* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

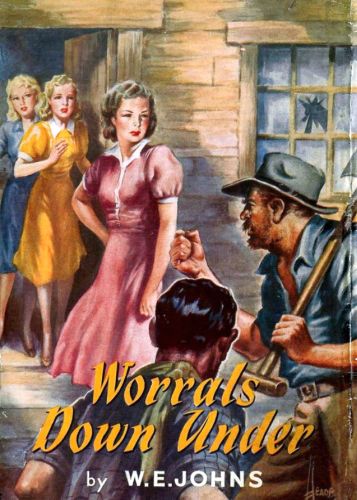

Title: Worrals Down Under (Worrals #8)

Date of first publication: 1948

Author: W. E. (William Earl) Johns, (1893-1968)

Illustrator: Reginald Heade (1901-1957)

Date first posted: April 13, 2023

Date last updated: October 13, 2023

Faded Page eBook #20230421

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

WORRALS

DOWN UNDER

by

W. E. JOHNS

LUTTERWORTH PRESS

LONDON and REDHILL

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

First Published 1948

To

Captain Duncan MacNiven, to whom I am

indebted for many of the details of the events

narrated in the following pages, this story is

respectfully dedicated.

W.E.J.

PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN

BY EBENEZER BAYLIS AND SON, LTD., THE

TRINITY PRESS, WORCESTER, AND LONDON

Contents

| Chapter | Page | |

| 1. | A Chance Encounter | 7 |

| 2. | Sundown at Wallabulla | 24 |

| 3. | Noises in the Night | 37 |

| 4. | Worrals Takes a Trip | 49 |

| 5. | Suspicions and Alarums | 72 |

| 6. | Reconnaissance | 94 |

| 7. | A Death at Wallabulla | 108 |

| 8. | Moran Pulls a Fast One | 120 |

| 9. | Shocks for Worrals | 134 |

| 10. | Moran Makes an Offer | 161 |

| 11. | Move and Countermove | 174 |

| 12. | Frecks Strikes Out | 189 |

| 13. | The Showdown | 200 |

| 14. | The End of the Trail | 212 |

“I always knew I should like Australia, and I was right. Of all the cities I’ve seen Sydney is the tops. It suits me fine.” Betty Lovell, more often known to her friends as “Frecks”, made the statement as one who speaks without fear of contradiction.

Her companion, Joan Worralson, one-time squadron-officer of the W.A.A.F., did not answer at once. She was looking across the street at a slim, neatly-dressed, fair-haired girl who was walking briskly along the opposite pavement.

“I say, Frecks,” she said suddenly, “isn’t that Janet Marlow over there—you remember, the girl who got the George Cross for keeping the station ’phones going that night at Hendon when we were blitzed? She was a flight officer, if my memory serves me correctly.”

Frecks’s eyes followed the direction indicated. “Good gracious! Yes, that’s Janet,” she confirmed without hesitation. “She looks different out of uniform, but I’m sure it’s Janet. I remember her saying something to me one day about going to Australia when the war was over.”

“Let’s have a word with her,” suggested Worrals, starting in pursuit.

After a few minutes’ sharp walking the subject of this conversation stopped and turned as a hand fell on her arm.

“Hallo, Janet!” greeted Frecks. “You remember me—Frecks Lovell? And Worrals? We were at Hendon with you that night Jerry came over and pranged the station good and proper—the night you did the show that put your photo in the papers.”

Janet smiled a smile of pleasure as well as of recognition. “Of course I remember you—particularly as the newspapers splashed your names more than once. What on earth are you doing in Australia?”

“What are you doing here, if it comes to that?” asked Worrals slowly, her eyes making a thoughtful reconnaissance of her war-time comrade. “You know, Janet, you aren’t looking too fit,” she went on frankly. “But why are we standing here? I think the occasion demands a minor celebration. How about a cup of tea?”

Janet hesitated. “Thanks very much, Worrals, but—er—as a matter of fact I’m in a bit of a hurry just now. I shall have to be getting along.”

Worrals’s hand closed firmly over her arm. “Oh, no you don’t,” she said softly. “You can’t get away with that. Who are you trying to kid? You’re coming with us for a cup of tea and a bite of something to eat. How long is it since you had a square meal, anyway?”

Tears came to Janet’s eyes. She did not answer.

“All right—hold it,” said Worrals shortly. “Let’s go somewhere and talk. Where’s the best place?”

“What about Prince’s?”

“Fine. Let’s go.” Holding Janet’s arm, Worrals started off.

“As a matter of fact, I have been a bit browned-off lately,” admitted Janet as they crossed the street.

“You needn’t tell us,” answered Worrals. “You’re not browned-off. You’re half-starved, my lady—that’s what’s wrong with you. Forgive me for being blunt, but that happens to be my unfortunate nature. Somehow I get along, though. Here we are.”

In five minutes they were in the restaurant, comfortably settled at a small table with a fairly substantial meal being served.

“What brought you to Australia?” Janet asked Worrals, who was pouring tea.

“I can satisfy your curiosity in a couple of sentences,” replied Worrals. “Frecks and I had an idea that we’d like to run our own airline: nothing very ambitious, you know; just a nice little private concern to keep us out of mischief. England was no use—the big companies have grabbed every run likely to show a profit; so we decided to have a look round the Empire to see what it had to offer. To make a long story short, finally we drifted here and, while we have nothing settled, I must say it’s the most promising territory we’ve struck so far. We like the country and the people, which is the main thing, and there are possibilities for those who, like us, have a little capital and don’t mind hard work. That’s all.”

“Did you bring a machine out?” asked Janet.

“No. We found air touring a bit too expensive,” returned Worrals. “There are plenty of good second-hand machines available should we find ourselves in need of equipment.”

Frecks looked at Janet. “How about you?” she prompted.

“And we’ll have the truth, if you don’t mind,” requested Worrals softly, as she refilled the cups.

“Oh, I don’t know. Mine’s a long story,” said Janet wearily.

“So what?” demanded Frecks. “We’ve got all day, haven’t we? Spill it. It’ll do you good to get it off your chest. We’re sympathetic listeners—aren’t we, Worrals?”

“Definitely,” agreed Worrals, smiling.

Janet shrugged. “I don’t see why I should worry you——”

“You’ll worry us far more by holding out on us,” broke in Worrals. “Go ahead. Take your time.”

Janet thought for a minute or two. “All right,” she agreed, “but don’t think I’m looking for help, or anything like that.”

“Fiddlesticks!” snapped Worrals. “Don’t be so dashed independent. If you’re going to beat about the bush, we shan’t get anywhere. Let’s get down to brass tacks. You’re broke, aren’t you?”

Again tears welled to Janet’s eyes. She nodded.

“You must have had a tough time,” murmured Worrals sympathetically. “All the same, you can’t go on like this. With G.C. tacked on to your name, you’ve got a reputation to live up to, you know. How did it happen?”

“I’ll tell you all about it,” decided Janet. “It’ll take some time.”

“No matter.”

“I’ll start at the beginning.”

“That’s always a good place to start,” agreed Worrals.

“It’s a year since I came to Australia,” began Janet. “I had a good reason for coming out—or I thought I had. But things didn’t work out as I anticipated—far from it.”

Worrals nodded. “That’s quite a common state of affairs.”

“I hadn’t much spare cash when I landed,” Janet went on. “It dwindled and dwindled, and finally gave out, except for a shilling or two, about a month ago. For the last week I have managed on a cup of tea and bun per day. I tried to find work, of course, but all I found was a lot of other girls looking for the same thing. You see, I’ve no real qualifications for a peace-time job. When you spoke to me I was on my way to cash in on my last available asset. I’d clung to it as long as possible, for sentimental reasons, but it was sell or starve.”

“What is this asset?” asked Worrals.

Janet opened her handbag and laid on the table an object about the size, and roughly the shape, of a hen’s egg. It was black, but in its heart there glowed and flashed like living fire all the colours of the rainbow.

Worrals was visibly moved by the sheer beauty of the thing, Frecks, more demonstrative, caught her breath sharply and cried: “What a glorious stone!—or is it a stone? What is it, Janet?”

“Opal,” answered Janet quietly. “Black opal. The finest opal in the world is found in Australia,” she explained. “This, I am assured, is something exceptionally fine, even for Australia.”

“Where did it come from?” asked Frecks.

“That,” replied Janet, “is what I’d like to know.”

“How did you get it?” asked Worrals.

“That’s the story I’m going to tell you, because, in a way, this is what brought me to Australia,” said Janet. “The tale begins a long time ago—in 1890, to be precise—when my Aunt Mary, then a young woman, and her husband, emigrated to Australia. Their dream of sudden wealth did not last long. In short, their experience was that of a lot of other people. I don’t know the details beyond the fact that they had a pretty thin time. Eventually they decided to go in for sheep. They acquired a piece of land from the government and ‘sat down’ on it, as they say out here. All this I learned in a casual sort of way from my mother before she died. In recent years, one by one, all my relatives died, so that, as far as I knew, Aunt Mary was my only living blood relation. Her husband died some years ago. Carter, his name was—John Carter. Curiously, perhaps, Aunt Mary always took a great interest in me. Maybe it was because she had no children of her own. I don’t know. All I know is, Mother sent her a photo of me when I was a baby, and as I grew up she sort of adopted me by post. She wrote me long letters, and was always talking of the day when she would have enough money to come home. Poor thing! It was very pathetic. In her heart she must have known that she would never see England again. That’s more clear to me now than it was years ago.” Janet stared for a moment at the tablecloth.

“She never complained of her lot, although it must have been grim,” she continued. “How grim it was, I have only just realized. She spent her life in a lonely, sun-scorched wilderness, ninety miles from the nearest white woman. Mind you, she wasn’t alone in that respect. A lot of women in Australia live that sort of life. I am quite sure my mother had no idea of these dreadful conditions, any more than I had until I saw the place. Perhaps pride made Aunt Mary refrain from saying how ghastly it was; or she may have been happy in her own way—who knows?” Janet poured out a fresh cup of tea.

“About seven years ago her husband died,” she went on. “With a blackfellow named Charlie, their only remaining servant, she buried him. Imagine what an ordeal that must have been! She stayed on at the so-called farm either because she had nowhere else to go, or because living there so long had made the place a habit from which she was too old and tired to break away. Anyhow, she stayed. The place, by the way, is called Wallabulla. She continued writing as before, but I had a feeling that she was getting near the end. It was all so hopeless.

“Then, in 1944, I had a most amazing letter from her. It came in a small parcel with this piece of opal. I’ll give you the letter to read in a minute. I’ve read it a thousand times, for reasons which you’ll understand presently. The gist of it was this. At last her dreams had come true. She had made her fortune—or, as she put it, she had struck it rich from the grass down. Thinking that I might be sceptical she sent me that stone to prove it. There were, she said, plenty more where that came from. She invited me to come out and join her in the fun of getting rich quick. What happened to her, she said, didn’t matter, because she had been to a lawyer in Adelaide and bequeathed the property to me in her will. While she was in Adelaide she had had the stone examined by an opal expert, who pronounced it to be of the very finest quality. She mentioned some other details, which I needn’t go into now. I was in the Service at the time, so I couldn’t do anything about it. Naturally, I expected to hear from her again, but I didn’t, and now I know why.

“When the war was over I packed my bag, put my rather slim savings in my pocket and came out. As soon as I landed I wrote to say that I was here, and how was I to get to Wallabulla? There’s no regular transport, of course—I knew that. There was no reply, so, after waiting about for a bit, I took a chance and set off for Wallabulla. It took me weeks to get there. An Afghan camel-driver, the man who delivers the mails in the region, took me over the last lap. When I got there and saw a comparatively fresh grave, I realized why Aunt Mary hadn’t replied. Charlie, the blackfellow, had gone. The place, a wooden shack that had been Aunt Mary’s home for most of her life, was deserted, abandoned.

“You can imagine into what a state of mind this threw me. All my plans came down with a crash. What was I to do? Well, I decided to stay—that is, if the lawyer confirmed that I had inherited the property. I went to Adelaide and saw him. Aunt Mary mentioned his name in her last letter. It was all as she had said. The deeds of the property were handed to me, and I went back to Wallabulla. Goodness knows why. I think I had some wild idea of trying to find the opal deposit, or, failing that, I thought I might run the place as a farm. I stayed at Wallabulla for three days. Then I came back to civilization. I haven’t seen Wallabulla since.”

Worrals raised her eyebrows. “Why not?”

Janet shuddered. “It’s a terrible place. You haven’t been here long enough to know what untamed Australia is like. For a start, imagine thousands of square miles of dreary, waterless wilderness. All that grows is mulga—that’s a shrub of the acacia family—and spinifex, which is a sort of spike-grass. It’s just a brown stony desert, with sandhills and rivers of sand, and ranges of hills, some of them volcanic with burnt-out craters. The heat is awful. They say that most of the middle of Australia is the bed of a dried-up sea, and I can well believe it. Actually, Wallabulla is below sea level.”

“But if there’s no water, how did your aunt live there?” asked Worrals.

“There’s a soak.”

“What’s a soak?”

“It’s a phenomenon that occurs in many of the waterless regions of Australia. It’s a depression where, by digging down a few feet, you come to water. The water is held in such places as it might be in a pan, by a clay bottom through which the water cannot pass. I didn’t mind that. It was the ghastly loneliness that got me, and, worse still, the noises at night.”

Worrals frowned. “Noises?”

“Moans, screams, and howls—frightful!”

“What makes these noises?”

“Nobody knows. Dingoes—wild dogs—may be partly responsible, I suppose. But the blackfellows say it’s ‘debil-debils’, spooks who inhabit the desert. All the same, I’m sure that no dog, wild or otherwise, made some of the noises I heard. I stuck it for three days and nights, then I bolted. Carrying a can of water, I walked to the railway line, ninety miles away, and stopped the train.”

Worrals shook her head. “You won’t mind my saying, Janet, that this sounds a pretty wild story, and a bit vague. Let’s try to sort the thing out. First of all, this letter that your aunt wrote to you. What exactly did she say?”

Janet took a much-thumbed letter from her handbag. “Here it is. Read it yourself,” she invited.

As Worrals unfolded the letter and glanced at the address she remarked: “I see she wrote this in Adelaide—not Wallabulla.”

“That’s right. She wrote it at the Post Office. I suppose she didn’t put a proper address, apart from the Post Office, because she knew she’d be gone before I replied. She probably stayed at a small hotel or boarding-house. Maybe she wrote the letter after she’d paid her bill and was on her way home. But that’s guess-work. What happened, I imagine, was this. After she and Charlie, the blackfellow, found the opal, she went off to Adelaide to have it examined by an expert. Having been told that it was the real thing, she made her will and wrote to me straight away. Then she set off for home.”

“I’m beginning to wonder what sort of chap this Charlie was,” put in Frecks.

“I’m sure he was trustworthy,” asserted Janet quickly. “He must have been a very old man, for she had mentioned him in her letters for years, and spoke most highly of him. She often said she didn’t know what she’d do without him.”

Worrals was reading the letter. “Pity she doesn’t mention the name of the opal expert she consulted,” she remarked. “If we knew who it was he might be able to tell us something. But she names her lawyer, fortunately. You saw him?”

“Yes. I found him a very nice man. As soon as I produced evidence of my identity, he handed me the relevant documents. He was most helpful.”

Worrals thought for a moment. “Poor old soul! She was determined that you should have the property. Then she went back to Wallabulla. She died, and Charlie buried her. I suppose that grave was hers?”

“I’m not certain, of course,” replied Janet. “I wasn’t likely to dig up the grave to see who was in it.”

“Of course not,” returned Worrals quickly. “I wonder what happened to Charlie.”

“After Aunt Mary died there was no reason why he should stay, was there? The lawyer told me it was almost certain that he’d go back to his tribe. They usually do at the finish.”

“If he’s still alive, and if we could find him, he should be able to give us some vital information—if, indeed, he couldn’t give us the answer to the whole mystery.”

“Yes, but what hope have we of finding him?” said Janet gloomily.

“Well, you never know,” replied Worrals cheerfully. “Tell me, Janet, is there any way we can get an idea of when Aunt Mary died? I mean, how long was it after she got back to Wallabulla? In what sort of a state did you find the house?”

“Pretty bad. It had obviously been empty for weeks, if not for months.”

“How big is this place, Wallabulla? I mean the whole property?”

“I don’t really know,” confessed Janet. “There are no fences. It seems to go on for ever. I had a walk round, but I didn’t get far.”

Worrals smiled. “No sign of any opals?”

“None.” Janet grimaced. “All I saw was gibbers, and there are plenty of those.”

“We shall have to learn to speak this language,” declared Worrals. “What are gibbers?”

“Round stones—water-worn, like those you see on the sea-shore. I saw some gypsum and mica. There are places where the desert sparkles with it. I didn’t know where to start looking for the opal. I had no clue. You see, opal is queer stuff.”

“In what way is it queer?” asked Worrals.

“Well, it’s unlike any other mineral or metal. Metals usually run in reefs, or lodes—but not opal. Nobody can say where opal is likely to occur. You just dig. It may be there, or it may not. Some men on their first trip stick a spade straight into enough to make them rich for life; others dig for years and find nothing. That’s the way it goes. Incidentally, ‘dig’ isn’t the right word. You gouge for opal. The men who make their living by finding it are called gougers. When opal is discovered in a certain locality, usually hilly country, the gougers make for the spot and dig holes, so that the place soon looks like a rabbit warren. Most of them live in the holes they dig. You can understand the fascination of it. There is always the hope that the next spadeful of dirt will uncover a thousand pounds’ worth of precious stone.”

“What is opal, exactly?” asked Frecks.

“I can answer that because, since I became interested in the stuff, I’ve swotted it up and asked questions about it,” answered Janet. “It’s a mineral, a crystal of silica, although it isn’t a crystal in the true sense of the word. It’s the only precious stone that can’t be made artificially. Those colours you see aren’t actually there. They are light rays. Somehow the spectrum is split by microscopic veins, and the brilliant colours are the result. If you burnt that piece on the table all you’d have left would be a little pile of grey limestone. Some opal is better than others. The price depends upon the quality. Black is the most valuable. It’s queer, fascinating stuff. It seems to mesmerize some people. They spend their lives looking for it.”

“And then lose their lives when they’ve got it,” put in Frecks.

“What are you talking about?” demanded Worrals.

“I always understood that opal was unlucky; that’s why a lot of people won’t touch it.”

Janet shrugged. “Other people say it’s lucky.”

“It didn’t bring your Aunt Mary much luck, did it?” remarked Frecks moodily.

“No, I must admit it did not,” conceded Janet.

Frecks shook her head suspiciously. “There must be something in it for such a superstition to start.”

“I’m told the Australian blackfellows are scared stiff of it; they associate it with their evil serpent gods. Don’t ask me why. Perhaps that was the origin of the superstition,” suggested Janet.

Worrals stepped into the conversation. “Just a minute, Janet,” she requested. “Who told you that the blackfellows are scared of opal?”

“Now I come to think of it, I read it in a newspaper article. Naturally, being interested in opal, I read anything about it. Why? What’s the point?”

“Only that this aboriginal fear of opal, this attribution to it of unholy power, may have a bearing on our case,” said Worrals. “What about Charlie? He knew about Aunt Mary finding opal—in fact, he was with her. What were his reactions? We don’t know. But in view of what you say, he may have been scared; he may have objected to her touching the stuff; he may have refused to handle it himself, or go near it. A scared native is capable of behaving in a way that would not occur to him if he were normal. I think that aspect is worth bearing in mind. As far as I, personally, am concerned, I judge the superstition about opals being either lucky or unlucky to be hooey. Absolute hooey. Never mind what the natives say. I refuse to believe that a piece of dead limestone can exert any influence on anything or anybody. Aborigines are the same the world over, once you get off the beaten track. Anything unusual is enough to put the wind up them. It’s always bad luck. They spend their lives dodging bad luck, with the result that, at the finish, they’re terrified of their own shadows. Let’s be intelligent. Show me a pile of opal, and I’ll risk taking it home.”

“Well, if it brings good luck to some people, maybe we’re among the lucky ones,” said Frecks hopefully.

“As I’m broke it’s unlikely that we shall have the chance of finding out,” put in Janet pessimistically.

“I wouldn’t say that,” disputed Worrals. “Actually, the thing boils down to this. You own a property, and on it somewhere there is a quantity of black opal—enough, presumably, to make you rich if you knew where it was.”

“Exactly.”

“What are you going to do about it?”

Janet made a grimace. “What can I do? I’ve no money, and even if I had, I don’t see how I could start off with a pick and shovel on the mere chance of finding a fortune.”

“Seems a pity,” murmured Worrals. “We haven’t unlimited money, but we have enough to go on with, and we have plenty of time at our disposal. I feel inclined to have a look for this treasure trove. It’s a gamble. If it came off, it would be more profitable than running an airline.”

Janet’s eyes sparkled. “You mean—you’ll help me to find it?”

Worrals looked at Frecks. “How do you feel about it, partner?”

“I’m crazy to start digging right away,” declared Frecks.

Worrals turned back to Janet. “Suppose we make it a business proposition?” she suggested. “We’ll finance the expedition and help you to find the stuff. If we strike lucky we split the profits three ways—that is, between you, Frecks, and me?”

“That sounds marvellous to me,” assented Janet enthusiastically. “Some kind angel must have sent you to Australia.”

“I doubt it,” said Worrals dryly. “If you asked me, I’d say it was my own restless spirit. But let’s be practical. We’ve got to get to Wallabulla.”

“It’s absolutely off the map,” warned Janet.

“Nothing is off the map for an aircraft, as long as there is somewhere to put it down,” stated Worrals.

“There are plenty of places at Wallabulla,” announced Janet. “In fact, you could land right in front of the house. It’s flat, sandy ground, with patches of dried-up spinifex.”

“Sounds easy,” replied Worrals. “We’ll see about buying an aircraft. I find myself growing more and more curious about this place, Wallabulla. For a start we’ll collect your kit, Janet. You’re moving into our hotel. We shall have to be together, because there are quite a lot of things I shall want to talk to you about.”

“Are you going to make the hotel our headquarters?” inquired Frecks.

Worrals looked thoughtful. “I don’t think so,” she answered pensively. “The place where we shall finish up sooner or later is Wallabulla, so we may as well push along right away and get our bearings.”

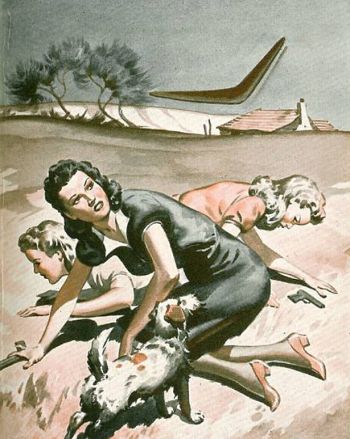

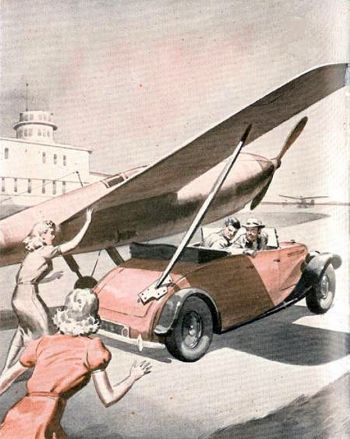

A week later, at four o’clock in the afternoon, a blue-painted aircraft, flying low, circled three times over Wallabulla before making a somewhat rocky landing on the rough but fairly level ground in front of the weather-bleached homestead. The door of the machine swung open, and from the aircraft stepped Janet, Frecks, and Worrals, in that order.

“There’s a lot of truth in the saying that many a good tune is played on an old fiddle,” remarked Worrals tritely, and she surveyed the machine with professional interest before throwing open the luggage compartment and lifting out several heavy bags. “This aircraft is as sound as the day it was built.”

The machine was, in fact, a Desoutter Coupé of ancient vintage, a single-engined cabin monoplane which, long before the war, had been popular for air-taxi work. Its advantages, as far as Worrals was concerned, were numerous. In the first place, on account of its age and low speed compared with modern machines, she had been able to buy it for a song—having satisfied herself, of course, that it was in good order, although, as it carried a Certificate of Airworthiness, there was no need to question this. A second advantage was that it provided seats for just as many passengers as were likely to require them—normally three, but four at a pinch, with accommodation for luggage. Another useful factor was an exceptionally wide undercarriage which greatly reduced the risk of overturning should a wheel strike an obstacle when landing away from a proper airfield. Again, the light engine was economical on fuel. As they were in no desperate hurry, speed was of little importance. As Worrals said, all they needed was transportation, so whether they travelled at a hundred or two hundred miles an hour didn’t really matter. Indeed, as the machine would probably be wanted to survey the territory, slow speed was an advantage rather than otherwise. Finally, the machine was quiet and easy to fly. In short, Worrals was well satisfied with her bargain, and she made a remark to this effect as she arranged the dust-cover over the engine.

“Let’s hump these stores over and have a look at this quaint residence of yours, Janet,” she suggested, picking up two heavy parcels and turning towards the homestead, a long, low, timber-built house with a rusty corrugated iron roof, the whole in a generally bad state of repair. No attempt had been made at decoration. It was evident that the building had been designed simply as a place to live in; just that and nothing more. There was no garden, no road, no path. The house stood stark in the wilderness, although a faint trail could just be discerned, leading away to the east, the direction of the distant railway line.

On all sides stretched a dreary sun-dazzled wilderness, dotted with the eternal spike-grass called spinifex, clumps of withered saltbush and occasional mulga shrubs. About fifty yards from the back of the house there was an area of reedy grass. This, Janet told them, was the soak from which water could be obtained, the water which made life possible, and was, of course, the reason why the house was there. The only other outstanding feature was a clump of sparse, stunted gum trees on a slight eminence to the left of the house. They formed a conspicuous landmark. These also helped to make the house possible, for from them had been cut the timber of which the building was constructed. Worrals observed that she would park the aircraft under these trees when not in use, as the shade they afforded would be some protection against the glare of the sun. To the north and west, in the middle distance, gaunt rocky hills rose sharply against a pale blue sky, unbroken by a suspicion of a cloud. In the intervening distance countless gibbers, the round water-washed stones of the dried-up sea, flung back the heat of the day. There were areas where the stones glistened with crystalline deposits. Not a living creature moved; not a bird of any sort, not an animal or reptile.

“You see what I mean about the place being lonely,” said Janet quietly, as, carrying their loads of necessary stores—“tucker” Janet called it—they walked on towards the house.

“Lonely!” exclaimed Frecks. “It’s worse than that. How anyone could live here for any length of time without getting the willies beats me. What sort of crops, or stock, did your Aunt Mary raise, anyway?”

“When her husband was alive they ran a few sheep, I believe,” answered Janet. “Towards the end, though, she lived mostly on dingo scalps. She mentioned that in one of her letters to me, although I hardly knew what it meant at the time. In her letter she says that she and Charlie were tracking dingoes when they found the opal.”

“I don’t get it,” announced Frecks bluntly. “What on earth are dingo scalps? Who wants them, anyway? What do you do with them?”

“The dingo is the native wild dog,” explained Janet. “He’s a cold-blooded murderer, who does an immense amount of damage among the lambs, for which reason the government has put a price on his head. To keep the numbers down, the state pays so much for each scalp—the scalp proving, of course, that a dingo has been killed. The reward paid varies in different counties, but it averages about a pound. The result is that some people earn a living by dingo-hunting. It isn’t easy. The dingo is a cunning beast, and it really takes a blackfellow to track him and hunt him down. Aunt Mary and Charlie used to go dingo-hunting. Charlie did the tracking and Aunt Mary the shooting. Somehow they managed to scrape a living.”

Worrals paused by two pathetic mounds of earth. One, obviously much older than the other, carried a small but well-made wooden cross at the head. The second one, with the earth still fresh, also carried a cross, but it was primitive in the extreme, no more than a rough bough with a twig tied across it.

“Those are the graves,” said Janet. “The one with the well-made cross is my uncle’s, I imagine. Aunt Mary must have made the cross. She lies in the other, having been buried, I suppose, by Charlie. It could have been no one else.”

“Poor souls,” murmured Worrals softly, and walked on. “By the way, Janet,” she continued, “you might have shut the door when you left.”

Janet looked up. “I did,” she asserted with some asperity. “I shouldn’t be likely to go away and leave the door open.”

“Well, it’s open now,” observed Worrals. “Either the wind blew it open, or else you’ve had visitors.”

They walked on.

Worrals and Janet arrived at the threshold together. Both stopped, looking into the room beyond, for the door opened straight into the living-room.

“Well, of all the——” began Janet, in a voice high with indignation.

“Is this how you left it?” inquired Worrals.

“Should I be likely to leave a house like this?” demanded Janet warmly. “What a pigsty! Someone has been here. Look at that!” She pointed at the table, which was a litter of dirty plates, cans, and empty bottles. The whole room was in much the same state. Cigarette ends littered the floor. Dust was thick on everything. All sorts of rubbish had been thrown into the fireplace.

“I left the place absolutely tidy,” declared Janet. “I put everything away. Someone has been here. I don’t mind that, but they might have had the decency to leave the house as they found it.”

“Some men are like that,” remarked Worrals philosophically. “No woman could leave a room in this mess. We’d better get busy and clean up before we do anything else.” She took off her jacket and rolled up her sleeves. “Let’s start on the cupboards so that we can put our tucker away.”

It needed two hours of hard work to put the house into a reasonably habitable condition. All the garbage was carried out and thrown in a pit which obviously had been used for the same purpose for years. The floors were swept, and the furniture, such as it was, dusted. The fire was laid and Janet fetched water from the soak. Worrals moved the aircraft into the trees. Preparations were then made for the night. There were only two bedrooms, one large and the other very small. It was decided to use only the large one, so in that the beds were made. By the time all this was done the sun was going down in a blaze of glory behind the western hills. Candles were put out ready for darkness.

Frecks went to the door to look at the sunset. Instantly she spun round with an exclamation of astonishment, not unmixed with alarm. “There are some men coming here,” she told Worrals tersely.

“Men?” Worrals, too, looked surprised.

“Three of them,” reported Frecks. “Two white men and a black. They’re carrying picks and shovels. They’re coming from the direction of the hills.”

Worrals frowned. “Is that so?” she said slowly. “I’m afraid we were a bit hasty in assuming that visitors had merely called here.”

“What do you mean?” asked Janet sharply.

“It seems more likely that they are staying here—or they were.”

“Staying here?”

“That’s what I said.”

“What a cheek!”

Worrals shrugged. “Maybe they found the house empty and decided that they might as well use it. If so, I’m afraid they’re going to be horribly disappointed when they discover that we’ve moved in. You’d better leave the talking to me.”

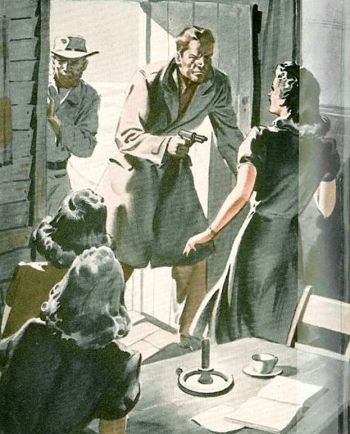

A few minutes later, as the last glow of sunset flooded the melancholy landscape with gold, heavy feet swished through the spinifex, and the men were at the door. There they stopped, staring at the new arrivals, their eyes wide and their expressions almost comical with incredulity.

Worrals considered the men dispassionately. As Frecks had said, there were three of them; two white men and a black. One was a stoutish, middle-aged man with red hair and a heavy moustache and rough beard of the same colour. Blue eyes were conspicuous in a florid, sun-tanned face, otherwise there was nothing remarkable about him. The second white man was an entirely different type. He was small, swart, and as lean as a desert rat. His hair was long and black. Like his companion he was unshaven, but the result was not so much a beard as a dark stubble below prominent cheek-bones. His eyes were dark, too, and deeply set. His expression was not improved by a livid scar that crossed his forehead to bisect the right eyebrow, lending to that eye a sinister squint. Both men were dressed as miners—rough shirts open at the neck, and dungaree trousers very much the worse for wear. If the white men were unprepossessing—and they certainly were, thought Frecks—they faded into insignificance when compared with the third man, the black, who wore only an old pair of shorts. Never could she have imagined, much less had she seen such a face. His nose was flat above enormous flabby lips. His lower jaw protruded to an abnormal degree. His hair, a filthy, tangled mop, hung down over brows that reminded her of a gorilla, an impression strengthened by his having a deep upper lip.

Worrals spoke first. “Do you want something?” she asked.

The red-haired man answered, resting on his shovel, although for a moment he appeared at a loss for words. “What are you doing here?” he demanded, in a hard, puzzled voice.

“I should be asking you that question,” returned Worrals. “You see, we happen to live here.”

“You—live here?”

Worrals nodded. “That’s right. By the way, are you the men who turned the place into a pigsty?”

The red-haired man frowned. Ignoring the question he asked: “Are you gals alone?”

“We are,” Worrals told him.

This answer seemed to puzzle the man still more. “What have you come here for?” he questioned.

“Surely people don’t have to give a reason for living on their own property?” said Worrals curtly.

“But you can’t stay here alone!”

“Indeed? And why not?”

For this the red-haired man apparently had no ready answer. “We’re living here,” he asserted, including his companions with an inclination of his head.

“You may have been living here, but you’re not living here any longer,” said Worrals firmly. “That’s quite definite,” she went on. “Who you are and what you are doing, I neither know nor care—but you’re not staying here. If you need water you can help yourselves at the soak; but you’re not coming into this house, and as it’s nearly dark you’d better start looking for new quarters.”

There was a short, rather embarrassing silence; then the dark man spoke—spoke with a curious accent that revealed that he was not British born. “For how long are you staying?” he queried.

“That’s something we don’t know ourselves,” replied Worrals. “It may be weeks, it may be months; but that’s no concern of yours, anyway, because, whether we are here or not, you have no right to break in.”

The two white men looked at each other. Then the red-haired man spoke again. “This place ain’t fit for girls,” he stated emphatically.

“We’re the best judges of that,” returned Worrals. “We’re staying, and that’s all there is to it. It happens to be our house, so let’s not have any more argument about it. Incidentally, you’re trespassing on this land, and you know it, so you’d better find some other place to dig.”

The red-haired man stared at Worrals as if he could hardly believe his eyes and ears.

Worrals met his gaze squarely. “I mean it,” she said, crisply.

The man stared a moment longer, and then nudged his companion. “Come on,” he said, and turning on his heel, followed by the others, he strode away into the gathering gloom.

Worrals walked over to the door to watch them go.

“That’s a nasty-looking bunch,” said Frecks, wrinkling her nose. “I’m glad to see the back of them.”

“If that’s what you’re thinking, you never made a bigger mistake in your life,” replied Worrals softly. “They won’t go far.”

“Why not?”

“Because, as you saw, they want to stay here.”

“But why should they be so anxious to stay here?” queried Janet, “They look like ordinary prospectors. Most prospectors are content to live in a bough-shelter.”

“That’s probably what they will do, now,” answered Worrals. “I fancy it is not so much the house they’re interested in as the whole property. If we live here, we shall be in their way; if only because we shall see what they’re doing.”

“But why should they be so interested in this particular place?” asked Janet.

“Obviously because they think there’s something here worth finding.”

Janet’s eyes opened wide. “They couldn’t possibly know about the opal.”

“Why couldn’t they?” Worrals’s manner was blunt. “How can you say that? You don’t know what they know. They’re not carrying picks and shovels for mere exercise, you may be sure!”

“But how could they possibly know?” persisted Janet.

Worrals shrugged. “Don’t ask me. Where’s Charlie? We don’t know. He knew about the opal. He may have talked.”

“I’d forgotten him,” admitted Janet.

Worrals drew a deep breath. “Those men know there is something here,” she insisted. “Their whole manner, and their reluctance to go, made that perfectly clear. Take it from me, they’re not just going to walk away because three nitwit girls have chosen to take up residence here. Oh, no! I’m sorry, but I’m afraid the presence of these men puts a very different complexion on our project. We’re in their way, and they’re bad types, all three of them. I’m beginning to take a different view of several things—your Aunt Mary’s sudden death and Charlie’s disappearance, for instance.”

“Good heavens!” Janet looked shocked.

“And what about your last visit?” went on Worrals. “I was always a bit suspicious about those noises that drove you away. I may be wrong, but I fancy I can see a hook-up there, too. We can’t be sure, of course, that these men are looking for opal; but if they are, then it would be a very strange coincidence that they should choose this particular spot. I’d like a little time to think about this.”

“But they’d never dare to hurt us,” said Janet nervously.

“They could do us all the mischief in the world without laying a finger on us,” returned Worrals in a hard voice.

“How?”

“One way would be by destroying or damaging our link with civilization,” answered Worrals. “We’re relying on the aircraft for food and stores. Without it, we should be in a pretty mess, shouldn’t we?”

“I didn’t think of that,” confessed Janet.

“I’m afraid we may have to do quits a lot of thinking in the near future,” observed Worrals.

“Do you think we ought to mount a guard over the machine?” asked Frecks.

“Not yet,” decided Worrals. “In the first place, we’ve no proof that these men are anything but what they appear to be. If they are, we shall soon know about it. If they have designs on this house, or the land, or the opals, for which reason our presence here would interfere with their plans, I doubt if they will resort to force to shift us until they have tried methods that would not bring them into collision with the law, should we complain to the police. Following the same line of argument, they will not interfere with the machine—yet; because—don’t you see?—if we were left without any means of getting away it would defeat their object. They would like us to go; of that we need have no doubt whatever; so they would be silly to sabotage our only means of transport. Later on, it may be a different story, but at the moment, nothing would please them more than to see the machine in the air, heading for where it came from. We shall see. In the meantime, there is no reason why we should starve. Let’s eat. This air gives one an appetite, if nothing else.”

“I should feel happier if I had a gun,” muttered Frecks, belligerently.

“Things haven’t come to that yet,” murmured Worrals.

“I noticed Aunt Mary’s rifle—the one she shot dingoes with, I suppose—in the store pantry,” said Janet. “It looked pretty ancient to me, but at a pinch it would be better than nothing.”

“We’ll bear it in mind,” said Worrals casually, opening a tin of bully beef.

Worrals said little during the meal. Observing that she was preoccupied, Frecks did not interrupt her train of thought at the table, but after the meal had been cleared and the crocks washed, she invited conversation by saying; “Well, what do you make of it?”

Worrals resumed her seat at the table, with her chin between her hands. “Until I saw those men it did not occur to me that this trip was going to be anything but a picnic—a picnic with an object, shall we say? I supposed that we should just potter about in our own time looking for opals. If we found some, well and good. If not—well, we shouldn’t lose anything, anyway. But now I have an uneasy feeling that we were treating the whole thing too lightly. There may be more in it, a lot more, than meets the eye at first glance. Things often work out that way when big money is involved, and there may be bigger money in this affair than we imagine.”

“Aunt Mary talked about a fortune, and I think she was too much of a realist to indulge in flights of fancy,” put in Janet.

“Exactly,” murmured Worrals. “When you said you had abandoned Wallabulla because you were scared of noises in the night, to be quite frank I thought you’d let your nerves run away with you. Not that there is anything to be ashamed of in that. Solitude has given men the heebiejeebies before to-day, and you were a girl on your own, without any experience of the Australian desert. Now I’m not so sure that your nerves did let you down. Really, it comes to this. You assumed, quite naturally, that Aunt Mary had said nothing to anyone about making a rich strike of opals at Wallabulla.”

Janet nodded. “Yes. I thought any sane person would keep a discovery of that sort secret.”

Worrals continued. “Aunt Mary probably knew as well as anyone that if the secret got out the usual human sharks would soon be along to grab what they could, particularly as they had to deal only with an old lady and a blackfellow. But she may have let the cat out of the bag, perhaps by a chance remark. The question is, did she? I can see now that so much would depend on it. Did she part with her secret? If so, where? To whom? Obviously it wasn’t here, because there was no one to talk to except Charlie, and he knew. It could only have been in Adelaide, when she was there. In view of what has happened here to-day, I feel inclined to run down to Adelaide and make a few inquiries.”

“Then you are definitely suspicious of these men?” interrupted Frecks.

“I am,” asserted Worrals. “These suspicions may be quite unfounded, but before we go any further we ought to know one way or the other, so that we can see just how we stand. Anything can happen in a place like this. I might pick up a clue in Adelaide.”

“How would you go about it?” asked Frecks. “I mean, where would you start?”

“Obviously, by calling on the people we know Aunt Mary spoke to when she was there. We know she talked to the lawyer. She may have talked to someone in the hotel where she stayed. She consulted an opal expert. For all we know, she may have talked, said more than was prudent, to some jeweller, or pawnbroker, or shopkeeper.”

“Why should she?” Janet asked the question.

“She sent you a piece of opal, didn’t she?”

“Yes.”

“All right. Let’s try a little logical thinking. It’s hardly likely that she would have sent you the one piece she possessed.”

“True enough.”

“Nor would she have said in her letter to you that she had struck it rich from the grass down on the strength of finding one small piece of opal. Surely it is reasonable to suppose that, having found one piece, she would promptly abandon dingo-hunting for the far more profitable pursuit of opal-gouging. The first thing any sensible person would do would be to ascertain the value of the discovery. The bare fact that she wrote that letter to you, and tore off to Adelaide to see her lawyer, suggests that she investigated her find and found it a rich one. Which means that she must have found more opal. Where is it?”

Janet looked hard at Worrals. “I didn’t think of that,” she said slowly.

“Well, I’m thinking of it—now,” rejoined Worrals. “I think we may accept it as certain that Aunt Mary found more opal, perhaps a lot more, than the fragment she sent to you. We’ve got to find it, or find out what she did with it. Either she kept it or she parted with it. If she kept it, she wouldn’t keep it lying about; she would hide it. And if she hid it, it would be somewhere in this house. She would keep only the piece which she took to Adelaide with her for expert opinion. If she parted with the rest, then it must have been to someone in Adelaide, because she went straight there and came straight back. Where else could she have sold it? If she sold that opal in Adelaide, the chances are that it would be to a regular dealer, in which case there should be a record of the transaction. If that is, in fact, what happened, we needn’t wonder how the secret of her find leaked out; and if the secret did get out, we needn’t wonder why these men are walking about Wallabulla with picks and shovels. At least, that’s how it seems to me. There’s only one snag. If she sold the opal, what happened to the money?”

“This is all getting very complicated,” muttered Janet moodily.

Worrals glanced up at her. “Things usually do get complicated when there’s a fortune in the offing. I’ve got an idea those men were already here when you came last time. In what sort of state did you find the house?”

“Rather the same as when we arrived to-day, but not so bad,” answered Janet. “I thought nothing of it then, supposing that Aunt Mary had been too ill to clean up before she died.”

“Those men were here,” declared Worrals. “They hadn’t been here long; that’s why they hadn’t got the place in such a mess. They must have seen you arrive, and decided to frighten you off as the easiest way of getting rid of you. They broke no law by doing that. It was all quite simple. They won’t find it so easy this time, though.”

Frecks opened her eyes wide. “Do you think they’ll try more tricks?”

Worrals smiled faintly. “I think it’s a certainty. They’ll try the same trick first. Why not? It worked last time. People always repeat an experiment that is successful—that’s where they go wrong. Sooner or later it lets them down. We shall soon know if I’m right. What sort of a night is it?”

Worrals went to the door, opened it, and looked out. Not a breath of air stirred. A young moon, a sickle of blue light, hung low in a sky bedecked with stars, some steady, some flashing like jewels. The earth was a vague, colourless expanse, that rolled away on all sides until it merged into the formless distance.

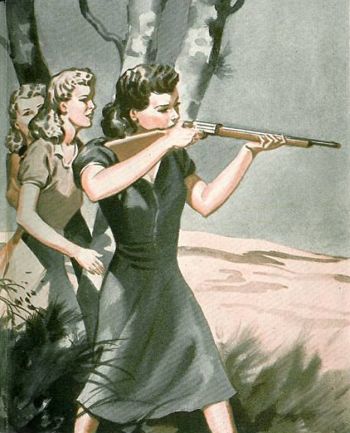

For a little while Worrals stood watching; then she closed the door and came back into the room. “Fetch Aunt Mary’s rifle, Janet,” she requested. “If any spooks start throwing their weight about to-night, we’ll see what effect hot lead has on them.”

Janet fetched the rifle and a handful of cartridges.

“There’s another point that has just occurred to me,” she said, speaking to Janet. “You say Aunt Mary’s lawyer made no bones about your taking over the Wallabulla property?”

“That’s right.”

“Did he just take your word for it that Aunt Mary was dead?”

“Apparently. He made me produce documentary evidence of my own identity, of course.”

“There seems to be something queer about that,” said Worrals thoughtfully. “Lawyers are not normally so ready to accept evidence of death on the mere word of the third party, particularly if that party happens to be a beneficiary under the will. I doubt if it’s legal, anyway.”

“He may have known Aunt Mary was dead.”

“Did you ask him if he knew?”

“No, we didn’t discuss it.”

“Was he surprised when you told him?”

“No, I can’t say that he was. He said he was expecting to hear from me, and after he had looked at my papers he took the will out of his safe.”

“And Aunt Mary’s death was sort of taken for granted?”

“Yes. You see, the order of things was this,” explained Janet. “Not knowing that Aunt Mary was dead, I went straight to Wallabulla. She wasn’t there. Nobody was there. I found the new grave, and assumed that she was dead. I can’t say that I was particularly surprised, because she was an old woman and her health was not good. It was then that I went to the lawyer named in her letter—Mr. Harding—and introduced myself. He seemed to take my word for it that Aunt Mary was dead.”

“Didn’t that strike you as odd?”

“No. After all, this isn’t England, where everything can be checked and cross-checked. Here, in a million square miles of out-back, they can’t verify everything. I imagine they often have to take the word of travellers about births and deaths. How can it be otherwise in a country where odd people—prospectors, for instance—are wandering about thousands of miles of practically uninhabited territory? Nobody knows where they are half the time. If a man dies of thirst, or by accident, as sometimes happens, his bones just lie there, or else the next man who comes along buries him. Later, months later perhaps, he reports that old Bill So-and-So is dead. That’s all there is to it.”

Worrals nodded. “Quite. I can see that now.”

“It was after seeing the lawyer that I came to Wallabulla, intending to stay,” went on Janet. “As you know, I didn’t stay long because I was scared.”

“You didn’t go back to the lawyer and tell him?”

“No.”

“You didn’t write to him and tell him about it?”

“No.”

“Why not?”

“Well, in the first place there didn’t seem any point in it. As I felt then, nothing would have induced me to come back here. He couldn’t do anything about it, anyway. Besides, think what a fool I should have looked, having to admit that I was scared of noises. He would have thought I was a complete nitwit.”

Worrals smiled, and then became serious again. “You told Mr. Harding that you intended coming here to live?”

“Oh, yes.”

“Then, as far as he knows, you’ve been here ever since?”

“I suppose so.”

“What was your impression of him? I seem to remember your saying that he seemed a decent sort of chap?”

“He was. I liked him. He was most helpful.”

“I may have a word with him——” Worrals broke off, stiffening to a listening attitude as, from outside, some distance away, a sound came floating through the silent night. It was a long-drawn wail that rose and fell like a cry of agony, until it ended in a choking sob.

Janet sprang to her feet. Her face had paled. “That’s it,” she breathed, in a tense whisper. “That’s the noise. Sometimes it’s far away, sometimes it comes close. There are other noises, too. Isn’t it horrible?”

Worrals looked doubtful. “I must admit it isn’t very pleasant, and I can well understand now why you were shaken,” she conceded. “Could it possibly be a dingo?”

“I don’t know. I’ve never heard one,” answered Janet, “Personally, I can’t imagine anything making such a ghastly noise.”

“Hark! Here it comes again,” said Worrals. She rose and, crossing the room quickly, opened the door. The sound was at once magnified.

“That’s enough to scare a platoon of V.C.s,” asserted Frecks in a thin voice, as the wail came sobbing and moaning across the wilderness.

“It doesn’t scare me as much as the wail of a falling bomb,” declared Worrals. “At least it doesn’t go off bang at the end.”

“The blackfellows say it’s the debil-debils who live——” began Janet.

Worrals cut in impatiently: “Debil-debils my foot! That tale may go down with blackfellows, but I, personally, have no faith in spooks, spectres, or what-nots. When I see one that can stop a bullet without flinching, I may change my mind.” She picked up the rifle, loaded it, and put some spare cartridges in her pocket.

“What are you going to do?” asked Frecks apprehensively.

“I’m curious to see how this baleful banshee reacts to musket balls,” answered Worrals in a hard voice. Then she smiled. “I may hit a dingo, and dingo scalps, according to Janet, are worth money. I’ll do the shooting; you two can do the skinning. If we can get enough scalps to pay our running expenses, that will be fine. If we have any luck, when I’m in Adelaide I’ll buy something a bit more up-to-date in the way of small arms equipment.” She moved towards the door. Looking over her shoulder she concluded: “Are you two coming out to watch the fun?”

“Fun!” snorted Frecks. “This isn’t my idea of fun.”

“Wait and see how our sortie turns out,” suggested Worrals, as she stepped into the darkness. The others followed close behind, Frecks closed the door behind her, and looked around.

The moon cast an eerie, unreal light across the arid plain, turning it into a grey lake in which little islands of spinifex seemed to move, to swim, like mist. Everything was exaggerated. The mulga bushes might have been haystacks or elephants. The clump of gums that housed the machine rose stark, like a monstrous medieval castle. The silence was uncanny, as of another world, a world from which all life had departed. It was, thought Frecks, an ideal place for debil-debils to haunt, and she felt a superstitious shiver run through her as the cry came again, a long gibbering wail ending in a sob.

“It comes from over there,” said Worrals in a low voice, pointing to a group of mulga bushes about two hundred yards away. “Let’s get nearer.” She walked on towards the gum trees which halved the distance, and there, leaning against a tree, the rifle half-raised, she waited, waited while the minutes passed slowly. For a time everything remained still, in a curious attentive hush. Then from the bushes burst such a hideous clamour of screams, shrieks, and groans that Frecks clapped her hands to her ears.

“Watch this,” said Worrals grimly. She raised the rifle, took aim at the bushes, and fired.

The report split the stagnant air like a thunderclap. Without waiting to see the result of the shot, Worrals jerked another cartridge into the breech and fired again; and this she continued to do until the magazine was empty, the bullets whistling and whining as they struck and ricochetted off the stony floor of the desert. Before the reverberations of the first shot had died away, the wailing stopped abruptly. At the fourth shot a dark, indistinct figure burst from the bushes, and sped away on a swerving course across the plain. When Worrals fired her last round, the figure turned at right angles, and a moment later disappeared from sight.

“Did you hit it?” asked Frecks quickly.

“No,” answered Worrals. “I didn’t particularly want to. We’ve no justification for killing a man, even if he was making a nuisance of himself.”

“You think it was a man, then?”

She waited while the minutes passed slowly. (Here)

“It wasn’t a dingo, and it certainly wasn’t a kangaroo, so what else could it have been but a man?” answered Worrals. “No white man could run like that; nor could a white man make such an appalling din unless he were raving mad. I fancy it was the blackfellow companion of our two white visitors. No doubt they put him up to it. I’ll bet my first shot startled him more than he startled us. That was something he didn’t expect. When he broke cover, running like a hare, he was bent double; that’s why he looked such an odd shape. Well, I don’t think we shall have any more music to-night; we might as well go home.”

They returned to the house. Worrals stood the rifle in a corner, and resumed her seat at the table.

“That’s that,” she said calmly. “If that howling humbug was the aboriginal companion of those fake prospectors, we may take it that they’re up to no good. There could only be one reason for to-night’s performance. They were trying to put the wind up us, as they scared Janet when she was alone. In simple words, they want us to go; and they want us to go, obviously, so that they can have the place to themselves. If they only knew it, if any inducement were needed to make me stay here, it was this. And now, as there’s nothing more we can do to-night, we might as well turn in. I’ll keep the rifle handy, just in case we have an encore. I shall probably slip down to Adelaide in the morning.”

“By yourself?” asked Frecks.

“Yes, by myself,” decided Worrals. “You two can stay here and hold the fort till I get back. Either of you left alone might get nervous, and reasonably so. You can amuse yourselves by trying to find Aunt Mary’s secret opal store. I’m pretty certain she had one—in this house, too. Even if she sold some, she would still keep a good piece for herself, if only to look at and gloat over. If those men come snooping round, don’t stand any nonsense from them.”

“Suppose they do, what do we do about it?” queried Frecks anxiously.

“Tell them that I’ve gone to fetch the police,” suggested Worrals. “That should make them think twice before starting any rough stuff.”

“O.K.,” agreed Frecks.

Worrals turned the key in the door. “Let’s hit the blankets,” she suggested. “I want to get cracking early in the morning.”

Turquoise dawn found Worrals in the air on her way to Adelaide, five hundred miles away, on a course almost due south-east. For the most part she flew over an undulating expanse of spinifex and saltbush, with never a town or village to challenge the sun-scorched wastes, a wilderness broken only by occasional flat-topped hills or a river long run dry. It was not, she thought, the most comfortable country to fly over. However, the engine ran sweetly, and by ten o’clock she was talking to the control officer at Parafield, the airfield for Adelaide, who promised to have the aircraft refuelled against her return later in the day.

“Where have you just blown in from?” he queried curiously.

“Wallabulla,” Worrals told him, “It’s a farm just south of the Everard Range. I’m helping a friend to run it.”

The officer looked serious. “You must be flying on a fine margin of petrol.”

“I am,” admitted Worrals. “But it isn’t as bad as it sounds. I carry a few spare cans, and a supply of water for emergency. At a pinch, I can always turn east to Mount Eba for fuel, or, farther south, drop in at Whyalla or Port Pirie.”

The Australian nodded. “Watch how you go, miss. You’re in bad country, should you find yourself on the carpet.”

“So I noticed,” answered Worrals. “Thanks all the same, for warning me.”

A car took her the eleven miles into the city, and ten-thirty found her in the office of Mr. Harding, Aunt Mary’s lawyer. He was a tall, good-looking man, younger than she expected, with a cheerful, breezy manner. Worrals liked him on sight. As she told the others later, there was no nonsense about him. She stated her business without preamble.

“My name’s Joan Worralson,” she began. “You don’t know me, but I’m a friend of Janet Marlow, the girl who inherited the Wallabulla property from Mrs. Mary Carter. You remember Janet?”

“Of course,” replied the lawyer instantly. “How’s she getting on?”

“Oh, she’s all right,” returned Worrals. “Another friend and myself are staying with her at the moment. We’ve got an aircraft, so we can get to and fro easily. But that isn’t what I came to see you about. The fact is, Janet wants me to have a word with you because there are one or two points about the property that seem to need clearing up.”

“Go ahead.”

“First of all, it struck us that you took rather casually Janet’s assertion that her aunt was dead.”

Mr. Harding looked astonished. “I didn’t take her word for it,” he corrected. “I knew Mary Carter was dead.”

It was Worrals’s turn to look surprised. “Oh, you did? May I ask how you knew?”

“Certainly. Dan Terry told me.”

“Who’s Dan Terry?”

“The mounted constable at Oodnadatta; that would be about a hundred miles or so east of you. It’s the old railhead.”

“How did he know?”

“The death was reported to him by Mary Carter’s blackfellow servant, Charlie. Charlie went into Oodnadatta and said she was dead, and that he had buried her. Dan rode out, saw the grave, and reported the death officially.”

“Wasn’t that a bit casual?”

The lawyer hesitated. “No. Not necessarily. In certain circumstances, it might have been, I’ll admit, but Dan knew them both well, had known them for years, and that made all the difference. Out here a lot depends on a person’s known character.”

“I see,” said Worrals, slowly. “So he knew them?”

“Wallabulla is on Dan’s beat. Naturally, he’d look in from time to time.”

“I understand,” murmured Worrals. “That clears up that point. As Aunt Mary’s lawyer, you were not surprised to see Janet Marlow when she rolled up?”

“Mrs. Carter told me she was expecting her.”

“Quite so,” rejoined Worrals. “It is interesting to know that Charlie spoke to someone before he disappeared. Is Constable Terry always at Oodnadatta?”

“He covers the district.”

Worrals nodded thoughtfully. “I must have a word with him some time. You see, Mr. Harding, there is more in this Wallabulla property than meets the eye. Did Aunt Mary, by any chance, mention to you a lucky strike she made just before she came to see you?”

The lawyer smiled. “I know about the opal, if that’s what you mean.”

Worrals drew a deep breath. “Good. That saves a lot of explaining. I imagine Aunt Mary told you in confidence?”

“One reason why she told me was because she was anxious to get an idea of the value of her find. She asked me for the name of the leading opal authority here.”

“Did you give her that information?”

“Yes. I advised her to see Felix Moran. I don’t know him personally, but he handles most of the opal business in these parts.”

“Would you give me his address?”

“Certainly.” The lawyer jotted the address on a slip of paper, and passed it over.

“One last question, Mr. Harding,” concluded Worrals. “Where did Aunt Mary stay when she was in Adelaide?”

“Chambers’s Hotel, on Waterside Road. It’s a small private hotel.”

“How long was she there?”

“Three days, I believe.” The lawyer looked at Worrals speculatively. “Don’t think I’m trying to pry into your business, but as you seem a level-headed young woman I must assume there is a definite reason for these questions?”

“There is,” answered Worrals frankly. “If I stay in Australia, I may need legal advice, in which case I hope you will act for me, Mr. Harding. And when I seek advice, I put all my cards on the table. Naturally, we—that is, Janet Marlow, my friend, and myself—are interested in Wallabulla chiefly on account of the opal strike which Aunt Mary made, and which we have every reason to believe is true. Unfortunately, we also have reason to think that someone else knows about it, and it was in the hope of getting confirmation of this that I came to Adelaide this morning.”

“As Mrs. Carter’s adviser, I haven’t mentioned it to a soul,” said Mr. Harding earnestly.

“I believe that,” returned Worrals. “It narrows the field of inquiry.”

“You’re not in any trouble at Wallabulla?”

“Not exactly. I’ll let you know if things get serious. What about this hotel? I wondered if Aunt Mary said more than was wise when she was there.”

“I think it’s extremely unlikely,” replied the lawyer quickly. “Mrs. Carter—Aunt Mary, as you call her—had been in Australia too long not to know the danger of chattering about a lucky strike. In fact, she told me so. Frankly, I don’t think you need bother about the hotel. Had Aunt Mary parted with her secret there, Wallabulla by this time would be overrun with prospectors and miners. That’s always the first thing that happens when word of a new strike gets out. The news travels like wildfire.”

“So I imagine,” said Worrals. “I’m glad you mentioned it.” She rose, and held out her hand. “Well, I’ll be getting along. Thanks for your patience with me.”

“If I can be of any help, let me know,” said Mr. Harding, as they shook hands.

“I will,” promised Worrals, and went out into the street.

Ten minutes later she was knocking on a door marked “Inquiries” in the offices of Felix Moran, opal dealer and expert. On being invited by a female voice to enter, she went in and found herself in what was evidently a small waiting-room. A girl sat at a desk on which rested a typewriter and sundry papers.

“I’d like to see Mr. Moran,” requested Worrals.

“Have you an appointment?”

“No,” admitted Worrals. “Mr. Moran doesn’t know me,” she added. “I’ve come to see him in connection with some business concerning opal.”

“Just a minute.” The girl went through a door marked “Private”, to reappear almost at once. “Come in,” she invited, holding the door for Worrals to pass through before returning to her desk.

Worrals walked on into a spacious, well-furnished office, in which, behind a massive desk, sat a man whom she disliked on sight, just as the reverse had been the case with Mr. Harding, the lawyer. In a dark town suit he was immaculately dressed—too immaculately dressed, thought Worrals. Not that she was concerned overmuch with clothes, although in this case they indicated a type with whom she rarely had anything in common. Apart from that, the face was not one to inspire confidence.

“You wish to see me?” he began smoothly, with a smile which, since there was no reason for it, Worrals believed to be insincere.

“I do,” she answered evenly. “I want to speak to you about a matter concerning which I am making some inquiries on behalf of a friend of mine.”

Moran’s smile faded. “Please proceed,” he said, in a curt, businesslike voice.

“Some time ago you were consulted by an old lady named Mrs. Carter about the quality of a piece of black opal which she showed to you,” stated Worrals distinctly.

Moran gazed at the ceiling, as if trying to recall the incident.

“Visitors with high grade black opal can’t be so common that you would be likely to forget the occasion,” prompted Worrals dryly.

Moran looked back at her. “Quite so. I remember now—yes, I remember her distinctly.”

“I thought you would,” murmured Worrals. “It was very good opal, I believe.”

“Yes, very good.”

“Did you ask her where she got it?”

Moran looked pained. “My dear young lady, my business is to answer questions, not ask them!”

“Then you have no idea where that opal came from?”

“None whatever.”

“She paid a fee for your advice?”

“Of course. That is my business.”

“You also buy opal, I believe?”

“Sometimes, when it is on offer.”

“Did Mrs. Carter offer to sell you any?”

“No.”

“How much had she, when she came to see you?”

“One piece only.”

“Was this the piece?” Worrals laid Janet’s specimen on the desk.

Moran picked it up, glanced at it, and handed it back. “Yes, that is the piece.”

“Was anyone else present when this interview took place?”

Moran frowned. “Please be careful,” he said shortly. “Are you implying that I would be likely to betray the confidence of a client?”

“I’m not implying anything,” answered Worrals. “I’m merely trying to ascertain some facts. You haven’t answered my question.”

“The interview to which you refer was conducted in private,” said Moran curtly. He stood up. “And now, if you will excuse me . . . I am a busy man.”

“Yes, I’m sure you are,” returned Worrals quietly.

She rose. “Thank you for answering my questions. Good day, Mr. Moran.” She went out.

In the outer office she stopped and threw a smile at the girl behind the typewriter. “No luck,” she murmured sadly.

The girl raised her eyebrows. “No?”

Worrals shrugged. “I thought I had found some really good opal, but it turns out to be poor stuff after all.”

The girl looked interested. “You don’t look much like an opal-gouger.”

“I’ve only just started,” explained Worrals.

“It isn’t easy, you know.”

Worrals sighed. “What I really want is someone to give me a few hints. I suppose you have most of the leading opal-gougers in here at some time or other?”

The girl nodded. “Yes, I know most of them.”

“I met one the other day,” went on Worrals. “Foolishly I let him go without asking his name, or I’d look him up. He was a small, dark chap with a nasty scar across his forehead, splitting the right eyebrow.”

The girl smiled. “That’s Manila Joe,” she volunteered. “His real name is Joe Barola.”

“He was with a big red-headed fellow.”

“That’s right—Luke Raffety. They work together. They have a black with them, a frightful-looking Arnhem-lander, named Yoka. The three of them have worked together for years. They’re real experts. They sell their stuff to the boss.” The girl inclined her head towards the private office.

“Where could I get hold of them, do you think?” asked Worrals ingenuously.

“They were in here not long ago, but where they went I don’t know,” replied the girl, “They’re probably at Coober Pedy—that’s the big opal field in the Stuart Ranges.”

“Thanks,” said Worrals. She had opened her lips to continue when the inner door was opened suddenly, and Moran appeared.

For a minute he stared at Worrals with undisguised suspicion and more than a hint of hostility. Then he spoke sharply to the girl. “I want you,” he said brusquely.

“Good morning,” said Worrals demurely, and went out into the street. For a minute or two she stood on the pavement, thinking; then, as if she had reached a decision, she returned to Mr. Harding’s office.

He looked up in surprise when she entered. “Hallo! You’re soon back. Did you forget something?”

“Yes,” answered Worrals. “What are the regulations in force about the purchase of firearms?”

Mr. Harding’s eyebrows went up. “What do you want with firearms?”

“We’re pestered with rather a lot of vermin at Wallabulla—dingoes, and so on,” explained Worrals. “We thought we might reduce the number a bit, or at least scare them off.”

“Why not try poisoning them?” suggested the lawyer. “A lot of the old hands carry strychnine for the purpose.”

“Not for me,” returned Worrals. “Poisoning is a nasty painful business—even for a dingo. I’d rather shoot ’em.”

“What sort of weapons do you want?”

“Something easy to carry. Say, a couple of thirty-eight automatic pistols, and a twelve-bore sporting-gun. We’ve got an old rifle.”

“You’d have to get a permit and a licence from the Commissioner of Police.”

“Do you know him?”

“Yes, quite well.”

“I wonder if you’d try to get us permits right away? You see, I must get back to Wallabulla to-day, and I may not be in town again for some time. If the Commissioner demurs, you can tell him that three girls on their own ought to have some sort of protection.”

The lawyer smiled. “You strike me as being well able to take care of yourself—but I’ll see what I can do. Where shall I find you?”

“I’m going along to Prince’s for lunch. Come in and have coffee with me.”

“Fine.”

“Thanks, Mr. Harding.”

Well satisfied with her morning’s work, Worrals went along to the restaurant and ordered lunch.

She had Just finished her first course and was gazing about her in an abstract sort of way when her eyes suddenly focused on a man who had entered and was walking briskly towards her table. It was Felix Moran, the opal expert. To her surprise he came straight to her table, pulled out another chair, and sat down.

Worrals stared. “I beg your pardon, Mr. Moran,” she said stiffly, “I don’t remember inviting you to join me.”

“You didn’t,” returned Moran bluntly, considering her with frank hostility. “I want a word with you, though.”

“This is hardly the way to go about it.”

“I didn’t want to lose sight of you,” explained Moran casually.

“You didn’t what? Do I understand that you’ve been following me?” Worrals’s astonishment was genuine.

“I had you followed after you left my office,” admitted Moran.

“Why?”

“That secretary of mine’s a nice girl, but she talks too much—and you ask too many questions.”

Worrals nodded. “Ah! I understand. You think she told me more than was prudent?”

“My business is confidential. I don’t like people coming into my office asking questions.”

“Of course. I can quite understand that,” said Worrals evenly.

The opal dealer regarded her critically. “What’s your game?” he demanded abruptly.

“I’m not playing a game, Mr. Moran,” returned Worrals. “The business I’m engaged in is just as serious as yours.”

“All right. Call it business. What’s your angle?”

“To what, precisely, are you referring?”

“What did you have to go and see that lawyer about?”

“Really, Mr. Moran, such a question amounts to impertinence. However, I’ll answer it for you. Mr. Harding is getting me some firearms permits. Since arriving in Australia I have learned that there are some very nasty snakes about. There’s only one way of dealing with snakes, and that is to shoot them. You would hardly believe it, Mr. Moran, and it may sound like boasting, but during the recent war I disposed of quite a number of snakes. But this catechism has gone on long enough. Would you mind finding yourself another table, or shall I call the head waiter and tell him that I’m being annoyed?”

Moran smiled. But only with his lips. His eyes were cold and hard. “You’re interested in this Wallabulla property, aren’t you?” he challenged.

“I am,” admitted Worrals.

“How about selling it to me?”

“It isn’t mine to sell.”

“But this Marlow girl would sell it if you advised her to.”

“She might.”

“O.K. Go ahead and tell her to sell. I’ll make it worth your while—say, ten per cent. How’s that?”

Worrals shook her head sadly. “How very crude you are! You know, Mr. Moran, the more I see of you, the less I like you. I’m expecting Mr. Harding with those permits at any moment. If he finds you here I may feel inclined to tell him why you came.”

Moran got up. “All right, if that’s how you want it,” he said in a hard voice. Turning on his heel, he strode away.

Worrals watched him go, a thoughtful expression in her eyes.

A few minutes later the lawyer came in and announced that he had been able to get the permits. There were some forms to be signed. Worrals thanked him, and over coffee signed the forms. They talked for a little while, and then Worrals, after a glance at her watch, said that she would have to be getting along.

“Let me know if I can be of further service,” said Mr. Harding.

“I certainly will, thanks.”

The lawyer became serious. “Be careful,” he warned. “There are a lot of nice people in Australia, but there are a few who are not so nice.”

“I’m just beginning to realise it,” returned Worrals quietly. “I’ll bear it in mind, and I’ll keep in touch with you.”

They parted at the door.