* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: The School Across the Road

Date of first publication: 1915

Author: Desmond Francis Talbot Coke (1879-1931)

Illustrator: H. M. Brock (1875–1960)

Date first posted: May 20, 2023

Date last updated: May 20, 2023

Faded Page eBook #20230541

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, Pat McCoy & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

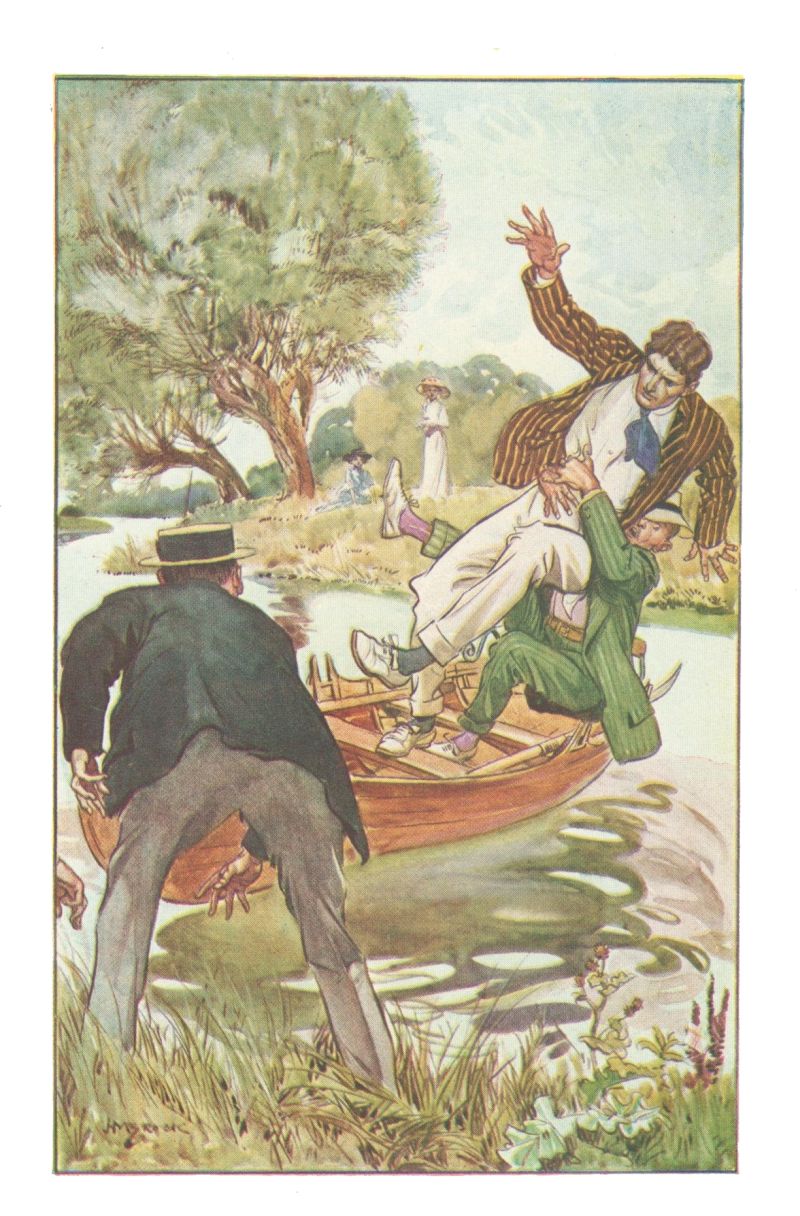

WITH A SPLENDID SPLASH THE TWO DISAPPEARED BENEATH THE WATER.

IN GRATITUDE

TO

THE HEAD MASTER OF CLAYESMORE

AND ALL OTHERS—WHETHER BOYS OR MASTERS,

KNOWN FRIENDS OR UNKNOWN—WHO

HAVE WRITTEN KIND THINGS TO

ME ABOUT MY SCHOOL-STORIES

REPRINTED 1927 IN GREAT BRITAIN BY R. CLAY AND SONS, LTD.,

BUNGAY, SUFFOLK.

CONTENTS

| PART ONE | ||

| THE FEUD | ||

| PAGE | ||

| CHAPTER THE FIRST | ||

| The Rival Schools | 11 | |

| CHAPTER THE SECOND | ||

| The Sham (?) Fight | 26 | |

| CHAPTER THE THIRD | ||

| Casus belli | 48 | |

| CHAPTER THE FOURTH | ||

| Rumours—and War | 59 | |

| PART TWO | ||

| OIL AND WATER | ||

| CHAPTER THE FIFTH | ||

| “Winton” | 87 | |

| CHAPTER THE SIXTH | ||

| The Methods of Peace | 104 | |

| CHAPTER THE SEVENTH | ||

| Parleys | 122 | |

| CHAPTER THE EIGHTH | ||

| Defiance | 140 | |

| CHAPTER THE NINTH | ||

| A Matter of Minutes | 149 | |

| CHAPTER THE TENTH | ||

| On the Football Field | 162 | |

| CHAPTER THE ELEVENTH | ||

| Dr. Anson’s Ultimatum | 175 | |

| CHAPTER THE TWELFTH | ||

| Mutiny on the—Roof-top | 192 | |

| CHAPTER THE THIRTEENTH | ||

| Grimshaw to the Front! | 209 | |

| CHAPTER THE FOURTEENTH | ||

| For the Sake of the School | 215 | |

| CHAPTER THE FIFTEENTH | ||

| In the Prefects’ Room | 230 | |

| CHAPTER THE SIXTEENTH | ||

| Odium | 250 | |

| CHAPTER THE SEVENTEENTH | ||

| A Change of Tactics | 259 | |

| CHAPTER THE EIGHTEENTH | ||

| At a Standstill | 274 | |

| PART THREE | ||

| FLOREAT WINTONIA! | ||

| CHAPTER THE NINETEENTH | ||

| A Lesson in Scouting | 283 | |

| CHAPTER THE TWENTIETH | ||

| Captive | 294 | |

| CHAPTER THE TWENTY-FIRST | ||

| Rough Justice | 302 | |

| CHAPTER THE TWENTY-SECOND | ||

| The Great Snow-fight | 317 | |

| CHAPTER THE TWENTY-THIRD | ||

| Floreat Wintonia! | 333 | |

However much Head Masters might deplore the fact, there was no doubt that the two schools, far from living in that harmony which suits close neighbours, really existed in a state of warfare. They had been foes from time immemorial—which is, of course, to say for so many terms as any boy in either of them could remember.

About the feud itself there could be no doubt: about its origin, no certainty. Not even the masters themselves, who had watched it flourish through changing generations of boys, could put any more definite cause to it than that the two buildings were extremely close, their grounds separated merely by a narrow roadway. And that, too, was almost the only thing that brought the establishments together. Considering that each aimed at educating boys to be fit for his Majesty’s army and navy, it would have been hard indeed to find two schools more altogether different.

You could make some guess at their nature, even from the names.

The Head Master of the vast, solemn buildings in white stone, liked to hear himself called “Dr.” Anson, and his school “Corunna”: whilst he of the less pretentious red-brick residence across the road, was well content to be plain “Mr.” Warner, and did not trouble to find any more dignified title for his establishment than simply “Warner’s.”

Of course, the Doctor was much more commonly known as “Old Anson,” or, quite simply, “Ass” (corrupted from the Latin asinus), and his school as “Anson’s”; but the mere fact that he sighed for those more ambitious names will show what sort of man he was.

Here lay the real difference: he was a Cambridge Wrangler, and Warner was an Oxford Blue.

Dr. Anson conducted his academy along lines that might roughly be described as mathematical. He prided himself upon his System. His prospectus, for the use of parents, with a school crest upon it, laid great stress on the smoothness with which everything worked in this wonderful Corunna. There were prefects, one gathered, and there were, of course, the masters (each with M.A. following his name), but really the school needed neither! Corporal punishment was “found superfluous, except in the most rare of circumstances.” The boys were “encouraged to regard their masters more as friends and counsellors than as tyrants and taskmasters.” A healthy interest in games was encouraged, but care was taken “not to sacrifice the healthy mind in perfecting the healthy body.” The rule of boys by boys (the whole thing ended) had always been encouraged, as making for responsibility and self-reliance: so that, in short, “Corunna, whilst exceptionally equipped for those intending to enter his Majesty’s services, possesses also the moral and social advantages of our great heritage, the Public Schools; with which, indeed, under Dr. Anson’s enlightened charge, it has a close affinity.”

All this was the work of Dr. Anson.

Warner, when parents applied for his prospectus, took that sort of thing for granted, and merely sent a four-side list of fees and regulations. He gave them the area of his playing-field, but said nothing about drains. His staff of masters was not rich, so far as M.A.’s went, but those who knew would recognize the name of more than one old Blue. There was nothing about Public Schools or punishment. He did not even comment on his system, which was, indeed, more practical than showy: to gain obedience from the mingled fear and admiration which his boys felt for him, and when anybody wanted thrashing, to give it him with all an athlete’s strength, and so ensure that he did not apply for it again.

Naturally parents—and more especially mothers—when offered the choice, found Corunna’s programme more attractive. As a result, against Dr. Anson’s roll of one hundred and twenty boys, Warner could show not quite sixty: and his numbers dwindled. Thus it was that if the Warnerites scorned the Ansonites as horribly proper, and in one word “smugs,” these last could despise their rivals as a failure. Each school regarded the other as undoubtedly inferior, and except for occasional brushes between little groups of rambling small boys, took good care to have no dealings whatsoever with it. Both spoke contemptuously of “the school across the road.”

Only once a year did the two meet.

The annual cricket match, known variously as the Warnerite or the Ansonite match (according as to which school mentioned it), always proved a rather difficult affair. They took it in turns, of course, to be visiting eleven, but whichever crossed the narrow road, entered the other ground with a feeling of scorn and of hostility. There was not much of the spirit of a friendly match about this fixture, and perhaps neither school displayed its sporting instinct to the best, when beaten. Fancy being licked by a place like that! It was jolly difficult to sit out the spread afterwards without saying what one really thought—which would, as it happens, have been very rude. . . .

Dr. Anson innocently welcomed this annual match and tea, as drawing the boys of the two schools together. He thought, himself, that Mr. Warner’s methods were mistaken; were, indeed, a libel on the race of school-masters, and he felt no surprise or sorrow at his failure; but he tried to be polite, and was anxious also that his boys should be on friendly terms with their close neighbours. Sometimes he suspected a slight feeling of hostility between them, and this worried him. He looked round for some means of curing this by arranging, possibly, another inter-school fixture, to make them foregather more frequently than once a year. He thought, of course, of football, and was going to suggest a match, until he reflected that Mr. Warner’s boys were very rough. Besides, they were also very good, he heard; and his own boys seemed, for some reason or other, to dislike being beaten by their neighbours more than by any other team whatever. So he said nothing, and began looking round again.

He was still doing this, in a vague sort of way, when circumstances themselves brought the required solution into view.

Both schools, as befitted their military nature, boasted a Rifle Corps, but in each it had, of late years, rather languished. There were many games to play, and other schools to beat at them, so that the martial ardour gradually died: for British boys are much like their elders in this way, that they would rather kick a ball about than learn how to defend their country. (The difference, of course, is that the elder cannot be bothered even with kicking the ball: he pays sixpence to watch.) Thus, both at Warner’s and Corunna the Rifle Corps had become rather despised—a thing for smugs, who were no good at games—since the enthusiasm and alarms of the Boer War.

But now, suddenly, England awoke. Somebody produced a play in London; a play which showed the Briton’s home invaded by a foreign soldiery, the British householder led out and shot, because, though a non-combatant, he raised a rifle in his own defence. Nobody had ever thought of that. The dweller in Tooting realized suddenly that even Tooting is not sacred to invading armies: that his small villa might well be demanded as a resting-place for foreign soldiers; that if he resisted, he might easily be shot. He had listened, unmoved, whilst great soldiers, Generals and Field-Marshals, begged him to defend the coast. The coast?—what did that matter? Was there not a fleet for that? But 19 Myrtle Villas, Upper Tooting? That was different! He went and swelled the Territorial Force.

London was wild about Invasion: nervous old ladies looked beneath their bed, for foreign legions; and soon the patriotic wave spread right across the country.

Dr. Anson caught it full.

At once he began to worry, to wonder why Corunna, with its lofty spirit and fine tradition (see prospectus), had been so behindhand in this matter. The parents obviously would wish their sons to be adequate defenders of their home; and besides, was it not a military school? Distinctly, he must talk to Sergeant Gore about it. Their little battalion must be enlarged, made more efficient: a new interest must somehow be stimulated, to draw the boys away from their perpetual games, and make them realize their duties as citizens and Britons.

Then he had his inspiration. Mr. Warner’s school! It, too, had a Rifle Corps, naturally smaller, but perhaps not too insignificant—he did not know its numbers—to be matched against their own battalion of seventy boys. A combined field-day: this was the very thing. Nothing, he reflected, roused interest like rivalry, and besides, here (he suddenly realized) was the very inter-school fixture for which he had been vainly seeking.

Thus it came about that, one day in the eighth week of the Easter term, he put on his top-hat and black overcoat and crossed the rustic lane to call on the master of the school, which he now regarded scarcely as a rival. Although the two were meant to be on friendly terms, they were too far apart in character for friendship, and their meetings usually concerned some friction between their respective pupils.

As he entered Warner’s playing-field, two boys, strolling arm-in-arm, looked curiously at him and touched their caps in a mechanical way that did not try to be polite.

“Hullo!” said one of them. “I wonder what’s up? Why’s old Anson nosing around here?”

“Oh, I don’t know. Some row or other,” replied his friend, with the careless ease of one who knows that he at least, for once, is innocent.

“Beastly cheek his coming, anyhow. Why can’t he stay in his own dirty hole?” with which they turned to a more pleasant topic.

Dr. Anson, meanwhile, with a gracious smile, had passed them and gone round to Warner’s private door. (“Never you trouble to ring and be shown in,” that genial soul had once remarked. “Just come in through my private entrance—round by the dining-hall, you know—and hammer at my study door.”)

Probably he would be out, playing football or something with the boys; but it was worth while trying. Dr. Anson was boiling with his project. He tapped upon the study door.

“Well?” came from within.

Dr. Anson was a stickler for etiquette: he did not enter. Clearly that remark could not be meant for him! He tapped again, with more authority.

“Hullo, hullo, HULLO!” loud and impatient from within.

Really, it was quite ridiculous: what a curious fellow Warner was! Who did he imagine was knocking? Still, it was obviously useless to wait until he said “Come in.” Dr. Anson entered.

Warner was sitting in an arm-chair by the fire. At least, his visitor deduced so much from what he saw—two legs, bare at the knee and clad in green stockings below, upon the mantelpiece, and smoke wreathing up from the chair-back which hid the rest of his anatomy.

As Dr. Anson closed the door, another comment came from the direction of the fire-place.

“Are you deaf, man? Can’t you hear me call?”

The Head Master of Corunna stood in silent amazement, not knowing what to say, and presently Warner, with an angry movement, swung about. He did not suffer fools gladly.

“Why, it’s Anson!” he cried in astonishment.

Dr. Anson always felt that, as nearly thirty years his junior, Warner ought to call him “Doctor.” “Yes,” he answered stiffly.

“I’m sorry,” laughed his host. “I thought it was one of the fellows. They’re so jolly shy about coming in; don’t you find, too? They seem to think they’re entering a lion’s den.”

“I always find” (he spoke with crushing dignity) “that when I say ‘Come in,’ they enter.”

“Ah, that’s it, then, probably,” replied the other genially, “I never remember to say that. I just shout any old thing that comes into my head! But do sit down, now you are here, won’t you?”

As he stood by the mantelpiece, smiling and smoothing down the thick black hair that had been ruffled by his lounging posture, he looked less thirty than eighteen; more of a boy than a Head Master. Enthusiasm and joy of life had left everlasting youth as heritage to his keen, clear-cut features. It was hard to believe that only thirty years stood between him and his visitor, who might have been his grandfather, at least.

Dr. Anson, still holding his stick and top-hat, pointed to the other’s costume.

“But I shall perhaps be detaining you?” he said.

“Not a bit, not a bit! Let me put your hat down? That’s it. I must apologize for my shorts: I was just going out to coach the eleven, as soon as I’d warmed up a bit. But that’s nothing: there’s heaps of time; and I am glad to see you.”

He wished that his visitor would get to the point. His boasted gladness was qualified a little by the fact that these visits always heralded some complaint or other. His boys had been making a noise at night, or some of them had called an Ansonite a smug, or thrown a snowball, or done something not less terrible! . . . He paused for a few moments, puffing at his meerschaum silently. Usually, that brought old man Anson to the scratch!

To-day, however, there seemed to be no moaning in reserve. Dr. Anson set his hands upon his knees, and plunged at once into the general conversation, which did not generally begin until Warner had promised rigorous punishment for the offenders.

“Have you seen this morning’s Times?” he started; then, not waiting for the answer, since he knew that Warner read only the Sportsman and the Daily Mail: “I really think that there are signs, at last, of England waking from her apathy about Home Defence. There seems no doubt that a very remarkable play——”

“Oh, yes,” said Warner hurriedly. “I saw about that in the Mail.” He had read the head-lines, and did not want to be delayed by hearing Anson’s version of the plot: they would be kicking off already!

Dr. Anson embarked at once on his proposal. “I was wondering this morning, whether you and I could not do something——”

“You aren’t suggesting that we should enlist?”

Dr. Anson strongly suspected a twinkle in his junior’s dark eyes. “No,” he said very seriously, “not that: our time for that is over. It is our task now to train others to serve.”

“And a rotten task it is, too!” Warner broke in. “I often think of chucking it: I’d rather do the serving, sometimes. If I do, Anson, will you buy my buildings from me?”

The elder man waved the jest aside as quite unworthy. “It seemed to me,” he went on, “that we could do our share by stimulating interest in our own Rifle Corps: and to do that, I thought—if you were willing—we might organize a combined field-day, with healthy rivalry.”

“Splendid!” cried Warner keenly. “A battle of the schools.”

“A sham fight? Yes, that would be admirable: my original idea: only—er—” (he hesitated for the tactful phrase) “er—now that your numbers are somewhat smaller, it has occurred to me, perhaps the two sides would be rather unequal?”

Warner smiled. “Don’t you worry about that, Anson: we make up for smallness by being keen! Who won the match this year, eh?” Dr. Anson made no answer. “How large is your corps?”

“It has seventy members,” answered Dr. Anson, with a certain pride. That might not be many; but it was nearly twenty more than the whole muster of his rival’s school!

“Ours has fifty-two,” said Warner quietly.

Dr. Anson was a little staggered. “I always find it hard to induce the boys to take up both games and the corps,” he said, with a new note, almost of apology.

“They do both here, or take a whacking,” answered Warner. “You’re too kind!” He smiled secretly to see the other squirm: there was a certain fun in ragging this old Anson! He almost envied the Corunna fellows.

“I think we have discussed that point,” replied the Doctor shortly. Then, in quite a different tone, “Then might we not arrange the sham fight for this term, always so destitute of interest for the boys?”

“Right you are! By all means—especially if we wait until the footer’s over. What about the last week of term, a deadly time?”

“You forget,” said Dr. Anson, with gentle superiority, “that would be examination week.”

Warner smiled as he bent down to knock his pipe upon the bars. “Does it matter, really?” he inquired. The Doctor’s look was quite decisive. “Well, then,” he went on, “what of the week before?”

Even that appeared a little unconventional to the other, but he felt that he must give way in his turn, perhaps. The date was definitely fixed, and Dr. Anson, never comfortable in the presence of this young man, whom he suspected of secretly deriding him, made haste to take his leave.

Warner, relieved at his departure, laid his pipe aside, and seizing up a sweater, dashed out on to the football field; whilst Dr. Anson, very stately, looking curiously like a bishop (except that he did not wear gaiters), crossed the road into his own domain, and sought out Sergeant Gore, to make inquiries as to Corunna’s efficiency in case of an invasion, and—more directly—with a view to the sham fight.

“I call the whole thing drivel,” Wren remarked to an admiring circle of small boys.

“What do you call drivel?” was the cold inquiry of Henderson, who strolled past at that moment. All the bigger fellows at Warner’s found a certain amusement in the views of Wren (popularly called “The Dove” by reason of their gentleness), though he gained few disciples. Corunna was the proper place for him: Dr. Anson would have praised his humane notions, whilst Warner merely told him not to be a little fool.

Henderson was Captain of Cricket and Head Boy (for that, too, went by athletic prowess in this sporting school), so that Wren decidedly qualified his views in his reply. He had been four years at Warner’s; was in the top form; but remained nobody: and Henderson was some one very great.

“I was talking about the field-day,” he said, going purple in the face, much to the entertainment of his audience. “I don’t see any point in it, I mean.”

“That doesn’t mean there isn’t one,” retorted Henderson. “Perhaps you’re not big enough to see it,” and he strode away, contemptuous.

“Sarcastic devil!” murmured Wren, after a safe interval; but he had lost the sympathy of those around him. The poor Dove, small, peaceful, insignificant and clever, was quite amusing, just to listen to: but when it was a matter of influence, he made no show beside Jack Henderson, tall, popular, athletic, in this sport-loving school. Here was the idol of all Warner’s; Captain both officially and by general consent. If Jack Henderson had said that the world was flat, probably the whole school would have deserted the geography and followed him, believing there must be some reason why this theory should be best for Warner’s. That was the great interest of every boy at Warner’s—his school, which he thought the best in the whole universe; and it was because the boys knew Jack’s whole mind to be devoted to the welfare of the place he ruled, that they followed him without questioning, in blind devotion.

As a matter of fact, until this fatal moment Wren had more or less carried the junior boys with him in his opposition to the great Sham Fight. They did not understand much (and cared less) about Arbitration and Universal Brotherhood, favourite phrases of the Dove, and derived from his father, President of the Universal Peace League, the English Speaking Union, and other societies less widely known: (though all this was very magnificent:) what they found “drivel” was the constant succession of drills and parades, which the Sham Fight seemed to render necessary.

“Warner doesn’t understand,” Wren had been expounding, two minutes before. “England’ll never be invaded. We don’t need a Navy or Volunteers or any rot of that sort. What use should we be?” (He paused dramatically for an answer.) “It’s Arbitration that’ll keep us safe. The spirit of the age is set against Warfare.” It was quite a good reproduction of his father.

“I don’t mind about that,” replied a squeaky voice. “What I object to is these beastly drills. Besides, even if we’ve got to ‘get efficient,’ why drag the beastly Ansonites into the business? That’s what I call drivel.”

“I call the whole thing drivel,” Wren had said: the which it was that Jack had overheard, as he went past the little Indignation Meeting—and he had spoken.

So now popular opinion swung round. Henderson saw some point in the thing: therefore there was one—what argument could be more clear? Henderson was seventeen; with a good chance of passing direct into Sandhurst; Captain of the School; and a jolly good sort. So that was all there was to say about it! Dove had found yet one more subject on which no one wished to hear his fluent rhetoric. The juniors dispersed, leaving him alone, disconsolate; and from that hour everybody joined with a real zest in the necessary drills. If any one was slack or got hauled up for anything, he ran the risk of a kicking from his file, afterwards: for that was how things got well done at Warner’s. It was painful to do badly what the whole school wanted good; and in a day or two, the place from top to bottom was mad on nothing except military training.

They would show Anson’s the real meaning of efficiency!

Across the road, too, though of course in a much smoother and more ordered way, all was preparation and enthusiasm. No one at Corunna was in any doubt as to the result. In a very proper and Public-Schooly manner, the whole thing was working on a settled system, and the fighting force thus produced must obviously strike the local Adjutant of the Depôt (who had promised to be Umpire), as much superior to the smaller contingent from Warner’s, trained in a haphazard way! Besides, whilst their rivals must rely upon civilian masters, had not they at Corunna the priceless assistance of their sergeant, Gore?

The last-named suddenly gained a new importance, almost popularity.

Sergeant Gore, despite his military calling and bloodthirsty name, was in reality the mildest and most plump of men. His service had been mainly of the home variety, never of the active: and since retirement (as lance-corporal), his occupation had been what is classed as “sedentary.” If he had not actually sat, he had merely stood and ordered others to be energetic. He was not of those sergeants who whirl around a horizontal bar, to show his boys the proper method, nor did he wear flannel trousers and a sweater; clad in a dark-blue uniform and wearing a peaked cap, he stood immovable and drilled the squad for punishment. In that alone did Dr. Anson see fit to let his establishment, as military, depart from Public School traditions: the penalty of idleness was in units, not of lines or of detention, but of drilling. Naturally the Sergeant, to whom this duty (among many others) fell, was not immensely popular. As he also filled the position of a sort of policeman on the school grounds, he was regarded with suspicion and hostility. Some of the bigger boys, almost ripe for Sandhurst, thought it “beastly undignified” that they should be subject to the fat old man’s espionage. You would not hear much good spoken of poor Sergeant Gore.

Now, however, among at least the members of the Corps, he came to be accounted a person with a distinct importance in the place: for would he not help them to defeat the Warnerite corps, and so wipe out the memory (secretly a little bitter) of the cricket match? At no costs must they be beaten again by a school so much smaller, and (even if it did happen to beat them!) so absolutely rotten.

Certainly, every one from Dr. Anson himself downwards, showed the utmost keenness. Grimshaw, the Head of the School and ex officio chief officer of the School Corps, put every ounce of energy and influence that he possessed into working up the interest. This probably was not worth much, for Grimshaw, in spite of his many (ex officio) dignities and honours, was not really a person of much power or prestige at Anson’s. The Doctor, of course, unlike Warner, did not consider this in choosing the school Captain. The best boy at work was Head Boy: voilà tout: and Grimshaw happened to be very good at work. That, unhappily, concluded the list of his abilities and even at a model school, based upon System, like Corunna, it will be found that boys rate Muscle higher than Mind, and as a subject for skill, prefer Cricket to Cicero. Dr. Anson and his sort may mourn the fact: but yet the fact remains, and everybody knows its stubbornness.

Nobody thought much of Grimshaw.

This stern, pale boy, with clear-cut features and broad shoulders, went through his school life, different in some way from the others—seeming older—and not much caring what those others thought.

Of course, he was beastly clever: all the school knew that: why, he wrote Iambics, just like Sophocles: and it was very wonderful—but rather a mistake! Of course, too, he did quite well as Head of the School, but Sinclair or any of the Eleven could do that just as well, and it would be a great deal more useful, if he would do something for the school at footer or somewhere! It was after leaving Corunna that fellows, looking back, came to respect Grimshaw as a strong man, and possibly to think less of others, whose might had been only in their arms and legs.

Yes, for the present, every one was much more influenced by what Sinclair thought. Sinclair was Captain of the Football and the Cricket: many thought he should be Captain of the School. He was, too, in one sense at least—that he guided its sympathies. Grimshaw could scarcely hope to carry a measure or enforce a rule, if Sinclair were against it: but having the wisdom to join tact with strength, he had not so far ever cared to make the effort. And in this case, their thoughts leapt as one: Sinclair, too, was taken with Invasion fever.

Thus Dr. Anson, Sergeant Gore, Grimshaw, and Sinclair, all for once combining, simply swept Corunna off its feet. Football, always shaky in its hold on popular affection at the end of Easter term, perished miserably: drilling was the thing! Nearly all who had so far scorned the Corps now joined it, urged by Grimshaw or threatened by Sinclair; and only regretted that, as too raw recruits, they would not be allowed to take part in the sham fight against Warner’s, and share the fruits of victory.

As to that victory, there could be no doubt.

It was the Great Day.

Up among the gorse-clumps of the hilly common-land, which the Umpire-Adjutant had chosen as appropriate, the rank and file of Corunna lay in a chill wind and waited for the enemy; waited, as it seemed, for hours.

No one altogether understood the scheme of operations, as drawn up by the Adjutant, but Sergeant Gore, at any rate, made some pretence. Mr. Warner’s young genel’men were an attacking force (A): so much was plain: and his boys (B) had got to keep them from advancing. The only thing that, secretly, he could not quite discover from the typewritten instructions, was the direction from which the force A might be expected to attack!

He confided to Grimshaw that he did not think the scheme well thought out or well worded. “Colonel Vernon, ’im as you’ve ’eard me speak of, sir” (who had not?), “ ’e would ’a made the thing clear, right enough. What’s all this ’ere about covering the approaches to the town? What town? That’s what hi should like to know;” with which he struck the paper scornfully.

“An imaginary town,” said Grimshaw, “just as this is an imaginary fort.”

“Well, where is it, then? That’s what hi should like to know, sir.”

But Grimshaw there was equally at sea: he could not tell, although he felt that he should certainly be able. But then he was only ex officio an officer. . . .

Meanwhile, they were on their fort: so much was definite, for the Adjutant had declared this hillock to be that: and Sergeant Gore, with a feeling of being a deep strategist, deployed his men at intervals around it, told them to lie flat and be very vigilant. When the enemy appeared, he would see their direction and could concentrate!

So there they lay in the long grass, knowing they were cold, and trying not to know that they were nervous.

“When the henemy appears, sir,” were the dashing orders of the Sergeant to Grimshaw, his lieutenant, ere he left for his own post, “hopen fire. Then we shall know where we hare, you see.”

For the present, nobody was sure.

Each of the seventy felt that his yards of hill-side were bound to be the spot selected for attack; the gorse-bushes kept shaking in the wind, as though concealing enemy; and it was miserably cold. Nobody confessed to it, but more than one felt chill shivers running down their backs, as these long minutes of anticipation passed. It was horrible to be all on edge, like this, waiting for something to happen. It would be right enough, when things began!

And presently they did begin, with startling suddenness.

It was Gibbs of the Upper Third who won eternal fame by being first to sight a lurking foeman. Excitedly he passed the word along. From mouth to mouth it flew until it reached the spot where Grimshaw lay.

Grimshaw was horrified. Sergeant Gore had thought that the attack would be upon the other side, and this was sickening, to have the full responsibility. However, “Open fire!” had been the order, and he must hand it on, so soon as he was certain that there was an actual force advancing. Feeling very cunning and more complacent, he crawled upon his stomach to the spot where young Gibbs lay, and followed a most shaky finger.

There could be no doubt: certainly a hat, and such a squash hat as the Warnerites were wearing, lurked behind a large-sized bush!

Grimshaw’s nervousness and hesitation vanished, now that he was face to face with the Real Thing. It seemed to him that instant action was essential. A moment’s delay might give the honours of this first encounter to the other side.

“Ready!” he shouted to the air at large; and then, excitedly: “Volleys—independent! Ready. At 200 yards. Present. Fire!”

Some in volleys, and some independent—this was no time to quibble as to a command—Corunna marksmen belched forth fire at the offending hat. There was the clatter and uproar of Sergeant Gore and his force, keen to concentrate: and in that same moment the intrepid scout who owned the hat, rose from his hiding-place and dashed away, well content to have done his mission in finding the enemy; also a little relieved that its ammunition was mere blank, and the stern Umpire safely out of sight.

“ ’M; retreating in bad horder!” diagnosed Sergeant, breathlessly arriving over the hill-top. He chuckled self-complacently. “And ’e’s a goner, too: shot dead.”

Grimshaw had a keener mind. “Yes, but he’ll tell the main force where we are, all the same.”

To Sergeant Gore’s intellect, scarcely that of a Napoleon, this aspect of the matter came as quite a revelation. He had thought himself the hero of an initial victory: it was rather annoying to find that he had merely helped a skirmisher of the other side.

“Very true, sir,” he said ungrudgingly. “Very true hindeed. . . .” He thought a moment, and then laughed somewhere deep within his frame. “So they thinks we are ’ere, sir, do you see? Well, so we is: just three or four, to fire a bit o’ powder! Meanwhile” (this he said magnificently) “the main force takes hup a position on the right,” and he waved towards a ruined mill which Grimshaw would have sworn was on the left.

To Grimshaw, innocent of military skill, this seemed very good, and it was done. In any case, the Sergeant was commanding, and thought his project reached the heights of strategy.

“It’s supple as does it, sir,” he said (meaning “subtle”). “That’s what the Colonel—Colonel Vernon—used to say. ‘It’s supple as does it: not your ’ack and ’ew’: many a time I’ve ’ad the Colonel say that to me, and it’s the truth, sir, mark my word.”

So twelve small Ansonites, thought useless for much else, were left to hold the hill as long as possible, and snipe freely, crawling about, to seem like a much larger force.

“When the last charge comes, sir,” said Sergeant Gore to their commander, “you falls back on the main force, if possible.”

“And if impossible?” the leader of this forlorn hope put in, nervously.

“If himpossible,” replied the ruthless generalissimo, “you surrenders at discretion.” And as he turned away, “But not before.”

He said this very sternly, and then with much taking of cover behind gorse and fences, he led his men up to the ruined mill. A stone wall ran around it, making quite a colony of little buildings, and as the Sergeant viewed the place, he knew it for a strong position. The hill up which they had just climbed ran down sheer, upon the other side, to the small river Ney. This side he felt that he could disregard, but round the others he distributed his men, and they awaited the arrival of the hostile force.

It proved to be rather a long wait.

There were, it is true, some sounds of firing upon what the Sergeant, to every one’s bewilderment, now called “the left front”: but not a great deal, scarcely enough to let the Warnerites imagine the hill-fort held by their enemy’s main force. Sergeant Gore was far from satisfied, and said he should have thought a dozen men could make a better show than that, with almost unlimited ammunition in hand.

As the minutes grew into a half-hour and nothing happened, he became very humorous at the expense of the invaders, and was encouraged to take a part that should be more than passive. He began thinking with an extreme degree of “supplety.”

The result certainly was striking, as explained to Grimshaw and a few favoured privates. The enemy, “being the force hA,” were clearly occupied with the so-called fort, which they believed occupied by “the force B, being hus.” Now, then, was the moment to attack them in the rear, or on the flank, or in one of the places so beloved by Cæsar.

In his means to this end, however, the Corunna sergeant totally surpassed the Roman general.

Down at the bottom of the hill, where the small stream Ney meanders through the valley, stands a little drawbridge, such as often spans these narrow waterways, for farmers’ use: a thing to be pulled up and down by means of a wood counter-weight. Unhappily, just now, the bridge was up: only to be lowered from the other side. But what was this to one who had studied “supple” methods under the great Colonel Vernon? Clearly, if the force B could cross this stream here, and then recross it by a lower bridge, they would have got behind the enemy in a method altogether unexpected: for the force A would have regarded this water as a kind of touch-line to the field of operations. Even the most realistic sham fight, in one’s school-days, does not include fording a river. The Matron would object to that!

Sergeant Gore, his plans already made, dashed down the hill-side, zigzag, from bush to bush; having just pointed out to his soldiers the importance of this example he was giving them in strategy, and exhorting them to watch him.

This they were willing to do. Was the fat Sergeant going to dive in and swim? Or would he take a flying leap? Either would be well worth watching: for the stream itself was some ten yards across, and even where erections jutted out from either side, to form a basis for the farmer’s drawbridge, there was an open space, deep water, of certainly twelve feet. Jumping or swimming—it would be a sight worth seeing!

But they had undervalued the wit of their commander.

Sergeant Gore, still treading very delicately, made his way to where a rustic boat, a sort of small pontoon, lay moored among the rushes. That reached, he took out the rough oars, and cast them from him on the grass with a dramatic gesture, as though to say a strategist would not have dealings with anything so obvious as that. Then he unloosed the punt, stepped into it, waved his hand magnificently at his troops above—clearly remarking once again, “Watch me”—and then, giving a kick to the bank, lay prone upon his stomach in the boat.

A sluggish current carried its heavy burden slowly on its breast. The punt majestically moved down stream. Nothing could be seen in it except the broad blue back of the old Sergeant, just beginning to wish that he had thought of bailing out a little bilge-water, before he settled down. When the boys reflected that this empty-seeming boat, so free from all suspicion to any watcher of the other force, must surely strike the further bank at the curved stream’s next bend, they were forced to admit that in his action he had carried out his great life-maxim, “It’s supple as does it. . . .” He would lower that drawbridge.

Then a Strange Thing happened.

Even while those on the height watched the scarcely moving boat, the promontory to which it floated filled suddenly with figures; figures in the accoutrement of Warner’s Corps. . . .

“By Jove!” muttered Sinclair, “they’ve crossed, by the other bridge!” And then—he laughed.

As to the others, nobody knew what to do. Grimshaw, left in command, had orders for almost every emergency but this. It was no use to shout and warn the Sergeant: he could not turn back, and it would only tell the Warnerites where the main force was. . . . Almost hypnotized with horror, they stood aloft and watched the punt, with that broad blue back protruding, drift inexorably towards the silent group of riflemen, who watched the curious phenomenon.

Somehow or other, it never occurred to any one within the mill to open fire upon the enemy. That was not part of this so subtle scheme!

And presently, with ever such a gentle bump, the punt beached itself upon the promontory of the river-bend. Sergeant Gore, well satisfied, if rather stiff and wet, got up and stood erect.

The first thing that met his gaze, as he did this, was the business end of probably a dozen rifles.

With one instantaneous consent his followers, up above, burst into a roar of laughter. They might be soldiers, whose commander had been captured: but above all else they were school-boys, whose hated Sergeant had been badly sold. This tragic end to all his “supplety” was altogether too delicious.

“Watch me!” mimicked one.

“No ’ack and ’ew!” exclaimed another.

“Silly old ass,” murmured Sinclair, rather impatiently. But even he could see the creamy humour of it.

And then—while they still craned over the stone wall, rocking in their merriment—a stern order came upon them from behind.

“Surrender!”

Immediately their laughter died; they swung about, and found themselves, in turn, facing the barrels of two dozen rifles. A Warnerite detachment stood across the entrance to the mill enclosure!

The order had come from Henderson.

“You’re our prisoners,” he said.

Grimshaw, terribly ashamed, looked from his own men, all in no order and rifles unloaded, even laid aside, to the row of Warnerites who covered them relentlessly: and logic had to own the fact. They were more in number, but they were cornered badly.

“I suppose we are?” he said to Sinclair, whom he always half unconsciously consulted. “The Umpire’d say so.”

“Umpire be blowed! Surrender to the Warnerites?” cried Dick: and then, to Henderson, “Come on and take us.”

“Volleys!” came Jack’s prompt order: and just as it was to be completed, Wren sprang towards him.

“Don’t fire at them, Henderson,” he shouted, excitable as ever. “You’ll blow them all to pieces at this distance.”

Jack smiled scornfully, yet saw the wisdom: this was too close a range, even for blank.

“Do you surrender?” he asked once again.

“No,” yelled back Dick, before Grimshaw had time to answer. “Not to you!”

“Charge, then!” Jack cried in anger, and suited the order by rushing straight at Dick: the scornful note upon that “you” had made the battle rather more than sham.

Muses, who helped old Homer in his battle-scenes, aid me now to tell of the great fight that then befell! Show how the useless rifles were now laid aside, trampled as to their sights, both back and front, by eager feet, while fists were used as more commodious weapons! Hymn the undying fame of Jenkins in the Fourth, who all alone held three Corunna men at bay, his back against the wall, and gave to each alike a beautiful black eye! Tell how the wall and force of numbers favoured Anson’s, but how anger and the sense of right emboldened Warner’s; so that the fight waxed long and hazardous! Up to the startled heavens rose the dust and roar of conflict, and who shall say what wondrous deeds were done within those hill-top walls?

Eminent above all others, as is fit, was the fierce conflict of the chiefs; the battle between Henderson and Sinclair. To and fro, this way and that, they reeled, locked body to body in a desperate struggle, caring nothing for the Umpire nor the subtleties of warfare; only resolved, each of them, Briton-like, to perish sooner than to own defeat. Henderson was certainly the stronger, and little by little, he bore Dick down towards the ground: but just as a wrestler, faced close by defeat, starts suddenly aside and up, so did Dick leap away, and seizing a rifle, stand upon the wall-top; threatening, at bay.

Jack, noting this new phase of the long battle, stooped, picked up a rifle at random, and rushed towards his foe.

“Surrender,” he shouted wildly, suddenly remembering the object of the fight, and whirling his new weapon madly.

“Surrender be blowed!” Dick answered once again, in heavy gasps, and as the other dashed in on him, he brought his weapon down heavily upon his head.

Jack tried to parry it; failed to get his rifle up; took the blow full on his soft hat; and fell motionless upon the ground.

Dick, horrified, suddenly remembered that this was a sham fight.

Great was the anger of the Warnerites, when they saw their idol, Henderson, carried off, huddled and motionless, upon a hurdle; nor did it die down in the days that followed. If Warner’s had formerly disliked its neighbours, it now hated them.

Dick, of course, had been the first to kneel beside the injured warrior and see what could be done, nor was he by any means least sorry of them all for what had happened: but Warner’s fellows, hurrying up, had none too gently elbowed him aside.

“We don’t want your help!” Wren had actually said, with bitterness: and Dick felt too anxious and miserable to retort.

One of the Ansonites, however, standing by, exclaimed: “Shut up, you silly little bounder,” and that very nearly started the mêlée again.

Away upon the far side of the mill, indeed, it had not ceased, because its combatants had failed to note the accident. Still full of feeling, burning with the rivalry and scorn of years, the smaller fellows of each school were grappling and pummelling each other. What little of military ritual the fight had ever boasted (and that was not much, thanks to the Sergeant’s and the Umpire’s absence), was by now totally neglected: the thing had become one of taunts followed by duels; every Warnerite engaged, the surplus Ansonites as keen spectators, ready to take the place of a defeated unit.

It was on such a scene that the Head Masters entered; Warner and Dr. Anson, trying to reach topics of common interest, and searching vainly for some sign of the fighting.

Now, suddenly, they found it.

Their eyes, confronted with so much in one brief moment, missed the group bending, ominously silent, over a figure prone upon the ground, and lit first on the more assertive tableau to their right.

Could these be their gallant, highly-trained defenders? This dense mass of whirling arms and well-spiced insults? No wonder the two pedagogues were horrified! Dr. Anson, in particular, felt this to be the conduct of a Board School rather than Corunna.

“No, no!” he fatuously shouted, with authority. “No, no!”

Warner, more practical, descended on the flock in warlike manner.

It is said that a walking-stick is the very worst means of stopping a dog-fight, since it encourages the injured hounds: but certainly it had quite an opposite effect upon these human combatants. Warner struck out at every one alike: any thigh that offered served him as a target; friend or enemy. Howls rent the air, suddenly: first one, then many, and hands—lately raised against a foeman’s face—now sought in agony another portion of their owner’s frame. Warner was a big man, armed with a big stick, and he found no need to hit twice. Indeed, when he had hit four or five victims once, the others, suddenly conscious of some new development, came to themselves; realized that they were themselves, and in presence of their Head; and felt altogether not a little foolish.

“Boys,” said Dr. Anson, with much grandeur, “I am ashamed of you.”

No one minded that immensely, but it seemed silly, somehow, to be dressed in military kit and yet to be without one’s rifle, standing there, in order anything but martial, under the cold eye of Authority.

An awkward minute followed, broken by the arrival of the Umpire.

“Now buck up, you men, and get to look something like something,” said Warner scornfully to his contingent. “Here’s the Adjutant.”

Captain Arundel was rather puzzled with the scene before him, which did not seem to fall into the same class, quite, as anything in all his years of service.

“What has been happening here?” he said helplessly, appealing to Warner for information on which to build a decision.

“I don’t know the military name for it,” came the grim reply, “but it is what I should call a common or garden street-row.”

“ ’M!” The Captain pulled at his moustache judicially. “Well,” he said finally, “I think there is no need to give a decision here, as the main action has been settled elsewhere.” The Corunna fellows, puzzled as to how that could be so, when they themselves formed the main body, closed around the Adjutant, to listen. This war business was a rummy game!

Captain Arundel cleared his throat once or twice; shook himself about a little, like a man preparing to drive off at golf; and was on the point of opening his remarks, when suddenly an interruption offered.

Wren, white and dishevelled, rushed up to Warner.

“Oh, sir,” he cried dramatically, “they can’t bring him round!”

“Bring who round? and where?” coldly replied Warner, who never sought to hide his scorn for Wren.

“Henderson, sir—on the ground. I think he must be dead.”

“Dear, dear,” exclaimed the Doctor, terribly perturbed.

But Warner knew the Dove. “Rubbish, man!” he answered. “Where is he? Buck up!”

Not waiting to hear any of the explanations that were jerked at him, he knelt by the boy’s side, and in a very workmanlike way, learnt upon the football field, began to examine him, with the calm and tenderness of a skilled doctor. The boys, of whichever school, stood round in a tense silence.

“He’s all right,” said Warner presently: and one could almost hear the fellows start to breathe again. “A little concussion. Here, hurry up, some one, and fetch a hurdle. We must get him home, and then he’ll be all right.”

But though he spoke lightly, knowing how easily boys magnify an accident into a tragedy, he secretly felt nervous; and waiting neither to say good-bye to the Umpire nor to hear out the Doctor’s regrets, he took one corner of the hurdle, and set out on the tramp home. Full of sympathy, and not caring to be left longer with the Ansonites, his boys were following, when he turned round upon them, almost angrily. They could not come, he said: they were soldiers, not nurses—though they did not seem to have remembered it! And so he left them, to end the work that they had got in hand. He was not one who would believe in shirking, even for the best of sentimental reasons.

Feeling a little crushed, more than a little angry, they stood in a group, shunning the Ansonites like something tainted with infection. Regarded as a means to friendship, the field-day was not vastly a success!

Captain Arundel, luckily, was too busy with his duties, and too used to casualties, to notice the strained position, which he just saved from developing into a new conflict by going on methodically with his business.

He was about to renew his synopsis of the day’s fighting, when a sudden clatter at the gateway drew every one’s eyes and attention to that spot. Sergeant Gore, plainly indignant, his head held scornfully erect, was being led in by his triumphant captors.

Captain Arundel smiled under his moustache.

“Ah, Sergeant,” he said, affecting not to notice his captive estate, “I was just going to sum up the result of the day’s operations.”

Sergeant Gore, in great relief, stepped from among his warders and saluted. “Yes, sir. Thank you, sir,” and he forced his way to the Captain’s side, feeling a new dignity, and trying to regain his usual importance.

“The force A,” resumed that last, “was given the task of pushing its way through an enemy’s country, to join an imaginary army. The force B was in occupation of a hill” (he waved his hand towards it), “supposed to be a fort, a strong position commanding the valley. I have just left the force A which, while the—er—skirmish was taking place here” (and he tried not to smile), “succeeded in joining that imaginary army; curiously enough, without a shot being fired by the force B. It is therefore my plain duty, as Umpire, to say that the day lies with the force A—that is to say, with Mr. Warner’s boys.”

Great were the cheers that burst from the Warnerites at that, and glum the looks upon the faces of those who had fought for the glory of Corunna.

“Er—as to the reasons for this bloodless victory,” Captain Arundel went on, more diffidently, “perhaps I may be allowed to say a word or two. The scheme of operations seems to have been a little—er, misunderstood by—er, the force B, which appears to have imagined that its duty was merely to be ready to repel attack, not actively to prevent the enemy’s advance. The force A was therefore able to achieve its aim without opposition, and the sole firing and—er, fighting took place between the outposts; at any rate, so far as the force A was concerned. The skeleton force representing their main—er, force, reached its goal without coming into conflict with the enemy. The force B, no doubt, was handicapped by the early capture of its commanding officer, and I hope—in fact, no doubt, future field-days, with more practice, will lead to operations strategically more satisfactory: and I think there is no need to dwell further upon that.”

“Hear, hear,” said Dr. Anson, as the Captain paused.

“What it is very encouraging to be able to comment upon is the admirable pluck and—er, resource shown by the boys of either side. I hope, and in fact no doubt, in future years of this—er, friendly rivalry, these qualities will be no more—that is, no less conspicuous, and combined also with more strategic skill.” At this point he pulled down his collar, and speaking with more ease, concluded: “I have much pleasure in congratulating Mr. Warner’s boys upon their victory, and in congratulating those of Mr.—that is, Dr. An—er, that is, Corunna—on their pluck and—er—resource.” And his voice died away.

“Three cheers for the Umpire,” shouted Grimshaw; and if the smaller Ansonites did not join in them quite so heartily as did the Warnerites, well, maybe it was only small-boy nature, after all. They felt it was a “beastly swiz,” and they thought almost nothing of the Adjutant as Umpire.

Even Grimshaw and the bigger fellows felt they had not been fairly treated. They might possibly have blamed the Sergeant, had he not fluently explained, all the way home, that Captain Arundel as a soldier was no more good than a sick ’eadache; exclaimed frequently, “call that a scheme of hoperations!”; vowed force B was the moral victor; and set forth at some length how Colonel Vernon—“now, ’e was a soldier, if you like”—would have explained the whole thing in a line, and not made this ridiculous mistake. . . .

But he had rather a chill audience, at best. The Sergeant, as a fighting man, had lost some of his prestige (gained by his own stories of past heroism) in the moment that they saw him helpless before the rifles of the Warnerites!

Besides, what was victory to the one side or defeat to the other? Each had grievances of far more import.

How like the Ansonites, said Warner’s boys angrily among themselves, to go and stun a fellow and give him concussion, all in a sham fight! Of course, it was like the beastly smugs to get sick at being captured by a smaller force: but they should have thought that was about the limit!

As to the Corunna fellows, they were equally indignant. Of course the thing had been an accident, and any one but bounders would have understood as much. Naturally Dick Sinclair would have apologized—did try to, and to bring the fellow round—but the beastly Warnerites shoved him aside, and that rotten little funk had actually dared to say they didn’t want his help! Jolly rough luck on Dick, who was awfully cut up! Besides, it was beastly cheek expecting a fellow to surrender: naturally he fought. And that great hefty swine Warner (whom secretly they all respected), coming and laying about with that great stick of his! All right lamming the Warnerites, of course, but what right had he to come licking them? Disgusting cheek! No wonder his fellows were such a set of swabs! . . .

In fact, only the end of term and a certain diplomacy upon the part of the Head Masters, who kept their boys well occupied, prevented the thing from ending in something more dangerous than words.

Episodes at school are generally bounded by the end of term: that is to say, no incident, however thrilling, usually survives the holidays. Jones may be in a terribly tight place, but if he can stave the row off until breaking up, he knows that he is tolerably safe. Brown and Robinson have been rather chilly with each other during the last weeks of the long winter term, but unless there is some really serious ground of quarrel, the Easter term will see their friendship taken up again. The holidays wipe the slate clean, and every one starts with a fresh account.

Of course, the feud between the schools was of those serious things that persevere: no holiday, however long, would kill it—now, more than ever: but at least this break in the school year made a considerable change in the form that it assumed.

Smarting with their recent grievances; bored in the last weeks of a boring term; the Warnerites hearing exaggerated rumours as to Jack’s injuries; the Ansonites furious at the reception of Dick’s later apologies; they were foaming for each other’s blood, in April. But when May came, it found them full of cricket and its prospects; busy with fresh interests; Jack in his place, as fit as ever; and the whole incident too stale to stand discussion. Each school was still furious with the other: but the actual longing to come to blows had passed. In fact, each really felt that it would be lowering itself by having any dealings whatsoever with the other! The former fierce anger had given place to a dull resentment, far more likely to be lasting.

Then came a startling bit of news. The annual cricket match was “off”!

At once rumour started on its round, and everybody had a different story. “The Ansonites have funked,” said Warner’s, “and darned sensible, too. They know they would have got another licking.” Corunna naturally had another version, in which their rivals were held up to ridicule as fearing to be clubbed upon the head with cricket-bats, poor little darlings! Each school got quite a lot of fun from its peculiar theory.

This for a while: but presently—when neither Head Master gave an explanation, and Dick and Jack, respectively, said they knew nothing more than that there would not be a match, this year—presently, another story began to be whispered in the studies of Corunna.

Gibbs of the Third, full of a longing to be superior, was first to start this story rolling.

“Nobody really believes that’s it,” he said magnificently, when one of his small-boy friends had repeated the stock explanation.

“Well, what is it, then?” came the triumphant answer: and the other was beaten, for a moment.

“Ah!” he said presently, with a great cunning, as one whose lips are sealed.

At once the news began to spread that Gibbs knew the real explanation about the Warnerite match, but wouldn’t tell it: and for an hour or two he lived upon his reputation. Then, of course, the scoffers came and shattered it.

“I don’t believe he knows, at all,” said some one, more by way of finding out than anything.

“Oh, don’t I?” Gibbs retorted weakly.

“Well, you simply mean that you think old Ass Anson funked there being a row? Because if so, that’s all stale bunkum, because the match is supposed to make us pally, and every one knows that.”

Gibbs replied with crushing slowness. “Well, as a matter of fact, I don’t mean that: so you are rather sold!”

Now, this negative sort of attitude might satisfy his fellows of the Third, but Gibbs (bitten with detective fever and the desire for further fame, since he had been the first to sight that Warnerite scout behind the gorse-bush) had dabbled with a bigger matter than he knew. Every one was talking of this sudden end to an old annual fixture, every one longing for an explanation. Travelling up the forms, in the mystic way that news runs through a school, the rumour of young Gibbs’ boasted private knowledge soon reached Dick, who, as cricket captain, was not a little interested.

After second school, he went along to number sixteen, Gibbs’ study. Several of the little boys who shared this small room with the hero of the hour, were idling in it—reading, talking, or fighting on the floor. Sinclair’s entrance caused quite a sensation. The Army and the Navy sides are separate at Corunna: and not often had number sixteen welcomed so superb a visitor.

“Here,” he said, as he entered, “what are you all doing, fugging in the study on a day like this? Clear on out.”

Sinclair was not a prefect, had no official power: but when one is twelve, it is ill arguing with an athlete of eighteen, and they duly “cleared on out.”

“Not you, Gibbs,” Dick cried, as they scuttled forth. “I want a word with you.”

Gibbs, very proud but rather nervous, came back from the door. The others went out, wondering.

“Look here,” Dick opened, when their noise had died away along the corridor, “what’s all this about your knowing why the match is off?”

Now, indeed, poor Gibbs’ pride was altogether flooded by his nervousness, for he was cornered. He looked up at the Cricket Captain, towering above him, one foot on a chair, and he knew that this was no time for such evasive answers as had served him until now. “Wouldn’t you like to know?” or simply the old, learned-sounding “Ah!”—these were not things to say to the great Sinclair! And if he owned that it had all been nothing, he was sure of a pretty sound kicking for being a little ass, and talking about things that did not concern him. . . .

It is said that the brain works more rapidly, more clearly, in a crisis than at other times: and that though the next minute may bring a reaction lasting months, this instant’s thought is often the most splendid of a life-time.

So it was with Gibbs. Even while Sinclair looked down on him, seeming to bulk larger every moment, he was given his great Inspiration. He remembered suddenly the several times of late when he had seen the Doctor cross the lane, and on that slender base he built a wonderful, convincing theory, for which—in periods of less peril—a month would probably have not sufficed.

“I don’t know, Sinclair,” he said timidly, in case of accident; “it’s only what I guessed.”

“Well, out with it! What is it?” Sinclair obviously would judge by results.

Gibbs took up an even humbler tone: already he could feel those big boots, menacing, behind him! “It’s only that Anson—I mean Dr. Anson, and Mr. Warner are always together now, and they’ve only got forty-seven fellows there, now, because five have just left, and there used to be a hundred—usedn’t there?—and so——”

“By gad!” cried Dick, not waiting for the stuttered argument’s conclusion. “I never thought of that. You mean Warner’s shutting down? The place is busting?”

“Yes,” answered Gibbs hopefully, with a new confidence. The boots looked smaller now.

Dick was thinking. “ ’M!” he said. “I shouldn’t wonder. . . . Anyhow, don’t go saying anything about it—see?” And without so much as “Thank you,” or “Clever of you!” he had gone.

Of course, Gibbs was much too proud of his own cleverness, too pleased at being able (unexpectedly) to show that he really did know, to obey the Captain about silence. Dick, too, spread the rumour freely. Within a week, everybody at Corunna said quite definitely that Warner’s was shutting at the end of term.

“And a jolly good thing, too,” was the usual addition.

When the visits between the two Head Masters continued frequent, almost daily, every one agreed that the old Ass was keen to be decent to Warner, now that he was a failure, and to part in peace.

The Doctor, indeed, shortly afterwards announced, in one of his periodic speeches, that the annual match had been abandoned because he wished the two schools, henceforward, to regard each other not as rivals, but as friends. Every one, however, (to the vast relief of Gibbs,) agreed that this was merely bluff.

From this time on, Corunna began to regard the other school with the sentiment which Dr. Anson was supposed to feel for Warner—pity, contempt, and the noble generosity due to a fallen rival!

After all, what was the use of lamming into them when they were down? They were a failure! Wasn’t that enough? And next term, the place would be healthier without them! (This was Gibbs’ contribution.) . . .

Warner’s, meanwhile, quite unaware of all these rumours (since nobody at either school would pass a word with anybody at the other), did not, for its part, worry to attack these contemptuous foes: for it was busy with others, of more active nature.

It need surprise no one that a school, open only to boys intended for the services, and conducted upon sporting lines, should be a little rough and pugnacious: what may be thought curious is that Winton, so small a village, should be chosen for no less than three seats of learning.

Yet so it was. Because of its climate, its low rents, or for whatever reason, there they were: Corunna, Warner’s, and the Agricultural College: and being only three, they naturally fought. If there had been twenty, or even a dozen, things might have been different. As it was, the three were always clashing. Warner’s and Corunna were naturally rivals, whilst Mr. Da Costa’s Agricultural College for the Training of Gentleman Farmers (to give it its full title), struck each of them as a convenient butt.

Mr. Da Costa’s pupils were not boys. There must be no error as to that! No greater insult could be offered to any one of them. They all had their allowances, and they might smoke and drink at will, nor were there any bounds set them in their excursions. They might have bicycles, horses, motor-cars, aeroplanes—anything they could afford—and most of them were over twenty.

In a word, they were magnificent, in their own opinion: in that of the boys, an “awfully good rag.” Nothing, for pure fun, came up to baiting the Costers (as they were usually called), and its chief joy lay in the fact that, in the process, they became extremely angry. They were not going to be interfered with by a “pack of boys”!

Warner’s fellows, during all this summer term, waged an especially unceasing war against these splendid people, and had succeeded with great joy in rousing them to a pitch of ferocity hitherto unknown. The college was for Gentleman Farmers, but that is a vague word, and they were rather a rough lot. Somewhat excessive was the vengeance meted out to any Warnerite stupid enough to fall into their clutches during one of these encounters. He was a “beastly boy,” and boys “wanted thrashing, don’t you know”! Such was the theory of the Costers, and on it they acted to a degree which might have caused inquiry, but that boys usually prefer to take the consequences of their own adventurings: and Warner never heard of these fierce vengeances upon some of his smaller fellows.

There were, however, others to avenge them.

Jack, in particular, happened to note the back of a boy in his dormitory, one night, while every one was washing, stripped to the waist, at the long row of basins. Great purple weals stood out across it.

“Hullo, Foster,” he exclaimed. “Has Warner been laying in to you? What for?”

“Oh, no,” answered Foster uneasily, trying to appear at ease.

“It was the Costers,” one of the fellows said, coming to the rescue: for nobody likes sneaking about himself, even to another boy.

Jack was utterly astonished. “But that was a week ago, or jolly nearly! They must have almost murdered you?”

“They did make me sit up a bit. It was up the river, and I only had a vest on.”

“The swine,” Jack exclaimed angrily, for Foster was only a small kid. “Who was it?”

But now Foster obviously did not wish to speak.

“The usual gang?” said Jack. “The Lightweight?” (The Lightweight was known in his own circles by the name of Featherstone.)

“Yes, more or less,” said Foster vaguely.

“Very well,” Jack muttered ominously. “I’ll make the little blighter pay for it.”

Now this was capital! The bigger fellows, until now, had always held aloof from the feud with Da Costa’s, regarding it as rather below their dignity, and as they would have called it, “kiddy,” to bait men older than themselves. The Costers, of course, were cheeky beasts and touts and everything of that sort: but their harrying could be left quite safely to amuse the juniors. These last were certainly amused with it, but they were also nervous, for their foes were a big lot, and Foster was by no means the first to come off badly as the result of an excessive rashness.

But now Henderson, who was more their size—(more their size? Why, every one at Warner’s believed that he could lick a dozen of the Costers!)—the great Henderson himself was going to join in the fray, and they had better jolly well look out!

The school settled down with pleasure to wait for their discomfiture.

Two or three weeks passed without the chance occurring, weeks too full of cricket, boating, and all the interests of a summer term; and then, like most things for which one has waited, it came quite unexpectedly.

It was a glorious July day, and—what seemed almost criminal—it was a Long Lesson: which is to say that there was work for every one from three o’clock till five. These days were rare at Warner’s in the summer-time, so long as the sun shone, for the old Blue believed that winter was the time for work, and usually found some excuse for a half-holiday: perhaps not a very good excuse, yet fully good enough to satisfy both himself and the boys. But if the sun persisted in shining on every Long Lesson day for a whole month, Principle demanded that work should be done now and then: and this was one of those occasions.

No cricket to-day! Every one was bored. Five o’clock, and lock-ups at six-thirty: what earthly use was that to any one? Some of the fellows played small game; others went for a short walk; and most of them did nothing except slack. (This last was Warner’s reason for hatred of these afternoons.)

Suddenly two of those who had chosen to walk, came hurrying back and rushed up to a group of idlers.

“Such a rag!” they cried. “What do you think? Lightweight’s got a picnic on the Ney! We saw him sweating up with a huge hamper in the stern.”

Here, indeed, was nothing less than a godsend for a dull afternoon! Everybody realized at once that this was a prime opportunity to annoy the enemy, and quickly the news spread, until it reached Jack Henderson.

“Oh, a river picnic?” he said, bored with inaction, and still indignant at the ill-treatment of young Foster. “We’ll river-picnic the bounders. Come along, you men!” and accompanied by O’Brien and three others of the First Eleven, he swung out through the school gates. The small boys, chattering and joyful, followed in a bunch behind this dashing leader, anxious not to miss a moment of his vengeance.

There is one traditional spot, leafy in shade, and with an easy landing-place, where picnickers upon the Ney do always congregate: and to Jack’s delight, even as he and his satellites arrived upon the bank, Da Costa’s men hove into sight along the bend. First came an oarsman, who strained heavily at a broad boat, the stern of which was almost submerged with the weight of a vast hamper. Great joy surged over the Warnerites as in the narrow back that bent to jerk those splashing oars, they did indeed recognize the hated Featherstone.

“Good! There’s the ‘Lightweight,’ ” said Jack ghoulishly: but almost immediately he added, with no less vehemence, “Oh, hang!”

Round the corner came, with more ease and less commotion of the water, a lighter boat wherein sculled Cursitor; his cargo two young ladies. It was not a picnic of Costers!

“They’ve got some girls with them,” Jack said. “That rots up everything.”

“Why?” queried Wren in disappointment. He had never felt so secure, in any raid against the doughty Costers.

“Why, we can’t rag them now, you silly ass.”

Henderson spoke so contemptuously that Wren hastened to say, “No, of course not,” though really he did not see why, at all. So much the safer, if two of them were only girls!

Jack was just about to turn away, when O’Brien said, with his slight brogue, “I don’t see why we wouldn’t stop and watch? It’s really darned amusing. Look at that silly ass the Lightweight doing all the work!”

“Yes,” said Jack, laughing, “but it’s rather rough luck to rag the swine, when they’ve got girls with them.”

“Who’s going to rag them?” replied the other. “I only want to see a little of the fun.”

Meanwhile the leading boat (which must have had a generous start) drove its nose gently into the bank, almost opposite to where the Warnerites were standing, hidden by the luxuriant undergrowth that makes the Ney so beautiful a stream.

Featherstone stepped on to terra firma, very timidly, as though in hideous fear of overbalancing into the water. He was dressed in a green flannel of alarming brightness and the latest cut. His shirt was mauve, and the cream-hued tie showed to its full length, because he wore no waistcoat. White shoes and a large turn-up of the well-creased trousers served to display a generous peep of purple socks. In spite of this magnificence, he was not particularly imposing, for Nature had not shaped him quite in the mould of the River Man. His shoulders, broad (at first sight) for so short and weak a man, proved (on a second) to be due less to athletics than to the tailor’s art. And when the summer breeze played with his trouserings, it almost seemed as though they flapped only against broomsticks. A moustache could be seen—by those of keener eyesight—distinctly beginning to hide some of his silly, self-conceited face.

Once safely upon shore, he did not worry about fastening the boat or starting to unload the cargo. With a quick glance at the rapidly approaching wherry, he set his legs slightly apart, removed his panama hat, and took out from his breast pocket a small mirror. This he held in his left hand, while with the right he smilingly smoothed the hairs of his head, and also the few of his upper lip.

The complacent way in which the little man gazed, almost sentimentally, at his own ugly image, was too much for the boys upon the other bank: and they made sounds of merriment, which reached him.

Hurriedly he put the mirror back into its resting-place, and peered across the water. A look of anger crossed his face, as he saw who had laughed.

“Go away, you boys!” he said, with an utterly absurd air of authority, and he waved his hand in the sort of gesture with which one frightens away flies.

He scored a great success, so far as laughter went. Even Jack was glad that he had stayed. And certainly he did not think of going, now that he was ordered—by the Lightweight!

But now the second boat arrived, in a less sluggish manner, and Cursitor leapt nimbly out, tied the painter to a bough, and steadied the boat while his passengers stepped on to the bank, each smiling at him as he took her hand. He was far less grand in his attire than Featherstone—white flannels, a cellular shirt and (once on shore) an old school blazer—but distinctly more impressive. He was a veritable giant, of the tall, athletic build, with long, straight limbs, and over them a face tanned and healthy, lighting up at times in a good-humoured and refreshing smile. He was certainly handsome, but let one fancy that he did not know it. Always roughly dressed, generally in old riding kit, he was the only Coster whom Warner’s and Corunna, by tacit consent, left out of the feud. His good-natured face (he was half Irish) and tolerant ignoring of their existence, set him somehow apart: and besides, if they had realized the truth, they admired—or even feared—his strength, and no one had ever thought of shortening “Cursitor” to “Cur.”

So his presence, combined with that of two very radiant young damsels in enormous hats, quieted the boys on the far bank. In a minute or so, doubtless, they would have gone away quietly, without letting any one but Featherstone know that they ever had been present at this private function.

But this indignant little person, who had been fussing aimlessly around while their guests landed, still had the sound of that derisive laughter in his ears: and it seemed to him that here was a good chance to show Edna and Fay Denton (the last of whom he thought rather admired him) what a strong man he was. After all, the beastly boys couldn’t very well be such bounders as to say anything or stop and rag, when there were ladies present. . . .

“Here, you boys,” he said, just as Jack was thinking it would really be more polite to go now; “didn’t you hear me tell you to clear off?”

“Dry up, Lightweight!” piped a treble voice.

Jack turned towards the junior, to tell him to shut up—of course, a kid wouldn’t understand how beastly rude this was, with women—when suddenly he saw one of the girls glance at the other; then both go off in an ecstasy of giggles. They had never thought of that grand name for Mr. Featherstone! “Tubby” they knew: but “Lightweight”——!

This changed Jack’s whole attitude. It appeared that the women were amused, and as to Featherstone, it really was disgusting cheek. He did not very well see how they could “clear off,” now!

“Clear off, yourself,” he shouted. “Have you bought the place?”

“Do you mind us breathing?” Wren cried out, thus encouraged, and then tried to hide. He did not care about being recognized. After all, he did not want to fight the Costers!

The Misses Denton were now tremendously amused. They thought it quite an adventure, and the boys were rather fun: besides, it was killing to see that stuck-up little Mr. Featherstone annoyed like this.