* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: European Journey

Date of first publication: 1934

Author: Philip Gibbs (1877-1962)

Illustrator: Edgar Lander (1872–1958)

Date first posted: Apr. 19, 2023

Date last updated: Apr. 19, 2023

Faded Page eBook #20230431

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

Other Books by

PHILIP GIBBS

The Cross of Peace

The Anxious Days

The Golden Years

The Winding Lane

The Wings of Adventure

and other little novels

The Hidden City

Darkened Rooms

The Age of Reason

The Day After To-morrow

Out of the Ruins

Young Anarchy

Unchanging Quest

The Reckless Lady

Ten Years After

Heirs Apparent

The Middle of the Road

Little Novels of Nowadays

The Spirit of Revolt

The Street of Adventure

Wounded Souls

People of Destiny

The Soul of the War

The Battles of the Somme

The Struggle in Flanders

The Way to Victory

2 volumes

More That Must Be Told

Now It Can Be Told

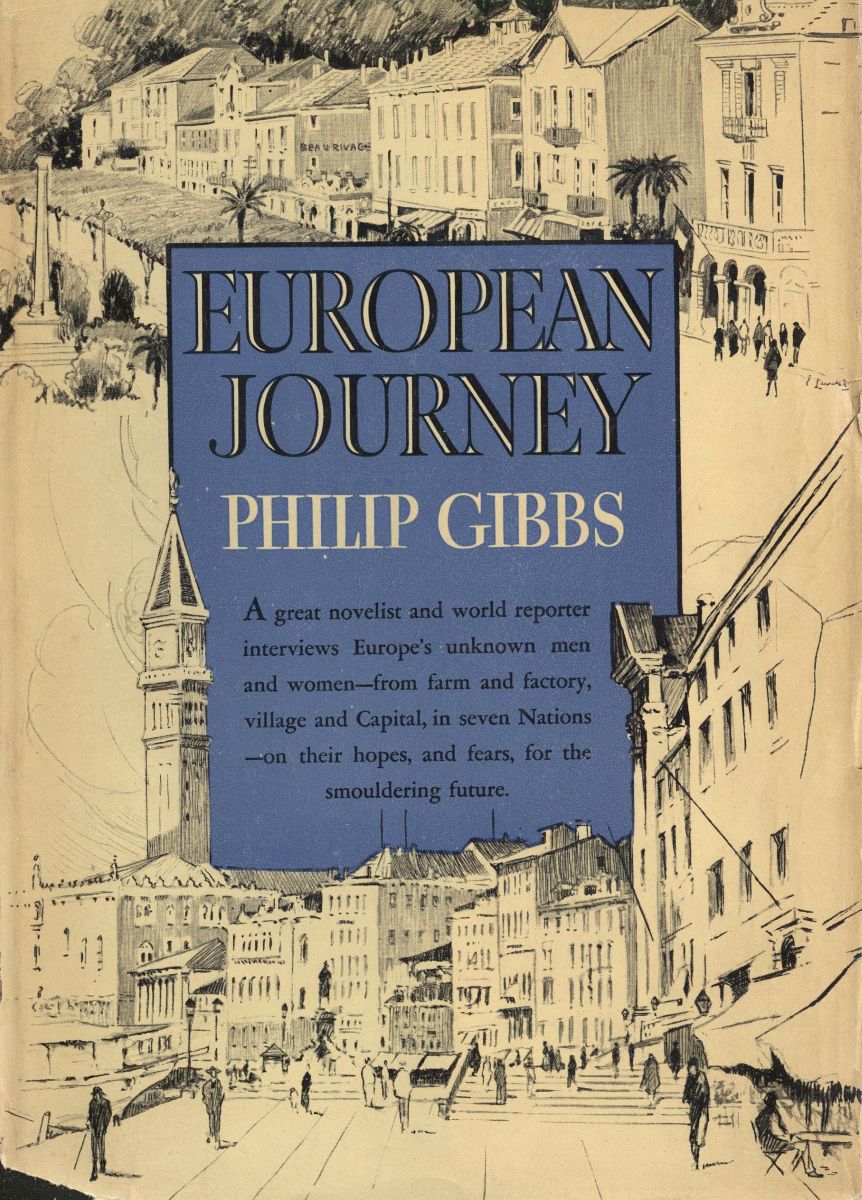

MORET

EUROPEAN JOURNEY

By PHILIP GIBBS

Being the Narrative of a Journey in France,

Switzerland, Italy, Austria, Hungary,

Germany, and the Saar, in the Spring and

Summer of 1934. With an Authentic Record

of the Ideas, Hopes, and Fears Moving in the

Minds of Common Folk and Expressed

in Wayside Conversations.

The Literary Guild

New York

PRINTED AT THE Country Life Press, GARDEN CITY, N. Y., U. S. A.

COPYRIGHT, 1934

BY PHILIP GIBBS

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

CONTENTS

CHAPTER I

Introduction

P. 1

CHAPTER II

The Way to Paris

P. 7

CHAPTER III

The Spirit of Paris

P. 13

CHAPTER IV

Provincial France

P. 35

CHAPTER V

A Swiss Sojourn

P. 101

CHAPTER VI

Italy under the Fasces

P. 138

CHAPTER VII

The Austrian Tragedy

P. 193

CHAPTER VIII

Hitler’s Germany

P. 225

CHAPTER IX

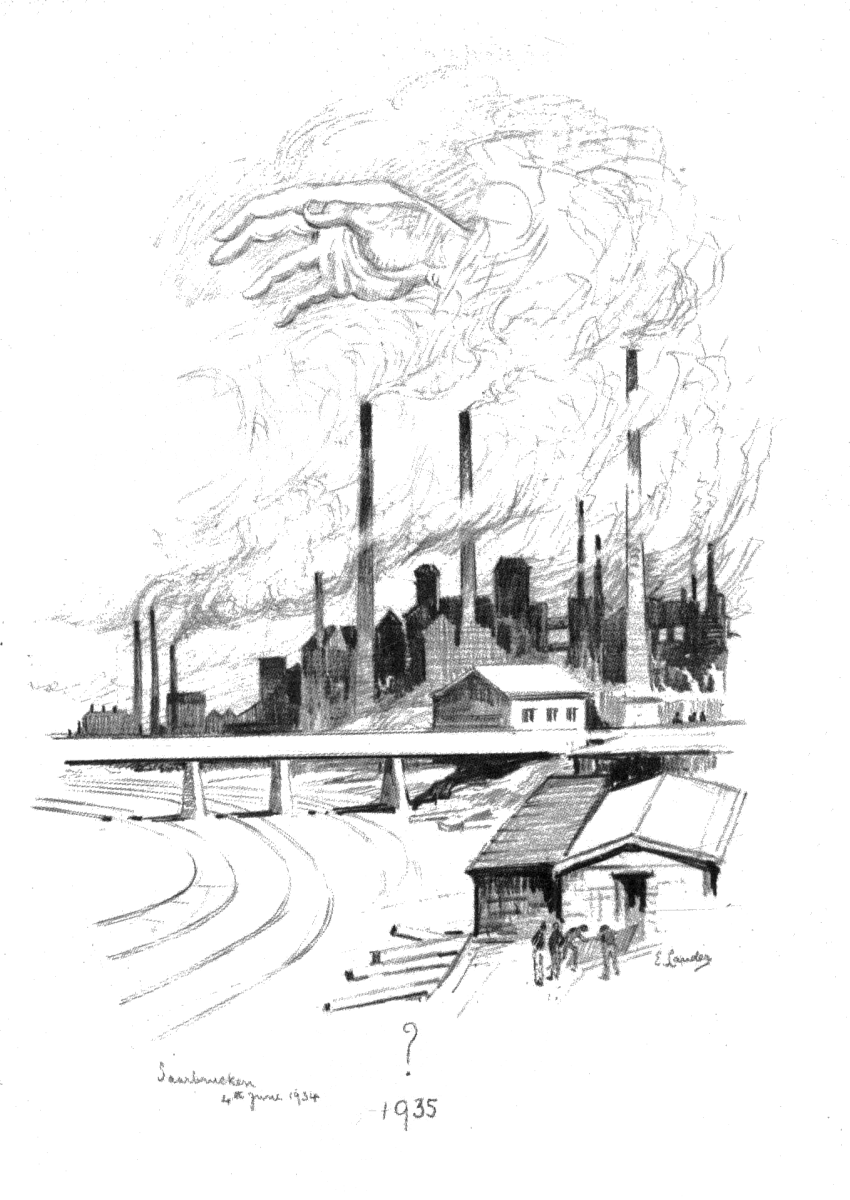

The Saar before the Plebiscite

P. 293

CHAPTER X

The Dilemma of Hungary

P. 301

CHAPTER XI

The Road of Remembrance

P. 314

Epilogue

P. 330

ILLUSTRATIONS

MORET

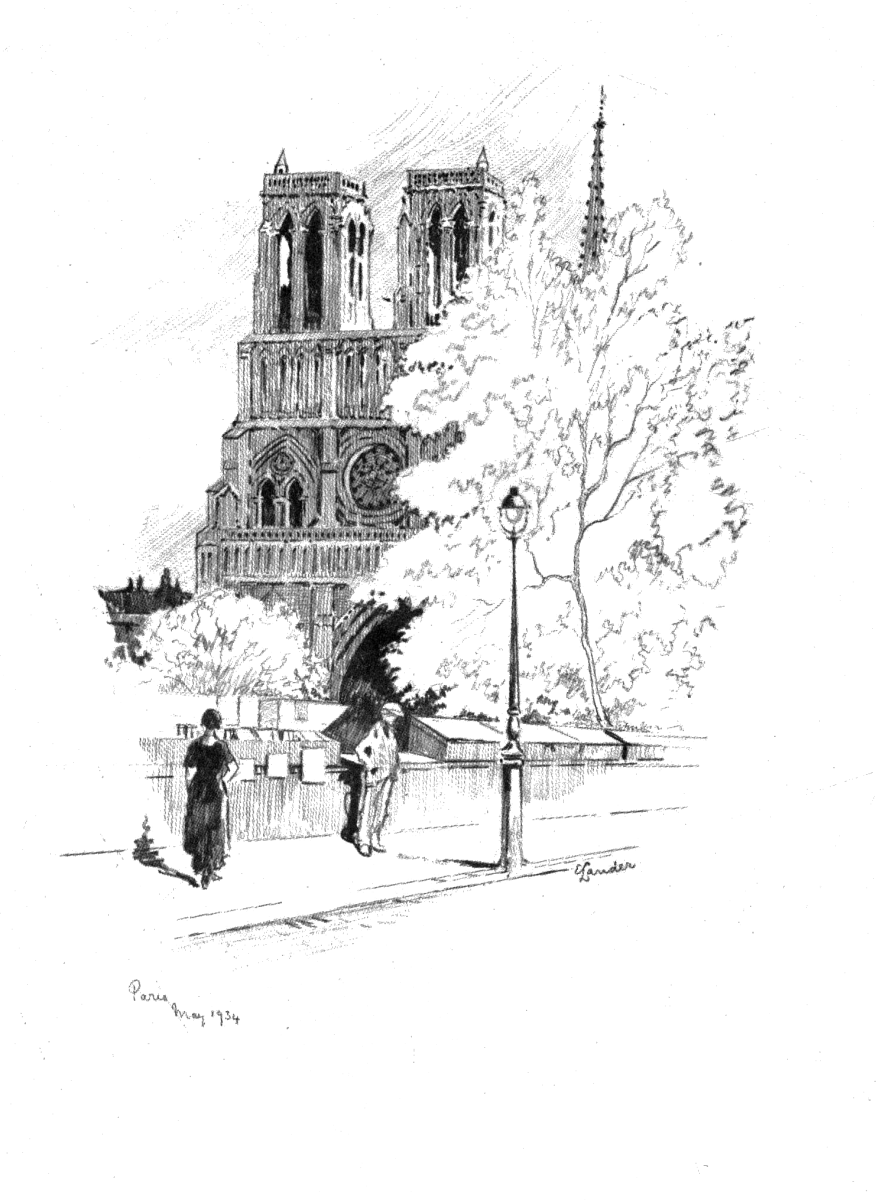

PARIS

P. 18

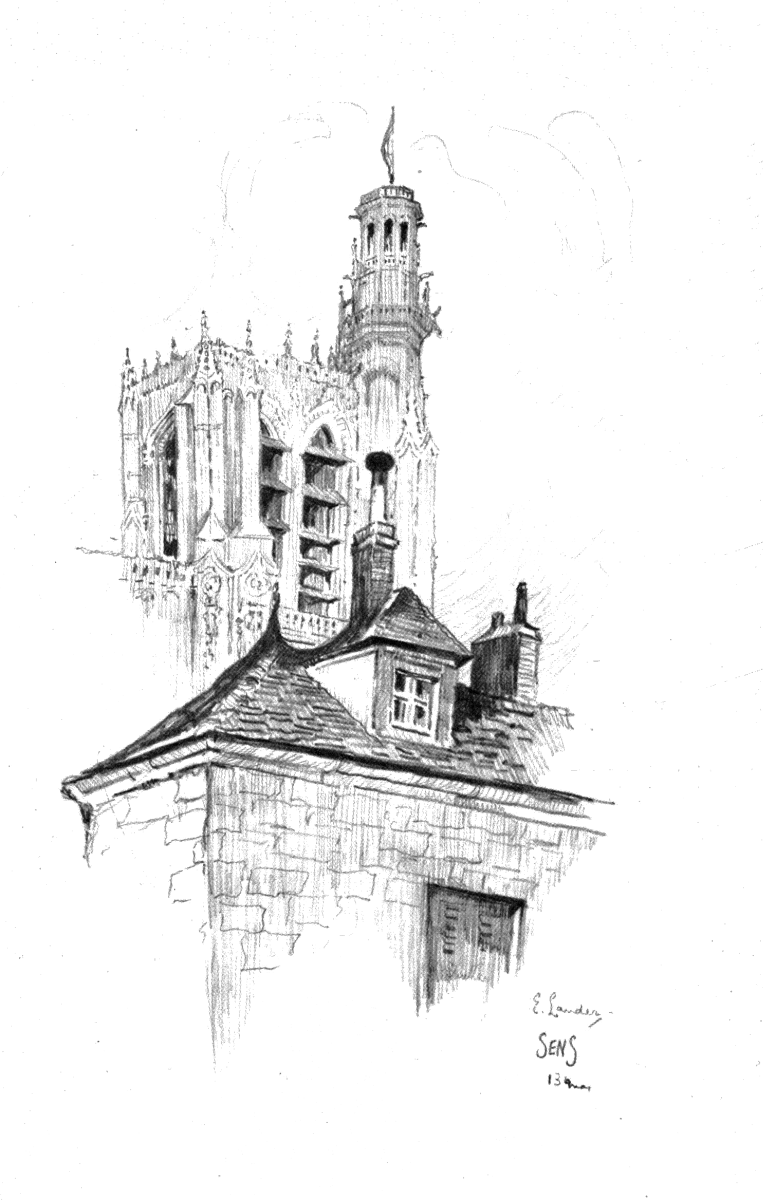

SENS

P. 54

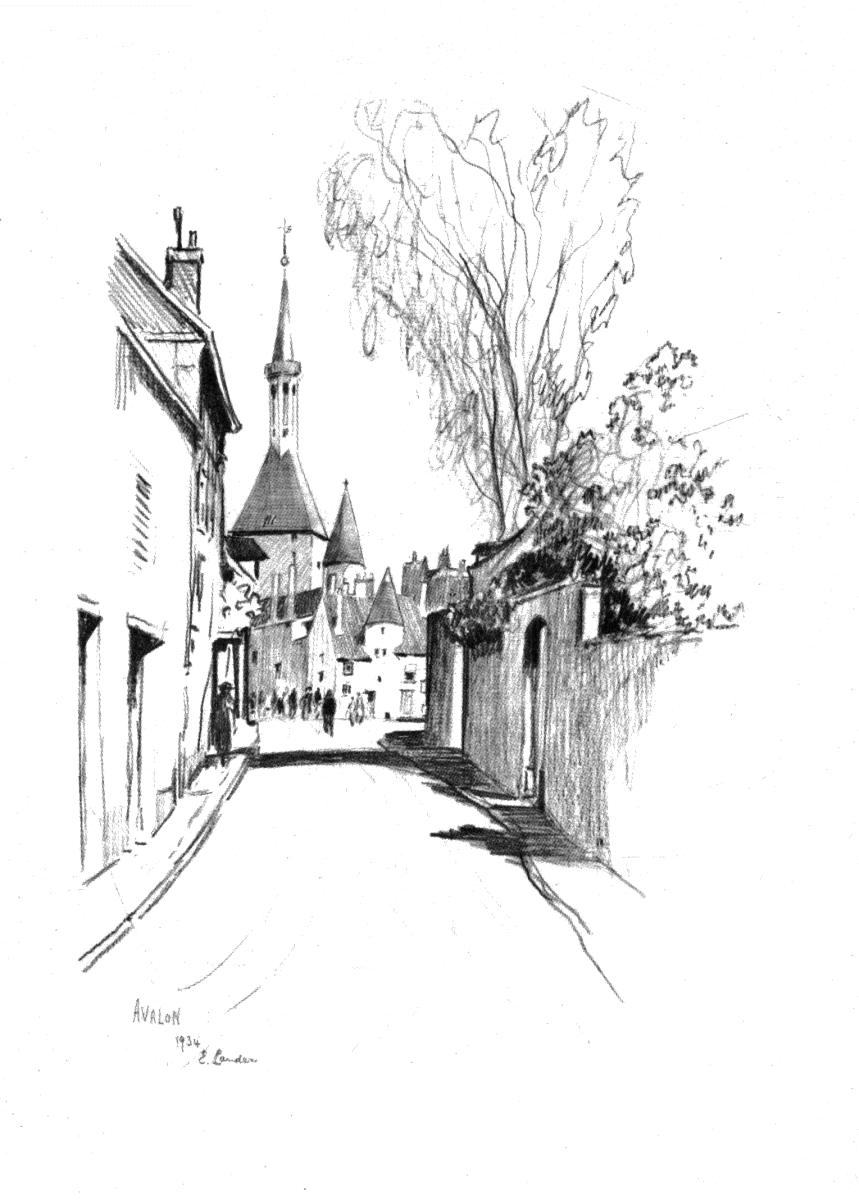

AVALLON

P. 58

VEZELAY

P. 66

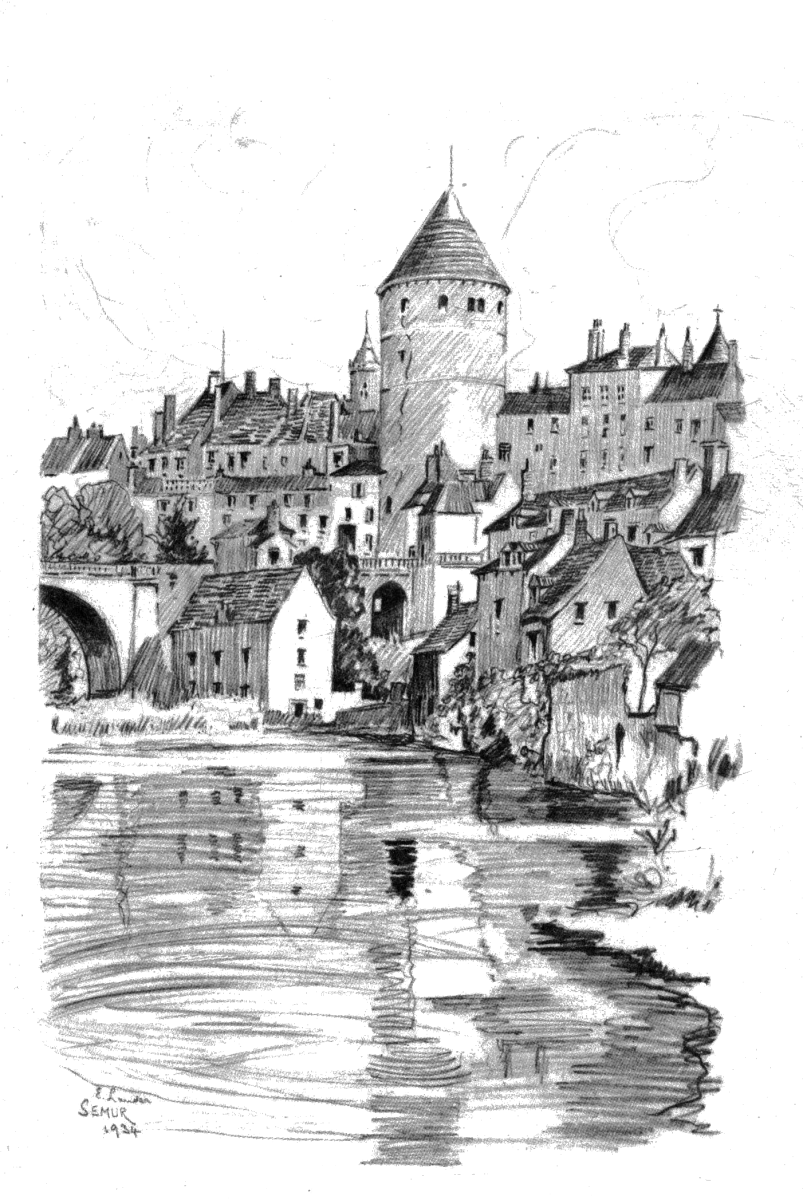

SEMUR

P. 70

CHÂTEAU DE MONTAIGU NEAR AUTUN

P. 74

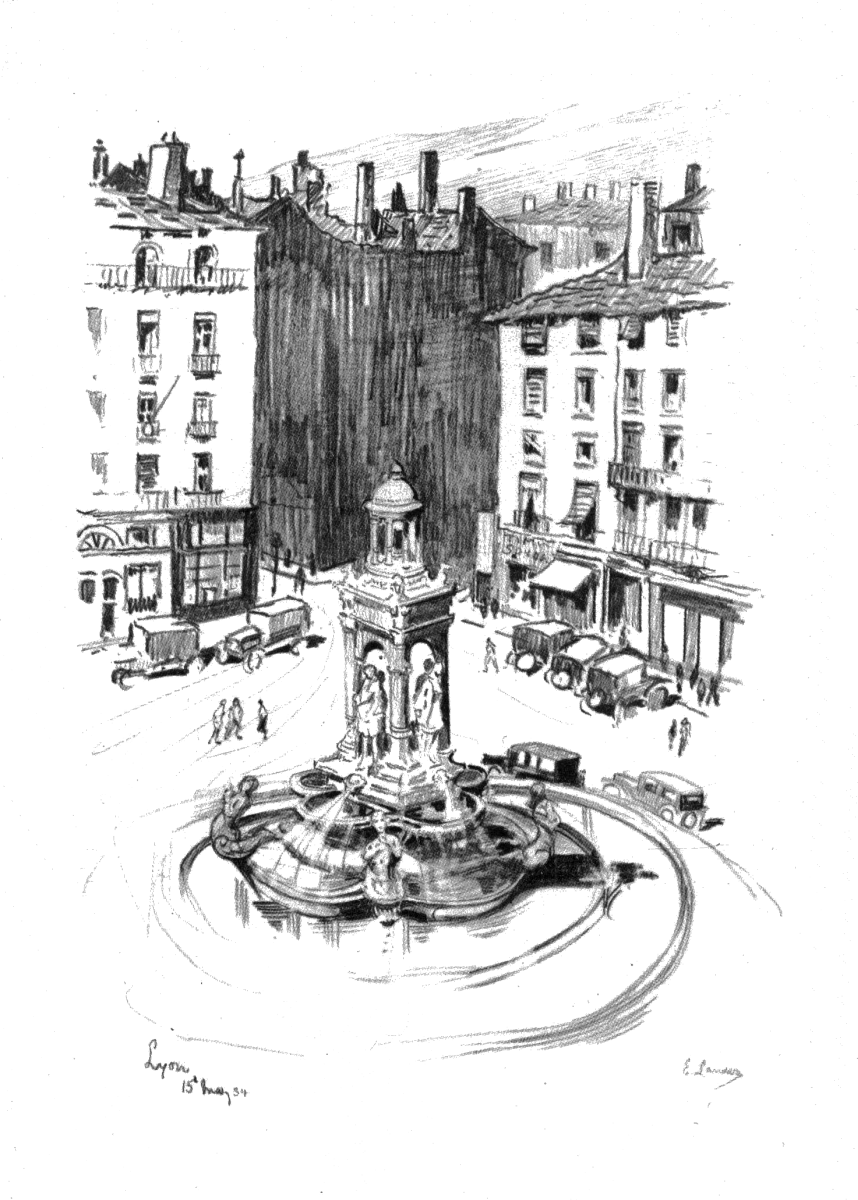

LYONS

P. 82

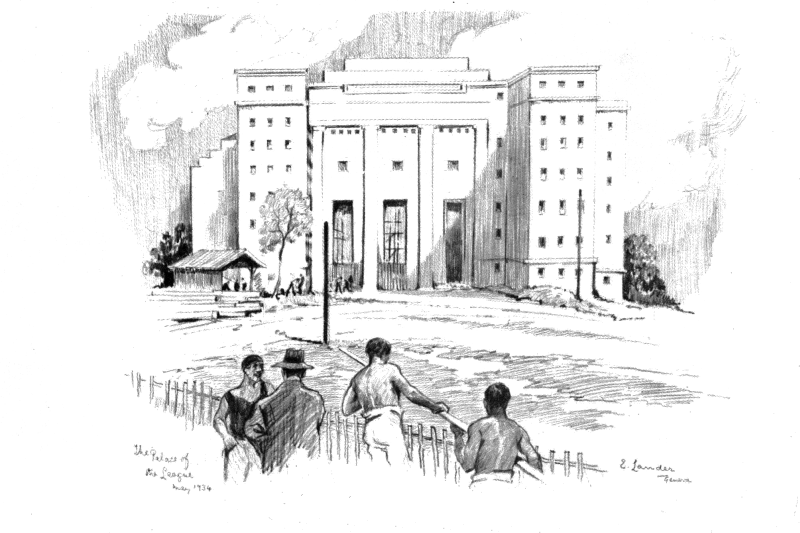

THE PALACE OF THE LEAGUE

P. 106

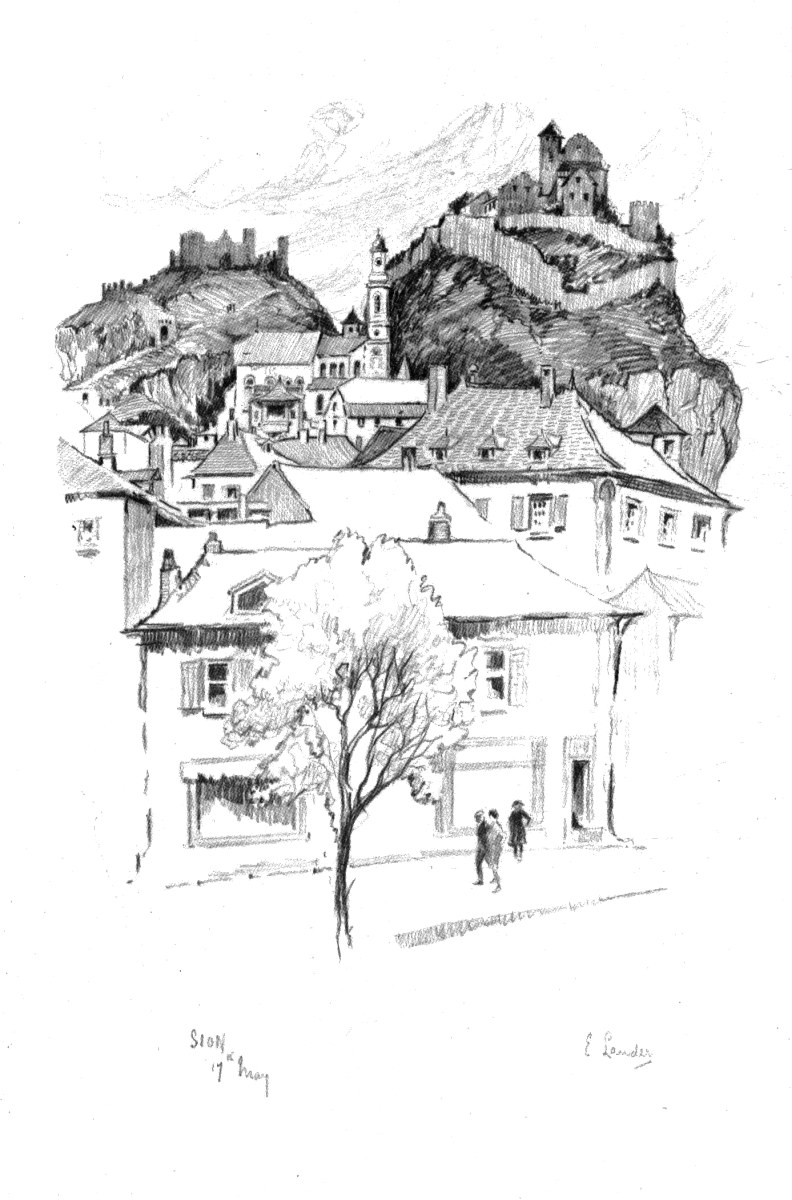

SION

P. 122

HAUT DE CRY, SION

P. 130

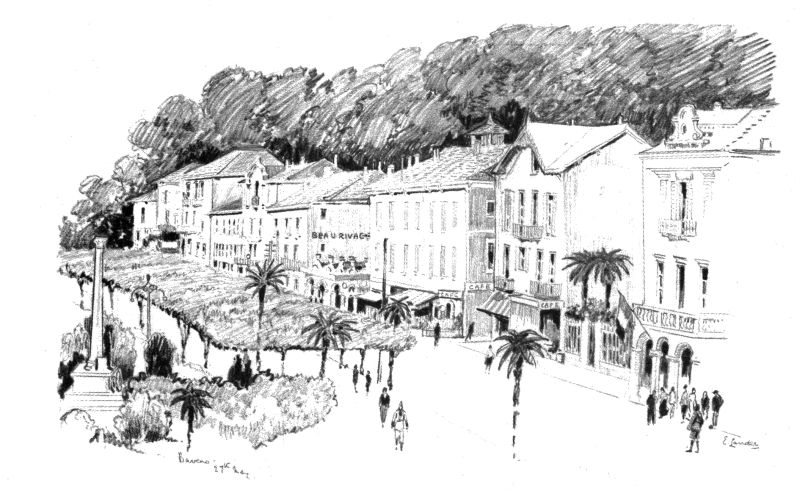

BAVENO

P. 146

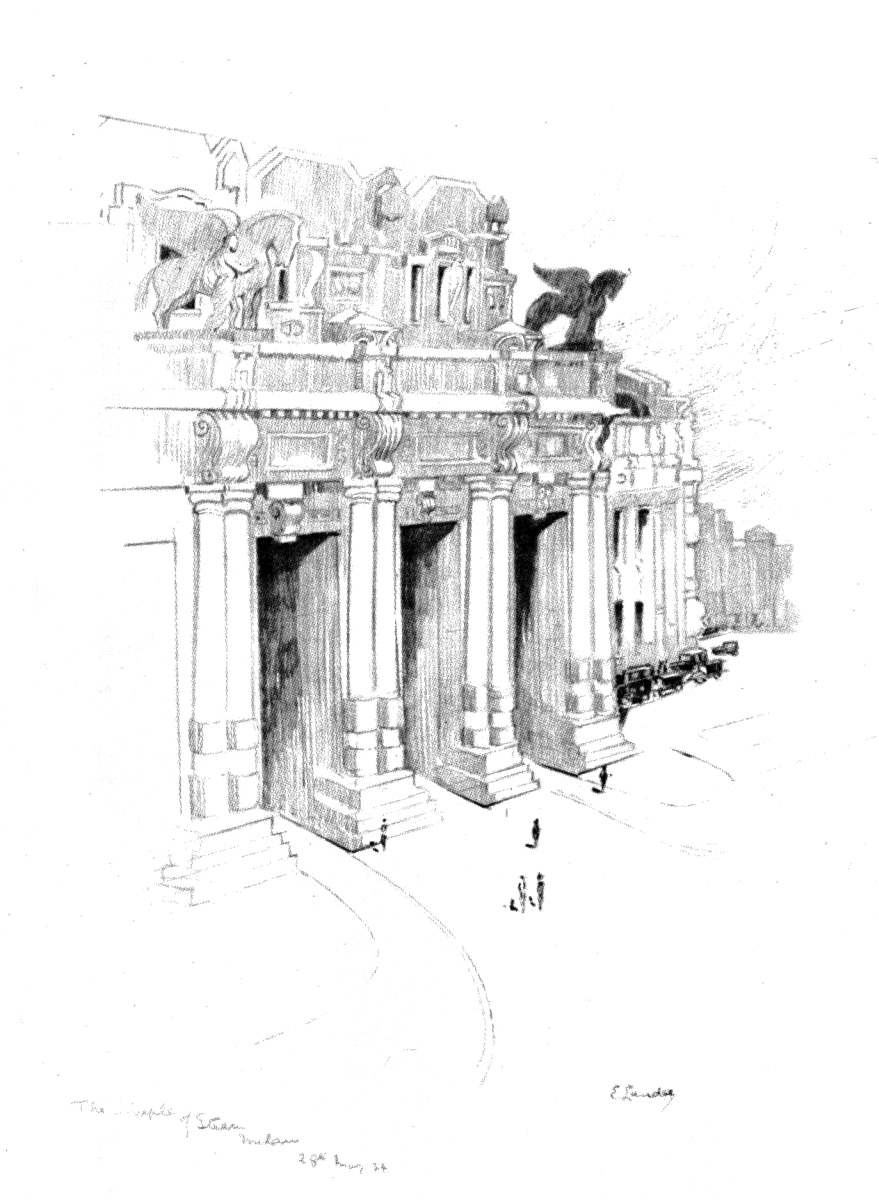

THE TEMPLE OF STEAM, MILAN

P. 150

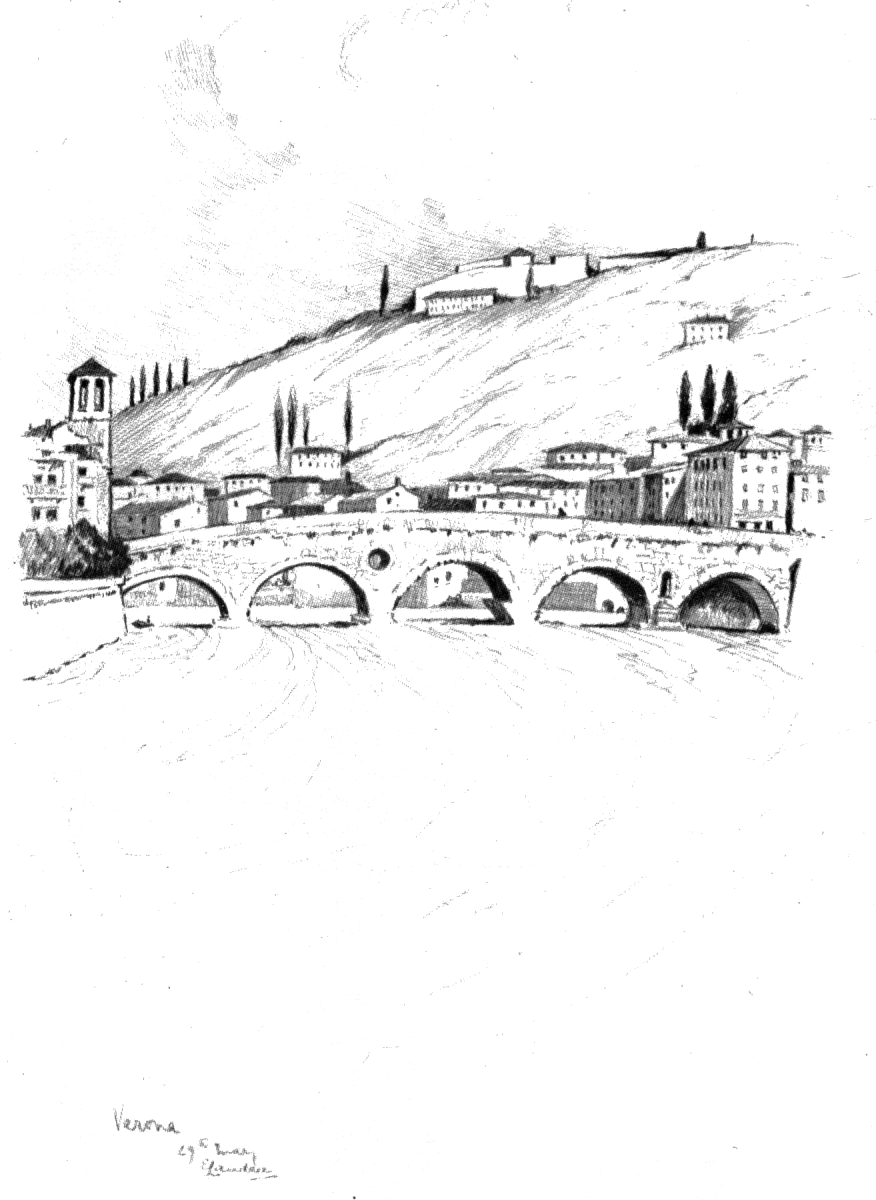

VERONA

P. 166

THE RIVA, VENICE

P. 170

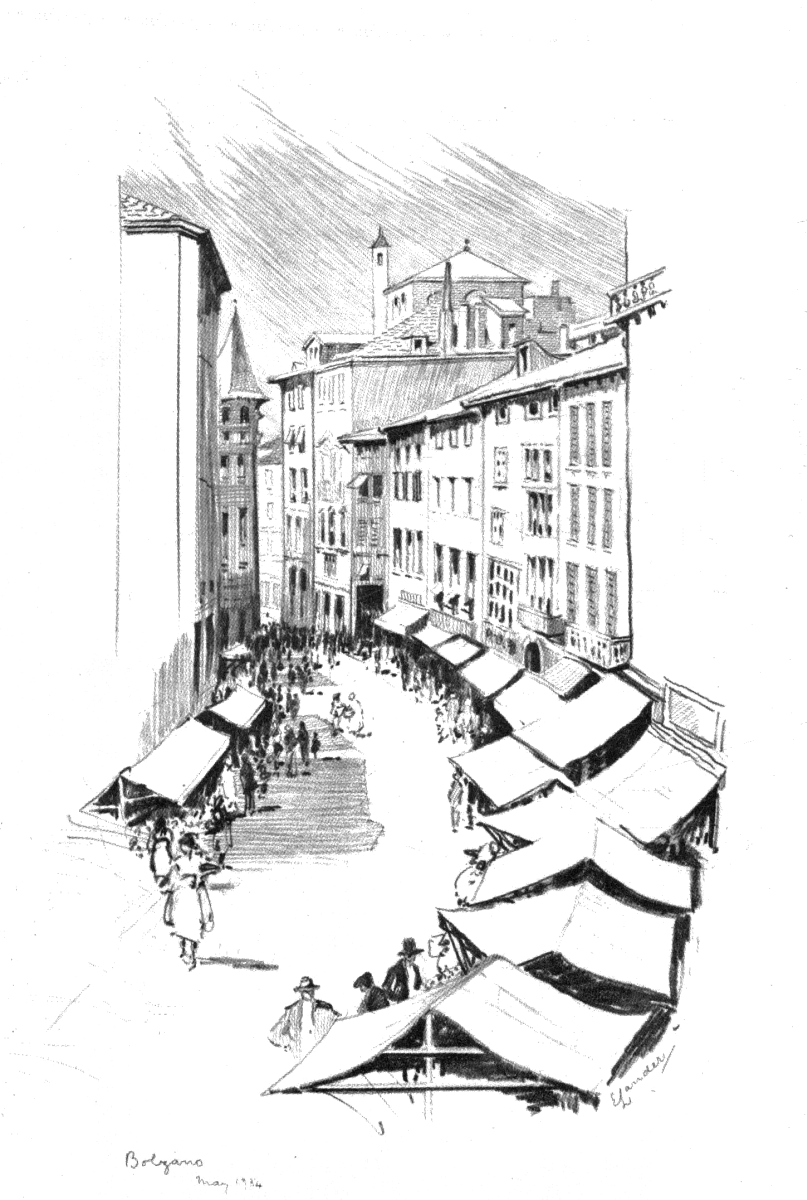

BOLZANO

P. 186

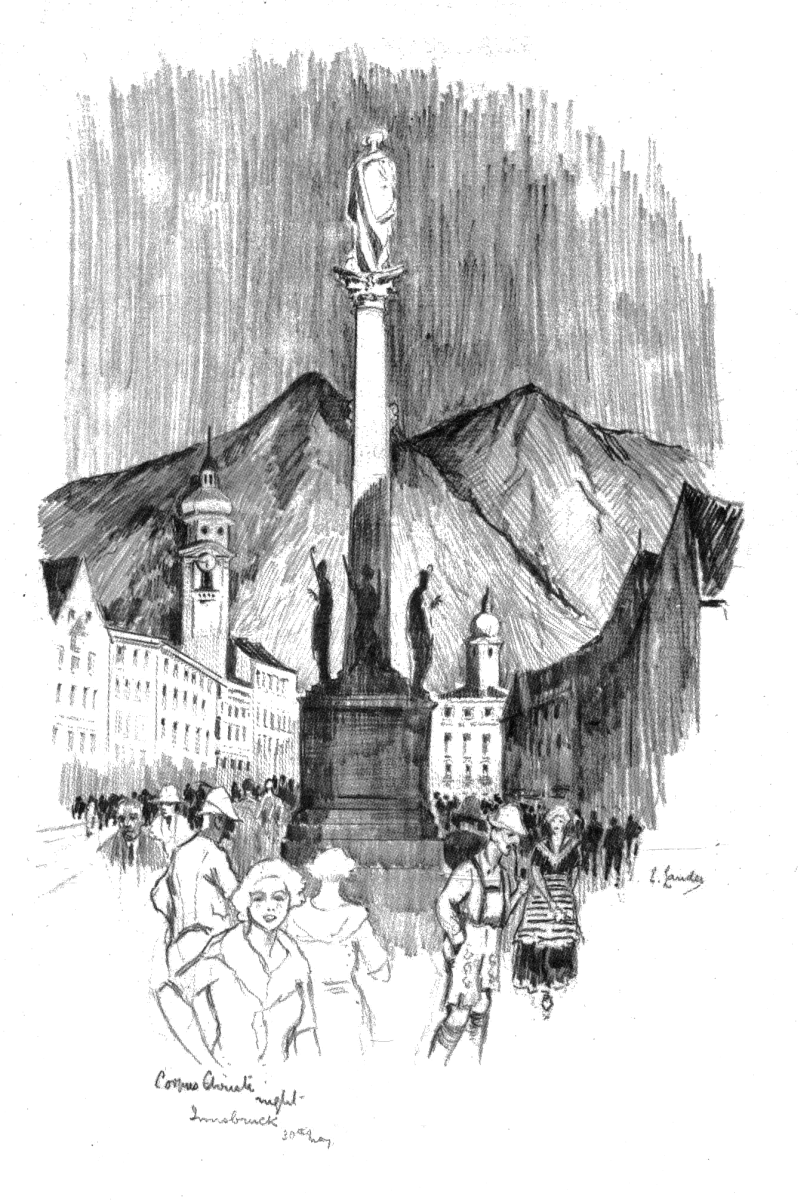

CORPUS CHRISTI NIGHT, INNSBRUCK

P. 210

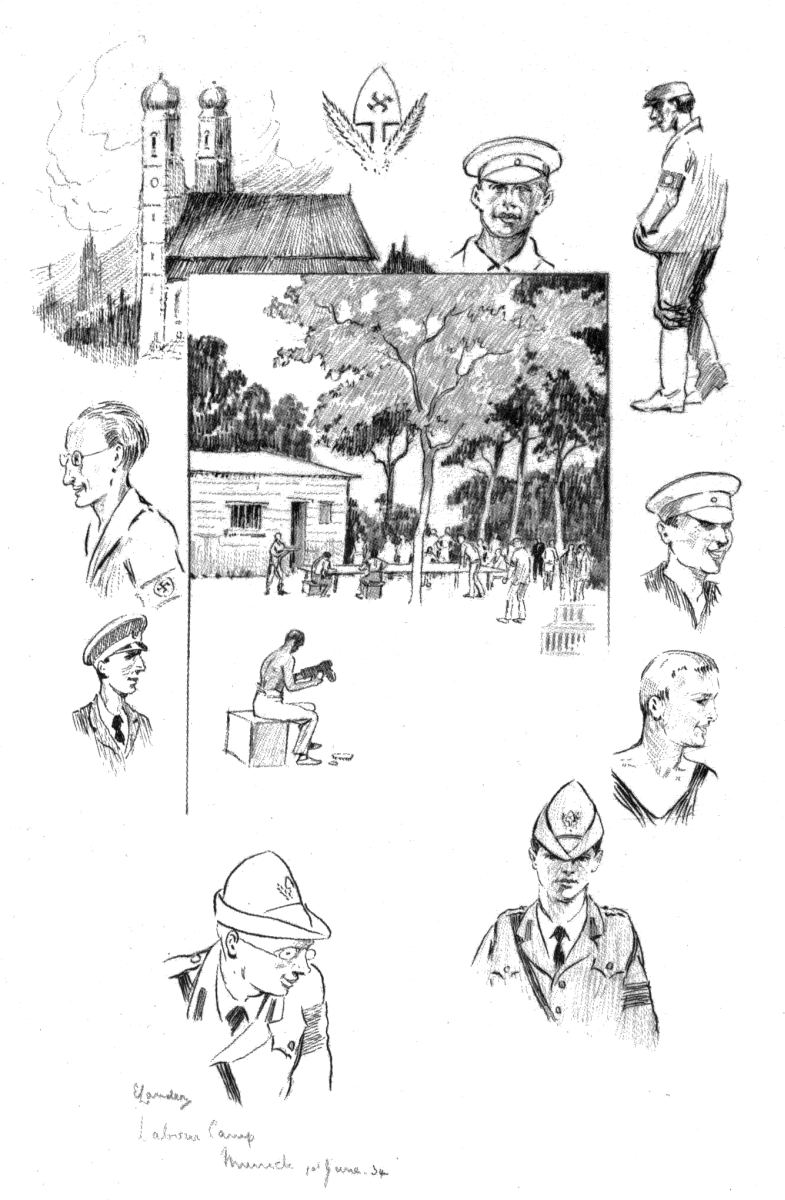

LABOUR CAMP, MUNICH

P. 262

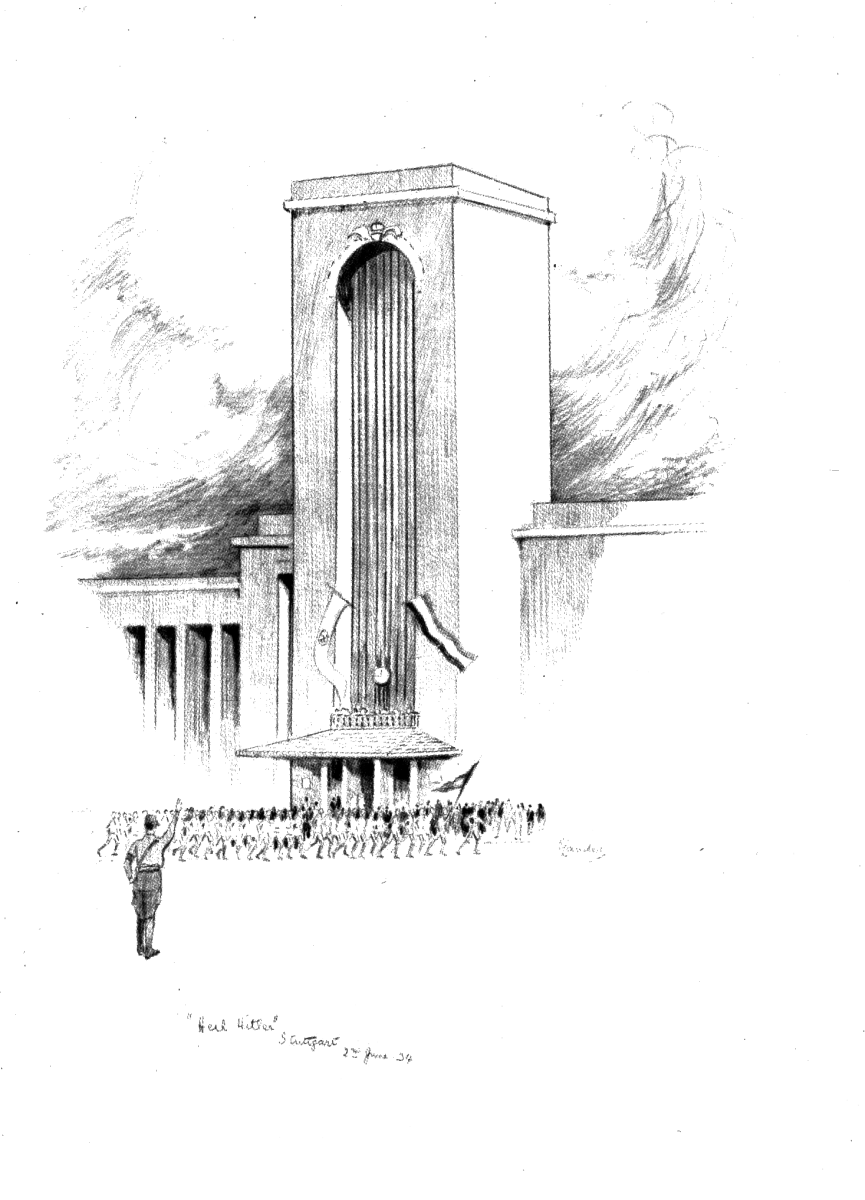

“HEIL HITLER,” STUTTGART

P. 278

SAARBRÜCKEN, 1935—?

P. 294

EUROPEAN JOURNEY

The idea of this book was to make a journey through Central Europe twenty years after the beginning of a war whose consequences are still unsettled and unpaid. My mission was not to interview statesmen and politicians, or the new rulers of the human tribes—one knows in advance what they will say—but to get into touch with the common folk whose lives are unrecorded and whose ideas are unexpressed. What are they thinking now, twenty years after that war which scarred the bodies and souls of those who survived? Do they ever think back to those days, or have they forgotten? How do they like these dictatorships which have put them under a new discipline? What hopes have they for the future? What kind of life is theirs, at a time when almost every nation is in the trough of a depression which is called “a crisis” but is, perhaps, the end of a system by which civilised peoples have, for a thousand years, carried on their life and industry? All that would be interesting. I was to take things as I found them, not writing a political discourse or getting answers to leading questions. It was to be a journey descriptive of things seen and heard in this Europe of 1934, including any beauty I might find, or any little adventure by the wayside. I might see places which do not find their way into the guide-books. I might give a picture of Europe not written by special correspondents despatching political news from the capitals, or accounts of crime and disaster. Villages might give me more than capitals, and peasants more than politicians. My material would be the minds of men and women in fields, and factories, small shops, and modest inns—the ordinary working folk who know nothing of secret diplomacy or high finance but try to get a living somehow, at a time when mysterious forces are at work, robbing them of the fruits of their labour and altering the values of work and wages. I might hear new points of view—the unknown philosophy of the ordinary man—by chance talks over café tables, and get a glimpse of truth below the surface of this bewilderment of life, in this time of transition between a past which is dying and a future which is unshaped. I might even get a clue to what is happening in the minds of young men who wear different coloured shirts and march about with strange devices on their way to new adventure.

The idea of such a book appealed to me, though I saw its difficulties. I should want a lot of luck to get into the minds of such people. They are not glib talkers, as a rule. In England they are inarticulate. Abroad they might not reveal themselves easily to a stranger speaking their languages badly. Could I be sure of getting good results if I sat down at a café table and tried to make conversation with an intelligent-looking fellow, absorbed in an illustrated paper, or watching the girls go by? The journey might lead to nothing but guide-book stuff, boring to my readers and failing to carry out the essential idea. But the risk was worth taking, and looking back at my journey now, before I begin to write about it, I am astonished at the way in which a number of men and women did talk to me, with a frankness and sincerity which was sometimes dangerous to them, and which was often illuminating. And I marvel at the intelligence of these people of humble class whom I met on the wayside or in the market places. They looked out on life with shrewd eyes. They were realists. They had summed things up. They were able to express their ideas, their fears, their bitterness—some of them were bitter—with remarkable clarity and gift of speech. That is a quality which we do not find so often in this country. These foreigners are good talkers. Their ideas jump into their words. I heard some unforgettable phrases, terribly ironical, as outside the new Palace of the League of Nations at Geneva, where some labourers told me things which made my hair stand up.

But there will be nothing sensational in this book for readers in search of that. It is a journey book in Europe today, with word pictures of life in villages, cities, inns, and market places. I was not exclusively interested in political ideas or economic facts. If a man talked to me about art, or the making of a horseshoe, I was as much interested as when another man talked to me about the political situation bearing down upon his life and liberties. But what I do hope will be found here is a true picture of this Europe—certain countries of it—as I have seen it in recent months, with a desire to keep my eyes clear of political bias and all prejudice.

Just before making this special journey for the purpose of this book, I had visited five capitals in Europe, and part of this experience finds a place here. It was a time of seething passion below a troubled peace. In France troops or police had opened fire on a vast crowd in the Place de la Concorde, stirred to indignation and fury by the corruption of politicians, revealed by the scandals of the Stavisky case. Something was stirring below the surface of French life, and many groups were forming and arming, I was told, with rival policies for a change in the structure of government. In Austria there had been the Fascist attack on the Social Democrats of Vienna, and a new dictatorship had been set up after a bombardment of the workmen’s dwellings. Germany was threatening to force a Nazi union with their Austrian sympathisers. A kind of ultimatum had been sent to the Dolfuss government. Italy was behind the Austrian Heimwehr—the Fascists—backing the independence of Austria against union with Germany. There was an ominous tension in Europe, as I found in those capital cities, and afterwards in the minds of villagers and small folk whose lives and business were involved in these political issues. It was, from the point of view of human interest, a good time for such a journey, though a bad time in the history of these peoples.

For the purpose of this book I decided that motoring was the only way of travel. Walking would have been better, as Hilaire Belloc went along the path to Rome, but to walk through Europe would have taken a long time, and the beginning would have been ancient history at the end of the walk, if I had gone far. A horse would have been good, but I am no horseman, and that animal is slow-going also for a hurrying age. A motorcar has great advantages. One can stop where one likes. It has room for companionship, and I am a fellow who detests loneliness, especially when journeying, though I have made many travels alone in this Europe which I was setting out to see again. My companions will be met in this book, now and then, as the Chorus of my wanderings. One of them I call the artist, because he happens to be one, though no one would suspect it by his face if they look for æstheticism and soulfulness. He has a humorous face which might belong to the skipper of a tramp steamer with a suitable vocabulary for stevedores, though it might also belong to an archdeacon with sporting instincts and a taste for old prints and old brandy. As an artist he used to draw with his left hand, as I knew when thirty years ago he and I went on many expeditions together to feed the maw of Fleet Street, he with his pencil and I with my pen. During the war, when, as a good officer of Fusiliers, his discipline was softened by a sense of humour which kept his battalion laughing at very odd times, a bit of steel smashed his left arm—just like the war, which was utterly without consideration for the fine arts!—and he had to learn to draw all over again with his right hand, and learnt very well. He is known by the name of Uncle in many cities as far away as Delhi, having a host of honorary nephews and nieces who have painted with him and laughed with him.

My other companion I call the novelist. He is in appearance a strange and attractive combination of Lord Robert Cecil as a young man and that great genius Grock in his noble moods. Temperamental, excitable and nervy, he has a childlike quality of responding to every new impression. He is well known as a novelist, critic and poet, and I inflicted great agonies upon him by claiming the literary copyright of all things seen and heard on this journey we were to make together. There were moments when he found this condition intolerable. His fingers itched to record his impressions. The scenes through which we passed incited him to prose and poetry. The sight of a piece of blank paper was a temptation he found hard to resist. Looking back on the journey I have a sense of guiltiness in having thwarted his genius. But it was my job. We joined him in Paris and dragged him down from the society of French dukes and other aristocrats to our social level, which was strictly limited to second-class hostelries and ordinary folk.

After Paris, where all good journeys start, we had another companion. He was the driver of a hired car and went by the name of “Gaston,” because he had once known a barber of that name in St. Petersburg, when he was the captain of a cruiser in the Russian Imperial Navy, before Revolution came, destroying all caste, and turning Russian nobles, if they escaped with their lives, into Parisian taxi drivers, or sword dancers in cabarets, or waiters in restaurants. Gaston, as we called him (until the last day, when he took off his chauffeur’s cap and parted with us on level terms), was a fine driver and a good companion. There were moments, as in the crossing of high mountains, when a little habit he had of taking both hands off the wheel to describe one of his adventures in the Russo-Japanese War, or to expound his philosophy of life as the driver of a hired car, was slightly disconcerting to a nervous man like myself. But confidence was quickly restored, and need never have been lost, because Gaston has the most tender regard for his passengers’ lives and has a record with American matrons and English spinsters unbroken by any accident. There was a competition to sit by his side, because of his dramatic narratives, his knowledge of life, his inexhaustible supply of amusing anecdotes. We suspected for a time that when we put up at second-class inns our Gaston was doing himself proud in the best hotel. We slunk round corners for cheap lunches of bread and cheese and beer, believing that our driver was regaling himself at a more expensive restaurant. Those suspicions were unfounded, though he needed a good lunch, having driven hard on certain days. But always in the evenings, when we three sat at some cheap café talking to a chance acquaintance, we saw our Gaston emerge to take in life as it might exist in a small provincial town. He was no longer in his chauffeur’s cap, but set forth with a felt hat at a fine angle and the swinging stride of a naval officer.

Later, for a week or so, we were joined by a lady. That was not part of the programme, and was a lamentable affair, as I shall tell.

I am not airminded, having no confidence as yet in that way of travel, and we went to Paris by train and boat. It is the way most people go, and I want to begin this journey in the ordinary way among ordinary people. They were very typical that morning on the platform of Victoria Station. In spite of the world “crisis” and the weakness of English money on foreign exchanges, there was the usual scurry of passengers. Among them was a group of gay lads in yellow and blue pull-overs, with neat-looking girls in tailor-made frocks. Somehow this class still contrives to exist in a world which is slipping beneath their feet. A young German and his wife sat in our carriage, busy with their accounts after an English holiday. Opposite me sat a Japanese gentleman, anxious about a box studded with brass nails. Unlike most of his countrymen, he was tall and thin, with skin drawn tightly over his high cheek bones. A Japanese business man, I thought, going to undersell every market in Europe with cheap goods made by sweated labour on depreciated yen. I was wrong there: he was a naval officer, as afterwards I learnt.

My artist friend sloped down the platform to buy himself a tin of tobacco.

“Remember the customs,” I warned him. “You’ll get into trouble.”

“Not a chance!” he answered. “I always say ‘blessé dans la guerre,’ and they let me through without a murmur. It’s a great asset in France—this war wound.”

He was reminiscent on the boat. We both remembered cross-channel passages when these boats were crammed with troops, mostly sick in foul weather, all wearing life belts because of German submarines. They were keen to get out to France, having trained until they were stale in English camps.

“Nearly twenty years ago, old lad, and now a dream!” said the artist. “It seems like yesterday, all the same.”

One of the stewards talked about that ancient history.

He had been soldier and seaman too, having served at the Dogger Bank and in the Dardanelles and then with the West Kents in France before he got a “packet” in his leg.

“The Froggies are not very happy with themselves just now,” he said, looking towards the coast of France. “I wouldn’t be surprised if there’s a lot of trouble. Queer world, ain’t it? People don’t seem to settle down.”

Another man looked towards the coast of France, now very near after an hour’s run. It was a man I knew slightly, very rich, and very prominent in the philanthropic world.

“Those are the people who are making all the trouble,” he said with his gaze on France.

He saw the query in my eyes and hastened to hedge.

“Of course, one understands their fear. Twice invaded, and with Germany growing strong again! One has to sympathise with their nervousness. All the same——”

He sighed heavily, smiled, raised his hand in a farewell salute as passengers began to get busy with their bags.

“Good old Calais!” said my artist friend, “and no temporary gentleman with a megaphone to direct all officers to the A.M.L.O. and the R.T.O., and other mystical potentates who directed the destiny of our little heroes and told them where to go and die.”

It was a mistake, perhaps, to harp like that on old memories of a forgotten war. It was a sign that we two were getting old. Nobody else gave a thought to that ancient history—nearly twenty years ago—as they went down the gangway and touched the soil of France. We scrambled through the customs and were duly passed, but my artist friend was startled when two sinister-looking men demanded to know what he had in his pockets. That “blessé dans la guerre” didn’t work this time. But the thing which bulged in his pocket was a fair-sized sketchbook with which, later, he was to record many old buildings and charming scenes.

“Strange!” he murmured. “Not even my honest-looking mug disarmed their nasty suspicions. Gave me quite a shock!”

The Japanese naval officer was our opposite companion in the train to Paris. In the corner, facing him, was one of those hearty ladies of uncertain years who carry the spirit of Surrey and Sussex to the uttermost parts of the world, where their husbands still govern a far-flung Empire in which something seems to be slipping. She refused the lure of the luncheon bell. She was well provided with sandwiches. Having eaten most of them, she looked over to the Japanese gentleman and thrust the remnants at him in a paper bag, like poking a bun to a bear.

“Have a bit!” she said cheerily.

The Japanese naval officer—a man of immense reserve and dignity—was startled. For a moment his ivory skin flushed slightly, as though he felt himself insulted. Then he understood. This was an English lady. He had met them before. She meant to be kind.

He raised one of his thin hands and smiled.

“You are very obliging. But I am not hungry.”

There were three other ladies in the carriage, one with dark and rather sad eyes, another sleepy in her corner, and the third more elderly but with the complexion of an English rose. The artist opened conversation with them. They were on their way to Singapore, and my friend was envious of such luck. He had always wanted to get out to that part of the world.

“You wouldn’t be so keen,” said the more elderly of the ladies, “if you had made twenty-five journeys out there, as I have.”

The dark lady with the sad eyes—until they were lit up now and then by laughter—had left a small child at school in England. Perhaps that accounted for the sadness. She was the mother of a Wee Willie Winkie, and I thought of other mothers I knew who have this wrench at the heart when they go back to husbands in Malaya and India. Truly this trainload of people on the way to Paris was typical of any train that goes from England, and no other nation would despatch such passengers. The Empire counts for something still as an outlet for the Mother Country, although the Dominions have shut down for a time on immigration, and have declared their independence. It would be harder for public-school men to find some job of work—it is getting harder every year—unless there were still places out East wanting managers, engineers, administrators and traders. If ever the Empire cuts away—if India goes more than it has gone—we shall be a little middle-class island overcrowded with place hunters, shabby-genteel if not poverty-stricken. Aren’t we getting like that, as far as those who used to be called the Upper Classes are concerned?

The restaurant car was fairly full as we passed Etaples. None turned from the food to look at the cemetery there in the sand dunes. Forgotten all that, and perhaps it’s just as well, twenty years after. I was one who remembered, having a morbid kind of mind. I remembered a hot day early in the war when a military band was playing the marvellous song of death, which is Chopin’s Funeral March, and when lines of men in khaki reversed arms as a coffin was carried past on a gun carriage, with the body of a man who had been a very cheery soul before he had a headache and knew that he had only one chance of escape in—I have forgotten how many chances—from a disease called cerebro-spinal meningitis, in which he was an expert. He was one of the heroes of the war, and around him in the sand dunes lie a crowd who were brought down from the battlefields on their way home.

“Vin rouge ou blanc, monsieur?”

“Encore du pain, s’il vous plaît.”

Amiens came after a heavy lunch—damnably expensive when one reckons the English exchange—and a doze in the corner seat. Amiens! It meant nothing to a young man in a blue pullover, smoking a cigarette in the corridor and very bored with this train journey. He was in his nursery when crowds of muddy men walked down the Rue des Trois Cailloux, looking through the plate-glass windows of the shops, after living in wet trenches under shell fire, to which in due course they would return. Round the corner of the cathedral was Charlie’s bar, until it was blown into splinters. A jolly good spot for young officers—English, Scottish, Canadian, Australian—who drank three eggnogs before dinner at the Godebert and slept at the Hôtel du Rhin, the last sleep they might have between sheets. There was a waiter at the Hôtel du Rhin, a Gascon type of fellow, boastful and amusing. I met him after the war. “France,” he said, “was the steel shield between England and Germany. France saved England, and there is no gratitude, because, after all, England is a nation of shopkeepers and with a few exceptions, monsieur, without a soul.” It was only a year or so after a million of our men, mostly boys, had fallen in French fields.

Creil. . . . Yes, I remembered Creil. It was Sir John French’s headquarters for a night or two on the retreat from Mons. There were many stragglers with bandaged limbs. “The Germans came on like lice,” they said. . . .

There was a team of English football players on the train. They talked with a northern burr, and looked forward to a good time in Paris. Their manager, as I think he must have been, was a little fellow, four feet six in his socks, who had drunk too much at lunch and was still drinking after tea but became more humorous as the hours passed. The young German whom I had noticed in the train at Victoria thought him priceless as a joke, and abandoned his wife to laugh at him. A little Italian also was vastly entertained. They sat in the restaurant car drinking whisky. The Scot paid, and when the waiter brought him his change, in French silver, he scattered it on the floor with a noble gesture of disdain. He saluted the young German—a handsome and merry fellow—by raising his right arm and shouting, “Heil Hitler!” He had moments of great gravity when he told the Italian that Mussolini was “a good lad,” and when he assured the young German that if ever he came north he would find some good Scotch whisky waiting for him. “I fought the Germans,” he said, “and I like them. A fine people. To hell with all enmity!”

The German laughed heartily and presented his card.

“I have a little villa in the Mediterranean,” he said. “You must be my guest.”

“You’re a bonny wee lad!” said the Scot, putting his arm round the neck of the Italian, who screamed with laughter.

The waiter pretended not to hear his call for more whisky.

The Scot thrust his hand into his pocket and pulled out a handful of silver which he scattered over the floor again.

“Trash!” he cried. “Trash! Bring me whisky, boy. Heil Hitler!”

There was no time for more whisky. We were getting into Paris, past the boxlike factories, past the allotments and shacks, past workmen’s tenements with washing hung from strings across the windows. There was the Sacré Cœur, white on the hills of Montmartre.

Paris!

I always get a thrill of excitement on arriving in Paris and plunging through the tumult of its traffic in a taxi driven by an acrobat like a trick cyclist, making astonishing swerves, and avoiding collisions with half an inch to spare. There seems to be no order in this chase. It seems to be go-as-you-please in a wild whirligig, but really there is some mysterious law governing this moving tide racing to the boulevards. Somehow—with luck—one escapes death.

But it is not this traffic which excites me. It is the spirit of Paris and a thousand memories of all that Paris means in my own life and in human drama. I can hardly guess what this city means to those who see it for the first time, and especially to those who have no knowledge of its history and people, like English trippers who nudge each other on cross-channel boats and look forward to a week-end in “Gay Paree,” with night life and naughty ladies. The hideous vulgarity of this tradition—exasperating to the French—still lurks in English minds of a certain class. To me Paris is still the city of Danton and Camille Desmoulins—I see their ghosts in the Palais Royal—and of Victor Hugo and his Misérables, and of Alexandre Dumas and all the pageant of historical romance. To me, as to many others, its old houses—they are pulling them down ruthlessly—are haunted by the lives of poets, and scholars, and poverty-stricken fellows, who had some little flame in their souls to keep them warm, though there was no carpet on the floor and Mimi hung her petticoat across the window against the draught. The Vie de Bohème still goes on. Thirty years ago I wandered, and lingered, by the bookstalls along the quays. They are still there, though so much has changed. One can still get cheap wine and good conversation in the restaurants on the Left Bank. Genius is not dead in Paris, nor wit, nor the audacity of youth, though the Parisian has lost some of his gaiety under pressure of anxious times. I have had many adventures in this city and made many friends. I go back to it always with pleasure—and a little sadness because one grows older and things change.

We put up at a modest hotel behind the Madeleine, and after dinner strolled out to breathe the air and get into the heart of Paris. It was not long after the shooting in the Place de la Concorde. We drank a vermouth at the Weber in the Rue Royale, and one of the waiters told me of what had happened there on the fatal night.

“This restaurant was a field dressing station. The wounded were carried in constantly. It was a tragic affair, and the politicians—those dirty dogs!—will have to pay for it. It was a massacre of honest folk—the anciens combattants de guerre—who were protesting against corruption. You have heard of the Stavisky scandal?”

Yes, I had heard—who has not? Every newspaper in France was crammed with details of its sinister ramifications implicating many famous names in France, if one could believe these newspaper accusations. Stavisky, one of the greatest swindlers of the world—most nations have produced one or two—had, it was said, bribed politicians, ex-ministers, even judges, for years after they knew that he was a forger of bonds sub-subscribed to by middle-class folk out of their small savings.

L’Action Française, the Royalist paper edited by Léon Daudet, had abandoned all restraint and was using every name in the vocabulary of abuse against the suspected personages, calling upon the youth of France to overthrow a government steeped in corruption and degrading public morality. Murderers and assassins were the mildest names applied to those who had given the order to fire on the crowd in the Place de la Concorde. It had been a middle-class crowd made up of ex-soldiers, clerks, business men, and boys of Royalist views belonging to L’Action Française and the Croix de Feu. They had marched down from the boulevards, smashing newspaper kiosks, and tearing up the railings round the trees as weapons of offence or defence. The Chamber of Deputies was their objective—that talking shop of politicians with whom they were furiously indignant. The police had been overwhelmed. The Gardes Mobiles had been unseated from their horses and badly mauled. Somebody had given the order to fire. Thirty people had been killed and a thousand wounded, including a little maidservant watching the scene from a window of the Hôtel Crillon. This shooting had aroused a storm of fury in public opinion. The French government under Daladier had yielded to this demonstration of rage and indignation and to the panic of the deputies, some of whom were chased like rats when they dared to show themselves. A brave old man—M. Doumergue—formerly President of the Republic—had been summoned to form a national government. He had made an eloquent appeal to the patriotism of the French people, promising a full inquiry into all scandals and the punishment of all who might be implicated. It had done something to appease passion, but when I arrived in Paris I was told that this government could not hold the situation very long and that there were all the symptoms of revolution in the mind and temper of the people. Young men belonging to many political groups of the Right and Left were buying cheap revolvers. Underneath the surface of French life there was, said my friends, a smouldering fire.

There was no sign of that when the artist and I walked across the Place de la Concorde after dark. It was a scene of peace and astonishing beauty. It seemed as though Paris were illuminated for a day of triumph, though it was not so. It was lit with lamps which flooded the public buildings. The statues of the cities were touched by these fingers of light, dazzling white in that great empty space where few people passed at this hour. We stood looking into the Tuileries gardens. The grass was turned to a vivid emerald, and down the vista towards the Petit Caroussel and the darkness of the Louvre a fountain was lit by a light which made its water like leaping crystal.

“Magic!” said my artist friend.

But the most magical was what we saw from the bridge leading to the Chamber of Deputies, guarded now by armed police. It was Notre Dame, flood-lit and perfectly white, with its tall towers and spire and pinnacles and gargoyles clear-cut against a velvet sky. It was dreamlike in its beauty—a cathedral of light in a city of enchantment.

We walked up the Champs-Elysées to the Arc de Triomphe. The business world has moved that way in Paris, away from the Boulevards where the best shops used to be. Under the Arc built to commemorate Napoleon’s victories a little flame was leaping, seeming to go out now and then, and then rising again from some hidden fire. It is the Flame of Remembrance for those millions of young Frenchmen who fell in the World War. The traffic surged round it unceasingly, and it was too rash an adventure to walk across the wide space, through that circling tide of motorcars and taxis, to get near the shrine. We stood watching it from afar. No hat was lifted, as far as we could see, because of that leaping flame and its message of the dead. The taxis hooted. Humanity went on its way to drink its vermouth or meet its women. Even the flame was dimmed by brighter lights down the Champs-Elysées advertising automobiles de luxe.

I became friendly with a man of early middle age in the hotel behind the Madeleine. He was a handsome man, with the warm complexion of a southern Frenchman, and very bright vivid eyes in which an inner fire shone. We had a talk in a salon furnished in the style of Louis Quinze, with faded tapestries and gilt-backed chairs, a little tarnished. In the same room a young man was talking earnestly to his mother-in-law who seemed to be annoyed with him, as I overheard. My new acquaintance with the vivid eyes was anxious to tell me about the political situation in France, but dropped his voice and looked round watchfully now and then across his shoulder.

“Monsieur,” he said, “you must understand that what happened on February the sixth in the Place de la Concorde was due to the indignation of respectable people with the disgusting immorality of a government which is entirely composed of assassins, thieves and charlatans. They have betrayed those who fell in the war, and those, like myself, who have survived the war. They are essentially corrupt. They sell France to forgers and robbers like Stavisky. They weaken France so that Germany becomes arrogant again. They paralyse all government by political intrigues for personal gain. The situation, monsieur, is intolerable. It must be changed. There are young men in France, and men not so young, like myself, who intend to change it.”

“In what way?” I asked. “What is the alternative?”

His vivid eyes looked straight into mine, and I saw the fire of fanaticism in them—a dangerous fire always, and one which alarms me.

“Nothing can save France but the return of the Monarchy,” he told me. “I am a Royalist, as I am proud to affirm. I was in the Place de la Concorde with the Camelots du Roi, who are all Royalists, as you know. With us were the young men of the Croix de Feu, not Royalist but strongly on the Right. Our movement is spreading rapidly. Everyone who believes in the ancient traditions of France, in its need of discipline, in the vital necessity of cleansing up this gang of ruffians who are now in power, is advancing towards the monarchical idea.”

“In the provinces?” I asked.

That question checked him for a moment. He thought within himself before answering.

“The provinces remain aloof,” he admitted. “They are tainted by a tradition of so-called democracy. They are more interested in beetroots and turnips and the market price of pigs. But it is Paris that counts. It is Paris which has always led the way. In Paris we make the revolutions which the provinces accept, as history tells. They will accept a king when he is crowned in Notre Dame.”

“The Duc de Guise?”

“Certainly! He is the legitimate King of France. We acknowledge him.”

He glanced over his shoulder again at that young man who was having earnest conversation with his mother-in-law.

“All this is a little dangerous,” he whispered. “Excuse me.”

He bowed to me politely and departed with his Royalist faith and hopes, leaving me much interested by his conversation but convinced that he exaggerated the Royalist feeling in France and the number of its adherents. Everything he had said was a paraphrase of leading articles in L’Action Française, which I read in my little bedroom, with the noise of traffic surging like an endless tide below my window. I did not believe then, and I do not believe now, after talking with many citizens of France, that the Duc de Guise will ever be crowned in Notre Dame.

It was outside Notre Dame that my artist friend made his first sketch, with a demi-blonde at his elbow, on the table of the terrasse at a corner café. I watched the faces of the passers-by, these types of Paris, going on their business—students from the Latin Quarter, shabby and ill-shaved; neat little shop girls with high heels tapping on the pavement; huge-shouldered fellows from the meat market; sallow clerks; young soldiers in horizon bleu; agents de police; old men stooping to pick up cigarette ends; and an endless stream of middle-class folk of no special costume or character which might fix them in any category. All their faces, I thought, looked anxious and strained, without gaiety, unless my imagination was falsely at work because of that tragedy in the Place de la Concorde. Paris was not amused just then with political, private, or world affairs. Business was bad, I was told a score of times. Once the most cosmopolitan city in the world, getting great wealth from its visitors, it was now without a tourist traffic. The artist and I had walked the whole length of the Rue de Rivoli—once crowded with our race—without meeting a single man who was obviously English or a single woman whom we could tell as our own. Amazing that! Gone were the boys who used to wear plus fours in the capital of civilisation, as though it were a golf course. Gone were the harassed patrons of cheap tours. The seller of unpleasant postcards edged near to us with his well-known leer, but slunk off at the scowl of an artist who is one of our bulldog breed. Business was bad for such exploiters of vice and the purveyors of meretricious pleasure. Night life in Montmartre had died.

PARIS

The cabarets were empty. An occasional American, keen to see the sights, sat alone listening to jazz music, wailed at him by a starving orchestra. All other kind of business was languishing. The jewellers’ shops in the Rue de la Paix saw only the noses of people who gazed at their glitter through plate-glass windows. Nobody was buying jewels, real or artificial. The modistes were bringing down their prices but not doing well. The middle-class Parisian was groaning under taxation, direct and indirect, which skinned him. He took no comfort in the fact—denied it indeed—that taxation is heavier in England. “La vie coûte cher,” he answered to any inquiry about the cost of living. “C’est effroyable.” And things had gone wrong in the government of his country, more wrong than ever perhaps since 1870. The Stavisky scandal had been a dreadful revelation. It was a profound shock to every honest Frenchman. It hurt his pride. It was the cause of fear. They had had no idea that things were as bad as all that. Then happened that shooting in the Place de la Concorde. A horrible crime! A new sensation was the murder of a judge named Prince—certainly a murder connected with the Stavisky crimes to hush up evidence against high personages. Every edition of every newspaper caused another shudder in the soul of Paris. I don’t think I was wrong in thinking that the faces of these Parisians, passing the corner café opposite Notre Dame, looked anxious and strained.

I went into the Cathedral. It was cold and quiet there. All these transitory troubles, these passing anxieties, assumed a different value inside that old shrine of history. It is strangely bare of memorials, unlike our Westminster Abbey, overcrowded with statues, and monuments, and tablets. It is stark in its austerity. But it is thronged with ghosts for those who remember history—the ghosts of all French life since the beginning of its glory. How many tears have been shed here by women whose names are like a lovely litany in the pages of French history books! How many crimes have passed through the brains of men standing here before the altars! How many cries for pity, for pardon, for the help of God, have been uttered here in aching hearts when France was unfortunate in war, when enemies were at her gates—no more than twenty years ago—when many sons of France lay dead on many fields! All the characters of Dumas came here—the Valois, princesses of Burgundy, and Henri IV, to whom Paris was worth a Mass. Ronsard stood here behind a pillar and watched the fair necks of pretty women. Victor Hugo stared up the high nave and peopled it with strange company. Marie Antoinette prayed here, knowing that Terror was creeping close. A host of genius, loveliness, gallantry, villainy, has passed between these aisles into the ghost world. . . . Outside the doors beyond this quietude there seemed to be trouble brewing again in this city, where human passion has fought so often behind barricades.

But there is always intelligence at work in single minds that stand aloof from the conflict. Paris has many philosophers in all her classes. One of them was down there below the Pont Neuf with a long fishing rod. L’Action Française might use up the language of vituperation, boys might march against the Chamber of Deputies and get shot on the way, but it is fine to fish in the Seine and to think of the folly of men. So I saw Frenchmen fishing during time of war when the Germans were very near Paris, and again, in Arras, when they were no more than four and a half yards away from the Maison Rouge which was held by the French, who received me politely, in a drawing room with plush-covered furniture, and let me look through the sand bags at the windows. The French are great fishermen.

I came in touch with French intelligence along the quays where the artist, having finished his sketch of Notre Dame, lingered over old books and old prints. He had found many a good thing at these bookstalls in the long ago—original sketches by Forain and Steinlen, sold for a few francs and now priceless.

I spoke to one of these book vendors who was arranging his stall.

“Did you see anything of what happened on February the sixth?”

Yes, he had seen most of what happened. It was not amusing.

He was an ancien combattant. He had hoped never to hear another shot, especially between his own people.

He was a middle-aged man, with a face tanned to the tint of old leather by this open-air life along the quays. He had a straight look in his eyes, and the nose of a Norman ancestor. When I asked him about the feeling in Paris and the spirit of the young men he took time for thought. One cannot sum up the spirit of a people or of a city without a moment’s reflection, and perhaps not then.

“Ninety-nine per cent of the French people are moderate,” he said. “That is my opinion. That is my experience. The danger comes from the two extremes who are in a small minority but make a lot of trouble. But France, in my judgment, will stay a long time in the middle. People talk more than they mean. Words are cheap. Socialism in France is not fanatical. It is not revolutionary. It represents the liberal-mindedness of the great majority, a little to the Left, but not too much to the Left. The Communists exist. In Paris there are numbers of them, but they too talk words which, mostly, are meaningless.”

“What about Fascism?” I asked him. “I am told that many young men in Paris are really Fascists, though they call themselves by different names, such as Royalists and Young Patriots.”

He dusted one of his books and placed it back carefully.

“Youth wants to take charge,” he said. “It wants to wrest power from older men. It’s impatient. Can you wonder? It’s a hard time for youth nowadays. There is much unemployment. The high cost of living keeps them poor, without much margin for amusement. They have many anxieties and sometimes a sense of anger. Over there—” he pointed to the Latin Quarter—“there are many young men who have to study hard without much hope. They do not always eat enough. I know. I talk to them.”

He told me that business was bad for books. Many stared at his store and dogs-eared them, but did not buy. His American customers had disappeared.

“One day they will come back,” he said hopefully.

He was silent for a few minutes, moving to arrange another pile of books. Presently he came back as though he wanted to say something else.

“The problem of life is always difficult, monsieur! In every age, no doubt. There is always change, and it makes trouble. It is hard to adapt oneself to change. Things get broken. Hearts too, sometimes. But life does not remain stationary. One must have change, unless there is death. Youth moves on to new ways. We older men don’t like it. We are afraid, perhaps. We suffer. But that is life, is it not? So in France now there will be changes. Youth will insist. There will be more trouble. But I assure you we are a moderate-minded people. We desire peace and order. We are not fanatical. Good-day, monsieur.”

I set down his talk exactly as he spoke. It seemed to me very wise and very true. He stood, down there by the Seine, for the common sense of France in middle age and in middle-class Paris. I respected him.

“La vie coûte cher,” say the French housewife and the French hotel keeper and the French peasant. That is true, especially to an Englishman who has exchanged his money into francs at a heavy discount.

That hotel behind the Madeleine was quite expensive for a small place. At least, a pound a day is not too cheap. And one could not lunch or dine, I found, at a place like the Cheval Pie or the Restaurant de Père Louis—one of those Normandy kitchens which are very popular in Paris now—under twenty-five francs, which amounts to six shillings or thereabouts. But one can still feed cheaply in Paris, if one looks about on the Left Bank for a place where students ease their hunger of body, if not of soul. The artist and I found such a place in the Rue St. Jacques. It was called La Belle Etoile—an attractive name—and it advertised, very plainly for passers-by to see, that déjeuner, of three courses including wine, was 5.75 francs.

“One and fourpence halfpenny. Not beyond our means!” said the artist, who was all for doing things cheap and leading the simple life.

A party of students sat at the next table outside this restaurant. The girls were hungry and studied the menu with care to find how much they could eat for five francs seventy-five. So did we. It seemed to be an admirable menu, of ample nourishment. But there was a snag somewhere. From the students’ table we heard an ominous word uttered at intervals by a good-natured waiter with a not-too-white apron to protect his black suit.

“Supplément, mademoiselle!”

“Mais, comment donc! Qu’est-ce-que vous voulez dire avec ce sacrè supplément?”

We met that snag early and often. My friend ordered petits pois, for which he has a passion.

“Supplément, monsieur,” said the waiter.

It was a supplément of twopence-halfpenny for petits pois. The same for choux-fleurs. The same again for pommes frites.

“To hell with all suppléments!” said my friend who has the soul, but not the face, of an artist. “I’m going to feed for five francs seventy-five.”

We stuck closely to the carte du jour, and with admirable results. It was a satisfying meal, including a quarter of wine for each of us, which, I swear, tasted like wine. It was as good a meal as afterwards, in reckless mood, we had at an expensive restaurant which nearly wrecked our financial programme. And we had excellent conversation with the waiter, who was a man of wit, good-humour, and sound ideas. When called upon to cut up the meat for my friend because of that smashed arm, he was quick with sympathy and consideration.

“You were then wounded in the war, monsieur? I also, but more lightly. It was not very amusing, that war!”

“Oh, I don’t know,” said an artist who was also a soldier. “It had its moments. Not a bad war! Any chance of another?”

He spoke in English, having the theory that any foreigner can understand his way of speech. The waiter laughed heartily, suspecting a joke from the humorous eyes of his customer. I interpreted the question, and it excited our little waiter and made him eloquent, to the annoyance of a student waiting for the blanquette de veau.

“Another war, messieurs? Do not think so! There will be no war if France is asked. Let me tell you what I believe and know. I tell you not only as a waiter in a restaurant but as an ancien combattant de guerre with many comrades. If a vote were taken—what is called a plebiscite—the whole of the French working class would be against war, for any reason, I wish you to understand. I say for any reason. There would be revolution first. . . . Excuse me, gentlemen, a moment.”

He was being hailed by the young man impatient for his blanquette de veau. One of the women students consulted him on an item in the menu, to which he answered with a familiar phrase.

“Supplément, mademoiselle.”

He came back, smoothing down his not-too-white apron, and I asked him whether there was much Communism in Paris among the working classes and the factory hands. There had been Communist riots following the shooting in the Place de la Concorde.

“Negligible!” he answered. “French Communism is not dangerous. It is on the lips only. Naturally, a few groups have scuffles with the police now and then and loot a few shops. That is their way of amusement, like your English football. All Frenchmen are, of course, critics of the government. It is our privilege. It is a tradition. I am myself a talker and a critic of the government. We read too many newspapers. That is a bad habit because the newspapers exaggerate everything. Those journalists, messieurs! Sacré Nom! Those journalists who make up lies and stir up hatreds and create false views of life! They are the cause of much evil in the world. Without them we should not hear so much about a war which they do their best to bring about.”

The artist was in cordial agreement with the waiter. He was in favour of shooting quite a number of journalists in every country pour encourager les autres.

Our waiter talked largely on life. And life passed down the Rue St. Jacques as we sat at the little table of the Belle Etoile. A loud speaker was giving forth noise—the shriek of a soprano singer—an evil innovation of Parisian life. Some nuns were escorting a procession of young girls dressed in white for their first Communion. I noticed how many coloured men were loping past our tables. Every minute or two one of these darkies went by. France has broken down the colour line, and North Africa is invading Paris—to the horror of the Germans who believe in Nordic blood for Europe. . . .

We ended a pleasant meal—sans supplément. It was worth one and fourpence halfpenny.

That afternoon we took the Métro to the Buttes de Chaumont, a place unknown to English tourists but interesting. It lies on the outskirts of Belleville and La Villette, the working-class quarters. The Butte de Chaumont is a small park in which there are several little conical hills from which one has a view over Paris. In the old days Forain and Steinlen, those great artists, used to come here to get their types of working folk and the squalid comedy of the poorest quarter. In their sketches frowsy women nurse their babies at the breast, and the children of poverty play about among grotesque types of ragged humanity. Under the bushes young sluts from the stalls in La Villette fondled their lovers from the meat markets and flea-infested tenements. My friend has some of these sketches, as I have said, and he looked round for the same types. They had gone. Some change had happened. Something had lifted from the life of the French working quarter—its squalid ugliness, its filthy poverty. The people in the Butte de Chaumont were like those one sees in Battersea Park. There were no ragged children. The mothers with their babes were neatly dressed, with stockings of artificial silk. Forain would not have known them.

We walked through Belleville. It was not always safe to walk through Belleville in the old days before the war. It was the home town of the apache. Now it is as safe and respectable as the Rue de Rivoli. Great gaps were being torn out of old streets, and new houses were going up. Here and there did I see bits of old Belleville as it existed before the war—seventeenth-century houses with blackened walls, courtyards overgrown with weeds or littered with refuse, wooden staircases, broken and unsafe, leading to rooms with dirty mattresses bulging through their windows for an airing. In the Rue de Belleville some of the old shops still stand. Jews were selling second-hand clothes. But the working classes in Paris, as well as in London, have reached a higher standard of life, in spite of the world “crisis,” and unemployment, and the cost of living.

We paid a surprise visit to Mr. and Mrs. Yellowboots and little Malvina, their daughter. Yellowboots, who has another and Russian name, was so called because he appeared, after frightful adventures in a war and revolution, in a pair of boots of that striking and attractive colour, and a suit of clothes hanging loosely about his body, which had shrunk in times of privation and peril without destroying his gift of laughter or the soul of an artist in him. He is one of those thousands of Russian refugees who have found a home and some kind of work in Paris, which has been kind to them. His wife, who is also an artist of great talent, was pleased to see us. Little Malvina gazed at us with wonderment and listened to our talk with big eyes in which a smile lurked. Yellowboots appeared later, having heard on the telephone of our arrival. He had a bottle of wine under his arm for our entertainment, but he nearly smashed it when he embraced my friend with cries of delight and kissed him a score of times on both cheeks.

“No more of that fondling!” cried my friend, pretending to be embarrassed, but inwardly delighted by this loving welcome.

We drank the wine, after raising our glasses and calling down blessings. We went on our hands and knees to look at the latest masterpieces by Yellowboots, who designs the most exquisite patterns for silk and other fabrics. At frequent intervals Yellowboots desired to kiss my friend’s bulldog face. We laughed for no reason at all, except this reunion of friendship. And then, later in the night, Yellowboots became serious and talked of the state of things in France—his adopted country. He was anxious. He didn’t like the look of things. That tragic happening in the Place de la Concorde had been a great shock. There were forces at work which were moving towards conflict. He had been through one revolution. . . .

I called on a French friend, who is famous for many books written with exquisite style and careful scholarship, to which he adds wit and irony. I had already notified my visit by telephone and had frightened him by asking him to tell me his views on the situation in France. He admitted his alarm when he held out his very thin and delicate hand.

“I am not a politician!” he said. “I know nothing about politics!”

I reassured him and glanced round his room, which is elegant.

“You are a philosopher,” I told him. “You know what is happening in the minds of men and women. Tell me what is happening in the French mind.”

He made a little grimace of amusement and then sighed.

“There are many minds,” he answered. “None of them thinks alike. One cannot say France thinks this—France thinks that.”

He handed me a cigarette and curled himself up in a deep leather chair, with one hand, so thin and delicate, over the arm.

“It is true,” he said presently, “that things are happening in the minds of France and especially in the younger minds. It’s inevitable that the younger men should become impatient with the Parliamentary system. They are touched by the same impatience which has led to some form of Fascism in other countries. They don’t like what is happening in Germany under Hitler, or in Italy under Mussolini, but they are inclined, here in Paris, to adopt the same methods of action, and to use sticks instead of votes to obtain decisive results in cleaning up the political situation. Everybody admits that it wants a lot of cleaning up!”

I gave him time to think things out. He went deep down in his leather chair. I almost lost sight of him.

“Paris has always been tempted towards dictatorship,” he said after that silence. “You remember the affair of General Boulanger? The present time is opportune for dictatorship—but no one exists. There is a great lack of leadership in France, due, no doubt, to the losses in the war. It’s the same in England, isn’t it?”

He explained the causes of contempt into which the French Chamber had fallen. The group system with its political bargainings to support or overthrow a government led to constant crises and unstable policy. The deputy had too much power, he thought. It put temptation in his way, and being ill-paid, he yielded.

“The power of the Executive will have to be increased,” he said, “in order to limit the independence and political corruption of the deputies. It’s the system which is at fault. It is the cause of corruption.”

He put one long leg over the arm of his chair.

“It’s not that French deputies are necessarily more corrupt than English members of Parliament,” he said. “But as Parliament cannot be dissolved in the English way they can’t be unseated and have a certain tenure of office. They have also more patronage in their hands. A provincial deputy is subject to constant pressure for jobs and influence. He’s hail-fellow-well-met in local society. He’s surrounded by sycophants eager for a place for their sons, their nephews, or their business friends. The patron of the café where he takes his apéritif shakes him by the left hand—nearest to the heart!—and whispers into his ear. Women surround him with flattery on behalf of their husbands, sons, or lovers. His patronage reaches down to the smallest provincial posts, and he likes to please the people who support him. Owing to the centralization of Paris the provincial deputy is the liaison officer between the provinces and the capital, so that rural France believes in Parliamentarism and feels itself in touch with the central government when a deputy returns to report on what he has done, or is pretending to do, for local interests.”

“Is there any real importance in the Royalist movement?” I asked.

My friend smiled from the depths of his chair.

“Royalism without a king, perhaps,” he answered.

Undoubtedly, he thought, there was a movement to the Right among young middle-class men, especially in Paris. They were disgusted with so many revelations of corruption in high places. The Stavisky affair had brought that to a head. They had been scornful of the Parliamentary system before then—like so many young men in Europe. They could not bring themselves to adopt the Fascist system or phraseology, but they were joining groups—La Jeunesse Patriote, La Croix de Feu, and so on, which called on them to rally in defence of discipline and order against the disintegration of the national spirit.

“The situation is undoubtedly serious,” said my friend. “There is an exasperation and bewilderment at the moment in the French mind. Some change will have to be made.”

On the last night in Paris, before we went motoring through France and countries beyond, the artist and I went up to the Dôme, where we had a rendezvous with Yellowboots and his wife Malvina. The novelist who was going to join us on the motor journey was also there with some of his friends. The Dôme at Montparnasse was an old haunt of my companion. He had known Kiki and many other models who, poor dears, had drunk too much absinthe there and had been too easy in their loves. He had known many members of his craft, who had come here in pre-war days with large portfolios holding the fruits of genius, which went begging in the market place until death brought dealers and many dollars. He had exchanged drinks with English and American art students who had called him “Uncle,” and laughed very loudly when he said, “Be your age, kid!” at some folly on their lips, or some confession of despair. He had watched with savage irony the antics of would-be artists, who posed for the public with long hair and La Vallière ties and dirty fingernails; and he had grinned at the simple tourists who came here to see the Vie de Bohème and thought these charlatans were marvellous. I also knew the crowd at the Dôme before the war, and afterwards, and must confess that I have seen the most poisonous collection of degenerates around the tables whom one might find in any city.

It was a fair evening, warm and light. Spring had come, and there were leaves on the plane trees, and a touch of ecstasy in the air of Paris, the most enchanting city except one, which is Rome, when spring comes. The traffic surged up the Boulevard Raspail, and from the direction of the Boul’ Mich’. Many tables were taken outside the Dôme. But I was quick to notice certain changes. Most of the people here were speaking French instead of American. It is very noticeable now in Paris that one hears people talking French. And the charlatans—those poseurs with long hair—had gone, swept away, poor wretches, by the brutal force of an economic crisis. Most of them perhaps had starved to death or had taken jobs in the Galeries Lafayette—serving out socks, instead of atrocities called Art. It was possible that they had cut their hair and cleaned their fingernails. There was no small boy selling dolls with limp legs and arms, for the cushions of American ladies who could afford to pay five dollars for one of these spineless creatures. The waiters had time to breathe, and there were empty chairs for late comers.

The novelist arrived, pleasantly excited by the thought of the journey ahead. He and the artist exchanged glances, like the touch of swords to try each other’s steel. Yellowboots and his wife were introduced, and I found my hand grasped by one of the novelist’s friends, a young Frenchman whom I knew already. He has a passion for England. He loves English people and English gardens and English weather—a proof that he is a very exceptional kind of Frenchman. The novelist raised his hand and smiled across the table, and I could see the glint of adventure in his eyes. He had another friend, whom he presented across a Grand Marnier. He was English, as I saw at a glance, with a good athletic figure and steel-blue eyes in a clean-cut face. I had heard of him. He controls a big organisation in Paris. He is a war-time flying officer who still pilots his own machine.

I sat between him and Yellowboots. Around us there was a buzz of talk and the clink of glasses and the traffic of Paris. Coloured lights gleamed across the pavement. Taxis circled round each other in the wild whirlpool. Somewhere a loudspeaker was blaring out jazz. Presently, of course, there was a street row. One can hardly sit for half an hour at any terrasse outside any café in Paris without seeing a street row. The crowd rushes out to see what happens. It interferes in any good quarrel. Complete outsiders argue fiercely on the merits of the case and sometimes fight it out. This was an arrest: some drunken fellow had been making a nuisance of himself and abusing an agent. He was resisting half a dozen agents. Some of the crowd were on his side. At least, that is what I guessed, without enough evidence to swear to facts. All very amusing! It is sad that one can’t sit down in London outside a café and watch life go by. In Paris there is no need of other amusement than to stare at faces as they pass; faces which are sometimes grotesque like a sketch by Forain, and sometimes very attractive, like a young man who went by the Dôme that evening. He was smiling to himself. A street lamp touched his profile. He had a little black moustache and Gascon-looking eyes. I knew him. It was D’Artagnan, back in Paris. A priest passed in his long soutane, not giving a glance at this crowd of ours. A Negro, with a long loose stride. Two lovers, with their arms round each other’s waists—a shop boy and his girl—as though they wandered in Arcady, though it was Paris by night with the hooting of the taxis. A body of young men in blue shirts—members of La Solidarité Française—marched along whistling. So they passed, old and young, sad and gay, haggard and anxious, ugly, commonplace, or good-looking—the faces of Paris.

Yellowboots was talking to me. We talked until it was time for bed. He was saying things worth attention. Before sleeping under a yellow silk counterpane in a small hotel with faded tapestries and gilt-backed chairs, I jotted them down.

“The French are obsessed by fear,” he said, in French, which is his adopted language. “That explains all their political actions. They are afraid of a new war which they believe is creeping close. It fills them with terror, that thought. They are the most pacifist people of any country in the world, but with this terrible fear in their minds they do the wrong things. It is like marriage. If there is no confidence between husband and wife nothing can be done but quarrel and make things worse. It poisons all their relationship. It’s the same between France and Germany, who ought to get on together. There is really no cause of quarrel between them. The Germans have given up Alsace-Lorraine. The Saar is bound to go to Germany. But it’s a paradox—a tragedy—that France will not believe in the possibility of peace with that neighbour and is helping to make war certain. It is not because they are militarists. There is no spirit of militarism in France. You will never see French children playing at soldiers or war games. Their parents forbid it. Anybody who was in the war is seized with horror at the thought of another. But they have this terrible obsession. They see Germany growing strong again, dynamic, more forceful than France. It is better organised. It is growing in numbers. One day, as every Frenchman believes in his heart, Germany will be ready to attack again. Meanwhile France is weakened by internal troubles. The French political parties—fiercely hostile—are becoming stronger. The younger men are recruiting. All the young men on the Right are arming against the Socialists and Communists, who are well organised and preparing for a fight. If it comes to a revolution it will be a bloody one. There will be barricades in Paris again.”

Somebody offered me a Cointreau. A group of students was getting noisy at neighbouring tables. A taxicab escaped a collision by a hairsbreadth. The artist was having an amusing time with Mrs. Yellowboots. The young Frenchman raised his glass and smiled into my eyes.

The Englishman on my right gave me his view of things. He had heard nothing of what Yellowboots had been saying.

“Unemployment is getting bad in France,” he told me. “They admit to over a million. It’s due to deflation, of course, exactly as it was in England before we went off the gold standard. They ought to bring the franc down to a hundred and ninety-four. With all their gold they could do it easily, with full control, so that it would not get out of hand. That would stimulate trade again and bring back the tourist traffic, without which they are going bankrupt in the big hotels and shops.”

I told him about my experience in the Butte de Chaumont, and he agreed that the standard of life among the working classes was now much higher.

“They resist any attempt to bring it down,” he said. “That’s going to lead to trouble.”

Without knowing what Yellowboots had said, he confirmed some of the views I had heard from that friend. Paris was in a state of nervous tension. Young men were buying cheap revolvers. Anything might happen if Doumergue lost his grip.

“They’re afraid of war,” he said. “They believe it’s coming.”

“Do you?” I asked.

He was thoughtful and answered after a pause.

“I don’t believe the Germans want war. I believe Hitler is sincere when he talks peace and offers friendship to France. That is the strong impression I brought back from Germany. But one young Nazi told me that they would fight for an ideal—equality, for instance—though not for possession. Of course, it would be easy to switch over to war, if something happened which they believed intolerable to their pride and race. An accident may happen.”

He had a theory new to me.

“The next war would be fought in the air, if it came, and for that reason I believe it’s impossible for Germany.”

He saw my raised eyebrows.

“They haven’t got the oil to fight a modern war in the air. They make it from coal, but that’s not enough.”

He hedged a little after that statement.

“Of course, it might be a quick business. Nobody knows what could be done by a swift, deadly knockout blow. A big attack on Paris would demoralise the whole city. They might not be able to stand the strain. They might scream for peace.”

“So might we! The air is an incalculable factor.”

My artist friend grabbed my arm.

“Time for bed! An early start tomorrow!”

The novelist promised to be outside our hotel at nine o’clock.

Yellowboots kissed the artist on both cheeks. They laughed with great amusement and affection on the curbstone beyond the Dôme.

“Bon voyage!” cried Mrs. Yellowboots.

The artist and I walked back part of the way to our hotel behind the Madeleine. The streets on the Left Bank were quiet. Paris had gone to bed in that quarter, except here and there where a lamp gleamed behind the blinds in some attic where a student read late.

I thought back to that conversation at the Dôme and to many things I had heard in Paris. It was obsessed with fear, they told me. Young men were arming. There was trouble ahead. The soul of this city was anxious, strained, restless, and divided by passion. There was no sign of all that as we walked through the quiet streets.

It was pleasant to leave Paris on a May morning for the open country, with a long journey ahead which would lead us to many places of beauty and ancient history, and across many frontiers, if we had luck on the roads. Our car was driven by a middle-aged man of great dignity who had been an officer in the French army. It was before the time of Gaston who appeared later, as I shall tell. We travelled light, with two bags apiece. On the rack was the artist’s sketchbook, with blank pages awaiting his pencil. The novelist excited the astonishment and admiration of France as we went on our way by a remarkable cap which he had bought in Italy. It was a white cap with a yellow peak of transparent celluloid, making him look like a yachtsman who had lost his yacht. I wore a béret which gave me a French touch, I thought, though nobody else did. The artist was determinedly English in a mustard-coloured suit crossed by brown lines at distant intervals in a chessboard pattern. We were in good spirits at the prospect of our future wanderings. We still had some English tobacco. All was well.

We left by the Porte d’Italie, after driving down the Rue des Gobelins. The old ramparts defending Paris had been demolished in 1922, useless as a defence against modern gunfire; but the city still ends abruptly where they stood, and beyond there is only a straggling line of wooden huts and sheds and the untidiness of rubbish heaps before the road stretches out to the fields and farmsteads. It was one of the long straight roads of France, built first by the Roman legions marching through Gaul. It was bordered by tall poplars, and away to our left the Seine made its way through the valley, with gentle hills in the distant haze.

We passed La Belle Epine, where there is an old coaching house at which the postchaises changed horses before the days of motorcars. The kings of France stopped here also, for the same reason, on the way from Versailles to Fontainebleau, with their mistresses and their favourites and their concourse of courtiers. There was a great blowing of horns and jangling of bits and spurs and swords. There was a kaleidoscope of colour, as gentlemen of France in silks and velvets swept off their feathered hats to ladies of great loveliness and easy laughter, who might whisper a word on their behalf to the bored-looking man who fondled them if he liked their allurement. All gone now!—kings and coaches and courtiers and pretty ladies. Our car sped by down a lonely road.

At Orly there is a big aviation camp, military and civil, with an immense hangar which was built for a Zeppelin captured from the Germans. At Ris-Orangis—queer name!—there used to be a post for diligences. Now there is a home for old and broken actors, at a time when so many theatres are half empty in Paris, partly perhaps because of four tall masts we passed beyond the village of Juvisy—the most powerful broadcasting station in France. At Essones the fields were strewn with gold, and in the cottage gardens lilac trees were in bloom, drenching the air with a sweet scent. At Plessis-Chenet the chestnut trees had lit their candles. Peasants were bending over the earth—those French peasants who are forever working from dawn to dusk, scraping, weeding, ploughing, reaping. We were in rural France beyond the restlessness and roar of the great city.

We were in no hurry. We were not going to rush through France like speed maniacs. We halted often by the wayside, and the artist would pull out his sketchbook and get busy, while I wandered round to talk to any human being who might be in sight, or now and then attempted a sketch of my own under the guidance of a master who could teach a man without hands to draw with his feet and make something of it. The novelist was not to be beaten. Later on his journey he bought materials—sketchbook, chalks and pencils—watched how the trick was done, became absorbed in this pursuit, and produced some very creditable efforts, startled into excited laughter at his own success. They were good hours. What more does a man want than to sit in a field of France with larks singing a silver anthem incessantly in a cloudless sky, with the air perfumed by a myriad flowers, and a little talk now and then on art and life? Now and then we wanted something more! A long drink of cold French beer—that was easy to get in any village—or something to stay the pangs of hunger. Bread and cheese were good enough, and often we ate it on the wayside.

We halted in a field outside Barbizon. It was the field where Millet painted his Angelus. The scene has hardly altered. There was his background almost as he saw it—here and there a new roof or two—beyond those two bowed figures, so simply and truly seen, without a touch of mawkish sentiment in their ugliness and beauty. But it was the novelist who first saw a signboard which spoilt the picture.

“Isn’t that too ghastly!” he exclaimed. “An outrage!”

The ghastly thing was an American advertisement for a roadside restaurant.

TUMBLE INN

AT ALF GRAND’S

OPEN AIR RETREAT

Real Food.

Mint Julep.

It was a relic of the days before 1929, when Paris was still the paradise of Americans, and the road to Barbizon was crowded with their cars. Now they too had gone, like the coaches and courtiers of the French kings. We were alone on the road to Barbizon.

We walked through the village with its old cottages and inns and flower gardens. Not much changed since Millet and Rousseau and Corot and other painters came to live here in dire poverty but fired by the flame of genius. Not much changed, except for a few restaurants for tourists, exploiting the fame of men who were paid beggarly prices for their work until they died, according to the rules in those days, and sometimes now.

We went into the studio of Rousseau—the painter and not the philosopher!—who died in 1867. It is next door to a little church with a wooden belfry and remains just as when he dropped his brush to die. On the wall was a charcoal sketch by Corot of a scene in the forest of Fontainebleau, and the well-known picture by Aimé Perret of the Return of the Harvesters. In this studio, I was told, that strange, alarming woman, George Sand, whose ugly face allured every man of genius who came under her spell of passion, first met Alfred de Musset, who became her slave and victim.

The artist was interested in the pictures, which I confess left me without enthusiasm because they seemed rather drab and dull. I had an interesting talk with the guardian, who was an Englishman in exile.

“Barbizon is in a bad way,” he told me with a laugh. “It is no time for art. Most of our artists are starving. They can hardly afford to buy their paints. The cost of a frame is beyond their means. Who is going to buy their pictures at a time when most people are having to economise on clothes and food? Why, even the peasants round here are all in debt and hardly able to carry on. They haven’t sold their last year’s grain. And there is no tourist traffic to keep up the inns and restaurants. It’s a treat to see you three gentlemen. Quite a crowd, it seems, after so much loneliness!”

He laughed as though he might be exaggerating the situation somewhat. Then he became grave again.

“France is having an anxious time. I hear a lot about it from my friends. But it’s the same everywhere in Europe, as far as I can make out. What’s going to happen? Something must be done, or we shall all be ruined. How’s little old England?”

I told him that little old England seemed to be doing rather better. We had come through our troubles rather well. There might be others ahead, of course—even worse.

I was sorry to hear sad things in the village of Barbizon. They spoilt its charm a little, and took the colour for a moment out of the wistaria which spilt its purple down whitewashed walls. It’s very rough on artists if they can’t afford to buy their paints! I wondered what I should do if I couldn’t afford to buy the paper on which I write so many words. “Starving,” said the guardian of Rousseau’s studio. Well, that no doubt was the language of exaggeration. I did not see any gaunt or hungry figures down the village street, and artists know how to feed cheap. Millet and his friend Rousseau lived on two francs fifty a day—equal to about two shillings in modern value. That included wine and lodging. I daresay they did very well and were not stinted in their wine. Money values have changed since then—and the prices of pictures, if they are done by dead men. Daumier, who painted here in Barbizon, was poor, like all his friends. Six years ago a collection of his paintings was sold for eight million six hundred thousand francs.