* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Dispatches From the Ruhr

Date of first publication: 1923

Author: Ernest Hemingway (1899-1961)

Date first posted: Apr. 8, 2023

Date last updated: Apr. 8, 2023

Faded Page eBook #20230413

This eBook was produced by: John Routh & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

Dispatches From the Ruhr

by

Ernest Hemingway

Articles from the Toronto Star

April 3, 1923—May 16, 1923

Explanatory Note:

In 1923, Ernest Hemingway lived in Toronto, Canada and was employed as a correspondent by the Toronto Star. The paper sent him to France and Germany to report on the occupation of the Ruhr Valley by French soldiers in response to a dispute over payment of war reparations as a result of the end of World War I.

This eBook is a compilation of ten articles written by Hemingway from April 3, 1923 to May 16, 1923.

Great Scandal of “Devastated-Region Millionaires” Not Unrelated to It. Caillaux May Yet Come Back as Premier—Communists Insult Poincare.

The following is the first of a series of articles on the Franco-German situation by Ernest M. Hemingway, staff correspondent of The Star.

In the Political Spotlight of France

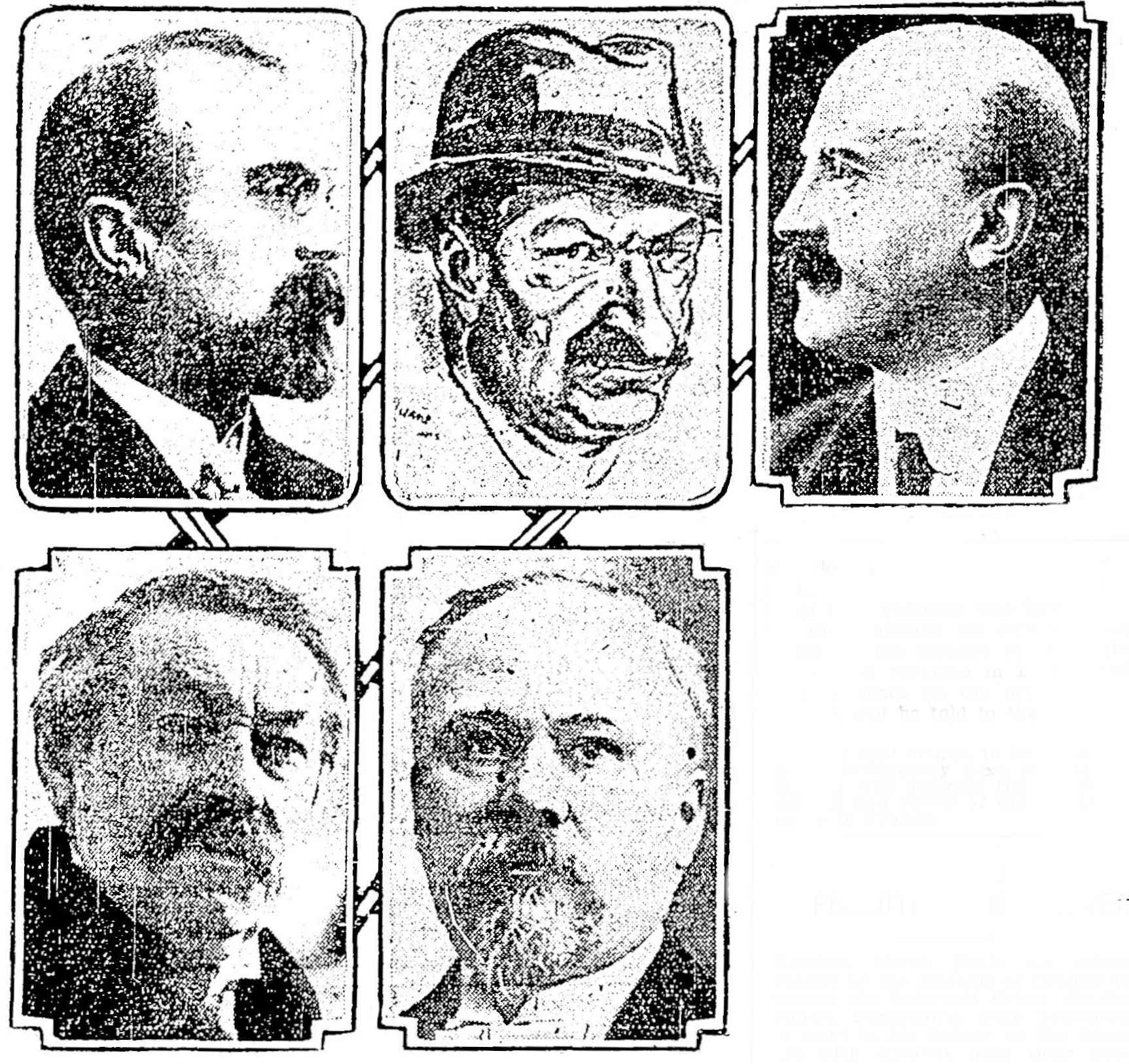

Top, left to right: Barthou, Cachin, leader of the French communists, and Caillaux, who may yet come back as premier.

Bottom, left to right: Briand and Poincaré

Paris, April 3.—To write about Germany you must begin by writing about France. There is a magic in the name France. It is a magic like the smell of the sea or the sight of blue hills or of soldiers marching by. It is a very old magic.

France is a broad and lovely country. The loveliest country that I know. It is impossible to write impartially about a country when you love it. But it is possible to write impartially about the government of that country. France refused in 1917 to make a peace without victory. Now she finds that she has a victory without peace. To understand why this is so we must take a look at the French government.

France at present is governed by a chamber of deputies elected in 1919. It was called the “horizon blue” parliament and is dominated by the famous “bloc national” or war time coalition. This government has two years more to run.

The liberals, who were the strongest group in France, were disgraced when Clemenceau destroyed their government in 1917 on the charge that they were negotiating for peace without victory from the Germans. Caillaux, admitted the best financier in France, the Liberal premier, was thrown into prison. There were almost daily executions by firing squads of which no report appeared in the papers. Very many enemies of Clemenceau found themselves standing blindfolded against a stone wall at Versailles in the cold of the early morning while a young lieutenant nervously moistened his lips before he could give the command.

This Liberal group is practically unrepresented in the chamber of deputies. It is the great, unformed, unled opposition to the “bloc national” and it will be crystallized into form at the next election in 1924. You cannot live in France any length of time, without having various people tell you in the strictest confidence that Caillaux will be prime minister again in 1924. If the occupation of the Ruhr fails he has a very good chance to be. There will be the inevitable reaction against the present government. The chance is that it will swing even further to the left and pass over Caillaux entirely to exalt Marcel Cachin, the Communist leader.

The present opposition to the “bloc national” in the chamber of deputies is furnished by the left. When you read of the Right and the Left in continental politics it refers to the way the numbers are seated in parliament. The Conservatives are on the right, the monarchists are on the extreme right of the floor. The radicals are on the left. The communists on the extreme left. The extreme communists are on the outside seats of the extreme left.

The French communist party has 12 seats in the chamber out of 600. Marcel Cachin, editor of l’Humanite with a circulation of 200,000, is the leader of the party. Vaillant Coutourier, a young subaltern of Chasseurs who was one of the most decorated men in France, is his lieutenant. The communists lead the opposition to M. Poincare. They charge him with having brought on the war, with having desired the war; they always refer to him as “Poincare la guerre.” They charge him with being under the domination of Leon Daudet and the Royalists. They charge him with being under the domination of the iron kings, the coal kings: they charge him with many things, some of them very ridiculous.

M. Poincare sits in the chamber with his little hands and little feet and his little white beard and when the communists insult him too far, spits back at them like an angry cat. When it looks as though the communists had uncovered any real dirt and members of the government begins to look doubtfully at M. Poincare, Rene Viviani makes a speech. Monsieur Viviani is the greatest orator of our times. You have only to hear M. Viviani pronounce the words, “la gloire de France” to want to rush out and get into uniform. The next day after he has made his speech you find it pasted up on posters all over the city.

Moscow has recently “purified” the French communist party. According to the Russian communists the French party was mawkishly patriotic and weak willed. All members who refused to place themselves directly under orders from the central party in Moscow were asked to turn in their membership cards. A number did. The rest are now considered purified. But I doubt if they remain for long. The Frenchman is not a good Internationalist.

The “bloc national” is made up of honest patriots, and representatives of the great steel trust, the coal trust, the wine industry, other smaller profiteers, ex-army officers, professional politicians, careerists, and the royalists.

While it may seem fantastic to think of France having a king again, the royalist party is extremely well organized, is very strong in certain parts of the south of France, controls several newspapers, including l’Action Francaise and has organized a sort of Fascisti called the Camelots de Roi. It has a hand in everything in the government and was the greatest advocate of the advance into the Ruhr and the further occupation of Germany.

There, briefly, are the political parties in France and the way they line up. Now we must see the causes that forced France into the Ruhr.

France has spent eighty billion francs on reparations. Forty-five billion francs have been spent on reconstructing the devastated regions. There is a very great scandal talked in France about how that forty-five billions were spent. Deputy Inghles of the department of the Nord, said the other day in the chamber of deputies that twenty-five billions of it went for graft. He offered to present the facts at any time the chamber would consent to hear him. He was hushed up. At any rate forty-five billions were spent wildly and rapidly and there are very many now “devastated-region millionaires” in the chamber of deputies. The deputies asked for as much money as they wanted for their own districts and got it and a good part of the regions are still devastated.

The point is that the eighty billions have been spent and are charged up as collectable from Germany. They stand on the credit side of the ledger.

If at any time the French government admits that any part of those eighty billion francs are not collectable they must be moved over to the bad side of the ledger and listed as a loss rather than an asset. There are only thirty billions of paper francs in circulation to-day. If France admits that any part of the money spent and charged to Germany is uncollectable she must issue paper francs to pay the bonds she floated to raise the money she has spent. That means inflation of her currency resulting in starting the franc on the greased skid the Austrian kronen and German mark traveled down.

When Aristide Briand, former prime minister, who looks like a bandit, and is the natural son of a French dancer and a cafe keeper of St. Nazaire, agreed at the Cannes conference to a reduction in reparations in return for Lloyd George’s defense pact his ministry was overthrown almost before he could catch the train back to Paris. The weazel-eyed M. Arago, leader of the bloc national, and Monsieur Barthou, who looks like the left hand Smith Bro., were at Cannes watching every move of Briand and when they saw he was leaning toward a reduction of reparations they prepared to skid him out and get Poincare in—and accomplished the coup before Briand knew what was happening to him. The bloc national cannot afford to have any one cutting down on reparations because it does not want any inquiry as to how the money was spent. The memory of the Panama canal scandal is still fresh.

Poincare came into office pledged to collect every sou possible from Germany. The story of how he was led to refuse the offer of the German industrialists to take over the payment of reparations if it was reduced to a reasonable figure, and the sinister tale that is unfolding day by day in the French chamber of deputies about how Poincare was forced into the Ruhr, against his own will and judgment, the strange story of the rise of the royalists in France and their influence on the present government will be told in the next article.

Have a Fascisti Called the Camelots du Roi—Have Received Tremendous Impetus in Some Mysterious Way—Leon Daudet the Leader.

The following is the second of a series of nine articles on the Franco-German situation. The next article will appear in The Star on Saturday.

By ERNEST M. HEMINGWAY. Special Correspondence of The Star.

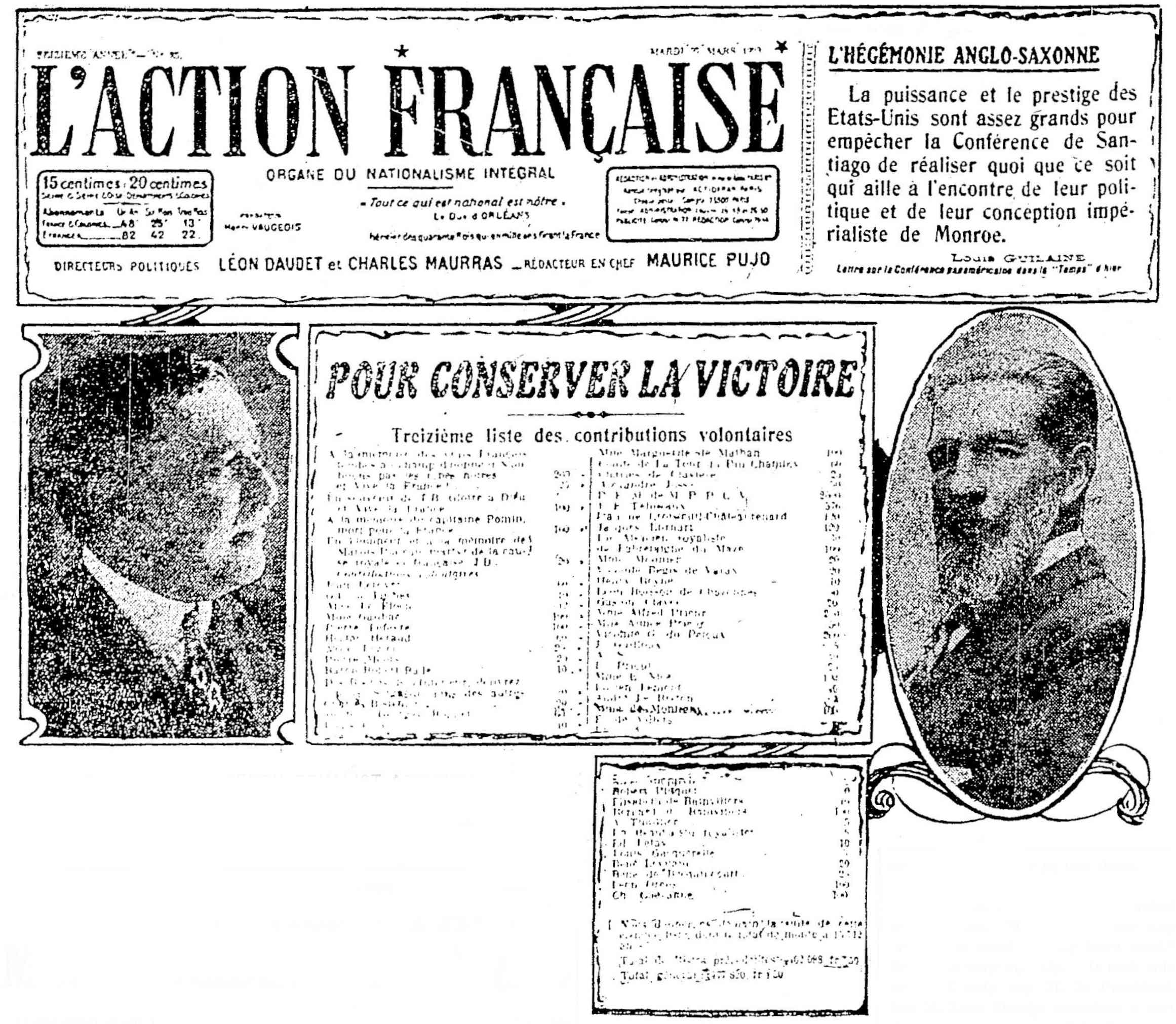

Evidence of French Royalist Activity

The letterpress reproduced above shows the title line of l’Action Francaise, organ of the French Royalist party, and a subscription list in some paper. On the LEFT Léon Daudet editor of the paper, and leader of the Royalists. On the RIGHT is Duc d’Orleans the Royalist candidate for King.

Paris. April 6.—Raymond Poincare is a changed man. Until a few months ago the little white-bearded Lorraine lawyer in his patent leather shoes and his grey gloves dominated the French chamber of deputies with his methodical accountant’s mind and his spitfire temper. Now he sits quietly and forlornly while fat, white-faced Leon Daudet shakes his finger at him and says “France will do this. France will do that.”

Leon Daudet, son of old Alphonse Daudet, the novelist, is the leader of the royalist party. He is also editor of l’Action Francaise, the royalist paper, and author of L’Entremetteuse or The Procuress, a novel whose plot could not even be outlined in any newspaper printed in English.

The royalist party is perhaps the most solidly organized in France to-day. That is a surprising statement to those who think of France as a republic with no thought of ever being anything else. The royalist headquarters are in Nimes in the south of France and Provence is almost solidly royalist. The royalists have the solid support of the Catholic church. It being an easily understood fact that the church of Rome thrives better under European monarchies than under the French republic.

Philippe, the Duc of Orleans, is the royalist’s candidate for king. Philippe lives in England, is a big, good looking man and rides very well to hounds. He is not allowed by law to enter France.

There is a royalist fascisti called the Camelots du Roi. They carry black loaded canes with salmon colored handles and at twilight you can see them in Montmartre swaggering along the streets with their canes, a little way ahead and behind a newsboy who is crying l’Action Francaise in the radical quarter of the old Butte. Newsboys who carry l’Action Francaise into radical districts without the protecting guard of Camelots are badly beaten up by the communists and socialists.

In the past year the royalists have received a tremendous impetus in some mysterious way. It has come on so rapidly and suddenly that from being more or less of a joke they are now spoken of as one of the very strongest parties. In fact Daudet is marked for assassination by the extreme radicals and men are not assassinated until they are considered dangerous. An attempt on his life was made by an anarchist a month or so ago. The girl assassin killed his assistant, Marius Plateau, by mistake.

General Mangin the famous commander of attack troops, nick-named “The Butcher,” is a royalist. He was the only great French general who was not made a marshal. He can always be seen in the chamber of deputies when Leon Daudet is to speak. It is the only time he comes.

Now the royalist party wants no reparations from Germany. Nothing would frighten them more than if Germany should be able to pay in full to-morrow. For that would mean that Germany was becoming strong. What they want is a weak Germany, dismembered if possible, a return to the military glories and conquests of France, the return of the Catholic church, and the return of the king. But being patriotic as all Frenchmen they first want to obtain security by weakening Germany permanently. Their plan to accomplish this is to have the reparations kept at such a figure that will be unpayable and then seize German territory to be held “only until the reparations are paid.”

The very sinister mystery is how they obtained the hold over M. Poincaré to force him to fall in with their plan and refuse to even discuss the German industrialists’ proposal to take over the payment of reparations if they were reduced to a reasonable figure. The German industrialists have money, have been making money ever since the armistice, have profited by the fall of the mark to sell in pounds and dollars and pay their workers in useless marks, and have most of those pounds and dollars salted away. But they did not have enough money to pay the reparations as they were listed, no five European nations could, and they wanted to make some sort of a final settlement with the French.

Now, we must get back to little white-whiskered Raymond Poincare, who has the smallest hands and feet of any man I have ever seen, sitting in the chair at the chamber of deputies while the fat, white-faced Leon Daudet, who wrote the obscene novel and leads the royalists and is marked for assassination, shakes his finger at him and says “France will do this. France will do that.”

To understand what is going on we must remember that French politics are unlike any other. It is a very intimate politics, a politics of scandal. Remember the duels of Clemenceau, the Calmette killing, the figure of the last president of the French republic standing in a fountain at the Bois and saying: “O, don’t let them get me. Don’t let them get me.”

A few days ago M. Andre Berthon stood up in the chamber of deputies and said: “Poincare, you are the prisoner of Leon Daudet. I demand to know by what blackmail he holds you. I do not understand why the government of M. Poincare submits to the dictatorship of Leon Daudet, the royalist.”

“Tout d’un piece,” all in one piece, as the Matin described it, Poincare jumped up and said: “You are an abominable gredin, monsieur.” Now you cannot call a man anything worse than a gredin, although it means nothing particularly bad in English. The chamber rocked with shouts and cat calls. It looked like the free fight in the cigaret factory when Geraldine Farrar first begun to play Carmen. Finally it quieted down sufficiently for M. Poincare, trembling and grey with rage, to say: “The man who stands in the Tribune dares to say that there exist against me or mine abominable dossiers which I fear to have made public. I deny it.”

M. Berthon said very sweetly: “I have not mentioned any dossiers.” Dossiers is literally bundles of papers. It is the technical name for the French system of keeping all the documents on the case in a big manilla folder. To have a dossier against you is to have all the official papers proving a charge held by some one with the power to use them.

In the end M. Berthon was asked to apologize. “I apologize for any outrageous words I may have used.” He did so very sweetly. It took this form: “I only say M. le President, that M. Leon Daudet exercises a sort of pressure on your politics.”

This apology was accepted. Poincare goaded out of his depression to deny the existence of papers that had not been mentioned is back in his forlornness. You cannot make charges in France unless you hold the papers in your hands and those that do hold dossiers know how to use them.

Last July in a confidential conversation with a number of British and American newspaper correspondents Poincare, discussing the Ruhr situation, said: “Occupation would be futile and absurd. Obviously Germany can only pay now in goods and labor.” He was a more cheerful Poincare in those days.

Meantime the French government has spent 160 million francs (official) on the occupation and Ruhr coal is costing France $200 a ton.

In the next article Mr. Hemingway will deal with the French press, telling how the papers are paid to print only what the government wants.

System Quite Open and Understood—Other Countries Pay for Their Space, Too—Prominent Men Oppose Occupation, But Do Their Duty as Patriots.

The following is the third of a series of articles on the Franco-German situation by Ernest M. Hemingway, staff correspondent of The Star.

By ERNEST M. HEMINGWAY. Special Correspondence of The Star.

Paris, April 10.—What do the French people think about the Ruhr and the whole German question? You will not find out by reading the French press.

French newspapers sell their news columns just as they do their advertising space. It is quite open and understood. As a matter of fact it is not considered very chic to advertise in the small advertising section of a French daily. The news item is supposed to be the only real way of advertising.

So the government pays the newspapers a certain amount to print government news. It is considered government advertising and every big French daily like the Matin, Petit Parisien, Echo de Paris, L’Intransigeant, Le Temps, receives a regular amount in subsidy for printing government news. Thus the government is the newspapers’ biggest advertising client. The railroads are the next biggest. But that is all the news on anything the government is doing that the readers of the paper get.

When the government has any special news, as it has at such a time as the occupation of the Ruhr, it pays the papers extra. If any of these enormously circulated daily papers refuse to print the government news or criticize the government standpoint the government withdraws their subsidy—and the paper loses its biggest advertiser. Consequently the big Paris dailies are always for the government, any government that happens to be in.

When one of them refuses to print the news furnished by the government and begins attacking its policy you may be sure of one thing. That it has not accepted the loss of its subsidy without receiving the promise of a new one and a substantial advance, from some government that it is absolutely sure will get into power shortly. And it has to be awfully sure it is coming off before it turns down its greatest client. Consequently when one of these papers whose circulation mounts into millions starts an attack on the government it is time for the politicians in power to get out their overshoes and put up the storm windows.

All of these things are well known and accepted facts. The government’s attitude is that the newspapers are not in business for their health and that they must pay for the news they get like any other advertiser. The newspapers have confirmed the government in this attitude.

Le Temps is always spoken of as “semi-official.” That means that the first column on the first page is written in the foreign office at the Quai D’Orsay, the rest of the columns are at the disposal of the various governments of Europe. A sliding scale of rates handles them. Unimportant governments can get space cheap. Big governments come high. All European governments have a special fund for newspaper publicity that does not have to be accounted for.

This sometimes leads to amusing incidents, as a year ago when the facts were published showing how the Temps was receiving subsidy for running propaganda from two different Balkan governments who were at loggerheads and printing the despatches as their own special correspondence on alternate days. No matter how idealistic European politics may be a trusting idealist is about as safe in their machinery as a blind man stumbling about in a saw mill. One of my best friends was in charge of getting British propaganda printed in the Paris press at the close of the war. He is as sincere and idealistic a man as one could know—but he certainly knows where the buzz saws are located and how the furnace is stoked.

In spite of the fact that great Paris dailies, which are so widely quoted in the States and Canada as organs of public opinion, say that the people of France are solidly backing the occupation of the Ruhr, it is nevertheless true. France always backs the government in anything it does against a foreign foe once the government has started. It is that really wonderful patriotism of the French. All Frenchmen are patriotic—and nearly all Frenchmen are politicians. But the absolute backing of the government only lasts a certain length of time. Then after his white heat has cooled the Frenchman looks the situation over, the facts begin to circulate around, he discovers that the occupation is not a success—and overthrows the government. The Frenchman feels he must be absolutely loyal to his government but that he can overthrow it and get a new government to be loyal to at any time.

Marshall Foch, for example, was opposed to the Ruhr occupation. He washed his hands of it absolutely. But once it was launched he did not come out against it. He sent General Weygand, his chief of staff, to oversee it and do the best he could. But he does not wish to be associated with it in any way.

Similarly Loucheur, the former minister of the liberated regions, and one of the ablest men in France, opposed the occupation. Loucheur is a man who does not mince words. During the period when France was pouring out money for reconstruction with seemingly no regard as to how it was spent or for what, Loucheur did all he could to control it. It was Loucheur who told the mayor of Rheims: “Monsieur, you are asking exactly six times the cost of this reconstruction.”

A few days ago M. Loucheur said to me in conversation, “I was always opposed to the occupation. It is impossible to get any money that way. But now that they have gone in, now that the flag of France is unfurled, we are all Frenchmen and we must loyally support the occupation.”

M. Andre Tardieu, who headed the French mission to the United States during the war and is Clemenceau’s lieutenant, opposed the advance into the Ruhr in his paper, the Echo National, up until the day it started. Now he is denouncing it as ill run, badly managed, wishy washy and not strong enough. M. Tardieu, who looks like a bookmaker, foresees the failure of the present government with the failure of the occupation but he wants to be in a position to catch the reaction in the bud and say: “Give us a chance at it. Let us show that properly handled it can be a success.” For M. Tardieu is a very astute politician and that is very nearly his only chance of getting back into power for some time.

Eduard Herriot, mayor of Lyons, a member of cabinet during the war, and dark horse candidate for next premier of France, after supporting the occupation in the same way that Loucheur is doing, has now sponsored a resolution in the Lyons city council protesting the occupation and demanding consideration of a financial and economic entente with Germany. This demand of Herriot may be the first puff of the wind that is bound to rise and blow the Poincare government out of power.

Now why are these, and many other intelligent Frenchmen, opposed to the occupation although they want to get every cent possible from Germany? It is simply because of the way it is going. It is losing France money instead of making it and from the start it was seen by the longheaded financiers that it would only cripple Germany’s ability to pay further reparations, unite her as a country and reflame her hatred against France—and cost more money than it would ever get out.

Before the occupation a train of twelve or more cars of coal or coke left the Ruhr for France every twenty eight minutes. Now there are only two trains a day. A train of twelve cars now is split up into four trains to pad the figures and make the occupation look successful.

When there is a shipment of coal to be gotten out, four or five tanks, a battalion of infantry, and fifty workmen go and do the job. The soldiers are to prevent the inhabitants beating up the workmen. The official figures on the amount of coal and coke that has been exported from the Ruhr and the money that has already been given by the chamber of deputies for the first months of the occupation show that the coal France was receiving on her reparations account is now costing her a little over $200 a ton. And she isn’t getting the coal.

At the start of the occupation certain correspondents wrote that it would be easy for France to run the Ruhr profitably, all she would have to do would be to bring in cheap labor—Italian or Polish labor is always cheap—and just get the stuff out. The other day I saw some of this cheap labor locked in a car at the Gare du Nord bound for Essen. They were a miserable lot of grimy unfit looking men, the sort that could not get work in France or anywhere else. They were all drunk, some shouting, some asleep on the floor of the car, some sick. They looked more like a shanghaied ship’s crew than anything else. And they were all going to be paid double wages and work half time under military protection. No workmen will go into the Ruhr for less than double wages—and it has been almost impossible to get workmen for that. The Poles and Italians will not touch the job. If you want any further information on the way it works out economically ask any business man, or any street railway head who has ever had a strike, how much money his corporation made during the time it was employing strike breakers.

Now that we have seen in a quick glance the forces that are at work in France in this war after the war, the situation of France, and the views of her people, we can next look at Germany.

French Will Have Won When the German Lemon Is Squeezed Dry—Berlin Using Up Its Gold to Carry On Fight.

The following is the fourth of a series of articles on the Franco-German situation by Ernest M. Hemingway, staff correspondent of The Star.

By ERNEST M. HEMINGWAY. Special Correspondence of The Star.

Offenburg, Baden, April 12.—Offenburg is the southern limit of the French occupation of Germany. It is a clean, neat little town with the hills of the Black Forest rising on one side and the Rhine plain stretching off on the other.

The French seized Offenburg in order to keep the great international railway line open. This line runs straight north from Basle in Switzerland through Frieburg, Offenburg, Karlsruhe, Frankfurt, Cologne, Dusseldorf, to Holland. It was the main artery of communication and commerce in Germany.

According to the French their occupation was to ensure the safe passage of coal trains on the main line between the Ruhr and Italy. They feared the Germans might shunt the cars off at Offenburg and ship them on a branch line up into the Black Forest, and eventually back into the industrial district of what French papers refer to as “unoccupied Germany.”

Germany denounced the occupation of Offenburg, located in the Duchy of Baden in the far south of Germany, some hundreds of miles from the Ruhr, as a breach of the treaty of Versailles. The French replied by expelling the burgomaster and some two hundred citizens who had signed the protest, from the town. The Germans then informed the French that no more trains would run through Offenburg on the great main Rhineland railway.

For almost two months now not a train has run through Offenburg. I stood on the bridge over the right of way and looked at the four wide gauge tracks stretching to Switzerland in one direction, and Holland in the other, red with rust. Trains stop three miles each way from Offenburg, north and south. Passengers get out with their baggage, and if they are Germans, can ride into Offenburg in a motor bus and get another bus to take them the three miles the other side of the town where they can continue their journey. If they are French they are allowed to walk, carrying their baggage.

No coal has gone through since the town was seized. Now the French face the problem—if they want to control the Rhine railway—of occupying every town along the whole length of it at an expenditure of at least four hundred thousand men, and then running the trains themselves. Otherwise the Germans say they will run trains to just outside the limit of the French occupation, and then stop them. It is their answer to the strategists who put their fingers on the map and said, “It is very simple. We will take this town here and that will control this railway. It will only take a few men, etc.”

The Franco-German commercial war has settled down to a question of which government goes absolutely broke first. All the Germans I have talked to say, “We could not do anything without our government. The government pays all the people who lose their jobs through the occupation. It pays all those who are expelled from the town. It pays the unemployed.”

The German government is now using up the gold to stabilize the mark that it ordinarily paid over to the reparations commission. It is using these marks that it buys at the fixed price of 20,800 to the dollar to fight the occupation. It is also already using a good portion of its hoarded gold. When through the crippling of German industries and the exhaustion of the gold supply the German government is no longer able to fight the occupation by putting the government resources back of the individuals who suffer by the occupation, and making good their loss with government money, the French will have won the struggle of attrition. But Germany’s gold will have been used up before she quits, her industries ruined, and she will be as profitable to France as a squeezed lemon.

On the day before I left Paris M. Poincare asked the chamber of deputies for 192,000,000 francs for the expenses of the first four months’ occupation of the Ruhr. Four months more of that, and if the German government goes under, the French government will have won a commercial victory at the cost of biting off its own nose to spite Germany’s face.

From Offenburg to Ortenberg, where there was a train. I rode in a motor truck. The driver was a short, blonde German with sunken cheeks and faded blue eyes. He had been badly gassed at the Somme. We were riding along a white, dusty road through green fields forested with hop poles, their tangled wires flopping. We crossed a wide, swift clearly pebbled stream with a flock of geese resting on a gravel island. A manure spreader was busily clicking in the field. In the distance were the blue Schwartzwald hills.

“My brother,” said the driver, guiding the big wheel with one arm half wrapped around it. “He had hard luck.”

“So?”

“Ja. He never had no luck, my brother.”

“What was he doing?”

“He was signal man on the railroad from Kehl. The French put him out. All the signal men. The day they came to Offenburg they gave them all twenty-four hours.”

“But the government pays him, doesn’t it?”

“Oh yes. They pay him. But he can’t live on it.”

“What’s the matter?”

“Well, he’s got seven kids.”

I pondered this. The driver went on in his drawling south German. “They pay him what he got, but the prices are up and where he was signal man he had a little garden. A nice garden. It makes a difference when you got a garden.”

“What’s he do now?” I asked.

“He tried working in the sawmill at Hausach, but he can’t work good inside. He’s got the gas like me. Ja. He’s got no luck, my brother.”

We passed another lovely clear stream that curved alongside the road. It had clear, gravel bottomed ripples and then deep holes along the bank.

“Trout?” I asked.

“Not any more,” the driver laughed. “When we had the revolution nobody knew what to do. It was in the papers and it was posted up. They sang in the streets and said ‘Down with the kaiser,’ and ‘Hoch the republic,’ and there was nothing more to do. But they had to do something, so because it was always trouble to get fishenkarten (fishing licenses), they went out to the stream with hand grenades and killed the trout and everybody had trout to eat. Then the police came and made them stop and put some in jail and the revolution was over.”

“Herr Canada,” said the driver, “how long do you think the French will stay in Offenburg?”

“Three or four months maybe. Who knows?”

The driver looked ahead up the white road that we were turning to dust behind us. “There will be trouble then. Bad trouble. The working people will make trouble. Already the factories are shutting down all around here.”

“It won’t be like the other revolution?” I asked.

The driver laughed, a hollow-cheeked, skin drum-tight, hollow-eyed laugh. “No they won’t throw any grenades at the trout then.” The thought amused him very much. He laughed again.

Talks French Where to Use Language Is to Invite an Attack—And Goes Through the Line Like Lionel Conacher.

The following is the fifth of a series of articles on the Franco-German situation by Ernest M. Hemingway, staff correspondent of The Star.

By ERNEST M. HEMINGWAY. Special Correspondence elsewhere to The Star.

Frankfurt-on-Main, April 28.—On the frontier between Baden and Wurtemberg I found my first Hater. It was all the fault of the Belgian lady who would insist on speaking French. In the roaring dark of going through a tunnel the Belgian lady had shouted something at me. I didn’t understand and she repeated, this time in French: “Please close the door.”

When we came out of the tunnel the Belgian lady beamed an enormous beam and began talking French. She talked French rapidly and interesting for the next eight hours in a country where to say one French word is to invite an attack.

During those eight hours we changed trains six times. Sometimes we stood on a platform at a little junction like Schiltach with a crowd of at least six hundred people waiting for the train to come. There would be four places vacant in the train. We always got two of them. That was the Belgian lady.

“You wait with the baggage,” the Belgian lady would say as the train came in sight down the track, “I will go in ahead of these boche and get two places. I will open the window and you throw the bags through. We will be comfortable.”

That was exactly the way it happened. The train stopped. The Belgian lady would go through “these boche” like the widely-advertised Mr. Lionel Conacher through the line of scrimmage. Four hundred perspiring and worthy Germans would be assaulting the door. A window would fly open. The smiling face of the Belgian lady would emerge triumphantly shouting “Voici Monsieur! The baggage. Quick!”

Some way or other I would get aboard a platform of the train and in half an hour of apologetic threading my way, get through the sardine-packed aisles of the cars to where the Belgian lady was saving my “platz.”

“Where have you been, monsieur?” she would ask anxiously and loudly in French. Everyone in the car would look at us blackly. I would tell her I had been making my way through the crowd.

The Belgian lady would snort a terrific Belgian snort.

“Where would you be if you did not have me to take care of you, I ask you? Where would you be? Never mind. I am here and I will look after you.”

So guided and guarded by the brave Belgian lady I crossed Baden, Wurtemberg and the Rhenish provinces in safety.

As we crossed the frontier into Wurtemberg a tall, distinguished-looking man with grey mustaches, came into the car.

“Good day,” he said and looked around keenly. Then asked politely but severely: “Is there an auslander in this car?”

I thought my time had come. There are at least four special visas that no one ever bothers to get in Germany, for the lack of which you can be thrown into jail and fined anything up to a million marks. It is much better to have these visas, but if you take the time to get them you will spend eight out of every twenty-four hours in police and passport control offices, and these officials will discover that you lack nine other special and highly-necessary visas that you have never heard of and throw you into the jug on general principles.

The grey mustached man took my passport and luckily opened it to a page covered with Turkish, Bulgarian, Croatian, Greek, and other incomprehensible official stampings. It was simply too much of a mess for him. He was too much of a gentleman to go into that sort of thing, he folded the passport and handed it back with courtly gesture, first carefully identifying the brave Belgian lady, from the picture of Mrs. Hemingway in the back of the passport, as my wife!

The lady whose picture appears in the passport has bobbed hair and has just finished a very successful season of tennis on the Riviera. I will not attempt to describe her, being prejudiced. The brave Belgian lady weighs, perhaps 180 pounds, has a face like a composite Rodin’s group of the Burghers of Calais waiting to be hanged, and sets this face off by a series of accordion type double chins. This evidence is offered in the case of The People vs. Passports.

It was just after the passage of the knightly official that the Hater got into action. The Hater sat directly opposite us. He had been listening to our conversation in French, and some time back had begun to mutter. He was a small man, the Hater, with his head shaved, rosy cheeks, a big face culminating in a toothbrush mustache. The strain of his rapidly increasing hate was telling on him. It was obvious he could not hold out much longer. Then he burst.

It was just like the time a bath heater blew up on me at Genoa. I could not catch the first eight hundred words. They came too fast. The Hater’s little blue eyes were just like a wild boar’s. When my ears got tuned to his sending speed the conversation was going something like this:

“Dirty French swine. Rotten French change hyenas. Baby killers. Filthy attackers of defenseless populations. War swine. Swine hounds, etc.”

The brave Belgian lady leaned forward into the zone of the Hater’s fire and placed one of her twelve-pound fists on the Hater’s knee.

“The Herr is not a Frenchman,” she shouted at the Hater in German, “I am not French. We talk French because it is the language of civilized people. Why don’t you learn to talk French? You can’t even talk German. All you can talk is profanity. Shut up!”

It seemed as though we ought to have been mobbed. But nothing happened. The Hater shut up. He muttered for a time like a subsiding geyser, but he gradually shut up and sat there hating the brave Belgian lady. Once more he broke out as he got up to leave the train at Karlsruhe. He was always too fast for me and I didn’t get it.

“Qu’es-ce que c’est, ca?” I asked the brave Belgian lady.

She snorted, her most devastating Belgian snort. “He makes some charge against France. But it is not important.”

The B. B. lady was traveling through Germany without a passport. She avowed that she didn’t need a passport anywhere. She and her “mari” were on the same passport and he was in Switzerland on business. If anyone demanded a passport she could always tell them that she was going to meet her husband at Mannheim.

“My husband is a Jew,” she said, “but he is tres gentil. One time in Frankfurt they would not let us stop the night at a hotel because he was a Jew. I showed them. We stayed there a week.”

We talked finance for a long time. The B. B. lady wanted me to tell her confidentially whether the dollar was going to rise or fall in France. She said it would be extremely important if her husband could know that, and she wanted me to tell her so she could tell her husband. I did my best. Luckily she hadn’t my address if I am wrong.

Then we talked about the war. I asked the B. B. lady if she had been in Belgium under the occupation.

“Yes,” she said.

“How was it? Pretty bad?” I asked.

The B. B. lady snorted, her most powerful Belgian snort, “I did not suffer at all.”

I believe her. In fact, having traveled with the brave Belgian lady, I am greatly surprised and unable to understand how the Germans ever got into Belgium at all.

Easy to Get Document From French Embassy, But the Germans are More Suspicious—No Tourists Allowed, No Newspapermen Wanted.

The following is the sixth of a series of articles on the Franco-German situation by Ernest M. Hemingway.

By ERNEST M. HEMINGWAY. Special Correspondence to The Star.

Offenburg, Baden. April 30—In Paris they said it was very difficult to get into Germany. No tourists allowed. No newspaper men wanted. The German consulate will not visa a passport without a letter from a consulate or chamber of commerce in Germany saying, under seal, it is necessary for the traveler to come to Germany for a definite business transaction. The day I called at the consulate it had been instructed to amend the rules to permit invalids to enter for the “cure” if they produced a certificate from the doctor of the health resort they were to visit showing the nature of their ailment.

“We must preserve the utmost strictness,” said the German consul and reluctantly and suspiciously after such consultation of files gave me a visa good for three weeks.

“How do we know you will not write lies about Germany?” he said before he handed back the passport.

“Oh, cheer up.” I said.

To get the visa I had given him a letter from our embassy, printed on stiff crackling paper and bearing an enormous red seal which informed “whom it may concern” that Mr. Hemingway, the bearer, was well and favorably known to the embassy and had been directed by his newspaper, The Toronto Star, to proceed to Germany and report on the situation there. These letters do not take long to get, commit the embassy to nothing, and are as good as diplomatic passports.

The very gloomy German consular attache was folding the letter and putting it away.

“But you cannot have the letter. It must be retained to show cause why the visa was given.”

“But I must have the letter.”

“You cannot have the letter.”

A small gift was made and received.

The German, slightly less gloomy, but still not happy: “But tell me why was it you wanted the letter so?”

Me, ticket in pocket, passport in pocket, baggage packed, train not leaving till midnight, some articles mailed, generally elated. “It is a letter of introduction from Sara Bernhardt, whose funeral you perhaps witnessed to-day, to the Pope. I value it.”

German, sadly and slightly confessed: “But the Pope is not in Germany.”

Me, mysteriously, going out the door: “One can never tell.”

In the cold, grey, street-washing, milk-delivering, shutters-coming-off-the-shops, early morning, the midnight train from Paris arrived in Strasburg. There was no train coming from Strasburg into Germany. The Munich Express, the Orient Express, the Direct for Prague? They had all gone. According to the porter I might get a tram across Strasburg to the Rhine and then walk across into Germany and there at Kehl get a military train for Offenburg. There would be a train for Kehl sooner or later, no one quite knew, but the tram was much better.

On the front platform of the street car, with a little ticket window opening into the car through which the conductor accepted a franc for myself and two bags, we clanged along through the winding streets of Strasbourg and the early morning. There were sharp peaked plastered houses criss-crossed with great wooden beams, the flyer wound and rewound through the town and each time we crossed it there were fishermen on the banks, there was the wide modern street with modern German shops with big glass show windows and new French names over their doors, butchers were unshuttering their shops and with assistants hanging the big carcasses of beeves and horses outside the doors, a long stream of carts were coming in to market from the country, streets were being flushed and washed. I caught a glimpse down a side street of the great red stone cathedral. There was a sign in French and another in German forbidding anyone to talk to the motorman and the motorman chatted in French and German to his friends who got on the car as he swung his levers and checked or speeded our progress along the narrow streets and out of the town.

In the stretch of country that lies between Strasbourg and the Rhine the tram track runs along a canal and a big blunt nosed barge with LUSITANIA painted on its stern was being dragged smoothly along by two horses ridden by the bargeman’s two children while breakfast smoke came out of the galley chimney and the bargeman leaned against the sweep. It was a nice morning.

At the ugly iron bridge that runs across the Rhine into Germany the tram stopped. We all piled out. Where last July at every train there had formed a line like the queue outside an arena hockey match there were only four of us. A gendarme looked at the passports. He did not even open mine. A dozen or so French gendarmes were loafing about. One of these came up to me as I started to carry my bags across the long bridge over the yellow, flooded, ugly, swirling Rhine and asked: “How much money have you?”

I told him one hundred and twenty-five dollars “Americain” and in the neighbourhood of one hundred francs.

“Let me see your pocketbook.”

He looked in it, grunted and handed it back. The twenty-five five-dollar bills I had obtained in Paris for mark-buying made an impressive roll.

“No gold money?”

“Mais non, monsieur.”

He grunted again and I walked, with the two bags, across the long iron bridge, past the barbed wire entanglement with its two French sentries in their blue tin hats and their long needle bayonets, into Germany.

Germany did not look very cheerful. A herd of beef cattle were being loaded into a box car on the track that ran down to the bridge. They were entering reluctantly with much tail-twisting and whacking of their legs. A long wooden custom’s shed with two entrances, one marked “Nach Frankreich” and one “Nach Deutchland,” stood next to the track. A German soldier was sitting on an empty gasoline tin smoking a cigaret. A woman in an enormous black hat with plumes and an appalling collection of hat boxes, parcels and bags was stalled opposite the cattle-loading process. I carried three of the bundles for her into the shed marked “Towards Germany.”

“You are going to Munich too?” she asked, powdering her nose.

“No. Only Offenburg.”

“Oh, what a pity. There is no place like Munich. You have never been there?”

“No, not yet.”

“Let me tell you. Do not go anywhere else. Anywhere else in Germany is a waste of time. There is only Munich.”

A grey-headed German customs inspector asked me where I was going, whether I had anything dutiable, and waved my passport away. “You go down the road to the regular station.”

The regular station had been the important customs junction on the direct line between Paris and Munich. It was deserted. All the ticket windows closed. Everything covered with dust. I wandered through to the track and found four French soldiers of the 170th Infantry Regiment, with full kit and fixed bayonets.

One of them told me there would be a train at 11.15 for Offenburg, a military tram: it was about half an hour to Offenburg, but this droll train would get there about two o’clock. He grinned. Monsieur was from Paris? What did the monsieur think about the match Criqui-Zjawnny Kilbane? Ah. He had thought very much the same. He had always had the idea that he was no fool, this Kilbane. The military service? Well, it was all the same. It made no difference where one did it. In two months now he would be through. It was a shame he was not free, perhaps we could have a talk together. Monsieur had seen the Kilbane box? The new wine was not bad at the buffet. But after all he was on guard. The buffet is straight down the corridor. If monsieur leaves the baggage here it will be all right.

In the buffet was a sad-looking waiter in a dirty shirt and soup and beer stained evening clothes, a long bar and two forty-year-old French second lieutenants sitting at a table in the corner. I bowed as I entered, and they both saluted.

“No,” the waiter said, “there is no milk. You can have black coffee, but it is ersatz coffee. The beer is good.”

The waiter sat down at the table. “No there is no one here now,” he said. “All the people you say you saw in July cannot come now. The French will not give them passports to come into Germany.”

“All the people that came over here to eat don’t come now?” I asked.

“Nobody. The merchants and restaurant keepers in Strasburg got angry and went to the police because everybody was coming over here to buy and eat so much cheaper, and now nobody in Strasburg can get passports to come here.”

“How about all the Germans who worked in Strasburg?” Kehl was a suburb of Strasburg before the peace treaty, and all their interests and industries were the same.

“That is, all finished. Now no Germans can get passports to go across the river. They could work cheaper than the French, so that is what happened to them. All our factories are shut down. No coal. No trains. This was one of the biggest and busiest stations in Germany. Now nix. No trains, except the military trains, and they run when they please.”

Four poilus came in and stood up at the bar. The waiter greeted them cheerfully in French. He poured out their new wine, cloudy and golden in their glasses, and came back and sat down.

“How do they get along with the French here in town?”

“No trouble. They are good people. Just like us. Some of them are nasty sometimes, but they are good people. Nobody hates, except profiteers. They had something to lose. We haven’t had any fun since 1911. If you make any money it gets no good, and there is only to spend it. That is what we do. Some day it will be over. I don’t know how. Last year I had enough money saved up to buy a gasthaus in Hernberg; now that money wouldn’t buy four bottles of champagne.”

I looked up at the wall where the prices were:

Beer, 350 marks a glass. Red wine, 500 marks a glass. Sandwich, 900 marks. Lunch, 3,500 marks. Champagne, 38,000 marks.

I remembered that last July I stayed at a de luxe hotel with Mrs. Hemingway for 600 marks a day.

“Sure,” the waiter went on, “I read the French papers. Germany debases her money to cheat the allies. But what do I get out of it?”

There was a shrill peep of a whistle outside. I paid and shook hands with the waiter, saluted the two forty-year-old second lieutenants, who were now playing checkers at their table, and went out to take the military train to Offenburg.

Single Room in a Hotel Costs 51,000 Marks With Taxes Extra—Costs Money to Go Without Breakfast in Germany Now.

The following is the seventh of a series of articles on the Franco-German situation by Ernest M. Hemingway.

By ERNEST M. HEMINGWAY. Special Correspondence of The Star.

Mainz-Kastel, April 22.—One hundred and twenty-five dollars in Germany to-day buys two million and a half marks.

A year ago it would have taken a motor lorry to haul this amount of money. Twenty thousand marks then made into packets of ten of the thick, heavy, hundred mark notes filled your overcoat pockets and part of a suit case. Now the two million and half fits easily into your pocketbook as twenty-five slim, crisp 100,000 mark bills.

When I was a small boy I remember being very curious about millionaires and being finally told to shut me up that there was no such thing as a million dollars, there wouldn’t be a room big enough to hold it, and that even if there was, a person counting them a dollar at a time would die before he finished. All of that I accepted as final.

The difficulty of spending a million dollars was further brought home to me by seeing a play in which a certain Brewster if he spent a million dollars foolishly was to receive six million from the will of some splendid uncle or other. Brewster, as I recall it, after insurmountable difficulties, finally conceived the idea of falling in love, at which the million disappeared almost at once only for poor Brewster to discover that his uncle was quite penniless, having died at the foundling’s home or something of the sort, whereupon Brewster, realizing it was all for the best, went to work and eventually became president of the local chamber of commerce.

Such bulwarks of my early education have been shattered by the fact that in ten days in Germany, for living expenses alone I have spent, with practically no effort at all, something over a million marks.

During this time I have only once stopped at a deluxe hotel. After a week in fourth class railway coaches, village inns, country and small town gasthofs, finishing a seven-hour ride standing up in the packed corridor of a second class railway car, I decided that I would investigate how the profiteers lived.

On the great glass door of the Frankfurter Hof, was a black lettered sign. FRENCH AND BELGIANS NOT ADMITTED. At the desk, the clerk told me a single room would be 51,000 marks “with taxes, of course, added.” In the oriental lobby, out of big chairs I could see heavy Jewish faces looking at me through the cigar smoke. I registered as from Paris.

“We don’t enforce that anti-French rule of course,” said the clerk very pleasantly.

Up in the room there was a list of the taxes. First, there was a 10 per cent. town tax, then 20 per cent. for service, then a charge of 8,000 marks for heating, then an announcement that the visitors who did not eat breakfast in the hotel would be charged 6,000 marks extra. There were some other charges. I stayed that night and half the next day. The bill was 145,000 marks.

In a little railway junction in Baden a girl porter put my two very heavy bags on to the train. I wanted to help her with them. She laughed at me. She has a tanned face, smooth blonde hair and shoulders like an ox.

“How much?” I asked her.

“Fifty marks,” she said.

At Mannheim a porter carried my bags from one track to another in the station. When I asked him how much, he demanded a thousand marks. The last porter I had seen had been the girl in Baden so I protested.

“A bottle of beer costs fifteen hundred marks here,” he replied, “a glass of schnapps, twelve hundred.”

That is the way the prices fluctuate all over Germany. It all depends on whether the prices went up to the top when the mark had its terrific fall last winter to around 70,000 to the dollar. If the prices went up they never come down. In the big cities, of course, they went up. A full meal in the country costs 2,000 marks. On the train a ham sandwich costs 3,000 marks.

Last week, investigating the actual living conditions, I talked to, among others, a small factory owner, several workmen, a hotelkeeper and a high school professor.

The factory owner said: “We have enough coal and coke for a few weeks longer, but are short on all raw materials. We cannot pay the prices they ask now. We sold to exporters. They got the dollar prices. We didn’t. We can buy coal from Czecho-Slovakia, where they have German mines they got under the peace treaty, but they want pay in Czech money, which is at par and we can’t afford to pay. We are starting to lay off workmen, and as they have nothing saved there is liable to be trouble.”

A workman said: “I cannot keep my family on the money that I am making now. I have mortgaged my house to the bank and the bank charges me 10 per cent. interest on the loan. You see, workmen who have plenty of money to spend, but they are the young men who are living at home. They get their board and room free and their laundry. Maybe they pay a little something on their board. They are the men you see around the wine and beerstubes. Maybe their father has some property in the country, a farm, then they are all right. All the farmers have money.”

The hotelkeeper said: “All summer the hotel was full. We had a good season. I worked all summer in the high season from six o’clock in the morning until midnight. Every room was crowded. We had people sleeping in the billiard rooms on cots. It was the best year we ever had. In October the mark started to fail, and in December all the money we had taken in all summer was not enough to buy our preserves and jelly for next season. I have a little capital in Switzerland, otherwise we would have had to close. Every other summer hotel in this town has closed for good. The proprietor of the big hotel on the hill there committed suicide last week.”

The high school professor said: “I get 200,000 marks a month. That sounds like a good salary. But there is no way I can increase it. One egg costs 4,000 marks. A shirt costs 85,000 marks. We are living now, our family of four, on two meals a day. We are very lucky to have that. I owe the bank money.

“People here in town cannot change their marks into dollars, and Swiss francs so as to have them when the mark falls again, as it will as soon as they settle this Ruhr affair. The banks will not give out any dollars or Swiss or Dutch money. They hang on to all they can get. The people can’t do anything.

“The merchants have no confidence in the money, and will not bring their prices down. The wealthy people are the farmers who got the high prices for their crops which were marketed just after the mark fell last fall and the big manufacturers. The big manufacturers sell abroad for foreign money, and pay their labor in marks. And the banks. The banks are always wealthy. The banks are like the government. They get good money for bad, and hang on to the good money.”

The school teacher was a tall, thin man with thin, nervous hands. For pleasure he played the flute. I had heard him playing as I came to his door. His two children did not look undernourished, but he and his frayed looking wife did.

“But how will it all come out?” I asked him.

“We can only trust in God,” he said. Then he smiled. “We used to trust in God and the government, we Germans. Now I no longer trust the government.”

“I heard you playing very beautifully on the flute when I came to the door,” I said rising to go.

“You know the flute? You like the flute? I will play for you.”

“If it would not be asking too much.”

So we sat in the dusk in the ugly little parlor and the schoolmaster played very beautifully on the flute. Outside people were going by in the main street of the town. The children came in silently and sat down. After a time the schoolmaster stopped and stood up very embarrassedly.

“It is a very nice instrument, the flute,” he said.

Tourists See No Hunger or Distress Except That Shown by Professional Beggars—Middle Classes With Fixed Income Are the Real Sufferers.

The following is the eighth of a series of articles by Ernest M. Hemingway, staff correspondent of The Star, on the Franco-German situation.

By ERNEST M. HEMINGWAY. Special to The Star.

Cologne, April 27.—Traveling on fast trains, stopping at the hotels selected for him by the Messrs. Cook, usually speaking no language but his own, the tourist sees no suffering in Europe.

If he comes to Germany, even traveling quite extensively, he will see no suffering. There are no beggars. No horrible examples on view. No visible famine sufferers nor hungry children that besiege railway stations.

The tourist leaves Germany wondering what all this starving business is about. The country looks prosperous. On the contrary in Naples he has seen crowds of ragged, filthy beggars, sore-eyed children, a hungry looking horde. Tourists see the professional beggars, but they do not see the amateur starvers.

For every ten professional beggars in Italy there are a hundred amateur starvers in Germany. An amateur starver does not starve in public.

On the contrary no one knows the amateur is starving until they find him. They usually find him in bed. Every hungry person does not walk the streets after a certain length of time. It sharpens that feeling that is dulled by bed. In writing of amateur starvers no reference is meant to the inhabitants of bread lines, soup kitchens or rescue missions. They have violated their strictly amateur standing.

A few case histories of amateur starvers are appended.

No. 1: Frau B. is the widow of the owner of an apothecary shop, who died before the war. She has a yearly income of 26,400 marks, the interest on mortgages. Before the war this yielded $100 a week. Her 29-year-old daughter is suffering from lung trouble and cannot work. Her 21-year-old son passed the final examination at the grammar school, but cannot go to the university, and is earning his living as a miner. Another 13-year-old is in school. The family was formerly very well-to-do. To-day their income for one year is the minimum for the existence of a family of four persons for a period of two weeks.

No. 2: The married couple P., 64 years old, who have been blind for the last ten years, receive from their capital, which they earned by hard work, an income of 3,400 marks a year. They were formerly able to live comfortably on this income. To-day it represents half a week’s wages of an unskilled laborer.

No. 3: Frau B., widow of an architect, is obliged to live with her two children of 9 and 6 years on a yearly income of 2,400 marks. This represents less than two days’ earnings of a laborer.

No. 4: The married couple K. receive 500 marks a month from the rent of their house. The husband, formerly a farmer, is suffering from heart trouble. A short time ago he was in bed a number of weeks as a result of poisoning. For six months the wife has been almost completely paralyzed. The medicines necessary to their illness cost more than their income. In normal times the income derived from the rent would have afforded these people a comfortable existence.

No. 5: The widow H., 48 years old, has four children, three of whom still attend school. She has a capital of 100,000 marks. This gives her 15,000 marks yearly. On this the family can live for one week.

These cases are not exceptional or isolated. They are typical of the situation of these people in the middle class in Germany who are dependent on a fixed income from savings. Neither are they German propaganda cases. All are taken from an appeal for the starving of Cologne signed by Mr. J. I. Piggott, commissioner, the Inter-Allied Rhineland High Commission, and Mr. D. W. P. Thurston, C.M.C., H. M. consul general, Cologne.

Cologne itself looks prosperous. The shop windows are brilliant. Streets are clean. British officers and men move smartly along through the crowds. The green uniformed German police salute the British officers rigidly.

In the evening the brilliant red or the dark blue of the officer’s formal mess kit that is compulsory for those officers who live in Cologne, colors the drab civilian crowds. Outside in the street German children dance on the pavement to music that comes from the windows of the ball room of the officers’ club.

Coming down the broad flood of the Rhine on a freight boat from Wiesbaden through the gloomy brown hills with their ruined castles, that look exactly like the castles in gold fish bowls, in 14 hours on the river, we only passed 15 loaded coal barges. All were flying the French flag.

Last September, in an express passenger boat, we passed an endless succession of them moving up the river toward the canal mouth that would take them, by a network of quiet waterways, to feed the Lorraine furnaces. Then France was getting the hundreds of barges of coal as part of German reparation payment. Now the fifteen barges we passed were part of the thin stream of coal that trickles out of the Ruhr through the mazes of arrested industry and military occupation.

Not Only the French That the Germans Hate—Nationalists and Workers Glare at Each Other—Communism Very Strong—French Run Things Smoothly.

The following is the ninth of a series of articles on the Franco-German situation by Ernest M. Hemingway, staff correspondent of The Star.

By ERNEST M. HEMINGWAY. Special to The Star.

Dusseldorf April 30.—You feel the hate in the Ruhr as an actual concrete thing. It is as definite as the unswept, cinder-covered sidewalks of Dusseldorf or the long rows of grimy brick cottages, each one exactly like the next, where the workers of Essen live.

It is not only the French that the Germans hate. They look away when they pass the French sentries in front of the postoffice, the town hall and the Hotel Kaiserhof in Essen, and look straight ahead when they pass poilus in the street. But when the nationalists and workers meet, they look each other in the face or look at each other’s clothes with a hatred as cold and final as the towering slag heaps back of Frau Bertha Krupp’s foundries.

Most of the workers of the Ruhr district are Communists. The Ruhr has always been the reddest part of Germany. It was so red, in fact, that before the war troops were never garrisoned here, both because the government did not trust the temper of the population and feared the troops would become contaminated with the Communist atmosphere. Consequently when the French moved in they had no barracks to occupy, and had a very difficult time billeting.

At the start of the occupation all of the Ruhr united solidly to back the government against the French, the night of the demonstration when Thyssen came home from his trial at Mayence, a German newspaper man told me he identified over a hundred men in the mob, singing patriotic songs and shouting for the government, who had been officers and non-coms in the Red Army during the Ruhr rebellion. It was a great revival of national feeling that molded the country into a whole in its opposition to France.

“It was most uplifting,” an old German woman told me. “You should have been here. Never have I been so uplifted since the great days of the victories. Oh, they sang. Ach, it was beautiful.”

That is finished now. The leaders of the workers are saying that the government has no policy, except passive resistance, and they are sick of passive resistance. Their newspapers are demanding that the German government start negotiations with the French. The French have seized millions of marks of unemployment doles, and as soon as the unemployment pay doesn’t come in the workers begin grumbling.

It was the beginning to look as though the workers would not hold out in the passive resistance, and the industrialists were extremely anxious to provoke an incident between the workers and the troops. Something to stir up a little trouble and revive the old patriotic fervor. They ordered sirens blown to summon workers for a passive resistance demonstration whenever French troops appears for requisitionings.

On the Saturday before the Easter the incident occurred. It cost lives of thirteen workmen. It would not have happened perhaps, if the young officer in charge of the platoon that came to requisition motor trucks had not been nervous. But it did happen.

I have heard at least fifteen different accounts of what actually happened. At least twelve of them sounded like lies. The crowd was very thick and pressed tight around the soldiers. It was in a big courtyard. Those that were in the front rank of the crowd were killed or wounded. You are not allowed to talk to the wounded. The troops are not giving interviews. In fact, they were sent a very long way away very soon after the last ambulance load of wounded had gone. Hearsay evidence is worthless, and there are plenty of wild stories.

Two things stand out. The French had no reason to make any bloodshed and wanted none. On the contrary, they had every reason to avoid any sort of conflict, as they were making every effort to win over the workers from their employers. The industrialists, on the other hand, had been provoking incidents and advising the men to resist.

Twenty different workmen swore to me that there were Nationalist agitators, former German “Green police,” in the crowd. The workmen say these men egged on the workers and told them they could swarm over the French, disarm them and kick them out of the courtyard.

All the workmen said the crowd ran at the first volley, which was fired over their heads. They had all served in the army and had no desire to attack armed troops unarmed once they saw they meant business and would really shoot. It is there that the question arises whether or not the lieutenant proceeded to fire unnecessarily. I do not know. All the men I have talked to swear they were running after the first volley and did not see anything. After the first volley the troops fired independently.

The funeral at Essen was delayed the last time because the French and German doctors could not agree on the nature of the bullet wounds. The Germans claimed eleven of the workmen were shot in the back. The French surgeon claims that four were shot in the front, five bullets entered from the side and two in the back. I do not know the claims on the two men who died since the argument started.

At present the Ruhr workmen are feeling decidedly unpatriotic. They believe that sooner or later negotiations will start, their steadily dwindling unemployment pay will stop, the mark will plunge down again, and that they will not be able to work full time, due to various sabotages and the general disorganization. None of them have any illusions that the government will be able to pay them unemployment pay indefinitely and they are demanding that the government start something.

The French seem to run the administration of the occupation admirably. The troops are kept out of sight as much as possible, and there is a minimum of interference with Germans going through from unoccupied to occupied Germany. They are all required to have red card passes, but the examination of these passes is purely perfunctory. A non-com. sees the red card, says, “bon,” and the line of Germans passes through the barrier.

They ran the military end smoothly, but are only able to move six trains of the one hundred and thirty-three from Essen each day. In three months of occupation France has obtained the same amount of coal she had been getting each week from Germany for nothing before the Ruhr seizure.

M. Loucheur, the millionaire ex-minister of the devastated regions under Briand, went to London and felt out public opinion on his own hook, although he told Poincare he was going, and reported to him on his return. Poincare was reported furious at Loucheur’s trip, which he regarded as a first step in a Loucheur drive for the premiership when the Chamber of Deputies again sits in May. Loucheur suffers in France from being called the French Winston Churchill, and has a record for brilliant performance and brilliant failure. His very sound credentials for the premiership will be that he has always opposed the Ruhr venture.

Aristide Briand is now working on a speech that he hopes will return him to power. He is planning to attack Poincare by stating the number of millions Briand got out of the Germans in reparations while he was prime minister and compare them with the money Poincare has lost since he came into office.

The Caillaux Liberal camp have started a new paper in Paris. Leon Daudet, the Royalist, says the first thing he will ask the chamber when it reopens is why M. Loucheur was permitted to go to England as an alleged representative of the government against the wishes of the government, etc.

Andre Tardieu has announced an attack on the Ruhr policy as it has been carried out. Things are beginning to boil.

The end of the Ruhr venture looks very near. It has weakened Germany, and so has pleased M. Daudet and M. Poincare. It has stirred up new hates and revived old hates. It has caused many people to suffer. But has it strengthened France?

The following is the tenth of a series of articles by Ernest M. Hemingway, staff correspondent of The Star, on the Franco-German situation.

By ERNEST M. HEMINGWAY. Special to The Star.

Düsseldorf.—Hiking along the road that runs through the dreary brick outskirts of Düsseldorf out into the pleasant open country that rolls in green swells patched with timber between the smoky towns of the Ruhr, you pass slow-moving French ammunition carts, the horses led by short, blue-uniformed, quiet-faced Chinamen, their tin hats on the back of their heads, their carbines slung over their head. French cavalry patrols ride by. Two broad-faced Westphalian iron puddlers who are sitting under a tree and drawing their unemployment pay, watch the cavalry out of sight around a bend in the road.

I borrowed a match from one of the iron puddlers. They are Westphalians, hardheaded, hard-muscled, uncivil and friendly. They want to go snipe-shooting. The snipe have just come with the spring, but they haven’t any shotguns. They laugh at the little Indo-Chinamen with their ridiculous big blue helmets on the back of their heads and they applaud one little Annamite who has gotten way behind the column and is trotting along to catch up, holding his horse’s bridle with sweat running down his face, his helmet joggling down over his eyes. The little Annamite smiles happily.

Then at forty miles an hour in a sucking swirl of dust a French staff car goes by. Beside the hunched-down driver is a French officer. In the rear I get a glimpse of two civilians holding their hats on in the wind and another French officer. It is one of the personally conducted tours of the Ruhr. The two civilians are American ministers who have come to “investigate” the Ruhr occupation. The French are showing them around.

Personally conducted tours are a great feature of the Ruhr. The two gentlemen in the car are typical of the way it is done. They obtained a letter of introduction to General Dégoutté from Paris. They wanted to make a full and impartial investigation of the Ruhr occupation in order that they might return to America and give their churches the facts. It is true they hadn’t thought of this when they came to Europe, but the Ruhr was the big headline news and to be an authority on Europe when you returned to America you must have seen the Ruhr. If the Genoa Conference had been on they would have gone to Genoa and so on.

They are at Düsseldorf speaking a very little French and no German. The French were delightful to them. A staff car and two officers were placed at their disposal and they were told they could go anywhere they wanted. They didn’t know much where they wanted to go so the French took them. At forty miles an hour they did the Ruhr in an afternoon. They saw towering mountains of coke, they saw great factories, they ascended the water tower and looked out over the valley.

“There,” pointed a French officer, “are the steel works of Stinnes, there are those of Thyssen. Beyond you see the works of Krupp.”

That night one of them said to me: “We’ve seen it all and I want to tell you right now that France is absolutely in the right. I tell you I never saw anything like it in my life before. I never saw such mines and factories in all my life. France did absolutely and un-ee-quivocally right to seize them. And let me tell you this thing is running like clockwork.”

Next in point of amusement to the personally conducted tours in the Ruhr are the rival French and German press bureaus at the Hotel Kaiserhof in Essen. The French press officer is a large blond man who looks like the living picture of the conventional caricature of the German. On the other hand the German press officer who arrived at the Kaiserhof to give his thirty minutes of propaganda immediately after the French press officer had functioned, looked exactly like the caricatured Frenchman. Small, dark, concentrated-looking. Both sides freely distorted facts and furnished false news.

Sir Percival Phillips, of the Daily Mail, after he had been badly let down by a piece of French news he used which proved false the next day, said he would use no more of either press bureau’s news without labeling it as from the press bureau. “My paper is pro-French,” he said, “but it might not always be my paper, and I have a reputation as a journalist to sustain.”

The French have a genius for love, war, making wine, farming, painting, writing and cooking. None of these accomplishments is particularly applicable to the Ruhr, except making war. The military end of the occupation has been carried out admirably. But to run this industrial heart of Germany, which has been pinched out and cut off by the military, requires business genius. Business genius is required to run it at all.

At the customs cordon which was designed to separate occupied from unoccupied Germany and yield tremendous revenue on taxes and duties, you see this spectacle: A long column of trucks on the occupied side of the imaginary line chained together, piled high with packages and goods, covered with tarpaulins, some of which had blown off. They have been standing there for weeks. The five douaniers or customs men have been too busy intercepting all goods to have time to search those they have held up. At the railroad siding there is a huge warehouse jammed to the rafters with held-up merchandise.