* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Marching Sands

Date of first publication: 1919

Author: Harold Lamb (1892-1962)

Date first posted: Apr. 20, 2023

Date last updated: Apr. 20, 2023

Faded Page eBook #20230433

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

This file was produced from images generously made available by Internet Archive/Lending Library.

MARCHING

SANDS BY

HAROLD LAMB

HYPERION PRESS, INC.

WESTPORT, CONNECTICUT

Reproduced from an edition published in 1930

by Jacobsen Publishing Company, Inc., New York

Copyright 1920 by D. Appleton and Company; copyright 1919

by Frank A. Munsey Company

Copyright © 1974 by Hyperion Press, Inc.

Hyperion reprint edition 1974

Library of Congress Catalogue Number 73-13258

ISBN 0-88355-113-6 (cloth ed.)

ISBN 0-88355-142-X (paper ed.)

Printed in the United States of America

| CONTENTS | ||

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | The Lost People | 1 |

| II. | Legends | 8 |

| III. | Delabar Discourses | 16 |

| IV. | Warning | 27 |

| V. | Intruders | 41 |

| VI. | Mirai Khan | 52 |

| VII. | The Door Is Guarded | 65 |

| VIII. | Delabar Leaves | 80 |

| IX. | The Liu Sha | 93 |

| X. | The Mem-Sahib Speaks | 106 |

| XI. | Sir Lionel | 118 |

| XII. | A Message from the Centuries | 128 |

| XIII. | The Desert | 146 |

| XIV. | Traces in the Sand | 159 |

| XV. | A Last Camp | 171 |

| XVI. | Gray Carries On | 186 |

| XVII. | The Yellow Robe | 197 |

| XVIII. | Bassalor Danek | 205 |

| XIX. | Concerning a City | 220 |

| XX. | The Talisman | 230 |

| XXI. | Mary Makes a Request | 245 |

| XXII. | The Answer | 258 |

| XXIII. | The Challenge | 267 |

| XXIV. | A Stage Is Set | 280 |

| XXV. | Rifle against Arrow | 293 |

| XXVI. | The Bronze Circlet | 302 |

Marching Sands

“You want me to fail.”

It was neither question nor statement. It came in a level voice, the words dropping slowly from the lips of the man in the chair as if he weighed each one.

He might have been speaking aloud to himself, as he sat staring directly in front of him, powerful hands crossed placidly over his knees. He was a man that other men would look at twice, and a woman might glance at once—and remember. Yet there was nothing remarkable about him, except perhaps a singular depth of chest that made his quiet words resonant.

That and the round column of a throat bore out the evidence of strength shown in the hands. A broad, brown head showed a hard mouth, and wide-set, green eyes. These eyes were level and slow moving, like the lips—the eyes of a man who could play a poker hand and watch other men without looking at them directly.

There was a certain melancholy mirrored in the expressionless face. The melancholy that is the toll of hardships and physical suffering. This, coupled with great, though concealed, physical strength, was the curious trait of the man in the chair, Captain Robert Gray, once adventurer and explorer, now listed in the United States Army Reserve.

He had the voyager’s trick of wearing excellent clothes carelessly, and the army man’s trait of restrained movement and speech. He was on the verge of a vital decision; but he spoke placidly, even coldly. So much so that the man at the desk leaned forward earnestly.

“No, we don’t want you to fail, Captain Gray. We want you to find out the truth and to tell us what you have found out.”

“Suppose there is nothing to discover?”

“We will know we are mistaken.”

“Will that satisfy you?”

“Yes.”

Captain “Bob” Gray scrutinized a scar on the back of his right hand. It had been made by a Mindanao kris, and, as the edge of the kris had been poisoned, the skin was still a dull purple. Then he smiled.

“I thought,” he said slowly, “that the lost people myths were out of date. I thought the last missing tribe had been located and card-indexed by the geographical and anthropological societies.”

Dr. Cornelius Van Schaick did not smile. He was a slight, gray man, with alert eyes. And he was the head of the American Exploration Society, a director of the Museum of Natural History—in the office of which he was now seated with Gray—and a member of sundry scientific and historical academies.

“This is not a lost people, Captain Gray.” He paused, pondering his words. “It is a branch of our own race, the Indo-Aryan, or white race. It is the Wusun—the ‘Tall Ones.’ We—the American Exploration Society—believe it is to be found, in the heart of Asia.” He leaned back, alertly.

Gray’s brows went up.

“And so you are going to send an expedition to look for it?”

“To look for it.” Van Schaick nodded, with the enthusiasm of a scientist on the track of a discovery. “We are going to send you, to prove that it exists. If this is proved,” he continued decisively, “we will know that a white race was dominant in Asia before the time of the great empires; that the present Central Asian may be descended from Aryan stock. We will have new light on the development of races—even on the Bible——”

“Steady, Doctor!” Gray raised his hand. “You’re getting out of my depth. What I want to know is this: Why do you think that I can find this white tribe in Asia—the Wusuns? I’m an army officer, out of a job and looking for one. That’s why I answered your letter. I’m broke, and I need work, but——”

Van Schaick peered at a paper that he drew from a pile on his desk.

“We had good reasons for selecting you, Captain Gray,” he said dryly. “You have done exploration work north of the Hudson Bay; you once stamped out dysentery in a Mindanao district; you have done unusual work for the Bureau of Navigation; on active service in France you led your company——”

Gray looked up quickly. “So did a thousand other American officers,” he broke in.

“Ah, but very few have had a father like yours,” he smiled, tapping the paper gently. “Your father, Captain Gray, was once a missionary of the Methodists, in Western Shensi. You were with him, there, until you were four years of age. I understand that he mastered the dialect of the border, thoroughly, and you also picked it up, as a child. This is correct?”

“Yes.”

“And your father, before he died in this country, persisted in refreshing, from time to time, your knowledge of the dialect.”

“Yes.”

Van Schaick laid down the paper.

“In short, Captain Gray,” he concluded, “you have a record at Washington of always getting what you go after, whether it is information or men. That can be said about many explorers, perhaps; but in your case the results are on paper. You have never failed. That is why we want you. Because, if you don’t find the Wusun, we will then know they are not to be found.”

“I don’t think they can be found.”

The scientist peered at his visitor curiously.

“Wait until you have heard our information about the white race in the heart of China, before you make up your mind,” he said in his cold, concise voice, gathering the papers into their leather portmanteau. “Do you know why the Wusun have not been heard from?”

“I might guess. They seem to be in a region where no European explorers have gone——”

“Have been permitted to go. Asia, Captain Gray, for all our American investigations, is a mystery to us. We think we have removed the veil from its history, and we have only detached a thread. The religion of Asia is built on its past. And religion is the pulse of Asia. The Asiatics have taught their children that, from the dawn of history, they have been lords of the civilized world. What would be the result if it were proved that a white race dominated Central Asia before the Christian era? The traditions of six hundred million people who worship their past would be shattered.”

Gray was silent while the scientist placed his finger on a wall map of Asia. Van Schaick drew his finger inland from the coast of China, past the rivers and cities, past the northern border of Tibet to a blank space under the mountains of Turkestan where there was no writing.

“This is the blind spot of Asia,” he said. “It has grown smaller, as Europeans journeyed through its borders. Tibet, we know. The interior of China we know, except for this blind spot. It is——”

“In the Desert of Gobi.”

“The one place white explorers have been prevented from visiting. And it is here we have heard the Wusun are.”

“A coincidence.”

Van Schaick glanced at his watch.

“If you will come with me, Captain Gray, to the meeting of the Exploration Society now in session, I will convince you it is no coincidence. Before we go, I would like to be assured of one thing. The expedition to the far end of the Gobi Desert will not be safe. It may be very dangerous. Would you be willing to undertake it?”

Gray glanced at the map and rose.

“If you can show me, Doctor,” he responded, “that there is something to be found—I’d tackle it.”

“Come with me,” nodded Van Schaick briskly.

The halls of the museum were dark, as it was past the night hour for visitors. A small light at the stairs showed the black bulk of inanimate forms in glass compartments, and the looming outline of mounted beasts, with the white bones of prehistoric mammals.

At the entrance, Van Schaick nodded to an attendant, who summoned the scientist’s car.

Their footsteps had ceased to echo along the tiled corridor. The motionless beast groups stared unwinkingly at the single light from glass eyes. Then a form moved in one of the groups.

The figure slipped from the stuffed animals, down the hall. The entrance light showed for a second a slender man in an overcoat who glanced quickly from side to side at the door to see if he was observed. Then he went out of the door, into the night.

That evening a few men were gathered in Van Schaick’s private office at the building of the American Exploration Society. One was a celebrated anthropologist, another a historian who had come that day from Washington. A financier whose name figured in the newspapers was a third. And a European orientologist.

To these men, Van Schaick introduced Gray, explaining briefly what had passed in their interview.

“Captain Gray,” he concluded, “wishes proof of what we know. If he can be convinced that the Wusun are to be found in the Gobi Desert, he is ready to undertake the trip.”

For an hour the three scientists talked. Gray listened silently. They were followers of a calling strange to him, seekers after the threads of knowledge gleaned from the corners of the earth, zealots, men who would spend a year or a lifetime in running down a clew to a new species of human beings or animals. They were men who were gatherers of the treasures of the sciences, indifferent to the ordinary aspects of life, unsparing in their efforts. And he saw that they knew what they were talking about.

In the end of the Bronze Age, at the dawn of history, they explained, the Indo-Aryan race, their own race, swept eastward from Scandinavia and the north of Europe, over the mountain barrier of Asia and conquered the Central Asian peoples—the Mongolians—with their long swords.

This was barely known, and only guessed at by certain remnants of the Aryan language found in Northern India, and inscriptions dug up from the mountains of Turkestan.

They believed, these scientists, that before the great Han dynasty of China, an Indo-Aryan race known as the Sacæ had ruled Central Asia. The forefathers of the Europeans had ruled the Mongolians. The ancestors of thousands of Central Asians of to-day had been white men—tall men, with long skulls, and yellow hair, and great fighters.

The earliest annals of China mentioned the Huing-nu—light-eyed devils—who came down into the desert. The manuscripts of antiquity bore the name of the Wusun—the “Tall Ones.” And the children of the Aryan conquerors had survived, fighting against the Mongolians for several hundred years.

“They survive to-day,” said the historian earnestly. “Marco Polo, the first European to enter China, passed along the northern frontier of the Wusun land. He called their king Prester John and a Christian. You have heard of the myth of Prester John, sometimes called the monarch of Asia. And of the fabulous wealth of his kingdom, the massive cities. The myth states that Prester John was a captive in his own palace.”

“You see,” assented Van Schaick, “already the captivity of the Wusun had begun. The Mongolians have never tolerated other races within their borders. During the time of Genghis Khan and the Tartar conquerors, the survivors of the Aryans were thinned by the sword.”

“Marco Polo,” continued the historian, “came as near to the land of the Wusun as any other European. Three centuries later a Portuguese missionary, Benedict Goës, passed through the desert near the city of the Wusun, and reported seeing some people who were fair of face, tall and light-eyed.”

Van Schaick turned to his papers.

“In the last century,” he said, “a curious thing happened to an English explorer, Ney Elias. I quote from his book. An old man called on me at Kwei-hwa-ching, at the eastern end of the Thian Shan Mountains, who said he was neither Chinaman, Mongol, nor Mohammedan, and lived on ground especially allotted by the emperor, and where there now exist several families of the same origin. He said that he had been a prince. At Kwei-hwa-ching I was very closely spied on and warned against asking too many questions.”

Van Schaick peered over his spectacles at Gray.

“The Thian Shan Mountains are just north of this blind spot in the Gobi Desert where we think the Wusun are.”

The historian broke in eagerly.

“Another clew—a generation ago the Russian explorer, Colonel Przewalski, tried to enter this blind spot from the south, and was fought off with much bloodshed by one of the guardian tribes.”

Gray laughed frankly.

“I admit I’m surprised, gentlemen. Until now I thought you were playing some kind of a joke on me.”

Van Schaick’s thin face flushed, but he spoke calmly.

“It is only fair, sir, that you should have proof you are not being sent after a will-o’-the-wisp. A few days ago I talked with a missionary who had been invalided home from China. His name is Jacob Brent. He has been for twenty years head of the college of Chengtu, in Western China. He heard rumors of a captive tribe in the heart of the Gobi. And he saw one of the Wusun.”

He paused to consult one of his papers methodically.

“Brent was told, by some Chinese coolies, of a tall race dwelling in a city in the Gobi, a race that was, they said, ‘just like him.’ And in one of his trips near the desert edge he saw a tall figure running toward him over the sand, staggering from weariness. Then several Chinese riders appeared from the sand dunes and headed off the fugitive. But not before Brent had seen that the man’s face was partially white.”

“Partially?” asked Gray quizzically.

“I am quoting literally. Yes, that was what Brent said. He was prevented by his native bearers from going into the Gobi to investigate. They believed the usual superstitions about the desert—evil spirits and so forth—and they warned Brent against a thing they called the pale sickness.”

Gray looked up quietly. “You know what that is?”

“We do not know, and surmises are valueless.” He shrugged. “You have an idea?”

“Hardly, yet—you say that Brent is ill. Could he be seen?”

“I fancy not. He is in a California sanitarium, broken down from overwork, the doctors informed me.”

“I see.” Gray scrutinized his companions. The same eagerness showed in each face, the craving for discovery which is greater than the lust of the gold prospector. They were hanging on his next words. “Gentlemen, do you realize that three great difficulties are to be met? Money—China—and a knowledge of science. By that I mean my own qualifications. I am an explorer, not a scientist——”

At this point Balch, the financier who had not spoken before, leaned forward.

“Three excellent points,” he nodded. “I can answer them. We can supply you with funds, Captain Gray,” he said decisively.

“And permission from the Chinese authorities?”

“We have passports signed, in blank, for an American hunter and naturalist to journey into the interior of China, to the Gobi Desert.”

“You will not go alone,” explained Van Schaick. “We realize that a scientist must accompany you.”

“We have the man,” continued Balch, “an orientologist—speaks Persian and Turki—knows Central Asia like a book. Professor Arminius Delabar. He’ll join you at Frisco.” He stood up and held out his hand. “Gray, you’re the man we want! I like your talk.” He laughed boyishly, being young in heart, in spite of his years. “You’re equal to the job—and you can shoot a mountain sheep or a bandit in the head at five hundred yards. Don’t deny it—you’ve done it!”

“Maps?” asked Gray dryly.

“The best we could get. Chinese and Russian surveys of the Western Gobi,” Balch explained briskly. “We want you to start right off. We know that our dearest foes, the British Asiatic Society, have wind of the Wusun. They are fitting out an expedition. It will have the edge on yours because—discounting the fact that the British know the field better—it’ll start from India, which is nearer the Gobi.”

“Then it’s got to be a race?” Gray frowned.

“A race it is,” nodded Balch, “and my money backs you and Delabar. So the sooner you can start the better. Van Schaick will go with you to Frisco and give you details, with maps and passports on the way. We’ll pay you the salary of your rank in the army, with a fifty per cent bonus if you get to the Wusun. Now, what’s your answer—yes or no?” He glanced at the officer sharply, realizing that if Gray doubted, he would not be the man for the expedition.

Gray smiled quizzically.

“I came to you to get a job,” he said, “and here it is. I need the money. My answer is—yes. I’ll do my best to deliver the goods.”

“Gentlemen,” Balch turned to his associates, “I congratulate you. Captain Gray may or may not get to the Wusun. But—unless I’m a worse judge of character than I think—he’ll get to the place where the Wusun ought to be. He won’t turn back.”

Their visitor flushed at that. He was still young, being not yet thirty. He shook hands all around and left for his hotel, with Balch and Van Schaick to arrange railroad schedules, and the buying of an outfit.

This is a brief account of how Robert Gray came to depart on his mission to the Desert of Gobi, as reported in the files of the American Exploration Society for the summer of 1919.

It was not given to the press at the time, owing to the need of secrecy. Nor did the Exploration Society obtain authority from the United States Government for the expedition. Time was pressing, as they learned the British expedition was getting together at Burma. Later, Van Schaick agreed with Balch that this had been a mistake.

But by that time Gray was far beyond reach, in the foothills of the Celestial Mountains, in the Liu Sha, and had learned the meaning of the pale sickness.

Gray had meant what he said about his new job. Van Schaick pleaded for haste, but the army officer knew from experience the danger of omitting some important item from his outfit, and went ahead with characteristic thoroughness.

He assembled his personal kit in New York, with the rifles, medicines and ammunition that he needed. Also a good pair of field glasses and the maps that Van Schaick furnished. Balch made him a present of twenty pounds of fine smoking tobacco which was gratefully received.

“I’ll need another man with me,” Gray told Van Schaick, who was on edge to be off. “Delabar’ll be all right in his way, but we’ll want a white man who can shoot and work. I know the man for the job—McCann, once my orderly, now in the reserve.”

“Get him, by all means,” agreed the scientist.

“He’s in Texas, out of a job. A wire’ll bring him to Frisco in time to meet us. Well, I’m about ready to check out.”

They left that night on the western express.

Gray was not sorry to leave the city. Like all voyagers, he felt the oppression of the narrow streets, the monotony of always going home to the same place to sleep. Wanderlust had gripped him again at thought of the venture into another continent.

He took his mission seriously. On the maps that Van Schaick and Balch had given him they had pointed out a spot beyond the known travel routes, a good deal more than a thousand miles into the interior of China. To this spot Gray was going. He had his orders and he would carry them out.

Van Schaick talked much on the train. He explained how much the mission meant to the Exploration Society. It would give them world-wide fame. And it would add enormously to the knowledge of humankind. Gray, he said, would travel near the path of Marco Polo; he would tear the veil of secrecy from the hidden corner of the Gobi Desert. It would be a victory of science over the ancient soul of Mongolia.

It would shake the foundation of the great jade image of Buddha, of the many-armed Kali, of Bon the devil-god, and the ancient Vishnu. It would strengthen the hold of the Bible on the Mongolian world.

If only, said Van Schaick wistfully, Gray could find the Wusun ahead of the expedition of the British Asiatic Society, the triumph would be complete.

Gray listened silently. It was fortunate, in the light of what followed, that his imagination was not easily stirred.

He looked curiously at the man who was to be his partner in the expedition. Van Schaick introduced them at the platform of the San Francisco terminal.

Professor Arminius Delabar was a short, slender man, of wiry build and a nervous manner that reminded Gray of a bird. He had near-sighted, bloodshot eyes encased behind tinted glasses, and a dark face with well-kept beard. He was half Syrian by birth, American by choice, and a denizen of the academies and by-ways of the world. Also, he spoke at least four languages fluently.

The army man’s respect for his future companion went up several notches when he found that Delabar had already arranged competently for the purchase and shipment of their stores.

“You see,” he explained in his room at the hotel to Gray, “the fewer things we must buy in Shanghai the better. Our plan is to attract as little attention as possible. Our passport describes us as hunter and naturalist. Foreigners are a common sight in China as far into the interior as Liangchowfu. Once we are past there and on the interior plains, it will be hard to follow us—if we have attracted no attention. Do you speak any Chinese dialects?”

It was an abrupt question, in Delabar’s high voice. The Syrian spoke English with only the trace of an accent.

“A little,” admitted Gray. “I was born in Shensi, but I don’t remember anything except a baby white camel—a playmate. Mandarin Chinese is Greek to me.”

Some time afterward he learned that Delabar had taken this as a casual boast—not knowing Gray’s habit of understating his qualifications. Fortune plays queer tricks sometimes and Gray’s answer was to loom large in the coming events.

Fortune, or as Gray put it, the luck of the road, threw two obstacles in their way at Frisco. Van Schaick had telegraphed ahead to the sanitarium where the missionary Brent was being treated. He hoped to arrange an interview between Brent and Gray.

Brent was dying. No one could visit him. Also, McCann, the soldier who was to accompany them, did not show up at the hotel,—although he had wired his officer at Chicago that he would be in Frisco before the appointed time.

Gray would have liked to wait for the man. He knew McCann would be useful—a crack shot, a good servant, and an expert at handling men—but Delabar had already booked their passage on the next Pacific Mail steamer.

“Van Schaick can wait here,” Delabar assured Gray, “meet McCann, and send him on by the boat following. He will join you at Shanghai.”

“Very well,” assented Gray, who was checking up the list of stores Delabar had bought. “That will do nicely. I see that you’ve thought of all the necessary things, Professor. We can pick up a reserve supply of canned foodstuffs at Shanghai, or Hankow.” He glanced at Van Schaick. “There’s one thing more to be settled. It’s important. Who is in command of this party? The Professor or I? If he’s to be the boss, all right—I’ll carry on with that understanding.”

Van Schaick hesitated. But Delabar spoke up quickly.

“The expedition is in your hands, Captain Gray. I freely yield you the responsibility.”

Gray was still watching Van Schaick. “Is that understood? It’s a good thing to clear up before we start.”

“Certainly,” assented the scientist. “Now we’ll discuss the best route——”

Van Schaick stood at the pier-head the next day when the steamer cast off her moorings, and waved good-by to the two. Gray left him behind with some regret. A good man, Van Schaick, an American from first to last, and a slave to science.

During the monotonous run across the Pacific when the sea and the sky seemed unchanged from day to day, Delabar talked incessantly about their trip. Gray, who preferred to spend the time doing and saying nothing, listened quietly.

The officer was well content to lie back in his deck chair, hands clasped behind his curly head, and stare out into space. This was his habit, when off duty. It satisfied him to the soul to do nothing but watch the thin line where the gray-blue of the Pacific melted into the pale blue of the sky, and feel the sun’s heat on his face. It made him appear lazy. Which he was not.

The energetic professor fancied that Gray paid little attention to his stream of information about the great Gobi Desert. In that, he did the other an injustice. Gray heeded and weighed Delabar’s words. Ingrained in him from army life and a solitary existence marked by few friendships was the need of reticence, and watchfulness. Nor was his inclination to idle on the voyage mere habit. Unconsciously, he was storing up vital strength in his strongly knit frame—strength which he had called on in the past, and which he would need again.

“You don’t seem to appreciate, my young friend,” remarked the professor once, irritably, “that it is inner Asia we are invading. Also, we are going a thousand miles beyond your American gunboats.”

“The days of the Ih-hwo-Ch’uan are past.”

Delabar shrugged his shoulders, surprised at his companion’s pertinent remark. “True. China is a republic and progressive, perhaps. But the Mongolian soul does not change overnight. Moreover, there are the priests—Buddhists and Taoists. Fear and superstition rule the mass of the Dragon Kingdom, my friend, and it is these priests who will be our enemies.”

Gray had spoken truly when he said he remembered nothing of China, except a white camel, but, subconsciously, many things were familiar to the soldier.

“At the border of the Gobi Desert, where we believe the Wusun to be,” continued the scientist warmly, as Gray was silent, “a center of Buddhism existed in the Middle Ages. The three sects of Buddhist priests—Black, Yellow and Red—are united in the effort to preserve their power. They preach the advent of the Gautama in the next few years. Also, that the ancient Gautama ruled the spiritual world before the coming of Christianity.

“So you can see,” he pointed out, “that the discovery of a white race—a race that did not acknowledge Buddha—in the heart of China would be a blow to their doctrine. It would contradict their book of prophecy.”

Gray nodded, puffing at his pipe. Presently, he stirred himself to speak.

“Rather suspect you’re right, Professor. You know the religious dope. And the religions of Asia are not good things to monkey with. But, look here.” He drew a map from his pocket and spread it out on his knee. “Here’s the spot where Van Schaick located the Wusun—our long-lost but not forgotten cousins. Well and good. Only that spot, which you and your friends call the ‘blind spot’ of Asia, happens to be in the middle of the far Gobi Desert. How do you figure people existed there for several centuries?”

Delabar hesitated, glancing up at the moving tracery of smoke that rose from the funnel, against the clouds. They were on the boat deck.

“The Ming annals mention a city in that place, some two thousand years ago. A thousand years later we know there were many palaces at this end of the Thian Shan—the Celestial Mountains. Remember that the caravan routes from China to Samarcand, India and Persia are very old, and that they—or one of the most important of them—ran past this blind spot.”

“Marco Polo trailed along there, didn’t he?”

“Yes. We know the great city of the Gobi was called Sungan. The Ming annals describe it as having ‘massive gates, walls and bastions, besides underground passages, vaulted and arched.’ ”

“European travelers don’t report this city.”

“Because they never saw it, my friend. Brent, who was at the edge of the Gobi near there, states that he saw towers in the sand. And the Mohammedan annals of Central Asia have a curious tale.”

“Let’s have it,” said Gray, settling himself comfortably in his chair.

“It was in the sixteenth century,” explained Delabar, who seemed to have the myths of Asia at his tongue’s end. “A religious legend. A certain holy man, follower of the prophet, was robbed and beaten in a city near where we believe Sungan to be. After his injury by the people of the city—he was a mullah—he climbed into a minaret to call the hour of evening prayer.”

Delabar’s voice softened as he spoke, sliding into more musical articulation.

“As he cried the hour, this holy man felt something falling like snow on his face. Only it was not snow. The sky and the city darkened. He could not see the roofs of the buildings. He went down and tried the door. It was blocked. Then this man saw that it was sand falling over the city. The sand covered the whole town, leaving only the minaret, which was high. The people who had done him the injury were buried—became white bones under the sand.”

“That story figures in the Bible,” assented Gray, “only not the same. You don’t consider the myth important, do you?”

“The priests of Asia do,” said the professor seriously. “And I have seen the memoirs of Central Asian kingdoms which mention that treasure was dug for and found in ruins in the sands.” He glanced at his companion curiously. “You do not seem to be worried, Captain Gray, at entering the forbidden shrine of the Mongols.”

Having been born thereabouts, the idea amused Gray.

“Are you?” Gray laughed. “The Yellow Peril is dead.”

“So is Dr. Brent.”

“You don’t connect the two?”

“I don’t attempt to analyze the connection, Captain Gray. Remember in China we are dealing with men who think backward, around-about, and every way except our own. Then there are the priests. All I know is that Dr. Brent entered on forbidden ground, fell sick, and had to leave China. Do you know what he died of?”

“Do you?”

Delabar was silent a moment; then he smiled. “I have imagination—too much, perhaps. But then I have lived behind the threshold of Asia for half my life.”

“I suspect it’s a good thing for me you have,” Gray admitted frankly.

Before they left their chairs that afternoon a steward brought the officer a message from the wireless cabin.

Van Schaick had sent it, before the steamer passed the radio limit. Gray read it, frowned, and turned to Delabar.

“This is rather bad luck, Professor,” he said. “McCann, the fellow I counted on, is not coming. He was taken sick with grippe in Los Angeles on his way to Frisco. It looks as if you and I would have to go it alone.”

The news of McCann’s loss, so important to the officer, Delabar passed over with a shrug. Gray wondered briefly why a man obviously inclined to nervousness should ignore the fact that they were without the services of a trustworthy attendant. Later, he came to realize that the scientist considered that McCann’s presence would have been no aid to him, that rifles and men who knew how to use them would play no part in meeting the hostile forces surrounding the territory of the Wusun.

From that moment he began to watch Delabar. It was clear to him that the professor was uneasy, decidedly so. And that the man was in the grip of a rising excitement.

It manifested itself when the steamer stopped at a Japanese port. Gray would have liked to visit Kyoto, to see again the little brown people of the island kingdom, to get a glimpse of the gray castle of Oksaka, and perhaps of peerless, snow-crowned Fujiyama.

But Delabar insisted on remaining aboard the steamer until they left for China. The nearing gateway of Asia had a powerful effect on him. Gray noticed—as it was unusual in a man of mildly studious habits—that the scientist smoked quantities of strong Russian cigarettes. Indeed, the air of their cabin was heavy with the fumes.

“We must not make ourselves conspicuous,” Delabar urged repeatedly.

At Shanghai they passed quickly through the hands of the customs officials. Their preparations progressed smoothly; the baggage was put on board a waiting Hankow steamer, and Delabar added to their stores a sufficient quantity of provisions to round out their outfit. In spite of this, Delabar fidgeted until they were safely in their stateroom on the river steamer, and passing up the broad, brown current of the Yang-tze-kiang—which, by the way, is not called the Yang-tze-kiang by the Chinese.

Gray made no comment on his companion’s misgivings. He saw no cause for alarm. There were a dozen other travelers on the river boat, sales agents of three nations, a railroad engineer or two, a family of missionaries, several tourists who stared blandly at the great tidal stretch of the river, and commented loudly on the comforts of the palatial vessel. Evidently they had expected to go up to Hankow in a junk. They pointed out the chocolate colored sails of the passing junks with their half-naked coolies and dirty decks.

For days the single screw of the Hankow boat churned the muddy waste, and the smoke spread, fanwise, over its wake.

The Yang-tze was not new to Gray. He was glad he was going into the interior. The fecund cities of the coast, with their monotonous, crowded streets, narrow and overhung with painted signs held no attraction for him. The panorama of Mongolian faces, pallid and seamed, furtive and merry was not what he had come to China to see. In the interior, beyond the forest crowned mountains, and the vast plains, was the expanse of the desert. Until they reached this, the trip was no more than a necessary evil.

Not so—as Gray noted—did it affect Delabar. The first meeting with the blue-clad throngs in Shanghai, the first glimpse of the pagoda-temples with their shaven priests had both exhilarated and depressed the scientist.

“Each stage of the journey,” he confided to Gray, “drops us back a century in civilization.”

“No harm done,” grunted the officer, who had determined to put a check on Delabar’s active imagination. “As long as we get ahead. That’s the deuce of this country. We have to go zig-zag. There’s no such thing as a straight line being the shortest distance between two points in the land of the Dragon.”

Delabar frowned, surprised by these unexpected displays of latent knowledge. Then smiled, waving a thin hand at the yellow current of the river.

“There is a reason for that—as always, in China. Evil spirits, they believe, can not move out of a straight line. So we find screens put just inside the gates of temples—to ward off the evil influences.”

“Look at that,” Gray touched the other’s arm. A steward stood near them at the stern. No one else was in that part of the deck, and after glancing around cautiously the man dropped over the side some white objects—what they were, Gray could not see. “I heard that some fishermen had been drowned near here a few days ago. That Chink—for all his European dress—is dropping overside portions of bread as food and peace offering to the spirits of the drowned.”

“Yes,” nodded Delabar, “the lower orders of Chinamen believe the drowned have power to pull the living after them to death. Centuries of missionary endeavor have not altered their superstitions. And, look—that does not prevent those starved beggars in the junk there from retrieving the bread in the water. Ugh!”

He thrust his hands into his pockets and tramped off up the deck, while Gray gazed after him curiously, and then turned to watch the junk. The coolies were waving at the steward who was watching them impassively. Seeing Gray, the man hurried about his duties. For a moment the officer hesitated, seeing that the junkmen were staring, not at the bread in their hands, but at the ship. Then he smiled and walked on.

In spite of Delabar’s misgivings, the journey went smoothly. The banks of the river closed in on them, scattered mud villages appeared in the shore rushes. Half-naked boys waved at the “fire junk” from the backs of water buffaloes, and the smoke of Hankow loomed on the horizon. From Hankow, the Peking-Hankow railway took them comfortably to Honanfu, after a two-day stage by cart.

Here they waited for their luggage to catch up with them, in a fairly clean and modern hotel. They avoided the other Europeans in the city. Gray knew that they were beyond the usual circuit of American tourists, and wished to travel as quietly as possible.

“We’re in luck,” he observed to Delabar, who had just come in. “In a month, if all goes well, we’ll be in Liangchowfu, the ‘Western Gate’ to the steppe country. What’s the matter?”

Delabar held out a long sheet of rice paper with a curious expression.

“An invitation to dine with one of the officials of Honan, Captain Gray—with the vice-governor. He asks us to bring our passports.”

“Hm,” the officer replaced the maps he had been overhauling in their case, and thrust the missive on top of them. He tossed the case into an open valise. “A sort of polite invitation to show our cards—to explain who we are, eh? Well, let’s accept with pleasure. We’ve got to play the game according to the rules. Nothing queer about this invite. Chinese officials are hospitable enough. All they want is a present or two.”

He produced from the valise a clock with chimes and a silver-plated pocket flashlight and scrutinized them mildly.

“This ought to do the trick. We’ll put on our best clothes. And remember, I’m a big-game enthusiast.”

Delabar was moody that afternoon, and watched Gray’s cheerful preparations for the dinner without interest. The army man stowed away their more valuable possessions, carefully hanging the rifle which he had been carrying in its case over his shoulder under the frame of the bed.

“A trick I learned in Mindanao,” he explained. “These towns are chuck full of thieves, and this rifle is valuable to me. The oriental second-story man has yet to discover that American army men hang their rifles under the frame of their cots. Now for the vice-governor, what’s his name? Wu Fang Chien?”

Wu Fang Chien was most affable. He sent two sedan chairs for the Americans and received them at his door with marked politeness, shaking his hands in his wide sleeves agreeably when Delabar introduced Gray. He spoke English better than the professor spoke Chinese, and inquired solicitously after their health and their purpose in visiting his country.

He was a tall mandarin, wearing the usual iron rimmed spectacles, and dressed in his robe of ceremony.

During the long dinner of the usual thirty courses, Delabar talked with the mandarin, while Gray contented himself with a few customary compliments. But Wu Fang Chien watched Gray steadily, from bland, faded eyes.

“I have not known an American hunter to come so far into China,” he observed to the officer. “My humble and insufficient home is honored by the presence of an enthusiast. What game you expect to find?”

“Stags, antelope, and some of the splendid mountain sheep of Shensi,” replied Gray calmly. Wu Fang Chien’s fan paused, at the precision of the answer.

“Then you are going far. Do your passports permit?”

“They give us a free hand. We will follow the game trails.”

“As far as Liangchowfu?”

“Perhaps.”

“Beyond that is another province.” The mandarin tapped his well-kept fingers thoughtfully on the table. “I would not advise you, Captain Gray, to go beyond Liangchowfu. As you know, my unhappy country has transpired a double change of government and the outlaw tribes of the interior have become unruly during the last rebellion.” He fumbled only slightly for words.

Gray nodded.

“We are prepared to take some risks.”

Wu Fang Chien bowed politely.

“It might be dangerous—to go beyond Liangchowfu. Your country and mine are most friendly, Captain Gray. I esteem your welfare as my own. My sorrow would greaten if injury happen to you.”

“Your kindness does honor to your heart.”

“I suggest,” Wu Fang Chien looked mildly at the uneasy Delabar, “that you have me visé your passports so that you may travel safely this side of Liangchowfu. Then I will give you a military escort who will be protection against any outlaws you meet on the road. In this way I will feel that I am doing my full duty to my honored guests.”

“The offer is worthy,” said Gray, who realized that the sense of duty of a town official was a serious thing, but did not wish an escort, “of one whose hospitality is a pleasure to his guests.”

Wu Fang Chien shook hands with himself. “But we have little money to pay an escort——”

“I will attend to that.”

“Unfortunately, an escort of soldiers would spoil my chances at big game. We shall pick up some native hunters.”

Wu Fang Chien bowed, with a faint flicker of green eyes.

“It shall be as you wish, Captain Gray. But I am distressed at the thought you may suffer harm. The last American who went beyond the Western Gate, died.”

Gray frowned. He had not known that one of his countrymen had penetrated so far into the interior.

“Without doubt,” pursued the mandarin, stroking his fan gently across his face, “you have a good supply of rifles. I have heard much of these excellent weapons of your country. Would you oblige me showing them to me before you leave Honan?”

“I should be glad to do so,” said Gray, “if they were not packed in our luggage which will not be here before we set out. But I have two small presents——”

The gift of the clock and electric light turned the thread of conversation and seemed to satisfy Wu Fang Chien, who bowed them out with the utmost courtesy to the waiting sedan chairs. Then, as the bearers picked up the poles, he drew a small and exquisite vase from under his robe and pressed it upon Gray as a token, he said, to keep fresh the memory of their visit.

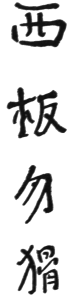

At their room in the hotel Gray showed the vase to Delabar. It was a valuable object, of enamel wrought on gold leaves, and inscribed with some Chinese characters.

“What do you make of our worthy Wu Fang—hullo!” he broke off. Delabar had seized the vase and taken off the top.

“It is what the Chinese call a message jar,” explained the scientist, feeling within the vase. He removed a slim roll of silk, wound about an ebony stick. On the silk four Chinese characters were delicately painted.

“What do they mean?” asked Gray, looking over his shoulder.

The Syrian glanced at him appraisingly, under knitted brows. His companion’s face was expressionless, save for a slight tinge of curiosity. Delabar judged that the soldier knew nothing of written Chinese, which was the truth.

“Anything or nothing, my friend. It reads like a proverb. The oriental soul takes pleasure in maxims. Yet everything they do or say has a meaning—very often a double meaning.”

“Such as Wu Fang’s table talk,” smiled Gray. “Granted. Is this any particular dialect?”

“Written Chinese is much the same everywhere. Just as the Arabic numerals throughout Europe.” He scanned the silk attentively, and his lips parted. “The first ideograph combines the attribute or adjective ‘clever’ or ‘shrewd’ with the indicator ‘man.’ A shrewd man—hua jen.”

“Perhaps Wu Fang: perhaps you. Go on.”

“The second character is very ancient, almost a picture-drawing of warning streamers. It is an emphatic ‘do not!’ ”

“Then it’s you—and me.”

“The third character is prefixed by mu, a tree, and signifies a wooden board, or a wall. The fourth means ‘the West.’ ”

“A riddle, but not so hard to guess,” grinned Gray, taking up his maps from the table and filling his pipe preparatory to work. “A wise guy doesn’t climb the western wall.”

“You forget,” pointed out Delabar sharply, “the negative. It is the strongest kind of a warning. Do not, if you are wise, approach the western wall. My friend, this is a plain warning—even a threat. To-day Wu Fang Chien hinted we should not go to Liangchowfu. Now he threatens——”

“I gathered as much.” Gray took the slip of fine silk and scanned it quizzically. “Delabar, do you know the ideograph for ‘to make’ or ‘build?’ ”

The scientist nodded.

“Then write it, where it seems to fit in here.”

Delabar did so, with a glance at his companion. Whereupon the soldier folded the missive and replaced it in the jar. He clapped his hands loudly. Almost at once a boy appeared in the door.

To him Gray handed the vase with instructions to carry it to His Excellency, the official Wu Fang Chien. He reënforced his order with a piece of silver cash. To the curious scientist he explained briefly.

“Wu Fang is a scholar. He will read our reply as: A wise man will not build a wall in the west. It will give him food for thought, and it may keep His Excellency’s men from overhauling our belongings a second time during our absence.”

Delabar started. “May?”

“Yes. Remember I left that message of Wu’s on top of these maps. I find it underneath them. The maps are all here. We locked our door, carefully. Some one has evidently given our papers the once over and forgotten to replace them in the order he found them. I say it may have been at Wu’s orders. I think it probably was.”

“Why?” Delabar licked his thin lips nervously.

“Because nothing has been taken. A Chinese official has the right to be curious about strangers in his district. Likewise, his men wouldn’t have much trouble in entering the room—with the landlord’s assistance. The ordinary run of thieves would have taken something valuable—my field glasses, for instance.”

Delabar strode nervously the length of the room and peered from the shutters.

“Captain Gray!” he swung around, “do you know there are maps of the Gobi, of Sungan, in your case. The person who broke into our room must have seen them.”

“I reckon so.”

“Then Wu Fang Chien may know we are going to the Gobi! I have not forgotten what he said about the last American hunter. What hunter has been as far as the Gobi? None. So——”

“You think he meant——”

“Dr. Brent.”

Gray shook his head slowly. “Far fetched, Delabar,” he meditated. “You’re putting two and two together to make ten. All we know is that Wu has sent us a polite motto. No use in worrying ourselves.”

But it was clear to him that Delabar was worried, and more. Gray had been observing his companion closely. Now for the first time he read covert fear in the professor’s thin face.

Fear, Gray reflected to himself, was hard to deal with, in a man of weak vitality and high-strung nerves. He felt that Delabar was alarmed needlessly; that he dreaded what lay before them.

For that reason he regretted the event of that night which gave shape to Delabar’s apprehensions.

At the scientist’s urging, they did not leave the room before turning in. Gray adjusted Delabar’s walking stick against the door, placing a string of Chinese money on the head of the stick, and balancing the combination so a movement of the door would send the coins crashing to the floor.

“Just in case our second-story men pay us another visit,” he explained. “Now that we know they can open the door, we’ll act accordingly.”

It was a hot night.

Gray, naked except for shirt and socks, lay under the mosquito netting and wished that he had brought double the amount of insect powder he had. Across the room Delabar had subsided into fitful snores. The night was not quiet.

In the courtyard of the hotel some Chinese servants were at their perpetual gambling, their shrill voices coming up through the shutters. On the further side of the street a guitar twanged monotonously. Somewhere, a dog yelped.

The warm odors of the place assaulted Gray’s nostrils unpleasantly. They were strange, potent odors, a mingling of dirt, refuse, horses, the remnants of cooking. Gray sighed, longing for the clean air of the plains toward which they were headed.

They were still far from the Gobi’s edge. The distance seemed to stretch out interminably. It is not easy to cross the broad bosom of China.

He wondered what success they would have. What was the city of Sungan? How had it escaped observation? How did a city happen to be in the desert, anyway?

What was the pale sickness Brent had spoken of? Brent had died. From natural causes, of course. Gray gave little heed to Delabar’s wild surmises. But the conduct of Wu Fang Chien afforded him food for thought.

Had the vice-governor actually known of their mission? His words might have had a double meaning. And they might not. The silk scroll meant little. Delabar had read warning into it; but was not that a result of his imagination?

Gray turned uncomfortably on his bed and considered the matter. How could Wu Fang Chien have known they were bound for Sungan? Their mission had been carefully kept from publicity. Only Van Schaick and his three associates knew of it. Men like Van Schaick and Balch could keep their mouths shut. And Delabar was certainly cautious enough.

Gray cursed the heat under his breath, with added measure for the dog which seemed bound to make a night of it. The chatter at the hotel door had subsided with midnight. But the guitar still struck its melancholy note, accompanied by the intermittent wail of the sorrowing dog.

No, Gray thought sleepily, Wu Fang Chien could not have known of their mission. He had let Delabar’s nerves prey on his own—that was all. Delabar was full of this Asia stuff, especially concerning the priests——

Gray’s mind drifted away into vague visions of ancient and forgotten temples. The guitar note became the strum of temple drums, echoing over the waste of the desert. The dog’s plaint took form in the wailing of shrouded forms that moved about gigantic ruins, ruins that gave forth throngs of spirits. And the spirits took up the wail, approaching him.

A green light flamed from the temple gate. The gongs sounded a final crash—and Gray awoke at the noise of the stick and coins falling to the floor.

He became fully conscious instantly—from habit. And was aware of two things. He had been asleep for some time. Also, the door had been thrown open and dark forms were running into the room.

Gray caught at his automatic which he always hung at his pillow. He missed it in the dark. One of the figures stumbled against the bed. He felt a hand brush across his face.

Drawing up his legs swiftly he kicked out at the man who was fumbling for him. The fellow subsided backward with a grunt, and the officer gained his feet. His sight was not yet cleared, but he perceived the blur of figures in the light from the open door.

He wasted no time in outcry. Experience had taught him that the best way to deal with native assailants was with his fists. He bent forward from the hips, balanced himself and jabbed at the first man who ran up to him.

His fist landed in the intruder’s face. Gray weighed over a hundred and seventy pounds, and he had the knack which comparatively few men possess of putting his weight behind his fists. Moreover, he was not easily flurried, and this coolness gave his blows added sting.

At least four men had broken into the room. The other two hesitated when they saw their companions knocked down. But Gray did not. There was a brief rustle of feet over the floor, the sound of a heavy fist striking against flesh, and the invaders stumbled or crawled from the room.

Gray was surprised they did not use their knives. Once they perceived that he was fully awake they seemed to lose heart. The fight had taken only a minute, and Gray was master of the field.

He had counted four men as they ran out. But he waited alertly by the door while Delabar, who had remained on his bed, got up and lit the lamp. Gray’s first glance told him that no Chinamen were to be seen.

He was breathing heavily, but quite unhurt. Having the advantage of both weight and hitting power over his light adversaries, he took no pride in his prompt clearing of the room. Delabar, however, was plainly shaky.

“What did they want?” the professor muttered, eyeing the door. “How——”

“Look out!” warned Gray crisply.

From the foot of his bed a head appeared. Two slant eyes fixed on him angrily. A Chinaman in the rough clothes of a coolie crawled out and stood erect.

In one hand he held Gray’s rifle, removed from the case. With the other he was fumbling at the safety catch with which he seemed unfamiliar.

Gray acted swiftly. Realizing that the gun was loaded and that it would go off if the coolie thought of pulling the trigger, inasmuch as the safety catch was not set, he stepped to one side, to the head of the bed.

Here he fell to his knees. The man with the rifle, if he had fired, would probably have shot over the American, who was feeling under the pillow.

As it happened the coolie did not pull the trigger of the gun. A dart of flame, a crack which echoed loudly in the narrow room—and Gray, over the sights of the automatic which he had recovered and fired in one motion, saw the man stagger.

Through the swirling smoke he saw the coolie drop the gun and run to the window.

Gray covered the man again, but refrained from pressing the trigger. There was no need of killing the coolie. The next instant the man had flung open the shutters and dived from the window.

Looking out, Gray saw the form of his adversary vaguely as the coolie picked himself up and vanished in the darkness.

The street was silent. The guitar was no longer to be heard.

Gray crossed the room and flung open the door. The hall was empty. He closed the door, readjusted the stick and string of coins and grinned at Delabar who was watching nervously.

“That was one on me, Professor,” he admitted cheerfully. “The coolie who bobbed up under the bed must have been the one I kicked there. Fancy knocking a man to where he can grab your own gun.”

Delabar, however, saw no humor in the situation.

“They were coolies,” he said. “What do you suppose they came after?”

“Money. I don’t know.” Gray replaced the shutters and blew out the light. “We’ll complain to our landlord in the morning. But I don’t guess we’ll have much satisfaction out of him. The fact that my shot didn’t bring the household running here shows pretty well that it was a put-up job.”

His prophecy proved true. The proprietor of the hotel protested that he had known nothing of the matter. Asked why he had not investigated the shot, he declared that he was afraid. Gray gave up his questioning and set about preparing to leave Honanfu.

“The sooner we’re away from Wu Fang’s jurisdiction the better,” he observed to Delabar. “No use in making an investigation. It would only delay us. Our baggage came this morning, and you’ve engaged the muleteers. We’ll shake Honanfu.”

Delabar seemed as anxious as Gray to leave the town. Crowds of Chinese, attracted perhaps by rumor of what had happened in the night, followed them about the streets as Gray energetically assembled his two wagons with the stores, and the men to drive the mules.

He made one discovery. In checking up the list of baggage they found that one box was missing.

“It’s the one that had the rifles and spare ammunition,” grunted Gray. “Damn!”

He had put the rifle that had been intended for McCann with his own extra piece and ammunition in a separate box. In spite of persistent questioning, the drivers who had brought the wagons to Honanfu denied that they had seen the box.

A telegram was sent to the railway terminal. The answer was delayed until late afternoon. No news of the box was forthcoming.

“It’s no use,” declared Delabar moodily. “Remember, you told Wu Fang Chien that our rifles were with the luggage. Probably he has taken the box.”

“Looks that way,” admitted Gray, who was angered at the loss. “Well, there’s no help for it. We’ll hike, before Wu Fang thinks up something else to do.”

He gave the word to the muleteers, the wagons creaked forward. He jumped on the tail of the last one, beside Delabar, and Honanfu with its watching crowds faded into the dust, after a turn in the road.

From that time forth, Gray kept his rifle in his hand, or slung at his shoulder.

While they sat huddled uncomfortably on some stores against the side of the jogging cart—nothing is quite so responsive to the law of gravity as a springless Chinese cart, or so uncomfortable, unless it be the rutted surface of a Chinese imperial highway—both were thinking.

Delabar, to himself: “Why is it that an imperial road in China is not one kept in order—in the past—for the emperor, but one that can be put in order, if the emperor announced his intention of passing over it? My associate, the American, who thinks only along straight lines, will never understand the round-about working of the oriental mind. And that will work him evil.”

Gray, aloud: “Look here, Delabar! We can safely guess now that Wu Fang would like to hinder our journey.”

“I have already assumed that.”

“Hm. Think it’s because the Wusun actually exist, and he wants to keep us from the Gobi?”

Delabar was aroused from his muse.

“A Chinese official seldom acts on his own initiative,” he responded. “Wu Fang Chien has received instructions. Yes, I think he intends to bar our passage beyond Liangchowfu. By advancing as we are from Honanfu, we are running blindly into danger.”

Gray squinted back at the dusty road, nursing his rifle across his knees. His brown face was impassive, the skin about the eyes deeply wrinkled from exposure. The eyes themselves were narrow and hard. Delabar found it increasingly difficult to guess what went on in the mind of the taciturn American.

“I’ve been wondering,” said Gray slowly, “wondering for a long time about a certain question. Admitting that the Wusun are there, in the Gobi, why are they kept prisoners—carefully guarded like this? It doesn’t seem logical!”

The Syrian smiled blandly, twisting his beard with a thin hand.

“Logic!” he cried. “Oh, the mind of the inner Asiatic is logical; but the reasons governing it, and the grounds for its deductions are quite different from the motives of European psychology.”

“Well, I fail to see the reason why the Wusun people should be guarded for a good many hundred years.”

“Simply this. Buddhism is the crux of the oriental soul. Confucius and Taoism are secondary to the advent of the Gautama—to the great Nirvana. Buddhism rules inner China, Tibet, part of Turkestan, some of India, and—under guise of Shamanism, Southeastern Siberia.”

Gray made no response. He was studying the face of Delabar—that intellectual, nervous, unstable face.

“Buddhism has ruled Central Asia since the time of Sakuntala—the great Sakuntala,” went on the scientist. “And the laws of Buddha are ancient and very binding. The Wusun are enemies of Buddhism. They are greater enemies than the Manchus, of Northern and Eastern China. That is because the Wusun hold in reverence a symbol that is hateful to the priests of the temples.”

“What is that?”

Delabar hesitated.

“The symbol is some barbarian sign. The Wusun cherish it, perhaps because cut off from the world, they have no other faith than the faith of their forefathers.” The scientist’s high voice rang with strong conviction. “In the annals of the Han dynasty, before the birth of Christ, it is related that an army under the General Ho K’u-p’ing was sent on plea of the Buddhists to destroy the Huing-nu—, the ‘green-eyed devils’ and the Wusun—the ‘Tall Ones,’ of the west. The military expedition failed. But since then the Buddhists have been embittered against the Wusun—have guarded them as prisoners.”

“Then religious fanaticism is the answer?”

“A religious feud.”

“Because the Wusun will not adopt Buddhism?”

“Because they cling to the absurd sign of their faith!”

Gray passed a gnarled hand across his chin and frowned at his rifle.

“Sounds queer. I’d like to see that sign.”

Delabar settled himself uneasily against the jarring of the cart.

“It is not likely, Captain Gray,” he said, “that either of us will see it.”

Whereupon they fell silent, each busied with his thoughts, in this manner.

Delabar, to himself: My companion is a physical brute; how can he understand the high mysteries of Asian thought?

Gray: Either this Syrian has a grand imagination, or he knows more than he has been telling me—the odds being the latter is correct.

Near Kia-yu-kwan, the western gate of the Great Wall, the twin pagodas of Liangchowfu rise from the plain.

In former centuries Liangchowfu was the border town, a citadel of defense against the outer barbarians of the northern steppe and Central Asia. It is a walled city, standing squarely athwart the highway from China proper to the interior. Beyond Liangchowfu are the highlands of Central Asia.

In exactly a month after leaving Honanfu, as Gray had promised, the wagons bearing the two Americans passed through the town gate.

Gray, dusty and travel-stained to his waist, but alert and erect of carriage, walked before the two carts. He showed no ill effects from the hard stage of the journey they had just completed.

Delabar lay behind the leather curtain of one of the wagons. His spirits had suffered from the past month. The monotonous road, with its ceaseless mud villages had depressed him. The groups of natives squatting in the sun before their huts, in the never-ending search for vermin, and the throngs of staring children that sought for horse dung in the roads to use for fuel, had wrought on his sensitive nerves.

They had not seen a white man during the journey. Gray had written to Van Schaick before they left Honanfu, but they expected no mail until they should return to Shanghai.

“If we reach the coast again,” Delabar had said moodily.

The better air of the hill country through which they passed had not improved his spirits, as it had Gray’s. The sight of the forest clad peaks, with their hidden pagodas, from the eaves of which the wind bells sent their tinkle down the breeze, held no interest for the scientist.

Glimpses of brown, spectacled workmen who peered at them from the rice fields, or the vision of a tattered junk sail, passing down an estuary in the purple quiet of evening, when the dull yellow of the fields and the green of the hills were blended in a soft haze did not cause Delabar to lift his eyes.

China, vast and changeless, had taken the two Americans to itself. And Gray knew that Delabar was afraid. He had suspected as much in Honanfu. Now he was certain. Delabar had taken to smoking incessantly, and made no attempt to exercise as Gray did. He brooded in the wagon.

The calm of the army officer seemed to anger Delabar. Often when two men are alone for a long stretch of time they get on each other’s nerves. But Delabar’s trouble went deeper than this. His fears had preyed on him during the month. He had taken to watching the dusty highway behind them. He slept badly.

Yet they had not been molested. They were not watched, as far as Gray could observe. They had heard no more from Wu Fang Chien.

The streets of Liangchowfu were crowded. It was some kind of a feast day. Gray noted that there were numbers of priests who stared at them impassively as he led the mule teams to an inn on the further side of the town, near the western wall, and persuaded the proprietor to clear the pigs and children from one of the guest chambers.

“We were fools to come this far,” muttered Delabar, throwing himself down on a bamboo bench. “Did you notice the crowds in the streets we passed?”

“It’s a feast, or bazaar day, I expect,” observed Gray quietly, removing his mud caked shoes and stretching his big frame on the clay bench that did duty as a bed.

“No.” Delabar shook his head. “Gray, I tell you, we are fools. The Chinese of Liangchowfu knew we were coming. Those priests were Buddhist followers. They are here for a purpose.”

“They seem harmless enough.”

Delabar laughed.

“Did you ever know a Mongol to warn you, before he struck? No, my friend. We are in a nice trap here, within the walls. We are the only Europeans in the place. Every move we make will be watched. Do you think we can get through the walls without the Chinese knowing it?”

“No,” admitted Gray. “But we had to come here for food and a new relay of mules.”

“We will never leave Liangchowfu—to the west. But we can still go back.”

“We can, but we won’t.”

Gray turned on the bed where he sat and tentatively scratched a clear space on the glazed paper which formed the one—closed—window of the room. Ventilation is unknown in China.

He found that he could look out in the street. The inn was built around three sides of a courtyard, and their room was at the end of one wing. He saw a steady throng of passersby—pockmarked beggars, flaccid faced coolies trundling women along in wheelbarrows, an astrologer who had taken up his stand in the middle of the street with the two tame sparrows which formed his stock-in-trade, and a few swaggering, sheepskin clad Kirghiz from the steppe.

As each individual passed the inn, Gray noticed that he shot a quick glance at it from slant eyes. An impressive palanquin came down the street. A fat porter in a silk tunic with a staff walked before the bearers. Coming abreast the astrologer, the man with the staff struck him contemptuously aside.

As this happened, Gray saw the curtain of the palanquin lifted, and the outline of a face peering at the inn.

“We seem to be the sight of the city,” he told Delabar, drawing on his shoes. “The rubberneck bus has just passed. Look here, Professor! No good in moping around here. You go out and rustle the food we need. I’ll inspect our baggage in the stable.”

When Delabar had departed on his mission, Gray left the inn leisurely. He wandered after the scientist, glancing curiously at a crowd which had gathered in what was evidently the center square of the town, being surrounded by an array of booths.

The crowd was too great for him to see what the attraction was, but he elbowed his way through without ceremony. Sure that something unusual must be in progress, he was surprised to see only a nondescript Chinese soldier in a jacket that had once been blue with a rusty sword belted to him. Beside the soldier was an old man with a wrinkled, brown face from which glinted a pair of keen eyes.

By his sheepskin coat, bandaged legs and soiled yak-skin boots Gray identified the elder of the two as a Kirghiz mountaineer. Both men were squatting on their haunches, the Kirghiz smoking a pipe.

“What is happening?” Gray asked a bystander, pointing to the two in the cleared space.

Readily, the accents of the border dialect came to his tongue. The other understood.

“It will happen soon,” he explained. “That is Mirai Khan, the hunter, who is smoking the pipe. When he is finished the Manchu soldier will cut off his head.”

Gray whistled softly. The crowd was staring at him now, intent on a new sight. Even Mirai Khan was watching him idly, apparently unconcerned about his coming demise.

“Why is he smoking the pipe?” Gray asked.

“Because he wants to. The soldier is letting him do it because Mirai Khan has promised to tell him where his long musket is, before he dies.”

“Why must he die?”

The man beside him coughed and spat apathetically. “I do not know. It was ordered. Perhaps he stole the value of ten taels.”

Gray knew enough of the peculiar law of China to understand that a theft of something valued at more than a certain sum was punishable by death. The sight of the tranquil Kirghiz stirred his interest.

“Ask the soldier what is the offense,” he persisted, exhibiting a coin at which the Chinaman stared eagerly.

Mirai Khan, Gray was informed, had been convicted of stealing a horse worth thirteen taels. The Kirghiz had claimed that the horse was his own, taken from him by the Liangchowfu officials who happened to be in need of beasts of burden. The case had been referred to the authorities at Honanfu, and no less a personage than Wu Fang Chien had ruled that since the hunter had denied the charge he had given the lie to the court. Wherefore, he must certainly be beheaded.

Gray sympathized with Mirai Khan. He had seen enough of Wu Fang Chien to guess that the Kirghiz’ case had not received much consideration. Something in the mountaineer’s shrewd face attracted Gray. He pushed into the cleared space.

“Tell the Manchu,” he said sharply to the Chinaman whom he had drawn with him, “that I know Wu Fang Chien. Tell him that I will pay the amount of the theft, if he will release the prisoner.”

“It may not be,” objected the other indifferently.

“Do as I say,” commanded Gray sharply.

The soldier, apparently tired of waiting, had risen and drawn his weapon. He bent over the Kirghiz who remained kneeling. The sight quickened Gray’s pulse—in spite of the danger he knew he ran from interfering with the Chinese authorities.

“Quick,” he added. His companion whispered to the soldier who glanced at the American in surprise and hesitated.

Gray counted out thirteen taels—about ten dollars—and added five more. “I have talked with Wu Fang Chien,” he explained, “and I will buy this man’s life. If the value of the horse is paid, the crime will be no more.”

The blue-coated Manchu said something, evidently an objection.

“He says,” interpreted the Chinaman, who was eyeing the money greedily, “that thirteen taels will not wipe out the insult to the judge.”

“Five more will,” Gray responded. “He can keep them if he likes. And here’s a tael for you.”

The volunteer interpreter clasped the coin in a claw-like hand. Gray thrust the rest of the money upon the hesitating executioner, and seized Mirai Khan by the arm.

Nodding to the Kirghiz, he led him through the crowd, which was muttering uneasily. He turned down an alley.

“Can you get out of Liangchowfu without being seen?” the American asked his new purchase. He was more confident now of the tribal speech.

Mirai Khan understood. Later, Gray came to know that the man was very keen witted. Also, he had a polyglot tongue.

“Aye, Excellency.” Mirai Khan fell on his knees and pressed his forehead to his rescuer’s shoes. “There is a hole in the western wall behind the temple where the caravan men water their oxen and camels.”

“Go, then, and quickly.”

“I will get me a horse,” promised Mirai Khan, “and the Chinese pigs will not see me go.”

Gray thought to himself that Mirai Khan might be more of a horse thief than he professed to be.

“The Excellency saved my life,” muttered the Kirghiz, glancing around craftily. “It was written that I should die this day, and he kept me from the sight of the angel of death. But thirteen taels is a great deal of wealth. It would be well if I found my gun, and slew the soldier. Then the Excellency would have his thirteen taels again. Where is he to be found?”

“At the inn by the western wall. But never mind the Manchu. Save your own skin.”

Gray strode off down the alley, for men were coming after them. In the rear of an unsavory hut, the Kirghiz plucked his sleeve.

“Aye, it shall so be, Excellency,” he whispered. “Has the honorable master any tobacco?”

Impatiently Gray sifted some tobacco from his pouch into the hunter’s scarred hand. Mirai Khan then asked for matches.

“I will not forget,” he said importantly. “You will see Mirai Khan again. I swear it. And I will tell you something. Wu Fang Chien is in Liangchowfu.”

With that the man shambled off down an alley, looking for all the world like a shaggy dog with unusually long legs. Gray stared after him with a smile. Then he turned back toward the inn.

That night there was a feast in Liangchowfu. The sound of the temple drums reached to the inn. Lanterns appeared on the house fronts across the street. Throngs of priests passed by in ceremonial procession, bearing lights. In the inn courtyard a group of musicians took their stand, producing a hideous mockery of a tune on cymbals and one-stringed fiddles. But the main room of the inn, where the eating tables were set with bowls and chop-sticks, was deserted except for a wandering rooster.

“I’m going out to see the show,” asserted Gray, who was weary of inaction.

“What!” The Syrian stared at him, fingering his beard restlessly. “With Wu Fang Chien in the town!”

“Certainly. There’s nothing to be done here. I may be able to pick up information which will be useful—if we are in danger.”

Delabar tossed his cigarette away and shrugged his shoulders.

“We are marked men, my young friend. I saw this afternoon that a guard has been posted at the town gates. Those musicians yonder are spies. The master of the inn is in the stable, with our men.”

“Then we’ll shake our escort for a while.” Gray’s smile faded. “Look here, Professor. I’m alive to the pickle we’re in. We’ve got to get out of this place. And I want to have a look at that hole in the wall Mirai Khan told me about. For one thing—to see if horses can get through it.”

Delabar accompanied him out of the courtyard, into the street. Gray noted grimly that the musicians ceased playing with their departure. He beckoned Delabar to follow and turned down the alley he had visited that afternoon. Looking over his shoulder he saw a dark form slip into the entrance of the alley.

“Double time, Professor,” whispered Gray. Grasping the other by the arm he trotted through the piles of refuse that littered the rear of the houses, turning sharply several times until he was satisfied they were no longer followed. As a landmark, he had the dark bulk of the pagoda which formed the roof of the temple.

Toward this he made his way, dodging back into the shadows when he sighted a group of Chinese. He was now following the course of the wall, which took him into a garden, evidently a part of the temple grounds.

He saw nothing of the opening Mirai Khan had mentioned. But a murmur of voices from the shuttered windows of the edifice stirred his interest.

“It is a meeting of the Buddhists,” whispered Delabar. “I heard the temple messengers crying the summons in the street this afternoon.”

Gray made his way close to the building. It was a lofty structure of carved wood. The windows were small and high overhead. Gray scanned them speculatively.

“We weren’t invited to the reunion, Professor,” he meditated, “but I’d give something for a look inside. Judging by what you’ve told me, these Buddhist fellows are our particular enemies. And it’s rather a coincidence they held a lodge meeting to-night.”

He felt along the wall for a space. They were sheltered from view from the street by the garden trees.

“Hullo,” he whispered, “here’s luck. A door. Looks like a stage entrance, with some kind of carving over it.”

Delabar pushed forward and peered at the inscription. The reflected light of the illumination in the street enabled him to see fairly well.

“This is the gate of ceremony of the temple,” he observed. “It is one of the doors built for a special occasion—only to be used by a scholar of the town who has won the highest honors of the Hanlin academy, or by the emperor himself—when there was one.”

Gray pushed at the door. It was not fastened, but being in disuse, gave in slowly, with a creak of iron hinges. Delabar checked him.

“You know nothing of Chinese customs,” he hissed warningly. “It is forbidden for any one to enter. The penalty——”

“Beheading, I suppose,” broke in Gray impatiently. “Come along, Delabar. This is a special occasion, and, by Jove—you’re a distinguished scholar.”

He drew the other inside with him. They stood in a black passage filled with an odor of combined must and incense. Gray took his pocket flashlight from his coat and flickered its beam in front of them. He could feel Delabar shivering. Wondering at the state of the scientist’s nerves, he made out an opening before them in which steps appeared.

They seemed to be in a deserted part of the temple. Gray wanted very much to see what was going on—and what was at the head of the stairs. He ascended as quietly as possible, followed by the Syrian who was muttering to himself.

A subdued glow appeared above Gray’s head, as the narrow stairs twisted. The glow grew stronger, and he caught the buzz of voices. Cautiously he climbed to the head of the steps and peered into the chamber from which came the light.

He saw a peculiar room. It was empty of all furniture except a teakwood chair. The light came through a large aperture in the floor. An ebony railing, gilded and inlaid, ran around this square of light. The voices grew louder.