* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

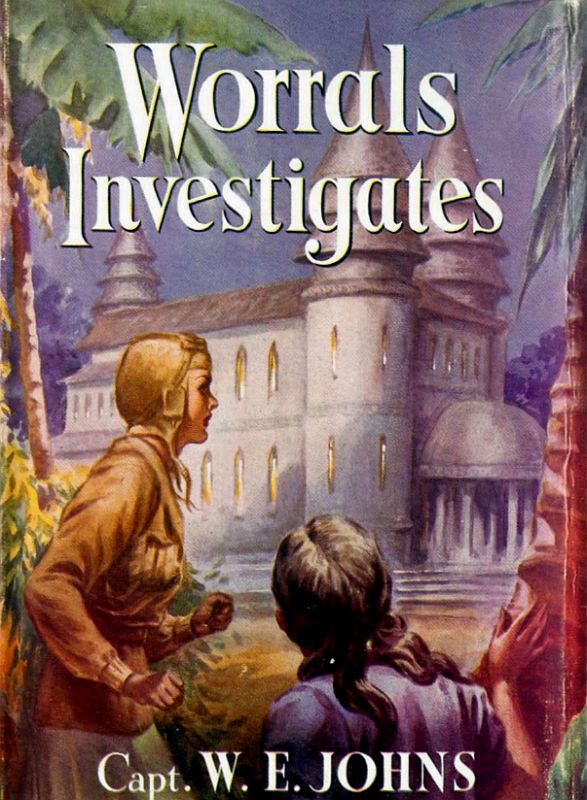

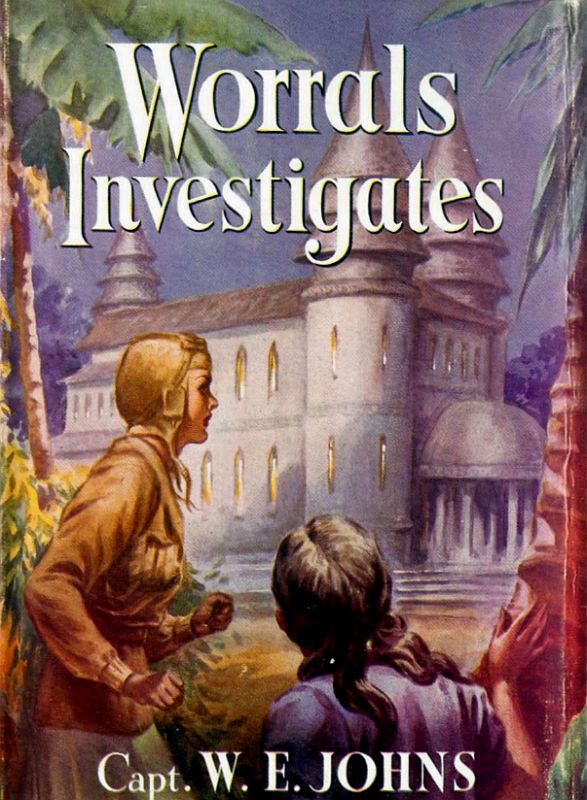

Title: Worrals Investigates (Worrals #11)

Date of first publication: 1950

Author: W. E. (William Earl) Johns (1893-1968)

Date first posted: April 23, 2023

Date last updated: April 23, 2023

Faded Page eBook #20230436

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

WORRALS

INVESTIGATES

A further adventure in the career of Joan

Worralson and her friend “Frecks”

Lovell, one time of the W.A.A.F.

by

CAPTAIN W. E. JOHNS

LUTTERWORTH PRESS

LONDON

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

First published 1950

MADE AND PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN

BY WESTERN PRINTING SERVICES LTD, BRISTOL

| Contents | ||

| Chapter | Page | |

| 1. | Coffee for Three | 7 |

| 2. | More Coffee for Three | 20 |

| 3. | Beyond the Blue Horizon | 37 |

| 4. | Mystery upon Mystery | 49 |

| 5. | A Curious Encounter | 67 |

| 6. | Frecks Goes Her Way | 77 |

| 7. | The Singular Story of Mabel Stubbs | 88 |

| 8. | Worries for Worrals | 104 |

| 9. | Taking the Bull by the Horns | 113 |

| 10. | Desperate Measures | 126 |

| 11. | Doubts and Dangers | 139 |

| 12. | Hard Going | 150 |

| 13. | Frecks Tells Her Tale | 158 |

| 14. | Home Again | 168 |

| List of Illustrations | |

| The little party halted | Frontispiece |

| facing page | |

| “Cartridge cases!” | 50 |

| “What are you doing here?” | 80 |

| “Am I addressing Miss Haddington?” | 115 |

| The machine came to rest | 165 |

Coffee for

Three

If Joan Worralson, better known to her friends as Worrals, hadn’t run into Air Commodore Raymond, Assistant Commissioner of Police at Scotland Yard, by accident in Piccadilly, the mysterious happenings on Outside Island might have remained a mystery for all time. With her friend, Betty—otherwise “Frecks” Lovell, she had just turned out of the Burlington Arcade, where they had been shopping, when they came face to face with the Air Commodore.

“Hallo!” greeted Worrals. “Are you sleuthing or just taking the air?”

“I’ve a lunch appointment at the Aero Club and decided to walk to stretch my legs,” answered the Air Commodore.

“Business slack?” inquired Worrals.

“On the contrary, it’s brisk—too brisk. Don’t you ever read the newspapers? I’ve been so overworked that I’m beginning to feel like the ragged end of a misspent life.”

Worrals shook her head sadly. “I never heard anything like you men for broadcasting misery. Do you need any help?”

“Not particularly, thanks. Our hands are mostly full of sordid crime. What are you girls doing?”

“Oh, struggling along, you know, to keep the wolf outside the door.”

“Speak for yourself,” grumbled Frecks. “I’m so bored it’d be a pleasure to dig my own grave.”

“How about a cup of coffee?” suggested the Air Commodore.

“We were just going along to Stewart’s to get one,” Worrals told him.

“Would you like me to come—and pay the bill?”

“That would be very nice of you,” agreed Worrals.

“Why not make it an early lunch?” suggested Frecks. “I am so hungry I could eat a dish of fried horseshoes.”

“Sorry, but I’ve got to meet a man,” said the Air Commodore apologetically.

Frecks sighed. “In that case I shall have to stave off the pangs with coffee and a couple of doughnuts.”

They walked along to the well-known café at the corner of Bond Street.

Having found a table and ordered coffee the Air Commodore remarked: “I’m afraid I’ve nothing in your line at the moment.”

“I suspected it, otherwise we should have heard from you,” averred Worrals with gentle sarcasm.

The Air Commodore rubbed his chin thoughtfully. “Just a minute though. I’ve just remembered something. There is perhaps one little matter . . .”

“Go on—don’t keep us waiting,” pleaded Worrals.

“The thought has just occurred to me that there is a little job in our files that might help to keep you out of mischief. It isn’t really important though.”

“Some wretched woman lost her ration book or something?”

“Plenty of people, men as well as women, lose their ration books, but this isn’t quite as prosaic as that. In fact, in a quiet sort of way it’s a pretty little mystery.”

“Do women come into it?”

“Oh yes.”

“Then tell us about it,” invited Worrals. “Maybe by turning on the female angle we can solve it for you sitting here.”

The Air Commodore smiled. “I see you are beginning to fancy yourself as a detective.”

“Well, you must admit that you have provided us with a fair amount of practice,” Worrals pointed out. “And anyway,” she went on, “one doesn’t have to be anything very wonderful to be a detective.”

“So that’s what you think, eh?”

“What I think is this,” returned Worrals. “There’s an awful lot of nonsense written about this detective business. Mysteries are made where none exists. Of course, that’s all part of the game. If there were no mysteries there’d be no Scotland Yard. All this talk about deduction makes me laugh. Boil it down and what have you? Just common sense. If a man can’t arrive at a conclusion by common sense plus scientific research, for which the Yard has every facility, then he has no right to call himself a criminal investigator. After a bit of practice one finds oneself deducting automatically, at least, I do. I wish I didn’t. Usually I have other things to think about.”

The Air Commodore laughed outright. “You know, you may have got something there,” he conceded. Then he became serious. “But don’t flatter yourself that it’s all easy. Whoever solves the little puzzle that I have in mind will have to travel a long way. I can think of no other way of getting to the bone of the thing.”

“Tell us about it and we’ll judge for ourselves,” requested Worrals.

They waited while the waitress served the coffee and the Air Commodore continued. “The riddle is wrapped around what is commonly called a desert island.”

“That’s a good start, anyway,” said Worrals approvingly. “Islands are fascinating things as long as they’re not too big. Where’s this one?”

“In that part of the Pacific where all the spare bits of land seem to have been tossed. It used to be called the South Seas, but is now more usually known by the French name Oceania. You know where I mean?”

“We went to school,” murmured Worrals.

“In that case you may have noticed that on the map the names of many of these islands are underlined in red. That denotes a British possession. Most other countries have a share. Until recently nobody bothered much about these islands—at any rate the smaller ones, of which there are literally thousands. You could have helped yourself to one, and as the postman doesn’t call it’s unlikely that anyone would have known about it for a long time. But lately these bits of rock and coral have taken on a new value because they form ready-made refuelling stations on the trans-ocean air-routes. However, in this particular case that aspect doesn’t enter into it, although it might later on. I only mention it because countries are getting touchy about foreigners landing on their islands without permission. Already there has been a spot of claim-jumping. Anyway, every island has now been claimed by some country or another. None, really, is privately owned. Very well.” The Air Commodore paused to light a cigarette.

“One of our islands enjoys the unromantic name of Outside Island. It was probably so named by the mariner who discovered it because it lies far outside the main groups of islands. With the exception of another small atoll, named Raratua, about ninety miles away—which is French property—the nearest land is the Paumotu archipelago, sometimes known as the Low or Dangerous Isles. The Paumotus belong to France. Being of coral formation they are not strictly islands, but atolls. Outside Island is also, strictly speaking, an atoll. While we are on the subject, as you’ll want it, I might as well give you all the gen available. I have had it looked up in Admiralty Sailing Directions and Findlay’s South Pacific Directory. Just a minute.” The Air Commodore took out his notebook and, selecting a slip of paper, read aloud.

“Outside Island. A lonely atoll lying three hundred miles east of the Paumotus. Once inhabited but now deserted. Shaped roughly like a letter S. Length approximately nine miles by half a mile wide. Highest point twelve feet above sea-level. In general features like other atolls but unusual in that it has two lagoons within the surrounding reef. The lagoon at northern end, five miles across, generally used by landing parties, but there are passages through the reef to both. They are narrow and dangerous. The island lies within the hurricane belt and is subject to inundation. It has the reputation of being haunted and is usually avoided by natives and consequently by trading schooners.” The Air Commodore folded and replaced the paper. “So much for the island itself,” he went on.

“Why is it uninhabited?” asked Worrals. “As these islands go, it’s large enough to hold a native population. Is it because of the risk of inundation or because of the alleged haunting?”

“That’s something I can’t answer,” replied the Air Commodore. “But there is a good reason why the island has a sinister reputation, and may account for the natives who once lived there abandoning the place. From early records it seems that they were a friendly lot. Many inter-island traders called because these lagoons yielded particularly fine pearls. Maybe that was the root of the evil. At all events, in the middle of the last century there arrived on the island a man named Prout, who claimed to be a missionary. Nothing is known about him but he seems to have had more than a touch of Hitler in his make-up. He was certainly a religious maniac, although when the world heard about his behaviour no church would acknowledge him. Anyway, he arrived, and he stayed, and he introduced the easy-going Polynesian population to something about which they knew nothing. Work. They didn’t work because there was no need. They could get everything they wanted without it. But this madman arrived and saw to it that everyone worked according to our standards. You might ask, for what? Apparently for his own glorification and enrichment. How he, one white man, did it, has always been a mystery—except that he seems to have gone about the thing in the modern totalitarian manner. Having frightened everyone to death with threats of hell-fire, by offering dispensations he was able to organize a private police force. The rest, men, women and children, became slaves pure and simple. Some had to dive for pearls; others had to plant coco-nuts, although there were already enough to support the population. The pearls, and the copra produced from the nuts, Prout sold to traders who, as they made money out of the traffic, said nothing about what was going on. Really, there was nothing unusual about this in the bad old days in the South Seas. But Prout carried the thing too far. His crowning piece of infamy was this. He forced the natives to build what he called a cathedral, but which was, in fact, a palace for himself, for by this time he was calling himself King of the island. Even the traders had to bow and call him King, or they got no pearls or copra. The palace still stands—derelict, of course. People who have seen it say it is an incredible building. Every slab of coral, of which it is built, was hewn with blood and sweat by the wretched natives.”

“How disgraceful!” put in Frecks indignantly.

The Air Commodore agreed. “Well, you can imagine what happened,” he went on. “The natives died like flies. Even sick men were made to work. Those who refused were murdered as an example to the others. For a time Prout replaced the casualties with natives brought from other islands by unscrupulous traders. But eventually even they were sickened and one of them reported what was going on. That was in 1900, by which time the natives were reduced to a mere handful of emaciated wrecks. Inquiries were set afoot, but before anything could be done a hurricane hit the island. Just what happened we don’t know for there were no survivors. Judging from the report of the next trader who called big seas must have washed right over the place carrying everything before them. Not a soul was left alive. The only thing still standing was Prout’s incredible palace. But all this has nothing to do with our mystery.”

“Are you sure of that?” put in Worrals.

The Air Commodore frowned. “What do you mean—am I sure?”

“What I say. How can you assert positively that this palace, or whatever it is, has nothing to do with the case? Has someone been to look at it lately?”

“No.”

“Never mind. I’m only trying to get my facts right,” murmured Worrals. “Go ahead.”

“As far as we’re concerned, the island is uninhabited,” went on the Air Commodore. “The first intimation we had that there might be someone there came in the form of a rather curt note from the French Foreign Office, passing on a complaint of the French Administrator of Oceania, at Papeete, in Tahiti, which is the metropolis of the Islands. In effect, their complaint was this. It seems that some of their Polynesian nationals from the Paumotus, at sea in one of their big canoes, called at the island for fresh water. Before they could land they were greeted by a volley of rifle shots, most of which, fortunately, went wide. But one man was killed. Naturally, as the natives had no firearms they did not persist in their attempts to land. The canoe returned to its own island and reported the incident to their Resident Administrator, who, quite naturally, took a dim view of it. According to him, this was no mere inter-tribal dispute. The natives reported that they were fired on by wild women, and these women were white women. One had red hair, which is something that just doesn’t happen in that part of the world.” The Air Commodore smiled. “Of course, such a fantastic story didn’t make sense,” he resumed. “It seemed to us far more likely that the natives had drunk too much kava—the local toddy—and got to fighting among themselves. One of their number was killed, and the rest, to account for his disappearance, concocted the story.”

Worrals shook her head. “It doesn’t sound that way to me.”

“Indeed! And why not?” asked the Air Commodore with a touch of asperity.

“Because, in the first place—although I’m no expert in Polynesian affairs—I can’t think of any possible reason why these men should invent such a story. All they had to say was that one of the crew had been washed overboard by a wave, or had been grabbed by a shark while bathing. Such a story would not have been doubted or questioned because it’s the sort of thing that must happen every day. You’re asking us to believe that these natives, who could quite easily have accounted for a missing man in a score of perfectly natural ways, deliberately sat down to concoct a yarn which was bound to be received with incredulity and suspicion even by the Administrator himself. The Polynesian may not possess a high degree of intelligence according to our standards, but I imagine he’s got more sense than to lie, knowing that the matter would be investigated—surely the last thing the crew wanted if they were trying to put something over. And to specify red hair, which is probably something not one of them had ever seen, is giving them credit for too much imagination. But go on. What was the basis of the French complaint?”

“As the island is ours, the behaviour of people living on it is our responsibility. We admitted that in our reply, but pointed out that we had no idea that anyone was there.”

“That was pretty weak, anyway,” averred Worrals.

“In what way?”

“If we own something, surely it’s our business to look after it, and know what goes on?”

“The truth of the matter was this,” confessed the Air Commodore. “We didn’t believe a word of the story, and neither, I’d wager, did the French Administrator. Naturally, we couldn’t say that in our reply. It would hardly have been diplomatic. But the French were quite right to complain, and we had to send a reply. Of course, there is just a chance that some white men were there—the crew of a trading schooner after copra, for instance; although it’s hard to see why they should fire on a native boat. On mature consideration, my personal opinion—and the Admiralty agree—is this. The Polynesians had gone to the island either for coco-nuts or pearls. Copra, by the way, which is the dried kernel of the coco-nut from which fat is extracted, is a valuable commodity to-day. As the island is ours the natives had no right to do that, and they knew it. Having got there, they found they had been forestalled. A party from another island was there on the same job. Seeing another boat coming, and being unwilling to share the loot—or perhaps they didn’t want to be identified—they smeared their bodies with wood ash and tried to frighten the newcomers away by pretending to be spooks. This having failed they opened fire. Doesn’t that sound reasonable to you?”

“I don’t find it very convincing,” answered Worrals dubiously. “There are several flaws in that theory. It presumes that the men already on the island were carrying rifles. Even if they possessed such weapons, which is unlikely, why take them ashore? There are no hostile natives, or wild beasts, on Pacific atolls. And in what sort of craft did these men reach the atoll? There’s no mention of a boat. Admittedly, we must allow for the fact that we have only got the Polynesians’ word for it that there was any shooting.”

“Very well,” answered the Air Commodore. “The alternative theory is that there are castaways on the island.”

Worrals shook her head. “That won’t do. Castaways normally receive a boat from the outside world with open arms, not musket-balls.”

“What an awkward woman you are,” protested the Air Commodore.

“You’re telling the story,” asserted Worrals. “If I’m not to do a little deducing on my own account, why waste your time telling it? If you’d rather I remained dumb in the face of these pretty but quite unconvincing theories, you have only to say so and I’ll endeavour to keep my tongue under control.”

The Air Commodore smiled. “Don’t do that. I am enjoying the argument. But there’s more to come and this coffee is cold. Shall I order some more?”

“That’s okay with me,” declared Frecks. “This is nearly as good as going to the flicks.”

“Our time is all yours,” Worrals told the Air Commodore.

The Air Commodore beckoned to the waitress.

More Coffee

for Three

“Now tell us what you did about this complaint,” invited Worrals, when fresh coffee had been brought.

“We told the French authorities that we’d look into the matter,” replied the Air Commodore. “We could do no less. But how were we going to look into it except by sending an expedition to the island? The French must have realized that. They must have known it would be unreasonable to expect us to ask the Navy to send a vessel on a special voyage to the other side of the world to check up on a vague and most unlikely story told by a party of Polynesians.”

“Unlikely, but not vague,” disputed Worrals. “These natives seem to have been particularly observant in the matter of detail—even to the extent of noticing the colour of a woman’s hair.”

“All right. Have it your own way,” said the Air Commodore. “But get ready to hold your hat. It now seems that there was some foundation of truth in the story.”

“Ah! Now we’re getting somewhere,” stated Worrals. “To me that’s been the most sensible explanation of the thing all along. Have you had confirmation?”

“Up to a point. The Admiralty doesn’t forget. Two months ago, having a sloop passing within a few hundred miles of Outside Island, the Skipper was ordered to look in and investigate. Standing by—naturally he wouldn’t hazard his ship by getting too close to the dangerous reef—he lowered a boat with half a dozen men under an officer. This boat was nearing the shore when a rifle shot rang out and a bullet hit one of the sailors in the arm.”

Worrals smiled. “The mad white woman with red hair had evidently had a spot of practice,” she commented. “Her shooting had improved.”

“I don’t know about that, but in view of this hostile reception the naval officer did the only thing he could. It wasn’t for him to risk the lives of his men so he went back to the sloop and reported what had happened. The captain was at a loss to know what to do. There was nothing in his orders about taking the place by storm. He did not want casualties himself, and to inflict them on other people might start an international row. It doesn’t take much nowadays to do that. In any case, it seemed silly to waste shells on coco-nut palms. He radioed to his base for instructions, at the same time stating that the glass was falling and he was on a lee shore. He was told to proceed on his way. There was no sense in risking a costly ship to save somebody who obviously didn’t want to be saved.”

Worrals nibbled a biscuit thoughtfully. “It was difficult,” she admitted. “Still, it seems a pity the thing wasn’t buttoned up while the ship was there.”

“Maybe so,” agreed the Air Commodore. “The fact is, the matter isn’t really important enough to give anyone a headache. Our chief concern is to settle the matter amicably with our French friends. We certainly don’t want their nationals shot on our territory. There’s enough bickering going on in the world as it is.”

“What about these alleged women on the island?” asked Worrals. “Did this naval officer see anything of them?”

“No. He had a good look at the place through his glass, but he saw no sign of life. The sharpshooter, whoever he or she was, was well hidden. The island is pretty well covered with coco-nut palms, which supports the copra theory. The palace is still standing. The top of it could be seen through the trees, though not in any detail owing to the distance.”

“And that’s how the thing stands at present?”

“Yes.”

“What are you doing about it?”

“Nothing at the moment. The Admiralty is against sending a ship all that way for the one purpose of looking at an island which nobody wants. When they have another ship passing that way it will be told to call.”

“But it begins to look as if somebody does want the island,” argued Worrals. “Not only wants it, but is prepared to fight to keep it,” she added.

“All the same, it would be an expensive business to send a ship all that way,” insisted the Air Commodore. “But it struck me just now—I don’t know why I didn’t think of it before—that a far more economical plan would be to send an aircraft. In fact, an aircraft would have several advantages. It would be quicker than surface-craft. It could land on the lagoon instead of taking chances with the dangerous passage through the reef. Indeed, it might not be necessary for it to land at all. It might see all that was necessary by simply flying low over the atoll.”

“Which, as the occupants are obviously all against publicity, would merely have the effect of sending them all diving for cover,” observed Worrals dryly. “I think you’ll find that it will be necessary for the aircraft to land. Are you suggesting that we do the job?”

“If you’ve nothing better to do. Frankly, I shan’t lose any sleep if nobody goes, although I suppose the thing will have to be sorted out sooner or later. We owe that to the French authorities. In suggesting that you go, I’m bearing in mind that if by any remote chance there should be females on the island you would be better able to cope with them than men. Women might be prepared to greet other women with something less hostile than gun shots.”

Worrals nodded. “True enough. Can you tell me this? What was the date of the last official British visit to the atoll?”

“The Admiralty have no record of any ship calling there since 1906.”

Worrals’s eyes opened wide. “That’s a long time ago. A lot could have happened there between then and now.”

“Some islands haven’t been visited for much longer than that. The Navy has more important jobs to do than sailing round the globe inspecting uninhabited islands.”

“And these Paumotuans? When were they last there—I mean, before the time they were shot at?”

“I didn’t inquire. I assumed it was their first visit.”

“I wouldn’t assume anything of the sort.”

“Does it matter?”

“It matters a lot. If on a previous occasion they landed unmolested we might get a rough idea of the date when the shooting party arrived. If one knew that to within a few months, or even a year, the information would be useful.”

“What makes you think that these natives might have been there before?”

“Several things. To start with, I can’t believe that these fellows were sculling about that particular section of the ocean with no particular object in view. They must know those waters as I know Piccadilly. They knew the island was there, in which case they must have known jolly well that there was copra to be had for nothing, or, maybe, pearls. They also knew they had no right there, and if one of their number hadn’t been shot they would have carried on poaching and no one would have known anything about it. I’d say those men made a special trip to the island, and in that case the chances are they’d been there before.”

The Air Commodore nodded. “I didn’t look at it like that,” he admitted.

“Would it be in order for you to ask the French authorities to question these men again, to find out if they had been there before, and if so, when? Make it clear that you’re not interested in their unofficial visit to the island, or they may lie about it. Say you’re merely following up the complaint with a view to getting the thing straightened out.”

“I could do that,” agreed the Air Commodore. “We should have a reply in a few days. But what’s the point of this?”

“Let us assume for the moment that the natives told the truth, and there are white women on the island,” suggested Worrals. “If there are, where did they come from? When did they arrive? Has nobody missed them? People do vanish, of course, and some have good reason. But most women have friends or relations, and when people go missing they soon start asking questions. Remember, the natives said women—plural; not a woman. There were several gun shots, not one. That means that at least two or three women are there. They must have arrived together. Has nobody missed them? If we could ascertain when they arrived it might tally with names on your list of missing women. I imagine you have such a list?”

The Air Commodore looked grave. “We have, but I’m afraid that won’t help you much.”

“Why not?”

“There are too many.”

“Too many! You shock me.”

“Odd women—and men for that matter, do disappear more or less regularly,” said the Air Commodore. “Some, no doubt, are concerned only with dodging conscription or national service.”

“But even they have to eat. What about their ration books?”

The Air Commodore shrugged. “Don’t ask me. Some time ago—it must be nearly two years now—there was such a crop of female disappearances that we became seriously alarmed. We had about twenty cases reported in a month.”

Worrals frowned. “Who reported them?”

“Parents, mostly.”

“Were none of these women ever found?”

“No. They just vanished leaving no trace, as we say.”

“But how frightful. What sort of women were they?”

“Girls mostly—girls of between eighteen and twenty-five.”

“Wasn’t that unusual?”

“Very.”

“From what sort of homes did these girls come?”

“They were all girls of good character. Some were domestic servants. Some were in good jobs, and until the time they disappeared seemed quite happy and contented. Apparently some of them knew what they were going to do because they took their best clothes and so on with them.”

Worrals stared. “You amaze me! Well,” she went on slowly, “you’ve certainly got my curiosity weaving. But let’s stick to the point. When do you want us to leave for Outside Island?”

“When you’re ready. There’s no hurry. Make your own arrangements. Get what you want and I’ll see the bills are okayed.” The Air Commodore looked at his watch. “But I must be getting along—I’m late as it is. Do I take it definitely that you’ll go?”

“Of course.”

“All right, then.” The Air Commodore got up, beckoned to the waitress and paid the check. “Look in and see me before you go. I shall want to know just what you intend to do.”

“And I shall want you to know,” returned Worrals warmly. “From all I’ve read a coral island can be a fascinating place, but that doesn’t mean that I’m pining to spend the rest of my life on one.”

With a wave and a smile the Air Commodore departed.

Worrals looked at Frecks. “Our shopping expedition looks like taking us farther than we thought,” she observed. For some time she sat pensively stirring her coffee. “The more you think about this business, the more odd it becomes,” she said at last. “I’m afraid we shan’t prove anything sitting here; but we can look at the thing from all angles and sort out the probable from the improbable. We must have some sort of line to work on. My feeling is, the Air Commodore is inclined to treat it too lightly. My instinct tells me there’s more behind this than has so far met the eye. Some of the most astonishing affairs have come to light through an incident far more trivial than the one about which we’ve just been told.”

“What’s your opinion of it?” asked Frecks.

“I haven’t one,” admitted Worrals frankly. “But let’s tackle the thing logically and try to arrive at one. The facts are quite simple. Some natives try to land at a British island supposed to be uninhabited. They are shot at. One is killed. We know that the first part of their story is true because it has been corroborated by the Navy. The next point is, as the first part of the native story is true, there seems to be no reason to doubt the second part. It sounds fantastic, but on that very account, to my way of thinking, it’s more likely to be true. As I said to the Air Commodore, why invent a story so incredible that it was certain to be doubted? What was this story? The natives saw white women. These women were behaving in a manner which they described as wild. Exactly what they meant by that we don’t know, but as these women were crazy enough to start shooting we can suppose they were in a state of high excitement. One of these women had red hair.” Worrals finished her coffee at a gulp.

“Put it like this,” she went on. “Either the natives were lying or they were telling the truth. If we say they were lying, we must find a better reason for such an outrageous lie than the one the Air Commodore provided—that it was simply to account for the death of one of the crew in the canoe.”

“The island is supposed to be haunted,” reminded Frecks, “The natives would know that and be ready to bolt.”

“They said nothing about spooks. And even if spooks were on their mind, they’d have the sense to know that spooks don’t carry rifles. They said they saw white women, and I’m prepared to believe they did—or thought they did. They certainly saw somebody. Nobody lies without a reason, and I simply can’t see why these natives should create white women if none were there. No, Frecks, these fellows tried to land and were shot at. That’s been proved. If we accept that, then we might as well accept the assertion that the shooters were white women.”

“Or natives dressed as whites?” suggested Frecks.

“A native dressed as a white wouldn’t dye her hair red, even if that were possible, which I doubt. Let’s examine this carefully. These natives must have known that their story would sound extraordinary even if they said the shooters were women, because women do not normally possess firearms. But they don’t stop at that. They qualify these women. They were white. They were wild. One had red hair. Native imagination will go a long way but don’t ask me to believe that it will go as far as that. These men themselves live on a lonely atoll. They can have seen very few white women in all their lives. They’d have about as much chance of seeing a woman with red hair as a dwarf would have of getting into the Life Guards. I doubt if they know that there are women with red hair.”

“I’m inclined to think they must be castaways gone out of their mind,” opined Frecks. “That’s the only reasonable explanation.”

“My dear Frecks, be yourself,” protested Worrals. “When people are shipwrecked, they stick to the ship while there’s any hope of it keeping afloat. When it becomes certain that they’re going to sink, they take to the boats. On such alarming occasions they’re concerned only with saving their lives. They don’t clutter themselves up with unnecessary junk, and I’d put rifles and cartridges into that category. Remember, these are friendly islands. The natives are not hostile. And then there’s the point I made to the Air Commodore. Castaways are only too anxious for the world to know of their predicament. Anyone cast away on Outside Island might stay there for forty years. One imagines that a diet of coco-nuts soon becomes monotonous. Why drive salvation away when it comes? No. These people aren’t castaways. They want to be there. They went there of their own free will and they don’t want to be disturbed. They are prepared to drive away invaders. That’s why they took rifles. What is there to shoot at on an atoll? Rats, crabs and seagulls. You don’t need a rifle to kill rats and you can’t eat seagulls.”

“The bluejackets didn’t see any women, white or otherwise,” remarked Frecks. “Why?”

“I can think of a reason.”

“What is it?”

“When the natives tried to land, the people on the island didn’t mind showing themselves. A bunch of natives didn’t matter. But when a ship flying the White Ensign steamed into the offing it was a very different matter. They took jolly good care to keep under cover.”

“Why? I’m not very bright this morning.”

“Because if the Navy announced that a party of white women were stuck on a lonely Pacific atoll the story would get into the papers and a public outcry would demand their rescue. From their behaviour that’s the last thing these wild white women want.”

“But how did these women get there? Neither the natives nor the Navy saw a ship?”

“That’s one I can’t answer,” admitted Worrals. “Of course, some people have had themselves marooned deliberately, as did Alexander Selkirk, the original of Robinson Crusoe. I’ll own it doesn’t sound feasible in this case. What is there on Outside Island to attract anyone? And how, if it comes to that, did these people know the island was there? Not one person in a million has ever heard of the place.”

“Maybe they looked at the atlas.”

“Okay. They looked at the atlas. I’ll bet the island isn’t marked. It takes the cartographers all their time to show the main groups of islands in the South Seas. Then all they can manage is a few pin pricks. Why pick on Outside Island—unless it was for the very reason of its remoteness? The main archipelago is remote enough in all conscience.”

“These people may be British. Outside Island is British. The Paumotus are French.”

“Yes, that’s sound reasoning.”

“There’s a ready-made palace there.”

“A palace on a South Sea island would be just about as useful as a wigwam in Piccadilly Circus.”

“That crook missionary, Prout, wanted a palace there, don’t forget.”

“That was probably to impress the natives, to boost his importance, so that they’d sweat their lives away making his fortune out of copra. I think we’d better reserve our opinion of this palace till we see it.”

“But all this is taking for granted that there are people on the island—living there,” Frecks pointed out.

“Rifles don’t fire themselves,” argued Worrals.

“But women!”

“If anyone is daft enough to choose that sort of existence, it might as well be a woman as a man.”

“There might be men as well.”

“I doubt it. When that boatload of natives came over the horizon, would it be natural for the men to run away and hide leaving the women to do the shooting?”

“No.”

“Of course not. Men are more accustomed to firearms, anyway. The shooting in the first place was poor. A volley of shots was fired. Only one hit the boat. That sounds like people unaccustomed to firearms.”

“All right,” agreed Frecks. “Where does all this get us?”

“Nowhere, except that I’ve shown you why I believe the natives’ story to be substantially true. The only way we shall arrive at the answer to all the whys and wherefores is by going to the island and seeing for ourselves just what goes on.”

“There’s nothing more we can do at home, you think?”

“There’s one angle we might explore,” said Worrals slowly. “I don’t set much store on it, but one never knows. If there are white women on Outside Island it’s pretty certain that they went there in a ship of some sort. What ship? When? Where is it now? Did it return to its home port after putting these Crusoes ashore? If it did, why haven’t the skipper or the crew said anything about it? Surely one of them would have talked? The ship may have been lost after landing these people. It might be worth while going through Lloyds’ Register of missing ships, covering, say, the past three or four years. There won’t be very many if we confine our inquiry to that particular section of the Pacific, because it’s only once in a blue moon that a ship is within hundreds of miles of the place, and then it could hardly be there from choice. It’s far from the main traffic routes.”

“A ship might have drifted there out of control.”

Worrals shook her head. “You’re still clinging to the castaway theory. Forget it. If women were cast away they’d have men with them, and the men would have done the shooting.”

“It’s women and children first in the boats, don’t forget.”

“But women don’t man the lifeboats, to pull on the oars and do the navigating. The ship’s crew do that. Apart from which, the theory won’t hold water because all ships carry radio, and the first thing they do when in trouble is send out an S.O.S. and give their position.”

“This ship might have done that.”

“In which case a search would have been made for possible survivors. If none was found, the ship would be presumed lost. If survivors reached Outside Island they’d want to be picked up—but we’ve been over all this before.”

“All right,” countered Frecks. “Your argument is that there are women on the island.”

“Yes.”

“They are not castaways?”

“That’s my contention.”

“The alternative is, they put themselves there deliberately.”

“Quite right.”

“That doesn’t make sense to me.”

“Why not?”

“You’re asking me to believe that a number of white women, sane women, of their own free will, planted themselves on a crust of land in the middle of nowhere, without a male escort, prepared to stay there.”

“I don’t remember saying anything about them being sane,” returned Worrals. “Alexander Selkirk had himself marooned on Juan Fernandez and was there for over four years.”

“He was a man.”

“So what? Is there any reason why a woman shouldn’t do the same thing?”

“That still doesn’t make sense to me.”

“Maybe not, but people don’t all think alike. What may not sound sense to you may be a brain-wave to some people. These women—assuming they are there—wouldn’t be the first to choose a life of absolute seclusion, and without male escort. Some religious orders do that.”

“Yes. In civilized countries. That’s a different thing altogether.”

“All right. What about Lady Hester Stanhope, in the middle of the last century? She was a famous society beauty. She renounced civilization and tucked herself away in the heart of a Syrian wilderness where she spent the rest of her days. And Syria was a wild place then.”

“What was that about? An unhappy love affair?”

“Nobody knows. What does it matter what it was all about? The fact remains, she did it. There’s no telling what some people will do if they get a bug in their brains. But we’ve done enough talking. It all boils down to this. We have three questions to answer. Are these white women there? If so, why are they there, and why do they shoot at visitors? Apart from the last item, they’ve done nothing wrong—as far as we know. The Air Commodore was right in one respect. We shall have to go to Outside Island to get the answers. Having got them we can come home. Apparently there’s no question of putting these people off the island, or bringing them home if they don’t want to come. Now we’d better go and see about getting things organized.”

Beyond the

Blue Horizon

Seven weeks after the conversations narrated in the previous chapters an aircraft droned its way across an infinity of blue water towards the rim of the world and a lonely island that lay beyond the woes and worries of civilization. Worrals was at the controls. Frecks sat beside her, her eyes on the waste of water where the ocean met the sky, a horizon over which marched a majestic pageantry of clouds. It seemed so long since the last land they had sighted had disappeared down the reverse slope of the sea that a feeling had grown on her that they were no longer on the earth, but had entered a new province of the universe.

They had made a leisurely trip out, for, as the Air Commodore had said, there was no great urgency about their mission. Nevertheless, there had been much to do at home, for Worrals knew only too well that the success or failure of a long-distance flight is something that, more often than not, is decided on the ground before the start. Arrangements for refuelling had to be made, and here the Air Commodore’s influence, through service channels, made possible facilities which would not have been available to ordinary civil aircraft. The same with the complicated travel and customs regulations. Of course, the fact that the machine and its crew were on official British Government business, as was noted on their documents—passports, log books, carnets and the like—smoothed out the usual difficulties.

The selection of an aircraft had been a consideration of first importance. And here they had been lucky, since not even the Air Commodore was in a position to demand from the Air Ministry just any machine that might seem best adapted for their purpose. But it so happened that there was a prototype, a flying-boat amphibian, that had not gone into production, readily available, and as it was precisely what Worrals needed she jumped at it. The Air Ministry had approved the design during the war. The machine had been built and paid for, but at the end of the war put on the obsolescent list, since the particular purpose for which it had been designed no longer arose. It was, it seemed, a sort of ugly duckling. At any rate, nobody wanted it. Worrals did not hesitate. As she remarked to Frecks, it was ‘just the job’.

The provisional name for the type was Seafarer, and as such it was known. As a type, its classification was Long-Distance Sea-Air Rescue. It was not a very attractive machine to look at, but Worrals was not concerned with looks. Strength and reliability were what she wanted, and since it was expected that the machine might have to land in heavy seas, these qualities had been kept to the fore by the designer.

Actually, the Seafarer was a monoplane with accommodation for four passengers in addition to the crew. The pilot’s cockpit, forward of the wings, was enclosed. An open cockpit amidships gave access to the cabin, conveniently close behind. Behind the pilot’s cockpit was a radio and navigation compartment, backed by a bulkhead through which a door gave access to the passenger cabin. The power unit was a single Bristol Mercury radial air-cooled engine of nearly nine hundred horse power, which gave the machine a top speed of one hundred and fifty miles an hour and a cruising speed of just over a hundred miles an hour. Normal endurance range was rather better than twelve hundred miles, but as all the seating in the cabin was not likely to be required Worrals had sacrificed some of it for the installation of an auxiliary fuel tank which lengthened the range to more than two thousand miles. There was no armament.

Worrals tested the machine and expressed herself well content. It was, she found, easy to handle both in the air and on the water. True, it was not fast, but it had a slow landing speed, which was more to be preferred considering the nature of the work on hand. The cabin accommodation would contain more stores than they were likely to need. So, taking it all round, Worrals was well pleased. Armament was not required, but personal weapons had been discussed in view of the reception accorded to recent visitors to the island. In the end, as weapons would only be needed in self-defence, they decided each to take a small automatic pistol and let it go at that.

Nothing is more boring than a long, over-water flight, and Frecks had lost interest in the unchanging scene below. They had passed over several small islands earlier in the day, but from an altitude of five thousand feet there had been little to excite curiosity, much less enthusiasm. The weather had been kind, and looked like holding, much to Worrals’s satisfaction, if only because with good visibility there would be less chance of missing the island—a circumstance which, even for the most experienced navigators, is always possible in anything but the best weather. This, really, was why Worrals maintained an altitude which otherwise would not have been necessary. From it, she reckoned, they could see a hundred miles in every direction.

With the Seafarer practically flying itself along its set course, Frecks nibbled a bar of chocolate as she kept a lookout ahead. And presently, when an isolated speck of land appeared, she remarked: “That must be Raratua: according to the book of words there’s no one on it. From all I’ve heard of desert islands it seems to fill the bill.”

“We’re on our course, anyway,” observed Worrals. “Only another ninety miles to go.”

Frecks watched the tiny atoll, looking pathetically lonely in so much water, pass below, and finishing her chocolate fixed her eyes on the horizon over which their objective should, from their altitude, soon creep into sight. Her mind, naturally, revolved round the known facts of their unusual enterprise.

Investigations at home had thrown practically no more light on the mystery. The Air Commodore had been in touch with the French authorities who, at his request, had ascertained that the Paumotuans, as Worrals suspected, had been to the island before. The previous time was over a year before, on which occasion there had been no one there. Of this they were sure, because they confessed to having removed some of the pearl shell that had been used to decorate the walls of the palace. This, as Worrals pointed out, meant that the present occupants—assuming they were still there—had arrived within a known period of about two years.

The next step had been to find out what ships had been lost in the region during that period. The results were disappointing. Inquiries at Lloyds and at the Admiralty revealed that no registered vessels had disappeared anywhere in the Pacific during that time. Indeed, only three ships had disappeared without trace during the last three years in all the oceans of the world. Others had, of course, been wrecked; but the details were known from survivors. The first of the ships that had vanished completely was a French freighter named Babette, which, in ballast, had disappeared between London and East Africa. There were no women on board. The second was a cattle-boat that had presumably gone down with all hands between Buenos Aires and Bristol. Weak S.O.S. signals had been received. After that, silence. It was not known if there were women on board, but it was unlikely that there would be any on a cattle-boat. The third was a privately owned luxury steam yacht named Vanity, outward bound on a pleasure cruise to California from Cowes, via the Panama Canal. It had not gone through the Canal so was presumed lost somewhere in the Atlantic. The weather was bad at the time. There was a party on board. Not all the names were known, but it included women, among them Lady Amelia Haddington, the owner, daughter of the late Sir Eustace Haddington, a millionaire ship-owner and yachtsman for whom the vessel had been built.

All these ships, the Air Commodore asserted, could be dismissed from the case, as none could have been within thousands of miles of Outside Island. Worrals agreed.

One point of interest, however, had come to light—not that Worrals paid a great deal of attention to it. The period between the two visits of the natives to the island coincided roughly with the time Scotland Yard was faced with the crop of female disappearances to which the Air Commodore had referred. But that, as the Air Commodore remarked—and Worrals again agreed—was almost certainly coincidence. Not by any method of reasoning, or exercise of imagination, was it possible to see how these girls, most of whom came from humble homes, could get to a remote island like Outside. None was known to have booked a passage for anywhere—not that any ship called at Outside Island. For the most part the girls were domestic servants, but there were typists, shop-assistants, and one or two university students. It was unreasonable to suppose that they had all taken it into their heads to do the same thing at the same time. They came from all corners of the United Kingdom and certainly could not have known each other.

“All the same,” Worrals had commented thoughtfully, “one feels that there might have been a hook-up somewhere. If these girls did not disappear voluntarily, they might have been actuated by the same motive, or agency. To suppose that they, not knowing each other, suddenly and simultaneously took it into their heads to disappear, would be a remarkable coincidence. There’s something fishy about that.”

The Air Commodore had smiled. “Well, I don’t think you’ll find them on the island, so you can leave them out of your calculations. Anyhow, if you can work out how they could have got there, you’re cleverer than I am.”

Worrals admitted that she could think of no way, and the matter was not pursued any further.

Frecks was aroused from the reverie into which she had fallen by a cry of “Land ho!” from Worrals.

Looking up with a start she saw a feathery fringe of palms showing above the ultramarine edge of the sea, slightly to the left of their line of flight.

“Nice work, Frecks!” went on Worrals. “Your navigation was on the top line.”

“Thank you,” acknowledged Frecks, who, now that she had something to look at, took more interest in the proceedings.

Very slowly the strip of land, looking tiny in such an immensity of ocean, crept over the horizon. Half an hour later, from a distance of about twenty miles, the entire plan of the atoll could be surveyed, although not with any detail. All that could be seen was the general shape of the narrow, curving strip of coral, which appeared as a belt of emerald palms outlined on one side in the snow-white foam of the surf. On the other side, the two lagoons lay tranquil under the sun, with their outer reefs again outlined in purest white where the great green rollers broke in a smother of foam. There was no sign of life anywhere, but presently a white tower broke through the verdant palms at the northern end, which was also the widest part of the atoll.

“That, I imagine, is the palace,” remarked Worrals.

A little pressure on the rudder bar put the aircraft on a new course that would take it clear of the southern end of the island, where lay the smaller of the two lagoons on which Worrals had already decided to make her landing. She was anxious not to be seen. Not that she thought there was much chance of this, for it is usually the noise of an aircraft that betrays its presence in the first instance, and the drone of their engine would, she thought, be drowned in the booming of the surf.

Not until she was level with the southern extremity of the island did she turn directly towards it. By that time she had cut her engine, and so was gliding noiselessly for the last two or three miles. There was still no sign of life, which was really no matter for surprise, for in discussing the project they had decided that the unknown population had most likely established itself at the northern end, where the island was at its widest and where the palace was situated.

Neither Frecks nor Worrals spoke as the machine glided the last few hundred feet towards the limpid waters of the lagoon. Not a ripple broke its surface. They crossed the reef with the engine idling, so that the noise of the surf came up like the rumble of distant thunder. The machine bumped a little. The roar of the surf became a growl. Looking down Frecks could see the bottom of the lagoon quite plainly. For the most part it appeared sandy, but here and there were luxuriant growths of coral. The shadows of fish moved across the lighter background, but as far as the actual depth of the water was concerned, she could not hazard a guess.

Worrals flattened out. The Seafarer glided on a little way, losing speed. Then the keel hissed as it touched the water. Creamy waves swept in a broad arrow from the bows. The aircraft lost way quickly and came to a stop about fifty yards from the southern tip of the island, or the point where it joined the reef which there swung round in a sweeping curve. A touch of the throttle took the machine right in. The engine died. Movement ceased. The only sounds were the sullen roar of the surf and the screaming of resentful seagulls.

Worrals straightened her back and stretched her arms. “Well, we’re here, anyway,” she observed.

“It’s pretty to look at too,” answered Frecks. “Shall I make fast?”

“Not for the moment,” returned Worrals. “If we are accorded the usual reception we might want to take off again in a hurry. If anyone saw us land, they’ll soon be along for a closer look, no doubt.”

“I could do with a bite of food,” said Frecks.

“We’ll attend to that in a moment,” promised Worrals.

Opening the locker she took out a pair of binoculars and studied the long sweep of beach for as far as it could be seen. “Don’t see a soul,” she murmured.

Frecks climbed out of her seat for a better view, and sitting on the cockpit cover contemplated a scene as enchanting as the imagination could conceive, for an atoll is an example of nature at its best.

Of the island itself little could be seen, for the view was curtailed by a grove of palms which grew on ground so close to water level that in the distance they appeared to be growing out of the sea itself. Between the trees there was a sparse covering of undergrowth, although not a blade of grass could be seen. All that could be observed clearly was a long curving beach of white coral sand that glistened in the sunlight. On the lagoon side the water lay as flat as a mere, a harmony of blue, with areas of vivid green marking shoals. The water was of a wonderful transparency. So clear was it that fish, which occurred in all sizes, shapes and colours, appeared to be floating in air. On the bottom lay an incredible variety of shells. On the far side of the lagoon, a circular cluster of small, rocky islets, from which palms sprang at many angles, gave a fairy-like touch to the picture. Overhead great white gulls passed on rigid wings as if inspecting the intruder. As a scene, decided Frecks, it was pretty rather than imposing or dramatic.

But on the seaward side of the island, along the outer rim of the reef, perhaps a hundred yards from where she sat, the effect was altogether different, and magnificent in contrast. Here the mighty ocean rollers rose up to hurl themselves against this impudent fragment of land, only to destroy themselves in showers of diamonds. The coral appeared to quiver under their ceaseless impact. It was easy to see how in a hurricane the island could be overwhelmed, and the recollection that such things did occur awoke in Frecks an uneasy feeling of insecurity. Worrals closed the binoculars. “All right,” she said. “Nobody seems to be coming, so we may as well make fast and go ashore to stretch our legs. We’ll take some food with us.”

“What are you going to wear?” asked Frecks. “It’s pretty hot.”

“I think a bathing costume is the best thing; then we can potter about in the water as much as we like. I shall wear a cotton frock over mine. I know what sunburn can do. Too much ultraviolet—and there’s plenty of it here—will tear your skin off as fast as boiling water. We shall have to wear beach shoes or we’ll be cutting our feet on the coral. Don’t forget your dark glasses. This glare is going to be hard on the eyes. Better put something on your head, too. We don’t want sunstroke to complicate matters. I’m keeping my gun handy. If that wild redhead starts shooting at me she’ll find two can play at that game. Being women we can meet on equal terms. One thing I can promise you: having come all this way I’m not leaving here until I’ve turned the mystery inside out. Come on; give me a hand to get this stuff ashore.”

“I think I’ll change in the cabin first,” decided Frecks.

“Okay,” agreed Worrals. “Don’t be long about it. I’ll follow you.”

Mystery

upon Mystery

Half an hour later, after a plain meal of biscuits, tinned butter, sardines and jam, Worrals got up and shook the crumbs from her skirt. “We might as well make a move,” she announced. “There’s no particular hurry, but having thought about this business so much I’m really curious to know what is going on here. Apart from that, the longer we’re here the more chance we have of striking dirty weather. The machine is safe enough where it is while this weather holds, but if it started to blow it would be a different story. She’d never ride out a full gale, not even in the lagoon. One good bump on that coral would be enough to tear her keel off. We’ve still plenty of time to walk the full length of the island and back before bedtime, so we might as well start. The next hour or two should tell us all we want to know.”

Frecks agreed, for she, too, was curious to know the secret of the lonely island.

“I’ll take the glasses,” went on Worrals. “Just a minute, though. I’ve got an idea. I think we might walk a little way out on the reef. That should give us a view of what lies beyond that bank of coral.” She pointed to a reef that rose to an exceptional height on the opposite side of the lagoon, nearly two miles away, from where they stood they could not see the beach behind it.

“Good enough,” concurred Frecks, and she followed Worrals to where the reef swung in to join the tongue of land that formed the end of the island proper.

At this point the reef was broad, but so low that the waves ran half-way across it. It might create a more accurate impression to say that the coral barrier consisted of not one, but a number of reefs, some large and some small, some straight and others curving round in crescent formations. Between them ran lanes of jade and amethyst water. On the seaward side the rollers swept in, mountains of water that rose up as if conscious of their might, with the whole weight of the ocean behind them. But the coral walls tripped them up, and they crashed helplessly on the reef in a spreading smother of white foam that sent up showers of glittering jewels. The coral itself was of every shape and size. In the limpid water of the many pools swam brightly coloured fish. Fascinated, Frecks would have stayed to study them, but Worrals did not stop until she reached a high bank of dead coral for which she had been making. She was about to sit down when an exclamation brought Frecks to her side.

“What is it?” asked Frecks quickly.

“Look!” Worrals pointed.

“Yes. Brass rifle cartridges. That settles one point definitely. Those natives were shot at all right—from here, apparently. They must have been making for the passage through the reef.” She indicated the narrow opening about a hundred yards farther along. “This is where the people on the island came to stop them.” She turned away to make a scrutiny of the distant beach, but almost at once startled Frecks again by exclaiming: “What’s that?” She pointed to the distant curve where the reef came back to meet the mainland.

Frecks was just in time to see something disappear into the palms of the island proper; but she did not get a clear view of it.

By this time Worrals had her glasses to her eyes, but although she watched for some time the object did not reappear. “What did you make of it?” she asked Frecks.

“I couldn’t even guess,” was the reply. “All I know is, something moved.”

“It looked to me like a human being.”

“It could have been,” agreed Frecks. “But it gave me more the impression of something crawling.”

“It was brown.”

“That means a native.”

“Not necessarily,” argued Worrals. “Anyone staying here for any length of time would get pretty well tanned, I imagine.”

“Could it have been an animal?”

“There couldn’t be an animal of that size on the island.”

“Don’t forget the island is supposed to be haunted,” reminded Frecks.

“You can forget that drivel,” replied Worrals curtly. “If you start talking about spooks in broad daylight, by the time it gets dark you’ll be seeing them. Forget it. I think we might as well go back. There doesn’t seem to be anything more to see from here.”

Frecks agreed. She didn’t say so, but the fury of the big combers pounding on the reef less than fifty yards away, causing the ground on which she stood to shake, filled her with vague alarm. Her common sense told her that the reef, which must have stood the onslaught of hurricanes for centuries, was not likely to crack at that moment; but there was something awe-inspiring in this spectacle of the ocean’s eternal war against the land. She kept well to the lagoon side. But here again she had a twinge of uneasiness when she caught sight of a long dark shadow gliding through the transparent water.

“There are sharks in the lagoon,” she observed moodily.

“Bound to be,” returned Worrals. “But they’re not necessarily man-eaters.”

“To me, a shark is a shark,” asserted Frecks. “What these particular specimens eat is something I shall not, I hope, have occasion to investigate. I’ll do my bathing in shallow water.”

Returning to their starting point, Worrals did not stop, but carried on diagonally across the beach towards the palms that fringed it some thirty yards from the water’s edge. The beach itself was a place of strange creatures. Hermit-crabs, carrying borrowed shells on their backs, moved clumsily. Battalions of red-backed soldier-crabs marched and counter-marched with military precision as if getting into position for battles which never took place. Nearer the palms, coco-nuts and dead fronds made an untidy litter. Reaching the trees they walked on in the welcome shade they provided.

“Keep your eyes open,” warned Worrals. “I’m quite sure we haven’t got this place to ourselves, although it may look like it at the moment.”

In the longish walk that followed only once did Worrals stop, and that was to look through an opening in the palms to the far side of the island where huge waves kept up a continuous booming and filled the air with spray. The distance across at that point was not more than two hundred yards, and the highest point, Frecks judged, could not have been more than ten feet above sea level. She was amazed that the two beaches, so near to each other, could be so utterly unlike. One was all noise and tumult. The other, the lagoon side along which they were walking, was a place of peace and tranquillity, where only the tiniest of ripples whispered to the silver beach.

Worrals went on, and did not stop again until they were nearing the high bank of coral that had obstructed their view—the same on which they had seen something move. She now proceeded with more caution. “Take it quietly,” she told Frecks. “We may get a surprise at any moment.”

This, in the event, proved true, but she little guessed what form it was to take.

Frecks nodded. She was already alert, and her heart was beating a trifle faster.

They went on slowly, their eyes, naturally, concentrating on the new length of beach that came into view. The result was disappointing. In all its length, a curving crescent of some miles, there was not a living soul. Nothing moved. There was not a house, a hut, or a wisp of smoke from a fire. The palace was still out of sight, apparently in the trees. Not that Frecks expected to see it, for she knew it must still be some distance farther on.

Worrals studied the ground for possible tracks, but here the beach was composed for the most part of broken shells and granulated coral, and would not have shown the footprint of an elephant, much less of a human being. Then, quite casually, she turned to glance at the bank of coral, now at their right hand and quite close. She did not speak, but at the expression on her face Frecks spun round with a quick intake of breath to see what she was looking at.

It was a ship. A ship of some size, but in such a state as she had never before seen. It was on an even keel, for which reason she at first supposed it to be at anchor, for it was some thirty yards from the reef, towards which it lay head-on, and fifty from the beach. But looking harder she saw that it was in fact wedged between two submerged shelves of coral that rose from the bottom of the lagoon to end in broken ridges like the backs of gigantic crocodiles.

Still staring Frecks saw that the vessel was, or had been, a yacht. It had once been a thing of beauty; but elegance was a quality it would never know again. The paint-work, once white, was now all brown and grey, blistered and peeling. Down her sides ran ugly lines of red rust. Some of the seams had opened. Some gaped. Her masts lay in a tangled litter of gear and cordage—which, Frecks realized, was why the vessel had not been noticed until they were right up to it. Strips of canvas that had once been a gay, red and white awning hung miserably from twisted stays.

Worrals was the first to speak. “Well, now at least we know how the shooters got here,” she said simply.

“I was right after all about their being castaways,” declared Frecks.

“I’ll reserve my opinion of that,” answered Worrals. “I still say that castaways don’t shoot at possible deliverers.”

“They may have been scared of the natives.”

“They couldn’t have been scared of the Navy.”

Frecks shrugged. “Okay, we’ll see. Are you going aboard?”

“Of course,” returned Worrals. “But just a minute, this needs thinking about. What’s her name, I wonder?” She moved her position until she was in line with the starboard bow, on which it was possible to read some faint painted letters. “Cleopatra,” she said softly.

“I know what you were thinking,” said Frecks.

“What?”

“You thought it was the missing yacht Vanity.”

“Quite right, I was,” admitted Worrals. “We know a yacht of that name disappeared, although it had no business in this part of the world. Why weren’t we told about the Cleopatra, I wonder? She most certainly must be missing, and has been missing for some time by the look of her. You know, Frecks, there’s something queer about this.”

“How long has she been here do you suppose?”

“Goodness only knows. I couldn’t guess. Some time, anyway. Of course, we don’t know what sort of state she was in when she got here. She must have been dismasted by a storm, and that was probably after she had run aground; on the open sea her masts would have gone by the board. The fact that they’re down explains why the Navy didn’t spot her. From the way she’s weathered to nearly the same colour as the coral I doubt if we should have spotted her even if we’d flown over the place.”

“I was thinking the same thing,” returned Frecks. “Hasn’t it occurred to you that there might be someone on board?”

“It did at first, but now I don’t think so,” answered Worrals. “Somebody might have been on board recently though. It was just about here that we thought we saw somebody move. Mind you, I’m still not sure that it was a human being, although, as I said before, I can’t think what else it could be. If it was a person, he—or she—might have been going to the wreck for something. That would be a reason for somebody being here, anyway.”

“How about having a closer look at her?” suggested Frecks. “We might strike a clue which would solve the whole mystery of the place.”

“Never mind a closer look, I’m going on board,” asserted Worrals, walking out along the reef. “It means swimming—not that it matters. I don’t think sharks would come in as close as this.” As she finished speaking she reached the point of coral nearest to the stranded vessel. She stopped suddenly and then threw a quick glance at Frecks. “I was right,” she said tersely. “Take a look at that!” She pointed to the coral near her feet. Comment from Frecks was unnecessary. What she saw spoke for itself. The coral was wet, but wet at only one place, as if someone had climbed out of the water at that spot. There was no question of waves being responsible for there were none. The water was motionless, without even a ripple where it touched the rock.

Worrals spoke, slowly. “When we were at the far side of the lagoon someone came here—or was already on the wreck. We just caught sight of the person when he, or she, was leaving.”

Looking across at the wreck, Frecks noticed steps hanging from the deck to the water. “Those steps are wet too,” she observed.

“Which proves that someone went from here to there quite recently,” said Worrals. “Had they been on board for some time, and then come ashore, the steps would be dry. This would have been the only wet place. The inference is, there’s nobody there now. I’m going over.” Worrals kicked off her shoes, advanced to the edge of the coral and took a stance as if she intended diving in. But that was as far as she got, for a very good reason.

From somewhere inside the wreck came a long drawn-out cry, so heart-rending, so melancholy in its anguish, that Frecks went cold all over. Her skin turned goose-flesh, to use the common expression. Saucer-eyed, she turned to Worrals, and saw that even she had turned pale. “What on earth was that?” she asked in a voice that she didn’t recognize as her own.

Worrals, tight-lipped, shook her head. “Don’t ask me.”

“It was frightful.”

“Frightful is the word.”

“No human being could make a noise like that,” declared Frecks, and then flinched as the sound came again.

Worrals drew a deep breath. “I’m going over,” she announced.

“Don’t be a fool!” Frecks’s voice was shrill with apprehension.

“I’ve got to know who is in there,” argued Worrals.

“Why?”

“Because that’s what we came here for,” averred Worrals. “We should be a bright pair of investigators if we bolted home at the first bleat. I’m going over.”

“All right, I’ll come too,” decided Frecks. “I’m not staying here alone.”

“Come on, then!” said Worrals. And with that she took a header into the water.

A dozen strokes took her to the steps. Seizing them she went up hand over hand to the deck and there waited for Frecks to join her. Another minute and they were together, surveying such a spectacle of ruin as would not be easy to describe, although in view of what they had already seen, this was only to be expected. Rotting cordage and canvas lay about in a tangle of running and standing gear that had come down with the masts. The deck had split in several places, the bolts protruding from pools of rust. From the state of everything gulls must have been using the place as a roost for a long time.

“What a mess!” breathed Worrals. “If that wouldn’t break a sailor’s heart, I don’t know what would.” She picked a path to the companion-way amidships. Halting at the top she looked down. Below, all was silent. “Anyone there?” she called.

A wild, terrified scream, mixed up with what sounded like gibberish, made her step back hastily.

Frecks began to back away. “For the love of Pete,” she pleaded. “Let’s get out of this.”

“And spend the rest of our lives wondering what made that noise?” sneered Worrals. “Not likely.” She started down the steps, and after a brief hesitation, Frecks followed her, marvelling at the state of what had been the interior of a smart yacht. Not only had the fittings been stripped, and everything portable removed, but even doors had been torn off and carried away. The yacht was, in fact, nothing more than an empty shell.

A low moaning and sobbing guided them at last to a door deep in the hold, although by the time they had reached it, the noise had stopped, as if their arrival had been heard.

Said Worrals, rather shakily, “Hallo there!”

There was no reply.

Worrals tried the door. It did not yield to her pressure. “Locked,” she said laconically.

“I couldn’t care less,” muttered Frecks.

“Whatever was making that noise is behind that door,” asserted Worrals. “The question is, has the door been locked from the outside or the inside?”

Frecks shrugged.

Worrals knocked sharply. “Hi there! Can you get out?”

Still no answer.

Said Worrals, crisply, to Frecks: “I’m going to open this door. It shouldn’t be difficult. Slip along to the engine room and find a tool of some sort—a lever if you can find one. A hammer, or spanner, would do, as long as it’s pretty heavy.”

Frecks went off. She was away about five minutes. Then she returned with a long, rusty, iron spike, flattened at one end.

“Just the job,” said Worrals, taking it.

She forced the flattened end between the door and the framework near the lock and then took the opposite end in both hands. “Hold your hat!” she said grimly, and pulled.

The door creaked as it took the strain. It groaned. The framework near the lock began to crack. Then, suddenly, with a splintering crack the door burst open, flying back on its hinges.

The next second Frecks was sent reeling as a black and white object leapt past Worrals and collided violently with her. It did not stop, but sped on like a streak and in a moment was lost to sight. Without hesitation Worrals dashed after it, and she, too, disappeared. Frecks, bewildered, and slightly dazed from shock, stood still for a moment or two, and then followed as quickly as she could. She heard a cry, a splash, and another cry. Silence followed. She hurried on, but as she reached the deck, she met Worrals coming back.

“What the dickens was it?” she demanded.

“A woman,” answered Worrals briefly.

“A woman!”

“A female, anyhow. Say a girl, if you like. Didn’t you see her long black hair?”

“I didn’t see anything to speak of,” admitted Frecks. “What was the white thing?”

“It seemed to be the rags of an ancient pinafore, and not too clean at that, tied round her. She went over the side like an otter before I could stop her. Still, I got a pretty good look at her, as she disappeared into the trees. To try to catch her then was a waste of time, so I didn’t go beyond the deck. I’d put her age at about sixteen—but, of course, a girl of that age is a woman in this part of the world.”

“But what in the name of goodness was she doing here?” demanded Frecks.

Worrals lifted a shoulder. “I wouldn’t know. One thing that seems pretty certain, though, is this; she wasn’t here from choice.”

Happening to glance at Worrals’s face, Frecks noticed that it wore a frown of perplexity. “What’s worrying you?” she asked.

“I’m thinking about that girl.”

“In what way? Was there anything odd about her?”

“Yes.”

“What was it?”

“For one thing she was black, or nearly so.”

“Surely it would have been more remarkable had she been white?”

“I don’t know that it would,” said Worrals.

It was Frecks’s turn to frown. “Sorry to be so dumb, but would you mind telling me what you’re getting at?” she requested.

“Not at all,” answered Worrals. “As you know, before starting on this jaunt, I read as many books as I could lay hands on about the Pacific. This is one of the things I learned about it. The South Sea Islands—we’ll call them that—cover an awful lot of ocean, and they are divided into zones known as Polynesia, Melanesia and Micronesia, these zones being determined by the racial characteristics of the inhabitants. Here we are quite definitely in Polynesia. The Polynesians are a nice shade of brown, some of them quite a pale tint of café-au-lait. The Melanesians, as the name suggests, are black, more or less. Their islands lie at least two thousand miles to the east of us. Micronesia is farther off still. Here again the people are pretty dark, and quite different, having mixed themselves with Mongolian or Malayan stock.”

Frecks blinked. “Never mind the school-book stuff,” she protested. “What does all this add up to?”

“Merely this,” explained Worrals. “That girl we saw just now was most certainly not a Polynesian. She was, I’d say, either a Melanesian or a Micronesian, but not being an expert I couldn’t swear to it. All that matters to us is, she wasn’t a Polynesian. How did she get here? And what is she doing here?”

Frecks looked vague. “Don’t ask me.”

“She no more belongs to this island than you do,” asserted Worrals. “And I’ll tell you something else. As she sprinted up the beach, I noticed some nasty-looking marks on her back. They may have been natural sores caused by thorns or poisonous coral, but I don’t think so. They looked to me more as if they’d been caused by a whip, or cane.”

Frecks stared. “How perfectly horrible! Who could have done such a thing?”