* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Leading Men of Japan, with an Historical Summary of the Empire

Date of first publication: 1883

Author: Charles Lanman (1819-1895)

Date first posted: May 4, 2023

Date last updated: May 4, 2023

Faded Page eBook #20230506

This eBook was produced by: Marcia Brooks, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

This file was produced from images generously made available by Internet Archive/American Libraries.

LEADING MEN OF

JAPAN

WITH AN HISTORICAL SUMMARY OF THE

EMPIRE

BY

CHARLES LANMAN

Author of “The Japanese in America,” Etc., Etc.

BOSTON

D. LOTHROP AND COMPANY

32 FRANKLIN STREET

Copyright, 1883.

D. Lothrop & Company.

This volume is the direct outgrowth of my work entitled The Japanese in America, which was published ten years ago, and widely circulated in the United States and England. It is divided into two parts, the first of which contains brief biographical sketches of the leading men who in recent times have been honorably identified with the marvellous career of the Island Empire of the Pacific. A goodly number of names have necessarily been omitted, for the reason that I could not obtain the needed data to do them justice; and, I regret, for the same reason, that several of the notices in the volume are far more brief than they deserve to be. I may say, however, that so far as I have been able to go, my statements will be found entirely authentic—the great bulk of my information, including the translations, having been obtained from Japanese scholars and various well informed friends residing in Japan. With the exception of the first two sketches—of the Emperor and his father—I have arranged them in alphabetical order, intending thereby to avoid even the appearance of favoritism. This is the first time that sketches of so many men from the Orient have been brought together in a single volume for the edification of the Western world, and I cannot but hope that these records will do something towards making the people of America and Europe better acquainted than ever before with the gifted, elevated, and progressive character of the Japanese people and Government.

In the second part of this work I have introduced a bird’s-eye view of the History of Japan, which I contributed to Johnson’s Universal Cyclopædia, together with several chapters bearing on the outlying possessions of the Empire, or directly connected with its history.

C. L.

Washington, Jan., 1882.

| CONTENTS. | ||

| PART I. | ||

| The Emperor of Japan | 7 | |

| Komei Tenno | 19 | |

| Arisugawa Taruhito | 24 | |

| Enomoto Takeaki | 27 | |

| Enouye Yoshikadsu | 31 | |

| Fujita Hio | 33 | |

| Fukuchi Genichiro | 37 | |

| Fukuzawa Youkichi | 43 | |

| Genpaku Sujita | 64 | |

| Goto-Sho-Jiro | 66 | |

| Heihachirô | 67 | |

| Higashi Fushimi | 78 | |

| Hiroyuki Kato | 81 | |

| Ijichi Masaharu | 83 | |

| Inouye Kaoru | 85 | |

| Ito Hirobumi | 101 | |

| Itagaki Taisuke | 103 | |

| Iwakura Tomomi | 104 | |

| Kabayama Sukenori | 108 | |

| Kawaji Toshiyoshi | 110 | |

| Katsu Awa | 112 | |

| Kawamoora Smiyashi | 114 | |

| Kido Takayossi | 115 | |

| Kono Benkai | 121 | |

| Kurimoto-Jo-Wun | 122 | |

| Kuroda Kiyotaka | 127 | |

| Neeshima Jo | 130 | |

| Miura Goro | 132 | |

| Mori Arinori | 135 | |

| Moshitsu Otsuki | 138 | |

| Mumeta Genjiro | 140 | |

| Naganori Asano | 145 | |

| Narushima Kiuhoku | 146 | |

| Oki Takato | 161 | |

| Okubo Toshimichi | 163 | |

| Okuma Shigenobu | 177 | |

| Otori Keisuke | 181 | |

| Oyama Iwa-o | 183 | |

| Oyano Iwao | 185 | |

| Rai Mikisaburo | 187 | |

| Saigo Takamori | 190 | |

| Sameshima Naonobu | 206 | |

| Saigo Tsugumichi | 208 | |

| Sanjo Sanetomi | 210 | |

| Sano Tsunetami | 213 | |

| Sato Shunkai | 215 | |

| Shibusawa Eichi | 216 | |

| Shimadzu Hisamitsu | 221 | |

| Soyeshima Taneomi | 223 | |

| Tanaka Fujimaro | 225 | |

| Tani Kanjo | 227 | |

| Terashima Munenori | 230 | |

| Toyama Masakazu | 232 | |

| Tsuda Sen | 234 | |

| Yamada Akiyoshi | 240 | |

| Yanagiwara Sakimitsu | 245 | |

| Yoshida Kiyonari | 246 | |

| Yoshida Torajiro | 251 | |

| Biographical Addenda | 256 | |

| PART II. | ||

| The Empire of Japan | 261 | |

| The Islands of Okinawa | 302 | |

| The Ogasawara Islands | 317 | |

| Corea | 326 | |

| Origin of the American Expedition to Japan | 391 | |

| Additional Notes | 409 | |

| Foreign Bibliography of the Empire | 415 | |

LEADING MEN OF JAPAN.

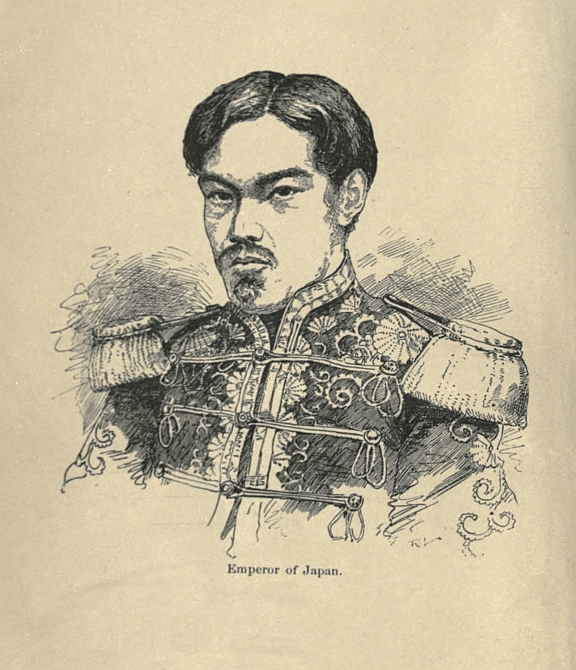

The Emperor of Japan was born in the Christian year 1852, or, according to the Japanese calendar, in 2512; a date showing that the Imperial dynasty had its origin in the seventh century before the Christian era. His name is Mûts-hito, the son and rightful heir of Osa-hito (or Komei Tenno, the name given after death), who died in 1867, after a reign of twenty years. Soon after that event the abdication of the Tycoon, known formerly by the name of Hitoty-bash, took place at Osaka; and as that was the pivot upon which the Japanese revolution was balanced, it is proper that we consider here the circumstances of this abdication.

The question of opening a port in the “inland seas” to foreign trade had been pending at that time for more than three years. In 1865, or perhaps 1866, the Government of the Tycoon was forced by the strenuous urging of the foreign representatives in Japan to consent that the port of Kobe should be opened on and after January 1, 1868. Immediately after this fact had been proclaimed a strong opposition was manifested by the leading Daimios, because it neither had been properly discussed by the authorities, nor received the sanction of the Emperor. This opposition arose not so much from any objection to the opening of a new port, as from the consideration that the Tycoon’s government had virtually been forced by the foreign powers to yield to them a right which required the royal sanction, and because it was a question in which the whole people were greatly concerned. By the more thoughtful statesmen of Japan, this premature concession was considered an act of cowardice; therefore hurtful to the national honor. Memorials were written and circulated throughout the Empire against the measure as well as against the previous blunders of the Tycoon’s government, in regard to foreign intercourse. Other demonstrations were also of frequent occurrence, and thus the fire was kindled which was to consume the foundations of the Tycoonate.

In the latter part of 1867 the Tycoon and the leading Daimios were summoned to the seat of the Imperial government, for the purpose of discussing the question of opening the port of Kobe, and they accordingly assembled in Kioto. The diplomatic agents of all the treaty powers, with their respective fleets, assembled in the Bay of Osaka, to watch the proceedings of the assembly. As the Tycoon had formerly made a hasty concession, he now advocated the immediate opening of the port of Kobe; but the other Daimios (for he was in reality one of them) still opposed the measure. Seeing clearly that the political tide was turned against the Tycoonate, Hitoty-bash found it necessary to resign his hereditary office; his abdication, which was soon presented to the Mikado, was at once accepted; and then, without further delay, the question of opening the port of Kobe was agreed to by the assembled Daimios and sanctioned by the Mikado. Thus an end was put to this question as well as to the hereditary Tycoonate. The reader may think it strange and illogical that the very question which caused the overthrow of the Tycoonate, a political institution which had lasted three hundred years, should have been settled thus without difficulty. Nevertheless, such was the fact. But the end of the old institution would have soon come, irrespective of this question; for even those who belonged by hereditary right to the Tycoon’s government, and faithfully supported it, and who had sufficient foresight, had long before advocated the abdication, because they had discovered that the old system was decaying from the effects of corruption, and that the demoralization was too general to allow of the continued existence of the long-established hereditary system. Thus, at the age of fifteen years, the Mikado, or Emperor of Japan, began his rightful reign.

At that time the residence of the Mikado was at Kioto, thirty miles from Osaka, while that of the Tycoon had been at Yedo. In 1868, those of the Daimios who were dissatisfied with the course pursued by the Tycoon began to manifest their hostility, and soon made known that they would not obey the orders of the Emperor. It then became necessary to put down this rebellious spirit by force of arms. Anarchy prevailed in various parts of the country, but especially in Yedo, where demonstrations were made against the Tycoon’s household; a naval engagement took place in the Bay of Yedo; a serious fire occurred in Kanagawa; and then in the district between Osaka and the Mikado’s capital, several battles were fought which resulted in the total defeat of the rebels and their disastrous flight. Their forces amounted to about thirty thousand apparently well-disciplined troops, while the Imperial army was very much smaller; but the tide had turned, and the Imperial government was triumphant; and, while the Tycoon fled for safety to his palace in Yedo, the Mikado, with his Regency or the Great Daimios, who were his chief advisers, was living in comparative peace in Kioto.

Since the year 1868 many remarkable events have occurred in Japan, and the reign of the young monarch promises to be unprecedented in its influence on the welfare of the Empire. During the troubles which followed the abdication of the Tycoon, the Mikado resided temporarily at Osaka, and it was in that city that his coronation took place on his reaching the requisite age of sixteen years. Almost the first step which he took after that event was to grant an audience to the representatives of the foreign powers, a concession that never had been made before by the Imperial dynasty. It filled the Japanese people with astonishment, and made them almost doubt the reality of the Imperial personage; nor was it much less astonishing to the Europeans to realize their situation in being permitted to see what millions of Japanese had never dreamed of seeing—the person of the Imperial ruler of the nation. It was not long, however, before all doubts were removed by the enactment of official measures calculated to impress the most skeptical conservatives that a new era of progress and civilization had dawned. A second step of the Emperor was to establish upon a firm temporal foundation the Imperial government, which had for so long a period been considered merely spiritual in its character. This was a consummation for which the patriots throughout the Empire had been pining for scores of years.

Before the close of the year 1868 the Mikado resolved to remove his residence to Yedo, and this event was commemorated by a royal decree, a part of which we may translate as follows: “Being now established in my reign, and in the government over all my people of Japan, I have taken into consideration that Yedo is well adapted for the seat of government, inasmuch as it is the most central, the greatest and the most populous city in the Empire. I therefore decree that Yedo shall be the seat of my government, and this city shall henceforth be called Tokio, or the Eastern Capital. This I do because I consider my whole Empire as but one body, and therefore I am anxious to show no partiality to either of the eastern or western provinces. Let all my subjects be informed that this is my decree.”

The disappointed followers of the Tycoon, having been unsuccessful in their movement against the forces of the Mikado near Osaka towards the close of 1868, retreated to the island of Yesso, intending to make a final effort there to retain power. As related in our sketch of General Saigo, they were the possessors of a naval fleet, commanded by Admiral Enomoto, who had under him a number of French officers. They made an attack on Hakodate, captured the place, and remained undisturbed there during the winter. In the meantime, while the Mikado and his great Councillors of State were not unmindful of these operations, certain important negotiations or transactions were taking place in Yedo. The representatives of all the foreign powers whose fleets were then at anchor off the port of Yokohama, having signified to the youthful Mikado that they were anxious to present their credentials to him, a favorable answer was returned, and the reception took place on the fifth of January, 1869. It was a grand affair, and was glowingly described by the local press. Soon after that event, the Mikado made a visit to Kioto, married a wife, and returned to Tokio, where he had determined to remain permanently, and where also the great Daimios of the realm had congregated in obedience to the Imperial order.

In the beginning of the summer reinforcements by sea and land were despatched by the Imperial government to Hakodate, for the purpose of entirely quelling the rebels, who there made a final effort at resistance. The insurgents under Enomoto were not only in a wretched plight in regard to food and clothing, but they were disheartened, so that the hostilities were of short duration, and the Imperial forces soon beheld their flag waving over the subdued port and fortifications of Hakodate. After the surrender, the leading rebels were imprisoned, but the rank and file were treated with great kindness. Not only were they all subsequently pardoned, but many of them have since been appointed to offices of trust and honor. Enomoto, their leader, was appointed Envoy Extraordinary to Russia. Indeed, the disposition of the Emperor to treat his erring subjects with the kindest consideration was something unprecedented in Japan. He even invited Hitoty-bash, the ex-Tycoon, to take part in the government; but the offer was not accepted.

Animated by noble instincts, the Emperor of Japan has ever since made no discrimination in appointing the responsible officers of his government, whether they were formerly supporters of the Tycoon or not; but he has always been anxious to find men of ability and lofty principle to assist him in public affairs, and he has usually been successful in his efforts. He has set aside the prejudicial distinctions which formerly existed in regard to appointing certain officers from certain classes; and though there still exists a marked line of distinction between the members of the royal family and the rest of the inhabitants—the nobility, the middle class, and the common people—yet what may be called aristocratic vanity is no longer tolerated, either by the Emperor or his subjects. A farmer or a mechanic may now become the head of any bureau or department, according to the personal worth of the man. Such things were altogether unknown in Japan in former times. Members of the middle class, or samurai—not to mention the nobility—were not permitted to marry legitimately the daughters of farmers and mechanics. But all such restrictions have been abolished by law, and now a farmer may marry the daughter of a nobleman or a samurai, and the daughter of a mechanic may become the lawful wife of a nobleman.

Among the events which thus far have distinguished the reign of the Mikado, perhaps none is so important as that which was brought about by the foremost Daimios, Satsuma, Chosiu, Hizen and Tosa, in voluntarily yielding up their feudal rights into the hands of the Emperor. This, which occurred on the fifth of March, 1869, was followed by similar concessions by nearly all the other Daimios of the Empire, and the abolition of feudalism was fully consummated before the close of that year. In rendering this truly wonderful sacrifice, these noblemen solemnly declared that their single object was to raise the national standing by perpetuating the centralization of power in the Imperial government, and thereby enabling the Empire to take its place side by side with the other civilized nations of the world. These sentiments were welcomed with enthusiasm, and the great deed of the fifth of March was imitated by the other Daimios so rapidly, that in a very few months the Empire was nominally unified.

How wonderfully have the desires of the Japanese patriots been hastened to a complete fulfilment! In proof of the earnestness which has ever animated the Mikado himself, we have but to glance at some of the results of his enlightened policy. He has sent ambassadors abroad for the purpose of informing themselves in regard to affairs of state; regular legations have been established in Germany, England, France, Italy, Russia, Austria, China, and the United States, and consulates in many of the ports of the world; railways have been built and steamship lines established; lighthouses have been built all along the coasts of the Empire; telegraphic lines have been constructed on land and sea; a regular army and a navy have been organized on the models of the western nations; institutions of learning and for benevolent purposes have been founded and liberally endowed; and able young men have been sent to foreign countries by hundreds, to be educated, to assist in the progress of the Empire towards a perfect civilization. Old laws have been revised, new laws have been instituted, and ancient usages that were barbarous have been abolished. Indeed, the laws of the Empire are to-day far more lenient than is generally supposed; the principles of the administration of justice are almost as perfect as those of the United States, and the habit of executing them is universal. The wicked are inevitably punished according to law, and the just and good are rewarded by the state in many ways. Even the old restrictions in regard to religious observances, which were very zealously enforced by the Tycoon’s government, have been greatly modified, and while we do not know that any proclamation for universal freedom in matters of conscience has been issued, it is clear that the spirit of the time decidedly tends in that direction. The question is a question of time only. In all these movements it seems plain that the young Mikado is the head and front, as he is the supreme ruler of the Empire.

One of the most remarkable events which has signalized the reign of the Mikado, is the Imperial proclamation or decree which was promulgated by him on the fourteenth of April, 1875. It had for its object the creation of a deliberative body, whose resolutions, founded upon such knowledge of the wishes of the people as may be obtained without direct representation, will be submitted to the Council of State, and, if approved, will then be referred to another organized body to be moulded into the forms of law. Of this document we have two translations before us, and upon the whole we think the following one will give the best idea of the original:

“On ascending the Imperial throne we assembled the nobles and high officers of our realm, and took oath before the gods (or heaven) to maintain the five principles, to govern in harmony with public opinion, and to protect the rights of our people.

“Assisted by the sacred memory of the glorious line of our ancestors, and by the union of our subjects, we have attained a slight measure of peace and tranquility. So short a time, however, has elapsed since the late restoration, that many essential reforms still remain to be effected in the administration of the affairs of the Empire.

“It is our desire not to restrict ourselves to the maintenance of the five principles which we swore to preserve, but to go still further, and enlarge the circle of domestic reforms.

“With this view we now establish the Genro-in to enact laws for the Empire, and the Daishin-in to consolidate the judicial authority of the courts. By also assembling representatives from various provinces of the Empire, the public mind will best be known and the public interests be best consulted, and in this manner the wisest system of administration will be determined. We hope by these means to secure the happiness of our subjects and ourself. And, while they must necessarily abandon many of their former customs, yet must they not on the other hand yield too impulsively to a rash desire for reform.

“We desire to make you acquainted with our wishes, and to obtain your hearty coöperation in giving effect to them.”

The other translation interprets the Emperor as saying: “We likewise call together the local officers, causing them to state the opinions of the people,” etc.; and in this connection a Japanese newspaper makes the remark that the freedom of the press has in that country preceded the conferring of any political power on the people, and that this inversion of the usual order of events is something quite remarkable.

Of all the events connected with the reign of the present Emperor, the most important occurred on the twelfth of October, 1881, when he issued a Decree or Rescript, for the establishment of a Constitutional Government. As a Japanese scholar wrote:

“This may seem to be nothing to outside nations, but if you take into consideration the rapid growth and influence of public opinion and the steady progress of political ideas among the people, it is the most important event in the history of the nation.”

IMPERIAL DECREE.

We, sitting on the throne which has been occupied by our Dynasty for over 2500 years, and now exercising in our own name and right the authority and power transmitted to us by our ancestors, have long had it in view gradually to establish a constitutional form of government, to the end that our successors on the throne may be provided with a rule for their guidance.

It was with this object in view that in the eighth year of Meiji we established the Senate, and in the eleventh year of Meiji authorized the formation of local assemblies, thus laying the foundation for the gradual reforms which we contemplated. These, our acts, must convince you, our subjects, of our determination in this respect from the beginning.

Systems of government differ in different countries, but sudden and unusual changes cannot be made without great inconvenience.

Our ancestors in heaven watch our acts, and we recognize our responsibility to them for the faithful discharge of our high duties, in accordance with the principles and the perpetual increase of the glory they have bequeathed to us.

We therefore hereby declare that we shall, in the twenty-third year of Meiji, establish a parliament in order to carry into full effect the determination we have announced; and we charge our faithful subjects bearing our commissions to make, in the meantime, all necessary preparations to that end.

With regard to the limitations upon the Imperial prerogative and the constitution of the parliament, we shall decide hereafter and shall make proclamation in due time.

We perceive that the tendency of our people is to advance too rapidly, and without that thought and consideration which alone can make progress enduring, and we warn our subjects, high and low, to be mindful of our will, and that those who may advocate sudden and violent changes, thus disturbing the peace of our realm, will fall under our displeasure. We expressly proclaim this to our subjects. By command of His Imperial Majesty,

SANJO SANETOMI,

First Minister of State.

In his personal appearance the Emperor of Japan is rather tall, compared with his countrymen generally; and he has a healthy physical constitution. He has had several children. Unlike many of the princes and royal personages of Europe, he is not addicted to self-indulgence, but takes delight in cultivating his mind; sparing no pains nor personal inconvenience to acquire knowledge. Although still young he frequently presides at the meetings of his Privy Councillors, composed of the first, second and third Ministers of State, together with the Sangi, or Councillors, whose numbers are not limited, but now comprise about ten honored names. He often visits his executive departments, and attends at all the public services where the Imperial presence is desirable. While prosecuting his literary as well as scientific pursuits, he subjects himself to the strictest rules, having certain hours for special studies, to which he rigidly conforms. In his character he is said to be sagacious, determined, progressive and aspiring; and from the beginning of his reign he has carefully surrounded himself with the wisest statesmen in his Empire, and these have naturally assisted in his own development; so that it is almost certain that history will testify that the crown of Japan has been worn in the present century by one who was worthy of the great honor. From all the glimpses that we have been able to obtain of this youthful Emperor of the far Orient, we are led to believe that in his unselfish patriotism, and in his zealous aspirations, almost free from prejudices, to adopt from other nations all that he deems beneficial for the promotion of the national welfare, he bears a striking resemblance to Peter the Great, of Russia. With such a vigorous ruler and such a progressive people as his subjects are proving themselves to be, the Empire of Japan may well count upon a future of prosperity and happiness.

As we have given an account of the present Emperor of Japan, it cannot but prove interesting to Western readers to learn something of his father, known as Kômei Tennô, who came to the throne in 1846, and died in 1867.

He was the fourth son of Kôjin Tennô, his mother being Shini-taiken-mon-in, who was the daughter of a Kuge named Ogimach-Sanemitsu. Kôjin Tennô died in the second month of the third year of Kôka (1846), and in the third month of the same year Kômei Tennô succeeded his father, and ascended the throne of Japan, being at this time sixteen years of age. Though so young, he was clever and endowed with sound judgment.

In the fifth month of the same year, an American vessel-of-war arrived off Uraga, and demanded that trade should be opened between the two countries. In reply to this demand Tokugawa Iyeyoshi, the then Shôgun, replied through one of his councillors, Okubo Tadatoyo, that Japan had from time immemorial abstained from all intercourse with foreign nations. The vessel therefore left in the sixth month.

In the ninth month of the following year the ceremony of the enthronement of Kômei Tennô was performed at Shi-shin-den (Hall of Ceremony). In the fourth month of the second year of Kaiyei (1849) an English man-of-war arrived at Uraga, and in the fifth year of the same a Russian war-vessel came to Shimoda. In the sixth month of the following year the American Envoy Perry arrived off Uraga with four vessels of war, bringing books and other presents to the Shôgun, and requesting that a treaty for purposes of trade might be drawn up between the two countries. Up to this time the only foreign vessels which had visited Japan had been the Korean and Dutch ships which came to Nagasaki. This arrival of American men-of-war was therefore altogether strange. The Dutch presented to the Government a memorial praying that the authorities would listen to the demands of the foreign powers; or that otherwise they might endeavor to open the country by force. Orders were therefore given to the different Daimios to construct fortifications at Omori and at Shinagawa.

At the castle in Yedo consultations were held as to the best steps to be taken. The decision was made known to the Imperial Court at Kioto by a member of the Shôgun’s council named Wakizaka. The Emperor was much disturbed by these events, followed as they were by the appearance of a Russian Commander with four men-of-war at Nagasaki, likewise demanding that the country should be thrown open to trade.

At this time, as peace had prevailed in the country for some three hundred years, the power of Tokugawa exceeded that of even Taira-no-Kiyomori or Ashikaga Toshimitsu. The samurai were entirely given over to luxury, thinking of nothing but dancing, singing and the like, and in no way occupying themselves with military studies. Thus their spirit had almost become extinct. When the state of affairs was made known throughout the country there was great excitement. Messengers were flying in every direction; foreign vessels were threatening the shores, and thus the Bakufu authorities decided in order to gain time for preparation and to evade the present difficulties, to grant the demands. In the meantime they requested the Imperial Court to make preparations for war. In reply to the Gorojiu (Shôgun’s Council) Hotta, the Prime Minister of the Mikado, replied that as the question was one of supreme importance it was the will of the Emperor that the Gosanké (the three families of Mito, Owari and Kii related to Tokugawa) and the whole of the Daimios, should consult together and make known to His Majesty the result of their councils, when he would decide what steps to take. While this was in progress, however, the Regent Ii Kamon-no-Kami concluded treaties with the foreign powers and opened certain ports for the purposes of trade.

The ex-Daimio of Mito, having received from the Mikado secret orders, raised the cry of Sonnô-joi! (Honor to the Emperor and expulsion of foreigners.) For this he was put in confinement by Ii Kamon-no-Kami. But the cry was taken up and became a popular one, and such men as Hashimoto Sanai, Rai Mikisaburo (the son of the great historian), and other prominent scholars, were made the victims of the wrath of the Bakufu and lost their lives.

In the first year of Bunkiu (1861) the sister of Kômei Tennô, Katsu-no-Miya, was married to Tokugawa Iyemochi. This was done in order to heal the differences which existed between the Imperial Court and the Bakufu. But the whole country was indignant at the course taken by the Bakufu in not following out the wishes of the Emperor with regard to expelling barbarians. Hence various evils arose. The Satsuma samurai having killed an Englishman at Namamuga, the English attacked Kagoshima with a fleet of seven men-of-war. In the third year of Bunkiu, Chiunangon Sanjô Saneyoshi and seven other Kuge fled to Chôshiu. By the order of the Imperial Court they were deprived of their rank, and the Chôshiu samurai were forbidden to enter Kagoshima.

In the sixth month of the first year of Gangi, a Chôshiu samurai named Fukubara, came to Fushimi and petitioned that the Daimio of Chôshiu and his son might be permitted to reside at Kioto, and that their title and rank might be restored to Sanjô and his companions. At the same time a Chôshiu samurai named Maki, stationed himself near Kioto, with a force of four hundred men. The inhabitants of the capital were thrown into a great state of alarm. H. I. H. Prince Arisugawa and seventy others petitioned that the Lord of Chôshiu and the eight Kuge should be pardoned, but Nashushima Noriyasu, the Daimio of Aidzu, demanded that they should be chastised. On hearing of this the Chôshiu men became infuriated and attacked the city of Kioto in the ninth month. The troops of Hitotsubashi guarded the Nakatachiuri gate while those of Yasushima were guarding the Hamaguri gate. Kabata, the commander of the latter, fell into an ambuscade of the Chôshiu men, and was killed, his troops being entirely routed. The Chôshiu men were advancing victoriously when they were attacked and utterly routed by the Satsuma and Kawana troops. Both the Chôshiu commanders Fukubara and Kurushimi were killed, and the rest either committed suicide or fled and hid themselves. By order of Noriyasu, the greater part of the city of Kioto was destroyed by fire.

In the meantime there was great alarm at the court. Some wanted to remove the Emperor to Kamo, but Noriyasu decided that he should remain. Prince Arisugawa and seventy Kuge being placed in confinement. In the same year a combined attack was made by the Dutch, American and other vessels upon Shimonoseki, and the affair was finally settled.

The troops of Tokugawa surrounded the provinces of Nagato, Chôshiu and Inô, but they could not make headway against the Chôshiu men, who obtained possession of Kokura in Bungo.

In the eighth month of the second year of Keiô (1866) the Shôgun, Tokugawa Iyemochi, died at Osaka. In the same month the Emperor died of small-pox at the age of thirty-six, and the whole country was plunged into mourning.

Thus although the great event of the Restoration, which placed the present Emperor in possession of full powers, took place in the following year, all those which brought it to pass occurred in the reign of Kômei Tennô, and thus his life was an eventful one and subject to constant anxiety.

He was born on the nineteenth of February, 1835, and is the present representative of the family founded by Prince Toshihito, the seventh son of the Emperor Go-Yozei Tenno, who reigned from 1587 to 1611. He was carefully educated at the Court in Kioto, where his youth and early manhood were passed, and attracted considerable attention from his elders, the young Prince giving ample evidence of possessing talents far exceeding those of the ordinary run of mankind, whether noble, bourgeois or peasant.

On the fifth of February, 1868, the Emperor took the final step towards the restoration of his imperial authority. By a decree issued on that day, Tokugawa Naifu and his followers were stripped of their honors and dignities, and a large army sent to overrun their territories. Recognizing the ability of the Prince, the Emperor placed him in supreme command of the “Army of Chastisement,” handing him at the same time a brocade banner and sword of justice, as the insignia of his important functions.

Marching against the adherents of the deposed Shôgun, now a contumacious rebel, the army under Prince Arisugawa—who was assisted by Saigo Takamori (Kichinosuke)—defeated the enemy in various engagements and marched by several roads to the assault of Yedo, capturing on the way the strong fortress of Oshi-no-Gioda. Arrived before Yedo, complete and unreserved surrender saved the city from the horrors of fire and plunder, Prince Arisugawa mercifully consenting to accept the submission of Tokugawa, just as the stormers were assembled and the torches lighted which would have laid Yedo in a smouldering mass of blood-stained ruins. The hot-bed of sedition being now under control, strong detachments were sent out in various directions to destroy the scattered band of disaffected ronins and followers of the Aoi, who still maintained a desultory resistance throughout the eastern provinces. The operations directed by Prince Arisugawa were attended with complete success, and on the entry of the Emperor to Yedo—thenceforward known as Tokio—on the twenty-sixth of November, 1869, His Imperial Highness had the satisfaction of returning into the hands of His Majesty the brocade banner and sword of justice in token of the complete pacification of the north and east. Rewards and honors were attendant upon the valuable services of the Prince, and he was shortly afterwards entrusted with the task of quelling the disturbances at Fukuoka, a duty which was quickly accomplished with slight bloodshed, and unaccompanied with the fearful scenes of slaughter which usually accompanied a victory in the times to which we refer.

In the eighth year of Meiji (1875) Prince Arisugawa was appointed to the Senate, shortly afterwards taking his seat as President of that august body upon the retirement of Mr. Goto Shokiro.

Two years subsequently—in 1877—the renowned Saigo Takamori raised the standard of rebellion in Satsuma, and commenced the sanguinary struggle which deluged with blood the southern provinces of Japan. The supreme command of the Imperial forces was conferred upon Prince Arisugawa, who landed in Kiushiu with his army. After many battles fought at first with varying success, the great rebellion was crushed and feudalism in Japan drowned in blood on the fatal field of Shirayama, where the gallant Saigo, the chivalrous Kirino, and many other dauntless leaders, fell upon their swords, and thus spurned the mercy their conqueror would gladly have accorded them.

On his return to the capital, His Imperial Highness was appointed Field-Marshal in the Imperial service, at the same time retaining his position as President of the Senate, and received the order of the Chrysanthemum, the highest decoration in the gift of the Emperor.

Upon the change in the Government at the commencement of the present year, the subject of our too brief sketch was appointed Sa-Daijin, or Junior Prime Minister, an exalted office he still holds.

His Imperial Highness was entrusted with the administration of the Government during the recent absence of the Emperor in the provinces; nothing, however, occurring which called for any exertion of his well-proved tact and ability.

Prince Arisugawa is recognized as among the foremost workers in the party who desire to join with closer ties the destinies of their country to those of Western nations, and, as no small proof of the sincerity and earnestness of his purpose, we find serving as a midshipman on board of Her Majesty’s ship Iron Duke, the son and heir of His Imperial Highness, Field-Marshal Prince Arisugawa Taruhito.

In after years when the hand of time has swept away existing prejudices and misconceptions, ample justice will be done by the conscientious historian to the chivalrous and devoted subject of this sketch, who in a remote portion of the Empire remained constant to the fealty he owed his feudal superior; and, disdaining like so many others to sever a tie consecrated alike by honor and gratitude, maintained a desperate struggle against the whole might of the Empire until the very hopelessness of the attempt rendered further resistance a crime. Then, and not till then, did Admiral Enomoto surrender his untarnished sword to the victors: defeated, but not dishonored, he wrested admiration from his foes, and how well and faithfully he served his former master afforded a bright augury, since amply fulfilled, of the loyalty afterwards so often proved.

Sprung from the best blood of the Tokugawa, Enomoto was despatched to Holland with two companions in the year 1863, to study the art of maritime war. Of his career in the land of canals and dykes, but still teeming with memories of great naval heroes whose glorious example must have excited a spirit of emulation in the young sailor, we have unfortunately no record, and we next hear of him in the autumn of 1867, when he returned to Japan on board the Kaiyo Maru, a man-of-war built by the Dutch for the Shôgunate.

Enomoto received the appointment of Assistant-Administrator of the Navy, an important position he occupied when those troublous times fell upon the country, during which he inscribed with his sword a stirring record on the page of history.

When the downfall was apparent of the feudal system, which under the rule of the Tokugawa had preserved Japan from the horrors of internecine strife for nearly three centuries, the last Shôgun was urged to commit hara-kiri, an insane proposal strongly and successfully opposed by Enomoto and others. Refusing, however, to despair of ultimate victory while a single hope remained, the admiral got his squadron—consisting of seven men-of-war—under way, and while the vanguard of the Imperialists entered the capital, he sailed from Shinagawa at night in the midst of a terrific storm of wind and rain. Negotiations which subsequently took place resulted in the surrender to the Imperial authorities of a portion of the war vessels, the remainder—still under Enomoto’s command—being bestowed upon the Tokugawa. Dissatisfied, however, with the conduct of affairs, Enomoto again sailed from Shinagawa, taking with him eight men-of-war and transports, a letter he left behind criticising the action of the government officials explaining sufficiently the reasons which prompted a step he must have since often and deeply regretted.

Enomoto then gathered together such scattered fragments of the Shôgun’s forces as could make their way to the seashore, as almost every means of egress was beset by overwhelming numbers of their adversaries. With these reinforcements a descent on Hakodate was determined upon, and, after some hard fighting, the town and district was captured. Here a conference was held with the foreign consuls, and, although we do not affirm that such a course was recommended or joined in by the representatives of the foreign powers, still as a matter of history these last remnants of the once powerful Tokugawa established a republic in Hakodate, Enomoto being elected President, Matsudaira Toro (now Consul at Vladivostock) Vice-President, and the other necessary officials duly appointed. Enomoto then sent a petition to the Imperial Government, through the kindly offices of the captain of a British man-of-war, and prayed that the island of Yesso should be granted to the Tokugawa clan, who would faithfully hold the “Northern Gate” of the Empire against all comers. This petition was refused and a powerful expedition fitted out to crush the last embers of disaffection then remaining in Japan.

The blow at last fell. After long continued resistance and the exhibition of a dauntless courage never surpassed in the brightest days of chivalry in old Japan, the day at length came when the generous offers of the Imperial commander had to be accepted, and Enomoto with his remaining comrades were transferred to the capital under arrest.

The Imperial clemency was shortly afterwards extended to the subject of this memoir, and he again entered the service of his country. Quick promotion soon followed.

In 1874 he received a commission as Vice-Admiral in the Navy, and was afterwards appointed Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary to the Court of St. Petersburg. During his stay in the capital of Russia, the admiral studied the language of the country and also French. His proficiency in the latter is considerably above the average, and he has translated from it into Japanese a work called The State of Corea.

On returning from St. Petersburg the admiral received further official promotion, and was appointed Naval Minister of the Empire.

Of commanding personal appearance, affable in manner, and possessing in an unusual degree the rare combination of admirable qualities requisite to produce an able administrator and successful leader, Admiral Enomoto is justly regarded as one of the most prominent men in the Empire. In 1881, he was attached to the Imperial Household, and is superintending the building of the new palace for the Emperor.

This rarely-gifted but ill-fated scholar was allied to a family of samurai, and was born near the castle of Fukuoka, Japan, July 6th, 1852. His father was poor and his early education was neglected, but his natural abilities having been reported to General K. Kuroda, that dignitary sent the young man to Nagasaki to be educated; in 1868, by the same patronage he was sent to America, and, under the guidance of Gilbert Attwood (one of the best American friends of the Japanese students) obtained a knowledge of the English language at Boston and its vicinity. He then turned his attention to law, entered the Harvard law school and made rapid progress; participated in various debates, and received from Harvard the degree of LL. B.; and several essays which were printed in the work entitled The Japanese in America, were greatly praised by the press in America and England. In 1874 he returned to Japan, and was appointed to a position in the Navy Department; but as he had lost the mastery of his native language, his services in that capacity were not satisfactory, and he resigned. He then established a private school for teaching the English branches of learning, but the Government wanted his services in the Imperial University, where he made himself of great use as a Professor of Law and English Literature; he also delivered lectures regularly outside of his routine duties on subjects connected with law; and although he married and was pleasantly settled in life, the fact (added to depression caused by bad health) that he had lost his Japanese tongue, preyed upon his mind, until by his own act his days were ended in January, 1879. In the following year an account of his life and character were written by Mr. Kentaro Kaneko, and with his collected writings was published in Tokio, a copy of which was presented to the present writer by Mr. Enouye’s pupils. That he was a young man of high character and very great abilities, was the universal verdict of his countrymen, and his untimely death was a public calamity.

Fujita Hio was a native of Mito, son of Fujita Itsusei, and his family was descended from Onono Takamura. At a certain time an ancestor of his house became a retainer of the Daimio of Mito. In his early days he was fond of military exercises, and he learned the arts of war from his father. After that he went to Yedo and acquired the sword-exercise from Okada, and the spear practise from Ito, always neglecting to pay the slightest attention to literature. In the seventh year of Bunsei an American ship which was sailing about stranded on the coast of Hidachi. The crew landed at Otsu-mura, attacked and robbed the people, and threw the village into confusion. As soon as this news was reported, Hio’s father was very much excited, and said to his son: “As you know, during the past few years, foreign barbarians have visited our coast very often, and sometimes they have made use of cannon, and so caused great disturbance among the people. But, alas! all our countrymen are contented with a momentary peace, and they take no heed of the danger of the future. I am deeply sorry for them, that they have no courage or spirit of patriotism. Now I advise you, my son, to go to Otsu-mura immediately, and to watch what the foreigners are doing; and when an opportunity occurs, slay them all, and afterwards report personally to the Government what you would have done, and bravely accept the judgment of the authorities. This will not be a service of the highest importance for the country, but we should be quite satisfied to manifest our yamato tamashi (conservative feeling) even in so small a way.” Hio, having listened to his father’s advice, quite sympathized in the scheme, and a stern resolve to carry it out was exhibited in his face. While he was making preparation for departure upon this errand, a report was brought from Otsu-mura to the effect that the Americans had retired, and that no foreigner remained on shore. He was disappointed and felt great regret at this circumstance, as it interfered with the execution of his father’s order. At that time he was only nineteen years old.

Not long after this it came to his reflection that the famous scholar Hokuwan had been noted for his want of military knowledge, and that Zuiriku, who was skilful in arts of war, was equally unfamiliar with literature. For this reason each was laughed at for his special ignorance by the ancients. Therefore Futija resolved to give attention to literary studies, and went to Yedo again and became intimate with Kameta and Ota, who were distinguished members of society. With them he learned the history of the Japanese political system. At this time Keizaburo, the second son of the Mito Daimio, wondering greatly at the assiduity of Fujita, wrote a motto consisting of two large characters, “Fu soku,” or “Without rest,” and gave it to him. Fujita hung this inscription on the wall of his study, where he could always look at it. While he was in Yedo his father died, whereupon he returned home, and after that was appointed Hensiu of a school named the Sho-ko-kuwan of Mito. In the course of his labors, he brought about the discussion of certain social principles in a manner that excited much admiration and favor among his followers and the public, who were delighted with his arguments, so that his fame suddenly increased very rapidly. Just then Seisiu, the Daimio of Mito, was very sick, and the question of appointing his successor was agitated throughout the province. The opinions of the people were not unanimous. Fujita thought Keizaburo, the second son before mentioned, would be the most suitable heir to the name and rank, and he went to Yedo secretly and had an interview with Matsudaira, Daimio of Moriyama, to endeavor to put his views in force. On all occasions he earnestly urged the selection of Keizaburo. His arguments were so eloquent and reasonable that the Bakufu government sanctioned the nomination which he advocated, and the new heir was honored by receiving the name of Nariaki from the Shôgun. Obtaining the joyful intelligence of his success, Fujita returned home, and began to employ himself in the service of the local government of Mito. His uniform kindness and his high character led his society to be much sought after by the most eminent men of the time. He was also distinguished for his ability in composing poetry—a faculty which he frequently exercised. In the first year of Kokuwa the Bakufu government ordered the lord of Mito to retire from his office and be confined in his private house, and Fujita was also imprisoned at the same time at a village called Komme.

Fujita was imprisoned three years. After his liberation he published some volumes entitled Hidachi Obi, and Kuwaiten Shishi. The chief purpose of these books was to demonstrate that his master, Nariaki, respected the Imperial government with all his heart, while he was at the same time endeavoring to assist the Tokugawa rulers. He also advocated the plan of colonizing Hokkai Do (Yezo) upon a system which, if carried out, would doubtless have greatly improved the condition of that island. All the intelligent and virtuous men quite sympathized with the statements and the arguments put forward in these works, and many scholars assembled day by day at Fujita’s house for the purpose of enlarging their knowledge of literature under his guidance. In the sixth year of Kaiyei an American ship of war appeared in a bay in the neighborhood of Yedo, and a desire to communicate with the Government was expressed. At that time the Bakufu authorities suddenly released Nariaki of Mito from confinement, and requested him to submit a plan for the defence of the sea-coast. Fujita went to Yedo with his lord and was employed in projects for strengthening the fortifications along the shore. But the Tokugawa officers being afraid of the foreigners, they agreed to negotiate a treaty without first obtaining the permission of the Emperor at Kioto. Fujita was exasperated by the cowardly conduct of the officials then in power, and wrote some verses in which his resolute temper was plainly indicated. All the patriotic feeling of society was aroused by the spirit which Fujita manifested, and he was honored by a special recognition of his services from the Emperor. While he was making this visit to Yedo a severe earthquake occurred, on the second of the tenth month of the first year of Ansei. Fujita hurried to the private room of Nariaki his master, and took him out into the garden for safety; but unfortunately the house was shattered to pieces as they were leaving it, and a large beam fell upon Fujita and caused his death. He was fifty years old.

This prominent member of the “Fourth Estate” of Japan was born at Nagasaki in 1840. While yet a young man he acquired a knowledge of the Chinese and Dutch languages, and forthwith became a kind of professional interpreter. About the year 1858, he removed to Yedo, where he devoted himself to the study of English, French and German, and became an interpreter in the Foreign Department of the Tycoon’s Government. In 1862, when an embassy was sent to the United States and Europe, Mr. Fukuchi was made a member and rendered important assistance by the use of his various acquirements. During the excitement attending the Restoration, he published the first newspaper ever issued in Japan, and, not hesitating to express his opinions with the utmost freedom, he offended the Imperial Government, was thrown into prison for his temerity, but soon released on the condition that he would not continue to issue his journal.

A few months afterwards he was invited to a position in the Treasury Department, and when it was decided to send a commission to the United States to investigate the banking and commercial systems of the country, he was made one of the members, with Messrs. Ito and Yoshikawa; and on his return he published a valuable book on the subjects which the commission had investigated.

When the Iwakura Embassy was organized in 1871, Mr. Fukuchi was asked to take the position of First Secretary, which he accepted, and accompanied the Ministers in their tour of observation around the world. On his return to Japan in 1873, he resumed the profession of a journalist in Tokio, and became the editor-in-chief of the Nichi Nichi Shimbun, which has ever since been one of the leading newspapers in the Empire.

In 1875 he became an officer of the Dai-jo-kwan, and acted as Secretary of the Assembly of Local Governors until its dissolution. He subsequently held an honorable position connected with the city government of Tokio. During the late rebellion in Satsuma, he joined the Imperial forces, and sent regular letters to his journal from the field of conflict. On his return to Tokio his friend Mr. Kido, then a private counsellor of the Emperor, had him presented at the palace, where he gave a minute account of his observations in Satsuma, which audience was followed by a dinner and the presentation of many valuable presents by the Emperor.

In 1878 he was again called to assist the Assembly of Local Governors; and in 1879, when the regular local parliament was opened, he was chosen a representative for the city of Tokio, and was made speaker or chairman of that important assembly or parliament. When General Grant was in Japan, Mr. Fukuchi was chairman of the special committee designated to assist in the various demonstrations organized to honor the noted American.

In casting about for a brief quotation which would give the foreign reader an idea of Mr. Fukuchi’s style of writing, we have selected the following, which, though written when his duties as the regular editor of the Nichi Nichi Shimbun had ceased, is undoubtedly from his pen; and it is especially interesting because of the fact that he had himself formerly been punished for disobeying the press laws. Alluding to the editors of the Japan Gazette and the Mainichi Shimbun, he proceeds as follows:

“They are contemporaneous newspaper writers. They are the controversialists living in one country. One of them is, however, limited by law in asserting his opinion, and is occasionally brought before the courts as a criminal, while on the contrary, the other uses his pen free from any peril of the law. A great difference exists between the positions occupied by these newspaper writers with regard to the limit and extent of their privileges, or the restrictions imposed upon them in our country. Toyama Unzo, the editor of the Mainichi Shimbun, has been summoned before the Yokohama Saibansho for having re-published in his paper a paragraph which appeared in the Japan Gazette, and was sentenced to one year’s imprisonment.

“The paragraph in the Japan Gazette is not altogether correct, and it is clear that that paragraph was written by the editor as a pure invention. But according to the sentence pronounced by the Yokohama Saibansho upon Toyama, the latter is declared guilty for reproducing the said paragraph in the Japan Gazette, for the purpose of causing trouble by announcing changes in the Government and disquieting the country. Referring to the action with regard to Toyama, the Japan Gazette has expressed an opinion criticising it as “strained and severe,” but we can say nothing about this judgment. Considering which of the two editors mentioned above has committed the greater crime, we find that the editor of the Japan Gazette published the offensive paragraph first, and the Mainichi Shimbun translated and re-published it; and on this account, the former cannot be considered less criminal than the latter. Taking the sentence passed upon Toyama into consideration, it is evident that the editor of the Japan Gazette ought not to escape imprisonment for one year—the same term as Toyama suffers for the offence he committed. Both the Japan Gazette and the Mainichi Shimbun are pursuing the same business in Yokohama, and they have published the same matter in their respective papers. For so doing, the editor of the Mainichi Shimbun was condemned to one year’s imprisonment, but the editor of the Japan Gazette is permitted to escape without receiving even censure. May we say that this is his good fortune, or say that it is the misfortune of the Mainichi Shimbun? We do not know which.

“The editor of the Mainichi Shimbun is a Japanese subject and governed by the Japanese law, while the editor of the Japan Gazette being a subject of England is under no obligation to our law. In Japan, newspaper regulations are in force, under which the native newspaper writers may criminate themselves; but there are no such regulations in England, and no English subjects who conduct newspapers receive even warnings. The editor of the Mainichi Shimbun is therefore condemned to one year’s imprisonment for having published the same paragraph as the Japan Gazette, while the latter is free even from censure. Great is the difference of fortune of men of the same occupation! shall we sympathize with the unfortunate editor of the Mainichi Shimbun? Or congratulate the good fortune of the editor of the Japan Gazette? No, we do neither; but we regret that owing to the existence of the extra-territoriality clause, the editor who published a paragraph in his paper for the purpose of causing trouble, by announcing changes in the Japanese Government and disquieting the country, has fortunately escaped the punishment which his crime deserves.

“In order to punish newspaper writers for their improper conduct, the press regulations were established; but they were not intended to prevent free discussion; they were also intended to prevent offensive expression of opinions, which might influence general feeling and violate the peace of the country. Thus the editor of the Mainichi Shimbun was condemned to one year’s imprisonment for having reproduced a paragraph in the Japan Gazette, calculated to disturb the government and people; consequently the original writer of that paragraph, the editor of the Japan Gazette, is equally a criminal, guilty of the same offence. Owing to the strong protection he enjoys under extra-territoriality, we cannot punish him directly by our law, but we cannot pass over his offence without discussion. Our Government ought to bring an action against him before the British Court in Yokohama, urging his proper punishment; if it be rejected there, the case should be appealed to the Supreme Court at Shanghai. Although there are no press regulations in England, the law of libel is now in force, and those who write for the purpose of creating trouble, by announcing changes in the Government, thereby disquieting the country, are turbulent persons and public enemies, who are prosecuted in any country of the world. If the English judge possesses right and just discrimination, like that used by the judge of the Yokohama Court, he will consider the opinions expressed by the Japan Gazette dangerous and turbulent, and he will punish the editor accordingly. The Japan Gazette and Mainichi Shimbun differ in their language, one being English and the other Japanese; but with regard to their crime for having published offensive matter, they are equal. For this reason, we believe that the Government cannot condemn one without proceeding against the other. But up to this date, neither the native or foreign press has advised an action against the editor of the Japan Gazette to be brought by the Japanese Government. Persons may ask the following questions, to which, we fear, we are unequal to give satisfactory answers. How is it that a paragraph in the Japan Gazette of a dangerous and seditious character cannot create a disturbance? What is the reason that the influence upon the people caused by this paragraph differs because of the Japanese and English language? How can we say that the Japanese read no English newspapers? How can we say that there is no danger to apprehend from spreading such unfounded reports in foreign countries by publishing them in the Japan Gazette?

“For the reasons referred to, we believe that the Government of Japan will bring an action against the editor of the Japan Gazette, before the British Court, and also that, notwithstanding the existence of the extra-territoriality clause, the Government will not permit his crime to escape investigation. We have no doubt, therefore, that the fortunes of the two editors guilty of a similar offence will be made equal.”

It seems to us that the most able journalists of London or New York would hardly acquit themselves with more ability and propriety under the same circumstances.

He was born in Nakatsu, Buzen, or what is now called Oida Ken, about the year 1834. He applied himself to the study of Chinese at an early age, and subsequently went to Osaka, where he acquired a knowledge of the Dutch language. In 1858 he went to Tokio, where he continued his studies with great zeal. In 1860, under the patronage of a naval officer, he went to America, where he remained several months. On his return he brought to his country the first Webster’s Unabridged Dictionary that was ever imported. In 1862 he again went abroad, this time to Europe, where he purchased a number of foreign books. In 1866 he graduated from the student into the author, by the publication of a volume entitled Sei Yo Jijo; or, Western Habits, a collection of translations, as is well known, from foreign literature. This was the first work of the kind that had appeared in Japan, and it instantly gained a wide popularity. After the appearance of the Western Habits, Mr. Fukuzawa again visited the United States, and on his return he was appointed one of the instructors in the old Kai Sei Jo, a position which he held till the breaking out of the war of the Restoration. He had already established his private school, the Keiogijiku, and begun to win recognition as a teacher. The political agitations consequent on the civil war drew attention to his Sei Yo Jijo, and increased its author’s reputation. Printed in an easy character, and treating of interesting subjects in an attractive style, the masses were not deterred from reading and appreciating it by the criticisms which some purists made on its form and methods. The “Mita fashion” became the fashion, in spite of the opposition of science.

In the seventh year of Meiji he published his celebrated Gakumon no Susume; or, Progress of Education, in which he advanced the opinion that Death is a democrat; and that the samurai who died fighting for his country, and the servant who was slain while caught stealing from his master, were alike dead and useless. This attack on the dignity of the military class aroused fierce opposition, and filled the newspapers with angry discussions. The debate excited universal attention, and resulted, we cannot doubt, in a general advance in public sentiment on the subject of natural rights. In the following year, the now famous schoolmaster opened a lecture hall in connection with his academy, and delivered, for its inauguration, an eloquent public address, by which act he imported the lyceum into his country. And as he gave a new sphere to the form, so he was no less instrumental in developing a scholarly association of a more retired character, the Mei Roku Sha, or Society of the Sixth Year of Meiji. This organization, established by Mr. Mori on his return from America, chose Mr. Fukuzawa as its first president, an honor which he resigned in favor of the young founder. He has, however, retained a leading connection with this body, which includes such representative men as the Mitsukuris, Nishimura, Kato and Nishi.

Though it is rather as a public instructor and a critic of government in the abstract than as an active politician that Mr. Fukuzawa has wielded influence, still in the debate on the establishment of a House of Commons, according to the plans proposed by Itagaki and Goto, his influence was earnestly exerted on the more conservative side, his opinion being that the time was not rife for such an experiment, while he advocated the formation of local assemblies as a preliminary step. His moderate views in this discussion, however, have not brought him into the confidence of a strong party in the Government, who look upon him as too extreme a radical. But his services to the cause of popular education and the evident sincerity of his patriotism make him universally esteemed.

He is married, and when congratulated by a friend on the birth of a son, he simply replied, “Yes, I am fortunate, but after all, the child is nothing but a poor Asiatic.” His love of learning was developed at an early age, and the moment he became impressed with the low condition of moral and intellectual culture in Japan, he was fired with a strong desire to do all in his power to elevate his countrymen, and has filled his self-appropriated mission with a success that is quite unprecedented in the annals of the East. It is now about eighteen years since he entered upon the life of a schoolmaster in Yedo; his school has been what we in America would call a boarding school. In it are represented all the provinces of Japan, and while his present number of pupils is from three to four hundred, the children whom he has educated can be counted by the thousand. Notwithstanding his constant and arduous labors as a teacher, he has found time to translate from English into Japanese a considerable number of valuable books, which have been published and had a wide circulation. He has always been averse to holding public office, and all that he has done has been done as a private citizen. With regard to the letter which follows, we have this explanation to make: The author had been upon a visit to his native place, and while enjoying the scenes of his boyhood, and talking with the friends of early days, he resolved to send to the latter a communication in regard to their condition and future welfare. His motives and the manner in which he carried out his purpose were fully appreciated by his old friends. They had the letter printed in Yedo, in pamphlet form, and proceeded to give it the widest circulation. For writing such a paper fifteen years ago he would probably have lost his life; but now he is universally applauded, not only for his courage, but for his wisdom and sincerity, and to all human appearances he promises to become one of the greatest benefactors of his race. The letter in question is sufficiently interesting on account of its merits alone, but what gives it importance is the fact that it comes from a native of Japan, and was written in the year 1872.

The letter is as follows:

“Man, in common with the brutes, is gifted with the senses of feeling, sight, hearing, smell, and taste, but is the only one of created beings who has a spirit or mind. It is this which makes him a human being, gives him power to conduct himself according to nature, and by which he is enabled to obtain knowledge, and learns how to provide for the wants and comforts of life, and treat his fellowmen with consideration. But more than this, it is a peculiar characteristic of human beings that they have the ability to secure liberty of mind and of actions. In this particular, from the most ancient times, the Chinese and Japanese have been ignorant. Liberty or freedom is not self-will—it is the power with which we do all we choose, without obstruction from others. It is right that the father and child, the master and retainer, and the husband and wife should all have this liberty—none of them to be interfered with in their proper desires. Men were not created with the blight of evil in them, and they are not led astray by nature. When they do things that are wrong against their fellow-beings, they offend both nature and heaven. Small offences deserve to be despised, but large ones ought always to be punished, and this without any regard to the position of the offender—whether a nobleman or a peasant, an old or a young man.

“The liberty of which I have spoken is of such great importance, that everything should be done to secure its blessings in the family and the nation without any respect to persons. When every individual, every family, and every province, shall obtain this liberty, then, and not till then, can we expect to witness the true independence of the nation; then the military, the farming, the mechanical and the mercantile classes will not live in hostility to each other; then peace will reign throughout the land, and all men will be respected according to their conduct or real character.

“All the human family came from one pair—a man and a woman—who were created by heaven; then came the conditions of parents and children, of brothers and sisters, which are to continue through all time. Heaven made no difference between man and woman in regard to freedom, but intended them to be equal. In looking at the history of China and Japan from the earliest times, we find that men often had several wives, whom they treated like slaves or criminals, and the husbands were not ashamed of their conduct. Was not this wicked on the part of the men, and most pitiful for the women? When men thus treat their wives, the example has an evil effect upon the children, and they do not treat their mothers with respect, nor listen to their instructions. When this is the case the mother is only a nominal mother, and the children are no better off than orphans, and their condition most unhappy. And when we know that the fathers are seldom at home, but away attending to business, who is there to instruct the children?

“The famous Confucius in his analects says that there should be one husband and one wife; and while the modern Chinese and Japanese believe this to be right, they do not always act upon his advice. Most certainly there should only be one pair, and between the husband and wife there should always be true friendship and courtesy. When they treat each other as strangers or without due regard, it is impossible that domestic life should be happy. When men have a plurality of wives, the children, as a whole, have one father and several mothers; and the laws of Confucius as well as of nature are disobeyed. If it is right for one man to have several wives, then why not allow one woman to have several husbands? I would ask any candid man how he would like to be treated by a woman as many husbands now treat their wives? But in another of his works Confucius tells us that in his time, it was common for men to exchange their wives, according to caprice, and he expressed his great sorrow on account of the bad customs of his time. He was a great philosopher, but I do not find that he condemned the particular custom alluded to, and hence I cannot but think that he was an insincere man, or has contradicted himself in his writings. He is sometimes a difficult writer to understand, and cannot always be well understood without the help of Chinese scholars.

“Let me now speak of the children. It is their duty to be good and obedient to their parents. The Government is always ready to help those who treat their parents kindly, but the children must never do this from interested or sinister motives. As is well known, the custom prevails that because the mother carries her child for three years in her arms, so the child should mourn for three years after the death of its mother as well as its father. But this is all wrong; it is against nature, and looks too much like a business transaction. It is well known, also, that children are always punished for disobedience to parents, but parents are not punished when they treat their children with unkindness. This is not right, and there is no reason for this inequality or distinction. It is wrong for parents to look upon their children as they do upon their furniture—which they may have made themselves or can buy with money—for those children are each a gift from heaven, and should be highly valued for that reason alone. Until they reach the age of ten years, they should be instructed by their parents in all useful things—with parental love should be directed in the good way. When old enough to attend school they should be sent to those appropriate to their station, and they should strive to become useful members of society. All these things should be done by parents, as a return to heaven for blessing them with children. (Here the line of argument is leveled at some of the ancient customs of Japan. For example, it was formerly the case, that parents might even destroy their children without being punished under the law; but if children killed their parents, then the offenders were severely punished; and instances are recorded where children have been torn to pieces by wild beasts for having taken the lives of their parents.)

“When children have reached the age of twenty years, then they are called men or women: are free to act for themselves; must obtain their own support; are no more subject to the orders of their parents, and are at liberty to do as they please in all things. But they must not forget in their subsequent lives to be kind to their parents, and always to help them when necessary. It is written in the books of enlightened nations, that when children have reached the age of maturity, the parents may advise, but never command them; and this is a golden custom which should last into eternity.

“The way to bring up children is not only to teach them how to read and write, but they should be made familiar with the right way in everything under the influence of good example. If parents are wicked, mean or vulgar, the children are apt to be like them; example is far more telling than words, both for good and evil. If parents are bad, how can they expect their children to be good? This is far worse for the children than if they were left orphans. Some parents love and treat their children well as far as they know, but from ignorance often force them to do things that are not for the best. Such parents are criminals and opposed to the wisdom of heaven. Without meaning to do so, they degrade their children to the level of the brutes. To love in a proper way should be their ruling idea. There are no parents in the world who do not feel an interest in the behalf of their children, and yet, to be degraded in mind, is worse than to be without health. The love of which I speak, which only looks after the body, is what I would call maternal, or merely animal love. As human faces differ in appearance, so is it with human hearts; but the aims of the truest love should be exalted.

“One of the peculiar facts connected with civilization is, that as it advances, bad people become more abundant; then it is that men have trouble in taking care of their property and persons; then comes the idea that the people must have representatives, whose business will be to form a substantial government, make laws, punish the wicked, and help those who need help in every way. If the people, in the aggregate, were always good, then there would not be any necessity of organized government. The head of a government is its ruler, and the people who keep him are officers. Such a government is indispensable for the prosperity of a people and for national defence. There are many kinds of business, as you know, but the business of governing the people is the most difficult and important. The dutiful and attentive, in every sphere of life, ought always to be rewarded according to the justice of heaven. The people who live under a good government should not be envious of the officers who receive large salaries, for generally speaking, such men earn by hard work all they receive. They should be respected. On the other hand, the rulers and officials must not forget the duties they owe to the people; their work should not be out of proportion to their pay; the same justice should prevail between the officials and the people, which prevails between the master and servant.