* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Bright Spurs

Date of first publication: 1946

Author: Armine von Tempski (1892-1943)

Illustrator: Paul Desmond Brown (1893-1958)

Date first posted: Apr. 8, 2023

Date last updated: Apr. 8, 2023

Faded Page eBook #20230414

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

This file was produced from images generously made available by Internet Archive/Lending Library.

BRIGHT SPURS

Books by Armine von Tempski

PAM’S PARADISE RANCH

JUDY OF THE ISLANDS

BORN IN PARADISE

THUNDER IN HEAVEN

BRIGHT SPURS

Copyright, 1946

By DODD, MEAD AND COMPANY, Inc.

TO MY BELOVED SISTER,

“HAUK”

IN MEMORY OF OUR DUDE-WRANGLING DAYS

AND

TO ALL ’TEEN AGERS WHO GIVE A HUNDRED

AND TEN PER CENT TO DAILY LIVING.

CONTENTS

| Chapter | Page | |

| I | Secret Return | 1 |

| II | Reunion | 9 |

| III | The Great Idea | 20 |

| IV | Static | 36 |

| V | Scrambled Take-off | 52 |

| VI | The Grenadier | 70 |

| VII | Keep Them Bright | 84 |

| VIII | The First Milestone | 101 |

| IX | Learning the Ropes | 110 |

| X | Honor Takes a Hand | 124 |

| XI | Rough Going | 146 |

| XII | Tricky Going | 165 |

| XIII | The Question of Honor | 182 |

| XIV | S——O——S! | 196 |

| XV | Rich Harvests | 211 |

| XVI | A Peep into the Past | 224 |

| XVII | End of the Rainbow | 240 |

| XVIII | Christmas | 250 |

| XIX | Change of Heart | 261 |

| XX | The Road | 271 |

| XXI | Out of the Blue | 280 |

ILLUSTRATIONS

| Page | |

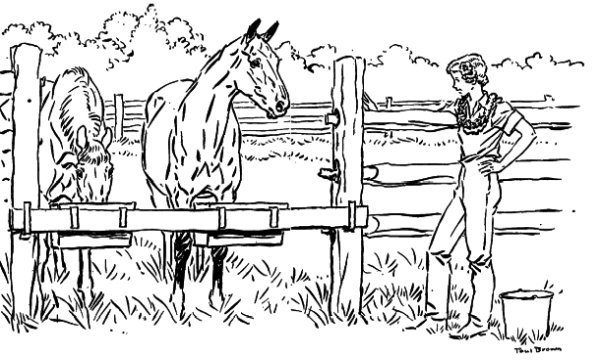

| Reaching Out His Long, Slender Neck, Happy Dropped His Beautiful Head into Her Outstretched Arms | 26 |

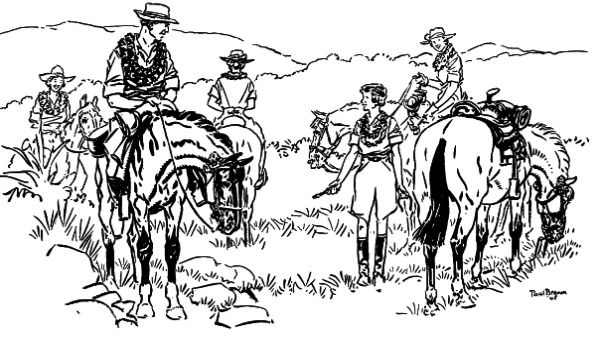

| “On This First Trip Hangs Our Future,” Gay Said Chokily. “If It’s Successful, It’ll Give Us Courage and Confidence. If It Ends in a Fiasco—” | 68 |

| Horses Began Walking Swiftly Through the Tall Grass, Eyes and Ears Alert. She Watched Them Fondly as They Hung Eager Heads Over the Bars | 90 |

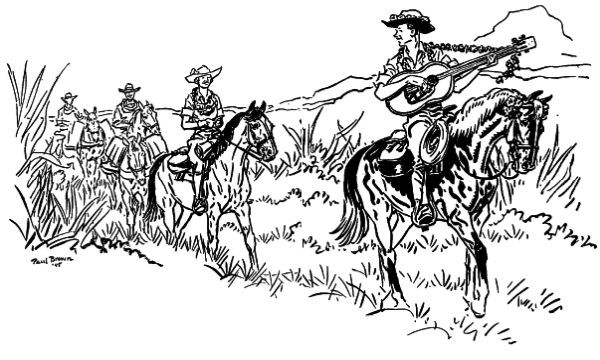

| When the Cavalcade Was Underway, Davie Dropped His Reins Over His Pommel, Swung His Guitar into Position and Began Singing a Haunting Mele | 128 |

| “That’ll Hold Till We Get Home,” She Announced, Straightening Up. Her Face Was Flushed, Her Hands a Trifle Unsteady | 154 |

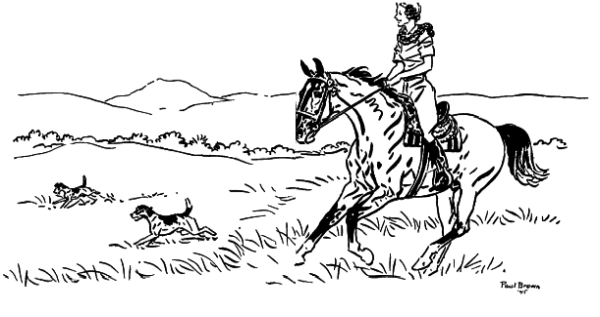

| In a Dim Way, She Was Aware of Her Horse’s Eager Feet Skimming the Earth, of Furry Little White Bodies Dashing Back from Excited Scentings | 176 |

| Gay Nursed Her Horse Over the Long Miles Between Waiopai and Home. Steadily, Happy’s Long, Swinging Trot Ate Them Up | 218 |

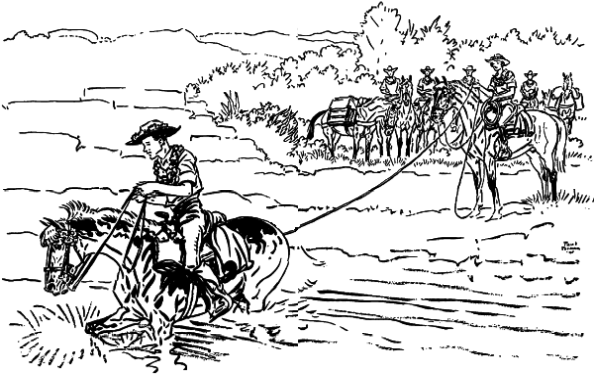

| When the Water Grew Deep, Davie’s Horse Began Swimming Across the Tossing Flood, Losing a Foot Sideways Every Yard | 232 |

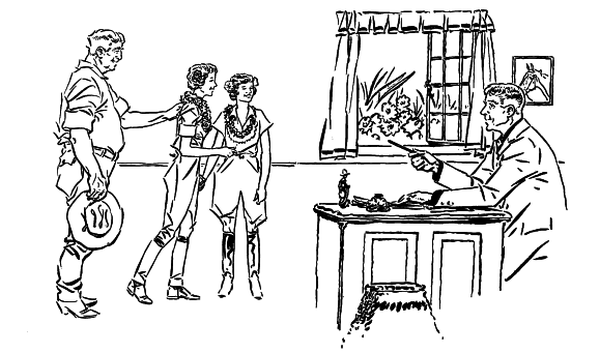

| “You Know, of Course, What the Place Is Valued at,” Sam Said, “and I Conclude You Have the Price—” | 246 |

Gay fastened her eyes on the turns of the road which the headlights of the car kept snatching up. Her fingers tightened about her fifteen-year-old sister’s hand. Cherry gripped back.

After a couple of months in the States they were home again, facing problems which made them feel hollow and weak. Gay looked at the broad shoulders of the Hawaiian at the wheel, silhouetted against the dim dashboard light. He drove his car as if the fare he was earning were a matter of small consequence. Large, loafing contentment poured from his big body, as though he figured that life was to be enjoyed rather than worried about.

“Cherry and I must be like that,” Gay thought, “confident, sure of ourselves.” An electric tingle went through her but it was followed immediately by the hollow sinking sensation of a moment before.

“We must do it, Cherry,” she said into the air.

“Yes,” Cherry agreed in a rather grim little voice.

In the cast, against fields of stars, was the loom of the extinct volcano, Haleakala, near which they had spent their happy childhood. The cold, clear wind swept past, smelling richly of wet forests, deep grasslands, fat cattle and sleek horses, recalling the secure years just behind them, watched over by their father, who had been mother and pal, too, for his two daughters. Thinking of the difficult future confronting them without him, Gay stared bleakly ahead, then flung up her chin, mentally defying the obstacles lying in the path Cherry and she had determined to follow.

The lines of her face, finely modelled, had courage and breeding in them, without actual beauty, but a lighted something shone from inside her and her back-combed curly hair looked so alive that it seemed as if wind was always streaming through it. Wide gray eyes, a delicate, rather irregular nose, ending in an enchanting tilt, gave her an elfin quality, but her forehead was gallant and courageous.

By the faint dashboard light, seeping back over the Hawaiian’s big shoulders, she could see her sister sitting taut and silent beside her. Cherry was an extra-special sort of person, she thought, direct and dependable. Her eyes were brown, fearless and steady, and shaded by thick lashes tipped with gold. But it was the way she held herself that made her stand out from other people, as if she were walking straight into the battle of life, confident that she would win it. Until their father’s death, Cherry had been rated the second finest rider in Hawaii. Now, she held first place. She had taken part in Stake races, roped wild bulls, broken horses and trained polo ponies since she was ten.

“We’d better tell Pili we want to be let out at the foot of the hill,” Cherry suggested in an undertone.

“And immediately he’ll want to know why,” Gay said edgily. “But if we drive into the garden, the dogs’ll start barking, the servants will rush out, adding to the uproar, then Sam Spencer will hear and come over. By noon everyone on the island will know we’re home!”

For a moment Gay looked as forceful as a person of twenty-seven, instead of seventeen. Leaning forward, she tapped the big Hawaiian on the back.

“Somekind you like?” he asked over his shoulder.

“Don’t drive into Wanaao, stop at the bottom of the hill,” Gay directed. Then she and Cherry braced themselves for the first of the thousands of questions they knew they would have to answer during the next few days. It came like an arrow.

“For why?” the man demanded in an amazed voice.

“You—and all Hawaii will know shortly,” Gay replied rather breathlessly.

“And don’t tell anyone we’re home, Pili,” Cherry cautioned. “We came on the late boat on purpose so no one would see us arrive. Here we are. Stop, please.” She indicated the steep road winding up a hill with tall eucalyptus trees, filling the night with their clean, strong smell.

Bringing his car to a halt, the driver shut off the motor. Gay opened the door and got out. Cherry followed. Pili emerged from the front, and heaved two heavy suitcases, which had been stacked beside him on the seat, onto the grassy bank. Then, rumpling his graying hair in a puzzled way, he confronted the girls.

“Why-for you kids not drive in? Why you sneak like thiefs into your own house? Meny, meny years now I know your papa and you kids. I got a big sorry when your papa make. Tough when young girls never having mama, then lose papa, too.” He stopped for an instant, giving a brief, silent tribute to the dead, then continued indignantly. “But every peoples in Hawaii speak the same kind. You kids make a big crazy to take so much your money and spend it going America. How you eat? What-kind you make now? What you getting for making this crazy-kind stunt?”

“You’ll find out,” Cherry said. “We have twenty horses, the house for a while—”

“Sure, I hearing what-kind Sam make when your papa die. Your papa make good hanahana—work, for Sam and it pololei for Sam to tell to you girls you can stop the old place for one—two years. But when papa die, salary pau and you pupule kids spent his life-insuring money going America,” he went on hotly. “I hear what-kind you talk while us drive. You only got little left and that go quick!”

“Pili we each have two hands, two eyes, two feet—”

“And big crazys in the head!” Pili exploded, cutting her off.

“Time will prove that,” Cherry asserted with more assurance than she felt just then. “But in the meantime, our business is our business,” she finished, stressing the next to last word.

“Okay,” Pili agreed with the quick, good-natured tolerance of the Polynesians. “But better I kokua you girls and carry the suitcases to the house. Too heavy.” He indicated the big bags.

“We’ll manage, Pili, thanks,” Gay said. “You see, even if our dogs are always shut up in their kennels at night, if you’re with us, they’ll smell a stranger and start barking. If Sam hears them, he’ll come over to see what’s up. After all, he owns the place. Pili, while Cherry and I were in America, visiting my godmother, we got an idea for earning our living in a way that never has been done before in Hawaii. But Daddy always said that thinking about doing a thing, and doing it were two very different matters—”

“That pololei—right,” the big Hawaiian agreed, watching the youthful pair with curiosity and compassion.

In the bright starlight the expression of tender regret for the loss of their father, and concern about their future, was plain on his fine, big features. Suddenly Gay felt young, helpless, and inexperienced. The night seemed to expand to vast proportions and to be filled with invisible enemies who would contest every step of the road along which she and Cherry were determined to go. Did they really have “big crazys in the head” to think they could do it? Before the thought was completed she flung it angrily from her mind and went on talking.

“Daddy taught us to face things, Pili, to think in straight lines, and we intend to prove his methods are right. Cherry and I have weighed our idea from every angle and feel we can swing it. But we want to get going before older people come swooping in with their ideas of how we should earn our livings, maybe getting us all tangled up in our minds and off the track. That’s one reason why we went away—to be able to think things out for ourselves. And besides, we just couldn’t bear to stay here after—” Her breath caught.

Pili gave the two girls a long, deep look. “Well, I not knowing what-kind you kids going to make and if you not like to tell me, that not my business. Anyhows, big Alohas and good lucks.”

Solemnly he gripped the girls’ hands, shaking them in a large, warm way. Then, doubling his big body, he got into the car and drove off.

Cherry and Gay gazed at each other. The night, rich and beautiful with remembered scents and sounds for which they had longed while away from Hawaii, was all at once awesome and empty. Island bred and raised, they had both responded to the fun and comfort that seems to fill life when a Hawaiian is around. Unconsciously during the drive they had been affected to a large degree by Pili’s unworried attitude about living. Now that he was gone, they realized that they were utterly alone, standing on the threshold of a major crisis of their lives.

“I feel about as big as a grain of sand on the bottom of the sea,” Gay said, finally.

“Me, too,” Cherry agreed in an undertone. “And when I think of the uproar and the avalanches of advice that’ll pour over us when people find out what we intend to do, I go all weak and wobbly inside.”

“We’ve got to get going before anyone finds out,” Gay insisted in a small, tight voice.

“If—we can.” Cherry stressed the words as if she doubted the possibility of such luck.

“Well, we’re not getting anywhere just standing here in a frozen panic at the bigness of the job ahead of us,” Gay announced. “Let’s get going, and every time we feel stampeded inside, we must remember that Dad always said a person can do anything, providing he wants to enough!”

“Yes, and that goes for us—too!” Cherry said staunchly.

Taking up their heavy suitcases, they crawled through the wire fence and began doggedly trudging up the hill. Fragrant guava bushes, the lusty smell of eucalyptus trees and the vital incense of earth and deep grass, damp from recent rain, filled the night.

The muscles in Gay’s arm ached at the drag of the heavy suitcase pulling against them. Silently, with frequent pauses for breath, she and Cherry toiled up the steep slope.

“Our life’s going to be like this,” Gay thought, “all uphill. Heaven only knows for how long. But if we can make the grade, reach the top—”

Cherry dumped her bag down and Gay followed suit. They stood for a moment, regaining their wind. In the starlight, the outlines of the island were plainly visible. To the west, the Iao Valley Mountains cut sharply into the sky. A long, dim shape on the horizon marked the Island of Molokai. Directly ahead, the monster dome of Haleakala filled the east, crowned by the dazzling beauty of Scorpio, blazing above the summit.

Gay’s heart caught into a knot as she recalled the countless times she and Cherry had lain wrapped in blankets, when they had camped on the 10,000 foot summit of Haleakala, while their father had taught them the names of the major stars and identified the jewel-like constellations in the majestic tropic heavens arching overhead.

Instinctively, her eyes turned to a familiar spot above the sea where the Southern Cross burned like an eternal beacon of hope. It had been the first star-cluster their father had showed them when they were little more than babies.

“Cherry,” she said chokily, pointing at it.

Together they gazed at the starry cross which they both loved most of all the constellations they knew. It symbolized their father, to whom people had instinctively rushed for help and advice in trouble, and also to share their joys: their father who had always insisted in his gay, brave way that even when life went against people, it was a worthwhile adventure. The sisters’ hands met and they stood silently for a moment. Then, taking up their heavy bags, they continued climbing the steep slope.

“One more heave and we’ll be there,” Cherry panted.

They plodded on and finally pushed through a hedge of oleanders and cypresses, which circled the big hilltop like a vast, fragrant garland. Acres of well-kept lawns, broken by flower beds, surrounded the low, rambling house in which they had lived so richly and widely with their father. Ginger, gardenias, frangipani, alamanders, hibiscus, Chinese violets, mingled with blossoms from colder lands, sent up a symphony of perfumes.

In the center, crowning the big hilltop, was Wanaao, the home they so loved—and did not own. Wanaao, named for the first promise of light in the sky, the dawn before the dawn, the herald of the unending marvel of day being born again. Happiness and sorrow had lodged under its roof, and its walls guarded yesterday, today and tomorrow. It was the focal point of all the memories they cherished of a childhood such as few girls have ever enjoyed.

Their father had made it his business to have his motherless daughters share every phase of the vigorous outdoor life he led in managing a sixty-thousand-acre cattle ranch. From the time they had begun to ride they had helped him work with the stock, knew every trail threading the vast flanks of Haleakala. They had learned how to saddle and pack horses, pitch tents, had acquainted themselves with the haunts of the wild game roaming the mountain. They had thrilled to seasons coming and going—spring with its new growth of grass and crops of calves and colts; summer, when roundup time brought an added uproar of living to the ranch, as herds of glossy red cattle poured down the hills and broke like lava through the forests, and corrals seethed with the business of branding and ear-marking new calves. In the autumn they had ridden with their father to select new sites for the thousands of trees he set out every year, and watched him supervise the planting of grasses imported from all over the world to enrich pastures where herds in his charge grazed and fattened. They had hunted wild turkeys, pheasants, hogs, and plover, roving the upper reaches of Haleakala, and in winter, when great Kona gales roared up from the equator, they had raced on horseback with their father, through the rain and wind, exulting in the new growth that such storms brought to the Islands.

“Wanaao,” they whispered softly, gazing at the many-winged house. “Wanaao—The Promise of Light.”

Their hands met again and locked fiercely, then, picking up their bags, they headed across the lawn toward it. They required no key to get in, for, Island-fashion, all the French doors on to the wide lanais stood wide open. Like thieves they tiptoed indoors. They needed no light to find their way about, since they knew by heart where every piece of furniture stood.

“Gay—we’re home!” Cherry choked.

Gay could not answer, for the same thought was surging through them both. If they made a success of what they planned to do, in time, they might be able to buy the place they both loved so deeply.

Gay awoke suddenly. For an instant she wanted to sink back into the safety of sleep, postponing for a while longer the myriad responsibilities confronting her. The idea which had brought the two sisters hurrying back to Hawaii sooner than they had planned had originated with her, and in the solemn hour of approaching dawn the fact struck home with full force. Chills raced over her skin like icy little breezes chasing each other across a lake. She must gather her wits together. No time must be wasted getting the machinery of their new life into motion.

Whipping to a sitting position, she worked around her bedroom. In a grass green voile nightgown, with her fair head flung back, she suggested a daffodil defiantly facing a rough wind, and she was facing one—the well-known wind of adversity. Only by fast, determined action could Cherry and she continue their old, splendid way of living, out-of-doors, on horseback, under blue skies. Embracing her knees fiercely, she sat in the middle of the mammoth four-poster, a lost but resolute little figure. For the hundredth time she reassured herself that she and Cherry had done the right thing in going to her godmother in America, where they could be far enough away from the Clan to think things out without feeling as if they were in the middle of a tug-of-war. It had only cost them their fare and they actually had worked out a plan for holding on to their beloved home—at least they hoped they had.

Haunted by the uncertainty of being able to remain at Wanaao beyond the stated period, she looked lovingly at the familiar objects in her room, just discernible in the gray light. She studied the great bed of finely grained koa wood. It had been a wedding gift to their father and mother from a Hawaiian princess. The head board and foot were elaborately and beautifully carved with designs of mangoes and bananas gracefully twined together, and the top of each post was crowned with an intricately fashioned pineapple.

Across the room was a little rosewood piano, with brass candlebrackets flanking the music rack, which her father had given to her on her twelfth birthday. Foolish, delightful pictures of Pierrots and Pierrettes hung on the walls and to one side of the mirror on her ruffly dressing-table was a silver framed photograph of a big gray horse and two imp-faced wire-haired terriers.

A set of open windows facing the east framed the mass of Haleakala, towering against the first faint light beginning to well into the sky. Through open French doors on the opposite side of the room, under the branches of a tree-fern that lifted its leaves above the roof, were dim glimpses of the Island sloping to the pale, polished sea. Over massed treetops in the pasture below the house, two long promontories showed, reaching from the knife-edged summits of the Iao Valley Mountains, like dark, out-flung arms guarding Kahului and Malaea Bays that bit into the narrow peninsular, joining east and west Maui.

On the plains that rose gradually into the mass of Haleakala, long fires glowed through the gray, ghostly light. It was grinding season, and plantation laborers were burning the dry leaves off stalks of sugar cane before the wind rose. Later the cane would be loaded on to cars and taken to the mills, whose twinkling lights showed like clusters of jewels. Here it would be made into sugar.

A wild sort of gladness at being home ran through Gay but it ended in an aching lump in her throat. Her room, the gracious old house, the garden, were outwardly as they always had been, but they would be different from now on because of the threat of eventually losing them.

Waves of longing for her father engulfed her. She wanted the firm grip of his hard hand, the ringing sound of his voice to assure her that she and Cherry had made a sound decision. Details of the scheme which had brought them home hadn’t been entirely worked out, but the main structure was as clear in both their minds and appeared solid.

“I’ve got to keep a tight hold on my emotions,” she thought, “or I’ll begin looking backwards, or thinking in circles, which never gets people anywhere.”

Sliding out of bed, she took a deep, steadying breath. The soundest thing to do was to go and see everything and get rid of any treacherous uprush of feelings which might break her down at the wrong moment.

Walking out to the palm- and fern-filled lanai, she stood entranced by the loveliness of her surroundings. Well-woven lauhala mats covered the floor of the eighty-foot-long lanai. Bamboo furniture was effectively grouped at strategic spots. Little glass wind bells tied to the branches of tree-ferns sent their fairy-like tinklings into the fresh morning. Transparent, handsomely designed Chinese lanterns hung from the beams at stated intervals.

Gay gazed at the flower-grown terrace, with a fountain in the center, at the lawns adding their green loveliness to the waking day. The garden tried to make itself felt with secret rustlings and whisperings. She was conscious of the presence of the great volcano behind the house. All the things of her childhood seemed to be ranging themselves about her for the battle ahead.

She let the impression sink deep into her, then walked to the living room, packed with a million memories. Above the mantel of the big fireplace, made of lava rock, a pair of wild bull horns, five feet three from tip to tip, was fastened with great bolts into the wall. Rows of silver racing trophies were arranged beneath it and on each side of the glittering array was a thoroughbred’s racing shoe, framing a picture of Cherry and of herself, taken when they were small.

Chinese vases, a yard high, with delicate traceries of flowers and birds, stood in their accustomed places. Many-times-read books filled long shelves at one end of the room. Deep chairs which had evidently been sat in and enjoyed, oil paintings, intimate trifles of ivory and porcelain, bowls of beautifully arranged flowers spun remembered magic into the atmosphere for Gay. She was particularly touched by the flowers. Faithful Suma had kept this special token of welcome constantly fresh for their return.

For an instant the beauty and fulness of her childhood memories rushed up and almost overwhelmed Gay, then she walked resolutely across the room and looked up at an enlarged photograph of her father hanging on the wall. From the back of a magnificent horse he smiled down at her and at the room he had loved and in which some essence of his personality seemed to linger.

Thoughtfully, Gay studied his features. His eyes, filled with intense joy in living, the flash of his smile, which made a person feel braver and stronger, set him apart from ordinary people. He had had the power to steady others in moments of stress, plus the gift of transforming commonplace or even upsetting happenings into adventures. Just through looking at his picture Gay felt fortified. Sinking into a near-by chair, she reviewed the events which had led up to the present.

During the first stark days after their father’s death, relatives and friends had taken it upon themselves to stay at Wanaao to try and soften the first blow of the girls’ loss. Because their father had never treated them like children and had insisted on their thinking things out for themselves and making their own decisions, she and Cherry had been bewildered and stunned by the salvos of advice hurled at them. All it had done had been to drive home the fact that their dearest and merriest companion had been snatched from them, that they were orphans with their own way to make—for with their father’s death his salary ceased—and that the house they loved was not their own.

Their father had been a two-handed giver. They had lived joyously and unstintedly, but nothing had been saved for emergencies ahead except a modest life insurance. Well-meaning relatives pointed out that it would carry the two orphans for a couple of years, until they were equipped to earn their livings—provided it was wisely spent.

Gay had finally determined to have a secret council with Cherry and one night, when the household was asleep, she had tiptoed into her sister’s room and wakened her.

Wouldn’t it be a sound move, Gay had suggested in a whisper, to accept her godmother’s invitation—to take their own bit of money they had in the bank, plus a little of Dad’s life insurance and get away from everyone and everything for a bit? In that way they could get a longer perspective on the situation confronting them, decide how they wanted to earn their livings, then come back and do it. . . .

They had weighed the idea from all angles.

“Yes, let’s clear out,” Cherry had agreed violently. “I’ll go wild if I have to listen to any more advice from Uncle Archibald. I don’t want to study to be a secretary. Think of sticking in an office all the time after the free, gorgeous way we’ve lived with Dad.”

“And I’ve no intention of teaching all my life,” Gay had whispered. “Let’s pay the servants ahead. We know we can stay here for a year, maybe two. Let’s get tickets for the mainland and when we have everything decided, we’ll spring our bombshell.”

“It’s a date!” Cherry had agreed.

Somehow their midnight decision made them feel as though their father were with them, plotting secret fun as he had done so often in the past when they had all gone off on some senseless, beautiful jaunt which, in the world’s eyes, didn’t add up, but which had remained a jewelled milestone in their lives ever after.

Gay’s eyes flashed up to her father’s picture. “Dear Dad,” she whispered with a choke.

Gay and Cherry had decided to tell one other person of their plan, young Napier Hamilton, who was as close as a brother. Naps’ parents were immensely wealthy but he preferred the simple, busy life of Wanaao to the lavish luxury of his own home and spent every possible moment he could with the Storm girls and their father.

Cherry had phoned him the next morning and finally, the three young people had managed to give everyone the slip. On horseback, among the green hills, with a soft wind singing past their ears, Cherry had told Naps what they planned to do.

“I’m for it a hundred per cent,” he had assured them. “You can’t think properly when dozens of people are pushing their own thoughts into your minds, especially girls brought up as you’ve been. Clear out as fast as possible. I’ll help you.”

“It may look crazy,” Gay had said, “spending so much of the little cash we have ahead right off for this trip. Actually, it isn’t. When we come home our low funds will force us to do something at once, instead of backing and filling, and still wondering what road is wisest to take.”

“Any notion what you and Cherry want to do?” Naps had inquired.

“Not the faintest,” Gay had replied.

“You girls don’t realize how lucky you are,” Naps had said thoughtfully. “You don’t know what’s ahead. Every step of my life is laid out. There are no hidden adventures waiting for me. I know when I’m through with high school I’ll go to Yale. When I’m pau college I’ll be Dad’s assistant on the plantation. You two have all the fun of making successes of yourselves—”

“Or falling flat on our faces,” Cherry had suggested, smiling for the first time in a week.

So they had gone away, in a very typhoon of protests. Naps had seen them off.

“When you come back, I’ll stand at your right hand and keep the bridge with you,” he had shouted from the wharf, quoting from the loved Horatius poem which their father had read aloud to them so often.

A warm glow went through Gay as she sat there before her father’s picture. Naps was tops in every way. He knew they were home, for Cherry had written him from San Francisco, telling the date of their arrival, warning him to say nothing about it, and asking him to come for breakfast the morning of their return, as they wanted to tell him about their ‘Great Idea.’

She and Cherry must get the stage set and wheels turning before anyone found out what they intended doing. There wasn’t a moment to lose. Today surely, possibly tomorrow, would be all they could hope for in the clear. But the fury of action would help to get them over the aching void of not having their father to fall back on in the undertaking looming ahead.

A clock struck five clear strokes, jerking Gay to her feet. The servants would be up shortly. She must wake Cherry. Her eyes went again to her father’s picture. It seemed, almost, as if he were with them on this bold venture, for a leap into the dark, such as they were planning, was exactly what he had reveled in.

Hurrying through the house, Gay went to her sister’s room and opened the door. Cherry was sprawled face downward in bed. Her close-cropped hair and lithe figure, clad in peppermint red and white striped pyjamas, made her look like a boy, but the curve of her cheek and the thick lashes shadowing it were all girl.

Cherry’s room reflected her dual personality. Dotted Swiss curtains draped the windows, her dresser top was covered with cut-glass perfume bottles, ruffly pincushions, a silver toilet set. But one wall was filled with lassos, bridles, polo mallets and rifles, and on the polished floor was the brindled hide of a wild bull which she had roped at ten years of age—and which had nearly cost her her life.

“Cherry,” Gay said.

Her sister sat up with a start, looked around, then caught her breath rapturously. “We’re home!” she cried. “Oh—Gay!”

Tossing back the covers, she leaped out of bed and hurried to the open door facing the mountain. Ten thousand feet it towered into the sky, impressively simple, wrapped with aloofness and mystery.

“Everything looks fine,” she said, after a moment. “There must have been lots of rain this spring. Get on your kimono and let’s turn the dogs loose. The uproar will bring the servants rushing out. Won’t they be surprised when they see us!” Her face was rosy with excitement.

“It’s going to be hard to tell Ah Sam, Naka and Suma that we can’t keep them on—” Gay began.

“Let’s put it off ’till tomorrow,” Cherry suggested. “Let’s all be happy together today. I want to realize I’m home.” Her voice curved lovingly around the word. “And sort of try to adjust to—” Breaking off, she stared at the mountain.

“To not having Daddy around?” Gay finished for her, with a question in her voice.

“Yes.”

“But, Cherry, Dad’s still here with us,” Gay declared. “He’s in everything around us, in the stock he imported from America and New Zealand, in the grasses he sent for from all over the world, in the hundreds of thousands of trees he has planted.” She gestured toward the thick groves on the mountain, like bluish-green regiments drawn up in squads saluting his memory.

“Yes, I feel him, too,” Cherry said. “Not in a sad way, but in a glad way. What a glorious start he gave us. I wouldn’t trade the way we lived for all the money in the world. Dear old Dada.”

They stood silent for a moment, then Gay went to her room and slid into a flame-colored kimono, with green bamboos slashing across the silken material.

“Hurry!” Cherry called.

“Coming,” Gay called back.

Barefoot, they stepped on to the dewy grass. Involuntarily they paused for a moment to enjoy the lavish loveliness of their surroundings.

Hawaii is a land of vehement beauty. It arouses a love incomprehensible to persons not born under its spell. Gay and Cherry locked hands briefly. This had become a habit of theirs recently. It was an unspoken signal that they were closely united in whatever they might undertake.

Silently they started for the kennels. Cherry whistled sharply and a wild dog-chorus of barks and yips split the morning air. Laughing with excitement, the girls unlatched the gate and a torrent of fuzzy white bodies spilled out and rushed into the garden.

“Hula! Coquette!” Gay choked, kneeling down. Four wire-haired fox terriers propelled themselves at her, licking her neck, wriggling, making delirious sounds of dog-joy.

Cherry was bending over two smooth-coated terriers, crooning, “Spot, Vixen.”

Happy dog-pantings filled the air, little tails nearly wagged themselves off. A door in the smaller of a pair of cottages flew open and a tall Japanese in a blue and white kimono looked out and ran an amazed hand through his gray hair.

“Hi-yah! When you fella come home?” he gasped, his face creasing into deep smile-wrinkles.

“Last night.” Gay laughed, tousling her dogs.

“I no hear car,” the old yard boy protested, hurrying toward them.

He was gaunt, angular and moved with odd, jerky notions, as if he were jointed at specific places. The girls straightened up among the madly leaping dogs and the old man, with tears in his eyes, wrung their hands.

“I torr glad, I torr happy you come,” he said. “See, I take good care every-kind.” And he gestured at the flower beds and closely-cut lawns.

“Everything looks swell, Naka,” the girls said in unison.

After a pleased chuckle, he shouted, “Banzai! Banzai! Cherry-san and Gay-san come home.”

An old Chinaman popped his head out of second door in the smaller cottage, signalled wildly and streaked toward them. A door in the larger cottage flew open and a Japanese woman, her hair falling in a wiry black tumble about her shoulders, rushed across the lawn and embraced Gay and Cherry. Hana, her thirteen-year-old daughter, with a delicately beautiful face, joined them. Hurriedly questions and half-finished answers were tossed into the air, while the dogs rushed madly about the garden, crazy with delight.

“I go light fire and make coffee,” the old cook said, finally. “Then I fix hot-style breakfast, not only rice and fish. Now I can make every kind like before, roast beef, swell curry, roast chicken and you eat all or I very huhu.” And he pretended to be ferocious.

Cherry and Gay looked at each other, carefully. It was going to be difficult to tell these devoted people that they must find other jobs.

“I go unpack my girl-sans lolis and catch more flowers,” Suma said, looking important and happy.

“The house looks beautiful, Suma,” Cherry and Gay assured her.

“All lanch fellas velly, velly happy when me speak you come home,” Ah Sam said in a large, delighted way.

“You—not any of you—must tell even the paniolos who worked for Daddy that we’re home,” Gay said. “Anyway, for a few days.”

The servants stared at her, stunned.

“Why-for make this kind?” Nakashima finally demanded.

“Cherry and I want to be alone for a bit.”

“Sure, more good,” Ah Sam broke in. “When too many fellas stop here, all samee clazy house. Too much humbugger when too much talk-talk. Like after Papa make.” He broke off and they were all silent, conscious of their common loss.

After a moment, the servants began dispersing to go about loved tasks.

“Well, that’s one obstacle behind us,” Cherry said into the pure morning air. “Old Naka seemed a bit suspicious for an instant but Ah Sam’s comment swung him into line.”

She stared thoughtfully at the mass of Haleakala, then her eyes swung to Gay’s. What did the future hold for them all?

“When I start really thinking,” Cherry stressed the last word, “way down deep I feel a bit panicky.”

“It’s no use trying to see ahead,” Gay declared staunchly. “And to look backward is senseless. There’s only now that we can wrestle with.”

“You sound like Daddy, Gay,” Cherry said in an honoring voice. Then, as if to brush off the sense of loss which intangibly shadowed their home-coming, she added briskly, “Let’s hurry up and dress and take a look at the horses and tack room before we eat.”

A short time later Gay in a gray tweed suit and Cherry in her ranch clothes opened the gate between the garden and pasture and began following a trail which wound through tall grass. Some distance away, twenty head of horses were busily grazing and enjoying the first warmth of early morning sunshine on their backs. As the girls drew near, the fine, glossy creatures raised their heads and pricked up their ears.

“Play Boy!” Cherry called. “Kaupo! Paniolo! Come here!”

A blood-bay gelding, six years old and obviously thoroughbred, blew out of coral-lined nostrils and began walking swiftly toward her. At his heels followed a small, but powerfully-built brown mare, with a perfect Arab head and prominent dark eyes. Behind her a rangy, less well-bred but dashingly put together bay gelding, with a blazed face and short tail, trotted eagerly forward, turning his head from side to side.

Cherry watched them come, her three favorites, with an expression of deep affection on her face. In the few hours since she had been home she seemed to have come into some greater inheritance which made her skin glow with the rich bloom of an apricot. As the horses crowded about her, her very being seemed to expand.

Gay looked on, thoughtfully, then called out, “Happy!”

A big gray gelding raised his head and began trotting toward her. Gay’s eyes shone, noting the perfection of his points; great sloping shoulders, a short back for quick turns, powerful quarters, deep ribs and clean legs. His alert, quickly-moving little ears suggested tiny silver birds changing positions on his head. Pride and power charged every movement of the rippling muscles under the polished gray and silver of his coat.

With a happy little gasp, Gay started toward him. Reaching out his long, slender neck, Happy dropped his small, beautiful head into her out-stretched arms.

Gay had trained Happy from the time he was a colt. A proud thoroughbred, intelligent, eager, but controlled, he had won cups at Country Fairs and distinguished himself on the Kahului race track.

“Look, Gay,” Cherry indicated the horses’ hoofs, “Naps has been over and shod Happy, Playboy, and Kaupo, so we can ride today.”

“How simply swell!” Gay exclaimed.

Cherry vaulted on to Playboy’s back without rope or bridle to guide him, and went streaming away. Her slender figure was part of the horse, which she guided with her voice and expert pressure from her legs, clamping like slim, steel springs about his powerful body. Gay watched her sister enviously, wishing she had put on her riding clothes instead of the good suit she had worn traveling.

“I’ll be out again for a ride in an hour or so, Happy,” she promised, while the big gray pushed his head urgently against her.

The beauty of the freshly-born day, filled with color and movement, tugged at Gay’s heart. Wind bowed the glittering tops of trees; leaves danced against the blue of the sky; horses went about their unending business of grazing; dogs scented through the grass for news of the night. Little moist black noses registered where a mongoose had ventured out of the stone wall, where a proud cock-pheasant had stalked haughtily through dew-laden grass, where a covey of quail had searched for early morning worms.

While Gay’s fingers mechanically went over her horse’s head, she watched Cherry galloping about the pasture. She looked wildly happy, utterly free, part of the green earth underneath and the blue heaven arching overhead. Slowly, a sort of curious defiance seemed to charge her figure, as if she were hurriedly assembling her forces to keep life at bay.

“Even if we break our backs, and hearts, it’s worth trying,” Gay thought. “It would be simply wicked for a person like Cherry to lead an indoor life. It would choke me.”

Cherry raced joyously back toward where her sister waited. She spoke quietly to her horse and he propped and came to a full stop. Sliding off, she flung a fond arm about Playboy’s neck, then slapped him on the rump and he trotted off to rejoin his mates, grazing in a far corner of the pasture. Gay gave Happy a dismissing pat and he cantered away, shaking his head, and giving an occasional joyous buck.

“Let’s take a quick peep at the tack room,” Cherry suggested. “My nose is hungry for the smell of good leather.” Her eyes were sparkling, a fiery rose color burned in her cheeks.

Gay smiled. “My nose is, too, Cherry.”

They headed for a small structure adjoining the stoutly-built corrals. Going up a short flight of steps, which ended on a tiny veranda, they opened the door and went in. Saddles, glossy and polished, blankets washed clean of any sweat, nose bags, rows of neck ropes, halters and bridles hung and sat on racks, or wooden pegs jutting from the wall. In one corner grain bags were stacked and above them was a shelf of curry combs and brushes. Another shelf held first aid remedies for horses; a large bottle of Creolin for washing cuts, gall-cure, picric acid, linseed oil, and carbolated vaseline, a hypodermic and ampules of adrenalin to counteract founder. . . .

Taking up a limp, well-oiled bridle rein, Cherry inhaled luxuriously, then the two sisters went systematically over the gear.

“Naka has kept everything in tiptop condition,” Cherry remarked in a satisfied way when, finally, they closed the door behind them.

They paused on the tiny platform outside the tack house. Over the trees lining the horse pasture, which shut off its lower slopes, the blue summit of Haleakala soared into the sky. Gay and Cherry never tired of watching Naulu and Ukiukiu—Trade-wind-driven clouds—swirling about the height and mass of Haleakala. Forever the opposing Cloud Warriors battled for possession of the summit, Naulu traveling along the southern flank of the mountain, Ukiukiu along the northern. Usually Ukiukiu was victorious, but a fair percentage of victories went to Naulu. Sometimes both Cloud Warriors called a truce and retreated to rest, leaving a clear space between heaped masses of vapor. The Hawaiians called the space Alanui o Lani—The Highway to Heaven.

“Haleakala,” Gay whispered, her eyes on the mighty volcano. Her face quivered a little.

Cherry slid her arm through her sister’s. They stood taut and close. Something solemn and breath-taking had them in its grip, the sensation that fills men setting out to explore an unknown, unchartered territory.

The staccato sound of fast-galloping hoofs shattered the stillness of the morning like rifle-shots.

“Naps!” they cried delightedly.

Rushing down the steps, they flew through the corrals, opened the gate into the garden and watched the driveway leading from the garden to the road. A black horse with a figure leaning low over the animal’s fast-moving withers burst into view. The girls waved and called out. Rushing his horse to within a yard or so of where they stood, Naps flung the animal to its haunches and vaulted off. His dark eyes were shining, his face lighted, even his tumbled black hair looked excited. Dropping the bridle reins, he strode forward and swept both girls into his arms. He gazed at them intently for a minute, then began pommeling them with boisterous, brother-like affection.

“Gosh, it’s swell to have you back!” he exulted. “You both look tops. I actually believe you’ve put on an ounce of flesh, String Bean!”

Cherry feinted at him, he sparred back, and then they all gripped hands.

“Well, here I am to ‘keep the bridge with you’—whatever it is,” Naps said. His brown eyes were deep and shining, his tanned face, with its merry mouth, was both gay and sensitive. “You’ve got me half nuts by your veiled allusions to the Great Idea you’ve come home to put over—”

“As soon as we’ve eaten we’ll tell you about it,” Gay promised.

“Okay, Big Chief,” Naps agreed good-naturedly. “I’ll tie up Elele then lets make tracks for the kitchen. This past week has seemed a million years long.”

“We thought it best to write ahead to you,” Cherry explained. “If we phoned, after we got home, someone else might have answered and found out we were back.”

Naps quirked an eyebrow at her as he tied his big black to the hitching rail. “And how long do you figure you can keep your return a secret—on Maui?” He laughed.

“We hope to for a day or so,” Gay answered.

“I give you till tonight—maybe,” Naps said.

Linking his arms through Gay’s and Cherry’s, he steered them toward the house. Talking in the disjointed fashion of close friends who have been separated for a long time, the three made their way among the flower beds, dogs trotting at their heels, and went into the kitchen.

The big table in the center was covered with beautifully-woven lauhala mats, which set off the blue and white china arranged at each place. There was a low bouquet of flowers in the middle. Nakashima was lolling against the sink, his seamed face filled with satisfaction. Suma was busily quartering golden papaias and handing them to Hana to scrape free of dark, bullet-like seeds. Ah Sam hovered over the big wood range. Bacon and eggs sizzled and spluttered on the stove, buttered toast added its tempting aroma, coffee bubbled contentedly in a pot, pitchers of fresh, foaming milk were on the table.

In the Storm family, as in most white-born Island families, the devotion of masters to servants and servants to masters enriched the days and years of life. Laughter, work, sorrow and happiness were shared, forging bonds that drew all concerned closer and closer.

Feelings too deep for words had Gay by the throat. It had always been a rite of her father’s that after an absence, family and servants had the first meal together, and it seemed as if at any instant he would come striding through the door.

“Okay, okay, eat papaia wikiwiki, then I give kaukau.” Ah Sam waved contemptuously at the fruit, then proudly indicated the food on the stove. “And no eat too much papaia,” he cautioned. “Me velly, velly closs spose you no eat evely kind I fix for breakfast.”

REACHING OUT HIS LONG, SLENDER NECK, HAPPY DROPPED HIS BEAUTIFUL HEAD INTO HER OUTSTRETCHED ARMS.

Everyone sat down. With ohs, and ahs of bliss, Gay and Cherry attacked the papaia as if they could not eat enough of it. Ah Sam watched cagily. Suma rose, replacing the first crescents of fragrant golden fruit with seconds.

“No eat enny more,” the old Chinaman ordered, and Suma smilingly snatched the plates from the girls, who exchanged amused glances. Ah Sam filled fresh plates with crisp bacon, fried eggs, fluffy omelette and small wedges of perfectly brown toast.

Naps eyed the plates, glanced at Cherry, then grinned. “If you eat all that, you’ll qualify for the Fat Lady of the circus.”

Everyone laughed uproariously and Ah Sam pulled out his chair.

“Amelika fella cook more good from me?” he asked, a secret, pleased expression lurking about his eyes.

“They can give you cards and spades,” Cherry teased.

“You speak velly big punipuni,” the old man retorted hotly.

“Cherry’s only making foolish with you, Ah Sam,” Gay assured him. “Nowhere we went in America did we eat such food as you cook.”

“I think so, too,” Ah Sam agreed, complacence oozing from his stringy old figure.

“Which place you go?” Nakashima asked, pouring liberal quantities of dark, salty Shoyu over his eggs.

Cherry described the places they’d seen, while Naps and the servants listened avidly. Gay sat absolutely still. Watching the faces around the table in the big, sunny kitchen, the sense of her responsibility as eldest struck home with full force. She was now head of the family and it depended upon her to steer the wisest and straightest course possible. She listened to the loved voices, to the chink of knives and forks working against plates and the tiny tick of wooden chopsticks scraping rice out of china bowls. All at once she felt small, inadequate, inexperienced and beset by problems affecting them all. Involuntarily her eyes went to the open window which framed Haleakala, lifting its blue summit like an altar to God.

Cherry launched into a description of the wonders of America.

“What’s eating you, Gay?” Naps inquired when, for lack of breath, Cherry’s voice gave out. “Usually you’re the one who bubbles about beauty, but you’re still as a mouse.”

“I’m thinking.”

“Why not think aloud?” Naps suggested.

Gay’s eyes went cautiously to Cherry’s, asking a question.

“You carry on from here, Gay,” Cherry suggested. “We might as well ‘shoot the works’ and get everything over with.” She bit off the last words. Her face was resolute but her eyes were faintly haunted, like those of a rider putting a horse at a jump which he isn’t quite certain can be cleared.

Gay stopped her mind from doing loops and circles, took a steadying breath and began. “Well, Godmother took Cherry and me to visit with friends of hers on their ranch. During the summers it’s run as a sort of Dude Ranch.” Her eyes caught Cherry’s excitedly. “One day while Cherry and I were trying to figure out some way to keep on living as we did while Daddy was alive, the idea bounced out of somewhere and landed in the middle of my mind . . . If people made a living Dude Ranching in America, why couldn’t Cherry and I do it in Hawaii?”

In her own ears the words went ringing off into space, but the servants said nothing and Naps only stared at her small, earnest face, a puzzled expression in the depths of his warm, brown eyes.

Gay forced her voice to a steadiness she did not feel. “It may sound utterly crazy, Naps,” she went on, “but actually I think we’re on the trail of something sound. Look at the setup. We know we can stay at Wanaao for a year or two longer; we have twenty head of fine saddle horses of our own; we know every trail on Haleakala—”

“You mean,” Naps burst out, “that you and Cherry are figuring to launch the first Dude Ranch in Hawaii?”

“Exactly,” Gay cried, her eyes sparkling.

Naps’ incredulous gaze was fixed on her. The servants looked puzzled. Outside the open windows the sunny day went calmly about its bright business.

“It seems to me, Naps,” Gay went on, “that Cherry and I are equipped to make a success of such a venture. When an animal is cornered, it fights with teeth and claws for existence. They are the only weapons it knows. We feel now that life’s cornered us and we have to earn a living, it’s sanest to fight in the same way, using things that we know, that we have!”

She stopped for breath and Naps looked from her to Cherry, a dawning light in his eyes.

“I get the idea, but Schultz and Yarrow have been taking people up Haleakala since Pluto was a pup. While, actually, they’re only guides, they’re in the field ahead of you—”

“But they do things in a slipshod way,” Cherry interrupted. “Their poor horses are galled, half-starved, badly shod—which makes miserable riding. Their saddles and bridles came out of the Ark. They feed the poor innocents who patronize them warped sandwiches, and give them cold water to drink at the top, even when it’s freezing. Their people have to sleep at the Rest House in dirty blankets which heaven only knows how many other persons have used. Gay and I intend to do things de luxe!”

A feeling of mounting excitement charged the kitchen. Shadows in the garden looked significant and the trade wind sighing past sounded like messengers tiptoeing along with important secrets.

“De luxe?” Naps asked finally, puzzled and intrigued.

“Yes, de luxe,” Gay answered. “Instead of charging five dollars per person for the trip to the top, we’re going to charge twenty-five—”

“Twenty-five!” Naps gasped.

“Yes, but we’ll give them their money’s worth, and a bit over for good measure. We intend to make our trips up Haleakala adventures instead of ordeals. We’ll start at noon, get to the summit well before sundown, settle our people as comfortably as possible and while they enjoy the view of the crater, we’ll cook supper. T-bone steaks, broiled over mamani coals, fried potatoes and hot Kona coffee, biscuits and canned fruit, or fresh pineapples or mangoes, when they’re in season, for dessert. And we’re going to take up clean sheets and pillowcases to protect our dudes from contact with used blankets. With our fine horses and tack, with slickers to keep people dry if Ukiukiu mist blows in—”

Naps threw back his head and the kitchen rang with his delighted laughter. “You’ve got something,” he exulted, banging the table with his fist. “It’s the old angle. ‘If you make a better mouse-trap than anyone else, the world will beat a trail to your door.’ My hat’s off to you both!”

“Then the idea doesn’t seem completely insane to you?” Gay cried, her voice shaky with relief.

“Crazy? In principle it’s as sound as Gibraltar, but—”

“Wait,” Cherry commanded. “As you know, Dad taught us to size up any situation from all angles. In this instance our liabilities about equal our assets, but not quite. Schultz and Yarrow are established in the tourist field ahead of us, that’s granted. Their price to the summit is cheap, ours is steep. But if we get two people to their ten, we’ll make as much money as they do, with less wear and tear on our horses and selves. So, that angle adds up.” Cherry’s voice was triumphant. “Of course, there’s the chance that because we’re girls people may hesitate to patronize us, but everyone in Hawaii knows we know our stuff. If lots of people do come and the pace gets fast and furious, we don’t know yet, for sure, whether our bodies will stand up under the hard work we’ll have to do, and keep doing—”

“Saddling and packing horses, wrestling with stiff ropes,” Naps interrupted, “cooking at high altitudes, being responsible for the safety of inexperienced riders on rough trails—all that will be a haggering business.”

“Because of Dad’s thorough training, we know what we’re going into,” Gay insisted. “It is hard work, even when you do it for fun. When you’re doing it for a living, it’ll be even harder because there can’t be any slip-ups or mistakes, but if you love what you’re doing—”

Naps grinned in his attractive manner. “I’ve a hunch you and Cherry will make the grade, Gay. You’ve lived like boys since you were knee-high to grasshoppers. Your Dad taught you everything he knew, and shared all he did with you. He’s . . . he was, tops in every way but, somehow—” Naps hesitated and his eyes wandered around the big room, “I simply can’t picture—”

“Wanaao filled with strangers paying for hospitality which was always free and two-handed—till now?” Gay suggested.

“Yes, Gay.”

Gay gazed thoughtfully out of the windows at the sun-drenched garden. “Maybe we’ll have to fix up our guest rooms a bit, everything’s clean but a bit old.” She looked a little concerned, then brightened. “But Cherry and I are not going to open till June tenth and it’s only the first today. If we work like mad between now and then—”

“I no onderstan what-kind you talk,” Nakashima interrupted.

Gay tried to explain. Ah Sam looked cagey.

“I see, make like hotel-styles?” he asked.

“Sort of.” Gay smiled.

“Mebbe-so not bad idea.”

“Suppose, just for argument’s sake,” Naps began, “that no one patronizes you. How’ll you pay Ah Sam and Naka and Suma?”

“Never mind if no can pay. All fellas got some money save-up,” Ah Sam said, his eyes as bright as a mouse’s.

Naps’ serious eyes traveled around the table. “But you all have to eat,” he insisted. Then suddenly he grinned at Gay and Cherry. “Go ahead and try it. If you run into the red—”

“Cherry and I aren’t running up any bills, or borrowing, even from you, Naps.” Gay’s small face was earnest and resolute. “We’ve got to—we intend to—find out whether or not we can stand on our own feet. We’re starting from scratch!”

“What do you mean—from scratch?” Naps demanded.

“Suppose we borrowed money and started up with trumpets and flourishes and the thing flopped? We’d be in debt so deep it would take our combined earnings as a nurse and a school-teacher,” she flung the words away, “years and years to pay back. If we begin in a small way and move carefully, we may, and probably will, make a go of it. Every bit of overhead must be cut down, so we intend to do all the work ourselves.”

She let the words hang in the room; then, with a choke in her voice, turned to the servants. “We can’t keep you on—for the present at any rate,” she finished.

“I think this big humbugger,” Nakashima announced hotly, pushing back his chair. “I go hanahana in the garden.” Rising, he started for the door, as if mentally washing his hands of the situation.

“Naka, wait!” Gay said.

He stopped.

“Look,” she went on. “I’m boss now.” Her voice fell like a wounded bird, then soared upward. “We can’t afford to keep any of you until we get our new business swinging. If it clicks, when we can afford it, we’ll re-hire you. But in the meantime, you all will have to find other jobs.”

Ah Sam glared at Gay. “You think us forget how many year us work for Mr. Guy?” he demanded. “You think us leave his girls—”

“But Ah Sam—” Gay began.

“Okay,” Nakashima interrupted. “If you speak us catch nodder jobs, I catch, but I sleep at Wanaao every night, just like always.”

Suma said nothing but wept in the silent way of Japanese women.

Gay wiped her moist eyes with her napkin. “Don’t cry, Suma,” she begged. “You’re the finest laundress on Maui and can make money taking in washing from families round here. Naka, you can get a job gardening any time with Mr. Spencer, Ah Sam—”

“I catch cook-jobs easy,” the Chinese broke in haughtily. “You boss. Might-be you velly, velly solly you speak I go. What you know about cook?” He indicated the big stove.

“I know a little,” Gay said weakly.

“Mebbe-so yes, mebbe-so no.”

Nakashima walked out of the kitchen. Ah Sam untied his apron, hung it on a nail and went to the back door for his after-breakfast pipe. Suma and Hana passed silently through the swinging door, as if to take a sorrowful farewell of the house they had tended so long with loving care. Gay blinked tears off her lashes, then looked at Cherry.

“Well, there’s another obstacle behind us—and it hurts,” she finished chokily.

“Look.” Naps crossed his arms on the table. “It seems to me that you and Cherry have bitten off more than you can chew.” His eyes challenged the two girls. “How can you possibly milk the cow, keep up the garden, chop firewood, shoe horses, cook meals, keep the house pretty and take people up Haleakala?”

“We can—if we want to enough,” Cherry said resolutely.

“You see,” Gay explained, “this goes beyond merely making a living, Naps. People have always questioned Dad’s way of bringing us up. We know, and are determined to prove his way is sound. Before our money runs out, God will send us some dudes,” she ended stoutly.

“Frankly—” Naps looked from Gay to Cherry.

“You may think we’ve shaved things thin, Naps. Maybe we have,” Gay agreed. “Maybe—”

“I do think you’ve shaved things thin,” Naps cut in, “but you probably have your own reasons for doing as you have—”

“We did it,” Gay’s voice rang, “for the same reason that Cortez burned all his ships.”

“I get the idea,” Naps declared. “Gosh, you’re swell, both of you! Let’s go for a good long ride and talk some about this. I’m all steamed up. When this bombshell explodes, it’ll rock Maui to its foundations.” He grinned, and then his face fell. “I wish you’d written me about it, though. I’m booked to visit my cousin Rudi on Kauai for two weeks. I leave tomorrow night and I’d give my eyeteeth to be around when the fireworks begin.”

“We’d like time to get our breath before things start exploding,” Cherry said, looking impish, yet demure.

“I’ll get into my riding togs.” Gay stood up. “I can hardly wait to give Happy a workout.”

“It was swell of you, Naps, to come over and shoe our horses,” Cherry declared.

“Loved doing it” Naps laughed. “I’ll saddle while you girls get ready. We have today, anyway, in the clear.”

The telephone rang.

Gay and Cherry froze. Naps grimaced.

“Uncle Archibald!” Cherry announced in stricken tones.

“Aunt Charity,” Gay prophesied, her young face looking all at once remote as she went to answer the phone call.

“Whoever it is, our ride’s shot. Why can’t they leave us alone?” Cherry said, a trifle venomously.

Naps flung a protective arm about her shoulders and gave her an affectionate shake. “No matter how rough the going may be, you and Gay are living at top speed. I envy you.”

He gazed out at the garden filled with color and light. The trees moving in the wind looked like huge birds resettling their bright plumage. The great mountain slept in the sun and the majestic breathing of the Pacific came faintly to their ears.

“When a person knows every step that’s ahead,” Naps told Cherry, “it takes the adventure out of things. I wish—” He broke off as Gay clicked down the phone and started back to where Cherry and he sat.

“You win, Cherry, sort-of. It wasn’t Uncle Archibald, but it was Aunt Laura. She’s all upset because we didn’t write ahead that we were coming back. She and Uncle Archibald have phoned Aunt Charity and they’ll all be here as fast as they can. But I suppose it’s just as well to get the tornado over with,” she finished, looking beset and resolute in one.

“You’d better do the talking, Gay,” Cherry suggested.

“Okay,” Gay agreed, a trifle grimly. “You’d better get dressed—”

“I’d rather keep on my riding clothes,” Cherry said. “I always feel braver in them.”

“I do, too, and we’re going to need every ounce of grit we have to stand up against the Clan. The hard part is, while they’ve never approved of the way Dad brought us up, behind their disapproval, they love us—in their own way. If they were out-and-out enemies—”

“Like Cousin Honor?” Naps suggested, grinning wickedly.

Gay flashed a look at him. “Yes, like Cousin Honor. Ever since I beat her in the first horse race we ever rode, she’s been after my scalp. And I simply can’t respect her. Like us, Cousin Honor belongs to a poor branch of the Storms, but she curries favor and tries to make herself indispensable to the rich ones—”

“Meeouw! Meeouw!” Naps teased. “For a nice girl—”

“I don’t know how nice I am deep down inside—where Honor’s concerned,” Gay admitted. “If she comes along—”

“She’s spending this week with Grandmother Storm,” Naps said roguishly. “It isn’t likely she’ll put in an appearance until that important occasion is over.”

“Suits me,” Gay retorted, then added in a sunk way, “When Grandmother Storm finds out what Cherry and I intend doing—”

Naps’ immoderate, delighted laughter filled the lanai.

When Gay and Cherry rose reluctantly Naps got to his feet with easy courtesy, announcing, “While you girls put on your armor for the fray I’ll try to smooth down the servants’ ruffled tail-feathers.”

“Thanks,” the sisters called as they hurried down the lanai.

“How on earth do you suppose our return leaked out so fast?” Cherry demanded as they prepared to take their showers.

“Maybe we were listed in the Honolulu papers yesterday as returning passengers on the Malolo,” Gay surmised. “Stupid of us not to remember that! The papers have been distributed in Wailuku and Kahului by now. Aunt Laura probably saw our names and probably phoned the wharfinger at Lahaina to find out if we came on the Mauna Kea last night.”

“Well, our time has come, Gay,” Cherry declared as she dressed. “But for some reason this reminds me a bit of when Dad used to jerk us out of school and take us to Hawaii to see Mauna Loa erupting, or like when—”

With lighted faces they gazed at each other, remembering high passages of their lives.

“Yes, Daddy, the darling old rascal, would relish what’s ahead,” Gay agreed. “He always insisted that it was healthful to explode an occasional bombshell in a family to jar people out of accustomed ruts.”

“But we’re such a large family,” Cherry almost groaned. “And we’re such, well, such assorted varieties of people.”

“Yes,” Gay agreed, smiling in spite of her fears.

They heard the faint hum of an approaching car. Cherry looked out of the window and saw a shiny black limousine sliding majestically along the driveway.

“Uncle Archibald and Aunt Laura,” she announced.

Two other cars followed in the limousine’s wake.

“There’s Sam!” Gay exclaimed. “How nice of him to come.”

Both girls were deeply fond of the man for whom their father had worked so long. Though he was years older than they were, Island custom permitted the use of his first name. They could not forget his many kindnesses, the many privileges he had extended to their father while he lived, or his generous gesture in regard to Wanaao, now that they were alone.

Cherry peered at the shabby rented car following Sam Spencer’s. Suddenly she gave a cry of delight.

“Look, Gay, Uncle Bellowing!” she exulted. “What luck he landed just at this time. For pure cussedness he’ll buck the others—”

Gay peered out the window and said thankfully. “It is Uncle Bellowing!”

Both girls loved this uncle who acted as First Mate on a second class freighter plying between Honolulu, Shanghai and other way-ports. His spaced visits were events that always carried a flavor of adventure.

They started for the living room with their steps firmer, but deep down inside they felt hollow, young, and scantily armed for the tussle ahead.

“The Clan can’t prevent us from at least taking a try at Dude Ranching,” Cherry said. “If we fail—”

“Let’s pretend Dad’s looking on, smoking his pipe and betting we’ll win, as he used to when we rode races at Kahului against a stiff field,” Gay suggested.

“Let’s,” Cherry agreed in a fierce young way.

They smiled valiantly at each other and walked quickly through the living room, filled with deep peace, then crossed the flower-crowded patio facing Haleakala.

“Let them do their talking first, Gay,” Cherry instructed. “Then give them both barrels!”

Gay nodded, trying to stifle the hurried beating of her heart. Remembering the typhoons of protest which had enveloped Cherry and herself when they left for the mainland, she dreaded the greater storm she knew would be unloosed when the Clan learned of what they planned to do now. While their father had lived, there had never been raised voices in the house. Each problem, as it came, was quietly talked over, then acted upon without fuss or uproar.

Naps was opening the door of the Cadillac. “Beat you to it,” he said laughingly as two solid, elderly people got out. “Cherry and Gay wrote me.” His voice was lightly teasing.

Aunt Laura directed a reproachful look at him. “It’s hardly kind of you—” she said on a quavering note.

“It was extremely inconsiderate of you young ladies not to inform us of the date of your arrival,” Uncle Archibald said icily.

He was a solidly built, handsome man, with an autocratic manner resulting from being, for forty years, the head of a large, important corporation and president of many local committees. His eyes were a cold, steely blue, his head devoid of hair, except for a scant strip across the back from ear to ear, but he wore his baldness as if it were not related to the common baldness of other men.

“But, Uncle Archibald, Cherry and I didn’t want anyone to know we were back,” Gay insisted in as steady a tone as she could command.

“Didn’t want anyone to know you were back!” Uncle Archibald exclaimed.

“Didn’t want anyone to know you were back?” Aunt Laura echoed.

She was a soft, fleshy woman, suggesting an over-powdered marshmallow. Safely established inside citadels of wealth, she had never been battered about by life, she had never been frightened, never challenged. When, as very young children, Gay and Cherry had lost their mother, she had wanted to mother—and smother—them. She had been horrified at the way in which they had been reared—“in breeches, on horseback”—but her disapproval had been tempered a little because the girls’ father had seen to it that they took turns running the house and officiating as hostesses in their home. Now that Gay and Cherry were orphans, she felt possessive once more. Weepingly, she embraced first one, then the other.

“Why didn’t you girls radio us that you were landing at Lahaina last night? We would have met your boat. Young people nowadays are so thoughtless, and you my own flesh and blood.” She dabbed at her streaming eyes with a morsel of handkerchief.

“Please don’t cry, Aunt Laura,” Gay begged. “I’ll explain in a few minutes why Cherry and I returned as we did.” And she went to meet a slender, blond, middle-aged man, with a gentle face and slightly anxious expression.

“Sam!” She held out both hands and he gripped them.

“It’s nice to have you girls home,” he said, quiet friendliness pouring from his person. “I kept an eye on the place while you and Cherry were gone, though it wasn’t necessary. The servants, of course, carried on just as if you’d been here.”

“Thank you, just the same, Sam,” Cherry said. Then she added, a bit unsteadily, “You don’t know what it means to us to know we can stay at Wanaao until we sort of get our bearings.”

“Forget it,” Sam Spencer advised. “Though I don’t know much about ranching, I’m determined to learn it. I haven’t any immediate use for this house. My own place,” he nodded at massed trees in a hollow about a mile distant, “is just as centrally located for ranch work, and since I’ve decided not to hire another manager to take your Dad’s place, Wanaao might as well be used as standing idle.”

“Still—we’re grateful,” Gay murmured, then headed toward a hulk of a man bundling out of the shabby rented car.

“Uncle Bellowing!” she cried, with a half-sob.

Uncle Bellowing engulfed her in one big arm, the other was in a sling. After kissing Gay, he embraced Cherry, then stepped back to survey them.

His features were blunt, and forceful, his eyes surprisingly blue in his ruddy face. He was a fine giant of a man who carried himself with an air of being a rollicking rascal. He had not been to Hawaii for two years, and was wrestling now with memories of his other visits when Guy Storm’s gay shout had welcomed him to Wanaao.

“Well, the Black Sheep’s on hand to see that your ship is safely launched,” he roared, trying to cover up emotions which might unman him. He eyed Aunt Laura and Uncle Archibald belligerently. “Fellows like us,” his eyes swept Gay and Cherry, “who haven’t got a mint of dough, got to rustle for ourselves. Laura and Archie have never really lived!”

Slow red burned under Uncle Archibald’s skin and Aunt Laura dabbed at her eyes once more, pretending not to hear.

In the awkward pause that followed a steel-gray sedan swooped to a stop in the driveway and a tall, hawk-faced woman emerged, followed by two still taller sons with flat, expressionless faces.

Aunt Charity awed Gay. She was handsome and high-tempered. She had crossed swords with the girls’ father on several occasions. Her sons, Luke and Ben, managed sugar plantations their mother owned, moving through life like mechanical figures animated by strings their mother pulled, but they both were smugly complacent about themselves and their ability.

With a sinking heart Gay greeted the trio.

“Well, now that you’re back from your orgy of spending—what little you had,” Aunt Charity’s voice had a stinging note, “what do you propose doing?” She eyed Gay and Cherry critically.

Hot resentment filled Gay but she kept tight hold of herself and kissed her aunt dutifully. “I won’t let them get me on the run,” she thought.

“It was nice of you all to come so soon,” she began bravely, trying to sound cordial.

“It was our duty to do so,” Aunt Charity said in brisk, incisive tones. “You and Cherry proved by your reckless behavior when you left Hawaii that you haven’t an ounce of common sense between you. Someone has got to take hold. Blood’s thicker than water. But whenever I think of your spending—”

“Stow it, Charity!” Uncle Bellowing shouted.

Aunt Charity wheeled on him, noticed the arm tied to his chest. “You’ve been fighting!” she accused.

“No, arguing,” Uncle Bellowing retorted truculently, with a quick twinkling glance at his nieces.

“Let’s go indoors and talk,” Gay suggested, trying to control her mirth at the shocked looks on the Clan’s faces, which Uncle Bellowing was relishing.

Flowers breathed peace into the day, the great mountain lay relaxed in the sun, but invisible dynamite charged the immediate atmosphere. Gay’s and Cherry’s eyes met, then dropped apart, a hint of apprehension showing in both their faces. Uncle Bellowing’s alert, cagey eyes noted this.

“I suppose, Charity,” he roared, “you and your spineless sons, are here to assist Archie and Laura in whipping Gay and Cherry into your ways of living. Let ’em be! They know more about life than the lot of you ever will. You’re all buried under money, though you walk around as if you were alive. Real living isn’t all smooth seas and following winds. It’s failures and triumphs, high moments and low ones, heartaches and back-breaks. It’s being torn to bits and tumbling down, then building bigger and better. It’s—” His voice gave out and he breathed like a whale.

“Looks as if it’s going to be a fine show,” Naps whispered encouragingly to Gay as she led the way indoors. “Let ’em roar, then stand up and give it back—with dividends.”

Gay managed a smile, but a feeling of complete unreality possessed her as she walked into the living room. She waited while the older people seated themselves. She felt as if life had pounced on her before she was ready for it. An impulse to run away surged through her, but she crushed it down. No matter how far or fast a person ran, he couldn’t outdistance life. It had to be faced and wrestled with. Through the open French doors, facing Haleakala, she saw the hundreds of thousands of trees her father had planted, standing proud and straight in the sun. In calm or storm, they stood their ground. Through drought or deluge they grew on. . . .

Gay’s misleadingly delicate little face set in lines of courage. Walking to the fireplace, she leaned her arm on the mantel and faced the room. Cherry came and stood beside her. Naps waited, a little apart.

The atmosphere seemed fairly to vibrate with the antagonistic principles and ideals, poles apart, which were ranging themselves for battle. Gay suspected that Cherry, like herself, was wincing from the ordeal ahead.

“I feel,” Uncle Archibald began, after a charged silence, “that I should tell you young ladies at once that you cannot look to me for support—”

“No such thought has ever entered our minds,” Gay interrupted hotly. “Cherry and I each have two eyes, two hands, two feet and our minds to work with—”

“To date, neither of you has given any evidence of the last,” Uncle Archibald cut her off. “We—” his glance gathered up the assembled relatives.

“Cherry and I know exactly how you all feel about what we did with the little money we had,” Gay cut in. “You made that quite clear before we left. But we just had to—”

“That’s aside from the matter we’re here to settle,” Aunt Charity said crisply. “Now your money’s spent, what do you propose to do?”

Sam Spencer moved uneasily in his chair. He had a remote, withdrawn air but concern poured invisibly from his slight person.

“Well, Cherry’s not going to train to be a nurse and I’m not going to teach school, at least, not for more than one year—I hope,” Gay added. “I’ve already signed up for the Makawao school this fall.”

“You mean—” Aunt Charity’s voice rose.

“I wrote and asked for a position right after Cherry and I got to San Francisco,” Gay explained. “Thanks to D. C. Lindsay’s Aloha for Dad, he fixed it up.”

“Well, that’s something,” Aunt Charity snapped, in a dashed way.

Off in the hills a cow lowed contentedly to the calf, and a horse gave a shrill, joyous neigh, like a trumpet call to freedom. Uncle Bellowing drew out a pipe, as knotty and rough-looking as himself, and began slowly filling it with strong-smelling tobacco. Aunt Laura sniffed unhappily. Aunt Charity, without moving, gave the impression that she was disgustedly jerking away her skirts.

“And what, if I may inquire,” Uncle Archibald began stiffly, “do you propose to do, Cherry? Gay’s salary at Makawao, eighty dollars a month, will hardly keep you both. It is now June first and the fall semester is still three and a half months away.”

“We’ve still some money left,” Cherry retorted defiantly.

The hollow laughter of Ben and Luke filled the room.

“It will require a lot of money to take you even through this month,” Uncle Archibald snorted.

“We’ve already told the servants to find new jobs,” Gay said, quietly.

“But that doesn’t clear up what we’re here to find out,” Uncle Archibald almost shouted. “Until school starts, how do you propose—”

Gay made a little gesture, silencing him. “I’ll tell you what Cherry and I plan to do,” she said. Gripping the mantel with icy fingers, she outlined their plan in a few terse sentences.