which frequently occur, and which, if reproduced, would have made the task of reading extremely difficult. I have, therefore, adopted what seemed to me the least unsatisfactory alternative; and, for the sake of clearness and uniformity, have modernized the spelling and punctuation throughout, except in the proper names. It is certain that one loses something by the loss of quaint and old-fashioned spelling; whether one does not lose more by preserving it is an open question. In an age like the Elizabethan, when every one spelt according to chance or whim, to reproduce this chaotic orthography is doing a certain injustice to a writer like Sir Henry Wotton, and gives an odd and almost illiterate character to the letters of one who wrote in the fashion of the highly educated gentlemen of his time. But, as I say, the dilemma is one for which (to my mind at least) there is no completely satisfactory solution;[2] I have at least followed the example of the classic in this style and for this period. I refer, of course, to Spedding’s Letters and Life of Francis Bacon.

I give in an appendix a list of Sir Henry Wotton’s writings, and of letters, printed and unprinted, arranged as accurately as I could arrange them in chronological order, with indications of the manuscript collections or printed volumes in which they are to be found.

In the second appendix I discuss certain points about the date and authorship of The State of Christendom (published under Sir Henry Wotton’s name in 1657), which could not be adequately treated in the narrative of his life. The third appendix contains all the important information which I have gathered about Wotton’s friends and correspondents. As the lives of many of these appear in The Dictionary of National Biography, a reference to its pages is often sufficient, though I am able sometimes to supplement the information contained in that treasure-house of facts. Of those who are not mentioned in this great dictionary I have attempted to give a more complete account. Sir Henry Wotton belonged to a group of cultivated men, who shared his tastes and interests, and to know him we must know his friends as well. The fourth appendix contains a list of Italian books compiled by Wotton, and extracts from the commonplace book of one of Wotton’s secretaries—a Character of the first Earl of Salisbury, and notes of the ambassador’s table-talk and witty sayings.

Sir Henry Wotton’s correspondence divides itself into three periods. In the first we have a record of the life of a young Oxford man abroad in the reign of Queen Elizabeth. In the second period the ‘poor younger brother’ has become a diplomatist charged with weighty and important negotiations. Wotton was sent as special ambassador, once to Holland, and once to Vienna, in the troubled times before the outbreak of the Thirty Years’ War, to try to avert the impending conflict. On the first occasion he saw much of the great Dutch leaders, Barneveldt and Count Maurice of Nassau; on the second he negotiated with the Catholic Princes, Maximilian of Bavaria and the Emperor Ferdinand II. He was also twice accredited to the Duke of Savoy; but it was at Venice that he lived as resident ambassador, and the main part of his diplomatic activity is connected with Venice and Italy, in which country he was for many years the only English envoy. Although most of the negotiations between Venice and England were not of great importance, there are incidents in his career as ambassador in Italy which still possess considerable historic interest. Chief among these is the support he was empowered to offer the Venetians in their famous quarrel with the Pope—one of the most courageous and successful actions in James I’s not very courageous or successful foreign policy—and the subsequent attempt, in secret combination with certain Venetians, the chief of whom was the great historian and statesman, Paolo Sarpi, to introduce religious reform into Venice.

A study of Wotton’s papers throws considerable light on the hitherto obscure history of this movement, and especially on the delicate and much-debated question of Paolo Sarpi’s connexion with it. As an attack made on the Pope almost in his own country, in the midst of the Catholic Reaction, by members of the English Church, under the guidance and advice of a Servite friar, who was the greatest of living Italians, this movement deserves to be better known.

Of more general interest, perhaps, is the contribution which I hope these volumes will make to our knowledge of English diplomacy—a subject which has not yet found its historian. Wotton’s letters and dispatches give an intimate picture of an English ambassador’s life in the time of Shakespeare; how he travelled, how he lived in the place of his charge, of whom his household was composed, and how such diverse duties as kidnapping and religious propaganda, the robbing of the posts and the suppression of pirates, were all part of his official occupation.

The materials in printed books and manuscripts for the study of Wotton’s life seem extremely abundant, when we consider the scanty information which has come down to us about many of the great Elizabethans. That his diplomatic papers should have been preserved is not surprising; but that nearly fifty letters should remain, written between 1589 and 1593, from Wotton’s twenty-second to his twenty-sixth year, when he was an obscure youth wandering about Europe, is somewhat remarkable, if we remember that James Spedding, with all his research, was only able to find seven letters written in the same early period of Francis Bacon’s life. For Wotton’s career as an ambassador, the mass of material becomes almost unmanageable; and, indeed, the difficulty of his biographer is not lack of information, but the means of condensing it into a book of reasonable proportions. This is particularly the case with regard to his life in Italy. In travelling to Venice he went into the province, and came under the observation of a government, whose officials were, for many centuries, the memoir-writers of Europe. In the famous archives of Venice are preserved full accounts of all his negotiations with that State. Sir Henry Wotton was not only a charming letter-writer, but a witty and accomplished orator as well, and not the least interesting of the documents in these archives are the verbatim reports, taken down by shorthand, of many hundreds of the speeches of this ambassador, who was a distinguished man of letters in the greatest age of English literature. These speeches are, of course, in Italian, a language almost as familiar to Wotton as his own; those for the period of Wotton’s first embassy, from 1604 to 1610, have been transcribed and translated by Mr. Horatio Brown in the tenth and eleventh volumes of the Calendar of Venetian State Papers. I have made extensive use of these admirably edited Calendars in my notes, and only regret that for the period of Wotton’s two later embassies I am compelled to rely on my own transcripts from the Venice archives. The correspondence of De Fresnes-Canaye, who was French ambassador at Venice for some years after Wotton’s arrival, has been published; that of the Tuscan residents there, Montauto and Sachetti, I have examined in the Florence archives. From these sources, from Wotton’s dispatches, and other documents in the Record Office, from letters written by his chaplain Bedell, and other members of his household, I have endeavoured to create a living and vivid picture of Sir Henry Wotton’s life and activities in Venice. If I have not succeeded in my attempt, the fault must be my own.

To the third and last period, the period of Wotton’s life at Eton, belong the letters which possess perhaps the most personal and literary charm. The courtier and man of the world had returned to the books and religious thoughts he had never really deserted; and the correspondence of this time, with Izaak Walton’s account of the Provost’s days and conversation, gives a picture of a gentle, pious, old age, spent among congenial friends and beautiful surroundings, which one would find it hard to equal in any literature.

A word remains to be said concerning the secondary sources of information about Sir Henry Wotton. His life has been written seven times, but never at great length, or by any one who has availed himself of Wotton’s extant correspondence, and all the other manuscript sources of information. Izaak Walton’s famous and inimitable biography is mainly a portrait of Wotton in his old age; and although Walton gives a short sketch of Wotton’s earlier career, his information is plainly of a hearsay character, and often inaccurate and confused. I cannot find that he made use of more than one or two of the letters which he himself had printed, even when in the second edition of the Reliquiae he added a number of pages to the biography prefixed to the first edition. But it would be pedantry to ask for dates and accurate statements from Izaak Walton, who could give in his own way, and his own golden style, something of such infinitely greater value—the conversation, the character, and the very soul of the man about whom he wrote. Save for the last years, therefore, of Wotton’s life, when Walton was his friend and often saw him, I do not place much reliance on his statements about dates and facts.

The eighteenth-century life of Sir Henry Wotton in the Biographia Britannica (1740) is of some interest, and adds a few facts and dates to Izaak Walton’s account. The next on the list is the Rev. John Hannah’s scholarly little book, Poems by Sir Henry Wotton, Sir Walter Raleigh, and Others, published in 1845. This is the most important piece of research on the subject that has yet been made. It gives the result of a considerable amount of original investigation; and is particularly valuable for the bibliography and variant readings of the poems which it contains, and for the indication of letters by Wotton among the Bodleian manuscripts. As the portion of the book containing a full account of the poems by Wotton, and the poems attributed to him, has been reprinted under the title of The Courtly Poets (1870), I have not included in these volumes any discussion of Wotton’s poems, or the poems themselves, except where I have been able to add to the information collected by Mr. Hannah.

In 1866 Mr. (afterwards Sir) Thomas Duffus Hardy published, as Deputy Keeper of the Record Office, a Report on the Documents in the Archives and Public Libraries in Venice, from Mr. Rawdon Brown’s transcripts, which contained a good deal of fresh information about Wotton’s career in Venice. Both these two volumes, and the life in the Biographia Britannica, appear, however, to have escaped the notice of Sir Henry Wotton’s subsequent biographers.

In 1898 Dr. Adolphus W. Ward published Sir Henry Wotton, a Biographical Sketch. This is more of a literary appreciation than a biography; and while interesting on account of Dr. Ward’s wide knowledge of the period, makes little claim to original research. In 1899 Mr. A. W. Fox included in his Book of Bachelors a life of Wotton which is of value for the references to the published correspondence of Wotton’s contemporaries, Casaubon’s letters, the Winwood Memorials, the reports of the Historical Manuscripts Commission, and many other volumes.

An article in the Edinburgh Review for April, 1899, is a sympathetic appreciation of Wotton’s character; and its author moreover has examined Wotton’s letters and dispatches in the Record Office, and those preserved at Eton (which were published by the Roxburghe Club in 1850), and made use of the information contained in these documents. Mr. Sidney Lee’s article in the Dictionary of National Biography is in the main a restatement of the information gathered by Dr. Ward and Mr. Fox, with however some additional references to printed sources. Both for the indication of sources, and for the general point of view, I am under a debt of obligation to these authorities. It is hardly necessary to say that Professor Gardiner’s great history of this period has been of the greatest assistance to me in many ways.

The new material of importance in these volumes may be briefly indicated. To Izaak Walton’s account of Wotton’s boyhood and Oxford life I have not been able to make fresh additions of any importance. For his first journey abroad, from 1589 to 1594, the only source of information hitherto available is the collection of letters to Lord Zouche printed in the fourth edition of the Reliquiae. I have reprinted with notes all of these which come within the scheme of this work, and have added to them six hitherto unpublished letters of considerable importance, as well as some references to him in the correspondence of friends he made abroad. I have also been permitted to see transcripts of seven of Wotton’s letters preserved in the Hofbibliothek at Vienna. For Wotton’s life in the service of Essex, and at the English Court (1594-1600), which is the period about which we have least information, I have added to the one letter in the Reliquiae seven others, two from the printed correspondence of Casaubon, and five from the Record Office and the Cecil Papers, one of which has already been calendared. I also add three unsigned letters which I found in the Burley Commonplace Book, and which I believe to have been written by Wotton in Ireland and sent to John Donne. These three are the only letters I am printing which may possibly have been written by some one else. But I think they are Wotton’s, and have therefore included them in his correspondence. I have found eleven letters written during Wotton’s second sojourn abroad (1600-1604), two in the Record Office, seven in the Florence archives, and two in the unpublished correspondence of Isaac Casaubon, now in the British Museum. None of these eleven letters have been printed or calendared; the two addressed to Casaubon were, however, first discovered by Mark Pattison. To Izaak Walton’s account of the journey to Scotland with the casket of antidotes I add information of some importance from documents in the Record Office and the Florence archives.

Of the three hundred and sixty letters and dispatches written during Wotton’s first embassy in Venice (1604-10) seventeen have been printed; I am now printing 140 complete or in part. For the remainder of Wotton’s active life until he retired to Eton there are more than four hundred letters still existing. Of these 120 have been printed and five calendared; I include 125 unprinted ones in these volumes, and reprint many of the others.

For the period of Wotton’s life at Eton, Izaak Walton’s biography and the seventy-six letters printed in the Reliquiae are the main authorities. To these I have added nineteen more letters, four from volumes of printed correspondence, eight from the Record Office, which have been calendared, and seven that have not been published.

To the new information about Wotton in the Venice archives, and in Mr. Horatio Brown’s calendars, I have already referred. I have attempted to identify all of Wotton’s references to events and people, and to discover the sources of his frequent Latin and occasional Greek quotations. In this I have received considerable help from correspondents in Notes and Queries, and in particular to Mr. E. Bensly, who has identified several of the Latin references. As Wotton sometimes mentions very obscure people, and quotes almost invariably from memory, in phrases of his own invention, there are a number of points which have eluded my research, and the absence of a note must be taken as a confession of ignorance on my part.

It only remains to express my thanks to the late Marquis of Salisbury, to the late Right Hon. G. H. Finch, to the authorities of the Bodleian Library, the Provost and Fellows of King’s College, Cambridge, and the President and Fellows of Corpus Christi College, Oxford, for permission to transcribe and print manuscripts in their possession. Mrs. Hervey Bruce has most kindly sent me three of Wotton’s letters from the recently-discovered manuscripts at Clifton Hall; and Mrs. S. A. Strong, the Duke of Devonshire’s librarian, has allowed me to include in these volumes the letters found at Lismore Castle by the Rev. A. B. Grosart, and printed in his edition of the Lismore Papers. On inquiring whether any of Wotton’s letters to his friend Blotius were preserved in the Hofbibliothek at Vienna, I was informed that there were nine of his letters there, which Herr Gottlieb of that library was intending to publish in his edition of the Blotius correspondence. Permission was given me to print one of these letters, addressed to Wotton’s mother; and I was allowed to see transcripts of the others, and to make use of information contained in them for my life of Wotton. I must not omit to thank the director of the Hofbibliothek and Herr Gottlieb for their kindness in this matter. I am under a great debt of obligation to the late Professor York Powell for kind encouragement, and I could not easily express how much I owe to his successor, Professor C. H. Firth, for his advice and help in many ways. The Rev. W. C. Green, with great generosity placed in my hands a manuscript edition which he had prepared of the letters in the Reliquiae Wottonianae; this has been of great service to me in the dating of undated letters, and the identification of names and places. He also supplied me with translations of Wotton’s Latin letters, which, however, owing to exigences of space, I have been forced to omit. But I am glad to make an acknowledgement of all that I owe to his help and kindness.

To Sir Henry Maxwell-Lyte, Deputy Keeper of the Records, to Mr. Warre-Cornish at Eton, to Mr. Horatio Brown at Venice, to Mr. F. Madan of the Bodleian Library, and to Mr. Doble and Mr. Milford of the Clarendon Press, I am indebted for much in the way of help and advice; Professor Bywater, the Rev. J. H. Pollen, S.J., Mr. R. A. Austen Leigh, Mr. Roger Fry, and Major Martin S. Hume have been most kind in answering inquiries and supplying me with information. Mr. Verity has kindly allowed me to make use of some notes in his edition of Milton’s early poems; my mother has helped me by reading this book in proof and making many suggestions.

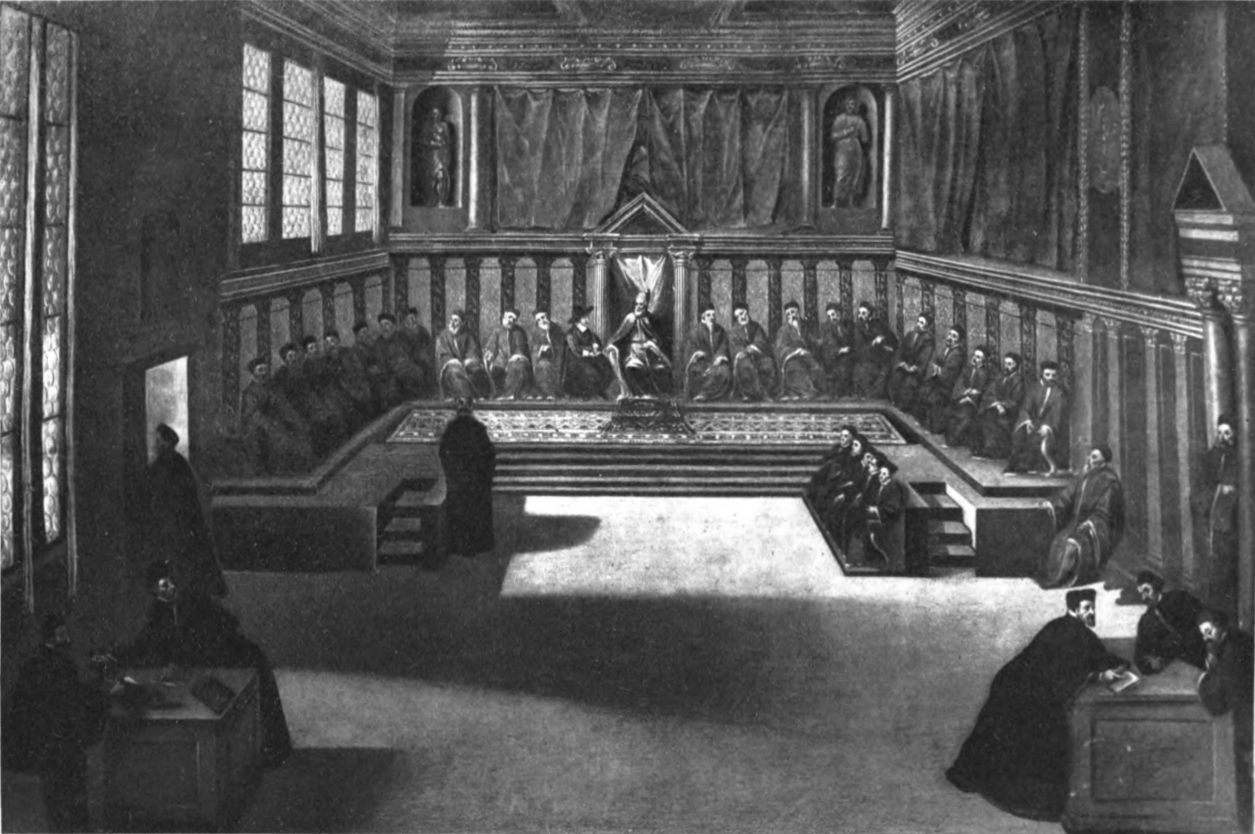

The frontispiece to vol. i is from a portrait of Sir Henry Wotton by an unknown painter, presented to the University of Oxford by Sir Edward Stanley in 1780, and now in the Bodleian gallery. The picture of an ambassador’s reception at Venice (p. 48), by Odoardo Fialetti, was bequeathed by Wotton to Charles I (see i, p. 216), and is now at Hampton Court. The ambassador’s figure (p. 64) is almost certainly a rough sketch of Wotton himself. These pictures are reproduced by permission of the Lord Chamberlain. The portrait of the first Earl of Salisbury (i, p. 452) is from a mosaic presented by Wotton to the second Earl, and now at Hatfield. It is published by permission of the Marquis of Salisbury. The frontispiece of vol. ii is from the portrait in the Provost’s Lodge at Eton, and is printed from a block kindly lent by Messrs. Spottiswoode & Co., Ltd. The specimen of Wotton’s handwriting (ii, p. 224) is from a MS. in Corpus Christi College, Oxford, and is reproduced by permission of the President and Fellows of the College. The portrait of Paolo Sarpi (ii, p. 370) is in the Bodleian gallery; a discussion of its history and authenticity will be found in vol. ii, pp. 478-9.

|

Book iii. chap. xiv, note. |

|

Any one interested in Sir Henry Wotton’s spelling will find his letters and dispatches textually reproduced in the volume of Eton Letters and Despatches, published by the Roxburghe Club, and in Archaeologia, vol. xl. |

It was Sir Henry Wotton’s usual, though by no means invariable, custom to date his letters according to the style of the country in which he wrote them, and he would generally give some indication of the system he was employing. Thus his letters written from Vienna are most, if not all, dated according to the ‘style of Rome’; that is, the Gregorian calendar promulgated by Gregory XIII in 1582, adopted by the German Catholics in 1584, and now almost universal in Europe. The ‘style of Venice’ was the same as that of Rome, save that the legal year began on March 1. The ‘stylo veteri’, or style of England, which Wotton always employed at home, and sometimes abroad, is of course the Julian or old style, according to which, in Wotton’s time, the days of the month were ten days behind those of the Gregorian calendar, and the legal year began (in England) on March 25. Thus a date, say February 10, 1608, would mean February 10, 1609, in the modern reckoning, if the style of Venice were employed, or February 20, 1609, if written in the English style. Wotton occasionally slipped into the error of confusing two styles, giving the day of the month according to one, and the year according to the other; but towards the end of his residence abroad he frequently indicates both the old and the new style, as for instance December 2/12, 1622. He places the dates of his letters sometimes at the beginning, sometimes at the end; for the sake of uniformity I have put them in each instance at the head of the letter, and when there is any confusion I give in brackets the correct date according to the modern reckoning. In the other cases where these brackets ⟨ ⟩ occur, they are used to indicate (unless it is otherwise stated) that I have supplied a word to fill up a lacuna or imperfection in the text. When words are spaced in the text, as for instance Rome, it indicates that they are in cipher in the original.

Many of Sir Henry Wotton’s letters are undated; these I have arranged in accordance with the endorsement or internal evidence, and in each case I give, at the head of the letter or in a note, my reasons for the arrangement. There is, however, a small number of letters which contain no definite indications of their date, and the placing of these is, and must be, of course, highly conjectural and uncertain. I can only say that I have done my best to arrange the letters in correct chronological order; and if I have erred, I hope I shall meet with the indulgence of those who know the extreme difficulty of dating undated documents of this period.

In the ‘Life of Sir Henry Wotton’, which follows, I have given the dates of English events according to the English and the Venetian according to the Roman calendar. But for days before March 1 or March 25 I give the years in the modern reckoning, following in this the example of Spedding and Professor Gardiner.

| VOLUME I | |

| PAGE | |

| Preface | iii |

| Note on the Chronology and Dating of Sir Henry Wotton’s Letters | xvii |

| Principal Abbreviations used in the Footnotes | xxi |

| LIFE OF SIR HENRY WOTTON. | |

| Chapter I. Parentage and Early Years, 1568-88 | 1 |

| Chapter II. First Visit to the Continent, 1589-94 | 8 |

| Chapter III. In the Service of Essex; Second Visit to the Continent, 1594-1603 | 27 |

| Chapter IV. Wotton’s first Embassy in Venice, 1604-10 | 46 |

| Chapter V. Wotton’s first Embassy in Venice—Continued; Negotiations with the Republic; Religious Propaganda, 1604-10 | 72 |

| Chapter VI. Negotiations with the Duke of Savoy; Wotton’s Temporary Disgrace, 1611-14 | 113 |

| Chapter VII. Ambassador at The Hague; the Treaty of Xanten, 1614-15 | 134 |

| Chapter VIII. Second Embassy in Venice, 1616-19 | 144 |

| Chapter IX. Embassy to Ferdinand II, 1620 | 167 |

| Chapter X. Third Embassy in Venice, 1621-23 | 176 |

| Chapter XI. Wotton Provost of Eton College; Last Years and Death, 1624-39 | 194 |

| Sir Henry Wotton’s Letters, 1589-1611 | 227 |

| Glossary | |

| Index | |

| Henry Wotton, from the original portrait by an unknown painter in the Bodleian Library | Frontispiece |

| An Audience with the Doge, from the original painting by Odoardo Fialetti at Hampton Court | To face p. 48 |

| Detail from the Same (Portrait of Wotton) | To face p. 64 |

| Portrait of Robert Cecil, First Earl of Salisbury, from the mosaic at Hatfield House, after a painting by John de Critz | To face p. 452 |

S. P. Dom. = State Papers, Domestic, in the Public Record Office.

S. P. Ger. Emp. = State Papers, Foreign, Germany, Empire, in the Public Record Office.

S. P. Ger. States = State Papers, Foreign, Germany, States, in the Public Record Office.

S. P. Holland = State Papers, Foreign, Holland, in the Public Record Office.

S. P. Ital. States = State Papers, Foreign, Italian States, in the Public Record Office.

S. P. Savoy = State Papers, Foreign, Savoy, in the Public Record Office.

S. P. Scot. = State Papers, Foreign, Scotland, in the Public Record Office.

S. P. Tuscany = State Papers, Foreign, Tuscany, in the Public Record Office.

S. P. Ven. = State Papers, Foreign, Venice, in the Public Record Office.

Docquet Books = Docquet Books in the Public Record Office.

Add. MSS. = Additional MSS. in the British Museum.

Burney MSS. = Burney MSS. in the British Museum.

Cotton MSS. = Cotton MSS. in the British Museum.

Eg. MSS. = Egerton MSS. in the British Museum.

Harl. MSS. = Harleian MSS. in the British Museum.

Lansd. MSS. = Lansdowne MSS. in the British Museum.

Sloane MSS. = Sloane MSS. in the British Museum.

Stowe MSS. = Stowe MSS. in the British Museum.

Ashm. MSS. = Ashmolean MSS. in the Bodleian.

Rawl. MSS. = Rawlinson MSS. in the Bodleian.

Tanner MSS. = Tanner MSS. in the Bodleian.

Arch. Med. = Archivio Mediceo, Florence.

Arch. Turin = Archivio di Stato, Turin (Lettere Ministri Inghilterra referred to).

Arch. Ven. = Archivio di Stato, Venice.

Atti = Atti degli Antelminelli, Archivio di Stato, Lucca.

Burley MS. = Commonplace Book, Burley-on-the-Hill, Oakham.

C. C. C. MSS. = MSS. in the Library of Corpus Christi College, Oxford.

Cecil MSS. = MSS. at Hatfield House.

Clifton MSS. = MSS. at Clifton Hall, Nottingham.

Esp. Prin. = Esposizioni Principi, Archivio di Stato, Venice.

Esp. Prin. filze = Esposizioni Principi, Archivio di Stato, original files.

Eton MSS. = MSS. in the Library of Eton College.

Hofbibl. MSS. = MSS. in the K. K. Hofbibliothek, Vienna.

King’s Coll. MSS. = MSS. in the Library of King’s College, Cambridge.

Lambeth MSS. = MSS. in the Library of Lambeth Palace.

Mus. Cor. MSS. = MSS. in the Museo Correr, Venice.

Andrich = De Natione Anglica et Scota iuristarum Universitatis Patavinae, 1222-1738. J. A. Andrich. 1892.

Arber = A Transcript of the Registers of the Company of Stationers of London. Edited by Edward Arber. 1875, &c.

Archaeol. = Archaeologia, Society of Antiquaries.

Berry = County Genealogies. William Berry. 1847, &c.

Berti = Vita di Giordano Bruno da Nola. D. Berti. 1868.

Biog. Univ. = Biographie Universelle.

Birch, Eliz. = Memoirs of the Reign of Queen Elizabeth. Edited by Thomas Birch. 2 vols. 1754.

Birch, Negot. = An Historical View of the Negotiations Between the Courts of England, France, and Brussels. Edited by Thomas Birch. 1749.

Birch, Pr. Henry = Life of Henry, Prince of Wales. Thomas Birch. 1760.

Brown, Ven. St. = Venetian Studies. Horatio F. Brown. 1887.

C. & T. Ch. = Court and Times of Charles I. 2 vols. 1848.

C. & T. Jas. = Court and Times of James I. 2 vols. 1848.

Cal. S. P. Col. = Calendar of State Papers, Colonial Series, East Indies, China, and Japan, 1513-1616. 1862.

Cal. S. P. Dom. = Calendar of State Papers, Domestic Series.

Cal. S. P. Ire. = Calendar of Documents relating to Ireland.

Cal. S. P. Scot. = Calendar of the State Papers relating to Scotland.

Cal. S. P. Ven. = Calendar of State Papers, Venetian.

Camd. Epist. = Cl. G. Camdeni et Illustrium Virorum ad G. Camdenum Epistolae. 1691.

Canaye = Philippe Canaye, Seigneur de Fresnes, Lettres et Ambassade. 3 vols. 1635-6.

Cas. Epist. = Isaaci Casauboni Epistolae. Curante T. J. ab Almeloveen. 1709.

Cecil Pp. = Calendar of the Manuscripts of the Marquis of Salisbury. 1883, &c.

Cent. Dict. = Century Dictionary.

Chambers = Poems of John Donne. Edited by E. K. Chambers. Muses’ Library. 1901.

Cigogna = Delle Inscrizioni Veneziane. Raccolte et illustrate da E. A. Cigogna. 6 vols. 1824-53.

Corbett = England in the Mediterranean. Julian S. Corbett. 2 vols. 1904.

Coxe = History of the House of Austria. William Coxe. 4th ed. 1864.

D. N. B. = Dictionary of National Biography.

Davison = The Poetical Rhapsody. Francis Davison. Edited by N. H. Nicholas. 2 vols. 1826.

Duffus Hardy = Report on Documents in the Archives and Public Libraries of Venice. T. Duffus Hardy. 1866.

Dumont = Corps Universel Diplomatique. J. Dumont. 8 vols. 1726-31.

Foley = Records of the English Province of the Society of Jesus. Henry Foley. 5 vols. 1877-9.

Foster, Gray’s Inn = Register of Admissions to Gray’s Inn, 1521-1889. Joseph Foster. 1889.

Foster, Ox. = Alumni Oxonienses, 1500-1714. Joseph Foster. 1891.

Gardiner = History of England, 1603-42. S. R. Gardiner. 1899-1900.

Gardiner, Letters = Letters and other Documents Illustrating the Relations between England and Germany at the Commencement of the Thirty Years’ War. Edited by S. R. Gardiner. Camden Soc. 1865.

Gardiner, 30 yrs. = The Thirty Years’ War. S. R. Gardiner. 1900.

Gosse = The Life and Letters of John Donne. Edmund Gosse. 1899.

Hasted = History of the County of Kent. Edward Hasted. 4 vols. 1778-99.

Hist. MSS. Com. = Historical Manuscripts Commission, Reports, &c.

Is. Ex. = Issues of the Exchequer. James I.

J. Hannah = Poems by Sir Henry Wotton, Sir Walter Raleigh, and others. Edited by the Rev. John Hannah, M.A. 1845.

Jas. I, Works = The Works of the Most High and Mighty Prince James . . . King of Great Britaine, &c. 1616.

Letters to B. = Letters of Sir Henry Wotton to Sir Edmund Bacon. 1661.

Lismore Pp. = The Lismore Papers. Edited by A. B. Grosart. 1886.

Lord Herbert = The Autobiography of Edward, Lord Herbert of Cherbury. Edited by S. A. Lee. 1886.

Maxwell-Lyte = A History of Eton College, 1440-1898. Sir Henry Maxwell-Lyte. 3rd ed. 1899.

Metcalfe = A Book of Knights. Walter C. Metcalfe. 1885.

Mornay = Mémoires et Correspondance de Duplessis-Mornay. Vols. x, xi. 1824-5.

Moryson, Itin. = An Itinerary. Written by Fynes Moryson, Gent. 1617.

Moryson, Sh. = Shakespeare’s Europe, unpublished chapters of Fynes Moryson’s Itinerary. Edited by Charles Hughes. 1903.

Motley, Barn. = Life and Death of John of Barneveld. J. L. Motley. 1875.

Motley, U. N. = History of the United Netherlands. J. L. Motley. 1876.

N. B. Gén. = Nouvelle Biographie Générale.

N. E. D. = New English Dictionary.

N. & Q. = Notes and Queries.

Nichols, Eliz. = The Progresses and Public Processions of Queen Elizabeth. John Nichols. 3 vols. 1823.

Nichols, Jas. I = The Progresses, Processions, and Magnificent Festivities of King James I. John Nichols. 4 vols. 1828.

Pattison = Isaac Casaubon. Mark Pattison. 2nd ed. 1892.

Ranke, Popes = The Popes of Rome. Translated by Sarah Austin. 2 vols. 1847.

Ranke, 17th C. = A History of England, principally in the Seventeenth Century. Leopold von Ranke. English translation. 6 vols. 1875.

Reliq. = Reliquiae Wottonianae. 1st ed. 1651; 2nd ed. 1654; 3rd ed. 1672; 4th ed. 1685.

Ritter = Briefe und Acten zur Geschichte des dreissigjährigen Krieges. Moriz Ritter. 2. Bd. 1870.

Roe = The Negotiations of Sir Thomas Roe in his Embassy to the Ottoman Porte, 1621-8. 1740.

Romanin = Storia Documentata di Venezia di S. Romanin. 1853-61.

Rox. Club = Letters and Dispatches from Sir Henry Wotton. Printed from the Originals in the Library of Eton College. Roxburghe Club. 1850.

Sarpi, Hist. Partic. = Historia Particolare delle Cose Passate tra ’l Sommo Pontefice Paulo V et la Serenissima Republica di Venetia. 1624.

Sarpi, Lettere = Lettere di Fra Paolo Sarpi. F. L. Polidori. 2 vols. 1863.

Sherley Bros. = The Sherley Brothers, an Historical Memoir. E. P. Shirley. Roxburghe Club. 1848.

Spedding = The Letters and Life of Francis Bacon. James Spedding. 7 vols. 1861-72.

State of C. = The State of Christendom. By Sir Henry Wotton. 1657.

Strafford Pp. = The Earl of Strafford’s Letters and Dispatches. Edited by W. Knowler. 2 vols. 1739.

Sydney Pp. = Letters and Memorials of State . . . Written and Collected by Sir Henry Sydney, &c. Edited by Arthur Collins. 2 vols. 1746.

Two Biog. = Two Biographies of William Bedell. E. S. Shuckburgh. 1902.

Walton, C. A. = The Compleat Angler. Izaak Walton.

Walton, Life = The Life of Sir Henry Wotton. Reliquiae Wottonianae, 1685.

Ward = Sir Henry Wotton: A Biographical Sketch. A. W. Ward. 1898.

Wicquefort = The Ambassador Abraham van Wicquefort. English translation. 1740.

Winwood Mem. = Memorials of Affairs of State, . . . Collected . . . from the original papers of Sir Ralph Winwood. Edmund Sawyer. 3 vols. 1725.

PARENTAGE AND EARLY YEARS. 1568-1588

Sir Henry Wotton was born on March 30, 1568,[1] at Boughton or Bocton Hall, in the parish of Bocton Malherbe, which lies in the centre of the county of Kent, about six miles from Charing. At the time of his birth Bocton Hall had been the seat of the Wotton family for about one hundred and fifty years, his father Thomas being fourth in descent from Nicholas Wotton, Lord Mayor of London in the reign of Henry V, who obtained the estate by marriage with the daughter and heiress of Robert Corbye. Once settled in this old house, and allying themselves by marriage with long-established Kentish families, the Wottons had prospered, and had risen to considerable positions in the service of the State. Among those sturdy and honourable families of country gentlemen, which were one of the main sources of the greatness of Tudor England, the Wottons were distinguished by a peculiar honesty, and old-fashioned piety, and simplicity of nature. A certain modesty in pushing their own fortunes was hereditary with them. In the time of the dissolution of the abbeys, and the plunder of the church lands, they none of them grew rich, though high in the public service; they habitually declined, rather than sought, court honours and preferment. Sir Edward Wotton (1489-1551), Henry Wotton’s grandfather, who was Treasurer of Calais in 1540, and one of the executors of Henry VIII, was said to have refused, out of modesty, the office of Lord Chancellor offered him by that King.[2] His more distinguished brother, Nicholas Wotton, who went as ambassador to many courts, and served under four English monarchs, refused a bishopric from Henry VIII, and Queen Elizabeth’s proffer of the See of Canterbury. ‘Though very wise he loves quietness,’ William Cecil said of him[3]; and this family love of peace and retirement was inherited by Sir Henry’s father, Thomas Wotton, who was a man, as Izaak Walton describes him, ‘of great modesty, of a most plain and single heart, of an ancient freedom and integrity of mind.’ A country gentleman of wealth and learning and many tastes, devoted to the Protestant cause, which his father Sir Edward had eagerly espoused, and for which he himself suffered imprisonment in the reign of Mary, he refused all offers of advancement, and lived most of his life at Bocton, which came into his possession at his father’s death in 1551.

By his first wife he was the father of three distinguished sons—Sir Edward Wotton, afterwards Lord Wotton of Marley, a well-known diplomatist and courtier in the reigns of Elizabeth and James I; Sir John Wotton, soldier and poet, who was knighted by Essex at Rouen in 1591, and who married a sister of the Earl of Northumberland. ‘A gentleman excellently accomplished both by learning and travel,’ Izaak Walton describes him, ‘but death in his younger years put a period to his growing hopes.’ The third of these sons was another soldier, Sir James Wotton, knighted at Cadiz in 1596.

Izaak Walton recounts how, after his first wife’s death, Thomas Wotton resolved that, should he marry again, he would choose a wife who had neither children nor lawsuits, nor was of his own kindred; and how he met in the law courts and married a lady who combined all these characteristics. This lady was Eleanor, daughter of Sir William Finch of Eastwell in Kent, and widow of Robert Morton.[4] Henry Wotton was the only surviving son of this second marriage.

A small portion of Bocton Hall still stands, now a farmhouse among disparked meadows, but retaining some evidences of its former splendour. We can picture it as it was in Henry Wotton’s youth, an old Gothic house, built and fortified with embattlements and towers in the reign of Edward III[5], enlarged by the first Nicholas Wotton, and standing on the brow of a hill, in ‘a fair park’ with the parish church adjoining. In this church are the tombs of many of the old Wottons, persons of ‘wisdom and valour’, whose memories and achievements lived as a model for the new generations, and an inspiration ‘to perform actions worthy of their ancestors’. High public service, love of learning and of Italy and poetry, were among the influences inherited from the past. These were kept alive no doubt by the visits of learned men, and of Henry’s elder brothers, riding home from the Court or the wars; the soldier and poet John Wotton, and the courtier Edward, who had spent part of his youth in Italy, and who, as the intimate friend of Sir Philip Sidney, could tell of that brilliant group of court poets, Sidney and Dyer and Fulke Greville and Spenser, the harbingers of the dawn of the great age of English literature.

Izaak Walton rightly insists on the importance of Bocton in the history of Sir Henry Wotton’s life. It was indeed the memories and traditions centred about this ancient house that played a predominant part in the formation of his character. From his family and ancestors he inherited that peculiar combination of culture and old-fashioned piety, of worldly wisdom and ingenuousness of nature, ‘the simplicity,’ as he called it, ‘of a plain Kentish man,’ which gave in after years a certain graceful singularity to his conduct, difficult for the courtiers among whom he moved to understand. He loved everything that savoured of Kent, all the local ways and phrases, and when ambassador abroad he surrounded himself with the sons of Kentish neighbours. Bocton he always regarded as his home, finding even the air about it better and more wholesome than other air; to the end of his life he returned thither when he could, although as a younger son he possessed no claim on the place save that of affection.

The English youths of this period, the younger sons of country gentlemen, honourably nurtured in old halls and manors, and going out to seek their fortunes in the romantic world, appear on the scene of many an Elizabethan play, and are among the most human and delightful figures of literature. It lends an interest to Henry Wotton’s life that he belongs to this world, that in his letters we possess probably the most complete existing record of the life of one of these young travellers and seekers after fortune; one who possessed the adventurous heart of the heroes of the contemporary drama, and was not without a touch of their noble eloquence. The conflict, moreover, between the ideals of the active and the contemplative life, which so long occupied Henry Wotton’s thoughts, is a theme which constantly recurs in the books and plays of the time, as well as in the lives of the famous Elizabethans. For though kingship shone then as a dazzling and almost divine attribute, and the chances of court favour were splendid, the great men of that great epoch were endowed with natures that desired a deeper self-realization than that which courts afforded, and could find no complete satisfaction in the external gifts of fortune.

The conflict of the two ideals was probably brought before Henry Wotton’s young eyes in a dramatic fashion by the visit of Queen Elizabeth to Bocton in July, 1573, where she remained two days, and attempted to draw Thomas Wotton from his retirement and country recreations to the Court, offering him a knighthood as an earnest of some more honourable and profitable employment.[6] These offers he refused; nor are we forbidden to imagine that Henry Wotton, then a boy of five, may have heard echoes, though with uncomprehending ears, of the debate between the great Queen and the quiet-loving Kentish squire.

Izaak Walton informs us that, after instruction first from his mother, and then from a tutor at home, the young Wotton was sent to school at Winchester at a very early age.[7] Of his life at Winchester we know nothing, save that (as he somewhat sadly recalled, visiting the school more than half a century later) ‘sweet thoughts’ and ignorant young anticipations of the joys of life then possessed him; and time, which, as he thought, should enable him to realize these hopes, seemed slow-paced to his boyish meditations.

In 1584 Wotton, then aged sixteen, went from Winchester to New College, Oxford.[8] But at New College he did not remain long; it was not unusual for students at that time to move from one college to another, and Wotton migrated first to Hart Hall, where he shared a room with Richard Baker (known afterwards as Sir Richard Baker, the historian[9]), and formed a lifelong friendship with the youthful John Donne. Donne entered Hart Hall at the early age of eleven in October, 1584, but apparently left Oxford in 1586.[10] In the same year, Wotton migrated to Queen’s, where he wrote a play for performance in the College. The subject was Tancredo from Tasso’s Gerusalemme Liberata (published in 1581). This play has not been preserved, and we know nothing of it, save what Walton tells us, that the gravest members of the College considered it ‘an early and a solid testimony of his future abilities’. The choice of subject shows that, even in his Oxford days, Wotton had some knowledge of the Italian language. This was no doubt increased by his friendship with the celebrated Alberico Gentili, who was appointed Professor of Civil Law at Oxford in 1587, and was the first of those Italian Protestant refugees with whom he was destined to have so much intercourse in after life. Wotton attracted the attention and won the friendship of Gentili by three Latin discourses de Oculo, in which he described, according to the current notions of the time, the construction of the eye, and ended with a commendation of the benefits of sight, from which Izaak Walton gives a quotation, though probably in his own and not in Wotton’s words.[11] These discourses, Walton writes, ‘were so exactly debated, and so rhetorically heightened, as among other admirers, caused that learned Italian, Albericus Gentilis (then Professor of the Civil Law in Oxford), to call him Henrice mi ocelle; which dear expression of his was also used by divers of Sir Henry’s dearest friends, and by many other persons of note during his stay in the University.’ Gentili, Walton adds, formed so great a friendship for Wotton that, if it had been possible, he ‘would have breathed all his excellent knowledge, both of the mathematics and law, into the breast of his dear Harry (for so Gentilis used to call him); and though he was not able to do that, yet there was in Sir Henry such a propensity and connaturalness to the Italian language, and these studies, whereof Gentilis was a great master, that this friendship between them did daily increase, and proved daily advantageous to Sir Henry, for the improvement of him in several sciences, during his stay in the University’.

It is probable that Henry Wotton was already looking forward to a career of public service, and had chosen, as his future occupation, what is now called the diplomatic profession. The profession, indeed, was not an organized one in his time, and even the word ‘diplomatic’ was not used in this sense before the eighteenth century. There were, however, two examples in his family which might naturally suggest a life of this kind; his great-uncle, Nicholas Wotton, had been a famous ambassador; and, while he was at Oxford, his eldest brother, Edward Wotton, had gone as Elizabeth’s envoy to Scotland in 1585, and to France in the following year. In his preparation for this career, the friendship and teaching of Gentili must have been of the greatest use. Gentili had recently published the most important book hitherto written on the duties, and qualifications, and rights of ambassadors[12], and was regarded as an authority on these subjects. The study of Roman Law was considered, moreover, if not a necessary qualification, at least a great advantage to a diplomatic career, and many of the ambassadors of previous reigns had been Doctors of Civil Law. But with the Reformation the interest in Roman Law had fallen to a low ebb in the English Universities. Its study was intimately associated with that of Canon Law, which was now abolished, and the books of Civil and Canon Law were set aside to be devoured by worms, as savouring too much of Popery.[13] The need, however, for a revival of a study of Civil Law had been felt; and the Protector Somerset had planned a College of Law in Cambridge to provide civilians for the diplomatic service, and for the consultations of the Privy Council.[14] At Oxford Gentili had done much to revive this study of Roman Law[15], and Wotton no doubt profited by his teaching.

In January, 1587, Thomas Wotton, Henry’s father, died, leaving, according to Izaak Walton, a rent-charge on one of his manors of one hundred marks a year to each of his younger sons. This sum, nearly sixty-seven pounds a year, and worth perhaps six or seven times as much in modern currency, was no inconsiderable portion for a younger son, according to the standards of the time[16]; there is, however, no mention of any such bequest in Thomas Wotton’s will[17]; and the provision, if made, must have been by means of a gift in his lifetime, or by instructions to his eldest son and heir.

On June 8, 1588, Henry Wotton supplicated for his Bachelor’s degree[18], but there is no record that the degree was ever granted.

|

The exact date is given by Anthony à Wood (Athenae, ed. Bliss, ii, p. 643), and in the copy of a pedigree dated 1603, in the British Museum (Add. MS. 14,311 f. 20). It is approximately confirmed by the age of sixteen years, given in the entry of Wotton’s matriculation in 1584; by the inscription on the Bodleian portrait ‘Aetatis suae 52 Ao 1620’, and by Izaak Walton’s statement that he died in 1639 in his seventy-second year. I think it may therefore be accepted, although in a letter of Dec. 12, 1622, Wotton speaks of his fifty-third (not his fifty-fifth) year drawing to an end. See ii, p. 254. |

|

Holinshed, Chronicles, 1587, p. 1402. The continuator of Holinshed says of Sir Robert Wotton (b. 1465), grandson of Nicholas Wotton mentioned above, and great-grandfather of Sir Henry Wotton, that he ‘was father to two such worthy sons, as I do not remember that ever England nourished at one time, for like honour, disposition of mind, favour and service to their country’ (Ibid.). These two sons were Sir Edward and Nicholas. ‘It is a singular blessing of God,’ he says, in concluding his account of the Wottons, ‘not commonly given to every race, to be beautified with such great and succeeding honour in the descents of the family’ (Ibid., p. 1403). Lives of Sir Henry Wotton’s grandfather, Sir Edward (1489-1551), his great-uncle Nicholas (1497-1567), his father Thomas (1521-87), his brother Sir Edward, Lord Wotton of Marley (1548-1626), are included in the D. N. B. A detailed history of the family is therefore not necessary here. |

|

D. N. B., lxiii, p. 60. |

|

The marriage was in 1565. A son, William, was born April 14, 1566, but died in the following July. Eleanor Morton was second cousin, once removed, of Thomas Wotton. Her grandfather, Henry Finch, married Alice Belknap, niece of Anne Belknap, who married Sir Robert Wotton, grandfather of Thomas Wotton (Berry, Kent, p. 207). |

|

Hasted, Kent, ii, p. 428. |

|

Walton, Life: ‘Mr. Wotton by his labour and suit was not then made a knight.’ MS. account-book of Richard Dering, quoted Nichols, Eliz., i, p. 334. |

|

Henry Wotton must have been a Commoner at Winchester College, as his name is not recorded in the list of Scholars. |

|

His name is entered in the University Register under the date of June 5, 1584, ‘Henry Wotton (Wolton), Kent, Arm. fil. 16’ (Register of the University of Oxford, 2, ii, p. 135). |

|

See Appendix III. |

|

Gosse, i, p. 15; see also Appendix III. |

|

Walton states that these discourses were read when Wotton proceeded to his degree of M.A., but this must be a mistake, as Wotton apparently never took even his Bachelor’s degree. They were probably read at disputations held in the College, like those ordained by the Statutes of Corpus Christi College. (T. Fowler, History of C. C. C., p. 41.) |

|

Alberici Gentilis De Legationibus Libri Tres, Londini, 1585. |

|

Inaugural Lecture on Albericus Gentilis, T. E. Holland, 1874, p. 25. |

|

J. B. Mullinger, ii, p. 132, quoted by F. W. Maitland, English Law and the Renaissance, 1901, p. 51. |

|

Holland, p. 25. |

|

Forty marks a year was considered a liberal allowance for a gentleman of no extravagant tastes. See A. Jessopp, One Generation of a Norfolk House, 1878, pp. 273, 283 n. |

|

Will of Thomas Wotton, dated Jan. 8, 1586⟨7⟩, proved Jan. 29, 1586⟨7⟩, 4 Spencer, P. C. C. He leaves bequests to his wife, to his eldest son Edward, and Edward Wotton’s wife, to various nephews, cousins, friends, and servants, but there is no mention of his younger children. |

|

Register of the University of Oxford, 2, iii, p. 151. |

FIRST VISIT TO THE CONTINENT. 1589-1594

It is the good fortune of Henry Wotton’s biographer that his history can be studied in his own correspondence, which begins at the age of twenty-one, and lasts with a few breaks till his death fifty years later. The earliest of his letters are addressed to his brother, Edward Wotton, and are printed in these volumes from transcripts preserved in the British Museum. Written in the autumn of 1589, they describe the young Wotton’s first journey abroad after leaving Oxford.

Foreign travel was almost a necessary part of the education of an ambitious youth in the reign of Queen Elizabeth. The young men went abroad, in Shakespeare’s phrase—

Some to the wars, to try their fortune there;

Some to discover islands far away;

Some to the studious universities.[1]

Their object was seldom or never mere sight-seeing and pleasure. The soldiers went to gain military experience in the foreign wars; the students to perfect their education in the foreign universities, and by the company and instruction of foreign scholars. But for young Englishmen of birth the main object of travel was almost always political. By observing different forms of government, by penetrating into the secrets of foreign courts, they both prepared themselves for the service of the State, and procured information likely to be useful to the Government at home.[2] They acted as informal spies on foreign princes, and on the English political exiles; and attempted to fathom the plots, and discover the warlike preparations, that were perpetually threatening England from abroad. So important for political purposes was foreign travel considered, that Queen Elizabeth was constantly sending young men abroad at her own expense to learn foreign languages, and to be trained up and made fit for the public service.[3] These young travellers, whether or not they were supported by the Queen, were not absolutely free, but by their licences (and without a licence to travel no one could go abroad) they were restricted to certain countries, and to certain periods of time. Their movements were more or less determined by orders from home; and it is plain from Wotton’s letters that he was acting under instructions in his various journeys.

Francis and Anthony Bacon, Robert Cecil, Raleigh, Essex, and indeed almost all of Wotton’s contemporaries, eminent in politics, spent some years on the Continent in their youth; but of these Elizabethan travellers Wotton is the only one of whose studies and journeys an adequate record remains. His letters are of interest for this reason, and also for the glimpse they give us of his character in his early years. Although somewhat cumbrous and stilted in style, they are not without the personal quality, and felicitous phrasing, of his later letters, and present a lively and pleasant picture of the thoughts and good resolutions natural to a serious and high-spirited youth at his first entering into the world—of the plans and hopes of a young Englishman setting forth, the year after the defeat of the Armada, for study and travel on the Continent. Europe lay before him, first the universities and great scholars of Germany, then Italy, the great school of state-craft, then perhaps Constantinople; and at last his return to England, the favour he hoped of some great man; and, after that, who knew what brilliant fortune? Wotton wrote to his brother that he felt he had hitherto been but a fool, and was beginning life anew at twenty-one, and he meant to convince his friends that he could teach his ‘soul to run against the delights of fond youth’. ‘It is knowledge I seek,’ he wrote to his mother, ‘and to live in the seeking of that is my only pleasure.’ Among the many departments of knowledge, his first object was to devote himself to the study of Civil Law. In this he was following the example of Nicholas Wotton, who had studied law abroad, and received a legal degree in Italy. But since the time of his great-uncle, learning had deserted Italy, and made its home north of the Alps; and it was Wotton’s ambition to become the pupil of one of the greatest of living jurists, the old and eminent François Hotman, then Professor of Law at Basle, ‘the second lawyer in the earth’ in his opinion, and only inferior to the famous Cujas. He writes again and again with boyish eagerness, begging his brother to procure him letters of introduction to this great man, with whom he hoped to live until he went to Italy. This choice of Hotman for his master is of interest, for Hotman was a leader of the new or humanist school of legal study, which combined the reading of polite literature with that of law, and in which the student’s attention was directed from glosses and commentaries to the texts themselves; while Alberico Gentili, Wotton’s Oxford master, belonged to the old Scholastic or Bartolist school, and was a bitter opponent of the French humanists.[4] It was therefore in search of a new and more elegant learning than he could find in England, and with the ambition of becoming ‘the best civilian in Basle’, that Wotton set sail from Leigh in pleasant October weather. After a voyage of four days, he landed at Stade in North Germany, not far from Hamburg.

Owing to the wars in France and the Low Countries, the course from England to North Germany was the safest and most frequented at this time. But even this crossing was not unattended with dangers; and although Wotton’s voyage was without incident, the ship in which, a year later, another English youth made the same journey was chased by Dunkirk pirates on its way. This youth was Fynes Moryson, who travelled over the Continent almost in Wotton’s footsteps. His Itinerary published in 1617, and his description of Europe, recently printed from the manuscript in Corpus Christi College[5], give much the same account of experiences and expenses as Wotton’s letters, and help to make clear many of his allusions.

Travelling on the Continent at this time was almost always done on horseback; but in the Low Countries and in Germany it was usual to journey in carts, or ‘coaches’, as they were called, lumbering vehicles with movable tops, holding about six people; and travellers going in the same direction would commonly combine to hire a coach and share expenses. At Stade Wotton waited four days, looking for such companions, and finding, after the manner of young Englishmen abroad, much subject for cheerful laughter in the aspect and customs of the natives of the place. Through Brunswick and Frankfort he travelled to Heidelberg, where he arrived on Nov. 26. At this University, which was then one of the most famous of the Protestant Universities of Europe, he spent the winter, studying German, and attending the law lectures and disputations. The legal instruction he found much superior to that of the English Universities; and while waiting for letters that should introduce him to Hotman, he prepared himself to take full advantage of that great scholar’s teaching.

Although our information about Wotton, when, young and obscure, he wandered over Europe, is almost all derived from his own letters, yet he does not pass altogether unnoticed in the correspondence of the scholars whose acquaintance he made abroad. In all these notices the impression is much the same, that of a youth of noble birth, brilliant and virtuous and witty, who delighted his friends with his literature and learning, and won their affection by that ‘sweet persuasiveness of behaviour’ for which he was afterwards noted. The first to mention him is the Scotch poet and scholar, Dr. John Johnston, then head of a College in Heidelberg, who had befriended Wotton at his arrival; and Wotton adds, had given him ‘the first sport in Germany with laughing at his dialect’. On April 10, 1590, Johnston wrote of Wotton to Camden (Wotton had brought with him a copy of Camden’s Britannia, which he had lent to Johnston), remarking that Wotton was then on the point of leaving Heidelberg.[6]

From Heidelberg Wotton went to Frankfort, and on the journey thither a piece of good fortune befell him. Delighting all through his life in the society and friendship of scholars, he shows, in his earliest letters, his desire to make the acquaintance of ‘the great learned men’ of the Continent. And now he fell in by chance with one of the greatest of European scholars, Isaac Casaubon, who had gone from Geneva to Frankfort in the hopes of meeting Lipsius, and to arrange for the publication of his edition of Aristotle, and was now extending his journey to Heidelberg.[7] We can picture the meeting at some wayside inn of the English youth, then twenty-two years of age, and the learned Frenchman, nine years his senior, querulous, ailing, and poor, but full of enthusiasm and generosity, and already famous in the world of scholars. They talked together for a little, and then went their several ways; but this encounter, or as Wotton called it ‘mere salutations in passing’, was the beginning of romantic friendship between them, and a few years later we find Wotton at Geneva living in Casaubon’s house.

After parting with Casaubon, Wotton went on to Frankfort, arriving in time to be present at the famous Mart, which was held there every spring and autumn, and was the great gathering place of Germany, and indeed of Europe, for merchants, travellers, authors, and scholars. Hither were brought silks from Italy, cloth from France and England, ironwork from Nuremberg, delicacies from Holland, and—what was of more interest to Wotton—hither to this ‘Fair of the Muses’ came not only booksellers from all over Europe, but the writers and learned men of the Continent, to meet each other, and to arrange with the printers of Frankfort for the publication of their works.[8] In the bookshops, or mingling in the crowd, or gathered around the bookstalls, the traveller would hear famous men lecturing and disputing with their friends; and it is possible that at this fair, or two years later in the bookshops of Padua, Wotton caught a glimpse of perhaps the greatest, and certainly the most interesting of living philosophers, Giordano Bruno.[9] That Bruno would be among the loudest and most eager of the disputants there can be little question; and the young Englishman may have listened to his profound and fantastic discourses about the plurality of worlds and the spirit of the universe, in which the deepest modern conceptions and the strangest allegory were so curiously mingled. At Frankfort he probably lodged with the hospitable printer, Andrew Wechel, in whose house seventeen years before his brother’s friend, Philip Sidney, had first met Languet. But of his stay at Frankfort we know nothing certain, save that here he made the acquaintance and won the friendship of the great botanist Clusius, or Lecluse[10], who was then resting at Frankfort after his many travels.

News had no doubt reached Wotton of the death, in the previous February, of François Hotman, from whose instructions he had promised himself such profit. He therefore abandoned his intention of travelling to Basle, and went to Altdorf, the little University of the town of Nuremberg, where he spent the spring and summer, residing in the house of a lawyer to whom his friend Franciscus Junius, Professor of Theology at Heidelberg, had introduced him.[11]

If the history of a man’s early years is largely the history of his friendships, this is particularly true of Henry Wotton, who had the gift of winning the interest and affection of older and more distinguished men. The next friend on his list was an Englishman, Lord Zouche, who happened to be then at Altdorf. Edward la Zouche, eleventh Baron Zouche of Harringworth, was perhaps ten or twelve years older than Wotton, and already a political personage of considerable note. He had been one of the peers who had tried Mary Queen of Scots, and in after years he was charged with diplomatic and other offices of some importance. He was living abroad at this time, partly for the sake of studying foreign affairs, and partly too for economy; for he had wasted his fortune not in the ways usual to spendthrift noblemen, but on gardens and horticulture. A man of cultivated tastes, the friend of Ben Jonson and of other poets, and interested in history and mathematics, he took the young Wotton under his protection, and they seem to have spent much of their time together. Wotton, writing to Lord Zouche nearly thirty years later, speaks of these days when they first met, and when he was a poor student at Altdorf, as the happiest of his life.[12]

In the last edition of the Reliquiae Wottonianae, published in 1685, was printed a series of letters from Henry Wotton to Lord Zouche, written between October, 1590, and August, 1593; and it is from these, and from the collection of Wotton’s letters preserved in the Hofbibliothek in Vienna, that most of our information about the next three years of his life is derived. Among the Vienna letters is one written at Altdorf, on Sept. 25, 1591, Old Style. It is addressed to his mother, and, like many letters of young men to their mothers, it is extremely pious in its tone. He informs his mother, however, that at Vienna, whither he was going, ‘the great learned men’ there, in the profession he followed, were all ‘marvellous devout papists’; but that did not trouble him, as he made a point of daily conversing with all sorts of men, yet in his own ‘manner and conscience’.[13]

Wotton left Altdorf towards the end of October, and after stopping at the Jesuit University of Ingolstadt, in Upper Bavaria, he arrived on Nov. 11, New Style, at Vienna; in which city, where his eldest brother had spent the winter fifteen years before in company with Philip Sidney, he remained for about six months. He had letters to two eminent Protestants in the service of the Emperor, Rudolf II: the Baron von Friedesheim, one of the judges of the Lower Court of the Province of Austria, and Dr. Hugo Blotz, or Blotius, a learned Dutchman, and librarian of the Imperial Library. With Friedesheim Wotton stayed for a week or two, and then went to live in the house of Dr. Blotius, adjoining the old Minorite monastery, in which the library was then lodged. His private study opened into the library, and he had the free use of this collection of about nine thousand volumes, for the most part manuscript. The cost of chamber, stove, table, and lights was two florins a week, and he had plenty of wine for himself and a friend who was with him. Altogether the expense of living came, he calculated, to about five pounds four shillings more a year than a good careful student would spend in the English Universities.[14]

Blotius seems to have been a kindly host; Wotton soon won his trust and friendship to such an extent, that when in January, 1591, the librarian had occasion to go to Neustadt, he allowed Wotton to remain in the house with his wife, though not without misgivings about the unconventionality of such a proceeding. Wotton, however, was able to assure him that the conduct of Frau Blotius, in the absence of her husband, was altogether above reproach.[15]