* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: The French Adventurer--The Life and Exploits of Lasalle

Date of first publication: 1931

Author: Maurice Constantin-Weyer (1881-1964)

Date first posted: Apr. 11, 2023

Date last updated: Apr. 11, 2023

Faded Page eBook #20230420

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, John Routh & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

This file was produced from images generously made available by Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries.

ROBERT CAVELIER DE LA SALLE

Printed in France under the title:

“CAVELIER DE LA SALLE”

Copyright, 1931, by

THE MACAULAY COMPANY

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

To the City of Montreal

I Offer the Homage of This Book

It is to you, oh Montreal, Ville Marie, that I dedicate these pages.

Not that Cavelier de la Salle was born or died on your soil. But among those whose fortunes have been, for an hour or for all time, bound up with yours, none is more worthy of your glory.

And Canada remembers more readily than France. . . .

There is indeed Rouen, which has guarded the memory of its adventurous son. But to what corner of Paris may we go to seek inspiration from his energy?

In our cities there are no squares devoted to Great Adventures, with statues and bas reliefs. . . .

There is no square for the Indies, with Dupleix and Lally-Tollendal.

There is no square for Africa, with Brazza, Flatters, Fourreau, Lamy, Baratier, Marchand or De Foucauld.

There is no square for the Americas, wherein Canada would have the better part. An entire city would be needed for all the statues. . . .

For if France gave to Canada Champlain, Maisonneuve, Talon, Cavelier de la Salle, Marquette, Tracy, Frontenac, Vaudreuil and Montcalm, Canada has given back to France the glory, unknown to Paris, of Papineau and those others who died for the French language.

And those great adventurers into the snows—Monseigneur Provencher, the three bishops, Tasché, Laflèche, Grandin, and that martyr of the Arctic circle, the Abbé Grollier.

Canada is filled with crosses, and many of them are crosses of glory.

Now I myself, in my time, was a coureur de bois. But the War led me so close to the gates of Death that I have never altogether lost sight of the threshold. . . .

That is why, when my work is done, I cannot find that repose which is the reward of other men.

To cheat insomnia and suffering, I sing songs to myself, as one sings to a child.

This is the song of Cavelier de la Salle.

M. C-W.

The French Adventurer—The Life and Exploits of Lasalle

The headwinds which had been blowing for two days slackened. The Captain, his hands thrust into his faded silk belt, beside his pistols, was shouting his commands. Barefoot sailors scurried forward. They furled the limp staysails, clambered up the ropes and clung to the mastheads. Astride the loftiest yards they reefed the skysails. Cavelier marveled that in spite of the ship’s rolling, apparently indifferent to it, they were able to handle the heavy canvas. He imagined that more than one of them must be gripping the spars with nervous legs. . . . Had they already forgotten that only three days ago a squall had swept an apprentice from the main royal? He had never reappeared! His leather cap had floated for a while. . . .

Leaning back against the gunwale the young man gazed toward the East whence the ship had come. He studied the sea and sky: blue silk slightly inflated and quivering,—a high window of transparent crystal shot with iridescent reflections. But when he turned he saw that the ship was bearing down on what seemed to be a wall of darkness. The bowsprit struck it first. The forecastle disappeared as if crushed. At the same moment the voices of sailors who were standing there seemed deadened. Then the foresail and the main mast vanished. Even the captain’s voice was muffled, although it usually dominated a storm without the aid of a megaphone. . . . All at once the young adventurer felt a longing for the snapping of taut sails, the roar of waves, the fury of a storm. But the ship seemed as if it had dissolved. It had plunged into the fogs of the Grand Banks.

A phantasm! It surpassed by far the misty veils of a Channel fog. It was both material and immaterial; heavy, yet not sufficiently so to crush the waves. A choppy sea dashed an oily spray against the ship’s sides. The waves, running obliquely toward the ship, were barely visible at a distance of a few yards. Deprived now of some of its canvas, borne onward only slightly by the wind, the ship yawed under the shock of the waves. The helmsman would bring her back to her course, while the keel groaned as if weary of its labors.

It required faith rather than sight to reach the forecastle. Cavelier could barely discern the lookout who, clinging to the jib-boom, peered ahead. Beyond him was the fog, so dense that Cavelier smiled at this vain attempt to penetrate the impenetrable. If there were a ship, a reef, immediately ahead, how could the vessel be swung round quickly enough to avoid it?

But the thrill of danger which pervaded the ship with the fog did not displease him. He amused himself by watching the lookout. Every time the ship heaved the bow dipped slightly. Sometimes, at that moment, the next wave struck, and the lookout then received the full impact of the sea. Cavelier would hear him rip out a curse and then see him cross himself, as if in penitence.

However, wet by the spray and wearied by the heavy cloak of fog, Cavelier longed for escape. He could find it only in dreams. He left the forecastle, and stripping off his coat, sank into his hammock. Memories assailed him there.

Two melodies accompanied his revery. That produced by the negro cook set his teeth on edge. During his off-hours the kinky-haired negro left the galley and trilled tunes on his flute in an adjoining cabin. Cavelier would have gladly dumped him out of his hammock, but except for God, the Captain was the sole ruler on board. This idea also irritated Cavelier.

For a while, however, he dreamily thought of the old sea dog. Is he taller than I, or shorter? he mused. Or just the same height? Is he stronger or less husky than I? Is he braver? (Certainly not! he murmured to himself proudly.) Or less brave? He is a man! Arrogant! Pugnacious! An expert with the compass and a skilled navigator. And on his proud, eagle-like face is a pink scar that ends above a moustache, tinged gold by the sea.

“Yes, he is a man!” thought Cavelier. “He has fought for the King against England, Holland, Spain. I should honor him for having served the same ruler. But he commands here, and what are men who command to me?”

To divert his thoughts he forced himself to ignore the negro’s dismal tune and listen only to the deep, harmonious lamentation of the ship. Each time the helmsman brought her back into her course, the bass voices of the keel and planking rose in a melancholy chant of the sea. Then, an octave higher, the decks would re-echo the refrain.

Years ago in Rouen when his classes in the Jesuit school had ended he had loved to stroll along the wharves. There galleons and caravels unloaded bales of rare spices whose odor subtly bore the promise of unknown empires. These precious bales would then be loaded on barges to be towed to Paris and sold to the nobility.

A babel of strange tongues. Quarrels would flare up and more than once he had seen knives flash like rays of light on the river. However, Robert’s older brother would tear him from his dreams.

“You pig-headed Norman!” Jean would exclaim. “Why weren’t you born in the days of Duke Rollon the Pirate? With your passion for ships and voyages you’ll lose both your soul and body!”

When they passed the church of Saint Heblard on their way home to their father’s shop they would doff their hats and cross themselves. . . . At home Dame Catherine Gert Cavelier in the light of smoking candles directed the setting of the table. Lights played on the diamond-shaped points of the somber buffet. Tall, strong, imperious, clad in a suit of rough serge, his hands carefully washed after he had laid aside his account books, the worthy Jean Cavelier would bow his bald head, place his hands on the earthenware tureen, and bless the meal.

Then there were the long hours with his Jesuit teachers; the boredom of Greek and Latin, the pleasure of geography. A Father Professor would describe the voyage of Columbus, the search for the Western route to China, or the quest for Cipango. The old Iberian names would ring like the verses of an epic. Cavelier would repeat them to himself, as the names of admired and hated rivals.

Don Pedro Alvares Cabral, who discovered the Amazon and the lands of Brazil.

Vasco Nunez de Balboa who, crossing Darien, was the first to behold the waves of the Pacific unfurling at his feet.

Juan Ponce de Leon, seeker of eternal youth, who eight days before Easter discovered Florida.

Fernando Cortez, bloody conqueror of Mexico.

And Pizarro who plundered the treasures of Peru.

Hernando de Soto, whose tomb was the giant river, the vast Mississippi.

Thus these names sang in his head, rhythmically, like memories of an epic. But to the Spaniards, whom he had learned to consider cruel and treacherous, he opposed those gallant Norman and French adventurers—Cartier, Landonnière, de Monts, Poutrincourt and Champlain. Faithful to their God and to their King they had planted the Cross of Jesus and the Fleur de Lys of France side by side in the soil of America.

His thoughts reverted to the gloomy school where the Jesuits had taught him both prayers and classics, geography and mathematics. He had liked especially Father d’Hocquelus who, being a Norman like his pupils, lectured with enthusiasm on the great discoveries. Tall, erect and broad shouldered, the Father would become more and more excited. Then springing from his chair, his skull cap over one ear, he would rap on the map with his ruler. The soul of an apostle rang in his voice. At such times he would extol the work of missionaries and their heroic sufferings. Quoting another apostle he would thunder in Latin:

“How beautiful are the feet of them that travel over the earth to preach the gospel of peace.”

Among all his pupils the Father was fondest of Robert who, to the astonishment of his schoolmates, was the only one who could name all the seas, capes and rivers with never a mistake. And when the Jesuit Father would question him mischievously about still unexplored regions, he would rise on tip-toe to reply in a strangely defiant voice, “Terra incognita.”

When they left the dark chapel the good Father liked to take his young pupil’s arm. He would then discourse on the glory of roving over land and sea in the service of God.

“Ah! What glorious privateering!” he would exclaim. “What rich plunder still awaits the King of Heaven!”

Then he would praise the vast enterprises of the Jesuits across the seas. In a trembling voice he would extol that empire of God in Paraguay where not a single heretic was tolerated. Thanks to an alliance between the Jesuits and the Catholic King of France, a vast colony of faithful souls was being founded there. Moreover, God had been careful to recompense His zealous servants. For this colony which had been created by Paraguayan converts on lands belonging to the Jesuits was not the least source of that Order’s revenue. He earnestly advised the young student to put his thirst for unknown lands to the service of the Jesuits and of God.

Father Guiscard who taught mathematics also liked this lad who was interested in the course of the stars and the calculations of distances. After class he would sometimes explain the nautical instruments employed by navigators to get their bearings.

But Father d’Antheuse, the classical Professor, was much more reserved in his praise. The story of his travels which Ulysses recounts to Alcinous was the only section of Greek literature that aroused Robert’s interest. But even so he had been flogged for expressing surprise that a man who could give way to tears should be held up as a model.

“This switch will make you give way to tears,” the teacher replied. But the lad accepted the punishment without a murmur.

“Of all the Greeks I like only the Argonauts,” he confessed to Father d’Hocquelus. “But alas! I fear they never existed.”

“When the Order receives you among them,” replied the priest, “it will be easy for you to make real voyages and to test your soul with danger.”

Cavelier then relived the long years as a novitiate. He had enjoyed certain privileges. His knowledge of geography had obtained him a position as substitute for a teacher who was ill. But all discipline irked him.

“Perinde ac cadaver! Like a corpse!” he exclaimed. “Am I really lifeless, a dead thing in the hands of my superiors? And later on if, instead of sending me to the West Indies where I wish to go, it should please the Father Superior to force me to teach the Euclidian theorems to brats, what shall I reply? Perinde ac cadaver! And again, if in America I should choose one road and am told to take a different one! Perinde ac cadaver! But I must either accept this stupid existence or forfeit my rights of inheritance, since such is the will of our good King.”

Thin, pale and obstinate in his dark cassock, he had argued so heatedly with the Father Superior that he had incurred solitary confinement. Then when he had been released he had argued with his own father.

At his first words the old man, as hot-tempered as his son, had raised his voice.

“What, return to the world again after you have left it to become a Jesuit? You who are too proud to measure lace and ruffles behind my counter! What demon is at work there under your cassock? I tell you it’s impossible to return to the world now. And if you should, I shall divide your inheritance among your brothers, and penniless you shall have to beg for a living.”

“Or earn it,” the young novitiate retorted proudly. “I have strong arms, sturdy legs, keen eyes, and his Majesty’s ranks are always open to husky recruits.”

“Bless me! So you plan to be a brigand or a privateer! With a hot head like yours you’ll end under the black flag or be hanged from the highest yard of one of His Majesty’s warships.”

“Whose disgrace would that be?”

“So you wish to avenge yourself by dishonoring my gray hairs and ruining my business? People will point at me and say: ‘There goes the father of Cavelier the Corsair, Cavelier the Pirate who was hanged.’ Yes, that will be the thanks I get for all the care I’ve given you!”

“Permit me, Father, to leave the Order and re-enter the world. If you do not entirely disinherit me I can earn an honest living there.”

Then to the irascible old man he outlined the plan he was developing. His older brother, a member of the Order of Sulpicians, had written him from Ville Marie that colonization along the St. Lawrence was doing very well. Land could be bought there cheap. The demobilized soldiers of the Canadian garrisons gladly consented to remain in the colony rather than to return to France.

“Yes!” the choleric old man interrupted. “Because they’ve acquired the habit of debauching Indian girls.”

Robert had not attempted to argue this point. It was important to prove to his father that with the aid of discharged soldiers he could easily build up a thriving colony. Others had done so and, as his brother had written him, were extremely successful. He cited names and figures. Undecided, the old man shook his head. Then dismissing his son he turned to the door. Stooping forward in his dark clothes, his thin legs bent at the knees, he paused as he placed his hand on the latch.

“My son, I shall think it over,” he said, turning. “Good-bye and don’t lose your head. May God give you the patience you lack.”

The heavy door quivered as it closed behind him.

Fog succeeded fog. A choppy sea buffeted the ship. Sometimes, however, the fog lifted and then the ocean became visible, streaked with green and black like a mackerel. Or perhaps a sunbeam would filter through the mist and spread over the waves like golden oil.

Nevertheless the Captain took no chances. Shortly before entering this sea of fog the other ships of the convoy had disappeared. Near the American coast there was danger, he said, of encountering pirates.

“Our ship is well-armed and a good sailer,” he explained. “In the open sea we could easily drive them off or show them our heels. But here, if a pirate ship heaved into sight a few yards off, before we could sound to clear the decks we would be boarded.”

For this reason he was never without his cutlass and frequently reloaded his pistols. He rebuked the gunners if they left their carronades for a moment. Following his example, Cavelier girded himself with a Damascene sword, the gift of his uncle Nicholas Gest, and slipped into his belt a brace of pistols he had bought in Rouen before leaving. The belt was heavy. In its buckskin lining his mother had sewn the ten thousand livres his father, in agreement with the other children, had advanced him on his inheritance the day he had abandoned the church for high adventures. Robert also remembered Father d’Hocquelus, who still resented the fact that he had not put his love of voyaging to the exclusive service of the Jesuits.

“One day you will learn,” he had said, “that it is better to serve the King of Heaven than all the Kings of the earth. Louis the Fourteenth cannot open the gates of Paradise to you. However, I can bear you no ill will. You were my best student and I am certain that a little faith still dwells in your heart.”

Spanish and English pirates did not loom up in the curtain of fog. The sun burst forth suddenly upon a glittering and gently swelling sea. A deep blue flooded the horizon. Not a sail was in sight.

The Captain ordered the sails set and at dawn the following day a coast pounded by high surf that gleamed against the dark cliffs lay in the far distance. Someone said it was Cape Breton. Then the joyous sailors greeted the sight of land and chanted in chorus:

“At Saint Malo, that harbor fine,

Three sturdy ships have just arrived.”

Meanwhile the course veered North by North-West.

As the ship neared land the plowed wake, a transparent emerald green between lanes of blue velvet, stretched toward the horizon where the arrows of the sun pitted the sea with splotches of light. Gulls flew out to meet the ship and played in the foam. Cavelier amused himself by tossing them pieces of bread and scraps of meat which they caught in their sharp beaks.

Late that afternoon the jib stood out against high land toward which the ship was bearing. The Captain informed Cavelier that it was Anticosti Island and that they were now in the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

He made ready to gybe. The ship groaned under the helm. The sails snapped in the wind. The jib-boom, the bowsprit and their sails, as if striving toward the setting sun, pierced it with their shadows.

Cavelier awoke in the dead of night. A gentle rocking had replaced the long swell of the sea. He leaped from his hammock, slipped on a cloak and went on deck. Silver streamed alongside the ship. The dwarfed and thick-set figure of the mate passed, carrying a lantern. Robert questioned him.

“We are riding at anchor,” he replied. “The river mouth has been sighted. There are buoys, of course, but at night it is the devil and all to find them. At dawn we will set the sails. Only a few will be necessary, just enough so the ship will answer the tiller.”

“Where is the reef?” asked Cavelier.

“It’s easy to see that you’re from Rouen. This is quite a different estuary from the Caudebec. The tide goes up here, I should say, further than the distance between Rouen and Paris. Besides, the river is wide and that keeps a bar from forming.”

He moved on.

“So at last I’m in Canada,” Robert thought. “So this is the country I have dreamed of. This water flowing like liquid moonlight is the water of this mysterious world. What course is my life to take from now on? Am I to face dangers immediately? Am I to be the first to penetrate unknown regions? Am I to experience the suffering of adventures? Am I to give my name to a new kingdom? Am I to discover the western passage to China which Christopher Columbus searched for?”

Thus was outlined the tapestry of his dreams.

Sometimes aided by the rising tide, sometimes impeded by it, the ship slowly ascended the gigantic river. Cavelier, eager to know the country, tirelessly scanned the distant horizon.

“Is it really a river?” he asked himself, when he saw, far to the north, the mauve peaks of mountains which the Captain assured him were very high.

The nearest shore seemed several leagues distant. He would have liked to ask the Captain many questions. But a head wind made it necessary to tack frequently, and the Captain had to oversee the rapid changes in the ship’s course.

Standing aft the mate continually took soundings. One would see him grease the lead, swing it above his head and then hurl it out into the water. Then he would haul it in, calling out the number of fathoms and the nature of the river bottom. The Captain shouted brief commands. The ship tacked gracefully, while, perched on the yards, quick to answer the shouted commands, the sailors took in or let out the sails.

On the evening of the second day of their course up the river, the anchor was dropped near a low-lying reef which the ebb tide was slowly revealing. Solemn cranes standing on their long legs were silhouetted against the bank. A wedge of bustards alighted there and breaking ranks swam in disorder toward the shore. Dark points among the spars, the sailors reefed the sails. A longboat was manned and rowed toward the shallows. Cavelier watched them cast a net and then empty a catch of silvery minnows in a wooden bucket. Then climbing back into the boat, they sounded at several cable lengths from the shore, and finding the bottom favorable dropped their fish lines.

“Fishing for bass,” the Captain explained.

Meanwhile dark figures were gathering on the shore. Calls of greeting drifted toward the ship.

“Indians who want to trade their furs,” the mate announced.

The Captain then ordered another boat manned, while Cavelier, suddenly remembering a quotation, repeated to himself:

“Eheu! Fuge littus avarum. . . .”

“A presentiment?” he asked himself, laughing. To overcome it he asked the Captain’s permission to accompany him. The Captain deliberated.

“Yes,” he replied. “A good companion is never in the way. You are a man pretty nearly of my tonnage. I’m sure the two of us could bring a few of these heathen to reason. Be sure to bring your pistols along. But above all don’t use them until I have fired mine first. These Iroquois want to trade. I don’t believe they’re in a fighting mood.”

They clambered down the swinging rope ladder to the longboat. Oars raised, the sailors awaited the Captain’s orders.

“Give way all!” he cried, and eight blades struck at the same instant, slashing the waters of the St. Lawrence into foam.

The longboat cut the current. The Indians grew in size. Arms raised, palms open, they signaled that they were unarmed. The boat drew up to the shore.

“They have their peace paint on,” the Captain whispered to Cavelier. “All is well. However, avoid mingling with them. Stick close to the boat. If there’s any danger I will shoot one of them. At that signal the head gunner will fire a blank charge.”

The Captain advanced, tall and arrogant. Cavelier admired him.

“A fine lesson in coolness,” he said to himself. “With neither braggadocio nor meekness, seemingly imperturbable, this man stakes his very life against these Iroquois. In fact that is how he dominates them.”

He followed the scene intently. Six men, naked to the waist, their bodies painted with red ochre, beardless, their heads partly shaved, tall, lithe and wiry, they greeted the Captain with calm reserve. Robert watched the Captain approach them. After sitting down on a rock he invited the Indians to do likewise. One of the Iroquois offered him a long pipe. First the Captain, then the six Indians, took three puffs of smoke. One of them arose. Slowly, deliberately, emphasizing his words with frequent gestures, he spoke. From where he stood, Cavelier could not understand the words. When the Iroquois had finished and sat down, the Captain in his turn rose to his feet. He spoke in his strong, loud voice, which he had trained to carry above the roar of a storm. Fragments of sentences drilled into Robert’s brain.

“Thank his brothers . . . very much . . . what they offer . . . but . . . sorry . . . price much too high . . . furs hard to sell now.”

Another Indian rose to his feet and spoke. Then Cavelier heard the Captain’s booming voice again. He admired the shrewdness with which the Indians’ offers were rejected.

“What bargaining! What diplomacy!” he enthused. “And if he were to die, he could exclaim, like the old Roman about whom the Jesuits once told me, ‘Now a great actor passes on!’ ”

The orators followed each other. When all had spoken and the Captain had replied six times, there was a silence. The pale smoke rose from the peace pipe as it was passed from hand to hand.

After having deliberated for a while, the Captain rose for the seventh time and spoke. His short sentences, broken by the wind, drifted toward Cavelier. He nevertheless caught the words “fire-water” and “fur.” At the conclusion of the speech the Indians appeared to take council, and the one who held the peace pipe made a gesture of assent. Then the Captain returned slowly to the longboat. Victory gleamed in his eyes.

“The game is won,” he murmured, as he passed Cavelier. “Young man, catch them with bait. There lies a barrel of cider brandy that will yield large returns. But mum’s the word. I will make you a fine present. However, don’t talk about it. His Majesty’s Steward doesn’t like anyone to trade with the Indians without paying him a bonus, which I do not care in the least to give him.”

“But what about the rights of the King?” Cavelier exclaimed.

“This is none of the King’s business. Believe me, when you have dealt with a few of the King’s agents you will learn why such rich lands yield France such little revenue. Understand that I am not stealing, I do not permit myself to steal, and I advise you to do the same. . . . But here are our Indians returning with the furs. You there!” he said, addressing the sailors. “Roll up the keg. Make haste to load the furs. And as soon as that’s done pull for the ship. We’ll join the other boat on the way back.”

The farther they progressed up the river, the more the country fascinated Cavelier. His soul became slave to all its majesty.

How could one fail to realize the solidity of this soil? Not even the vast current of the St. Lawrence in its swift course to the sea could wear down the little islands that strove to maintain themselves against it.

At ebb tide the Captain pointed out Grosse Island. Smoke from a settler’s cabin, turquoise and amber in the play of light and shadow, rose above the trees and drifted off through the air. A herd of red cows, caught by the tide on a flat to the east, were swimming back to the island. Waves foamed against the rocks.

Farther along the Captain pointed out a larger island—the island of Orleans. There the spirals of smoke were more numerous, and in spite of the distance, the inhabitants there ran along the shore waving their hats in greeting to the ship.

“Two years ago,” said the Captain, “a murder was committed on that Island. A certain Jean Serreau, a Poitevin, had settled there and his labors bore fruit. But along came a Swiss, a man named Terme, Jean Terme, I believe. I was putting in port here, for I had some cargo to drop. Now this Jean Serreau had for wife a girl named Boileau, who was pretty but who, it must be admitted, was not overly virtuous. This fellow Terme began hanging about and visiting the Serreaus a little too often. Jean Serreau became suspicious. As he was gentle and patient, according to all his neighbors, he peacefully requested this fellow Terme not to visit his wife so often. He told him that there was gossip already and that he did not wish a public scandal. He also remonstrated with his wife. Both of them promised not to see each other again, swearing to the husband that nothing had happened between them.

“But only eight or ten days later Serreau again surprised his wife and her lover. It is said that they were conducting themselves in a manner that was both indecent and unseemly and one towards which any husband might conceive a legitimate resentment. Serreau lost his temper, threatened his wife with a club and Terme with his fists, which were as hard as rocks. There were no blows, as Terme took to his heels.

“Serreau then threatened to turn his wife out, but the Priest persuaded him against doing so. He then exacted a promise from his wife that she would thereafter lead a strictly virtuous life. Now two leagues from the Serreau home was a certain Maurile, a good-hearted man who had cleared a piece of land to raise cattle on. Serreau placed his wife with Maurile. For though he had pardoned her, he felt the necessity of not seeing her for a while. Then quite suddenly he decided to go and fetch her back. With a wife away from home the cows don’t get the proper care and no one in the house eats. No one can get along without a female except a sailor.

“Now half way between his house and Maurile’s, Serreau met the girl strolling along with her gallant. Terme had his sword along with him and Serreau was unarmed, except for his cudgel. Serreau could not keep himself from speaking sharply to Terme. The latter laid his hand upon his sword hilt. Serreau swung his cudgel and knocked Terme stone dead. Then fearing the law he hid away in the woods.

“But those who had witnessed the killing testified that he had done it in self-defense. So the Priest could implore a pardon of Seigneur de Tracy who then governed the country. Today it is governed by Monseigneur de Courcelles. Seigneur Tracy thereupon withdrew the case from the courts and referred it to His Majesty, who pardoned Jean Serreau. It was I myself who brought the pardon. That is how I learned the story.”

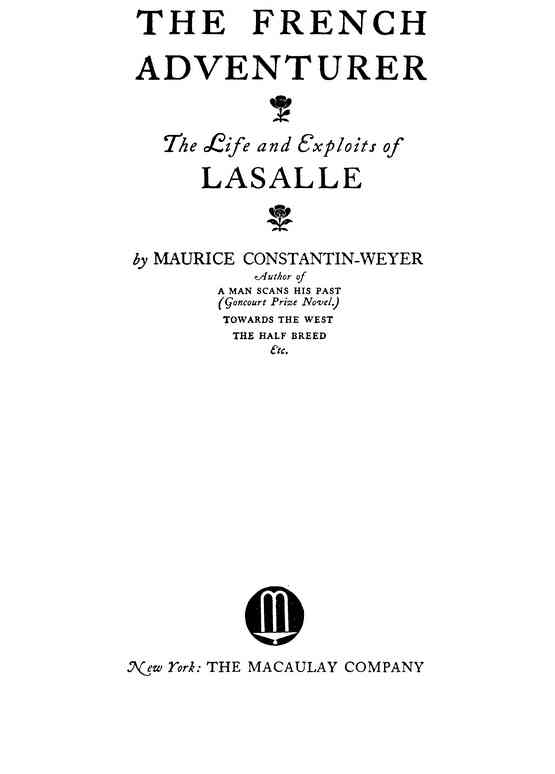

In the meantime they were nearing the north shore. In the distance were slender waterfalls, which the Captain said were at least a hundred feet high. They were the falls of Montmorency. Then, barring the river, almost strangling it, was the city of Quebec and its high cliffs.

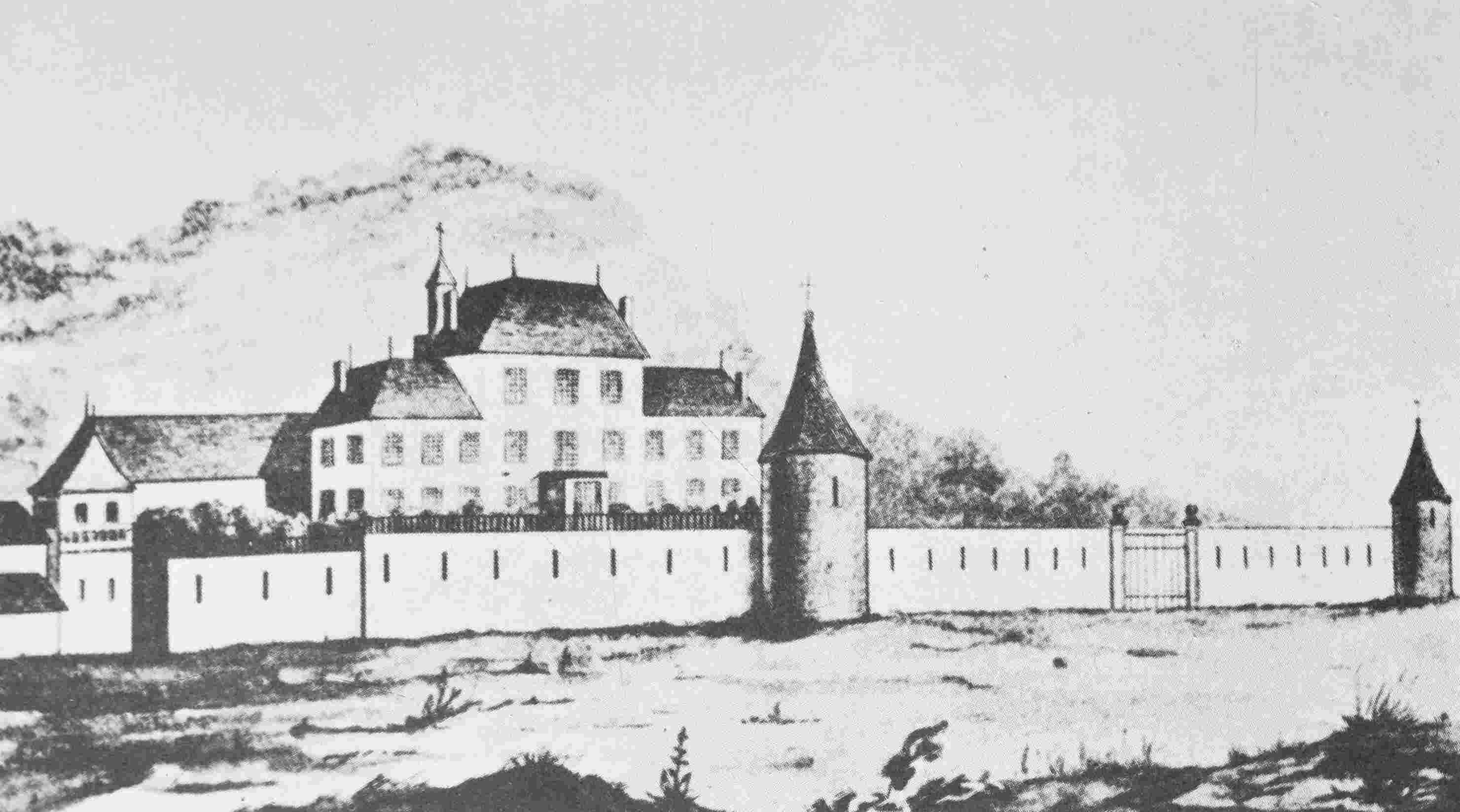

Quebec as it looked at the Period when La Salle Settled in Canada.

From a contemporary print.

They did not go ashore, even though there was time enough while the ship’s papers were being put into order. The cargo was consigned to Ville Marie, to the Sulpician priests among whom was Jean Cavelier. According to the Captain’s statement, the largest ships of His Majesty’s navy could sail up the river as far as Ville Marie, and even farther, he said, if it weren’t for the rapids near that city, which made the river unnavigable.

During this long progress up the river, Cavelier was astonished at its great width even at Three Rivers, where adventurous settlers were clearing the good land.

And on the first of July, 1667, they landed at Ville Marie.

The Abbé Jean Cavelier welcomed his brother in the reception room of the Sulpician Mission. A breeze fresh from the St. Lawrence came through the open window. Great clouds passed in procession, sweeping both the blue sky and the blue water. In the distance a low beach supported the dark blue fringe of the forest, while above the tree tops the mauve halo of the horizon was obscured by mist.

Face to face the two brothers scrutinized each other. The Abbé, who had not seen Robert for many years, inquired of the family, asked after the health of his father, mother, his sister, his two younger brothers. Then followed a barrage of “Do you remembers?”

A glass door reflected their images. The same prominent forehead, the same expressive aquiline nose, the same obstinate mouth. The only noticeable difference was the light moustache which shadowed the mouth of the younger.

“How did you leave your Jesuit fathers?” demanded the Abbé. “On good or bad terms?”

Robert shrugged.

“Neither good nor bad,” continued his brother. “So much the better. Here in Canada, Jesuits and Franciscans share the influence. The Jesuits have the good will of His Majesty’s Intendant. But the Franciscans have the ear of the Governor. And that is not so bad either. We Sulpicians maintain very cordial relations with the Franciscans.”

“And also with the Jesuits, I hope. They too are men of God.”

“Hum! Our relations are less cordial. Men of God. That is understood, my dear Robert. But you argue like a man of the world. You laymen are such queer people. You imagine, don’t you, that a priest has no right to personal sentiments? Perhaps that is true of the Jesuits.”

“Perinde ac cadaver,” Robert muttered half to himself.

“Perinde ac cadaver—that is just it. I was sure, knowing you as I do, that discipline alone would lead you to break your allegiance.”

“Were you angry, brother?”

“Heaven forbid! As a servant of God I admire the Jesuits, their zeal, their discipline and their work. But, my dear brother, for all that I may be a man of God, I am none the less a loyal subject of His Majesty.”

“Do you mean to insinuate that the Jesuits are less so?”

“They are Romans, my brother. They bow only to God. . . . His Holiness himself. . . . Sint ut sunt, aut non sint. . . . You know all that. In short, I fear that the work of the Jesuits is more Catholic than French.”

These Gallic sentiments in no way astonished Robert. He listened to his brother’s account of the Jesuits’ work. Indefatigable, ardent, heroic to the point of martyrdom, their members braved the waste lands and preached to the most savage tribes. For the triumph of their faith, many of their Order had already endured the cruelest torture and the most ignominious death under the claws of the Indian women. But the Jesuits, in the opinion of the Abbé, did not devote a sufficient part of their heroic energy to serving the King of France, who nevertheless gave them his highest protection here. Bitterly he reproached them for thinking only of the glory of their Order. Entirely different, he said, was the spirit of the Franciscans.

“Nevertheless,” he affirmed, “they are just as good servants of God.”

Cavelier disputed these assertions. He spoke enthusiastically of the work of the Jesuits in Paraguay. He recounted the stories of his masters, of Father d’Hocquelus, of Father Guiscard. However, the Abbé concluded with a final word:

“You must maintain cordial relations with your former masters. But, believe me, you should not lean too heavily on them. They would paralyze your initiative.”

Impatient and ambitious, Cavelier told his brother of his desire to set out for himself. The hospitable Sulpicians urged him, on the contrary, to remain with them longer in the narrow whitewashed cell which they had at his disposal. He was invited to taste the marvelous products of the country. Enormous golden perch with metallic scales, monstrous pike, gray trout, salmon with black spots, and great sturgeon, brought there by the fishermen, abounded in the kitchen. Sometimes a Christianized Huron, his two black oily braids hanging on either side of his sorrel face, came to offer a gift of venison, moose, or caribou. Wild duck and bustards, too, were plentiful; and the monastery garden produced marvelous cabbages and carrots.

The Father Steward, who was fat and jolly, admired the hearty appetite of his young guest, but jokingly reproached him, heavy eater that he was, for not being sufficiently gourmet. Then he took this as the text for establishing a neat distinction between a gourmet and a gourmand.

“The former, my dear child,” he said, “makes an indirect eulogy of Creation. That such a variety of tasty dishes should have been dispensed to mankind is certainly reason for giving praise to God. Politeness demands that we appreciate them. Such is a gourmet—a connoisseur of the excellences of Divine Creation. But what can be said for the other? He is tempted, even possessed, by a demon. He eats beyond his hunger, and as a sort of terrestrial penance, Heaven deprives him of the complete enjoyment of the flavor of his food. Weighed down with fat, he passes a sad old age, beset by maladies of the stomach. Therefore, be gourmet, my son, and you will be absolved at the tribunal of penance.”

Cavelier was annoyed by these remarks. Still he replied politely. But the meal barely ended, he hurried up to his room. It gave on the rear of the monastery, whence he could see the somber mass, rocky and wooded, of Mount Royal. He scarcely looked at it. Instead he avidly read accounts of explorations, borrowed from the library of which the Fathers were extremely proud.

His brother found him there.

“There is,” he said, “some very beautiful country above the rapids and on the other side of the river. It is rarely visited by Indians. With the recommendation of the Father Superior, we could easily obtain the concession for you. It appears to be worthless because it is partly covered by marshes. I am sure that by deepening certain coulees, the stagnant water could be drained back into the river. Thus, at small expense, you can establish yourself on a domain whose future appears to me to be certain. It is not far from us, and is protected from the enemy by His Majesty’s garrisons.”

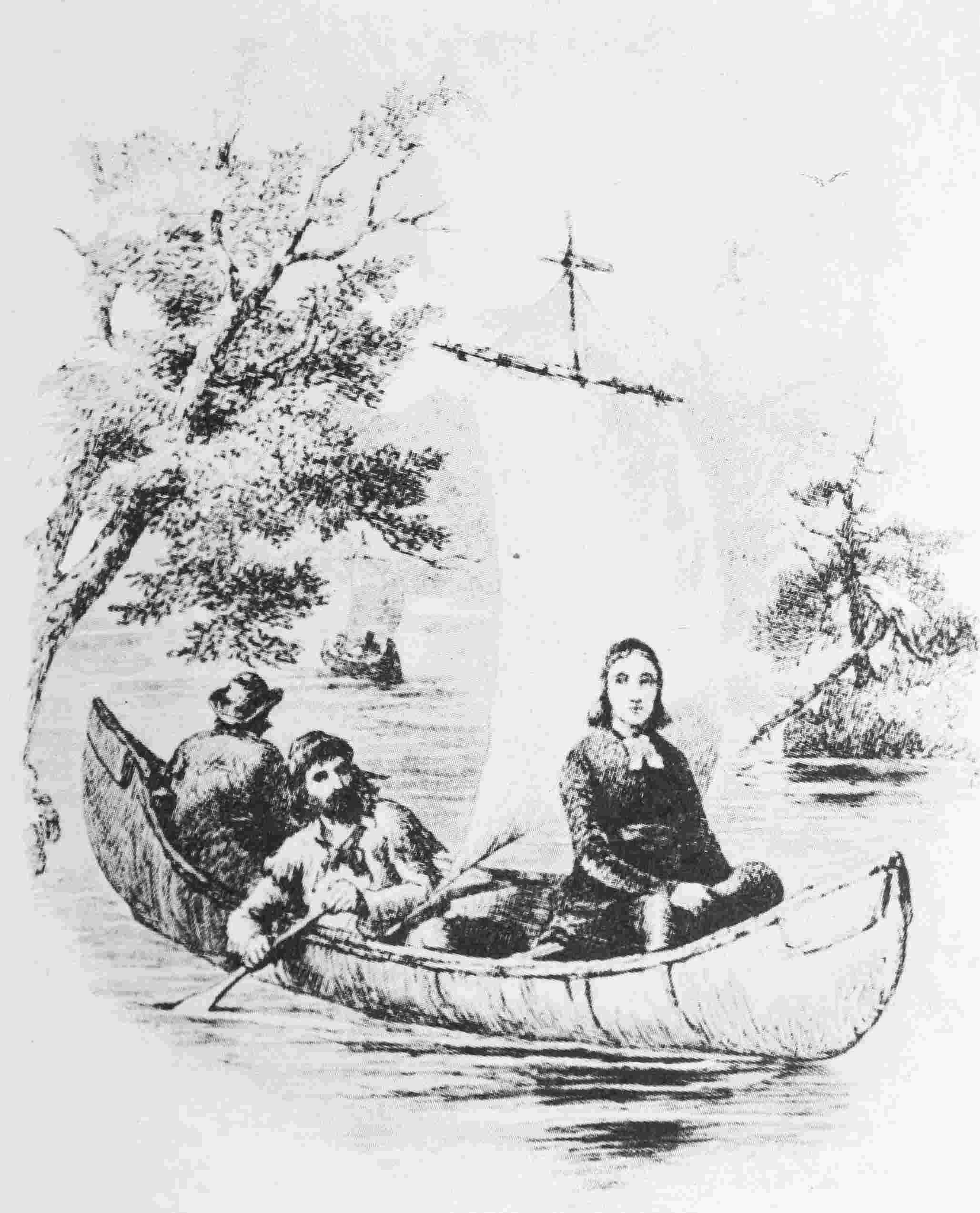

A Huron took them across in a canoe. The wind was strong and the immensity of the St. Lawrence was ruffled by blue-green billows. Kneeling in the bow of the canoe, the Huron paddled without evident effort, profiting, it seemed, by the least eddy to make the canoe advance. Cavelier marveled at him. At that very instant his heart was torn between a desire to brave the forests and adventures, and a desire to clear his land in peace and tranquillity.

They landed on a low muddy shore. A little above them foamed the fury of the rapids. The Abbé explained that the granite of the Canadian soil is so resistant, that after millions of years the river at this point had not yet worn it sufficiently to cut itself a passage.

Cavelier recalled the Captain’s assertion that if the rapids were not there, the largest boats could ascend the river much higher. Delighted to display his knowledge of the country, the Abbé launched upon a passionate geographical account of the St. Lawrence. He explained that it had its source in a veritable inland sea, composed of several large lakes. The Indians said there were five. In truth, no white man had yet completely explored them. Even Lake Erie and Lake Ontario guarded most of their secrets. The Indians spoke too of the imposing Falls of Niagara, the noise of which could be heard at a great distance, troubling the solitude of tall forests. At one point there were a thousand islands in the river. The lakes were supposed to be navigable and, according to the Indians, they communicated with one another.

Cavelier suggested that perhaps beyond them, another river, twin to the St. Lawrence, opened a similar water route to the other ocean. The Abbé could not confirm it, but nevertheless he considered it possible. He had heard the Indians speak of another great river, but he knew little about it.

“A route to China,” murmured Cavelier.

Amid willows, firs and maples, they walked over the concession. On the edge of the marshes they startled a covey of ducks. The mother duck pushed her ducklings toward the bank, made them disappear into the reeds, and disappeared in her turn.

The Abbé pointed out to his brother a swimming musk rat.

They were in the midst of a wild waste. The Abbé, more accustomed to the stimulating effect that “wilderness” has on the human soul, picked up clods of earth, examined them closely, judged them knowingly. He also calculated rapidly the probable level of the marshes and the river. Robert was surprised to discover him to be so versed in agriculture. Meanwhile, the Sulpician was giving advice——

“Here, you see, you have a cluster of sugar maples. It would be better to leave them. Moreover, I should advise you to cultivate them; in the Spring the sap will flow in greater abundance. Maple sugar sells at a good price in Ville Marie and Quebec.”

Farther on he said,

“This soil is equal to the richest soil of our beautiful Normandy. You might plant a fine orchard here. What cider it would give!”

Or again,

“Here is a plateau on which I should like to see a fine field of Indian corn. Indians are fond of it, but they are lazy. Not far from here are peaceable Algonquins and Christianized Hurons who will come to buy it. They know how to cultivate the ground, but they prefer hunting. A deer skin, well tanned, is worth an ecu. Three ecus are paid for the skin of a wild cat, three for a bear skin, five for a beaver. They would gladly trade their furs for your corn. In a country like this you must know how to make money. Besides, our father is a mercer, and are we less honored to be his sons? It is only at Court that commerce is considered degrading. Nevertheless, many things are bartered there—even the least honorable.”

They walked on, their boots covered with mud. Before them, clearing a passage, the Huron glided, his feet turned inwards. His supple moccasins made no sound. Cavelier, thinking more of the future than of the present, promised himself to wear them when he explored the forest.

His opinion was confirmed when his brother, having halted to drive away the mosquitoes, which were numerous, with a branch, asked the savage if there was a possibility of showing his brother some game.

“Ugh,” replied the Indian, his slant eyes blinking, “French shoes make too much noise. Much too much. Moose become frightened. Hide in the wood from French.”

Slowly they made their way back to the river. Robert scarcely heard his brother’s explanations. He cut him short with an impatient—“Yes, yes, it is agreed. I shall settle here.” But in his heart he did not know whether or not he was taking a wise step. It mattered little to him. Was not his real desire to go much farther, in quest of unknown lands, in quest, even, of the possible route to China?

“Cavelier, the colony of Cavelier. . . . Or even Caudebec. Those are fine names for a settlement. What do you think, brother?” asked the Abbé. Trembling, Robert replied,

“My colony is to be called La Chine.”

There was a silence. A tumult of conflicting thoughts stirred him to the depths of his being.

In an attempt to distract him, the Abbé had the Indian portage the canoe up stream. They descended the river by shooting the rapids. The Abbé smiled at his brother’s pleasure.

In every city there is a place to find men without work—the docks, where new arrivals wander, still bewildered. Oh, the fine Breton peasants with embroidered vests and silver buttons, large rough felt hats with floating ribbons! Their carved wooden shoes clumped noisily on the cobble-stones. But would they know what to do, torn from their gorse covered land?

Cavelier wandered along the docks, scrutinizing the faces of the men he met. . . . Lashed to their moorings were three tenders and many fishing barks, their sails reefed. An old man was darning his nets, singing. A sailor was unwinding a rope and braiding a splice, singing. A blacksmith was repairing the shackle of an anchor chain, singing. Each sang his trade, his joys and his sorrows.

Thus Cavelier went from one man to another. He admired the straightforward glances, aflame with the fire of adventure. He disliked such and such a poltroon, thrown by chance on the shores of the New World after having fallen into the hands of a “press gang,” and who wandered in a daze, not yet quite sure of being on land once more.

At the neighboring tavern was a man, drinking cider . . . good face, round and open; a wrinkle of disappointment at the corners of his mouth, a wrinkle of laughter at the corners of his eyes. Such is life, good and bad. . . . For all his youth, Cavelier well knew that such a man is able to laugh, after suffering. He sat down at the table and ordered a pitcher of cider.

“Monsieur honors me,” said the man. And he added, “Great joy is mine. Pardon for Jean Serreau.”

Cavelier was immediately interested. He recalled the story told off that Island of Orleans which stretched blue, yellow and green to the starboard of the ship. The man continued,

“Last year the King pardoned me. Pardon for Jean Serreau. I don’t know how to read, worse luck. But our Curé read it for me from the parchment. At present I am hunting for my wife, Monsieur. I have looked for her in Quebec, I have looked for her in Three Rivers, and only Ville Marie is left. As for me, I was in the woods, awaiting my pardon. But—pardon for Jean Serreau. Monsieur—perhaps you don’t know that I committed murder?”

“Yes, I know,” said Cavelier, “I have heard your story. And do you pardon your wife?”

“One must pardon, so our religion tells us. The King pardoned me—pardon for Jean Serreau. I pardon my wife—pardon for Marguerite Boileau. It is the way life goes . . .”

“And will you live with her again without reserve, freely?”

“Certainly. The lover is dead, and fear is a good guardian of the home.”

“And you still love her?”

“Aye, more’s the pity! I have pardoned her in full, as I was pardoned.”

Elbows on the table, hat pushed back on his peruke, sword dragging on the ground, Cavelier studied the man. “Good soul,” he told himself, “and more virtuous than I should be in his place. However, I have no desire for the sins of the flesh. But would I pardon thus readily? Frank and laughing face, robust body, hands made to wield the axe . . .” and aloud,

“Will you work for me? I am looking for strong men who know the country and who are able to swing an axe and drive a plow.”

“Gladly, Monsieur, I know how to do all that. In addition I know how to harness horses, and make them work. Nevertheless, I do not swear at them. The law would punish me for it . . .”

“Talkative,” thought Cavelier.

“And I also know how to swing and grind an axe. And I will enter into Monsieur’s service if he will pay me. But I will have to bring my wife and live with her.”

“But you do not know where she is.”

“She isn’t in Quebec, or in Three Rivers, so she must be in Ville Marie.”

“So be it. I give you eight days to find her. In a week’s time ask for me at the Sulpician Mission. I am called Monsieur Cavelier. In the meantime you may hire me other men, if you find them. Good men, understand. Hardened to labor and fatigue. I want no idlers. Here is an ecu on account.”

He paid and departed, thinking, “Such men are often more intelligent in their work than in their daily lives.”

Behind him, in the tavern, Jean Serreau merrily clinked his glass against the pitcher and repeated to himself, “Pardon for Jean Serreau.”

High booted, pacing with long strides over his new domain, Cavelier flourished a branch, as he had seen his brother do, to ward off the annoying mosquitoes. He congratulated himself upon having hired Jean Serreau, when he saw the skill with which the Poitevin directed the work.

“Knowing how to choose men,” Robert told himself, “is the mark of the chief. I made a lucky find—this Serreau is valuable.”

Serreau had arrived on the appointed day, shoulders bent under the weight of his “treasures.” Tied up in a big brown canvas slung on a stick over his shoulder, was his clothing. Behind him followed, smiling and coquettish, Marguerite Boileau his wife, whose eye brightened every time she was sure of escaping her husband’s glance. A dirty faced child clung to her skirts; another was in her arms. Cavelier, who liked children, asked his brother to give them a piece of maple sugar, which they sucked greedily.

Then came some twenty men hired by Serreau. The names of many of them testified to a military past: Laramée, Lavenue, Lafresnière, Larrivé, Lespérance, Lapipe—Cavelier recognized therein nick-names dear to the hearts of His Majesty’s soldiers. One by one, he questioned them at length. But above all he sought to gauge their energy by the cut of their chins, the curve of their noses.

Christianized Hurons, acting as ferrymen, pushed off their canoes from the Island of Hochelaga. The houses of Ville Marie and of Montreal de Maisonneuve drew away, became indistinct. The color of the foliage faded. The inverted image woven in the water seemed to be washed by the current. In the middle of the river a large blue spot mirrored the sky.

Thus they debarked at La Chine. A few chopped trees served to fortify a temporary camp. The men had divided their first days between wood-chopping and sentry duty. For it was wise to be on the watch for an unexpected visit from the Iroquois. The Abbé had warned his brother of the nature of these dangerous savages. One day far away, the next day near at hand, armed with guns supplied by the English; killing, scalping, torturing, burning, pillaging.

Axes resounded through the forest. Tall fir trees crashed to earth, breaking the branches of neighboring trees, crushing saplings in their fall. As soon as the tree was felled, woodsmen were ready with their axes. They stripped off the branches, cut it up into long logs, and then peeled the logs. A teamster arrived, his horse harnessed to a whipple-tree. He tied a rope around the trunk, set the animal hauling. The log was dragged away to an already cleared space of an acre or more, where a pile of them was being assembled.

Here the excavators had already dug foundations and had filled them with dry stones. A moderately large house was being erected, of the type common to that country. It was of logs laid flat, properly squared, dovetailed at right angles, and joined under the meticulous measure of Jean Serreau’s plumb line. Swinging from their hips, the sawers were cutting boards for the flooring, the doors, the interior planking, the roof. A former mason was mixing clay to make chimneys.

In the meantime, under a tent, Marguerite Boileau, assisted by two Huron squaws, was roasting enormous quarters of meat.

Even before the house was built—and it had been erected speedily—the men were primed for quarreling. Masterful, strong of mind and body, Cavelier with a commanding voice checked them sharply. He threatened to deliver the most quarrelsome to the Officer of Justice, and pointed with his finger across the space already cleared, and across the St. Lawrence to the smoke of Montreal and Ville Marie, where the sentinel would take care of delinquents. Order reigned. . . .

Since the year was well advanced, it was useless to think of clearing more ground. The Abbé would gladly have urged his brother to do so. But Jean Serreau was there. Consulted by Robert, Serreau, in a sententious voice, respectfully enumerated on his fingers the reasons why a late clearing would be a waste of effort. Half seriously, half mockingly, Cavelier agreed with him, despite the Abbé’s evident mortification.

Nevertheless, the men were not idle. They dug trenches destined to drain the marshes.

Robert reconquered the good graces of his brother by asking him to plan the draining outlets. Flattered, the Sulpician floundered about in the water, frightening the ducks and water hens, falling into muskrat holes, and always saved just in time by Serreau. Despite the impassibility of the latter and the ostentation with which he hurried to the aid of the Abbé, Cavelier detected the joy with which the workman welcomed these frequent misadventures. He would willingly have begged his brother not to expose himself to such ridicule. But knowing him to be of as haughty a disposition as himself, he judged it wiser to say nothing. Besides, the work was quickly and well done.

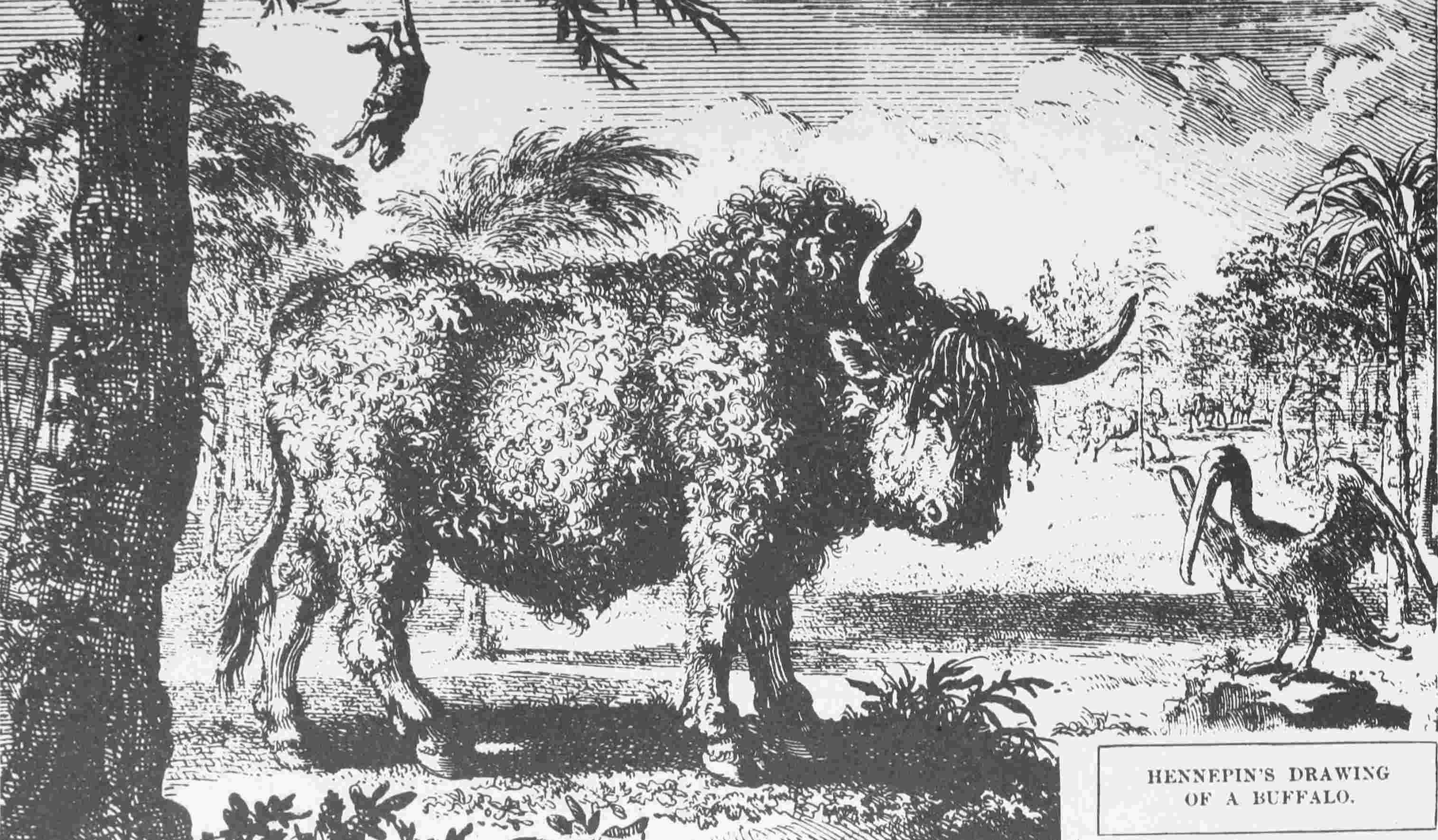

An Old Fort at La Chine, Site of the Colony Established by La Salle, from the Profits of which he Organized his Exploring Expeditions.

In everything connected with the defense of La Chine, Cavelier relied upon no one. He himself laid out the plan of the palisades, built of heavy pointed posts and fortified by wooden towers. The Cadet d’Aubagne, Gentleman, who was serving in the army and who came from Hochelaga to visit the domain, approved with the air of a connoisseur. While he was taking refreshment he used the fortifications of La Chine as a pretext to describe his campaigns and to put his own exploits in the most favorable light.

The workmen were set to other tasks. Axe or pick in hand, they dug up stumps and stones in order to prepare the ground for the plow, in the coming Spring.

Then Winter covered all with a thick blanket of snow, and the workmen did nothing but chop wood.

Spring arrived, preceded by the perfumed bursting of pussy-willows. In the morning the forest still seemed like chased silver. But the sun soon sent this metal to the foundry. On the St. Lawrence could be heard the noise of ice floes, striking against one another in their course, assembling to form ephemeral dams which were broken, just in time, by the sovereign weight of the waters.

Cut off by the river thaw, the Abbé Cavelier, who had been visiting Robert, was forced to remain. The ardent and bustling priest, at heart less energetic perhaps, but outwardly more active than his brother, busied himself, with the aid of Serreau, in gathering the precious maple sap.

In respect to his wishes, the clump of trees had been left intact. More than that, during the last days of Autumn, Serreau had set his best men to work clearing out the surrounding underbrush. The tall straight trunks with tender new sprouts had now a most imposing aspect.

“My cathedral,” said the Abbé. Gesticulating, enthusiastic, smiling happily, he called the trunks “my pillars” and the branches “my vaults.” At times interfering with Serreau, bothering the workmen, he criticized the way they pierced the trunks, cut the bark drains, or placed the crude troughs to catch the sap, which was gathered by two other men and set to boil.

The great gray clouds of a rainy April disappeared. Only light mists dragged lazily across a clear sky.

Swollen by the rain, the St. Lawrence was a headstrong and irresistible mass, in whose current floated an accumulation of trees torn violently from the soil.

The sight pleased Cavelier. From time to time he enjoyed crossing, in a canoe guided only by Jean Serreau, the dark whirling eddies of the river.

Hochelaga was settled with new houses and new fields. Ville Marie, Montreal, the missionary colony and that of Maisonneuve endeavored to unite their gardens, in which the first shoots of Indian corn were piercing the soil with their tender spears. A blue haze rose from the river, scaled the escarpment of Mount Royal, and lost itself in the brushwood.

Returning from one of these crossings, as Serreau was beaching the canoe, Cavelier asked him to push on to the rapids. Two of his men joined them, muskets on their shoulders. Almost at once they saw before them the furious foam.

“Look—Indians!” exclaimed Serreau.

Cavelier raised his eyes, following the direction indicated by Serreau’s paddle. In the middle of the rapids, four men were struggling desperately with a long bark canoe. His hand shading his eyes, Cavelier watched their efforts anxiously.

“They will be drowned,” he cried.

“Good riddance! The dirty dogs! It’s an Iroquois canoe,” grumbled Serreau.

With a gesture, Cavelier turned aside the already leveled musket of one of his companions. In that instant he lost sight of the canoe. When he looked again the empty craft was whirling in an eddy below the rapids. Four copper-colored heads floated in the mad waters. Seizing the long light paddle from Serreau, Robert threw it adroitly. It fell a few feet from one of the savages, who succeeded in grasping it. With its aid he skillfully held himself above water. Almost immediately his three companions disappeared, carried away by the furious torrent.

The man with the paddle, however, let himself drift. Using a stroke unknown to Cavelier, his left hand described a curve above the water, struck out straight from the shoulder and reappeared at the thigh. Every stroke brought him nearer the shore. Almost running to keep up with the current, Cavelier descended to meet the castaway. At a point lower down, the Iroquois was able to land, and Robert aided him without thinking of wetting his velvet suit.

Exhausted as he was, the Indian rose immediately to his feet. Half nude, with wide and fringed leather trousers, he regarded the river.

“That mixture which is dripping from his cheeks and chest,” thought Robert, “is his paint diluted by the water. There is black, white and ochre. . . . War paint. The St. Lawrence is surely bearing away the eagle’s feather which was stuck in his topknot.”

The man was tall and good looking, with a face almost noble, had it not been for the inordinately high cheek bones. He examined Cavelier for a moment, and his face, stern until then, suddenly softened. His eyes narrowed more than ever as he said,

“Ugh! My white brother threw me the paddle just in time. My red brothers are gone. . . . They now swim with the fish, seeking the hunting and fishing grounds of Manitou. . . . Tomorrow three squaws of my people will have no men to bring them meat.”

“Come with me,” said Cavelier.

With his elbow he pushed aside Jean Serreau who, rising on tip-toe, whispered in his ear,

“Monsieur is wrong. . . . My good master would have done better to let the dirty dog drown. . . . A dog of an Iroquois. . . . I tell you, Monsieur, they are men you can’t trust. They belong to . . .”

“Silence, Idiot!”

Serreau scowled, but was silent.

The Indian accompanied Robert. Had he or had he not heard Serreau’s words? There was no telling, so placid was he. His hand made no move toward the scalping knife hanging from his belt. That belt was ornamented with human hair.

“Trophies of war,” thought Cavelier. “Is Serreau right? Bah! . . .”

A fire burned on the hearth. Cavelier motioned the savage to a wooden chair beside it. The Indian looked at the chair, then sat down on the floor, leaning on his elbow. Cavelier was momentarily undecided. . . . Did the situation demand courtesy? He hesitated only a moment. Deliberately he too sat down on the floor, facing the savage, resting his hand negligently on the chair.

“I am being ridiculous,” he thought. He was more and more confirmed in his opinion upon seeing Serreau standing transfixed, his mouth and eyes wide open. “Serreau is asking himself if I have gone mad. That is the last straw,” Robert told himself. “Now how am I going to preserve my dignity? Does it matter?” With a sharp command he ordered food brought.

Serreau departed backwards. Not hearing the door close, Cavelier looked. Serreau was gone, but a sentinel, his musket in readiness, was leaning against the door jamb.

There was silence. Should he emphasize the impropriety of this suspicion toward a guest by discharging the sentinel? On the other hand, had not the Indian, despite his impassiveness, already felt the affront? Robert decided. . . .

“Will my Indian brother,” he said, “permit me to let that man retire? He is here to do honor to my brother—(‘How am I going to save the situation?’ he thought, as he continued)—to my brother, who is surely a chief among his people. But my brother is tired, and perhaps wishes to remain alone with me?”

The savage nodded his head affirmatively. Was his indifference real or feigned? At Cavelier’s command the man departed, closing the door. The Iroquois, lost in revery, watched the dance of flames in the shadow.

Minutes passed silently. There was a rap at the door. . . . At a word from Robert it was opened by disgruntled Serreau, carrying a plate piled high with food. In a low voice Cavelier ordered him to put it on the floor, between himself and the savage, and to retire. Serreau withdrew.

“My brother has need of food,” said Robert quietly. “His day has been hard. Will he share my meal?”

The Iroquois raised his head and his serious eyes met those of Robert. His face gleamed in the firelight. The Frenchman was better able to examine his guest, and saw that he was a man in the prime of life. Had it not been for his slanting eyes and high cheek bones, Cavelier thought, he might have been remarkably handsome.

Slowly, with negligent fingers, the Indian undid his belt. It sailed across the room, together with the knife it carried. The unknown guest had disarmed.

Meanwhile Robert served him, carefully choosing the best pieces. But before eating, the savage spoke:

“My white brother,” he said, “is surely a great chief. He saved my life. Many men with red faces or with white faces would not have done as my brother did. Ugh!”

Cavelier was surprised by the ease with which the Indian expressed himself. Certainly his grammar was incorrect. And those guttural intonations! . . . But they were not without charm, and his vocabulary was ample.

“My brother is a great chief,” the savage continued. “He knows, like a chief, the laws of hospitality. He sent away the warrior that the man who does not like me” (evidently a reference to Serreau) “put there to kill me. As if I had a coward’s heart! As if I could strike one who received me as a brother! But my white brother had confidence, and he was right.”

Suddenly silent again, he ate. No doubt he felt that he had uttered the essential words. He ate with a hearty appetite the food Cavelier offered him.

But when they had finished eating and had smoked the same pipe, in the Indian manner, he replied without hesitation to the questions put to him.

“From where was I coming? . . . From the country of the Great Lakes. But it is not my own country. My people are a three days’ march from here, towards the rising sun. What was I doing on the Great Lakes? . . . My brother was looking awhile ago at the scalps hanging from my belt. Eight months ago, some young men of my people were voyaging on the Great Lakes. The Chippaways took three of their scalps. I have been to pay my debt to the Chippaways. . . .

“My friend also wishes to know whether I am friendly to the Whites. . . . I shall speak openly to my brother. There came among my people Black Robes who bore words of peace. From those Black Robes I learned the language of my brother. I learned also that following after the Black Robes came white men, who crossed the Great Salt Lake, with boats as big as villages and winged like gulls. And these men, who pretended to follow the Black Robes’ religion of peace, did not bury the tomahawk. They came to us and said, ‘Cursed savages! Your land is good—we are going to take it from you.’ Then we were obliged to go farther away, toward the setting sun, without being able to take with us the bones of our fathers, who slept on the shores of our rivers. And the white men passed with horses and plows over the tombs of our fathers. We hunted for the tombs and we found Indian corn. Ugh! Could the bones of our fathers be replaced by ears of corn? So then we were obliged to go toward the setting sun. There we met other peoples. The Illinois, who are between the lakes and the great river, and the Chippaways, who are to the north of the lakes. And other men, too, who are not of our people, but who have, like us, red skins. . . . And then we were obliged in our turn to see if we could drive away the other red people, and take their place, because the whites drove us away, and took our place. Then, men of the Yanguie people, who drove out the Mohicans as my brother’s people drove us out, said, ‘Cursed savages! They think only of killing.’ But, my brother! Before the arrival of white men, a man sometimes lived half his lifetime without war. And when there was a war it was because a bad Indian—there are bad Indians—had hunted in the hunting grounds of another people and stolen the game which the Great Spirit had sent them to eat. Then, if he were caught, killed and scalped, vengeance was necessary. But they were little wars which did not last long. Right away the messenger of peace was sent. He said, ‘Chiefs, enough blood has been shed. Today we must smoke the pipe of peace and bury the tomahawk deep. And we have provisions. Tell us if you will come to feast with us, or if, having plenty yourselves, you wish us to come and rejoice with you, like brothers with brothers. Today my white brother knows that we are obliged to make war. The white warriors think that our wives are their wives. Perhaps, if they came to us with presents and if they asked us for our daughters, we would give them our daughters for them to keep forever—unless they had a just grievance—and to care for them tenderly and generously. But it happens that they have taken some of our women from us. And that has made war between us. They also claimed that certain lands were theirs, whereas they were lands to which the Great Spirit sent us our game. . . . For the red man must hunt if he wants to live. . . . He does not know the white man’s occupations, and he does not want to know them. And I tell you this: my name is Mashquah, which you would call Big Bear. And I am a chief and I know how to make my way through the woods, the mountains, and the rivers, like the bear whose name mine is. And I hate the French. But because you have received me like a brother, you and yours, save for a mortal offense, will be spared by my warriors. And if you wish to visit me, I will teach you the secrets of the woods. But now that I have told you everything you want to know, tell me where I may stretch myself to sleep, for tomorrow, when the sun rises, I must go to carry three women the news that their men will never hunt for them again. One has three children. And the Great River took those three men, as you saw.’”

While the savage slept soundly in the bed which Cavelier had made for him in his own room, the young man reflected that here was the guide who would perhaps open to him the route to China. . . .

He resolved to see him very soon again, and learn from his Indian experience how to travel through the forests.

He who has eyes already possesses the world, Cavelier told himself.

At every bend of the river, the canoe, left behind it a flight of mottled water, successions of light and shade, and the play of color on trees and rocks; but each of those same turnings offered, in place of what it took away, waters just as richly inlaid, shadows just as fresh, lights just as warm, and a play of color just as capricious. Thus Robert did not have to turn his head to stamp upon his memory the images of things seen. Others ahead were just as alluring.

The glorious wilderness was bedecked with all the ancient and inexhaustible treasure of Autumn. Copper and gold rivaled each other. The leaves of the ash tree were of flawless brass. Those of the oak proved the tree’s time-honored nobility by their patina of solid gold. But the brilliance of the maples even surpassed them.

Animal life appeared always in an unexpected fashion. Kneeling in the bow of the canoe, the Indian, Big Bear, paddled with even and rhythmic strokes. His ease surprised Cavelier. The canoe was moving against a strong current. But with a simple bend of his body, Big Bear gave the necessary propulsion with the paddle; the canoe cleaved the current lightly, and attained the small eddy, unsuspected until then by Robert, which carried it forward. Then another stroke of the paddle.

But even more astonishing than his skill was his capacity for observation. He would seem to be intent upon avoiding a rock or a dead tree imbedded in the river, but at the same moment he would turn toward Cavelier and point out to him the wild flight of a deer or marten, the pursuit of a giant trout over the river bed. Nothing in the air, on the ground, or in the water escaped him, and he immediately called everything he saw to the Frenchman’s attention, knowing he was anxious to learn and to possess all the secrets of the wilderness.

For several days these two men had lived together in solitude. Faithful to a promise made on leaving La Chine, the Iroquois returned one day (to Serreau’s great terror) to take the master of the domain away with him. The Abbé Cavelier, who liked to command, had obtained authorization from his superiors to replace Robert during his absence.

After a breakfast of broiled fish, the men at dawn boarded their canoe and paddled upstream, silently, without even disturbing the delicate song the river sang to herself.

Shortly before sundown the Iroquois headed for shore. There, after beaching the canoe, they camped. The Indian told his companion the names of animals and things in a songlike language. The sound translated them so exactly that each time Cavelier was astonished that such words were not universal. How could other words have occurred to the minds of white men? The study of the Iroquois language was far more interesting to him than the classical beauties taught formerly by the professor of Latin at the college of Rouen.

He acquired other knowledge. . . . All summer, on rainy days and particularly in the evenings, they had been bothered by mosquitoes. He had learned to suffer the ceaseless torture without scratching, until protection could be found in the smoke of their campfire. There were also stinging flies and other insects, imperceptible to the eye, which dug cruelly into the skin. . . .

Sometimes they encountered Indian camps. They were always Iroquois, for it was in the very heart of their country that Robert was learning woodland lore. Even though they were evidently nomadic—at least by instinct—Big Bear always seemed aware of their presence. He greeted them, but did not mingle directly in their life. Only after the evening meal, while Cavelier smoked, did the Indian talk with the men of his own race. The slant eyes of the squaws brightened at some story which Cavelier heard without understanding, but of whose musical qualities he never tired. There were guttural intonations similar to the sound of a theorbo; others had the resonance of an alto.

But Cavelier remained the White Man. Men, women and children, despite the courtesy with which they bade him farewell before going away to try their luck at fishing, maintained toward the stranger a cold and somewhat haughty reserve.

One afternoon the voice of a distant waterfall silenced the murmur of the river.

The canoe was then gliding in calm, almost oily water, made even smoother by the shadows of mossy rocks and gigantic pines. Big Bear landed the canoe between two rocks and pronounced the single word: Portage.

Cavelier sighed. The shock of the landing, for all its lightness, reverberated like a wave in his heart. Dreams were broken, and it was with sorrow that he thought of their disappearance forever. It is difficult to grasp again the broken threads of a dream when there is a portage to make.

Before him, an Indian path cut a tunnel through the forest, whose obscurity was lighted here and there by the gleam of dry leaves. Several hundred rods from the river, the path climbed a steep hill.

Robert followed the Indian. The latter easily carried the greater part of the baggage, and on it he had succeeded in loading the bark canoe, so light, but so cumbersome when out of water.

Nevertheless, Big Bear marched tirelessly on, whereas Robert, lightly laden with only eighty pounds slung on his back by a wide strap across his forehead, was bothered by the musket which he carried in his hand.

Shortly before arriving at the summit of the hill, he stopped. Head and shoulders freed from their burden, he took a deep breath. Then, to rest the muscles of his neck, stiff from having been too long curved forward under the weight, he raised his head.

He saw then that giant pines rose on all sides. Enormous trunks stretched some sixty feet from the ground without a branch, their rough bark catching a few orange lights through the deep violet shadows. The lowest branches, bowed from having held so many winter snows, swayed gently. Higher still, at one hundred feet or more from the ground, the pointed tops, although invisible, probably swayed rhythmically at the will of an unsuspected wind. That, no doubt, accounted for what seemed to be the vibration of an æolian harp, chanting high above—celestial melodies of which the ears perceived only the muted echo.

Robert was enchanted. He remained motionless, spellbound, so long that the Iroquois, who had continued his route, returned without his load, the portage having ended. He smiled at his young companion, without a word, and assumed the burden himself. The smile seemed to Robert the extreme limit of cordial blame. A trifle ashamed, he followed.

“A feast for the ears,” he thought. He was certain that the ascent would offer an equal feast for the eyes.

They reached the summit. Before them hundreds of ancient trees had been felled by a storm, and the view stretched a great distance without encountering an obstacle. Below them was a lake, all aquiver under the play of light, while on its opposite shore there rose a semi-circle of sister hills, each crowned alike with pines, each one as beautiful and as friendly as the others.

Cavelier asked the name of the lake. The Iroquois word was so melodious that it seemed to have been chanted by the pines themselves, or at least to have been whispered by them to the Redskin chief. But doubtless only an Indian could pronounce it without sacrilege or ridicule. He envied Big Bear for speaking naturally a language so noble, and out of respect, even though he did not know the meaning of the word, he would not ask for a translation.

“A lake of sighs,” he told himself. “No doubt it must be called Louis, or Talon, or Colbert. But why? I am the guest of an Iroquois here, and can I impose on his friendship by giving it a name he would abhor? For my part, I hear the wind playing hymns in the tree tops. Sighs! That is it, no doubt, with something more religious in the meaning of the word. But among so many words, how can I find one which has not been profaned? This savage word is so musical, that by virtue of its very music, it assumes an element of mystery.”

Complacently, the Indian had stopped. He enjoyed the astonishment of his white companion. Who spoke of impassibility? The narrowed eyes, the sorrel face smiled, as did his mouth. No doubt he was happy that a white man was not solely preoccupied in bargaining for furs, or stealing land. Perhaps, because of this, he pardoned the white man for not being of Indian blood. How otherwise explain the fact that not only did he tolerate the admiration of a stranger for this magnificent country, but also to make it possible, he himself voluntarily carried the stranger’s load?

Cavelier attempted to absorb this beauty. He felt himself both intoxicated and oppressed. There was too much of it for the human soul to conquer all at once, even if aided by the best eyes in the world. Between Nature and man, it is Nature who is much the stronger. Strong enough to employ her strength with gentleness, a gentleness so insinuating that Robert was captivated without realizing it.

He turned to Big Bear and said:

“We shall camp here tonight.”

Big Bear laughed softly and pointed to the sun, still high. Cavelier misunderstood. He repeated, “We shall camp here.” But gravely the Indian turned to him—

“My brother will camp tonight with my people—we have arrived.”

At a bend in the path they saw smoke. Trotting sideways, hostile dogs came to meet them. A word from the chief changed one of them, the largest, from a wild beast to a domestic animal, and the rest of the pack ceased barking.

Behind the firs, silhouettes moved. . . .

Days, in this village, were woven in a tapestry of great blue woods. Cavelier learned to understand the Indians. The simple dignity of their lives astonished him. At first aloof, but respectful because of their chief’s attitude toward him, they in turn learned to like the tall, broad-shouldered and energetic paleface. They delighted in taking him hunting, in teaching him the art of navigating without a compass across the ocean of verdure, and how to stalk moose, which gives meat—that is to say, life. They revealed to him such secrets as white men do not know:—what roots and barks are edible, what lichen is nourishing. Also the art of walking noiselessly, shod in soft-soled moccasins, through the woods. The forest was filled with the songs of birds, the rustle of dead leaves, the discreet breaking of dried branches. There was also the strange noise which holds one breathless until one learns that it is caused by a dead tree, half felled, rubbing gently against the branches of other trees as it sways in the wind. And again, the murmur of the stream or the choir of waterfalls. Afar off the noise of a cataract. The grandiose symphony of Life. But perhaps it conceals the unforeseen chant of Death.

There were games of hide-and-seek played by the copper-colored boys with slant eyes. Here a little chap skillfully glides from tree to tree, unseen by his comrades until he appears farther along, triumph shining in his eyes. . . . One day he will thus avoid the hostile Ottawas or Illinois. Then here another bright-eyed lad plays at being captive. Two older boys, making terrifying faces, grasp his puny arms and tie his little body to a tree trunk, mimicking the tortures their fathers practice. Their prisoner heaps insults upon them. A tall boy, with a long hooked nose, scalps with a wooden knife the rabbit he has just shot with an arrow. . . . Games of death.